Number 88 September–November 2009

The museum’s unique venues, sweeping city skyline, water views and fine catering will make your wedding day one to remember!

Drinks on destroyer Vampire … dinner for 150 in the elegant Terrace Room ... harbourside Yots Café … or up to 300 in our North Wharf marquee (mid-November to mid-December).

Award-winning Bayleaf Catering is renowned for innovation, quality menus and fine service delivery. A special place to

02 9298 3649

email venues@anmm.gov.au www.anmm.gov.au/venues

tie the knot

SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009 Page ii

Signals

Signals

COVER:

COVER:

A 2-foot model skiff self-steers under spinnaker, and the watchful eye of its skipper. Feature stories beginning page 2 herald a renewed interest in these fascinating craft that raced on Sydney Harbour in the first half of the 20th century. Photographer J Mellefont/ANMM

A 2-foot model skiff self-steers under spinnaker, and the watchful eye of its skipper. Feature stories beginning page 2 herald a renewed interest in these fascinating craft that raced on Sydney Harbour in the first half of the 20th century. Photographer J Mellefont/ANMM

ABOVE:

ABOVE:

The topmast of the museum’s 40.5-metre, 1912 signal mast – originally located at Garden Island naval dockyard – is sent down before the mast is unstepped for repairs and relocation.

The topmast of the museum’s 40.5-metre, 1912 signal mast – originally located at Garden Island naval dockyard – is sent down before the mast is unstepped for repairs and relocation.

ABOVE RIGHT:

ABOVE RIGHT:

The museum’s restored Taipan – Ben Lexcen’s revolutionary 1959 18-foot skiff – was displayed at the Sydney International Boat Show in August, where ANMM Fleet staff spoke to the public while looking after the priceless heritage craft. Left to right: acting manager Warwick Thomson, apprentices Andrew Mann and Tim Sheil. Photographs J Mellefont/ANMM

The museum’s restored Taipan – Ben Lexcen’s revolutionary 1959 18-foot skiff – was displayed at the Sydney International Boat Show in August, where ANMM Fleet staff spoke to the public while looking after the priceless heritage craft. Left to right: acting manager Warwick Thomson, apprentices Andrew Mann and Tim Sheil. Photographs J Mellefont/ANMM

Australian National Maritime Museum’s quarterly magazine

Number 88 September–November 2009

Australian National Maritime Museum’s quarterly magazine Number 88 September–November 2009

Contents

Contents

2 Reincarnation of a class

2 Reincarnation of a class

The vanished model racing skiffs are making a comeback

The vanished model racing skiffs are making a comeback

10 Revisiting Endeavour’s scrap yard

10 Revisiting Endeavour’s scrap yard

Our archaeologists visit the reef where Cook nearly lost Endeavour

Our archaeologists visit the reef where Cook nearly lost Endeavour

16 More power to Krait

16 More power to Krait

Volunteers give a new lease of life to this famous vessel’s diesel motor

Volunteers give a new lease of life to this famous vessel’s diesel motor

18 X for unknown

18 X for unknown

New acquisitions recall the tragic loss of asylum-seeker boat SIEV X

New acquisitions recall the tragic loss of asylum-seeker boat SIEV X

21 Museum program pages

21 Museum program pages

Members’ spring calendar, exhibitions, events for visitors, schools

Members’ spring calendar, exhibitions, events for visitors, schools

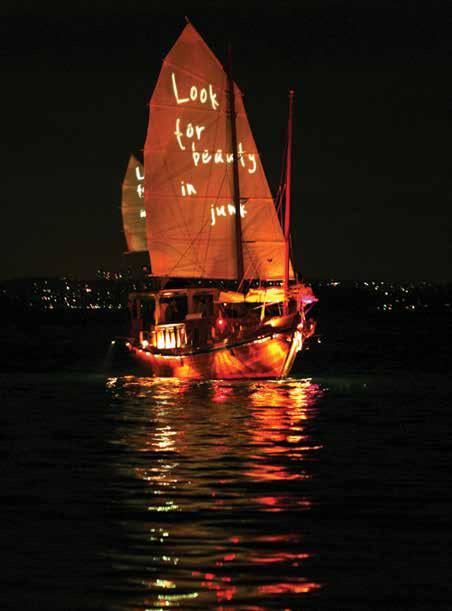

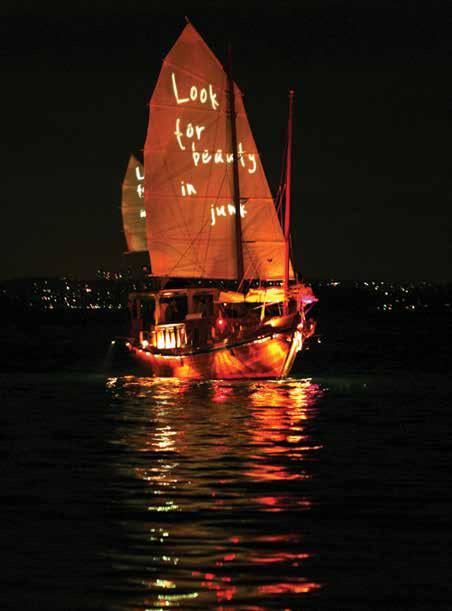

30 The extraordinary life of Suzy Wong

30 The extraordinary life of Suzy Wong

An exotic vessel becomes an intercultural art show

An exotic vessel becomes an intercultural art show

35 Signals in online archive

35 Signals in online archive

Our library is digitising valuable research resources for instant access

Our library is digitising valuable research resources for instant access

36 Ways of watching weather

36 Ways of watching weather

A meteorological program for schools inspired by Darwin exhibition

A meteorological program for schools inspired by Darwin exhibition

40 Australians regain sail speed record

40 Australians regain sail speed record

Ingenuity and determination break the elusive 50-knot barrier

Ingenuity and determination break the elusive 50-knot barrier

42 Tales from the Welcome Wall

42 Tales from the Welcome Wall

Cultutral adjustments – Chahin Baker

Cultutral adjustments – Chahin Baker

44 Off-watch reading

44 Off-watch reading

George & Elizabeth Bass love letters; Captain Cook was here

George & Elizabeth Bass love letters; Captain Cook was here

Signals and the environment:

Signals and the environment:

This journal is printed on Media Silk Art, an elemental chlorine-free paper with Forest Stewardship Council and ISO14001

certification, using vegetable based inks.

This journal is printed on Media Silk Art, an elemental chlorine-free paper with Forest Stewardship Council and ISO14001 accreditation, using vegetable based inks.

46 Currents

46 Currents

Birthday celebrations for ‘The Bat’

Birthday celebrations for ‘The Bat’

48 From the director

48 From the director

Page 1 SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009

Page 1 SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009

SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009 Page 2

Reincarnation of a

class

Racing these unique model skiffs was a workers’ wintertime diversion that flourished for half a century before being displaced by other, more modern, pastimes. David Payne, curator of this museum’s Australian Register of Historic Vessels, chronicles their past and applauds their comeback.

THE MODEL racing skiffs associated with Sydney Harbour for the first half of the 20th century have a cheeky character and a colourful history to match their bigger, fully crewed cousins, the internationally recognised 18-foot skiff class. With their over-sized rigs and improbable hull proportions, these pocket-sized caricatures proved that what was good for the real skiffs was good for them too. Not to be upstaged, they shared the same open waters of Sydney Harbour and other nearby locations for their fiercely competitive races, and the same spectator ferries came out crowded with enthusiasts barracking for – and betting on – their favourite craft.

Until recently all this was just a memory, since the races stopped half a century ago. But it did happen, as some of the pictures published here prove, and it’s starting to happen again. Old model skiffs have been resurrected over the last 20 years by collectors, or dusted off by the skiffs’ owners and their families. Now they’re being joined by new hands; the hobby and craft of the model skiff has been reborn in suburban homes and sheds, but this time it’s spread all around the country.

The model racing skiffs are small, which is of course the essence of models, but they are definitely not scaled-down versions of bigger craft. They are more than models, almost deserving to be

included as another skiff class.

Conceptually they share the same freespirited, ‘anything goes’ attitude of the full-sized skiff classes. As long as the boat’s hull is the right length for the class, the proportions, the rig and appendages are up to the builder.

established at Berrys Bay, in North Sydney. Soon afterwards a club was created on the opposite shore at Balmain, and another started nearby at Iron Cove. In 1918 the NSW Model Sailing Council was formed, with various pond and open water clubs participating.

Conceptually they share the same free-spirited, ‘anything goes’ attitude of the full-sized skiff classes

The origins of the big skiffs go back to the 1870s when a number of classes raced regularly on Sydney Harbour. The 1890s saw the 18-footers begin their rise to dominance as the showpiece skiff class, and their massive big brothers the 22s and 24s faded into history. Meanwhile, there were people playing with and racing model boats, largely on ponds and lakes. To the south of the city of Sydney the natural water plains and ponds that drained toward Botany Bay had been landscaped to become parklands, now known as Centennial Park and Moore Park. The lakes were ideal model boat venues and the pond boats were a regular weekend feature. Around 1908 or 1909 some model yachtsmen developed the idea of openwater model skiffs, sailing on the harbour or Parramatta River. The first club was

At least 10 clubs were formed in Sydney to race the little skiffs on open water. Some were short-lived, while others such as the Iron Cove 2-Foot Club spanned almost the entire history of the racing model skiffs. Most were located in the inner western suburbs along Parramatta River, but there was an outpost at Sans Souci on the Georges River and, briefly, another at Cammeray on Middle Harbour.

OPPOSITE: Balmain shipwright, skiff sailor, and maker of 2-foot model racing skiffs, George McGoogan. Photographer unknown, ANMM collection

ABOVE: Sailmaker Dennis McGoogan with the 2-foot skiff built by his father George (pictured opposite page), during a demonstration of model skiff racing that Dennis and other enthusiasts staged for museum Members last year. Photographer ANMM Member Peter Nichols

Page 3 SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009

The model skiffs were raced in winter, often by the people who in summer were racing the full-size skiffs

Racing appears to have ceased by 1954, but the clubs were extremely active during the preceding four decades. During this heyday the designs evolved, the racing was highly competitive and the support from spectators was very strong. The model skiff and pond classes became quite numerous, from eight or 10 inches up to 32 inches (25.4–81.28 cm). For the open water skiffs the predominant classes seemed to be the 12-inch and the mighty 2-foot class (30.48 and 60.96 cm).

The model skiffs were raced in winter, often by the people who in summer were racing the full-size skiffs. The little skiffs were followed by their skippers in rowing boats – and they were no ordinary rowing boats either. For the 2-footers the dinghies needed to be at least three metres (10 feet) long; the skipper sat in the bow while the rower sat aft and faced forward. The rower could be a colleague of the skipper or a member of his family, and many were women – sisters, cousins or girlfriends.

It was a team effort, but the rower’s principal job was to manoeuvre the dinghy alongside while the skipper made adjustments to his skiff’s rudder, keel and sail settings during the race. He would also tack or gybe the craft, and set or take in a spinnaker. While the skipper and rower had their independent tasks, they could work together on tactics and shared observations of the conditions and their rivals’ positions. The rower had to make sure he kept clear of other skiffs and their rowers. Interference or contact with the opposition could bring instant disqualification from the officials

adjudicating the race. The skipper had a pair of oars too, and after adjusting his model he had to row as well to help them keep up as the little contraptions sped away.

With 20 or more skiffs racing in a strong breeze, the sight was panoramic to behold. Spread out over a bay was a migrating flock of little white sails with their distinguishing emblems, herded and chased by people in clinker dinghies.

The big picture shows a gradual procession clearly heading somewhere as one fleet. Zoom in to watch more closely and each model skiff has an individual ‘watch me, dad’ mind of its own, that’s reined in by its dinghy and crew.

from sheet and stock sections; there were halyards and sheets with sliding cleats and Japara-cotton sails. It was all bigboat design and construction down to a ridiculous scale, not just for show under a glass case, but required to work in a good breeze out there on the harbour.

The art of sailing these extraordinary machines is all about that mystery of yachting called balance (see the section on the next pages about design of the skiffs). As the skiff is being built it’s a question of putting the mast in the right place, getting the sails in the right proportions, finding the right geometry of keel and rudder. When it’s launched it should then be down to fine-tuning the set and trim of the sails. If everything is just right, the little yacht would sail steadily maintaining its course relative to the wind direction and strength. Getting it just right only came with experience, so each design was usually

After adjusting his model the skipper had to row as well to help keep up as the little contraptions sped away

This was serious business for the skippers. Some of the craft were built professionally, but many skippers designed and built their own craft at home – the working men’s terraces and cottages of those inner harbourside suburbs. Even if built on the kitchen table, the hulls and fittings reveal expert craftsmanship. These days they are so treasured as artefacts that some owners won’t allow them back in the water.

The early examples were hollowed out from a solid block of timber, usually the light Queensland red cedar, but later craft show a real miniature skiff construction with keels, frames, floors, planks, beams and knees. Brass fittings were hand-made

a progression from a previous one. For everyone involved there was the same satisfaction that comes from sailing the real thing, as they tinkered and watched their diminutive craft strive like infants to be grown-ups.

A resurgence of interest began in the 1980s, and featured names such as Fred Thomas from Sans Souci and the McGoogans of Balmain, people who as youngsters had been part of the model racing in the 40s and 50s. They were joined by the late Nick Masterman, the dedicated heritage shipwright and enthusiast for Sydney Harbour’s maritime past, who encouraged people to restore the old craft as well as

Page 4 SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009

highlighting the model’s story in the local media and boat shows. Since then others have come aboard, people who have inherited dad’s or uncle’s old skiff, or picked one up from an antique shop, garage sale or other source.

In August last year we contacted all the model skiff enthusiasts that we could find and organised a demonstration sail on the waters of Iron Cove, observed by our Members in a heritage ferry. An art that had been dormant was stirring to life, and the momentum is increasing as new craft are being constructed.

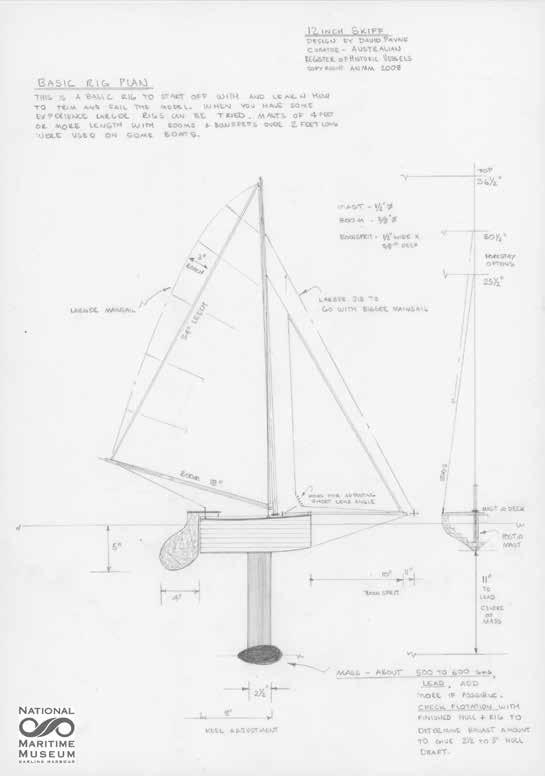

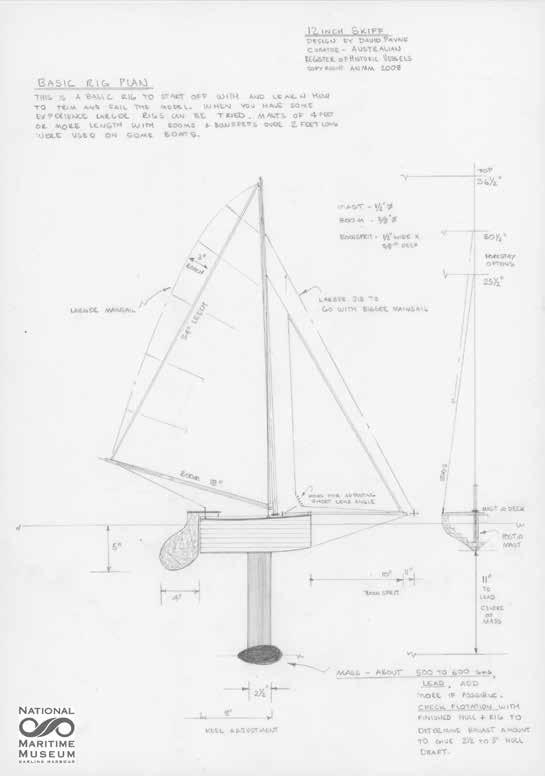

The Australian National Maritime Museum is keen to encourage this revival. We have chosen to focus on the 12-inch skiffs. This class is quite manageable to build, store, transport and sail, and provides all the performance qualities and owner satisfaction of the big 2-foot class. A traditionally inspired design by the author of this article, illustrated above, is available as a PDF which can be enlarged to full scale for builders to work directly from, or to use as a point of reference for their own ideas.

ABOVE: The author of this article, yacht designer David Payne, has developed these plans for the 12-inch class of skiff, to help people take up the old art of building racing models. They are available from the museum.

OPPOSITE LEFT: Unidentified skipper shepherds his creation between Point Piper snd Shark Island, positioning his boat upwind. Photographer unknown, ANMM collection

OPPOSITE RIGHT: Museum shipwright Lee Graham has taken up the challenge of building racing model skiffs. He’s pictured with a model displayed at a recent Classic & Wooden Boat Festival here at the museum. Photographer Bill Richards/ANMM

Page 5 SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009

Two-footer recollections

Harry Hugh McGoogan, born in Balmain in 1927 and a Cockatoo Island shipwright by trade, recalls the last days of 2-foot model skiff racing. This account is edited from his handwritten notes.

FROM THE AGE of five years I was interested in sailing boats. Each Sunday I watched and helped the sailors rig their boats in Mort Bay, Balmain, and as I got older I would be invited to crew in a boat as the bailer boy, on a windy day. They raced from Clark Island to the Sow and Pigs. In the winter months, when the skiff season was over, the Balmain 2-foot model sailing boats raced off White Horse Point each Sunday. They had a fleet of approximately 16 starters. My uncle Hugh McGoogan sailed the Marie, its colour patch was a round black circle. My father George McGoogan was his rower.

I first became involved with the 2-foot boats in 1942, when I was 15 years old, the year before I was apprenticed at Cockatoo Island. Brother George made sails and fitted out a boat called the Jean. I was his rower. We sailed at the North Sydney 2’0” Model Sailing Club for one year, and the following two seasons we sailed with the Drummoyne club. A group of sailors from Balmain got together and formed the Birchgrove 2’0” Model Sailing Club. They held their meetings on Sunday mornings in Mr Dodds’ boat shed at Birchgrove, and raced around Snails Bay in the afternoons.

Brother George then built me a 2-foot clinker boat called the Joan, named after his wife. My handicap was eight minutes. My father George, an experienced rower, rowed for me and I learned a lot from him

about 2-foot sailing. I won four races during my first season. Brother George was a shipwright by trade, he built a number of 2-footers in his early years. His rower was brother Jack McGoogan, whose nickname was ‘Up Jackie’! During their racing career George’s was usually the scratch boat.

The combination of skipper and rower was important to racing 2-footers. The rower could position the dinghy to assist the 2-footer into the wind, or pull it away to achieve fast speed through the water. Likewise, off the wind the position of the dinghy could change the direction of the model boat without the skipper doing any adjustments to the sails, rudder or fin. When a strong westerly or nor’easter blew it was necessary to have two pairs of oars in the dinghy to catch the model boat.

Two-foot model boats had four sets of sails. The biggest was used in light conditions, then there were intermediate, second and the small heavy weather rig. The sails were made of Japara silk or unbleached calico. Model boats were built in a jig. The keel consisted of Huon pine (when available) planked with cedar and fastened with swaged boat nails. The construction was generally carvelbuilt, though the early models were dug out of solid cedar logs. The 2-foot models had a sliding fin fabricated from mild or stainless steel, 25” long, 4” wide and carrying 22 pounds of lead.

In 1946 I built a new 2-footer called the Margaret after my girlfriend Margaret Ritchie, whom I later married. She volunteered to be my rower and was extremely good. The Margaret model is now 62 years old and in excellent condition. I sailed her off the Drummoyne shore in an easterly breeze not all that long ago.

In 1946 moorings were placed in Snails Bay to berth the timber ships from overseas. This prevented further sailing in Snails Bay. The Birchgrove club moved their courses adjacent to Cockatoo Island and started their races off Cove Street wharf, Birchgrove. The club was changed back to Balmain 2’0” Model Sailing Club. It had a big following, and hired a 60-foot ferry every Sunday to follow the race. Sailor families were on board and for those who were interested in having a bet on the race, the bookmakers’ prices were advertised on a blackboard.

During the racing season there were various inter-club races and State championships sailed down the harbour off Shark Island. Sailing continued during the 1940s and until the 1950s. It probably ended because people’s way of life changed. Families started getting motor cars and they might go for a Sunday drive instead. The television arrived in Sydney not long after and that was the end of a great winter sport sailed on Sunday afternoons.

Page 6 SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009

The author, keen to see a resurgence of model skiff racing, has developed his own version of the 12-inch class, taking full advantage of the skiff classes’ lack of design restrictions other than the length of hull. Named Flotsam, it’s made of scrap materials scavenged, seagull-like, from anywhere.

Photographer A Frolows/ANMM

The physics of Neverland

Despite their improbable proportions, model racing skiffs sail straight and true. David Payne, curator of this museum’s Australian Register of Historic Vessels, reconciles tradition, art and science.

THE DELIGHTFULLY comical proportions of the racing model skiffs are rather confounding for many people. How does something so short, so wide, so deep – and with all that sail – actually work? Why can’t it look more normal? Why aren’t they just scaled down from an 18-foot skiff to the specified length of the model class, of one or two feet (30.48 or 60.96 cm)?

The really simple answer is that these are not models in the first place. They are yachts in their own right, and subject to the same principles that shape any vessel. A study of these principles, and the way they are calculated, fills

Page 7 SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009

books. Indeed it is a university course, and becomes quite complex rather quickly. In contrast, the model skiffs we are focusing on have traditionally been created by eye, drawing solely on the maker’s experience – but the factors that govern a big yacht’s ability to sail still apply to these little model skiffs.

Let’s return first to the notion of a scaled-down 18-foot skiff. If you did build a mini 18-footer with exactly scaleddown hull and rig, it would capsize. To sail it in a modest wind you would need an extraordinarily deep keel carrying

Meanwhile the more complex form stability – something that is affected by the vessel’s water plane area and water plane beam – has become 32 times greater. In practical terms this is all far more than is required, because sail area has increased only four times while resistance and heeling forces have increased eight-fold. As noted in the venerable text on yacht design, Elements of Yacht Design by Norman L Skene (first published 1927), when dimensions are scaled upwards the ability to carry sail increases much more than the heeling forces and this ‘is the reason in a nutshell

How does something so short, so wide, so deep – and with all that extraordinary sail area – actually work?

just a small amount of lead, because that’s all its volume would support. This is because when scaling the boat down, while the linear dimensions of length, breadth and so on remain in the same relative proportions, areas and volumes and their effect on displacement and stability change quite dramatically compared to the original, full-sized craft.

What is being observed here is a historic element of the design process, an engineering principle called the Law of Mechanical Similitude, also known as Froud’s Law of Comparison. This law sets out the way in which a scaling change affects linear dimensions, areas, volumes and force measurements in quite different proportions to that of the simple scale variation. These principles play a role in explaining why the model skiffs are so oddly proportioned, and while it is doubtful that many of the model builders where schooled in the numbers, they certainly understood the principles from experience.

The numbers can be fascinating, as an example will show. If we simply scaled up a mid-sized 15-metre racing yacht by a factor of two, so that it’s up to the Sydney–Hobart maxi yacht length of 30 metres, what else happens? As well as being twice as long, the new boat would then be twice as wide and twice as deep. This, however, would then give it eight times as much volume or displacement, a huge increase.

By far the biggest increase is in the two ways that its stability has improved. Stability from its displacement or weight is increased by 16 times, assuming the same location of its centre of gravity.

why large sailing yachts are so much stiffer [more stable] than small ones, even with relatively much less draft and beam’. It stands to reason that when scaling in reverse, the smaller vessel becomes much less stable and its ability to carry sail decreases. Reduced to the size of the 2-foot skiff, everything has gone downhill exponentially. To compensate for the losses in stability some factors can be increased, relative to the hull’s length. You can help the stability inherent in the boat’s displacement or weight by

wider hull and a deeper, heavier keel were needed to support the sail area, especially when they sailed in conditions that were testing for even a full-sized skiff. Despite the seemingly obese hull characteristics common to many of the class, they still work like any other successful yacht because their stability numbers have been sorted out.

In some respects they work better – and this is another confounding thing about these little racing models. How do they stay on track sailing to windward and – even more astounding – downwind while carrying a spinnaker, when there is no crew on board constantly trimming the sails and rudder?

A sailing vessel operates in a constant state of change, always reacting to wind and wave variations. It is enormously complex to identify the various forces pushing and pulling on a yacht’s hull and rig, measuring their resultant strength and direction, then reconciling their opposing reactions to reach equilibrium. Tank testing and wind tunnel analysis give today’s designers a better chance to assess and predict what happens, with an engineer’s precision and accountability. Previously, however, it was rules of thumb derived from experience that guided the positioning of sail area relative to the combined hull, keel and rudder profile to achieve harmony between the two.

The best of the model skiffs seem to plough on regardless with a nothing-will-stop-me attitude of fierce determination

lowering the centre of gravity with a heavier bulb of lead and a much deeper keel as well. The hull must then develop a more voluminous shape so that it can support the heavy lead bulb, and this increases the beam of the boat – makes it wider. As the engineering principles showed, the small linear increase in width gives a much bigger proportional gain in form stability.

However, this is still only part of the answer, because the models also carry a hugely oversized rig, even by normal skiff proportions (and the skiffs of those days were famous for their enormous rigs). This requires even more stability. Therefore the already exaggerated shape is further inflated to support additional ballast, and the hull gains even more width. The model builders knew that a

It more or less came down to calculating the location of the geometric centres of the sail plan and of the hull’s underwater profile as they appeared on a plan of the vessel. These bear no relation to the actual centres of pressure, but they seemed to be as good a guide as any based on the premise that one should fix the two centres in positions relative to each other that had worked before on similar vessels. If the designer had developed from sailing experience a sense and an eye for what was right, they could be confident enough to move things around until it felt comfortable. At this point it becomes a case of what looks right is right – hopefully!

This is good news for the enthusiast and reminds us that the development of the model skiffs and their handling owed

SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009 Page 8

much to imagination and to trial and error, two design tools guaranteed to spice up what might in a later era have deteriorated into a dull numbers game for the white-coat brigade. Spontaneity is preserved along with the tradition of passing on the secrets and hard-learned lessons from one generation to the next. The artistry of the model skiff’s creation and sailing often started on the kitchen table where many of the hulls were shaped by eye, and a hand running across the surface feeling the imagined flow of the water. The rig, keel and rudder were set up with subtle changes to size or shape prompted by last year’s experience, and once the varnish was dry and the stitching complete, it was time to test it on the water.

It’s largely about trim and compensation. The intriguing sliding keel running on a track – an idea from left of field –allows the craft to be trimmed fore and aft and also changes the underwater centre of pressure relative to the rig’s centre of pressure. When combined with adjustments to the trim or set of the sails, there is a huge range of variations that can be trialed until the craft is balanced and sails in a straight line relative to the wind direction. The rudder can be fixed slightly off centre to help correct any yawing tendencies, and the sails are cut and set so that as wind strength and direction change, the craft automatically compensates and realigns itself relative to the wind.

The best of the model skiffs seem to do this quite smoothly, and plough on regardless with a nothing-will-stop-me attitude of fierce determination. Indeed nothing will stop it other than the rapidly approaching shore, unless the rower can keep pace and allow the skipper to grab hold of his errant charge when things don’t go according to plan, or when the time comes to turn into the next leg of the course.

The model skiffs are perpetually stuck in a kind of Peter Pan existence, little yachts that will never grow up. For their skippers it’s a bit like Neverland as time stands still while they play with their craft with all the intent dedication they give to the real boat races that they will return to every summer.

TOP: Unidentified Sydney model posing with the unrigged hull of a 2-footer model. The proportions of the skiff hull are explained in the accompanying article. Photographer unknown, ANMM collection

ABOVE: A racing skiff model works into a winter westerly off the shoreline between Point Piper and Double Bay . Photographer unknown, ANMM collection

TOP: Unidentified Sydney model posing with the unrigged hull of a 2-footer model. The proportions of the skiff hull are explained in the accompanying article. Photographer unknown, ANMM collection

ABOVE: A racing skiff model works into a winter westerly off the shoreline between Point Piper and Double Bay . Photographer unknown, ANMM collection

Page 9 SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009

The Australian National Maritime Museum has a small collection of historic model skiffs of different classes, photographs, programs and rule books associated with model skiff sailing.

Revisiting Endeavour’s scrap yard

SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009 Page 10

Early this year archaeologists from the Australian National Maritime Museum surveyed a site of great historical significance to Australia – the reef where James Cook went aground on Endeavour in 1770. Expedition member, curator and maritime archaeologist Nigel Erskine reports.

OF THE MANY 18th-century European voyages of exploration, James Cook’s expeditions are renowned. The three expeditions he led between 1768 and 1779 changed European knowledge of the world profoundly, filling Pacific charts with hundreds of islands and providing surveys of much of the Pacific littoral, including Australia’s east coast. In addition to geographic discoveries, Cook’s expeditions provided some of the first detailed scientific data from the Pacific and brought back important botanical, zoological and ethnographic collections to Europe. The artistic results of the voyages were similarly impressive and the three voyage accounts were best-sellers – ensuring that Cook’s reputation survived, well after his untimely death in Hawaii.

For Australians, the 1770 voyage of the Endeavour along the east coast is

ABOVE: Diver with part of the steel marker structure left by the 1969 expedition that recovered the six jettisoned cannon. Photographer Xanthe Rivett

LEFT: Vue de la riviere d’endeavour sur la cote de la nouvelle hollande ou le vaisseau sur mis a la bande (View of Endeavour River, in New South Wales, the ship Endeavour bark laid on the shore) Hand coloured engraving after a drawing by Endeavour artist Sydney Parkinson, published Paris, France 1774. It shows the ship being repaired on the shore of what we now call Queensland. ANMM collection

compelling description of the events of 11 June 1770 in his journal:

… a few minutes before 11 [2300 hrs] … before the man at the lead could heave another cast the ship struck and stuck fast. Immediately upon this we took in all our sails hoisted out the boats, and sounded round the ship, and found that we had got upon the SE edge of a reef of

Sailing by moonlight along the coast of New Holland, the vessel struck a coral reef threatening destruction of the ship

intrinsically linked to the foundation of modern Australia, but things could have turned out very differently! Twenty-two months into the voyage, after recording the transit of Venus, successfully charting New Zealand and sojourning in Botany Bay, the expedition suffered a disastrous setback. Sailing by moonlight along the tropical coast of New Holland, the vessel struck a coral reef –threatening the destruction of the ship, and along with it, Cook’s survey of the east coast and all Joseph Banks’s natural history specimens. Cook left a

coral rocks having in some places round the ship 3 and 4 fathom water and in other places not quite as many feet … Unable to haul the vessel off the reef, Cook ordered the ship to be lightened so that it might float free on the next high tide.

… we went to work to lighten her as fast as possible which seem’d to be the only means we had left to get her off as we went ashore about the top of highwater. We not only started water but throw’d over board our guns, iron and

Page 11 SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009

stone ballast, casks, hoops staves, oyle jars, decay’d stores etc ...

These actions were successful and after getting off the reef, Cook was fortunate to find a river mouth on the nearby coast, where the Endeavour was sufficiently repaired to sail to the Dutch East India Company shipyard at Batavia. Cook finally arrived back in England with the Endeavour in 1771.

In 1969 the exact site of Endeavour’s stranding was located by a team from the Academy of Natural Sciences

(Philadelphia) and the six cannons and much of the ballast were recovered. An anchor was recovered later in 1971. These objects form an integral part of the national connection that we and other nations feel for Cook and the Endeavour – and in 1970 the Australian Prime Minister, John Gorton, formally presented one cannon each to representatives of the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences, the British government, the New Zealand government, the Australian government, the New South Wales and the Queensland governments.

SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009 Page 12

Chart of Endeavour Reef and environs by Richard Pickersgill, master’s mate on Endeavour. Courtesy of UK Hydrographic Office

The cannons are now located at the Academy of Natural Sciences (Philadelphia), the National Maritime Museum (London), the National Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Wellington), the National Museum of Australia (Canberra), the James Cook Museum (Cooktown) and Botany Bay National Park Discovery Centre. Forty pieces of iron ballast and 56 pieces of stone ballast, some remains of ironwork from the gun carriages, a cannonball, powder charge and hemp wadding (found in one of the cannon) plus a number of concretions are now held by this museum and form an important part of the National Maritime Collection.

Readers of the article ‘We find the missing Mermaid’ in Signals number 86, by curator and maritime archaeologist Kieran Hosty, will know that he led the museum’s maritime archaeology team on an expedition to far north Queensland in January this year. While the main achievement of the expedition was to successfully locate the remains of the important colonial vessel HMCS Mermaid, wrecked in 1829 somewhere in the area of the Frankland Islands, an additional aim of the project (weather and time permitting) was to visit Endeavour Reef and inspect the site where Cook’s ship was stranded in 1770.

Our opportunity came sooner than expected when on day nine of the expedition, with weather conditions deteriorating, work on the Mermaid wreck site was halted and the expedition vessels headed for shelter behind a reef further north. Endeavour Reef lies approximately 80 nautical miles north of

‘We … throw’d over board our guns, iron and stone ballast, casks, hoops staves, oyle jars, decay’d stores etc’

the Mermaid wreck site and the expedition vessel Spoilsport arrived there two days later – having stopped to investigate two other wreck sites en route.

In fact Spoilsport’s skipper had been playing a skilful game of ‘cat and mouse’ with a tropical low moving south from the Gulf of Carpentaria and out into the Coral Sea. For this was cyclone season and although this period produces statistically the greatest daily average of calms in the year, providing the best conditions for diving, it is also the period when dangerous cyclones may form.

Approaching through rain squalls just after dawn, at first glimpse Endeavour Reef appeared as a jade-green band suspended between a dark metallic sea and low scudding clouds. The reef lies only 13 nautical miles off the mainland and high peaks of the Mount Finlayson Ranges appeared and disappeared through the fast-moving rain squalls.

Endeavour Reef is imposing, appearing from Spoilsport’s upper deck to stretch endlessly from east to west. It is, in fact, about five nautical miles in length and must have been a daunting prospect to those involved in 19th-century attempts to

TOP: This Endeavour four-pounder cannon and iron ballast pigs, retrieved from Endeavour Reef, were displayed when the museum first opened. The cannon (on a replicated gun carriage) remained here for 17 years before moving to the National Museum of Australia in Canberra. Photographer J Carter/ANMM

LEFT: Large concretion removed from one of Endeavour’s cannon, showing the imprint of the royal cipher or monogram cast into its breech. ANMM collection

locate the site of Endeavour’s stranding. In 1887 the harbour master of Cooktown, Captain John Mackay, tried to find Endeavour’s cannons by visually searching the waters off the southern edge of the reef. Unsurprisingly, he was not successful, and the location of the cannons remained unknown until the 20th century when advances in technology greatly improved the chances of finding the Endeavour stranding site.

The breakthrough came in 1969 when an Academy of Natural Sciences expedition led by Dr Virgil Kauffman, using a magnetometer, successfully located a large magnetic anomaly on the southern edge of Endeavour Reef. A magnetometer registers slight variations in the earth’s magnetic field and by the 1960s they were being used extensively in geological surveys. Towed in the water behind a small boat, the magnetometer reacted to

Page 13 SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009

Rivett

the iron ballast and cannons on the seabed, pinpointing the spot for divers to search. However, even with this breakthrough it took some time for the expedition divers to identify the heavilyconcreted cannons among the numerous coral outcrops on the reef.

Using the published reports of the 1969 expedition, we were able fairly quickly to find a steel marker left to indicate the site where the Endeavour cannons and ballast were recovered. It was known that the original expedition had used explosives to crack the solid mass of iron ballast and we expected that the reef would show some evidence of this. Happily, although evidence of a blast crater was found in one area, our overall impression of the reef was of a healthy, and quite unexpectedly beautiful, environment rich in colourful corals, giant clams and tiny tropical fish.

After a second dive later in the day, the weather conditions deteriorated further and Spoilsport motored westward to round the reef and anchor in its shelter for the night. Rounding the western edge of Endeavour Reef we could see the tiny sand cays that Cook named the Hope Islands (in the hope of surviving the ordeal) lying about five miles further west.

After a restless night, we returned to the site next morning and completed a final dive. The Endeavour stranding site is actually on a small detached reef just off the main edge of Endeavour Reef and under water appears something like a loaf of bread in section – with a high, rounded central spine, dropping away steeply on either side to a flat sandy bottom. Cook was perhaps fortunate to strike this isolated reef rather than find himself aground on the edge of Endeavour Reef itself, where it is probable he would have found it impossible to free the ship.

During this final dive, the team found a small number of isolated ballast stones (recognisable from the recovered stones

Spoilsport ’s skipper had been playing a skilful game of ‘cat and mouse’ with a tropical low moving into the Coral Sea

Concretion is the term given to the hard casing of corrosion products that forms around iron objects that are submerged in the sea for long periods. The thickness of a concretion increases over time, sometimes making it difficult to identify the object beneath. While they are the result of corrosion, once they have formed concretions create a microenvironment that actually reduces the rate of corrosion, helping to preserve the encased object.

in the National Maritime Collection), as well as occasional concrete blocks used by the 1969 expedition to anchor marker buoys on the site, but in general the reef appears to have returned once more to its natural state. We would have liked to have spent more time at this place where, in 1770, the course of Australian history hung in the balance, but with the wind turning once again and strengthening, our time was up and we headed back southward to complete our work on the Mermaid site.

TOP: Diver with magnetometer approaches the reef where Endeavour ran aground. Photographer Xanthe

BOTTOM: Diver with one of the small ballast stones remaining on the site. Photographer Xanthe Rivett

SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009 Page 14

Page 15 SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009

More power

Meet the volunteer engineers who have given a new lease of life to the big Gardner diesel that powers Australia’s famous World-War-II commando raider, Krait. Story by the museum’s media and communications manager Bill Richards

IT’S JUST FOUR STEPS down a crude wooden ladder into the engine room on MV Krait, and you’re there … beside the big six-cylinder Gardner diesel that turned in a magnificent service for the Allied cause in the Pacific in World War II. A little surprisingly perhaps after all this time, the engine – gleaming in a new coat of grey paint – looks in great shape. It takes two strong men with crank handles to turn it over, but when they start it up it pounds away contentedly, ready to drive Krait through the water at a good 12 knots or more.

One suspects this Gardner is almost as good as new; that is, good as when it was installed in this one-time Japanese fishing boat on the waterfront in Cairns, North Queensland in July 1943.

It replaced the vessel’s original fourcylinder Deutz diesel which had broken down completely on the voyage north from Sydney that year, threatening to scuttle its top-secret wartime mission. The Gardner had been earmarked for the

Army, but the secret maritime operation was given precedence and the two-ton engine was flown to Cairns.

Krait proceeded from Cairns south to Townsville for supplies, then north again to Thursday Island and right across the top of Australia to Exmouth Gulf in Western Australia. From Exmouth, British Major Ivan Lyon and his crew of 13 special military personnel (11 Australian, three British) sailed this low-profile 20-metre vessel 2,800 km to Japaneseheld Singapore and launched the raid on which they blew up 37,000 tons of enemy shipping in Singapore harbour.

The devastation was accomplished by just six men. Paddling collapsible canoes from an outer island, they attached limpet mines to the ships in port then retreated. But it was the trusty Krait that transported the party from Exmouth to Singapore, masquerading as the Japanese fishing boat she originally was, and brought them safely home again.

Operation Jaywick was one of the most audacious, spectacular and successful Allied special-service actions in the whole Pacific War. And the big Gardner diesel performed its part magnificently, says Lynette Ramsay Silver, historian and author of several books on Operation Jaywick, its successor Operation Rimau and the men of Special Operations.

‘The engine kept going and going – which was just as well,’ she says.

‘If anything had gone wrong, it would have been the end. There were no second chances …’

Krait departed Exmouth on 2 September and returned on 19 October with its mission completed. Throughout this time the Gardner was managed and operated by Leading Stoker J P (Paddy) McDowell, a World War I veteran who migrated from Scotland to Australia between the wars and who, according to Silver, was perfectly content to line up for his adopted country in the Pacific conflict. This ‘engineer extraordinaire’,

Page 16 SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009

to Krait…

LEFT: Krait between Sydney Heads in 1989, shortly after the ship was entrusted to the museum. Photographer J Mellefont/ANMM

RIGHT: Krait volunteers Col Adam and Bob Bright. The model 6L3 Gardner diesel develops 103 bhp at 800 rpm and has 2:1 reduction gear. It cost £2,250 in 1943.

Photographer A Frolows/ANMM

as she calls him, was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for his work in Krait’s engine room.

Today there’s similar devotion to the engine, but the faces have changed. Krait, owned by the Australian War Memorial, is now on permanent display at this museum. The museum’s conservation plan for this extremely important vessel recognises that the Gardner has ‘exceptional heritage significance’ for its war service.

The big, low-speed, high-torque, British-manufactured Gardner diesels are considered by some to be the Rolls Royce of marine powerplants.

L Gardner and Sons Ltd, founded in Hulme, Manchester, England in 1868, started building engines around 1895 and became renowned for stationary, marine, road and rail diesel engines.

of the most fulfilling work in their now lengthy careers.

‘It’s very satisfying being able to call on skills you’ve learnt over a lifetime, and put them to work here,’ says Bob Bright, now 78. ‘And it’s not like when you’re working for money. There’s not the same pressure. You’ve got more time to consider things. Talk about them. And get it all right.’

Bob has had a fondness for old engines, particularly steam engines, since he started out as an apprentice fitter with NSW Railways. He went to sea as an engineer then came ashore again to work in a manufacturing plant, and from this developed his hobby of restoring old engines and bringing them back to life. By chance he met up with the Australian National Maritime Museum’s fleet manager, Steven Adams, at a railway

The big six-cylinder Gardner diesel turned in a magnificent service for the Allied cause in the Pacific in World War II

The company ceased engine production in the mid-1990s as emission standards and the move towards high-speed, turbocharged diesels made its product obsolete.

Two men now have hands-on responsibility for the maintenance and upkeep of Krait’s warrior engine. Bob Bright and Col Adams are both museum volunteers. Both are retired motor engineers and, having formed a firm working partnership in Krait’s engine room, both rank this as some

historical rally in 2000, and Adams immediately recognised a talent in retirement who could help maintain the museum’s historic vessels.

Col Adam’s career was different. For most of his working life he managed R H Adam and Sons, the automotive engineering company that his grandfather established at Bankstown in 1934. His son is now working in the company and Col, 76, has been withdrawing from active involvement over the past few years. He came to the museum as a tourist

12 months ago and got talking to people about their work on engines. Before he really knew what had happened, he too had joined the ranks of museum volunteers.

‘I’m very happy to be working on boats,’ he says. ‘Restoring car engines would have been like just another job for me.’

Working together just one day a week, over the past 12 months the two volunteers have given Krait’s venerable Gardner a super service. They have worked their way through the whole engine, adjusting all the working parts to get the timing right, changing all the oils, cleaning out the sumps, cleaning out the salt and fresh water cooling systems, overhauling the pumps, replacing the hoses and all.

‘It starts a lot more easily now, and runs beautifully,’ says Col. ‘I’d be happy to take it on a long voyage.’

The two engineers will now turn their attention to reinstalling three auxiliary machines that were in place on Operation Jaywick: a small petrol engine, an air compressor (to start the big engine) and a generator (to charge radio and other batteries on Jaywick).

‘I like working down there,’ says Bob. ‘There’s quite a lot of space. It’s a good engine to work on.’

It’s thanks to Bob and Col, when you descend into the engine room and hear the big Gardner turning over, you can easily imagine that you’re on your way towards enemy territory, relying for life on this disguise as a Japanese fishing boat. It’s a little chilling.

Page 17 SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009

Two new acquisitions to the National Maritime Collection recall the tragic loss of 353 lives at sea when a boat carrying asylum seekers sank on an ill-fated voyage from Indonesia to Australia. Kim Tao, curator of post-Federation immigration, explains the museum’s ongoing interest in the story of refugees and ‘boat people’.

unknown X for

SIEV X remembered

SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009 Page 18

SIEV X Affair by Glenn Morgan, 2008. Wood, steel, acrylic. ANMM collection

SIEV X is the name given to a decrepit, overcrowded fishing boat that embarked from the port of Bandar Lampung in Sumatra, Indonesia, on 18 October 2001, carrying over 400 asylum seekers who had fled Afghanistan and Iraq. After a night sailing in horrendous weather the boat foundered en route to the offshore Australian territory of Christmas Island, drowning 353 people – 146 children, 142 women and 65 men.

More than 100 people survived the initial sinking and floated helplessly for 20 hours ‘like birds on the water’ in the words of survivor Ahmed Hussein. During the night, according to those in the water, two large vessels arrived and shone searchlights, but failed to rescue the survivors. The identity of these vessels has never been established. The following day, only 44 asylum seekers remained alive. They were eventually picked up by passing fishermen. A 45th survivor was rescued some 12 hours later.

The Australian National Maritime Museum has recently acquired a wood and steel sculpture titled SIEV X Affair by Victorian artist Glenn Morgan, depicting the vessel’s sinking.

SIEV X stood for ‘Suspected Illegal Entry Vessel Unknown’ in the language of Australian naval and immigration authorities who were intent on tracking and deterring the many vessels then attempting to ferry people without visas to Australia, where they hoped to make a claim for asylum. As the vessels came under surveillance they were assigned an official number. SIEV X, when it sank in Indonesian waters, had not yet been allocated one. Most of these boats were, like SIEV X, small, ramshackle Indonesian fishing or trading craft – cheap and expendable to the people smugglers who charged the asylum seekers for their passage.

As part of its focus on migrant voyages to Australia, the museum has been vitally interested in the experiences of seaborne asylum seekers since it began collecting in the 1980s. At that time it acquired one of the many small craft that carried a wave of Vietnamese ‘boat people’ to Australia in the aftermath of the Vietnam War.

Called Tu Do (meaning ‘freedom’), it has

been maintained in operating condition in our historic fleet, and the museum has developed close links with the family who sailed it here, in order to tell their story.

The topic of people making such voyages to claim asylum in Australia has always been controversial, stirring the full gamut of responses in the Australian community – from compassion and support to resentment and xenophobia. Australia was an early signatory to United Nations conventions and protocols that recognise the rights of people to seek asylum in another country. Yet, since the era of Vietnamese boat people, governments in Australia have taken determined steps to deter refugees from arriving in such an uncontrolled manner.

in order to secure refuge in Australia. Shortly afterwards the government introduced its ‘Pacific Solution’.

This aimed to prevent refugees from reaching Australian territory where they could legally claim asylum, and detained them in cooperating foreign countries such as the Pacific island of Nauru while their refugee status was being assessed.

These events – all following closely on the September 11 terrorist attacks in the United States – set the tone for the November 2001 Federal election, when issues of asylum seekers, boat people and border protection were fervently contested. It is in this context that the strength of responses to the SIEV X tragedy must be understood.

More than 100 people survived the initial sinking and floated helplessly for 20 hours ‘like birds on the water’

Such measures have included laws enforcing mandatory detention of unauthorised arrivals, introduced in 1992 under the Labor government of 1983–1996. In 1999 the Coalition government (1996–2007) introduced Temporary Protection Visas for unauthorised arrivals who had been assessed as genuine refugees. This new type of visa removed the rights of refugees to have their family join them, or to re-enter the country if they needed to leave.

Many of the ill-fated passengers on SIEV X were women and children desperately attempting to join husbands and fathers in mandatory detention or on Temporary Protection Visas in Australia.

The SIEV X tragedy came two months after the incident in which the Norwegian cargo ship MV Tampa rescued 438 Afghan refugees from a sinking fishing boat in international waters but was prevented by the government from landing them in Australian territory. It was two weeks after another refugee boat, SIEV 4, had sunk after being intercepted by the Australian Navy, which pulled its passengers from the water. This was the incident that generated claims – later shown to be erroneous – that asylum seekers had deliberately thrown children overboard

Glenn Morgan’s sculpture SIEV X Affair depicts the sinking taking place before a row of government onlookers. It is a theatrical, tactile, narrative art work that reflects Morgan’s response to the incident. While the sculpture’s whimsical, childlike appearance may belie the seriousness of the subject, the presence of the onlookers offers an explicit political commentary about the role of the government at the time.

Morgan says, ‘The piece is about my disgrace at the SIEV X affair.

The bureaucrats and government knew it was happening and let it happen, simply for the sake of curtailing immigration. The figures looking over the edge of the work are those government figures watching on, uncaring. I wanted to make a point about that disregard.’

Unlike the Tampa and ‘children overboard’ affairs of 2001, there is no known visual documentation of SIEV X or its sinking. In the absence of photographs or video, the sculpture is an attempt by Morgan to imagine the tragedy, to render it tangible and to validate its place in Australia’s recent maritime history.

Validation is a critical element in the SIEV X story. While terms such as Tampa, children overboard and Pacific

Page 19 SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009

Solution are now firmly entrenched in public discourse, the name SIEV X is less well recognised. Even though this was the worst maritime tragedy in our region since World War II, disturbingly little compassion was shown for the 353 victims.

In 2003 well-known Tasmanian psychologist and author Steve Biddulph sought to commemorate this incident by bringing together a team of friends, based in the Uniting Church, to build a national memorial to SIEV X on the shores of Lake Burley Griffin in the national capital Canberra. The concept for the memorial evolved through a nationwide schools art project, in which thousands of high school students learned about SIEV X and responded with designs for a memorial.

SIEV X National Memorial concept drawing by Mitchell Donaldson, 2004. ANMM collection, gift from SIEV X National Memorial Project SIEV X National Memorial in Weston Park, Canberra, 2007. Photographer Belinda Morgan Pratten. Reproduced courtesy SIEV X National Memorial Project

More than 140 schools participated in the project, submitting concept drawings and paintings that captured a range of emotions – bewilderment at the lack of media coverage of SIEV X, anger at the nation’s treatment of asylum seekers and disbelief at the scale of loss of life.

In 2004 an exhibition of student designs was installed at the Pitt Street Uniting Church in Sydney and the Wesley Church in Lonsdale Street, Melbourne. In 2006 memorial project coordinators donated a selection of concept drawings to the Australian National Maritime Museum, including the winning design by Brisbane student Mitchell Donaldson.

Donaldson’s proposal consisted of a series of painted wooden poles forming the shape of a boat and running down

into the lake. ‘I designed this memorial to make people think about the mistakes we made when the boat people needed help,’ he explains. ‘It’s designed to be partly on the land and partly in the water to represent how close the people were to safety. There are 353 bars, which is the number of people who died, and they are in the shape of a boat. The bars also represent that the people were trapped and the low bars on the side show that they could have been saved if we’d helped them.’

Schools, churches and community groups throughout Australia were invited to contribute a decorated wooden pole for the memorial. The memorial was to have been assembled temporarily in Canberra in October 2006; however the consent of the National Capital Authority

The topic of people making such voyages to claim asylum in Australia has always been controversial

was not granted in time. Nevertheless on 15 October more than 2,000 people arrived at the lakeside site to raise the decorated poles in a ceremony opened by the Australian Capital Territory’s Chief Minister Jon Stanhope. In 2007, on the sixth anniversary of the tragedy, the ACT Government allowed the memorial to be erected for six weeks in Weston Park, Yarralumla. Negotiations continue for permission to install the memorial permanently on the shores of Lake Burley Griffin as an enduring feature of the national capital and the national conscience.

The Australian National Maritime Museum continues to collect objects relating to the experiences of migrants and refugees who arrive by sea. The collection includes a lifebuoy and lifejacket from MV Tampa and material linked to the Flotilla of Hope, a convoy of yachts that sailed from Australia in 2004 to deliver gifts and messages of support to asylum seekers detained on Nauru.

The museum is committed to developing its collection to reflect recent maritime incidents and changing immigration policy, as well as contemporary responses to them. Glenn Morgan’s sculpture and the SIEV X National Memorial concept drawings are two artistic responses that help to remember an incident that might otherwise have faded into the unknown.

SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009 Page 20

Message to Members

From Members manager Adrian Adam

AS THE TEMPERATURE warms up there’s no better time to get involved in some of the activities that we’re running over spring. Our exhibition Exposed! The story of swimwear has proved a great hit. Cossies have been in the news again with all that recent controversy over world records, making this exhibition quite timely – but then swimwear has always created shock waves. So do check it out – you’ll learn how we went from scratchy woollen neck-to-knee togs that nearly drowned us, to super-fast competition swimsuits that turned us into dolphins.

The swimwear theme carries over to our spring school holiday program. Bring along your youngsters for handcrafts and dress-ups at our popular activity centre, Kids on Deck, inspired by screen sirens, bathing beauties and Olympians. Meet our new resident artist Jennie Pry as she draws inspiration from the museum’s extensive swimwear collections to create paintings and collages in her gallery studio space.

November brings the intriguingly named International Polar Palooza: Polar Science for Planet Earth on the evening of Thursday 12. ‘Palooza’ implies a multi-faceted festival, and this one brings together international researchers working in biology, geology, oceanography and climate studies. This show has been hailed for the way it raises environmental awareness – see page 27. There’s a related family day on Sunday 15 November for more hands-on demonstrations and interactive activities.

On the water especially for Members, a selection of harbour events includes the big 10th anniversary of our ever-popular Jacaranda cruise – the perfect spring fling. Our continuing lecture series brings back ship expert Peter Plowman to talk

about Australian migrant ships 1900–1939, and introduces the authors of The Wolf to explain how one German raider terrorised Australian shipping during the World War I. Eminent Cook scholar and author, John Robson, brings us Captain Cook’s War and Peace: The Royal Navy Years 1755–1768. And outdoor movies are returning to the upper deck of HMAS Vampire in September with a program of classic movies. For these and other Members events check out details overleaf.

Cossies have been in the news again with all that recent controversy over world records

Great new things are happening at our absolute-harbour-frontage Yots café this spring, inspired by the newly built performance platform adjacent to Yots and the water’s edge. Weekends in September and October bring Weekend Swing with live jazz music from 2 pm to 5 pm. On Fridays from 5 pm to 7 pm we have Five O’Clock Shadow – happy hour with good sounding vibes, and a delicious share-plate menu fresh off the BBQ. Members receive a 10% discount at Yots.

I hope I have whetted your appetite to spring into spring with us, and Claire, Zara and I at the Members office look forward to seeing you at the museum soon.

Members’ kids dangle a line from the new performance deck during the workshop Fishing 4 Kids, which we’ll be holding again in October. Member Amelia Wilson-Williams (right) landed the blue groper. Photographers A Adam/ANMM, Louise Roberts/Fisheries DPI.

Page 21 SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009

Events for Members

How to book

It’s easy to book for the Members events on the next pages … it only takes a phone call and if you have a credit card ready we can take care of payments on the spot.

• To reserve tickets for events call the Members office on 02 9298 3644 (business hours) or email members@anmm.gov.au. Bookings strictly in order of receipt.

• If paying by phone, have credit card details at hand.

• If paying by mail after making a reservation, please include a completed booking form with a cheque made out to the Australian National Maritime Museum.

• The booking form is on reverse of the address sheet with your Signals mailout.

• If payment for an event is not received seven (7) days before the function your booking may be cancelled.

Booked out?

We always try to repeat the event in another program.

Cancellations

If you can’t attend a booked event, please notify us at least five (5) days before the function for a refund. Otherwise, we regret a refund cannot be made. Events and dates are correct at the time of printing but these may vary … if so, we’ll be sure to inform you.

Parking near museum

Wilson Parking offers Members discount parking at nearby Harbourside Carpark, Murray Street, Darling Harbour. To obtain a discount, you must have your ticket validated at the museum ticket desk

ABOVE: Members tour the Malt Shovel Brewery, home of James Squire beers, courtesy of brewer and generous sponsor Chuck Hahn who taught us how to match ales, pilsener and porter with fine foods. Photographer J Mellefont/ANMM

LEFT: A man at home with ships, David Mearns – the world’s foremost shiphunter – told Members how he located the pride of the WWII fleet HMAS Sydney. Photographer A Adam/ANMM

Members events calendar

September

Fri 11 Talk & view: Exposed! lunchtime tour

Tue 22 – Special: Movies by moonlight on Vampire

Thu 24

Sat 26 On water: Sydney Flying Squadron/18-ft skiffs

Sun 27 Talk: Australian Migrant Ships 1900–1939

October

Sun 4 Talk: The Wolf

Thu 8 Tour: Vampire behind-the-scenes & breakfast

Sun 11 Talk: Captain Cook’s War and Peace

Thu 15 Tour: Garden Island heritage tour

Sun 18 For kids: Fishing 4 Kids

Thu 22 For kids: After dark torchlight tour

Sat 24 On water: Jacaranda 10th anniversary cruise

November

Sun 1 Tour: Endeavour behind-the-scenes & breakfast

Sun 8 On water: Bundeena and Royal National Park

Thu 12

Lecture: International Polar Palooza

Fri 20 Tour: Wharf 7 behind-the-scenes

Sun 29

Special: 18th Members anniversary lunch

SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009 Page 22

Lectures & talks

Lunchtime curator talk & viewing:

Exposed! The story of swimwear

12–1.30 pm Friday 11 September at the museum

Movie sirens, aquatic stars, bathing beauties, athletes, sporting icons, swimmers and designers have all played their part in the evolution of the modern swimsuit. Blurring the boundaries between underwear and outerwear, the swimsuit continues to make shock waves.

Exposed! places Australian swimwear in a global context, and shows how Australian swimwear designers have responded to the environment, our strong swimming and beach culture, and international fashion trends. See this new exhibition and hear the story behind it with curator Daina Fletcher and artist in residence Jennie Pry.

Members $15, guests $20. Includes light lunch, Coral Sea wine, cheese and James Squire beer

Australian Migrant Ships 1900–1939

2–4.30 pm Sunday 27 September at the museum

Following the success of Australian Migrant Ships 1946–1971, maritime historian Peter Plowman now turns his attention to the story of the ships that brought migrants to Australia and New Zealand between 1900 and 1939. When war broke out in 1914 migration temporarily came to a halt, but in 1922 no less than 15 liners joined the Australian migrant trade. In the late 1920s there was a dramatic rise in numbers of Italian migrants heading for Australia, a trend that continued until all migration again ceased with the outbreak of WWII.

Members $20, guests $25. Two lectures, afternoon tea and reception with Coral Sea wine, cheese and James Squire beer

The Wolf: A WWI German raider in Australian waters

2–4 pm Sunday 4 October at the museum

Hear Australian journalists and authors Peter Hohnen and Richard Guilliatt talk about The Wolf – the story of a German ship hell-bent on making life difficult for southern ocean shipping during World War I. Sent on a suicide mission to the far side of the world, the task of this formidable and ingenious commerce-raider was to inflict maximum destruction on allied shipping using all the latest warfare technology –torpedoes, mines, smokescreens, wireless receivers, even a seaplane. Drawn from eyewitness accounts, declassified government files, unpublished diaries and correspondence uncovered during five years of research, this is one of the most remarkable yet little-known episodes of WWI.

Members $15, guests $20. Includes Coral Sea wine, cheese and James Squire beer

Captain Cook’s War and Peace:

The Royal Navy Years 1755–1768

2.30–4 pm Sunday 11 October at the museum

Why was James Cook chosen to lead the Endeavour expedition to the Pacific in 1768? At a time when social position and connections counted for more than ability, Cook, through his own talents and application, rose through the Navy ranks to become a remarkable seaman respected by men of influence. Adding surveying, astronomical and cartographic skills to expertise in seamanship and navigation, Cook saw action, became master of 400 men, and learned first-hand the need for healthy crews. By 1768, he was supremely qualified to captain the Endeavour. Author John Robson presents his original research in this important new book – for Cook scholars and armchair explorers alike.

Members $15, guests $20. Includes Coral Sea wine, cheese and James Squire beer

International Polar Palooza:

Polar Science for Planet Earth

6–8 pm Thursday 12 November at the museum

Celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Antarctic Treaty and many years of peaceful international Antarctic exploration, Polar Palooza brings together an international research team working in the areas of biology, geology, oceanography and climate studies. This show features mesmerising presentations and high-definition videos of wildlife from both poles, plus a series of remarkable visualisations generated by NASA satellite showing shrinking sea-ice. View polar artefacts, fossils and even ancient sea-ice cores. This project is made possible by support from the American National Science Foundation and in Australia, by speakers from the Australian Antarctic Division.

Members $20, guests $25. Includes presentation and light refreshments. Bookings essential 02 9298 3644

BOOKINGS AND ENQUIRIES

Booking form on reverse of mailing address sheet. Phone 02 9298 3644 or fax 02 9298 3660, unless otherwise indicated. All details are correct at time of publication but subject to change.

Page 23 SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009

Events for Members

Tours & walks

HMAS Vampire tour and breakfast

8–10 am Thursday 8 October on board the ship

Come and enjoy a behind-the-scenes look at destroyer HMAS Vampire with our specialist guides. See parts of the ship not usually open to the public, such as the senior sailors mess, wardroom, Captain’s day cabin, sonar room, gyro compass and more. The tour will conclude with a barbecue breakfast in the sailors mess and a talk by a former Commanding Officer. Members only, adult $20, child $10. Meet in the museum foyer

Garden Island heritage tour

10 am–1.30 pm Thursday 15 October at Garden Island

Don’t miss this opportunity to take a behind-the-scenes guided tour of Garden Island’s heritage precinct with representatives from The Naval Historical Society of Australia. The tour will visit secure areas such as the Kuttabul Memorial, the Chapel, as well as heritage buildings including the original boatshed and the top of the Captain Cook Dock. You will then have the opportunity to take a self-guided tour of the RAN Heritage Centre before you leave.

Members $25, guests $30. Includes morning tea and entry to RAN Heritage Centre. Some walking and climbing of stairs involved. Catch the 10.10 am Watson’s Bay ferry from Circular Quay to Garden Island

HM Bark Endeavour guided tour and breakfast 8–10 am Sunday 1 November on board the ship

Enjoy a welcoming glass of champagne on the quarterdeck before embarking on a detailed guided tour of the ship. With a small group you’ll see areas not usually accessible to the public, including the engine room. Hear what life was like sailing with Cook and his men in the 18th century. Then we will go down to the 20th-century mess and enjoy a hearty barbecue breakfast. Members: adult $20, child $10. Guests: adult $25, child $15. Includes glass of champagne and breakfast. Meet in the museum foyer

BOOKINGS AND ENQUIRIES

Booking form on reverse of mailing address sheet. Phone 02 9298 3644 or fax 02 9298 3660, unless otherwise indicated. All details are correct at time of publication but subject to change.

Wharf 7 Heritage Centre behind-the-scenes tour 11 am–12.30 pm Friday 20 November at Wharf 7

View sections of our Wharf 7 special storage areas that are usually closed to the public, and see objects from the museum’s extensive collection. Visit our preservation laboratory, where manager Jonathan London will explain how artefacts are preserved and prepared for exhibition.

Members only, $15. Includes light lunch. Limited places. Meet in Wharf 7 foyer

On the water

Ferry cruise and tour: Sydney Flying Squadron and heritage 18-ft skiff race

12 noon–4 pm Saturday 26 September on the harbour

Join this relaxing afternoon ferry cruise to view the historic 18-ft skiffs that race out of Sydney Flying Squadron headquarters at Careening Cove. Visit the Squadron’s historic clubhouse and see pre-war replicas Britannia, Tangalooma, Mistake and Yendys and many more on the water. Also view the modern skiffs and thrill to the colour and excitement of the harbour’s fastest racers. A Sydney Flying Squadron representative will be on hand to provide a commentary. Members $55, guests $65. Includes a light lunch and refreshments on board. Meet at the Heritage Pontoon next to submarine Onslow

Spring, spray and jacarandas 10th anniversary cruise 10 am–2 pm Saturday 24 October on Lane Cove River

The spring garden holds many delights including jacarandas in bloom. And there’s no better way to see them than on a leisurely cruise up the Lane Cove River aboard historic ferry Lithgow Adam Woodhams, award winning gardener, radio personality and assistant editor of the popular Better Homes and Gardens, will provide expert botanical and historical commentary. This is one of our most popular annual events; lots of prizes and a glass of bubbly for our 10th anniversary cruise. Book early! Members $45, guests $55. Includes brunch on board. Meet at the Festival Pontoon next to submarine Onslow

SIGNALS 88 September–November 2009 Page 24

Day trip: Bundeena and the Royal National Park

9 am–3.30 pm Sunday 8 November

Step aboard historic ferry MV Tom Thumb II and enjoy a leisurely cruise on Port Hacking – with its many bays and inlets one of Sydney’s most unspoilt waterways. See breathtaking views of the Royal National Park and learn about early explorers of the district, historical settlements, and sacred Aboriginal sites. Disembark at the historic town of Bundeena, take an easy bushwalk with a National Parks and Wildlife Ranger, and enjoy lunch in the town. Then rejoin the ferry for the trip back to Cronulla.

Members $65, guests $75. Includes morning tea and lunch. Meet at the public wharf at Tonkin St, Gunnamatta Bay, just below Cronulla Station. Parking available

For kids

Fishing 4 Kids

10 am–12 pm or 11 am–1 pm Sunday 18 October at the museum wharves

Supported by the NSW Department of Primary Industries and the Recreational Fishing Trust, this workshop teaches children responsible fishing practices. Children will learn about conservation of fish habitats, sustainable fishing, knot-tying, line-rigging and baiting, casting techniques and handling fish. They will also find out about what fish live in and around Darling Harbour – and what they eat. A simple quiz session will provide each child with a prize and fishing tackle to take home, plus a certificate of achievement.

Members $25, guests $30. Limited numbers. Suitable for children 7–14 years. Includes morning tea and refreshments

After dark torchlight tour

6–7.30 pm Thursday 22 October at the museum

Bring your torch for a night of ghoulish adventure at the museum. Meet our long-time museum caretaker Spanker Boom who has wandered the museum after dark for many a year. He’ll shed some light on what really happens after dark in the museum and maybe you’ll discover what goes ‘bump’ in the night! Listen to scary stories and join in some songs and activities along the way. Mums and dads can enjoy a glass of Coral Sea wine and view our exhibitions.

Member child $15, guest $20. Includes refreshments and light supper. Suitable for children 4–8 years. Remember your torch!

Special events

Movies by moonlight on HMAS Vampire

6.15–8 pm Tuesday 22, Wednesday 23 & Thursday 24 September on board HMAS Vampire

The upper deck of HMAS Vampire will be transformed into an alfresco movie theatre as we screen these films against the X-gun turret. Each screening preceded by a guided tour of HMAS Vampire from 5 pm.

Strictly limited places per screening. Members: adult $20, child $10 per film. Guests: adult $25, child $15. Includes refreshments and popcorn on arrival. Screening may be subject to cancellation due to weather conditions. Dress warmly

Tuesday 22 – For Kids: Peter Pan (2003)

The Darling family children receive an unexpected visit from Peter Pan, who takes them to Never Never Land, scene of an ongoing war with the evil Pirate Captain Hook. Based on the classic story by J M Barrie. Directed by Australian P J Hogan, starring Jason Isaacs and Jeremy Sumpter.

Wednesday 23 – Newsfront (1978)

In Australia in the late 1940s, before the advent of television, Len Maguire (Bill Hunter) and his young sidekick Chris (Chris Haywood) cover the big news stories for Cinetone newsreel company. An old-school cameraman, Len is loyal to the company, the Labor Party and the Catholic Church. But times are changing… Directed by Philip Noyce, Newsfront is a classic – and a contender for best film ever made in Australia.

Thursday 24 – Up Periscope (1959)