Arctic Yearbook Special Issue: Arctic Pandemics

Spence, J., H. Exner-Pirot, & A. Petrov (eds.). (2023). Arctic Pandemics: COVID-19 and Other Pandemic Experiences and Lessons Learned. Akureyri, Iceland: Arctic Portal. Available from https://www.arcticyearbook.com

ISSN 2298–2418

This is an open access volume distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY NC-4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial.

Cover Image Credit

Amber Webb

Guest Editors

Jennifer Spence| jennifer_spence@hks.harvard.edu

Heather Exner-Pirot | exnerpirot@gmail.com

Andrey Petrov | andrey.petrov@uni.edu

Editorial Board

Anastasia Emelyanova, Postdoctoral Researcher, Thule Institute, University of Oulu

Heather Exner-Pirot (co-chair), Senior Fellow, Macdonald-Laurier Institute

Selma Ford, Program Director, Gordon Foundation

Lassi Heininen, Editor, Arctic Yearbook and Professor Emeritus, University of Lapland

Solveig Jore, Senior Researcher, Norwegian Institute of Public Health

Christina Storm Mienna, Associate Professor, Umeå University

Embla Eir Oddsóttir, Director, Icelandic Arctic Cooperation Network

Andrey Petrov (co-chair), Professor, University of Northern Iowa

Norma Shorty, Instructor, Yukon University

Jennifer Spence (co-chair), Senior Fellow, Belfer Center Arctic Initiative, Harvard University

Eydís Kr Sveinbjarnardóttir, Associate Professor, University of Iceland

About Arctic Yearbook

The Arctic Yearbook is the outcome of the Northern Research Forum (NRF) and UArctic joint Thematic Network (TN) on Geopolitics and Security. The TN also organizes the annual Calotte Academy.

The Arctic Yearbook seeks to be the preeminent repository of critical analysis on the Arctic region, with a mandate to inform observers about the state of Arctic politics, governance and security. It is an international and interdisciplinary peer-reviewed publication, published online at [https://arcticyearbook.com] to ensure wide distribution and accessibility to a variety of stakeholders and observers.

Arctic Yearbook material is obtained through a combination of invited contributions and an open call for papers. For more information on contributing to the Arctic Yearbook, or participating in the TN on Geopolitics and Security, contact the Editor, Lassi Heininen.

Acknowledgments

The Arctic Yearbook would like to acknowledge the Arctic Portal [https://arcticportal.org] for their generous technical support, especially Ævar Karl Karlsson; Sai Sneha Vankata Krishnan and Sarah Seabrook Kendall for their assistance with copy editing; and our many colleagues who provided peer review for the scholarly articles in this volume.

Section I: State of Knowledge

Section III: Arctic Impacts and

Preface

Anne ZinkWe had landed in Dillingham, Alaska in the spring of 2020. Located 331 miles from Anchorage, the flight had been smooth, but the tension was high. Countries had closed their borders; cities were shut down and the world grappled w ith understanding and responding to a worldwide pandemic for the first time in most peoples’ memories. The salmon, on their own schedule, prepared to make their mass migration to Bristol Bay, spawning to begin the next generation. This annual migration has sustained the land, the people, and the fish for thousands of years. Not only was the salmon migration going to happen regardless of policies, politics, or pandemics, it was the economic life force and cultural fabric of Alaska Native communities, who have lived, played and worked for as long as the stories have been told. It was also a critical source of food for the world. But throughout history, with the migration of fish had also come disease. During the 1918 pandemic, the great influenza outbreak, or “Great Death” as it has been commonly referred to, the flow of infected people following fish had been the primary means that disease was introduced into communities. The results were devastating.

The experience of Arctic communities during the COVID-19 pandemic was one where lived experience along with an understanding of the land and unique geography were intertwined into the response; where the crucible of necessity and austere conditions forged creative and resilient solutions; and where lessons learned from history, and carefully handed down from generation to generation, echoed their way through every layer of preparation, response, and recovery.

Stories of previous trauma experienced by many Alaska Native communities during the response to the 1918 pandemic have endured. The history of these communities was not housed in books

Anne Zink, MD, Chief Medical Officer, Alaska Department of Healthas much as it lived in the stories, made the foundation and was built into the walls of the communities . The hospital was initially constructed as an orphanage as parents, grandparents, aunties, and uncles were taken by that deadly disease. The ceiling kept out the rain and snow, but its walls echoed a great sadness of the past. And during COVID-19, the caregivers worked to not only heal ailments of the present, and prevent another pandemic, but also to heal the past

One of the local leaders, Chief Tom Tilden of Curyung Tribe shared some of the stories his grandmother told of leaving her community for a year during the Great Death, only to return to a village devastated by disease where only dogs and small children had survived. He had been told these stories and he planned to learn from them and keep his community safe. Charged with the care of his people, he was not about to allow this new unknown virus that had shut down New York, was already devastating the Navajo Nation, and had been slowly creeping across the country, make its way to his community.

Communities lost a generation, language, and culture. The 1918 pandemic was not a single event. It was a seismic s hift, and its destruction, amplified by systemic inequities, are echoed in the disparate health outcomes of Alaska Native people.

However, the lessons of the past created the strength and resilience of today. Alaska Native People, like so many Indigenous Peoples of the Artic, overcame tremendous odds, and the lessons learned forge a path for all for the challenges that lay ahead.

This special issue of the Arctic Yearbook contains a time capsule of these truths and stories. It highlights the innovations, partnerships, and knowledge gained. Together, this research reflects the knowledge of this great illness and the amazing resilience of individuals, families and communities that have lived to tell about it. They highlight the importance of sovereignty, the strength that comes from Indigenous ways, as well as paint a path of health and wellness that can be a guiding light towards future readiness or better yet, prevention of disease.

These papers chronicle our experiences, our discoveries and the lessons w e collectively learned. My sincere hope is that what will be remembered is great strength, rather than great death. Across the Arctic, communities came together, used traditional ways of knowing and braided them with modern science and technology, ultimately creating uniquely resilient, s overeign, strength-based responses in some of the most remote and challenging conditions.

As Johanna Coghill, a community health practitioner in Nenana, said, “we are making new stories.” As she remembered epidemics of past generations and incorporated the ways communities cared for each other, using existing infrastructure for immunizations to distribute vaccinations and test kits, she continued, “It’s one of those things we’ll talk about 100 years from now.”

The learning curve for humankind across the globe was steep. But there is great beauty in the understanding that continues to emerge. When the value of community and Indigenous ways of being that have existed for thousands of years were recognized, honored, and brought to the forefront of governmental responses, people thrived The ancient truths, carefully handed from one elder to the next, from one generation to the next, contain wisdom and power that transcend the relative blip in time of modern medical advances.

How we remember and recover from this pandemic will be as important as how we initially responded. This special issue of the Arctic Yearbook is like a packaged gift for current and future health practitioners, policy makers, elders, and leaders to come.

A dear friend and mentor once shared with me knowledge that an elder had imparted to her. She asked, “What are you doing with the lessons you've learned? This is not your knowledge to keep.” So, to the authors, researchers and publis hers, thank you for sharing these lessons. The gift you give to those who will come after us, as we all understand, is not your knowledge to keep. And to the readers, please accept and enjoy this precious gift.

Lest we forget…

Jennifer Spence, Heather Exner-Pirot & Andrey PetrovThe idea for this special issue of the Arctic Yearbook started with the beginning of the COVID19 pandemic. As we all tried to come to terms with the magnitude of this event, we realized that the pandemic was global, but the experiences and impacts in the Arctic would be distinct.

Early on, we recognized that understanding the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Arctic would require a broad lens. We needed to consider the health impacts of the pandemic, but we also wanted to understand the social, cultural, and economic implications. We wanted to assess the impacts of the virus, but we also needed to examine the impacts of the various risk management measures put in place in response to its spread.

We knew that the COVID-19 pandemic needed to be understood in context – in relationship to past (and future) pandemics, colonial injustices, existing infrastructure deficits, current and future impacts of climate change, and other distinct features of the region. We knew that communities in the Arctic would face unique challenges, but this would also be an opportunity to observe and learn from their resilience in the face of extensive and rapid change.

We were humbled to be able to draw together a strong editorial board from across the Arctic region to guide the creation of this special issue and mobilize their networks to encourage a variety of relevant, high-quality contributions. We are also particularly thankful to the Arctic Yearbook for their willingness and commitment to support this effort. It is through their innovative and flexible approach that we were able to invite a diversity of contributions (including academic peer reviewed articles, case studies, commentaries, and any other form of contribution people chose to submit) and make this collection accessible as an open-source volume. We wanted to reach and inspire dialogue between experts and knowledge holders, and we knew we could only be so successful with this project because many people believed that it was important.

The result is a collection of 15 peer reviewed articles and 11 shorter contributions that cover an impressive range of issues and experiences. We are particularly proud that this volume places an emphasis on Indigenous and community-based experiences and issues with pandemics. Our editorial board agreed that this was a critical aspect of the project and we are pleased that the final product respects this vision.

The contributions are organized into three sections: 1) state of knowledge, 2) Arctic responses from Alaska to Murmansk, and 3) Arctic impacts and innovations. It was not easy to separate these diverse contributions into distinct categories. In many cases, the placement of an article in one section over another is somewhat arbitrary. Many of the articles take a holistic approach in the scope of their research, analysis, and findings, which is perhaps another common (and valuable) feature of Arcticrelated research. It was not our intention to force our authors into silos and we encourage community leaders, policymakers, researchers and other readers to review and take note of the important connections between the sections.

At the heart of all the articles in this volume is a desire to share the experiences and circumstances of Arctic communities with COVID-19 and other pandemics. This collection is grounded in a desire to expose what pandemics generally and COVID-19 specifically tell us about the unique strengths and vulnerabilities of Arctic communities. This special journal issue is an effort to remember and learn from Arctic experiences with COVID-19 and other pandemics in order to inform our responses to future pandemics and other regional and global shocks that we can expect to face in the future.

As COVID-19 increasingly is seen as a thing of the past that people prefer to move on from, it is critical that knowledge holders, researchers, and policymakers continue to dedicate time, effort and resources to learning from these experiences and ensuring that it informs our future actions. We hope that this volume is a useful contribution to this effort.

Section I: State of Knowledge

The COVID-19 pandemic in the Arctic: An overview of dynamics from 2020 to 2022

Since February 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has been unfolding in the Arctic, placing many communities at risk due to their remoteness, limited healthcare options, underlying health issues, and other compounding factors. This paper assimilates diverse sources of COVID-19 data in the Arctic from 2020-2022 and provides a preliminary analysis at the regional (subnational) level. The results suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic outcomes to date (infections, mortality, and case-fatality ratios) were highly variable, but mortality generally remained below respective national levels. The Arctic has persevered through COVID-19 with less dire consequences despite the region’s preexisting vulnerabilities. Based on the varying trends and magnitude of the pandemic, we classify Arctic regions into several groups.

As of October 1, 2022, the Arctic has experienced about 2.4 million confirmed cases and over 29,000 deaths from COVID-19. These outcomes are not uniform across the Arctic region and are greatly influenced by Northern Russia, given its sizable Arctic populations. Greenland, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, Northern Canada, and Northern Norway reported just under 60 cumulative deaths per 100,000 population, while Alaska, Northern Russia, and Northern Sweden had over 180 deaths per 100,000. This study summarizes the COVID-19 epidemiological outcomes in the Arctic by its regions from February 2020 to October 2022, with a goal of shedding

Andrey N. Petrov, ARCTICenter and Department of Geography, University of Northern Iowa, USA; Sweta Tiwari, ARCTICenter and Department of Geography, University of Northern Iowa, USA; Michele Devlin, ARCTICenter, University of Northern Iowa and United States Army War College, USA; Mark Welford, Department of Geography, University of Northern Iowa, USA; Nikolay Golosov, Department of Geography, Pennsylvania State University, USA; John DeGroote, Department of Geography, University of Northern Iowa, USA; Tatiana Degai, ARCTICenter, University of Northern Iowa, USA and Department of Anthropology, University of Victoria, Canada; Stanislav Ksenofontov, ARCTICenter and Department of Geography, University of Northern Iowa, USA.

Andrey N. Petrov, Sweta Tiwari, Michele Devlin, Mark Welford, Nikolay Golosov, John DeGroote, Tatiana Degai & Stanislav Ksenofontovmore light on the factors that determine the pandemic’s spatiotemporal dynamics in the Arctic. The COVID-19 epidemiological variability across the Arctic, to a large extent, is explained by geographical isolation, the effectiveness of COVID-19 public health prevention measures, the nature of the health care system, and varying vaccination rates, among other reasons.

Lessons learned by examining the patterns of COVID-19 spread and pandemic outcomes, such as mortality and morbidity their relationships with underlying public health conditions and healthcare resources, as well as socioeconomic characteristics, prevention and mitigation policies, and experiences of the Indigenous Peoples can inform responses to current and future pandemics.

Introduction

COVID-19 (or formally SARS-CoV-2) has, since December 1, 2019, advanced rapidly around the world (Ciotti et al., 2020; Kapitisinis, 2020; MacIntyre, 2020). In fact, SARS-CoV-2 is the fifth pandemic to affect the world since the 1918 flu outbreak, known as “Spanish flu.” The others are the 1957 Asian flu, 1968 Hong Kong flu, and 2009 Swine flu. The February 1918 to April 1920 pandemic infected ~500 million and killed between 17-50 million including large numbers of Arctic inhabitants. The 1957-1958 flu infected in-excess of 100 million and killed ~1.1 million, the 1968 flu killed 1 million, and the 2009 flu killed in-excess of 200,000 (Barro et al., 2020; Kilbourne, 2006; Simonsen et al., 2013).

Although pandemic morbidities have declined over the last 100 years, intense globalization has accelerated the spread of these pandemics. Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic to date (2020-2022) positive cases totalled over 660 million and 6.7 million people perished due to the disease (JHCRC, 2023) and many were left permanently compromised. In other cases, infected individuals barely noticed their infection yet were infectious (JHCRC, 2023; Liu et al., 2020). Research from China, Italy, and Singapore suggested that early morbidity from SARS-CoV-2 was elevated among those individuals suffering from hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, cancer, dementia, or with a medical record of strokes (Singh et al., 2020). Past evidence from China and Italy suggests ~20% of all COVID-19 sufferers who visited hospitals or were hospitalized will suffer subsequent heart disease, while 40-60% of those individuals infected with SARS-CoV between 2002-2004 and who survived continue to suffer heart problems (Bansal 2020). Stringent public health policies and subsequent mass vaccination campaigns conducted in 2021-2022 around the world have slowed down the pandemic (Watson et al., 2022), although the outbreaks continue to persist (JHCRC, 2023).

The Arctic is considered particularly vulnerable to pandemics due to factors such as limited infrastructure and healthcare options, remoteness, difficult socioeconomic conditions, and painful histories of colonization and neglect from central governments in the past (Huot et al., 2019; Petrov et. al, 2021a; Adams & Dorough, 2022). Arctic populations are characterized by high rates of comorbidities including hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease (Erber et al. 2010; Murphy et al. 1997, Arctic Council, 2020) as well as health disparities (Chatwood et al., 2012). In turn, many observers have pointed out that the COVID-19 pandemic has also exacerbated the existing socioeconomic and health vulnerabilities of Arctic residents (Markova et al., 2021, Lemieux et al., 2020, Jaakko et al., 2021, Cook & Johannsdottir, 2021, Men & Tarasuk, 2021 and Golubeva et al., 2022). At the same time, Arctic communities possess capacities that contribute to their resilience to the pandemic, most notably through control over implementing anti-pandemic measures and Indigenous knowledge and practices. In particular, reliance on Indigenous knowledge, generational wisdom, leadership, self-determination, and rapid vaccination have been instrumental in reducing the potential impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in some Arctic jurisdictions, including Alaska, Northern Canada, and Greenland (Petrov et. al, 2021a; Richardson and Crawford, 2020; Fleury & Chatwood 2022).

COVID-19 was first recorded in the Arctic in February of 2020, and by January 1, 2023 there have been 2,677,457 positive COVID-19 cases and 29,492 deaths. Past analysis indicates that the pandemic’s dynamics varied among Arctic regions, with some areas more affected than others (Petrov et al., 2020, 2021b; Tiwari et al;., 2022). There are some indications that while infections, mortality, and case-fatality ratios were highly variable, mortality generally remained below respective national levels (Petrov et al., 2021a).

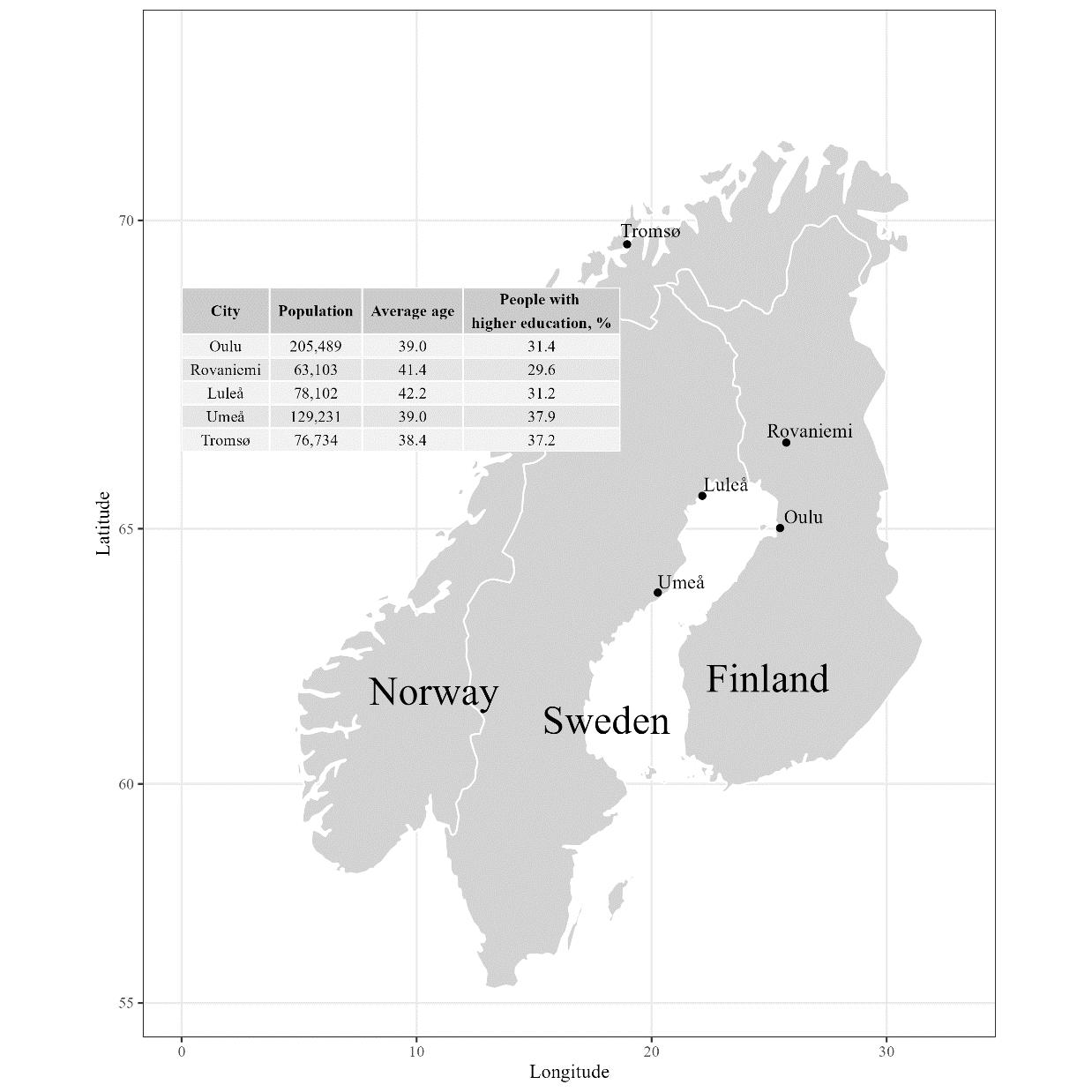

This paper examines COVID-19 data in the Arctic from February 2020 to September 2022 and provides a preliminary analysis at the regional (subnational) level with a goal to shed more light on the pandemic’s spatiotemporal dynamics and outcomes in the Arctic. We used the ARCTICCOVID (ARCTICenter, 2023) dataset for COVID-19 cases and deaths for 52 subnational political units within ten Arctic regions: Alaska, Faroe Islands, Iceland, Greenland, Northern Canada, Northern Norway, Northern Russia, and Northern Sweden.

Dataset and methods

This study utilized data on COVID-19 positive cases and fatalities collected at the subnational (regional, county) level for 52 regions in eight Arctic countries (Figure 1). This follows the Arctic boundaries used in the Arctic Human Development Report (Einarsson et al., 2004) that were revised by Jungsberg et al. (2019).

The data was collected by the project team through the pandemic (Petrov et al., 2020, 2021a) by acquiring daily case and death information from a variety of global, national and regional sources (John Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html), the Public Health Agency of Sweden (https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/), the National Institute for Health and Welfare of Finland (https://thl.fi), the Government of the Russian Federation (https://стопкоронавирус.рф), and Verdens Gang (Norway) - https://vg.no). The data were extracted at 17:00 GMT each day, stored, and published daily on the Arctic COVID-19 dashboard (https://arctic.uni.edu/arctic-covid-19). The temporal coverage extends from February 21, 2020 (the first documented case in the Arctic) to the present. However, for the purposes of this study, we focused on COVID-19 dynamics between February 2020 and September 2022. The data after October 1, 2022 were not included due to changes in data availability as some jurisdictions discontinued regular COVID-19 reporting. We used the ArcticVAX (2021) tracker to obtain information on vaccination trends for the same period.

Figure 1. Study area Variables and definitions

Key epidemiological variables were analysed and are defined here. Confirmed cases are individuals detected with SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid or antigen in their clinical specimen (ECDC, 2020) Daily increase is the number of cases confirmed within 24 hours after the previous reporting. Incidence rate represents a cumulative number of confirmed cases per 100,000 residents in a given period of time. Confirmed deaths are the number of deaths resulting from a clinical illness due to COVID-19 infection (ECDC, 2020). Mortality rate is the number of confirmed deaths attributable to COVID19 infection per 100,000 residents in a given period of time. Case Fatality Ratio, or CFR, is the total number of deaths divided by the total number of confirmed cases at a given point in time. Given that data are from diverse sources and multiple jurisdictions, the specific definitions used by the reporting agencies may inevitably vary and have to be interpreted with some caution.

Results

Pandemic outcomes

The analysis of the key pandemic variables (positive COVID-19 cases and deaths (totals), cases and deaths per 100,000 and CFR) indicates that the pandemic had a severe impact on many Arctic regions, although the levels of morbidity and mortality varied considerably. The Arctic as a whole had 20,234.1 positive cases and 234.8 deaths per 100,000 (as of September 1, 2022). A number of regions had elevated case load (e.g., Iceland, Faroe Islands, Alaska) partially because of small population numbers. In contrast, Northern Canada, Norway, and Russia had relatively low incident rates, although the reasons for that may vary (from low levels of infection to underreporting). At the same time, the highest mortality indicators are found in Northern Russia (283.8 per 100,000),

Northern Sweden (191.7) and Alaska (188.8). These figures likely reflect public health policy, healthcare, and vaccination campaign challenges in these regions. High mortality also corresponds with the elevated CFR in these countries. If in the Arctic as a whole the CFR stood at 1.2%, in Northern Russia it was 1.7%, in Northern Sweden it was 0.7%, and in Alaska it was 0.5%. It is notable, however, that in all Arctic regions (with the sole exception of Russia) the mortality and CFR were below the national levels of the respective countries. For example, in Alaska mortality was 188.8 per 100,000 versus 324.0 in the U.S. and the CFR was 0.5% versus 1.1% (Table 1). Therefore, most Arctic jurisdictions experienced a less severe COVID-19 pandemic than more southern regions of the same Arctic states.

Table 1. Key COVID-19 pandemic outcomes by Arctic region and county (Data on Sep 1, 2022)

Source: ARCTICenter (2023).

Spatiotemporal dynamics of the COVID-19 pandemic

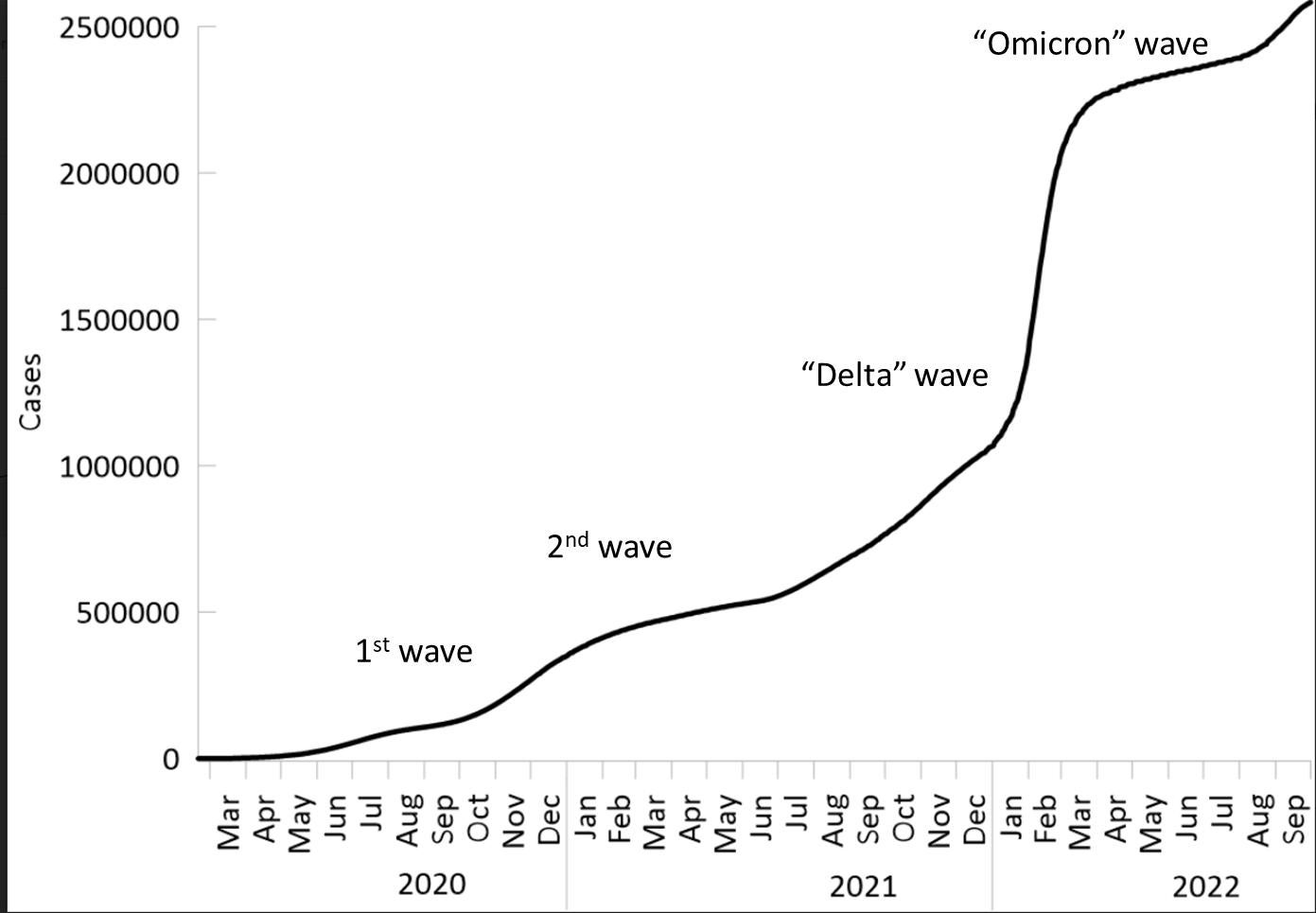

Figure 2 shows the cumulative number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in the Arctic from February 2020 until October 1, 2022. As can be easily seen, the pandemic has gone through several “waves” (surges in incidents of the infection followed by a substantial decrease sustained over a certain period (Zhang et al., 2021)). Often these waves are given a label derived from a predominant strain of SARS-CoV-2 at the time of its occurrence, although multiple strains co-existed throughout every wave. Overall, the pandemic started relatively late in many Arctic regions, and the first wave did not occur until summer 2020 (Petrov et al., 2020). A delayed start may have been related to the remoteness of Arctic regions, as well as the strict preventive policies implemented in some jurisdictions. In the first year of the pandemic, new COVID-19 cases peaked again around midDecember 2020 (“second wave” (Petrov et al., 2021b)) and then decreased in the early months of 2021. The second and the third (“Delta”) waves were well-pronounced, with the “Delta” wave clearly detectable in October-December of 2021 (Tiwari et al., 2022). This was immediately followed by the fourth, “Omicron,” wave in the early 2022, which dwarfed previous infection rates

The COVID-19 pandemic in the Arctic: An overview of dynamics from 2020 to 2022

(Figure 3). The Omicron wave brought major outbreaks to the Faroe Islands and Iceland, which previously had very few COVID-19 instances. This wave receded by summer of 2022, but positive cases increased again in the fall after many COVID-19 healthcare measures were relaxed. A rise in infections in fall of 2022 clearly indicates that the COVID-19 pandemic in the Arctic was continuing.

Cumulative COVID-19 cases and fatalities per 100,000 for each region of the Arctic are demonstrated in Figure 3. The dynamics of COVID-19 deaths likely reflect a differential timing of pandemic onset, difference in anti-COVID policies, and variable success of vaccination campaigns. For example, due to strict public health measures, early in the pandemic COVID-19-related deaths were low with the exception of Sweden, which also posted dramatic early CFRs (Figure 4). Each subsequent wave brought about a spike in death rates. For instance, during the Delta wave of 2021 in the Arctic, there was an increase of 205.8 percent in cases and 334.8 percent in deaths compared to the previous year. At the same time the Omicron wave of infections in early 2022 did not lead to a distinct increase in mortality. The CFR actually declined in all jurisdiction within a few months after introduction of COVID in the given jurisdiction, except for Northern Russia, where CFR did not decline until the start of 2022. In 2020-2022, the Arctic’s cumulative CFR was 1.2%, which is relatively high compared to the global and European ratios (Alrasheedi, 2023, JHCRC, 2023), but mostly influenced by the high CFR in Russia with other Arctic regions experiencing CFRs under 1%.

Northern Russia, due to its large population size, has been a driving force behind Arctic COVID19 cases and fatality trends. Although detected infections per 100,000 in Northern Russia were lower than in some other Arctic regions, the cumulative mortality and CFR were higher, especially later in the pandemic (Figure 3). Northern Russia was one of only a few Arctic jurisdictions with

both COVID-19 mobility and fatalities rates higher than in the southern parts of the country. For most Arctic states, the northern regions exhibited lower rates than the national figures (Petrov et al., 2021a).

Alaska experienced similar waves as the rest of the Arctic. The initial COVID-19 spike took place in summer of 2020 (prompted by summer travel and fisheries) with a big wave in the fall. In late 2021, confirmed COVID-19 incidents per 100,000 precipitously increased marking the very pronounced Delta and Omicron waves. During that period, Alaska COVID-19 indicators were more than twice as high as the Arctic as a whole. The growth in infections slowed in March, but rose again in summer of 2022.

Northern Sweden is a very interesting region in respect to the COVID-19 dynamics given its initially relaxed approach to public health emergency policies (Kamerlin & Kasson, 2020). Sweden, including its northern parts, demonstrated rapid growth in COVID-19 cases and deaths very early in the pandemic (spring 2020). Notably, CFR in this period was nearly 9% and CFR five to eight times higher than elsewhere in the Arctic. Both reported infections and fatalities per 100,000 in Northern Sweden were also high during 2021, but in the fall of 2021, the region experienced only a modest increase in new confirmed cases and deaths, seemingly avoiding a distinct Delta wave. Still the Omicron wave in early 2022 was well pronounced.

Greenland, Iceland, and the Faroe Islands reported relatively few positive COVID-19 cases and deaths throughout the pandemic. Iceland went through a short period of growth and decline in new cases between mid-July and October of 2021 followed by a rapid increase in the cases from November onward. Meanwhile Greenland, after mid-July 2021, experienced an upward trend in new cases that further accelerated in late fall and spring of 2022 constituting an outbreak associated with the Omicron wave. A similarly drastic rise was observed in the Faroe Islands. Although both Greenland and the Faroe Islands had very low COVID-19-related mortality during the earlier stages of the pandemic, they saw an increase in the number of deaths in November of 2021.

Northern Norway and Northern Finland had few reported infections and deaths for the first eighteen months of the pandemic. Following a gradual increase starting in spring 2021, new cases quickly rose from November 2021 to March 2022 constituting the Delta and Omicron waves. In Finland elevated daily positive cases extended until June. The number of deaths also grew in this period. Northern Canada had a relatively mild pandemic until summer 2021, when infections started to climb during multi-spike Delta and Omicron waves. Still, Northern Canada, along with Northern Norway and Finland, remain the least pandemic-affected Arctic regions (Figures 3).

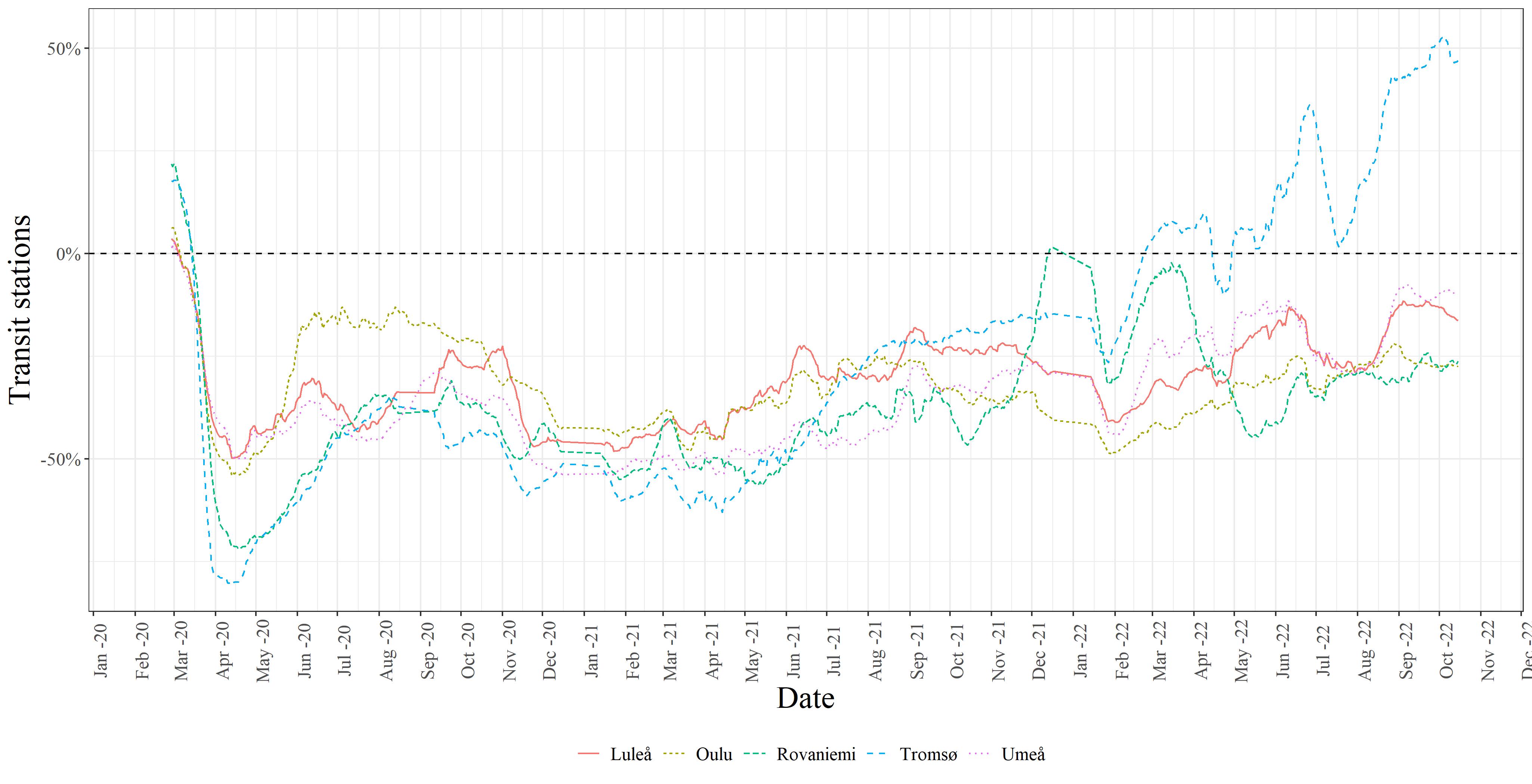

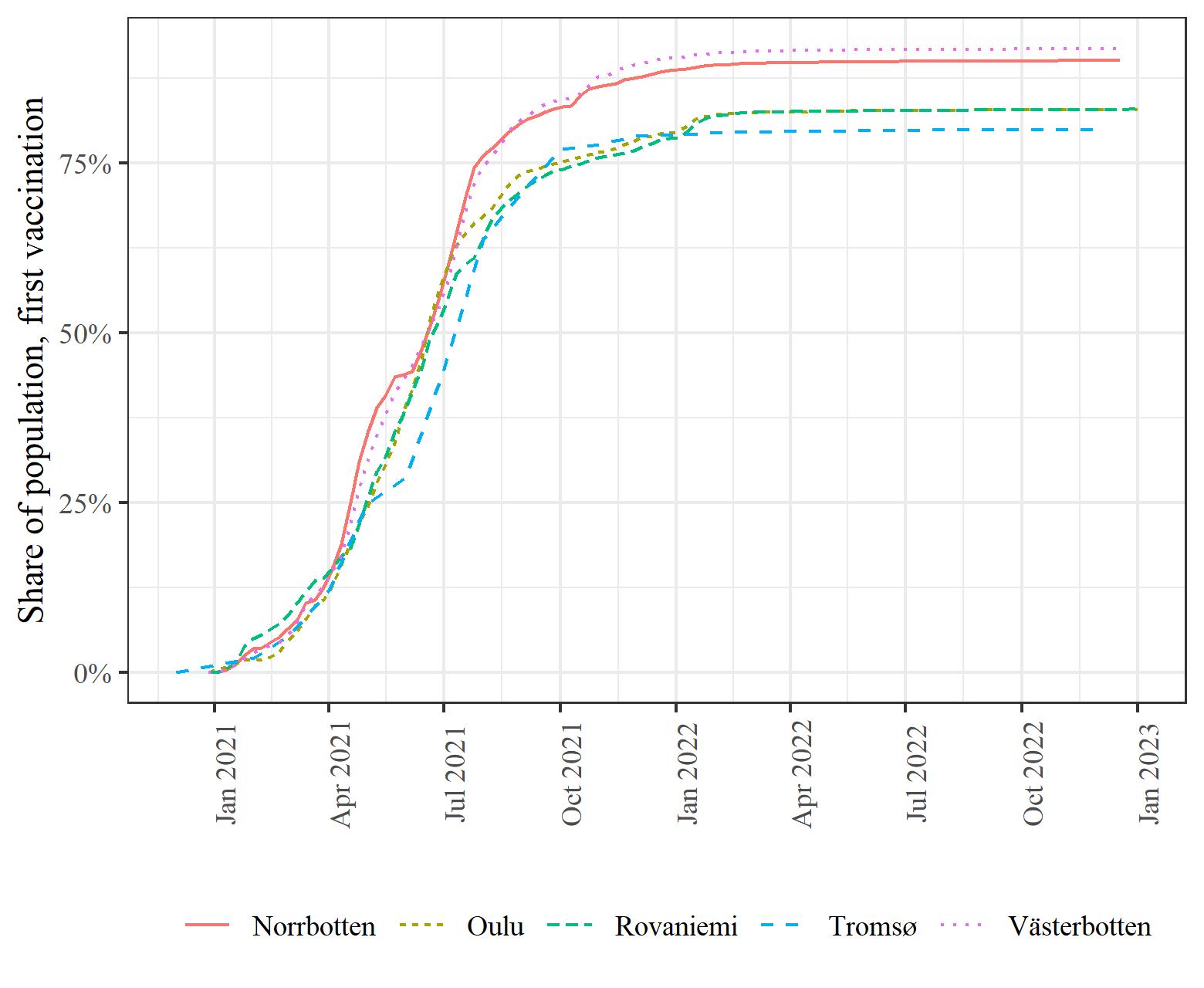

Spatiotemporal dynamics of vaccination in the Arctic

As of September 2022, nearly 70% of Arctic residents were fully vaccinated (as defined by a given jurisdiction). The Arctic presents a globally interesting case for examining the spatiotemporal dynamics of COVID-19 vaccination implementation. In fact, some Arctic regions were among the first places in the world where vaccines were broadly distributed and used (Petrov et al., 2021nature, Figure 5). In particular, Alaska and northern Canada started vaccination campaigns as early as December 2020. Northern Canada reached a 50% mark of fully vaccinated population by May of 2021. Although other Arctic jurisdictions started vaccinations later, most of them rapidly increased vaccination rates and attained a 60-70% attainment level by fall of 2021 (Figure 5). The exceptions were Alaska and Northern Russia. In Alaska, despite the December 2020 start, the vaccine uptake was lagging in the subsequent months. In Northern Russia the vaccination campaign was slow and conducted with limited success due in part, to higher vaccine hesitancy (Lazarus et al., 2023) and resistance (Roshchina et al., 2022).

Discussion and conclusions

Overall dynamics: patterns and regional differences

The COVID-19 pandemic in the Arctic is not over: a rise in reported infections in fall of 2022 indicates it very clearly. Although the general course of the pandemic in the Arctic was similar to global and national trends, the COVID-19 pandemic in the Arctic exhibited several important and distinct characteristics. First of all, the onset of the pandemic in most regions was delayed. In part this was due to the remoteness of Arctic communities, and in part because of the stringent antiCOVID measures instituted in most jurisdictions. Remoteness is thought to initially help in delaying the beginning of the pandemic, and thus, to secure more time for preparation for its eventual arrival. On the other hand, when infections and morbidity rise, distant locations of Arctic communities may become an impediment (the “curse of remoteness, Petrov et al., 2021a) for delivering timely high-quality healthcare. This delayed onset, with subsequent major outbreaks, were evident in the Faroe Islands, Greenland, Iceland, and many other Arctic regions. Thus, even though the arrival of a pandemic appears to be inevitable, remote communities can be better prepared for dealing with the disease with careful planning. Notably, mortality and CFR in most northern localities (with the exception of Russia) were considerably below the levels found in more central, southern regions of the same Arctic states. In addition to a delayed onset, factors like strict enforcement of anti-pandemic polices, rapid vaccinating campaigns, ability to exercise selfdetermination in healthcare, and the engagement of Indigenous knowledge contributed to this outcome (Petrov et al., 2023).

There have been studies that identified typologies of Arctic regions based on COVID-19 trends (Petrov, et al. 2022, Tiwari et al., 2022). Tiwari et al (2022) suggested distinguishing four regional types of pandemic dynamics in the Arctic: the first type is characterized by drastic spikes and lows in the

daily positive cases. This type of dynamic is observed in Greenland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Northern Norway, Northern Finland, and Northern Canada, which were relatively unaffected by the pandemic until late 2021 largely due to strict quarantine measures and subsequent vaccination and battled major surges of infections and deaths during the Delta and Omicron waves. Alaska’s represents a separate type, with relatively similar early dynamic, but with a very large outbreak of COVID-19 later in the pandemic (fall 2021-spring 2022), when most anti-COVID restrictions and mandates were ended. Northern Sweden and Northern Russia could be recognized as two additional types of the COVID-19 dynamics. In Northern Sweden a protracted wave was associated with less strict preventive policies in 2020 that determined high infection and mortality rates throughout year one, which subsequently reduced due to tightening measures. Northern Sweden generally avoided the Delta wave, but experienced an Omicron wave in winter-spring 2022. Finally, Northern Russia’s trend was characterized by persistently high daily cases and deaths. The pandemic appears to be more severe in the Russian Arctic than elsewhere in the Arctic or in Russia, potentially reflecting the inconsistent and top-down anti-COIVID policies, limited healthcare capacities, and poor availability and/or uptake of vaccines in remote communities (Åslund, 2020).

Lessons learned

As mentioned, many Arctic jurisdictions experienced a less severe COVID-19 pandemic than southern regions of the same states despite greater socioeconomic, infrastructure, and health vulnerabilities in Arctic communities. This is an important notion that may have implications for public health policies. The availability of additional sources of resilience associated with Indigenous knowledge, cultures, and practices may have plaid a major role in the pandemic outcomes. In most notable cases, the Arctic Indigenous communities were able to capitalize on multigenerational memories of the past epidemics, engage Indigenous knowledge and practices, and exercise selfdetermination in order to combat the pandemic (ITK, 2020; Foxworth et al., 2021; Petrov et al., 2023). For example, Indigenous communities in Alaska and Northern Canada instituted very strict quarantines and other preventive measures, utilized the knowledge of the land to practice isolation and healing, implemented their own priorities in administering western and traditional healthcare (such as focusing on elders, culturally-appropriate treatment, spiritual healing, etc.), and exercised control over vaccination campaigns and other healthcare activities thus asserting their sovereignty in public health affairs. Exercising self-determination, in part or in full, appears to be a factor of pandemic severity among Indigenous communities. Consequently, a strong consideration should be given to recognizing and investing in the Indigenous Peoples’ capacity to manage their own healthcare (in the Arctic and elsewhere in the world) as a key policy to ensure preparedness for combating this and future pandemics.

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by NSF PLR #2034886.

References

Adams, L. V., & Dorough, D. S. (2022). Accelerating Indigenous health and wellbeing: the Lancet Commission on Arctic and Northern Health. Lancet (London, England), 399(10325), 613614.

Alrasheedi, A. A. (2023). The Prevalence of COVID-19 in Europe by the End of November 2022: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus, 15(1).

ARCTICenter (2023) Arctic COVID-19 dashboard (https://arctic.uni.edu/arctic-covid-19 )

Accessed on January 15, 2023.

Arctic Council. (2020). COVID-19 in the Arctic: briefing document for senior arctic officials. Available from: https://oaarchive.arctic-council.org/handle/11374/2473

Åslund, A. (2020). Responses to the COVID-19 crisis in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 61(4-5), 532-545.

Bansal, M., 2020. Cardiovascular disease and COVID-19. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews.

Barro, R.J., Ursúa, J.F. and Weng, J., 2020. The coronavirus and the great influenza pandemic: Lessons from the “spanish flu” for the coronavirus’s potential effects on mortality and economic activity (No. w26866). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Chatwood, S., Bjerregaard, P., & Young, T. K. (2012). Global health A circumpolar perspective. American Journal of Public Health, 102(7), 1246–1249.

Ciotti, M., Ciccozzi, M., Terrinoni, A., Jiang, W.-C., Wang, C.-B., & Bernardini, S. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences, 57(6), 365–388.

Cook, D., & Jóhannsdóttir, L. (2021). Impacts, Systemic Risk and National Response Measures Concerning COVID-19 The Island Case Studies of Iceland and Greenland. In Sustainability (Vol. 13, Issue 15). https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158470

Einarsson, E., Larsen, J. N., Nilsson, A., & Young, O. R. (2004). Arctic human development report 2004. Stefansson Arctic Institute, Akureyri, Iceland 242pp.

Erber, E., Beck, L., De Roose, E. and Sharma, S., 2010. Prevalence and risk factors for self-reported chronic disease amongst Inuvialuit populations. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 23, pp.43-50.

Fleury, K., & Chatwood, S. (2022). Canadian Northern and Indigenous health policy responses to the first wave of COVID-19. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 14034948221092185.

Foxworth, R., Redvers, N., Moreno, M. A., Lopez-Carmen, V. A., Sanchez, G. R., & Shultz, J. M. (2021). Covid-19 Vaccination in American Indians and Alaska Natives Lessons from Effective Community Responses. New England Journal of Medicine, 385(26), 2403-2406.

Golubeva, E., Emelyanova, A., Kharkova, O., Rautio, A., & Soloviev, A. (2022). Caregiving of Older Persons during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Russian Arctic Province: Challenges and Practice. In International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health (Vol. 19, Issue 5). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052775

Huot, S., Ho, H., Ko, A., Lam, S., Tactay, P., MacLachlan, J., & Raanaas, R. K. (2019). Identifying barriers to healthcare delivery and access in the Circumpolar North: important insights for health professionals. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 78(1), 1571385.

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK). (2020). The Potential Impacts of COVID-19 on Inuit Nunangat. Ottawa.

Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center (JHCRC), 2023. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality Accessed on January 14, 2023.

Jungsberg, L., Turunen, E., Heleniak, T., Wang, S., Ramage, J., & Roto, J. (2019). Atlas of population, society and economy in the Arctic.

Kapitsinis, N. (2020). The underlying factors of the COVID-19 spatially uneven spread. Initial evidence from regions in nine EU countries. Regional Science Policy & Practice, 12(6), 1027–1045.

Petrov, Tiwari, Devlin, Welford, Golosov, DeGroote, Degai & Ksenofontov

Kilbourne, E.D., 2006. Influenza pandemics of the 20th century. Emerging infectious diseases, 12(1), p.9

Lazarus, J. V., Wyka, K., White, T. M., Picchio, C. A., Gostin, L. O., Larson, H. J., ... & ElMohandes, A. (2023). A survey of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance across 23 countries in 2022. Nature Medicine, 1-10.

Lemieux, T., Milligan, K., Schirle, T., & Skuterud, M. (2020). Initial impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Canadian labour market. Canadian Public Policy, 46(S1), S55–S65.

MacIntyre, C. R. (2020). Global spread of COVID-19 and pandemic potential. Global Biosecurity, 1(3).

Markova, V. N., Alekseeva, K. I., Neustroeva, A. B., & Potravnaya, E. V. (2021). Analysis and forecast of the poverty rate in the Arctic Zone of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). Studies on Russian Economic Development, 32(4), 415–423.

Men, F., & Tarasuk, V. (2021). Food insecurity amid the COVID-19 pandemic: food charity, government assistance, and employment. Canadian Public Policy, 47(2), 202–230.

Murphy, N.J., Schraer, C.D., Theile, M.C., Boyko, E.J., Bulkow, L.R., Doty, B.J. and Lanier, A.P., 1997. Hypertension in Alaska Natives: association with overweight, glucose intolerance, diet and mechanized activity. Ethnicity & Health, 2(4), pp.267-275.

Petrov, A. N., Dorough, D. S., Tiwari, S., Welford, M., Golosov, N., Devlin, M., ... & DeGroote, J. (2023). Indigenous health-care sovereignty defines resilience to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet (London, England).

Petrov, A. N., Welford, M., Golosov, N., DeGroote, J., Degai, T., & Savelyev, A. (2020a). Spatiotemporal dynamics of the COVID-19 pandemic in the arctic: early data and emerging trends. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 79(1), 1835251.

Petrov, A. N., Welford, M., Golosov, N., DeGroote, J., Devlin, M., Degai, T., & Savelyev, A. (2021a). Lessons on COVID-19 from Indigenous and remote communities of the Arctic. Nature Medicine, 27(9), 1491–1492. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01473-9

Petrov, A. N., Welford, M., Golosov, N., DeGroote, J., Devlin, M., Degai, T., & Savelyev, A. (2021b). The “second wave” of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Arctic: regional and temporal dynamics. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 80(1), 1925446. https://doi.org/10.1080/22423982.2021.1925446

Richardson, L., & Crawford, A. (2020). COVID-19 and the decolonization of Indigenous public health. Cmaj, 192(38), E1098–E1100.

Roshchina, Y., Roshchin, S., & Rozhkova, K. (2022). Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Russia. Vaccine, 40(39), 5739-5747.

Simonsen, L., Spreeuwenberg, P., Lustig, R., Taylor, R.J., Fleming, D.M., Kroneman, M., Van Kerkhove, M.D., Mounts, A.W. and Paget, W.J., 2013. Global mortality estimates for the 2009 Influenza Pandemic from the GLaMOR project: a modeling study. PLoS Med, 10(11), p.e1001558

Tiwari, S., Petrov, A. N., Devlin, M., Welford, M., Golosov, N., DeGroote, J., ... & Ksenofontov, S. (2022). The second year of pandemic in the Arctic: examining spatiotemporal dynamics of the COVID-19 “Delta wave” in Arctic regions in 2021. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 81(1), 2109562.

The COVID-19 pandemic in the Arctic: An overview of dynamics from 2020 to 2022

Watson, O. J., Barnsley, G., Toor, J., Hogan, A. B., Winskill, P., & Ghani, A. C. (2022). Global impact of the first year of COVID-19 vaccination: a mathematical modelling study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 22(9), 1293-1302.

Zhang, S. X., Arroyo Marioli, F., Gao, R., & Wang, S. (2021). A Second Wave? What Do People Mean by COVID Waves? - A Working Definition of Epidemic Waves. Risk management and healthcare policy, 14, 3775–3782. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S326051

The state of research focused on COVID-19 in the Arctic: A meta-analysis

The Arctic region faces unique risks and challenges as a result of both the COVID-19 pandemic and the actions taken to respond to it. Arctic communities have distinct health, social and economic needs and circumstances that were more pronounced during this pandemic. Research offers an important opportunity to understand the region’s unique conditions and characteristics for pandemic management. Only by systematically examining its impacts can public officials, community leaders, medical professionals and other decision-makers have the knowledge needed to decrease further harm due to COVID-19 and leverage this opportunity to support the resilience of Arctic communities. This article contributes to this knowledge building effort by surveying the literature (peer reviewed and grey) that explicitly focuses on COVID-19 in the Arctic between 2020 and 2022. We analyze this emerging body of work with a focus on identifying overarching trends (time, countries studied, scale of analysis, specific populations). We also map the themes and topics considered in this literature with a focus on highlighting topics that are prominent and those that are conspicuously underrepresented. This analysis seeks to inform our understanding of, and response to, the pandemic and other global shocks in the short-, medium- and longer-term.

Introduction

On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the spread of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) to be a global pandemic (WHO, 2020b). In the following months, this infectious disease spread rapidly and reached all regions of the globe at a pace unprecedented in human history. The COVID-19 pandemic represents a rapid global shock that has severely disruptive consequences (OECD, 2011). However, while the presence of COVID-19 has been pervasive, people’s experiences with the pandemic have been diverse. As a consequence, there is an emerging literature that explores the varying impacts of the pandemic on different countries, industries, socioeconomic statuses, age groups, genders, etc. This research is critical not only to understand the differentiated impacts of the pandemic, but to examine the broader systemic and

Jennifer Spence, Senior Fellow, Belfer Center Arctic Initiative, Harvard Kennedy School Sai Sneha Venkata Krishnan, Researcher, Belfer Center Arctic Initiative, Harvard Kennedy School Jennifer Spence & Sai Sneha Venkata Krishnanstructural biases within our societies. Lessons and insights learned from the pandemic offer an opportunity to inform our actions to effectively break down barriers and build resilience.

In June 2020, a preliminary assessment of the impacts of COVID-19 in the Arctic and the actions taken to respond to the pandemic was released by the Arctic Council (2020) in a briefing document prepared for Senior Arctic OfficialsClick or tap here to enter text.. This report, released early in the pandemic, was produced using available material and data; however, given the short timeframe, gaps in information, and the evolving circumstances, the report recommended that additional research would be needed.

Research to examine the experiences of Arctic residents and communities with COVID-19 offers an important opportunity to understand the region’s unique conditions and characteristics for pandemic management. It also helps in advancing our understanding of the specific impacts and lessons learned from the spread of COVID-19 and related public health responses in the Arctic. This article surveys this new literature focused on COVID-19 in the Arctic. Through this form of meta-analysis, we contribute to building our region-specific knowledge by examining where research is taking place and the common themes and issues that have been explored regarding COVID-19 in the Arctic.

The goal of this article is to raise awareness among researchers and decision-makers and deepen their understanding of the responses to and impacts of COVID-19 in the Arctic. This analysis provides the Arctic research community with opportunities to examine common themes and identify research synergies. It also highlights areas with limited research and invites experts and knowledge holders to reflect on why these gaps exist and to what extent this analysis could inform future research priorities. Furthermore, we aim to provide an overview of this emerging literature for decision-makers – those responsible for future policy actions in the Arctic at every scale. We seek to demonstrate that research related to COVID-19 in the Arctic provides decision-makers with important resources that can contribute to evidence-based actions that advance the resilience of Arctic communities in the face of a pandemic and other major shocks, including climate change, geopolitical crises, and massive socio-economic pressures.

This article begins by providing an overview of the methodology used to conduct a meta-analysis of the literature focused on COVID-19 in the Arctic. We then present key findings from this analysis. We begin by analyzing the overarching trends in this emerging literature over time, geography, scale of analysis, and key populations. We subsequently examine the issues and themes identified in this literature using three broad categories: pandemic spread and public health responses, pandemic consequences, and lessons for the future

Methodology

There are different types of meta-analysis that serve different purposes and, by extension, depend on different methodological approaches (Levitt, 2018) This research project aims to provide a descriptive overview of an emerging body of literature that focuses on the impacts of COVID-19 in the Arctic. Data collection and analysis procedures for this form of meta-analysis were designed with this aim in mind. Data collection involved a broad search of source materials. Google Scholar was used to create an initial list of source materials published between January 2020 and December 2022. Search teams used were: “COVID-19”, “pandemic”, and “Arctic”. As we intended to include all relevant materials, this search included all publications with these search terms anywhere in the article and included any type of publication included in the Google Scholar database (peer reviewed, grey, citations). The search was limited to English language search results. We recognize that the search engine, search terms, focus on English search results, and a manual review of the dataset would not capture all the work that contributes to this emerging body of literature or produce a comprehensive dataset. Additional research will improve our understanding of this literature, but

the findings presented in this preliminary survey of the literature confirms the value of efforts to examine and understand research taking place in this space.

The Google Scholar search produced 17,100 sources. An initial review of these sources, based on titles, removed a substantial number of duplicates. A second phase of review culled sources using the title and abstract (if available) to exclude sources based on their relevance. In particular, we excluded sources where COVID-19 was not a core component of the article. This included source materials that only mentioned COVID-19 in passing or peripherally. Additionally, we excluded articles that did not differentiate Arctic and non-Arctic regions within the countries being studied. Given the purpose of this meta-analysis and the emerging nature of this body of literature, we decided not to limit the dataset to peer-reviewed sources. However, we did exclude sources that provided no substantiated information or analysis (e.g. editorials, commentaries, project descriptions, etc.). After this initial filtering, the dataset included 171 sources. We then conducted a more comprehensive assessment of these sources and excluded an additional 52 sources based on specific criteria, which included 1) not substantially focused on COVID-19 (26), 2) not substantially focused on the Arctic (16), and 3) not able to locate the publication for analysis (10). The resulting dataset includes 114 sources.

The data analysis procedures associated with this review were similarly designed to align with the goals of this research. We focussed on mapping the source materials into broad categories and specific topics of study. This enabled us to observe patterns in this emerging literature. We did not attempt to analyze the findings in the source materials or assess their quality.

We adopted a hybrid approach to structuring our mapping and categorization of the source materials. The initial structure used to classify source materials was based on the broad categories and specific topics/issues introduced in the Arctic Council assessment report (2020). This initial analytical structure was a useful guide for the meta-analysis because it was developed at the beginning of the pandemic by over 50 Arctic experts with a diverse range of expertise and interests. These Arctic experts developed this initial frame with the intention of articulating the types of information and knowledge that could be important to guide research and policy making. The categories and topics identified in this report are outline in Table 1.

Category Topic

Existing Public Health Actions and Activities Across the Circumpolar Arctic

Available epidemiological data

Infectious disease monitoring and assessment

Patient care

Public health information sharing, awareness, and education

Risk management and mitigation

Consequences of Pandemic and Public Health Responses

Physical well-being and mental health

Regional and local economies by sector/industry

Social and cultural environments

Vulnerable persons

Knowledge production Mobility

Enabling public infrastructure

The state of research focused on COVID-19 in the Arctic: A meta-analysis

In addition to mapping articles using these predefined categories and topics, we remained open to including additional categories and topics that emerged from the dataset. Using this flexible approach, we included one additional category, “Lessons for the future”, and seven new topics. In the pandemic spread and responses category, we included the topics: access to relevant health data and community and culturally grounded responses. In the category of pandemic consequences, we identified five new topics: environment/climate, food security/sovereignty, community-level impacts, political impacts, and geopolitical impacts In analyzing the dataset, we also made the decision to move the topic of enabling infrastructure to the pandemic spread and responses and lessons for the future categories because we found that the literature was primarily focused on to what extent the physical and social infrastructure was sufficient to support pandemic responses rather than providing commentary on the consequences of the pandemic. The final list of categories and topics used for this meta-analysis is presented in Table 2.

Table 2: Categories and topics used for analysis

Category

Topic

Pandemic Spread and Responses Available epidemiological data

NEW: Access to relevant of health data

Infectious disease monitoring and assessment

Patient care

Public health information sharing, awareness, and education

Risk management and mitigation

NEW: community and culturally grounded responses

Enabling public infrastructure [moved from pandemic consequences]

Pandemic Consequences

Impacts on physical well-being and mental health

Impacts on regional and local economies by sector/industry

Impacts on social and cultural environments

Impacts on vulnerable persons

Impacts on knowledge production

Impacts on mobility

NEW: impact on environment/climate

NEW: impact on food security/sovereignty

NEW: community-level impacts

NEW: political impacts

NEW: geopolitical impacts

Lessons for the Future

Enabling public infrastructure [moved from pandemic consequences]

Other

Source materials were analyzed for their inclusion in all relevant categories and topics. For example, one source might include content relevant to the pandemic spread and responses category and the pandemic consequences category. Similarly, a source could cover multiple topics, such as risk management and mitigation, impact on regional and local economies, and impacts on mobility. In addition to these categories and topics, the source material was analyzed for the countries covered (Canada, Kingdom of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, United States), the scale of analysis (local, sub-national, national, sub-regional, pan-Arctic, global), and specific population lenses (Indigenous Peoples, vulnerable persons, gender).

Findings: Overarching trends

The dataset of 114 sources provides us with some rich insights regarding the emerging literature focused on COVID-19 in the Arctic.1 We will start by reviewing some of the overarching observations about this body of work and then examine specific findings regarding the themes and issues addressed.

Research over time

The articles analyzed were published from January 2020 to December 2022. Figure 1 demonstrates that researchers interested in studying COVID-19 in the Arctic responded quickly. Two grey literature products were released almost immediately after the pandemic was confirmed in March 2020 – one article focused on the impact of travel restrictions in Norway on Arctic research (Vogel, 2020), and one policy brief focused on Inuit Nunangat that emphasized the importance of Northern research related to the pandemic and Inuit perspectives and experiences (Penney & Johnson-Castle, 2020). Furthermore, the first peer reviewed article was published shortly after in April 2020 and considered the impacts of COVID-19, public health responses, and travel bans on the relationship between Greenland and Denmark (Grydehøj et al., 2020).

Articles

Figure 1: Number of articles published from January 2020 to December 2022

The number of publications grew throughout 2020 and again in 2021 with publications peaking in the summer of 2021. Following mid-2021, we observe a decline in the literature being published in this space. In fact, publications from 2022 make up only 24% of the total dataset whereas 2021 saw approximately 50% of sources published. While this decline in publications is perhaps consistent with general “pandemic fatigue” observed globally (World Health Organization, 2020a), the timing of this decline seems premature to build a solid base of knowledge in this field. It should be of concern for those who recognize the importance of short-, medium- and longer-term research and analysis of such an important global event, especially in the Arctic.

Arctic State coverage

This meta-analysis provides us with useful insights about the geographic areas that have been the focus of study in this literature. What stands out in Figure 2 is that the Russian Arctic (33%) followed by Norway (25%) and Canada (25%) are the most studied in the dataset. Whereas, Iceland has been least studied in this literature (11%). It is difficult to come to any conclusions about why we observe these variations in the geographic areas studied. The strong presence of the Russian Arctic in this literature at the very least indicates a clear interest by researchers in understanding the unique conditions, characteristics, and consequences of pandemic management in the Russian Arctic, especially when you consider that data collection was conducted in English. However, the

1 More detailed information about the dataset is available upon request by contacting Jennifer Spence.

weaker showing of Iceland in this dataset may not fairly represent the production of relevant research and may be more an indication that “Arctic” is not an appropriate search term for identifying Arctic-relevant research related to the pandemic in Iceland.

centred) and sub-regional (i.e. various sub-groupings of Arctic states) scales of analysis took up similar shares at 16% and 17%, and national- and global-level studies that substantively considered the Arctic were lowest at 9% and 12% respectively.

This analysis is further nuanced when we combine the Arctic state coverage with the scale of analysis used (Figure 3). We observe three interesting findings. First, 55% of sources that included the Russian Arctic used the sub-national level as the unit of analysis, and on the flipside, 44% of the research done at the sub-national level focuses on the Russian Arctic. This finding reinforces the research interest and capacity that is dedicated to studying the Russian Arctic. It also suggests that the specific context and experience of the Russian Arctic during the pandemic is seen as an important area of research. Next, we observe that 32% of all source materials that included the Canadian Arctic focused on a local scale of analysis, and 56% of the local-level research involved communities in the Canadian Arctic. No solid conclusions can be made about the reasons for this result. This finding may be driven by the types of research interests that are relevant in the Canadian Arctic, but it also may provide evidence that the community-based research approaches that have been championed in the Canadian North are taking hold. Lastly, it is interesting to observe that none of the publications in the dataset adopted the Nordic region as a unit for analysis. The absence of this form of sub-regional research is notable given the potential common experience, and opportunities for comparison and shared lessons learned. It is also interesting because of the

existence of Nordic research funding programs that could easily enable this form of sub-regional collaboration if there was interest.

Figure 3: Articles by country across scales (local to global) Population lenses

Finally, we analyzed the dataset using specific population lenses that are relevant in the Arctic context: Indigenous Peoples, vulnerable persons, and gender. Our first finding is that 37% of publications in the dataset focused on or provided an Indigenous perspective on the impacts of the pandemic in the Arctic. 38% of these publications include a focus on the Canadian Arctic and 57% of the publications that study the Canadian Arctic incorporate Indigenous issues and/or perspectives. Also notable, 90% of the publications that focused on the Canadian Arctic at the local level include Indigenous perspectives and experiences. This finding is particularly interesting when we recall that Canada had the largest share of locally focused research, which may provide some insights on the types of research related to the pandemic that are more relevant to Arctic Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

Research related to the impact of the pandemic on vulnerable populations was identified in only 16% of the literature. These publications covered a broad range of issues, including older populations, mental health, remote communities, food security, and human rights. No one Arctic state stands out as being the focus of this research, rather the scale of analysis is more interesting

Half of the articles focused on vulnerable populations adopted a sub-national level of analysis, which again is likely appropriate given the level at which public health responses are most actively managed. Pan-Arctic studies represented 28% of the publications that highlighted the experiences of vulnerable populations. This observation may provide guidance regarding an area where future Arctic-focused research could be valuable.

Lastly, work incorporating a gender lens or issues into research related to COVID-19 in the Arctic was notably low in the dataset. Some consideration of gender was included in only 6% of publications and in none of these was gender a primary focus. This emphasizes the importance of projects, such as Understanding the Gendered Impacts of COVID-19 in the Arctic (George

The state of research focused on COVID-19 in the Arctic: A meta-analysis

Washington University, n.d.), that dedicate specific attention to important area of research. Initiatives like this will hopefully share analyses that will help to fill this gap in the literature.

Findings: Themes and issues

The broad categories (pandemic spread and responses, pandemic consequences, lessons for the future) used to structure this meta-analysis provide a frame to analyze the dataset and present relevant themes that are covered in the literature. 45% of publications include a focus on understanding pandemic spread and responses, articles that analyzed the pandemic consequences represent 68% of the dataset, and 40% of the articles incorporate lessons for the future. Figure 4 provides us with an overview of the prominence of publications in each of these categories over time. We observe that, while the largest number of articles focused on understanding COVID-19 spread and responses were published in 2021, this category represented the largest share of articles (52%) in 2020. We also observe that research related to the consequences of the pandemic assumes the largest share in all years and follows a similar trend.

As outlined in the methodology section, we subsequently included a third category for analyzing the publications. We were interested in capturing those source materials that offered lessons for the future. We thought it could be useful to acknowledge the portion of this emerging literature that provides insights for researchers and practitioners that could inform further action. What we observe is that 40% of the dataset (with a relatively consistent proportion of publication each year) provide some future-oriented insights.

There are two additional observations worth noting about the placement of these source materials into these higher-level categories. A notable percentage of articles in all three categories include Indigenous issues and/or perspectives. Articles in the pandemic response category had the highest share of articles (50%), while the pandemic consequences and lessons for future categories included 36% and 40% of articles respectively. This helps to substantiate the narrative that Indigenous Peoples hold a prominent position in the Arctic and emphasizes that research that includes Indigenous perspectives and interests is treated as a priority. A second observation is that sub-national analyses make up the largest share of all of these categories, and they also form the most consistent share of each (pandemic response 41%, pandemic consequences 41%, lessons for the future 32%). The reasons for, and consequences of, this finding are beyond the scope of this article; however, considering the strength and diversity of research at this scale and others warrants further consideration.

Pandemic spread and response

As previously mentioned, the topics identified to classify the literature were initially drawn from the Arctic Council’s assessment report (2020) released early in the pandemic. In our analysis of the dataset, we identified two additional topics: access to relevant health data and community and culturally grounded responses. We also included the topic of enabling public infrastructure in this category rather than in the pandemic consequences category because it was a more appropriate fit given the focus of the publications analyzed.

In classifying the source materials, it is perhaps not surprising to observe in Figure 5 that the largest number of articles focus on risk management and mitigation (36%). It is also interesting that close to 80% of publications in this topic area were released in 2020 and 2021 and only 20% had this focus in 2022. These articles covered a broad range of topics (e.g. public health measures, travel bans, food security, fisheries, etc.). This literature provides important insights about the unique characteristics of pandemic management in different Arctic contexts and informative accounts of the context-specific experience of implementing risk management measures in the Arctic.

Figure 5: Topics under Pandemic Spread and Response

The topic of enabling infrastructure also received a significant amount of attention in the publications studied (30%). In Penny and Johnson-Castle’s (2020) early analysis of the risks of COVID-19 in the Inuit Nunangat, they signalled that the pandemic would make the infrastructure gaps faced by Inuit “even starker” (p.3). The subsequent publications in this dataset confirm the diversity of issues related to physical and social infrastructure risks and challenges. Articles covered a range of topics: health-related equipment and supplies, housing, internet connectivity, food supply chains, emergency response, and access to social services. In many ways, the pandemic provided concrete and vivid illustrations of the infrastructure gaps that Arctic communities have raised concerns about for decades (Arctic Council, 2020; Nunavut Tunngavik, 2020)

The state of research focused on COVID-19 in the Arctic: A meta-analysis

The newly added topic of community and culturally grounded responses also held a prominent place in the literature (25%). This topic included a diverse range of issues and experiences that provided an interesting counterpoint to the infrastructure challenges articulated above. In addition to emphasizing the importance of community-driven responses to the pandemic, articles highlighted the strength and resilience of Arctic communities in the face of the pandemic, such as the importance of country foods and food sharing systems, on-the-land initiatives, and social and cultural support systems.

Of equal importance in this analysis are the topics that received limited attention. Experts in the initial Arctic Council report emphasized the critical importance of reliable, high quality epidemiological data to understand the spread of COVID-19 in the Arctic and respond to and mitigate health risks. They also acknowledged that this type of data is often not easily accessible in many Arctic jurisdictions (2020). The University of Northern Iowa Arctic COVID-19 project provides an interesting example of efforts to collect and analyze Arctic-specific data about COVID-19 cases and deaths using accessible data sources (University of Northern Iowa, n.d.). It illustrates the value of dedicated efforts to collect, organize and analyze data that can strengthen our understanding of the Arctic context and inform appropriate responses. However, the limited number of publications identified under this topic (13%) and under the newly added collection of health data topic (8%) suggests that there is much more work that can be done to empirically assess the spread of COVID-19, the pandemic response, and the pandemic consequences in the Arctic.

Pandemic consequences

In the category pandemic consequences, we also started with the topics identified in the Arctic Council report, and as previously mentioned, incorporated five new topics based on issues identified in the source material: environment/climate, food security/sovereignty, community-level impacts, political impacts, and geopolitical impacts

Figure 6: Topics under Pandemic Consequences

In Figure 6, we observe not surprisingly that the topic of impacts on health (43%) was strongly represented in this category. What is perhaps most interesting about articles included under this

topic is the rich diversity of issues that have been connected to health. Several publications considered different Arctic factors that might facilitate or impede the spread of COVID-19 (e.g. weather and climatic conditions, health delivery systems, the size and remoteness of communities, digital service delivery, etc.). Similarly, the types of issues connected to health impacts was notably diverse, including mental health, Indigenous Knowledge, economies, food, and education.

The impact of the pandemic on Arctic economies also consumed a substantial amount of attention (34%). The most prominent sub-topic was the pandemic’s impact on various Arctic industries with tourism, energy, extractive industries, and fisheries receiving the most attention. A smaller collection of articles examined the impact on labour markets, and others provided analyses of the broader economic impacts of the pandemic. These sub-topics provide some important insights about aspects of Arctic economies that are being studied; however, it also invites a consideration of the gaps in what has been studied and where more research might be valuable.

The newly added topic whose prevalence in the literature is perhaps the most surprising is the impact of the pandemic on the Arctic environment and climate (29%) – from increases in ozone and sea ice to decreases in black carbon and aerosol emissions. Researchers seem keen to study the environmental impacts of a massive disruption in human activity, and the Arctic region seems to be a focal point for this research. Moving forward, it will be interesting to see to what extent the scientific findings from this period might be integrated into and considered in longer term climate and environmental research. In a somewhat different vein, research also emerged about how COVID-19 public health measures (e.g. masks, gloves, and other personal protective equipment) contributed to increased marine plastic pollution in the region.

Lessons for the Future

The final category that we added to classify and analyze the source material was those publications that provided some future-oriented advice or commentary. 40% of all articles include some form of lessons for the future. This category captures a diverse range of contributions in terms of the focus and purpose of the lessons that were shared. 80% of the publications touched upon risk management and mitigation, community and culturally grounded responses, or enabling public infrastructure. Earlier publications provided lessons learned for the immediate management of the pandemic (public health responses, community-specific approaches, travel bans, etc.) or proposed critical research that should be undertaken to understand the pandemic (collection of health and environmental data, experiences of communities, effectiveness of risk management measures).

As the pandemic progressed, lessons regarding the vulnerabilities that the pandemic exposed emerged, and increasing consideration was given to how to improve the resilience of Arctic communities for future pandemics or other major shocks. More than 40% of the articles covering consequences on health, research and education, environment, and tourism offered lessons for future pandemics. However, there was limited insights on the impacts on social and cultural environments, labor markets, tourism, and geopolitics. This suggests that there is a need for additional literature in these areas to strengthen Arctic resilience.

Some articles identified the experience with the pandemic as an opportunity to expose existing gaps and promote appropriate action (connectivity, health infrastructure, transportation, and food systems). A few articles argued that the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated an urgent need to respond to permafrost thaw and improve Arctic resilience. Others identified the pandemic as an opportunity to challenge the status quo and introduce innovation (scientific research, education, green transition, community capacity development). Many of these articles focused on digital transformation of research and education and large Arctic projects.

For the purposes of this analysis, we did not catalogue or critically examine the lessons that were presented; however, our preliminary analysis suggests that the literature focused on COVID-19 in the Arctic may offer a valuable resource to inform future research and action. It provides

The state of research focused on COVID-19 in the Arctic: A meta-analysis

information and knowledge that the research and policy communities could draw on to systematically assess pandemic responses and the pandemic consequences, learn from these experiences, and consider how this knowledge will guide and inform future work.

Conclusion