SPRING 2024

SPRING 2024

NATIONAL CHAMPION FENCER

ANNE CEBULA ’20 IS HEADING TO THE PARIS OLYMPICS

BOXER ZINNAT FERDOUS ’16 HAS HER EYE ON BANGLADESH’S FIRST OLYMPIC MEDAL

THE WOMEN’S BASKETBALL TEAM’S RECORD-BREAKING SEASON OF FIRSTS

USA in the 2024 Paris Olympics — a dream long in the making

20

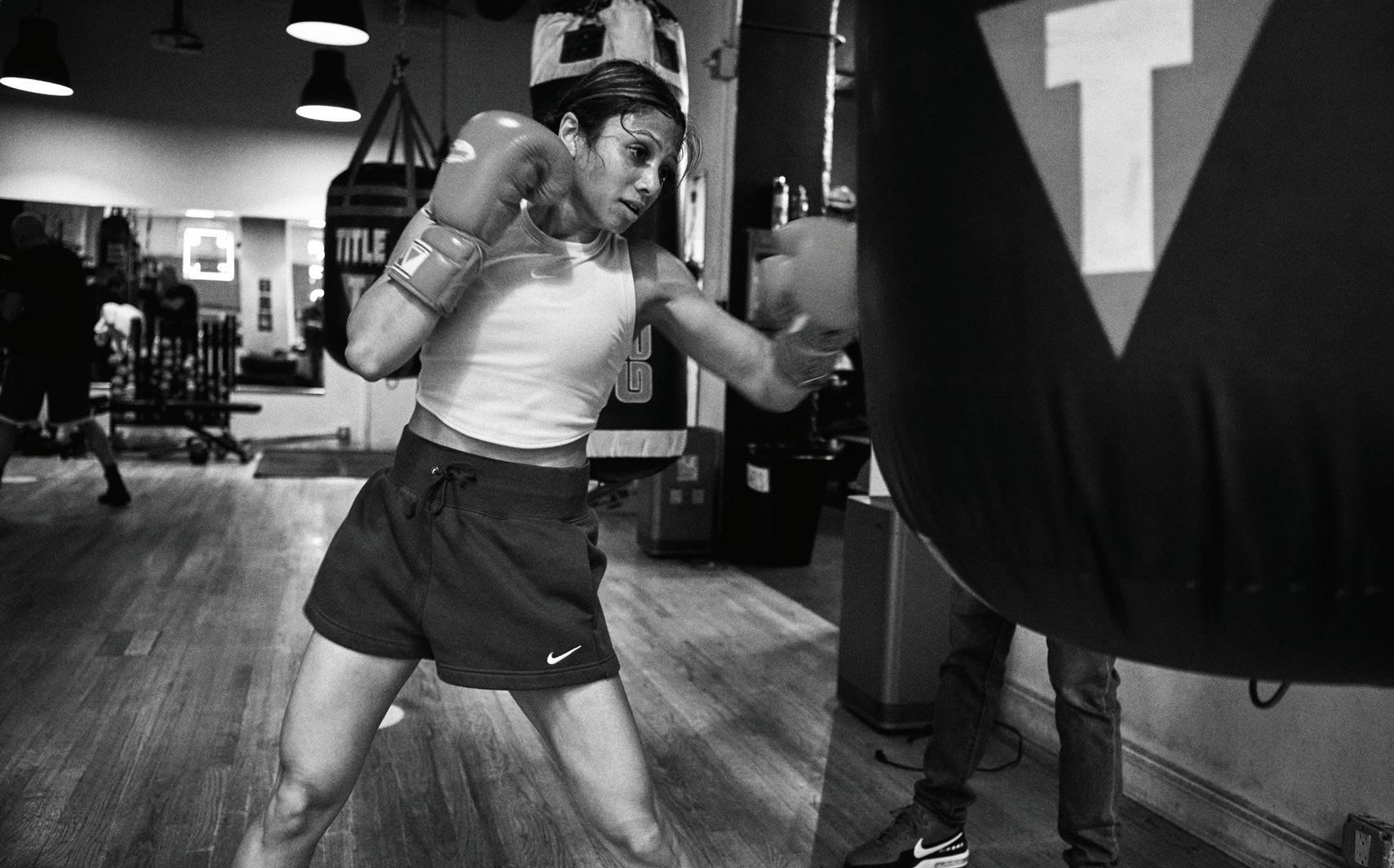

The Good Fight by Gabriel Baumgaertner ’21JRN

Boxer Zinnat Ferdous ’16 is aiming for Bangladesh’s first Olympic medal

Hoops Hype by Anne Stein ’90JRN

In a season filled with successes, Barnard studentathletes played a key role on the Columbia women’s basketball team

2 Contributors & More

3 From President Rosenbury

4 From the Editor

5 Dispatches

Headlines | R&D Science Center Update; TEDx Comes to Campus; Nancy Friday Papers to Barnard’s Archives; Ruth Levy Gottesman ’52 Donates $1 Billion; Meet Barnard’s New Provost

11 Discourses

Read Watch Listen | Bookshelf; Anna Quindlen's After Annie audiobook; Ana Cruz Kayne ’06; Alicia Hall Moran ’95

Strides in STEM | Leading in Artificial Intelligence

Advocacy & Community | Shelby Semmes ’06

38 Off the Field | Dr. Merle Myerson ’78; Alexandra “Ola” Weber ’24

41 Noteworthy

Perspectives | Sarah B. Miller ’98

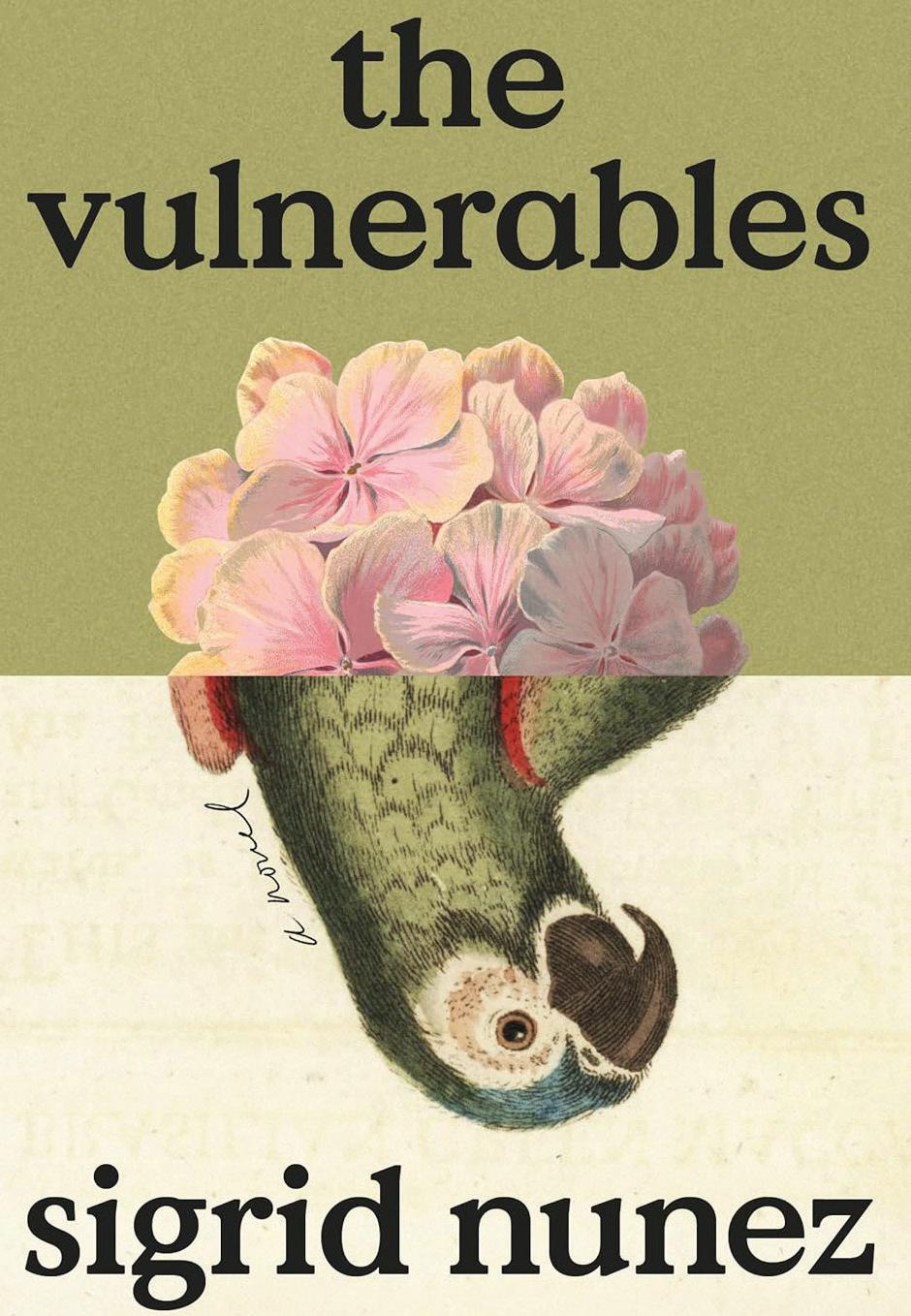

Q&Author | Sigrid Nunez ’72

AABC Pages | From the AABC President; Millie's Friends; Meet Mike Farley; President's Welcome Tour; Pass the Torch: Mentorship Spotlight Class Notes

Alumna Profile | Ariane Greep ’82

Passion Project | Mia Katigbak ’76

In Memoriam

Obituary | Marilyn Forman Spiera ’59

Last Image

Crossword

On the Cover

Photograph of Zinnat Ferdous ’16 by James Farrell

Back Cover

Photograph of Anne Cebula ’20 by Laura Barisonzi

PHOTO BY JAMES FARRELLContributors

Laura Barisonzi (“On Point,” p. 28) is a photographer and director who lives in New York City. She graduated from Brown University and has been lucky enough to be a professional photographer for the past 18 years. She started as a painter but now brings her love of color and composition to her professional photo and video work, in which she often focuses on athletes and other inspiring portrait subjects. She has photographed for a wide range of clients, including Adidas, the NFL, UPS, and Comcast, as well as many higher education institutions.

James Farrell (“The Good Fight,” p. 20) is an action photographer who specializes in capturing the pulse of movement and emotion. With a passion for adventure sports, he has mastered the art of freezing adrenaline-fueled moments. Originally from northern Michigan, Farrell is now based in New York City. His clients have included Nike, Athleta, Peloton, Men’s Fitness, Forbes, Sports Illustrated, Runner's World, Bicycling magazine, and ESPN.

Anne Stein ’90JRN (“Hoops Hype,” p. 32) is a Chicago-based journalist, former bike racer, and triathlon coach specializing in sports features, health and wellness news, and profiles. A graduate of Columbia Journalism School, her work has appeared on the ESPN website and in the Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, People, Christian Science Monitor, and Bicycling magazine, among other publications. She covered the Chicago Bulls for two decades —unfortunately not the Michael Jordan years — before discovering women’s college basketball, thanks to the 2023 women’s NCAA national championship battle between Iowa (Caitlin Clark) and LSU (Angel Reese). Today she splits her time between writing and teaching Zen-based mixed martial arts. (www.annestein.net)

DID YOU MISS?

Gabriel Baumgaertner ’21JRN (“The Good Fight,” p. 20) is a writer and researcher living in Washington, D.C. He received his M.A. at Columbia Journalism School (Business and Economics) in 2021. His work has appeared in Bloomberg, The Guardian, AARP Magazine, and Sports Illustrated

Here are the top performing stories online from our Winter issue:

“Object Lesson”: Barnard curators discuss the objects that inspire them barnardbold.net/curators

“Radio Days”: In a new book, Brooke Wentz ’82 unearths rare interviews with musical luminaries barnardbold.net/radiodays

“Music as Ministry”: Award-winning producer Ebonie Smith ’07 remixes the music business barnardbold.net/musicasministry

In “Bookshelf” (Winter 2024), we misspelled the name of the editor of Yankee Stadium, 19232008: America’s First Modern Ballpark. It is Tara Krieger ’04. We regret the error.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Nicole Anderson ’12JRN

CREATIVE DIRECTOR David Hopson

MANAGING EDITOR Tom Stoelker ’10JRN

COPY EDITOR Molly Frances

PRODUCTION DIRECTOR Lisa Buonaiuto

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS N. Jamiyla Chisholm, Kira Goldenberg ’07

WRITERS Marie DeNoia Aronsohn, Mary Cunningham, Isabella Pechaty ’23, Preetica Pooni

ALUMNAE ASSOCIATION OF BARNARD COLLEGE

PRESIDENT & ALUMNAE TRUSTEE Sooji Park ’90

ALUMNAE RELATIONS

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Karen A. Sendler

ENROLLMENT AND COMMUNICATIONS

VICE PRESIDENT FOR ENROLLMENT AND COMMUNICATIONS

Jennifer G. Fondiller ’88, P’19

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS

Quenta P. Vettel, APR

VICE PRESIDENT OF DEVELOPMENT AND ALUMNAE RELATIONS

Michael Farley

PRESIDENT, BARNARD COLLEGE

Laura Rosenbury

Spring 2024, Vol. CXIII, No. 2. Barnard Magazine (ISSN 1071-6513) is published quarterly by the Communications Department of Barnard College.

Periodicals postage paid at New York, NY, and additional mailing offices.

Postmaster: Send change of address form to: Alumnae Records, Barnard College, Box AS, 3009 Broadway, New York, NY 10027-6598

Barnard Magazine, Barnard College, 3009 Broadway, New York, NY 10027-6598 | Phone: 212-854-0085

Email: magazine@barnard.edu

Opinions expressed are those of contributors or the editor and do not represent official positions of Barnard College or the Alumnae Association of Barnard College. Letters to the editor (200 words maximum) and unsolicited articles and/or photographs will be published at the discretion of the editor and will be edited for length and clarity.

For alumnae-related inquiries, call Alumnae Relations at 212-854-2005 or email alumnaerelations@barnard.edu.

To change your address, write to: Alumnae Records, Barnard College, Box AS, 3009 Broadway, New York, NY 10027-6598 Phone: 646-745-8344 | Email: DevOps@barnard.edu

As this semester comes to a close, I’ve been reflecting on the past academic year — my first as president of Barnard College. It has been a great privilege to lead this incredible institution. I am grateful for the support, the ingenuity, and the fierce passion of our entire community. Together, we’ve accomplished a great deal, from mapping out our “Bold History, Fearless Future” vision to doubling down on our commitment to access, which will pave the way for our first-ever loan forgiveness plan in the fall of 2024.

We’ve experienced some joyous moments. We’ve cheered on the Columbia Lions women’s basketball team as they vied for the championship title of the Ivy League Tournament. And I say with pride that four Barnard student-athletes were an integral part of the team’s success. We stood together on Futter Field and watched the solar eclipse. We raised $3.4 million for financial aid at Barnard’s 2024 Annual Gala, while honoring two remarkable women — Helene D. Gayle ’76, M.D., MPH, and Francine A. LeFrak — who are leaders in public health and wellness.

But I know this has also been a profoundly difficult time. The conflict in the Middle East has left so many of us reeling, sowing division and causing pain within our community and around the world. Yet amid this disagreement, we also share much common ground. At Barnard, we are all committed to participating “together in intellectual risk-taking and discovery,” as our mission statement asserts. Sometimes this collaboration is uncomfortable, but it leads to better understanding of one another, and that understanding is crucial as we all seek to make a difference in this world.

For our entire community to thrive and reach their potential, we have to champion wellness in all its aspects: the life of the mind, mental and physical well-being, financial fluency, and a sense of belonging. This is key to our “Communities of Care,” a foundation of the College’s vision for the future. With the Francine LeFrak Foundation Center for WellBeing, we have made important strides in uplifting wellness at Barnard. But there’s still more work to do.

For us to fulfill our mission to nurture leaders of the future, we must continue to build our resources and programming and further invest in our infrastructure and technology. Over the winter, we announced a fundraising campaign to grow our endowment to $1 billion by 2030. Michael A. Farley, our new Vice President of Development and Alumnae Relations [see page 48], will play a critical role in helping us to achieve this ambitious goal. Mike joined us in early April from the University of Florida’s Levin College of Law, where together we raised critical funding for the school. I know that Mike will bring the same enthusiasm, commitment, and expertise to Barnard’s fundraising efforts.

Commencement and Reunion are just around the corner. I look forward to celebrating the incredible achievements of the Class of 2024. The students who make up this class have shown such resilience and fortitude from the moment they started at Barnard at the height of the pandemic in 2020. I am so proud of our graduating seniors for all they’ve accomplished, and I know that they will flourish and lead in their next endeavors. I am also excited to welcome alumnae back to campus for a fun weekend of connecting with fellow classmates, friends, and the College. These occasions are so meaningful because they bring us together and give us the chance to feel the power of our strong, caring, and talented community. B

When we first met, my non-sports-spectating husband was surprised to learn that I’ve long been an avid NCAA basketball fan. Every year, I gear up to watch March Madness. It started in eighth grade when a few close friends introduced me to the tournament. I filled out a bracket, made some totally uninformed but lucky choices, and won — much to the chagrin of my more knowledgeable friends. I never did win again, but no matter, what really got me hooked was the element of unpredictability. While there are certainly teams that tend to dominate, you can never anticipate the upsets. The underdog can always make the next round or come out on top. Every game offers a potential plot twist.

This year, I found myself glued to the women’s NCAA basketball tournament. I didn’t only watch the games, I consumed articles on players like Iowa’s Caitlin Clark, LSU’s Angel Reese, and of course, Columbia’s Abbey Hsu. These stories weren’t designed for stats-oriented sports fans — which I am definitely not — but for readers who are interested in understanding people at their core and how sports have played an essential role in their personal narratives. What were their motivations? The obstacles they had to overcome? The lessons they came away with?

Our Athletics Issue intends to do just that — tell the stories of our student and alumnae athletes. And the timing worked out well. This year, the Columbia Lions women’s basketball team had a record-breaking season. With four Barnard players on the roster, they won their second straight Ivy League regular season title and made it to “the Big Dance,” the NCAA Tournament. Writer Anne Stein details how Barnard players — thanks to the ColumbiaBarnard Athletic Consortium — have helped to make the Lions such a powerhouse team.

With just a few months until the Olympic Games in Paris, we share the journeys of two alumnae athletes who’ve been working hard for their chance to compete on this international stage — coincidence or not, both of them happen to be New Yorkers, one raised in Queens and the other in Brooklyn.

Bangladeshi American boxer Zinnat Ferdous ’16, who graces our cover, discovered the sport after college, and in just a short time, has already made a name for herself in the boxing world. In addition to her full-time job at Google, Ferdous is training for upcoming matches in hopes of qualifying for the Olympics. We also spoke with national champion fencer Anne Cebula ’20 about fulfilling her lifelong dream of going to the Olympics. In March, Cebula was selected to the U.S. Olympic Team in women’s epee.

For both athletes, it wasn’t an easy or straight path to their success. It has taken intense training, dedication, and dogged persistence to arrive at this moment. They’ve had to advocate for themselves, convince family members, and commit time and money to their training and pursuits.

The stories in this issue are about defying expectations and taking risks, whether it’s being a first-generation American woman boxer vying for Bangladesh’s first Olympic medal or a young fencer who fought tooth and nail to be the best in her sport, despite financial hurdles and a global pandemic. These are stories about the human experience, albeit awe-inspiring and extraordinary. I’ll definitely be tuning into the Olympics and rooting the athletes on.

Nicole Anderson ’12JRN, Editor-in-Chief

Nicole Anderson ’12JRN, Editor-in-Chief

The Roy and Diana Vagelos Science Center is poised to be a hub of scientific discovery and knowledge when completed in 2026

When Barnard announced its Year of Science in the fall of 2021, fundraising was already underway to transform Altschul Hall, the school’s current science hub, into a state-of-the-art center for scientific education and research. Then, in March 2022, Diana T. Vagelos ’55 and her husband, P. Roy Vagelos, M.D. ’54, pledged $55 million toward that end, the largest single donor gift the school had ever received. The rest is history.

Upon completion, the structure’s footprint will increase by 20%, morphing from 143,000 square feet to 169,000 square feet, with research lab spaces nearly doubled. Perhaps most significantly, all of Barnard’s experimental sciences will be housed in one edifice, constructed with both inclusive design principles and high-reaching sustainability goals top of mind.

The architecture firm behind the center, Perkins & Will, is targeting LEED Gold certification, and the building will be all electric, a significant step toward improved energy efficiency. “With advanced research labs, teaching labs, and community spaces that engage the campus, the project will be the first net-zeroready operational carbon, all-electric academic science building in New York City,” notes Emily Grandstaff-Rice, the Perkins & Will project manager.

The Roy and Diana Vagelos Science Center (R&D Science Center) is currently undergoing a series of surveys and probes to evaluate the existing building, with construction set to begin in May 2024 and completion slated for the summer of 2026.

“All the science faculty are deeply involved in the planning for the Roy and Diana Vagelos Science Center — from details down to what size drawers they

want in their lab to larger building issues,” says Dina Merrer, chemistry professor and Dean of Science Education and Infrastructure.

A committee composed of faculty representatives from each of the science departments involved — Biology, Chemistry, Environmental Science, Neuroscience & Behavior, Physics & Astronomy — has been meeting weekly for more than two years to discuss all aspects of the project. By July, Altschul Hall will be emptied, with many of Barnard’s science courses and research efforts relocating to various locations on the Columbia campus.

The ambitious undertaking, which has a $250 million budget, will see the future-proofing of a structure that will allow for more efficient use of space and increased flexibility. In addition to becoming fully electric, the R&D Science Center will maximize the material reuse of Altschul Hall to set a precedent for climate-smart architecture in an urban context.

“Having the confidence that our new building will support whatever contemporary equipment we bring into it will be significant,” says Merrer.

As President Laura Rosenbury ushers the College into a new era, several of her priorities — from “investing in infrastructures of excellence” to growing Barnard’s endowment to $1 billion by 2030 and reaching net-zero carbon emissions by 2040 — dovetail seamlessly with the creation of the R&D Science Center, a building that has the potential to empower many an aspiring scientist.

Bridget Moriarity

On February 15, the Barnard Speaking Fellows held their first-ever TEDxBarnardCollege event on campus, featuring nine talks delivered by students and one alum. While varied in topic, all the speeches included a call to action, from reckoning with the history of gentrification and climate vulnerability in Harlem to shifting one’s attitudes toward first-generation, low-income (FLI) students.

“We were highlighting the fact that student speech can be a tool for meaningful change and advocacy both on campus and in the wider community,” says Abby Bonat ’25, one of the Speaking Fellows who helped organize the event.

Olivia Bobrownicki ’24, whose talk illuminated some of the more covert ways society caters to men, discussed how the majority of medications are never tested on women. “Think back to the last time you took a medication. When you looked at the bottle, did you see a different dose based on your height, your weight, or your sex?” Bobrownicki asked her classmates. “Chances are you didn’t because we live in a society where we treat all bodies like the average male.”

Olaedo Udensi ’26 shared the power that comes with reclaiming your identity. At age 11, Udensi left Nigeria for boarding school in the U.K. After dealing with a litany of incorrect pronunciations, she began using her childhood nickname: “I renamed myself Ola to make sure that I didn’t stand out any more than I already had.” Her message to her peers was one near and dear to her own experience: Don’t let the fear of society dictate how you present yourself to the world. “What I hope we can all recognize is that every person, regardless of their name, deserves to showcase their complex identities without having to think about how palatable they are,” she said.

The event, organized by the Speaking Fellows Program, drew around 100 in-person attendees as well as additional viewers tuned in via Zoom. In handing over the stage to their peers, the Speaking Fellows were making the point that everyone has something to say — and there’s no one right way to say it. The program’s motto — “Say what you mean” — served as their guiding principle.

“In offering students a platform, we were quite

literally allowing them the space to say what they mean,” says Anusha Merchant ’25, one of the organizers.

Another motivation for the event was to get the Speaking Fellows Program — what Merchant calls an “underutilized resource” on campus — on more people’s radar.

Operating against the backdrop of an increasingly interconnected world, the Speaking Fellows are helping students develop their verbal and nonverbal communication so that they can effectively voice their thoughts when the right moment arrives, whether in the classroom or elsewhere. The space allows students to practice their speaking style and receive constructive feedback from peers without judgment. As explained on the program’s web page, “Authenticity and ethos matter more than any form of rhetorical device.”

Given TEDxBarnardCollege’s success, the Speaking Fellows plan to turn it into an annual tradition. As Merchant explains, the event — and the Speaking Fellows program — is more vital now than ever before. “The most important thing we should be using is our voice, given the consequences of the world that we live in,” she says. “So we wanted to kind of amplify and echo that resource.” —Mary Cunningham

“WE ARE BUILDING COLLECTIONS THAT DOCUMENT NOT ONLY THE HISTORY OF BARNARD AS AN INSTITUTION ... BUT ALSO BROADER FEMINIST HISTORIES.”

This past summer, staff from the Barnard Archives completed processing the Nancy Friday Papers, a gift from the late author and pop psychologist (at left), who believed that “wild, delicious, wonderful sex” could sit “alongside good manners.” While the donation complements the archives’ existing materials on women’s sexuality, it also represents an uptick in donations from people outside of the College community who are beginning to recognize its well-established feminist focus, says Martha Tenney, director of Archives and Special Collections.

“We are building collections that document not only the history of Barnard as an institution and the people who have come into contact with the institution but also broader feminist histories,” says Tenney.

These broader feminist histories contain several niche areas, including archives on sex-positive feminist thought that the Friday papers complement. For example, the Barnard Center for Research on Women (BCRW) produced the 1982 Scholar & Feminist Conference on Sexuality, which is often cited as a high-water mark of the “feminist sex wars” of the late 1970s and early 1980s, when anti-pornography feminists crossed intellectual swords with sex-positive thinkers like Friday, who died in 2017.

Tenney says that the archives’ focus has increasingly homed in on “feminist worldmaking,” activism, organizing, and art making, as well as addressing “archival silences and gaps” within its overall feminist collection. To that end, the team seeks out voices and experiences that might not otherwise find their way into an academic setting.

One example — another recently acquired collection — came from the Coalition for Women Prisoners and was facilitated by BCRW. That donation provides materials on anti-carceral organizing and the experiences of incarcerated women throughout New York State.

“I think this collection has the power to contextualize … this moment in the prisonindustrial complex and the growth of incarceration in the United States and in New York State,” says Tenney. “But it also has the ability to serve as a resource for people who are currently organizing and are looking at strategy.”

It’s no coincidence that, as the collection has grown, so too has its reputation as a safe haven for sensitive material at a time when school boards nationwide are attempting — often successfully — to ban books. Tenney pointed to the Sabra Moore NYC Women’s Art Movement Collection and the Dianne Smith Papers documenting the New York art scene from the 1970s through the 2020s as other “outside” donations to the Barnard Archives that buck the trend away from freedom of expression. Moore organized antiwar protests and worked in New York City’s first legal abortion clinic. Smith, an artist based out of Harlem, has shown her work primarily in nonprofit and Black-owned spaces. Her papers include a prototype of a Black Lives Matter mural from 2020.

“Feminist scholarship doesn’t necessarily just mean the study of the history of feminism, it means thinking about any area of study using a feminist lens,” Tenney says of the artists’ papers. —Tom Stoelker

By any standard, the $1 billion donation that Ruth Levy Gottesman ’52 gave to Albert Einstein College of Medicine on February 26 is record-shattering. It’s the largest gift given to any medical school in the nation and ensures that no medical student at Einstein will have to pay tuition — ever. Gottesman, who earned her master’s and doctoral degrees from Teachers College at Columbia, taught at Einstein for more than 50 years before retiring as clinical professor emerita of pediatrics; she is currently chair of the board of trustees. The fortune came from her late husband, David Gottesman, an early investor in Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway. In a self-effacing and gracious gesture, she stipulated that the school retain the Einstein name. Gottesman delivered the good news to the diverse student body herself, which prompted raucous cheers, tears, and stunned looks of disbelief. —Tom Stoelker

Scholar and teacher Rebecca L. Walkowitz, who is currently the Dean of Humanities and distinguished professor in the Department of English at Rutgers University’s School of Arts and Sciences, has been named Barnard’s new Provost and Dean of the Faculty.

On June 1, Walkowitz will succeed Linda A. Bell, who has served as Provost and Dean of the Faculty since 2012 and will remain a member of Barnard’s faculty. Walkowitz’s appointment resulted from a comprehensive national search process that began last fall following Bell’s decision to step down from her administrative role.

“Barnard College is thrilled to welcome Rebecca, and her passion for crossdisciplinary teaching and research, to our tight-knit community,” says President Laura Rosenbury. “Rebecca’s academic leadership will ensure that Barnard remains one of the most dynamic colleges in the world.”

“I am enormously excited to join the Barnard community,” says Walkowitz. “I am looking forward to working with President Rosenbury, faculty, and staff to identify and nourish new areas of interdisciplinary collaboration, to expand access and success for all members of the College, and to articulate the ongoing impact of the liberal arts and sciences on our local, national, and global communities.”

—N. Jamiyla Chisholm

To read the full announcement, visit barnardbold.net/rebeccawalkowitz

Reunion is a wonderful time to share your Barnard spirit by paying it forward to current students, and the Race to Reunion Giving Challenge is the perfect opportunity to increase the impact of your gift in support of Barnard’s Annual Fund. We invite you to select a designation or direct your gift to where Barnard needs it most, in honor of your Reunion.

This year, Race to Reunion is taking a dynamic new form: We’re thrilled to introduce an interactive social fundraising platform designed to make the act of giving fun, collective, and meaningful.

The Race to Reunion Giving Challenge will now include:

Our new platform features leaderboards that place milestone reunion classes in a spirited competition to see who can rally the most donors and dollars for the Race to Reunion Giving Challenge!

Help your class to move up the Race to Reunion leaderboards by setting up a match or challenge for others to participate in with incentivizing goals that help unlock lead donor funds when achieved.

Give a gift and then spread the word to your network on social media! Share your Barnard pride, upload a video message for support, and inspire others to join by celebrating progress during the challenge!

BECOME AN ADVOCATE!

Sign up today to access your milestone reunion class-specific landing page and start spreading the word, checking your class’s progress, and celebrating with fellow alums!

Visit our.barnard.edu/reunion-giving to get started!

Ideas. Perspectives. A closer look.

Guest artist Yaching Cheung performs in ECHO, part of the Movement Lab’s Artificial environments/ environmental Intelligence (Ae/eI) Festival. PHOTO BY CARRIE GLASSER

A Second Chance for Yesterday by R.A. Sinn (Rachel Hope Cleves ’97 and Aram Sinnreich)

Historian Rachel Hope Cleves and futurist Aram Sinnreich are a sibling writer duo collaborating under the pseudonym R.A. Sinn. In their dystopian science fiction novel, overworked programmer Nev Bourne gets caught up in her own time-travel tech and is sent back through time, one day at a time, in a story of second chances and queer love. (Simon & Schuster)

Committed: On Meaning and Madwomen by Suzanne Scanlon ’96

As a Barnard student in the ’90s, Scanlon underwent a difficult transition to adulthood while grieving the loss of her mother. With authenticity and care, Scanlon uses a blend of memoir and literary criticism to unpack her attempt to take her own life while a student and her subsequent years in the New York State Psychiatric Institute. She mines the “madwoman” trope — in the writings of Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath, and others — and describes how it can help us with understanding both personal discovery and institutional failures. (Penguin Random House)

The Times That Try Men’s Souls by Joyce Lee (Sitrin) Malcolm ’63 Malcolm tracks the toll of the American Revolutionary War on some of the era’s prominent families and shows how an “ideological” war leaves a unique kind of damage on relationships beyond the battlefield. Malcolm offers a new way to look at this moment in American history by tracing how the revolution tore at the burgeoning nation’s social fabric, leading to unrest and eventual violence in civil society. (Simon & Schuster)

Scattered and Fugitive Things by Laura

E. Helton’00

The early 20th-century work of archiving Black American history was nothing short of revolutionary, conducted in a time when the nation didn’t conceive of it as a worthy discipline. Helton follows its major contributors — the librarians, curators,

and historians — who took great risks to preserve “archival material” and in doing so stimulated new conversations about Black culture. Helton explains how archival work, rather than being fixed in the past, can be a source of resistance and possibility and an important avenue for change. (Columbia University Press)

Toni Morrison and the Geopoetics of Place, Race, and Be/longing by Marilyn Sanders Mobley ’74 Mobley provides new lenses for readers to view the famed works of Toni Morrison, approaches that engage with the interdisciplinary expanse of Morrison’s rich prose. Her novels dialogue with history, politics, and culture to create “spaces” for readers to better interact with her layered narratives. (Temple University Press)

István Szabó: Filmmaker of Existential Choices by Susan Rubin Suleiman ’60

István Szabó, an internationally renowned Hungarian filmmaker, made his mark on the world through a provocative cinematic style, receiving an Academy Award for his 1981 film Mephisto. Suleiman’s book examines his style through the fraught political context of the mid20th century and shows how Szabó navigated ideas like authoritarianism and antisemitism, nationhood and personhood, and seeking or giving up on community, through his art. (Bloomsbury Academic)

Art of Japan: Highlights from the Philadelphia Museum of Art by Felice Fischer ’64 and Kyoko Kinoshita Fischer and fellow curator Kinoshita present a selection of pieces from the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s Japanese art collection, from the Neolithic through the present day. From ceramics to calligraphy, the collection has a legacy that hearkens back to the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition in 1876. The new book acts as a historical guide to Japanese art and its broader cultural significance. (Philadelphia Museum of Art) B

The

audiobook recording session for Anna Quindlen’s After Annie brought together the talents of three Barnard alums

For a few days in December, three Barnard alums brought their unique gifts together in a Los Angeles studio for a kind of accidental collaboration between alumnae spanning generations. Anna Quindlen ’74, the acclaimed and decorated writer, didn’t realize it at the time, but her latest novel became an audiobook at the hands of two Barnard alums.

Actor Gilli Messer ’10 narrated the book, and audiobook producer Molly Lo Ray ’17 produced the recording. Quindlen’s novel After Annie, which came out in February, follows Annie’s husband, oldest child, and best friend as they grapple with her sudden death. Lo Ray read it months earlier in preparation for producing

the recording.

“This one stopped me in my tracks,” says Lo Ray, who produced the audio version of Quindlen’s book on writing, Write for Your Life, and jumped at the chance to work with Quindlen yet again, especially on this novel. “The writing is gorgeous; the characters are so real. It was definitely far and away the most moving book I worked on last year,” says Lo Ray.

It was Lo Ray’s idea to contact Messer to narrate the novel. The two had worked together in the past. Once they discovered they’d both attended Barnard, they reveled in the connection.

“There’s such a sense of warmth,” says Lo Ray. “It’s amazing.”

As Lo Ray read Quindlen’s manuscript, she could already hear Messer’s voice telling the story. “She is such a brilliant narrator. There’s a coolness to her narration, a detachment, but at the same time, her voice has love in it. It was the perfect tone for the book.” Lo Ray reached out to Quindlen, offering her the audition tapes of a few narrators, hoping she’d choose Messer. “I didn’t lead her towards Gilli, but immediately she wrote me back and said, ‘It’s got to be her,’” recalls Lo Ray.

Making the recording was a labor of love for Messer and Lo Ray. Messer, who began narrating audiobooks several years ago, said when Penguin Random House Audio approached her about performing the narration, she was thrilled to be working with Lo Ray again. When she found out she’d be recording Quindlen’s new novel, she was beside herself: “I said, ‘Oh my gosh, [she’s] iconic.’ I was freaking out.”

The novel is drawing rave reviews from top media outlets. For Messer, the beauty of the work made it difficult to record at times. “I literally would have to stop all the time because I would just be crying. It’s so sad, so good, but amazing. So moving. The director would have to pause and give me a hug. I don’t know how [Quindlen] does that,” says Messer. When Quindlen found out both Lo Ray and Messer were Barnard alums, she was surprised, but then again, she wasn’t.

“On the one hand, I’m thunderstruck,” says Quindlen. “I had no idea when I listened to Gilli’s tape, and concluded that she was perfect for this, that she was a Barnard woman. Add Molly, and it seems uncanny. And yet, how many times has this happened to me? I’m interviewing a smart judge or a wonderful doctor, and after a while, it emerges: We all went to Barnard. The College produces women who do great things.” — Marie DeNoia Aronsohn

‘A

In

writing scripts or acting on screen, Ana Cruz Kayne ’06 draws from her multicultural background

Film and television actor Ana Cruz Kayne ’06 may be increasingly recognizable since her recent stint playing Supreme Court Justice Barbie in the 2023 movie. But she has been acting since early in her Connecticut childhood, a penchant that continued straight through her time at Barnard.

“When I was maybe 6 or 7, my mom had my oldest brother in some community theatre production of The King and I, and she just pushed me up on the stage” during auditions, Kayne recalls. “I loved it. I loved all aspects of it, and I think it was very suited to my personality as I continued to grow up.”

That personality was forged in a uniquely multicultural household. Her father is an endocrinologist of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. He and her mom — a Catholic first-generation immigrant from the Philippines — met as college undergraduates. Kayne and her two older brothers grew up steeped in both sets of traditions. Her eldest brother, Michael Cruz Kayne — now a writer at The Late Show With Stephen Colbert — was bar mitzvahed atop the ancient mountain fortress Masada in Israel. Kayne herself has fond memories of visiting Lourdes, France, one of Catholicism’s most prominent pilgrimage sites, with her grandmother.

“There’s no mentorship for what it means to grow up with such a diverse background,” she says. “It’s like a U.N. inside of me.”

Kayne’s close-knit family survived a series of tragedies that she was able to process through her acting. Shortly before her King and I audition, the family home burned down, Kayne said, uprooting them for the months it took to rebuild. A few years later, her middle brother was diagnosed with osteosarcoma. The bone cancer “was basically the star of our family show until I left for college,” Kayne says. (He survived the ordeal.) Acting “took me out of the immediacy of my brother’s illness, of moving houses. It was this constant thing that as a child felt uniquely for me.”

At Barnard, where Kayne majored in psychology and Italian literature, she continued to act in at least one production every semester. She appeared alongside Barbie co-star Kate McKinnon CC’06 in a Barnard Theatre Department production of Caryl Churchill’s play The Skriker and with Barbie director Greta Gerwig ’06 in the King’s Crown Shakespeare Troupe’s 2004 production of The Tempest.

“It was fun and weird and great,” reminisced Gerwig, who emailed her memories the morning after attending the Oscars. “I just always knew she [Kayne] was terrific. She had such command of the language but made it seem easy and effortless and funny.” The friends first worked together professionally on Gerwig’s 2019 remake of Little Women, in which Kayne, true to form, played an actor in a Shakespeare play.

“I had wanted to find something bigger that we could do, and the wildness of Barbie, with its ‘multiplicity of Barbie,’ felt like the perfect fit,” Gerwig says.

That deliberately expansive redefinition of Barbie — historically the buxom blonde target of endless feminist critiques — gave Kayne the opportunity to showcase her culture. In the film’s final scene, Kayne wears a terno, a traditional Filipina dress with

distinctly structured butterfly sleeves.

“To get to sit there as a Filipino and say, ‘No, I’m representing a very specific nation, a very specific culture,’ it just means everything to me,” she told Vogue Philippines. “It was a triumph for me in my journey as an artist,” she later added.

Post-Barbie, Kayne’s star has continued to rise; she played an attorney in the Netflix miniseries Painkiller, and she is writing several scripts that draw on her self-described “multi-culti” upbringing.

But that all came later. Before Barbie ’s worldwide release. And before the film gained a larger sociocultural significance and earned $1.4 billion at the box office, making an irrefutable argument for more investment in movies by and about women. Back in 2022, it was a few gals reuniting in London on the pinkest movie set that ever existed.

“When I saw Kate [McKinnon] come in, it was like you see water in the desert,” Kayne says. “You show up vulnerable and hope everyone loves you, and then you see someone you’ve known since you were a child. It’s so special to have had these long histories with these incredible artists.”

The feelings were mutual.

“Having her on set nearly every day as one of the Barbies was perfectly dreamy,” Gerwig said. “She was the person I’ve always known her to be — wildly talented, uproariously funny, deeply kind, and willing to try anything. It’s all I could ever want from an actor, and I am very blessed that she is also my best friend of 20-plus years.”

Kira Goldenberg ’07

Mezzo-soprano Alicia Hall Moran ’95 combines her unique talents for a performance like no other

In mid-March, mezzo-soprano Alicia Hall Moran ’95 took center stage to sing a song from the musical The Wiz. The twist? She did so while gliding across the ice. The performance took place at the annual ice show hosted by the nonprofit Figure Skating in Harlem, which is the first of its kind to combine access to figure skating with education and leadership development for girls of color.

Moran Hall, a celebrated opera singer, premiered her first skating show in 2016 at National Sawdust, a women-led venue in Brooklyn, but the world of cold-weather athletics and singing are not new for Hall Moran, who practiced both, albeit separately, throughout her high school years in Stamford, Connecticut. She was a member of an off-campus synchronized ice skating team and performed with her school’s advanced chamber ensemble, the Westhill Chamber Singers. Hall Moran went on to earn two bachelor’s degrees: one in music from Barnard and another, after graduation, in classical vocal performance from the Manhattan School of Music.

Since graduating from Barnard, Hall Moran has shown how best to make use of her creative time, from her 2012 Broadway debut in the Tony-winning revival of The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess to collaborations with artists like Carrie Mae Weems — not to mention her performance in Breaking Ice, which is about the U.S. figure skater Debi Thomas’ rivalry with East Germany’s Katarina Witt.

This spring, Moran was recognized by Figure Skating in Harlem for her work as a volunteer skating instructor. “I feel a sense of responsibility and excitement about keeping two trains running,” says the singer and figure skater. “If you’re a Black woman and you say that you sing, nobody’s shocked; there’s no resistance.” But say that you’re a Black woman who sings beautifully while ice skating, and people pay attention.

Whether she is performing off the ice or performing on skates with a musical quartet backing her up, Hall Moran has places to go and audiences who can’t wait to see what’s next. —N. Jamiyla Chisholm

and far-reaching. After parsing a variety of definitions, the group conceded that artificial intelligence means different things to different people. A chemist might see AI one way, while an artist might see it another way. Likewise, faculty, students, and staff hold different views depending on their department or discipline.

AI isn’t coming; it’s here. And while not everyone on campus is using the technology, conversations grappling with the meaning and challenges of AI are being held in offices, classrooms, labs, and studios. Barnard’s faculty, staff, and students are delving deep on task forces, through research, and in publications — often breaking ground and leading other institutions of higher ed to take notice.

“We’re going to have to think about how artificial intelligence [and] the speed of innovation affects our curriculum, our teaching methods, but also how all of us do our work,” said President Laura Rosenbury in a recent town hall.

While there’s much to learn and understand about this formidable technology, the Barnard community has been quick not only to engage with it but to innovate.

for Pedagogy, as faculty grading papers started to suspect that students were drawing on the technology. Professors began knocking on Wright’s door looking for guidance. Wright and her team got to work. By mid-January 2023, the Center had published recommendations on the College website under the heading “Generative AI and the College Classroom” — making Barnard one of the first institutions of higher ed to do so.

Wright says they weren’t operating in a silo on campus. Not long after the guidelines were published, several staff and faculty members formed the AI Operations Group, which meets weekly to discuss the ever-changing AI landscape. In addition to Wright, the cohort includes Melanie Hibbert, director of Instructional Media and Technology

If one is to engage, then it should be done competently, carefully, with transparency and training, says Melanie Hibbert, who recently submitted a paper, “A Framework for AI Literacy,” for review to the higher-ed tech journal Educause Hibbert and her co-authors, Wright and IMATS colleagues Elana Altman and Tristan Shippen, prioritize the framework in four levels: Understand AI, Use & Apply AI, Analyze & Evaluate AI, and Create AI.

According to the paper, understanding involves basic terms and concepts around AI, such as machine learning, large language models (LLMs), and neural networks. When using the technology, one should be able employ the tools toward desired responses. “This has been a particular focus at Barnard, including handson labs, or real-time, collaborative prompt engineering to demonstrate how to use these tools,” the authors say. When analyzing and evaluating the work, users should pay attention to “outcomes, biases, ethics, and other topics beyond the prompt window.” The authors note that while Barnard has provided workshops at the Computational Science Center for users to begin creating with AI, this is an area that’s still evolving.

made using AI algorithms treat people fairly and equitably.

Cooley says that users should always be aware of where large language models and visual images are taken from. For example, Wright notes that many images and texts draw from the public domain databases populated with male painters, male photographers, and male writers.

“We are a feminist College, and we are letting you know that there’s a century of male-dominated scholarship and textual repositories that take away our voices,” she says.

Victoria Swann says her primary ethical concern centers on the commercialization of the science.

“The danger is not, you know, the Terminator is Continued on page 76

Conservationist Shelby Semmes ’06 is working to protect forested areas to build a livable future for allby Natalie Schachar

’12

A key part of the work that Shelby Semmes ’06 does as the New England vice president of Trust for Public Land — an organization dedicated to creating parks and protecting the outdoors — is to identify areas of privately held land that would benefit from public ownership or conservation status. So when an industrial timber company put 31,367 acres up for sale in the Katahdin region of Maine in late 2022, Semmes and her colleagues knew they had to act fast.

Situated near the base of Mount Katahdin, the forested land is home to 4,000 acres of wetlands and 53 miles of streams, as well as an aquatic and wildlife habitat that includes moose, bear, Canada lynx, salmon, and wood turtles. It also abuts the Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument, a giant swath of acreage along the East Branch of the Penobscot River.

And significantly, the property is the ancestral land of the Penobscot Nation — an area sacred to the tribe’s community and culture.

“We bought it thinking about who was best fit to take it long term,” says Semmes.

In November 2023, Trust for Public Land announced a plan to “return nearly 30,000 acres of land taken from the Penobscot Nation in the 19th

BY

century,” representing the largest land return between a nonprofit and a tribal nation in the United States.

The organization comes to this project with years of experience restoring tribal and Indigenous lands across the U.S., from California to Hawaii.

“Part of the problem we’re working to address is that Indigenous people in the U.S. steward and maintain only 2% of their ancestral lands, and in Maine, that’s even lower,” says Semmes.

Studies have found that Indigenous-protected areas often function as well as, or even better than, those managed by government agencies or established conservation groups.

“We’re hoping to have a historically significant partnership to restore the land to not only Penobscot management but their natural resource expertise and knowledge,” Semmes says. As legal stewards of the land, the Penobscot Nation will be the decision-makers on all conservation and land-use matters, from overseeing the protection of wildlife to mitigating the effects of climate change.

When the land transfer is completed, Semmes says, “it will be a true highlight of my career that has sincere roots in my time at Barnard.”

Her interest in environmental conservation, however, started even before college, when she spent summers and long weekends visiting the White Mountain National Forest, where her family owned a homestead perched near the Sandwich Range. On the edge of the wilderness, Semmes would roam unsupervised in the woods for hours at a time — paddling in a pond, exploring brooks and wetlands, and discovering frogs.

“I don’t think I realized how unusual it was to have such a deep understanding and exposure and access to a national forest,” Semmes says.

But it wasn’t until her time at Barnard that her love for and connection to the outdoors blossomed into her life’s purpose. At Barnard, Semmes studied anthropology with a minor in economics. She took courses with anthropology professor Paige West, who was then focused on studying the flaws of fortress conservation, a model based on the idea that biodiversity is best protected through ecosystems that function in isolation, away from human disturbance.

Public Land are currently working with tribe leaders to establish public roads to the Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument to further enhance access for the Maine communities of Millinocket, East Millinocket, Medway, and others. “We hope that it will create a right of way or the road will become a part of the national monument to allow visitors access,” explains Semmes.

They also hope to ensure trail connections, which bring an economic boost to surrounding communities through associated tourism. But there is still a long road ahead. Trust for Public Land and the Penobscot Nation are currently fundraising in an effort to reach their goal of $32 million to transfer the property to the Nation.

“We’re $6 million into this, and we’re looking at

“Part of the problem we’re working to address is that Indigenous people in the U.S. steward and maintain only 2% of their ancestral lands, and in Maine, that’s even lower,” says Semmes.

It was West’s scholarship, Semmes says, that helped inspire her to pursue environmental work. “I wanted to think about natural resources and communities who benefit from them — not only recreationally but for their livelihoods.”

After pursuing a master’s in forestry from the Yale School of the Environment, Semmes got a job at Trust for Public Land, which, she says, takes a people-centric approach to land conservation. “The idea that lands are managed through participatory and, in many cases, public governance models felt very aligned with me in terms of the conservation work I wanted to be doing,” she says. “That stuck with me.”

After more than a decade of doing conservation work, Semmes has quite a few professional milestones under her belt. She has helped to protect the biggest patch of unconserved private land in the Green Mountain National Forest, established community forests for rural development through participatory management processes, and addressed the outdoor equity gap in Boston and other cities.

As part of the land transfer with the Penobscot Nation, Semmes and Trust for

the role of private philanthropy and public grants,” Semmes says.

Likewise, the vision to make roadways available will rely on enactment of new federal legislation to authorize the National Park Service to acquire property interests on the roads and associated lands.

The challenges for conservationists like Semmes are great. By the end of 2060, New England states are projected to lose 1.2 million acres of forested land and 17% of their carbon storage capacity — partly as a result of low-cost subdivision and land development.

For Semmes, however, the uphill battle only solidifies her belief that her work is more important than ever.

“Investments in land conservation are part of how a life well lived is accomplished,” she says. “By having people embrace and experience that reality, we’ll have a better chance.” B

Boxer Zinnat Ferdous ’16 is aiming for Bangladesh’s first Olympic medal

by Gabriel Baumgaertner

’21JRN | Photos by James Farrell

by Gabriel Baumgaertner

’21JRN | Photos by James Farrell

Zinnat Ferdous ’16 was not dreaming of becoming an Olympian in early 2017. All she wanted was to get her boyfriend, Edmund, a nice gift for his birthday.

She chuckled when Edmund shadowboxed at stoplights, in the bathroom, and “anytime there was a void.” Until she watched him pound a heavy bag during a visit to the gym, she had no idea she had been dating an amateur boxer for the past few months. So when one of his friends told her that a world championship fight was coming to Madison Square Garden, she splurged on two tickets about a dozen rows from the ring.

Seeing two elite fighters battle on the world’s grandest stage, she says, was intoxicating. This wasn’t just two people pummeling one another, she thought. This was a strategy game.

Seven years after that fight — and just four years after punching a bag for the first time — Ferdous is looking to qualify for the Paris Olympics as a member of the Bangladesh national team. She would be the first woman boxer to represent a country of over 170 million and the most populous country to never win an Olympic medal. And she’ll do it while managing a $70 million advertising program at her full-time job at Google.

“My friends and family would like to describe me as an extreme person,” Ferdous says. “I think when I take a liking to anything that I do, I really go in and I get the job done.”

For an athlete to qualify for the Olympics usually means a lifetime of training. Some athletes are able to try other sports to keep their dreams alive. Qualifying for the Olympics when you’ve never played an organized sport is highly unusual, if not unprecedented.

But it’s within reach for the 30-year-old Ferdous, the daughter of two Bangladesh natives who settled in Astoria, Queens, in the late 1980s. Since partaking in her first boxing match

in November 2021, Ferdous has medaled in six amateur tournaments and defeated some of the top-ranked American boxers in her weight category. She became the first woman boxer to represent Bangladesh on the international stage at the Asian Games last October and will travel to Thailand at the end of May for her last chance to qualify.

In under three years, Ferdous has logged 30 bouts in rings from Toledo, Ohio, to the Dominican Republic and Russia. Her trainer, Colin Morgan, can’t remember such a grueling schedule in his four-decade career.

“I would prefer if she gets some rest, but I don’t think that’s possible in New York City,” Morgan says. “You’ve got to work, then you’ve got to train, and you’ve got to go home and work again and then come back to the gym.”

Ferdous grew up around a lot of boys — a brother, and male cousins who lived just blocks away — and gravitated toward physical sports, but her household had a strict curfew well before sundown and emphasized academics, not recreational sports.

“When I brought home a 90,” Ferdous says, “they asked where the 100 was.”

Still, Ferdous always loved a challenge, and she found plenty once she arrived at Barnard. She immediately sensed the rigor of the school’s academic environment by witnessing the study habits of her freshman roommate, who had aspirations of being a doctor. After graduating with a psychology degree, Ferdous dabbled in the worlds of fashion (an internship at Marc Jacobs) and finance before choosing the world of tech sales.

To excel in this field requires lots of cold calling, engaging even the fussiest and most indecisive clients, and executing sales under pressure. Some projects require swagger, others

“I think I quickly realized there’s not many people that have my profile,” Ferdous says.

“I would say the primary ethnic groups for females [in boxing] tend to be white, Black, Hispanic. And then there’s this Bengali Muslim, firstgeneration American girl that comes on the scene, and they’re like, ‘Who is this?’”

persistence. All of them call for confidence and preparation, lessons Ferdous would take to the ring when she’d begin her boxing career five years later.

“I believe that performance starts the second your ring walk starts,” Ferdous says.

In 2019, Edmund introduced Ferdous to his longtime trainer, Danny Nicholas, who quipped, “I don’t train cardio boxers. So if you’re interested in fighting, let me know.” By now, boxing was a shared obsession between them, and Ferdous understood why her boyfriend — soon to become her husband — kept training even though he hadn’t fought competitively in years. Being a fighter meant early wake-ups for training and long sessions dedicated to minute details of footwork and punch delivery. The physical demands were grueling, but the payoff was addicting. The tactical side of boxing was like learning to play chess, except a wrong move meant getting hit in the face.

Her older brother loved that she had found a new passion. Her parents were concerned that the amount of time she was dedicating to this hobby would interfere with her work at Google.

“I would tell them I was going to train and gradually let them know details but not let them know about fighting,” Ferdous says. “I’d prime them in conversations and tell them, ‘I’m thinking about fighting.’ They were completely against it.”

Under Nicholas’s tutelage, Ferdous learned how to train like a fighter, but her progress was derailed by the pandemic and a foot injury. Once Ferdous returned from surgery and the city reopened, Nicholas took her to train at Bout Fight Club in lower Manhattan, where she met Morgan.

In the summer of 2021, Morgan watched Ferdous spar with a woman several inches taller and about 40 pounds heavier than her. “She doesn’t really know how to punch yet,” Morgan thought to himself. “But that other girl isn’t hitting her either.”

“This girl was trying some really big punches [on Zinnat],” Morgan says. “And [Zinnat] just makes sure she isn’t getting hit. … Her defensive skills were already really good. She just needed somebody to teach her some offense, and she could turn into something really special.”

After seeing her spar, Morgan huddled with Nicholas and then approached Ferdous: If you train with me, he told her, I can get you to the 2024 Olympics.

“In my head, I’m like, ‘All right, I don’t know who this guy is,’” Ferdous says. “And so I quickly went back home and looked him up.”

She found a trainer with over 40 years of experience who has trained multiple professional world champions and several amateur gold medalists. Still, the most decorated women fighters in the world had logged dozens of competitive fights or had been raised in the sport since they were young. Ferdous had little formal training, no official fights, and no competitive athletic background to speak of.

To be ready for a competitive fight — much less dream of qualifying for the Olympics — Ferdous would need to dedicate several hours of training a day to achieve and maintain proper fitness, on top of mastering the technical instruction that could get tedious. And all of it would have to be done outside of her job at Google, where she had recently been promoted.

As Ferdous puts it, she had to scratch the itch. She wanted to compete.

“I think I quickly realized there’s not many people that have my profile,” Ferdous says. “I would say the primary ethnic groups for females [in boxing] tend to be white, Black, Hispanic. And then there’s this Bengali Muslim, first-generation American girl that comes on the scene, and they’re like, ‘Who is this?’”

Since starting to train with Morgan in late 2021, Ferdous’s weekday evenings and weekend afternoons have been spent in a gym sandwiched between a law firm and a chiropractor’s office on the second floor of a lower Manhattan office building.

Over three hours, Ferdous will work with various punching bags: heavy bags that stand 5 feet tall and weigh around 50 pounds to practice power punches and speed bags shaped like raindrops that weigh just 8 ounces for quick hits. That comes after about 15 minutes of jumping rope to warm up and perfect the lateral bounce required to glide across the ring.

Then it’s time to shadowbox. She works the forms of her jab (quick, straight strikes), hooks (quick, rounded punches), and uppercuts (long and powerful U-shaped blows). In between the ropes, Morgan offers focused instruction on minute details. During one session, he guides Ferdous and a few fighters on proper pivot form to assure that the fighter is ideally positioned to evade an opponent’s punch and ready to throw one. After that, Ferdous won’t just spar with her female teammates, she’ll do two three-minute rounds with a male teammate who is undefeated in 15 professional fights. Once the sparring ends, Ferdous hits the ground to do around 30 minutes of calisthenics. Ferdous never sits or stands still for more than a few seconds throughout the entire session.

“It’s like climbing stairs one at a time, you can’t just try to jump from the bottom and go to the top,” Morgan says about Ferdous. “But at the same time, I’m doing [training] at a fast rate because there’s not much time [to qualify for the Olympics].”

Focused training will build technical proficiency and stamina, but it doesn’t teach you how to handle prefight nerves or how to recover after getting hit in the face. So Ferdous scheduled her first fight in November 2021 at a charity event called Haymakers for Hope. Her parents remained resistant to how much time she spent in the ring, but she convinced them to attend after raising over $30,000 to commemorate her aunt who died of stomach cancer.

Even before the fight began, her mother grew emotional, and when Ferdous won by unanimous decision, she shed tears of pride, Ferdous says. When she invited them to watch her fight at Madison Square Garden as part of the New York City Golden Gloves tournament, her father pulled her aside and told her, “I thought you looked like Muhammad Ali out there.”

“Sometimes they’ll still ask me when I am going to stop with this stuff,” Ferdous says. “But I think they understand now that this is more than a hobby. It’s a passion. And they see me representing Bangladesh.”

By spring 2023, Ferdous thought she was going for a chance to represent the United States, but Morgan lobbied for her to get dual citizenship with Bangladesh since she was a firstgeneration immigrant. She leveraged the cold-calling skills she refined at her first tech sales job to connect with a former Google colleague named Bickey Russell, a former cricket player with friends who were connected to the Bangladesh Olympic Association. By July, she was

flying with Morgan to meet the association in Dhaka, where security guards picked them up. “It felt like I had already won a gold medal,” Ferdous jokes.

The federation welcomed Ferdous but wanted to see her train and fight before officially granting her the opportunity to represent the country. She arrived at the Muhammad Ali Boxing Stadium in Dhaka, where only male fighters trained. After watching her sparring sessions with two male fighters and exhibition bouts with two female athletes, the federation wanted Ferdous’s citizenship expedited so she could qualify for the upcoming Asian Games.

Since then, Ferdous has adjusted to the unexpected media scrutiny that comes with becoming an Olympic hopeful in a country with no history of success. When her status as a Bangladeshi athlete was confirmed, outlets swarmed her with interview requests and buzzed that this might be the person to get the country an Olympic medal.

But when Ferdous lost to the eventual bronze medalist at the Asian Games in September, the questions were harsh and direct from the couple dozen Bangladeshi reporters in attendance.

“I was just mobbed with questions like, ‘What could you have done better?’ ‘Why did you lose?’” Ferdous says. “These were harsh questions, and you have to hold your composure. I never thought about training or preparing for that.”

She asked Inam Ahmed, the chairman of the Bangladesh Cricket Board and a mentor since Ferdous joined the national team, how it was possible to handle such intense media scrutiny if she didn’t win every fight. He explained that Bangladesh is in its infancy of understanding how to follow sports. As the sports industry grows, he told her, they will come to realize that wins and losses are part of the athlete’s journey.

Even with the pressure building before her final chance to qualify in May, Ferdous marvels at how her life — and perspective — have changed since she chose to pursue boxing not even five years ago.

“I remember after one of the training sessions in Bangladesh, this little girl came up to me and said, ‘I never knew girls can punch like that; I thought only men can,’” Ferdous says. “And I think that one instance showed me that what I’m doing — it’s kind of more than just me, right?” B

National champion fencer Anne Cebula ’20 is on her way to represent the USA in the 2024 Paris Olympics — a dream long in the making

by Nicole Anderson ’12JRN | photos by Laura BarisonziSome people need time to figure out what they want to do. They meander and dabble until they land on something. But for Anne Cebula ’20, there was no equivocation, no trial and error. She knew her calling from the moment she watched the 2008 Beijing Olympics at just 10 years old from her home in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn.

“I saw fencing for the first time, and I just fell in love. This is unlike anything I’ve ever seen,” she recalls. “And I remember I saw it, and I said, ‘Well, I want to do that. And I want to do that there.’”

In March, USA Fencing announced that Cebula had been selected to the U.S. Olympic Team in women’s epee. This summer, she will head to the 2024 Paris Olympics — a goal she has worked tirelessly to achieve since she first discovered the sport on the international stage 16 years ago.

It isn’t, however, a surprise that she made the cut. She has been breaking records and winning championships since she became part of the Columbia Lions fencing team. Cebula — who is currently ranked No. 2 in the U.S. and No. 27 in the world in epee — was a member of the World Championship Epee Team in 2023 and took gold in the individual North American Cup in October.

As a Barnard undergrad, Cebula contributed to the overall success of the Lions. She won the NCAA Individual Epee Championship in 2019, making her the first Barnard student-athlete to win an individual NCAA title in any sport. She was also the first women’s epeeist to take home the NCAA crown for the Lions. Cebula earned All-America honors twice during her career and helped the team win an Ivy League Women’s Championship and the NCAA combined title in 2019.

Despite her impressive track record, Cebula is unusually self-effacing. Michael Aufrichtig, head coach of the Lions fencing team, credits this humility for helping to shape her into the competitive athlete she is today. “I’m not sure if Anne ever realized how good she actually is … and that’s not a weakness,” says Aufrichtig. “But I saw some quote [that said], ‘Even those who are the best are always training like they’re not’ … and that drove her even more.”

‘GIRL

The 2008 Beijing Olympics marked a turning point for Cebula. She became laser focused on learning how to fence. The spectacle of the event might have been what initially drew her in, but it was the art of the sport — the physicality, the technical skill, and what she describes as the “opera”-like emotion — that made her want to pursue fencing. “It’s dangerous, but there’s a ballet aspect involved. It is super athletic.”

After some research, Cebula told her parents about a club and a summer program where she could learn. These were all expensive options, and her parents weren’t convinced that it wasn’t just a passing phase, so they told her to wait. Years later, when it came time for Cebula to choose a high school, the decision was a no-brainer. She opted for Brooklyn Technical High School because it had great academics and “they had a free fencing club, and I was like, ‘This is it. I need to do this,’” she says. “‘I’m gonna be captain by the time I graduate.’”

Cebula emailed the coach the first day of high school, and he told her to come on by. There was a mix of levels, she says, and the coach deliberately didn’t open the equipment closet until late spring. Without the allure of using weapons, the group thinned out over time. “All he did was make us do footwork, footwork, footwork,” she says. “It was like, ‘Oh, you want to fence? You have to wait.’ I waited.”

By the end of the year, 10 people were left on the team — including Cebula. During the summer, she attended a fencing-focused day camp where she had the chance to compete in a small tournament. She won, earning her coach’s high

praise and her parents’ support. She continued to participate in local competitions and build her skills. But she wasn’t able to compete in national tournaments due to the high costs, which put her at a disadvantage for college recruiting. By the time she was ready to apply to schools, coaches told her it wouldn’t be possible without a national ranking. So when Fordham University offered her a good financial package, she accepted — even though the school didn’t have a fencing program — with a plan to transfer out.

“And I was like, I’m gonna fence for one more year. If I can’t transfer out to Barnard, my dream school, then I’ll quit fencing,” Cebula says. “And so at Fordham, I was just the girl with the fencing bag.”

Cebula first crossed paths with Coach Aufrichtig around 2016 at a tournament where Cebula, competing for the Fencers Club, went up against New York Athletic Club, a highly competitive fencing program that produces Olympic medalists and national champions and where Aufrichtig is chairman.

“So we’re going against the Fencers Club with some very strong women epee, and there’s this tall, skinny young girl, who happened to be Anne Cebula, and we’re like, ‘We don’t even know who she is, but we got to beat her, right?’” he recalls. “And Anne beat us … so after that, we invited her to come train with us at the New York Athletic Club.”

Aufrichtig saw Cebula’s potential. But she hadn’t previously been on his radar for recruiting. Then one day, he got an email from her that she was applying to transfer to Barnard. “I ran over to Barnard. …

I didn’t have any more recruiting spots, but I just wanted to put in a good word. Of course, she had great grades and did well at Fordham,” he says.

At Barnard, Cebula, a neuroscience and behavior major, split her time between labs and practice, coursework and competitions. It could be hectic, but she was thrilled to have a place as a walk-on on the team. “It was nuts, because I don’t think people realize how prestigious or high level this team is — like, I had teammates who were [trying to qualify] for the Olympics at 18 or 19 years old,” she says.

Outside of college, fencing is an individual sport, and being on a team drove her to work even harder. “It helped that I was a transfer because I didn’t understand the gravity. I was just kind of like, ‘I get to go to NCAA and I can’t let my team down. I need to win as much as possible.’ I was just so happy to be a part of the team.”

Throughout her career, Cebula has specialized in epee, which is one of three disciplines in modern fencing that are differentiated by the weapon. (In addition to epee, there’s foil and sabre.) Each uses a different blade and has different rules. With epee, the target area covers the entire body from the mask down to the feet. “There’s a lot more cardio, which is why everyone kind of has a distance-runner build,” says Cebula, who fits that description at 5 feet, 11 inches.

Although her height is certainly an asset, it is Cebula’s mental fortitude and technical precision that has made her into such a powerful athlete.

“I will say that the way she fences is very on point…. She is able to put blinders on and really focus on each touch very intentionally,” says Aufrichtig. “One big aspect of fencing is you have to be present in the moment — and that is definitely one of her strengths.”

“I’m either going to the Olympics or not, but I’m retiring after this,” she says.

Competing at such a high level requires a large financial commitment, from training to travel and entry fees. In some countries, fencing programs are government funded, but not in the U.S. Cash prizes for tournaments are modest (and often nonexistent) compared with major sports like tennis. Cebula hopes that after she retires, she can help “make fencing more accessible” and increase its visibility.

“A big chunk of my journey and story is I put it off because I couldn’t do it [financially],” she says.

Cebula’s senior year — and season — came to an abrupt close when COVID hit. Upon graduating, she mapped out a four-year plan to get to the Olympics. But seeing how quickly things can get upended, she wanted to balance out the training with other goals. During this period, she completed a remote postbaccalaureate program for medical school and worked as an administrative assistant for Dr. Lorraine Chrisomalis-Valasiadis ’83, an OB/GYN. She also signed with Elite Model Management and worked in New York, Paris, and London.

Meanwhile, Cebula kept training and competing. Her ranking improved. “Every tournament, I was kind of learning more and more about myself — how to be an international athlete. So things like how to adjust to the time zone really quickly, how to adjust if you get sick from food poisoning, how to pack,” says Cebula. “So that kind of felt like my training-wheels period.”

Gradually, Cebula ramped up training to five or six days a week. To get into optimal shape, she has worked with coach Sergey Danilov as well as a personal trainer. When the Olympic qualification process began, she decided, "I am all in.”

So when Cebula set her sights on being an Olympian, she knew the 2024 Olympic Games was her chance. In March, she got news that she’d qualified. “Twenty percent of me was overjoyed, and 80% of me is like, ‘All right, get back in the hamster wheel, we’ve got a tournament,’” she says.

Cebula says that when it comes to bouts, she relies on muscle memory. Some countries have certain fencing styles, but it comes down to feeling out competitors. Even with the stresses of competing, she finds joy in the whole process. Today, she feels “more motivated than ever.”

“I’m going harder in my trainings because I want to end on a good note,” she says. “I mean, the note is going to be good anyway because we’re ending it there.” B

On a late night in mid-March in Blacksburg, Virginia, the starting five lineup of the 2023-24 Columbia women’s basketball team stepped onto the court at Virginia Tech to play the first Division I NCAA Tournament game in program history. The women pushed Vanderbilt to the limit, but in the end they came up heartbreakingly short, 72-68. Though the Lions’ March Madness debut didn’t go as hoped, it was a massive step forward for Columbia women’s sports — as well as for the Barnard student-athletes.

In a season filled with successes, Barnard student-athletes played a key role on the Columbia women’s basketball teamby Anne Stein

For 38 years, Columbia women’s basketball has been a member of the Ivy League, but it wasn’t until the March 2016 arrival of head coach Megan Griffith ’07CC that the team embarked on what’s become a record-setting journey of firsts: In 2023, they won their first Ivy League regular season title (which was repeated in 2024), and this year, Abbey Hsu — Ivy League Player of the Year and thirdround draft pick for the WNBA’s Connecticut Sun — became Columbia basketball’s all-time leading scorer. The team fought all the way to the WNIT Championship finals last year, and this season they made it to “the Big Dance,” the NCAA Tournament.

Griffith, a two-time Ivy League Coach of the Year, and her staff have rebuilt the team by instilling a new philosophy, scheduling games against tougher opponents, and recruiting in areas nationally and internationally where they’d rarely gone before.

A former assistant coach for a highly successful Princeton squad, Griffith is now the program’s winningest head coach, with a 122-83 record prior

to the NCAA Tournament game. She was a superachieving player too, serving as Columbia women’s basketball captain for three seasons and twice earning All-Ivy League honors.

“Columbia is my home,” said Griffith, a day before the team’s NCAA tourney game. “I grew up there. I walked on campus in 2003, and here we are, 21 years later, with the dreams that I had as a player coming true now as a coach.”

But it’s not just Columbia students who’ve been along for the ride. Barnard is the only women’s college in the nation that offers students the opportunity to play Division I sports, and since Griffith and associate head coach and recruiting coordinator Tyler Cordell arrived, they have put an emphasis on recruiting Barnard student-athletes.

This year’s squad has the most Barnard students ever, with senior Nicole Stephens and first-year players Habti Calvo, Blau Tor, and Emily Montes. The women are there because of the Columbia-Barnard Athletic Consortium, a unique arrangement allowing Barnard students to compete with Columbia undergraduates in NCAA Division I athletics.

“When I was a student-athlete here, we always had Barnard student-athletes on our teams,” says Griffith, “and when I came back it was only Columbia College students, so that was super intriguing to me. I was like, ‘What happened?’”

Along with recruiting internationally (in addition to Spain’s Calvo and Tor, Australian sisters Fliss and Kitty Henderson and the U.K.’s Susie Rafiu are on the squad), Cordell was tasked early on with finding talented basketball players who were interested in Barnard.

“The diversity on our campus and having the multiple undergraduate college experiences available is really a great asset,” Griffith explains. “So we leaned into that hard and created more financial aid opportunities for athletes and students in general, and that was a big part of how we could grow that part.”

The connection between the coaches and Barnard has grown stronger in recent years. “The people are amazing, the support there is fantastic, and the relationships we have from all parts of the College are great,” Griffith says.

Nicole Stephens was Cordell’s first Barnard recruit, with both hailing from the same hometown in Ohio. Stephens played in all 30 games this season, averaging nearly 20 minutes a game off the bench and helping lead the team.

“If there’s a player on the court who has my brain, it would be her, and to have that advantage is huge,”

says Griffith. “Nic brings tremendous leadership from that standpoint, and she’s also got a great ‘take care of the young kids’ mindset. She makes sure the young players get their reps in and has been a great mentor to the team.”

Stephens has a phenomenal basketball mind, Cordell says. While injured last season, Stephens worked with coaches and led from the bench, game planning, scouting opponents, and communicating with teammates. “I joke that we gave her a clipboard and she just ran with it,” says Cordell.