Oyster reef regeneration

A new ceramic habitat

A nawi journey

Building canoes, building respect

Tugboat technology

Might and power

Oyster reef regeneration

A new ceramic habitat

A nawi journey

Building canoes, building respect

Tugboat technology

Might and power

THE MUSEUM IS A FAMILY that values our people – our volunteers, our staff and our visitors. Recently, we and the maritime community sadly lost a wonderful member of the family, Martyn Low.

Scott Grant, our Fleet Manager, sent out on behalf of the Fleet team the most beautiful message.

To pay tribute to Martyn, I would like to share it with you as it perfectly sums up our museum family.

It is with a heavy heart that we farewell our dear colleague, shipmate and friend Martyn Low.

Martyn died peacefully in his sleep yesterday following a short battle with leukemia.

We in Fleet are devastated, as I am sure others in the museum and the wider community who knew him are, particularly his shipmates at Sydney Heritage Fleet. He is survived by his loving wife, Elizabeth (Libby) and son Christopher.

There was no one quite like Martyn. A true mariner, steam engineer, North Sea sailor and legend within the maritime community. Martyn Low is irreplaceable.

No one can fill the hole he has left. Not only was he larger than life and one of the most capable marine and steam engineers on the high seas, but he was also kind, funny, warm hearted and generous. Everyone looked up to Martyn.

Being a true steam engineer, Martyn’s pride of the Fleet was certainly Steam Yacht Ena . The love he had for that vessel, as well as for the Ena crew (Andy, Graeme and Hannah), was obvious and beautiful.

Martyn always said that he wanted to work right up to the end. He didn’t ever want to retire – and he didn’t.

It was only a few weeks ago that he climbed out of the Ena engine room, sadly for the last time.

Martyn was and always will be an absolute legend, in the true sense of the word.

Thank you, Martyn, and thank you, Scott.

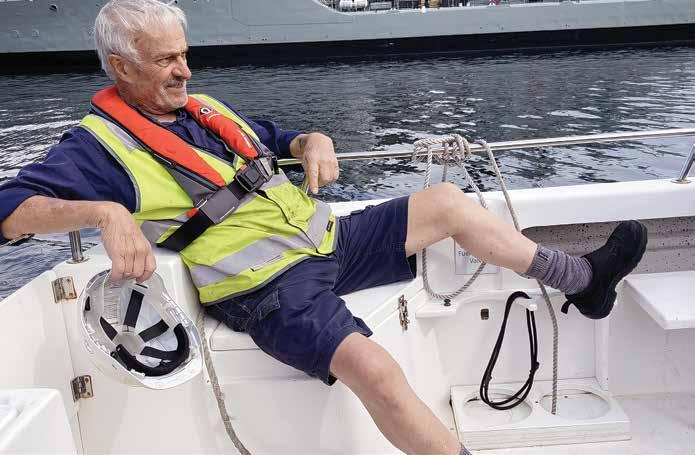

Daryl Karp AM Director and CEO Martyn Low kicking back en route to SY Ena on 1 March 2023, just three weeks before he died. Photograph by SY Ena ’s second engineer, Graeme CurranThe Australian National Maritime Museum acknowledges the Gadigal people of the Eora nation as the traditional custodians of the bamal (earth) and badu (waters) on which we work.

We also acknowledge all traditional custodians of the land and waters throughout Australia and pay our respects to them and their cultures, and to elders past and present.

The words bamal and badu are spoken in the Sydney region’s Eora language.

Supplied courtesy of the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council.

Cultural warning

People of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent should be aware that Signals may contain names, images, video, voices, objects and works of people who are deceased. Signals may also contain links to sites that may use content of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people now deceased.

The museum advises there may be historical language and images that are considered inappropriate today and confronting to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The museum is proud to fly the Australian flag alongside the flags of our Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander and Australian South Sea Islander communities.

2 Boat folk flock to Hobart

A feast for the eyes of classic boat lovers

8 The ingredients for change

Business leaders’ summit brings hope for the oceans

10 Long-lost war grave

Science provides closure

14 Working together with respect

Passing on the skills for building nawi – traditional tied-bark canoes

22 The ecosystem engineers

Science and art work together to save native shellfish

30 The evolution of tugboats

The symbiotic relationship of ships and tugboats advances both

38 Piners’ punts

Uniquely Tasmanian workboats

42 The Dunbar disaster

The museum’s plans to preserve the history of the wrecked Dunbar

44 History in a bottle

A granddaughter’s tribute to Agnes Gibson’s journey to Australia

48 Beneath the surface

Free online and onsite talks and tours by our curators and conservators

50 Members news and events

Your calendar of winter events for members and their guests

54 Exhibitions

Our temporary and travelling exhibitions this season

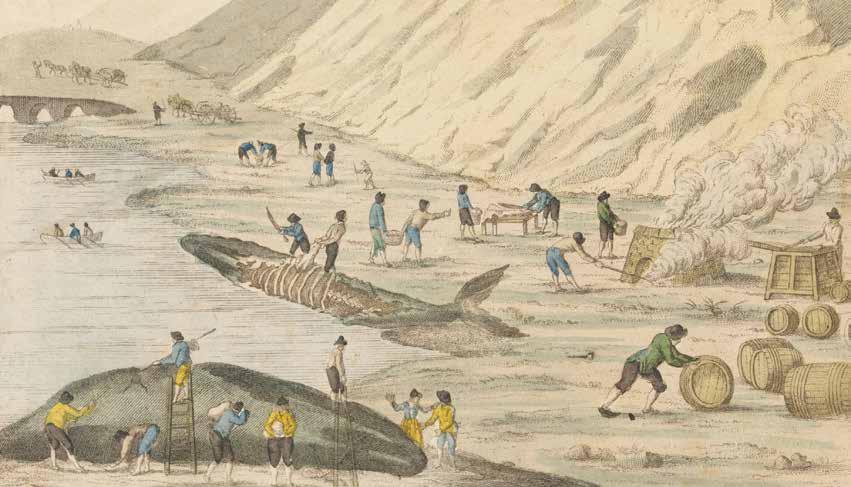

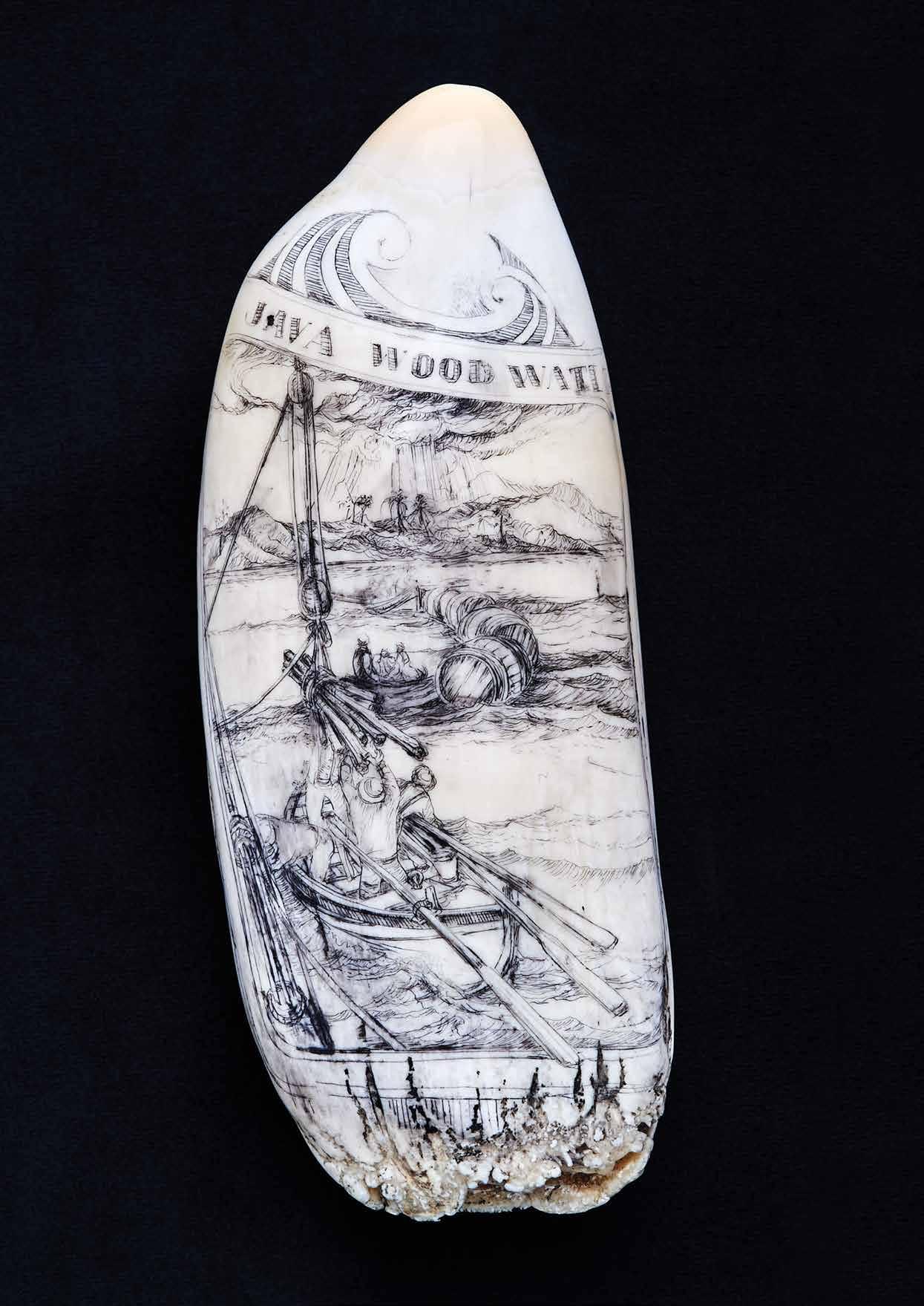

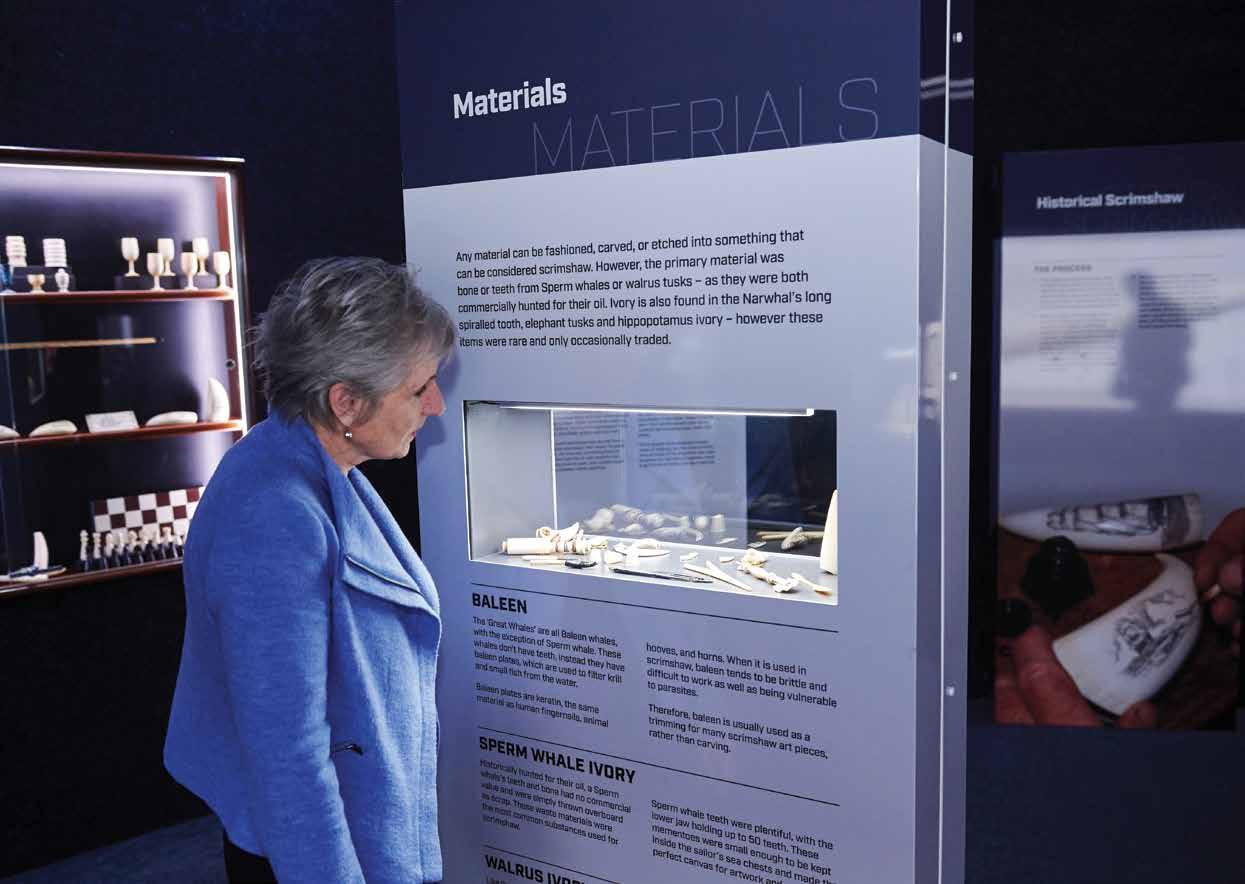

58 The art of scrimshaw

How a tradition of ‘wasting time’ has helped record life on the sea

66 Settlement Services International

The welcome program for newly arrived refugees

68 Readings

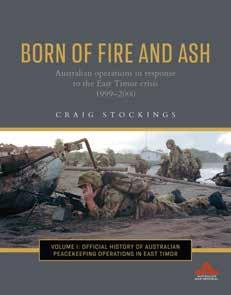

Born of Fire and Ash: Australian Operations in East Timor in 1999–2000

72 Currents

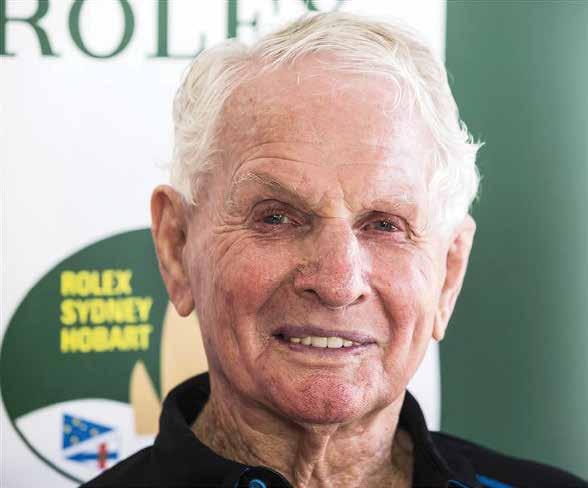

Vale Paul Hundley, Ken Warby and Syd Fischer

80 Currents

National Cultural Institutions Showcase; Ship Modellers Expo 2023

The smaller vessels impressed equally, both on display and while participating in regattas over the weekend

Small craft dressed for the festival at Kings Pier. All images David O’Sullivan/ ANMM

After a four-year hiatus due to the pandemic, the famous and feted Australian Wooden Boat Festival has once again brought boats, boaties, trades and visitors from around the world to Hobart, Tasmania. David O’Sullivan, Australian Register of Historic Vessels Curator, shares some highlights.

TO SAY THAT WOODEN BOAT ENTHUSIASTS had plenty to catch up on during Tasmania’s long weekend in February would be a huge understatement. The biennial Australian Wooden Boat Festival (AWBF) was in full swing for the first time since February 2019, and Hobart’s Sullivans Cove was once more packed with vessels of all kinds, classes and sizes.

The AWBF site stretched from the Tasmanian School of Creative Arts and Media, through the historic Victoria and Constitution docks and all along the waterfront to Murray Street Pier. As vessels began to arrive at Kings Pier for their weekend berthing, I headed up to the Maritime Museum of Tasmania to prepare for a presentation on the Australian Register of Historic Vessels (ARHV) that evening.

This presentation had been organised to recognise owners of vessels recently listed on the register, and who were attending the festival. It was also a chance for others involved with the register, such as ARHV councillors, volunteers and supporters, to gather together. Since my role with the ARHV began in late 2020, I had been unable to attend any physical events, so it was special for me to finally meet all of these people in person.

Four vessels from four different Australian states were awarded on the night. The first was the recreation yacht Barameda, built in 1967 at Hobart’s famous Battery Point boatshed by the highly regarded Purdon Brothers. Next up was the 66-foot (20-metre) former pilot cutter MV Goondooloo, which originally worked in Sydney and Newcastle harbours and is now the subject of a local restoration initiative in Hobart. An award was given to the elegant motor cruiser Pedare, from South Australia, notable for its service as a Royal Australian Navy coastal patrol vessel during World War II. The final award went to the Northern Rivers-based Waitoa, a Torres Strait pearling lugger, constructed in 1904 and one of the oldest of its kind known to still exist.

A large proportion of the attending vessels took part in the Parade of Sail, the event that traditionally opens the festival

01 Author David O’Sullivan with Deb Ludeke, owner of ARHVlisted vessel MV Goondooloo

02

The Parade of Sail is popular with both participants and spectators.

On the opening day of the festival, I had a proper chance to look at the numerous other historic vessels visiting Hobart. One that caught my eye was the former America’s Cup contender Gretel II – and word was out that John Bertrand, winning skipper of Australia II and true yachting royalty, was in town.

Many of the restored and replica tall ships were impressively aligned on one pier, such as Windeward Bound, Lady Nelson and the Australian National Maritime Museum’s very own Duyfken. The smaller vessels impressed equally, both on display and while participating in regattas over the weekend. They included various Couta boats (a few of which had made the treacherous trip across Bass Strait); Tassie Too, of the 21-Foot Restricted class; and the fantastic Merlin, a Derwent class yacht recently listed on the ARHV.

A large number of the attending vessels took part in the Parade of Sail, the event that traditionally opens the festival. For this, more than 100 craft headed out onto the Derwent River, then formed a procession back up the river and to their berths. Tall ships, rowboats, sailboats and steamboats all joined in.

Wandering around the site after the parade, I took in the museum’s Boatbuilders of Australia display – an exhibit contained within a dinghy – which illustrated the approach taken in designing and constructing a smaller historic sailing vessel. Craft workshops and displays abounded across the festival, including ropemaking, the various trades in the shipwrights’ village and a DIY boatbuilding challenge for younger attendees.

Hobart’s Constitution Dock was once more packed with vessels of all kinds, classes and sizes

Day two began for me with the Australian National Maritime Museum’s Wooden Boat Symposium, which was comprised of a series of presentations and panel discussions on various maritime subjects, and was held in the School of Creative Arts and Media. A lead sailor from Duyfken, Mirjam Hilgeman, began the talks with an informative and entertaining account of the history of Duyfken ’s construction and the skills needed to take the 16th-century Dutch replica on a voyage from Sydney to Hobart. The museum’s Maritime Archaeology Manager, Kieran Hosty, presented on a vessel causing much wonder and excitement at the moment – the Barangaroo boat. With construction dated to the 1830s, this early colonial vessel is believed to be the oldestknown example in New South Wales of an Australianbuilt European-style timber boat.

I followed the symposium with a sail on Rhona H, a ketch built in 1942 and originally used in Tassie waters for crayfishing, but which now operates as a commercial sailing and charter vessel. Rhona H would later take part in the festival’s ‘ketch review’, vying with other ketches to be the fastest on the Derwent. Highlights of the rest of the day included going aboard the recently listed MV Goondooloo and attending the Royal Institute of Naval Architects drinks aboard the World War II launch ML Egeria, which was also the vessel to host the Tasmanian Governor, The Hon Barbara Baker.

The final day of the festival fell on the second Monday of February, a public holiday in Tasmania known as ‘Regatta Day’. I was lucky enough to be invited aboard Westward for the Admiral’s sail. This, the closing event of AWBF 2023, was a sail-past by all vessels at the festival. It was a serene but spectacular affair out on the Derwent, and it felt particularly special to be on Westward, the only Tasmanian yacht to have twice won the Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race, in 1947 and 1948. It was a superb end to a successful and fascinating weekend.

It was impossible to fit in every boat, every talk, every workshop and every sail, so AWBF 2023 left me, and no doubt many others, keen for more. I will definitely be seeing many of you boaties again soon. Until then, fair winds and fine sailing!

The Australian Register of Historic Vessels is an online national heritage project, devised and coordinated by the Australian National Maritime Museum in association with Sydney Heritage Fleet. For more information, see sea.museum/arhv.

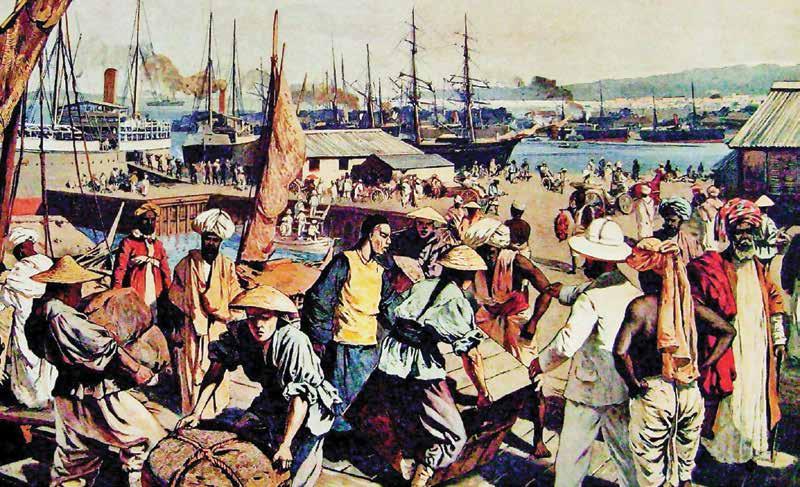

What do you get when you cram state and federal government officials, titans of industry, powerful non-government organisations, community leaders, lawyers and youth influencers together in one room for two days? You get the ingredients for real change, writes Emily Jateff.

AS PART OF THE UNITED NATIONS Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021–2030), the first Ocean Decade Australia ‘Ocean Business Leaders’ Summit’ was hosted by the museum on 1 and 2 March. More than 200 passionate, hand-selected attendees furiously engaged in finding a collaborative way forward for ocean energy, ocean food, ocean finance and ocean health.

The summit provided a forum for discussions on some of the biggest issues facing the ocean today – from the creation of new marine parks to regulatory frameworks for offshore renewable energy. Some of the most interesting discussions were around the social licence to conduct works, allowing for transparent data collection and dissemination, clarity for investors in green futures, and potential partnerships for storytelling that engage audiences as active influencers of our ocean’s future.

Minister for Environment and Water, The Hon Tanya Plibersek MP, announced the government’s new National Sustainable Ocean Plan. Andrew Forrest AO, Chair of Fortescue Metals and the Minderoo Foundation, spoke of sustainable fisheries, a reduction in ocean plastics and other aspects of future ‘flourishing oceans’, and he committed the Minderoo Foundation to financing and resourcing efforts to find solutions. Many conversations during the summit made the point that five years ago a group of this calibre would not have gathered. High-level conversations are a crucial part of the path toward action, and this summit helped to pave the way forward.

Minister Plibersek also emphasised the government’s approach to prioritising First Nations issues, and she spoke about the songlines found on Sea Country managed by the Murujuga Aboriginal Corporation in Western Australia. In January, the federal government nominated the Murujuga Cultural Landscape for inclusion on the UNESCO World Heritage List. If accepted, it would be the second First Nations cultural site in Australia included on the list, joining the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape in Victoria. Central to the Murujuga story are 7,000-year-old stone tools, recently recovered from below the low-water mark, which offer evidence of songlines and the extent of Sea Country. These tools will be on display at the museum as part of the refurbished Shaped by the Sea gallery later this year.

The aim of the summit was to coalesce all discussion points into a white paper that will be submitted to the federal government as a suite of industry- and community-led solutions for our changing ocean. Through supporting Ocean Decade Australia by hosting this summit, the museum has been a part of the voice for Australia’s future, facilitating the conversations that will hopefully begin to transform our relationship with the ocean.

The author wishes to express her gratitude to Ocean Decade Australia: Jas Chambers and Lucy Buxton, Summit Organiser Andra Müller and the Advisory Council for Ocean Decade Australia.

Emily Jateff is the museum’s Curator of Ocean Science and Technology.

01

South Pacific Regional Environment Programme Youth Ambassador Brianna Fruean addresses the crowd at the Ocean Business Leaders’ Summit Youth Breakfast.

02

From left: Lucy Buxton and Jas Chambers from Ocean Decade Australia; Tanya Plibersek, Minister for the Environment and Water; museum Director and CEO

Daryl Karp AM; museum Chair

John Mullen AM Images Yve Lavine Photography

For more than 80 years, generations of Australians had no idea where their relatives died

Under the stewardship of the museum’s Chair, John Mullen, the Silentworld Foundation has again brought one of the ocean’s secrets to light.

Peter Fray spoke to Mr Mullen about finding the wreck of the Montevideo Maru.

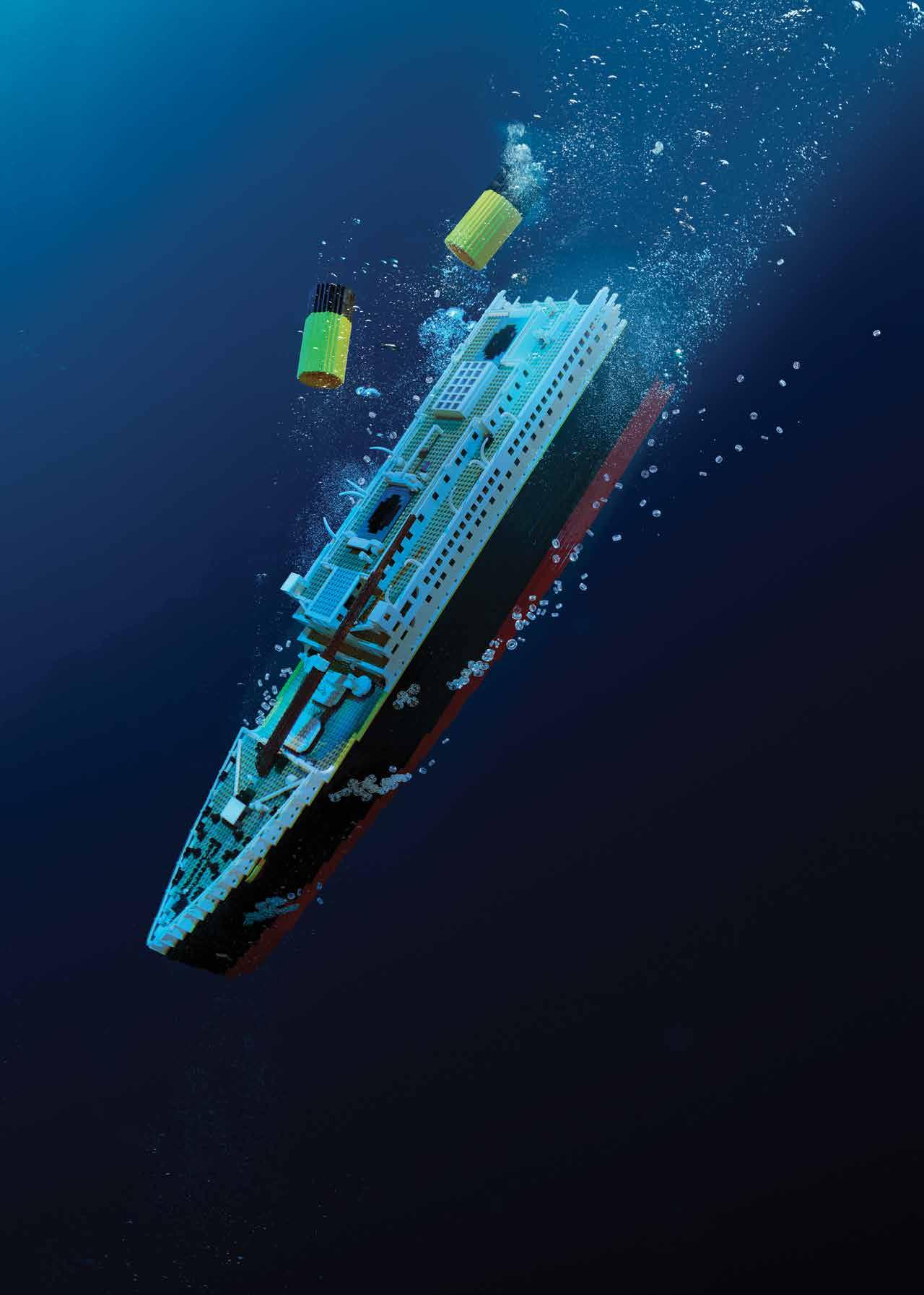

MORE THAN 4,000 METRES below the surface of the South China Sea lies the wreckage of Montevideo Maru, the final resting place of almost 1,000 Australians who perished when the Japanese transport carrying Allied prisoners of war was torpedoed by a US submarine in July 1942.

The Americans on the USS Sturgeon did not know that 987 Australians were on board and for more than 80 years, generations of Australians had no idea where their relatives died, in what is the country’s worst maritime disaster. Some were officially told the place was ‘known only unto God’.

That changed in April this year when, after five years of planning and two weeks of searching, Montevideo Maru was discovered about 120 kilometres off the northern Philippines by the private not-for-profit Silentworld Foundation. Supported by the Department of Defence, the expedition was led by John and Jacqui Mullen, along with a team of Australian and international experts.

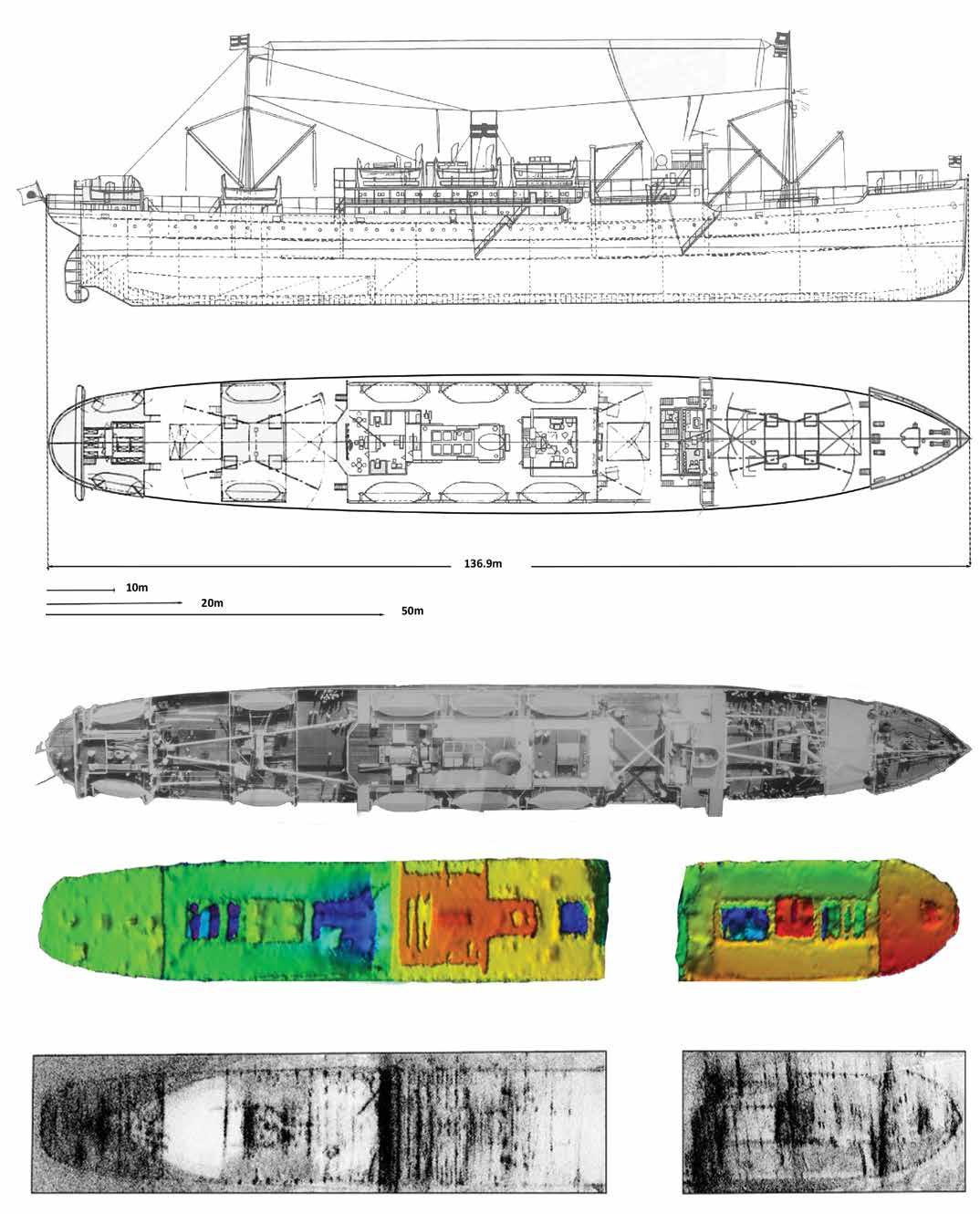

A composite image comparing archival plans and an aerial photograph of the Montevideo Maru with the bow and stern multi-beam sonar scan (MBSS) image (4th from the top) and AUV image (bottom). Imagery obtained by Fugro Equator and the Silentworld Team.

All images courtesy Silentworld Foundation

Silentworld, founded 20 years ago to explore the nation’s maritime history, came to international prominence in 2017 when it helped to find the location of Australia’s first submarine, AE1, which disappeared off the coast of then-German New Guinea in 1914.

Both discoveries are testament to the tenacity and personal commitment of John Mullen, Chair of the Australian National Maritime Museum Council and of Telstra, as well as logistics company Brambles. But it is the recent discovery of the wreck of Montevideo Maru by Silentworld that has highlighted the foundation’s contribution to maritime history, both in Australia and internationally.

‘The reaction has been mind-boggling,’ Mr Mullen says. ‘You might be surprised how much difference the discovery means to people, to relatives. They [the passengers] were all sons, fathers and brothers of families who have never been forgotten.

‘You would be absolutely amazed at how many people – many, many families – have lived and breathed this tragedy, handed down through the generations. For them, knowing where their relatives died has brought a sense of closure, of relief.’

Making it even more poignant, the discovery was confirmed just a few days before Anzac Day. That was unplanned but timely. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said he hoped the find would bring a measure of comfort to relatives and other Australians, including former government ministers Kim Beazley and Peter Garrett, both of whom have spoken of their personal connection to the tragedy.

01

MBSS of the stern section of Montevideo Maru lying in more than 4,000 metres of water off the coast of the Philippines. Using data obtained from the MBSS the team could accurately measure the length and beam of the hull and its various features such as holds and superstructure, and then compare this with archival information on the vessel.

02

The Silentworld Foundation team on board Fugro Equator. From left: Commodore Tim Brown (Rtd), Max Uechtritz, Captain Roger Turner (Rtd), Neale Maude, John Mullen and Andrea Williams. Image Tim Brown, Silentworld Foundation.

‘There was a sense of elation tinged with great sadness. We were looking at the gravesite of 1,000 people’

The first images of the ship were taken by an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) which was operating off Fugro Equator, a survey vessel belonging to the Dutch deep-sea survey company, Fugro.

On board Fugro Equator, Mr Mullen recalls the moment of discovery as a mixture of emotions. ‘There was a sense of elation tinged with great sadness. We were looking at the gravesite of 1,000 people, who died in the most horrendous circumstances.’

The Fugro Equator crew included Andrea Williams, Chair of the Rabaul and Montevideo Maru Society, whose grandfather Philip Coote died in the sinking. As Mr Mullen remembers, ‘there were a few tears’.

The story of the Montevideo Maru is far from over, but the wreck site will not be disturbed in any way. And, as Mr Mullen explains, the depth of the wreck – greater than the Titanic ’s – means it is unlikely to become a magnet for casual treasure hunters.

There is still much to be done in photographing and surveying the wreckage in greater detail, using a remotely operated vehicle, or ROV, and the next phase is likely to prove very costly.

Arrangements are under way to formally remember those who perished. Mr Mullen and others are planning services in Japan, which lost 60 guards and sailors on the ship, and Norway, which had 26 nationals on board.

In Australia, the discovery is an opportunity for the nation to finally and fully accept what happened to the Montevideo Maru, and to acknowledge that for many years those who died were denied recognition.

As Mr Mullen notes, there are many terrible stories in the tragedy’s wake: families were split up; children sent to orphanages. There were reports of suicide. ‘The [wartime] government covered up the true magnitude of what had happened,’ he says.

John Mullen is in his second and (as stipulated by legislation) final term as chair of the Australian National Maritime Museum, but he hopes to support and be associated with the museum for many more years to come.

No matter what happens, there is little doubt that Mr Mullen’s love of all things maritime will continue. First forged by childhood adventures in Portugal and Spain, and nurtured by a lifetime on boats in this country, the biggest file in his life’s database would be labelled, ‘Human Interaction with the Sea’. ‘I have grown up loving the ocean’, he says. ‘It’s been a wonderful time. It still is.’

The next edition of Signals will carry a full report on the science behind the discovery of the Montevideo Maru

Peter Fray is a journalist and former newspaper editor.

For over a decade, the museum has been collaborating with Aboriginal communities to reinvigorate the practice of making nawi (tied-bark canoes). These canoes are more than just practical craft – they embody layers of culture and generations of knowledge. David Payne reflects on what has been achieved, learnt and shared.

A display of models made by local schoolchildren at Bankstown Arts Centre in 2022. Images David Payne unless otherwise noted

A display of models made by local schoolchildren at Bankstown Arts Centre in 2022. Images David Payne unless otherwise noted

Patience, observation, responsibility, respect

I HAVE BEEN REMINDED of these four words many times over the years I have been building nawi (tied-bark canoes), working closely with Aboriginal communities and their elders. They are directions everyone should live by, and the long nawi journey the museum and I have taken since 2012 has been guided by them. Looking back along the waters we have travelled together, I can see how this has brought rewards to all involved. We have been building tangible objects, and the process has delivered intangible messages.

Nawi and the museum have an enduring connection. It began in 2012, with the conference ‘Nawi – Exploring Australia’s Indigenous Watercraft’, and continued through workshops, events, a second symposium in 2017, and other community and cultural collaborations. Some of this has been highlighted in articles or blogs, but other things have gone by quietly, without fuss, and greatly appreciated by those they have helped. The skills to make nawi are alive and this knowledge is being shared whenever opportunities arise.

Separately, my personal connections to nawi and community have not only endured since those early days, they have evolved in a way I never anticipated. There has been friendship, support and acceptance as an active, respected member of their community.

The COVID-19 period brought many things to a standstill, including our nawi work. Personal tragedy over this same time made me focus on family and relationships. Our true colours were on show, and they were the right ones.

01

Two large nawi made for Bankstown Arts Centre in 2022.

02

Yarning around the campfire during men’s cultural health camps held in August and November 2022.

The skills to make nawi are alive and this knowledge is being shared whenever opportunities arise

Reconnecting in May 2022 with mentors, Saltwater elders Uncle Dean Kelly (Yuin) and Uncle John Kelly (Dunghutti), highlighted another aspect not immediately obvious. Building nawi is also an opportunity to bring people together for much bigger things. We made much more than just the canoes. We made friendships, we listened to the elders and teachers, we made ourselves understand and practise those behaviours of patience, observation, responsibility and respect, and we talked, yarning openly about personal issues. As both uncles said to me, ‘This will be healing for you, brother’. It has helped me through a difficult period, and it’s brought a lot more to others inside and outside of our group.

So, let’s build a nawi.

Grey, red, yellow, fire, forming, finishing

These are the individual chapters in the story I tell for building a nawi. First, the colours – the inverted sheet of bark sits with its grey outside layer showing. Peel this off to reveal a stronger red bark. Now trim this back just enough until the body of the nawi can be formed, then start to thin the red bark at the ends of the sheet to reveal the yellow layers, which have the strongest fibres. They are the inside face next to the hardwood trunk of the living tree, whose outer rings carry a flow upwards from the roots to the branches and leaves. But these yellow layers are also very much alive – they take the downward flow back to the base of the tree, adding to the spirit and life that are always in the nawi, and come from Mother Earth and Grandfather Sun.

Fire is a tool to respect, and a friend to work with; use it to heat the thinner ends to help soften them further. Forming the nawi, you take the sheet off the fire, bring up the sides to make a body, and then fold the softened ends inwards to create a raised bow and stern. Finishing requires you to peg and bind the folded ends, then hold the sides apart with branches that push out against the cross-ties that pull in.

Now it’s done. We have shared the knowledge and our nawi is complete. It’s hard, physical work. Our hands are dirty, but we have a feeling of great satisfaction. For everyone, the process of working the bark into a nawi has taken patience, observation and respect for the material, along with personal responsibility and respect for others to work as a team. The finished nawi has its own individual look, but in concept it is the same as all those that have come before it – a mark of respect for the elders and their knowledge which has been passed on, observed and now preserved in another generation. The many nawi-building projects for 2022 began in May with two events held in Sydney over consecutive weekends. The first, facilitated by City of Sydney, supported the opening of bara, a monumental fish-hook sculpture by Aboriginal artist Judy Watson. The second was an initiative of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, managed by Wesley Shaw. On Gadigal land, we built two full-size, three-metre nawi and almost 20 models,

close to the waters where nawi were once a common sight. Father’s Day had us engulfed, making 28 models in one morning on the shoreline at Barangaroo, working with family participants, while two separate day-long events with Bankstown Arts Centre produced another three-metre canoe and half a dozen models, made with local schoolchildren, whose works then became their display. Next, filming for a day at Bobbin Head for the National Parks and Wildlife Service website produced nawi models with kids, teachers and rangers. Finally, in December, I was restoring two museum nawi to display condition for community to borrow – an appropriate way to bring the year to a close. All of this involved much preparation on our part, practising ceremony and respecting culture at each event, with leadership and teamwork essential components, all making it an enjoyable experience for the participants.

The success of the workshops can be measured in the enthusiasm of the Indigenous and non-Indigenous participants, their smiles and enjoyment as they worked together, their satisfaction and genuine thanks for what they had learnt and achieved. The take-home possessions – the gorgeous models, or the full-size nawi the team stood proudly behind – served to remind everyone of the other things they had learnt along the way.

These were among the ‘tick box items’ we had to bring with us to a pair of three-day men’s cultural health camps held in August and November. These are structured cultural exercises for the Indigenous community, led by the elders, to pass on and strengthen their long-held values and beliefs. They are an initiative by Uncle Dean, Uncle John and fellow elders to continue the hugely valuable work started by the late Uncle Max Harrison. They demonstrate again how teachings are developed alongside the activities provided. Ceremony and responsibilities throughout the camp are handed by the uncles to younger members so they can gain experience and confidence. Directions and teachings are followed and campsite jobs are shared by all. Three days seems too short to take it all in.

Things changed for me at the camp in August. I had always seen myself supporting the elders with the practical side of building nawi, often taking the lead responsibility for instruction, and managing the construction. This time we built three 4.5-metre-long nawi, big ones, but I now held the same responsibilities as the other uncles. I’m part of the mob now – Uncle David. And that’s how it’s been in all the subsequent events, and I am treated with the respect this title brings.

We have been building tangible objects, and the process has delivered intangible messages

Building nawi is also an opportunity to bring people together for much bigger things

01 Yula-Punaal camp, 2017: a canoe brings people of various ages together to yarn away as they apply clay to its interior.

02

Two bronze nawi now permanently on display at Kamay Botany Bay National Park, cast from two nawi made at Yula-Punaal Men’s Cultural Health Camp in 2019 by Uncle Dean Kelly, Uncle John Kelly, Uncle David Payne and Uncle Richard ‘Cooma’ Swain.

As a whitefella uncle, I have an extraordinary privilege, and I recognise this brings significant responsibility. Uncle Dean has always said that knowledge is only useful if you pass it on, and while I have been able to share my own knowledge to help build nawi, I have been taught more knowledge in the process. I have been patient and I’ve respected those I’ve worked with, but now that’s just a beginning. There is so much more to observe, understand, learn and absorb from the caring community who have taken me in. And I can share this within my other community to help people understand about the value of working together with, and learning from, Indigenous communities.

In short, this means working together with respect, learning from each other. The first two nawi events in 2022 bookended National Reconciliation Week (27 May–3 June). This promotes the broad concept that reconciliation involves ‘creating a nation strengthened by respectful relationships between the wider Australian community, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’. All the nawi events served to strengthen the traditional culture within the Indigenous community as they prioritise maintaining their culture and its origins while living alongside another world. However, the events and my rare personal experiences show that reconciliation could be much more than the simple notion of Indigenous people becoming reconciled to living with us.

Turn it around: reconciliation can allow today’s society to learn and gain from listening to Indigenous culture, understanding Country, even playing a part. In this way, it can develop respect for all our elders and the authority they have earned, respect for what they pass on to us, and respect for the environment that supports our needs.

The nawi journey will continue for me and the museum in 2023, taking along with it patience, observation, responsibility and respect. These four elements are vital to the nawi-building process, enabling the group to work together – but as we have seen, that becomes a lesson and metaphor for applying these values every day. While everyone who has helped build a nawi creates a tangible object, on that journey they have also been observing, experiencing and gaining the intangible, Indigenous cultural knowledge and understanding, along with a message in life. The rewards come in many ways, and participation makes everyone involved more comfortable within this country.

For more information, see Signals issues 99 (June 2012), 100 (September 2012), 120 (September 2017) and 122 (March 2018).

David Payne is an Honorary Research Associate of the museum and its former Curator of Historic Vessels.

On Kangaroo Island in South Australia, the local community is lending its support, industry and knowledge to the restoration of a vital ecosystem, with the help of a Tasmanian ceramicist.

By Keely Jobe .

Alexandra Comino installing ceramic razorfish shells on a native oyster reef restoration site, 2023. Most of the shells made for this project were porcelain or white stoneware, with a few in terracotta (yellow/orange) or buff stoneware. Image Stefan Andrews

A project to restore Kangaroo Island’s native angasi oyster reefs is under way quite literally below the surface

TO MAKE LASTING, POSITIVE MATERIAL CHANGES to a threatened species or ecosystem might sound like a lofty aim, but dreaming big seems to be a standard approach in conservation circles. Yet while the aims of conservation are sometimes grand, the labour often goes unseen and the contributors themselves can fly under the radar. This is the case on Karta Pintingga, or Kangaroo Island, in South Australia, where a project to restore the island’s native angasi oyster reefs is under way quite literally below the surface. Here, in the island’s northern coastal waters, where the bays are sheltered from brutal southerlies and mammoth seas, the locals are not only trying to regenerate the occurrence of a native species, they’re hoping to revive an ecosystem in the process.

Kangaroo Island once had a thriving native oyster population. Although its history of human habitation is mixed and inconsistent, there is evidence of First Nations communities having some connection with the island 16,000 years ago, when it was still joined to the mainland. What’s more certain is that with the arrival of European settlers, the local native oysters were quickly harvested to the brink of extinction and it took around 100 years for angasi oysters (Ostrea angasi ) to be almost obliterated from the island’s coastal waters. Usually, when a species is under threat, the challenges it faces are numerous and increasing, originating from different sources and directions, but the angasi’s disappearance was due mostly to overfishing. What remained on the sea floor was then dredged up so the shells could be crushed for lime mortar to provide roads and buildings for the community. This colonial building practice is not unique to Kangaroo Island – a history of shellfish harvesting resides in the infrastructure of many Australian towns and cities.

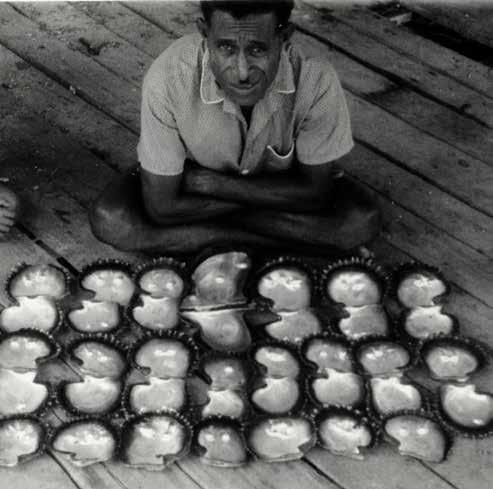

I should note at this point that I love oysters. If my wallet allowed it, my appetite for oysters might even be referred to as unsustainable. But until I spoke to Alexandra Comino, marine biologist and manager of the Kangaroo Island Landscape Board’s Native Oyster Reef Restoration Project, I didn’t know much about these shellfish. Alex tells me that oysters like to grow on oysters – they do best when cosied up together – but there are other basic elements they need to really thrive. They need calcium in spades, for example. They also need currents to spread their spat (larvae), but nothing so strong that the spat can’t settle in. Angasi oysters do particularly well in a thriving ecosystem, in an intricate web of diversity. When all of these things are offered, an oyster reef can flourish and expand.

In the coastal waters of South Australia, there are two key bivalve species whose presence or absence can make or break an ecosystem. Together they provide the perfect substrate for other species to grow on and around, to hide in, to feed in, to rest in, to make a home. The angasi is one of these species. The other is the razorfish, or pinna (Pinna bicolor). A much larger bivalve growing up to 60 centimetres in length, it burrows into the sand, leaving most of its shell exposed. They cut a magnificent profile on the seabed, standing upright like the sails of a yacht filled with wind. Along with the angasi, their populations have been in decline on Kangaroo Island since European settlement, which means that the ability for other species to survive and thrive in this area has also been drastically reduced.

01

A razorfish covered in a diversity of marine life, including an angasi oyster towards the top of the shell.

Image Stefan Andrews02

Ceramic razorfish shell forms 12 weeks after installation, with attached angasi spat (larvae) and tube worms. Clay is an ideal medium for artificial habitats such as these, as it is of the earth, stable in the marine environment, biosecure once fired, and can be crafted to a form that embraces biomimicry.

Image Brodie Philp

Razorfish cut a magnificent profile on the seabed, standing upright like the sails of a yacht filled with wind

Ecologies operate in a graceful multi-species entanglement, a circular system of reliance

01 Jane Bamford in the studio making razorfish shell forms. She prototyped five clays, then settled on a porcelain and a stoneware. Jane made 1,000 forms over five months, for which the University of Tasmania gave her an artistin-residency. Her work was supported by a grant from the Australia Council for the Arts.

Image Peter Whyte

02

Members of the Kingscote Men’s Shed making an improvised artificial oyster habitat from an old pallet and roof tiles.

Image Alexandra Comino, courtesy Kangaroo Island Landscape Board

There is a poetic balance at play here, because while these two species of shellfish flourish in a healthy ecosystem, that same ecosystem needs the shellfish to really prosper. Without the shellfish, the ecosystem is debilitated. This is generally how ecologies operate, in a graceful multi-species entanglement, a circular system of reliance. For a conservationist, it means that focusing on a single species is not really useful, or even possible, without also acknowledging and giving care to the species surrounding it.

Alex Comino demonstrates this expanded care when she explains the positive cascading effect that this project offers. With the return of the angasi and pinna reefs, a raft of other species look to benefit, including threatened and iconic syngnathids such as pipefish and leafy seadragons, numerous kelp species, other shellfish like scallops and mussels, recreational fishing species such as King George whiting and southern calamari, and a whole host of invertebrates from tube worms and blue swimmer crabs to octopus. In addition to this biodiversity boost, the return of the angasi and pinna will also mean an improvement in conditions for adjacent seabound communities like the nearby rocky reefs and seagrass meadows, the latter of which sequester huge amounts of carbon – a valuable trait in our rapidly changing climate. This project might seem humble now, but there may be many exciting benefits ahead. It’s not surprising that Paul Jennings of the Kangaroo Island Landscape Board, whose brainchild this project is, refers to these shellfish as ‘ecosystem engineers’. The project he envisioned is designed first and foremost to assist in the role that the shellfish play.

Members of the Kingscote Men’s Shed have designed their own reef modules using recycled pallets and roof tiles

If this is not the story of a single species, neither is it the story of a single conservationist, a single scientist, or a single government working group. Like the ecosystem upon which it focuses, native oyster reef restoration on Kangaroo Island brings together a much larger cast of characters, led by Paul and Alex.

Jane Bamford, a Tasmanian ceramicist whose pieces are made almost exclusively for the non-human world and regularly straddle the line between art and conservation, has been brought on board to create clay forms that mimic the razorfish. In the past, Jane has worked on clay habitats for little penguins and the critically endangered spotted handfish, so her skills are well suited to this watery task. When grouped together in the coastal waters off Kangaroo Island, Jane’s ceramic razorfish make for an organic, negatively buoyant, non-polluting and biosecure alternative to the real thing. Above water, these ceramic forms are stunning. With their creamy textures and graceful arching lines, their shape is something ancient and elemental. But it’s under water, placed in the habitat for which they were made, that the forms really sit in communion with their surroundings, quickly attracting a colourful diversity of lifeforms, including the sought-after angasi oysters. Though she lives in another state, on another island, Jane visited Kangaroo Island before commencing her ceramic contributions, because connecting with place is a crucial part of the process for her. It goes without saying that her engagement with place includes engaging with community, both above the waterline and below it. She has now made over 1,000 of these pieces for the project, and her objectives are as clear as ever. Her contribution is a supportive one. The best-case scenario for this area will be the return of the real razorfish in healthy numbers. Until that happens, Jane’s forms will go some way to supporting the regeneration of the ecosystem.

Oysters like to grow on oysters –they do best when cosied up together

01

Alex Comino diving on a bed of newly installed ceramic shells. Jane Bamford made forms in three slightly different concavities to enable the team to trial these variations.

02

Dead razorfish shells hosting various marine invertebrates, including some large, colourful sponges and old angasi oyster shells.

Images Stefan Andrews

02

With the return of the angasi and pinna reefs, a raft of other species look to benefit

Along with Paul, Alex and Jane, a number of local community members have also come on board, bringing a diversity of skills and resources to the restoration. Members of the Kingscote Men’s Shed, some of whom remember a time when the angasi were plentiful in the bays of Kangaroo Island, have designed their own reef modules using recycled pallets and roof tiles. Their solution is both creative and practical, using what’s affordable and at hand. According to Alex, these modules are already proving effective – when it comes to alternative substrates, life under water is not discriminating. In addition to the Men’s Shed, local business Kangaroo Island Shellfish offers the use of their vessels to deploy the reef modules. They also collect their own discarded oyster shells, which are then sun-cured and sprinkled onto the reef modules, creating a substrate that mimics the real oyster reefs and makes the modules more attractive to spat. There is evident pride in this voluntary work and great optimism for the future of the ecosystem.

All restoration and conservation projects start with uncertainty and a lot of study and labour is brought to bear with no guarantee of success. What’s clear with this project is that it would not have much chance without the support, industry and knowledge of the local community. Their diverse inputs mirror the ecosystem they support, and this is entirely fitting because in a place like Kangaroo Island, where the idea of home extends beyond a person’s four walls, and the idea of community includes a cornucopia of non-human lives, the sea and the coast have not only commercial value but cultural and social value too. That the word ‘ecosystem’ can be traced back to the word ‘home’ rings true here. It can be seen in the recovering non-human community below the surface, once again finding somewhere to settle. And it can be seen on land, where the Kangaroo Island community are doing everything they can to help restore the vulnerable environment they call home. Despite its uncertain outcome, this project demonstrates that conservation works best when it brings together a network of participants from varying walks of life, working collectively.

Keely Jobe is a PhD candidate at the University of Tasmania. She lives by the sea on the east coast of lutruwita/Tasmania.

For more information on this project, see landscape.sa.gov.au/ki/ native-plants-and-animals/oyster-reef-restoration

Jane Bamford is a Tasmanian artist who has become known for creating functional forms in species support which embody creative problemsolving, functionality and compassion for the non-human world. Instagram @janebamford_ceramics; website janebamford.com

For articles on more ceramic artificial habitats created by Jane Bamford and other artists, see Signals 131, June 2020 (the critically endangered spotted handfish) and Signals 138, March 2022 (little penguins).

As tugs became more powerful, bigger ships were built, and demand for bigger ships inspired improvements to tugs

The often overlooked workers of the sea

Tugboats and the ships they serve have long had a symbiotic relationship. Randi Svensen looks at the developments in tug technology over the centuries.

A FRIEND RECENTLY DECLARED, most emphatically: ‘Numbers are boring!’ Equally emphatically, I disagreed. In the time I spent researching and recording the history of Australia’s tugboats, I found that it’s the developing numbers – horsepower, bollard-pull, tonnage, size – that tell so much of the story.

While the term ‘horsepower’ has been refined since it was first described by James Watt in the 1780s (see box on page 37), it is essentially understood as he explained it, as being based on the number of horses the engines replaced in the work they did. Australia’s first tugboat, built in 1831, was the 50-horsepower Sophia Jane, but 21st-century tugs deliver 5,000 horsepower and more. How did the power of 50 horses morph into that of five or ten thousand in less than 200 years?

It can be safely said that the invention of the marine steam engine revolutionised how the world traded. A motorised vessel could guide a sailing ship into and out of port in all but the worst conditions, thus removing dependence on winds and currents and making voyage times predictable and mostly reliable. For years, though, the limitations and cost of steam engines meant that long-distance trade still relied on sailing ships – but already, tugs and ships had developed a symbiotic relationship. As tugs became more powerful, bigger ships were built, and demand for bigger ships inspired improvements to tugs.

So, how did the technology of tugboats develop from those first steamers to the powerful vessels we see today?

The most important contribution to the establishment of the ‘towage’ industry, both in Australia and abroad, was the invention of the marine steam engine. The first successful use of steam power in boats was in 1783 in France, when the Pyroscaphe steamed on the River Saône for 15 minutes.

By the time Sophia Jane completed its first tow in Sydney in 1831, the technology was well established, and coal-fired steam would remain the dominant power source for the next century, despite shipping moving on to internal combustion oil or diesel engines, which were more suited to long voyages. Tugs rarely ventured far from port, so had no need of huge stocks of fuel. Coal was also more cost-effective, although the physical and financial threat of a boiler explosion was ever-present, especially if the engineer liked a drink and forgot to top up the water in the boiler (a scarily common occurrence).

As technology advanced, steam tugs were often converted from burning coal to oil and, at times of fuel shortages, some burned what we now call biofuels. In a classic example of the resourcefulness of the industry, during the Great Depression a tug steamed Sydney Harbour fuelled by copra, the smell of coconut wafting behind it. Some tugs had their steam engines replaced with oil-burning internal combustion engines, and dieselfuelled engines followed. Diesel was more economical and much safer, as the fuel was less volatile, especially in a wet environment – although Rudolf Diesel’s first engine nearly killed its inventor when it exploded!

But, as with the ‘life’ of any engine, the long-lived steamers gradually lost power – as seen in Brisbane’s once-mighty Forceful and Fearless, which were reduced to the ignominy of being known as the ‘Forceless’ and ‘Fearful’. The old steamers were gradually replaced, although some around the country have been restored and are on display. Forceful was restored by the Queensland Maritime Museum some years ago, but sadly is soon to be broken up. In the maritime tradition of recycling, however, many of its parts will surely be re-used in other, still viable, steam vessels.

Tug engines have long been rated by their ‘bollardpull’ – a figure determined by the tonnage a tug can pull against a static object, like a bollard. Along with horsepower, bollard-pull is one of the industry’s go-to comparison figures. The increase in bollard-pull numbers during the 20th century was staggering.

Early steam tugs had to multi-task. As well as towing, they did duty as cargo and passenger carriers

01

The Adelaide Steam Tug Company’s Yatala. Side paddlewheels were more suited to Australian conditions. Image ANMM Collection ANMS0047[355]

02 Kort nozzles could be retro-fitted and increased bollard-pull by 30 to 40 per cent. Betts Bay ’s hydroconic hull can also be seen in this photograph. Image Ron Montgomery, courtesy Graeme Andrews

Early steamers were propelled by paddlewheels, either one on the stern or one on each side. In Australia, side paddle-wheels were mostly used, and were adopted by riverboats for their manoeuvrability in winding waterways. They also allowed for towing barges. Originally designed by Archimedes in the third century BCE for the movement of water uphill, the screw propeller became a part of the marine industry in Europe in the early 19th century, to a design by Joseph Ressel. Its adoption in Australia was slow, but by the 1880s most new tugs were screw-propelled, either single or double. Tug masters loved the dexterity of twin-screw propulsion, although management weren’t as impressed, since two of everything meant higher maintenance costs. Once screw propulsion became the norm, however, other advances followed, sometimes unexpectedly. In 1932 in Germany – while attempting to find a way to reduce the damage to canal walls from propeller wash –Ludwig Kort developed a tube that could be fixed around the tug’s propeller. While the so-called ‘Kort nozzles’ did reduce canal damage, although affecting manoeuvrability a little, owners were thrilled to discover that they also increased a vessel’s bollard-pull by 30 to 40 per cent. And the nozzles were quite easily retro-fitted to existing vessels. Definitely a win-win for the bean counters! While Kort nozzles are still used on conventional propellers, propulsion designers have also developed two different technologies.

01

21st-century tugs are controlled by joysticks rather than steering wheels, although in a nod to tradition a ship’s bell is usually on board. Image Randi Svensen

02

The Voith-Schneider propulsion system employs a vertical propeller. Image Wikipedia

03 A Voith-Schneider tug’s wheelhouse is built in a square shape to accommodate a set of controls on each of its four sides. Image Randi Svensen

The most common in Australia is the Azimuthing Stern Drive system (ASD). This comprises two propulsion units aft, which can be separately rotated up to 360 degrees for maximum manoeuvrability and, if arranged so they either face each other or away from each other, they put the tug in ‘neutral’ without the need for gears, an important time-saver in tight situations. In the wheelhouse, the ASDs are controlled by joysticks and are a world away from the traditional wooden steering wheel so often associated with the romantic age of steam tugs.

Another, rather perplexing, system is the Voith-Schneider cycloidal propulsion system, which looks like two very large vertical egg-beaters under the hull. Invented in 1928 by J M Voith and Ernst Schneider, the design has been rarely seen in Australia, as the system, while delivering superior manoeuvrability, requires deep water and the open units are vulnerable to damage from flotsam. Australia’s Voiths came here almost by accident, as Carrington, Mayfield and Wickham were built for a port in the Middle East but were bought by BHP in a plan to break the domination of Newcastle Ports Towage Services (NPTS) in New South Wales. The resulting dispute became known as the ‘Newcastle Tug War’ and because the port required the use of four tugs for a ship movement – one to be borrowed from NPTS – BHP found itself frozen out. The tugs were based at the mouth of the Hunter River, where floodwaters often carry dangerous debris, so one could say that of all Australian ports, Newcastle would be one of the least suited to Voiths. But suitability was trounced by the urgent need for vessels. The tugs have square wheelhouses, with controls on each of the four sides, and a directionally-challenged visitor (well, this one) has trouble remembering which way is the bow and which the stern!

Early steam tugs had to multi-task. As well as towing, they did duty as cargo and passenger carriers, and it wasn’t until towage became their focus that their design changed, albeit gradually. At the turn of the 20th century, tugs were still ‘pulling’ the tow, rather than pushing (which we now know helps control a ship’s movements), and this influenced hull design. As larger ships were built, tugs had to deliver more and more power and, although timber tugs were still built, iron and steel hulls allowed for heavier onboard machinery. Hulls were deep, for stability. By the middle of the century, designs were being adapted for specific purposes. Tugs had gone from being all-rounder, multi-purpose vessels, to being built for purpose: high fo’c’sles for ocean-going tugs; large after-decks for salvage tugs; huge tugs for oil-rig support, medium-sized tugs for harbour ship handling; and small tugs to move barges around harbours.

In 1952, an innovative new hull design appeared. Dubbed the ‘hydroconic hull’, the solid underwater structures of the past made way for a sleek uplift towards the stern, allowing for a very large propeller encased in a Kort nozzle, and for increased water flow around the propeller, thus increasing thrust. The streamlined design allowed for maximum efficiency and also increased fuel economy.

With the exception of a failed experiment in Japan using suction pads, all tugs use towlines. As with other aspects of tugboats, towlines have been developed over the years. From the first heavy lines made from natural fibres – sometimes with a diameter as large as 30 centimetres –towlines have become much more sophisticated. These days, they are often a combination of materials, from synthetics for lighter weight and more flexibility, to steel for strength. Nylon, for example, is great for ocean tows, but not good in confined areas. Steel, while stronger, is less flexible, so by using steel on the end of a fibre line the elastic quality is maintained while minimising the risk of chafing where the line has contact with fairleads or bitts. Chafing is the enemy of tugboat lines and can (and did) result in horrific accidents if not spotted in time. As one skipper recounted to me: ‘The engineer went out on deck to check on one of the aft winches just when the polypropylene stopper broke. It smashed him through the bulwarks and killed him.’

01

Old tyres are still in use as fenders and leave a doughnutshaped mark on even the most expensive hulls.

02

Myall shows off her high-tech moulded rubber bow fender.

Images Randi Svensen

How did the power of 50 horses morph into that of five or ten thousand in less than 200 years?

An enduring image of cartoon tugs is their fenders. Traditionally, ‘puddening’ (or ‘pudding’) fenders were woven from natural fibres, but with the advent of rubber tyres the classic image of a tug lined with tyres was born. They are still used, and deliver a very satisfying squelching sound as the tug moves along the hull of a ship, its rubber joining the circular marks of other tugs from around the world. While still deploying tyres on the side, most high-tech tugs now have custom-made moulded rubber fenders on their bows. I’ve been told that ‘towage is a contact sport’, and damage costs valuable time and money.

No account of the development of tug technology would be complete without the story of how tug skippers communicate with ship captains, pilots and each other.

Before radios, the impending arrival of a ship was noted by signal flags on the shore or daily notices at post offices, or the ships were seen by lookouts. Tugs were often kept in steam and if word went around that a ship was expected, skippers would round up their crew and go ‘seeking’. The first tug to arrive traditionally won the tow – although there were exceptions to polite behaviour in the early days, when the likes of Ballina’s Thomas Fenwick rammed his competitor’s boat in retaliation for not winning a tow. In Sydney, a manager might be despatched to local watering holes to round up the crew and, on at least one occasion when crew were missing, skipper Paddy Brinkworth was heard to lament, ‘The ship is rounding Bradleys and there’s not a whore in the house!’

Eventually, radios replaced whistles. For example, if the pilot tells a tug skipper, ‘Bow to port’, the tug skipper replies to confirm that the instruction has been understood – much like the ‘yes, chef’ of towage. The pilot also has to ‘release’ a tug when its job is complete. But, as professional as crews are, humour is often just below the surface. There must have been much merriment after one company named their tugs after Australian rivers, when the pilot’s final words to the tug would have been: ‘Thank you, Darling. Good night.’

Randi Svensen is the author of a number of books, including Heroic, Forceful and Fearless: Australia’s tugboat heritage (Citrus Press and the Australian National Maritime Museum, 2011).

Brake horsepower (bhp) The power delivered by an engine measured by a brake unit attached to the shaft coupling.

Indicated horsepower (ihp) A measure of actual cylinder pressures and piston speeds. It is usually about 8–10 per cent higher than the horsepower at the propeller.

Nominal horsepower (nhp) The power generated by the engine.

Shaft horsepower (shp) The power delivered to the propeller shaft. It can be measured or can be estimated using the indicated horsepower with allowances for loss of power in transmission.

Little boats seldom make much mark in recorded history, but their contribution to it has always been immense. Graeme Broxam profiles the piners’ punt, a workhorse of Tasmania’s high-country river systems.

Structurally, the piners’ punt is a derivative of the Scandinavian pram or praam dinghy, a type of flat-bottomed boat that can be traced back to the Viking era

THE WOODEN BOAT GUILD OF TASMANIA (WBGT) was pleasantly surprised to learn that it had won the Australian Community Maritime History Prize 2021 for its publication Tasmanian Piners’ Punts: Their history and design. This award helps to validate the guild’s quartercentury of work promoting this uniquely Tasmanian contribution to naval architecture.

When public attention turned to Tasmania’s centralwest coast during the Gordon-below-Franklin dam controversy of the 1970s and 80s, among the items of cultural significance to be ‘discovered’ was a rather distinctive style of small rowing boat that had until recently been used to move timber workers, prospectors and surveyors through the river systems of western and south-eastern Tasmania. They were known locally as punts or sometimes puntos, and Richard Flanagan appears to have first coined the term ‘piners’ punt’ in his book A Terrible Beauty (1985). This term reflects the timbers that the timber workers most sought: Huon pine, and King Billy pine, which grows at higher altitudes than Huon pine.

So what, then, is a piners’ punt? Varying from about 3 to 6 metres in length, they are rowing workboats with a flat or snub bow, and a narrow curved, or ‘sprung’, keel. Structural strength is attained by affixing this keel perpendicular to the keelson, a horizontal batten that forms the floor of the boat, to which the garboard planks are affixed to make a strongly braced structure. Traditionally the boats were clinker-built, but batten-seam carvel construction became popular after the 1920s. Smaller punts were light enough for several men to take them out of the water to haul around rapids and other obstacles (a process known as ‘portage’), and sometimes to be carried many miles overland to more navigable stretches of the river systems.

The origins of the punt having been lost to time, many strange stories have been told to explain its genesis. Some claimed that the design was derived from a conventional dinghy that had its bow knocked off in an accident, and a flat snub was the easiest repair. It has also been stated, perhaps more accurately, that the snub nose was by design, making it easier to alight from the boat when rowed into a riverbank. Also, the snub has distinct advantages when loading a boat from the bow, as is often required of working boats. Others claim that punts were invented by a timber harvester named Thomas Doherty, who worked on the Davey River in Tasmania’s rugged southwest, and whose sons took the concept to Macquarie Harbour when they relocated there in the 1880s.

Recent research reveals that, structurally, the piners’ punt is a derivative of the Scandinavian pram or praam dinghy, a type of flat-bottomed boat that can be traced back to the Viking era. Better known these days as a boat-tender with broad, load-bearing stern quarters, those vessels intended to be rowed in fast-moving waters were much finer aft, as is a piners’ punt. The praam traditionally has no external keel, which is the only significant difference between the praam and the piners’ punt. Indeed, in northern Europe, the words ‘pram’, ‘praam’, ‘punt’ and ‘punto’ were essentially interchangeable. In Van Diemen’s Land (as Tasmania was then known), punts were used on the Huon River by the late 1840s, where timber cutters used them to access the higher tributaries such as the Picton River, where scarcer timbers like Huon pine grew. The first documented evidence for their use on the west coast is in 1859 by Thomas Doherty and a mate who were then ‘pining’ on the Davey River, north of Port Davey. A former mariner, who as a convict had worked on the Huon in the late 1840s, Doherty may have taken the known technology of the punt from the Huon to Port Davey. However, timber cutters and shipbuilders had been based at Port Davey since the late 1830s, so in reality there is no way of knowing when punts were first used there. The same goes for punts further north on the west coast, like Macquarie Harbour and the Pieman River, where timber cutters were sporadically active throughout the middle decades of the 19th century. Little boats seldom make much mark in recorded history.

The origins of the punt having been lost to time, many strange stories have been told to explain its genesis

01

Adrian Dean (1931–2023) working on Claude, which the Wooden Boat Guild of Tasmania built to his Franklin design for the owners of the hotel Lenna of Hobart, where it is now on display. The boat was constructed upright on its keel using the ‘Viking plumb bob’ method, without moulds. This method may have been used by early punt builders. Image Peter Higgs

02

Members of the Wooden Boat Guild of Tasmania enjoy a spot of fishing in the 4.27-metre Teepookana at Little Swanport in March 2022. Image Graeme Broxam

There are three punts from the 1920s and 30s currently on the Australian Register of Historic Vessels (ARHV): Fee (HV000808), Gordon (HV000434) and Punt (HV000404). Owners of other punts are encouraged to nominate their boats for listing on the register via the museum’s website at sea.museum/collections/arhv.

Not until mineral discoveries opened Tasmania’s west coast to more intensive exploitation in the 1870s did punts become better known. Early prospectors and miners used punts to get around, just as the piners had before them. The mining industry brought with it the need for timber, and so the piners and their punts soon followed the prospectors and miners of the river systems running into Macquarie Harbour, such as the Gordon and its tributaries. Punts continued to be used for this purpose into the 1950s, after which the outboard ‘tinny’, and in some cases also the helicopter, made getting around the high country quicker and easier.

Most probably starting in the early 1930s, well-known Strahan timber-miller and boatbuilder Harry Grining introduced a new kind of punt, of batten-seam construction. These craft were intended to be towed from Strahan to the rivers by steam or motor launch loaded with stores, including fodder for the horses and donkeys that were used to haul timber.

Boats of both types continued to be built in everdecreasing numbers into the 1960s, often as recreational fishing boats. A small number were commercially licensed as fishing boats, including the biggest punt ever built, the aptly named Limit, a 23-foot (7-metre) half-decked centreboard sloop. Several punts around Strahan were fitted with wet-wells, or lined with timber to make them useful as net-boats. While early boats had provision for a sculling oar at the stern, many later boats had solid stern plates on which an outboard motor could be fitted. All had thwarts and rowlocks, for from between one and four rowers, seated in tandem.

As no official list was ever made of them, it is difficult to estimate how many punts were built and used in the river systems. Electoral rolls from 1914 to 1980 show that about 200 men worked in the industry during that period, but only a couple of dozen were active at any one time. Multiple generations of the same families worked the rivers, including the Dohertys, Abels, Grinings, Cranes, McDermotts, Morrisons and Nielsens. Some, like the Grinings and Morrisons, are still involved in the timber industry at Strahan.

Assuming two men used one punt, it is unlikely that there were more than a few dozen in use at any one time, but with the attrition from the inevitable harsh usage, they were evidently built in considerable numbers. Some, built by established boatbuilders in Strahan, were creditable specimens of the shipbuilders’ art, while others appear to have been ‘knocked together’, possibly in the wilderness, and though strong were quite roughly presented. Such a boat is the WBGT’s Gordon, probably built in the 1920s, and later used by the Tasmania Forestry Department.

Punts also raced from the 1890s into the 1950s at the Strahan Regatta, in a multitude of events that included men, boys, women and mixed pairs. There was a brief revival in the 1990s and again at the 2023 Australian Wooden Boat Festival in Hobart.

No new punts were built between the late 1960s and the 1990s. In 1994, former shipwright and Queenstown teacher, Adrian Dean, designed the 14-foot (4-metre) ‘Franklin skiff’, based on various original punts that had come into his possession. The then-recently formed WBGT completed the replica punt Teepookana to this design in 1998, and several others have followed. The WBGT travelled to Strahan on several occasions, photographing and gathering evidence on the surviving punts, which was used to compile a report on punts for the Australian National Maritime Museum under its Maritime Museums of Australia Support Scheme (MMAPSS) program in 2018. By 2023 we had identified some 43 extant punts, either ‘original’ or post-1990s replicas, some of them still under construction. After decades in the literal wilderness, the piners’ punt has returned as a much-loved and practical small boat.

For further information, see woodenboatguildtas.org.au.

Graeme Broxam is a retired scientist and intellectual property administrator with a long and deeply held interest in Tasmanian maritime history. He is an author, proprietor of Navarine Publishing (a specialist publisher on Australian history), President of the Association of Heritage Boat Organisations and secretary of the Wooden Boat Guild of Tasmania, Inc. He is also owner of two boats on the Australian Register of Historic Vessels: yacht Clara (HV000544, 1892) and fishing boat Casilda (HV000781, 1915).

The Australian National Maritime Museum Foundation works to support the acquisition, conservation and interpretation of artefacts from our maritime history. Our end-of-financial-year campaign focuses on one of Australia’s worst shipwrecks, and we invite you to support the preservation and presentation of relics from the Dunbar. By Dr Kimberley Webber. ON THE EVENING of Thursday 20 August 1857, a night of driving rain, dark skies and even darker waters, colonial Australia suffered one of its most tragic shipwrecks when, bound for Sydney Harbour, the sailing ship Dunbar hit the cliffs of South Head, side-on. The only survivor, able seaman James Johnson, later recalled: ‘With the first bump the three topmasts fell … it was not more than five minutes after she struck that she began to break up.’ 1 Altogether, 63 passengers and 58 crew drowned.

The National Maritime Collection includes some 4,000 items from the wreck site. Together with contemporary engravings, first-hand accounts and photographs, these objects are a powerful reminder of the tragedy. They bear witness to the impact that this wreck and others – such as the intercolonial steamer Admella off South Australia in 1859, and the clipper Loch Ard in Victoria in 1878 – had on the colonies during a period of rapid growth and essential reliance on shipping.

Most of the museum’s collection was assembled by John Gillies, an accomplished spearfisher, who discovered the wreck site in the 1960s. Over the next decade, he recovered many small artefacts that had once been Dunbar ’s cargo, as well as personal effects of passengers and crew. At the time, such wrecks were unprotected.

In 1976 the Commonwealth Government enacted the Historic Shipwrecks Act, which today ensures the protection of historically significant wrecks from unauthorised interference and damage. Dunbar and its relics were provisionally declared a historic shipwreck in 1989 and, in 1993, the Commonwealth declared an amnesty from prosecution to encourage people with material from this and other wrecks to come forward. As a result, John Gillies officially declared his collection and gained permission to sell it. Concerned about inevitable loss should it be broken up, the museum negotiated to acquire the collection, which was made possible by the Andrew Thyne Reid Charitable Trust.

For our 2023 end-of-financial-year campaign, we are seeking support for the conservation and interpretation of the Dunbar collection.

Conserving and documenting the 4,000 Dunbar objects is a major undertaking. A plan has been developed that includes surveying the largest single grouping of objects (1,708 coins and tokens) ahead of deciding on the most efficient way to preserve and rehouse the collection. This includes high-resolution photography to make the collection digitally available through a future online exhibition and the first comprehensive filming of the wreck site. All donations received will directly assist this vital work.

The Foundation raises funds to support the preservation and development of the National Maritime Collection, including the museum’s historic fleet. Most recently, supporters donated funds towards the refurbishment of HMAS Vampire, ensuring that it remains on public display.

Now we are inviting you, our members and supporters, to be involved by supporting this important project.

1 Quoted in Kieran Hosty, Dunbar 1857: Disaster on our doorstep, Australian National Maritime Museum, 2007.

Dr Kimberley Webber is the museum’s Project Officer –National Encyclopedia of Maritime Objects (NEMO).

A selection of the objects acquired from the John Gillies collection, including coins, shop tokens, keys, clock and watch parts, and the remains of a set of false teeth. Purchased with the assistance of the Andrew Thyne Reid Charitable Trust. Image Jenni Carter/ANMM

Please donate by

• entering details online at sea.museum/donate

• depositing funds directly into the Foundation’s account with your name as reference: BSB 062 000 Account number 16169309

• completing the enclosed form and mailing it to the museum

• or phoning Matt Lee on 02 9298 3777.

All donations are tax deductible.

Agnes Gibson left Scotland in 1912 to join her fiancé in Australia.

One hundred years later, her granddaughter, Anne Field, undertook her own journey, one of commemoration.

MY GRANDMOTHER, Agnes Nicol Gibson, was born in 1878 in Lanark, Scotland, one of six daughters to Agnes Nicol and Robert Gibson. She emigrated to Australia in 1912 to reunite in Sydney with her fiancé, Robert Cochrane, who had arrived on a ship from Liverpool, England, three years earlier.

From Glasgow, a train had taken Agnes to London, where she boarded the steamship Pakeha as a thirdclass passenger. A ship belonging to Shaw Saville and Albion Ltd, Pakeha was carrying 1,150 immigrants, including 200 agricultural labourers, 25 Cornish miners and 60 bricklayers and carpenters. After leaving London on 12 March 1912, the ship stopped at Cape Town on 3 and 4 April, then made a direct passage to Sydney, arriving on 23 April. Agnes and Robert married at The Manse in Balmain, Sydney, the very next day.

Agnes and Robert set up home at Holmesville, near West Wallsend in Newcastle. They had three daughters: Agnes, my mother Elizabeth, and Margaret. Grannie died in 1961, aged 83. I still have her original ticket and her log from her journey, as well as my grandfather Robert’s Baltic pine trunk from 1909.

To honour my grandmother and acknowledge the risky voyage that she had undertaken, I decided on an unusual method: to put a bottle into the sea with her story in it. Agnes was an excellent record keeper, and in her voyage log she had noted each day’s weather conditions, latitude, longitude and distance travelled. Grannie’s record-keeping made my task much easier.

I planned to put my bottle in the sea from Albany, Western Australia. When asked for assistance, the Albany Tourism Bureau referred me to Mark McRae of Southern Ocean Sailing in Albany, who had also committed a bottle to the ocean when he and his crew were rounding Cape Horn in 2009.

By 19 April 1912, Grannie had sailed to 44 degrees 27 minutes south, 123 degrees 2 minutes east, in the Roaring Forties. Exactly 100 years later, with my empty wine bottle, Mark, a friend and I headed out of Albany to send my bottle on its way.

Mark prepared my wine bottle as he had prepared his bottle at Cape Horn. Grannie’s history was rolled around a pencil and put into an airtight sandwich bag, which was then sealed, rolled and put into the bottle. Tartan ribbon was placed in the top of the bottle, which was screwed tight and then wrapped in waterproof tape. My bottle was ready for its journey in the Southern Ocean.

At 10 am on 19 April 2012, I read the second verse of Robert Burns’ poem, where he says ‘My love is like a red, red, rose’. In a four-metre swell, and with some difficulty, I then threw the bottle overboard 60 nautical miles south of West Cape Howe at 36 degrees 1 minute south, 118 degrees 22 minutes east, wishing it ‘God speed’.

It was a surreal experience being out in the Southern Ocean. The albatrosses were flying overhead, the waves were very high energy, and one certainly needed a firm grip to hold on. It was not an experience for the faint-hearted.

Back in Sydney, my story soon took an unexpected turn. I was contacted by Russell and Raelene, from Perth, who had found my bottle on the beach at Bremer Bay during a fishing holiday. It had been in the Southern Ocean for about 32 days. They asked what I wanted them to do with the bottle and I suggested they take it back to Perth, as I needed to go there soon. Raelene was able to meet me in July 2012 for a handover and lunch. Raelene and Russell later sent me photos of Bremer Bay, and I was able to visit there later, in 2017. I am pleased that my bottle washed up in such a stunning location.

I still have Grannie’s original ticket and her log from her journey, as well as my grandfather’s Baltic pine trunk from 1909

01

Anne Field off the coast of Albany, Western Australia, with the bottle containing her grandmother’s story.

02

Anne and skipper Mark McRae prepare to throw the bottle into the Southern Ocean.

All images Anne Field

In her voyage log, my grandmother Agnes had noted each day’s weather conditions, latitude, longitude and distance travelled 01 Anne

Richard and Anne prepare to throw the bottle (helpfully labelled) into the water off Eden,

Back in 2012, I wrapped the bottle in a towel once more for its journey in my hand luggage back across the continent to Sydney, thinking what a shame it could not earn frequent flyer points, given the kilometres it was racking up!

Dr David Griffin, a physical oceanographer and atmospheric researcher at the CSIRO in Hobart, explained to me that my bottle had washed back in because the Leeuwin current, off Western Australia, is always trying to reattach to the coast. The East Australian current, however, moves away from the coast. He recommended Eden, on the New South Wales far south coast, as a good place to recommit Grannie’s bottle.

It took some time to locate an Eden operator who went far enough out to sea, but eventually Richard Buckingham, who operated the Connemara for fishing trips, was able to assist. Early on 30 September 2012, we made it out to the Continental Shelf, 16 nautical miles offshore. In the distance, we could see the spray from humpback whales on their journey south to Antarctica. Once again, albatrosses were flying overhead, as were Siberian mutton birds.