SIGNALS quarterly

COMING FROM SWEDEN Vikings, more than just superb seafarers

AMERICA’S CUP LEGEND

That epic victory 30 years later

RAN FLEET CENTENARY

100 years of pride in our fighting ships

COMING FROM SWEDEN Vikings, more than just superb seafarers

That epic victory 30 years later

100 years of pride in our fighting ships

RELOCATING TO AUSTRALIA AFTER several years working at the National Maritime Museum in the UK brings with it an exciting sense that we are a part of the world’s most dynamic emerging region, the Asia-Pacific. Most of you will have heard of the Australian Government’s white paper Australia in the Asian Century, which canvasses the strategic possibilities that brings. This museum has always had strong interests in the region through Australia’s many historic links with it. Our recent exhibition East of India – Forgotten trade with Australia, several years in the making, is just one of many examples of that.

We look forward to contributing to more Asian cultural projects while knowing there’s much to be learned in return

That engagement and commitment are going to be even more important under the new historical master-narratives that I have commissioned from our staff, to shape the way our collection and galleries develop in the coming years. Some of that focus will, naturally, be on the region’s emerging giant, China, with whom the museum’s links are already strengthening.

The internationally renowned architectural firm responsible for our own superb museum building, Cox Richardson, has recently won a global contest to create the massive new National Maritime Museum of China, to be located in the metropolitan port of Tianjin. This is China’s largest coastal city, gateway to the national capital Beijing. It’s part of a wave of ultra-modern museums emerging in China to showcase the depth of their culture and history, which in the case of maritime and navigational achievements is profound indeed.

I’m delighted that the Australian National Maritime Museum will be involved in the project in Tianjin, since Cox Richardson have asked me to review and guide the new

museum’s approach to interpretation and exhibition structures. For that I’ll draw, in part, on experience developing the modern new Sammy Ofer wing at NMM Greenwich.

The approaches and challenges of working in China, and understanding its unique cultural environment, were very much on the agenda during the time I spent in the middle of this year at Cambridge University, undertaking the residential component of an advanced leadership program I had begun during my recent years in the UK. In fact one of the world authorities on China whom I met there in June this year, Professor Peter Williamson, will be visiting us soon for further discussions.

Some readers may remember an article in Signals on the opening of the China Maritime Museum in Shanghai in 2010, another major project to which our museum had also contributed its expertise. In January this year I was invited to the opening of another impressive new Chinese cultural facility, the Hong Kong Maritime Museum located at the site of the Star Ferries terminal, a gateway to mainland China. Like our own museum and the one in Tianjin, this is another example of a major redevelopment of old waterfront infrastructure featuring a maritime museum.

The Hong Kong Maritime Museum brings together a number of private and public collections, with new digital technology used cleverly to interpret fragile old documents – such as an extraordinary Qing Dynasty scroll recording the way that Chinese authorities dealt with the region’s notorious plague of pirates that we mostly hear about through the filter of colonial histories. Interestingly, that new museum’s director is the expatriate Australian heritage expert Richard Wesley.

We look forward to contributing to more cultural developments in Asia – while knowing there’s much for us to learn from their innovations.

Kevin Sumption

Not the first but the most famous – and most often misunderstood – of Europe’s seafarers

International Fleet Review celebrates a naval centenary on Sydney Harbour

What winning the America’s Cup 30 years ago meant to Australia’s national identity

From the museum’s collection and library come excerpts of voyagers’ recollections

A strange tale from the 1930s emerges from the museum’s Samuel J Hood Studio Collection

Your calendar of activities, tours, lectures and excursions afloat

The

in our galleries this

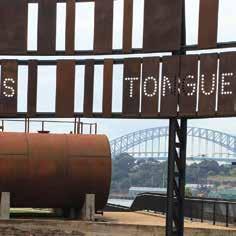

First contact memorial; tall ship

cover: Appearing in our exhibition

The only example of a complete Viking helmet in existence, this is a replica of the so-called Gjermundbu helmet, named after the farm from which it was excavated in Ringerike in central Norway. All photographs reproduced courtesy of the Swedish History Museum, unless otherwise specified.

This exhibition prompts us to look beyond the stereotypical image of Vikings as marauding plunderers, to the domestic, cultural, artistic and mercantile side of Viking-age cultures

From 19 September 2013, we host Vikings – Beyond the legend, a superb international exhibition from the Swedish History Museum, Stockholm, that explores the fascinating cultures of the Viking age. This glimpse of the exhibition’s attractions comes from ANMM curator Dr Stephen Gapps, who’s been investigating diverse aspects of Viking life.

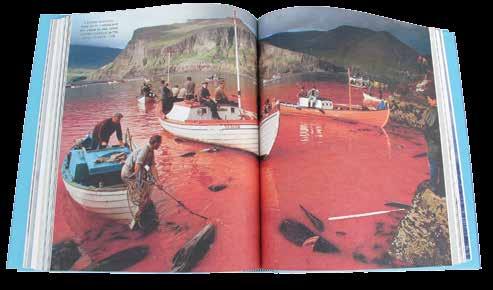

FROM SEPTEMBER, DARLING HARBOUR will be home to three Viking vessels when the exhibition Vikings – Beyond the legend arrives at this museum. One is the reconstruction of a small, two-oared craft, the Årby boat. The second is a reconstruction of a larger vessel that went under sails as well as oars. Both are part of an exhibition developed by the Swedish History Museum, Stockholm, with the support of MuseumsPartner, Austria.

The third vessel to be displayed at the museum will be an Australian interpretation of the famous Gokstad ship, the longship that was recovered from a Viking-age burial mound in the late 19th century and is now on display at the Viking Ship Museum in Oslo, Norway. The operational reconstruction built in Western Australia will be in the water and available for inspection at the museum wharves.

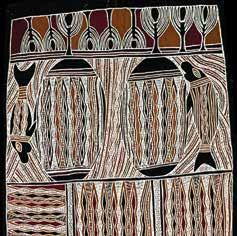

As its title suggests, this exhibition prompts us to look beyond the stereotypical image of Vikings as marauding plunderers, to the domestic, cultural, artistic and mercantile side of Viking-age cultures. Recent archaeological finds (many of which will be seen in the exhibition) show that these cultures were not homogenous; there were distinct variations in regions now known as Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Russia and Eastern Europe, Iceland and Greenland as well as other places.

In fact, we should not really be calling them Vikings at all! The real meaning of the Norse word ‘viking’ referred to those ‘going a-viking’, perhaps best translated as ‘adventuring’. In fact the vast majority of Scandinavians during the Viking age stayed at home working on farms, or lived and worked in towns and villages. It was only later that all Scandinavian peoples

from that period between the 8th and 11th centuries were labelled ‘Vikings’. At the time they were most often referred to as ‘the people from the north’, or Norsemen.

The exhibition explores the lives both of the people who ‘went a-viking’ and those who stayed at home. It has more than 500 archaeological artefacts from the Swedish History Museum collection, many of which have never been seen in Australia before. They include finely crafted silver and bronze jewellery, and simple domestic items made from animal bone such as combs, flutes and even a pair of bone ice skates.

One of the highlights for me is the oldest-known Scandinavian crucifix. While there’s a strong association of Vikings with paganism, in fact for much of the Viking age many were converts in an increasingly Christianised Europe. At the beginning of the Viking age, around 750 to 800 CE (Common Era, the equivalent of ‘AD’), Scandinavian cultures practised an indigenous religion known as the Aesir Faith. By around 1100, this had been replaced by Christianity, although some older pagan practices survived, merged with the new beliefs. Archaeologists have found increasing evidence of the fusion of the two religions during this period, such as the silver pendant shown opposite in the form of a crucifix.

The Old Norse religion was characterised by cult worship and ritual involving a pantheon of gods and goddesses that reflected a cultural focus on family and lineage. When the first Norse rulers took up Christianity, with its focus on a single

god and universal system of salvation, it provided a model for a supreme king that strengthened local rulers’ positions of power. Religious change was accompanied by social change, towards a more patriarchal and hierarchical, feudal structure.

The set of 35 gilded pendants and abox-shaped brooch on display in the exhibition show this fusion of religious iconography. The fish-head shaped pendants are all adorned with crosses, while the matching brooch displays the gripping-beast style of imagery common to the Old Norse traditions.

While the exhibition emphasises the often-neglected aspects of Scandinavian Viking-age stories, this was a period of massive expansion in Norse trading and settlement that often included the violent seaborne raids for which the Norsemen became so well known. Included in the exhibition are typical arms of the Viking-age warriors. While a common image has Viking warriors wielding swords and long-handled ‘Dane axes’, in fact the warrior’s primary weapon was more likely to be a spear. The tactics of shield-wall fighting are most effective with spears protruding from interlocking shields. They have a greater reach than swords and can be thrown as well. Odin, the Norse god of war, is portrayed in sagas and images with his spear named Gugnir, suggesting the importance of spears at the time. Swords were less common as they were costly to make. They were pattern-welded, a technique in which strips of iron and steel

The Old Norse religion was characterised by cult worship and ritual involving a pantheon of many gods and goddesses that reflected a cultural focus on family and lineage

are twisted and forged together, giving the blade a band of patterning. Swords were a sign of social status and could also be elaborately decorated.

When it comes to Viking ships, the longship full of armed warriors springs first to mind. However, in the spirit of the exhibition – to go beyond the legend – the museum will have three different styles of Viking-age vessels on display. Watercraft in the Viking age comprised a diverse array of types suited for different purposes such as fishing, transport and trade. The longship was but one example.

As noted by Gunnar Andersson, the Swedish History Museum’s curator of this exhibition, boats and ships were important to Vikingage cultures ‘as a form of transportation in real life as well as a symbolic and psychological gesture’. Boat funerals – both buried beneath mounds and the remnants of funerary pyres – have been found by archaeologists throughout Scandinavia. Many Viking-age burial finds include masses of iron nails that were used to fasten wooden planks, suggesting the boat had been burnt during a cremation and all that was left for archaeologists were the iron nails.

Importantly, boat burials were not just for warriors and kings, but for men and women, young and old, and from all levels of society. The widespread ritual practice of boat burials seems to be part of a belief in the ship as a form of transport ‘to the other side.’ It may also promise a return from the world of the dead, as described in the Scandinavian Prose Edda story where

01 Set of women’s jewellery made from bronze, gold and silver: 35 pendants shaped as fish heads and a brooch. It was found in a hoard from Krasse, in Gotland, Sweden.

02 Silver figure of a Valkyrie with a drinking horn. Valkyries were the mythological female creatures who decide which warriors die in battle and which live, and then choose which of the slain to convey to Valhalla where the war god Odin rules the afterlife. Found at Klinta, Köping, Öland, Sweden.

03 Viking picture stones were found exclusively on Gotland, Sweden’s largest island, in the Baltic Sea. The stones show mythological scenes – here, a warrior’s journey to Valhalla. The vessel depicts a fascinating sail structure with complex control lines. 8th–9th century CE, Tängelgårda, Lärbro, Gotland.

04 This silver pendant is the oldest known representation of a crucifix found in Sweden, from the rich Birka site in Adelso, Uppland. It has never before been seen in Australia.

The picture of watercraft in the Viking age is one of a diverse array of types suited for different purposes such as fishing, transport and trade; the longship was but one example

01 The Oseberg ship, built c 800 CE, displayed in the Viking Ship Museum, in Bygdoy, Norway. Photographer David Payne/ANMM

02 Jorgen Jorgenson, the Western Australian reconstruction of the Gokstad ship, goes on display at the museum during Vikings – Beyond the legend Enthusiastic historic re-enactors are the author (left) and marketing manager Jackson Pellow. Photographer A Frolows/ANMM

the much-loved god Baldr – deceitfully slain by the jealous Loki – was cremated in his ship. Baldr was mourned by all the gods in their home Asgard, and Odin’s son Hermod was sent to retrieve him from Hel, mistress of the realm of the dead. Hel promised that if the whole world wept for Baldr, she would release him. All the world did weep, except the sinister Loki – and so Baldr could not return.

The exhibition includes two replica vessels from Sweden. A reconstruction of the small, two-oared fishing or transport craft known as the Årby boat reminds us that both small and large boats were important in Viking-age maritime contexts, as well as in burials. The original was found in 1933 in a grave dating from 850 to 950 CE, while the reconstruction was made by the eminent maritime historian and ethnologist Dr Basil Greenhill of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

The other vessel is larger – eight metres in length – and was designed for both the Baltic Sea and the riverways of Eastern Europe. It has a large, braided square sail, three rowing stations and can take a crew of 10 or 11. Named Krampmacken, it’s a reconstruction of a vessel found at Bulverket on the Swedish island of Gotland. In 1983 the reconstruction was sailed, rowed and portaged from Gotland to Istanbul (or Miklagard, as the Norse called this great city) in Turkey. This re-enacted the Vikings’ great eastward migrations through the rivers of Europe as far as the Middle East – less well known to many of us than the westward voyages that led to settlements in the Faroe Islands, Iceland, Greenland and North America.

The third vessel representing the Viking age at the museum was actually made in Perth, Western Australia, in 1987. It is a reconstruction inspired by the famous

Gokstad ship, which was unearthed from a burial mound in Sandefjord, Norway, in 1880. The Gokstad ship was a Viking type called a karvi, a coastal ship that was smaller than the longship used for raiding overseas. This was an immensely important find that stimulated some of the earliest experimental archaeology projects to reconstruct and learn about the forms and performance of Viking vessels. The karvi from Perth, named Jorgen Jorgenson, demonstrates how far the fascination with Viking seamanship has spread. While it is not a faithful replica, and is built with locally available timbers and modern fastenings, it is an evocative reconstruction that gives us a good understanding of the workings and capabilities of a Viking vessel.

It was named after the Danish adventurer Jorgen Jorgenson (1780–1841) who led a fascinating life with notable connections to Australian history. Some can be gleaned from the title of his autobiography: The Convict King: Being the Life and Adventures of Jorgen Jorgenson, Monarch of Iceland, Naval Captain, Revolutionist, British Diplomatic Agent, Author, Dramatist, Preacher, Political Prisoner, Gambler, Hospital Dispenser, Continental Traveller, Explorer, Editor, Expatriated Exile, and Colonial Constable

The vessel Jorgen Jorgenson had a mixed life too, operated for a period as a charter vessel licensed to carry 76 passengers and crew. It was the rather down-at-heel green Viking ship that readers may have seen moored under Sydney’s Anzac Bridge in recent years. Its refurbishment has been a community outreach plan driven by the Pyrmont Heritage Boating Club, which operates just along the harbour from the museum. The club was established in 2005 to ‘revive inner city boating,

engage youth in heritage, community and maritime industry and to provide community access to harbour culture’. Their Longship Project engages long-term unemployed, disabled and disadvantaged people in restoring the vessel to sailing condition. It aims to operate the vessel as a mentoring, sail-cadetship and leadership training enterprise for the local community.

The Australian National Maritime Museum has established a collaboration with the Pyrmont Heritage Boating Club to assist in completing much-needed restoration and major work on the vessel above and below the waterline. A mast is being stepped so that it can be easily raised and lowered, a feature of Viking-age vessels. A sail, rigging, oars and shields lining the gunwales will complete the picture and Jorgen Jorgenson will become an attraction at the museum wharves for the duration of the exhibition Vikings – Beyond the legend. It will introduce visitors to aspects of Viking ships and to the legacy of the Gokstad vessel and the reconstructions that it inspired.

The Gokstad find was a remarkable early archaeological discovery that, along with other ship finds at Oseberg and Tune, has added immensely to our picture of Viking-age ships. It was discovered in 1880 when the sons of the owner of the Gokstad farm in Sandefjord, Norway, were inspired by other late-19th-century discoveries in their region to dig into the knoll that had long been locally known as the Kongshaugen or king’s mound. They uncovered the bow of a boat, and shortly after the antiquarian Nicolay Nicolaysen took over and began a controlled archaeological investigation.

Although the barrow had been looted in the past – no weapons and few objects remained in the burial chamber – the grave

The exhibition includes more than 500 archaeological artefacts from the Swedish History Museum collection, many of which have never been seen in Australia before

robbers had not destroyed the burial ship, which was extremely well preserved in the blue clay used to build the mound. The Gokstad vessel was painstakingly recovered and moved to the University of Oslo. By the early 1900s three large Viking-age vessels had been recovered remarkably intact and a dedicated Viking ship museum was constructed.

The Gokstad vessel was built around the late ninth century at the height of Norse expansion in Dublin, Ireland and Jorvik (York), England. It is clinker built, and made almost entirely of oak. It has 16 pairs of oars requiring 32 oarsmen for a complete complement, but could have carried around 70 people if required. It is 23.24 metres between the extreme points, the maximum beam is 5.2 metres, the height from the bottom of the keel to the gunwale amidships is 2.02 metres and the estimated weight is 20.02 tonnes.

Viking-age vessels were famed for their versatility, speed and ability to sail across seas or travel along rivers. The wide beam and relatively flat bottom meant such ships could easily be beached – perfect for a lightning raid.

The Gokstad ship is stunningly beautiful with its elegant lines and sculptural form. It has been described as ‘severe simplicity combined with well-nigh functional perfection’. Unlike the earlier (circa 800) Oseberg ship find, which was highly decorated and has wonderful carved, scrolled finial ornaments scarfed onto the stem and stern, the Gokstad has no figurehead – and certainly no dragon’s head, so familiar to us all from popular culture.

Three ship finds – Gokstad, Oseberg and Tune – are all relatively similar in size and shape and belong to a class of ship described in the sagas as karvi – small vessels for the use of chieftains and their warriors and retinues for cruising along the coast. The Gokstad is more sturdily constructed and less ostentatious than the Oseberg ship; it was probably more functional, with a greater seagoing ability. A reconstruction of the Gokstad ship built in 1893 was sailed across the Atlantic from Europe to North America for the

Iron sword found in a grave from Bengtsarvet and Härvadsarvet, Sollerön, Dalarna, Sweden. Swords were a sign of social status and could also be elaborately decorated.

World Exhibition at Chicago. It became a great hit, despite taking the gloss off the quadricentennial celebrations of Christopher Columbus’s ‘discovery’ of the New World by adding weight to the growing evidence that Vikings had crossed to North America well before him.

The 1893 reconstruction proved most seaworthy and its captain, Magnus Andersen, paid high tribute to it. Part of the reason for this is the strength of the keel, cut from one massive oak tree, and its higher sides – with 16 strakes compared to 12 on the Oseberg ship. The two upper strakes are above the oar holes, which could be closed with shutters when sailing. The top strakes are relatively thin and were supported by dedicated top ribs. Here, a shield rack was fixed inside the ship and two shields per oar could be hung, overlapping, outboard along the gunwale and fastened by straps. Remnants of all 64 shields were recovered from the Gokstad find, each about one metre in diameter, built of thin, planked wood and painted black and yellow.

Intriguingly, we know more about Vikingage vessels than some important, later types of European ship … more, for example, than we know about the caravels of the Portuguese explorers who began the global expansion of the West from the 15th century. As well as the preservation of ships in Viking burials, a notable find of five ships that were scuttled and preserved in silt at the bottom of Roskilde Fjord in Denmark has added immensely to our knowledge of Viking ship design. They included two longships, a ferry, a coastal trader and a deep-sea trader, or knarr

The knarr was the robust, seaworthy trader that enabled the Vikings’ North Atlantic colonies to be settled. Knarrs had long been known from Norse sagas, but no-one knew what they looked like … until the Roskilde finds gave a template for their exact form and proportions. Another of the Roskilde vessels, built around 1025, was the longest Viking-age ship yet discovered. It would have measured 36 metres and had about 40 pairs of oars, with 80 oarsmen to serve them.

There are many very good reasons why Viking ships and cultures capture our imaginations, as an early but now wellunderstood episode of northern European seafaring. Their legacy is rich, but I’ll end with one small but profound example. Our terms port and starboard derive directly from Norse ship design. Viking ships were steered by an offset rudder that was always mounted on the right-hand side of the hull, attached and pivoting on a rawhide thong that passed through the shaft of the rudder and the hull. The name of that side of a vessel, ‘starboard’, comes from the Norse term for steering board. In port a ship always tied up with its left-hand side to the dock, to avoid damaging the rudder and its mounting. That side was thus known as ‘port’.

The name Viking has always been synonymous with exploration, leading the way where others follow. Sail with the world’s leading river cruise line to experience inspiring destinations, beautifully crafted itineraries, expert tour guides, revolutionary ships, fine cuisine, excellent service and remarkable value.

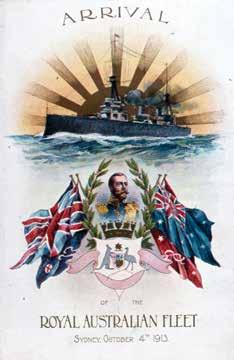

Australian symbols, including sprigs of the national flower wattle, abound on this souvenir program recording the celebratory events when the nation’s new fleet of warships made its first entry into Sydney Harbour. It features the female personification of Australia draped in the national flag. ANMM Collection

This October marks 100 years since the Royal Australian Navy’s first fleet of warships was welcomed into Sydney Harbour with pomp and fanfare. This centenary will be commemorated in similar fashion with the International Fleet Review, a spectacular week-long program of events from 3–11 October. Senior curator Lindsey Shaw – who, after 27 years of service to the museum, retired in July this year – examines the origins of our navy.

R EACHING 100 YEARS IS A MILESTONE in anyone’s life, and our own Royal Australian Navy is no exception. A century ago this October, the Australian Fleet Unit – the nucleus of the Australian Navy – was loudly and emphatically welcomed into Sydney as a sign of both our nationhood and a strong future as an independent member of the Dominion.

To remind Australians and an international public of the significance of this occasion, the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) will hold a series of commemorative events and activities over a nine-day period on the harbour and around Sydney, under the banner of the International Fleet Review. From 3 to 11 October, Sydney will be hosting navies from around the world. Alongside our 20 RAN ships there will be at least 23 international warships, 17 tall ships and an aviation program featuring more than a dozen types of helicopters and other aircraft. Sydney

will be abuzz with sailors and ships, bands and parades, flypasts and fireworks. It’s going to be bigger than the 1988 Bicentennial celebrations, so don’t miss it!

Sydney will be abuzz with sailors and ships, bands and parades, flypasts and fireworks

The formation of the Australian navy didn’t happen overnight. The idea of an Australian fleet of warships had been much discussed in naval and political circles since the Federation, in 1901, of the Australian colonies into a single nation. At the Imperial Defence Conference of 1909 in London, it was decided that one battle cruiser, three second-class cruisers, six destroyers and three submarines would be constructed to form an Australian Fleet Unit.

The purpose of this unit was to defend Australia and to support the rest of the British Empire as and when required.

At Federation the various, ageing naval ships from the colonial state governments were known collectively as the Commonwealth Naval Forces; however, while adequate for coastal defence, they fell short of being a naval force with which to be reckoned. A squadron of Britain’s Royal Navy was stationed in Sydney for the protection of both Australia and New Zealand, with £200,000 being contributed annually –and somewhat grudgingly – towards the maintenance of this fleet. But at any time this British squadron could be removed, leaving Australia without naval protection. It was time to have our own modern navy.

‘First-born of the Commonwealth navy, I name you the Parramatta. God bless you, and those who sail in you. May you uphold the glorious traditions of the British navy in the dominions overseas.’ With these

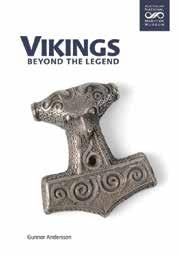

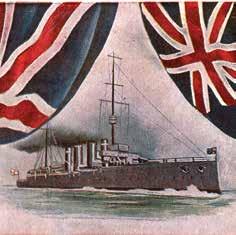

01 The formation of the Royal Australian Navy was a significant step forward in Australia’s nationhood, and the battle cruiser HMAS Australia was the navy’s first flagship. The Sydney Morning Herald reported Australia as being ‘a living, sentient thing, whose mission is to guard our shores and protect our commerce and our trade routes’. HMAS Australia was the biggest warship of that period to enter Sydney Harbour. ANMM Collection

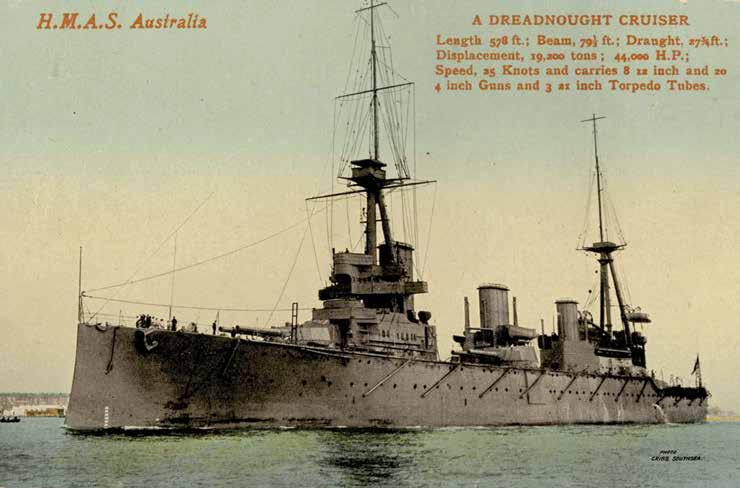

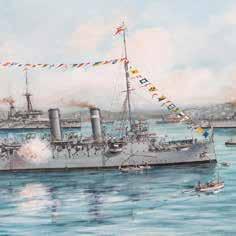

02 The light cruiser HMAS Melbourne was built by the famous shipbuilders Cammell Laird & Co Ltd of Birkenhead, England, in 1913. On 4 October of that year, Melbourne led the light cruisers – ‘Australia’s greyhounds’ – through Sydney Heads. This postcard emphasises Imperial unity through the slogan ‘One King, One Fleet, One Nation’. ANMM Collection

03 As well as the public program produced for the day, a program was also published for invited guests. It lists the VIPs associated with the great day, the names from the Citizen’s Committee who put together many of the social events, and a list of the festivities for the period 4–11 October 1913.

ANMM Collection

christening words the destroyer HMAS Parramatta was launched by Mrs Asquith, wife of the Prime Minister of England, at Govan on the River Clyde in Scotland on 10 February 1910.

The idea of an Australian fleet of warships had been the subject of much discussion throughout naval and political circles since Federation in 1901

The next six years saw the construction of the destroyers Yarra, Warrego, Huon, Torrens and Swan; the battleship Australia; the light cruisers Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane ; and two submarines with the latest technology, AE1 and AE2

But ships need maintenance, provisions and personnel, so the government established bases, repair and victualling yards and barracks around Australia to support the fleet. A strong desire was to have as many Australians as possible on these Australian warships. However, it was realised that men of the British navy would be needed in training and operating roles in the Fleet Unit’s formative years. Training schools and colleges were also established to turn men and boys into officers and sailors. This new navy replicated the Royal Navy in hierarchy, organisation and structure, but went on to create its own style. Exciting opportunities awaited those who signed for the Australian Fleet Unit, and it was ‘so popular that there was a superabundance of candidates for the privilege of entering it’ (Admiral Sir George King-Hall, 1912). Many of the Royal Navy sailors transferred to the Royal Australian Navy and settled in Australia, bringing their families with them or starting life with Australian girls.

The official arrival of the Australian Fleet Unit into Sydney on 4 October 1913 was received enthusiastically by Sydneysiders and visitors alike. Thousands lined every vantage point along the harbour shores and boats of all kinds were on hand to watch as the fleet entered in formation, with the battlecruiser HMAS Australia leading. It was followed by the light cruisers Melbourne, Sydney and Encounter (which had been transferred on loan to the Australian navy from the Royal Navy), then the destroyers Warrego, Parramatta and Yarra. They were greeted by the governor and premier of New South Wales and a roaring crowd of citizens, and these warships entering through the early morning mist must have been a profound sight. A deafening salute from the 12-inch guns of the flagship HMAS Australia reverberated up and down Port Jackson, and the stately procession was loudly and proudly cheered on as it made its way to Garden Island naval dockyard and Farm Cove.

The entry of the ships marked the start of week-long celebrations. Schoolchildren played their part in the great event with a massed schools’ display at the Sydney Cricket Ground, the highlight of which was a formation of 8,000 boys and girls into a living shield within a map of Australia. Special tours of the flagship HMAS Australia were a highlight for some 3,000 children.

A formal banquet was held to welcome the new fleet and its officers, and the Prime Minister, Andrew Fisher, and Leader of the Opposition, Joseph Cook, both delivered speeches punctuated by cheers from the audience. The Sydney Morning Herald reported: ‘they were at one in their assertion that in the hour of danger the Australian unit will be found where it can do the greatest service’. And indeed that is what happened a mere 10 months later, when Australia declared its support of Great Britain and the country went to war against Germany. The Royal Australian Navy was quick off the mark, taking German New

While the public tends to view World War 1 more as a soldiers’ war, Australia’s navy served across the globe in this ‘war to end all wars’

Guinea in a matter of weeks. The first Australian casualty of the war was a sailor

– Able Seaman William Williams, fatally wounded on 11 September 1914.

While the public tends to think of World War 1 more as a soldiers’ war, Australia’s navy served across the globe in this ‘war to end all wars’:

• The Australian Naval & Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF) launched Australia’s first land engagement of the war, seizing stations and winning control of the seas of our north and routing Admiral Graf Spee’s fleet

• HMAS Australia sank the German auxiliary Eleanore Woermann in the North Pacific

• Warships successfully escorted troopships to the Middle East and beyond

• HMAS Sydney soundly defeated the German raider SMS Emden in battle off the Cocos Islands in November 1914

– Australia’s first naval fight

• At Gallipoli the navy was the ‘first in, last out’, with the RAN Bridging Train building bridges, jetties and pontoons for the landing and evacuation of the troops

• Our ‘Navy Blue ANZACS’ were at the forefront of naval attack, with the submarine AE2 being the first allied vessel to successfully navigate through the dangerous Dardanelles Straits and disrupt Turkish and German shipping

• In the North Sea and the Mediterranean, our ships joined the British Fleet in countless months of patrolling and sweeping the seas in search of German submarines and mines

• In the Atlantic our ships monitored neutral ports for signs of enemy activity and patrolled the waters leading to the Panama Canal, safeguarding it from any German interference or use

• In Africa HMAS Pioneer (transferred to the Australian navy in 1913 from the Royal Navy) took part in the bombardment and disarmament of the German colony of Zanzibar (Tanzania)

• When the German High Seas Fleet capitulated, HMAS Australia was given the privilege of leading the port column of the allied Grand Fleet as the two divisions steamed out to meet the Germans at Scapa Flow in Orkney, off northern Scotland.

01 This bronze medalet was issued to all New South Wales children. As a bonus they were granted the day off school to take part in this important historic event. Thousands of young spectators dressed in red, white and blue to welcome the national fleet. ANMM Collection, gift from D Coffey

02 The last flagship of the Australia Station HMS Cambrian, by John Bastock. This second-class protected cruiser is dressed overall saluting the arrival of the Australian Fleet Unit. Cambrian fired a 13-gun salute to Rear-Admiral Sir George Patey on board HMAS Australia ANMM Collection, gift from John Bastock.

03 Australian and British sailors and officers of the flagship HMAS Australia, commissioned in Portsmouth in June 1913. King George V had just inspected it before the ship’s departure for Australia. ANMM Collection, gift from Olive Wilks

By war’s end the Royal Australian Navy counted its losses – 15 officers and 156 sailors had died for their country, including the entire complement of the submarine AE1

This year, 2013, marks the centenary of the Australian Fleet Unit’s arrival as a cohesive naval force, and as we approach the centenary of World War 1 it is an opportune moment to reflect on 100 years of cooperation between Australia and other world navies, especially the interoperability of the Commonwealth navies in the 20th century.

The formation of Australia’s own formidable naval force at the beginning of the 20th century is celebrated here at the museum with our own ‘fleet unit’ – the Daring class destroyer HMAS Vampire, the Oberon class submarine HMAS Onslow, the Attack class patrol boat HMAS Advance, and the officers’ motor launch MB172

Make a special visit to the museum during the International Fleet Review and help us celebrate the RAN’s contribution to the nation in the past, the present and far into the future.

See the Members events pages (page 40ff) for details of International Fleet Review events.

Australia II was purchased for the nation by Prime Minister Bob Hawke’s government, after the yacht’s return from winning the America’s Cup in 1983. It was displayed at the Australian National Maritime Museum (left) from its opening in 1991 until 2000. The famous 12-Metre yacht then returned to its hometown Fremantle as the centrepiece of a redeveloped Western Australian Maritime Museum. Photograph A Frolows/ANMM

Thirty years ago, Australia’s victory in the 1983 America’s Cup caused an outpouring of nationalist sentiment. Sailor and historian Carlin de Montfort looks at the place of sailing and yachting in the Australian identity.

I REMEMBER SEEING THE YACHT

Australia II towering in the gallery of the Australian National Maritime Museum when I was a young sailor. I would run up and down the stairs to see the winged keel, the sails and the pale-green deck from different angles. A poster of Australia II took pride of place on my bedroom wall. It was a close-up of the cockpit with the crew ready for action in their green-and-gold jerseys as the yacht surged through the water. The image was always close and familiar to me.

The posters were presented to the junior sailors at the Middle Harbour Yacht Club in Sydney at the end of my first sailing season, but I was too young to remember the event that they depicted. A decade had passed since Australia II defeated the American yacht Liberty to win the America’s Cup in September 1983. The campaign was funded by Western Australian businessman Alan Bond and culminated in spontaneous displays of national celebration as the New York Yacht Club’s monopoly of this event was brought to an end. Many Australians had sat up until 2 am watching or listening to the live broadcast from Newport,

Rhode Island. Celebrating the victory, the then Prime Minister Bob Hawke famously stated: ‘Any boss who sacks a worker for not turning up today is a bum’. The context of 1980s nationalism, and later the failed defence of the trophy in 1987 and the eventual bankruptcy of Alan Bond, meant little to me. Instead, the America’s Cup victory simply meant that Australians were the best sailors in the world.

My experiences growing up engrossed in sailing culture informed my PhD thesis on the cultural history of sailing and yachting in Australian waters. I studied the rise of recreational sailing that included the navigation and handling of small boats, and yachting, which was more often associated with wealth and status. Events such as the 1983 America’s Cup convinced me that sailing and yachting were significant components of Australian culture. Researching and writing my thesis, which included using the resources of the Australian National Maritime Museum and its Vaughan Evans Library, I reconsidered the myths and legends of the sport that had been so important to my identity.

The poster of Australia II stayed on my wall for the best part of a decade. For me it came to signify how pervasive the legend of the America’s Cup is, how quickly the complexities and context of the campaign were forgotten, and how easily the simple stories of the race can be communicated across generations.

The wealth associated with yachting, particularly highprofile competitions such as the America’s Cup, sat uneasily next to the popular images of Australian identity

The 1983 America’s Cup remains a landmark in Australian sporting successes. When Cadel Evans won the 2011 Tour de France cycling race, Peter FitzSimons compared it to a number of Australian

victories in a Sydney Morning Herald opinion piece. Speaking of the America’s Cup, he said that ‘back then we knew little and cared less about sailing per se – a fairly dreary sport for the spectator, after all – but we knew that the Americans cared deeply about it, had held it for no fewer than 132 years, and were convinced that no one would ever take it from them. And that was good enough for us.’

In comparing the Tour de France to the America’s Cup, FitzSimons also revealed the underlying ambivalence regarding the yacht race in Australian culture. The wealth associated with yachting, particularly highprofile competitions such as the America’s Cup, sat uneasily next to the popular images of Australian identity. FitzSimons argued that the Tour de France has a greater sense of history and is more widely coveted than the America’s Cup, but: ‘More importantly, while the America’s Cup was pursued by millionaires and billionaires, Cadel Evans is the “little Aussie battler,” writ large’. The idea that yacht racing is an elitist sport and therefore ‘un-Australian’ was reinforced by some of the online comments. ‘Drew’ wrote: ‘The America’s Cup … is for “fat rich” and is way off the radar of your average Aussie’s interests’. ‘Biggles’ from Brisbane said: ‘Yacht racing – well it is a comedy piece isn’t it’. Other commentators defended the victory from criticism. ‘Jaffa’ claimed that the America’s Cup was still Australia’s ‘greatest sporting conquest’ and that it ‘brought together people from many walks of life’. And ‘Will B’ argued that the sailors who claimed victory were not millionaires: ‘They [the crew] earned $10 a day in expenses and dedicated years

of hard work and pain to achieve their goal. Let us not diminish that achievement in the short sweep of an ill informed sentence.’

The same divisions were evident in 1983 when the Australian journalist Bruce Stannard claimed the ‘battler’ status for the America’s Cup crew. He explained in the Sun-Herald why Australia II ranked alongside Donald Bradman and Phar Lap in uniting the nation. Defending the America’s Cup from the criticism that it was ‘a rich man’s toy, a plaything for the idle, decadent upper crust’, Stannard claimed that ‘the men who crew Australia II are about as representative a mob of Australians as you might find on the 7.30 express from Hornsby to the City any weekday’. The editorial neatly articulated the mythology of the America’s Cup victory. It was the ‘men’ crewing Australia II, not Alan Bond, who ‘galvanised their fellow countrymen’. And the contest gave the ‘entire nation a sense of unity that had implications far beyond a boat race’; it showed that Australians were still capable of working as a ‘world class’ team despite differences within the nation.

Academic accounts of the 1983 America’s Cup revealed the way that politicians, the mass media and entrepreneurs appropriated the outpouring of nationalist sentiment. University of Queensland academic Jim McKay critiqued Australian sport in the 1991 book No pain no gain: sport and Australian culture. He used a case study of the America’s Cup victory to demonstrate how dominant groups such as government and the media can ‘frame’ sport to legitimise their values. This argument was repeated in a number

01 Australia II ’s skipper John Bertrand holding the 100-Guinea Cup, aka the America’s Cup.

Courtesy Fairfax Photos

02 Then Prime Minister Bob Hawke and Alan Bond, the wealthy entrepreneur and yachtsman who financed the 1983 America’s Cup campaign. Courtesy Fairfax Photos

03 Australia II tacking ahead of the American yacht Liberty during Australia’s successful 1983 America’s Cup campaign.

Photographer Sally Samins, ANMM Collection

of sport histories where the temporary nature of the celebrations in 1983 are pointed out. In One-eyed: a view of Australian sport, published in 2000, historians Douglas Booth and Colin Tatz noted that: ‘Like all sporting moments, the yacht euphoria faded, quickly: it couldn’t, for example, sustain the nearly four million struggling on benefits’.

One outcome of McKay’s thesis is that sailing and yachting have been dismissed as Australian sports. McKay claimed that: ‘Sailing is one of the most unpopular sports in Australia’. He cited a recreational participation survey conducted by the Department of Sport, Tourism & Recreation in Canberra to demonstrate that less than one per cent of the population participates in sailing, and stated that America’s Cup sailing is one of the most exclusive and expensive sports in the world. McKay wrote: ‘So, in a nation where tall poppies are cut down, it seems odd that such an esoteric and costly activity generated such attention’.

Critics should not have been surprised by the patriotic sentiment that victory in the America’s Cup generated.

Australian challenges for the trophy were associated with ideas of progress and achievement from the first campaign, sponsored by Sir Frank Packer through the Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron in 1962. This campaign dominated the yacht club’s centenary year and P R Stephensen wrote about it in the club history. He argued that ‘this was an event which would add to Australia’s renown, and proclaim to the world, as the holding of the Olympic Games had done in Australia six years previously, and as many other achievements in sport,

Australian challenges for the trophy were associated with ideas of progress and achievement from the first campaign in 1962

The

people of the ‘Great South Land’, in their island continent – ‘the last sea-thing dredged by Sailor Time from space’ – had developed to maturity among the nations of the world

in the arts, in commerce, and in the grim tasks of war had proclaimed, that the people of the “Great South Land”, in their island continent – “the last sea-thing dredged by Sailor Time from space” – had developed to maturity among the nations of the world.’

In Stephensen’s words, the campaign was in the spirit of ‘giving it a go’, ‘characteristic of Australian temperament, win or lose’ and the donations of materials and cash from Australian business were justified as ‘representative of Australian achievement’. Looking back in 1980, yachting journalist Lou d’Alpuget recalled a moment of success in that 1962 challenge where Australians captured the attention of the world. The challenger Gretel surfed on a wave downwind in a gusty 28-knot wind, ‘a feat never before achieved by a heavy deep-keeled vessel of her 12-Metre class’. Gretel passed the American rival to win the race. D’Alpuget wrote: ‘It was a spectacle that astonished and delighted thousands of people on the wind-driven stretch of the Atlantic Ocean off Newport, Rhode Island, USA. Millions more saw it on television. It was to inspire a cascade of words of praise in a dozen languages for the men who had created and sailed the boat that almost flew downwind. It was also to establish Australia firmly as one of the world’s greatest yachting nations and as the USA’s major rival in a field of sophisticated sailing to which even countries with a dozen times our technical, scientific and industrial resources had never dared to aspire –challenging for the America’s Cup.’

Exploring the geopolitical dimensions of Packer’s 1962 challenge, media historian Bridget Griffen-Foley revealed similar connections between the America’s Cup and Australian status. She explained that after Gretel ’s ‘surge to the finish’ the Australian contingent sang ‘Waltzing Matilda’ and their unofficial theme song ‘Beer is Best’. Reports of the win made front-page news throughout the world, and the publicity convinced the Australian government that ‘the challenge could boost both Australia’s profile abroad, and the Australian people’s confidence to strut on the world stage’. After more unsuccessful challenges for the cup, Packer eventually sold his 12-Metre yachts to the English migrant Alan Bond, ‘who was, ironically, reinventing himself as a media tycoon’.

The attention awarded to the Australian challenges for the America’s Cup since the 1960s suggested two things to me: that the national sentiment identified in accounts of the 1983 victory was part of a longer process and more deeply ingrained in the culture of yachting than first thought, and that sailing and yachting were not such anomalies in Australian culture.

Links between sailing and yachting, progress, and aspects of Australian identity developed in the mid-19th century at the same time as the America’s Cup was established. The competition began as an adjunct to the Great International Exhibition of 1851, held in London. A fast American yacht named America, built along shallow, sleek lines, defeated the yachts of the Royal Yacht Squadron, based in Cowes on the Isle of Wight, and claimed the trophy – the ornate silver ‘100-Guinea Cup’. Paul James argued that the America’s Cup became a symbol of the vigour of competitive capitalism and the surpassing of the old by a ‘new nation’. It became a competition between nations that drew upon the aristocratic tradition of yachting while reformulating it in a modern context.

Sailing and yachting were already popular public sports in the Australian colonies. They commanded great status as respectable activities distinguished from the rowdy and sometimes violent pastimes of the colonial society, and from 1837 they were conspicuous features of the Anniversary Day holidays that celebrated British colonisation. Sailing and yachting were described in accounts of the ‘progress and history’ of the Australian colonies during the 1888 centenary. Sometimes they were the only sports mentioned and in other cases they were given their own sections over and above other sports, including cricket, football and horse racing. Regattas also took place in Sydney, Melbourne, Hobart and Fremantle during the year.

The Victorian International Regatta, held in conjunction with the Centennial International Exhibition in 1888, had some of the hallmarks of the initial America’s Cup. Both events were associated with exhibitions and international contests. Competitors from the ‘great yachting centres of the world’ were invited to Port Phillip to take part the Victorian regatta. The Australian National Maritime Museum’s

oldest vessel, the cutter Akarana, built that year by Robert Logan to represent the Auckland Yacht Club, joined competitors from Sydney and Hobart to make up the ‘international’ contingent and race for the ‘honour of New Zealand’.

At the same time in 1888, Walter Reeks, a naval architect from Sydney, travelled to America and England on behalf of a syndicate of Sydney yachtsmen to study the feasibility of a challenge for the America’s Cup. He studied the Volunteer, Mayflower, Puritan and other fast American yachts and planned to build a 90-foot (27.4-metre) yacht for the challenge.

A sense of colonial pride motivated Reeks. In an article on sailing and yachting published in the Illustrated Sydney News, he described an innovative yacht designed and built in Sydney during the 1850s by Richard Harnett. With the patriotic name Australian, the yacht influenced local design for some time. Reeks claimed that with ‘Australia’s honour as our reward’, we shall ‘cease to speak of the American type and the English type, and have a type of our own, which other countries will look at with envious eyes, and call Australian’.

Another local yacht, Xarifa, was an example of this ‘Australian type’ that defeated the imported English yacht Chance in a race from Sydney to Newcastle and back. The match was described by Stephensen in the history of the Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron. In a strong southerly breeze that was developing into a gale, Xarifa carried away its topmast and Chance disappeared ahead into the distance. With no sign of the English yacht, Xarifa continued on as the crew made repairs for the sail back to Sydney, which would be ‘in the teeth of a gale which showed no signs of abating’. At 8 pm the yacht reached Newcastle, made a clean manoeuvre in the dangerous seas and began the return journey: ‘Throughout the night … the gallant little vessel thrashed into the teeth of the gale and against an evil sea’. The crew of Xarifa supposed that Chance was in the lead. But they had passed their competitor in the night as Chance struggled in the seas, and Xarifa soundly won the race.

Stephensen noted that ‘It was memorable too, because it had some of the elements of an “international” contest in which Australian yacht building and yachting

skill won the acknowledgement of well-earned cheers’. Lou d’Alpuget also described the race as a contest between types. ‘It was a two-boat challenge match arranged to test the qualities of Xarifa, a Sydney-designed-and-built woodenhulled cutter of 30 tons, against Chance, an English-designed-and-built iron-hulled schooner of 71 tons’. Of course, ‘Charles Parbury’s Xarifa thrashed the daylights out of William Walker’s Chance ’. In hindsight, the race had become yet another legend of Australian sporting victory.

A tradition of yachting as an international sport underpinned Australian challenges for the America’s Cup from the 1960s and it was not unusual for the challenge in 1983 to be associated with Australian success. Although the celebrations in 1983 were ‘fleeting’, the symbolic connections between sailing and yachting and Australian identity were well established. The connections are ongoing. For example when Jessica Watson joined Australian sailors Kay Cottee and Jesse Martin as a record-breaking solo circumnavigator in 2010, the then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd stated: ‘Here you have a young Queenslander, young Australian who has shown great courage, great determination … I believe she’s an inspiration to all Australians’.

Carlin de Montfort grew up racing and cruising on the waters of Sydney Harbour, Pittwater and Georges River. He recently completed a PhD in history at the University of New South Wales with a thesis titled ‘Sailing traditions: a cultural history of sailing and yachting in Australian waters, 1888–1945’. He has been published in the International Journal of the History of Sport, Sydney Journal and Dictionary of Sydney

The 1:3 tank test model of Australia II on display at the museum’s Wharf 7 Maritime Heritage Centre. It was one of several scale models built in The Netherlands to undertake rigorous tank testing and computer analysis for the innovative and controversial winged-keel design developed by the Australian yacht designer Ben Lexcen (formerly Bob Miller). Photograph Andrew Frolows/ANMM

Personal diaries written by all manner of travellers to and from Australia can now be accessed via the internet, giving fascinating glimpses into past lives. The museum’s technical services librarian Jan Harbison delves into some of them and finds vivid accounts of adventures, exploration and everyday activities at sea.

A ship draws near. All hands on deck to get a peep … How very pleasing to meet & speak with those exposed to the same dangers as ourselves

tough it must have been for an immigrant in the 1800s relocating to a new country on the other side of the world, and the dangerous journey to be completed to get there. The diaries tell both personal and social histories of immigration, the gold rush, ocean travel, settlement and much more. For historians they are a valuable resource, and for the general public they are incredibly entertaining. When reading them I sometimes feel transported to the time, and can almost feel the roll of the ship and the wind in my hair. Sometimes I even feel that I know these people, and am privy to their thoughts and feelings.

Requests for copies or access (where copyright law allows) have increased enormously in recent years, as a basic Google search for the name of a ship can lead the researcher to our library’s holdings. As technical services librarian, I catalogue all of the diaries onto the Australian National Bibliographic Database, where they appear in the National Library’s Trove database under ‘Diaries, letters, archives’: http://trove.nla.gov.au/collection

Wednesday 9 January 1884. Still in the Cape de Verde latitude … early in the forenoon a steamer was espied on the horizon & coming towards us. As it drew near it became apparent that a chance of getting away letters was at hand, but this was made known too late to enable anyone to prepare a proper & full letter, and although I had commenced one it was but indifferently advanced and so almost useless: however off it went.

Sometimes when another captain came on board, gifts would be exchanged between the ships, as a passenger on the Renown writes in 1876:

… both ships exchanged several little things with each other, for instance potato for some bottles of chutney & curry powder … but the most thankful [sic] was cigars and tobacco.

This narrative is dedicated to my dear wife and children for their amusement and my employment and as it is most agreeable to me to sometimes hold converse with them, it is only intended for their eyes or those akin to them.

So begins the diary of Captain John Buttrey of the brig Dart in 1865. He could not know that nearly 150 years later, his diary might be accessed by a worldwide audience through the Internet, as are the blogs of today.

The museum’s public research facility, the Vaughan Evans Library, has many diaries written by travellers, immigrants, crew members, sea captains, naval men, ships’ surgeons, whaling captains, a captain’s wife, a matron and a convict. Some are very brief and factual, while others are beautifully descriptive and often very personal accounts revealing emotions and humour. Some have been donated by family members who might have found the diary in an attic; others have been purchased by or donated to the museum. All of the library’s manuscript diaries are unpublished copies or transcripts. Many published diaries also exist, some of which the library holds.

Of all primary sources, diaries must be the richest mine of information about life at the time. It is hard to comprehend how

I write a quite detailed summary for each diary. Some requesters are interested because their own relation came to Australia on that particular ship, or even that actual voyage. We have also had requests by diarists’ descendants. Reading such diaries gives them some insight into their ancestors’ experiences.

In this age of email and Twitter, contact and information exchange are instant. We sometimes forget that letter writing was once a necessity, communication was primarily by beautiful copperplate handwriting, and it could be weeks or months before a letter was received.

People often wrote diaries to pass the time, or as a kind of long letter to their loved ones, as did Captain Buttrey. So did a crew member on the Parma in 1936:

Dear Mother, I have decided to write this letter in diary form, that is, I will start it now and add to it from time to time. It will save me writing half a dozen long letters on arrival in England and besides, I can give a better description of the trip as things happen

At other times letters would be hurriedly written when a homeward-bound vessel was seen nearby, as related by a passenger on the Loch Moidart to Sydney:

Even ‘chatting’ to a passing ship using signals was a treat, as a passenger on the Alfred noted on a voyage to Plymouth from Sydney in 1864:’ A ship draws near. All hands on deck to get a peep. Our Capt. asks her name. Betty Jones from Liverpool to Demerasa ... How very pleasing to meet & speak with those exposed to the same dangers as ourselves.’

Signalling was also done to report to the authorities. In Lloyd’s List, the daily newspaper of shipping movements, there is a column of ‘Vessels spoken with’ or ‘Speakings’, with the date, location and names of the ships that spoke, such as ‘Laguna (ship), London to Sydney, 78 days out, 30th Oct., off King’s Island by the Eliza Corry, [Capt.] Slater, at Adelaide’. In the case of the grain clippers, this was vital to their business; their location would indicate their expected arrival date, so they relied on passing steamships to read their signal saying ‘Please report us to Lloyd’s’.

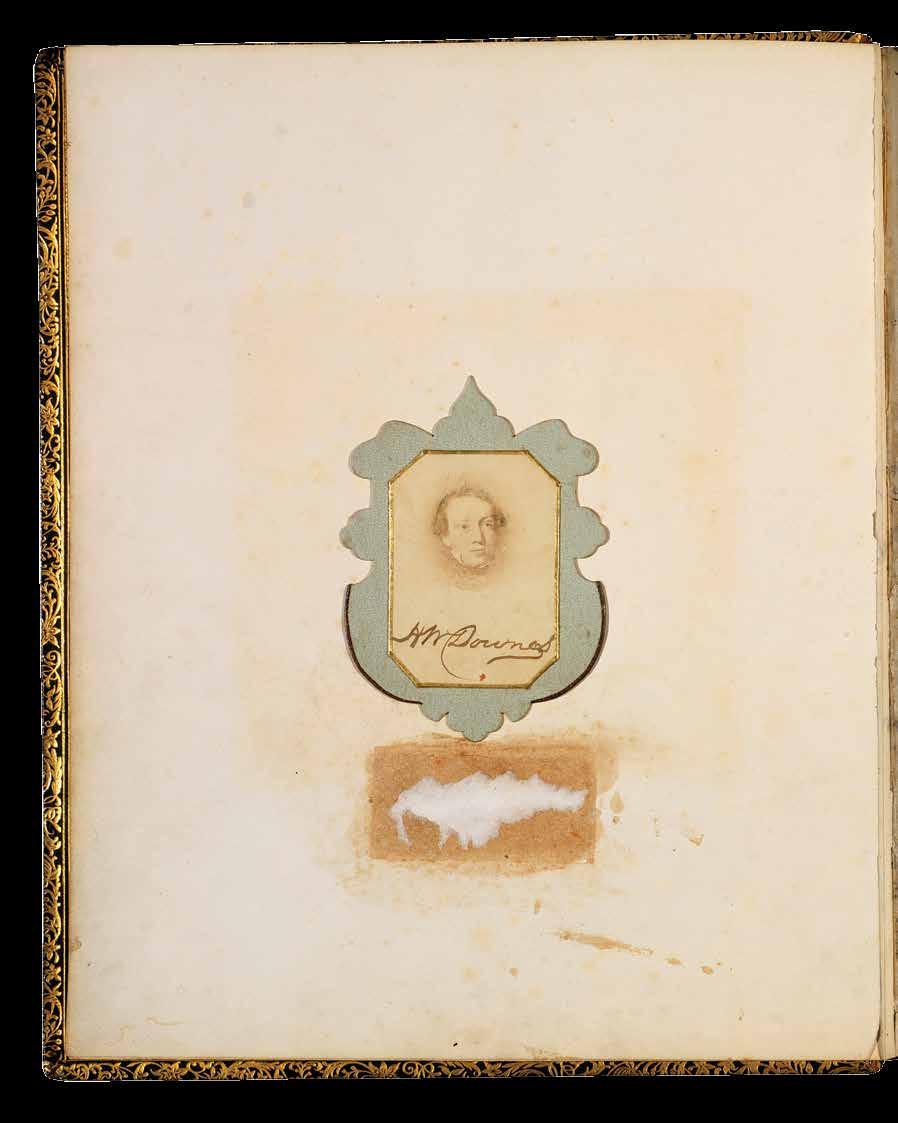

Not everyone wanted to ‘speak’ to other vessels. Henry Downes, captain of the whaler Terror, says: ‘We had a ship in sight this forenoon but I do not propose speaking any vessel until we get [something] to report … No. No. if possible I’ll [not] send word home until I am in a position to advise the capture of a whale.’

The diary quoted at the beginning of this article is a wonderful one. Captain Buttrey commanded a brig that travelled to the South Sea Islands in 1865 to collect bêchede-mer (sea cucumbers) and tortoiseshell. As well as writing letters home to his

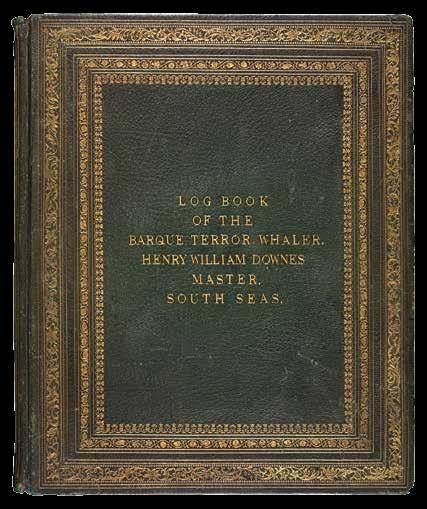

01 Previous pages: A watercolour portrait of the whaling barque Terror and a photo of the artist, Captain Henry Downes, appear at the front of the ship’s log book.

02 The cover of the Terror log book.

03 On a 10-month journey out of Sydney, Captain Henry Downes filled the log book of the whaling barque Terror with lively descriptions and accomplished illustrations. All photographs by A Frolows/ANMM

Captain lowered a boat today for the purpose of a little shooting … shot missing bird, but shot striking a few of the passengers

family, he kept the diary, which gives an insight into life at sea, interactions with the islanders, and his life at home, with frequent references to what his wife and four boys would be doing at that time of day.

It is a diary full of affection for his family. He looks at their ‘likenesses’ every day:

I have [been] looking at your likenesses again today and have been pictureing [sic] you all at home. Our time is about 10 minutes in advance of Sydney so I say now they are at breakfast.

goods and tobacco, their appearance and canoes. The original diary includes some sketches and watercolours of people, canoes and landscapes. He doesn’t appear to have been a very talented artist, especially when depicting people (although his son William Lister became a famous landscape painter, winning the Wynne prize seven times)

01 Some ships issued passengers with customised diaries for their voyage.

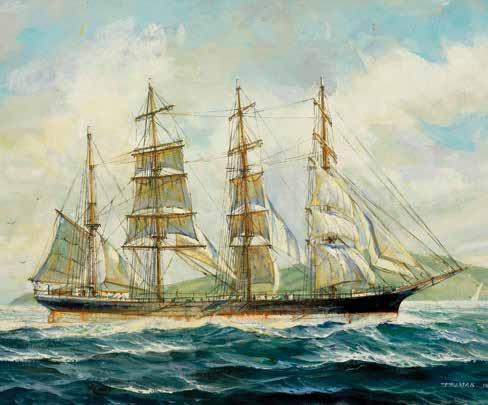

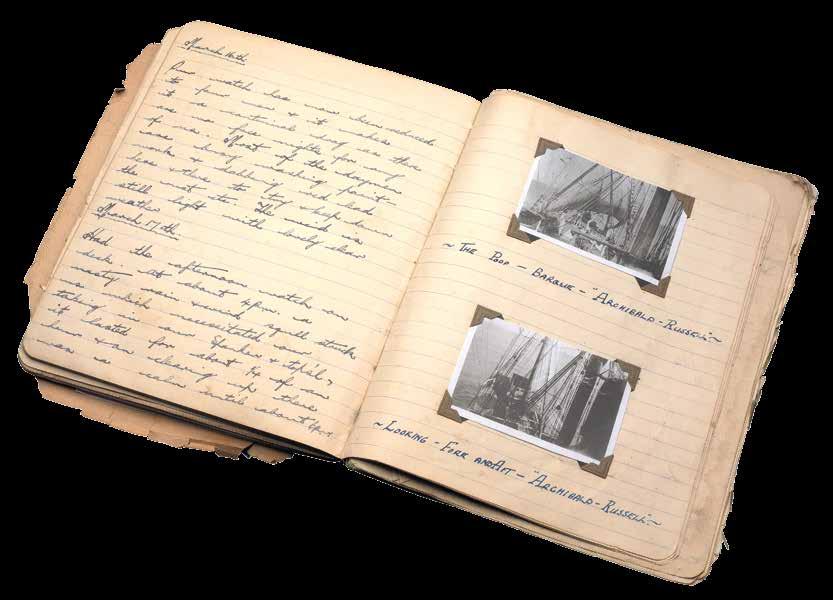

02 Four-mast steel bark Archibald Russell, built in Scotland in 1905, subject of the diary opposite. This oil on canvas is by American merchant mariner and marine artist Thomas W Wells (1916–2004), painted in 1939 when he was serving on the windjammer Passat and was anchored alongside Archibald Russell, Moshulu and Lawhill in Spencer Gulf, South Australia, loading grain for Europe. ANMM Collection, purchased with USA Bicentennial Gift funds.

03 This diary, illustrated with photographs and magazine clippings, traces the experiences of Raymond Oswald Poole, a seaman working on the barque Archibald Russell

Baby looks as if he was trying to imitate Lister with his mouth – Bateson looks as if he were brim full of mischief … Marshall appears as a staid gentleman & one of deep thought. The principal one Mama looks indescribably loveable.

He even plays imaginary games with his sons:

It is Marshall’s turn to guess today –Guess what I saw today Marshall? –A Whale, no, a flying fish, no; a ship, no –Do you give up – Yes Papa I give it up –a Portuguese Man of War.

Apart from these personal observations, he provides the historian with a wealth of information about the South Sea Islands, writing about employing islanders and the difficulties in doing so, paying them in

Captain Buttrey also talks of collecting specimens for his ‘Good friend the curator of the Museum’, and he occasionally makes sketches of his finds. His collecting was not always successful – ‘We brought out of one of the canoes a sand crab, but before I could get it among my collection the Elea boys had cooked & eaten it’ – but later he reports, ‘I am picturing my dear [Bateson] going with me to the Museum to see the Curator when I present my various specimens … many of them are very rare I should imagine’.

The beauty of the internet age is that a simple search on Buttrey’s name in the Trove newspapers website retrieves an article from the Sydney Morning Herald for 11 April 1866, which tells us which museum he was referring to:

List of donations to the Australian Museum during January and February, 1866 … Reptiles, fishes, molluscs and crustacea, from the South Sea Islands, By Mr J A Buttrey.

England in 1868. A search of the English census for 1871 shows the family settled in Bedfordshire, with another child born there. Two servants are also listed, and at the age of 52 Buttrey is listed as ‘retired merchant’, so it seems his endeavours in Australia and the South Seas were reasonably lucrative.

The journey covered by Buttrey’s diary took more than three months. Such a separation from one’s family was nothing to whaling men, however, who might be away from their families for years on end – the author of the Terror diary, Captain Henry Downes, noted in 1846 that one whaling captain had been away for seven years, and another was home only one out of every nine years.

Downes worked for Ben Boyd, a famous and flamboyant Sydney businessman. His diary is another entertaining one, in which he speaks not only of his frustrating search for whales, but also of his bad moods, anxiety, and some reminiscences of his life on land.

Downes is also a talented artist, and many beautiful paintings are interspersed through the diary, yet he says: ‘Such a view as I have sketched … if this log was intended for anything but private use I would be ashamed of such a daub’.

Whales, dogs & madmen are said to feel her influence & should we continue without oil [ie whales] for many months more I fear becoming one of the latter’; then the excitement of spotting one –lowering the boats, the frantic activity of the kill, then cutting up the whale and collecting the oil. He sarcastically compares it with what he calls the ‘more fashionable sport of fox hunting’:

I can only say there may be some slight shadow of a resemblance provided one could hunt a whale in a smooth water bay & when he was killed, row quietly home and sit down to a rump [steak] and Dozen [clarets or oysters], hearing no more of the matter save that after his servants had boiled the flesh and sold the oil his portion of the prize came to a considerable sum … When close to land, islanders would bring alongside ‘elegantly shaped boats… ornamented with shells & feathers …’ and sell the whalers fresh fruit and vegetables: ‘… such a scene in Sydney would attract no few spectators’, Downes comments. Another canoe he deems tasteful enough for his employer, Ben Boyd: ‘One in particular was ornamented with much taste having

pieces of shell and mother of pearl inlaid so as to form birds etc. round the sides … She would have suited our Owners Yacht the “Wanderer” nicely.’

I always imagine sailing ships alone on the ocean, but many of the diaries indicate that a few vessels might travel together for weeks before one would move ahead out of sight. A crew member on the Khimjee Oodowjee in 1878 says, ‘It is dead calm & very very hot, the crew have been overboard bathing … there are no less than 16 vessels in sight’. This must have been quite a spectacle, on a glassy sea with the creaking of timbers and the occasional flapping of sails.

When becalmed the captain might lower a boat for shooting – apparently a dangerous pastime, as a passenger on the Renown noted in 1876: ‘Captain lowered a boat today for the purpose of a little shooting … shot missing bird, but shot striking a few of the passengers’.

A favourable wind was vital for sailing ships, and superstitions abound about the wind. A passenger on the Alfred from Sydney to Plymouth in 1864 wrote: ‘A very fine morning but a head wind … the ladies & gentlemen is busy throwing old hats overboard. An old custom for a fair wind to spring up’.

The diaries tell both personal and social histories of immigration, the gold rush, ocean travel, settlement and much more

In unfavourable winds the ships would have to tack frequently, so a long distance might be travelled without making much progress.

‘Our ship has made 160 “miles” in the last 24 hours,’ recorded a passenger on the Alfred, ‘but this is not all to our advantage as the Capt. has had to tack a good deal’.

On the Suffolk in 1863 a passenger talks about the difficulty of sleeping in a ship that was tacking:

We are falling off to sleep when a breeze springs up and the ship is put about so that we have to change our pillows to what was the foot of the bed, that being the highest. About 2 in the morn my spouse wakes me up to change the pillows again the ship having tacked again and when we awake in the morning we find our heads lower than our heels, so they must have put the ship about once more whilst we were asleep … Slept well last night in spite of the ship being on the obnoxious tack.

Some people, it seems, will complain about anything: ‘Crossed the 180 degree Meridian [the international date line] early in the evening so we will have two days in succession much to our disgust’, grumbles a crew member on the Archibald Russell in 1933.

Others find humour in small things, with a passenger on the Hereford talking about crossing the equator, which was commonly known as ‘the line’: ‘… at last we have reached the Equator … some of the passengers are having others on finely. They have fastened a hair across the telescope & are telling them it is the line we have crossed.’

When looking back from 2013 it appears that human nature has not changed much since the 1800s and 1900s, with the same social issues faced, the same humour, the same gossip and nastiness. On the Renown in 1876 there is one entry that in today’s language would almost equate to a Twitter or Facebook post, with ‘likes’, ‘re-tweets’ or ‘flames’:

… there is a young lady on board who has taken a great fancy to one of our Mess Mates who turns out to be a married man … all her companions have cautioned her but all to no effect, the sailors are there fore writing placards & sticking them up in several places about this man concerning his affairs … so this is causing a great bit of fun with all concerned.

Another entry, from a young female passenger in 1847 on the Tasmania, could be likened to today’s schoolgirl bullying:

… Miss Palmer. For description, comely face, excessively good-natured, and says the most extraordinary things, she is extremely fat, short and thick, not the slightest degree of grace, wears no bustle so of course can have no style about her.

The only difference is that in 2013, we know our blogs and tweets can be read by anyone at all. These diarists could never have imagined our world of social media, yet it’s a world in which their very private scribblings can be read by an audience interested in the small similarities – and vast differences – between life then and now.

Author Jan Harbison, technical services librarian for the museum’s public research facility the Vaughan Evans Library, is retiring as this article is published. So too is her colleague, library manager Frances Prentice; both were founding staff of the library and among the museum’s longest-serving employees.

Quote from the Parma diary is from The search for the Kobenhaven and other true sea stories of the Depression years, published by Graeme K Andrews Productions, Epping, NSW, 1984. Reproduced with permission.

Quote from the Suffolk diary is from From England to Australia: the 1863 shipboard diary of Edward Charlwood, published by Burgewood Books, Warrandyte, Vic, 2003. Reproduced with permission.

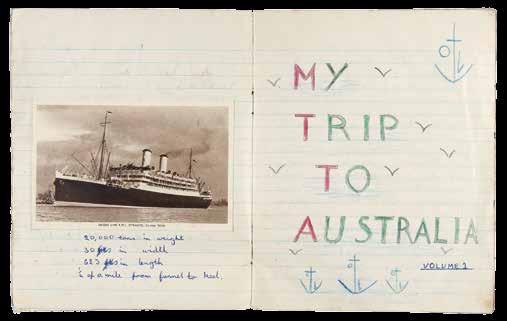

01 This child’s diary records Maureen Mullins’ experiences in 1952 when she sailed unaccompanied from Britain to Australia, to take up a new life in a Fairbridge Farm School in country New South Wales. The diary was borrowed for display in the museum’s travelling exhibition On their own – Britain’s child migrants

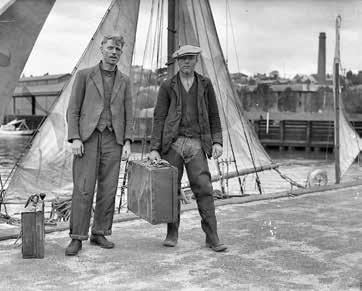

Lord Howe Island was the exotic locale for an early Australian ‘talkie’, and the launching place for a disastrous voyage that claimed two of its actors. Museum researcher Nicole Cama drew on our Samuel J Hood Studio Collection, and records of the National Film and Sound Archive, to reconstruct the last voyage of the aptly named Mystery Star

W HY DO THEY DO IT ? Is it the promise of adrenaline-pumping adventure that draws sailors to defy the odds? Or is it the prospect of the finish line crowded with admirers eagerly awaiting their arrival that spurs them on? Perhaps it is the attraction of the unknown, or an irresistible desire to explore a deep blue expanse that promises all manner of peril to those brave enough to sail across it.

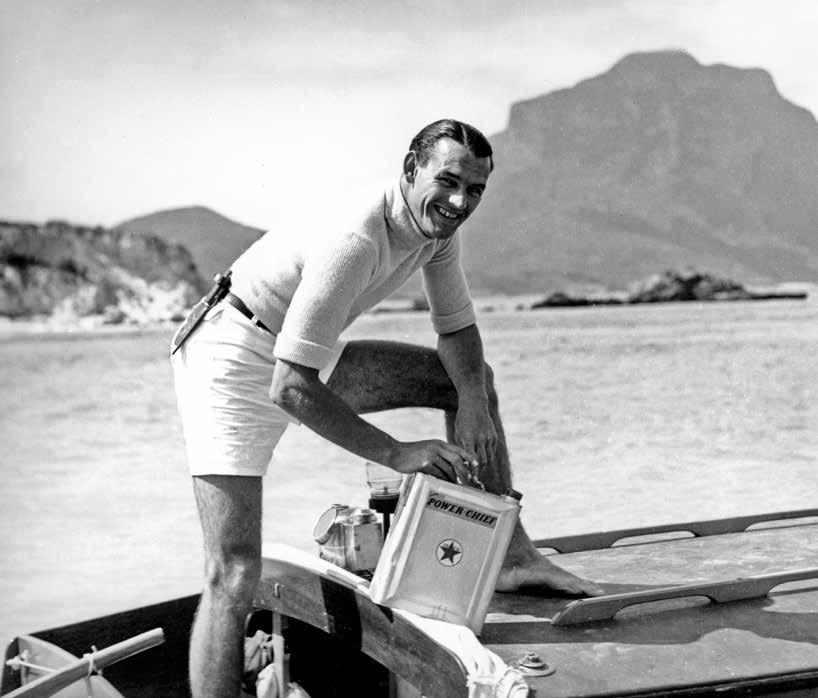

On 5 September 1936, crowds gathered at Wharf 10 in Walsh Bay, Sydney, to farewell the cast and crew of a new Australian ‘talkie’, Mystery Island. Among those about to board the Burns Philp liner SS Morinda was actor Brian Abbot (real name George Rikard Bell), who was recorded by commercial photographer Samuel J Hood farewelling his wife, Grace Rikard Bell. In his photo, in the museum’s collection, they happily embrace, completely unaware that this would be the last time they would see each other. Over a month after this photograph was taken, Brian Abbot and fellow castmate Desmond Hay (real name Leslie Hay Simpson) set off to cross the ‘stormy Tasman’ from Lord Howe Island back to Sydney – and were never seen again.

For months preceding Morinda ’s departure, newspapers had reported that the film would be shot in an exotic South Sea location. The all-Australian cast and crew were to sail to Lord Howe to work on the Commonwealth Film Laboratories’ first feature-length film with sound. Articles also profiled the film’s leading lady, Jean Laidley (real name Jean Angela Laidley Mort), greatgranddaughter of Thomas Sutcliffe Mort, industrialist and founder of Mort’s Dock in the Sydney harbourside suburb of Balmain. Laidley was tall, slim and golden haired,

with a movie-star air that matched Abbot’s dashing good looks. Sam Hood captured the excitement and glamour of the emerging sound-film industry in photographing the cast. Laidley was Audrey Challoner, the archetypal beautiful damsel in distress, and Abbot was the handsome hero, Morris Carthew. As they waved goodbye that day, while streamers were thrown over the side of Morinda, it is easy to imagine that the passengers were eagerly anticipating the next few weeks.

Reports trickled back home of life filming on the island. In one story, Laidley’s ‘fortitude’ was tested as she picked up a bird which ‘proved so wild that it pecked her arm and hand severely’. Another dramatic report described how one evening, after filming on the Admiralty Group of islets, the cast and crew had been unable to return to their base on Lord Howe as the seas were too rough. The filming was fraught with other complications due to variable weather. It rained six days a week on average, poor electricity meant make-up had to be applied by candlelight and the sound crew were constantly plagued by noise interference from the crashing waves.

The most fascinating and mysterious parts of this story are an article published in The Australian Women’s Weekly on 24 October 1936 and the events that unfolded after filming wrapped. Brian Abbot wrote a letter to the magazine that contained these ominous sentences: I shall be attempting a very dangerous voyage in October … However, I have strong personal reasons for no word of this trip of mine to be published until it has actually begun.

‘I shall be attempting a very dangerous voyage in October … However, I have strong personal reasons for no word of this trip of mine to be published until it has actually begun’

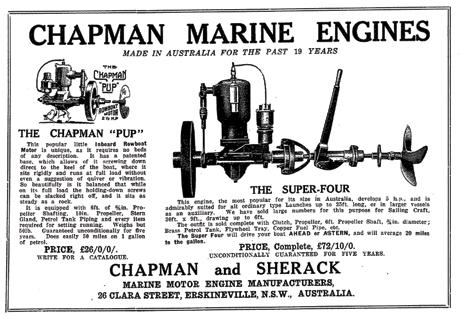

01 An ad in Australian Motor Boat and Yachting Monthly from 1 July 1927, page 32, for the company that built Mystery Star’s engine. Vaughan Evans Library, Australian National Maritime Museum

02 Brian Abbot and his motor launch Mystery Star in Lord Howe Island lagoon. Image courtesy National Film and Sound Archive

No hint was given as to why the trip should be shrouded in secrecy; nor is much known of why Brian Abbot chose to attempt such a risky venture. The film’s producer, George D Malcolm, claimed that the voyage was undertaken as an ‘adventure’. Despite Abbot’s dramatic words, it is clear that the voyage was not decided on a whim. Abbot had taken his motor launch, Mystery Star, from Sydney to Lord Howe, reportedly with a view to making the 725-kilometre return trip in that vessel rather than Morinda Whatever Abbot and Hay’s reasons were, however, newspaper reports and witness statements appear unanimous about one crucial detail – that the two men were ill equipped and unprepared for rough conditions.

On 6 October 1936, as Morinda returned to Sydney, Abbot and Hay were still on Lord Howe Island preparing for their dangerous voyage. Abbot posed for publicity shots under the bright sky pretending to sail away while waving to a crowd of onlookers. Hay is noticeably absent from the photographs. At 10.15 pm, however, the real journey commenced. The pair set off in the 16-foot (4.88-metre) launch, reportedly equipped with a two-and-a-half-horsepower engine, 40 gallons (180 litres) of water, two cooked legs of mutton, biscuits and chocolate. Abbot claimed they would reach Sydney in six to eight days.

As the eighth day came and went with no sign of the two actors, concerns for their safety trickled through the press.

It rained six days a week, make-up had to be applied by candlelight and the sound crew were plagued with noise interference from the crashing waves

At least two newspapers noted that these ‘grave fears’ were being eased by the ‘definite information’ that the launch was ‘unsinkable’. This claim was outweighed by most reports, which focused on the precarious nature of the adventure and on information that the two men were relying almost completely on the engine. In a bid for self-preservation as much as to reassure ‘anxious relatives’, Mr G Chapman of Chapman and Sherack, the Sydney company that manufactured the engine for the launch, told the press that the vessel had been fitted with two buoyancy tanks, which would ensure that the vessel would ‘float with a foot [30 centimetres] of freeboard even

when completely swamped’. A ‘waterproof canvas apron’ had also been designed to securely cover the opening of the cockpit. Chapman said that Abbot had previously visited their factory to understand how their engines were made and even took a test trip on the ocean off the coast of Sydney in a craft similar to Mystery Star. According to Chapman, ‘the only possible source of danger which could be foreseen … was that the boat might take a large quantity of water aboard, and that the magneto might be put out of action’.