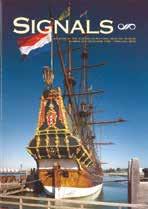

SIGNALS quarterly

ANTARCTIC ELYSIUM

A visual epic of landscapes, flora and fauna

WAVES OF MIGRATION

Innovative light show on a scale never seen before

DEATH OF AN ERA

A shipping line’s demise signals the end of sail

A visual epic of landscapes, flora and fauna

Innovative light show on a scale never seen before

A shipping line’s demise signals the end of sail

IN JANUARY THIS YEAR, JUST BEFORE Australia Day, a large and distinguished contingent of guests joined me on the helideck of our Daring class destroyer HMAS Vampire for the launch and premiere of an exciting new show in a dynamic medium that’s never been seen at our museum before – or any other museum in Australia. With the flick of a switch, a spectacular light show called Waves of Migration swept across the whole expanse of the roof of our landmark building. With vivid imagery it explored the history of migration to Australia – that uniquely layered story of how this nation has become what it is today, how we achieved the texture of our vibrant society.

Waves of Migration is a thought-provoking show that weaves together a selection of the rich migration stories that we at the museum have been collecting now for over 20 years.

Our light show was a first on several counts. It’s the first time any museum has combined stories from its collections to create a digital exhibition on such an enormous scale. Our canvas was the iconic roof of our unique museum building, designed by Philip Cox ao to evoke sails and waves. At over 1,700 square metres it is surely the largest continuous projection surface in Australia. The show went live on Australia Day and screened each night for the rest of the summer for the crowds that pour across the Pyrmont Bridge into Darling Harbour – and everyone in the city with a line of sight on our spectacular building. With 44 percent of our 22 million population born overseas, or having a parent who was born overseas, Australia is truly a multicultural country. Since 1788, close to

10 million settlers have moved from across the world to start a new life in Australia –the majority by sea. The many waves that brought them here swept across our roof in this light show. Their human potential has shaped and enriched Australia.

The Australian National Maritime Museum considers these migration stories to be an incredibly important part of our history that we tell through the objects in our collection and also through our Welcome Wall, representing over 20,000 families who have arrived in Australia from countries all over the world.

As we headed towards Australia Day last January, we thought it crucial to look back through that lens of history. We were delighted at the number of guests who responded to our invitation, parliamentary representatives and cultural administrators, and a strong international roll call from the diplomatic community. We were equally honoured to have with us two people whose migrant stories appeared in our light show: Jean Lederer, whose family fled Nazi-occupied Austria in 1938, and young Hedayat Osyan, who was recently forced to leave his family behind as he fled Afghanistan for his very life.

You can read both their stories in the following pages of this edition of Signals, which comes to you this autumn with a new look that speaks of the new directions in which we are taking the Australian National Maritime Museum. On a larger scale, beaming onto our rooftop this summer, the infrastructure and technology that we installed in order to make Waves of Migration possible demonstrate our aspirations to push the boundaries of the newest communication technologies. That will help to ensure the museum can continue to reach out to all Australians to tell the nation’s important maritime stories.

Kevin SumptionThe museum’s innovative roof-top light show illuminates stories of

Samuel Hood photographs capture a family and their fleet of doomed, giant sailing

Who was the lady with flair posing elegantly on a visiting Dutch warship?

This exhibition puts you in the shoes of a rescuer: do you have what it takes to be a hero?

Stunning images of the last great wilderness, above and below the ice, in this new exhibition

Annual MMAPSS grants fund an exhibition on a curiously named riverboat … and much more

Your

This

Graeme’s

– a local legend inspires this private re-creation of a ship of

Rural flood boats are among the new additions to this vital national

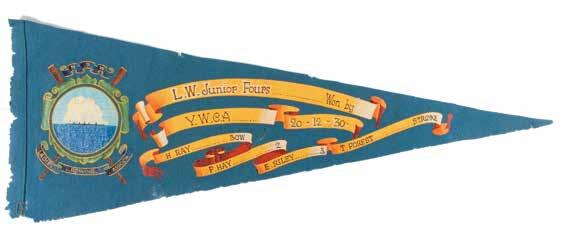

The Trixie Forest collection – memorabilia of a

Barbary

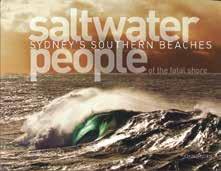

Saltwater

cover: Videographer

Canoes

The museum roof burst into light this summer with a unique presentation of migration themes represented in our collection. Kim Tao, the museum’s curator of post-Federation immigration, introduces two special guests who were with us for the launch of our light show Waves of Migration – and whose stories feature in it.

SETTING THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL Maritime Museum apart from many other maritime museums around the world is our focus on social history. We explore Australia’s links with the sea through the lens of people’s experiences, an approach that creates a powerful emotional engagement with our audiences. It is of particular significance to the core thematic area of immigration.

Migration by sea is a key theme in our maritime history and for many Australians the long sea voyage remains a defining narrative of the migrant experience. That was central to our summer light show Waves of Migration that played out so spectacularly across the museum roof. I wrote about its development in the last issue of Signals, and on the first page of this current issue director Kevin Sumption has written of what it means for us as a museum to explore our subject through this innovative new medium.

Here in the following pages we present the voices of two people whose stories not only appear in the light show, but who were with us for its premiere on 24 January. One of them is Jean Lederer, who spoke to the audience that night about her family’s experiences as they escaped Nazi-occupied Austria in the 1930s on the liner SS Orama, carrying the few precious possessions that connected them to their homeland.

Jean and her husband Walter later donated these possessions to the museum, adding to our strong holdings about Jewish refugees

and the many others who were part of the enormous post-World War 2 migration from Europe and Britain on the large migrant liners. Over the years we have told many of these stories in our exhibitions.

But the history of seaborne migration did not end with the last passenger liners. It is a history still in the making as asylum seekers fleeing recent conflict in the Middle East and Sri Lanka make dangerous boat journeys to Australia. One of the priority areas identified in the museum’s Collection Development Policy is to document the experiences of seaborne refugees and asylum seekers, as well as political and public responses to them.

The museum holds a rich collection of material representing refugees from the wars in Indochina, which includes the restored Vietnamese fishing boat Tu Do (Freedom) that carried the Lu family to Darwin in 1977. Tu Do made an appearance in the light show. Museum staff have worked closely with the Lu family to tell their stories and to personalise the Vietnamese exodus by providing our visitors with a compelling insight into the nature of refugee journeys.

The museum also has a developing collection related to more recent asylum seekers and people smuggling, and a growing archive of oral histories that explore the migrant experience, the emotions of leaving a homeland and the process of becoming part of a multicultural Australia.

The other guest at our light show premiere whose story appeared in it was 20-year-old

The history of seaborne migration did not end with the last passenger liners ... it is a history still in the making

Afghan refugee, Hedayat Osyan. In 2012 I conducted an oral history interview with him. Hedayat donated a traditional Hazara handkerchief to us – a gift from his sister that he carried in his pocket during his escape from Afghanistan to Australia in 2009. It was one of his few personal possessions, a tangible link to his family and homeland. With his oral history, it is a valued addition to the museum’s collection. An edited extract from the oral history appears on the following pages.

During our interview Hedayat spoke powerfully of his gratitude for the freedom, equality and opportunities available to him in Australia. He embarks on a university degree in Asia-Pacific studies this year and hopes to one day be reunited with his mother, sister and brother. Hedayat’s story reminds us that Australia’s immigration history is living and evolving, and that the Australian National Maritime Museum plays a vital role in collecting, documenting and interpreting this history as it unfolds.

01 Steamship Changsha carries non-European migrants during the period of the White Australia policy. Waves of Migration was developed and written by museum staff working with architectural projection specialists from The Electric Canvas. 02 ‘Ten-pound Poms’ were among those in the last wave of migrants to arrive by ocean liner. Photography by Andrew Frolows/ANMM

They came with very few possessions, and a cardboard box containing documents, correspondence and the key to their homeJean Lederer

Jean was the guest speaker at the public launch of Waves of Migration in January this year.

I NEVER THOUGHT IN MY LIFE THAT I would be standing here to talk about my family, the Lederers, but first I want to thank the maritime museum for bringing history to life. First you published our story in your recent book 100 stories from the Australian National Maritime Museum, getting it spoton about the Lederers’ escape from Vienna, and now it’s in your new light show. I want to thank the whole team of the maritime museum for doing it so well.

Arthur and Valerie Lederer and their son Walter came to Australia in 1939 on the Orient liner SS Orama with very few possessions and a cardboard box. It contained documents, correspondence, and the keys to their home and business, and my knowledge comes from the stories Walter told me about each and every item in the box. You see, Walter became my husband.

Valerie Lederer was a gracious woman and although their entire belongings were lost in the war, she brought with her trinkets that were precious to her. They included the key to the house and a teeny little heart-shaped cardboard brooch that was the very first gift Walter ever gave her. Walter was born with a silver spoon in his mouth and Valerie brought that spoon with her.

To narrow down the history of the Lederer family, I have chosen two highlights.

Arthur Lederer had a business making regalia uniforms and formal outfits for royalty, nobility and famous people around the globe. His clients included Hungarian

counts, the Knights of Malta, the Prince of Japan, the Maharajah of Jaipur in India, King Farouk of Egypt, the Vatican, the Vanderbilts in America; each is a story of its own.

Back in the 1930s there were no photocopying machines. So Arthur Lederer had photos taken of some valuable documents, thinking wherever he ended up he would start up again. One document refers to an order by Franz Joseph, Emperor of the Hungarian-Austrian Empire, for a field marshal’s uniform as a gift to King Edward VII of England.

Why am I telling you this? Outside our Conservatorium of Music here in Sydney, on Macquarie Street, there is a statue of King Edward VII on a horse in a uniform. Every time we drove past, we elbowed each other and said ‘Is that the uniform?’

At the time the Lederer family was trying to leave Vienna because of the German occupation, Arthur wrote to his exalted customers from around the world, asking them to invite him into their country because the bureaucraçy made it impossible to get exit papers. They all wrote back ‘Sorry, but good luck’.

Arthur Lederer wrote a poem in June 1939 while still in Vienna and it is titled ‘Doors’. The poem is highlighted in the museum’s book 100 Stories. The gist of the poem is that some doors are friendly and some are grey and uninviting … and he hoped his doors would always be welcoming.

To my romantic mind I felt he had written this poem under dire circumstances, in 1939 under German occupation, disappointed that none of his customers had offered to help. However, to my delight, a ballet choreographer called Carol Maddox noticed that poem in the Lederer showcase here

01 Opening night: Hedayat Osyan and Jean Lederer (front row) at the light show launch, flanking the show’s curator Kim Tao.

02 A simple keepsake embodied powerful links to the home they were forced to flee. ANMM Collection, gift from Walter and Jean Lederer donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program

03 Scenes from the Lederer family’s departure from Nazi-occupied Austria.

at the museum. To my everlasting happiness she choreographed a ballet dedicated to this poem. She had a door on the stage through which the dancers danced. The performance took place in the Glenbrook Theatre, to a full house!

On the ship to Australia, Arthur Lederer sent a Marconigram (telegram) from ship to shore to the Maharajah of Jaipur, to advise they were passing through Colombo in Ceylon, now Sri Lanka. Walter told me that the Maharajah welcomed them and took them to lunch. They were seated at a long table and behind each guest there was a male servant in livery. Luxury sublime!

Do you remember in the movie The Sound of Music, when the Von Trapp family sang their farewell song on the stage of the Salzburg Theatre? Well back in 1935, the Lederers were on holiday in Salzburg and Walter as a young boy stood in the doorway and collected autographs of the famous people performing at the Salzburg Festival … people such as Toscanini, Fritz Kreisler, Bruno Walter, sopranos and tenors from the Milan Opera. These autographs popped out of the cardboard box and have been placed in a gallery in New York.

Sadly, Arthur Lederer died after one year in Australia. But his wife and son Walter – my husband – integrated quickly and made a life for themselves. Walter married me, a native Aussie. He became a bespoke tailor following in his father’s footsteps and spent most of his spare time doing benevolent work here in Sydney.

I had better round off here. I wish the maritime museum every success with the light show. I thank you all for listening and I thank the museum for giving me this honour to address you.

Hedayat

During our interview

Hedayat spoke powerfully of his gratitude for the freedom, equality and opportunities available to him in Australia

Hedayat is a member of Afghanistan’s Hazara minority, who have a long history of persecution by the country’s dominant ethnic groups. After the Taliban took his father, he was forced to flee for his life.

I WAS BORN ON THE FIRST OF J UNE 1992 in Ghazni province, in the centre of Afghanistan. I moved between Kabul and Ghazni province studying at high school. I have a sister, 16, and one small brother, 14. My mother worked at home, my father was a teacher at high school. He was kidnapped by the Taliban and disappeared in 2006, because he was working for the government. The Mujahideen and the Taliban have power still in Ghazni, especially in the countryside where I lived, and because of my [associations] they tried to arrest me and kill me. Although I was responsible for looking after my family I had to leave everything, I had no choice. I was 16. It was 2009.

I hid in Kabul for about two months. Some friends in Iran and Pakistan provided some money to take me to Indonesia. I came by plane from Kabul to Dubai, and then to Malaysia. From Malaysia to Indonesia took three days and nights by boat; we had no food, no drink. It was very hard. When we landed in Medan [Sumatra], the Indonesian authorities arrested us because we had no documents. So they put us in jail for one month.

The jail was a small room, a small house, we were 15 people there and we hadn’t enough food or drink. We had to buy more from the guards. There was just a small toilet, we had to shower in there, and we were not allowed to go outside. I realised that if I stayed here there’s no time limit, there’s no way to put in our application

for UNHCR. We had to escape. We broke through the window during the night when it was raining and the guards couldn’t hear us, and hid in the jungle for five days. One of us had a phone and we contacted an Indonesian lady in Medan who took five of us to Jakarta.

We stayed for six months in a small house we rented, in Bogor [near Jakarta], there were also people from Iran and Sri Lanka. I had only a hundred dollars, not enough money to give to [people] smugglers. They said, ‘You don’t have money, we don’t want to take you.’ Other people went by boat to Christmas Island. I just stayed there until some of my friends working in Pakistan and Iran lent me more money, they sent it to a smuggler’s agent in Pakistan. The price for me was US$7,000.

First the smuggler took us from Jakarta to Mataram [in Lombok, eastern Indonesia] by plane. We stayed there for two days in a small house. One night the smuggler came and took us to the boat. We walked for one hour, in a small group [of] about 45, two families, young children, but a lot of young people like me, by themselves. It was December 2009.

There were no officials, no-one in uniform but definitely some police were there. There was no wharf, we went out to our boat in small canoes. The smuggler [had] said, ‘We have a big boat and safety jackets, food, drink, fruit, everything.’ But when we got to it there was a small fishing boat, it was very old and the engine was very small. We had to sit like this [with knees to the chest]. There’s no safety jacket, there’s no toilet. Everyone was shocked. How can we get from here to Christmas Island? I thought it will break down on the second day. But we had no choice. If we tried to negotiate the smuggler would leave us and the police would catch us. We had to stay calm.

I don’t know anything about where this fishing boat was built or when, it didn’t have a name. It was very old, very poor condition, it was grey. There were a lot of cockroaches. It was smaller than that [points to ANMM Vietnamese refugee boat Tu Do, 18.25 metres]. Very small and not too high. We couldn’t put our legs out straight. There’s one small cabin in the front, the captain was there, and around 15 people, the rest were in the back. No beds, no seats, no galley or kitchen. No toilet, just [had to use] the back of that boat. On board I had just one friend. He was in the back, I was on the front.

The engine made too much smoke. Everyone had to stay inside, we couldn’t move and it was very hard. Everyone was sick, everyone was vomiting. In Afghanistan we don’t have water or boats, so everybody got sick. The engine was very noisy, very old, small, and after six hours, seven hours, it would stop for half an hour. They had to put in some oil. One time the captain jumped in the water and went under the boat to fix it.

We didn’t bring any food on board because we hadn’t anything to take with us. I had a small, small bag. Every day they gave just one small bottle of water. We were very thirsty, during the day it was very hot. Everyone lost their energy, some were unconscious. They just give us some biscuit, and some kind of bread, that’s it, just once every day at 11 o’clock. Some people couldn’t eat that food, couldn’t eat for days. Vomiting. There was nothing inside, just vomiting. After three days in the boat some people went crazy and tried to jump in the water. We caught them and tried to calm them down.

It was a seven-day voyage. We didn’t stop anywhere else in Indonesia. We didn’t see any other boats because we just stayed inside, we were not allowed to go out.

The water was leaking inside too much. We thought, if the Australian Navy or Indonesian police don’t come to rescue us we will die this night

We came out from inside after seven days because the captain said we were in international waters, there’s no problem, we can get out.

During the night when storms were coming, the water came inside and everyone was crying and praying, especially the first three nights and days that were very stormy. [December is the stormy wet monsoon in these waters. Ed] The boat was rocking, it was very small and [carried] too many people. Everyone thought, ‘Tonight we will die.’ It was leaky and we had a small bucket, we just divided the people into two, to take turns to get out the water. Even though everyone got sick and hadn’t enough energy to do that. When the rain came, the water came inside from the holes in the roof. Our clothes were wet.

There were just two crew on the boat, the captain, about 50 years old, and the son about 30. They didn’t have a compass or any charts or any satellite technology. No radio. They just steered from the sun. They were quite friendly. Some of us could speak a little Indonesian, but we couldn’t talk with them too much because they were busy and we had to stay inside. The smuggler was paying them very little. They are very poor people and they haven’t got a job in Indonesia. They know if they come to Australia, just once, they would be put in jail for five years. But they’re very poor, miserable.

On the seventh day of the voyage when the engine stopped we thought it was like usual, maybe the oil is finished, but the captain said, ‘The engine is broken, I don’t think

I can fix it.’ We didn’t have any telephones to call somewhere, because when we got to the boat the smuggler took all the mobiles. We stayed for four or five hours, rocking from side to side, everyone was vomiting and crying and the water was leaking inside too much. We thought, if the Australian Navy or the Indonesian police don’t come to rescue us we will die this night. We just thought how to stay afloat in the water, if the boat was sinking, because we had nothing. No safety jacket, no nothing.

At 12 o’clock during the day a plane came and everyone was waving. We found a little bit of hope, maybe they will see us.

After four or five hours we saw the Navy ship appear. First it was very small, it was so far away, but when that ship approached and become bigger and bigger, and when we saw the Australian flag, everyone was crying, really happy to be found alive. Especially the women and children.

Five officers came by small boat and said, ‘Where have you come from, why did you come?’ I was the only person [who] can speak a little English. They listed everyone’s name and they brought some food and drink. After two or three hours, they brought some safety jackets and took five or six people [at a time] to the ship. When everyone was off [the Indonesian boat] sank.

On the Navy ship they searched our bags, our clothes, and gave us some blankets and towels. Everyone had to stay in a small [compartment] in the front of the ship [near] the anchor, which made a lot of noise and we couldn’t sleep. We were five days on the

Navy ship. We were confused and scared. Why didn’t they take us to Christmas Island? Will they take us back to Jakarta?

We arrived at Christmas Island, I think it was the 13th of December. They separated teenagers from the adults, the families. We went first to a big dinner hall, and they gave us some milk and small burger, vegetarian. The interpreter and an officer came [with] forms and they put us in separate block because we were not allowed to talk with others who had already come. Once a day they took us to the ground to play soccer, for one hour. For the rest we had to stay inside. But everyone was very happy. Everything was okay there.

I was two months on Christmas Island. I was in Melbourne in detention for one month. It was for teenagers and families, only 15, 20 people. Every day they took us to the school, they took us to the park, the gym. It was a very happy time. I couldn’t imagine Australia. It was very clean and very peaceful. I never experienced [this] in my life, everyone, everything was very good.

After Hedayat was granted his visa he went to Sydney to join an uncle already there. He attended the Intensive English Centre at Marsden High School in West Ryde, and last year sat his Higher School Certificate. He works with the Hazara Federation helping other refugees settle in, and begins university this year. His mother, sister and brother fled Afghanistan and live as illegal immigrants in Pakistan, but he has so far been unsuccessful at sponsoring them to join him in Australia.

01 Simple, touching images in Waves of Migration convey Hedayat’s story.

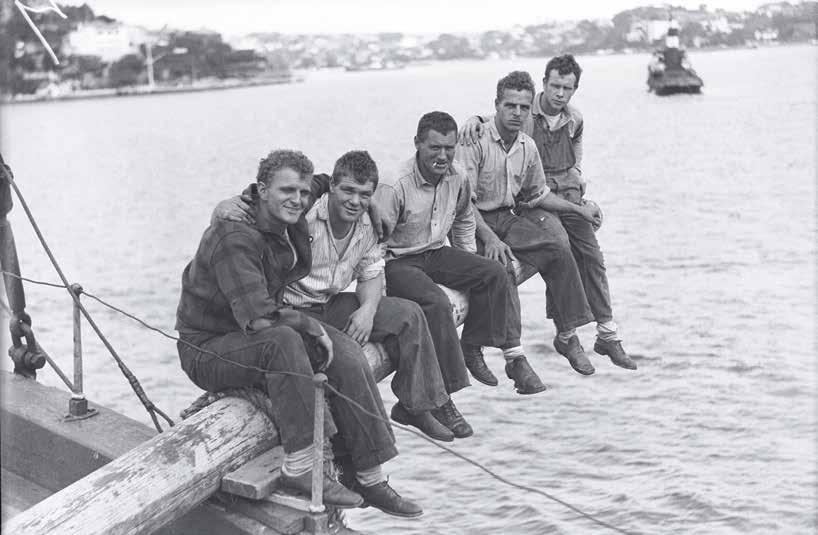

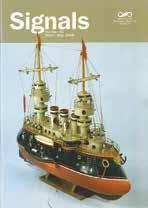

The captain’s beloved six-masted barquentine E R Sterling under sail in all its splendour. All photographs from the museum’s Samuel J Hood Studio Collection of some 10,000 glass-plate and nitrate negatives comprising the maritime work of this versatile photographer whose career spanned the first half of the 20th century.

A trail of misfortunes destroyed Captain Edward Robert Sterling’s beloved fleet of giant sailing ships. Curatorial assistant Nicole Cama found this story hidden among the vast holdings of the museum’s Samuel J Hood Studio Collection, which records this family of North American shipowners and their links with Australia.

IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY, photographer Samuel J Hood was discovering new ways to make his mark in an industry that was only just gaining momentum. His tactic was simple but effective – he would take his trusty Folmer & Schwing Graflex camera to Sydney Harbour to photograph vessels and their crews. Before his later career in photojournalism flourished, he relied on the income from portraits he took of captains and their families.

One of the families he photographed was that of Captain Edward Robert Sterling, an American shipowner and sea captain with Australian interests. Over the years, Hood documented their lavish lifestyle, which seems to come alive through his camera lens for viewers almost 100 years later. What these photographs cannot show, however, are the tragic events that were to unfold shortly after the images were taken. This is the story of a family who experienced the high life and had it snatched away, and of a man whose undying passion for the great sailing ships was crushed by financial ruin as his beloved fleet, one by one, fell victim to merciless seas and the Great Depression.

Captain Edward Robert Sterling was born on 3 October in about 1860 in Sheet Harbour in Nova Scotia, Canada.

From an early age he was exposed to the sea; growing up in a coastal town, his love for seafaring would have developed as he watched sailing vessels of all types come into port. According to one news report, he ran away from home at the age of nine to begin his career at sea, and by 21 he was a captain. At some point after this and possibly before he migrated to the United States in 1883, he married Helen B Watt (b 1866), also from Nova Scotia, and the daughter of a ship’s captain.

Sterling and his wife were based in Seattle, Washington, and had three children: Ray Milton (b 1894), Ethel Manila (b 1895) and Helen Dorothy (b 1896), who was known by her second name. Ray later followed in his father’s footsteps and became captain of the family’s six-masted barquentine E R Sterling. By 1919, Captain E R Sterling was listed as the president and general manager of Sterling Shipping Company in Blaine, Washington.

Throughout the 1910s and 20s, Sterling plied the timber trade between America, Australia and New Zealand. He often made

the journeys himself as captain, along with his family, and it seems that the Sterlings enjoyed their trips to Australia. Hood’s photographs show the family at the races and happily driving and picnicking around Sydney. On 17 December 1916 Ray married an Australian woman, Ethel May Francis, and within a couple of years their daughter, Margaret Francis, was born.

Sterling’s fleet of schooners and barquentines comprised some of the largest timber sailing vessels ever built

The series of intimate portraits taken on board E R Sterling between 1910 and 1925 are Hood’s best photographs of the family. They depict family and crew seated in the vessel’s state-of-the-art saloon which, according to the Cairns Post, moved beyond ‘cramped quarters’ and ‘hurricane lamps’

These were clearly golden years for the family, and the portraits of the captain and crew members illustrate their sense of attachment to the ships of the Sterling Line. Little did they know that a crippling series of disasters awaited the fleet

to a player piano and a gramophone, which Sterling had concealed in the room’s centre table, an ‘ingenious combination’ of music and dining table. These were clearly golden years for the family, and the portraits of the captain and crew members illustrate their sense of attachment to the ships of the Sterling Line. Little did they know that a crippling series of disasters awaited the fleet.

The first occurred in 1922, when on 21 January the Helen B Sterling – a fourmasted schooner that cost Sterling £15,000 and which he named after his wife – was partially dismasted by a gale off the Three Kings Islands, north-west of New Zealand, while en route from Newcastle in New South Wales to San Francisco. Captain G R Harris, in command of the ship at the time, ordered a wireless SOS call to be put out which stated, ‘We are waiting for her to go down’. The message was received by the crew of HMAS Melbourne, who set out in search of the stricken vessel. They sent a message in reply, which simply read, ‘We are certain to find you. Keep good heart’. At midnight, the crew spotted the sinking schooner with the aid of searchlights and launched a rescue cutter with 16 volunteers. All 18 crew and passengers were rescued and all of the Australian naval men who risked their lives were awarded gold medals by US President Warren G Harding. The vessel and its freight, however, were not only lost, they were uninsured, and according to one news report, Captain Sterling claimed he was left with losses totalling £53,000.

The next unfortunate occurrence concerned Sterling’s beloved six-masted barquentine, E R Sterling. On 16 April 1927, the ship left Port Adelaide for London with a cargo of between 40,000 and 50,000 bags of wheat. All was going well until it rounded Cape Horn and encountered icebergs stretching for 500 miles (800 km). After navigating through those, the crew faced a heavy gale north of the Falkland Islands on 4 July and the barquentine was partially dismasted. With only four masts remaining, Captain E R Sterling made the fateful decision to sail on and forgo refuge at the port of Montevideo. After crossing the equator at 4 am on 4 September near the Cape Verde Islands, E R Sterling was hit by a hurricane. Four gruelling hours later, the foremast was lost and Chief Officer Roderick Mackenzie was fatally injured as he attempted to rescue the rigging. There was no doctor on board and Captain Sterling tended to the wounded man in his quarters. Two hours later,

the captain read the committal sentences as the chief officer’s body was sent over the side into his watery grave.

SS Norman Monarch eventually answered their SOS calls and offered to tow the vessel into port, but Captain Sterling declined the offer. Instead, he and the crew made their way to Saint Thomas in the US Virgin Islands, in the West Indies. According to the captain’s report, they sailed 2,212 miles (3,560 km) in poor weather and vessel conditions before arriving in port on 15 October. The cargo was transferred to a steamer, then on 15 December E R Sterling began a tow of 4,000 miles (6,430 km) to London, arriving at the Thames in a shambles on 28 January 1928. It had been a horror voyage that took a total of nine months. On 24 March 1928, E R Sterling made its last voyage to Sunderland, where it met its end at the hands of shipbreakers.

Adding to the family’s misfortunes, in May 1926, Sterling had purchased the fourmasted schooner Hawaii, renaming it Ethel M Sterling after his daughter. After it sailed to San Francisco in September 1927, only months after E R Sterling had commenced its fateful voyage, Sterling Shipping Co was forced to sell the schooner because they were unable to pay for the two 240-horsepower diesel engines they had installed shortly after it was acquired. The next event in this tale of woe befell the sister ships that Captain Sterling senior had named after his daughter and wife: the six-masted wooden schooners Dorothy H Sterling and Helen B Sterling (the second ship of this name). Both were built in Portland, Oregon, around 1920 and were originally named Oregon Pine and Oregon Fir respectively. It was reported that Oregon Pine was one of the largest sailing vessels then built, at a cost of £50,000. After a series of unsuccessful voyages, E R Sterling purchased the vessel and changed its name to Dorothy H Sterling in 1928. Again, his ownership was short lived. In 1929, the vessel arrived in Port Adelaide carrying a load of timber from America. Sterling Shipping Co found that they could not pay the harbour dues and crew wages. Consequently, the crew was forced to abandon ship. The vessel was auctioned for a mere £50 to the Harbors Board, which then recouped part of the ship’s debts by selling it to shipbreakers. In 1932, after selling everything of value,

the shipbreakers planned to tow the hull to the Adelaide suburb of Ethelton to be torn apart by the unemployed for firewood. The hull would not fit through Jervois Bridge, however, and it was towed to the North Arm of the Port Adelaide River to be abandoned in the Garden Island Ships’ Graveyard, where the skeleton of its hull remains to this day, a relic of the past.

A similar fate befell its sister schooner, Helen B Sterling (the former Oregon Fir).

In January 1927, Captain Sterling purchased the vessel and, as with Dorothy H Sterling, it made only one voyage under his name, carrying more than two million feet of lumber to Australia. Sterling was forced to sell the schooner to Mr W S Payne of the Pacific Export Lumber Company, who then changed its name back to Oregon Fir

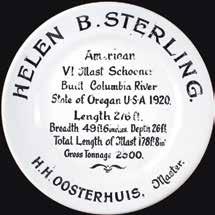

In 1930, the vessel was seized in Sydney for outstanding debts. The ship’s master, Henry H Oosterhuis, reportedly stayed with the vessel for 15 months. As it lay idle in Sydney Harbour, Oosterhuis made headlines in the newspapers for opening the vessel at night as a ‘floating cabaret’ to host wild ‘Bohemian parties’. Sydney Morning Herald journalist Macleod Morgan described the vessel’s final months with a great sense of nostalgia:

Here are the old-timers, such as the Helen B Stirling [sic] , who have seen the greatest days of life, and are now passing their twilight hour in these reaches of the harbour. There they rest placidly amid the ripples, vessels which have helped to build Australia. (SMH, 18 March 1933)

In March 1934, after it was dismantled and stripped of anything of value, Helen B Sterling, as it was still affectionately known, was set on fire in 20 places in its ‘last resting place’, aptly known as Kerosene Bay (now Balls Head Bay near Waverton).

Little information is currently available about what happened between this period and E R Sterling’s death, possibly in 1943.

An article after the E R Sterling disaster states that he had had a ‘long and adventurous seafaring life’ and ‘seemed little the worse for his experiences’ (The Argus, 24 March 1928). Another report in The Mail on the same date described him in one word – ‘heartbroken’. Journalists’ impressions aside, Captain Sterling was a traditionalist. He could not, in his own words, ‘abide steam’, he revelled in the ‘beauty and mystery of the ships, and the magic of the sea’ and he had a profound pride in his vessels and crew. Based on this and the

fact that he named all but one of his vessels after the women he loved most in his life, it seems likely that these misfortunes would have had an adverse effect on him. Captain Sterling was first and foremost a ‘real sailor’, second a shipowner. He had an affinity with the sea and a love affair with the sailing ship that endured all his life. He was of a certain school that bitterly rejected the development of steam-powered vessels as banal and stubbornly stood by his fleet of sailing vessels, with devastating consequences. In the end, Sterling was a man torn between his love for the tall sailing ship and the stark economic reality caused by his unwillingness to embrace the modern age.

Sterling’s fleet of schooners and barquentines comprised some of the largest timber sailing vessels ever built, in a belated attempt to keep sail economically competitive in an age of iron and steam. Their design had distinct pros and cons. They were built to carry enormous bulk cargoes such as lumber, with reduced operating costs thanks to relatively small crews. However, they were vulnerable to harsh weather and were often in port, idle for months on end, waiting to source sufficient cargo to fill their enormous holds.

03

E R Sterling was the largest barquentine in the world and the key to its design lay in the gaff sails it carried on all of its many masts, except the foremast. They could be raised, reefed or furled from the deck with the aid of a donkey engine for halyards, enabling ‘10 men to achieve what it would ordinarily take 24 men to do on a square rigger’, as the Cairns Post reported (1 February 1922). Yet although it sailed with some success, E R Sterling lay without charter for months in Adelaide before the 1927 voyage that led to its demise. Similarly, Dorothy H Sterling wasted away in port for months before it was finally sent to Port Adelaide and ripped apart. The small number of crew coupled with these vessels’ size proved a dangerous combination when they encountered bad weather. Despite their majesty, the ships of the Sterling Line have passed into maritime folklore.

The sad fate of the Sterling Line contrasts with Hood’s photographs of happier days, before industrial change and economic hardship took their toll. Amid the heartbreak, Hood’s images hint at stories that may otherwise have been left untold. Discoveries like these not only underline the significance of the Hood collection to Australia’s maritime history, they reinforce

the nature of his photographs. They show a time when ships’ portraits were popular among crew members, before steam superseded sail and the demand for Hood’s portraiture declined. Moreover, they display the human face of sailing that Hood so rigorously pursued. They depict the crew’s camaraderie and the close relationship they shared with their vessels.

Apart from Hood’s photographs and a few objects from the collection, all that remains for us to see today are the barest bones of the Dorothy H Sterling, which appear at low tide in the Port River in Adelaide –destroyed after shipbreakers had ‘wrenched all her beauty from her’, and abandoned to ‘that graveyard of broken ships where the waves lap sadly and the wind sighs mournfully through the timbers of what were once graceful craft’ (The Advertiser, 5 February 1932). The bones of Dorothy H Sterling are remnants of a bygone era; they are mementos of the boy who fell in love with sailing and ran away to sea.

With thanks to Steve Reynolds of The Marine Life Society of South Australia and his work on the Sterling ships, in particular ‘The Schooner Dorothy H Sterling (and other ships associated with her)’, MLSSA Newsletter No 355, June 2008.

This is the story of a family who experienced the high life and had it snatched away, and of a man whose undying passion for the great sailing ships was crushed by financial ruin

01 Ceramic plate commemorating the schooner Helen B Sterling. Henry Oosterhuis was the vessel’s last master. ANMM Collection

02 A day at the races: (right to left) Captain Edward Robert Sterling, his son Ray Milton Sterling and Australian daughter-in-law Ethel May Sterling, with unidentified friends.

03 Captain E R Sterling’s son, Ray Milton Sterling, seated next to a symbol of modern invention, the player piano. The saloon of E R Sterling was reported as most beautiful, equipped with a range of contemporary gadgets built for ‘comfort and convenience’.

As the power of the internet spreads more of our collections wider and wider, online sleuths help museum curators to identify images that have lain anonymous for decades in archives and storage cabinets. Curatorial assistant Nicole Cama writes of one such case.

RECENTLY THE WORLD MARKED FIVE years since the launch of Flickr Commons, an online image-sharing facility that has been embraced by many museums as a way of getting their holdings out to a wider audience – and tapping into a worldwide bank of knowledge and enthusiasm. In those five years, about 250,000 images from the photographic collections of 56 different libraries, archives and museums – including some of our own – have been uploaded. Audiences around the world have embraced the spirit of The Commons, putting their own time and energy into researching people, places and key events in previously unidentified images.

Here is one of my favourite photographs from the museum’s Samuel J Hood Studio Collection – the Sydney photographer whose work appears on the previous pages. For me, it’s one of the most beautiful portraits I have seen, and we published it in Signals No 100 last September (page 25) even though the identity of this stylish young woman had remained a mystery as I researched that story. She was part of Sam Hood’s coverage of the October 1930 visit of a Dutch warship, HNLMS Java, and an onboard reception that attracted the cream of Sydney’s fashionable society. Time and time again I would go back to this photograph, trying to spot the elusive clue that would lead to a name and then, hopefully, to a story. I wasn’t alone.

Ever since we posted this image on the photo-sharing website Flickr Commons, it has had users spellbound. So imagine my delight when one of them, doing their own research recently, stumbled across her name and let me know! They had found the answer on page 52 of the November 1930 edition of The Home quarterly magazine, which had first published our Samuel Hood photographs depicting that reception on HNLMS Java

She was Miss Hera Roberts, Sydney painter, designer, illustrator and socialite. A 1929 advertisement described her as a lady with ‘amazing flair’, and her appearance in The Home was no coincidence. Hera designed and illustrated more than 50 of its covers and was considered an arbiter of taste when it came to interior decorating. The Home, subtitled Australia’s ‘Journal of Quality’, was dedicated to all that was sophisticated and à la mode in the world of art, interior design and fashion, during an era marked by the bold and modern exuberance of Art Deco.

Hera Roberts was also a muse to many of Australia’s most talented artists and photographers. Max Dupain and Harold Cazneaux both captured beautiful portraits of her, and Thea Proctor, her cousin and one of Australia’s most renowned female artists, also paid homage to Hera in her work The rose (1927). George Lambert painted what for me is the most beautiful portrait

of her, in 1924. The work, reproduced here courtesy of the National Gallery of Victoria, depicts a youthful Hera in a pose strikingly similar to Hood’s photograph, hand on hip, neck craned to reveal her slender figure.

These portraits echo the theme behind many of her Home journal covers: the modern woman should be elegantly though nonchalantly poised. The Sydney Morning Herald of 13 November 1929 quotes her directly: ‘More than ever … is the search for personal beauty essential in the modern world where Beauty is demanded on every side – the underlying motif for comfort and harmony. Isn’t there an old Greek adage–“Beauty is the gift of Nature, but beautiful living is the gift of Wisdom”? ’

This world of Sydney fashion and aesthetics has been opened up to us, firstly through a glass-plate negative from our collection of the life’s work of that talented photojournalist Samuel J Hood, and then courtesy of one of the super sleuths of Flickr Commons. So to our helpful online researcher who goes by the username ‘quasymody’ … thank you!

01 Hera 1924 by George Lambert, oil on canvas. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Felton Bequest 1925

02 Hera Roberts at a reception on board the Dutch light cruiser Java moored in Circular Quay, Sydney, 10 October 1930. Samuel J Hood, ANMM Collection.

Time and time again I would go back to this photograph, trying to spot the elusive clue that would lead to a name and then, hopefully, to a story

Navigating through a choppy swell, communicating under thunderous chopper blades, conquering your fear of heights … our new interactive exhibition Rescue, from Scitech in Western Australia, encourages visitors to develop a deeper understanding of the science and technology used in a rescue. Do you have what it takes to be a hero?

SEARCH AND RESCUE OPERATIONS TAKE place every minute, every hour, every day, all around the world. Whether in the air, on sea or on land, these services are lifelines to countless people in times of need. But what does a rescue really involve? Who are the teams that put themselves in these dangerous situations? And would we know what to do if we found ourselves in need of rescue?

Rescue, from Western Australia’s Scitech, gives families the opportunity to experience and react to high-pressure rescuebased scenarios where people’s lives are potentially at stake in land, sea and air rescues. Museum visitors can take part in ‘rescues’ as either the rescuer or casualty. By putting themselves in both positions, they can learn how rescue technology works and also how the skills and experience of talented rescuers assist people in peril. Visitors can try pulling themselves out of a simulated sea of blue plastic balls onto a real life raft, and feel what it’s like to clamber aboard when the raft tips and shifts in the chaotic surroundings. Or they can step into the shoes of a helicopter team as they climb aboard a life-sized helicopter and fly a simulator, while using an infrared camera to search around the exhibition.

Dramatic advances in technology mean that rescues are now faster and safer than ever before. Breathing apparatus has transformed the work of firefighters, radio beacons are fundamental in locating missing persons and infrared cameras allow rescuers to spot casualties even at night. The exhibition integrates examples of rescue technology,

01 Specialist operations by EMQ Helicopter Rescue, Queensland Department of Community Safety. Photograph supplied courtesy of exhibition major partner, the Australian Maritime Safety Authority.

02 A life-sized helicopter allows visitors to fly a simulator and use an infrared camera to search around the exhibition. Photograph courtesy of Scitech

Dramatic advances in technology mean that rescues are now faster and safer than ever before

What does a rescue really involve? And would you know what to do if you found yourself in need of rescue?

such as jetskis to simulate the rescue of a swimmer in danger, or the ‘jaws of life’ that can cut apart a car to rescue an accident victim trapped inside.

Recent natural disasters such as the 2009 Black Saturday fires and 2011 and 2013 Queensland floods are strong reminders that rescues would be impossible without the brave people who perform them.

‘Rescue is a very human endeavour, so this exhibition focuses on the personal aspect of rescuing people as well as revealing the technology and equipment that support the process,’ the museum’s director, Kevin Sumption, says.

The exhibition is suitable for children from five to 12 years and their carers, and encourages whole-family interaction and teamwork through interactive exhibits. Primary-aged school students particularly will benefit from interacting with exhibits that involve collaboration and assistance in physical rescue situations. Secondary students will be able to explore more complex rescue concepts through exhibits

involving search patterns and wave rescues. There is also a school program tailored to students from eight to 12 years, which challenges them to identify particular examples of rescue technology in the exhibition and find out how they work or what they are used for.

Rescue operations require a high level of training and are undertaken by specialist squads who often push themselves to extremes both physically and mentally. Visitors to Rescue are encouraged to put themselves in the shoes of a rescuer and examine their own reactions and feelings. They can take command of a search team to map out a route to find a missing bushwalker, or walk across a balance beam perched above a simulated raging ravine to understand how rescuers must often overcome their own fear to save others. Above all, the exhibition emphasises that despite all the advanced technology available to rescuers, rescue depends on humans, and their skill, co-operation and bravery.

Rescue runs from 16 March to 14 July 2013 in the museum’s Gallery One, and is suitable for children from five years and their carers.

Want to hear about a real-life rescue?

Join us on Tuesday 16 April, when Captain Mike Taylor of Orion Cruises talks about his rescue of solo round-the-world sailor Alain Delord after his yacht was dismasted in the Southern Ocean. See page 40 for details.

01 Crossing a narrow beam over a simulated deep ravine gives an idea of how rescuers have to overcome their own fears to save others.

02 This interactive challenges visitors to navigate jetskis around obstacles to rescue a swimmer in trouble – in just three minutes.

03 In a sea of blue plastic balls, visitors can get a feeling for how difficult it is to climb aboard a raft in heaving seas.

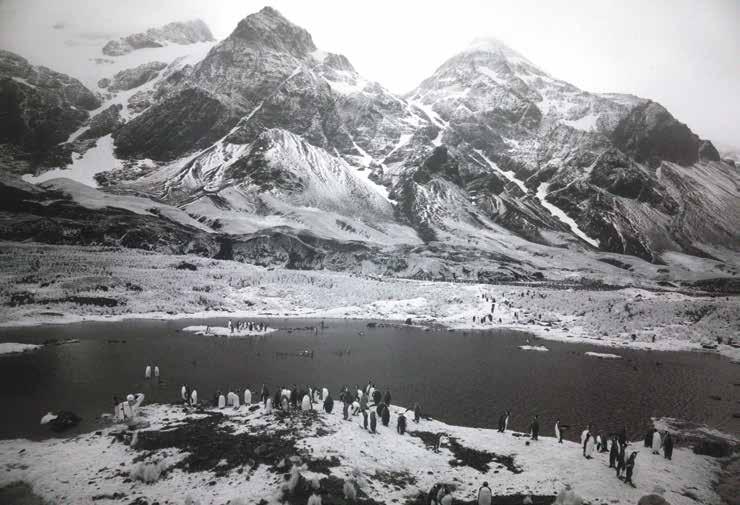

A new exhibition, Elysium Antarctic Visual Epic, captures stunning images of this last great wilderness, documenting life above and below the ice, the fauna and flora, glaciers, and magnificent land and seascapes.

I N 2010 A TEAM OF E x PLORERS comprising wildlife photographers, filmmakers and scientists embarked on an expedition from the Antarctic Peninsula to South Georgia, in the footsteps of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s famous Endurance expedition. Their mission was to scout, record and analyse this land of ice and snow and to produce a feature documentary, a book and a visual library of the impact of climate change on the southern polar region.

The 57 members from 18 countries, convened by Australian project director Michael Aw of the Ocean Geographic Society, included some of the world’s most celebrated artists, photographers, filmmakers, musicians and scientists.

Its aims were to document the flora and fauna of the region; to record the diversity and biomass of its animals, glaciers, land and seascapes; to produce a feature documentary and book to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition; and to establish an image database to serve as a reference index of the Antarctic Peninsula and South Georgia. It also hoped to make landfall on Elephant Island, where

22 of Shackleton’s men were stranded for four and a half months (see story opposite page) while Shackleton and five others sailed away in search of help.

The route of the expedition – from Ushuaia in Argentina, through the Weddell Sea to the Antarctic Peninsula, then across the Drake Passage to South Georgia and back to Ushuaia – approximated that of Ernest Shackleton and his crew after their ship Endurance was crushed and sunk by ice. One of its objectives was to document the sounds and sights of the region that Shackleton’s explorers would have seen.

The expedition sailed on Professor Molchanov, a Finnish-built oceanographic ice-class research vessel refitted as a passenger ship. It set off on 13 February 2010, entering the normally treacherous Drake Passage in calm conditions just after midnight. On Shackleton’s birthday, 15 February, the ship reached the Melchior Islands, encountering fur, Weddell, leopard and crabeater seals, humpback whales, and birdlife including skuas, blue-eyed shags and Arctic terns. The next day at Pleneau Bay, a few fortunate photographers were able to interact underwater with a couple

Elysium Epic is about extraordinary explorers using advanced imaging technologies to document the last wilderness on our planet

01 Previous pages: Adélie penguins, Petermann Island, Antarctica. Photographer Michael Aw. Photographs courtesy of ElysiumEpic.org

02 Leopard seals, Astrolabe Island, Antarctica. Photographer Steve Jones

03 Antarctic fur seals at Fortuna Bay, South Georgia. Photographer Jenny Ross

04 Fortuna Bay, South Georgia. Photographer Ernie Brooks

SIR ERNEST S HACKLETON’S Antarctic journey of 1914–16 is regarded by many as the most remarkable rescue saga in maritime history. The aim of his Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition was to be the first to cross Antarctica coast to coast via the South Pole. The expedition’s two ships were Aurora, under Captain Aeneas Mackintosh, which was to head to the Ross Sea and establish supply depots, and Shackleton’s ship Endurance

A 144-foot (44-metre) three-masted barquentine, Endurance was built in 1912 as a tourist ship for polar-bear hunts, and christened Polaris. Possibly the strongest wooden ship ever built, it was designed and constructed specifically for polar conditions. It was later bought by Shackleton, who renamed it Endurance after his family motto Fortitudine vincimus – ‘By endurance we conquer’.

Shackleton’s 27 fellow explorers set sail from Plymouth, England, in August 1914. In Buenos Aires they picked up Shackleton, who had been delayed in England on expedition business, then sailed on towards Antarctica. In late January 1915, in sight of land,

Endurance stuck fast in the Weddell Sea ice. The ship drifted with the floes for months until, in early October, the movement of the thawing ice began to crush the hull. Supplies and three lifeboats were transferred to the ice, and the crew settled down to wait. Endurance sank on 21 November, stranding the crew with no hope of rescue in the windiest, coldest, most uninhabitable place on earth.

For five months, Shackleton and his men camped on the ice, surviving on penguins, seals and sea birds, and marching more than 100 kilometres dragging their lifeboats laden with supplies. In April the ice floe they were camping on broke in two, and Shackleton decided that they should put to sea in their three small lifeboats and search for land. After seven days at sea, pinpoint navigation landed them 556 kilometres away, on Elephant Island – an inhospitable place far from any shipping routes, and a very poor location to wait for rescue. So, on 24 April 1916, Shackleton and five of his fittest men set sail for South Georgia in a 20-foot boat, surviving the 1,300-kilometre journey across the world’s most treacherous

ocean – a journey that was re-enacted by six expeditioners from Australia and Britain earlier this year, led by Tim Jarvis. Their gear and clothing were authentic to Shackleton’s period, and they sailed an exact replica of Endurance’s lifeboat James Caird

On South Georgia, Shackleton and two companions trekked for 36 hours across mountainous terrain to the tiny whaling settlement of Stromness, from where Shackleton began to organise a rescue. The first three attempts failed, but on 30 August, a seagoing tug lent by the Chilean government rescued the men on Elephant Island, where they had been stranded for four and a half months, and took the entire crew back to Valparaiso, Chile, and civilisation.

The entire ordeal had taken more than 20 months, but despite the dangers and privations, not one of Endurance’s crew was lost. Their support party was not so lucky; Aurora successfully established depots on the Antarctic continent for the Endurance expeditioners, but three sailors died in the attempt.

The Antarctic Peninsula is regarded as one of the most enchanting regions of our planet, yet it is fragile, volatile and under severe threat from global warming

of boisterous leopard seals. There, as the weather closed in, explorers in Zodiac inflatable boats observed masses of krill leaping from the water to avoid the vessels.

On following days, the underwater team documented nudibranchs and crustaceans, and managed more close encounters with leopard seals, which have a reputation for ferocity that was not borne out by the expeditioners’ encounters with them.

The underwater photographers also documented the behaviour of Antarctic fur seals both above and below the water, including unusual activities such as a seal catching and killing an Adélie penguin.

As well as abundant wildlife, the expeditioners encountered something much less common to Antarctica: rain.

The principal expedition scientist and chief scientist of the Australian Antarctic Division, Dr Steve Nicol, commented that in 25 years of surveying Antarctica, this was the first rain he had experienced. Rain is a sign of global warming; while it may encourage plant life, it is probably detrimental to the health of many of the breeding birds, which get damp and cold. Increased atmospheric moisture also results in more snow falling, and this too can affect birds if it falls during their incubation period, burying their eggs. Other signs of climate change were seen at Cuverville Island in the presence of two plants, a moss and a grass, that are crucial indicators of warming weather.

The science of this expedition centred on plankton and how it is being affected by climate change. Plankton, along with krill, is a major food source for many marine animals and plays a vital role in the Antarctic ecosystem. It appears that the jelly-like marine herbivores called salps are becoming more abundant in the Southern Ocean due to global warming and are displacing the krill, changing the ecosystem, which in turn could affect many other creatures right the way up the food chain. The expedition collected krill and salps in the West Antarctic Peninsula and South Georgia regions, then froze them in liquid nitrogen for later DNA analysis, which will show whether the populations in the two areas are connected.

A highlight of the trip was managing to land all of the expeditioners on Elephant Island, where 22 of Shackleton’s crew spent more than four bleak months awaiting rescue. The island is home to colonies of chinstrap and Adélie penguins, and several fur seals. When Shackleton and his party arrived here, there would have been no seals; hunters stripped these islands of their seals in the 18th and 19th centuries, and the populations are only just beginning to recover.

On the next leg of the voyage, from Elephant Island to South Georgia, the team’s focus was plankton science. They set holographic cameras and plankton nets to sample and record data about these creatures. During sampling sessions, when the ship slowed and the equipment was lowered, it didn’t take long for the ship to be surrounded by albatross, apparently conditioned by fishing boats to expect a free snack.

On 23 February the team landed at South Georgia, where Shackleton’s rescue attempt culminated and where in 1922, just about to start another expedition, he died of a heart attack, aged 47. At his wife’s request, he was buried there. The entire Elysium expedition team gathered for a memorial at his grave, proposing a toast with Irish whiskey to the man who was the inspiration for their journey.

Edited by Janine Flew from Elysium Epic materials. For more about the expedition, see www.elysiumepic.org.

Elysium Antarctic Visual Epic 13 April to 11 August www.anmm/gov.au/elysium

A feature documentary and book about the expedition have been produced. See page 40 for details about a special Members exhibition and film preview, talk and book launch.

Shackleton’s Antarctic Visual Epic (SAVE) will be a visual database established with images taken on the expedition. It will serve as a reference of the Antarctic Peninsula and South Georgia, with a curator appointed to manage the archive and curate new images of the region. This archive will be made available for educational and scientific reference for climate change study.

sponsor

Supporting sponsors

Equipment sponsors:

Seacam

Amphibico

Waterproof

Nikon

Atomic

MMAPSS GRANTS AND INTERNSHIPS 2012–13

Do you have a maritime heritage project that would benefit from one of our annual MMAPSS grants or a museum internship?

Find out more about them at www.anmm.gov.au/mmapss

MMAPSS GRANTS AND INTERNSHIPS 2012–13

Our annual heritage-project grants and internships continue to support maritime conservation, research and interpretation around the country. This year, projects range from the construction of traditional Aboriginal bark canoes to a display of Zane Grey memorabilia. One of last year’s grants produced an exhibition on a paddle steamer with the unusual name of The Wandering Jew

ONE OF THIS MUSEUM’S MOST NOTABLE outreach programs is the Maritime Museums of Australia Project Support Scheme (MMAPSS), a generous series of annual grants that contribute towards projects to conserve and promote Australia’s maritime heritage. Administered by us and funded jointly by us and the Commonwealth Government’s Department of Regional Australia, Local Government, Arts and Sport, the scheme provides support and training to regional and remote maritime museums and historical societies – most of them community based and run by volunteers. The main criterion for eligibility is that the organisation or activity is run on a not-forprofit basis.

With the grants scheme is a parallel program awarding internships that bring those community museum personnel to Sydney to work and learn alongside our own staff here at the Australian National Maritime Museum, providing financial assistance for travel and accommodation.

Applications for both MMAPSS grants and internships fall mainly into the categories of conservation, presentation or collection management. The majority tend to be conservation related, since remedial treatment of individual objects is an

essential but frequently costly component of managing a collection. Most regional museums and historical societies do not have access to a fully equipped conservation lab or a team of highly skilled conservators, so often they must engage conservation consultants. The remoteness of many regional institutions is another challenge: objects must either be couriered to the consultant using specialist freight carriers or the conservator must travel to the regional location. Either way, significant expenses can be incurred.

ANMM conservation manager Jonathan London is sympathetic to the challenges faced by regional and remote institutions in maintaining best practice standards. He recommends a ‘prevention rather than cure’ strategy.

‘Although it can be necessary to treat individual objects requiring immediate attention to ensure their long-term survival, a holistic approach to the preventative care of an entire collection is more cost effective,’ he says. This can be achieved by undertaking a survey and developing a conservation management plan to assess the entire collection, its environmental and storage conditions, and its handling and display methodologies. The conservator can

then make recommendations on improving these aspects, as well as suggesting building improvement and integrated pest management strategies. MMAPSS strongly supports this approach and encourages applications for projects focusing on preventative care.

Wandering Jew and Walgett District Historical Society Museum

Paddle steamers played a vital role along the Barwon and Namoi rivers in New South Wales in the 18th and early 19th centuries. The first ever to arrive at the regional hub of Walgett, in 1861, was Gemini, the second steamer of Captain William Randell, who pioneered riverboats on the Murray–Darling with his famous, home-built Mary Jane. The largest steamer to visit Walgett was Excelsior, which was converted to a passenger vessel and only visited once. For half a century, boats like these brought provisions such as fencing materials and furniture to isolated riverside properties and townships, and returned downriver towing barges laden with wool for sale in Sydney or Adelaide.

One of the more frequent visitors to Walgett was Wandering Jew, a paddleboat steamer that travelled the rivers for more than four decades. Wandering Jew began its life

Though its name might now be thought offensive, Wandering Jew was called after a previous owner, a peripatetic Jewish businessman named Daniel Berger who steamed up and down the river in his boat

in Echuca in 1886, registered as Riverina It was 22 metres long, 4.5 metres wide and had a draft of 1.5 metres – unusually deep for riverboats, which generally had shallow drafts, sometimes as little as 50 cm. It was propelled by side paddles and powered by a 10-horsepower steam engine.

The vessel was damaged by fire and subsequently repaired on at least three occasions, in the years 1875, 1883 and 1890. By 1890, the owner was George ‘Nobby’ White, who reduced the boat’s tonnage from 76 to 48 tonnes and renamed it Wandering Jew. This name, which might today be thought offensive, was inspired by the previous owner, said to have been a peripatetic Jewish businessman called Daniel Berger, who steamed up and down the river in his boat.

Under Captain White the boat plied its trade between Walgett and Wentworth, at the junction of the Murray and Darling rivers, although in its latter years it mainly travelled between Walgett and Brewarrina. Captain White married a woman from a station near Brewarrina. Mostly Mrs White lived in Brewarrina, but she travelled on board with her husband when times were tough. On the boat she liked to have some refinement, and two fine coloured-glass vases that she kept on board were proof of this.

Wandering Jew was the very last paddle steamer to visit Walgett, in the year 1912. The old boat finally tied up in the Barwon

above Brewarrina and was used as a floating store until 1914, when fire totally destroyed the vessel. Its skeletal remains rest in the Barwon River mud, and have been covered by water since the Brewarrina Weir was constructed.

The $3,200 MMAPSS grant received by the Walgett District Historical Society Museum in the 2011 round has contributed to an exhibition that examines paddle steamer history around Walgett, focusing on Wandering Jew. The grant enabled investigations into models, and as a result a fine, detailed 1:25 model of Wandering Jew, based on the evidence of early photographs, was made by two members of the Dubbo Wood and Woodturning Group, Paul Nolan and Brian White. They also made a model of the Barwon Inn, where many of the steamers moored when they came to Walgett. The exhibition is displayed at the Walgett District Historical Society Museum, and will be on loan to the town of Brewarrina for its sesquicentenary celebrations in April 2013.

With thanks to Margaret Weber of the Walgett District Historical Society and Nanette Hart (great-granddaughter of Captain George White) for information about Wandering Jew, and to ANMM staff member Sharon Babbage for administering our MMAPSS grants and providing details of the grants awarded.

The Maritime Museums of Australia Project Support Scheme is supported by the Australian Government through the Australian National Maritime Museum.

Bermagui Historical Society Incorporated – In-kind support

For the services of an ANMM designer to assist with display cases for an exhibition relating to the famous US pulp-Western writer Zane Grey, who made Bermagui the base for his game-fishing holidays.

Clyde River & Batemans Bay Historical Society

$5,000

For the Canary of the Clyde project. An ANMM curator will assist with developing a conservation plan for a turpentine-wood oyster punt, an artefact that is important to the commercial history of local oyster farming, and for interpretive signage.

Eden Killer Whale Museum

$1,200

For establishing a museum environment monitoring system, through the purchase of six USB data logging units to monitor and adjust the current collection storage conditions at this South Coast fishing port.

Fort Scratchley Historical Society

$8,500

For stage one of the restoration and structural works to the site of the western barbette at Fort Scratchley, the 80-pound rifled muzzle-loading gun and its gun mount, to interpret this important site guarding the entrance to the port of Newcastle.

Holbrook Submarine Museum

$5,000

For the Masts for the Future project, to replace the existing false array of periscopes, snorkels and aerials on the conning tower of this inland town’s Oberon class submarine HMAS Otway. They will be upgraded to original hardware authentic to the class when it was in commission through the 1970s, 80s and 90s.

Jerrinja Local Aboriginal Land Council

$5,000

For the Jerrinja Traditional Canoe Making project, to construct four Aboriginal bark canoes to revive traditional techniques and practices. The council will mentor and work with Aboriginal youth recruited from the juvenile justice system and local schools.

Lady Denman Heritage Complex

$5,000

For conservation of the historic fishing launch known as Crest or Ninon, supporting essential restoration and preservation work supervisrf by a qualified shipwright.

Mid North Coast Maritime Museum

In-kind support

For the Let There be Light project, support will be provided by an ANMM designer to visit, review and provide recommendations on display lighting.

River Canoe Club NSW Inc

$3,300

For the Australian Canoeing and Kayaking Heritage Preservation project, funding for the digitisation component of archival Super 8 and standard 8-mm films.

Tamarama Surf Life Saving Club

$4,000

For the Tamarama Heritage Project, stream two, stage one: for a significance assessment and collection plan, relating to digitising and conserving heritage items.

01 Wandering Jew and barge at Brewarrina. Photograph courtesy Walgett District Historical Society Museum

02 The unusual sight of an Oberon class submarine planted in the municipal park of a NSW country town hundreds of kilometres from the sea. Photograph from Holbrook Submarine Museum

03 Fishing boat Ninon in shipwright Alf Setree’s original boatshed. Photograph from Lady Denman Heritage Complex

Darwin Military Museum $5,000

For a conservation plan for the two 6-inch guns from HMAS Brisbane that formed part of Darwin’s defences during World War 2, so they can be restored for display.

Blackbird International Ltd $10,000

For the Saving Torres Strait Pearls project, to record the history, songs, dances, stories and photographs relating to the pearling lugger Antonia, which is currently undergoing restoration in Townsville.

National Trust of Queensland –James Cook Museum $3,000

For the May-Belle project, for an ANMM specialist to document the lines and develop a vessel management plan for the May-Belle and for interpretation materials (see article on page 50).

Queensland Maritime Museum $3,000

For the World-War-2 era River class Frigate HMAS Diamantina Type 271 radar installation and interpretation project.

Alexandrina Council –Friends of PS Oscar W $5,000

For the project Paddle Steamer and Barge Building at Goolwa 1853–1913, to build on the existing education program for schools and the general public with a digital film documentary on paddle steamer and barge building at Goolwa.

Mannum Dock Museum of River History

$10,000

To design, plan and cost stages three and four of the All Steamed Up project at the Mannum Dock Museum of Murray river steamboat history.

Mid Council/PS Canally Restoration Committee $5,000

Towards the restoration of PS Canally project stage 2, with prior research and development of a vessel management plan.

Australian Maritime College In-kind support

For an ANMM registrar to provide support and assist in researching and recording objects of maritime significance.

Maritime Museum of Tasmania $3,000

For the Surfing in Tasmania travelling exhibition on the history of surfing and surf culture in Tasmania.

Narryna Heritage Museum Inc

$1,500

For a project to conserve the Sir John Rae Reid ship’s portrait and frame, for research into the painter and provenance of the portrait.

Steamship Cartela Trust

$1,500

For the disassembly of Plenty and Sons triple-expansion steam engine, for a member of Sydney Heritage Fleet with experience in vintage steam engines to conduct a survey of the original 1912 engine.

Wildcare Inc Friends of Maatsuyker Island (FOMI) $2,800

To catalogue heritage objects in the Maatsuyker light station, light tower and on the island from the last 121 years of European occupation.

Flagstaff Hill Maritime Village

$9,545

For the Flagstaff Hill Shipwreck Collection Discovery Trail project, to develop video podcasts that will link the existing Heritage Victoria Shipwreck Discovery Trail and detail the links between the actual sites of wrecks and the collection pieces held by the organisation.

Glenelg Shire Council

$8,000

For the Conservation of the Portland Lifeboat project, for essential structural and some cosmetic works on the vessel as identified in the Portland Lifeboat Conservation Management Plan 2010.

Koorie Heritage Trust Inc

$5,000

For the Ganagan (Deep Water) Waterways in Koorie Life and Art project, for content development for an online component complementing a physical exhibition. This funding will allow artworks and associated stories from the exhibition to be featured on the website.

Ross James will apply these skills to the restoration of Cartela, a 123-foot timber river steamer built in Hobart in 1912, in order to keep her operating into her second century

Mallacoota & District Historical Society Inc $5,000

For the Mallacoota’s Sea Mine Field project, for a research project to further develop the interpretation of the region’s military maritime history from World War 1.

Melbourne Steam Traction Engine Club Inc $1,420

For digitising and conserving engineering drawings of the New Zealand-built Lyttelton II steam tug, the engineroom of which is being preserved by the club.

Museums Australia (Victoria)

$7,800

To provide training to non-professional museum workers in the management of collections of maritime artefacts, in particular shipwreck materials.

Carnarvon Heritage Group Inc

$1,500

For interpretation and restoration work on the historic vessel Little Dirk, a Shark Bay pearler or cutter that had many names and uses in its life.

Norfolk Island Museum $5,000

For the museum’s Start-Up Education Program, to develop an education program and associated materials for the museum and to train museum personnel in their delivery.

The museum’s internship program offers assistance to enable workers in small and volunteer-based museums to travel to and stay in Sydney, and spend time with mentors on the staff of the Australian National Maritime Museum. The following are the internships awarded in 2012; the first two have already been carried out.

Ross James is the project manager of SteamShip Cartela Ltd, Tasmania. He spent one week here absorbing aspects of ship restoration and volunteer management to apply to the restoration of Cartela, a 123-foot (37.5 metre) timber river steamer built in 1912, with the aim of keeping the vessel running on the Derwent River in her original role as a passenger boat.

Cartela was built by Purdon & Featherstone of Battery Point, Hobart, and plied the Derwent River for more than 100 years. Until now, a number of minor updates have been enough to keep her in operation, but in early 2013 Cartela was donated by the current operators to the SteamShip Cartela Trust to undertake her restoration. Though she is now diesel powered, her original steam engine has been purchased by the new trust and, once refurbished, will be reinstalled in the vessel. The fouryear project will cost an estimated $3.7 million. After a total rejuvenation of the ship’s hull and superstructure, and installation of the reconditioned steam engine, the vessel will once again work her home waters every day, at the beginning of her second century as a steamship.

The restoration plans include a close collaboration with the Franklin Working Waterfront Association, whose aim is to create a maritime heritage precinct in Franklin, on the banks of the Huon River south of Hobart. This will accommodate traditional riggers, sailmakers, shipwrights, a bronze foundry and other maritime trades and associated skills, creating a tourism venture specialising in the interpretation of Tasmanian maritime heritage. Its centrepiece would be Cartela under restoration.

Kirsty Parkins volunteers at the Frank Partridge vc Military Museum, Bowraville, NSW, cataloguing their library collection.

Kirsty’s first assignment at ANMM was working with textile conservator Julie O’Conner, learning to cover coat hangers and to make a hat stand, a skill she will use to put hats on display and in storage at the museum. With conservator Sue Frost she examined ways to display flags, and will apply this knowledge to one of her own collection’s flags, which has a bullet hole in it. Kirsty also worked with paper conservator Caroline Whitley, learning how to store photographs in Mylar to prevent fading and damage, and to store highly flammable nitrate negatives safely and securely. She also learnt from Caroline how to use a suction table to clean watercolours. A further session was spent with ANMM registrars, learning about digitising photographic archives.

This involved practice scanning and numbering photographs on the computer, determining their dimensions and entering them into a photographic database.

Kirsty plans to use her newfound knowledge at the Frank Partridge Museum to preserve delicate artefacts. She would like to thank ANMM staff members Sharon Babbage and Michael Crayford for their help in organising her internship, and all the people who helped her while she was at the museum.