Our Design DNA

At The Bartlett School of Architecture, we have been publishing annual exhibition catalogues for each of our design-based programmes for more than a decade. These catalogues, amounting to thousands of pages, illustrate the best of our students’ extraordinary work. Our Design Anthology series brings together the annual catalogue pages for each of our renowned units, clusters, and labs, to give an overview of how their practice and research has evolved.

Throughout this time some teaching partnerships have remained constant, others have changed. Students have also progressed from one programme to another. Nevertheless, the way in which design is taught and explored at The Bartlett School of Architecture is in our DNA. Now with almost 50 units, clusters and labs in the school across our programmes, the Design Anthology series shows how we define, progress and reinvent our agendas and themes from year to year.

2022 Idiosyncrasy

Simon Dickens, CJ Lim

2021 Acts of Kindness

Simon Dickens, CJ Lim

2020 What If? An Alternative Urbanism History

Simon Dickens, CJ Lim

2019 The Virtues of Urban Resilience

Simon Dickens, CJ Lim

2018 In Search of Architectural Narratives and Manifestos

Simon Dickens, CJ Lim

2017 Relocation: The Making of Utopia

Simon Dickens, CJ Lim

2016 Poetics of a Resilient City

Bernd Felsinger, CJ Lim

2015 Redefining Utopia

Bernd Felsinger, CJ Lim

2014 Fauna City Bernd Felsinger, CJ Lim

2013 The Imaginarium of Urban Ecologies

Bernd Felsinger, CJ Lim

2012 SF Cities

Bernd Felsinger, CJ Lim

2011 An Imaginary Guide to Locality

Bernd Felsinger, CJ Lim

2010 Happy is the City which, in Times of War, Talks of Food Bernd Felsinger, CJ Lim

2009 Connections

Bernd Felsinger, CJ Lim

2008 Something Urbane, Something Kitsch, Something Imaginary

Bernd Felsinger, CJ Lim

2007 Building Assemblage of our Travels Bernd Felsinger, CJ Lim

2006 Adapting RED Bernd Felsinger, CJ Lim

Idiosyncrasy Simon Dickens, CJ Lim

Idiosyncrasy

Simon Dickens, CJ LimIdiosyncrasy in architecture and urbanism assumes many forms. The projects that fly in the face of reason are modern-day wunderkammern – crammed with randomly juxtaposed curiosity and with varying degrees of validity, they could empower the disenfranchised by embracing equality, diversity and identity.

From the metaphoric Delirious New York of Rem Koolhaas to the make-believe constructs of The Truman Show’s Seahaven, Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel and Gary Ross’s Pleasantville, idiosyncrasy offers liminal conditions of being in a space somewhere between lived experience and fairytale possibility. The telling architectural-cultural episodes from Koolhaas proved, above all, the city’s dedication to the most rational, efficient and utilitarian pursuit of idiosyncrasy.

Idiosyncrasy also comes in the form of micro-nations: the Vatican City inside Rome, the Principality of Sealand and the Danish island of Elleore, for example. Established as a gentle satire of the government structure and royal traditions of Denmark, Elleore has its own idiosyncratic traditions including a ban on the novel Robinson Crusoe (1719) and the use of ‘Elleore Standard Time’, which runs 12 minutes behind national Danish time. Locations of cities and communities can be equally eccentric and illogical. Tehran, Los Angeles, Kolkata, Tokyo, Jakarta and New Orleans all face a constant threat of potential calamity from earthquakes, monsoons, floods or tsunamis.

Our idiosyncratic weather and seasons can also be treated as resources. In the case of Jukkasjärvii’s IceHotel in Sweden, ice is harvested for construction in late November from the frozen Tome river. By April the sun’s rays have begun to melt the building and during June the IceHotel eventually dissolves completely into water. No two hotels are the same. From the river the ice came and to the river it shall return; all that remains are memories. In Djenné, Mali the immense undertaking of the epic one-day event known as the crépissage (plastering) ensures that the Great Mosque survives the brief but brutal rainy season. The shape of the mosque, along with the town’s traditional adobe homes, alters ever so slightly each year. Whether by bold environmental gestures or by subtle entrepreneurial spirit, our love affair with the city and its architecture is constantly rewritten. In the process, we build a fundamentally different idea of society at different times and in different places.

Year 4

Jasper Choi, Christopher Collyer, James EatonHennah, Kin (Anson) Hau, Hanna HendricksonRebizant, Francis Magalhaes Heath, Joseph Singleton, Kwan Yau Soo, Chuzhengnan (Bill) Xu

Year 5

Luke Angers, Yang Di, Shuwei Du, Tsun (Xavier) Lee, Shaunee Tan, Roman Tay, Rebeca Thomas

Technical tutors and consultants: Xiaoliang Deng, Philip Guthrie, David Roberts, Edmund Tan, Vilius Vizgaudis, Matthew Wells, Eric Wong

Critics: Peter Bishop, Andy Bow, Brian Girard, Simon Herron, David Roberts

10.1 James Eaton-Hennah, Y4 ‘Remaining Grounded: The Great British Staycation’. Idiosyncrasy is the interruption and provocation of everyday lives and routines through imaginative redefinitions of caution and logic. In partnership with Amazon, Flyme and the UK government, the proposal sees a reimagined Southampton Airport embrace the Covid-19 pandemic to redefine current notions of travel and retail for those choosing to remain grounded within the UK. During lockdown, airports – particularly domestic airports –sat disused and empty. At the same time, there was a rapid growth in ‘staycations’, with parts of the UK becoming overrun with British tourists. While addressing the environmental impact of air travel on the planet, the project harks back to the golden age of Victorian British seaside holidays and our yearning for Mediterranean landscapes.

10.2 Roman Tay, Y5 ‘The Un-forgetful Nature’. Idiosyncrasy is when forgetfulness erodes time, offering the wonder of the unfamiliar and new to disseminate origin stories. Colonisation has forced native communities to assimilate, losing both their culture and rights to their land. Situated on the salt flats of the Great Salt Lake Desert, the proposal starts by returning ownership of the sacred land to Native Americans to bring back its original identity. The uninhabitable landscape is infused with mythologies and beliefs to cultivate fresh water through the use of sea asparagus (samphire). Engagement with nature brings awareness of how changes in the forgotten communities could empower a country, while salt is a new resource for building climate resilience.

10.3 Shaunee Tan, Y5 ‘The Island of Water’. Idiosyncrasy is seeking refuge from the inhospitable, allowing us to yearn for what we often take for granted. Without human colonisation of the local ecology, how can the landscape provide all the resources required for living? Situated on Christmas Island, the project challenges the notion of yearning and critiques consumeristic human behaviours. In a slow-paced development choreographed by nature, the new inhabitable landscape acts as an interface for the symbiotic relationship between ecology and humans, striking a balance between nature and the built form. This education and research community provides a radical repositioning of what constitutes ‘living within our means’, suggesting that for humans to be saved from themselves, they must first protect nature.

10.4 Shuwei Du, Y5 ‘Freetown’. Idiosyncrasy is the ability to embrace climate malfunction, offering the potential to balance inequalities and foresee social and environmental metamorphosis. Subject to devastating flooding and uneven development, Jaywick, a coastal village in Essex, has been named one of the most deprived areas in Britain. Adopting the philosophy of the Freetown movement, Jaywick respects nature and harnesses the inexhaustible free resources of sea-level rises to liberate its citizens from the economic burden, material limitation, spiritual bondage and political restriction of a capitalist and consumerist society. In an exploration of the opportunities at the threshold of an equal society, waste mountains, wind farms, swallows’ nests, Cypress forests, vineyards and amphibious housing replace infertile land, planning restrictions, administrative inaction, poverty, unemployment, food insecurity and even health crises.

10.5 Christopher Collyer, Y4 ‘The House of Wisdom’. Idiosyncrasy is found in the in-between world, a superimposed refuge made from what was stolen and where forbidden knowledge of one’s own reality is discovered. Located at the border between Egypt and Sudan, an arid, rocky desert at the intersection of disputed colonial borderlines, the architecture is a place of temporary settlement and pilgrimage for Egyptian and

Sudanese women who have been denied an education. Alongside their studies, they work among light gardens, which harvest solar energy and nurture the newly greened land. The women subvert the traditional notion of male wisdom with ancient Earth-wisdom, utilising the ground, water, wind and sun to cultivate shelter and sustainable peace across borders, with shade being the key protagonist.

10.6 Yang Di, Y5 ‘Mount Epistle’. Idiosyncrasy is the attempt to engage human interactions in order to alter time, space and convention to attain self-consistency without reliance on technology. The civic infrastructure explores the potential of paper, namely through handmade paper-crafting during the day and a public letter-writing hub at night, reclaiming lost crafts and tactility with our surroundings and humanity. Renamed Mount Epistle, the old Mount Pleasant Mail Centre is an alternative public space that offers opportunities for human interaction and provides Londoners with a refuge from digital technologies. The shape of the mountainous truss beams and the plans are derived from the love letters of Henry VIII, who is believed to be the founder of the Royal Mail.

10.7 Tsun (Xavier) Lee, Y5 ‘The City: Falling/Fallen’. Idiosyncrasy is a scar from hell, sprinkled with love. Like society’s outcasts, the Kowloon Walled City has been a scar on governance and misunderstood by the rest of Hong Kong. The project is a social commentary on the current situation in Hong Kong. Light, water, air and sound are brought together in a vast and complex urban development as a metaphor for empowerment. Each protagonist responds to their specific functional calling and is no longer frowned upon but is a true saviour of the city. By this twist of fate, the reimagined Kowloon Walled City – once believed to be hell – is a love letter to the lost freedom and independence of old Hong Kong.

10.8 Rebeca Thomas, Y5 ‘Mr Murakami’s Place’. Idiosyncrasy is repeatedly carrying out the futile Sisyphean tasks that are unlikely to offer answers to the questions of climate change. Told through the nine lives of Haruki Murakami’s cat, the nine protagonists (from nine of Murakami’s novels) travel to the very ‘end of the world’ in search of the author-cum-agony uncle for answers. Instead of meeting the author, they are met with nine futile tasks, which they must endure for nine days. Within the extreme climatic context, the metaphor of the feline forms the architectural constructs on unresolved, uncertain and curious islands. By the ninth day, just like the endings in Murakami’s novels, the protagonists leave without answers, with only memories of hope to help them reflect on their personal impact on the environment. 10.9 Luke Angers, Y5 ‘The United Natures of Yestermorrow’. Idiosyncrasy is the expression of unexplainable, unpredictable and unaccountable phenomena, perceived through the anomalies of chance. Under the guise of environmental protection, preventing sea-level rise and cooling the Arctic, the United States performs a covert land reclamation of the ice floes in the Bering Strait. The Americans surreptitiously salvage drifting ice to grow the footprint of Little Diomede year-round, creating a landmass ever closer to the surface area of Russia’s Big Diomede. The ‘gift’ of world diplomacy in the form of the UN headquarters is akin to a Trojan horse, disguising the export of American nuclear waste to the farthest corner of their territory. The new American architectural espionage is offered as a model of sustainable environmental design, generating warmth for the delegates’ accommodations and diplomacy at the speakers’ tables.

Acts of Kindness

Simon Dickens, CJ Lim

Acts of Kindness

Simon Dickens, CJ LimIn the age of pandemic, protests and politics, we need to nurture kindness and compassion in the multi-engagements and practices of the built environment. Kindness is not a cure but it can be a tool to help prevent the negative impact of violence, fear and subsequent discriminatory behaviours. Without individual or collective acts of kindness, there is no hope for equity, democracy and diversity. This year PG10 asked, How might kindness from different perspectives – cultures and communities, economies and ecologies, politics and policy – promote social transformations of cities and buildings? How might networks of compassion and forgiveness build resilience and address the challenges posed by climate change?

Protecting our planet is an act of kindness. George Orwell, after witnessing the destruction of London’s trees during the Blitz, wrote the essay A Good Ward for the Vicar of Bray suggesting that ‘… every time you commit an antisocial act, make a note of it in your diary, and then, at the appropriate season, push an acorn into the ground. And, if even one in 20 of them came to maturity, you might do quite a lot of harm in your lifetime, and still… end up as a public benefactor after all’.1

Patriotism is an act of kindness; contrary to popular perceptions of merely being ornamental melancholic buildings of no useful purpose, follies were mechanisms for maintaining national social good during times of unrest. The construction of Conolly’s Folly (1740) in County Kildare, Ireland, was intended to provide employment for starving farmers stricken by successive cold and wet winters, without robbing them of their dignity by issuing unconditional handouts. Improving quality of life is an act of kindness; by showing kindness towards others, we strengthen our sense of interconnectedness and the wellbeing of our communities. Maggie’s centres – a network of drop-in centres across the UK and Hong Kong, which aim to help anyone affected by cancer – are not in any form a substitute for hospital treatment. The network of buildings offers informed advice, therapy and daily practical and emotional support, and are there to improve quality of life for patients and families.

The discourse on kindness started with three workshops on two-and-a-half dimension drawings, animations and speculative narratives. Each student posited a divergent status quo to establish an intellectual position and visionary ideas to address the world in crisis. Whether it is a national campaign, an informal community initiative or simply an individual act, the heart of this year’s architecture narrative was where we discovered the true potential of our human condition.

Year 4

Luke Angers, Tu-Ann Dao, Shuwei Du, Leo FrançoisSerafin, Tsun Lee, Thabiso Nyezi, Elliot Pick, Jignesh Pithadia, Shaunee Tan, Roman Tay, Rebeca Thomas, Alexander Venditti

Year 5

Billie Jordan, Hiu Chun Kam, Yongwoo Lee, Jiashi Yu

Technical tutors and consultants: Philip Guthrie, Jon Kaminsky, Christopher Matthews

Workshop consultants: Xiaoliang Deng, David Roberts, Edmund Tan Hong Xiang, Vilius Vizgaudis, Matthew Wells, Eric Wong

Critics: Peter Bishop, Andy Bow, Christine Hawley, Simon Herron, David Roberts

1. George Orwell (1946), ‘A Good Ward for the Vicar of Bray’, Fifty Essays, (Oxford City Press), pp398–401.

10.1 Luke Angers, Y4 ‘A Columbarium of Dark History’. In John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men (1937), an act of kindness is also an act of grim sacrifice. Just as historical sacrifices of resources have transformed the built environment, so too can personal and symbolic sacrifices reshape our future responsibilities, with a little technological help. The project investigates the decline of oil-producing American states and proposes a specific intervention in the derelict town and oil field of Drumright, Oklahoma. Through a process of disassembly, the disused industrial ‘accomplices’ of airplanes and automobiles feed the construction of a mechanical landscape to reclaim the oil field. Disassembled materials are painted white using limestone pigment to reflect sunlight, creating a new micro-climate that attracts insects and flora. The operable fuselage roof structures act as large insect-capturing mechanisms that attempt to control rising populations of crop-eating locusts, while providing a sustainable protein source for the nearby population in Oklahoma City.

10.2 Shaunee Tan, Y4 ‘The Anatomy of Being Chinese’. Kindness is the navigation of love and lies in Lulu Wang’s film The Farewell (2019), highlighting the differences between Western and Chinese family values, perceptions and prejudices. The Chinese Embassy in London aims to provide a counter-argument in response to the misconception of China, its community and the second generation Chinese-British immigrant. The spatial versatility of a traditional Chinese courtyard house is reimagined as the home of an ambassador, providing a full range of diplomatic and consular services. By rotating the courtyard outwards, the typically personal and vulnerable typology of a home is exposed to welcome all. It no longer faces heaven, but towards humanity. Concepts of care, navigation, transparency and progress are synthesised into an essay of porcelain blue, collectively representing the nation and what it means to be Chinese, by the Chinese, to the British public.

10.3 Rebeca Thomas, Y4 ‘The Silhouettes of Christmas’. The urban strategy supports the vulnerable, mediates unconscious bias and redefines the act of giving as an act of kindness itself. The inhabitable silhouettes of the first 11 days of Christmas are distributed along the River Thames – the lightweight constructs enable community involvement through donation of tinned food and allotments. Located next to the Houses of Parliament is the 12th day, featuring a piccalilli store with more allotments and a mushroom farm where food is cultivated all year round for the Christmas dinner. Critical thinking is further embedded through the architectural collage of the silhouette structures to form the seasonal building, a metaphoric spatial extension of the Common’s Library. Since the UK Parliament is often referred to as the House of Commons, the spatial layout of the project reflects diverse architectural aspects of ‘the people’s palace’. The architecture of silhouettes is a socio-political commentary on the modern consumerist Christmas and responsibilities of Parliament. 10.4–10.7 Yongwoo Lee, Y5 ‘Dear My Beloved Mircioiu’. Kindness is patience and with true love, memory and hope we can erase divisions and borders. Inspired by a true story in which North Korean orphans were sent to Eastern Europe in the 1950s as a result of the Korean War, the project explores how kindness and emotions are resources for the built environment. Narrated through the imagined diary of Cho in North Korea and the fragmented information from his wife Mircioiu in Romania, the principle design strategy is to apply the atrocities of the war as a landscape of memory and patience to restore hope, love and humanity. Against the inevitability of time, architecture is regarded as a continuous process, existing through diverse

interpretations, incorporating timescales of transformation. The constructed metaphor takes the form of social architecture with communal benefits supported by the authoritarian regime. Cho exploits the constructed reality to make his personal idealism tangible and real. Taking on the idiom ‘hidden in plain sight’, each tectonic has a dual function and meaning: social benefit and Cho’s hope, memory and love for his wife. 10.8–10.9 Jiashi Yu, Y5 ‘Kindness Is Farewell?’. The accelerating divorce rate in China has become a destabilising force. Can the Great Wall, which once served as a powerful national defence infrastructure, protect familial and social stability? Taking inspiration from Marina Abramović and Ulay’s performance The Lovers (1988) – over 90 days, the then-lovers walked from opposite sides of the Great Wall and met in the middle to break-up – couples contemplating divorce embark on a journey along the wall to reflect and possibly reconcile their differences. The reimagining of the Great Wall is an homage to Chinese family values, but also a criticism of the wall’s history and the feudalistic mindset it represents. The conceptual lines and materiality of the new architecture captures the fragility of marriage and the maintenance required for an enduring one. While a single line might be easily broken, weaving them together creates resilience and strength. This bitter-sweet architectural story of kindness can impact China’s future built environment and offers an alternative analysis and appreciation of historical monuments.

10.10–10.13 Hiu Chun Kam, Y5 ‘A Love Letter to My Childhood Hero’. In Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird (1960), an act of kindness is not presented under the scrutiny of light but in its purest form, hidden within the intangible realm of shadows. The project is a love letter to a domestic helper called Sonia, whose day of rest on Sunday may seem mundane but, through the imagination of a child, is a fantastical journey of self-empowerment using shadows. Statue Square in Hong Kong is transformed into an ephemeral garden harvesting shadows for the earthly foolishness of consumerism, which has cultivated an obsession with fair skin in China. In an ironic twist of fate, domestic helpers are the guardians of that sought-after resource. The imaginative retelling of Sunday gatherings is a whimsical and satirical sociopolitical story of shadow that reaffirms the ‘mockingbird’ values of care, empathy and kindness. 10.14–10.15 Billie Jordan, Y5 ‘The Perfect Storm’. Within the magic of literature, kindness is repentance, reconciliation and recuperation: Prospero repents in the last act of Shakespeare’s The Tempest (1611), just as Britain repents for its past ecological destruction by allowing for the coastline to be given back to the sea; the retreat of the British coastline provides a new zone of international sovereignty that welcomes climate refugees of all nationalities, reconciling a post-Brexit Britain with the international community; the protagonists of the floating city are appointed as environmental warriors to pioneer new sustainable utopian communities, recuperating the damaged British coast. The new community embraces Ariel, the representative of rising sea levels, climate change and the wild spirit of ecology. The two faces of humanity are both practical and romantic, logical yet ideal – Prospero’s idealism allows us to venture into the unknown, embracing the fluctuation of ecology and the emancipatory power of Ariel’s storm. The poetic and magical tempest in Prospero’s books empowers and redeems the citizens. Can the naive fantasies of Prospero recuperate the societies and ecologies which were once destroyed?

What If? An Alternative Urbanism History

Simon Dickens, CJ Lim

What If? An Alternative Urbanism History

Simon Dickens, CJ LimIn their 1971 song, John Lennon and Yoko Ono invited us to imagine: ‘…there’s no countries / Nothing to kill or die for / And no religion, too / Imagine all the people / Living life in peace.’ After the Great Fire of 1666, five different architects drew up plans to rebuild London. The Roman-style grid plan of Sir Christopher Wren, with large piazzas geometrically linked by long, wide boulevards was deemed not to be cost- or time-effective. But what if Christopher Wren’s architectural dream for London had been implemented? London would have missed the opportunity to be a kaleidoscope of smells and shadow of architectural styles. What if San Francisco had been rebuilt after the 1906 earthquake with a Japanese motif, and renamed Sansokyo as featured in Chris Williams and Don Hall’s film Big Hero 6 (2014). Similarly, history could have taken a different direction with Philip Roth’s novel The Plot Against America (2004) in which Franklin D. Roosevelt is defeated in the presidential election of 1940 by Charles Lindbergh. If we maintain the same critical thinking as Lennon, Roth et al. – and focus on the imagining of alternative built environments – what could urbanism in Europe, southeast Asia, or the USA look like without inherited or imposed Roman, British Colonial, or modernist influences?

Humanity constantly holds a mirror to the present. The speculative concept ‘what if?’ can apply equally at the macro/ societal level and at the micro/personal level. In Frank Capra’s film It’s A Wonderful Life (1946), a desperately frustrated man is shown by an angel what life would have been like if he had never existed. It is in the opportunity for alternative histories that the unit can better understand how to address the world in crisis, resulting in the evolution of resilient architecture and planning tailored for the determining factors of climate, resources and the idiosyncrasies of humanity.

In Project One this year, students identified the ‘what if?’ for an alternative history, and its related issues and consequences in the present day. Through research, analysis and critical thinking, students formulated a narrative with specific timelines and protagonists which provided a speculative programmatic framework for the year.

In Project Two, the narrative and critical thinking from Project One were applied to a location that is ‘undesired’ – due to climate, economy, geography, lack of inhabitation or indifference. Students were encouraged to present curious, bold and even naive alternative urbanisms and architectural polemics (and not necessarily sensible solutions or enlightenment values) to develop at least an innovative commentary on the crisis of the present day. Just imagine…

Year 4

Nnenna Itanyi, Joel Jones, Billie Jordan, Hiu (Hugh) Chun Kam, Yongwoo Lee, Jiashi (Jess) Yu

Year 5

Xiaoliang Deng, Edmund Tan, Tyler Thurston, Ka (Karen) Tsang, Kit Wong

Thanks to our technical tutors and consultants Jon Kaminsky, David Roberts, Chris Matthews, Philip Guthrie

Tyler Thurston, Y5 ‘What if George Had the Recipe to Create EU-topia?’. The strategy, fiction as a tool for awareness, reconfigures the EU by protecting the Mediterranean Sea, and encourages an alternative participatory democracy. Inspired by Roald Dahl’s book George’s Marvellous Medicine, through the lens of George and other children from all EU states and North Africa, the architecture examines the thresholds between ideology and pragmatism when engaging with nature, landscape and weather, with the aim of eroding politics and geography. Environmentally-friendly ingredients including salt, eggs, plant pigment, beeswax, pea, and olive oil are cultivated to protect water safety and equality for all. Looking towards the unconventional, the architecture is designed to be a series of delightful learning experiences, in a similar way to a Dorling Kindersley book, in which knowledge is delivered by inspiring curiosity and play. In this synthesis of responsibilities and innocence, children are the champions of their own sustainable future, adapting the core message of love and hope for the EU. 10.6 Edmund Tan, Y5 ‘What if Civilisation were Given a Second Chance?’. What sort of society would we want to be, and how does nurturing nature help recalibrate our wasteland into a resilient Arcadia? Instead of shepherds in idyllic visions of pastoralism, the project finds WALL-E (and later EVE) in a hypothetical near-future urban scenario in Manhattan – inspired by the ‘Eye of Providence’ on the USA one-dollar note, symbolising faith watching over humanity. Drawing on climate change, environmentalism, and consumerism, the eventual symbiosis between nature and built form are events of urban ‘responsibilities’ at varying scales to be encountered in the future. The timeline is considerable and defines the new ages of evolution as the city cleanses itself of past neglect. Like a sliding puzzle, the city carefully shifts with repurposed public spaces and a filigree of new infrastructure. While the robots are the key facilitators, the idiosyncrasies and symbolism of the cats provide the heart and wit for this eccentric redefinition of the Arcadia romance. This cautionary tale does not promise ‘happily ever after’ in which a clean planet is handed back to humans, but aims to bring awareness, decelerate our current fast-paced society and embrace climate change as a resource. The characters of WALL-E and EVE are from Pixar Animation Studios’ animated film ‘WALL-E’ (2008). 10.7 Ka (Karen) Tsang, Y5 ‘What if Narratives Turn Environmental Tokenism into Genuine Sociopolitical Benefits?’. Globally, green groups have dismissed the glut of climate change forums and environmental largesse from businesses, cities and states. Narrative, rather than statistical scientific data, is the machinery for commentary and is more likely to capture the public’s awareness and expose philanthropic hypocrisies. The heart of this architectural story is where we discover the true potential of our human condition, especially for women of ethnic minorities. The protagonist, Aleqa, a Greenlandic woman exposes the hubris of environmental tokenism and a way to rise above it – adapting the ugly truth as a resource for independence, equality and social change in a larger context and for a higher cause – climate change. The strategy of the floating ‘Ice Garden’ in Odense, inspired by the two weavers in Hans Christian Andersen’s ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes’, exploits Denmark’s vanity and self-proclaimed environmental superiority. The unintended empowerment of the women outweighs the country’s hypocritical deceit, and ultimately, the project is a love letter to humanity.

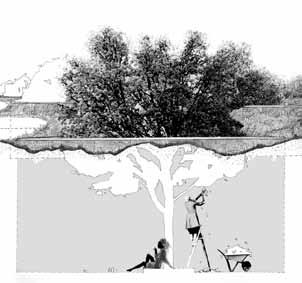

10.8–10.11 Xiaoliang Deng, Y5 ‘What if the Tree of Life is not Science but a Nuanced Artform of Reincarnation?’. It is our human right to decide our own death, and to pass onto the next phase of life’s journey. History is littered with deeply profound architecture relating to dying and death,

but perhaps ecological dispositions are better than philosophical translations? Embracing climate change the design weaves life into sunken histories and invites the landscape to participate in transcendental contemplation, offering sensitive spaces in which to reframe the belief in diverse interpretations of reincarnation. The vignettes on the Isle of Thanet adapt old values of Christianity into a new universal faith of atonement towards nature. The conscientious interventions display a delicate and temporal relationships with the existing landscape – a reminder of our transitional existence on earth. As with karma and the cyclical transmigration of souls in David Mitchell’s novel The Cloud Atlas, the first vignette – the reception – is also the final vignette, the crematorium. There is a symbiotic recurrence of time: at every hour when the clock’s bell chimes, a soul is embraced in heaven. 10.12 Kit Wong, Y5 ‘What if Liverpool is Never Winter, but Always Christmas?’. As with real social integration, effective environmental efforts are shaped primarily by a civil society. How can syncretic cohesion between foreign and domestic cultures rebirth a resilient urbanism? ‘Always winter and never Christmas; think of that!’ Unlike C.S. Lewis’ hypothetical question, the student’s grandfather, who arrived in Liverpool as an immigrant in the 1930s, is the embodiment of transcultural idealism that is always Christmas. Never restricted by existing contextual planning and cultural conservatism, the grandfather’s metaphorical narrative of acceptance and cohesion delivers a majestic northern powerhouse grandeur as the Mersey gateway. Protein-providing plants and bamboo are cultivated side-by-side to celebrate diverse values and identities in a romantic rebirth of the landscape which is vertical and on water. The bold agrarian sustainable economy erodes the negative culture of ghettoised urbanism with a new multicultural Sino-Mersey development that strategically ‘bridges’ Liverpool and Birkenhead. This heartfelt project is a legacy of climate change that would forever alter the perception of Chinese people in Britain.

The Virtues of Urban Resilience Simon Dickens, CJ Lim

The Virtues of Urban Resilience

Simon Dickens, CJ LimFaith, hope and charity are theological virtues, but they functioned as supremely civic virtues during the flowering of communes, guaranteeing good government. This is because love of the city one calls home has its roots in charity, and the actions of justice are animated by faith and by hope for divine guidance.1

It is certainly true that faith builds, as seen in the holy cities of Mecca or Varanasi, or in the hubris skyscrapers of Dubai that are propped up by belief in the oil economy. In the US in the 1920s and 30s, the Hoover Dam and Boulder City in Nevada came to symbolise hope for the millions of dispossessed Americans in the depths of the Great Depression. President Herbert Hoover feared public dependency on the federal government and realised the dam could unite public work and private enterprise, improve mass-employment and quality of life, support the economy and promote patriotism. In 19th-century Paris, urban planner Baron Haussmann (1809-1891) was both celebrated and despised for building much of what has since become synonymous with the city. By driving sweeping boulevards through the urban slums barricaded by the revolutionaries, he transformed Paris into a city of light and trees in an effort to improve living and working conditions. Whether by bold gesture or subtle attrition, cities are constantly rewritten. Henri Lefebvre (1901-1991), the French sociologist and author of the seminal text Critique of Everyday Life, argued that every society produces its own spatial practice. At every critical juncture, the shape of the space that will help us contest climate change, social deprivation and deficiencies in food, water and energy has to be reimagined. In 1967, Le Corbusier lamented that, ‘The world is sick. A readjustment has become necessary. Readjustment? No, that is too tame. It is the possibility of a great adventure that lies before mankind: the building of a whole new world.’ 2 This comment might appear prescient, but it could have been written at any time in history. In the age of Trump and Brexit, Frugoni’s virtues, faith, hope and charity, are key in redefining the built environment and the notion of citizenship: not only access to the rights guaranteed by the nation-state but more active and pluralistic forms of participation that promote community resilience.

For their project this year, Year 4 students chose a painting and employed a narrative that prioritised and redefined the spatial poetics of either faith, hope or love. The interpretations and identified issues provided a speculative programmatic framework for the year.

Year 5 students were required to identify a feature of their chosen site that qualified it as ‘undesired’, be it the weather, economy, geography, lack of inhabitation or indifference. The symbiosis between place and narrative informed their visionary urban design and architectural proposals.

Year 4

Lap Yan Chow, Xiaoliang Deng, Adrian Hong, Luke Hurley, Edmund Tan, Tyler Thurston, Ka (Karen) Tsang, Kit Wong

Year 5 Nicole Cork, Junchao Guo, Peter Hougaard, Jinrong Lai, Benjamin Simpson, Vilius Vizgaudis, Ananda Wiegandt

Thank you to Jon Kaminsky for his teaching of the Design Realisation module, David Roberts for the Manifesto Workshop and Matthew Wells for the Structures Workshop

Thank you to our consultants: Nathan Blades, Peter Brickell, Nathan Blades, Michela Martini, Chris Matthews, Sam Smith, Rachel Yehezkel

1. Chiara Frugoni, A Day in a Medieval City, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), p21

2. Le Corbusier, The Radiant City: Elements of a Doctrine of Urbanism to be Used as the Basis of our Machine-Age Civilisation, (London: Faber & Faber, 1967), p92

10.1 Ananda Wiegandt, Y5 ‘The Valley of Harmony’. Grant Wood’s American Gothic (1930) depicts the determination of the Midwestern rural population to work with the land during the Great Depression. The new landscape in ‘The Valley of Harmony’ promotes neighbourly love and provides earth-sheltered sustainable housing for the disenfranchised elderly and migrant populations, and facilitates an influx of seasonal cultural visitors. The extensive cultivation of pollen-emitting trees in the brown coal open-cast mines supports the creation of an environmental cooling spine through Europe, which aims to mitigate the effects of the changing climate, whilst the tree conveys notions of ‘cohesion’, ‘resilience’ and ‘tomorrow’.

10.2 Peter Hougaard, Y5 ‘The Garden of Difference’. Yayoi Kusama’s psychological illness and society’s misfits are the creative inspirations behind her artworks. Similarly, in ‘The Garden of Difference’ weakness is strength, limitations are possibilities and difference is everyday’s normal. Sexual and social misfits, disfranchised individuals and minority cultures work side-by-side with the citizens of Northallerton in Yorkshire to redevelop their high street and address increasing social monotony, prejudice and hostility. The architecture introduces social metaphors to unconventional construction techniques and materials, and questions conservative values: arcades made from living trees decorated with chandeliers of marijuana; hedges filled with worms fed to salmon in a park; cardboard box hotels; scaffolding platforms for selfie-taking tourists; and a carpark with former prostitutes eager to listen and discuss the state of the town.

10.3–10.4 Jinrong (Jerome) Lai, Y5 ‘The Appreciation’. This project draws similarities to Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Netherlandish Proverbs (1559) and is a propaganda to unmask human follies. Chinese President Xi Jinping believes that both morality and water quality in China are polluted. To bring faith and morality back into society and the environment, this project employs greed to cultivate awareness and encouragement in protecting against irresponsible outcomes, following the discovery of contaminated water resources due to unregulated industrialisation. Informed by shan shui paintings, the architecture creates not a perfect society but an acceptable equilibrium with nature. 10.5–10.6 Ben Simpson, Y5 ‘A Portrait of Self-Love and Self-Reliance’. In response to Theresa May’s proposed ‘Festival of Brexit’, the project seeks not to revitalise national pride in clichéd short-lived event formats but, instead, invests in the regeneration of undesirable parts of the UK. A renewed ideology of ‘Britishness’ draws from the much-disparaged weather, agriculture and resources of pride identified in Lucas Cranach the Elder’s Cupid complaining to Venus (c.1525): apples, timber, deer, honey, wool, myrtle and water. The new ‘green corridor of self-love and self-reliance’ protects areas of conservation that have seen recent industrial decline, as well as those that have lost industry due to Brexit. It provides a continuous passage for deer from Inverness to Cornwall, and is punctuated by community participation ‘Self Stores’, apple orchards offering employment, produce depots and intergenerational social spaces.

10.7 Nicole Cork, Y5 ‘The Renaissance of Burnley’. Derived from Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s poem ‘The Lady of Shalott’ (1842), ‘The Renaissance of Burnley’ symbolises hope and depicts a pivotal moment of change empowered by nature. Under the new doctrine of the ‘Post-Industrial Sisterhood’, stems an appreciation of context and strategies to heal nature and rehabilitate the ground. By adopting the 2050 UK Climate Agenda and Fifth Carbon Budget, the post-industrial coal mining town is transformed into a clean-energy producing inhabitable landscape and nature reserve. It explores the opportunities of canal engineering with hybridised housing, addressing the issues of dereliction, unemployment, emigration of the working age, fuel poverty and contaminated waterways. 10.8 Junchao Guo (Julian), Y5 ‘V for Virtue: The Landscape of Tranquility’. The hope to relieve fraught political relations between China and Tibet is rooted in the principles of Buddhism and the harmony between human and nature. Within the ‘Ring of Life’ and the qingke barley landscape are five seasonal interventions made primarily from ice, appearing only in the coldest part of winter to teach the virtues of peace: ‘Sky Road’ (the path of forgiveness), ‘Pavilion of Humility’ (communal dining), ‘Moonlight Podium’ (a floating structure to contemplate afterlife), ‘Bodhi Trees’ (the library of enlightenment) and the ‘Earthly Disciples’ (short-term mud lodgings for Tibetan farmers). Through this sublime landscape, Tibet is offering China a form of salvation and spiritual repent from their relentless industrialisation. 10.9–10.10 Vilius Vizgaudis, Y5 ‘The Gift: Freedom, Equality and Diversity’. Analogous to the Hieronymus Bosch painting The Conjurer (c.1502), French President Emmanuel Macron hopes to convince American President Donald Trump to rejoin the Paris Climate Agreement. ‘The Gift’ rethinks the American city of Paris in Texas through the values of the Climate Agreement and the romantic French-Parisian lens symbolising freedom, equality and diversity. This new 21st-century Statue of Liberty promotes not only hope for urban climate resilience but, also, neighbourly love and humanity. The protagonist of ‘The Gift’ is a new, suspended River Seine that runs through the city and elevates the importance of water. The project provides shared housing, clean energy, local food, water and employment for an increasing number of American climate-change holidaymakers and refugees: people temporarily or permanently forced out of their homes due to extreme weather events.

In Search of Architectural

Narratives and Manifestos

Simon Dickens, CJ LimYear 4

YueZai Chen, Nicole Cork, Junchao Guo, Peter Hougaard, Jinrong Lai, Hoi (Kerry) Ngan, Benjamin Simpson, Phot Tongsuthi, Vilius Vizgaudis, Lu Wang, Ananda Wiegandt

Year 5

Anna Andronova, Elliott Bishop, Jason Hon Ho, Mohamad Qaisyfullah Bin Jaslenda, Tristan Taylor

Thank you to Jon Kaminsky for his teaching of the Design Realisation module and David Roberts for the Manifesto Workshop

In Search of Architectural Narratives and Manifestos

Simon Dickens, CJ LimRoland Barthes comments that ‘narrative is present in every age, in every place, in every society; it is simply there, like life itself.’ It is therefore significant that buildings and cities, as physical repositories of and monuments to human culture and history, should now imply meaning beyond their quotidian functions. In pre-secular times, it was not unusual for buildings to be constructed of and around narrative, and determined by metaphor. In his 1978 book Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan, Rem Koolhaas employs this strategy, depicting the city as a metaphor for the diversity of human behaviour. However, not only is narrative unfashionable in contemporary practice, but the modern age has also been unkind to architectural manifestos. Many manifestos in their purest forms are uncompromising calls for change. In 1914, Antonio Sant’Elia wrote in the Manifesto of Futurist Architecture that ‘every generation must build its own city, and for which we fight without respite against traditionalist cowardice’. Even Walter Gropius, a scrupulously practical architect, called for architects to ‘engrave their ideas onto naked walls and build in fantasy without regard for technical difficulties’; he suggested they make ‘gardens out of desert’ and ‘heap wonders to the sky’. Nearly every important development in the modern architectural movement began with the proclamation of these kinds of convictions. The manifesto for Ebenezer Howard’s garden city, for example, was inspired by Edward Bellamy’s utopian tract, Looking Backward: 2000–1887. Published in 1888, Bellamy’s novel immediately spawned a political mass-movement and several communities adopting its utopian ideals – open space, parkland and radial boulevards that carefully integrated housing, agriculture and industry.

This year, Unit 10 focused on the potential of architecture and urban design to address the fundamental human requirements to protect, to provide and to participate. The design projects explore issues of sustainability, resilience and the challenges posed by climate change, and the reciprocal benefits of simultaneously addressing the threat and the shaping of cities. Climate change offers the opportunity for imaginative interventions, as a new lens through which cities are forced to rethink priorities and established dogma. No longer should climate change be considered solely in the realms of scientific policy: the effects of climate change on architecture include changes in culture, behaviour, demographics, population growth and economic environment. Narrative is most valuable in its speculative function, and can inform the built environment. The stimulus of our projects derives from postulated narratives and processes gleaned from literature and fiction as well as the current body of scientific knowledge regarding changing environmental impacts on architecture and cities.

Fig.10.1 Tristan Taylor Y5, ‘New Martha’s Vineyard: A “New World” Colony for the Reverse Climate Pilgrims of America’. Inspired by the extraordinary journey of the Pilgrim Fathers, a new tribe of American Climate Pilgrims, disenfranchised by the anti-environmentalist stance of Donald Trump, embark on a reverse pilgrimage back across the Atlantic to plant a new colony in Aberavon, South Wales. Figs. 10.2 – 10.3 Elliott Bishop Y5, ‘The Sweet Proposal: A Cautionary Tale of the Corporate City’. Nestlé converts the city of York into a corporate dystopia veiled in a façade of sweetness inspired by F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. The confectionery city is a critique of urban privatisation where corporate infrastructures control our governance, employment, housing and nutrition.

Figs. 10.4 – 10.5 Anna Andronova Y5, ‘The Grand Paris of Niger’. This sublime, lush oasis on a major human trafficking route aims to empower local communities and discourage their dreams of migrating to Europe. Regeneration is made possible through a holistic water management system of harvesting, treatment and usage.

Figs. 10.6 – 10.7 Mohamad Qaisyfullah Bin Jaslenda Y5, ‘The Holy City of Detroit’. Highlighting the delusional state of Trump’s America, the project aims to critique the policies under his administration, and the manipulation of Christianity for political and economic gain. Figs. 10.8 – 10.9 Jason Hon Ho Y5, ‘The United Kingdom in the Southern Hemisphere’. A branch of the UK in the post-Brexit era, the retirement wonderland protects the British economy, ecology, the National Health Service, and the hydrocarbon zone within the territorial waters of the Falkland Islands. Inspired by the portable floating Mulberry Harbour developed by the British Army during the Second World War, the extraordinary project transforms water into inhabitable land in 12 days.

Relocation: The Making of Utopia Simon Dickens, CJ Lim

Year 4

Anna Andronova, Qaisyfullah Bin Jaslenda Mohamad, Jason Ho, Gintare Kapociute, Kannawat Limratepong, Alfie Stephenson-Boyles, Tristan Taylor, Yui Wong

Year 5

Damien Assini, LiJia Bao, Nathan Fairbrother, Isabelle Lam, Kai Hang Liu, Zhang Wen

Thank you to Jon Kaminsky for his teaching of the Design Realisation module

Relocation: The Making of Utopia

Simon Dickens, CJ Lim"Arrival of the Floating Pool after 40 years of crossing the Atlantic, the architects/lifeguards reach their destination. They have to swim toward what they want to get away from and away from where they want to go," Rem Koolhaas, ‘The Story of the Pool’, 1977.

In Koolhaas’ ‘Delirious New York’, in the tradition of the science fiction tropes of Jonathan Swift and Jules Verne, Russian Modernist architects used a portable pool infrastructure to escape Soviet oppression and make it to the United States of America. Meanwhile, the architects of the ‘Wandering Turtle’, Brodsky and Utkin, opted instead to remain in Russia to produce “an escape into the realm of the imagination that ended as a visual commentary on what was wrong with social and physical reality, and how its ills might be remedied”. The decisions to relocate or to remain are both basic human rights, and can be applied as strategies for the making of utopia. According to the 2006 Stern Review, around 200 million people will be permanently displaced by 2050, through an amalgamation of complex economic, social and political drivers, exacerbated by increasingly unpredictable environmental conditions. Rather than ‘fighting’, governments, together with planners and architects, need to envision built environments that embrace the enemy.

Relocation of capital cities is not uncommon. The ancient Egyptians, Romans and Chinese changed their capitals frequently. Some countries choose new capitals that are more easily defended in a time of invasion or war; others build in undeveloped areas to spur unity, security and prosperity. The decision to relocate the Brazilian capital from Rio de Janeiro to Brasilia was intended not only to relocate the seat of national power symbolically but also to shift the demographic and economic focus away from the country’s European colonial powers and towards the vast hinterland.

Can the appropriation of fiction and narrative inform the shaping of an urban and architectural vision, while addressing real and urgent sociopolitical, economy and environmental concerns? In PROJECT 1, students will speculate, prioritise and redefine the poetics of ‘relocation’ and ‘utopia’. The interpretations and identified issues will provide a speculative framework and programme for the year. In PROJECT 2, utopia has to be located at a place of ‘undesired’. Does ‘utopia’ occupy the territory of ‘urban’, ‘suburban’ or ‘landscape’? We encourage expressions of personal ideology, scale and working methods in search of visionary and innovative architectural proposals.

10.2 10.3

Fig. 10.1 LiJia Bao Y5, ‘Splendour: The Eastern Cultural Capital’. An attempt to rebrand its political image, China relocates its cultural investments to the disputed territories in the South China Sea. Splendour aims to be the ‘open’ pilgrimage destination for all Chinese-speaking global citizens. Figs. 10.2 – 10.4 Damien Assini Y5, ‘The Re-Imagination of HS2’. The UK government claims that the high-speed rail that links London with the Midlands will boost productivity. Through the socioeconomic lens of the Guardian newspaper, the project speculates what the urban alternatives might have been instead of the transport link. Fig. 10.5 Zhang Wen Y5, ‘The Liquid Gold Odyssey’. China exploits Greece’s financial woes to gain an economic and investment foothold in Europe, and relocates the Port of Shanghai to the Cyclades. Inspired by

Homer’s ‘Odyssey’, the new development provides a strategic trading outpost for Chinese merchants to source high-grade ‘liquid gold’ – olive oil for the ever-growing market in the East. Fig. 10.6 Isabelle Lam Y5, ‘Moonrise Kingdom’. The alternative Legislative Council of Hong Kong is a network of recycling centres and prefabricated temporary floating homes, and implements policies of anti-consumerism, pro-democracy and philanthropy.

10.7 10.8

10.10 10.9

Figs. 10.7 – 10.11 Kai Hang Liu Y5, ‘Sin City’. Seven DC comic supervillains metaphorically strategise the urban redevelopment of Boston in Lincolnshire. The project demonstrates a hard post-Brexit scenario where sins question the traditional canon of building typologies, and vice facilitates socioeconomic programmes through anti-EU legislation. Immortality, greed and envy can be celebrated without consequence. Figs. 10.12 – 10.13 Nathan Fairbrother Y5, ‘A Festival of Brexit’. The urban regeneration of Wolverhampton celebrates the metaphors and imagination of ‘Mary Poppins’ by P.L. Travers. By empowering local people to take back control over employment, health and education, the project aims to provide a hopeful and positive vision for Brexit.

Poetics of a Resilient City

Bernd Felsinger, CJ Lim

Year 4

Damien Assini, LiJia Bao, Eleanor Downs, Nathan Fairbrother, Isabelle Lam, Kai Hang Liu, Sachi Oberoi, Oskar Olesen, Zhang Wen, Jonathan Wren

Year 5

Chun Ting (Sam) Ki, Ka Man Leung, Michael Quach, James Smith, Eric Wong

Unit 10 would like to thank Simon Dickens for his teaching of the Design Realisation module

Poetics of a Resilient City

Bernd Felsinger, CJ LimWhat makes a city resilient? Accra, Athens, Bangkok, Barcelona, Chennai, Dallas, Enugu, London, Mandalay, New Orleans, Pittsburgh, Rio de Janeiro, Rome, Singapore, Wellington – a few locations from the long list of the Rockefeller Foundation’s ‘100 Resilient Cities’ tasked with this very question. Cities, rich or poor, are particularly vulnerable, and will increasingly be affected by anomalous climate change, natural catastrophe and urban stresses including population migration, high unemployment, inefficient public infrastructure systems, endemic violence or chronic food and water shortages.

The Rockefeller Foundation’s president, Judith Rodin, has defined resilience as “the capacity to bounce back from a crisis, learn from it and achieve revitalization. A community needs awareness, diversity, integration, the capacity for self-regulation and adaptiveness to be resilient.” Cities, as organisms, act as indicators of spatial, social and economic trends in a manner arguably far more sensitive than any governance; this can be attributed to the synergy and symbiosis between the urban centre and its inhabitants, quotidian activity and social interaction. A society can only be resilient when the city delivers basic functions to its entire community, in both good times and bad.

The resilience movement also has important roles to play in both ensuring that current architecture assets and cultural heritage are protected from long-term and acute affects, and in developing revolutionary new spatial programs and systems fit for the challenges of the 21st century. The effects of climate change on the built environment are, for example, not limited to changes of weather, but include the impact on architectural efforts towards changes in behaviour, demographics, population growth and economic environments. Globally, governments are now acknowledging that future environments built on resilient efforts can provide potential multiple co-benefits to cities.

The Unit’s objective is to assess the potential urban transformation opportunities from the resilience movement. Individuals are required to establish an intellectual critical position on ‘What makes a city resilient?’ and focus on the spatial and phenomenological speculations that emerge when predictive fiction and its poetic function are applied to cities. In PROJECT 1, we will speculate, prioritize and redefine the poetics of urban resilience, focusing on one or a combination of issues around awareness, diversity, integration, self-regulation or adaptiveness. In PROJECT 2, the city will be informed by individual studies to establish core interests and should form the basis of a complex narrative and program. We encourage expressions of personal ideology, scale and working methods in search of visionary and innovative urban architectural proposals.

Figs. 10.1 – 10.3 Eric Wong Y5, ‘Cohesion: The Blueprint for a United Kingdom’. Inspired by ‘The Blazing World’ (1666) by Margaret Cavendish, the new capital city of the UK is the speculative driver and investigative model to cultivate accessibility, green sustainability and compassion. The narrative aims to reunite an arguably broken Britain in the 21st century, providing for the disenfranchised within the UK as well as for increasingly dislocated global communities. While the UK’s Parliament performs as the head of foreign policy, the Queen is the champion of national unity. Fig. 10.4 Ka Man Leung Y5, ‘The Making of Hong Kong: Democracy or Money?’. Through whispers, gossips, and myths, a collection of speculated archaeology of Victoria City reimagines Hong Kong’s adaptability to survive through time – from a fishing

village to an industrialised town and world financial centre under British Colonialism, to the handover of sovereignty to China. Is the new urbanism driven by concerns of climate change, food and water security, democracy; or by local economic influences at different scales? Fig. 10.5 James Smith Y5, ‘Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil’. A response to the Eurozone crisis of 2015 – the economic collapse of Greece and the influx of Syrian refugees – Britain in partnership with Thomas Cook would lease Faliraki off the Greek Government. Brits are encouraged to spend in the new hedonistic holiday resort, while the intervention would offer the refugees a new home, and with it security, retraining and financial independence in the new sovereign land of Rhodes.

10.6 10.7 10.8 10.9

Figs. 10.6 – 10.10 Chun Ting (Sam) Ki Y5, ‘Yen Town: Purity on the Disputed Senkaku Islands’. In mainland China, high pollution and contamination levels caused by industrialisation and capitalism are steering the Chinese elite to search for quality environments and foods of ‘purity’. Yen Town is located on Uotsuri-shima (Diaoyu Dao) of Senkaku Islands, the disputed territory between Japan and China. Japan can only retain sovereignty in exchange for clean soil, water, air and pure salt and onsen (hot springs). The Chinese Communist party uses Yen Town as the reward for loyalty whilst promoting communist beliefs. The island would be developed by 5 ‘honourable’ corporations which have long been the favourite brands of the Chinese.

especially promises of a fulfilling life after retirement, is the currency of the intervention. The reimagining of the Emerald City in ‘The Wizard of Oz’ and an interpretation of Grayson Perry’s ‘Tunbridge Wells’ looks at how the current government and the Conservative party could exploit planning strategies to manipulate the demography into gaining more northern constituencies. The urban development of Morely & Outwood metaphorically forms the critique of social and political aspiration for the elderly, and highlights third age consumerism as a potential way to boost national GDP.

Redefining Utopia

Bernd Felsinger, CJ Lim

Year 4

Chang Cui, Chun Ting (Sam) Ki, Ka Man Leung, Yolanda Leung, Michael Quach, James Smith, Eric Wong

Year 5

Ran (Julia) Chen, Marcin Chmura, Lauren Fresle, Alfie Hope, Ashwin Patel

Unit 10 would like to thank Simon Dickens for his teaching of the Design Realisation module

Redefining Utopia

Bernd Felsinger, CJ LimUtopia: an imagined place or state of things in which everything is perfect. The word was first used in the book Utopia (1516) by Sir Thomas More. By definition an unreachable destination, broadsides on utopia have been launched since its very inception. The word ‘utopian’ is more often than not used in the pejorative, pertaining to proposals featuring alternate realities rather than dealing with society’s real and pressing ills. Such criticism misses the point and dismisses the potency of the utopic vision. Plato’s Republic (400 B.C.), Thomas More’s Utopia (1516) and Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis (1627) were intended as neither fantasies nor blueprints for reification, but reflections on the societies in which they were written.

Ebenezer Howard’s garden city, for example, was inspired by the utopian tract, Looking Backward: 2000-1887, by the American lawyer, Edward Bellamy. The third largest bestseller of its time when it was published in 1888, Bellamy’s novel immediately spawned a political mass movement and several communities living according to its ideals. Letchworth Garden City and Welwyn Garden City in the UK are founded on Howard’s concentric plan of open space, parkland and radial boulevards. Housing, agriculture and industry are carefully integrated, and the developments remain two of the few recognised realisations of utopia in existence. The cost of utopia is what lies outside of utopia, the forgotten communities and infrastructure is required to support it, a counterpoint that is sharply observed in the Peter Weir film The Truman Show, depicting the new urbanist town of Seaside in Florida.

The urban condition raises recurring as well as fresh challenges for every generation. In the past, architects have not been slow to offer forth their vision of utopia or ideal city, ranging from the polemic (Ron Herron’s ‘Walking City’, 1964) to the serious (Le Corbusier’s ‘Radiant City’, 1935), the futuristic (Paolo Soleri’s arcologies) to the Arcadian (Frank Lloyd Wright’s ‘Broadacre City’, 1932). Utopian visions, whether or not they are accepted, are reflections of society in which they are imagined and have a powerful influence on the public consciousness. This year, students were required to establish an intellectual critical position on the interpretation of ‘Utopia’ and redefine the utopian city through narratives. JG Ballard has written that the psychological realm of fiction is most valuable in its predictive function, projecting emotion into the future. We encouraged expressions of personal ideology, scale and working methods in search of visionary architecture and urban utopian speculations.

Fig. 10.1 Eric Wong Y4, ‘The Institute of Moral Compass’. The corporate image of Disney is reconfigured as a morally responsible institute. Through reimagining the animated as spatial storytellers, the proposal becomes a moral and public insertion in the heart of London that aims to shape a more diverse and holistic city. Fig. 10.2 Alfie Hope Y5, ‘Growing Land in Bristol’. Sea Rise City is a floating infrastructure for future urbanism on water, replacing land lost to sea level rise; an enterprise of ‘growing’ land made from bamboo grown on floating fields. Fig. 10.3 Ran Chen Y5, ‘The Cloud Bank 2061’. The future of Singapore’s national security relies on the creation of a sustainable water-independent state before the water supply agreement. Inspired by the natural cloud system, the water management strategy aims to transform the urban

strategy and redefines the city’s priorities. Fig. 10.4 Chun Ting (Sam) Ki Y4, ‘Goodbye Berlin!’. Inspired by Christiane’s view from the film Goodbye, Lenin!, the masterplan looks back in time, to erase contemporary Berlin and construct a staged inhabitable green backdrop consisting of dwellings, civic centres and urban wheat fields supported by a wastewater treatment system. Fig. 10.5 Lauren Fresle Y5, ‘The Oasis of Peace’. Utopia is a place before heaven, set in Latrun Salient, Israel. The intercultural experiment of Jewish and Arabic community acts as a centre for global democratic peace. The Garden of Life, the Garden of Knowledge and the Throne collectively present community cohesion through education and cultivation of sustainable agricultural techniques and water resource management.

Fig. 10.6 Michael Quach Y4, ‘The Reformed Parliament, Hull’. The proposal explores the idea of creating political reform through architecture and affordable forms, using decentralisation of London and its temporary status as a catalyst for a better future in some of the most deprived parts of the UK. Fig. 10.7 Ashwin Patel Y5, ‘SuperTuscany’. Global warming foresees an ecologically induced migration of terroir from Tuscany to the Thames Estuary. Due to sea rise, by 2100 the estuary has increased in size, presenting an opportunity to host an

industrialised landscape of floating vineyards with manufactured soils assembled over flooded marshlands. Figs. 10.8 – 10.9 Marcin Chmura Y5, ‘The United Suburbs of AmeriKa’. The United Suburbs of AmeriKa is desperate to rekindle the ‘American Dream’, turning to real estate to alleviate the National Debt. The US takes on the role of Global Waste Importer, exploiting environmental concerns to surreptitiously acquire nuclear waste and cheap materials with which to manufacture landmasses, marketed to foreign investors as a real estate investment.

Fauna City Bernd Felsinger, CJ Lim

Year 4

Ran Chen, Marcin Chmura, Lauren Fresle, Manuel Gonzalez-Nogueira, Alfie Hope, Kagen Lam, Ashwin Patel

Year 5

Nick Elias, Siyu (Frank) Fan, Ryan Edward Hakimian, Anja Leigh Kempa, Woojong Kim, Jason Lamb, Chun Yin (Samson) Lau

Unit 10 would like to thank Simon Dickens for his teaching of the Design Realisation module

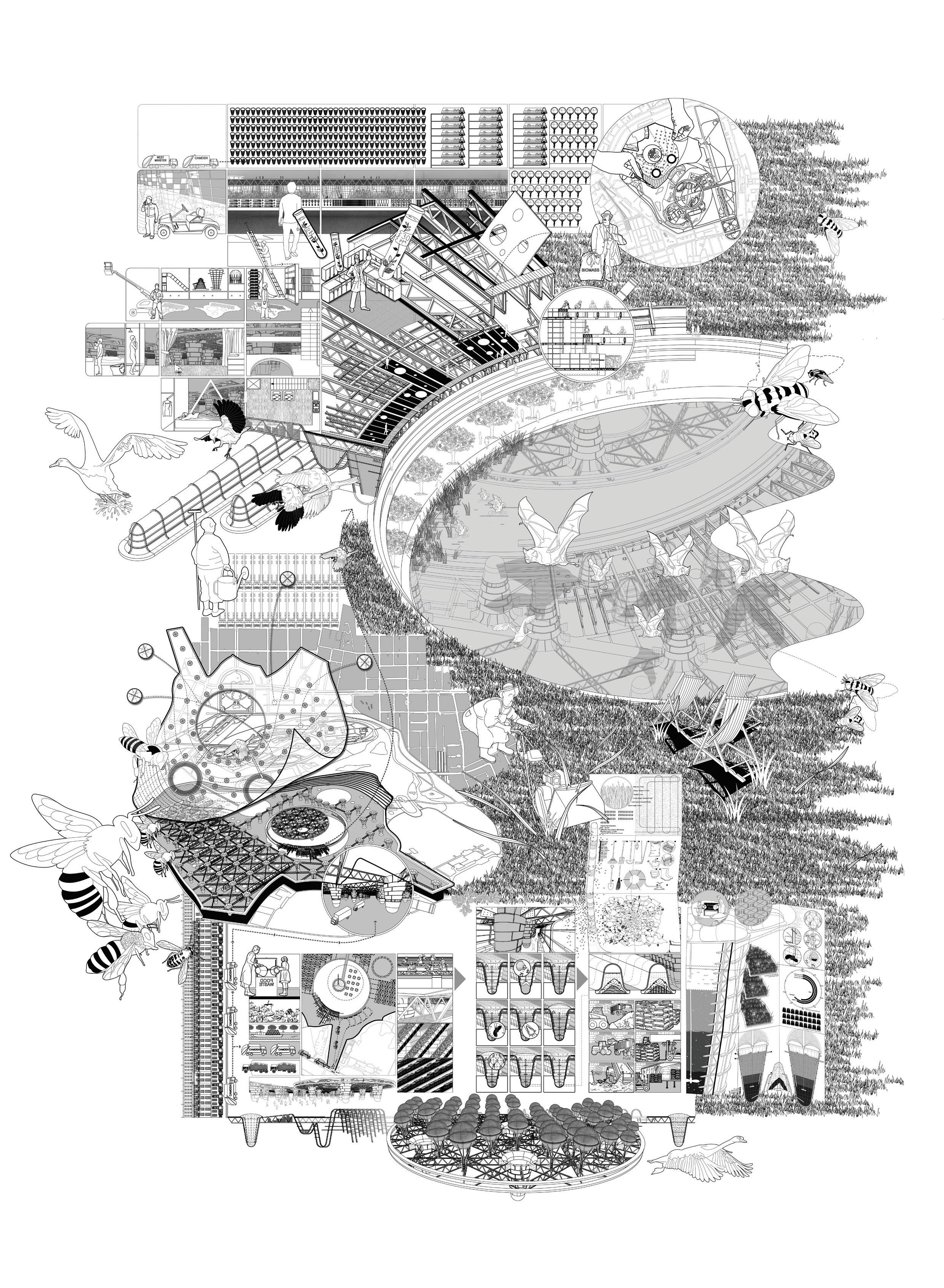

Fauna City

Bernd Felsinger, CJ LimThe March Hare and the Hatter were having tea, a Dormouse was sitting between them, fast asleep… the table was a large one, but the three were all crowded together at one corner of it. ‘No room! No room!’ they cried out when they saw Alice coming. ‘There’s plenty of room!’ said Alice indignantly, and sat down in a large armchair at the end of the table. 1

Whether pest, pet or livestock, the relationship between humans and fauna has always been fundamental to the urban, cultural and economic consequences of communities in cities. On a visit to New York City in 1842, Charles Dickens noted that on Broadway, the well-to-do ladies in bright clothes and parasols were mixing with portly sows and hogs. Many urban centres have historically been places of animal cultivation, processing and trade. In London, before the arrival of modern food transportation, it was reckoned that each cow lost about 20 pounds in weight on every 100-mile walk to Smithfield Market.

Regardless of our dwindling appreciation of fauna in cities, our dependency on them is ever increasing. Oysters once covered much of the east coast of the USA. The impact of the seemingly small actions of individual oysters carving out reefs is so huge that it has been attributed to tempering the wave action in the area; so much so that Shell Oil Company has even invested US$1 million in an oyster shell recycling scheme to reinvigorate the oyster populations around the coast. The oysters are also integral to the ecosystem, creating habitable conditions for many other species.

In his ‘animal farm’, George Orwell elevated animals to positions of governance. What appearance will a city take and what kind of social spaces will result in such a scenario? The discourse of the Unit often takes the notion ‘What if…’ as its starting point. Interests in technical exposition and environmental science to stimulate programmes and spatial innovation strengthen the use of poetics and fictional narrative in projects. In Project 1 ‘Learning from Nature’, we speculated and invented alternative realities by ‘adopting’ a member of the fauna, and in the process took lessons of sustainability from the ecological system. Project 2 ‘The City’, was informed by individual studies and critical thinking to establish an urban design proposal with a complex narrative and programme. We invited students, as with Alice, to posit a divergent status quo on the city of the twenty-first century, taking speculative and sometimes impossible ideas into visionary wonderlands.

Fig. 10.1 Nick Elias Y5, ‘PoohTown’. 1920s Slough, introducing Winnie the Pooh as the protagonist, to exploit ‘happiness’ as an alternative industry. Pooh re-evaluates covert responses to socio-political exclusion by prescribing idealised happy architecture in a nostalgic make-believe pilgrimage around Slough, ultimately for financial gain. Fig. 10.2 Woojong Kim Y5, ‘The City of Sleep’. Located in the Bristol Channel, the City of Sleep investigates the spatial and symbolic potential of cathedrals. The floating infrastructure facilitates a community of the third age in deep sleep through cryogenics, while providing a safe haven for local sea birds. Fig. 10.3 Anja Leigh Kempa Y5, ‘Remembering Spring in Tokyo’. Climate change threatens Japan’s iconic emblem of Spring, the cherry blossom. Remembering Spring integrates an urban garden

infrastructure, revitalising native symbolism and traditions to inform a sustainable energy initiative through the recreation of spring. Fig. 10.4 – 10.5 Chun Yin (Samson) Lau Y5, ‘The European Seat of Climate, Confidence and Credibility’. The ECCC is an investigation into the urban consequences of a carbon sequestration backed monetary system in the EU. Through five key architectural characters, the carbon-negative capital comments and tackles the financial hubris, political incompetence and environmental ignorance of the post-2008 financial crisis European Union.

Fig. 10.6 Ryan Edward Hakimian Y5, ‘To Go the Way of the Dodo’. The archaic views and ideologies of Prince Charles are applied to re-imagine London’s Tower Hamlets. Is looking backward the best way to step forward? Fig. 10.7 Siyu (Frank) Fan Y5, ‘Obama’s Ark’. An architectural placebo, Obama’s Ark is a disaster relief center located in Cape Disappointment. The masterplan employs the construction of an artificial moon as a piece of political propaganda to recapture the faith and confidence of Americans towards their federal government. Fig. 10.8 – 10.9 Jason Lamb Y5, ‘Frackpool: The Legacy of Hydraulic Fracturing’. Chinese investment prompts the transitory integration of hydraulic fracturing in Blackpool for the exploitation of shale gas. The hydraulic fracturing instigates urban regeneration and provides a framework for new

The Imaginarium

of Urban Ecologies

Bernd Felsinger, CJ Lim

The Imaginarium of Urban Ecologies

CJ Lim, Bernd Felsinger‘Cities are particularly vulnerable in that they are immobile. As such, the historic sense of place, and rootedness of residents are critical attributes of cites. These strengths of place can, however, become liabilities if the local ecosystems are unable to adapt to the climate-induced changes. Climate change poses serious threats to life, and entire urban systems.’ The World Bank, Cities and Climate Change, 2010

Increases in global temperature have caused sea levels to rise at an accelerating pace, changing patterns and quantities of precipitation as well as the probable expansion of subtropical deserts. According to the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the greatest threat of climate change is the profound manner in which it could impact upon every aspect of our lives, from health to ecological security. By understanding the urgency of climate change as a ‘security’ issue, we need to recognise the importance of revolutionising and innovating our cities and its programmes; adapting to climate change is not just a matter of managing risk. No longer should the issue of climate change be considered solely in the realms of scientific policy, but is an issue that is multidisciplinary – the professions of the built environment including architects, planners, geographers and ecologists have a crucial role to contribute. Like many scientific policies, the strongest design visions and planning policies will simultaneously address problems in multiple domains and function, and to become constructs for the practice of everyday life for all ecological forms in the urban environment. The sustainability and transformation of cities can address climate security challenges, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, alleviate water insecurity, and provide economic and social benefits, but could simultaneously help establish an ecological symbiosis between nature and built form. Innovative responses and solutions should present new paradigms for urban living, while some believe that for humans to survive, we need

a re-equilibrated ecosystem where we commit to coexisting with nature.

Beekeepers in the US have been reporting losses of their hives; while the British Beekeepers Association has warned that the honey bee could disappear from Britain by 2018. It seems that the bees are in crisis as a result of new and intensive farming practices. Monoculture agriculture, organised irrigation, the heavy use of pesticides, chemical fertilizers, and plant growth regulators, alongside climate change has increased the mortality rate of bee colonies at an alarming speed. The disappearance of bees threatens global agriculture that relies on pollination by bees to produce our food supply. The city and the hive, two complex systems, are under risk.

The pigeon towers of Isfahan represent one of the most remarkable examples of eccentricity in Persian architecture and an unusual exemplar of mutual interest between humans and nature. The now derelict large-scale towers adorn a landscape that is somewhat redolent of naval forts stranded hundreds of miles inland. The useful but unromantic purpose of the towers was to collect pigeon manure, a substance that had been found to be beneficial to the orchards and gardens in the surrounding plains during the 16th century. Agriculture in the fertile but nitrogen-lacking Isfahan plains was largely supported in this manner, fuelling large melon crop production in the region.

The floating, walking and flying propositions of Buckminster Fuller, Archigram, the Metabolists et al have all but floated, walked or flown away in recent times. Despite the marked shift, we encourage visionary propositions of architecture and the city, and the realisation of fictional speculations for a re-equilibrated real world ecosystem. We believe in speculative propositions to question the way we experience and engage with our urban environment. It is vital to fundamentally re-think how cities work in a symbiotic relationship between man and nature.

Project 1, ‘What if…’, speculates on alternative realities to re-evaluate the city from nature’s point of view and investigate the possibilities of how nature can be a sustainable resource for the city. Project 2, ‘The City’, is informed by earlier individual studies to establish core interests and should form the basis of the final complex narrative and programme.

Unit 10 would like to thank Simon Dickens for his teaching of the Design Realisation module, and Pascal Bronner for his workshop ‘The Drawing Imaginarium’.

Year 4

Nick Elias, Frank Fan, Ryan Hakimian, ZhiYu Huang, Anja Kempa, WooJong Kim, Jason Lamb, Samson Lau, Haaris Ramzan

Year 5

Yu Wei (John) Chang, Thandi Loewenson, Steven McCloy, Viktor Westerdahl

Fig. 10.1 – 10.2 (previous spread) Steven McCloy, Y5, EU: The Gardens of Fantastica, Paris. An allegorical city masterplan for Paris reimagining post WWII Europe as a catalyst for food & energy security, the influence is spread as the headquarters periodically move across Europe. The boulevards, city walls, landmarks, catacombs and parks of Paris are transformed and showcased with surreal energy and food infrastructure, tended to by Members of European Parliament. Fig. 10.3 Viktor Westerdahl, Y5, The Liquid Light of Diego Garcia. A bee ecology on the remote island Diego Garcia captures the full potential of solar energy as, ‘Liquid Light’. To harness this energy, without disrupting the islands fragile ecology, people settle in floating villages. These are assembled from a collection of light components, designed to minimise the

impact on the island’s material metabolism. Fig. 10.4 Yu Wei (John) Chang, Y5, The United States of Mormon Republicans, Salt Lake USA. With a population of 70,000, the Mormon community of American and the Republican Party members funds the city. The strategy is to demonstrate the impossible - sustainable living, food and energy production on the barren and environmentally harsh Great Salt Lake, and eventually leading the Republican Party to victory in the presidential election.

Fig. 10.5 Samson Lau, Y4, The Royal Borough of Summer Countryside, London. The new Royal Borough reimagines the city as a temporary event. Situated over a series of train stations, the temporary architectural icons unfold every year during the summer parliamentary recess, with country produce brought into London. Milkmaids, trapeze artists collecting eggs and children picking strawberries choreograph the making of ‘Eton Mess’ – all mixed in with a dash of the summer sun! Fig. 10.6 Nick Elias, Y4, Newham: The Utility City, London. Constructed communities are rehabilitated within a new Utility City that processes London’s waste through communal efforts. Active residential hives lie within a lace of green infrastructure, which is knitted into the existing Newham, where the residents work for their own upkeep and create ownership of their

architecture via meticulous maintenance. Fig. 10.7 – 10.8 Thandi Loewenson, Y5, Melencolia, City of Sadness: A study of the anthropocene city after the end times. Melencolia is a psychotopography, existing in the mind of a failed explorer and fragmented into three ‘states’ of id, ego and superego. The Melencolia of the plumber, the postman and the councillor –metaphoric protagonists for each ‘state’ – reveals urban design proposals for the physical and psychological dimensions of the human-induced ecological crisis of the ‘anthropocene’ age..

SF Cities Bernd Felsinger, CJ Lim

SF CITIES

CJ Lim, Bernd Felsinger“…I chose to write science fiction in the beginning is that it offered me a way in which I could remake the landscapes of the England I knew in the 1960s and 1970s, in the way the surrealism worked, to make them resemble, unconsciously, the landscapes of wartime Shanghai… it’s the psychological realm where science fiction is most valuable in its predictive function, and put the emotions into the future.”