The Bounty mutiny

Australian pirates in Japan

Colonial convicts a long way from home

Wildlife Photographer of the Year

Winning images now on show

The Bounty mutiny

Australian pirates in Japan

Colonial convicts a long way from home

Wildlife Photographer of the Year

Winning images now on show

MOST PEOPLE ARE SURPRISED TO LEARN that the museum’s remit includes migration to and from Australia. In fact, we are the only museum focused on the national migration story and the only national cultural institution with a permanent gallery dedicated to migration.

In April this year we published From across the sea – Australia’s national migration story. This e-booklet, on our website, provides an overview of the museum’s impressive achievements in sharing the national migration story.

There are more than 14,450 objects in the national migration collection and our Passengers Gallery is permanently dedicated to the stories of Australia’s migrants. Our Welcome Wall has almost 30,000 names of people who have travelled across the sea to make Australia home, and more than 260,000 people have viewed our migration-themed digital artworks projected onto the museum’s rooftop. We have hosted 29 temporary exhibitions exploring migration issues and history, and how these communities have helped build our nation. We also have a migration education portal for teachers and curriculum-aligned education programs and public programs.

The Australian National Maritime Museum is enormously proud of its role in researching and exhibiting these stories – but all these wonderful accomplishments have been overshadowed by the shocking attacks on Muslims praying in Christchurch on 15 March 2019. All the museum’s staff take incredibly seriously their remit to educate and enlighten Australians on our country’s rich migrant history; so, justified or not, many of us felt a sense of collective failure. This is why I convened a meeting in April of Australia’s migration and major community museums, to discuss the ways in which museums can build greater understanding of diversity to help address discrimination against migrants, refugees and their families.

In May, we began screening Boundless Plains , a documentary created by the Islamic Museum of Australia. It depicts the search by four Muslim men – Jehad Debab, Moustafa Fahour, Ash Naim and Peter Gould – to understand Australia’s Muslim history. They are shown at the replica of Australia’s first mosque in Marree, South Australia. Image courtesy Islamic Museum of Australia

Events in Christchurch and many disturbing attacks on mosques across Australia demonstrate that Islamophobia can lead to the most horrendous acts of terrorism. Muslims have lived in Australia for generations, as our exhibitions show. The first showcase that visitors see in our Navigators Gallery highlights the encounters between Muslim traders from Sulawesi and Aboriginal people in the far north of Australia. These trading relationships were established hundreds of years before European colonisation.

Our new museum alliance has agreed to pursue a major national collaborative exhibition to build greater empathy, as well as conduct a joint research project and collectively develop our educational resources.

As someone who was born overseas of Welsh ancestry with strong cultural ties to South Africa, the Netherlands and Cyprus, I am privileged to lead an organisation that is committed to sharing the stories of Australia’s migrants. And it is my sincere desire that by working together, museums can find new ways to tell the stories of how millions of migrants have contributed to the success of modern Australia.

Kevin Sumption psm Director and CEOAcknowledgment of country

The Australian National Maritime Museum acknowledges the Gadigal people of the Eora nation as the traditional custodians of the bamal (earth) and badu (waters) on which we work.

We also acknowledge all traditional custodians of the land and waters throughout Australia and pay our respects to them and their cultures, and to elders past and present.

The words bamal and badu are spoken in the Sydney region’s Eora language. Supplied courtesy of the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council.

Cultural warning

People of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent should be aware that Signals may contain names, images, video, voices, objects and works of people who are deceased. Signals may also contain links to sites that may use content of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people now deceased.

Cover Ice-Cave Blues , Georg Kantioler, Italy. Glacier caves are often carved out by water running through or under a glacier’s ice. Georg used natural light to capture the interior of this cave, in Stelvio National Park, Italy, including the distant larch trees and alpine scenery. © Georg Kantioler/Wildlife Photographer of the Year

2 A mutiny and a mystery

Fletcher Christian, the Bounty mutineers and their secret settlement

10 Elysium Arctic

Artists and scientists act for environmental awareness

14 International Project of the Year

Gapu-Mon_uk Saltwater honoured with major award

16 Celebrating heritage and tradition

The MyState Bank Australian Wooden Boat Festival 2019

22 The repulse of the Cyprus Colonial convict pirates in 1830s Japan

30 Bringing science back aboard Endeavour Museum and CSIRO collaborate on a pilot learning program

32 Treasures see the light of day

Changes to the Copyright Act open more collection items to the public

36 A Californian conflict

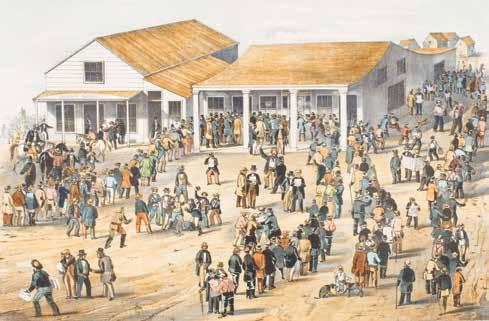

Gold rush clashes: the Sydney Ducks and the San Francisco 49ers

42 Honours for Wiradjuri heroes Yarri and Jacky Posthumous bravery awards for 1852 flood rescuers

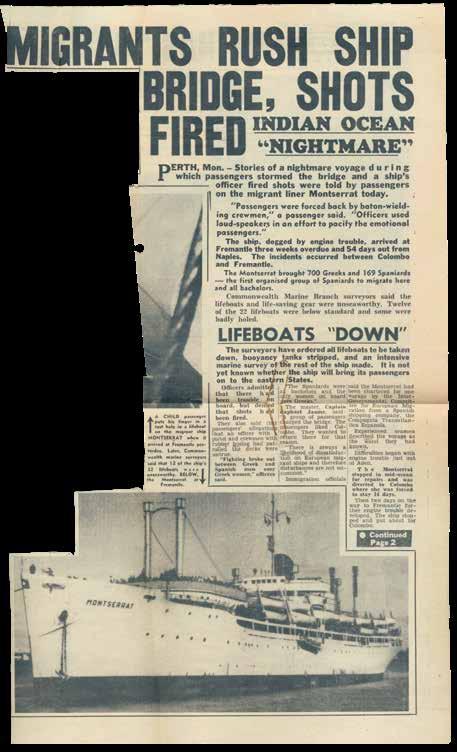

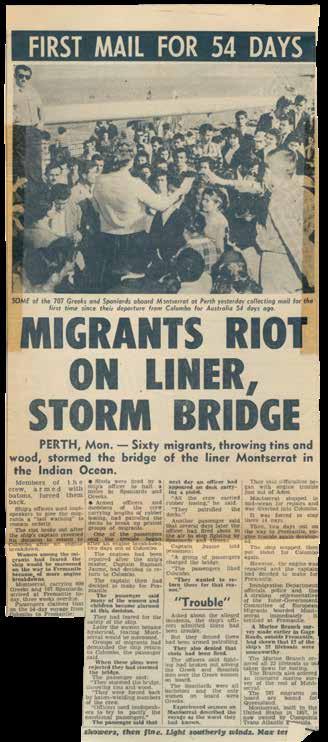

44 Mutiny on the Montserrat

The 60th anniversary of a troubled migrant voyage

48 Message to Members and museum events for winter Your calendar of activities, talks, tours and excursions afloat

54 Winter exhibitions

Bligh: Hero or Villain?, Massim Kenu, Elysium Arctic and more

58 Collections

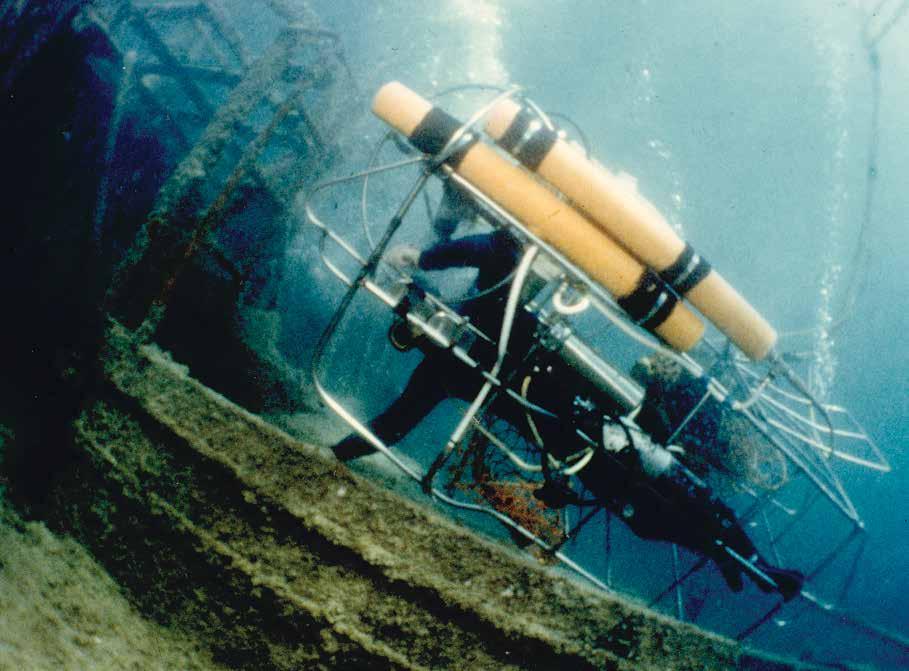

Classic Aussie ingenuity: inventing the self-propelled shark-proof cage

62 Foundation

Introducing the Captain’s Circle, our new supporters’ group

64 Australian Register of Historic Vessels

A sleek ski-boat and a functional flood boat: a study in contrasts

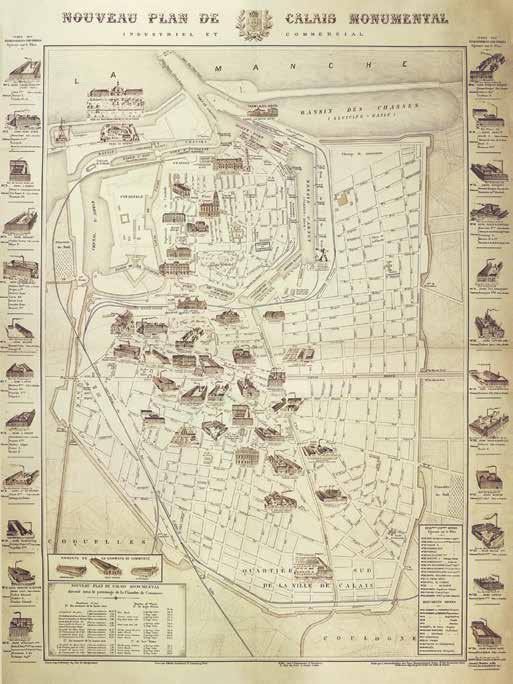

68 Tales from the Welcome Wall Workers in tulle: The English lacemakers of Calais

72 Readings

Empire of the Winds by Philip Bowring

74 Currents

Vale John Hooke CBE; model ships on show at Expo 2019

In a remarkable feat of seamanship, Bligh and the men in the open boat survived a six-week voyage to finally arrive at Timor

In July the museum will open its new exhibition Bligh – Hero or Villain?, which looks at the extraordinary life of William Bligh, a British naval officer whose career would have been largely unremarkable but for a mutiny aboard his ship the Bounty in 1789. This made his name a household word, and his actions the subject of fierce public debate for the rest of his life. By Head of Research, Dr Nigel Erskine .

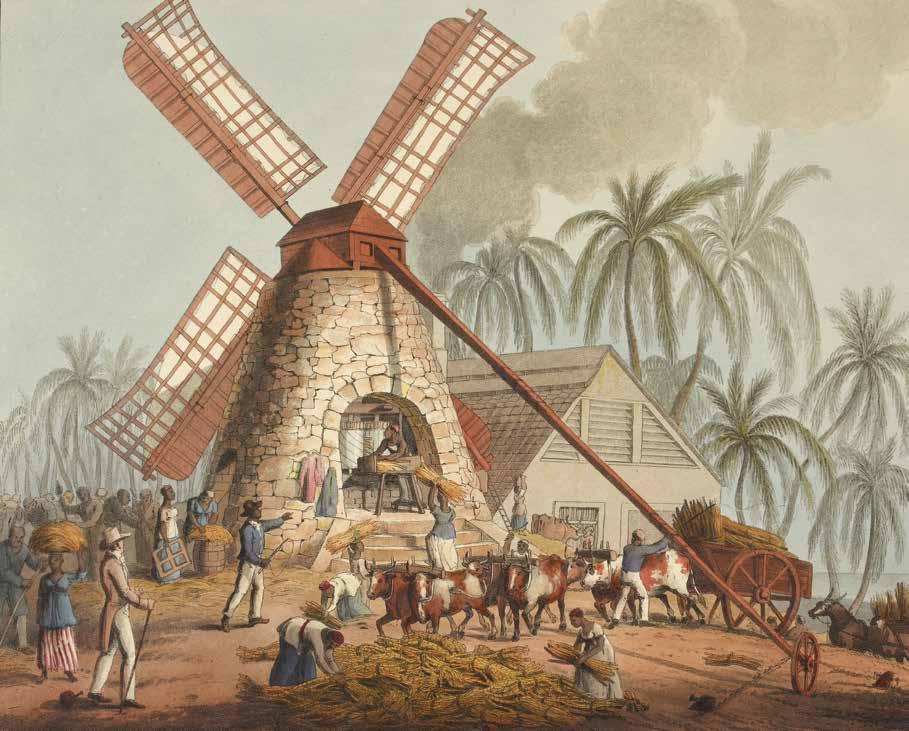

Bounty ’s mission was to transport breadfruit plants from Tahiti to British sugar plantations in the Caribbean to provide food for slaves

THE BOUNTY ’S MISSION WAS TO SAIL from England to Tahiti, where the expedition’s gardeners would collect young breadfruit plants to take to Britain’s colonies in the West Indies, where it was hoped they would become a staple food for the slaves working on the sugar plantations. The ship had been delayed in its voyage out and arrived at Tahiti at a time when the breadfruit plants were not ready to cultivate. As a result, Bligh was forced to wait five months before the plants were collected and the ship ready to leave – long months during which discipline on board lapsed. Three weeks after leaving Tahiti, some of the crew mutinied and took over the ship.

The mutiny occurred in the early hours of 28 April 1789, when Fletcher Christian (acting lieutenant and officer of the watch on duty) and other crew members armed themselves and, breaking into the captain’s cabin, woke and arrested Bligh. In the hours that followed, Bligh and 18 loyal followers were forced into Bounty ’s seven-metre launch and set adrift, while Christian and the other 24 mutineers remained aboard the ship.

The mutiny happened very quickly and apparently without warning, and although there was a hard core of mutineers centred about Christian, others had simply found themselves unwittingly swept up in events.

In a remarkable feat of seamanship, Bligh and the men in the open boat survived a six-week voyage to finally arrive at the Dutch settlement of Coupang on the island of Timor. After recuperating and making their way to Batavia (now Jakarta), Bligh and the surviving men ultimately made their way back to England. But what happened to Fletcher Christian and the Bounty mutineers?

At the time of the mutiny, Bounty was in sight of the volcanic island of Tofua, about 2,700 kilometres west of Tahiti, where many of the mutineers had established relationships with Polynesian women. The mutineers knew, however, that sooner or later the Royal Navy would come searching for them, and Tahiti would be the first place they looked.

Our knowledge of this part of the story is based on the account written by mutineer James Morrison, bosun’s mate aboard Bounty, and an observant and capable writer. Looking through Bligh’s books left on board, Fletcher Christian found a reference to Captain Cook’s discovery of the island of Tubuai, some 640 kilometres south of Tahiti, and it was there that he took the ship, arriving a month after the mutiny.

At Tubuai, the mutineers found the indigenous inhabitants unwelcoming. Despite this, Christian thought it was a suitable place to establish a permanent settlement. He determined that after a brief stay, they would sail to Tahiti to get animals and supplies, and to bring their Polynesian former partners and friends back to the island.

Ultimately the attempt to settle on Tubuai lasted just two and a half months, and in the face of escalating armed opposition to their presence and deteriorating mutineer morale, Christian agreed to return to Tahiti, where he allowed those who wished to leave the ship to do so. Sixteen mutineers chose to go ashore; nine (including Fletcher Christian) remained with the Bounty The ship remained at Matavai Bay for a day while the men’s sea chests, hammocks and a proportion of the arms, ammunition and other supplies were shared out and taken ashore in the only remaining serviceable boat.

Breadfruit ( Artocarpus incisa). Rex Nan Kivell Collection, National LIbrary of Australia, nla.obj-135498865

02

A highly sanitised view of life on a British sugar plantation, from Ten views in the island of Antigua, William Clark, London, 1823. © 2010 The British Library Board

With the departure of the Bounty from Tahiti, all trace of Fletcher Christian and his followers disappeared

01

Rear-Admiral William Bligh, Alexander Huey, 1814. National Library of Australia nla.obj-136207002

02

Transplanting of the bread-fruit trees from Otaheite [Tahiti], painted and engraved by Thomas Gosse, 1796. National Library of Australia nla.obj-135292190

Three weeks after leaving Tahiti, part of the crew mutinied and took over the ship

In the early hours of the morning, when the Bounty left Tahiti for the last time, there were some 26 Polynesians aboard in addition to the nine mutineers, but this number was reduced when one woman chose to jump overboard and swim ashore, and when some of the older women were transferred to a passing canoe. With the departure of the ship, all trace of Fletcher Christian and his followers disappeared. Not until 1808 – 19 years later – was the mystery of what happened to them finally solved.

The mutineers who stayed at Tahiti, were, as anticipated, hunted by the Royal Navy. In March 1791, the frigate HMS Pandora dropped anchor in Matavai Bay and soon sent armed parties ashore to find the Bounty men. Of the 16 who had landed from the Bounty, two had since been murdered. Having completed part of his orders by capturing the mutineers living at Tahiti, Pandora ’s commander, Captain Edwards, next aimed to find Fletcher Christian and the Bounty, and so he headed west across the Pacific, searching the islands for any sign or word of the mutineers.

But he was searching in the wrong direction, steadily putting more and more miles between his ship and the mutineers, and drawing ever closer to the great and hazardous barrier reefs that protect the north-east coast of Australia.

Hearing that the navy had sent Pandora to the Pacific, Bligh had predicted that Captain Edwards would never find his way through Endeavour Strait. His words proved prophetic when, after months of unsuccessful searching, HMS Pandora was wrecked on a reef off the Australian coast, in August 1791.

Four mutineers and 31 of Pandora ’s crew were drowned in the wreck. Like Bligh more than two years earlier, Captain Edwards and his people were forced to take to open boats and make their way to Coupang.

The ten surviving Bounty prisoners eventually returned to England where, at a court martial in April 1792, four were acquitted and six were found guilty and sentenced to death. Only three were actually executed; two received the king’s pardon; and another was discharged due to a procedural error.

Of the two men who received the king’s pardon, midshipman Peter Heywood benefited greatly from his influential family connections. Fletcher Christian’s family was also influential. Although unable to deny his role as the instigator of the mutiny aboard the Bounty, they worked hard to suggest that Bligh’s constant abuse of the officers and crew had ultimately driven Fletcher Christian to mutiny. Edward Christian, Fletcher’s elder brother and a barrister, did this by publishing the minutes of the court martial’s proceedings with an appendix containing ‘A full account of the real causes and circumstances of that unhappy Transaction, the most material of which have been hitherto withheld from the Public’.

At the time of the court martial, Bligh was at sea in command of a second expedition to bring breadfruit to the West Indies and was therefore unable to defend himself against Edward Christian’s publication and the damage it did to his reputation. He must have received reports, but not until he returned to England did Bligh fully appreciate how much public sentiment had shifted against him.

Edward Christian had interviewed several of the mutineers for his damning publication, and after returning to England, William Bligh set about a similar process, gathering supportive affidavits from men who had remained loyal during the mutiny. Some, such as the sailmaker Lawrence Lebogue – who had sailed with Bligh in the West Indian trade and on both the Bounty and Providence breadfruit expeditions – gave their information willingly, but there is also evidence of Bligh’s attempts to manipulate statements.

In a letter to his nephew Francis Godolphin Bond, who had been his first lieutenant aboard the Providence for the second breadfruit voyage, Bligh asked Bond to get Michael Byrne (the almost-blind fiddler aboard the Bounty, who was then serving under Bond) to answer a set of carefully contrived questions calculated to show Bligh in a favourable light.

If he disavows having said anything disrespectful of me to Christian, and affirms, which every man must, that I did all that a good Commander could do, and as you know, I have done; I will be obliged to you to write it down.

When you have arranged what Byrne says, I think it would be well to make him write it himself if he can see well enough.

Throughout the second half of 1794, Bligh gathered material and in December published his rebuttal of Edward Christian’s accusations in ‘Answer to certain Assertions’. In the end he didn’t use Byrne’s statement, but the evidence still surviving in the archives shows the extreme lengths to which he was prepared to go to protect his reputation.

By this time, Fletcher Christian and several other mutineers were dead. When the Bounty had departed from Tahiti for the last time in September 1789, it had sailed south-east, away from the main Society Islands group. The attempt to settle at Tubuai had proved a disaster due to the opposition of the Polynesian inhabitants and now, with far fewer mutineers in his party, Fletcher Christian had resolved to find a remote and uninhabited island to establish a settlement.

After a period of unsuccessful searching – during which they sailed as far west as the Tongan archipelago – once again Bligh’s books left on board provided a possible place to look. In an account of Philip Carteret’s 1767 voyage around the world in HMS Swallow, Christian found a reference to an island that: … appeared like a great rock rising out of the sea: it was not more than five miles in circumference, and seemed to be uninhabited; It was however, covered with trees, and we saw a small stream of fresh water running down one side of it. I would have landed upon it, but the surf, which at this season broke upon it with great violence, rendered it impossible.

Adding to this promising description, the location of the island – which Carteret had named Pitcairn – seems to have been incorrectly identified through a navigational error, and Captain Cook had failed to find it on either his second or third voyage.

Reasoning that Carteret had made an error in calculating his longitude, but that the latitude he recorded for Pitcairn was probably correct, Fletcher Christian took the ship to that latitude and sailed east until finally sighting the island in January 1790. A search of the island showed that it was indeed uninhabited and had fresh water, good soil and lush vegetation. Very soon the mutineers started to take ashore everything from the ship that they thought they might need.

Apart from the nine mutineers (Fletcher Christian, Edward Young, John Mills, Isaac Martin, William Brown, William McCoy, John Adams and John Williams), there were five Polynesian men, one boy, 12 women and a baby girl aboard when the Bounty arrived at Pitcairn. However unlikely, these 28 were to form a settlement that continues to the present day.

As Carteret had thought, there was no secure anchorage at Pitcairn, and after removing all they wanted from the ship, the mutineers set fire to it, in what is now known as Bounty Bay, to hide all evidence of their existence on the island. In the same manner, when building their houses, they located them behind a screen of vegetation to make them invisible to any ship that might approach the island, and then relied on the rugged coastline to dissuade closer investigation.

Although long uninhabited, there were ample signs of earlier Polynesians living on the island, and the new settlers soon discovered rock carvings, a morai and a site where stone for tools had been quarried, as well as many food plants typically cultivated by Polynesians.

In establishing the settlement, the mutineers divided the island among themselves and each European had a Polynesian woman to live with. This arrangement left only three Polynesian women as partners for the six Polynesian men, leading to violent jealousies that were soon exacerbated by the death of mutineer John Williams’ partner, Faahotu.

When Williams took another woman from those living with the Polynesian men, the men decided to kill the Europeans and throw off their servitude. Unfortunately for them, the women warned the mutineers and two of the men were killed, thus establishing a brooding end to the violence.

In 1793, however – just three years after settling on the island – five of the mutineers, including leader Fletcher Christian, were killed when the remaining Polynesian men rose up again. But their victory was short-lived and they in turn were killed.

After these killings, life on the island remained relatively stable until 1799, when mutineer William McCoy suicided by jumping off a cliff into the sea. Later that same year, Edward Young and John Adams killed Matthew Quintal after he threatened them and their families. When Edward Young succumbed to an asthma attack in 1800, the mutineer John Adams was left the last man standing, to become the unlikely patriarch of a settlement of women and children.

John Adams was listed on the Bounty muster as Alexander Smith (a common ruse of seamen who had deserted).

After the violence of the first decade of settlement, and now finding himself responsible for the community, he turned to religion. Among the books that had been brought to the island he found a prayer book, which he used to instil at least the basic tenets of Christianity into the Pitcairn community.

Eighteen years after the arrival of the Bounty at Pitcairn, the community’s isolation was at last broken

Pitcairn Island from the east. To the left of the image is Bounty Bay, where the ship was deliberately destroyed. © Claude Huot/ Shutterstock

Eighteen years after the arrival of the Bounty at Pitcairn, the community’s isolation was at last broken when the American whaleship Topaz happened to stop at the island. Mindful of his mutineer status, Adams remained ashore, but the Topaz ’s crew was surprised when a canoe paddled out from the shore carrying several young men, and amazed when they hailed the ship in English! Very soon Topaz ’s captain, Mayhew Folger, realised that he had discovered the home of the Bounty mutineers and finally solved the mystery of what happened to Fletcher Christian and the Bounty

The 19th century and beyond

Located in the middle of the Pacific, Pitcairn gradually became a regular port of call for whalers and other ships during the 19th century. Six years after the Topaz visited, John Adams seemed destined to hang when the British warships Briton and Tagus stopped at the island. Instead, the ships’ commanders allowed him to remain on the island, so impressed were they by the religious influence he held over the community of just over 40, comprising seven of the original women settlers and very young men and women. Adams died on the island in 1829. A few sailors had chosen to join the Pitcairn community before his death and one of these, George Hunn Nobbs, became the island’s leader.

British warships became regular visitors, and over time the Pitcairners looked to the visiting commanders to rule in local disputes, ultimately leading to Pitcairn becoming a Protectorate of Great Britain in 1838. Today Pitcairn is a British Overseas Territory.

By the middle of the 19th century, with the population close to 200 and after a series of droughts had ruined crops, the island’s leaders began looking for a larger place to resettle the community. After discussions with the British authorities, in 1856 the entire population was removed to Norfolk Island.

From its earliest days, Norfolk Island had been a convict settlement, and although the convicts had all been removed before the Pitcairners arrived, the prison infrastructure and other buildings remained fully intact and some of these were soon occupied by Pitcairner families. Today a large percentage of Norfolk Island’s population still traces its history back to Pitcairn.

And what of Pitcairn Island? A few years after the move to Norfolk Island several families chose to return to Pitcairn, establishing the basis of the population that continues to live there. Whereas overpopulation confronted their forefathers, today’s Pitcairn community faces the issues of a dwindling and ageing population, with an ever-decreasing number of islanders available to undertake the routine heavy work of living on a remote island in the Pacific. Only time will tell if they are able to turn things around, but the future is certainly full of challenges.

Bligh – hero or villain?

As the title of the exhibition suggests, Bligh – Hero or Villain? asks visitors to judge Bligh based on his actions throughout his long career. It features ‘treasure’ objects – such as the notebook Bligh used during his epic open-boat voyage, the Bounty ’s log with Bligh’s description of the mutineers, the record book from the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, and Bligh’s signet ring. It also looks at his interactions with family, fellow officers and patrons through immersive and interactive experiences, including a wall of animated (and very vocal) portraits and a simulated boat experience. We are pleased to say that this is not your traditional Bligh exhibition, so expect the unexpected!

1 Bligh to Francis Godolphin Bond, 26 July 1794, reproduced as letter 35 in Mackaness, G, Fresh Light on Bligh – being unpublished correspondence of Captain William Bligh and Lieutenant Francis Godolphin Bond, RN; original manuscript BND/1 in Caird Library, National Maritime Museum, London.

2 Hawkesworth, J 1773, An Account of the Voyages by Commodore Byron, Captain Wallis, Captain Carteret and Captain Cook, Strahan and Cadell, London, 3 vols.

Dr Nigel Erskine became aware of the Bounty story in 1987 when he and his wife stopped at Pitcairn Island for a few days while sailing across the Pacific. Meeting the descendants of the Bounty mutineers sparked a lifetime interest, and later as an archaeologist, he returned to Pitcairn to investigate the remains of the Bounty, eventually leading the team that raised the last Bounty cannon from beneath the surf of Bounty Bay. During that period he also worked on the Queensland Museum’s excavation of HMS Pandora, the ship sent by the Admiralty to search for the mutineers in the Pacific.

In 2000 he was appointed Director of the government museum at Norfolk Island, home of the Pitcairn Islanders after 1856. In 2004 he came to the Australian National Maritime Museum, where he has pursued the Bounty story nationally and abroad.

Bligh – Hero or Villain? opens at the museum on 26 July. An exhibition catalogue is in production and will be available from the Store.

We are now seeking donations to support the development of Bligh: Hero or Villain?. Donations can be made online at sea.museum/donate or call the Membership office on 02 9298 3646.

A team of explorers, photographers and scientists banded together to inspire social change in Elysium Arctic, the museum’s newest outdoor exhibition. Sailing through Svalbard, Greenland and Iceland, the Elysium team braved subzero temperatures and uncertain seas to capture the Arctic on film. Their goal was to document the effects of climate change on the unique Arctic ecosystem through art and science. What did they find in the world’s northernmost regions?

Darrienne Wyndham explores the incredible stories behind Elysium Arctic.

Michael Aw has spent his career documenting the diverse flora and fauna that populate the marine environment

MICHAEL AW BELIEVES IN MAGIC. The internationally acclaimed wildlife photographer, explorer and conservationist has spent more than two decades shooting across the globe, and is certain that if magic exists, it can be found in the ocean. From the lush tropics of the Coral Triangle to the teeming waters of South Africa’s Sardine Run, Aw has spent his career documenting the diverse flora and fauna that populate the marine environment. It was this passion that drove him to found Elysium Epic, a conservation group with a difference. As well as being an activist, everyone engaged in Elysium Epic is an artist, a photographer or involved with marine science. Every few years, Aw handpicks a team to embark on an expedition to one of the world’s at-risk marine environments. In 2015, the Elysium team travelled as far north as they could go and arrived in the wilds of the High Arctic, a region populated by polar bears and devastated by climate change.

Elysium, assemble!

Aw called on old friends and new during the preparation for Elysium Arctic, securing the polar-certified vessel Polar Pioneer through Aurora Expeditions. Aw wanted to produce a body of work that documented the effects of a changing climate on the delicate Arctic ecosystem. Each photograph would showcase the region, inspiring others to fall in love with the Arctic and join the crusade to save it. These photographs would become the base of the Elysium Arctic exhibition. 01

Michael Aw doesn’t ask just anybody to join him on an Elysium expedition. His carefully chosen team totalled 66 people, including crew and Aw’s two young children. His first recruits were fellow photographers David Doubilet and Jennifer Hayes, who had joined him on a previous expedition to the Antarctic. Hayes and partner Doubilet are prominent members of National Geographic ’s Explorers Club, with Doubilet winning the prestigious Lowell Thomas Award for outstanding photographic exploration in 2000. After hearing of Aw’s new venture, they jumped aboard immediately. Doubilet describes the expedition as ‘one of the most rewarding experiences of my ocean life, capturing the sights, sounds and soul of this world to create a body of work that inspires change’.

Another colleague whom Aw was thrilled to include was Dr Sylvia Earle, who acted as chief scientist for the expedition. One of the world’s foremost ocean activists, she is the founder of Mission Blue, SEAlliance and Deep Ocean Exploration and Research, and the first female Chief of the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Known in the marine science community as Her Deepness, Dr Earle has logged more than 7,000 hours underwater and led 100 expeditions. Celebrating her 80th birthday on board Polar Pioneer, she snorkelled through icebergs at 81°N and enjoyed a cocktail on the sea ice.

On 28 August 2015, the team left Longyearbyen Fjord in Svalbard under a heavy Arctic sky. As they travelled in a northward loop, the temperature plunged to -3°C at the expedition’s northernmost point, 81°26.876'N and 17°13.737'E.

The Arctic Circle is an imaginary line drawn across the top of the globe, traversing the upper regions of Canada, Russia, Alaska, Greenland, Norway and Iceland. Known by children worldwide as the home of Santa Claus, the Arctic is riotous, colourful and freezing cold. The landscape is diverse and dramatic, encompassing sea ice, tundras, mountains and 14 million square kilometres of ocean. Beloved wildlife such as reindeer, polar bears, seals and puffins inhabit the cliffs and valleys. Glaciers calve in the great bays of the Arctic, producing enormous icebergs that cruise silently through the ocean. The reflective cap of Arctic ice also plays an important role in regulating the climate. ‘Sea ice reflects the light and heat of the sun back into space and helps keep our planet cool,’ explains Aw. ‘As sea ice melts, dark ocean water is revealed and it absorbs heat. More heat means more melt and more exposed ocean, and the poles are warming faster than anywhere else on our planet.’

Arctic puffins, Svalbard. Image Michael Aw 02 Polar Pioneer enters pack ice, Svalbard. Image James Stone

It’s not too late to save the Arctic’s delicate ecosystem. ‘No-one can do everything, but everyone can do something’, says Michael Aw

The high Arctic made an unforgettable impression on the Elysium team. From long dives with harbour seals and walruses to snorkelling with giant icebergs, every day was different. After a week with no sightings of any polar bears, artist Wyland decided to make one for himself. Using a shovel, Wyland traced a huge polar bear in the fresh snow, with coffee grounds marking out a nose, mouth and two dark eyes. The 35-metre sketch was the largest piece of art ever created in the Arctic, and might have evoked some of Aw’s ‘ocean magic’ – the team saw their first polar bear the following evening.

Science writer Cheryl Lyn Dybas described the Arctic as ‘beginning and ending with ice’. Since 1992, more than 80% of the Arctic ice platform has been lost. This is a greater melting pace than at any other time in human history, posing a huge threat to wildlife habitats and hunting methods. Polar bears use sea ice to trap prey, sniffing out a seal’s breathing hole and waiting for the seal to surface. As sea ice melts, the bears are forced to roam for their food, even eating human garbage. The Elysium team witnessed a young polar bear arduously climbing bird cliffs at Alkefjellet in search of guillemot chicks to eat. ‘It was akin to someone climbing a mountain in Yosemite for a bag of chips,’ says Aw.

Reminders of the region’s environmental threats were never far away. ‘Sometimes we would sit in near silence just taking in the ethereal scenery,’ says project manager Alex Rose:

We could hear an extremely faint but constant popping sound [that] was coming from tiny air bubbles in the ice bursting as they melted in the unseasonably warm water. Imagine walking across a sheet of bubble wrap – that’s what it was like.

The Polar Pioneer ’s captain helped artist Toby Wright to understand the long-term effects that climate change has had on the Arctic ecosystem:

I saw the captain’s 40-year-old map for the fjord we were entering in Greenland. This map had a new line pencilled in every year for the safety boundary from the glacier’s edge. I could see the ghost lines from previous decades, and it was a one-way scenario. Each new line clearly indicated a retreating glacier, and it was accelerating.

Alongside their scientific documentation, the photographers and artists created thousands of pieces featuring the polar icons of the north. Michael Aw believes that the combination of art and science can motivate people to take meaningful action about climate change. Though the current melt rate is dire, it’s not too late to save the Arctic’s delicate ecosystem. ‘No-one can do everything, but everyone can do something’, he says.

The arresting photographs taken by the Elysium team are the centrepiece for the Elysium Arctic outdoor exhibition, opening on 1 August outside the museum’s Wharf 7 building. Inspired by Michael Aw, and sponsored by Aurora Expeditions, the museum has ensured that the exhibition’s materials are recyclable for minimal impact on the environment. Walk through a stunning collection of works showcasing a unique environment that is rapidly disappearing, and experience magic for yourself. 01

A lion’s mane jellyfish drifts near an iceberg in Greenland waters. Image Foo Pu Wen 02 High on a nesting cliff, a young polar bear hunts birds, Svalbard.The Australian National Maritime Museum’s exhibition Gapu-Mon_uk – Journey to Sea Country won ‘International Project of the Year with a budget of less than £1 million’ at the Museums + Heritage Awards in London in May – one of the world’s most prestigious international museum awards. By Stefania Kubowicz .

01

Indigenous Programs Manager Beau James (right) is shown receiving the award from the host of the event, Reverend Richard Coles. Image courtesy Callaghan Photography

02

The exhibition on display at the museum, 2018. Image Andrew Frolows/ANMM

THIS ACCLAIMED EXHIBITION documents the fight of the Yolŋu people of north-east Arnhem Land for recognition of Indigenous sea rights and their success in the Blue Mud Bay legal case. It was designed, curated, executed and even marketed by Indigenous people in an example of holistic community engagement.

It is a display of some 40 Yirrkala Bark Paintings of Sea Country (also known as the Saltwater Bark Collection) by 47 Yolŋu artists from 15 clans and 18 homeland communities in east Arnhem Land. The works were created in a response initiated by Madarrpa clan leader Djambawa Marawili AM in 1997 to document ownership of Sea Country, following the discovery of illegal fishing on a sacred site in his clan estate. As Djambawa says, the paintings are more than just beautiful artworks; they are spiritual and legal documents.

Some of the paintings in the exhibition were used in evidence in a legal case in the High Court of Australia which confirmed, in July 2008, that traditional owners of the Blue Mud Bay region in north-east Arnhem Land, together with traditional owners of almost the entire Northern Territory coastline, have exclusive access rights to tidal waters overlying Aboriginal land. In 2008 a landmark decision was made by the High Court giving the traditional owners the rights to manage their oceans and waterways.

The museum is very proud that the exhibition was completely led by Indigenous community throughout – the curation, design, the marketing agency and video producers were all Indigenous. The museum is putting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices first and foremost when curating First Peoples stories.

Kevin Sumption PSM , Director of the Australian National Maritime Museum, considers this to be one of the most important exhibitions in the museum’s history: ‘The essence of the show is that we are working with and for community, not just throughout every element of this exhibition, but throughout the museum as a whole.’

Diane Lees CBE, Director General of the Imperial War Museums and Chair of the 2019 judging panel, said of Gapu-Mon_uk : ‘This impressive exhibition is brave, original, meaningful and political, it successfully reframes the way we value art and has helped generate better public understanding of the subject matter.’

The awards celebrate innovative and ground-breaking initiatives from museums, galleries and heritage visitor attractions across the UK and overseas.

Anna Preedy, Director of the annual Museums + Heritage Awards, commented: ‘These awards recognise the amazing achievements, creativity, innovation, hard work and utter commitment evident throughout the museums and heritage sector. The awards have become the benchmark for excellence and the shortlistees and winners represent the very best of the best.’

While the exhibition has finished showing at the Australian National Maritime Museum, we are exploring options to tour it around Australia and internationally.

The museum would like to acknowledge and thank the Yolŋu people of North East Arnhem Land for allowing us to host their stories, inspired by the leadership of traditional Yolngu custodian Djambawa Marawili AM

‘This impressive exhibition is brave, original, meaningful and political, it successfully reframes the way we value art and has helped generate better public understanding of the subject matter.’

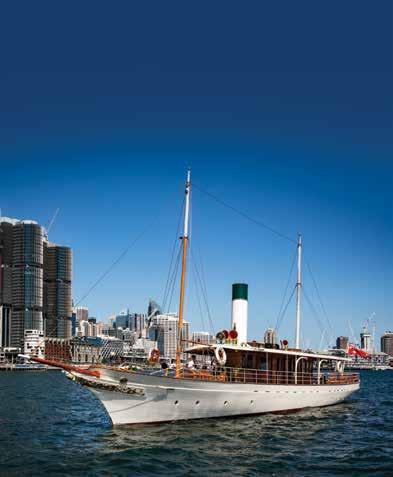

The MyState Bank Australian Wooden Boat Festival 2019

Large crowds thronged the vibrant Hobart waterfront for four days of wooden boat excitement in February. The Australian National Maritime Museum played a big part in the festivities, sponsoring the International Wooden Boat Symposium and sending the HM Bark Endeavour replica to be part of the event. The symposium presented a fantastic line-up of international and Australian presenters, including the museum’s director, Kevin Sumption, and staff members Emily Jateff, John Dikkenberg and David Payne. Our photo essay gives a flavour of this globally renowned event.

A new competition for wooden boat photography resulted in some beautiful images on display, including this prize-winning shot Ketch race (detail) by veteran AWBF photographer

The MyState Bank

Australian Wooden Boat Festival is the largest wooden boat festival in the Southern Hemisphere, and is presented entirely free to the public

In the small boat-mad town of Franklin, almost-finished boats by the visiting American team were threatened by devastating bushfires, but a daring earlymorning rescue mission got them to safety

01

American craftsmanship was on show as the festival welcomed a team from the Northwest School of Wooden Boatbuilding in Washington State. Image © Graeme Hunt/AWBF

02

Preserving and passing on boatbuilding knowledge in the Shipwright’s Village: traditional skills are an important part of the festival’s theme. Image © Ashlie Hill/Ballantyne Photography

03

A new feature at the festival was a display of ships-in-bottles, setting a new Australian record, with 256 individual items. Image © Mary Lincoln/Ballantyne Photography

04

Junior boatbuilders can get a head start at the MyState Australian Wooden Boat Festival. Image © Syd Reinhardt/ Ballantyne Photography

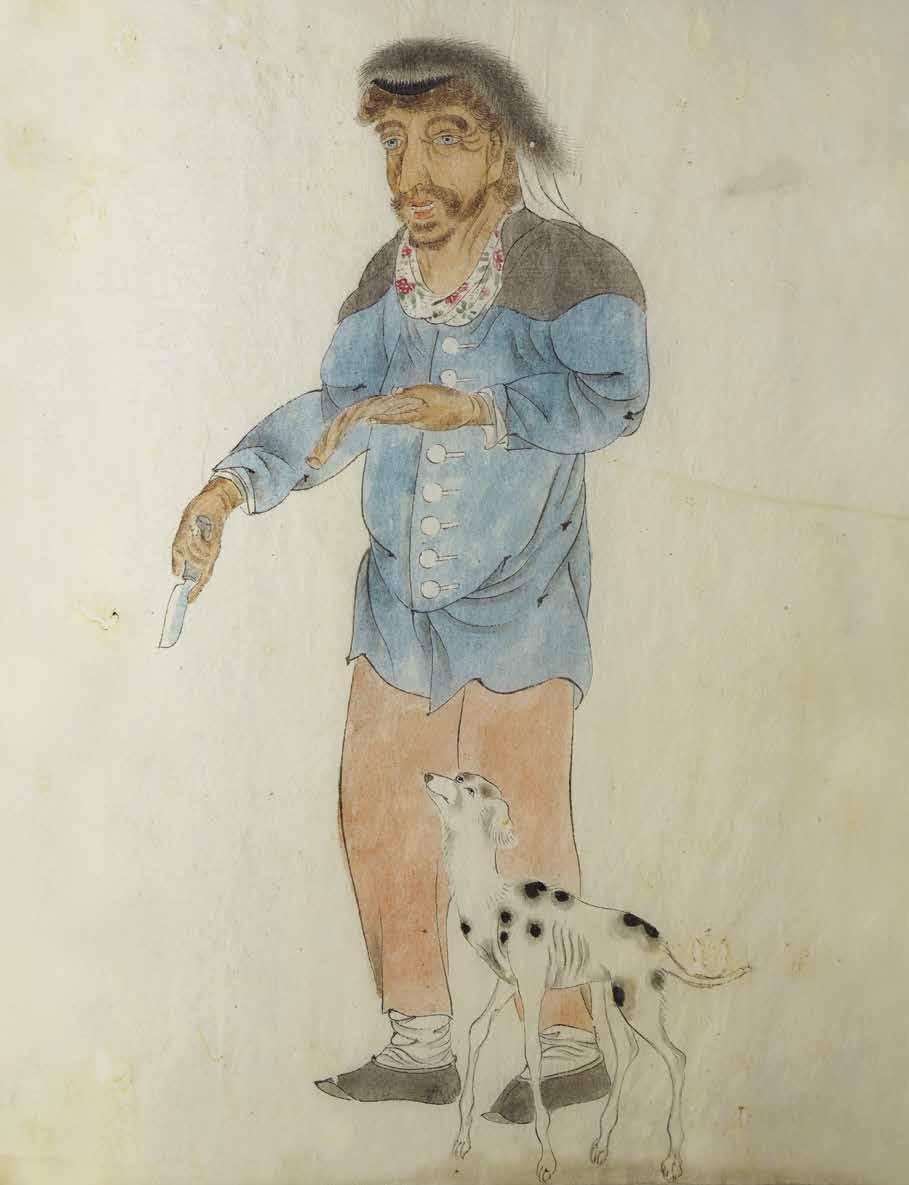

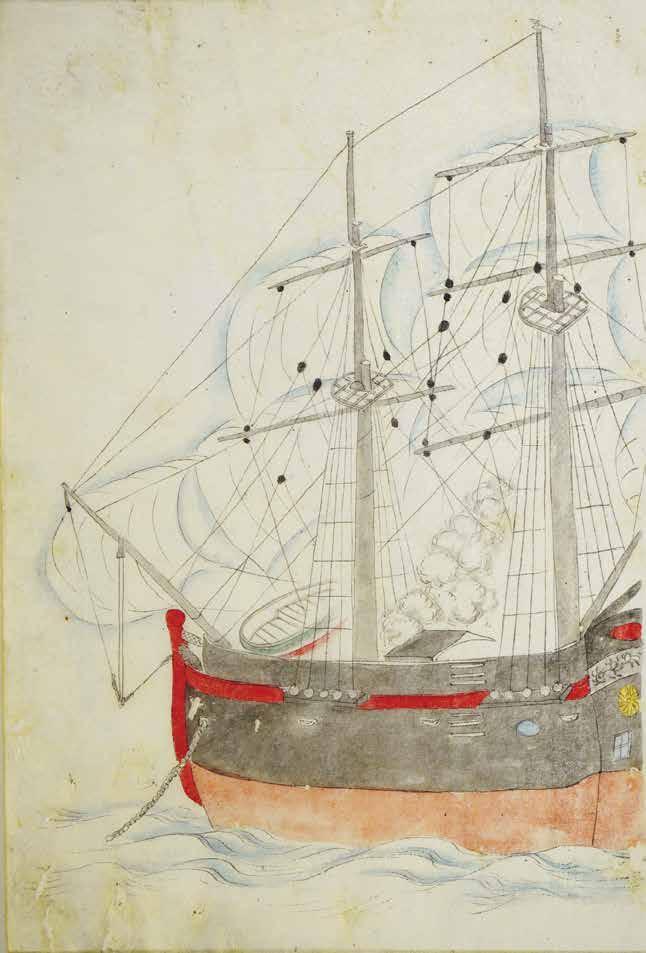

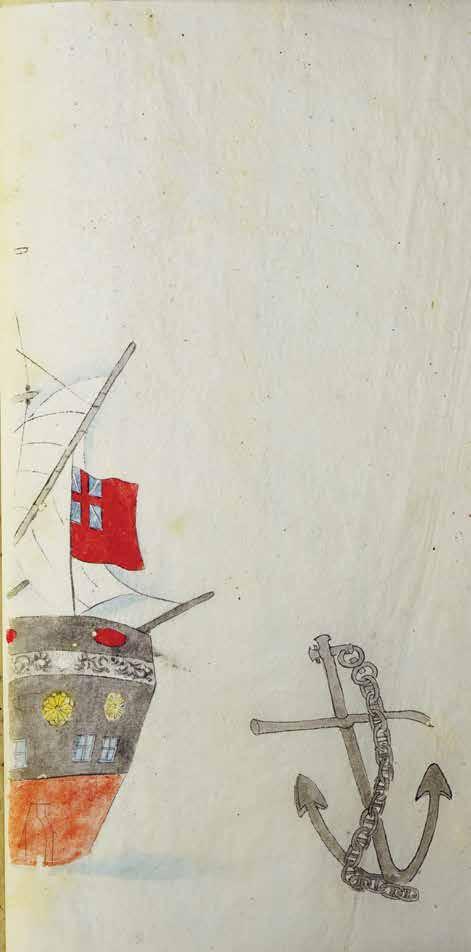

Hamaguchi wrote: ‘The skipper, who looked about 50 (the others all looked more like 25 or 26), was wearing a black fur hat with tightly woven wool fabric hanging down at the back … he was holding a small knife and a length of ropelike dark red tobacco …’. Of the dog, he noted, ‘It did not look like food. It looked like a pet.’

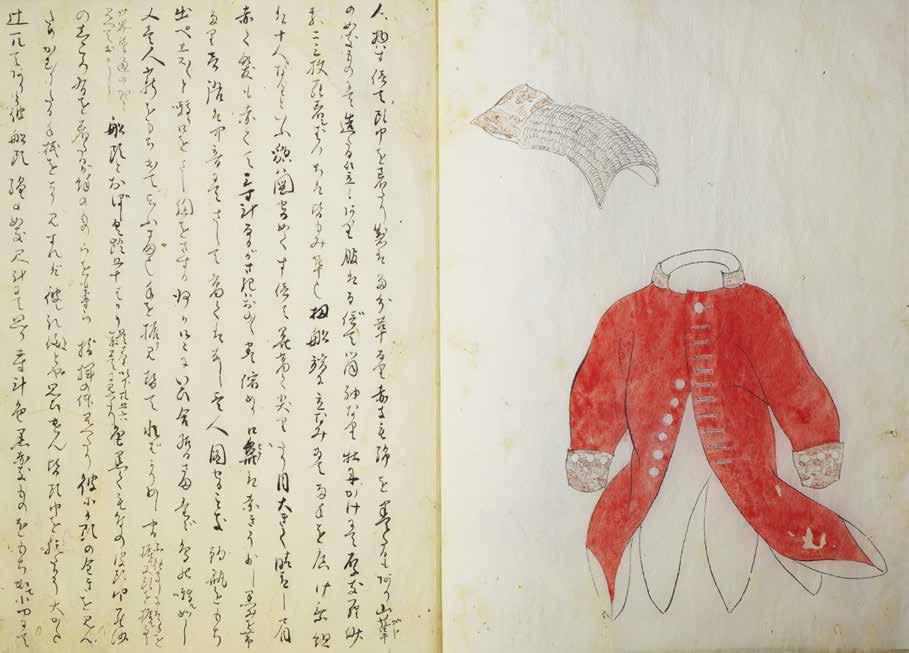

Unless otherwise credited, all images from An Illustrated Account of the Arrival of a Foreign Ship, by Hamaguchi Makita, 1830. Courtesy of Tokushima Prefectural Archive. ©Tokushima Prefectural Archive 2006. Photographs © Nicholas Russell 2019

An unlikely encounter between colonial convict pirates and Japanese samurai has come to light in a series of manuscripts in a Japanese archive. Nick Russell traces the story of William Swallow and his fellow pirates through the eyewitness account of chronicler and artist Hamaguchi Makita.

When Swallow and his fellow convicts seized the Cyprus, it was bound for the worst prison in the British Empire: Macquarie Harbour Penal Station, on the inhospitable and isolated west coast of Van Diemen’s Land. Some of the convicts on board had been there before and were said to favour death over returning to that ‘place of tyranny’, as it was described in ‘The Ballad of the Cyprus Brig’. 3

ON 5 JANUARY 1830, THE CYPRUS and its crew of 10 convict pirates appeared off the coast of Tosa Province (now Kochi Prefecture), Edo Japan.1 After seizing the colonial brig in Recherche Bay, Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania) on 14 August 1829, they had entertained another ship’s company at Cloudy Bay, New Zealand; pillaged a sealer camp at the Chatham Islands; been driven away from Tahiti by contrary winds; and stayed for six weeks on Niuatoputapu, Tonga. They had also left men in their wake, figuratively and in one case literally: William Brown, a pressed2 convict shipwright, was reported as lost overboard in a storm between New Zealand and the Chatham Islands, and seven others decided to stay on Niuatoputapu, while the rest continued to Japan.

Their captain, William Swallow, also claimed to have been pressed, but this may well have been a contingency laid by this master escape artist, unlucky thief and loving family man. Of his five known escapes, four initially ended in freedom and reunion with his wife and children in England. All arrests but his last were theft related, and he dodged being labelled a re-offender by using aliases, of which Swallow was just one. Born in Sunderland, England, in 1792, he was apprenticed on a collier in the North Sea (as was James Cook), was pressed by the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic wars, worked as a master of a coastal trader as well as first mate in the Mediterranean, and even sailed to the Baltic. However, the need to support his family during the postwar depression appears to have led to stealing.

The Cyprus was from a shipyard in Swallow’s hometown of Sunderland, so would have been of a type immediately familiar to him. However, this escape from Recherche Bay was undoubtedly his most audacious. His crew included only two other men described as seamen or mariners, and possibly one other with experience, as opposed to the usual complement of 12. He knew he was sailing into the Tasman Sea in winter and would face at least one Roaring Forties storm on a downwind run to the unfamiliar lee shore of New Zealand. This baptism by fire for his new crew would have consolidated his command, as they relied utterly on his seamanship and experience.

While still disembarking the guards, crew, passengers and nonparticipating convicts at Recherche Bay, the Cyprus ’s new crew are reported to have drawn up ‘piratical articles’, the contents of which can only be guessed at. The hugely popular A General History of Pyrates (1724) cites examples that include clauses covering conflict resolution, punishments, democratic process (including selection of a captain), division of spoils, the treatment of women, and even days off for musicians. The drawing up of articles was very probably prompted by Swallow as a means of maintaining order.

But off the coast of Japan, the now hungry and thirsty Cyprus crew ran into trouble. While moored off Murotsu Village, eastern Tosa Domain, in January 1830, they made three attempts to land. Each time, the longboat’s crew was driven back by warning musketoon fire from the seafront. Finally, after one of the pirates broke down and cried out, begging for succour, a local merchant sent out a boat with more than 100 kilograms of rice and water. The merchant had intended to give them ten times this amount, equivalent in value to a small house. This level of largesse was atypical, but is confirmed in an earlier Tosa Domain source that reported Murotsu merchants sharing food during times of famine.

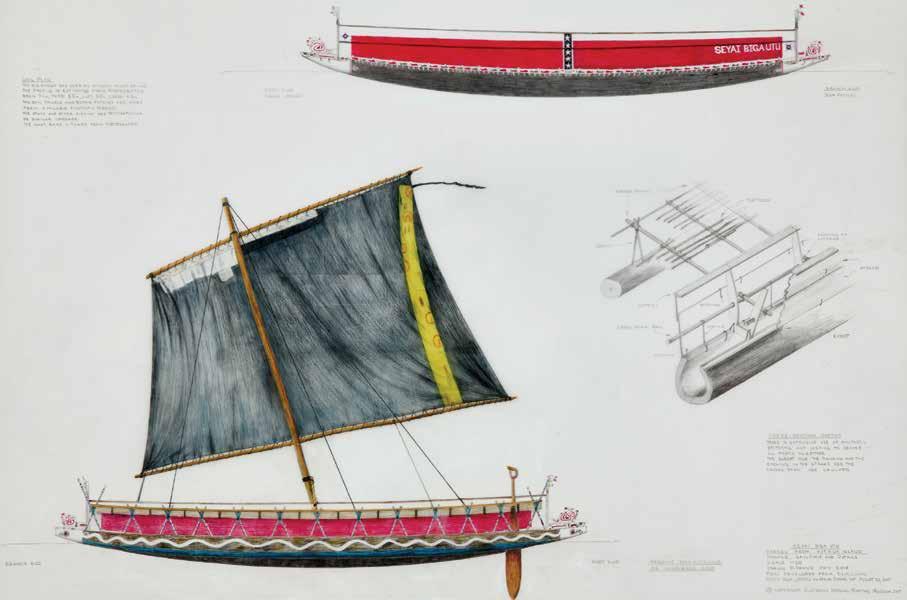

Disguised as fishermen, the samurai agents rowed out to the brig, under orders to make detailed pictures of anything that looked like a weapon.

‘We saw not a single weapon’, Hamaguchi wrote, but he recorded considerable detail of the ship and its rig and the interactions between the brig’s crew and the samurai.

‘The barbarian ship was now surrounded by our small boats, including both of our commanders. Our guns were at the ready to blow them to bits’

Early on the morning of 6 January, the Cyprus weighed anchor and sailed away as a storm blew up, pushing the brig further out to sea. Five days later, on 11 January, it reappeared off Hiwasa, Awa Domain (now Tokushima Prefecture), 100 kilometres to the north-east up the coast of Shikoku. After drifting back down the coast for 20 kilometres, it dropped anchor in 15 metres of water, about 600 metres from the north-eastern end of Teba Jima Island and three kilometres off Mugi Ura Cove.

The pirates’ behaviour and reception off Tosa Domain and Awa Domain were different: this time they did not try to land, but requested water, firewood and a week or so for repairs. Their longer presence gave the Awa Domain samurai time for an organised response in line with the Shogunate’s isolationist policy of maritime restrictions, which not only limited trading countries and the ports to which they were welcome, but also domestic maritime technological development and overseas visits. Because of its recent history of incursions, Britain had the status of least-welcome nation. Fortunately for the Cyprus, the samurai’s flag reference book listed the brig’s ensign as that of Angleterre (the French word for England), and the Japanese did not initially recognise it as a British vessel.

Due largely to these British incursions, the Shogunate’s strictest shoot-first edict had been in effect since 1825, mandating samurai to use warning shots to deter any ship that approached the coast and immediately kill or imprison any foreigner who set foot on Japanese soil. Historically, such edicts were not unique to Japan: the Ming Dynasty in China had had a similar policy in place at the beginning of the Edo period. The rationale was that if the nation were self-sufficient with internal peace, why allow in potentially disruptive or colonial foreign influences?

Each domain’s assessment of their response and repulse also differed: Tosa’s had not been resolute enough, and there is a Domain manuscript documenting their reassessment of their defences and preparedness. However, Awa Domain’s appears to have been textbook perfect, as samurai manuscripts list the honours bestowed on the participants. Led by the Shogunate’s feudal overseer to the Domain, Hayami Zenzaemon, the threat was assessed, an ultimatum made, the vessel engaged and the repulse successful, with no loss of life on either side. However, despite sporadic interest in academic circles, the incident was wiped from the folklore of the local fishing communities of Mugi Ura and Teba Jima. This social amnesia might have been because the holing and repulse of a vessel requesting respite for repairs did not sit well with the communities’ seafaring tradition, which dictated assistance in such situations.

Of the eight Cyprus-related manuscripts that have so far come to light, two accounts have been partially translated into English. The first is that of Hamaguchi Makita. A direct subordinate of the top samurai field commander Yamauchi – who was second only to the Shogunate’s feudal overseer, Hayami Zenzaemon –Hamaguchi was literate, artistic and trusted. Hamaguchi’s father was a samurai whose unwitting involvement in a scandal led to his suicide and the loss of the family’s hereditary title.

His primary role seems to have been similar to that of a secretary, but he was tasked with the important and potentially dangerous reconnaissance of the Cyprus, its crew, their capabilities and level of threat. Despite the essential role that he filled, however, he is not mentioned by name in other samurai sources due to his lowly rank. His perspective and detail are unique, providing a fly-on-the-wall account of the feudal overseer’s and two field commanders’ intelligence reports, discussions, decisions and orders, as well as his illustrated description and threat assessment.

The second translated manuscript is by Hirota Kanzaemon, a lower-ranked local samurai from Mugi Ura, who details initial interaction between the pirates and other curious local samurai and fisherfolk who row out to get a closer look.

When the first reports arrived of a ship being sighted off the neighbouring domain of Tosa, the Awa Domain samurai dispatched an agent to gather information about the brig from the locals there. This appears to have been normal procedure: if the vessel then arrived off Awa, a repulse might be required; if it was disabled, it might have to be towed along the coast of Awa en route to Nagasaki, the nearest port open to foreign vessels.

As soon as the brig was sighted off Hiwasa, Awa Domain, on 11 January, word was sent to Tokushima Castle, 50 kilometres to the north. After late-night discussions, a force was mustered, and its vanguard – including Field Commander Yamauchi and his secretary-cum-spy Hamaguchi – departed early the next morning. They rode as far as Yuki, a village six kilometres north of Hiwasa, and proceeded by boat to Mugi Ura, passing within one kilometre of the brig in the murky light of the half moon. From there, Hamaguchi was dispatched to Teba Jima Island with a gunnery team, musketoons and a twopound cannon, the largest of those deployed by the samurai.

01

Hirota Kanzaemon’s manuscript contains a small pictogram of an object that he notes was offered to the headman of a neighbouring village who had rowed out. It looks very much like a returning boomerang. Whether this was a mainland Aboriginal artefact, and whether, as G A Robinson reported,4 a Tasmanian Aboriginal woman was on board the Cyprus , still remain unanswered questions.

From A Foreign Ship Drifts in Off Mugi Cove, by Hirota Kanzaemon, 1830. Courtesy of Hirota Family Archive. ©Hirota Family 2018. Photograph © Nicholas Russell 2018

02

Japan, with the island of Shikoku highlighted; right: schematic map of the passage of the Cyprus along the coast of Kochi and Tokushima Prefectures, Shikoku, and that of the samurai who intercepted them. Images Jo Kaupe from data supplied by the author

This was a relative pea-shooter compared to the 12-, 24-, 32- and 42-pounders of Royal Navy ships of the line at Trafalgar. However, it was easy to move and quick to set up.

After delivering the cannon in the early hours of 16 January, Hamaguchi was sent out to reconnoitre the Cyprus. He does not report boarding the brig, but the perspectives and detail in the drawings by him and another artist who was present seem inconsistent with their standing in a fishing skiff and peering through the brig’s scuppers. At this time, Hamaguchi was busy with his written description as well as his sketches, some of which appear to have been finished from memory back on shore. He was there later when the pirates were fired on and were waiting for an offshore wind to flee the samurai, and details in a reworking of the manuscript by him that has recently come to light are closer to what we would expect. For example, in the original the cuffs of what is thought to be the lieutenant’s jacket seem excessively ornate for his rank, while in the reworking the simpler leaf design is closer to known examples in collections. On his first visit, Hamaguchi records Swallow’s first words of greeting as sounding like ‘Pace! Pace!’ – presumably ‘Peace! Peace!’. Ironically, for the Japanese this was the most diplomatic of encounters with Australian colonial or British captains, who were usually imperious and bellicose.

Swallow and his crew failed to recognise their artistic visitors’ humble fisherfolk disguise; instead, they offered them a shared circling glass of rum and tapped their heads, which was possibly an early form of Napoleonic salute. The ‘fishermen’ declined the rum and took the salute to be a gesture indicating its intoxicating effect.

Hamaguchi gave his report back in Mugi Ura and the samurai discussed what should be done. Mima, the other field commander, was more openly hostile than Hamaguchi’s superior Yamauchi, and characterised the beguiling effect of Swallow and his crew on visitors as ‘Christian sorcery’. Intriguingly, this quote is crossed out in Hamaguchi’s first manuscript but not his later reworking – almost as if Mima had leaned over his shoulder and told him to delete it. Mima thought they were pirates and should be crushed. Two local sword-carrying landowners were then sent with a ‘large cannonball’ and by ‘motions and signs’ informed Swallow that he and his crew should leave immediately. If they complied, they would be provided with water and firewood; if not, they would be fired upon.

Shuttle-boat diplomacy commenced. Swallow asked for five days’ grace to carry out repairs to the brig. This was refused, so he asked for three. That also was refused, and when one of his crew started to get angry and shout, Swallow defused the situation by encouraging the envoys to leave quickly, but not before he handed them a sealed envelope. Yamauchi was furious with his messengers for accepting the letter, as any formal communication would be in breach of the Shogunate’s edict. They rowed out one last time to toss the unopened letter back over the brig’s gunwale, then pulled hurriedly away.

A signal fire was lit on the mainland, and the first report rang out from the two-pounder on Teba Jima. The cannonball was pitted to make it scream as it flew between the brig’s masts. The crew’s response was to leisurely spread a sail, which further infuriated the samurai commanders. From their attempted landings in Tosa, the pirates by now probably thought that they understood the samurai’s rules of engagement.

Four Japanese patrol boats with gunnery teams were despatched and again fired around the brig. The finer details of European maritime technology, however, had been lost in transmission. The samurai knew that European ships possessed the technology to sail upwind, but the samurai commanders overestimated the brig’s ability. Consequently, when the brig failed to sail away upwind and instead sailed downwind towards the samurai fire, the samurai’s reaction became more vigorous. Hamaguchi wrote, ‘At about this time the feudal overseer realised it was a British ship and became extremely angry’. A previous incursion had led to the suicide of the Shogunate’s representative at Nagasaki Port. ‘They ordered fire to be directed at the waterline in the red copper-sheathed area. Two cannonballs hit and shook the ship badly. The barbarians were standing and yelling.’ Hamaguchui continues:

Commander Yamauchi from his boat orders his patrol boat gunners to concentrate their fire on the rudder area at the stern on the starboard side of the ship. One of Nishizawa’s three-quarter-pound cannonballs reduced a two-foot square area of the sturdy hull to splinters and ricocheted off to port. One or two of brig’s crew appeared to have been killed or injured as they were lying on the deck. The others turned towards Commander Yamauchi’s boat, all removed their hats and appeared to be praying. Out on the water the samurai heard random cries of ‘Roubin! Roubin! Rou!’ [Pronounced like ‘rue’ and ‘bin’; possibly they heard ‘Row men! Row men! Row!’]. The barbarians all showed themselves blowing into cupped hands. They were gesturing that the wind was no good. Commander Yamauchi asked when the wind might change. His boatmen responded that after sundown a wind would blow up from Asakawa but it would not reach them there. Later, however, just off Mugi Cove there would be an offshore breeze.

01

‘All of the men were wearing hats: most of leather, but one of wound red cotton cloth and another like a thatched farmer’s hat’, Hamaguchi reported.

02

What is thought to be Lieutenant Carew’s dress uniform, of which Hamaguchi wrote: ‘Next the skipper brought out a tightly-woven scarlet woollen coat to show us … This was a thing of great beauty but excessively fancy ... The cuffs were stitched with gold thread and the buttons were silver plated’.

Commander Yamauchi was good enough to share this knowledge with the barbarians through gestures and they swiftly turned the brig across the wind. Unlike our large ships, the barbarian ship turned tightly but it could not, in fact, sail directly into the wind as we had thought; it could only sail across the wind. The barbarian ship was now surrounded by our small boats, including both of our commanders. Our guns were at the ready to blow them to bits. If they grabbed the ropes to go over the side or put up a fight, we were ready to shoot. A foul stench was coming from the ship. The musketeer, Nishizawa, threatened them by shouldering his big gun. The barbarians looked worried, cried out and trembled with fear. Some of them even pointed to their sides and fell down praying. We took this to mean that one of Nishizawa’s musketoon balls had reached its mark and taken a life.

It was later reported in The Times that one shot had knocked Swallow’s spy-glass from his hand, but none of the pirates reported any fatalities or even injuries from this encounter. Hamaguchi wrote that ‘as dusk fell a strange beguiling pipe and singing could be heard. The sound was like that of a child’s pennywhistle; nothing like a real flute. It was eerie.’ A single defiant musket report was heard from the brig as it sailed out of sight, to which the samurai replied with a single cannon shot into the darkness from Teba Jima. The repulse had been successful: no barbarian foot had touched Japanese soil and the foreign ship had been driven away, in line with the Shogunate’s 1825 edict.

Early in 1830, at the far west end of the Tosa Domain, local people reported seeing a ship and hearing a musket shot off Kashiwa Jima. It may have been the Cyprus.

About a month after leaving Japan the brig arrived off the Pearl River Estuary in China. There were disagreements between the crew, and ‘to avoid apprehension as pirates’ four of them hacked a hole one metre below the waterline and sank the brig. Having left the ship in three groups, all 10 eventually ended up in Canton, where the East India Company’s Supercargo took statements, and detained some of them when they gave different names for their captain. From there, three escaped to Mexico and the rest ended up in the dock back in London. Two of them became the last men hanged for piracy in England. Swallow talked his way out of two death sentences and was sent back to Van Diemen’s Land, where he died of consumption a few years later. The brig Cyprus probably still lies on the seabed, somewhere off the Pearl River Estuary, a wrecked testimony to the first cross-cultural engagement between Australia and Japan. The irony that the pirates and the Japanese came into conflict when they were both avoiding British imperialism might have disappeared along with the Cyprus, but for the discovery of the Japanese manuscripts detailing the encounter.

Of the eight Cyprus-related manuscripts that have so far come to light, two accounts have been partially translated into English

1 The Edo Period (1603–1868) was a time of peace and isolationism achieved by the feudal military government of the Tokugawa Shogunate through strict control of the feudal lords and populace. It came after the anarchy of the Warring States Period and before the coup d’état of the Meiji Restoration. It saw growths in economy, education, logistics, production, popular culture and mass media.

2 Impressment (‘pressing’) – the forcible enlistment of ships’ crew – was used by the Royal Navy in times of war. On pirate ships it was often feigned in front of witnesses in the case of specialist crew members, such as carpenters and doctors, to give them the excuse of duress if they were ever captured by the authorities. Swallow, on the seizure of the Cyprus , convinced the doctor on board that he was a pressed man. Later this worked to his advantage when the doctor gave evidence in his defence.

3 ‘The Ballad of the Cyprus Brig’ is attributed to ‘Frank the Poet’ in an 1891 transcription by Thomas Whitley held at the State Library of NSW. It contains the lines: ‘For navigating smartly Bill Swallow was the man, / Who laid a course out neatly to take us to Japan’.

4 A Mr G A Robinson on Bruny Island, Van Diemens Land (Tasmania), reported a local Aboriginal man, Mangana, as saying that his wife had been taken on board by soldiers and then gone to England. Robinson later reports someone saying she was found dead in the water. He and his young secretary, Charles Sterling, are the only known sources on the Australian side of this story.

Sources and further reading

Durham County Advertiser, 14 April 1821.

Van Diemen’s Land newspapers, 1829.

Carew’s court martial transcript: The Tasmanian, 30 October 1829. The Times , 1830.

Hue and Cry, The Police Gazette, March 1830.

Swallow’s Petition to Peel, December 1830.

Deveron: The History of Tasmania, John West, Vol 2, 1852.

Chatham Islands: Whaling and Sealing at the Chatham Islands , Rhys Richards, 1982.

The Man Who Stole The Cyprus , Warwick Hirst, 2008.

Contrary Winds , John Williams, 2012.

Tosa Domain samurai account of Murotsu merchants, in presentation by Dr Luke Roberts, Kochi Castle Museum, 3 April 2018.

Nick Russell is a resident of Japan who came across illustrations of the brig online while investigating the local history of Teba Jima, where he had just bought a holiday cottage. As a Brit he felt destiny bound to solve the mystery of what a ship bearing the red ensign was doing moored just 600 metres off his new back garden in 1830. Two years later, on the verge of giving up, he Googled ‘mutiny 1829’ and when the Cyprus story appeared, he immediately made the connection. Nick and some of his students translated the manuscript into English and then back into modern Japanese. After the initial media attention, a samurai descendant showed Nick a 35-year-old private letter in which a Japanese amateur historian suggested, but never published, a Tasmanian convict link.

Science was a large part of life on HMB Endeavour in the 18th century. From tracking the transit of Venus in Tahiti to collecting and classifying thousands of plant specimens, the Endeavour voyages contributed a vast swathe of knowledge to European science. In February 2019, a new pilot project called Observations at Sea sought to bring science back aboard the Endeavour replica and, in the process, inspire the next generation of scientists, engineers and thinkers. By Graeme Buckie, Bill Flynn and Elle Shepherd from CSIRO.

An 18th-century tall ship presents a number of very different, and sometimes unexpected, challenges while undertaking seemingly simple tasks

OBSERVATIONS AT SEA is a partnership between CSIRO Education and Outreach and the Australian National Maritime Museum. Conceived after conversations between the two institutions about opportunities to highlight the scientific history attached to voyages of exploration, it was designed to test the viability of conducting a science education program aboard Endeavour

The pilot is based on CSIRO’s existing Educator on Board program, where teachers spend time at sea aboard research vessel RV Investigator, supporting scientists with their research. After the voyage, the teachers develop classroom resources to share with other teachers across the country; promote real-world applications of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM); and showcase the research being undertaken in the marine sciences.

To test the new idea with museum vessels, four CSIRO staff members joined separate legs of HMB Endeavour ’s journey to and from Hobart in February this year. Collectively sailing more than 1,400 nautical miles (2,600 kilometres) along the picturesque Australian east coast, CSIRO staff served as voyage crew, balancing their sailing responsibilities with undertaking trials of five different scientific activities. These were carefully selected to reflect the work of CSIRO researchers and to provide important classroom links to the Australian National Curriculum, while still being suitable for a replica 18th-century vessel with limited space and equipment.

After learning the ship’s ropes and settling into its disciplined watch routine, the CSIRO staffers were able to regularly deploy expendable bathythermographs (XBTs) – probes used to provide real-time measurements of ocean temperature down to a depth of 800 metres. With support from the ship’s engineer, who rigged a conveniently placed earth line to allow the probes to transmit back to the ship, the XBTs were launched successfully from Endeavour ’s stern. They brought instant data back to the deck, displaying a graph comparing the expected temperatures based on existing temperature models and the temperatures measured by the probe. The temperature profiles collected on Endeavour will be used to develop and update these scientific models, giving researchers greater insight into major ocean currents and temperatures.

While on board, the CSIRO team tested the use of a portable net used to undertake surface trawls and collect data for the CSIRO Global Plastic Pollution Project. These nets have been successfully deployed from different ships around the world to collect plastic and microplastic floating on the sea’s surface. The plastics gathered by these nets are then separated and catalogued by size and type. Details of how much plastic was found, and where, are recorded along with the ship’s heading, location and weather conditions. These readings are then added to a global dataset that is used to help researchers better understand the sources and distribution of marine debris.

When attempting to deploy this net, one thing became clear very quickly – Endeavour is a very different vessel to those regularly used by CSIRO researchers, and an 18th-century tall ship presents a number of very different, and sometimes unexpected, challenges while undertaking seemingly simple tasks. The CSIRO crew worked with the ship’s boatswain to enable these to be overcome so the net could be deployed.

Finally, the CSIRO crew members focused on making oceanic observations at sea. These included the use of citizen science apps to collect data on water quality, recording the estimated turbidity and levels of light reflected from the water at a number of points along both legs of the voyage. They also undertook designated observations for Trichodesmium – little-understood rafts of algae known to the crew and scientists aboard the original Endeavour as ‘sea sawdust’ –and bioluminescence. No Trichodesmium was seen on these voyages, but bioluminesence was regularly spotted glowing in the ship’s wake.

With the pilot activities now complete and the crew back on land, CSIRO Education and Outreach and the Australian National Maritime Museum are reviewing the pilot to analyse what was learned from the trial voyage activities, contemplate the feasibility of developing this trial into an extended program and examine the potential for future activities. It is hoped that observations and data from the Maritime Museum’s vessels can be given to teachers and students around Australia to promote real-world applications of STEM and highlight the importance and history of the marine sciences aboard Endeavour.

01 Elle Shepherd retrieves a trawl from the marine plastics net. 02 Bill Flynn prepares to launch an XBT (expendable bathythermograph) from Endeavour ’s stern. Images courtesy Mary Alice Campbell‘we got our muskets and arms ready –this coast is much infested by pirates’

Recent changes to the Copyright Act have made it easier for cultural institutions to publish more of their collections. ‘Orphan works’ – those whose creator is unknown – and manuscript works can now be publicly shared, meaning that many fascinating and significant journals and other documents can finally emerge from their vaults. By Library Coordinator Karen Pymble .

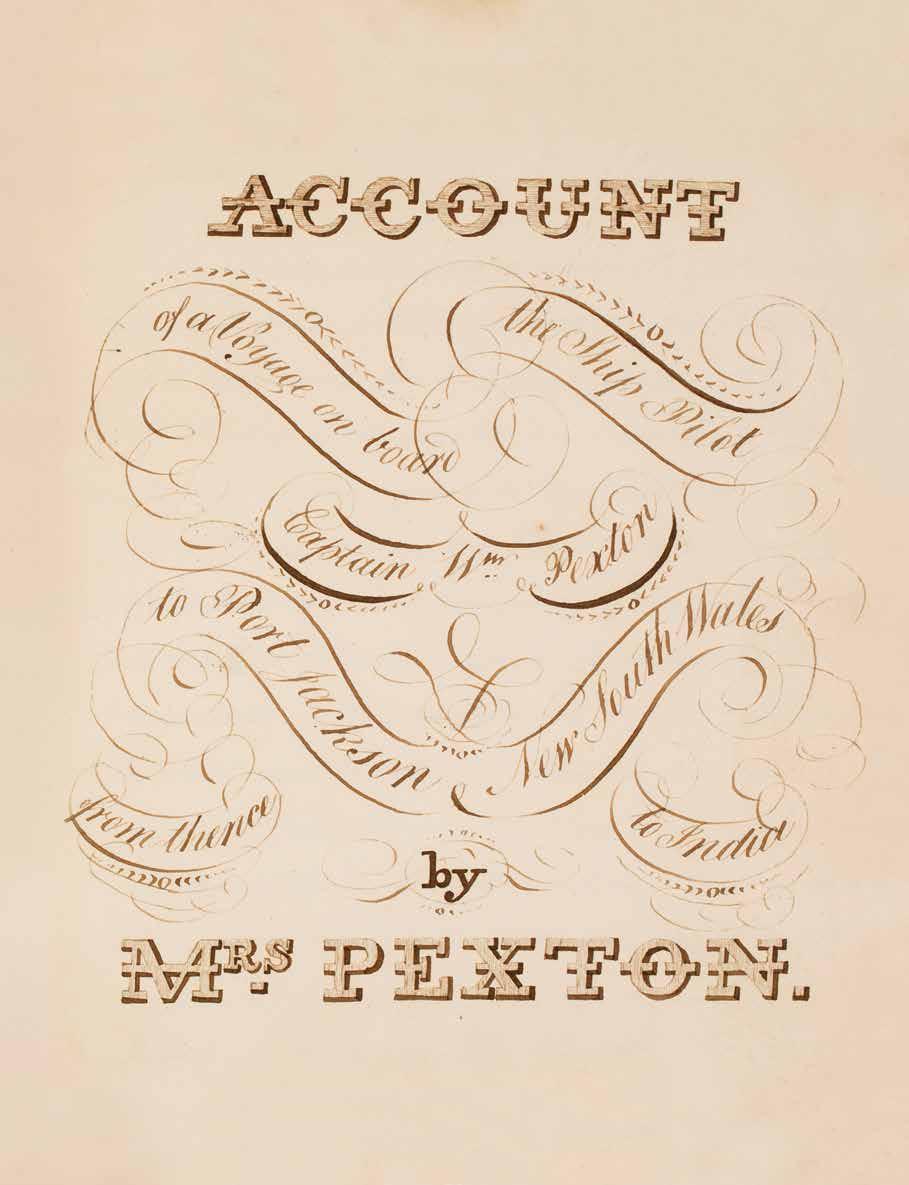

AMONG THE MUSEUM’S HOLDINGS is a rare original account of life on board a convict transport ship. It is particularly unusual in having been written by a female passenger, Mrs Pexton, who accompanied her husband, Captain William Pexton, on the ship Pilot from London to the penal colony of Port Jackson (Sydney) in New South Wales.¹

Departing on 18 December 1816, they first sailed to Cork, Ireland, where they embarked 120 male convicts and a military guard of a sergeant and 30 privates. About half of the journal describes the seven-month voyage out – including a stopover in Rio de Janeiro and an attempted mutiny by the convicts – and her time in New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). Arriving in Sydney in July 1817, Mrs Pexton writes interestingly of the town and vicinity, the social life and the convicts, along with descriptions of the inhabitants, Aboriginal people and wildlife (including a tame kangaroo).

Mrs Pexton then accompanied the Pilot as it transported 280 convicts – ‘The very worst which they can make nothing of at Sydney’ – to Van Diemen’s Land. She describes the Hobart area, where she stayed: ‘there are very few settlers but the land cultivated is in very good order. I believe it will grow anything, fruit of every kind will grow particularly English’.

On her return to Sydney, Mrs Pexton talks about the natives, and their being naked and liking spirits. She says she is tired of Sydney, and Australia will spoil anyone who stays.

The transport ship then took on a cargo of horses, and departed for Batavia (now Jakarta), Indonesia. Storms, illness and a leaking ship forced the Pextons to take up residence there for several months, before leaving on 7 May 1818.

The ship returned to England via Isle de France (Mauritius), India (‘we got our muskets and arms ready – this coast is much infested by pirates’) and St Helena. They sighted England on 26 November 1818: ‘I have only been [away] two years and I am not able to express half the pleasure I feel at the sight of it’.

These very personal reflections, like many other fascinating historical records, are among the diverse collection of material housed at the Vaughan Evans Library, the research hub of the Australian National Maritime Museum. This story, like many others, has not always been accessible online – but recent changes to the Australian Copyright Act will open up access to a wealth of historical maritime stories.

Specifically, in 2017, the Australian Government introduced major changes to the copyright term provisions of the Australian Copyright Act. This was done as part of the Copyright Amendment (Disability Access and Other Measures) Act 2017 (CADM). These changes replace Australia’s existing copyright term provisions and came into effect on 1 January 2019.

The change to the legislation came about due to the Marrakesh Treaty, which is the first international copyright treaty to facilitate access to published works for persons who are blind, visually impaired or otherwise print disabled.

The title page of Mrs Pexton’s lively account of her voyage from London to Australia and back, on a convict transport ship captained by her husband. ANMM Collection 00045200

As of 1 January 2019, the museum’s collection of diaries, letters and other unpublished works is now in the public domain, for anyone to access and use

Robert Rose’s World War II journal, kept when he was a prisoner of war, includes photos sent to him by his wife, as well as descriptions of everyday life, details of sporting competitions and addresses of comrades. ANMM Collection 00044998 Reproduced courtesy Robert Leslie Rose

02

One of the finest shipmaster logs in the museum’s collection was written and illustrated by Captain William Henry Downes during a whaling venture aboard the barque Terror in 1846–47. ANMM Collection 00038301

The four main changes are:

1. Disability These new amendments replace two current provisions (statutory licence and s200AB) with two new provisions:

• Exception for institutions providing access to those with a disability

• Fair dealing for providing access for those with a disability.

2. Preservation Libraries and archives are no longer required to wait until material has been damaged or suffered deterioration before making preservation copies. They are permitted to make multiple preservation copies, and to make available electronic preservation copies to the public, without infringing copyright.

3. Education This simplifies the statutory licence.

4. Copyright term Previously, there were different rules for published and unpublished material, and unpublished materials could remain in copyright in perpetuity. CADM ends perpetual copyright and replaces with life of the author + 70 years, or 70 years from the creation of an orphan work, regardless of whether it is a published or unpublished work. Where the creator of the material cannot be identified, the term of protection is 70 years after the date of making. The standard term will be effective for works created before 1 January 2019 that are unpublished by that date.

Matthew Rimmer, QUT Professor of Intellectual Property and Innovation Law, explains why this was long overdue:2

Australia’s laws were an anomaly. Unpublished copyright works received perpetual protection – as long as they were not published. This led librarians to protest with the Cooking for Copyright day of action when they baked goods from unpublished recipes to illustrate the problem of this default copyright position. Setting finite terms for copyright in unpublished works is a sensible move by the Australian Government and keeps Australia in line with other comparable jurisdictions like Canada, the United States, and England. Libraries, galleries, museums, and archives have certainly welcomed the proposed law reform.

The amendment to the copyright term will have the greatest impact for us at the museum. Changing the term to 70 years from the creation of an orphan work is simple and fairer and makes it much easier to access a large number of old materials. These new terms were introduced to help get around the concept of perpetual copyright for unpublished works. This rule of legacy meant that all national institutions holding letters and diaries could never introduce them to the public domain; even material that was hundreds of years old was still protected by copyright in Australia. As of 1 January 2019, however, the museum’s collection of diaries, letters and other unpublished works is now in the public domain, for anyone to access and use.

New copyright protection terms from 1 January 2019

• Works (literary, dramatic or musical) – 70 years after author’s death

• Works with unknown author –70 years after making or 70 years after first made public (if within 50 years of making)

• Sound and film recording –70 years after making or 70 years after first made public (if within 50 years of making)

• Crown (Commonwealth, State or Territory) – 50 years after making

The museum’s Registration department has been working hard on digitising the original diaries and logs. These items include whaling logs and personal diaries written by travellers, immigrants, crew members, sea captains, ship’s surgeons and matrons. Digitised items can be publicly accessed via ‘Collections’ on our website.

The Vaughan Evans Library holds many diaries and letters. All of the library’s manuscript diaries are unpublished copies or transcripts. These manuscripts are often requested by the public in the course of their research. Diaries are one of the richest primary resources for information of the time, giving us insight into what it was like to be a passenger or crew member. Many of the diaries and letters were written to help pass the time; others are brief and factual, mainly noting the weather and the latitude and longitude.

This welcome amendment to the Australian Copyright Act will vastly expand the range and variety of Australian maritime stories that anyone across the globe can access. Digitising this part of the collection will take time, but this valuable resource will serve many generations to come.

Footnotes

1 Diary of Mrs Pexton aboard the Pilot . ANMM Collection 00045200 2 qut.edu.au/law/about/news-events/news?news-id=116058, 4 April 2017, accessed 16 May 2019.

Information in this article has been adapted from Australian Libraries Copyright Committee libcopyright.org.au

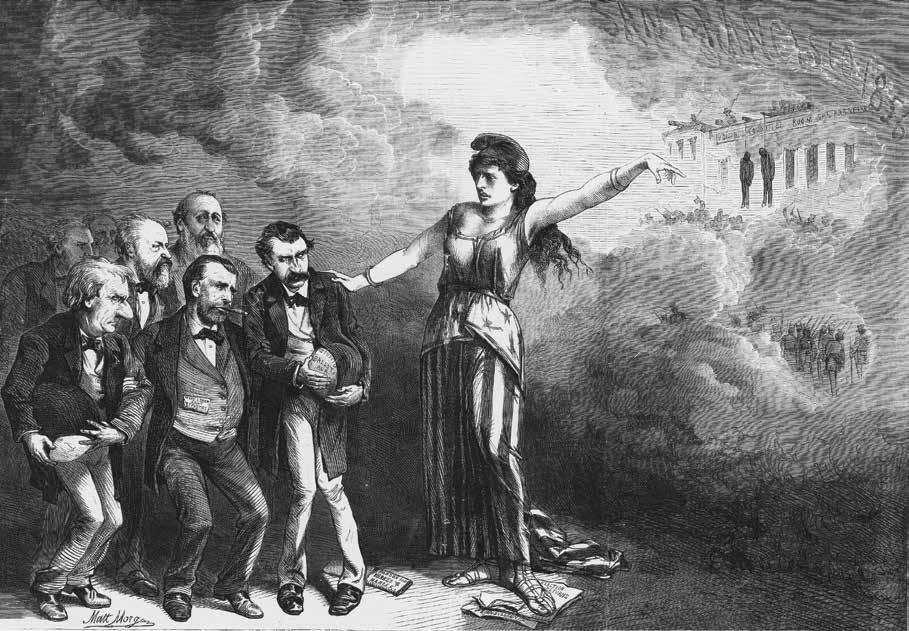

As museum staff digitise our collection, they often come across intriguing objects. In a box containing 263 engravings on various topics, Nicole Dahlberg found one from 1872 whose subject immediately grabbed her attention: a public lynching. She traces the story back to San Francisco during the lawless days of the Californian gold rush.

01 Beware! Engraving by Matt Morgan, 1872, published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. ANMM Collection 00019630

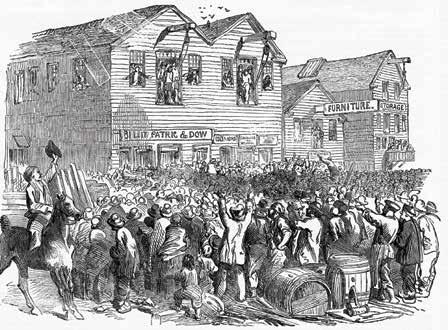

02 A lynching in San Francisco, published in the Illustrated London News on 15 November 1851. ‘Sydney Ducks’ Samuel Whittaker and Robert McKenzie were killed before a crowd of 15,000 on 24 August 1851. ANMM Collection 00005965

The engraving by Matt Morgan demonstrates how one humble object can carry many layers of history and meaning