Brickwrecks

Behind the builds

Pacific Sea Gardens

Indigenous mariculture sites

The Sydney Punchbowls Enigmatic and unique

Brickwrecks

Behind the builds

Pacific Sea Gardens

Indigenous mariculture sites

The Sydney Punchbowls Enigmatic and unique

As our busiest season approaches, I am delighted to say that visitation is returning to a more normal pattern, following the huge disruptions of recent years. With 435,412 onsite visitors, 804,259 visitors to our travelling exhibitions, 286,672 students and teachers in virtual and online courses, and almost one million website visits, we had a remarkable 2.6 million engagements with our visitors and supporters, whether physically or online. What’s particularly rewarding is that this is despite the COVID-19 closure of the site between June and September last year.

As we race towards the end of the year, then sail into 2023, we have an exciting summer period planned. The exhibition Brickwrecks – Sunken ships in LEGO ® bricks, which we developed with the Western Australian Maritime Museum, opens just before Christmas. It will take visitors both young and old into the stories of shipwrecks such as Pandora, Vasa and Titanic

And once again we are part of the Sydney Festival, with an immersive show Shipwreck Odyssey, and the New Beginnings Festival in conjunction with our friends at Settlement Services International. Details for all our activities can be found on the website as well as in this edition of Signals

Summer will also see some big movements at the museum, with HMAS Vampire being dry docked for some much-needed maintenance and Duyfken heading to Hobart for the Australian Wooden Boat Festival.

Inside the museum we have some gems – The Wharfies’ Mural exhibit (thank you to the Maritime Union of Australia), an Endeavour cannon (thank you, NSW Parks and Wildlife) and the wonderful Sydney Punchbowls. This display partners the museum’s 1820s bowl with its companion from the State Library of New South Wales.

We recently welcomed the Seabin Foundation’s Ocean Health Lab to the museum and are excited to see the results of their continual monitoring of rubbish in the harbour. This is their first Health Lab in the world and we are proud to be an integral part of their next phase of ocean science research.

And finally, I would like to pay tribute to our wonderful volunteers, who, in the last financial year, contributed almost 19,000 hours of passionate work.

I am always happy to hear from the museum family about what matters to you, so please, if you have any ideas, drop me a line to thedirector@sea.museum. I may not be able to respond personally to every message, but please be assured, different voices are both welcome and encouraged.

Daryl Karp AM Director and CEO Stephen Schmidt, Fleet Services volunteer. Image Cassandra Hannagan PhotographyThe Australian National Maritime Museum acknowledges the Gadigal people of the Eora nation as the traditional custodians of the bamal (earth) and badu (waters) on which we work.

We also acknowledge all traditional custodians of the land and waters throughout Australia and pay our respects to them and their cultures, and to elders past and present.

The words bamal and badu are spoken in the Sydney region’s Eora language.

Supplied courtesy of the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council.

Cultural warning

People of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent should be aware that Signals may contain names, images, video, voices, objects and works of people who are deceased. Signals may also contain links to sites that may use content of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people now deceased.

The museum advises there may be historical language and images that are considered inappropriate today and confronting to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The museum is proud to fly the Australian flag alongside the flags of our Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander and Australian South Sea Islander communities.

Cover A ‘brickscape’ depicting divers on the Pandora wreck site, from the exhibition Brickwrecks: sunken ships in LEGO® bricks. Image courtesy The Brickman Team

2 Sea Gardens across the Pacific

Recording a renaissance in Indigenous mariculture

10 Rediscovered treasures

The magnificent Sydney Punchbowls on display together

16 Team-building Brickwrecks

Creating LEGO® ship models on a grand scale

22 Maritime history prizes

Announcing the winners

26 Young guns and champions

The latest inductees to the Australian Sailing Hall of Fame

30 The Australian Wooden Boat Festival 2023

Head to Hobart in February for a feast of maritime culture

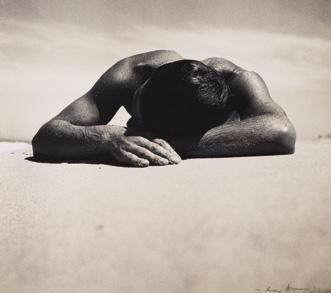

34 The longest journey

Former refugee vessel Tu’ Do embarks on a new stage of its life

42 James Watt

The Scottish maritime artist who recorded the working life of the Clyde

50 Help us preserve HMAS Vampire

Seeking your support for our end-of-year campaign

53 Members news and events

Your calendar of summer events for members and their guests

56 Exhibitions

Our temporary and travelling exhibitions this season

60 Education

Seaside Stories, a new program for people with dementia

64 Collections

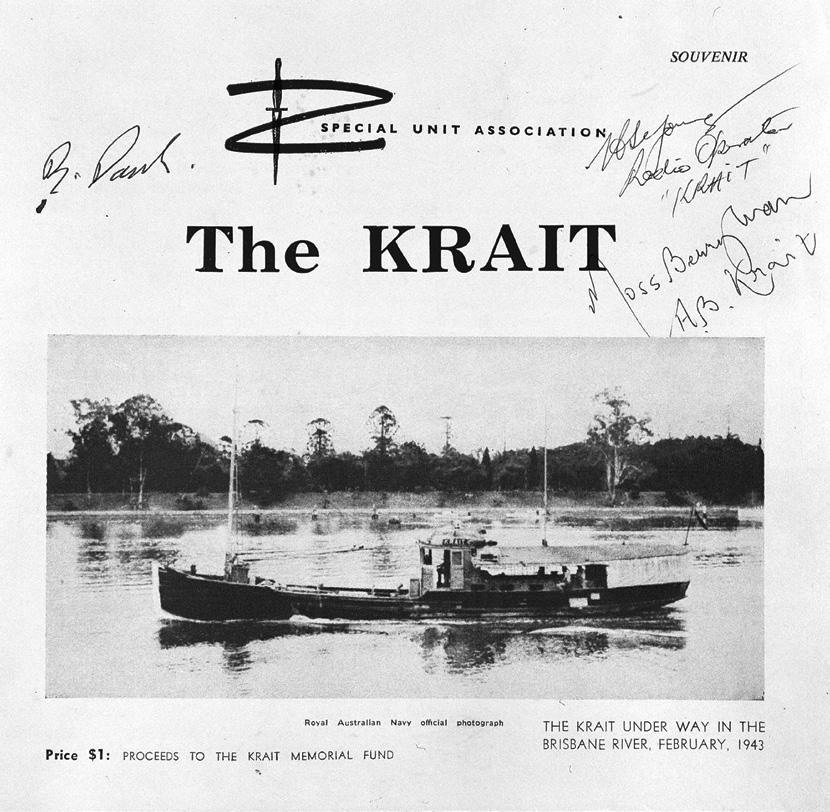

How to hide in plain sight, Operation Jaywick style

70 National Monument to Migration

Hundreds of new names added in a joyous ceremony

74 Settlement Services International

The New Beginnings Festival celebrates cultural diversity

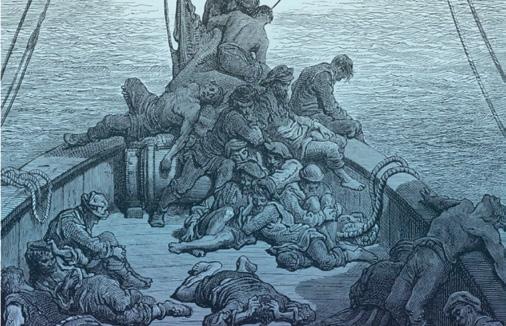

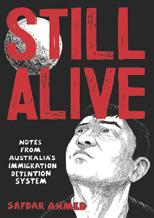

76 Readings

Still Alive; Opposing Australia’s First Assisted Immigrants

84 Currents

Seabin Ocean Health Lab; Fishers Lost at Sea memorials

‘One of the most important aspects of restoring these places is restoring people’s relationships with them’

Showcasing an Indigenous mariculture renaissance

Sea Gardens Across the Pacific is a new ‘story map’ that gathers information about Indigenous mariculture practices across the world and emphasises the importance of revitalising these practices for food sovereignty and resilience, writes Samantha Larson.

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES have been stewarding the ocean for thousands of years. This stewardship has appeared in many different forms around the world, all of which represent a reciprocal relationship between humans and the sea rooted in deep place-based knowledge. From eel ponds in Budj Bim, Australia, to octopus houses in Haida Gwaii, Canada, an Indigenous mariculture renaissance is making waves as groups across the Pacific seek to revitalise these ancient techniques and traditions.

For the first time, information about a multitude of Indigenous cultivation practices has been collected into a cohesive online repository. Sea Gardens Across the Pacific: Reawakening Ancestral Mariculture Innovations is a new, interactive, ‘living’ story map that synthesises knowledge about Indigenous aquaculture throughout the Pacific region, including the west coasts of North, Central and South America; the east coasts of Asia, Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand; Oceania; and coastlines in between. The project shows these local initiatives are not one-off projects, but rather pieces of a global story. It’s a story that is being told by Indigenous knowledge holders, and further amplified by diverse collaborators who created the story map. Many ancestral mariculture practices were subverted over time by colonialist attitudes and policies that targeted the erasure of Indigenous cultures and the separation of people from wilderness. As ocean change caused by industrialisation continues to imperil marine resources, reviving ancient practices could help to protect these ecosystems and the people who rely on them today.

An Indigenous mariculture renaissance is making waves as groups across the Pacific seek to revitalise these ancient techniques and traditions

For example, clam gardens – which are typically created by constructing a rock wall in an intertidal zone, thus expanding habitat for clams and other species – can locally reduce the impacts of warming ocean temperatures. Skye Augustine is an Indigenous scholar at Simon Fraser University, Canada, and a collaborator on the new story map. Augustine spearheaded the restoration of clam gardens at two sites in the Gulf Islands of British Columbia. ‘One of the most important aspects of restoring these places is restoring people’s relationships with them,’ she says:

It forces us to re-examine the idea that humans only have negative impacts on our ecosystems, and remember that for millennia we have had positive and reciprocal relationships with the places we belong to, and that we can have those kinds of relationships once again.

Kii’iljuus Barbara Wilson, a Haida matriarch and Indigenous scholar from the Cumshewa Eagle Clan, collaborated with the team to highlight the octopus houses of Haida Gwaii, an archipelago off the coast of British Columbia. She states:

In this time of climate change, it’s really important to acknowledge Indigenous mariculture as conservation and recognise First Nations governance over our land and resources. It’s time to put the library back together and learn about all the things our ancestors did to ensure that there was enough fish and octopus – looking after and respecting the environment. We managed to live in the world for thousands of years without the massive ecological destruction that’s happening now. It’s very much about not taking more than you need.

From left: Larry Raigetal, Keli‘i Kotubetey and Ann Singeo draw in the sand, demonstrating how the beng of Palau would have looked and functioned. Image Momi Afeli

The Gunditjmara people (also known as the Dhauwurd Wurrung) built channels and pools over an area of about 10,000 hectares

01 An eel pond at Mount Eccles (Budj Bim). Image Mertie, licensed under CC BY 2.0

02

Remains of Aboriginal stone eel traps at Budj Bim. Image denisbin, licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

The movement to revive Indigenous aquaculture practices is occurring in modern-day Australia as well.

As described in the story map, the Gunditjmara people (also known as the Dhauwurd Wurrung) built channels and pools over an area of about 10,000 hectares in what is now Victoria, including Budj Bim National Park. This aquaculture system is estimated to have supported gatherings of up to 1,000 people.

After the arrival of European settlers in 1834, however, Lake Condah was drained to increase the land available for livestock grazing, which reduced wetland habitat and rendered the eel traps inoperable. As part of the Lake Condah Sustainable Development Project, the Gunditjmara have put forward a vision for restoring the practice of eel ponds. Their vision is that ‘Gunditjmara people will experience the landscape, engage in eel and fish harvesting using the stone trap systems, and apply traditional knowledge practices in land and water management.’ As the water returns to the landscape, they hope to learn more about the ways in which previous generations cared for and used the land: ‘We will pass what we learn on to the next generation so that traditions and knowledge are never lost again.’ As of now, 24 out of the 82 identified traditional eel traps have been reactivated.

The story map creates a broader frame of reference for these initiatives. ‘It’s so lovely to have a visual representation of these practices, and to be able to see the spatial extent of Indigenous aquaculture and caretaking of coastal environments,’ says Brenda Asuncion, a collaborator on the story map, who co-ordinates a network of Native Hawaiian fishponds with Kua‘āina Ulu ‘Auamo, an organisation that supports traditional practices. ‘They aren’t isolated phenomena.’

Asuncion says that the story map is a way to share knowledge about Indigenous aquaculture, with the potential for an even greater reach to showcase similar community-led efforts around the Pacific.

The story map is one of many collaborations fostered and co-ordinated by the Indigenous Aquaculture Collaborative Network, which is a community of practice consisting of Pacific-region Sea Grant offices; Northwest Tribes and First Nations; Native Hawaiian and Indigenous communities; and organisations and universities working to advance Indigenous aquaculture. In addition to projects and gatherings that take place in virtual settings, the group prioritises opportunities for the community to meet and learn from one another in the real world. In February 2020, the collaborative’s first gathering was held on O‘ahu in Hawai‘i, during which more than 125 participants representing dozens of Indigenous groups from across the Pacific helped to rebuild a seawall to support a loko i‘a (Hawaiian fishpond).

In July 2022, a smaller group of Indigenous aquaculture practitioners gathered for a knowledge exchange in Palau. Local mariculture systems known as beng , in which an obstruction is placed in tidal waters to direct or trap fish (also known as fish weirs), were once commonly used in Palau but now the technique has fallen from use. Participants in the knowledge exchange visited the remnants of a beng in Ngkeklau, and many of the participants shared their own experiences with wall-building from elsewhere in the Pacific Basin. Weaving rocks to enhance habitats for customary foods is one of the many common practices that link unique place-based cultures across the Pacific – from the tidelands of the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community, who are building the first known modernday clam garden in the USA, to the loko i‘a in Hawai‘i. ‘The fellowship of the group was incredible,’ says Larry Raigetal, who is a Pwo master navigator and boatbuilder as well as the co-founder of Waa’gey, an organisation that applies traditional skills and knowledge to addressing the social, economic and environmental challenges faced by the people of Micronesia’s remote islands:

Reviving ancient practices could help to protect these ecosystems and the people who rely on them today

01

Cross-Pacific knowledge exchange participants join Ann Singeo, executive director of the Ebiil Society, to learn more about beng , a traditional mariculture system of Palau. Image Kimeona Kane

02

Palau’s beng had an arrow-like shape. At high tide, fish are directed inside the trap. As the tide recedes, they are trapped inside. The shape of this beng is similar to the aech of Yap, Federated States of Micronesia; Shi hu in Taiwan; and the tidal fish traps of the Salish Sea. Image Reid Endress

It was a great experience, one that sends us off to the different places we are now. I think the momentum that took us from Palau is ongoing. When there is no wind and we need to get somewhere, we paddle while chanting – and the current will take us home. Whether sailing or drifting, we need to be continuing to share this knowledge.

With this momentum, the Ebiil Society is reviving the Ngkeklau beng for community food-fishing rooted in Palauan cultural heritage. ‘We’re hoping we will be able to add our beng to the growing sea garden map,’ says Ann Singeo, the Ebiil Society’s executive, who hosted the knowledge exchange.

The idea for the story map began when Anne Salomon, a marine ecologist at Simon Fraser University, was told by renowned fisheries scientist Daniel Pauly that she could elevate the recognition of the importance of clam gardens by placing them within a global context. ‘These innovations have been present for thousands of years, but much of the world doesn’t know about them,’ Salomon says. She introduced a synthesis and analysis of Indigenous mariculture into her graduate class on social–ecological resilience, and her students came up with the idea of an interactive story map.

As part of the class, students attended the Indigenous Aquaculture Collaborative Network’s gathering in Hawai’i and took part in the restoration of the fishpond. ‘What was so powerful there was the energy, momentum, and the sense of community that flowed from taking part in the revitalisation of that practice,’ says Heather Earle, who co-led, designed and created the story map. ‘As we’ve worked with practitioners, knowledge-holders and researchers across the Pacific to compile this map, we’ve seen that same energy and momentum again and again.’

Salomon reached out to Melissa Poe, who co-ordinates the Indigenous Aquaculture Collaborative Network. Poe immediately saw the potential: ‘These features exist worldwide. If people better understood their diversity, functionality and extent, I’m convinced that more communities would be empowered to restore them.’

While both Salomon and Poe say the current story map only ‘scratches the surface,’ they believe that publishing this current edition will help bring other practices into the public light. As the conversation around Indigenous mariculture continues to gain traction, and as recognition of the innovation and resilience of these biocultural seascapes grows, the contributors see them as time-tested solutions to some of our most pressing coastal challenges.

In other words, this global perspective can help affirm and push forward the local ones. ‘The power is to first understand that almost the same idea exists across cultures, and that many of the same things are important to these seascapes across the world. For example, the wisdom of the elders is very important,’ explains story map collaborator Jaime Ojeda, who contributed to the story map’s piece on corrales de pescas – a practice that Ojeda’s grandmother, a Mestizo–Chiloté elder, grew up with in Patagonia. ‘In terms of the past, but also in terms of right now. Sometimes people think this is history –it has happened. Part of the power is for people to see, oh, this is happening. In many places, this is happening.’

To explore the story map, see seagardens.net

Samantha Larson is the science writer at Washington Sea Grant.

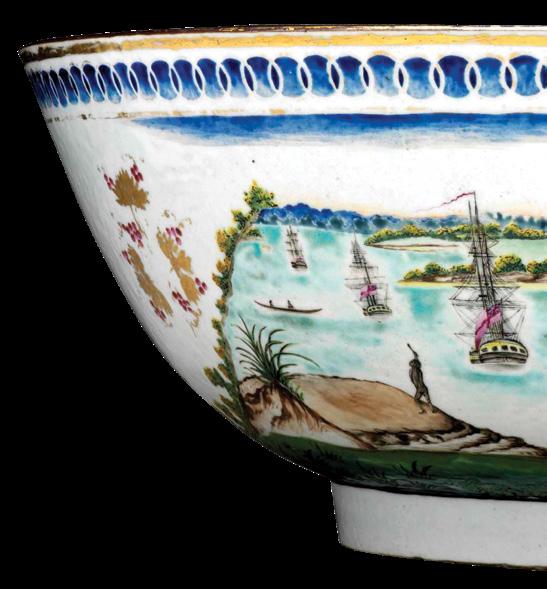

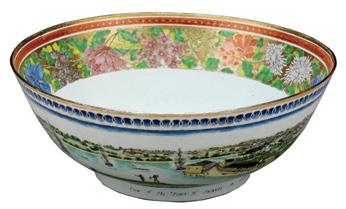

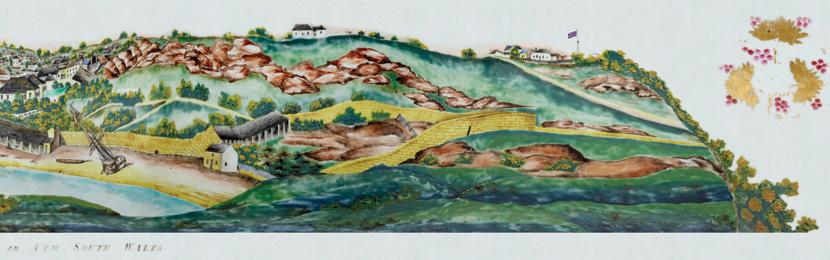

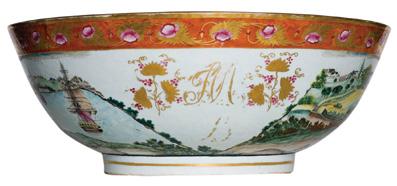

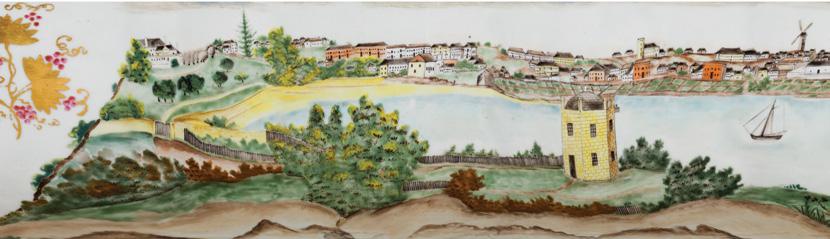

For the next six months, visitors to the museum will have a rare opportunity to see two treasures of early Sydney on display, reunited for only the second time in their history. By Dr Kimberley Webber.

IN ABOUT 1820, someone familiar with Governor Lachlan Macquarie’s Sydney commissioned Chinese artists in Canton (now Guangzhou) to paint a pair of large punchbowls with panoramic views of Sydney Cove. One was to show the view from the east, and the other from the west. The punchbowls are a ‘harlequin pair’ – similar but not identical – and there is some overlap between the two panoramas.

The commissioner must have provided the artists with engravings or drawings of the relatively new town, as the results were surprisingly accurate. A highlight of this exhibition, which features both bowls, is the use of large-scale digital imagery to reveal the fine details of the panoramas and to identify significant buildings.

First Nations people are present on the foreshores at Tallawoladah (Miller’s Point) and Tubowgule (eastern Circular Quay), in fishing canoes on the harbour and in the centrepiece inside each bowl. This was intended as a surprise reveal once the contents were drunk. Depicting a traditional Aboriginal marriage ceremony, it may have been meant to convey to a European viewer the pitfalls of marriage. Historian Elizabeth Ellis OAM has traced the image to an 1802 drawing by Nicolas-Martin Petit, an artist on Baudin’s expedition of 1800–1803, who made some of the earliest ethnographic studies of Australia’s First Nations.

Although the bowls have been extensively researched, much of their history remains unknown

On the museum’s punchbowl, the view is from Dawes Point (now the site of the southern pylons of the Sydney Harbour Bridge). Although the source is unknown, the painters would have drawn upon contemporary engravings; panoramic views were particularly popular at the time.

ANMM Collection 00039838 Gift from Peter Frelinghuysen through the American Friends of the Australian National Maritime Museum and partial purchase with the USA Bicentennial Gift funds

The presence of these figures on the punchbowls is also a reminder of the tragedy inflicted upon Aboriginal people on these once verdant and peaceful harbour foreshores. By the time these images were made, their lands had been taken and their water supply polluted, and many had died following the introduction of European diseases.

Although Ellis has extensively researched the bowls, much of their history remains unknown. Were they commissioned by someone in Sydney and brought back to the colony? Or, as Dr James Broadbent suggests, were they perhaps purchased as souvenirs of New South Wales and never sent here? Adding to the mystery, both turned up in England within a few years of each other.

The ‘eastern’ bowl was found in a London bookshop by William Little in 1926. Recognising the importance of this ‘relic of early Sydney’, he brought it back to Australia and donated it to the State Library of New South Wales.

Six years later, the ‘western’ bowl came to the attention of the National Art Collections Fund in England. The chairman, Sir Robert Witt, wrote to the director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales suggesting that it would be ‘a splendid asset’ for a museum. His letter was referred on to the library, which declined on the basis that it already had a similar bowl.

A view of the town of Sydney in New South Wales ANMM Collection 00039838. Gift from Peter Frelinghuysen through the American Friends of the Australian National Maritime Museum and partial purchase with the USA Bicentennial Gift funds

02

Inside both bowls is the same image of Aboriginal people and the same wide band of traditional flowers, although each bowl is seemingly painted by a different hand.

1

The rear promontory is Mrs Macquarie’s Point, so named as it was a favourite vantage point of Governor Lachlan Macquarie’s wife, Elizabeth.

2

The next promontory is Bennelong Point, where the Sydney Opera House now stands.

3

The large ships fly the British Ensign. Also visible are smaller European sailing craft and two Aboriginal nawi; several Aboriginal people are depicted in the foreground.

4

Between the second and third of the larger British ships, Billy Blue’s Cottage is just visible.

5

In the distance on the eastern shore is Government House, its substantial domain and the residences of senior officers and civil personnel. In December 1817, construction commenced on Fort Macquarie (now the site of Sydney Opera House); there is no sign of it here, suggesting that the artists were copying an earlier image.

6

Dominating the right-hand half of the view is Robert Campbell’s compound. His trading premises were at the bottom of George Street and secured by a large wooden gate (just visible between the two yellow buildings).

7

Robert Campbell’s substantial whitewashed home.

8

A ship is careened in Campbell’s Cove.

9

Campbell’s compound included three acres (1.2 hectares) of lush walled gardens, where white peacocks and emus (not pictured) used to roam.

10

Clearly visible are the boulders and sandstone outcrops that gave this area, The Rocks, its name.

11

Fort Phillip, flying a large British flag, was the main signalling post for the town and was on the site of what is now Sydney Observatory.

The entire panorama of the museum’s bowl, looking from east to west.

The museum’s collection includes an 1820 engraving by W Preston of a similar view to that featured on the punchbowl.

The punchbowls are a ‘harlequin pair’ – similar but not identical –and there is some overlap between the two panoramas

01 The library’s punchbowl bears a monogram, although who it relates to has not been determined.

02 The complete view pictured on the State Library’s bowl. Billy Blue’s hexagonal stone house is prominent.

Images reproduced courtesy of Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, SAFE / XR 10

1

Government House, a prefabricated structure brought out with the First Fleet as Governor Arthur Phillip’s residence. It shows the various additions that he and his successors made. The site is adjacent to what is now the Museum of Sydney on Bridge Street.

2

The beach forming the head of Sydney Cove would once have been a pristine site for First Nations people, with the Tank Stream flowing into the bay nearby. In 1841 this would be reclaimed to create Circular Quay.

3

The long brown building is the Military Barracks, a substantial complex that surrounded a parade ground, of which a remnant remains today in Wynyard Park.

4

The Dry Store, built in late 1790. It is now Sirius Park.

5

The hexagonal two-storey building in the foreground was built for Governor Lachlan Macquarie’s harbour watchman, the former convict Billy Blue. Born in Jamaica, Blue may have been a freed African–American slave.

6

St Philip’s Church, with its clearly visible tower, was built in 1810 as the first church in the colony. Rebuilt in 1856, it still stands near Wynyard Station.

7 James Underwood’s house. A prominent shipbuilder and merchant, Underwood had arrived as a convict on the Third Fleet, in 1791.

8

The Military Mill was one of 15 windmills built by the government and private individuals. They were in great demand, as convicts and settlers needed their monthly rations of grain ground into flour so they could bake bread and cook porridge, two staples of their diet.

George Street Gaol was the site of public executions in Sydney.

The Commissariat was the main storehouse for foodstuffs and other goods. It stood on the site of what is now the Museum of Contemporary Art.

Fort Phillip was the main signalling post for the town.

12

The large complex of white buildings at the far right of the panorama was owned by Robert Campbell. The youngest son of the Laird of Ashfield in Scotland, he was a merchant who came to Sydney in 1800 after working for a firm of merchants in India. He leased a large portion of waterfront land (close to where the Overseas Passenger Terminal is today) and built a substantial home, wharf and storehouses. 13

A small yellow flag flies over Dawes Point Battery, the first permanent fortification in Sydney.

By then, however, the bowl had been sold to Adaline Frelinghuysen (née Havemeyers) of Philadelphia, USA, who, with her husband, assembled an important collection of Chinese export ware. The bowl was not seen again in public until 1996, when it was included in an exhibition organised by the Peabody Essex Museum, USA, and the Hong Kong Museum of Art. Fortunately, it came to the attention of curators from the Australian National Maritime Museum and in 2006 Peter Frelinghuysen II generously agreed to donate it, with a partial purchase using USA Bicentennial Gift Funds and the support of the American Friends of the Australian National Maritime Museum.

In a remarkable coincidence, just as this display was being planned, Mrs Alison Carr offered to donate her replica Sydney Punchbowl to the museum. In 2014, noted Australian antiquarian dealer Hordern House commissioned a limited series from the same region where the originals were made. As a result, when the library’s bowl is returned in 2023, the replica will take its place, ensuring that visitors can still enjoy these wonderful views of early Sydney.

Dr Kimberley Webber is the museum’s Project Officer –National Encyclopedia of Maritime Objects (NEMO).

All of the components used to build the ship are standard, everyday LEGO® pieces

Despite its singular name, ‘The Brickman’ is actually a team of skilled LEGO® brick artists led by Ryan McNaught (also, slightly confusingly, known as ‘The Brickman’). Together, and in collaboration with the museum’s Creative Producer Em Blamey, they created the stunning models for the Brickwrecks exhibition. Three Brickman team members share some insights into how they did it.

Luke Cini and Rena

BUILD MANAGER LUKE CINI built the stunning model of Rena, a container ship that wrecked on a reef off New Zealand in 2011, spilling oil and cargo and creating that country’s worst maritime environmental disaster. He says:

To begin any LEGO® build, the first step is to research and gather images and inspiration for the project. It is important to have sufficient knowledge of what the subject matter is before beginning any design work. When sourcing imagery for the build, I searched for photos and 3D models that helped tell me what features stood out and made the subject matter recognisable. For example, on the Rena, the containers stood out to me in the photos, so I knew that it was important to represent them well in the build, and gathering enough photos helped put together a more cohesive picture of the build. The 3D model was also a great reference to have – even though we didn’t use it to produce a brick model, we used it for referencing the shaping of the ship.

The next stage was to draw a basic concept of what the finished model would look like. This is a crucial step to get a better understanding of the project. This concept stage enables us to work out what bricks we will be using and how much time we will need to allocate for each part of the build to ensure success. All that was required in this step was a basic sketch of the model, with rough dimensions.

When it came to building the model, we had a flat piece of aluminium that we began the build on. This allowed us to start with a nice, solid, robust base. We then mapped out where the Rena would sit and what pieces would work well with the angle we wanted the ship at. We found that having the ship on an angle of 75 degrees would fit perfectly with the factory LEGO® wedge plates, allowing us to neatly finish the edges of the ship into the water.

We had a lot of fun adding in the small details once the main components of the build were complete. We included a block of cheese, which had fallen from the ship and which we had seen in a video.

Toppling containers, floating debris and an oil spill: the 2011 Rena wreck captured in LEGO®. Image courtesy The Brickman TeamDarren Ballingall and Pandora

Model Maker Darren Ballingall faced the challenge of re-creating the Pandora wreck site accurately enough to allow actual photographs of archaeologists excavating the wreck to be overlaid on the model, using Augmented Reality:

The wreck of HMS Pandora – which sank in 1791–became a large model that utilises special features. This required a lot of co-ordination between the builder and the multimedia experts. Making sure that there was plenty of space for the imagery to appear, and that it could be aligned properly, was one of the more important considerations, and careful planning was needed.

For the layout of the wreck, we used a lot of research that was kindly supplied by the helpful representatives from the Australian National Maritime Museum.

Without these photographs and diagrams, the model wouldn’t have been possible. We like to make models as accurate as we can, so using all of this reference material was essential. We use a special program that imports images and diagrams, so we can change the scale and plan out the size of the LEGO® model. From here it was a matter of building everything to the correct scale. A lot of the Pandora wreck is hidden beneath the sand, so only fragments of the actual ship needed to be made.

The human figures of the divers were a fun and complex challenge

The human figures of the divers were a fun and complex challenge – we needed to make posable human figures to the correct scale and full of accurate detail, as well as making them appear to be floating and swimming under water. One of the hardest things in creating LEGO® models that appear to be floating is being able to support the weight without it looking too much like it’s attached to the base. Luckily the diver models aren’t very heavy and only need one or two supports to keep them steady.

Then the fun parts came at the end – decorating with coral and adding little schools of fish. Fun touches like this really help to set the scene and bring a model to life.

01 A LEGO® diver in a hair-raising situation. The models of the divers are supported on slender transparent rods. 02 LEGO® divers excavate the Pandora wreck site.

When beginning a model based on history, the first and most important step is research

Liam Tullett and Batavia

Liam Tullett, Model Builder and Team Leader, faced the challenge of building Batavia, one of the most complex models in the exhibition. With its stunning, stark-white, billowing sails, expertly created from thousands of LEGO® pieces, it’s a highlight of the show. Liam says:

The Batavia was a ship built in 1628 by the Dutch East India Company. On its maiden voyage in 1629 from The Netherlands to Batavia (now Jakarta), it was steered off course, crashing and stranding the passengers and crew on islands off the coast of Western Australia.

When beginning a model based on history, the first and most important step is research. Luckily for us, a full-scale replica of the Batavia was built in 1995 and still exists today, so it was very easy to find lots of high-quality images and videos to base our design on. We did a lot of reading about the history of the ship and its voyage – it was a fascinating tale of wreck and mutiny.

To begin the actual build process, we converted a 3D model of the ship’s hull into custom LEGO® software that allows us to edit and view a digital version of the LEGO® model layer by layer, not unlike a CT scan. This requires us to follow that plan, building the model with a hollow interior to use fewer pieces, and to allow a steel skeleton inside the hull and masts to keep the ship strong during its travel as an exhibition piece.

Once the 3D model is finished, the real fun can begin. After building the hull following our plan, it was back to the photos and videos of the replica ship, and accounts of the real thing, to build all of the more intricate details. We used bricks with a groove in the side, typically used to depict brick walls, to simulate the long horizontal planks making up the sides of the ship. We also used thousands of white plates attached sideways to create all the sails on the ship. This technique allows the sails to be a lot stronger, and for them to look full, as if the ship is moving.

01 The Batavia model under full sail. The cutaway gives a glimpse below decks.

02 LEGO® Batavia is as crowded as the real thing.

03

Minifigures making mischief.

We also used almost all current gold LEGO® elements to re-create the intricate decorative details on the rails and rear of the ship.

All of the components used to build the ship are standard, everyday LEGO® pieces – the only part of the build that isn’t LEGO® is the six metres of twine used to re-create the ship’s rigging! This rigging was more than decorative – it actually helps to stabilise the masts and sails and stops them wobbling when the model is moved.

Many accounts of the ship reported that it was full of passengers and soldiers, so we included more than 200 minifigures packed in over the many decks of the ship, and even one tangled up in the rigging. Posing the minifigures and telling stories with them is always the best part of the build.

Building a model of this scale and scope was a fun challenge, and it was an honour to bring an iconic and historic ship to life using LEGO® bricks.

Brickwrecks – sunken ships in LEGO ® bricks is a new family-friendly exhibition that tells the stories of a number of shipwrecks from around the world, using a unique combination of LEGO® models, hands-on interactives, AV experiences and real shipwreck objects.

As The Brickman himself, Ryan McNaught, says:

‘The Brickwrecks exhibition is the most underwater fun you can have without getting wet!’

Brickwrecks – sunken ships in LEGO ® bricks opens at the museum on 17 December. For more information, see sea.museum/brickwrecks

The Australian Association for Maritime History and the Australian National Maritime Museum are delighted to announce the winners of the 2021 round of two key biennial maritime history prizes.

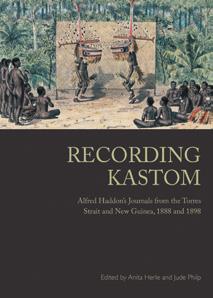

Anita Herle and Jude Philp (eds), 2020, Recording Kastom: Alfred Haddon’s journals from the Torres Strait and New Guinea, 1888 and 1898, Sydney University Press, Sydney

Frank Broeze Memorial Maritime History Book Prize

THE AIM OF THE FRANK BROEZE Memorial Maritime History Book Prize is to further the study and enjoyment of maritime history in Australia. The winner receives an award of $6,000.

The judges considered the quality of research, the liveliness of the writing, the likely audience appeal and the enduring value of the work as a contribution to maritime history. Overall, it was encouraging to survey the health of Australian maritime history, including works that focused on individuals and families, maritime communities ashore and at sea, vessels and voyaging, and First Nations cultures and their complex relationships with the colonising process.

The four shortlisted titles all satisfied the judging criteria and are recommended to readers, researchers and libraries around Australia. Ultimately, the judges’ decisions were unanimous and we congratulate the winner, extending our commendation to the three runners-up. We thank all authors and their publishers for contributing to the 2021 competition and look forward to entries submitted for the 2023 prize.

The editors present Cambridge zoologist and anthropologist Alfred Cort Haddon’s personal journals of his visits to the Torres Strait, New Guinea and North Queensland in 1888 and 1898. During these trips Haddon gathered an extensive and significant collection of Torres Strait materials, including artefacts and sound and film recordings, all now held in British, Irish and Australian institutions. Haddon realised the importance of his work as perhaps the last opportunity to record traditional customs in the region as they were being affected by colonialism. His private journals give a greater insight into Haddon’s personal views and life in the region at the end of the 19th century. His informal writing style is engaging and readable, in the descriptive manner of a 19th-century traveller’s account. His observations of the many Indigenous, colonial and other characters he meets as he voyages through the region reflect both his excitement when encountering new and valuable information, as well as period prejudices. The book is well footnoted and richly illustrated with Haddon’s sketches and watercolours from his journals, alongside modern photographs highlighting significant items from the anthropological collections mentioned in the text. The authors consulted extensively with both Traditional Owners and Haddon’s family to contextualise the journals, which include modern anthropological reflections and perspectives. This is a high-quality work of enduring value that does justice to the richness of Torres Strait Islander and New Guinea peoples’ culture, spirituality, voyaging, trade and interactions.

Model of a mask, Op le meket

with pearl-shell

Collected Mer, Torres Strait, 1898. MAA Z 9399

Haddon realised the importance of his work as perhaps the last opportunity to record traditional customs in the region

sarik, made for Haddon.

Painted wood

eyes and goa nuts, string, feathers, shells.

sarik, made for Haddon.

Painted wood

eyes and goa nuts, string, feathers, shells.

Sarah Laverick , 2019, Through Ice and Fire:

The adventures, science and people behind Australia’s famous icebreaker Aurora Australis, Pan Macmillan Australia, Sydney

Through Ice and Fire relates selected highlights from Aurora Australis ’ 30-year career as the first and only Australian-built Antarctic flagship. The result is an endearing and exciting account of the life of the ship and the people who lived and worked aboard it in extreme conditions, including surviving the dangers of shipboard fires, maritime rescues and running aground. Laverick brings unique insight both as an Antarctic scientist – she describes well the range of Antarctic science programs and the global contribution of the scientific community who worked on the vessel – and as a member of the shipbuilding family who built the ship at Carrington Slipways in Newcastle. Her interviews with key figures among the builders, crew, scientists, voyage leaders and vessel managers give readers a direct insight into all aspects of the workings of the vessel, and of Australia’s Antarctic program. This book exudes the salty tang of the Southern Ocean and will be enjoyed by anyone with an interest in polar science and the history of Australia’s Antarctic research program. No endnotes or footnotes are provided, although sources are listed for each chapter.

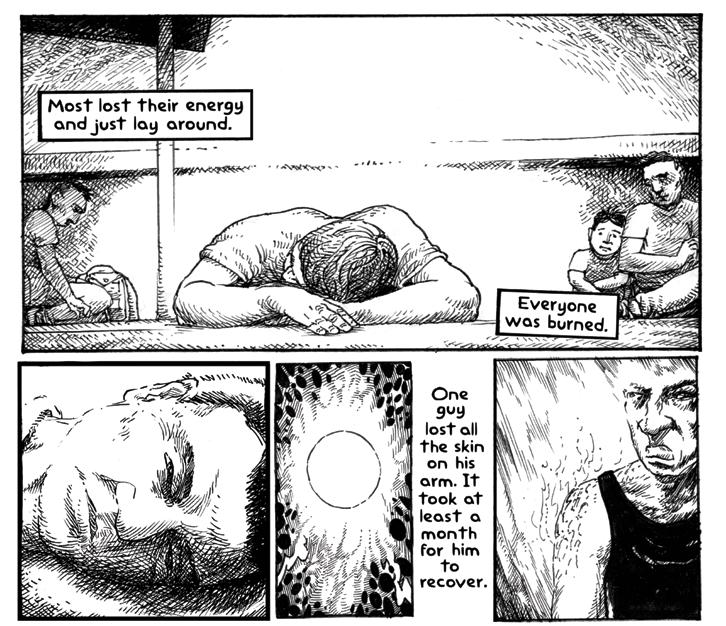

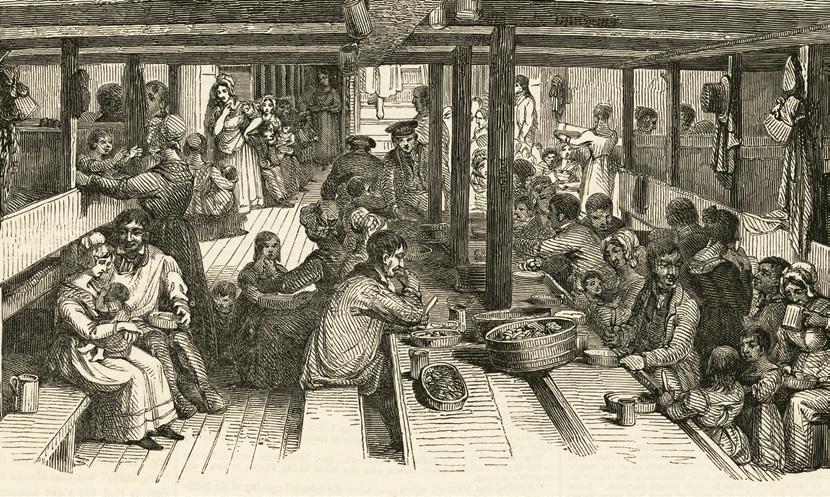

Jane Smith, 2019, Ship of Death: the tragedy of the Emigrant : The Voyage – The Quarantine – The Aftermath, Independent Ink, Carindale Ship of Death is a comprehensive account of the tragic voyage of the Emigrant, which sailed from the United Kingdom to Moreton Bay, Queensland, in 1852.

During the seven-month voyage and quarantine period at Dunwich Quarantine Station on North Stradbroke Island, 48 of those aboard would die of typhus fever, including two surgeons. Smith’s in-depth research into many of the passengers, crew and medical staff is a testament to the fates of the people aboard, both those who died and those who survived to make their lives in the colony of Moreton Bay.

Smith contextualises the voyage within the backdrop of wider events that occurred, providing a window into early European settlement of Queensland, immigration and medical practice generally. For example, in assisting the reader to understand the issues surrounding the management of disease, Smith explores the state of British medical education, research and accepted treatments in the mid-19th century. Overall, Ship of Death is an excellent example of how genealogical research can be transformed into an engaging, historically contextualised narrative. The book is well written and researched, with endnotes.

John Ogden, 2020, Whitewash: The lost story of an African Australian, Cyclops Press, Sydney

Whitewash tells the story of George Bernard (Bernie) Showery, a Native American–African–Australian man whose interesting family background and life included being an expert swimmer and lifesaver in the Freshwater Bay Surf Club, fighting in World War I in the legendary 7th Light Horse Regiment, being injured in the war and returning home to become a soldier–settler. In exploring how race and historical events shaped Showery, and in providing context and comparable examples to fill in the gaps, the book explores diverse subjects globally such as racism, slavery, Indigenous rights and beach culture.

Australian Community Maritime History Prize

This prize acknowledges a community-based work that advances the field of Australian local maritime history. The winner receives an award of $2,000.

Winner

Graeme Broxam (ed), 2020, Tasmanian Piners’ Punts: Their history and design, Wooden Boat Guild of Tasmania, Battery Point

This is a valuable contribution to the record of a specific boat type and a maritime industry. The book offers a neat combination of oral history, newspaper research and a survey of surviving piners’ punts. Shaped from fragmentary sources, it is well written and full of evidence, intended to serve as a reference rather than a narrative account. It will be a valuable guide for historic, ethnographic and archaeological studies of small Tasmanian boats and their construction.

Runner up

Mission to Seafarers Victoria, 2020, Harbour Lights –women with a mission 1914–1918, Mission to Seafarers VIC/Wind and Sky Productions, Melbourne

This is a well-made short film about the Mission to Seafarers, historical and contemporary. In 20 minutes it outlines the mission’s role and relevance as a unique community outreach service for mariners who came ashore away from home. The production is well scripted and accessible, narrating the forgotten contribution of women to the welfare of merchant sailors during World War I.

Judges

Dr Ross Anderson, Curator, Maritime Heritage, Western Australian Museum and President, Australian Association for Maritime History

Dr Peter Hobbins, Head of Knowledge, Australian National Maritime Museum

Dr Wendy van Duivenvoorde, Associate Professor of Maritime Archaeology, Flinders University

Mission to Seafarers volunteers preparing and serving a meal in the mission’s kitchen to visiting seafarers.

Nominations are now invited for the 2023 round of prizes, which total $10,000. For criteria and how to nominate, see www.sea.museum. maritimehistoryprizes Nominations close on 30 March 2023.

In 2009, at the age of 16, Jessica Watson become the youngest person to sail solo non-stop around the world

Sixteen-year-old Jessica Watson aboard Ella’s Pink Lady rounding the southern tip of Tasmania after six months at sea. Image Sam Rosewarne/ Newspix

The latest inductees to the Australian Sailing Hall of Fame include the youngest ever, Jessica Watson OAM, at 28 years of age. Joining her are Mathew Belcher OAM, Australia’s most successful Olympic sailor, and Olympians and world champions Tom King OAM and Mark Turnbull OAM . By David O’Sullivan and Daina Fletcher.

SINCE 2017, THE AUSTRALIAN SAILING HALL OF FAME has sought to acknowledge the depth and breadth of Australian sailing, from the sport’s early years in 19th-century colonial Australia to today. It recognises achievement, impact and contribution by an individual or a team and covers all disciplines of the sport, including those in supporting roles such as coaches and designers.

Jessica Watson has been honoured for her role as an ambassador for younger sailors. She is widely known for her landmark achievement of becoming the youngest person to sail solo non-stop around the world, at the age of 16. Watson completed a southern hemisphere circumnavigation on Ella’s Pink Lady, heading northeast across the equator in the Pacific Ocean before crossing the Atlantic and Indian oceans. Her voyage entailed passing the infamously challenging four capes: Cape Horn (Chile), Cape Agulhas (South Africa), Cape Leeuwin (Western Australia) and South East Cape (Tasmania). She endured 210 days alone at sea and survived seven knockdowns, one of which pushed her vessel 180 degrees into the water.

Watson’s voyage was shorter than the required 21,600 nautical miles to be considered a global circumnavigation, and it followed on from the World Speed Sailing Record Council abolishing its under 18 category.

Regardless, it struck a chord as a hugely inspiring personal journey that garnered massive national and global publicity. Returning to Sydney on 15 May 2010, three days before her 17th birthday, Watson was met with great public fanfare and was declared an Australian hero by the then Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd. Watson was quick to downplay the high praise from the PM, famously stating:

I don’t consider myself a hero, I’m an ordinary girl. You don’t have to be someone special to achieve something amazing, you’ve just got to have a dream, believe in it and work hard. I’d like to think I’ve proved that anything really is possible if you set your mind to it.

Watson’s love of the ocean was instilled at a young age, when she spent five years living on a 50-foot (15-metre) cabin cruiser with her parents and two siblings on the Gold Coast. She took great inspiration from Jesse Martin’s ground-breaking 1999 circumnavigation, and at the age of 11 decided to commit to training towards her own voyage, which she completed in 2009. In 2011 Watson went on to skipper the youngest crew so far to enter the Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race. All were under 21 and finished second in their division. Watson was named Young Australian of the Year in 2011.

In 2000 Tom King and Mark Turnbull won the coveted 470 double – the Olympic gold medal and the 470 World Championship

01

02

Tom

Mat Belcher’s three medals – two gold and one silver –have earned him the accolade of Australia’s most successful Olympic sailor

Joining Watson in this year’s round of inductees are Mathew Belcher OAM, Tom King OAM and Mark Turnbull OAM. All three have shown their prowess sailing the 470 dinghy, an Olympic class with a crew of two. The dinghy is named after its 4.7-metre length and is a modern fibreglass planing design with a large sail-areato-weight ratio. It is fitted with a spinnaker and trapeze, making teamwork vital to success. The 470 dinghy is further demanding in a large fleet setting where speed differences between vessels are small. It has often been said to be the toughest and most dynamic vessel to sail at the Olympics.

Belcher made history at the Tokyo 2020 Olympics after winning gold with William Ryan OAM in the 470 final, adding to the silver he won in Rio in 2016 (also with Ryan) and gold at the London 2012 games (with Malcolm Page OAM). His three medals have earned him the accolade of Australia’s most successful Olympic sailor. In addition, he has won a staggering ten world titles in the 470 class.

Belcher’s prolific racing career began at just six years of age, when he competed at the Southport Yacht Club on the Gold Coast. His victories at the 2012 Olympics and in the 2010 and 2011 World Championships were completed alongside existing Hall of Fame honouree and 2008 Beijing Olympic champion, Malcolm Page. Like Page and Ryan, Belcher is a long-term student of the esteemed ‘medal maker’, 470 class coach Victor Kovalenko, who taught him to follow his dream. Belcher capped off his dream as flag-bearer at the closing ceremony of the Tokyo Olympic Games.

In 2000, Tom King and Mark Turnbull won the coveted 470 double: the Olympic gold medal, also under the tutelage of Kovalenko, and the 470 World Championship. King and Turnbull both grew up sailing in Victoria, and as juniors were national champions in the Mirror and Sabot classes respectively. Their 2000 Olympic win came minutes after Jenny Armstrong and Belinda Stowell (also Australian Sailing Hall of Fame honourees) won in their own class, breaking a very long Olympic gold medal sailing drought for Australia. The nation had last won a sailing gold nearly a quarter-century earlier, at the 1976 Montreal Olympics. These victories heralded a new beginning for Australian 470 sailing. It’s a lineage that links several of our inductees to the Australian Sailing Hall of Fame, including Ukrainian immigrant sailing coach Victor Kovalenko.

This is the fifth round of awards to the Australian Sailing Hall of Fame. The stories of all inductees so far can be seen on its website sailinghalloffame.org.au. We encourage you to nominate for the next round of inductees, who will be announced in 2023.

Daina Fletcher is the museum’s Head of Acquisitions Development and Manager, Australian Sailing Hall of Fame. David O’Sullivan is a former curator of the Australian Register of Historic Vessels.

The Australian Sailing Hall of Fame is a program developed between the Australian National Maritime Museum and Australian Sailing.

Gold medallists in the men’s 470 class, Mathew Belcher (left) and Will Ryan, on the podium at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. Image Clive Mason/Getty Images King (left) and Mark Turnbull in the men’s 470 class final at the 2000 Sydney Olympics. Image Pip Blackwood/Newspix

The Australian Wooden Boat Festival hosts the largest and most spectacular collection of wooden boats in the southern hemisphere. Gail de Raadt outlines the museum’s involvement in next year’s festival.

The free event will be held across the Hobart waterfront from 10–13 February 2023

Tall ships lead the magnificent Parade of Sail at the 2019 Australian Wooden Boat Festival. Image courtesy AWBFDuyfken will participate in the Parade of Sail, then berth alongside other tall ships

01 Boats afloat on the Hobart waterfront at the 2019 festival. Image AWBF

02

Duyfken will sail from Sydney to Hobart, where it will be open to the public for top-deck tours for the duration of the festival. Image ANMM

After 14 days at sea, the tall ship Duyfken will participate in the glorious Parade of Sail on Friday 10 February and berth alongside other stunning vessels Enterprize, Young Endeavour, Soren Larsen, One and All, James Craig and local boats Lady Nelson, Julie Burgess, Rhonda H, Kerrawyn and Windeward Bound Duyfken will be open to the public for top-deck tours throughout the festival.

FROM ITS HUMBLE BEGINNINGS IN 1994, the Australian Wooden Boat Festival has grown to become the most significant event of its kind in Australia. The free event will be held across the Hobart waterfront from 10–13 February 2023, and as well as boats both afloat and ashore, will include talks, exhibitions, films, music, demonstrations and family-friendly activities.

The Australian National Maritime Museum partnered with the festival in 2017 and 2019, supported it in 2021 with a modified COVID-19 program, and will partner again in 2023. For this festival, the museum will send tall ship Duyfken to Hobart and will again sponsor the Australian National Maritime Museum Wooden Boat Symposium, which promotes wooden-boat culture and conversation. We will support the new Australian National Maritime Museum Boat Builders of Australia marquee, which will showcase traditional boatbuilding. The centrepiece of this display will be a 14-foot gaffrigged sailing dinghy, built in 1939. In the Boat Builders of Australia marquee, visitors can also enjoy displays from 14 of the most significant historic boatbuilders and designers from around Australia.

The Governor of Tasmania, Her Excellency the Honourable Barbara Baker AC , will open the two-day Wooden Boat Symposium, also sponsored by the museum, which will commence on Saturday 11 February. The symposium will feature an impressive line-up of 15 professionals and enthusiasts sharing their love of wooden boats and their expertise on their specialist topic. Three of the speakers will be from the museum. Keynote speaker, Honorary Research Associate David Payne, will open the symposium with his discussion ‘The first wooden boats – Indigenous watercraft in Australia’. Marine Archaeology Manager Kieran Hosty will present on ‘The Barangaroo boat: archaeology and conservation of an early colonial vessel’. Our third speaker, Mirjam Hilgeman, who has spent 14 years sailing and caring for Duyfken, will speak on ‘Duyfken: a 16th-century challenge’. All the talks will be recorded and released over the next 12 months in the festival newsletter and through the museum.

As Australia’s national institution for maritime collections, exhibitions, research and archaeology, the museum is proud to partner with the Australian Wooden Boat Festival in 2023. To find out more, visit australianwoodenboatfestival.com.au. We encourage all boat enthusiasts to visit this world-renowned festival in beautiful Hobart, Tasmania.

Gail de Raadt is the museum’s Sponsorship Manager.

Tu . ’ Do had been constructed for one specific mission: helping a group of desperate people flee Vietnam by sea

Photographer Michael Jensen took this and other stunning images of the boats arriving on 21 November 1977 in Darwin.

Left is PK 3402 with its 47 passengers, right is Tu’ Do with 31. Image © Michael Jensen

Photographer Michael Jensen took this and other stunning images of the boats arriving on 21 November 1977 in Darwin.

Left is PK 3402 with its 47 passengers, right is Tu’ Do with 31. Image © Michael Jensen

The many lives of refugee vessel Tu . ’ Do

On 21 November 1977, six refugee vessels entered Darwin Harbour with 218 people on board. One of them is now a central artefact of the Australian National Maritime Museum: Tu . ’ Do (Freedom). For the 45th anniversary of Tu . ’ Do ’s arrival, Curator of Post-war Immigration Dr Roland Leikauf uses new research to trace its history, from its construction in Vietnam to its exciting present in the museum.

A boat in the parking lot

ANYONE TAKING A RIGHT TURN on Murray Street in Sydney’s suburb of Pyrmont will be stopped by a large, sleek shape clothed in plastic. Behind the Australian National Maritime Museum rests one of its most important artefacts: the refugee vessel Tu’ Do. Conservators in personal protective equipment are hard at work, making repairs and preserving it for future generations.

The vessel was given its bright blue hull on Phú Quo � ´ c, a small island close to Vietnam and Cambodia. However, the person who had the boat built in July 1975 would have been very surprised that it still survives in 2022. It had been constructed for one specific mission: helping a group of desperate people flee Vietnam by sea.

Tan Thanh Lu had commissioned the vessel because he had to act quickly. In the aftermath of the Second Indochina War (or Vietnam War), the new communist government of Vietnam was strengthening its grip on the country. Anyone like Mr Lu, who ran a successful business and had connections to the now-defunct South Vietnamese government, was in grave danger.

To avoid suspicion, Tu . ’ Do (‘Freedom’) was built as a typical Vietnamese dragnet fishing vessel. The 39 conspirators would have to make do with a space designed for a crew of 10. Their plan called for leaving Vietnam under the pretence of a standard fishing trip, but instead crossing the Gulf of Thailand to reach Malaysia. Here, the refugees could try to gain entry into another nation, such as the United States.

Even though many had lived in places close to the water – Phú Quo � ´ c , Rach Giá or Long Xuyên – travelling on a small boat like Tu’ Do was not easy for the voyagers. Only some had maritime experience, and the boat was not built to cross large distances on the open ocean. Their journey had to be slow, following the coast except when large crossings, such as through the Gulf of Thailand, were inevitable. It took 60 hours to cross the gulf, and another two days along the Malaysian coast to Mersing.

Tu’ Do was well built, well provisioned and had a new, oversized engine. Many other people had to flee Vietnam under significantly worse circumstances. Some had no time to prepare for the journey; others could only procure unsafe boats. Engines broke down, provisions ran out; danger and catastrophe were part of the refugee experience. It is impossible to know how many vessels and passengers were lost on the way. Being discovered could mean helpful fishermen one moment and ruthless pirates the next. Survivors tell stories of theft, torture, rape and murder, but also of selfless help.

The colloquially named ‘boat people’ were part of one of the last events of massed migration to Australia by sea

Tu’ Do ’s voyagers were able to outrun the pirates and outsmart most patrols, and they arrived in Malaysia safely. They were not able to secure visas for the USA, however. Most decided to dare a second, much longer journey: passing Jakarta in Indonesia and the Lesser Sunda Islands to reach the coast of Australia. This time, they would cross not hundreds, but thousands of kilometres.

What was life on board like? The passengers often had to pretend to be fishing for hours to fool patrol boats. They could never be sure if the officials would be helpful or hostile – only that they would insist on sending them on their way. As a new boat with a well-prepared crew, Tu’ Do braved all the challenges the sea and other humans posed along the way. When authorities discovered the vessel close to the coast of Australia, the patrol boat HMAS Aware was sent to escort it into Darwin.1

Refugee vessels that were discovered from the air or were known to have left harbours close to Australia were often escorted by patrol boats. The Attack class patrol boat was one type of coastal defence vessel on active duty in the Royal Australian Navy. One of these vessels, HMAS Advance, is now part of the fleet of the Australian National Maritime Museum.

While there is some contradictory information about Tu’ Do ’s course, this is the most likely path the vessel could have taken, based on oral histories and official documents. Crossing the Timor Sea was the last challenge before the voyagers saw the Australian coast near Port Keats, after a journey of more than 5,000 kilometres.

Being discovered could mean helpful fishermen one moment and ruthless pirates the nextVietnam Phú Quốc Malay Peninsula Australia Darwin Port Keats Mersing Cambodia Borneo Sumatra Jakarta Java Sulawesi Lesser Sunda Islands Reok Timor Timor Sea Gulf of Thailand

Reuniting the vessel with Tan Thanh Lu and his family was an emotional experience for the voyagers

01

The Lu family aboard Tu’ Do at the museum in 2002: mother Tuyet (second from right) and children (from left) Mo, Dzung, Dao and Quoc Lu. Image Andrew Frolows/ANMM

02 Tu’ Do after it had been purchased by the museum and repaired, but before the Lu family had been found to provide advice on its original fitout and colour scheme. Image ANMM

For the refugees, arrival in Australia meant the beginning of a new life. The voyagers spread all over the country and began to work, start families and forge futures. The vessels that brought them to Australia, however, were deemed to be illegally imported ships, and many were destroyed by the authorities or abandoned by their owners.

Mr Lu showed initiative and sold his craft early after arrival. Tu’ Do ’s second life, as a working vessel in the waters of the Northern Territory, began. It changed hands several times, was repainted and received a new name.

While many of the vessels of the ‘junk armadas’ supposedly threatening Australia during the 1970s and 80s were irrevocably lost, new institutions became interested in telling the stories of these refugees. 2

In the mid-1980s, the staff at the National Museum of Australia and the Australian National Maritime Museum decided to work together to acquire a refugee vessel even before their institutions had officially opened.

The first of these, Hong Hai, proved an excellent addition to the collection of the National Museum, but all efforts to make it seaworthy failed. When the Australian National Maritime Museum sent curators to the northern coast of Australia to look for an alternative, few of the vessels they inspected were still recognisable as Vietnamese. Only one, called We Believe, could not hide its origin as a Vietnamese fishing boat.

With the help of the current owner, the museum uncovered that this extraordinary vessel was the renamed Tu’ Do. When the museum decided to acquire it, Tu . ’ Do ’s third life began – again with a long journey. It sailed to Sydney on its own power and without incident.

The first mention was small: under the headline ‘Desperate voyages’, the museum noted in its magazine Signals in spring 1990 that it had acquired a ‘South Vietnamese fishing boat’. It also sent out a multilingual call for help: ‘Museum seeks Tu’ Do voyagers’. Through community engagement, contacts were established until all passengers had been either found or identified. Reuniting the vessel with Tan Thanh Lu and his family was an emotional experience for the voyagers, and their knowledge and stories proved invaluable for the museum.

01

Tan Thanh Lu, with his son Mo, at the helm of the restored Tu’ Do in 1995. Image Jeni Carter/ANMM

02

Wrapped and protected, Tu . ’ Do rests behind the main building of the Australian National Maritime Museum while undergoing extensive conservation and repair work. The space is accessible to the public and popular with visitors to the museum. ANMM Image

Removing a vessel from the water is like taking a fish from the sea; the sudden change can cause

devastating, irreversible damage

For years, Tu’ Do was part of many of the museum’s events and programs. People could see it in the water, go on board and discover its interior. However, a fishing boat of its kind is not meant to last forever. In 2021, Tu’ Do was removed from the water and it began another journey – but this time the destination was only a few hundred metres away.

Tu’ Do’s present and future

The vessel had become such an essential part of the museum’s offering to its visitors that a compromise was reached – repairs and conservation projects would be carried out in a space where the vessel was still accessible to the public.

The goal of these treatments is ambitious – to transform Tu’ Do from a vessel at home in the water to an artefact that prefers a completely different environment. Major parts of the process include adhering loose paint fragments, rinsing chlorides from the hull and reversing deterioration from environmental damage and attack by marine animals like shipworms (Teredo navalis). The real challenges, however, are the stabilisation treatments. Slow, controlled drying of the timbers using dehumidifiers, while constantly monitoring the wood, is vital. Removing a vessel from the water is like taking a fish from the sea; the sudden change can cause devastating, irreparable damage. Most visitors won’t notice any major difference once the process is completed, but this careful approach will protect the timbers of this unique vessel from shrinking, warping or even cracking – damage that would be irreversible.

Many of the vessels that were abandoned in the Northern Territory faced this fate. While crises like the MV Tampa affair or the sinking of SIEV (Suspected Irregular Entry Vessel) X in 2001 did keep the plight of refugees arriving by boat in the public consciousness, the colloquially named ‘boat people’ were part of the last events of massed migration to Australia by sea. If the curators hadn’t acted immediately, all their boats would have been lost forever.

Conserving an artefact like Tu’ Do is an important part of the Australian National Maritime Museum’s mission, but it also empowers refugees and their families and communities to reflect on and tell their stories in a public space. Like the Lu family and their fellow voyagers, many refugees have become integral to the Australian community. Once the conservation process ends, Tu . ’ Do will begin a new journey, most likely into the museum building. It will be essential then to ensure that it still can provide a space where those who came to Australia to stay and to belong can interact with the vessel and reflect about their past and their dreams for the future.

1 Tu’ Do and other boats trying to reach Darwin were often several hundred miles off course. Tu . ’ Do reached the coast of Australia on 20 November 1977 and the port of Darwin the next day.

2 Papua New Guinea Post-Courier, ‘Junk Armada on Way to Australia’, 28 July 1977, page 6.

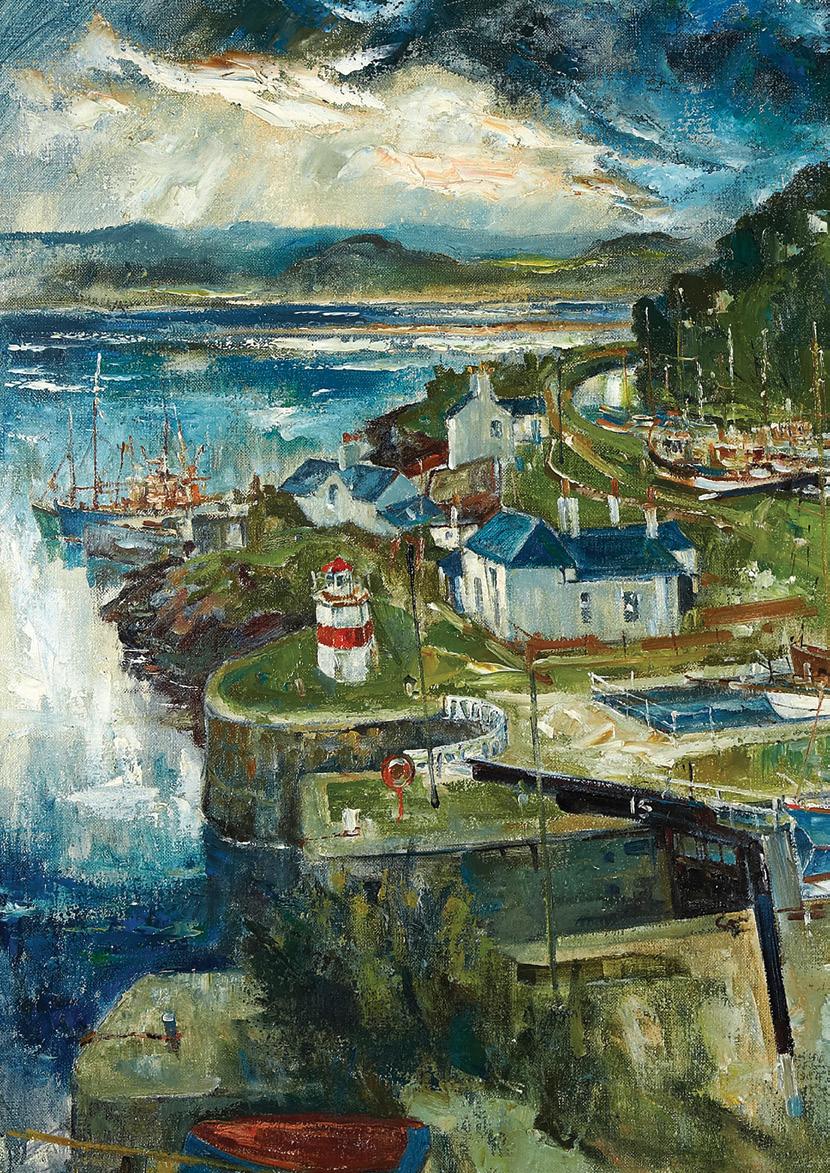

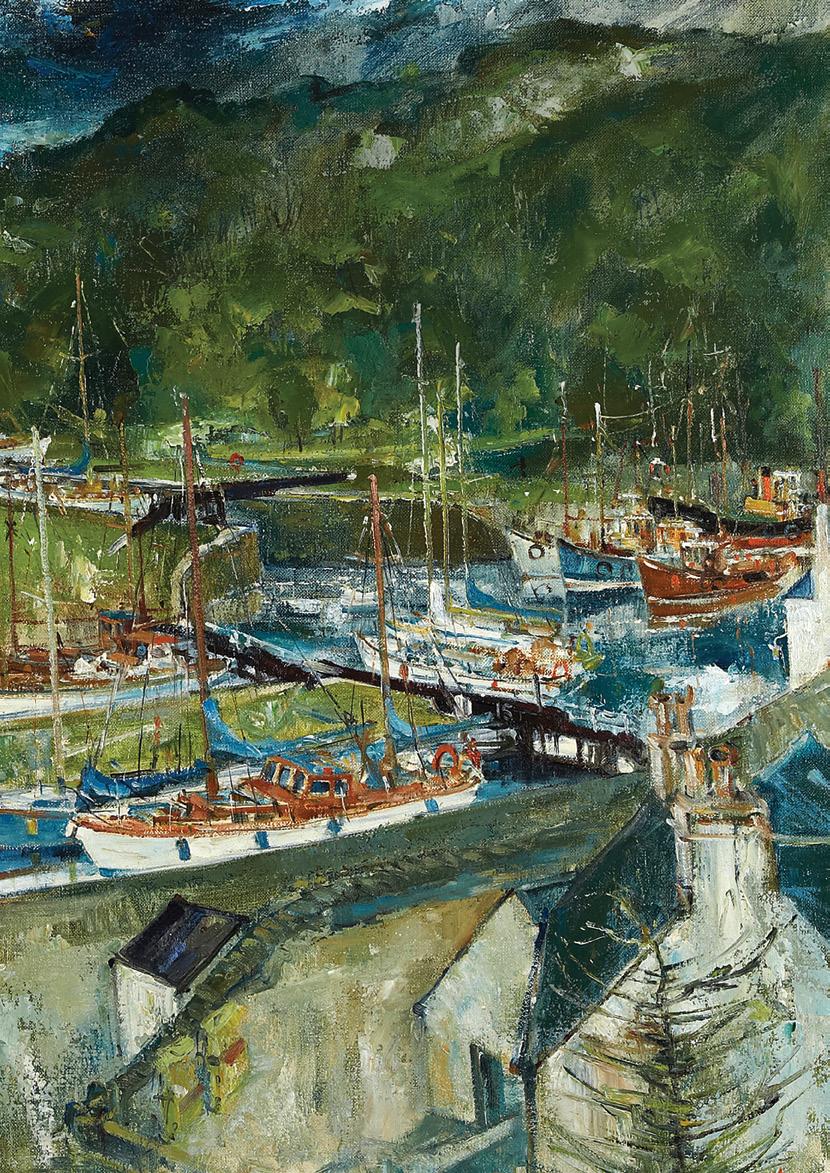

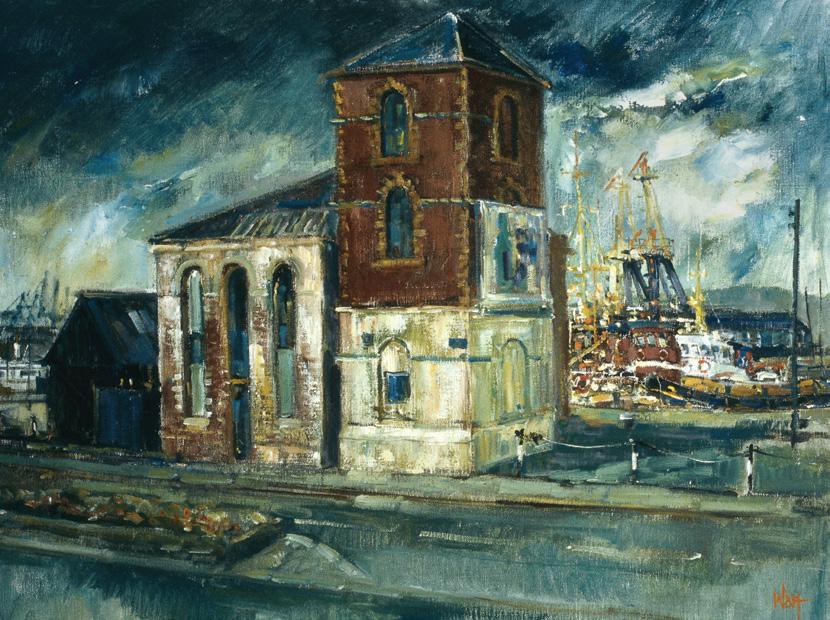

James Watt’s death at the age of 90 leaves the maritime world bereft of a great artist, but blessed by his unique legacy. As Scotland’s pre-eminent marine artist of the 20th century, Watt’s tireless work in capturing the industrial heritage of the Clyde is an unparalleled record of the era in which Scottish craftsmen built the most beautiful ships in the world. Bruce Stannard AM had the privilege of a poignant, personal meeting with Watt at the artist’s home on the banks of the Clyde.

THE CRYSTAL-CLEAR WATERS of the Firth of Clyde lap the shelly beach at the foot of James Watt’s garden at Largs in Ayrshire. Stretching away to the west, the isles of Great Cumbrae, Bute and Arran lie like battleships in line astern, their distinctive shapes bathed in subtle, successive shades of blue and grey. Curlews, eider ducks and goldeneyes dabble in the shallows, and far out in the depths of the Largs Channel, where fussing tugs manoeuvre giant coal ships towards Hunterston, there are whales, dolphins and porpoises at play. The Clyde is a different place these days; so peaceful, so placid, so utterly unlike the hammering cacophony

The Clyde, then the greatest industrial conurbation in Britain, was home to an army of craftsmen justifiably proud of their trade skills

of the artist’s childhood in the smoking shipyards of Port Glasgow over three quarters of a century ago. The change reminds us how quickly the apparent certainties of this world can be turned upside down, and how extraordinary it is that, in less than the span of one man’s life, an entire industry and the hundreds of thousands of people associated with it have been swept so completely away. How incredible that throughout it all, only one artist of any stature was on hand to capture the greatest sea-change in Scotland’s industrial history. How fortunate that artist was James Watt.

James Watt’s wonderful oils are alive with vibrant colour, vitality and the bold, confident brushstrokes of an artist who knew his subject intimately. Year after year he took his paints, brushes and canvases down to the teeming river and there, in all weathers, he captured the clanging, humming essence of Clydeside: the famous shipyards bristling with cranes, the handsome profiles of great ocean-going vessels, humble rust-encrusted puffers and salt-caked dredgers, barges, lighters, skiffs and tugs, all depicted under the threatening glare of ferocious skies. Today, Watt’s paintings hang in many of Britain’s most important collections. The British royal family has three. Early in our conversation, Watt made the point that before anyone can truly appreciate his work, they must first understand something of his own life and the experiences that informed, enhanced and shaped each one of his canvases. It is an extraordinary story.

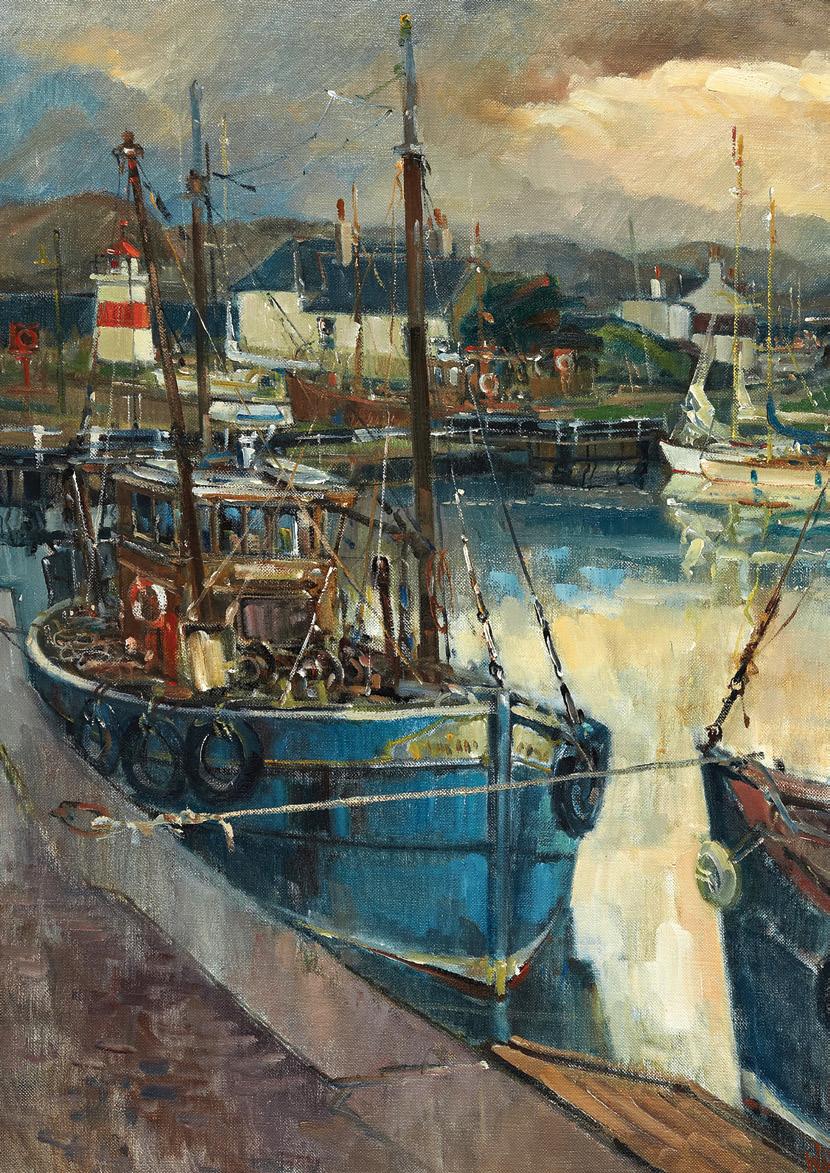

Crinan Basin, 1985, 91 x 122 cm.

For over 20 years one of James Watt’s favourite painting areas was along the Crinan Canal.

From the eastern sea entrance at Ardrishaig to Crinan Basin and the sea lochs with their stunning views to the west, he found inspiration every step of the way.

James Watt’s wonderful oils are alive with vibrant colour, vitality and the bold, confident brushstrokes of an artist who knew his subject intimately

James Watt was born in the gloomy depths of the Great Depression. He was one of five brothers whose father, grandfather and uncles were all riveters, eking out a meagre hand-to-mouth existence on the lowermost rungs of the shipbuilding ladder. Life for James and his brothers therefore held no greater prospect than continuing in the unrelenting hard, dirty and dangerous work of the shipyards that sprawled before them at Port Glasgow. There, in a tiny two-room tenement, one of hundreds stacked cheek-by-jowl on the steep brae above the river, they looked out over the bristling cranes and the masts of ships. The Clyde, then the greatest industrial conurbation in Britain, was home to an army of craftsmen justifiably proud of their trade skills. The term ‘Clydebuilt’ was, in those days, not only a guarantee of superb engineering, it was a badge of honour, but one which also masked a grim reality. Watt told me:

The men who built those wonderful ships were among the finest craftsmen the world has ever known, and yet they spent their lives in abject poverty. Wages on the Clyde were terrible. Working conditions were awful. Many a family, my own included, scraped their way through life, living from one week to the next. This was typical of shipbuilders on the Clyde. It was a way of life that was based on the impoverishment of its workforce. For generation after generation we were locked into that cycle of poverty and there was just no way out financially.

Riveting was one of the most physically demanding of all the shipbuilding trades. Watt explained:

The riveters worked in four-man squads. Two men wielded heavy, long-headed hammers, one right-handed and the other left-handed, while another, known as a holder-on, had to dolly the rivet-head. The squad also included a boy whose job was to heat the rivets whitehot. The hammermen worked at such a tremendous speed that their blows sounded like machine guns. Speed was vital. The base of the rivet had to be hammered flat so that when it cooled its contraction drew the steel plates together so tightly that they formed a waterproof seal. In those days ships were built frameby-frame and plate-by-plate and hundreds of thousands of rivets were used to hold them all together. The ships were all built out in the open and the men were expected to continue working in all weather, summer and winter. It was a ferocious workplace in winter. Men worked down by the riverside with a bitter northerly wind coming over the snow-covered high ground. They were always very badly clothed. There was no concept of health and safety in the shipyards and for the most part the men were very ill-clad for the job. It was all cloth caps and old tweed suits.

The term ‘Clydebuilt’ was, in those days, not only a guarantee of superb engineering, it was a badge of honour

‘The men who built those wonderful ships were among the finest craftsmen the world has ever known, and yet they spent their lives in abject poverty’

02

‘It was a ferocious workplace in winter. Men worked down by the riverside with a bitter northerly wind coming over the snow-covered high ground’

It was work that bred a very hardy race of men. James Watt remembered them as ‘small and tough and wiry.’ Most were around five feet six inches (168 centimetres) tall and although many were much shorter, they had the upper bodies of very big, powerful men. ‘Sons were expected to follow their fathers into the shipyards,’ he said:

Boys of 14 would leave school on a Friday and start work with their fathers on a Monday. If you started a trade you would stay in it all your life. It was common to have three generations of the same family all working together.

Although the shipyard workers’ houses were tiny, the families in them were large. Families with six children were common; some even had 10. They lived in houses that had one or two rooms and a single cold-water tap. An outside toilet was generally shared with up to three other families. Watt recalled:

In those days married women did not work. Once married, women were expected to give up their jobs in the rope and canvas factories and concentrate instead on what were known as ‘domestic duties’, that is to say, looking after their men-folk and their families. My mother did everything in the home. I don’t think my father made even so much as a cup of tea. One of the things I look back on with regret is that in spite of the fact that there were five sons in the house, not one of us ever lifted a finger to help our mother. It was grossly unfair, but my mother did the lot: washing, cooking, ironing, cleaning. She even brushed our boots. Yes, that was women’s work.

We had a two-room house in which my mother looked after my father, myself and my four brothers. One of the rooms was a kitchen with the cold-water tap and an open coal-fired range for cooking and heating. That room also had two beds in it, one for my parents and the other for the youngest son. The other room, which we simply referred to as ‘The Room’, contained a double bed and that’s where the other boys slept head-to-toe like kippers in a box. There was no electricity, only gas lighting. Our living conditions were pretty horrendous and yet, at the time, we weren’t conscious of our poverty. There were people all around us who were in exactly the same boat so, in a sense, we didn’t know any better. That was our lot. People accepted it. There was a great sense of community, a sense of shared deprivation I suppose. In times of trouble people helped each other and backed each other. Port Glasgow was incredibly congested, but it meant that within a hundred yards radius of our house I had two sets of grandparents, three or four uncles and dozens of cousins. They were proud people. They knew who they were. They knew what they were. They were Clydeside shipbuilders and they had no doubts whatsoever as to their own worth. They had what Scots refer to as ‘a good conceit of themselves.’ They thought, ‘We’re Clydesiders. We’re the best in the world.’ In drink their favourite toast was: ‘Here’s tae us, wha’s like us, damned few, an’ they’re deid.’

James Watt, born 17 November 1931, died 7 July 2022.

The author wishes to thank Alison Watt for permission to reproduce her father’s paintings.

Bruce Stannard AM is a renowned maritime author and a Life Member of the Australian National Maritime Museum.

01 James Watt in his studio at Largs, Scotland, 2013. Image Angus Blackburn/ Shutterstock Pumphouse, Victoria Harbour, 71 x 91 cm

The last of the big-gun warships

01

HMAS Vampire at sea.

Australian National Maritime Museum 00028535 Gift of Royal Australian Navy

Signal flag from HMAS Vampire, made on board in about 1970. It features the ship’s logo, a vampire bat with open wings. Australian National Maritime Museum 00037591 Gift of Norman Cooke

IN JANUARY 2023, one of the museum’s most treasured vessels will undergo a major refurbishment. We are inviting our members and supporters to contribute to this project, to ensure that HMAS Vampire remains on public display.

This Royal Australian Navy destroyer was built to a modified British Daring Class design at Sydney’s Cockatoo Island Dockyard and was launched in 1956. The last of the major gunships to be built, it originally had six 4.5-inch dual-purpose guns in three twin mountings; two single and two twin 40/60 mm Bofors AA guns; a Mark 10 Limbo anti-submarine mortar; and a quintuple 21-inch torpedo launcher. The standard ship’s company comprised 20 officers and 300 sailors.

HMAS Vampire served from 1959 until 1986 and, despite its firepower, had a peaceful career. In the 1960s, the ship escorted troops to Vietnam and in 1977 it was the RAN escort for HMY Britannia during the Queen’s Silver Jubilee tour of Australia. In 1980, it was refitted as a training ship. After its decommissioning, the ship was one of the first to be opened for display at the Australian National Maritime Museum for our 1991 launch.

In January 2023, as part of the ship’s five-year docking cycle, it will be towed to the Captain Cook Graving Dock on Garden Island. Vampire will undergo a four-week preservation program that involves ultrasonic fitness testing below the waterline to map rust and deteriorating plates. After doubler plating to reinforce the hull where needed, the vessel will be cleaned and repainted to enable its continued life as a world-renowned museum exhibit. Meanwhile, the curatorial and fleet teams are developing fresh plans to enhance our visitors’ onboard experience.

We invite you to give to this conservation program for our end-of-calendar-year fundraising campaign. You have the option to donate:

• online at sea.museum/donate