SIGNALS quarterly

EAST OF INDIA

Forgotten trade with Australia TEA BY THE SEA

The first global mass commodity MOUNTAINS TO SEA Ansel Adams epic landscapes

Forgotten trade with Australia TEA BY THE SEA

The first global mass commodity MOUNTAINS TO SEA Ansel Adams epic landscapes

WITH A SUCCESSION OF WORLD WAR 1 centenaries rapidly approaching – including the big one that’s already getting lots of news coverage, the ANZAC landing at Gallipoli in April 1915 – there’s a related centenary that’s upon us already, as you receive this issue of Signals. On 18 June this year, it’s 100 years since the launch of AE2, the Royal Australian Navy submarine that played a heroic role in the campaign to capture the Dardanelle Straits, to knock Germany’s ally Turkey out of the war and secure supply lines to Britain’s ally Russia.

As we all know, the Gallipoli campaign failed. Until recently, however, very few Australians knew of AE2 ’s daring exploits in that campaign. Nor that she sits to this day on the floor of the Sea of Marmara, relatively intact and in good condition. She is one of the few, and certainly the largest, relic remaining from that campaign that forged our nation. AE2 has rightly been termed ‘The Silent ANZAC’.

That raises some big and very interesting questions, and I believe it is the role of this national museum to stimulate a conversation about them.

The first question is, when does a historic vessel take on the mantle of national significance? When it does, what should the nation do about it? AE2 ’s situation opens up fascinating possibilities.

The 750-ton, 181-foot (55-metre) AE2, built by Vickers Armstrong in England for £105,000, made the longest voyage undertaken by a submarine to reach Australia with her sister boat AE1 Returning to the northern hemisphere, in April 1915 she was the first Allied submarine to penetrate the Dardanelles narrows as the Gallipoli landings took

place, and drove off a Turkish battleship bombarding Allied forces. Commander Henry Stoker RN scuttled AE2 after an engagement with the Turkish torpedo boat Sultanhisar. He and his crew of Australians and Britons became POWs.

A Turkish dive team found AE2 in 1997, sitting upright in 73 metres of water, and in 1998 an Australian expedition ‘Project AE2 ’, led by Dr Mark Spencer and maritime archaeologist Tim Smith, undertook site analysis. The AE2 Commemorative Foundation, chaired by Rear Admiral Peter Briggs ao csc ran (retired), was formed and has worked with the Australian Government and Turkish authorities to plan for the submarine’s future. A 2008 Turkish–Australian workshop recommended preservation and protection where the boat rests, and public education about it. The aim is to make the story of AE2 at Gallipoli as well-known as Simpson and his donkey. The Australian Government has pledged Anzac Centenary Fund backing.

However, ship recovery projects elsewhere in the world that have galvanised national interest and pride, such as Mary Rose in the UK and Vasa in Sweden, surely make the possibility of raising AE2 one that can be revisited. The raising in 2000 and long-term conservation of the US Civil War ironhulled monitor, the Confederate Hunley, demonstrates the technological feasibility. Two major considerations in AE2 ’s case are an unexploded torpedo that remains in the hull, and the 15-year treatment in a laboratory tank that would be required to stabilise the metal once it returned to the atmosphere. And with Turkey having an equal stake in the vessel’s history and significance, any final disposition would certainly be a collaborative matter.

Whatever the complexities, as the centenary of the Gallipoli landings approaches, it is certainly the time for a wider conversation about ‘The Silent ANZAC’. Kevin Sumption

India was vital to the infant Australian colonies, say the exhibition curators

The

Archaeology program investigates ships of the India trade wrecked in the Coral Sea

Tea, the first global commodity for the masses, impacted on worldwide trade and culture

Water

Introduction to this Sydney Harbour heritage site by a museum conservator

2013 Phil Renouf Memorial Lecture by John Young of the Wooden Boat Centre, Tasmania

Your calendar of activities, tours, lectures and excursions

The

Queensland’s maritime history is being preserved on Brisbane’s South Bank

Two fine yachts, power and sail, are among the new additions to this vital national database

By schooner from the Isle of Man to the Victorian

The

The Australian Wooden Boat Festival 2013

cover: Lord Wellesley’s boatman, from a publication showing the privileged life enjoyed by some Europeans living in India in the early 1800s. Hand-coloured engraving by Charles Doyley, Plate 12 from The European in India by Captain Thomas Williamson, published London 1813 by Edward Orme. ANMM Collection

Australian links with India go back to the earliest years of our European settlement when the infant colony, struggling to survive, desperately needed supply lines far closer than Britain. Our newest exhibition outlines the place of India in a world of global commerce, long before the currently heralded ‘Asian century’, the rise and fall of England’s East India Company and its impact on Australia. By senior curator Dr Nigel Erskine

02

01 Previous pages: East India Company ships were among the largest wooden merchant vessels built, this one over 1,300 tons. Launch of the Honourable East India Company’s ship Edinburgh, watercolour by William John Huggins about 1825. Lent by the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich UK. Green Blackwall Collection

02 Crew abandoning HMS Guardian after being wrecked on an iceberg on 25 December 1789 on a voyage to deliver supplies to Botany Bay. Handcoloured engraving by Robert Dodd, published by J & J Boydell, Pall Mall London 1790. ANMM Collection

03 The Mint, Calcutta, from the sketchbook of William Prinsep, an artist who lived in Calcutta from 1817 until 1842 and worked with the export firm Palmer and Company, which sent many vessels to Australia. Pencil and ink on paper c 1830. Lent by Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales. Caroline Simpson Collection

FOR SYDNEYSIDERS CIRCULAR QUAY

is a bustling hub, a place of buskers, cafes and crowds. But before all that it was Sydney Cove, a snug anchorage with a creek of fresh water at its head, chosen by Arthur Phillip as the site of the first European settlement in Australia. Today in our world of global connections it is almost impossible to appreciate the isolation of those early settlers sent half-way around the world to start a new colony – ‘... distance from great Britan 13,106 miles …’, as convicted forger Thomas Barrett engraved in a spidery script on an improvised medallion when his ship, the transport Charlotte, finally arrived.

The voyage had gone remarkably well, but the real test lay ahead. When most of the 11 ships of the First Fleet had sailed for home, leaving behind just over a thousand convicts, marines, officers and settlers at Sydney Cove, their task was enormous. Stores were limited, few of the settlers had any farming skills and the land was far from fertile. The first years of the settlement were marked by uncertainty and privation. Just nine months after arriving, Governor Phillip was forced to send one of his two remaining

ships, HMS Sirius, around the world to fetch supplies from Cape Town. Its return eight months later brought temporary relief, but the situation continued to deteriorate.

Marine Captain Watkin Tench captured the general air of pessimism hanging over the settlement early in 1790: ‘… thirty-two months from England … From intelligence of our friends and connections we had been entirely cut off, no communication whatever having passed with our native country since the 13th of May, 1787 … Famine besides was approaching with gigantic strides, and gloom and dejection overspread every countenance.’

Governor Phillip decided to send half the population to Norfolk Island, where a small settlement established in early 1788 was flourishing. Unhappily, the plan went disastrously wrong when HMS Sirius, which had sailed to Norfolk with Supply in March 1790, ran onto rocks at the southern end of the island, became a total loss and most of the supplies intended to support the new arrivals were damaged or lost. With the population spread between two settlements 1,600 kilometres apart, Governor Phillip

dispatched the single remaining vessel Supply to the Dutch settlement of Batavia (now Jakarta, Indonesia) to purchase emergency relief supplies.

Surely the situation could not get any worse and the long-awaited store ship from England must soon arrive?

In truth it got worse. The store ship Guardian had sailed from England six months earlier, ahead of the Second Fleet and loaded with supplies, and should have arrived in Sydney Cove in 1790. But two weeks after leaving Cape Town the ship had struck an iceberg, in the early hours of Christmas Eve. Half of those aboard took to the boats, most never to be seen again, leaving Captain Edward Riou and about 60 men to nurse the waterlogged ship back to the Cape – an incredible feat that they achieved after two months.

While the Second Fleet finally arrived in mid-1790, carrying stores but bringing even more convict mouths to be fed, the Guardian disaster highlighted the risk of relying totally on a supply line stretching half-way round the world. It brought about

a change to government policy with regard to supplying the colony from India.

For almost two centuries India had been a bastion of England’s East India Company, whose monopoly on all English shipping east of the Cape of Good Hope gave it privileged access to the enormous wealth of Asia. Since a vessel sailing from Sydney Cove could reach Calcutta in less than two months, it might be expected that trade between the colony of New South Wales and the East India Company’s trading centres in India would have been encouraged from the start. In fact, however, Governor Phillip’s instructions ordered him to prevent every sort of contact between the new colony and the East India Company settlements by every possible means. This was probably intended to prevent convicts escaping.

News of the Guardian disaster influenced attitudes in Britain and a new policy direction from Home Secretary Lord Grenville to Governor Phillip arrived with the ships of the Third Fleet in August 1791. It read, in part: ‘I had suggested to Lord Cornwallis [Commander-in-Chief of HM forces in India] the idea of supplying the

settlement under your command either wholly, or at least to a very great extent, from Calcutta ... or some other of the Company’s settlements in India.’

Acting on this, Governor Phillip contracted one of the Third Fleet ships, Atlantic, to sail to Calcutta to buy supplies for New South Wales. When it returned to Sydney the following year with rice, flour and a variety of livestock, it marked the beginning of a trading relationship between Australia and India that grew in importance throughout the 19th century. The story of this early relationship with India is the focus of the museum’s exhibition East of India - Forgotten trade with Australia, featuring a wealth of items from the museum’s collection and borrowed from leading collections in Britain and India.

How did India became a centre of British power in Asia – one that would come to be called the jewel in the Imperial crown? Europe had long been an eager market for valuable Asian products. From around the 2nd century BCE luxury goods such as silk, jade, ivory and spices were carried overland

Surely the situation could not get any worse and the long-awaited store ship from England must soon arrive?

to Rome along the Silk Route and, by the start of the Christian era, Roman traders had established direct links with western India, shipping cargoes through the Arabian and Red Seas. The rise of Islam from the seventh century CE, culminating in the fall of Constantinople in 1453, put control of these routes in the hands of Christian Europe’s chief rivals. It was this that led the Portuguese navigator Vasco da Gama to pioneer a new sea route around southern Africa to India in 1498. His voyage opened a gateway to the wealth of Asia, and for the next century, Portugal took over the monopoly of Asian trade to Europe.

By the end of the 16th century, however, powerful merchant companies from England and the Netherlands were challenging Portuguese trade. The East India Company was granted a monopoly of English trade east of the Cape of Good Hope by Queen Elizabeth 1 in 1600. Initially it tried to compete with the Dutch East India Company in the spice islands of South-East Asia (today’s Indonesia) but was gradually forced out, establishing trading centres on the Indian coast. By the end of the 17th century the company had built fortified trading bases at Surat, Madras, Bombay and Calcutta and, with its regularly renewed monopoly of all English trade between the Cape of Good Hope and the Magellan Strait, was well on its way to becoming a corporate

giant with some similarities to modern conglomerates such as Microsoft, General Electric or McDonalds.

From 1657 the company organised its finances as a joint stock company, facilitating long-term investment in infrastructure and trade. It was closely associated with London and its investors included members of the city’s financial and political elite. But unlike modern corporations, its charter privileged it to mint coins, administer justice including the powers of life and death, and to wage war in its overseas territories. The backbone of the company – which came to be known as the Honourable East India Company, and colloquially as ‘John Company’ – was its fleet of armed East Indiamen.

The predominant power the British encountered was the Islamic Mughal empire, which controlled many of the fragmented states of India and was at a peak in the 17th century under Shah Jahan, builder of the Taj Mahal. By the middle of the 18th century it was in decline, producing instability and tensions that threatened the company’s bases and forced it to increase its garrisons. During the Seven Years War (1754–63), when Britain and France were once again in conflict, the company continued to build its land forces as it successfully countered threats from both French and Indian sources. It was during this period that forces commanded by

Around 100 ships arrived from India between 1813 and 1833 while over 250 ships left for India from Sydney or Hobart

01 J G Hughes opened his grocery store in 1834, promoting teas and coffee shipped directly from India and China. Engraving by William Moffitt, reproduced courtesy National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

02 India House in London was one of the great centres of British commerce. Statues of distinguished East India Company servants gaze down like Roman heroes. India House, The Sale Room, aquatint by Joseph Stadler after Thomas Rowlandson, published London 1808. Lent by The British Library

Colonel Robert Clive (‘Clive of India’) won a pivotal battle against the Nawab of Bengal at Plassey, a triumph that transformed the company.

Following this victory, the treaty of Allahabad granted the East India Company the right to tax some 20 million people of the Indian states of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. This right, known as diwani, provided an enormous source of wealth, although many observers were outraged by the idea that a company whose primary responsibility was to make a profit for its shareholders should be administering large parts of India.

Senior company officials in India were accused of corruption and mismanagement resulting in severe famines in Bengal, which killed around five million people. The company also became embroiled in unsuccessful and expensive military campaigns that forced it to seek financial assistance from the British government. As a result, in 1784 Parliament passed the India Act appointing a Board of Control to oversee company activities in India. This shift in power was further highlighted by the appointment two years later of

a Governor General and Commander in Chief of British Army forces in India – Lord Cornwallis, whom we met earlier, permitting Governor Phillip to buy supplies from India.

It was anticipated that these appointments would end costly military adventures, but this proved wrong.

With declining Mughal power, several native Indian rulers attempted to expand their influence. The most successful of these was Tipu Sultan in the rich southern state of Mysore. Opposed to British power in India, he fought a number of successful wars against them until he was killed at the battle of Seringapatam in 1799. In the years that followed, while the colony of New South Wales was developing, British power expanded across most of India through conquest, annexation or alliance.

At the height of its powers and monopolies the company’s interests included textiles and tea, sold in great quantities to home markets in Britain, but also a huge and damaging trade of Indian opium into China. In 1813 the East India Company’s monopoly of Indian trade was finally dissolved but its monopoly on China trade was renewed for a further 20 years.

01 When the son of General Sir Hector Munro was killed by a tiger in Bengal, his enemy Tipu Sultan, ruler of Mysore, felt no sympathy. Tipu, who styled himself the ‘Tiger of Mysore’, commissioned a lifesize, mechanical automaton that re-enacted the fatal attack. The tableau was copied in this glazed earthenware figure, Munro killed by a tiger, Staffordshire c 1830. Lent by the Victoria & Albert Museum, London. Robert Breckman bequest

02 Grand vase bearing the East India Company coat of arms, granted by Queen Elizabeth I as a symbol of her confidence and royal patronage. Porcelain, Barr, Flight & Barr, Worcester England 1830. Lent by the Victoria & Albert Museum, London. Bequeathed by Herbert Allen

03 Portable drop-front cabinets were made by Indian craftsmen for Europeans travelling in Asia; valued for ornate decoration, they were traded in India and Europe. Mughal design elements, 17th century. Lent by Victoria & Albert Museum, London

04 Voyages between England and India could take six months and, despite social hierarchies, often brought people together in unexpected ways. Caricature by George Cruikshank depicts the grand cabin on board an East India Company ship. Publisher G Humphry, London 1818. ANMM Collection

01 Philip Gidley and Anna Josepha King, and their children Elizabeth, Anna Maria and Phillip Parker. Watercolour portrait by Robert Dighton. Reproduced courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW.

02 Evening dress of fine white Bengal muslin, decorated with silver-plate embroidery in a sprig-and-spot pattern, is believed to have belonged to Anna King, the wife of Governor King (pictured top of page). It demonstrates the simplicity of the Empire style with high waist, narrow bodice back and short, puffed sleeves. Dating from 1805, and probably made by a colonial seamstress from imported Indian fabric, this is one of the oldest surviving examples of clothing worn in the colony. Lent by National Trust of Australia (NSW).

03 Indian gold coin, ‘Star pagoda’, about 1790–1807. Collection Powerhouse Museum, Sydney. Photographer Penelope Clay

Goods imported from India

included candles, soap, sugar, rice, tea, Chinese ceramics, shoes, rum, cotton textiles, clothing, tobacco, leather, canvas, rope, iron and general household goods

In Australia, the period following the opening of India to new English traders saw a surge in ships arriving from and leaving for Indian ports. Some of these, such as the Eliza, which we see in the exhibition, brought rice, sugar, tea and other sundries from Bengal. Others like the Britannia brought new convicts – 10 imprisoned British soldiers from Calcutta.

Around 100 ships arrived from India between 1813 and 1833 bringing goods including candles, soap, sugar, rice, tea, Chinese ceramics, shoes, rum, cotton textiles, clothing, tobacco, leather, canvas, rope, iron and general household goods. But in the same period over 250 ships left for India from Sydney or Hobart, reflecting the common practice of many convict transports and other ships arriving from Europe, of continuing to India after unloading their cargo in Australia. In many cases the real profit of the voyage was made from the Indian cargo that was carried back to Britain.

While Australia was a ready market for Indian goods, it was more difficult to find suitable Australian exports for India. These included timber, skins, coal, sandalwood, and later a live trade in horses for military and other purposes. Some ships such as the Royal Charlotte, which arrived in Sydney in 1825, were chartered to carry British troops from Australia to Calcutta or Madras at the end of their deployment in Australia. In fact, most of the British Army regiments that served in Australia during the first half of the 19th century were sent on to India.

And like Royal Charlotte, not all the ships bound to India from the Australian colony made it there safely.

The route from Sydney to India depended on the season. In the southern summer the preferred route was westwards across

the Great Australian Bight and then north into the Bay of Bengal, but during winter strong westerly winds often made this route unviable. The preferred winter route was north through the Coral Sea or inside the Great Barrier Reef, then west through Torres Strait and on to the Bay of Bengal sailing south of Java. This route meant sailing through the hazardous reef systems of north-eastern Australia.

The charting of safe shipping routes, a priority for colonial development, was initiated by Matthew Flinders, and was carried forward between 1817 and 1822 by Phillip Parker King. The vessel he used for most of his survey work was an 84-ton cutter, Mermaid, that was built in Calcutta. King’s detailed mapping made much of the Australian coast safer for shipping, but areas such as the Great Barrier Reef, Coral Sea and Torres Strait continued to claim sailing ships throughout the 19th century. In recent years the museum’s maritime archaeology team has located and surveyed a number of these wrecks in collaboration with the Silentworld Foundation and Sydney University through an Australian Research Council grant. They include Royal Charlotte and Mermaid. The latest such expedition appears on page 18.

People as well as trade goods were moving between India and Australia. Tasmania was highly regarded by Europeans in India as a healthy environment in which to recuperate or retire, particularly after the publication of Augustus Prinsep’s Journal of a Voyage from Calcutta to Van Diemen’s Land in 1833, which praised its ‘beauties and interests’, including its business opportunities. Rather ironically, his journal was published posthumously by his wife, since he did not survive long after his voyage to Tasmania.

Faring better was Captain Andrew Barclay who, after serving the East India Company during a lifetime at sea, settled

in Tasmania and became a wealthy farmer. In 1811 Barclay had commanded the ship Providence carrying 180 convicts and a detachment of Governor Macquarie’s 73rd Regiment to Sydney. As well as the 23 European crew, the ship carried 70 Indian sailors, who were among very large numbers of Indian seamen who passed through Australian ports in this period. An article following this one expands on the topic of the Indian seafarers known as lascars.

From about 1815 the European population of Australia grew rapidly and by 1850 was 405,356. as settlements expanded and the colonial economy developed around wool and other rural commodities. The settlement of Albany (1826) and the Swan River (Perth) three years later signalled British claims to the entire continent. For some Europeans living in India the establishment of closer new settlements in Australia offered obvious benefits. One of them wrote: ‘As Calcutta, Madras and Bombay are only six weeks sail from Port Adelaide, it is conceived that many children of Anglo-Indian parents, instead of being separated from home for years, would be sent to school in the colony, if an establishment sufficiently wellconducted were founded.’

The opportunities in Australia also attracted British investors, resulting in the establishment of large pastoral consortiums such as the Australian Agricultural Company in 1824, among whose many well-heeled investors were the chairman, deputychairman and five directors of the East India Company.

The discovery of gold in the Port Phillip district in 1851 and the subsequent influx of new settlers to the region marked a radical shift in colonial dynamics. Victoria became the first Australian colony to achieve self-government (1855), followed by Tasmania, South Australia, New South

Wales and Queensland. In 1858 the European population of Australia reached over one million, amid the general euphoria and optimism as the country celebrated 70 years since the arrival of the First Fleet in Sydney Cove in 1788.

Looking into the future, this exhibition reminds us that the roots of our trade with India run deep

In India the situation of the East India Company during the same period was one of decline, culminating in the revolt of sections of the Bengal Army in 1857. Following a tumultuous and bloody year reasserting British dominance, responsibility for administering East India Company territories in India was taken over in 1858 by the British Government. In a final symbol of its dramatic fall from power, the company’s magnificent London headquarters, East India House, was demolished in 1861.

For many Indians, the events of 1857 that the British call the Indian Mutiny represent a turning point in the nation’s history and the first revolutionary step towards independence. The scale of the uprising underlined a widespread desire for change that the East India Company was ultimately

unable to suppress. Its long innings had finally come to an end and while a further 90 years would pass before India finally gained its independence from Britain, the nation’s tenacious spirit had been revealed. In the 21st century that same tenacity is on display as India assumes an increasingly significant political and economic role on the world’s stage. India is now one of the world’s third-largest economies with one of the fastest-growing middle classes in Asia. This growth is providing new opportunities for Australian trade, and India is now our eighth-largest trading partner. In 2012, Australia was India’s largest supplier of coal, while India was the second-largest source of international students studying in Australia. India is the third-largest source of immigrants to Australia, adding to an existing Indian community of around 450,000.

The Australian Government’s recently released White Paper Australia in the Asian Century highlights the resurgence of Asia as the world’s economic powerhouse and the opportunities for Australia. These are undoubtedly exciting times, but in looking into the future, the museum’s exhibition East of India - Forgotten trade with Australia reminds us that the roots of our trade with India run deep.

This article employs the Anglicised spellings of Indian place names commonly used in the period under discussion, and familiar to most readers. Post-independence forms include Chennai, Kochi, Kolkata and Mumbai.

01 During the 90-day siege of Lucknow, part of the rebellion that the British called the Indian Mutiny, a soldier’s wife dreams of hearing the bagpipes of Scottish troops coming to her rescue. The Relief of Lucknow [Jessie’s Dream] by Frederick Goodall, 1858. Reproduced courtesy Museums Sheffield/ Bridgman Art Library

02 Celebrated warrior queen, the Rani of Jhansi Lakshmi Bhai, killed in 1857 fighting the British for the restoration of her kingdom. Chromolithograph print, Chitrashala Press, Poona, late 19th–early 20th century.

Lent by the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Gift of Jim Masselos 2011

IN FEBRUARY THIS YEAR THREE MUSEUM staff members travelled to India funded by a grant from the Australia-India Council, as part of a continuing dialogue between the Australian National Maritime Museum and Indian cultural institutions, in major port cities that are key locations of maritime trade and have their origins in colonial and earlier periods. The visit reflects the sort of peopleto-people engagement so important for the development of productive and long-term relationships between the museum and key counterparts in India. It consolidated a number of links with institutions forged during the period researching the exhibition and negotiating loans for it from Indian collections.

Assistant director Michael Crayford, senior curator Dr Nigel Erskine and design manager Johanna Nettleton gave presentations on current developments at ANMM, during professional development workshops in Mumbai (formerly Bombay) and Kochi (formerly Cochin, in Kerala State). These included sessions on the Indian focus of the museum’s recent maritime archaeology program, and on the design of exhibitions. Other presenters included AusHeritage chairman Vinod Daniel and architect

Steve King speaking about conservation and the principles for establishing sustainable museum environments. AusHeritage is a network of Australian cultural heritage management organisations, established by the Australian Government in 1996 to facilitate the engagement of organisations for the Australian heritage industry in the overseas arena.

In Mumbai the forum was hosted by Chathrapathi Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya museum (CSMVS) and brought together museum professionals from across India. Participants in Kochi included archaeologists from the Muziris Heritage Project and students from the Centre for Heritage Studies at the Hill Palace Museum, specialising in museum studies. Muziris is the name of an ancient Indian trading port located 40 kilometers north of the modern port of Kochi. The Kochi workshops were held in collaboration with the Vasant J Seth Memorial Foundation, established in memory of the founder of the Great Eastern Shipping Company, now one of the largest in India. The foundation supports initiatives highlighting and preserving India’s maritime heritage.

01 Johanna Nettleton, manager of ANMM design, in Kochi with students from the Centre for Heritage Studies, Hill Palace Museum.

02 Author of this article, senior curator Dr Nigel Erskine, at the Victoria Memorial, Kolkata

Lascars – seamen from the Indian subcontinent – constituted a major seafaring subculture over several centuries, speaking a patois incorporating Arabic, several Asian and European languages. ‘Klassee’ meant an ordinary sailor. © The British Library Board WD314no.50

Researching the exhibition East of India – Forgotten trade with Australia has provided fascinating glimpses of unknown Indians who were part of our colonial tapestry. Contemporary Indian-Australian perspectives were also gathered for the exhibition’s short film Indian Aussies: terms and conditions, writes curator Michelle Linder

I was so insufficiently fed, that I was obliged to purchase a bag of rice at my own expense, on which I lived for a whole month. I made my complaint to Mrs Browne; she said she would not redress me. I said I would go to the governor. She said can the governor pull the hair off my head; he is only the keeper of thieves and cannot interfere with me. I know nothing of the agreement I entered into, or the particulars of it. I was turned on board ship without going to the police office. I desired to be returned to my own country. I have been so ill used by Mr Browne I will remain no longer with him; if he would give the best dish I could eat, I would not stop with him. This country does not suit me; I was coaxed to come here being told that I should have all the privileges I have in my own country.

THE MOST FASCINATING ASPECT OF the connections between India and Australia that emerged during my research for our exhibition East of India – Forgotten trade with Australia were the experiences of Indian-born workers in the colony. While few in number, local newspapers reported on issues involving their conduct, their employers and allegations of mistreatment against them. Workers from India were largely sailors (known as lascars), domestic servants and agricultural labourers. The testimony above was given by Meer Juan, an Indian servant who worked in Australia from 1816 until 1819. He was sent back to India along with 34 other Indian-born employees on the orders of Governor Lachlan Macquarie in 1819. A few settlers arriving in the Australian colonies from India brought domestic servants with them, usually one or two, although the practice was discouraged by authorities. Mr and Mrs Browne imported numerous servants from India in 1816 to supplement the convict labourers assigned to them to work on their farm at Abbotsbury near Prospect. Mr Browne was later granted land at Camden and in the Illawarra region. The servants caused Mr Browne

some trouble, with complaints made in 1817 about them trespassing on the government Domain, and in 1818 for washing in the ‘public tanks’ [a practice that would have been universal in their communities in India].

Indian servants were promised a decent wage, adequate food and clothing, payment for their remaining family members in India and a return passage home

In June 1819 a number of servants made serious allegations of mistreatment to Governor Macquarie and he ordered a special inquiry to investigate. Numerous servants gave testimony, with a servant who worked for another employer translating.

There were accounts of being underfed or starved, beaten and whipped. Some revealed

that their families in India had not received promised payments; female servant Buck Tien stated she had never received any pay and was treated as a slave. Woodchub complains he was forced to eat with the ‘mahomatens’ (presumably Muslim lascar sailors) aboard ship, and thereby lost his caste. Their complaints were upheld and the colonial government took 24 male and 11 female Indians from the custody of Mr and Mrs Browne and shipped them back to India on the Mary, departing Sydney for Calcutta on 22 July 1819. Mr Browne was sent a bill for the cost of shipping, which he refused to pay. He argued the servants had come to the country legally and voluntarily. The colonial government failed in the Supreme Court to recoup the costs from him. Letters from Mr Browne held in the Colonial Secretary’s records refute some of the servants’ allegations and agree to ship back those whose term of agreement had expired.

The case of Mr and Mrs Browne and their Indian servants may have been an isolated one, yet when you read the servants’ testimonies, you think about the experiences of people who were persuaded to travel far from their homes to work in a distant colony. They were promised a decent wage, adequate food and clothing, payment for their remaining family members in India

and a return passage home after their time of agreement had expired. It appears nearly all of them were severely let down by Mr Browne. Yet there’s more to the story of Mr Browne and his Indian servants.

In 1824 Mr Browne sent a letter to Governor Brisbane requesting that land to work cattle be granted to Ramdial, a Hindu Indian agricultural worker whom he recommended as an efficient and hard worker who had been in the colony for six years and in his employ for 20 years. It is unclear if Ramdial received the grant though he did continue to work for Mr Browne. The census records for 1828 record the sole ‘Hindoo’ residing in NSW as an Indian stockman named Ramdial living on the Browne’s family farm. Did Ramdial have a much better experience working for Mr Browne in Australia than the servants shipped back to India, or was he also a victim of cruel treatment? I guess the answer will remain unknown.

For our exhibition, actors from two Sydneybased Indian theatre companies, Abhinay and Nautanki, have recorded a selection of the servant testimonies. The official records pertaining to the servants were sent to government authorities in India and were later considered in a wide-ranging inquiry focused on slavery in India. All 35 testimonies can be found in the House of Commons Parliamentary Papers

Online in the paper titled Slavery in India – Return to an address of the Honourable House of Commons, dated 13 April 1826

The seamen, known as lascars, who worked on the ships that sailed to Australia were by far the largest group of Indian workers that locals in Sydney may have encountered. Most ships transporting cargo and troops from India to Australia had lascar crews, yet there is little information available about their time in port beyond a few scant reports in the colony’s first newspaper the Sydney Gazette, published from 1803 until 1842.

Lascars (from the Persian, meaning a troop) were seafarers from the Indian subcontinent, including today’s Pakistan, India and Bangladesh, and were employed by the East India Company to meet its shipping needs. They were a feature of British and other European nations’ merchant fleets for centuries, forming a distinct seafaring subculture despite their varied ethnic origins. In the colonial period a ship’s captain usually negotiated with a broker in Calcutta (Kolkata) or other ports to recruit crew for six to 12 months. The lascars were poorly paid, receiving less than a sixth of the wage of their European counterparts. Many lascars lost their lives at sea, and the prevailing attitudes are reflected in a report of a storm encountered by the ship Lady Barlow in 1804: ‘Happily only one of her

The seamen, known as lascars, who worked on the ships that sailed to Australia were by far the largest group of Indian workers that locals in Sydney may have encountered

Lascars ferry horses, exported from New South Wales and known as ‘walers’, ashore at the exposed and dangerous open-roadstead anchorage of Madras on the Bay of Bengal. All cargo and passengers had to be transferred in these locally built and crewed lighters called masula. Watercolour attributed to J B East, c 1834. Reproduced courtesy Dixson Collection State Library of New South Wales.

people, a lascar, was lost.’ The number of lascars was sometimes recorded on the ship’s manifest, yet their names were rarely listed. Sydney Cove, shipwrecked in Bass Strait in 1797 carrying much-needed stores from Bengal to the colony of New South Wales, had a crew of 44 lascars. Its master Captain Hamilton recorded that the lascars were issued with extra blankets and warm clothing to cope with the cool temperatures in the southern oceans.

The Sydney Gazette provides a glimpse of the time that lascars spent in port before their ship left with a cargo of export goods or passengers bound for China, India or the United Kingdom. A religious procession of Bengali seamen celebrating the Islamic procession of ‘Hassan’ was reported in March 1806, in the back streets of the area we now know as The Rocks in Sydney. The Gazette wrote that the participants had demonstrated ingenuity in constructing a temple composed of cane-work and beautifully decorated paper. The article’s focus is on the oddity of the event, the music and the effort involved in holding it. It mentions that spectators had seen similar festivals in Asia. The account is quite positive, with no ridicule or denigration of the seamen’s’ beliefs and practices.

On 17 March 1810 the Gazette reported that several lascars had absented themselves

from Sydney and had been employed by an unknown person. Captain Earl, for whom they were originally engaged, states that if the lascars are not returned to him, he will not be responsible for their maintenance in the colony.

Yet these brief reports lead to further questions. Was this the first non-Christian religious procession seen in the streets of Sydney? Were there other processions that were not reported in the press? Did many lascars try to find alternative employment, and settle in the colony?

A selection of newspaper articles mentioning Indian workers, the trade in horses from New South Wales (known as ‘walers’), shipwrecks and the importation of Indian goods have been highlighted by our exhibition designers in the exhibition. Access to thousands of Australian newspapers dating from 1803 that have been digitised for the National Library of Australia’s website Trove (which you can visit at www.trove.nla.gov.au) has been invaluable during the development of East of India – Forgotten Trade with Australia The articles do not provide answers to all my questions, yet combining these articles with shipping records, government archives and journals of seafarers certainly allows a more complete picture of the forgotten histories of Indian workers in Australia to be gleaned.

A short film titled Indian Aussies: Terms and conditions apply will be a major feature of the East of India exhibition, commissioned by the museum from Anupam Sharma of Sydney-based Film and Casting Temple Pty Ltd. Anupam is creator of the Australian Film Festival in India and was a 2013 Australia Day Ambassador. His experience working on Bollywood productions and knowledge of the Indian Australian community will be reflected in an insightful, colourful film revealing the influences and ties that bind our two nations. His team have been busy capturing cultural events on film and interviewing a diverse range of Indian Australians from Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide. They reflect on and highlight their experiences, both good and bad, in Australia. The stories include those of the first Indian female train driver in NSW, a shipping executive, small business owners, students, artists, business professionals, doctors and children. We look forward to audience feedback on the film via email web@anmm.gov.au, Twitter@ ANMMuseum#eastofindia or our Facebook page www.facebook.com/anmmuseum.

Director Anupam Sharma and Dop Caz Dickson producing the exhibition film, featuring new Indian-Australian radio host and commentator Shailja Chandra (top picture) . Photographer Karan Mandhian Films and Casting Temple

The hidden reefs of the Coral Sea snared many ships plying the vital supply route between the Australian colonies and India. The Australian National Maritime Museum and the Silentworld Foundation’s maritime archaeology team continues its work locating and recording these historic wrecks, writes curator of archaeology Kieran Hosty, in a collaborative project with the University of Sydney and the Australian Research Council.

ON 7 APRIL 1841 THE INDIAN-BUILT, 555-ton, armed three-masted ship Fergusson was wrecked on a reef in the Coral Sea, en route from Port Jackson to the Bay of Bengal. On board were 170 rank and file of the 50th (Queen’s Own) Regiment of Foot, who had sailed for the Australian colonies as convict escorts and now were bound for Madras on India’s Coromandel Coast. There they were expected to fight for king, country and the East India Company in some of the many struggles being waged to secure India as the jewel in Britannia’s imperial crown.

Fortunately they were sailing in convoy with the Orient and Marquis of Hastings and, along with the crew of Fergusson, were rescued by the accompanying vessels and taken on to India, where death and glory awaited. There the 50th would fight with distinction (and considerable losses of officers and men) in the Gwalior campaign of 1843 and the Anglo-Sikh Wars of 1845–46. The remains of the teak-built Fergusson were subsequently auctioned but only limited salvage work was ever carried out. Remnants were visible on the reef top for a number of years, acting as an informal beacon for those navigating this particularly hazardous section of the route to India.

The ship would bequeath its name to the reef – although somewhere along the way the reef came to have one less ‘s’ than the

ship, spelled Fergusson in its Indian Board of Trade registration papers.

Ferguson Reef lies on the outer edge of the Great Barrier Reef, 1,040 nautical miles north of Brisbane and 50 nautical miles south of Raine Island, which marks an entrance to the labyrinth of reefs that are a feature of these tropical seas.

A major debate in Australian colonial history during the first half of the 19th century was about the safest and quickest shipping route between Sydney and India via Torres Strait. Some navigators, such as Phillip Parker King, favoured the inner route following the Australian coast inside the Great Barrier Reef, while other equally respected navigators, such as Matthew Flinders, recommended the outer route through the Coral Sea.

Both routes converged near the Raine Island Entrance, where ship captains had the choice to switch from one route to the other depending upon weather and other circumstances. The isolation of the area, the lack of fixed navigational marks (until construction of a beacon on Raine Island in 1844), and the complex nature of the passages through the Great Barrier Reef resulted in the loss of more than 36 ships on Ferguson, Martha Ridgeway, Cockburn, Great Detached and Yules Detached Reefs between 1800 and 1850.

Although these isolated reefs have been visited by sports divers, archaeologists from the Queensland Museum and some commercial operators, the wrecks on them remain largely unknown to archaeologists and historians alike. The sites are a resource for the study of transport corridors to Asia, in particular India, and their role in the development of colonial Australia; they encompass themes of exploration and survey, colonial industry and enterprise, emigration and settlement.

The work of the Australian National Maritime Museum’s maritime archaeology team locating and recording some of these historic wrecks, in a major collaboration with project sponsor and partner the Silentworld Foundation, has been reported in detail in previous editions of Signals Following the fourth expedition with Silentworld Foundation, locating the Indiatrade ship Royal Charlotte at Frederick Reef in January 2012 (Signals No 98 March–May 2012), the team assessed options to continue its work on early 19th century India–Australia trade and Indian shipbuilding. Based on a number of factors including the availability of safe anchorages, we decided to investigate Ferguson Reef and the Raine Island Entrance, the ocean junction of the Inner and Outer Shipping Routes.

The site had been located by well-known Queensland diving identity Ben Cropp

The sites are a resource for the study of transport corridors to Asia, in particular India, and their role in the development of colonial Australia

Author Kieran Hosty investigates the anchor of Fergusson located in a compact assemblage of artefacts including possible iron field ovens. All photographs by expedition photographer Xanthe Rivett, Silentworld Foundation

Author Kieran Hosty investigates the anchor of Fergusson located in a compact assemblage of artefacts including possible iron field ovens. All photographs by expedition photographer Xanthe Rivett, Silentworld Foundation

in the early 1970s and has been visited on a number of occasions since, but a number of questions remained about its extent and the possible presence of another shipwreck close to Fergusson Our investigations suffered several delays, due to two late-season cyclones pounding the Great Barrier Reef. One of the expedition vessels, Nimrod Explorer, was held up in the Solomon Islands, leaving a much-reduced project team embarking in Cairns on 20 March on Silentworld II and an alternative charter vessel Hellraiser 2 The team arrived at Ferguson Reef on 23 March and quickly settled down to work.

Thanks to information supplied by former State Maritime Archaeologist Ed Slaughter and Ben Cropp, the site of the Fergusson shipwreck was quickly located in between 2.5 and four metres of water approximately 25 metres west of the surf break on the eastern side of Ferguson Reef. Over the next six days the team surveyed the site, recording numerous iron knees, iron boxes (possibly field ovens or stoves for the troops), two large anchors lying flat

on the reef top, four carronades, numerous iron concretions, rudder fittings and a good scattering of artefacts including glass and ceramic fragments, iron fastenings, rigging and copper-alloy gun components. A large pile of concreted stud-link anchor chain marked the original position of the Fergusson chain locker.

Just 30 metres north and slightly inshore of the Ferguson site is another anchor complete with iron stock. Attached to it is a long run of stud-link chain stretching 208 metres across the reef top towards the northwest. Scattered along the run of chain are numerous bits of iron concretion, copper-alloy and iron fastenings and what appears to be several pieces of iron ballast. Although very close to the Fergusson wreck, several clues suggested that the anchor and chain are from another, as yet unidentified, wreck or stranding on this reef.

While at Ferguson Reef the team participated in a series of live webcasts into a number of regional NSW high schools. Hosted by ANMM education officers Jeff Fletcher and Anne Doran, the webcasts connected to

schools through DART (Distance & Rural Technologies – the Connected Classrooms arm of the Department of Education & Communities). Titled Archaeology in Action, the webcasts in the form of a video conference focused on the museum’s maritime archaeology collection, how and why archaeologists investigate wreck sites, what shipwrecks can teach us about the past, and the museum’s role as leaders in archaeological investigation. It connected with schools from Year 4 through to Year 12, from areas such as Armidale, Coffs Harbour, Queanbeyan, Ardlethan and Wee Waa. There were also studio audiences from Gorokan High School and Shoalhaven Anglican High.

Leaving Ferguson Reef the team next attempted to locate the wreck of the Indian-built opium trader Morning Star, lost in 1814 some 10 nautical miles inshore of Ferguson Reef, in the vicinity of Quoin Island, Fison and Eel Reefs.

The circumstances surrounding the wreck of the Morning Star are a real mystery. On 30 September 1814 the crew of the

colonial vessel Eliza, on a voyage from Sydney to Calcutta, observed a flag flying from a makeshift flagpole on Booby Island at the entrance to Torres Strait. There the crew of Eliza found five shipwreck survivors who reported that they were from the two-masted, copper-sheathed, 135-ton brig Morning Star which, after a very successful trading voyage to Sydney with tea, spices, alcohol, cotton and silk, was returning to Calcutta when it was wrecked three months earlier on a coral reef near Raine Island. They had, along with their captain Robert Smart and nine other surviving sailors, made for Booby Island in the ship’s longboat.

However, Captain Smart had departed Booby Island with the other survivors, bound for Timor, only a few days before the five castaways were picked up by Eliza Nothing was heard of Smart or the others for another four years when the three-masted ship Claudine anchored overnight off Murray Island in Torres Strait in September 1818 and picked up Shaik Djamal, a lascar or Indian sailor, from the wreck of the Morning Star. The longboat, Djamal related, had

capsized and he alone had managed to get ashore. No more was ever heard of Captain Smart and the other Morning Star survivors.

From 31 March to 3 April our team carried out extensive magnetometer and swimline surveys in the area around Quoin Island, Fison Reefs and Eel Reefs, and detected significant magnetic anomalies – possible evidence of ferrous masses such as cannons, anchors or chain – on the eastern side of Eel Reef in 10–12 metres of water. Additional metal detector and visual surveys of the area failed to locate the anomaly and no shipwreck material was located on the surface.

Given the soft, sedimentary nature of seafloor in those areas it is possible that the anomaly is heavily buried. An associate, Frits Breuseker of SeeSea Pty Ltd, has agreed to analyse the remote-sensing data and contour the information, which may allow us to more accurately pinpoint the anomaly and, if given the opportunity to re-visit the site at a later date, locate whatever lies beneath.

A major debate in Australian colonial history during the first half of the 19th century was about the safest and quickest shipping route between Sydney and India via Torres Strait

The Ferguson Reef Project 2013 was a collaborative project with the Silentworld Foundation, the University of Sydney and the Australian Research Council and was greatly assisted by Benn Cropp, Warren Delaney, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, Peter Illidge, James Cook University, Maritime Archaeological Association of Queensland, Mundingburra Medical Centre Townsville, Oceania Maritime Pty Ltd, SeaSee Pty Ltd, Ed Slaughter, Queensland Department of Resource Management, Xanthe Rivett Photographic Services.

01 John Mullen, CEO, Silentworld Foundation, goes to work with a metal detector.

02 Anchor chain, possibly from an unknown shipwreck rather than Fergusson itself, laid out in a line across the shallow Ferguson Reef top, on a day of close to ideal conditions.

Tea was the first global commodity for mass consumption, influencing trade and culture around the world. Mariko Smith explores objects she discovered in the museum’s collection while working on a new display about colonial Australian regattas that reflect this favourite brew’s place in Anglo-Australian maritime heritage.

Merchant and fast clipper ships were vessels of change, bringing social, cultural, economic and political transformations to far-flung countries

TEA IS TRULY DIVERSE, BOTH IN flavour and in the many ways that it has shaped our daily lives. From the robust taste of the popular English Breakfast black tea, to the refreshing lightness of green tea varieties and the wine-like muscatel notes of Darjeeling blends, tea has provided a refreshing alternative to coffee for getting us through the day – but it has also played a significant role in modern world history, geography and maritime heritage.

Tea can be considered as the first global commodity for mass consumption, and the maritime industry was crucial to this achievement by transporting chests of tea between ports around the world. Key players in the supply and demand for tea included large multinational merchant companies in Europe, most notably the United Dutch East India Company (VOC) and Britain’s own East India Company, which dealt in important trade goods such as tea between the Far East and Europe from the 17th to 19th centuries. Readers can find out more about the activities of the East India Company in the museum’s new exhibition East of India – Forgotten trade with Australia (1 June–18 August 2013). These companies played important roles in exploration and discovery as well as commercial trade. Ships of exploration and commerce, the East Indiamen and the

later fast clipper ships that raced each other to bring home a season’s first cargo of tea, can be all considered as vessels of change: they brought significant social, cultural, economic and political transformations to nations such as Britain and Australia, simply through importing this fragrant cargo.

The beverage we know and love today as tea is said to have originated around the Yunnan province in China and to have been consumed in Asia since ancient times. There is no conclusive story of origin, but one popular Chinese legend has it that in 2737 BC some aromatic leaves from the tea plant Camellia sinensis fell into Chinese emperor Shen Nung’s bowl of freshly boiled water, producing a pleasant-tasting and restorative drink. A later tale from the 6th century AD runs along more mythical – and macabre – lines, detailing how tea bushes came into being when the founder of Chan Buddhism, a forerunner of Zen, accidentally fell asleep after a long period of meditation and was so disgusted by this momentary weakness that he cut off his own eyelids to ensure that it wouldn’t happen again. They fell to the ground and took root as tea plants, and tea was consequently promoted as a stimulant for students of Chan Buddhism to drink during meditation!

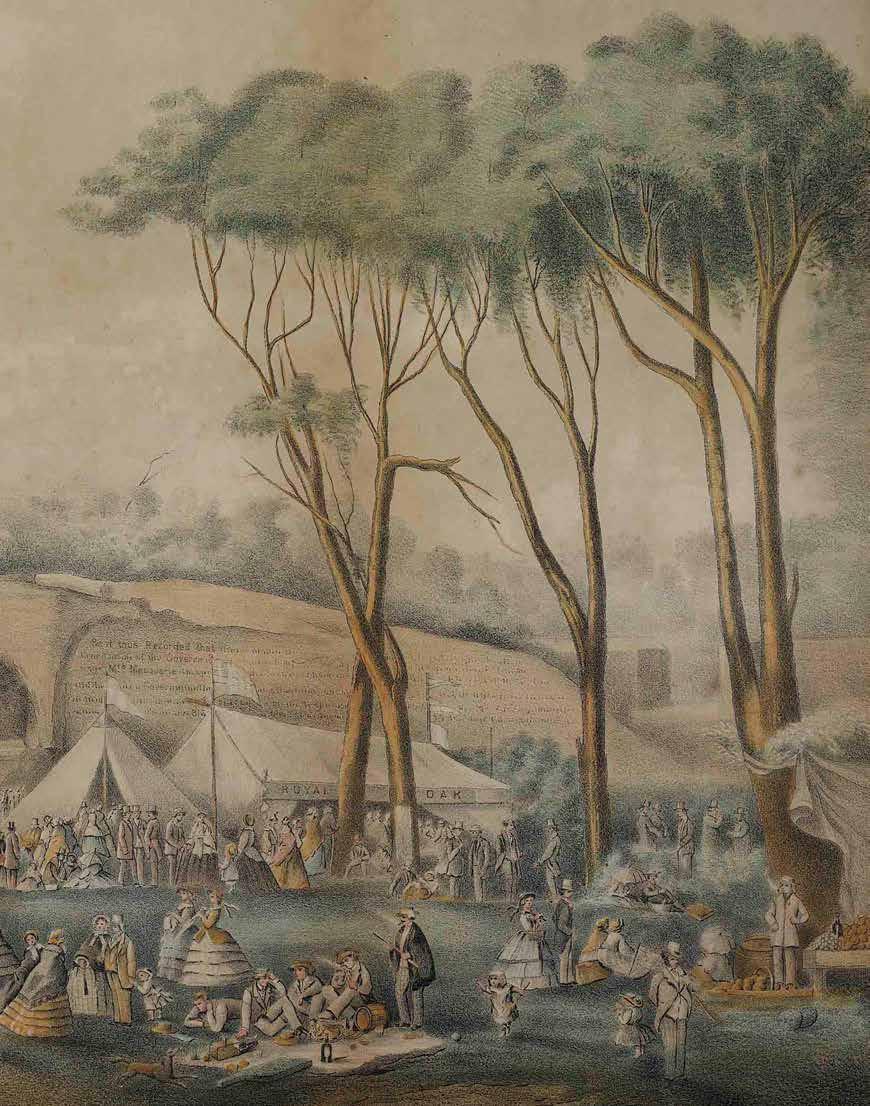

01 Previous pages: detail of a hand-coloured lithograph of a public picnic held at Mrs Macquarie’s Chair on Sydney Harbour in 1852. ANMM Collection. All photographs A Frolows/ANMM

02 Flying Cloud, by Frederick Schiller Cozzens 1909, watercolour ship portrait of the famous clipper ship built by Donald McKay in 1851, East Boston. In its later years the vessel transported tea from China to London, on one occasion making the journey in 123 days. ANMM Collection. Purchased with USA Bicentennial Gift funds

Infusing tea leaves in water developed into a time-honoured tradition in the East, and drinking tea eventually became a hit in Europe too, through Portuguese and Dutch trade connections with China. There it was initially enjoyed by the continental European aristocracy for its prestige and supposed medicinal properties; it was considered so valuable that it was kept under lock and key. By the mid-17th century, tea was widely consumed across Europe and had travelled to England through royal circles. The nature of the dried product made it suitable for longdistance, bulk transport and so both its popularity and affordability could increase together, creating profitable opportunities for international maritime trade.

According to BBC Radio 4’s In our time profile on tea in 2004, Britain’s trade in tea began with a modest official import of just two ounces (60 g) during the 1660s, and grew to an annual supply of some 24 million pounds (11 million kg) by 1801. By the turn of the 20th century it was one of the most widely consumed substances on Earth; rich and poor alike were sipping an average of two cups a day and every Briton was using on average six pounds (3 kg) of tea leaves per year. Tea’s ability to transcend class was not lost on commentators such as English merchant philanthropist Jonas

Hanway, who warned European society in an essay written in 1757 that ‘your servants’ servants, down to the very beggars, will not be satisfied unless they consume the produce of the remote country of China’.

It is fascinating that what was originally an exotic foreign luxury item would become Britain’s national drink, and in doing so help to define the essence of ‘Britishness’ and even symbolise the might of the British Empire. Imperialism ensured that the habit of tea-drinking was transferred from mother Britain to her colonies in America and Australia. The colonial context transformed tea into a political symbol and a tool of power, influence and control. The adoption of tea as the beverage of choice in the colonies was seen as a standard-marker of civilised conduct – despite the facts that it was often drunk sweetened with sugar from Caribbean slave plantations, and that Britain exported huge shipments of Indian opium to China during the 18th and 19th centuries to pay for all that tea.

Britain moved to produce its own tea in commercial plantations established in its imperial domains India and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) during the early to mid1800s. This challenged the long-standing Chinese monopoly on tea production, and also confirmed Britain’s dominance as an influential economic and military

superpower. The importation of tea was also a very important source of tax revenue for Britain, and political decisions regarding this issue created waves for both the economy and society as a whole.

In 1773, the British Parliament passed the Tea Act, which gave the East India Company a monopoly on the tea trade between the British colonies, with the government retaining a three-pence-perpound duty on tea for the privilege. It was a move to bail out the financially struggling company, whose profits suffered in part from widespread illegal smuggling and adulteration of tea cargo, although American colonists were quick to suspect it was yet another way for Britain to keep them on a short leash. In The Glorious Cause –The American Revolution, 1763–1789, Robert Middlekauff mentions a letter written by Abigail Adams – eventually the wife of the second American president and the mother of the sixth – to Mercy Warren on 5 December 1773 referring to tea as the ‘weed of [British] slavery’. Anyone who allowed tea to be brought into American ports by company ships risked landing themselves in hot water (so to speak) with the locals, being deemed an enemy of America. On 16 December 1773 the protest culminated in some 90,000 pounds (41,000 kg) of British East India Company tea,

valued at £10,000, being tossed by American patriots into Boston Harbor – a pivotal event in the American independence movement now known as the ‘Boston Tea Party’.

Tea seems to have had a more peaceful reception in the Antipodes. Beginning with its journey on the First Fleet in 1788, Australians developed a much-loved tradition of making a billy or a ‘cuppa’ in any season and for all sorts of occasions, very much in the attitude later embodied in the British wartime motto of ‘keep calm and carry on’. Australia’s love of tea – whether served hot with dainty scones baked by the Country Women’s Association, or refreshingly cold with ice and citrus slices at the beach, or inspiring many a nannaknitted tea-cosy – continues to demonstrate strong cultural connections with Britain. This is a theme I was keen to tease out and develop while planning an update for the museum’s Watermarks exhibition, in the context of colonial celebrations such as the Australian regatta scene.

Regattas presented ideal occasions for people to gather and socialise, often over refreshments brought from home. Enjoying a cup of tea with some homemade sweet and savoury delicacies during these events wasn’t just a matter of satisfying one’s appetite – it was also a chance to reflect on and reinforce Anglo-Australian identities.

01 Silver-plated trophy consisting of a tea kettle on a silver stand, awarded to the yacht Pleiades in January 1883. Made in Sheffield, England, by Martin Hall & Co, it may originally have had a burner placed underneath the stand to heat the kettle. ANMM Collection.

Gift from Dr David Lark 02 English-made Royal Doulton china teacup decorated with an oval-shaped brown, blue and cream transfer scene of the Hobart Regatta, and with a gilt rim and handle. ANMM Collection

With this in mind, I searched through the museum’s extensive database of objects that relate to travel, tourism, sport and leisure, and came across several interesting objects that provide a range of visual and contextual representations of tea in Anglo-Australian maritime heritage.

Most striking is a late-19th-century trophy in the form of an intricately detailed silverplated tea kettle with wicker-wrapped handle on a silver stand. It was awarded to the nine-ton cutter yacht Pleiades for second place in the Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron’s Commodore’s Handicap race on 20 January 1883. The engraving on the front of the trophy also gives details about the other placegetters, Mabel, Ione and Doris Pleiades was designed and built by W Langford at Berry’s Bay in Sydney in 1874. Connections to trade and commerce are evident through its first owner E W Knox, son of the manager of Colonial Sugar Refining Co Ltd (CSR). In 1883 it was owned by Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron member F B Lark.

Another object visually connected to the theme of tea by the sea is a lovely Englishmade Royal Doulton china teacup. It features a coloured transfer depicting a scene from the 1909 Royal Hobart Regatta, including HMS Powerful, flagship of the Royal Navy’s Australia Station and also of that year’s regatta. Souvenirs such as this were produced in their thousands for spectators wishing to take home and enjoy a little slice of Australian maritime history. A major sporting and social event in Tasmania’s calendar year, the Royal Hobart Regatta began in 1838 and continues today as a series of aquatic competitions and social activities held on the Derwent River in Hobart.

A major motivation for proposing a display on tea by the sea was to incorporate more feminine and family-focused perspectives

and narratives in an area often dominated by male experiences. Tea’s associations with domesticity and respectability often led to brands being targeted specifically at women and families, and indeed the product was firmly entrenched in typically feminine rituals involving getting together and sharing news.

By the turn of the 20th century, tea was one of the most widely consumed substances on Earth; rich and poor alike were sipping an average of two cups a day and every Briton was using on average six pounds (3 kg) of tea leaves every year

Picnic held at Lady Macquarie’s Chair Sydney N S Wales in 1852 is a detailed hand-coloured lithograph print from the 1870s, attributed to artist J Henderson, depicting spectators at a public picnic held during a sailing regatta on Sydney Harbour in 1852. It is said to be based on a large oil painting by an unknown artist from about 1855 or 1856. The scene may be of an Anniversary Day Regatta, an annual holiday festivity held every year from 1836 to commemorate the establishment of the colony of New South Wales. Now known as the Australia Day Regatta, it is considered the oldest continuous sailing regatta in the world. The picturesque rocky headland

known as Mrs Macquarie’s Chair, located in today’s Domain, was a popular vantage point for crowds of all classes to enjoy picnics and watch regattas. This scene shows groups of men, women, children and even their pets enjoying a day by the sea, picnicking and cavorting in groups on the foreshore and clustering around tents set up for entertainment and refreshments that most certainly included tea.

An example of the feminine connections to tea in regatta celebrations is a notice regarding a planned afternoon tea at the Frankston Yacht Club Open Day in October 1966, which details the sorts of culinary delights enjoyed by attendees at sailing-related events. It also illustrates the traditional roles played by women on the social side of the Australian sailing scene leading up to the 21st century. For instance, the language used in the notice indicates the ancillary, behind-the-scenes role they played in sailing clubs and associations in making sure the official guests and members were provided with refreshments during the event.

These fascinating stories are ones that the Australian National Maritime Museum is dedicated to sharing with visitors, connecting them with not only the museum’s vast object collections but also the formation of our Anglo-Australian heritage.

Author Mariko Smith was an assistant curator in the museum’s Travel, Tourism, Sport and Leisure collecting area during 2012. Her research into an exhibition update – and her love of chai lattes and Lady Grey tea served black with no sugar – inspired her to write this article.

The great American photographer Ansel Adams (1902–1984) is best known for his detailed black-and-white landscapes that capture the epic spaces of the US continent. The museum brings his spectacular work to Australian audiences, combining famous images with extraordinary lesser-known works that focus on the artist’s exploration of water in all its forms. The Americans curators of the Peabody Essex Museum explore the techniques of this brilliant pioneering modernist.

WATER WAS ONE OF ANSEL ADAMS’ favourite subjects. He photographed it consistently and repeatedly, from his first pictures in 1915 until his death in 1984. He found it in his beloved Yosemite Valley, in waterfalls, rivers and rapids, and in clouds, ice and snow. It was present on the coast, on the shores of his childhood home at Bakers Beach, San Francisco, in the shipwrecks he discovered on the Pacific headlands, and in crashing waves and seascapes. And water was evident in quiet places, too – in ponds, basins and spillways, eroded rocks and tidal pools. He carried this interest with him wherever he went, from the islands of Hawaii to the rocky shores of New England.

Adams’ interest in photography developed early. His parents bought him a Kodak Box Brownie camera in 1916, on the second day of a summer vacation trip to Yosemite, and he began making photographs. By his mid-teens, he was already an accomplished photographer, and the love affair with Yosemite that began on this trip would last his entire life.

When Adams began his career in the 1910s, photography was in turmoil. An old guard still clung to the idea, dating from the late 1800s, that only photographers who made pictures that looked like paintings or drawings could be considered true artists. These photographers, loosely called pictorialists, used soft focus, textured papers and coloured emulsions to give their pictures a handmade, personal look, often evoking stories from mythology or literature.

After the brutality of World War 1, many viewers came to see pictorialist photographs

as hopelessly sentimental and nostalgic. Gradually, harder-edged forms took hold. At first in Europe and New York, and later in California, artists sought to ‘let the camera speak’. They believed that photographers should embrace the mechanical qualities of camera and lens, making pictures that looked like no other art form. This new attitude, which paralleled developments in painting and literature, came to be known as photographic modernism.

Adams was one of the leading figures in this new movement. Using rapid exposure to freeze motion in time, photographing in sharp focus and presenting his pictures in sequence, Adams demonstrated how the camera could capture something as complex as a shifting tide, and as subtle as the bend in a river. Fluid and irregular, even the most tranquil body of water is in a constant state of flux. This makes it an attractive subject to photograph, because the camera can stop action that is happening faster than the human eye can see.

Photographing waterfalls, rapids and crashing waves, Adams froze motion in time, making pictures of things moving so quickly that not even he could predict exactly how they would look when the film was developed. Adams was also one of the first photographers to work in the large-scale mural format that has now become standard among contemporary artists.

In 1932, Adams and a small group of like-minded photographers, including his friends Edward Weston and Imogen Cunningham, founded the group ƒ/64. Although it did not last long, effectively disbanding three years later, its influence

was far reaching. The group took its name from ‘ƒ-stop’ 64, the smallest aperture, or lens opening, commonly found on lenses of the time. Photographs made at this setting are exceedingly sharp and have maximal range of focus from foreground to background, a quality that photographers call depth of field. Many of the photographs Adams made after 1932 maintain sharp focus across the entire picture. This unnatural effect was considered radical at the time. However, ƒ/64 artists did not want to represent the world the way the eye sees it; instead, they wanted to make pictures according to the unique capabilities of camera and lens.

In this exhibition, drawn from the Ansel Adams Archive at the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona, viewers have the opportunity to view a wide range of Adams’s work. Both grand and intimate at turns, these personal and sometimes experimental photos express his thoughts about the natural world, and often push the boundaries between realism and abstraction. From the tiny to the monumental, from the subtle to the dramatic, these images explore Adams’ enduring fascination with the mysterious, ephemeral and transitory nature of water as a photographic subject.

At the museum 4 July–8 December 2013. Organised by the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts. Support for the exhibition was provided by David H Arrington, and the Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona. Funded at ANMM by the USA Bicentennial Gift.

This article was edited by Janine Flew from material provided by the curators of the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts.

Adams demonstrated how the camera could capture something as complex as a shifting tide, and as subtle as the bend in a river

01 Ansel Adams and the American Clipper, Ross Landing California. Photograph by Alan Ross

02 The Tetons and the Snake River, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming, 1942. Photograph by Ansel Adams, Collection Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona.

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

01 Shipwreck Series, Lands End, San Francisco, c 1934. Photograph by Ansel Adams, Collection Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona.

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

02 Waves, Dillon Beach, 1964. Photograph by Ansel Adams, Collection Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona.

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

03 Waterfall, Northern Cascades, Washington, c 1960. Photograph by Ansel Adams, Collection Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona. © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

One of the museum’s conservation team, Julie O’Connor, takes us kayaking to historic Me-Mel, or Goat Island, in Sydney Harbour, and describes how the roles of conservator and conservationist sometimes meet. If you’d like to explore the island for yourself, we’re offering a Members’ tour as part of our winter program this August; details page 46.

AS A CONSERVATOR AND MUSEUM professional, I am often asked to explain the difference between a conservator and a conservationist. From my perspective, conservators usually take care of material culture, and conservationists work to conserve living culture and the environment – but both value historic sites, their interpretation and how the environment contributes to our understanding of their cultural significance.

Centrally located in Sydney Harbour, Goat Island is managed by NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS).

As part of the recent Sydney Harbour National Parks Management Plan, NPWS plans to encourage greater use of the island.

NPWS officers are working with volunteer organisations such as the Willow Warriors and the Mud-crabs to preserve the botanical and biological environment surrounding the island’s buildings. The Willow Warriors are a group of conservation kayakers who navigate waterways to clear rivers of invasive willow trees. The Mud-crabs are mostly involved with clearing pollution, monitoring water quality and developing wetlands along the banks of the Cooks River.

During August, September and October 2012, I made three visits to historic Goat Island with a group of conservation kayakers from these organisations, which offered an insight into the island’s maritime history.

On each visit to the island, we launched our kayaks from Birchgrove Park, and then circumnavigated the island from east to west. Approaching from the south-east, we passed an Aboriginal shell midden, a pile of discarded shells on the shore.

This is the last dietary remnant of the Sydney Aboriginal people who used Goat Island before its colonial occupation from the 1820s. It later became a source of lime for mortar during the construction of buildings on the island.

The waters surrounding the island were a rich seasonal source of fish, including salmon, tailor and kingfish varieties, for Indigenous people. The rocky sandstone shorelines supported shoals of east-coast species of bream, mullet, whiting, luderick, flathead, groper, cod and leatherjacket, as well as other marine fauna and flora, including brown kelp, prawns and shellfish.

The partially submerged pylons of a disused finger wharf came into view as we paddled along the eastern shoreline. Further along the shore, more recent concrete slabs have been positioned among a tangle of disused communication cabling on the north-eastern shore to help slow erosion caused by weathering and the wash of passing vessels.

Rounding the northern tip of the island we paddled past the water police station, built in 1938 of grey sandstone quarried on the island, to a design prepared by renowned colonial architect Mortimer Lewis. From this vantage point, with its commanding view of the harbour, it is obvious why the water police were based here, and why Sydney Aboriginal people called the island ‘Me-Mel’, or ‘a place from which you can see far’.

On the western side of the island, we paddled around wharves constructed by the Sydney Harbour Trust in the 1940s and extended by its successor the Maritime

With its commanding view of the harbour, it is obvious why Sydney Aboriginal people called it a ‘place from which you can see far’

Services Board. We landed our canoes at Barney’s Cut, a quarried geological feature named after Captain George Barney of the Royal Engineers, which divided the water police station on the northern tip of the island from the potential danger of the gunpowder magazine and surrounding buildings on the southern tip of the island. Sandstone quarried from this area in the early 1830s was also used in some buildings in nearby Sydney Cove.

The main garden path from Barney’s Cut slopes gently up toward the harbourmaster’s residence, built around 1903. Situated in the centre of the island, it commands a 180-degree view of the harbour from the balcony and the ‘widow’s watch’ at the top of a replica cedar staircase that replaces the original, which was burnt during a period of disuse.

01 Previous pages: Goat Island, looking southwards to Simmons Point, Balmain. Mark Merton Photography

02 Cooperage (left) and gunpowder magazine buttress (rear). Photographer Robert Newton, Office of Environment and Heritage

03 Foreman’s quarters or barracks constructed c 1838

04 Conservation kayakers paddle from Birchgrove Park to Goat Island in Sydney Harbour. Photograph Jeff Cottrell, co-ordinator of Willow Warriors

The gardens surrounding the harbourmaster’s residence feature significant botanical species that are indigenous to Goat Island, including smooth-barked apple (Angophora costata), coastal banksias (Banksia integrifolia), wattle (Acacia longifolia, A. suaveolens, A. terminalis, A. binervia, A. ulicifolia), Port Jackson fig (Ficus rubiginosa), bangalay (Eucalyptus botryoides) and lomandra (Lomandra longifolia).