COMMUNITY-BASED SETTLEMENT PROFILE

Individual & Focus Group Discussions

24 2 focus group discussions community members involved

Transect Walk

8 sessions (2 in each zone) community members involved

24

72 Priorities & Ranking

6 sessions (1 in each zone, one general and one for women)

72

Timeline community members involved

6 sessions (1 in each zone, one general and one for women)

community members involved

5 COCKLE BAY SETTLEMENT PROFILE 5 COCKLE BAY COMMUNITY PROFILE

1 2 3 4 WC

Cockle Bay in context

Where is the community located and how did it develop in time?

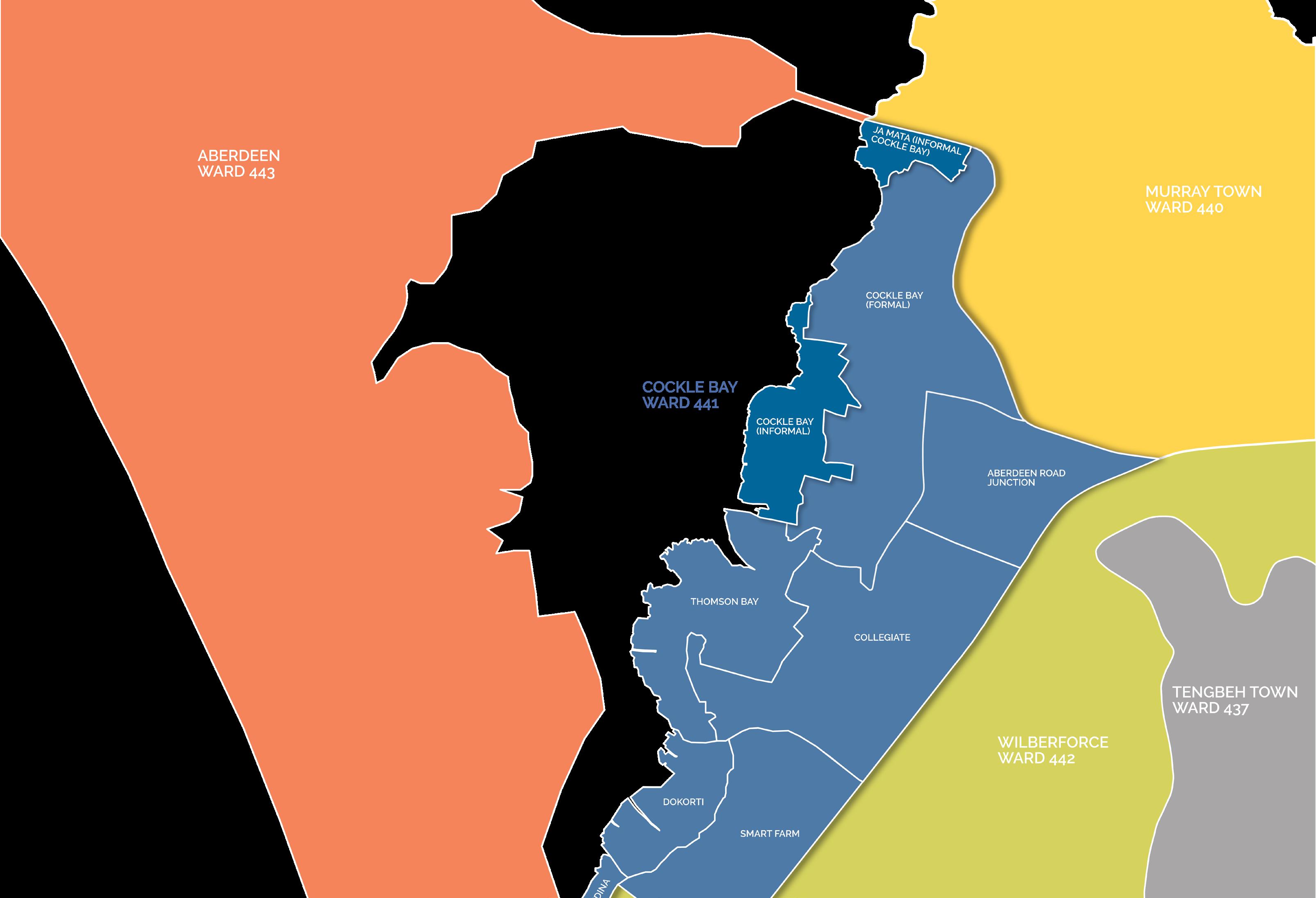

The informal settlement of Cockle Bay is part of a wider formal community called Cockle Bay and is located on the shores of the Aberdeen Creek in the west of Freetown. The settlement is 186 hectares in size constructed on land that has “mostly been reclaimed from the low-lying mangrove forest, much of Cockle Bay is built on land that lies between 0-1 meters above sea level. As a result, the settlement is highly susceptible to coastal flooding and rising sea levels.” (SLURC and ASF-UK, 2019).

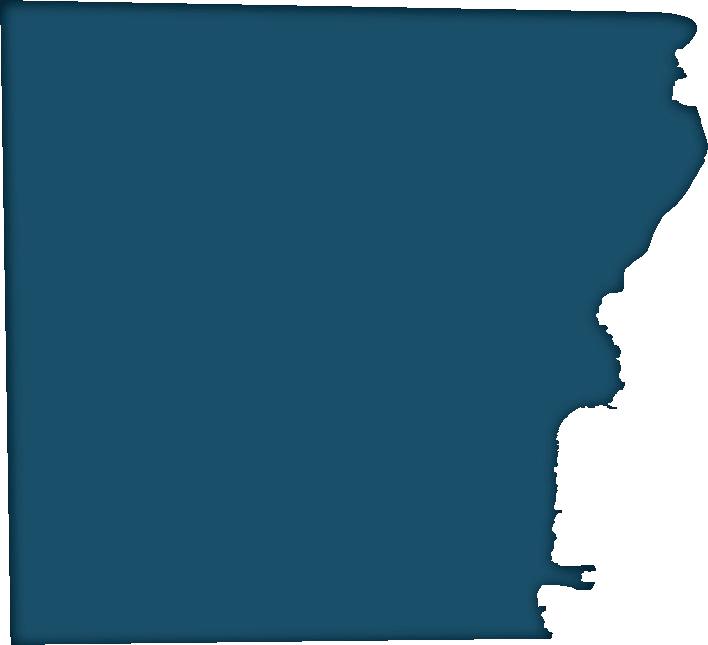

Politically, the settlement is situated in constituency 130 and in ward 441 (see diagram on next page). Cockle Bay is located about 5km from the city centre with an estimated 20,000 inhabitants and 1,350 households living in 540 structures (Allen et al., 2017; SDI, 2016).

The name Cockle Bay came from the cockle production that used to be a key source of income within the settlement before the cockle population declined due to the destruction of the local ecosystem. Cockle Bay has been occupied since the 1940s. at the time, residents mostly lived along the shore of the Creek. In 1955 makeshift houses started being built in the settlement.

During the civil war from 1991 to 2002, many rural populations migrated from the countryside of Sierra Leone to Freetown where Cockle Bay became a prime settling location. During that period, the settlement experienced rapid growth, combined with the lack of planning control, unplanned streets and poor layout

of buildings. The settlement is now experiencing major challenges such as, poverty, unemployment, poor literacy, poor hygiene, inadequate skills and low democratic participation.

Access to essential services is limited because residents generally lack formal land titles to allow for formal provision. Coupled with the acute lack of infrastructural protection, residents are disproportionately affected whenever there is disaster and many residents either sustain injury or lose relatives, dwellings or other belongings.

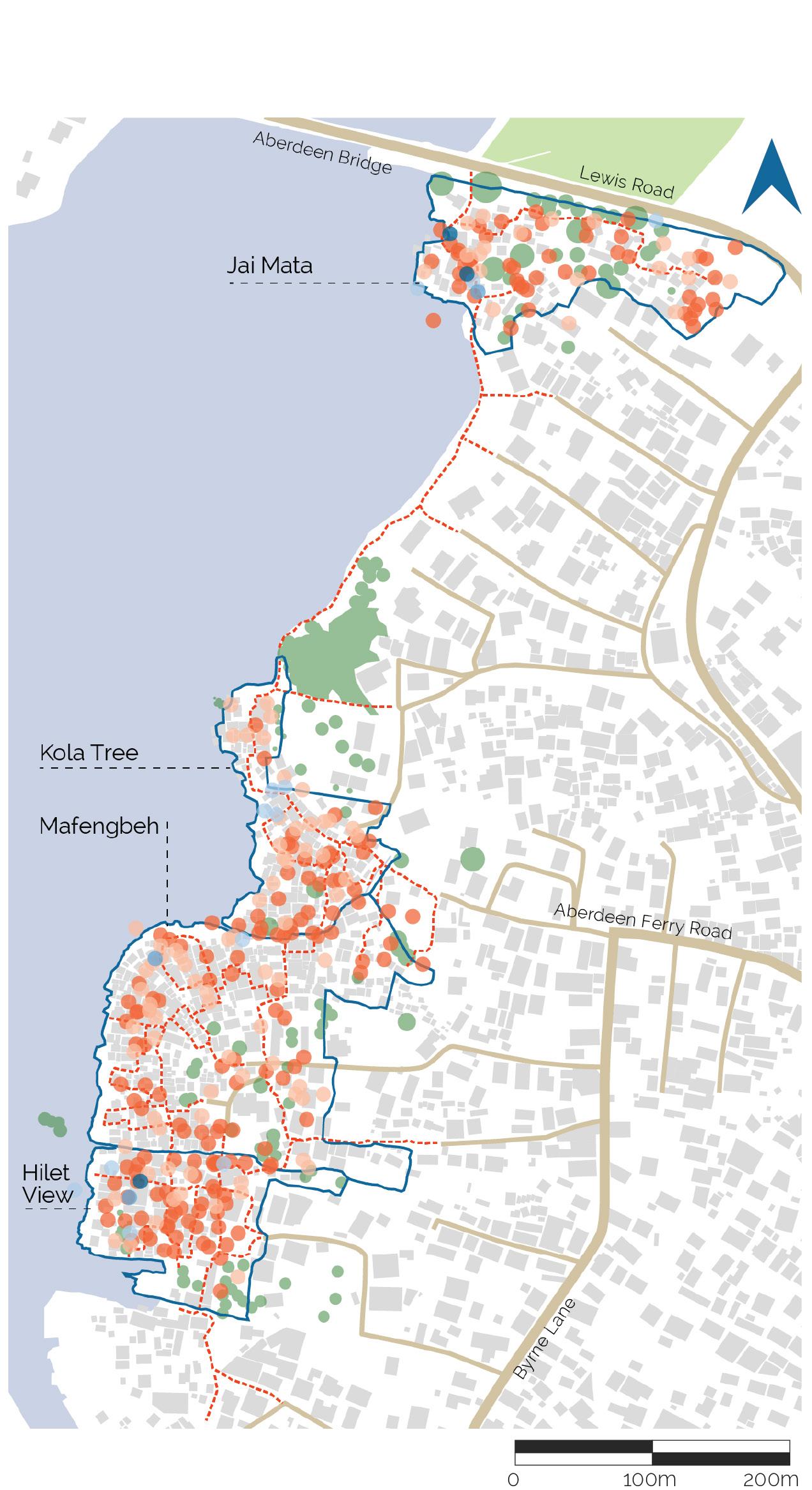

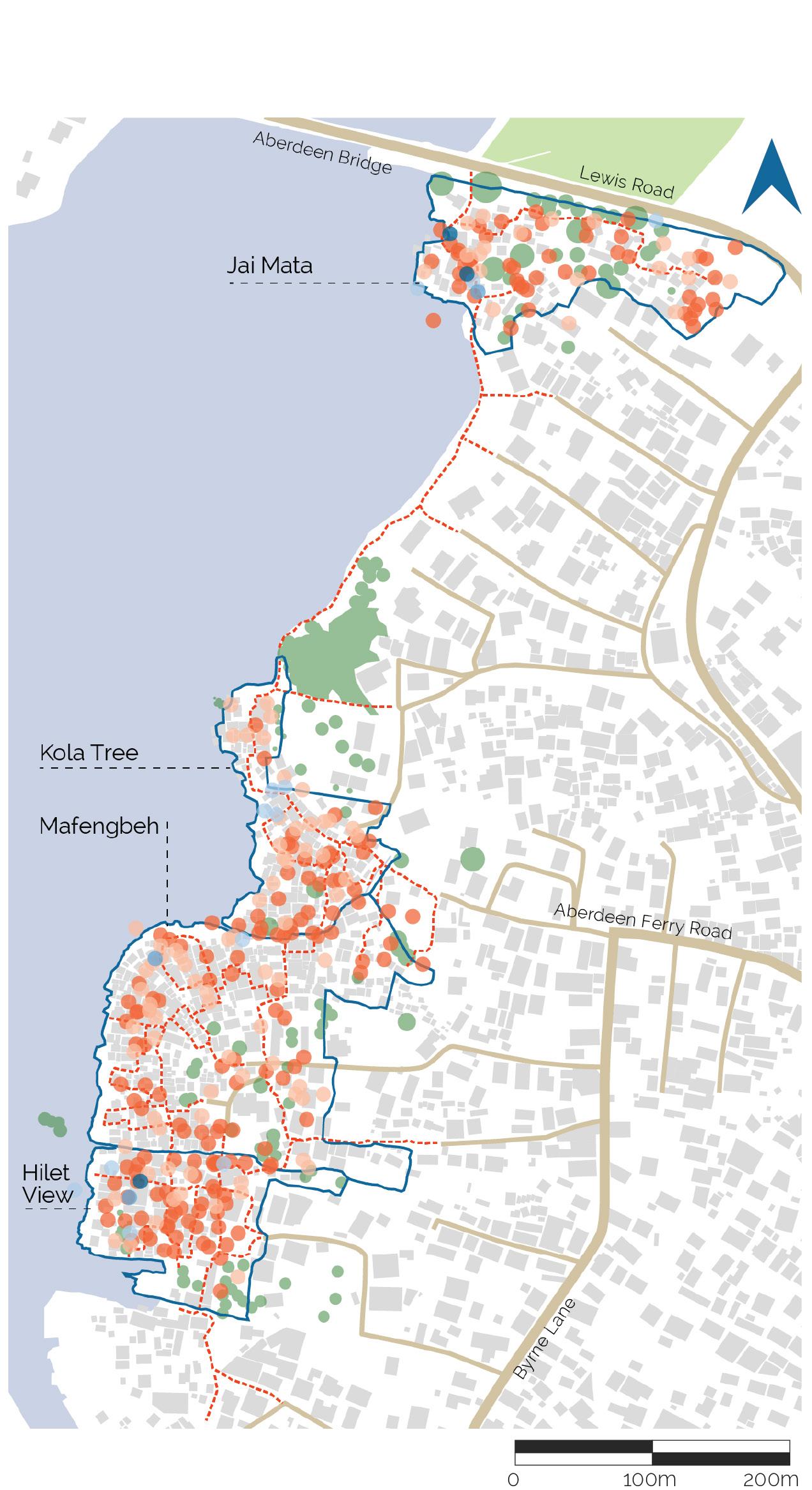

The settlement is unofficially divided into four zones named; Kola Tree, Jai Mata, Mafengbeh and Hilet View.

“The land is a reclaimed land. People pay little or no cost to acquire it and the rent rate is relatively cheap. The settlement is also close to the city centre which makes it easier for those living here to quickly access the city centre to do their business. Some people are born in this community and they have nowhere else to go, while some were not born here but have very strong family ties in here. All these are reasons that made people to stay in the community.

Focus group discussion

6

Above: Isometric view of Cockle Bay in context

Localities and wards

7 COCKLE BAY SETTLEMENT PROFILE

Historic growth of Cockle Bay

The community of Cockle Bay expanded rapidly during and in the aftermath of the civil war, especially between 2005 and 2015. In 2018 the settlement measured roughly 18.2 hectares in size. Much of the land that Cockle Bay is built on was previously mangrove forest located within the foreshore. This means that much of Cockle Bay is built on land that lies below sea level or between 0-1 meters above sea level. As a result, the settlement is highly susceptible to coastal flooding and rising sea levels.

Efforts have been taken to reduce further expansion into the Aberdeen Creek. Concrete pillars installed by the government mark out a boundary to restrict further outward growth. This means that some in the community are building taller buildings to accommodate incoming residents.

1986-1990

1991-1995

1996-2000

2001-2005

2006-2010

2010-2015

2016-onwards

Development of the built area

“Most people settled in Cockle Bay during the Civil War (1991-2002) and in its immediate aftermath.

In the 1960s, the Luis family—the major land owners in the formal part—were hiring people to look after their properties, and these care takers decided to build houses next to their masters’ places, close to the sea. Some started reclaiming the land through banking. This banking was continued by the relatives of these care takers, to a point that made the settlement attractive to many people, especially war displaced who were looking for a place to stay in Freetown.

8 2005 2018 2015 Year of moving into Cockle Bay 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50%

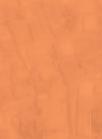

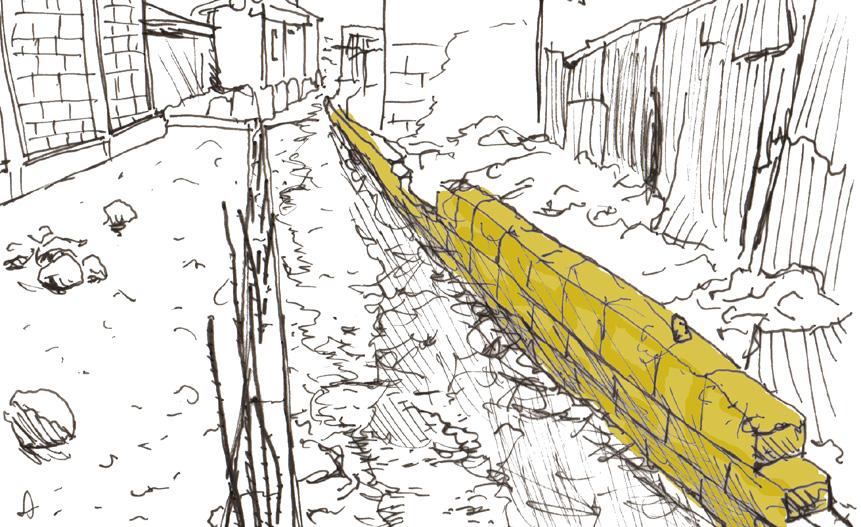

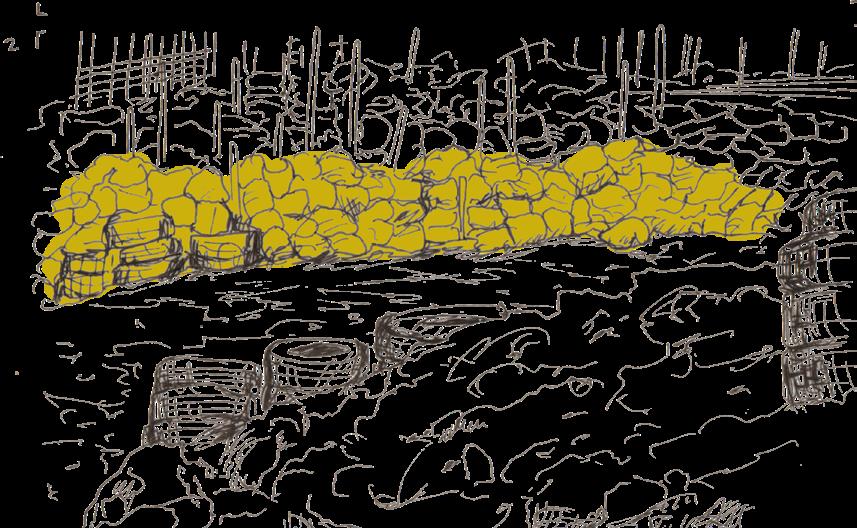

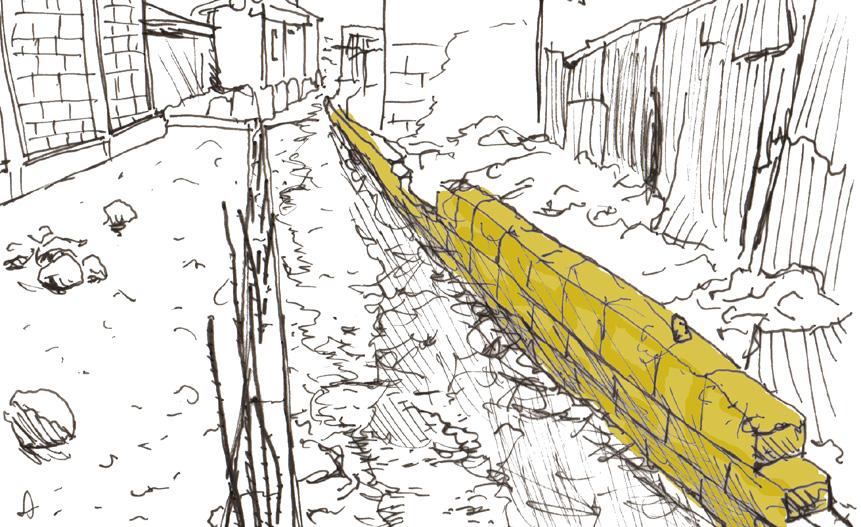

Banking in Cockle Bay

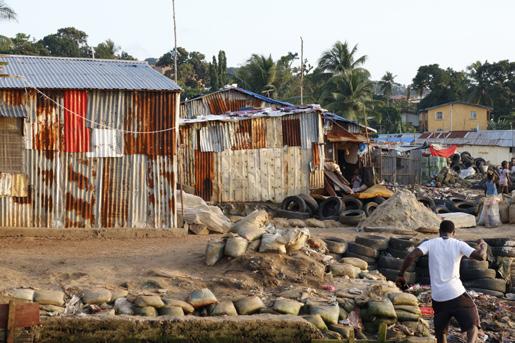

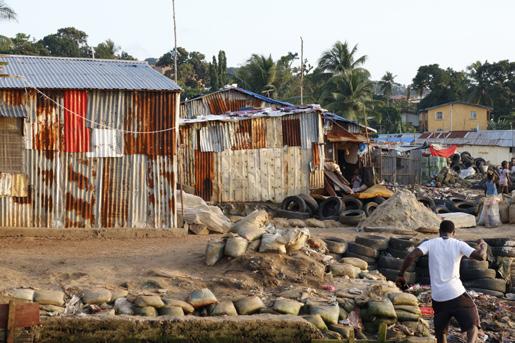

Community workers dredge mud and sand from the creek bed and gather it in bags. The photo to the right reveals how community members use the rising tide to transport bags of mud and sand using rafts.

Bags of mud and sand are piled up vertically to form step banks. Car tires are then piled in front of the bank of bags and filled with rubble, dirt and rubbish. The car tires face off the banking: an example can be seen in the photos to the right of this page.

Over time the banks of rubble and tires are consolidated with concrete block walls.

Concrete blocks are protected by car tyre and rubble banks until they are all replaced by set concrete and iron rod walls, which are the most robust and long lasting reclamation structures.

9 COCKLE BAY SETTLEMENT PROFILE

Cockle Bay was discovered

? ?

First water tap was built

First concrete house was built Fishing and cockle picking started

First panbody house built

Kola Tree established

First school opened in the community

First mosque opened in community (tarpaulin)

Massive migration to the community Office setup (Tissue)

Banking land and reclamation started

Jai Mata established

Sand mining started

First shared toilet in the community

?

First concrete houses constructed First blacksmiths workshop opened

First church opened

Spring water discovered

Major cutting down of mangrove trees

Major sanitation problem in the community

Socially positive developments in the community

Political events in the community

Disaster events in the community

Other Important events in the community

Environmental events in the community

10

Cocke Bay community timeline

>> POSITIVE EVEN T S NEG A TIVE EVEN T S << 1955 1957 1970 1978 1985 1990 1991 2000 2002 2005 1992 1999 1987

Bridge linking formal and informal community constructed

Football field established Pharmacy opened

First bakery opened

First CBO established

?

First paved road leading to the community constructed

Quarry opened

Crowning of first tribal chief

Construction of court barray in community

First retaining wall constructed to hold back tides

Plastic waste recycling centre opened

First councillor elected in community

? ?

Electricity was extended to the community

Properly constructed mosque built

Interventions of NGO

Fire outbreak

Cholera outbreak

Flooding event

First Chairperson elected

Cinema Opened Water tank installed by YMCA

First public toilet constructed by FEDURP

Major cholera outbreak Ebola outbreak

Major Flooding

Fire outbreak

Ebola Outbreak (two deaths)

Formation of savings group for roads established

Community member lost in parliamentary election

Water Crisis

Fire Outbreak

11 COCKLE BAY SETTLEMENT PROFILE 2007 2008 2010 2012 2017 2006 2009 201 1 2013 2014 2015 2018 2019

Conditions in Cockle Bay

What are the current conditions of housing and community spaces in Cockle Bay?

Homes in Cockle Bay are constructed using corrugated iron (pan body). Other materials used are mud bricks, broken stone, tarpaulin, cement, car tyres and timber. The density of housing is extremely high and generally unplanned, homes change in size and material to suit the needs and income of the residents, in many areas there is less than half a meter separating structures. Buildings are generally low in height occupying only the ground level, some homes incorporate internal courtyards or small enterprises.

Basic amenities are not well provided. Although more than 80% of households have access to toilet and bathroom, the conditions of such facilities are rated as unsatisfactory. Drainage and sanitation facilities are two areas which the community feels are significantly underserved across the settlement. There is a lack of access to fresh running water. Most households have access to electricity but the supply is erratic and most respondents view it to be poor quality.

Cockle Bay has two schools, furniture shops, religious buildings, food shops, informal markets and communications (SDI, 2016). However, there is a lack in basic facilities including medical centres, public parks and community centres. The community map highlights shared spaces and facilities that were mapped as part of the data collection for this profile.

Conditions of housing and basic facilities

How would you rate the condition of your house / of the following facility?

Very poor

Poor

Fair

Good

Very good

When discussing facilities, residents reported poor drainage as a main issue, followed by toilets and bathrooms.

12

House 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% Toilet Bathroom Kitchen Drainage Electricity Road access

Above: Image of Aberdeen Creek from Cola Tree

Above: view over Cockle Bay.

Jai Mata is located to the North East of Cockle Bay and is connected to the rest of the informal settlement located along Aberdeen Creek. Jai Mata is built on a steep slope where it is close to the sea, but the slope levels off moving East. The settlement has good access to the city from Aberdeen Road.

Kola Tree

Kola Tree is the hilliest part of Cockle Bay and has the most compact housing. The community has a focal area which has developed around the church, mosque and access road which runs between them. Food growing also takes place on the slopes between the informal community and the formal community to the East.

Mafengbeh

Mafengbeh is the heart of the Cockle Bay informal settlement. This neighbourhood has the largest population in Cockle Bay. This area hosts important community buildings and spaces, including a school, mosque, bakery, and the chief’s residence (Chief Baray). Mafengbeh has one kay access point which is taken from Byrne Lane.

Hilet View

Hilet View is the least dense and most organised neighbourhood in Cockle Bay characterised by wide paths which motorbikes can fit down. The homes here are larger and often better constructed with space to grow food. Hilet View is where the majority of land reclamation has occurred. The neighbourhood has a mosque, playing field, market and water well.

Aberdeen Ferry Road

13 COCKLE BAY SETTLEMENT PROFILE ByrneLane

Bridge Lewis Road

ByrneLane Aberdeen

Zoom 2

0 200m 100m

Jai Mata

Zoom 1

Zones in Cockle Bay

Access and transport in Cockle Bay

Cockle Bay has limited formal access roads. However, the settlement is relatively permeable as walking is the main mode of transport. Most paths are made up of rubble and dirt, in some cases decorated with cockle shells. The settlement has three key vehicle access points that connect it with the city. In the main settlement, these connect through the formal neighbourhoods of Cockle Bay, via Aberdeen Road and Collegiate. Access roads are the Aberdeen Ferry Road and the lanes that connect to Byrne Lane, where residents can catch a

range of other public and private transport modes such as poda poda (public mini-bus) and taxi. For residents of Jai Mata, vehicular access is from Aberdeen Road. The major type of public transport operating to and from the community are motor bikes (okada) and tricycles (kekeh), shared taxis and minibuses. Very few reported using government buses; this was attributed to their availability and accessibility challenges. Others preferred trekking or walking to work. On average, the transport cost for okada/kekeh to the city centre and around the Cockle Bay community was estimated to range between Le. 5000 ($0.49) and Le. 10,000 ($0.98) per trip.

Circulation map

Dual carriageway

Primary road

Secondary road

Minor road

Pedestrian footpath

Mode of transport to work

0.7% Government Bus

22.7% Mini Bus (Poda Poda)

32.7% Okada/Kekeh

1.3% Privately owned transport

30.3% Shared Taxi

12.3% Walking

“The issue of public transport and access is very difficult, because the settlement is poorly constructed. There are no access roads within the community due to poor planning, as there is no space between the structures for the movement of motorbike and other transport means. There is only one point for motorbikes and light weight vehicles to go out of the community, which is sometimes very difficult for people, especially at night.

Focus group discussion

14

Jai Mata benefits from good transport links due to its location next to the main road, however this also means it is the most visible part of the settlement.

This pathway, linking Jai Mata to the rest of Cockle Bay, is only accessible during low-tide.

When the tide is low, the seaside area becomes a vast public space for the community.

Zoom 1

Jai Mata

Zoom 2

Kola

Kola Tree’s focal area, devel oped around the church and mosque, is popular for shopping and extra curricular activities and is one of the first parts of the settlement to develop.

Mafengbeh has an area for taxis and motorcycles which relay residents to Wilkinson road and beyond.

Hilet View has some good amenities but is far from road access, there is a large open space which is currently used for football but residents would like to use for a commu nity facility if they can get access to the land.

Community Map

Community Map

Community Map

ACCESSIBILITY AND TRANSPORT

P

Kekeh Okada

Poda

ACCESSIBILITY AND TRANSPORT

Walkway

Kekeh (tricycle) station

Car accessible road RELAY

Kekeh (tuk-tuk) station

Okada (motorbike) station

Taxi

P

Okada (motorbike) station

Poda poda (bus/van) station

Taxi station

Poda poda (bus/van) station

Taxi station

Parking space

P

Parking space

COMMON SPACES AND SOCIAL SPOTS

Mosque

Church

COMMON

Mosque

Parking Church

Secret Court

COMMON SPACES AND SOCIAL SPOTS

Mosque

Secret society

Church

Court Barrie

Sport field / playground

Secret society

Focal area

Court barray

Focal

FACILITIES

Focal area

Informal market

Pharmacy

Educational facility

FACILITIES

Informal market

0 200m 100m

Pharmacy

Educational facility

FACILITIES

Informal Pharmacy Educational

15 COCKLE BAY SETTLEMENT PROFILE

P

P P

Tree, Mafengbeh and Hilet View

The Wharf is where the community plays football, collects cockles and goes fishing

There are a variety of existing streams which run through the community which can flood in the rain season

The Court Barrie is where the community seek justice and decisions

16

Lagoon Court Barrie

Bridge and stream

School and church

Water point

Wharf

Mangroves

A walk through Cockle Bay

There is a variety of large houses mixed in with informal small houses

Religious spaces are extremely important to the community

Moving away from the coast, properties get larger and more affluent

The bakery was set up by a charity and is an employer in the community

The football field is a major focal point in the community

The market is where the community can buy a variety of goods as well as collect water

17 COCKLE BAY SETTLEMENT PROFILE

Bakery Market

Sports field

Mosque

Settlement demographics, tenure and ownership

Who lives in Cockle Bay?

The most recent survey conducted by Slum Dwellers International revealed that Cockle Bay has roughly 20,000 inhabitants and 1,350 households living in 520 structures, 500 of which are residential (SDI, 2016). This means that there are approximately fourteen people per dwelling. There are on average of 4.66 people per household – by which we mean the people or family members living together in the same compound. This is a high figure, but in line with other informal settlements. Most household heads are male 81.3%, with only 18.7% female-headed households. The population in the community is on average very young, with 68.7% of the population less than 40 years old, and only 7% older than 56 years.

Most of the population migrated to Cockle Bay from the Western Area surrounding the capital city (31.7%), followed by the Northern Province (31.0%), and almost all arrivals occurred in the decade between 1996 and 2005, during the Civil War and right after it. As many as 40% declared that their main reason for living here is closeness to friends and relatives, combined with the cheap rents (39,4%) and closeness to the city centre (9,3%).

Cockle Bay is built on land that is officially owned by the government and is not recognised by the local council or government and has no tenure rights or security. Residents are faced with the on-going risk of eviction. There have been yearly eviction threats from the local authority, based on the claim that the settlement is in a high-risk flood area, with subsequent

Household size Gender of Household Head

4,66 persons per household

Places of origin

18,7% Women

81,3% Men

Household composition by age and gender

Men

Reasons for staying in the community

Over 60 years

46 – 59 years

36 – 45 years

26 – 35 years

15 – 25 years

06 – 14 years 0

Eastern Province

Northern Province

Southern Province

Western Area

“I came to this community when there were very few houses, just about six. It was bushy and full of monkeys and snakes. There were no banking or reclaimed land. This was around 1993, during the NPRC [National Provisional Ruling Council] military regime. There was no lights, no electricity, the area was remote. It was the Limba tribe that was dominant, the Temnes and Fula were very minor. John, 45

18

31,7% 22,3%

31% 15%

Women

4

48.8% 51.3% Rent is cheap Close to friends /relatives Located close to the city centre I was born in the settlement I’ve lived here since my childhood days Others 39,4% 40% 6,3% 3% 2% 9,3%

–

years

risks for disease outbreaks. Furthermore, Cockle Bay is a RAMSAR site (Wetlands of International Importance), which further restricts tenure rights for the community (Koroma, 2018: 12).

As with other informal settlements in Freetown, most residents in Cockle Bay do not have formal land claims. Over the years, in a struggle for legitimacy, residents have sought tenure security by paying the city rate to Freetown City Council (FCC), or by applying for legal tenure status from the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Country Planning (MLHCP ), which is often either

rejected or left pending (Leong et al., 2018). This historical and systematic lack of recognition by all levels of government have led to the framing of Cockle Bay as ‘illegal’ and not eligible for service provision.

Land ownership

“Does your household own the land on which the structure sits?”

“Does your household own the land on which the structure sits?”

Community workshop in Cockle Bay

Yes No

Yes No

95.7% of Cockle Bay’s households have no land ownership ; consequently, eviction represents a shared fear for 92,7% of respondants.

Fear of evicition

Fear of risk of eviction from community

Fear of risk of eviction from community

Land ownership 7,3% No 92,7% Yes

Land ownership 7,3% No 92,7% Yes

95.7% of Cockle Bay’s households have no land ownership ; consequently, eviction represents a shared fear for 92,7% of respondants.

95.7% of Cockle Bay households have no land ownership. Consequently, eviction represents a shared fear for 92.7% of respondents.

19 COCKLE BAY SETTLEMENT PROFILE

Public and environmental health

What are the conditions of health, sanitation, and waste in Cockle Bay?

Public health

The most common health problems in the community are malaria and typhoid followed by diarrhoea/gastro problems related to water and sanitation. These conditions are preventable with improved living conditions. The majority of households do not have adequate access to health care services (99.4%).

Water access and quality

The majority of residents do not have access to a water source in their home and need to fetch water from points inside the community. The main source of water is from a tap with piped water there are also several wells and at least two natural springs. When asked about the quality of water in the settlement almost 64% of people surveyed said the water was good.

Sanitation

Mapping undertaken by SDI in 2016 found 1 communal toilet block in Cockle Bay with 100 working toilets across the settlement which is equal to 1 toilet per 129 people however recent mapping suggests this has improved. In this study the toilet facilities that were most common were hanging toilets (which hang over drainage channels) followed by pit latrines and flush toilets. Almost 90% of people surveyed said they had access to sanitation in their home or wider compound, but also rated toilet facilities in the community as poor (70.0%). A huge majority described the drainage

Most prevalent health problems

Malaria

Typhoid

Diarrhoea

Skin diseases

STIs

Respiratory inf.

Allergies

Anaemia

GBV

47.7% of households experienced diseases or health problems at the time of the survey.

Challenges to improving sanitation

Lack of finance

Lack of knowledge on how to do this

Lack of interest ofother household members

Lack of skilled people to construct

Landlord does not want to invest

Others

Don’t know

Though sanitation is identified as a major problem, improvements are hindered by a lack of finance, knowhow, and mobilisation.

20

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

Toilets in Cockle Bay

Quality of water

Quality of water

Quality of water

63,7%

Aberdeen Bridge Lewis Road

36,3%

Good Satisfactory

63,7%

36,3%

Good Satisfactory

Sources of water supply

Sources of water supply

Sources of

Location of water sources

Bore holes

Bore holes

Streams

Streams

Communal water standpoint

Communal water standpoint

Piped water connected inside house

Piped water connected inside house

Piped water connected outside house

Piped water connected outside house

Protected spring

Protected spring

Sources of water supply map

Pipe water

Springs

Tank water

Wells

Areas with lower access to water

Car accessible road

Walkway

Unprotected spring /wells

Spring water

Unprotected spring /wells

Aberdeen Ferry Road

The main sources of water are piped water and springs. Only a minority of households has immediate access to water; most people have to fetch it somewhere within the community.

The main sources of water provision are piped water and springs. Only a minority of households has immediate access to water, with most people having to fetch water outside, within the community.

What does this map tell us?

Spring wells are located in the interior areas; closer to the coast, piped water is the main form of provision.

There are some densely populated areas lacking water access.

The Jai Mata zone is entirely dependent on piped water.

There are only one well and one water tank in the community.

21 COCKLE BAY SETTLEMENT PROFILE

Hilet Hilet View

Mafengbeh

Kola Tree

Jai Mata

Byrne Lane

200m 01 00m

200m 01 00m 01

water supply Location of water sources

slum Elsewhere

somewhere inside slum 5,7% 24% 0,7% 69,7%

In own dwelling In own yard/compound Elsewhere –outside

–

0,3% 0,7% 7% 6% 38% 4,3% 23% 20,6%

0,3% 0,7% 7% 6% 38% 27,4% 20,6%

condition to be very poor (84.0%). The main challenge to improving conditions of sanitation is the lack of finance, there also needs to be coordination across the settlement to make drainage improvements.

Waste disposal

There is a lack of facilities for waste disposal which leads to the majority of residents using the sea or drainage channels for household waste. This results in the blocking of channels that increase risk of flooding and serious pollution in the lagoon which also increases water related health problems.

Waste disposal

In the sea

In drainage

Own refuse dump

Shared refuse dump

Waste is mainly disposed of in the sea with drainages flowing into it, resulting in serious pollution

“The biggest challenge to improving sanitary conditions is the lack of finance, as most people do not have the money to invest in improvements. Also, some residents lack interest in improving facilities, because Cockle Bay is located near the sea and many prefer to use hanging toilets, which are less costly to build and maintain. People are also using the sea as a dumping site for waste, which later returns to them when the tide comes.

Focus group discussion

22 67% 19,3 % 7% 6,7%

Images from left to right: shared toilet facility; waste dumping into stream; pollution in the lagoon.

.

Access to sanitation and other services in house or compound

Yes No

Water supply

Toilets

Electricity

Bathroom

Kitchen Waste disposal

Health care

Most residents have access to toilets and bathrooms, however their quality is not satisfactory. The drainage system is considered awful by 94% of respondents.

Most residents have access to toilets and bathrooms, however their quality is not satisfactory. The drainage system is considered awful by 94% of respondents.

(See page XX)

Improving access to healthcare and sanitation is among the main priorities in the community (See pg.XX).

Improving access to healthcare and sanitation is among the main priorities in the community.

Toilet facility

Bucket latrine

Flush toilet

Flying toilet

Hanging toilet

Pit latrine

Shared toilet

Others

Kola Tree

Mafengbeh

Hilet

Aberdeen Ferry Road

Waste and sanitation map

Waste and sanitation map

Hanging Toilet

LEGEND

Public toilet (Flush)

Hanging Toilet

Public toilet (Pit latrine)

Public toilet (Flush)

Shower and wash facility

Public toilet (Pit latrine)

Stagnant water

Shower and wash facility

Waste disposal site

Stagnant water

Waste disposal site

Open dumping

Open sewer/drainage

Open dumping

Pit dumping

Open sewer/drainage

Pit dumping

Car accessible road

Walkway

Car accessible road

Walkway

What does this map tell us?

Hanging toilets are concentrated on the shoreline, emptying out directly in the sea.

What does this map tell us?

Inner areas are mostly served by public flush toilets and pit latrines.

Hanging toilets are concentrated on the shoreline, emptying out directly in the sea.

Most dumping sites are located near the sea, causing pollution.

Inner areas are mostly served by public flush toilets and pit latrines.

Most dumping sites are located near the sea, causing pollution.

23 COCKLE BAY SETTLEMENT PROFILE 200m 0 100m

2,3% 26% 0,7% 38% 28,5% 3,7% 1%

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

Hilet View

Jai Mata

Byrne Lane Aberdeen Bridge Lewis Road

Economy and Livelihoods

How do Cockle Bay inhabitants make a living? How do they cope with economic hardships?

There are many different livelihood activities in the community, Cockle picking, Sand mining and fishing had previously been the predominant livelihood activities in the community but due to environmental conditions this is changing. The survey carried out by SLURC found that petty trading was the most common occupation, this trading is predominantly self-owned micro and small enterprise. Work as civil servant and in construction were also common livelihoods in Cockle Bay.

Fishermen repairing nets in Cockle Bay

Main occup a tion

Main occupation Household

Nature of main occupation

Educational status of the househld’s head

The main occupation for Cockle Bay’s inhabitants is pe tt y tr ading , but there are also many civil servants and construction workers.

The main occupation for Cockle Bay’s inhabitants is petty trading, but there are also many civil servants and construction workers.

94% of Cockle Bay’s households’ monthly incomes is below 1.000.000 Leones (10USD).

94% of Cockle Bay’s households’ monthly incomes is be lo w 100.000.0000 Leones (100 USD ) .

Noteonexchangerate:atthetimeofwriting(2020),1USDollarwasequivalentto10.000Leones..

24

100,000-250,000 251,000-500,000 501,000-750,000 751,000-1,000,000 1,001,000-1,250,000 1,251,000-1,500,000 1,501,000-1,750,000 1,751,000-2,000,000 >2,000,000

Househo ld mo nthl y in come Na ture of main occup a tion 18.3% 11.3% 5.7% 10% 2% 7.3% 41.7% 3.7% Civil

Construction worker

/porter Not working/ disabled Servant/maid Student Trader Transport worker 65% Informal 35% Formal 32% Informal 68% Formal

0% 20%40% 60% 80% 100%

servant

Daily wage labourer

E duc a tiona l st a tus of the househo ld s heads

income

monthly

Formal No formal education education

504,000 Le average monthly income per household

With an average monthly income of 504,000 Le, almost 3/ 4 of households don’t manage to meet their basic needs or save some money.

With an average monthly income of 504.000 Le, almost 3/4 of households don’t manage to meet their basic needs or save some money.

Perception of household livelihoods generally

Hilet

Not meeting basic needs

Meeting all basic needs but not saving

Meeting all basic needs and little saving

Meeting all basic needs and accumulating assets

Monthly household income map

Monthly household income map

LEGEND

0 - 500,000 Le

500,000 - 1,000,000 Le

1,000,000 - 1,500,000 Le

1,500,000 - 2,000,000 Le

> 2,000,000 Le

Car accessible road

Walkway

What does this map tell us?

Monthly income across Cockle Bay is almost everywhere below 1,000,000 Leones.

We can see a concentration of households with income below average (less than 500,000) in Hillet View, Kola Tree and Jai Mata. The few wealthier households also concentrate in these areas.

Income disparities are starker in Hillet View, Kola Tree and Jai Mata. Mafengbeh seems to be a zone with more income equality.

25 COCKLE BAY SETTLEMENT PROFILE

Number of people with form of income in household 3% 44.7% 26.7% 28% 0% 13% 43% 5% 36% No income 1 2 3 4 5

Over 80% of respondents are employment (including self-employed), while 18.3% are not in employment (including retired). Two-thirds of the respondents (65.0%) in employment are mostly employed in the informal economy, which includes trading, home based enterprises, construction work, labouring/ porter, while 35% were in the formal sector.

Income Levels

The survey revealed that 62.3% of the households earn low income of Le 500,000 and less per month. 18% of respondent’s income earning falls within the minimum wage of Le.600,000 and 13.7% earned moderate income, only 6% earned above Le.1,000,000.00 ($100). This is evidence that 62.3% earned less than national minimum wage of Le.600,000.00 ($60). Jobs are usually worked at a subsistence level, on small scales

with little or no capital support. Limited access to credit coupled with a lack of skills attributable to low level of formal education accounts for this problem. The monthly household income map shows that the income levels differ across the settlements.

Meeting Basic Needs

In terms of household income meeting basic needs, perceptions vary. The majority (44.7%) believe their income is not meeting their basic needs. Although, 28% of the respondents believe their household income is meeting their basic needs and allows for a little savings, while 26.7% perceived household income is generally meeting all their basic needs but not enough to save. Only (0.7%) of the community participants reported that their income met all their household needs and at the same time accumulating assets.

“I am a house wife depending on the husband. I don’t know his income and expenditure, because my traditional background does not allow a wife to be asking lot of questions in the house as a married woman. What is brought home is what I receive, monies are given to the children by my husband to go to the market and cook. I don’t have enough money to save.

Food is the largest expenditure for households, with 71% experiencing difficulties in satisfying their needs and resorting to coping strategies, especially reducing food intake.

26 Monthly expenditures Coping strategy 71% Yes 29% No Borrow money Take food on credit Reduce food qualities Reduce food quantities Go hungry Others 0 100,000 200,000 300,000 400,000 500,000 600,000 Food Rent/maintenanceElectricityTransportEducation ClothingWaterHealthcare 0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

Tity, 45, Hillet View

Sand mining

Historically one of Cockle Bay’s key sources of income is sand mining, which takes place at low tides in the lagoon of Aberdeen Creek. Koroma and Rigon explain that the “sand is then transported and sold for use in the building industry across Freetown” However, the extraction and sale of sand mined in Aberdeen Creek by the residents of Cockle Bay is prohibited by the National Protected Area Authority (NPAA), who monitor this and inform local authorities of any violations (Koroma, Rigon et al, 2018: 33). Sand production was at its height during the 1990s, but due to over-exploitation of the resource, and increasing restrictions on where sand can be mined there is currently less sand available close to Cockle Bay (Koroma, Rigon et al, 2018: 33). The resource has also been made less lucrative over the last five years, as the “Environment Protection Agency of Sierra Leone has engaged communities around the beaches to tackle the issue of illegal and unauthorized sand mining along the coast in the Western Area” and have created designated sand collection areas that will be regulated by the authorities and guided by public sand mining guidelines (Koroma, Rigon et al, 2018: 36).

Cockle picking

During the civil war, cockle picking was an attractive source of income for women and men with few alternatives. However, cockles rely on specific environmental conditions to thrive and much of their environment has been destroyed, leading to them become bitter tasting. Picking is also a seasonal activity with better harvests in the rainy season, which means that it is not a year-round stable source of income (Koroma, Rigon et al, 2018: 36). Fishing and crab fishing also take place in Cockle Bay.

“There are many livelihood activities in the community which are petty trading, sand mining, bike riding, fishing, cockle picking and masonry. Fishing and sand mining used to be the main livelihood activities in the community, but this has slightly changed over the years as most people are practicing more petty trading and bike riding as their main source of livelihood. Petty trading is the most profitable and common livelihood activity in the community.

Focus group discussion

27 COCKLE BAY SETTLEMENT PROFILE

On the left, from top: Sand mining in Aberdeen Creek; Charcoal shipment from Lungi; Cockle Picking in Aberdeen Creek