Signals

From April 2011 to May 2012 the magnificent replica of James Cook’s HM Bark Endeavour will follow in the wake of our earliest European explorers, visiting major and regional ports right around Australia.

Applications are now open for voyage crew and supernumerary berths – numbers are strictly limited – book your place now!

Bookings & information

Telephone 02 9298 3859 Freecall 1800 720 577 www.endeavourvoyages.com.au

Contents

2 Renewing Endeavour’s standing rigging

cover: What is it, and where would you find one? The answer is in our feature article, starting on page 2, that first unravels and then ties up all the mysteries of traditional standing rigging on ships like the museum’s replica of James Cook’s HM Bark Endeavour – now undergoing extensive rerigging prior to her 2011–12 circumnavigation of Australia. For those who can’t wait to find out: it’s called a mouse, it's located on the upper end of a stay and is built up by layers of servings, then pointed over with decorative weaving. Its job is to position the spindle eye in the end of the stay. If that’s still unclear, the article reveals it all. Photographer Anthony Longhurst/ANMM

Signals magazine is printed in Australia on Impress Satin 250 gsm (Cover) and 128 gsm (Text) using vegetable-based inks on paper produced from environmentally responsible, socially beneficial and economically viable forestry sources. 2 40 14 42

A complicated refit prepares the replica of Cook’s famous ship for its Australian circumnavigation

12 Tayenebe – Tasmanian women’s fibre work

Tasmanian Aboriginal women and girls have revitalised the weaving skills of their ancestors – a visiting temporary exhibition

14 Bridging troubled waters

A little-known unit, the 1st Royal Australian Naval Bridging Train, wrote its own chapter of ANZAC history

22 Love, loss and lighthouses

Our 2010–11 MMAPSS maritime heritage grants support projects around the country

27 What’s on for Members and visitors

The autumn calendar of tours, talks, seminars, activities afloat, exhibitions, school-term and holiday programs

38 New frontier in learning

A new digital curriculum resource based on our collection, developed by the museum’s education unit

40 Youthful perspectives

Young visitors armed with digital cameras take a fresh look at our maritime heritage precinct

42 The floating world of Cambodia

Sharing a unique maritime tour with Members

48 Australian Register of Historic Vessels

New additions to this important national database

52 Tales from the Welcome Wall

The upwardly mobile First Fleet convict Esther Abrahams

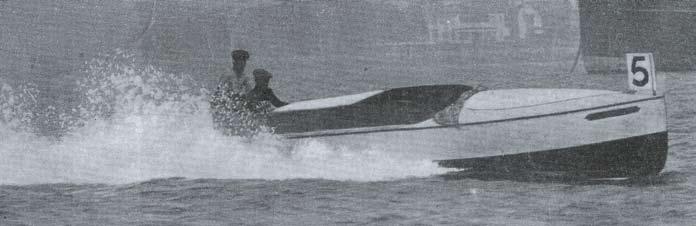

54 Collections – Nautilus II

A very early, very significant Australian powerboat

56 Readings

William Dampier, a buccaneer of literary merit

57 Currents

Bill Lane Fellowship; Allied losses; AMSA sponsorship

60 Bearings

From the director

Renewing Endeavour’s standing rigging

In preparation for a 15-month circumnavigation of Australia, the Endeavour replica’s standing rigging is being completely renewed for the first time since the ship was launched in 1993. Anthony Longhurst, ANMM leading hand shipwright and rigger, reveals the intricacies of traditional rigging techniques –beginning with his visit to the 17th-century ropewalk at England’s Chatham Dockyard, to watch the ship’s new ropes being manufactured.

The replica of James Cook’s HMB Endeavour has sailed twice around the world since her commissioning in 1994. She has logged many additional sea miles under the Australian National Maritime Museum’s management since 2005. Her rigging has been exposed to dust from a Sahara sandstorm blown out to sea, snow in Europe, hot and humid conditions in the tropics, storm-force winds and the strains of breasting huge seas. From the beginning the rig has undergone methodical maintenance, and judicious replacement of parts of it, but now the time has come to replace Endeavour’s entire standing rigging. For definitions see the glossary on page 11.

The original Endeavour carried standing rigging constructed of hemp. Hemp was widely used throughout England and Europe in the 18th century; the best came from the southern steppes of Russia. For the Endeavour replica’s standing rigging, built and installed in the early 1990s, manila was chosen instead of hemp. Manila fibre was more readily available than hemp and was cheaper. It also has a higher natural resistance to mildew: unlike hemp, the fibres do not easily absorb and hold moisture. A synthetic rig had initially been considered, but the tendency for synthetic rope to continue stretching and thus to give inadequate support to the masts ruled it out.

rope that is twisted right-handed, and is generally found in your hardware store or chandlery. Second there is cable-laid rope, in which three hawser-laid ropes are twisted together in a left-handed direction. Lastly, we have shroud-laid rope, a righthand laid rope built up of four strands around a central, hawser-laid core.

opposite: The main items of standing rigging visible in this view of the ship’s fore and main masts are the shrouds (with their ratlines or rope ladders) giving the masts lateral support, and various stays running diagonally downwards from the masts.

Our replica’s standing rigging comprises a variety of rope sizes ranging from three millimetres in diameter for small seizings, up to 104 mm diameter for the anchor cable. Endeavour uses ropes of three different constructions. First there is hawser-laid rope, the basic three-strand

A rope holds its form and gains its strength by applying opposing twists during the different stages of construction. First, the rope’s constituent fibre is spun clockwise or right-handed into a yarn. The yarns are then spun in the opposite direction – anticlockwise or left-handed – to form a strand. In hawser-laid rope, the diameter of the strand is half of the finished rope’s diameter, and so the quantity of yarns used in a strand varies accordingly. Three strands are then twisted together clockwise or right-handed to close the hawser-laid rope. If you then take three hawser-laid ropes and twist them together anticlockwise or left-handed, you will have a cable-laid rope.

above right: Hawser-laid rope of coir (coconuthusk fibre) at left, with a cable-laid rope of manila (right). All photographs of ropemaking and rig construction by Anthony Longhurst/ANMM unless otherwise specified.

clockwise from above:

The rope works at Chatham Dockyard, home of the ropewalk where the Endeavour replica’s new manila rigging was manufactured.

Manila yarn is led from spools to forming dies where it is spun into the strands that will be twisted up into finished rope.

Manila fibres enter the Number 2 spreader in the ropewalk at Chatham Dockyard before being spun into yarn.

The historic Chatham Dockyard to the east of London is the only such facility to have survived since the age of sail. Its ropewalk, quarter of a mile long, dates back to 1618

packaged into 125-kg compressed bales before being shipped.

Ropes of natural fibres used to be laid up in establishments called ropewalks. In James Cook’s time there were numerous Royal Navy ropewalks. The Portsmouth ropewalk was blitzed during World War II and others have closed down due to the diminishing need for large supplies of traditional rope, as synthetics and different types of manufacture, such as braid, took over. There are now few ropewalks left in the world that produce natural-fibre rope spun using the traditional methods. In February 2010 I was given the opportunity to work with the rope makers in the historic dockyard at Chatham, to the east of London – the only dockyard to have survived since the age of sail. Located within Chatham Dockyard is the ropewalk, quarter of a mile long. Rope making on the site dates back to 1618. The ropewalk is now operated by Master Rope Makers Limited, who have constructed some of the rope that is being used to build Endeavour’s new standing rigging.

Making our manila rope

Manila fibre is obtained from the leaves of a species of banana native to the Philippines locally known as abacá. Once the plant reaches maturity (18 months to two years), it is cut down and the long fibres are taken from the overlapping sections of the leaves where they form a false trunk. The fibres are exceptionally strong and durable and are generally 1.5–3.5 metres long. Once the fibre has been extracted from the sheaths of the leaves, it is left to dry and then

At the ropewalk, the fibre is separated and cut to lengths of no more than 1.5 metres. Any longer and the fibres would tangle and be torn during the initial combing process, while if the fibres are too short they weaken the finished rope. After being sorted, the fibre is sent though the first of six combing (hatchelling) machines. Here, the fibre is progressively combed and knit together as it is passed through progressively smaller combs. An emulsion of mineral oil, natural waxes, fatty acids and water – called batching oil – is added to help the fibre comb out easier, and as a waterproofing agent. Originally, whale oil was used. Before the introduction of hatchelling and spinning machines, the fibre was hatchelled by hand. It was drawn though steel spikes that were set into boards known as hatchelling boards. These came in a series of grades, the pins of which became progressively finer and set closer together. This ensured the fibre was straight and evenly fine before being sent to the spinner.

The spinners were regarded as the most skilled tradesmen employed in the ropewalk. The quality of their work governed the strength of the finished rope. The spinner would gather a ‘streak’ (a 60-pound [27.25 kg] bundle) of fibre around his waist with the ends at his back. A small loop was drawn out and attached to a hook on a spinning wheel that was operated by a young boy. The spinner walked backwards down the length of the walk uniformly feeding in the combed fibre as the yarn was spun by the revolving hook. To keep the yarn off the floor, it was placed onto stakes every 10 metres or so. An experienced spinner was capable of spinning 1,000 feet (305 metres) in 12 minutes.

Today the spinning is performed by a machine. The spinning machine used for Endeavour’s yarn is able to spin the yarn onto 24 spools, each containing a little over 900 metres of yarn. Each cycle takes approximately 20 minutes to produce over 20 kilometres of spun yarn.

At the ropewalk the spools of spun yarn are arranged onto a frame (bank) that enables the yarn to feed freely when being drawn out to form the strands. The required number of yarns are led from the banks, through a register plate that keeps the yarns separated and directs them into the die (a tight tube). The die controls the forming of the strands as the yarns are drawn through it and twisted by the strand-forming machine as it travels

down the length of the walk. Up to three strands can be spun at once and they are drawn to a length of approximately 250 metres. The forming machine that was used for Endeavour’s rope is known as Maud, and dates from 1811. It is the oldest machine employed in the ropewalk.

Once the strands have been formed, they are cut and secured under tension to posts at either end of the ropewalk and left to rest for 24 hours. This allows the tension in the fibres to release and relax before the strands are twisted again and closed into rope.

For this final process, the strands are transferred to rotating hooks on machines called the ‘jack’ and the ‘sledge’. The jack is stationary, while the sledge moves along rails. This is because the length of the strands shortens while they are being twisted for closing, thus requiring the sledge to move. The sledge has weights attached, to act as a drag and keep tension on the length of rope to prevent it from kinking.

The strands are attached to a single rotating hook on the sledge and to separate rotating hooks on the jack. A top (a conical-shaped piece of timber with grooves) is placed between the strands near the sledge. As the strands are twisted together the top moves along allowing the strands to close into rope behind it. The completed rope is coiled and weighed. A short length is cut from every batch and sent to be break-tested, to ensure that it meets the required standards.

Making Endeavour’s standing rigging

Of the 17 kilometres of rope ordered for the replacement of the Endeavour replica’s standing rigging, only four and a half kilometres are made of manila. The rest is polyester. The manila makes up the main components of the standing rigging: shrouds, stays and backstays. These are the components that transfer all of the stresses and forces imposed by the sails and movement of the ship down to the hull. We use the polyester only for the seizings, servings and worming. These are components that require strength and are applied very tight, so there is very little concern about them stretching.

Endeavour’s standing rigging comprises all the types of rope mentioned earlier – hawser-laid, cable-laid and shroud-laid – although not necessarily in the way you might expect from the terminology! Endeavour’s fore and main lower shrouds are cable-laid. All lower and topmast stays are shroud-laid. All other standing rigging is hawser-laid.

left top: As the strands are twisted together a piece of timber called a top is drawn along, allowing the strands to close into rope behind it.

left bottom: Cable-laid shroud, wormed and parcelled.

above: Cable-laid shroud, wormed and tarred.

right top: Author of this article, Anthony Longhurst, putting an eye splice into a main shroud at Sydney’s garden Island dockyard where the museum stretched, tarred and constructed Endeavour’s new rigging. Photographer Amy Spets/ANMM

right: Ross Pearce (left) and Ben Willoughby (right) demonstrate the use of a serving mallet.

Once our new manila rope was delivered from England, the coils of rope were opened, the required lengths were cut and the rope ends were whipped. Before construction of the rigging could commence, however, there were a number of preliminary steps of utmost importance. These steps are the foundation of the rigging’s stability and survival in the years to come.

The lengths of rope were pre-stretched for a minimum of 24 hours by attaching a weight equivalent to their working-load limit, to let the fibre reach its maximum stretch and then relax and settle. Once manila has been pre-stretched, it has similar stretch characteristics to wire. Depending upon the rope’s construction and how hard it has originally been laid, you can expect the stretch to be anything from 8% with hawser-laid rope to almost 15% for shroud-laid rope.

Shroud-laid ropes need a different treatment during stretching. As noted above, they are built up of four strands twisted around a core of hawser-laid rope. The core adds no strength, acting only as packing to keep the strands from falling into the void that would otherwise occur at the centre. The core stretches less than the strands around it. For shroud-laid rope to be properly stretched, the inner core needs to be broken in several places. This removes any loading from the core and lets the strands take it instead. If the core were unbroken, the strands would become loose and not sit properly after stretching, thus weakening the rope.

If the standing rigging is not sufficiently pre-stretched, it will continue stretching in operation and provide insufficient support for the masts. The stays and shrouds will need regular re-seizing around the deadeyes at their lower ends. As the rope stretches there is also a reduction in its diameter. If the rope continues to stretch on the ship, servings and seizings (integral to the strength of the rigging) will loosen. Proper pre-stretching before construction makes it easier to set up the finished rigging and ensures that all of the rigging shares the stresses equally.

The next step in the preparation is to preserve the manila rope. This is done by soaking it in raw and natural Stockholm tar, a residue left after distilling a gum that is extracted from pine and fir trees. It has been used for many centuries to preserve rigging and timber on sailing vessels. Soaking in Stockholm tar takes a minimum of 24 hours depending upon the size of the rope and the viscosity of the tar. If the weather is cold, the tar may

The rigging has been exposed to dust from Sahara sandstorms, snow in Europe, hot and humid conditions in the tropics, stormforce winds and the strains of breasting huge seas

require thinning to penetrate into the middle of the ropes. While the tar is not absorbed by the manila fibres, it coats the fibres and fills any voids between them, sealing out any moisture.

Once these preparatory measures have been completed, we can start turning the ropes into ship’s rigging.

All the ropes that are to become standing rigging are stretched out firmly, but not tight, between strong posts. The centres of the eyes that sit over the mastheads are marked along with the areas that are to be served; these areas are then wormed. The lower shrouds are wormed over their full length, including portions that will not be served. This adds extra strength, but is a technique that has been subject to debate in square-rig circles due to the possibility of the worming trapping water. The Endeavour replica’s first set of standing rigging survived with no problems in this respect; the concern probably originates from the problems encountered when using the more rotprone hemp rigging.

After worming the rope is stretched out tight again, under loads similar to those that the rigging will encounter upon the ship. This allows us to accurately place all the required seizings at the lower ends. We have load-measuring equipment so we can apply uniform weight to the ropes throughout the construction.

The worming, already installed, pulls uniformly tight with the rope. The rope then acquires another coat of tar before a layer of parcelling is wound spirally with the lay of the rope, from the lower end up toward the eye that will fit over the masthead. The overlapping of the parcelling acts like shingles on a roof. If water were to penetrate through the

serving it would run down and be shed away from the underlying rope. If the parcelling were applied the opposite way, the water would be directed into the rope and become trapped, leading to permanent dampness that will ultimately rot the rope. The parcelling then receives another coating of tar prior to the serving being applied.

The serving is then applied against the lay of the rope and in the opposite direction to the parcelling. Hence the age-old sailor’s expression, ‘Worm and parcel with the lay, turn and serve the other way’. Serving is applied using a serving mallet, and is wound on as tight as possible.

Once the ropes are served, the eyes are either seized or spliced into the ropes where they sit over the mastheads. Endeavour’s lower masts have seven shrouds on each side. Six of them are made as pairs, that is, one length of rope making two shrouds, with an eye seized in the middle to go over the masthead. The odd shroud needs to have an eye spliced in its upper end to sit over the masthead. The spliced eye is made oversize, well tarred, parcelled and served, and is then also seized to close the top of the splice. Seized eyes are preferable to splices due to the difficulties of sealing water out of the splices.

clockwise from above: Main lower shroud with a fitting called a cable stocking that allows a weight to be attached for pre-stretching.

Rigger Amy Spets seizing the turn for a deadeye in the end of a stay.

The spindle eye at the upper end of a stay, parcelled ready for serving.

Lower ends of shrouds turned and seized ready for the placement of the deadeyes.

One of the reasons for building a replica is to learn about the problems that the original ship faced. Another is to keep skills from being lost to history.

the stay. The entire spindle eye, taper and a percentage of the stay is then well tarred, parcelled and served over. The mouse is then raised upon the stay with serving and shaped roughly like a pear. This is then pointed over (a form of weaving) with smaller rope.

The lower ends of standing rigging are always seized around a deadeye or block rather than spliced. This allows adjustments to be made to the length of the rigging, if required over time, as well as maintaining the strength of the rope. A splice weakens the rope, whereas seizings do not. Where blocks or deadeyes are turned in, there is always a minimum of three seizings. They are the throat seizing (closest to the block or deadeye), middle seizing and end seizing. The end of the rope is whipped and cut off close to the end seizing, and then has a tarred canvas cap placed over it to prevent it from absorbing water.

Next, the lower ends of stays and shrouds are marked and are turned and seized ready for the placement of the deadeyes. In the standing rigging alone, there are almost 500 seizings and approximately 400 metres of serving. If we then add the seizings of ratlines and all the other components such as futtock staves, futtock shrouds and catharpins, the number of seizings comes closer to 1,000. If all of the blocks and components employed in the running rigging are included, this figure can easily be doubled again.

The eyes for the larger stays are constructed a little differently, so they can be replaced without housing or removing the topmasts and topgallant masts as is necessary for the replacement of the shrouds. The stays have a small eye, called a spindle eye, in the upper end. Once the eye is passed around the mast, the bitter end (tail) of the stay is passed through it and the loop is pulled up tight until the eye comes to rest on a rope bulge that is made on the stay, called a mouse.

The eye is too small to accommodate a secure splice. It is made by firstly unlaying several feet of the rope right back to its individual yarns. A round piece of timber referred to as the spindle has two bulges raised upon it with spun yarn, to act as a cradle for the yarns when they are individually taken over it and halfknotted to one another. The yarns are then tapered down and laid back along

Once the rigging is completed and placed into service upon the ship, the focus changes to full-time preservation. The number-one enemy is chafe, held at bay by the addition of leather, rope mats and additional lengths of serving. The rig requires regular retensioning until it settles in, and tarring is constant. Add to this the oiling and upkeep of nearly 700 blocks, eight kilometres of running rigging, 30 spars (masts, yards and booms) and 10,000 square feet (930 m2) of canvas that make up Endeavour’s sails. It is little wonder that the original Endeavour carried a sailing crew of 60 seamen.

You may wonder why we bother with all this detailed work that most people will never notice, when there are stronger, longer-lasting synthetic products that could be used instead. One of the reasons for building a replica vessel is to learn about the problems that the original ship faced in its construction and components. Another is to keep skills that modern technology has superseded from being lost to history. We gain insights into the evolution of the sailing vessel, and build an appreciation for the men who built and sailed these impressive ships.

Author Anthony Longhurst is a leading hand, shipwright and rigger with the museum’s Fleet team. His involvement with tall ships began in 1986 at age 13 and from 1995 until 2000 he sailed the world on the HM Bark Endeavour replica as a watch leader, shipwright, sailmaker and boatswain. Anthony’s involvement with Endeavour continued in 2005 when she came under ANMM management.

Futtock shrouds

Stave

Catharpins

Standing rigging: Ropes that remain fixed, used to support the masts – shrouds, stays, backstays etc.

Running rigging: The ropes leading through various blocks, and to different places of the masts, yards, sails, and shrouds, which are moved according to the various operations of navigation. Running rigging includes lifts, braces, sheets, tacks, halyards, clewlines, buntlines, leechlines, bowlines, spilling lines, brails, downhauls etc.

Shrouds: A range of large ropes, extended from the mastheads to the port and starboard sides of the vessel, to support the masts laterally.

Stays: Strong ropes to support the masts forward, extending from the masthead towards the fore part of the ship. The stays are named according to their respective masts: lower stays, topmast stays, topgallant stays.

Backstays: These support the topmasts and topgallant masts from aft. They reach from the heads of the topmast and topgallant mast to the channel on each side of the ship, and assist the shrouds when strained by a press of sail.

Deadeyes: Round blocks with three holes, fitted at the ends of standing rigging. Lanyards threaded through the holes of a pair of deadeyes allow for adjusting and tensioning the rigging once it is on the ship.

Splicing: Joining one rope to another, by interweaving their ends, or uniting the end of a rope into another part of it. The eye splice forms an eye or circle at the end of a rope on itself, or round a block. The cunt splice or cut splice forms an eye in the middle of a rope. The long splice rejoins a rope or ropes intended to reeve through a block, without increasing the rope’s diameter. The short splice is made by untwisting the ends of a rope, or of two ropes, and placing the strands of one between those of the other. Other specialised splices exist.

Seizing: The joining together of two ropes, or the two ends of one rope, by taking several close turns of small rope, line, or spun yarn round them.

Serving: Encircling a rope with small rope, line or spun yarn, for all or part of its length, to preserve it from being chafed.

Worming: Winding a rope close along the cuntings or contlines (the groove between the strands), to strengthen it, and make a fair surface for parcelling and serving (qv).

Parcelling: Wrapping worn canvas around ropes, to prepare them for serving.

Whipping: To encircle the end of a rope with multiple turns of thread, to prevent its unravelling.

Adapted from Steel’s Elements and Practice of Rigging and Seamanship, 1794

Tayenebe Tasmanian Aboriginal women’s fibre work

Tasmanian Aboriginal women and girls have revitalised the fibre skills of their ancestors, in an exhibition from the Tasmanian Museum and Art gallery that demonstrates unique connections with the land and sea. Andy Greenslade, curator at the Tasmanian museum’s partner organisation the National Museum of Australia, describes the cultural significance of these ancient practices.

As I ease up the drive of one of the cottages at Larapuna, in the Mt William National Park in north-eastern Tasmania, there’s little sign that a big workshop is in progress here. The stiff breeze coming off Bass Strait has a bite to it, and despite the clear and sunny skies, the air is distinctly chilly. Inside the cottage, a group of women sits in a circle weaving, in easy conversation – the state of the fibres, the evenness of the weave, the latest stand of grasses to be collected.

This is the last of seven workshops that make up tayenebe, a project to revive traditional weaving practices in the Tasmanian Aboriginal community.

A collaboration between Arts Tasmania, the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, and the National Museum of Australia, the workshops have been held at different locations across Tasmania, with over 30 women and girls attending each group.

This 10-day workshop is the longest and most ambitious, yet it has a very high participation rate. Everyone is determined to continue their weaving after the workshop finishes, but from now on it will be within their circle of friends and families.

There is a powerful atmosphere here. This is the last workshop and there is a desire to get the very best out of it. It is the only workshop held on traditional country for the majority of participants. It has been an emotionally charged time, because news arrived during the workshop of the passing of Auntie Muriel Maynard. An important and respected elder, Auntie Muriel’s interest, commitment and love of weaving were strong. She was a fine weaver. Although too unwell to participate fully in tayenebe, Auntie Muriel supported its aims. As a measure of their respect, the weavers

[Weaving] tells me a lot about our early people, about our mothers and their families and their movements in the seasons

Audrey Frost, weaver

jointly created a basket, each completing two or three rows with their individual styles and skills.

The purpose of tayenebe springs from pioneering work begun by Alan West in the early 1990s. Former curator and now research associate at the Museum of Victoria, West started researching the plants and weaving techniques of baskets made in the 1800s.

Building on West’s work, Jennie Gorringe, an arts worker at the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre, became involved in one of the first efforts to revive traditional fibre skills. Gorringe arranged events and camps for local women, inspiring them to become engaged in weaving practice. Then in 2005, Moonah Arts Centre held an important exhibition by three skilled weavers: Eva Richardson, Colleen Mundy and Lennah Newson. Sadly, Lennah Newson passed away before tayenebe began, but perhaps her passing gave it greater impetus.

This groundwork was important in reviving the tradition, but expertise was still not widespread, and some traditional methods remained undiscovered. Tayenebe sought to address this. Based on a workshop format conceived by Arts Tasmania’s Lola Greeno, the project sought to revive many of the old ways across different locations and with a mix of participants. This approach led to a depth and variety in the reinvigoration of the tradition. For example, variations in plant stocks in the different locations influenced the weaving works – the use of sea plants as well as land plants resulted in a revival of the use of bull kelp for containers.

‘Tayenebe’ is a south-eastern Tasmanian Aboriginal word meaning ‘exchange’ – appropriately, since the success of the project depended on sharing and exchanging many sources of knowledge and experience. Although the historical baskets

in museum collections contained information vital to reproducing the exact style, they contained much more than technical data. The women who studied these precious objects saw them as a link to the Old People, a manifestation of the women who made them.

Only 37 baskets and fibre works from the 1800s survive in collections today. Of these, only five are by known makers – two by Trucanini and three by Fanny Cochrane-Smith. The rest are likely to have been made by some of the 70 women resettled at Wybalenna on Flinders Island and later at Oyster Cove south of Hobart from 1835 to 1874, having been taken there by George Augustus Robinson. Unlike these earlier weavers, the women who took part in tayenebe will not be unnamed.

Over 100 baskets were created during tayenebe, and 70 of these are on display in the exhibition. Some have a traditional purity of technique and material and sit eerily alongside the old baskets, the time between their making seemingly evaporating. Others are contemporary in style, the material often dictating the final form. Still others are experimental in their combination of materials or expression of ideas.

Materials are used to illustrate connections to wider culture.

For example, the addition of a strand of fibre in a twisting figure of eight by Vicki maikutena Matson-Green reflects the flight of the moonbird, or mutton bird, which was thought to fly to the moon before returning to its nesting ground the next season. The inclusion of a swirl of maireener shells on the inside of Patsy Cameron’s basket creates a vortex representing the Milky Way, the materials and design creating connections between the land, sea and sky.

There are examples of unique Tasmanian Aboriginal kelp containers. These have the leather look of the dried sea plant, warm in tone and shiny,

above: Eva Richardson, Water carrier, 2005. Bull kelp (Durvillaea potatorum), tea tree (Melaleuca sp.), river reed (Schoenoplectus pungens).

opposite: Tasmanian Aboriginal baskets of white flag iris (Diplarrena moraea). Left to right: by Vicki maikutena Matson-green, Patsy Cameron (also second from right), Dulcie greeno, Audrey Frost. Photographer Simon Cuthbert, TMAg

its curved forms belying the firm and brittle nature of the dried fronds. There is no known kelp container in Australian collections, so the shape of these containers was informed by prints from Baudin’s voyage of exploration (1800–1804), and an image of a container (about 1850) held in the British Museum. These records show differing versions of the form.

A viewing of this subtle and elegant exhibition makes it clear that the works are not merely the product of weaving tutorials focusing on technique alone. Rather, they are suffused with ideas, speculations and connections.

The weavers state their strengthened link to culture through the act of weaving, walking the country in search of fibres, and knowing that they are pursuing a process that was once an everyday part of life for their ancestors.

The author is indebted to curator Julie g ough for permission to draw freely on her 2009 exhibition catalogue. This Tasmanian Museum and Art gallery travelling exhibition appears in our North gallery from 26 March to 8 May 2011. It is supported by Visions of Australia, an Australian g overnment program that assists the development and touring of cultural material across Australia. With thanks to the National Museum of Australia for permission to reprint this edited version of an article that appeared in Friends magazine (June 2010).

Bridging troubled waters

As ANZAC Day once more focuses on the exploits of Australians at gallipoli during World War I, a recent acquisition of personal memorabilia belonging to a veteran of Suvla Bay draws attention to a littleknown but much-decorated Australian naval unit.

Inspired by the Douglas Ballantyne Fraser collection, curator Peter Gesner has researched the story of the 1st Royal Australian Naval Bridging Train.

Australia’s role in World War I has been thoroughly researched and extensively written about. The units that served at Anzac Cove, in the Middle East and on the Western Front have received close attention and admiration for their heroic deeds and sacrifice. Yet the achievements of one small naval engineering unit have been relatively unheralded. It was called the 1st Royal Australian Naval Bridging Train, a specialist unit whose task was building piers and bridges in combat zones, and it was one of the most decorated Australian naval units of the war. Its commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander Leighton Bracegirdle, was awarded a Distinguished Service Order (DSO) and another 20 men were decorated for their service. Their skills and very effective work output contributed to the sound reputation for competence, bravery and doing an exceptional job, that they quickly came to enjoy among British and Commonwealth troops fighting at the Suvla Bay beachhead, some five miles (9 km) north of Anzac Cove. Yet, oddly, their presence there was generally unknown among the ANZAC troops.

A recent acquisition of personal memorabilia has highlighted the service of a member of this much-decorated though little-known unit.

Douglas Ballantyne Fraser (1895–1975) was a reservist in the Royal Australian Naval Brigade who was called up at the outbreak of war and subsequently volunteered for the 1st Royal Australian Naval Bridging Train. He served overseas in Gallipoli (Suvla Bay), along the Suez Canal and in Palestine from June 1915 to May 1917. His daughter, Mrs Helen Clift

of Cremorne, NSW, has donated a collection to the museum including a personal war diary, medals and campaign ribbons, insignia, letters, papers, maps, photographs, news clippings and postcards that mainly reflect Douglas Fraser’s service at Suvla Bay and in Egypt. The collection also sheds light on aspects of his life and interests after the Great War, which he was fortunate enough to survive physically unscathed.

The 1st Royal Australian Naval Bridging Train (1st RANBT) was officially formed on 24 February 1915. Its members were naval reservists from the Royal Australian Naval Reserve and came from all over Australia. Almost to a man they were skilled in some technical aspect of the wide range of trades they represented. They included master mariners and engineers as well as stokers, boilermakers, carpenters and hard-hat divers. They set up training camp in the Domain Gardens in Melbourne and, partially supervised by Australian Army engineers, started their training in bridging operations there. Here they also received – loaded on horse-drawn carts and wagons – their first pontoons, built in Sydney at the Cockatoo Island naval dockyard.

The designation of ‘bridging train’ in the title of Douglas Fraser’s unit refers to its origins as a mounted logistics unit, equipped with some 60 pontoons carried on horse-drawn wagons – in other words, a wagon train.

The pontoons and the carts and wagons carrying them were based on designs and specifications that had been perfected by British Royal Engineers (RE) Corps officers in the late 1860s. Pontoon or bridging units had evolved

in the course of 19th-century warfare, but their origins can be found in even earlier conflicts. The RE Corps had been formed in 1716 from a unit called the Ordnance Train that had been with the British forces in Flanders, fielded against Louis XIV’s armies in the 1690s.

During Britain’s 19th-century imperial wars – conflicts such as the 1st Sikh War (1846), the Zulu War (1879) and the Boer War (1899–1901) – bridging operations were mainly carried out by troops from the Royal Engineers’ Bridging Battalion. They frequently operated with additional support from naval brigade troops. These were naval officers and ratings called upon by the Army for their special skills, for instance, as signalmen and roperiggers and as auxiliary light infantry to operate, guard and protect bridges and ferries (so-called ‘ponts’) built by the Bridging Battalion. During the Zulu War, naval brigade contingents helped save the day for hard-pressed British army units struggling to contain thousands of spearwielding Zulu warriors defending their homeland in Natal province against British and Afrikaner colonisation.

When the 1st RANBT was being formed in early 1915, RE Corps units –popularly referred to as ‘pontoon troops’ – were already operating with the British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front. The intention was that the similarly modelled and resourced 1st RANBT would be seconded to the Royal Naval Division’s battalions fighting on the Western Front, to perform comparable services to those being carried out by the RE’s pontoon troops. Their engineering skills were much sought-after, especially as the military

Incoming Turkish artillery fire was a daily occurrence but, miraculously, only two men were killed by it … however, 60 men were wounded

campaigns were increasingly becoming bogged down in the mud of Flanders and north-western France.

Douglas Ballantyne Fraser joined the Royal Australian Naval Brigade (RANB) as a 16-year-old in 1911. Upon the outbreak of war, being in the Naval Reserve –the RANR, as the RANB had by then come to be designated – Fraser was called up to serve as a signalman on the Sydney Harbour pilot vessel Captain Cook III His job on board included signalling to the Army’s gun battery on South Head to direct fire if necessary on ‘any suspect vessel leaving Sydney failing to heed directions to stop’ and board them for ‘examination’, as he related many years later in an article published in Navy News

In the first week or so of war two of our own coasters were smartly stopped by shots across the bows for ignoring our signals and one German tramp was arrested by a boarding party delivered by us between the Heads, they being quite unaware there was a war on… It must be remembered that very few vessels carried wireless in those days! (Douglas Fraser, Navy News, 27 October 1961)

Six months later Fraser – by then promoted to Leading Seaman –volunteered for overseas service by joining the 1st RANBT. After several months spent training in Melbourne, the unit departed on 3 June 1915 in the transport SS Port Macquarie. The men would soon distinguish themselves as members of a highly effective engineering and logistics unit.

Although initially bound for the Western Front via England, the unit was diverted en route and directed to Lemnos, a Greek island in the Northern Aegean, with revised orders to support the imminent Allied landings at Suvla Bay on Gallipoli. In his diary on 18 July 1915 Fraser noted that he was ‘disappointed’ they would no longer be going to England.

After arriving in Lemnos, Fraser and his companions received five days of intensive training in pontoon-bridge

and pier construction on nearby Imbros Island. On 6 August 1915 they boarded SS Itria which took them to Suvla Bay where, 24 hours later, following the British assault troops that had gone ashore before them, they landed under heavy fire. Suvla Bay was nearly five miles to the north of the Australian and New Zealand battalions fighting at Anzac Cove. The RANBT’s talent for pontoon-bridge and pier building was evident from the moment they landed. Having been ordered to ‘Old A’ beach to install a pontoon pier, they quickly secured it and, within 20 minutes, British wounded were being evacuated from the pier to hospital ships offshore.

Based at a campsite called Kangaroo Beach, 1st RANBT continued its operations in Suvla Bay until midDecember 1915. During this time it was responsible for a variety of logistics tasks that included building and maintaining wharves and piers, unloading stores from lighters and delivering and controlling a drinkable water supply. Incoming Turkish artillery fire was a daily occurrence at Suvla Bay but, miraculously, only two men were killed by it. However, 60 men were wounded and several others died from illness or accident.

The Gallipoli beaches from 6 Aug 1915 to 19 Dec 1915 were not exactly ideal pleasure resorts but some of us had occasional diversion sneaking out at night in a 10 foot pontoon section to one of the battleships or cruisers in Suvla Bay and invariably getting a great welcome, much rum and tobacco, and welcomed tinned food from the canteens. (Douglas Fraser, Navy News, 27 October 1961)

Eventually the decision was made to evacuate all of the Allied forces from Gallipoli, including the troops at Suvla Bay. Evacuation of the RANBT started on 17 December and most men had left by the evening of 18 December 1915. Fraser mentions destroying pontoons and buoys with a party of men before embarking on a steamer with ‘about a thousand Tommies’ and ‘we lay in heaps on the decks where movement was impossible, and those between midships and the scuppers were made painfully aware of the inexorable law of gravity’. (Douglas Fraser, Navy News, 27 October 1961)

His party was not the last to leave. A 50-man squad from the 1st RANBT had been sent to Lala Baba Beach to guard the wharf from which the British rearguard would be leaving the beachhead. The men, under Sub-Lieutenant Hicks, guarded the wharf until the rearguard’s

top: Douglas Ballantyne Fraser in RANBT uniform, 1915 – an Army uniform with naval insignia. Probably Melbourne, two days before the RANBT shipped out. bottom: Douglas Ballantyne Fraser (left) poses for the classic World-War-I souvenir photograph –servicemen on camels at giza outside Cairo, Egypt.

departure and, after wrecking its pontoons and setting fire to stores and equipment abandoned on the beach, they also left. It was 4.30 am on 20 December 1915. They were therefore the last Australians to leave the Gallipoli Peninsula, 20 minutes after the last Light Horse troops left Anzac Cove. Fraser mentioned seeing a ‘big fire at Anzac’ as they steamed for Lemnos.

Following the evacuation from Gallipoli, the RANBT was deployed to Egypt in February 1916 to guard, operate and maintain pontoon bridges across the Suez Canal. Before their posting to the Suez Canal, however, the RANBT had a month’s rest on Lemnos, which Fraser noted on 20 December 1915 as being ‘under canvas’ and ‘almost like civilization – nurses, football, cricket, canteens and Australians’. According to Fraser’s reminiscences more than 40 years later, Lemnos was also where they ‘made first contact with the 1st and 2nd Australian Divisions from ANZAC, which occasioned a reunion with brothers, relatives and Australian cobbers in those two Divisions’ (Navy News, 27 October 1961). Fraser’s elder brother was serving in an AIF battalion at Anzac Cove.

On Lemnos the unit’s initiative was demonstrated again when they acquired ‘by means which cannot be related… a perfectly good 16-foot clinker-built bumboat’ that army bolts of canvas turned into a sailing craft, ‘available to visit daily any of the hundreds of vessels in the magnificent landlocked harbour of Mudros’ for the purposes of obtaining hospitality. This craft would accompany them to the Suez Canal, to be used for similar enterprises (Navy News, 27 October 1961).

During the RANBT’s service at Suvla Bay, Fraser had served as ‘confidential writer’ and signalman for the CO Lieutenant Commander Leighton Bracegirdle, and so was also a member of Bracegirdle’s command staff. After the actions in Gallipoli and along the Suez Canal, he was promoted to Petty Officer and joined a 1st RANBT detachment sent to assist the landing at El Arish on the Mediterranean coast of the Sinai Peninsula in December 1916, in support of the subsequent Allied campaign into Palestine in 1917.

The detachment performed well at El Arish, and it was decided to withdraw the rest of the RANBT from its duties along the Suez Canal and make them available to support the Allied advance into Palestine. They were to be based at El Arish. Before they could all be fully

redeployed, however, they were withdrawn from the Middle East.

The withdrawal was the result of earlier complaints made by some of the men about carrying out menial, non-combatant work, and feeling their skills were being under-utilised along the Suez Canal. There had also been reports about mutinous behaviour in Lemnos, when 189 men had failed to fall in at morning parade after not receiving pay for almost six weeks – an action for which they were subsequently absolved by the naval Commander-in-Chief in the Eastern Mediterranean. Politicians in Australia had investigated the matters and the result was a decision by Federal Parliament to disband the RANBT and allow its members to choose re-enlistment as soldiers in the AIF, to serve in the Royal Navy or to return to Australia.

On 27 March 1917 the 1st RANBT was officially disbanded. Seventy-six men from the unit elected to transfer to the AIF (most went to artillery units, following another 80 men who had been allowed to transfer in February); 43 men elected to serve with the Royal Navy; while 187 men, including Fraser, opted to return to Australia to consider their future. On 29 May 1917 they embarked at Suez on HMAT Bulla, bound for home. The unit arrived in Melbourne on 10 July 1917 and was dispersed.

Upon demobilisation, Fraser joined the NSW Registrar General’s Department (opposite St Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney) and also read Law at Sydney University. He was awarded a Bachelor of Laws in 1924 and then qualified as a solicitor, a profession he practised until retirement in the late 1950s. He kept in touch with fellow RANBT veterans and was an active member of the 1st RANBT Association; his efforts in this respect were apparently much appreciated by his peers as he was twice awarded the association’s Distinguished Service Cross. In 1965, on the 50th anniversary of the Gallipoli campaign, Fraser returned to Mudros and Gallipoli with a group of veterans of both wars, on an extensive tour that included the World-War-II battlegrounds Tobruk and Alamein.

Fraser’s postwar interests included a love of tall ships and he was also active in amateur theatre. These civilian-life interests are reflected by some of the material in this collection. There is a large album of newspaper clippings recording arrivals and departures of the last of the windjammers. The collection also contains a paperback copy of R G Sherriff’s play Journey’s End (1929), which

This may well have contributed towards the characterisation of the typical Australian digger as effective, practical, big-hearted, easy-going, unpretentious and irreverent

above: Suvla Bay at gallipoli. The annotated newspaper clipping has RANBT landing places penned in by Douglas Ballantyne Fraser.

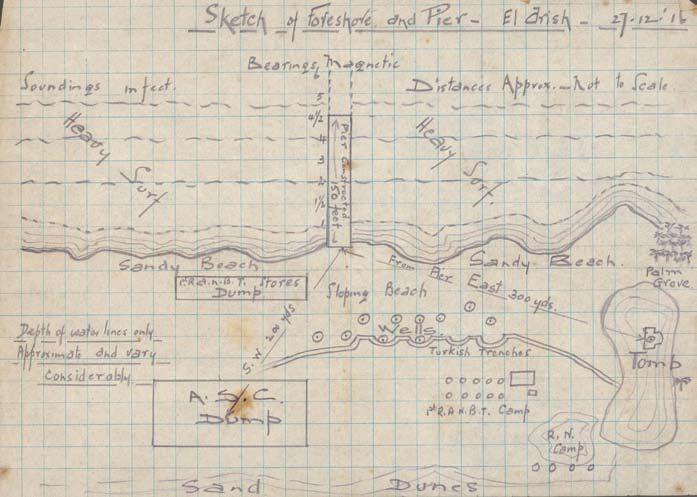

above left: Sketch map drawn by Douglas Ballantyne Fraser showing the pier built on the beach at El Arish, December 1916

left: Imperial origins of the bridging train lay in Britain’s colonial wars. The Zulu War: Colonel Pearson’s column crossing the Tugela, Illustrated London News, 1879, Saturday 8 March. Reproduced courtesy of Powerhouse Museum

Fraser most probably used when learning lines to play the part of 2nd Lieutenant Raleigh in a 1933 production of this play, a best-selling and award-winning, antiwar work. Like Fraser, the rest of the actors were also former servicemen. The production was staged as a fundraiser at the Empire Theatre in Goulburn by the Goulburn Diggers amateur theatre group, in aid of the Graythwaite Home for convalescent World-War-I servicemen in North Sydney.

An ongoing interest in the logistics involved in seaborne military assaults is also apparent: in the collection are three booklets from the French series Les Grandes Heures de 1939–1945. The booklets describe the Allied invasion of Normandy during World War II and include pictures and descriptions of the beachhead docking facilities, including the prefabricated pontoons that made up Mulberry Harbour. These were put in place by Allied naval engineers to land the huge numbers of Allied troops and the millions of tonnes of equipment, fuel, ammunition, vehicles and supplies needed to defeat the German Army during the ensuing Battle of Normandy.

Fraser may have been in awe – and perhaps even a little envious – of the nighunlimited resources apparently made available to the World-War-II Allied beach-masters and the engineering and logistics units in Normandy. It must also have given him considerable satisfaction to see that the tactical lessons of the Gallipoli campaign – the folly of carrying out poorly equipped and inadequately resourced and supported seaborne assaults on well-defended coasts – had apparently been learned by World War II’s Allied military planners. With similar logistical support the ultimate objective of the Gallipoli campaign – the capture of Constantinople – may well have been achieved.

Among the newspaper clippings of the Fraser collection is one describing the exploits of two men in the 1st RANBT, which was described as ‘as queer a unit as was ever devised’ by its author George Blaikie. In this unattributed and undated clipping headlined ‘Sailors all at Sea’, Blaikie relates a story of two RANBT ratings who were absent without leave from their camp one afternoon. Unbeknown to their officers, they had gone off to engage in some ‘sport’, in other words stalking and shooting Turkish soldiers in retribution, so they argued, for being incessantly shelled by Turkish artillery. During this episode on the front line they saved the life of

a wounded English stretcher bearer serving with the British Army’s 32nd Field Ambulance, based near the RANBT’s camp. They had found the wounded man pinned down by Turkish snipers in No-Man’s Land and, having dealt with the snipers, they rescued the wounded man and returned him to a casualty station in his camp.

The RANBT men requested that their heroic deed remain anonymous because they were keen to avoid sparking off an enquiry into how they had come to find the wounded man in the first place, to preempt the disciplinary measures they knew would be taken against them for being AWOL. This story is corroborated in the Suvla Bay reminiscences of a British sergeant in the 32nd Field Ambulance called John Hargrave – later a controversial anti-militarist – whose 1916 published description of this event appear in his memoirs called At Suvla Reports of an incident such as this may well have contributed towards the British characterisation of the typical Australian digger as effective, practical, big-hearted, easy-going, unpretentious and irreverent.

One German tramp steamer was arrested by a boarding party delivered by us between the Heads, they being quite unaware there was a war on

top: A certificate from Douglas Ballantyne Fraser’s employer, the NSW Registrar general’s Department, welcoming him home from war.

bottom: In 1965 these gallipoli veterans including Douglas Ballantyne Fraser spent 21 days on a Turkish steamer visiting war sites including Anzac Cove, on the 50th anniversary of the landing.

opposite: Lyndon O’grady, the Australian Maritime Safety Authority’s senior technical officer responsible for heritage aspects of lighthouses and artefacts for 388 sites Australia-wide. Photograph courtesy of AMSA

The story of a lost 19th-century lighthouse lens, a former intern’s detective skills and a unique wedding emerged from the 2010–11 Maritime Museums of Australia Project Support Scheme – MMAPSS for short! MMAPSS coordinator Clare Power relates another success story from the museum’s long-running grants program.

The Cape Wickham Lighthouse was built in 1861 at Currie, King Island. Standing 48 metres high, it is Australia’s, and the southern hemisphere’s, tallest lighthouse. John Ibbotson’s Lighthouses of Australia (2001) notes that King Island was often the first land that a ship encountered after departing England several months, and some 20,000 kilometres, earlier. The lighthouse was established as a response to the many shipwrecks that occurred along the King Island coast, including the catastrophic sinking of the Cataraqui in 1845, with 406 lives lost.

In 1946 the original fixed lens was removed from the lighthouse to convert Cape Wickham into a rotating light.

The lens was placed in storage for four years, and was then installed in the Point Quobba Lighthouse in Western Australia. This was unusual, as a lens of this size is not often reused. The lens remained at Point Quobba until the site underwent an upgrade in 1988 and was converted to low-voltage solar operation. Again, the lens was removed and placed in storage, where it remained for more than two decades.

Today the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) provides maritime and navigation services that can be traced back to the establishment of the Commonwealth Lighthouse Service (CLS) in July 1915, after the proclamation of the Lighthouses Act 1911. The CLS eventually came to assume responsibility for all the lighthouses in Australia. Today, the Navigation Safety section of AMSA is all that remains of the old CLS. Lyndon O’Grady, the section’s senior technical officer, is responsible for heritage aspects of lighthouses and artefacts for 388 sites Australia-wide. The AMSA heritage artefacts collection dates from the 1850s and includes over 1,000 individual objects.

MMAPSS

The Australian National Maritime Museum offers grants of up to $10,000 to non-profit regional museums and organisations to help them preserve Australia's rich maritime heritage. The grants fund projects in the following categories:

• Managing a collection (including registration, storage and research)

• Conservation (for example, documenting and caring for collections, developing methodology)

• Presentation (exhibition design, interpretation)

Our grants program, the Maritime Museums of Australia Project Support Scheme, is jointly funded by the museum and the Australian g overnment. Since 1995, the scheme has given more than $850,000 to organisations in Queensland, New South Wales (including Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands), Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory.

All non-profit maritime museums and historical organisations are encouraged to apply. We also welcome joint applications from two or more eligible institutions. The grant funding may be used to supplement other funding, including sponsorship. Applications for the 2011–12 round of grants will open in 19 August 2011. For information contact the museum or visit http:// www.anmm.gov.au/mmapss.

Not only is the Cape Wickham Lighthouse our tallest, it also has the first lighthouse lantern room in Australia in which a marriage ceremony has taken place

below: A component of the original Cape Wickham Lighthouse lens discovered in storage. Photographer Lyndon O’grady

bottom: Memorable moment for Lyndon and Stephanie, Tess, Ella and and Rohan at Cape Wickham Lighthouse, King Island. Photograph courtesy of Lyndon O’grady

In 2008, Lyndon received one of this museum’s MMAPSS professional development internships. During his stay he worked with our fleet, conservation and registration sections, enhancing his skills in the packaging of artefacts for transportation, conservation principles and cataloguing methodology. Along with practical skills, Lyndon has developed close working relationships with many staff members of the Australian National Maritime Museum.

On his return to AMSA Lyndon applied his new-found knowledge to undertaking a large-scale collection management project that included cataloguing the AMSA heritage collection, a tagging program, photographing every artefact and ensuring the correct display and labelling of all objects. To examine them, Lyndon had to visit each site where AMSA artefacts are on loan. This means Lyndon has visited nearly every maritime museum in Australia!

In 2009 Lyndon completed an audit of 40 pallets of artefacts on loan to the Western Australian Maritime Museum, located in their vast offsite storage facility. This audit raised many questions, as most of these AMSA objects were without recorded provenance. One item that stood out, due to its sheer size, was a large lighthouse lens with its many component pieces packed on 22 pallets.

When he inspected the boxes and their contents, marked as ‘Lens Point Quobba’, something didn’t seem quite right. The Point Quobba light was first lit in 1950 and the lens he was inspecting was of a much earlier type. Lyndon noted that by 1950 ‘no one was making the beautiful large glass lenses anymore’. Also unusual was the lens’s manufacturer, H Wilkins & Co, which supplied very few lenses to the Australian market. Curious, Lyndon contacted his friend Garry Searle from the heritage organisation Lighthouses of Australia, who set about researching the matter. Their investigative efforts narrowed the lens down to a small number of possible sites of origin. These were then cross-checked against the AMSA register of over 10,000 technical drawings of lighthouses. The lenses in the pallets in Western Australia and the drawings of Cape Wickham Lighthouse were an exact match. As the lens had been built specifically for the Cape Wickham lighthouse, no other lens of this type existed; it is unique in all of Australia.

The lens appears to be in good condition and it was decided that it should be returned to Cape Wickham,

entrusted to the care of the King Island Historical Society. AMSA offered to meet the expenses of transporting the prisms to Melbourne, provided that the complete lens was suitably displayed in time for the 150th anniversary of the inauguration of the light. A lighthouse’s birthday is celebrated on the day the light was first lit. For Cape Wickham that day is 1 November 2011.

MMAPSS awarded the King Island Historical Society $6,589 to refurbish a display room to house the lens, alongside the lighthouse. The society has set about planning celebrations to mark the 150th anniversary of the light.

AMSA will open the lighthouse for public access for four days to mark this special occasion, including special tours for school children. It has also had a commemorative brochure and takehome model made.

In a lovely footnote to this tale, there is another record Cape Wickham Lighthouse holds. Not only is it our tallest lighthouse, it also has the first lighthouse lantern room in Australia in which a marriage ceremony has taken place!

On 17 December 2010, Lyndon and his partner Stephanie married, with their three children (Rohan, 7, Tess, 5, and Ella, 2) and Stephanie’s parents, Patricia and Brian, present. Lyndon had to seek permission from the CEO of AMSA and the responsible Minister to conduct the ceremony there, and this is believed to be the first time in the history of the Commonwealth that such permission has been granted.

The lighthouse-loving family chose Cape Wickham because it is the tallest lighthouse, because of the beauty of the rugged King Island coastline, and because of the hospitality they have always received from the King Island residents.

In recognition of Lyndon’s work managing and preserving Australia’s lighthouse heritage he was awarded the Outstanding Achievement Award in AMSA’s 2011 Australia Day Awards. ‘In performing this role, Lyndon has consistently gone above and beyond what would be expected of someone performing these duties,’ AMSA CEO Graham Peachey said. ‘His heritagerelated work is fitted in around his dayto-day aids to navigation maintenance contract tasks, and this award recognises Lyndon’s sustained efforts not just throughout 2010, but over a number of years.’

With thanks to Lyndon O’grady for his help with this article.

2010 MMAPSS awards

Do you work with community maritime heritage, in a local history association or museum? Look at the projects that gained MMAPSS awards this year, and ask yourself if your project could be listed here next year. For information visit www.anmm.gov.au/mmapss

Krawarree Project Inc, Mudgeeraba QLD $8,500

For a conservation assessment of the historic army hospital vessel Krawarree AH1733.

Albury City Council, Albury NSW $6,000

For The Murray River Experience research and heritage interpretation project.

Lady Denman Heritage Complex, Huskisson NSW $8,000

For the restoration of the forward saloon of the historic ferry Lady Denman Museum of the Riverina, Wagga Wagga NSW $5,225

To conserve the lifesaving reel and men’s one-piece Speedo swimsuit from the Wagga Wagga Surf Life Saving Club collection.

Narooma Lighthouse Museum, Narooma NSW $8,000

For the Narooma Lighthouse Museum upgrade.

Norah Head Lighthouse Reserve Trust, Toukley NSW $8,000

For the restoration and conservation of semaphore flags including archival storage.

Norfolk Island Museum, Norfolk Island NSW $6,400

For the high-priority conservation of objects from First Fleet flagship HMS Sirius

Port Stephens Historical Society, Nelson Bay NSW $1,700

To remount and reframe photographs for the Inner Light Museum Make-over project.

Shoalhaven Historical Society, Nowra NSW $957

To conserve a pocket compass.

Echuca Historical Society Inc, Echuca VIC $5,390

For a preservation-needs assessment and preservation/disaster planning workshops.

Port Albert Maritime Museum Inc

Gippsland Regional Maritime Museum, Port Albert VIC $2,231

To digitise and copy two significant books.

Queenscliffe Maritime Museum, Queenscliff VIC $4,871

For a significance assessment of the museum’s collection to aid participation in the Museum Accreditation Program.

The Maritime Trust of Australia, Castlemaine VIC $8,000

For the restoration of the 27-foot Montague whaler wooden pulling boat.

King Island Historical Society, Currie TAS $6,589

To transport the Cape Wickham Lighthouse lens from Melbourne to King Island, and towards the refurbishment of the lens’ display room (see article on pages 22–25).

Maritime Museum of Tasmania, Hobart TAS $8,000

Towards the restoration of the doghouse and companionway of the historic yacht Westward

Wooden Boat Guild of Tasmania Inc, Battery Point TAS $6,400

For the project Tasmanian Piners Punts – History, Design and Heritage.

Spring Bay Maritime and Discovery Centre, Triabunna TAS $2,500

For conservation treatment of convict boat pieces.

National Trust SA Willunga Branch, Willunga SA $2,565

To upgrade the exhibition of relics from the Star of Greece shipwreck.

South Australian Maritime Museum, Port Adelaide SA $6,000

For an oral historian to identify interviewees linked to the Nelcebee’s history, compile a list of relevant questions in consultation with curators at SAMM and conduct and record 15 interviews.

Carnarvon Heritage Group Inc, Carnarvon WA $9,740

For a shelter structure to aid the preservation of the historic vessel Little Dirk

FRIDAY, 21 OCTOBER

Members

Tall ships come and go News

grey skies on Boxing Day didn’t dampen the excitement of the Sydney–Hobart yacht race start for Members who enjoyed the buzz on the harbour.

Photographer: Member Brian Rule

Members enjoyed the colour and fun of Australia Day harbour festivities on two vessels, luxury cruiser MV Bennelong and heritage ferry MV Radar (Radar appears at the centre of the photograph, below right).

Our guests got stirred up in the wash of the famous Ferrython, the spectator fleet, the tall ships and enjoyed Navy and Air Force flyovers as well.

Photographer: Member Bronwyn gault

A special welcome to all new Members who joined up over the summer months. Another lively year of activities and events is unfolding here and you can be assured of stimulation, entertainment and fun... as the following pages of autumn events reveal.

In shipping news, our replica of HMB Endeavour is closed to visitors as she readies for her circumnavigation of Australia beginning in April this year. The first port of call will be Brisbane, followed by gladstone, Townsville, Cairns and Darwin. There are still berths available on some of the legs of this voyage. We are also on the lookout for volunteer guides and overnight shipkeepers for some ports of call. If you would like to be involved please contact the volunteers office or visit our website to register your interest. Don’t miss our Endeavour farewell cruise on Saturday 16 April – see page 30 for details.

The good news is that as one magnificent replica leaves, another arrives! As I write we’re getting ready to welcome the replica of Duyfken (‘Little Dove’), the 17th-century Dutch scout ship or jacht that made the first recorded landing on the Australian continent in 1606 under her master Willem Janszoon. He made the earliest known chart of Australian coastline and this was the first European encounter with Aboriginal Australians. Members will be able to visit her free of charge. Stand by for

related programs and activities – including a chance to sail on her.

Our summer attraction Planet Shark –Predator or Prey, The Exhibition, which is closing as Signals goes to print, was an exciting success. Still proving popular is the exhibition On their own – Britain’s child migrants, which continues until mid May, and as a farewell to it we’re hosting highprofile author David Hill – details are on page 31. Then see page 34 for more about the fascinating exhibitions coming in autumn.

The next big visiting exhibition will be coming our way in June from the Natural History Museum in London and Canterbury Museum and Antarctic Heritage Trust in New Zealand in June. Scott’s Last Expedition brings the story of Captain Robert Falcon Scott who led two expeditions to the Antarctic. During his ill-fated second venture in 1912, Scott was beaten to the South Pole by Norwegian Roald Amundsen; on the return Scott and his four comrades all perished from exhaustion, starvation and extreme cold.

I look forward to welcoming you on your visits to the museum and at our events and activities through the rest of 2011. And please remember, we love receiving feedback and ideas from Members on how we can serve you better, so I encourage you to contact me or any of the Members team if you have any thoughts or suggestions.

Adrian Adam, Members manager

Members events

Calendar Autumn 2011

March

Sunday 13 Seminar: A history of Sydney sea pilots

Thursday 17 Illustrated talk: The floating world of Cambodia

Friday 25 Tour: Wharf 7 collection behind-the-scenes

April

Sunday 3 Day tour: National Museum & Australian War Memorial

Tuesday 12 For kids: Fishing 4 Kids

Wednesday 13 Curator talk and tour: Eora & Tayenebe

Saturday 16 Special: HMB Endeavour farewell cruise

Thursday 21 For kids: ghosts, pizza & pyjama night!

Thursday 28 Tour: garden Island Naval Heritage tour

May

Sunday 1 Talk: HMAS Toowoomba, a year in deployment

Sunday 8 Talk: A brief history of cruising

Sunday 15 On the water: Autumn leaves annual garden cruise

Sunday 21 Double bill: Forgotten Children and Gold with David Hill

Sunday 29 On the water: Vintage model skiff race

Special seminar

A history of Sydney sea pilots

1.30–5 pm Sunday 13 March at the museum

Watsons Bay has long been associated with Sydney sea pilots and their watermen. The first official pilot is named as Robert Watson (appointed harbour pilot in 1811), but pilotage existed before 1805 and some say as early as 1792. The early pilots were commercial operators, but after the tragic loss of the Dunbar near South Head in 1857, the authorities set about improving and regulating the port’s pilotage. Hear the history of the sea pilots and the important job they carry out around the ports of Australia from former pilots John Biffin, Ted Liley and Joe Crumlin, and current serving sea pilot captain Rowan Brownette. Harry Hignett from the UK will provide a European perspective.

Members $20, guests $30. Includes afternoon tea and evening reception

How to book

It’s easy to book for these Members events… have your credit card details handy:

• book online at www.anmm.gov.au/ membersevents

• phone (02) 9298 3644 (business hours) or email members@anmm.gov.au Bookings strictly in order of receipt

• if paying by mail after making a reservation, please include a completed booking form (on reverse of your Signals mail-out address sheet) with a cheque made out to the Australian National Maritime Museum

• if payment is not received 7 days before the event your booking may be cancelled

Booked out?

We always try to repeat the event.

Cancellations

If you can’t attend a booked event, please notify us at least five days before the function for a refund. Otherwise, we regret a refund cannot be made. Events and dates are correct at the time of printing but these may change…if so, we’ll be sure to inform you.

Parking

Wilson Parking offers Members discount parking at Harbourside Carpark, Murray Street, Darling Harbour. You must have your ticket validated at the museum ticket desk.

EMAIL BULLETINS

Have you subscribed to our email bulletins yet? Email your address to members@anmm.gov.au to ensure that you’ll always be advised of activities that have been organised at short notice in response to special opportunities.

Early pilotage at Sydney heads

Illustrated talk

The floating world of Cambodia 6–7.30 pm Thursday 17 March at the museum

In November last year 15 museum members enjoyed a 17-day tour of Cambodia, exploring the country through the fascinating perspective of its maritime history and continuing maritime traditions. Join tour leader Jeffrey Mellefont for an illustrated talk and hear about the group’s experiences on the rivers, lakes and coasts of this fascinating land.

Members $10, guests $15. Includes refreshments

Tour

Wharf 7 collection behind-the-scenes

11 am–1 pm Friday 25 March at Wharf 7

go behind-the scenes in our special Wharf 7 storage areas not open to the public and see where many of the objects from the National Maritime Collection are housed. Hear the stories behind some of the amazing objects and artefacts stored there – many of which have never been displayed. Learn how our preservation lab operates with ANMM conservation manager Jonathan London, who will show objects being preserved and prepared for exhibition. Members only, $15. Includes light lunch after the tour. Limited numbers. Meet in Wharf 7 foyer

Day tour

National Museum of Australia and Australian War Memorial

7 am–7 pm Sunday 3 April

Canberra

A new exhibition opening soon at the National Museum of Australia – Not just Ned: A true history of the Irish in Australia – explores the Irish presence and their extraordinary influence in Australia since the arrival of a small number of Irish convicts, marines and officials with the First Fleet in January 1788. Enjoy a curator-led tour of the exhibition and marvel at the armour of the four Kelly gang members, fragments of the Eureka flag, and the Rajah quilt. Then visit the Australian War Memorial for a tour of the remarkable Anzac Hall gallery.

Members $85, general $99. Includes return luxury coach to Canberra, lunch at the museum and refreshments on board

For kids

Fishing 4 Kids

10 am–12 noon OR 11 am–1 pm Tuesday 12 April at our wharves This workshop teaches children responsible fishing practices. Learn about conservation of fish habitats, sustainable fishing, knot-tying, line-rigging and baiting, casting techniques and handling fish. Find out about the fish that live in and around Darling Harbour – and what they eat. Each child receives a prize and fishing tackle to take home, plus a certificate of achievement. Members $25, general $30. Includes refreshments. Ages 5–12 years (children will be fully supervised by RFT education officers)

Curator talk and tour

Eora & Tayenebe: ancient arts and Indigenous collections

6–7.30 pm Wednesday 13 April at the museum

A group of Tasmanian Aboriginal women have undertaken a determined process of cultural retrieval to reconnect with the ancient crafts of their Ancestors. Tayenebe: Tasmanian Aboriginal women's fibre work showcases handwoven articles made by women in a series of community workshops across Tasmania. Join Tasmanian Museum and Art gallery curator Julie g ough for an introduction and tour of the exhibition. Then examine our own Indigenous collection in the Eora gallery with ANMM curator Lindsey Shaw. ‘Eora’ means 'first people' in the language of the Darug and the exhibition takes us on a journey from Tasmania to Far North Queensland and the Torres Strait, exploring the deep connection of Indigenous cultures with the land and sea.

Members $15, guests $20. Includes refreshments

BOOKINGS AND ENQUIRIES

Booking form on reverse of mailing address sheet: phone 02 9298 3644 fax 02 9298 3660 (unless otherwise indicated). All details are correct at time of publication but subject to change.

Members events

Special

HMB Endeavour farewell cruise

8–11 am Saturday 16 April on the harbour and alongside Endeavour

Join us for a special early morning champagne harbour cruise as we head out to see HMB Endeavour pull up anchor and depart from Sydney Harbour on her 15-month circumnavigation of Australia. Join us to say farewell and good luck to the ship and her stalwart company as we follow her to Sydney Heads. A speaker will be on board to provide an historical overview and talk about the voyage ahead, which proceeds up the east coast stopping at Brisbane, gladstone, Townsville, Cairns and Thursday Island. A feature article starting on page 2 discusses some of the perparations that the ship has undergone for this ambitious voyage.

Members $40, guests $50. Includes cruise and refreshments, light champagne breakfast on board. Meet next to HMAS Vampire

For kids

Ghosts, pizza and pyjama night!

5.30–9 pm Thursday 21 April at the museum

Parents and carers can take a well-earned break while our long-time caretaker Spanka Boom leads the kids on a tour of our ghostly ship HMAS Vampire. They’ll find out what really happens in the museum after dark! There’ll be ghost stories, lots of fun activities, and a pizza dinner. Then they can roll out a sleeping-bag, grab a pillow and lie back to watch the spooky movie The Addams Family (1991) on the big screen, complete with a choc-top and popcorn!

Member child $25, general $35. Includes pizza, refreshments, craft activities and movie. Bring a torch, pillow and sleepingbag. Children will be fully supervised (parents/carers not required to stay).

Ages 5–12

Tour

Garden Island naval heritage tour 10 am–1.30 pm Thursday 28 April at Garden Island

Don’t miss this opportunity to enjoy a behind-the-scenes guided tour of garden Island heritage precinct with representatives of The Naval Historical Society of Australia. The tour will visit areas within the secure precinct including the Kuttabul Memorial to the naval personnel lost during the Japanese midget submarine attack on Sydney Harbour in 1942; the chapel with its fine stained galss windows commemorating RAN ships and actions; and heritage buildings including the original boatshed and the top of the Captain Cook Dock. You will then have an opportunity to take a self-guided tour of the RAN Heritage Centre, with its rich array of naval artefacts, arms, instruments, small craft – and, one of its centrepieces, the centre section of one of the Japanese midget submarines that were destroyed in the attack on Sydney Harbour.

Members $25 general $30. Includes guided tour, entry to RAN Heritage Centre, morning tea. Requires some walking and climbing stairs. Catch the 10.10 am Watsons Bay ferry from Circular Quay to garden Island (ferry ticket not included)

EMAIL BULLETINS

Have you subscribed to our email bulletins yet? Email your address to members@anmm.gov.au to ensure that you’ll always be advised of activities that have been organised at short notice in response to special opportunities.

Talk

HMAS Toowoomba, a year in deployment

3–5 pm Sunday 1 May at the museum