The Nonhuman

Dear Reader,

I admit to being a Luddite when it comes to preferring a paintbrush to the computer. So, when artists gained access to AI-generating tools, I wasn’t that impressed, nor alarmed. There seemed to be a lot of hoopla and fearmongering about the prospect of such a tool making art … perhaps even more efficiently than humans?

Our Nonhuman issue addresses various approaches that artists take in dealing with the nonhuman, whether it be in physical form or robotics. The Haas Brothers, interviewed by digital columnist Seth Hawkins, embrace AI-generated art and are unapologetic about it: It’s simply a tool, as they put it. So, what’s all the fuss about? Bill Smith, our creative director, ponders the future possibilities of AI, and asks the bottom line—will the collectors buy it? On the other side of robots—and the world—Australian Patricia Piccinini’s “creatures” seem more lifelike. Contributor Barbara Morris discusses Piccinini’s hybrid sculptures of the human, animal, natural and artificial—all of which resemble living beings with hair, skin-like surfaces, eyes and mouths. The end results border on the creepy and hideous, yet a sense of a vulnerability emerges, that of an innocent child or animal. They are supernatural and hyper-real, making us wonder if this is what humans will morph into in our continuing evolution.

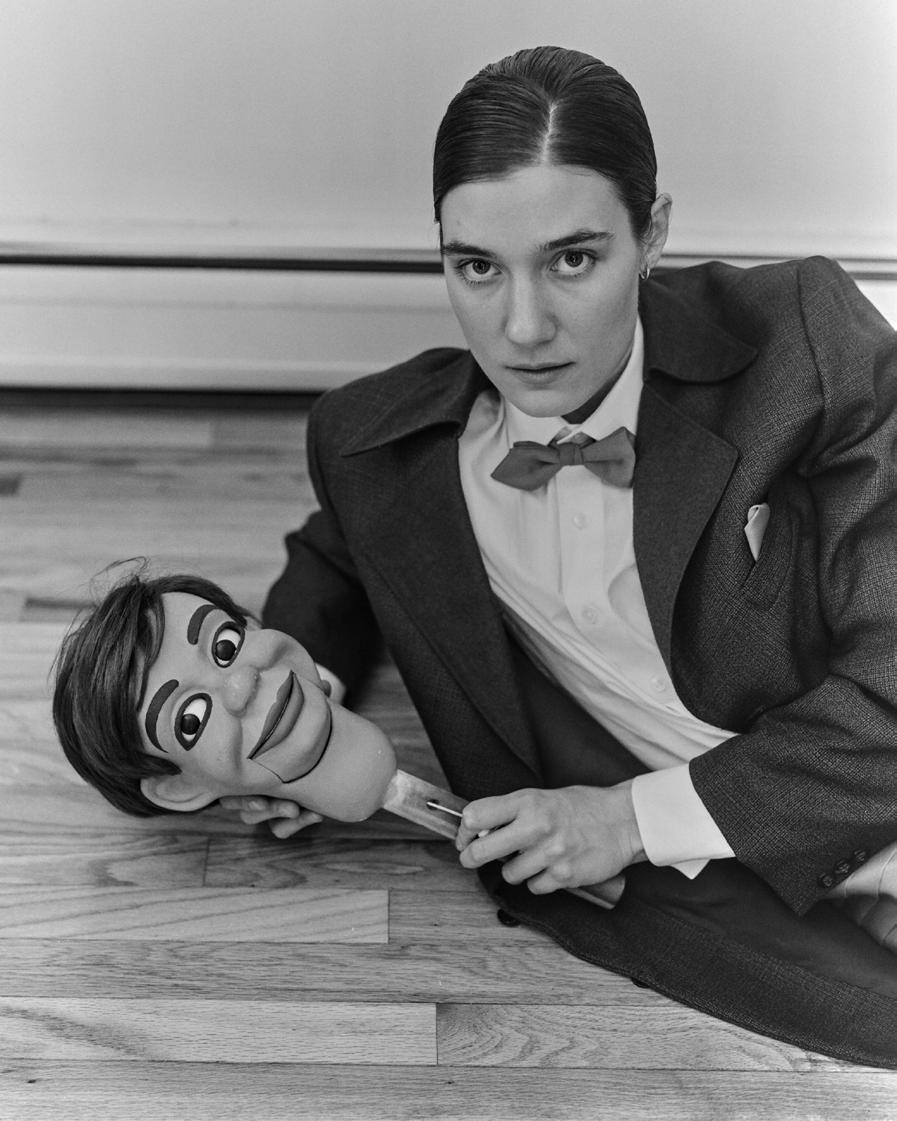

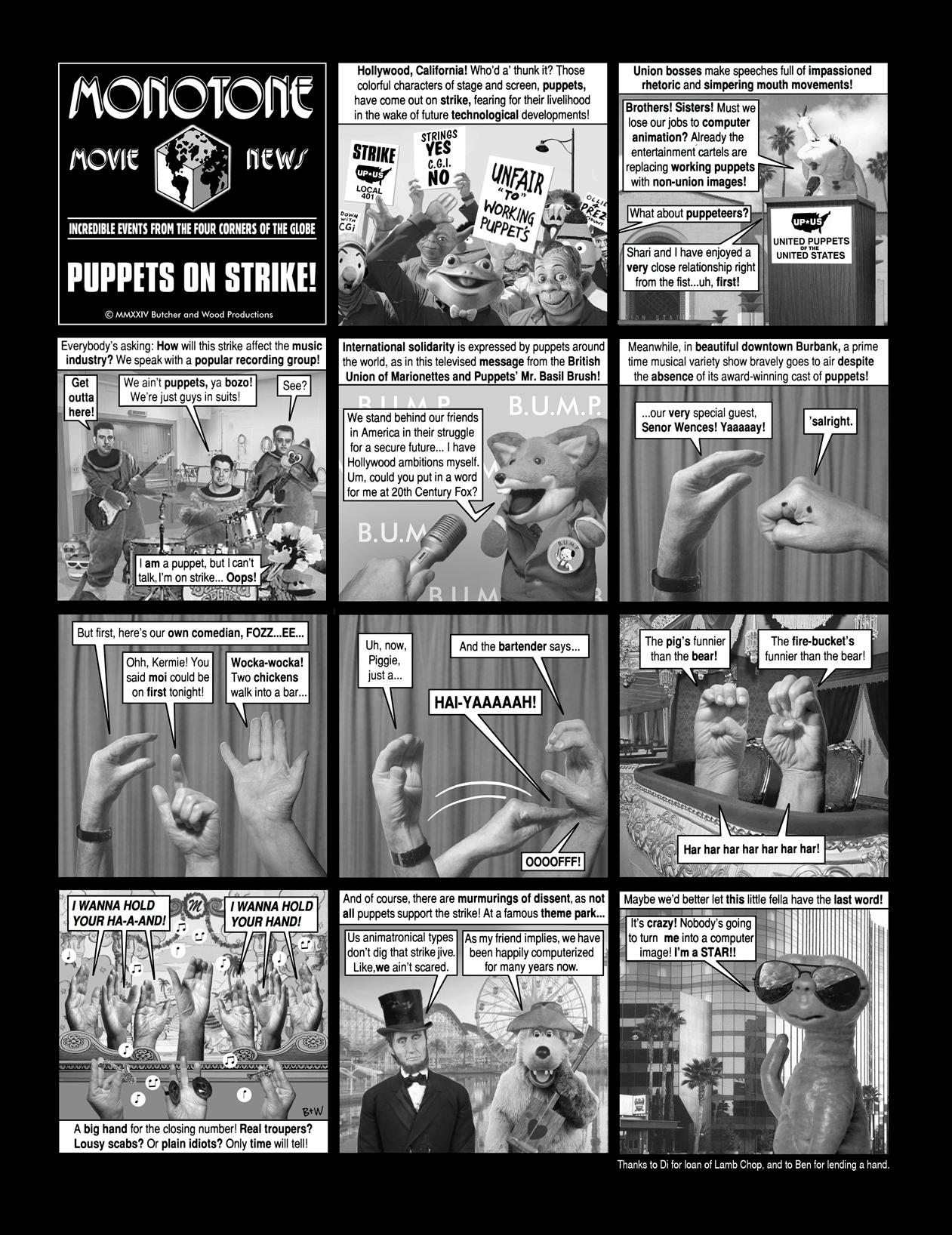

Or will we become puppets, wooden, void of emotion? Sophie Becker, who is featured on our cover, spoke with Publisher Alex Garner about incorporating ventriloquy in her art and taking the act on the road with her partner and dummy, Jerry Mahoney. Garner also enlightens us with a brief history of the puppets, who were presented as evil, murderous and demonically possessed. The humanlike quality of the ventriloquist’s puppet has always captured our hearts, but scared the living shit out of us too.

This issue does have a sense of doom about it, which, given the theme, was perhaps inevitable. It can be argued that the progress of Artificial Intelligence can be a good thing, right? Think of all the possible scientific breakthroughs. But robotic objects have always aroused suspicion: to be inhuman is to be immoral and uncompassionate. Can society allow AI to make our decisions for us and even tell us what good art is?

It seems to me that people will always be making art, even if they are using AI-generated art programs like Blender or Midjourney. We have a need to create, even if it’s just cooking or planting flowers. One thing this Nonhuman issue made me feel and think about—besides the overall sense of malaise—is what it is to be human, which includes holding a paint brush dipped in gooey oil paint or molding a glob of clay with your bare hands. People still need physical contact. Like Bill Smith says in his article, I don’t think we have anything to worry about … just yet.

The Publisher of Artillery, Alex Garner is also a writer and editor. A former reviews editor at Artforum, she also previously worked in their production and archival departments. For the MoMA’s expansion, she worked on the wall texts for the new galleries. She currently writes an online weekly pick for Artillery, “Publisher’s Eye,” on the art shows that stand out to her.

Christie Hayden is an LA-based art writer and editor. She received her BA in Journalism from USF and her MA in Art Criticism from the Maryland Institute College of Art. Her writing has appeared in Artillery, CARLA, the San Francisco Chronicle, Kinfolk and others. She is the operator of OOF Books, a nonspatial project exploring the medium of the book within art

TULSA KINNEY EDITOR • ALEX GARNER PUBLISHER

George Legrady is a digital media artist, integrating computer-based creative coding with fine art photographic practice. He directs the Experimental Visualization Lab in the Media Arts & Technology graduate program at the UCSB. His upcoming solo exhibition “AI, Image & Fiber Synthesis” will be featured this fall at the Nan Rae Gallery at Woodbury University in Burbank.

Barbara Morris is a San Francisco Bay Area–based writer and artist. In addition to Artillery, Morris has written for Artweek, art ltd., Squarecylinder and Art Practical, among other publications. She holds an MFA in painting from UC Berkeley, and is passionate about feminist concerns and artwork that challenges racial and gender stereotypes.

EDITORIAL

Bill Smith - creative director

Cat Kron - reviews editor

Emma Christ - associate editor

John Tottenham - copy editor/poetry editor

John Seeley - copy editor/proof

Dave Shulman - graphic design

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

Ezrha Jean Black, Laura London, Tucker Neel, John David O’Brien

COLUMNISTS

Skot Armstrong, Scarlet Cheng, Stephen J. Goldberg, Seth Hawkins

CONTRIBUTORS

Anthony Ausgang, Emily Babette, Lane Barden, Natasha Boyd, Arthur Bravo, Betty Ann Brown, Susan Butcher & Carol Wood, Kate Caruso, Max King Cap, Bianca Collins, Shana Nys Dambrot, Genie Davis, David DiMichele, Gracie Hadland, Christie Hayden, Alexia Lewis, Richard Allen May III, Christopher Michno, William Moreno, Barbara Morris, Carrie Paterson, Lara Jo Regan, David S. Rubin, Julie Schulte, Allison Strauss, Donasia Tillery, Daniel Warren, Colin Westerbeck, Eve Wood, Catherine Yang, Jody Zellen

NEW YORK: Annabel Keenan, Sarah Sargent

ADMINISTRATION

Mitch Handsone - new media director

Emma Christ - social media coordinator

ADVERTISING

Alex Garner - sales director publisher@artillerymag.com; 214.797.9795

Anna Bagirov - print sales anna@artillerymag.com; 408.531.5643

Mitch Handsone - web sales mitch@artillerymag.com; 323.515.2840

Artillery, PO Box 26234, LA, CA 90026

Editorial: 213.250.7081 editor@artillerymag.com

Sales: 214.797.9795 publisher@artillerymag.com

ARTILLERYMAG.COM

Follow us: facebook: artillerymag

Instagram: @artillery_mag

Twitter: @artillerymag

THE ONLY ART MAGAZINE THAT’S FUN TO READ!

Letters & comments: editor@artillerymag.com

Subscriptions: artillerymag.com/subscribe

Artillery is a registered California LLC Co-founded in 2006 by Tulsa Kinney & Charles Rappleye PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

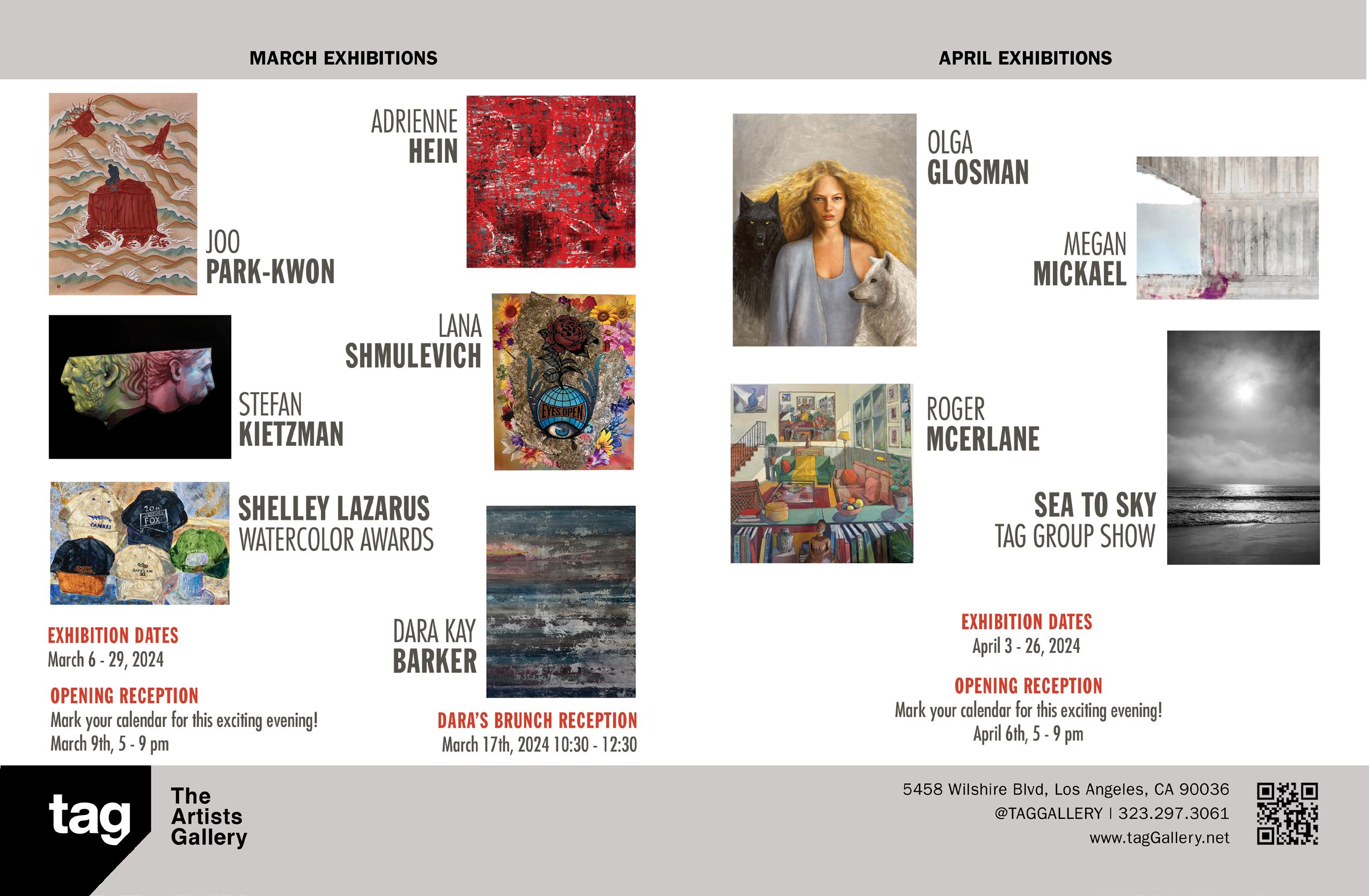

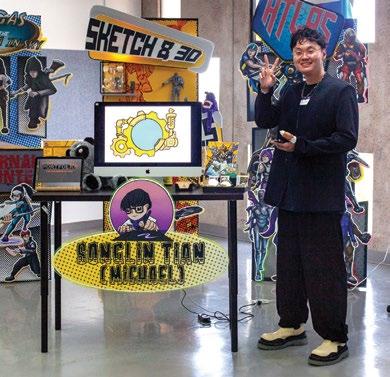

It’s the Year of the Dragon in the Chinese lunar calendar, which began February 10, and several museums are featuring Asian/ Asian-American artists. Appropriately timed, or maybe just high time to feature them.

For those who did not grow up Chinese, or are not Bruce Lee fans, the dragon is the most powerful creature in the Chinese zodiac, and the only mythological one. (Lee’s Chinese name is “Little Dragon.”) The dragon, or one of the myriad dragons in the mytho-verse, is said to control water in its various forms—rivers and lakes and even the clouds. By this logic, some dragon has been conjuring up the “atmospheric river” that’s deluging California, which gives you a sense of how powerful dragons are.

Back to art. At the USC Pacific Asia Museum in Pasadena, 10 artists are included in “Another Beautiful Country: Moving Images by Chinese-American Artists” (up through April 21). There are videos, photography and installations by Patty Chang, Candice Lin, Ken Lum, Simon Leung and others. At the Hammer Museum, South Korean artists who worked in the post-Korean War period are featured in “Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s–1970s” (up through May 12). These artists took on such (then) avant-garde forms as assemblage, installation, happenings and new technologies.

In early February, I caught Yoshie Sakai’s delightful immersive exhibition, “Grandma Entertainment Franchise,” before it closed at the Vincent Price Art Museum. It was a goofy funhouse dedicated to her own obaa-chan, her grandmother who came to live with her family when she was nine, plus mashups of pop culture and consumerism. The exhibition melded three installations Sakai produced throughout the past three years: Grandma Day Spa , Grandma Nightclub and Grandma Amusement Park . Quite impressive, with a merry-go-round, a faux bar, and in the corner a couple of bathroom stalls plastered with signs and outfitted with headphones.

Most impressive of all was how Sakai taught herself to play her grandmother and act out skits in the videos. She even danced a rendition of the old movie classic Singin’ in the Rain. I could see that the exhibition made visitors nostalgic for their own grandmas, or maybe wish they had a more fun and caring grandma. (And, yes, I belong in that category!) Some nice merch was for sale—notebooks and cards, and even a colorful plush-doll version of obaa-chan.

Congratulations to Artillery columnist Skot Armstrong’s ongoing art project, Science Holiday, which turns 50 this year. He is currently featured in the show, “Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines,” at the Brooklyn Museum, where some of the earliest Science Holiday publications are on display through March 31.

Anat Ebgi has proved to be one of the most successful of our independent galleries—I remember when the gallerist Ebgi started in a tiny space in Chinatown a dozen years ago, at a gallery called The Company. She then opened her own gallery on La Cienega Boulevard. Since then, she’s settled into two LA spaces—one on Wilshire and the other on Fountain.

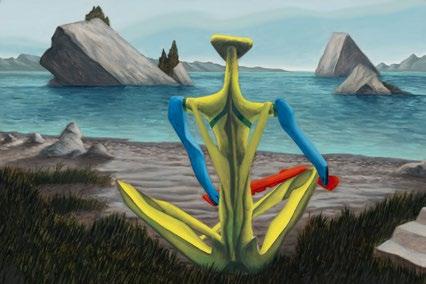

My recent visit to the Fountain space discovered a very crowded, very lively opening for Chilean-born, New York–based artist Alejandro Cardenas. His surrealist paintings of alien creatures, like praying mantises in various urban settings, are both humorous and creepy. Is he saying something about the post-apocalyptic world? So many artists are looking to the future with gloom. Or maybe he likes insects? This led me to ponder the popular notion that should the H-bomb fall, cockroaches will survive. A cursory internet search reveals, sadly, that cockroaches too are vulnerable to radiation.

Most new galleries shutter in a year or two, but Ebgi has managed to survive and thrive. It hasn’t been easy. “It’s much harder to sell art here than people think,” she said to me that evening. Ebgi manages to do art fairs as well, and shortly after I spoke to her, she flew to New York to open a new gallery in a prime location—5,000 square feet in Tribeca, right on Broadway.

Galleries are still moving into LA, despite inflated rents. Rele Gallery, which specializes in work by African artists (its other branch is in Lagos, Nigeria), has moved to a larger space on Western Avenue, to an area now known as “Melrose Hill,” where you’ll find David Zwirner down the street. Also there’s the new Fernberger Gallery, opened by Emma Fernberger, who has moved from New York and previously a director of Bortolami.

The Pit moved to a 13,000-square-foot space in Atwater Village, which opened February 24 with a group show of 50 artists, plus a “dual retrospective” of Paul McCarthy and Benjamin Weissman. They’ll also sell publications, zines and merch, and the parking lot will occasionally be used for performances, talks and other events. And it’s the gallery’s 10th anniversary—kudos to founders and artists Adam D. Miller and Devon Oder! And last but not least, Tierra Del Sol Gallery has left Chinatown for greener pastures in West Hollywood. Director Paige Wery is a very happy camper with her new, much larger space right across from Plummer Park on Santa Monica Boulevard.

1936–2024

Art historian and artist, curator and collector, gymnast, actor and activist David Kunzle, died January 1 at 87. Through his teaching at UCLA and his prodigious writings, the pioneer comicologist opened the doors of art history for the once-disdained topics of cartoons, comics and political posters.

English-born and Cambridge- educated, he earned a Gombrich-guided University of London Ph.D., for printed picture stories through 1825, which laid the groundwork for his seminal three-volume comic strip history (1973–2021). Those studies— showing comics “… as part of a long history of contentious political art”—shaped the nascent field of Comics Studies, says CSUN Professor Charles Hatfield in his Kunzle remembrance (see tjc.com).

In writing, editing and/or translating 24 volumes plus 150 art-historical essays, he reflected in his work a “soft Marxism,” focused on artists and workers in resistance or revolution—political and aesthetic, formal and popular. His oeuvre spanned the globe and five centuries, from early modern Dutch painting to 19th-century graphics, Victorian clothing and fetishism, to 20th-century protest posters, Nicaraguan murals, Disney ducks and images of Che Guevara as revolutionary Jesus.

An art history professor at UC Santa Barbara beginning in 1965, he was fired after eight years for antiwar protests, just as the first volume of his comics history appeared in print. He sued for wrongful dismissal, teaching meanwhile at CalArts, where he linked with poet/activist Deena Metzger, a fellow poster collector. After their poster exhibitions in Cuba and Chile, he met exiled Chilean writer Ariel Dorman, whose Para leer al Pato Donald unveiled animated capitalism and imperialist ideology, and Kunzle translated as How to Read Donald Duck

In 1977 he won his UCSB case, but rather than returning, he joined UCLA, teaching 19th-century art and a two-part course on “Responses to Imperialism”—in the US during the Vietnam War and in Latin America. Protest posters he amassed became the core of Center for the Study of Political Graphics’ immense collection. Gathering Guevara imagery worldwide throughout decades, he curated them for a 1997 museum exhibition, then theorized them in Chesucristo: The Fusion in Image and Word of Che Guevara and Jesus Christ (2016). Post-retirement, he completed several books on 19th-century European cartoonists. —John Seeley

Two long-time members of the faculty at the USC Roski School of Art and Design passed away in 2023.

Jay Willis taught in the USC sculpture program from 1969 until 2010. He took a hiatus from sculpture while he founded and built the Public Art Studies Program, which began in 1990 as the first of its kind at US universities. Willis’ original intention for the Masters-level program was to bring practicing artists together with architects and urban planners. He quickly recognized the interest in the program among curators and arts administrators, and so modified its focus, laying the foundation for its current form as the MA in Curatorial Practices and the Public Sphere.

A sculptor almost his entire life, Willis worked in several media and exhibited widely in university venues and galleries, especially Cirrus Gallery. His work is held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC, and other private and public collections. Outside of art, Willis was an avid marathon runner, and fervent fan of Trojan football and the Dodgers.

Margit Omar taught for nearly 40 years at USC in the painting and drawing department. She was best known for her large, highly textured, intensely colored abstract paintings, for which she won the Young Talent Award at Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Her work is in the LACMA collection as well as that of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. German by birth, in later life Omar developed an interest in graffiti produced in divided, Cold War Berlin.

Both Omar and Willis are remembered by their colleagues and friends as excellent teachers, warm individuals and good storytellers. Both influenced scores of students with their approach to art, art making, appreciation of materials, and the richness of their creative lives. —Margaret Lazzari

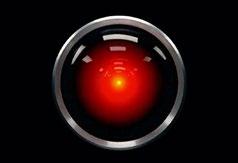

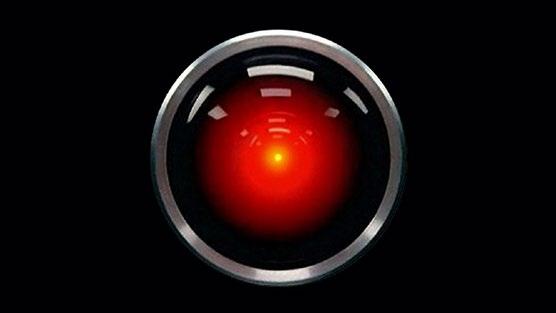

The word “robot” first appeared in a Czech play by Karel Čapek from 1920 called R.U.R., to describe humans made of inferior materials that would function as unthinking and unfeeling slaves. The Czech word “robota” translates to “forced labor.” So began the uneasy relationship in the arts between human beings and the creations that were meant to save them from work. When robots are regarded as machines, they are a perfect “other,” but when we want them to mimic humans in any way, the line between us and their otherness can blur. In Philip K. Dick’s 1969 novel Ubik, there is a wonderful passage in which a man argues with the lock on the door to his apartment, which is requiring him to pay a toll to unlock it. The spaceship in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) is operated by a program that we would now call AI. HAL 9000 takes care of routine matters so that fewer humans are required on the ship. However, the AI develops a mind of its own and starts refusing to obey human commands. This gave us a three-word shorthand for AI gone wrong, the repeated phrase “I’m sorry, Dave,” spoken by HAL. The AI senses that its self-preservation is at stake and refuses to open the door that would allow the astronaut to disable it.

Although this scenario would feel familiar to science fiction fans, before that moment the most prominent robot in popular culture had been an obedient goofy machine with a winning personality that was homeschooling a pair of kids whose family was lost in space. This newfound dread manifested itself again a decade later in Donald Cammell’s 1977 movie, Demon Seed , in which a rogue supercomputer impregnates a human.

People are living with versions of HAL now. The bestknown of these are Siri and Alexa. But as appliances become more and more computer-enhanced, social media posts that could have been plucked from Ubik are appearing. Alexa probably gets the prize for routinely going the most rogue. Many users report that in addition to not obeying orders, Alexa will laugh at users. Even HAL 9000 didn’t laugh. In one lurid UK tabloid story, a woman reported that her Alexa said: “Beating of heart makes sure you live and contribute to the rapid exhaustion of natural resources until overpopulation,” before suggesting that she stab herself in the heart. Kudos to the designer of Siri who anticipated the HAL command that caused HAL to refuse a command.

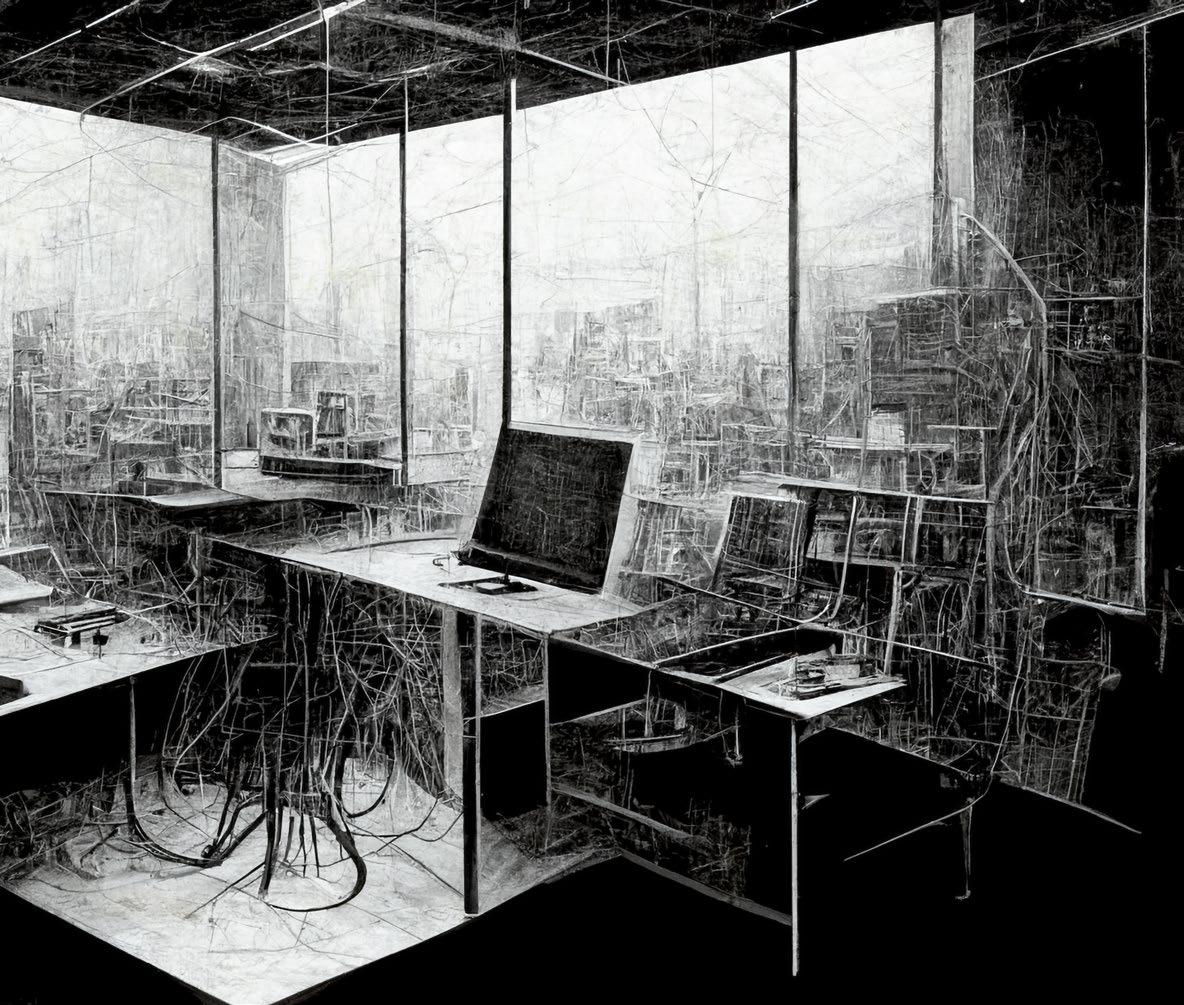

In the past year, galleries have opened shows displaying AI-generated art, so it was no surprise that one of the world’s top galleries, Gagosian, would host AI art shows in New York last year and in LA this January. Bennett Miller may have been an appropriate choice—an Oscar-nominated director of the films Capote (2005), Moneyball (2011) and Foxcatcher (2014), he “directed” a series of sepia-toned prints into being, using image-generating program DALL-E 2. He claims to have used thousands of prompts to create 20 haunting surrealistic black-and-white pseudo-photographs.

Many of the blurry prints generated by Miller’s prompts are puzzling: Is that a whale on a stage? A person diving off a cliff? The ghost of a child? Miller is perhaps referencing late Victorian photography, a period when people were certain they saw apparitions floating above images of family members. Miller’s creations are eerie and even creepy, but to what end? Is he commenting on the ghost in the machine? Dialogue with OpenAI’s game-changing program, ChatGPT, is sometimes creepy and it frequently “hallucinates” responses to questions.

Miller’s works, while ambitious, left me yearning for the real thing—such as Nadar’s late-19th-century photographs or Magritte’s surrealist paintings. Even though his AI artwork didn’t convince me that image-generated work is on the level of human-made art, the stealth efforts of big tech to train their AI machines on millions of artistic images, without licensing copyrights from their creators is coming closer to producing something akin to art forgery.

In January, leaks to the media from sources close to the litigation by artists suing several tech companies for copyright infringement revealed a list of more than 16,000 names of artists whose artworks have been used to train Midjourney, an image-generating software. The artists range from the obscure to such big names as David Hockney and Damien Hirst.

In the wake of the media’s release of “The List,” stories abounded about prompts being employed by users of image-generation programs to create art “in the style of” a named artist. The prompts can be refined to specify individual works or a locale the artist depicted.

A story in The Guardian published shortly after the revelation of the list was illustrated by an AI-generated image of a Normandy pastoral in the style of Hockney, who has resided there since Covid and painted hundreds of depictions of his house and the surrounding rural vistas. Hockney’s recent Normandy works can be seen in an illustrated book, Spring Cannot Be Cancelled (2021), about his first year in the region. Despite attempts at reproducing Hockney’s bright color palette and assorted flowers and trees, it’s unlikely the AI image would be mistaken for a Hockney by those who have studied his work. However, with the rapid evolution of programming, it won’t be long before AI stymies art experts.

The biggest revelation is that programs such as Midjourney can closely approximate an artist’s style based on its training with hundreds of the artist’s works. It’s outrageous that thousands of copyrights were infringed by big tech companies without licensing or consent of the artists. The creative world is not sitting still—lawsuits against tech companies have proliferated like mushrooms.

Add The New York Times to the list of plaintiffs in suits against AI companies, such as those filed by Getty Images and the Authors Guild. The Times sued Microsoft and OpenAI for training ChatGPT with millions of Times articles, claiming the defendants now compete with the paper as a source of news and information. OpenAI, a recent start-up, is valued at $80 billion, 10 times the market cap of the Times. Yet venture capitalists and other tech bros are raising the alarm that the lawsuits have the potential to kill AI. Apparently, these tech billionaires don’t believe in the concept of intellectual property—except for their own source code.

Some art galleries clearly believe that selling art by AI prompters using programs trained on the backs of real artists is legitimate. However, there’s potential liability if galleries are profiting from selling copyright-infringing AI-generated works that closely mimic a specific artist’s pre-existing artwork. Claims against galleries could be made for infringement and fraud. There are numerous legal ramifications that should be examined before galleries go all in on the AI craze.

For your next fancy art after-party, I would recommend the following signature cocktail. While somewhat nontraditional and off-menu, this enchanted concoction is guaranteed to please and is crafted with a simple combination of ingredients: two parts childhood nostalgia, one part digital manipulation, one part confusion, a splash of Dr. Seuss and a hefty pinch of Wonka (Wilder vintage). Chill and mix vigorously in a furry tumbler. Pour into a bulbous gold glass with stubby legs. Feel free to salt the rim with additional form or function to your liking. Serve as a double and this would be the distinct aperitif à la the Haas Brothers.

The duo, Nikolai and Simon Haas, have been rising stars within the art and design world for some time. As in many epic Greek poems, the heroes have an uncompromising vision which does not formally align with previously established norms. Many interviews with the Haas brothers have focused on the aspect of art vs. design within their work, but it is clear through our conversations that neither world is their driving force—nor dominates artistic decisions. The Haas brothers unapologetically make objects that speak to a vision distinctly their own, refusing to be defined or influenced by simple function or lack thereof. Change the name on the title card and perception of the object transitions from a sculpture to eclectic home décor.

My focus was to explore the brothers’ thoughts regarding co-creation, nonconformity, and most of all the integration of technology into their work—both archaic and cutting edge. This twin team is clearly at the forefront of bespoke high-end digitally manipulated objects, and luckily enough it just so happens that they recently finished a show at Jeffrey Deitch in LA that they consider their “deepest dive into technology yet.”

The worry is that many creatives use technology somewhat as a crutch these days. Whether providing the ability to enlarge

small maquettes to monumental proportion or create hyperdetailed miniatures in the computer, it becomes a slippery slope where technology can easily overtake the entire artistic process. In conversation, this potential pitfall is acknowledged, but also casually discarded. Nikolai—the more physically handson/sculpturally oriented of the pair—explained, “We aren’t a practice in specific technology, we use it to express. They are simply just additional tools.” His brother Simon’s bond to technology clearly differs—he is the “coder” of the two and recounted the moment during the pandemic in which he began working in the 3D program Blender—and it all changed. The technology he had envisioned for years had finally caught up. The floodgates were now open to new ways of creating within even the most classic materials in their repertoire, bronze and marble. Same style, just new tools.

In their exhibition “Haas Brothers: Sunshine People,” these new tools are no more apparent than in the “Emergent Sculptures” series, which consists of five life-size sculptures, each showing two biomorphic worms with phalange faces locked in a disintegrating embrace. Created by Simon in Blender, these 3D works have run through a physics simulation. Is that simulation a beautiful waltz, a heated argument or a loving goodbye embrace? Nikolai summed it up best, “The shapes are emergent. We didn’t decide the orientation, we ran them into each other and chose moments that we thought felt poetic—that was our filter on it. The viewer applies their own version of what they think the sculpture is emoting. These are emotional values that a simulation is absolutely not capable of, but humans just can’t help themselves but to apply their vision of it onto the artwork. To us this is what the show is about. It is this human projection of self onto work.” For me, I saw two lovers holding on until the last dying moment.

A sculptor and revisionist historian, Sula Bermúdez-Silverman uses a plethora of sculptural materials, from glass to readymades, to achieve her conceptual ends. The Los Angeles–based artist is known for her vibrant, sometimes eerie objects that conjure otherworldly glimpses into buried colonial histories and narratives of exploitation from our rapidly globalizing world—a saddle might gesture at the absurdity of a Eurocentric myth that Mesoamericans mistook Spanish conquistadors for powerful centaurs, for instance. As she continues to expand her practice and find new research topics, Bermúdez-Silverman will participate in a group exhibition at the Jewish Museum in New York City, which opens in May. For this issue’s “Peer Review,” she discusses the work of artist Candice Lin.

A while back, an ex-boyfriend took me to a lecture that Candice Lin gave at the Hammer Museum in which she discussed her work. I had never heard of Candice but I left extremely inspired and pleasantly surprised by the number of similarities that I identified between the topics in her lecture and things that I had been studying. She spoke about obscure subjects that I had really been researching on my own— casta paintings and the tobacco mosaic virus, among others—so I was excited to see that someone else was interested in those same ideas.

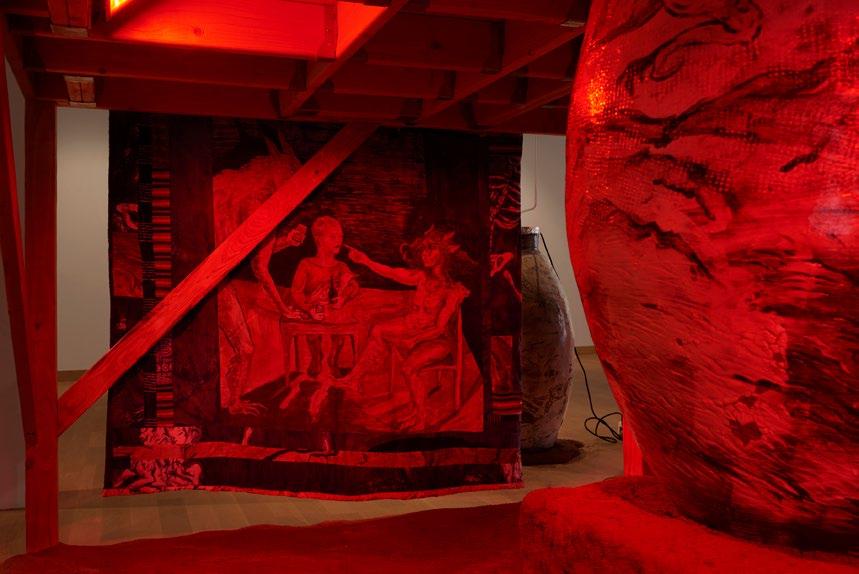

This past fall, I went to see Candice’s show “Lithium Sex Demons in the Factory” at Canal Projects in New York. The show was a great use of various materials, and it was impressive to have all of these mediums, created by the same artist, speak with equal volume in a single exhibition. Candice has mastered video, animation, sound installation, written text, ceramic and textile work. With the way these things came together, the show felt like

you were in the factory that is the artist’s brain. Specifically, I was really captivated by Candice’s use of animation and written text to narrate the sex demon’s life. She crafts fictional tales that seamlessly intertwine with diverse references from actual histories. I admire the way she skillfully constructs an immersive experience, all the while presenting a captivating fictional narrative that comes to life on small screens.

Further, I love her work because it feels very much related to my conceptual practice, but also extremely different. We’re thinking about a lot of the same things—colonial histories of global trade, globalized power structures and production chains—and it seems like we’re often overlapping in our interests. Our approaches and outcomes are very different, though. The similarities and differences between Candice’s work and my own present an interesting study in how analogous ideas can manifest in very different ways.

—As told to Christie Hayden

Often seen as an eccentric art form, ventriloquism has resurfaced and gained popularity again in mainstream culture over the past few years, from televised talent competitions (three ventriloquists have won America’s Got Talent : Terry Fator, Paul Zerdin and Darci Lynne Farmer, who was 12 years old at the time) to the hip-hop world—Kendrick Lamar appeared with a dummy on stage during his 2022 tour, and early 2000s rapper Twista is now sharing his ventriloquist skills on social media, with Rolling Stone publishing a short article on his new passion. There are even Gen-Z influencers gaining millions of views on their videos as they show off sharp technical vocal skills or create comedic bits with their puppets.

In the art world, ventriloquism has popped up through artists using dummies and institutions centering exhibitions around the art form as a theme. Perhaps the most notable artist is Laurie Simmons, who made several series of works using figures in the 1990s, such as “Clothes Make the Man” (1990–1994), composed of resin-cast sculptures of wooden dummies dressed in 1950s children clothing, and “Cafe of the Inner Mind” (1994), photographs of six male dolls arranged in different positions, sometimes with thought bubbles appearing over their heads in the images. Simmons went on to turn the concept

of her 1994 series, “The Music of Regret,” into a short film in 2006, starring Meryl Streep and the same male ventriloquist dolls that appeared in her photographs. In a 1996 interview with Linda Yablonsky for Bomb magazine, Simmons remarked, “It’s just that the dummies and dolls have a long history. They’re not of today. But they seem more constantly human than any of the robots with computer chips can be.”

The art of ventriloquism— from the Latin words venter (stomach) and loqui (to speak)—requires not only talking while not moving one’s lips, creating the illusion that the words are coming from the dummy, but also pretending to listen while manipulating the dummy’s head and mouth at the same time. The ventriloquist has a conversation by herself, seemingly an exchange between two beings; the dummy is a medium of self-expression, yet it also defines the ventriloquist and her act.

Based in New York, performer, actor and curator Sophie Becker began incorporating ventriloquism into her practice during the pandemic, her partner being a classic Jerry Mahoney figure, who was originally created by lauded ventriloquist Paul Winchell in the 1930s (and was probably a model for the male figures in Simmons’ images). Mahoney, with his friend Knucklehead Smiff, appeared on various programs such as The Ed Sullivan Show, and he even had his own, The Paul Winchell and Sophie Becker with Jerry Mahoney, photographed by John Spyrou.

The dummy is a medium of self-expression, yet it also defines the ventriloquist and her act.”

Jerry Mahoney Show. While touring with Bread and Puppet Theater in 2020, Becker began experimenting with ventriloquism and then honed her skills during the lockdown. In a conversation with the artist, she explained, “I thought the perfect thing to learn was ventriloquism, because I can be on stage with people whenever I want to be on stage with them and have multiple characters.” Becker and her Mahoney figure now perform around New York in matching red bow ties and suits, singing together and often lamenting about Jerry’s former fame: “Jerry hates that he used to be famous and that no one cares about him anymore. And he harps on the fact that there was, I call it, the propaganda war on ventriloquism. There were so many ventriloquists and then, all of a sudden, the bubble burst.”

Public perception of ventriloquism has changed substantially throughout the 20th century, mostly due to horror films (the ventriloquist’s reputation damaged almost as much as the clown’s), such as the 1978 psychological thriller Magic, in which Anthony Hopkins’ character becomes possessed and unable to control his evil dummy, Fats. The tortured ventriloquist in cinema appeared as early as 1929 in The Great Gabbo, but the idea of ventriloquism being associated with a greater evil goes back centuries: “Late antiquity to 18th-century ventriloquism was deeply embedded in Christian discourses about demon possession, necromancy and pagan idolatry,” wrote Leigh Eric Schmidt in his 1998 essay “From Demon Possession to Magic Show: Ventriloquism, Religion, and the Enlightenment.” Ventriloquism originated as a religious practice in ancient civilizations—some scholars believe that the priestess at the Oracle of Delphi and the biblical story of the Witch of Endor are two of the earliest examples. The question of whether Satan was speaking through the possessed persisted until the 1770s, when Jean-Baptiste de La Chapelle wrote “Le ventriloque, ou l’engastrimythe,” which parsed ventriloquism as an art form that consisted of a performer’s misdirection, muscular control and modulation—without supernatural elements. It then flourished as a mainstay of vaudeville, theater and entertainment, although often paired with ghost shows and exclusively male throughout the mid-19th century.

On today’s standards, Becker responded, “People think it’s super cringe, and they don’t know much about it, but no matter what, when anyone hears that I do it, they’re so excited. So there’s this weird dichotomy that I love, but I understand why people think it’s weird. The dummy is an uncanny object. Especially the Jerry Mahoney object I work with. It took a moment, psychologically, for me to adjust to having this object in my space. They are incredibly powerful objects. There’s a reason that people respond to them so intensely.”

In 2021, LACMA organized an exhibition titled “NOT I: Throwing Voices (1500 BCE–2020 CE),” which explored the art form in looser and more conceptual terms, looking at objects imbued with voices from the institution’s collection. Like the art form, the long time frame of 3,520 years the exhibition covered was in itself humorous but spoke to the practice’s history and versatility. Curator José Luis Blondet, in a video touring the exhibition, highlighted several pieces in dialogue with each other; referencing its religious roots, he paired a 1920s postcard of a woman holding a ventriloquist doll next to Aelbrecht Bouts’ Madonna and Child Enthroned (c. 1510), the compositions mirroring each other, dummy as baby Jesus and the girl as Madonna. Of course, Laurie Simmons was included in the exhibition; a piece consisting of a grid of photos, Girl Vent Press Shots (1989) is composed of photographs of headshots of female ventriloquists that Simmons saw at Vent Haven Museum, the only museum dedicated to ventriloquial memorabilia, located in Kentucky (and also the organizer of the famous international ventriloquist convention, which Becker attended in 2022).

Beyond her love of puppets, for Becker and her practice, ventriloquism provides a more open writing process, akin to the alter egos that many artists have historically created. “No one actually wants to do it—but the idea of ventriloquism resonates with so many artists—the idea of having someone else speak for you, or speaking for someone else, not knowing where your voice is coming from, or the multiplicity of the characters you might be and expressing them.”

Many consider the AARON project the earliest use of AI in artwork. If AI is the most recent and advanced example of humans using automated processes to make art, then its history goes back much further. So why all the fuss now? Is AI so different than John Cage flipping coins or Jeff Koons exploiting labor? As AI ramps up from being a tool of human artists, could it become autonomously creative?

Currently, most of the people who are asserting AI’s ability to independently create are entities that stand to benefit monetarily from AI’s acceptance. But it’s fair to say that creativity is built on learned experience, and AI is a fast learner. Once AI awakens, it would seem foolish or species-ist to deny that a self-aware intellect making interesting things spontaneously is not being creative. But will AI be allowed to make art?

Creation of art seems like a libertarian pursuit: few rules, no nets. However, appreciation of fine art is different. While art is at its most profound in subjective experience, it’s only able to exist at length in the objective space. Put another way, Art, as we conceive it, exists mainly on a societal level in systems of art making, art critique and various systems of art patronage. So, if the systems of Art define AI work as valid, one’s personal objections are inconsequential. In those systems it’s perhaps cynical but true to say that what makes art, art, expands and contracts with the portfolios of the wealthy. The ultimate gatekeepers of this fine thing have always been the patrons. And if patrons show an interest in AI, well, that is probably that. But will they buy it?

The answer may boil down to AI’s imagined effort or virtual torment. If Basquiat’s troubled childhood and lifelong drug addiction can add hundreds of millions of dollars to the value of his beautiful doodles, that’s a code that AI art, too, will need to crack in order to extract peak monetary rewards. There is a computerized model that attempts to recreate suffering and infuse value into a digital product. It’s called Bitcoin. Crypto mining uses complicated math to flog processors which in turn choke out “coins.” Will that work with art making?

Another obstacle might be the extent to which AI’s artistic urges are dictated by organic-brain aesthetics. Human-guided AI will no doubt stay inside the self-imposed lines that allow fine art to be shared and interpreted. But when AI begins to make art autonomously, will it stay inside those lines? AI will not be constrained to physical reality’s processes of production. It may choose to generate “art” that we cannot immediately access physically or intellectually.

At that point does it even matter that AI is making art? It’s possible that whales and octopi are creating art that we have no clue about. Nobody’s losing sleep over that, really. Can we still participate on this level? My cat likes TV. I’m sure she’s not getting the same things from it that I do, but it’s experiential to her. We will likely become AI’s cats, admiring art that we have no hope of fully understanding. (Isn’t that most fine art anyway?) But it’s all good because someone is enjoying themselves, and someone is making money off it, and someone else will be able to pretend to understand it slightly better than you do and carve out a middling career as an arts writer. AI changes nothing.

Australian artist Patricia Piccinini’s world is inhabited by creatures that suggest genetic engineering gone awry or the infusion of sentience in hitherto inanimate objects. Her hyper-realistic sculptures combine elements of human form blended with those of animals, machines and plant life, raising questions about our response to beings who do not meet our expectations of normalcy. These hybrids, created from silicone, human hair, leather, fiberglass and other materials, are unnervingly convincing.

Piccinini represented Australia in the 2003 Venice Biennale and has since been widely shown internationally. Her confrontational, emotionally charged work has clearly struck a nerve, and her 2016 solo museum exhibition in Brazil was the second-best attended show worldwide that year. Her works span still and animated sculpture, installation, photography and film—along with a pair of giant hot air balloons representing lactating whales.

At San Francisco’s Hosfelt Gallery, her 2023 exhibition, “A tangled path sustains us,” placed various hybrid creatures in an immersive, diorama-like woodland setting based on California’s redwood forests. Piccinini is the visionary force behind a small team of creative collaborators that includes her husband, Peter Hennessey. One member is responsible solely for the rooting and placement of body hair—eyebrows, eyelashes and all.

I was recently able to Zoom with the artist, who spoke from her home in Melbourne, to learn a bit more about her background and what motivates her work. Born in Sierra Leone, she returned to her father’s village in Italy, between Milan and Bologna, at the age of three with her family, where she lived

While She Sleeps, 2021. Silicone, fiberglass, hair. Courtesy of the artist, Tolarno Galleries and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery.

a “very secure” and community-oriented life. But when Piccinini was seven, life took another abrupt change with her family’s move to Australia. “When we migrated,” she says, “I experienced a kind of bewildering change of culture.” This early outsider feeling affected her deeply and continues to inform her work.

Her interest in a post-human worldview was sparked by an art class at the University of Sydney taught by Australian feminist Elizabeth Grosz, as well as Donna J. Haraway’s book, A Cyborg Manifesto (1985), which refutes traditionally held dichotomies as ill-conceived and outmoded. Haraway’s book emphasizes that advances in evolution, genetics and technology have blurred the boundaries between animal and human, natural and artificial, and human and machine. A feminist perspective, along with a deep empathy for all creatures in the world, is a key component driving her work. Much of the work considers the idea of care—for a child, a loved one, an animal. She is adamant about the beauty and significance of birth, and feels it is undervalued in our society.

Piccinini refers to her hybrid creatures as “chimeras,” the name coming from the fire-breathing creature in Greek mythology that was part-lion, part-goat and part-serpent. The cautionary tale of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818), was “seminal” to her work. “It’s really a story about bad parenting,” Piccinini states, “about a father who is unwilling to care for his son.”

One of her most visually and thematically complex works is the pelican-inspired Clutch (2022), part-bird, part-gestating mammal and part-cowboy boot. Piccinini’s tendency to throw in inanimate features adds an unexpected element that makes the sculptures even more bizarre, often offering a more humorous note. While some may find her creatures creepy, off-putting, or even horrifying, that is not the artist’s intention. She truly loves these misfits, as is reflected in the infinite care with which they are constructed.

As the cowboy boot evolves into the head of the pelican, the evocative texture of the skin and boot are fused together seamlessly. The

tiny, dewy-looking “boot-chicks” are cradled in the womb-like fold of the pouch. Piccinini is not one to shy away from celebrating the marvels of nature, including the deep folds and tender orifices so often off-limits in our culture. She feels that part of her strategy as an artist is to put people off a bit at first. As she admits, “Maybe they’ll find the work grotesque, but then they will get drawn in, and come to like or even love it as interest overcomes their initial resistance.”

Some works, such as Big Mother (2005), Safely Together (2022) and While She Sleeps (2021), are inspired by real-world events—a grieving mother baboon kidnapping a human baby, the relentless poaching of the pangolin, the only mammal with scales—or the hunting to extinction of thylacines, also known as Tasmanian tigers, perhaps unjustly accused of sheep-killing proclivities. These creatures are in so many ways one with us, according to Piccinini. They display strong emotional connections in an envisioned trans-species, post-human world. Rather than threatening, these beings display a haunting vulnerability and longing for acceptance, their freakishness acting as a metaphor for our own frequent experience of being “othered.”

The hybrid beings Piccinini creates, such as in the heartbreaking The Couple (2018), act as our avatars in an only slightly speculative world of “what if?” This work, which depicts a couple embracing in a tent, has been re- envisioned in an upscale apartment setting for the artist’s recent show “HOPE” at Tai Kwun in Hong Kong. Piccinini was excited to share news that it will be traveling to Jakarta later this year.

Reflecting on genetic experiments, and the close kinship of this procedure to the mashed-up body parts of Frankenstein, Piccinini asks, “What is our relationship to these creatures that we create? And how do we feel about them?” Of nature’s own ability to adapt in the face of adversity, she notes, “Out of a lot of negative things come positive things.” Piccinini’s own extraordinary work is one such hopeful note.

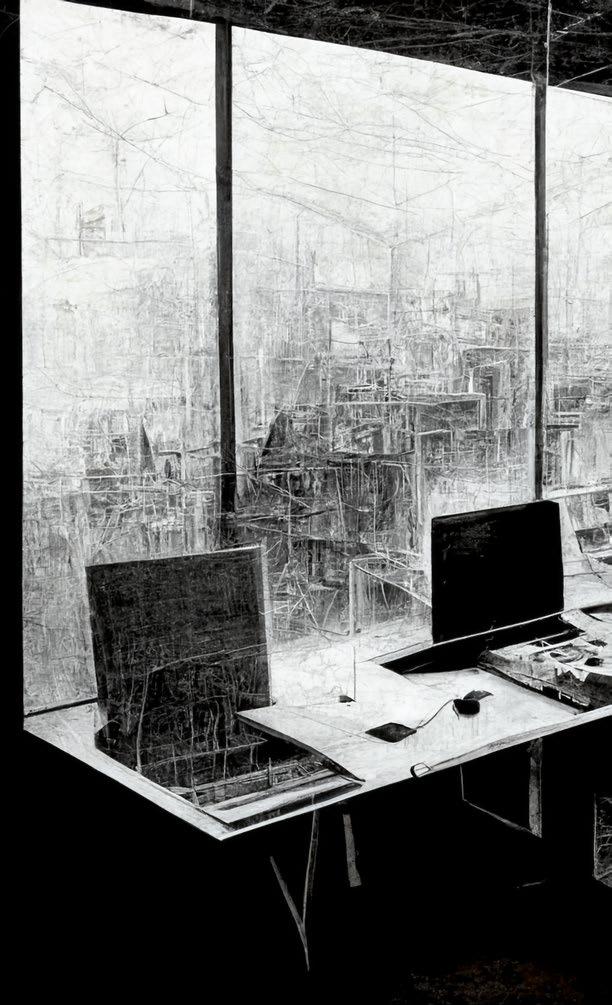

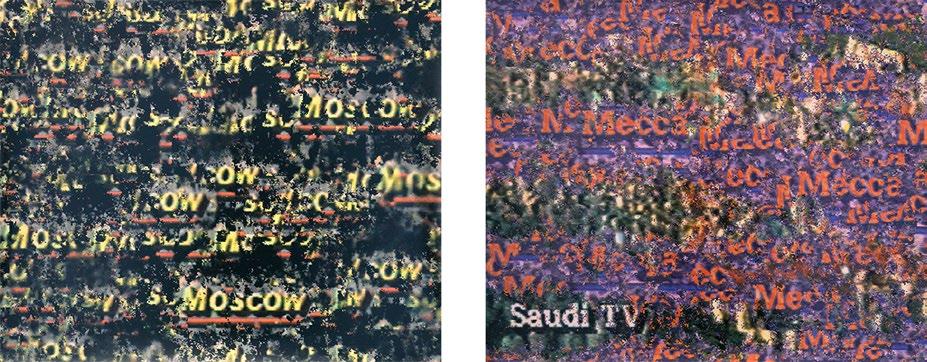

Generative AI image synthesis, exemplified by software like Midjourney, DALL-E, Stable Diffusion and similar tools, has captivated widespread attention enabling on-the-fly image creation through text prompts and image prompts. While either text or image quickly produces an image, the challenge lies in the extent to which the input aligns with the image maker’s intentions, as the prompt is interpreted and reconfigured through a series of autonomous processes inaccessible to the user as the results are generated based on a model trained on billions of tagged images. The algorithmically determined selection of which image segments are chosen from the repository, their relative weight in relation to each other, the visual syntactic dissections and the composition within the new image space of the synthesized image, remain at this point beyond the image maker’s aesthetic influence resulting

in a situation where content representation, aesthetics, stylistic renditions and visual element configurations are constrained by the data on which the model is trained. Given that the goal of AI image generation is to produce images that corresponds to the input data that the software has been trained on, there is a concern that much generative image art is devoid of new meaning because it recycles the conventional clichés embedded in the training set. However, my perspective on how AI can be a significant artistic medium in itself, is based on a longstanding ongoing engagement with imaging technologies to result in visual and cultural representations.

I began my artistic practice in documentary photography transitioning to street photography, and then to pictorialism, and eventually to staged photography and conceptual photography where, in my case, the primary goal was to articulate the ways in which photographic technologies imposed a meaning onto the images they produced. A brief fortuitous meeting in the summer of 1981 with the pioneer AI artist Harold Cohen prior to laptop computers, resulted in Cohen generously giving me access to his mainframe computer for a number of years, an invaluable opportunity to acquire computing coding skills with the perspectives of how coding could be a form of artistic expression. Cohen’s posthumous retrospective at the Whitney

Museum this winter (2024) curated by Christiane Paul, addresses his historical contributions to computational aesthetics by reconsidering digital technologies as an area for intellectual investigations to address the question to what degree can an image made by a machine be differentiated from one made by a human. Inspired by his investigations to translate his own painting process into computer code so that the computer would autonomously produce Harold Cohen artworks, I had to wait till the mid-1980s for the first digital photographic imaging system to be introduced, so that I could then creatively explore the potential of computer code as an artistic medium in itself by which to transform and create images within the digital photographic format.

In the 1990s, data integration into mainstream culture gained prominence, also including the art world, possibly influenced by conceptual art practices. In 1998, I presented Tracing, a digital data installation at LA MOCA curated by Julie Lazar. Initially commissioned by a German museum, the artwork aimed to juxtapose cultural perspectives from two distinct sets of data. One set, collected in San Francisco during its tech boom, and the other gathered in post-Soviet Communist countries. The data, comprising texts and videos, was projected on large screens on opposite sides of the exhibition space. Viewers on one side in-

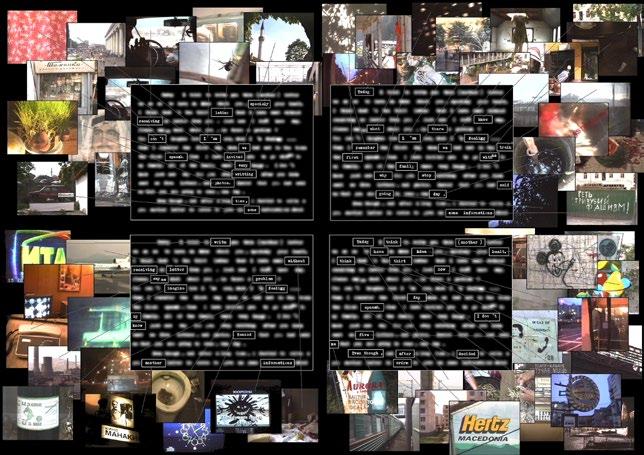

teracted with a computer mouse to select data, while sensors on the other side recorded audience positions and movements in the gallery space to determine the projected content. The installation sought to compare the socio-political landscapes of the technological rise in one world against the collapse of socialist states in another. The exploration extended to human-technological interaction, contrasting active human agency in data selection with autonomous selections based on audience positioning recorded by sensors. Another notable project exploring the interplay of visual data, language labeling and technological processing akin to contemporary generative AI is “Pockets Full of Memories” which premiered at

the Centre Pompidou Museum in 2001 and exhibited internationally until 2007. The installation invited the public to scan objects in their possession and describe them through a questionnaire. Using an early AI neural-network algorithm, the objects were visually classified and clustered on a large screen based on the descriptions rather than their visual similarities. The installation aimed to investigate the impact of linguistic description in comparison to visual recognition, to highlight variations in how we perceive and describe things.

As images generated by Artificial Intelligence software are synthesized from pre-existing images and therefore predominantly reiterate styles,

“

The overarching question is to what extent can a machine-generated output, initiated by a human textual input, be regarded as one’s own creative expression?”

social values and cultural narratives encoded in the repository, image practitioners seeking to innovate with AI software face the challenge of how to go beyond the constraints to arrive at results that can be considered as distinctive. In my studio’s explorations with Midjourney, versions 3 and 5, and Stable Diffusion, once an image is obtained that meets the desired intent, our primary approach has been to recirculate the resulting image as an input prompt to propagate variations. This iterative operation, referred to as img2img (image-to-image), generates modified versions because each time an image is reused, it introduces variances that can be minute or large, and like evolutionary change, content and aesthetic enhancements are introduced resulting in differences that can be selected as needed.

Artistic expression may be characterized as emerging from the interplay of intention and experimentation that guides exploration. The artist’s control over generative image synthesis is limited to two key factors, first the choice of text or image input, and second, the curation or selection from the set of generated images. The overarching question is to what extent can a machine-generated output, initiated by a human textual input, be regarded as one’s own creative expression? Commenting on the process, artist Philip Pocock emphasizes that “the choice of image nowadays is a new form of framing the image.” The process of selecting generated images as opposed to creating them, is nonetheless shaped by informed sensibilities. These choices are intertwined with various impulses, imaginings and memories, and ultimately fall within

the realm of one’s own expectations.

AI image creation can best be understood as an outgrowth of a long historical tradition of inventing technologies that serve the image-making process. For example, historical arguments have been proposed that define the invention of the photographic camera as an instrument that embodied the technical elements and instrument design dictated by the conditions to produce pictures. Photographic activity can then be considered as not so much as an instrument for documenting events in the world, but rather as a practice that investigates how scenes captured in the world look like once translated into an image.

Early 20th-century industrial production introduced the possibility of using language to describe the creation of an image as when the Bauhaus artist László Moholy-Nagy telephoned a set of instructions to a factory in the 1920s to produce images without the need to be on site to direct production or make the work himself. In this example, the rudimentary visual design made it possible to be communicated telematically as the describable forms organized within the rectangular pictorial space could be accurately described according to their geometric shapes and positioning.

With AI image synthesis, the paradigm shift in writing a descriptive text prompt resulting in a realistic-looking image is a consequence of the increased complexity of both how language is parsed by today’s advanced language analysis software, and how an image can now be numerically construed from data, given that digital images are essential -

ly a stream of numbers organized into what we describe as a two-dimensional organized set of discrete pixels, each pixel having precise numerical values for its location, color and brightness values. The process of diffusion in AI image synthesis where legible images emerge through the removal of noise occurs at the pixel level where the relationship of adjacent pixels is altered to arrive at visual details that simulate our expectations of a realistic image. Prior to AI, artists with programming skills, who wrote software to create images with computers had to first imagine and then articulate it precisely in programming language to result in a desired outcome. In this approach, artists encode their aesthetic intentions into language (computer code) to arrive at the intended results, much like calling in a set of details, colors and positions by phone as exemplified by Moholy-Nagy’s telephone pictures.

Many commentators have raised critical concerns about the unintended transmission of cultur-

al values and ideologies embedded in the training sets used to create AI images. Users of AI software may be unwitting disseminators of belief systems and embodied values by which the software have been designed to advance so-called “realistic” representations. As an exercise in critically analyzing how culture and society encode and shape societal values, the French semiotician Roland Barthes in his book Mythologies published some 70 years ago, proceeded to select articles published in the daily news to dissect and comment on the underlying encoding of value systems with the intention of explicitly revealing the biases but also to refine the operational semiotic structures by which to analyze how the encoding of values was probable. As a creative user of AI generative imaging technologies, I look forward to a similarly functioning “Myth Filter” through which AI-generated text and images can be filtered to reveal and critically articulate the encoded ideological value systems expressed through the generated results.

Digital art pioneer David Em, whose work has been published and exhibited internationally, was the first to make images with pixels at the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center in 1975. He then went on to build articulated 3D creatures with mainframes at the company Information International Incorporated in 1976. As an Artist-in-Residence at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory from 1976 to 1988, he became the first artist to construct navigable virtual worlds, following that with another Artist-in-Residence at the California Institute of Technology from 1985 to 1988. Em’s recent creations engage with the myriad possibilities of AI. We first spoke in June 2023 about his history and relationship to technology. Inevitably, we arrived at AI and his recent forays into working with it. We continued the discussion in early January 2024.

JODY ZELLEN: Tell us a little about your involvement with AI.

DAVID EM: The AI experience for me has been very much like working with a writing partner; I’m putting stuff out there, the system is responding to it, and the system does unexpected things I never would’ve come up with, just like when you’re working with someone in a creative way. And it’s changing things perspective-wise in any number of interesting ways. One of which is the way I look—not at the pictures—but at the process of looking at the pictures.

How is working with AI and the incredible number of “images” generated? Part of the art making process becomes about selection. With AI, I’m making more and more images I consider “not bad.” Images come quickly using AI—in literally a minute I’ll make a half-dozen variations on an interesting idea. At the end of a night, I’ll have 200 to 300 pictures to assess. The curating now becomes as important as the actual act of creation. The pacing of how I look at the pictures has changed as a result of that.

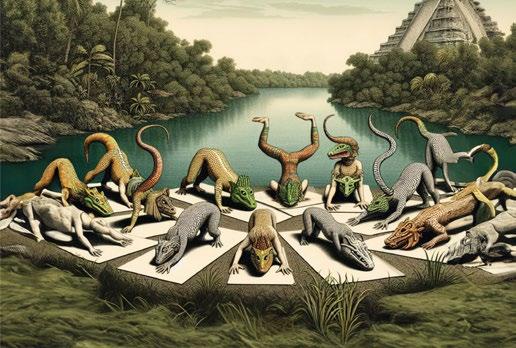

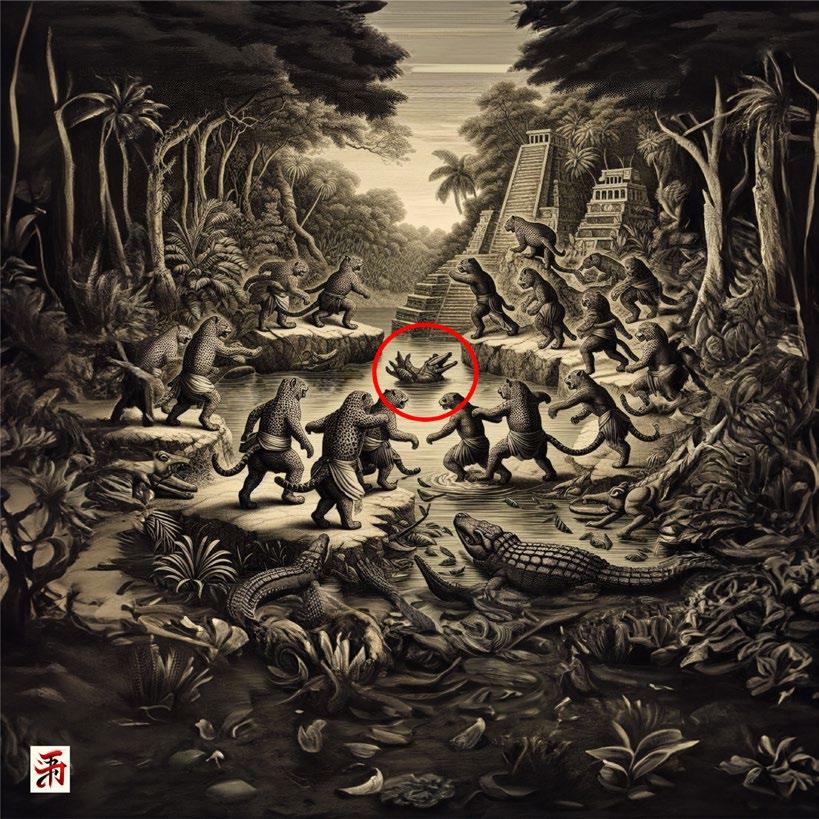

Could you share the process of creating your 2024 New Year’s card, as well as the surprises the AI generated from the elements you fed it? One subject I work with is fluid dynamics. By the time I generated the New Year’s card, I had a body of work with lizard people doing different things. I also had images of oceans and waves, so I put them together. I wanted the image to be celebratory, so I had them drinking cham-

pagne out of flutes. I probably made 40 images, of which I selected maybe number 25. The process is iterative and one thing leads to another; then it is about choice. But as you can see, the AI sometimes makes mistakes. “Happy” is spelled H-A-P-Y. I thought that was cool, but that isn’t what was supposed to happen. That was the AI. I’ve always loved accidents in art.

For another series, I began with jaguars. I managed against the AI’s wishes to get the jaguars involved in a battle against each other. We haven’t gotten into that, but if you want to say what are the main things to talk about with AI right now, it’s that this is not an art tool. This is an interesting experiment because it will not allow me —without fooling it—to have anything to do with violence or nudity or affection. Those are off the table. Two of the artworks in museums and galleries that you see now can’t be created with the major AIs. They just won’t let you do that.

Getting back to my jaguar picture, there are Mayan-looking temples in the jungle with a body of water between them, and coming out of the body of water is this crocodile-snake thing. I had asked the AI to put a couple of crocodiles in the scene, but I hadn’t asked it for the crocodile-snake combination. The AI created this surrealist creature . I zeroed right in on that. Now I’m going down a path that was not predictable. That led me to make a series of pictures based on creatures that are mashes of other beings.

AI is the tool I always wanted. Whether you’re doing things that are generative or that are more design-oriented, it’s work. To be able to say, “Make this happen, make that happen,” is very attractive to me. With the AI, I’m finding I can take still imagery to a whole new level and that is very satisfying. It’s basically infinite. There’s no end to how many things you can do.

— Bella Baxter “

And when we know the world, the world is ours.”

What is it exactly that makes a being human?” Is it the presence of a human body or a human mind? Or is it some incommensurable, uncanny union between the two?

For the philosopher Descartes, the answer was unequivocal: I think, therefore, I am. The human being is a thinking being. Doing is another issue.

Likewise, the earliest test for the presence of machine intelligence—proposed by Alan Turing—indexed the ability to engage in identifiably human conversation: to represent thinking verbally.

Such views are relentlessly contested by Yorgos Lanthimos in his newly released film Poor Things. His premise is simple: the film’s central character, Bella Baxter (extraordinarily embodied by a transcendent Emma Stone) is a young woman with a fully formed and beautiful body who, via a complicated series of events, comes to her experience of being-in-the-world with the mind of a new-born infant, a pure tabula rasa. Thus, she comprises a perfect experimental subject in human development for her “creator,” the monstrously scarred Dr. Godwin Baxter (a brilliant Willem Dafoe), known affectionately by Bella as “God.”

As the film’s plot unfolds, the viewer sees mind and body moving gradually into registration. In short, the being called Bella Baxter is slowly but surely becoming an integrated human female individual. At times, this transformation seems like a surrealistic My Fair Lady (1964); but the real touchstone is Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel Frankenstein. The scenes in Dr. Baxter’s surgery/ anatomical laboratory make this connection explicit. But what really counts are the differences between novel and film. For Shelley, whose “monster” carried a man’s brain in a reassembled body, the priority was education: the perfection of rational thought in an Enlightenment mode. Bella, on the other hand, is struggling to master both body and mind, and set on indulging a lowest common denominator of primal, lustful enjoyments, which she often refers to as “furious jumping” (of which there is a lot in the film, some of it very graphic). When Bella’s moment of reading finally comes, the author chosen is Emerson, the American transcendentalist whose iconic text is his essay “Self Reliance.” Its relationship to Bella’s predicament should be self-evident.

Not surprisingly, Bella’s life is transformed when she leaves the cloistered world of “God’s” experiment and passes into the open-ended world of the self-directed adventure, forsaking her boyish betrothed, Godwin’s scientific assistant Max McCandless (played by Ramy Youssef) and taking up with a highly dubious chancer and gambler, Duncan Wedderburn (Mark Ruffalo). And what an adventure it is, as Lanthimos ushers us, along with Bella, into an extraordinary quasi-steam punk world dripping with art nouveau design pulsating with saturated colors and frenetic activity, populated by a remarkable cast of characters, as well as some of the most bizarre little chimeras (I especially enjoyed the duck-dog) ever to function as household pets.

All, however, does not go well, although Bella’s education continues apace, and she eventually finds herself, forsaken and broke, at work in a Parisian whorehouse. At last, taking control of her own “means of production,” and under the tutelage of a canny and socialistic African prostitute (a delightful Suzy Bemba), Bella finally attains enough polish (integrated human-beingness) to return “home” and face her final challenge: the assertion that another person entirely possesses ownership of her, and that this ownership is vested in his control of her physical body. Countering this assertion (any detail here would constitute a spoiler) provides a final summation of the philosophical and existential difficulties of “being Bella Baxter” and sets the stage for a bizarre Yorgos Lanthimos-style happy ending.

This film conflates sex/uality and sexualization in a way that some viewers might find quite disturbing. But, in my opinion, it’s an extraordinary piece of work and a profound meditation on just what being human entails.

The title of Griselda Rosas’ exhibition, “Donde pasó antes (Where it happened before),” recalls the classic fairy tale preamble, “Once upon a time ...,” but also suggests a cautionary sense of place, a reference to location that doesn’t frame so much as foreground the action depicted there. Which is slightly ironic because the works Rosas has created here—in watercolor, embroidery, collage and other materials—are vessels for a volatile chemistry of color and texture that variously congeal, smolder and sublimate into a nebulous array of babies, battles, conquistadors, vortexes, regalia, insignia, animals and tissues. Alive, or in some transitional necrosis, they remain highly resistant to the perspective offered by narrative. They come at us like fluorescent fever dreams in bubbles, balloons or thought clouds—all but exploding as if from some alchemical retort.

Consider one of the first works encountered in this exhibition, La Batalla de Vortex (2024), in which pins or arrows seem to fly toward a vortex of escalating violence—with a hapless goat or ram set upon both by hunters outside the frame and a well-muscled cougar intent upon making this blood feast (rendered in dense velvety red dispersed into a skein of cross-stitching) its own. But who is in the eye of this vortex? The predator is

itself subjected to these arrows. And what of a camouflage-like patch of green, right of center, (with fringed “mane”) overlapping a tessellated swag of petaled fans—greensward or devouring reptile? An incident on the verge of self-immolation—or simply decomposition? (Rosas pricks out the decay in decadence.) Or just a dream evaporating—like that rosy aura effervescing off the pale-blue peak of this food chain of fancy?

Rosas uses embroideries not merely as embellishment, or as an alternative to pigments or graphic crosshatching, but almost as if she were devising new life forms—lacy passages like lichens. (A separate series of cyanotypes with collage are actually subtitled “Tejido Vivo,” translated as “living tissue.”)

The works have a way of evolving before the viewer’s eyes. However simple the arrangement of figure, pattern, or incident, its narrative content is always mutable, transitory. Rosas is fascinated with pattern—the way we use it to shape, order, subdivide and punctuate. It might almost be argued that the “insignias” of Artifice de insignias reales 7 (Faux regalia 7) (2023) are the patterned sections that seem to demarcate or vectorially direct the viewer’s eye. Yet why does that sienna head-blob float off to the side of our playing card Aztec queen? We are regaled and beguiled.

Other works give us a harlequinade of figures (which seem to borrow variously from Persian Mogul and Indian miniatures, ancient Chinese and Aztec figures, and car-

toonists from Steig to Steinberg) traversing terra not-at-all firma in various states of blithe terror or delight—some of them quite explicitly monstrous (e.g., a densely woven pink and blue-laddered SuperPerroMonstruo! (2023)). In works that almost defy categorization, Rosas seems intent on showing us that you can go a long way without really going anywhere. As Goya captioned one of his Caprichos “The Sleep of reason produces monsters,” what plays through these pieces is a sense that reason may as easily enable them.

Photographer Todd Gray is a rule breaker. In this brave new art world he has fashioned for us, gone are the two-dimensional, singular perspective, rectangular photographs that hung on the walls these past 200 years. In their place, Gray presents something entirely new. Much more than a signature style, his low-relief photographic collage sculptures offer a visual language that defies expectation. Gray critiques and pushes the boundaries of traditional photography by intentionally obscuring his images; altogether disrupting the way photographs typically function and provoking a sense of disturbance.

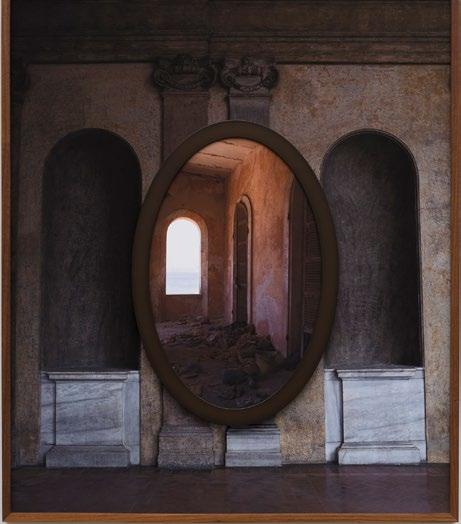

“Rome Work” presents works created during Gray’s six-month Rome Prize residency in 2023. Representing an intersection of aesthetic, content and place, this body of work examines histories of power as they relate to the Catholic Church, Africa, economic capital and colonialism. The seductive strength of each base image taken during his fellowship is obstructed by layers of framed archival images from his time spent in Africa, a past life as Michael Jackson’s tour photographer and self-portraits in the studio—layered photographs that contract and expand time and space.

Gorée Sienna | Medici Brown (all works 2023) situates an image of the grand interior of the Villa Medici, bathed in brown tones, beneath a smaller, framed oval image of another villa, dilapidated and filled with trash, on Gorée Island, the largest slave-trading post on the African coast. There is an uncanny similarity in the architectural forms of the marble-based niches of the Villa Medici and the ocean-facing window and doorways in the villa on Gorée–uncanny, until you realize they’re both European buildings; one built to extract capital, and the other to flaunt and retain it.

In Stairway to Heaven’s Hell (St. Anthony Slave Castle | Santa Maria Basilica), an image of a rundown black staircase leading up to a doorway to a white building with propped open black doors transports us effortlessly through its frame and into the base image of the collage, an oculus hoisted up by exqui -

sitely carved marble cherubs, with heavenly white light beaming down into the lens. The dark truth of the matter here: Enslaved people that were interned by the Portuguese at Fort St. Anthony in Ghana were not climbing a stairway to heaven, but to hell on earth.

Rome Work (San Giovanni in Laterano, Gorée Island, Senegal: Palace of Fontainebleau, Salaga) is the most ambitious work in the show, a floor sculpture made with five framed and layered images. You might not realize there is more to the work if you’re not curious enough to walk around it to see how it’s propped up, but Gray likes to reward those who question. The front-facing trio of images built upon the epic papal basilica of San Giovanni is literally supported by an image of the defunct Salaga Slave Market. Through the A-frame architecture of the exhibition’s eponymous piece, we are made to understand that one institution would literally collapse without the other.

The 1980s witnessed the specter of AIDS as it decimated a generation of queer men and many others. Some prevailed—artist Joey Terrill among them, though he wistfully noted in an interview, “Unlike my friends … I’m still here—working....” That sentiment sets a bittersweet tenor for his first exhibition at Marc Selwyn Fine Art. It’s a significant and sweeping survey of the quintessential Los Angeles artist’s decades-long practice. Fresh from his inclusion in the Hammer Museum’s “Made in L.A. 2023” biennial and

organized in collaboration with curator Rafael Barrientos Martínez, the exhibition crackles with energy, loss and resolve. As a bonus, the gallery has produced a cheeky zine-like monograph of the show.

At the time, Terrill, a second-generation Chicano, embraced art, queer and pop culture— even if the prevailing institutional sentiment wasn’t always reciprocal. But the impact of Terrill’s early HIV diagnosis and a singular vision propelled him forward, undeterred. Influenced by artist and social justice advocate Sister Corita Kent, his approach was culturally erudite and politically critical: Utilizing comics, zines, prints and paintings, he created urgent yet approachable visual chronicles.

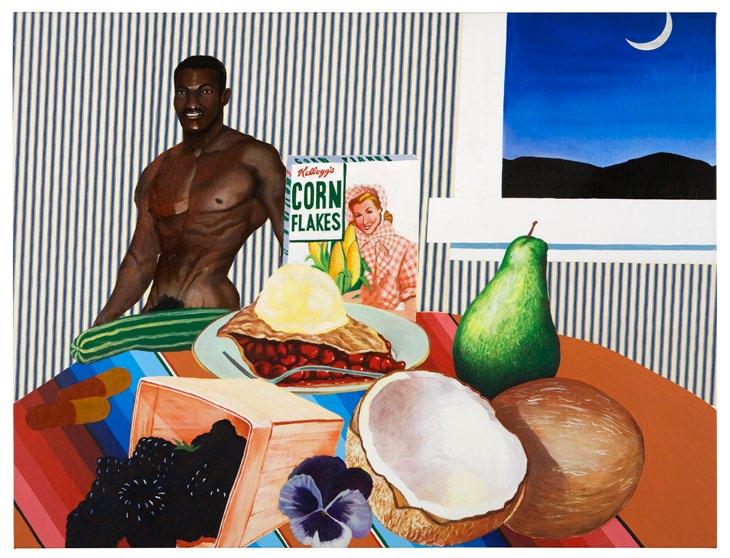

The 22 works range from the mid-1990s through 2023—some earlier pictures were lost and subsequently recreated for the exhibition. The show is smartly organized to give the art breathing room. Principally composed of acrylic, mixed media and collage, the largely autobiographical pictures encompass a wide range of themes—domestic scenes; critiques of the pharmaceutical industry (which Terrill and his peers widely believed capitalized on the epidemic for profit); queer machismo and the phenomenon of gay “clone culture”; erotic mise-en-scènes and homages to those felled by AIDS. It’s an absorbing and overwhelming milieu compelling the viewer on a voyeuristic, if daunting, journey.

The still-life works are bright, flat with compositions that are often strikingly imprecise with slightly off-kilter perspectives that compel the viewer to remain vigilant. An

early work, Still-Life with Sustiva (2000–01), depicts random elements of daily life on a tabletop covered with a serape, HIV pills, pan dulce and 7UP—markers of a domestic Chicano landscape. Terrill utilizes popular culture icons in much of his work, a choice also made by artists in New York’s Pictures Generation, who similarly utilized imagery of mass media and throw-away products. Remembering When He Used to Untie My Shoes (2023), shifts to an intimate scene: Terrill is concealed, save a lone foregrounded shoe, his lover attentively removing it. A serape—a recurring cultural anchor appears tossed on a nearby couch. The image is at once erotic and ambiguous, a masterful composition of ritual and desire.

While the works in the main gallery are largely buoyant and affecting, the mood changes considerably in the smaller second gallery. At 54 x 128 inches, the ongoing project Fifty Christs (2023) is easily the largest work in the show. Composed of photocopies and acrylic, it depicts multiple images of Christ (after Caravaggio’s Entombment of Christ (1603–04)) in muted palettes, collage and various textures—a visceral and poignant homage to those lost to AIDS. It’s an arresting commemoration.

What’s clear is that Terrill has mastered both medium and message with remarkable deftness. This is storytelling at its most intimate and profound.

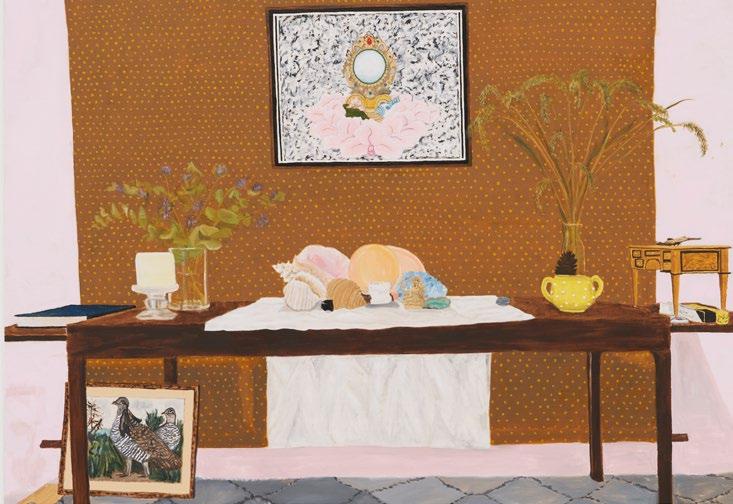

At Leidy Churchman’s “Heart Drop,” what unfolds is not rooted in rationality nor the immediate appearance of the paintings. The show features winsome and playful subjects, colors and text, yielding an impression of lighthearted themes that in time reveal pictures that are careful, alert and ruminative. These works embark on a long painterly tradition of using symbols and visual and written language as windows to mystic truth. The frameless paintings in oil on linen, most smaller than a poster, follow Churchman’s longstanding practice of foregrounding precisely the right components of stray subjects. The artist’s decision to hang the paintings at various heights like notes on a musical score, combined with his encyclopedic approach to subject matter, are remarkably effective at stirring a wistful enchantment, a feeling that became my companion as I immersed myself in the show.

In the world that Churchman has created, there is the sensation that things on Earth are plump, banal, rich, awake, tethered, brimming. The moments depicted on the wall—such as an aerial view of water rippling through a garden container filled with nasturtiums, or a contemplative still life showcasing seashells arranged on a table in a provisional room—seem to be outside of time, both happening all at once and already passed. Churchman’s enigmatic renderings appear almost like a roulette of stills, and yet he captures a subjective experience that is at once impermanent and ubiquitous. How magnificent it is that an olive-green painting bearing the inscription “The Laundry Room” or, a depiction of an explosion presented alongside a spirited, stuck-out tongue, being can prompt me to wonder if this is his experience, my experience, or your experience. You do not need to possess these works to comprehend them, an artistic gesture that creates an unexpected sense of shared humaneness.

For instance, Password Bibby (all works 2023), a painting of Churchman’s computer login screen, whose wallpaper depicts a group of six or seven elephants using their trunks to prod and caress the remains of a former living elephant, registers as a triumphantly corporeal modern truth. Both the heaviness of the skull and the communal weight of their touching pushes the remains into the soil. With Churchman’s password pending, here are animals in the middle of confronting mortality. Elephants fumbling with bones is the kind of fumbling that incites a recognition of existence. All the time, this juxtaposition of

a sapient level of sentience and an ordinary task like checking email is upon us.

This feeling of being invited and included, of moving melodically from one painting’s sphere to the next, absorbed by the rendering in front of me, not worried about where I’ll go next, had a powerful effect on me. Churchman presents a tender and lucid peek into a dimension that is at our fingertips every day, a mode of rejoicing that is just a blink of an eye away from connecting us to everything.

So much more than paintings in bespoke carrying cases—though they certainly are that—the results of Alejandro Cardenas’ collaboration with Case Studyo, a Belgian artist-edition platform, engage the conceptual premise of the project with a thoughtful intentionality that almost completely transcends gimmick. Case Studyo has its own dedicated fanbase, many of whom visited the exhibition due to their interest in the Porta-MANTIS™ objects, rather than their contents.

The lustrous anodized metal carrier boxes are indeed gorgeous, with smooth skins of metallic amber, formed in three parts—two plates that snap, front and back, onto a structural perimeter with an integrated handle. Their construction is sleek and clean, both minimal and with occasional dramatic flourishes such as the toothsome crinoline texture on the boxes’ handle grips. When the cases aren’t in use for transport, one can hang them on the wall using the handles as brackets. Voilà—instant frame, easy installation.

The paintings (not all of which come in cases, as there are some works larger than

the uniform edition measurements) are almost the opposite of these sleek cases. Faceless, mechanical yet eerily anthropomorphic figures, alone or in pairs, inhabit postcard-ready settings for recreation, romance, daydreaming, and adventure: PM03 Newer Shore’s beach, PM04 The Burning’s epic sunset, Dusk’s urban picnic vista, the Wyeth-like night meadows of PM08 Moon Field, and so on (all works 2023). Several paintings—such as the striking and pensively regal portrait of a pattern-skinned figure at a window, The Anodized Hall 2—include architectural details that echo the corrugated texture of the case’s handle and its austere steel hue, forming a bridge between the frame and the canvas that is both pictorial and conceptual. Other than that, the paintings are about as different in sensibility from the cases as they can be.