Film, Animation & Video

Film, Animation & Video

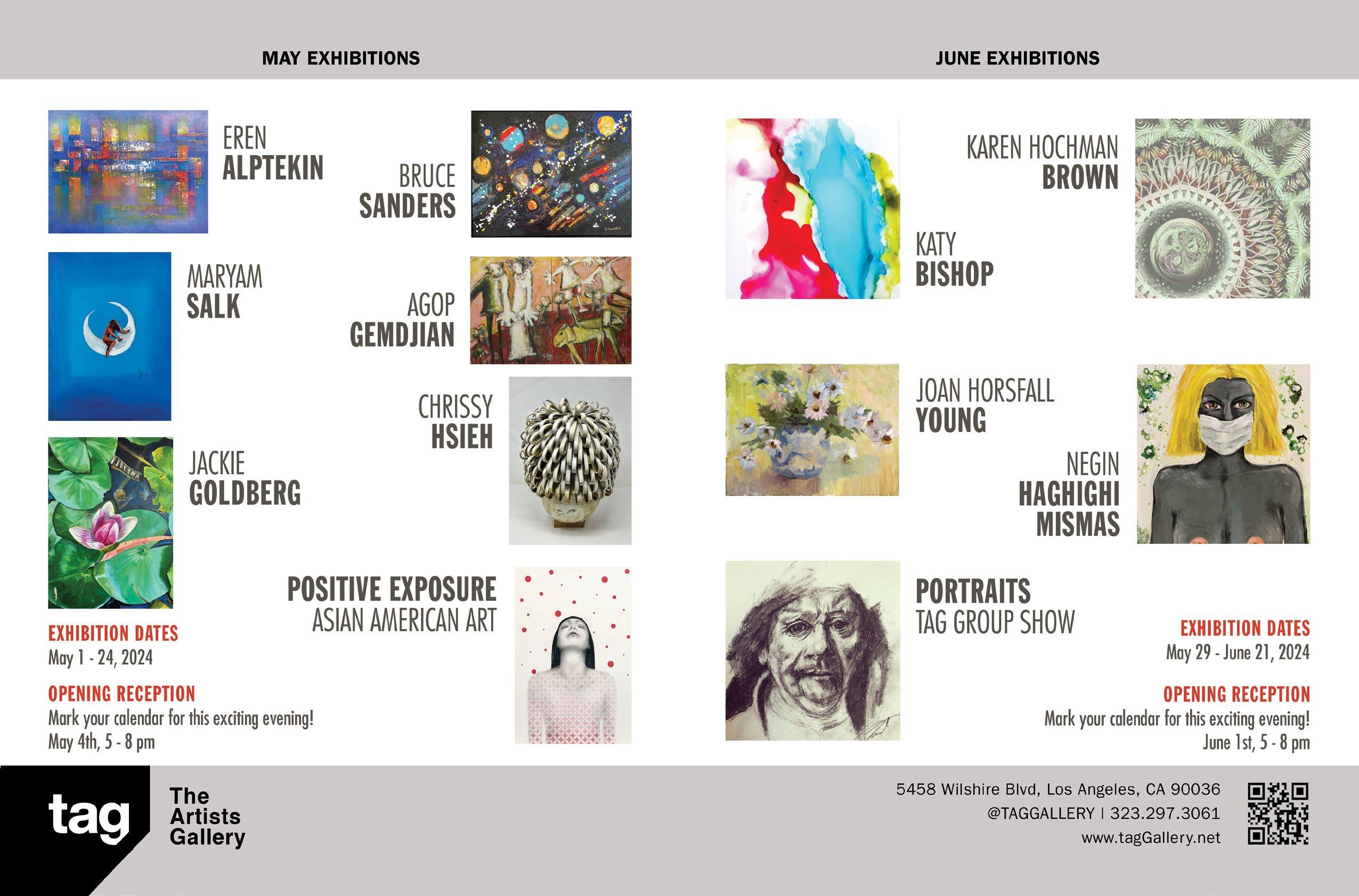

VOLUME 18, ISSUE 5, MAY–JUNE 2024

Ethel Lilienfeld: 28

Our Virtual Selves

Annabel Keenan

Shattered: Basel Abbas 32 & Ruanne Abou-Rahme

Tara Anne Dalbow

Deborah Stratman: 38 Abyss of Time

Natasha Boyd

Jónsi: Realm of 42 the Senses

Franco Rossi’s Smog

Luca Celada

Emma Christ A New Restoration of 44

Bunker Vision: Turn-On 21

Skot Armstrong

Art Brief: Wendy Posner 22

Stephen J. Goldberg

The Digital: Tala Madani 24

Seth Hawkins

Peer Review: Olivia Mole on 26 Fox Maxy

Brad Kronz 46

Gaylord Apartment s

Nora Turato 46

Sprüth Magers

Se Oh 47

Stroll Garden

Gilbert & George 58 Centre, London

William Moreno

Shop Talk: LA Art News 18 Scarlet Cheng

Ask Babs: For the Dogs 60 Babs Rappleye

Poems: Caitlin Brady, 60 John Tottenham

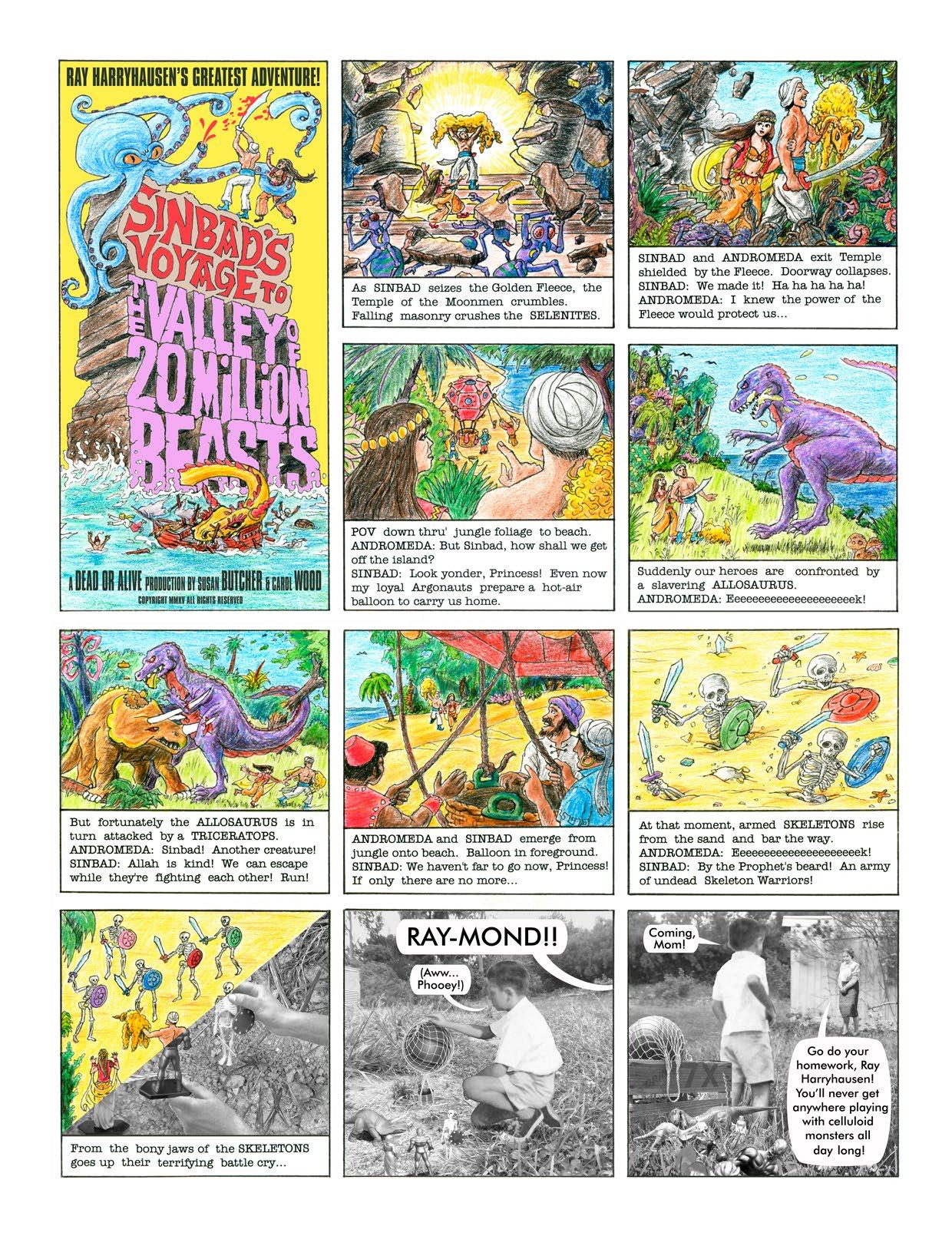

Comics: Sinbad’s Voyage 62 Butcher & Wood

Zizipho Poswa 48 Southern Guild

Marianne Wex 48 Tanya Leighton

Paul McCarthy and Benjamin Weissman 49 The Pit

Marc Camille Chaimowicz 49 Gaga & Reena Spaulings LA

Judithe Hernández 50 Cheech Marin Center

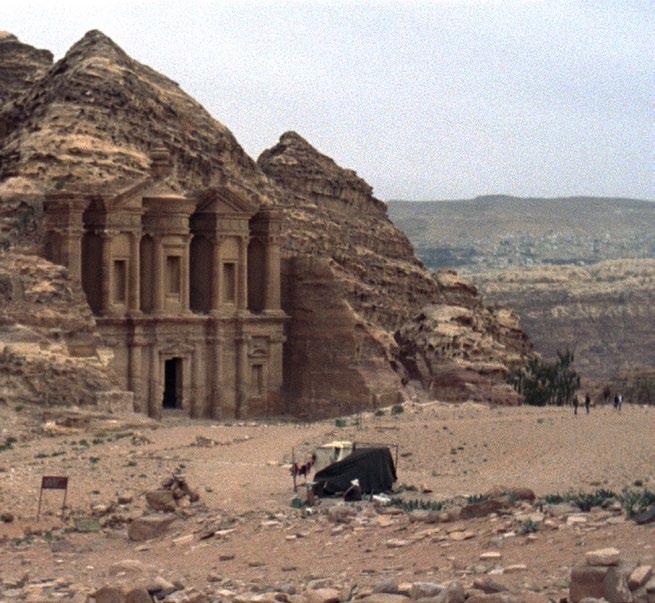

ON THE COVER: Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme, May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth, 2022 (detail). MoMA, NY. Photo by Jonathan Muzikar. • OPPOSITE PAGE, clockwise from top left: Ethel Lilienfeld, EMI, 2023. Production: Le Fresnoy—Studio national des arts contemporains. Courtesy of the artist; Turn-On, 1969; Basel Abbas and Ruanne AbouRahme, still of May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth: only sounds that tremble through us, 2020– ; Jónsi, Silent sigh (dark), 2023. Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery; Tala Madani, still of Mr. Time, 2018, Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery; Rest (detail), © The Gilbert & George Centre (UK) Ltd. Photo by Prudence Cuming; Olivia Mole, Cuddle Puddle, 2021. Photo by Ian Byers-Gamber; Benjamin Weissman, Hamlet, 2022–24. Photo: Jeff McLane. Courtesy of The Pit; Tulsa Kinney, Trudy, 2019; Deborah Stratman, still from O’er the Land, 2009.

Dear Reader,

In the early Artillery days, I assigned a writer to critique the films and videos that were showing in the sprawling 2007 MOCA exhibition, “WACK!: Art and the Feminist Revolution.” There were more than 20 films and videos included, mostly viewed on the original, portable black-and-white television sets or small analog monitors with bulky VHS recorders and other archaic equipment. Thick black cords, oversized headphones and extraneous hardware gadgets were in full view, making them part of the dated presentations.

After seeing the massively impressive, exhaustive exhibition (full disclosure: I pretty much skipped over the videos), it dawned on me that I should return and really watch the videos, all of them, in their entirety. The low-budget (or nearly no-budget) production of most of the work provided a window into the then newly discovered medium being used in art—video.

Besides my desire to go back, I thought that others might feel the same way. (Don’t most museumgoers skip watching the entire films at big exhibition shows?) I found myself drawn to the crude videos with the grainy black-and-white closeups of women’s faces and naked body parts—usually the artists themselves— always full-frame. Contemplative observations, confessions, questions, concerns and self-absorption seemed to be a running theme in a lot of the films. But really, could I sit through all of them? Perhaps I should’ve included a rating system when giving the writer his assignment to cover the show.

There doesn’t seem to be much need for help in making those decisions these days. In this Film, Animation & Video issue, we feature six female artists that make it impossible to walk away from their moving image pieces. For one thing, it’s usually the main thing in the exhibition, filling the gallery entirely, not tucked away in a darkened side room. Technology has leaped into a big fast-forward since the days of the “WACK!” show. Although Palestinian artists Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme draw on the past for inspiration, their multichannel, multisensory films look very different from the days of the portable blackand-white TVs. But they still talk about the things that are important to them, whether personal, familial, political or emotional, as reported by writer Tara Anne Dalbow. Admittedly, there are new matters to explore 20 years later. For instance, multidisciplinary artist Ethel Lilienfeld delves into 21st-century concerns, such as “self-image and the filters that augment—or completely change—our appearances,” writes New York contributor Annabel Keenan. Lilienfeld explores our virtual selves, or rather how we present ourselves in the virtual world. Women especially fall victim to the superficiality of social media, even to the point of going to plastic surgeons with their “filtered” double as a model.

In the end, the writer finally turned in his copy on the “WACK!” show, claiming he did as well as one could in the three hours he spent watching the videos and films. He came up with a rating system, and one of the films he watched in its entirety—and claimed to have been “mesmerized” by—was 27 minutes long. Our contemporary tools make the art of creating moving images a much easier process. But the message remains the same, as you will see in these pages.

Annabel Keenan is a New York–based writer specializing in contemporary art, sustainability and market reporting. Her work has been published in The Art Newspaper, Hyperallergic, Brooklyn Rail and Cultured, among others. She holds an MA in Decorative Arts, Design History and Material Culture from the Bard Graduate Center.

Natasha Boyd is a writer and poet from Los Angeles. Her work has been featured in The Nation, The Drift, Contemporary Art Review L.A., Los Angeles Review of Books, Pioneer Works and elsewhere. You can read more of her writing at natashakboyd.com.

William Moreno is currently principle of William Moreno Contemporary, an art advisory and consulting firm with a mission to provide informed, personalized advice that meets each collector’s particular aspirations. He is also a curator, writer, executive coach and consultant for arts organizations and artists focused on issues of sustainability, marketing and management practices.

Emma Christ, Artillery ’s associate editor, is a Los Angeles–based curator, writer and art historian. She holds a BA in art from Reed College, and an MA in curatorial practice from USC, where she wrote her thesis on osmotic and transcorporeal relationships in contemporary art.

TULSA KINNEY EDITOR • ALEX GARNER PUBLISHER

EDITORIAL

Bill Smith - creative director

Cat Kron - reviews editor

Emma Christ - associate editor

John Tottenham - copy editor/poetry editor

John Seeley - copy editor/proof

Dave Shulman - graphic design

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

Ezrha Jean Black, Laura London, Tucker Neel, John David O’Brien

COLUMNISTS

Skot Armstrong, Scarlet Cheng, Stephen J. Goldberg, Seth Hawkins

CONTRIBUTORS

Anthony Ausgang, Emily Babette, Lane Barden, Natasha Boyd, Arthur Bravo, Betty Ann Brown, Susan Butcher & Carol Wood, Kate Caruso, Max King Cap, Bianca Collins, Shana Nys Dambrot, Genie Davis, David DiMichele, Lauren Guilford, Gracie Hadland, Christie Hayden, Alexia Lewis, Richard Allen May III, Christopher Michno, William Moreno, Barbara Morris, Carrie Paterson, Lara

Jo Regan, David S. Rubin, Julie Schulte, Allison Strauss, Daniel Warren, Colin Westerbeck, Eve Wood, Catherine Yang, Jody Zellen

NEW YORK: Annabel Keenan, Sarah Sargent

ADMINISTRATION

Mitch Handsone - new media director

Emma Christ - social media coordinator

Anna Bagirov - senior advertising sales

I don’t know about you, but I’m still recovering from Frieze LA (Feb. 29–March 3), and the art week that was. In addition to the main event, there were many gallery openings and events, and also the Felix and Spring/ Break art fairs. At Frieze there were fewer galleries this year—about 95 versus last year’s 120—all packed into one big custom-built tent at Santa Monica Airport. Last year, most of the galleries were in the big tent, with a selection down the hill at Barker Hangar. Ironically, last year I heard complaints from gallerists relegated to the latter location, but Anthony Meier told me this year, “We did quite well after all, so we were happy.”

After attending the Thursday preview, I returned Saturday afternoon for some people-watching. Art fairs have become part of weekend entertainment, and Frieze drew an enthusiastic crowd, despite its high-priced admission. The aisles were jammed with friends on the hunt for new artists, young parents with toddlers in strollers and couples on dates. Kudos to the galleries that had one-person and thematic exhibitions; they really stuck in my mind.

Let’s take The Pit, with its walls paint-

ed in pleasing pastels, the back one dotted with white squiggles and shapes, which were ceramic pieces by Allison Schulnik that tell of the faceoff between two creatures outside her desert home, south of Joshua Tree. For an hour she watched as a snake and a cottontail rabbit confronted one another. “At first I was afraid for the bunny. I thought he’d be killed,” she told me. “Then I realized that the rabbit was the aggressor, sometimes moving in to nip at the snake.” The snake lunged forward, which made the rabbit jump and run away. This drama was depicted in several pieces on the wall: the snake lurching forward, the rabbit falling back into a curl. “Fortunately, they both came out alive,” Schulnik reported.

Los Angeles–based Gary Tyler won the 2024 Frieze Los Angeles Impact Prize, an honor saluting an artist who has “made a significant impact on society with their work.” He had a solo project at Frieze LA and received a $25,000 award. Tyler learned quilting during his 42-year incarceration, and he has used the medium to tell stories about his time in prison and the people he met. With quilting, he has said, “I had found my calling.”

For a break, I went to Spring/Break in Culver City—and found it refreshingly creative and friendly. Spring/Break has entered its fifth year in Los Angeles with some 90 exhibitors. Twelve years ago, Ambre Kelly and Andrew Gori launched the fair in New York as a fun alternative to the mainstream art-fair scene. They drew independent curators, artists without major gallery representation, or a combination of both. In Los Angeles this year, at least one stand was organized by two artists— Alonsa Guevara and James Razko, who curated each other’s work.

When Kelly and Gori started the Los Angeles fair, they were downtown. However, they always wanted to be arranged and geographically close to Frieze, which moved from Hollywood to Beverly Hills to Santa Monica. So Culver City seemed to be a good location this time, especially, as Gori points out, with an arts district nearby.

Inside the red brick building the fair occupied, there were walls dividing exhibitors, but hardly a plain vanilla cube was to be found. “We discourage white walls unless there’s a purpose for it,” Gori said. “These spaces come with their own character.” The exhibitors try to exhibit some personality, as well. They paint their walls different colors or give them a special treatment. They provide comfortable seating and linger in the aisles to chat and invite visitors in. Claire Foussard gave her walls a cement coating, and Yiwei Gallery painted trompe l’oeil Doric columns to frame its space. Others created installations—Z Behl + Walker Behl + Tavet Gillson built an immersive, 3D version of their board game, Storm the Capitol: THE “BIG” EDITION, a darkly comic look at the insurrection on January 6 in Washington, DC. Meanwhile, Hicham Oudghiri set up a tent that people could enter and sit in.

Foussard also featured two very intriguing artists. Angelica Yudasto created ethereal drawings floating in layers of kiln-formed glass, while Jiwon Rhie made a slapping machine mounted on an outside wall—a kinetic sculpture of a padded hand that swings around to smack you in the face. It was her way of venting the rejection she felt from various institutions after moving to the United States. At one point, Rhie bent over to demonstrate, putting her cheek in line with the hand. She smiled when I look concerned, and assured me, “It’s very gentle.”

On Seward just north of Santa Monica Boulevard is a new gallery that quietly opened last year—new to us, but the first American branch of one of Korea’s leading galleries, Gana Art. They opened an exhibition of work by Japanese artist Chiharu Shiota the weekend before Frieze, titled “In Circles.” Last year Shiota created that sensational installation using interconnected red string which engulfed the lobby of the Hammer Museum, one of the best transformations of that space. It felt like the inside of a magical spider’s lair. The gallery is housed in two small buildings, one featuring Shiota’s smaller works in display cases and on panel, the other a room-sized version of her installation work, based on three gigantic hoops. It was a wonder to walk throughout the exhibition.

The artist is now based in Berlin, but she paid a visit for the opening of her Gana exhibition in LA. In person, Shiota is quite modest and soft-spoken. She told me that as a child in Japan, she had seen the works of Dalí in the Sunday newspaper, and then became interested in art. She began drawing all the time: “It’s like my secret world, my own world.” To this day her art feels like a secret world: one we feel privileged to visit.

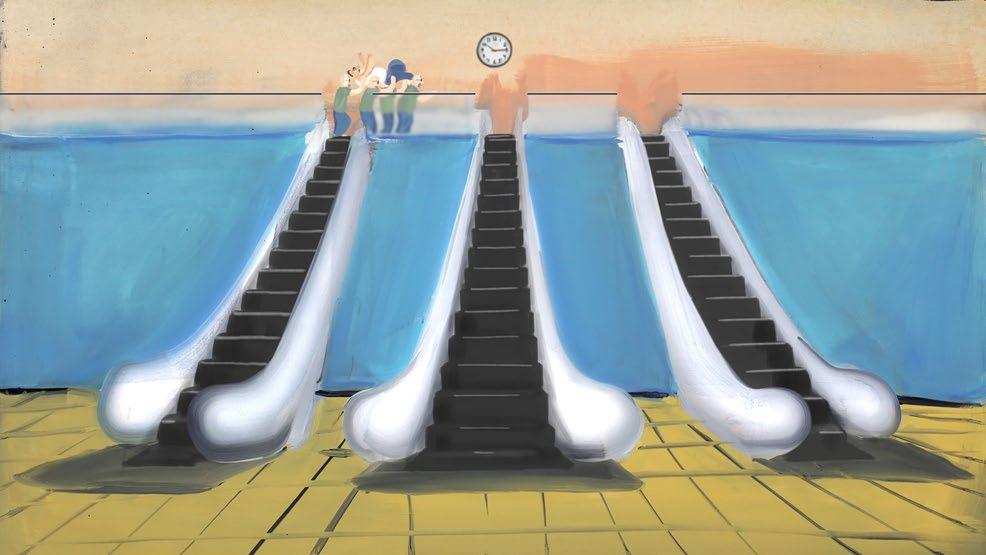

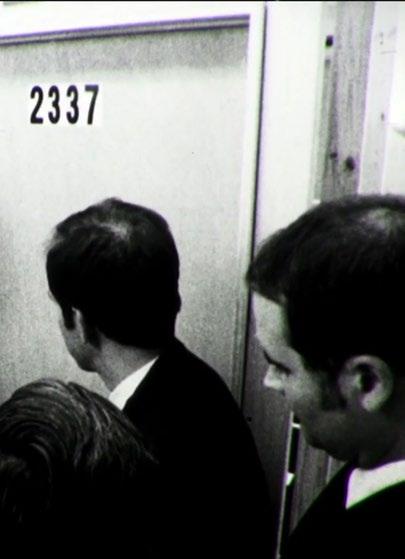

The history of film is full of paradigm shifts. Once people got used to the idea that the train on the screen wasn’t going to burst into the theater, they had to adjust to editing. When a character had a memory, the idea of linear time was disrupted. One of the biggest shifts arrived with the debut of MTV in 1981. Until it arrived, the most likely way one would have seen those rapid edits would have been in a film history class that was studying Russian cinema, or such underground works as Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising (1963–73). This might help one to understand how shocking a TV show called Turn-On was to the uninitiated viewer in 1969. A year earlier, a television show called Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In (1968) featured rapidly edited blackout comedy sketches. But these were offered in the context of a show that had tuxedo-clad hosts and Hollywood production values.

By contrast, Turn-On billed itself as the world’s first computerized show. This premise allowed them to dispense with sets, as the skits would appear with a white background with Moog synthesizer sounds instead of a laugh track. The show was shot on film (unusual for the time) and the screen would sometimes divide into four images. Animation, videotape, stop-action film, electronic distortion and computer graphics

Screen capture from Turn-On, Episode One, 1969.

were employed for what was intended as an audio-visual assault. Going with the mistaken idea that Laugh-In had broken more ground than it had with censorship and fast-paced editing, the creators of Turn-On sought to push the boundaries even further. The edits became faster, more random, and were used to sneak in things that might get past the censors. In this pre-VCR era, such things were quite literally a blink, and you missed it. You couldn’t stop the picture or rewind what you had just seen.

Within minutes of the show starting to air its premiere episode on the East Coast, the switchboards were lit up at every station that aired it. Viewers weren’t just upset by the content; they were experiencing a form of sensory overload that nothing had prepared them for. Households where more than one set of eyes were on the screen were catching those hidden bits in the montages. Stations started pulling the show off the air during the first commercial break, and some stations further west were refusing to air it altogether. Despite having a second episode in the can, the show was canceled and thought lost. Recently, both episodes turned up on YouTube. It hasn’t aged especially well, but it’s wonderful to remember a world in which millions of primetime viewers got to see an underground film.

Wendy Posner is the CEO of Posner Fine Arts, an international art advisory based in Los Angeles. With a global roster of artists, publishers and gallerists, she builds relationships with both established art stars and new talent. She has traveled to more than 20 countries regularly attending art fairs and making studio visits. I’ve known Wendy for 10 years, sometimes as a client of my legal practice. We discussed how the role of art advisor is facing the challenges of mega-galleries that have recently added in-house advisory services.

STEPHEN GOLDBERG: What are the challenges of mega-galleries, such as Hauser & Wirth, expanding into the art advisory field?

WENDY POSNER: Most of the large galleries have now added advisory arms to their business, outside of doing private sales, where they’re even looking for secondary market pieces for their clients, not just the primary works that gallery is selling.

As a fine art advisor, the main conflict of interest is that we would normally take our clients to the galleries to purchase artworks, and if they’re also now acting as advisors, they might take those clients from us because they have offerings that we don’t have access to—from their collectors that they work with, in addition to their primary works. If any collector walks into a mega-gallery, they’re going to be offered the same discount that’s offered to advisors, so that incentivizes the way that we would normally be paid. How do we pass off a discount to our collectors, when the percentage that the gallery is offering the collector is the same as what they’re offering to the advisor?

Mega-galleries have deep pockets. They’re able to go and market directly to the collectors, and they have more funds for

staffing. In the traditional way of art advising, it wasn’t something that you charged your clients an hourly fee for; your time was paid for in the sale of the work. It’s become exponentially more difficult because unless a collector buys a piece of art, we don’t make any money.

If you’re competing with the mega-galleries who know which of their collectors own works by certain artists, they can always go back to their collector base and start selling their works into the secondary marketplace. Now the level of transparency has completely changed with more information online, and collectors at a certain level are much savvier. And charging for the services is really where the money is going to be made, not just in the sale of the markup.

Are there any examples of losing clients to a gallery?

I had a collector that was looking for a painting by a specific artist. We had worked for about six months to find works by that particular painter, and it ended up that the collector backdoored us and went to a gallery directly. The gallery gave them the same discount that we would have gotten as an advisory to make the sale. We were completely cut out of that deal. I

Above: Art advisor Wendy Posner.

think that’s part of the issue when you’re taking collectors to the art fairs and introducing them to the galleries, and you’ve curated artworks for them to see with specific galleries, that even if they don’t end up making the sale through you they could easily turn around at a later date and go directly to those galleries—unless the galleries protect you.

What about an agreement upfront that would permit you to be able to bill clients for your time?

That’s what a lot of advisors are starting to do, create this new business model. But with collectors that we’ve worked with for 30 years, if that isn’t a traditional methodology of which they’ve acquired artworks for, how do you re-educate them in terms of a new business model? So there’s definitely a shift in the marketplace. The other part of it is that the discounts we were able to get in the past were much steeper than the discounts that are now customary across the board. The galleries have a standard discount for commission. With other galleries that we have long-term relationships with, the discounts could be variable, and they could be much more than the standard. But if a known collector walked into that same gallery, they’re

STEPHEN J. GOLDBERG, ESQ.going to be offered the standard discount to make the sale. So you’re in competition with yourself and with your collectors for that discount rate. Unless it’s a mega piece, you’re making a nominal amount of money for the time that you’ve spent with the client to acquire that.

Are you giving collectors a written contract?

We put together agreements for our collectors that we’re working with, because we have to be able to protect ourselves. But with the mega-galleries there has to be some sort of relationship established upfront before we even take our collectors to those galleries.

Do you have a conversation with them?

Yes. You have to have some sort of terms of agreement with them and everything is negotiable. So it has become much more complex.

This is part one of a two-part series. In the next installment we will discuss online sites such as Artsy and the auction houses that have now expanded into the art advisory space.

Have you ever howled at the moon? Stood up to your demons and screamed until your lungs ached? I have once. It was in the wee hours of the morning in Thailand. It was a pivotal moment in my story, and to scream without judgment was where I found solace, but that is a tale for another day.

Darkness exists both in this world and in the shadowy corners of our consciousness. How do we deal with that? Some confront our demons more naturally while others keep them under lock and key. This darkness is where our inner voice is not censored or muted—where our most extreme visions are exposed without judgment or humility. There is an old saying about strength and secrets: Strength doesn’t come from having ones secrets protected but rather from exposing them.

Enter Iran-born artist Tala Madani, who for decades has

explored the visual space that would make others cringe. In the South-Park methodology, strong subject matter is dealt with in a backhanded and seemingly juvenile way. Madani saunters through the shadows with a childlike grace of style and sensibility, because in the end who doesn’t love a good scat joke?

Madani’s paintings—some of which provide the foundation for her animations—exist in large format, and as we talk about technology and the crossover into art, she jokingly says that her interface with technology typically exists at the most basic level, “taping a longer stick to a paintbrush so it can be extended, knowing when to switch from a paintbrush to a mop.” While there is a subtle layer of both humor and truth to her statement, I would argue that the veins of digital manipulation run more deeply as one explores her prolific body of work.

Madani’s animations are a testament to that depth—you lean into what you have and toss aside the rest. There is something viscerally exciting that happens in her animations, essentially stop-motion activations of her paintings that simply cannot be reproduced in a magic computer box. The fact that it can take 2000 paintings to make a two-minute video opens a portal in which her paintings step through, as if from the plot of B-grade horror movie. Painterly movements are accentuated, viewing angles change, and even if slightly— characters develop.

For example, in her early animation Hospital (2009), a male figure lies in a bed covered in bedding, with only his head revealed. Another figure enters the room, stands beside the bed, then walks out. Soon a diaper-clad baby crawls (in a

beautifully creepy way that stop-animation allows) in from the adjacent patient’s room, separated by a curtain. The baby pulls its way up onto the bed and makes a thumping motion on the man’s chest that is suggestive of a worshipful gesture. The scene quickly changes from playful to dark as the baby’s hands, the entire bed and man’s head gradually transform to a blood-red pigment. The baby then crawls off of the bed and exits the scene, the video ending.

The rough flip-book style animation draws one in as it plays off the painting, and, inversely, the paintings play off the animations. As in much of Madani’s work, light and shadows are paramount to the visual scene—her digital connection provides the illumination to reveal all the perverse secrets hiding in the darkness.

London-born, Los Angeles–based video artist and animator Olivia Mole is known for her recurring characters in many of her works, seen in pieces presented at the Hammer as well as in her solo show at Gattopardo last year, “A Bear Shits in the Woods.” Always with a sense of humor, Mole’s work probes pop and consumer culture and verges on the absurd. Mole’s exhibition at Tiffany’s, organized by Adam Verdugo, opened in April and is titled “Dopesheet Batman”; based on an original animation dope sheet of the iconic moment of Daffy Duck stating, “I’m Batman,” Mole’s new body of work explores the gaps between aspiration, identity and presentations of self.

I saw Fox Maxy’s Gush play at the Hammer last year because my friend Vanessa Gonzalez Medina recommended it to me, so I went into it pretty cold. It’s intense and exhilarating to watch; superficially it’s like an extended sort of TikTok, like watching a cascade of short videos one after the other. Some scenes are more designed and constructed as opposed to the way that everyone uses their camera in their life. Maxy is Payómkawichum and Mesa Grande Band of Mission Indians, and she has made a lot of work about the colonization of Indian land within the USA and at the border of Mexico. The complexity in her work—it’s not as simple as the colonizer versus the colonized—exists in setting the vicissitudes of daily life within the diverse struggles of Native American people to protect their land, status and existence. It adds to its genius that she is working really solidly within a cultural landscape of video, cinema and social media while dealing with this grand subject matter of surviving as a part of a generation coming up in the terrifying narrative of global warming.

The thing that really clicked with me was the animations in the film—every so often the film goes into

CG animation with floating innards of the body, very shiny guts, eyeballs and organs writhing around in space, little moments of blood. While I was watching the film, absorbing all of it, I realized it’s like a deconstructed horror film, fragmented and not put back together, in a constant state of flux. It defies Hollywood narrative structure. Furthermore, when accounts about the end of the world and the apocalypse arise in mainstream media, it’s as if the end is yet to come. But for Native American people and other colonized people, it has already come, and it’s like Gush is set within that. It seems to be so unstructured yet is tied to a cinematic genre that is usually very set with tropes and expectations. She messes with the foundation and then brings “real stories” into that with horror as a stealth genre. But it’s also so energetic and filled with vitality and humor. It doesn’t suggest a submission to what’s happening, to just have a good life with what we can. Nor is it defeatist in the face of catastrophe. It’s full of pain, joy and sadness, inhabiting this kind of state of horror with a fierce commitment to life.

—As told to Alex Garner

Technology cannot be separated from the world we live in today. Indeed, post-pandemic, we are experiencing even more of our daily lives virtually. This phenomenon lies at the core of French multidisciplinary artist Ethel Lilienfeld’s work. Using video, installation and photography, Lilienfeld examines our relationships with technology and the virtual body—avatars we create to engage in digital realms. In recent years, she has considered self-image and the filters that augment— or completely change—our appearances.

“I am interested in exploring the codes of representing femininity throughout art history and examining how these codes have evolved in today’s digital age, especially on social media,” Lilienfeld, who was born in 1995, said in an email interview. “The relationship we have with our own image has changed and is now continuously archived and updated online.”

As technology advances, social media has become a tool through which humans grapple with the self and the truth behind what we view and consume online. We are now capable of creating virtual bodies regardless of whether or not they reflect reality. “This way of perceiving ourselves, especially through filters, has given rise to new neuroses, such as Snapchat Dysmorphia, a pathology characterized by the compulsive desire to

Opposite page and above: INVISIBLE FILTER, 2022. Production: Le Fresnoy–Studio national des arts contemporains. Courtesy of the artist.

resemble one’s digitally filtered self,” she explained. “It leads some people to go to the surgeon with their ‘filtered’ double as a model.”

This past March, Lilienfeld presented her work for the first time in the US in the 2024 FotoFest Biennial, the storied Houston photography exhibition. The artist’s four-channel video installation INVISIBLE FILTER (2022), was a standout of the biennial, which centered on “Critical Geography” and considered the broader ways and spaces in which we live and engage with the world today. Lilienfeld’s presentation is accessible and impactful: Featuring two identical women of markedly different ages, the work highlights the tension between fiction and reality, as well as the norms and biases perpetuated through social media, particularly those of age and beauty.

On one of the four screens in INVISIBLE FILTER, the two women appear in a sparse room. They move slowly in an unsettling way, pausing and kneeling next to a large basin. The younger woman cries into the tub and the older woman bathes

her own face in the tears. A digital beep sounds as the tears hit the surface, joined by choppy gasps for air. On another screen, the older woman looks into the camera, her face covered by a youthful digital filter that smooths her skin, a stark contrast to her heavily wrinkled neck. A third screen shows a reflection of what appears to be the older woman in the basin of tears, recalling Narcissus becoming enamored with his own image. “It could also evoke the story of Dorian Gray,” Lilienfeld explained. Closer inspection reveals it is the reflection of the younger woman, who is presumably aging as her tears drain her of youth. On the final screen, which is on the back of the third, forcing the visitor to move around the installation to reveal the story, the viewer watches from outside the house and sees that the tear-filled basin acts as a youthful elixir for the older woman.

In creating this work, Lilienfeld was inspired by socialmedia personalities and influencer culture, including the popular Chinese vlogger, “Your Highness Qiao Biluo.” During a 2019 livestream, a glitch revealed that the youthful Qiao

Biluo was in fact an older woman wearing a filter. She was suspended from the streaming platform Douyu and the story of her downfall went viral, a “contemporary fable,” as Lilienfeld called it. The incident sparked conversations about the ethics of filters, beauty standards and if online personalities owe their audiences the truth about their identities.

For her most recent project, EMI (2023), Lilienfeld addresses these themes directly. An interdisciplinary piece, EMI (an acronym for the French term for near-death experience) includes a film, website and NFTs. The project features a virtual influencer engaged in a frenetic advertisement-tutorial hybrid.

“Virtual influencers created from scratch have a story to tell, sharing their tastes, passions and vision with their community through a transmedia narrative,” Lilienfeld said. “They promise to stay eternally young and fashionable, and never have reputation problems.”

Produced with Le Fresnoy— Studio national des arts contemporains and co-produced with La Fédé ration Wal -

The incident sparked conversations about the ethics of filters, beauty standards, and if online personalities owe their audiences the truth about their identities.” “

lonie-Bruxelles, the project combines artificial intelligence, real footage and computer-generated images, demonstrating how advances in technology blur reality and fiction. The influencer overindulges on opulent food, drinks off-putting health supplements and uses beauty tools that pull on her skin, revealing glitchy eyes. “Behind its seductive form, EMI explores the increasing capitalization of the body online, inviting us somewhere on the edge of the beautiful and the repulsive, the real and the fictitious, the living and the dead,” Lilienfeld said.

For the NFT component, collectors become stewards of the influencer’s organs, a metaphor for the sense of ownership that people have about public figures and online personas. The organs come with a description similar to that of an autopsy report. As twisted as this might seem, it’s not unlike wearing another face through a digital filter—an act we’ve normalized on social media. Indeed, while Lilienfeld’s work is intentionally dystopian, it’s hard not to wonder if it’s that far removed from reality after all.

EMI, 2023. Production: Le Fresnoy–Studio national des arts contemporains. Co-Production: La Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles. Courtesy of the artist.

Installation view of Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme: May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth, 2022. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Digital Image ©2022 The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo by Jonathan Muzikar.

Installation view of Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme: May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth, 2022. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Digital Image ©2022 The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo by Jonathan Muzikar.

In the 18th century, when the Iranian elite heard rumors of the grand mirrored halls of Europe, they sent merchants to procure as many sheets of brilliant reflective glass as their boats could carry. Still, the mirrors cracked in their elaborate frames somewhere between Venice and Tehran. Rather than attempt to reassemble the shattered glass, artisans inlaid the thousands of pieces in sweeping geometrical patterns along walls and across ceilings. The mesmerizing designs accentuated these tesserae pieces but also distorted the surface reflection, fragmenting the viewer’s image and intermixing it with that of peripheral objects and other people.

Palestinian artists Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme create similarly revelatory mosaics not from glass but from pieces of archival footage, original documentary imagery, soundscapes and text. Their multisensory installations mirror the dispossession of diasporic communities, evoking fracture on a visceral level.

Abbas and Abou-Rahme first met in 2007 when their respective performance-based practices converged: Abbas’ DJing and Abou-Rahme’s work in video design. More than a decade later, performance remains at the heart of their ongoing collaborative practice. Through their nondiegetic sound collages and multiscreen projections, they position performance as political action in which collective movement engenders resistance and resilience. According to the collaborative duo, collective sound and movement rituals— including song, poetry, dance and gesture—afford displaced communities a critical means for resisting their own erasure while reclaiming a sense of self and fraternity.

Their immersive installations are poised at the intersection of body, affect and space, negotiating between physical, digital and virtual realms. A three-channel video projected onto overlapping screens project film clips, graphic animation and excerpts of text by the artists and other authors. At the same time, enormous speakers produce pounding bass lines and rhythmic chanting. A phantasmagoria of moving images breaks apart, flashes, descends and dissipates across a collage of small and large rectangular screens, producing a disjointed viewing experience not unlike that of looking into a tessellated mirror.

In their decade-long project, May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth (2010–ongoing), Abbas and AbouRahme intermingle original footage with video clips sourced from online archives and social media posts of people singing and dancing in Palestine, Yemen, Iraq and Syria. Using a handheld camera, they record

people’s improvised interactions with the land, preserving the real-time unfolding of a moment that, in their words, “can activate something that was otherwise inactive,” and gesture to the invisible just beneath the material surface. By merging archival and original film, the artists forge connections across time and geographical locations and visualize the legacy of resistance in a way that allows the past to instruct and inspire the present.

“We are engaged in producing a nonlinear reading of ‘our’ time that allows for a sense of multiplicity both conceptually and formally,” say the artists. To that end, their projects are formally malleable, continuous, “unbounded” and capable of accommodating shifting responses to ongoing events.

For example, their most recent work, Only sounds that tremble through us (2020–22), first shown at the Museum of Modern Art in 2022 and now open at MIT List Visual Arts Center, revisits the material and concep -

“ Their immersive installations are poised at the intersection of body, affect and space, negotiating between physical, digital and virtual realms.”

tual concerns animated by May amnesia. In collaboration with Palestine-based performers—dancer Rima Baransi, electronic musicians Haykal, Julmud and Makimakkuk—Abbas and Abou-Rahme filmed their respective performative responses to the original archival footage of people dancing and singing at weddings, funerals, political demonstrations and impromptu social gatherings. These fresh improvisations both echo and evolve the inherited gestures, lyrics and rhythms. The looping voices and images increase in urgency, capturing the perpetual dream of Palestinians in the diaspora to finally return to “the lost ground of our origin, the broken link with our land and past,” in the words of PalestinianAmerican literary critic Edward Said.

Juxtaposition, symmetry and abstraction precipitate resonant connections between the seen and unseen, the spoken and the unspoken, without imposing any artificial structural unity onto the flux of images and texts.

While complex layers of rhythm and repetition celebrate the generative possibilities of mutability, simulating how someone, in becoming other, can become more fully themselves. In this way the installation unites the degradation and violence of colonial conditions with the exaltation of collective endurance and ingenuity in Möbius strip continuity.

Through montage, the artists accommodate the complexity and multiplicity of experience—and the stories we tell about experiences—while pointing toward radical new formulations of identity and culture that disregard geopolitical boundaries. Just as the shattered glass recast perception, intermingling the self and other, Abbas and Abou-Rahme’s segments and soundbites envisage the possibility of “transcending the material constraints of individuality to see ourselves reflected in the glittering constellation of everyone else.”

“I’m not sure satisfaction is a thing I feel while making art. I get satisfied from stuff like getting my laundry done or digging a trench or putting away my books,” mused director Deborah Stratman in a recent interview with Documentary magazine. Perhaps this questing, open-ended relationship to her practice is why, at age 57, Stratman has nearly two dozen films to her name. An associate professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago, where she’s based, Stratman has exhibited work as far and wide as the Whitney Biennial, MoMA, Centre Pompidou, Hammer Museum, ICA London and pretty much every international film festival circuit. By some accounts, her video assemblages are the first to be described as “experimental documentary.”

Typically, Stratman directs, shoots, edits and designs the sounds for all her films, which eschew narrative conventions of causality or linearity in favor of the associative logic of a collagist. The gestation period for each production is unpredictable,

Stills from Last Things, 2023.

sometimes lasting months, sometimes years, although “there’s a tipping point where if I were to keep collecting, a film loses momentum and I get bored,” as Stratman explained in a conversation about Last Things (2023), her latest documentary. “For essayistic films like this one, I accrue way more material than I can use. Then I condense that unruly, amorphous cloud to try to say as much as I can in as few moves as possible.”

The opening shot of Last Things is the earliest known rendering of the Milky Way, a drawing by astronomer William Herschel from 1785. It resembles an approaching figure, with our sun where the heart would be. “All the world began with a yes,” quotes the clear, softly accented voice of filmmaker Valérie Massadian, one of two that will echo in voiceover throughout Stratman’s “science factual” film. “One molecule said yes to another molecule and life was born,” Massadian continues, “but before prehistory there was the prehistory of prehistory.” This epoch is the focus of Last Things. A mes-

merizing collage of video, images and quotation—this first line is from Clarice Lispector’s 1977 novel The Hour of the Star—Last Things radically decenters mammalian development from our narrative of the planet’s becoming. This is evolution from the geological perspective: 16-millimeter footage of wildly spiraling, propagating crystals, glowing stalactite caves, microbiological family trees and other ephemera from the mineral world conjure a fruitful planet in which humankind is a peripheral organization of matter.

Some scientists have called the Anthropocene “the geologic turn,” since the planet is experiencing change on a scale not known in human history. Last Things, likewise, faces backwards and forwards, describing both the past and the possible post-human future. Stratman fuses together two stories by the 19th-century speculative fiction novelist J.-H. Rosny to form a narrative voiced by Massadian, in which inorganic alien life forms—the geometric Xipéhuz and the crystalline, iron-

“One molecule said yes to another molecule and life was born.”

eating Ferromagnetics—have colonized Earth, laying waste to human society and leaving only a few unlucky survivors to bear witness to the new geological order.

The other voiceover in Last Things comes from geologist Dr. Marcia Bjornerud , partially from interviews recorded with Stratman, and partially from lectures given for a course known as HELL (the “History of Earth and Life”) at Lawrence University in Wisconsin. Acting as an ambassador from the geo-biosphere, Bjornerud advocates for a “poly-temporal” worldview that incorporates the overlapping rates of change that effect our planet, particularly those that are so powerful they mostly surpass the scale of human perception. Rocks, too, can adapt, evolve and go extinct, she explains; but their lifetimes are beyond anthropocentric comprehension.

The enormity of planetary timescales, which render almost any form of life fleeting, carry a kind of inherent violence. For her part, Stratman has said that “low-grade terminal

anxiety” about being in the midst of the sixth great extinction was the catalyst for making Last Things, which has been slowly migrating to independent theaters across the United States. Her filmography often contextualizes human activity within a topographical scope—in such films as O’er the Land (2009) and The Illinois Parables (2016), Stratman foregrounds the landscape as constructed by various ideologies but ultimately resistant to it; no matter how territory is divided or appropriated, human struggles play out upon an unfeeling terrain. Nobody talks about global warming in Last Things, but they don’t have to—extinction proves cyclical, change once again the rule.

I was able to catch a late-night screening of Last Things at a local theater on a special limited run. Afterwards, stepping into the night air outside the theater, I had the profound sense that I was just visiting. It’s a relief to leave behind the messy, fleshy human world for something more perfect and enduring.

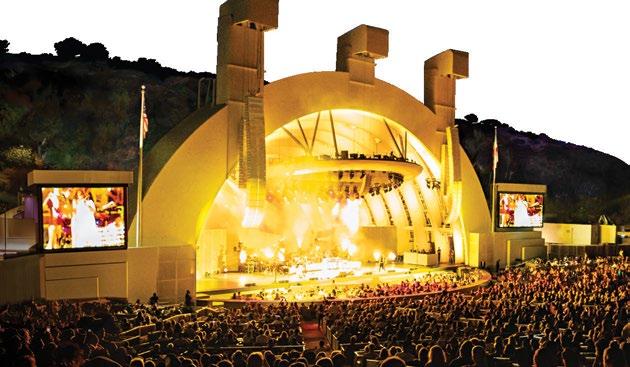

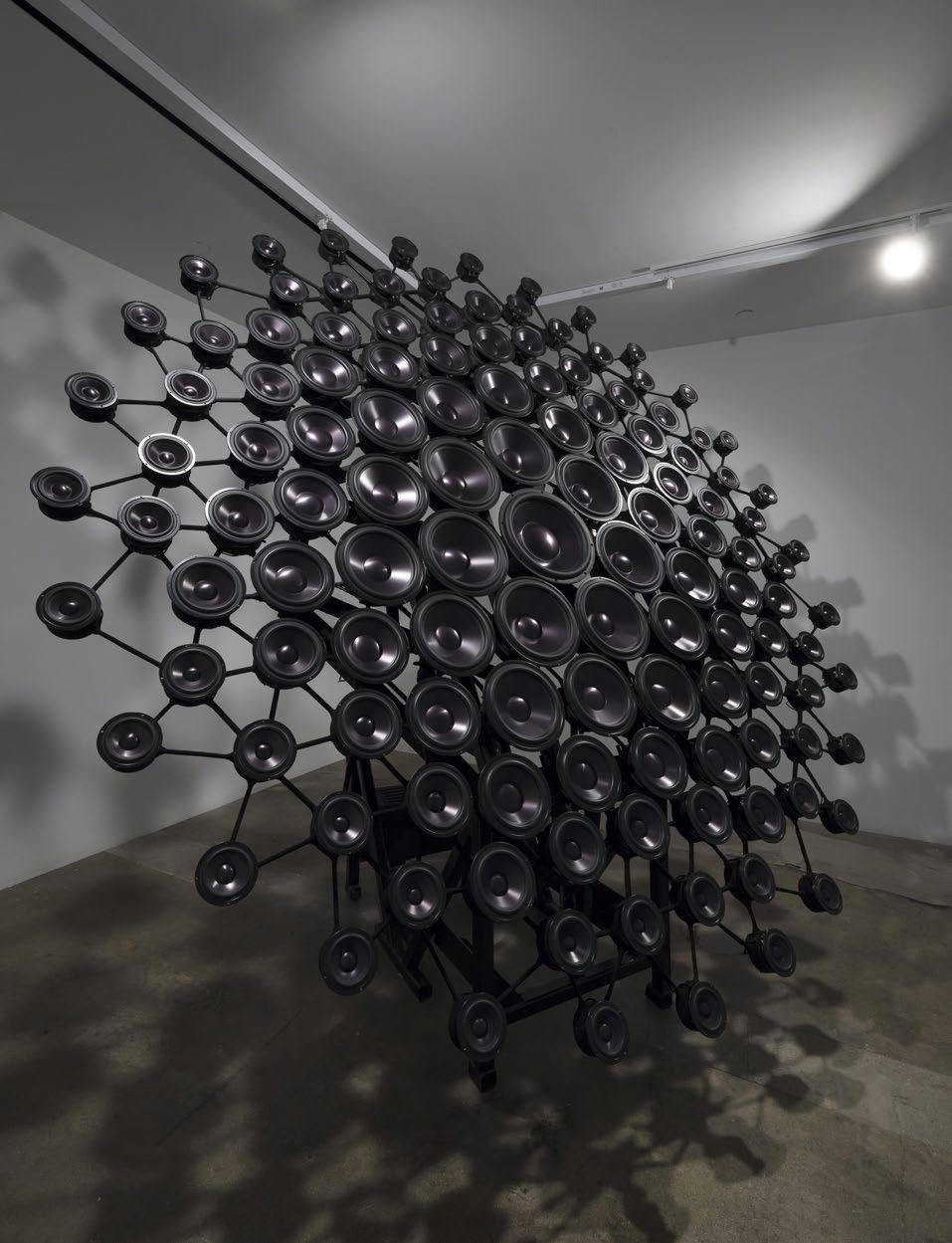

Jónsi, artist and frontman of Icelandic post-rock band Sigur Rós, masterfully crafted a recent show titled “Vox” which challenges the definitions of visual, sonic and olfactory art, merging the mediums to form a multi-sensory exhibition that plays on the viewer’s mind and body.

The entry point to the show is Var (safespace) (2023), a tapestry of hundreds of micro speakers draped over a rope strung diagonally from one corner of the room to the other. Reminiscent of a rudimentary tent, the speakers emanate a mixture of bubbling water, faint whistling, ambient techno and other sounds that swirl together in a surprisingly gentle cacophony. The intensity of noise shifts as you walk around and under the sculpture, creating new sensations with every pass, all accompanied by a faint smell of cis3-Hexen-1-ol, the semiochemical associated with the scent of freshly cut grass. Closing your eyes, the soothing and often nostalgia-inducing aroma intertwines with the sounds to transport you to a tranquil space of your choosing.

In a separate enclave of the gallery is Silent sigh (dark) (2023), a large sculpture, the face of which is a circle made of 100 different-sized speakers arranged with the largest in the middle and the smallest on the fringes, like some organism growing outward. A deep,

metallic arpeggio-like sound filters out of them, and with each beat the speakers softly pulsate—pushing the noise from the sculpture’s center to its edges and back again, like a rock skipping on water or a heartbeat. Each note becomes physical as the speakers hammer forward with each note. The subtle throbbing creates a visual ripple that carries your eye through the sound.

Combining the multitude of senses of the two sculptures, the immersive installation shines as the focal point of the exhibition experience. Behind a heavy black curtain, the darkened room is illuminated by four LED screens that run the length of each wall. In the center is a bench, with speakers underneath that vibrate through the body of anyone who sits on them. A deafening combination of Jónsi’s voice and AI-generated vocals resound throughout the room, passing beyond intelligibility as they mix in a dissonant yet beautiful sound. Fog-like air embraces you as vetiver and other earthy notes are vaporized into the room. The multisensory work builds on the basest interpretation of video art as light displays morph across the screens in response to Jónsi’s voice. In the thick atmosphere, the installation is all enveloping, with each breath contributing to the work. This deeply corporeal but highly ethereal show—even with your eyes open—is almost a holy experience.

Franco Rossi’s restored Smog plays like a Nouvelle Vague travelogue, with protagonists seemingly lost in an urban landscape that amplifies their inner malaise. That backdrop is Los Angeles and the long-lost 1962 film (now finally available in a pristine 4K restoration by Cineteca di Bologna and UCLA Film & Television Archives) is also a snapshot of the city in its modernist “adolescence.”

At the time Rossi was one of the very first European directors to film entirely on location in the US, and director of photography Ted McCord (East of Eden (1955), The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948)) captured the sprawl in stark black and white, including lost Hollywood landmarks, Pierre Koenig’s iconic Stahl House (Case Study House #22), the Baldwin Hills oil fields and (at the time) a just remodeled LAX. Vittorio, a Roman lawyer, played by Enrico Maria Salerno, is forced to spend 48 hours in the city due to a missed flight connection. Confounded by the undecipherable geography and its rootless inhabitants, he is both attracted and repulsed by what he considers the vapid lives of the Italian expatriates he encounters, including enigmatic Gabriella (Annie Girardot). The film uses the Los Angeles location to explore themes of mobility and impermanence, identity and displacement, a metaphorical gaze on the city, which was becoming a subject for artists such as Ed Ruscha, Joan Didion, Dennis Hopper, David Hockney and Charles Bukowski—as well as the locus for a veritable explosion of mid-century architecture. The movie, which also includes a haunting score by Piero Umiliani and Chet Baker, screened that same year at the Venice Film Festival before disappearing, unreleased, into the vaults from which it just now re-emerges as a singular time capsule.

Stills and original poster from Smog, 1962.

For his untitled exhibition at Gaylord Apartments, Brad Kronz created what looked like a kind of deinstallation—the last few items left in an apartment before moving out, things you don’t know whether to leave or to stack on top of an already packed car: an auxiliary chair, a few Wi-Fi routers and wires, scraps of defunct wood furniture. But upon closer inspection the objects had each been carefully placed, some altered by the artist.

The wall works on view, several of which looked like finished wood floors or tabletops, left the viewer with an opaque surface where there should have been something to look into: a mirror, a window or a painting. Instead, a smoothed wooden surface on top of a layer of drywall conceals matter sandwiched between them. Around the edges of both Designer of the cross and Fake spirituality filled with darkness (all works 2024), something pokes out where insulation might be. In the former,

it’s wool that looks like human hair; in the latter, a thick black cord is wound around the work’s interior. Kronz addresses a gap we don’t often see but only sense beneath the surfaces that surround us.

Floating in the middle of the room was a similar-looking piece, Lives in NY, Works in Cincinnati, a wood support and drywall surface with wool in the middle. But with this work there was something to look into. Mounted where a peephole might be is a sepia-faded photo of an open door. The work has a wire on its back as if it’s intended to be mounted on the wall. Kronz creates an infinity effect with these sculptures but with the end result of opacity rather than clarity. A door within a door, a wall on a wall; the viewer’s perspective hits a limit.

In the short text he wrote to accompany the show, Kronz offers a Duchampian philosophy: art offers to “resolve,” as he writes, the implicit problem posed by objects, suggesting that once it is art, “the object is never again your problem.” In making art with or about these random objects, Kronz develops a way to deal with their adjunct presence. The work that addresses this most directly is My car lives outside, a sculpture made of the bottom half of a stool turned upside down, its inverted legs supporting two pieces of bluntly cut wood that display two Wi-Fi routers with cords coiled in the space underneath. This is the most frustrating work in the show but perhaps the most evocative. It has a pesky stupidity—both as an inane subject for art and then in the impotency of its unplugged cords, which render it useless while leaving us to deal with its bluntly dull appearance. But Kronz doesn’t fuss too much over it, or push this imperative to find “poetry in the mundane.” In fact, he asks us to sit with the prosaic, the objects that may, in fact, be just objects—or art, which perhaps too, is sometimes just boring.

“Self is source. Self is pure positive energy. Self is worthy. Self is full of vitality. Self is healthy. Self is eager about life. Self is amazing.” One might imagine this incantation spoken in a low, meditative tone, as though by uttering the words with enough intention the speaker might manifest this vision in their own life. But artist Nora Turato chirps the staccato affirmations quickly, her cadence upbeat, like that of a motivational speaker selling you on

tools to transform you—finally—into someone who can “get to [their] ultimate destiny.”

Critically, that destiny and those tools are never disclosed in Turato’s 47-minute video pool 6 (all works 2024), which occupied one half of the two-room exhibition “it’s not true!!! stop lying!” at Sprüth Magers. Instead, she sutures plaintive cries for healing, hackneyed wellness jargon and interrogations of selfhood into a sweeping monologue, which was present both as large red subtitles and as audio, her caricatured voice booming throughout the space.

Like pool 6, Turato’s text-based enamel wall works and murals distill an affective mode prevalent in recent years: that of the wellness aspirant. One enamel-on-steel work reads in blocky red lettering “I NEED SOME HEALING.” Another wall-spanning piece reads “speaking my TRUTH!!!” Each is composed solely of text on a monochromatic ground, employing scale and capitalization to register a frantic tone. Much of Turato’s text sounds confessional, but the phrases appear without context, like floating signifiers awaiting a subject to adhere to.

Such anxieties about authenticity, healthfulness and personal achievement channel the market consciousness of a $5.6 trillion wellness industry. The artist appropriated her text from films, online forums, motivational talks and ad copy. Turato arranged the resulting pool of language in a book, which she then edited into monologues for her videos and performances, enamel panels and murals. Rather than offering viewers a glimpse into the private consciousness of another, she ventriloquizes the afflictions and affirmations that structure the wellness market’s faddish vocabulary.

Turato’s anti-lyricism is furthered by the works’ industrial aesthetic. Made of steel, vitreous enamel and emulsion paint on sometimes billboard-level scales, Turato’s

works are not intimate, despite their emotional tenor. Instead, they suggest that the language of self-optimization pushes in on us by way of contemporary marketing strategies, infiltrating not only our speech but our innermost feelings as well.

One might feel superior to the anxious desperation voiced by the more plaintive of these works. Others are ironic and detached in tone, such as authenticity haha, in which the titular words emblazoned large-scale walls at the gallery’s entrance as if inviting viewers in on a joke. And in pool 6, Turato’s magnificent performance at times can seem spiteful. But at the same time, as she estranges and thus critiques the idioms of an industry profiting from personal and social ailments, she mirrors some of its allure. Backgrounding the text in pool 6, clouds move in real time through a pale blue sky. Viewers were drawn into the video’s atmosphere, its heavenly image mirrored by the shiny floor below as though beckoning interlopers to enter its space. Once you’re in, it’s hard to exit.

As a Korean-born queer person who was adopted at nine months by a conservative white Christian family in the Tennessee Bible Belt, Se Oh struggled for years with the trauma of rejection, including from their adoptive parents who believed that homosexuals don’t make it into heaven. In the two-part exhibition “Elegies (Little Deaths/The Witnesses),” Oh enacted a symbolic purging of painful memories and the emotional wounds they

suffered simply for being Asian American and gay, while paving a road to self-affirmation.

Part I of the exhibition consisted primarily of “Little Deaths” (2024), a wall-mounted installation of 60 small, handmade porcelain vessels. Arranged on a grid of shelves, these are loosely based on Korean funerary objects that are traditionally buried with the dead. Stylistically, the vessels simulate forms found in nature, with their mouths opening like flowers. Metaphorically, the overall grouping was intended to represent the unpleasant or regrettable experiences, habits or relationships that punctuate our lives, and that, through will and resilience, we are able to put behind us. Oh also suspended two clusters of vessels from the ceiling, titled A Mother’s Tears and A Father’s Tears, (both works 2023) as representations of their own parents’ grief.

At the opening reception for Part I, Oh invited visitors to participate in a ceremonial catharsis through which they too could lay some bad recollection to rest. Each attendee was asked to write their memory on a piece of incense paper soaked in essence of chrysanthemum, a flower associated with Korean funeral rites. The papers were then lit and burned in a ceramic vessel. Oh’s participatory healing ritual is similar in process and format to Kim Abeles’ Pearls of Wisdom: End the Violence project (2011), in which the artist led workshops for victims of

domestic abuse and their supporters, who each wrote traumatic memories on pieces of paper that they concealed in oyster-shaped sculptures they made themselves.

More than a month into the exhibition, Oh added Part II, “The Witnesses,” (2024) a series of new, larger vessels based on Old Testament depictions of angels. While still mimicking floral or vegetal formations, these symbolic observers of the artist’s “Little Deaths” have eyes peering out from them. Additionally, they have been coated with celadon, a green-tinted glaze that originated in China and is common in Korean ceramics.. In wedding JudeoChristian subject matter with a medium tied to their ethnicity, Oh cleverly unites their birth and acquired heritages.

The second half of the show also included a number of newly created vessels that focus on rebirth and rejuvenation. Conceptually, this idea was expressed through recycling the ashes from the earlier ceremony. For added hanging works such as Ego Death (2024), the artist mixed the ashes into the celadon glaze, giving them a new life and context. This technique was also used for the interior sections of new “nested vessels,” where one ceramic object is lodged inside another. The artist views the exterior vessels as flowers that open to reveal one’s inner self. While presenting us with a delicate and poignant form of visual poetry, Oh appears to have found a path to acceptance and peace.

Zizipho Poswa’s monumental ceramic and bronze sculptures hold court like an enclave of demigods. While not figurative per se, they are anthropomorphic in the way all ceramic vessels are: All are additionally crowned with towering, ornate objects that radiate ceremonial significance whether or not one is conversant in their Pan-African cultural references. However, the viewer who takes the time to learn these references is amply rewarded. Returning to the works with a fuller understanding of their matriarchal, ceremonial, artisanal characters, one finds their evocation of protective feminine forms even more powerful.

The objects-turned-crests that rest atop Poswa’s five freestanding sculptures are interpretations of objects from the realms of beauty, adornment and healing drawn from a cluster of African cultural traditions including the artist’s own—partly as a means of personal narrative, partly as an ode to the enduring and unparalleled skills of African craftspeople and finally as a reminder of the histories of sophisticated and thriving matriarchal societies across the wealthy Nubian kingdom. But rather than enlarged depictions, Poswa’s ceramic and metal pieces are the result of transformative actions and are shaped as much by contemporary sensibilities of theatricality and emotion as by treasured legacy.

To accomplish this feat, the artist enlisted the support of legendary boundary-pushing ceramicist Tony Marsh and the Center for Contemporary Ceramics (CCC) at California State University, Long Beach, with the result that the final works were largely produced here in Los Angeles and informed by this community’s stature as an international crossroads for the medium. One example of Poswa’s nods to modernity within this discourse is the way pigments (bright blue, red and yellow tussling with inky black splatter) are applied to the ceramic “bodies” of the works. In an assertively modern way, these painterly moments read like Abstract Expressionism. In lieu of the anticipated pattern or illustration of an important scene, the energetic gestures are disruptive of tradition in a way that feels expansive rather than subversive.

This strategy is evident in Akan (all works 2024), in which a vessel cloaked in lapis-lazuli blue dripping into a gradient of terra cotta is crowned with an embossed bronze crest that evokes a traditional emblem of the Asante

queen mother. In Fulani, the reference is to gold earrings traditionally worn by women in West Africa as symbols of social status or wealth—the bigger the better. Its body is an explosion of fiery red and yellow and has an unmissable resonance with mid-century abstraction. The bird-shaped comb form atop Cisakulo comes from what is now Mozambique, but its chic black-and-white, two-cavity body with its perfectly placed splash of pigment could have come straight from the runway. In each case, the elevated object/image that crowns these sculptures feels authentic and resonant. Their scale is at once operatic and temple-ready; and their meaning is also capacious—they are able to hold forms of personal significance and references to 20th-century art history alongside cultural inheritance and a dazzling vision of the future.

TANYA LEIGHTON

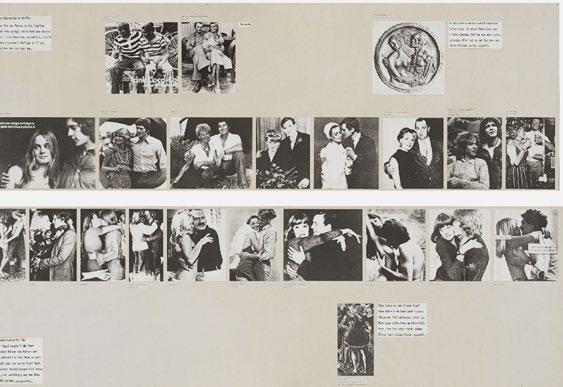

By Carol ChehLong before it was called out as a public nuisance, the phenomenon of manspreading was exhaustively, perhaps definitively, documented by the German feminist artist Marianne Wex (1937–2020) in a wide-ranging collection of images titled “Let’s Take Back Our Space” (1977). Fascinated by body language, Wex took photographs of people on the streets of her native Hamburg in the early 1970s while also collecting

Marianne Wex, Let’s Take Back Our Space: ‘Female’ and ‘Male’ Body Language as a Result of Patriarchal Structures (Possessive Holds), 1977/2018. Courtesy of Tanya Leighton.

images from commercial advertising, art books, pornography and photojournalism. Amassing an enormous archive of thousands of images, Wex first produced an artist’s book to help her process her findings. Then, she organized the images into a series of more than 200 groupings that focused on various themes, with each grouping pasted onto a large panel with occasional captions. In 2018, she worked with gallerist Tanya Leighton to select 18 of those panels to reproduce as editions of five.

The eight panels on view here presented a precise comparative taxonomy of several forms of manspreading as well as other manifestations of gender difference, through imagery ranging across cultures, social strata, geographical location and centuries. Wex’s sprawling work brings into sharp focus one of the essential edicts of gender difference: Men are taught to take up as much space as possible while women are taught the opposite.

Let’s Take Back Our Space: ‘Female’ and ‘Male’ Body Language as a Result of Patriarchal Structures (Standing Legs) (all works 1977/2018) features 16 men from different walks of life—businessmen, policemen, soldiers, entertainers—all standing with legs planted firmly and far apart, arms crossed or jammed into pockets, in postures

that are unmistakably aggressive. Beneath them are eight women of various ages and body types, all standing with their legs held daintily close together and their heads lowered modestly. Besides the marked difference in how each group took up space, I was also struck by how the men’s clothes signified their position in the world whereas the women’s nondescript outfits seemed to point to their lack thereof during a time when the primary occupation available to them was still that of housewife.

The image clusters included some variations, and these often had a cheeky and/ or queering effect. Standing Legs features one of a naked man, probably taken from gay porn, upright in a classically feminine way with hips tilted and legs close together. Let’s Take Back Our Space: ‘Female’ and ‘Male’ Body Language as a Result of Patriarchal Structures (Possessive Holds) focuses on the positions assumed by male-female couples when they embrace; the man always has his arm draped possessively over the woman, while the woman always clings to the man as she looks up at him passively. In the top right corner of this panel is an image of an ancient coin bearing the classic “death and the maiden” motif, blending in seamlessly with the other images on the board.

“Let’s Take Back Our Space” is Wex’s only surviving artwork; soon after making it, a critical illness forced her to pivot her life in another direction. A massive and revelatory achievement comprising a treasure trove of sharply observed images, this body of work remains as rich and relevant today as it was when it was created nearly 50 years ago.

Don’t be fooled by the name: The Pit in Atwater Village is a snake-free, gleaming, new 13,000 square-foot space, zippy with colorful work. After the first two galleries, there was a huge room devoted to “Cognitive Surge: Coach Stage,” a striking, memorable show of paintings, drawings and sculptural installations done individually and together by Los Angeles artists Paul McCarthy and Benjamin Weissman, two old friends and longtime collaborators.

Acrylics on paper by Weissman abutted those on canvas by McCarthy in this densely packed exhibition. Individually, each artist contributed a hefty 3D piece that took up part of the floorspace, while large canvases occupied three walls, with Weissman’s carefully rendered figures (in charcoal, oil pastel and ink on acrylic-gessoed paper) contrasting with McCarthy’s violently gestural abstracts. The two also collaborated on dozens of black-and-white drawings grouped together on one large wall.

In The Pit’s press release, artist Reuben Merringer describes the two men as involved with “the abject, the grotesque, the surreal, the repressed, the crazed.” That’s a pretty accurate list of adjectives for what one sees. The collaborative drawings certainly represent the “abject and grotesque” parts of their sensibilities. Filled with scrawled penises and “fucks,” they mark out and inhabit a scatological space that will feel excitingly liberating to some, drearily adolescent to others. More to my taste were the “surreal, repressed” parts of the terrain Merringer maps, represented by Weissman’s 10 large canvases and his sculptural installation of toy-sized wooden huts, Hamlet (2022–24).

Weissman’s little village grabbed my attention right away. I thought: Somebody else remembers playing with Lincoln Logs! But the huts are made not of notched logshaped blocks but of rough wooden sticks held together with resin and glue. Each hut is slightly irregular, and some have paths, little gardens or other bits of homemade fussiness. It was impossible not to imagine Grimms fairy tale characters living here among various shades of brown—or that they did until very recently; the hamlet seemed freshly evacuated, a perfect set for a spooky dream. Even as one inspected it, the piece’s mood transformed from the cozy to the death haunted. Could the absent hamlet-dwellers have been taken away?

Hamlet suggests why Weissman’s work is the sort that tends to stay in one’s mind: It contains enough paradox to transform itself as one looks at it. His paintings achieve

a similar effect, but in the opposite way. They’re almost overfilled with color, faces and text. But like the empty huts in Hamlet, the multiple figures in his paintings subvert any sense of comfort by returning repressed history to a contemporary situation.

For example, in Weissman’s Holiday (2023), a large canvas floats a carefully drawn elder standing behind a box of Yehuda Matzos as a bottle of Manischewitz hovers to his right. Yet this figure, framed as a painting-within-the-painting, is being carried away by workmen. Above them, we see a Christmas tree and a fireplace. Something uncomfortable about Jewish identity within gentile culture looms over this painting—possibly over the whole show. (What really happened to those hamletdwellers after they were taken away?)

At its best, that’s what “Cognitive Surge: Coach Stage” does: It invites the viewer into the contemplation of the dreadful secrets that might lie behind bright colors.

An escapist, fantasizing indulgence reverberated throughout Marc Camille Chaimowicz’s solo exhibition “Emma Dreaming of California.” Just as Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary—from which Chaimowicz extracted his protagonist, recontextualizing Emma Bovary within present-day California— titillates its reader with exacting details of its

characters and their settings, Chaimowicz also lingers on the minutiae of personal possessions and what they might indicate. Representing Emma through sculptures that appear to be household readymades, alongside collages and installations, the artist gave the viewer a peek into the world of the fictional character as well as his own retreat into this imagined universe.

On the far wall of the exhibition, a grouping of 33 x 23-inch works on paper hung in a row. The base layer of each pastel-hued swatch is a printed variation on the delectably intricate patterns that Chaimowicz has long utilized. Adorning each of these patterned bases is a photograph enhanced with various writings and embellishments. E.B. in L.A., no. 21 (1993/2023–24) depicts Emma as a dolledup Isabelle Huppert with the upside-down cross and butt crack of Man Ray’s Hommage à D.A.F. de Sade (1929) stuck to her face like a scarlet letter. Comedically captioning this collage are the words “EMMA FACING EXCOMMUNICATION AND APOLOGY ISABELLE HUPPERT.”

In distinct groupings throughout the gallery were collections of domestic objects that congregated around Chaimowicz’s sculptural furniture. Blurring the line between design and art throughout his career, the artist here included the functional Coffee Table Lilac (2024), Piano Stool (Burgundy) (2014) and Ashtray (2015)—all of which reference and flatten the flamboyance of Baroque detailing, commingling this sumptuous style with his own—to indicate the trappings of Emma’s indulgent new life in California. By literally placing these furnishings on a pedestal, the artist elevated a fictionalized scene of domestic discord to the level of art as if it were a still-life painting, suggesting the import of these functional objects is more about the story they tell than reflecting their use value.

Walking through “Emma Dreaming of California,” one wondered what is gained or lost in inserting the character of Emma within contemporary California. “IF ONLY EMMA HAD BEEN AWARE OF SELF EMPOWERMENT” [sic] one of Chaimowicz’s collages reads, implying that Emma’s dalliances would likely be more acceptable now. The artist’s speculation seemed keenly aware of itself in the joking captions and lavish scenes; he seems to poke fun at all this frivolity while simultaneously relishing it. The artist drew comparisons between times past and present but kept Emma squarely in the realm of entertainment—he granted her potential freedom from moral judgment by recontextualizing her character, while simultaneously undermining this generous

Judithe Hernández, Soy la Desonocida, 2022. Courtesy of the artist.

gesture by keeping her a spectacle to be ogled by the viewer’s amusement. Chaimowicz ultimately maintained his subject’s status as the haphazardly pleasure-seeking anti-heroine who must eternally cater to pleasure-seeking spectators, though—with this exhibition’s concept coming about in the depths of the pandemic—the artist’s expression of lighthearted condemnation for neglectful leisure was likely directed at himself as much as the character.

At the retrospective “Judithe Hernández: Beyond Myself, Somewhere, I Wait for My Arrival,” mounted by The Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture of the Riverside Art Museum, the full spectrum of an artistic career of more than 50 years was on view. Beyond Hernández’s masterful depiction of the figure, which she renders in vivid pastels on paper, a recurring narrative within this expansive exhibition was the artwork’s capacity to redeem and empower the women it portrays. The show was structured by Cheech’s artistic director, María Esther Fernández, into four sections based on her conversations with the artist: “Ni una más: Bearing Witness,” “The Evolution of the Female Archetype,” “Surrealist Landscape” and “Reimagining Eve.” Throughout, the only female member of the 1970s Chicago artist collective Los Four has painted with consistent, uncompromising clarity.

The works in “ Ni una más : Bearing Witness” harness symbolically potent imagery to address such issues as corruption within the Mexican government, the United States’ imperialist agenda and the epidemic of femicides that continues to ravage the American/Mexican Border. Soy la Desconocida (I am the Unknown) (2022) speaks to the invisibility of women.

An expressionless woman seen in profile floats, eyes closed, amid murky green weeds. Spiraling around her in the water are multicolored stemless flowers, while behind her two birds in flight hover in a forebodingly cloudy night sky. The birds carry a winding pink ribbon on which is strung a burning card with a rose on its face. Hernández’s searing iconography suggests the marginalization experienced by women and the feeling of desolation it yields.

The “Reimagining Eve” grouping assaults the traditional, phallocentric interpretation of the biblical creation story. The Seduction of Adam (2010) presents the tightly cropped head and shoulders of Adam, his face caressed from below by two hands, blue and red. A pair of bound purple hands, rope sinuously encircling them like a serpent, reach toward him from above and linger over his forehead; his eyes are closed as if reflecting destiny’s implication regarding free will. And in fact, the end of the rope has transformed into a gold-scaled snake whose flickering tongue slithers just below the subject’s chin, suggesting the correlation between choice and temptation.

The show was enhanced by ephemera that included sketchbooks, copies of Aztlán: Chicano Journal of the Social Sciences and the Arts , a 1974 Los Angeles Times news clipping about the mural painted by Hernández on the wall of the city’s Century City Playhouse and a video interview in which she discusses her early days as a student at Otis College of Art and Design. Collectively, they provided evidence of how Hernández interrogates sexist perceptions of women with her visceral voice. The work she has produced throughout her career has merged into a singular canon, reflecting an artistic journey drawing on the artistic modes of social realism, Surrealism and the Chicano Movement, which has forged a singular personal aesthetic borne of her unique synthesis of religious and political iconography and conceptual tactics.

Studio System brings the dynamism of the artist’s studio into the museum space by encouraging audiences to interact with working artists to discuss inspirations, sources, and more as they create new artworks over a month-long period.

PARTICIPATING ARTISTS: Clarisse Abelarde, Wayne Martin Belger, Taylor Moon Castagnari, Raphaele Cohen-Bacry, Justine Di Fiore, Craig Knight, Snezana Saraswati Petrovic, Ashton S. Phillips, Tania Salha, Gwen Samuels, Sarah Svetlana, Dilan Torres, Jacqueline Valenzuela

JUNE 01 - 29,

Gallery Two & Dark Room

RESONANCE

A Solo exhibition by photo-based conceptual artist Alanna Airitam inspired by 17th century Renaissance paintings and early Black studio photography.

TAM Hallway

An updated site-specific installation by artist Darel Carey.

April 27 — November 29

April 27 — June 1: on view in the gallery, opens with public reception April 27th, 2 – 4pm

June 1st, 7pm – 10pm soundpedro2024 CHARIVARI on-site installations & performances

August — November: Online Programming & Artist Curated Events

Gilbert & George, the quintessentially British pioneering queer artist-duo have staked a clear position within the milieu in which they operate. They have scant tolerance for art-world conventions, yet it is precisely that peevishness and their enduring, long-term collaboration that created the context for the creation of their provocatively lurid and iconic works.

On a recent trip to London, I made my way to their fairly new public art center— situated in the once dodgy Spitalfields district of East London. Gentrification has since transformed the area into a fashionable yet unpretentious neighborhood. The entrance to the Centre, approached from a quiet lane, is gloriously framed by an extravagant green wrought-iron gate distinguished by a rococo G&G flourish. Opened in 2023, the museum holds three gallery spaces in a renovated 19thcentury brewery building.

Important figures in British Conceptual art, these two self-proclaimed monarchists—Gilbert Prousch, born in Italy, and British-born George Passmore—are now in their 80s. They are renowned for their nearly identical modes of dress— usually matching suits, which serve as a kind of domestic performance art and mediating foil for reactions to some of their more outré artworks, which often include self-portraiture. They have been constant partners since meeting at Saint Martin’s School of Art in the 1960s—a ferocious and storied alliance that

resulted in, as Passmore quipped, “Two people, one artist.” Early formative works included The Singing Sculpture (1969–91), in which the pair painted themselves bronze and sang local public dirges—garnering much attention as a result—and Coming, 1975 (1975), a controversial suite of nine black-and-white photographs depicting ejaculation. In the 1990s, their works took on an increasingly scatological bent, with palettes of hallucinogenic intensity.

In some ways the Centre seems like an attempt to hedge their bets—to create a permanent edifice devoted solely to their output. It was always envisioned as a free public venue, in line with their “Art for All” philosophy. Rather than overwhelm the visitor with architectural excess, the brick-enveloped ambiance embraces one with a cocoon-like sensation; the building and its inner courtyard are quietly elegant and tranquil.