Pacific Standard Time

+ Last Letter from the Editor, Tulsa Kinney

+ Last Letter from the Editor, Tulsa Kinney

HOW QUICKLY CAN ART RELAX YOU? QUICKER THAN A COCKTAIL? CAN ART REDUCE TENSION FASTER THAN YOGA CAN? CAN ART BOOST SEROTONIN AND IMPROVE YOUR SLEEP?

CAN IT STOP TEETH GRINDING?

CAN IT RELEASE DOPAMINE AND HELP YOUR MOOD?

CAN IT INCREASE OXYTOCIN?

CAN IT FEEL LIKE LOVE?

CAN ART EASE ANXIETY? IF ART DECREASES CORTISOL, CAN IT ENHANCE MEMORY? AND MAKE YOU A BETTER STRATEGIC THINKER? DO ART LOVERS HAVE FEWER REGRETS?

800+ 70+

Closing soon on Sept 29

5 September – 26 October 2024

525 West 22nd Street, New York

SEPTEMBER 14 - DECEMBER 6, 2024

Public Opening Reception September 14th, 2pm - 4pm

METHOD is a group show embodying the spirit of experimentation across and beyond conventional frameworks. Juried by Kira Xonorika.

In collaboration with SUPERCOLLIDER supercollider.la

SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 14, 2024

11AM - 9PM

Free Admission or $5 Suggested Donation Learn more at http://opaf.info

Participants Beta Epochs • What’s my Thesis? • Escolar • sspatz LAWWSS • serving studio • Bedside Gallery • The Artist's Contract

Franco Castilla • ::JACOB’S:: • Cake666 • Frank M. Doyle Arts Pavilion (Orange Coast College) • Underscore • Triangle Projects Daylighting • QuorumQuorum • Momma • Harborview and Pole Frame Weave • The DMV (Departure from Music Venues) Jane Galerie + Melrose Botanical Garden • Quarters Gallery Print Shop LA • Court Space • Gene’s Dispensary A History of Frogs • Outback Projects • 839 • Place Settings

Harvest & Gather • KCHUNG …and more!

SAVE THE DATE: OPEN STUDIOS DAY • NOVEMBER 16, 12PM - 4PM

3601 S. Gaffey Street San Pedro, CA 90731 (310) 519-0936

angelsgateart.org

21825 Hawthorne Blvd

Torrance, CA 90503 vefagallery.com

Crenshaw Dairy Mart: 38

Abolition in Action

Bianca Collins

Heavy Water: 42

Rethinking the LA River

Renée Reizman

Lucia Monge: 46

Nature’s Way

Eva Recinos

Lita Albuquerque: 50 The Stars are Aligned

Shana Nys Dambrot

Shop

Scarlet Cheng

Peer

Ellen

Seth

Skot Armstrong

Markus Lüpertz & 56

Pierre Puvis

de Chavannes

Michael Werner

Bernard Cooper 57 Gattopardo

A Sense of Wonder: 52

The Islamic World

Barbara Morris

Performance: 54

Death of a Star

Gracie Hadland

by Lynda Burdick

Ask Babs: No Wacky Paint Party

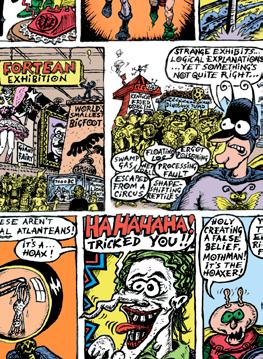

Babs Rappleye Poems: Hans Wagner, 62 John Tottenham Comics: Fortean Adventures 64 Butcher & Wood

Kyungmi Shin 57

Craft Contemporary

Chris Eckert 58

Long Beach Museum of Art

Chiffon Thomas 58 Michael Kohn Gallery

Uta Barth 59 1301PE

ON THE COVER: Hayv Kahraman, Eye-dates, 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Pilar Corrias. OPPOSITE PAGE, clockwise from top left: Crenshaw Dairy Mart, abolitionist pod at the Hilda L. Solis Care First Village in Chinatown, LA. 2022. Photo by Gio Solis; Jennifer Steinkamp, Swoosh, 2024. Photo by Iwan Baan; Jenny Kendler, Forget Me Not, 2020. Photo by the artist; Bernard Cooper, Cross Pollination, 2023. Photo by Chris Hanke. Courtesy of the artist and Gattopardo; Kelly Wall, Higher Self, 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Various Small Fires; Comics by Susan Butcher and Carol Wood; Lita Albuquerque, Malibu Line, 2024. Photo by Marc Breslin. Courtesy of the artist and LAND; Lucia Monge, Mientras una Hoja Respira (While a Leaf Breathes) presented at ArtYard in 2023 and Hampshire College Gallery in 2024; Lauren 2Dope, still by Sydney Morrell; Ellen Schafer, Suit I, Suit II and Suit III, all works 2024. Photo by Josh Schaedel. Courtesy of the artist.

Dear Reader,

I have good news and bad news. Let’s start with the bad news: This, after 18 years, is my last editor’s letter. What an incredible journey it has been. Here’s the good news: Artillery will still carry on! More on that later.

I started this magazine with my late husband, Charlie Rappleye, in the summer of 2006. This career-turn was a surprise to me, as being an editor of a magazine was never on my list of what I wanted to be when I grew up. I’ve been an artist all my life. Whether I want to reenter that world after this, is another question. After being the editor of a contemporary art magazine in Los Angeles for nearly two decades—I now feel that I know too much. I’ve seen the machinations of the art world, and it’s not the prettiest picture, certainly not one I want to jump right back into as an artist.

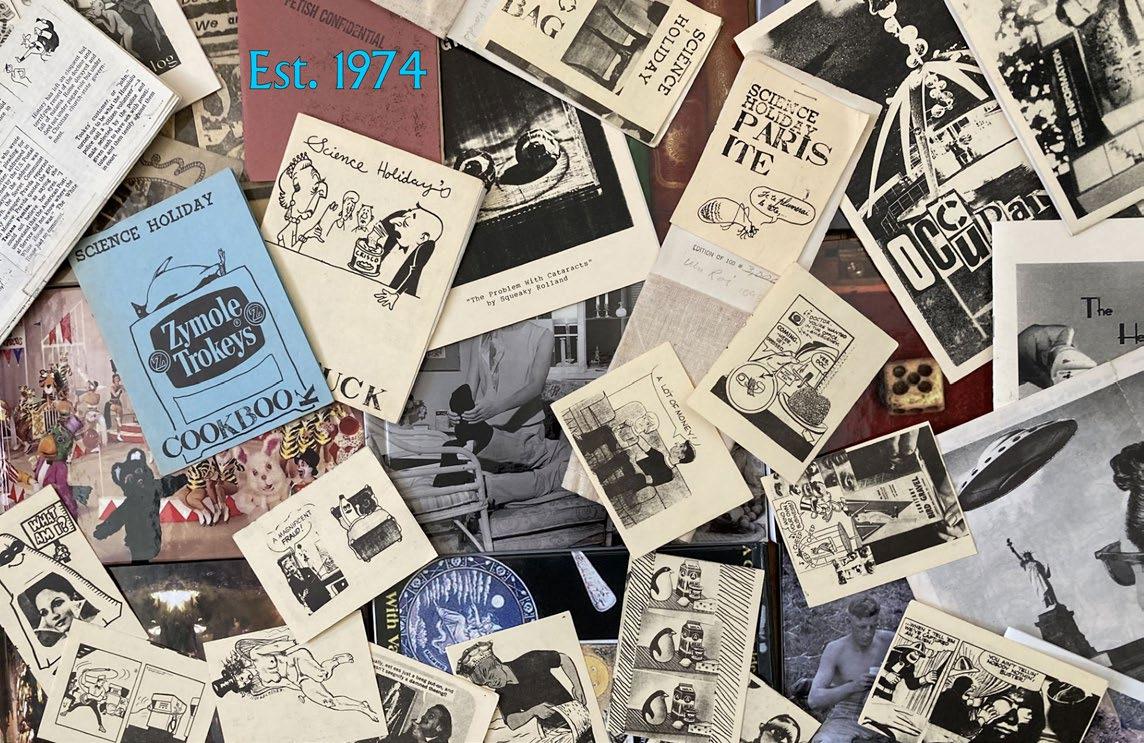

But for now, I’d like to reflect on that incredible journey with the art world. Back in 2006, there was a severe dearth of readable LA art publications. A few quarterly nonprofit academic art journals were in circulation, but I found them to be deadly, and most people would silently agree. I had edited the local naughty art zine, Coagula, for a year, and enjoyed that immensely: I loved publisher Mat Gleason’s unfiltered take on the art world, but I wanted something in between—something that reflected the real world of an artist, something more daring and iconoclastic. Some humor, even?

By Artillery’s third year, a new tag line was added to our logo: The Only Art Magazine that’s Fun to Read! At that point we had comics, poetry, opening-party photo spreads, reports from Gotham City. There were fleeting columns with names like Throttle, The Poseur, Outer Space, Retrospect (by THE Mary Woronov), Under the Radar, AmmuNation, Private

Eye, Off the Wall—and my fave, On the Wag with Mitchell Mulholland, our gossip column that was so snarky and sardonic that I was forced to kill it in the interest of survival.

We were off to a good start: The LA art world embraced us, and we hired Paige Wery at the end of our first year. Paige had never been a publisher, but none of us had experience in running an art publication either, so we took a chance. Turns out, she was a natural and boosted the magazine to another level. We went to art fairs, book fairs, threw parties, poetry readings and art debates. We traveled to New York, San Francisco and Miami. We were a great team—certainly a highlight for me in the magazine’s early years.

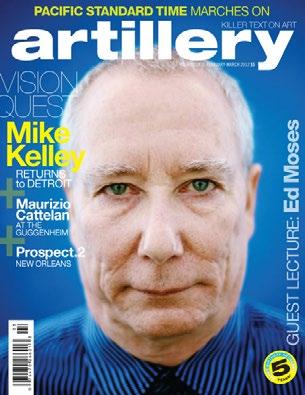

Getting to know the art world through a different lens sometimes soured me. Often, it just wasn’t my scene; I felt like an interloper. Then I’d run into artists like Mike Kelley, and all the sourness would disappear. He was so real and unpretentious. At art openings he was a delight, and we would crack wise. I would routinely pester him to let me interview him and eventually he agreed. I told him I’d contact him soon.

That’s when Kelley preempted me and sent a “letter to the editor” that bitch-slapped me about being maligned in our gossip column, and he demanded we cancel his subscription immediately. He added that he was looking forward to wiping his ass with the magazine, especially the Mitchell Mulholland page.

I think we all know how this story ends. Yes, I did get an interview with Kelley, but tragically it was his last interview. He was on the cover of our January 2012 issue when he took his own life. The interview was extraordinarily profound and eerily prescient. What happened was beyond heartbreaking.

Of course, I will never be able to blot that out of the maga-

zine’s trajectory. The irreplaceable loss of Mike Kelley seemed to take the life out of the art world for a while. Why did he do it? He was right on the edge of grand success, the kind artists strive for, having just signed on with Gagosian. But he didn’t seem to be relishing it. In our interview he kept mentioning to me how his father referred to him as a Martian.

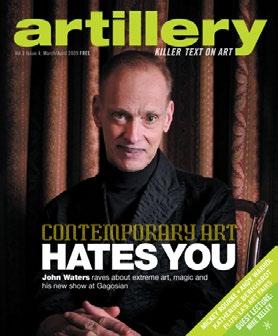

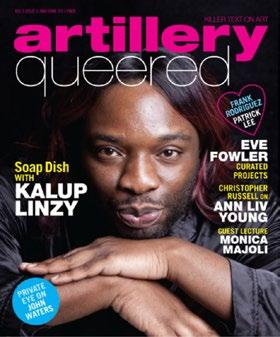

Being an artist or even proclaiming you were an artist used to feel like being an outsider or someone on the fringe. It wasn’t as acceptable or widely embraced as it is today; it certainly wasn’t thought of as a prudent career choice. With the plethora of art schools in Southern California churning out artists who have chosen to stay in LA, Artillery found no shortage of content to cover. A few times I invited our contributors to edit a theme they wanted to delve into, and many ended up as our most provocative issues. Contributor Tucker Neel pitched a “Queered” issue back in 2011. He gleefully pointed out that our cover of New York artist Kalup Linzy was the complete opposite of LA’s other art magazine, which at the time featured Ed Ruscha on its cover. I probably don’t have to spell it out, but, uh ... straight old white male vs. queer young Black artist? In many ways, I felt Artillery was ahead of its time, certainly a unique publication. We had a 2008 issue on race long before the BLM movement, and a sex issue that had clients vow that they would never advertise with us again. One coverline, Contemporary Art Hates You (my John Waters interview) had my publisher screaming, “It looks like it says, ‘Artillery Hates You’”—I secretly loved that. Our Celebrity issue with Martin Mull on the cover was sort of genius, I must admit. I truly felt our magazine was the only art magazine that was fun!

And I did have fun with the magazine, but now, I’m not having as much fun, and for me, that means it’s time to move on. I believe what I created was and is something important to Los Angeles, being a significant art center. I hope you do too. That’s why it’s time for me to go and let someone else come in with fresh ideas and shake things up a bit. My successor is Daniela Soberman, whose first issue will be November. She believes in Artillery and knows its value in a big city like LA, as I did, and knows it can grow and maintain its integrity and devotion to quality art journalism.

With that, I bid my adieu. It’s been a great ride. I cannot thank my loyal freelancers and staff enough for all their dedication, hard work and enthusiasm. Many of you will be lifelong friends— such a treasure to me. And our advertisers, you literally kept us alive with your support and belief in Artillery. I know some of you had to rob your piggy bank to pay for that ad, but you knew the importance of having an excellent art magazine. Journalism is a dying art, and I have such respect for our advertisers that wanted to reward and keep that alive. And I didn’t forget about you, Dear Reader, for we simply would not exist without you.

Lastly, Artillery carried me through good and bad times in my own personal life. I never missed an issue, even when my husband died, going on six years now. I knew it would be the only thing that could get me out of bed during that deeply dark time in my life. Charlie believed in Artillery and wanted it to succeed in every way. I want that too, and now I get to sit back and watch its legacy live on.

Bianca Collins

amplifies the work of female, nonbinary, trans and BIPOC artists. Previously, she was editor of KCRW’s “Art Talk” during All Things Considered with Edward Goldman. A queer woman of color, she produces public art experiences in, with and for historically marginalized communities as director of public programs for Zócalo Public Square.

Renée Reizman is

an interdisciplinary artist, writer and curator. She coauthors dialogues in diverse communities to study the ways infrastructures shape our culture, policy and environment. Her writing appears in Hyperallergic, Art in America, New York Magazine, The Atlantic, Vice, Teen Vogue and more. Follow her on Instagram or Twitter @ reneereizman.

Eva Recinos is an arts and culture journalist and creative nonfiction writer based in Los Angeles Her reviews, features and profiles have been published in the Los Angeles Times, KCET, The Guardian, Hyperallergic, Art21, Aperture, Poets & Writers Magazine and more.

Shana Nys Dambrot is an art critic, curator and author based in Los Angeles. Formerly LA Weekly arts editor, now the co-founder of 13ThingsLA, she is the recipient of the Rabkin Prize, Mozaik Prize and the LA Press Club Critic of the Year award (twice). Her novella Zen Psychosis was published in 2020.

EDITORIAL

Bill Smith - creative director

Cat Kron - reviews editor

Emma Christ - associate editor

John Tottenham - copy editor/poetry editor

John Seeley - copy editor/proof

Dave Shulman - graphic design

Fiona Perkocha - intern

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

Ezrha Jean Black, Laura London, Tucker Neel, John David O’Brien

COLUMNISTS

Skot Armstrong, Scarlet Cheng, Stephen J. Goldberg, Seth Hawkins

CONTRIBUTORS

Anthony Ausgang, Emily Babette, Lane Barden, Natasha Boyd, Arthur Bravo, Betty Ann Brown, Susan Butcher & Carol Wood, Bianca Collins, James Cushing, Shana Nys Dambrot, Genie Davis, David DiMichele, Lauren Guilford, Gracie Hadland, Christie Hayden, Alexia Lewis, Richard Allen May III, Christopher Michno, Isabella Miller, William Moreno, Barbara Morris, Carrie Paterson, Lara Jo Regan, David S. Rubin, Julie Schulte, Allison Strauss, Daniel Warren, Colin Westerbeck, Eve Wood, Catherine Yang, Jody Zellen NEW YORK: Annabel Keenan, Sarah Sargent

ADMINISTRATION

Mitch Handsone - new media director

Emma Christ - social media coordinator

Anna Bagirov - senior advertising sales

PO Box 26234, LA, CA 90026 Editorial: 213.250.7081 editor@artillerymag.com

Here’s something different: I am going to talk about the Olympics that were opening in Paris as I wrote this column. Especially exciting were the athletes floating down the Seine in a series of boats—so improbable, but so original, and so picturesque against the bridges and the banks of the freshly cleaned river.

A magnificent spectacle accompanied the boat parade—a relay of people bringing the Olympic torch across Paris, from underground tunnels to rooftops, to light the flame. They managed to get in so much art and design, so much history—moving from the Eiffel Tower to the Grand Palais, the Louvre and the Tuileries with dancers, singers, acrobats and the ghost of Marie Antoinette. The torch bearer at the Louvre found the Mona Lisa missing. There was lots of humor and quite a bit of camp, especially in a scene of colorful characters seated at a long table, which served as a runway for some over-the-top fashion.

The next day, the news was full of outrage against an alleged parody of da Vinci’s The Last Supper —the pileup included French clergy and politicians and some Americans on the right. The US House Speaker, Mike Johnson, declared, “Last night’s mockery of the Last Supper was shocking and insulting to Christian people around the world.” Who knows where this warped notion began? I never once thought of The Last Supper while watching the opening ceremony. Presiding over the festivities was a full-bodied woman with a radiant crown—no Jesus, no ritual drinking or eating, no backstory of betrayal. However, the conservative right invents make-

believe insults in order to continue the culture wars. Thomas Jolly, the ceremony’s artistic director, explained “The idea was to have a pagan celebration connected to the gods of Olympus.”

So, what will Los Angeles do when the Olympics open here in 2028? Granted, we do not have the long history and scenic wonders of Paris. Here, we will be using existing facilities, such as the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, which was used in the 1932 and 1984 Olympics in LA.

The arts have long been a part of the Olympics, in their own competitions during the early years from 1912 to 1948. The Los Angeles 1984 Olympics offered the Olympic Arts Festival. Paris 2024 has an arts and culture program, the Cultural Olympiad. In June, Hollywood producer and arts supporter Maria Arena Bell was named Chair of the LA28 Cultural Olympiad, and I cannot wait to see what her team comes up with.

LA28 will also be using some new arena venues, such as those in the revitalized Hollywood Park. I have just been to openings for two more venues—Cosm Los Angeles, a new immersive venture, and Intuit Dome, the new home of the LA Clippers, which commissioned seven pieces of public art from our own SoCal artists. Six are completed—I was especially impressed by Jennifer Steinkamp’s pivot to lighting design—the Dome covered by hundreds of diamond-shaped panels with embedded LEDs not only changing color but making patterns that “move” across the surface.

Known for her life-sized stained-glass sculptures of intertwined lawn chairs, Kelly Wall uses sculpture and time to explore perspective in different ways, turning familiar objects into something uncanny and almost disorienting. In her recent outdoor show at Various Small Fires, “Time After Time,” Wall created careful constellations of aluminum sculptures of everyday objects centering around her fused lawn chairs, the shadows of the colored glass moving slowly with the sun. Including forms of rats, crushed cans and seashells, her aluminum works set on the ground in a circle became points in time, all of the elements of her show relating to each other to create a greater whole. For this issue’s “Peer Review,” Wall discusses the work of Ellen Schafer.

Ellen Schafer is a sculptor, but I really see her as an installation artist. Her scenes are set for the viewer to come into, which is why seeing the work in person can be such a different experience from seeing it in photos. There are ideas of characters involved in her scenes, presented through their wardrobes, and it makes you question who the missing character is.

In Schafer’s recent duo show with Nicolas G. Miller at Timeshare, titled “Plaza,” the artists created a ’90s mall environment with a soundtrack they made specifically for consuming goods; Schafer’s works included three classic clown suits, like those of a commedia dell’arte clown, with neck ruffles and polka dots, placed on metal hangers enclosed on the rack. Set up as a space created for objects to be bought, the show drew parallels between mainstream, pop consumerism and the fine-art world, honing in on the fact that making or buying art is similar to our other consumer experiences in the world. In that show, I wondered, are we the clowns? Or is the consumer the clown?

In Schafer’s work—and this is also an intention in

my own practice—she doesn’t answer questions, but rather poses them. As you go through her spaces, you start asking more things. It keeps me on my toes, and I never feel like I know exactly what the answer is, but I keep moving through it. When I first saw her work at a two-person show she had with Kerstin von Gabain at the Mak Center, I was blown away with the level of execution in her sculptures. She works with textiles a lot, and in that show she had two costumes on display of sheer pink-and-white bunny suits, one for a child and the other for an adult.

Her work is a back-and-forth play of found objects being used as readymades, creating objects so highly fabricated that they look like they could be a readymade or mass-produced item. Every time I think I know what’s happening, something slightly shifts. It’s a very active experience of sculpture—sculpture takes time because you have to move in space to look around it, and this unfolding through time is such a treat to the viewer.

—As told to Alex Garner

There are few places on this earth where I have stood and felt humbled, in awe of the grandeur of human achievement, where art and architecture intentionally merge with consideration of form and function—and where sexy-ass aesthetics rule the day. These sites are what the contemporary canon looks to as pinnacles of achievement, moments that defined the human race, where the construction ambitions of those in power were matched by the artistic prowess of the craftsman tasked with fulfilling those lofty dreams.

This past week, I sat anonymously in the crowd as art consultant Ruth Berson (formally deputy director of curatorial affairs at SFMOMA) gave a speech to a small group gathered in a cavernous interstitial space between the faceted skin of the Intuit Dome and the actual entrance to the arena. This odd space is voluminous, containing artistically illuminated escalators and polygonal openings in the facade, allowing the planes landing at LAX to interrupt and interject into Berson’s speech and the environment as a whole. I was blindsided by my emotions as this seemed to be the most unlikely of locales. Formally, it could be defined as a multibillion-dollar sports arena, the new home of the Los Angeles Clippers, the location

where the upcoming LA Olympics 2028 will host basketball games and where Bruno Mars will perform in a couple weeks for the official grand opening. Those are the practical functions of the space, but conceptually—and in almost a more important double agent status—are the aesthetics, the form, the intangible community.

The list of contributors to this impressive public art collection is already lengthy and touted, all of them having significant ties to the LA region. Jonas Wood designed the actual basketball court and Clippers’ uniforms; Charles Gaines has a large work yet to be unveiled and Catherine Opie has a series of LA-centric images being shown within the stadium. The exterior of the expansive new structure includes several other monumental murals. In the interest of transparency, I was a part of the flagship sculpture that welcomes patrons into the Dome—a 60-plus-foot Clipper ship in which the sails are transformed into basketball backboards.

The reason I was reverential was not because of what I knew about this project, but rather what I did not. I was in awe of the scope and vision with which this was conceived. This is not a handful of shiny sculptures plopped in a plaza to

SETH HAWKINS

reflect the sky, but rather monumental works that thoughtfully intersect our community—each oddly thematic in their own obvious or subtle way. What stole my attention were the monumental digital works by Refik Anadol and Jennifer Steinkamp.

After crossing the new pedestrian bridge and entering the Intuit Dome, I was grabbed by Anadol’s digital paintings, titled Living Arena (2014), rippling in the distance—the artwork exists as the back wall of a public basketball court in the exterior plaza. On a monumental LED screen (40 x 70 feet), it was undeniably more impressive as I got closer, but the real magic happened later. After the introductions, speeches and public thank yous, guests were released to peruse the complex, explore the art, socialize, drink champagne and shoot hoops in front of Anadol’s work. As the silhouettes of the patrons athletically danced in the foreground of the undulating AI paintings, that special and unexpected thing happened in which art, architecture and the viewer merged into something worth so much more than the sum of its parts. The interaction of scale, humans and relevant data merged into a 3D digital art ballet. Who knew that watching

AI-generated data points bounce around on a humongous screen in some contemporary version of Pong would be so entertaining.

I was enthralled with the imagery produced as the sun set in the plaza, but with the darkness, my attention turned to the master-jewel. With the night came the true effect of the Steinkamp’s Swoosh (2024). It is somewhat hard to view in its entirety without either a private helicopter or on an LA flight— because it is the building. Berson regarded Steinkamp’s art in the most poetic way: “You could call the roof (of the dome) her canvas, and the embedded lights her pigment.”

In a night filled with contradictions, I left feeling artistically hopeful for once. Who the hell would have thought that I would be so impressed at a privately funded basketball arena complex because of the art?

So if you happen to be in first class flying out of LAX at night—raise a glass of champagne, look out your window as the lights dance across the Intuit Dome’s facade and make a toast to the fact that I was once again proven wrong. There still is hope in the new millennium for form and function to unite on a grand scale.

Getty’s Pacific Standard Time (PST) is back after its last round in 2017. This year’s focus “Art & Science Collide,” explores the terrain where the two disciplines touch, mingle, sometimes even merge. Almost every SoCal art institution (and some strictly science) are on board, beginning now, continuing through 2025. See pages 38 through 53 highlighting exciting exhibitions now on view.

ARTEONICA*: ART SCIENCE, AND TECHNOLOGY IN LATIN AMERICA TODAY MOLAA

9/7/24–2/23/25 (see p.46)

WONDERS OF CREATION: ART, SCIENCE, AND INNOVATION IN THE ISLAMIC WORLD

San Diego Museum of Art 9/7/24–1/5/25 (see p.52)

GROWING AND KNOWING IN THE GARDENS OF CHINA

The Huntington Library 9/14/24–1/6/25

ART AND THE INTERNET IN LA

Human Resources

10/5/24–10/27/24

NO PRIOR ART: ILLUSTRATIONS OF INVENTION

Los Angeles Public Library

9/14/24–5/11/25

BLUE GOLD: THE ART AND SCIENCE OF INDIGO

Mingei International Museum 9/14/24–3/16/25

FROM THE GROUND UP: NURTURING DIVERSITY IN HOSTILE ENVIRONMENTS

Armory Center for the Arts

8/9/24–2/23/25

FUTURE IMAGINARIES: INDIGENOUS ART, FASHION, AND TECHNOLOGY

Autry Museum 9/7/24–6/21/26

SANGRE DE NOPAL/ BLOOD OF THE NOPAL: TANYA AGUIÑIGA AND PORFIRIO GUTIÉRREZ EN CONVERSACIÓN/ IN CONVERSATION

Fowler Museum at UCLA 7/21/24–1/12/25

MATERIAL ACTS: EXPERIMENTATION IN ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN

Craft Contemporary 9/29/24–1/5/25

NATURE ON NOTICE: CONTEMPORARY ART AND ECOLOGY

LACMA at Charles White

Elementary School Gallery 12/21/24–8/1/25

DESERT FOREST: LIFE WITH JOSHUA TREE

MOAH

9/7/24–12/29/24

BEATRIZ DA COSTA: (UN) DISCIPLINARY TACTICS

LACE 9/1/24–1/5/25

BREATH(E): TOWARD CLIMATE AND SOCIAL JUSTICE

Hammer Museum 9/14/24–1/5/25

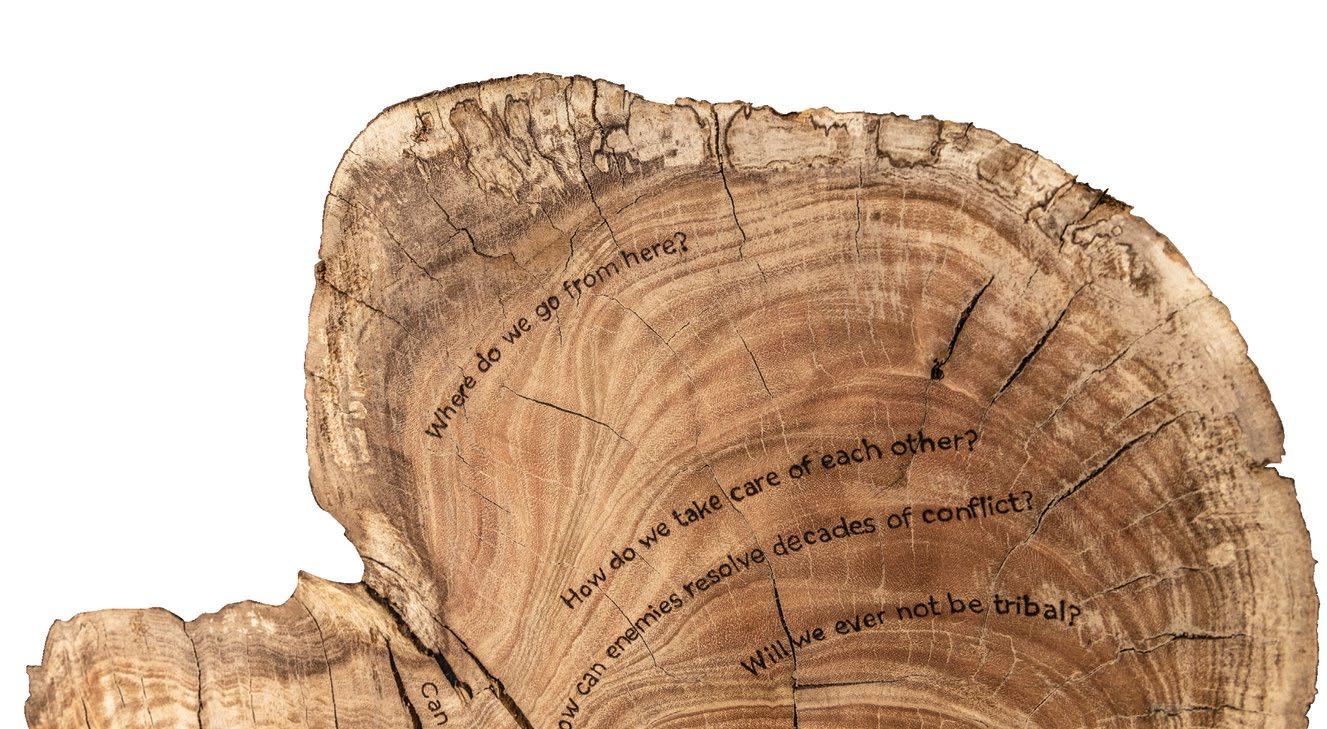

ANCIENT WISDOM FOR A FUTURE ECOLOGY: TREES, TIME, AND TECHNOLOGY

Skirball Cultural Center 10/17/24–3/2/25

OPEN SKY

Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College 8/14/24–1/4/25

REFRAMING DIORAMAS: THE ART OF PRESERVING WILDERNESS

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County 9/15/24–9/14/25

SINKS: PLACES WE CALL HOME

Self Help Graphics & Luckman Gallery at Cal State LA 9/21/24–2/15/25

STORM CLOUD: PICTURING THE ORIGINS OF OUR CLIMATE CRISIS

The Huntington Library 9/14/24–1/6/25

TRANSFORMATIVE CURRENTS: ART AND ACTION IN THE PACIFIC OCEAN Oceanside Museum of Art 9/7/24–1/19/25

WORLD WITHOUT END: THE GEORGE WASHINGTON CARVER PROJECT CAAM 9/18/24–3/2/25

WE PLACE LIFE AT THE CENTER/ SITUAMOS LA VIDA EN EL CENTRO

Vincent Price Art Museum 9/28/24–3/1/25

BLENDED WORLDS: EXPERIMENTS IN INTERPLANETARY IMAGINATION

NASA’s JPL and Glendale Library, at Brand Library and Art Center 9/21/24–1/4/25

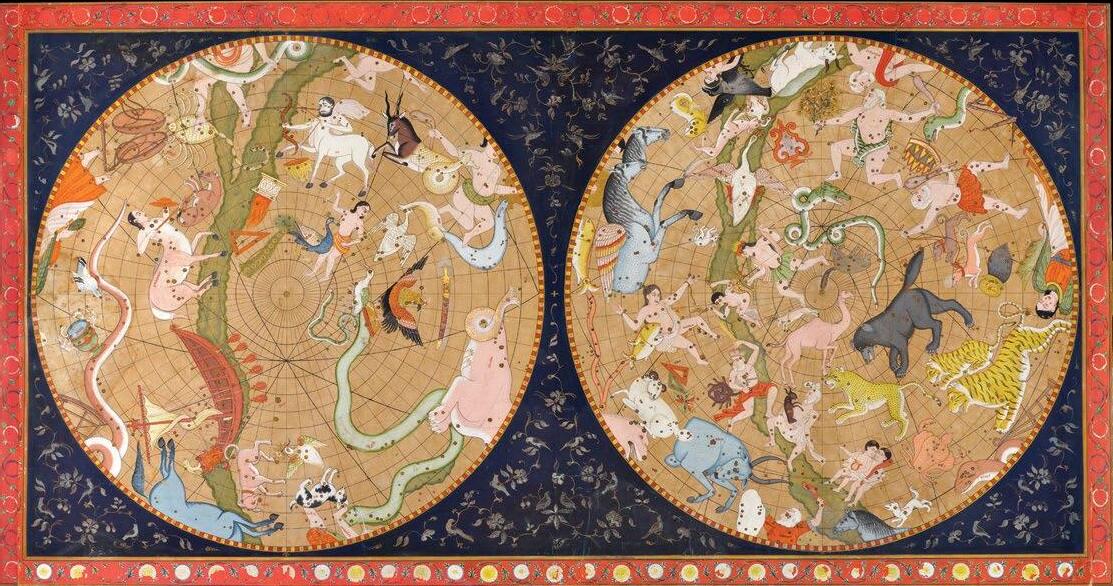

MAPPING THE INFINITE: COSMOLOGIES ACROSS CULTURES

LACMA

10/20/24–3/25/25

RISING SIGNS: THE MEDIEVAL SCIENCE OF ASTROLOGY Getty Center 10/1/24–1/5/25

ATMOSPHERE OF SOUND: SONIC ART IN TIMES OF CLIMATE DISRUPTION

UCLA Art | Sci Center presented at CAP UCLA

9/14/24–5/31/25

Liam Young is an Australian-born speculative architect and world-builder who constructs digital models of potential futures. With a background in architecture, his designs are grounded in plausible science and technology.

Young’s Planet City envisions a future where the entire human population of 10 billion lives in a single city powered by renewable energy and indoor farming, occupying only 0.02% of Earth’s surface. With new components of this transmedia project on display at the upcoming PST exhibit, “Views of Planet City,” held at SCI-Arc and the Pacific Design Center Gallery, I reached out to Liam Young for an interview, where we spoke over the phone.

Artillery: When exactly did you start building Planet City?

Liam Young: Planet City began at the start of the pandemic, when I thought the world needed different kinds of stories about the future. It’s an ongoing project that’s really not complete until we wake up and realize that the true fiction is not this fictional planet city at all. It’s the idea that we can keep on doing what we’re doing, imagining and building cities in the way that we have been for the last 100 years.

Do you feel throughout the process of constructing Planet City you were shaken out of an apathy towards climate change? What that told me is that if we think about what a hopeful or utopian future looks like today, it doesn’t look like Planet City. What we were trying to do is put into the popular imagination new images, what I call “new planetary imaginaries,” that are radical in scale, collective, planetary. But they’re also ecological and sustainable, mindful of Indigenous relationships to land and mindful of the history of colonial infrastructure, but that also can be big and bold.

Have you gotten any feedback based on Planet City where people are incorporating elements of your ideas into actual architecture?

It’s less to say that people looked at Planet City and went, “oh, we could create this amazing wall of vertical solar panels.” Instead, I was taking the research that’s often lost inside the pages of peer-reviewed journals, buried in the back of the latest IPCC climate report. I’m just visualizing what they would look like if we really built them, so that people can connect and relate to it and maybe get on board.

It’s not to say that Planet City is the right choice, but it’s to start having those conversations because that’s where we are. There’s no space in between. It’s either consolidate and live within our means, or it’s shrink.

Liam Young, courtesy of SCI Arc.

PARTICLES AND WAVES: SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

ABSTRACTION AND SCIENCE, 1945–1990

Palm Springs Art Museum

9/14/24–2/24/25

ENERGY FIELDS: VIBRATIONS OF THE PACIFIC Fulcrum Arts co-presented with Chapman University

9/15/24–1/19/25

LUMEN: THE ART AND SCIENCE OF LIGHT

Getty Center

9/10/24–12/8/24

ULTRA-VIOLET: NEW LIGHT ON VAN GOGH’S IRISES

Getty Center

10/1/24–1/19/25

OLAFUR ELIASSON: OPEN MOCA

9/14/24–6/7/25

ABSTRACTED LIGHT: EXPERIMENTAL PHOTOGRAPHY

Getty Center

8/20/24–11/24/24

CYBERPUNK: ENVISIONING POSSIBLE FUTURES THROUGH CINEMA

Academy Museum of Motion Pictures

10/6/24–4/12/26

DIGITAL CAPTURE: SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA AND THE PIXELBASED IMAGE WORLD

UCR Arts at UC Riverside 9/21/24–2/2/25

EXPERIMENTATIONS: IMAG(IN) ING KNOWLEDGE IN FILM

Los Angeles Filmforum 9/14/24–2/1/25

SCIENCE FICTIONS AGAINST THE MARGINS

UCLA Film & Television Archive in partnership with UCLA Cinema & Media Studies Program

10/4/24–12/14/24

ALL WATCHED OVER BY MACHINES OF LOVING GRACE REDCAT 9/12/24–2/23/25

FUTURE TENSE: ART, COMPLEXITY, AND UNCERTAINTY

Beall Center for Art + Technology at UC Irvine 8/24/24–12/14/24

SEEING THE UNSEEABLE: DATA, DESIGN, ART Artcenter College of Design 9/19/24–2/15/24

SENSING THE FUTURE: EXPERIMENTS IN ART AND TECHNOLOGY (E.A.T.)

Getty Center 9/10/24–2/23/25

CAI GUO-QIANG: A MATERIAL ODYSSEY

USC Pacific Asia Museum 9/17/24–6/15/25

COUNTER/ SURVEILLANCE: CONTROL, PRIVACY, AGENCY Wende Museum 10/12/24–4/6/25

INVISIBILITY: POWERS AND PERILS

Oxy Arts 9/13/24–2/15/25

REMOTE SENSING: EXPLORATIONS INTO THE ART OF DETECTION

Center for Land USE Interpretation; DRS 9/13/24–2/16/25

EMERGENCE

Japanese American Cultural & Community Center 10/8/24–12/25/24

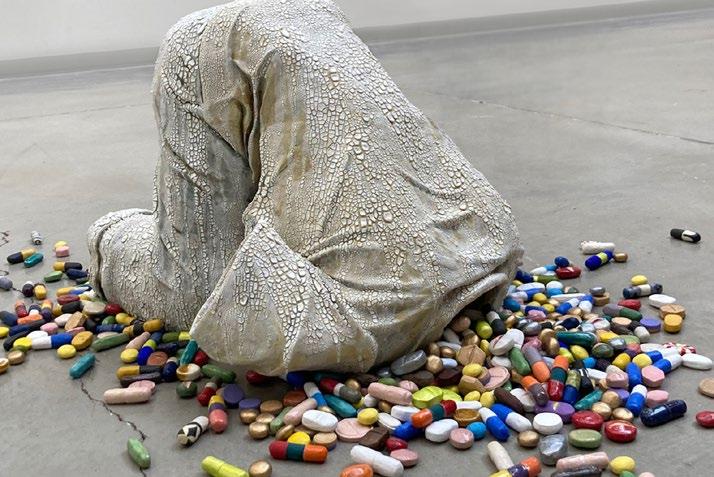

FOR DEAR LIFE: ART, MEDICINE AND DISABILITY

Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego 9/19/24–2/2/25

LIFE ON EARTH: ART AND ECOFEMINISM

The Brick 9/15/24–12/21/24

SCIENTIA SEXUALIS

ICA, Los Angeles 10/5/24–3/2/25

SCI-FI, MAGICK, QUEER LA: SEXUAL SCIENCE AND THE IMAGI-NATION

One Archives at the USC Libraries at USC Fisher Museum of Art 8/22/24–11/23/24

OPENING DOORS

Caltech 10/4/24–12/7/25

QUANTUM VIBRATIONS

USC Annenberg School 10/4/24–11/17/24

LA PLAZA DE CULTURA Y ARTES: COMMUNITY HUB

LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes 9/13/24–2/27/25

One of the places where art and science can interact as a powerful force is in outsider art. This is especially true when the outsider’s goal is motivated by a belief that what they are doing is scientific. Self-educated artists are often likely to follow their own logic when constructing models or putting their ideas on paper. One could transport many mad scientist labs from cinema history into a gallery or museum setting and have them regarded as viable art installations. Conversely, artists who deal with scientific subjects might be regarded as outsider scientists.

In the film Gagarine (2020), a Black teenager named Youri is neither an artist nor a scientist. He is among the last residents of a crumbling apartment block in France named after the cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin. The apartment block is a real place and the filmmakers found press footage of the building’s opening at which the cosmonaut was treated like a rock star. The idealism that ushered in that moment has long since waned and concerns over asbestos, cracked walls and vermin have caused the building to be slated for demolition. Throughout the film, residents with nowhere else to go hold out for as long as possible from the crews that are sent to evict them.

Early in his life, Youri bonded with the figure of the cosmonaut in such a powerful way that it feels organic when he starts converting the abandoned apartments into a space station. The teen grasps the idea of a space station well enough that what he builds has a weird internal logic about it, helping the filmmakers show what is happening through Youri’s eyes. The project came about when the building was first slated for demolition and the filmmakers were asked by the architects to interview the residents of the building. They obviously empathize with everybody who still lives there, as they use them as extras in the fiction film. The humanity of these residents is captured and the film transcends the poverty-porn that it could easily have become.

As more and more neighbors leave, Youri increasingly lives in his dreams of space travel. The space station that he constructs in the abandoned apartments (he keeps knocking out walls to expand it) could easily become the star attraction in any of the galleries involved in the PST theme of art colliding with science. One might compare this to the obsessive quality of Close Encounters of the Third Kind, but with better production design and a lot more heart.

The artist-of-color-led arts organization and collective in Inglewood, Crenshaw Dairy Mart (CDM), is continuing a legacy of Black-led art spaces in South Los Angeles. Co-founded by multi-hyphenate artists Patrisse Cullors, alexandre ali reza dorriz and noé olivas, it has been operating largely under the radar since its inception in 2020. As the kids say, “If you know, you know.”

The art world’s awareness of CDM, its mission and programming—all orbiting around the radical concept of abolitionist aesthetics, defined by Cullors and dorriz in a UCLA Law Review paper as the “contemporary artistic movement where artists, collectives and organizations have employed the arts to address abolition of the prison-industrial complex toward an effective social and political change”—has been a slow burn.

But, after successfully self-advocating to be included in the third iteration of the Getty Foundation’s epic PST art program, CDM is officially a prevetted, card-carrying contributor to the “in-the-know” art world. I spoke over the phone with dorriz, olivas and Programming Director Vic Quintanar, to learn more about their program.

The two prongs of the prison-industrial complex abolition movement—or simply, abolition—are the removal of harmful systems and the imagining of alternatives to those systems, such as mutual aid, liberation and rehabilitation. CDM’s exhibition “Free the Land! Free the People!” will present the evolution of abolitionist pod (2021–ongoing): geodesic-domed modular standing-garden installations that reimagine community care and other tenets of abolition, such as the capacity to resist capitalism through autonomy and reconnecting with the earth.

The prototype abolitionist pod was created during the height of the COVID-19 lockdown, when hospi -

talizations and food insecurity were at record highs. The co-founders saw an opportunity to imagine a new way forward. “What would this have looked like if we lived in abolitionist mainframe?” said dorriz.

When The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) invited CDM to be its partner for the 2021 “We Rise” project focusing on mental health, the CDM team began brainstorming how to manifest the tenets of abolition visually and engage community meaningfully and safely. How could they leverage abolitionist aesthetics to counter a food apartheid that, noted dorriz, already “existed in the ether and was exacerbated by the pandemic, by systems within capitalism?” More importantly, how would they convince the museum to provide security trained to de-escalate, rather than calling in the police? “MOCA was concerned about people climbing or damaging” the abolitionist pod (prototype) (2021) during episodes of mental illness, recalls olivas, as the pod would be installed publicly outside MOCA Geffen. They said, “‘We’ll need to call the LAPD.’ We were like, ‘No, the structure doesn’t matter, we care about people.’” CDM included language in their agreement with MOCA that they would hire their own security. “I wouldn’t even call them security, I would call them caretakers, to be honest,” said olivas. And thus, an abolitionist security template for future partnerships was established.

Olivas, who has a background in architecture, took the lead in designing the prototype pod, inspired by R. Buckminster Fuller’s seminal dome design and the ’90s film Bio-Dome. The pod was made with such natural materials as bamboo and hemp planter bags. “It was a 20-foot-in-diameter community fridge,” dorriz told me, that featured yoga, meditation, plant swaps and fireside chats.

The prototype pod ’s materials had room for improvement, and a second pod was designed with more durable yet sustainable resources to be permanently installed at the Hilda L. Solis Care First Village. The property in downtown LA, “in the shadow” of Men’s Central Jail, was originally acquired to expand the jail. But community organizers and LA County Board of Supervisors Chair Hilda L. Solis stepped in to stop the plan and successfully advocated to instead provide 232 units of transitional housing for formerly incarcerated, system-impacted and unhoused individuals. CDM co-developed trauma-informed curriculum for the Hilda L. Solis Care First Village abolitionist pod (2022–ongoing) with Huma House, Community Services Unlimited, Dignity and Power Now, and Creative Acts. This was abolition, in action.

To frame the project within the scope of PST’s Art & Science Collide, dorriz said, “We’re pulling at the threads of abolition as a scientific discourse.” Olivas continued, “How can we look at abolition as a scientific finding? How can we study that as a collective and communicate that?”

“So much of abolitionist discourse is about prototyping …” said dorriz. “Imagination is a scientific process. Things are going to fail; things are going to work out.”

The prototype pod will be open to the public during regular operating hours at CDM and will be activated with three special days of programming, “each associated with a tenet of our mission,” said Quintanar, “First abolition, then ancestry, then healing.” The abolitionist pod is “a space that opens you up,” said Quintanar. They hope folks will experience it as they do, as a reminder of what we can co-create when “you build the skills to trust people—not just structurally and physically, but internally. The pod, for me, is a big symbol of healing.”

“The two prongs of the prison-industrial complex abolition movement ... are the removal of harmful systems and the imagining of alternatives to those systems, such as mutual aid, liberation and rehabilitation.”

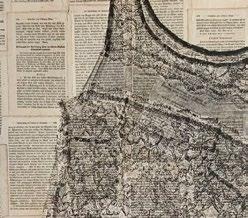

The Los Angeles River is a permanent topic of fascination for artists in this city. In order to establish the city, bureaucrats and businessmen fought to colonize this humble waterway. They tore it away from Indigenous people, encased it in concrete, then rerouted it past the rancheros and into the burgeoning metropolis.

Even if one never visits the Los Angeles River, its presence has informed freeway construction, neighborhood character and the local ecosystem. These relationships are explored through “Brackish Water Los Angeles” at California State University, Dominguez Hills (CSUDH), part of the Getty’s PST Art: Art & Science Collide bonanza. The show, co-curated by CSUDH University Art Gallery Director Aandrea Stang and the artist Debra Scacco, grew out of a five-year collaboration, which included courses about art and water, and student field trips to the river and other estuaries across the city.

The show’s titular term, “brackish water,” refers to water that is neither fresh nor salty. Usually, this state of limbo occurs when rivers meet the sea. Brackish ecosystems tend to be muddy, swampy and hostile to humans. Because they are an eyesore and can’t rake in revenue through leisurely activities, they’re often paved over. Sites of brackish water can be found all over Los Angeles County. Torrance, right in CSUDH’s backyard, has a treatment facility that desalinates brackish water, making it potable.

“There are going to be different instances of brackishness, where the sea is infiltrating the land so much, it could potentially threaten drinking water sources,” she explained in an interview. “It’s something that we’re going to hear more about, unfortunately, due to the climate crisis.”

Modern research, however, shows that brackish ecosystems are also protective spaces. It’s where salmon lay eggs, and its porous soil absorbs and stores water, which prevents flooding and keeps the area lush even during times of drought. Stang and Scacco’s class taught art students the science behind brackishness, and invited hydrologists, environmentalists and marine biologists to campus so they could understand how the phenomena impacted their own lives.

“We acknowledge the students as experts,” Scacco said. “The course was really an invitation for the students to be our research throughout the process.”

Stang enlisted Scacco as a collaborator because she has been making work about the river and memory for over a decade. She has studied the ways the river has moved over time, not as a rushing body of water, but as a wanderer. Sometimes the river was forced to move due to human engineering, as Scacco illuminated in her work Lineage (2022) in which she noted the sites of dams with gold-leaf dots; but historic maps, like the ones referenced in her series “Topographic Works: Los Angeles River” (2015–16), where ink on shimmering

Dura-Lar recreates the delicate, straying paths of the river over time, show that it also changed course naturally. Scacco, a first-generation Italian-American who has lived in Atlanta, London, New York City and Los Angeles, finds kinship with the meandering nature of this body of water.

The ethos of her personal artwork translates into the curatorial direction for “Brackish Water Los Angeles.”

Some of the pieces include two-tonal photographs from Catherine Opie’s “Freeways” series (1994–95), Untitled #23 and Untitled #24 , where concrete highways crisscross the concrete riverbed; a visual poem by the Tongva-Chumash-Chicano filmmaker Isaac Michael Ybara, Ooxono (From Here) (2023) which explores the conflict experienced as an urban native by juxtaposing preserved landscapes with urban infrastructure; and an installation by Alfredo Jaar, who the curators learned about through a student’s research in their art and water class. His piece, Untitled (Water) E (1990) takes the show beyond the Los Angeles River and into the South China Sea. Waves, illuminated against lightboxes, partially block the view of

The addition of these pieces makes the exhibition difficult to categorize. It’s situated somewhere between an art gallery and a science center.” “

mirrored photographs that depict Vietnamese immigrants held in overcrowded detainment centers in Hong Kong.

“Brackish Water Los Angeles” places these contemporary artworks in dialogue with historical and scientific documents. There are maps of the river, sourced from the university archives, indicating its reach and topography in the early 1900s. F.H. Maud’s tiny, hand-painted magic lantern slides, such as the serene landscape in Los Angeles River, Near Los Feliz, come from the Autry Museum of the American West’s collection. The glass plates, created sometime in the late 19th or early 20th century, show the river pooling in a fertile wetland that is now an urbanized neighborhood. And a preserved specimen of a fiddler crab, Uca princeps (Smith, 1870) which comes from the Natural History Museum Los Angeles, showcases the fauna that once thrived in the floodplain. The addition of these pieces makes the exhibition difficult to categorize. It’s situated somewhere between an art gallery and a science center.

“We really like to describe the show as being about the paradox of the in-between,” Scacco said.

While nods to the past are entrenched in the exhibition, it also looks towards the future. The augmented reality piece by Nancy Baker Cahill, Mushroom Cloud LA / Proximities (2022) anticipates a grim nuclear war that will annihilate our environment, but her pessimism is countered by multimedia work by Metabolic Studio, Portable Wetland for Southern California (2019), which shows how the artist Lauren Bon is ripping up concrete to restore the LA river to its natural state.

“The idea of interdependence is so critical, and it makes me a more empathetic person,” Scacco said. “I want to think seven generations ahead.”

“We want people to leave feeling like they have access and agency,” Stang added. The gallery will provide handouts that highlight local climate justice organizations and activities, so people will be able to donate to them or volunteer.

Stag and Scacco frame “Brackish Water Los Angeles” as a site of transition, mutability and resilience. It can destroy worlds, be a lifeline, and, in the age of climate change, become a political battleground.

As a kid, Lucia Monge often gazed at birds through her grandfather’s binoculars, taking in the wonders of nature at an early age. Sometimes the birds looked so extraordinary and colorful that she pondered: Could they be real? Or were they something from a fairy tale?

Those formative years in Lima, Peru, shaped Monge’s focus as an artist. “A garden is a great privilege,” she said in a recent phone interview, thinking back to those weekends when her grandfather would entertain her and her brother. Their houses were close to each other, so her grandfather made them breakfast and entertained them in the family’s shared garden. “That garden was my first classroom,” Monge said.

Currently based in Massachusetts, Monge received her BFA from Universidad Católica del Perú in 2008, with a focus on painting, and her MFA from Rhode Island School of Design in 2015, with a focus in sculpture. In 2018, she was a fellow at the Oak Spring Garden Foundation, where she researched and recreated Charles Darwin’s “experiments on the movement of climbing plants,” according to the foundation’s website.

Mientras una Hoja Respira (While a Leaf Breathes) presented at ArtYard in 2023 and at Hampshire College Gallery in 2024.

As her work incorporated more and more biochemistry, Monge began to see the power of breaking through the strict categories of science versus art. In order to not generate more waste,

“The artist’s focus on connecting people to plants also extends to Plantón Movil, a ‘walking forest performance’ that has taken place in London and Minnesota, among many other places, for over a decade.”

Monge started brainstorming how an artwork might live on after the end of its exhibition. Compostable materials, for example, are a way for the elements of an artwork to return to the earth.

Now, the artist folds nature into every aspect of her practice, blurring the line between science and art in projects that examine elements such as seeds, fungi and natural dyes. Earlier this year, Monge presented a project at Hampshire College Art Gallery that focused on stomata, the pores that make it possible for plants to absorb carbon dioxide. “Mientras una Hoja Respira (While a Leaf Breathes)” involved a living installation in which every part of the artwork was compostable. Working with biomaterials, mushrooms and other living elements has become an integral part of Monge’s process.

“It’s not like plaster, where you know that in an hour it starts to set,” Monge said. Her practice has brought her closer to the ways in which plants can heal or cleanse the air. In this sense, visual art and such fields as botany are both important to her work. A scientist, she says, might quickly dismiss her work as nonscientific, and earlier in her career it was hard for people to even fully accept it as visual art. Now, that slippage feels significant and fruitful.

“Being in this in-between space allows me a lot of freedom,” Monge said. “Because each discipline has certain expectations according to certain parameters or names that we give them. But if [the process] is difficult to define, then it escapes the confines of its categorization a bit.”

Monge’s work will be on display in the Museum of Latin American Art exhibition “ARTEONICA*: Art, Science, and Technology in Latin America Today,” on view through February 23, 2025. The exhibition’s curatorial jumping-off point is the work of Brazilian artist Waldemar Cordeiro, who created a treatise, and exhibition, called “arteônica,” a concept that “frames the computer as an instrument for positive societal change, one that could democratize art and culture,” according to the Getty’s PST exhibition page. The show pairs the work of computer artists in the 1960s and 1970s with Latin American contemporary artists.

Monge’s “First Contact” displays a rendering of the human body, with plants nearby that have medicinal or cultural significance. Visitors are then encouraged to choose a plant and doodle it on a piece of paper, or write something about it. The pencil has a tiny microphone inside, which captures the sounds each stroke makes.

“The invitation to draw or write about the plants is, in reality, an invitation to pay more attention,” Monge said. “It requires you to look again—to see how long this leaf is, or what shape to draw next, instead of drawing a preconceived idea.”

The artist’s focus on connecting people to plants also extends to Plantón Movil, a “walking forest performance” that has taken place in London and Minnesota, among many other places, for over a decade. Each walk ends with the installation of a public garden. Each event happens only when the artist is invited by a gallery or community space in a city.

Some of the events have happened without Monge being there in person; at others, she has hosted workshops on how to make “plant and human connectors,” contraptions that allow people to attach plants to their heads or shoulders. Aerial photographs of the walks show the impact of greenery interrupting city spaces.

During one walk, Monge remembers that she said a few words via a megaphone, then handed it off to a person nearby. That person said a few words and gave the floor to someone near them, who started making monkey noises. Someone else in the crowd made clucking noises, like a chicken. Soon, the group became a roving zoo and their animal cries helped keep everyone together.

Spontaneous moments like these keep Monge curious and excited about her work. The interdisciplinary nature of the “ARTEONICA*” show appeals to her interest in connecting humans to nature, and using the tools available to make that bond stronger.

Like Plantón Movil, the installation “First Contact” is another invitation to pay attention to plants as individuals. It might not create a lifetime bond, said Monge, but at least it encourages viewers to look more closely at what’s around them.

A matriarch of the Land Art movement that is closely associated with the American Southwest, Lita Albuquerque has engaged with the surface of Earth from the South Pole to Saudi Arabia, Peru to Paris. But she has always given special attention to the music of the stars, and to the desert—a fixture of both her Tunisian heritage and her life in LA. Albuquerque’s iconic celestial blueand-gold sculptural paintings are often likened to interdimensional portals, but her multivalent work extends to architectural installation, dancebased performance, film and investigations in the natural and observational sciences.

“Oh, I can talk about science!” Albuquerque exclaims over a Zoom call. “It started in 1969, when our car broke down in the Sahara. We saw a house in the distance and as we walked towards it, we realized it belonged to friends. When we arrived, they were watching the Moon landing live on TV! It could not have been more extraordinary; it rocked my world. Seeing Earth from space was a revolution in perspective as big as the Renaissance.”

Six years later, alone in the sarcophagus hall of The Met, she heard a disembodied voice say, “Pay attention to the feet.” Only later in the studio did she realize the message she was meant to receive: “Pay attention to the Earth.” She did. Albuquerque’s seminal 1978 piece Malibu Line the first of what would become a signature process of laying organic pigments in geometrical patterns, activating energies of the land-

scape to connect body, earth and sky—was a cliffside trench of blue pigment that seemed to extend from her feet on the ground out to the horizon of sea and sky.

In June of this year, Albuquerque reimagined this piece. The new version was set further back into Malibu’s steep, winding canyons, giving the feeling of being at the source of a mountain stream carving its path down the hillside toward the sea. Though partly inspired by PST’s 2024 theme of art and science, Albuquerque’s Nomadic Division-supported recreation largely flowed from her communion with curator Ikram Lakhdhar, who is Tunisian herself. “We got to talking, and of course I grew up in Carthage, a site of history of the earth, the sea, the middle of the sky, the cosmos,” she says. “That side of me is so much a part of my work. I think the new Malibu Line came to be because Ikram saw that the line was really a longing for home.”

The stars have long figured in Albuquerque’s work. “Some of my most grounding research is in 9th- to 12th-century Islamic science and astronomy,” she says. “When I did Stellar Axis in 2006 at the South Pole, I chose 99 of the brightest stars in the Southern hemisphere and

made a symphony from their names. Just about all of them are in Arabic—named by the people who discovered them.” For Albuquerque, in contrast to traditional Western thought, the scientific has always been in concert with the spiritual. “The sacred aspect,” she explains, “I think that’s what we’ve forgotten.”

With PST, Albuquerque has two further opportunities to explore these ideas closer to home. Researching California’s intertwined excavations of space and gold, she learned that in 1952, two Caltech astrophysicists won the Nobel Prize for their work on nucleosynthesis, positing that heavier elements like gold form by exploding supernovae. At Caltech’s Pasadena campus, she’ll be gold-leafing a bridge in their honor. A Moment in Time opens in September, and in honor of its culmination on December 15, there’ll be a performance with dancers and singers, and a musical score inspired by the heady theory. She’ll also open a solo show in September, at Kohn Gallery, in which she will place a vast, thin layer of granite that looks as if the floor was removed to reveal the earth. As people carefully walk around its edges, she notes, they’ll really need to “pay attention to their feet.”

Centuries before Leonardo da Vinci lived and worked in Italy, a Persian astronomer, physician, geographer and writer was conducting research into the nature of the cosmos and man’s place in it. Zakariya al-Qazwini (d. 1283) wrote and illustrated The Wonders of Creation and Rarities of Existence (1280), a remarkable 13th-century document cataloging the earth, the heavens and the many forms of life. This fall, The San Diego Museum of Art will take the beautifully illustrated text as a point of departure for an exhibition of works of art, texts, scientific instruments, magic bowls and commissioned works by contemporary artists Hayv Kahraman and Ala Ebtekar.

Ala Ebtekar is the Berkeley-based child of Iranian immigrants, and Kahraman is an Iraqi refugee now based in Los Angeles. Kahraman has used science and geometry, including work with 3D-scanning and mapping, with the female body—her own—as subject and object in her large-scale figure paintings. Often writhing or contorted, the images explore issues of identity and othering.

The “sense of wonder,” with its emphasis on cosmology, is at the core of Ebtekar’s recent work. Coming from a background in painting, he received his BA from the San Francisco Art Institute and his MFA from Stanford, where he now teaches. The artist has pivoted to more conceptual work and process-oriented techniques, often inspired by the night sky and images brought to Earth via the Hubble Space Telescope. A beautiful immersive tile installation, Luminous Ground (2023–25), created for San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum, presents the cyanotype process as a type of alchemy—using light and time to transform organic substances into new forms, their colors shifting from those of earth to sky.

I recently had the opportunity to speak with Ebtekar. He had just returned from a trip to Dubai, where he had an exhibition—“The Sky of the Seven Valleys”—at The Third

Ala Ebtekar, Safina (exhibition view), 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

Line gallery. It is fitting that Ebtekar, the great-nephew of an esteemed Iranian poet, H. E. Sayeh, framed many of his responses in a poetic fashion. For the PST show, Ebtekar is working on a project that utilizes photogravure and copper etching plates, and imagery of the sun. Underlying the work is an ancient story. The version told by Sufi poet Jalal Rumi describes a contest between two teams of artists—one Chinese, and one Roman— working for the favor of a Persian king. By polishing their own wall to reflect the arduous labors of the beautiful waterfall painted by the other, one clever team clearly finesses the situation. Ebtekar’s wall installation, a grid of rectangular copper plates, will present viewers with their own reflected images as well as a striking composite image of the sun.

Since ancient times, the sun has inspired awe and offered creative power, embodying the very essence of optimism. Ebtekar explains, “I see my work as a journey towards truth, a way to illuminate the path ahead. In these dark times, I search for the morning light that brings hope.” Often, we are driven to produce at a rapid pace, with more and faster, seen as our ultimate goals. As suggested by the meditative objects and thoughtprovoking works on display, it can be equally valuable to slow down, step back and allow our consciousness to drift for a while in the shifting currents of perception.

The tedium of a particular self-consciousness ascribed to Generation Z was on full display in The Death of a Star, a performance and self-proclaimed “reality show,” directed by Jasmine Johnson, which had a sold-out four-day run at New Theater Hollywood (NTH) this June. The black-box theater, run by the artists Max Pitegoff and Calla Henkel, which has quickly made a name for itself as one of the city’s most interesting venues for performance, presented Johnson’s show in four parts. After an introduction by a sort of “Greek chorus” figure, five of the show’s six cast members (sans Peggy Noonan, who apparently fell out with the rest of the cast and moved to New York City during the show’s run) appeared from behind the screen when their names were called and remained onstage throughout the screening, with occasional interjections. The artistic premise—that the cast becomes both viewer and viewed with its attendant implications around the uncanny nature of reality television—wore thin at this point.

The film they are watching, the show within the show, follows five girls and one gay guy, under the presumption that

they are trying to make it in Hollywood, though their ambitions for fame are vague and halfhearted. An inherent, overarching ambivalence toward the things the characters want or say they want informs these performances. Fame is not really the thing they are after—these kids know that this kind of fame no longer exists. However, overeducated in this kind of reality TV script, they know how to perform like people who are trying to achieve fame. What they really want is ambiguous; it is hard to tell if they want anything at all.

The film begins with a kind of roll call in the very theater we are all in. It seems late; everyone is visibly drunk on cheap wine, giving the camera a glassy-eyed stare. Each character says an ad-libbed platitude; their bodies are all somewhat droopy, slumped over in the red-velvet theater seats. Victoria Davidoff, a young woman with a blasé gape and a missing finger, says with a sigh, “I don’t know what I want from LA, I just don’t know where else to go.” The character Deevious begins each address to the camera with “Hey guys,” as though she is addressing her TikTok fans. There is an energized aim-

lessness as the cast wanders around the theater, as if they are trapped by the same force as in Luis Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel. In this way, at least, the film manages to capture some of the strange ennui of life within reality TV that is not written, yet somehow feels rehearsed and constructed.

Perhaps it is appropriate that the best part of the work is its short introduction, which functions as a sort of trailer—a 60-second montage of the cast walking around Hollywood in trashy early-2000s garb, smoking cigarettes, vaping, going in and out of liquor stores, breaking into a park at night, hanging out in the bathroom at parties, all washed in an eeriness reminiscent of David Lynch’s 2006 experimental psychological thriller Inland Empire. A disembodied Kim Gordon recites the film’s only scripted lines. One goes, “In the battle of existence, talent is the punch; tact is the clever footwork.” Everything in that short clip, as in the rest of the film, is well-photographed and sounds good—Noonan in her room talking about a bullet that went through her window, Davidoff explaining how her finger got cut off. Moments like these

effectively suggest something authentic is being captured, but they quickly crumble into pastiche. What the director or the actors are trying to say is muddled by layers of irony. This is insisted upon in the refrain that there “is no format,” or that the film is about just that: looking for the format. But it seems to me that this formlessness and reliance on irony allow the director to evade the task of having to follow through with a full idea. A form might have emerged if the camera was more decisive and less ambient, and it would have been welcomed.

The film is burdened by a self-awareness that prevents it from fully indulging in its wildness. The actors are too wellversed in reality TV and too aware of themselves on camera, such that the cumulative work becomes strained with affectation—that is not to say they might not make interesting subjects. After the show, as the theater emptied out, there was loud snorting coming from the dressing room. I did want to know what these people were doing and what it would look like if the cameras captured the NTH’s backstage—getting behind the behind-the-scenes.

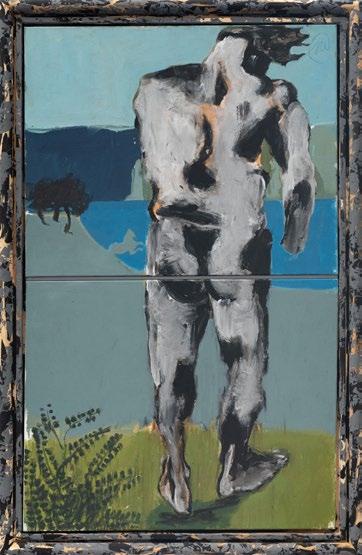

body of work (18 paintings variously executed between 2013 and 2022) amid 38 paintings, drawings and sketches by Puvis. This aspect of the show, which abundantly evidences Puvis’ extraordinary gifts, also serves to track his enduring influence on avant-garde art.

MICHAEL WERNER

By Ezrha Jean Black

There is something inherently contentious about an exhibition juxtaposing the work of a contemporary artist with another whose work has some place within the art-historical canon, more particularly one of the most resonant antecedents of the late 19th- and early 20th-century avant-garde. Markus Lüpertz, who has practically made a career of this sort of provocation, has engaged the work of, among others, Corot, Courbet, Picasso and Poussin.

The artist selected here for appropriation, deconstruction and more is the willfully classicizing proto-Symbolist painter Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (hereinafter Puvis), who exerted a profound influence on PostImpressionist artists including Gauguin, Cézanne, Van Gogh, Bonnard, even early (e.g., “Blue” period) Picasso, and still later, various Surrealists. For this show, Lüpertz and his curatorial colleagues at Michael Werner contextualized the contemporary artist’s

Art historian (and Puvis scholar) Aimée Brown Price writes in the catalog for the show, “[Puvis] was an aesthetic wolf in classicizing sheep’s clothing.” This might be a slight exaggeration, but there was no denying the lupine ferocity of his pursuit of beauty, a specifically French understanding of classicism and a sheer mastery of execution. Lüpertz might be similarly described. Generally characterized as Neo-expressionist, Lüpertz’s work has zigzagged over the years, encompassing everything from Pop to the quasi-conceptual. But what comes across most consistently is an unsettled, even distrustful, relationship with both the past (especially classicism) and the very notion of an avantgarde. In one of the very first paintings seen here, Lüpertz remakes Amor + Psyche (2020)—against an almost schematically color-field backdrop, with its chubby, blackeyed Cupid figure all but fleeing his would-be seductress, both figures modeled in slashing high-contrast strokes—into an allegory of petulant disavowal.

Where Puvis meets his muse in a domain of infinite Baudelairean “correspondences,” for Lüpertz, such correspondences may be entirely illusory, or simply don’t apply. Consider the two “classical” figures that faced each other across the same gallery set against almost identical riparian or estuarial landscapes (no less “classical,” but perhaps closer to an actual German landscape familiar to Lüpertz). In both Caput Mortuum (2020) (literally “dead head,” also a purple-brown pigment) and Russian Green (2020), some portion of the setting, or the figures’ engagement with it, is suppressed, as if to suggest the “pastoral idyll” is itself an arbitrary construct.

Lüpertz’s approach is not simply to appropriate, but to isolate, to foreground, to take apart—sometimes physically: not just diptychs, but even dividing the field into multiple panels, as in the six-paneled Lido (2020), within the same frame. Here too, he draws from disparate classical sources, including Titian and Ingres, as well as Puvis. But more telling are those works in which the isolating—a kind of collage or flotation effect—happens in a single, self-contained field, as in Untitled (2016), with its uprooted and slightly unhinged “allegory.” Here, inconvenient details intrude on already displaced, defrocked “gods”: the fractured trees on the horizon, the soldiers’ crosses at the feet of a “Venus” or “Daphne.” Without

overstating the contextualization of the Puvis master drawings here—e.g., a Christ with Tormenters (1858), that is almost a perfect inversion of the Daphne/Venus in the Lüpertz painting—could such an “Eden” be anything but a killing field?

Setting aside the strengths (or weaknesses) of the derailed allegories of the first gallery, the strongest works exhibited may be the paintings dominated by a solitary figure, only one of which owes a clear debt to Puvis ( Narziss II [2016]—the title figure appropriated from La Fantaisie [1887], with Puvis’ own “blue hour” palette intensified to a twilight translucence). Lüpertz has a way of articulating what’s misshapen about a subject within a minimalist schema. In Orpheus (2014), a vertical diptych, the full figure viewed from the rear, head bowed and roughly modeled in Lüpertz’s aggressively tachiste slashing strokes, is pitched forward into an almost monochromatic and flattened lake-centered landscape. In both Nacht and Rotes Boot (2013—essentially the same composition), the same silhouette viewed from the waist up (also from the rear) emerges from the prow of a boat.

Plainly referenced here is Puvis’ somber, iconic Le Pauvre Pêcheur (1881), a study which was included in the show. But although Lüpertz seems to underscore a contradictory aspect within the overall body of Puvis’ work— more explicitly in Besuch von Pierre (2018), inserting his palette, soldier’s helmet and skull into the foreground—Puvis was in pursuit of something well beyond this fatalism: the overview as well as the underside, vast and transcendent.

By James Cushing

If you’ve read any of Bernard Cooper’s books, you know about the care with which he constructs his sentences, how he gives each detail its own breathing room. (If not, Maps to Anywhere [1990] and his 2006 memoir The Bill from My Father are especially recommended.) Cooper has also been painting for 10 years now, and his debut exhibition, “An Insomniac’s Guide to the Night,” at Gattopardo suggests the public entrée of a doubly gifted rarity, along the lines of William Blake or Louise Brooks. A vivid, confident demonstration of contemporary American surrealism, the show proves that Cooper is not a writer who also paints but rather a consummate artist in the most expansive sense.

“An Insomniac’s Guide to the Night” was a super-saturated Rorschach test of an exhibition. Entering the gallery, the viewer encountered 16 jet-black birch panels against which mysterious and colorful “events” appeared to be taking place. The figures depicted—bright, bulbous shapes that suggest organic plant-life seen under a microscope in a mad scientist’s laboratory—connect in unpredictable ways; their mercurial progress across the canvas is echoed by the works’ physical formats, many of which diverge from the standard rectilinear frame to encompass additional, smaller canvases that serve as appendages or growths, suggesting a Rube Goldberg-like dream logic. The result was gloriously disorienting, a perfect balance between the enigmatic and the transparent, the forbidding and the inviting, the gnostic and the familiar. A Cooper painting takes the viewer up to a moment before its mystery is about to be revealed—and then suddenly vanishes into a charged black silence.

Consider for example Amuse-bouche (2022), at 8 x 10 inches one of the smaller works included. Against the painting’s deep black ground, a green flask pushes a looped

green stem up out of its mouth-like orifice. The stem is connected by a loop-ended crimson bungee cordlike form, and by a couple of wrinkly strings, to a Sherlock Holmes-esque pipe. The pipe’s bowl emits a cone of fuzzy light that relinks to the crimson bungee. It’s a still life in which nothing lies still, not even the identity of the objects. Cooper’s ability to render the uncanny visible speaks to his expertise as a draftsman—but even more so to the images’ refreshing lack of symbolic meaning. The artist allows these shapes to be themselves and do what they do; he never bullies his images into signifying X, Y or Z.

In his 1988 essay “How to Draw,” published in The Georgia Review, Cooper admitted, “I possess, against every cultivated judgment that came with my master’s degree, a preference for amateur art, for that which others often label ‘kitsch.’” But if we consider that amateur is derived from amor, we find him as endorsing a more sincere conviction in art than that espoused by “kitsch”—and instead, one that presupposes the artist as lover, whether of language or of shape and color. Cooper’s night shapes have been loved into being.

By Tara Anne Dalbow

In The Head in the Tiger’s Mouth (2021), the first composition in Kyungmi Shin’s kaleidoscopic exhibition, my eyes immediately landed on the luminous collection of swirls and stripes suggesting the calligraphic form of a tiger before catching on the colorful tableau in the painting’s background: a man holding up an instrument, a woman swathed in red, a young boy in blue. As the figures disappeared into the surrounding milieu of bamboo and pine trees, my eyes slipped toward the intricate slate-gray pattern overlay. Above—or amidst—that, float the shimmering silhouettes of a husband, wife and their two children, borrowed from an old photograph of the artist’s family. Poised between ghosts from the ancient past and outlines of a burgeoning generation yet to come, they are of this world and beyond it.

The seven photo-collage paintings in “Kyungmi Shin: Origin Stories” at Craft Contemporary demand extended looking, and in exchange provide the delight of ongoing discovery. Vintage family photographs, archival images, art-historical motifs and

acrylic paint coalesce in portraits striving to convey the complexity of identity and the discordant narratives that form and deform history. Shin locates the point where the personal and the universal meet: where the urgency of the present intersects with the languid grandeur of the past. Within her frames, ancient shaman deities, Italian revival furniture and François Boucher pastorals coexist. While her multivalent references deftly evince the effects of colonization and cultural dissemination, they also realize a sort of magical thinking—a world where one influence doesn’t subjugate or eradicate the rest.

Shin’s own variegated narrative began in South Korea, where her father was a Christian minister (Christianity itself a colonial import to Korea in the late 1800s) until the family immigrated to the United States when she was 19. It would take Shin more than 10 years to understand herself as a Korean American and to grapple with what that meant Her prismatic paintings account for this reckoning, though they don’t suggest a new assimilated identity so much as expose its many antecedents, valences and inconsistencies. They are both unified portraits and the sum of their distinct parts, recalling Édouard Glissant’s assertion that “we know ourselves as part and as crowd … our boats are open, and we sail them for everyone.”

The largest work in the show, Careful you don’t hurt somebody with all that flash (2024), inspired by both European “grand style” historical paintings and monumental Buddhist devotional sculpture, envisions an epic meeting between a Holy Roman Emperor and fellow

embattled crusaders, a dragon-riding spirit from Korean folklore, and a crowd of Korean men in suits and ties. By contrast, the show’s most intimate, tender work, Three Magi (2022), transposes a drawing of her mother and baby sister over a 15th-century painting of the Three Wise Men bearing gifts for the newborn Christ Child, wherein one offering is a chinoiserie cup of gold coins. Again, I felt pulled between the radiant Virgin Mary, the Chaekgeori-inspired flower arrangement, and the metallic millefleur background. But I returned again and again to the artist’s mother’s face, a gentle reminder that we, all of us, are born of the same source.

LONG BEACH MUSEUM OF ART

By William Moreno

Incessant texts and social-media alerts are inescapable facets of contemporary life, and artist Chris Eckert attempts to make sense of this glut of seemingly endless data. Eckert has successfully melded backgrounds in the fields of mechanical engineering and professional art-making—disciplines with seemingly opposite agendas—into a singular and timely practice. With the Getty Foundation on the cusp of launching its PST: Art & Science Collide region-wide initiative, his current exhibition seems an apt, if serendipitous, contribution to industrial technique-driven art. Eckert is probably best known for his automated tattooing machine, Auto Ink (2010), a polychrome sculpture that tattoos random religious symbols directly onto participants’ skin—a conceptual provocation. The artist notes, “My work is a reflection of ideas and questions I find perplexing. While some find machinery cold and impersonal, I find [it to be] a vehicle for exploration and introspection.”

“Overload,” his current exhibition at the Long Beach Museum of Art’s downtown annex, is a testament to Eckert’s vision and facility as a sculptural virtuoso. In technical collaboration with Martin Fox and John Green, he has created a deceptively austere landscape of walls lined with seemingly innocuous, semi-autonomous devices. Each machine object was individually hand-wrought and programmed. These sculptures are not static by any means, functioning as both aggregators and reflectors of an increasingly cacophonous world. In essence, the machines capture data streams from the internet or cameras installed in the gallery and reinterpret the information within a variety of formats. Building on the

uncannily anthropomorphic characteristics of the recently deceased Alan Rath’s mechanical sculptures, Eckert takes the notion one step further, inviting the global information miasma into the gallery via the sculptures. It’s a dynamic, revelatory experience, and Eckert attempts to shape the information into something that is both thought-provoking and waggish.

Crosstalk (2024) is an installation of 20 polychromed-metal machines that capture newsfeeds for various national and international sources, morphing them into musical compositions ranging from Ennio Morricone’s “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” to “She Drives Me Crazy” by Fine Young Cannibals. The intent is to transform the onslaught into something contemplative and engaging. Mixed Messages (2017) is arranged as a phalanx of 24 sculptures, also in polychromed-metal, that translate data via what’s known as a telegraph “sounder,” a 19th-century receiver, into Morse code. The data are an amalgam of news sources, but the machines’ physical presence and insistent clacking create an impression that is relentlessly urgent, strident and oddly euphonious.

Ultimately, Eckert’s approach to information overload makes for both a sobering and entertaining spectacle. Blink (2018) takes an altogether different tack with a focus on surreptitious surveillance. Ten metal sculptures are each embedded with an animatronic “eye” that contains a sensor that tracks and records visitors’ presence, and, in a separate gallery displays the projected

images of these hapless subjects. That is the predicament of modern life.