WINTER 2024

THE ARTS ISSUE

AWARD-WINNING MUSIC

PRODUCER EBONIE SMITH ’07

MUSEUM CURATORS ON OBJECTS OF INTEREST

A COURSE PAIRS STUDENTS WITH GUEST ARTISTS

20

Object Lesson

Curators of the country’s top art institutions on the objects that inspire them

Features Departments

28

Music as Ministry by Kenrya Rankin

How

32

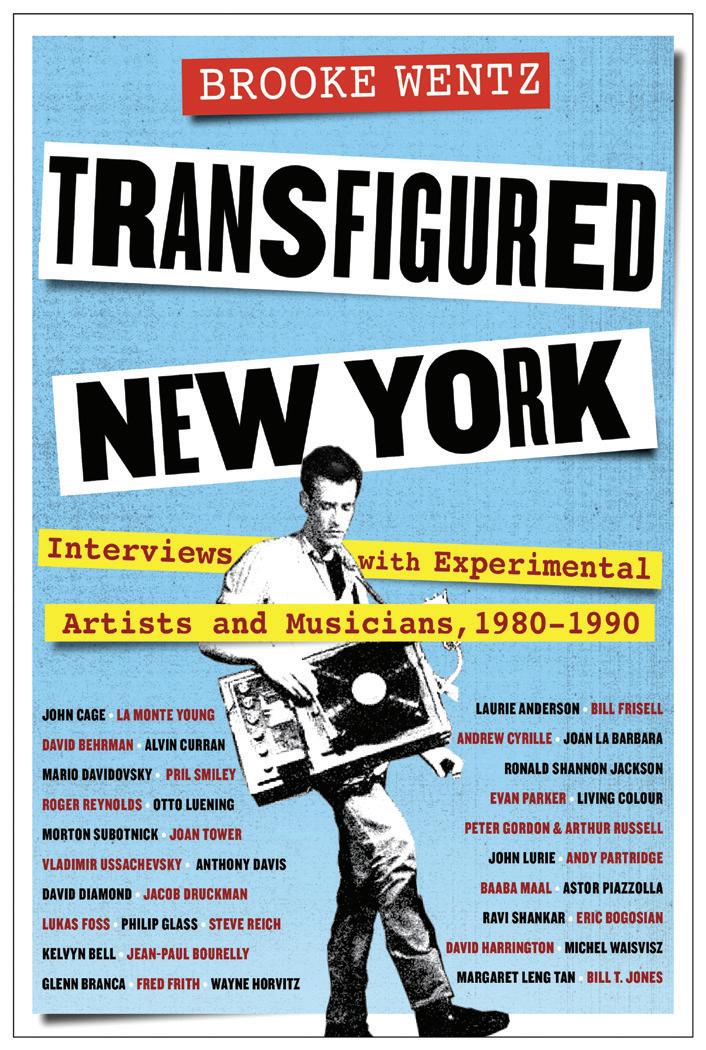

Radio Days by Michael B. Dougherty

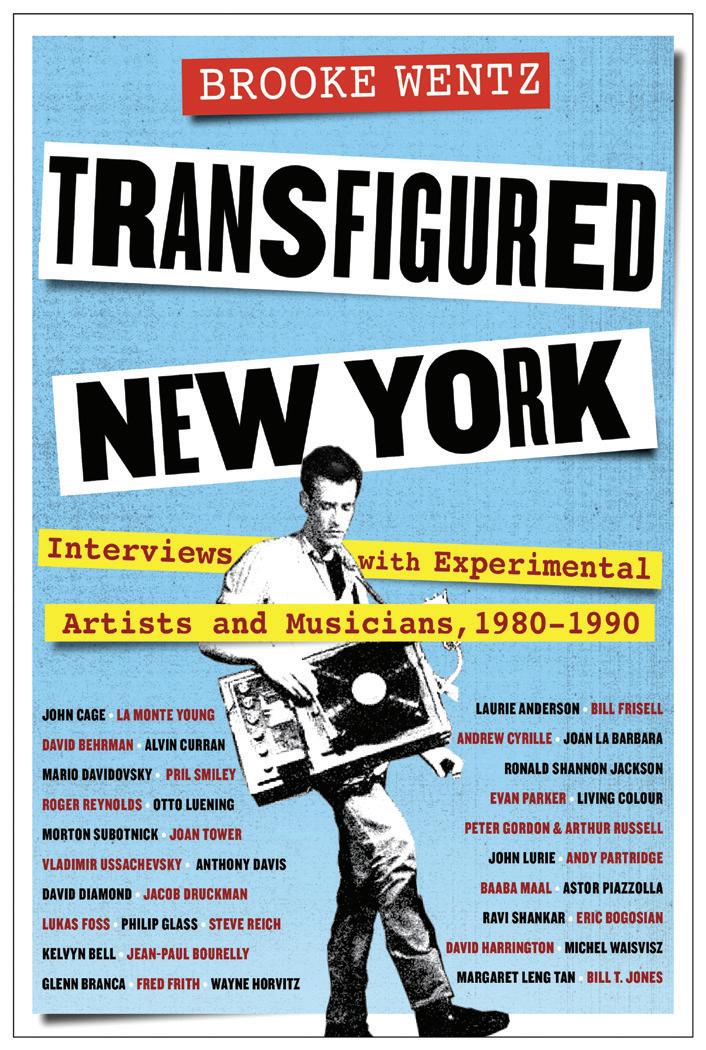

In a new book, Brooke Wentz ’82 unearths rare interviews with musical luminaries she met while deejaying at Barnard

2 Contributors & Feedback

3 From President Rosenbury

4 From the Editor

5 Dispatches

President Laura Ann Rosenbury’s Inauguration

Headlines | Film Fellowship; Jennifer Finney Boylan Elected President of PEN; Barnard Zines at the Brooklyn Museum

11 Discourses

Faculty Focus | Achiro P. Olwoch

Read Watch Listen | Bookshelf; We Live Here: The Midwest; Lift; The Wise Unknown; Black Cake

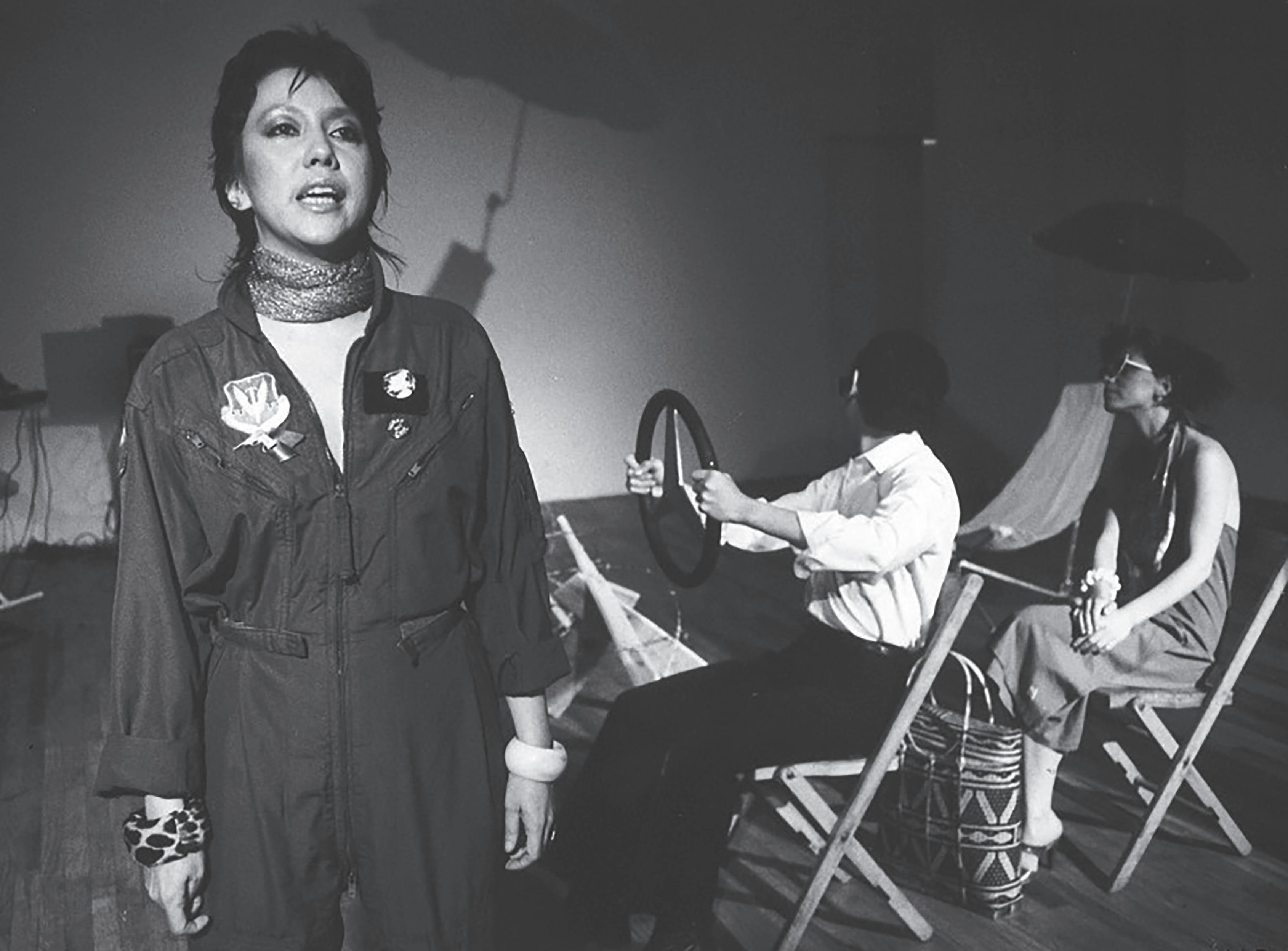

Backstage at Barnard | To Dance On Fire

37 Noteworthy

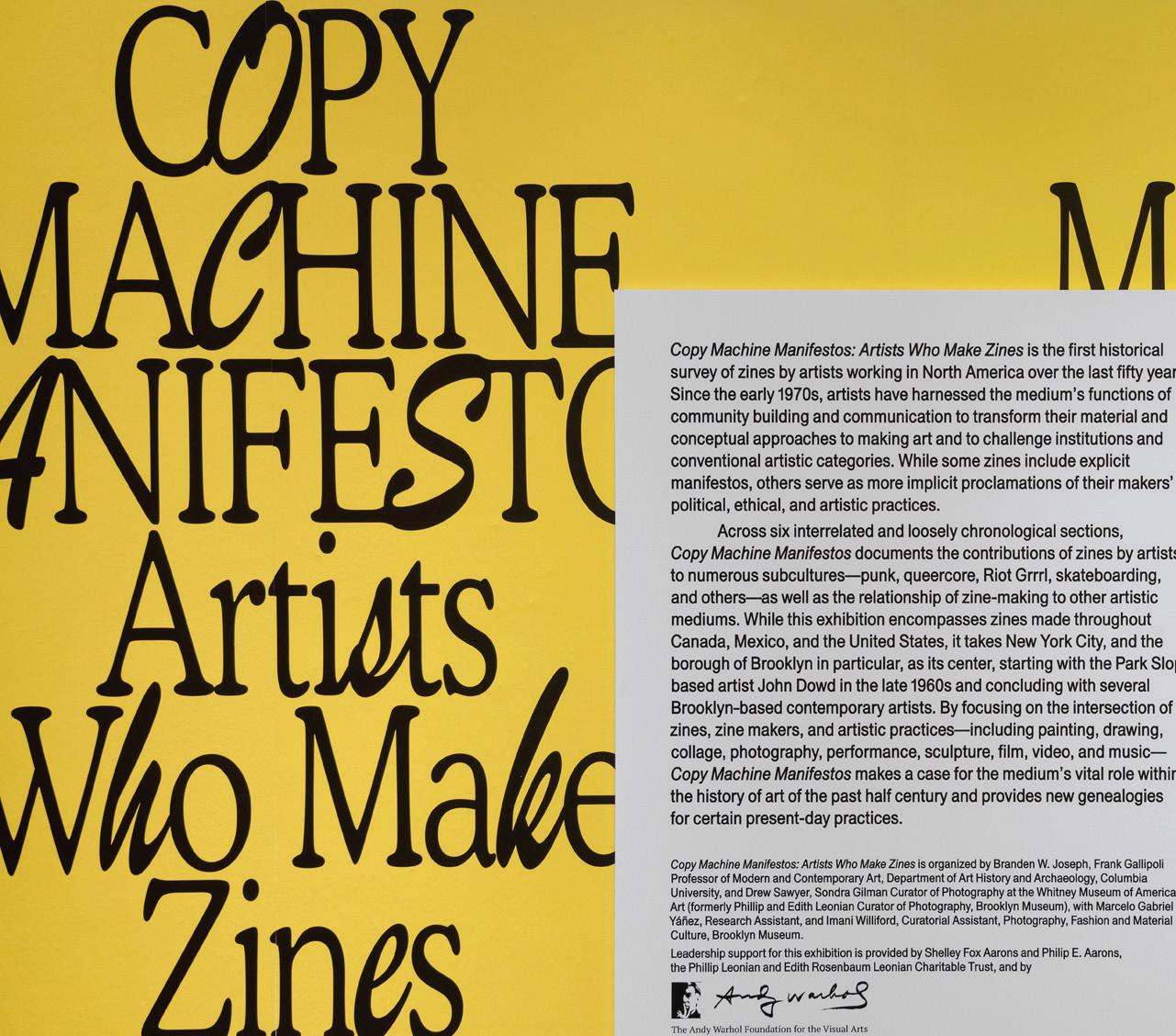

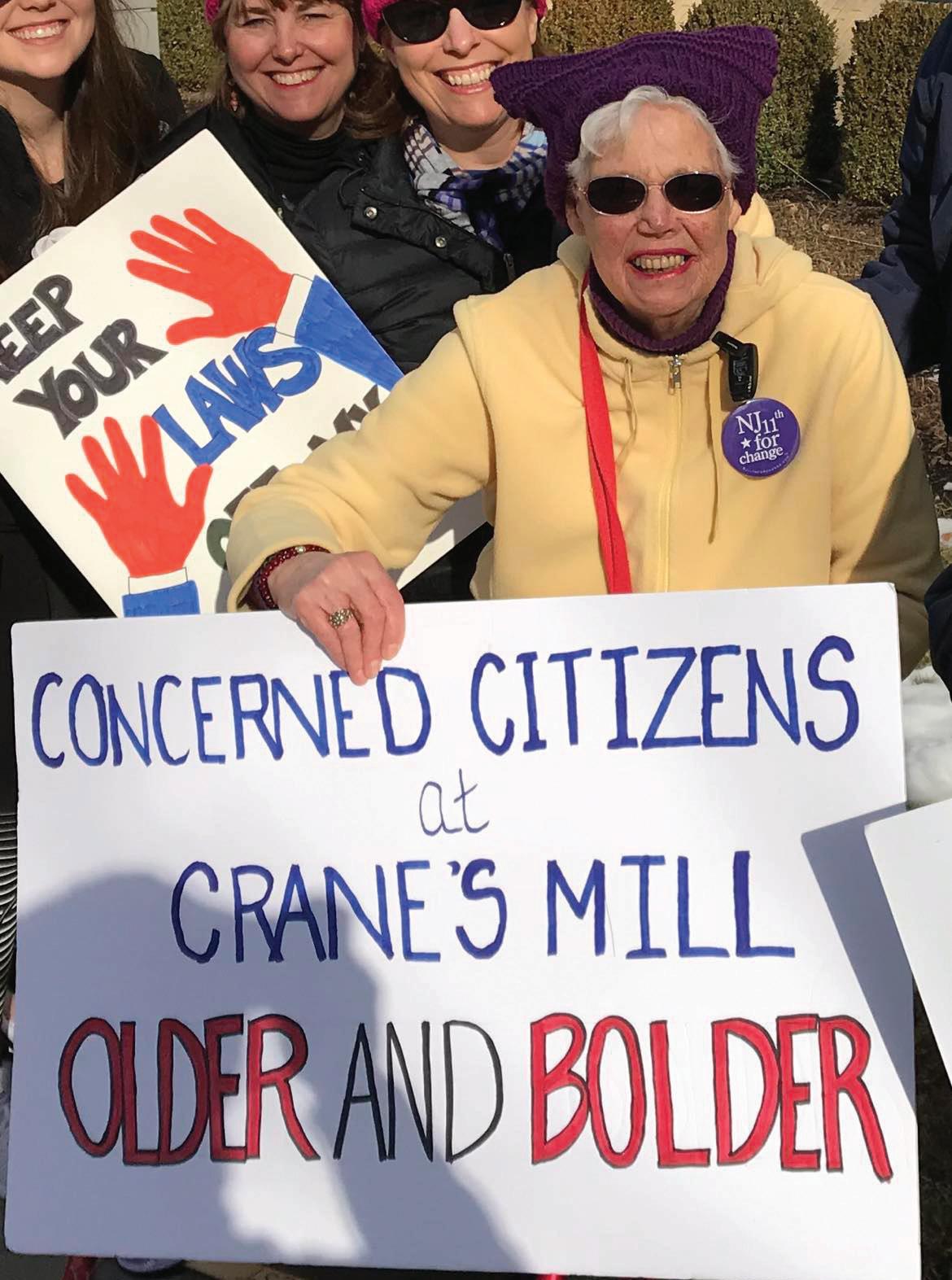

Perspectives | Akosua Barthwell Evans ’68

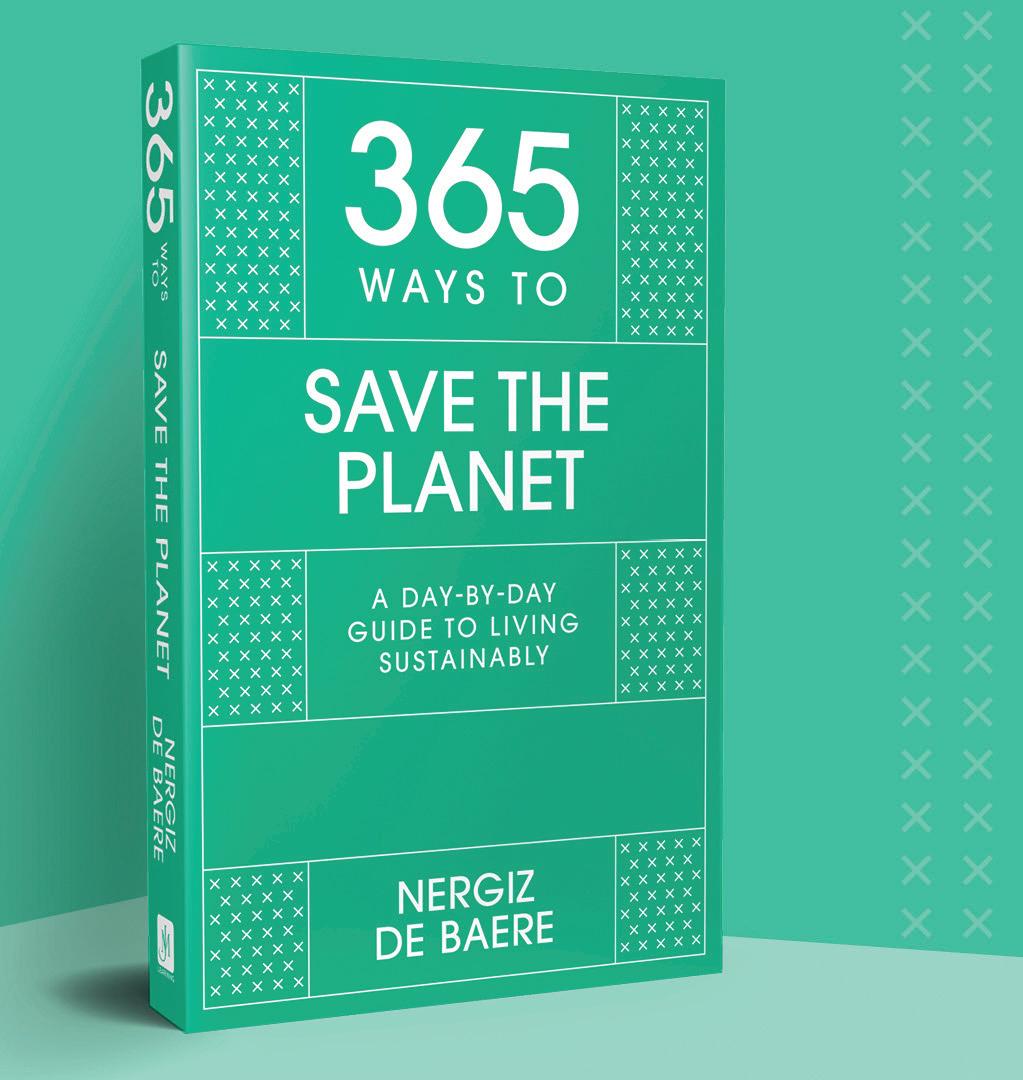

Q&Author | Nergiz De Baere ’18

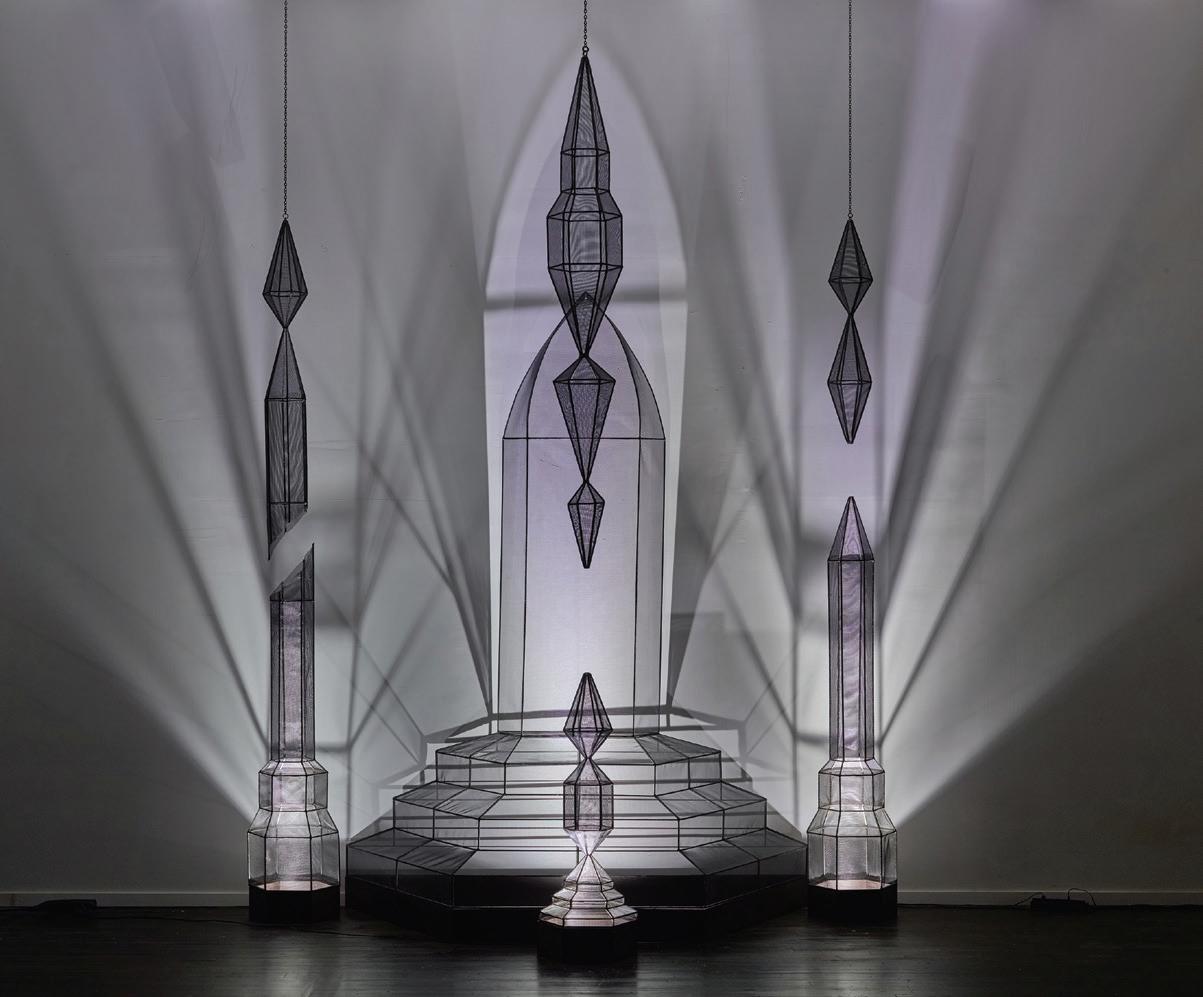

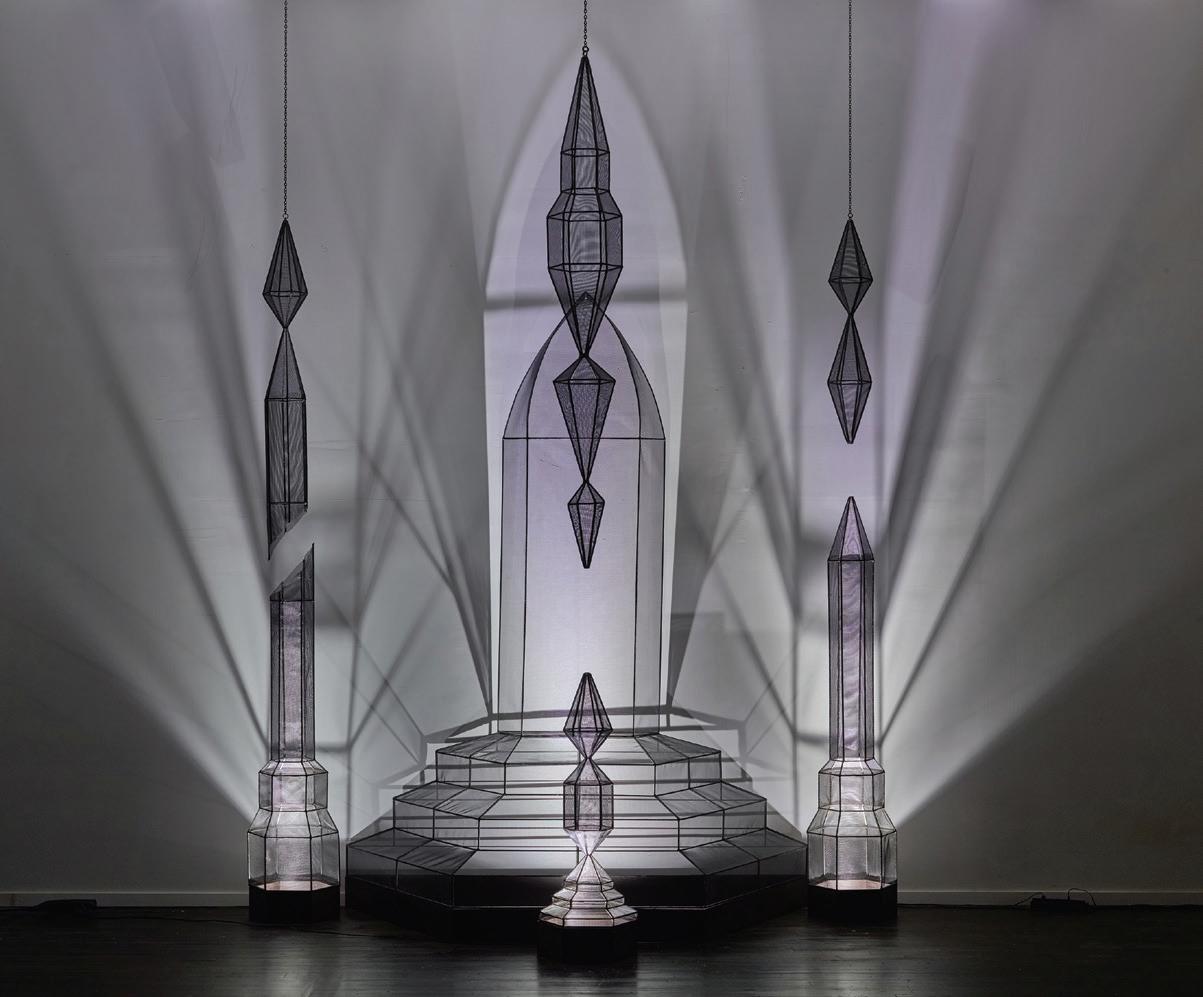

Sketchbook | Afruz Amighi ’97

AABC Pages | From the AABC President; Millie's Friends; AABC election nominees

Class Notes

In Memoriam

Tribute | Margarida Pyles West ’50 and Rebecca Lubetkin ’60

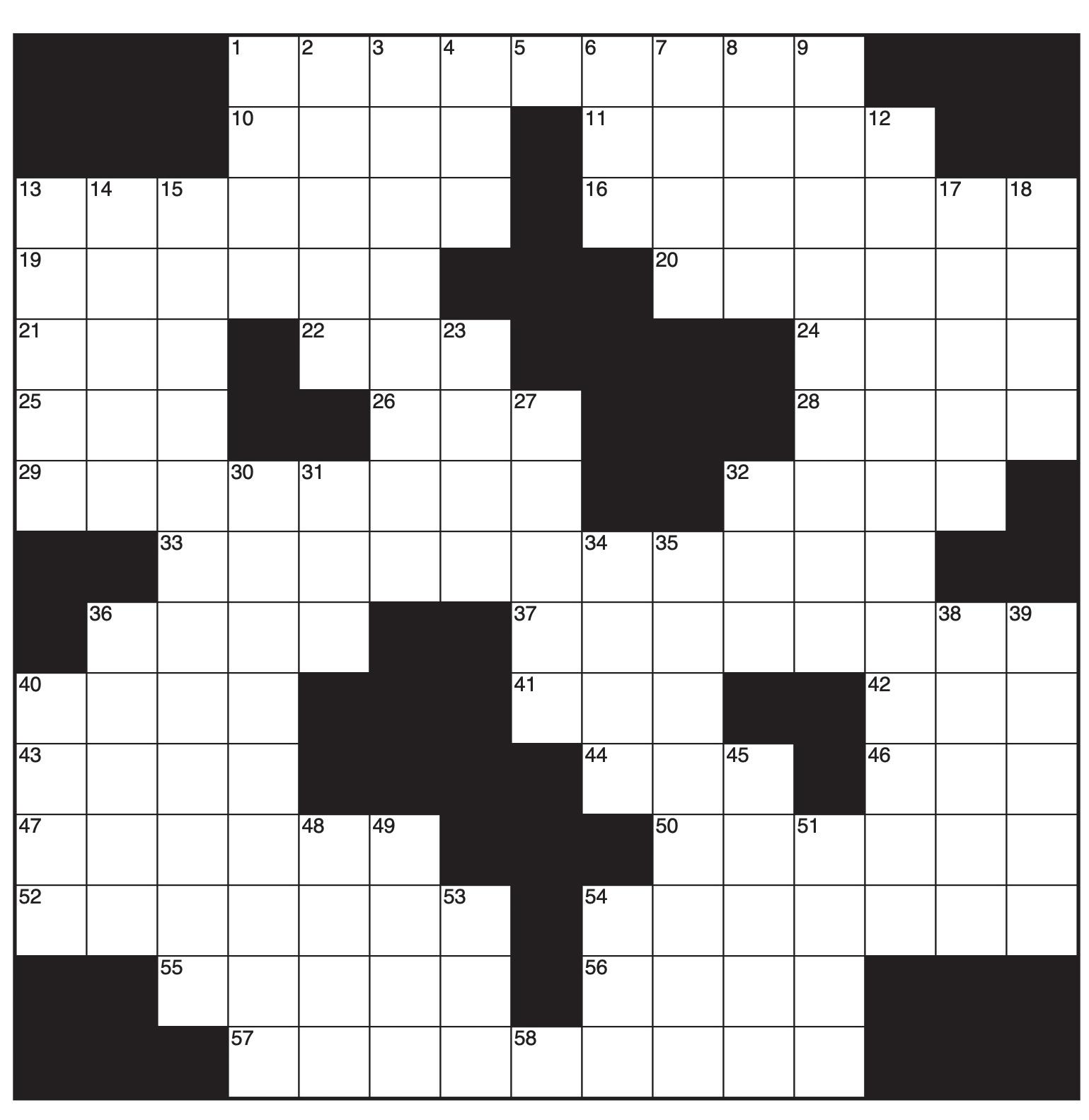

Crossword

On the Cover

Photograph of Ebonie Smith ’07 by Matt Fajardo

Opposite Page

Dancer With Necklace, 1910, by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Purchased with funds provided by the Robert Halff Endowment Fund, Modern and Contemporary Art Acquisition Endowment Fund, Modern Art Acquisition Fund, Robert Gore Rifkind Foundation, Modern Art Deaccession Fund, and LACMA’s 50th Anniversary Gala, in honor of Stephanie Barron, the museum’s Senior Curator of Modern Art

Back Cover

Photograph by Carrie Glasser

the music business

award-winning producer Ebonie Smith

’07

is remixing

PHOTO BY MATT FAJARDO

Contributors

KENRYA RANKIN (“Music as Ministry,” p. 28) is an award-winning author, journalist, editorial consultant, and producer. She works on movement building at the intersection of AI and justice at Mozilla Foundation, is a contributing books editor at Essence, serves as principal at the editorial consultancy Perfectly Said Studio, and has authored five books, including How We Fight White Supremacy: A Field Guide to Black Resistance. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Reader’s Digest, Ebony, Fast Company, and many other national publications and has been translated into 21 languages. Rankin holds degrees from Howard University and New York University. She lives in Washington, D.C., where she enjoys Beyoncé dance parties with her kid and belly laughs with her partner. (Kenrya.com)

MARIE DENOIA ARONSOHN (“To Dance On Fire,” p. 18) leads strategic communications at Barnard College and has had an Emmy Award-winning career as a TV journalist with a vast body of work. Her experience includes producing, writing, and reporting for major media outlets, including NJTV, WCBS-TV, CBS, MSNBC, WNET, and NJN. She has also served as a professor of media and creative writing at Rutgers University. Aronsohn led communications at Columbia’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, serves as a communications consultant to the Columbia Climate School, and has written dozens of articles on climate science. She earned her MFA in fiction writing at Columbia University in May 2023, is the mother of two adult children, and lives in Rockland County, New York.

MERRI ROSENBERG ’78 (“Tribute,” p. 78) is a freelance writer and editor specializing in education and social justice issues. During her four-decade career, she has written for national publications such as Parents and Jewish Week and has been a contributor to Barnard Magazine since 2000. Rosenberg regularly freelanced for the Westchester section of The New York Times, ultimately penning the “In the Schools” column. After Barnard, she earned a master’s in French at Columbia as well as a master’s from its Graduate School of Journalism. Rosenberg lives in Westchester County with her husband (SEAS ’77) and their rescue poodle mix. She is the mother of two adult children and an ecstatic grandmother of three.

FEEDBACK

Many compliments on the Fall issue. The layout and composition are truly wonderful. The whole issue was a special treat, especially getting to know President Laura Rosenbury.

—Dr. Joyce Rosman Brenner ’61

The Summer digital edition began the first whole summer of the pandemic, with off-site work for staff and general disruption of routines given as the reasons. We have been out of the pandemic for some time now, and I have been asking when we will restore the print edition for the summer.

—Catherine B. Cretu ’71, Class Correspondent

Our reply: Thank you for your letter and commitment to the magazine, particularly as a Class Correspondent. The pandemic did initially require us to pivot to a digital summer issue due to College-wide budget cuts. However, since then, printing and mailing costs have continued to rise well above pre-pandemic levels, necessitating that we continue to print three issues a year in addition to our digital summer edition.

EDITORIAL

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Nicole Anderson ’12JRN

CREATIVE DIRECTOR David Hopson

MANAGING EDITOR Tom Stoelker ’10JRN

COPY EDITOR Molly Frances

PRODUCTION DIRECTOR Lisa Buonaiuto

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS N. Jamiyla Chisholm, Kira Goldenberg ’07

WRITERS Marie DeNoia Aronsohn, Mary Cunningham, Isabella Pechaty ’23, Preetica Pooni

ALUMNAE ASSOCIATION OF BARNARD COLLEGE

PRESIDENT & ALUMNAE TRUSTEE Sooji Park ’90

ALUMNAE RELATIONS

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Karen A. Sendler

ENROLLMENT AND COMMUNICATIONS

VICE PRESIDENT FOR ENROLLMENT AND COMMUNICATIONS

Jennifer G. Fondiller ’88, P’19

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS

Quenta P. Vettel, APR

PRESIDENT, BARNARD COLLEGE

Laura Rosenbury

Winter 2024, Vol. CXIII, No. 1

Barnard Magazine (ISSN 1071-6513) is published quarterly by the Communications Department of Barnard College.

Periodicals postage paid at New York, NY, and additional mailing offices.

Postmaster: Send change of address form to: Alumnae Records, Barnard College, Box AS, 3009 Broadway, New York, NY 10027-6598

EDITORIAL OFFICE

Barnard Magazine, Barnard College, 3009 Broadway, New York, NY 10027-6598 | Phone: 212-854-0085

Email: magazine@barnard.edu

Opinions expressed are those of contributors or the editor and do not represent official positions of Barnard College or the Alumnae Association of Barnard College. Letters to the editor (200 words maximum) and unsolicited articles and/or photographs will be published at the discretion of the editor and will be edited for length and clarity.

The contact information listed in Class Notes is for the exclusive purpose of providing information for the Magazine and may not be used for any other purpose.

For alumnae-related inquiries, call Alumnae Relations at 212-854-2005 or email alumnaerelations@barnard.edu.

To change your address, write to:

Alumnae Records, Barnard College, Box AS, 3009 Broadway, New York, NY 10027-6598

Phone: 646-745-8344 | Email: alumrecords@barnard.edu

2

PHOTO BY DOROTHY HONG

From President Rosenbury

Our Fearless Future

For nine months now, I’ve had the honor of serving as the president of Barnard. It was thrilling to stand at the podium at Inauguration and see colleagues, students, alumnae, and my family and friends all together inside Riverside Church. As I said on that special afternoon, the day affirmed what I knew from the first day I set foot on campus — that Barnard is where I am supposed to be.

Paving the path for Barnard’s future must be a collaborative and pluralistic effort. I’ve spent the past nine months listening and learning. I’ve had the opportunity to get to know our brilliant and dedicated faculty and staff and our fearless and passionate alumnae and students. Through the Shaping Barnard’s Future Together initiative, I’ve had meaningful conversations with the many individuals and stakeholders who are committed to and responsible for the College’s success. Their recommendations have been pivotal in helping us determine priorities that are bold in scope and ambition. Through our collective resources, contributions, and skill sets, and with open dialogue guiding us every step of the way — even when it is challenging or uncomfortable — I know Barnard will build upon our historic strengths and lead into the future.

Bold History. Fearless Future. This vision is based on five foundations that will strengthen our communities of care, reimagine our infrastructure, embrace “OneBarnard,” lead for tomorrow, and grow our resources. We will prepare to tackle some of the biggest challenges we face today, from the climate crisis to the AI revolution, and strive to continuously innovate. We will reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2040 with the help of our own sustainability experts. We will continue to lead on issues of gender, from reproductive health to political engagement. We will double down on our commitment to access, making sure Barnard continues to be a place that the most extraordinary young women in the world — no matter their background or their ability to pay — want to attend and are able to attend. We will cultivate community on campus, support well-being, and build relationships with our Harlem and Morningside Heights neighbors. We will invest in state-of-the-art technology, upgrade our dorms, and foster a spirit of partnership on campus.

Critically, we will grow Barnard’s endowment over the next decade so that we will reach our first billion dollars in sustained, perpetual support. With this endowment growth, we will protect the programs that mean so much to the mission of Barnard. We will ensure our financial aid program is best-in-class. This will enable us to be on more equal footing as we compete with other elite colleges and universities. I extend my sincere gratitude to Roy and Diana T. Vagelos ’55 and Board of Trustees chair Cheryl Milstein ’82, P’14, and her husband, Philip, for making the first generous contributions toward this goal at a pre-inauguration dinner.

Yes, we have set the bar high. But I know we can reach it — because we are capable, and we are fearless. As Alexa Easter ’23 said so eloquently at Inauguration: “Here, tradition means pushing against tradition and imagining something else — something bigger, dare I say, bolder.” B

Visit barnard.edu/bold-history-fearless-future to learn more.

WINTER 2024 | BARNARD MAGAZINE 3

Setting the Stage

I am writing this letter on a chilly day in early February, just after an exciting, historic moment for us at the College: the inauguration of Barnard’s ninth president, Laura Rosenbury, on February 2. We wanted to celebrate this landmark event in our issue (see pages 6-7), so the Magazine is reaching you a little later than usual. We appreciate your patience. Without further ado, I am happy to introduce our Arts Issue. In these pages, we’re throwing a spotlight on the many artistic endeavors and professional pursuits of Barnard’s alumnae, students, and faculty members. You’ll read about individuals from different creative fields, including curators, filmmakers, sculptors, playwrights, dancers, deejays, and more. Some with less obvious paths, others who knew their calling from a young age. But what they share, as many alums explain, is that at Barnard they found a place that nurtured their interests and set the stage for a future in their respective professions.

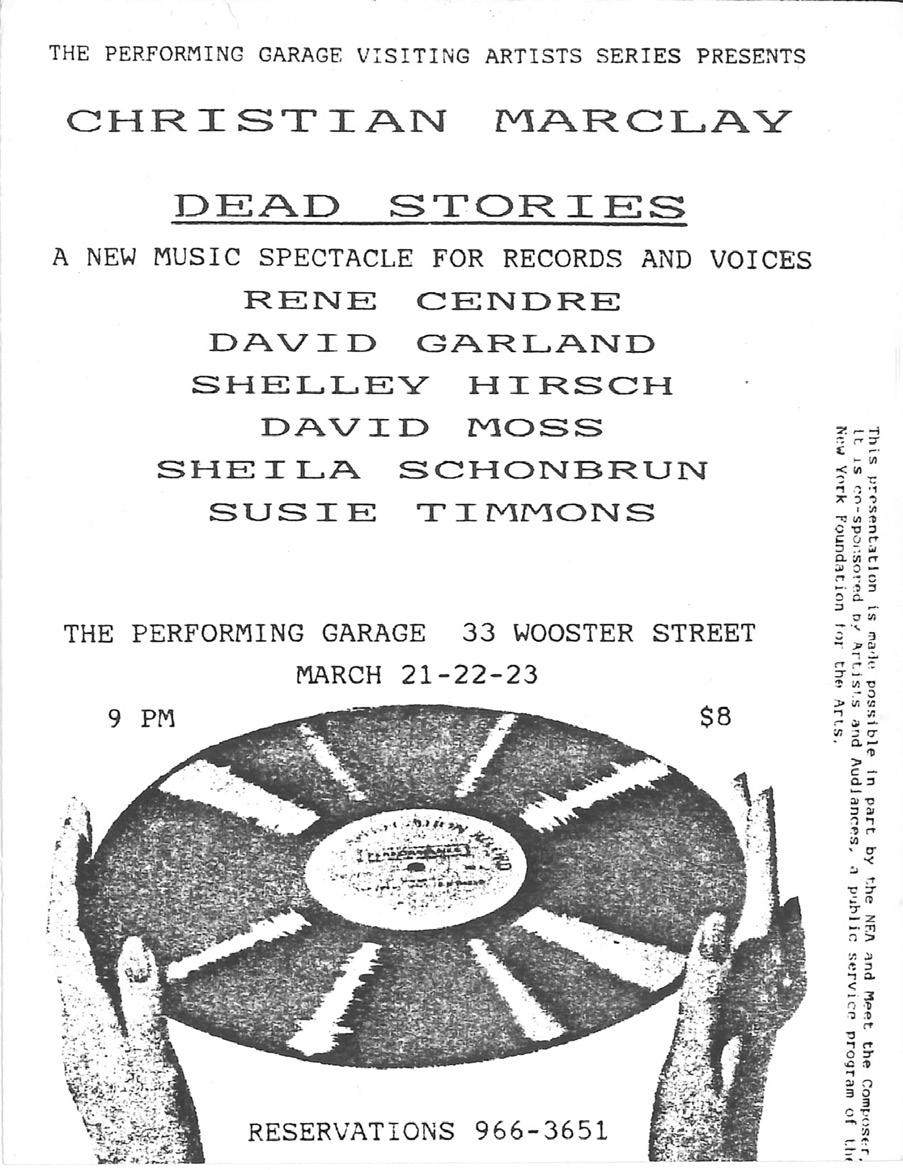

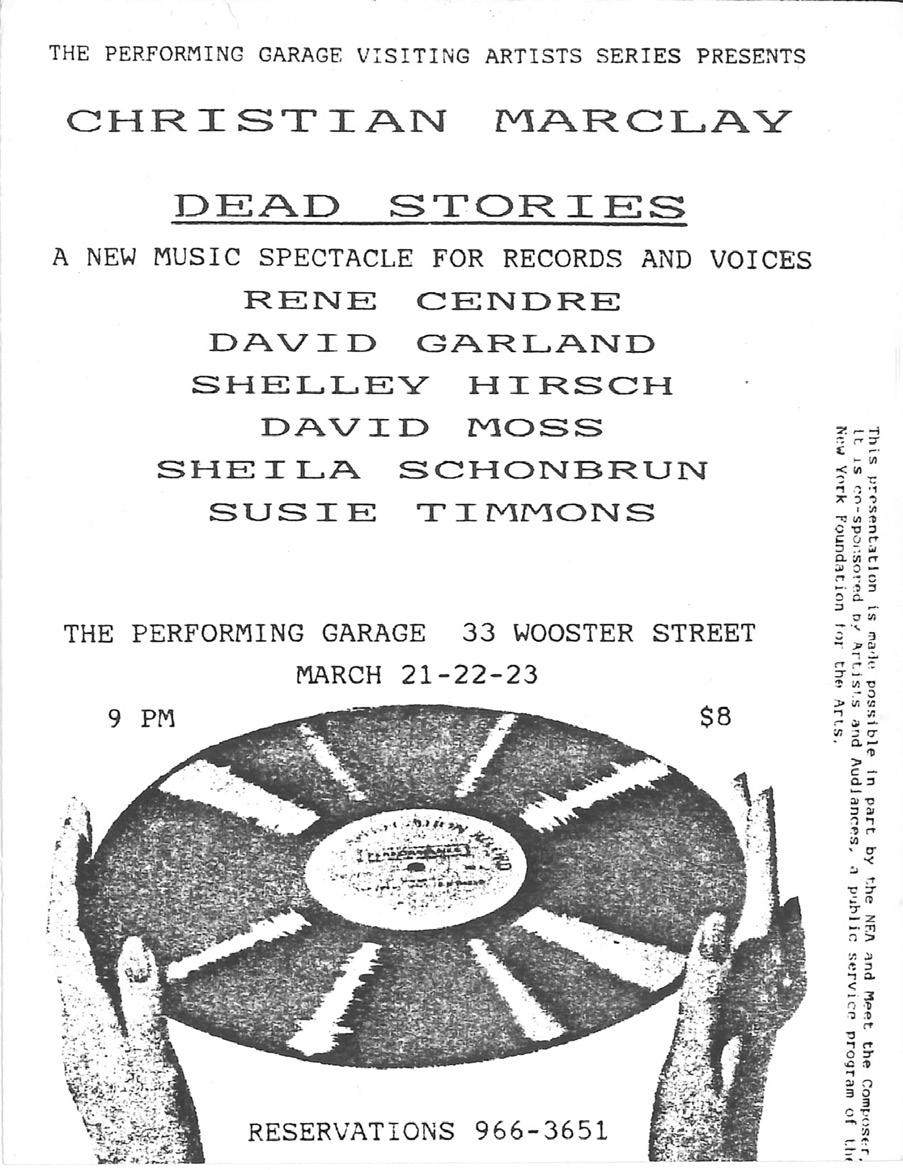

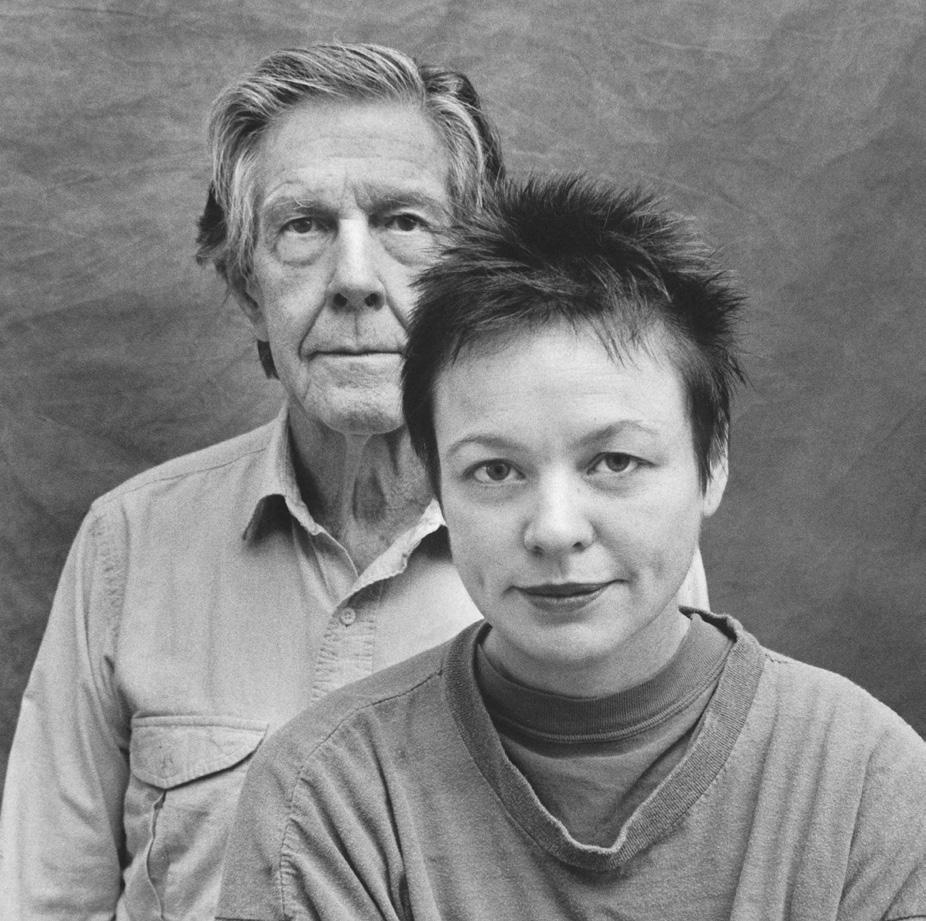

For Brooke Wentz ’82, a gig hosting the radio show Transfigured Night on Columbia University’s WKCR-FM during her undergrad years was an auspicious start to a career as an expert on music rights and licensing. That seminal experience on air exposed her to the luminaries of the avant-garde music scene and provided the material for her new book, featuring those very conversations with musicians such as Laurie Anderson ’69 (page 32).

You’ll also learn about Makeda Best ’97, the Deputy Director of Curatorial Affairs at the Oakland Museum of California, whose early interest in photography was further encouraged by Dean Vivian Taylor, who suggested that Best exhibit her black-and-white portraits in the Dean’s Office when she was a recent transfer student (page 20).

In our cover story, we bring you into the studio with Ebonie Smith ’07, an awardwinning music producer, audio engineer, and singer-songwriter. At Barnard, Smith created an academic program for herself that bolstered her love for music and furthered her dedication to gender equity, culminating in the launch of the Gender Amplified conference, which continues on as a nonprofit that supports women and nonbinary music producers (page 28).

Putting this issue together has made me reflect on the purpose of the arts — why we create art, why we seek it out. I keep going back to something Smith said: “Music transcends differences. … It creates equilibrium and allows us to enjoy each other.” And for this reason, the arts are more vital now than ever before.

Nicole Anderson ’12JRN, Editor-in-Chief

Nicole Anderson ’12JRN, Editor-in-Chief

4

From the Editor-in-Chief

PHOTO BY NINA WURTZEL

Dispatches News. Musings. Insights. PHOTO COURTESY OF BARNARD COMMUNICATIONS

6

Top: President Laura Rosenbury offers her inaugural address. Above, left to right: Student Government Association president Mariame Sissoko ’24; Columbia's President Minouche Shafik, Board of Trustees co-vice chair Diana T. Vagelos ’55, President Rosenbury, Board of Trustees chair Cheryl Glicker Milstein ’82, P’14; President Rosenbury shares a moment with Nalini P. Kotamraju, her longtime friend and first-year roommate at Harvard-Radcliffe College.

Milestones

The Inauguration of President Laura Ann Rosenbury

On February 2, the Barnard community came together for the inauguration of the College’s ninth president, Laura Ann Rosenbury. Students, faculty, staff, alumnae, and trustees — alongside representatives from government and academic institutions — filled Riverside church to celebrate this historic moment. Rosenbury’s family, friends, and former colleagues were in attendance and spoke from the podium, and in a tribute video, to honor her accomplishments and wish her the best of luck in her new role.

“Laura and Barnard are a perfect fit. Starting with me, she has supported young women in realizing their dreams,” said President Rosenbury’s younger sister, Linda Rosenbury. “I am confident that she will continue Barnard’s long-standing commitment to excellence in women’s education.”

From her time at Harvard-Radcliffe College, where she studied under professor (and now senator) Elizabeth Warren, to Rosenbury’s scholarly work, in which her reimagined feminist theory in law, attendees gained fresh insight on the president’s many accomplishments and her impressive career. Longtime friend and college roommate Nalini P. Kotamraju spoke of Rosenbury’s deep-seated passion for feminist ideals. “When Laura told me she had accepted this role, I laughed aloud in joy at the absolute rightness of the fit,” she said. Rosenbury’s mentor and friend Martha Minow, the Harvard University 300th Anniversary University Professor, assured the crowd, “For Laura, schooling is not just a means to an end but also a vibrant world of present experiences.”

Board of Trustees chair Cheryl Glicker Milstein ’82, P’14, said the board knew they made the perfect choice for president, especially at this moment in time. “We wake up every day in a world where women see our fundamental rights under attack,” she said. “We have a leader in Laura who has devoted her life to taking on these fights ... who leads with a quiet strength and conviction and provides an example for every one of our students to emulate.”

Columbia University’s President Minouche Shafik highlighted how Rosenbury joins a University community that remains “proud to count some of the most celebrated women in the world as partners and friends” for more than 135 years.

Taking the podium after an introduction by Kotamraju, Rosenbury shared her vision for Barnard in her inaugural address by reminding the audience of what makes Barnard special — its bold ability and commitment to meet and solve tough challenges, regardless of the time period. She then discussed her priorities, which fell into five distinct areas: build communities of care, reimagine our infrastructure, embrace “OneBarnard,” lead into the future, and grow our resources.

“We pursue different passions, and we passionately disagree,” she said, concluding her remarks with, “I know that all of us will come together right now, in this moment, to begin our work together as one community, as one Barnard, boldly leaning into our history — what makes us special, what we will never lose, while fearlessly leading into a new future.” B

WINTER 2024 | BARNARD MAGAZINE 7

Film Fellowship Brings Industry to Campus

Two rising filmmakers talk technology, teaching, and claiming space

Students in Barnard’s Film Studies Program explore many facets of cinema, often through a feminist lens, from courses on film production to screenwriting. Recently, the College began offering courses taught by industry practitioners well versed in

the latest tastes, trends, and technological advances.

The initiative has been made possible through a $3 million gift from American film producer and philanthropist Regina K. Scully’s Artemis Rising Foundation, which has, in turn, funded the Artemis Rising Foundation Filmmaker Fellowship.

This spring, students have snapped up seats in classes taught by the fellows on such topics as writing for television, using found footage, and storytelling with archives. “The response has been overwhelming,” says Ross Hamilton, program director for the past two decades and chair of the

8 Headlines

PHOTO BY TOM STOELKER

Writer-director Sushma Khadepaun and cinematographer Victoria Sendra

English Department. “One waiting list has over a hundred students.”

A committee of faculty from Barnard and Columbia helped choose the fellows with an assist from Victoria Lesourd, chief of staff of the Athena Center for Leadership, which runs the Athena Film Festival (February 29 - March 3), for which Artemis Rising is the founding sponsor. The festival, which showcases films highlighting women’s leadership by filmmakers of all genders, gives students yet another inside-the-industry experience. There, they can mix with fellow filmmakers and feature their films at the festival’s annual Student Showcase.

“One of the most powerful forces we have is fellowship, collaboration, and storytelling, especially when we put smart, creative women together and give them entrée into this field,” says Scully. “Because the greatest barrier to entry is exposure and, honestly, financial support.”

This past fall, the program — which is housed in the English Department — brought two fellows to campus. Sushma Khadepaun, a writer and director, taught a semester-long writing course on crafting a global short film. Victoria Sendra, a cinematographer and camera operator, taught a workshop on camera movement, employing her background as a dancer. Barnard Magazine brought the two together the last week of classes to discuss their courses, their students, and the industry.

Though based in New York, Sendra had never been to Barnard before. She says she was delighted to be back on a college campus, though she spends quite a bit of time on the campus of Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, where she is an associate producer and videographer of dance films. Her own work as a cinematographer and camera operator has been screened at festivals including Nowness, Dance Camera West, San Francisco Dance Festival, and Film at Lincoln Center.

With such dance filmmaking chops, it’s not surprising to see Sendra’s videos employ a camera that interacts with the dancers. This is not a camera on a tripod sitting in the audience statically watching the action. While students in her course did learn the basics of the camera, they also participated in contact improvisation, a dance technique that explores boundaries, balance, and the dancers’ relationships with the other dancers on stage.

“Students had partners, and they learned to react to each other, so the relationship between the camera and the subject became a push and pull between the two as well,” Sendra says. “I’m very interested in a camera that is moving with the subject to create really immersive and engaging filmmaking.”

While Sendra’s class provided a kinetic workshop atmosphere, Khadepaun’s class was decidedly writing intensive. Khadepaun was one of Filmmaker magazine’s 25 New Faces of Independent Film in 2021 as well as a recent fellow at the Film at Lincoln Center’s Artist Academy, and her films have played at festivals in Venice, Stockholm, Atlanta, Dublin, and Palm Springs. Her work, which explores ideas of home and identity, has been featured on NPR and in BOMB magazine.

Although Khadepaun is currently developing her first feature-length film, Anita, she remains committed to “shorts,” a genre, she says, her students seem woefully unfamiliar with. She noted that most students watch features and series while trying to make short films.

“An important part of the class is learning from shorts that are very diverse and global. They’re more contemporary films, as opposed to the sort of classical cinema that often tends to be white, male, and straight,” she says.

Khadepaun says the films shown prompted conversations with students regarding what’s happening in editing rooms elsewhere, such as whether there should be a trigger warning before some film screenings. If so, what material would warrant it? They discussed representation, such as how filmmakers often portray women, people of color, and LGBTQ+ characters. Of course, she says, students asked

“IT’S INCREDIBLE FOR STUDENTS TO SEE WOMEN IN THE FIELD ... GETTING INSPIRED ... AND DOING THEIR OWN VERSION OF THAT.”

what it is like to be a woman in the industry.

“I had a student ask, ‘Is it difficult for you to be a female director?’, because they heard that directors always have to be confident. It is such a relevant question, because as a female director you are expected to go the extra mile to show that you are strong and capable.”

She added that to portray strength, women filmmakers need to strike a balance between authority and collaboration. In an art as collaborative as filmmaking, a woman director needs to hear the other voices in the room without fear that she will come across as someone who doesn’t know what she is talking about. Speaking from experience, Khadepaun says she hardly lacks confidence, but when on set she factors in “society’s sexist gaze” when working with others. “It’s a legit concern, especially if you’re working with a male cinematographer, because there are a number of cases where they will take over with a female director. That happens a lot,” she says.

Both say that fellowships like the one that brought them to Barnard can help other young filmmakers about to head into the profession. “It’s incredible for students to see women in the field doing our thing, learning from us, and hopefully getting inspired and going out there and doing their own version of that,” says Sendra.

“I agree,” says Khadepaun. “I know the difference it made for me to see women filmmakers, teaching and learning from them. It made a huge impact on my work, who I am, and the possibility that I could make work and have a voice. That’s a big reason why I teach.” B

WINTER 2024 | BARNARD MAGAZINE 9

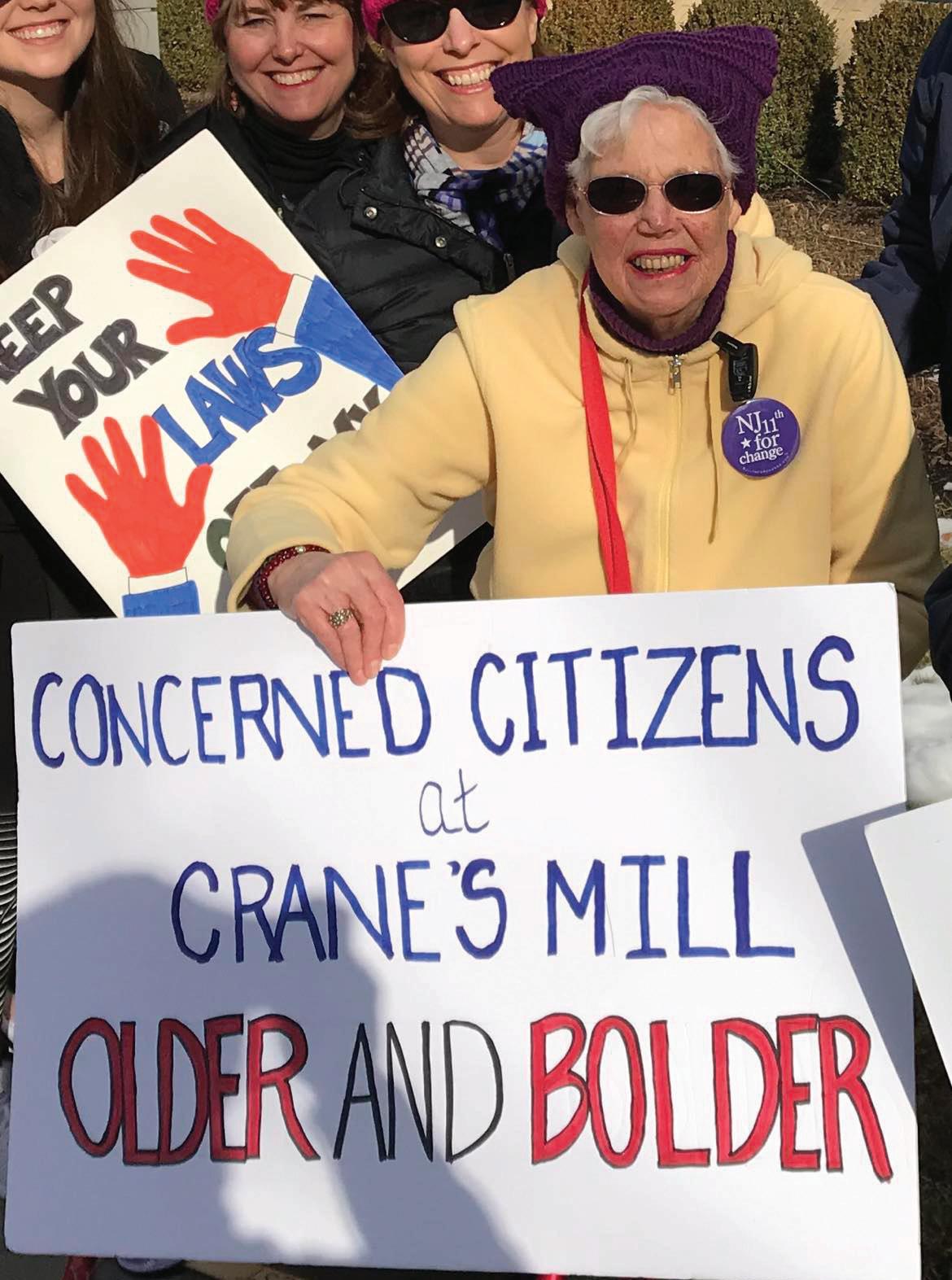

Zines in the Spotlight

Brooklyn Museum’s groundbreaking zine exhibition draws from Barnard’s own collection

Zines from Barnard’s collection are now on display in the Brooklyn Museum’s landmark exhibition “Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines” (November 17 – March 31, 2024).

According to the museum, it is “the first exhibition dedicated to the rich history of five decades of artists’ zines produced in North America.” The four zines featured from Barnard’s Zine Library are I Lie Like a Rug by Felix Endara, Aim Your Dick and Slant #5 by Mimi Nguyen, and Mamasita #1 by Bianca Ortiz.

Professor and Author Jennifer Finney Boylan Elected President of PEN America

Jennifer Finney Boylan, the College’s inaugural Anna Quindlen Writer in Residence, has been selected to lead PEN America, the nation’s foremost free speech organization. Boylan, an LGBTQ+ rights activist, takes the helm of the organization at a time when cancel culture and book banning present challenges to free speech. Fully aware of the inherent dichotomies of her new role, Boylan told The New York Times, “As PEN president, it is my job to fight for free expression on the right and the left.” —Tom Stoelker

Barnard zine librarian Jenna Freedman first proposed a zine library at Barnard back in 2003. (Zines — short for fanzines and/or magazines — are self-published booklets of texts and images, usually made with a copy machine.) “Zines were on the shelves a year later,” she says. In 2010, Freedman initiated the Zine Club, an unofficial organization, which has thrived at the College. The library and its reputation have since grown — it now is home to over 1,400 zines.

“The reason people make zines is because there’s a greater intimacy, more like one-to-one communication,” says Freedman. “My favorite zines are the ones that have content you wouldn’t want to put online. So I appreciate the vulnerability. I appreciate the intimacy.”

It is a busy year for Barnard’s Zine Library, which celebrates its 20th anniversary on April 5. The following day, it will host the New York City Feminist Zinefest, a popular non-Barnard affiliate event that draws dozens of area zine-makers to display, sell, and workshop zines. —Marie DeNoia Aronsohn

10 Headlines

Discourses

Ideas. Perspectives. A closer look.

PHOTO COURTESY OF BARNARD COMMUNICATIONS

PHOTO BY JORG MEYER

Lessons From an Artist in Exile

A writer’s ‘blood, sweat, and tears’ and — finally — triumph

by Marie DeNoia Aronsohn

In June 2022, Achiro P. Olwoch witnessed — what was to her — a miracle. Her play, The Survival, opened at Lincoln Center as part of the Criminal Queerness Festival. The production was the culmination of a dream that Olwoch fled her home in Uganda to realize, after enduring persecution and suffering bodily injury.

“When I say it took blood, sweat, and tears, it’s literal,” says Olwoch. The name Achiro means “the resilient one” in her native language, Acholi, and considering her life’s journey so far, it is fitting.

Olwoch, who is a playwright, novelist, filmmaker, television showrunner, and this year a visiting Barnard professor, knows all too well what it is to suffer for her art and to persevere. She is gay and from Uganda. Olwoch was born in exile in Nairobi, because the brutal military dictator Idi Amin was targeting her father’s tribe. She returned with her family to Uganda as a child and grew up in Kampala, the country’s capital. As a writer, she has risked it all to tell her truth. In Uganda, being a gay artist determined to tell stories with LGBTQ+ themes is to be in peril.

The East African nation has a long history of anti-gay policies. Since 2009, the Ugandan

12 Faculty Focus

ILLUSTRATION BY KUUKUA WILSON

government has proposed several bills to codify the nation’s traditional practice of punishing same-sex relationships. The legislation was passed in February 2014, only to be annulled by Uganda’s Constitutional Court a few months later. In May of this year, it was signed into law. But according to Olwoch, the long and winding legislative process was only one dimension of the threat. She says the unwritten law on the street was one of violence against gay people.

Since Ugandan culture frames gay sex as “unnatural” or wrong, Olwoch says that “everybody — if they can’t justify [doing] something evil — they say, ‘our culture says’” as a way to sanction the persecution of gay people.

Her play, The Survival, reflects and rebels against this reality. “It is a story about a woman who gets pregnant out of wedlock with a homosexual man in a culture that loathes the subject of either,” says Olwoch. “This play explores the thin line between culture and modernity in a typical African society. It also explores the reactions to this news, of all the characters involved, and how their reactions emanate from the laws that the society has placed.”

After a reading of the play in November 2016, word of The Survival and its themes drew fury. Olwoch began receiving threatening phone calls and texts. One evening in late 2017, while walking home from a local theatre where she’d been working as a stage manager, Olwoch was violently attacked. She says the beating was a result of not heeding warnings to “stop promoting homosexuality” with her play and works.

She suffered lasting injury. “All of 2018, I was horizontal. I couldn’t move. I couldn’t walk. I couldn’t sit or stand because I developed sciatica,” she explains. In 2020, Olwoch was back to work, making a short film with an LGBTQ+ theme, which attracted media attention. That’s when she received more warnings. She kept going.

Despite the aggression and the threats that arrived via calls and texts, Olwoch remained in Uganda until 2021. She says that as soon as the U.S. lifted COVID-19 travel restrictions, she came to Brooklyn, New York.

“I had a valid visa to the U.S., and I knew that in the U.S. I would be safe. I did not come initially to seek asylum, I came to clear my head with the intention of going back home after a while,” says Olwoch.

In mid-2022, she joined the Scholars at Risk program, a nonprofit that protects scholars under threat by arranging temporary research and teaching positions at institutions that have opted into its network. And that led her to Barnard. This semester, Olwoch is coteaching the Performing Women course with senior lecturer Shayoni Mitra.

“I love that the students are open to learning, and they are interested in what I have to say,” says Olwoch. In October, she gave a playwriting workshop on campus. This year, the Theatre Department has planned several events with Olwoch, including screenings of her films, readings of her work, and a panel discussion on artistic responses to queer persecution globally.

Though Olwoch is grateful for her time at Barnard and for her new life in the U.S., she says it’s difficult to be away from her homeland and her family, especially since her own immigration status is not yet resolved. “My papers are filed, but they haven’t yet been approved, so that literally means I don’t necessarily belong anywhere. I don’t even know how to describe it, but it almost feels like you’re dangling.”

Even with this looming uncertainty, she continues finding many outlets for her seemingly endless creativity. (Back in Kampala, she was the head writer/showrunner for one of her country’s top television series.) “Right now, I’m focusing on honing my plays. Also, I’m writing books,” says Olwoch, who completed her first novel last year.

For Olwoch, the production of The Survival was a triumph, and she is excited about plans for the staging of the play at the Perelman Performing Arts Center next June.

“I was in tears seeing this on stage last year. Seeing two men holding hands and, at some point in the play, they kiss. All that would never have happened in Uganda. They would have arrested them and the whole audience. So, it was just almost surreal,” she says. “Until I actually saw it on stage, I still didn’t believe it.” B

WINTER 2024 | BARNARD MAGAZINE 13

Bookshelf

by Isabella Pechaty ’23

FICTION

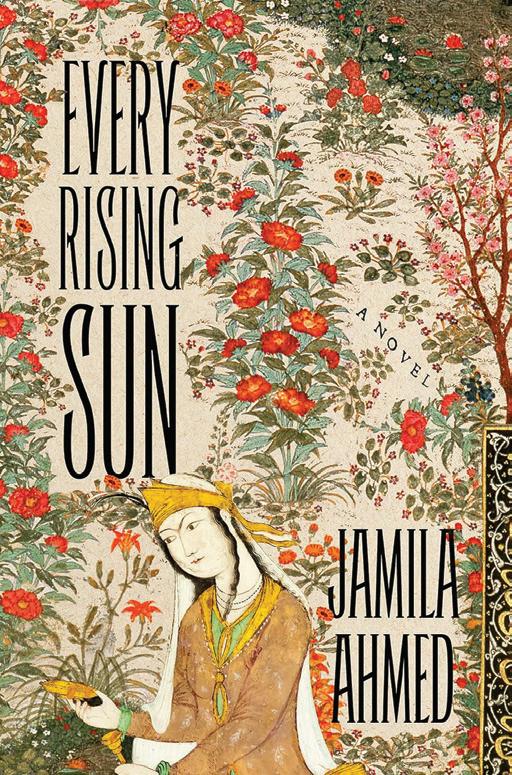

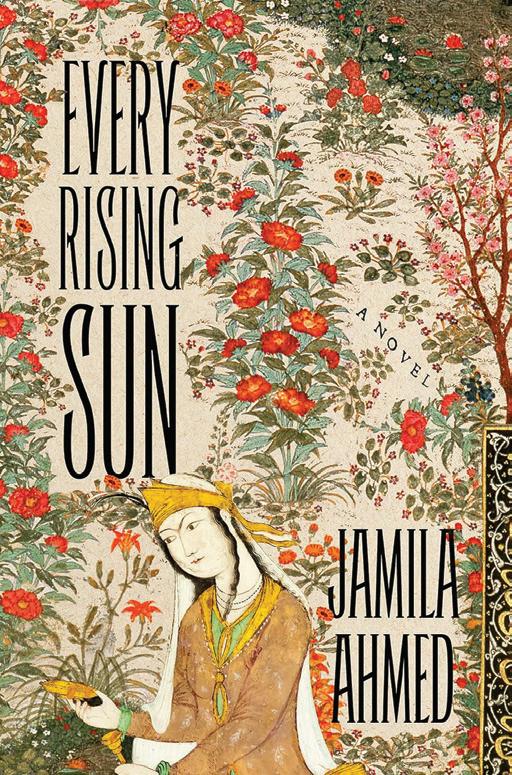

Every Rising Sun

by Jamila Ahmed

Ahmed’s novel is a captivating retelling of the classic One Thousand and One Nights via the vibrant narration of Shaherazade, a 12th-century Persian woman who fends off her own beheading through a never-ending string of mesmerizing stories. The book celebrates a renowned tale through its most timeless female character and reimagines the story as a testament to Shaherazade’s masterful wit and storytelling. (Henry Holt & Company / Macmillan Publishers)

Burr

by Brooke Lockyer

’04

Lockyer delivers a compellingly grim tale — set in southern Ontario, Canada, in the 1990s — about a 13-year-old girl grappling with the death of her father and its eerie reverberations in her rural community. The author explores the transcendental world of death with a yearning physicality and infuses her characters with an unexpectedly beautiful zest for life, full of haunting, fantasy, and wilderness. (Harbour Publishing)

The Vulnerables

by Sigrid Nunez ’72

Through one woman’s pointed narration, Nunez’s novel — the National Book Award winner's ninth — cuts to the emotional heart of the plight of humanity in the post-pandemic, modern age. Her brief but incisive stories on singular moments of connection show our refreshingly recurring need for one another, no matter what. (Penguin Random House)

NONFICTION

Yankee Stadium 1923-2008: America’s First Modern Ballpark

edited by Tara Kreiger

’04

In celebration of Yankee Stadium’s 100th anniversary, Kreiger has collected essays that cover the wealth of history housed in this famed sports institution. Including writings on the hallmark events held there — boxing matches, track and field meets, wrestling competitions, rodeos, concerts, and religious and political assemblies — as well as on historic ballgames played on the field, this compilation celebrates the 85 years of the House That Ruth Built. (Society for American Baseball Research)

The Death of a Jaybird: Essays on Mothers and Daughters and the Things They Leave Behind by Jodi Savage ’00

In lovingly sincere essays about her grandmother and mother, Savage reflects on how time can illuminate the ones we love. Her relationships with these two women — Alzheimer’s and cancer diagnoses, intergenerational dynamics of both strength and difficulty — offer a tender and insightful picture of Black womanhood in America. (Harper Collins)

My Life at the Wheel: Toward a Memoir by Lynne Sharon Schwartz ’59

Schwartz shares her life as a series of sprawling, interconnected experiences in conversation with one another. Her dryly humorous and self-scrutinizing essays draw from her life as a writer and translator, her conversations with friends, and her encounters with ill health and global tragedy. (Harper Collins)

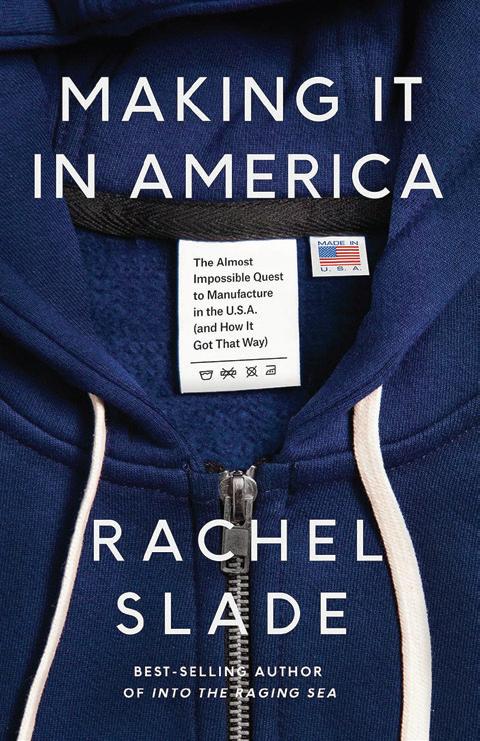

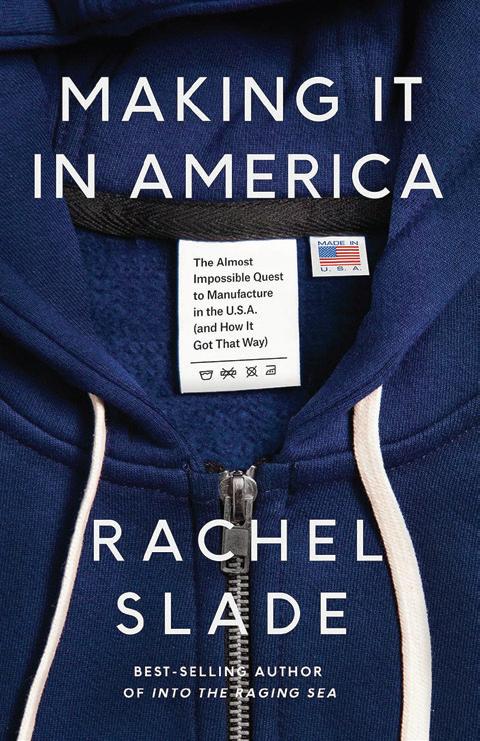

Making It in America: The Almost Impossible Quest to Manufacture in the U.S.A. (and How It Got That Way)

by Rachel Slade ’91

Slade gives an involved and illuminating account of a young optimistic couple, Ben and Whitney Waxman, as they attempt to produce a hoodie that is entirely sourced from American labor and resources. Their personal fight for labor equity touches on globalscale issues of fraught economics and trade wars and makes the current state of manufacturing in the U.S. a pressing issue for all Americans. (Pantheon)

POETRY

Phantom Captain

by Kim Rosenfield ’87

Winner of the Ottoline Prize, Phantom Captain draws on the author’s experience as both a poet and a psychotherapist to contend with — honestly and occasionally with humor — the difficulty of being human and the despair engendered in a world that sometimes feels headed toward apocalypse. (Fence Books) B

14 Read Watch Listen

Documentary Spotlights Queer

Families in the

Midwest

Melinda Maerker ’87 finds heart in the heartland

Queer families have woven themselves into the fabric of urban life in coastal cities like New York City and Portland, Oregon. But what is it like today to live as a queer family in the middle of the United States? In the new documentary We Live Here: The Midwest, airing now on Hulu, director and co-producer Melinda Maerker ’87 sets out to answer the question through the stories of five queer families living in America’s heartland.

While the small-town charm is similar across the states for these families, their experiences differ. The film opens in Iowa with a trans/queer family seeking a new community after being ousted from their church. While day-to-day suburban existence isn’t always easy for the trans/queer parents, the children seem to hold a “no big deal” attitude. Then there’s a Black gay couple with a baby daughter in Nebraska, who, surprisingly, find friendship and acceptance with a Trump-voting family living down the street.

A gay educator in Ohio makes school a safe space for LGBTQ+ students, while the child of one lesbian couple in Kansas recalls dealing with aggressive bullying in school. And we meet a nonbinary kid whose classmates don’t believe people like them are even a real thing: “I mean, I’m here right now, so we do kinda exist.”

The local bullying often parallels a deeper and more disturbing form of rejection. Minnesota state representative and queer mother Heather Keeler faces death threats but continues to bring LGBTQ+ issues to the forefront. “Marriage equality did a lot for us,” she says. “I think though, now, we’re missing the acceptance of

the family structure, what our legal rights are with families. ... I think we have a long ways to go to be really accepting there.”

Amid this pervasive theme of the Midwest’s resistance to change, viewers see acceptance in real time as Maerker follows each family for about a month and simply lets them do their thing. “Finding these families was a long process and involved everything from joining social media groups to personal referrals through family and friends,” Maerker says. “A few families were unable to participate because they feared recrimination at their jobs or in their communities. We refer to our families as courageous first and LGBTQ+ second.”

Why the Midwest? Maerker, who was born in Ohio and raised in the Southwest, decided to make it the focal point of this film because “it’s considered the heartland of American family values — a term that has been co-opted by many on the right. Yet at its core, [American family values] is a lovely, universal concept that means, among other things, being kind and helpful to your neighbors,” she says. “So it’s rather ironic that LGBTQ+ families are often excluded from this inclusive term. We wanted to explore that in a story-driven, authentic way.”

As viewers are invited into the families’ worlds, they gradually see a love that runs deep, not just for each other but for the communities they want to stay a part of. — Gina Vergel

WINTER 2024 | BARNARD MAGAZINE 15

PHOTO COURTESY OF HULU

Rising Above

The documentary Lift, produced by Mary Recine ’92, tells a powerful story of three young dancers overcoming personal hardship

When Mary Recine ’92 was a student at Barnard, she floated through various disciplines, feeling unsure of what she wanted to do with the wide-ranging knowledge she was gaining.

“I went to Barnard not really knowing exactly what I would study. I always dabbled in photography and storytelling,” she says. “I wanted to tackle the world’s big questions.” She chose to major in philosophy but also delved deep enough into history to acquire a job in that department. She was working there one day when two filmmakers came in seeking a professor to showcase in their work. A faculty member who knew about Recine’s interests introduced her to them. “They asked me, could I carry heavy camera equipment? And I said sure,” she says. And that is how her broad interests set the course for her subsequent career as a film producer — one that includes working with notables ranging from Joan Didion to Spike Lee.

“I’ve always been drawn to stories about people and their identities and stories about artists,” she says. Since graduating, Recine, a lifelong New Yorker, has produced documentaries, films, and events exploring the inner lives of artists and writers. She has won three Peabody Awards and earned multiple Emmy nominations, and her work has premiered at prestigious film festivals like Sundance and Tribeca.

Her most recent documentary, Lift, follows three young New Yorkers with unstable housing — some living in shelters, others with Section 8 rental subsidies — for a decade through their participation in New York Theatre Ballet’s scholarship program.

“I’m interested in entering worlds with films and having an entree that you would not have if it wasn’t for your own commitment to looking and listening,” says Recine. The length of the commitment to Lift was unanticipated at the outset, but “the gift of time allowed us to film collaboratively. That helped us scrupulously avoid stereotypes and emphasize their nuanced aspirations.”

Viewers watch the children — Victor, Yolanssie, and Sharia — grow, dance, and grapple with the difficult hand life has dealt them. The film simultaneously lays bare both the daily hardships of untenable commutes and unreliable work schedules and also the beauty of ballet’s elegant, methodological discipline, in which the children blossom. (Victor is now a dancer at New York City Ballet.)

“I hope this film invites a conversation about arts and poverty and inequity but also the promise of these children,” Recine says.

The film centers the children but views them through the eyes of their mentor, former program participant and professional dancer Stephen Melendez, who is now the artistic director of New York Theatre Ballet. The camera follows as he returns to the shelter where he spent part of his childhood to introduce ballet to the children now living there. He finds the door to his former home and promptly passes out.

“He had a very intense, dramatic reaction,” Recine says. “We didn’t really know what was happening, but we knew that was where the journey would begin.”

Melendez wrestles with his past while remaining a steady, supportive mentor to the young dancers. The film ends with a performance of his choreography, a work that incorporates the lived experiences of the children and their parents.

“[Steven] was retelling himself his own story through the process of choreographing a dance about what it’s like to grow up in poverty,” Recine says.

This deep engagement with the narratives of her projects makes Recine more than just a standard “find funding” sort of producer; she works in creative partnership, an approach that influences her eclectic — but always fascinating — oeuvre.

“I make films about people or places or topics that I respond to in some real way,” she says. “I don’t fit in a box, and I think the films I make don’t either.”

Kira Goldenberg ’07

16

COURTESY OF LIFT DOCUMENTARY LLC

Words of Wisdom

Introducing listeners to the ‘wisest people no one has ever heard of’

“Bring to mind the most grounded person you know. Chances are that person isn’t making a living as a ‘wisdom figure,’” says Courtney E. Martin ’02 in her new podcast, The Wise Unknown, which dropped on Apple Podcasts in October. In the series, Martin deconstructs common notions of who holds wisdom in our society by gleaning life lessons from everyday people. “We spend so much money and time trying to find our ‘wisdom figures’ when they might just be our barber, our neighbor, our crossing guard,” Martin says.

Martin starts each podcast with a different celebrity who introduces listeners to the “wisest person no one has ever heard of.” After they introduce their wisdom mavens, Martin kicks the famous people off the line and lets their gurus take center stage. What’s left are stripped-down conversations that center on themes such as falling in love with yourself and the idea that there’s no “one size fits all” when it comes to wisdom.

Listeners meet Idalia Rodriguez (actress Rosario Dawson’s bestie) and journalist Twilight Greenaway (chef and New York Times best-selling author Samin Nosrat’s confidant), among others.

The show, Martin says, was a natural product of her love for interviewing “regular” people and her unremitting commitment to finding what makes a meaningful, ethical life. “This podcast feels like the love child of those intersections,” she says.

Mary Cunningham

From Debut Novel to Hulu Series

A traditional Caribbean confection serves as metaphor for life in the show Black Cake

Baking is a love language — and sometimes a rather complex one. For Charmaine Wilkerson ’82, her mother’s recipe for Caribbean black cake provided the inspiration she needed to blend a series of short stories into what would become her bestselling debut novel, Black Cake, which is now also a critically acclaimed series on Hulu.

Black cake is a rum-soaked-fruit confection that can take at least a week to prepare and is traditionally served around the holidays and at special occasions like weddings. Wilkerson says there was no question that the preparation of black cake, often undertaken by the family matriarch, would anchor the book.

“The traditional Caribbean fruitcake plays a role in the drama at the center of the novel. It also serves as a symbol of how cultures influence one another — for better or worse — and how food helps us to share stories and community,” says Wilkerson, who is from New York and spent much of her childhood in Jamaica.

The series, whose executive producers include Oprah Winfrey, centers on a family drama wrapped in a murder mystery with underlying themes of romance, new beginnings, and the resilience of immigrant women.

The main character of the story is Eleanor, a woman who, after her death, comes clean to her children about her true identity. They learn that their mother was originally Coventina “Covey” Lyncook, an Afro-Chinese Jamaican girl forced by tragedy to flee to the United Kingdom, eventually taking a different name. Viewers travel from the beaches of Jamaica to the city of London, misty Scotland, and sunny California. Not surprisingly, the series offers sumptuous shots of Covey cooking Chinese and Jamaican cuisine and baking that delicious cake.

Wilkerson, who was just 16 when she started at Barnard in 1978, says she drew from her experience at the College when writing about how the teenage Coventina navigated the patriarchal norms of 1960s Jamaica.

“It was an advantage to be surrounded by so many smart, confident women in that phase of my adolescence,” she says. While her professors consistently empowered students to know they were special, Wilkerson says Barnard’s greatest gift to her was instilling the confidence to pursue her academic and personal goals — whether or not she achieved her original objectives — a value reflected in both the novel and the series.

“In my novel, the teenage character Covey and her friend Bunny take for granted that they will excel,” says Wilkerson. “Things do not go as planned, and therein lies much of the drama in the tale. But as young women, their sense of certainty in their own resourcefulness and determination to be loyal to one another turn out to be driving forces throughout their lives.” — Gina Vergel

COURTESY

OF COURTNEY E. MARTIN (TOP); COURTESY OF CHARMAINE WILKERSON (BOTTOM)

To Dance On Fire

A signature course in live performance gives students a chance to collaborate with choreographer Iréne Hultman

by Marie DeNoia Aronsohn

It’s a Wednesday night in early November, and 15 students are warming up in studio 305 in Barnard Hall. The mood is light, friendly but ready. With a word from visiting artist Iréne Hultman, the music starts. An instrumental by Nigerian bandleader Fela Kuti blares from speakers, setting the students in motion. They reel, contract, expand, and pirouette, orbiting the floor, filling the space, interpreting the music in ways personal and unique. This is the warm-up to a three-hour rehearsal. The dancers are preparing for an 18-minute piece called Episodes to be performed in just a few weeks at New York Live Arts, the venue founded by celebrated choreographer Bill T. Jones.

This group is one of four sections in the Barnard Dance Department’s popular course Rehearsal and Performance in Dance, which is offered each fall and spring. The class provides students with the opportunity to work with visiting professional dancer/choreographers and take part in the development of a live dance production as performers, choreographers, designers, or stage technicians.

Colleen Thomas-Young, the chair of the Barnard Dance Department and a professor of professional practice, says this course is foundational to Barnard’s dance program and to students who want to pursue dance. “Getting the time to create a work with these guest artists, these professionals in the field, is the most amazing way [for students] to transition to this sort of field,” she explains. “I always try to hire a diverse group of guest artists.”

One of those artists is Hultman. Thomas-Young was drawn to the choreographer because of the work she’d seen early in Hultman’s career. “It was almost cinematic,” says Thomas-Young of Hultman’s early performances. “I hadn’t really seen work like that. There was this underlying emotion that you could feel watching [Hultman]. There’s this sensitivity and a way that she gets at the feeling of a piece. There’s a kinetic transference.”

The Swedish-born Hultman has long been a luminary of the New York City dance world. She performed for five years with the Trisha Brown Dance Company, where she later worked as rehearsal director. In 1988, she founded Iréne Hultman Dance, which received international renown for its work over the next 15 years. She is currently a lecturer in theatre and performance studies at Yale University. This is her first time teaching at Barnard.

“I was very pleased when Colleen asked me to do something,” says Hultman, who finds working with students to be an interesting challenge. “It’s different when you choose your dancers from a big professional crowd. When you have students, it’s impossible to know who they are. [At Barnard], I wanted to make something new. It’s been such a pleasure to work with these students.”

Dance students must audition to be placed in one of the four sections. Each section is led by a different visiting professional choreographer. In addition to Hultman, guest artists MX Oops, Gabrielle Lamb, and Roderick George taught the course this fall.

Dance major Eliza Voorheis ’25 transferred to Barnard from Scripps College for her sophomore year. Barnard’s Dance Department — including the Rehearsal and Performance course — was a big factor in that decision. “This opportunity just shows that

18

MARK MANN (THIS PAGE); JULIA DISCENZA (OPPOSITE PAGE)

Backstage at Barnard

dance is being taken very seriously here,” says Voorheis. “It’s not just considered an extracurricular activity.”

Voorheis, who grew up in Massachusetts, began dancing when she was around 4 years old. This is the third time she’s taken the Rehearsal and Performance Dance course. Voorheis has enjoyed Hultman’s course and finds the visiting artist’s approach to improvisational modern dance both a challenge and an opportunity to stretch her range.

“The improvisational work we’ve done in this has surprised me because it’s so specific,” says Voorheis. “At times, I think of improvisation as this very wide, expansive world in which you can go off and do whatever you want. But that’s not [Hultman’s] philosophy — or at least not for this specific case. She really knows what she wants, and that’s been very demanding. But it’s also really cool to see what comes out of that and how you get creative within these restraints.”

For Katie Sponenburg ’24, a dance and economics double major from New Jersey, the opportunity to blend dance and academics is what drew her to the College. While at Barnard, she’s been focusing on postmodern dance and exploring what she calls “extremes in physical exertion.” Her work in Episodes is intense. “As challenging as it is, I find it more exciting. I love the freedom of getting what I want to do. And I just try to roll with that. I mean, the piece is about desire,” she says.

Sponenburg, too, has taken the Rehearsal and Performance course several times. For this semester, she auditioned only for Hultman’s section. In past years, she would make a point of auditioning for all of the guest artists. “I thought there was a lot of wisdom that she had that I wanted to be part of. That’s what informed me to make this move,” says Sponenburg.

“Postmodern dance — they describe it as dancing from your bones,” says Sponenburg. This was a different way of moving for the Barnard senior, who describes herself as an athletic dancer, and was a challenge she embraced. “[Hultman’s approach] is more like a release of energy and just trying to do movement for movement. So, because it’s self-guided, I get to take these risks that maybe I wouldn’t necessarily have the opportunity to take. Here I get to build on what I want to explore.”

“Katie and Eliza are great,” says Hultman. “At first I thought I should [bring to Barnard] all these conceptual ideas. But the students have been making all the movements. I wanted [them] to start in the now.”

Hultman then bases the choreography on the students’ improvisations created from her direction. During rehearsal, if a dancer misses a movement, she gives a kind laugh and gentle correction. The work they’ve created together has a sense of random physical, intimate expression, but each move is sculpted and repeated with exactitude. Yet there’s also flexibility in the shaping.

“[This piece] is like worlds away from where it started,” says Hultman. “So it’s kind of hard to keep up with my brain and my body. I’m learning it new and keeping up. But my vision of the piece has become something of its own.”

Episodes is set to four very different musical pieces, including a baroque instrumental as well as the Doors’ “When the Music’s Over,” ending with Louis

Armstrong’s “What a Wonderful World.”

“The Armstrong song acts as a coda,” says Hultman.

In “When the Music’s Over,” the students move with intensity and grace, facing and mirroring each other, filling the stage — they spiral and leap — all in conversation with the driving rock beat and incantatory lyrics of the Doors.

When the music’s over

Turn out the lights

Turn out the lights

Turn out the lights

Well, the music is your special friend

Dance on fire as it intends

Three dancers, including Voorheis and Sponenburg, circle one another, mirroring a move Hultman calls “the mermaid.” They slither and sink to the floor, undulating back up in perfect unison and down again. The physical expression is poignant, a moment of unity in motion. The piece ends with three other dancers in tableau. Two are on the floor; another squats and brings her palms together as in prayer. Hultman paces and laughs, clearly pleased. B

You can view Episodes at barnardbold.net/episodes

Opposite page: Acclaimed choreographer and dancer Iréne Hultman

Below: Eliza Voorheis ’25 and Katie Sponenburg ’24 share a duet.

Curators of the country’s top art institutions on the objects that inspire them

What goes into building a museum collection? From the Los Angeles County Museum of Art to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, six alums in the curatorial field share with us the objects in their institutions' collections that have special significance to them — and why they matter personally, culturally, and to the scholarship of art history.

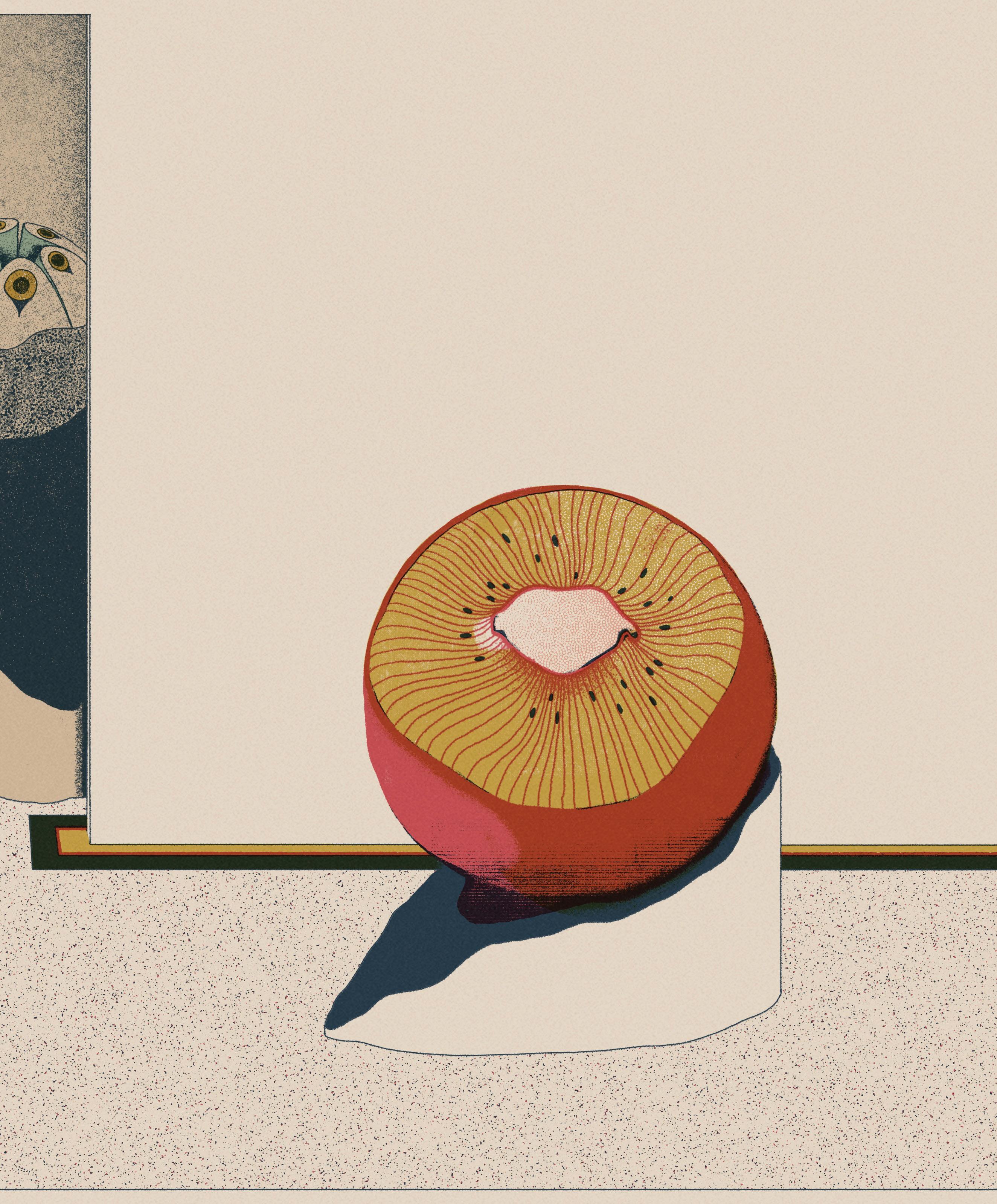

ILLUSTRATION BY JUAN BERNABEU

Stephanie Barron ’72

Senior Curator and Department Head, Modern Art

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Because I’ve been curator of modern art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) for over 40 years, there are quite a few acquisitions that have personal meaning for me, but there is one of which I am exceptionally proud. In 2015, the museum was able to purchase Dancer With Necklace, a rare carved sculpture by German expressionist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Although the German expressionist artists are best known for their paintings and prints, many explored the making of sculpture, primarily in wood. These roughhewn works became a particular target of the Nazis, who attacked modern art as “degenerate.” Kirchner created over 140 sculptures, but only 60 have survived — the majority of his carved oeuvre was lost or destroyed during the Nazi years.

This sculpture — Kirchner’s very first free-standing figural nude, which he carved in 1910 in his Dresden studio — was most likely based on his companion Doris Grosse, or “Dodo.” The carving technique is visible, and the chisel marks are small and delicate. The dancer seems to twist her way out of flat frontality into fully three-dimensional space. The sculpture, thought to be a casualty of the Nazi era, was known only through documentation of Kirchner’s studio.

While researching my exhibition “German Expressionist Sculpture” (1984), an assistant mentioned that family friends in Philadelphia had a sculpture that looked similar. It seemed like a long shot, since most people don’t have Kirchner sculptures sitting atop their piano, but remarkably, thanks to some detective work and pure luck, I was able to identify it through studio photos and comparisons with Kirchner’s drawings and prints. I went to see it and negotiated the exhibition loan.

The sculpture was originally acquired shortly before World War I by a German collector, who then passed it to his son. He gifted it in the early 1950s as a wedding present to a couple who kept it on their piano, where it became a beloved family possession. Dancer With Necklace remained on long-term loan at LACMA in our German expressionist galleries. Eventually, the owners’ children made it available to us to buy, and with the help of many supporters, finally, 30 years after I first saw it, the sculpture belonged to the museum. I smile whenever I see her in the galleries.

Dancer With Necklace, 1910, by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (Germany, 1880–1938). Painted wood, 21 3/8 by 6 by 5 1/2 in. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Purchased with funds provided by the Robert Halff Endowment Fund, Modern and Contemporary Art Acquisition Endowment Fund, Modern Art Acquisition Fund, Robert Gore Rifkind Foundation, Modern Art Deaccession Fund, and LACMA’s 50th Anniversary Gala, in honor of Stephanie Barron, the museum’s Senior Curator of Modern Art.

22

Photo of Barron: © Fredrik Nilsen.

Andrea Myers Achi ’07

Mary and Michael Jaharis Associate Curator of Byzantine Art Department of Medieval Art and The Cloisters Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has one of the most significant collections of Byzantine art in the world, with just over 5,000 works of art under my purview. It has been a deep privilege for me to be steward of this material. Because of the breadth of the collection, I am able to curate innovative exhibitions, such as the show “Africa & Byzantium” (November 19, 2023–March 3, 2024), which features an important work, the mounted rider textile known as Fragment from a Coptic Hanging.

Mounted riders, woven in black wool, race across this textile with their hunting dogs. Nude and harnessed, the men hold stones and bows. Men on horseback have traditionally represented symbols of political, military, or religious power. The other figures in the textile, winged women and an additional rider, are woven with pink and white threads. Diverse figures appeared in various media in late antique art across the Mediterranean basin and northern Africa, but the purpose of marking skin-color differences in this material has yet to be determined.

The depiction of these figures points to the multicultural environment of Byzantium. The textile comes from early Byzantine Egypt (4th-7th century CE), which was one of the most vital provinces in Byzantium. In many respects, this province was an intellectual, religious, and artistic center — impactful ideas, monumental works of art, and dynamic individuals came from Egypt at that time. Interestingly, this textile points to significant themes in early Byzantine art related to victory, success, and prosperity and represents the vibrant material culture of Byzantium.

The works of art from northern Africa in the “Africa & Byzantium” exhibition, such as this textile, have long been recognized as important examples of Byzantine art, but their African context has rarely been studied or privileged in scholarship on the material. Because these exhibitions present new ways of looking at pre-modern art and provide space for groundbreaking research, they will shift the field of art history and museums.

WINTER 2024 | BARNARD MAGAZINE 23

Fragment from a Coptic Hanging, 5th century, attributed to Egypt. Linen, wool; plain weave, tapestry-weave; 40 15/16 in by 24 13/16 in. Gift of George F Baker, 1890. Photo of Achi courtesy of Eileen Travell.

Jessica S. Hong ’09

Senior Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio

I came to this field accidentally. After attending a high school that was sociopolitically engaged, I arrived at Barnard with an interest in studying political science. To fulfill a requirement, I took an art history survey that altered my trajectory. I realized then that the arts entwine the social, the political, and the cultural — and have relevance and influence on our everyday lives. However, it is also at Barnard that I recognized the limitations of this field and what narratives, experiences, and even material have been excised from the dominant, Westerncentric art scholarship in which it is still rooted.

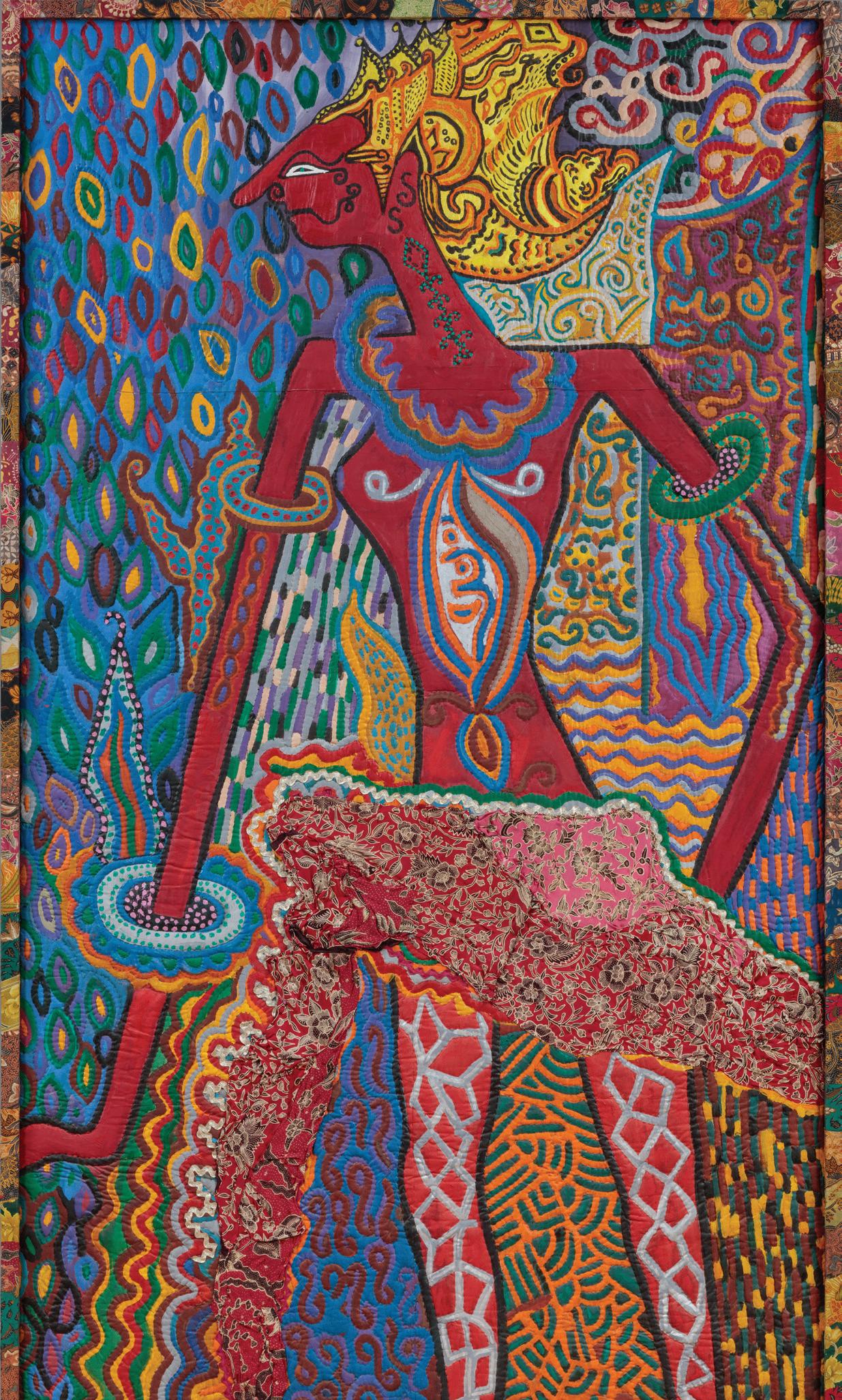

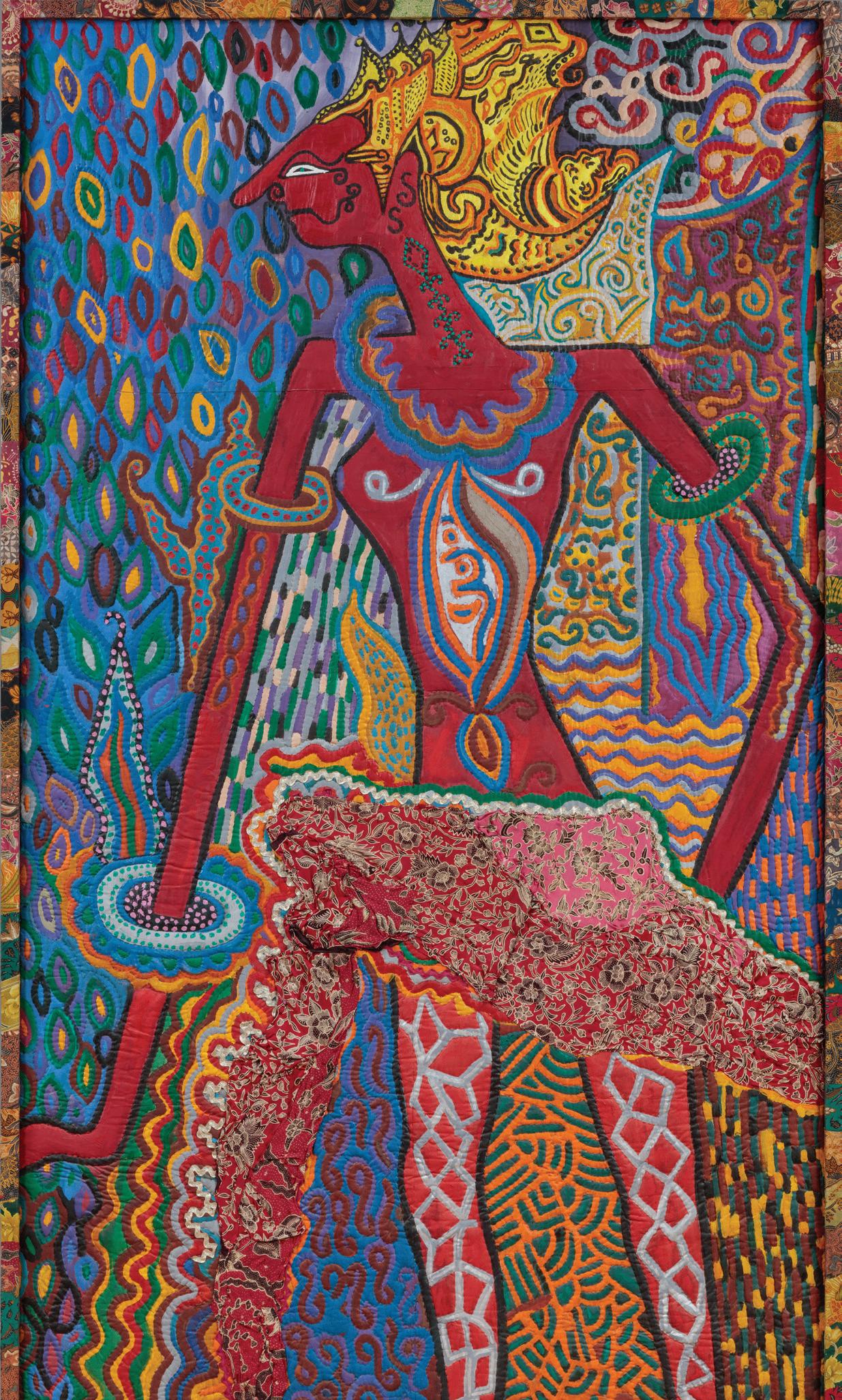

At the Toledo Museum of Art, a new generation of curators (alongside colleagues far and wide) is actively contending with the colonial legacies of museological practice. Committed to thoughtfully broadening the collection, I recently acquired the work Rama (1982) by artist Pacita Abad. Throughout her global travels, Abad would engage and learn directly from local practitioners to incorporate a range of visual and cultural traditions primarily from the Global South. This is most notable in her trapunto paintings — padded and stitched canvases — from the late 1970s and early 1980s.

After her first visit in 1983 to Indonesia, she was inspired by the Ramayana tales — a popular Sanskrit epic from ancient India — as performed through the ancient tradition of wayang kulit (Indonesian shadow puppetry). In this work, part of her “Masks and Spirits” series (1981-2001), Abad depicts Rama, a central figure in the Ramayana tales and one of the most widely worshipped Hindu deities, by stitching together ikat, batik, and other textiles found at local Indonesian markets and painting with vibrant, dynamic colors on top.

Long relegated to the margins, Abad is finally gaining broader recognition and weaves together traditions, techniques, objects, time periods, and cultural contexts, as her work embodies the interconnected world in which we live.

Each acquisition, as seen with Abad’s Rama, helps shape and reshape the contours of an institutional collection. As a result, the institution will continue to change as long as we remain responsible, rigorous, and intentional stewards.

24

Rama, by Pacita Abad (Basco, Philippines, 1946–2004, Singapore), from the “Masks and Spirits” series, 1982. Fabric, painted. 96 by 53 1/2 in. Toledo Museum of Art, purchased with funds from the Florence Scott Libbey Bequest in memory of her father, Maurice A. Scott. Photo of Hong: Richard Goodbody.

Makeda Best ’97

Deputy Director of Curatorial Affairs

Oakland Museum of California

In 1991, when I was 15, my father took me to see photographer Brian Lanker’s exhibition at the Oakland Museum of California, “I Dream A World: Portraits of Black Women Who Changed America.” As I was already a fan of photographic portraiture, which I eagerly sought out in the pages of magazines like Vanity Fair and books such as Richard Avedon’s American West, seeing all these portraits of African American women and reading their stories was transformative. Lanker’s portraits are so subtle in the moods they capture and in the way they draw on the possibilities of black-and-white film and printing. This was the first photography exhibition catalog that I owned, and I still have it.

I already had a camera, and I’d always made photographs of my family. Following the Lanker show, I got inspired to work on my portraiture and to shoot in black and white. Some of the portraits I made were exhibited in the Dean’s Office at Barnard shortly after I arrived as a transfer student in the fall of 1994. I had shown them to Dean Vivian Taylor, and she suggested putting them up in the waiting area above the couches.

Seeing Lanker’s exhibition opened up something else for me too, beyond the inspiration to make my own photographs. Along with the catalog, I got the calendar. When the year was done, I wanted to keep the pictures, so I started pulling apart the calendar. I also had a collection of photo postcards about African American life. I had a box of James Van Der Zee postcards. One of my favorite postcards was a photograph by Leonard Freed of Martin Luther King Jr. in Baltimore in 1964 — he’s riding in the back of a convertible through a crowd, and his hand is outstretched and the crowd is rushing to touch him. I took the postcards and the Lanker pictures and put them up in my bedroom. And then I took a picture of my cousin standing in my first “exhibition.”

In August 2023, I joined the Oakland Museum in my new role as Deputy Director of Curatorial Affairs — it was moving for me to visit the gallery where the exhibition was held and to discover the poster in the collection.

WINTER 2024 | BARNARD MAGAZINE 25

“I Dream A World” poster, work on paper by Brian Lanker, 1991. Offset lithograph paper; 28.125 in by 18.25 in. Inscription: “Portrait of Septima Poinsette Clark (1898–1987) © Brian Lanker 1989” printed in black at the bottom left corner of the poster. All Of Us Or None Archive. Gift of the Rossman Family. Copyright to Brian Lanker Archive.

Carla AcevedoYates ’00

Marilyn and Larry Fields Curator Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago

Having received an all-women’s education from elementary school until college, it has always been important to me to highlight and uplift women artists in the work that I do as a curator. The sculpture Muxeres en Mi / Womyn in Me (1) was shown at the MCA Chicago in the first exhibition I organized shortly after I started working at the museum in 2019, and it was acquired by the museum shortly thereafter.

The piece was part of the exhibition “Carolina Caycedo: Desde el fondo del río / From the bottom of the river,” which surveyed the previous decade of artist Carolina Caycedo’s practice, focusing on works that addressed the environmental destruction caused by dams and mines, as well as recognizing the women leading environmental and political movements around the world. The exhibition was part of the MCA’s Women Artists Initiative, an institutional effort toward gender equity that foregrounds the work of women artists and their ideas. This initiative has led the MCA on the path of having a program that is dedicated 50% to women-identified artists.

Muxeres en Mi / Womyn in Me (1) is a hanging sculpture made of garments that were donated mostly by friends and colleagues of Caycedo’s, sewn together to form a large-scale tapestry and then embroidered with the names of women artists who have been influential to the artist. As its title expresses, the work recognizes the previous generations of women who live within the artist and, by extension, the collectivity that exists within all of us.

The sculpture is meaningful in an art historical context because it sheds light on overlooked but seminal Latinx and Latin American women artists, who are often excluded from the art historical canon as well as from museum spaces. This work is also personally significant to me as a Puerto Rican because Carolina, who lives in Los Angeles but was born in London to Colombian parents, lived in Puerto Rico and is part of a generation of artists on the island, my own generation, whose work is socially and politically engaged.

26

Muxeres en Mi / Womyn in Me (1), 2019, from the Mujeres en Mi series (2010–) by Carolina Caycedo (Colombian, b. 1978; lives and works in Los Angeles). Embroidery on clothing, synthetic yarn, and thread, 12 × 6 ft. Gift of Mary and Earle Ludgin by exchange. Photo of Acevedo-Yates: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago.

Jessica May ’99

Managing Director, Art and Exhibitions and Artistic Director

deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum Lincoln, Massachusetts

This past fall, we completed a years-in-the-works commission, Huff and a Puff, by New York-based artist Hugh Hayden. The work is part of our ongoing program of commissions called Art & the Landscape, where we work with artists to develop largescale, site-specific outdoor sculpture at the deCordova and throughout Massachusetts on properties cared for by our parent organization, The Trustees. Typically, these works are loans, but we are overjoyed to welcome Hugh’s incredible sculpture for the long haul by committing to care for it in perpetuity.

The work is profoundly resonant in our 30-acre sculpture park in Lincoln, Massachusetts. Huff and a Puff is a meticulous re-creation of 19th-century naturalist and philosopher Henry David Thoreau’s cabin at nearby Walden Pond (itself a 20thcentury reconstruction of the original) — but at 20-degree angles forward and to one side. The work leans; it might be falling, or maybe just adopting what the artist calls the “offensive position.” Its mirrored windows reflect ground on one side, sky on the other. Every single element — every shingle, every brick — is hand shaped with a slant to keep us viewers off-kilter.

Our chief curator, Sarah Montross, has inspired me with her description of this work as twisting and bending our sense of history. Indeed, in ways hard to pinpoint, Huff and a Puff has done a number on my own mental map of the stories of Thoreau and Emerson, of Walden, of transcendentalism and 19th-century American life and letters. It keeps me thinking about contingency and interconnectedness in American history, the push and pull of people and nature, and even, or especially, the values I associate with being upright.

The absolute best thing about working with artists on public commissions is that they invite us to see the environments around us through very different perspectives; they push us, hard sometimes, to reconceive of the familiar in our everyday lives. Hugh has a deep sense of humor but holds a razor-sharp view of American culture and history — Huff and a Puff entertains, but the impression is deep, lasting, upending. B

WINTER 2024 | BARNARD MAGAZINE 27

Huff and a Puff, 2023, by Hugh Hayden (b. 1983, Dallas). Wood, mirrored glass, brick, steel. Lead support for Art at The Trustees is provided by Mr. Richard M. Coffman and Mrs. Gabrielle C.F. Coffman. Additional support provided by Lisson Gallery, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Next Generation Fund of the Roy A. Hunt Foundation. Photo of May: Mel Taing.

PHOTOS BY MATT FAJARDO

Some things just stick with you. Ebonie Smith ’07 was in high school when she first heard her honors chemistry teacher say, “Water is the universal solvent.” Perched atop a stool, feet dangling below the lab table at East High School in Memphis, Tennessee, Smith didn’t think it registered beyond one more lesson in a long day of learning. But more than two decades later, those five words continue to inform her understanding of music.

“Water can pretty much dissolve anything. To me, music is the same way. Music transcends differences,” says Smith, who serves as senior music producer and engineer at Atlantic Records. “Whether you’re in church, listening to the radio, or at a jazz bar, it creates equilibrium and allows us to enjoy each other. That’s how I understand it sonically and culturally. Music always has a function.”

In Pursuit of Music

Music as Ministry

How award-winning producer Ebonie Smith ’07 is remixing the music business

by Kenrya Rankin

Around age 4, Smith walked into the living room of her family’s home to find a miniature white baby grand piano on the green shag carpet. (Imagine Charlie Brown’s buddy Schroeder, but swap in a little Black girl, her pigtails dangling over the black and white keys.) Smith was elated. It’s her earliest musical memory, and she was serious enough about playing that her grandmother started taking her to lessons in the third grade.

“My mother had a great influence on my musical tastes,” Smith says, who says she was obsessed with Michael Jackson and the Jackson 5 after her mother gave her a CD for Christmas ’93. “As a child I listened to a lot of hip-hop and contemporary R&B. Some of my favorite record labels during that time included So So Def, Bad Boy Records, and LaFace Records.”

But by the time she walked through Barnard’s gates in 2003, she was more focused on basketball and STEM, having spent three summers in the Math and Science for Minority Students program at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts. “My college counselor at Andover recommended Barnard,” says Smith. “She thought it would be a good fit. She was right.”

Smith eventually decided to major in Africana studies but couldn’t escape the music when she got to college.

“Ebonie and I met near the beginning of the school year,” recalls Sydnie Mosley ’07, the founding artistic and executive director of the dance collective SLMDances, who now considers Smith family. “She was in the first floor lounge of Brooks Hall playing piano, and I remember saying hello, sharing a love of music, and showing each other what we could play.”

She doesn’t remember what tune Smith was playing that day, but she does remember being impressed. “She was brilliant,” Mosley says. “And she still is!” In 2021, the two joined forces to create What Does PURPLE Sound Like?, an interactive dance installation inspired by the work of revered playwright and poet Ntozake Shange ’70. “I trust Ebonie so much as an artist. Her insight and the way she is able to metabolize what I’m doing and translate that sonically is a gift,” says Mosley, who calls Smith her favorite musical collaborator.

“I always loved music, but I took it for granted until I got to Barnard and realized

WINTER 2024 | BARNARD MAGAZINE 29

I still had that passion and wanted to pursue it,” Smith says from her home in Los Angeles. So she crafted an interdisciplinary program of study for herself that allowed her to focus on technology through classes at Columbia’s Computer Music Center. “Technology is the convergence of my two worlds. It’s a fascinating space where science and music meet, where [the] left and right brain come together,” Smith says.

In the fall of her senior year, she studied abroad at Université de Yaoundé in Cameroon. There, she spent five months working in a studio and playing live gigs with two bands, including one called the Black Roots. “I was singing and doing a little bit of songwriting, but that experience showed me that I liked the functionality of being a working engineer and producer,” Smith says. “That’s when I set my focus on production.”

Stepping Out on Faith

When she returned stateside, she asked her academic advisor, Kim F. Hall, professor of Africana studies and the Lucyle Hook Professor of English, if she could make women music producers the topic of her thesis. “And she was down with it. And not only was she down with it, but she invested in a related music conference that I wanted to throw, too.”

Janet Jakobsen, Claire Tow Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, remembers that conference well. In fact, it was the topic of her very first conversation with Smith. “Ebonie and Kim asked me if the BCRW could sponsor the Gender Amplified conference,” says Jakobsen, who was then the director of the Barnard Center for Research on Women (BCRW). “It was to be on gender and the production

of hip-hop, and it was massive and important and impressive. It was such a great idea that I said yes, and we were able to work together and sponsor it.”

That first event, held in April 2007, drew students to Barnard Hall in droves to hear from Tricia Rose, author of such influential books as Intimacy and Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America, and DJ Spinderella of Salt-N-Pepa fame.

“It happened organically,” says Smith. “Barnard gave me the space, time, resources, and guidance to actually realize it. There was so much trust. They treated me like an adult, somebody that they felt had good ideas and great potential.”

Gender Amplified lives on as a nonprofit — with Hall and Jakobsen on the board — supporting Smith’s mission to bolster women and nonbinary music producers via training, accessible studio space, mentorship, and community building. “I get to contribute as she takes a gender-inclusive approach to supporting people who are traditionally excluded from the music business. I believe in the project, and I want to support Ebonie,” says Jakobsen. “Ebonie has a vision. That’s very valuable, and it’s something that you want to participate in.”

Doing the Work

After graduating from Barnard, Smith immersed herself in the industry, heading downtown to New York University (NYU), where she earned her Master of Music in music technology in 2010. While there, she interned at Sirius XM Radio and served as a music production assistant at NYU’s Clive Davis Institute of Recorded Music, maintaining equipment and helping whenever high-profile guests (think KRS-One, Alicia Keys, and Q-Tip) came to campus. She landed at

30

Atlantic Records in 2013 and has been there ever since. “Making music is my happy place and my love language,” Smith says.

When she’s not working in the studio with charttopping recording artists, including Lauryn Hill, Santigold, Melanie Martinez, and Cardi B, or with Gender Amplified, Smith serves as co-chair for the Recording Academy’s producers and engineers wing. She earned her first Grammy certificate and platinum plaque in 2016 for her contributions to the Broadway cast recording of Hamilton.