POINTS OF ENTRY

The boundless imagination of choreographer Sarah Silverblatt-Buser ’15

The boundless imagination of choreographer Sarah Silverblatt-Buser ’15

Giving Day is a unique opportunity to extend the reach of your giving, with each gift contributing to our collective impact! Whether you make a gift, motivate your friends and classmates to give, or share your favorite college memories on social media, you add to the Barnard spirit that we hope to magnify on Giving Day.

When we come together as one community, our ability to realize a limitless future for Barnard’s next generation of women is unstoppable. Every contribution, of any amount, demonstrates our care for each other and helps drive meaningful change in the lives of our students.

To learn more about Giving Day 2024 and how you can be part of this special event from wherever you are in the world, visit:

18

Rowing in Tandem by Tom Stoelker

The Women’s Rowing Team forges enduring friendships on the New York waterfront

28 Points of Entry by Tom Stoelker

Sarah SilverblattBuser ’15 unites audiences by fusing artistic modes

24

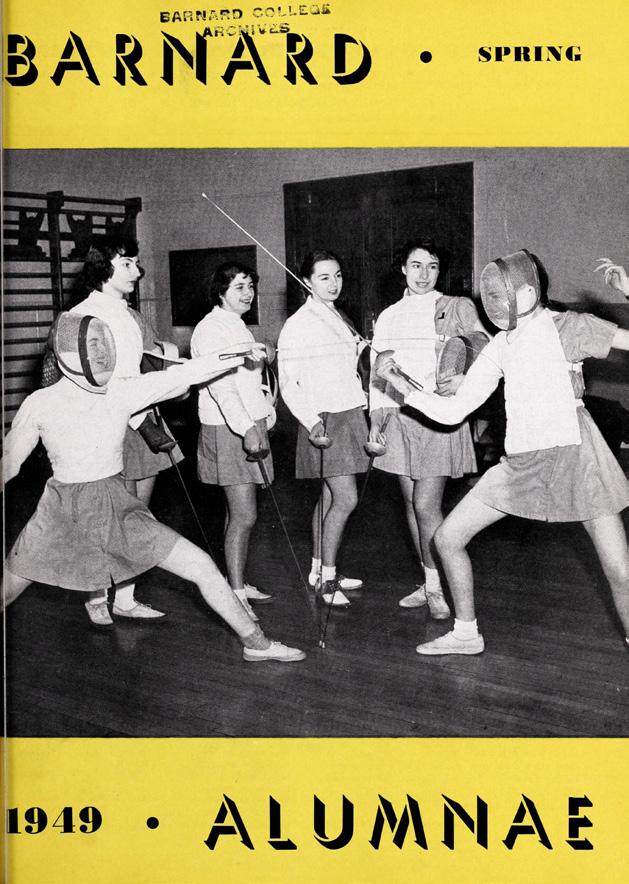

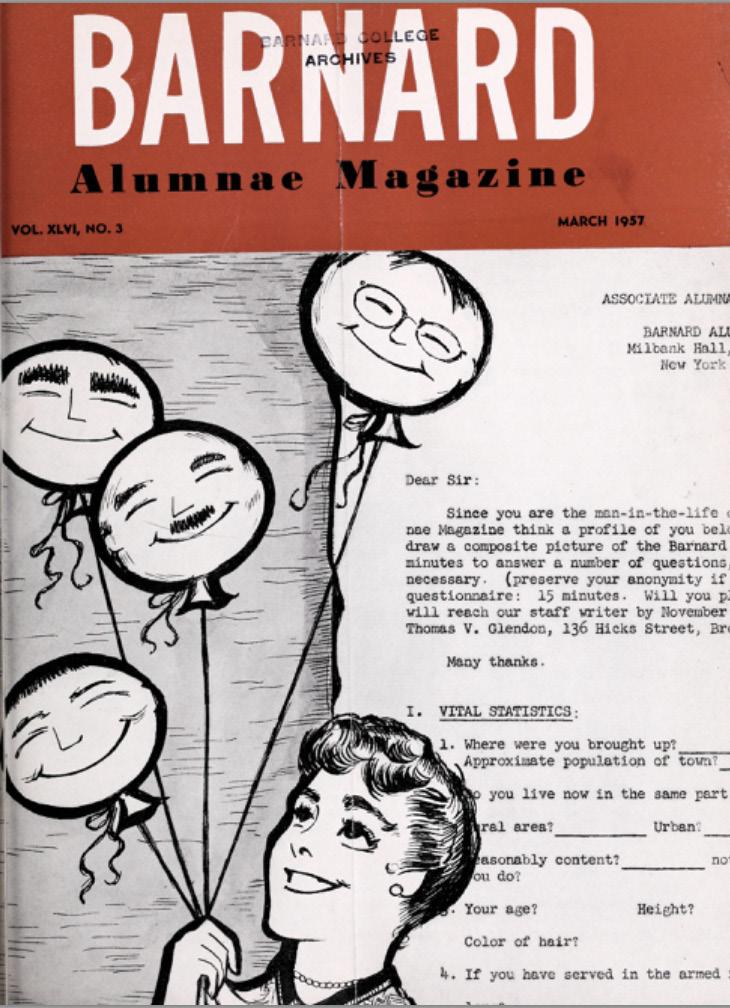

Cover to Cover by Tom Stoelker

A look back at Barnard Magazine over the years

COURTESY OF BARNARD COLLEGE ARCHIVES

4 Views & Voices

5 Dispatches

Headlines | Our Titan Arum Blooms a Third Time; Greta Gerwig ’06 Heads the Jury at Cannes; Barnard’s Gala Raises $3.4 Million; The Liman Law Fellows Program Makes an Impact

11 Discourses

Read Watch Listen | Bookshelf; An Alumna Delves Deep for the “Pope of Trash” Exhibition in L.A. Faculty Focus | Professor Logan Brenner

35 Noteworthy

Passion Project | Tee O’Fallon ’86

Q&Author | Kim Rosenfield ’87

AABC Pages | From the AABC President; Video: Through the Years Class Notes

Alumna Profile | Whitney Latorre ’02 In Memoriam

Last Image | Ellen Stockdale Wolfe ’72 Crossword

On the Cover

Photo of Sarah Silverblatt-Buser ’15 by Suzanne Distain

Back Cover

Photo by Carrie Glasser

Amanda Loudin is an award-winning freelance writer with bylines in The New York Times, National Geographic, The Washington Post, and more. She enjoys the wide variety of assignments that come with university publications and is a big believer that movement and writing go together. Find more of her work at amanda-loudin.com.

Bruce Morrow (SOA ’92) is a co-editor of Shade: An Anthology of Short Fiction by Gay Men of African Descent and a former fiction editor of the literary journal Callaloo. His first short film, In Dreams Begin..., earned Best LGBTQ Jury and Audience Awards at the 2023 Paris Short Film Festival and has been presented in 11 film festivals.

The 2024 Summer Olympics is officially underway in Paris. Keep an eye out for national champion fencer Anne Cebula ’20, who graced the pages of our Spring 2024 Athletics issue. She will be representing Team USA as she competes in women’s epee for both the individual and team events. Read more about Cebula’s path to the Olympics at barnardbold.net/onpoint

In 2020, professional skateboarder and architect Alexis Sablone ’08 competed in the Summer Olympics in Tokyo, placing 4th in the women’s street skateboarding final. This year, she’ll be there coaching, and you’ll see Olympians sporting her designs. Nike SB tapped her to design their U.S. skateboarding federation kits for the Paris Olympics. Read more about Sablone’s design work at barnardbold.net/skatingbydesign

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Nicole Anderson ’12JRN

CREATIVE DIRECTOR David Hopson

MANAGING EDITOR Tom Stoelker ’10JRN

COPY EDITOR Molly Frances

PRODUCTION DIRECTOR Lisa Buonaiuto

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS N. Jamiyla Chisholm, Kira Goldenberg ’07

WRITERS Marie DeNoia Aronsohn, Mary Cunningham, Isabella Pechaty ’23, Preetica Pooni

ALUMNAE ASSOCIATION OF BARNARD COLLEGE

PRESIDENT & ALUMNAE TRUSTEE Sooji Park ’90

ALUMNAE RELATIONS

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Karen A. Sendler

VICE PRESIDENT FOR STRATEGIC COMMUNICATIONS

Natalie Raabe

VICE PRESIDENT OF DEVELOPMENT AND ALUMNAE RELATIONS

Michael Farley

PRESIDENT, BARNARD COLLEGE

Laura Rosenbury

Summer 2024, Vol. CXIII, No. 3. Barnard Magazine (ISSN 1071-6513) is published quarterly by the Communications Department of Barnard College.

Periodicals postage paid at New York, NY, and additional mailing offices.

Postmaster: Send change of address form to:

Alumnae Records, Barnard College, Box AS, 3009 Broadway, New York, NY 10027-6598

Barnard Magazine, Barnard College, 3009 Broadway, New York, NY 10027-6598 | Phone: 212-854-0085

Email: magazine@barnard.edu

Opinions expressed are those of contributors or the editor and do not represent official positions of Barnard College or the Alumnae Association of Barnard College. Letters to the editor (200 words maximum) and unsolicited articles and/or photographs will be published at the discretion of the editor and will be edited for length and clarity.

For alumnae-related inquiries, call Alumnae Relations at 212-854-2005 or email alumnaerelations@barnard.edu.

To change your address, write to: Alumnae Records, Barnard College, Box AS, 3009 Broadway, New York, NY 10027-6598

Phone: 646-745-8344 | Email: DevOps@barnard.edu

The titan arum (Amorphophallus titanum), better known as the corpse flower, is a showstopper — for both its appearance and its pungent smell. People who might not otherwise be drawn to greenhouses and botanical gardens line up to view the massive plant, which often surpasses 6 feet tall and 4 feet in diameter. The stinky bud that bloomed this summer at Barnard’s Arthur Ross Greenhouse attracts similar fanfare. Prior to the flower’s opening, greenhouse director Nick Gershberg power-washed the floors, installed livestream cameras, and readied the flower for the oncoming onslaught. It takes the plant 10 years to reach reproductive maturity before blossoming every two years. The first time the flower opened was during the pandemic, leaving only Gershberg to appreciate its majesty in person. This year, dozens of visitors passed through. In the days leading up to the big event, Gershberg stood admiring a less celebrated moment of the flower’s life span — just before it opened. “It goes from giving some futuristic deco vibes and then the ribbing is like a neoclassical Victorian scarab beetle kind of thing — but really it’s stunning at every stage,” he says. —Tom Stoelker

Filmmaker Greta Gerwig ’06 — who co-wrote and directed the global box-office hit Barbie — broke ground yet again this May when she became the first-ever female American director to serve as jury president at the Festival de Cannes. (She is also the second youngest person to assume the role.) The star-studded, 10-day affair kicked off with Gerwig and the jury awarding an honorary Palme d’Or to actress Meryl Streep.

“First of all, I have to say this is beyond a dream come true. It is a huge honor. I can’t stop pinching myself,” said Gerwig at a press conference. “I love watching films and discussing them, so to do that here in Cannes, with all these artists, is thrilling.”

For festival organizers, Gerwig was the right person for the job. “Beyond the 7th Art, she is also the representative of an era that is breaking down barriers and mixing genres, and thereby elevating the values of intelligence and humanism,” stated festival president Iris Knobloch and general delegate Thierry Frémaux. Nicole Anderson

Barnard’s 2024 Annual Gala raises $3.4 million for student financial aid

In April, the Barnard community came together at Cipriani on 42nd Street in Manhattan for the College’s Annual Gala. Co-chaired by Barnard trustees Amy Crate ’94, P’24, P’27, and Caroline Bliss Spencer ’09, this year’s sold-out event celebrated the College’s commitment to wellness, honoring two remarkable women — Helene D. Gayle ’76, M.D., MPH, and Francine A. LeFrak — and raised $3.4 million for financial aid at Barnard.

Barnard’s Annual Gala — a tradition spanning more than three decades — raises critical funds each year that are dedicated to supporting need-blind admissions at the College. This year’s Gala recognized the profound impact both honorees have had on holistic wellness for women especially.

Helene Gayle, who received her award from Barnard trustee and acclaimed talent attorney Nina Shaw ’76, is the current president of Spelman College. She was honored for her distinguished career in public health and her groundbreaking leadership that has paved the way for a new generation of young female scholars. Dr. Gayle thanked Barnard “for giving [her] the determination and courage to try to be a changemaker throughout [her] career.”

Barnard trustee Francine LeFrak was presented with her award by Barnard alumna and award-winning documentary film producer Sheila Nevins ’60. LeFrak is a dedicated social entrepreneur, women’s rights advocate, and philanthropist who was honored for her first-of-its-kind approach to wellness at Barnard, focusing on three pillars of wellness: physical, mental, and financial. “When women have the courage to take control of their finances, their mental and physical health improves, ensuring a chance for independence,” said LeFrak.

Later this year, Barnard will open the Francine LeFrak Foundation Center for Well-Being. This state-of-the-art facility will provide holistic support to students and the community.

President Laura Rosenbury spoke to attendees about Barnard’s unique position as a leader in campus wellness and what it means more broadly to supporting women. “Wellness isn’t just physical or mental but also financial,” she said. “We

want Barnard to be a place where the most exceptional students in the world can come to learn and grow into changemakers, regardless of their ability to pay.”

President Rosenbury shared that the College has received a $10 million challenge grant from Diana T. Vagelos ’55 and P. Roy Vagelos, M.D., P&S ’54. All funds raised at the Gala scholarship auction would be matched dollar for dollar — giving participants twice the impact.

“As former scholarship recipients themselves, Diana and Roy Vagelos understand the challenge of achieving educational goals without adequate financial means,” said President Rosenbury.

The Vagelos gift inspired enthusiastic support from the room that evening, with a lead gift from Ina and Howard Drew P’13. A total of $1.9 million was raised during the auction, which was led by Lydia Fenet, acclaimed author and auctioneer.

“Barnard is setting the standard for educating the whole woman,” said Spencer, one of the co-chairs. “Together, we will continue to ensure that financial constraints never hinder any deserving young woman from receiving a Barnard education.”

The

Liman Law Fellows Program, established

by Ellen Fogelson Liman ’57, helps Barnard students make a powerful impact in the world

by Amanda Loudin

Mary Ingram ’23 has a passion for investigative work, something she feeds with her current role at Brooklyn Defender Services. The former political science major might not have discovered that passion, however, were it not for her internship there. And that internship might not have been possible were it not for her participation in the Liman Law Fellows Program. “I became interested in immigration law during an internship the year before and wanted to continue with it the following summer but couldn’t afford it,” Ingram says. “My fellowship allowed me to work on investigations, going out into the field and gathering evidence for our clients. I loved the work.”

Today, Ingram continues her investigative work with the organization and even manages the current roster of interns. “I’m so happy Barnard is a part of Liman,” she says. “It affirmed this is the right field for me and completely changed the trajectory of my career.”

Ellen Fogelson Liman ’57, president of the Liman Foundation, established the program at Barnard in 2005 in memory of her husband, Arthur Liman, an esteemed attorney. The summer fellowships are coordinated in partnership with the Arthur Liman Center for Public Interest at Yale Law School, which was named in honor of Arthur, a 1957 graduate of the law school, whose distinguished career, as the Center states, was dedicated to serving “the needs of people and causes that might otherwise go unrepresented.” Through funding and support from the Liman Foundation to Beyond Barnard (the College’s one-stop shop for career development

and exploration), the fellowship has flourished.

“The program is particularly important today, at a time when positive public service is critical,” says Liman, whose family has deep ties to Barnard, with three generations of Liman women having attended the College, including her daughter-in-law Lisa Liman ‘83, P’22, and her granddaughters Amanda Liman Arnold ‘25 and Abigail Liman ‘22. “It has become highly selective and sought after, and it informs the lives of the students long after the experience.”

Each year, four Barnard students become Liman Law Fellows; the program offers funding and support to students seeking work at an organization serving the public interest. The College is one of eight institutions nationwide offering the fellowships — and each fellow spends the summer gaining professional experience like Ingram’s — in organizations that provide law-related services for the public or conduct advocacy and policy work for underserved communities.

Liman Law Fellows receive a $5,000 stipend and are eligible for subsidized on-campus housing and eight to 10 weeks of in-person summer work at a publicly funded or nonprofit public interest, social service, cultural, or government agency. Additionally, they attend the Liman Colloquium at Yale Law School in the spring, where they learn from voices like Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor and social justice activist Bryan Stevenson and network with former Liman Law Fellows, among others. Any student entering their second, third, or fourth year may apply, regardless of their major.

“The Fellowship Program covers an area of high interest but also one that typically doesn’t have paid internships,” says Christine Valenza Shin ’84, executive director of Beyond Barnard. “The program allows us to fund more students in public interest law and advocacy work.”

Liman says that the fellowship ties directly to her family’s long legacy of philanthropy. “We’ve always been very interested in social causes,” she notes.

If Isadora Ruyter-Harcourt ’16 were to point to one of the most pivotal experiences of her career, it would be her time spent working with the Southern Center for Human Rights in Atlanta. As an intern there, RuyterHarcourt carried out impact litigation work that aimed to eliminate discriminatory practices that prevented residents from accessing basic utility services if they owed unrelated court debt to the city. “I interviewed these people and got to know them,” Ruyter-Harcourt says. “I still think about that work today.”

The experience — made possible by the Liman Law Fellows Program — informed her career decisions, which eventually led to her current position as a trial attorney at New York County Defender Services. “I had just graduated from Barnard and didn’t have work lined up for the summer,” says Ruyter-Harcourt. “The Center doesn’t pay for internships, so the fellowship made it possible for me to get that experience before I went on to work as a paralegal at Federal Defenders of New York that fall.”

Like Ruyter-Harcourt, Anusha Merchant ’25, a rising Barnard senior, is passionate about social justice advocacy but was unsure she could afford a summer internship in the field without pay. The Liman fellowship allowed her to serve as a legal intern at the Government Accountability Project in 2023. In this position, Merchant worked to support whistleblowers, one related to scientific integrity and another related to immigration. “The program wasn’t just about the financial support,” Merchant says, “but also the ability to network and learn.”

A first-generation student, Merchant didn’t have many lawyers in her prior orbit, so she took full advantage of the Liman network. “I had a list of Liman fellows and reached out to a variety of them to build connections I otherwise wouldn’t have known existed,” she says.

This summer, in fact, Merchant is putting those connections to good use. She’s working at the Brennan Center for Justice on the liberty and national security team. “My co-worker is a former Liman fellow from Yale,” she says. “The network remains a part of your life, and its reputation helps you build credibility.”

That’s just what the program aims to do, says Valenza Shin: “The program puts a name to something the students are interested in but don’t know how to find otherwise. It allows them more than a vague hope and gives them concrete, valuable experience while they’re still in college.”

The Liman program has been so effective at Barnard that it has become a model for other programs as well. The Reinhart Richards Journalism Internships and the Zwas Community Impact Internships financially support students interested in journalism and community-focused organizations. “Liman became an example for us to put in front of alumnae and foundations with similar interests,” says Valenza Shin. Having the Liman Law Fellows Program serve as a role model to other programs is exactly what Ellen Liman loves to see. “The impact extends well beyond the four Barnard fellows every year,” she says. “When you involve college students in public service, it multiplies the positive effect.” B

by Isabella Pechaty ’23 and Molly Frances

Murder Buys a One-Way Ticket by Laura Levine ’65

In the latest (and 20th!) installment of Levine’s Jaine Austen mystery series, the freelance writer — accompanied by her cat, Prozac — accepts a new job with a long train-ride commute and a tyrannical, gym-owning client, Chip “Iron Man” Miller. But when Jaine suddenly discovers Chip dead in his cabin, she finds herself racing to clear her name and unmask the real killer. (Kensington Books)

Disability Worlds by Faye Ginsburg ’75 and Rayna Rapp Ginsburg and her co-author deliver a groundbreaking text in disability studies, telling the stories of disabled people living in New York City, incorporating the experiences of their own children along with parents, activists, artists, and experts. They undertake an anthropological investigation into disability awareness (or lack thereof) in public and private life, the many logistical limitations imposed by the city, and the resilient creativity of the disabled community in developing new paths for justice. (Duke University Press)

Write Like a Man: Jewish Masculinity and the New York Intellectuals by Ronnie

Grinberg

’01

During the postwar era, notable writers and critics of New York’s intellectual scene adopted a “secular Jewish machismo,” grounded in fierce, acerbic debate. This unique rhetorical style was used by men and women, Jewish and non-Jewish people alike, including such figures as Norman Mailer and Mary McCarthy. This conception of Jewish masculinity, argues Grinberg, played out in popular discourse on pressing cultural topics from civil rights and feminism to radicalism, which, in turn, helped to bring American Jews from the margins into the mainstream. (Princeton University Press)

The Nature of Politics: State Building and the Conservation Estate in Postcolonial Botswana by Annette A. LaRocco ’10

This case study of Botswana, where 39% of the country’s land is set aside for conservation, focuses on the state-building qualities of biodiversity conservation in southern Africa. The book’s key innovation is its conceptualization of the

“conservation estate,” a term most often used as an apolitical descriptor denoting land set aside for conservation. LaRocco argues that this description is inadequate and proposes a novel and much-needed alternative definition that is tied to its political elements.

(Ohio University Press)

Haggadah Min HaMeitzar: A Seder Journey to Liberation by Gabriella Spitzer ’13

Spitzer provides a fresh and progressive iteration of traditional Seder texts. The original translation is presented alongside selected artwork, discussion prompts, and commentary that illuminate the source material for new generations, and hones in on four “voices” that correspond to the different names of Passover, through lenses such as environmentalism and storytelling. (Ben Yehuda)

Nineteenth Century America in the Society of States: Reluctant Power edited by Cornelia Navari ’63 and Yannis A. Stivachtis

As both editors and contributors, Navari and Stivachtis examine a crucial period of U.S. international relations, a time when the nation’s newfound independence necessitated establishing diplomatic relations with European states. The book discusses how the U.S. situated itself sociologically and politically in the international order and engaged with the rest of the world, shaping its own positions and those of the broader international community. (Routledge)

The World Is a Muddy Place by Ann Spier ’63

On the Death of a Civilization translated by Inez Fitzgerald Storck ’67

Storck’s translation of the original 1949 text by Marcel de Corte is particularly relevant today as people find themselves increasingly alienated from their environment and one another. The 20th-century philosopher explores how these sentiments arose from unchecked capitalism and consumerism as well as a rejection of the transcendent. De Corte proposes possible solutions through a return to a religious moral framework and small-scale communities that facilitate closer relationships to the environment and between people. (Arouca Press)

In this deeply optimistic book of poems, Spier faces head-on the specter of climate change and the damage to the planet caused by corporate greed. She finds guidance in the late Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh’s words “No mud, no lotus,” and her work reflects her determination not to wallow in pain but to find joy and hope in beauty and creativity. (Outskirts Press)

CHILDREN’S BOOKS

Fenway and the Loudmouth Bird by Victoria J. Coe ’83

This year’s winner of the Sid Fleischman Honor Award tells a spirited story about a dog named Fenway in competition with a talking bird for the attention of his favorite human. Unlikely interspecies friendships abound in this humorous story for young readers. (Penguin Random House)

Connor Kissed Me by Zehava Cohn ’96 Miriam doesn’t know how to react when her friend Connor kisses her. In this picture book about the importance of consent, geared for kids from kindergarten to second grade, Miriam consults her best friend, the recess monitor, her teacher, and her mom. After she asks herself how she feels about the kiss, Miriam finds her voice and asserts her boundaries. (Lee & Low Books)

Bundharam Kundharam by Rumjhun Sarkar ’81

After she suffered a massive stroke in 2019, doctors thought author Monica Edinger wouldn’t be able to breathe or eat on her own, let alone write. Demonstrating extraordinary determination and resilience, Edinger, along with co-author Leslie Younge, was nonetheless able to complete Nearer My Freedom

Amid writing a law manuscript, Sarkar was inspired to bring her mother’s language to the page instead — “Her words sing,” Sarkar says, “and are a precious gift to me.” In the resulting English-Bengali book for children 8 to 12, a lovable “grandfatherly figure” adventures his way through international destinations, aided by his ability to talk to animals, flowers, and puppets. (AuthorHouse) B

Nearer My Freedom: The Interesting Life of Olaudah Equiano by Himself by Monica Edinger ’74 and Lesley Younge Edinger and Younge adapt the firsthand writings of Olaudah Equiano, a formerly enslaved African who bought his freedom and went on to become a hairdresser’s apprentice and an abolitionist activist abroad. Chronicling his journey from the Caribbean to Virginia, Europe, and beyond, the co-authors present Equiano’s remarkable life story in “found verse” and offer annotations that provide historical context. (Zest Books)

by Tom Stoelker

When Emily Rauber Rodriguez ’09 was a teen, her family moved from California to the suburbs of Baltimore, which she quickly assessed as not exactly the hippest place on the planet.

“Everyone has like a white picket fence; I knew I was not a white picket fence type of person,” she says. “It felt like a deeply uncool place to be, and I was kind of worried about my own coolness at that moment as a kid.”

Then she discovered the work of Baltimore native John Waters, the director of underground cult film classics such as Pink Flamingos and Female Trouble as well as mainstream hits such as Hairspray, Cry Baby, and Serial Mom — all of which are set in Baltimore, celebrate the city’s offbeat denizens, and poke fun at the squareminded ones.

“He also came from this kind of place and was still creating fabulous, weird stuff. And he was cool. That was a very hopeful moment for me,” she says.

Today, Rauber Rodriguez, who holds a doctorate in cinema and media studies from the University of Southern California, is a curatorial assistant at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles, where she recently helped mount “John Waters: Pope of Trash,” which runs through August 4.

The exhibit features a montage of scenes from his films, costumes, and memorabilia. One of her many research responsibilities included identifying a nude male model by his tattoos from a book of erotic photography — an amusing, if unusual, use of her freshly minted Ph.D.

“I love that he’s not worried about what makes his work appeal to a broad audience, which is what a lot of filmmakers are tempted to do,” she says of Waters, before adding that his sometimes outrageous approach also posed a challenge for the museum. “His work was never designed to be for mainstream Hollywood audiences. That was the thing we had to tangle with.”

A lot of visitors with kids may be familiar with the family-friendly musical Hairspray, but they may not be as prepared for Waters’ bawdy early work featuring the late great Divine, arguably the most famous (and outrageous) drag queen of the 20th century. To this day, Divine remains a much-loved LGBTQ+ icon, having busted open notions of gender identity well before it became part of the national conversation.

“[Waters has] obviously been very inclusive with gender identities, with sexual identities … and Hairspray also sends a very explicit racial message,” she says.

It’s just such conversations on identity that excite Rauber Rodriguez. (The focus for her dissertation was

on the cross section of race and the media as it relates to the Latinx community.) She often taps her expertise when she, along with other members of the curatorial team, examines the didactics of the text and montages used in an exhibition.

Many of Rauber Rodriguez’s colleagues have trained in the film industry or in the museum world. But her background melds the two worlds with an academic focus, which she says started at Barnard when she double majored in psychology and film studies.

At that time, film studies was still a somewhat nascent program, with most courses offered at Columbia. However, her production class was held at Barnard, which proved to be an unexpectedly formative experience. Years later, she recalled comparing notes with another woman who studied film elsewhere. “This line was burned into my head — she said the guys never let her touch the camera.”

It’s a scenario that would’ve never happened at Barnard, she says. While she appreciated access to Columbia and could’ve taken a production class at either school, the Barnard environment fostered a confidence she carries with her to this day: “I just felt a little more free to express myself in an all-women’s space.” B

Professor Logan Brenner is part of an international collaboration to drill into the ocean’s past

by Marie DeNoia Aronsohn

For assistant professor of environmental science Logan Brenner, working on Expedition 389: Hawaiian Drowned Reefs was a dream opportunity.

The expedition, overseen by the International Ocean Drilling Project (IODP), offered Brenner a chance to work among a group of scientists that spanned nations (including Austria, China, France, Japan, and the U.K.) and disciplines (physicists, geochemists, sedimentologists, paleomagnetists) and to further her own research into the planet’s past.

Brenner is a paleoclimatologist — a scientist who studies the planet’s prehistoric

past to understand the impacts of climate then, now, and into the future — who earned her Ph.D. in earth and environmental science from Columbia University and the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

The expedition, Brenner explains, involved sending a small crew out to sea, for two months this past fall, to gather samples from 12 fossil coral reefs drowned by rising sea levels and exposure to the ever-growing volcanic archipelago of Hawaii. According to the IODP, this area of the deep ocean contains unique reefs that hold important information about past climates and how coral reefs responded to changing conditions. Scientists can reconstruct sea-level change during important time periods in Earth’s climate history by studying coral samples.

Brenner, who was expecting her second child in April, did not go out to sea but joined the onshore members of the mission in Bremen, Germany, in February. There, the team identified the coral samples and began deciding which ones to analyze. Brenner is on the team of researchers who will begin to examine and discover the hidden past of the corals to help explain what the planet was like as many as 500,000 years ago.

The process of examining corals begins by cutting the cylindrical core in half and extracting a small part or flat slab to study. Brenner will use X-ray imaging, which can reveal subtle differences in density as the coral grows over time. This helps researchers to narrow down which parts of the coral they will analyze using geochemistry.

“As the corals grow, they have a calcium carbonate skeleton, and this skeleton often reflects the composition of the water that it’s growing in,” says Brenner. “It’s taking in different metals, different isotopes, and different nutrients, depending on the water that’s flowing around it. And the composition of the waters, or the way in which coral actually calcifies, can be influenced by climate. So essentially, [we] have within the skeleton a record of environmental change as it’s growing over time.”

The world’s oceans absorb huge amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2), which has helped to slow global warming. However, escalating climate change is warming the oceans and changing their chemistry, which has damaged coral reefs

“Reefs are constantly facing vulnerability now, so it’s important to understand the conditions in which they were able to grow — or not grow — in the past,” says Brenner. “Maybe there was this sudden rise in sea level. How did the reef react in the past? How did it recover? Did it recover? So that could potentially inform the situation we could be facing today.” B

Welcome to Your Barnard Communities …L.A.…London…Lahore…management…motherhood… your retirement…your empowerment…your new career…your new network

Whether you’re moving out or moving up, starting a new business or starting a new chapter, there’s a global network of more than 38,000 bold, brilliant Barnard alums to connect with on your journey — all just a click away. Engage directly with fellow classmates or alums in your area or industry by logging in to Barnard Communities, a private digital platform provided exclusively for Barnard alumnae. 32 Clubs. 9 International Groups. 68 Classes. 38,000 Possibilities.

The women’s rowing team forges enduring friendships on the New York waterfront

by Tom Stoelker

Shortly after Maggie Storino ’02 started her senior year as captain of the women’s crew team, the tragic events of 9/11 occurred. At the time of the attacks, she was, as usual, at practice at the opposite end of the island of Manhattan in a bucolic setting. As few of the athletes had cell phones, Storino gathered the phone numbers of her teammates’ parents so that her mom could call to tell them that their kids were okay and sheltering at the boathouse.

“You saw these big battleships … come to the Hudson; they came down the Harlem [River]. … We were sitting there, and they all came through. I mean, it was kind of wild,” she recalls.

Her first thought was supporting her teammates, most of whom had different connections to the city. “You were there to support your friends no matter what was going on in your life,” she says. “And that has continued to this day.”

More than two decades later, her inner circle is still composed of those boatmates. Over the years, the women she rowed with have excelled in the fields of architecture, tech, finance, and law. Storino says that rowing was key to their success, in part because the sport forces one to set aside self-interest and focus on a common goal.

“It’s so corny, but [it’s] the idea that all ships rise together,” she says. “My success is my friend’s success. So seeing that and approaching life in that way has allowed me to make mistakes and feel comfortable making mistakes.”

Spuyten Duyvil

About a hundred blocks north of Barnard’s campus, at the Baker Athletics Complex, is the Columbia Boat House, a 19th-century structure that was moved from 116th Street and the Hudson River to its current home in 1989. The building, which sits next to its modernized 21st-century sibling, boasts a room with paneled walls carved with the names of the men’s heavyweight rowing teams dating back to 1883. It wasn’t until a century later, when Columbia went coed, that women began rowing on the team. Barnard women have been part of that newfound tradition ever since, thanks to the Columbia-Barnard Athletic Consortium. The bonds they form are, to them, every bit as permanent as letters carved in wood.

The “new” location is far better situated in New York’s estuary. The mile-wide Hudson can often get as choppy as the Atlantic, not an ideal spot for sculling. That’s not to say that the top of Manhattan, where the Harlem River meets the mighty Hudson, is a cakewalk. It’s home to Spuyten Duyvil, which

roughly translates to “spinning devil” in Dutch, named for the whirlpools that form when the two rivers meet. The team usually avoids that area, opting to hook sharp right off the dock and head to practice on the Harlem. It’s into this incongruent bit of nature amid dense urban sprawl that Bailey Griswold ’12 got into a boat for the first time. As a “walk on,” she was not recruited and not exactly experienced or prepared. But she was part of the team.

“You think of the city, and you think of concrete, steel, and buildings, and then you’re in Inwood on the Harlem River,” Griswold says of her first visit to the boathouse. “It’s so picturesque, and you’re in nature. And you’re like, ‘What? I’m in New York City? What am I doing floating down this river?’”

The Lions compete at Overpeck County Park in New Jersey — a far cry from the turbulent salt waters they train on. Griswold recalled pushing off the dock as strong tides pulled rowers south down the Harlem.

“The worst is when you go out with the tide, because you’re going to shoot out so far, and then you’re like, ‘Ooookay, now we have to turn around and then go back’ — and it’s gonna take twice as long because you run against that tide.”

Unlike teams that practice on fresh lake water, the Lions have to wash saltwater off the boats and equipment lest corrosion set in. It is their last push before heading back downtown for morning classes.

Teams build camaraderie, but the 5 a.m. call brews another kind of bond, says Griswold’s former teammate and current close friend Sylvie Krekow ’13.

“Other teams might also have had early practice schedules, but with rowing, you want to get up early in the morning because the water is typically the best early. It’s the flattest; it’s when the wind is the weakest,” she says. “We had practice Monday through Saturday, 7 a.m., every morning. Because our practice is off campus, we had to all show up at a bus and then go up to the boathouse and then get in a boat and row on the Harlem River, which is inhospitable. It’s pretty brutal.”

The shared conditions create a “hardcore” bond, she says, and winter practice adds another layer of mental tedium. As it’s too cold to be on the water, hours must be spent on the rowing machine without a view, which requires concentration and stamina.

“I think the only way that I got through that is by having a group of girls who were my friends who I could go with, to row next to, listen to music with, get it done, and then all get a nice big breakfast afterwards,” she says.

Another distinction from other sports is synchronicity. If the teammates aren’t in sync, you simply flip the boat, she says.

“There’s one person in the front, the stroke, who’s setting the pace, and then you have to be super in tune and aware of exactly how the girl in front of you is moving, when her back starts moving forward, when her legs go up,” she says. “You develop this rhythm with each other. I can tell, even though I’m behind this person and I can’t see their face, [that] they’re pulling really hard right now or they’re starting to rush and I need to pick it up.”

That’s not to say the teammates are without competition. There are first, second, and third varsity boats, and teammates strive to be in the first boat. But, unlike basketball or softball, no one on the crew gets benched, she says.

Beyond the boat, later in life, she says, the experience translates to work and beyond.

“When you gather your people together and you’re in your boat, [and] you put your head down [and row], you can get through almost anything,” she says. “That is definitely something that I learned from rowing in college.”

Natalie Rutherford ’13 concurs with Griswold and Krekow. Like her dear friends and former teammates, Rutherford says the lessons she learned on the river she now uses in life and work.

“I think rowing is like a lot of discipline, obviously, like being on time,” she says. “But the biggest thing with rowing for me is that you can’t be a good rower if you blame other people in the boat. All that you can control in rowing is your own movements.”

She says if you show poor sportsmanship, you probably won’t last.

“I think that’s my favorite lesson of rowing. … It’s like everybody in the boat has to be kind of selfless in that way.” B

“When you gather your people together and you’re in your boat, [and] you put your head down [and row], you can get through almost anything.”

In May 1912, with little fanfare, Barnard alumnae published the first volume of The Bulletin of the Associate Alumnae. The forerunner of today’s Barnard Magazine, the pamphlet wasted little time getting down to business. On page 1, under the headline “Gifts,” a straightforward report outlined the terms of the residence scholarships created to honor the memory of Lucille Pulitzer, daughter of the famed newspaper baron, who had died of typhoid fever 15 years earlier. Dean Virginia Gildersleeve penned a section on student academics, followed by faculty updates, undergraduate interests, alumnae activities, and, of course, class notes. It wasn’t until April of the following year, in Vol. 2, that the editors of The Bulletin acknowledged its very existence and purpose:

The Bulletin, after years of probation, trusts that it has become an established institution; it even dreams of appearing twice a year. The Editors hope that it may carry with its news of college and alumnae the sense of goodfellowship and warm college spirit. As all we alumnae are united by our common experiences at Barnard, so we have common interest in the growth and progress of the college and the importance and repute of its graduates. Write us what you are doing and what your friends are doing — the rest of us want to know. If you are not a member of the association, we want to know about you just the same; but please join, for we think you are interested in our news and we cannot send you The Bulletin unless you will help us pay the printer.

By December 1922, with more than 2,000 alumnae out in the world, the magazine’s volunteer staff tapped the Columbia Alumni Federation for their “addressograph,” which helped save time and money on getting the Bulletin out to alumnae. Four years later, the editors celebrated the growth of what was once a slim mailer with annual reports into a larger booklet with editorial content.

“We were a pamphlet; we are now a magazine,” they declared — albeit a rather thin one, at just 32 pages. Over the years, the magazine continued to evolve, becoming Barnard College Alumnae Monthly, then Barnard Alumnae, and finally Barnard Magazine, which debuted its bold masthead on the Summer/Fall 1993 cover and featured President Judith Shapiro alongside a quote from her inaugural address: “Virginia Woolf had it right. As she might have put it if she were from the Upper West Side, ‘Give a woman enough subway tokens and college of her own, and let her tell it like it is.’”

After growing from a pamphlet with a few fee-paying readers from the alumnae association to a full-fledged magazine delivered to more than 38,000 alums, the Magazine continues to deliver a “sense of goodfellowship and warm college spirit,” more than a century later — online and in print. On the following pages, today’s editors share a few favorite covers and images that have appeared in Barnard Magazine over the decades. —Tom Stoelker B

Early issues of the Magazine, then referred to as a bulletin, were printed pamphlets. The December 1918 edition was dedicated to Barnard’s war efforts, reporting that “about 136 alumnae have applied to the Barnard Ward Service Corps for over-seas work in the Barnard Units.” The issue includes letters from Barnard alums recounting their day-to-day experiences volunteering abroad for the Red Cross or the YMCA.

As the United Nations building was nearing completion on Manhattan’s east side, the December/January 1952 issue celebrated “Five Continents on Campus,” focusing on students from Argentina, Bolivia, Bulgaria, England, Hungary, Indonesia, Russia, New Zealand, and others from the 60-plus foreign students enrolled that year.

At the height of the Civil Rights Movement, the Fall 1963 issue pointedly highlighted Nigerian exchange students who were at Barnard as part of the African Scholarship Program of American Universities. The article was preceded by a reminiscence by Charlotte Grantz Neumann ’50 about her medical work in Ghana and another article on Juanita Clarke ’65, who was participating in a program that developed science labs and sports fields near Daloa on the Ivory Coast.

The Spring 1970 issue explored “feminism in its various forms,” wrote the editors. This issue also examined the complicated relationship between the College and Columbia in the years before Columbia went coed and included “The Columbia Women’s Liberation Report on Discrimination Against Women Faculty.”

The Fall 1981 issue provided a straightforward “Women at Work” headline on the cover. The issue examined the future of work for American women alongside the continued responsibilities of child rearing. The issue also featured an essay and photos by Merry Selk Blodgett ’67 highlighting starkly different opportunities for women working in China at the time.

Two covers featured quotes that encapsulated former President Judith Shapiro’s eloquence and succinct style. On the Fall issue celebrating her inauguration, a quote blazed across her portrait. Shapiro riffed on the words of Virginia Woolf in A Room of One’s Own: “Give a woman enough subway tokens and a college of her own, and let her tell it like it is.”

The Fall 2001 issue, which came out in the wake of 9/11, also highlighted a quote from President Shapiro, this time against a stark black background, striking a somber note to commemorate the tragic events. Inside were faculty essays, alumnae’s first-person accounts from Ground Zero, and personal reflections from students.

The Summer 2012 issue is one of the few in Barnard Magazine’s history to feature a man on the cover: Barack Obama, who gave that year’s Commencement address while he was the sitting U.S. president. Obama stunned New Yorkers when he chose to speak not at his alma mater, Columbia, but at the all-women’s college across Broadway, making for a historic event and a highly collectible cover.

Sarah Silverblatt-Buser ’15 unites audiences by fusing artistic modes

by Tom Stoelker

What do the circus, parkour, augmented reality, and Edgar Degas’s sculpture Little Dancer Aged Fourteen have in common? For choreographer and director Sarah Silverblatt-Buser ’15, the various forms of art and media represent points of entry for audiences from a variety of backgrounds to experience art that they might not otherwise see or hear.

“I’ve always been really attracted by how we can build bridges between different ways of thinking, but you can’t always be thinking, you also need to feel,” she says. “Art is a good way to sort of hit you in your guts.”

Silverblatt-Buser, who has been based out of Paris since 2018, came back to Barnard last fall to teach a dance class in digital performance at the Movement Lab using virtual reality. The foundation for the class rested on poet Federico García Lorca’s In Search of Duende, a collection of philosophical writings that underpin much of her work. She also taught a class on improvisation.

In the book, García Lorca probes duende, an indescribable and elusive spirit that Silverblatt-Buser says inhabits the performer “sometimes, when you’re lucky.” She adds that duende isn’t just what artists seek but what attentive audiences search for too. She stresses to her students that duende isn’t limited to the stage; it can be found on other platforms, such as VR or AI.

“My whole thesis is when we’re dealing with technology, it is never using it just for technology’s sake but finding how it can bring us back to something that’s even more human,” she says.

Trained as a sociologist as well as a dancer, Silverblatt-Buser credits her liberal arts background with giving her a sense of the “larger picture,” ultimately providing a holistic vantage to view most art. She sees making art as a way to participate in society.

“I always felt frustrated seeing art that felt like it was being made for other artists, for those already indoctrinated into that world,” she says. “My senior thesis at Barnard was on Lincoln Center’s education programs, on teaching artists, and their role as a bridge between the community and the institute.”

Her search for access points and for the ever-elusive duende has led her to many unexpected places, both

“I’ve always been really attracted by how we can build bridges between different ways of thinking, but you can’t always be thinking, you also need to feel.

... Art is a good way to sort of hit you in your guts.”

literal and figurative. Colleen Thomas-Young, chair of the Dance Department and professor of professional practice in dance, sparked the search by encouraging Silverblatt-Buser to enroll in Barnard’s Dance in Paris summer program.

“That was when I first really saw that dance could be many other things, that movement could be many other expressions, that dance didn’t have to live in one kind of space,” she says.

Within four years, she was back in Paris as a professional, working with Yoann Bourgeois, an acclaimed French choreographer noted for his background in the circus as well as his “decompartmentalized” artistic approach.

“Yoann’s work has sort of an acrobatic circus element to it,” she says, adding, “I wouldn’t call myself a circus artist, but I did like horse vaulting when I was young in New Mexico.”

In 2021, her versatility caught the attention of the multimedia director known by the mononym Gordon. He approached her to choreograph and perform as part of an augmented reality experience commissioned by the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. In the piece, she performed before a motion capture camera as Degas’s Little Dancer. Amid pandemic social distancing, the performance “opened” the museum through technology.

With her experience — from horse vaulting and circus acrobatics to becoming a little ballerina — it

would seem that parkour would not be a terribly difficult transition for the artist. Parkour, the acrobatic street art of moving around obstacles by running, climbing, or leaping efficiently, is somewhat akin to American skateboarding in its daring. In 2022, Gordon, working with music director Julien Masmondet, asked her to create an in-person return to the museum with parkour artists and an acrobatdancer. The choreography incorporated the museum’s massive nave and exterior and was set to the minimalist music of Steve Reich.

“Not only was parkour an entry point to the museum, and sort of highlighting the museum as this incredible architectural space, but also an entry point to music that might not be otherwise deemed accessible by young people,” Silverblatt-Buser says.

Likewise, Reich fans were probably encountering parkour for the first time. “It was definitely quite a diverse audience, in terms of generations and where people were coming from,” she says. “I just loved seeing my friends who brought their kids. They were glued to the entire performance, which, you know, try bringing a 10-year-old to a Steve Reich concert.”

The success of the performances brought about yet another commission, this time from Lincoln Center, to create a multiuser, movement-based experience in VR called Collective Body. Silverblatt-Buser used her time at Barnard to research that piece in the Movement Lab, and it will premiere next summer.

Meanwhile, back in Paris, her collaboration with Gordon continues as she co-directs Masmondet’s next concert, Rave-L Party, linking Ravel’s Bolero with techno music. The work will debut next year, transforming the august Théâtre du Châtelet into a contemporary rave.

“A lot of people think that technology might take us further away from our reality, but you can actually use it to bring us back to our embodied selves,” she says.

Regardless of the medium or platform, physical reality centers the work — more specifically, the body.

“Because we express ourselves through movement, if we don’t express ourselves in our bodies, who are we as humans?” she asks, before paraphrasing philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty: “Our body is the medium into the world and how the world receives us.” B

by Marie DeNoia Aronsohn

In the novels of Tee O’Fallon ’86, love always wins. Her genre is romantic suspense, and she’s found myriad ways to bring together heroines and heroes, devising diabolical obstacles to pull them apart, crimes for them to solve, and surprising turns to reunite them. The “happily ever after” conclusion is de rigueur in the romance fiction business, but first come the complications.

“The skeletal structure of all romances is the same,” says O’Fallon. “There’s an initial attraction and a conflict between the hero and heroine, but it’s the ups and downs, the journey to happily ever after, that makes every book different, and that depends on how the author writes the story and the plot.”

Romantic suspense, in particular, has similar but more rigorous requirements than straightforward romance novels. “In the same number of pages, you have to put together a fully developed romance, plus an investigation, a crime plot that has to be solved. The bad guy has to be caught,” she explains.

Today, with 12 novels published and a loyal and growing following, O’Fallon is filled with ideas to complicate the love lives of her characters. It’s no wonder: Her own trajectory to professional novelist has some of the earmarks of her fiction. From her book series —“NYPD Blue and Gold,” “K-9 Special Ops,” “Federal K-9”— a few overarching themes emerge: law enforcement and an affinity for canines. O’Fallon has two Belgian sheepdogs and a backstory filled with career adventures, and both inform the narrative twists she brings to the page.

O’Fallon’s turn to fiction was not an obvious plot point. Her mom was a pediatrician, and her dad was a geological scientist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. At Barnard, O’Fallon initially studied architecture, then switched to major in environmental science. After graduation, she worked at the Army Corps of Engineers and then at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

While working at the EPA, another career beckoned from behind a mysterious door in the federal building. A colleague mentioned that he knew every inch of the federal building where they both worked. But he told her that there was one door he couldn’t get into.

“I asked what was behind that door, and he said that’s where the special agents are,” O’Fallon recalls. “I was so intrigued. I started investigating and decided that’s the kind of work I want to do.”

O’Fallon was soon hanging up her civilian credentials and signing on as a federal agent. She discovered within herself a great capacity for the work.

“My brain just quickly perceived what I need to do to get to the next step of an investigation and to put a case together that could be successfully prosecuted,” she says.

After working federal cases for 27 years, another opportunity drew her in: the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, where she became a police investigator stationed at John F. Kennedy International Airport.

“It’s an interesting agency,” she says, “because it’s one of the few in the U.S. that straddles two states.”

Along the way, O’Fallon, who had always loved reading, was writing her

first novels on her own time. As a teen on vacation with her family, she found her first romance novel in a Hilton Head hotel, started reading, and got hooked on this genre of love and adventure.

“I came from a family of doctors, engineers, and scientists, and we didn’t read romance in our house,” she says, laughing. After that vacation, O’Fallon started going to the library to find more romantic favorites.

About 10 years after graduating from Barnard, she took another beach vacation in North Carolina, this time with her then boyfriend. She brought her beach read — a romance novel, of course — but found it lacking.

“I was so disappointed, I literally threw it into the sand,” says O’Fallon. That’s when her boyfriend suggested she write her own, pointing out that she’d always been a good writer. O’Fallon took to the idea then and there.

“My boyfriend, being a very thoughtful guy, buys me a purple leather-bound binder to start. Over margaritas, we began talking about my first book ever,” she says.

This novel and the next one didn’t land her a publishing deal, but O’Fallon didn’t give up.

“The third time was the charm,” she says. The novel Burnout is about a New York City detective who wants to switch careers to become a chef and stumbles onto an opportunity at a restaurant, but intrigue finds her there. Enter the romantic lead (whose ripped physique graces the book’s cover), and the story takes off. O’Fallon landed a publishing deal for Burnout and two more books to create her first series.

For aspiring writers at Barnard now and everywhere, O’Fallon, who is set to publish her 13th novel in the fall, offers advice based on solid, thoroughly investigated evidence: “The main thing is perseverance. Don’t ever give up. Don’t ever stop trying. Don’t ever stop writing.” B

Poet Kim Rosenfield ’87 draws from her psychotherapy background in new book

by Bruce Morrow ’92SOA

With six volumes of poetry, Kim Rosenfield ’87 has established herself as a versatile and insightful writer of our times. Her latest book, Phantom Captain, won the 2023 Ottoline Prize from Fence Books, an independent nonprofit literary journal and press. Her previous book, USO: I’ll Be Seeing You, from Ugly Duckling Presse, explored the surreal world of comedians entertaining the military in war zones. A poet and psychotherapist based in New York City, Rosenfield writes poetry intended to make readers laugh out loud while guiding them toward imagining new possibilities.

Bruce Morrow: A big congratulations on Phantom Captain winning Fence Books’s

2023 Ottoline Prize. It’s so well deserved. What inspired you to write this dark and humorous book of poetry?

Kim Rosenfield: All my books are collections of everything in my life at that moment, whether it’s what I’m reading or what I’m experiencing emotionally. I keep notebooks, and I write everything out in longhand.

Writing has always been the way I process the world and my life. During the time I started on Phantom, I was reading a lot of philosophy. I was particularly drawn to Buckminster Fuller, despite his controversial reputation. His chaoticness, strangeness, and hope for the future really anchored me during that time, which was during the aftermath of the 2016 election and at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

And just when we thought the world couldn’t get any worse, we find ourselves in the midst of these

major wars, which is why politics is always part of the backdrop of my work. It influences my role as a psychotherapist, reflects the issues my patients bring to the table, and always centers my personal experiences.

BM: Your books capture the intersection of psychoanalysis and poetry so well. I’m curious to know more about the connections you see between Phantom Captain and the unconscious influences that guide our psyches and lives.

KR: I love, love the unconscious. You know, a lot of people don’t believe in its existence, but it’s a guidepost for me. It’s the deeper spiritual realm, in a way. There’s some neuroscience behind it, too. But the poet is always connecting to the unconscious. The poet puts it into words, and when you’re reading it, you connect these specific things that might not typically seem connectable, and that’s the unconscious world. And that’s what happens in clinical work, too. The psychoanalyst is trying to get you to tune into your unconscious, name the unnameable, or put it into a form, shape, or language. It’s a shift in a feeling or what feels unreachable.

BM: Does this have something to do with the “I” in Phantom Captain? Is the “I” autobiographical?

KR: I think everything’s autobiographical. In a way, even if you’re writing about someone else, the choices you make are what you’re drawn to, but not in the traditional sense of autobiography. You can think of it another way, too. The Argentine psychoanalyst Haydée Faimberg says in “Listening to Listening” that there are always at least two to three generations in the room during psychoanalysis. I feel it’s the same in writing — there’s a whole room full of people in the room with me while I’m writing.

BM: That’s so beautiful, how the “I” becomes “we.”

KR: But I always feel like the odd one out, even though I want to fit in and be a part of the “we.”

BM: How about when you were at Barnard? Did you feel part of the “we” there?

KR: Yes, even though I was from suburban California and everyone at Barnard seemed very sophisticated, I knew it would be a good fit for me. I had never used the subway and had never lived in an old building before. I brought my little sheaf of newspaper clippings and portfolio for my interview at Barnard. I was so green. I remember the admissions counselor talking to me about poetry and what poets had attended Barnard and suggesting I go to the East Village and go to Life Cafe. I just felt so seen and heard, and that was extraordinary to me.

Excerpt from Phantom Captain

I am 20 thousand leagues under my epicenter what forms me is molten endurance experience pressed through my own skin

I’m able to recognize carnival gloss for what it is an heirloom emptied out blood box for seeing recycled water bottle of my own tears

Able to see history for what it is of the feminine and the sculptural

Are sculptural conditions required (avenir) intervenes space mines objects mired within ruins of pressed-down hate and love

Eventually, I found my way to a theatre program called Performance in the Arts. Although I had already published a book of poetry before coming to Barnard, I wanted a break from it all and became heavily involved in theatre. However, I still included a performance of a Roland Barthes essay in my senior thesis, which related to my poetry. At Barnard, in every class, there was so much exposure to women’s writing and thinking in the world. It was profoundly influential and important in my life.

BM: So what’s next? What projects are you working on? Are there specific things that you want to accomplish in your next book?

KR: My next project picks up where Phantom Captain left off. It’s about aging, war, and suffering. I’m doing a deep dive into the Spanish Inquisition. That’s the basic springboard. I’m sure I’ll go in all the directions I always go in. But my dream is to move to Madrid. I actually had a reading in Madrid in the fall of 2023. I went to the Prado. I loved it so much I bought a year pass, even though I knew it would be impossible for me to return. It was wishful thinking. Who knows? I love Goya. I have his biography by Robert Hughes sitting right next to me. I love the way he subtly stuck it to the aristocrats who supported him. I love his daring politics, his paintings, and his silver engravings, which are still shocking. They speak about war and poverty, which is so relevant today. B

Leadership Assembly 2024 November 1 & 2 Barnard Campus

Hear updates from College administrators, participate in volunteer development sessions, learn about current Barnard volunteer opportunities, and most importantly, connect with other Barnard graduates to share your experiences. All alums are welcome!

HAVE IDEAS FOR THE 2024 LEADERSHIP ASSEMBLY? Scan the code with your camera to take our quick survey!

Dear Bold, Beautiful Barnard Alums,

As I conclude my first year as AABC president, I’m feeling even more humbled, grateful, and proud to represent my beloved Barnard. Juggling work-life balance as an entrepreneur while participating in countless Barnard networking, social, and regional events sometimes made balance seemingly impossible to attain. I chose to view such challenges as catalysts and opportunities to improve, build, and grow personally and professionally. And also in these moments, I turned to my Barnard community, to my mentors and my coaches. We all need this, and I’m going to advocate that we proactively engage in self-care and prioritize our physical, mental, and emotional wellbeing.

Many times this year I’ve had to reach inside to tap into the bold, confident Barnard woman that’s in my DNA, especially on those days when I was just not feeling it. I’m reminded of a woman who encouraged me during a semester when it felt like I was an impostor, lacking what it took to support my findings in my organic chemistry lab work. I am so grateful for Professor Toby Berger Holtz. She graciously made me a priority, helped me after class, met me during her lunch hour, and became the gentle, approachable teacher and friend that I desperately needed at that time. Her help and confidence in me gave me the conviction to believe in myself and see the importance of engaging in our community. So let’s seize the day and make the most of these summer opportunities to recharge, engage, and be part of this amazing Barnard alumnae community! Here are a few ways to be involved while paying it forward:

Support a scholarship that gives a deserving student the chance to obtain a Barnard education. Consider attending a Regional Summer Send-Off to meet a new student and their family. Post a paid internship or short-term project through Beyond Barnard to help mentor and grow a current student’s portfolio. Or connect with alums on the new Barnard Communities site (our.barnard.edu/communities) — perhaps even offer to have an informational coffee chat with a fellow alum who is considering a move to your industry or city.

In my first letter in this magazine a year ago, I wrote that I’m a firm believer that women need other women to champion, advocate, and cheer for one another. Our community has been challenged in the months since then, and if there’s one thing that I’ve learned, it’s that this bold, dynamic community is, and always will be, #BetterTogether.

This fall, I’m looking forward to creating more of the opportunities that will help fellow alumnae and the next generation of Barnard women to grow, thrive, and succeed. Until then, enjoy your summer! Let’s stay connected online and in person and please reach out — I am a resource and friend.

With gratitude,

Sooji Park ’90 AABC President, Alumnae Trustee

Ask a few Barnard alumnae the same question, such as “Where are you from?,” and the answers come back as diverse as their backgrounds: the Bronx, Denver, Qatar. Ask them questions about Barnard and their answers come back in a remarkably similar fashion, regardless of their age, background, or career. Robin Whitney ’68, Juliana Flynn ’72, Ada Ferraro ’88, Sooji Park ’90, and Nora Hassan ’21 sat down with Barnard Magazine to discuss their Barnard experience.

To view the video, visit barnardbold.net/throughtheyears

by Rebecca Goldstein ’07

1 Thick slice of cake

5 The Barnard Store’s Dad Hat, for one

8 ___ acid (protein building block)

13 Spelunker’s spot

14 Frigg’s husband

16 Given a moniker

17 Destroy

18 Perlman who played Ruth Handler in Barbie

19 Furious

20 Tossed in

23 According to

24 Spicy, in a way

25 Shuttle vehicle, maybe

26 “Crikey!”

28 Gummy bear ingredient

32 Marine mammals often referred to as “river wolves”

36 The Gilded Age network

37 “Highway to Hell” band

38 Liquid for frying latkes

39 Work in the garden

40 Watch

41 Savory pastries

45 “It’s possible”

47 Deep desire

48 Singular

49 Scribble in the margins, maybe

51 Relaxation station

54 Psychology Department program focused on child development, or a hint to the circled letters

57 Madrid museum

59 Focus of chem professors Merrer and Rojas

60 Helper

61 Mes de verano

62 Event ___ (space in the Diana Center)

63 “Let’s do it!”

64 It’s not a good look

65 Conclude

66 Celebratory suffix

1 Leftover fabric or paper

2 Magna cum ___

3 Bookworm

4 Fine, in Florence

5 Espresso bar order

6 For a specific purpose

7 Religious devotion

8 Lions and tigers and bears, e.g.

9 Yacht spot

10 Where to see the big picture?

11 Hockey goal material

12 Lauding lines

15 “Count me out”

21 “Shucks!”

22 Happily ___ after

27 Enby, maybe

28 Chanukah coins

29 “Don’t rush”

30 Skeptical comment

31 Shows interest in a lecture, or not

32 Quick breath

33 Frozen treat with Pina Koala and IguaNana flavors

34 ___ Restaurant, Morningside Heights diner seen in Seinfeld

35 Aunt, in Spanish

39 Move like an excited puppy’s tail

41 Oven for naan

42 Guest piece in the Spec, say

43 Sleeping through the party in the next room, say

44 Maggie the Magnolia, for one

46 Comfy layer that may zip up

49 Brain cell

50 Brain, e.g.

52 Toe treatments

53 Isn’t for you?

54 Word after fairy or folk

55 British bathroom

56 Newbie

57 Possible outfit for an 8 a.m. lecture

58 Jog in Riverside Park

Rebecca Goldstein ’07 is a scientist and crossword constructor who lives in the Bay Area with her wife. She was named 2023 Constructor of the Year at the annual ORCAS awards. Answers on page 63