Curated by Grace Samboh 17 June — 31 July 2023

2 – 15 Merapal bala Dewi, mematung gambar, sanggul-menyanggul: ya, semuanya!

GRACE SAMBOH

16 – 37 Artworks — Sculptures

36 – 49 Chanting the Dewi’s legion, sculpt-drawing, bun-curling: yup, everything!

GRACE SAMBOH

60 – 75 Artworks — Drawings 76 Biodata

80 Acknowledgements

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Merapal bala Dewi, mematung gambar, sanggul-menyanggul: ya, semuanya!

GRACE SAMBOH

Pada mulanya adalah sesosok perempuan anggun dengan badan cenderung tinggi, mengenakan kebaya, berbalut kain, bersampir selendang, dan rambutnya digelung sanggul. Ia berdiri dengan pose yang kelihatannya biasa-biasa saja, mengangkat kedua tangannya dan menyerahkan piring kepada sesosok laki-laki yang berdiri di sebelahnya. Sang laki-laki telanjang dada, bercelana pendek, mengenakan caping, berkalung pistol dalam sarung di pinggangnya dan memanggul bedil. Tanpa adanya alat pertanian pun, kita digiring untuk memandang mereka sebagai pasangan petani dalam kesehariannya di masa peperangan. Namun bukan pasangan petani sembarangan: mereka sepasang figur monumental di sebuah bundaran di pusat Jakarta, walaupun tidak ada yang tahu—apalagi kenal—siapa mereka sesungguhnya. Toh orang mengenal kawasan bundaran ini lewat julukan bagi mereka, Tugu Tani.

Saya dan Nadiah memanggil sosok perempuan ini “mbak”—sebagaimana orang Jawa mengalamatkan perempuan lain yang dihormati, disegani, atau sekadar lebih tua. Sejak akhir 2019, kami sering bercakap mengenai mbak yang menyandang tugas berat ini. Bagaimana tidak berat; ia dicanangkan menjadi perwakilan perempuan kaum tani, harus tampil prima—menyanggul bukan pekerjaan sebentar—namun, perannya

2 ESAI KURATORIAL

WANI

dibekukan saat memberi makan sesosok lelaki yang ada di sebelahnya. Padahal, kaum tani tahu persis bahwa perempuan juga pergi ke sawah membawa arit—yang juga bisa jadi senjata. Pada awal 1960-an, Sukarno menggagas Tugu Pahlawan—demikian nama resmi bundaran serta sepasang patung ini—, memesan patungnya kepada kakak-beradik pematung asal Rusia, dan meresmikannya pada 1963.1

Percakapan kami bergulir ke berbagai kegiatan perempuan dalam

“era mengisi kemerdekaan”—demikian Sukarno menyebutnya. Seperti di tempat-tempat lain di belahan bumi ini, nafas kemerdekaan, kebebasan, kemandirian, dan kesetaraan berhembus berbarengan. Usai proklamasi kemerdekaan, gerakan perempuan yang memusatkan diri pada gerakan penyetaraan pengetahuan melalui beragam bentuk literasi bermunculan di mana-mana. Dalam membicarakan riak gerakan perempuan ini, nama-nama tokohnya ikut seliweran dan kami juga mengalamatkan mereka dengan “mbak”—selain karena kami bercakap di tanah Jawa dan, tentu, menghormati mereka, kami juga tidak ingin serta-merta “menuntut” mereka menjadi “ibu”. Dalam percakapan-percakapan ini, kami jadi punya kebutuhan untuk bisa mengidentifikasi sang sosok perempuan di Tugu

Tani itu lebih dari sekadar mbak. Kami pun memanggilnya Mbak Wani.2

Mbak Wani adalah tokoh utama dalam Merapal Mantra untuk Gerakan (Casting Spells for the Movement, 2021), instalasi Nadiah berupa

sebuah patung berukuran sama dengan sosok perempuan di Tugu Tani

serta tiga buah televisi layar datar yang secara bergantian menghadirkan percepatan gerakan perempuan. Saya akan jabarkan instalasi video ini dari layar pertama, yang paling kanan, hingga yang paling kiri. Layar pertama dimulai pada sisi paling kanannya. Sejumlah perempuan dengan

baju sehari-hari masa kini berdiri dengan pose yang sama dengan Mbak

Wani—mengangkat kedua belah tangan seolah sedang memegang piring. Secara perlahan, mereka menurunkan tangannya, kemudian berjalan ke arah kiri layar. Setelah para perempuan ini hilang dari layar pertama, mereka mulai bermunculan di layar kedua. Mereka juga berjalan menuju

sisi kiri, layar ketiga, namun langkah mereka menjadi lebih cepat. Begitu perempuan terakhir hilang dari sisi kiri layar tengah ini, segera rombongan perempuan ini muncul di layar terakhir. Mereka berlari dari sisi kanan layar ke sisi kiri layar, seolah keluar dari layar dengan larian. Ya, pada setiap layar, langkah mereka menjadi semakin cepat. Dalam Merapal

3

Mantra untuk Gerakan , Nadiah mengklaim-ulang Mbak Wani sebagai simbol untuk gerakan perempuan lintas-masa.

Rasanya kita perlu satu esai khusus untuk membahas video sehubungan dengan kehadiran tubuh-tubuh manusia di dalamnya, bagaimana tubuh-tubuh ini digerakkan, dan bagaimana pilihan cara memancarkan gambar gerak ini di dalam ruang pamer berakar pada pemikiran keruangan seorang pematung. Lihat karya-karya Nadiah, misalnya, Terpesona dengan kegelisahan (Charmed by anxiety, 2022) dan Ketidaknyamanan (Insecurity, 2023). Tubuh-tubuh manusia, nyaris apa adanya, diarahkan untuk melakukan hal-hal yang memang tak asing buat mereka (menari, atau senam?, bersama bagi para tentara dan laku ndhodhok bagi para abdi dalem Kraton Yogyakarta). Demikian juga para perempuan dalam pakaian kesehariannya pada Merapal

Mantra untuk Gerakan, dimana mereka sesederhana berpose seperti Mbak

Wani, kemudian berjalan, sampai akhirnya lari. Gerakan tubuh yang tidak asing itu mengingatkan kita pada salah satu karakter disiplin patung dimana kualitas material bahan adalah alasan pemilihan sekaligus metode dan tujuan kerja.

GAMBAR-NAN-PATUNG

“Gambar-gambar saya adalah akumulasi dari metode yang sudah saya kembangkan dalam upaya guna memanipulasi kertas untuk senarai hasil tertentu. Saya bekerja sangat dekat

dengan asisten saya, ialah yang menangani kejelimetan

pembuatan tekstur pada permukaan kertas, kemudian menempelkan semuanya. Sekarang kami mesin yang mulus

bekerja dalam pembuatan tekstur.” 3

Hampir 15 tahun terakhir ini kita mengenal Nadiah melalui gambar-gambar arangnya yang cenderung realis. Kebanyakan gambar

Nadiah ini tidak dibingkai dan dipasang berjarak dari dinding pemajangannya. Dalam kosakata pembuatan-pameran (exhibition-making), kita

bisa dengan entengnya menyebut karya-karya macam ini sebagai wallpiece —karya yang dipasang di dinding, bisa lukisan, patung, gambar, sketsa, arsip, atau apapun. Dalam percakapan, Nadiah menyebut

4 ESAI KURATORIAL

karya-karya ini sebagai drawing, gambar. Pada label karya, Nadiah menulis drawing on paper collage , gambar di atas kolase kertas. Namun, proses pembuatan karya ini sejatinya adalah proses mematung, bukan menggambar—bahwa hasilnya bisa kita sebut sebagai “gambar”, ini soal lain. Kalau kita membicarakan pembuatan gambar-gambar Nadiah dengan kosa patung, Nadiah bekerja dengan proses penambahan, laiknya assemblage atau pembuatan model dengan tanah liat untuk persiapan cetak (casting).4 Kolase kertas berarti tumpuk-menumpuk, tempel-menempel kertas di atas kertas lainnya. Arang diterapkan Nadiah pada sobekan-sobekan kertas ini dengan teknik usap (blending) untuk menghasilkan kepekatan ( shading ) yang berbeda-beda. Tempelan sobekansobekan ini serta-merta menjadi matra ( dimension ). Bila pada pinggir sobekan kertas usapan arang ditebalkan, matranya menjadi lebih tebal, lebih “dalam” sehingga mata kita akan melihatnya sebagai bayangan. Saya akan coba merinci dua karya Nadiah sebagai upaya untuk memahami apa yang disebutnya sebagai “senarai hasil” dari kerja menyobek, menumpuk, menerapkan arang, dan menempel kertas di atas satu sama lain. Perhatian selanjutnya patut kita layangkan pada kata “sobek”, “arang”, dan “tempel” sebagai kinerja pembuatan barik. Dalam menggambar, yang disebut barik adalah motif dalam bentuk citraan datar. Sementara dalam khasanah patung, barik bergantung pada bahan, cara pengolahan bahan, dan proses pengupamannya (polishing). Matra dalam karya-karya gambar Nadiah ini adalah hasil dari proses menyobek dan tempel-menempel kertas yang telah diterapkan arang—ia tak menyebutnya mewarnai atau menggambar. Karena proses yang ditempuh Nadiah ini, saya menyebut

karya-karya gambar Nadiah sebagai: Gambar-nan-patung.

Sebagai “mesin yang mulus bekerja dalam pembuatan tekstur”, kerja

sama antara Nadiah dan asistennya, Desri Surya Kristiani, amat luwes. Saat

mengawali proses pameran Dewi , begitu penasarannya saya akan teknik

gambar-nan-patung ini, saya mewawancarai keduanya. Dari wawancara itu, saya belajar bahwa keduanya bisa menyelesaikan kalimat satu sama lain saat

membicarakan teknik, kosa kata, dan ulang-alik langkah dalam pengerjaan

gambar-nan-patung ini. Mestinya saya tak heran, mereka telah bekerja sama

selama hampir 15 tahun. Kepercayaan satu sama lain akan langkah-langkah

yang akan diambil serta keyakinan bahwa mereka menuju ke arah yang sama begitu besar. Tadinya, saya ingin menyanggah pernyataan “mesin yang

5

bekerja mulus”, karena manusia tentu bukan mesin. Namun, tak usahlah. Lagipula, “kesalahan” dalam proses pembuatan gambar-nan-patung ini bisa kita anggap tidak ada. Jika satu bentuk yang ingin dicoba atau dicapai gagal, keduanya menerima kegagalan ini sebagai pelajaran. Keduanya percaya bahwa medium yang mereka gunakan—kertas, arang, lem, tangan, dlsb— adalah batasan alamiah dari apa yang bisa mereka capai. Dari setiap kegagalan, mereka belajar hal baru mengenai bahan serta kemampuan mereka sendiri. Walau tidak ada catatan dalam bentuk tulisan, kosa kata khusus yang mereka gunakan untuk membicarakan proses bekerja sama ini adalah bukti

nyatanya.

Jika kita melihat karya-karya gambar Nadiah di ruang pamer, ada semacam panggilan untuk mendekati dinding dan melihat karya ini dari samping—baik untuk tahu bagaimana cara karya dipasang atau untuk melihat ketebalan kertasnya. Kalau kita pindah sudut pandang sebentar—dari patung ke gambar—, maka sudut-sudut sobekan kertas ini bisa juga kita sebut garis. “Garis-garis” ini menciptakan efek kedalaman. Meskipun sumber cahaya dalam karya-karya gambar Nadiah ini umumnya lurus dari depan, bak gambar yang dihasilkan dalam studio foto, kertas yang ditempel di atas satu sama lain menghadirkan pengalaman keruangan yang lain sama sekali dengan kebanyakan gambar di atas kertas.

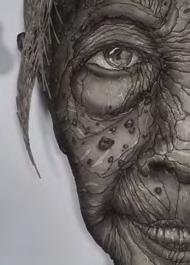

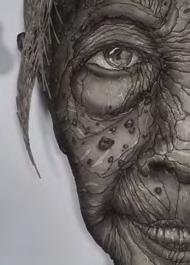

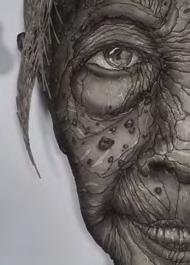

Nadiah menggunakan empat nuansa abu-abu, dengan kata lain, ada empat ketebalan terapan arang pada sobekan-sobekan kertasnya yang

membentuk rambut sang Sundal Bolong (gambar 1). Abu pertama, yang paling muda, adalah bidang umum sang rambut. Kedua abu

10 A+NadiahBamadhaj-TheReckoning-Catalogue-FA.indd

A+NadiahBamadhaj-MengamankanEkspektasi-catalogue_3.indd

6 ESAI KURATORIAL

10 A+NadiahBamadhaj-TheReckoning-Catalogue-FA.indd 11

14 A+NadiahBamadhaj-MengamankanEkspektasi-catalogue_3.indd 15 Gambar 1. Gambar 2.

selanjutnya—pada level ketebalan kedua dan ketiga—memberi dimensi pada bidang rambut. Abu keempat, terakhir, yang paling tebal usapannya, memunculkan kedalaman, kesan ruang. Abu yang terakhir ini diusapkan

Nadiah hanya pada pinggiran sobekan kertas pada gelungan konde. Maka terciptalah bayangan sang konde. Terapan arang yang relatif tipis dan halus—level ketebalan dua dan tiga tadi—digunakan Nadiah secara bergantian pada sobekan kertas di bawah konde, memunculkan kesan ikal pada rambut sang Sundal Bolong.

The Reckoning (gambar 2) dipamerkan di artjog, Yogyakarta (2021) dan artina , Sarinah, Jakarta (2022). Kerut wajah figur yang diinspirasi oleh Calon Arang ini menjadi tegas karena Nadiah menerapkan arang lebih tebal pada pinggiran sobekan kertasnya. Dalam salah satu percakapan kami, Nadiah bilang, “Sobekan kertas itu aku garis lagi, mbak.”

Secara teknis, ia bukan menggarisi pinggiran sobekan kertas itu, melainkan mengusapkan lebih banyak arang. Pada bagian rambut, usapan arang

Nadiah cenderung sama ketebalannya. Dari mana kita bisa mengenali setiap helai rambut figur ini? Kenyataannya, setiap helainya adalah sehelai sobekan kertas!

Benar bahwa, dalam ruang pamer, karya Nadiah akan dengan mudah kita sebut sebagai gambar. Namun, secara pembuatan, proses yang ditempuh Nadiah adalah proses mematung. Satu-satunya istilah gambar yang digunakan Nadiah untuk membicarakan karya-karya ini adalah pembuatan-bayangan (shading). “Tekstur-tekstur itu adalah hasil dari himpunan bertahun-tahun pengalaman kerja reka kertas—mengupas, menyobek, memberi bayangan, meratakan, menempel, dan memberi bayangan lagi. Kinerja yang penuh kesaksamaan antara saya dan kertas.” Dalam khasanah gambar, pembuatan-bayangan adalah kebutuhan untuk memunculkan kedalaman—dengan kata lain keruangan—objek yang digambar.

CALON ARANG, WEWE GOMBEL, SUNDAL BOLONG DAN KUYANG

Belum pernah gambar saya itu mengalir keluar dari diri saya. Gambar saya butuh konsentrasi, pengambilan keputusan, dan, seringkali pagi-pagi, seni mengatasi ketakutan.”6

“[pada dasarnya], gambar saya adalah [...] senarai keputusan.

7

“Saya merancang sebuah objek menggunakan Photoshop, sebagai semacam motif dasar gagasan. Kemudian, saya membangun objek itu dengan senarai tekstur. [...] Bertahuntahun ini, saya telah menghimpun kosakata tentang apa dan bagaimana caranya agar saya bisa mengekspresikan gagasan-gagasan. Awalnya, saya pikir saya hanya bisa menangkap kulit (pada potret), tetapi kemudian saya mencoba kain, lalu saya menemukan cara menggarap pakaian dan batik. Segera setelah itu, saya menemukan cara untuk menggarap kabinet, rak, dan gubuk. Lama-lama saya memiliki banyak sekali stok ‘cara’ untuk mencapai apa yang ingin saya gambarkan [...]”7

Kisah Calon Arang yang terus dilanggengkan adalah ketika ia telah menjadi perempuan tua dan janda (maka tak lagi dianggap menarik atau “berguna” untuk reproduksi) yang ditakuti karena kekuasaannya (sehingga dituding sebagai penyihir atau penyebab kekacauan). Pada skala sejarah nasional, pemerintah Orde Baru bahkan mengarang sebuah tragedi yang secara langsung menghubungkan citra Calon Arang dan Gerakan Wanita Indonesia—belum ada yang benar-benar meluruskannya hingga sekarang! Sekali mendayung, dua tiga pulau terlampaui.

Bagaimana kisah hidup, pilihan sikap, dan posisi politik perempuan digunakan—baik atau buruk—oleh pihak lain yang berkepentingan bisa kita baca dalam buklet berisi percakapan antara Nadiah dan kurator Alia

Swastika yang mendampingi The Reckoning (2021).8 Beberapa laku pembacaan mengenai Calon Arang, seperti Pramoedya Ananta Toer yang menguak kompleksitas posisi perempuan tersebut dalam Cerita Calon Arang (1951; The King, the Witch and the Priest, 2002), dan Calon Arang: Kisah Perempuan

Korban Patriarki (2000) oleh Toeti Heraty, telah membuka kesempatan agar posisi, reputasi, dan sejarahnya dikaji ulang. Sementara bagi Nadiah, tuanya usia Calon Arang, beriringan dengan pengalamannya sendiri menuju fase mati haid, adalah peluang untuk mengklaim kebijaksanaan, setidaknya, atas tempaan beragam pengalaman hidup.

Berbeda nasib dengan Calon Arang, Wewe Gombel, Sundal Bolong dan Kuyang mati dalam usia muda. Ketiganya adalah “nama panggung” para perempuan yang lebih kita kenal sebagai setan, hantu, monster, atau

8 ESAI KURATORIAL

momok dalam kehidupan sehari-hari. Seperti Mbak Wani, mereka adalah tokoh-tokoh simbolik. Bukan hanya di nusantara, tetapi di seluruh kawasan yang sekarang disebut Asia Tenggara. Bedanya, Mbak Wani adalah simbol perempuan ideal, sementara ketiga perempuan yang “disetankan” ini sebaliknya. Wewe Gombel bunuh diri karena tudingan tak bisa memberi keturunan. Sundal Bolong mati saat ia mengaborsi anak yang dikandungnya akibat pemerkosaan. Kuyang dituduh serakah karena ingin berkuasa dan hidup selama-lamanya. Mereka dijadikan perwakilan atas keburukan sejak entah kapan dan terus-menerus dilanggengkan bermacam kekuasaan sampai sekarang tanpa pernah ada pembahasan mengenai konteks tindakan-tindakan mereka. Misalnya: Lingkungan sosial macam apa yang menyudutkan seorang perempuan yang tidak bisa berketurunan hingga ia mengakhiri nyawanya?

Apa yang terjadi pada si pemerkosa Sundal Bolong? Dihukumkah? Jadi

setan jugakah ia? Kenapa Kuyang dianggap butuh berkuasa? Mengapa sosok monster laki-laki yang "ingin berkuasa" tidak ada dalam legenda masyarakat kita? Dst.

Wewe Gombel, Sundal Bolong, dan Kuyang, yang biasanya hadir dalam penampilan luar biasa menyeramkan, digambarkan Nadiah dalam pose—dan raut wajah—yang teduh, tenang, dan bijaksana. Jika kita tetap menganggap mereka menakutkan, mungkin kita perlu bertanya apa penyebabnya: Mengapa begitu sulit bagi kita melepaskan diri dari anggapan

bahwa mereka menakutkan? Nadiah menggarisbawahi perubahan penampilan—dari momok menjadi sosok—mereka dengan menggunakan tubuh dan wajahnya sendiri pada penggambaran ketiga tokoh ini. Kial atau gestur penggunaan dirinya—tubuh dan wajah—ini luas spektrumnya.

Paling tidak kita bisa membacanya sebagai dua hal berikut: Pertama, ini salah satu cara untuk mengklaim sebuah kenyataan sosial—tuntutan pada kaum perempuan—yang masih “itu-itu saja”: menjadi alat reproduksi, pendamping, sekaligus pelayan. Kedua, kita bisa melihatnya sebagai bentuk kesetiakawanan sesama perempuan, sesama manusia.

Pada pameran Mengamankan Ekspektasi, Jakarta (2021), Wewe

Gombel, Sundal Bolong, dan Kuyang yang tak lagi menakutkan ini sedang berusaha “mengamankan” Mbak Wani dari posisinya sebagai simbol hiper-feminin.9 Mereka hadir dalam bentuk gambar-nan-patung, sementara

Mbak Wani hadir dalam bentuk citraan digital, yang dicetak di atas bidang aluminium, dalam lingkungan yang hitam kelam, seolah antah-berantah.

9

Mbak Wani ini bukan sosok yang sama dengan yang bisa kita lihat di bundaran Tugu Tani. Tubuh, pose, rambut, dan piring yang dibawanya sama, namun sosok Mbak Wani ini adalah hasil gambaran-ulang Nadiah menggunakan peranti lunak 3d. Dengan bekal gambar 3d ini, Nadiah jadi bisa membebaskan citra Mbak Wani—mulai dari sudut pandang, kial, pose, bahkan raut wajah. Mbak Wani yang sedang “diamankan” oleh ketiga perempuan ini adalah Mbak Wani yang telah diklaim-ulang oleh Nadiah sebagai simbol dari gerakan perempuan dalam Merapal Mantra untuk Gerakan.

SKALA, MATRA, DAN LINGKUNGAN

“Saat merancang karya, ada sesuatu yang hilang bila saya belum tahu dimana karya ini akan dipajang atau dimana ia akan hidup. Rasanya seperti bekerja dalam gelap. Skala, matra, lingkungan, dan, ya, termasuk pemirsanya, punya masukan pada bentuk yang saya garap. [...] Segala bagian dari lingkungan ruang dimana karya itu akan dipajang punya masukan terhadap karya, dan tidak sebaliknya, dimana saya dengan narsisnya membangun ruang khusus bagi karya tsb. tanpa mempedulikan lingkungannya.”10

Merapal Mantra untuk Gerakan lahir dalam percakapan-percakapan yang dihantui slogan: “Membangun sejarah bersama”. Waktu itu, saya—dan

Rachel K. Surijata yang juga mengelola pameran Dewi—anggota tim kuratorial Jakarta Biennale 2021 esok ( jb2021 esok). Salah satu lokasi pameran jb2021 esok, Museum Kebangkitan Nasional (stovia), menolak pemasangan karya ini di ruang kelas dimana mereka “membekukan” sejarah dengan diorama ukuran-asli para tokoh Boedi Oetomo. Patungpatung resin yang dimanipulasi warnanya untuk menyerupai perunggu

itu semuanya laki-laki. Tentu saja gerakan perempuan bukan tidak ada pada masa mereka duduk di ruang kelas itu, pada 1908. Sekolah itu bahkan punya sejumlah murid perempuan. “Membawa” Mbak Wani ke dalam ruangan ini, dan memajangnya “dalam dialog” dengan para tokoh

dalam kelas ini, adalah pengingat-ramah (friendly reminder) akan posisi perempuan dalam penulisan sejarah secara umum.11

10 ESAI KURATORIAL

Penolakan itu tentu tidak menghalangi kami untuk memamerkan Merapal Mantra untuk Gerakan. Di lobi Museum Nasional Indonesia, sekitar dua kilometer dari Tugu Tani, Mbak Wani berdiri dengan anggun, dikelilingi karya-karya yang menggugat hubungan antarmanusia dalam konteks nasionalisme (masing-masing negaranya) sehubungan dengan posisi internasional yang diambil masing-masing negara tsb. Pengantar saya mengenai tokoh Mbak Wani di awal naskah ini hanyalah salah satu cara untuk memaknai kelahiran kembali Mbak Wani, dengan Nadiah sebagai bidannya. Tentu ada bermacam cara dan sudut pandang lain untuk membahas karya ini. Berikut cuplikan pengantar untuk kehadiran Mbak

Wani dalam jb2021 esok yang juga memperkenalkan isyarat gugatan-gugatan lain terhadap elemen otoritarian negara:

Apakah kamu kenal perempuan ini? Barangkali, sepuluh menit lalu, kamu baru saja berpapasan dengan kembarannya.

Nadiah membawa sosok ini ke sini, ke museum ini, dalam kesempatan ini, untuk mengingatkan kita dengan tegas bahwa perempuan-perempuan sepertinya sesungguhnya

selalu bergerak, dan pergerakan mereka bergaung dalam

hidup kita hari ini. Pernah terpikirkah siapa sosok perempuan itu sesungguhnya? Atau, siapa yang sedang ia wakili?

Di bundaran yang kita kenal sebagai Tugu Tani itulah monumen pesanan Sukarno pada duo pematung Rusia itu bertempat. Menariknya, monumen-monumen yang diteliti, ‘dikecilkan’, dan dipertanyakan Onejoon dari banyak negara di Afrika adalah buatan studio patung dari Korea Utara sejak 1970-an. Hingga taraf tertentu, kita bisa bilang bahwa semua monumen nasional ini tampak sama, dan kira-kira auranya juga sama.

Adaptasi ulang lagu kebangsaan Republik Rakyat Tionghoa yang dilakukan Song Ta juga terasa akrab. Peristiwa restorasi

liriknya sangat tenar dan versi aslinya diterima sebagai lirik

resmi pada 1982 setelah adanya pergeseran nilai-nilai selama puluhan tahun sebelumnya yang penuh pergolakan. Ini

11

barangkali punya arti bagi banyak dari kalian, mengingat awal tahun ini terjadi perdebatan panjang mengenai lagu kebangsaan Indonesia, yang ternyata tak pernah dinyanyikan dalam versi utuh di sekolah-sekolah dan kesempatan-kesempatan kenegaraan.12

Dalam percakapan seputar kesetiakawanan, internasionalisme, dan bagaimana periode tertentu mengubah alur pemikiran seputar kata-kata kunci tersebut, Merapal Mantra untuk Gerakan menjadi tengara dalam alam

pikir saya dan Rachel dalam konteks penelitian dan pameran Rewinding

Internationalism di Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, dan Villa Arson, Nice (2022–2023).13 Pada presentasi hasil penelitian tsb., kami “mengajak” Mbak

Wani untuk berdialog lintas-masa, lintas-geografi, dengan Sikan, satu-satunya karakter perempuan dalam budaya Abakua yang digarap oleh Belkis Ayón

Manso (l. Havana, 1967; m. Havana, 1999); dengan pilunya perubahan ekologi yang disebabkan oleh keserakahan manusia, kapitalisme, dan politik pada karya-karya Semsar Siahaan (l. Medan, 1952; m. Tabanan, 2005); serta avantgardisme para anggota kelompok Gorgona dari Kroasia, persis setelah

Yugoslavia bubar. Ketiga hal ini hadir dalam sebuah ruangan yang mengulik perihal kesetiakawanan antarbangsa dari latar belakang negara-negara NonBlok. Pada jarak 14.000 kilometer dari “kembarannya” di Tugu Tani, Mbak

Wani menjadi tengara dalam konstelasi ini. Ia berdiri hampir di tengah ruangan sementara karya, kisah, dan arsip lain seputar pencarian ini mengitarinya. Saya telah belajar banyak dari obrolan mengenai dan seputar Mbak

Wani—sebagai tokoh, sejarahnya, wujudnya, perubahannya, dst.—sampai

dengan kenyataan bahwa ia adalah karya yang berukuran relatif besar, yang tidak mudah dibawa atau dipindah. Mbak Wani tingginya hampir 2.5 meter!

Selain pada jb2021 esok, Merapal Mantra untuk Gerakan pernah tampil

sebagai presentasi khusus di Art Jakarta 2022. Pada kesempatan yang sama, di Art Jakarta 2022 yang hanya berlangsung sekian hari itu, Nadiah me-

mamerkan Wewe Gombel, Sundal Bolong, dan Kuyang yang sedang berusaha

“mengamankan” Mbak Wani. Baru-baru ini, tepat pada hari pembukaan

pameran Dewi, di Yogyakarta, pameran Rewinding Internationalism di Villa Arson, Nice, Perancis, juga dibuka. Di sana, Mbak Wani kembali menjadi

tengara di dalam salah satu ruang pamer. Mbak Wani telah melanglang buana. Batalnya penampilan Mbak Wani di ruang dimana kami mengawali

12 ESAI KURATORIAL

percakapan mengenainya tidak membatasi ruang gerak, baik secara fisik, bentuk, maupun interpretasi atas karya ini.

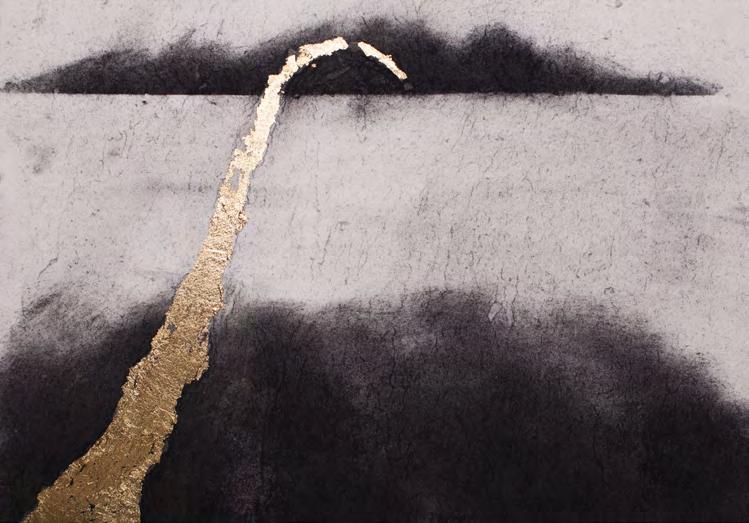

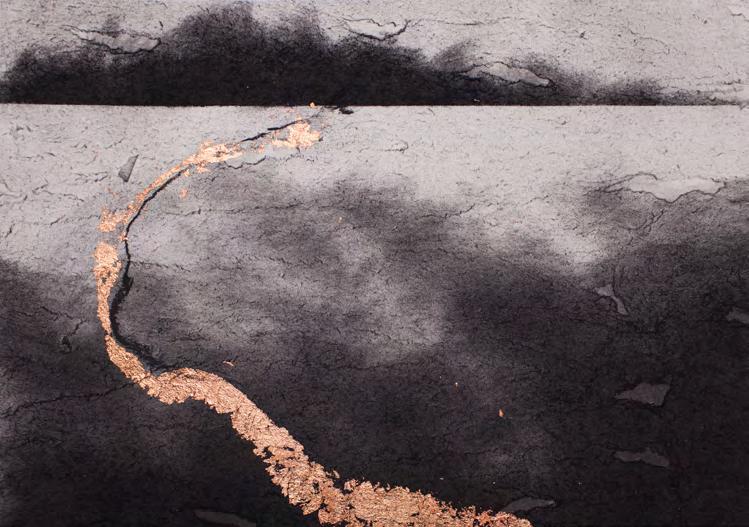

DEWI —SEBUAH RUKIAH

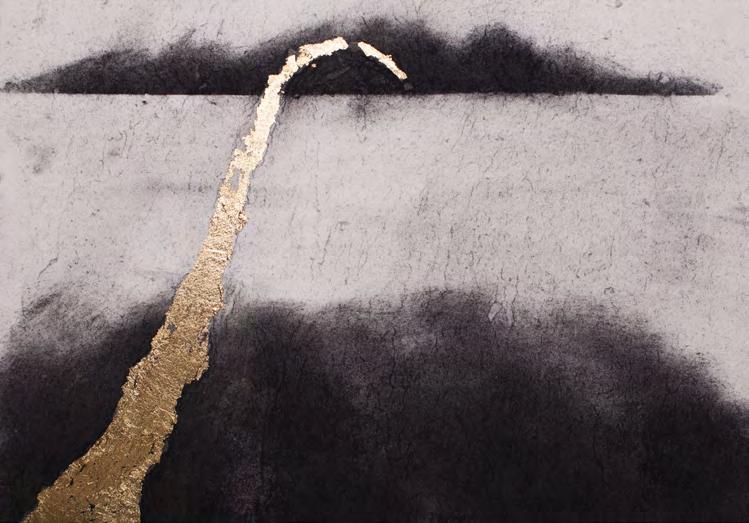

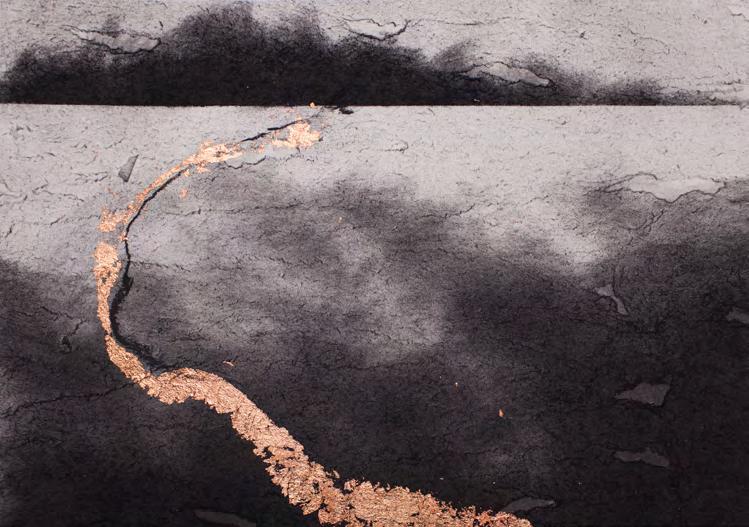

Sejatinya, Nadiah adalah seorang pematung. Gambar-gambarnya yang kita kenal selama ini pun dikerjakannya dengan metode mematung yang ia bangun sendiri ritualnya. Persis karena praktik gambarnya adalah tradisi buatannya sendiri, saya rasa kita perlu menamainya: gambar-nan-patung. Kali ini, untuk Dewi, Nadiah menggambar dalam artian yang paling sederhana: Ia memperlakukan arangnya sebagai alat untuk menggaris dan “mewarnai”. Dalam Dewi , gambar-gambar Nadiah punya “warna” lain selain hitam dari alat gambarnya, arang. Melalui serial gambar Light in Landscape Study dan Sculpture in Landscape Study, Nadiah memperkenalkan

“warna” dengan sikap seorang pematung: Memunculkan bahan lain, gold leaf dan copper leaf yang secara alami berbeda dengan arang—demikian serta-merta ia menjadi “warna” dalam gambar-gambarnya.

Dalam Dewi, tidak ada sesosok pun figur. Objek-objek yang digarap

Nadiah juga tak semuanya punya muasal bentuk. Ada wujud-wujud yang bisa segera kita kenali seperti kepang, keris, tulang panggul, dan biji; ada wujud-wujud yang belum tentu segera bisa kita kenali seperti kepompong atau wadah jimat; dan ada pula wujud-wujud nirada (abstract) yang, jika saya tuliskan, maka dia bergantung pada bagasi pengetahuan saya akan benda-benda.

Jika tak bermuasal, perlukah kita mengidentifikasinya sebagai sesuatu? Bisa jadi. Untuk sekarang, saya rasa cukup untuk mengenali wujud-wujud nirada ini sebagai sebuah kemungkinan, sebagai sebuah keterbukaan—ia bisa jadi apa saja yang kita butuhkan dalam bentangalam Dewi.

Horizon yang tak pernah absen dalam serial gambar Light in Landscape Study dan Sculpture in Landscape Study adalah upaya Nadiah untuk membangun bentangalam baru dalam proses berkaryanya, sebuah khasanah baru dalam praktik artistiknya. Sebagian bahan yang dijelajahi Nadiah dalam Dewi baru baginya. Belum pernah ia bekerja dengan lampu, umban baja antikarat (stainless steel sling), kulit kerbau, atau kulit kambing. Untuk apa semua kebaruan ini? Untuk membangun alam baru, dunia baru! Bagi siapa? Baginya, bagi kawan-kawannya, bagi tetangganya, bagi lingkungan

13

hidupnya, dan bagi yang kemudian membutuhkannya. Dewi adalah sebuah komunitas, kata Nadiah, dalam obrolan kami setelah pemajangan karya selesai. Dewi adalah sebuah kemungkinan, sahut saya. Dewi itu tentang energi, sambung Nadiah. Dewi itu sebuah gagasan, lanjut saya. Obrolan ini tak berujung, tak perlu berujung—setidaknya untuk sekarang.

Mari kita berkenalan dengan Dewi! Semoga Anda sekalian menikmati kejutan-kejutannya! Terima kasih untuk kerja keras, kerja sama, dan pertemanannya, Nadiah! Selamat menikmati pameran ini!

Yogyakarta, 17 Juni 2023

Grace Samboh

Grace Samboh Tak bisa duduk diam, Grace terus mencari kemungkinan bentuk kerja kuratorial di dalam ruang hidupnya. Klaim bahwa Indonesia kekurangan infrastruktur negara dianggapnya ketinggalan zaman. Ia bersijingkat peran dalam beragam elemen dan lembaga seni di sekitarnya sebagai peneliti, penulis, produser, dan kurator seni rupa. Ia tergabung dalam Hyphen —, rubanah Underground Hub, dan sedang menempuh pendidikan doktoral di jurusan Kajian Seni dan Masyarakat, Universitas Sanata Dharma.

Kerja kuratorialnya yang terkini adalah Jakarta Biennale 2021: esok; serta Collecting Entanglements and Embodied Histories, proyek bersama Galeri Nasional Indonesia, maiiam Contemporary Art Museum, Singapore Art Museum, Nationalgalerie – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, dan Goethe-Institut (2017–2022). Sementara beberapa tulisannya bisa dibaca antara lain di jurnal parse (Gothenburg University); Southeast of Now (nus Press); dan jurnalkarbon. net (ruangrupa); atau dalam buku Curating After the Global (mit Press, 2019); Making Another World Possible (Routledge, 2019); Tom Nicholson: Lines towards Another (Sternberg Press, 2018).

14 ESAI KURATORIAL

1. “Patung Pahlawan”, dalam Monumen dan Patung di Jakarta, 1993. Jakarta: Dinas Museum dan Sejarah Pemerintah Daerah dki Jakarta, hal. 76-77.

2. Wani dalam bahasa Jawa berarti ‘berani’; wani juga bisa kita anggap sebagai kependekan dari wanita (dalam bahasa Indonesia berarti ‘perempuan, kekasih, istri’; nuansa ‘dimiliki oleh yang lain’ ini bersumber pada kata vanita dalam bahasa asalnya, Sansekerta).

3. “A Conversation between Nadiah Bamadhaj and Lee Weng Choy”, from the catalog Anthropocene Series: A triptych by Nadiah Bamadhaj, exhibited in Singapore as part of s.e.a. focus curated: hyper-horizon, 20–31 January 2021. Kuala Lumpur: A+ Works of Art, 2021, hal. 13–14. (Penebalan untuk penegasan oleh penulis.)

4. Pahat dan ukir, misalnya, adalah teknik dasar patung yang sifatnya pengurangan.

5. “The story of my silence is deafening—in scale and form”, from the catalog The Submissive Feminist, exhibited at Kiniko Art Yogyakarta, 5–26 June 2021. Kuala Lumpur: A+ Works of Art, 2021, hal. 32.

6. “A Conversation between Nadiah Bamadhaj and Lee Weng Choy”, from the catalog Anthropocene Series: A triptych by Nadiah Bamadhaj, exhibited in Singapore as part of s.e.a. focus curated: hyper-horizon, 20–31 January 2021. Kuala Lumpur: A+ Works of Art, 2021, hal 13–14. (Garis bawah untuk penegasan oleh penulis.)

7. The Submissive Feminist, 2021, hal. 32.

8. “Essay by Alia Swastika”, dalam katalog Mengamankan Ekspektasi, pameran tunggal Nadiah Bamadhaj di Art Jakarta, 26–28 Agustus 2021. Kuala Lumpur: A+ Works of Art, 2021, hal. 2–6.

9. “Artist’s statement” dalam katalog Mengamankan Ekspektasi, 2021, hal. 8–9.

10. The Submissive Feminist, 2021, hal. 31.

11. Catatan panjang saya seputar penyelenggaraan jb2021 esok bisa dibaca dalam katalog pascaacara. Lihat: Grace Samboh, “Bekal untuk besok-besok: Waktu, kegagalan, kehendak, kesuksesan, keterbukaan, dll.” dalam, Farah Wardani (ed.), Beyond Esok: Notes & Postscript from the Jakarta Biennale 2021. Jakarta: Komite Seni Rupa, Dewan Kesenian Jakarta, 2022, hal. 30–45.

12. Pengantar di ruang pamer oleh tim kuratorial Jakarta Biennale 2021: esok (Akmalia Rizqita “Chita”, Grace Samboh, Rachel K. Surijata, Sally Texania, dan Qinyi Lim). Kedua karya lain yang disebutkan di sini: seri International Friendship (2013-sekarang) oleh Che

Onejoon yang menginvestigasi pembuatan monumen gigantik berbahan perunggu di berbagai negara Afrika yang dikerjakan oleh studio artisan Korea Utara; dan karya Song Ta, March of the Volunteers Songta Remix (2019), yang mengolah-ulang lagu kebangsaan Republik Rakyat Cina dengan semangat kekinian.

13. Lihat: Bojana Piškur, Grace Samboh, & Rachel K. Surijata dalam percakapan dengan Nick Aikens, 2023. “Aligning Research and The Non-Aligned” dalam Nick Aikens (ed.), Rewinding Internationalism. Scenes for the 1990s Today. Eindhoven: Van Abbemuseum, hal. 41–56.

15

The Whip 2023

Buffalo hide, stainless steel sling, light

ø 53 cm, h 300 cm

16

18

resin, light ø 64 cm, h 300 cm 20

The Harvest 2023 Buffalo hide,

22

Jimat 2023

Buffalo hide, patina cast brass, light

ø 44 cm, h 255 cm

24

26

Lanang Pijar

2023

Goat hide, resin, patina cast brass, light

ø 75 cm, h 250 cm

28

30

Solar Plexus

2023

Goat hide, resin, patina cast brass, light

ø 78 cm, h 60 cm

32

34

35

36 CURATORIAL ESSAY

Chanting the Dewi’s legion, sculpt-drawing, bun-curling: yup, everything!

GRACE SAMBOH

So our tale began with a female figure, who was rather tall, wearing a kebaya and a shawl, with her hair in a bun. She was standing in a seemingly ordinary pose; her hands were mid-air as she was handing a plate to male figure standing beside her. The man was bare-chested, wearing only short pants and a straw hat. He was carrying a gun holster at his waist, with a rifle on his shoulder. Even without any visual presence of farming tools, this image led us to perceive them as a couple farmers in their everyday clothes during the war. However, they weren’t just ordinary farmers: they were monumental figures, standing on a busy roundabout at the centre of Jakarta, even though no one knew—or had any idea—who they actually were. And yet, people called the roundabout by their nickname: Tugu Tani, or the Farmer’s Monument.

Nadiah and I call the woman “mbak”—just as how the Javanese would address women who are respected, revered, or just older in age. Since the end of 2019, we’ve often talked about this woman who had such a heavy task. Imagine: she was elected to represent female peasants, and she also had to appear flawless—wouldn’t a nicely done hair bun take forever to finish? Meanwhile, they chose to immortalise her in a certain way: when she fed the man who stood next to her. Even though the peasantry knew very well that female farmers also went to the fields with sickles—which these women could also use as weapons. In the early 1960s, Sukarno came with the idea of the Tugu Pahlawan, or the Heroes Monument—which was the official name for the roundabout and the statues. Later, Soekarno ordered the statues from Russian sculptors, who were also siblings, and inaugurated the statues in 1963.1

Our conversation took a turn to the various women’s movements during “the era of serving the independence”—as Sukarno called it. As in other places around the world, the spirit of independence, freedom, autonomy, and equality blew simultaneously in Indonesia. After the proclamation of independence, the women’s movements emerged everywhere, and many of them specialised in creating more equal access to knowledge through various literacy programs. When we discussed the surges of the women’s movements, names were coming and going; we decided to address all of them as “mbak”—since our discussion took place in Java and, of course, we

37

WANI

respected these women, and we didn’t want to necessarily “force” them to become “ibu”, or “mother”. In our conversation, we also were aware of our need to identify the feminine figure at Tugu Tani as more than a nameless “mbak”. Thus, we call her Mbak Wani.2

Mbak Wani was the main character in Nadiah’s installation Casting Spells for the Movement (2021), which displayed a statue of the same size as the female figure at Tugu Tani, along with three flat-screen televisions—which displayed women in accelerated motion. I will describe the video installation from the first screen, which was the one on the right to the one on the left. The first screen started from the one that was far right. There, a handful of women with daily attire were standing in the same pose as Mbak Wani— raising their hands as if they were handing someone a plate. Slowly, they lowered their hands and walked to the left side of the screen. After these women disappeared from the first screen, they emerged on the second screen. They moved towards the left side, the third screen, but their steps were accelerated. As soon as the last woman disappeared from the left side of the centre screen, immediately they all appeared on the last screen. They ran across the last screen, as if they were exiting the screen. And, everytime they left a screen, their steps became faster. In Casting Spells for the Movement, Nadiah reclaimed Mbak Wani as the symbol of the women’s movements across time.

We probably need a separate essay to discuss the video in relation to its depiction of human bodies, how these bodies were directed, and how the technique in which these moving images were displayed in the exhibition space came from the spatial thinking of a sculptor. Take Nadiah’s works, Terpesona dengan kegelisahan (Charmed by anxiety, 2022) and Ketidaknyamanan (Insecurity, 2023), as an example. Human bodies, shown as they were, were directed to do things that were natural for them (dancing or doing gymnastics for the soldiers, and laku ndhodhok , or squat walking, for the courtiers of the Kraton Yogyakarta). It went the same for these women who wore daily attire in Casting Spells for the Movement ; they simply posed like Mbak Wani, and they walked, and, in the end, they ran. The familiar body movements reminded us of one of the characteristics of the sculptural discipline in which the material quality was the ground for the picking of the material, and also the method and the purpose of the work.

38 CURATORIAL ESSAY

SCULPTURESQUE DRAWING

“My drawings come from an accumulation of methods that I have developed in order to manipulate paper to produce a particular series of results. I work closely with my assistant on this, as she does most of the meticulous texturing of the surface of the paper, whereas I tear and charcoal, and she then glues it all down. We are now a well-oiled machine of textures.”3

For almost the past 15 years, we have known Nadiah through her charcoal drawings, which are leaning towards realism. Most of Nadiah’s drawings came with no frames, and were installed with spaces between the drawing and the wall. In the vocabulary of exhibition-making, we can simply call these kinds of works as wall-pieces—works that are displayed on a wall, which can be paintings, sculptures, drawings, sketches, archives, or anything. In our conversation, Nadiah referred to these works as drawings. In the caption, Nadiah referred to them as drawing-on-paper collage. However, the process of making these works was actually a process of sculpting, not drawing—that we can call the results “drawing”, is another matter.

If we speak of Nadiah’s drawing process using sculptural terms, we can say that she used the additive process, as in an assemblage or model making with clay for casting.4 Paper collage meant the stacking and sticking paper on top of another. Nadiah applied the charcoal to the paper scraps using a blending technique to produce different shadings. Patches of these scraps thus became dimensions. If the charcoal blend was thickened at the edges of the scraps, the dimension would also look thicker, and “deeper”, so that our eyes would perceive them as shadows.

I will try to examine two of Nadiah’s works in an attempt to comprehend what she referred to as the “a set of results’’ of tearing, stacking, applying charcoal, and sticking papers on top of each other. We should also give more attention to the words “tear”, “charcoal”, and “sticking” as the technique of creating texture. In a drawing, the texture is a motif in the form of a flat image. Meanwhile, in sculpting terminology, the texture depends on the material, the processing method of the material, and the

39

polishing process. The dimensions in Nadiah’s drawings were the result of the process of tearing and sticking papers that had been applied with charcoal—she didn’t refer to these methods as colouring or drawing. Because of the process that Nadiah went through, I decided to call her drawings: Sculpturesque drawings.

As “a well-oiled machine of textures”, the collaboration between Nadiah and her assistant, Desri Surya Kristiani, was indeed seamless. At the beginning of preparing for the Dewi exhibition, I was so curious about the sculpturesque drawing technique that I decided to interview both of them. From the interview, I learned that they could finish each other’s sentences when talking about the techniques, vocabularies, and the detailed steps of the making of these sculpturesque drawings. It should come as no surprise to me, they have been working together for almost 15 years. Their trust in each other regarding the steps they were going to take and their conviction that they had the same purpose was profound. At first, I wanted to refute their statement—“a machine working seamlessly”—because humans were certainly not machines. However, how could I? After all, the “mistakes” in the process of making these sculpturesque drawings could be considered non-existent. If they failed when trying to achieve the desired form, both would accept the failure as a lesson. They both believed that the mediums they used—paper, charcoal, glue, hands, etc.—were the natural limitation of what they could achieve. From each failure, they learned something new about the material and their aptitude. Even though there were no written records, the distinctive vocabulary they used to talk about the process of working together was already a piece of empirical evidence.

If we look at Nadiah’s drawings in space, there is a kind of temptation to approach the wall and see the works from the side—either to know how they were assembled or to see the thickness of the paper. If we adjust our point of view for a moment—from looking at a sculpture to a drawing—the edges of these paper scraps could be seen as outlines. These “lines” gave the sense of depth. Although the light source in Nadiah’s drawings generally came from the front, similar to images from a photo studio, the papers pasted on top of each other displayed a spatial experience that was completely different from most drawings on paper.

Nadiah applied four shades of grey, or in other words, there were four thicknesses of charcoal applied to the scraps of paper that make up the

40 CURATORIAL ESSAY

hair of the ghost Sundal Bolong. The first shade of grey, the lightest one, was the general area of the hair. The next two shades of greys gave dimensions to the hair. The fourth and the last grey, the thickest grey, brought depth and a sense of space. Nadiah rubbed the last grey only on the edges of the torn papers used to form the hair bun, and this created the shadow of the bun. The relatively thin and fine charcoal applications—the second and the third—were used alternately by Nadiah on the scraps of papers under the bun, bringing out the impression of curls in Sundal Bolong’s hair. The Reckoning was exhibited in artjog, Yogyakarta (2021) and artina , Sarinah, Jakarta (2022).) In this work, the wrinkles on the face of the figure inspired by Calon Arang looked bolder because Nadiah applied thicker charcoal to the edges of the torn papers. In one of our conversations, Nadiah said, “I outlined those scraps of paper again, mbak.” Technically, instead of making lines along the edges of the scraps, she rubbed more charcoal on them. For the hair, Nadiah’s charcoal strokes tended to have the same level of thickness. How could we identify each strand of the figure’s hair? In fact, every single one of them was a scrap of paper!

It is true that, in an exhibition space, Nadiah’s works will more likely be seen as drawings. However, considering the techniques, Nadiah went through a sculpting process. The only drawing term that Nadiah used to talk about these works was shading. “Those textures are created from years of manipulating paper—peeling, tearing, shading, lining, glueing, and re-shading again. It is a rigorous practice between me and the paper.” 5 According to the drawing lexicon, shading was needed to bring out the depth—in other words, the spatiality—of the object being drawn.

10

A+NadiahBamadhaj-MengamankanEkspektasi-catalogue_3.indd

A+NadiahBamadhaj-TheReckoning-Catalogue-FA.indd 10 A+NadiahBamadhaj-TheReckoning-Catalogue-FA.indd 11

14 A+NadiahBamadhaj-MengamankanEkspektasi-catalogue_3.indd 15

41

Figure 1. Figure 2.

CALON ARANG, WEWE GOMBEL, SUNDAL BOLONG AND KUYANG

“[fundamentally], my drawing is […] a series of decisions. My drawings have never flowed out of me, they take concentration, decision making, and, most mornings, the art of overcoming fear.” 6

“I design an object in Photoshop, as a template of ideas. But then I build up the object with a series of textures. [...] Over the years I’ve built up a vocabulary of what and how I can express my ideas. Initially, I thought I could only capture skin (in portraits), then I went further to cloth, and found I could express clothing and batik. Then I found I could render objects, cabinets, shacks and huts. As the years went by, I built up a sound of stock of what I could do.” 7

The version of the story of Calon Arang that continues to be told is the one in which she was an old woman and a widow (therefore no longer considered attractive and “useful” for reproduction), who was feared because of her power (thus she was accused of being a witch or a chaos bringer). On the level of national history, the New Order government even concocted a tragedy that directly linked the story of Calon Arang with Gerakan Wanita Indonesia (Indonesian Women’s Movement)—no one had rectified this until now! Such an example of killing two birds with one bullet. In a booklet containing a conversation between Nadiah and curator Alia Swastika, which accompanied The Reckoning (2021), we can read about how women’s life stories, behavioural choices, and political stances are—either in a good or bad way—utilised by other people. 8 There are some retellings of the story of Calon Arang, such as by Pramoedya Ananta Toer, which revealed the complexity of the women’s position in Cerita Calon Arang (1951; The King, the Witch and the Priest, 2002), and by Toeti Heraty, Calon Arang: Kisah Perempuan Korban Patriarki (2000; Calon Arang: Stories of a Woman Victim of the Patriarchy), which opened up the possibility to reexamine Calon Arang’s position, reputation, and history. Meanwhile, for Nadiah, Calon Arang’s old age, with her own experience of going through menopause,

42 CURATORIAL ESSAY

has become an opportunity to at least claim wisdom that came along with the plethora of life experiences.

Wewe Gombel, Sundal Bolong, and Kuyang all died at a young age, unlike Calon Arang. These three are the “stage names” for women who are known more as demons, ghosts, monsters, or scourges in our everyday lives. Like Mbak Wani, they are all symbolic figures. Not only in Indonesia, but also throughout what is now known as Southeast Asia. Mbak Wani, however, is a symbol of an ideal woman, while the other three “demonised” women are the opposite. They are sources of terror, horror, and scourge. Wewe Gombel committed suicide because she was accused of being barren. Sundal Bolong died when she aborted the child she was carrying due to rape. Kuyang was accused of being greedy because she wanted to rule and live forever. Since time immemorial, they have been made the representations of evil, and this view has always been perpetuated until now without anyone ever discussing the contexts of their actions. For instance: What kind of society cornered a woman who could not bear a child that she chose to end her life? What happened to the rapist of Sundal Bolong? Did he get punished? Was he a demon too? Why was Kuyang thought to crave power? Why don’t our legends tell tales about male monster figures who wanted to overpower the world? Etc.

Nadiah gave Wewe Gombel, Sundal Bolong, and Kuyang—all usually appeared exceptionally terrifying—poses and facial expressions that were calm, serene, and wise. If we still see them as scary, maybe we ought to question: Why is it so difficult for us to let go of such thoughts?

Nadiah emphasised the change in their appearance—from demons to humans—by using her own body and face to depict these three figures. The utilisation of one’s gestures—both body and face—had a wide spectrum. At least we can read it in the following two ways: First, this was one way to claim a social reality—endless demands against women—that continued to be “unchanged”: a woman being a means of reproduction, a partner that is a servant as well. Second, we can see it as a form of solidarity among women, among fellow human beings.

In the exhibition, Mengamankan Ekspektasi (“Securing the Expectation), Jakarta, 2021, it is no longer damnable, Wewe Gombel, Sundal Bolong, and Kuyang are now trying to “gatekeep” Mbak Wani from being positioned as a hyper-feminine symbol. 9 The trio emerged in the form of sculpturesque

43

drawings, while Mbak Wani existed in the form of digital images, which were printed on an aluminium plate, with a dark surrounding, as if they were in the middle of nowhere. Mbak Wani wasn’t the same figure that we could find at the Tugu Tani roundabout. She still carried the same body, pose, hair, and plate, but this figure of Mbak Wani was re-drawn by Nadiah using 3d software. With these 3d images, Nadiah could set free the figure of Mbak Wani—her point of view, gesture, pose, and even facial expression. Mbak Wani who was being “gatekept” by these three women is the Mbak Wani who was reclaimed by Nadiah as a symbol of the women’s movement in Casting Spells for the Movement.

SCALE, DIMENSION, AND SURROUNDING

“When designing a work, it’ll feel that something is missing if I haven’t known where this work would be displayed or where it will live. It’s like working in the dark. Scale, dimension, surrounding, and, yes, the viewers, all have an influence on the form I work with. [...] All parts of the spatial environment where the work will be displayed will influence the work, and not the other way around, which is narcissistically building a specific site for the work while disregarding its surroundings.” 10

Casting Spells for the Movement was born within conversations that were haunted by the slogan, “Building history together.” At that time, Rachel K. Surijata—who also manages the Dewi exhibition—and I were among the members of the Jakarta Biennale 2021: esok ( jb2021 esok) curatorial team. Museum Kebangkitan Nasional (Museum of National Awakening) (stovia), one of the exhibition venues for jb2021 esok, refused to display this work in the classroom where they “immortalised” history with life size dioramas of Boedi Oetomo figures. The statues, which were made of resin and had their colour manipulated to resemble bronze, were all male figures. Of course, the women’s movements were not inexistent when they sat in that classroom, in 1908. The school even had a number of female students.

“Bringing” Mbak Wani into this room, and displaying her “in dialogue” with

44 CURATORIAL ESSAY

the figures inside, was a friendly reminder about the position of women in history writing in general. 11

Of course, the refusal didn’t prevent us from exhibiting Casting Spells for the Movement. In the lobby of the Museum Nasional Indonesia [National Museum of Indonesia], about two kilometres from Tugu Tani, Mbak Wani stood gracefully, surrounded by works that challenged the idea of human relations in the context of nationalism (of each of their country) in relation to the international stance held by those countries. My introduction to the figure of Mbak Wani at the beginning of this essay was just one way to interpret Mbak Wani’s revival, with Nadiah as her midwife. Of course, there were various ways and viewpoints to examine this work. The following was an introductory snippet for Ms. Wani’s presence at jb2021 esok—indicating its own criticism towards states’ authoritarianism:

Do you recognize this woman? Perhaps, ten minutes ago, you just crossed paths with her twin. Nadiah brought this figure here, to this museum, on this occasion, to firmly remind us that women are always actually on the move, and their movements echo in our lives today. Have you ever thought about who this woman really was? Or who was she representing?

The monument ordered by Sukarno from the Russian sculptor duo is located at the roundabout that we know as Tugu Tani. Interestingly, the monuments that Onejoon examined, “shrank”, and questioned in many countries in Africa were made by a North Korean sculpture studio since the 1970s. To some extent, we can say that all these national monuments look the same, and have roughly the same aura.

Song Ta’s re-adaptation of the national anthem of the Chinese People’s Republic also felt familiar. The restoration of the lyrics was very popular and the original version was accepted as the official lyrics in 1982 after there were shifts in values during the previous countless turbulent decades. This may have significance for many of you, bearing in mind that earlier

45

this year there was a long debate over the Indonesian national anthem, which apparently has never been sung in its full version in schools and on state occasions.12

In conversations around solidarity, internationalism, and how certain periods changed the way of thinking around these keywords, Casting Spells for the Movement became a turning point for Rachel and me in the context of Rewinding Internationalism’s research and exhibition at the Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, and Villa Arson, Nice (2022 –2023).13

In presenting the research results, we “invited” Mbak Wani to have a cross-time, cross-geographical dialogue with Sikan, the only female figure in Abakua culture, worked on by Belkis Ayón Manso (b. Havana, 1967; m. Havana, 1999); with the despair of ecological shifts caused by human greed, capitalism, and politics in the works of Semsar Siahaan (b. Medan, 1952; m. Tabanan, 2005); and with the avant-gardism of Croatian members of the Gorgona group, just after Yugoslavia split apart. These three things were present in the room that examined international solidarity from the standpoint of Non-Aligned countries. At a distance of 14,000 kilometres from her “Tugu Tani”, Mbak Wani became a landmark in the constellation. She stood almost in the middle of the room while other works, stories, and archives of findings surrounded her.

I have learned a lot from conversations about Mbak Wani—her as a figure, her history, her form, her transformations, etc.—up to the realisation that she is a relatively large work, which is not easy to carry or move. Mbak Wani is almost 2.5 metres tall! Apart from jb2021 esok, Casting Spells for the Movement had also appeared as a special presentation at Art Jakarta 2022. On the same occasion, in the Art Jakarta 2022 that was only up for three days, Nadiah exhibited Wewe Gombel, Sundal Bolong, and Kuyang who were attempting to “gatekeep” Mbak Wani. Recently, on the opening day of the Dewi exhibition, in Yogyakarta, the Rewinding Internationalism exhibition at Villa Arson, Nice, France, was also opened. There, Mbak Wani again became a landmark in one of the galleries. Mbak Wani has travelled throughout the globe. The rejection for Mbak Wani’s appearance in the room where we started the conversation about her didn’t limit the space for her movement, both physically, in form, and in the interpretation of this work.

46 CURATORIAL ESSAY

DEWI (LITERALLY: GODDESS) —AN INTERCESSION

Truly, Nadiah is a sculptor. All of her drawings that we know so far were worked on by the sculpting method, in which she built her own ritual. Precisely, her drawing practice is a tradition of her own making, I think we should call it: Sculpturesque drawing. This time, for Dewi , Nadiah drew in the simplest sense: She treated her charcoal as a tool for stroking and “colouring”. In Dewi, Nadiah’s drawings had “colours’’ other than the black from her drawing tool, charcoal. Through the series of drawings in Light in Landscape Study and Sculpture in Landscape Study, Nadiah introduced “colours’’ with the attitude of a sculptor: Applying other materials, gold leaf and copper leaf which were naturally different from charcoal—thus they immediately became the “colours” in the drawing.

In Dewi , there was not a single figure. Not all of the objects that Nadiah had worked on also had an origin form. There were forms that we could immediately recognize such as braid, dagger, pelvic bone, and seed; there were forms that we might not immediately recognize such as cocoon or amulet container; and there were also abstract forms which would rely on my baggage of knowledge of things, if I wrote them down. If they had no origin, should we identify them as something? Probably. For now, I think it’s sufficient to recognize these non-existent forms as a possibility, as an openness—they could be anything we need in the landscape of Dewi .

The horizon, which had never been absent in the series of drawings in Light in Landscape Study and Sculpture in Landscape Study, was Nadiah’s attempt to construct a new landscape in her working process, a new scope in her artistic practice. Some of the materials that Nadiah explored in Dewi were new to her. Never before had she worked with lamps, stainless steel slings, buffalo hide, or goat hide. What was all this novelty for? To build a new realm, a new world! For whom? For her, for her friends, for her neighbours, for her environment, and for those who need it later. Dewi is a community, said Nadiah, in our chat after the display of works was over. Dewi is a possibility, I said. Dewi is about energy, Nadiah replied. Dewi is an idea, I continued. The conversation was endless. It didn’t need to end—at least for now.

47

Let’s get to know Dewi! Hope you all enjoy the surprises! Thank you for the hard work, cooperation and friendship, Nadiah! Enjoy the exhibition! Yogyakarta, 17 June 2023

Grace Samboh

Grace Samboh cannot stay still, Grace is in constant search of what comprises a curatorial work within her surrounding scene. She jigs within the existing elements of the arts scene around her, be it as a researcher, a writer, a curator, a producer, etc, for she considers the claim that Indonesia is lacking art infrastructure especially the state-owned or state run as something outdated. She is attached to Hyphen —, affiliated to rubanah Underground Hub, and is currently undertaking a doctoral program at Arts and Society Studies, Sanata Dharma University, Yogyakarta. Her recent curatorial endeavours are Jakarta Biennale 2021: esok; serta Collecting Entanglements and Embodied Histories, a collective project between Galeri Nasional Indonesia, maiiam Contemporary Art Museum, Singapore Art Museum, Nationalgalerie – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, and Goethe-Institut (2017–2022). Some of her recent writings can be read in journals such as parse (Gothenburg University); Southeast of Now (nus Press); and jurnalkarbon. net (ruangrupa); or in books such as Curating After the Global (mit Press, 2019); Making Another World Possible (Routledge, 2019); Tom Nicholson: Lines towards Another (Sternberg Press, 2018).

48 CURATORIAL ESSAY

1. “Patung Pahlawan” [“The Heroes Statue”], in Monumen dan Patung di Jakarta [Monuments and Statue in Jakarta], 1993. Jakarta: Dinas Museum dan Sejarah Pemerintah Daerah dki Jakarta, pg. 76–77.

2. Wani in Javanese means ‘brave’; we can also think of wani as the short for wanita (which means ‘woman, lover, wife’; the notion of being ‘owned’ comes from the word vanita in its original language, Sanskrit.)

3. “A Conversation between Nadiah Bamadhaj and Lee Weng Choy”, from the catalogue Anthropocene Series: A triptych by Nadiah Bamadhaj, exhibited in Singapore as part of s.e.a. focus curated: hyper-horizon, 20–31 January 2021. Kuala Lumpur: A+ Works of Art, 2021, pg. 13–14.

4. Chiseling and carving, for example, are basic sculptural techniques that are subtractive in process.

5. “The story of my silencing was deafening—both in scale and form,” Lee Weng Choy in conversation with Nadiah Bamadhaj about The Submissive Feminist”, from the catalogue The Submissive Feminist, a solo exhibition by Nadiah Bamadhaj, at Kiniko Art Space, Yogyakarta, 5–26 June 2021. Kuala Lumpur: A+ Works of Art, pg. 32.

6. “A Conversation between Nadiah Bamadhaj and Lee Weng Choy”, from the catalogue Anthropocene Series: A triptych by Nadiah Bamadhaj, exhibited in Singapore as part of s.e.a. focus curated: hyper-horizon, 20–31 January 2021. Kuala Lumpur: A+ Works of Art, 2021, pg. 13–14. (Underlined for emphasis, by the writer.)

7. The Submissive Feminist, 2021, pg. 32.

8. “Essay by Alia Swastika”, from the catalogue Mengamankan Ekspektasi [Securing the Expectations], a solo exhibition by Nadiah Bamadhaj at Art Jakarta, 26–28 August 2021. Kuala Lumpur: A+ Works of Art, 2021, pg. 2–6.

9. “Artist’s statement” from the catalogue Mengamankan Ekspektasi [Securing the Expectations], 2021, pg. 8–9.

10. The Submissive Feminist, 2021, pg. 31.

11. My long notes regarding jb2021 esok can be found in the postevent catalog. See: Grace Samboh, “Bekal untuk besok-besok: Waktu, kegagalan, kehendak, kesuksesan, keterbukaan, dll.” [“Provisions for days to come: Time, failure, purpose, success, openness, etc.”] in Farah Wardani (ed.), Beyond Esok: Notes & Postscript from the Jakarta Biennale 2021. Jakarta: Komite Seni Rupa, Dewan Kesenian Jakarta, 2022, pg. 30–45.

12. Exhibition room introductory note by Jakarta Biennale 2021: esok curatorial team (Akmalia Rizqita “Chita”, Grace Samboh, Rachel K. Surijata, Sally Texania, dan Qinyi Lim). The other two works mentioned here: the International Friendship series (2013-present) by Che Onejoon who investigated the creation of gigantic bronze monuments in various African countries by an artisanal North Korean studio; and Song Ta’s March of the Volunteers Songta Remix (2019), which is a rework of the national anthem of the People’s Republic of China in a contemporary spirit.

13. See: Bojana Piškur, Grace Samboh, & Rachel K. Surijata in conversation with Nick Aikens, 2023. “Aligning Research and The Non-Aligned” in Nick Aikens (ed.), Rewinding Internationalism Scenes for the 1990s Today. Eindhoven: Van Abbemuseum, pg. 41–56.

49

60

Light in Landscape Study I 2022

Charcoal and gold leaf on paper

25 × 19 cm

Collection of Vivian Law and Hew Kok Hoong

Light in Landscape Study II

2022

Charcoal and gold leaf on paper

25 × 19 cm

Private Collection, Kuala Lumpur

62

Light in Landscape Study III

Charcoal and gold leaf on paper

25 × 19 cm

Collection of Nik Arshad Nik Mohamed and Mariza Azen Mat Resip

2022

Light in Landscape Study IV

2022

Charcoal and gold leaf on paper

25 × 19 cm

Private Collection, Kuala Lumpur

64

Light in Landscape Study V

Charcoal and gold leaf on paper

25 × 19 cm

2022

Light in Landscape Study VI

2022

Charcoal and gold leaf on paper

25 × 19 cm

Collection of Jaspreet Gill

66

Light in Landscape Study VII

Charcoal and gold leaf on paper

25 × 19 cm

2022

Sculpture in Landscape Study I

2022

Charcoal and gold leaf on paper

35 × 26 cm

68

Sculpture in Landscape Study II

2022

Charcoal and gold leaf on paper

35 × 26 cm

Sculpture in Landscape Study III

2022

Charcoal and gold leaf on paper

35 × 26 cm

70

Sculpture in Landscape Study IV 2022

Charcoal and gold leaf on paper

35 × 26 cm

Sculpture in Landscape Study V

2022

Charcoal and gold leaf on paper

35 × 26 cm

Collection of Rizal and Jan

72

Sculpture in Landscape Study VI 2022

Charcoal and gold leaf on paper

35 × 26 cm

Sculpture in Landscape Study VII

2022

Charcoal and gold leaf on paper

35 × 26 cm

Private Collection, Singapore

74

Sculpture in Landscape Study VIII

Charcoal and gold leaf on paper

35 × 26 cm

2022

Nadiah Bamadhaj (born 1968, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia) resides permanently in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Trained as a sculptor in New Zealand at the Canterbury School of Fine Arts, she creates collaged drawings, sculpture, site-specific installation, digital video and print. She has lectured in Fine Arts in Kuala Lumpur, written several articles and publications on human rights in Malaysia and Indonesia, received grants from the Nippon Foundation’s Asian Public Intellectual Fellowship in 2002 and 2004, the Indonesian Directorate General of Culture and the Arts Council of New Zealand in 2022. She is currently on the board of Yayasan Kebaya, a HIV/AIDS homeless shelter in Yogyakarta. In 2019, a survey book of 18-years of her artwork Nadiah Bamadhaj was published by Italian-based SKIRA, and she was recently featured in Vitamin D3: Today’s Best in Contemporary Drawing published by London-based PHAIDON. Her artwork currently focuses on the social intricacies of life within Indonesian society.

Nadiah Bamadhaj

b. 1968, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia. Lives and works in Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

Education

1993 Bachelor of Fine Arts, Sculpture –1989 and Sociology, Canterbury University, Christchurch, New Zealand.

Awards

2022 Arts Grant, Creative NZ, Art Council of New Zealand Toi Aotearoa.

Grant from Directorate General of Culture, Ministry of Education, Culture, Higher Education, Research and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia.

2004 Asian Public Intellectual –2002 Fellowship and Follow-Up Grant, funded by the Nippon Foundation, administered by the Institute of Malaysian and International Studies (IKMAS), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

2001 Juror’s Choice, Philip Morris Malaysia Art Awards.

2001 Artist-in-Residence, Rimbun –2000 Dahan, Artist Residency Program, Kuang, Malaysia.

Projects & Presentations

2023 Co-curator, ARTJOG 2023, Motif: Lamaran, Jogja Nasional Museum, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Presenter, Youth of Today Workshop, Cemeti Institute, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

2020 Presenter, Artists’ Practice in Indonesia, Australian Consortium for ‘In-Country’ Indonesian Studies (ACICIS), Universiti Sanata Dharma Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

2019 Presenter, The Cooler Earth Sustainability Summit, CIMB Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur Convention Centre, Malaysia.

2017 Lecture Performance, A King in a Republic, FIELD MEETING Take 5: Thinking Projects, Asia Society, New York City, USA.

76 BIODATA

Solo Exhibitions

2023 Dewi, Jendela Institute, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

2022 Mengamankan Ekspektasi, Art Jakarta, Jakarta Convention Center, Jakarta, Indonesia.

2021 The Inconsistencies of Success, Small Shifting Spaces, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

The Submissive Feminist, Kiniko Art, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

2020 Ravaged, Richard Koh Fine Art, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Dreaming Desire, Richard Koh Fine Art, Singapore.

2019 Lush Fixations, Richard Koh Fine Art, Singapore.

2018 Ravaged, Chambers Fine Art, New York, USA.

2016 Descent, Richard Koh Fine Art, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

2014 Poised for Degradation, Richard Koh Fine Art, Singapore.

2012 Keseragaman, Richard Koh Fine Art, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

2008 Surveillance, Valentine Willie Fine Art, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

2004 enamlima sekarang (sixtyfive now), Galeri Lontar, Komunitas Utan Kayu, Jakarta, Indonesia.

2003 enamlima sekarang (sixtyfive now), Benteng Vredeburg Museum, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

2001 1965 – Rebuilding Its Monuments, Galeri Petronas, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Biennales & Group Exhibitions

2023 Kiwari, Tumurun Museum, Solo, Indonesia.

Artina #2: Matrajiva, Sarinah Building, Jakarta, Indonesia.

2022 Rewinding Internationalism –Scenes from the 90s, Today, Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, The Netherlands.

MACAN Museum Fundraising Gala Exhibition, MACAN Museum, Jakarta, Indonesia.

Curtain Call, CIMB ART & Soul 2022, Menara KEN TTDI, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Chaos and Calm, Bangkok Art Biennale, Bangkok Thailand.

Art Jakarta Spot, Art Jakarta, Jakarta Convention Center, Jakarta, Indonesia.

A+ Works of Art Anniversary Exhibition, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Voices of Longing Calling You Home, Broken White Project, Acehouse Collective, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

ARTJOG MMXXII: Arts in Common – Expanding Awareness, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

Synthetic Condition, UP Vargas Museum, Manila, Phillipines.

2022 A+ Preferred, A+ Works of Art, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. chance constellations, S.E.A FOCUS, Artspace@ HeluTrans, Singapore.

2021 ESOK: Jakarta Biennale, Museum Nasional, Jakarta.

ARTJOG MMXXI – Time(to) Wonder, Jogja Nasional Museum, Yogayakarta, Indonesia.

hyper-horizon, S.E.A FOCUS, Artspace@ HeluTrans, Singapore.

2020 ARTJOG Resilience, Jogja Nasional Museum, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

2019 The Body Politic and the Body, ILHAM X SAM Project, ILHAM Gallery, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Aura, Art Collection Reflection, Galeri Petronas, Malaysia.

ART-staged: No Booth, Richard Koh Fine Art, Singapore. Of Dreams and Contemplation: Selections from the Collection of Richard Koh, The Private Museum, Singapore.

Taipei Dangdai, Richard Koh Fine Art, Taipei, Taiwan.

2018 Contemporary Chaos, Vestfossen Kunstlaboratorium, Norway. Art Central Hong Kong, Richard Koh Fine Art, Hong Kong.

ART STAGE Singapore, Richard Koh Fine Art, Singapore.

2017 We are here, Richard Koh Fine Art, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

ACAW Thinking Projects, C24 Gallery, New York, United States. Di Mana (Where Are) Young?, National Art Gallery, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

2016 Incomplete Urbanism: Attempts of Spatial Critical Practice, NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore, Gillman Barracks, Singapore.

Encounter: Art from Different Lands, Southeast Asia Plus Triennale 2016, National Gallery of Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia. Crossing: Pushing Boundaries, Galeri Petronas, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

2015 Art of ASEAN, Bank Negara Museum and Gallery, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

A Luxury We Cannot Afford, Para Site, Hong Kong.

I am Ten, Richard Koh Fine Art, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

2014 Medium at Large, Singapore Art Museum, Singapore. START, Saatchi Gallery, London, UK

77

2013 Parallax: ASEAN, Changing Landscapes, Wandering Stars, ASEAN-Korea Contemporary Media Art Exhibition, ASEANKOREA Centre, Seoul, South Korea.

Bersama, Muzium Dan Galeri Seni Bank Negara Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Welcome to the Jungle: Contemporary Art in Southeast Asia from the Collection of Singapore Art Museum, Contemporary Art Museum Kumamoto (CAMK), Kumamoto, Japan.

Convergence: Cultural Legacy, Galeri Petronas, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

2011 It’s Now or Never Part II, Singapore Art Museum, Singapore.

Beyond the Self: Contemporary Portraiture from Asia, National Portrait Gallery, Canberra, Australia.

Works from Southeast Asia, Richard Koh Fine Art, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

2010 Creative Index, The Nippon Foundation’s Asian Public Intellectual Fellowship’s 10th Anniversary, Silverlens Gallery, Manila, Philippines.

Agenda Kebudayaan Gusdurisme, 100-day memorial for Abdurrahman Wahid @ Gus Dur, Langgeng Gallery, Magelang, Indonesia. Beacons of Archipelago: Contemporary Art from Southeast Asia, Arario Gallery, Seoul, South Korea.

2009 Jogja Jamming: Jogja Biennale X, Taman Budaya Yogyayakarta, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

Earth and Water: Mapping Art in Southeast Asia, Singapore Art Museum, Singapore.

Photoquai 09: 2nd Biennale Photographic Festival, musée duquai Branly, Paris, France. Cartographical Lure, Valentine Willie Fine Art, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Jakarta Biennale XII: Fluid Zone, Galeri Nasional, Jakarta, Indonesia.

Littoral Drift, UTS Gallery, University of Technology, Sydney, Australia.

Code Share: 5 continents, 10 biennales, 20 artists, Contemporary Art Centre, Vilnius, Lithuania.

2008 Wonder, Singapore Biennale, Singapore City Hall, Singapore. East-South, Out of Sight, South and Southeast Asia Still and Moving Images, Tea Pavilion, Guangzhou Triennale, China. The Scale of Black, Contemporary Drawings from Southeast Asia, HT Contemporary Space, Singapore.

2007 Out of the Mould: The Age of Reason, 10 Malaysian Women Artists, Galeri Petronas, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Photofolio, Jogja Gallery, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

Fetish: Object Art Project #1, Biasa Artspace, Denpasar, Indonesia. Selamat Datang ke (Welcome to) Malaysia: An exhibition of contemporary art from Malaysia, Gallery 4A, Sydney, Australia. Processing the City: Art on Architecture, The Annex Gallery, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Never Mind, Video Art Exhibition, ViaVia Café, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

2006 Fast Futures: Asian Video Art, The Asia Society India Centre, Little Theatre Auditorium, NCPA, Mumbai, India.

The War Must Go On, Clockshop Billboard Series, corner of Fairfax and Wilshire, Los Angeles, USA. TV-TV, Week 34, Video Art Festival, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Building Conversations: Nadiah Bamadhaj and Michael Lee, Singapore Art Museum, Singapore.

Signed and Dated, Valentine Willie Fine Art Gallery, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Holding Up Half the Sky by Women Artists, National Art Gallery, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Rethinking Nordic Colonialism: A Postcolonial Exhibition Project in Five Acts, Act 3: Faroe Art Museum, Tórshavn, The Faroe Islands, Denmark.

Biennale Jakarta 2006, Beyond the Limits and its Challenges, Galeri Lontar, Komunitas Utan Kayu, Indonesia.

Fast Futures: Asian Video Art, Asian Contemporary Art Week, Rubin Museum of Art, New York, USA. Home Productions, Video Art Exhibition, Singapore Art Museum, Singapore.

78

2005 Consciousness of the Here and Now, Biennial Yogya VII 05, Kandhang Menjangan Heritage Site, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

Home Works II: A Forum on Cultural Practices, Lebanese Association for Plastic Arts, Ashkal Alwan, Beirut, Lebanon. 147 Tahun Merdeka (147 Years of Independence), in collaboration with Tian Chua, Reka Art Space, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Urban Culture, CP Biennale, Museum of the Indonesian National Bank, Jakarta, Indonesia. you are here, Valentine Willie Fine Arts Gallery, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Media in “f”, The 9th International Interdisciplinary Congress on Women, EWHA Women’s University Campus, Seoul, South Korea.

2004 Flying Circus Project: 04, Seeing with Foreign Eyes, Theatreworks, Fort Canning Park, Singapore.

Batu Bata Tanah Air (Building Blocks of Homeland), a collaborative project with Tian Chua, Cemeti Art House, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

Living Art: Regional Artists Respond to HIV/AIDS, Queen’s Gallery, XV International AIDS Conference, Bangkok, Thailand.

Paradise Found/ Paradise Lost, WWF Art for Nature Fundraising Exhibition, Rimbun Dahan Gallery, Kuang, Malaysia.

Seriously Beautiful, Reka Art Studio, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Gedebook, Group Fundraising Exhibition, Kedai Kebun Forum, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

2002 Asean Art Awards, Bali International Convention Center, Nusa Dua, Bali, Indonesia. Touch, WWF Art For Nature Fundraising Exhibition, Rimbun Dahan Gallery, Kuang, Malaysia. Pause, Gwangju Biennale 2002, Exhibition Hall 1, Gwangju, South Korea.

2001 Philip Morris Art Awards, National Art Gallery, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Exhibit X, Taksu Gallery, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Flashpoint, WWF Art for Nature Fundraising Exhibition, Rimbun Dahan Gallery, Kuang, Malaysia. Exhibit A, Valentine Willie Fine Arts Gallery, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

2000 Arang, Taksu Gallery, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Art Collections

Galeri Petronas, Malaysia. Khazanah Nasional Berhad, Malaysia. Museum Azman, Malaysia. Muzium & Galeri Tuanku Fauziah, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia. National Gallery of Victoria, Australia. National Gallery, Singapore. National Visual Arts Gallery, Malaysia. Singapore Art Museum, Singapore. Tumurun Museum, Indonesia. Urban Museum, Malaysia. Zain Azahari Collection, Galeri Z, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

79

Nadiah Bamadhaj and A+ Works of Art would like to thank the following individuals for their support and contributions to this publication and presentation:

Lanang Pijar Lentera

Arie Dyanto

Helen Todd

Desri Surya Kristiani

Catur Putra Krissutanto

Iwan Srihartoko

Eko Mei Wulan

Manggala Art Studio

Yudha Kusuma Putra

Arief Budiman

Handiwirman Saputra

Jumaldi Alfi

Kelompok Seni Rupa Jendela

The Collection who so generously lent their works to the exhibition:

Jaspreet Gill

Nik Arshad Nik Mohamed and Mariza Azen Mat Resip

Rizal and Jan

Vivian Law and Hew Kok Hoong

Other private collections

80

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Published in conjunction with Dewi, a solo exhibition by Nadiah Bamadhaj, curated by Grace Samboh. Held at Jendela Institute, Yogyakarta, from 17th June to 31st July 2023.

ARTIST

Nadiah Bamadhaj

CURATOR

Grace Samboh

PROJECT MANAGER

Rachel K. Surijata

ARTIST’S STUDIO ASSISTANTS

Desri Surya Kristiani

Catur Putra Krissutanto

Iwan Srihartoko

TRANSLATOR (ID TO EN)

Norman Erikson Pasaribu

GRAPHIC DESIGNER

Kenta.Works

GALLERY SITTERS

Fredy Hendra

Mara

PHOTOS AND VIDEOS

Courtesy of the artist

A+ WORKS of ART is a contemporary art gallery based in Kuala Lumpur, with a geographic focus on Malaysia and Southeast Asia. Founded in 2017 by Joshua Lim, the gallery presents a wide range of contemporary practices, from painting to performance, drawing, sculpture, new media art, photography, video and installation. Its exhibitions have showcased diverse themes and approaches, including material experimentation and global conversations on social issues. Collaboration is key to the ethos of A+ WORKS of ART. Since its opening, the gallery has worked with artists, curators, writers, collectors, galleries and partners from within the region and beyond, and continues to look out for new collaborations. The gallery name is a play on striving for distinction but also on the idea that art is never without context and is always reaching to connect — it is always “plus” something else.

Published by A+ WORKS of ART d6 – G – 8, d6 Trade Centre 801 Jalan Sentul 51000 Kuala Lumpur

Malaysia

+6018 333 3399

info@aplusart.asia

www.aplusart.asia

Instagram/Facebook

@aplusart.asia

Copyright © 2023 A+ WORKS of ART, and Nadiah Bamadhaj. All rights reserved.

All articles and illustrations contained in this catalogue are subject to copyright law. Any use beyond the narrow limites defineded by copyright law, and without the express of the publisher, is forbidden and will be prosecuted.