women’s issue

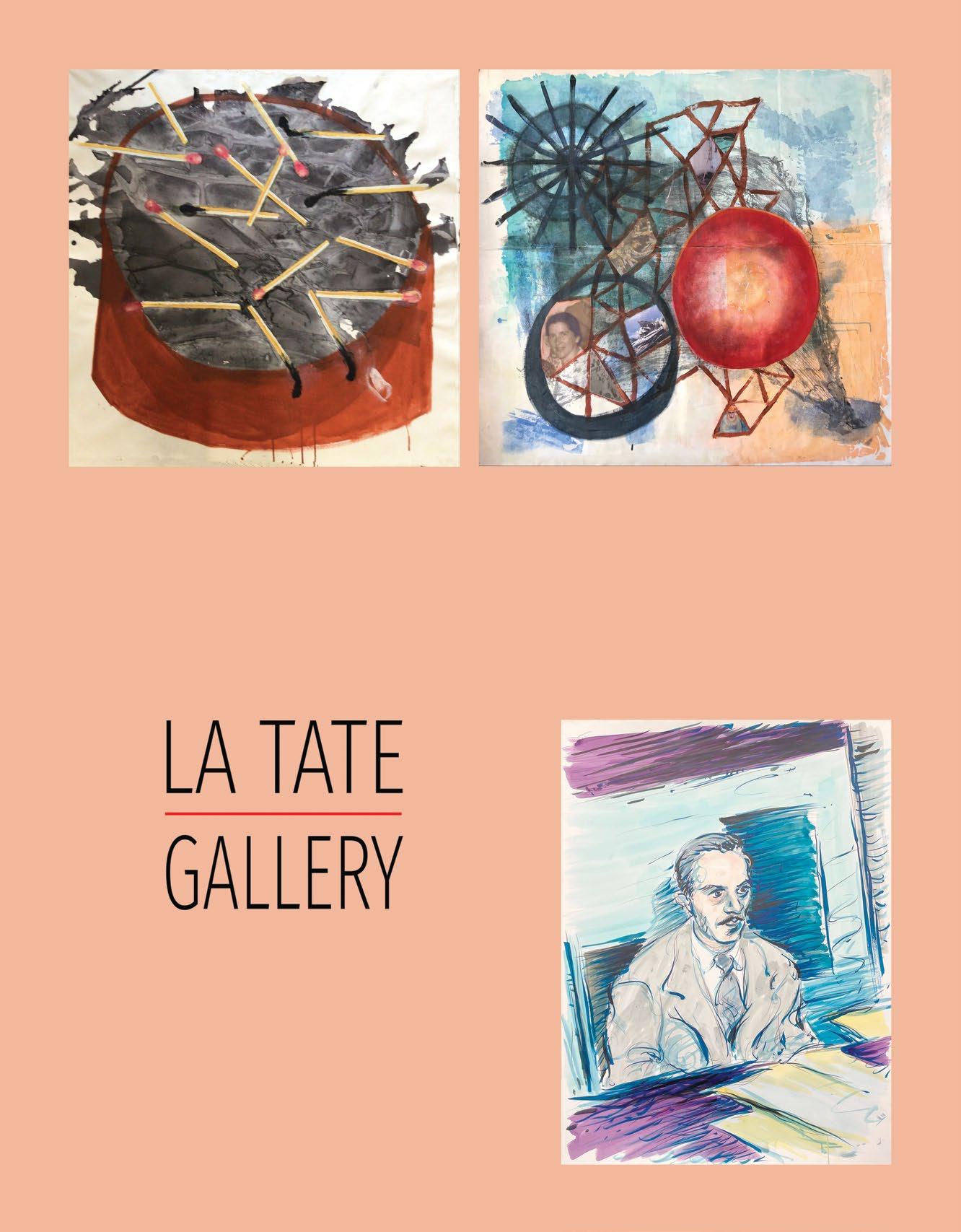

Hatter, 2022 18 x16" (45.7 x 40.6 cm)

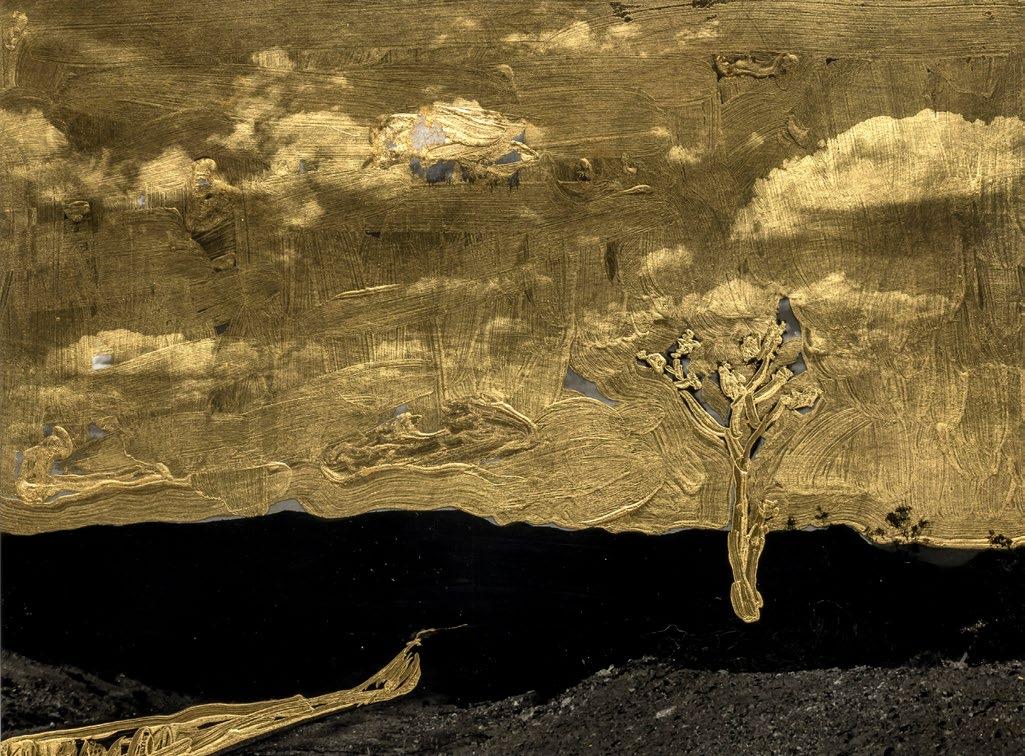

Wishful inking, 2022 28 x 48 ½" (71.7 x 123.2 cm)

Rabbit, 2022 16 x13" (40.6 x 33 cm)

Multi-color screenprint/collage prints with leafed elements, collaged to museum board, based upon The Mad Hatter’s Tea Party from Lewis Caroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland Editions of 60 gemini g.e.l. 8365 MELROSE AVENUE LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90069 323.651.0513 EDITIONS @ GEMINIGEL.COM

Duke, 2022 18 x14" (45.7 x 35.6 cm)

Michele Pred: Our Bodies, Our Business - by barbara morris 28

Michelle Stuart: About Time - by ezrha jean black 30

Calida Rawles: Fire & Water - by scarlet cheng 32

Astra Huimeng Wang: Decorum & Decay - by julie schulte 36

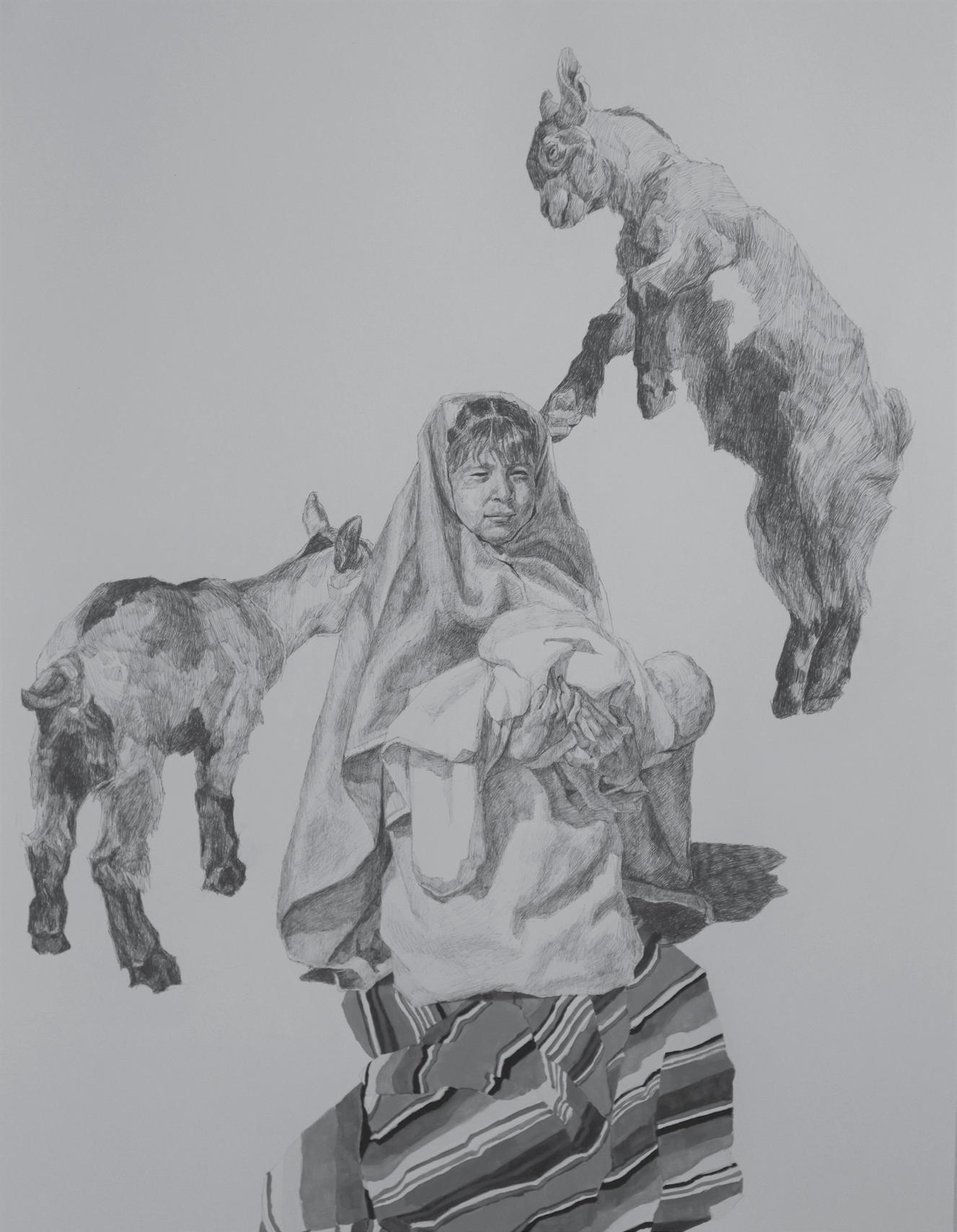

Samuelle Richardson: Animal Kingdom - by genie davis 40

More Women: Six Short Profiles

Kristin Bedford; Andi Campognone; Eileen Cowin; Penda Diakité; Samantha Fields; Gala Porras-Kim 42

ART BRIEF: AI Artists - by stephen j. goldberg, esq 22

DECODER: The Hotel Lobby - by zak smith 23

THE DIGITAL: Superchief’s Super Party - by seth hawkins 24

BUNKER VISION: Ulrike Ottinger - by skot armstrong 52

CONTINUED »

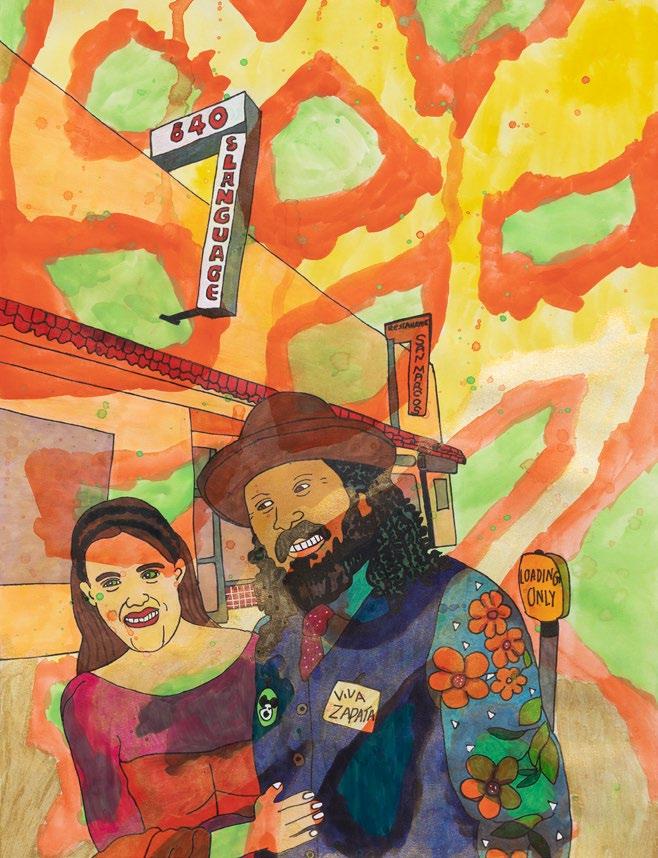

ON THE COVER: Kristin Bedford, No Soy De Ti / I Don’t Belong to You , 2018, (detail) Los Angeles, courtesy of the artist. See page 43.

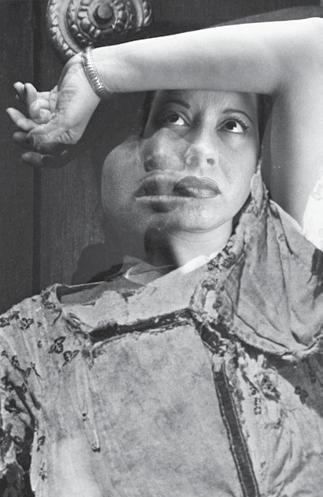

ABOVE : Samuelle Richardson in her studio, photo by Genie Davis.

RIGHT: Astra Huimeng Wang in her downtown Los Angeles Studio, courtesy of the artist and Make Room, Los Angeles.

NEXT PAGE, Top: Calida Rawles, Radiating My Sovereignty , 2019, (detail) acrylic on canvas, 84 x 72 in., courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London.

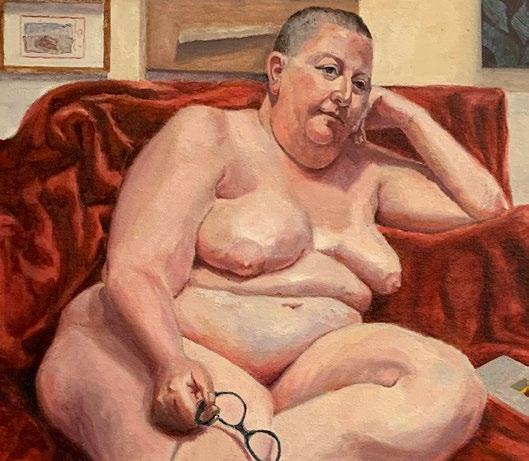

Bottom: Inclusion in “Percieve Me,” an installation by Kristine Schomaker: Nurit Avesar, Private and Public (2019), (detail) oil on canvas, 21 x 31 in., courtesy of Coastline Art.

OFF THE WALL: LA River Confidential - by anthony ausgang 54

SIGHTS UNSCENE: Protests Post-Roe - by lara jo regan 56

ASK BABS: Over-The-Hill Artist - by babs rappleye 58

SHOPTALK: OCMA; Fairs; LA Museums - by scarlet cheng 18

POEMS - by caitlin brady; john tottenham 58

COMICS: Margaret Keane - by butcher & wood 63

Madeline Hollander @Jeffrey Deitch 46

Group Show @Williamson Gallery, Scripps College 46

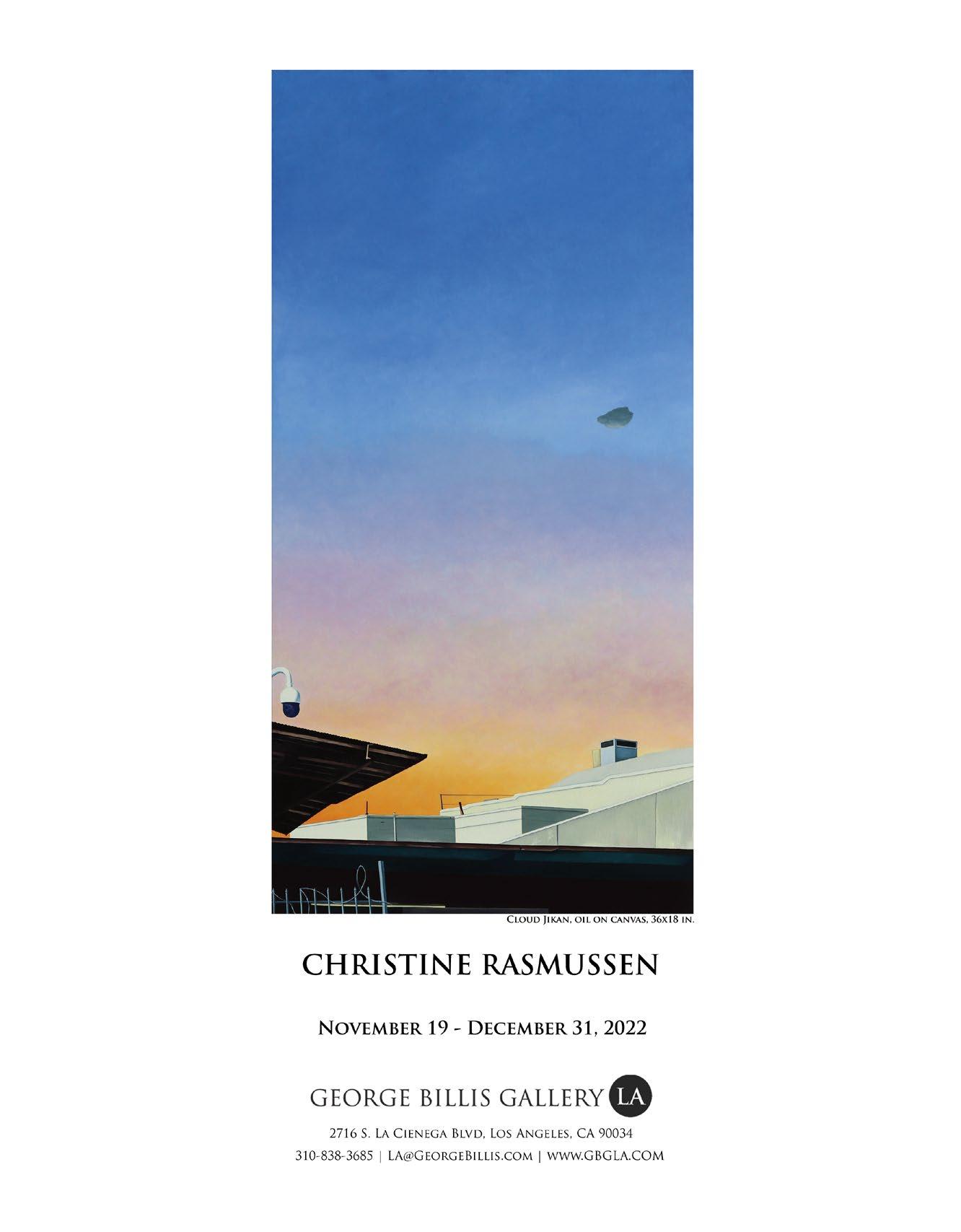

Angela Dufresne @M+B Doheny 47

Kaari Upson @Sprüth Magers, Los Angeles 47

Kristine Schomaker @ Coastline Art Gallery 48

David John Attyah @Los Angeles LGBT Center 48

Trenton Doyle Hancock @Shulamit Nazarin 49 Sharon Ellis @Kohn Gallery 49

Wolfgang Tillmans @MoMA 50 Diego Rivera @SFMOMA 50

This Women’s issue is not our first, but we welcome any opportunity to celebrate women artists, curators and dealers. Normally our Novem ber/December issue is our Interview issue, but in light of the recent over turn of Roe v. Wade, we made the decision to exclusively profile and interview women in the arts. As with all our themed issues—our unique Artillery modus operandi—I person ally worry about who we might have left out. (Ah, the stress of being an editor.) So, bear in mind, we simply cannot cover every worthy female artist, but this time around we wanted to champion the particular women featured in this issue.

One woman who did not make it into this issue that I would like to personally celebrate and acknowledge is Diane Arbus. I was recently in New York and had the opportunity to see the rare showing of all of Arbus’ original photographs from her famous Aperture book and MoMA 1972 retrospec tive at the David Zwirner Gallery in Chelsea. We’ve all seen the photos in the book, and a smattering of those images in museums, but the complete series hung with deft curation was a sight to behold. I thought of this artist—a privileged white woman, for sure—going around the streets of Manhat tan in the 1960s with her Rolleiflex camera in hand, asking passersby if she could take their photograph. Her confidence and unabashed behavior must be applauded. In a way she was rebelling against her wealthy upbringing by turning the spotlight on people that were not part of her world. Some might call it exploitation, but I hardly see it that way at all.

She was an inspiration to me as an artist, as I’m sure she still is for many women artists. One thing I always remem ber, from the excellent biography by Patricia Bosworth, was how Arbus told her students to go out and take a picture of what they most feared. As a teacher I followed her lead, and as an artist myself I listened to this daring but sage advice. By receiving trust from the people she photographed, she bared her own soul in those images. How in the world did she manage to get invited to the giant’s home to take a family portrait? How did she get those twins to confront the cam era, motionless? How did she get that perfect moment of an infant with tears streaming down her face?

There will only be one Diane Arbus. She was a trail blazer with a message. Isn’t that what art is all about? Many of the artists we feature in this issue follow their heart just as Arbus did. Michele Pred works with wom en’s issues such as abortion rights; Calida Rawles stud ies the complexity of being a Black woman; Astra Huimeng Wang explores the Western world’s fictions from the perspective of her native China; and Kristin Bed ford photographs the subculture of Latina women and lowriders with as much empathy and compassion as Arbus brought to the streets of New York. Her cover photo aptly exemplifies this and speaks to a world full of women with a most important message. The Latina’s tattoo No Soy De Ti, translates to “I Don’t Belong To You.” I think that says it all.

;Etel Adnan

CAConrad

Moyra Davey

Demian DinéYazhi´

Shannon Ebner

John Giorno

Otis Houston Jr.

Jibade-Khalil Huffman

Félix González-Torres

The Song Cave

Cecilia Vicuña

Organized

1700 S Santa Fe Ave, Los Angeles, CA 90021 +1 213 623 3280 vielmetter.com

Barbara Morris is a SF Bay Area-based writer and artist. In ad dition to Artillery, Morris has written for Artweek, art ltd., Squarecylin der, and Art Practical, among other publications. She holds an MFA in painting from UC Berkeley, and is passionate about feminist concerns and artwork that challenges racial and gender stereotypes.

Julie Schulte is an LA-based writ er. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from UC Irvine where she teaches a course on the rhetoric of motherhood. She writes about art and culture and her nonfic tion has appeared in publications such as The Atlantic. Instagram: @ julesvernova

Scarlet Cheng writes regularly about the visual arts, film and cul ture. In past lives has been asso ciate editor and picture editor at Time-Life Books, and managing editor at Asian Art News (Hong Kong). In this life she is a frequent contributor to the Los Angeles Times and teaches film history at Otis College of Art & Design.

Ezrha Jean Black is a writer and journalist based in Los Angeles. She also writes scripts and plays very bad piano. She’s currently writ ing a historical novel and develop ing a psychological thriller coming to a small screen near you any day now. She’s also a critic—a condition which appears to be chronic.

Genie Davis is a writer who loves and writes about art as well as a wide range of other subjects as a journalist, biographer, novelist and WGA-W screen and television writ er. You can see her work on the arts in Artillery, Art & Cake and Riot Ma terial, as well as on her own www. diversionsLA.com.

Bill Smith - creative director

Max King Cap - senior editor

John Tottenham - copy editor/poetry editor

John Seeley - copy editor/proof Dave Shulman - graphic design Emma Christ - editorial assistant

Ezrha Jean Black, Emma Christ, Laura London, Tucker Neel, John David O’Brien

Skot Armstrong, Anthony Ausgang, Scarlet Cheng, Stephen J. Goldberg, Lauren Guilford, Seth Hawkins, Lara Jo Regan, Zak Smith

Emily Babette, Lane Barden, Natasha Boyd, Betty Ann Brown, Susan Butcher & Carol Wood, Kate Caruso, Bianca Collins, Shana Nys Dambrot, Genie Davis, David DiMichele, Alexia Lewis, Richard Allen May III, Christopher Michno, Yxta Maya Murray, Barbara Morris, John David O’Brien, Carrie Paterson, Leanna Robinson, Julie Schulte, Eli Ståhl, Allison Strauss, Cole Sweetwood, Donasia Tillery, Colin Westerbeck, Eve Wood, Catherine Yang, Jody Zellen

NEW YORK: Arthur Bravo, Annabel Keenan, Sarah Sargent

Anna Bagirov - sales Mitch Handsone - new media director Emma Christ - associate communications editor

Anna Bagirov - print sales Mitch Handsone - web sales Artillery, PO Box 26234, LA, CA 90026

editorial: 213.250.7081, editor@artillerymag.com advertising: 408.531.5643, anna@artillerymag.com;

Follow us: facebook: artillerymag, instagram: @artillery_mag, twitter: @artillerymag

the only art magazine that’s fun to read!

letters & comments: editor@artillerymag.com subscriptions: artillerymag.com/subscribe

Artillery is a registered California LLC Co-founded in 2006 by Tulsa Kinney & Charles Rappleye PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

What a roller coaster we’ve been on these last three years. Hard to believe how the world shut down in March 2020, and now California’s Governor Gavin Newsom announces that our State of Emergency will be over next Feb. 28. The museums have largely reopened—one in a brand new space, see below—and the art fairs are back in business. (The galleries stayed open throughout, due to some fortunate glitch.) During this time the rich got richer, and now have a lot more money to buy a lot more art. While some scramble to make ends meet, the art business is big business, and record prices for the works of living artists are being set.

The new Orange County Museum of Art building in Costa Mesa opened to the public on October 8 with a 24-hour event that brought people in droves. Designed by the architecture firm Morphosis and costing a cool $94 million, the tile-clad building has an undulating surface, matte beige in color. Director Heidi Zuckerman was hired in January 2021, and has given us a taste of the programming she is prioritizing—curating one of the three main opening exhibitions herself, “13 Women.”

“Something that I’ve been talking about as an overall mis sion” she says, “[is] this idea of looking back to look forward, and recognizing where we’ve come from, where we are currently, and where we hope to go.” “13 Women” is a show from the muse um’s own collection—13 featured artists to honor the 13 women

Left to right: Orange County Musuem of art, interior, 24-hour opening. Early Cinema, Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898–1971, Academy Museum of Motion Pictures,

who founded the museum in 1962 in Newport Beach. The first round of artists include Joan Brown, Vija Celmins, Catherine Opie, Barbara Kruger and Agnes Pelton. With periodic rotations of work during the next year, the exhibition will feature as many as 100 different artists. The two other main exhibitions are the relaunch of the California Biennial 2022 and “Fred Eversley: Re flecting Back (the World).”

It’s great to see the Biennial back—we do need it—this time curated by former OCMA Chief Curator Liz Armstrong, with co-curators Essence Harden and Gilbert Vicario. They met on Zoom and visited some 100 artists, both well-known and un der-the-radar, such as Sharon Ellis, Raúl Guerrero and Ben Sa koguchi—okay, nix Sakoguchi who was disinvited after museum staff objected to the appearance of a swastika in his painting, Comparative Religions 101. The swastika references Nazi Ger many, with which Japan was allied during World War II, and it appears in a section about the rise and fall of Emperor Hirohito as a revered figure. It’s regrettable that the museum decided to eliminate his work, rather than provide material that would put the work in context. Others in the Biennial include Alex Ander son—whom I’ve written about before in Artillery —Alicia Piller and Clare Rojas. The 20 selected artists work in a gamut of media including ceramics, painting and assemblage. Congratulations!

“The White Album: California, 1964–1988”: Noah Purifoy, Watts Uprising Remains , ca. 1965–66, found-object assemblage. 24 x 24 x 6 in.,

At the Academy Museum “Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898–1971” (through April 9) is a true delight, and a real learning experience for most of us. The large exhibition explores the contribution of Black directors, actors and other talents to Amer ican cinema, from silent film days to the Civil Rights era. I was especially intrigued by the early all-Black-cast movies illustrated with posters and photographs, including Richard E. Norman’s Regeneration, an attempt at a swashbuckling “romance of the high seas” in 1923. As racial barriers began to fall after World War II, Black participation in narrative cinema increased.

The Hammer Museum recently opened two shows that are exceptionally interesting, and quite smartly curated. “Joan Didion: What She Means” (through Feb. 19) is a tribute from one writer, New Yorker contributor Hilton Als, to another. It’s also a tribute to the extraordinary times through which Didion lived—most vividly the ’60s, with its hallucinatory combination of sex, drugs and revolution. The exhibition uses memorabilia, photography and video, and art—including works by Betye Saar, Vija Celmins, Maren Hassinger, Ed Ruscha, Pat Steir. The exhibi tion was organized by Als with Chief Curator Connie Butler and Ikechukwu Onyewuenyi, curatorial assistant.

While there, don’t miss the smaller “Picasso Cut Papers” (through Dec. 31), a delightful exhibition of about 100 of his pa per works—torn, cut, folded, painted, inserted into other work— in a specially designed gallery that has a box within a box. This is an original exhibition from the Hammer’s Grunewald Center, curated by Cynthia Burlingham and Allegra Pesenti, and won’t be traveling, so be sure see it here.

Get ready for the fairs coming up early next year. In February we’ll see the return of Intersect Palm Springs (Feb 9–12) to the Palm Springs Convention Center, the LA Art Show (Feb. 15–19) to the LA Convention Center, and Frieze LA (Feb 16–19) moving from Beverly Hills to the Santa Monica Airport. I for one applaud the latter move—it was doggone hard to park in Beverly Hills.

Next March photoLA (March 2–5) returns after a hiatus—this time to the Barker Hangar at Santa Monica Airport. Welcome back to our longest continuing art fair! No word about another homegrown fave, Felix, however. Let’s see if they survived the return of Frieze last year, which had terrific art and appeared to be very successful sales-wise.

Lastly, Happy 10th Anniversary, Shulamit! I remember visiting the Shulamit Nazarian gallery when it was still in Venice, in a gal lery/house space—but the larger new La Brea space has enabled full-scale exhibitions of such emerging and mid-career artists as Annie Lapin, Bridget Mullen, Fay Ray, Charles Snowden, Michael Stamm, Cammie Staros, NaamaTsabar and one of my favorite contemporary artists, Summer Wheat. It’s an impressive list. This summer they celebrated a 10th anniversary show, co-organized by Nazarian and gallery co-owner Seth Curcio.

The age of artificial intelligence (AI) has arrived whether we like it or not and now it has come to the art world. That should not really be much of a shock. It’s now five years since AlphaGo defeated the best Go players in the world. Writers have auto-complete options readily available. AI is facilitating incredible advances in the bio-sciences with AlphaFold. The latest frontiers are the creative ones—writing fiction, composing music and making visual art.

This column has periodically explored the question of just what constitutes art. My very first column explored digital art and devices that assist artists such as David Hockney, who has produced prodigious quantities of stunning artwork made on his iPad. A recent column concluded that NFTs are not art but really entries on Blockchains (not surprisingly NFT values crashed during the summer 2022 crypto apocalypse).

Now we are dealing with the controversy surrounding the advent of AI image generating programs such as DALL-E 2, Midjourney and Stable Diffusion. The complex programming process known as diffusion is evolving fast. It is estimated that DALL-E 2 produces images four times more detailed than the first iteration introduced a little more than a year ago.

A computer engineer, Jason M. Allen of Pueblo, Colorado, achieved instant notoriety when a “work of art” he created strictly with descriptive word prompts on the Midjourney pro gram won an annual art contest at the Colorado state fair this summer. The work he titled “Theatre D’opera Spatial” won a blue ribbon and a $300 prize—and millions of dollars worth of publicity. Some of the judges confessed they had no idea the work was AI-originated, but they said it wouldn’t have changed their votes.

The media anointed Allen’s entry the first wholly AI-generat ed artwork to win an award, neglecting the fact that Bessie the cow also won first place in the bovine division at the same fair. Yes, cowboy, we’re a long way from the Venice Biennale. Howev er, the story was deemed important enough to make it into The New York Times, Washington Post, and BBC News.

As the Times put it, “Users type a series of words in a mes sage to Midjourney; the bot spits back an image seconds later.” Algorithms are used to recognize descriptive artistic patterns among millions of online images. The user can refine the images with further prompts and use of Photoshop. Allen’s winning image was indeed sophisticated and mysterious and some major art critics were duly impressed. A Washington Post art critic, Sebastian Smee, compared it to the work of Gustave Moreau, the 19th-century artist associ ated with the Symbolist movement.

Midjourney and other AI programs have generated social media opprobrium with their dependence on bots to scrape the internet of art and other images (much of which is copyrighted) providing an instantly generated unique image or series of images. Allen received considerable hate and dislikes on social media. Some artists were appalled that their work was essentially pimped out by AI programs, but the resultant image rarely, if ever, relies on a copy of an individual artwork.

Nevertheless, it will only be a short time before some enterprising lawyer and his artist client file a test case, claiming copyright infringement based on substantial similarity. Of course, the AI “artist’s” defense of fair use will be based on the argument that the generated image was transformative of the original artist’s work.

In reaction to the controversy, Allen was quoted in the Times as saying, “Art is dead, dude. It’s over. AI won. Humans lost.” Whoa, pardner—human-made art is more alive than ever. However, AI-generated art should be categorized as a hybrid creation made, not just by a human, but primarily by a machine. When Christie’s holds its first auction of AI art—likely not too long from now—full disclosure of the genesis of each AI artwork should be made.

“A Cubist painting of Artillery art magazine November issue.” Image generated by DALL-E/OpenAI.

As always in the art world, fakes and frauds will become a problem. The Big Eyes scheme is sure to arise, but instead of a flamboyant Walter Keane fronting for Margaret, his artist spouse, we are sure to encounter imposters attempting to hide their dependence on Midjourney or WALL-E 2, claiming to be the next Jeff Koons. Eventually, we may be unable to tell if it’s the real thing, or the ghost in the machine.

From the outside, the hotel lobby appeared to have (or be?) a gift shop—and an audaciously hip one. It said “porn” in awfully big letters, especially for a hotel lobby. I investigated.

It didn’t have a gift shop, it was just a lobby, but it was a very fancy lobby. Think now of what a splendid and splendidly expensive hotel lobby might imply: a dazzling beaux-arts concatenation of marble and arch? A playground of modernist geometry with manta-ray wing chairs and space-age lamps? Grand hotel lobbies always distill some version of their era’s taste down to occupiable form.

This particular lobby was a verdict on the Art of Context, the art historical move ment that began with Duchamp, went mainstream in the ’60s, peaked in the ’90s and… is still around. It tells us what the business of figuring out where the modern upscale traveler would like to wait for their aunt has decided is desirable and sexy about the world of putting a museum label on a toy duck.

The first thing you notice is a sculpture which is a familiar parody of a popular Pop-art sculpture. Or a reproduction of the parody—was there ever an original? I don’t know. There are painted skateboard decks flanked by rows of photogenic books, a bunch of little keychains with a little guy on them like the kind you might see in a junk drawer with forgotten stuff in a house anyone might have, except they’re isolated in vitrines like jewelry, typewriters wall-mounted as if on display in the MoMA design department, jerseys of important local sports guys stretched like canvases, some fine art that was treated like fine art (with a wall label and everything) commissioned or just acquired by the hotel. Then there were framed Polaroids of some people, kitschy little animal sculptures—lots of the same one—presented on plinths and other tactics of display meant to contrast their kitschiness with the pale severity of said display tactic, Andy Warhol wallpaper (of course), paintings up-anddown the taken-seriously scale placed cheek-by-jowl, neon art, plants, mismatched vases, all flanking relatively stylish tables, chairs and chandeliers.

Visually, if you wanted to be generous, you might say it operates according to a system combining density, clarity and democratiza tion to allow every mismatched thing, no matter how humble, to present itself as a dramatic actor in an infinite game of juxtaposi tion . (This may just be a crappy papier-mache leopard, but I bet you didn’t expect it to be next to taxidermy!) If you wanted to be ungenerous you might say it looks like a store.

The lobby also decisively asserts that several things the fine art world has traditionally thought of as different aren’t. The curator— whose job it is to decide which objects are worth looking at—isn’t much different than the interior designer—whose job is to make a space seem worth hanging out in. Neither are very much different than the appropriation artist—whose job is to assert one object they didn’t make is more worth looking at than all the others they didn’t make. The commercial designer—whose job is to decide on the visual specifics of the next commercial tchotchke to get sold—is not different than the artist—whose job is, well, much debated. The boardwalk painter, the skateboard painter, and the much-celebrat ed painter are likewise all equal, along with the typewriter-designer. And the typographer. The collectible, the historical artifact, and the image-made-for-image’s sake are all the same.

The public doesn’t care about the philosophical heft of trans porting all these objects from one Sphere of Discourse to the next. In the end, it’s a lobby competing with other lobbies. You can hang out in the Parisi Udvar’s lobby or you can hang out here. Both present visions of excess, but in different ways:

While the classically gorgeous European hotel might present the visitor with an image of conspicuous consumption represented by paying some Milanese stone mason to chisel away at an angel’s wing on top of a column for half a year, this lobby presents an image of conspicuous consumption represented by spending an equivalent amount to pay for a glass box, a white pedestal and several square feet of now-unusable floor space in a major metropolitan area to display a soup ladle. While Renaissance art patrons wanted to overwhelm us with the variety of craftsmen their money could muster and master, these new overlords want to impress us with the spare money they’ve got to waste on the space needed to display the ladle, the spare time and brain cells they have to waste on dreaming up why they’d want to, and the spare drugs they have to waste on making that seem fun.

After parking on an ominous street, dodging detritus on the sidewalk and being ushered through the door by an equally ominous bouncer—we enter a sprawling fog-filled industrial space just south of DTLA. Loud music plays, neon flashes and the walls are literally covered floor to ceiling with digital canvases (essentially large televisions). Upon entrance a commotion erupts in the center of the space. The outline of a giant sphere hung from the trusses can be discerned through the mist. Art collectors in dress shirts retract to the edges of the gallery while several younger patrons advance with large sticks and subse quently begin to smash the artwork with a vigor only matched by a Rage Against the Machine mosh pit. Welcome to Superchief; let the party begin.

Granted this may not be the art gallery to take your mother—if you are in search of adventure, are not a risk-adverse hu man, and have some inkling toward digital art on the blockchain—LA is home to the world’s first permanent NFT gallery. Before visiting, prepare yourself as you will leave with at minimum a slight buzz, a loud ring ing in your ear, possibly a raunchy T-shirt, your first NFT artwork or even a black eye. I wouldn’t suggest wearing your Sunday white’s.

The gallery has been a longtime staple in the art/party scene in NYC, Miami, LA and after a decade, they still go hard. Don’t get caught off guard, while the gallery may give the vibe of a rocker that has been on the road too many years, its provenance speaks for itself. Artists such as Swoon and epic partnerships with the likes of Christie’s Auction House, Scope Art Fair and OpenSea (the world’s larg est NFT marketplace) are impossible to discount. Once again, Scope Art Fair has teamed up with Superchief as its official digital media partner for Miami Basel 2022. If you happen to notice the monumental 60-foot curated digital stage as you enter the fair—that is them.

While Superchief was originally founded in Brooklyn circa 2012 by Edward Zipco and Bill Dunleavy, the focus on the digital began in 2016. The story told by co-founder Zipco may sound like that of many galleries at the beginning—long hours, little pay, nights spent sleeping in the space. As with many superheros’ origin stories, ultimate strength is earned from near-destruction. For the prophetically named “Superchief” this defining moment was in early 2020 when an explosion occurred in the building neigh boring its original Los Angeles location. Fire/chaos ensued and while luckily no one in the gallery was injured, the damage to the building lead to the forced closure of this location.

Through COVID and a string of unforeseen events, NFTs stole the art world’s attention. The timing couldn’t be better and as if a phoenix rising from the literal ashes, Superchief returned after lockdown with a renewed vigor, an exhibition space of double the size and, as Zipco describes it—“a mission to help artists dream in web3.”

Don’t think the excitement is over as in almost the next breath he speaks of a recently received compliment. The collector re counted—“I really enjoyed the vibe at the gallery, it was ex citing and colorful, but on some level you could just tell it felt dangerous.”

For the ultimately authentic Superchief NFT Gallery this is part of the history, their pulse and not something they are willing to give up. Patrons: Just remember to keep your head on a swivel!

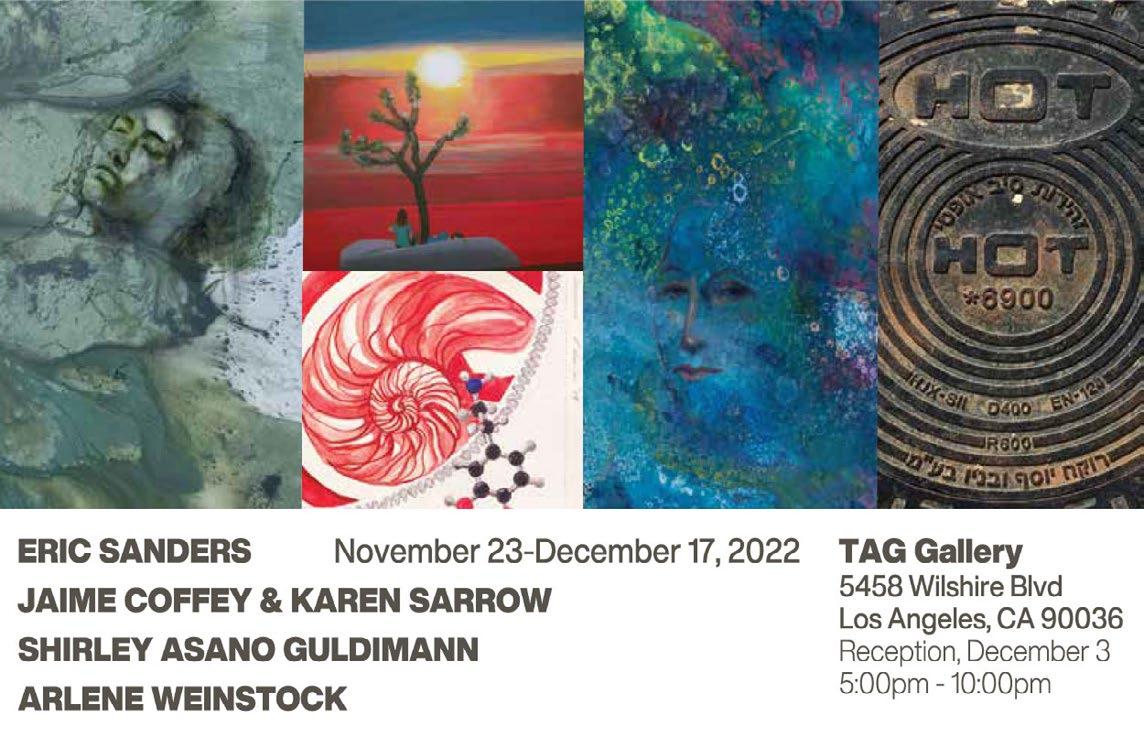

November 23–December 16, 2022 Opening December 3, 5–9 pm

TAG Gallery

5458 Wilshire Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90036 taggallery.net

StudioSanders.com

Instagram: @eric_sanders_art

Oakland-based Swedish-American artist Michele Pred achieved notoriety in the early 2000s for her conceptual sculptural installations of items like Swiss Army knives and manicure scissors confiscated by airport security. Pred’s witty and dramatic work, with a strong Pop-inflected emphasis on bright colors and geometry, clearly hit a nerve.

In 2014, she was inspired to shift to vintage purses as a primary medium, fashioning words out of glowing EL wire:“Pro Choice,” “Feminist as Fuck,” and “Pussy Grabs Back”a few of the options. The purse, as both a symbol of oppression of women, and of their economic power, offered a double-sided tool. Pred’s work has suddenly acquired an even deeper significance, with the overturn of Roe v. Wade. A dark time, certainly. I caught up with Pred hoping she might shed some light on the subject.

ARTILLERY: You grew up in Berkeley, where your father was a professor at UC and a political activist, and your mother was from Sweden, with a feminist perspective. Can you tell us a bit about your upbringing and how it informs your art practice?

MICHELE PRED : My father was in the department of cultural geography and very much an activist; coming from Sweden, my mom was a socialist and a feminist. We spent summers there, so I grew up seeing different possibilities, like socialized med icine, and free education.

What steered you in the direction of fine art? It was always in my blood. I respond to and comment on the world around me by making things. I started out in photography. Then at California College of the Arts I was already doing political work around women’s body issues, and reproductive rights. And that was in 1990!

Tell us a bit about how you began combining vintage purses with electroluminescent wire bearing feminist slogans.

I have always been very interested in using my body as a canvas, and have been in trigued by purses, by what we carry in them. I had been doing a lot of neon pieces on cases, that you couldn’t carry around, with feminist slogans. And I started thinking it would be really fun to carry them. So I made the first purse and took it to the opening night of The Armory Show in 2014, it said “Choice” on it… and people really responded strongly to the purse! Art galleries are such privileged spaces—taking the work out into the streets and engaging with people is interesting to me.

Your purses have been carried by some amazing women. What are some of your favorite ways they’ve been taken into action?

Hillary Clinton and Amy Schumer have been photographed with them; Amy showed hers on Instagram. One side says “Pro Choice” and the other side “Nasty Woman.” They’ve been on the red carpet at the Oscars. Ariana DeBose owns one, and Nadezh da Tolokonnikova of Pussy Riot recently took hers on stage. She says she’s obsessed with it.

Your show this fall, “Equality of Rights” at Nancy Hoffman Gallery, includes replica abortion pills. Can you tell us a little about this new work?

Yes, the abortion pills, I had a thousand of them fabricated in resin, enlarged so no one would mistake them for actual pills, and I’m making a flag. I have also just made these sterling-silver abortion-pill necklaces; I’m really excited about them! Then there are works using the scales where I’m using dollar bills I’ve painted pink, which relate to my “Art of Equal Pay” Project.

Where you are asking women artists to commit to raising their prices by 15% to address the fact that women artists earn on average 15% less than men?

Yes, and I’m also asking curators, gallery owners and collectors to pledge to support the artists by showing and collecting their work at the higher prices. You can sign up online at theartofequalpay.com, and there’s a survey. It’s a longterm project.

You are also curating a Pro-Choice billboard exhibition, “Vote for Abortion Rights,” to be installed across the country. How many billboards will be included?

We’re hoping for 10. They won’t necessarily be in California—we don’t need them here.

Your work is important and timely. Are there other projects you’d like to mention?

“The Talking Tree A Space for Civic Discourse.” I want to bring together people from different viewpoints and have conversations—to try to find a middle ground. I think we have to. We have to do that.

Monumentality is not the point of Michelle Stuart’s work. “Con nection” doesn’t exactly sum it up either, although it’s always there. Transit or transition would be closer to it—although it would have to be understood within a post-Einsteinian view of the universe and its moving and multi-dimensional aspects.

I wanted to trace those connections and transitions in Stuart’s work to that connective sense she forged early on, growing up in Los Angeles and Southern California before explosive urban de velopment transformed the landscape into what we know today.

At one point, I asked her about grid formats she’s applied frequently in her works over the years, and her response under scores what distinguishes her art from the monumentally scaled work of some of her peers.

ARTILLERY: Was that about time or mapping or both?

MICHELLE STUART: Absolutely both. As far as I’m concerned, they go hand in hand. We’ve made time calendrical. The time element is maybe the most important—time elements were really the seeds of my development.

These are excerpts from two conversations I had with Stuart— first remotely from LA and later at her New York studio—lightly edited for clarity.

MICHELLE STUART: None of the works that I did out in the land were meant to be permanent pieces. They weren’t meant as monuments. I thought of them as experiments in a way. They were things I’d thought of and wanted to do, or commissions I was given and decided to re-do into something I actually wanted to do.

You started very early playing with ideas about the moon and the moon’s connection with the earth and its oceans. I started doing drawings of the moon in the late 1960s. I grew up in California. Anybody who grows up in California must feel that. I went to the ocean all the time, and you’re almost always involved with the tides, the moon.

It’s very much on a similar wavelength with writers like Rachel Carson, making that connection between the moon, the oceans, and the rest of our planet as a living, breathing biomass—that emerging sense of both topography and cosmology. You always felt it at the beach. You felt the pull of the tides. Even if you look at the stones that you find on the beach …

The very early Americans—especially the Mayans—were very much on that wave. We now know [from archaeological evidence] that a lot of the hieroglyphs we have from the Maya are about cosmology and the moon, pairing different things they encountered as part of their being.

Your works frequently take the form of mappings, also classi fication and calendaring—the gridding of time. Where do you think that approach towards the actual tracing of time began in your work?

I think I started working with the grid in the 1960s—I did moon drawings with grids, too.

When I started doing seed drawings in Oregon—they start ed out as calendrical drawings …That piece in Oregon—Stone Alignments/Solstice Cairns —that was a calendrical piece the connection with the land; and the movement in time.

“That piece,” as she puts it, is nothing less than one of the most important (and given its setting alone, one of the most beautiful) earthworks produced in the wave of Land Art or Earth works between the late 1960s and 1970s, pioneered by (among many others) Robert Smithson, James Turrell, Alan Sonfist, cura tor Willoughby Sharp and the gallerist, Virginia Dwan. From rocks piled into cairns set into axial points of a somewhat hexagonal ring (approximately 100 feet in diameter) of stones pulled from the Hood River (by Stuart and an assistant—and some distance from this glacier-chiseled gorge of the Columbia River), Stuart marked the point of sunrise and sunset at the summer solstice. Stuart’s journal notes documenting the piece, which reference poetry, are themselves nothing less than poetry.

Although the relative lack of preservation of this work seems (to me) nothing less than scandalous, the work itself, among sev eral others I mentioned to Stuart, acknowledged this possibility.

There’s this consciousness in your work that it will fade with time. And that seems to be part of it, part of what you’re talking about. It’s interesting to bring up permanency because one piece I did in the mid-1980s for the Rose Museum (at Brandeis University, in Waltham, MA)—Ashes in Arcadia—I wish had been permanent because it was really a very early cry for what we’re doing to our world.

You were doing a lot of [earth-filled] boxes then. And books? At that time I was doing paintings; and they were giving me a big painting show. And the curator said, “You know we have this room …” and I said, “I’ll take it.” I had this piece in my mind I wanted to do—and that was what I did.

It was a huge room with units on the wall I made from wax with garbage; and the entire floor was filled with ashes and books and pieces of twigs and branches and hidden lights behind the walls. You couldn’t really walk into it—you would just walk about five feet from the door into this room and there was the sound of a humpbacked whale. And you would be completely engaged in it.

The whale was indicative of what we were doing to our

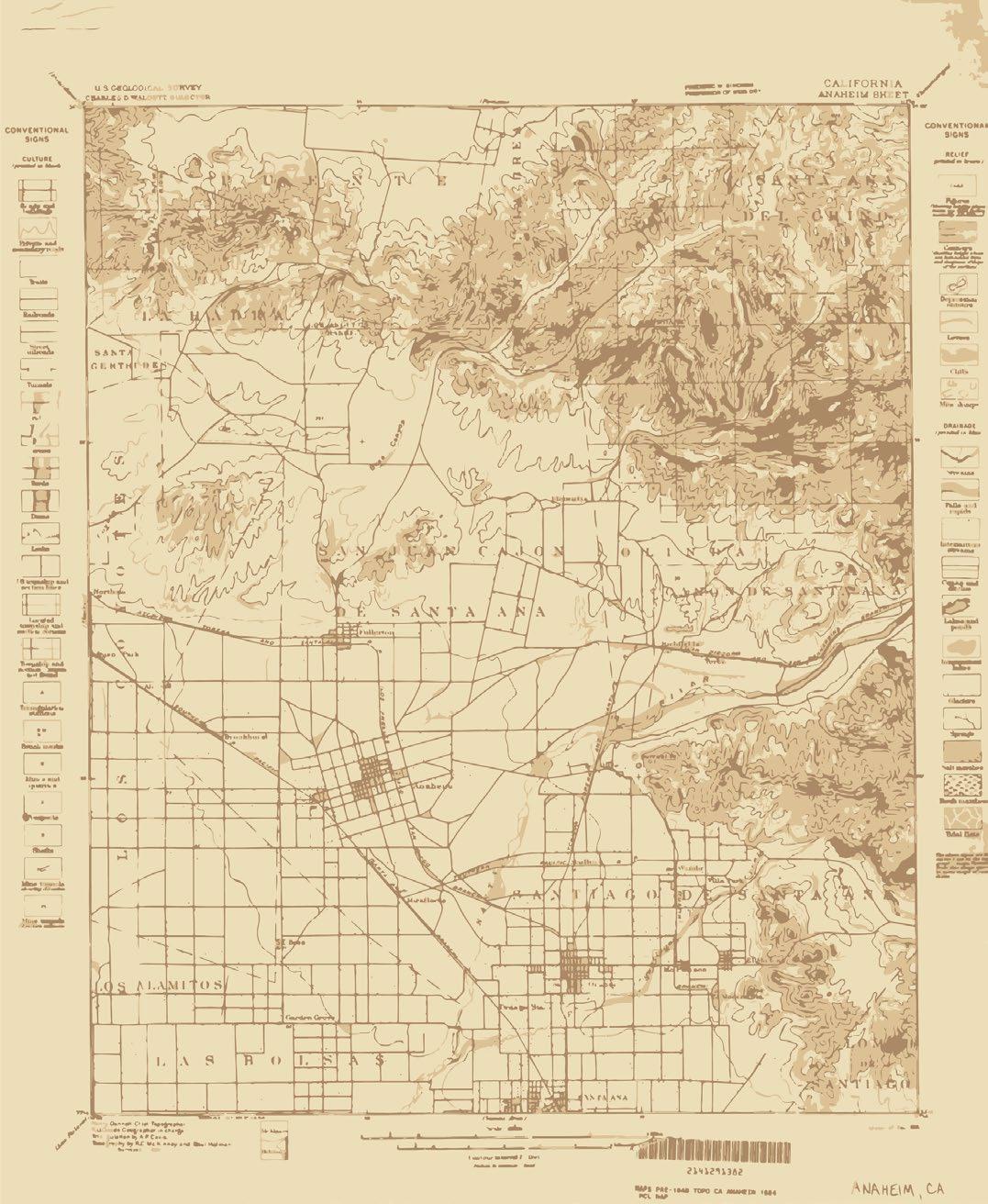

These Fragments Against Time, 2018, Wall: Suite of 130 archival inkjet photos; table: wood, beeswax, earth, rocks, sand, various fragments of fossilized shells, bones of various animals, collection SFMOMA, ©Michelle Stuart, courtesy of Galerie Lelong & Co., New York.

world—at first by killing them. And now we’re fucking up the ocean with plastic. It was almost unbelievable how moving it was. Now something like that I wish had been made into a permanent room in the museum. Well naturally it wasn’t. Yes—I was doing books, too.

In a lot of the earth drawings, whether they emerge as land scape or they’re gridded with this notional classification or time trace, there’s the sense of connection between earth and sky— and an ambiguity to it. When were you conscious of moving in that direction—towards these kinds of projects?

That’s hard to answer. Certainly with pieces like Niagara Gorge Path Relocated, I thought of the whole piece as water going up to the sky and coming down and hitting the earth and going into the river—that was in 1975. I wanted the viewer to be engaged physically with going into the piece—not just looking at it on the wall, but actually entering the space. And people sometimes would say, “it’s like coming to a cliff …”

We were talking about that sense of connecting to the sky, the atmosphere. What’s extraordinary [in Seeded Site (1969–70), Tate Modern] is this juxtaposition of the lunar landscape, which you’ve made longitudinal—with those inset seeds …

It was kind of the first seed piece in a way. I kept thinking at the time that how the moon relates to us—or how we relate to the moon. Certainly one of the ways was magnetic forces. It’s more than that of course. It’s the tides—the whole thing makes what grows grow.

And here [in Nazca Lines Star Chart and Southern Hemisphere Constellation Chart Correlation (1981)], you have this palpable sense of correspondences between the Earth and the stars. I went there the same time as I went to the Galapagos—between 1981 and 1982. It’s in Peru—about 200 miles south of Lima. I drove down.

Stuart, 89, has long been fascinated with exchanges between cultures in various proximities with one another—both close and distant. Deep memory of distant sea voyage is all but imprinted into her DNA. In addition to Darwin, her childhood (and forever) heroes were Melville and Captain James Cook, whose explora tions mapped virtually the entire Pacific “ring of fire.” But she is conscious of the extent that “ring” swept her up during her formative years in California.

As a child I was constantly going up the [Highway] 101 with my parents. There are some cliffs for you! That were falling down all the time. That’s like a perfect example of seeing time. Strati fication. California is full of that.

Some of those early grid pieces, those frottages really had to do with earthquakes—the fault lines [Sequence Development: Fault Line is the title of a 1969 triptych, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art]—so they, too, harkened back to my background in California, although I did them in New York.

Did you ever experience a California earthquake? Who didn’t? I remember when I was a child, my father told me that not long after I was born, there had been a huge earthquake and he rushed me to the door, to stand in the door frame ...there’s an earthquake a day in California.

In 2004 Calida Rawles moved from New York to Los Angeles, and she found an art scene brimming with life. Trained as an art ist, she longed to become part of that world, and asked herself whether she would become a collector or a painter. She decided to give herself the chance to be a painter and made an agree ment with her husband that she would take a year to find her way, without any expectations of financial return. She rented a studio—the studio we are in now, in a repurposed industrial build ing in Inglewood—and she began to explore and experiment.

Among the first works to emerge were self-portraits of herself crammed into an acrylic box. She still has that box—it’s in a cor ner of the studio, and now holds snacks and a small refrigerator to keep the drinks cool on this hot, hot summer day. “I pressed myself against this box, took pictures of myself when I was preg nant with my last baby,” she says. “Then I painted myself getting out of the box and turning into water. Those are the first ones using water as this metaphor of my release.”

Rawles was born in Wilmington, DE, to working-class parents. “Artistic expression was big in my family,” she recalls. Her mother was happy to buy art supplies for her kids, and Calida took her first painting lessons as a child. Later, she majored in studio art when she attended Spelman College in Atlanta. She wanted to continue and applied to New York University, partly because she thought her parents would be pleased that she was going to such a prestigious school.

It ended up in discouragement. “I had been so nurtured at Spelman, and then I went there [NYU], and it was a very differ ent, tough experience.” She’s fine with how things turned out, she says, but “before I went to grad school, I think I needed to be a little bit more mature. I needed to know who I was more and have a better understanding of my voice.” It was also a time when some instructors were critical of figurative work, and ques tioned her focus on the Black body.

Today Rawles has clearly found herself—and gallerists and collectors have found her. In 2020 she had her first solo exhibi tion, “A Dream for My Lilith,” at Various Small Fires.

Rawles says she’s often more influenced by literature than by other art, and this show explored the myth of Lilith, said to be the first wife of the Biblical Adam. The artist separated Lilith from her traditional reputation of failed womanhood and moved her repre sentation towards the notion of strength and liberation embodied by Black women and girls. Those paintings were in the main gal lery, while the smaller gallery featured studies done for Ta-nehisi Coates’ book, The Water Dancer (2019). Unfortunately, that show closed early due to the COVID shutdown, but shortly thereafter Rawles was picked up by Lehmann Maupin in New York. The latter gallery featured her exhilarating portrait of a woman floating in blue water, The Way of Time, at this year’s Frieze LA.

Water is a pervasive leitmotif in Rawles’ work. In her paintings people are often seen floating or swimming in a watery environ ment, and they are nearly always clothed. About the time Rawles

got her studio, she also began to take swimming lessons. She found that she loved both the sensation of swimming and being able to see how water captures and refracts light, and the shifting net patterns it forms. Her figures are radiant, sometimes smiling, as the subject of The Way of Time is, or sometimes with their eyes closed in meditation or serenity.

These days Rawles works in acrylics, although she has recently done some pastels. She still takes photographs, sometimes by the hundreds, to prepare for a painting. Most of the subjects are friends and family, and she photographs them in pools. Later she goes through the photographs, selecting which elements to use, such as how legs bend and become wavy when you view them through the water. As a Black woman, she is keenly aware of the politics of the Black body, and equally conscious of how lagging this country is in the treatment of Black people and of women. The ease and the confidence with which her figures navigate water are powerful statements about being in the world—we are here, we belong here, we thrive.

Rawles likes to work large, but often makes a smaller study first to work out the details. The one on her easel now features her youngest daughter, as if she were being shot out of a can non—head forward and one arm behind her. Rawles has men tioned Degas before, and I say this one reminds me of Degas’ young ballet dancer—the bronze the Norton Simon has a version of. “I see that, too,” she says. “I think that it will be inevitable that people make associations with that work.”

In a 2021 essay for Artnet News, Roxane Gay praised Rawles’ alternative look at Black suffering. “When I first saw Calida Rawles’ 2021 painting High Tide, Heavy Armor, I felt, as I often do when I am experiencing great art, that she was offering a different way of bearing witness. In the painting, a Black man floats in crystal blue water. The photorealism of the painting is uncanny—the smooth ness and glowing brown of the man’s skin, the range of blues of the water, the reflection of the sun,” Gay wrote. “There is no one near him to question or challenge his right to be in these waters. He doesn’t have to justify or explain his leisure.” The painting is a visual elegy for Kurt Reinhold, a Black man who was the father of a child at Rawles’ daughter’s daycare. In 2020 in San Clemente, he was stopped by sheriff’s deputies on suspicion for jaywalking, and during the ensuing struggle, he was shot and killed.

Such tragedies are addressed in Rawles’ work; she doesn’t shy away from sociopolitical issues. However, the painting itself is quite beautiful, as Gay says, and is in its way a celebration of life. “I want my work to inspire others,” says Rawles. “I try to be the best version of myself as I can be—I’m not always successful at it, but I’ll try as much as I can.”

This fall Rawles will be featured at the Lehmann Maupin booth at Frieze London (Oct. 12–16), and she will have a solo at their New York location in fall 2023. The large mural version of The Way of Time, made with a team of assistants, is now on an exterior wall on a walkway at Hollywood Park in Inglewood.

BY JULIE SCHULTE

BY JULIE SCHULTE

On a sweltering September afternoon, I visited artist Astra Huimeng Wang as she was in the final stages prepping for her first solo show of paintings at Make Room LA. Her studio is nestled above a discount clothing store in LA’s Fashion District, where crowded shop windows are filled with children’s pajamas that double as Disney cos tumes. I paused before an outdoor rack of candy-colored tulle princess dresses being tossed about by the hot wind. It was as if these festive garments were little spirits preparing me to enter Wang’s work. Arriving at the studio and looking at her paintings felt like confronting Renais sance polymath Giulio Camillo’s Theatre of Memory: the relics of tender moments filling the audience seats for a single spectator who stands alone on the stage.

Wang is an LA-based multidisciplinary artist who grew up in Hohhot, in China’s Inner Mongolia region. She has held residencies at Otis College of Art and Design, earned a MacDowell Fellowship and most recently participated in the group show “Machines of Desire” at Simon Lee Gallery in London. In Wang’s latest body of work the viewer is invited to reflect upon familiar moments from Western ceremony. As we spoke about decorum and decay, Wang gleefully showed me her collection of tossed-away ephemera: cutesy wedding cake toppers, tiny 1950s toys includ ing a functional, doll-sized oven and refrigerator, and lavish wedding albums. As she turned to the faded picture that inspired her painting for the group show “Machines of Desire,” she commented on the fas tidious planning and care that goes into a wedding day “so it can be preserved in the decadent album, only to be discarded and end up in my hands for a dollar at a flea market… all these precious moments.” Wang told me how growing up before social media in a culturally homogenized Inner Mongolia, her only access point to the West was literature and films: “If you grew up in Western culture these relics are what’s left of important moments, but to me they were con densed representations of Western civilization and utterly disconnected from reality. All were part of the fiction I consumed.”

Exposing fiction as fiction has long been Wang’s aim and what first led her to experiment with flock ing techniques. She told me, “In one of my earlier projects, a three-day performance, four people were having a dinner party in a 10x10-foot box-like mov ie set with red velvet curtains on three sides. I was referencing Luis Buñuel’s The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie where the rise of a red velvet curtain be hind the dinner guests reveals that they are actually

Opposite page: Beneath a Dreamy Chinese Moon, Where Love Is Like a Haunting Tune , 2022. Flock, acrylic, acrylic medium on birchwood panel 48 x 60 inches. Above: A Continuum of Positively Captivating Behavioral Expectations , 2022. Flock, acrylic, acrylic medium on birchwood panel, 60 x 60 inches. Both courtesy of the artist and Make Room, Los Angeles.

on stage. The idea that red velvet suggests a departure from reality became so symbolic to me that I began experimenting with red flock to create these velvet-like surfaces when I started to make sculptures.” I was vaguely familiar with flocking as the artificial snow sprayed onto Christmas-lot pine trees giving those in warmer climates the illusion of a white Christmas, and as the synthetic lining used inside children’s jewelry boxes that lends a gauche, regal-adjacent opulence. I asked Wang more about its origins and about working with the material. She explained that the process of attaching ground fibers to fabric with resin originated in China 3000 years ago and only later was used to paint onto hard surfaces: “Flock-painting needs to be done like a marathon because once dry, it’s almost impossible to make any adjustments. I’d sometimes work 15 hours without any breaks to get something right. The process requires skill, precision and just enough room for coincidences. It feels akin to what happens in any performance.”

Right after this, the studio’s A/C unit broke and we watched it, like a stubborn rain cloud, slowly dripping fluid down onto the materials below. “Happy accidents,” Wang mused, “that’s just the effect I am hoping for with the final bit of red I am adding to the wedding scene.”

Wang had been finishing a painting where a couple lovingly clasp hands over a knife just before slicing their wedding cake. In Western culture, the cutting of the cake as husband and wife is another wedding “micro-event” and as important as the tossing of the bouquet. In Hollywood Romcoms, the cake has become another predictable source of hijinks, its fragile nature always inviting a disaster. We’ve come to expect the cake will be de stroyed in transit, a child will scoop his hand in for a greedy bite, or a Labrador will run off with the topper. In the painting it might appear that this scene is going off without a hitch—meaning the couple have made it to the moment unscathed—but the framing renders the couple headless and we cannot see their expressions or the guests’; the flocked outlines show the cake, the moment— the couple are already melting into time.

As I considered this tidal destruction I was reminded of Aud en’s poem “As I Walked Out One Evening”—specifically the line “the glacier knocks in the cupboard” and his promise that pesky time will always cough when we would kiss. But Wang speaks with sincere wonder and affection about the ways these interruptions function as “the moment of crisis,” the dramatic instance where nature and time disturb the little one-act play we are forever constructing for others. She mentioned a similar occurrence in an early performance piece, “A Beginner’s Guide to the Art of Throwing the Perfect Chocolate Fountain Party,” where during the shooting a fly snuck in the studio and buzzed around the fountain. “Of course, there would be a fly at this dinner. The actors sat for three days at a set table with decadent food and warm chocolate—it’s delicious! It became one of my favorite elements in that show,” she proclaimed.

There is something revolutionary in Wang’s process of invit ing ruin into Western ceremony, informed perhaps by a lifetime

of engaging with the Western canon for the sake of learning English, and subsequently seeing herself rendered on the page through an Orientalist gaze. She showed me a brimming binder where she collects literary passages to work with and through in her art. Her latest show’s title, “In My Experience the Spider is the Smallest Creature Whose Gaze Can Be Felt,” is lifted from a passage in Iris Murdoch’s 1954 novel Under the Net where the speaker Jake experiences the uncanny sensation of being watched and finally notices a set of masks “whose slanting eyes were turned mournfully in my direction,” commenting on their “Oriental mood.”

The sense of being watched is most keenly felt in the painting Beneath a Dreamy Chinese Moon, Where Love is Like a Haunting Tune (2022). Here horses are being paraded in a circle; the sense of pageantry and showmanship is cleverly undermined by the ice-blue flocking that creates a chilling effect and casts a ghostly mood. All we see are the horses and riders’ amorphous silhou ettes as they melt into the valley landscape. While the show goes on, the aubergine sky looms and draws the eye to a second, truer splendor—nature’s. The patch of yellow and tiny green clouds lend their own lighting effects toward a different focal point. Rather than stage footlights, our eye is drawn to an aurora bore alis that calls our gaze out beyond the constructed reality. Where a stage curtain might hang, we instead see a sprawling spider web. The flocking here blurs the delineation between web and spider body, of spectator and spectacle.

If the Modernists’ inheritance this past century has been to see nothing but “a heap of broken images,” Wang flips through the discard-pile of cultural memory, repurposing these fractured pictures to create a new narrative in painting: one that draws our eyes to the red velvet, the spectacle, all the while winking from stage left and asking the viewer—Who is watching whom?

A group exhibition of Chicana/o/x artists recapturing and reconstituting concepts of nature, featuring Jackie Castillo, Juan Gomez, Álvaro D. Márquez, Narsiso Martinez, Aydinaneth Ortiz, Jynx Prado, Gloria Gem Sánchez, Christopher Anthony Velasco, and curated by Dakota Noot.

A group exhibition of local, regional, national, and Indigenous artists who honor the history, culture, and natural wonders of Avi Kwa Ame (Spirit Mountain) in the Mojave desert landscape south of Las Vegas, in light of the recent proposal to permanently protect the area as Nevada’s fourth National Monument. Curated by Kim Garrison, Checko Salgado, and Mikayla Whitmore.

(714) 432-5738, www.orangecoastcollege.edu/DoyleArts

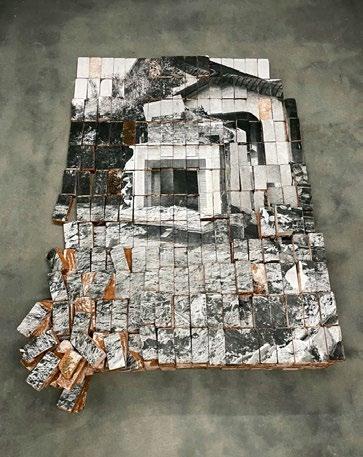

Caption info: Jackie Castillo, Untitled (Turning No°2), 2022, laser print, transfer medium, reclaimed brick

Exhibitions organized by Frank M. Doyle Arts Pavilion. Major support for programs at The Doyle provided by The Rallis Foundation, John & Yasuko Bush, Sylvia Impert, Orange Coast College Foundation, and Associated Students of Orange Coast College.

Caption info: Jackie Castillo, Untitled (Turning No°2), 2022, laser print, transfer medium, reclaimed brick

Exhibitions organized by Frank M. Doyle Arts Pavilion. Major support for programs at The Doyle provided by The Rallis Foundation, John & Yasuko Bush, Sylvia Impert, Orange Coast College Foundation, and Associated Students of Orange Coast College.

Samuelle Richardson is a sculptural textile artist who began her career as a painter. Her painting itself evolved from stud ies in anatomy, for which she made 3D skeletal models. But by chance—or fate, when her painting studio became unavailable 10 years ago—she switched to her current technique in sculp ture. “You might say that my work has come full circle,” she says.

While her fabric sculptures emphasize the handmade quality of her creations, her classical art training is also quite evident, as she builds her figures from the inside out, from skeleton, to muscle, to skin.

Her art has a strong ecological bent, focusing on shaping animals that live on, even in the face of our rapidly changing climate. According to Richardson, “As the natural world is di minished by modern society, I reflect on an era when the order was reversed. I’m rewinding our story to a time when mankind believed that beasts had divine power. Ancient man and the animal were spiritually interdependent, and I like to play with the hierarchy of value, imagining how today we might be different.”

Regardless of her subject, Richardson looks for “good de sign qualities that support poetic rather than literal imagery,” she says. A pleasing arrangement of shapes and materials are important to her, with the subject “characterized by the sublime, appealing to all that is deadly and beautiful,” she adds.

The sculptures themselves are solid constructions created of wire and foam rubber wrapped in fabric. Their textural quality allows viewers to imagine, or intuit, the presence of fur, feather,

tooth or talon. Her work is both firmly rooted in recognizable portrayals and magically alive. The differences between an actual, living creature and Richardson’s constructs is a kind of alchemy. The viewer knows the animals—whether lion, bird, “ghost dog,” or human—are not real, yet they are imaginatively very much alive, fairy-tale creatures that have transcended their mythology.

The artist says she knows when she’s truly “onto something” in the work she creates, noting that this click of recognition comes “when I picture my idea being made by an artist from mid-century West Africa. There is a simple visceral quality in African art that really speaks to me.”

She begins each sculptural project working from pictures that reveal both gesture and expression. “Metaphorically, I am chas ing down the ephemeral and getting it onto the page. Getting something down is much different to me than making it up… I edit to achieve ‘believability’ over realism.”

Richardson is about to embark on a new trajectory with her animal sculptures, spending the fall as a resident visiting artist and scholar at the American Academy in Rome. Her proposal to the program was based on a connection between her sculp tural work and the Etruscan animals seen in artifacts. She’ll be presenting some of the new pieces she plans to create there in February at Keystone Art Space, Los Angeles, where (along with Snezana Saraswati Petrovic) she will be in “Leaving Eden”—an exhibition on climate change, lost habitats and the lifeline of environmental activism.

“Bird Series,” photo by Tony Pinto, courtesy of the artist.

The sprawling, splintered and paradoxical poetics used to de scribe Los Angeles are evoked in the work of Gala Porras-Kim, each bubbling with alternatives ripe for excavation. Porras-Kim rearranges and reframes cultural artifacts, objects and docu ments to unhinge and de-center the heterogeneous modern ist subjects that have long dominated museum practices and shape the so-called “cultural mainstream.” While her work is not confined to subjects and institutions in Los Angeles, this city lends itself to the motivations underlying Porras-Kim’s practice that promote expansive representations of identity and cultural heritage. For most of the 12 million people of the greater LA area, it’s nearly impossible to avoid feeling the tensions of dayto-day life in a city segregated by design and oriented around shifting modes of capitalism in an increasingly globalized world. Porras-Kim prioritizes the many “other” lived experiences and embodied histories that have been marginalized or omitted from institutional discourse.

Porras-Kim’s practice serves as a vital reminder that this work will never end—nor should it—because as arbiters of knowledge and culture, museums must remain expansive and malleable to allow for new systems of care, representation and learning to occur. Her work emerges from the challenges embedded in LA’s cultural landscape and the city’s legacy of artists and alternative practices that continue to push art and institutions forward.

—Lauren GuilfordThroughout her 50-plus-year career, Eileen Cowin has created enigmatic and beautifully sequenced multi-panel photographs and single-channel, multi-channel video installation works, in addition to large-scale public art projects. Cowin’s emotionally charged imagery is narrative-based and often draws from literary or news sources, yet in Cowin’s worldview nothing can be taken for granted. She exults in the unexpected, be it a photograph of an urban deer caught in the headlights—a metaphor for lost innocence and hesitation—or a multi-panel narrative like her newly commissioned photo-narrative: “You are heading in the right direction,” installed in the Martin Luther King Jr. station of the Metro Crenshaw/LAX line, which invites viewers to imagine the lives of the people depicted in the pictures as they travel on the trains. Cowin’s dreamlike images are simultaneously fantasy, fact and fiction.

In her recent works, meaning comes from juxtaposition, as in the differing expressions of loss in recent large-scale images of flowers set against black backgrounds. Cowin has created an expansive and thoughtful sequence of images that poetically address increased anxieties over the current political climate.

An astute looker and reader, Cowin analyzes personal and universal moments in her work, presenting the everyday as something extraordinary.

—Jody ZellenIf we’re talking about LA women artists who are blazing right now, we’ve got to talk about photographer Kristin Bedford. Bed ford spent 2014–19 exploring lowrider culture in East LA, greater Southern California and Nevada. The resulting series, “Cruise Night,” consists of color photographs as exquisitely saturated as a custom paint job on a 1964 Chevy Impala. Bedford photo graphed not only the cars, but their driver/creators (including many women), their tattoos and family snapshots with former ve hicles. She also recorded oral histories, giving her subjects voice within the project. Never a gawker and hardly a motorhead, Bedford was interested in the personal and collective creative expression of this culture.

Italian publisher Damiani released Cruise Night as a photo book in March 2021. A #1 bestselling photobook on Amazon, it has since sold out—the lowrider community being a big part of that. In October 2021, Just Memories Car Club organized a Cruise Night book signing and car show at the Autry Museum, attended by over 1,000 people and hundreds of lowrider vehi cles. Meanwhile, Bedford’s photographs have enjoyed interna tional exhibitions—a rare appreciation for authentic LA outside the home ground. “Cruise Night” is at Galerie Catherine et André Hug in Paris this November.

—Allison Strauss

—Allison Strauss

I am a long-time admirer of Malian-American artist Penda Diakité, whose work explores what it means to inhabit a body codified as both Black and woman.

So often, the bodies of Black women and femmes are relegated to categories that center only our productivity and usefulness: caretaker, laborer, birther. But in Diakité’s world, these reductive categories are deprived of their power. Through her mixed-media collages, Diakité reveals the many colors, tex tures, stories and memories that constitute Black womanhood. Her subjects are profoundly multidimensional, demanding the viewer’s earnest consideration, refusing monolithic classification. Viewing Diakité’s work, I feel my own complexities—my rough edges and tender vulnerabilities—avowed in mosaic splendor.

When speaking of her work, Diakité has said that she explores Black feminine identity as if “our soul’s experience was reflected in our appearance.” I am thankful for her willingness to tell the fuller richer truths of those souls, which are bursting at the seams with new stories to tell.

—Donasia Tillery

—Donasia Tillery

We can never cover all the deserving women artists in one issue, so in a modest gesture, we asked our writers to pitch a woman artist they’d like to champion in 200 words, to squeeze in just a few more.

Andi Campognone began her professional career as an artist, creat ing photographs that compelled viewers to engage with—and par ticipate in—her images. She transitioned into curatorial work, run ning two commercial galleries and serving as curator of the Riverside Art Museum. In 2011, Campognone became founding director of the Museum of Art and History (MOAH) in the City of Lancaster in the Antelope Valley region of California’s vast Mojave Desert.

While building innovative exhibitions at MOAH, Campog none has focused on collaboration and community building. She has partnered with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the LA County Department of Arts & Culture on projects intended to serve wider audiences. In 2014–15, for example, she worked with social-practice artist Suzanne Lacy and the LA Arts Commission on the “Antelope Valley Art Outpost.” The “placemaking” program used art and public practice as “tools to inspire development in the communities of the Antelope Val ley.” Campognone remains a passionate advocate of connecting artists and government in problem-solving issues like the envi ronment, sustainability and education.

In 2016, Campognone founded Kipaipai, an ongoing series of workshops and residencies for artists that supports career development and builds community. Kipaipai (“to inspire” in Ha waiian) has served artists throughout the US, sewing the threads of connection across the country.

—Betty Ann BrownSamantha Fields’ paintings unfold along a darkly fanciful and increasingly multifaceted continuum of disaster and perception in storm fronts, fires, abandoned dreams and other metaphors for societal decline, mediated by uncanny photographic inter cessions. She’s currently painting storms—their violent clash ing and cleansing suits the era, and opportunities to expand her jewel-toned naturalism are many. She started on them pre-lockdown, after photographing multi-tornadic phenomena in Texas. When everything changed—BLM, the lengthening pan demic, the insurrection, massive wildfires—she turned instead to the “American Dream” paintings: landscapes of winter’s discon tent festooned in confetti and party balloons.

Recently, in Texas again, she photographed myriad storms which will be on view at Rory Devine Fine Arts in October. Her prismatic “Worlds Within Worlds,” based on dreamlike, anxious ly shifting photos of her own backyard, were shown this summer at Berkeley’s Traywick Contemporary, and her affecting wildfire paintings are in two institutional shows this year. Along the way she became chair of the art department at California State Uni versity, Northridge—the first woman to hold the post—where she’s focusing on access, interdepartmental collaboration, and local and international exchanges. “When I came on board,” she says, “I kept asking, ‘Can I do this? Can I do that?’ and the answer was always, ‘You can do whatever you want.’ So, hell yeah, let’s do all the things!”

—Shana Nys Dambrot

Dancer turned artist Madeline Hollander is best known for per formance works that explore the evolution of human body move ment and the intersection between choreography and visual art. She has begun to show her pieces in galleries and museums, creating large-scale, technically sophisticated installations, two of which are now presented at Jeffrey Deitch. A neon work, Tomorrow Will Be Nothing Like Today Will Be Nothing Like Tomorrow (2022) forms an italic script circle five feet in diameter of the title words. Weights and chains from vintage cuckoo-clocks hang from and surround the neon sign, calling attention to the passage of time and the uniqueness of each day. The association with clocks and time is also key to Sunrise/ Sunset, the installation that fills the main space.

Originally commissioned by BMW and presented at Frieze Lon don in 2021, Sunrise/Sunset builds on a previous installation shown at Bortolami Gallery in New York in 2020. In that piece, titled Heads / Tails: Walker and Broadway, Hollander collected headlights and taillights from junkyards and collision centers in Los Angeles and repurposed them for the site-specific installation where they were installed salon-style on opposing walls. The headlights were pro grammed to correspond to the sunrise and sunset of a given loca tion, changing from their fog setting to bright depending on the time of day. In essence, they were always on. The taillights were syn ched to a traffic light on Walker Street and Broadway in Manhattan. Whenever the traffic light turned red, the taillights in the installation would go on. When the traffic light turned green, the taillights would go off. The installation became a visual representation of continually changing time and traffic flow.

Sunrise/Sunset comprises 96 BMW automobile headlights in stalled on a curved wall in a grid that is four-lights-high by 24-lightsacross to correspond to the 24 time zones on Earth. The headlights are mapped to each of these different zones, metaphorically be coming a clock that tracks sunrises and sunsets across the globe— turning on when it becomes night and off when it becomes day. The rhythm of the specific lights that are illuminated undulates in synch with a score using the different sounds made by the various BMW turn signals, created by the artist’s sister, composer Celia Hollander.

As light and sound fill the space, viewers are drawn to the nu ances of difference—the design and structure of each headlight and the relationship between the blinking orange and steady white LEDs. Through the day the sounds intensify and lull, based on the movement of the illumination as it makes its ways from left to right, from east to west. The work is a technological achievement, con necting the individual headlights so that they perform a dance of light, and although the installation is meant to reference “global connectedness” and “the body in motion,” it also can be seen as a wall of eyes; as the headlights resemble faces, they can also be seen as the people of the world.

Three movement artists—Maria Gillespie, Nguyên Nguyên and Kevin Williamson—are grandly projected on as many walls but re vealed in divergent locations. The panoramic videos depicting the bodily trials of these artists in demanding landscapes envelop the 2800 square-foot gallery as the performers shift from wall to wall and location to location; climbing, crawling, rolling. Yet, like memory and expectation, they each take their unnamed yet recognizable land scape with them. They are far from home, evidenced by the three cubbies on the unprojected wall, where the performers are seen in a miniscule video reflection of their endurance travels.

Williamson tramps through snow and stumbles over bogland as location dictates his path ultimately toward the sea, a desired target that appears to relocate in response to his approach. There is a pain ful yet elegant endurance in his earnest trek aimed at an unknown terminus. His no doubt painful contortions are his chosen demands upon his elbows, knees and hips as he slides down hills, sometimes tumbling, often reaching for the few and small brittle shrubs around him that offer little purchase. Perhaps his journey is as much one of remembrance as rigor, for opposite the vast panoramic projections are a trio of small compartments, open closets of mementos. In one of the compartments, where fragments of broken crockery are strewn over shattered bark, viewers may watch miniature videos of the alternating performers, in and out of their exertions. Williams is first seen shaving away the ragged beard suggestive of his marshland trials, then coloring his lips a gleaming ruby red and blowing us a kiss.

Gillespie, hair gone white in search of her past, visits an abandoned home then turns away as if the past is no longer able to reveal its secret histories: a pity and a mercy. It is too weatherbeaten, too desiccated to speak. She moves on, rolling herself upward then downward over stone stairs, toward and away from the sun, climbs a shifting and indifferent sand dune, then digs in the swollen earthen muck, yet the vast emp tiness withholds its secrets. Her corresponding cubicle is walled with abandoned shoes, tattered and unlaced, large, small and lost.

Between standing stones Nguyên slithers with eyes closed, his hands smoothly feeling his way over the wind-worn surfaces. He uses his outstretched arms, pliable not stiff, to navigate a sightless path between the menhirs. In another scene, this one distinctly manmade, the artist runs his fingers and tilted shoulder along a cement wall while his long shadow protrudes before him like a divining rod. Once more, this time in a location that suggests the border between city and wilderness, Nguyên comes to a barrier fence and follows along it, where it leads is unknown. The last cubicle—perhaps his, possibly all of theirs—is laced with disparate curtains, and a crudely layered shrine holding mysteries that continue to deepen. The projections then repeat their stories, as if the aching figures having clearly been given one lesson cannot help but ache and yearn for one more.

I’ve always imagined Angela Du fresne as an essentially cinematic artist whose high-concept films end up expressed as series of painted works on canvas. It’s as if she went directly from film school to a major film production in trouble, where the executives have planted her in the guise of an art director to save the picture and bring it in at a number that won’t bankrupt the studio. Picture and studio go down in flames anyway, but in the mean time, Dufresne’s series of concept/ composite shot sketches for the di rector and DP have essentially be come their own fantastical movie.

Once upon a time I would have thought Dufresne might actually team up in such a fashion with a director like, say, Robert Altman or Werner Herzog; and to my aston ishment her current show is actually informed and inspired in part by an other film-making Werner—Werner Schroeter, a German film (also opera) director, active in the 1970s and 1980s, who influenced filmmakers including Herzog himself. The exhibition title is drawn from a line uttered by the iconic Magdalena Montezuma (who appeared in most of Schroeter’s films) in Eika Kat appa (Scattered Pictures, 1969), and it speaks to the desperation all around us at this tipping point moment.

Dufresne is in fact a painter of “composite shots”—except that she usually adds more than subtracts from what becomes the finished painting. The title work, Life is very precious, even right now (all works 2022), exemplifies Dufresne’s approach and technical range. She’s simultaneously operatic and Altman-esque here in a scene focused on human figures begging, imploring or invoking some presumably cosmic force, while other figures variously look on with anger, concern or curiosity, walk away, or converse amongst themselves. The back ground elements—like green islands floating in an amorphous glacial sea churned out of something between Nolde, abstract (or German) expressionism, and Italian trecento painting—seem both suspended and in motion, a scrim to dissolve within moments. Even a supporting actor’s dog seems to be looking for another picture to sign onto. It’s a Sondheim moment in an Altman—I mean Schroeter—I mean Dufresne film—I mean painting. “Stop worrying …just move on.”

Which might just be a theme of the show. Past a master shot (e.g., Willow Springs Odyssey, or How Circe Is What the West Needs—lu minous with topaz yellows and amethyst purples), the scenes get re written, and the shots recomposed seemingly continuously; she’s not afraid to “tear up the script”—and the set with it, or simply turn her movie into an opera. Complex underpainting may be interrupted or obliterated by a bold swath of lavender, pink, red or umber; e.g., Wer ner and Circe Turn Some Mediocre Assholes (to make room for a “Su pervixen” or two). A complex chromatic scheme frequently evolves into something more monochromatic—which doesn’t remotely dampen the drama. Consider the pretzel-logic choreography of Magdalena Pumping the Gas That Isn’t There floating above its com plicated underpainting. (Is there such a thing as apocalypse-realism?)

Our relationships to places are fickle at both ends, and we look to our seers and sorcerers to navigate our way through them. Dufresne explodes the mythography of that fraught transit with this devastating and luminous show.

The lighting is low. The furniture and wallpaper appear disheveled. It soon becomes clear that everything is dilapidated; floor cushions are deformed, lumpy and discolored. The couch is disproportionate. It faces a scarred wall where instead of a fireplace there is a pile of disparate furniture legs. To the left is a large cone that sags like a battered wizard’s cap and from behind the wall voices emerge from a film: a woman or women talking to themselves about a place de scribed in detail that reveals it as equally rundown.

In one room there are very large drawings on irregular paper surfaces that appear to have been both drawn and written on from every imaginable position so that the vortex literally spins a viewer’s head. The fragments of writing range from descriptions of art pro cesses and theory to more mundane or cryptic phrases that might derive from the everyday. The most urgent message is how these stream-of-consciousness patterns are layered and built up on one another, crisscrossing in an irreconcilable jumble of thoughts.