Wildlife Photographer of the Year

Inspiring and impactful

Classic & Wooden Boat Festival

Coming again this May

Sea Shepherd

Southern Ocean whaling

Wildlife Photographer of the Year

Inspiring and impactful

Classic & Wooden Boat Festival

Coming again this May

Sea Shepherd

Southern Ocean whaling

LAST YEAR NEW ZEALAND OBSERVED 250 YEARS since the first encounters between Māori and Pākehā (Europeans) in 1769, when British explorer James Cook arrived in Poverty Bay sailing on HMB Endeavour.

This significant time in history was marked by Tuia 250, a celebration of Aotearoa New Zealand’s Pacific voyaging heritage. It was a unique national opportunity for ‘all New Zealanders to hold honest conversations about the past, the present and how the country was to navigate its shared future’.1

The Australian National Maritime Museum’s Endeavour replica was chartered by the New Zealand Government’s Ministry of Culture and Heritage to take part in a special voyaging flotilla, a major element of the Tuia 250 celebrations.

From October to December last year, the flotilla sailed to and engaged with communities across New Zealand. It visited sites of cultural and historical significance and gave Māori iwi (nations) and communities the chance to share stories of arrival and their encounters with Tupaia, James Cook and his Endeavour crew.

The impressive flotilla comprised a double-hulled voyaging canoe, Fa’afaite, from Tahiti; two Māori waka hourua, Haunui and Ngahiraka Mai Tawhiti, from Aotearoa New Zealand; and three European tall ships: R Tucker Thompson, a traditional gaff-rigged schooner; the three-masted barquentine Spirit of New Zealand, which is believed to be the world’s busiest youth training ship; and our own replica Endeavour. Hundreds of New Zealanders took the rare opportunity to sail on one of the flotilla ships in a series of voyages around the country.

Large family-friendly events took place at port stops during the voyages, where the public could board the vessels and learn about Pacific, Māori and European sailing and navigation. Almost 20,000 people visited our replica Endeavour, including more than 1,000 students.

Tuia 250 also provided a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for the museum’s own voyaging crew and support staff, who were honoured to be invited by local Māori iwi to their marae (meeting grounds). The crew recount powerful and emotional moments as Māori elders spoke of their iwis ’ own encounter stories and the lasting impact these had on their communities.

1

I, too, had a chance to sail on Endeavour during Tuia 250 as a crew member and to participate in the iwi welcome to the Waitangi Treaty Grounds. My overwhelming impression was of an incredible professional crew, led by captain Frank Allica, who successfully sailed Endeavour in some very challenging weather, and also represented the ship and its history in an impeccable way that reflected so positively on the museum.

As the custodians of the replica Endeavour, we are proud that the ship and our crew took part in this extraordinary voyage – one of great national significance for New Zealanders. The New Zealand Ministry of Culture and Heritage Tuia 250 website states:

The Tuia 250 commemoration has left a legacy for future generations. The legacy has been created through voyaging and encounters education and conversations that took place during the commemoration, through new physical markers and signage at sites of significance, through the changing of place names to reflect dual heritage, and through the healing that has occurred in communities and the strengthening of relationships.

This year and next, the museum will offer to communities all around Australia a unique commemorative program marking Cook’s 1770 voyage. Collectively called Encounters 2020, it comprises exhibitions, film, digital and educational initiatives and a series of voyages by Endeavour around the country, accompanied by a travelling exhibition of Indigenous art. The program will commence in Sydney in April. Importantly, our program explores dual perspectives, of both the view from the ship and the view from the shore. We know – as we witnessed with the New Zealand experience – that there will be difficult conversations taking place throughout Australia about the lasting impact of Cook’s arrival 250 years ago, particularly for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Our aim, however, is for Encounters 2020 to also leave a legacy for future generations of Australians by providing a platform for all of us to reflect on, discuss and re-evaluate the lasting impact of this pivotal event.

Kevin Sumption psm Director and CEO New Zealand Ministry of Culture and Heritage, Tuia 250 website.The Australian National Maritime Museum acknowledges the Gadigal people of the Eora nation as the Traditional Custodians of the bamal (earth) and badu (waters) on which we work.

We also acknowledge all Traditional Custodians of the land and waters throughout Australia and pay our respects to them and their cultures, and to elders past and present.

The words bamal and badu are spoken in the Sydney region’s Eora language. Supplied courtesy of the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council.

Cultural warning

People of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent should be aware that Signals may contain names, images, video, voices, objects and works of people who are deceased. Signals may also contain links to sites that may use content of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people now deceased.

The museum advises there may be historical language and images that are considered inappropriate today and confronting to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Cover Pondworld by Manuel Plaickner (Italy). © Manuel Plaickner/Wildlife Photographer of the Year

2 Canoes and culture

A visit to the Massim communities of Milne Bay, Papua New Guinea

8 Thanks to our supporters

News from our Membership and Foundation sections

10 Head to the harbour

The Classic & Wooden Boat Festival gears up for May

16 Nature in focus

The best of Wildlife Photographer of the Year

20 ‘Volleys of small arms’

The military nature of Pacific voyages of exploration

24 Bound for South Australian

A field expedition uncovers more about a colonial wreck

30 ‘She will be the first woman that ever made it’

The 18th-century circumnavigation by Jeanne Baret

38 A relic of the Southern Ocean whaling wars

The museum acquires a Sea Shepherd boat

46 From shoal to market

Technology tracks the provenance and quality of seafood

48 Museum events

Your calendar of talks, tours and excursions afloat

54 Autumn exhibitions

HERE: Kupe to Cook ; Sea Monsters; Defying Empire and more

58 Encounters 2020

Commemorating the 1770 encounters around Australia

60 A scientific circumnavigation

The Schmidt Ocean Institute deploys RV Falkor in Australian waters

64 Paths for peace

High school students reflect on the Pacific theatre of World War II

70 Tales from the Welcome Wall

Las Balsas, the world’s longest raft journey

74 Currents

National awards recognise conservation staff and volunteers

The war canoes that are part of the traditional culture of these Milne Bay communities have now evolved into a means of working together

Alotau, on the shore of Milne Bay in Papua New Guinea, is a place of spectacular scenery steeped in culture and tradition. Curator of Historic Vessels David Payne travelled there in October 2019 to attend the opening of the Massim Canoe exhibition at the Massim Museum and Cultural Centre.

THE MASSIM CANOE EXHIBITION displayed the 22 plans of these communities’ traditional outrigger and war canoes that I had drawn after a month-long trip by motor launch in August 2017, documenting the various traditional watercraft of this remote region of Papua New Guinea (see Signals 121).

Facsimile copies of the plans had been sent ahead, and on arrival we worked with staff of the Massim Museum and Cultural Centre to reorganise the museum’s rooms, sort the plans and drawings into groups, mount them on the walls, set up the banners and help them create the display that they had in mind. We had it all together just in time, including a good interview on camera with the local media representative, Priscilla Waikaidi.

Susan Abel is a driving force behind the Massim Museum, which was set up by her father-in-law, Sir Chris Abel. She deserves much credit for the energy she put into making this happen at the Alotau end with her team: organiser Roz, trustee Jeff, staff member Lucinda and volunteers.

The Australian National Maritime Museum helped by funding all the design and printing, the stand-up banners, transport and incidental costs of the exhibition material. As part of the initiative, we engaged a local graphic designer to create the banners. The Australian High Commission generously sponsored the opening night, along with support from local businesses.

Sea and air transport are Alotau’s only connections to the rest of the country, but despite this it was a gala evening for the township, bringing many people together to talk over drinks, as well as look at the display. The Australian High Commissioner Bruce Davies and Consul General Jo Stevens attended, along with Allanah Banning and Edwina Sinclair from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, and key local community leaders from Alotau, including Provincial Administrator Ashan Numa and his deputies, Mayor Gita Elliot, Kenu and Kundu Festival chairman Harold Tabua and tourism CEO Sioni Sioni.

It was satisfying to hear first-hand how complimentary they were of the plans and the research involved, enjoying and respecting the detail and time needed to bring them up to a high standard. While we talked about them being a valuable record for the future, the speeches also reflected on the importance of the wonderful Massim canoes to the culture of the communities who built them, and the need for future generations to continue making them.

The next day the annual Huhu Bay War Canoe Festival began, across the bay at Wagawaga. This was an extraordinary experience, with a community vibrantly celebrating their tradition and culture with pride and passion. The Maritime Museum’s Indigenous Programs Curator Helen Anu and I were among just a dozen visitors and tourists at the event.

At Wagawaga the village chief, Dago Alisa, warmly welcomed us and explained some of the background and proceedings. Our group was very kindly looked after by the small team from Maxine Nadille’s Egwalau Tours. Maxine had helped me in August 2017 with introductions to the festival chairman, Kaimouyoni Ila, who had allowed me to record Kaoha, one of the canoes from his village, Maiwara.

War canoes leave the beach at the Kenu and Kundu Festival, Alotau. All images David Payne/ANMM

This is a major cultural event for the village communities on the shore of Milne Bay: Maiwara, Gibara, Camadoudou, Kilakilana, Gwavili, Gabuganabuna and the host for this festival, Wagawaga. In earlier times their war canoes were used for raids, but now the gebo or lopou war canoes come together in a festival to share food and friendship and make new connections.

It started with tepali, the arrival of feasting parties with their gifts of food and live pigs for the village chief. The pigs are trussed to tree trunks carried on shoulders, and part of the ceremony often involved ramming the trunk and its open roots against a tree next to the chief’s house. This was a symbolic gesture of old practices, as was the gift of a live pig. Pigs would be exchanged among the community, with only one becoming part of the feast. The men, carrying spears, led in the women, who were dressed in grass skirts or pandanus leaf bindings. As they approached the open area in front of the hut the men began an aggressive action timed to the beat of kundu drums, leaping forward at the crowd with spears and dressed with war paint, pig’s teeth adornments and colourful feathers. At the hut the food was deposited – or in some instances hurled up at the chief and his helpers – while each pig was placed under the hut.

Primary and secondary school groups also took part, dancing and singing as they came in, and at times groups that had already arrived broke into their entry procession dance again as we waited for the next group to come in. It rained, the wind blew, the sun came out, all adding to the wonderful atmosphere.

There was a shift in proceedings when a primary school group sang the national anthem then recited the Lord’s Prayer in the local Suau language supported by Emalyn, their cultural teacher, holding her grandfather’s ceremonial axe. The mix of cultures here includes a strong Christian faith among many of the community.

Culture was the keynote in the four speeches that were then delivered, beginning with the chairman of the festival, Kaimouyoni Ila, and ending with the local member of parliament, Charles Abel, who gave a strong speech emphasising that preserving and teaching traditional culture and developing leadership in youth were vital to future generations.

The war canoes that are part of the traditional culture of these Milne Bay communities have now evolved into a means of working together. In the afternoon, eight war canoes up to 23 metres long, with 10 to 20 warriors paddling them, moved out from the shore in a fine demonstration of the teamwork needed to control the craft. The smallest had a youthful crew with two older boys as mentors sitting bow and stern, and at least one of the larger canoes had a very young boy up front, where a light person is well placed for trim.

Teamwork is needed to build a canoe and the cultural practices still observed are reflected in many of the stages of construction. Talking with two of the builders, they indicated that younger people were learning from them, too.

Youth and elders were evident in everything we observed, and the signs are very promising that this festival will be an important part of local culture into the future. Plans are already under way for the 2020 festival.

My next task was to deliver a copy of the plans of the epoi Ealami Etana to where it was built and documented in Waluma East Village No 3 on Fergusson Island, and hopefully meet the owner, Terry Ronal, again. With delays, the trip took three days, and on arrival we found the landing too rough to bring the boat in close, and virtually no one on shore to call out to for a canoe. One of the deckhands swam ashore to ask for Terry, but he was away in his garden. Eventually we decided to swim the laminated plans onshore to leave there with his mother and son. Despite not seeing Terry Ronal, it was gratifying to know that the museum has been able to return the plans for this epoi to the community where it was documented two years ago.

At the end of the week the Alotau waterfront came alive again with the National Kenu and Kundu Festival, a huge gathering of community, stalls, dancers in traditional costume with kundu drums, singing groups, war canoes and sailing canoes. On the Friday I was interviewed on camera by PNG TV identity John Eggins from EMTV and the PNG Tourism Promotional Authority, before heading down to the shoreline for the action. The war canoes led things off with a call from a conch shell, demonstrating their paddling skills then finishing off by heading toward each other in two lines at great speed.

The Huhu Bay War Canoe Festival is a major cultural event for the village communities on the shore of Milne Bay

01

Sailau – single outrigger canoes – stage a sailing demonstration on the Alotau waterfront.

02

Facsimile plans of the Massim canoes drawn by David Payne on display at the Massim Museum and Cultural Centre in Alotau.

The National Kenu and Kundu Festival is a huge gathering of community, stalls, dancers, drummers, singing groups, war canoes and sailing canoes

This demonstration was repeated the next morning, but then they formed up beside each other way out in the distance, offshore. This was the real spectacle – a re-creation of a canoe raid. This spectacular sight started quietly, then the wall of canoes on the horizon became larger and approached faster and faster. We began to hear their chant and the sound of paddles striking the hull on each stroke, all craft in unison, before we picked out the individual boats and the mass of paddlers now coming at great speed. Arriving at the beach, paddles became weapons as warriors leapt from their craft, where they were met by a challenge from on shore.

On the Saturday afternoon, smaller sailing canoes gave a sailing demonstration, before starting a race from the shore to the other side of the bay and back. These craft – isuabiabi from Suau Island and kebwakebwai from Basaliki and Dobu Islands – were types that I had not seen in 2017, so early next morning I met owners of the craft and was able to measure up an example of each to document and draw when back in Sydney.

The on-water activities were matched on land by an extraordinary display of dancing and drumming from groups in the region. It started as they arrived in decorated,

covered trucks, packed together but already drumming a beat on their kundu. Dressed in costume, they each had many turns at performing in the arena, then gave impromptu displays off to the side, posed for photos and caught up with friends.

A tepali was held on the Saturday before the official opening and speeches. The guests were high profile – the Prime Minister, Mr Marape, Finance Minister and local member Charles Abel, along with senior administrators. This festival is a big occasion. Before returning home there was one more meeting arranged, at the National Museum and Art Gallery in Port Moresby.

There I spent time with Military Curator Dr Andrew Connelly, looking at exhibits and discussing the collection before meeting Director Dr Andrew Moutu. The National Museum and Art Gallery houses an impressive collection of artefacts and research, and is a fine showcase of the diverse Papua New Guinea culture.

Flying back to Sydney provided a chance to wind down and reflect on what had been an action-packed, vibrant and satisfying 16 days in this challenging and ultimately irresistible country – progressing the work from 2017, renewing previous contacts, making new friends and supporting the community in Milne Bay.

nationalgeographic.com.au/cosmos /natgeoau

Our Members and Foundation offices provide opportunities for you to get more involved in the museum, from supporting specific appeals to attending special events. The museum must raise more than 40 per cent of its running costs annually, and donations help to fund vital programs and exhibitions. All donors will receive an invitation to a special event to thank them for their generosity.

Thanks to our generous donors in 2017, the 1:48 scale model of SS Orontes was secured at auction. Now begins the painstaking restoration process to ensure the model is ready for display and to be enjoyed for generations to come.

This intricate model, measuring 4.2 metres long, was built in 1929 in the model workshop of the shipbuilders in England as part of the vessel’s commissioning. It is a fine example of the modelmaker’s craft in an age when ships were the largest and most technologically advanced machines in the world.

The model cost £856 pounds to build (equivalent to about $65,000 today) and was presented as a showpiece for the Orient Line Building in Sydney.

The conservation of this important model will start shortly and take up to 18 months to complete. A highlight of this process will be an X-ray to determine construction details and also confirm whether the modelmakers hid a note inside the model, as was common practice. You can be part of this important restoration project by completing the donation slip in this edition of Signals and returning it in the reply-paid envelope provided. Donors will be invited to a special white-glove tour and briefing to keep them informed of progress.

OVER THE FIRST QUARTER OF THIS YEAR, the museum has been able to pursue important programs, thanks to much-appreciated donations.

The replica of HMB Endeavour is ready to set sail with new essential fittings because of this support. Its new hammocks were funded by a generous donor, and new ropes and sail repairs were also funded by donations. To those who gave to this campaign, thank you. Your support will help inspire a nation as Endeavour travels around Australia.

The glamorous steam yacht Ena is back cruising Sydney Harbour. The museum’s new Ambassadors, Dr David and Mrs Jennie Sutherland, have contributed significantly to Ena ’s refit and the planned reconstruction of its elaborate 120-year-old boiler. One of the Foundation’s newest board members, David Mathlin, is also an Ena enthusiast and has contributed liberally to help return this Edwardian beauty to the museum’s fleet. Visitors to the museum can tour Ena daily and the vessel is also now available for private charter.

On 28 February the Australian National Maritime Museum Foundation hosted its first Annual Fundraising Gala. Its principal purpose was to generate important income for the museum. This wonderful event showcased the museum to 200 people, who enjoyed a performance by musicians from the Sydney Symphony Orchestra and a meal designed by award-winning chef Giovanni Pilu.

For more information on Foundation projects, please contact Foundation Manager Marisa Chilcott on 02 9298 3619.

For more information on upcoming events, please see pages 48–52 or phone Members Manager Oliver Isaacs on 02 9298 8349. We look forward to seeing you at the museum soon.

If you would like to donate, please go to www.sea.museum/donate

01

Some of the Members who attended the Anniversary Lunch last November, with Director Kevin Sumption PSM (second from left) and Members Manager Oliver Isaacs (far right). Image Andrew Frolows/ANMM

02

Endeavour ’s Master, John Dikkenberg, with new hammocks that generous donations enabled us to buy. Image Andrew Frolows/ANMM

Behind-the-scenes tours will focus on items from the museum’s collection

Some of the fleet of immaculately restored former Halvorsen hire cruisers at the 2018 festival.

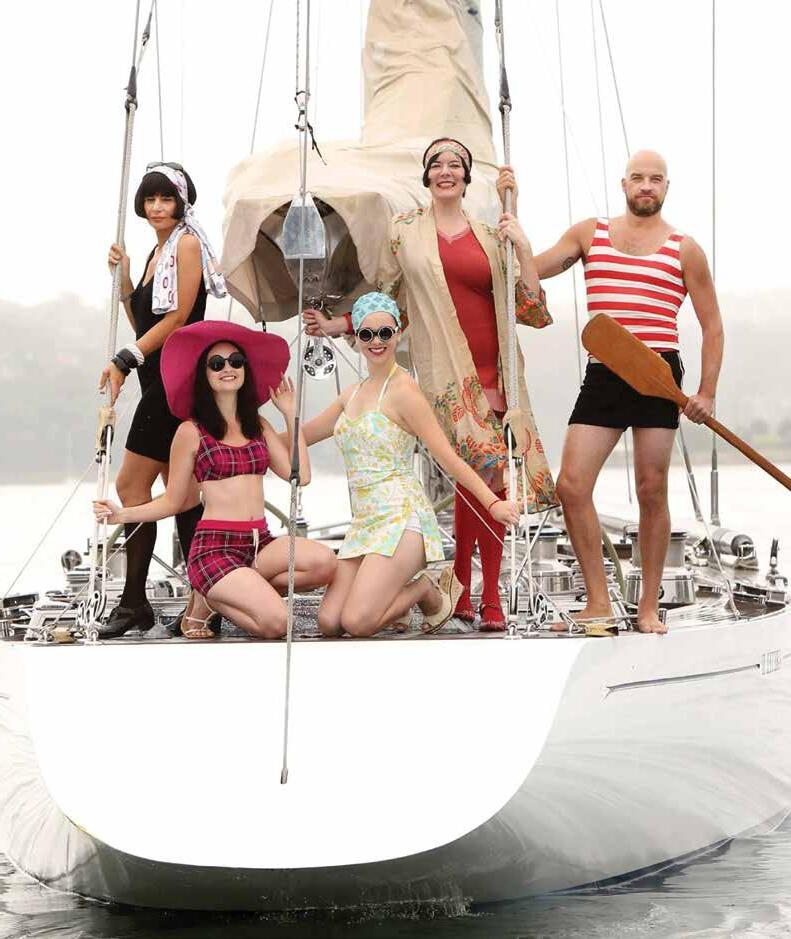

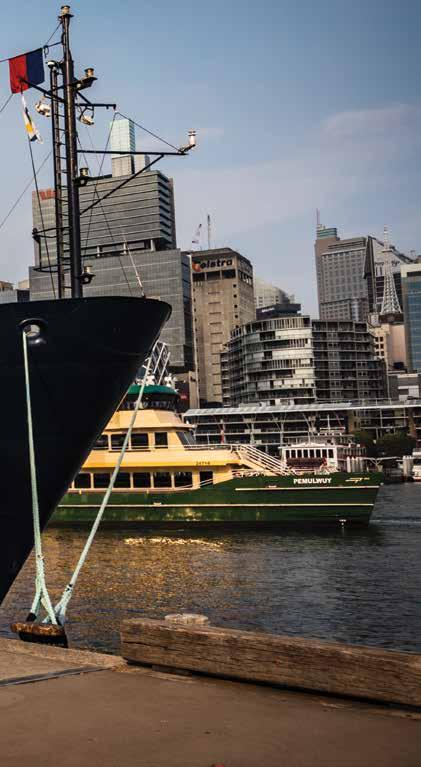

The 2020 Classic & Wooden Boat Festival is coming to the museum’s waterfront in May. It coincides with the early stages of the museum’s national program Encounters 2020, during which the replica HMB Endeavour will undertake a 14-month voyage around Australia alongside a travelling Indigenous art exhibition to mark 250 years since James Cook charted the east coast in 1770. David Payne and Alana Sharp provide a preview.

SINCE THE LAST CLASSIC & WOODEN BOAT FESTIVAL, the museum has continued to further develop this event. It will celebrate all classic and wooden boats, acknowledge traditional boatbuilding skills and showcase the passion of the dedicated craftspeople who make these unique and celebrated vessels.

More than 140 boats will join an array of stallholders at the museum from 1–3 May. The museum’s magnificent SY Ena will be one of the outstanding craft on show, along with the Sydney Heritage Fleet’s schooner Boomerang and the recently restored Southwinds, and a proud display of yachts that have contested the Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race. Also featured will be historic International 5.5, 6, 8 and 9 Metre class boats, a couple of Ranger class yachts, vintage motor craft and classic dinghies. The Halvorsen Club will showcase a huge range of this historic firm’s valuable motor cruisers and yachts, most of which are now collector’s items.

The festival program will include many other boats both afloat and on land around the museum, as well as a maritime marketplace where trades and market stalls of all types will bring out their wares for festival-goers to peruse and purchase. Further craft will be on display across the water in Cockle Bay.

Behind-the-scenes tours will focus on items from the museum’s collection, and visitors will be able to cruise on some of Sydney Heritage Fleet’s vessels, taking in the atmosphere of the festival and our beautiful harbour. The extremely popular swimwear parade will return, using the museum’s extraordinary range of ‘cossies’ from its education collection.

Throughout the day there will be music, entertainment and roving performers, workshops and trade displays, a shipwrights’ village, Kids’ Boat Shed and the very popular ‘Quick and Dirty’ Boatbuilding Challenge.

More than 140 boats and an array of stallholders will take part in the event

01

Boats of various sizes, on the shore and in the water, attracted more than 33,000 people to the 2018 festival.

02 The Quick and Dirty Boatbuilding Challenge tasks teams of children and adults to build a boat in four hours, then test its seaworthiness.

03 The popular swimwear parade focuses on the evolution of beach fashion.

The extremely popular swimwear parade will return using the museum’s extraordinary range of ‘cossies’ from its education collection

Keep the first weekend of May free to come to the museum and feast your eyes on glorious boats of all shapes and sizes

A series of talks in the museum’s theatre promises to be a highlight, with panel sessions on diverse themes: ‘World Sailing Women’, featuring Wendy Tuck and Kay Cottee; ‘Rust to Ritz’, in which Simon Sadubin, Ian Smith and David Payne will talk about restoration projects; ‘Australia’s Sailing Legends’, with Adrienne Cahalan, Mike Fletcher and John Stanley; and ‘The Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race: History, Hazards & Heroes’, with veteran sailors focusing on the great yachts and individuals who have helped make this race one of the world’s great ocean classics. For more details about these talks, please see page 50.

Make sure to keep the first weekend of May free to come to the museum, feast your eyes on glorious boats of all shapes and sizes and talk to the owners and other enthusiasts. For more information visit our website at sea.museum/cwbf or sign up for our email updates at cwbf@sea.museum.

Star vessels

Yachts

Caprice of Huon

Southwinds

Fidelis

Acrospire IV

Kelpie

Maris

Boomerang (Sydney Heritage Fleet)

Britannia skiffs – the museum’s original and Ian Smith’s replica versions

Motor vessels

Dorothy T Goolara

Bennelong

Athena

SY Ena

Hammondcraft clinker ski boats

More than 140 boats and an array of stallholders will take part in the event

Wildlife Photographer of the Year returns to the museum, celebrating the very best nature photography and photojournalism. On display are the top 100 images chosen from almost 50,000 entries worldwide.

The winning images challenge us to consider both our place in the natural world and our responsibility to protect it

01

Sleeping like a Weddell by Ralf Schneider (Germany).

Hugging its flippers tight into its body, the Weddell seal closed its eyes and appeared to fall into a deep, contented sleep. Shooting from a boat, Ralph tightly framed the sleeping seal against the ice-covered background.

© Ralf Schneider/Wildlife Photographer of the Year

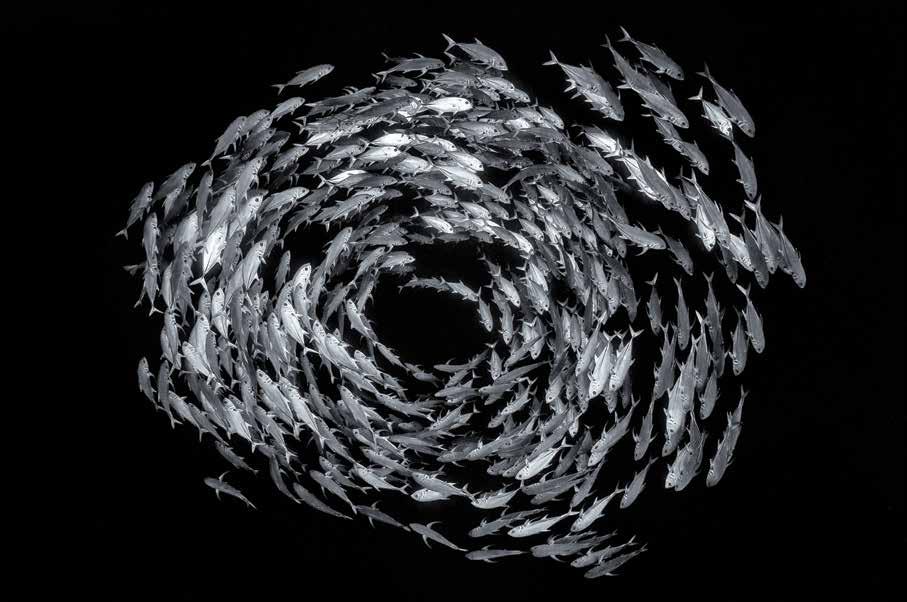

02

Circle of life by Alex Mustard (UK).

In the clear water of the Red Sea, a shoal of bigeye trevally circles 25 metres down at the edge of the reef. For the past 20 years Alex has travelled here, to Ras Mohammad – a national park at the tip of Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula – to photograph the summer-spawning aggregations of reef fish. © Alex Mustard/ Wildlife Photographer of the Year

A SLEEPING SEAL, a zombie beetle and a tragic turtle are just some of the captivating and emotive images from the Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition, which is now in its 55th year.

The competition, developed and produced by the Natural History Museum, London, features the world’s best nature photography and photojournalism. The winning images showcase wildlife photography as an art form and challenge us to consider both our place in the natural world and our responsibility to protect it.

The origins of the Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition go back to 1965, when the three available categories attracted around 600 entries. Even then, it was the leading event of its kind for nature photographers. It grew in stature over the years and in 1984, the competition as it is known today was created.

The international judging panel comprises respected wildlife experts and nature photographers. Images are chosen for their artistic composition, technical innovation and truthful interpretation of the natural world.

Dr Tim Littlewood, Director of Science at the Natural History Museum and a member of the judging panel, says:

For more than 50 years this competition has attracted the world’s very best photographers, naturalists and young photographers, but there has never been a more important time for audiences all over the world to experience their work in our inspiring and impactful exhibition. Photography has a unique ability to spark conversation, debate and even action. We hope this year’s exhibition will empower people to think differently about our planet and our critical role in its future. Wildlife Photographer of the Year opens on 5 March. 03

Pondworld by Manuel Plaickner (Italy). To take this image, Manuel immersed himself and his camera in a large pond where hundreds of frogs had gathered.

© Manuel Plaickner/Wildlife Photographer of the Year

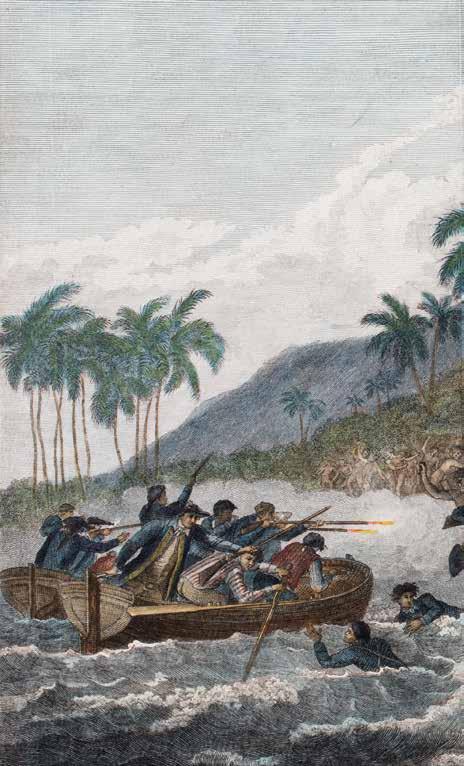

During the great age of Pacific voyaging, ‘scientific’ expeditions also had colonial goals and were backed by military power and strategy. From the earliest days, they were also resisted by Pacific peoples. By Dr Stephen Gapps .

IN EARLY SEPTEMBER 1770, when Lieutenant James Cook had sailed his ship HMB Endeavour from Australian shores and was passing Papua New Guinea en route to Timor and then Batavia, a strange event occurred. Along with naturalists Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander, and with only a few crew, he landed a small boat on what seemed to be a deserted beach, but did not feel safe to venture into the close, thick bush ‘in fear of an ambuscade’ (ambush).1

Officers on board Endeavour watched through telescopes as Cook and his men suddenly came under attack by New Guinea locals. Alarmingly, and to their surprise, they saw puffs of smoke that looked like the powder flash of flintlock muskets. According to Cook’s report, the men on Endeavour genuinely believed he was under attack by firearms: 2

… what appear’d most extraordinary to us was something they had which caused a flash or fire or [smoke], very much like the going off of a Pistol or sm’ll Gun … When 4 or 5 would let them off all at once [this] had all the appearances in the world of Volleys of Small Arms …

Cook thought these weapons might have been used in imitation of firearms, but could only guess at their use. It seems that the weapons were bamboo poles with burning tinder inside that could cloud the user in smoke and serve as a threat or challenge. Whatever the case, ‘small parties of natives’ advanced from the woods, causing Cook and his men to return to their ship. He ordered that they sail westward and leave the coast.

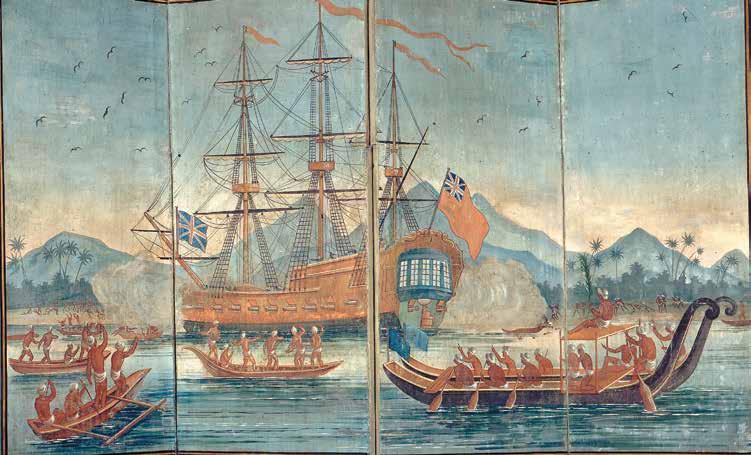

This was not the first, nor the last, time that European voyagers in the Pacific, such as Cook, were deterred by local people. In 1595, the Marquesas Islanders had repelled the Spanish navigator Alvaro de Mendana; in 1760, a four-day battle ensued between islanders and Europeans when Samuel Wallis, in the Dolphin, landed in Tahiti; and in 1789, William Bligh was forced from Tofua by a hostile local reception (see Signals 128). These commanders, like many European voyagers in the Pacific, did not choose their routes or landings, but were often bounced around islands and coasts according to military advantages or disadvantages.

Mort de Cook (Death of Cook), 1887. This handcoloured engraving is based on an original painting by

The military nature of Endeavour ’s voyage is often overlooked or downplayed

John Webber, the official artist for Captain Cook’s third voyage of the Pacific. ANMM Collection 00002925

John Webber, the official artist for Captain Cook’s third voyage of the Pacific. ANMM Collection 00002925

Imperial science and conquest

When Endeavour left New Guinea, both Cook and Banks noted that the crew’s morale improved. Banks put it down to nostalgia, but another factor may well have been the knowledge they were finally heading toward European colonies, and no longer needed to maintain a constant state of military alert.

During the New Guinea episode, Endeavour had only four cannon, having jettisoned six of them to lighten the ship’s load when it foundered on the Great Barrier Reef several weeks earlier. 3 Cannon such as those dumped overboard by Cook now make good museum objects and monuments in public parks. Inert and detached from their original purpose, they rarely tell the story of what they were designed for, or their critical role in the colonisation of Oceania. Often, like those on Endeavour, they were rarely, if ever, used – the power of artillery fire had been swiftly learned by Pacific peoples after Europeans first arrived in the 1500s, many years before Cook (see Signals 128).

There are few overarching military histories of the resistance warfare that occurred across the Pacific from the 1500s right through to conflicts such as Samoan resistance to German imperial rule in 1908. Long, inexorable and disparate warfare and conflicts are not the terrain of heroic or packageable histories. Military historians tend to focus on modern wars as ‘proper’ military history. Yet conflict across the Pacific was surprisingly interconnected over time and across vast regions, and even influenced military thinking back in London.

Before Endeavour left Plymouth in 1768, its complement of marines and arms, and even tactics when encountering Pacific peoples, were all refined by reports from other voyagers such as Wallis.4

The military nature of Endeavour ’s voyage – as part of an aggressive reconnaissance as well as a floating defence against indigenous resistance and counterattack – is often overlooked or downplayed, despite the many instances of conflict and the use of musket fire to teach lessons of British military superiority that underscored almost all of Cook’s Pacific encounters with indigenous peoples.

In the broader strategic sense, Cook’s voyages – like all scientific expeditions of the 18th and early 19th centuries – were also part of a European drive to conquer people and claim resources that would support the expansion of the British empire. During the great age of Pacific voyaging, expeditions always had several goals. Victory in the Seven Years War (1756–63) caused a surge in British imperial ambition, and Cook’s first voyage came soon after, at the height of the promotion of ‘imperial science’ as a critical part of both establishing an empire and managing the development and control of the state during the upheavals of industrialisation in Europe.

‘Scientific’ voyages were primarily a 19th-century development after the Napoleonic Wars, when science and spying had become fine arts under commanders such as Nicholas Baudin. 5 Even Cook, as was expected of any seagoing commander visiting distant stations, made military reconnaissance notes.

Conflict across the Pacific was surprisingly interconnected over time and across vast regions, and even influenced military thinking back in London

01

Captain Samuel Wallis attacked in the Dolphin by Otahitians (detail), artist unknown, c 1800. The painting on this folding screen was copied from an engraving in John Hawkesworth’s 1773 book of Pacific discoveries. ANMM Collection 00006125

02

Neptune raising Captain Cook up to Immortality, a Genius crowning him with a wreath of oak, and Fame introducing him to History, engraver J Nagle. Frontispiece to New System of Geography by the Reverend Thomas Bankes, publisher J Cooke, London, c 1790. ANMM Collection 00001398

In November 1768, when Endeavour provisioned at Rio de Janeiro, the local viceroy was suspicious of a voyage supposedly to observe the transit of Venus, and he considered that Cook was seeking to extend British influence in the Pacific. Cook duly noted down in his journal the state of local defences, and that it ‘would [only] require five or Six sail of the Line to insure Success’.6

Even though Cook felt insulted at being carefully watched and was annoyed by the viceroy’s scientific ignorance, the latter was indeed correct. After opening his supplementary instructions, or so-called ‘secret orders’, Cook headed off to find and claim for Great Britain the southern land that was thought to exist in the vast southern ocean.7

Every European ship that voyaged the Pacific was, in the first instance, a floating fortress and an independent command, able to send out small shore parties or to concentrate firepower as needed. And this was at the heart of all contact, all encounters, all attempts at communication with Pacific and other peoples. Make no mistake, though; restraint in British policy and conduct with indigenous peoples in the Pacific could be done securely from behind the barrel of a gun.

Cook has often been fêted as one of the few 18th-century voyaging commanders who was tolerant of indigenous people and cultures. But this must be tempered as a tactic; it was tolerance in pursuit of domination. The best military commander rarely has to resort to open conflict.

Cook’s exploration did not take place in uninhabited lands and seas, but among thriving voyaging cultures that were ultimately forced to submit to Europeans. It is important to remember the military factors in Cook’s and all other voyages in the Pacific and around Australia. They remind us of what underlined, if not defined, cross-cultural encounter moments. Addressing the fact that these expeditions were all of a military nature reminds us that European colonisation was resisted from its very first moments nearly 500 years ago.

References

1 J C Beaglehole (ed) 1955, The Journals of Captain James Cook on his Voyages of Discovery, Volume 1, Hakluyt Society, Cambridge University Press, p 409.

2 Ibid

3 The remaining cannon may now lie in Newport Harbor, Rhode Island –see Signals 125.

4 The secret orders note that Wallis described the Tahitians as ‘treacherous’. Beaglehole, op cit, ‘The Instructions’, page cclxxx.

5 See John Gascoigne, Science in the service of empire: Joseph Banks, the British state and the uses of science in the age of revolution, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1998.

6 Beaglehole, op cit, p 31.

7 The secret orders can be viewed in Under Southern Skies (the museum’s refurbished Navigators Gallery) from late April. They are also available online at the National Library of Australia: nla.gov.au/nla.obj-229102048/view

South Australian was one of the earliest vessels to ferry European settlers to the colony of South Australia

01

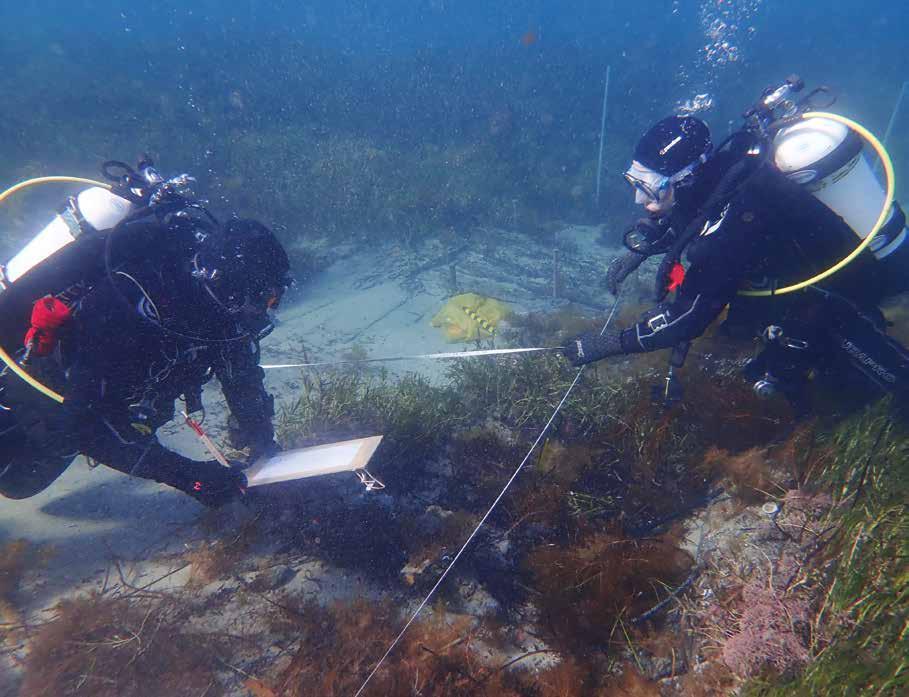

Silentworld Foundation maritime archaeologist Irini Malliaros and Flinders University Master of Maritime Archaeology student Tim Zapor document South Australian ’s bow section in June 2019. The vessel’s stem post and bow cant frames are visible in the foreground. Image James Hunter/ANMM

02

This early-19th-century ceramic mineral water bottle was one of the artefacts that helped confirm South Australian ’s identity. It was very likely manufactured in Germany, the world’s largest manufacturer of mineral water at the time. Image Irini Malliaros/Silentworld Foundation

Nearly 200 years after its loss, the barque South Australian was relocated by a research consortium that included the museum’s maritime archaeology team. Dr James Hunter and Kieran Hosty share the story of South Australia’s oldest recorded European shipwreck, and the effort to find, document and preserve it.

SHORTLY AFTER 5 AM ON 8 DECEMBER 1837, Captain J B T MacFarlane peered into the grey dawn with a growing sense of dread. From the weather deck of the barque South Australian, he could just make out the lee shore of Rosetta Harbour, a short distance to the north and west. Located along the southern coast of the Fleurieu Peninsula in the fledgling colony of South Australia, Rosetta Harbour was the anchorage for three shore-based whaling stations and the watercraft that supplied and supported them. South Australian was one such vessel, and had been moored in the harbour for about a week as its crew prepared to load the whaling stations’ takings for the season. The harbour was suitable when seas and winds were calm, but completely open to the south and southeast, and susceptible to the worst weather the Southern Ocean could throw at it.

‘A very heavy gale with a tremendous sea’

MacFarlane now found his vessel at the mercy of a southeasterly gale that steadily increased in fury as the sun rose above the horizon. At 10.05, the chain to South Australian ’s starboard bower anchor parted; MacFarlane mustered all hands and ordered them to quickly deploy the barque’s sheet anchor –an action of absolute last resort. This steadied the barque, but the reprieve was brief: at 11 am, a severe squall screamed through the anchorage, followed by another at 2 pm that caused South Australian to ‘labour and pitch very heavy’ at its two remaining anchors.1 The wind and sea state were still increasing three hours later when both anchor cables parted from the strain. Now adrift, South Australian was pushed towards a thin strip of reef that divided Rosetta Harbour from east to west. The barque struck at 5.30 pm, and its rudder was wrenched away as it passed over the reef. Adrift once more, South Australian finally grounded and bilged in shallow water a short distance from shore.

Nearly 200 years later, in April 2018, we were part of a collaborative team comprising maritime archaeologists, museum specialists, students and volunteers from Silentworld Foundation, South Australian Maritime Museum, South Australian Department for Environment and Water, MaP Fund and Flinders University that successfully located South Australian. The discovery is of considerable importance, as the vessel is South Australia’s oldest known European shipwreck. It was also one of the earliest vessels to ferry European settlers to the colony of South Australia, and is currently the only example in the world of a purpose-built postal packet to have been archaeologically investigated.

Postal packet to processing platform

South Australian was launched as Marquess of Salisbury at Falmouth, England, in 1819. 2 Originally rigged as a ship, the 236-ton vessel was designated a Falmouth packet, a unique class designed to quickly carry mail between Great Britain and overseas ports within its far-flung empire. Its owner and master, Thomas Baldock, was a former naval officer who had served with distinction in North America during the War of 1812. In 1824, Marquess of Salisbury was purchased by the Royal Navy, renamed HMS Swallow and commissioned as a naval packet. Baldock was reappointed to the Royal Navy the same year and given command of Swallow, then embarked upon a number of transatlantic voyages to North and South America and the Caribbean. While under the command of Baldock’s successor Lt Smyth Griffith in 1834, Swallow was dismasted in Cuban waters during a hurricane and underwent significant repairs in Havana. Two years later, it was decommissioned and sold to the South Australian Company (SAC), a British mercantile enterprise founded in 1835 to establish a colony of free European settlers in what is now South Australia.

After the SAC acquired Swallow in September 1836, it was re-rigged as a barque and renamed South Australian. The hull was adapted to transport migrants, although the SAC’s ultimate intention was to use the vessel for whaling upon its arrival in the colony. South Australian departed Plymouth in December 1836 under the command of Captain Alexander Allen. Aboard was a contingent of primarily British and German emigrants, including David McLaren (the SAC’s second commercial manager), John and Samuel Germein (credited as the founders of Germein Town, South Australia) and ship’s surgeon Dr William H Leigh. The passengers were mostly skilled labourers. Also aboard were breeding stock including bulls, heifers, pigs and cashmere goats. South Australian arrived at Kingscote on Kangaroo Island on 22 April 1837, where its passengers and cargo were discharged.

In May, South Australian left Kangaroo Island with whaling equipment and provisions for shore-based whaling stations at Rosetta Harbour. While there, Captain Allen was ordered to refit it as an offshore whale processing platform, or ‘cutting-in’ vessel. South Australian completed one last round-trip voyage to Kangaroo Island in November 1837. Now under the command of Captain MacFarlane, it arrived back at Rosetta Harbour at the end of the month and the crew prepared the whaling station’s produce for shipment aboard Solway, another SAC vessel.

During the wrecking event on 8 December, South Australian grounded in front of the Fountain Inn, the only structure then present on Rosetta Harbour’s shoreline that still stands today. Aboard were David McLaren, John Hindmarsh Jr (son of South Australia’s first governor, Rear-Admiral Sir John Hindmarsh) and Sir John Jeffcott (South Australia’s first chief justice). The wreck was extensively salvaged over subsequent weeks, although South Australian ’s logbook notes that the lower hold was flooded and could not be accessed. In an ironic twist, Solway finally arrived at Rosetta Harbour two weeks later than expected, but was lost on 21 December 1837, under circumstances almost identical to those of South Australian.

In subsequent years, South Australian broke up and eventually disappeared, its exact location lost to memory. Historic charts and sketch maps created shortly after the wrecking event, however, provided a relatively clear indication of where the loss occurred. This information, as well as anecdotal evidence from local residents and the results of remote-sensing surveys conducted in the 1990s by maritime archaeologists affiliated with South Australia’s then-Department of Environment and Heritage, enabled our team to establish a refined search area for the wreck in early 2018.

The survey area was split into 12 grids, each 10 metres square. Due to inclement weather during the first three days of fieldwork, our efforts initially concentrated on inshore reef flats. A metal detector survey was undertaken to search for debris that could help pinpoint the shipwreck’s location. On the first day, several artefacts of interest were identified, including iron fasteners, copper sheathing and hull timber fragments – the latter of which featured adhering copper-alloy sheathing and/ or fasteners. On 19 April, with weather improving, the team undertook a magnetometer survey seaward of the reef edge. We located a number of large magnetic anomalies, one of which was tentatively identified as iron standing rigging.

Early the next morning, the shout of ‘pink tubes!’ could be heard across the waters of Rosetta Harbour when a team member located a series of copper-alloy bolts poking above the sand and seagrass in shallows directly offshore from the Fountain Inn. During subsequent dives, we recorded additional hull features and small finds that – when taken in conjunction with the site’s geographic location – confirmed its identity as South Australian.

01

Double planking in the recentlyexposed midships section was probably used to repair and reinforce South Australian ’s ageing exterior hull. Note the higher degree of preservation exhibited by the planks when compared to the worm-eaten frames just above them that have been uncovered for much longer. Image Kieran Hosty/ ANMM

02

From left: Maddy Chadrasekaran (Flinders University maritime archaeology student), Rick Bullers (maritime archaeologist, SA Department for Environment and Water) and Tim Zapor conduct a metal detector sweep within shallows just inshore of South Australian ’s wreck site. Image Irini Malliaros/Silentworld Foundation

Historic charts and sketch maps created shortly after the wrecking event provided a relatively clear indication of where the loss occurred

01

Irini Malliaros removes a timber sample from one of South Australian ’s ceiling planks. Some of the ‘pink tubes’ (copper-alloy bolts) that led to the shipwreck’s discovery are visible in the foreground. Image Tim Zapor

02

James Hunter (left) and Kieran Hosty use baseline-offset mapping to record the hull structure in South Australian ’s bow. Image Tim Zapor

The wreck site has until very recently been protected by a covering of sediment and seagrass, which for some reason is now eroding away

Despite the shipwreck’s exposed position, most – if not all –of its lower port hull survives intact, while the starboard side is less well preserved. Articulated hull components include the keel and keelson, floors and futtocks (the frames, or ‘ribs’, of the ship), bow cant frames, hull (external) planking, ceiling (internal) planking, remnants of the foremast step and portions of the stem assembly. The remarkable state of preservation indicates that the site has up until very recently been protected by a covering of sediment and seagrass, which for some reason is now eroding away.

The arrangement of the bow cant frames suggests a vessel with relatively fine lines. This reinforces the site’s identity as South Australian, given that Falmouth packets were typically designed for speed. The lower portion of the hull is doubleplanked and covered in copper-alloy sheathing, indicating that the vessel operated in tropical waters and underwent extensive refit and repair to prolong its use. Species identification of timber samples recovered from the wreck revealed the vessel was constructed mainly from white oak (Quercus robur); however, other samples yielded unusual or unexpected results. For example, the exterior layer of the double hull planking was Swiss pine (Pinus cembra), while some treenails were teak (Tectona grandis). Both species are atypical for early19th-century British-built ships (which were almost exclusively constructed of white oak) and were probably used in later repairs to South Australian ’s ageing hull.

A range of artefacts was observed, including intact glass bottles, glass and ceramic fragments, bricks, wooden barrel staves, gunflints and various copper–alloy and iron fastenings. The bottles and decorated ceramics all date to the early 19th century, and the bricks and barrel components could comprise whaling supplies that were stowed in the vessel’s lower hold and could not be salvaged. Taken together, the date range and types of artefacts in the assemblage all support the wreck’s identity as South Australian.

In the wake of South Australian ’s discovery, follow-up surveys and site inspections were carried out in May and July 2018, and again in June 2019. These visits revealed that sediment has steadily eroded from the site and uncovered extensive hull structure in the bow and midships areas. This has been beneficial in documenting the site, but has also exposed the wreck’s fragile timbers and artefacts to damage and destruction from natural processes, including marine borers, wave action and sediment scour. Previously buried portions of the port hull have progressively become more visible since April 2018, and a large seagrass-covered sediment mound that still protects much of the stern was observed to be eroding in June 2019.

The speed and extent to which these areas have been uncovered has alarmed our team and underscored the need for additional investigation of the wreck and the development of strategies to aid South Australian ’s future management and protection. The team hosted a community meeting in Victor Harbor in December 2019 to announce our findings and gauge community support for conservation management options. These range from completely covering the site in sandbags to partial or complete archaeological excavation. Community consultation is ongoing, and we plan to revisit the site later this year to continue our investigations.

1 Logbook of the Barque South Australian (27 October – 21 December 1837), Entry for Friday, 8 December 1837. Royal Geographical Society of South Australia, MS 95c.

2 Although officially named Marquess of Salisbury, the vessel is listed in some archival sources – including Lloyd’s Register of Shipping – as Marquis of Salisbury. The variation in spelling is likely a common transcription error in which the French ‘Marquis’ was used in place of the English ‘Marquess’. Marquess of Salisbury was named for the 7th Earl of Salisbury, James Cecil, who was bestowed the title 1st Marquess of Salisbury in 1789. Cecil served as Joint Postmaster General from 1816 to 1823 and oversaw the Falmouth packet service during his tenure.

Further reading

Bullers, Rick, 2018, ‘South Australian news: Search and discovery of South Australian ’, AIMA Newsletter, Vol 37 No 2, pp 12–14.

Bullers, Rick, Malliaros, Irini and Hunter, James, 2018, ‘The barque South Australian: Discovery and documentation of South Australia’s oldest known shipwreck’, AIMA Newsletter, Vol 37 No 2, pp 15–19.

Heritage South Australia, DEW, 2018, Historic Shipwreck South Australian (1819-1837): Conservation Management Plan. Government of South Australia, Department for Environment and Water, Adelaide.

Hunter, James, ‘Barque South Australian ’, SA History Hub, History Trust of South Australia (sahistoryhub.com.au/things/barque-south-australian). Accessed 12 February 2020.

Parsons, Ronald, 1981, Shipwrecks in South Australia, 1836–75. Ronald Parsons, Adelaide.

Pawlyn, Tony, 2003, The Falmouth Packets 1689–1851. Truran, Truro (Cornwall).

Commerson’s cabin boy, ‘Jean’, was actually a woman named Jeanne Baret

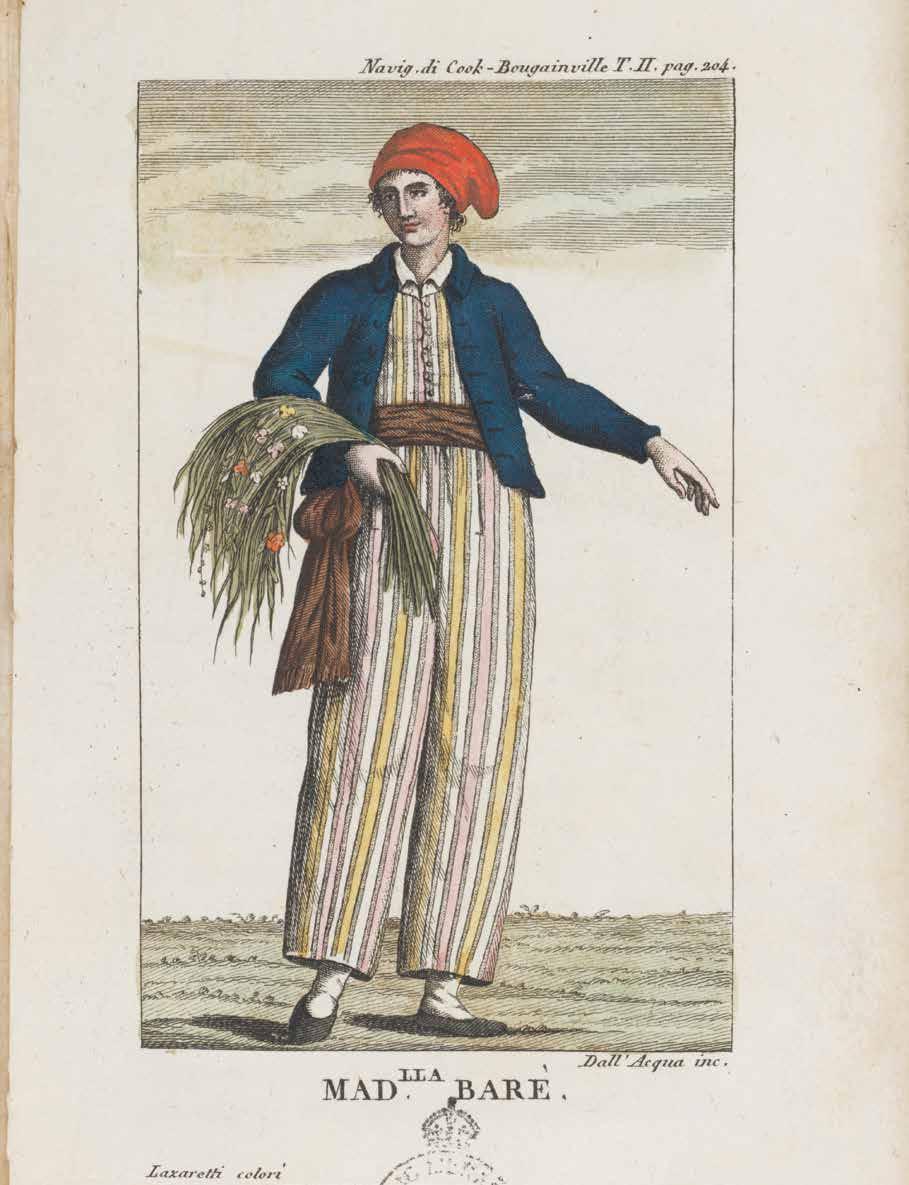

The first known image of Jeanne Baret, from 1816. Although her disguise is unlikely to have looked like this (especially with a revolutionary cap), the foliage signifies her dedication to botany.

From Navigazioni di Cook del grande oceano e intorno al globo, Volume 2, 1816, Sonzogono e Comp, Milano. Reproduced courtesy State Library of NSW FL3740703

‘She will be the first woman that ever made it’

Jeanne Baret was a talented and ambitious young woman who escaped a life of rural poverty in the mid-18th century and, disguised as a man, set out on a risky journey of botanical discovery. In doing so she became the first woman known to circumnavigate the globe, writes Myffanwy Bryant .

IN SEPTEMBER 2019, 77-year-old British woman Jeanne Socrates became the oldest person to circumnavigate the world alone, non-stop and unassisted. It was an enormous achievement in the history of sailing. She attributed her success to the fact that she had ‘persevered and overcome so many problems on the way around’.1 Another Jeanne, 250 years earlier, might well have laughed wryly at this understatement. In her own way she had also circumnavigated the world and overcome various trials, although in her case it had taken nine long years to get home.

In 1767, Europe was in the midst of the Enlightenment. European powers had a mania for exploration and were scrambling for new territories and trading partners. With scientific aspirations and wide political support, King Louis XV of France agreed to an expensive round-the-world expedition headed by Louis de Bougainville. This ambitious journey – the first of its kind for France – was as much a display of power and influence as a practical expedition of discovery. The ships assigned for the trip were the frigate Boudeuse and the slower supply ship Etoile. The Etoile carried a mixed bag of officers and crew under the leadership of the experienced and level-headed Captain François de la Giraudais.

Philibert Commerson was awarded the role of expedition botanist directly by the king, and was directed to ‘make all the observations and relative discoveries on the coasts and even in the interior of the various countries’.2 Such an ambitious undertaking allowed Commerson his own cabin to house the extensive equipment and resources that would be required. He was also permitted to bring a personal assistant. Commerson was known for being particularly zealous in his collecting, often at a high physical cost to himself. His intensity was also reflected in a difficult personality. He was described as ‘waspish’, with little tolerance for those who did not support his endeavours. Ambitious, judgmental and single-minded, he was not the ideal candidate for a two-year journey at sea. It would be difficult to imagine a more hostile environment than below the decks of an 18th-century naval ship, where hardened men lived by their own rules to survive in cramped and confronting conditions for years on end. So at Rochefort in western France in February 1767, when Commerson and his servant boarded the Etoile, their trepidation must have been considerable. Neither had been on a ship before and neither could have anticipated the conditions they were walking into. This was perhaps more so for Commerson’s cabin boy, ‘Jean’, who was actually a woman named Jeanne Baret.

With scientific aspirations and wide political support, King Louis XV of France agreed to an expensive roundthe-world expedition

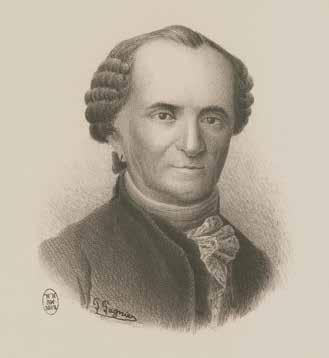

01 Portrait of Louis de Bougainville by Louis Boilly. Bougainville was a highly acclaimed naval and military commander who also showed sensitivity and respect for Jeanne, and ensured she was not forgotten later in life. National Library of Australia nla.obj-296177599

02 Philibert Commerson by P Pagnier, 19th century. Image © Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris

Jeanne had been born in rural Poil, in central France. Although poor, she was clearly intelligent and determined enough to make her way out of her tiny village to the nearby town of Toulon-aux-Arroux, a world away from where a woman in her circumstances could have expected to end up at that time. Here she became housekeeper for Commerson and began to assist him in his botanical work. Over time, with Commerson’s physical ailments restricting him more and more, Jeanne seems to have become indispensable. When Commerson moved to Paris to further his career, Jeanne accompanied him.

Much has been made of Jeanne’s devotion to Commerson and she is often referred to primarily as his lover. But while she was in a relationship with Commerson, theirs was not an adolescent romance – they were 27 and 40 respectively – nor did Commerson’s personality suit the ideal of a romantic hero. This narrow view also reduces Jeanne’s role in Commerson’s life to an accessory and certainly undermines her own individual achievements. For it is clear that both were ambitious, and over time their partnership grew into one of dependency and collaboration. They never married, although they had a son together whom they adopted out, and their story was much more complex than that of a master and a housekeeper restrained by class conventions.

We can only speculate on what happened when Commerson was awarded his coveted role on Bougainville’s expedition, and it is easy in hindsight to attribute reasons for the risks the pair took. Did Jeanne ask to accompany Commerson out of loyalty, or because of her own intellectual pursuits or a desire for new experiences? Or did Commerson ask Jeanne to come, realising that he was unlikely to achieve his scientific goals without her assistance? While a male apprentice might have provided professional support, Commerson’s persistent ill health now required a personal carer also, and to reveal this might have jeopardised his prized royal appointment. In Jeanne, he had the best of both roles. Their decision probably combined all of these reasons, both knowing this opportunity was too important to turn down.

Jeanne was certainly not the first male impersonator in the 18th century. Some, such as soldier Hannah Snell or pirate Mary Read, both British, were celebrated through ballads, books and stage shows. There were probably other women whose true identity was never revealed. Of those who were exposed and told their stories, there were accepted reasons – mainly romantic or patriotic – that explained their unconventional actions. Mostly, they were thought to have assumed a disguise to follow a lover – with the assumption that they would later live happily ever after – or to fight for their country. Whatever narrative was spun, these wayward women would always return safely home and resume a traditional female life. Part of the appeal of such stories for the public was how the women managed to keep their disguise amid groups of men. For Jeanne, heading into open oceans for years, it was of particular concern.

From the outset, life on the crowded 104-foot (32-metre) Etoile was difficult. Commerson was sick for weeks and a persistent leg ulcer confined him largely to the cabin. Although this might have supplied a plausible reason for ‘Jean’ to be constantly by his side, including sleeping in his cabin, suspicion grew quickly on board at the devotion the cabin boy showed his master. When the Etoile reached Rio de Janeiro in June, the suspicions about Jeanne appear to have become more solid, with one source suggesting that de la Giraudais was informed of the deceit happening under his nose. 3 When the expedition left in November, however, Jeanne and Commerson remained aboard, accompanied by a bulging collection of specimens foraged ashore.

Bad weather dogged the onward journey and unresolved tensions continued to fester. Commerson equated shipboard life to living like a mouse in a trap, where ‘nothing can be done and one can only gnaw at the bars’.4 When the exhausted expedition reached Tahiti in April 1768, the ruse was finally exposed –not by the Etoile crew, but by the Tahitians. Bougainville records that they took one look at Jeanne and knew she was a woman. His journal entry on the event is brief but very telling, and records the lies Jeanne told in an attempt to mitigate the deception:5

For some time there was a report in both ships, that the servant of M de Commerçon, named Baret, was a woman. His shape, voice, beardless chin, and scrupulous attention of not changing his linen or making the natural discharges in the presence of anyone, besides several other signs, had given rise to, and kept up this suspicion. But how was it possible to discover the woman in the indefatigable Baret, who was already an expert botanist, had followed his master in all his botanical walks, amidst the snows and frozen mountains of the Strait of Magellan, and had even on such troublesome excursions carried provisions, arms, and herbals, with so much courage and strength, that the naturalist had called him his beast of burden? A scene which passed at Tahiti changed this suspicion in to certainty. M de Commerçon went on shore to botanise there; Baret had hardly set his feet on shore with the herbal under his arm, when the men of Tahiti surrounded him, cried out, It is a woman, and wanted to give her the honours customary on the isle. The Chevalier de Bournand, who was upon guard on shore, was obliged to come to her assistance, and escort her to the boat. After that period it was difficult to prevent the sailors from alarming her modesty. When I came on board the Etoile , Baret, with her face bathed in tears, owned to me that she was a woman; she said that she had deceived her master in Rochefort, by offering to serve him in men’s clothes at the very moment he was embarking; that she had already before served a Geneva gentleman at Paris, in quality of a valet; that being born in Burgundy, and become an orphan, the loss of a law-suit had brought her to a distressed situation, and inspired her with the resolution to disguise her sex; that she well knew when she embarked that we were going round the world, and that such a voyage had raised her curiosity. She will be the first woman that ever made it, and I must do her the justice to affirm that she has always behaved on board with the most scrupulous modesty. She is neither ugly nor handsome, and is no more than twenty-six or twenty-seven years of age. It must be owned, that if the two ships had been wrecked on any desert isle in the ocean, Baret’s fate would have been a very singular one.

Despite Bougainville’s obvious admiration for Jeanne, and Commerson’s insistence that he had also been deceived by her disguise, the captain knew the situation must be resolved, both for Jeanne’s safety and French naval regulations at the time. While Bougainville clearly could not abandon Jeanne in Tahiti, neither could he return to France with her still on board after years at sea. And so Jeanne remained on Etoile, sequestered from the disgruntled men, enduring the ordeal as the months wore on. And wear on they did. The expedition became fraught with difficulties and was now a voyage of endurance rather than discovery. Food and water shortages exacerbated the sickness that ravaged the ship. After resorting to eating the ship’s rats, Bougainville at last ordered the ship’s dog to be served up to his starving officers. Adverse weather reduced the voyage to a sluggish crawl until at last the two ships limped into the colonies of the Dutch East Indies, and deliverance.

During their time at Mauritius, Jeanne and Commerson dedicated themselves to studying the flora of the region, collecting and recording more than 1,000 species

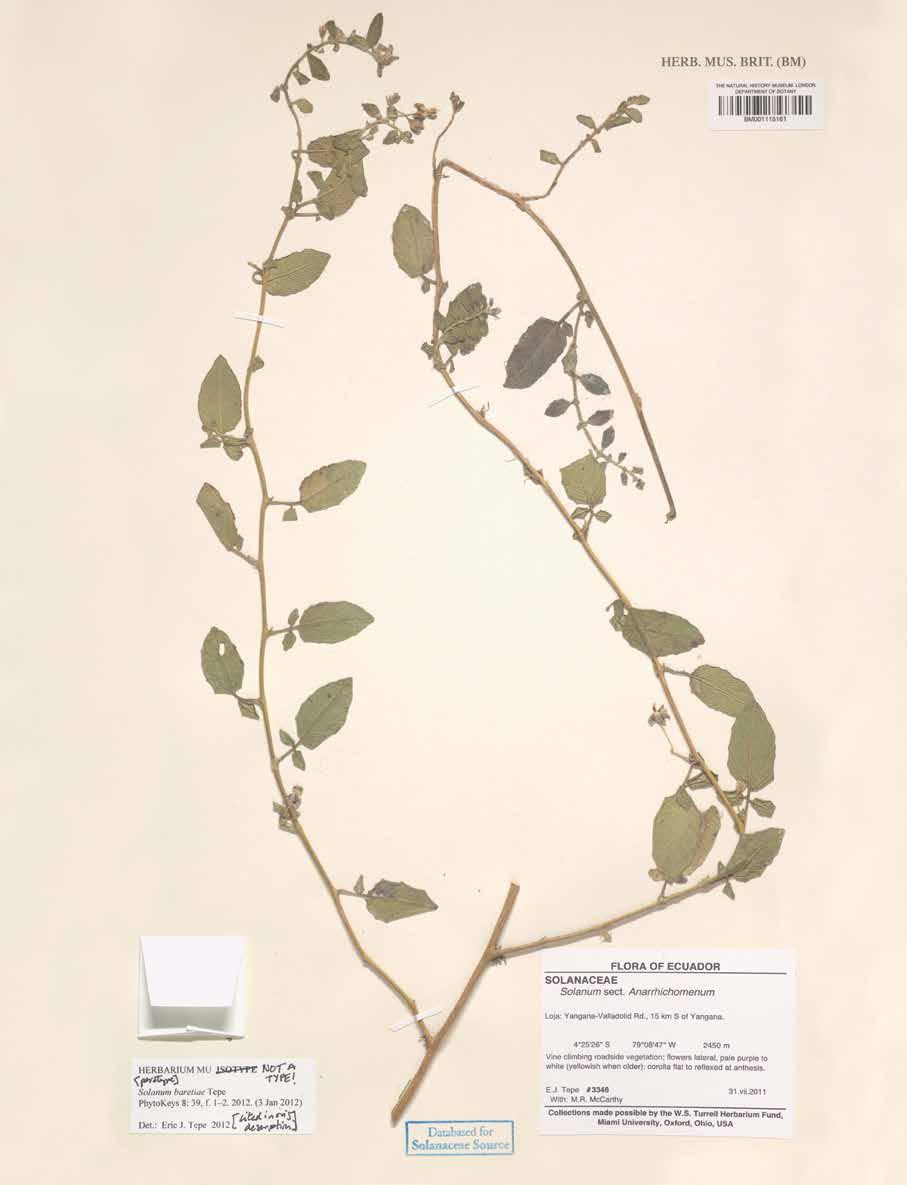

Solanum baretiae Tepe. Image courtesy Natural History Museum, London. Collection number BM001115161

While the most pressing concerns of the expedition had now been resolved, others lingered. It is likely that Bougainville realised that the scientific and exploration potential of the voyage was exhausted, as disappointing as that must have been. He set a course for the French settlement at Mauritius and home. And of course, there was still Jeanne. Bougainville had not forced her ashore in Batavia (present-day Jakarta, Indonesia) and perhaps he had always intended to leave her in Mauritius. He does not mention her again in his journal, but certainly when the expedition left Mauritius five weeks later, Commerson and Jeanne were left behind in Port Louis with the French governor, Pierre Poivre.

This arrangement did not raise as many questions as it could have, as Poivre himself was an avid botanist and had established an impressive botanical garden outside of Port Louis, which remains to this day. He enthusiastically engaged Commerson to study the surrounds, including Madagascar, and of course Commerson’s loyal servant remained with him. And so, after 22 months of hellish shipboard life, Jeanne found herself back on land and in relative safety. There is no record to indicate whether she shed her male disguise, but we do know she remained with Commerson on Mauritius until he died in March 1773. During their shared time there, the couple dedicated themselves to studying the flora of the region, collecting and recording more than 1,000 species, despite Commerson’s persistent ill health and dwindling finances.

With the death of Commerson, Jeanne was left to fend for herself. As had been the case on Etoile, Commerson had made few friends on the island, and dispatches back to Paris referred to him as being an ‘ill-natured man, capable of the blackest ingratitude’.6 Without money, status or social support, Jeanne survived; court records show she opened a tavern in Port Louis and in 1774 was married to Pierre Duberna(t).

Jeanne eventually received a pension from the French navy for her courage and exemplary behaviour on the voyage

On her eventual return to France with her husband the following year, no publications appeared revealing salacious details. There were no theatre tours, ballads or public appearances. Nor were there any botanical publications authored by her or any discoveries attributed to her. Jeanne, true to the quiet fortitude she had always displayed, claimed some money that Commerson had left her in his will and settled into a rural life. But she had not yet been completely forgotten. Ten years after her return to France, Jeanne Baret was paid by the French navy. Despite having broken French naval code by joining the journey in disguise, Jeanne received a pension for her courage and exemplary behaviour on the voyage. It would seem that Bougainville, still an admirer of the very qualities he had observed a decade earlier, was now officially able to recognise Jeanne’s extraordinary achievement.

And so Jeanne passes quietly into history, largely unheralded and voiceless in a story where the voice most needed is hers. The novelty of Jeanne’s disguise, and the drama of her exposure and subsequent tribulations, should not overshadow the significance of her uncredited scientific achievements. Although the objectives of the Enlightenment directed much of her life, they were not intended for women of her class, of whom very little was expected. Jeanne’s ability to successfully overcome the restrictions of her origins, to embrace the mental and physical challenges of early botany, to constantly care for Commerson while in restrictive disguise and personal danger, is nothing short of extraordinary. And by making it back to France, she became the first woman known to have achieved a circumnavigation, of which Bougainville was well aware.

It was most likely Jeanne Baret who, in 1767, collected the popular bougainvillea plant that adorns so many Australian gardens today –yet no plant was officially named for her until 2012, when Solanum baretiae, a species of nightshade, was finally given the honour.

Commerson, despite his many faults, did try to name a species for Jeanne. They collected the plant that Commerson wanted to call Baretia in 1771 at Bourbon (now Réunion), but a decade later its name was changed to Quivisia

Despite this, Commerson’s sentiments at the time still hold true: 7

This plant is dedicated to the valiant young woman who, assuming the dress and temperament of a man, had the drive and audacity to travel throughout the world ... inspired by some divinity, she frustrated the schemes of men and beasts, risking on many occasions both her life and honour. We are indebted to her heroism for so many plants that have never before been collected, for so many herbaria carefully put together, so many collections of insects and shells, that it would be an injustice on my part, as it would be for any other naturalist, if I did not pay her the greatest tribute by dedicating this plant to her.

References

1 Aamna Mohdin, ‘British woman, 77, becomes oldest person to sail around the world alone’, The Guardian, 10 September 2019.

2 John Dunmore, Monsieur Baret, Heritage Press, Auckland (2002), page 35.

3 John Dunmore, The Pacific Journal of Louis-Antoine Bougainville 1767–1768 , Hakluyt Society, London (2003), page 228.

4 Dunmore, Monsieur Baret, page 55.

5 Bougainville, Louis, A Voyage around the World ..., John Nourse, London (1772), page 300.

6 Dunmore, Monsieur Baret, page 179.

7 Jeannine Monnier et al, Philibert Commerson, Association SaintGuinefort, Chatillon-sur-Chalaronne, 1993, page 98.

Myffanwy Bryant is a curatorial assistant at the museum.

Solanum baretiae, a species of nightshade named by Eric Tepe in 2012 in recognition of Jeanne Baret. Image courtesy Eric Tepe from the University of British ColumbiaMake a difference now and for generations to come.

Circle members

The Australian National Maritime Museum Foundation is the fundraising arm of the museum and holds funds to acquire major objects, conserve our collection and provide support for the museum and its programs.

Support our appeals in Signals

Whether small or large, every donation is greatly appreciated and makes a difference to the museum achieving our goals.

If you are planning to leave a gift to the museum in your will, we would appreciate knowing of your intention. We would welcome the opportunity to thank you and acknowledge your support by including you in our Benefactors’ Program. You will receive invitations to VIP events and tours and also be listed as a benefactor on the museum’s Honour Board. sea.museum/bequests

The museum seeks the support of maritime enthusiasts dedicated to supporting us to expand our collections and restore and conserve important artefacts. Donors who pledge $1000 each year for three years can join the Captain’s Circle and become VIP donors of the museum. These donors are acknowledged for their support and invited to our special events and we take you behind the scenes for money can’t buy experiences. sea.museum/captainscircle

Ambassadors

Ambassador status is given to those who have contributed more than $100,000 to the museum. These significant donors have helped acquire important works or supported historic vessels to ensure they are enjoyed for generations to come. Ambassadors are recognised on our Honour Board.

Here are some projects currently seeking support:

OBJECTS

The Souter Murals

Restoration work

DISCOVERY

The search for the Endeavour Sample analysis

EDUCATION

Underwater Museum

Program development

MIGRATION STORIES

Faces of Australia 2020

Exhibition development

INDIGENOUS

Alick Tipoti retrospectiveSpiritual Patterns

Purchase of artworks

For more information go to sea.museum/donate

Or contact Foundation Manager, Marisa Chilcott (02) 9298 3619

marisa.chilcott@sea.museum

Captain’s enjoyed a private tour of HMAS Hobart and were escorted by Lieutenant Dylan Woodland RAN.The museum acquires Sea Shepherd Australia’s Delta boat

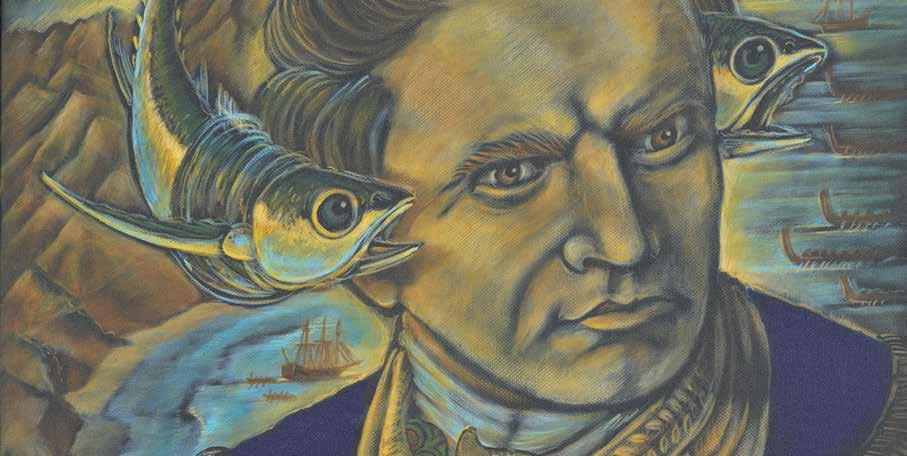

The Australian National Maritime Museum aims to acknowledge more than one perspective on our national maritime story. Curator Emily Jateff argues that ‘contentious histories’ like that of Sea Shepherd deserve a place alongside more mainstream narratives, and conservator Nick Flood outlines the behind-the-scenes work required to add a Sea Shepherd boat to the museum’s collection.

Sea Shepherd’s current mission is ‘to safeguard the biodiversity of our delicately balanced oceanic ecosystems and ensure their survival for future generations’

01

Tenders on board Steve Irwin during Operation Musashi, Sea Shepherd’s fifth Antarctic whale defence campaign. The Steve Irwin chased the Japanese whaling fleet for 3,200 miles, severely disrupting the hunt and saving more than 300 whales. Image © Sea Shepherd Australia

02 The small boat Humber in front of Steve Irwin during Sea Shepherd’s 10th Antarctic whale defence campaign, ‘Operation Relentless’. Image Eliza Muirhead/ © Sea Shepherd Australia

IN 2019, THE MUSEUM ACQUIRED Sea Shepherd Australia’s Delta rigid hull inflatable boat (RIB) for the National Maritime Collection, following the decommissioning of Sea Shepherd Australia’s flagship MY Steve Irwin. The Delta RIB is a black rubber and fibreglass ‘stealth boat’ with hand-painted shark jaws below the waterline on the bow.

The Delta RIB was acquired by Sea Shepherd Australia in 2006 as part of the ship’s complement of FPV Westra, an ex-Scottish Fisheries Protection Agency vessel rechristened MY Robert Hunter on arrival and changed to Steve Irwin in 2007. The Delta was used to conduct marine biological and ecological research, documentation and ‘non-violent direct action’ against whaling, shark finning and illegal by-catch fishing vessels via various campaigns in Australian and international waters from 2006 to 2018. From 2008 to 2015, MY Steve Irwin and its tenders, including the Delta, featured in seven seasons of the Animal Planet show Whale Wars. Alistair Allen, captain of Sea Shepherd’s MY Sam Simeon, says:1

The Delta is a very special boat in Sea Shepherd history ... It is the symbol, the fighter jet, the top gun. It was instrumental in Whale Wars , those little boats cutting in front of big ships. It went through everything. It has had an engine blow up, it has washed ashore, it has been beached in Antarctica and it has battled on. It is like Sea Shepherd, it keeps going.

In the early 1980s, the International Whaling Commission (IWC) called for a non-binding moratorium on commercial whaling from the 1985–86 season. This effectively limited the capture and killing of whales for commercial purposes, with special provisions for scientific research and localised and culturally significant subsistence whaling. In 1994, the IWC declared all areas below 40 degrees south latitude as the Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary. The sanctuary drops to 55 degrees latitude in some areas of the Indian Ocean and to 60 degrees near the tip of South America and into the South Pacific.

Sea Shepherd began its operations in the Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary with the specific directive to make commercial whaling financially non-viable. From 2005 to 2017, annual Southern Ocean operations departed from Hobart, Tasmania, and engaged each year with whaling vessels from the Japanese Institute for Cetacean Research (ICR). Sea Shepherd claims that during this period, they saved 6,000 whales.

The ICR conducted annual whaling operations in the Southern Ocean from 1987 to 2018 via the Japanese Whale Research Program, under Special Permit in the Antarctic (JARPA I and II), with the resultant whale meat sold to the Asian market in line with Article III.2 of the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling. Sea Shepherd’s contention was that the ICR disguised commercial whaling for economic profit as scientific research. Author Jun Morikawa states that Sea Shepherd’s activities actually increased Japan’s resolve to continue whaling. 2

In 2010, Australia and New Zealand took the government of Japan to the International Court of Justice for conducting commercial whaling under the guise of scientific research. The court ruled against Japan on 31 March 2014 and refused to grant further scientific research permits to the ICR. A series of claims and counterclaims related to the Antarctic Treaty and its waters ensued, but the ICR continued to hunt for whale within the Southern Sanctuary. In 2017, Sea Shepherd suspended anti-whaling activities, stating that they could not compete with the ICR’s modern surveillance tactics. The ICR also concluded Southern Ocean whaling operations in 2018, ending its formal association with the International Whaling Commission and stating its intent to resume commercial whaling within its own waters from July 2019.