Design Anthology UG2

Architecture BSc (ARB/RIBA Part 1)

Compiled from Bartlett Summer Show Books

Architecture BSc (ARB/RIBA Part 1)

Compiled from Bartlett Summer Show Books

At The Bartlett School of Architecture, we have been publishing annual exhibition catalogues for each of our design-based programmes for more than a decade. These catalogues, amounting to thousands of pages, illustrate the best of our students’ extraordinary work. Our Design Anthology series brings together the annual catalogue pages for each of our renowned units, clusters, and labs, to give an overview of how their practice and research has evolved.

Throughout this time some teaching partnerships have remained constant, others have changed. Students have also progressed from one programme to another. Nevertheless, the way in which design is taught and explored at The Bartlett School of Architecture is in our DNA. Now with almost 50 units, clusters and labs in the school across our programmes, the Design Anthology series shows how we define, progress and reinvent our agendas and themes from year to year.

2024 Radical Repair: Designing Through Self-Build Practices

Zachary Fluker, Jhono Bennett, Hannah Corlett

2023 1:1 Systems of Exchange

Jhono Bennett, Zach Fluker

2022 Eco-Promethean

Maria Knutsson-Hall, Barry Wark

2021 Natural State

Maria Knutsson-Hall, Barry Wark

2020 Between the Object and the Picturesque

Barry Wark, Maria Knutsson-Hall with Levent Ozruh

2019 Urban Cliff

Maria Knutsson-Hall, Barry Wark

2018 High Density

Soomeen Hahm, Aleksandrina Rizova

2017 Spontaneous Procedures

Soomeen Hahm, Aleksandrina Rizova

2016 Sprezzatura

Damjan Iliev, Javier Ruiz

2015 SimbioCity

Damjan Iliev, Julian Krueger

2014 Interstitial Ecologies

Damjan Iliev, Julian Krueger

2013 Newtopia

Damjan Iliev, Julian Krueger

2012 Gimme Shelter

Damjan Iliev, Julian Krueger

2011 Infill and Overspill

Ben Addy, Julian Krueger

2010 Twist and Insert, Add and Alter

Ben Addy, Julian Krueger

2009 Urban Sting

Julia Backhaus, William Firebrace, Julian Krueger

2008 Urban Flip

William Firebrace, Julian Krueger

2007 Urban Blending

William Firebrace, Julian Krueger

2006 Isolated and Insulated Landscapes

Agnieszka Glowacka, Sabine Storp

2005 Tales of Two Moods

Felicity Atekpe, Karl Unglaub

2004 Icon

Felicity Atekpe, Karl Unglaub

Zachary Fluker, Jhono Bennett, Hannah Corlett

Our rapidly urbanising world will require more material resources than are currently available in our planet’s already fragile ecosystem. Driven by this need to reconsider resource use in line with pressing environmental, social and economic considerations, built environment practice is on a path towards radical change in how we produce and, more importantly, repair and maintain our built fabric.

This shift in how we make requires more inventive means of material reuse, existing building reconfiguration and a critical rethink on how we work together as spatial practitioners. UG2 embraces this dynamic challenge and works to develop architectural interventions that respond to the contextually nuanced needs of the people and the communities who make up our cities. From user-centric built-in furniture to high-level spatial strategies, the unit’s projects explore the potential for how repair could empower and support new relationships between individuals and the city.

On-site research and first-hand experience on how acts of repair have shaped and impacted architecture and the city were gathered during the unit trip to Berlin. While there, we visited the reconfigured Neues Museum, Neue Nationalgalerie and the retrofitted Tempelhof Airport. Back in London, the unit explored the district of Limehouse where a dense urban environment in the former docklands provided fragments of latent land and defunct infrastructure. Unravelling the potential of these sites through careful analysis and documentation has led to proposals that integrate multiple layers of natural and built infrastructures. By adopting a critical position on repair, each project identifies how actions of re-cycling, re-configuration and re-use can drastically re-shape the spatial context of Limehouse.

For UG2, ‘radical repair’ represents a design methodology that anticipates the future and provides a framework for transformation that positions people and their relationship to the city at the forefront of design. Within this framework, each project identified a user group within Limehouse that guided the building programme and nature of the intervention. This outlook on developing human-centred design leads directly into the unit’s interest in self-build construction and the role that co-produced architecture plays in a more equitable urban future for our planet.

Year 2

James Tyler, Odin Verden, Graeme Wong

Year 3

Jaeho (Leo) Cho, Laura Dietzold, Harshal Gulabchandre, Esin Gumus, Regan Reser, Nora Seferi, Chunyi (Sally) Sun, Lettie Vera-Sanso Talbot

Technical tutors and consultants: Wolfgang Frese, Alberto Fernández González

Critics: Katerina Dionysopoulou, Maria Fulford, Billy Mavropoulos, Maxwell Mutanda, Jörg Majer, Thomas Parker, Elly Selby, Mira Yung

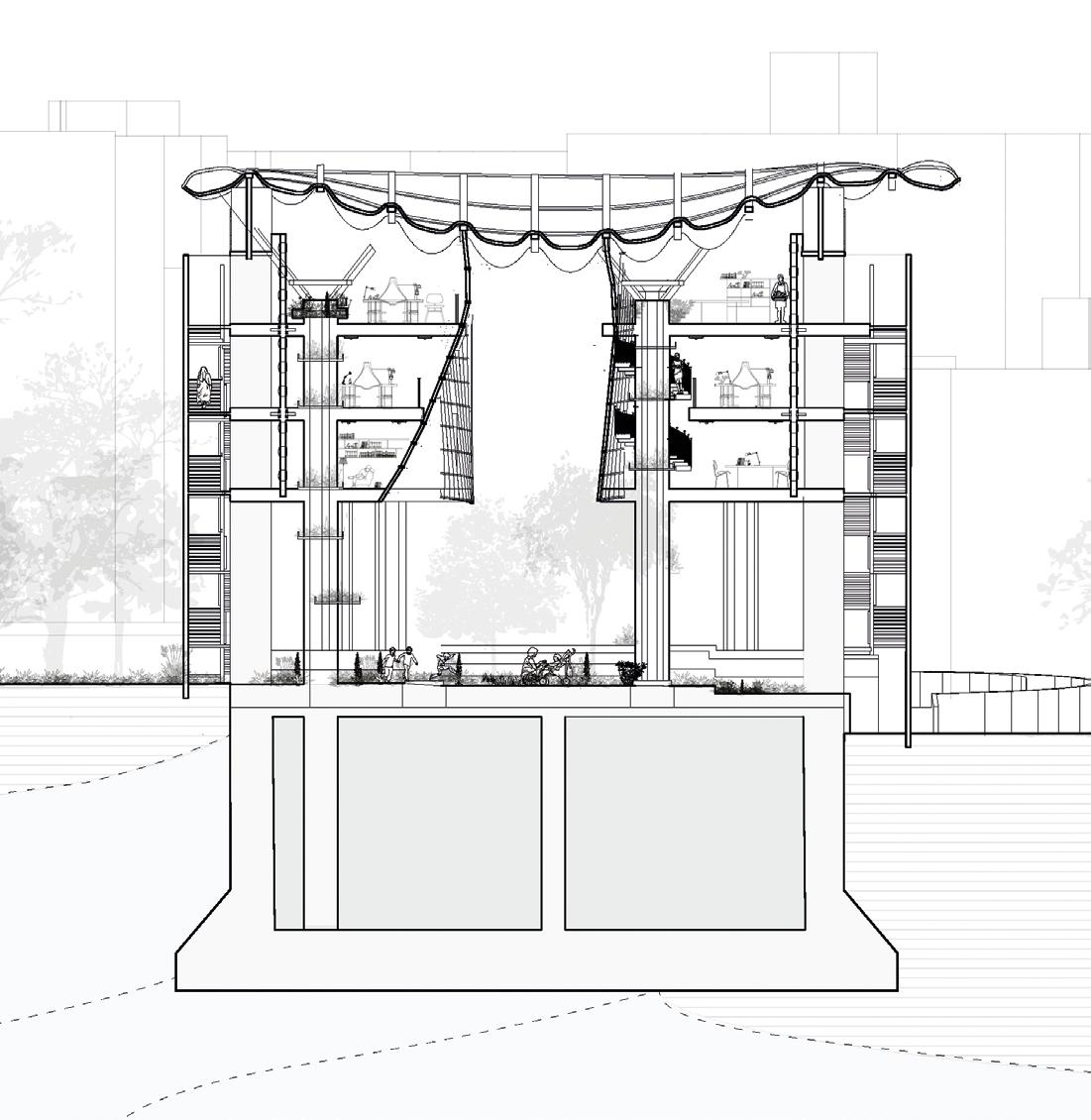

2.1, 2.14, 2.18 Harshal Gulabchandre, Y3 ‘The Kitchen Estate‘. Commercial Road High Street in East London has a range of socioeconomic and ecological disparities which require urban repair. The diasporic Bangladeshi community residing on this high street face a multitude of intersectional housing and food insecurities. The project addresses these systemic issues through a community kitchen, vertical farm and social housing. Using selfbuilt rammed earth construction as a vehicle for sociotechnical community engagement and material localism on the high street, the building repairs local disparities and empowers local people.

2.2–2.4 Chunyi (Sally) Sun, Y3 ‘Tailor Made’. This project proposes a new site of craft for a sewing community of migrant women in Limehouse. The buildings are based on a self-build modular system derived from the women’s working patterns and the grid of old concrete foundations. Engaging with reuse and reconfiguration, the design features timber elements and adjustable footings for disassembly, adapting to community fluctuations. Leftover concrete foundations are repurposed into landscape elements, maintaining a connection to the site’s history. Textile waste is upcycled using the women’s skills to create light baffles. The site is divided into production, education and retail areas, with sewing workshops, classrooms and public-facing shopfronts. Small, configurable units create intimate spaces, emphasising the community’s familial nature.

2.5, 2.7 Jaeho (Leo) Cho, Y3 ‘Upcycling Playground’. The project creates a spatial intervention in Limehouse, involving repair through the upcycling of waste materials. Inspired by a child’s ability to transform seemingly worthless items into personal treasures, the project begins by creating a catalogue of handmade papers using tools and waste paper found at home. On-site research leads to the development of leaf bricks, which became the focal point for the repair intervention. Based on interviews with locals, the project provides an educational playground for children at the local nursery. The design focuses on making the upcycling process accessible and inviting for children to interact with voluntarily. The project’s aesthetics, user interface and scale are shaped by its educational aspect and exclusive use by children.

2.6 Nora Seferi, Y3 ‘Loafers Lair’. This project investigates how the principles of spectral light can be applied to the design of a therapy centre that utilises this type of light therapy to trigger serotonin and melatonin production in the body. Digital tools are used to craft and create layered façades that regulate the amount of natural light and urban vegetation growth the building will have. Additionally, internal conditions are created where these qualities can be altered to benefit the mental health of users, accommodating their varying waking times and working hours.

2.8 Lettie Vera-Sanso Talbot, Y3 ‘Rogue Histories’. In London’s East End, where historical erasure is a pressing issue, this project proposes a civic space called the Centre of the Unconventional Historians to research and celebrate the city’s past. The project focuses on hobbyist historians who scavenge the Thames to uncover lost relics and give voice to underrepresented lives. These unconventional historians provide a more egalitarian account of London’s past that is overlooked. The project investigates how reuse methods can support a space for these historians and the public to share local histories of the Thames and surrounding areas. The architecture embodies a three-fold register of the city’s past: a repository of ‘lost’ artefacts, a platform for previously unrepresented lives and a structure built from waste material found within the Thames.

2.9–2.10 Laura Dietzold, Y3 ‘An Act of Continuous Repair’. Significant sea level rise in London is predicted under high emission scenarios, affecting infrastructure and the built environment in flood-prone zones near the Thames. Current flood defence infrastructure takes a simplistic approach, attempting to ‘design our way out’ of the challenge with walls and barriers. This project proposes a retrofitted form of flood defence infrastructure that encourages controlled flooding, allowing the city to make use of water as a precious resource. By focusing on retrofitting existing infrastructure and adapting it to future needs, the proposal creates a symbiotic relationship between the built and natural environments, rather than relying on complex and expensive infrastructure that disconnects us from water.

2.11–2.12 Regan Reser, Y3 ‘The Ritual’. The project is a spa for Limehouse Basin boat dwellers. It fulfils the basic human need for bathing while aiding mental and physical health through relaxation rituals. Inspired by the stages of water purification and the site’s historical accumulator tower, the spa filters wastewater supplied from the boats. This creates an off-grid water recycling system that mimics the boat dwellers’ lifestyle and alleviates the burden on London’s sewage system. The building utilises both mechanical and ecological forms of purification, with wetland roofing as the first level of filtration before the water enters mechanical processes for use in cleaned pools and steams. Black water is used to create biogas to power the spa. The project combines a study of historical infrastructure, consideration of users’ needs and innovative water recycling.

2.13, 2.16 Graeme Wong, Y2 ‘Avian Arcadia’. This proposal for E1 Waterbird Welfare, a community group in Limehouse, presents a sanctuary for injured waterbirds that serves as a symbol of renewal. Beyond rehabilitation, the building provides a space for education where volunteers and students learn about safeguarding urban wildlife. The design, echoing a bird’s wing, symbolises the journey to recovery and return to the wild. The project embodies self-build and repair, empowering individuals to actively restore their environment and foster stewardship. Together, the community works to rescue, save and rehabilitate urban wildlife, ensuring a thriving ecosystem for the future.

2.15 Esin Gumus, Y3 ‘Thames Interpretation Centre’. The project explores Limehouse’s vanished maritime history through its shoreline, focusing on Limehouse Hole Stairs. Inspired by the scattered rubble and remnants along the shore, a pier design incorporating an exhibition space is proposed. The pier’s accessibility changes with the tides, creating a dynamic interaction with the site’s historical narrative, allowing people to engage with and learn about Limehouse’s past. The project also includes a Thames interpretation centre, showcasing the river’s historical significance and its evolving relationship with communities. It promotes river restoration, rewilding and the use of materials dredged from the river in traditional crafts. The centre fosters skill sharing and strengthens community ties through these activities.

2.17 Odin Verden, Y2 ‘Velo Hub’. The project interprets repair as enhancing performance in cycling by balancing speed and comfort. By making changes to the bike and body, the project improves overall performance. When introduced to a site, the same methodology is applied to identify interventions that can increase the area’s performance. Just like in cycling, any intervention will involve a trade-off, but the project resolves both issues while encouraging the development of new skills in documentation and modelling. The ultimate goal is to use this repair-for-performance methodology in future projects, optimising systems by addressing multiple factors simultaneously.

Jhono Bennett, Zach Fluker

As spatial practitioners, we are intrinsically shaped by our situated experiences, knowledges, values and beliefs when called upon to design. The way we see, think and act in our built environments is fundamentally formed by the various reciprocal 1:1 exchanges that make up our contemporary built environment systems: our cities. These moments of exchange range from the items we buy at the nearby hardware store for home repair to the recommended content on social media platforms and the kind of dwellings we dream of occupying in the cities we aspire to inhabit. Such intimate, multi-scalar moments within the built environment reveal the ever-emerging dynamics of me:us, and offer the opportunity to inform a more grounded and critically contextually responsive approach to architectural design.

Urban crises of varying degrees are affecting many large cities worldwide. London now faces multiple socio-spatial challenges that are only worsening access to affordable living and housing. Despite the UK’s rich history of self-made actions, the potential of self-build practices to address the problem remains largely unexplored. As a unit, we are deeply interested in exploring the untapped opportunities that lie within the socio-technical dimensions of such systems. We believe in the power of grassroots processes that tread responsible lines between the individually made and mass-produced, the virtual and the physical, the small scale and large scale. Through these investigations, we seek to understand the role that contemporary designers can play in unlocking these large-scale, human-centred, community-based systems through very real exchanges of what the unit refers to as hand-made data and other contextually valuable resources.

During the first iteration of 1:1 Systems of Exchange, our focus was directed toward exploring methods that could leverage self-build practices as a means of furthering existing potential within communities of East London. At the same time we took into account the unique socio-spatial factors at play, including the positionality of the researcher/designer in framing these strategies. By concentrating on the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, our approach involved developing our own documentation techniques to understand better the nature of the conflicts between urban systems of exchange in both physical and virtual realms. We questioned the concept of DIY culture and assessed the potential of self-build practices in empowering individuals to shape our cities.

Year 2

Maria Gasparinatou, Aryan Kaul, Shuheng Wang, Zhi Qi (Tina) Wu

Year 3

Magdalena Gauden, Zuzanna Jastrzebska, Fardous Khalafalla, Archie Koe, Arushi Kulshreshtha, Jack Powell, Rauf Sharifov

Technical tutors and consultants: Simon Beames, Beatrice De Carli, Alberto Fernández González, Tamara Khan, Jakub Klaska, Tony Le, Rowan Mackay, James Palmer, Thomas Parker, Liz Tatarintseva

Critics: Egmontas Geras, Sarah Harding, Margarita Garfias Royo, Elly Selby, Isaac Simpson, Liz Tatarintseva, Unit 21

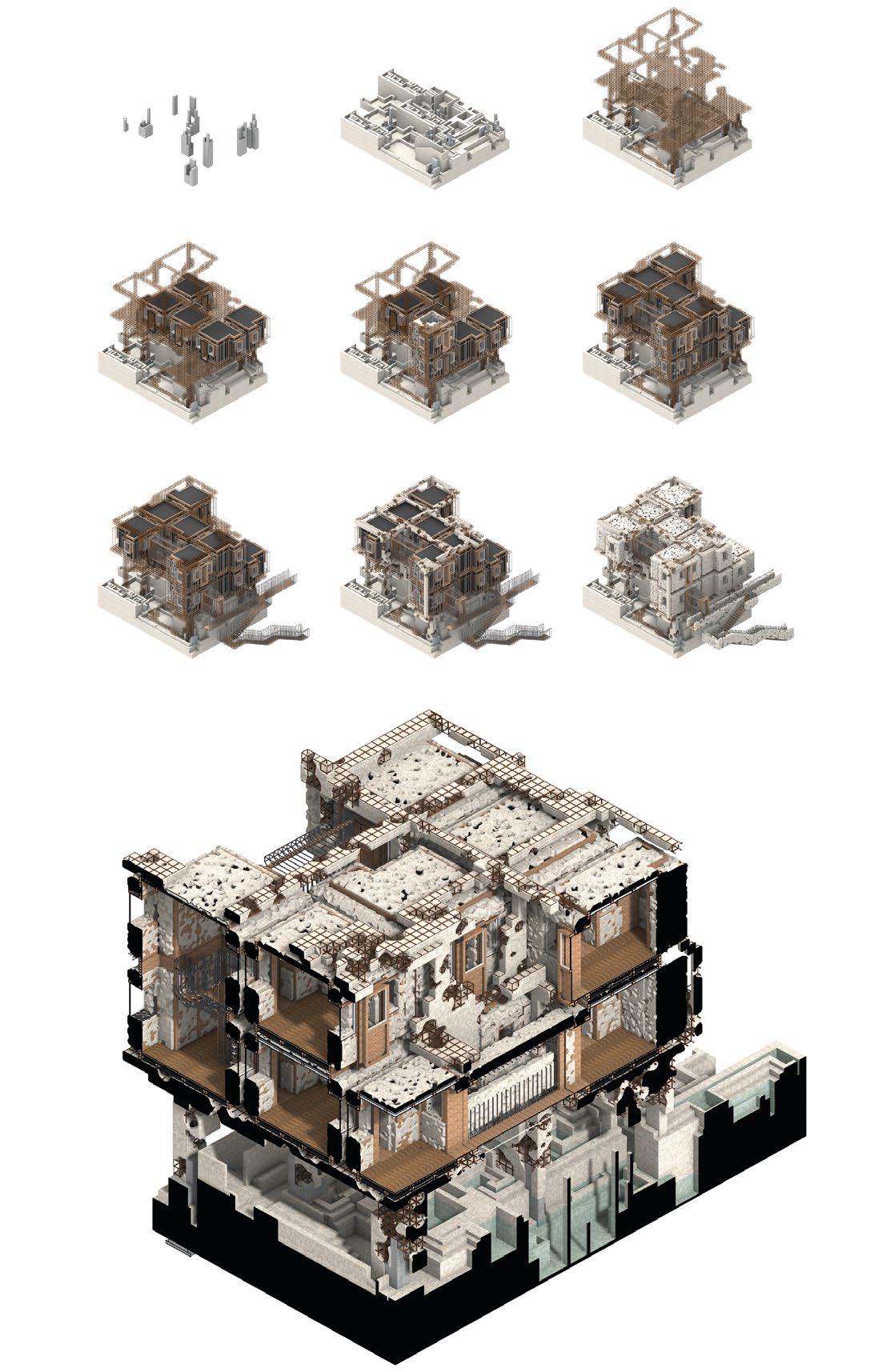

2.1, 2.22–2.23 Aryan Kaul, Y2 ‘The Meanwhile Repair Collective’. In collaboration with Meanwhile Gardens Community Association, this project addresses a collapsing factory building through a self-build scheme. It rehabilitates existing spaces, such as offices, storage, workshops and meeting areas, and fosters social cohesion. Interviews, tours and volunteering inform the design process. Drawing inspiration from a Moroccan self-build practice, the project explores rammed earth construction in London and incorporates recycled materials. Digital fabrication simplifies construction, using timber columns for both structure and formwork. The incremental development process respects the site’s self-build community, minimising interruptions and preserving usable spaces.

2.2–2.3, 2.24–2.28 Jack Powell, Y3 ‘Bookbinding Vernaculars’. The LCBA Workshop is a public factory owned by the London Centre for Book Arts and serves as a hub for bookmaking, ideas and art. Built by independent thinkers in East London, the building reflects the craft of bookmakers while elevating materials such as paper and thread. It is part of a growing network of waterfront workshops, bridging canal-dwellers and bookbinders. These workshops and publishers protect against censorship, encourage free discourse and foster intellectual and artistic expression.

2.4–2.6 Archie Koe, Y3 ‘The Audiophile’s Sonic Sanctuary’. The Audiophile’s Sonic Sanctuary is a psychoacoustic therapy centre in Tower Hamlets that uses rain-generated frequencies for mental healing. By combining holistic sound therapy practices with scientific psychoacoustic research, the centre offers customised treatments for anxiety, depression and insomnia. The building’s design incorporates acoustic research and exoskeleton strategies to create isolated therapy spaces. It addresses the mental health epidemic among young individuals and helps foster a sense of hope and community.

2.7–2.8 Zhi Qi (Tina) Wu, Y2 ‘The Augmented Strayed Homes’. This project reimagines laundrettes as communal spaces through self-build methods. It combines a laundrette with shared areas to encourage social interaction and make laundry time more engaging. Inspired by Edwina Attlee’s Strayed Homes the project merges private and communal spheres, fostering user interaction and creating an immersive ambience. The architectural design defines the boundary between public and private realms in Limehouse, London.

2.9–2.10 Zuzanna Jastrzebska, Y3 ‘Urban Scout Centre’. The project draws inspiration from adventure playgrounds to celebrate self-build activities in urban environments. Focusing on a local Scout community in Whitechapel, the design is influenced by pioneering Scouting and utilises a round timber skeleton with a mass timber shell structure. 3D scanning and digital analysis enable the incorporation of natural wood qualities. The resulting Scout shed design combines hi-tech and primitive building methods to create an adaptable and engaging scout centre that brings the camp atmosphere to an urban context.

2.11–2.12 Maria Gasparinatou, Y2 ‘Putting on a Show for 45 Lark Row’. Why is dance often hidden? The project addresses this question by proposing a dance centre that operates throughout the day, offering classes, performances and club nights by Regent’s Canal. Located at 45 Lark Low, the building engages with the relationship between passerby and dancer. The design concept revolves around the interplay of skin and bone. A steel structure supports a draped wire mesh that creates varying levels of transparency, framing the building like an open theatre.

2.13–2.15 Shuheng Wang, Y2 ‘Metaphor of Mycelium’. The project looks at how a London community could work together to remediate heavily contaminated soil through collective production. The project involves soil removal and the subsequent construction of a self-build building with two functions: mycelium remediation of contaminated soils and a mycelium studio for nearby residents. The construction spans five phases over approximately eight years, engaging the local community and strengthening bonds. The project’s significance lies in its involvement of families to solve London’s soil pollution crisis through self-building.

2.16–2.18 Magdalena Gauden, Y3 ‘Baking Bonds Between Us’. This community-based project fills a void in interaction spaces by placing a bakery at its core. Through bakery workshops showcasing diverse cultural products, it fosters bonds among residents of various backgrounds. The community is involved in both the bakery and the building transformation, contributing to ceramic cladding production. Retaining onsite trees promotes wellbeing, while the building’s design encourages human interaction, relaxation and collaborative hand craft activities for passers-by.

Inspired by Gabriel Epstein’s Lansbury Estate, the project aims to bring delight and enjoyment to the local community.

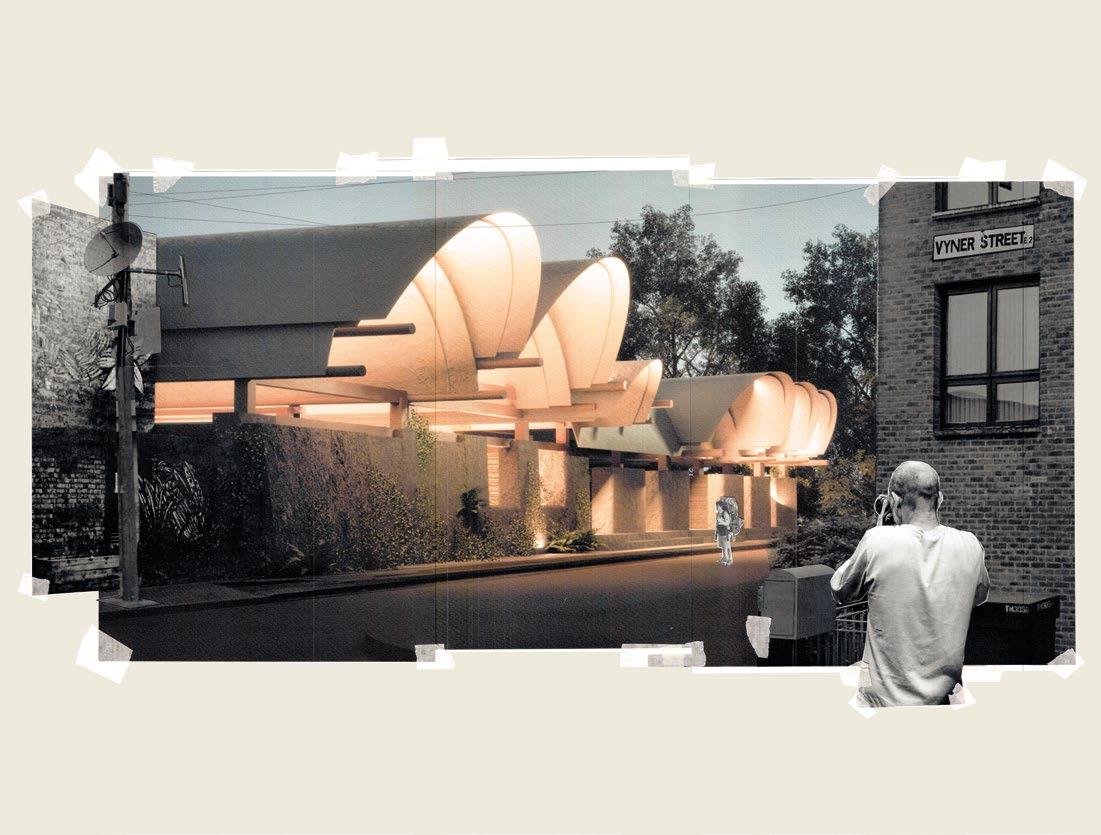

2.19 Arushi Kulshreshtha, Y3 ‘Lights, Camera, Action!’. This project revitalises a neglected community garden near Regent’s Canal into a vibrant space for local businesses and aspiring filmmakers. It explores the intersection of theatre, film and architecture, incorporating stories and studio systems into the design. Located in Tower Hamlets’ Vyner Street, the building offers filming spaces, workshops, meeting rooms and flexible areas. It addresses sustainability by repurposing film waste into building materials, reducing carbon emissions and promoting a circular, self-build film studio and set construction workshop.

2.20 Rauf Sharifov, Y3 ‘Delivery Driver Union Hub’. The proposed project is a multifunctional centre for delivery drivers, constructed using self-recycled and self-manufactured polymer building materials. It provides a supportive and safe environment for drivers and addresses their neglected needs. The building incorporates a skill development scheme focused on plastic recycling and uses materials collected by drivers. It features a translucent façade, personalised spaces and an efficient flow to enhance driver comfort and create a sense of community.

2.21 Fardous Khalafalla, Y3 ‘If You Know, You Know’. This project focuses on the street fashion community of East London’s Brick Lane, catering to enthusiasts of the popular subculture of streetwear. Streetwear fashion emphasises exclusivity, limited edition releases and a direct-to-consumer approach. The project provides a dedicated space for urban creatives who connect through social media, showcasing their designs made in makeshift studios and photographed in makeshift sets. It recognises the need for infrastructure to support these designers and seeks to fill that gap through a centre that supports self-build fashion.

Maria Knutsson-Hall, Barry Wark

In Greek mythology, Prometheus was a Titan who moulded man from clay and stole fire from the Gods to give to humanity. He was so inventive that in Western classical traditions he became a figure who represented the quest for innovation. In giving fire to the humans, Prometheus had disobeyed Zeus and was severely punished; thus his name has also become associated with the unintended consequences of our actions and mass suffering.

In a more contemporary sense, Prometheanism is a term popularised by theorist John Dryzek. It describes an environmental orientation that views the Earth as a resource whose utility is determined primarily by human needs and interests, and whose environmental problems are overcome through human innovation. The unintended consequences of this anthropocentric world view have leveraged technology to accelerate productivity beyond sustainable levels and led to the exploitation of natural resources, creating the so-called Anthropocene age. We are presented on a daily basis with the devasting impact of human activity on the planet, revealing how our actions (predominantly in the Global North) are creating seemingly irreversible, ultimately horrific changes.

A monumental shift in how we perceive our relationship to the natural world is needed. We can no longer view humans and our artefacts as privileged, separate and impervious to everything on the planet, but must rather understand that all things on earth are enmeshed in a global ecology. Ecocentrism is an ontological and ethical belief that refutes existential privileges or divisions between human and non-human beings and could help to redefine how we see our place within the biosphere.

This year UG2 reinvigorated the environmental project in architecture with a sense of hopefulness, asking how ecocentric values might redirect Prometheanism towards creating buildings that could mitigate or even reverse environmental destruction. Students focused on innovation and lateral thinking, harnessing various technologies across design, simulation and fabrication. Projects were undertaken in Glasgow, the year the city hosted COP26, with proposals ranging from carbon capture facilities to refurbishment and reuse of derelict buildings and to new forms of spaces that help us connect with the environment.

Year 2

Magdalena Herman, Sophie Hoet, Jazzlyn Jansen, Arushi Kulshreshtha, Sze Chun Liu, Rauf Sharifov, Annika Siamwalla, Yong (Benedict) Siow, Besim Smakiq, Pasut Sudlabha

Year 3

Blenard Ademaj, Yuto Ikeda, Zahra Parhizi, Elijah Ramsay, Zuzanna Sienczyk, Elise Wehowski

Many thanks to our technical tutors and consultants: James Palmer, Levent Ozruh, Tony Le

2.1, 2.11–2.12 Yuto Ikeda, Y3 ‘The Clyde C: Urban Carbon Capture’. Inadequate progress in reducing carbon dioxide emissions has only aggravated advancing climate change. The project mitigates this from an architectural perspective, with a largescale installation of carbon capture technology. ‘The Clyde C’ is a project that integrates carbon removal within a residential programme. The site is situated on an abandoned dock in Govan, Glasgow, providing its industrial history of shipbuilding as a contextual background. The developed procedural system which generates computational aggregations helps optimise carbon capture performance and the integration of programmes. In addition, a stable carbon sink of biochar is introduced as an acoustic buffer between domestic and technical spaces, as well as for interstitial growth enhanced by its fertile characteristic. 2.2–2.4 Zuzanna Sienczyk , Y3 ‘Wool Experience’. Nearly 80% of building insulation is made from synthetic fibres whose production is a major contributor to climate change. This project examines the possibility of turning back to the use of a natural, often forgotten resource – wool. Through the use of a water jet machine, wool fibres can be embedded into timber, offering a level of insulation comparable to the synthetic alternative, while decreasing its environmental impact and reviving British industry. The main scope of the project is focused on designing an insulation system that will allow for the refurbishment of old buildings that currently lack insulation. Fleece as an insulator would not only benefit the environment, but also the Scottish economy, where the wool market experienced an unprecedented downturn during the pandemic, forcing numerous shepherds to burn their harvests to avoid rising costs.

2.5, 2.13 Jazzlyn Janssen, Y2 ‘Rewilding the City: New Botanical Gardens’. Inspired by the natural vegetation scattered around the edges of Glasgow’s historical façades, a bioreceptive building celebrates the too often discarded foliage. Focusing on the overlooked beauty of moss, the public open-air theatre on the west side of Glasgow embraces and designs for the effects of the natural environment on the architecture, encouraging biodiversity and coexistence. The controlled rewilding of its walls and the varying filtration of light play foundational roles in activating these spaces as flourishing human and non-human zones. This new method of engaging, experiencing and interacting with the environment balances the urban and the wild, allowing for ecological restoration and reconnection in a new form of botanical garden.

2.6 Sze Chun Liu, Y2 ‘High Rise’. The project speculates on an alternative future for the now demolished concrete Whitevale Towers in Glasgow’s east end. The project considers the anonymity of high-rise living and looks to foster community between residents through rezoning the tower into vertical neighbourhoods. The project is also driven by the importance of building reuse, with a particular focus on 20th-century residential towers, which are ubiquitous across the city of Glasgow.

2.7 Zahra Parhizi, Y3 ‘Living Claycelium’. This project uses mycelium as a bonding agent for clay, with 3D-printed ‘claycelium’ creating an active multilayer wall system with exceptional structural integrity and cladding properties. The architecture’s wall allows mycelium to continue to grow inside the clay, strengthening the building over time.

2.8–2.10 Elise Wehowski, Y3 ‘Carbon Building’. A new eco-conscious structure to unite the neighbourhood of Haghill, Glasgow, with a sheltered public plaza serving as a central meeting point. Biochar is produced by heating biomass and can store up to 70% of carbon present in the original material. The project integrates as much biochar as possible to help create a reusable carbon

sink. The component-based design allows for quick disassembly and can be reused many times. The designs are also cast in part-based moulds that can be assembled in any shape.

2.14–2.15 Blenard Ademaj, Y3 ‘The Scottish Multi-Faith Society’. Grottos occupy a space between architecture and garden, allowing humans and non-humans to coexist within a single environment. The project takes this notion of grottos and uses the unmaintained conditions of the site to create a language within the building, blurring the barrier between architecture and nature to enable us to bring forth new methods of construction.

2.16 Elijah Ramsay, Y3 ‘Eco Anxiety Retreat’. As awareness around the environmental crisis increases, many people are left filled with anxiety, hopelessness and a sense of nihilism. The building creates a space for users to experience the therapeutic and biophilic properties of natural landscapes and simultaneously witness the role of technology at work in mitigating environmental degradation. The project uses maerl, a natural entity similar to coral that sequesters carbon. Through environmental analysis, the spa is designed to propagate maerl in increasing amounts. The project is seen as a prototypical condition that could be replicated along the Scottish coast.

2.17 Arushi Kulshreshtha, Y2 ‘Clydeside CPA’. Located along the north bank of the River Clyde, the project transforms the Clyde riverside into an inclusive performance space and proposes Glasgow’s first external covered public space.

2.18 Magdalena Herman, Y2 ‘MycoClinic’. The MycoClinic provides biodegradable 3D-printed roofs made of mycelium and soil. After the mycoroof cladding decays and falls onto the ground, the process of mycoremediation begins to positively impact the environment.

2.19 Besim Smakiq, Y2 ‘Museum of the Glasgow Style’. The project explores ideas around camouflage and context through the use of neural-network styletransfer algorithms.

2.20 Yong (Benedict) Siow, Y2 ‘Co-Space’. The project speculates upon a series of structures for both humans and non-humans within the Scottish landscape.

An object of observation can be, in a number of different ways, partly natural, partly artefactual, and something that is a natural object might nevertheless not be in a natural state.1

The above quote by English philosopher Malcolm Budd describes how one might engage and appreciate natural objects. It alludes to the fact that even if the origin of the object is natural, if it is not in a natural state then it ceases to be appreciated as such. This year, UG2 considered the reverse: If the object in question is a human artefact and is in a natural state, can we begin to appreciate it in the same way that one appreciates the natural world?

The effects of natural phenomena, such as erosion, staining and flora propagation, perpetually alter buildings. It is, therefore, interesting to consider ‘green’ architecture’s call to bring nature in when it is already there, we simply invest energy in design and maintenance strategies for its removal.

UG2 investigated biospatial conditions that encourage and embrace the visibility of their environment to dissolve the notion that they are separate and impervious to the natural world. The students explored projects in Rye, East Sussex, and considered how the wider environment has impacted the fortunes of human settlements, both positively and negatively. This is particularly pertinent for Rye, which is situated two miles from the sea at the confluence of three rivers, as the predicted rise in sea levels will severely affect the community, flooding entire neighbourhoods and returning it to a seaside town.

In addition to considering how to design for these scenarios, the students’ proposals endeavoured to develop novel aesthetic sensibilities of what ecological architecture could be beyond its current offerings. The projects work with new biomaterials, explore architecture’s role within ecology and create spaces that engage users’ imaginations to consider their sense of place within the biosphere.

Year 2

Seb Bellavia, Bogdan Botis, Grace BoytenHeyes, Kyra Johnston, Clara Popescu, Charmaine Tang, Chan Tou (Antonio) Yang

Year 3

Ho Kiu (Jeffrey) Cheung, Lavinia Fairlie, Tilly Grayson, Mankiran Kundi, Charles Liang, Harrison Maddox, Ioana-Stefania Petre

Technical tutors and consultants: Levent Ozruh, James Palmer

We would like to thank our critics: Hadin Charbel, Andreas Koerner, Deborah Lopez Lobato, Justin Nicholls, Levent Ozruh

1. Malcolm Budd (2002), The Aesthetic Appreciation of Nature: Essays on the Aesthetics of Nature (Oxford: Clarendon Press), p14.

2.1 Seb Bellavia, Y2 ‘Camber Pier’. The project develops the coastal village of Camber, East Sussex, through socio-economic and infrastructural means and acts as a coastal defence against erosion and rising sea levels. Utilising framework mesh elements and biorock to accrete material, the coastal defence becomes part of the beach itself and transforms the surrounding environment into a coexistent experiential space.

2.2 Harrison Maddox, Y3 ‘Myco House’. A project that explores the potential of mycelium-derived composite materials to create a modular and deployable flood defence system, with integrated housing units, for flood-prone areas in Rye, East Sussex. The project demonstrates the potential such a system has in relation to transit compatibility, interchangeability and bio-contribution.

2.3–2.4 Tilly Grayson, Y3 ‘Reforging Communites’. Focussing on Rye’s industrial history – ironworks and Cinque Ports – is a proposal for a museum as an homage to the past. The museum functions as a community hub to combat feelings of isolation in the community. The structure is designed for deconstruction and reconstruction, and questions whether iron has a place within an ecological future.

2.5–2.6 Ioana-Stefania Petre, Y3 ‘The Dungeness B Recommissioning Project’. The project recommissions the existing Dungeness B Nuclear Power Station to integrate the existing nearby community and to preserve the area’s authenticity. The building uses emblematic parts of the power station as a base for the proposal that includes housing, a library and art spaces.

2.7 Kyra Johnston, Y2 ‘Asylum Seeker Sanctuary’. A sanctuary for asylum seekers is situated around 45 minutes from the port of Dover, where most asylum seekers land after crossing the English Channel. The project explores how biophilic architecture can accommodate asylum seekers in a way that is empathetic and tranquil.

2.8 Charmaine Tang, Y2 ‘Out of Place’. A ‘natural state’ is often perceived as dirty or out of place. The project reimagines a crèche as a landscape and encourages children to explore, understand and learn from nature, not simply within the binary definitions of ‘dirty’ and ‘clean’, but in a respectful and playful way.

2.9 Clara Popescu, Y2 ‘Geomorphous Awareness’. The project approaches the problem of dune destabilisation in Camber Sands, East Sussex. Sitting at a key break within the dune environment, it shelters the site from prevailing winds and exploits sand deposition processes. The design allows for the integration of the environment into the building with the incorporation of nooks for plant and animal inhabitation.

2.10 Bogdan Botis, Y2 ‘The Preservation of Rye’s Salt Marshes’. The project explores the impact of flooding and coastal erosion on the salt marshes of Rye Harbour Nature Reserve, East Sussex. It proposes a series of structures that generate new opportunities for salt marshes to develop, adapt and thrive in the everchanging environmental conditions that they face.

2.11 Grace Boyten-Heyes, Y2 ‘Hydrobotanical Bathhouse’. A bathhouse that adapts to tidal flooding. Water intake is filtered using hydrobotany forming gardens that double up as social spaces. The building also monitors changing water conditions and responds to the return of Rye’s old coastline using the transitioning landscape to question object permanence and anthropocentric views of buildings as defying nature.

2.12–2.13 Mankiran Kundi, Y3 ‘A Revitalisation of Human and Biophilic Expression’. The project brings new life to the town of Rye, East Sussex, through the creation of spaces for self-expression, specifically graffiti. Biophilic design strategies, including the gradual propagation of moss, promote occupant wellbeing.

2.14–2.16 Lavinia Fairlie, Y3 ‘A Transient Harbour’. The proposed harbour in Rye, East Sussex, works as a system that responds to the shifting landscape threatened by rising sea levels and daily tidal fluctuations. The harbour retains the local seafaring community’s connection to the land, while improving marine biodiversity and water quality in the River Rother.

2.17–2.18 Ho Kiu (Jeffrey) Cheung, Y3 ‘By Land, Sea and Air: Reconfiguring fishing’. It is a global issue that current fishing methods destroy sea habitats. If these trends continue there will be little or no seafood available for sustainable harvest by 2080. Rye, East Sussex, is an inshore town with a rich history of fishing. The project explores drone fishing and biorock as sustainable approaches to reverse man-made damage.

2.19 Charles Liang, Y3 ‘Otter Daycare’. Otter spotting was first recorded in 1864 in a survey manual produced by the Sussex Wildlife Trust. An apex predator at the top of the food chain in its ecosystem, any river and wetland pollution results in a huge decline of otter numbers. The project proposes a kindergarten with an area for otter holts that achieves harmonious coexistence between humans and nature.

2.20–2.22 Chan Tou (Antonio) Yang, Y2 ‘Cohabitation

Within the Fluvial Landscape’. This project addresses the disappearance of public open spaces in UK coastal towns due to rising sea levels. A theatre and public space celebrate and embrace the natural rhythms of tidal movements. Glimpses of human/non-human habitation and interaction is observed through different zones of coexistence. Control and access are traded between species by the changing of the tides.

Between the Object and the Picturesque Barry Wark, Maria Knutsson-Hall with Levent Ozruh

Barry Wark, Maria Knutsson-Hall with Levent Ozruh

In many cities our primary interaction with nature is through one of two perceptive models of appreciation, either as objects or as the picturesque. We commonly experience these objects of nature as potted plants and small items scavenged from their context and turned into sculptural artefacts. We consume images of nature through documentaries and social media feeds where we bask in their aesthetics.

Nature is neither object or image, it is a wide variety of environments and spaces in which we have evolved in and experienced for millennia. It is a complex ecosystem; it evolves over time and seasons; it is fragile and volatile; and it has the power to comfort and unnerve us. Our built environment has increasingly controlled and minimised the natural world to the point where we have become physiologically and perhaps psychologically separated from it. With this in mind, we looked to challenge the way we experience nature in our buildings, between the object and the picturesque.

Continuing our investigation of cities in desert biomes, this year we travelled to Amman, Jordan. The city is facing many challenges, such as its lack of urban mobility due to poor planning and steep topography; the prevalent use of air conditioning to cool its buildings; and a severe water shortage. The latter has led to the government anticipating that Amman will run out of water by 2025. That said, Jordanians have survived its harsh conditions for millennia. The Nabateans were masters of both rock-cut architecture and water management systems, allowing them to build the spectacular city of Petra.

This year’s projects imagine what impact further environmental degradation might have on the communities of Amman. We propose buildings that could mitigate these projected environments through passive design whilst still offering new forms of public and private space that respond to the evolving needs of urban life. We explore what an immersive nature space would mean in Amman, working with its idiosyncrasies and challenging the notion of sustainable architecture beyond its current image. Projects control the sand blown into the city by dust storms to create spatial effects; celebrate the rain, turning it into a precious spectacle to be appreciated; and develop novel bioaesthetics derived from the Wadi Rum desert and Petra. The resulting buildings engage with nature in novel ways, in the hope of strengthening citizens’ sense of place within their beautiful but precarious landscape.

Year 2

Sahba Akbar, John Krenshaw Clayson, Crina (Bianca) Croitoriu, Jina Gheini, Serim Hur, Meg Irwin, Yushen (Harry) Jia

Year 3

Hazel Balogun, Alisa Baraboshkina, Heather Black, Victoria Blackburn, Ocian Hamel-Smith, Evelyn Jesuraj, Yeree Kim, Luke Topping

We would like to thank James Palmer for his continued invaluable support in teaching the technology module

Thank you to our critics for their generosity in time, knowledge and spirit: Barbara-Ann CampbellLange, Marcos Cruz, Gonzalo Herrero, Casper Johnson, Laura Mark, Justin Nichols, Hannes Mayer

Thanks also to Mazen Alali for his expertise and guidance in Amman

2.1 John Krenshaw Clayson, Y2 ‘Figures of the Picturesque’. This project is a versatile market area that facilitates both formal and informal market vendors as well as aiding urban mobility in Amman. It uses convolutional neural networks to replicate drawn figures of nature and begin an exploration into a translation between analogue and digital tools. The scheme acts as a criticism of the way nature manifests in modern cities, especially in the West, where plants are often experienced as objects or as the picturesque. This is emphasised in Western planning through its concentration on vista; a characteristic not present in Arabic planning and perhaps evidential in arguing for the inherent biophilic qualities of Arabic planning.

2.2–2.3 Heather Black, Y3 ‘Arab League Headquarters’. The project explores notions of security architecture and its conservative approach to public interface. It challenges the traditions of secure spaces using the context of a new headquarters for the Arab League in Amman, Jordan. The design strategy of the site is focused on ‘sand flooding’ which changes the accessibility and security of the building. During events, the landscape is flooded and it is subsequently drained when the event has finished, returning the space to public use.

2.4, 2.6, 2.19 Hazel Balogun, Y3 ‘A System for Urban Flow’. Amman’s rapid expansion, topography and urban grid have contributed to poor pedestrian conditions. With the agenda of improving urban mobility in the city, the project provides an accessible route across one of the city’s hillside topographies. Influenced by modern and vernacular hydraulic technologies, the landscape captures seasonal stormwater to reduce the intensity of local flash-flooding.

2.5 Ocian Hamel-Smith, Y3 ‘Amman Marketplace’. The market, and its square, serves the most vulnerable demographics of Amman’s population, especially those whose right to work formally is not permitted due to various tiers of citizenship. This project aims to solidify an existing market, located on a floodplain, as a democratic space, with added commercial facilities to allow the local skilled tradesmen a space to feel safe and fulfilled.

2.7–2.8 Evelyn Jesuraj, Y3 ‘A Workplace for Women’. This project aims to address issues surrounding the high unemployment rates among female university graduates in Jordan. In order to bypass the law, many employers do not hire women as it triggers a policy where childcare facilities would have to be provided onsite. The design for an engineer’s office tackles this head-on by proposing a building where the workspace and creche are integrated in a novel construction system.

2.9 Luke Topping, Y3 ‘A New Direction for Ornament’. This project is a theatre in Downtown Amman positioned above the locally famous Jafra Café. The architectural investigation was inspired by a fascination with 21stcentury ornamentation in the Middle East, positioned from a contemporary digital discourse. The building is composed of geometries that tessellate between the scale of the building and the scale of the ornamental. The geometry provides directions North, South, East and West through large architectural gestures and the composition of its facades.

2.10 Yeree Kim, Y3 ‘Amman Building Centre’. This project investigates how contemporary design and fabrication tools could recreate the aesthetic qualities and passive environmental strategies found at Petra, Jordan. These topics are explored in a centre for the built environment in downtown Amman. The building acts as exhibition space and construction laboratory where the public can navigate and experience the spatial conditions of Jordan’s ancient architecture.

2.11 Jina Gheini, Y2 ‘Nature Play’. This project is an after-school activity centre. It focuses on creating outdoor and indoor playgrounds for children, increasing their

physical activity, as there is currently a lack of play areas in Amman. The design aims to provide spaces in which children can experience nature that is overgrown and wild, which has been shown to be beneficial for both their mental and physical health.

2.12–2.13 Alisa Baraboshkina, Y3 ‘Wedding by the Water’. This proposal is a wedding and events venue that endeavours to create a building system that alleviates its water demands within the context of Amman’s water-shortage crisis. This is investigated through a collection system of fine mesh panels, drawing moisture from the air in the mornings and providing solar shading in the daytime.

2.14 Crina (Bianca) Croitoriu, Y2 ‘Bedouin Heritage Centre’. This project provides the nomadic Bedouins with a space in the city to temporarily inhabit. It is also a place in which they can educate others about their culture and traditions aiding to the preservation of a culture which is predominantly transferred through speech.

2.15–2.16 Sahba Akbar, Y2 ‘Civic Mobility’. This project explores the challenges of urban mobility in Amman which are a product of its challenging topography and rapid expansion over the last 50 years. A cable-car system which terminates in downtown Amman is designed for the city. The building proposal is focused on this terminus, which also integrates space for an informal market and eating spaces. As a strategy to collect pollutants from the air and form a new spatial identity for the network, the work explores bioplastic as a disposal building skin.

2.17 Yushen (Harry) Jia, Y2 ‘The Saltwater Hammam’. This building is a bathhouse that uses filtered grey water to raise awareness of recycling water, an ever-dwindling natural resource in Amman. The building focuses on a journey of intensification. As visitors descend the spiral staircase, the concentration of space, light, vegetation, steam, and salt becomes denser.

2.18 Meg Irwin, Y2 ‘Alternative Health Centre’. The project for a healthcare centre in downtown Amman is inspired by the ancient architecture of Petra and how the Nabateans mastered their environment to provide passive thermal comfort. The project studies and implements these strategies, including the integration of water; working with hybrid construction and rock-cut spaces; and retreating behind the natural rock formations onsite which provide shade. The result is a building that opens a dialogue between natural and made, in the creation of a biophilic building.

2.20 Serim Hur, Y2 ‘Urban Cliff Techtonics’. This project explores the urban cliff hypothesis that states that our cities are akin to the habitat templates of cliffs. From observing the historic structures in Amman, the plant growth occurs where the stone blocks decreased in size, creating more gaps for water retention. Inspired by the iconic Hashem restaurant in downtown Amman, the building develops the ‘backstreet’ as a public space culture of the city in the creation of a kitchen and café.

2.21 Victoria Blackburn, Y3 ‘Al-Lweibdeh Preschool and Shelter’. The Al-Lweibdeh Preschool is an adaptable building, which delivers education for the local community and can transform to provide shelter and relief during times of crisis. The building both embraces and mitigates the increasing intensity of sandstorms in the Middle East, to raise local consciousness about the impact of global warming on the Jordanian environment.

Urban Cliff Maria Knutsson-Hall, Barry Wark

This year, we explored the ‘urban cliff’ hypothesis, which identifies that our cities are often akin to the habitat templates of cliffs. This is based upon the similarities in their physical composition, whereby both have a lack of soil and rooting space, with moisture ranging from dry to waterlogged due to their hard and impervious surfaces. These conditions are apparent in abandoned buildings, pavements and along railway lines where our built environment is less polished and forgotten. Rather than try to implement a superficial and manicured nature, the unit instead looked to exploit these qualities and viewed it as fertile ground for the exploration of moments of wilderness in architecture.

We travelled to Morocco’s Eastern border with the Sahara Desert and the Atlas Mountain range, visiting Fes, Chefchaouen, Marrakesh and Ait Ben-Haddou. During our excursions, we cast a critical eye on traditional construction and vernacular architecture, observing and examining how these tight-knit cities form out of a necessity to escape the intense heat. The unit focused on civic architecture in Marrakesh, addressing projections on near future scenarios. The proposals explored issues such as mismanagement of natural resources, tourism, gentrification of the medina, education and other social services. Many projects also integrated new forms of public space into central Marrakesh to facilitate the varying lifestyles of the inhabitants of Ville Nouvelle and those of the old city.

In searching for urban cliff conditions, it was impossible not to take influence from Marrakesh’s famous riads, or courtyard houses. The calm, vegetated interiors of the buildings, with their delicate ornament, formed a strong contrast to the more robust and austere external conditions of the medina. Many of the students’ projects play on this internal/external duality found throughout the city, and employ the same passive cooling systems to regulate the thermal conditions in their proposals.

Inspired by the energy of the city, its deeply textured walls and its overgrown courtyards, the projects endeavoured to capture these qualities in an architecture that is at once progressive and, at the same time, inspired by its context. Balancing moments of high intensity with serenity, the work reimagines a variety of traditional materials through avant-garde design and fabrication tools. The proposals ultimately integrate water and vegetation in novel, considered and meaningful ways, to create alluring moments of atmospheric wilderness within the Marrakesh medina.

Year 2

Jean Bell, Nicholas Collee, James Della Valle, Ceren Erten, Paul Kohlhaussen, Ian Lim, Sut (Eunice) Lo, Natali Rayya, Josef Stoger, Kar (Tiffanie) Tseng

Year 3

Sheryl Beh, Katarzyna Dabrowska, Imogen Dhesi, Karishma Khajuria, Yue (Nicole) Ren, Benjamin Webster

Many thanks to our technical tutor James Palmer for his invaluable contribution to the unit and to Sonia Magdziarz for her passion and positivity in the teaching of the skills workshops

Thank you to our guest critics and those offering their comments and support throughout the year: Richard Beckett, Tom Budd, Barbara-Ann Campbell-Lange, Sir Peter Cook, Christina Grytten, Shireen Hamdan, Simon Herron, Andreas Koerner, Chee-Kit Lai, Justin Nicholls, Sara Shafiei, Sam Welham

We are grateful to our sponsor Populous for their continuing support of the unit

2.1 UG2, Y2 and Y3 ‘Model Display’. Collective output of the units model-centred, design methodology. These include spatial studies, material composites, tectonic assemblies and final building models.

2.2, 2.3, 2.7, 2.10 Imogen Dhesi, Y3 ‘Riad Al Nisa’. This project is a building for the women of Marrakesh who have become isolated or ostracised from their communities. Developed from the riad typology, it provides accommodation, vegetated courtyards and a new public space. This space functions as a mint tea garden and enables the building’s residents to interact and foster relationships with their neighbours. It is characterised by an opulent water feature, adapted to the Marrakesh climate, that passively cools the building whilst also providing an acoustic and atmospheric experience.

2.4–2.5 Benjamin Webster, Y3 ‘Modular Tectonic Experiments’. Early experiments investigating the potential of extruded earth and ceramic components to be assembled into larger structures.

2.6 Sheryl Beh, Y3 ‘Chinese Tourism Centre’. Chinese tourists visiting Morocco have increased since a visa requirement was removed. This project creates a building that assists these tourists in orientating themselves within the medina and, also, in training local tour guides in basic Mandarin language skills.

2.8 Ceren Erten, Y2 ‘Visiting School’. This project creates a school where children from rural areas can come and stay for a period of time in Marrakesh and access facilities that might not be available to them in their villages. The aim is that it will allow the country to develop its literacy rate and further its digital skills. The building is composed of classrooms and accommodation and, simultaneously, creates a cool underbelly, forming much-needed public space.

2.9 Josef Stoger, Y2 ‘Fashion School’. Motivated by the rich heritage of fashion in Marrakesh, the project looks to foster a culture that rejects the global fashion industry in the creation of a style that is idiosyncratic to the city. The proposal is for a dedicated fashion school where the building is inspired by the Berber tents and loose-fit fabrics adorned by older generations.

2.11 Yue (Nicole) Ren, Y3 ‘Souvenir Auction House’. Many souvenirs in the Marrakesh medina are not the product of careful hand-craft but are mass produced and imported from China. This proposal is for an auction house where traders can bid on larger quantities of these goods. It draws upon the smoothed-out aesthetic of many of the city’s buildings where, over time, they become bulbous as more layers of earth and clay are applied to their façades.

2.12 James Della Valle, Y2 ‘Light Entertainment’. This project builds on idea of the souk as a space for entertainment and performance. The proposal refurbishes a dilapidated collection of buildings to the north of Jemaa el-Fnaa Square, creating a series of urban incisions composed of lightweight walls, amphitheatres and rooftop canopies that act to frame and promote informal performance. The model is a 1:20 detail of how these incisions might meet the existing fabric.

2.13 Nicholas Collee, Y2 ‘House of Football’. This project creates a much-needed sports amenity in a poor part of the medina. It explores components and in-situ ‘post-carving’, after construction, to create visual complexity as a wayfinding strategy.

2.14 Ian Lim, Y2 ‘Souvenir Riad’. With Instagram tourism on the rise, what value is there in pictures as a souvenir? Questioning this phenomena, this project proposes that true value in travelling might be to obtain a unique experience or handmade souvenir. The result is a workshop building where visitors can create their own souvenirs guided by local craftspeople.

2.15 Katarzyna Dabrowska, Y3 ‘The Felt Garden’. This project explores notions of life and death in the creation of a garden, where felt urns are filled with seeds and the ashes of the deceased. Over time, the seeds germinate and become luscious plants. As generations pass, the felt bags disintegrate, allowing for new residents to bring life to the garden.

2.16 Jean Bell, Y2 ‘Rooftop Renewal-Casting Experiments’. This project embodies ideas about how one might capture the materiality and richness of the historic medina in which it is sited. It looks at casting with rubber moulds taken from existing wall conditions. The formwork of the new proposal is lined with the casts.

2.17 Karishma Khajuria, Y3 ‘Unfulfilled Aspirations’. This project endeavours to create a space where the women of Marrakesh are able to fulfil life ambitions. The building provides sanctuary, education and leisure. Conceived as a small neighbourhood with several riads and passageways, it is cooled and thermally regulated by screens and water channels.

2.18 Benjamin Webster, Y3 ‘Bab Doukala Riads’.

As the medina of Marrakesh is becoming gentrified, many people are being displaced to the outskirts of the city. The proposal is for new affordable housing in the interstitial space between the old medina wall and the new city. The housing design, inspired by the riad typology, is arranged around central courtyards hosting vegetation and water. The structure is created out of modular elements which utilise the courtyards to passively cool the building.

2.19 Sut (Eunice) Lo, Y2 ‘Medina Market’. There are many places to buy food in the medina but few places to sit and enjoy it. This project explores a new kind of market space for the medina that is, at once, a series of food stalls and, at the same time, a shaded and vegetated public space.

2.20 Natali Rayya, Y2 ‘Equine Veterinary Clinic’. Donkeys are still widely used throughout the medina to transport goods. Working long hours under intense heat can often put a lot of strain on these animals. This project creates a clinic where the animals can have check-ups and treatment, and is supported by a visitor centre where they can interact with retired and recovering animals in a garden courtyard.

2.21 Kar (Tiffanie) Tseng, Y2 ‘Tannery Working Men’s Club’. Morocco is known for its tanneries. The intense heat and smell during the production process can be too much for many visitors. The workers, however, endure these conditions daily with little respite or retreat. This project creates a humble working men’s club for the tanners where they can shower, rest and converse, away from the harsh sun. The building is thermally regulated through a series of wind towers that can be seen poking up from the medina floor.

2.22–2.23 Paul Kohlhaussen, Y2 ‘Hammam Bab Doukala’. The hammam in Morocco forms one of the most democratic and inclusive public spaces. This project explores the idea that the hammam can bridge the widening gulf between those of the medina and the new city, as Marrakesh evolves with increased tourism. The building is formed of a series of spatial gradients ranging from gender specific to mixed, hammam to spa and inside to outside. The design is characterised by new ceramic ornaments inspired by the interiors of the city’s architecture. These ceramics vary to either filter water or create ceiling conditions where condensation is collected and reused.

Year 2

Sadika Begum, Yu Chow, Bryn Davies, Rusna Kohli, Hugo Loydell, Szymon Padlewski, Wei Tan, William Zeng

Year 3

Jie Yi Kuek, Jiyoon Lee, Linggezi Man, Joanna Mclean, Patrycja Panek, Renzhi Zeng

Special thanks to COBE Architects, BIG and Henning Larsen for welcoming us to their offices and giving us insight into their design approach and projects in Copenhagen and beyond

Thank you to our Year 3 Technical Tutor, David Edwards and to Thomas Bagnoli and David Edwards for Digital Workshops

Thank you to our critics: Yota Adilenidou, Thomas Bagnoli, Ping-Hsiang Chen, Mollie Claypool, Serena Croxson, David Edwards, Alicia Hidalgo, John McElgunn, Federico Nassetti, Jack Newton, Igor Pantic, Knot Saenawee, Jeroen Van Ameijde

UG2 investigates ideas through digital simulations, analogue prototypes, material tests and digital fabrication. We are keen to go beyond the conventional and explore building prototypes that are innovative, adaptive and responsive to the programme, users and context. Students develop individual architectural projects utilising algorithmic design methodology, iterative process physical and digital models and installations. This year we explored the notion of high density on a material, architectural and urban scale.

Students began the year by designing a small-scale architectural proposal: a pavilion, inspired by making and construction techniques, material studies and environmental performance. The projects question how architecture relates to time by looking at states of transformation from temporary to permanent on a material and spatial scale. Students adopted hybridised analogue and digital design methods in order to achieve highly articulated spatial constructs. The pavilion project informed the architectural language of the main building project whilst bringing in new parameters such as programme, context and local materials.

In response to our theme of ‘high density’, we investigated multi-use and multi-programmatic architectural typologies. The building projects are situated in Copenhagen, known for years for its horizontal skyline broken only by the spires and towers of its churches and castles. Its mixed-use centre is recognised as an example of best practice in urban planning. In recent years there has been a boom in urban development and modern architecture with large-scale, high-density projects being realised in the areas around the city centre. We looked at the juxtaposition between the medieval inner city of Copenhagen and the newer residential boroughs on the outskirts featuring new types of urban planning and high-density, mixed-use contemporary schemes by BIG amongst others.

Most of our sites are located in Nordhavn, a harbour area in Copenhagen which is the largest metropolitan development masterplan in Scandinavia. The projects raise a series of questions. How can we design for the future of co-working, co-living and cohabiting whilst improving the sense of community and relationship to nature? Can we create density without compromising space or quality? Can density improve the way we inhabit our cities? The final building projects are contextually sensitive while being contemporary and innovative in their architectural agenda. They are diverse in their scale and include a mixed-use bee hub, an innovative co-working centre and a boat repair house to name a few.

Fig. 2.1 Jiyoon Lee Y3, ‘Community Bee Farm’. Located in the centre of Copenhagen, the project proposes a new typology for urban living, integrated with an active vertical bee farm. A carefully choreographed dense system of porous filters allows for the cohabitation of bees and people. The beehive becomes the central piece in the proposal serving as an urban beacon in the area. Figs. 2.2 – 2.3 Wei Tan Y2, ‘Modular Aggregation’. By adopting modular aggregation techniques the project introduces a range of possible symbiotic inhabitations. Studies in material weathering and modular connectivity inform a flexible pavilion that responds to the user and weather. Fig. 2.4 Szymon Padlewski Y2, ‘Cancellous Pavilion’. The project investigates the spatial qualities of cancellous bone using digital simulations and material prototypes. The

final pavilion features porous concrete shells that appear to grow naturally from the landscape. Fig. 2.5 Renzhi Zeng Y3, ‘Inhabited Bridge’. The project proposes a structure that connects two important facilities on site: the Orientkaj metro station and Copenhagen International School. The building is designed as an inhabited bridge which functions as both infrastructure and social space for the local students. The envelope of the building was explored though a range of digital and physical models focused on optimised mesh tessellation.

Fig. 2.6 Joanna Mclean Y3, ‘Living Landscape Pavilion’. Situated in the Serpentine Gallery grounds in Hyde Park, London the project explores the constant and ever-changing process of destruction and renewal, catalysed by the natural geological processes of erosion, weathering and deposition. The landscape pavilion augments in response to rainfall and time. Fig. 2.7 Yu Chow Y2, ‘Nordhavn School’. The building presents ways of facilitating non-verbal communication between the students by utilising vertical atria and classrooms on different levels. Sleeping pockets and play areas are hidden within the façade and a central spine wall, all hidden under a large landscaped roof accessible to the public on the outside.

Fig. 2.8 Linggezi Man Y3, ‘The Elevated Theatre’. The building comprises an elevated auditorium within a dense lightweight

woven structural system. A series of physical and digital prototypes using threads and points were made to achieve the optimal structural system. Multiple cycle and pedestrian paths weave through the building and connect to the existing infrastructure, allowing visitors to freely pass through and over the building at any time.

Fig. 2.9 Jie Yi Y3, ‘Hydrotherapy Rehabilitation Centre’. Located in the Nordhavn Harbour area, the building consists of an integrated system of public and private routes, pools and enclosed volumes, all woven together by a complex timber structural system. Variations of wood bending and layering are used to create primary structure, shading devices and transitions between slab and façade. Fig. 2.10 Bryn Davies Y2, ‘Public Market’. The project is inspired by initial studies of local Danish allotments. The building features elevated stepped allotment platforms which overlook a flexible market place on the ground underneath. Fig. 2.11 Jiyoon Lee Y3, ‘Folding Pavilion’. The pavilion explores the idea of folding and unfolding in response to time and solar movement. A series of physical devices trace and capture various lighting conditions

throughout the day. Figs. 2.12 – 2.13 Jiyoon Lee Y3, ‘Community Bee Farm’. The symbiotic relationship between bees and people is controlled by a series of meshed filters with a range of opening sizes. The building also incorporates modular vertical gardens which provide an improved acoustic environment but also food source for the bees. The accommodation units feature private gardens and courtyards, allowing for views towards the central beehive and beyond.

Fig. 2.14 Joanna Mclean Y3, ‘Charlie and The Green Juice Factory’. The proposal is an organic fruit and vegetable market place, providing fresh goods to the growing community of Nordhavn. Produce unsold in the market is transferred into juice production, whereby the traditionally linear production process is reconfigured vertically and exposed in order for the visiting public to wander, explore and experience the process of fresh juice production. A variety of green juices are produced, changing in accordance with the available produce. Figs. 2.15 – 2.16 Patrycja Panek Y3, ‘Water House’. The project aims to explore entropic architectural design in the context of the hydro-environmental education and wellbeing centre in Copenhagen. The design encompasses two distinctive spectrums of experience, inside and outside, via bioengineered

brick façades and natural light filtering. The light is diffused via wall perforations and cascading waterfalls. The user is encouraged to engage with and explore the methods of water purification by visiting various zones within the landscape.

Figs. 2.17 – 2.18 Rusna Kohli Y2, ‘Elderly Community Villas’. In response to Nordavn’s mission to be the most sustainable district of Copenhagen, the project interweaves public and private activities, through layered landscape and greenhouses organised by a water channelling system. The project is comprised of modular living quarters under a horizontal system of water pools and falls, establishing a new horizontal density typology. Fig. 2.19 William Zeng Y2, ‘Street Food Market’. Inspired by traditional market arcades and canopies, the project incorporates covered streets and pavilions under an undulating colourful roof. Layers of perforated panels filter the light, creating an ever-changing spatial experience throughout the day. The roof structure is used to organise the spaces and circulation at ground level.

Figs. 2.20 – 2.22 Hugo Loydell Y2, ‘Maritime Education and Training Centre’. Located in Redmolen, an island to the east of Nordhavn, the centre incorporates sailing teaching facilities and communal space. The site is known for its nautical past, originally having been rebuilt from industrial docks. A series of digital fragment studies inform the overall structural system, which consists of large glulam structural timber frames and concrete deck. The new water inlets are sculpted to better integrate the boats with the internal working of the building. With the main harbour of Nordhavn located to the left of the building, the structure rises to open itself to the public. The main atrium provides access to the workshop, boat inlets, lecture theatre and classrooms. The timber structure transitions from the roof into the interiors to envelop

circulation and internal volumes, allowing the public and sailing students to navigate the space fluidly while still experiencing the building’s aesthetics.

Year 2

Paul Brooke, Yuqi Cai, Wei Ning Chung, Sebastian Fathi, Grey Grierson, Kyuri Kim, Samuel Martin

Year 3

Rupinder Gidar, Ziyu Jiang, Rachel Lee, Tung Yi Leung, Rory Noble-Turner, William Stephens, Yu Wu, Qiming Yang

Thank you to:

Consultants:

Year 3 Technical Tutor and Digital Workshops – David Edwards (Herzog & de Meuron)

Digital Workshops:

Wang Fung Chan (Heatherwick Studio), Niran Buyukkoz (Zaha Hadid Architects), Andrew Chard (Heatherwick Studio)

Guest Critics: David Edwards (Herzog & de Meuron), Konstantinos Chalaris (Chelsea College of Art), Aleksandar Bursac (Soomeen Hahm Design), Pereen d’Avoine (Russian for Fish), Nilesh Mahendra Shah (Russian for Fish), Serena Croxson, Manuel Jiménez García (The Bartlett, UCL), Caroline Lundin (Sundae Creative), Igor Pantic (Zaha Hadid Architects)

Guest Critics: David Edwards (Herzog & de Meuron), Konstantinos Chalaris (Chelsea College of Art), Aleksandar Bursac (Soomeen Hahm Design), Pereen d’Avoine (Russian for Fish), Nilesh Mahendra Shah (Russian for Fish), Serena Croxson, Manuel Jiménez García (The Bartlett, UCL), Caroline Lundin (Sundae Creative), Igor Pantic (Zaha Hadid Architects)

In Unit 2, we develop ideas through digital simulations, analogue prototypes, material tests and digital fabrication. We encourage digital and analogue making, shifting quickly between the hand and the computer. We are inspired by local materials, textures, architectural and urban typologies and local context.

Our students’ projects this year are situated in Mexico City, a large metropolis with an ever-growing population. Our theme focused on the notion of spontaneous procedures on an architectural and urban scale. Through an understanding of algorithmic design methodology, we asked the students to juxtapose organised and spontaneous systems – could we design through transformation, adaptation, re-organisation? We looked at the interfaces between stasis and flux, local and global, bottom-up and top-down, natural and artificial. Throughout the year, students developed highly spatial and architectural individual approaches informed by sophisticated urban, spatial and material research.

The year commenced with a short research project where students developed a range of analogue and physical prototypes informed by a procedure – a making technique. These initial constructs were then developed into architectural spatial systems, resulting in intricate structures, elaborate skins and integrated inhabited spaces. Students were encouraged to combine a range of design techniques in order to achieve highly articulated spatial hybrid constructs.

After the field trip in January, students chose individual sites and developed building projects in Mexico City. We were fascinated by the Mayan ruins still visible in the city, Louis Barragan’s beautiful use of colour and texture and the urban mix of various programmes, rituals, and ornament and building styles. We drew inspiration from the growing urban patterns in the city, the naturally occurring slum areas and defined modernist city blocks, and the interaction between natural and urban landscapes. We explored Mexico City as a spontaneous urban system and asked students to respond to its emerging contradictions. The projects are contextually sensitive while being contemporary and innovative in their architectural agenda. They vary in scale – from a secluded nunnery to a large infrastructural hub in the historic centre – with each responding to the cultural and urban diversities we found in the city.

Fig. 2.1 Tung Yi Leung Y3, ‘Reconstructing Mayan Architecture’. Based in the heart of Mexico City, the aim of the project is to reinterpret and reconstruct Mayan relief patterns with modern digital technology. Inspired by the geometric architectural decorations on the ornamental zoomorphic entrance from the Rio Bec, Chenes and Puuc regions from the 7th to 10th centuries, the building consists of a reusable building fabric that constantly changes according to the reconstruction that is taking place. Fig. 2.2 Rupinder Gidar Y3, ‘Reconfigurable Laminated Structures’. The building project is a new factory typology where flexible surfaces control visibility and light. Fig. 2.3 Kyuri Kim Y2, ‘Woven Structure’. The project studies the behaviour of woven strands through large-scale physical prototypes of foam and concrete. Fig. 2.4 Rachel Lee Y3,

‘Liquid Formations’. A particular interest in fluid dynamics and substances interaction was tested through a series of casts and moulds. These initial tests informed the notion of generating unique spaces using simulation in the building project later on. Fig. 2.5 Paul Brooke Y2, ‘OsteoFabricate’. The project focused on the transformation of fluid, freeforming material such as expanding foam into a structured and controlled architectural proposal. The resulting porosity and opacity gradients allow for varying quality of light. The material was tested using a bespoke apparatus in order to create a family of structural joints.

Fig. 2.6 Wei Ning Chung Y2, ‘Mexican Pottery Workshop’. The building consists of modular timber-frame components which can be adapted for various uses – housing market stalls, or creating stairs and roof platforms. The structures plug into the existing market street, creating a dialogue with the context and existing activities. Fig. 2.7 Samuel Martin Y2, ‘Cinema Complex’. The project is located in a residential area in Mexico City. Dynamic façade patterns are used as projection devices, creating an ever-changing building skin. The building skin also guides visitors through the building, creating a smooth transition between inside and outside.

Fig. 2.8 Yu Wu Y3, ‘Dancing School’. The design is inspired by traditional Mexican dresses with their rich layers of patterns and materials. Studies into the movement of a Mexican dress

led to the development of a complex hyperbolic roof structure. The roof folds create shading for the outdoor performance area and also establish a highly spatial experience for the dancers inside. Fig. 2.9 Sebastian Fathi Y2, ‘Glimpses into a Political Symbiosis’. The site in Mexico City is adjacent to Bazar El Oro which is a local ‘tianguis’ (temporary market). The proposal plays with a very particular political idiom in the city – the exchange between the market union leaders and the political delegate of the borough. The building provides a hostel for the tianguis market vendors between their nomadic trips across the city visiting other markets, office space for the local delegate and the vendors, and in addition, it augments the existing tianguis by introducing a new through-route.

Figs. 2.10 – 2.11 Grey Grierson Y2, ‘Student Housing’. The project reinterprets the traditional ‘Vecidade’ model (collective housing) for Mexico City’s student population. The angular outer geometry of the building is designed to draw away from the noise of the busy traffic on the adjacent motorway. The idea of the fold is taken from the entrance through to the communal courtyard landscape and the student rooms. The doors of the student units are able to fold across, allowing the students to create a highly social atmosphere. The skin is inspired by the geometric nature of traditional Mexican textiles which blend patterns of various geometries and sizes into one another. Figs. 2.12 – 2.14 Qiming Yang Y3, ‘Piñata Children's Workshop’. Piñata plays an important social role in Mexican’s festival culture. The building provides space for children to

design, make and showcase their own piñatas. The content of the building would eventually attract both locals and tourists so that they could experience the palace of piñatas as well as the nearby park. A series of study models reveals a deep façade with inhabited pockets and intricate structures, allowing for views and light to penetrate the building.