THE FIGHT GOES ON

What’s next in a post-Roe America? Alumnae and faculty weigh in.

Serving Community by Kira Goldenberg ’07

What’s next in a post-Roe America? Alumnae and faculty weigh in.

by Laura Raskin ’10JRN

In the early 1970s, Abby Pariser ’67 became part of Jane, a clandestine group helping Chicago women obtain safe abortions. More than 50 years later, she’s still championing women’s reproductive rights

PHOTO BY NINA WURTZEL

PHOTO BY NINA WURTZEL

2 Views & Voices

3 From President Beilock

4 From the Editor

5 Dispatches

Headlines | Welcome, Class of 2026; Emma Wolfe ’01; Barnard Fulbrights; Lehman Hall on Canvas; Playwriting Residency Honors Ntozake Shange ’70; College Presidents on Abortion Access

11 Discourses

Arts & Letters | Jhumpa Lahiri ’89

Bookshelf | Books by Barnard authors

Strides in STEM | Horowitz Dog Cognition Lab

45 Noteworthy

Passion Project | A Revolution of Thought in West Africa

Q&Author | Delia Ephron ’66

AABC Pages | The Blue & Bold Society; From the AABC President

Alumna Profile | Megan Watkins ’97

AABC | The Young Alum Connection In Memoriam

Obituaries | Nancy A. Garvey ’71, Azita Raji ’83

Last Word | Emily Winograd BC/JTS ’12 Crossword

Photograph from the Barnard College Archives of unidentified students protesting against the anti-choice group Operation Rescue, circa 1990s.

PHOTO BY WANDA CHAN

I just received Barnard Magazine [Spring 2022]. Looks like another great issue. Please advise what the abbreviation following the name of editor Nicole Anderson ’12JRN means. Perhaps others may wonder as well. Best wishes for continued success!

—Carol Schott Sterling ’58

Our reply: Those sometimes mysterious initials that appear after alums’ names and class years are abbreviations for the colleges affiliated with Columbia University.

“JRN” denotes the Graduate School of Journalism. The full list of initialisms can be found at wikicu.com/Style_guide_for_alumni_pages

WHAT ALUMS ARE SAYING ABOUT THE SPRING ISSUE’S COVER STORY, “FARM TO CENTERPIECE,” ON LINKEDIN

“I loved reading that article!” —Morgan McGill ’97

“Spectacular story highlighting talented young alumnae.” —Merri Rosenberg ’78

“Beautiful work, you brilliant Barnard alumnae!” —Rosara Torrisi ’09, Ph.D.

Spring 2022:

“Seeding the Future in Organic Farming”

“A Bridge Between Worlds” “A Thousand Moral Miles”

Summer 2022: “When Opposites Attract ” “A Reunion to Remember ” “Research Reflections”

The caption on page 39 of the Spring 2022 issue should have read “Barnard Banjo Club, circa 1895.”

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Nicole Anderson ’12JRN

CREATIVE DIRECTOR David Hopson COPY EDITOR Molly Frances

PRODUCTION DIRECTOR Lisa Buonaiuto

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS N. Jamiyla Chisholm, Georgi DeMartino, Kathryn Gerlach, Kira Goldenberg ’07

WRITERS Marie DeNoia Aronsohn, Mary Cunningham

STUDENT INTERNS Zuyu Shen ’24, Tara Terranova ’25

PRESIDENT & ALUMNAE TRUSTEE Amy Veltman ’89

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Karen A. Sendler

VICE PRESIDENT FOR ENROLLMENT AND COMMUNICATIONS Jennifer G. Fondiller ’88, P’19

ASSOCIATE VICE PRESIDENT FOR EXTERNAL RELATIONS AND LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT Emma Wolfe ’01 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS Quenta P. Vettel, APR

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, DEVELOPMENT AND ALUMNAE RELATIONS Lisa Yeh P’19

Fall 2022, Vol. CXI, No. 4 Barnard Magazine (ISSN 1071-6513) is published quarterly by the Communications Department of Barnard College.

Periodicals postage paid at New York, NY, and additional mailing offices.

Postmaster: Send change of address form to: Alumnae Records, Barnard College, Box AS, 3009 Broadway, New York, NY 10027-6598

Vagelos Alumnae Center, Barnard College, 3009 Broadway, New York, NY 10027-6598

Phone: 212-854-0085 | Email: magazine@barnard.edu

Opinions expressed are those of contributors or the editor and do not represent official positions of Barnard College or the Alumnae Association of Barnard College. Letters to the editor (200 words maximum) and unsolicited articles and/or photographs will be published at the discretion of the editor and will be edited for length and clarity.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU! Share your thoughts, ideas, or questions with us at magazine@barnard.edu

The contact information listed in Class Notes is for the exclusive purpose of providing information for the Magazine and may not be used for any other purpose.

For alumnae-related inquiries, call Alumnae Relations at 212854-2005 or email alumnaerelations@barnard.edu.

To change your address, write to: Alumnae Records, Barnard College, Box AS, 3009 Broadway, New York, NY 10027-6598 Phone: 646-745-8344 | Email: alumrecords@barnard.edu

The Convocation ceremony has always been a tradition I’ve looked forward to. But this one was particularly bittersweet, as it marks my last as president of Barnard. Walking down the aisle of Riverside Church, I experienced once again that special warmth and vibrancy that I first felt in 2017 as I began my tenure at the College. Back at the podium this fall, I had the chance to look out at the students, faculty, and staff who’ve made my five years here so very extraordinary. It was a full-circle moment and one that brought me back to my first convocation, where, joined by my mother and daughter Sarah, I first addressed and was welcomed by the Barnard community. Back then, like I do now, I felt inspired by all the remarkable young women in the pews in front of me and energized by the College’s mission and rich academic legacy.

At the time, I also had the opportunity to introduce our keynote speaker, Carol Dweck ’67, a leading psychologist, professor, and admired colleague of mine. Carol, who is renowned for her groundbreaking research in the field of motivation, discussed her work on the “growth mindset,” which she explained to the audience means that “everyone can develop their abilities through dedication, good strategies, and lots and lots of mentoring.”

During my time here at Barnard, I’ve witnessed firsthand the efficacy of the “growth mindset.” Our committed faculty and staff continuously work hard to ensure that all our students have the resources and guidance they need to — in Dweck’s words — be inspired to “reach beyond what they would otherwise reach for.” In doing so, we, as an institution, have benefited, enabling us to reach new heights in our scholarship and research, our health and wellness programming, our community outreach and career development offerings, and so much more.

We’ve done all this in the face of a global pandemic, turning formidable challenges into opportunities for learning and growth. We’ve contributed knowledge to tackle big problems, and we’ve been responsive to the vicissitudes of our fast and ever-changing world to best meet the needs of our community.

This brings me to the Supreme Court’s recent decision to eliminate the constitutional right to legal abortion, which has, as history and research has shown, dire consequences for women’s futures. As many of our very own experts explain in “The Impact of Overturning Roe v. Wade” (p. 25), this ruling will have profoundly negative effects, from lowering graduation rates to hindering employment opportunities. It is expected that it will disproportionately harm people of color and those with limited incomes.

At Barnard, we want to do everything we can to bolster our students’ health and wellness. That is why we announced on October 6 that we will expand student options by ensuring that our campus providers are prepared and trained in the provision of medication abortion by fall 2023. In addition, we will continue to partner with national and international abortion experts at Columbia University Irving Medical Center (CUIMC), who also offer services via telehealth. Together, and under the leadership of Marina Catallozzi, M.D., MSCE, our Vice President of Health and Wellness and Chief Health Officer, we will provide students with the best possible care.

This is an important step that underscores our institution’s steadfast commitment to our community’s health and well-being. It is one that I am proud to support in my final year as Barnard’s president. B

“The problem created by our abortion laws is not a female problem, it is a human problem.”

Jimmye Elizabeth Kimmey, a former professor of government at Barnard, wrote these words in 1969 in an opinion piece, “The Abortion Argument: What It’s Not About,” that appeared in Barnard Magazine ’s Fall issue — four years before the passage of Roe v. Wade. It was the first major story in the Magazine’s pages to not only cover abortion but also advocate for its legal reform.

Kimmey was then the executive director of the Association for the Study of Abortion (ASA), an organization whose founders included obstetriciangynecologists Robert E. Hall and Alan F. Guttmacher, who at the time was the president of Planned Parenthood. During her decade-long tenure at ASA, she penned numerous publications pressing for legal abortions, organized the largest international conference on the issue, and, most notably, is credited for coining the slogan “right to choose.”

Fifty-three years after the publication of Kimmey’s article in the Magazine, the battle for women’s reproductive rights continues on — and so does our coverage.

Upon learning of the Supreme Court’s ruling to overturn Roe v. Wade in June, we decided it was incumbent on us to dedicate space in the Fall issue to this subject. One of the first things we did was to dig into the Magazine’s archives. Searches for “abortion,” “reproductive rights,” and “Roe v. Wade” yielded more than 200 results. Sometimes it was only a mention in a story or Class Notes; other times, an entire article focused on the topic. And that’s how we came across Kimmey’s writing.

Turning to Barnard’s experts is something we do again in this edition. We have a piece, which first appeared on Barnard.edu, that asks faculty and staff from different disciplines to weigh in on the consequences of the SCOTUS decision to terminate federal protection of abortion rights. Whether from the perspective of economics or that of gender studies, we read about how this ruling will have far-reaching, and likely deleterious, effects on women and on society at large.

In our feature “The Fight Goes On,” we tell the story of Abby Pariser ’67, who spent much of her career advocating for women’s reproductive rights, from her high-risk work in Jane — an underground group helping Chicago women obtain safe abortions — to opening a Planned Parenthood clinic and initiating sex education in her local school district.

Members of the Barnard community have been at the forefront of the abortion rights movement for over half a century. They’ve courageously, and often at their own peril, stood up for women’s rights, and they’ve been quick to react to setbacks. If there’s one thing I am sure of, it is that our faculty, students, and alumnae will keep doing the work — whether that is through activism, scholarship, or professional endeavors — to ensure that women have the power to make their own decisions about their health and well-being.

Nicole Anderson ’12JRN, Editor-in-Chief

News. Musings. Insights.

PHOTO BY NINA WURTZEL

News. Musings. Insights.

PHOTO BY NINA WURTZEL

Welcome, Class of 2026!

Get a sneak peek into the fabulous and diverse first-years joining campus this fall.

JACK

JACK

Every fall semester, Barnard’s campus buzzes with the excitement of new students, transfers, and those returning to Morningside Heights. Year after year, New York City’s only all-women’s college has broken its own application record, and this year is no exception — the College received 12,009 applications, compared with last year’s 10,395, and admitted 9% of those applicants, beating out last year’s lowest record-breaking admissions rate. Of the 1,080 students admitted this year, 66% chose to enroll.

A diverse cohort, the incoming Class of 2026 represents 29 countries — such as Australia, Colombia, Indonesia, Switzerland, United Arab Emirates, and Zimbabwe — 41 states/territories, and Washington, D.C. Nineteen percent identify as first-generation college students, and 24 were recruited via Barnard’s first year partnering with Questbridge, which connects the College with high-achieving, low-income students from around the country. Whether it’s academics or sports, these firstyears cover a lot of ground: Nearly 300 students expressed an interest in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM), with 39 coming from Barnard’s PreCollege Program, 10 from the Pathways Bridgewater Scholars Program, and six from the Science Pathways Scholars Program (SP)2. A total of 16 athletes will join the community to compete in a range of sports, including rowing, track and field, and swimming and diving.

“We are so excited to welcome the Class of 2026 to Barnard,” says Leslie Grinage, Dean of the College. “The creativity, interests, and knowledge they will bring to campus will only be strengthened over the next four years, and our entire community — faculty, staff, and alumnae — are honored to be a part of their journey into adulthood.”

Learn more about the incoming Class of 2026 and why the College is so excited to welcome them.

More than a dozen athletes from around the world will join the Columbia/Barnard Athletic Consortium to compete in NCAA Division I athletics, including sabre fencing, squash, swimming, and track & field.

The Class of 2026 follow their own leads and interests, such as raising goats, working as a sushi chef, training for a pilot’s license, and launching a rural COVID-19 care packages initiative.

From Arizona to Pakistan, first-years find ways to create space for others wherever they are in the world, such as starting a nonprofit to provide all-girls schools with educational supplies; working with a senator to ban corporal punishment in schools; co-founding E-Waste Warriors and recycling over 10,000 pounds of electronic waste; and establishing Chicas for Change to empower female students inside schools.

Before Barnard, many members of the Class of 2026 had already acquired diverse skill sets. One first-year was an a capella captain, field hockey player, debate club president, and swim teacher; another founded a two-week musical theatre summer camp; and there’s an inaugural Bridgewater Scholar cohort participant who is also an owner of a convenience store.

Emma Wolfe ’01, who first walked through Barnard’s gates as a new student in 1997, has returned to the College after more than two decades working in activism and city government — including 12 years with Bill de Blasio during his tenure as NYC’s public advocate and then mayor. In her role as the Associate Vice President for External Relations and Leadership Development, she will enhance Barnard’s relationships with government officials and expand leadership development opportunities for students, staff, and faculty.

Wolfe filled us in on her time at Barnard and what it means to participate in community activism.

How did your studies at Barnard inform your career?

I was in the Urban Studies Program, and it was this great mix of learning how cities worked, the histories of them, and interesting research. In our coursework, we got assignments that forced us out into neighborhoods where we interacted with New Yorkers from all walks of life. The program was a direct pipeline to the work I would end up doing. It really opened my eyes to the different ways that people impact change in urban environments. Once you get a dose of that, it’s incredibly compelling, and I didn’t want to let it go.

What does leadership development look like on a granular level?

It’s thinking about how to move people into leadership roles. To have any kind of functional organization, people have to step up in all kinds of ways. Organizing is not just the things that people often associate it with, like going door to door and getting petitions signed or standing up with a bullhorn. Some of the best organizers I’ve ever met have a real keen sense of how to build a team who can really feel like they’re growing and maximizing themselves. That’s leadership.

Why is it important for Barnard to cultivate relationships with the New York City community? New York City is a rich place for policymaking and for innovation. There’s such an opportunity for impact. There are people and places in the public and the private sector, plus effective nonprofit organizations and grassroots, that make up the fabric of the city. If we can connect the work that’s happening there with the desire for activism and service here at Barnard, it’s a win-win.

Any advice for students interested in community organizing or politics?

I think it’s important to understand that there are different ways to make change. Students shouldn’t feel like they are pigeonholed into social or publicfacing roles. Nowadays, there’s this association with politics and organizing with speaking truth to power. That has a place, but it is one very distinctive place. And if that is not something that you vibe with, that doesn’t mean you cannot contribute. You can do research, you can start up your own company, you can work in public service, you can volunteer, you can organize behind the scenes. The beauty of creating change in New York is there are a million ways to do it.

Record-Breaking Year at Barnard for Fulbright Grants

This year, out of the approximately 2,000 grants given to U.S. scholars annually, 11 Fulbrights were awarded to Barnard alumnae — the College’s highest number of honorees to date. In addition, three alumnae were chosen as Fulbright alternates. The grants will support students’ work abroad as English Teaching Assistants (ETAs), researchers, and graduate students. “What’s especially exciting to me about the record number of recipients is that it will almost certainly encourage even more students and graduates to apply,” says A-J Aronstein, Dean of Beyond Barnard and Senior Advisor to the Provost. —Mary Cunningham

The Public Theater, the Barnard Center for Research on Women, and the Ntozake Shange Literary Trust recently established the Ntozake Shange Social Justice Theater Residency. Conceived by inaugural playwright Erika Dickerson-Despenza, this two-year playwriting residency is named for the late Ntozake Shange ’70, a revered writer, playwright, and fierce advocate for women and the dignity of humankind. Awarded to a distinguished woman, femme, trans, or nonbinary playwright of the African Diaspora, the residency will provide a salary with benefits and full support to pursue their creative work as a playwright.

Those nostalgic for Barnard’s architectural past can now revisit Lehman Hall — the midcentury monolith that formerly housed the library — in Cynthia Talmadge’s pointillist oil painting displayed in Milbank Hall. The artwork arrived in May 2022, via an anonymous loan, and is a part of the painter’s Seven Sisters series. —Mary Cunningham

In response to the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, President Sian Leah Beilock joined the presidents of five other colleges founded for women — Bryn Mawr, Mount Holyoke, Smith, Wellesley, and Vassar — in writing a letter to The New York Times, published on June 28. Together, the presidents pledged “to work to inform students of the best way to obtain access to the full range of reproductive health care.” —Zuyu Shen ’24

Stella — beloved dog of Barnard Magazine creative director David Hopson — seems happy, but is she? What is it actually like to be a dog? Researchers at the Horowitz Dog Cognition Lab aim to find out. (Story on page 16.)

PHOTO BY NINA WURTZEL

Stella — beloved dog of Barnard Magazine creative director David Hopson — seems happy, but is she? What is it actually like to be a dog? Researchers at the Horowitz Dog Cognition Lab aim to find out. (Story on page 16.)

PHOTO BY NINA WURTZEL

Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist and translator

Jhumpa Lahiri ’89 is returning to Barnard as the Millicent C. McIntosh Professor of English and Director of the College’s Creative Writing Program. Lahiri took over the program’s leadership from the beloved professor Timea Széll ’75, who retired after 43 years on the English faculty. Széll taught thousands of students during her Barnard tenure — including Lahiri, who considers her Barnard English courses fundamental to her subsequent writing life. Here, they converse about mentorship, the complexities of translation, and how Lahiri’s literary interests have influenced her teaching philosophy.

Timea Széll: I never taught you in a creative writing class, and I don’t believe that you took any at Barnard. So I’m very curious about your path to fiction writing.

Jhumpa Lahiri: My love of writing, or my interest in writing, has roots in my childhood. I wrote stories and invented things and copied versions of books that I read. So writing has always been there, but I think that as I grew older, and especially in my later adolescence, thinking of myself as a writer and putting myself on the page felt intimidating, so I avoided it. As an undergraduate, I focused on literature courses, and reading and thinking about language. The first tentative steps toward creative writing came after I graduated from Barnard, between college and what eventually became the long haul of my postgraduate studies and doctoral work. It was in that interim when no one was looking over my shoulder — when I wasn’t writing to fulfill the requirements of the class or engage with a certain professor.

TS: I appreciate that sense of being in a kind of intellectual solitude. And the whole notion of saving the adjective “creative” for fiction writing, poetry, etc. — I have a bit of a problem with that. I read your critical work and that by wonderful colleagues, and it has all the elements of creativity. And to students who say, “Well, I prefer creative writing; I think academic writing is too dry,” I always say, “By all means, let it be a creative piece of academic writing.” This leads me to ask — did you carry some of Barnard’s legacy or fingerprints, so to speak, on your thinking, on your imagination?

JL: Barnard was the root of my trajectory. My college years exposed me to an

undeniable rigor and seriousness when it came to the question of language and literature. I agree with you, I think this word “creative” writing is very problematic as well, because of course, there is imagination involved in all forms of writing. And I think it creates a false separation that needs to be reexamined. This is something I’d like to try to explain to students — that creative writing is fluid and hybrid and elastic. And that the imagination doesn’t exist on one side of this divide. What is writing but thinking, meditating, seeing, reflecting, processing, and then reworking experience with words? And yes, there can be basic sorts of differences — perhaps, in a “creative” project, I’m making up a character or working off an emotion or a personal observation. But the key is — and this goes back to “How did Barnard prepare me for all of this?” — my writing comes out of an alchemical reaction between my life, my sensory reality, my emotional reality, my reading, and my relationship to books, poems, novels, essays,

Jhumpa Lahiri ’89 talks with her former teacher, retiring professor Timea Széll ’75, at a moment “beautifully braided with meaning”PHOTO

and so on. That’s what brings forth the writing, and that conversation includes reading critical works as well and seeing how carefully things can be read, should be read.

TS: I agree profoundly. I was just reading your most recent work, and so much of it centers on the craft of translation, the meanings of the word “translation,” the ways in which each translation is, as you say, a “unique shadow.” That also makes me think of how I taught Critical Writing. I usually took a few English translations of a specific passage from Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, and we talked about the ways in which they differed. What are the ramifications of some of the decisions made by the translators of the original classical Greek?

JL: I remember looking at Agamemnon with you in that Critical Writing course, and I took a page out of your book at Princeton in my translation workshops. I used Agamemnon, among other texts, comparing translations, which is always revelatory for me as well as for the students. If I’m teaching a course in which the idea is to write an analytical essay, on, say, Dante’s “Inferno,” I try to walk the students through how to close read a text as you did for me. They need to cite the text; they need to have something to say. On the other hand, that text should be engaging and beautifully written. It should have a beginning, a middle, and an end. All of these things are relevant, whether you’re teaching them to write an analytical three-page paper or a nine-page story or 12-line poem. The point is to be attentive to structure, to how you’re using language, and to determine whether your words have impact, grace, and uniformity in terms of tone. Whatever I’m teaching, I would hope that it’s relevant no matter what the student is going to go on to do. I’ve taken, I want to say, at least 50 literature courses in my life. It feels like more — could it be 100? Meanwhile, how many creative writing courses have I taken? Maybe 10? Less? And then we see the fruit of that journey, which is that I’ve written much more fiction and a comparatively smaller body of nonfiction and critical work.

TS: In the impressive chapter on Echo and Narcissus in your newest book, Translating Myself and Others, you write: “The hierarchy of original and derivation dissolves. To self-translate is to create two originals: twins, far from identical, separately conceived by the same person, who will eventually exist side by side.”

JL: I was following the idea of Echo and Narcissus as translator versus text and realized at a certain point that the analogy really wasn’t as clear-cut as I thought it would be. And then, yes, there’s the bit about self-translation: Is it a solipsistic act? Or is it the ultimate creative act? I don’t have the answer to that. This experimentation goes back to my undergraduate years, when I was exposed to authors like Nabokov and Beckett. Any author you read whose first language is not the language she is writing in is already a sort of self-translator. So even when I was writing in English, given that I was raised in another language, writing about Bengali culture and experiences in English involved a form of translation. Language is so intensely, intimately bound up with the question of identity, and whether we can be truly ourselves in different languages is a question that I ask myself. And it’s a question that has been asked of me as I’m going out farther and farther on a limb of ongoing exploration.

TS: How much time do you give to workshopping and reading short stories or novels?

JL: My courses are extremely reading heavy. Reading is like the food pyramid. You should be eating a lot of fruits and vegetables and a lot of whole grains and then eat less meat and even less of the sugars at the very top. So in a way, the creative writing part is like that special treat, and what is going to really nourish you is the reading. One of the courses I just taught last spring, which I hope I will teach again at Barnard, is a semester-long, close reading of one of my very favorite texts, which is The Periodic Table by Primo Levi. We read two elements a week, very carefully. And that’s what we’re focusing on for at least half of the classroom session. That’s typically how I would teach what is commonly thought of as a creative writing workshop. If students are going on to be writers, they have the rest of their lives to write whatever they want, and they will have no prompts, no professors saying, “Use this as a first sentence” or “Try to incorporate this form of imagery.” I like to work with restraints, and I try to teach my students that total freedom isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. But the main thing, I repeat, is that a writer should always be in conversation with her reading. You can’t play the game until you understand this basic fact. The undergraduate years are incredibly precious, they’re finite, you don’t have that kind of freedom later on. Life just gets more complicated, in beautiful ways, but in ways that eat up your time. And you’re being asked to do different things. You’re not necessarily being asked to read 200 pages of Anna Karenina for the next class session. So college is when you do it. And that’s what I will continue to urge my students to do.

TS: I am excited to see what you do, and I look forward to continuing this conversation soon and to many more similar conversations in the future.

JL: I’m happy to talk to you. It’s beautifully braided with meaning, this moment of transition for both of us: one of us going and the other arriving. It’s very much connected. Thank you for being my mentor and my guide for all these years.

TS: Oh, please! Would you say something about mentoring students?

JL: I think the best mentors, like you, are a bit like how Joyce, loosely translating one of Flaubert’s letters, describes the artist: one who “remains within or behind or beyond or above his handiwork, invisible … paring his fingernails.” The point is

In this coming-of-age story set in a modern Orthodox Jewish community in an American suburb, Drazin introduces readers to sixthgrader Milla Bloom and her best friend, Honey Wine. Unlike Milla’s emotionally reticent family, Honey’s enviably loving one exudes a charming confidence. The two girls undergo dramas at school and at Jewish holidays while Milla struggles to cast off Honey’s shadow and define her own strengths.

Medoff narrates a feverish family drama from the Upper East Side of Manhattan, in which the ultrawealthy and seemingly perfect Quinn family exposes its deep fissures when the youngest son, Billy, is accused of assaulting his former girlfriend. As family members strive to defend Billy at all costs, they risk revealing their hidden guilt to the public.

This debut novel follows Emilia, a young artist reeling from recent heartbreak, on her journey toward self-discovery and an understanding of the ways in which her musician father’s successes and betrayals have overshadowed her own identity. Giacco celebrates the beauty of Rome and the joys of Italian food, music, and art as Emilia wanders through the city in contemplative reverie.

A group of American spiritual seekers settle in at a Swiss chalet for a weeklong summer retreat in Shaw’s most recent book, which strings together 10 short stories that incorporate joy, humor, mindfulness and genuine transformation.

In Wong’s second novel, the Brightons, a biracial Chinese American family who’ve built a shopping empire known as Kaleidoscope, grapple with themes of identity,

family, grief, and the particular bonds of sisterhood. After a sudden, tragic loss, younger sister Riley sets off on a journey with an unlikely companion to look for the truth about the people she thought she knew, including herself.

Dandelion Salad in Brooklyn by Carol Falvo

Heffernan ’65

Heffernan’s account of her early life in an ItalianAmerican family in Brooklyn during the 1940s and ’50s provides rich content in feasts and foodways, including the recipes that help define her culture’s traditions and roots. Her memoir reminds readers that each wave of immigrants confronts prejudice and barriers while striving to become American.

Day to Day the Relationship Way: Creating Responsive Programs for Infants and Toddlers by Alice Sterling Honig ’50

Honig — an accomplished psychologist, professor emerita, and author — and co-author Donna S. Wittmer examine how early childhood relationships with educators influence and further babies’ socioemotional and intellectual development.

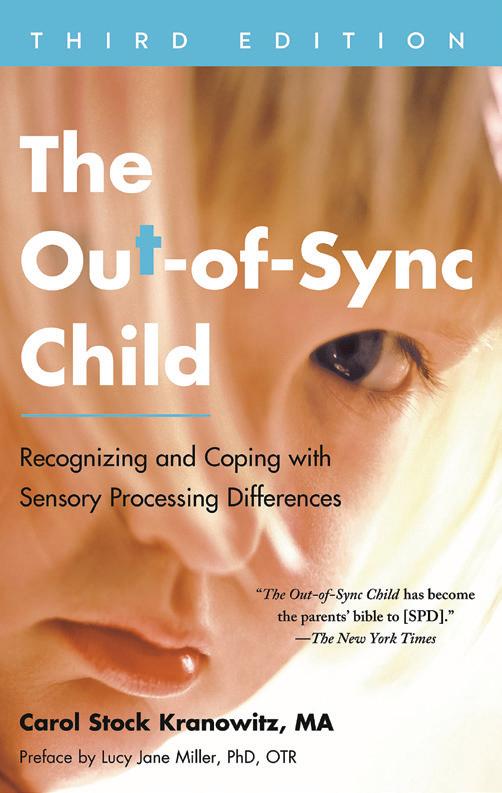

The Out-of-Sync Child, Third Edition and A Year of MiniMoves for the InSync Child by Carol Stock Kranowitz ’67 With a focus on sensory-motor development and activities, A Year of Mini-Moves (co-authored by Joye

Newman) provides parents with digital pages detailing two weekly schedules that incorporate quick movement activities into everyday life. And in the most recent edition of The Out-of-Sync Child, Kranowitz aims to provide both children with sensory processing differences and their parents with the support they need regarding such topics as oversensitivity, undersensitivity, and confusion.

This insightful memoir recounts the author’s origins — her single lesbian mom decided a man she met at a Beverly Hills salon would be the sperm donor of the child for which she yearned — and her calamitous childhood with her unstable mother and mysterious father. Bilton shows unwavering love for her unconventional, fascinating family through compassionate storytelling.

Protecting Mama: Surviving the Legal Guardianship Swamp by Léonie Rosenstiel ’68

Protecting Mama is Rosenstiel’s deeply personal account of her 14-year battle with the court-appointed guardian of her mother, who suffered from Alzheimer’s disease. The book is her attempt to help others find their way through the complicated morass that legal guardianship can be.

by Nancy Woloch

by Nancy Woloch

A history professor and a writer, Woloch skillfully recounts former Barnard dean Virginia C. Gildersleeve’s contradictory career in academia and public life while serving at Barnard College from 1911 to 1947. This biography examines Gildersleeve’s devotion to higher education, her ambitious striving for influence in the academic arena and in the world of foreign affairs, and her opposition to demands for women’s equal rights, grounding her story in the histories of education, international relations, and feminism.

This informative and fun dinosaur picture book serves its readers abundant knowledge through interactive guessing games and touch-and-feel skeletons. Balkan cleverly arranges the 10 dinosaurs so that a connection among the animals is established, while myriad other resources are highlighted for curious readers.

Sniffy the Beagle by Rita S. Eagle ’55

In her debut children’s book, Eagle, a clinical psychologist, tells a story that celebrates exceptionality and respecting others’ differences. While Tommy wants a dog who plays and fetches, Sniffy is focused on sniffing at all times. The tale resolves when Tommy finds a creative way to put Sniffy’s talents to good use.

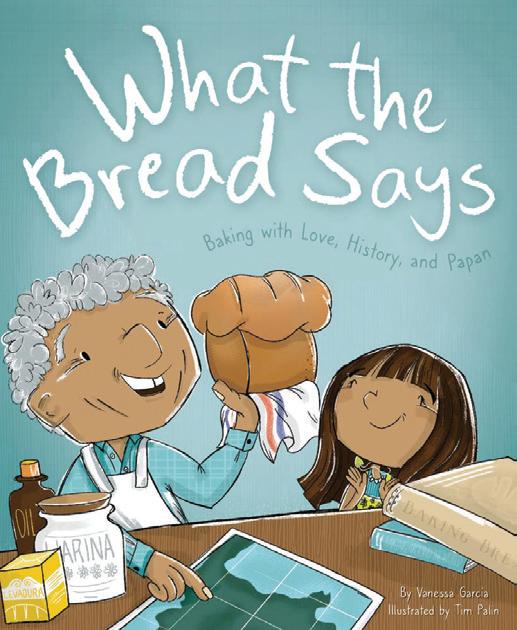

What the Bread Says: Baking with Love, History, and Papan by Vanessa Garcia ’01

In this heartwarming picture book based on the author’s early life, Vanessa learns about her roots while baking with Grandpa Papan on Saturdays during the hours her mother is at yoga class. Garcia ingeniously weaves through the timelessness of baking, history, and family connection, and Vanessa starts to rethink her present, her future, and the power of family while contemplating her grandfather’s life adventures.

by Hila Ratzabi ’03

by Hila Ratzabi ’03

Ratzabi’s first poetry collection observes the beauty of life while simultaneously commenting on the instability of our planet due to the climate crisis. Themes of mortality and uncertainty position the reader to meditate on climate change and its irreversible effects.

Dogs. There are an estimated 800 million of them in the world today, and they occupy a unique position in our society. They share our homes, our yards, and for some of us, even our beds. We love them, we worry when we leave them, we feed them, we walk them, but who are they really? What is it like to be a dog? Renowned dog cognition expert and psychology professor Alexandra Horowitz believes the tendency to answer those questions from a strictly human perspective misses a profound opportunity.

In her March 2018 New York Times opinion piece entitled “Is this Dog Actually Happy?” Horowitz urges dog lovers to refrain from perceiving their canine companions as “quadruped” versions of human beings. She makes a case that as

beloved by and attuned to people as they can be, their experience of the world is distinct, mysterious, and worthy of respect and understanding.

Investigating the thought processes and behaviors of dogs has been at the center of Horowitz’s research, teaching, and — as evidenced by her opinion pieces and bestselling books — deepest concerns. Her discoveries have helped to elucidate the mysteries behind those wagging tails, floppy ears, and searching eyes. So much of what makes a dog a dog stems from their noses and their highly sensitive and powerful olfactory receptors, their sense of smell.

“I am fascinated by olfaction, which is so keen in dogs and thus makes up a large part of their experience. It’s challenging and interesting to study what they know or think through smell since we visual creatures don’t have great olfactory imaginations,” says Horowitz.

At the Horowitz Dog Cognition Lab at Barnard, she and her team, which includes as many as 10 Barnard

Dogs Don’t Smile Canine cognition pioneer Alexandra Horowitz studies the inner lives of humanity’s best nonhuman friendsKelly Chan, Alexandra Horowitz, and Carol Arellano ’23, with Briscoe, faithful companion to editor-in-chief Nicole Anderson / PHOTO BY NINA WURTZEL

student researchers and a lab manager, have devised methods to leverage this olfactory imperative to dive into the psyche of a dog. They are currently studying whether smells can be paired with positive experiences such that the smell brings about an associated positive state of mind. (The lab is funded by a generous gift from April Benson ‘73.)

“If so, people could potentially use those smells as anxiolytics [anxiety relievers] to help dogs in stressful or anxiety-provoking situations,” says Horowitz. In another study, the lab is exploring the dog-owner relationship and whether different enrichment toys have different effects on dogs’ general well-being.

The lab also serves as a training ground for aspiring researchers. Carol Arellano ’23 began working with Horowitz during her sophomore year. “Since starting my work with the lab, my perspective on how dogs perceive the world has definitely changed,” says Arellano. “I’ve learned to isolate my human biases from my observations and adopt an entirely new perspective when considering how dogs experience and engage with the world.”

Among Horowitz’s earlier findings are those that have debunked beliefs about how dogs think and feel. For example, many owners tend to believe when their dogs cower and tuck their tails between their legs, they are feeling guilty for breaking a rule. Her study, however, on this behavior found that dogs will cower in this manner even if they haven’t broken a rule but rather if they anticipate being scolded. “The guilty look can be seen as a response to the cues that an angry owner gives to their dogs rather than the product of guilt,” explains Arellano.

Kelly Chan is a lab manager. “Alexandra has this great dynamic in the lab rooms,” says Chan. “She lets you design your own studies and work in the group.” This can be a creative and intellectual challenge. “Since we cannot measure a dog’s response and behavior in the sense we can with humans, we need to be sure we are designing [the studies] properly and running statistical analysis. It’s the best of both worlds: creativity and science.”

What brought Horowitz to study dog cognition? It wasn’t a focus of her early life. Having grown up in the foothills of Colorado, she wasn’t even especially interested in the sciences. She was drawn to philosophy, and that became her focus in college. It was in graduate school at the University of California, San Diego, that she became compelled by nonhuman animal minds and how they work. Scientific questions about what other animals know, perceive, and understand — and how we can find out — fascinated her.

“I believed that ethology, studying animal behavior in their natural environment, was the most promising method — and I thought play behavior was a promising means of entry,” says Horowitz. That idea led her to notice the most ubiquitous of nonhumans, dogs. A bonus: they happen to play all the time and right before our eyes.

“While big-brained animals like chimps and dolphins were popular research subjects, no one at the time — at my school, or anywhere, as far as I knew — was studying the dog mind. But I found a biologist who looked at canine behavior who could guide me, and I had a very open-minded dissertation committee, and so I began a study of the evidence for the theory of mind in the dyadic play of dogs,” says Horowitz, who found herself on the leading edge of the first wave of dog cognition research. As such, the field was wide open for discovery.

“I became interested both in the perceptual abilities of dogs — how they see the world through olfaction — and, completely separately, in the anthropomorphisms we make of dogs in our relationships with them. And of course, I still study play and am impressed by the skill with which they play with not just dogs but people and even other species.”

Along the way of a career trajectory that continues to ascend, Horowitz has

authored several books. Among them are the #1 New York Times bestseller Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know; Being a Dog: Following the Dog Into a World of Smell; and Our Dogs, Ourselves: The Story of a Singular Bond. Her newest book, The Year of the Puppy: How Dogs Become Themselves — which has been widely covered in the press, including The New Yorker and The New York Times — is a scientific memoir tracing the critical early development of her family dog Quiddity’s first year of life.

For Horowitz, there’s unequivocal value in really understanding dogs and giving their unique sensibilities respect: “We share this planet with nonhuman animals: We own them, use them, live with them, eat them. I think it’s important on a basic level to know about them, to understand their abilities and capacities.”

Her advice to those who want to know more about the canine in their life is simple: Observe them.

“If you look at the dog in front of you and try to imagine them as an unknown, alien creature, instead of making assumptions about everything you think you know about that dog — what they’re like, what they want, who they like or don’t like — you begin to see what their actual behavior is.”

And above all, she adds, “as we see the world, your dog smells it. Let them sniff that thing, sniff you, sniff each other. It’s their way of knowing about the world.” B

We share this planet with nonhuman animals: We own them, use them, live with them, eat them. I think it’s important on a basic level to know about them, to understand their abilities and capacities.”

In the early 1970s, Abby Pariser ’67 became part of Jane, a clandestine group helping Chicago women obtain safe abortions. More than 50 years later, she’s still championing women’s reproductive rights by Laura Raskin ’10JRN

Itwas at a pregnancy testing center where she volunteered in 1970 that Abby Pariser ’67 first saw an index card tacked to a bulletin board: “Pregnant? Call Jane.” These cryptic signs were popping up everywhere, posted around Chicago and printed in underground newspapers.

Pariser didn’t know at the time that “Jane” was officially known as the Abortion Counseling Service of Women’s Liberation. But within just a few months, Pariser, a passionate social activist, would be entrenched in the day-to-day operations of the underground group, which helped an estimated 11,000 women throughout Chicago obtain access to safe, affordable abortions at a time when they were illegal and criminalized in most of the U.S.

Pariser had recently arrived in Chicago with her husband, Peter Gollon, “a Columbia guy,” whom she married the summer after graduation. Peter, a nuclear physicist, got a job at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory just outside of the city in Batavia, Illinois. And Pariser was pursuing a master’s degree in American history at Roosevelt University, which was founded in 1945 with an explicit mandate to admit a racially and economically diverse student body. Pariser’s decision to go to Roosevelt was largely one of geographical convenience, but it was a lucky match, pairing a radical institution with a woman who had marched against the Vietnam War in Washington, D.C., and campaigned for anti-war presidential candidate Eugene McCarthy.

As Pariser found her footing in Roosevelt’s history department, she became an active member of a fledgling group called the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union (CWLU). Officially founded in 1969, the CWLU was one of the most significant of the socialist feminist women’s unions, pushing for equal rights for women, racial and sexual equality, and freedom from what its members saw as the oppressive chains of capitalism.

Soon, she and some of her fellow CWLU members began working on the creation of a one-room pregnancy testing center in Back of the Yards, a heavily industrialized Chicago neighborhood immortalized for its pollution, squalor, and poverty in Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel The Jungle. Pariser helped out at the testing center wherever she was needed, from the lab to the reception desk. Working at the clinic was an eye-opening experience for Pariser and made a lasting and compelling impression. “I had no idea that healthcare could be so warm, kind, and educational,” she says in a recent telephone call from her home in Huntington, New York.

The pregnancy testing center provided essential services and resources to women, but that index card on the bulletin board — signaling women to “call Jane” — offered a critical lifeline for women with very few and very risky options. Pariser felt called to do more.

Now 77, she recently shared her experience with Jane in the HBO documentary The Janes, along with other former members. Directed by Tia Lessin and Emma Pildes, the

film — which debuted less than three weeks before Roe v. Wade was overturned in June — is a candid telling of the inner workings of the group and its members, who, even at their own peril, went to great lengths to help women access safe abortions. (The Janes was the Spotlight film at Barnard’s 2022 Athena Film Festival in March.)

Speaking with Barnard Magazine, Pariser recalled her time in the groundbreaking group and the anguish of seeing Roe v. Wade overruled.

The group that came to be known as Jane was initiated by Heather Booth, a University of Chicago student who had helped a friend’s sister access a safe abortion by contacting leaders in the medical arm of the local civil rights movement. Word spread, and soon Booth was fielding more requests than she could handle. The group, founded in her dorm room, eventually recruited others to help field calls, counsel women, evaluate doctors, and follow up after procedures.

“Jane” was a purposefully dull and unsuspicious pseudonym. It helped shield the clandestine group and simultaneously evoked the democratic and ubiquitous nature of the need for safe abortions. Teenagers, mothers, married, single, wealthy, or struggling — they all came to Jane in search of the same thing, though Booth and the other Jane members mostly helped women of color and those without the means to travel long distances to safely terminate a pregnancy. These were the women most likely to end up at Chicago’s Cook County Hospital, which, in the late 1960s and early ’70s, until Roe v. Wade passed, had a dedicated 40-bed septic abortion ward. There, doctors waited to triage women who were so desperate to end a pregnancy that they ingested poisonous chemicals or perforated their uterus, vagina, bladder, or rectum. Infections and burns were common, and so was death, as Allan Weiland, a retired OB-GYN, wrote in an essay for BuzzFeed News in June 2019. The goal of Jane was to divert as many women from these experiences as possible.

As she had at the pregnancy clinic, Pariser went where she was needed: to the drugstore to buy sanitary pads and rubbing alcohol, to the phone to take calls from scared women. When it was revealed that the man whom the group had been paying to provide the abortions was not, in fact, a doctor (though he had been regularly administering safe procedures), Pariser and other Jane members learned how to perform abortions themselves, using the common dilation and curettage (D&C) method, in apartments borrowed from friends or rented in a high-rise.

Pariser describes the intimate and high-stakes procedures without a hint of squeamishness, dread, or fear. “We kept up a stream of description of what we were doing,” she says. “And the other Jane sister would be sitting at the woman’s head and holding her hand. We called the woman that night, the next day. We wanted them to take their temperature, fill their prescription for [antibiotics], and go to their doctor or Planned Parenthood in two weeks. And we were very pushy about [saying],‘You need to use birth control.’ We also said, ‘You could be part of us.’”

In 1972, one of the Jane apartments was raided by the police. Seven Jane members, including Pariser, were arrested and charged with 11 counts of abortion and conspiracy to commit abortion, carrying a maximum prison sentence of 110 years. The women’s

This page: Members of the Janes in 1972, featured in the HBO documentary directed by Emma Pildes and Tia Lessin.

Opposite: Abby Pariser (center) with fellow Jane members in 1972.

PHOTOS COURTESY HBO

PHOTOS COURTESY HBO

attorney was able to delay court proceedings, knowing the Supreme Court was likely to take up Roe v. Wade. The court’s ruling in that case decriminalized abortion nationwide, and the charges against Pariser and her Jane sisters were dropped.

Pariser grew up in Scarsdale, New York, the oldest of three. Though her parents were not activists, Pariser rode a collective wave of post-war optimism and idealism into her college years. “It felt like ‘we’ had to inform the government that they were on the wrong path and we were entitled to the right to assembly and the right to redress one’s government.”

She had watched the terror of the Cuban missile crisis. Now the government was sending Americans to a deeply divisive war in Vietnam. There were plenty of things to protest. Pariser had transferred to Barnard for her sophomore year, after beginning college at Cornell University. “I was unhappy [there],” she says. Her Cornell peers seemed unaware or uninterested in the moral crises of the moment. Once, a student saw Pariser browsing Russian literature in the library stacks and scoffed when she revealed she was looking for something to read that wasn’t assigned in class.

At Barnard, she found the level of ferment she was looking for. “We felt like the government was hiding stuff from us. If we gathered enough people to march in Washington, D.C., we believed they would say, ‘Oh yeah, you’re right.’ It was interesting when we marched, to see sharpshooters on the top of buildings. We were carrying signs. We didn’t have grenades,” she recalls.

Inspired by her love for her AP U.S. History class, Pariser majored in the same subject at Barnard and studied with Columbia’s James Shenton, a renowned historian of 19thand 20th-century America who founded the Double Discovery Center, a tutoring and mentoring program for low-income teenagers in New York.

Pariser’s activism and exposure at Barnard and Columbia to those on the front lines

fighting for social progress had fortified her for risky and vulnerable work, as did a certain amount of youthful naiveté. “I think it was the first or the second orientation meeting for Jane when they said we are doing something totally illegal. ... I went home to the suburbs, and it was a little scary, but then you’re just doing the day to day,” says Pariser. “The importance of each woman’s story carried beyond, ‘Oh my god, I’m a criminal.’”

Peter, Pariser’s husband, supported her work and was active in the ACLU. Someone had to step up, the couple agreed, and it might as well be Abby. Her parents worried. Pariser’s time with Jane aligned with the murders at Kent State and the Orangeburg massacre in South Carolina, where protestors demonstrating against racial segregation at a bowling alley were shot by highway patrol officers.

But Pariser and the other Jane members remained steadfast in their mission. “As Heather Booth said, the laws were wrong and we were right. You have to take the world into your own hands and do what’s right,” says Pariser.

After her arrest and the passage of Roe, Pariser joined a group in Wheaton, Illinois, that was opening a Planned Parenthood clinic. “Our county had no doctor who would prescribe birth control. No tubal ligations. We ran the clinic for nine years, until the health department took it over,” she says, which was the goal all along.

The co-op atmosphere was familiar to Pariser. She and her colleagues were crosstrained to take a patient’s history and run tests in the labs. The clinic was in the basement of an Episcopal church. “Each night, after the work was over, everything went into a closet. Wheaton was and still is a relatively conservative place, and who knows what they thought when they saw a line of teenagers waiting to go into the church basement. But we never had a problem.”

Along the way, Pariser finished her master’s. Four years into her Planned Parenthood work, her daughter was born. She and Peter moved back east, to Huntington, to be closer to family. Pariser got involved with the National Organization for Women and pushed to get the local school district to provide before- and after-school care, as well as sex education. She was never too far from her history with Jane and in the early 1980s was contacted to help a woman in the Suffolk County Jail obtain an abortion; the sheriff wouldn’t let her. Pariser got a lawyer and successfully advocated on the woman’s behalf.

Some in Pariser’s circle never thought they would see Roe v. Wade overturned, but when the draft of the Supreme Court’s decision was released in May 2022, she saw what was coming. “When the septic abortion wards start happening again, and daughters and nieces and wives and mistresses of people in power start getting homegrown abortions and they get ill, it may change people’s minds,” she says.

Though cynicism and defeat would be understandable, Pariser remains an activist, involved in feminist politics and going door-to-door for local Democratic political candidates. She’s an active member of her Reconstructionist synagogue, a passionate folk dancer, and a “haphazard gardener.” She and Peter continue to be involved in the ACLU and go on service trips with the Sierra Club. Her daughter and son have children of their own. Pariser brings her grandkids to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Broadway shows.

It was never an option to stand idly by, she says. “I’ve spent my adult life trying to make the world a better place. ... I had to be part of the movement to make women’s health services more humane, feminist, and more educational.” B

Barnard experts offer insights on the Supreme Court’s decision to end federal protection of abortion rights

On June 24, 2022, the Supreme Court reversed Roe v. Wade, ending women’s constitutional right to an abortion after nearly half a century. Following the announcement, a number of states moved swiftly to enact restrictive laws that have already changed the abortion landscape for women across the country.

At the time this issue went to press, 12 states have banned abortion, and five have imposed gestational limits to the procedure as early as six weeks.

According to The Washington Post, 1 in 3 women in the United States have lost their access to abortion, and in the months to come, more abortion bans and restrictions are expected to go into effect.

On the following pages, experts at the College speak out about the potential consequences of this decision and how the ruling will impact their fields of study.

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE BARNARD COLLEGE ARCHIVESThe Court’s decision on Dobbs v. Jackson is devastating because it denies those of us who can give birth the right to safely access a procedure that has always been a necessary part of reproductive healthcare. But the decision is also a chilling reminder that so many of us — gender nonbinary, trans, queer, Black, immigrant, Indigenous, disabled people, and financially vulnerable women — are still not seen as fully human in the eyes of the State, and our bodies are often criminalized. We now have to struggle even more fiercely for reproductive justice — the ability to maintain autonomy over our bodies, live free from systemic violence and harm, and sustain the kinds of families we want to form. Questions of bodily autonomy have always been central at BCRW, which held its first conference one month after the 1973 Roe decision, and we will continue to use our archives, publications, and events to support activists, artists, and scholars who are teaching and organizing around these issues.

Claire Tow Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies

In particular, the debate over Roe v. Wade is often framed as one between religious morality, where “religion” predominantly means conservative Christianity, and a secular commitment to gender equality. This framing is misleading, and each of the fields I work in speaks to the problem somewhat differently.

The leading view of the field of women’s studies is that the basic protection provided by Roe v. Wade should be placed within a broader framework of racial justice, economic possibility, and community well-being. The Reproductive Justice framework, which has been developed through the leadership of women of color in activist organizations like SisterSong in Atlanta, broadens the framework for understanding the importance of reproductive issues and why they are connected to many struggles for justice. SisterSong defines reproductive justice as “the human right to maintain personal bodily autonomy, have children, not have children, and parent the children we have in safe and sustainable communities.” Reproduction is not a side issue but a necessary part of creating safe and sustainable communities, and, concomitantly, creating safe and sustainable communities is necessary to support everyone’s reproductive lives. The loss of even the basic protection offered by Roe takes U.S. society away from the social relations that will allow people to have and raise children in safe and sustainable communities. Without Roe and a recognition of the need for reproductive justice, U.S. society is further away from the possibility of jobs with a living wage that could support families, or of a world without police violence, or of a safe educational environment for all children.

Framing the debate about Roe v. Wade as a conflict between religious morality and gender equality makes it seems as though one group’s rights will inevitably triumph over another. It seems that either religion or gender equality must prevail. Instead, debate over Roe v. Wade can better be understood as a question of religious freedom for everyone. Religious views on abortion have varied historically, both within religious traditions, including Christianity, and among religious traditions. Different traditions have different views of abortion. For those who believe that life begins at conception, their freedom

Senior Associate Director, Barnard Center for Research on Women (BCRW)Janet Jakobsen

to organize their lives in relation to this belief is not threatened. Roe offered protection against the use of the force of law to impose this belief on people who do not share it. Religious freedom protects both religious people, whatever their tradition, and those who are not religious from having to organize their lives according to religious values, beliefs, and traditions they do not share. The loss of Roe then, not only puts significant burdens on reproductive health and the possibility of safe and sustainable communities as advocated in the reproductive justice framework, it is also a step away from the promise of religious freedom for all.

We know from a very robust body of research that growing up in poverty harms children across virtually all dimensions, hurting their health, educational attainment, earnings, and more. Women in the U.S. face large earnings penalties for having children across socioeconomic levels and, in particular, are highly likely to enter poverty directly after a child is born — thanks to a lack of paid leave, a lack of affordable child care, and a lack of the type of child allowance common in other rich countries. That’s the case even now, with legal access to abortion, in a context where women are able to plan their families and their births for when it’s the best time in terms of their work and family situation.

We also know from recent research that has followed women who were unable to get an abortion under new laws — because they came to a clinic just after, instead of just before, a gestational cutoff in their state — that they are much more likely to be poor in the years afterward, much more likely to get evicted, in much worse mental and physical health, and more likely to be in an abusive relationship. Their existing children — 60% of women seeking an abortion are already mothers — end up with poorer developmental outcomes. All of these results portend badly for women’s futures and their children’s.

In other words, when more women lose the right to choose whether their current circumstances are the best ones into which to bring a new child — economically and in terms of their education, career, and family context — there will be more women and children facing material hardship, dealing with poor health, and enduring domestic violence. So the benefits of legalized abortion are quite great today, and there will be major costs to losing it.

Nara Milanich Professor of HistoryThis is a devastating moment for proponents of reproductive rights and justice in the U.S., but it is not the first time that advocates have faced such a sobering political landscape. In Latin America, feminists have long faced powerful resistance to reproductive rights — from conservatives, the Catholic Church, evangelicals, but even from parts of the left. As recently as five years ago, 97% of people in Latin America and the Caribbean lived in countries where abortion was illegal or severely restricted.

But today, the three largest Spanish-speaking countries — Argentina, Mexico, and Continued on page 81

PHOTO BY HAMISH SMITH FOR ORDER DESIGN

PHOTO BY HAMISH SMITH FOR ORDER DESIGN

ommunity erving by Kira Goldenberg ’07

From Manhattan to the Bronx, these six alums are changing New York City’s food scene — all while nourishing their local communities

Barnard may not officially offer a food-focused course of study, but the College consistently graduates its fair share of professionals in the culinary field.

“Food was not academic,” New York Times food writer Melissa Clark ’91 reminisced in a 2016 Reunion panel held at the College. Still, passionate alumnae, from Clark to chef and cookbook author Julia Turshen ’07, have applied their undergraduate education to building New York-based culinary careers, creating spaces that showcase not only how delicious food can be but also its crucial role in thriving communities and in social justice work.

“Food is another pillar of our urban life, like housing and access to healthcare and education,” says Liz Neumark ’77, owner of the catering company Great Performances and its extension café in the South Bronx, Mae Mae.

Neumark and five other Barnard food-industry entrepreneurs based in New York City demonstrate that while their work may differ in the details — genre, location, revenue model — they have commonalities that exceed, and perhaps result from, their college degree: Each has mentored employees, served their neighborhoods, forged partnerships, and taken inspiration from New York City’s unrivaled food culture.

“I think there’s something about the education at Barnard that leaves you [with] very clear thinking on how you can achieve your goals,” says chef and Food Network mainstay Alex Guarnaschelli ’91. “There’s nothing more valuable than that.”

In a sunny conference room in a large warehousestyle building in the South Bronx, Liz Neumark is conducting business ensconced in a Barnard hoodie. Neumark is the CEO of Great Performances, a catering company she founded in 1979. Though her prestigious clients range from the Plaza Hotel to the Brooklyn Academy of Music, Neumark, who graduated from Barnard an aspiring photographer, first built the company so that she and fellow women artists would have flexible income streams while pursuing their passions.

“Within the first two years, we brought men onto the staff because we had clients who just couldn’t believe that there were going to be female bartenders,” she says.

Great Performances spent decades renting office space in downtown Manhattan’s Hudson Square but moved to Mott Haven in 2019. The move spanned about seven geographic miles, Neumark says, but the new headquarters — adjacent to multiple highways and seemingly endless construction zones — is “a

million years away just in terms of demographics, amenities, social services, and people.”

So Neumark, who also serves on the board of the city-based food equity organization GrowNYC, is leading Great Performances’ efforts to build relationships in the company’s new home, from participating in community workforce development programs to opening a new incarnation of Mae Mae Café, whose first iteration was as a small, well-regarded farm-to-table bistro at the prior office site. The reimagined Mae Mae, partly a plant store, serves Latinx-influenced vegan food, nods to both the neighborhood’s culinary traditions and to Great Performances’ food education philosophy.

“It’s just the beginning of our outreach into the community,” Neumark says, though she admitted that area construction workers are occasionally taken aback to learn they can’t stop in for a bacon, egg, and cheese. “It’s a beachhead.”

Great Performances is also working to create jobs in the South Bronx and to forge community connections

to Neumark’s sister enterprises. She owns Katchkie Farm in Kinderhook, N.Y., which grows some of the organic food used in the company’s catering and at Mae Mae. Katchkie is also the source of a seasonal CSA — weekly, prepaid farm-share boxes filled with the latest harvest — distributed out of the café and in partnership with other sites around the city. And the farm hosts the Sylvia Center, a nonprofit started by Neumark that educates New York youths about food and cooking through both farm- and city-based afterschool programs.

“Being able to use the platform we’ve built and the world of food to storytell, to educate, to uplift, is what thrills me,” she says.

When Barbara Sibley opened Mexican restaurant La Palapa a few months after 9/11, Manhattan’s food landscape looked very different than it does today.

“If I opened today, everybody would be like, ‘Oh, it’s so artisanal,’” she says. “But when I opened back then, I had to make all my own cheese. I had to make my own mole. I had to make my own chorizo. There wasn’t anywhere to get it. I would sometimes have to repurpose things from Chinese cuisine, or Thai.”

That cultural crosspollination was already a concept Sibley had pondered at length: After growing up in Mexico City and then falling for New York City’s melting pot, she majored in anthropology at Barnard, where she studied how Western investment in developing nations can alter their societal structure.

She considered getting a master’s degree in anthropology but ended up enamored with restaurant life. After working in other

people’s kitchens, she decided she wanted to open a restaurant to cook the food she missed eating. That idea ended up as a deep dive into Mexican food history, which, over two decades later, continues.

“There are very common dishes that are considered part of the canon in traditional Mexican cuisine that have really changed over the years,” Sibley says. One thing she did was source convent recipes from the 1400s. These were collaborations between Spanish nuns and the indigenous cooks hired to work with them. “So you start to have, in those convent kitchens, cross-pollination between the indigenous Mexican cuisine and the Spanish, which also has a lot of North African, a lot of Arabic influence.”

The result of Sibley’s research is a menu so beloved by her St. Mark’s Place community that she continued to offer all the dishes straight through the pandemic, when many other restaurants simplified their offerings in the frenzied pivot to takeout.

Customers “wanted what was really going to make them feel comforted,” she says. “In New York, our communities revolve so much around restaurants.

When times are uncertain, people walk by and they’re so glad that you’re still there,” Sibley told Zagat.

La Palapa also began cooking for frontline medical responders, eventually teaming up with World Central Kitchen. “I ended up specializing in meals that were super delicious, super nutritious, in one bowl, and you could basically eat it with one hand if you needed to,” Sibley says.

It was an adaptation all too familiar to longtime La Palapa employees who did the same after 9/11 and after Hurricane Sandy — a drumbeat of New York City crises reflected in one restaurant’s commitment to its broader community.

It’s impossible to enter The Bakery on Bergen in Prospect Heights, Brooklyn, without being tempted by the cupcakes and cookies on offer. That’s partially because its interior was redesigned into a chic, eyecatching pastiche of pink, red, black, blue, and white on an episode of Get a Room With Carson & Thom,

a 2018 Bravo show hosted by two members of the original Queer Eye, Carson Kressley and Thom Filicia.

And it’s partly because the baked goods look delicious — the perfect combination of moist cake and buttercream bouffant. But it’s mostly because owner Akim Vann’s presence makes the space feel like a welcoming community hangout, great for the taste buds and for the spirit and less great for glucose levels. Or as Vann terms it, a “sober Cheers.”

“We employ community,” she says. “We’re a safe space. We converge in here. And you will find every single walk of life in my bakery.”

The Bakery on Bergen is just the latest chapter in a captivating life. Vann’s father, Teddy Vann, was a Grammy Award-winning songwriter and producer who featured his daughter on the album and single “Santa Claus Is a Black Man” when she was 5. Vann, whose mother is Chinese, was also a cast member on Sesame Street throughout her childhood.

At Barnard, despite a childhood penchant for math, Vann majored in political science and then matriculated to study for a public policy master’s degree at the New School. It wasn’t the right fit, she says, so she left a few credits early. In 1996, she married Reggie Ossé, an entertainment attorney, better known professionally as hip-hop podcaster Combat Jack In the midst of raising their four children and tutoring math, Vann and a pastry-chef friend decided to open a bakery in 2014. Vann didn’t have baking experience, but she did not let that dissuade her.

“Because I could cook and because baking is math, I took to it really easily,” she says. The friend’s subsequent illness forced her to step back, and The Bakery on Bergen became Vann’s solo venture. Since then, she has partnered with a local YMCA chapter to mentor high school interns, many of whom

she ends up hiring at the bakery.

Other than a short closure at the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, Vann has kept The Bakery on Bergen open, seeing a surge in delivery demand as quarantining neighbors sought comfort food. And thanks to support from Brooklyn community members and organizations, as well as boosts like a profile in the Instagram account of Humans of New York, The Bakery on Bergen has remained afloat.

“We all have crazy lives,” Vann says. “But my life is a testimony to understanding that everybody has ups and downs and you can’t let them defeat you.”

When the pandemic hit New York, the South Harlem restaurant Vinateria, a Mediterraneaninspired restaurant and wine bar, already had a large, inviting outdoor dining area. So owner Yvette Leeper-Bueno kept Vinateria open straight through 2020 to support her employees and serve her community.

“So many customers came to me later and said, ‘This place meant the world to me during pandemic isolation,’” she says. Like at Barbara Sibley’s La Palapa, Vinateria partnered with World Central Kitchen to make food for first responders and community members in need, sending a total of 20,000 meals to Harlem Hospital, Mount Sinai Morningside, and foodinsecure residents.

Leeper-Bueno, a New York native, opened Vinateria in 2013 after a first career in children’s fashion and then a few years at home with her two sons.

During that time, she hosted an annual school fundraiser in her Harlem home, complete with a hired wine expert and homemade hors d’oeuvres. “It was so much fun. I used to love to organize them and entertain,” she says.

The menu at the fundraisers was often reflective of the love of Mediterranean culture she acquired while studying at Barnard: She majored in foreign area studies with a focus on Italy, then took a post-college trip to study in Buenos Aires, which has a strong Italian influence, a result of a wave of immigration from Italy at the turn of the 20th century.

“When I got to college, I took an intro to Italian class and I loved it,” she says. “It just took me to a whole other world.”

Her husband and a close friend noticed how much

she enjoyed serving Italian food and wine to a crowd. They suggested she try opening a restaurant. The idea clicked. “I figured, I’m a Barnard lady; I can figure it out,” Leeper-Bueno says. She originally conceptualized a small wine and tapas bar, but the plan changed as soon as she saw a larger space at Frederick Douglass Boulevard and 119th Street.

Today, the restaurant’s menu features housemade pastas and flavorful, seafood-forward small and entree-size dishes prepared with a Mediterranean flair. It’s accompanied by an extensive wine list focused around Italy, Spain, and France.

Despite, or because of, Vinateria’s global flavor,

Leeper-Bueno creates a space where all Harlem denizens — longtime residents and newer ones alike — feel comfortable converging.

“It’s a neighborhood place. It’s a place to come, bring your family, let your hair down,” she says.

New York City native Alex Guarnaschelli started cooking professionally immediately after graduating from Barnard with an art history degree.

“My father always said, ‘Do what you like because,

whatever it is, you’re going to be doing it a lot,’” she says.

She worked in New York City for a couple years, then attended culinary school in France, staying there for about seven years to work at Guy Savoy’s Michelin-starred restaurant. Upon returning to the U.S., she worked at Daniel Boulud’s Daniel in New York and at Patina in Los Angeles before opening Butter in 2002. It was initially located downtown on Lafayette Street and moved to its current midtown location in 2013.

Guarnaschelli connects the art of cooking directly back to her academic studies. “Learning to cook is also being a spectator and observer, and those powers are highly developed with education,” she told a group of Barnard students in a fall 2020 virtual Q&A for the annual Big Sub event, which invited students to share their own sandwich recipes. The conversation focused on sandwiches but covered far broader terrain around the connections between cooking and studying.

“If you want to be a good chef, you have to be ready for repetition like you can’t imagine,” she told the students. “I think the way you study for an exam and [how] you cull all the facts from your notes and your reading and you memorize them and you write them down over and over — you have to be ready to do that with chicken breasts and broccoli and really be able to get joy from that repetition.”

Her own career has become far less repetitive. Besides being chef and owner at Butter, where she oversees a menu featuring seasonal, elevated comfort food, Guarnaschelli is a cookbook author and a perpetual presence on the Food Network, where she hosts the shows Supermarket Stakeout and Alex Versus America. She also co-hosts The Kitchen and often judges on Chopped, Grocery Games, and Beat Bobby Flay, all with her trademark calm, wry demeanor.

In addition to everything else on her plate, Guarnaschelli is in the early stages of partnering with fellow alumna Liz Neumark on a new food venture. The two women are friends, but they’re also philosophically aligned on the role food plays in bringing people together.

“Food and community intersect in so many different ways,” Guarnaschelli says. “Our philanthropic endeavors match our common interests. We love helping people. We love feeding people.”

Sohui Kim entered Barnard planning to become a lawyer at her father’s behest.

“He held onto those traditional beliefs that you pursue higher education to become professionals,” says Kim, whose family emigrated from South Korea to the Bronx when she was 10. “And to him, that was doctor, lawyer, a very straight and narrow path toward professionalism. By the time I was actually at Barnard, my father passed away, so I felt like I was carrying on the weight and the burden to live out his dream.”

Thankfully for Brooklyn’s restaurant scene, the plan changed. Kim started cooking for friends in her dorm and exploring the city’s cheap eats. After graduation, she took a job in architectural publishing, still planning to apply to law school. But she also continued hosting meals and exploring New York’s endless food options.

“I took the LSATs, and I had this sort of ‘aha moment’ while I was taking them” that practicing law wasn’t her passion, she says. “I found the whispering answer: It was food.” Kim quit her day job in 2000 to make the shift.

“I knew that the pay sucked and the hours were

long, but there was something intriguing about the whole food world that I really wanted to explore,” she says. She embarked on a course of culinary study that included an externship at Blue Hill and a job working under Anita Lo at her former Michelin-starred joint, Annisa.