Our Design DNA

At The Bartlett School of Architecture, we have been publishing annual exhibition catalogues for each of our design-based programmes for more than a decade. These catalogues, amounting to thousands of pages, illustrate the best of our students’ extraordinary work. Our Design Anthology series brings together the annual catalogue pages for each of our renowned units, clusters, and labs, to give an overview of how their practice and research has evolved.

Throughout this time some teaching partnerships have remained constant, others have changed. Students have also progressed from one programme to another. Nevertheless, the way in which design is taught and explored at The Bartlett School of Architecture is in our DNA. Now with almost 50 units, clusters and labs in the school across our programmes, the Design Anthology series shows how we define, progress and reinvent our agendas and themes from year to year.

2022 Reformulating Practice

Murray Fraser, Michiko Sumi

2021 Stealth Ecology

Murray Fraser, Michiko Sumi

2020 Multitude

Murray Fraser, Michiko Sumi

2019 Continuum

Murray Fraser, Michiko Sumi

2018 Material Display

Murray Fraser, Michiko Sumi

2017 Pleasure!

Murray Fraser (on sabbatical), Tamsin Hanke, Sara Shafiei

2016 Soft City

Murray Fraser, Justin C.K. Lau, Sara Shafiei

2015 Urban Rituals

Murray Fraser, Justin C. K. Lau, Sara Shafiei

2014 Movement London

Murray Fraser, Justin C.K. Lau

2013 Exchange

Murray Fraser, Kenny Kinugasa-Tsui, Justin C.K. Lau

2012 The Edge of London

Murray Fraser, Pierre d’Avoine

2010 Collections, Collectors and Hoarders

Abigail Ashton

Reformulating

Practice

Murray Fraser, Michiko Sumi

Reformulating Practice

Murray Fraser, Michiko SumiIn recent years UG0 have explored social and environmental sustainability in an inventive and sensuous manner, with projects tackling issues such as energy consumption, environmental damage, everyday ecosystems and urban biodiversity. While these urgent matters continue to inform the unit’s creative direction, this year students also reflected on what they will be doing in their future careers and were asked to think of potential ways to reformulate how architects practice today.

Architectural practice need not be as it is now, yet what else might it become? Taking London as the location for projects, while also studying key examples of alternative forms of practice from around the world, the unit examined issues of ethics, justice, inclusivity and cultural identity.

An obvious question to ask is why is this issue important to architectural students? In the main part, many people study architecture because they want to make a real difference to society, primarily through the act of designing higher quality and more sustainable built environments. Yet, within a condition of neoliberal capitalism, there are extremely powerful socio-economic forces that make social improvement difficult. Most architectural practices opt to operate within the limits set by neoliberal capitalism, arguing that it is impossible to do much if one tries to escape the system and that it is better to tackle matters from within. In contrast, however, some contemporary architects have explicitly tried to find new ways of practice in the belief that a resistant, even revolutionary stance is required.

With this in mind, this year’s field trip was to Bristol, where UG0 met with artists, architects and environmental researchers, among others. They also visited the collective art studios in Spike Island where different forms of creative practice are being forged.

Year 2

David Abi Ghanem, Ani Begaj, Esin Gumus, Rabiyya Huseynova, Fahad Zafar Janjua, Tran (Thu) Lai, Milen Purewal

Year 3

Luke (Taro) Bean, Vanessa Chew, Maria Garrido Regalado, Wei Lim, Joseph Russell, Shannon Townsend, Nathan Verrier, Yeung (Julie) Yeung

Technical tutors and consultants: Nicholas Jewell, Ewa Hasla (Atelier One Engineers), John I’Anson (Atelier One Engineers), Tea Marta, Matei Mitrache

Critics: Anthony Boulanger, Eva Branscome, Pedro Geddes, Ifigeneia Liangi, Ana Monrabal-Cook, Thomas Parker, Luke Pearson, Stuart Piercy, Neba Sere, Ben Stringer, Dan Wilkinson

Sponsors: Bean Buro, KPF Architects

0.1 Maria Garrido Regalado, Y3 ‘The Rituals of Architecture’. Model. This close-up shot gives a roof plan view of a small timber-framed baldachin where a solitary, obsessive architect works. In the various spatial pockets of this tiny structure, the architect can enact the ten key rituals of their everyday routine as a practitioner of this ancient yet modern profession.

0.2 Luke (Taro) Bean, Y3 ‘Waterworks Baths and Studios’. City Road Basin, EC1. Exploded axonometric. This diagrammatic drawing shows the servicing system for a building that includes three medium-sized architectural studios intermixed with a suite of public and semi-public baths. It outlines the different networks for recycling water from the adjacent Regent’s Canal or from the aquifer below, as well as for filtered water collected by the building’s roof.

0.3–0.4 Shannon Townsend, Y3 ‘The Euston Sanatorium’. Euston Road, NW1. Isometric section; plan. Sitting on one of the most polluted roads in London, this scheme improves urban air quality and human health by adopting a bio-reactive façade and a series of internal filtering systems which will naturally cleanse the flow of air through the building. As an action to tackle the climate crisis, this will help improve our chances of reaching pollution targets that seem out of reach.

0.5 Luke (Taro) Bean, Y3 ‘Waterworks Baths and Studios’. City Road Basin, EC1. Sketch plans. This is one of the early iterations of the building’s possible spatial arrangements and was fundamental in coming up with a subtle mix of architectural offices and swimming pools. Stressed employees, as well as members of the wider public, can luxuriate in these pools as a retreat from the busy city around them.

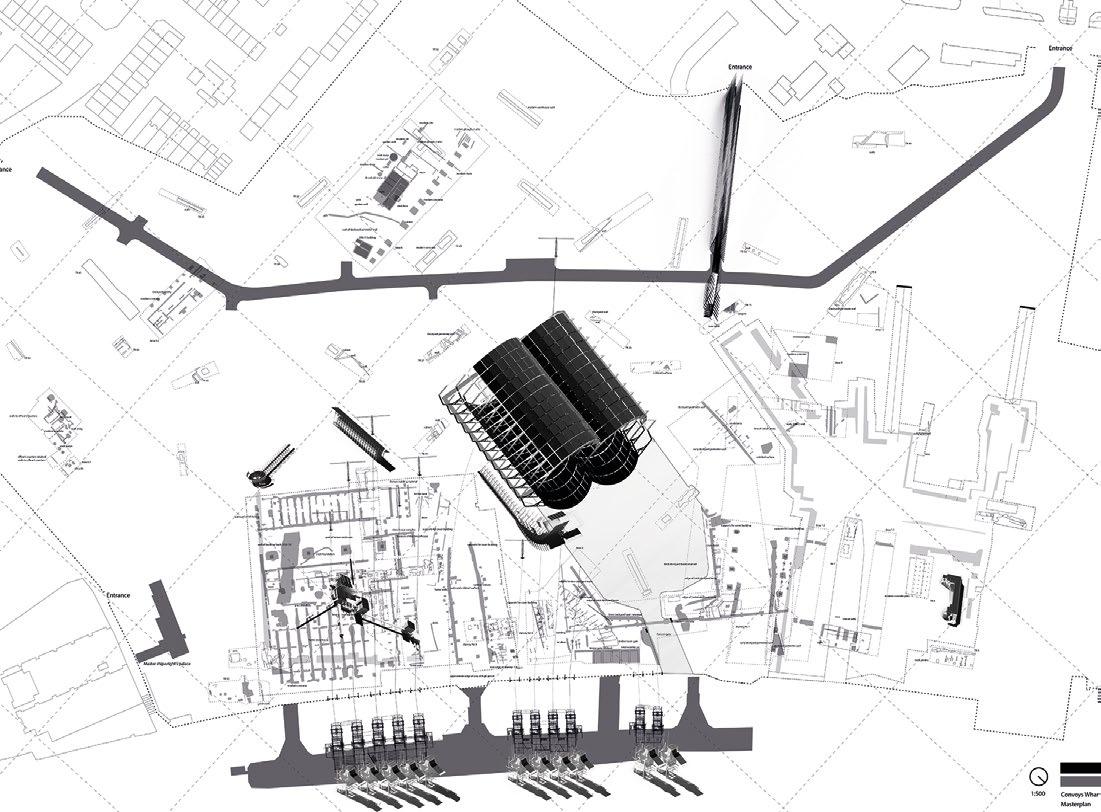

0.6 Nathan Verrier, Y3 ‘Deptford Creek’. Convoy’s Wharf, SE8. Bird’s-eye perspective. Convoy’s Wharf is one of London’s most significant historical sites but it has lain abandoned and a new development plan threatens to swamp it with luxury housing. Adopting a different approach entirely, this scheme envisages a rewilded forest with a new forestry commission building that also includes community spaces for residents. The wider purpose is to enable coexistence between humans and nature.

0.7 Vanessa Chew, Y3 ‘Proposal for an Intergenerational Amalgam’. Dalston, E8. Interior renders. The project uses colour theory and natural materials to enhance user experience and promote intergenerational interaction within a new type of architectural office. A series of interior spaces encourage the architects to engage with the building’s other occupants. This in turn enables them to design more meaningful and thoughtful projects for children and the elderly alike.

0.8 Joseph Russell, Y3 ‘Tightening the Green Belt: Oakwood Mews’. Enfield, N14. Roof plan. This design for new housing and associated community facilities in a woodland setting tackles the current housing shortage in the UK, and particularly London, by rethinking the concept of the Green Belt. The chosen site is in Enfield, opposite Oakwood Underground Station, designed by Charles Holden along with several other stations on the Piccadilly Line. The proposal is for a more ecological, sustainable form of suburban development.

0.9–0.10 Vanessa Chew, Y3 ‘Proposal for an Intergenerational Amalgam’. Dalston, E8. Model; planometric drawing. Given its location in the heart of Dalston, the building’s programme imagines an intergenerational architectural practice that is an antithesis to the mainstream projects which exclude minority age groups, notably absent from Dalston’s recent gentrification. Instead, there are a range of buildings for old, middle-aged and young people within a lively, colourful and playful landscape.

0.11–0.14 Wei Lim, Y3 ‘The Aylesbury “Renewal” Initiative’. Walworth, SE17. Isometric view; elevation; perspective section; view of walkway in the sky. The project situates itself in the Aylesbury Estate to propose an alternative, slow-paced refurbishment strategy for the estate’s recovery. It proposes to blur the boundaries of the construction site – its processes, builders and councilhouse tenants – reconceiving them so that existing residents are not displaced while refurbishment takes place, in a coexistence of inhabitation and construction. 0.15–0.17 Yeung (Julie) Yeung , Y3 ‘Reimagining Bermondsey through Craft’. Bermondsey, SE1. Interior perspectives; technical prototypes. An arts-and-crafts community centre that fuses two interrelated processes: coffee brewing and the manufacture of ‘coffee leather’ from waste coffee grounds. It builds on Bermondsey’s lost history of leather tanneries, while the architecture, as a living automaton, reveals workshops, archives, a theatre and café chambers, where walls become the canvas and instruments become the walls. 0.18 Luke (Taro) Bean, Y3 ‘Waterworks Baths and Studios’. City Road Basin, EC1. Elevation. For the exterior design of the new architectural offices combined with public and semi-public baths, the building wears its woven cladding panels like the armour of a samurai. This enables its skin to breathe in summer and winter alike, with the hot water steaming into the air on chilly days after being released via the chimneys and cowls on the rooftop.

0.19–0.20 Joseph Russell, Y3 ‘Tightening the Green Belt: Oakwood Mews’. Enfield, N14. Aerial perspective; elevations. Cockfosters London Underground depots are set to be demolished. The building materials, such as bricks and steel, can be repurposed to build housing and community facilities nearby. The scheme also adopts a hyper-local approach to harvested materials: adjacent arable land can provide straw for insulation and thatched roofs, while pine trees can provide timber. This localised sourcing significantly reduces the project’s carbon footprint.

Stealth Ecology Murray Fraser, Michiko Sumi

Stealth Ecology

Murray Fraser, Michiko SumiThis year students were asked to think about social and environmental sustainability in an inventive and sensuous manner. A collective approach to building cities is vital if we are to reduce energy consumption and subsequent environmental damage, even if free-market capitalism challenges such aspirations. To do so, radical thinking about the relationship between humans and nature, and how we organise society, is required. Increasingly, in ecological terms, the modern metropolis is both the cause and effect of this struggle encompassing power, economics, culture and nature. Why is ecological thinking such a crucial challenge today? The shift towards the East, notably China and India, in terms of capital and power, is one obvious consequence of globalisation. This can be viewed positively, e.g. our growing understanding of global networks and their relationship to the planet as a complex ecosystem, and negatively, e.g. the severity of the Covid-19 pandemic. Biodiversity is the subject of the moment; the biodiversity of cities is essential for social, cultural and economic life. Cities must not be seen in opposition to nature; rather, they exist within a sophisticated system where the preservation of animal and plant life is equally as important as reducing carbon emissions and energy consumption, possibly even more so.

UG0 examined many aspects of biodiversity and social and environmental sustainability in relation to building programme, construction, theory and architectural meaning. We designed novel and captivating proposals using interventions that seek to improve urban biodiversity for birds, mammals, reptiles, insects, fish, trees, flowers and plants. As ever, the aim was for students to carry out a process of intensive research into contemporary architectural ideas, urban conditions, cultural relations and practices of everyday life, and learn how to use these findings to create innovative and challenging forms of architecture for the contemporary city. Since there was no field trip, students spent time testing their designs by inserting 3D digital models into a real-time model of London.

Year 2

Marius Balan, Alannah Fowler, Jack Powell, Rupert Rochford, Luke Sturgeon, Karla Torio Rivera, Isobel Watson

Year 3

Eudon Gray Desai, Megan Irwin, Angharad James, Ye Ha Kim, Rebecca Miller, Sirikarn (Preaw) Paopongthong, Konrad Pawlaczyk, Jiayi (Silver) Wang

Technical tutors and consultants: Thomas Bush, Ewa Hazla, Nick Jewell, John I’Anson

Critics: Sabina Andron, Julia Backhaus, Johan Berglund, Anthony Boulanger, Eva Branscome, Malina Dabrowska, Pedro Font-Alba, Millie Green, Ben Hayes, Jonathan Hill, Kaowen Ho, Becci Honey, Bruce Irwin, Anja Kempa, Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Hazel McGregor, Ana Monrabal-Cook, Oliver Morris, Aggie Parker, Luke Pearson, Theo Games Petrohilos, Stuart Piercy, Joshua Scott, Ben Stringer, Mika Zacharias

Sponsors: Bean Buro, KPF, VU City

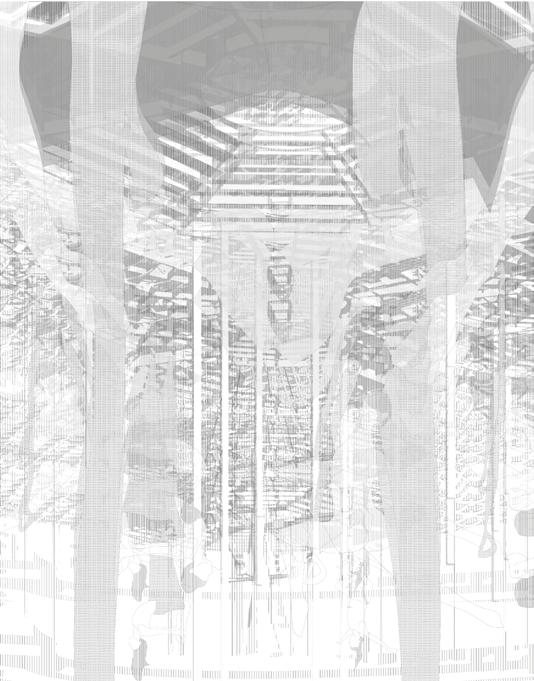

0.1, 0.3–0.4 Ye Ha Kim, Y3 ‘Digital Grotesque/Liquid Gold, W1’. The scheme proposes a DNA centre using liquid honey as a data-storage medium, thereby merging the natural honey-making process of bees with innovative methods of recording environmental information. Honey contains crucial ecological data about the floral ratio of the ecosystem at any given time. Collecting this data can inform future land preservation and reclamation strategies. This is particularly timely in relation to predictions that central London will be completely flooded by the year 2100 due to climate change. Over time, the digitally differentiated surfaces of the columns on the façade will create an inhabitable ecosystem for bees, whereas beneath, in the drowned world, corals will flourish symbiotically.

0.2, 0.21 Sirikarn (Preaw) Paopongthong, Y3 ‘An Agrarian Agenda, Bangkok’. A proposal for a new kind of agrarian village in suburban Bangkok, Thailand, that serves as a central hub for agricultural practices alongside an innovative residential model. Covering a large area of arable land and irrigation channels that are connected to the local canal network, a return to the traditional practice of family-based subsistence farming allows a suburban village to become self-reliant. Cultivation processes important to agrarian production, specifically paddy-field rice farming, are incorporated to devise localised earthen construction techniques.

0.5–0.6 Konrad Pawlaczyk, Y3 ‘What Do Bats Find Beautiful?, E5’. Experimenting with reversing the anthropocentric power dynamics of architecture on a site along the River Lea in Hackney Marshes, East London, the design focusses on understanding the perspectives and needs of horseshoe bats. As a result, human activity is located solely in the negative space that is left over by the bats’ activities. The building’s primary function is to create spaces that accommodate different activities in the daily life of bats. The constructed habitat mediates between underground tunnel spaces that serve mainly as roosts for hibernation or as overground summer ‘social roosts’ that function as nurseries to raise young bats.

0.7 Luke Sturgeon, Y2 ‘A Falcon’s Place, NW1’. The gradual return of the peregrine falcon to major cities in Europe in recent years is both a natural occurrence and a result of artificial reintroduction. Building upon a new ecological appreciation of this endangered bird of prey, the project reveals changes taking place within London’s wider ecosystems. It also considers the types of relationships that can be fostered between humans and avifauna – birds of a particular region – through a better understanding of the natural systems in our cities. The site is an ultra-narrow sliver of land behind St Pancras International in London.

0.8–0.9 Megan Irwin, Y3 ‘Chateau Camden, NW1’. The global wine industry is reshaping its agricultural activities as climate change affects weather patterns. The poleward shift of warmer temperatures is predicted to shake-up the geographic distribution of wine production; a process already underway as English winemaking expands. The project imagines an urban agricultural exploration, based on the prediction that London’s climate will be like Barcelona’s is today by 2050. It creates a circular economy for winemaking that revolves around three key phases: growing, making and recycling.

0.10–0.12 Rebecca Miller, Y3 ‘Theatricalities of Chalk, Surbiton’. Located in a disused Victorian-era reservoir at Seething Wells, South West London, the project mediates the slow and unseen geological timescales of the Arcadian Thames, with a specific focus on chalk and seashells imported to the site during its initial construction. The proposed landscape of hedonistic leisure – including a theatre, gallery and community centre – sits directly across from the pleasure gardens

of Hampton Court Palace. These leisure activities are spatially subordinate to a chalk research facility, the purpose of which is to remind people of the threat that Britain’s natural chalk faces from urban development. 0.13 Rebecca Miller, Y3 ‘Observatory of Natural Timescales, Ham’. Sited at Ham House, Richmondupon-Thames in London, an ‘ecological condenser’ heightens occupants’ visual and haptic perception of the natural landscape. The observatory reveals natural timescales, both above and below ground, that are often imperceptible to human understanding. The gridded building rakes in light from the surrounding environment and allows itself to be overtaken by natural weather conditions via disposable skin-like cladding elements.

0.14, 0.20 Angharad James, Y3 ‘Gospel Oak Piano and Timber Factory, NW5’. The northern hemisphere is home to ectomycorrhizal root systems: fungi that connect tree roots in what is known as the Wood Wide Web. These fungi act as major carbon sinks, yet they now face decimation due to climate change. At around 30%, the London Borough of Camden has one of the highest rates of tree-cover in Britain. The project investigates the borough’s industrial past as the international centre for piano manufacturing, and proposes a new piano factory and connected forest on Hampstead Heath. As trees grow best in rich ecological forests with soundscapes of between 115–250Hz, the factory is designed to produce a new soundscape in harmony with the forest.

0.15–0.16 Eudon Gray Desai, Y3 ‘Reindustrialising Regent’s Canal, E3’. The project proposes a cultural and economic regeneration of Regent’s Canal in London using two naturally occurring biomaterials – bacterial cellulose and chitin – that can be sourced from the canal. Three distinct canal-side structures are situated on the stretch between Victoria Park and Limehouse Basin, and create the foundational infrastructure for the proposed biopolymer revolution. The canal-side structures include a material production factory, a water-treatment facility and a marketplace.

0.17, 0.19 Jiayi (Silver) Wang, Y3 ‘Tilbury-on-Thames, Essex’. This project asks whether tourism can regenerate riverside towns in Essex, using Tilbury as a test site. Examining existing environmental and social problems, such as vulnerability to flooding and high unemployment, the urban masterplan provides a flood-resistant townscape and a multi-level cruise terminal along the riverfront. The cruise terminal operates as a community centre and produces energy through a bank of specially designed water turbines – a dramatic architectural view that welcomes arriving boats. Parts of the structure are designed to collapse to allow for simple rebuilding after extreme storms and for maintenance.

0.18 Jack Powell, Y2 ‘Thamesmead Archipelago: Speaking with mycelium’. The project facilitates interspecies relationships by reconnecting humans with their senses. Mycelium is used as a potential collaborator in the context of climate change and rising sea levels. Utilising this underground organism to re-mediate a hazardous landfill site creates a new experiment in the wake of previous architectural interventions in the area, including the Royal Arsenal in Woolwich and the Thamesmead estate, the latter as featured in Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971). As we enter a new age of information, finding ways to communicate with, and extract data from, other living species will provide our biosphere with tangible value.

Multitude Murray Fraser, Michiko Sumi

Multitude

Murray Fraser, Michiko Sumi‘I contain multitudes’, wrote the American poet Walt Whitman. Architecture does even more so – not least because every building serves in some way as a social condenser. Cities teem with population and so it becomes the role of architects to rethink and redesign the organisation and division of urban spaces. Yet ‘multitude’ can also refer to building materials, thousands of pieces of which need to be used for even the humblest of houses. Multitudes are equally environmental and ecological, and in future they will include for instance a profusion of robots and cyborgs amid our daily lives. Dealing with such conditions of multiplicity was the broad challenge that we asked UG0 students to take on board in their design projects this year.

London is a city that can be seen in terms of multitudes, whether in terms of its population, its buildings, its urban spaces, its wildlife, its economics flows, and its cultural outpourings. To start things off, therefore, students were required to scrutinise these divergent ideas of multitudes in London as a large and complex and diverse global city. This involved them in rediscovering those ignored or neglected spaces and landscapes, and also in exploring the invisible infrastructure of daily life in the city. Hence the presence of the ordinary lives of London’s diverse citizens needed to be a key aspect of the themes that they chose to investigate, and the projects they designed design. We wanted them to consider, for example, how the everyday urban environment might be re-read as a multitude as well as a space of pleasure, enjoyment, and such like.

Following an initial project of their own devising in Term 1, students then went on to develop their own individual briefs for buildings or other urban interventions on sites they had selected around London. This year’s field trip was to Xi’an and Luoyang, precisely at the moment in mid-January when the Covid-19 pandemic was erupting in adjacent Hubei province. We encountered none of this while there, and instead visited the Terracotta Warriors, Longmen Grottoes, ancient Buddhist temples, and heard an inspiring talk from Liu Kecheng, the most talented local architect and former head of the Xi’an School of Architecture.

The unit’s underlying aim was for students to learn how to carry out a process of intensive research into contemporary architectural ideas, urban conditions, cultural relations, and practices of everyday life – and then to learn how to use these findings to create innovative and challenging forms of architecture for the contemporary city.

Year 2

Zijie Cai, Yiu (Raymond) Cham, Peter Cotton, Andrei Dinu, Tharadol (Robin) Sangmitr, Hei Ming (Leo) Tse

Year 3

Temilayo Ajayi, Mohammed (Doori) Al-Doori, Tisha Aramkul, Maria (Masha) Gerzon, Rebecca Honey, Edmund King, Yiu (Anson) Lee, Zi Qi (Angel) Lim, Yingying (Iris) Lou, Yue (Miki) Yu

Thanks to our digital tutor

Tom Bush, technical tutor Nicholas Jewell and consultants Ewa Hazla and John I’Anson

Thank you to our critics

Alessandro Ayuso, Anthony Boulanger, Eva Branscome, Barbara-Ann CampbellLange, Nat Chard, Maria Federochenko, Stelios Giamarelos, Mimi Hawley, Marcus Hirst, Hazel McGregor, Ana MonrabalCook, Aggie Parker, Luke Pearson, Stuart Piercy, Ben Stringer, Simon Withers, Mika Zacharias

0.1, 0.4–0.5 Rebecca Honey, Y3 ‘Hampstead Waterworks, NW3’. Conceptual overview; model components; perspective. Set between two of Hampstead Heath’s main ponds, the building monitors/measures climate change in London, carrying out adjustments and dramatising its architecture through the landscape’s unpredictable performance. The Heath has been altered by humans through the extraction of earth and redirection of water, creating its Picturesque topography. Likewise, the building’s purpose as a meteorological centre taps into the ‘Technologies of the Picturesque’, framing environmental changes by echoing how weather is depicted in Romantic paintings.

0.2, 0.12, 0.21 Yue (Miki) Yu, Y3 ‘Thames Book Pier, SE1’. Axonometric; model; site sections. A concrete casting workshop harvests aggregate and water from the Thames to erect a pier on the Coin Street riverbank. The pier has fixed and floating elements that create an aquatic book village where readers enjoy a constantly changing relationship with river tides. Its components operate as instruments that transmit the sound of waves via concrete pipe-organs, warning of unpredictable tidal flows. The casting workshop also makes concrete boats to take readers on leisurely river cruises.

0.3, 0.11, 0.19 Zi Qi (Angel) Lim, Y3 ‘Reshaping the Chelsea Physic Garden, SW3’. Aerial perspective; plan; riverfront elevation. Britain is a major market for cut flowers, with billions of stems consumed and wasted every year. Here the investigation is of flowers as the building material for a flower-arranging school and plant-recycling workshop along the southern boundary of Chelsea Physic Garden. This historic garden is surrounded by a high brick wall supposedly creating a conducive microclimate. The project questions this claim, instead proposing a timber-framed wall, clad with plant-fibre panels which introduce floral scents to interiors.

0.6–0.7 Yiu (Anson) Lee, Y3 ‘Sheep in the City, W1’. Section; roof plan. In Cavendish Square a 1970s subterranean car park is being closed, probably to become a shopping mall. This project envisages an alternative future by the integration of sustainability and architecture, via an urban farm that creates a circular economy for foodstuffs. Emulating a successful Parisian precedent, it grows mushrooms and endives, and farms sheep. The scheme acts as a ‘digestive system’ for local food retailers and restaurants, mitigating food waste. Mushrooms create mycelium as a low-cost temporary building material.

0.8, 0.10 Edmund King, Y3 ‘The Digital Detox Clinic, SE16’. Perspective; section. As a rehabilitation centre hovering over the entrance to Southwark Park, and aimed at those suffering from technology addiction, the problem of self-isolation is rectified through a process transitioning between different soundscapes. The building aids these changing sensations by using tactile materials like handbeaten/weathered copper and charcoal-burnt timber. A side programme is research into spatial cognition. Here the building acts as a neural network with many paths, allowing researchers to examine how users navigate these spaces and routes.

0.9 Edmund King, Y3 ‘The Neoliberal Pavement’. Model. A speculative investigation into behavioural patterns and rhythms on London’s pavements. With the neoliberal notion of technological individualism trickling down into our lives over the last few decades, how we walk and interact with each other on pavements has gradually shifted. Sounds and rhythms taken from a sample section of pavement outside The Bartlett are transformed into performance pieces.

0.13 Tisha Aramkul, Y3 ‘Unplasticising the Thames, SW10’. Interior render. This microplastic filtration/research centre provides a visible statement about cleaning the

Thames. Fully committed to the circular economy, with material experiments displayed to visitors within a large hall, communal workshops fabricate soil/plastic composite blocks using microplastic fragments harvested via a collection chamber jutting out on a pier. River microplastics thus become a substitute for traditional aggregates in rammed-earth construction, minimising environmental impact. At the end of its lifecycle the building can be broken down into its essential components.

0.14 Mohammed (Doori) Al-Doori, Y3 ‘Dragitecture (The Vauxhall Drag Palace), SW11’. Roof plan. A new mixed-use public hub (archival/educational/performative) in Vauxhall Gardens celebrates and documents the artform of drag. On offer are workshops, classes and jobs for drag performers. Anyone interested in escaping their identity for a while can attend one of the performances or change their own façade by following the drag transformation process. The project’s aim is thus to reimagine our contemporary conceptions of social performativity through architectural design, dissolving itself within the queer history of Vauxhall. 0.15 Andrei Dinu, Y2 ‘Urban Relocation, SE17’. Exterior render. This programme is for a co-living facility that provides affordable dwellings and a community hub in Elephant and Castle. Formerly home to the (demolished) Heygate Estate, the area is being rapidly gentrified. Local people are relocated with little compensation, often having to move out of London and lose their jobs. Instead, taking inspiration from collective housing precedents, the design encourages a community-like spirit among residents by sharing social spaces like gardens and laundromats, while letting the ordinary public engage too.

0.16 Maria (Masha) Gerzon, Y3 ‘Plastic Patchworks, E3’. Material experiments. Waste is embedded into Western consumerist culture, with Britain having the highest clothing consumption in Europe and the greatest waste. If we alternatively re-purposed materials for more durability, showcasing their beauty, a new lifestyle could emerge. A fashion school aims to revitalise a canalside area in Bow via a warm, playful design that encourages people to express their imaginations amid a sea of colour, texture and tactility – also educating about sustainability by creating garments with a cyclical life.

0.17 Tharadol (Robin) Sangmitr, Y2 ‘The Brixton Brewery, SW2’. Exploded isometric. The programme is for an underground micro-brewery and theatre located in Brixton’s Windrush Square, harnessing the area’s diverse cultures. Conceived as a beacon/attractor, the building’s strong sculptural presence at ground level and the social pull of beermaking and musical events increase footfall and awareness of the adjacent Black Cultural Archives. The design celebrates the process of making by immersing the sequential flow required for the brewery process into its other spaces, linked together by enticing aromas.

0.18 Temilayo Ajayi, Y3 ‘London’s Little Lagos, SE15’. Part-elevation. We naturally begin to accumulate objects around us, transforming our homes into places of storytelling. The theme of a multitude of personal objects – spurred by research into Black British history portrayed in archives and museums – underpins this project on a Peckham site known as ‘London’s Little Lagos’ because of its Nigerian links. The design celebrates social activities so usually ignored but fundamental to our lives today, creating a community-led heritage centre in the rooftop intertwined with a residential/commercial terrace.

0.20 Zijie Cai, Y2 ‘A Thousand Flakes’. Test model. Inspired by a famous Chinese poem titled ‘I Wonder if it’s the Milky Way Falling from the Skies’, a freefall testing device is created in order to explore the links between multitude and lightness. Cameras are also rigged up as part of this experimental model to examine the after-effects, thereby recording the myriad broken shards.

Continuum Murray Fraser, Michiko Sumi

Continuum

Murray Fraser, Michiko SumiOne doesn’t need to study a building for too long to realise that it is a continuum, not an artifact. Buildings are not fixed entities or static objects but are, in fact, never finished. They change over time, in their spatial atmosphere and patterns of usage and programmes, and they get added to and subtracted from until their eventual decline. What does this mean for architects when designing a building? How should, or can, one allow for change and transformation over the lifespan of individual architectures? How does one draw a line between what is included within a building – ostensibly its interior – and what is not – its exterior? How do new modes of trans-spatial communication and lifestyle transform the idea of buildings as cultural continuums?

Equally crucial, buildings also need to negotiate with the surrounding city, with the latter formed of a myriad collection of buildings that, likewise, exist as continuums. To what extent, then, do the users of buildings become creative participants, even agents, in the process of becoming? To what extent do buildings exist within their own relatively autonomous state, changing only under their own defined conditions? As potential mediations between these two opposing poles, the spatial and material investigations carried out by architects consider the connections and disruptions that coexist within a building when treated as a continuum.

Following an initial project of their own devising, students were asked to develop their individual briefs for buildings, or other urban interventions, on sites they selected around London. This year’s field trip was to Bangkok, where we visited floating markets, the ancient temples in the former capital of Ayutthaya, and a range of recently designed buildings, including the Kantana Film Institute designed by Boomserm Premthada (winner of this year’s Royal Academy Dorfman Award).

As ever, the unit’s underlying aim is for students to learn how to carry out a process of intensive research into contemporary architectural ideas, urban conditions, cultural relations and practices of everyday life, and then learn how to use these findings to create innovative and challenging forms of architecture for the contemporary city. Students are expected to use the unique speculative space offered by academic study and combine this with a commitment to social engagement and urban improvement. A clear understanding of the technological, environmental and developmental issues involved in design projects is vital. Furthermore, to develop their design proposals, students are expected to capitalise on the full range of methods of investigation and representation available to them: physical models, digital fabrication, photography, drawings, computer models, renderings, animations, films, and more.

Year 2

Charlotte Carr, Yuge (Julie) Chen, Sofya Daniltseva, Alice Guglielmi, Dongheon (Julian) Lee, Aaliyah McKoy, Hanlin (Finn) Shi, Tao Shi, Amy Zhou

Year 3

Daeyong Bae, Bryn Davies, Benedict Edwards, Millicent Green, Yiu (Anson) Lee, Yingying (Iris) Lou, Agnes Parker

Thanks to our critics and consultants: Tim Barwell, Anthony Boulanger, Eva Branscome, Matthew Butcher, Barbara-Ann Campbell-Lange, Jun Chan, Sam Coulton, Malina Dabrowska, Tamineh Hooshyar Emami, Guillermo Grauvoge, Ewa Hazla, Jonathan Hill, John I’Anson, Guan Lee, Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Luke Olsen, Achilleas Papakyriakou, Stuart Piercy, Jack Sardeson, Jack Sargent, Sara Shafiei, Ben Stringer, Mika Zacharias

Partners: Atelier One, Faber Architects

Thanks to our sponsors: Bean Buro, Forterra Building Products Ltd

Daeyong Bae, Y3 ‘The Dentist’s Chair’. This close-up shot is of the underside of an abstracted process model that encapsulates the four classic pillars of dentistry: excavation, bracing, bridging and veneering. In conceiving the human mouth as a continuous construction site that requires work throughout one’s life, the model sets the feel and tone for the proposed building project to follow.

0.2, 0.8–0.9, 0.15 Daeyong Bae, Y3 ‘Self-Excavating Building’. Convoy’s Wharf in Deptford is a significant historic site, dating back to before a dockyard was established there in the early-16th century. A development plan recently threatened to swamp the site with luxury housing. This proposal adopts an alternative approach, envisaging a vast archaeological park for residents to enjoy and watch tall scratching devices slowly remove the soil. Shown first in its mechanical model form, in which scratchers sit on their pontoons, powered by tidal drop; then, its poetic expression; a sgraffito plan drawing made using erasure to suggest the gradual revealing of the sub-layers; and lastly, a site strategy plan, depicting viewing walkways and platforms. The overall scheme includes two crucial reused elements: the twin-vaulted Olympia Building with its 1850s cast wrought-iron frame, veneered with mottled whitewashed timber shingles. A sequence of new laboratories and community spaces are clipped onto the existing timber jetty that runs parallel to the shoreline.

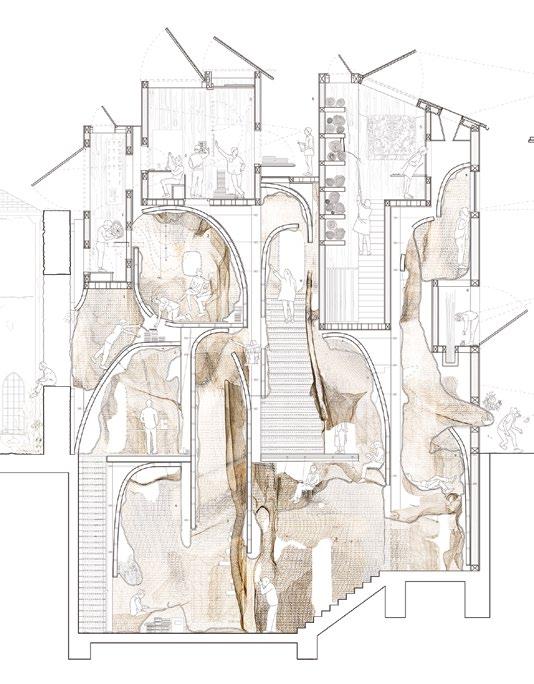

0.3–0.5 Millicent Green, Y3 ‘The School for Dexterity’. Plan; collection of process models; hybrid clay-etched sectional drawing. Situated in Bow Locks in Limehouse, the proposed school explores the relationship between hand and machine through the tactility of clay – the quintessential, unpredictable London material – and our desire to touch. Acting as a teaching device in itself, the building is comprised of imperfect ergonomic spaces used for dexterous activities. Here, the clay is developed by machine and intervenedwith by hand, thereby allowing for human error within the mechanised process. The wider ambition of the project is to question where beauty can be found in construction today.

0.6 Hanlin (Finn) Shi, Y2 ‘Park Conveniences’. Material model. CAD-CAM digital fabrication techniques are used to simulate the pattern made by leaves dried out and stiffened with resin. The resultant form is used to shape the roof over a suite of semi-sunken public conveniences on the Outer Circle in Regent’s Park in London, designed to provide a pit-stop for park goers.

0.7, 0.14 Hanlin (Finn) Shi, Y2 ‘Made in China Chelsea’. Keen to undercut the prices of the East India Company’s porcelain imports from China, Britain’s first chinaware factory opened in the mid-18th century, close to Cheyne Walk in Chelsea. On a site nearby (Upper Cheyne Row), this project seeks to revive the industry in acknowledgement of the longstanding cultural link between the two countries. The drawing shows the dominating presence of the large ‘bottle kilns’ used to fire porcelain goods, as well as the careful combination of the sweeping Chinese timber roof forms, traditionally found in temples, with local vernacular of London stock brickwork. 0.10–0.11 Benedict Edwards, Y3 ‘An Alternative Building Site’. Partial perspective section; rendered bird’s-eye perspective. A prototype scheme located on Cleveland Street in London, as a response to the construction industry in post-Brexit Britain and foreign workers being replaced by drones and robots. By rethinking the construction site through a focus on the suppression of dangerous dusts and the facilitation of near-future robotics, a double-diagrid envelope system is proposed, to be reused at building sites around London, with almost every element modular and able to be rented. The ‘flesh’ envelope holds the site facilities, with a small technical college atop it, alongside larger event spaces for hire

0.12–0.13 Bryn Davies, Y3 ‘Night and Day’. Partial section; rendered night-time perspective. This proposal for a ferry terminal at Westferry Circus in Canary Wharf, offers a transitional node for social interaction and increased physical/mental wellbeing for shift-workers. Set on the riverfront, it constructs a synergy between the River Thames’s natural cycles and the regimented timetable of Canary Wharf. Through layered translucent materials and screens, the building offers a regulated progression of spatial and lighting conditions to prepare the circadian clocks of shift-workers.

0.16 Charlotte Carr, Y2 ‘Stage-Set Journey’. Using the exaggerated perspective effects of theatrical stages –like the Teatro Olimpico Vicenza in Italy – and the pastel colours of Wes Anderson’s films, this distorted model represents the key moments on a bus journey from Camden to The Bartlett in Bloomsbury. The final upper balcony is a landing on the twisting steel staircase that snakes up inside The Bartlett’s building.

0.17 Tao Shi, Y2 ‘Four Times of the Day’. Overlaid perspective. For this project, William Hogarth’s 1736 series of paintings Four Times of the Day was dissected and used as a guide to review London at the time. A new pavilion next to St Paul’s Church in Covent Garden –depicted by Hogarth – is proposed. The design connects the past to the present, thus equating architecture with historical commemoration. This idea of a continuum in time and space was taken further in the main project, for the old Foundling Hospital in Coram’s Fields, of which Hogarth was a patron.

0.18 Amy Zhou, Y2 ‘Landscape of Buildings’. Cutaway axonometric. This project is sited on Brent Reservoir in an area of London with a large Chinese population. It proposes a natural garden influenced by ancient Chinese gardens, and includes inhabitable community spaces for socialising. The design explores the idea of a continuum of time and the four seasons, with the evolution of the nature-scape considered in relation to the seemingly consistent state of the built elements. Taking inspiration from Feng Shui, the elements of water and wood are dominant, and views over the adjacent reservoir enhance the naturalistic feel of the site.

0.19 Aaliyah McKoy, Y2 ‘Vertical Market’. This model is part of a concept for a high-density market building on Ridley Road in London that sits vertically in a thin tower rather than horizontally on the street. The sense of being on a rambling promenade is enhanced by the design’s highly irregular form, complete with external staircases and lifts to take people and goods up and down.

0.20–0.23 Agnes Parker, Y3 ‘Towie: Toxic Overflow Waste in Essex’. Material model; concrete test pieces; plan; section. 1,264 landfill sites along the British coastline are eroding, leaking and spilling into the water; the majority of which are in the Thames flood zone. These landfills contain material from the Anthropocene age: whole items, broken fragments and toxic chemicals. Sited on a rubble-strewn beach in Tilbury in Essex, this project proposes laboratory residences for climate researchers and artists. The structures dot the terrain and have thick concrete cores to encase toxic elements beneath them. Slow erosion reshapes them gracefully as they crumble away into the sea.

Material Display Murray Fraser, Michiko Sumi

Material Display

Murray Fraser, Michiko SumiYear 2

Victoria Blackburn, Kai (Kelvin) Chan, Alys Hargreaves, Celina Harto, Holly Hatfield, Karl Herdersch, Noriyuki Ishii, Francis Magalhaes-Heath, Sung (Ryan) Wong

Year 3

Ella Adu, Jack Barnett, Eleanor Evason, Shu (Michelle) Hoe, Maya Patel, An-Ni Teng, Chun (Derek) Wong

Thank you to our consultants and critics: Laura Allen, Alessandro Ayuso, Tim Barwell, Anthony Boulanger, Eva Branscome, Matthew Butcher, Rhys Cannon, Mollie Claypool, Marjan Colletti, Sam Coulton, Tamineh Hooshyar Emami, William Firebrace, Ewa Hazla , Jonathan Hill, John I’Anson , Luke Olsen, Thomas Parker, Stuart Piercy, Frosso Pimenides, Sophia Psarra, Sara Shafiei, Manolis Stavrakis, David Storring, Ben Stringer, Elly Ward, Henry Williams, Stamatis Zografos

We are grateful to our sponsors: Bean Buro Forterra Building Products Ltd

What are the kinds of materials – whether physical or intangible – that make up the architectural fabric of a global city like London? How can architects participate in the material production of this city, and what insights and techniques might we bring to the design and making of innovative urban materials?

It is important always to ask where materials come from, and how they are transformed and applied. Yet materials are not merely about physical or aesthetic qualities: their meaning also derives from how they are framed and presented. London, like other cities, is as much about the act of display as it is about ordinary social and economic processes. Within an urban setting, therefore, how might architecture play its part in revealing and presenting people, objects or buildings? The Latin origin of the word ‘display’ suggests unfolding, dispersing and scattering: could this be used to provoke different ideas about what it means to design for display? Might an investigation into the concept of display in relation to materials itself create innovative spatial forms?

Following an initial project of their own devising, students in UG0 were each asked to develop their individual briefs for buildings or other urban interventions on sites they selected around London. This year’s field trip was to eastern India, notably Kolkata, Chennai and Pondicherry, where we saw different approaches to the idea of materials and how they can be displayed within the urban realm.

The unit’s underlying aim was for students to learn how to carry out a process of intensive research into contemporary architectural ideas, urban conditions, cultural relations, and practices of everyday life – and then to learn how to use these findings to create innovative and challenging forms of architecture for the contemporary city. Students used the unique speculative space offered by academic study, and combined this with a commitment to social engagement and urban improvement as if their projects were actually going to be built. A clear understanding of the technological, environmental and developmental issues involved in design projects was vital. To develop their design proposals, students capitalised on a wide range of methods of investigation and representation including physical modelmaking, digital fabrication, photography, drawing, computer modelling, rendering, animation, and filmmaking, to allow for intuitive and spontaneous design-based reactions to the issues being investigated. After all, a strong design idea produced by speculative or lateral thinking can stimulate specific theoretical insights just as much as the other way around.

2018

Fig. 0.1 Shu (Michelle) Hoe Y3, ‘Swan Island Boatyard, Thames Tideway, Twickenham, TW1’. Part elevation. This detailed colour study of the façade for a brand new boatyard on a small island in the River Thames shows the concept of a web of glistening threads, formed by the rigging ropes and canvas sails covering much of the building and reflected in the water. Fig. 0.2 Jack Barnett Y3, ‘Building Maintenance Exposition (BME), Bridport Place, Islington, N1’. Elevation drawn onto cyanotype tiles. This proposal speaks to the increasing public concern for the conservation and ecology of buildings. It proposes a ‘taskscape’ wherein architectural components are dismantled for preservation purposes or auctioned off for new-build schemes. The various pavilions, both permanent and transitory, hint at interventions that change our perception of

permanence and invite building maintenance to play a role in the design process. Fig. 0.3 Alys Hargreaves Y2, ‘Haptics of Fire, Faraday Gardens, SE17’. This early study model uses a rotational ‘fore-casting’ process that would lead to the design of a haptic pavilion and obfuscated heat shaft for the extension of the Bakerloo Line. Fabricated from four distinct materials, the structure is formed through a process of rotation, each stage of casting is rotated by 90 degrees to provide the formwork for the next stage. The architecture becomes a material display of its own creation. Fig. 0.4 Ella Adu Y3, ‘Brockwell Park Community Centre, Tulse Hill, SW2’. Model. A mass of materials salvaged from a partially demolished 1970s housing scheme are recast and reshaped into brick rubble walls and other constructional

elements for an extension to a small existing community centre on the western side of this popular South London park. Fig. 0.5 Jack Barnett , Y3 ‘Soane’s Mnemonic Museum, Lincoln’s Inns Fields, WC2’. Cyanotype ‘memory’ plan. Initially, this famous museum was 3D-scanned to create an interactive virtual model. Paradoxically, this process neglected Soane’s key legacy, which is the realisation that drawing is an act of creating. Hence the making of a virtual 3D computer game that is envisaged as a virtual ruin in which the players, acting as ‘conservationists’, draw in space their own memories of the museum as well as they can remember, providing a steadily accumulating digital archive.

Figs. 0.6 – 0.7 Maya Patel Y3, ‘Inherited Residue, Hammersmith Bridge, W6’. Oblique projection; perspective from water level. With London’s high land values making dwellings so much smaller, this tower provides a space to store and release the religious objects currently held in domestic Hindu shrines. It reinterprets the Thames as an ancient sacred river, with the tidal rhythms and flows powering the decay and destruction of these precious personal objects. Fig. 0.8 Victoria Blackburn Y2, ‘Billingsgate Roman Baths, Lower Thames Street, EC3’.Geometric projection. Currently buried away in the basement of an office block, this fine surviving example of a well-to-do house and baths from the time of the Roman Empire’s rule is now made accessible through a twisting structure that also links above to the

ruins and gardens of St Dunstan in the East. Fig. 0.9 Alys Hargreaves Y2, ‘Haptics of Water (The Urban Well), Shadwell Basin, E1’. Slip-cast models. These diverse, repeated components and formworks were utilised in sequence to make the haptic changing rooms for the visitors to public baths located within a quiet low-rise docklands site. Water is channelled behind the slipped panels, amplifying the sound and atmospheric temperatures created by water whilst hidden from sight, playing with the concepts of wet and dry. The building is connected to an adjacent open-air lido and Shadwell Basin.

Figs. 0.10 – 0.12 Eleanor Evason Y3, ‘Con[curve], Lots Road, Chelsea Creek, SW10’. Interior view; physical prototype models; ground floor plan. Inventing a technique to produce water-formed precast concrete as ultra-thin curvaceous pieces, to be patented as ‘Con[curve]’, a vast tank set into this riverside site in Chelsea has a gantry overhead and associated services buildings above and below ground. Over time the building’s elevations will grow thicker with more concrete test panels. Fig. 0.13 Shu (Michelle) Hoe Y3, ‘Swan Island Boatyard, Thames Tideway, Twickenham, TW1’. Site plan. A special viewing tower for Mike Webb to use when visiting is located on the river’s eastern side in the Hamlands, with a ferry over to the boatyard and to Twickenham beyond, creating a much-needed river crossing in this area.

Figs. 0.14 – 0.15 An-Ni Teng Y3, ‘Extreme Yoga Centre, Regent’s Park Canal, NW1’. Prosthetic model; perspective view. On the canal cut next to London Zoo, a leafy landscaped building for various intensive forms of yoga is composed of timber colonnades and walkways, with its pools and service areas dug into the ground. Aided by prosthetic devices that stimulate the contortion and stretching of the human body, users can happily partake in the likes of aqua yoga, aerial yoga, wall yoga and hot yoga.

Fig. 0.16 Sung (Ryan) Wong Y2, ‘Stockwell Skatepark Skin, Stockwell Road, Brixton, SW9’. Also known as ‘Brixton Beach’, this well-known site is under threat from a new luxury high-rise development. This design imagines a thin protective wall that can safeguard the skatepark, like a crust, while also allowing skaters to glide through it as they wish. Fig. 0.17 Kai (Kelvin) Chan Y2, ‘Death as a Commons, Temple Place, Victoria Embankment, WC2’. Model. London becomes a necropolis in this proposal for a new form of inner-city crematorium that mixes facilities for funeral services with an open public park where other citizens can simply eat their lunch, walk their dogs, relax or play sport. Fig. 0.18 Noriyuki Ishii Y2, ‘Reading Rooms, Charlotte Street, W1’. Collage. Intended as a largely unprogrammed space for free and adaptable use as an urban

commons and for the numerous students in central London, this slim tower makes allusion to Mies van der Rohe.

Figs. 0.19 – 0.20 Chun (Derek) Wong Y3, ‘Post-Brexit Foxskin Hattery, Duck Island, St James’s Park, SW1’. Interior view; exploded isometric. In an impoverished Britain after Brexit, to meet nationalist demands for self-sufficiency, the Queen’s Guards are to be kitted out with foxskin busby hats, made using the pelts of foxes that die regularly in London. Where else to site the hattery but in St James’s Park, in plain sight of Horse Guards Parade and Buckingham Palace? The skinning, curing, cutting and stitching of the pelts takes place in a tall tower, as processes in descending layers.

Fig. 0.21 Karl Herdersch Y2, ‘Unitised Urbanism, Russell Square, London SE1’. Isometric studies of interior spaces. This project is realised by creating a cultural condition for a ‘life without work’, imagining a Universal Basic Income in the future. A kit of parts creates an apparatus for agency for a community within an inhabitable wall. This apparatus is pushed to the limit until the urban condition begins to resist variation and moves towards mass homogeneity.

Pleasure! Murray Fraser (on sabbatical), Tamsin Hanke, Sara Shafiei

Year 2

James Carden, Yoojin Chung, Theo Clarke, Dan Johnson, Megan Makinson, Chloe Woodhead, George Wallis

Year 3

Freya Bolton, Jun Chan, Ella Caldicott, Elliot Nash, Jimmy Liu, Dan Pope, Claudia Walton

Thank you to:

Mike Arnett, Edwina Attlee, Tim Barwell, Matthew Butcher, Joanne Chen, Max Dewdney, Stephen Gage, Ruairi Glynn, Ewa Hazla, Jessica In, Lilly Kudic, Chee Kit Lai, CJ Lim, Mads Peterson, Jonathan Pile, Richard Townend, Emmanuel Vercruysse, Patrick Weber

Sponsored by Bean BuroPleasure!

Murray Fraser (on sabbatical), Tamsin Hanke, Sara ShafieiOur theme for the year was pleasure. This is a complex concept, but also a deeply important one. From Ancient Greece through to more recent historical thinkers, such as Jeremy Bentham, Sigmund Freud and Henri Lefebvre, pleasure has long been one of the guiding principles of human existence. We conceived of pleasure in its widest sense, and as such, included the wide range of architectural, spatial, social and cultural discoveries that can be found in the modern city. How, then, can architects contribute to a contemporary concept of pleasure? Urban tactics for a city like London suggest a need for play, subversion, fantasy, temporariness, mobility and transgression. This year, therefore, Unit 0 students were asked to investigate and conceive projects that hinged upon ideas of urban delight.

To start the year, students scrutinised the pleasures of everyday existence for those living in London. This involved them in rediscovering ignored, or neglected, acts of utility and function, and investigating manoeuvres and behaviours carried out instinctively. How might the process of recording these activities or things come to be seen as a moment of pleasure, perhaps by enhancing or subverting the course of the everyday, or by taking delight in silent but novel ways of capturing moments of happiness? Students imagined how the everyday might be re-read as a thing of surprise, disruption and enjoyment, thereby creating spaces or objects of delight.

Our unit field trip in early January was to Mumbai and Ahmedabad, along with some stepwells in the Gujarat province, where we studied the conditions of pleasure to be found there in many guises. We uncovered the excitement held within ancient pieces of architecture and relived the anticipation of modernist architects as they broke ground. Students visited craftsmen who daily find inspiration and materials from the landscapes around them, and met with those in architectural schools and practices there.

Fig. 0.1 Freya Bolton Y3, ‘A Tailored Sanatorium’, Vale of Health, Hampstead, NW3. A day-care health centre helps those affected by pollution as London’s air quality becomes increasingly hostile. Conceived as a protective suit and sited in the appropriately named Vale of Health, occupants are alienated from the city around them. The breathable garment shrouds the building’s body at points where the drench of rain would be felt, yet it never wholly seals the interior. Rather, the building embraces its surroundings while acting as a defensive barrier to external pollutants. Fig. 0.2 Ella Caldicott Y3, ‘Aseptic/Administrative IV Clinic’, East India Dock Basin, E14. This walk-in clinic for IV (intravenous) therapy has two halves on either side of the dock inlet: on one side is an aseptic drug preparation facility, and on the other the administration clinic

– with the pharmacy acting as a ‘kissing gate’ between them. These elements are normally never placed together, yet here their subtle intercommunication produces its own sense of functional ornamentation. Fig. 0.3 Jun Hao Chan Y3, ‘Capability Brown’s Unfinished Landscape’, Fenstanton, Cambridgeshire. The influential eighteenth-century landscape architect, Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, owned this site but never got a chance to design it. This project therefore aims to translate the uniform horizontality of the landscape into a series of rotationally cast interventions that bring out both its picturesque and its sublime qualities.

Figs. 0.4 – 0.5 Jun Hao Chan Y3, ‘Institute of Geographers’, Mudchute, Isle of Dogs, E14. How can the concept of horizon, as the intersection of ground and sky, be translated and challenged architecturally? Just southwest of Mudchute City Farm, a new Institute of Geographers responds to the alliance between human and physical geography caused by scientists’ declaration of a new geological epoch, the Anthropocene. The building interacts directly with the site’s geology through raw excavation, using special foundation techniques and the earth as formwork for concrete casting. As a result, the boundaries between earth, ground plane and inhabitable space become blurred, promoting a novel spatial experience for users. Figs. 0.6 – 0.7 Ella Caldicott Y3, ‘Survival of the Prettiest’. Beauty and pleasure are interlinked through factors such as symmetry,

thus also serving a functional purpose in evolutionary adaptation. Here a scientific study of butterflies and geometric patterns creates intense delight through slicing, folding and dissecting. Figs. 0.8 – 0.9 Freya Bolton Y3, ‘The Pluviophile’. Encapsulating the duality of an experience when felt in two different places, London’s rain – harsh drops ricocheting off concrete surfaces – stands in contrast to the immersive, atmospheric rain in the northern woods outside Preston. The culmination is a suit for a Pluviophile, someone who loves rain. When worn, the suit invokes sodden and restrictive clothing, thereby reminding its wearer of home amidst the nondescript rain in London. Fig. 0.10 Daniel Johnston Y2, ‘The Insurance Market’, St Dunstan-in-the-East, City of London, EC3. Next to a derelict City church, this project

alternates between the formal space of an insurance broker and an everyday repair market where you can simply get something fixed. Suspended leather for the insurance office hints at the opulence and comfort of traditional banks, creating – perhaps – a false sense of security when buying insurance. Breaks within the stitching form pockets to file documents, stash cash, or quiet spaces to console oneself after a heavy claim. Figs. 0.11 – 0.12 Chloe Woodhead Y2, ‘A Natural Education’, Forest Road, Dalston, E8. Amidst a square of London’s dwellings, an after-school facility is buried into the soil beneath an exquisitely undulating roof – partly occupied and partly planted – to encourage 4- to 11-year-old children to immerse themselves and learn through play within the natural environment. Fig. 0.13 Claudia Walton Y3, ‘The Memory

Theatre’, Carey Street, WC2. Directly behind the Royal Courts of Justice, an innovative type of courthouse is proposed that uses theatre and set design to reconstruct the physical environment of the case being tried, so as to counteract the inaccuracies and distortions of witnesses’ memory of criminal events. 0.10 0.11 0.12 0.13

Fig. 0.14 James Carden Y2, ‘30 Minutes’, Shoreditch High Street, E1. In an abandoned petrol station in trendy Shoreditch, a night-time observatory within a pocket urban park allows occupants to glimpse the stars and planets above. The choreographed walking route through the project takes half an hour to complete, allowing for one’s eyesight to acclimatise to this microclimate of darkness in the city. Fig. 0.15 Elliot Nash Y3, ‘Resting the Black Cab’, Stoke Newington Common, N16. The iconic and nostalgic black cab is a mobile landmark within London, yet cabbies are suffering. This project forecasts change by imagining a future in which only one hundred London cabbies exist: their prices have been forced up, and they have become an exclusive service. The building serves and monumentalises the cab, welcoming back the Victorian

cabmen’s shelter as an exclusive place of rest. Fig. 0.16 Megan Makinson Y2, ‘A Factory of Domesticity’, Barnard Park, N1. Within a Victorian terraced street, the building provides a space for three families to inhabit and make wallpaper, thereby reviving a traditional manufacturing process. Hung paper screens act as the membrane between the domestic and the factory, allowing visitors the pleasure of peeling back a layer of wallpaper to glimpse the inhabitants’ lives.

Fig. 0.17 Claudia Walton Y3, ‘Spatialising Memory’. This is an exploration of differing perceptions of time during an event, particularly temporal illusions during moments of stress, and the effects these can then have on the space around us – such as in the personal memory of falling from a bicycle. Fig. 0.18 Jimmy Liu Y3, ‘Kensington Cuteness’, Kensington, W8. Using dwellings near to Holland Park, the project seeks to cutify London’s terraced houses. Starting by deforming their front elevations through mathematical/geometrical rules, a series of structural interventions and material injections strip away Victorian conventions. Fig. 0.19 Dan Pope Y3, ‘A Stage for Poplar’, Jamestown Way, E14. A watery riverside landscape offers stages for protest in East London, as part of a broader scheme to amplify protest. Elements are conceived of as

deployable interruptions within the public space, manipulating how the protests are viewed and broadcast. Strategically placed inflatable silhouette screens capture and project people’s movements, whilst urinals clip together in pockets to encourage gathering. Fig. 0.20 Dan Pope Y3, ‘What Happened to Irene?’ On 18 April 1964, the body of Irene Lockwood, who had been murdered, was discovered on the Thames bank in Hammersmith. This project forensically reconstructs viewpoints from multiple witnesses through a material language that distinguishes ‘known’ from ‘unknown’. 3D scanning technology proves an unreliable witness, as metallic surfaces in the model glitch the scanner, creating spaces of narrative ambiguity.

Ensure image ‘bleeds’ 3mm beyond the trim edge.

Soft City Murray Fraser, Justin C.K. Lau, Sara Shafiei

Year 2

Peter Davies, Qi (Nichole) Ho, Simina Marin, Carolina Mondragon, Rosie Murphy, Elena Real-Davies, Louise Rymell, Felix Sagar

Year 3

Linzi Ai, Angus Iles, Cheuk Wang (Chaplin) Ko, Ka Wing (Clarence) Ku, Maryna Omelchenko, Achilleas Papakyriakou, Sophie Percival, Bethan Ring, Ben Sykes-Thompson

Thanks to our consultants and critics: Julia Backhaus, Tim Barwell, Anthony Boulanger, Eva Branscome, Matthew Butcher, Mollie Claypool, Pierre D’Avoine, George Epolito, Pedro Font-Alba, Stephen Gage, Penelope Haralambidou, Ewa Hazla, Jonathan Hill, Johan Hybschmann, Tim Ireland, Mary Johnson, Hazel McGregor, Martin Manfai, Roy Nash, Jack Newton, Justin Nicholls, Luke Olsen, Stuart Piercy, Aleksandra Rizova, Bob Sheil, Matthew Springett, Ben Stringer, Michiko Sumi, Richard Townend, Graeme Williamson

Thanks to our sponsors Bean Buro

Soft City

The theme of the unit for this year was the ‘soft city’. Students were asked to investigate ways of looking differently at a major global city such as London, seeing it not as a harsh or alienating environment, or as existing only in the realm of economics and other systems, but rather as an open and fluid entity that allows for many readings of ‘softness’. This term could be understood literally, in terms of the relative density/hardness of the materials which are used to create buildings and urban spaces; or else more metaphorically in terms of the flows and interactions of human bodies, energies, weather patterns, trees, plants and animal species within the city; or else poetically through the expression of feelings such as love, warmth, openness and communality. How can designing the spatial practices and physical qualities of softness contribute to our urban experience, including the enhancement of sensations such as health and wellbeing? How might softness and hardness be designed together, whether in opposition or symbiosis, or indeed as some complex hybrid form?

To start the year, students were asked to investigate their personal understanding of London through an artefact, or perhaps a series of artefacts, which explored ideas of softness in relation to a specific area of the city. The aim of designing and/or making this artefact(s) was to introduce a diverse set of sensibilities and ideas about London as a ‘soft city’. These investigations then fed into the main design project for each student, in which they developed their own particular theme on a site of their own choosing within London in order to engage more substantively with ideas of softness in metropolitan life. These projects were asked to deal with aspects of social and cultural life (eating, sleeping, congregating, etc); economic exchange (business, shops, markets, etc); ritualised ceremonies (religion, shopping, education, etc); urban performances (media, theatre, sport, etc); or environmental conditions (parks, gardening, seasonal activities, etc).

Our unit field trip, from late November to early December, was to northern India, during which we visited the cities of Delhi/New Delhi, Chandigarh, Jaipur, Jodhpur and Agra. There we encountered very different cultural attitudes and traditions towards issues of softness/ hardness, openness/closure, official/unofficial within the city, and this in turn greatly enriched the projects that students designed this year.

Fig. 0.1 Ben Sykes-Thompson Y3, ‘Sensing Silvertown, Millennium Mills’, Rayleigh Road, E16. Geometric projection of entire scheme. A disused flour mill in the Royal Docks is turned into a sensory park based upon sight, sound and smell. In part of the older tradition of parks providing repose within the city, here that is accentuated by inserting new facilities through which citizens can self-diagnose early-stage problems developing in their eyes, ears and noses. As a landscape project and a creative reuse of a powerful existing building, a novel community-distributed model of healthcare is promoted. Figs. 0.2 – 0.3 Ben Sykes-Thompson Y3, ’Memory Mapping’. Folded section; physical model. We understand cities not through maps or fixed notions of time, but by individual journeys through the urban continuum. In doing so, we link

together seemingly disparate places based on our durations of travel and occupation, as shown by a series of models and folded drawings. Fig. 0.4 Rosie Murphy Y2, ‘Centre for Slow Sports’, Finsbury Square, EC2. Basement plan; time-stretched basement plan. Urban workers need places to escape the frantic pace of London, so a slow sports centre in the City of London offers a chance to engage in time-honoured pursuits like bowls, chess, tiddlywinks, and staring contests. Sunk into a basement car park below an urban square, sensations of time are investigated graphically in sliced and extended drawings.

Fig. 0.5 Simina Marin Y2, ‘Edible Eden’, Camley Street Natural Park, King’s Cross, N1. Physical model. In the much-loved but much-threatened Camley Street park, an innovative strategy aims to resist the gentrification and displacement of the King’s Cross redevelopment by building a nutrition school for local children. By introducing them to the processes involved in growing and cooking food, the revised park will stimulate play, physical pleasure, and a healthier diet for these children.

Fig. 0.6 Peter Davies Y2, ‘Softening Brutalism’, Barbican Estate, EC2. Physical model; render; general projection showing lines of views. Examining Brutalism's legacy, it is clear that the clichéd views about its harshness and inhumanity are grossly exaggerated. By careful analysis of the Barbican Estate through light and colour, a softer and more nuanced appreciation is derived. Fig. 0.7 Felix Sagar Y2, ‘Psychological Thresholds’, Prince Albert Road, Regent’s Park, NW1. Geometric projection. The boundary edges of Regent’s Park offer scant preparation or protection for those who suffer from psychological conditions like agoraphobia, and find its open spaces terrifying. A new after-school centre and playground helps children with such anxieties to develop a happier relationship with this loveliest of Royal Parks.

Fig. 0.8 Carolina Mondragon Y2, ‘Incendiary Institute’, Bethnal Green, E1. Physical model. In a dense urban site near Brick Lane, a test facility is created for experimental new materials being developed by the digital artisanal culture now developing in that area. Visitors can walk around and enjoy the burning of materials to experience the softness of ashes, probably the softest of all our urban materials. Fig. 0.9 Cheuk Wang (Chaplin) Ko Y3, ‘Prisoners of Knowledge’, Camden Road, Holloway, N7. Physical model. In this twist on the ‘halfway houses’ used to re-introduce prisoners to society, here the emphasis is on rehousing/training those who worked as prison librarians. Deep shade and bright light highlight the book displays that are open to the public, especially local children. Fig. 0.10 Linzi Ai Y3, ‘The Snug’, Princess Louise Pub, Holborn,

WC1. Embossed drawing. Within the toughness of Victorian London, the city’s pubs offered decorative oases of rest and indulgence, made especially soft in the snug bars of the Princess Louise and other pubs. Now this sense of material and decoration can be reused to design places of drinking in contemporary London. Fig. 0.11 Ka Wu (Clarence) Ku Y3, ‘Flying Breakfast’, City Airport, Hartmann Road, E16. Test models. Flight crews coming in and out of the increasingly internationalised City Airport are provided with a special hotel where they can stop over, and above all, enjoy wondrous 'Full English' breakfasts that incorporate bacon, eggs and other produce grown on site. 0.0

Fig. 0.12 Maryna Omelchenko Y3, ‘Farm/Temple of Falling Water’, Commercial Road, Limehouse, E14. Geometric projection. In gritty Limehouse, close to the canal basin, a new urban farm is inserted that also serves as a place of contemplation for those who wish to walk through it. Aeroponic tubes are fed with water that is collected on a large disused railway bridge, thereby linking the local environment directly to the building’s programme. Fig. 0.13 Elena Real-Davies Y2, ‘The Museum of Impermanence’, Rochester Square, Camden, NW1. Poster. Housing rights in London are being eroded through escalating prices and punitive legislation, so in a Camden square a group of squatters take action. A political campaign to defend their occupation is then turned into a museum that occupies the

square and local houses, and which records the displacement of people and their possessions from London over time. Figs. 0.14 – 0.15 Bethan Ring Y3, ‘Lund Point Mash-Up’, Carpenters Estate, Stratford, E15. Geometric projection, pattern book construction sheets. Stratford is one of London’s development hotspots but this is leading to the erasure of the communities that once lived there. So, rather than demolishing a tower block on the Carpenters Estate, this design strips it back to basics and provides facilities for a diverse mixture of users: allotments for existing residents, live/work studio spaces for artists, digital fabrication laboratories for UCL students, and a rooftop vantage point for West Ham football fans.

The Bartlett School of Architecture 2016

Figs. 0.16 – 0.18 Sophie Percival Y3, ‘Holly-Burb-Land’, Hampstead Garden Suburb, NW11. Physical models of bricks; section; ground-floor plan. So successful has Hampstead Garden Suburb been in defying change that it has become perhaps what it was always destined to be, a television and film set for endless Edwardian class-based dramas. Here a few existing houses are stealthily tuned into studios by peeling back walls, inserting luminous pink bricks, and hiding camera positions into the ubiquitous hedges that line the estate. Fig. 0.19 Achilleas Papakyriakou Y3, ‘Asclepeion by the Thames’, Doon Street, South Bank Centre, London SE1. Ground-floor plan; section. In Ancient Greece, those experiencing mental health issues could retire for a while to an asclepeion, a retreat that included bathing pools, theatres,

0.16

libraries, and other places to sit and think and recover. Using the Greek-inspired Olivier Theatre and the cultural facilities of the South Bank as its trigger, this scheme offers sumptuous relaxing baths to citizens on what is currently a grungy car park. 0.17 0.18

Urban Rituals Murray Fraser, Justin C. K. Lau, Sara Shafiei

Year 2

Bingqing (Angelica) Chen, Minesh Patel, Duangkaew (Pink) Protpagorn, Sheau Wei (Amanda) Tam, Fei Waller, Xinyue (Angell) Yao

Year 3

Samuel Coulton, Kelly Frank, Katja Hasenauer, Jun Wing (Michelle) Ho, Jessica Hodgson, Ka Wing (Clarence) Ku, Tomiris Kupzhassarova, Shirley Ying Lee, Matei-Alexandru Mitrache, Henrietta (Etta) Watkins

We would like to thank our consultants and critics: Ben Allwood, Scott Batty, Anthony Boulanger, Matthew Butcher, Rhys Cannon, Aran Chadwick, Nat Chard, James Cheung, Mollie Claypool, Hannah Corlett, Ben Cowd, Kate Davies, Stephen Gage, Manuel Jimenez Garcia, Nasser Golzari, Penelope Haralambidou, Ewa Hazla, Colin Herperger, Bill Hodgson, Konrad Holtsmark, Tom Hopkins, Jessica In, Chee-Kit Lai, Guan Lee, Hazel McGregor, Jamileh Manoochehri, Jack Newton, Luke Olsen, David Patterson, Lukas Pauer, Stuart Piercy, Frosso Pimenides, Jack Sardeson, Natalie Savva, Yara Sharif, Bob Sheil, Neil Stacey, Sven Steiner, Richard Townend, Nina Vollenbröker, Bill Watts

We are grateful to our sponsors, Bean Buro

Urban Rituals

Murray Fraser, Justin C. K. Lau, Sara ShafieiThe aim of UG0 is for students to learn how to carry out intensive research into architectural ideas, urban conditions, cultural relations, practices of everyday life, and similar matters – and then use these findings to create innovative forms of architecture for the contemporary city.

This year’s theme was ‘urban rituals’, taken in the very widest sense. Ever since humans organised themselves into communities, the importance of ritual has been paramount. We are no different today in our highly technologised capitalist society. It is just that the rituals have changed. This leads to some intriguing questions. How do people inhabit cities through the performance of rituals? What are these differing beliefs and practices? What is the role of ritual within the processes of everyday life, or as part of exceptional spectacular events? How can architecture and urbanism either help or hinder such activities, and connect them to vital issues as energy consumption and urban biodiversity?

Standard definitions of ritual refer to factors such as time, rhythm, routine, pattern, habit, location, beliefs, value systems, behaviour, observance, custom, tradition, celebration, ceremony, performance, acting, and so on. Rituals can thus be ultra-low-key in the sense of those carried out repeatedly and consistently as part of daily life. The word can equally apply to the psychological desire for events and spectacles which on the surface might claim to be unique, unrepeatable and deviant, but yet are in themselves an acknowledgment of the need for an agreed temporary respite from normative practices.

Indeed, there can be seen to be an overlap between the needs for repetition and exception, and in that sense we can conceive of performance as being part of the theatre of everyday life, with the streets and urban spaces of our cities forming the open space for theatrical performance. How can looking into urban rituals in London – a vast multi-ethnic constellation that contains many different value systems – trigger new ideas about architecture and its role in society?

The students’ initial projects were framed as proposals for an object, space, installation, pavilion or other form of insertion into London, with a particular focus on ritualistic behaviour. Their main projects were then on sites they chose where powerful forms of urban ritual already exist, and could thus be added to. In late November, our unit field trip was to Shanghai, where we experienced a vibrant and economically booming city in which pressures of development are creating new kinds of urban rituals, while also frequently coming into conflict with older patterns of everyday life. Other highlights were the beautiful water gardens of Suzhou, where ritual and landscape are fascinatingly blended together.

Fig. 0.1 Samuel Coulton Y3, ‘Wallbrook Solar Credit Union, City of London, EC4’. Series of physical models. This project proposes the setting up of a Credit Union to look after the interests of the low-paid cleaners in the City of London who have to work through the night. Their bank is situated inside the first large park to be created in that part of town, protected all around by a thin, inhabited wall of poche spaces. The rays and energy from the sun are collected by giant metal ‘flowers’ in the park, with the light and heat then being funnelled down into sunken spaces below the ground. Figs. 0.2 – 0.3 Duangkaew (Pink) Protpagorn Y2, ‘The Soho Congee Club, D’Arblay Street, W1’. Low-relief section; physical model. Chinese migrant workers are badly exploited in Soho, working hard for almost no pay and with little care being given

0.2

to their living conditions. Here a new collective facility functions as a temporary club for migrants, hidden behind a typical London façade, filled with prefabricated cubicles in which the residents can sleep, wash, eat and play. Figs. 0.4 – 0.5 Samuel Coulton Y3 ‘Wallbrook Solar Credit Union, City of London, EC4’. Geometric projection; partsection. Drawing on precise analysis of the proportions of Wren’s St Paul’s and St Stephen Wallbrook, a cluster of alabaster domes and carefully designed scoops capture and transmit sunlight to the Credit Union and the underground sleeping rooms for cleaners. In another act of public generosity, the Wallbrook Rover is excavated to enhance the environmental biodiversity of the City of London’s new-found park. 0.4