Design Anthology UG10

Architecture BSc (ARB/RIBA Part 1)

Compiled from Bartlett Summer Show Books

Architecture BSc (ARB/RIBA Part 1)

Compiled from Bartlett Summer Show Books

At The Bartlett School of Architecture, we have been publishing annual exhibition catalogues for each of our design-based programmes for more than a decade. These catalogues, amounting to thousands of pages, illustrate the best of our students’ extraordinary work. Our Design Anthology series brings together the annual catalogue pages for each of our renowned units, clusters, and labs, to give an overview of how their practice and research has evolved.

Throughout this time some teaching partnerships have remained constant, others have changed. Students have also progressed from one programme to another. Nevertheless, the way in which design is taught and explored at The Bartlett School of Architecture is in our DNA. Now with almost 50 units, clusters and labs in the school across our programmes, the Design Anthology series shows how we define, progress and reinvent our agendas and themes from year to year.

2024 Welcome to the Multiverse

Pedro Gil, Neba Sere

2023 Polyrhythms: Guyana

Pedro Gil, Neba Sere, Colin Smith

2022 Polyrhythms: Haiti

Pedro Gil, Neba Sere

2021 Polyrhythms

Freya Cobbin, Pedro Gil

2020 Jackdaw Dream

Kyle Buchanan, Mellis Haward, James Purkiss

2019 Reality and Other Stories

Pedro Pitarch, Sarah Stevens

2018 Informed by Materiality

Kostas Grigoriadis, Guan Lee

2017 Vital Forces in Architecture

Guan Lee, Arthur Mamou-Mani

2016 Intimate Immensity

Tamsin Hanke, Guan Lee

2015 The Nature of Digital Structure

Guan Lee, Peter Webb

Welcome to the Multiverse Pedro Gil, Neba Sere

This year UG10 explored the concept of the Multiverse.

We asked our students to imagine universes rooted in alternative visions for our world. Drawing inspiration from cultural and social references spanning the globe, our students were urged to envision universes that could be radically different from our own. These were inspired by diverse sources such as science fiction (and fact), Afrofuturism, eco-futurism, history, politics, art, fashion, television, film and more. These could have been multiverses where superheroes are real, or popular figures are deified, or regions like Africa and Latin America were never colonised.

Students were asked to design and construct architectures, proposals and buildings that are both responsible and responsive. They were encouraged to use naturally occurring or grown materials like timber, stone and earth, which have a low carbon footprint, and to consider the natural environment as a key stakeholder in their designs. This approach is both a response to resource scarcity and a responsible commitment to sustainable architectural design.

UG10 studied and drew inspiration from the Latin American country of Mexico. Our field trip to Mexico City provided our students with a chance to delve into the city’s rich history and culture, meet incredible Mexican architects such as Tatiana Bilbao, Alberto Kalach and Leticia Lozano, and explore local construction methods and materials as well as alternative narratives and folklore. Along with their own interests and knowledge gained from their studies, these experiences informed a range of innovative design projects that spanned from Mexico City to London.

UG10 is committed to developing architecture as a vehicle for social justice through the lens of decolonisation and decarbonisation. We are excited to present new visions for the world that are more equitable, sustainable and just.

Year 2

Xander Dean, Alexander Harrison, Xin Heng (Maggie) Lee, Ateh Nkohkwo, Luke Osborne, Joode Umweni, Gracie Whitter

Year 3

Laura Diekmann, Jio Ryu

Technical tutors and consultants: Ruth Cuenca, Alberto Fernández González, Stephanie Poynts

Critics: George Aboagye Williams, Prince Henry Ajene, Eman Alamin, Abigail Ashton, Nana Biamah-Ofosu, Remi Connolly-Taylor, Hannah Corlett, Tahmineh Hooshyar Emami, Tom Holberton, Gwenaël Jerrett, Paul Karakusevic, Seun Keshiro, Níall McLaughlin, Maxwell Mutanda, Giles Nartey, Stephanie Poynts, Arturo Reyes, Isaac Simpson

A very special thanks to our supporters: Paul Karakusevic, Femi Oresanya, Marsha Ramroop and everyone who contributed to our field trip fundraiser

Thanks to our contributors for their amazing workshops and seminars: Dele Adeyemo, George Aboagye Williams, Andrew Clarke, Olalekan Jeyifous, Allyah Mitra Nandy, Arinjoy Sen, Isaac Simpson

Thanks to our wonderful hosts in Mexico City: Miquel Adria, Tatiana Bilbao, Juan Carlos Calanchini Gonzáles Cos, Alberto Kalach, Leticia Lozano

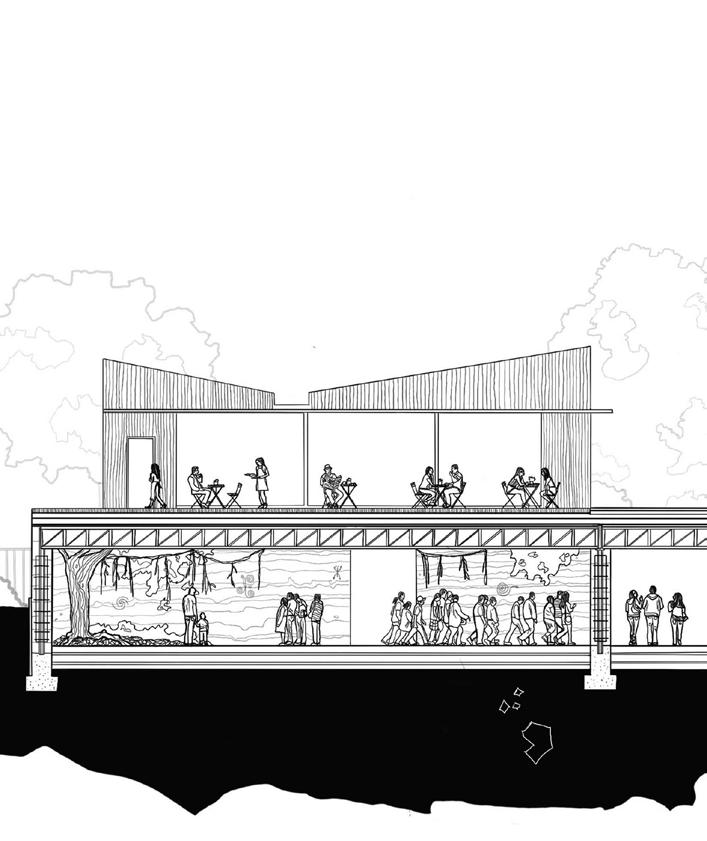

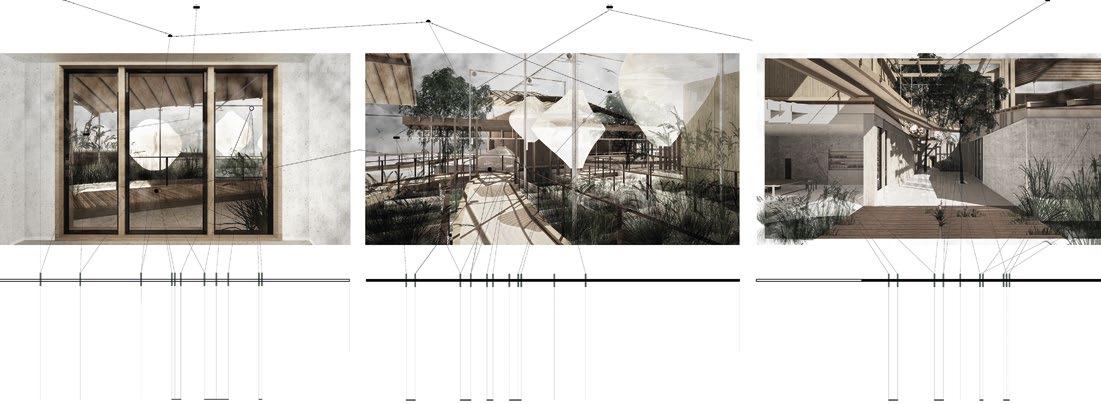

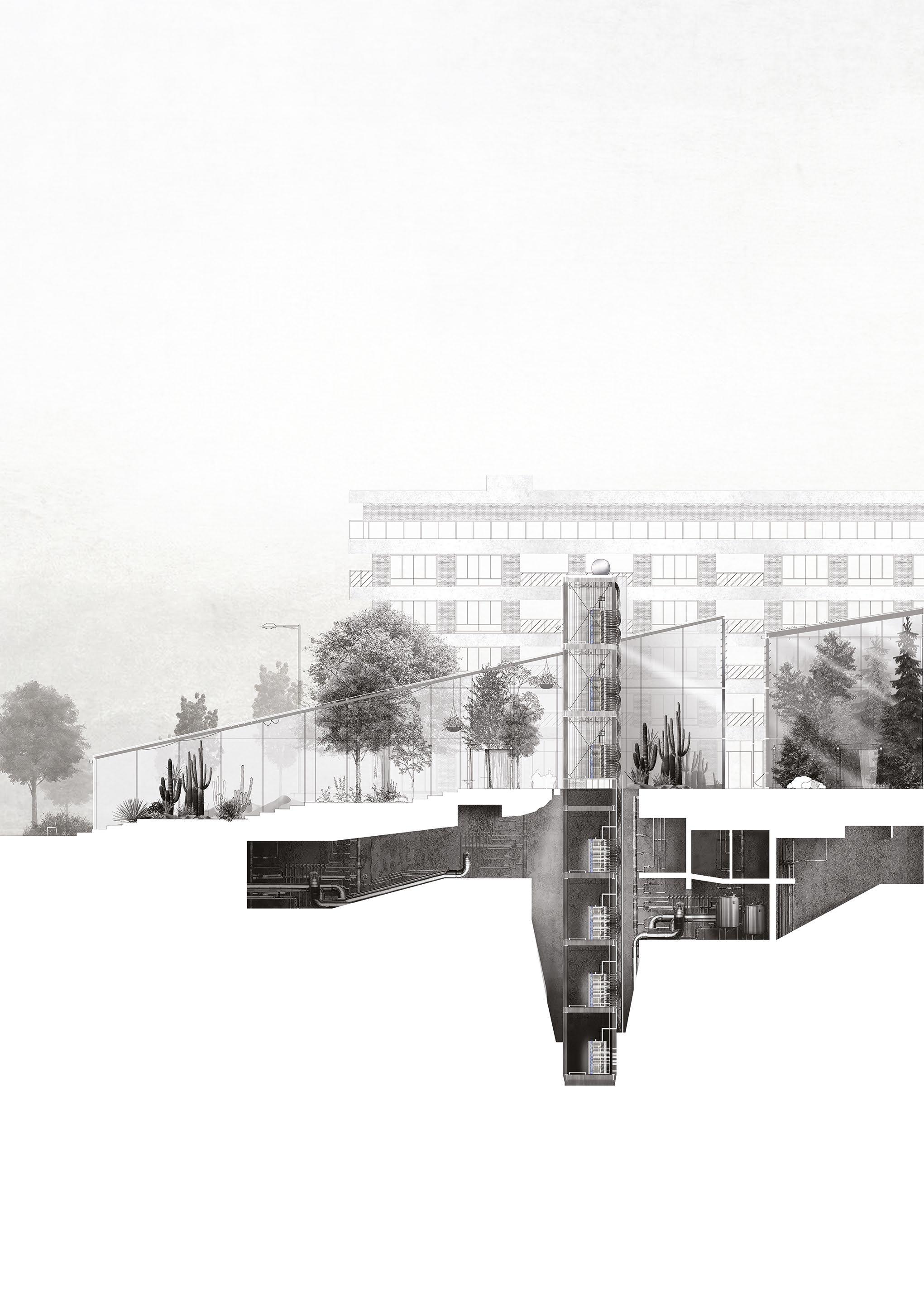

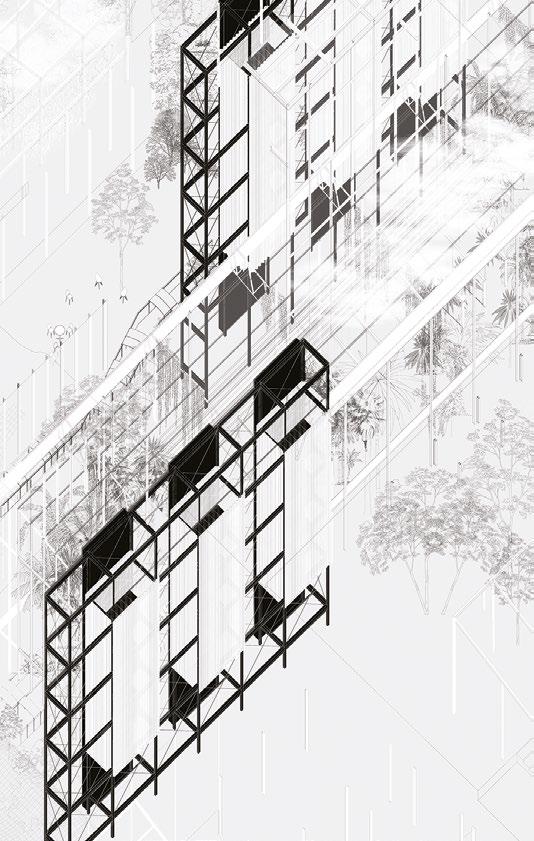

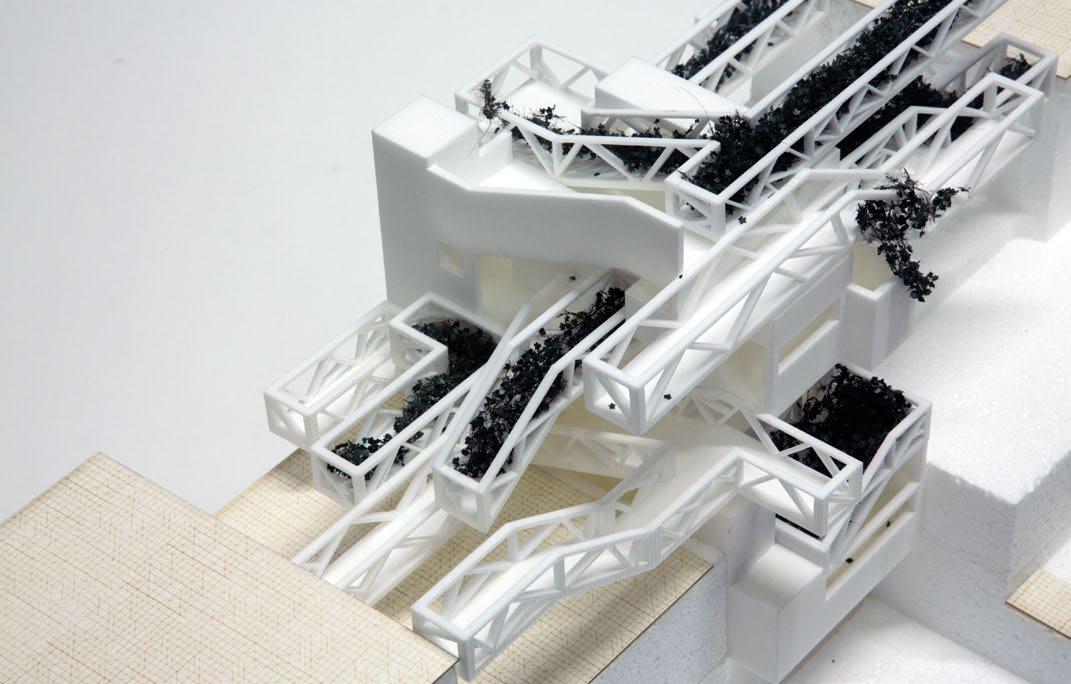

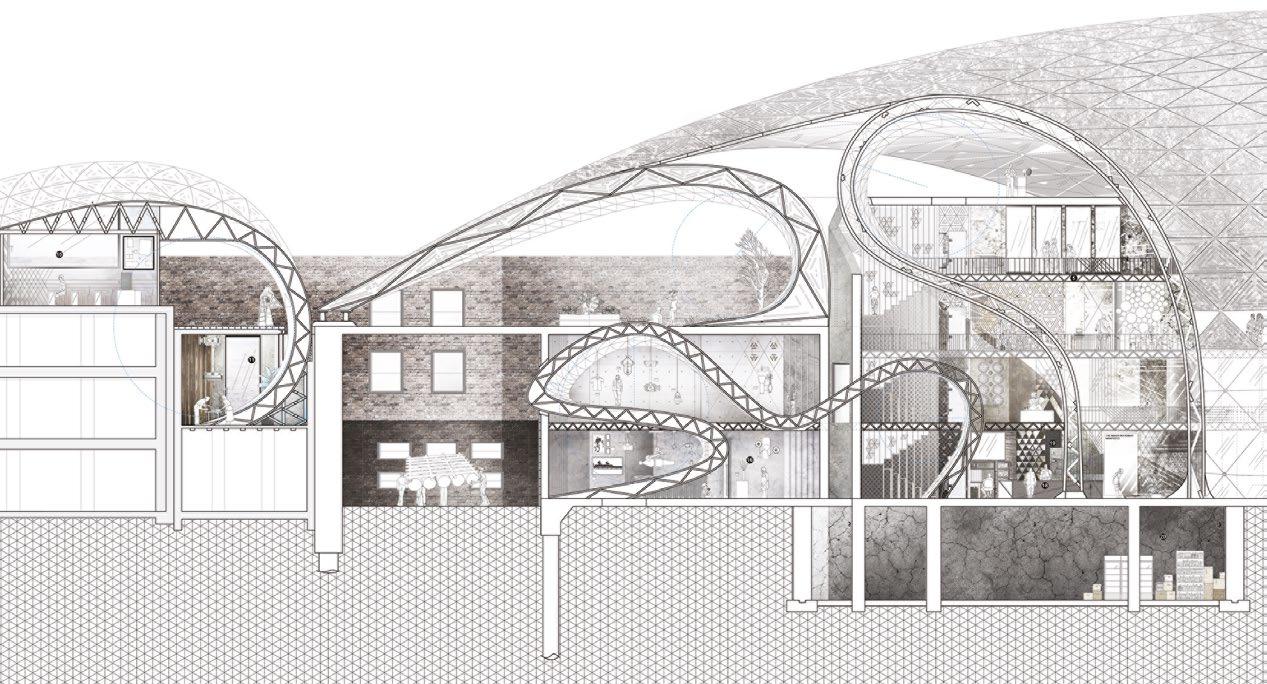

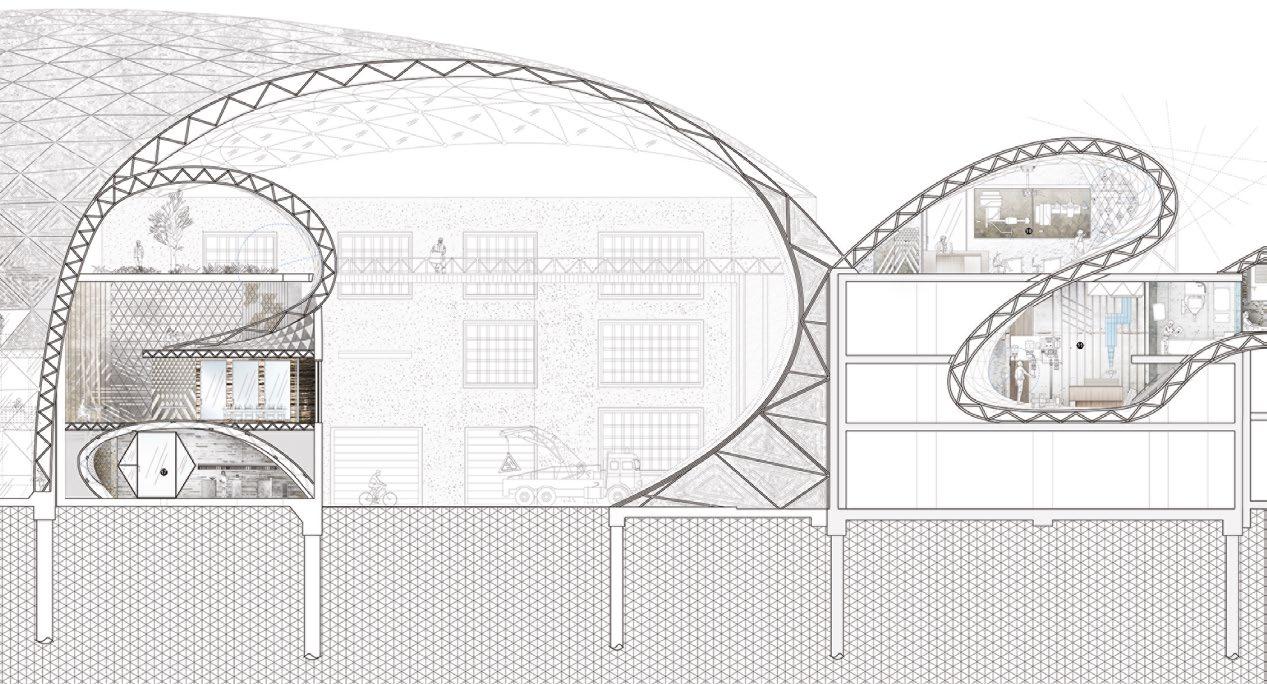

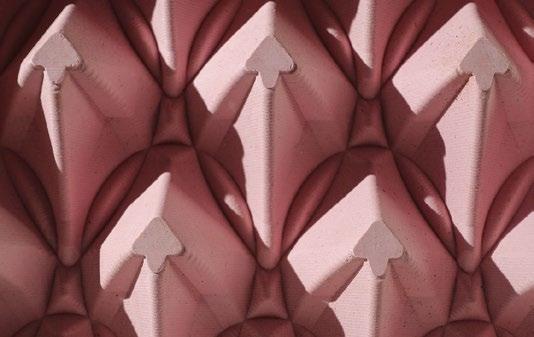

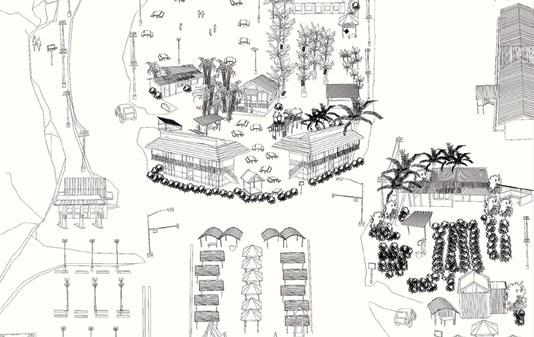

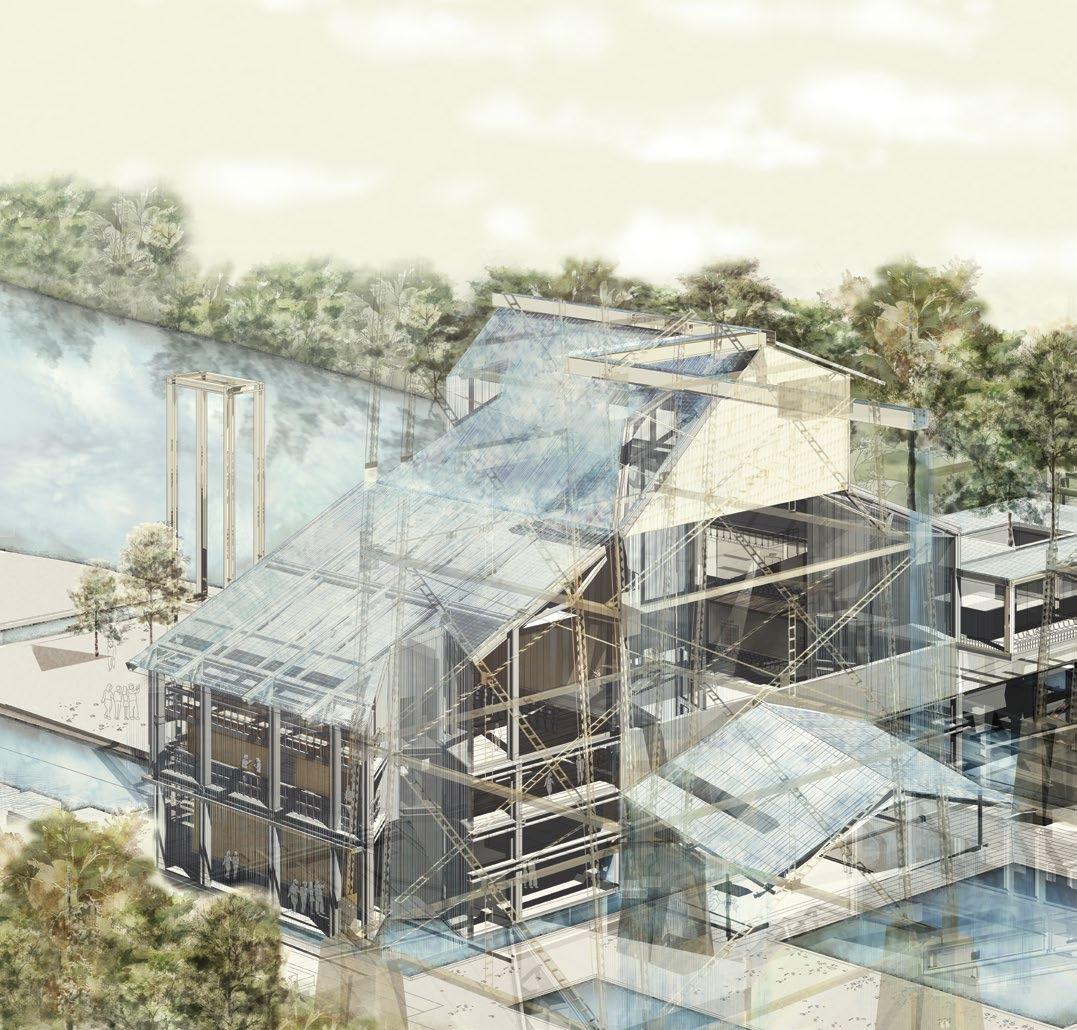

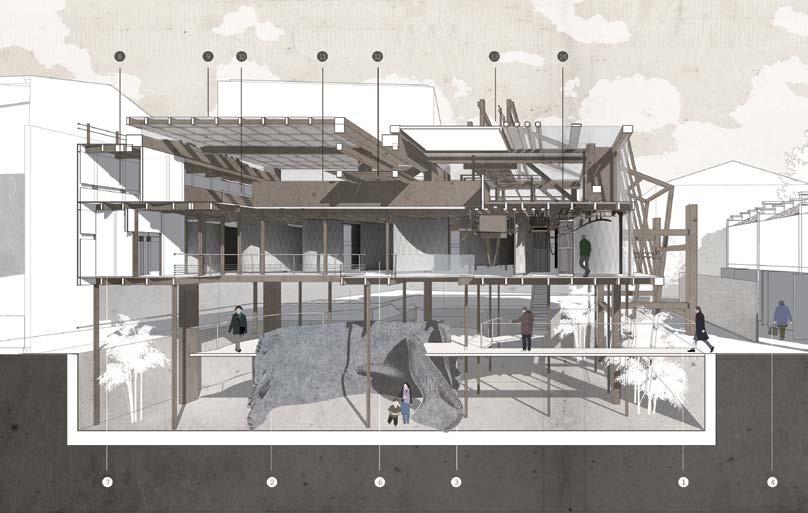

10.1, 10.4–10.6 Jio Ryu, Y3 ‘Growing Absolute Immunity: Plant Urban Immunity Research Lab’. Since the Covid-19 pandemic (2019–2022), humanity has prioritised disease research. Inspired by their ancestors’ struggles with European diseases, modern Mayans, with their deep knowledge of agriculture, have partnered with London scientists in a long quest (2024–2049). Their solution: boosting plant immunity. This has resulted in pesticidefree crops that have strengthened human immune systems too. Pioneered in London’s Stratford district, this ‘absolute immunity’ system is now being implemented worldwide. This project marks a turning point in human health and stands as a testament to Mayan knowledge and international collaboration.

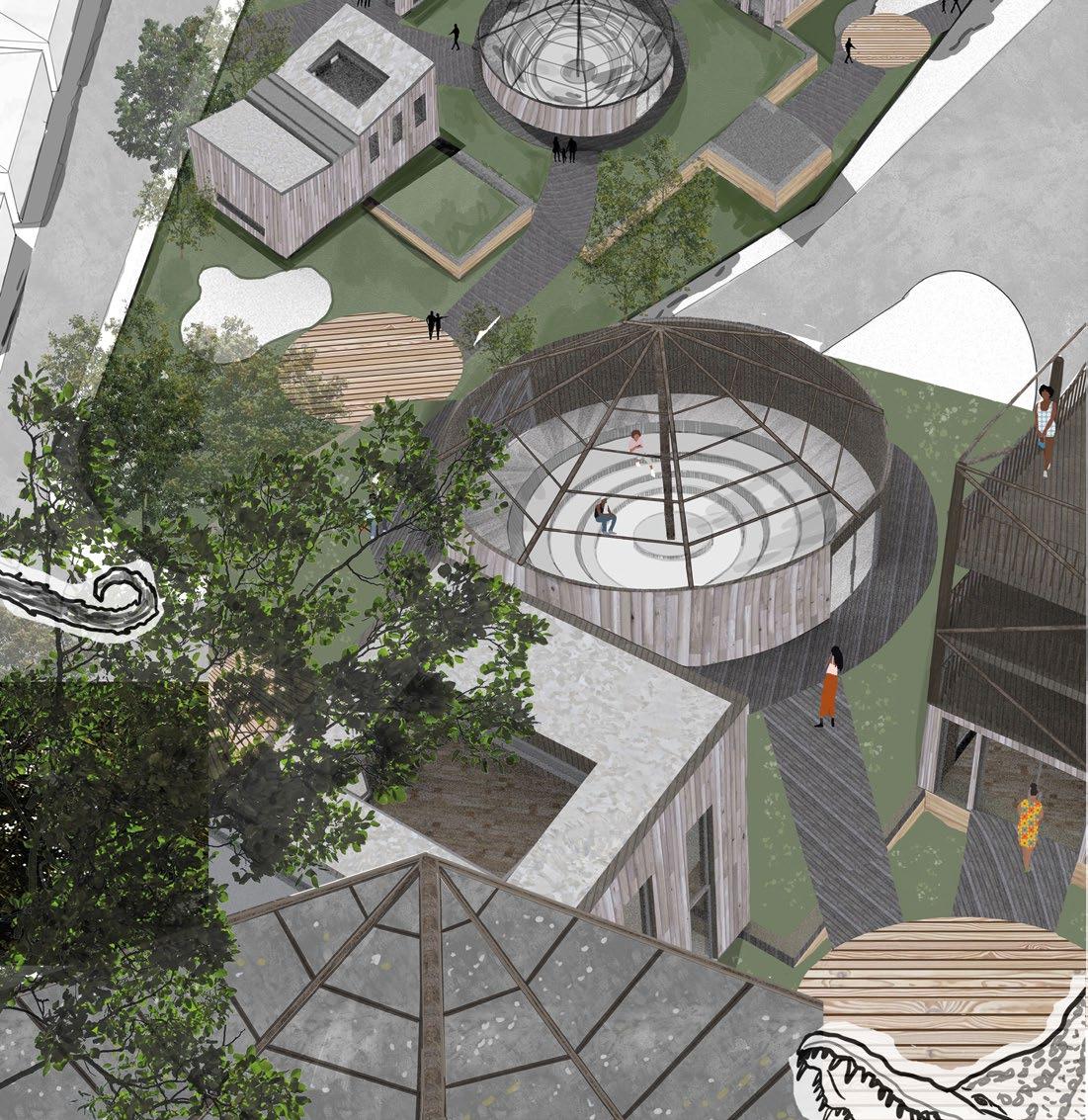

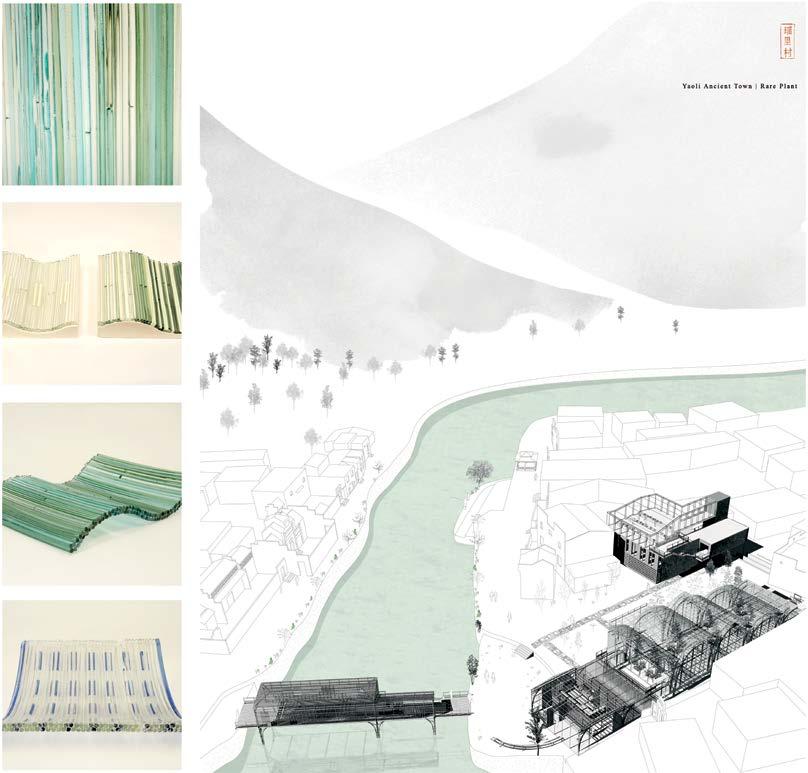

10.2, 10.12–10.14 Xin Heng (Maggie) Lee, Y2 ‘Sylvan Synthesis’. The project reimagines urban resilience through a botanical solution. This community garden and botanical centre showcases alternative building methods that can reduce the impact of earthquakes, such as the devastating 1985 Mexico City quake. By cultivating a local ecosystem in previously dry, post-earthquake zones, the project harnesses the power of plant roots. These roots trap moisture and bind the loose lakebed soil, improving stability. Additionally, the programme focuses on cultivating plants suitable for timber construction, promoting an undervalued yet sustainable building material that aligns with South America’s rich biodiversity.

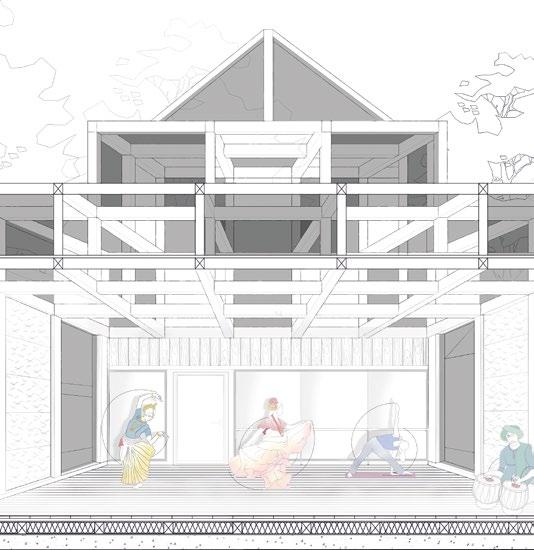

10.3 Joode Umweni, Y2 ‘The Afro-Mexican Dreamscape’. This project celebrates Afro-Mexican culture through a vibrant outpost designed for the Coyolillo festival, a celebration with roots in Veracruz’s Afro-Mexican community. Inspired by the festival’s colourful costumes, the architecture utilises the costumes as a material palette, with the structure representing the body and materials adorning it. This fusion of tradition and innovation creates a culturally significant space that transforms throughout the year, becoming an art studio and exhibition space for pre-teens, particularly the children of Black Mexicans navigating life in central Mexico.

10.7–10.8 Alexander Harrison, Y2 ‘Limbo’. The project fosters a connection between Tlatelolco residents and their patron saint altars. It functions as a one-stop shop, offering a florist, dye and recycling workshop, as well as a public garden. Residents can purchase fresh flowers for their shrines and rejuvenate old ones by recycling them into vibrant face paints for Day of the Dead celebrations, upholding local tradition. The design adapts to Mexico’s hot climate; ventilation blocks and movable screens regulate airflow, offering shade and privacy while converting into indoor furniture pieces.

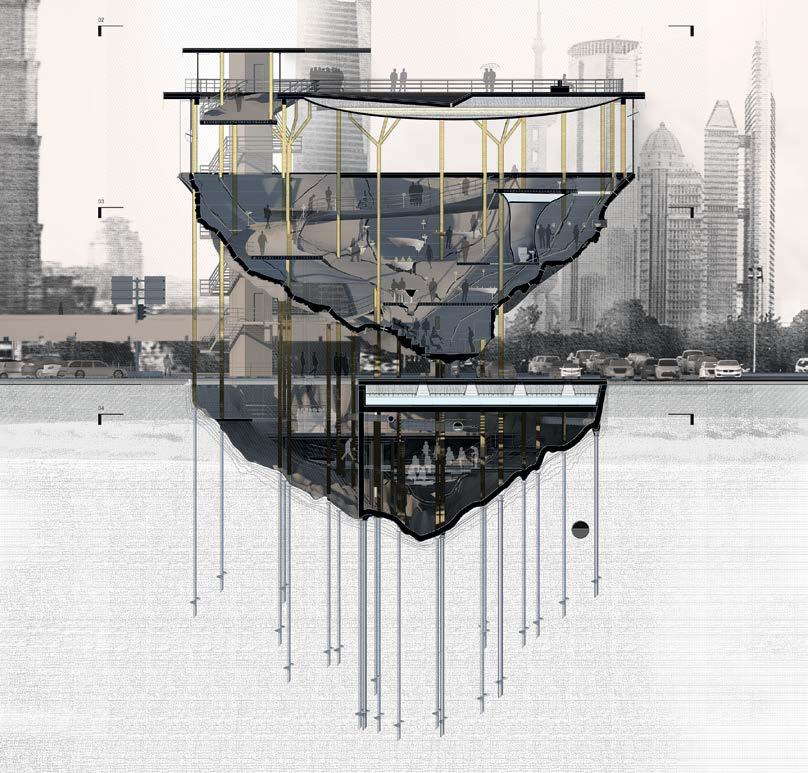

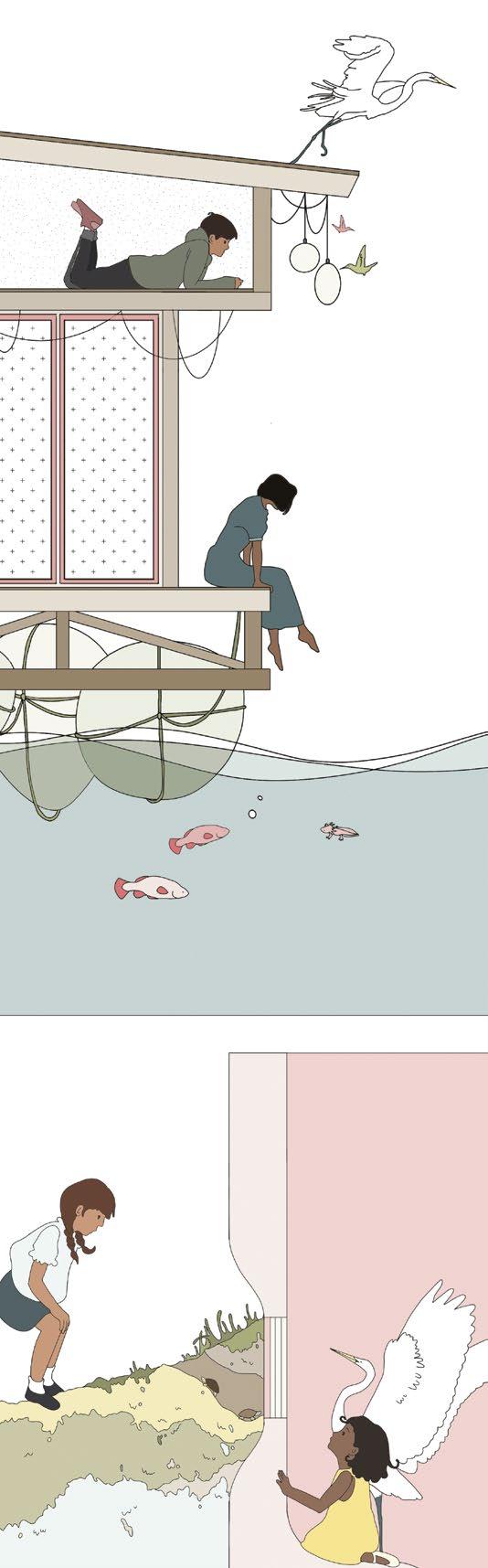

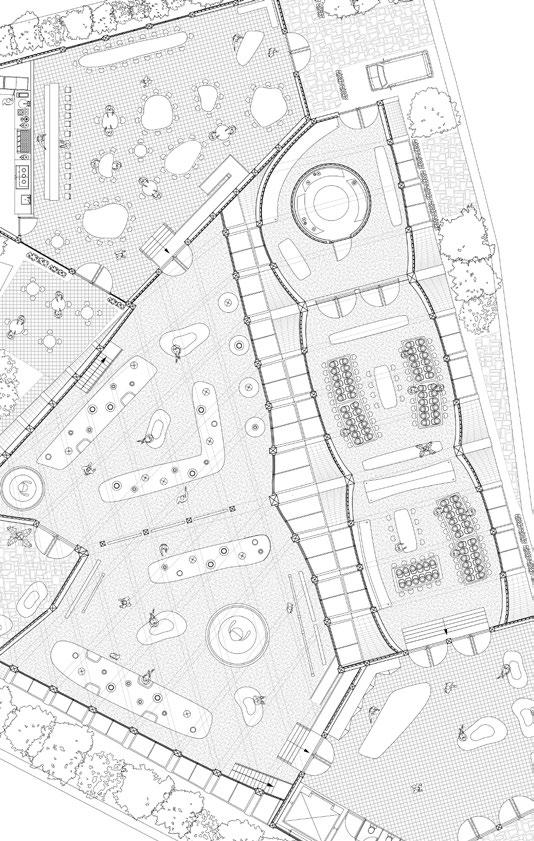

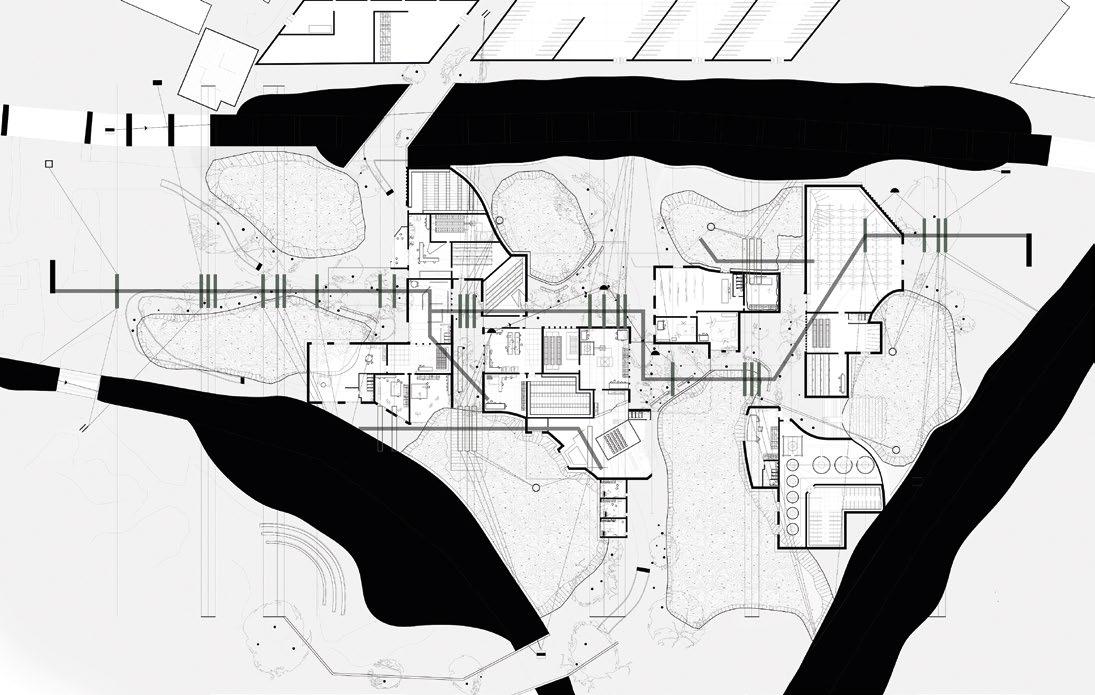

10.9–10.11 Gracie Whitter, Y2 ‘Re-saturating Mexico City: Lake Xochimilco Nature Park’. The project proposes amphibious architecture for a flooded future, drawing inspiration from Aztec chinampas. It addresses environmental challenges stemming from the draining of the city’s lakes. Lake Xochimilco, a remaining fragment, is transformed into a nature park and visitor centre. Here, design coexists with humans, animals and plants, fostering interaction with five key species: great egret, axolotl, Mexican mud turtle, tree frog and free-tailed bat. Reconnecting with water offers a sustainable, decarbonised and decolonised future for Mexico City. 10.15–10.17 Luke Osborne, Y2 ‘House of Muxe’. In a future celebrating LGBTQ+ expression, the Muxe people of Mexico establish cultural hubs globally. London’s ‘House of Muxe’ features rotating Muxe residents sharing traditions such as craft embroidery and a shimmering sanctuary garden inspired by Derek Jarman. The building itself reimagines church architecture, transforming spaces of fear into havens, echoing the Muxe message of acceptance that empowers LGBTQ+ communities worldwide.

Pedro Gil, Neba Sere, Colin Smith

UG10 is committed to exploring architecture as a vehicle for equity and social justice. We are interested in exploring themes of decolonisation and what this means in an architectural and social context through spatial concepts and tectonics. Students are encouraged to explore Indigenous architecture through an understanding and celebration of these construction techniques. The unit positions itself to learn from global cultural and social references that are delivered through physical and illustrative architectural propositions.

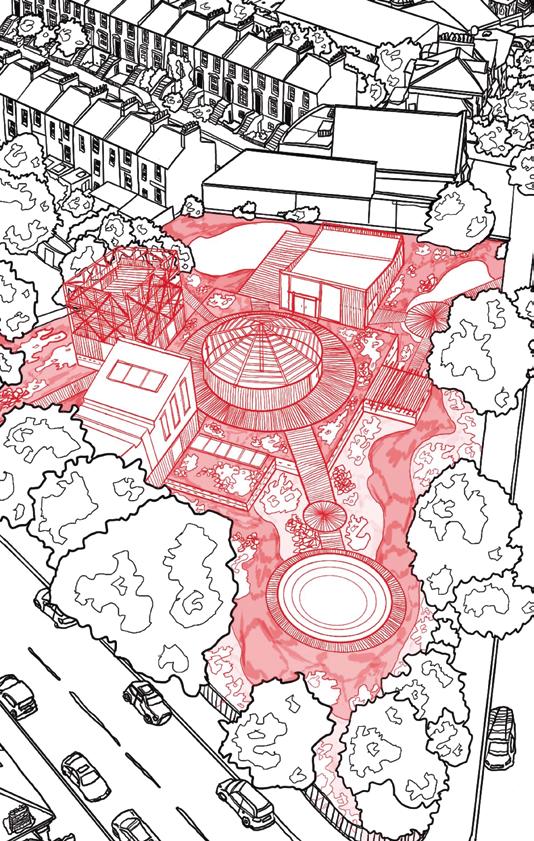

Each year UG10 selects a Latin American region to focus our investigations into typologies that include construction idioms and techniques, funding streams, design activism and material iterations. We promote speculations on radical ideas, design solutions, resilient futures and alternative visions. This year we looked to Guyana, situated in South America and bordered by the Atlantic and Caribbean Oceans to the north, Brazil to the south and southwest, Venezuela to the west and Suriname to the east. Guyana enjoys a mix of ethnicities including the African diaspora, Indian (South Asian), Amerindian (Indigenous Native Indian and European mixed heritage) and Chinese, among others. The country also possesses strong cultural and ethnic links with nearby Caribbean islands.

Guyana is predominantly an English-speaking country due to its history as a former British colony. It was colonised by the Dutch before coming under British control in the late 18th century, and was then governed as British Guiana until the 1950s. British Guiana was once one of the main colonial ports in the trans-Atlantic slave trade between Europe, Africa and Latin America. It gained independence in 1966 and officially became a republic within the Commonwealth of Nations in 1970. Geographically, Guyana is one of the least densely populated countries on Earth. Due to this low human densification, it enjoys a wide variety of natural habitats with high biodiversity, reflected within the vernacular construction typologies and materials.

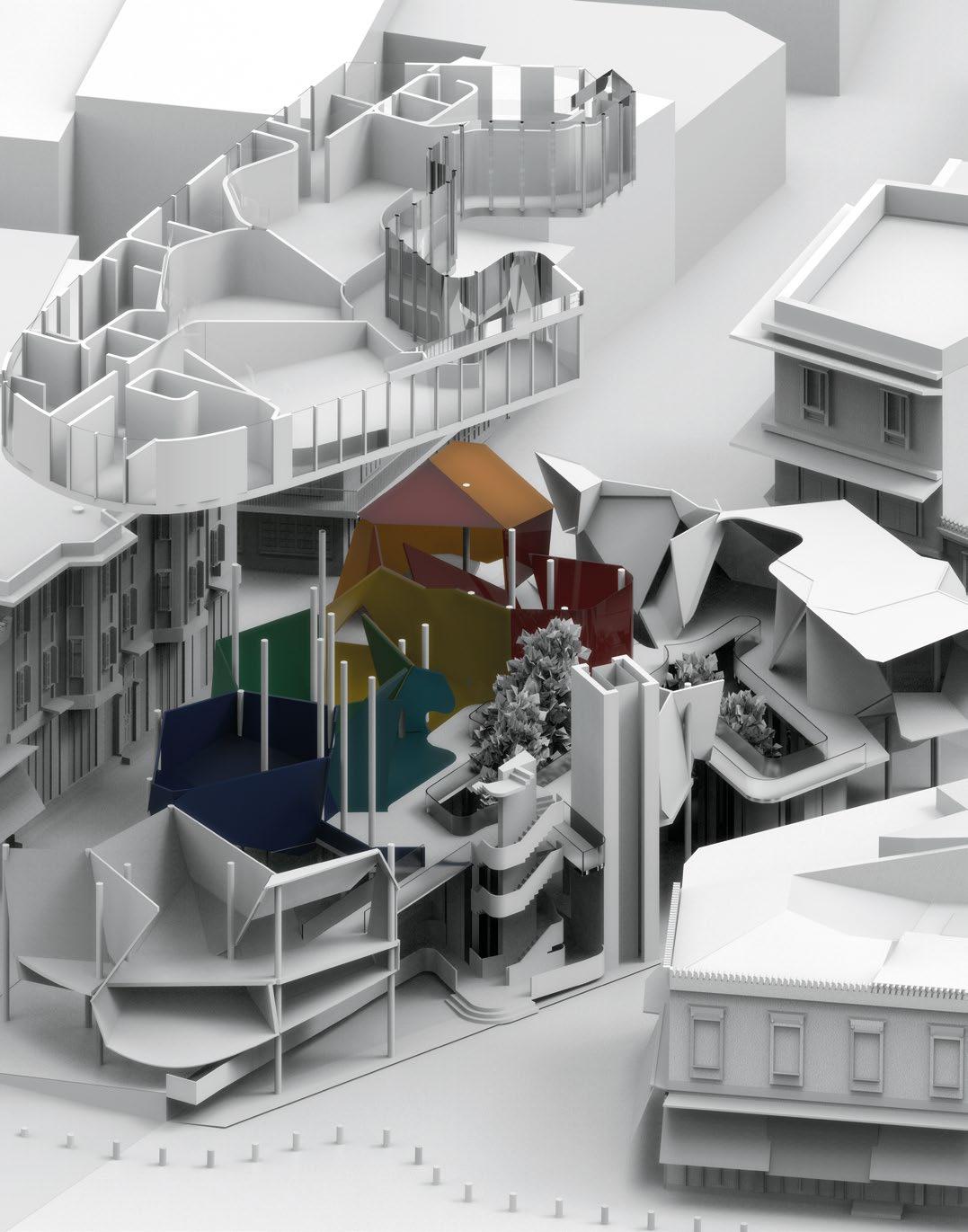

UG10 design projects are situated in the London Borough of Lewisham, which has one of the highest populations of AfroCaribbean heritage in the UK. Named as the Mayor of London’s Borough of Culture in 2022, Lewisham is on the verge of widespread regeneration within which our students’ work sits. We have learned from, been inspired by and celebrate Guyana in our design proposals for the city.

Year 2

Siya Bhandari, Laura Dietzold, Holly Hunt, Allyah Mitra Nandy, Akif Rahman, Regan Reser, Hossain Takir

Year 3

Arnold Freund-Williams, Maria Hussiani, Giulia Mombello Perez

Technical tutors and consultants: Alberto Fernández González, Stephanie Poynts

Critics: Reni Animashaun, Jhono Bennett, Akua Danso, Alberto Fernández González, Colin Glen, Jemima Harold-Sodipo, Jakub Klaska, Ana Monrabal-Cook, Maxwell Mutunda, Giles Nartey, Stephanie Poynts, Jessica Tang

Sponsors: Karakusevic Carson Architects, HOK

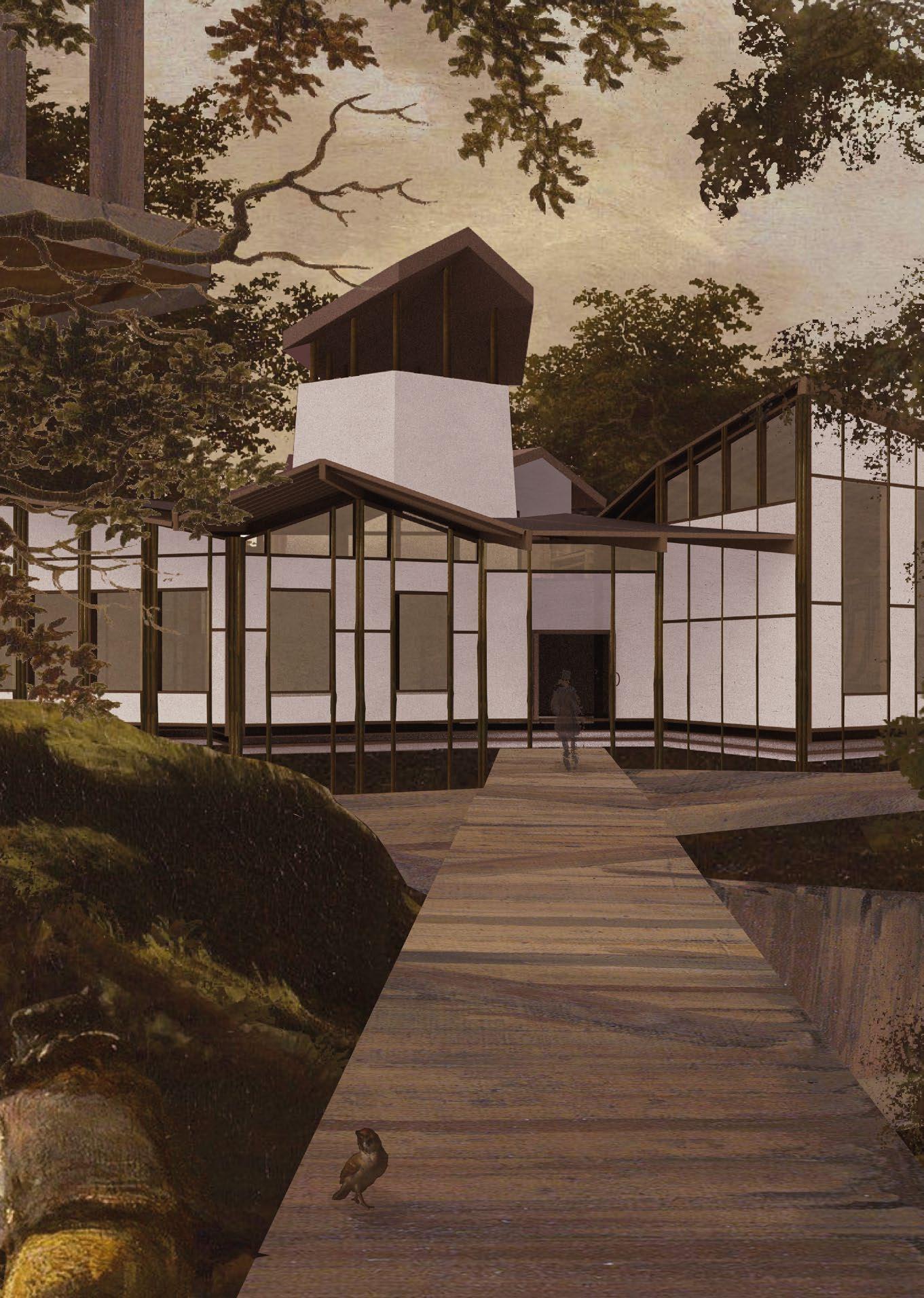

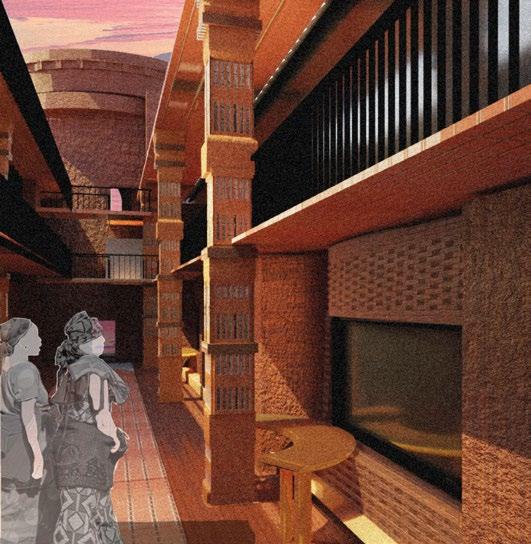

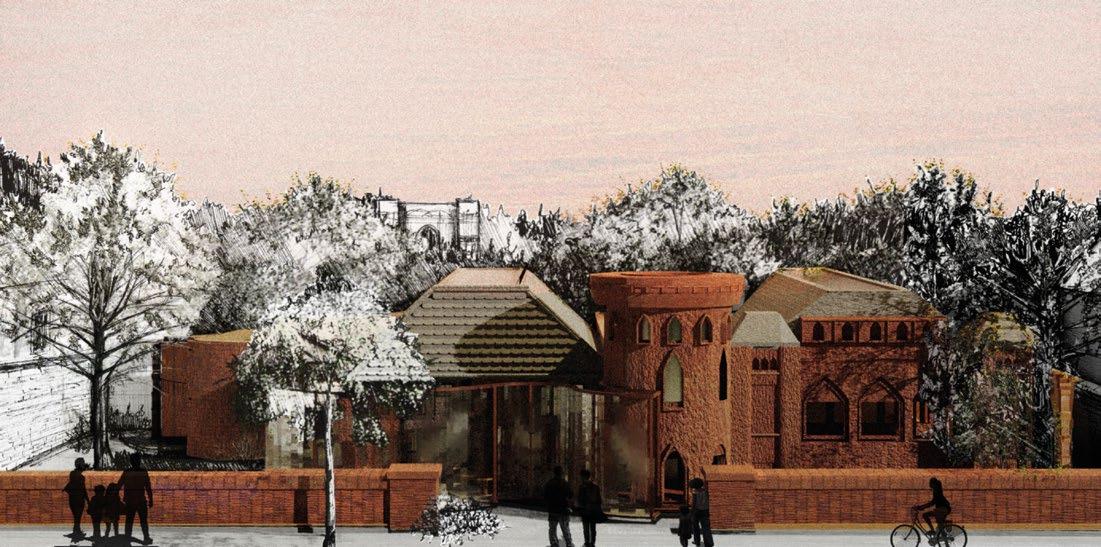

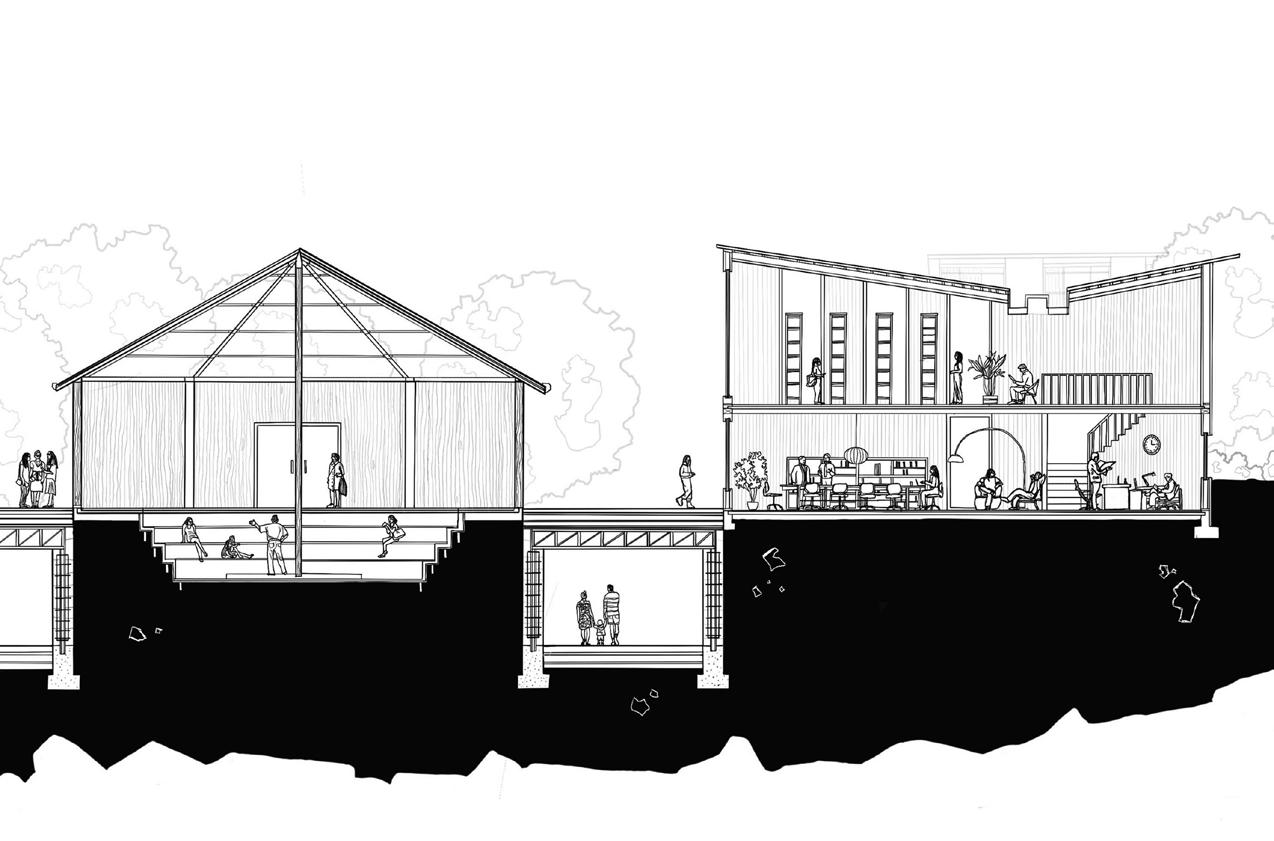

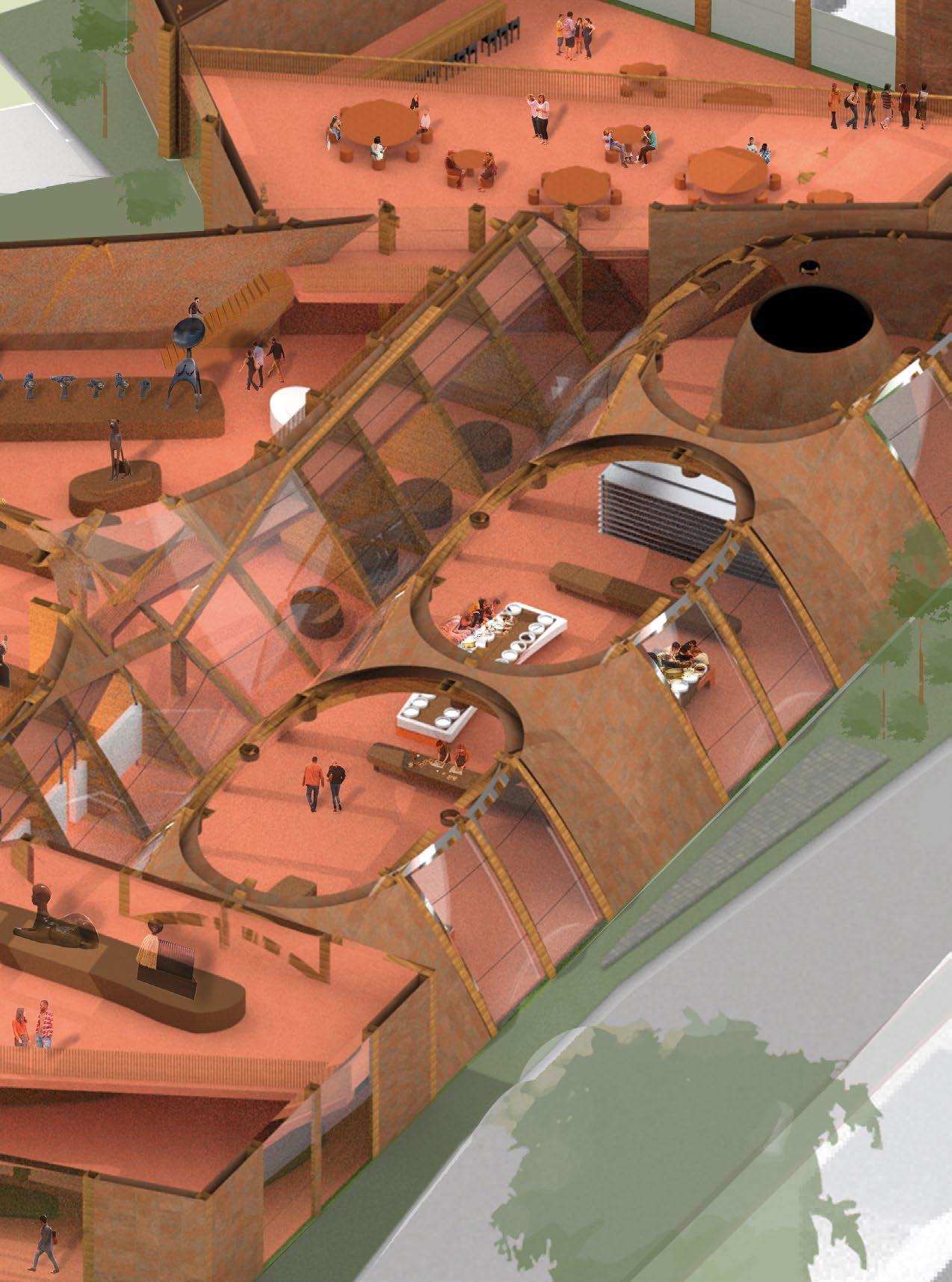

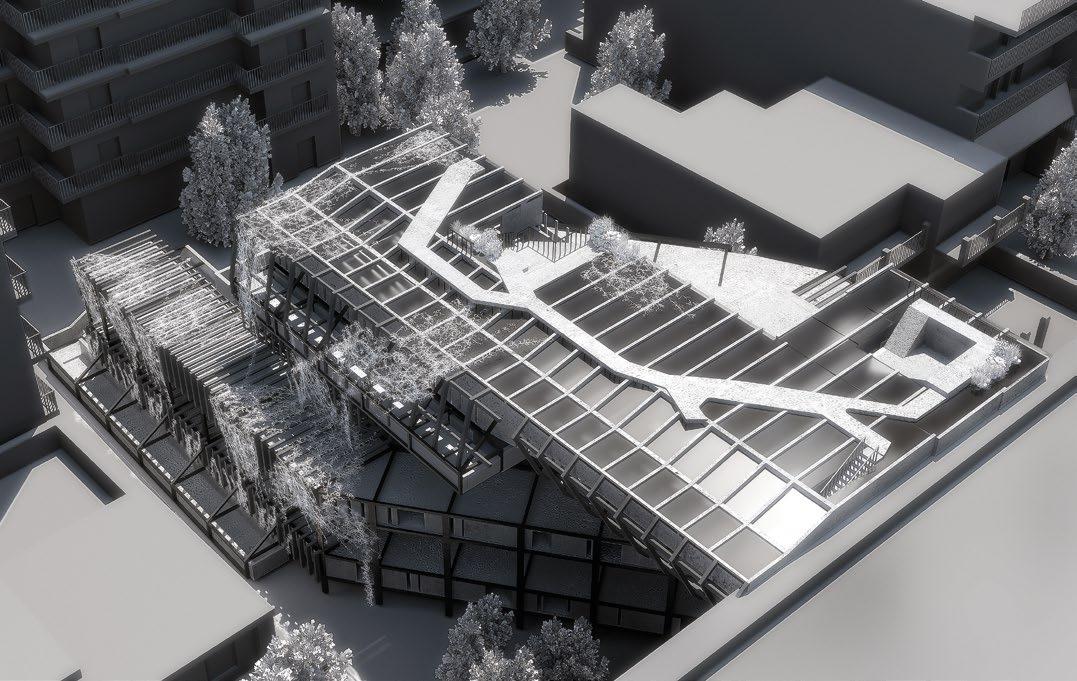

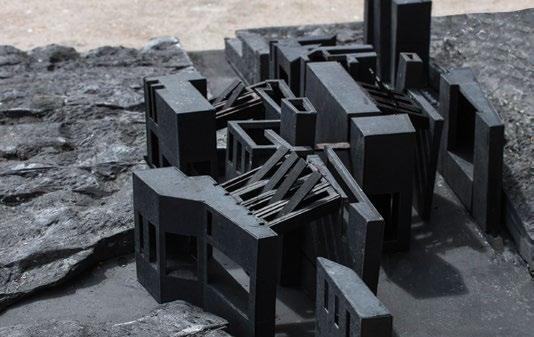

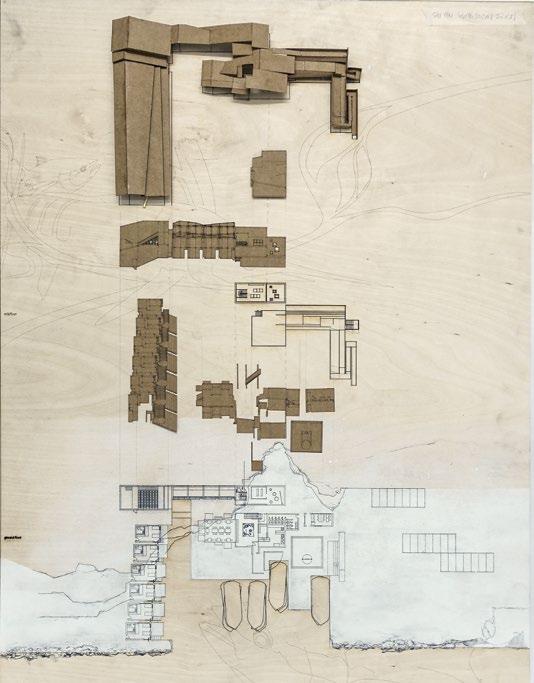

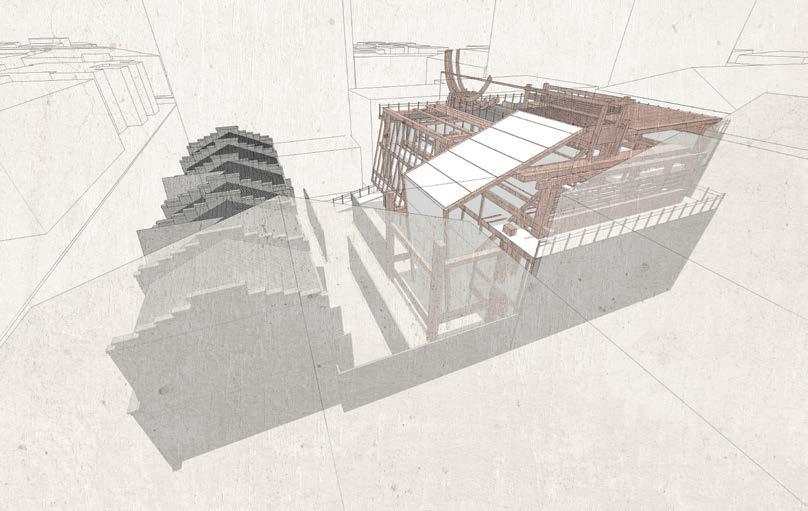

10.1, 10.4 Arnold Freund-Williams, Y3 ‘Forest Kiln Gallery’. Fire, decay and regrowth. This project explores fire and its broader relationship with indigenous groups within the Amazonian region with a focus on a sustainable and circular way of occupying a site. It utilises lowcarbon materials to produce a building that embraces fire, using bundles of low-calibre elements to produce columns from lower-grade timber units. The programme of the building is centred around provision for local artists working with clay through the inclusion of studio spaces and provides the local community with a new park and community spaces.

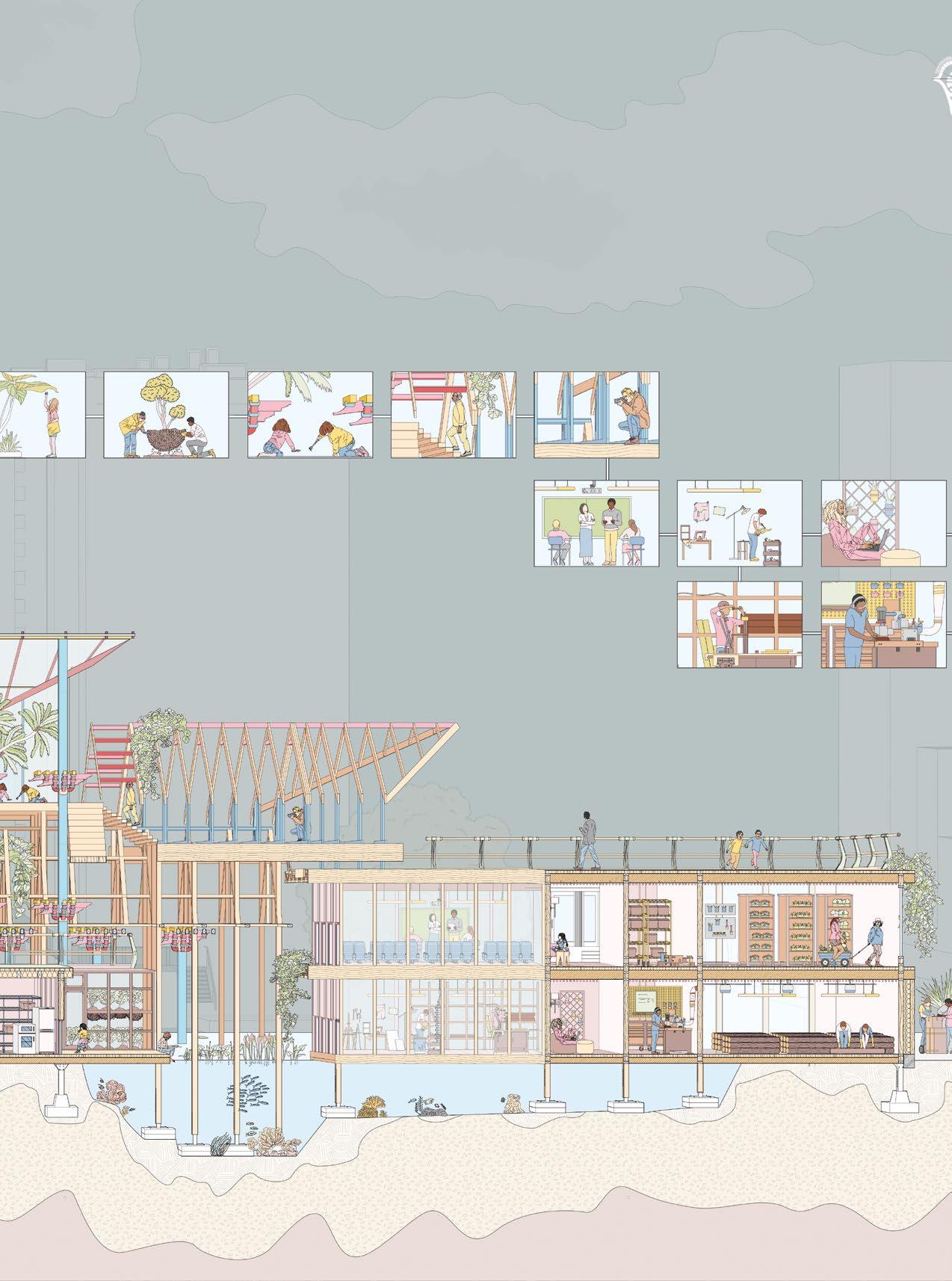

10.2, 10.21 Maria Hussiani, Y3 ‘The House of Jewellery’. The project draws inspiration from the diaspora of Guyana. The country’s conflicting relationship with migration is reflected in its rich cultural heritage and architecture, which is also prominent in the country’s gold jewellery. The proposal is a jewellery-making workshop, exhibition space, jewellery shop (including a learning room) and nursery. There is a focus on enabling local migrant women to learn new skills so they can enter the job market. The project creates a new story for Lewisham’s proud history of activism, celebrating and providing the opportunity and space for developing craftsmanship and skills.

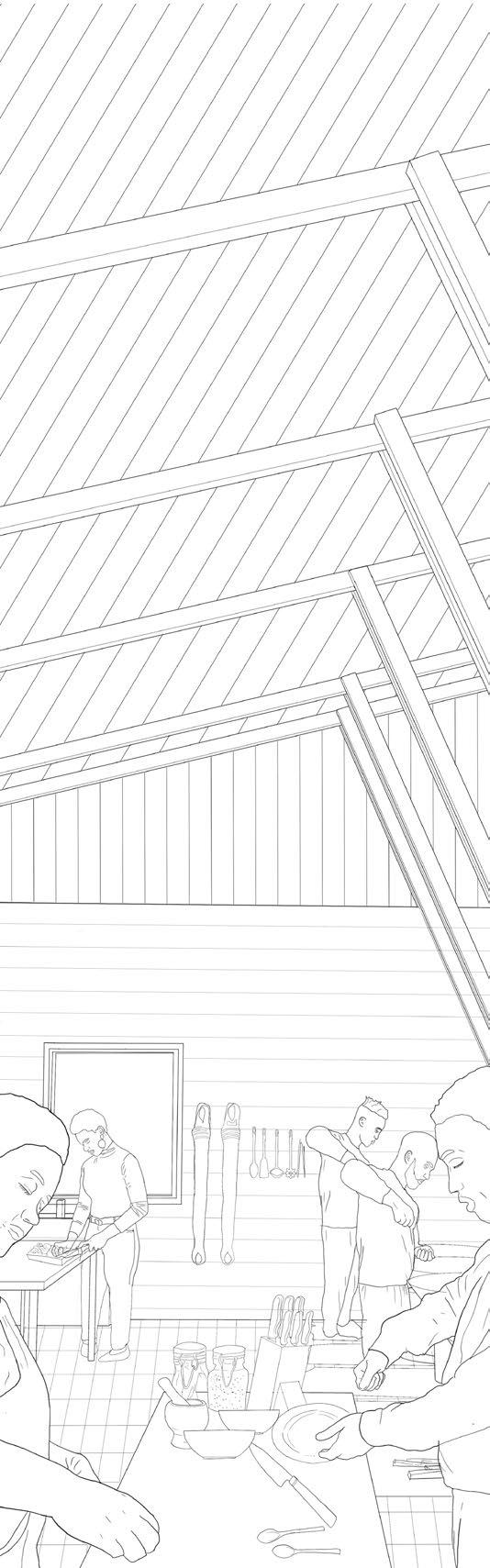

10.3 Hossain Takir, Y2 ‘Pepperpot House’. A cultural hub for the Guyanese community. The pepperpot is the national dish of Guyana. It is a stewed meat dish flavoured with Cassareep (a sauce made from the cassava root), often served during Christmas and special occasions. The design features multiple spaces, including a museum showcasing a collection of traditional indigenous cooking utensils from Guyana, a kitchen where visitors can actively engage and learn the cooking process, and a greenhouse dedicated to growing some of the ingredients needed. The central eating space is where users can enjoy their cooked pepperpot dish together. The project provides a platform for sharing and preserving Guyanese heritage, enabling the community to deepen their understanding and appreciation for their own culture.

10.5–10.8 Allyah Mitra Nandy, Y2 ‘The Ladywell Migrant’s Weaving Workshop and Community Centre’. Revitalising the play tower’s communal history through a decolonised lens that focuses on weaving as a celebration of immigrant identities. The programme is divided into two buildings: a community market hall situated within the existing play tower, and a newly designed weaving workshop which spatially contrasts with the existing form. At the core of the project is the question of how to decolonise community spaces such as museums through reinterpreting immigrant narratives and experiences via the language of fabric.

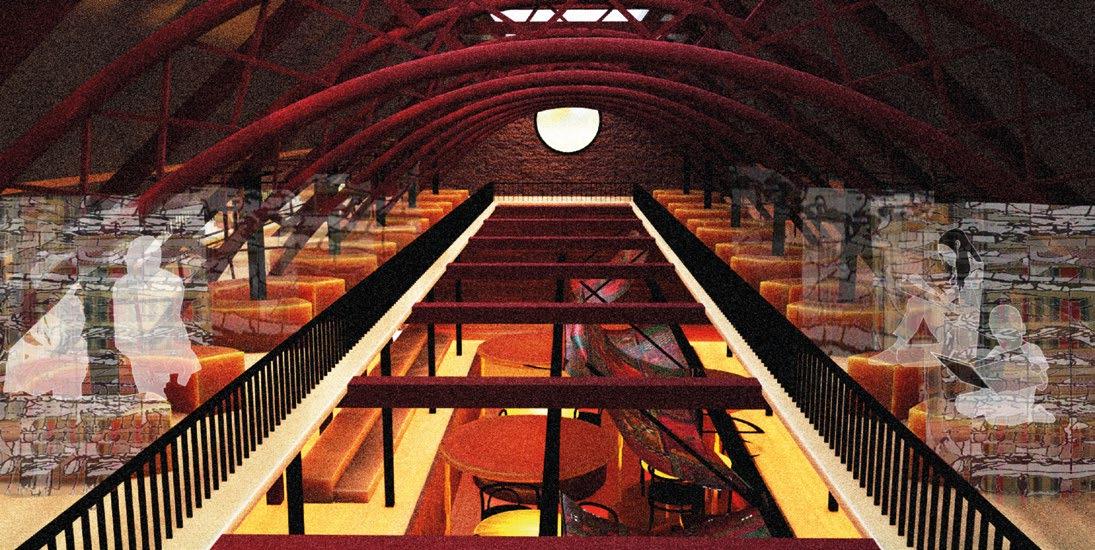

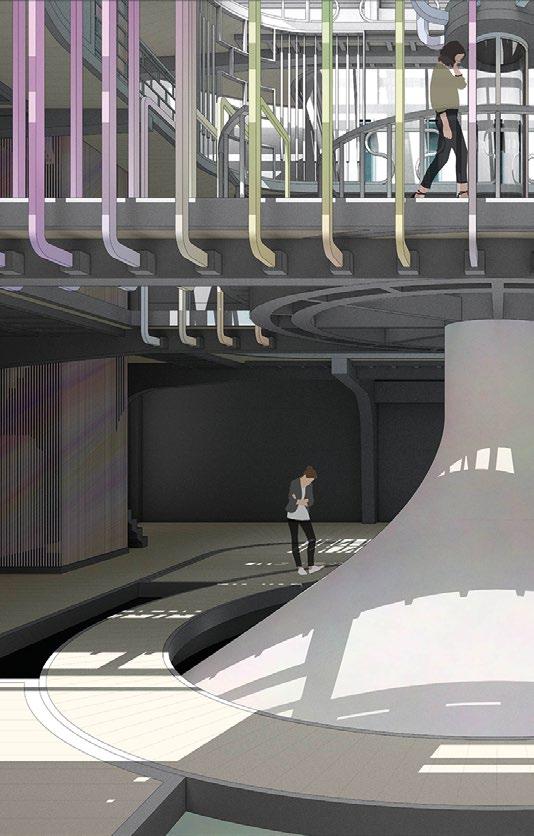

10.9–10.10, 10.20 Regan Reser, Y2 ‘Museum of Caribbean and West African Folklore’. The Caribbean has a rich tradition of oral storytelling that has its origins in West Africa. The museum enables the audience to engage with folktales and history via real-life sensory experiences that centre the visitor as the main character. The main exhibition space hosts a series of rotating folktales from Africa and the Caribbean. At the centre of the museum is the auditory atrium which guest speakers and local organisations can use. The use of rammed earth and timber construction is also firmly rooted in the vernacular architecture of the Caribbean and West Africa.

10.11–10.12 Laura Dietzold, Y2 ‘A Museum of Indigenous Guyanese Architecture in Lewisham’. The project is a celebration of the diversity of indigenous Guyanese architecture and will display vernacular architecture techniques such as thatch. Indigenous South American architecture has informed much of what we know about

architecture today, but the Western world tends to criticise and stigmatise this type of vernacular architecture by describing it as ‘primitive’ and ‘uncivilised’, while European architecture is hailed as ‘modern’ and ‘progressive’. This museum will therefore not only exhibit indigenous Guyanese architecture but also demonstrate what can be achieved with these techniques to teach their possible application in this environment.

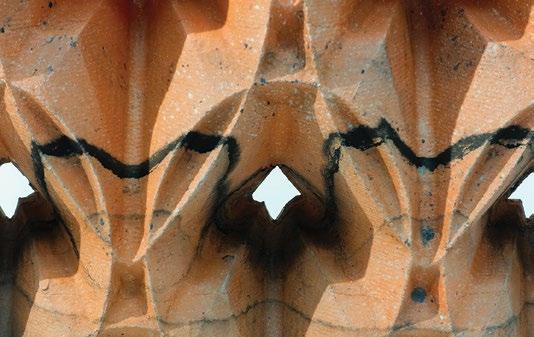

10.13–10.15 Giulia Mombello Perez , Y3 ‘Pottery Workshop and Exhibition Space’. A Tribute to Guyanese and Caribbean Art and Crafts. The project draws inspiration from Guyanese and Afro-Caribbean pottery art and artists as well as the traditional British use of terracotta to create a new community space for Lewisham. The building celebrates pottery through all its stages, from the materiality itself to the activities inside and the showcased exhibition. There is a focus on celebrating and supporting the local Afro-Caribbean community with a space that will serve as a platform to exhibit their artistic talents while providing an open pavilion for those interested in pottery.

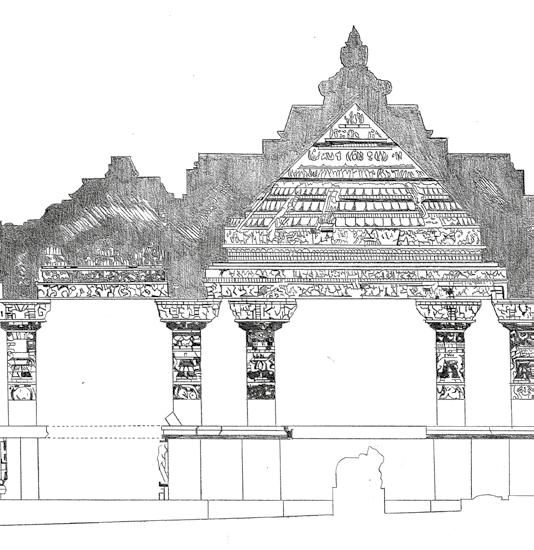

10.16–10.17 Siya Bhandari, Y2 ‘Museum of IndoGuyanese Culture’. The project’s programme is inspired by the migration of Indo-Guyanese people from Guyana to Lewisham. The building is informed by studies of Hindu architecture within temples and comparison with the Lewisham Kovil Temple which is in close proximity. Instead of using stone material, straw bales are utilised to create a building that can be experienced from both the inside and the outside.

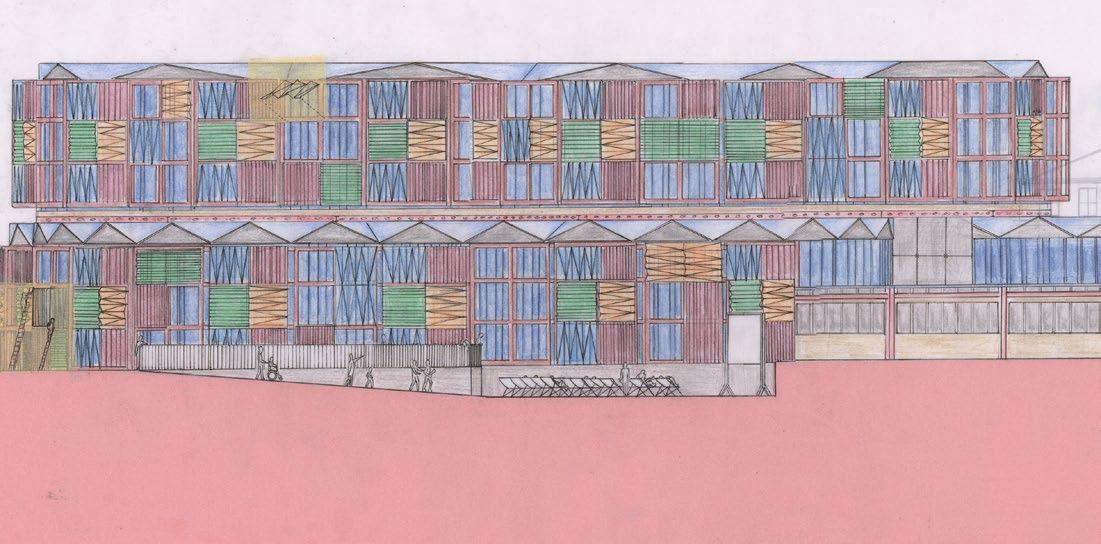

10.18 Holly Hunt, Y2 ‘Lewisham Museum of Indigenous Crafts and Textiles’. The project is located in the heart of Lewisham market, creating a new public space for Lewisham High Street which celebrates the area’s diversity, culture and community. The museum is the antithesis of the typical Western colonial model and instead focuses on ‘making’ activities from the Global South. The workshop where users can print their own fabrics is inspired by Ankara, a traditional wax-printing technique found in Guyanese and West African communities. These fabrics can then be exhibited or traded. This encourages users to craft their own narratives and elevates the cultures of Lewisham’s migrant communities.

10.19 Akif Rahman, Y2 ‘Lewisham’s Celebration of Performance’. The project celebrates the art of performance through various creative mediums that showcase a diverse range of artists. The building contains two large installation spaces, referencing the commune in indigenous architectural spaces. Spaces for a permanent collection of art display a wide array of films and artefacts from across the world. The building’s structure uses pleating in its roof structure and façade elements as a visual representation of the spirit of performance.

Pedro Gil, Neba Sere

UG10 acknowledges the Global North/South paradigm and recognises residual tensions and paradoxes as methods to explore both contemporary and historical relationships between the UK and Latin America. The unit draws attention to the differing phenomena and cohabitations between these diverse contexts, exploring what has been borrowed, drawn upon and taken from either side of the Atlantic. We highlight what remains of those actions, dialogues and exchanges, in relation to migrant communities, architectures, visual arts, literature, music and ideas.

Architecture and architectural practitioners have a responsibility to understand the socio-economic context in which they are operating. In a city such as London, it is crucial that we understand how communities are impacted by regeneration and development. The effects are not always positive for everyone and marginalisation of the most disadvantaged in society happens through gentrification. Architecture is therefore always political.

Each year UG10 selects a Latin American region upon which to focus its investigations into typologies, including construction idioms and techniques, funding streams, design activism and material iterations. We promote speculations on radical ideas, design solutions, resilient futures and alternative visions. This year UG10 celebrated Haiti, Blackness and Afro-Latin American ‘AfroLatinidad’ culture through the lens of our London-based design projects.

Situated in the Caribbean, Haiti is one of the countries in Latin America with significant African heritage. It has a long and proud legacy of culture, history, art, literature and architecture. Its population is predominantly Black, with strong ethnic and ancestral links to Africa dating back to the 15th century. UG10 studied Haiti and its culture while looking for progressive lessons that can be applied to London and its rich multi-cultural setting. We are interested in Haiti and the erasure of Blackness in the (Latin-American) cultural context.

Design projects are situated in the London Borough of Enfield, the proud home to one of the highest populations of African and Caribbean diaspora in the city.

Year 2

Amy Bass, Zeynep Cam, Amy Daja, Fardous Khalafalla, Kah Miin Loh, Iga Najdeker, Maria Pop, Skylar Smith, Alara Taskin, Tsz (Vivianne) Wong

Year 3

Minh (Dominik) Do, Michela Morreale, Junyoung Myung, Natnicha (Amy) Ng, Thananan (Orm) Sivapiromrat

Technical tutor and consultant: Freya Cobbin

Critics: Shade Abdul, George Aboagye Williams, Prince Henry Ajene, Julia Backhaus, Umi Lovecraft BP, Remi Connolly-Taylor, Akua Danso, Murray Fraser, Jonathan Hagos, Ben Hayes, Fabrizio Matillana, Stephanie Poynts, Max Rengifo, Gurmeet Sian, Michiko Sumi, Jessica Tang

Sponsors: Adrem, Atelier Red, HOK

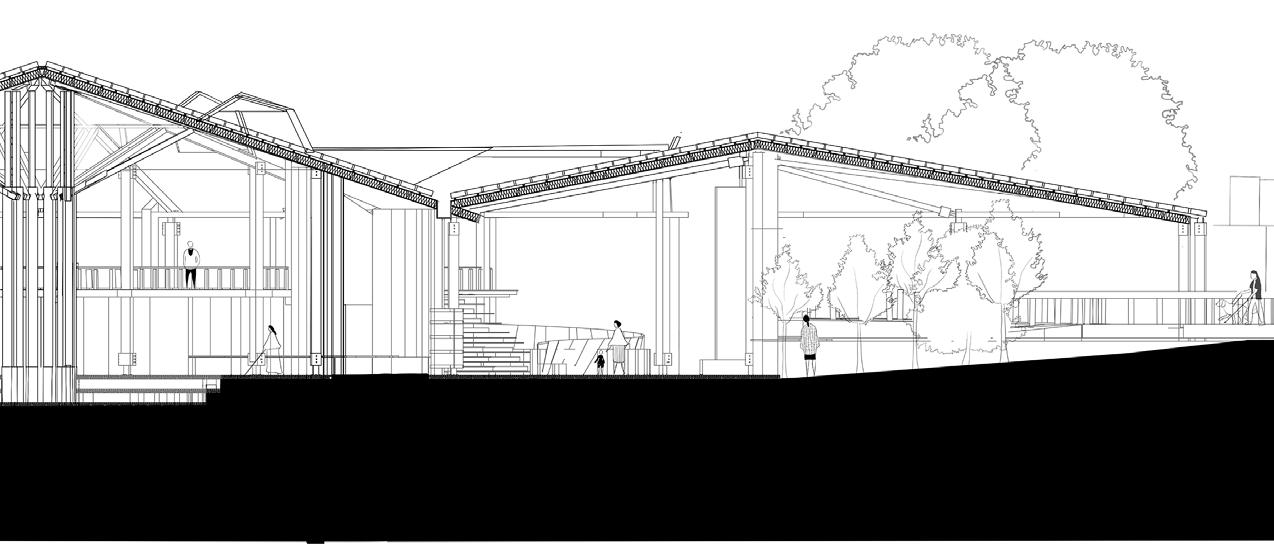

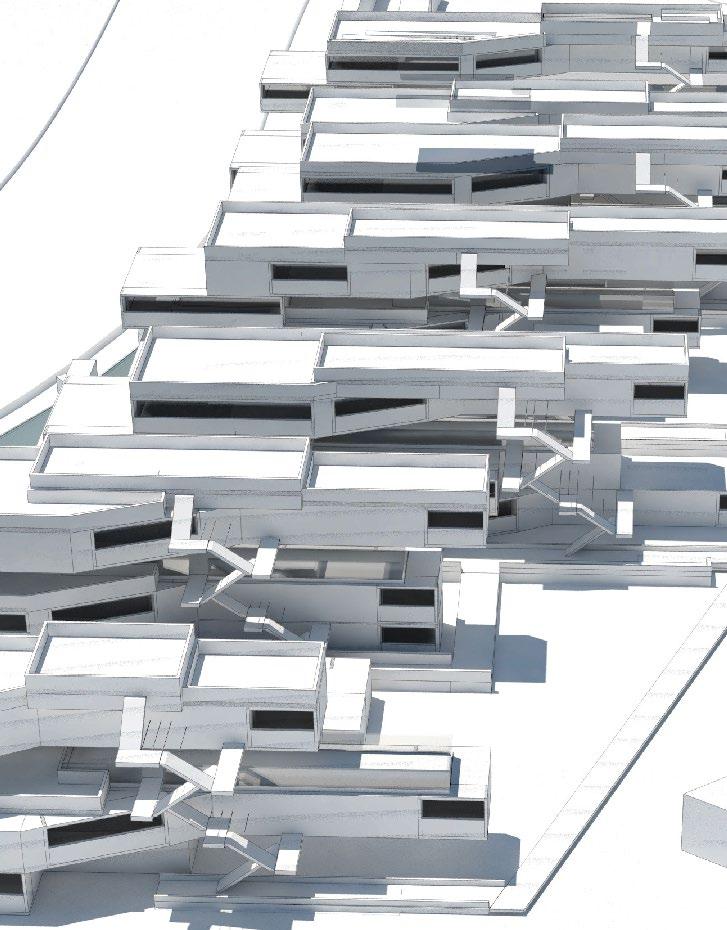

10.1–10.5 Minh (Dominik) Do, Y3 ‘Letters of Character’. The refurbishment and extension of an existing library to house a modern youth centre with the mission of decriminalising young people in public spaces. The project promises a safe environment which offers creative opportunities through literature. The programme allows young people to pass on their newly acquired understanding to the general public by holding regular exhibitions. The library is envisioned as an asset that serves the wider Ponders End community. 10.6–10.8 Kah Miin Loh, Y2 ‘The Connection between Nature and Living’. A housing project with regreening interventions brings the spirit of the Yanomami indigenous peoples’ shapono (community housing) from Venezuela to Fitzrovia. The housing is designed for families or individuals who work in Fitzrovia and have an interest in taking part in collective climate action. It serves as a precedent for the regreening and rewilding of Fitzrovia and London on a wider urban scale.

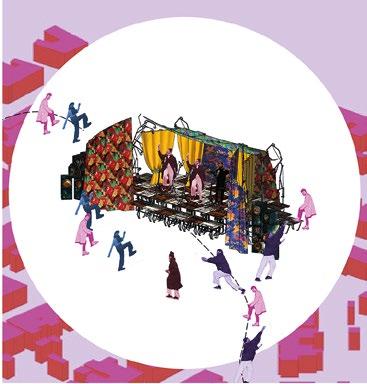

10.9 Fardous Khalafalla, Y2 ‘The Instrument of Culture’. The project takes inspiration from the tradition of Haitian carnivals by celebrating the work of musicians and providing a platform for them to launch their careers through showcasing their work. The design is inspired by Haitian carnival floats, where artists perform above crowds who watch from the streets below. The project fulfils the need for a purpose-built structure that celebrates music as a cultural commodity in Enfield.

10.10 Tsz (Vivianne) Wong , Y2 ‘The Garden of Eden in Enfield’. Inspired by Haitian literature, the project adds nature to a busy high street in Enfield by introducing a lightweight timber frame structure that sits on top of existing roofs. Referencing the Mayor of London’s aspiration to turn the capital into the first national park city in the world, the project creates a calm green space in the city for the local Enfield community.

10.11–10.12 Zeynep Cam, Y2 ‘Playschool for Enfield’. The project proposes an alternative nursery where children educate themselves via their senses and have fun while doing so. The design of a playscape empowers children to take initiative and learn freely. By giving younger generations a space for creative learning through play, the project builds a strong sense of community, with the hopes of inspiring children to contribute to their local area in the future.

10.13–10.14 Iga Najdeker, Y2 ‘FunTech Centre of Edmonton’. The project addresses the problem of digital exclusion and the limited access to learning, amplified during the pandemic, for young people from disadvantaged backgrounds. The proposed technology centre is a place where children between the ages of 10 and 16 can visit to participate in after-school activities. The project proposes several areas of emerging technology, creating future employment opportunities for children through skills and knowledge transfer while helping them to advance their digital abilities in a fun, innovative way.

10.15–10.16 Amy Bass, Y2 ‘F.I.G. (Female Integrated Gym)’. The gym is an urban oasis and a safe space for the women of Enfield and beyond. Inspired by Haitian martial arts, the design has four design principles: female empowerment, reuse, regreening and cultural sensitivity. The retrofit project serves as a framework for how post-pandemic, vacant buildings can be repurposed to create community spaces while educating and helping the wider society.

10.17–10.18 Amy Daja, Y2 ‘The Resident’s Hounfor’. Vodou is an integral part of Haitian history and culture that is often misunderstood by the West. The pilgrimage to the grotto of St Francis de Assisi is an annual event for Haitian vodouists that can be traced back to religions from West Africa, where the Atlantic slave trade

originated. The project proposes an extension of the new library as part of the Fore Street, Joyce Avenue and Snell’s Park regeneration to create much-needed community space for the local tenants, and residents’ association.

10.19–10.20 Junyoung Myung, Y3 ‘Shapes of Differentia’. The London Borough of Enfield has a diversity of ethnicities among its different communities. Religion is one of the aspects that can help unite people and bring them together. The project proposes a multi-faith festival centre that allows different religious communities to freely celebrate their traditional events, have festive meals and interact with one another. The design is inspired by Haiti’s culture of recycling and repurposing, as well as the gingerbread timber frame construction prevalent in Haiti.

10.21 Skylar Smith, Y2 ‘Bamboo Hub for Enfield’s Caribbean Community’. The project celebrates the way in which the local Caribbean community can become a part of the high street. By refurbishing the existing office building, the new multifunctional centre will include a bamboo recycling workshop, dance studios, kitchen areas for local food entrepreneurs and public spaces to host events and markets. The varied activities will foster the cultural exchange between Haiti and London.

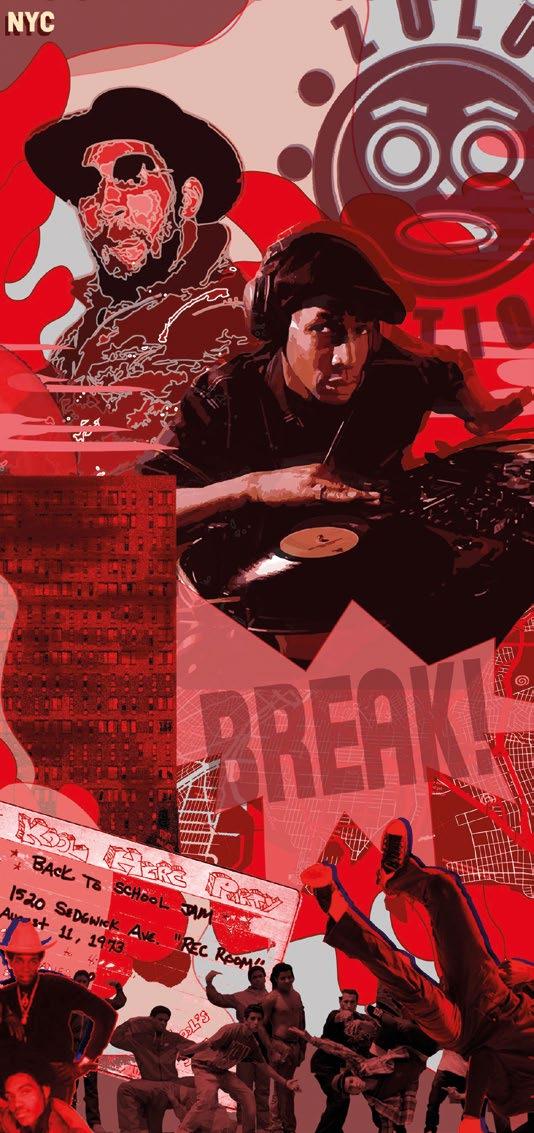

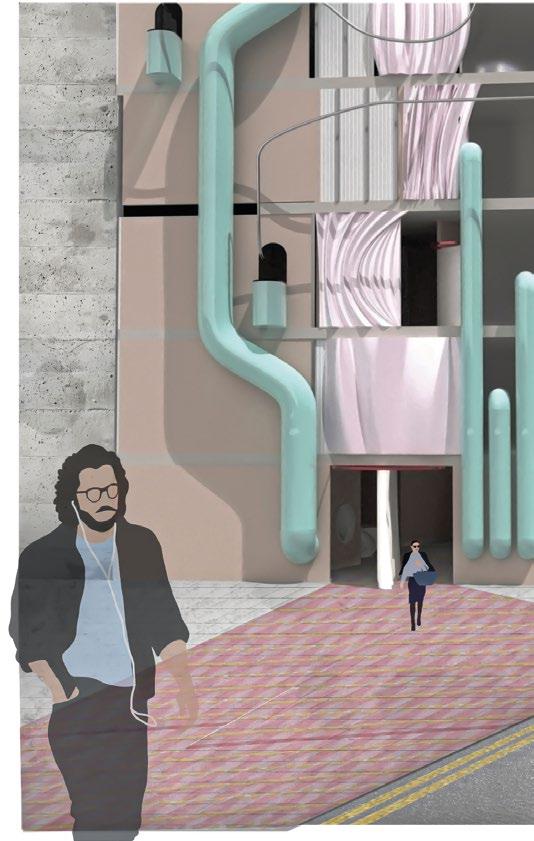

10.22 Natnicha (Amy) Ng , Y3 ‘R.A.G.E. Academy of Music (Rap And Grime Entertainment)’. The project addresses the need to educate local working-class young people on the culture of Haitian hip hop music as a method to develop confidence, self-expression and a sense of belonging. In response to the lack of spaces celebrating Black music, the project decolonises the existing spaces of music performance, creating a new typology which represents Black music and allows it to thrive. The design is derived from sampling and mixing an amalgamation of coded forms, Haitian construction techniques and a material palette inspired by Haiti and Enfield.

Freya Cobbin, Pedro Gil

Freya Cobbin, Pedro Gil

UG10 acknowledges the Global North/South paradigm. In doing so, we aim to expand the curriculum by raising awareness of Latin American culture, using its traditions as a lens through which to design. Within our unit’s agenda we explored both contemporary and historical relationships between the UK and Latin America and engaged in radical ideas across design activism, entrepreneurialism, resilient futures and transculturation. Our work highlights the differing phenomena and cohabitations between these diverse contexts, exploring what has been borrowed, drawn upon and taken from both sides of the Atlantic.

For our inaugural year, we selected Venezuela as our region of focus due to its rich and diverse history, people, land, nature, art, architecture, music and food. In the first term, we generated a series of postcards in response to The Bartlett’s ‘Build a better future’ manifesto,1 and set up a socio-environmental framework for the year. This short exercise led to the production of small-scale propositions, following in-depth research into Venezuela’s various social, political, historical, economic and/or environmental cultures.

In terms two and three, we built on the manifesto and socioenvironmental framework, in order to develop proposals in and around a London-based site: Grafton Way in Fitzrovia. This locality has a long-term connection with Venezuela, dating back to the 19th century, when key political figures, including Francisco de Miranda and Simón Bolívar, lived there in order to secure fiscal and military support for the country’s (and much of South America’s) independence from Spain. More recently, establishment buildings and institutions have opened, including the Venezuelan Consulate and cultural arts centre Bolivar Hall, continuing the country’s presence and influence in Fitzrovia.

Our projects demonstrate a diverse range of themes, addressing issues including water scarcity, future food production, female and under-represented community empowerment, consumerism, mental health and wellbeing.

In place of a field trip, we organised a virtual series of talks and presentations, fashioned as a miniature cultural festival, presented by various Venezuelan guest contributors including designers, architects, academics and artists.

Year 2

Blenard Ademaj, Nasser Al-Khereiji, Emma Bush, Eunice Cheung, Aaron Green, Lolly Griffiths, Eleanor Hollis, Jovan Jankovic, Kah Miin Loh, Esma Onur, Zahra Parhizi

Year 3

Noor Alsalemi, Conor Hacon, Dongheon (Julian) Lee, Asya Peker, Michael Rossiter, Fergal Voorsanger-Brill

We are very grateful to all our guest contributors and workshop tutors: Liam Bedwell, Maelys Garreau, Alex Mizui, Levent Ozruh, Neba Sere

Critics: Barbara-Ann Campbell-Lange, Edward Dension, Rosie GibbsStevenson, Jaime Gili, Mina Gospavić, Stefan Gzyl, Carlos Jiménez Cenamor, Christo Meyer, David Ogunmuyiwa, Rebeca Ramos, Layton Reid, Max Rengifo, Josymar Rodríguez, Neba Sere, Bob Sheil, Jessica Tang

Venezuelan contributors: Rodolfo Agrella, Rodrigo Armas, Cruz-Diez Art Foundation, Jaime Gili, Stefan Gzyl, Alejandro Haiek, Julio Kowalenko, Ana Lasala, Isabel Lasala, Tomás Mendez, Rebeca Ramos, Max Rengifo, Josymar Rodríguez, Ignacio Urbina Polo

1. The Bartlett (2021), ‘Build a better future’, The Bartlett (accessed 6 June 2021), ucl.ac.uk/ bartlett/about-us/ourvalues/build-better-future

10.1, 10.8 Asya Peker, Y3 ‘La Casa del Agua’. The project explores the relationship between rainwater and the built environment. Following research into the ecocosmological belief systems of the Ye’kuana – a rainforest tribe who live in the Caura River and Orinoco River regions of Venezuela – the project asks how an architecture can facilitate an understanding of the natural world and re-situate humans within a larger ecosystem. Set in the year 2070, on Grafton Way in Fitzrovia, the location of the Venezuelan Consulate in London and once home to the revolutionary Francisco de Miranda, the building and public exhibition space conserves, harnesses and celebrates rainwater.

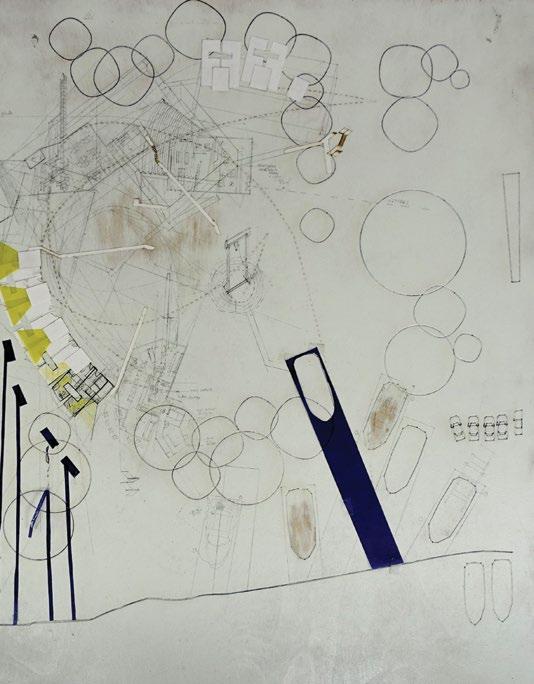

10.2–10.3 Fergal Voorsanger-Brill, Y3 ‘Polyrhythms’. A musical festival in Leytonstone, East London, that celebrates the unacknowledged, yet culturally important, music of Venezuela. The festival is a platform that encourages collaboration between musicians from Venezuela and the UK. The project visualises the intrinsic and overlooked influences that underpin our music and lives.

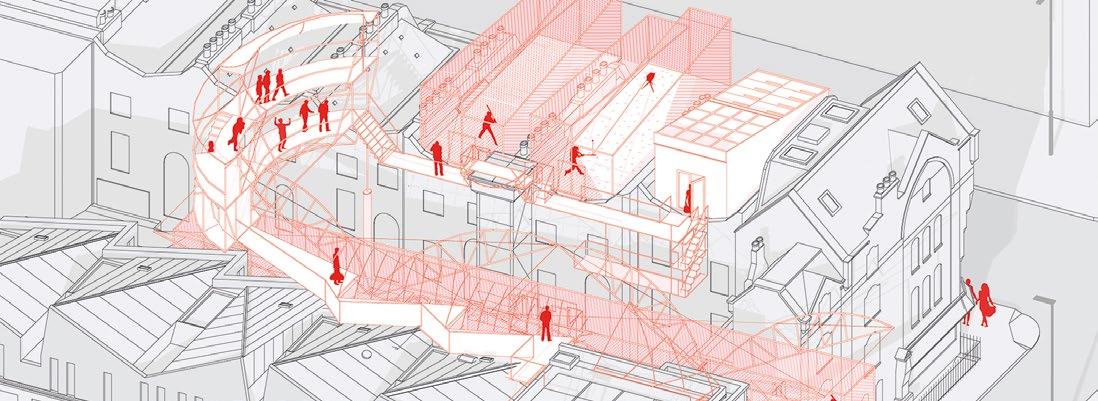

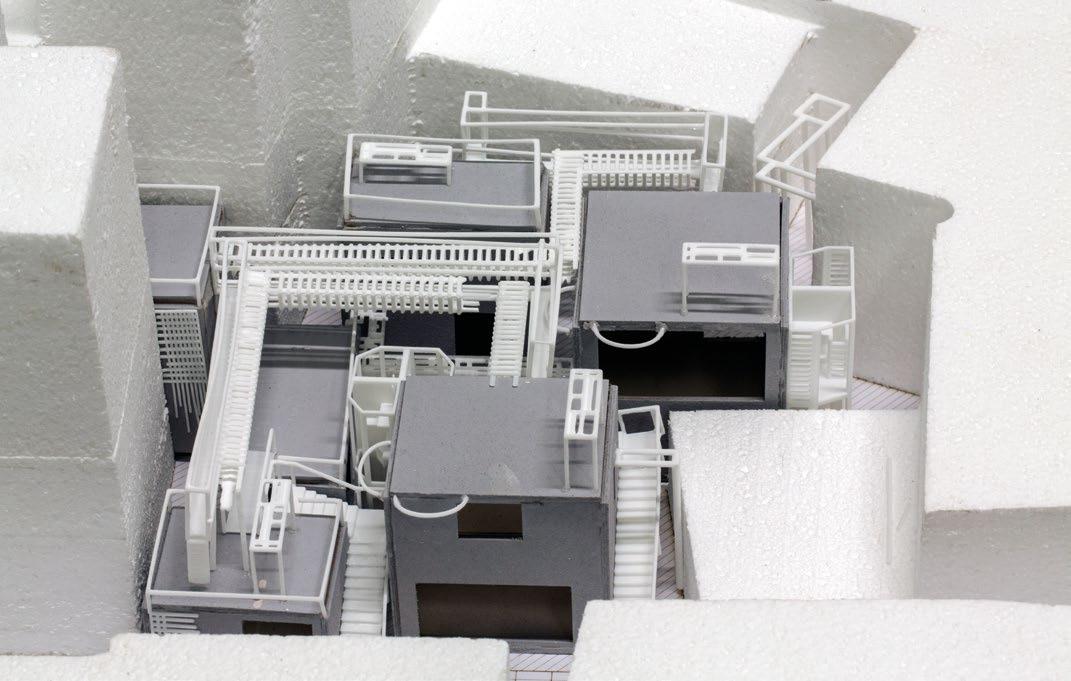

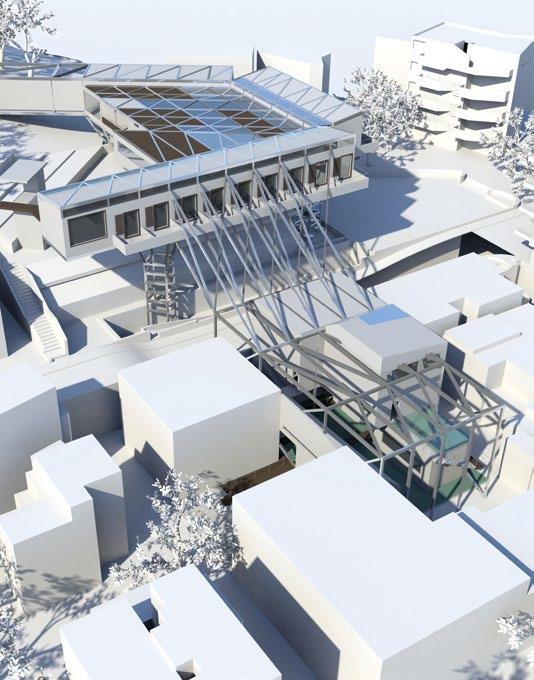

10.4–10.5 Aaron Green, Y2 ‘Learning Above London/ Aprender encima de Londres’. The project investigates areas above the London streetscape as viable spaces for use. It proposes a London satellite for the Central University of Venezuela’s international relations department. Akin to informal developments in Venezuela, the project’s activities are split to form small architectures that fit into the spaces between roofs and leave little lasting impact on the existing structures.

10.6–10.7 Zahra Parhizi, Y2 ‘Escuela De Danza Venezolana’. A Venezuelan performing arts and dance school in the garden of Fitzroy Square, London. The layering and curvature of the architecture is inspired by joropo dresses, traditional Venezuelan clothing worn for national dances. The project is designed to theatrically communicate dance and allow the building to become an interpreter between the dancers, the audience and the architecture.

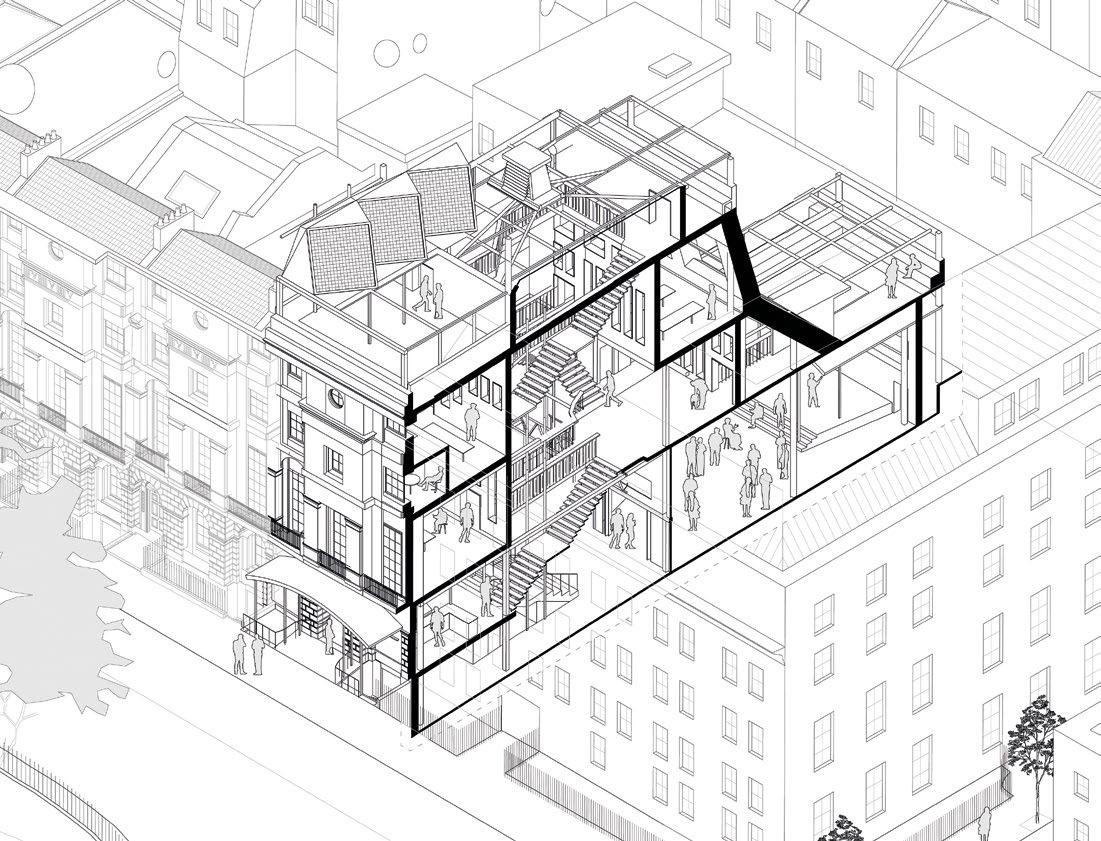

10.9–10.10 Michael Rossiter, Y3 ‘Centre for the Venezuelan Diaspora’. 5% of the world’s displaced people are Venezuelan, and many have found themselves in London in search of a community. The project proposes a new civic hub for London’s Venezuelan community in an appropriated Georgian terrace in Fitzrovia. The centre’s agenda is to maintain and celebrate Venezuelan culture, to empower Venezuelans in London and connect them to NGOs at home.

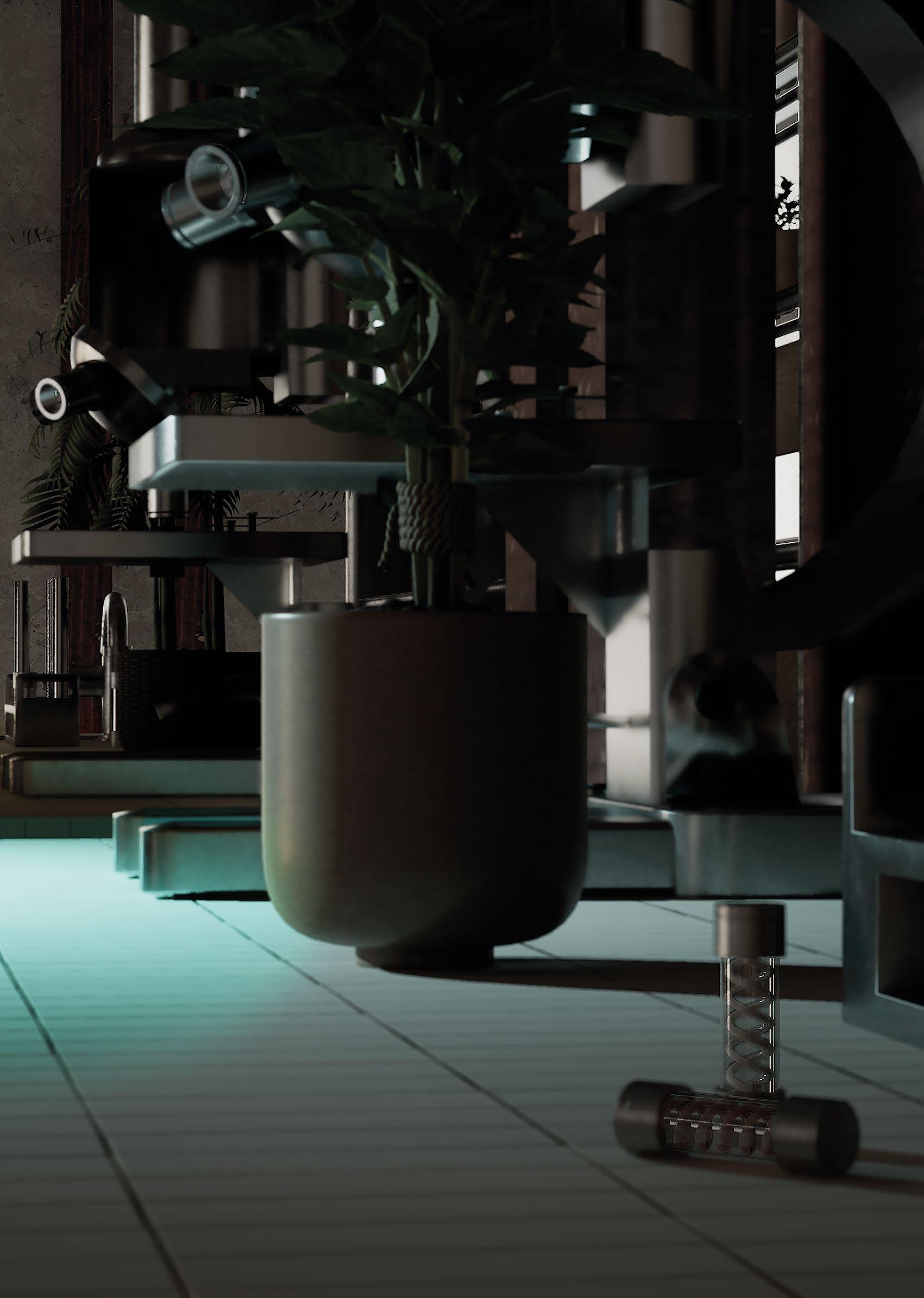

10.11–10.13 Dongheon (Julian) Lee, Y3 ‘Psychological Hidden Oasis’. The project encapsulates the experience of finding sudden peace and quietness in the middle of a busy city. It provides a hidden space where people can achieve mental relaxation and personal welfare through various types of meditation exercises.

10.14–10.15 Eunice Cheung, Y2 ‘Arepa School of Culinary Arts’. Political turmoil in Venezuela has led to many of its citizens seeking refuge in foreign countries. As a result, Venezuelans have found it difficult to source yellow cornflour in their new homes. Yellow cornflour is an essential ingredient in arepas; a round cornmeal cake typically stuffed with meat and cheese and a cornerstone of a Venezuelan diet. Sited in Fitzrovia, London, the culinary school provides space to prepare arepas and facilitates the dissemination of this culinary craft to a new generation. By 2040, the UK will be warm enough for the building to be surrounded by a cornfield, turning the landscape into a visual spectacle.

10.16–10.17 Conor Hacon, Y3 ‘Sweet Chestnut Coppice’. We may consider artefacts to be object-tools that we use to navigate the world, and metaphors might be described

as abstract-tools for the same ends. This project investigates how our object-tools shape our encounters with the world.

10.18–10.19 Lolly Griffiths , Y2 ‘Latin American Student Centre’. The project explores how architecture can be used as a tool to narrow the attainment gap at UCL and provides practical space, resources, community and a platform for educational equity. The proposal revolves around a rectangular module, where each unit is available for appropriation and students are encouraged to use it as a framework for adaptation. Equitable structures for higher education counteract educational spaces that manifest and perpetuate racial and structural inequalities. The building is part of the institution’s pledge to invest equitably in the future of its students.

10.20–10.21 Nasser Al-Khereiji, Y2 ‘RE_TELIER’.

Located on Oxford Street, London, the building challenges high-street fast-fashion culture to foster a meaningful relationship between garment and wearer. Adopting the atelier model of traditional fashion houses, and taking inspiration from transgenerational mochila bags –hand-woven using local materials by the Wayuu tribe of Venezuela – the project injects a sense of intimacy, missing from disposable fashion, between humans and garments.

10.22 Jovan Jankovic, Y2 ‘Beisbol Barrio’. The project is a rooftop baseball club, inspired by research into urbanism and sports in Caracas, Venezuela, where architectural interventions are made within the unplanned barrios (neighbourhoods) that lack amenity spaces, such as sports enclosures and public squares. The proposed ‘club de beisbol’, a ubiquitous typology in Venezuela, is situated on a rooftop on Grafton Way, Fitzrovia.

10.23–10.24 Blenard Ademaj, Y2 ‘The Cult of Healing’. The project creates a place that celebrates the Venezuelan cultural practice of rituals that use smoke to connect to spirits and heal. A space for therapy by day and aromatherapy by night, the programme promotes healing through nature and burning as a method to restore, celebrate and unite. Through everyday use, the building comes alive with smoke, steam and mechanisms that create a relaxed and reflective atmosphere.

Kyle Buchanan, Mellis Haward, James Purkiss

In UG10, we believe that to have agency, architects need to develop better ways to engage and communicate with people from a wide range of backgrounds. Recognising that how we communicate is as important as what we design, we started the year by making tools to start conversations around our core themes of ‘home’, ‘identity’ and ‘community’. We used these tools to explore fundamental questions around what makes a home and how it relates to our individual and collective sense of self and asked: Can a national housing crisis be interpreted as a national identity crisis?

We expanded on our personal experiences of home by visiting radical housing projects in the UK and abroad. On our field trip we travelled by train through the lowlands of Holland and Belgium to visit projects that demonstrate a collective ‘identity of place’.

Throughout the year, we have engaged with people who are working to address the housing crisis, including commissioners of housing and community projects, policymakers and people experimenting with radical new ways of living together. As well as being our critics and guides, these people have also been our clients.

We are indebted to our Year 2 students’ clients, the staff and residents of Phoenix Community Housing, a resident-founded, resident-led housing association based in Lewisham. By contrast, the Year 3 students identified and reached out to their own clients, ranging from healthcare workers to a recycling charity.

To get the most from direct engagement with these clients, we have had to learn to ‘speak to their language’. Gaining a first-hand understanding of our clients’ needs, priorities and the pressures on them has allowed us to speculate how we can contribute our skills as architects to help address their problems. All of our projects have been formed and iterated through conversations: we have drawn collaboratively with mothers, toddlers and nurses; we have presented our projects to residents and community leaders, charity organisers and board-game societies; and we have attended sewing clubs, coffee mornings and Transition Town meetings.

We had to adapt our methods of communication as a new crisis emerged in the second term which confined us to our homes. The Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted the impact of housing inequality. It has also instigated new community connections. We all intend to draw on our experiences this year to help facilitate community-led projects that will be crucial in shaping the ‘new normal’.

Year 2

Reem Taha Hajj Ahmad, Ho (Jeffrey) Cheung, Alice Guglielmi, Megan Hague, William Hodges, Charis Makmurputra, Wiam Mostefai, Jamie Stewart

Year 3

Isabelle Gin, Maria Mendoza Guerrero, Olivia Hoy, Seng (Aaron) Lim, Barbara Sawko, Alice Shanahan, Amy Zhou

Thank you to our technical tutors and consultants

Ione Braddick, Tom Budd, Juliette Mitchell, Greg Nordberg, Frances Wright

Thank you also to our critics Claire Bennie, Duncan Blackmore, Bill Hodgson, James Masini, Huma Mohyuddin, Elizabeth Owens, Paul Quinn, David Roberts, Claire Richards, Naomi Rubbra, Kathryn Timmins

Our partners Phoenix Community Housing were extraordinarily generous clients to our Year 2 students. Thank you to Steve Connor, Pat Fordham, Angela Hardman, Anne McGurk, Leon Yohai and to all the resident critics

10.1 Staff and residents of Phoenix Community Housing reviewing a Year 2 site model, March 2020.

10.2 Olivia Hoy, Y3 ‘Reconstructing Memory’. This project is a collaborative reconstruction of a grandmother’s spatial and material memories of a previous home.

10.3 Isabelle Gin, Y3 ‘Let’s Get Cultured’. This project takes the form of a board game exploring the intergenerational transference of knowledge, values and traditions at the Chinese dinner table.

10.4–10.5 Seng (Aaron) Lim, Y3 ‘Towards A SociallyEngaged Architecture’. This project seeks to develop tools to empower the public as co-designers. Taking inspiration from socially engaged art practices, the proposed tools aim to create transparency and foster trust between participants.

10.6–10.8 Maria Mendoza Guerrero, Y3 ‘Loneliness, An Epidemic with a Social Solution’. A pilot concept for a new suburban infrastructure to help the UK adapt to support an ageing population. The pilot project is sited in Galleywood, a suburb of Colchester in Essex. The current demographic of the village is representative of the predicted UK 2050 average but it lacks a GP surgery. The design of the building, which accommodates a broad spectrum of intergenerational services, is centred around an experiential wait to see a GP. When someone like Ann, an older resident in Galleywood, spends time in the waiting room, she find herself at the centre of the village.

10.9–10.10 William Hodges, Y2 ‘(Re)defining Living ’

Responding to the Homelessness Reduction Act 2017, this project addresses youth homelessness through prevention and rehabilitation, horticulture education and therapy.

10.11–10.13 Alice Shanahan, Y3 ‘Making Noise’. Responding to ongoing discourse regarding the representation and consideration of acoustics in planning policy and design, specifically Policy D13 of the Draft New London Plan, this live-work scheme, sited in Tottenham Hale, is designed with acoustics at the helm. Desirable soundscapes are achieved through alternative noise mitigations which facilitate otherwise clashing uses to coexist.

10.14–10.15 Isabelle Gin, Y3 ‘Intergenerational Living’. This intergenerational cohousing community focuses on re-establishing the links between different generations. It promotes a more sustainable way of living by facilitating social cohesion of these generations for mutual dependence.

10.16–10.17 Olivia Hoy, Y3 ‘Playing at Home’. Co-located housing and kindergarten for 15 displaced mothers at the centre of FocusE15’s campaign for ‘social housing not social cleansing’. The project has been guided by workshops with children from the FocusE15 group, using playable models based on educational play materials known as Froebelian gifts.

10.18–10.19 Reem Taha Hajj Ahmad, Y2 ‘Echinacea’. A culinary club and therapeutic garden for the Downham and Bellingham Young Carers Club. Echinacea helps young carers relieve their strain in a productive way through collective gardening and cooking. At Echinacea they can make new friends, gain life skills and regain their confidence.

10.20 Amy Zhou, Y3 ‘The Seen and Unseen’. A collaboration with Thames Water to tackle the ‘fatberg crisis’. Using methods of shock education, this public toilet installation project reaches out to the community by implicitly engaging them, educating them, and enticing them to change one small habit.

10.21 Charis Makmurputra, Y2 ‘Value: A Space Odyssey ’. The scarcity of space within London has supported the assumption that more space equals value. However, with an ageing population, older generations are finding themselves living in homes that are too large for them. Situated in Lewisham, Millcroft House is an eight-storey residential building currently managed by Phoenix

Housing. Working with Phoenix, this project proposes an intergenerational co-living scheme that reconnects a disconnected group of elders back into their community through shared living.

10.22 Wiam Mostefai, Y2 ‘Sewing as Therapy: Stitching Communities Closer Together’. A wearable tablecloth inspired by the Algerian La Nappe mixing bright colours from Algiers with earthy tones of London as well as traditional Kabyle and British quilting techniques.

10.23 Barbara Sawko, Y3 ‘Rituals of Everyday Life’. A proposal to elevate the mundane routine of clothesdrying to encourage residents to reclaim and repurpose an underused communal space.

10.24 Ho (Jeffrey) Cheung , Y2 ‘A Communal Approach to Recycling’. This project challenges this hidden cycle of waste, and poses a new highly visible infrastructure where waste can be considered as a valuable resource.

10.25 Megan Hague, Y2 ‘Wellbeing’. A child-focused centre specifically designed to accommodate a range of targeted therapies using verbal communication, sensory play and creative expression to help children articulate their emotions and learn tools to aid the coping process.

10.26 Alice Guglielmi, Y2 ‘Phoenix’s Therapeutic Garden’. Solitude and relaxation are increasingly becoming commodities in London, whilst rates of mental ill-health soar nationwide. Phoenix’s Therapeutic Eden is a scheme devised to better engage with residents of Phoenix Housing, in a ward where rates of mental illness are 40% higher than the national average.

10.27 Jamie Stewart, Y2 ‘Gardens on Our Doorstep ’. A high-density housing scheme with a front garden for every property. Front gardens bursting with roses were once characteristic of the existing LCC estate. They were spaces for neighbourly interaction and a source of local pride. This project seeks to reverse the disappearance of front gardens to make way for parking. Front gardens will not solve all the problems faced by Phoenix Community Housing, but when it comes to strengthening a community, your doorstep is a good place to start!

Pedro Pitarch, Sarah Stevens

‘What you’re seeing and what you’re reading is not what’s happening.’ Donald Trump, 24 July 2018

This year, UG10 were interested in design as a way to challenge the stories we build around ourselves. These stories govern our world, defining our actions and their implications; from the stories we tell ourselves to those told to us, and the stories woven around us by the media that become more real than we are. Our built environment grows from these stories, offering them physical form so that they submerge us and influence our perception of reality. From the skyscrapers of Manhattan to King Ludwig’s castles in Bavaria, all embody stories interpreted as truths. In challenging this, we draw forth architectures that inhabit alternate presents, making new realities visible through shifts in thought. Such architectural interventions offer a critique of contemporary society, whilst also proposing new routes forward. Research is rapidly superseded by individual architectural languages.

We explored the fractures in our constructed world to navigate crumbling landscapes of thought, divining individual trajectories to narrate stories from our own critical positions. Our stories lie shattered around us, as we attempt to navigate a world dominated by uncertainty and impermanence. Our desire for understanding is overwhelmed by a never-ending stream of information. Truth has become multiple; misinformation and ‘fake news’ contort our view and have become new threats to democracy. Brexit has threatened our belief in government, whilst the US enters a world inhabited by multiple truths, where history is being rewritten. All the while, unimagined storms ravage, heatwaves parch, mental health issues spiral and untold species silently disappear. We have reached an impasse, for which new stories are needed before our future is lost.

The Netherlands, a constructed breathing machine woven from stories, was home to many of UG10’s explorations this year. We challenged assumed, emerging and infiltrated stories to propose new futures and realities in speculative proposals for new institutions sited within fabricated landscapes. We asked what architectures might inhabit such a world of uncertainty? What if we discard the false reassurances and illusions of control to seek out creativity in the contradiction and poetry of impermanence?

Year 2

Sumayyah Jannat, Evelyn Jesuraj, Su (Yen) Liew, Jiying (Emily) Luo, Sarfaraz Salim, Anastasiia Stoliarova, Sinziana Vladutu, Wenxi Zhang

Year 3

Alexander Balgarnie, Arseniy (Danya) Baryshnikov, Amanda Dolga, Noriyuki Ishii, Megan King, Thomas Roylance, Jake Williams

Special thanks to our technical tutors Peter Lenk, Jack Morton, and to Jason Coe, Matthew Turner, Charlotte Bovis and Sarish Yarish for their digital workshops

Our thanks to OMA and MVRDV, for generously opening their offices to us during our field trip, with particular thanks to Maria Aller, Ana Melgarejo and Stavros Gargaretas

Thank you to all our critics for their invaluable feedback: Laura Allen, Andrew Best, Iain Borden, Charlotte Bovis, Peter Cook, Simon Herron, Jessica In, Chee-Kit Lai, Ifigeneia Liangi, Bakul Pakti, Jonathan Paley, Matthew Rosier, Sara Shafiei, Giles Smith, Mark Smout, Sabine Storp, Uieong To, Martin Walsh

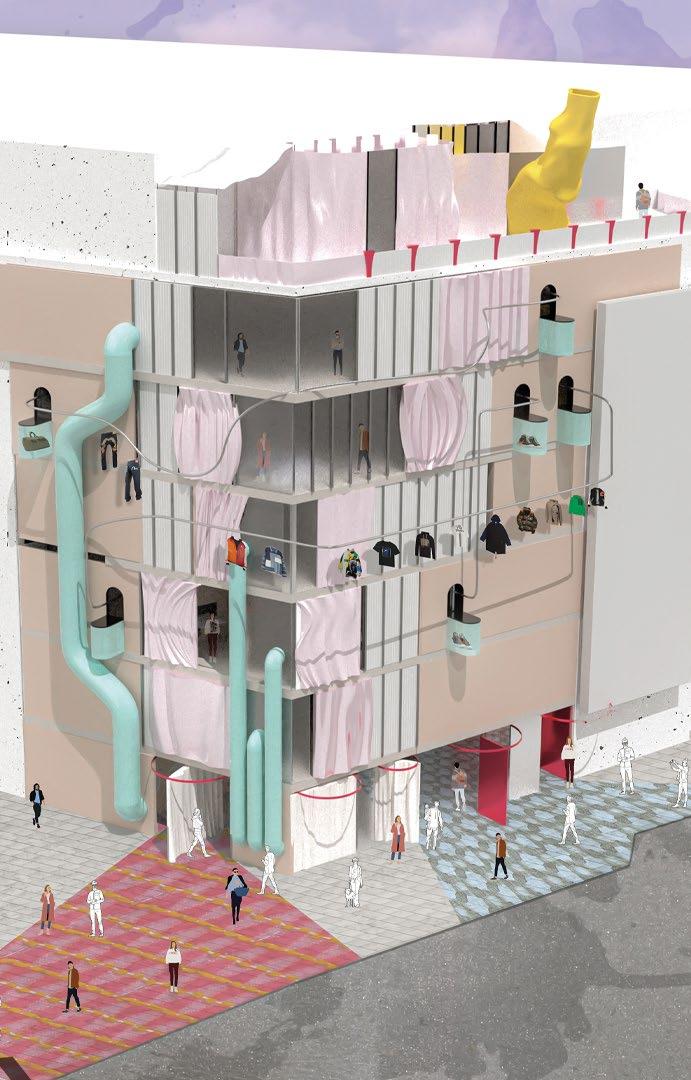

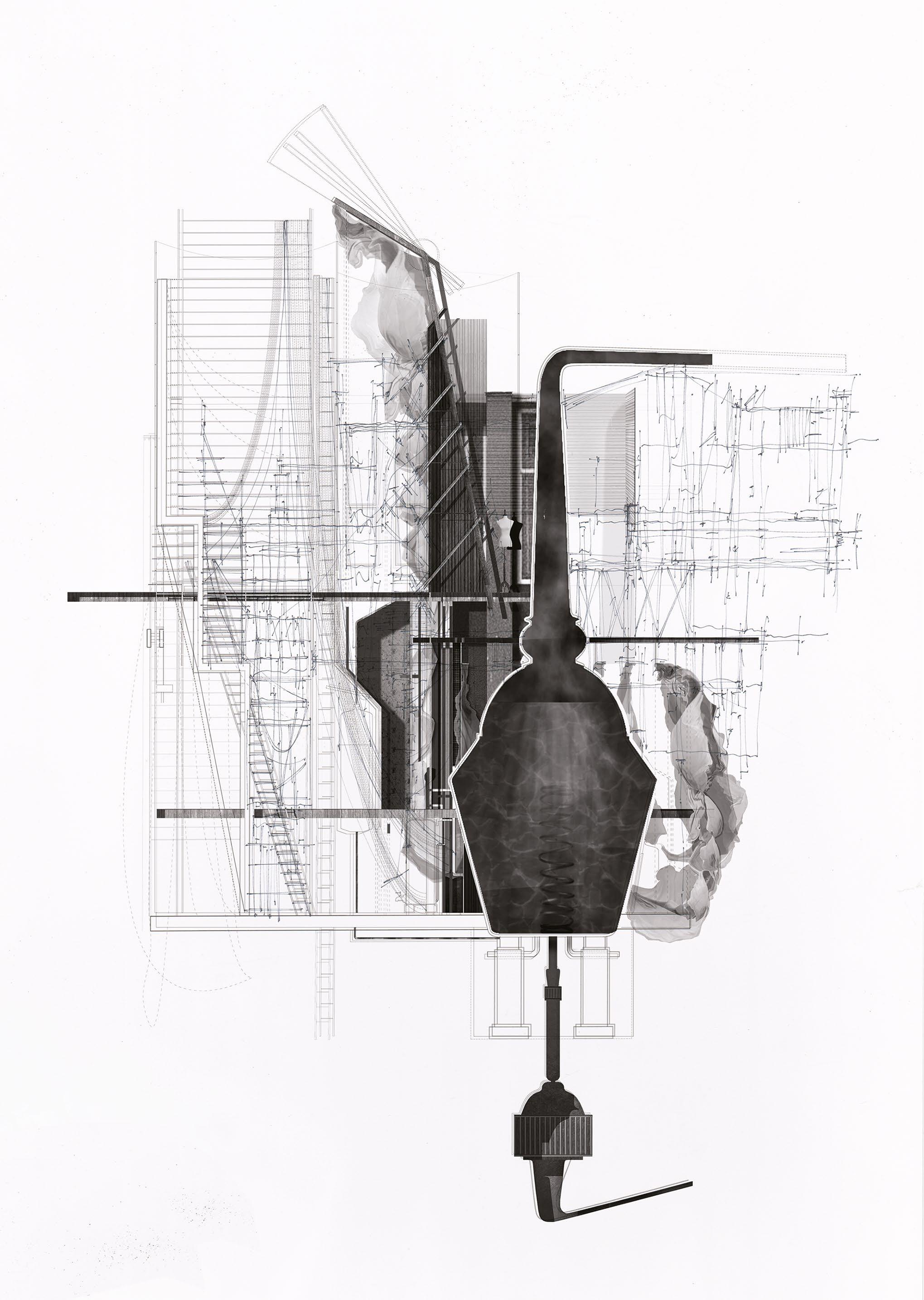

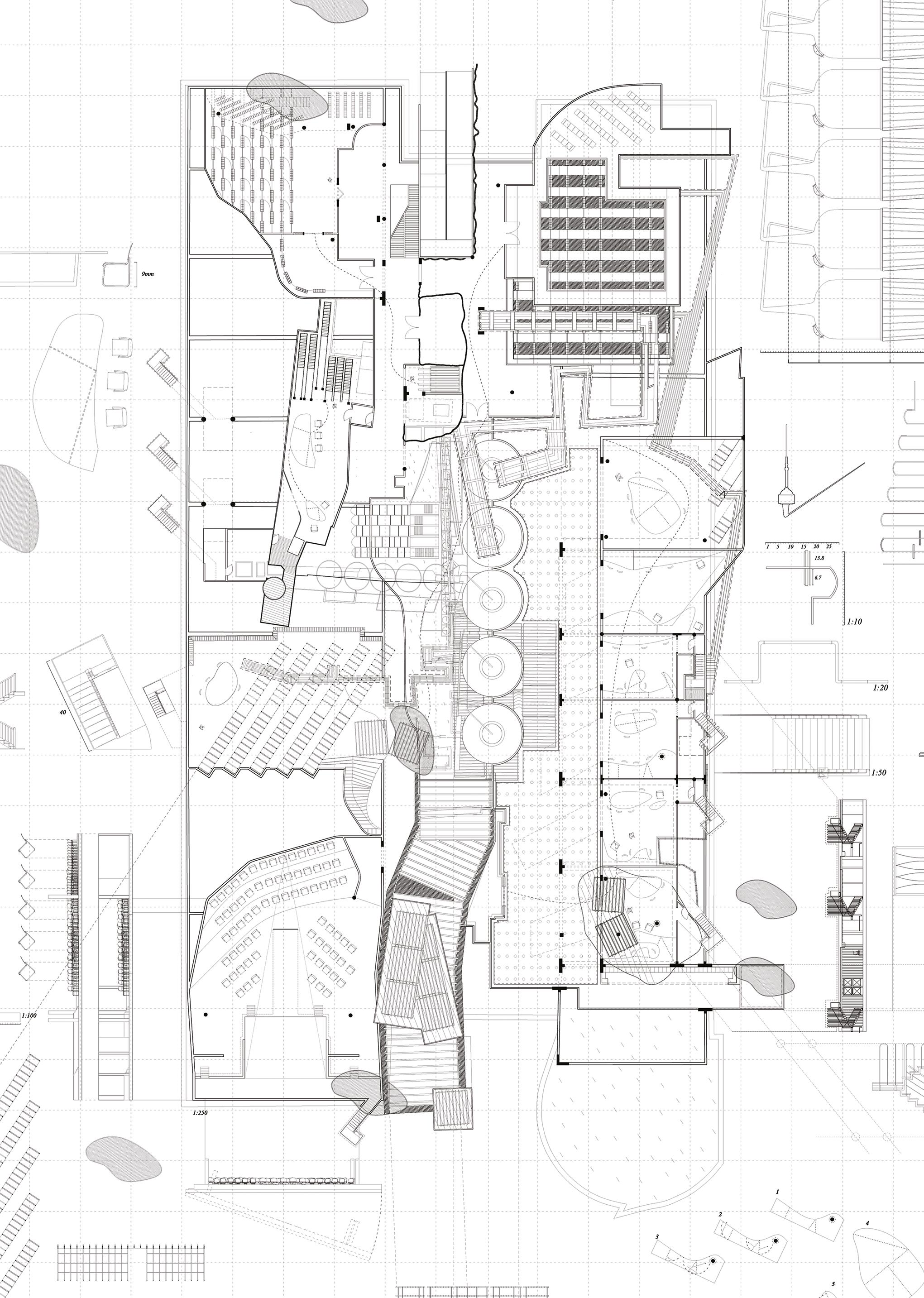

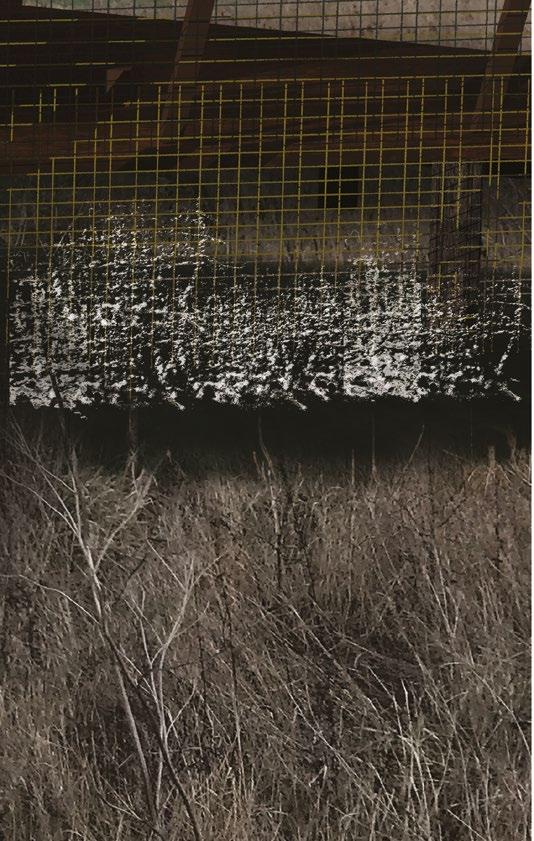

10.1, 10.12–10.16 Megan King, Y3 ‘The Lijnbaan Seam, Rotterdam’. Part of the 1950s reconstruction of Rotterdam, the Lijnbaan was the fashionable home of boutiques and jazz clubs. By the 1990s, however, it had descended into another form of notoriety: vandalism and crime. This project aims to revitalise the area, echoing its heritage in a sustainable couture fashion house for independent makers. Challenging fast fashion, it utilises organic fibres for the fabric of both the garments and the architecture. Embedded processes – such as the growing of organic fibres and natural dying and drying of fabric – feed the architectural language. The project is a social commentary on sustainable fashion and highlights the potential of organic fibres by offering an alternative sustainable reality that clothes both people and architecture. 10.1 shows the southern end of the site, highlighting the water tanks and drying racks used in the production of organic and recycled fabrics.

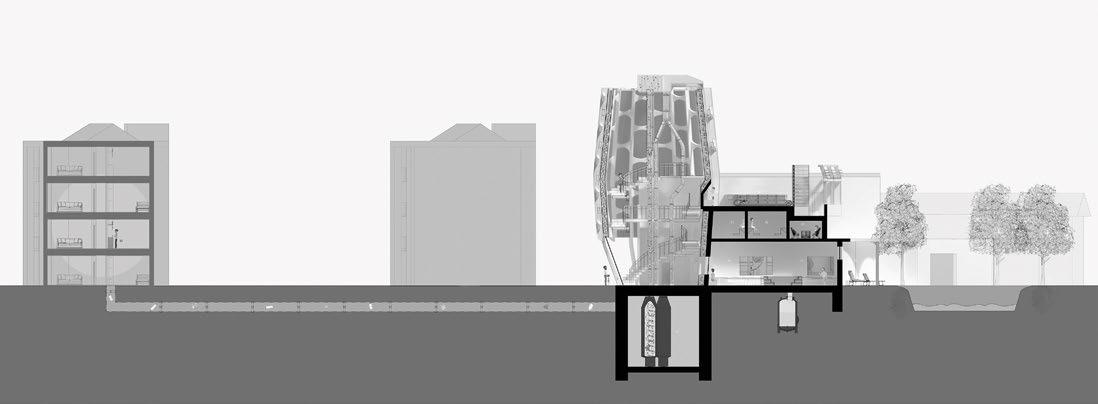

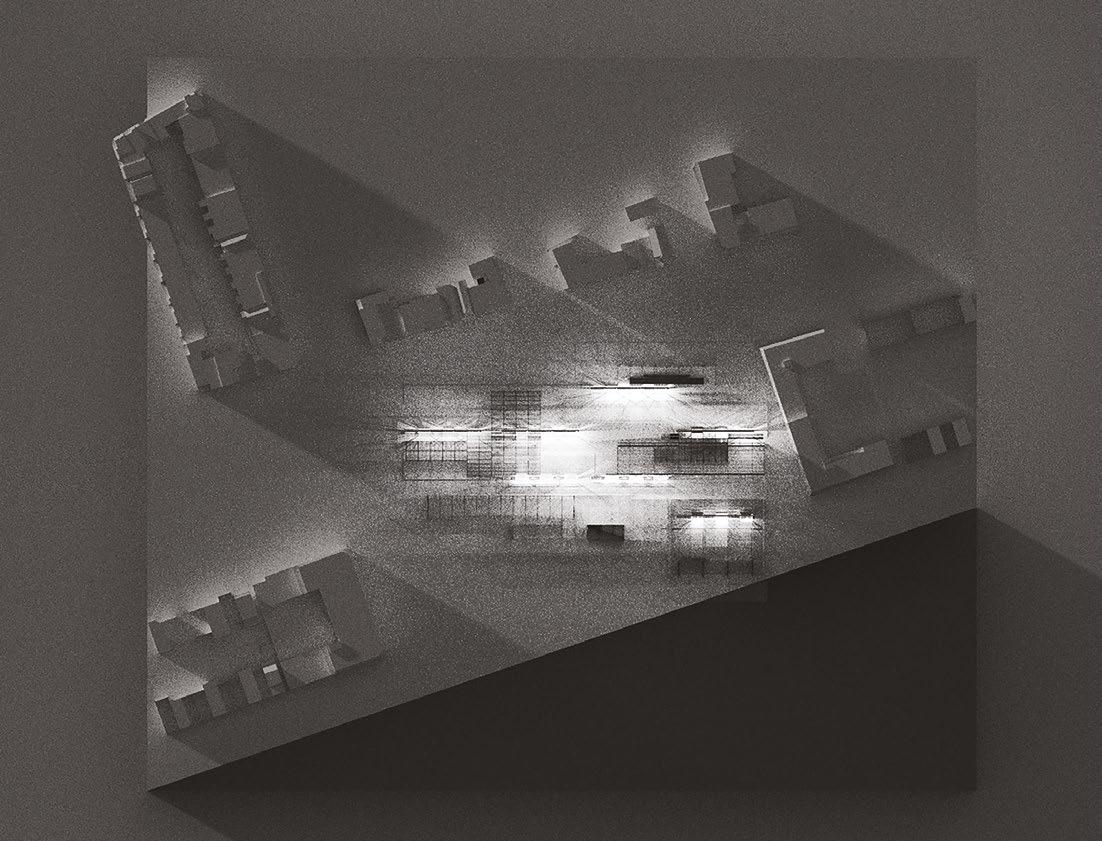

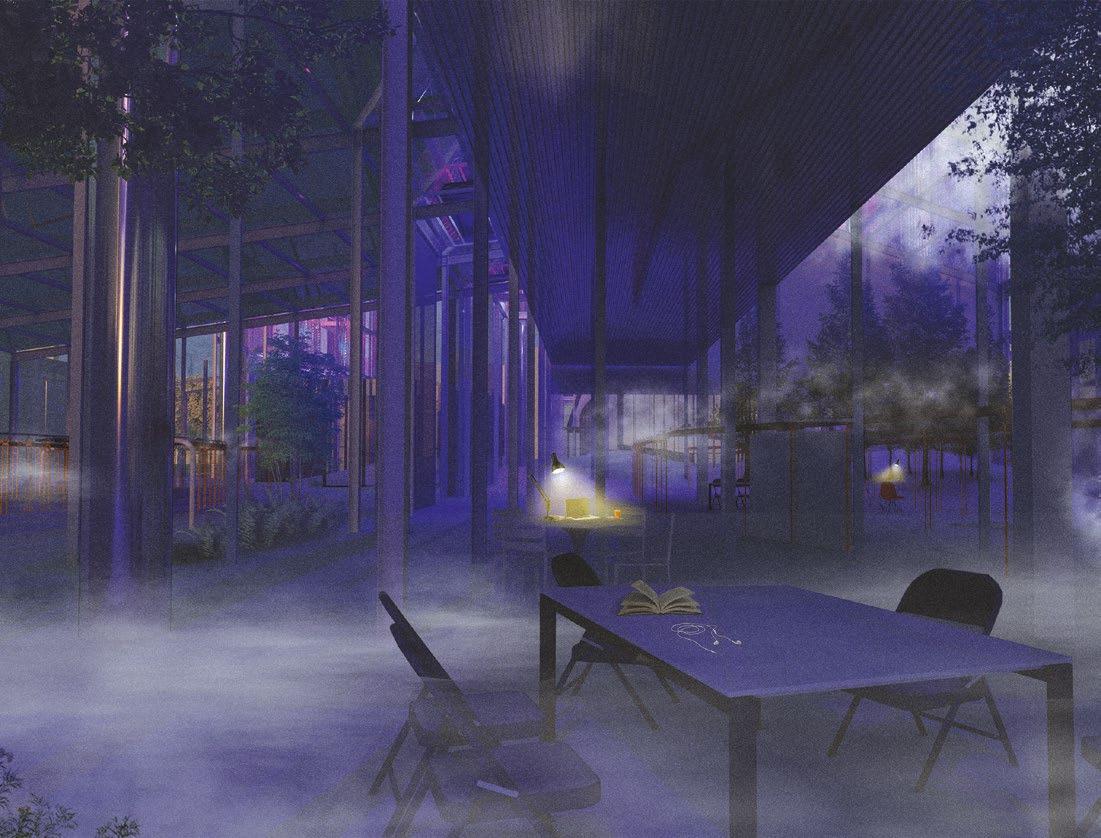

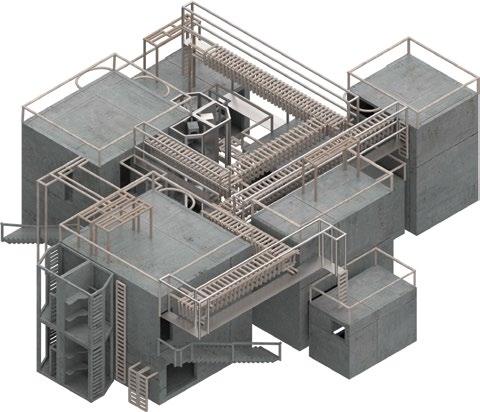

10.2–10.4, 10.6 Amanda Dolga, Y3 ‘Head in the Clouds, Rotterdam’. In this project, digitally induced weather inhabits a re-imagined data centre. There are over 7,500 data centres worldwide, with over 2,600 in the top global cities alone, and an estimated construction growth of 21% per year through 2018. The average data centre consumes over a hundred times the power of a large commercial office building, whilst a large data centre uses the electricity equivalent of a small US town. This project critically reflects on the physical ramifications of the digital world. Climatic gardens, warmed by the residual heat of the centre, serve as direct indicators of data consumption, as internal weather systems, mists, clouds and rain are induced when internal climate tipping points are reached.

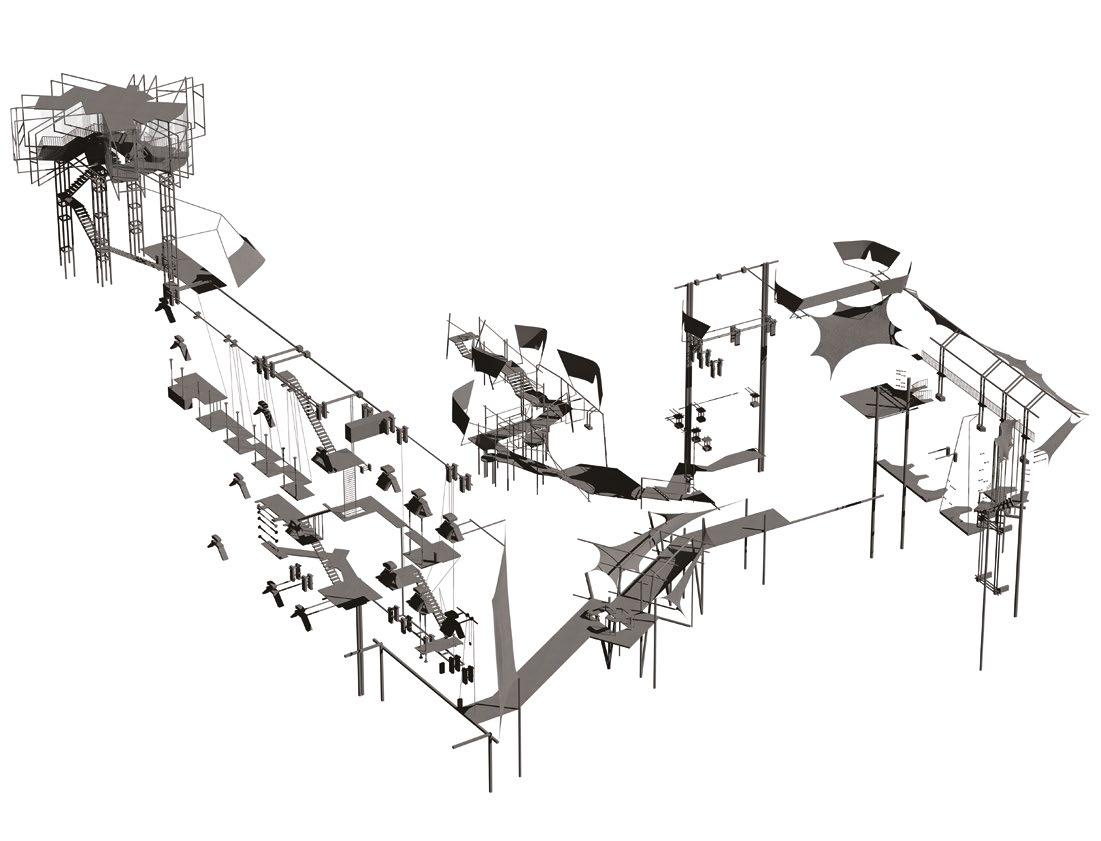

10.5 Su (Yen) Liew, Y2 ‘Parliament Playground, London`. In the midst of the current political turmoil, this project takes a critical look at contemporary politics, challenging the separation of the populace from the governance of their country and the inner battles of the power hungry. The speculative proposal re-envisions the Houses of Parliament as a playground fuelled by commentary on its entrenchment in age-old traditions and rituals. A new ‘House of Peoples’ is proposed to remove the physical barriers and allow the populace to take an active, welcome role in the governing of their country.

10.7 Jake Williams, Y3 ‘Institute for Transient Populations, Rotterdam’. This project responds to dramatic changes in social patterning and the absence of an appropriate housing to compensate. The failure of the housing market to evolve with the rapidly changing patterns of living means that people not only cannot afford to live where they want, but often cannot live the way they want. A collective housing prototype views shared resources as an exciting prospect and a way of fostering a community.

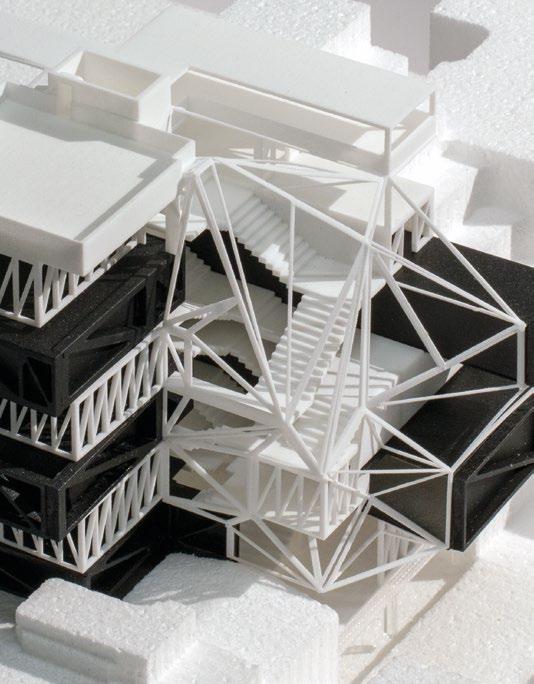

10.8 Alexander Balgarnie, Y3 ‘Housing Prototype, Rotterdam’. This project proposes an institution that combines community facilities with temporary housing for displaced individuals and families, and understands architecture as a spatial and technical offering for the user/inhabitant. The approach is a structural response to questions of use, sustainability and ecological crisis. The strategies employed eliminate waste and throwaway culture.

10.9 Arseniy (Danya) Baryshnikov, Y3 ‘Unveiling the Unreal, Whitehall London’. Drawing on Jean Baudrillard’s ‘Hyperreality’, this project challenges the existing symbolic landscape of Whitehall through the addition of architectures to re-frame it as ‘pure form’. This subversion of the function of Whitehall’s monumental architecture aims to challenge the saturation of overlaid narratives that are endlessly echoed by the media.

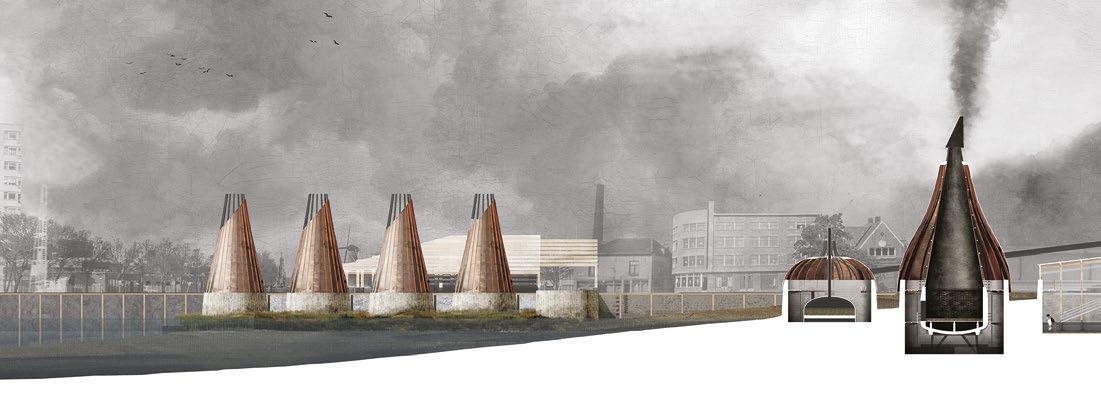

10.10–10.11 Thomas Roylance, Y3 ‘Van de Maas, Rotterdam’. A jenever distillery operates on a number of time-scales, from the finely tuned malting and distilling timetable to the centuries-old lineage of distillers on the Nieuwe Mass. This project challenges the notion of buildings as static. It promotes a vision of buildings as neverending continual processes, drawing them into a meaningful relationship with the locality.

10.17, 10.19 Evelyn Jesuraj, Y2 ‘Therapeutic Retreat from Cognitive Overload, Rainham Marshes, Thames Estuary’. Anxiety is seen as a new epidemic; in one study, one in five Londoners said that they had high anxiety. This project proposes a therapeutic retreat set within the salt marshes on London’s outskirts, and offers a space for release from cognitive overload. Veiled by reeds encrusted with salt drawn up from the marshes, screens shield the occupants within. The project acts as a commentary on the impact of disconnection from the natural world, offering proposals for temporary respite within delicate pavilions of reed and salt that step across a fragile landscape within sight of the city. Experimental salt drawings explore the agency of salt within the work.

10.18 Sarfaraz Salim, Y2 ‘Conservational Research Facility, Southwark, London’. This project engages with the territory of memory within the fast changing infrastructure of Southwark. A re-imagined 19th-century warehouse acts as a repository for artefacts found during ever-present construction works. These artefacts become the focus of curiosity and research, as archaeologists populate hanging repositories of uncovered fragments.

10.20 Noriyuki Ishii, Y3 ‘Nature as Privatised Space, Parliament Square, London’. An invisible field of laws controls behaviour and construction in Parliament Square, making occupation or interventions a virtual impossibility. This speculative proposal subverts regulations, in the form of a transformational structure offering seating, shelter, water and nighttime lighting, under the guise of a maintenance platform that protects damaged grass and restores it with water and light.

10.21 Amanda Dolga, Y3 ‘Another Brick in the Wall, Whitehall, London’. This project explores the concept of ‘hyper-surveillance’ by establishing and mapping means of security, tracking and online data collection. It creates a testing ground for a space that exists between the physical and the digital. The plan reveals the unseen eyes of CCTV cameras that follow our every step within Whitehall. The act of seeing, the boundary between public and private, is being partially obliterated. The digital reality (the Internet), and data collection and tracking, reverse the act of seeing to the act of being seen, questioning one’s privacy not only within the city but also within one’s own room.

Year 2

Sheryl Beh, Issariyaporn Chotitawan, Katarzyna Dabrowska, Maria De Salvador, Bengisu Demir, Benedict Edwards, Nanci Fairless Nicholson, Yiu Lee, Lucy Millichamp, Mimi Osei-Kuffuor, Sam Rix

Thank you to our partners: Grymsdyke Farm

Thank you to our consultants and critics: Monika Bilska, Boon Yik Chung, Sam Esses

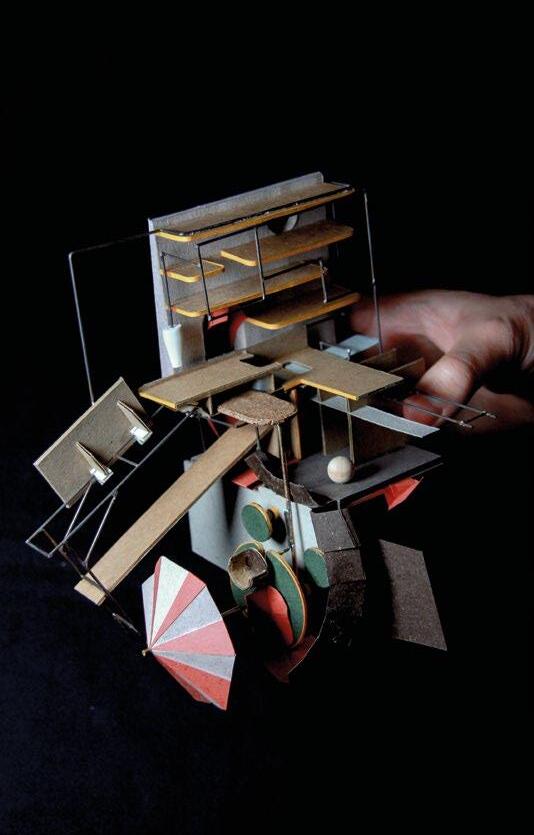

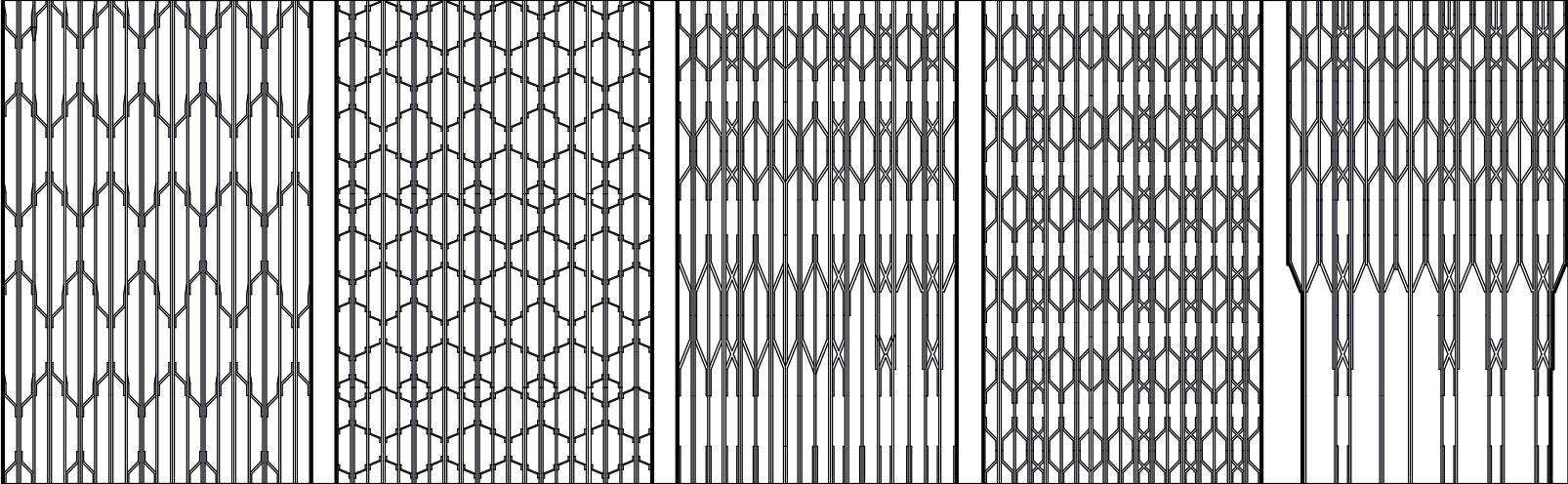

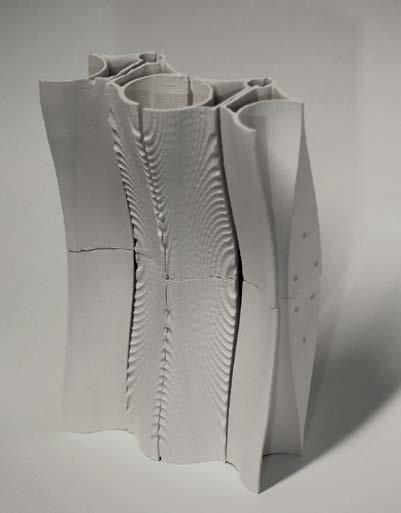

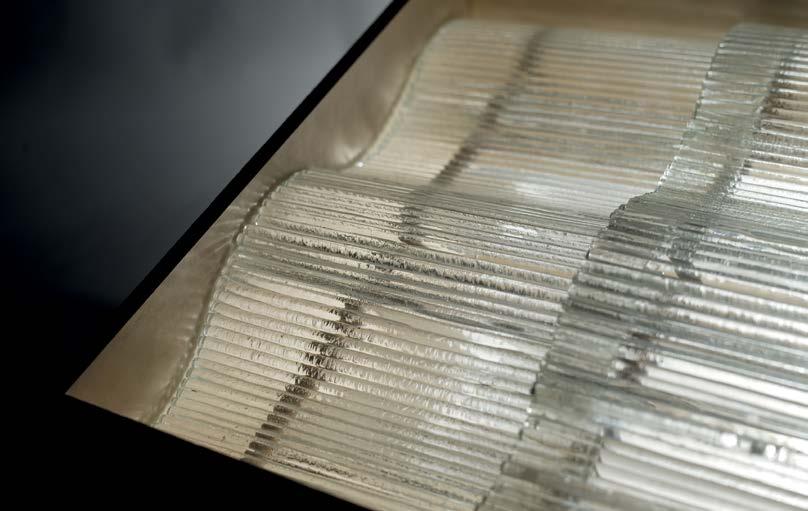

UG10’s interests are firmly set in the realm of buildings and architecture shaped by engagement with material tectonics. Every student engages hands-on with materials in an architectural design project. Our emphasis on making serves both as a vehicle for experimentation and as a theoretical framework for exploring ideas in design. Materiality is not an abstract condition but a tangible one. The unit’s interests lie not only on the surface but also at the core of construction. Our conversations surrounding materials – whether they are industrially manufactured or bespoke – typically go beyond their properties, and revolve around their cultural and social implications. Our design proposals critically examine material characteristics that are ‘least like nature and yet most natural’. This type of thinking around tectonics in architecture is inevitably tied to the processing and assembly of matter in its various states.

Athens was the site for deploying these interests – a city that is characterised by great conflicts generated by years of unregulated urban development and augmented by the current financial crisis. On a material level, the life of the city is driven by architectural artefacts: built, used, being replaced or in the pipeline. In effect, the cohesion and dynamism of its neighbourhoods are often intimately linked to the ‘yet to be’ and the ‘no longer there’. Its urban infrastructures are, as a result, constantly in flux.

Responding to all this, we used recursive making explorations and drawing studies to generate unique urban, architectural, and most importantly material proposals that address the various problems and conflicts currently latent in this contemporary metropolis in crisis.

Our aim, in effect, was to become urban acupuncturists, strategically placing our proposals in unique and conflicting contexts and attempting to reconcile diverging and overlapping infrastructural, cultural, spatial and social parameters.

At a material and tectonic level, our projects aimed to provide continuity and resonance at different scales. This ecology of construction demanded us to ‘work with’ and not ‘work on’ the context. Focusing on notions of fabrication, we endeavoured not to produce buildings devoid of context, but to use the environment itself as means of intervention.

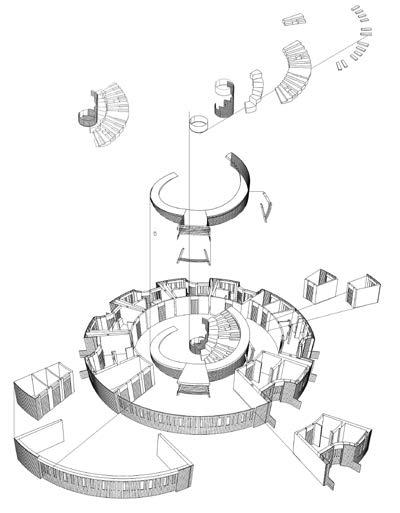

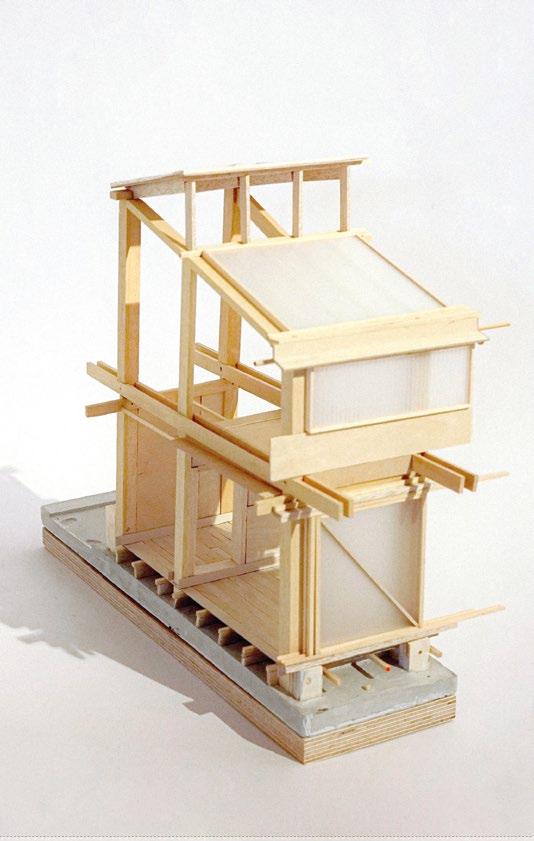

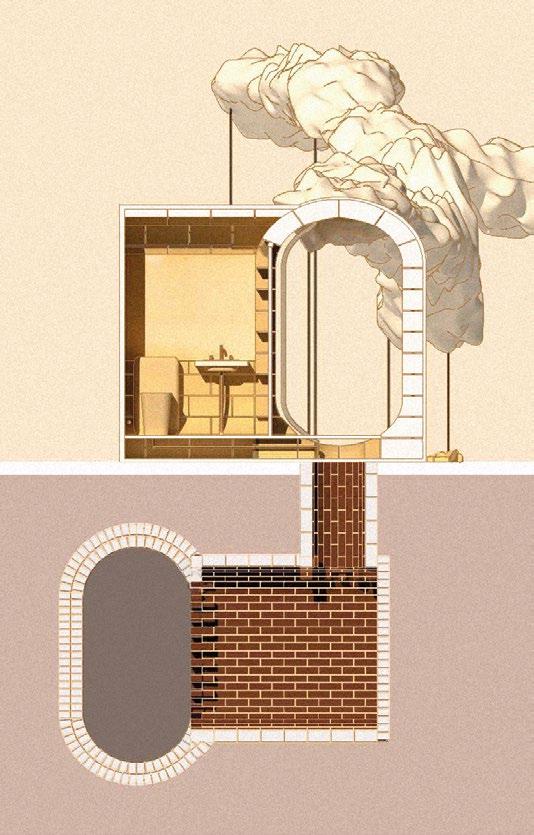

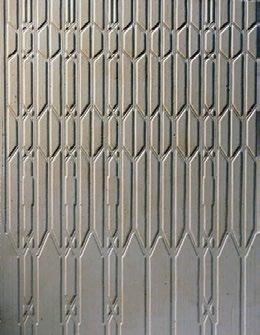

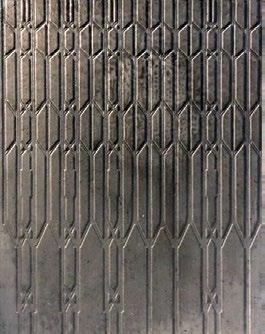

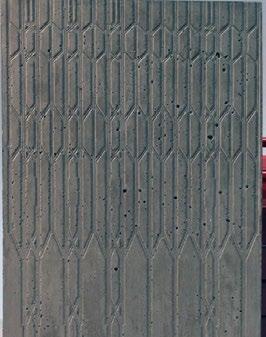

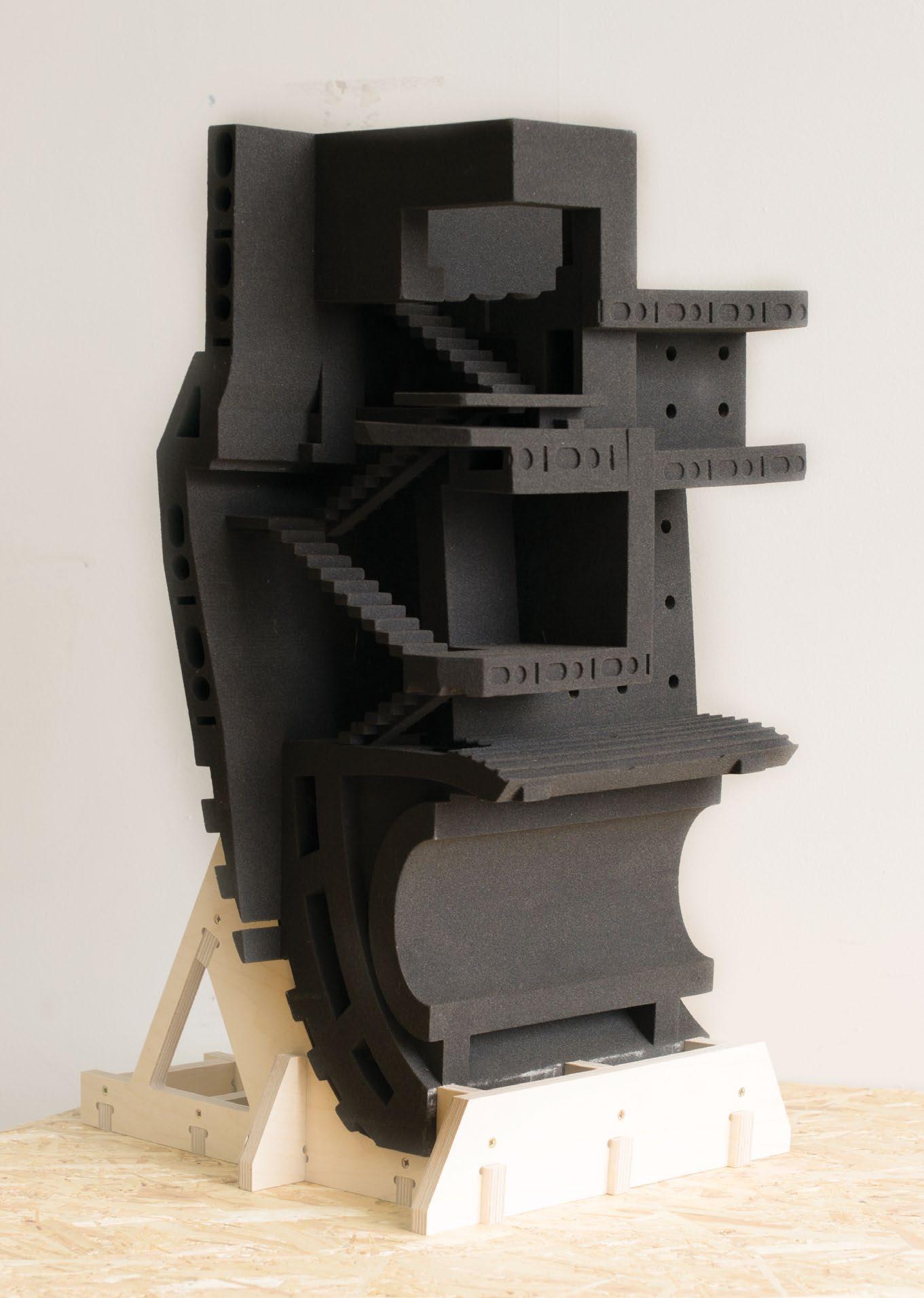

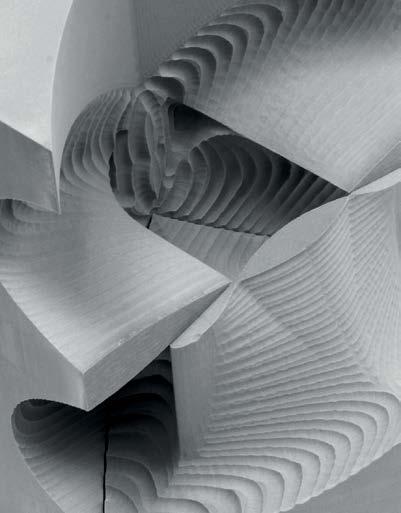

Figs. 10.0 – 10.1 Katarzyna Dabrowska Y2, ‘The Piraeus Bathhouse’. Structure model and bird’s eye view render. The project presents itself as an opportunity to rethink and reintroduce the public bathhouse in the contemporary city. The role that bathing plays within a culture reveals its attitude towards human relaxation. It is a measure of the degree that individual wellbeing is regarded an indispensable part of community life. The intent here is for the urban public bathhouse to become more than a place for bathing, in effect initiating new social dynamics, and new public and communal behaviours. Fig. 10.2 Katarzyna Dabrowska Y2, ‘The Piraeus Bathhouse’. Façade water channel drawings. Sculpted façade panels allow water to travel through not only the bathhouse areas, but also the surfaces that define the various spaces.

Fig. 10.3 Issariyaporn Chotitawan Y2, ‘Honey Production Facility and Process Museum’. The building consists of a series of connected gardens that maximise the spaces for bee pollination and allow the organisation of the various other production and public programmes around them. The beehives themselves are organised strategically to maximise the natural and undisrupted environment for each bee colony, as well as to distribute honey production evenly throughout the building. Public educational areas are dedicated for people to walk around and experience glimpses of the production processes and to educate the public about honey production. Fig. 10.4 Nanci Fairless Nicholson Y2, ‘The Colour Museum’. The intention of this project for a Colour Museum is to augment the experience of colour through light and form. The main aim is to convert its

various spaces that are painted in different colours used in antiquity or are designed to form immersive installations to experience the environmental colours of Athens, into full-scale exhibits themselves.

Fig. 10.5 Issariyaporn Chotitawan Y2, ‘Street Essential Oils’. On the streets of Athens there is an abundance of bitter orange trees. Too bitter to be consumed by people in the city, they are left to grow and decay. To make use of this asset, the building explores the production of essential oil extracts from these citrus fruits, as well as Neroli blossoms, to generate economic value in a city that has not yet recovered from the devastation of the recent financial crisis. Fig. 10.6 Sheryl Beh Y2, ‘Ethnic Retail and Hotel’. A place for the ethnic groups in the centre of Athens to mingle, trade and rest. The retail and hotel spaces are organised around a central atrium/energy core that generates the appropriate environmental conditions for the various areas of the building through passive cooling and heating. This system enables the vertical retail spaces to

have the atmosphere of local outdoor markets, with a series of communal gardens acting as semi-outdoor spaces for interaction between the traders, and the hotel guests.

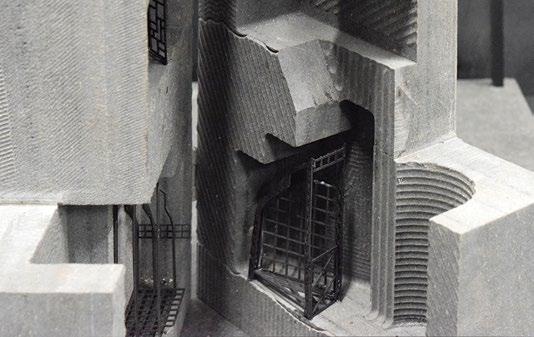

Figs. 10.7 – 10.8 Maria De Salvador Y2, ‘Recycling and Creating in Athens’. Physical model and process design study. The project consists of temporary housing for rotating workers, as well as a place where various restaurants and shops around the area of Psyrri in Athens can bring their plastic waste in order to recycle it, repurpose it and make it useful again for other industries. Byproducts of the process get converted into 3D-printed tectonic building elements, while the programme of the building is also reflected in its aesthetic of exposed services and expressive structural organisation.

Fig. 10.9 Maria De Salvador Y2, ‘Recycling and Creating in Athens’. Recycled plastic wall study. Fig. 10.10 Yiu Lee Y2, ‘Urban Monastery’. The project is a place for apprentice monks to learn the techniques of traditional Orthodox wood carving, as well as to provide accommodation for them. The design objective is for the building itself to become part of the educational experience, an aim which is manifested in the so called ‘didactic’ core, placed in the centre of the project and made entirely out of wood that can be carved openly by the apprentices exposing the process to the rest of the building’s inhabitants. Fig. 10.11 Bengisu Demir Y2, ‘Care Home and Animal Shelter’. The building houses domestic animals that have been abandoned due to the financial crisis in Athens. In addition, it accommodates elderly people who can no longer

be housed in state institutions due to the collapse of the welfare state. The design seeks to accommodate both in a threedimensionally arranged network of continuously connected spaces, facilitating the mutually beneficial engagement of human and animal life. Fig. 10.12 Benedict Edwards Y2, ‘Exarcheia Rehabilitation Centre’. The project is a temporary response to the public drug epidemic in Exarcheia, Athens, in the form of various harm reduction services. The neighbourhood offers opportunities due to its self-imposed anarchist culture that the government cannot, providing services that probe the barrier into illegality, such as a supervised injection facility and research chemical shop. The design itself plays with illegality, moulded by the idea of concealment. The other part of the project comprises a rehabilitation centre designed with an

emphasis on the environmental psychology of healing and utilising the benefits of nature by drawing the adjacent park into the design. Fig. 10.13 Yiu Lee Y2, ‘Urban Monastery’. SLS print of the ‘didactic’ core of the building. Fig. 10.14 Issariyaporn Chotitawan Y2, ‘Street Essential Oils’. Process photographs showing the making of the 1:1 concrete detail of the topologically optimised structure. Fig. 10.15 Yiu Lee Y2, ‘Urban Monastery’. CNC wood detail showing the various stages of the wood carving learning process. Fig. 10.16 Katarzyna Dabrowska Y2, ‘The Piraeus Bathhouse’. A series of prototypes built in concrete, plaster, and plaster mixed with mortar to test out the hydrophobic properties of each material.

Fig. 10.17 Bengisu Demir Y2, ‘Care Home and Animal Shelter’. Physical model. Fig. 10.18 Katarzyna Dabrowska Y2, ‘Votanikos

Inhabitable Flood Barrier’. A series of curved barriers redirect the excess river water generated during the frequent flash floods in the area into a three-dimensionally organised system of pools. The water then goes through filtration cycles, eventually being used for cooling in the hot summer season, as well as in communal pools that are shared by the housing community living above and within this aquatic landscape. Fig. 10.19 Benedict Edwards Y2, ‘Exarcheia Rehabilitation Centre’. Bird’s eye view of the project showing its integration into the adjacent residential and institutional context.

Fig. 10.20 Lucy Millichamp Y2, ‘Public Vehicle Market’. The proposal resolves a congested, high density car park through the hybrid combination of the parking of vehicles with the selling of produce in a market-type setting, as well as providing units of temporary accommodation. The journey which market-sellers make into the centre of Athens, at various times throughout each week, forces these individuals to seek a place to park their vehicle, a place to sell their produce and a place to stay overnight. For each seller, the opportunity to sell their produce from their own vehicle in an internally controlled environment could have great advantages. This architectural proposal is a space in which all three conditions can occur.

Year 2

Poppy Becke, George Brazier, Young To (Toby) Chan, Camille Dunlop, Linggezi (Yuki) Man, John Mathers, Anna O’Leary, Edward Taft

Year 3

Nour Al Ahmad, Yin Zara Chen, Wai Nam (Tiffany) Chong, Hanadi Izzuddin, Holy Moore, Ke Yang

Thank you to our guest critics: Robert Aish, Alisa Andrasek, Francis Archer, Anthony Boulanger, Andy Edge, Michael Hadi, Colin Herperger, Steve Johnson, Constance Lau, Mike Lim, Thomas Pearce, Stuart Piercy, James Pockson, Mike Tonkin, Mario Tsiliakos, Ben Sweeting, Toby Burgess

Special thanks to: Riyad Joucka (SHoP Architects), Dewitt Godfrey, Gustav Fagerström (Walter P Moore), Michael DiCarlo (Associated Fabrication)

Thank you to: Mike Lim and James Pockson (drawing workshop), Pamela Casey and Ralph Ghoche (archive visit at Avery, Columbia University), Paul Jeffries (technical tutor)

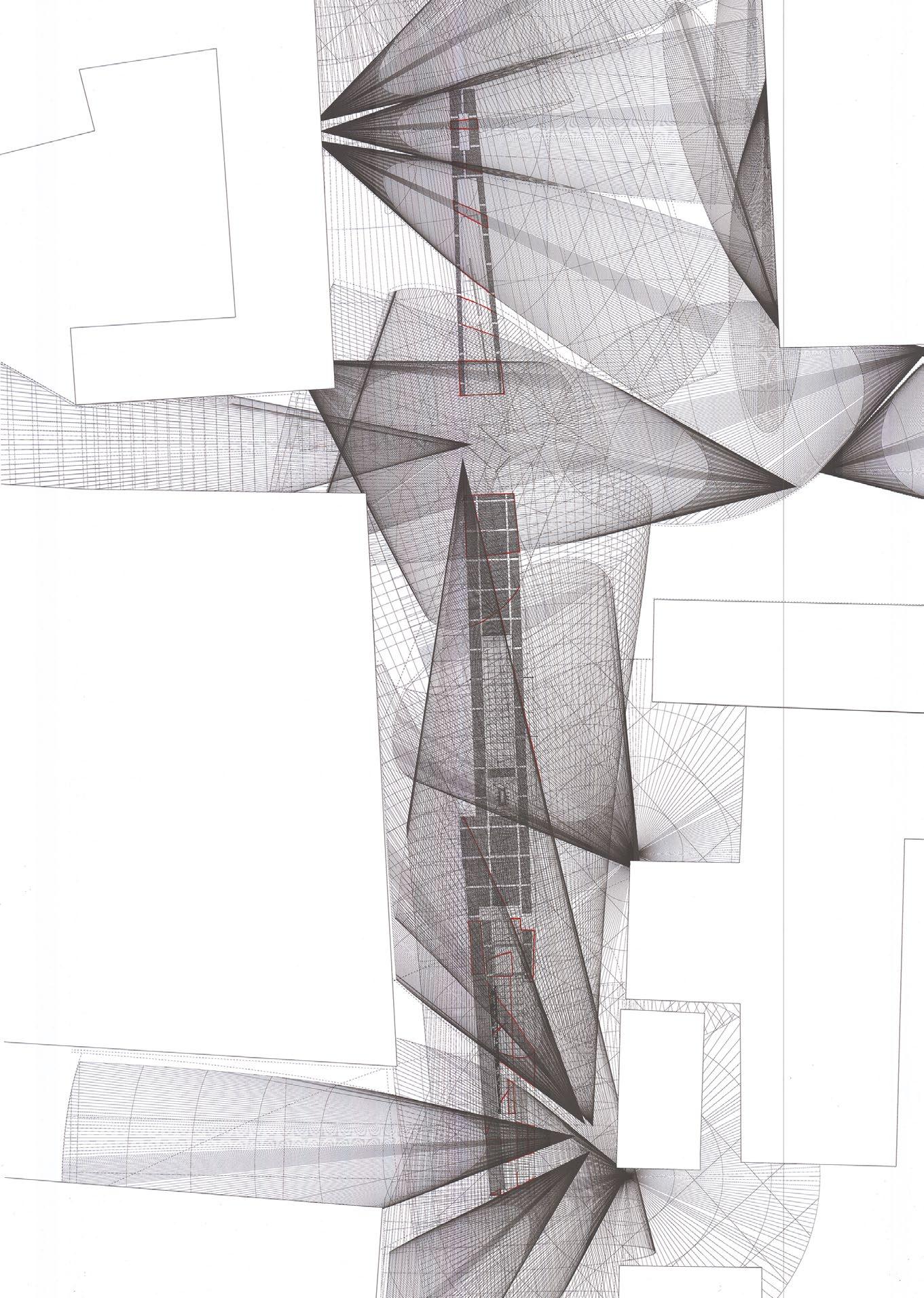

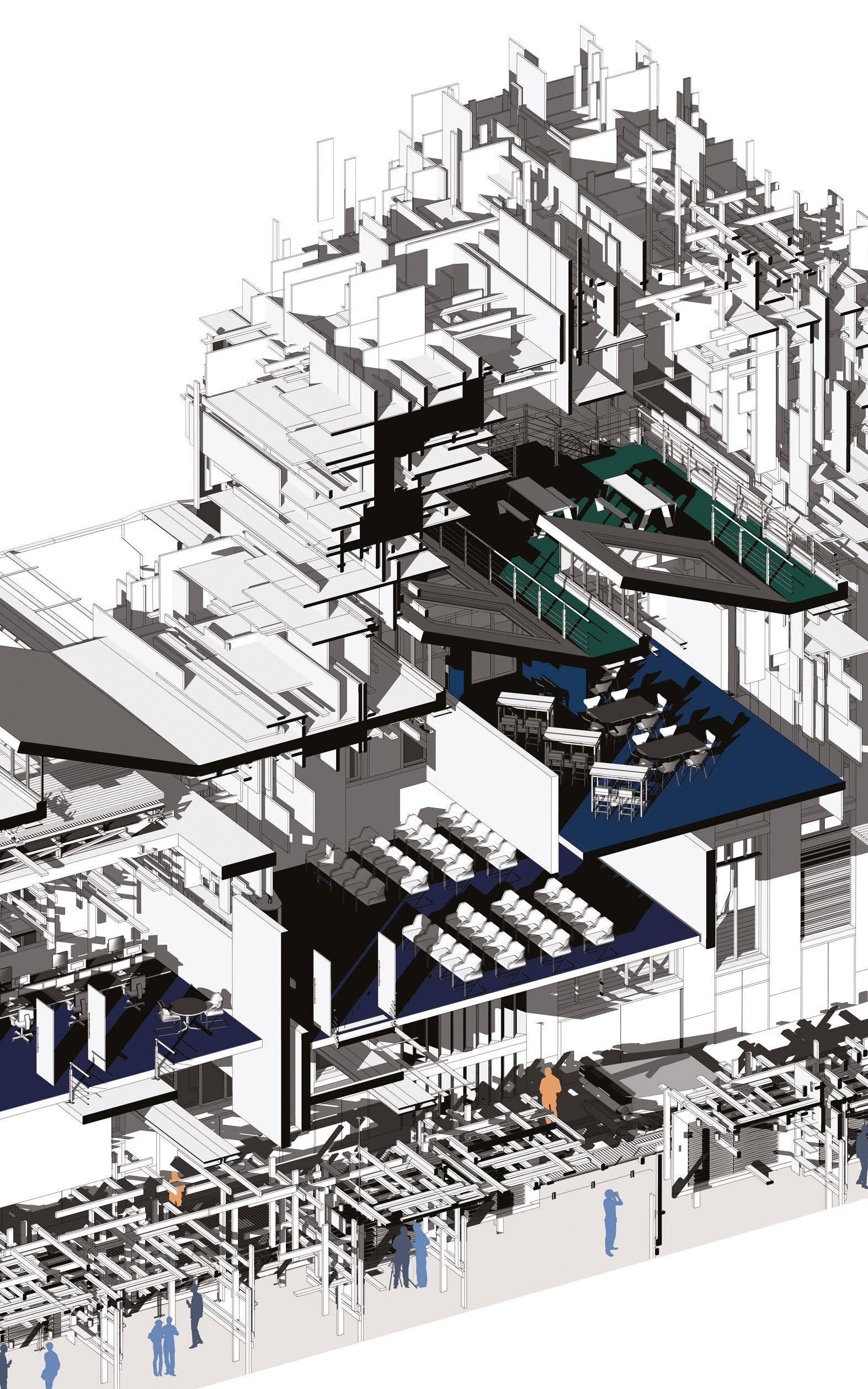

The ‘Maker Movement’ is enabling young designers to learn how to collaborate with other designers and work with machines directly to materialise their ideas. Open-source and parametric online platforms are accelerating this process, turning each contributor into an active node of a much larger and ever-growing system. Design, engineering and fabrication processes are merging, giving birth to a new kind of digital polymath role which replaces the different related professions. Creative studios, minifactories and open workshops, dotted around the London boroughs of Tower Hamlets and Hackney, form an energetic and dynamic part of East London, an area of London declared by Time Out as the ‘maker’s new breeding ground’. More than one year on, a lot has happened, but most importantly in this context the UK has voted to leave the European Union. The question of how London’s local economies can adapt has emerged as a critical issue.

Students started the year by considering ‘What is parametric design?’ They proposed a small architectural intervention based on simple digital scripts and material constraints. Methods of design moved between digital intentions and physical modelling in order to test the nature of materials alongside computational logic. The building projects that followed ask the same question at a larger scale, with the added challenge of programmatic considerations. Some students gravitated towards the design of construction systems, while others focused on the potential of formal possibilities. Questions were raised about the economic future of small craft-based practices in the East London area and how a community can work more collaboratively. This changing landscape of small industries has provided inspiration for students to rethink how we design and make.

With the rise of digital fabrication technology, architecture is evolving into an ecosystem of codes. These codes can be interlinked to inform each other through the use of structural and environmental simulation as well as material behaviour. Similar to the empirical process that was key to the evolution of cathedrals, the design of building components can optimise itself via an accelerated digital process. If buildings become self-optimising codes and cranes become 3D printers, what will be the role of the client, architect, engineers, quantity surveyors, project managers and the contractor in the near future? Which vital forces will drive and infuse the humanless codes? In relation to questions of aesthetic and tradition, will these forces be naturally implicit within the systems?

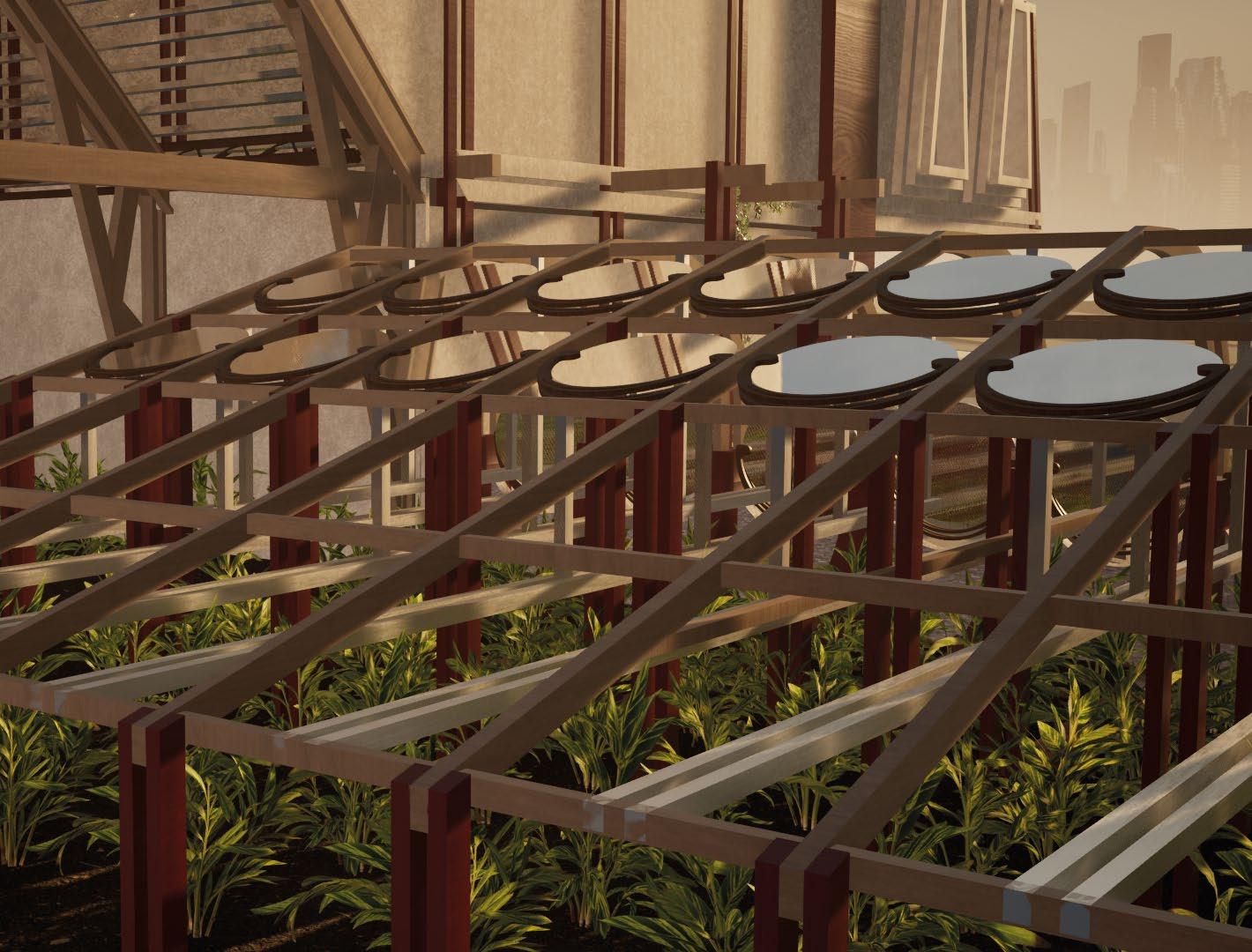

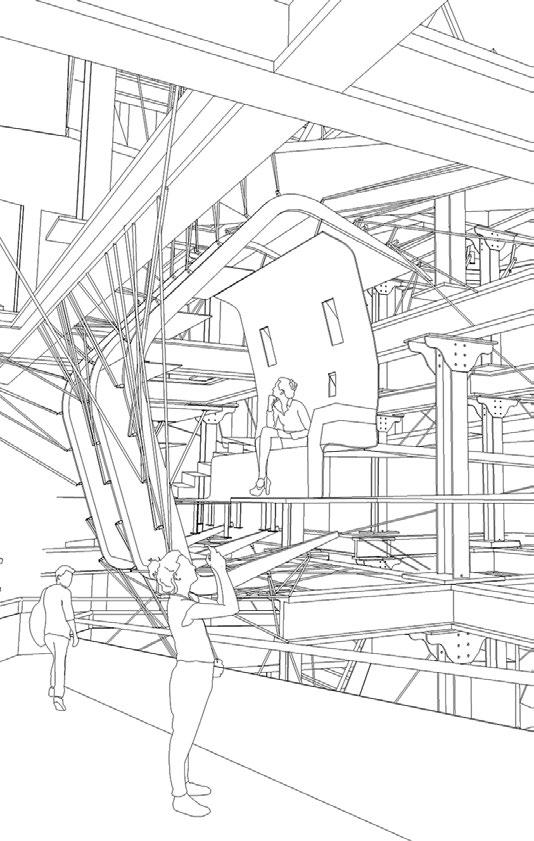

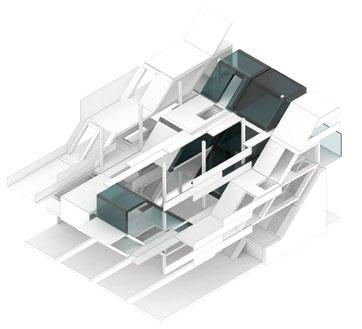

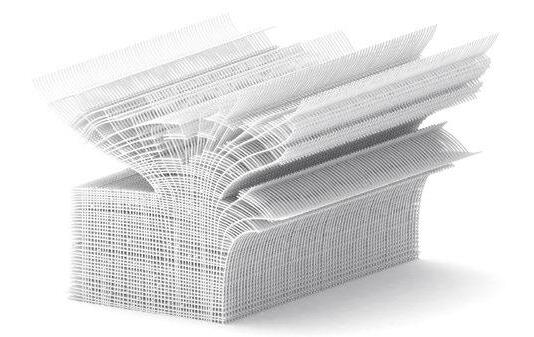

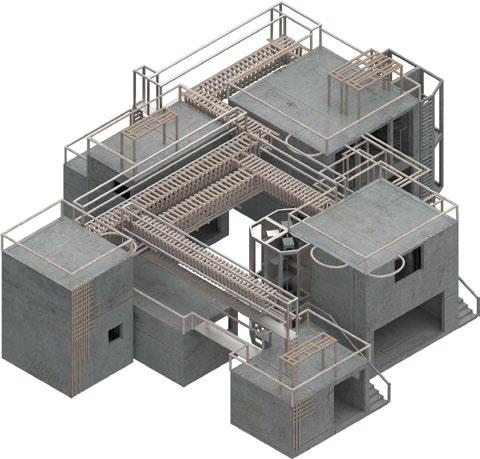

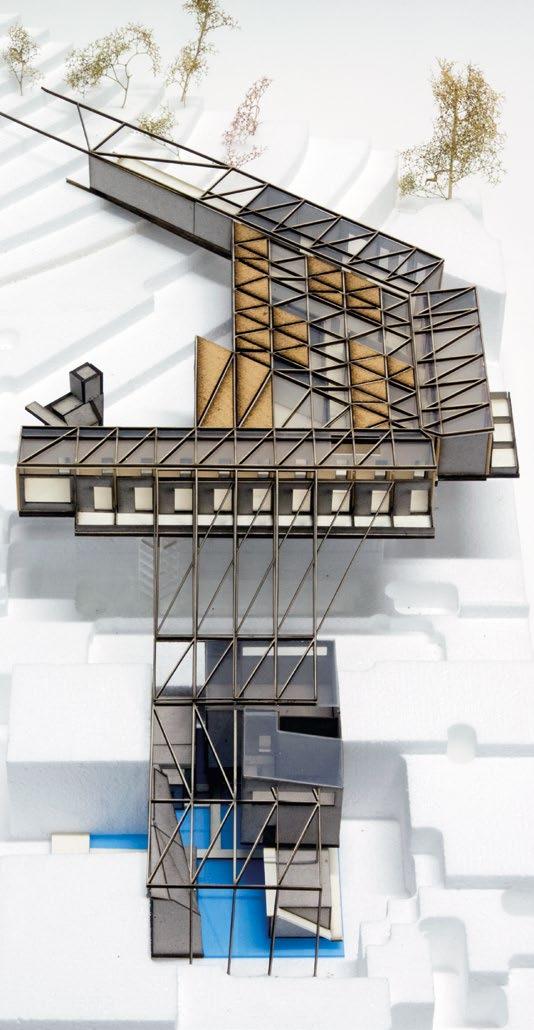

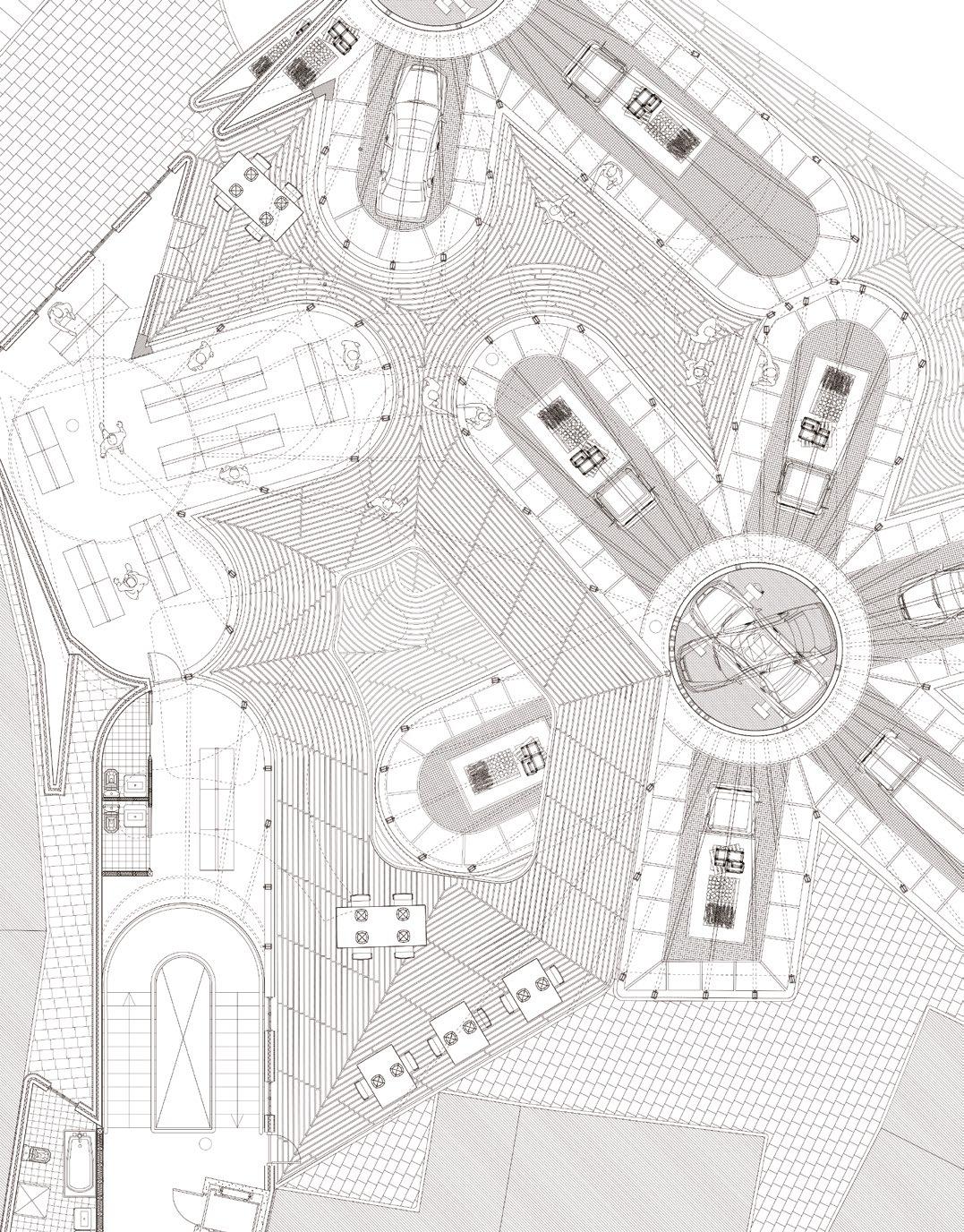

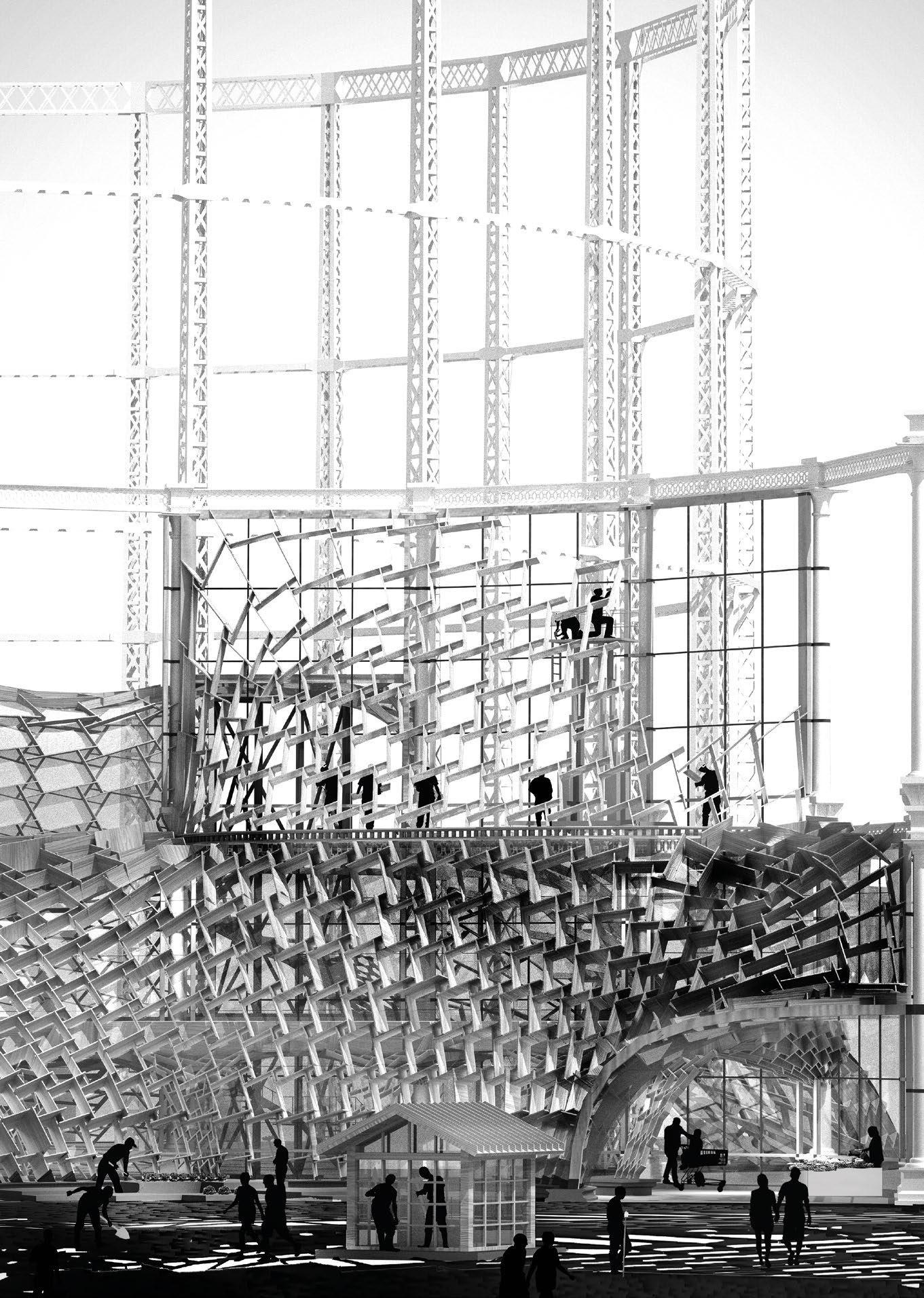

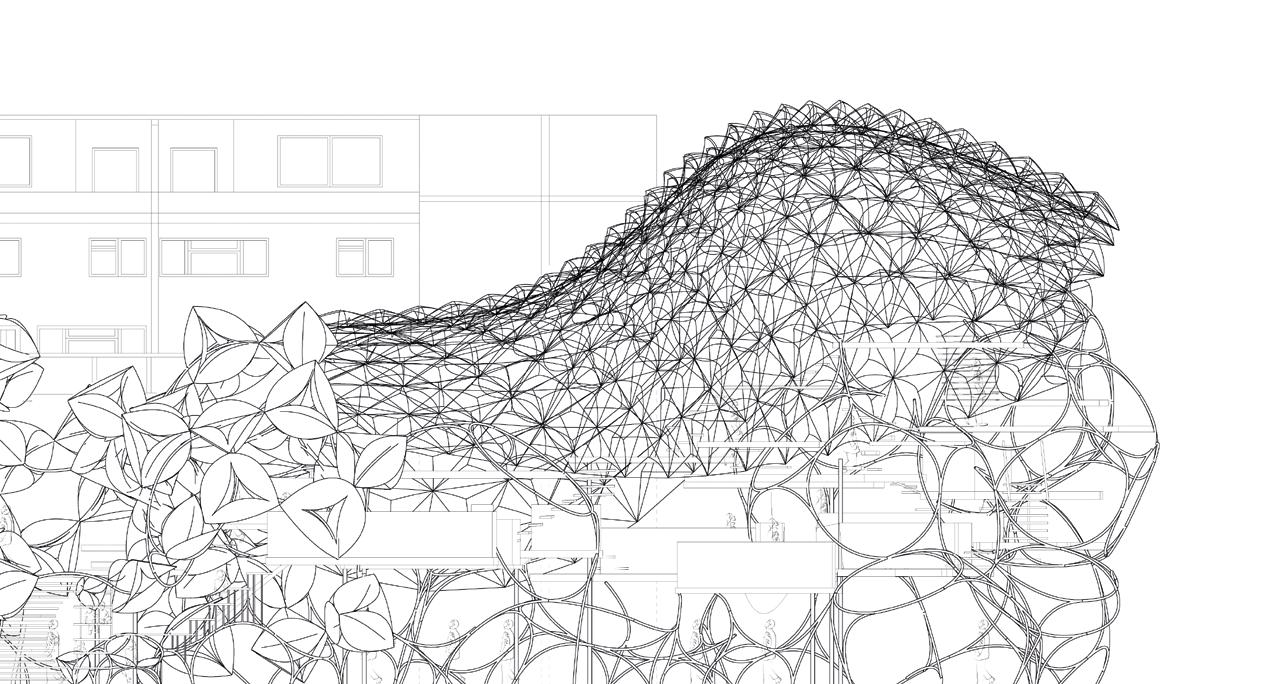

Fig. 10.1 Ke Yang Y3, ‘(re)Store’. This is a project about humanising parametric architecture. It is a series of selfbuild timber structures that create an urban agricultural landscape. The aim is to create a structure that can resonate with the existing Victorian gas-holders while restoring the contaminated site. Fig. 10.2 Hanadi Izzuddin Y3, ‘Through The Roof’. This is a project using gridshell morphologies to unite ‘makers’ on Vyner Street in Hackney across its existing flat roofscape. This project envisions cheap, lightweight, deployable structures to create a school of making as a rooftop extension to the street’s existing maker spaces. Various kerf-cut incisions on a triangular lattice hinge component investigate how a two-dimensional pattern can modulate three-dimensional space both structurally and

environmentally – in other words, how it can become a functional ornament. Fig. 10.3 Linggezi (Yuki) Man Y2, ‘Hackney Hydros’. A learning and communication centre with indoor greenhouses and leisure spaces for visitors to participate in the processes of growing vegetables, idea sharing and enjoying their produce as a community.

Fig. 10.4 Wai Nam (Tiffany) Chong Y3, ‘Institute of Process’. A museum where local artists in Hackney Wick use the principle of Process Art to respond to the pollution of the River Lea, which has arisen due to the area’s over-development. The project focuses on the materiality of plaster and its ability to translate pollution into art. Fig. 10.5 Anna O’Leary Y2, ‘Disruptive Innovation: A Contemporary Workspace’. This project explores disruptive innovation and how this can be encouraged in a workspace. The building encourages disruption through maximum interconnectivity: it connects to local creative companies in the Oval through a series of walkways, which allows unexpected interactions and communications to occur. Within the building, there are unconventional suspended spaces, both static and moveable, in which these unexpected

and creative interactions can take place. Figs. 10.6 – 10.7 Holly Moore Y3, ‘Museum of Making’. A museum of making that questions how art is made and how it is displayed by proposing ordered maker spaces and disordered exhibition spaces that challenge convention. A 1:50 model was made using CNC machining techniques to explore the creation of two contrasting spaces using digital form-finding tools and traditional tile-vaulting as a method of construction. Combining maker spaces with exhibition spaces, this created a building that celebrates the entire making process from concept to completion.

Figs. 10.8 – 10.9 Camille Dunlop Y2, ‘Progressive Extraction and Corruption of the Traditional: a Contemporary Dance Centre’. This series of renders travels through spaces that are progressively corrupted as dance studios. This is a sectional render of the vertical progression in corrupted dance studios. Fig. 10.10 Yung To (Toby) Chan Y2, ‘London Tube Playground’. The project refurbishes Bow Road Underground Station by replacing the existing roof structure with a playground to serve the family-based communities of Bow. The playground features pockets of intensities which borrow from the rules and strategies in the game ‘Hide and Seek’. The project celebrates the act of waiting, and questions accessibility and visibility in public space.

Figs. 10.11 – Fig. 10.12 George Brazier Y2, ‘Hackney Wick YMCA: Harmonising Religion with Mind, Body and Spirit’. This project proposes a faith-led community YMCA, combining physical fitness, spirituality and accommodation. Its aim is to illuminate a polluted void in Hackney, located under the A12. Fig. 10.13 Edward Taft Y2, ‘CLT Futures’. This project uses algorithmic systems to explore the capabilities of CLT and give expressive form to a typically uniform construction material. This sectional drawing shows a mixed programme factory and innovation centre within an algorithmically generated structure.

Year 2

Nur (Sabrina) Azman, Sam Grice, Clementine Holden, Carmen Kong, Shi Yin Ling, Elissavet Manou, Gabriel Pavlides, Sam Price, Sam Rix

Year 3

Bingqing (Angelica) Chen, Hoi Man (Christy) Cheung, Romario (Yik Yu) Lai, Dunkaew (Pink) Protpagorn, Sheua Wei (Amanda) Tam, Xinyue (Angel) Yao, Michelle Yiu

Thanks to Joshua Scott (Technical Tutor), Callum Perry (Digital Fabrication) Igor Pantic (Digital Modelling) and Jessie Lee (Ceramic and Glass)

Thanks also to our guest critics: Alice Brownfield, Mollie Claypool, Matthew Butcher, Kate Darby, Holly Galbraith, Colin Herperger, Christine Hawley, Jonathan Hill, Nic Moore, Igor Pantic, Callum Perry, Stuart Piercy, Michael Ramage, Bob Sheil, Victoria Watson, Peter Webb, Ivana Wingham, Paolo Zaide

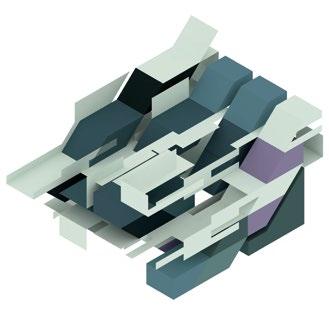

UG10 is interested both in making things and the environments in which they are made. Students have worked to make and think simultaneously at the scale of the tool and the scale of the landscape, to study the methods and materials from which architecture is produced and how these can be drawn from, and continue to respond to, a place.

The unit considered the idea of a conserved wilderness, questioning whether continuing to focus upon preserving islands of Holocene ecosystems in this Anthropocene age is anachronistic and counterproductive. Human infrastructure and cultural context are changing as fast as their natural counterparts and allowing them to evolve in parallel is critical to the sustainable future of development. In Hawaii, the accelerated condition of dynamism allowed students to question whether it may be possible to be optimistic about the impact that we can have, by using an understanding of context to propose a positive way to engage with place.

The unit travelled to the Big Island of Hawaii, a landscape of extreme and constant change. Lava flows perpetually alter and evolve the topography through volcanic activity bubbling just below the surface. Communities must adapt to living on the edge of destruction, and space is compromised by the protection of large pieces of the island for international conservation.

Students started the year by considering ‘on what basis do we begin to build?’. They proposed a vessel based on a research agenda and a material practice that they took from sites around Hawaii in order to propose a new type of architecture that responded to both physical and contextual landscapes of violent change. Methods of construction moved between digital intentions and physical modelling to test the nature of materials alongside the computational generic.

These ideas were developed through building projects that considered the issue of material use in a place that has to ship all of its construction materials at least half way across the Pacific. Some tried to find a new material language of extraction or harvest, working directly to propose landscapes of timber, and extractive methodologies of volcanic mud and lava rock. Others considered the island’s aggressive military history and the ongoing fight for independence after the highly ambiguous annexation to America in 1893. Questions were raised about the economic future and land ownership on an island where, day by day, the sea reclaims territory built on a soft and sandy bedrock of volcanic activity.

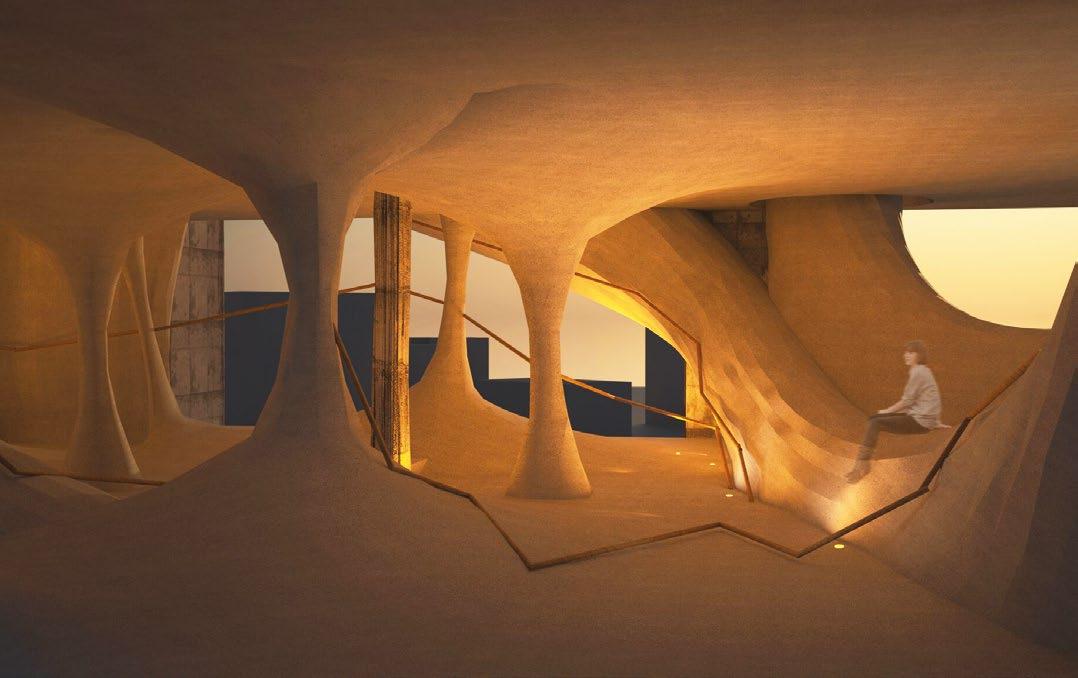

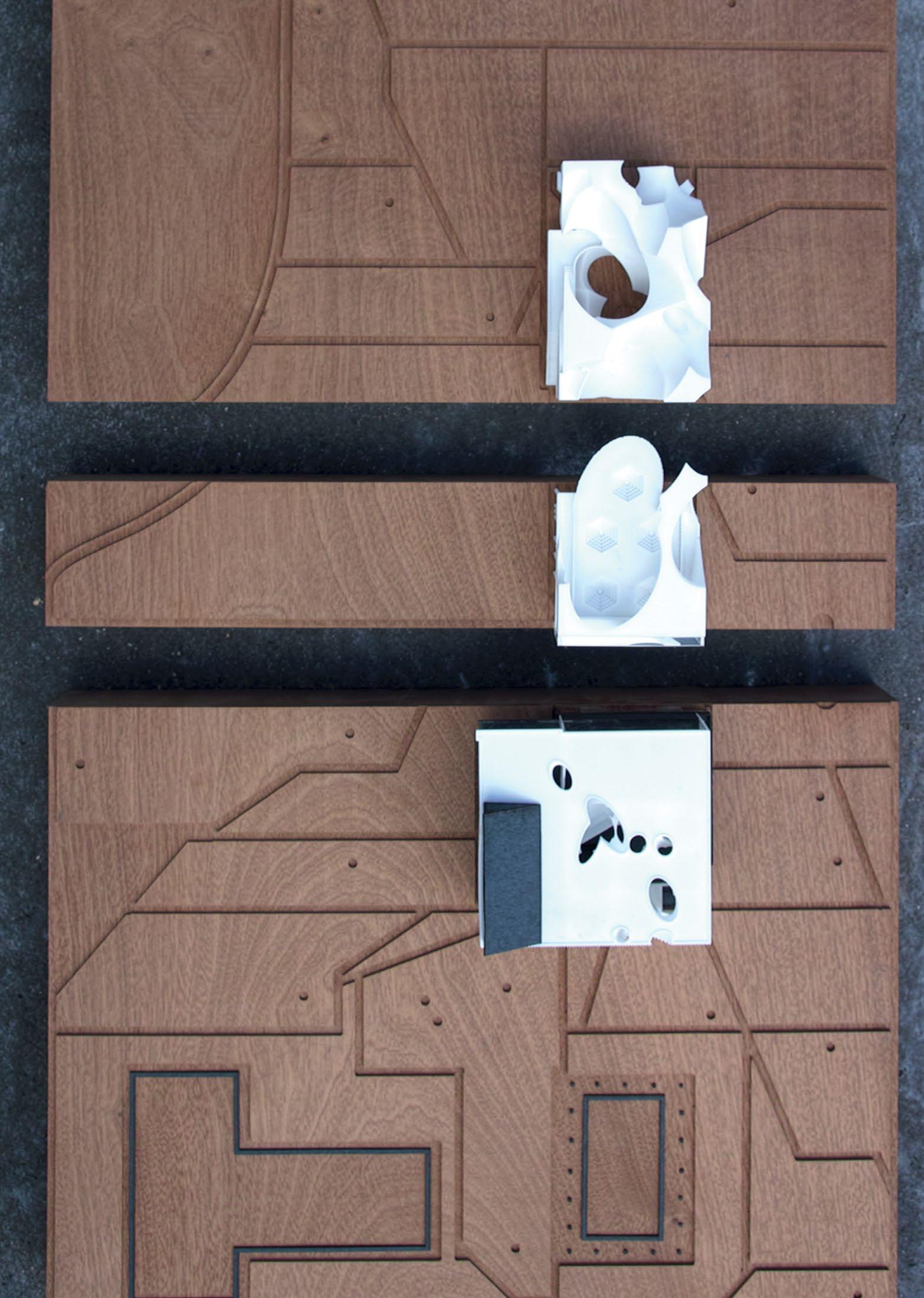

Fig. 10.1 Michelle Yiu Y3, ‘Palette Under The Sun’. Earth buildings at Kakkako waterfront park. Honolulu has a distinct diversity in soil types due to volcanic activity. This offers a palette of materials that could reduce Hawaii’s dependency on imported construction material. The mud drawing in this photograph shows the buildings using different construction techniques and soil types from Hawaii to create new textures as landscape and architecture. The building looked to use the distinct qualities of these techniques to propose crossover spaces for a multi-programme educational facility. Figs. 10.2 – 10.4 Yik Yu (Romario) Lai Y3, ‘Figure Of Voices’. Native Hawaiians have been fighting for their rights since its annexation in the 1890s. Situated in Honolulu, the architecture of carved void/hollowed solid acts as a neutral space for

native Hawaiian, all unrepresented nations and people to establish dialogues with the UN. The quality of space is also investigated through 1:1 cast concrete building fragment. The waste mould is made of polystyrene and the cast is made with high strength, low shrinkage flow concrete. The 1:200 final building model is combination of 3D-printed parts and laser cut paper, while the hardwood base is CNC machined.

Fig. 10.5 YikYu (Romario) Lai Y3, ‘Figure Of Voices’. Fragment of building proposal cast in concrete. Figs. 10.6 –10.7 Shi Yin Ling Y2, ‘The Bill’. A building to host festivities and competitions during the game fishing season. Sited in a poorly maintained but densely occupied harbour, the building tests combinations of materials to register change and ageing.

Fig. 10.8 Sheua Wei (Amanda) Tam Y3, ‘Against The Flow’. Kalapana Community Centre. Sited on the most active lava field on Hawaii’s Big Island, the building supports the reclusive community that build their homes in this extreme landscape. Studies tested the thermal capacities of materials to propose a refuge robust enough provide shelter during a future flow. Inspired by Dolosse, this fragment of a column was developed through large-scale CNC punched prototypes at 1:5 and 1:3.

Fig. 10.9 Bingqing (Angelica) Chen Y3, ‘Super Spring’. A deep sea water research centre and restaurant in Honolulu. Borrowing from the technology used to pump cold, nutrientrich deep sea water to power air conditioning in surrounding office blocks, the project looks for alternative uses for this resource. Fig. 10.10 Carmen Kong Y2, ‘Sunset to Sunrise’. CNC milled pigmented plaster cast with soft brick aggregates.

Fig. 10.11 Carmen Kong Y2, ‘Sunset to Sunrise’. A nocturnal building for amateur astronomers sited mid-way up Mauna Kea. The site is charged with conflict between a global scientific community and the significance of the dormant volcano as a culturally sacred place. The design uses channels of moonlight and shifts in ground level to guide users through the architecture in the dark. Fig. 10.12 Samuel Grice Y2, ‘Wayfinding’. A walker’s retreat and rescue centre for explorers lost on the black, scale-less lava fields of Kalapana. The architecture explores stereotomy as a way of using local lava stone as a structural material. Model, showing the proposal as part of a landscape of cut lava, 1:200. Fig. 10.13 Sam Price Y2, ‘Excavating The Erased’. Considering the additive erasure of Kalapana, as layers of lava repeatedly covers land which is