12 minute read

Crestview Bypass Project Innovates Through Supply Chain Issues

As new construction, the project has fewer concerns with traffic control. “We don’t have to worry about the traveling public,” Buchanan said. “We’re almost in complete control, and that makes these types of projects really nice.”

TBY SARAH REDOHL The town of Crestview, Florida, is located along Florida State Road 85, U.S. Route 90 and just north of Interstate 10. It’s a major route for tourists making their way south to Florida’s many beaches and Eglin Air Force Base 20 miles south of town. “A large population travels from Crestview down to Eglin or the Gulf Coast to support the military and tourism industry,” said Jason Autrey, director of Okaloosa County Public Works. Pair that with the city’s population increasing by 30% between 2010 and 2020, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, and Okaloosa County faced “a classic case of a community growing and the need to find a better way for the people of Crestview to get around town.”

That’s why Okaloosa County began work on the Southwest Crestview Bypass more than 15 years ago, the first four phases of which included the widening of P.J. Adams Parkway connecting I-10 and

SR-85 from a two-lane roadway to a four-lane roadway. In September 2021, Anderson Columbia Co. Inc., Marianna, Florida, began the largest phase of the Southwest Crestview Bypass.

Anderson Columbia is performing both the Phase Five Corridor, which includes 3.1 miles of a four-lane roadway, as well as the EastWest Connector, 2.2 miles of two-lane roadway. “Phase Five is the missing link to complete the Bypass,” said Kevin Buchanan, project manager and estimator for Anderson Columbia.

“We’re confident the work on Phase Five will have a huge impact on our local area,” Autrey said. “The community really needs this new route. Once Phase Five opens up, it’s sure to be heavily utilized and appreciated.”

Anderson Columbia is also performing the work on a related Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) project, a new interchange on I-10 near P.J. Adams Parkway in Crestview. “We won that job about 8 months after we won the bid on Phase Five and the East-West Connector,” Buchanan said, adding that construction began in the summer of 2022.

The interchange will be known as Exit 53 and is the first new FDOT interchange in 30 years, Autrey said. “That will also have a dynamic impact on the way traffic moves through Okaloosa County.”

“Our big goal, which is still many years out, is to create a loop road around Crestview,” Autrey said, adding that the county is actively working on a Project Development and Environment Studies (PD&E) timeline for the northwest quadrant of the eventual loop road. “We’re constantly thinking about how to improve traffic flow in the future.”

ONTO PHASE 5

When Anderson Columbia won the bid for Phase Five and the East-West Connector, it seemed like an ideal project for the company. “This type of project is right in our wheelhouse,” Buchanan said. “Plus we had an asphalt plant just 5 miles from the project and local crews available, so the timing was perfect.”

Anderson Columbia was started by Joe Anderson Jr. in 1958 as Anderson Contracting. When the company later bought out an asphalt company called Columbia Paving, Anderson Columbia was born.

Now, the company has around 1,250 employees and performs heavy highway and bridge construction, mostly for state departments of transportation, in Florida, Texas, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia and Alabama.

“We may have started out in earthwork, but it was asphalt paving that has allowed us to become what we are today,” Buchanan said. “Although we are an asphalt paving company, we also perform grading, base, drainage, concrete and build bridges. We’re a one-stop shop.”

The $44 million project requires 1.7 million yards of earthwork, construction of a 1,700-foot bridge over the Florida Gulf and Atlantic railroads and roughly 17 lane miles of asphalt paving.

With a contract time of 1,100 days, Anderson Columbia began work in August 2021. The project is currently 40% complete and is expected to be finished in 2025.

Already, asphalt has been placed on the very southern end of the project in the northbound lanes. “The bridge is the controlling factor,” Buchanan said. “Right now, we’re working on the foundation and are facing some challenges with driving the piles.”

Ultimately, the pavement design on the four-lane portion of the project will have 12 inches of stabilization, which Buchanan said is typically stabilized with clay because the existing material in the region is primarily sandy. That will be followed by 8 inches of limerock base and three lifts of asphalt: 3.5 inches of structural course followed by a 2-inch lift, a 1 ½ inch lift, and ¾ inches of open graded friction course. The two-lane part will also be stabilized to a depth of 12 inches, followed by 8 inches of base, 2 ½ inches of structural asphalt and 1 inch of friction course.

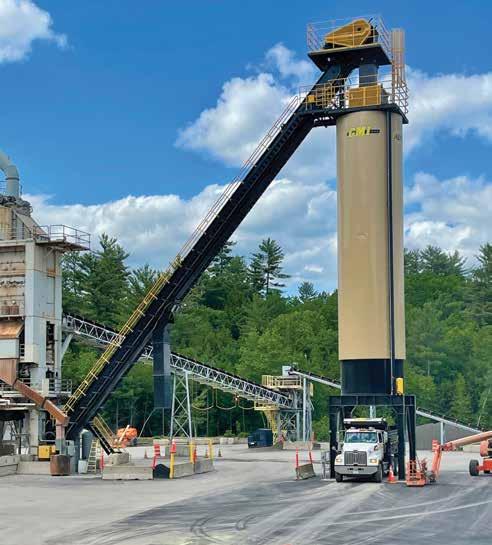

In total, the project will require 33,000 tons of asphalt, all of which comes from Anderson Columbia’s Astec drum plant in Holt, Florida, one of Anderson Columbia’s three asphalt plants in the Florida panhandle and 11 asphalt plants in the state.

NOT ALL EASY

Although the project’s location, scope and schedule seemed ideal, extenuating circumstances have made what was otherwise a

Join Women of Asphalt’s 2O23 SessionS: Women in the Workforce: Recruit, Retain, and Promote

Taking place at BOTH:

NATIONAL PAVEMENT EXPO January 26 | 8:30 - 10:00 AM Charlotte, NC

CONEXPO-CON/AGG March 17 | 1:00 - 2:00 PM Las Vegas, NV

Diversity and inclusion are key to our future sustainability as an industry. This session will discuss management efforts to recruit, retain, and promote women into the asphalt industry. A panel of industry leaders will address the importance of attracting qualified women and addressing the needs of women to keep them in the industry, while developing a culture of inclusivity.

womenofasphalt.org

The agency, Okaloosa County, is also offering fuel and bituminous cost adjustments on the Phase 5 Corridor.

straightforward project more challenging. These include material shortages, cost increases and trucking shortages.

“In our particular part of the Panhandle, we’re experiencing such an economic boom that material shortages have been particularly bad,” Buchanan said. This includes aggregate for asphalt and concrete as well as roadway base material.

“It isn’t unusual to call up a concrete company for a night job for the DOT when they won’t allow daytime lane closures and struggle to find a company willing to keep the plant open at night,” he said. In some cases, Anderson Columbia is left to use a volumetric concrete mixing truck to self-supply concrete.

“The aggregate shortages related to asphalt are mostly driven by the railroads not being able to deliver material we need consistently,” Buchanan said. The company has a rock quarry operating under the name of Junction City Mining that supplies its aggregates for its asphalt operations in Florida out of Talbotton, Georgia. “All our plants in the panhandle of Florida are serviced by rail from that mine.”

Buchanan said this leaves the company dependent on the rail companies, which are frequently unable to supply the volume of aggregate needed. “If we normally get 60 cars every two weeks, we might get 30 cars every four weeks.”

Anderson Columbia is also facing challenges finding labor, for this job and beyond. “It’s hard getting people to work for us because of the type of work we do,” Buchanan said. “If they can go make $15 an hour at McDonalds, they may not choose to work in the heat or at night in order to make a little more money.”

He said they are hiring new people every day, but are only keeping an average of one out of every five new hires. “Many people who apply never get back to us, while others don’t make it through the drug test, don’t show up for their first day, or work half a day and decide it’s not for them,” Buchanan said.

BREAK AC’S WAY

Despite these challenges that are pervasive across many regions and industries, there are several aspects of the Crestview Bypass project that are helping overcome some of the supply chain and labor issues Anderson Columbia is facing.

“The work hours on these jobs are also nice,” Buchanan said. “There are almost no nights on this job. It’s like working bankers’ hours, at least until we get to the very end.”

As new construction, the project has fewer concerns with traffic control. “We don’t have to worry about the traveling public,” Buchanan said. “We’re almost in complete control, and that makes these types of projects really nice.”

Autrey also noticed the benefits of this being new construction, and also the relative rarity of local governments building new roadways. “Most municipal and even state work these days is to augment existing facilities,” Autrey said. “But the notion of putting in a new roadway that opens up new corridors and alternative routes, while bringing new opportunities for commercial development and activity? You don’t see that very often these days.”

The construction costs of Phase Five and the East-West Connector are funded in large part through a grant from Triumph Gulf Coast Inc., a nonprofit that oversees the expenditure of funds recovered by the Florida attorney general for economic damages to the state that resulted from the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

“The fact that there are no federal or state funds involved in this project, the county has more control,” Buchanan said. “That makes it more appealing because there is less paperwork, and federal wage rates and mandatory training programs don’t apply.”

Although Triumph funding is a major component of the construction costs of Phase Five and the East-West Connector, Triumph is just one of four major funding sources contributing to costs related to the bypass, including other phases as well as design, land acquisition and PD&E studies.

“The reality is we couldn’t have received the $64 million grant from Triumph without the $35 million from the county and the DOT’s commitment to construct the new interchange at a cost of $100 million,” Autrey said. The money from the county is coming from a half-cent surtax for infrastructure enacted in 2019. The city of Crestview also contributed some of its funds from the half-cent surtax. “I think [the four major

In total, the project will require 33,000 tons of asphalt, all of which comes from Anderson Columbia’s Astec drum plant in Holt, Florida.

funding sources of the bypass] have done a fantastic job leveraging the dollars available for this project.”

“This is a community/regional partnership,” Autrey said. “Ultimately, Okaloosa County is the contracting entity on this project outside of the new interchange, but it couldn’t have happened without Triumph funds.”

This project is also earthwork-heavy, with most of the dirt coming from the site itself. “That way, we don’t have to rely on on-road haul trucks to bring material to the job site,” Buchanan said, adding that they have off-road trucks available to move the material around the project site. What on-road trucks the project does require, Anderson Columbia strives to make as efficient as possible, “We’ll load them up with something that needs to go that way anyway so no truck ever runs empty.”

The agency, Okaloosa County, is also offering fuel and bituminous cost adjustments. “The fuel adjustment and bituminous adjustment really help with fuel and asphalt liquid prices continuing to increase,” Buchanan said.

“Every cubic yard, square yard or ton of material is loaded into a spreadsheet factoring in fuel usage to calculate the cost to move that material compared to the cost of fuel when we bid the job. We‘ll eat the first 5% up or down, but anything beyond that and we get an adjustment where the county gets money back if fuel prices drop or we get extra money if fuel prices go up,” Buchanan added.

Although that’s quite common on DOT jobs, Buchanan said it’s less common on county projects like this one. “Given the current climate, we’re very grateful they’re doing it that way.”

Autrey said fuel and bitumen cost adjustments are common for long-duration projects in Okaloosa County. “We may not offer [adjustments] on a 6-month contract, but when you’re talking about a project of this size, volume and duration, that’s the only way to be fair for both the contractors and the county,” Autrey said. “We recognize what’s happening in the global oil market right now.”

Along with others, Anderson Columbia is trying to encourage more local municipalities to adopt FDOT specs and standards, and this is one of those instances where the county has done so, Buchanan said. He added that doing so streamlines the bidding process because contractors are more familiar with what is expected. “When that happens, we don’t have to spend as much time or resources educating our crews on what is expected. It removes one extra hurdle and makes the process more uniform.”

Buchanan said Okaloosa County in particular has come a long way in adopting DOT specs, along every phase of the bypass. “We’ve done a lot of work with them in the last three or four years,” he said. “We have a great relationship with the county.”

According to Autrey, the vast majority of Okaloosa County’s design standards are consistent with FDOT’s standards. “We don’t need to recreate the wheel,” he said. Not only are FDOT’s standards proven methods of roadway construction, but Autrey said utilizing state specs also creates consistency among roads within the county, adding that the bypass will function a lot like many of the state roads passing through Okaloosa County.

Autrey said Okaloosa County strives to streamline the construction process on all its projects. “The most difficult aspect of any project is getting decisions made,” he said. That’s why Okaloosa County aims to make decisions quickly and identify and mitigate problems as early as possible. “We never want analysis paralysis to slow our projects down.”

“Our mission statement when we make a contract is that we’ll pay good money for good work,” Autrey said. “As long as the contractor is doing a good job, we want to let them do their thing and say thank you at the end. And Anderson Columbia is doing a great job.”

Other than the supply chain and labor issues, the project is quite straightforward, and Buchanan is grateful for that. “There’s nothing very complex about this project, which is good given the difficulties of the world we’re currently living in,” he said. “We’re trying to do all we can with the trucks, material and people we have while remaining profitable. How can we do more with less? That’s the big question we’re asking ourselves a thousand times a day.”

Although we may not know when these challenges will subside, Anderson Columbia’s project on the Crestview Bypass is an example of just some of the ways creative problem solving can help contractors overcome these issues.

CLEAR THE AIR AT YOUR ASPHALT PLANT

The Blue Smoke Control system from Butler-Justice, Inc., captures and filters blue smoke from emission points in your plant — with 99.9% overall efficiency.