Signals

After renovations, Yots and the Ben Lexcen Terrace are open again for venue bookings – revitalised on the inside with the same fantastic views outside.

For formal dinners, stylish cocktail parties and memorable product launches, your guests will be delighted by our magnificent waterfront venues overlooking the historic fleet.

Award-winning Laissez-faire Catering offers flexible and exclusive menus. Book now for Christmas by the water.

T: +61 2 9298 3625 venues@anmm.gov.au www.anmm.gov.au/venues

Enjoy your wedding ceremony or reception at our unique waterfront setting. Located on the western shore of Darling Harbour, the venues have splendid city skyline and harbour views.

Enjoy pre-dinner drinks on the decks of the HMAS Vampire before moving into the glassed Terrace Room.

Laissez-faire Catering, renowned for their innovative cuisine, along with delivering service of the highest standard, are the venue’s exclusive caterers.

T +61 2 9298 3625

venues@anmm.gov.au www.anmm.gov.au/weddings

Cat and fish by William Buelow Gould (1803–53), oil, 1849. Lent by Kerry Stokes Collection Perth. Photographer

Paul Green. It appears in our major new exhibition Fish in Australian art, the first attempt to comprehensively document this subject from rock art to contemporary art practices. It features vibrant and intriguing works by artists ranging from the unknown to major figures in Australian art, lent by more than 55 institutions and individuals.

Signals magazine is printed in Australia on Impress Satin 250 gsm (Cover) and 128 gsm (Text) using vegetable-based inks on paper produced from environmentally responsible, socially beneficial and economically viable forestry sources.

2 Bearings

New director Kevin Sumption looks at contemporary museum practice

4 Fish in Australian art

Fish and fishing, a timeless subject for artists from prehistory to the present

18 Finding the Royal Charlotte

Our maritime archaeologists locate another historic wreck

20 Whale Song: home on the wave

A visiting research vessel with a live-aboard family

24 Titanic: a ship of myth and legend

Marking the centenary of an unforgettable disaster

24 Travels with Harold Lowe

A new book about a heroic Titanic officer

31 Members message and autumn events

34 Autumn exhibitions and attractions

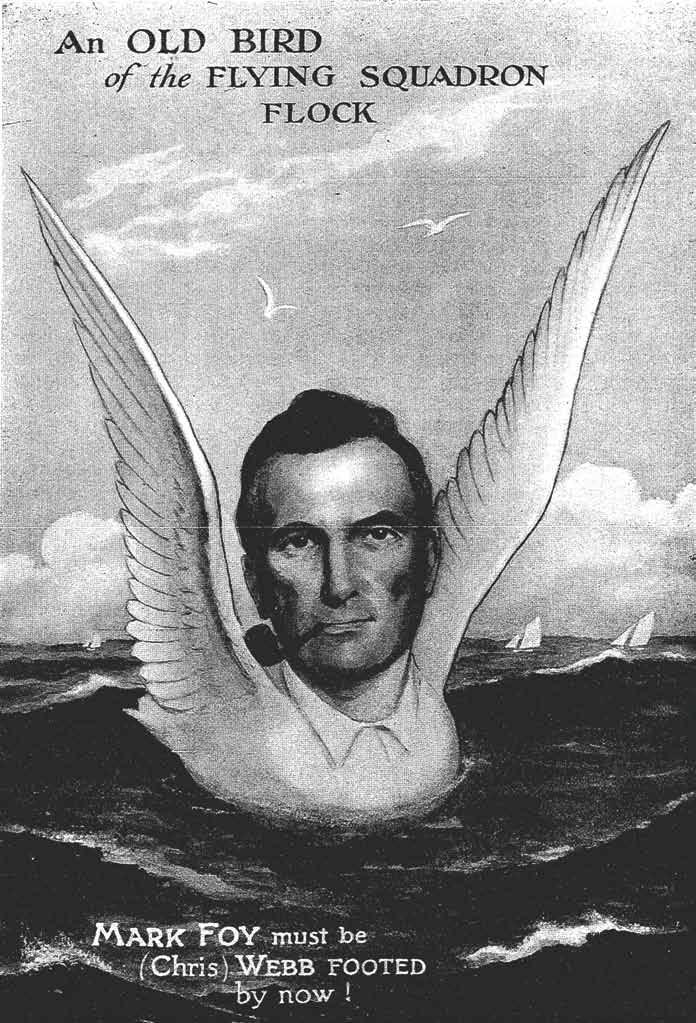

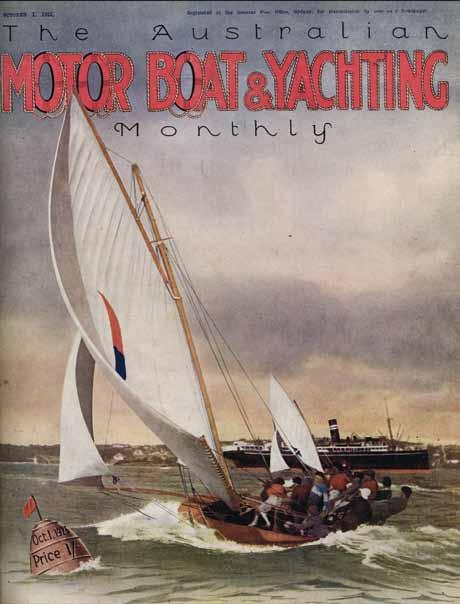

36 The coloured sails club

Legends of Sydney 18-footer history come in for a forensic re-examination

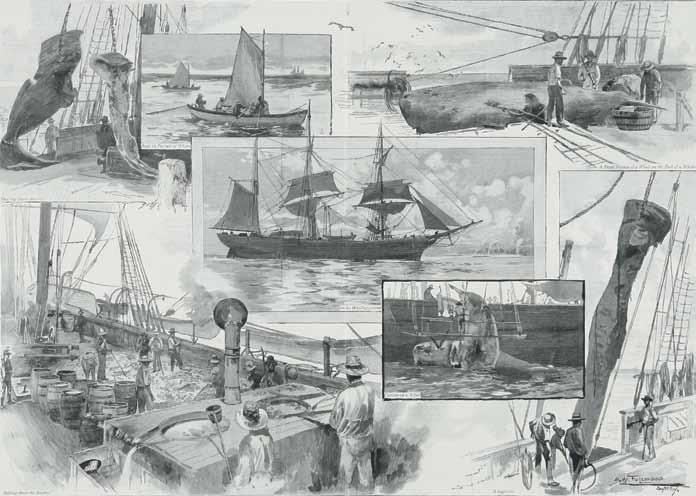

42 Whaling in Jervis Bay

From a hazardous, early Australian industry to a booming tourist sector

46 Edwin Fox: respect for age

The last surviving convict transport, in Picton, New Zealand

50 Australian Register of Historic Vessels

New additions to this important national database

54 Tales from the Welcome Wall

From Russia with love

Cert no SGS-COC-006189

56 Collections – extending cabin bed

A must-have accoutrement for the well-heeled traveller

58 Readings

Three authors argue the centrality of the sea in our lives

63 Currents

Farewell to an old hand

As I reflect upon the many exciting challenges that lie ahead for the Australian National Maritime Museum, I believe that learning from current best practice in museums will be crucial. So I wanted to use my inaugural column to reflect on some of the most significant museum projects I’ve encountered while working at the Royal Museums Greenwich.

A week before departing London for Sydney, I visited the new Scheepvaartmuseum in Amsterdam. Here inside the magnificently restored 1656 Arsenal building, visitors traverse 400 years of Dutch maritime history. In one gallery I joined a small group on a virtual-reality experience starting with the golden age of the Netherlands Republic and travelling forward to World War I. In another wing a combination of thematic galleries, together with a set of immersive audiovisual projections, allowed me to explore the port of Amsterdam, both its history and contemporary operation. Finally, in the maritime paintings and navigational instruments galleries, Uwe Brückner’s strikingly designed showcases highlighted the treasures of the Scheepvaart’s collection. From the reaction of people around me, it was clear that the museum had very carefully considered visitors’ varied interpretive needs. And in response they had created

a rhythm, pace and variety of storytelling, group interaction and object display experiences that supported a very diverse set of visitor learning preferences.

Eighteen months earlier I had again been in Amsterdam, on this occasion to give a keynote address at the Europeana conference. Here I spoke to museums, libraries and art galleries from across Europe about the value of online user-generated content (UGC) projects. UGC often employs ‘crowdsourcing’ techniques to encourage the general public to generate high quality, researchdriven content for websites. My paper explored how the Royal Museums Greenwich (RMG) had successfully used web-based projects such as oldweather.org and Solarstormwatch.com to not only conduct important historical and scientific research, but to also build new relationships with hundreds of thousands of people from around the globe.

What both the Scheepvaartmuseum galleries and UGC projects demonstrate is what I believe to be an important emerging trend for museums: to use new technologies together with their collections to create more effective learning experiences, both in the gallery and online. This trend was also very evident in cultural institutions across London, where I have spent the last three and a half years.

left to right:

Director Kevin Sumption at his former berth, Britain’s National Maritime Museum. Photograph courtesy of NMM, Greenwich UK

At the new Scheepvaartmuseum in Amsterdam, strikingly designed showcases highlight the treasures of the collection. Visitors interact with a touchscreen to select the pieces they wish to learn about. Photographer Kevin Sumption

Like Sydney leading up to 2000 Olympic Games, the 2012 games have been a catalyst for significant museum redevelopment in London. One of the most ambitious projects of recent years has been the Natural History Museum’s new Darwin Centre. Opened in late 2009, the Darwin Centre not only provided new storage for 20 million collection specimens, but also incorporated a new public collection research facility called NaturePlus. It equips every visitor with a card that enables them to access collection information at terminals throughout the centre. When returning home or to their classroom a visitor can use their NaturePlus cards to go online to access their own personalised view of the collection. The same website also allows visitors to delve deeper into the entire collection, as well as connect with museum curatorial and education staff through a series of blogs and forums. Compellingly, NaturePlus uses the web to break down the barriers between physical galleries and visitors’ homes and helps build new interactions between museum staff and visitors.

During my time in London many museums began to re-focus their temporary exhibition programs. Some embraced new themes and stories that drew deliberately on the familiar and commonplace activities of life.

The idea was to create new programs that deliberately challenged sometimes deeply-felt beliefs, preconceptions or long held opinions. Nowhere has this been more imaginatively done than at the Wellcome Collection, a new medical museum that opened in 2007. The Wellcome Collection explores the connections between medicine, life and art and has a public program regime led by the catch-cry ‘A free destination for the incurably curious’. From this ethos the Wellcome has created an array of programs including: Miracles and Charms; Madness and Modernity; Dirt: the filthy reality of everyday life All of these challenge visitors to rethink their relationship with historic and contemporary medical technologies and treatments.

Just as compelling has been the Imperial War Museum’s (IWM) new series of exhibitions exploring the frontline stories of British soldiers. In an attempt to better contextualise ‘distant’ historic collections with the voices and lives of current soldiers, the IWM developed the exhibition War Stories: Serving in Afghanistan Here museum photographers and curators interviewed returning servicemen and women to create a series of vivid and highly personal video and photographic portraits. These are

displayed in the IWM’s main entrance against a backdrop of World War I and II technological icons. The portraits create a powerful new entrance experience that, through the voices and images of servicemen and women, link historic military campaigns to contemporary British overseas deployments.

While based in Europe I was fortunate to work with a number of European maritime museums, many of which are at the forefront of new ways of engaging visitors. My favourite of these is the Galata Museo del Mare, in Genoa Northern Italy, housed in a 17th-century building on the site of slips once used for Genoa’s famous galleys. It brings to life the technology, history and art of the maritime republic of Genoa through a series of carefully researched historic character studies, juxtaposed with detailed replicas and a series of panoramic, immersive experiences. Recently Galata began to assemble an historic fleet, the latest in 2010 being a Nazario Sauro class submarine. Making submarine technology accessible and understandable for the public can be difficult. So Galata conceived of a package that combined both a guided tour of the submarine, together with a largescale cinematic presentation. Together these powerfully brought to life both the stories of the men who served on board

S518, while explaining some of the basic operating principles and technologies found on board.

Two significant European maritime museum projects are due for completion. In late 2012 the Wilkinson Eyre-designed Mary Rose Museum in Portsmouth Historic Dockyard will open. This will be followed by the new Danish Maritime Museum currently under construction in the old Elsinore Shipyard. In existence since 1915, the creation of this new home has allowed the museum to reconsider its mission and add an important new role, as a worldwide ambassador for the Danish maritime industry and profession. Both these projects are engaging some of the world’s foremost exhibition designers and cultural planners and will be worth following closely.

As I hope this very brief survey of contemporary European museum practice demonstrates, museums are never static and are constantly looking for new ways to engage visitors in a meaningful dialogue. As we move forward with the next phase of the ANMM’s development, I am sure these examples - as well as others from Australia - will inform our planning and act as an important springboard for discussion.

During a lifetime of researching, collecting and writing about Australian art, Stephen Scheding was intrigued by the different ways in which fish have been depicted. yet while there have been major exhibitions and books on birds, flowers and plants in Australian art, there was nothing on fish. Stephen worked with the museum’s curator of sport and leisure history, Penny Cuthbert, to create Fish in Australian art, the first attempt to comprehensively document the subject from rock art through to contemporary art practices.

Cat and fish by William Buelow Gould (1803–53), oil, 1849. Lent by Kerry Stokes Collection Perth Photographer Paul Green

Cat and fish by William Buelow Gould (1803–53), oil, 1849. Lent by Kerry Stokes Collection Perth Photographer Paul Green

Fish have been a timeless subject for artists in many cultures. They have been on the human menu from the earliest times as homo sapiens spread along coastlines and developed early marine technologies. For many societies fish have been a primary source of dietary protein; for others, a high-priced luxury. In Australia, Indigenous people have created remarkable images of local fish on rock surfaces for thousands of years. Explorers, convicts, naturalists, ethnographers, scientists, artesans, and artists, both amateur and professional, have put fish into the picture to scientifically document, to decorate, to delight or to provoke. Fish appear in all our visual media and have been present in art movements as diverse as 19th-century Salon Painting and 20th-century Surrealism.

This exhibition tells a story of people’s enduring fascination with both fish and fishing, and explores how fish have touched the lives of individuals and communities. It might also be viewed as a history of Australian art, told through fish.

The earliest printed image in this exhibition is from an atlas published in 1540, before Australia was discovered and mapped by Europeans. Cartographers often introduced imagined creatures to convey the mysteries and dangers of uncharted places. In Sebastian Munster’s 16th-century map of the world, a fanciful sea monster swims where the Australian continent should be.

During long sea voyages to South-East Asia and the Pacific, English explorers such as William Dampier and James Cook took crew who had trained as artists and their illustrations were later used in published accounts of the voyages. The colourful buccaneer Dampier was also a significant natural historian. Fish he studied appeared as engraved plates in his A Voyage to New Holland &c. in the Year 1699, which became a best seller in England. Although we do not know the identity of the artist these are the first known published drawings of Australian fish.

One of the world’s rarest books was devoted to fish. Only 34 copies of Louis Renard’s 1754 edition of Fishes, Crayfishes and Crabs … are known to exist. The extraordinary illustrations have been judged by zoologists to be ‘crudely drawn and barbarously coloured’ but they were based on actual specimens collected and sketched by an artist for the Dutch East India Company. Included are fish species identified as inhabiting Australian waters – as well as some complete fabrications

such as a spiny lobster that ‘lives in mountains [and] climbs trees’, and a mermaid.

The earliest European accounts of Australia often include descriptions of Aborigines fishing. While comments were often belittling, the Europeans admired their fishing skills. It is now recognised that Aborigines had developed sophisticated land-care strategies and their fishing practices appear equally wellplanned and sustainable. Our exhibition conveys a sense of this in images by convict artist Joseph Lycett and an 1848 lithograph after a sketch by Captain Westmacott. The latter shows Aborigines fishing at Condon’s Creek in the Illawarra district of New South Wales, using a preparation derived from the bark of the ‘dog tree’ to stupefy fish which were then easily caught and thrown onto land. The fish soon recovered and were ‘apparently none the worse for the dose administered’.

One of the great mysteries of Australian colonial art is the identity of ‘The Port Jackson Painter’, the artist (or artists) responsible for an important body of unsigned work produced immediately after the arrival of the First Fleet in Port Jackson in 1788. Possible contenders are Henry Brewer, a midshipman and friend of Governor Phillip, and Francis Fowkes, a former midshipman transported for theft. The Natural History Museum in London has over 500 watercolours by both ‘The Port Jackson Painter’ and the convict artist Thomas Watling, representing an astonishing visual record of the colony’s first years, including many watercolours showing the Aboriginal owners of Port Jackson fishing. Their detailed inscriptions, such as ‘A Native going to Fish with a Torch and flambeaux, while his Wife and children are broiling fish for their supper’, reflect the European attempt to understand Aboriginal life. A watercolour of four fish by Thomas Watling is inscribed with the Aboriginal names of the fish.

Watling was one of at least 20 convict artists who produced significant work in Australia, including paintings featuring fish and fishing. Some had training prior to their transportation or had worked in trades such as printing, coach and sign painting or in commercial potteries. Over half of these artists had been convicted of forgery, a serious crime for which the penalty was death or transportation for life. Watling had taught drawing to ‘Ladies and Gentlemen’ at Watling’s Academy in Scotland before being charged in 1788 with forgery of banknotes. Joseph Lycett continued

making forgeries in Sydney and was sent to Newcastle, a place of secondary punishment.

So was fellow convict artist Richard Browne, whose works provide detailed information about Aboriginal fishing techniques and equipment. While Browne produced accomplished natural history drawings of birds and flowers, his portraits of Aborigines appear awkward and amateurish. It is unclear whether they are intentional caricatures. Their style might derive from the silhouette tradition, popular at the time, or could be the result of the artist using stencils to make multiple copies for sale to colonial visitors.

Another convict artist, William Buelow Gould, painted the delightful composition Cat and Fish. Gould had studied painting with a teacher from the Royal Academy in London and had been a leading draftsman for well-known publisher and printseller Rudolf Ackermann before being sentenced to seven years transportation for stealing clothing. As an ex-convict in Hobart he lived in poverty with his wife and five children and was gaoled again for stealing. He drank heavily and is said to have paid for alcohol by giving hoteliers his work. Hoping to appeal to the taste of wealthy settlers, he painted still lifes in the prevailing European style, almost invariably including European flowers, fruit and game. However, in the painting on pages 4–5 it appears that the cat is about to pilfer Tasmanian redbait.

Gould is also responsible for the remarkable sketchbook of 36 watercolours of fish and other marine life, commonly known as Gould’s Sketchbook of Fishes They were probably painted while Gould was a convict on Sarah Island at Macquarie Harbour in Van Diemens Land, about 1832–3, working as a house servant for Dr De Little. The sketchbook accurately recorded species of fish found in Tasmanian waters for the first time and is still a visual reference for scientists today. It now has World Heritage status. Fish and fishing continued to be depicted in Australian art throughout the 19th century. Artists were often commissioned to paint pastoral properties that affirmed colonial land ownership and that, in many cases, would have included fishing spots. However, the oil painting Residence of George Augustus Robinson on the Yarra River, attributed to George Gilbert about 1840, may offer a different perspective. Robinson’s official title was Protector of the Aborigines. The prevailing view had been that Robinson hindered rather than helped the

The sketchbook accurately recorded species of fish found in Tasmanian waters for the first time and is still a visual reference for scientists today

clockwise from bottom left:

Detail of Residence of George Augustus Robinson on the Yarra River attributed to George Alexander Gilbert (1815–c89), oil on canvas, about 1840. Lent by Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Poissons, Écrevisses et Crabes … Que l’on Trouve Autour des Isles Moluques et sur les Côtes des Terres Australes Plate XLV by Louis Renard (c 1678–1746), hand-coloured etching in bound volume. Published by Chez Reinier & Josué Ottens, Amsterdam 1754. Lent by Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Pygmy seahorse by Roger Swainston (1960–), acrylic on paper, 2009. Reproduced courtesy of the artist

Southern pygmy leatherjacket by Ferdinand Bauer (1760–1826), watercolour on paper, 1801–03. Lent by the Natural History Museum, London

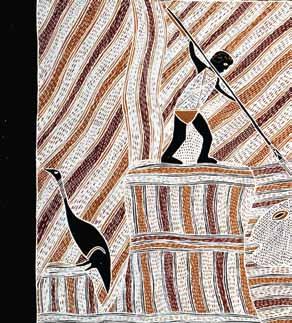

Aboriginal bark

paintings represent a social history, an encyclopedia of the environment, a place, a site, a season, a being, a song, a dance, a ritual, an ancestral story and a personal history

Djon Mundine OAMAborigines, with historian Manning Clark describing him as ‘that great booby’. But more recent studies (including Stephen Scheding’s The National Picture) have shown Robinson in a more sympathetic light. In the idyllic view on page 6, both Robinson and Aborigines are shown fishing the same river.

Colonial artists could exhibit their work at the various Mechanics Institutes, in occasional intercolonial exhibitions, or at the annual exhibitions of the fine-art societies which were increasingly common in the major cities from 1870 onwards. Artist Henry Short arrived in Melbourne in 1852 and specialised in rather grandiose still-life paintings in a 17th-century Dutch style. He exhibited at venues such as the Victorian Society of Fine Arts and the Victorian Industrial Society and his paintings were also offered as prizes in art unions, which was a way for the better-known artists to ensure income. In Still life with Fish Short has placed his Dutch-looking fish in the Australian bush.

The tender genre painting, Fisherboy by Aby Alston typifies the best work being painted and exhibited at the end of the 19th century, just before the Heidelberg school of Impressionism stole the limelight. (Interestingly, it is hard to find an actual fish being depicted by an Australian Impressionist, although restful scenes of river fishing are not uncommon.) Alston studied at the National Gallery School in Melbourne for about five years before winning the school’s travelling scholarship in 1890. He never returned to Australia.

From the beginning of the 20th century artists responded to rapidly

Balanay u by Galuma Maymuru (1951–), earth pigments on bark, 1998. ANMM Collection purchased with the assistance of Stephen Grant of the GrantPirrie Gallery

changing social and political forces and developed new ways of seeing and expressing. Many artists left Australia to study overseas and styles were informed by international movements such as Cubism, Expressionism and Surrealism. John Wardell Power was the first Australian-born artist to explore surrealism and his painting A wreck on the shore clearly shows a connection with British Surrealism, particularly the work of Tristram Hillier. Power had trained as a doctor in London, inherited a fortune from his father in 1906 and subsequently turned to art. In 1961 his bequest of £2 million was gifted to Sydney University to establish the Power Institute of Fine Arts ‘so as to bring the people of Australia in more direct touch with the latest art developments in other countries’. There were also home-grown developments in Australian art.

For example Clarice Beckett’s tonalist paintings of the 1930s, like the exhibition’s Low Tide, Black Rock, were influenced by the controversial artist and teacher Max Meldrum who polarised a generation of Australian artists. Painting mostly in the early morning and evening around the shoreline of the Melbourne bayside suburb of Beaumaris, Beckett exhibited her work regularly from 1923 but often received harsh reviews and sold few works. In the late 1960s hundreds of her canvases were discovered rotting in a farm shed, but enough could be saved to stage a succession of highly-acclaimed exhibitions. Beckett’s biographer Rosalind Holingrake has described the artist’s ability to transform a mundane subject into ‘a pictorial poem, evocative of some eternal yet always elusive truth’.

In the 1930s and 40s the George Bell School in Melbourne produced many fine, but now lesser-known, modernist artists such as Yvonne Atkinson and Ian Armstrong. In 1951 Armstrong and two friends held a joint exhibition in Melbourne. One of the artists was Fred Williams, now regarded as one of Australia’s greatest painters. However, Arnold Shore, a leading art critic at the time, wrote that ‘Mr Armstrong is the most accomplished craftsman and possibly the most talented artist of the trio’. Armstrong’s Girl with Fish was bought by the National Gallery of Victoria. None of the works exhibited by Fred Williams sold.

In the late 1930s a number of artists studying at the George Bell School, including Russell Drysdale, Peter Purves Smith, David Strachan and Yvonne Atkinson, cultivated an ‘innocent eye’ approach, producing colourful and somewhat naïve scenes that had the appearance of theatre sets, ‘all front and no background’. In Atkinson’s charming painting, Fisherwoman with cat (page 13), a ‘play’ about fishing is staged with a cat as the leading player.

The Antipodeans, a group of artists who championed figurative art in the 1950s, included Arthur Boyd who is now considered one of Australia’s most important artists. His enigmatic work Ventriloquist and skate, with its painterly allusions to Rembrandt, was created in the artist’s studio at Bundanon on the Shoalhaven River. In an interview in the Independent Monthly in 1995 it was suggested that Boyd intended the skate to also represent ‘both a … symbol for wastage… and a nuclear mushroom cloud’.

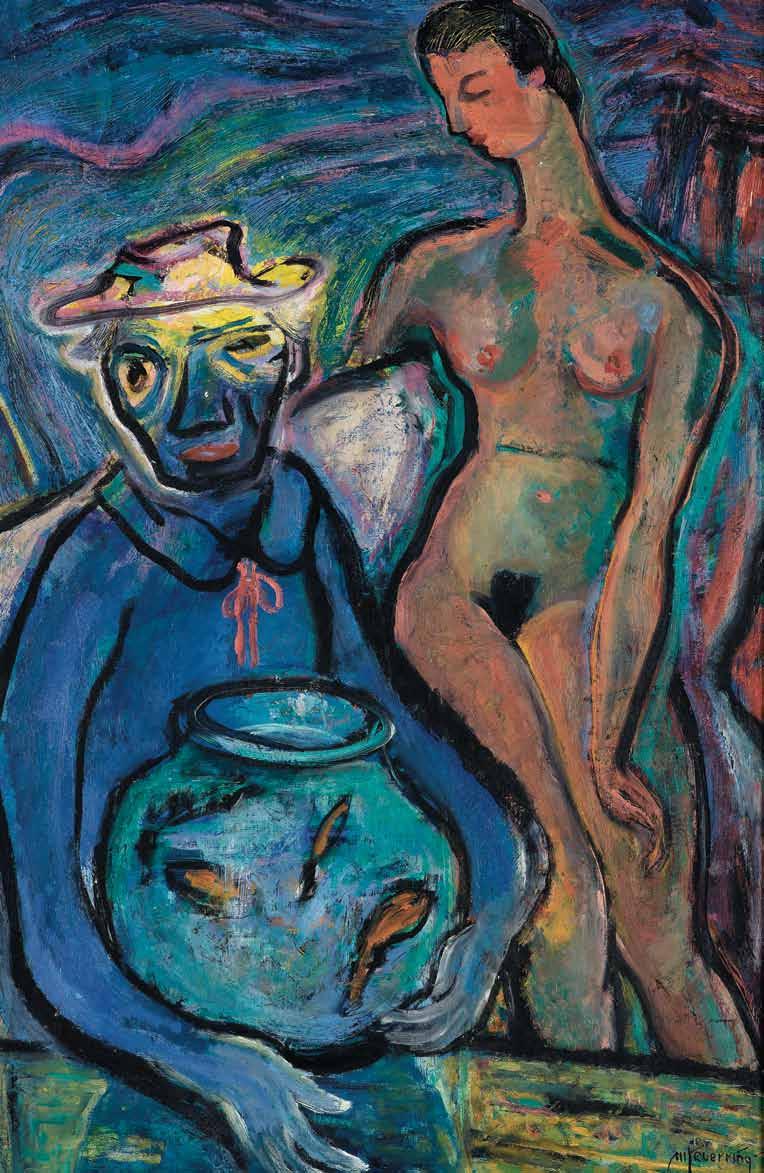

Several paintings in the exhibition include goldfish bowls or tanks, and in each case the goldfish serve remarkably different purposes. John Brack’s fish tank (page 15) is placed in a 1950s suburban Australian house. His vision of suburbia has been described as monotonous and lifeless – ‘an existential wasteland’ exuding a sense of isolation and alienation. In The Fish Tank, the eternally balanced relationship between the three fish might suggest a holding pattern of bland suburban life.

The goldfish confined in their bowl in Maximillian Feuerring’s Man with goldfish and nude (page 14) may have symbolic significance in terms of the artist’s traumatic personal story. Called up as an officer in the Polish army, Feuerring was imprisoned in a World War II prisoner-ofwar camp. Fifty-two members of his family, including his wife and parents, perished in concentration camps. After the war Feuerring migrated to Sydney.

While Australian art forged its own identity it often looked back and drew on art history and on the work of the acknowledged masters. Margaret Olley’s Still life with pink fish includes references to both Renaissance and Roman art while Justin O’Brien’s Miraculous Draft acknowledges the work of Hieronymus Bosch.

With growing community concern about the environment in recent decades it is not surprising to see Australian contemporary artists addressing such issues, including those relating to fish and fishing. A very direct example is Carole Wilson’s poster Plastic’s got us, hook line and sinker – recycle now. This was first produced on a large scale in 1989 and

displayed on 100 billboard sites around metropolitan Melbourne and regional Victoria. It won the prestigious Special Jury Prize at the 1992 3rd Chaumont Poster Festival in France before being reissued as a poster in November 1992.

Brian Blanchflower’s large oil painting Nocturne 3 (Whale Rock) is one of a series of works painted by the artist following a disturbing trip in 1979 to the whaling station at Albany, Western Australia, which was the last to operate in Australia. The artist witnessed the flensing of a whale – where the skin or blubber is stripped away – and was horrified by the experience.

Digital artists such as Craig Walsh work with multimedia technologies and popular culture to engage the viewer. Walsh’s Incursion (Water) documentation consists of filmed documentations of an installation originally constructed by the artist in Toronto, Canada, in 2007 and recreated at various locations since. In this work an empty restaurant slowly fills with water and is then occupied by giant barramundi and crayfish that take the role of consumers, rather than the consumed.

In addition to the chronological overview of fish in Australian art, some works in the exhibition are grouped into six major themes:

Since the 1970s awareness and appreciation of Indigenous art in Australia has dramatically increased. A flourishing of art from communities around Australia has produced a variety of significant works, with many Indigenous artists now nationally and internationally acclaimed. Representations

of fish and fishing by Indigenous artists speak of place, spirit, community and connectedness. Inherent in many of these artworks are stories that reaffirm Indigenous people’s custodianship of freshwater and saltwater country. At the source are the Ancestors who gave their people designs, language and law that hold the secrets of country. Arising from these traditions is a richness and inventiveness to the way fish are depicted and stories are shared.

Yvonne Koolmatrie’s woven eel trap is modelled on traps placed in stone weirs to catch eels during their annual migration through the south Australian swamplands. Koolmatrie’s signature style uses a coiled basketry technique, a tradition of Ngarrindjeri people living along the Lower Murray River in South Australia. Weaving was a social activity. During the warmer months women and children collected sedge grass and rushes that were dried and woven by men and women into a variety of objects. While the work has a practical heritage Koolmatrie’s artistry has been internationally recognised, and she represented Australia at the Venice Biennale in 1997.

Galuma Maymuru’s bark painting Balanay u tells the Yolngu story of Balanay u, the sacred rock in the saltwater country of Njarrakpi. The ancestor Muwandi of the Manggalili clan is depicted spearing Nguykal, the ancestral Kingfish. Nguykal swam away and left a path through the Yirritja lands that now connects the various kinship clans in north-west Arnhem Land, Northern Territory. This work is from one of this museum’s major collections: 80 bark paintings created for the

Saltwater project instigated in 1996 and used as legal documents in a Yolngu High Court land/sea rights case in 1998.

In the 19th century whales, not fish, provided the most dramatic maritime subjects for professional artists. The lucrative pursuit of the whale, its capture, killing and ‘cutting in’ were the main subjects explored in this genre. Whaling expeditions could last months if not years. On board the ships, art was often produced by the crew in the form of carved whalebone known as scrimshaw, or by ship’s officers who chose to illustrate their log books.

William Duke was a carpenter by trade who arrived in Sydney from Ireland in 1840 as an assisted immigrant and found employment as a ‘mechanist’ and scenepainter in a theatre. In Hobart between 1845 and 1850 he produced a series of four whaling paintings titled The Chase, The Flurry, The Rounding and The Cutting in. These were reproduced as lithographs and were very favourably received.

Marine artist Oswald Walter Brierly’s watercolour Amateur whaling, or a tale of the Pacific shows hunters pursuing a harpooned right whale, assisted by a pod of killer whales. Brierly refers to the men in the title as ‘Amateurs’, even though

paper, 1847. ANMM Collection

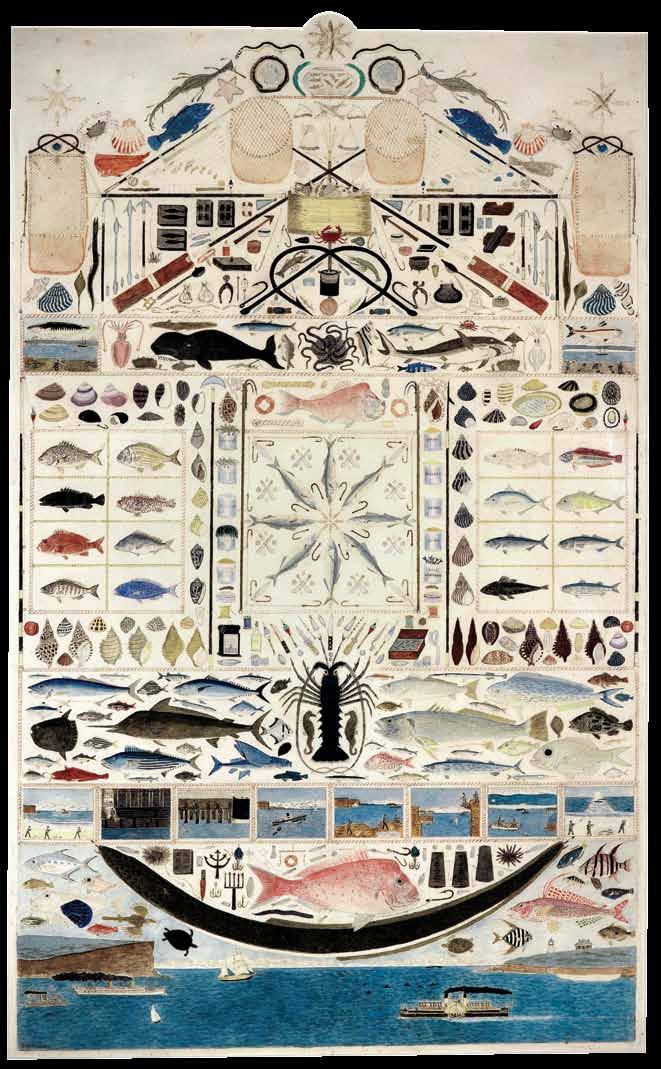

opposite: The marine Life of Sydney Harbour by J R Pearson (dates unknown), watercolour, about 1900. ANMM Collection

they were part of a commercial enterprise. The ‘Tale’ of the title suggests both the unfolding of the dangerous and bloody hunt, and a play on the whale’s fluke.

The art of scrimshaw provided a creative outlet for seamen on long whaling voyages and often depicted scenes of whale hunts, marine creatures and ships.

In the 18th and 19th centuries scientific artists illustrated specimens from direct observation, often as the objective records of scientific collecting expeditions. The original works might be kept by the artist or others associated with the expedition, or could be sent to publishers for engraving and printing. Scientific illustration has come to be regarded increasingly as art, and collecting such material is still a passion for both public institutions and amateur enthusiasts.

Two natural-history paintings in the exhibition, produced 200 years apart, show some remarkable similarities. Southern pygmy leatherjacket was painted by Ferdinand Bauer who accompanied Matthew Flinders on his circumnavigation of Australia in the first years of the 19th century. Pygmy seahorse was painted by Roger Swainston who has continued the tradition over the past 30 years and whose definitive volume Swainston’s Fishes of Australia has just been published. Swainston’s finished paintings are based on his drawings produced underwater, his sketches of specimens and photographs. Both works exemplify the artists’ powers of observation and ability to create life-

like renderings of marine species. A wonderful oddity is J R Pearson’s watercolour The marine life of Sydney Harbour, painted about 1900. Painted in a naïve style, it shows a comprehensive collection of the identifiable marine life in Sydney Harbour, the tools needed to catch it, and some recommended fishing spots. On the lower left is the Royal Yacht Ophir, which visited Sydney in 1901 as part of the Federation celebrations and, on the right, the harbour ferry Brighton Unfortunately, virtually nothing is known about the artist.

In 1792 George Tobin painted a sailor heading off to fish, rod in hand, at Adventure Bay, Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). This watercolour from the artist’s sketchbook, titled ‘Views from the South Sea Voyage in the Providence’, is almost certainly the first painting of a European angler in Australia. The widelytravelled artist had joined the Royal Navy at the age of 11 in 1780; in 1791 he joined HMS Providence for Captain William Bligh’s second expedition to the South Seas (the first having led to a mutiny). Recreational fishing is still one of Australia’s most popular pastimes. It is accessible to anyone with hook, line and sinker. Many Australian artists have conveyed its appeal, whether the quiet solitude of angling from beach, boat, wharf or rocks, the excitement of competitive game fishing or the angler’s pride in the catch of the day. Among the many memorable images of recreational fishing are Kenneth Macqueen’s

above: Amateur whaling, or a tale of the Pacific by Oswald Walter Brierly (1817–94), watercolour on

The Beach Fisherman and James Northfield’s Great Barrier Coral Reef Australia. Northfield’s poster was commissioned by the Australian National Travel Association in the early 1930s. It used game fishing and natural beauty to entice tourists to coastal Queensland.

Fish in design and display

The boundaries of art extend beyond paintings, prints and sculpture to include a broad range of objects designed for commercial or domestic use. Fish appear in illustrations, advertising, photography and as motifs in designer items such as jewellery, textiles, clothing, leatherwork, metalwork, glassware and pottery. The fascination with fish and marine life in design can be taken to the extreme, as seen in the exhibition in an extravagant fishing trophy, a bizarre custom-made lamp and an ingenious ship model with a fish-like motion.

Australian design flourished with the influence of the International Arts and Crafts Movement, a reaction against mass production of goods in the late 19th century. By the early 1900s more

women than men enrolled in art and design classes and were a driving force behind the movement. They also became involved in commercial production, a factor that helped accelerate women’s social emancipation.

Just prior to World War I the Sydney Technological Museum, now the Powerhouse Museum, presented a display of fish in applied art. Vases by Mildred Lovett and Frank Piggott Webb and a tooled leather blotter by Edith Loudon were included in this display. These works were also illustrated in Fishes of Australia and their Technology by T C Roughley, published by the Sydney Technological Museum in 1916.

Graphic art has provided employment opportunities for artists in Australia since the 19th century. Examples of fish-themed published work on display include a cover from the stylish Australian monthly magazine The Home; illustrations for newspapers such as the Illustrated Sydney News, the Illustrated Melbourne Post and the Australasian Sketcher including extraordinary engravings of shark attacks; and posters originally intended as

ephemeral work for short-term display. Few copies of the vaudeville poster Natator the Man Fish for example, have survived. Perhaps the oldest form of graphic art is book illustration, some of the most renowned book illustrations having been produced for children’s picture books.

Photographs, candid or staged, have captured many facets of fishing from the pleasures of recreational fishing to the hardships of commercial fishing. In the mid-20th century fishing attracted the interest of photojournalists such as David Potts, who produced dramatic and disturbing images of shark-hunting at Ceduna, South Australia, and Jeff Carter, who documented the Sicilian fishing community of Ulladulla, New South Wales.

Creative design is also an integral part of specialised fishing equipment and trade displays. Fly fishing in particular requires elaborate and ingenious design solutions. Lures known as ‘flies’ are created to imitate insects eaten by fish such as trout or perch, and can replicate all phases of an insect’s life cycle.

pages 12–13, clockwise from top left: Home from the market by Eugenie Durran (1889–1989), oil on canvas, about 1916. Lent by Geelong Art Gallery

Fisherwoman with cat by yvonne Atkinson (1918–99), oil on board, 1937. Reproduced courtesy of the artist’s children. Lent by Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art at the University of Western Australia

The Beach Fisherman by Kenneth Macqueen (1897–1960), watercolour, 1934. Lent by New England Regional Art Museum, Armidale. Gift of Howard Hinton

left: Man with goldfish and nude by Max Feuerring (1896–1986), oil on masonite, 1950s. Lent by private collection

top right: The Fish Tank by John Brack (1920–99), oil on canvas, 1957. Reproduced courtesy of the artist’s estate. Lent by Kerry Stokes Collection Perth

bottom right: Plastic’s got us, hook line and sinker – recycle now by Carole Wilson (1960–). Silkscreen poster (RedPlanet Posters reprint Melbourne), 1992. Lent by Powerhouse Museum

Each new and innovative design is usually named by its maker. This art of imitation reached new heights with the publication of Alfred Ronald’s The Fly-Fisher’s Entomology in 1836.

Fish for the table

Throughout art history images of fish as food have been produced by artists, to convey bountiful catches, social etiquette, religious ritual or simply gastronomic delight. John Olsen’s passion for food, as well as painting, is well known. His The Bouillabaisse was painted for his 2010 exhibition Culinaria –The Cuisine of the Sun and to illustrate his cookbook of the same name.

Genre paintings, which depict scenes of everyday life, can reveal much about social history and Home from the Market by Eugenie Durran is a classic example (page 12). Painted during World War I this scene around the kitchen table captures the women of the house, mistress and domestics, in an intimate and friendly exchange over produce from the local market, including a catch of fresh fish.

Fish often appear in still life paintings and it is perhaps interesting to think about the different ways artists might choose to arrange them compositionally. One of Australia’s most important modernist artists, Margaret Preston, painted her Fish, Still Life in 1916. In 1929 she compiled and published a list of 92 aphorisms about art. Number 46 was: ‘Why there are so many tables of still life in modern paintings is because they are really laboratory tables on which aesthetic problems can be isolated.’ Peter Churcher’s pair of paintings Good diet and Bad diet, painted in 2010, should provoke a thoughtful response on a weighty contemporary theme.

This fish-eye view of Australian art history reveals a remarkable and surprising body of work that ranges from the purely descriptive to the emotional or dramatic, and from the deeply sacred to the humorous and eccentric. The art in this exhibition can be appreciated on many levels: for the historic or scientific value, social significance, or for aesthetic pleasure. Or just for the fish.

Fish in Australian art runs from 5 April to 1 October 2012. It features works by artists including Margaret Olley, William Dobell, Arthur Boyd, yvonne Koolmatrie, John Olsen, Rupert Bunny, John Brack, Michael Leunig and many more, with works generously lent by the following individuals and institutions.

Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts, Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office

Anne Schofield

Anne Zahalka

Art Gallery of Ballarat

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Art Gallery of South Australia

Australian Museum

Australian War Memorial

Brian Abel

Col Fullagar

David Dodd

Deborah Halpern

Dr Ailbhe Cunningham

Geelong Art Gallery

Gold Coast City Gallery

Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales

Jocelyn Maughan

Keith Free

Kerry Stokes Collection

Lin Onus Estate via Coo-ee Aboriginal

Art Gallery

Manly Museum and Art Gallery

Michael Leunig

Museum Victoria

Natural History Museum, London

New England Regional Art Museum

National Library of Australia

National Gallery of Australia

National Gallery of Victoria

Newcastle Art Gallery

Peter Churcher, via Australian Galleries

Powerhouse Museum

Private Collection via Douglas Stewart

Fine Books

Private Collection via Rex Irwin Art Dealer

Private Collection via Sotheby's Australia

Pty Ltd, Melbourne

Private Collection via Sotheby's Australia

Pty Ltd, Sydney

Private Collection via Tim Olsen Gallery

Private Collection Weld Club, Perth

Queensland Art Gallery

Reg Mombassa

Roger Swainston

South Australian Museum

State Library of New South Wales

State Library of South Australia

State Library of Victoria

State Library of Queensland, John Oxley Library

Stephen Scheding

The Fishing Museum

Thomas J Edwards

Tim Lenehan

Trevor Kennedy

University of Western Australia, Cruthers

Women’s Art Collection

W L Crowther Library, Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office

yvonne Boyd

left: Self Portrait with Shark by David Potts, 1957–58, silver gelatin print 1994. ANMM Collection

left: Self Portrait with Shark by David Potts, 1957–58, silver gelatin print 1994. ANMM Collection

A team from the Australian National Maritime Museum has located an 1825 shipwreck that marooned sailors, soldiers, convicts and civilians – and a pair of emus –on a desert cay on the Great Barrier Reef. The museum’s chief maritime archaeologist Kieran Hosty tells of this summer’s expedition with the team that in 2009 located the government schooner Mermaid wrecked in 1829, 20 km south of Cairns.

On 29 April 1825, the Indian-built, three-masted ship Royal Charlotte arrived in Sydney from Portsmouth, England under the command of Captain Corbyn RN with 136 male convicts and their guard from the 57th Regiment under the command of Major Lockyer. It had been an eventful voyage with an attempted convict mutiny, leading to eight of the convicts being placed in triple irons and allegations of misconduct, ill treatment and poor rations made by several of the passengers against Captain Corbyn. After a month in port Corbyn must have breathed a sigh of relief when he secured a contract to take detachments of the 20th, 46th and 49th Regiments and their families from Sydney to India. However, his run of bad luck continued and when he attempted to leave Sydney on Sunday 12 June 1825 the crew refused to work the ship and it was left to the

soldiers and officers to raise the anchor, hoist the sails and prepare to put to sea.

After departing Sydney the ship took a course known as the Outer Route, sailing to the east of the Great Barrier Route. The company encountered a series of severe southerly gales that persisted until the evening of the 20 June 1825 when the ship ran aground on the inaccurately charted Frederick Reefs, a large, fish-hook-shaped reef system that lies 450 kilometres north-east of Gladstone, Queensland.

Piling up onto the south-east edge of the reef, the Royal Charlotte fell onto its beam ends and was constantly raked by the huge seas as the soldiers and sailors worked together in a desperate bid to save the vessel. The ship’s masts were cut away to steady the ship and its guns and deck cargo, including two emus, were cast over the side in an attempt to lighten the ship. Morning light revealed a small sand cay to the north of the ship, where two very wet and bedraggled emus could be spied making their way towards it.

Over the next days the ship was slowly abandoned as most of the crew, the soldiers and their families moved to a small sand cay (now called Observation Cay), partially submerged at high tide. The survivors built up the sand cay using timber and cargo from the wreck. They repaired one of the ship’s boats and it was dispatched under the command of First Officer Parks for Moreton Bay to seek help from the distant colony. After six weeks clinging perilously on the wind- and water-swept sand cay, living on water and provisions salvaged from the shipwreck, the survivors were rescued by the government brig Amity. All but three had survived both shipwreck and the castaway life.

On 4 January 2012 a team of 24 divers and observers led by the Australian National Maritime Museum, in partnership with the Silentworld Foundation, left Gladstone for Frederick

Reefs in an attempt to locate the wreck site of the Royal Charlotte, and hopefully the remains of the survivors’ encampment on Observation Cay.

Guided by two survivor accounts, that of Lieutenant Parkes and Sergeant McRoberts, the team narrowed down the search zone to an area just south of Observation Cay. With incredible luck on the first day at Frederick Reefs, the divers – hauling magnetometers (submersible metal detectors) from small boats – immediately began to locate shipwreck material, including a large iron staple knee and some hull planking, in the sandy lagoon at the back of Observation Cay.

Over the next days other finds surfaced including more deck planking, a lead scupper for draining water off a ship’s deck, rigging components, rudder fittings, ship’s fastenings, unidentified iron fittings and copper alloy tubing. All were located within a nautical mile of the Cay, but the question arose, were they from the Royal Charlotte? We knew from historical accounts that other vessels, including an iron-ore carrier, a United States Navy submarine and a World War II landing barge had all come to grief on Frederick Reefs and had been partially or fully salvaged. What of the material we were finding?

Thanks to some careful plotting and a captive brain’s trust of museum curators including Paul Hundley and Dr Nigel Erskine, professional mariners, archaeologists, commercial and volunteer divers from Oceania Maritime Pty Ltd and the Silentworld Foundation, and Lee Graham from the museum’s fleet section, it became evident that most of the older material formed a very neat, almost south-to-north, 800-metre-long line. It stretched from the south-eastern edge of the reef, over the reef top and into the lagoon at the back of the cay.

As the sea conditions moderated teams of divers worked both ends of this line

Morning light revealed two very wet and bedraggled emus making their way towards a small sand cay

of wreckage, with one group reporting back that they had not only located a large, early-19th-century anchor on the very edge of the reef, but also several iron cannon. Another team located part of the vessel’s keel lying in the more sheltered waters of the lagoon.

Analysing the timbers, knee staples, anchor, ship and rudders fittings confirmed that we had located an early19th-century, copper-sheathed, ironfastened sailing vessel of around 450 tons. This along with the information gleaned from the survivors’ accounts indicated that the ANMM and its collaborative partner the Silentworld Foundation had located the remains of the ex-convict transport Royal Charlotte

The team was elated. Very few Indian-built ships have been identified and surveyed, and locating the remains of the Royal Charlotte provides historical detail and information on convict and troop transportation in the 19th century.

The museum’s 18-day expedition operated from the Gladstone-based vessel MV Kanimbla and Silentworld II, and was mounted in collaboration with Silentworld Foundation, part of Silentworld Ltd, an Australian shipping company that operates in the South Pacific and the Caribbean.

The Silentworld Foundation was established to further Australian maritime archaeology and research, and to improve Australia’s knowledge of its early maritime history.

The expedition is part of an Australian Research Council project, a joint project between the Australian National Maritime Museum, the Silentworld Foundation and Sydney University.

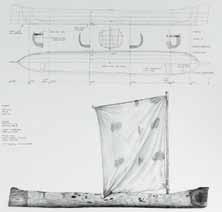

Team divers Lee Graham (ANMM, left), James Hunter and Maddy Fowler (Flinders University, above) working to locate and record timbers and an anchor from the Royal Charlotte. Photographs by expedition photographer Xanthe Rivett

A handsome research vessel that moored here this summer introduced museum visitors to a unique family who roam the oceans of the world, studying the oceanic environment and its most charismatic denizens. ANMM education officer Lauris Harper spoke to our guests about their lives and work.

What do a family home, a working ship and the language of cetaceans have in common? The answer is Whale Song, a research vessel built to conduct whale research throughout the world’s oceans, capable of traversing icy seas. She is owned by two scientists, Canadian Curt Jenner and his Australian wife Micheline, who live on board with daughters Tasmin (12) and Micah (17), conducting research that contributes to the documentation, recognition and protection of cetacean species (that is, the whales).

The museum’s visiting vessels program has brought some outstanding attractions to our wharves, including a Soviet Foxtrot submarine, the replica of the Dutch East India Company flagship Batavia, and currently the Australian-built replica of Duyfken, the first known European ship to visit Australia. Whale Song was with us from 29 November 2011 until 5 January 2012.

After this brief Sydney stopover, Whale Song headed south studying pygmy blue whales, killer whales and sperm whales en route to Fremantle where she will have completed her first circumnavigation of Australia. The following months will be spent satellite-tagging blue whales and humpback whales in preparation for an expedition to the Antarctic in the summer of 2012–13.

Their sponsors have included State and Federal Governments, International Paints, Baileys Marine Fuels and private individuals. The latest five-year program examining the behavioural effects of seismic air guns on migrating humpback whales off the Queensland Sunshine Coast was funded by US oil and gas group, Joint Industry Partners. Prior to that Whale Song was in the Kimberley region of north-western Australia measuring blubber thickness

with stereo cameras set up on her gimballed, 12-metre boom crane and applying satellite tags to north-bound humpback whales off Western Australia’s Ningaloo Reef.

Whale Song combines high-quality, yacht-like accommodation and finishes with state-of-the-art research facilities. Her hull and machinery, sound-dampened as they are on navy submarines, enable whale songs to be heard while towing a series of underwater microphones called acoustic arrays. She has forward-searching sonar and military-specification nightvision cameras for locating whales in the most challenging conditions, from the tropics to the poles. There are additional cameras for photo-identification; instrumentation to measure ocean conductivity, temperature and depth; computer networks; and all navigation equipment. Stabilisation systems and climate control allow the scientists to work at sea at maximum capacity. Whale Song can steam continuously for six weeks and has already been to both polar regions and right around the world.

Curt and Micheline Jenner have been interested in and involved with whale research for almost their entire lives.

As a nine-year old, Micheline admired her brother’s career aspirations, but later had to decide between the forest and the sea – terrestrial ecology studies or marine biology. Curt’s interest stemmed from a commercial whale-watch experience with Pacific Whale Foundation, Maui, Hawaii, at the end of his marine biology degree. He secured work with their research division, and it was there he met Micheline in 1987 – who was his boss! Married two years later, they worked on a study of killer whales, and in 1990 initiated their cetacean research in Western Australia. As whale biologists they are respected both Australia-wide and internationally.

Whale Song, built in 2000 in Florida, USA, is one of several live-aboard research vessels the family has owned. The Jenners have raised their family on board, offering their children the delights of new lands and cultures, learning about marine biology, cooking and maritime skills.

Signals: What types of whales do you study and why those in particular?

Curt: We study all whales and dolphins we encounter, because so little is known about them in Australian waters. However, our favourites are humpback whales and blue whales. Humpbacks are amazingly inquisitive and interactive with humans despite our history of decimating their numbers. Their coastal migratory habits still make them vulnerable to human impacts and this gives our research added importance. Similarly, blue whales are increasingly coming into contact with human activities as we spread our use of the oceans into deeper and deeper waters. Unfortunately blue whale numbers aren’t doing as well as humpbacks and protecting these massive animals has become our main task for the next 10 years.

What data do you collect and then how is it used?

Micheline: A variety of tools are used to collect data. For humpback whales, we take left dorsal, right dorsal and tail fluke photographs. The black-and-white markings on the underside of their flukes are unique, just like our fingerprints. Since 1990 we have catalogued 6,000 humpback whales and 250 pygmy blue whales. For the latter we also take left and right body shots as well as opportunistic tail fluke images. We also satellite-tag individual whales. The tag emits signals that allow us to plot their paths and understand why a whale is where it is and at what time.

Biopsy or skin samples are collected using a crossbow or, more recently, modified .22 rifles. This sample, about three centimetres long, is processed by geneticists and yields information about toxin levels within the tissues of the blubber. From the skin layer they determine stock separation and gender. Recordings of male humpback whale song, designed to attract females for breeding, is an unusual way to understand population dynamics. We shared our Western Australian song with some east-coast whale researchers and in 1996 something unique happened – two eastcoast whales were singing the west-coast song! In 1997, 50% of singing whales were singing this new song and by 1998 almost all of the recordings had whales singing

top to bottom: Home at work: Curt and Micheline Jenner entertaining on board Whale Song Photographer J Mellefont/ANMMour WA top 40! This was deemed a cultural revolution, novelty being the driver of change: east-coast males must have thought this was a new song and good for pulling the chicks, so they all tried it! Nonetheless, the whales also continued to evolve their own songs.

All these techniques give us critical information on cetacean’ habitats, particularly the humpback whale bedroom and nursery in the Kimberley, resting area in Exmouth Gulf and Shark Bay, and their kitchen in the Antarctic.

In what parts of the world do you carry out your research?

Curt: Whale Song is a globally unrestricted vessel with an ice-class rating so that we can work in the polar regions where the whales feed during summer months. Our next big project is to tackle the question of why blue whale numbers are not recovering. We plan to work around the southern hemisphere on each population of blue whales, both in their Antarctic feeding areas and in their equatorial breeding grounds, to try to establish what is limiting their recovery. As a family, we recently brought Whale Song from Malta back to Australia via West Africa, enjoying wonderful markets and cultural places in Gibraltar, Canary Islands, Cape Verde Islands, Namibia, South Africa and Mauritius.

What is your specific role in the research as opposed to Curt’s?

Micheline: The strength of any personal and professional relationship is the mix of roles and capabilities brought to the table. Certainly Curt and I bring such a mix, creating a balance within our research.

I often describe my role as ‘I look, cook and do the books!’

I am the chief scientist on deck looking for, observing and describing the whales and dolphins, and ensuring the data is collected correctly in this initial sighting. I love taking the photo-ID images to record the cetaceans as well as any other particularly important moments on board the vessel – scientific, navigational or social! Having been at sea for so long, Curt and I both qualified as Master Mariners, and five years ago I received my Master 5 Captain certification allowing me to navigate. I take the midnight to 3 am ‘graveyard shift’, and enjoy the moon, stars and dolphins bow-riding. For the last 22-odd years I have produced all the daily cooking but am now sharing this when off-shore with Resty, our Filipino Chief Engineer, who treats us with delicious traditional dishes from his country. For the last 12 years

I have home-schooled our daughters Micah and Tasmin. The Western Australian Schools of Isolated and Distance Education provide mailed and computer-interactive material for oceanic vagrant types like us! Micah, who plans to do marine science at university next year, started boarding school in Year 9 and Tasmin will most likely do the same. The other books I do are the quarterly financial records.

What has been one of the most interesting moments in your research?

Curt: When we discovered that blue whales we had satellite-tagged near Perth migrated north to Indonesian waters. This was a collaborative project with the Australian Antarctic Division, funded by Woodside Energy, that brought 10 years of tag development to an exciting new level. The tag lasted for four months, at the time the longest in the southern hemisphere, and has stimulated us to expand our research to include a new global perspective. Blue whales are not limited by artificial boundaries and borders, yet humans have the potential to greatly disrupt their migrations, feeding and breeding habits. Most of this disruption is unintentional, and through public education we hope to pave the way for blue whales to once again roam freely through the world’s oceans.

What has been the most alarming moment in your research?

Micheline: A most disturbing situation unfolded when we came across an adult humpback whale with a small calf swimming nearby. While working to gather photo-ID data on both whales, the adult – possibly its mother – swam away quickly, southbound, and left the calf circling us uttering sad social sounds. Suddenly the calf spotted a pair of adults travelling northward and swam toward them, but they appeared uninterested in caring for a calf. Deliberately zigzagging back and forth, the calf was becoming desperate to be accepted by adult company. However, being in what we call the humpback highway, another pair of adults appeared, heading southward. The calf came alongside this pod, joined them and with relief we watched all three continue travelling together. We had discussed caring for the calf ourselves but the need for 300-odd litres of milk per day, of 40-50% milk-fat, made this extremely difficult. Sadly, this little calf had a poor prognosis for survival, and so we were reminded of the circle of life … we had observed nature in the raw without any softening of appearances and consequences.

We must protect ocean ecosystems to maintain species diversity, habitat integrity and a functioning hydrology cycle

Micheline

Jenner

Curt and Micheline hope that through their research, critical habitats for cetacean species will be documented, recognised and protected. They continue to educate the community through their website, public lectures and school presentations. School groups are excited to see an operating research vessel, particularly one of such quality. Skipper, the ship’s lively black-andwhite Jack Russel terrier, is the star of the show! The Jenners’ message to all visiting groups is simple: ride bikes, shop locally, recycle anything and everything, reduce consumerism, keep chooks and write letters to politicians to voice concerns. Small actions by many people will make a difference.

At the museum we deliver an education program called ‘Don’t Mess with the Junksons’, which investigates the impact of human activity on the built environment, on oceans and waterways. Students are encouraged to draw conclusions from their observations and record practical ways in which they can help manage our waterways and oceans so that they remain sustainable. Visit the Jenners’ web site www.cwr.org.au

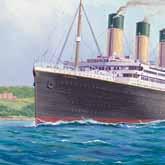

Titanic Departure from Southampton, oil on linen by Australian marine artist Stan Stefaniak. Showing the ship on her maiden voyage from Southampton to Cherbourg on Wednesday 10 April 1912, this ship portrait was painted specially for the anniversary.

One hundred years since the sinking of Titanic on that night to remember, 14–15 April 1912, can we separate the myths from the facts?

Ocean liner historian and author Peter Plowman provides some answers, and will reveal more in his next lecture for the Members program, coming up on the anniversary Sunday 15 April.

It is one of those strange quirks of history that the ship which for many people is the most famous ever built is one whose active career lasted a mere four days. Of course, it is not Titanic’s short career that makes her famous, but the tragic circumstances of her loss. One question almost never asked, however, is why Titanic and her sisters were built. It was not some capricious whim of the owner of White Star Line, but a deliberate commercial strategy to improve the company’s standing in the important North Atlantic trade.

At the start of the 20th century, White Star Line was the dominant company on this route. Their major competitor was Cunard Line, which achieved total supremacy in 1907 with the introduction of two four-funnelled liners of 32,000 gross tons, Lusitania and Mauretania They were the largest and fastest liners in the world, and everyone wanted to travel on them. White Star Line was suddenly left behind, and the only way they could restore their fortunes was to order two new liners that would be able to compete with Cunard’s pair.

The White Star ships would be 46,000 gross tons, one and a half times the size of the Cunarders, but not as fast, placing more emphasis on comfort. White Star gave their new liners names befitting

the biggest liners in the world: the first became Olympic and the second Titanic As originally designed, the two ships would have only three funnels, but then a dummy fourth funnel was added to greatly enhance their reputation and appeal. This applied especially to the migrant passengers, who believed that more funnels made a ship safer and whose revenue was far more important to the shipping line than that of the opulent first class.

Olympic entered service in 1911, and would have a long and mostly successful career lasting almost 25 years. Cunard Line placed an order for a new liner of similar size to the White Star rivals, and it entered service as Aquitania in 1914. White Star also ordered another ship in 1911, which would be slightly larger than the earlier pair. To emphasise the fact that this ship would be the biggest in the world, it was originally to have been named Gigantic. After Titanic sank, it was renamed more sedately as Britannic This vessel was sunk during World War I while operating as a hospital ship, without ever having made a commercial voyage.

Today there are frequent documentaries about Titanic on television, not to mention the extremely costly movie that brought the story of the disaster to an even bigger audience. So how accurate is the information they convey, or do they add to certain common myths and misapprehensions?

For one thing, Titanic is frequently referred to as a ‘cruise ship’ in the TV shows, whereas she was a liner, built for the sole purpose of carrying a large number of passengers between the old and new worlds. The accommodation on the ship is usually described as ‘luxurious’, backed up by pictures of spacious open decks, elegant lounges, sumptuous dining rooms and beautifully furnished staterooms. It is often overlooked that this was only in first class, where 900 of the 2,600 of the ship’s passengers were accommodated. The amenities for the 560 second class passengers were comfortable rather than luxurious,

What does seem certain is that the legend and the myth of Titanic will continue to fascinate and to intrigue many generations to come

while the cramped, overcrowded, noisy and uncomfortable quarters into which the 1,140 third class passengers were crammed go largely unnoticed. Due to the enormous loss of life when Titanic sank, White Star Line is frequently criticised for providing insufficient lifeboats. In fact the liner had more lifeboats than were required by the regulations then in force. Had any other Atlantic liner been involved in an identical situation the loss of life would probably have been on a similar scale, since none of that era’s liners carried enough lifeboats to hold everyone on board. As is so often the case, it took a tragedy such as the loss of Titanic to make lawmakers implement new regulations that stipulated lifeboats for everyone on board.

A sensational moment in the Titanic enquiry, in an illustrated English weekly magazine The Graphic Australian National Maritime Museum collection

Probably the greatest myth surrounding Titanic is that it was unsinkable. This was never claimed by White Star Line or Harland & Wolff, who built the ship in Belfast. When Titanic was completed, an article appeared in a leading British newspaper that included the phrase ‘virtually unsinkable’ in a description of the attention paid to safety, in particular the ship’s watertight compartments. In essence this was true, as the ship should not sink under most adverse conditions. It was always stated that Titanic would remain afloat with four watertight compartments flooded. The liner was condemned to its fate when six compartments were breached by the iceberg.

Of course, in 1912 the sinking of Titanic was news around the world, but two years later an even worse catastrophe occurred, when the world went to war. If there was one major shipping tragedy that was remembered after the war ended, it was the sinking of Lusitania by a German submarine. Through the 1920s and 1930s this incident was the one that people talked about, while the loss of Titanic was increasingly forgotten. In 1939 the world plunged into war again, with more death and destruction. One of the more surprising things to happen in the war was a decision in Germany to make a film about the sinking of Titanic. At a time when it might be thought that every resource would be directed to the war, the former liner Cap Arcona, serving as a barracks in Hamburg, was used for making the film, and the men living on board became extras.

In the decade after the end of World War II Titanic remained in obscurity, and probably would have continued to do so had it not been for one American and a book he wrote. Walter Lord became intrigued with the loss of Titanic, managed to locate 63 survivors to tell him their stories, and put together a gripping account of that fateful voyage. This was published in the United States in 1955 under the title, A Night to Remember It became a worldwide best-seller, and suddenly Titanic was back in the public eye. In 1958 a film based on the book was made in Britain. The old Royal Mail liner and migrant carrier to Australia, Asturias, ready for scrap at the breakers yard in Scotland, was used as the main exterior prop, while interior scenes were shot on studio sets. Photographed in black and white, and using an almost documentary style, the film became a huge hit around the world.

Other, far-from-accurate Titanic films were made in the United States, one particular shocker having American actor George C Scott playing Captain Smith with an American accent. In a thoroughly ridiculous scene, Captain Smith was depicted on the bridge talking to visitors while standing at the wheel steering the ship, something the real captain would never have done. In the early 1980s, American novelist Clive Cussler published Raise the Titanic, in which the wreck of the liner was found in one piece, brought to the surface and towed into New York. This was also made into a highly successful film.

The discovery of the wreck of Titanic in 1985 brought the ship to the forefront of international attention, a position it seems to have retained ever since. This was enhanced by the release of the blockbuster movie in 1998, which combined a totally fictitious love story with the true story of the sinking. However, I do know of one lady who, after seeing the film, said she found it excellent except for the unbelievable ending where the ship sank!

Today the activity of submersibles around the remains of the liner is having a detrimental effect, and there are fears the wreck could collapse unless restrictions are introduced. While some of the ship has survived for a hundred years, at this rate there will be much less of it left after another century has passed. What does seem certain is that the legend and the myth of Titanic will continue to fascinate and intrigue many generations to come.

Learn even more about the Titanic before, during and after her sinking in the author’s anniversary lecture at the museum on 15 April. On display will be marine artist Stan Stefaniak’s brand-new ship portrait, which illustrates this article. See page 33 for details and booking information.

Our exhibition Remembering Titanic – 100 Years opens on 29 March and explores the controversy, the construction, the disaster and the rediscovery.

Other Titanic activities include a Titanic movie marathon and Kids Deck activities on Sunday 15 April, and Fateful Feasts on 20 May, where gastronomic lecturer Diana Noyce describes how the food served on board showed Edwardian society in microcosm. Stage 5 high school debaters will be coming to grips with this famous sinking (dates TBA). Information on our website anmm.gov.au or call 02 9298 3777

P&O Cruises can trace its heritage back 175 years to the formation of the Peninsula Steam Navigation Company which held the British Government contract for a weekly mail service to the Iberian Peninsula. In 1840 the company was renamed the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company – creating P&O.

At this time ships were built for the purpose of transporting cargo and passengers only travelled out of necessity. However, thanks to the vision and innovation of Arthur Anderson and Brodie McGhie Willcox the concept of leisure cruising was born.

Today, P&O Cruises strive to innovate and improve much like its forefathers to cater for an ever-growing number of passengers and to provide an unforgettable holiday experience for everyday Aussies.

visit pocruises.com.au

Among a flood of new books marking the centenary of the sinking of Titanic is this one by an Australian National Maritime Museum staff member, who recalls an epic journey of discovery and research that’s occupied much of her life. This article is by the author of Titanic Valour and personal assistant to the museum’s director, Inger Sheil

Author Inger Sheil, whose fascination with the social history of the 20th century’s early decades has inspired

Spending a childhood on Sydney’s northern beaches, the sea was a part of daily life. My grandmother shared my taste for documentaries, and together we’d watch Jacques Cousteau explore the world’s oceans. The first shipwreck I encountered on screen, however, was not the one that can lay claim to being the most infamous of all, but the more recent Andrea Dorea. As it lay in depths accessible to scuba divers, I watched in fascination as they explored the submerged wreck, and listened to the dramatic stories of survivors who described the terrible collision that sank her in 1956 off Nantucket, Massachusetts. It was this human element that was to draw me to the Titanic some years later when I was introduced to the story of that great tragedy of the Belle Époque. A second-grade school friend showed me a book, and the outline of the famous story began to solidify for me – the lack of sufficient lifeboats, the ‘unsinkable’ reputation, the wealthy who were able to take lifeboat places when the third-class passengers could not. It would be many years before I found that the truth was not quite so simple, but the broad brushstrokes were there. Tucked into my childhood ephemera is a sketch I made in the journal I kept as a seven year old. Stick figures play out the story on a ship pitched at a dramatic 75 degrees to the sea’s surface, with terrified passengers and crew handing small children down to mothers in lifeboats. A sequel illustration of the scene ashore shows dripping survivors demanding their money back from ticket agents.

Growing up, I picked up books on the subject where I could. I had just moved to Singapore when the Titanic was rediscovered in 1985. The challenges of a new school in a new country couldn’t compete with the fascination of the Time magazine cover painting of the lost ship on the ocean floor. With my interest reignited, I was able to locate such classics as Walter Lord’s vividly narrated A Night to Remember But access to information was limited to some books and the occasional television program. No one in my immediate circle shared the fascination.

All this changed in 1996 when I first gained access to the internet. It enabled me to track down and order books and magazines on the subject from around the world, and to contact other enthusiasts. My bookshelf was soon creaking with the works of over 80 years of writing on the subject, and I became absorbed in online discussions about every aspect of the ship, from the minutiae of the lives of those connected with it to the placement of its rivets.

In fact it was the social history that most interested me. It was not so much the passengers – that cross-section of Edwardian British and American society along with immigrants from around the globe – but rather her crew that drew me in. These were the men and women for whom Titanic wasn’t a means of flitting from one continent to the other or a vehicle to a new life in a foreign land, but a career and a way of life on the sea.

Gradually I became aware of one name in particular. It belonged to a man who

seemed to appear when anything interesting was being said or done during the sinking and aftermath. He was a junior deck officer who told the chairman of the White Star Line to ‘go to hell’ when he thought he was interfering with the lowering of the lifeboats; who, in response to a question at the American inquiry about what icebergs were composed of, answered ‘Ice, I suppose, Sir’; and who had commanded the only lifeboat to return to pick up survivors. He was the man whom Walter Lord called a ‘tempestuous young Welshman’ who was ‘hard to supress’, and who emerged vividly as an engaging character. His name was Harold Lowe. Intrigued, I looked for more information. Surely, given the millions of words that had been expended on just about every aspect of the disaster, someone must have researched and written more extensively about this particular individual. I found, however, that not only had no full-scale biography been written, but very little at all was to be found in print about his pre- and postTitanic life. He emerged briefly from obscurity before fading back into it. He never commanded his own vessel, he had retired at some point after World War I, and he died in Wales in 1944. Any details beyond the outline of his career given at the American inquiry were scarce indeed.

At this stage I was fortunate enough to encounter on the far side of the world someone who shared my interests – Kerri Sundberg, a mid-western American girl with a love of the sea even though she’d only seen it once in her life, on a visit to

clockwisethe West Coast. We began corresponding, and she shared with me 1912 newspaper articles that she’d found in archives and other scraps of information she’d been able to put together. We discussed creating a website on Harold Lowe and his colleagues to correct some of the misinformation about them that circulated online, and to facilitate further research. We made contacts and connections with the Lowe family, thanks to fellow researchers like author Dave Bryceson, who kindly put us in contact with Harold Lowe’s son, Harold William George Lowe. Harold W G Lowe, in turn, introduced us to more friends and family members, such as his own son and daughter and his nephew.

To add to the material the family shared with us, I engaged proxy researchers to look for information in UK archives. It was slow going, however, as many archives had not yet put their collections online. While email was becoming more commonly used, much of our correspondence was still done by snail mail. Scanners were almost unheard of, and there were long and anxious waits for packages of documents from overseas.

But at every turn we were finding new information. With the exception of some who resented young upstart researchers like us, the Titanic community was overwhelmingly supportive. Finally we decided that the scope of information we were accumulating far exceeded that of a website, and we began tentatively to look towards a print publication.