Our Design DNA

At The Bartlett School of Architecture, we have been publishing annual exhibition catalogues for each of our design-based programmes for more than a decade. These catalogues, amounting to thousands of pages, illustrate the best of our students’ extraordinary work. Our Design Anthology series brings together the annual catalogue pages for each of our renowned units, clusters, and labs, to give an overview of how their practice and research has evolved.

Throughout this time some teaching partnerships have remained constant, others have changed. Students have also progressed from one programme to another. Nevertheless, the way in which design is taught and explored at The Bartlett School of Architecture is in our DNA. Now with almost 50 units, clusters and labs in the school across our programmes, the Design Anthology series shows how we define, progress and reinvent our agendas and themes from year to year.

2018 Disruptive Architectures

Jeroen van Ameijde, Mollie Claypool

2017 Architecture Made of Parts

Mollie Claypool, Manuel Jimenez García, Gilles Retsin

2016 The Laboratory of Mereology

Mollie Claypool, Manuel Jiménez Garcia, Gilles Retsin

2015 Becoming-Ever-Different

Mollie Claypool, Manuel Jiménez Garcia

2014 The Living Spaces of the Algorithmics

Mollie Claypool, Manuel Jiménez Garcia, Philippe Morel

2013 The Living Spaces of Algorithmics

Kasper Ax, Mollie Claypool, Philippe Morel

2010 Innumerable Eccentricities and the Hedingham Report

Neil Spiller, Phil Watson

2009 Parallel Botany, Parallel Biology and Parallel Architecture

Neil Spiller, Phil Watson

2008 Pushing the Boundaries

Neil Spiller, Phil Watson

2007 Smearing Architecture

Neil Spiller, Phil Watson

2006 Spelling Architecture

Neil Spiller, Phil Watson

2005 Clinimanic Studies

Neil Spiller, Phil Watson

2004 The Pataphysical Exceptions of Reflexive Architecture

Neil Spiller, Phil Watson

Disruptive Architectures

Jeroen van Ameijde, Mollie Claypool

Year 4

Darren Buttar, Alessandro Conning-Rowland, Ossama Elkholy, Docho Georgiev, Kin Keung Kwong, Emilio Sullivan, Shogo Suzuki, Alexis Udegbe, Artur Zakrzewski

Year 5

Milot Pireva, Alfie Stephenson-Boyles, Wonseok Woo, Lianjie (Li) Wu

Thanks to our partners: Design Computation Lab at The Bartlett School of Architecture; UCL Institute for Digital Innovation in the Built Environment; The Bartlett School of Construction and Project Management

Thanks to our collaborators Efrosyni Konstantinou and Claire McAndrew, to our Design Realisation tutor Michal Wojtkiewicz and to our Scripting Workshop tutors Andrea Bugli and Yutao Song

Thank you to our critics: Diann Bauer, Alessandro Bava, Roberto Bottazi, Peter Cook, Manuel Jimenez García, Efrosyni Konstantinou, Claire McAndrew, Lukas Pauer, Barbara Penner, Gilles Retsin, Aleksandrina Rizova, Kerstin Sailer, Jack Self, Alvise Simondetti, Julian Sivaro, Yutao Song, Harald Trapp, Marco Vanucci, Manijeh Verghese, Michal Wojtkiewicz

Thank you to our field trip hosts and helpers: Henriette Bier, Lonneke Bakkeren, Javier Arpa Fernandez, Alex Retegan, Bastiaan van der Sluis

Disruptive Architectures

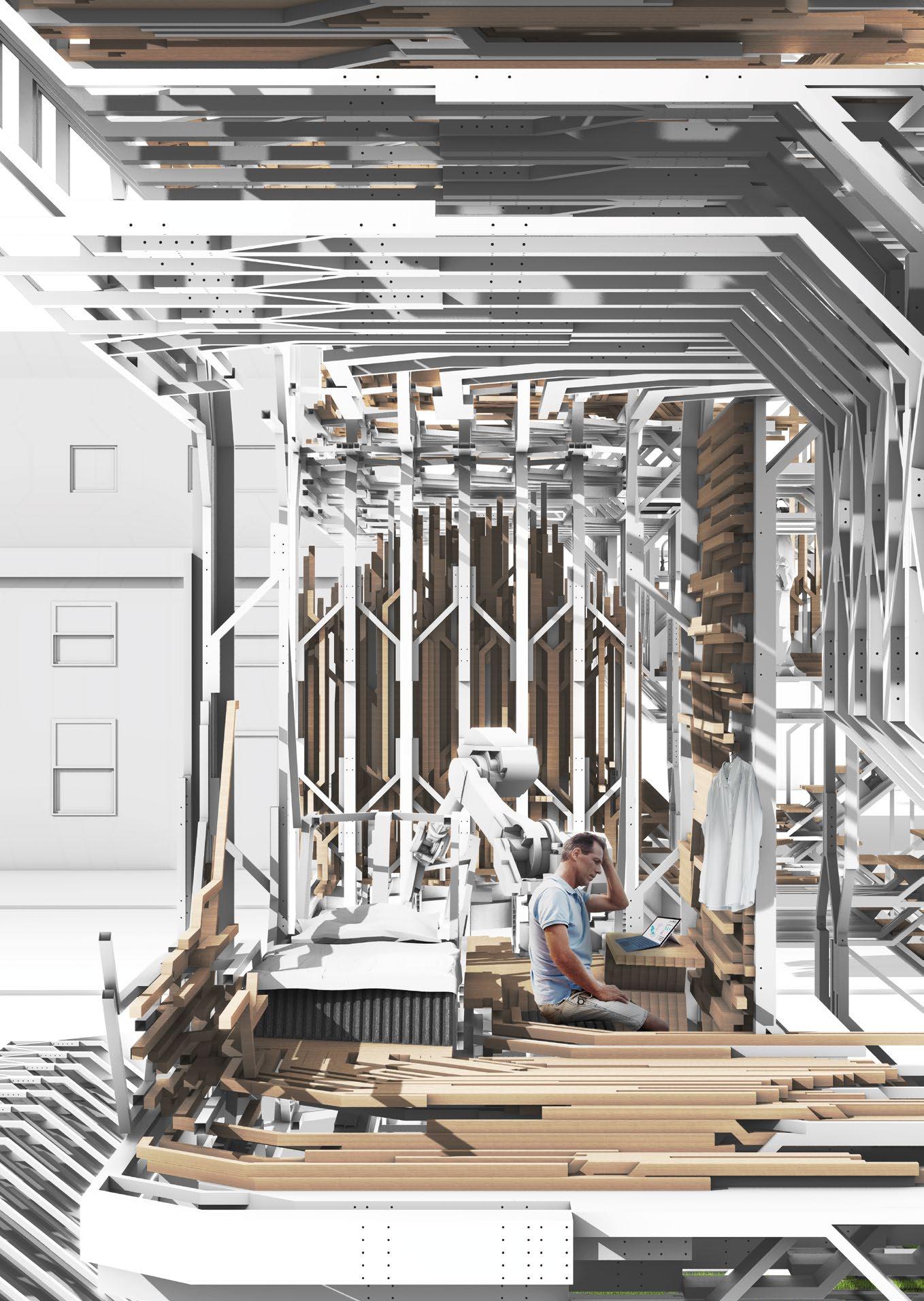

Jeroen van Ameijde, Mollie ClaypoolUnit 19 aims to challenge the contemporary status of building design and the construction industry, in which the role of the architect appears to have been reduced to that of an aestheticist at the service of commercial modes of project development. The unit explores how the architectural discipline could expand its control, through engagement with different models of ownership, construction and inhabitation. We develop specifically designed catalogues of discrete parts that allow architectural structures to be assembled through user-driven scenarios that unfold through time.

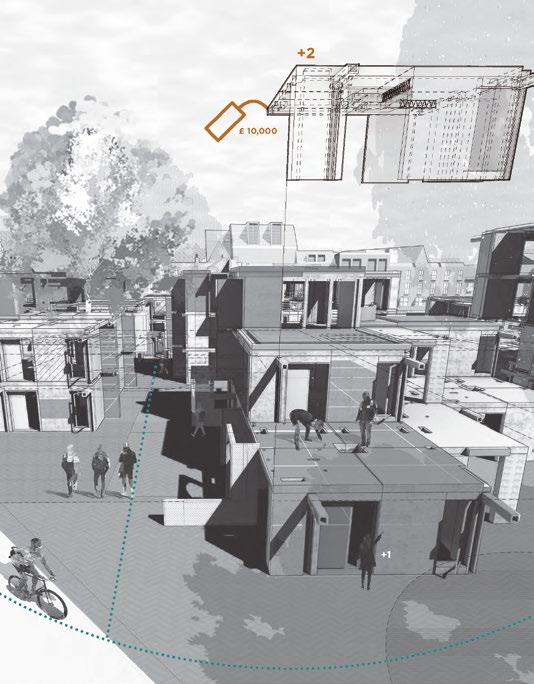

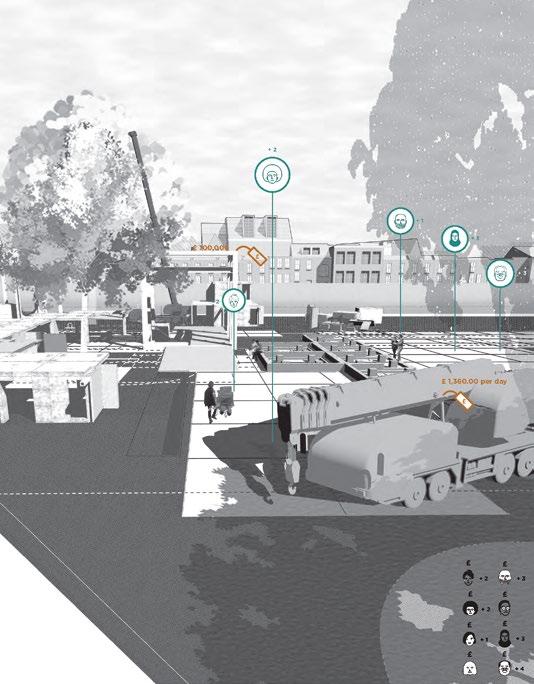

This year, we continued to focus on the most pervasive architectural typology worldwide: the house, or housing. Commercial housebuilders favour the most risk-averse typologies of residential blocks and apartment layouts, which are increasingly insufficient in a society moving towards more varied types of family structures and organisational patterns of life and work. Our projects explored how a diverse range of social structures, activities and relationships can drive the arrangement of domestic spaces, creating a greater range of housing options and offering residents the opportunity to participate in the decisionmaking process. By breaking down the traditional notions of housing, such as one-, two-, and threebedroom apartments, lift lobbies and private entrances, we explored more open-ended types of domestic space that stimulate engagement within resident communities and establish more synergetic, yet disruptive, relationships between buildings and their contexts.

We have placed a particular focus on the material articulation of our kit-of-part systems, scrutinising the manufacturing ecologies and value systems that currently limit the production of housing within the UK. We have embraced new technologies in digital design and manufacturing, speculating on new models of prefabrication and onsite assembly processes that use digital negotiation protocols to project future scenarios of inhabitation. This application has allowed us to test innovative architectural proposals that could be realised in the near future.

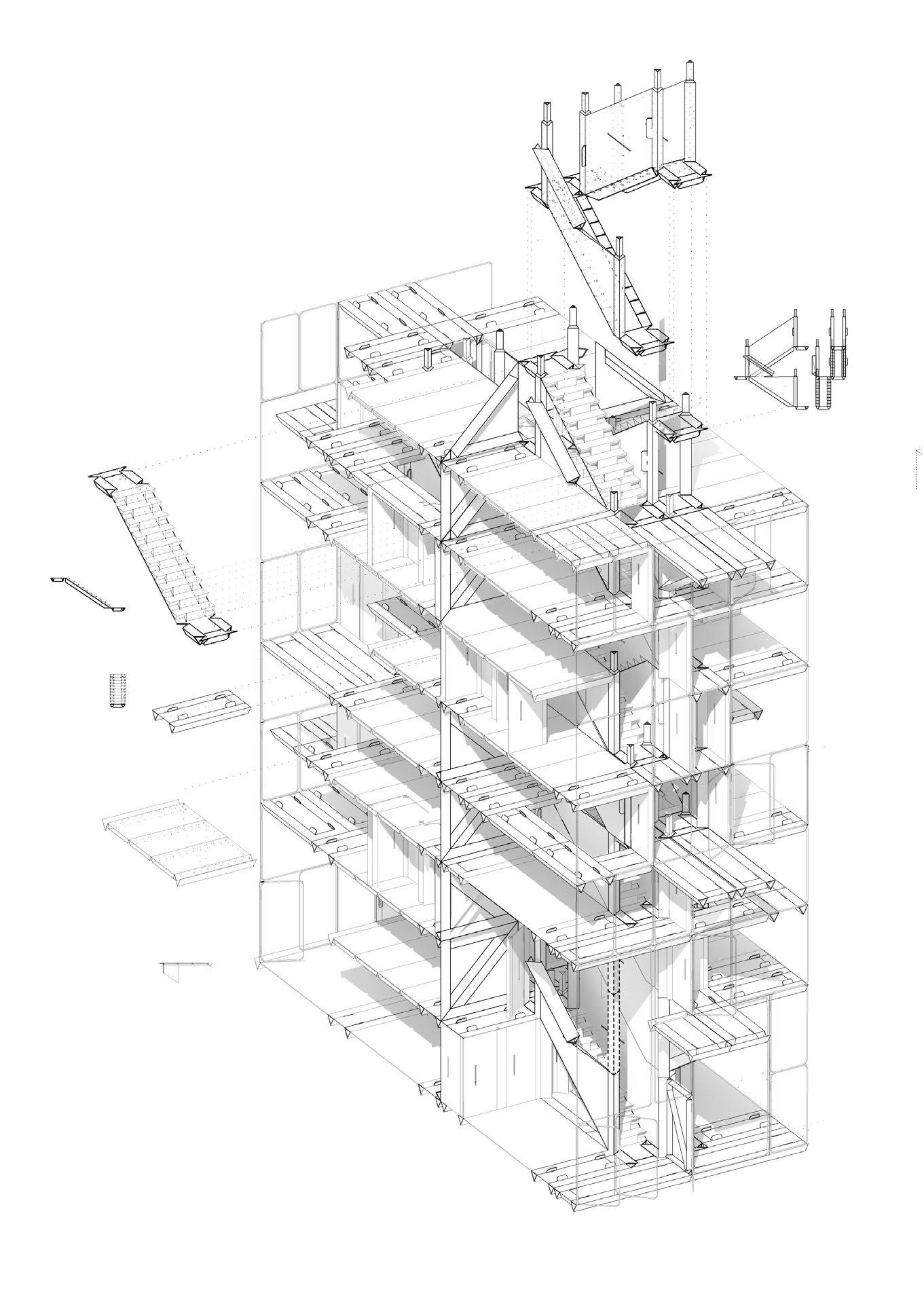

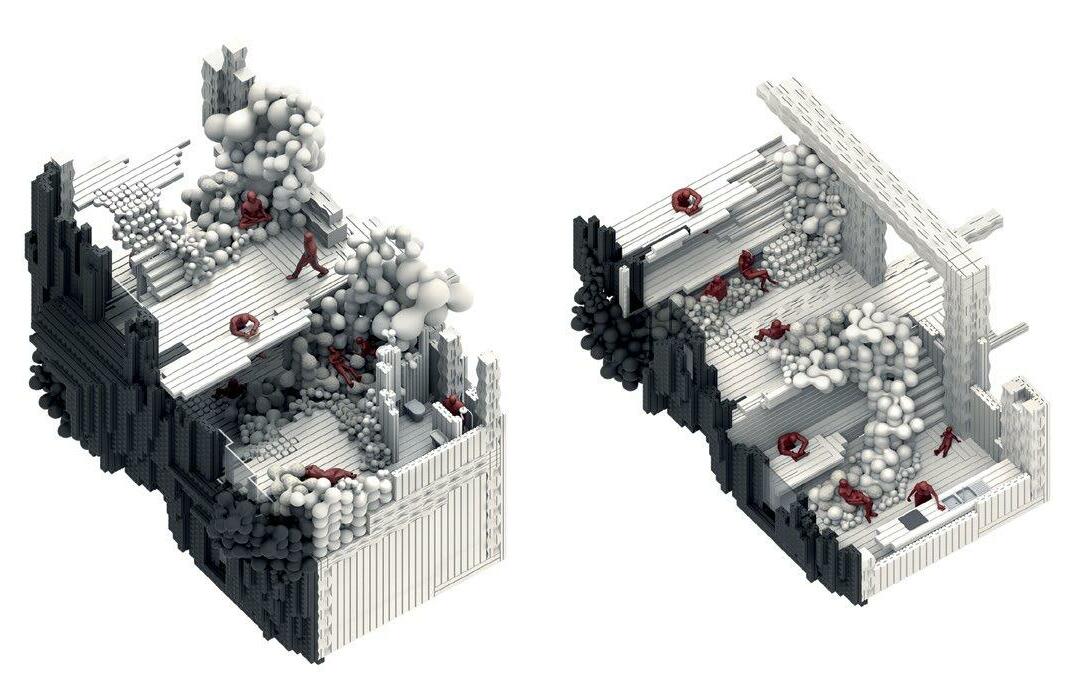

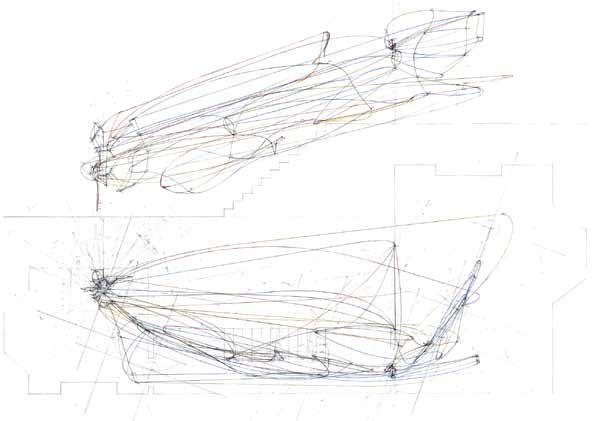

A central strategy within the unit’s approach was to combine computational design processes with the idea of part-to-whole relationships, considering architecture as ‘wholly digital’ in both process and artefact. Conceiving new types of living environments as assemblies out of discrete elements allowed us to establish a direct link between the spatial and organisational principles developed in the digital design environment and how these would perform in real life.

The projects produced in the unit cover a range of scenarios that subvert or strategically alter the existing economies of development within the housing sector, proposing typologies and spatial environments that imagine new scenarios of urban life. They respond to contemporary social, economic and cultural challenges and opportunities, imagining architectures that push beyond our current models for society.

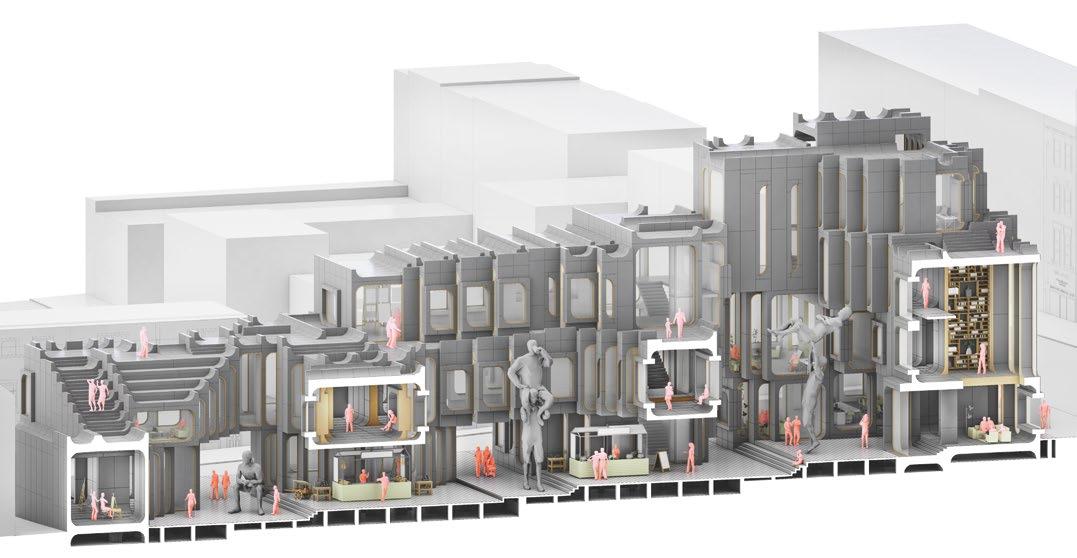

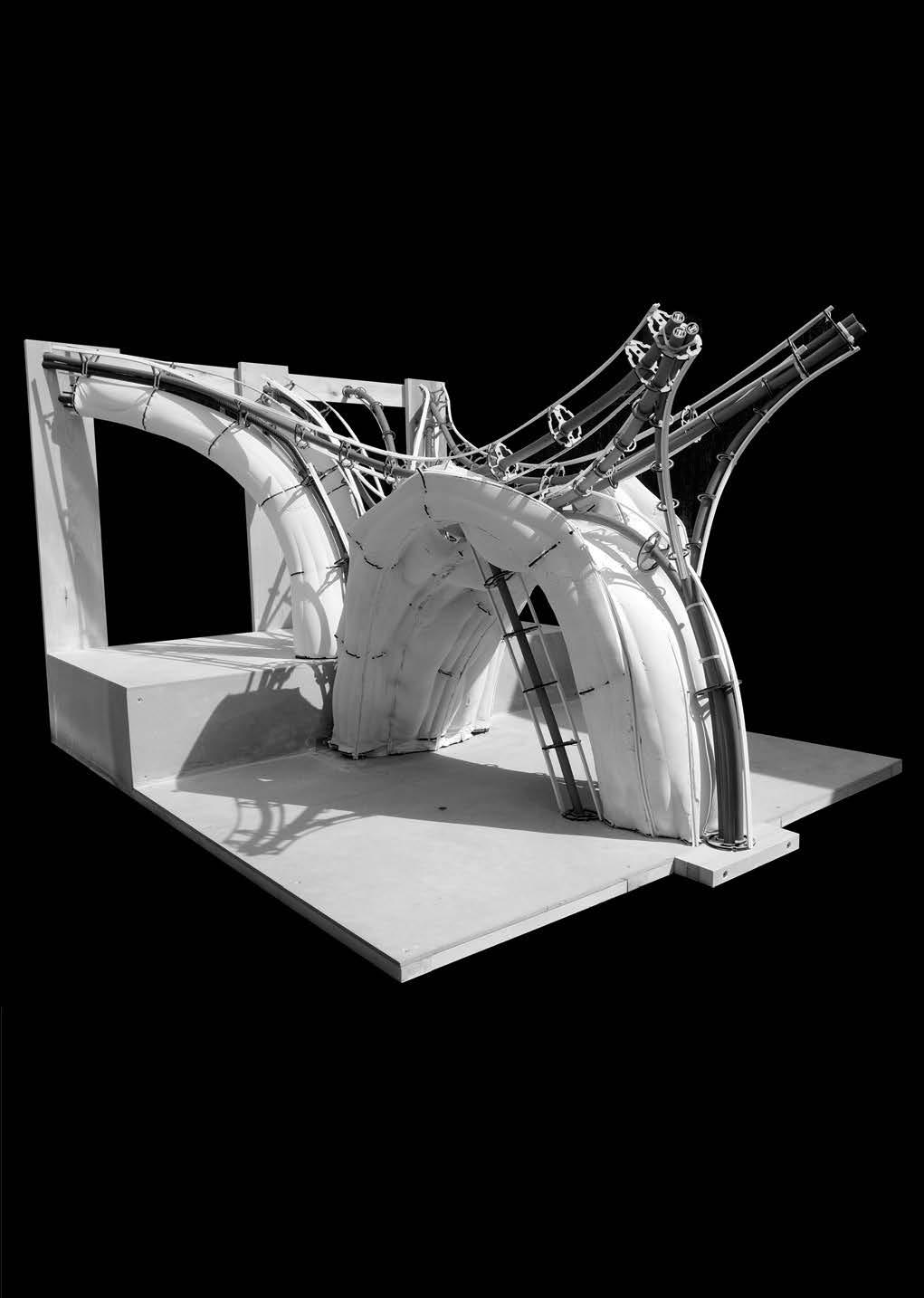

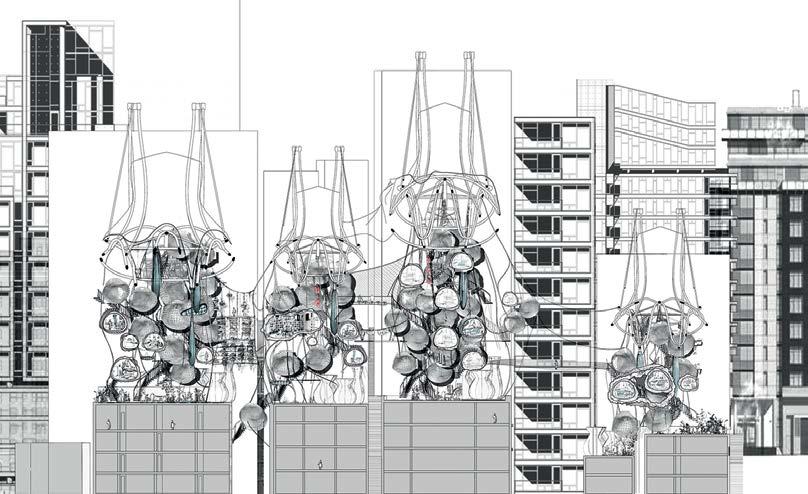

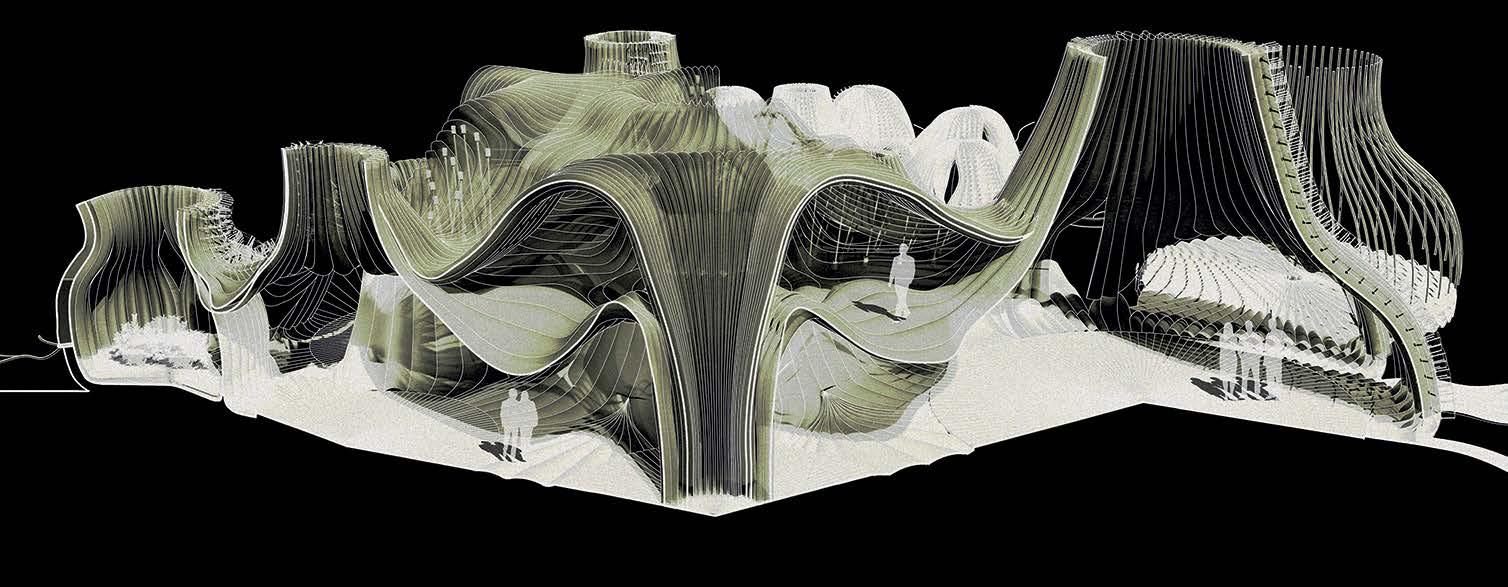

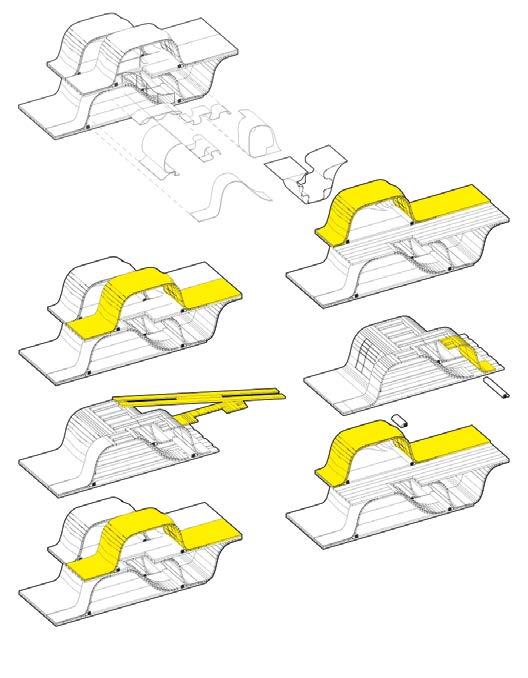

Figs. 19.1 – 19.2 Lianjie (Li) Wu Y5, ‘Beyond the Shell’. The project proposes a large scale community-build scenario where a community can collectively design their masterplan informed by the expertise of architects. The ‘naked’ shells of unfinished spaces that are the outcome of this process can then be further customised by the community, tailored to their evolving and changing needs over time. As a result, the unfinished naked shell helps to address the issue of over-finished yet unaffordable housing supply currently in London’s housing market, providing a strategy to take advantage of residents’ communal labour to cut down the construction cost and lower prices. Through questioning the limitations of modular living units and communal spaces in contemporary housing models, the project proposes an

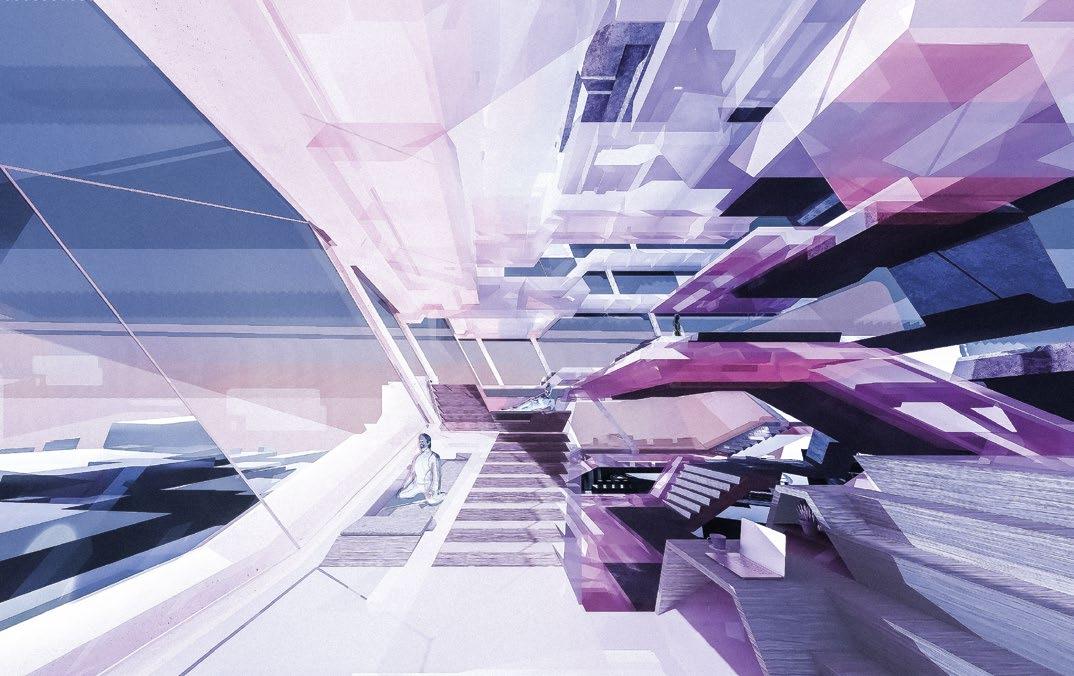

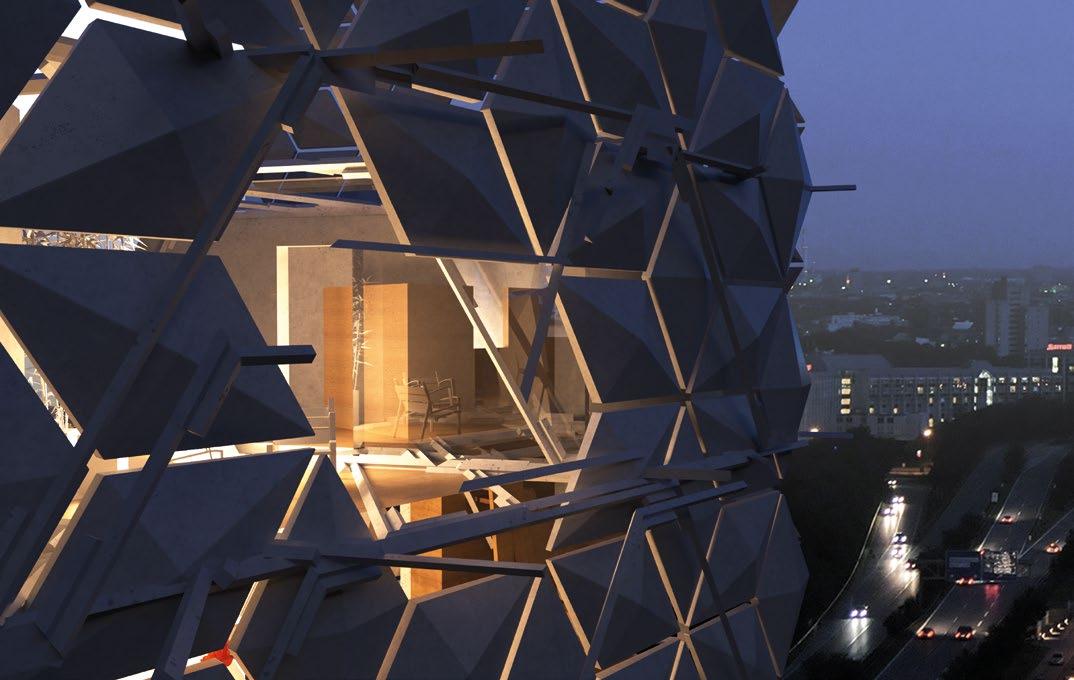

alternative housing model for London. Figs. 19.3 – 19.4 Kin Keung (Gigi) Kwong Y4, ‘Oblique’. This project proposes a system that replaces vertical and horizontal spatial qualities of living space, resulting in housing without walls. The project uses the oblique to compose a vertically assembled landscape for living. The kit of parts consists of multiple angles to define interpersonal hierarchies and how our bodies experience a space to arrange a range of domestic activities, integrating programme, circulation and structure as a whole in one continuous landscape. Furthermore it challenges the developers’ for-profit model of room-oriented housing by removing internal walls, re-conceiving the political and social aspects of ownership and privacy between residents.

Fig. 19.5 Artur Zakrzewski Y4, ‘A Global Village’. The project proposes the launch of A Global Village, a company that produces a Universal Building System, providing rental credit-based accommodation around the world. Occupants would be able to live for free at any A Global Village franchise, once they accumulate membership credit either by making an initial startup capital investment or renting monthly until full credit is acquired. The project in this iteration speculates on how the kit of parts for A Global Village would be deployed on a site in Dalston, East London – the first franchise of A Global Village. This speculative scenario provides artists with an alternative shared housing facility, combined with studios and exhibition areas that blur the boundaries of living, working and consuming. Figs. 19.6 – 19.7 Alessandro Conning-Rowland

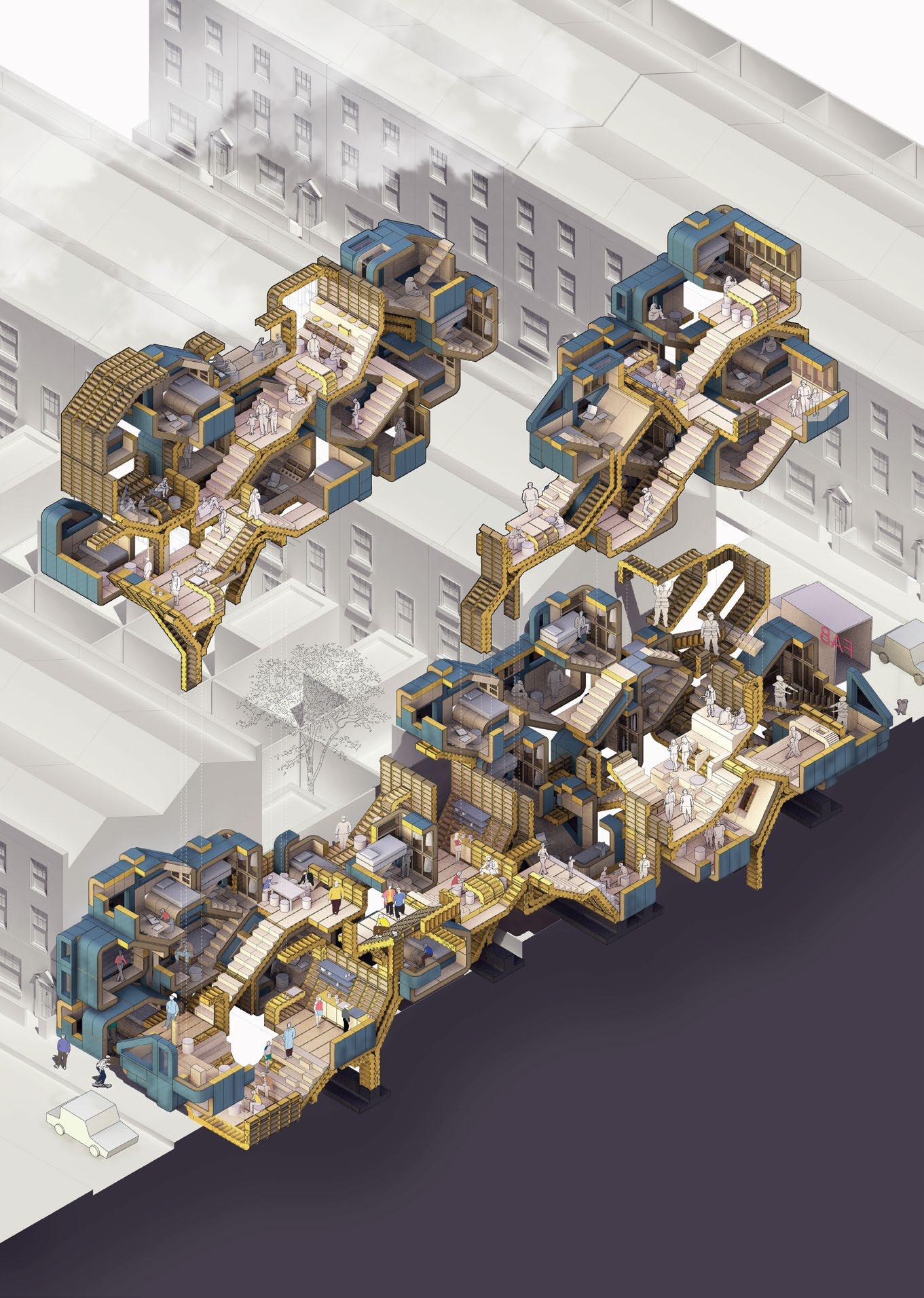

Y4, ‘Chamfer: A Cooperative Housing Platform’. The project proposes a cooperative housing platform based on a family of discrete parts. The project aims to disrupt London’s asset -driven housing market by creating a viable alternative using the idea that through sharing, we can have more. The Chamfer platform enables resident-initiated, funded, democratically designed, self-constructed housing; made possible through the utilisation of shared living, shared knowledge and the combinatorial possibilities of chunks. The geometry of these chunks promotes desired spatial and social outcomes, such as division of space through level change and shared circulatory landscapes, whilst embracing low-cost materials and highly accessible fabrication technologies.

Fig. 19.8 Docho Georgiev Y4, ‘The Incubator’. The project responds simultaneously to the global influence of the Third Industrial Revolution and to the local impact of the housing crisis in London. The Incubator attempts provides an alternative to the typical contemporary office. By mixing living and working within the boundaries of a three-dimenisonal field of ‘work’ and ‘live’ modes, the project responds to the changing nature of work. While not in use during the day, each dwelling’s living room can be rented out by the owners as a ‘dedicated desk’ space, thus creating an economic model that benefits all inhabitants of the project. Figs. 19.9 – 19.10 Wonseok Woo Y5, ‘The Negotiated Live-Scape’. The basic principle of this project is to share idle space in each flat through communication within the community of the building. Such an approach

proposes that a more efficient use of space can actively respond to the requirements of the residents in the future –necessitating spatial change through a set of sliding and moving interconnected kits of parts that define each flat within a housing block. Fig. 19.11 Alfie Stephenson-Boyles Y5, ‘Estate Platform’. How can estate densification be achieved in a way that satisfies both the need for additional and diverse housing, whilst also creating the conditions for social exchange? The project imagines a scenario where the residents of housing estates in London are able to form a housing cooperative, whose aim is to improve conditions on the estate; to provide a platform for social exchange, income, jobs and additional, diverse and open-ended housing. It directly positions itself against the current model of decanting housing estates in

London. An framework of in-situ cast concrete supports provide an organisational platform for reconfigurable CLT housing units and amenity space that can be expanded or contracted over time dependent on the inhabitants needs.

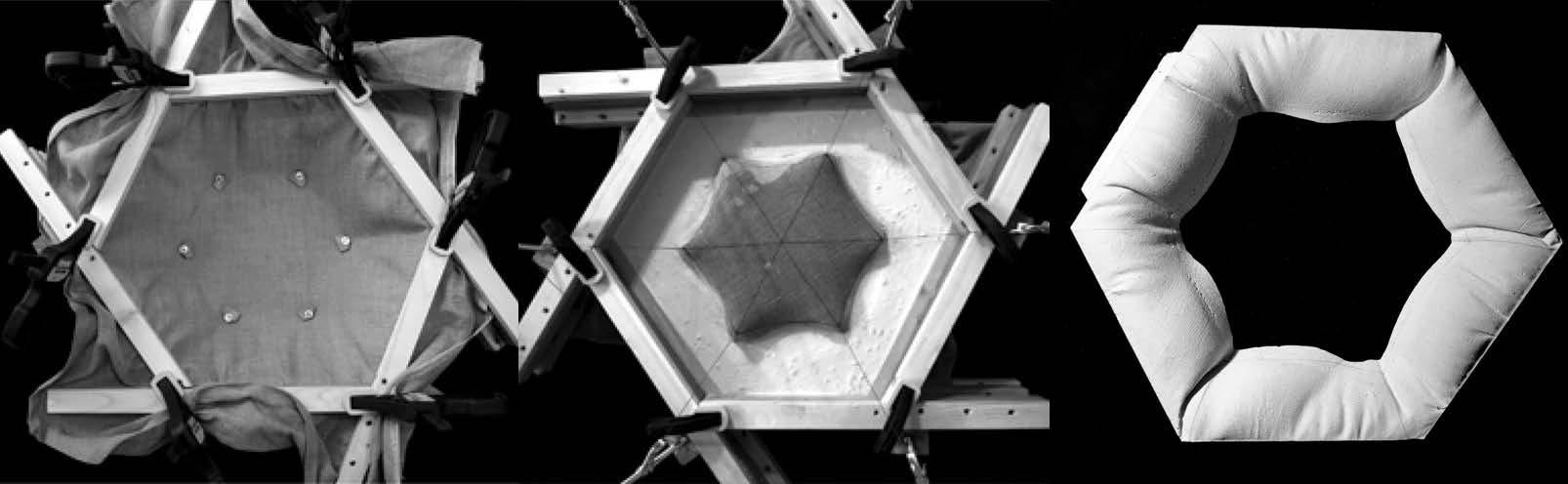

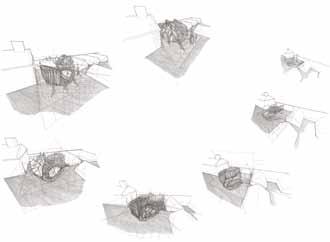

Figs. 19.12 – 19.13 Ossama Elkholy Y4, ‘Let’s Negotiate’. Today developers and investors are banking vacant plots of land with high building potential, profiting from their trade at the expense of building affordable homes. This project explores the notion of a small community adversely possessing these vacant sites. A discrete kit of moulds are used to assist in a quick initial deployment and occupation of the sites. This kit consists of a set of moulds which allows the users to attach their units onto one another, enabling them to negotiate living space with their neighbour by rotating the combined uncast

pieces. Casting the moulds adds permanence to the squatters’ dwellings, but more importantly becomes a negotiation tool for further adaptation, expansion or evolution of the building as a whole.

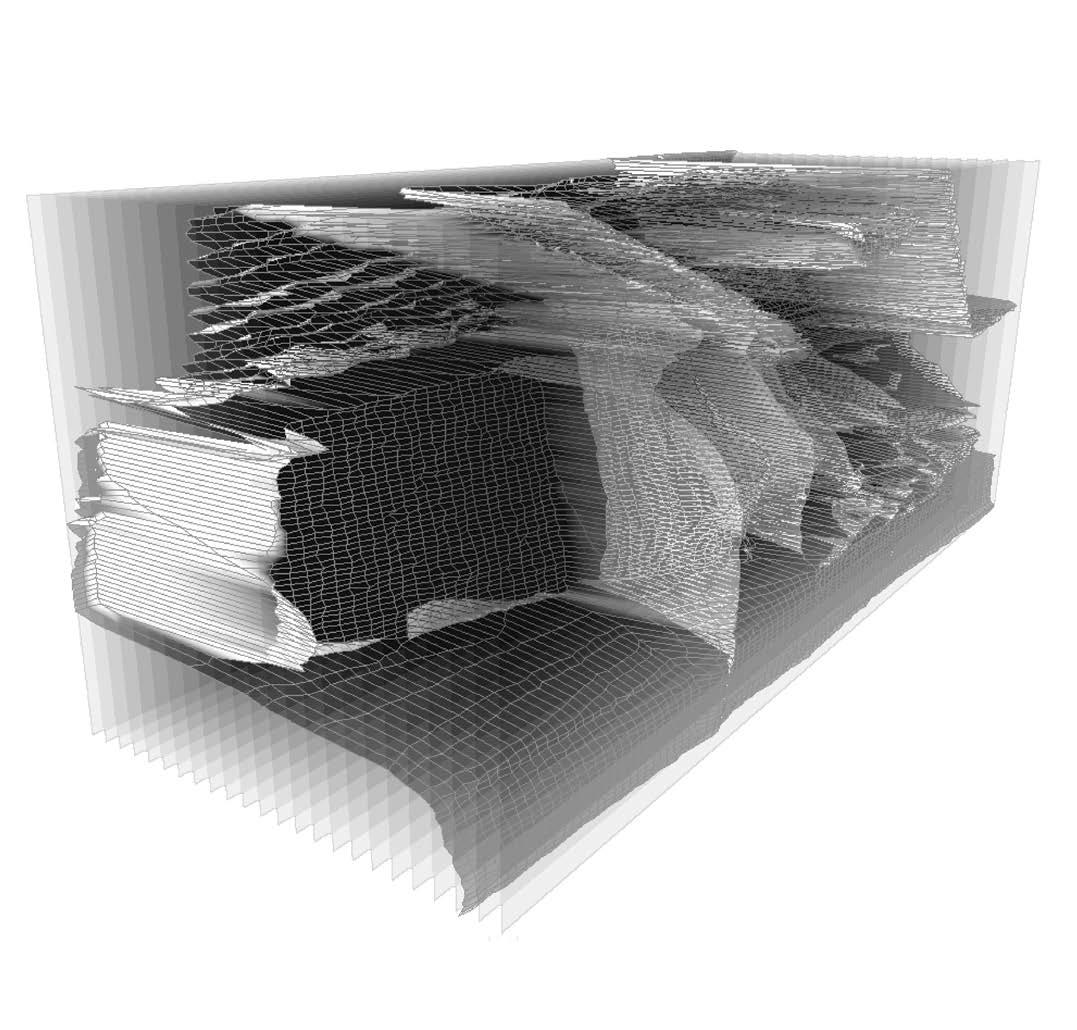

Figs. 19.14 – 19.15 Emilio Sullivan Y4, ‘Staying Put’. The project looks to disrupt the current model of community exodus in the face of regeneration by challenging authorship and negotiation on a spacial and financial level. Systematic self-assembly enabled by spatial grids allows the system to grow holistically in combination with a discrete kit of parts. This ‘bottom-up’ configuration emboldens the variability that can be found in a city block, due to its layering over time and authorship of several different designers, meaning the resulting outcomes are fluid and responsive to needs.

Fig. 19.16 Milot Pireva Y5, ‘Pressing Matters’. A circular, incentive-based housing procurement model is proposed, driven by a group of individuals, who legally become capable of administrating government’s funds for affordable housing.

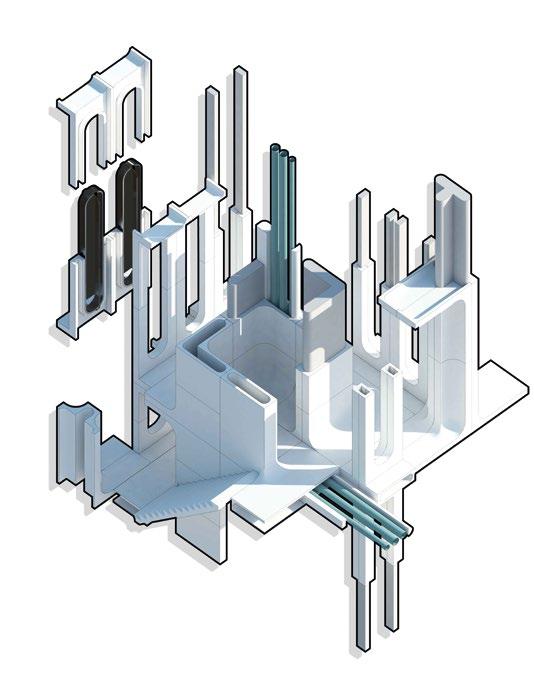

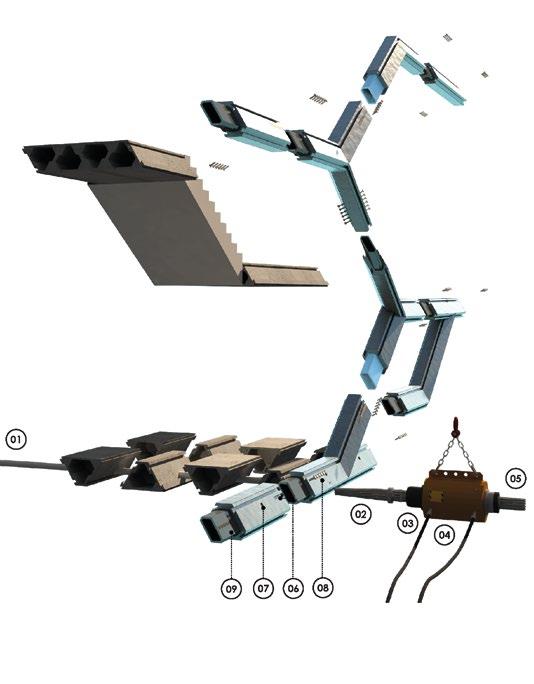

The users and inhabitants are in charge of orchestrating a system of private and public investments. This is achieved with the help of architects to define spatial uses, programming the masterplan and local conditions through a developed kit of parts. Fig. 19.17 Shogo Suzuki Y4, ‘Digital Metabolism’. The project reduces the unit of a Metabolist-era capsule and megastructure into digital materials which are small and generic on their own. These can be configured into structurally and spatially different dwellings through discrete parts and connections, removing the need for predefined spaces. Robotically bent and assembled steel is used for the structure and volume of space, and timber parts of the same geometries are used to control the inhabitable space itself.

Architecture Made of Parts Mollie Claypool, Manuel Jimenez García, Gilles Retsin

Year 4

Elliot Bishop, Alya El-Chiati, Sara Martinez, Milot Pireva, Jevgenij Rodionov, Liangjie Wu, Hui Ye, Michael Zieja

Year 5

Tzoulia Baltsavia, Gintare Stonkute, Ivo Tedbury, Oscar Walheim

Thank you to our consultants and critics: Jakub Klaska, Harald Trapp, Mario Carpo, Lei Zheng, Nils Fischer, Moa Carlsson, Patrik Schumacher, Sofia Krimizi, Jeroen van Ameijde, Brendon Carlin, Isaïe Bloch, Elliot Mayer, Julian Siravo, Vicente Soler, Alessandro Bava, Effie Kostantinou, Claire McAndrew, Antón García Abril, Aldo Sollazo

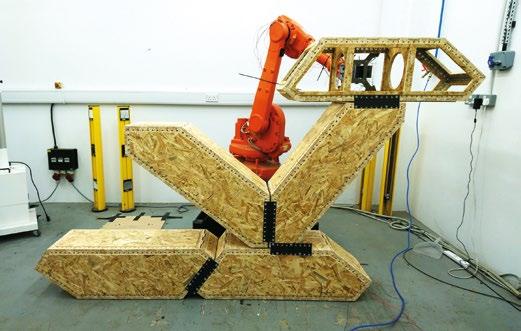

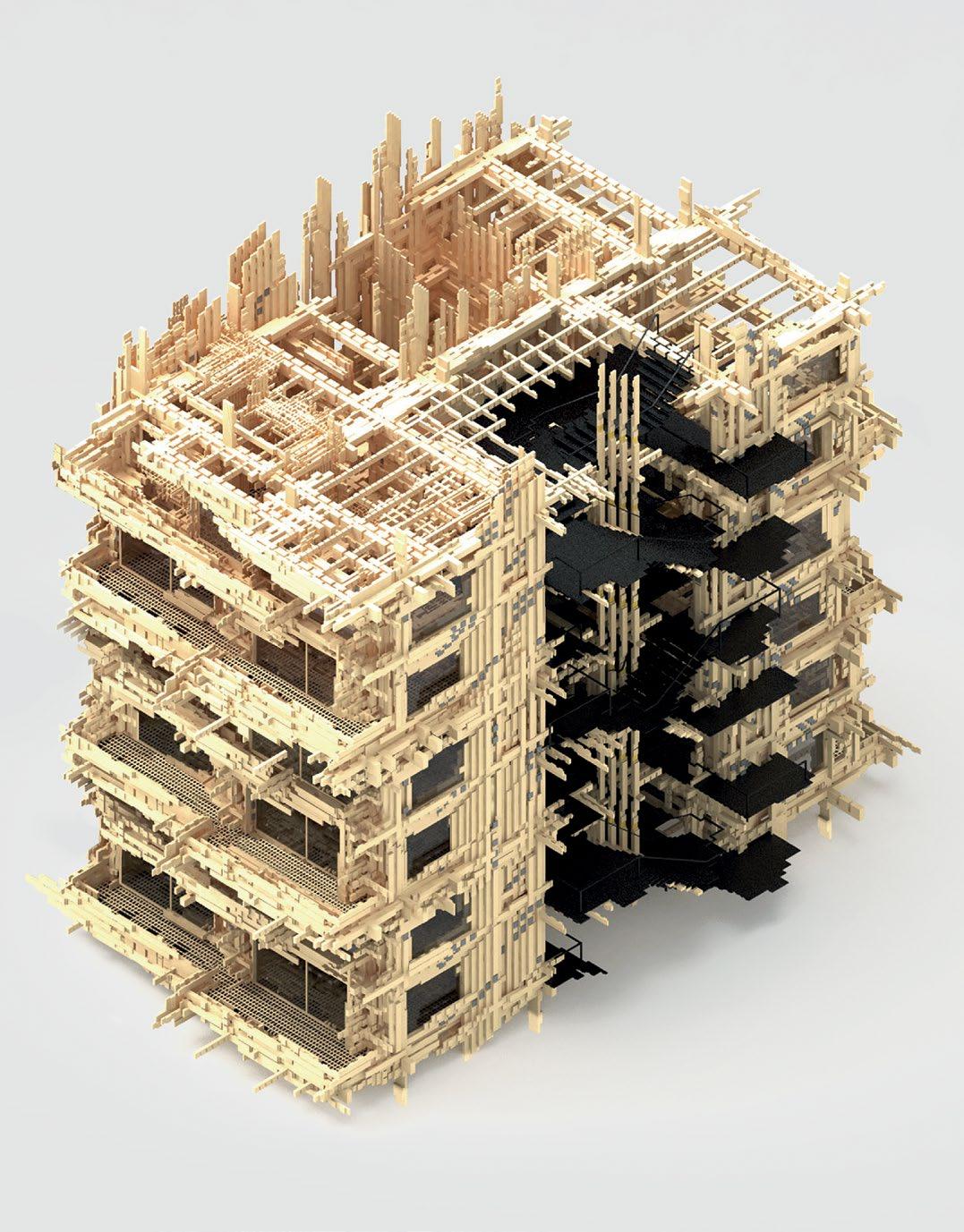

Architecture Made of Parts

Mollie Claypool, Manuel Jimenez García, Gilles RetsinSet in post-crisis Avila, Spain, Unit 19 looked into digital production and mass housing. The unit understands digital fabrication technologies not just as tools for mere formal differentiation, but first and foremost as a new mode of production containing a much more subversive agency for political and social change. The unit fundamentally questioned the approach of architects to both digital design and digital production, developing strategies for fully automated, distributed and discrete manufacturing of housing. Students engaged with a range of questions, from contemporary domesticity to the digital economy, robotics and post-capitalism. At the same time, the unit was also deeply invested in design issues such as part-to-whole relations, composition, differentiation and algorithmic design.

This year’s research started with case studies looking into modes of production of housing – looking at historic precedents such as Jean Prouvé’s Maison Tropicale and Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion House, as well as contemporary work by Antón García Abril and the WikiHouse Foundation. The unit attempted to understand the complexities of the housing crisis, both in Spain and London. We debated contemporary forms of domesticity, such as Airbnb, micro-dwellings and self-build initiatives. This initial research was combined with readings by Neil Gerschenfeld, Christopher Alexander and Jeremy Rifkin, as well as computational workshops with Processing and Unity.

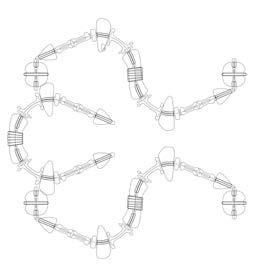

Students were then asked to develop a set of parts, in relation to a specific digital fabrication technology. These parts were defined as open-ended, universal and versatile building blocks, with a digital connectivity logic. This discrete method advances a theoretical argument about the nature of digital design as fundamentally discrete, and also responds to ideas coming from open-source, distributed modes of production, typical for a digitised economy.

By questioning and designing the system of production behind their building blocks, students developed provocative social and political scenarios intrinsic to their design projects. These scenarios range from micro-housing projects built out of folded sheet-metal (Alya El-Chiati, Year 4), to large collective housing projects based on technologies such as 3D printing or robotic foam-cutting (Tzoulia Baltsavia, Gintare Stonkute, Year 5, Jevgenij Rodionov, Year 4). Other projects are based on discrete robotic assembly (Ivo Tedbury, Year 5) or investigate an entire set of building typologies based on a sophisticated discrete syntax (Oscar Walheim, Year 5). Social scenarios such as youth unemployment in Spain are addressed (Sara Martinez, Year 4), giving rise to new building typologies for mass housing (Liangjie Wu, Milot Pireva, Michael Zieja, Year 4). Projects also took on board questions of a post-scarcity society, resulting in new shared living typologies (Elliot Bishop, Hui Ye, Year 4).

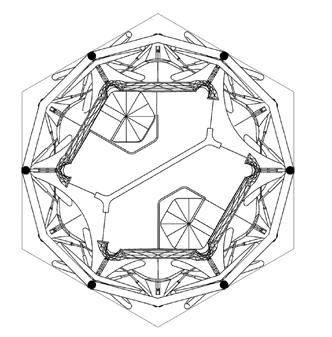

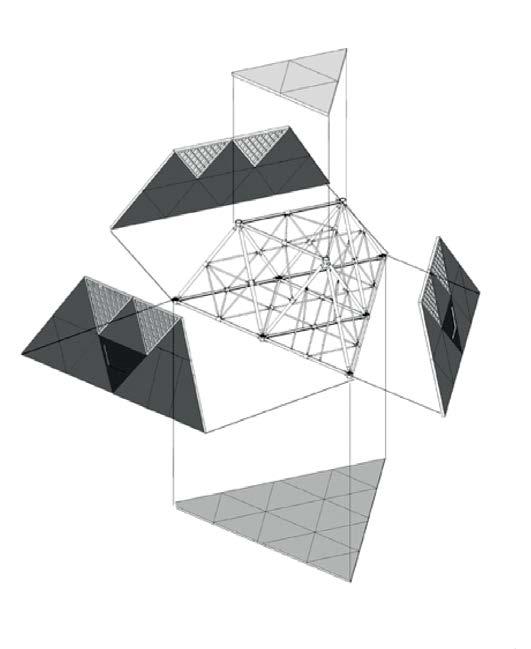

19.2

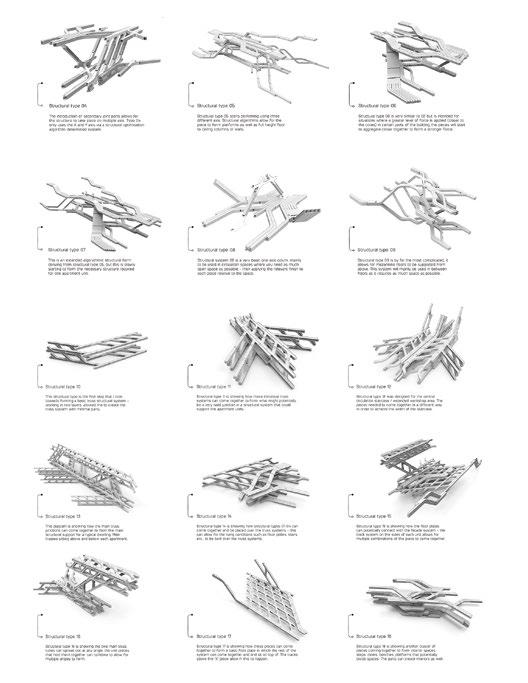

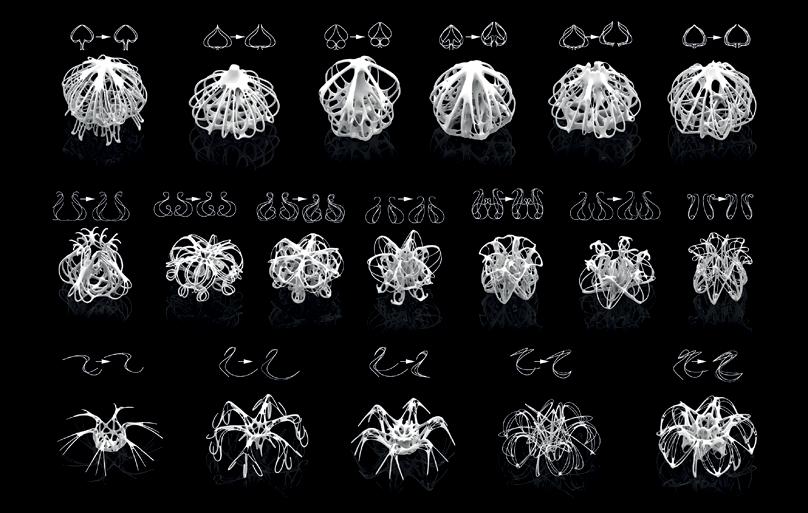

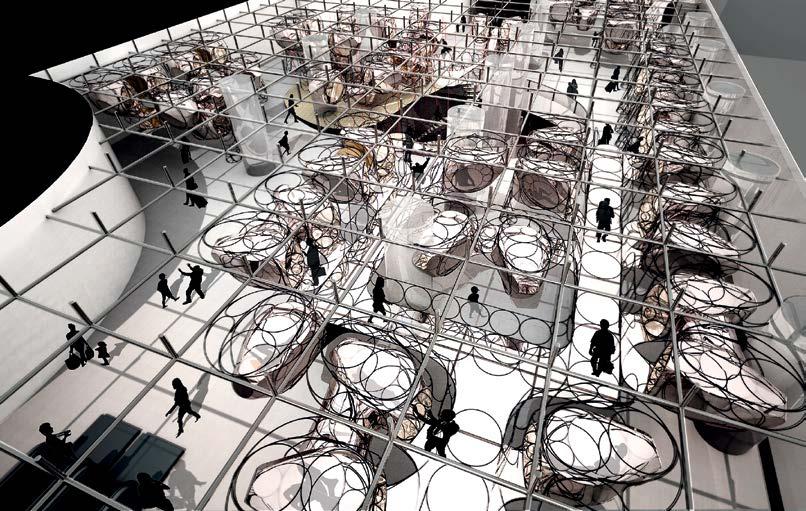

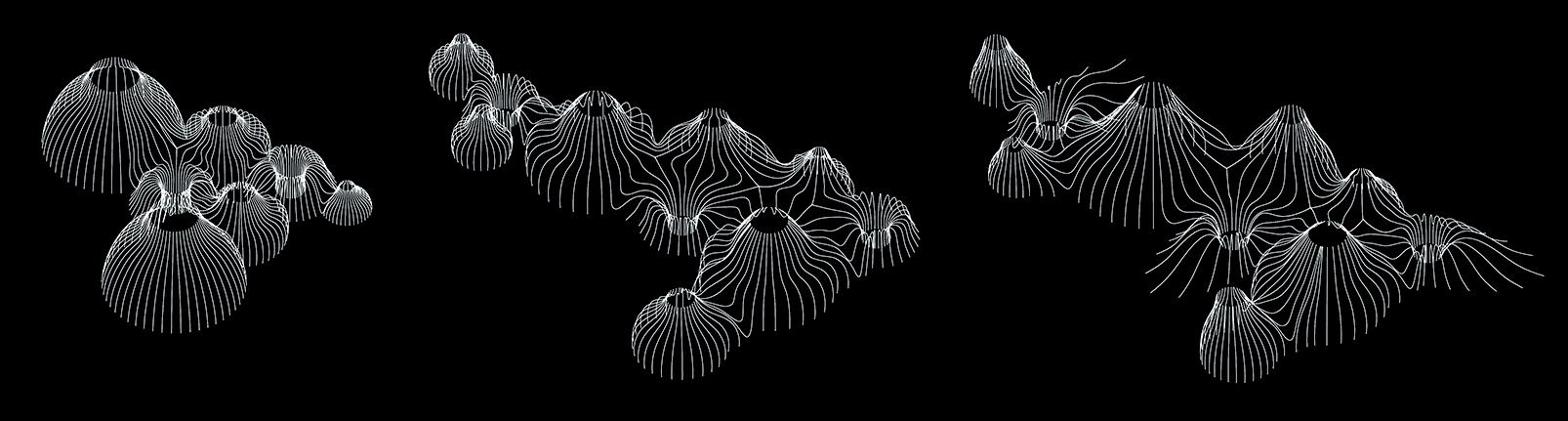

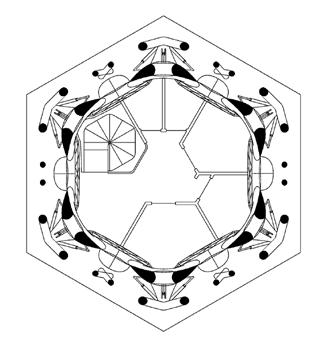

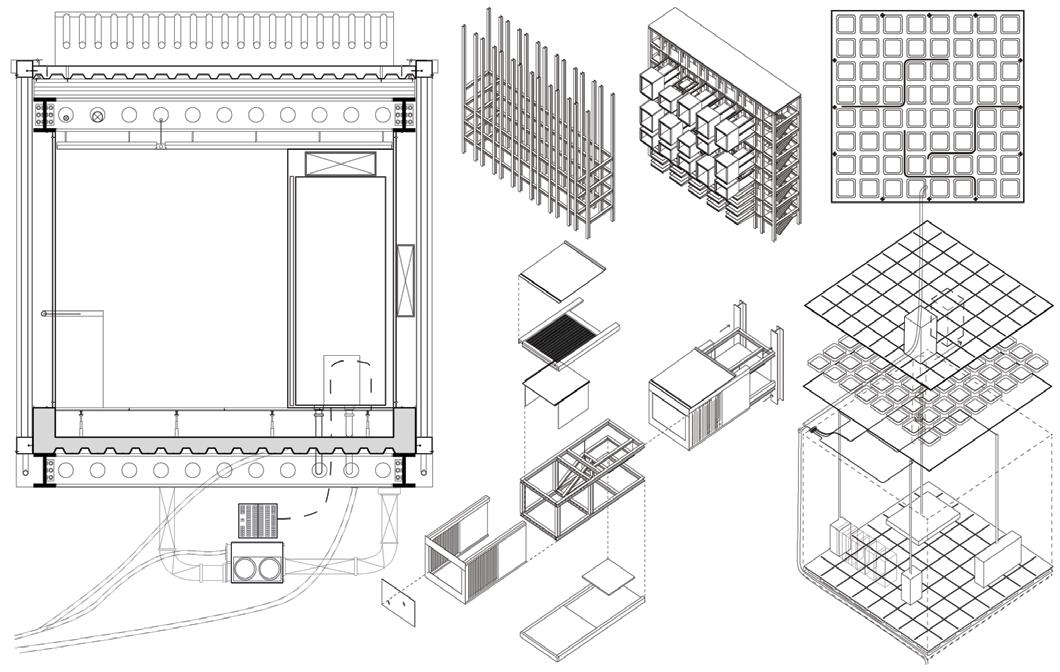

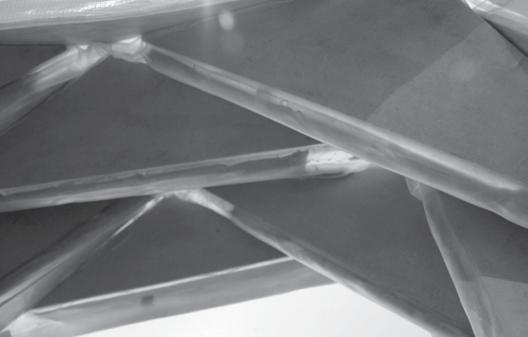

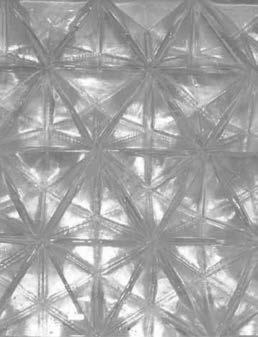

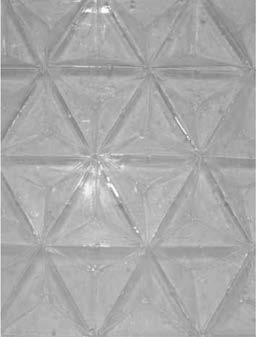

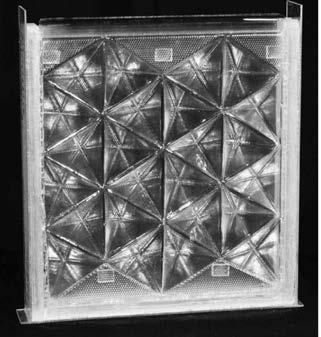

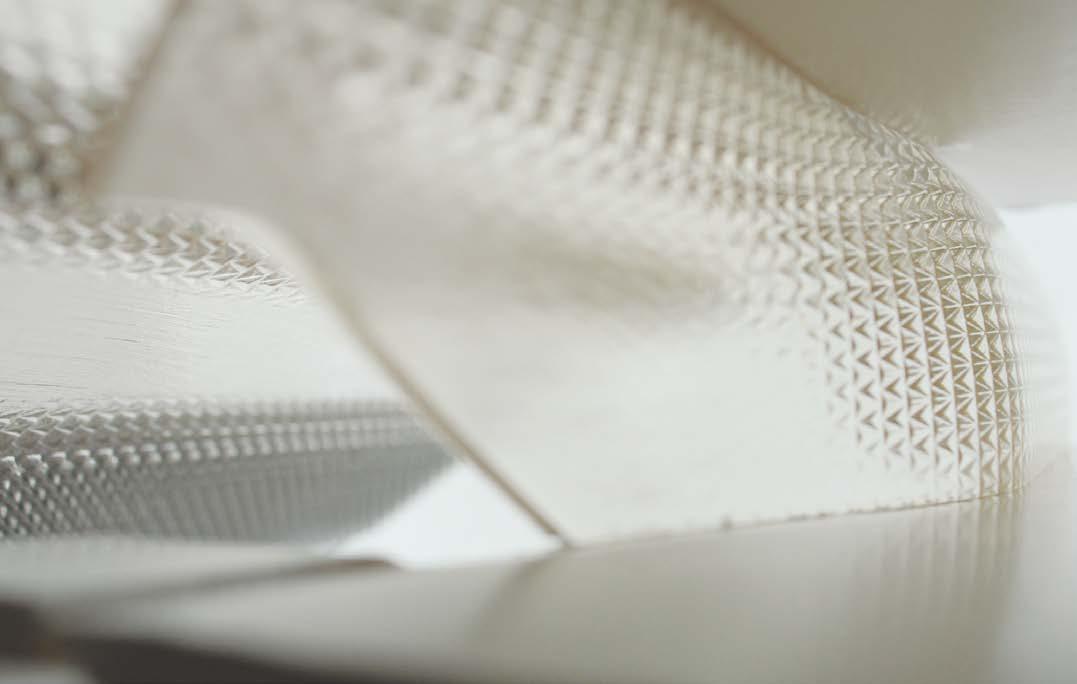

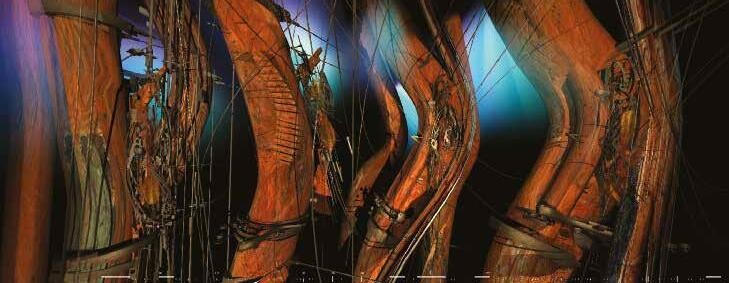

Figs. 19.1 – 19.2 Oscar Walheim Y5, ‘Avila Automatic’. This project develops a new construction ecology – a self-replicating, recombinant architecture. Deploying vacuum-forming as a simple, intuitive and fundamental process, Avila Automatic explores the potential of discrete digital formwork in the generation of precast architectural elements. The recombinatory techniques facilitated by the process result in a new kind of construction ecology. Developing a multitude of typologies, the project explores the formal syntax and modes of inhabitation resulting from this new mode of production. Fig. 19.3 Hui Ye Y4, ‘Free-Form Assembly’. Thin timber sheet material is combined into boxlike building elements, with a male-female connection system. The elements establish differentiated interior conditions,

characterised by undulating, stepped surfaces. Different structural and architectural conditions are emergent properties of the continuous recombination of parts, rather than predefined types. The resultant typology is a multi-family house, where the ground floor is left open as a communal space, connected to a green public space. Figs. 19.4 – 19.5 Tzoulia Baltsavia Y5, ‘I-Architecture’. The project proposes an open-source system based on a kit of parts that can be fabricated using robotic hot-wire cutting. These elements allow for rapid and efficient deployment of an open-ended and adaptive housing product. The discreteness of the kit of parts allows for scalability, something current approaches to open-source architecture often lack.

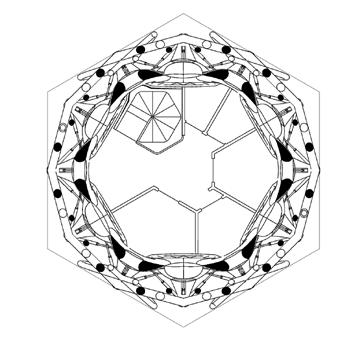

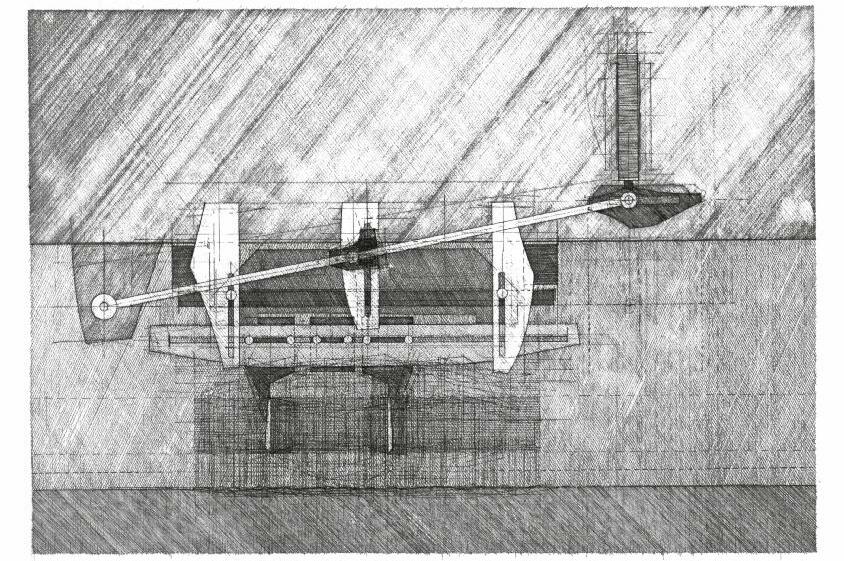

Fig. 19.6 Gintare Stonkute Y5, ‘Print My Village’. The project combines 3D printing technology with prefabricated mass housing. Instead of using large and expensive 3D printers, which would have to be larger than the building itself, the project uses small machines to fabricate a set of universal parts. These parts can then be assembled into larger housing blocks, allowing for a shorter production chain and more flexibility. Figs. 19.7 – 19.8 Ivo Tedbury Y5, ‘Semblr’. Semblr is a construction platform that enables the automated production of dwellings and other structures. It uses discrete timber bricks and distributed robots which move relative to the structures they assemble. The project states that the use of robots to construct buildings and other structures should lead to shared prosperity in society. This requires an open-source

syntax, common to both robotic systems and to the design of the assembled product. An example scenario shows the platform as tool to house people made redundant because of job automation. Leaving behind the capital-based static housing of labour culture, they begin their new post-work lives in Semblr dwellings automatically assembled at a location of their choosing. The physical and temporal flexibility of the system, and the fact that it operates at near-zero financial and environmental cost, means both quasi-nomadic and quasi-luxury living is possible. Fig. 19.9 Ivo Tedbury Y5, ‘Semblr’. The system’s technical foundation is a single syntax for cross-discipline coordination in the form of connection point object-oriented programming (OOP) ‘objects’ on the edges of the bricks, integrated systems and the robot end

effectors. This shared DNA between brick and robot allows fluid digital and physical interactions, and radically expands the remit of BIM modelling to include robotic assembly and changes to the building over time.

Fig. 19.10 Milot Pireva Y4, ‘Hands-On Living’. A limited but open-ended set of composite steel/timber elements can be used to construct a variety of spaces and structures. The construction system makes use of affordable materials and widely available CNC machines. This set of parts is deployed on a porous, longitudinal housing block that combines communal production spaces with apartment units. Fig. 19.11

Jevgenij Rodionov Y4, ‘Universal Housing Block’. Universal Housing Block is a contemporary take on the social housing production models prominent in Britain. The project proposes a digitally driven system which aims to democratise the production of housing by making design and production methods accessible to the public. Fig. 19.12 Sara Martinez Y4, ‘H-ome’. The project proposes a new collective housing

typology for the so-called ‘Ni estudia, Ni trabaja’ (not studying, not working) generation in Spain. The project aims to provide an affordable method of construction, provided in this case by local authorities as part of a defined government plan, which will allow the ‘NiNis' to enter the housing market and move out of their parents’ homes.

Fig. 19.13 Ayla El-Chiati Y4, ‘Tiny Living London’. Using a set of folded steel sheets, this project organises sixteen microapartments on the plot of Victorian House. Structural ribs and folds increase the strength of the steel sheets. The thin steel construction elements reduce the thickness of floors and allow a greater density of units.

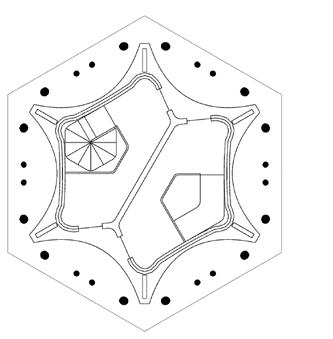

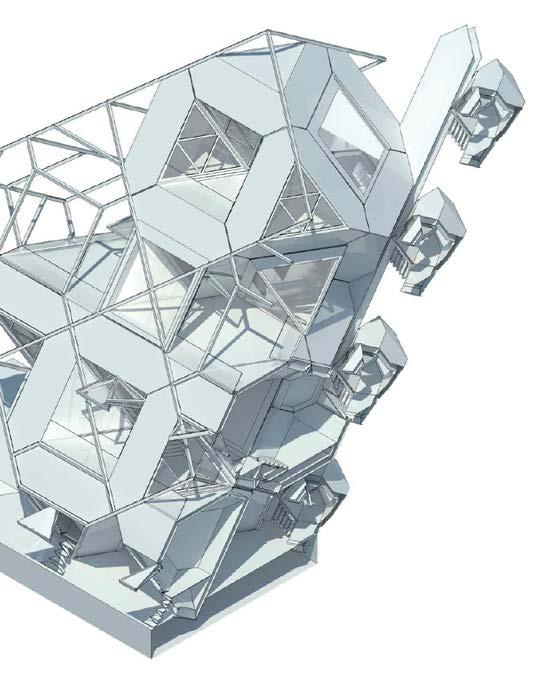

Fig. 19.14 Lianjie Wu Y4, ‘Branch Part System’. The project develops a high-rise housing typology based on a space frame structure. This frame can be constructed from standardised timber elements and a set of nodes, which use curve-folded thin steel sheet formwork. Fig. 19.15 Elliott Bishop Y4, ‘Foam Town’. This proposal theorises a building system that maximises the automation of building production and construction for the social commons. Engaging with new forms of production and reproduction through the process of CNC hot-wire cutting, and automated drone construction assembly, the project actively rethinks traditional construction techniques. Fig. 19.16 Michael Zieja Y4, ‘HEX’. Current building techniques are inefficient and rely heavily on manual labour and a skilled workforce. HEX v.3 proposes a redefined building

method, relying on a kit of parts that is inherently digital. Therefore, by providing users with an intuitive dataset or alphabet of parts for how the system can be best adapted to suit different uses, it gives people the ability to influence their future through direct action and join a community of HEX v.3 developers. Fig. 19.17 Gintare Stonkute Y5, ‘Print My Village’. This axonometric drawing shows the construction process of 3D-printed mass housing units in Avila. Building blocks are printed on the site using a farm of small-scale 3D printers. The elements are then assembled into larger structures, establishing a porous, cloud-like building with gradients of density.

The Laboratory of Mereology Mollie Claypool, Manuel Jiménez Garcia, Gilles Retsin

The Laboratory of Mereology

Mollie Claypool, Manuel Jimenez Garcia, Gilles RetsinYear 4

Tzoulia Baltsavia, Jaspal Channa, Zuzana Sojkova, Gintare Stonkute, Ivo Tedbury, Joshua Toh, Kuba Tomaszczyk, Oscar Walheim, Xin Zhan

Year 5

Elliot Mayer, Sukriye Robinson, Julian Sivaro

Many thanks to our supporting tutors: Vidal Fernandez (Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners), Design Realisation Tutor Christian Dercks (Arup), Structural Consultant

And many thanks to our invaluable critics: Isaïe Bloch, Brendon Carlin, Tomasso Franzoloni, Evan Greenberg, Kostas Grigoriadis, Sofia Krimizi, Hseng Linter, Javier Ruiz, Harald Trapp, Tomas Tvarijonas, Manijeh Verghese

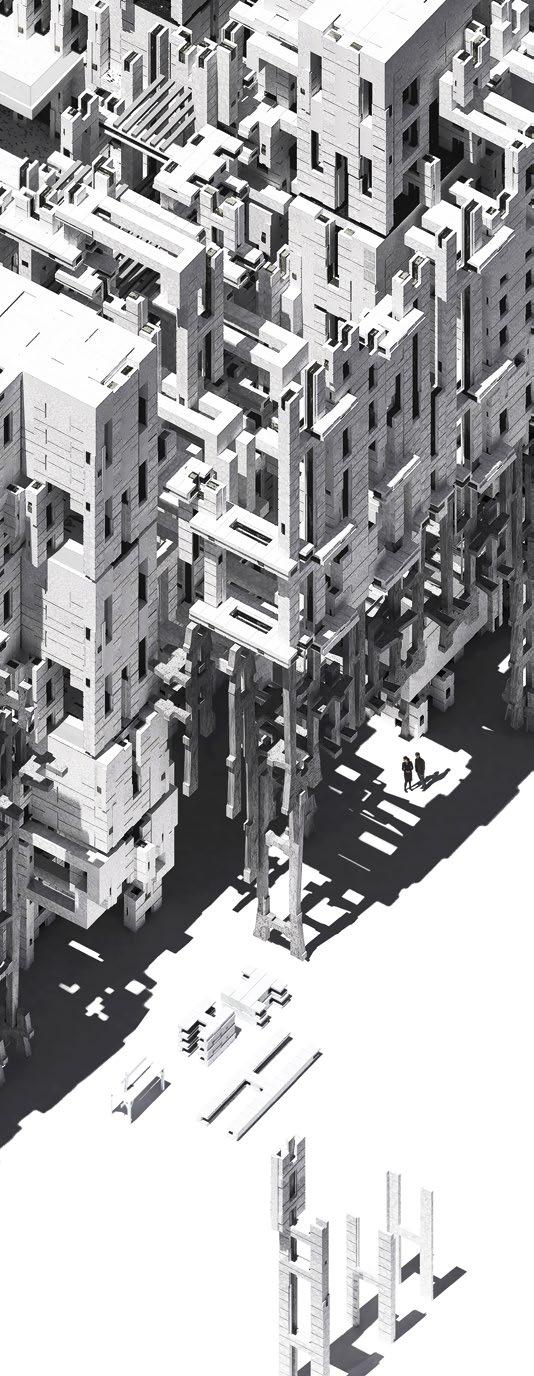

Thanks to our sponsor ABC Printing

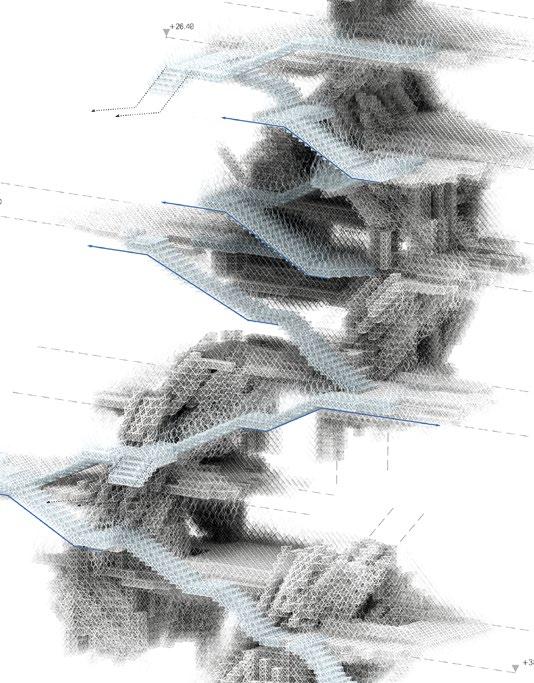

Set in Argentina, particularly in the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires, this year, Unit 19 proposed novel housing models based on a new understanding of serialisation and discreteness, enabling an increased automation of architecture while exploring new territories for design.

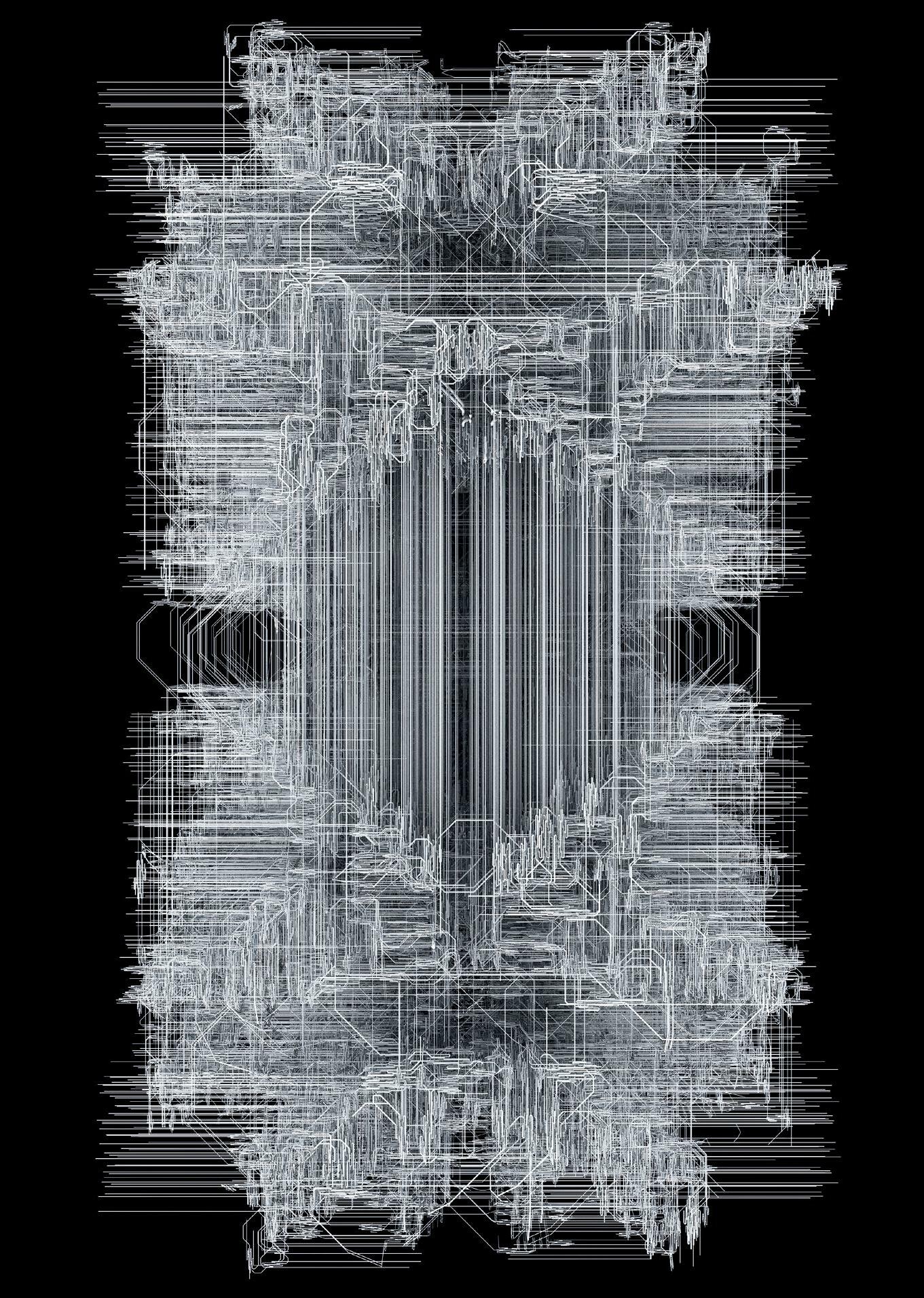

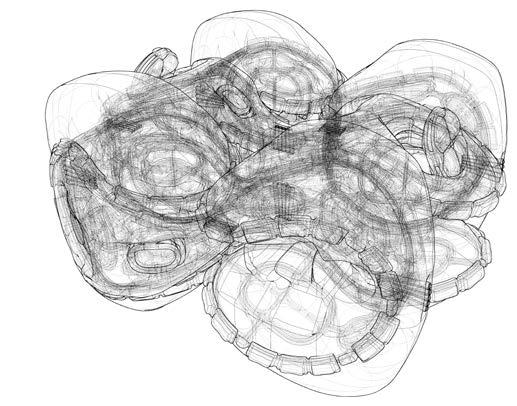

The unit work questioned the prevailing paradigm for computation in the past two decades, one that understood architecture as a continuously evolving organic body, growing and adapting under external forces. Rather than borrowing models from nature, the students investigated an architectural ontology based on sharpening the tension between architecture and its parts.

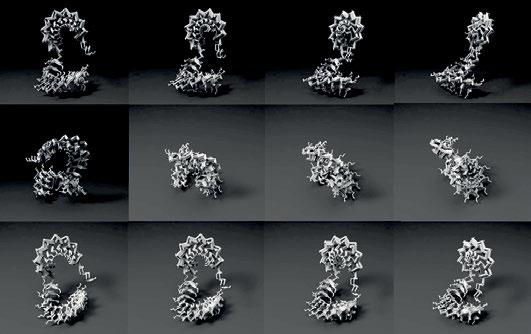

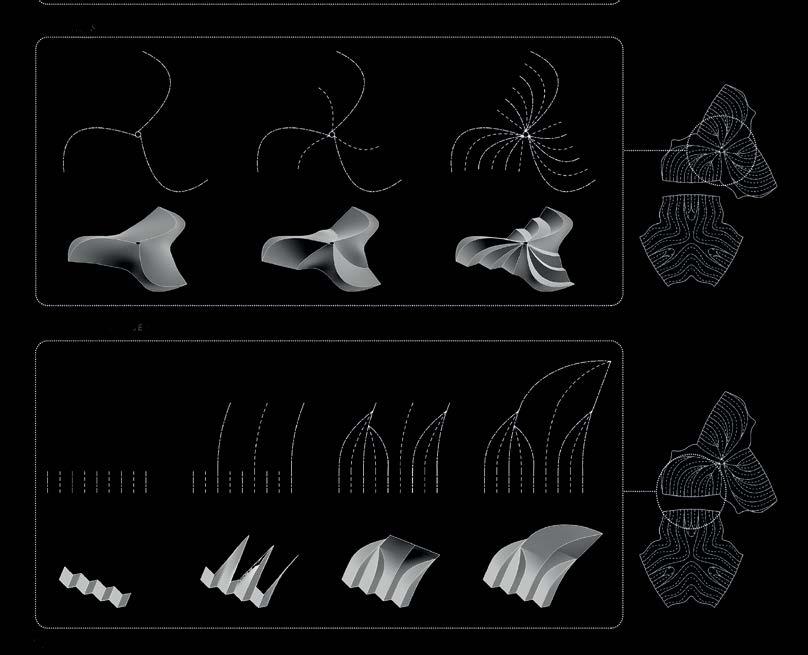

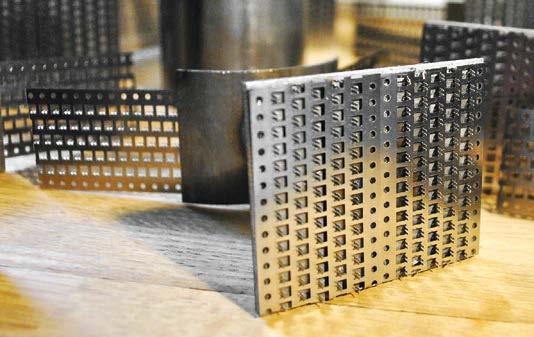

This year’s research explored fabrication techniques that are fundamentally digital, rather than analog, discrete rather than continuous, and increasingly fast and assemblage-based. Discrete, or ‘digital’ fabrication processes are based on a small number of different parts connecting with only a limited number of connection possibilities. The design possibilities (spatial, typological, tectonic, material) – or the way elements can combine and aggregate – is defined by the geometry of the element itself. Given the framework of discrete fabrication, where the geometry and definition of a part generates the whole, mereology (the theory of parthood relations, of the relations of part to whole and the relations of part to part within a whole) became an important concept for the work.

We looked into establishing novel types of methods for design and fabrication based on low-cost, simple, quick and reversible methods of assembly into highly-detailed, heterogeneous and structurally sound architectures. Increased computational capabilities are able to push the initially modernist understanding of architecture as an assemblage of prefabricated, discrete elements into an unexpected new domain of previously unachievable detail, materiality, structure and aesthetics.

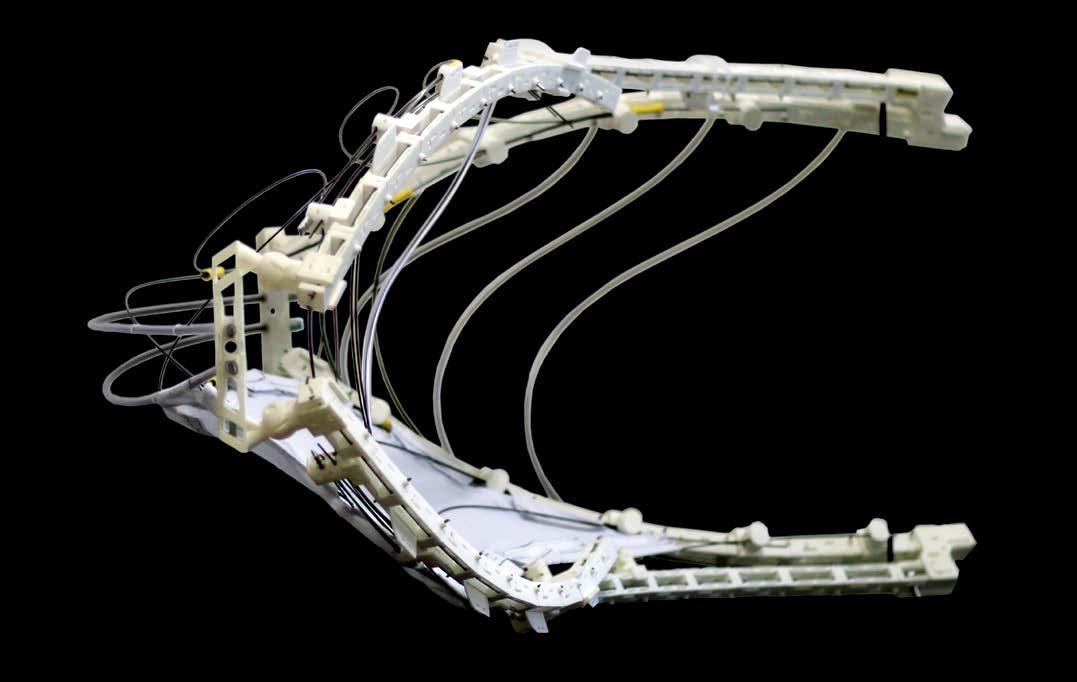

By questioning and designing the system of production behind their building block, students developed provocative social and political scenarios intrinsic to their design projects. These scenarios range from exploring a fully automated society without work (Julian Sivaro, Year 5), to collectively-owned self-assembling robotic exoskeletons which enabled continuously adapting buildings (Ivo Tedbury, Year 4). Other projects question the impact of the digital on the way we handle data, create instruction and think about authorship and originality (Elliot Mayer, Year 5 and Oscar Walheim, Year 4). Projects also took on board questions of analogue craft and digital materiality in mass production, designing prototypical systems for manufacturing (Sukriye Robinson, Year 5 and Jaspal Channa, Year 4), amongst others.

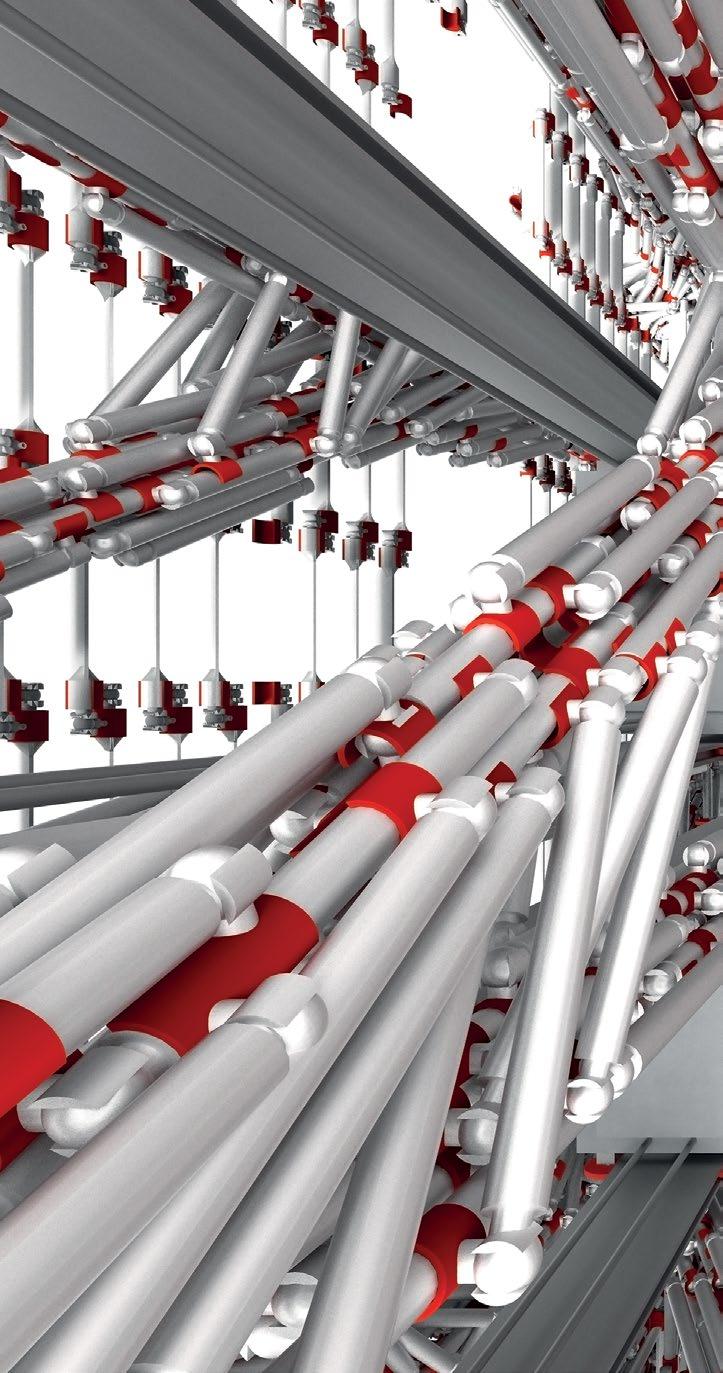

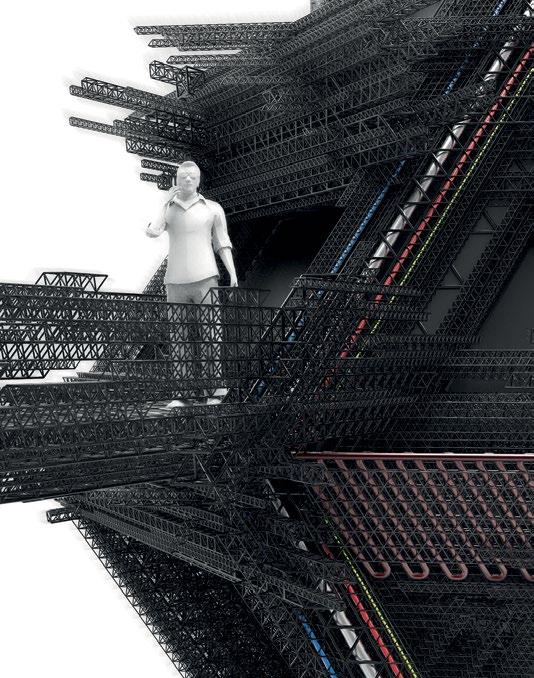

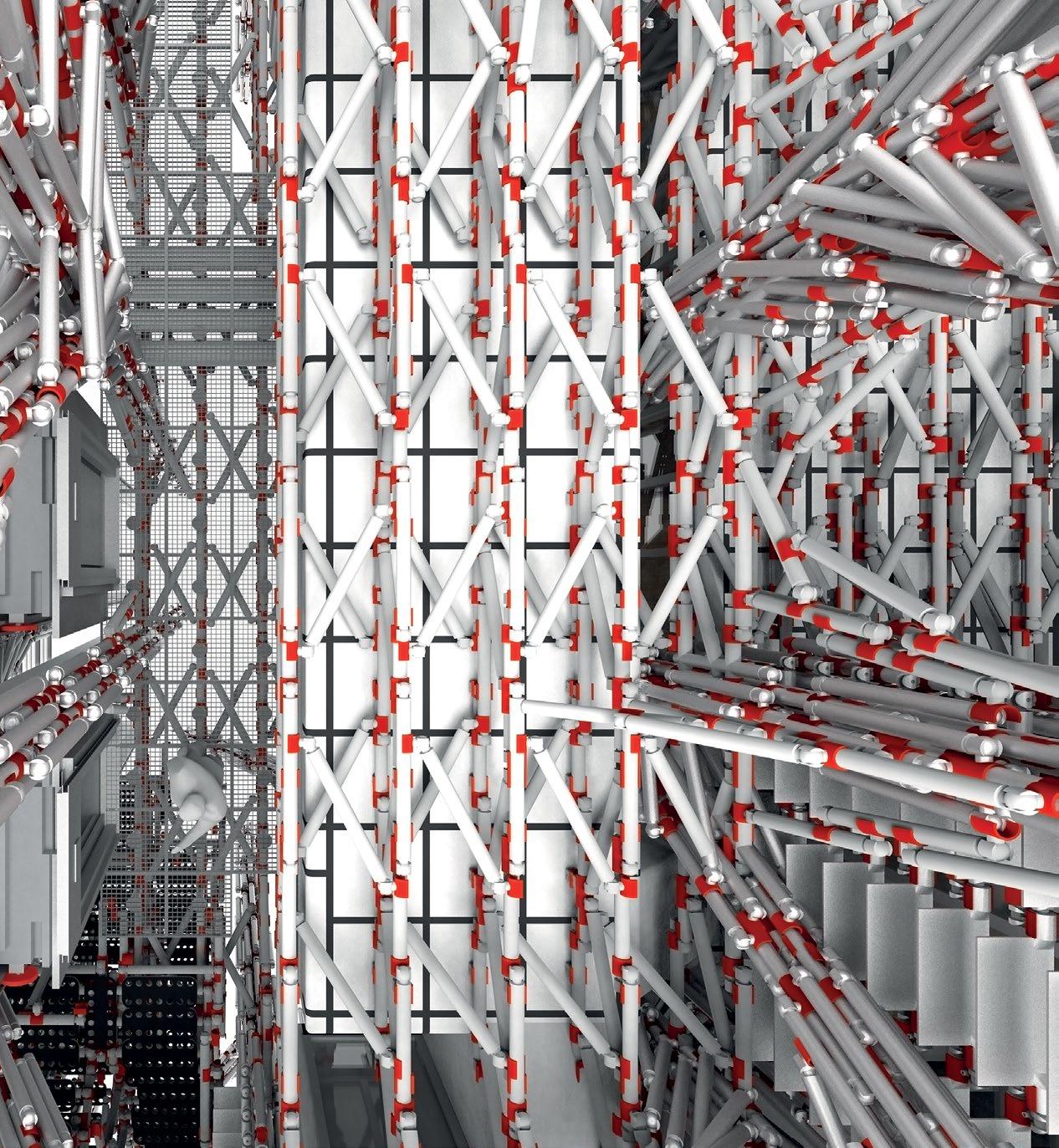

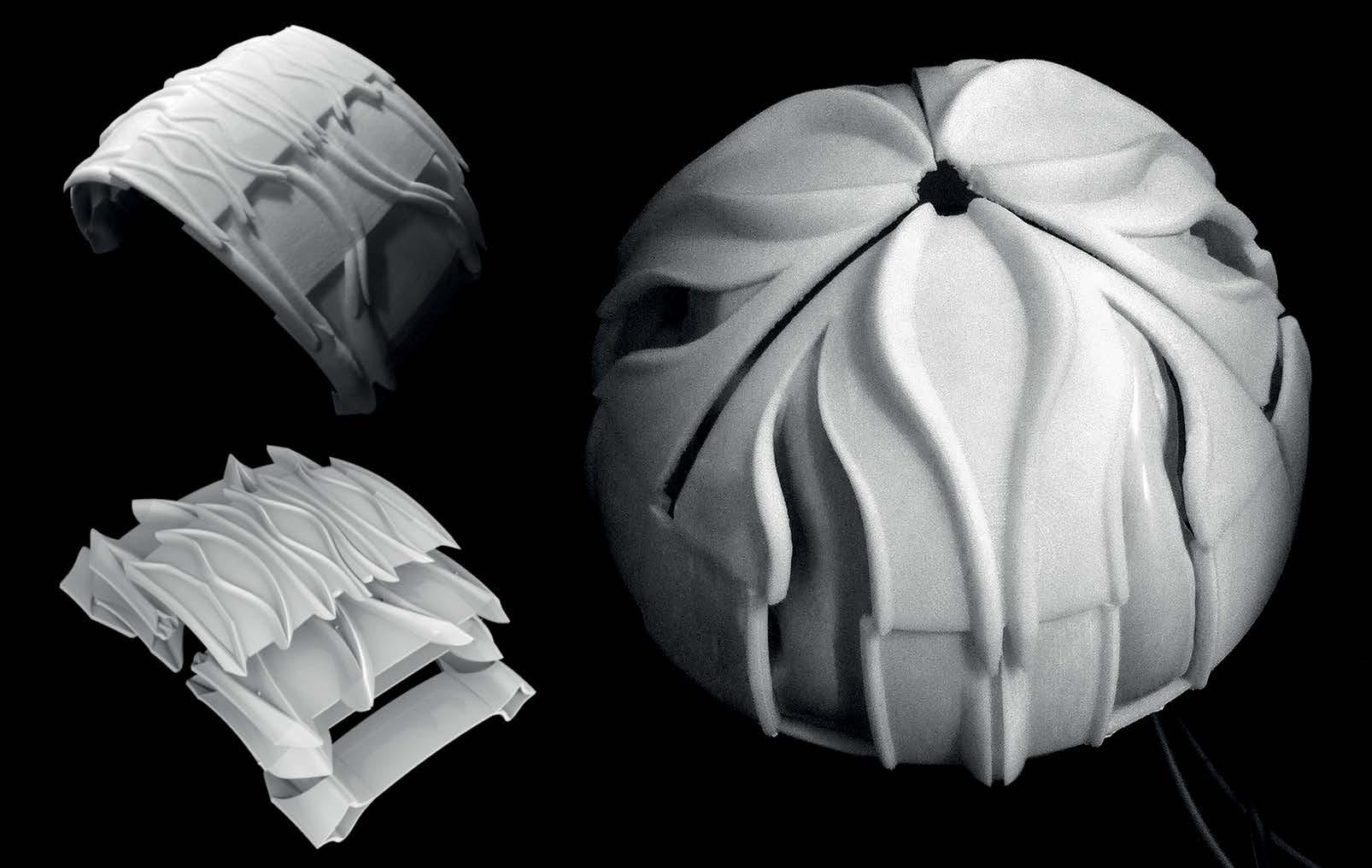

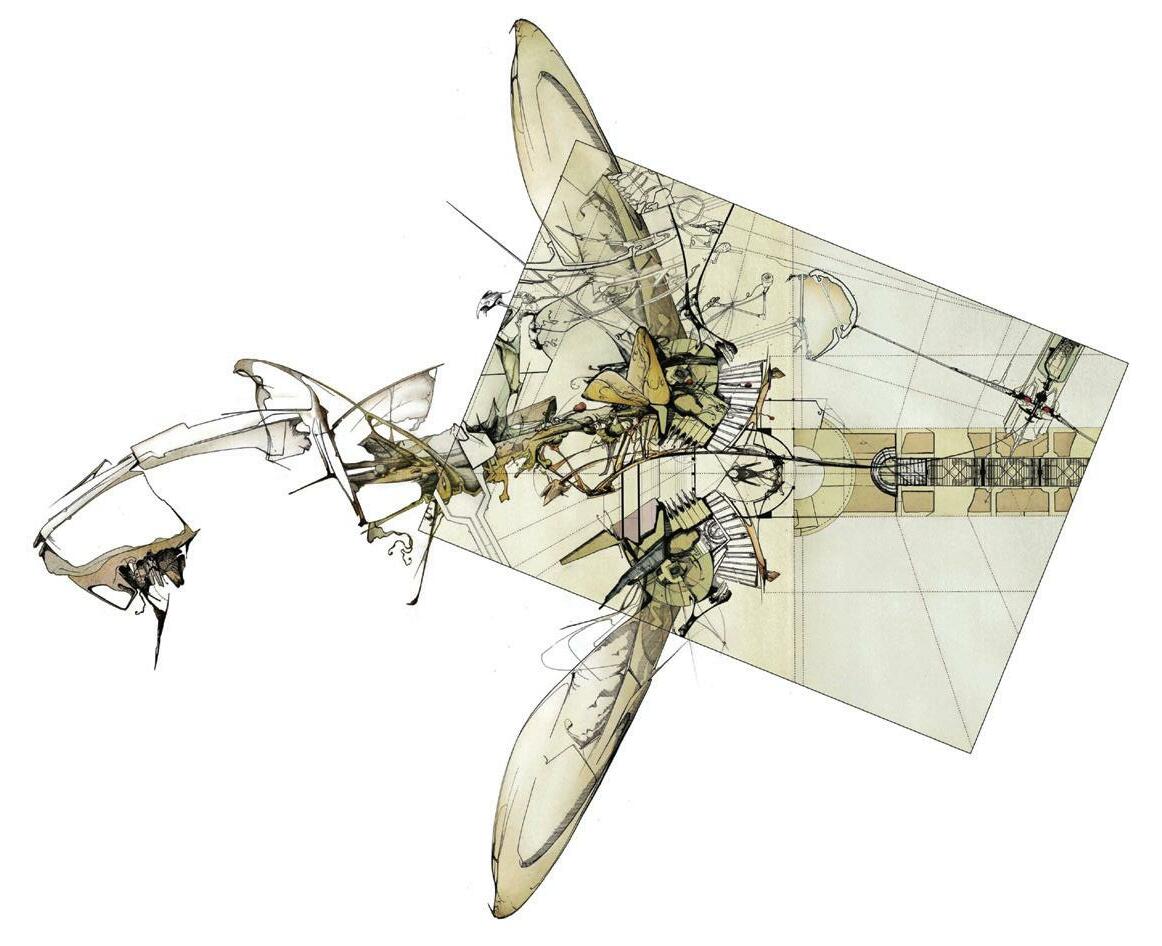

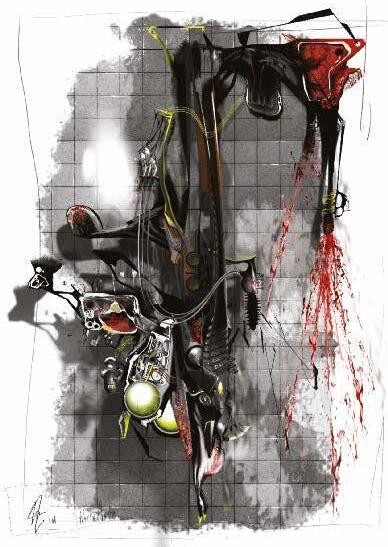

Figs. 19.1 – 19.2 Elliot Mayer Y5, ‘Vectonics’. The project developes mechanisms that extract fundamental attributes of built space, deriving the creation of new digital forms through an indexical organisation of discrete parts that simulate these attributes. The development of a radical tectonic and programmatic assemblage is built upon the computational folding and sequential interlocking of standardised bent metal pipe geometries. These generated interlocking aggregations are fundamentally dictated by overarching generic laws of interaction prescribed by both the designed manner of the brick-to-brick connection and the repetitive sequence embedded in the collective formations. Advanced concepts of generative part-to-whole relationships explore the subversive concept of digitising the interpretation of space through the

reproduction of a series of distinct architectural typologies identified within the urban grid plan of Buenos Aires. This discourse devolves the architectural engagement with spatial design by empowering the relevance of automated digital manufacturing in an age where the limitations of urban architectural production are confined to given programmes of space. This radical building logic is constructed in the order of: typological precedent (existing building), classification (identification of spatial hierarchies), extraction (record of representative data), assimilation of features (reinterpretation), and reinvention of architectural form.

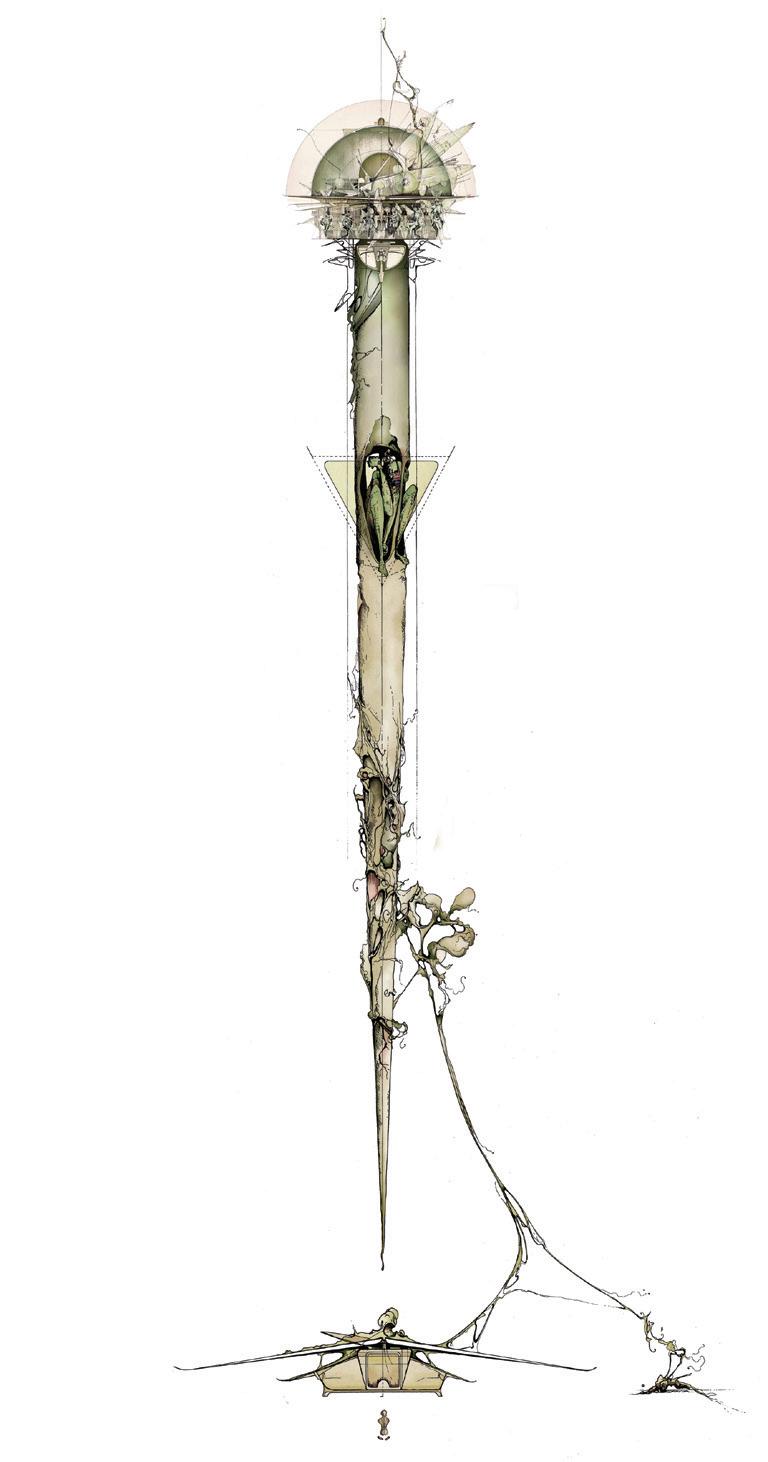

Fig. 19.3 Julian Sivaro Y5, ‘Post-Work City’. This project imagines a future in which most jobs have been automated, in which the conflict between labour and capital has been

resolved through public ownership of automata. The writings and drawings try to imagine the infrastructure of full automation and the spaces of full unemployment, placing them in the Delta del Paraná, north of Buenos Aires. Digital materials are not only the means to successfully automate the construction process, but the symbol and working parts of a shared housing program in constant flux. This program prefigures a post-familial and form of living, predicated on sharing domestic labour and enjoying each others' company.

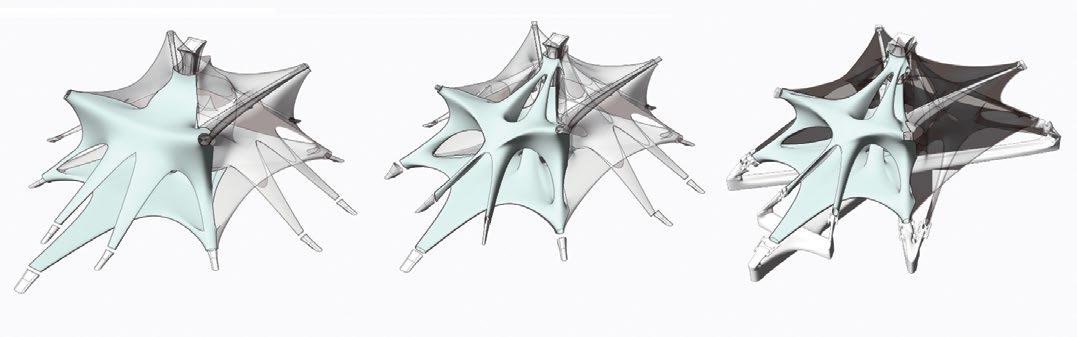

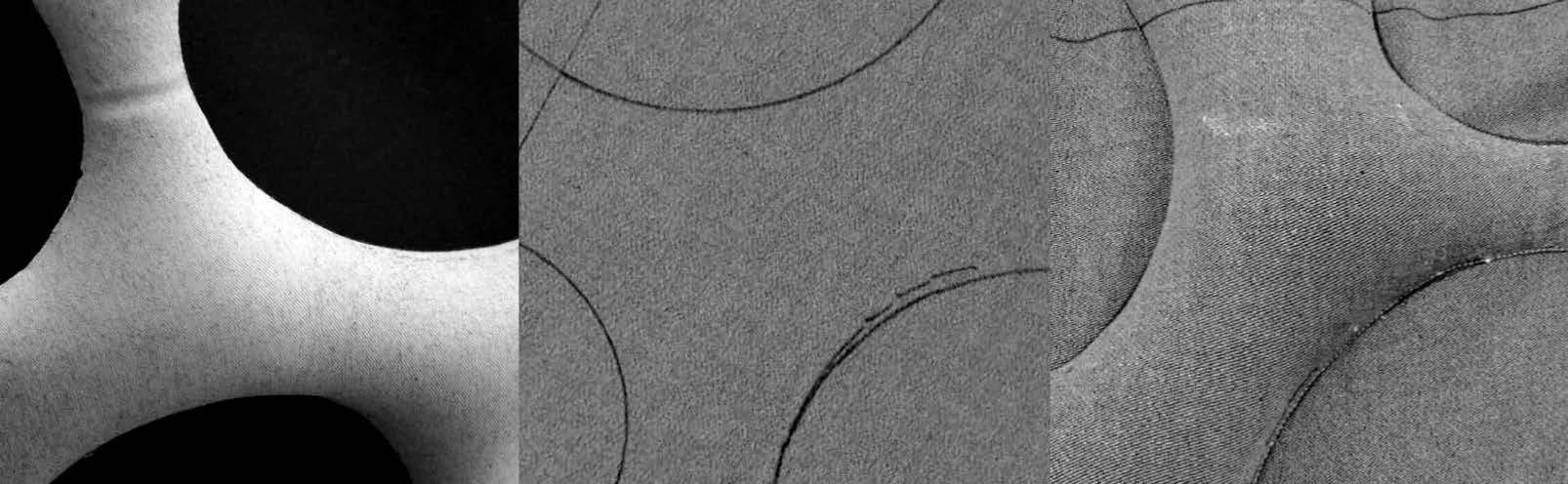

Figs. 19.4 – 19.5 Sukriye Robinson Y5, ‘Fiberoo’. The project is an innovative production system for both discrete and continuous architecture. Through rigorous testing, a new bamboo fibre composite was designed. Using bamboo on each of its scales creates a holistic approach to materials – utilising

a low-cost, highly renewable natural material. Addressing part-to-part and part-to-whole relationships, individual robotically fabricated elements come together to create an innovative architectural solution. The system can respond to any site conditions and parameters through the capability of total customisation. The bamboo composite opens the door for bamboo to become a standardised construction element – something the construction industry currently struggles with for such a variable natural material. Structural analysis is used to inform the robot of material distribution. The system gives the freedom for customisation as well as standardisation through a universal kit of parts or bespoke elements.

Fig. 19.6 Tzoulia Baltsavia Y4, ‘RWG’. The mereological brick system questions the predominant modernist architecture of discrete elements, as we know them today. Instead, it proposes a breakdown of these elements into individual components that come together to form a continuous building environment where spatial boundaries are blurred. The building proposal breaks away with the ‘functionalist’ living environment of the Maison Domino, while dealing with a range of brick aggregations that are non- deterministic. The system is conceived to be easily assembled and disassembled, dealing with concepts of spatial adaptability and material recycling. Working with discrete building components allows for cost-effective solutions in fabrication and rapid construction processes in a competitive

and automated market of tomorrow. Fig. 19.7 Joshua Toh Y4, ‘[FA]BRIC’. The aim of this research is to explore the architectural possibilities of a stuctural 3D woven fabric, a concept that facilitates the realisation of seamlessly integrated multiple surfaces, allowing for a complexity of geometry and surface that is otherwise difficult to realise. Design research into the possibility of designing a nonstandard architecture of pure seamless surface was conducted, and a deployable system of lightweight housing proposed. Fig. 19.8 Xin Zhan Y4, ‘Artist Hub and Gallery’. Taking mereology as the main subject of research and experimentation, the structures of this architecture are constructed from reinvented ‘brick’. It could be manufactured from weathering steel (COR-TEN) or other bendable sheet

19.7 19.8 19.9

material using a special programmed robotic machine. The method of on-site manufacturing process could speed up the process of construction. The architecture fragments of facade, roof, wall and floor consist of same elements, and the definition of each fragment therefore could be redefined and reconsidered. The project is therefore an experimental project of applying a mereological brick system to a prototypical site.

Fig. 19.9 Gintare Stonkute Y4, ‘vOxel’. The project proposes a rethink of a brick, its function and its relationships to other details of the building. vOxel investigates how a universal piece can be used to form parts of a building, whilst improving speed of construction and assembly as well as financial benefit. The project investigates the requirements and constraints of Buenos Aires, revealing how the aggregation of parts can meet

social needs and, unlike its modular predecessors, still provide architectural expression. The project developed a universal brick based on a voxel system, which can be articulated into two different versions (sharp or blobby), displaying adaptation possibilities for buildings of other functions. The relationship of these articulations blurs boundaries between structural and building elements, and inside and outside, providing transition between open and private spaces and an opportunity for residents to shape spaces.

Fig. 19.10 Jakub Tomaszcyzk Y4, ‘Uni-Truss’. The Uni-Truss system is a reinterpretation of a traditional truss structure. Conventionally, steel trusses are designed for worst case loads. However, the Uni-Truss system’s biggest scale components are designed for medium loads which, if needed, can be reinforced with smaller-scale components to provide more strength. This increases the structure’s performance and reduces material use, which is an important parameter when responding to the housing crisis in Buenos Aries. The system is also able to integrate insulation and services, making the construction process easier with all the layers of the building contained in one system. A series of rules are implemented to inform the construction process. For instance, plastic welding as a connection method and the action of cutting are

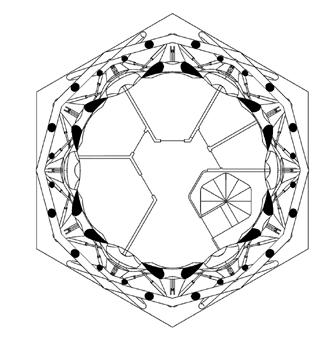

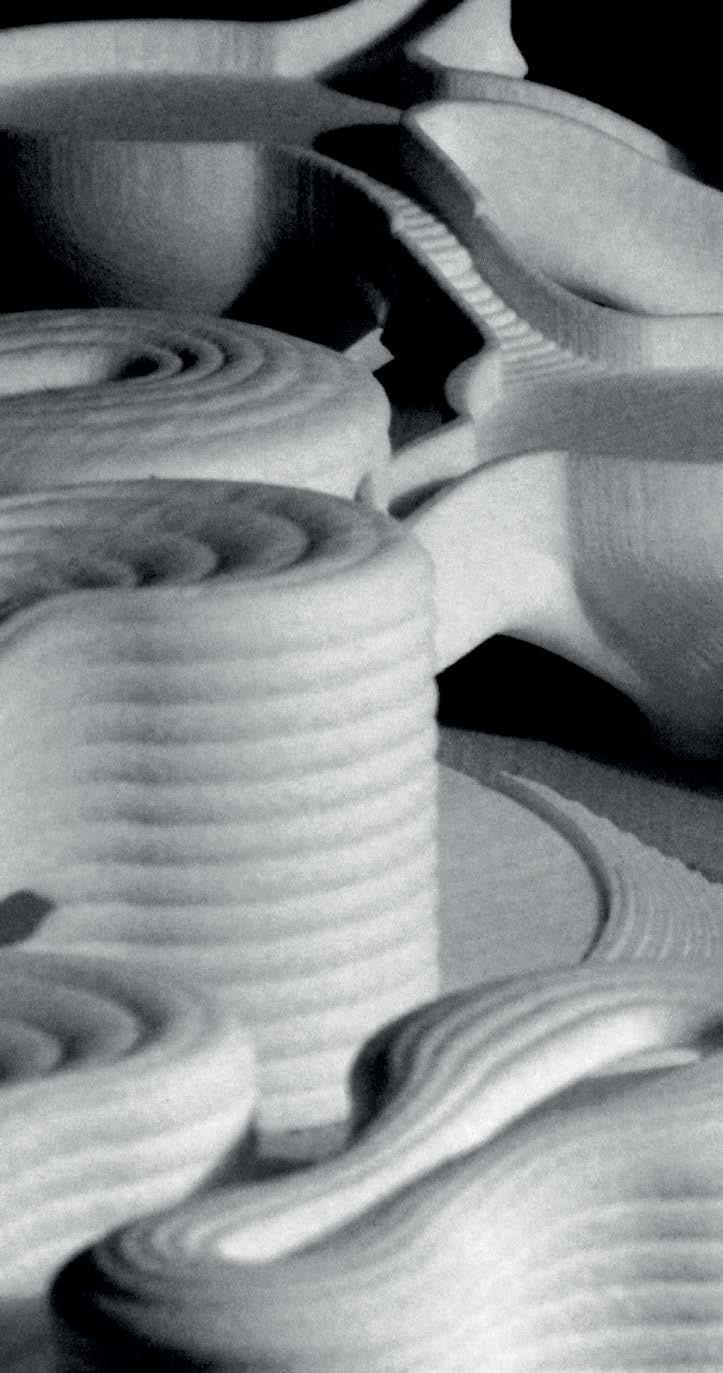

forbidden – these allow irregular forms to appear naturally without formally designing them. This can be understood through Mario Carpo’s ‘sensual experience of design without thinking’ where, in the case of this system, the main restriction is a limited set of components that, as a natural consequence, regulates the aesthetics of the generated architecture. The Uni-Truss system addresses the Zero Waste policy in the Buenos Aires Plan. Architecture is created out of recycled plastic bottles and turned into Uni-Truss components. Assuming a 40-year lifespan, this system is then recycled along with existing raw plastic waste and turned into new components. Figs. 19.11 – 19.12 Zuzana Sojkova Y4, ‘Landscape for Habitation’. The project explores conditions of habitation through a design of a discrete building element.

Through a bottom-up approach to the project, the bricks and their connection system are developed at the beginning and subsequently multiplied and aggregated. The priority is to create a building system that rethinks traditional construction methods rather than a single building that responds to a particular site. When moving to the architectural scale, the project attempts to integrate mechanical and electrical services into the accessible hollow brick cores by connecting them into continuous channels. This approach creates a dynamic environment – a landscape for habitation that influences how people move through the space. Fig. 19.13

Ivo Tedbury Y4, ‘Dynamic Construction Tower’. Operating within the context of the Buenos Aires housing crisis, which affects 500,000 people, the project proposes the radical separation

of the ‘home’ from the ‘building’ it resides within. The ‘building’ is composed of a discrete system of self-assembling ‘Dynamic Construction Particles’ (DCPs) which provide structure, circulation and environmental control (making use of exo-muscular robots to give the particles individual self-locomotion). The ‘home’ is composed of a separate discrete system of floor, ceiling and wall elements which can be arranged according to the occupant’s needs. The occupant only owns the enclosure elements, hugely reducing the financial cost of the home, and can purchase more or sell them over time according to their specific demands, while the DCPs rearrange the surrounding building to support these changes.

19.14

19.15

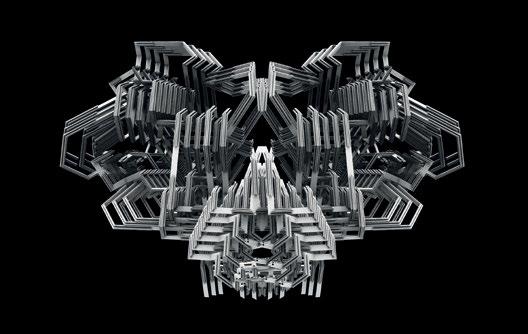

Figs. 19.14 – 19.15 Oscar Walheim Y4, ‘Rood i Geel’. Taking the ‘Cartesian Joint’ employed in Gerrit Rietveld’s Rood Blauwe Stoel as a starting point, this project investigates a new form of ‘universal brick’ that connects in three axes – a serially repeated discrete building element that can create new architectural tectonics. This discretisation of architectural construction questions both the modernist model prevalent in contemporary architecture and the more recent notion of continuous construction that accompanies advances in 3D printing. Ultimately, this leads to new methods of describing and translating architectural information itself. The investigation uses three studies to guide the research; the re-interpretation of a 1920s Modernist apartment plan, a contemporary building proposal located in Buenos Aires and

a speculative exploration of the building system’s potential. Fig. 19.16 Jaspal Channa Y4, ‘States of Permanence’. This developed from an initial investigation into an elongated timeframe of construction; overlapping with the idea that dwelling can occur concurrently within this. The backdrop of a speculative pilgrimage route leading up Argentina’s vast Pampus provided a scenario for the system to aggregate into a series of nomadic sanctuaries scattered along this route for pilgrims and travellers to dwell in. It uses the process of manufacturing through a series of machines and moulds to enable localised, continual manufacturing, whilst incorporating knowledge from historical nomadic traditions of Latin America. The project’s aim is to create a unique, yet familiar, language explored within individual, bespoke architecture.

Becoming-Ever-Different Mollie Claypool, Manuel Jiménez Garcia

Becoming-Ever-Different

Mollie Claypool, Manuel Jimenez GarciaYear 4

Che-Hung (Jasper) Chien, Rania Francis, Elliot Mayer, Sukriye Robinson, Tom Savage, James Tang

Year 5

Maria-Cristina Banceanu, Yuan Xing (Lisa) Liu, Yiting Lu, Annabel Monk, Le Lin (Stacy) Peh, Tomas Tvarijonas, David Ward

Many thanks to our Design Realisation Tutor Manja van de Worp and our Structural Consultant Christian Dercks

Thank you to our critics:

Robert Aish, Kasper Ax, Isaïe Bloch, Roberto Bottazi, Brendon Carlin, Ryan Dillion, Vidal Fernandez, Evan Greenberg, Kostas Grigoriadis, Christine Hawley, Carlos Jiménez Cenamor, Alice Labourel, Theo Lalis, Guan Lee, Ricardo de Ostos, Christopher Pierce, Gilles Retsin, Rob Stuart-Smith, Bob Sheil, Manolis Stavrakakis, Manijeh Verghese, Daniel Widrig, Zaynab Dena Ziari

Special thanks to our Summer Show sponsors RS Components and ABC Imaging

The world today is the most dense, mobile and temporal it has ever been. As the edge of the so-called ‘city’ continuously grows, shrinks, becomes blurry and undefined, its inhabitants are more likely to need the city to be able to adapt and change with urgency than ever before. It is these conditions that Unit 19 was interested in exploring this year: where the architecture of the city begins and ends, shrinks and expands. Here the user or inhabitant is viewed as a stakeholder that holds agency, acting as a catalyst for architecture that can adapt to changing material, environmental or ecological demands.

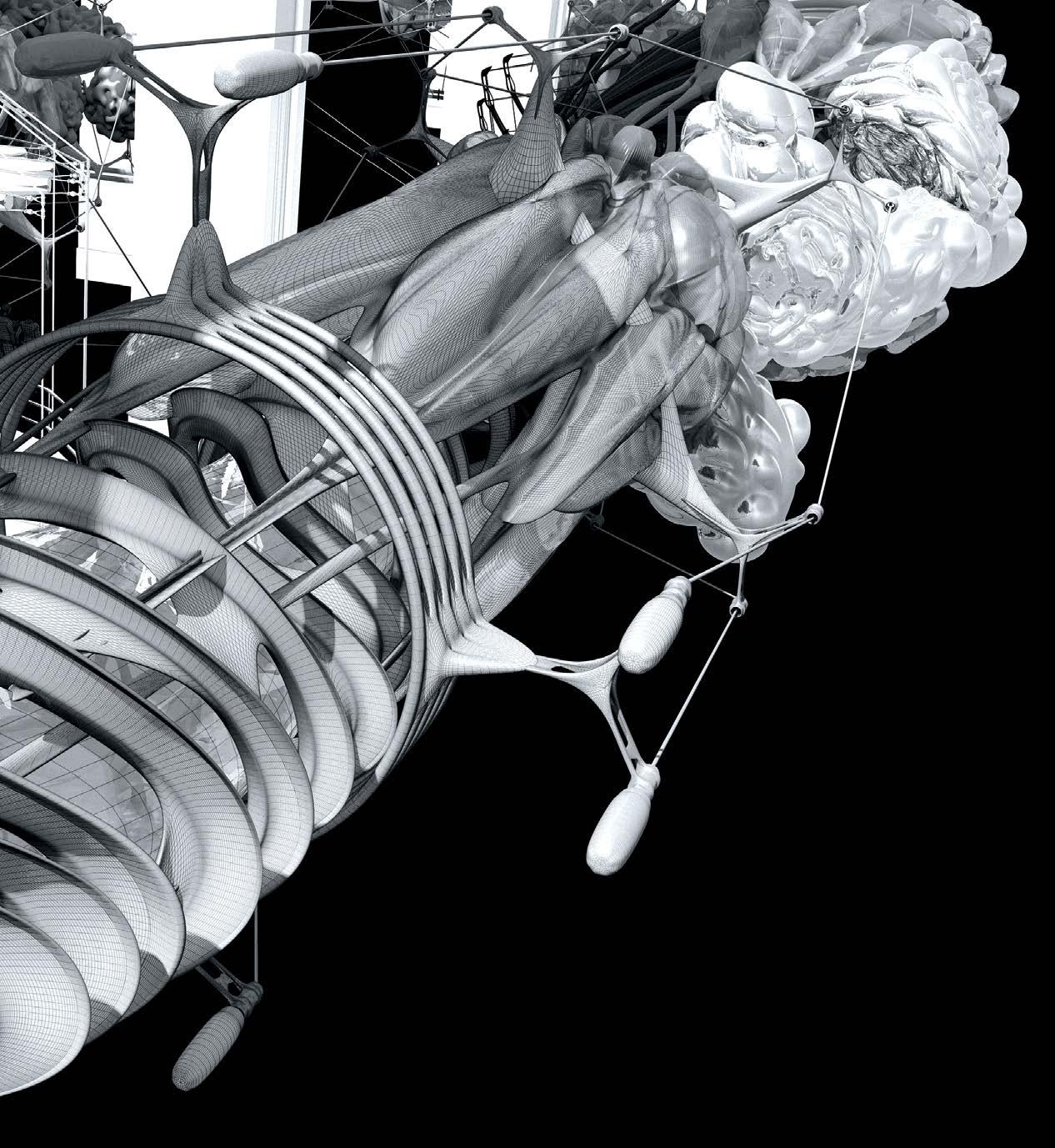

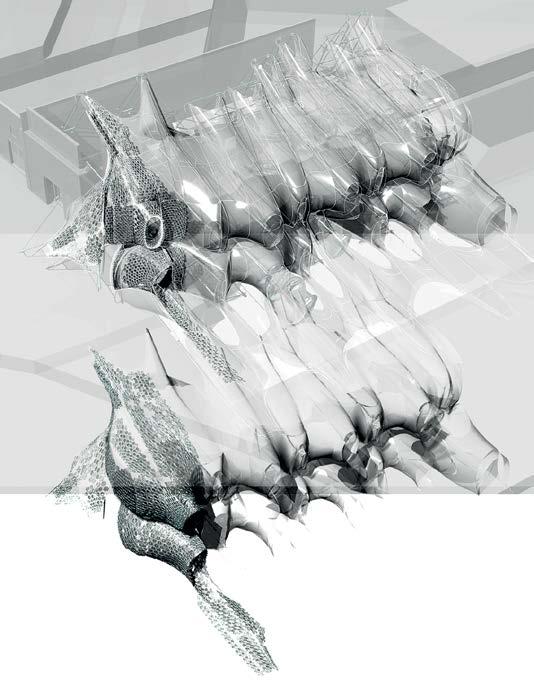

With this, we embarked into the second year of a design agenda of deployable housing. We pursued living spaces that are ‘becoming-everdifferent’ and have an in-built wildness, that are both multiplicitous and prototypical. Each student began the year identifying a material system, ranging from inflatables to fabric formwork, that they then developed through digital and analogue computational and fabrication methods to be able to react, respond and adapt in time to designed parameters and constraints. Through a steady and rigorous ‘scaling up’ process, the students began to extract a making, material and actuation logic which they then developed into new tectonics for dynamic architectures. The work harks back to the 1960s, 70s and 80s avant-garde experiments in living of Coop Himmelb(l)au, Haus-Rucker-Co and David Greene, to list some, but not all, of our favourite references. Later, this was scaled up again to that of a larger architectural proposition, with Year 4 working at the scale of a prototypical cluster of living spaces while Year 5 developed a making and fabrication logic specific to a wider polemic about inhabiting deployable structures and also related to their theses.

This year we travelled to Japan, experiencing diverse and extreme situations in every location we visited – from the peacefulness of Kyoto to the hyper-reality of Tokyo to the recovery-mindset of Sendai and the smooth emptiness of Yokohama. We met with roboticists at the University of Tokyo, architects at the University of Sendai, members of the disaster relief organisation ArchiAID, and several architectural practices such as Kengo Kuma and Japanese design and construction giant Takenaka Corporation.

The work of the unit this year is both speculative and critical, responding to fluxing densities of inhabitation in surprising and novel ways. The projects address issues such as natural disasters, fluxing environments and lifecycles, extreme lifestyles and surreal economic and social structures. Through the utilisation of novel digital design and fabrication methods, our work deploys, erects, suspends, hangs, inflates, deflates, ripples, bubbles, is continuous, composite and discrete.

Fig. 19.1 David Ward Y5, ‘[Fabric]ated Growth’. Concrete framed structures, and those formed using fabric formwork, typically require heavy modification to allow for new additions and extensions. The intention of this project was to challenge this notion of concrete structures as static monoliths that resist change and explore a new structural system tailored for growth through the production of fabric formed prototypes, with an emphasis on expanding the structural roles of formwork elements. The project is influenced by the additive nature of traditional Japanese housing, proposing a self-build, integrated structural system that is designed to be additive, growing in accordance with occupants’ needs, whilst maintaining structural and spatial continuity and minimising as much disruption to the site and surroudning context as

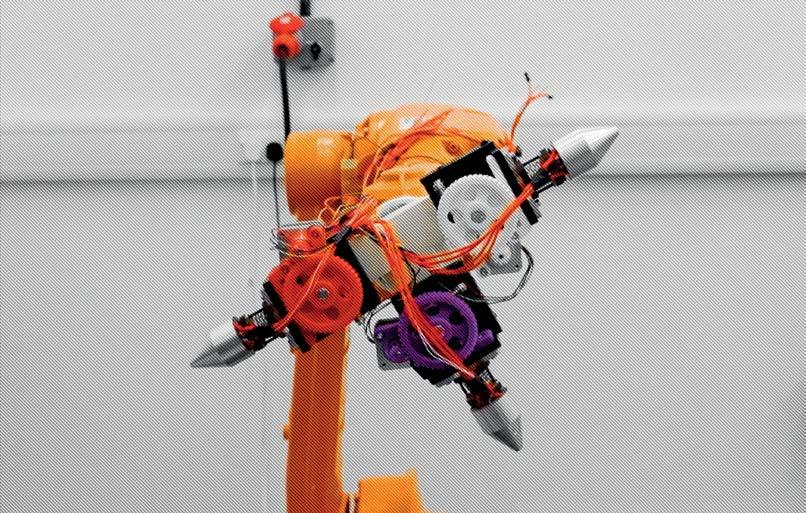

possible. Figs. 19.2 – 19.3 Tomas Tvarijonas Y5, ‘Atectonics’. The project proposes an architecture of fusion rather than assembly, light chemical connections instead of heavy mechanical connections and articulated gradients over discrete and articulated joints. Through the development of an end effector for an industrial robot with three custom plastic extruders, and hacking into the material and making process for 3D printing, the project developed a manufacturing process for a bespoke, highly customisable, inflatable and seamless architecture.

19.4

19.5

Fig. 19.4 Annabel Monk Y5, ‘The [Great] Wall of Japan’. The project is a speculative proposal based upon the integration of disaster relief housing and civil engineering strategies along the sea wall in post-tsunami Japan. Following a study trip to Sendai and meeting with the main post-disaster relief organisation, ArchiAid, the scheme aims to critique the existing hard engineering sea wall solutions and hilltop recovery shelters. The notion of disaster; earthquakes, tsunamis and their after effects, is embedded within the life and culture of the country. This scheme is a mythic proposition for the transference of the destructive energy of a tsunami into a positive intervention within coastal cities. Figs. 19.5 – 19.6 Yuan Xing (Lisa) Liu Y5, ‘The Inhabitable Scaffold’. The project looks at providing integrated living for workers that are in the

19.6

construction industry for the preparation of the 2020 Olympic Games in Tokyo, Japan. The dispersion of sites in the Tokyo Bay area happens in stages over a five-year period from 2015 to 2020, and is situated near the construction site. It has two different modes: active, in which case the residential site would also be activated with prefabricated capsules attached to a pre-designed scaffold frame, that acts as the circulation and service area for an active site and a viewing platform and as a service area for the Olympics when it is inactive. This design is to serve a purpose even after the workers are no longer in need of it, giving a sense of legacy that is left behind by its prior occupants.

19.7 19.8

Figs. 19.7 – 19.8 Maria-Cristina Banceanu Y5, ‘The Capsule Cloud’. The project is based on deep ornamentation as component driven architecture which employs exoskeletons obtained through shape grammar algorithms. The algorithms are the end result of a research that demonstrates the existence of underlying shape grammars in art nouveau motifs. The project uses exoskeletons in the form of inflatables to implement hostel pods in a heterogeneous aggregation. The intention is to preserve the identity of a historic district in Tokyo by accentuating the duality of the space: above and below, light and dark, new and old, mystery and clarity.

19.9

19.10

Fig. 19.9 Le Lin (Stacy) Peh Y5, ‘A Vending Machine for Living’. The project explores the potential of combining soft and hard material systems for the design of a deployable living unit that is flexible and adaptable. Urban voids in Tokyo, Japan are used as prototypical sites; temporal and low impact. The project proposes a vending machine for living, a new economic model that generates passive income while addressing demands for short-term rental accommodation. Fig. 19.10 Yiting Lu Y5, ‘Urban Breathalyser’. The design revolves around the cultural phenomenon of the night life in Tokyo, Japan. The proposal is hung and stretched in the middle of the largest intersections around the city, acting as a second layer to existing pedestrian pathways. Actuated by air inflation, sleeping and bathing pods are deployed during the night for intoxicated businessmen.

The pods are in a deployed and active state throughout the night and are inactive during the day, acting as a pedestrian tunnel, connecting the city in a new layer above ground.

Figs. 19.11 – 19.12 Elliot Mayer Y4, ‘Pneumaticity’. The project proposes a disaster relief shelter in Tokyo, Japan that facilitates the need for those affected by a future earthquake to utilise the stable communications infrastructure built into the expressways throughout the city. The building design’s function is to remain inactive, as a pedestrian space linking across the major freeways and providing additional access connecting to existing pedestrian networks until an earthquake occurs. When it is activated post-earthquake, it provides a temporary shelter with direct access to internet and telephone lines. This requirement for rapid deployment and flexibility of space has led to a research on inflatable composite structures, evolving the concept of tensairity to develop a soft and hard pneumatic structural system.

Fig. 19.13 Rania Francis Y4, ‘Waterpods’. The population boom that Tokyo has experienced in the last decades has pushed the city to expand further out. The design intent of the project has been to create flexible housing within the denser business areas of Tokyo to accommodate for the fluctuating population shifts caused by the influx of people traveling into the city for work, tested in this scenario in Omotesando, a district with a dense high street of office skyscrapers and behind it, a low-level neighbourhood of domestic buildings. By inhabiting the negative space between the high-rise offices and domestic buildings, the project can expand and contract over time according to demand. The flexibility of the units arises from the concept of soft ergonomics that is implemented by the use of furniture made up of water harvested from local

rain, the daily lifecycle of the users of the pods and their water consumption. Fig. 19.14 James Tang Y4, ‘Pop-up Hotel’. The project proposes short-term living capsules located within Tokyo’s busy Shibuya station, providing a short-stay amenity to the users of an existing network of transport, entertainment, food and toilet facilities. It provides resting spaces required by businesspeople working in Shibuya, commuters in transit as well as tourists shopping and sightseeing in the area. The lightweight material system of bent PVC pipes layered with flexible textile membrane allow quick and easy deployment to suit varied needs of the users. The ‘pop-up’ capsules stored within the ceiling space are only deployed when needed, and connected together to form larger inhabitation spaces when required by users of the capsules.

19.15 19.16

19.17

Figs. 19.15 – 19.16 Tom Savage Y4, ‘Inflate[w]orks’. The project aims to solve issues of temporal space in rapidly changing dense urban areas. It is located in Tokyo, one of the most densely populated cities on earth, with inhabitants that aspire to build their own brand new personalised detached homes, often at any cost, leaving large parts of the cities many housing blocks with leftover and unusable space. The proposal is a new fabrication technique capable of erection in tight site parameters and geometries that can traverse the odd shaped plots left over by rapid detached home building, and, if need be, expand into further plots as they become vacant. The project developed an inflatable balloon casting system which cuts down significantly on required formwork for casting of structural and non-structural elements of the building.

Fig.19.17 Sukriye Robinson Y4, ‘Gelatin Retreat’. The project is formed of an embryological cluster of capsules made of custom novel building materials developed this year in the unit. Located on the harsh landscape of Mount Fuji, the project offers refuge to climbers and hikers all year round. The material strategy of the building is intensely site-specific as the cold climate is perfect to set the newly developed gelatin compound, with body heat of extreme weather enthusiasts warming the interior and softening the hard beds into soft jelly pillows. The summer weather transforms the project as it becomes softer and more tactile, its density and material behaviour helping to control the interior environment of the proposal. Fabricated entirely of soft, gelatin-based materials, a cable network anchors and suspends the mass to the

19.18

volcanic crater. The bright colours and the tactile surfaces provoke a sense of adventure and exploration that contribute towards the overall experience of the sacred mountain.

Fig. 19.18 Che Hung (Jasper) Chien Y4, ‘Curve-folded Living’. This project proposed the idea of curve-folding flat aluminum sheet into 3D building components and casting formwork to build lightweight capsules that can float along the coastline on Tokyo Bay. The figure of the capsule has three different material textures weaving together: concrete, aluminum, and inflated ETFE panels. These floating capsules are connected by a designed pier system that provides public space along the shore of Tokyo Bay, a programme currently not actively available in Tokyo. Both the capsules and the pier system are composed by custom geometric specific modules

that were developed through a research into curve-folding that allow them to be reconfigured into different plan shapes in order to fit the changing urban context. Additionally the project speculates on the use of curve folding and casting to provide structural retention, reinventing traditional construction methods of retention in water.

The Living Spaces of the Algorithmics Mollie Claypool, Manuel Jiménez Garcia, Philippe Morel

Year 4

Shi Qi An, Maria-Cristina Banceanu, Yuan Xing (Lisa) Liu, Yiting Lu, Annabel Monk, Stacy Peh Li Lin, Ran Shu, Tomas Tvarijonas

Year 5

Stuart Colaco, Matthew Lacey, Jeffrey Lim, Liu Meng, Sang Yong Seok, Shuo Zhang

Thank you to our Design Realisation Tutor Manja van der Worp, and thanks to Vicente Soler for technical support

Thanks also to our critics:

Nuria Alvarez Lombardero, Sebastian Andia, Torsted Broeder, Matthew Butcher, Brendon Carlin, Marcos Cruz, Marjan Colletti, Apostolis Despotidis, Ryan Dillon, Vidal Fernandez, Evan Greenberg, Christine Hawley, Carlos Jimenez, Katya Larina, Jorge Mendez, Drew Merkle, Gilles Retsin, Yael Reisner, Pablo Ros, Stefan Rutzinger, Carles Sala, Thibault Schwartz, Kristina Schinegger, Vicente Soler, Claudia Pasquero, Jeroen van Ameijde, Manja van de Worp, Naiara Vegara, Michael Weinstock, Manja van der Worp, Emmannouil Zaroukas

Many thanks for the generosity of our critics over the course of the year, the workshop and DPL staff for their support as well as students of GAD RC5 and the Y5 students’ thesis tutors

The Living Spaces of the Algorithmics

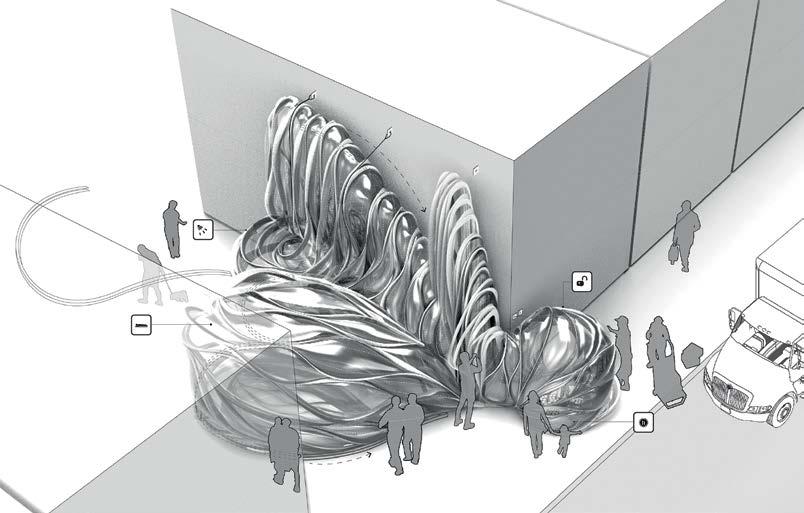

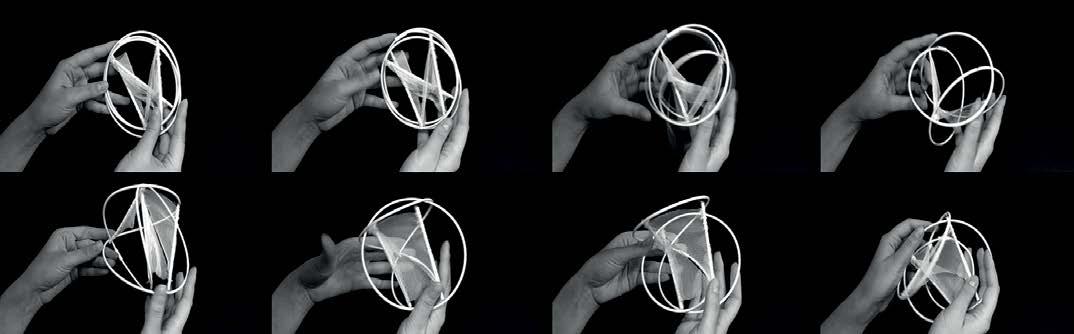

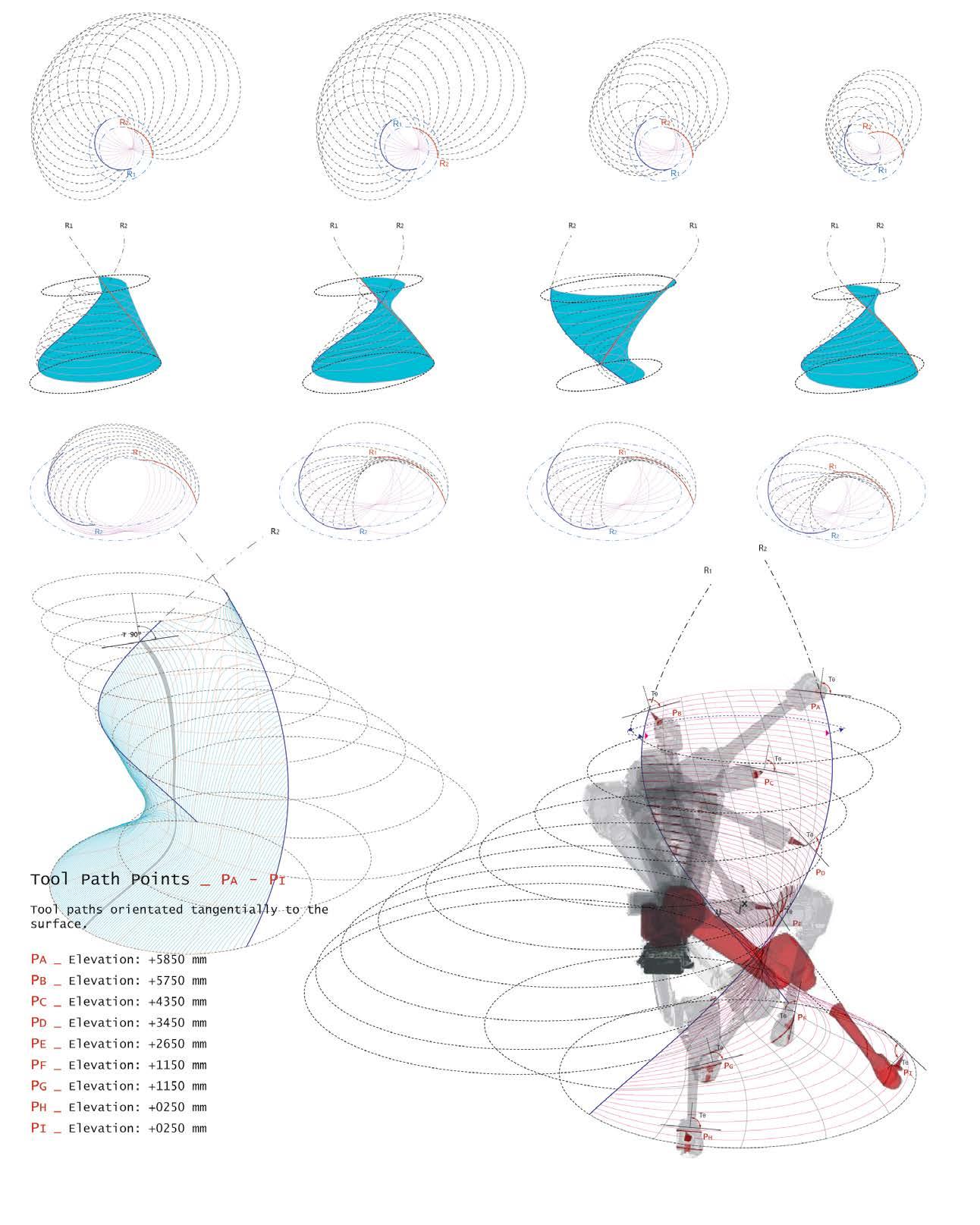

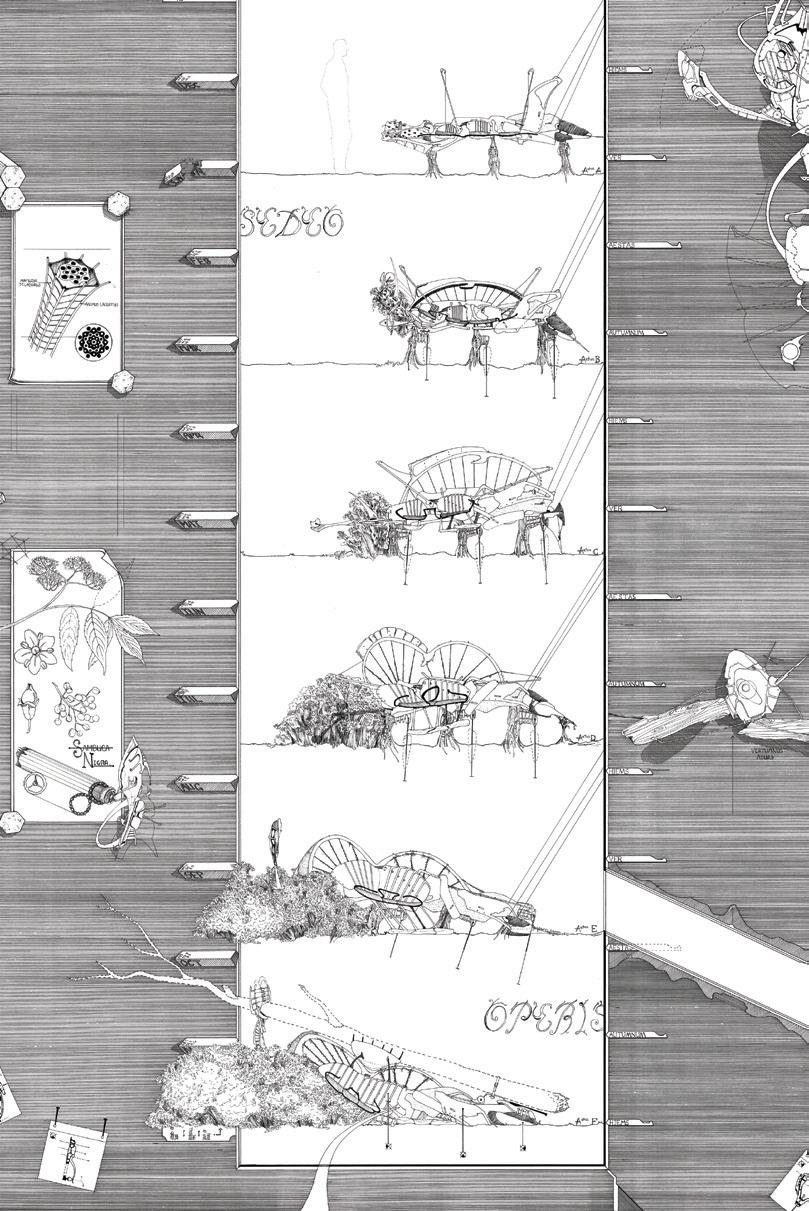

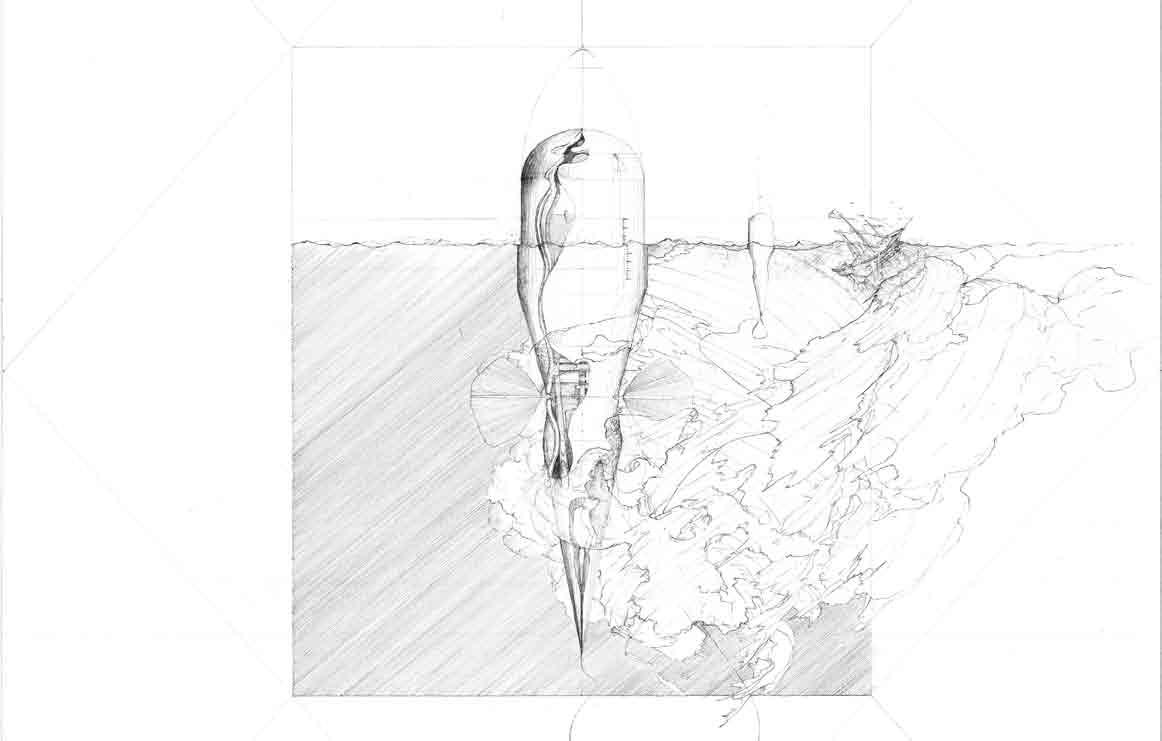

Mollie Claypool, Manuel Jiménez Garcia, Philippe MorelIn 2014 the largest problem we face as designers is how to house the world’s exponentially increasing population. In 2050 it is estimated that the world population will surpass 10 billion and the world will become the most dense, and most temporal, it has ever been. Where will we house all of those people? How will we house them? What kinds of needs will they have? This year, we have continued a research agenda into the problem of housing, situating ourselves in Sicily, a site which has been a important geographic fulcrum for population shifts throughout history due to its position in the Mediterranean: it is the gateway to Europe from Africa and parts of the Middle East. Its ever-changing population due to migration has resulted in a new kind of domesticity and housing becoming necessary, one which must be continuously in flux, adaptive and temporal, as well as sensitive in terms of economic and social relationships.

As a means of opening this as a design research problem, we began the year studying patterns of delinquency, nomadism, escapism, alienation, isolation and exile, and how this relates to these shifts and variances in population architecturally and spatially. With an exponential increase in the ways in which architects can understand the world due to the computational revolution, architects now have the capacity to design for this variability as well as difference. Each student designed a 1:1, 1:5 or 1:10 apparatus which had to transform mechanically, with several uses or functions designed into the piece. This was then simulated using algorithmic processes, and a structural, geometric or material logic was abstracted. This logic was used as the main driver in design research into novel material strategies, adaptable and kinetic structures and geometries and novel fabrication technologies, with the design of a housing ‘unit’ being the output of this work. As a result, almost all of the projects designed for a single inhabitable housing unit to be capable of being differentiated within an overall logic, enabling the same logic to be utilised for different functions. A single unit can achieve different kinds of inhabitable spaces when aggregated with density logics to form housing ‘clusters’ and then, on a larger scale, an urban strategy for housing. Each project brief is individual to the student’s own interests within housing, ranging from short-term or longer-term solutions for the housing crisis we are now in. For Year 5 this is a continuation of research begun in the unit last year and is tied to the work done for the Thesis. For Year 4 it was tied to the Design Realisation project as well as building a clear research agenda to take into Year 5 next year.

19.2

19.3

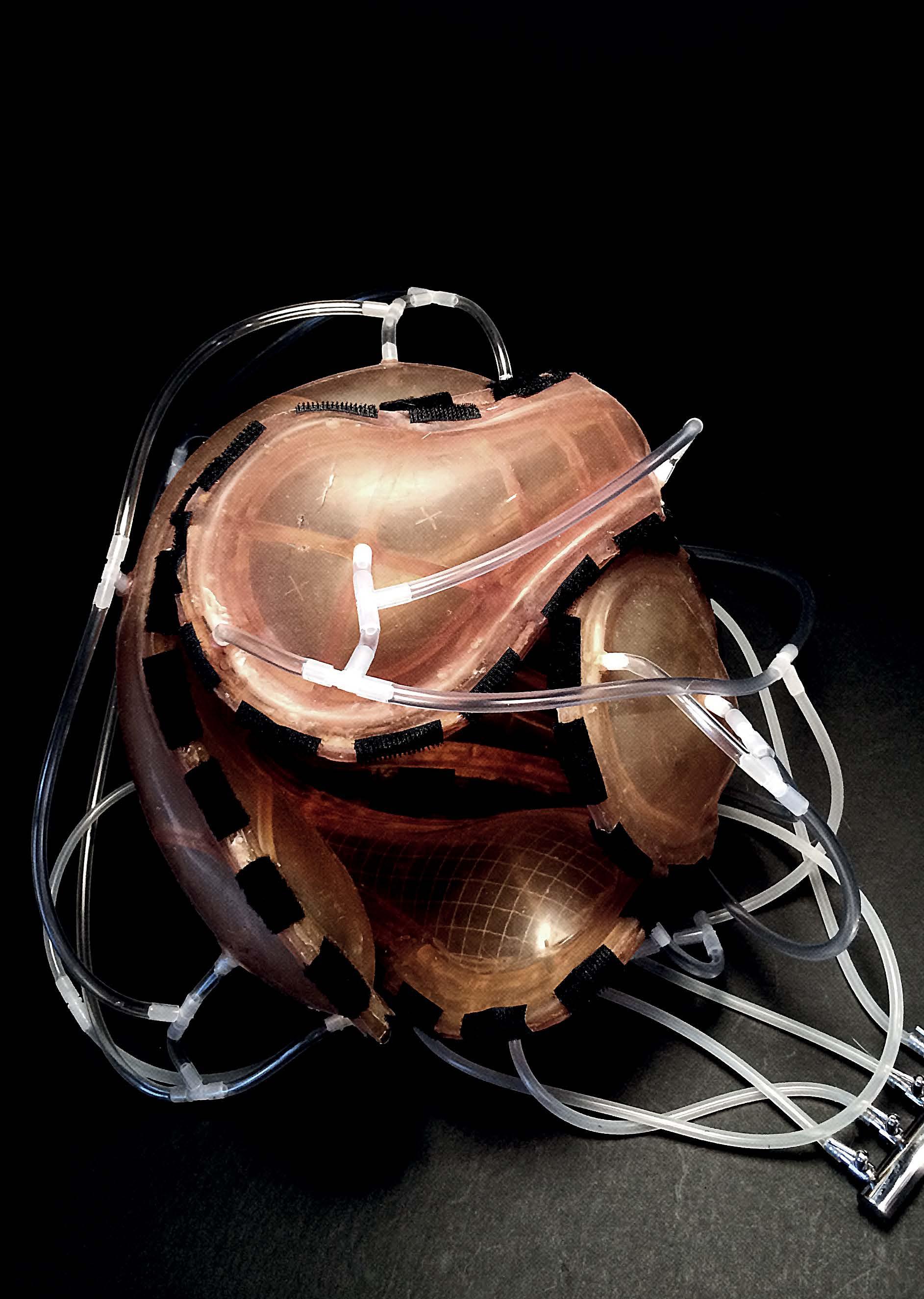

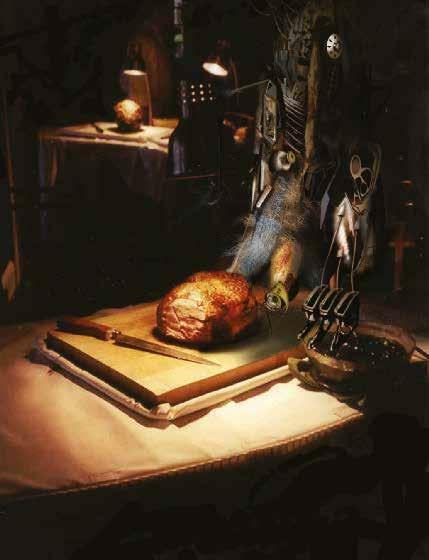

Fig. 19.1 Liu Meng Y5, inflatable prototype model study for a housing unit made of cast latex and silicon, part of a series of test models made during Unit 19’s prototyping workshop in Term 2. Fig. 19.2 Liu Meng Y5, drawings of inflatable housing unit, clustered (top left), unrolled (top right) and the structural frame (bottom). Fig. 19.3 Tomas Tvarijonas Y4, 3D prints made of a latex cast exploring ways to fabricate lattices which could then be inflated to be made structural, or embedded with mechanical technologies Fig. 19.4 Tomas Tvarijonas Y4, overall view of materially-intelligent prototypical system deployed on site on the underside of unused highway infrastructure, showing public space (foreground) and housing clusters (background).

19.4

19.5

19.6

Fig. 19.5 Stuart Colaco Y5, model of frame of prototypical housing unit in deployed state showing spline system. Fig. 19.6 Matthew Lacey Y5, sectional perspective showing corrogation of skin, interaction between forms and interior spaces. Fig. 19.7 Annabel Monk Y4, prototype of structural strategy for catenary system using inflating to deploy. Fig. 19.8 Yiting Lu Y4, early studies of flat pack system for deployment of the structure for a single unit. Fig. 19.9 Sang Yong Seok Y5, plans of modules for housing.

19.10 19.11 19.12

Fig. 19.10 Maria-Cristina Banceanu Y4, view of one of four scenarios for the deployment of housing module within overall structural frame. Fig. 19.11 Jeffrey Lim Y5, overall view of capsule housing system deployment in deactive (above) and active (below) states. Fig. 19.12 Yuan Xing (Lisa) Liu Y4, sectional perspective through inflated expandable column system on site. Fig. 19.13 Ran Shu Y4, exploded axometric of housing unit showing structure and panel system. Fig. 19.14 Shi Qi An Y4, studies for deployment strategies of a housing unit onstructuted of a series of foldable lines with varying fold patterns. Fig. 19.15 Stacy Peh Li Lin Y4, view of housing units deployed on site in Mazara del Vallo.

The Living Spaces of Algorithmics

Kasper Ax, Mollie Claypool, Philippe MorelThe Living Spaces of Algorithmics

Philippe Morel, Kasper Ax, Mollie Claypool‘We must turn our attention for a moment to something even more substantial than architectural design, and that is the question of how we live. […] We must indeed admit that we do not live as we would wish to live, so that even more difficult question arises as how we want to live and what our ideals really are. In asking ourselves this question we have to be careful to define all three of its elements: we, want, live.’ Constantinos A. Doxiadis, Architecture in Transition, 1963.

The question ‘how do we want to live?’ has driven our design research this year, coupled with a devotion to the utilisation of theories of computation, the philosophy of science and mathematics and new fabrication and construction technologies. The projects have taken this question and these tools to formulate an advanced theoretical approach in order to inform pragmatic investigations of what could be a new analytic view of the house. Unit 19 sees this question and computation as deeply interconnected, as computation has become more and more normative in our everyday lives: in the way we communicate, in modes of industrial production and in research and design. This paradigm is not novel, for the post-WWII Case Study House Programme in Los Angeles, signified the beginning of this evolution, with the shift from balloon frame construction to steel and other new materials and technologies.

The Case Study House Programme was a response to the context of post-WWII Los Angeles as an apogee for the war industry and laboratory for aeronautical engineering. This led to what Arts & Architecture editor John Entenza called a new kind of ‘domesticity’ of the post-war house. This new domesticity was made of high levels of performance, efficiency and hygiene in conjunction with low levels of cost that were seen as being inseparable from fabrication and construction. The banality of the house is countered by the notion that it could be the space for the synthesis of architect, engineer,

designer, anthropologist and user into the making (design, fabrication/construction) process. Entenza therefore saw the house as singularly holding the potential for mass capitalisation on the revolution of industry and economy by the war effort. This was our starting point for the year.

In our first project, each student chose a Case Study House, which they found provocative, analysing it rigorously in terms of material, tectonics, construction, fabrication and social and cultural influences. This drawing exercise was countered with in-depth research into the evolution and dissemination of new technologies starting from post-WWII scenarios up until the present day. This research informed and was the driver for further drawing and modelling exercises beyond the initially selected Case Study Houses of each student, diversifying their projects – from research by Neil Keogh into the history of the plastics industry to inform his design of an affordable carbon fibre house; Shuo Zhang with the development of cybernetics and robotics from John Neumann onwards to confront the ever-more present issue of flexible working and living; or Stacy Peh tracing the breakdown of the post-war domestic model of the kitchen and our relationship to the automobile – making each student a specialist in their own right in a strand of architectural research from the last 60 years.

It has been our Unit’s hypothesis this year that there is an inefficient and inconsistent relationship between initial idea, representation, production and execution in the architectural process. In order to reconcile this, we have implemented a working methodology that utilises various mathematical and computational tools to produce actual and virtual output in the form of physical models and prototypes – such as the use of cellular automata and fractal models by Matt Lacey in his project for an infinitely-expandable house for a growing family, the logic and mathematics of origami folding

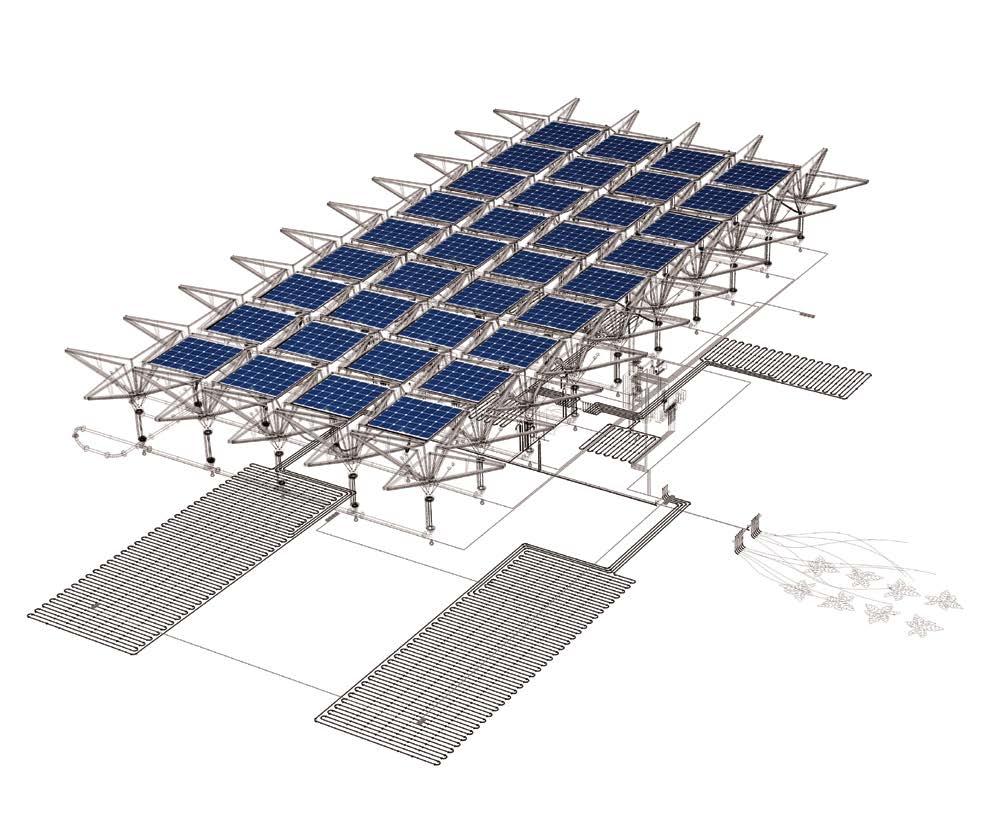

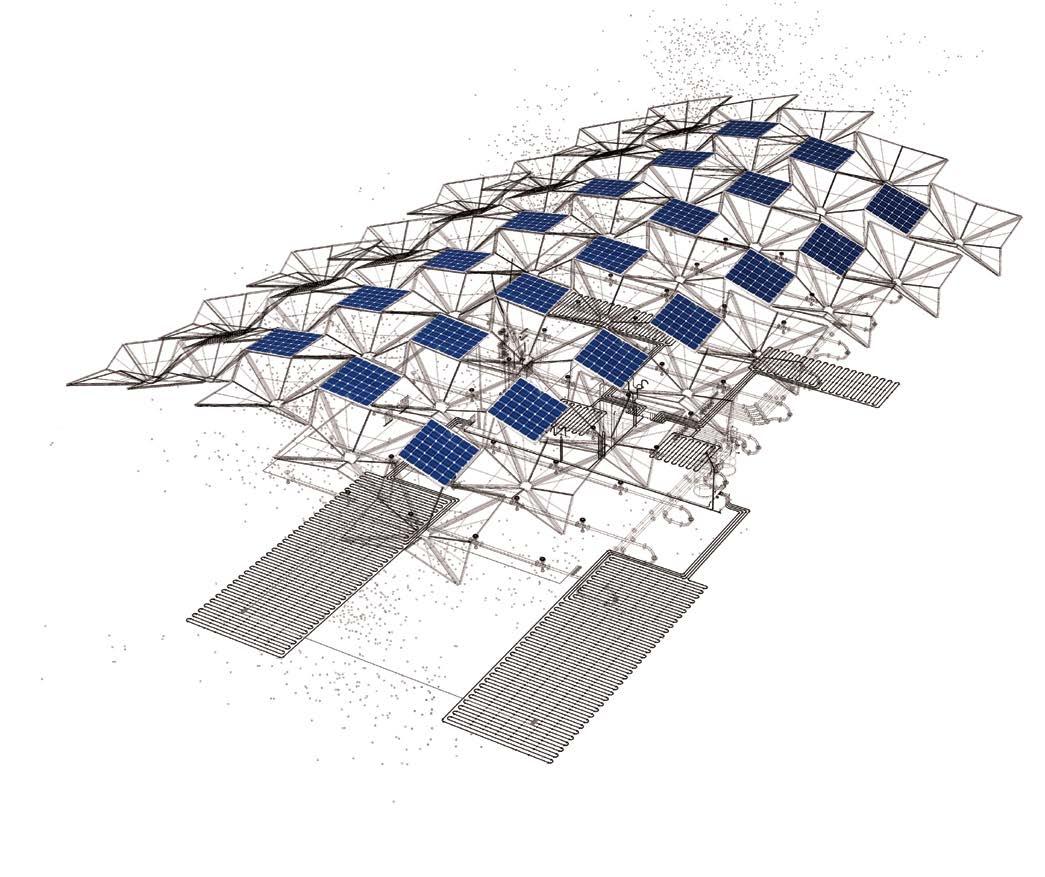

patterns by Mihir Benodekar to design a flat-pack housing system, or Stuart Colaco’s work on optics and prisms to produce a prototypical wall system that manipulates user perception and experience of ‘place’. David Ward’s work on a 1:1 concrete component system and Jeffrey Lim’s project utilising the corrugated surfaces of shipping containers to prototype a modular framework for social housing in Los Angeles tackled these issues from the opposite end of novel processes fabrication and construction, while Catherine Francis’ project attempts to build a new framework for energy collection and consumption in areas of the United States most devastated by the recession of the last five years.

Our Unit’s Design Realisation project was supported by robotics and software workshops with Research Cluster 5 of the MArch GAD programme and Manja van de Worp. Thibault Schwartz further informed our method of production, as did meetings with material scientist Justin Dirrenberger. A Unit trip to Los Angeles enabled us to not only have first-hand experience of many of the Case Study Houses which were the inspiration for the Unit this year, but also enabled us to meet with experts in Los Angeles housing such as UCLA Professor Mark Mack, partake in a review of Peter Testa’s robotics studio at SCI-Arc and meet with Andrew Witt, Director of Research at Gehry Technologies.

Year 4

Stuart Colaco, Matthew Lacey, Jeffrey Lim, Stacy Peh, David Ward, Shuo Zhang

Year 5

Mihir Benodekar, Catherine Francis, Neil Keogh

19.1 19.3 19.4

Fig. 19.1 Shuo Zhang, Y4, Tracing the robot trajectory as a path-finding experiment. Fig. 19.2 Shuo Zhang, Y4, Reconfigurable envelope for a flexible live/work building.

Fig. 19.3 David Ward, Y4, Detail of David’s Fabric formwork concrete façade components. Fig. 19.4 David Ward, Y4, The fabric formwork jig and resultant façade components.

Fig. 19.5 David Ward, Y4, Fabric formwork concrete façade components.

19.2

Ensure image ‘bleeds’ 3mm beyond the trim edge.

19.6 19.9 19.7

Fig. 19.6 Stacy Peh, Y4, Construction process of solar passive apartments by showing technical devices concealed in steel frame construction. Fig. 19.7 Matthew Lacey, Y4, Detail drawings showing the lattice panel system of the unit component for infinitely expandable modular house. Fig. 19.8 Matthew Lacey, Y4, Velcro model for simple expansion and reconfiguration of panel components. Fig. 19.9 Matthew Lacey, Y4, Detail of panel component using Metaklett ‘steel velcro’ Fig. 19.10 Catherine Francis, Y5, Design for a pneumatic roof that reacts to the sun, collecting water vapor in the air through a fog-catching fabric and mechanism, also providing shade.

19.8

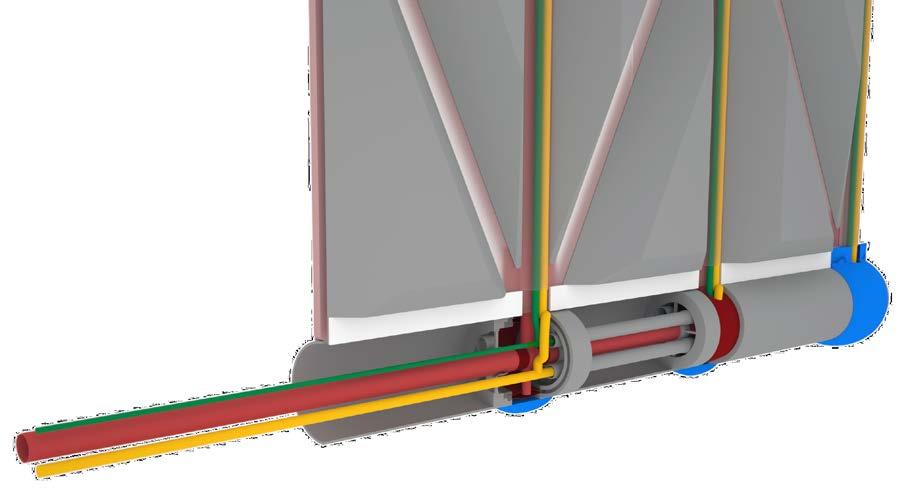

Vacuumatic Beam Detail

GRP tube

GRP channel

Plastic water/heating conduit

Plastic vacuum tube

Plastic electrical cable conduit

Outer vacuumatic mechanism support ring holder

19.11 19.13 19.14 19.15

Inner vacuumatic mechanism support ring holder 9 Vacuum tube connector 10 Vacuum tube flexible bellows 11 Flexible electrical cable 12 Flexible water/heating pipe 13 Vacuum splitter 14 Vacuum control valve with pressure sensor - beam 15 Rubber vacuumatic support ring 16 Vacuumatic stretchy breathable aggregate bag 17 Vacuumatic stretchy airtight membrane 18 Insulating jacket 19 Vacuum control valve with pressure sensor - building fabric 20 Water/heating supply through building fabric

Plastic conduit holder

21 Electrical cable through building fabric 22 Latex utility casing 23 Vacuumatic airtight membrane 24 Vacuumatic breathable aggregate bag 25 Outer latex layer 26 Outer rigid plywood panel 27 Aluminium strips for membrane attachment 28 Inner rigid plywood panel 29 Inner latex layer 30 Interior insulating panels 31 Assembled vacuumatic beam unit 32 Assembled beam containing services 33 Reinforced air conduit 19.12 Fig. 19.11 Jeffrey Lim, Y4, Determining the angles for a corrugated sheet metal panel system for Jmodular container house. Fig. 19.12 – 19.13 Mihir Benodekar, Y5, The vacuumatic beam detail for house prototype for nomadic artists. Fig. 19.14 – 19.15 Mihir Benodekar, Y5, Details of the 1:5 prototype of design for a flat-pack panelling system for the façade of his house prototype. Fig. 19.16 Neil Keogh, Y5, search for a service core constructed of carbon fibre which twists along a ruled surface utilising the trajectory of the robot. The robot in red shows the automatic detection of an unreachable position by HAL 004.5 (for Grasshopper).

19.20

19.21

19.22

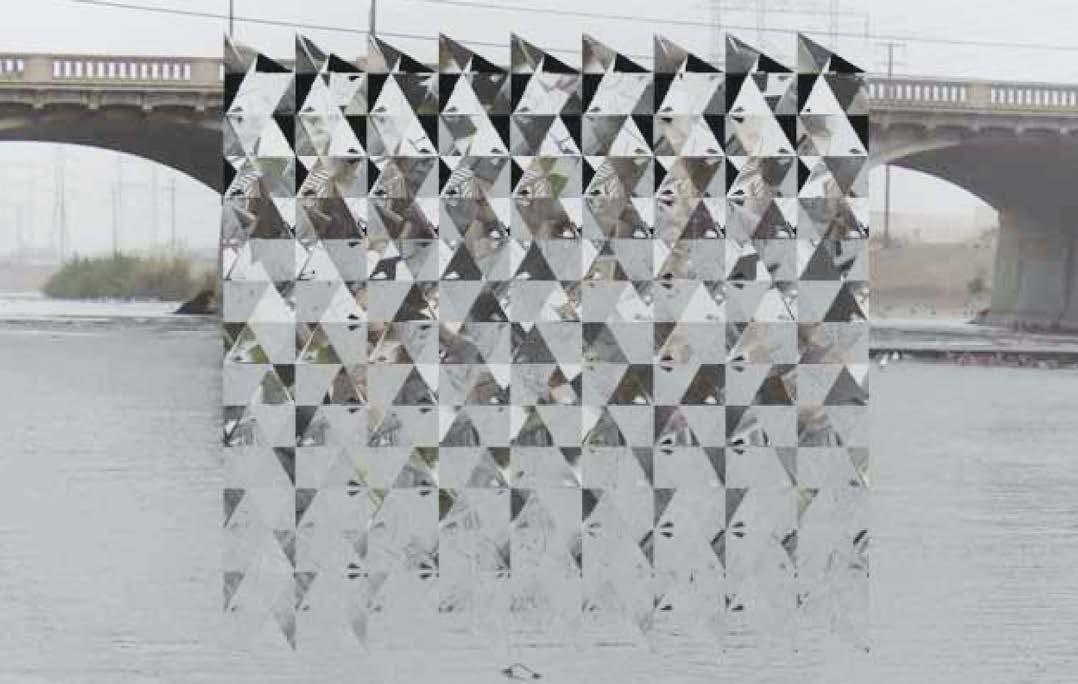

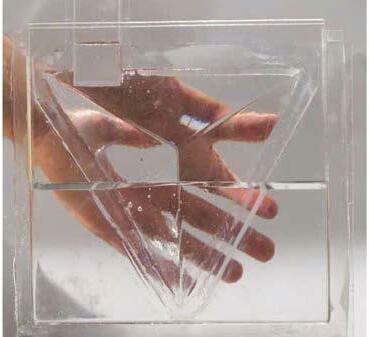

Fig. 19.20 Stuart Colaco, Y4, Façade simulation with a geometrical component gradient looking out over the Los Angeles river. Fig.19.21 Stuart Colaco, Y4, Model experiments for the design of refractive façade components utilising inverse tetrahedrons filled with water in three phases. Fig. 19.22 Stuart Colaco, Y4, A 1:4 scale model of 1.5mm thermoformed right angle tetrahedron moulds set inside an acrylic tank as part of the design process for a house façade. Fig. 19.23 Stuart Colaco’s, Y4, Photograph of 3D-printed model of perception and vision-shifting façade for a house. Fig. 19.24 Stuart Colaco, Y4, A volumetric luminosity histogram of house.

Innumerable Eccentricities and the Hedingham Report

Neil Spiller, Phil Watson4:

Yr 5:

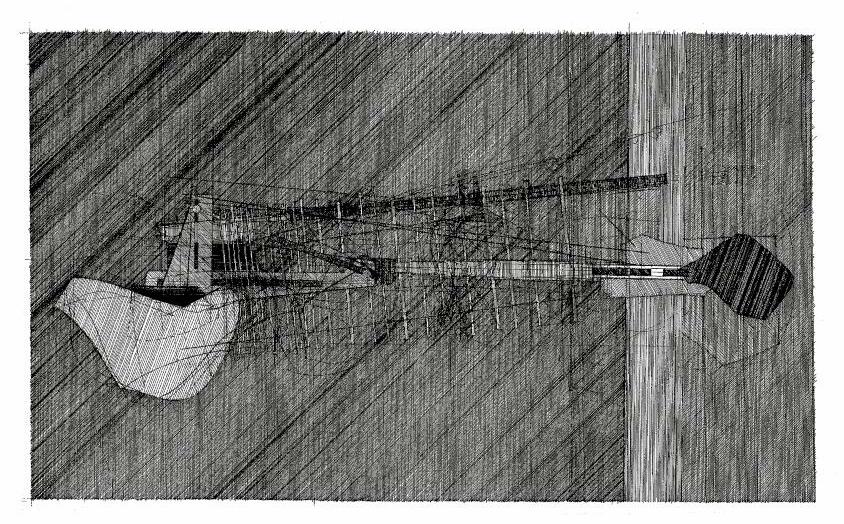

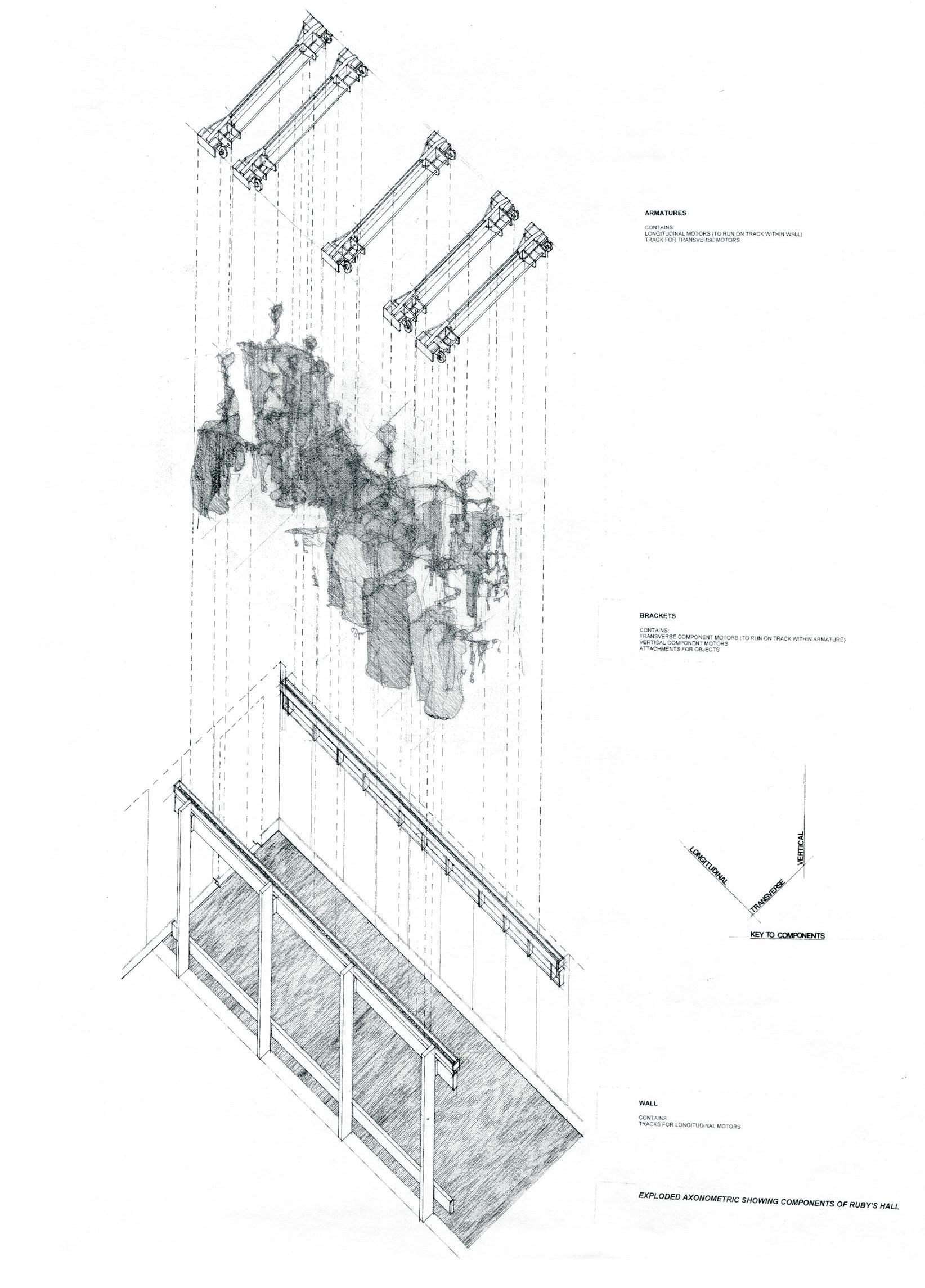

Innumerable Eccentricities and the Hedingham Report

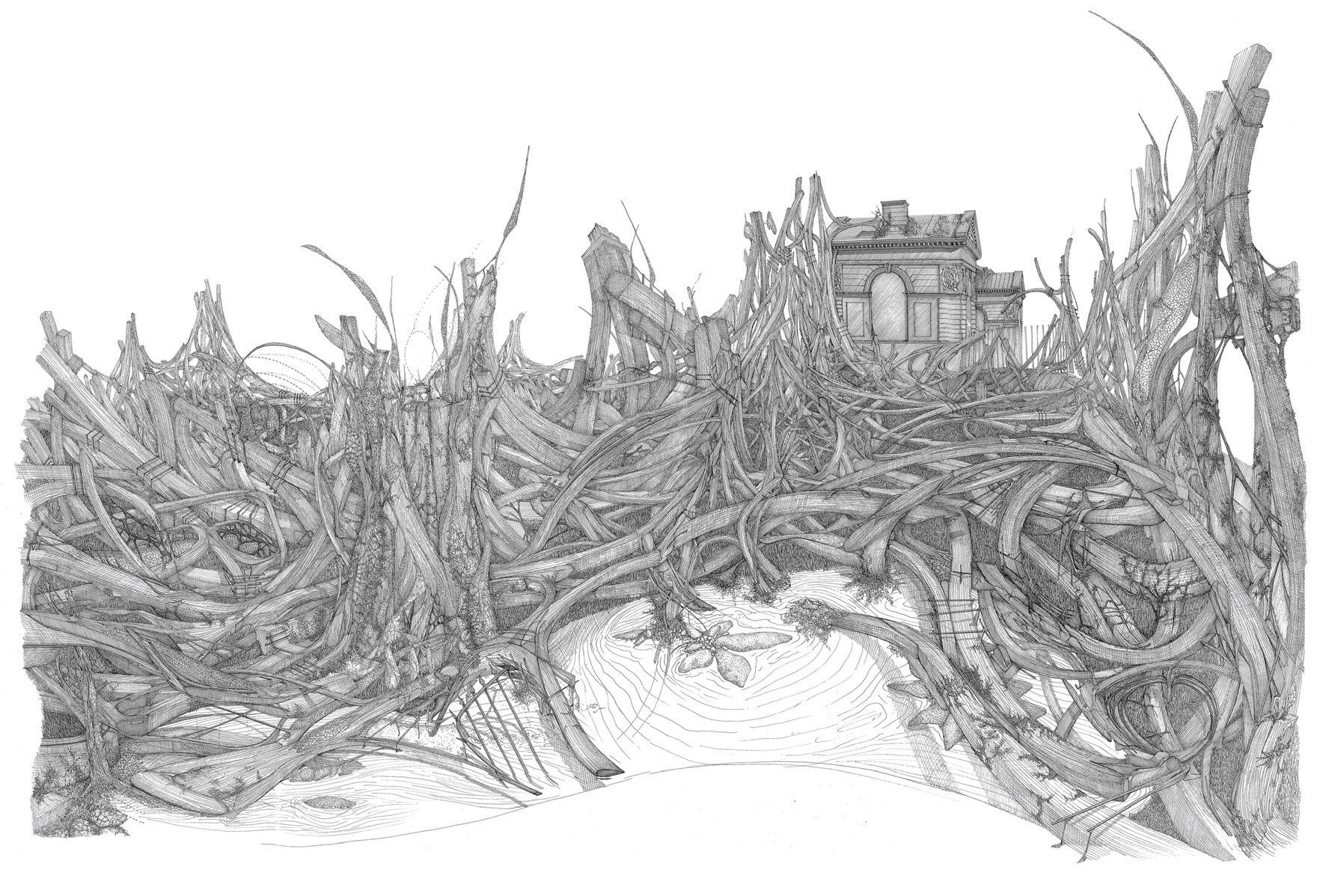

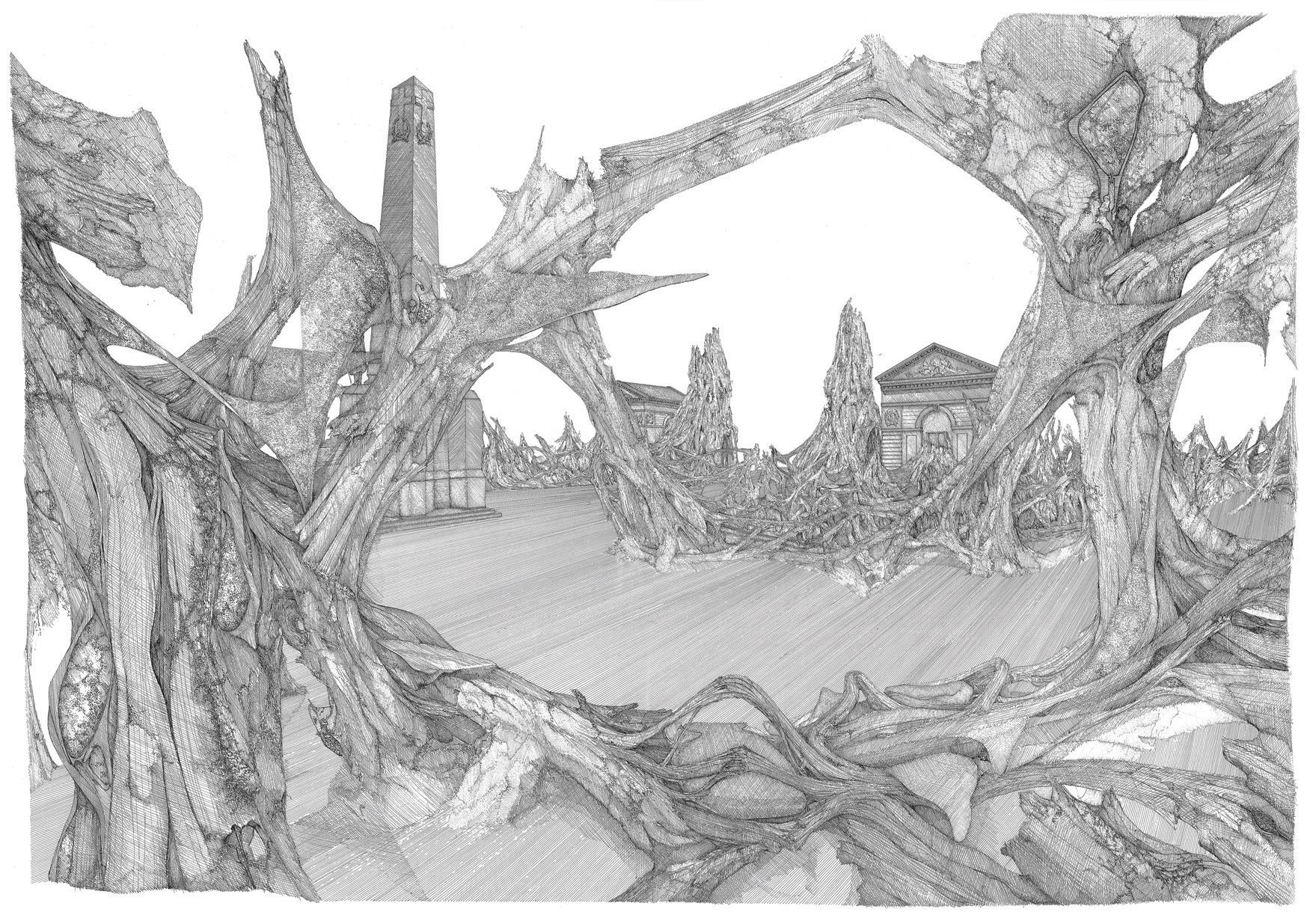

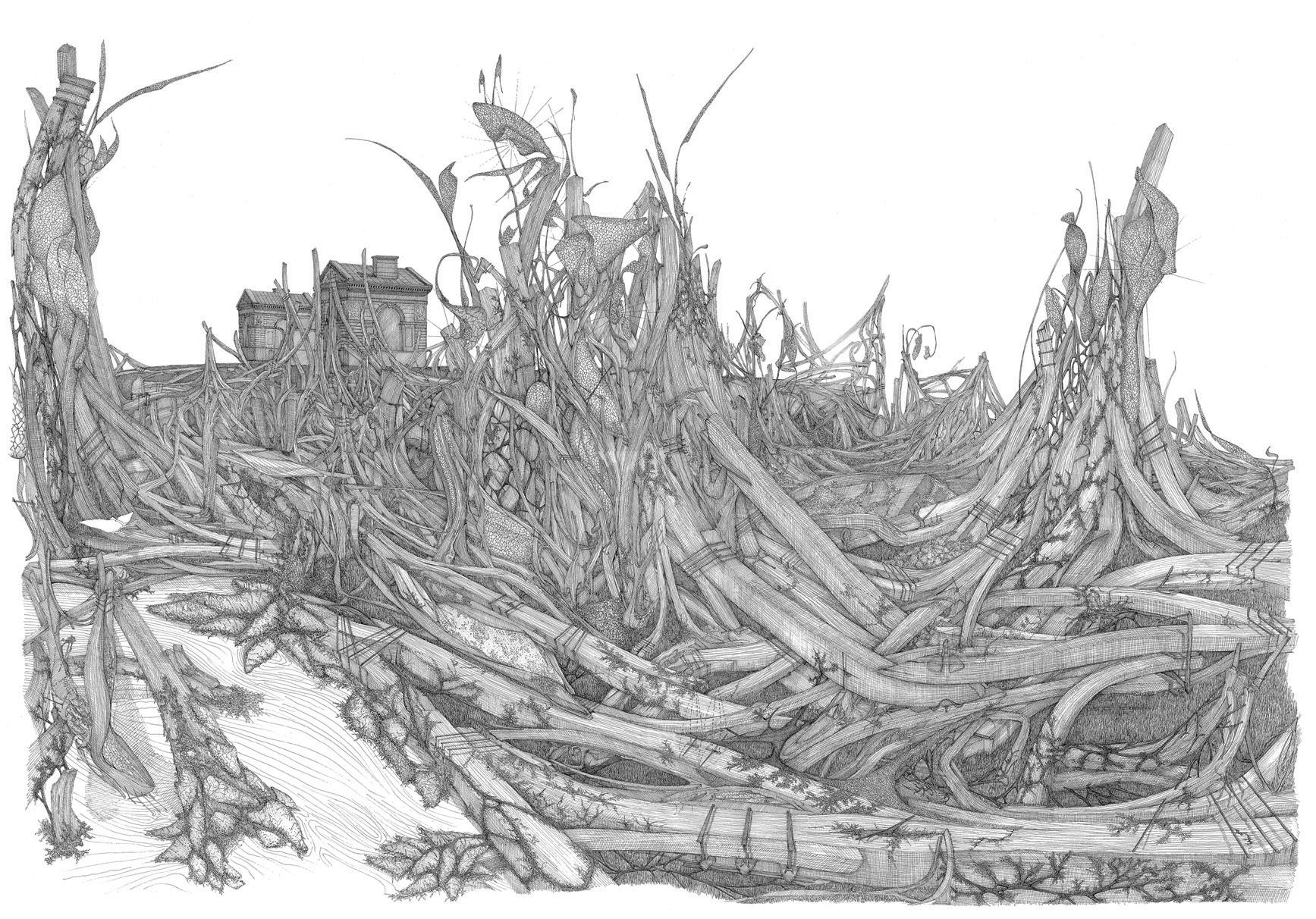

In 1984-5 Peter Wilson and his students considered the fading stately home and grounds of Clandeboye. Their intention was to investigate a range of regenerative strategies, appropriate to the ambiance of the place and project a useful vision of the future, balancing private, public and institutional requirements. A document, ‘The Clandboye Report’, was produced in 1985. Now, 25 years later, Unit 19 conducted a similar, different and contemporary series of exercises in and around the historic estate of Hedingham Castle in Essex. Each student produced their own ‘Hedingham Report’ and vicariously contributed to the discussion of this most rarefied architectural brief.

Our first move to inaugurate the cascade of architectural ideas was to investigate the magical operations of collage and blend these operations with the Innumerable eccentricities of cartography. Further, we re-used and redefined the ‘list of stimulants’ described in the Excursus of Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter’s Collage City – nostalgia producing instruments, stabilizers, set pieces, gardens and ambiguous and composite buildings in a rural estate and medieval village setting.

Now is an exciting time to be an architect. Technology is allowing architects to mix and augment the actual with the virtual, question the inertness of materials, link and network all manner of spaces and phenomena, create reflexive spatial relationships, blend the organic and the inorganic and be non-luddite about ecology and sustainability. Simultaneously the doctrines of Modernism are being questioned, decoration and baroque distortion are respectable again. The whole issue of what might constitute architecture is up for grabs.

Adam Draper, Rebuilding the Euston Arch. Top: The Garden after 10 years. Opposite top: after 15 years. Bottom: after 25 years. Opposite Bottom: after 27 years.

Adam Draper, Rebuilding the Euston Arch. Top: The Garden after 10 years. Opposite top: after 15 years. Bottom: after 25 years. Opposite Bottom: after 27 years.

Clockwise from top left: James Redman; Tim Bradford; Richard Meddings; Winston Luk.

Clockwise from top left: James Redman; Tim Bradford; Richard Meddings; Winston Luk.

Top: Greg Skinner. Middle and bottom: Richard Meddings, Re-cycled Landscapes, Arran.

Top: Greg Skinner. Middle and bottom: Richard Meddings, Re-cycled Landscapes, Arran.

Parallel Botany, Parallel Biology and Parallel Architecture

Neil Spiller, Phil WatsonDip/MArch Unit 19

Parallel Botany, Parallel Biology and Parallel Architecture

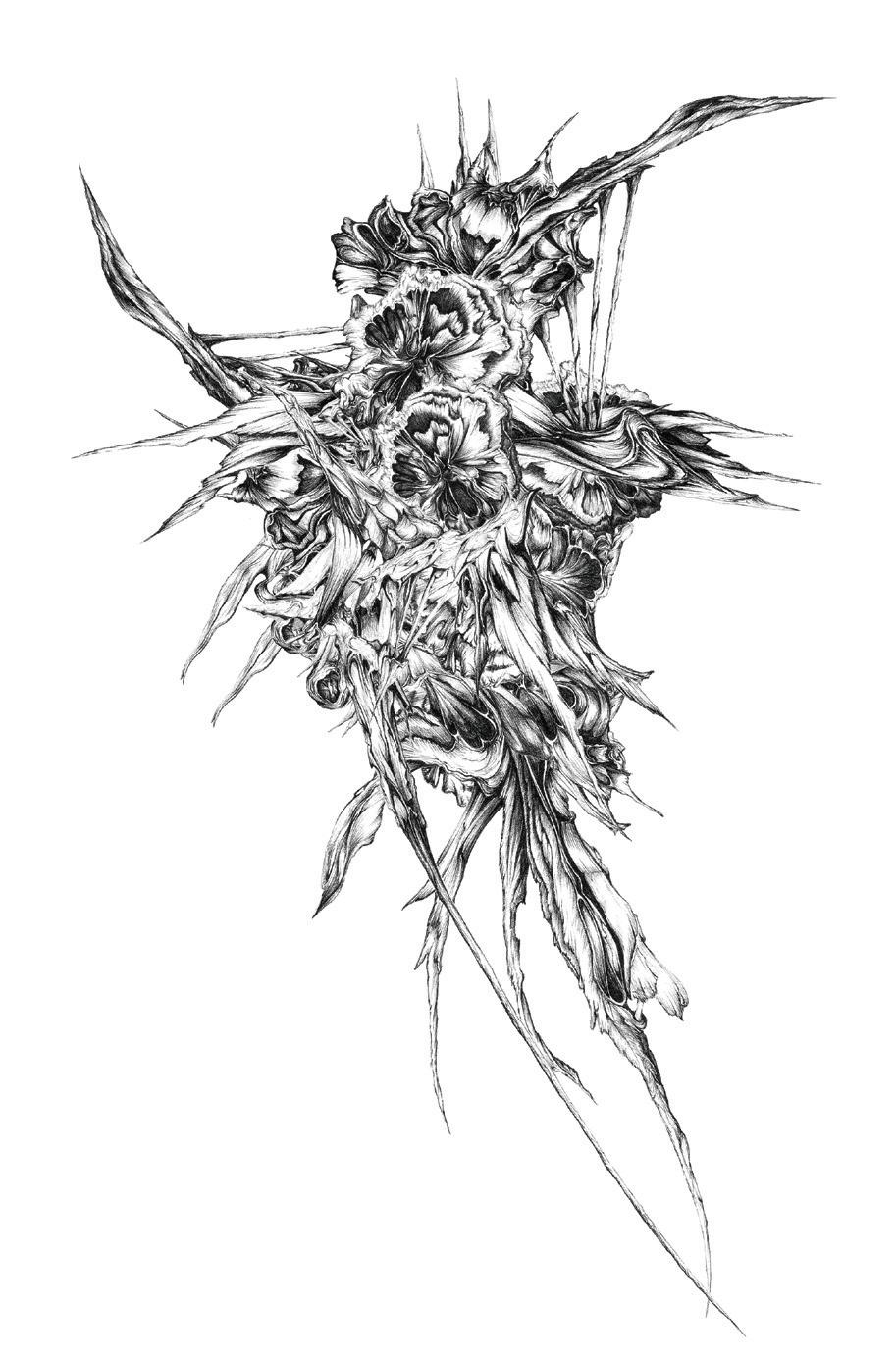

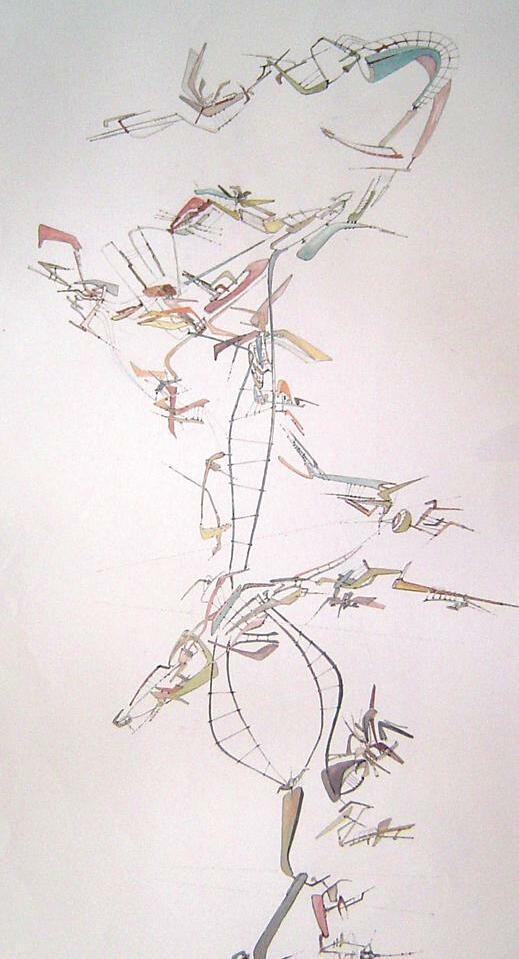

With precision, with authority, with wit, with inefferable brilliance of supreme scholarship, Leo Lionni , in his book “Paralell Botany”, presents the first fullscale guide to the world of parallel plants – a vast, ramified, extremely peculiar, and wholly imaginary plant kingdom. It is a botany alive with wonders from Tirillus silvador of the High Andes (whose habit it is to emit shrill whistles on clear nights in January and February) to the woodland Tweezers ( it was a Japanese parallel botanist Uchigaki who first noticed the unsettling relationship between the growth pattern of a group of Tweezers and a winning layout of Go) to the Artisia (whose various forms anticipate the work of such artists as Arp and Calder – and some believe, the work of all artists, including those not born).

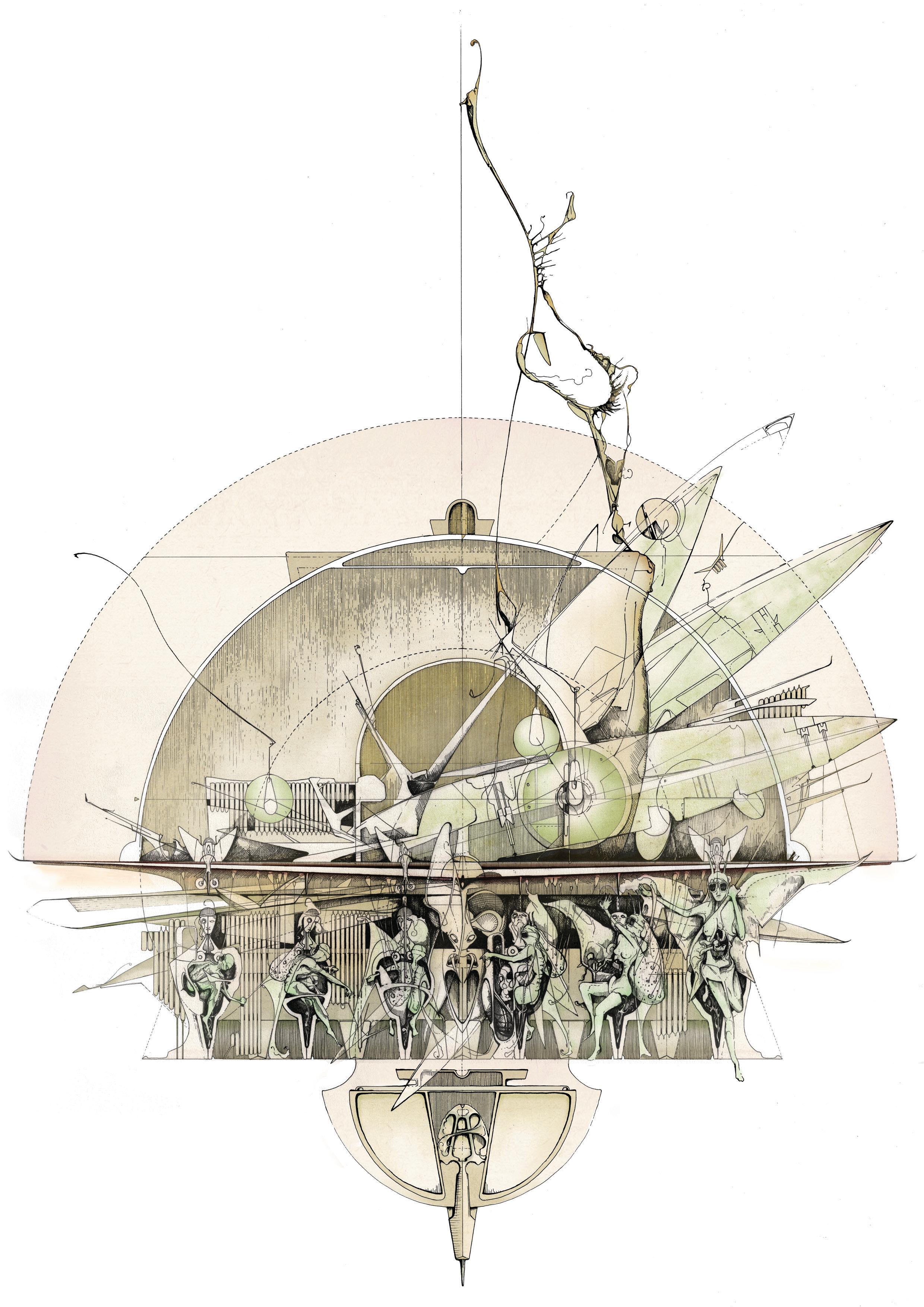

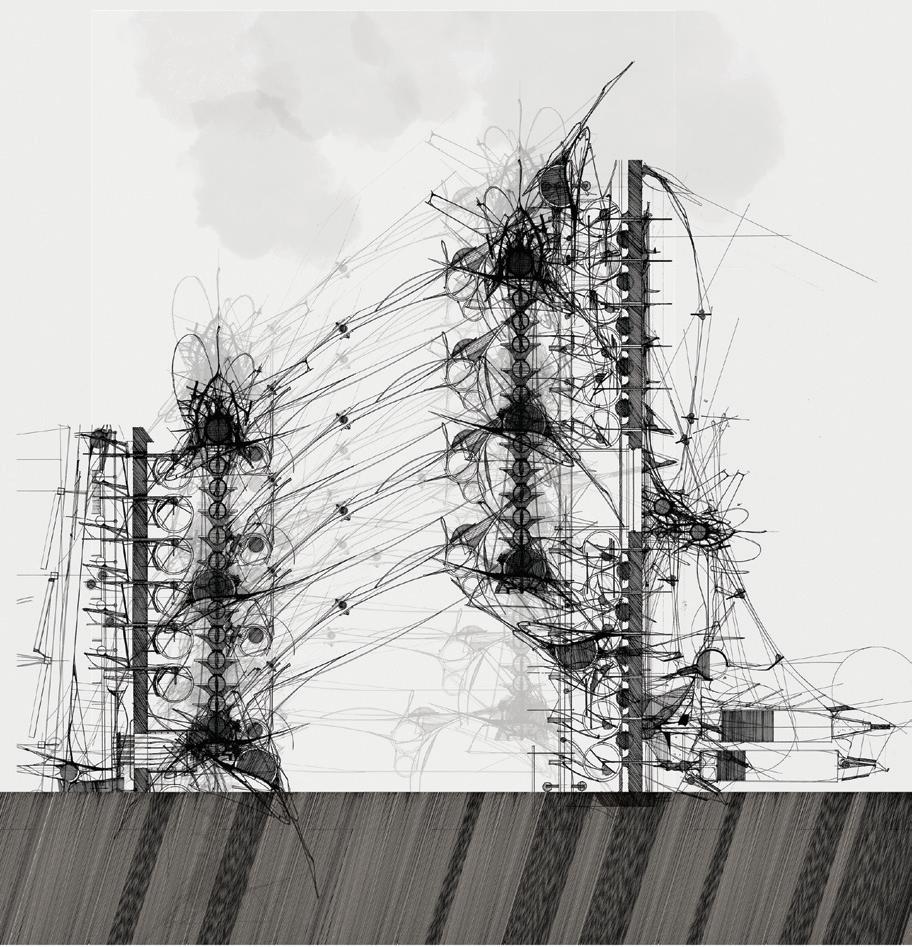

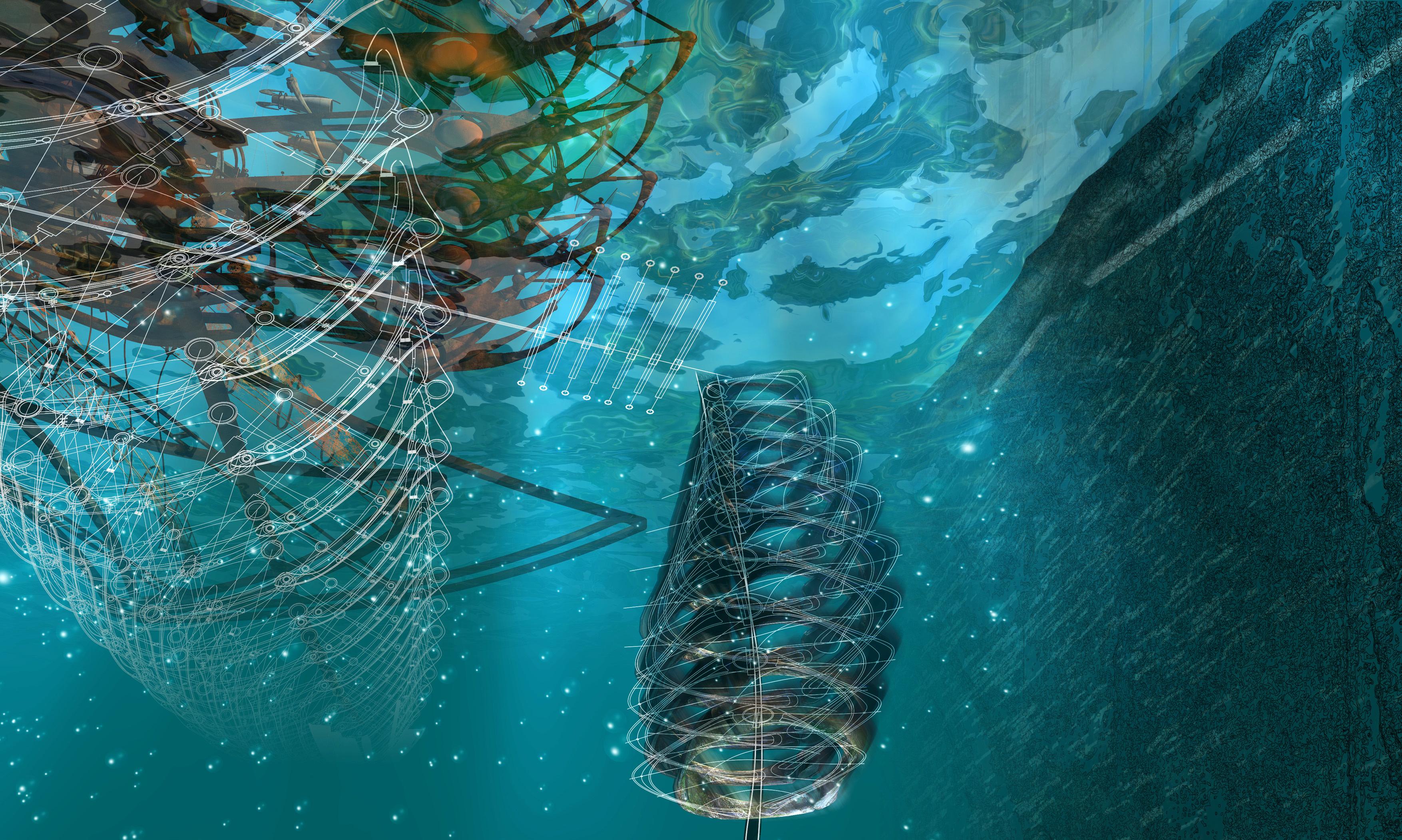

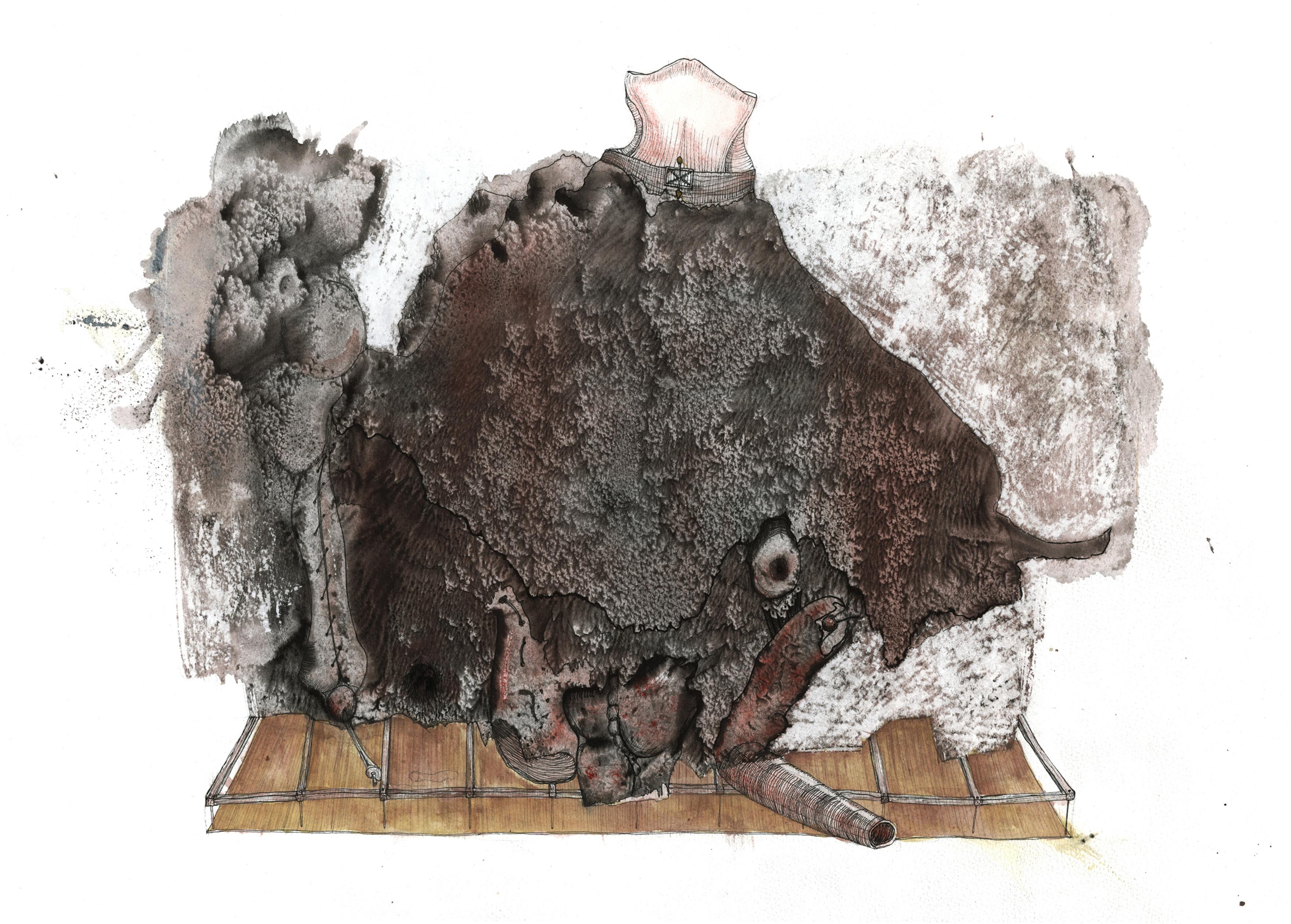

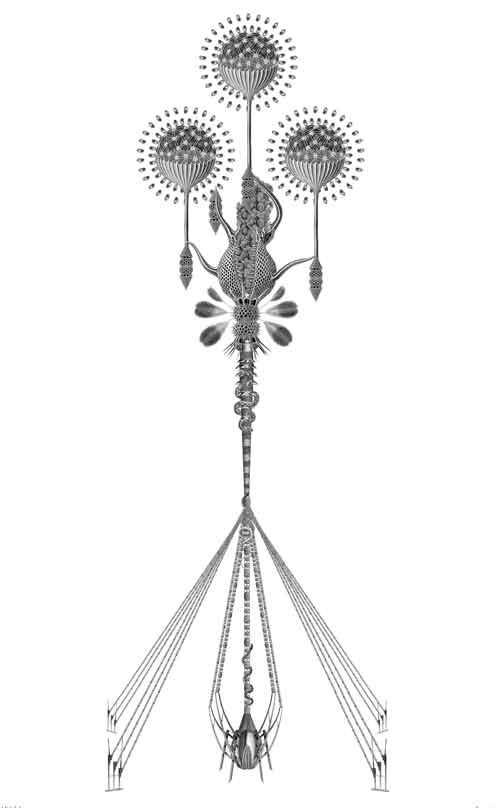

This year Unit 19 considered Parallel architecture and its bio-engineered linaments. It found suitably complex sites and created great works of Parallelism. These works pushed the boundaries of architecture deep into botany and biology and talk of time-based architectural space, ethics and new technology, ecology, different ways of seeing, ascalarity, epistemology, cyborgian geography and archaeology.

In conclusion there is little that is impossible, florescent rabbits have been bred, stem cells have been wired up to drawing machines (what status has art when its artist was never born?). Stelarc has grown an ear on his arm and many, many more polemic biotechnical art projects have been created. It is now time for architects to address these very important issues and ethics.

Y4: Adam Draper, Roaya Garvey, Richard Meddings, Dan slavinsky, Isabella Theofanopoulos.

Y5: Thomas Cartledge, Liwei Chen, John K Fulton, Xiaowei David Liang, Andrew Paine, Thomas Richardson, James Robertson, Matthew Seaber, Mandi Tong.

Neil Spiller and Phil Watson

Y4: Adam Draper, Roaya Garvey, Richard Meddings, Dan slavinsky, Isabella Theofanopoulos.

Y5: Thomas Cartledge, Liwei Chen, John K Fulton, Xiaowei David Liang, Andrew Paine, Thomas Richardson, James Robertson, Matthew Seaber, Mandi Tong.

Neil Spiller and Phil Watson

Pushing the Boundaries

Neil Spiller, Phil WatsonYr 4:Marc Borrowman, Thomas Cartledge, Xiaowei Liang, Andrew Paine, James Robertson. Yr 5: Nicholas Adams, John Kyle Fulton, Robert High, Linnea Isen, Phil Joon Jeon, Kristian Kristensen, Nook Szz Law, Oliver Moen, Peter Nilsson, Timothy Norman, Gro Sarauw, Mandi Tong.

Pushing the Boundaries

Post-digital (where the computer is totally synthesised into reality) design must attempt to be immune to sophist arguments of style and good taste. It should rejoice in the particular and the “I” who and whatever is the “I” (we must remember that objects can now become “I” to a growing extent.)

Above all, post-digital design is relativistic, glocal, ascalar and constructed from a genius loci that does not just include anthropomorphic site conditions but also includes deep ecological pathways, mnemonics, pychogeography and narrative.

The continuums of architectural composition at the beginning of the twenty-first century. The experience of contemporary designers is one of positioning their work in relation to seven continua. These are:

Top: Kyle Fulton. Bottom: Nick Adams.

Top: Kyle Fulton. Bottom: Nick Adams.

Top: Oliver Moen. Bottom: Robbie High.

Top: Oliver Moen. Bottom: Robbie High.

Top: Linnea Isen. Bottom: Peter Nillson.

Top: Linnea Isen. Bottom: Peter Nillson.

Tim Norman.

Tim Norman.

Smearing Architecture

Neil Spiller, Phil WatsonYr 4: Nicholas Adams, Kyle Fulton, Robert High, Kristian Kristensen, Maria Law, Oliver Moen, Tim Norman, Mandi Tong. Yr 5: Neil Charlton, Charlotte Erckrath, Linnea Isen, Dominique Laurence, Peter Nilsson, Alan Pottinger, Richard Vint. MArch: Christian Kerrigan.

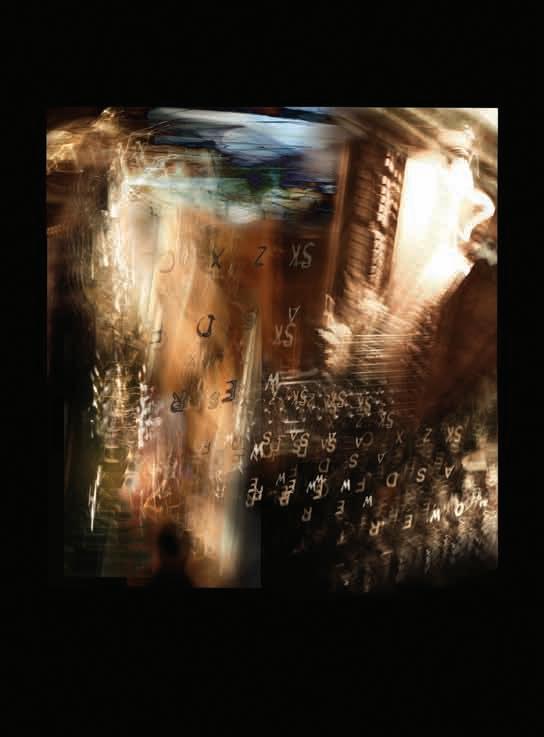

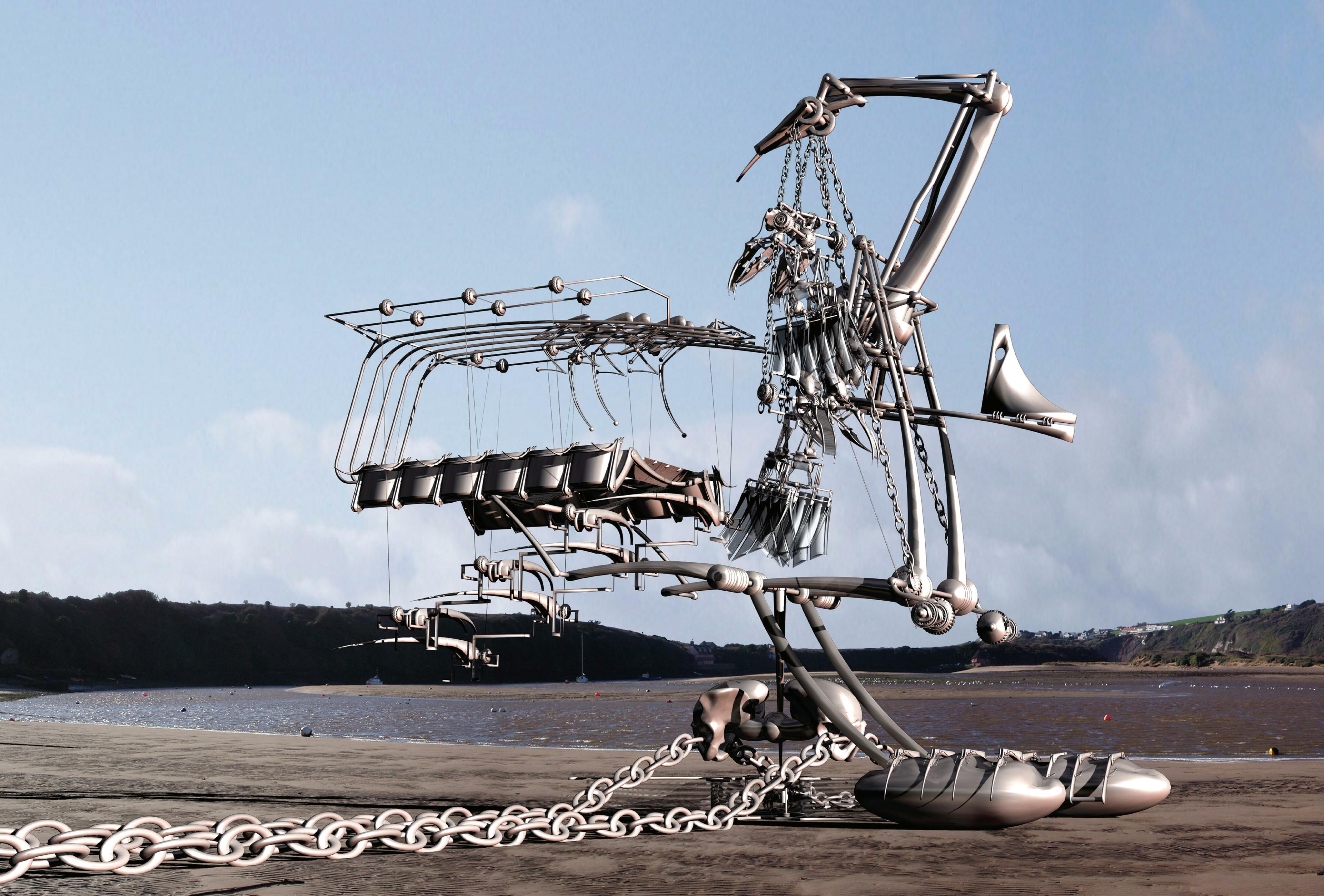

Smearing Architecture

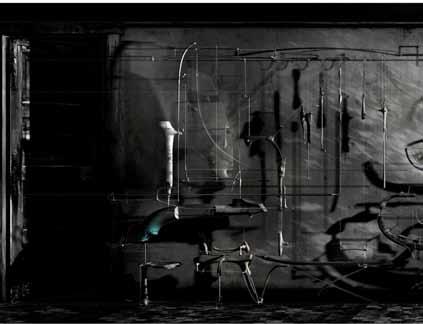

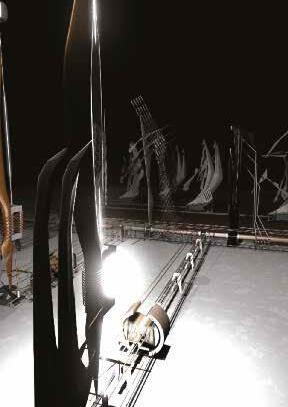

If we see our interaction with digital technologies and their peculiar landscapes as smears, then the more advanced a technology the more easy it is for us to smear them across virtual and actual geographies. We smudge our smears across space-time across the landscape and through machines. Where they are fleetingly registered, classified, filed, transmitted or erased, reconstituted and retransmitted.

These tools for augmented bodies are not passive. They coerce, trick, titillate and pull us towards and between them. As technology’s flow forever on, our smears encounter less and less friction. Our researches concoct technological slime, that allows us to slip and slide through the landscape. Yet our traditional architectural design and discourse offers little of the porosity that we currently require.

Unit 19’s aims are to explore, polemicise and develop architectural ideas and solutions that understand the digital smear in all its aspects. These include the virtuality continuum, ecology and sustainability.

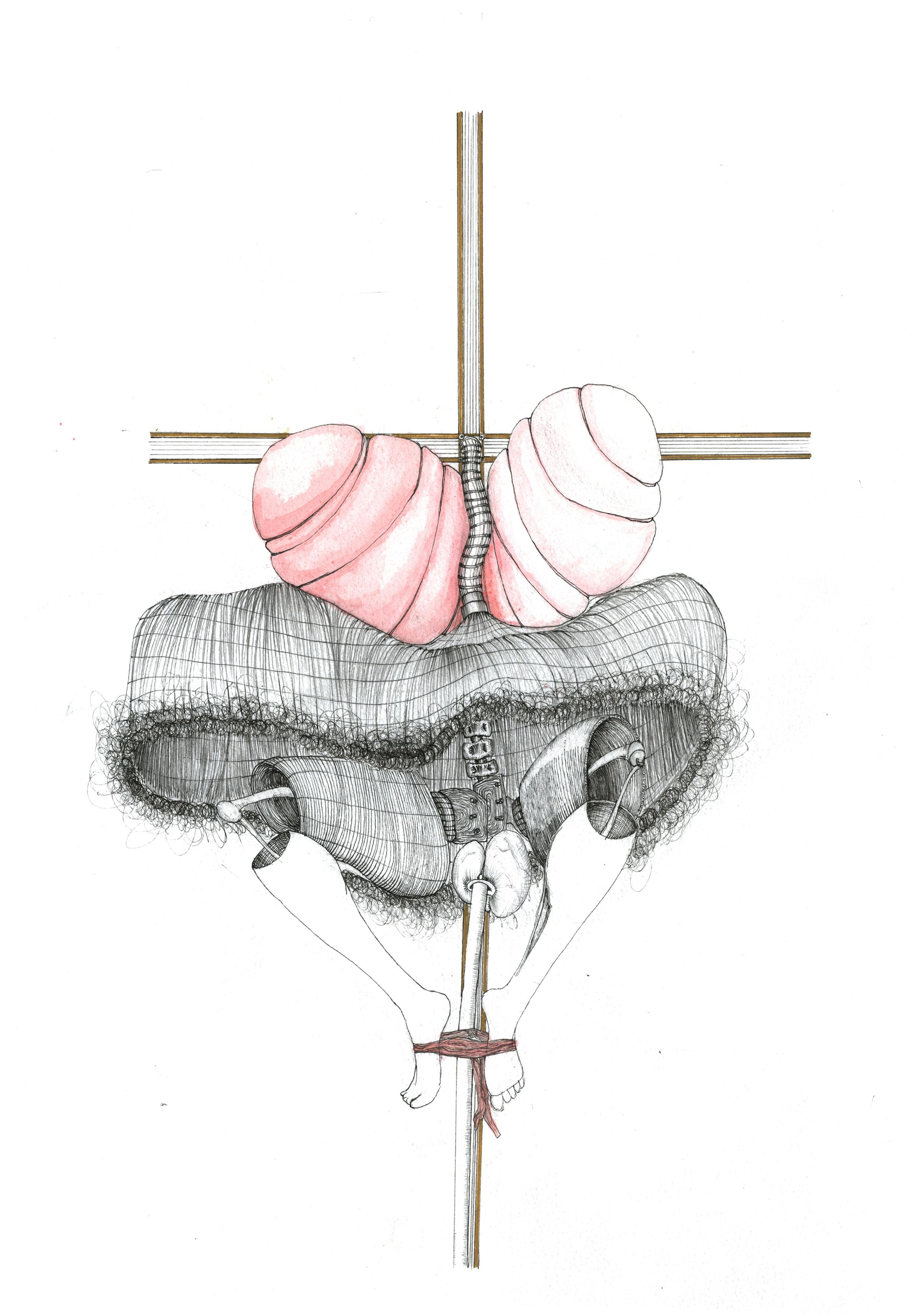

The new ecstatic architectures will be biotechnical, cybernetic, fleeting and be much concerned with facilitating information flow. They will be crucial to forcing and penetrating the smear connecting the distal body to enable specific actions and vectors. That is to say, they will act as transitory conduits allowing swift reconfiguration of some or all of the technological, fleshed and digital, paraphernalia of the smeared body. These architectures and landscapes will interact through us and us through them.

Top: Tim Norman. Middle: Kyle Fulton. Bottom: Richard Vint.

Top: Tim Norman. Middle: Kyle Fulton. Bottom: Richard Vint.

Top left and bottom: Charlotte Erckrath. Top right: Dominique Laurence.

Top left and bottom: Charlotte Erckrath. Top right: Dominique Laurence.

Top: Charlotte Erckrath. Bottom: Dominique Laurence.

Top: Charlotte Erckrath. Bottom: Dominique Laurence.

Spelling Architecture

Neil Spiller, Phil WatsonDip Unit 19

Yr

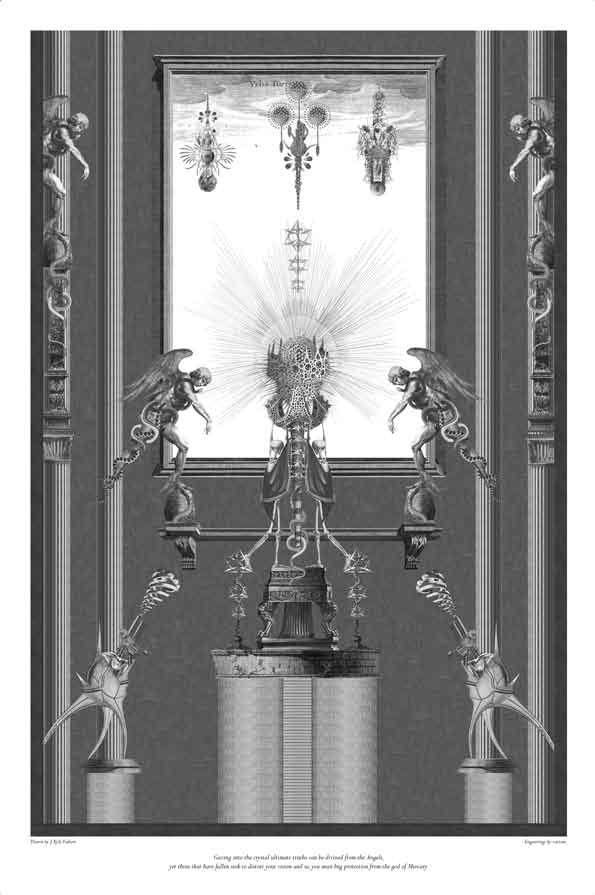

Spelling Architecture

Over the last fifteen years Unit 19 has been at the forefront of architectural education Its basic premise is to educate architects that understand fully the implications of advanced technology (such as virtuality, biotechnology and nanotechnology) and its surreal ramifications

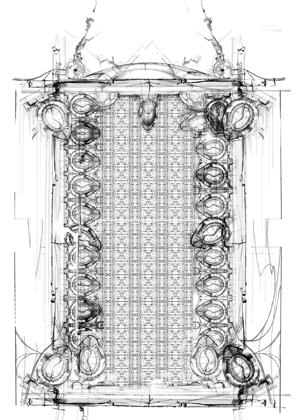

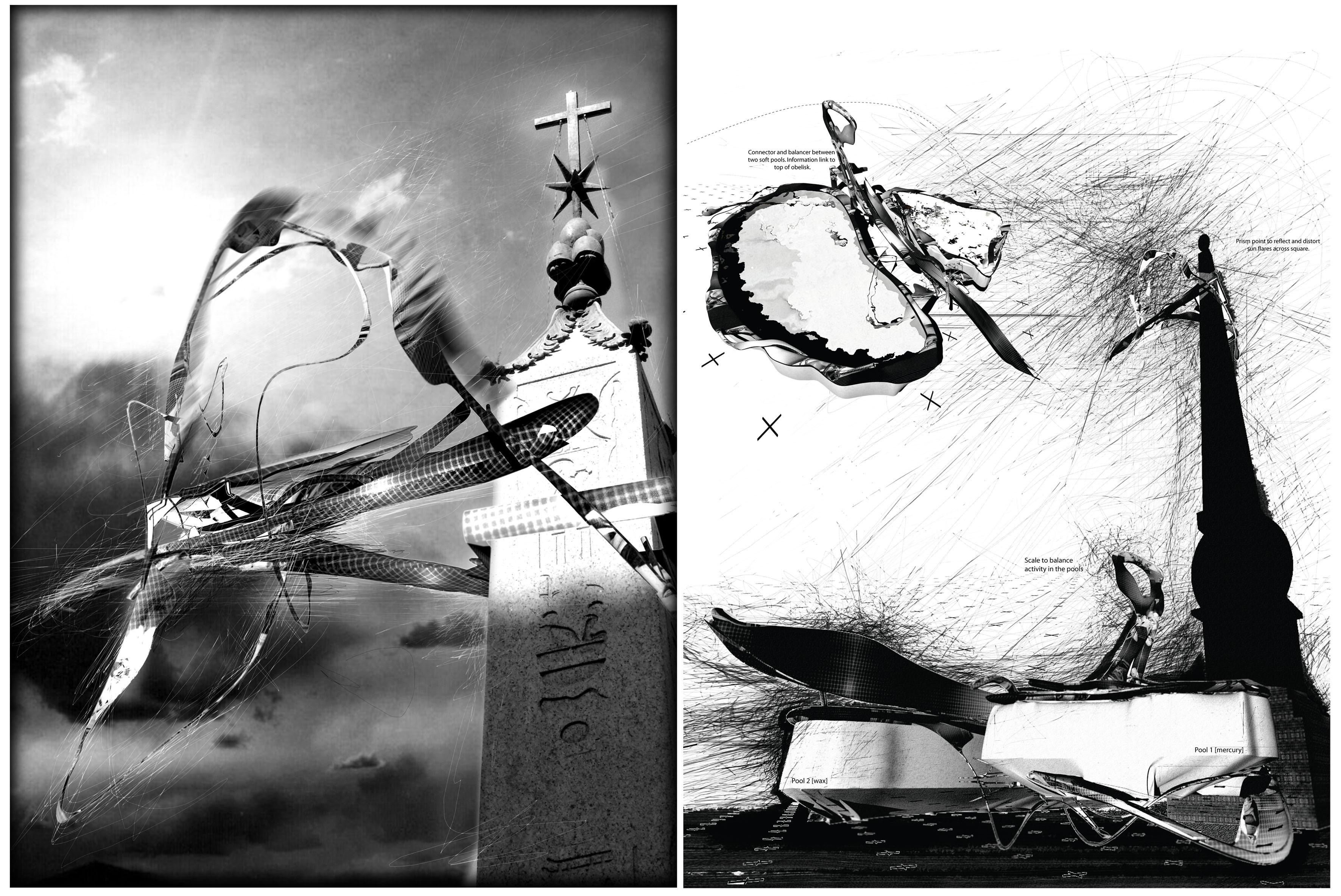

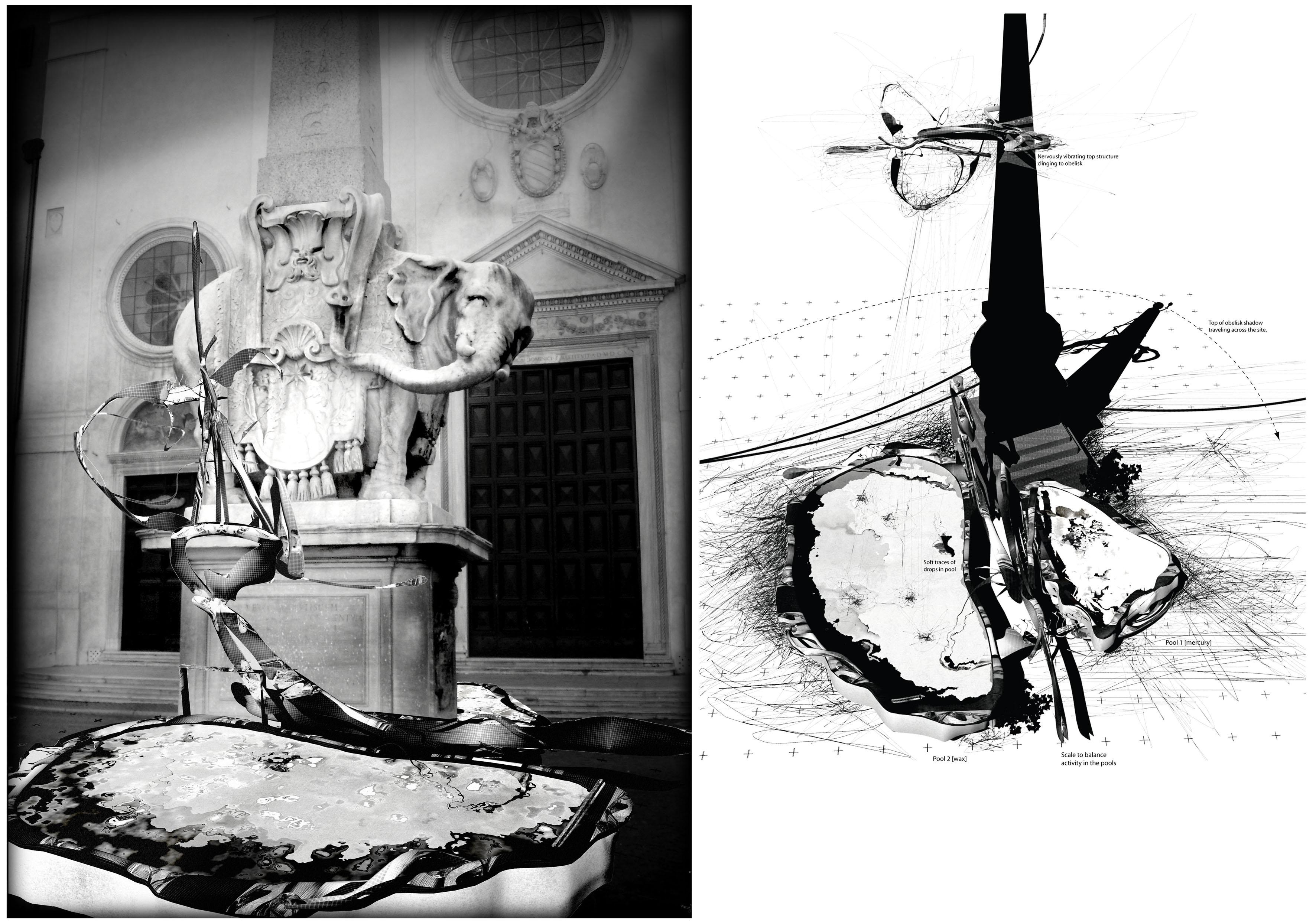

This year students and staff went to Rome to investigate Classical Architecture, the sculpture of Bernini, mythology and Popes and the pregnant fecundity of Borromini

The fourth year were inducted into the magic of the great architectural opus, the notions of the choreo graphy of space, the split site and the collage of contemporary technology and how it slides along the virtuality continuum

The fifth year has been exceptionally successful this year Its members have made the connection between hypertext and anamorphosis, grown a ship inside a willow copse, created a cybernetic memory theatre inside Grandma's derelict house and implanted the Greek myths into a butchers sho p Our MArch student, Ben, (now three years under the unit 19 banner) has bathed old ladies and made a paper knife for Satre

‘Esoteric?' We hear the least imaginative of you mutter But no, this is the architecture of the future An architecture that is personal, mnemonic, philosophically based, cybernetically rigorous and loaded with symbol, which coerces itself from the virtual to the actual Simultaneous ly these architectures seek a synthesis between the natural and the machinic that is not Luddite but creates cybrid ecologies of actions and objects that are driven by the vicissitudes of daily life and the movements and perceptions of observers

Neil Spiller and Phil Watson Yr 4: Neil Charlton, Linnea Isen, Pil Joon Jeon, Peter Nilsson, Harriet Roderiques, Richard Vint, Karuga Koinange 5: Christian Kerrigan, Lenastina Andersson, James Curtis, Melissa Clinch, Ben Sweeting Clockwise from top left: Linnea Isen, Peter Nilsson, Richard Vint, Pil Joon Jeon, Neil Charlton

Christian Kerrigan Top: Amber clock As the trees slowly evolve the 'Amber clock' strapped to the tree registers the passing of time with a two hundred year hourglass Upper Middle: Tree evolution As the forest matures the 'Amber clock' is consumed with the body of the trees It acts as an artifact for the artificial system of manipulation Middle: Lake view A silhouette of the ships growth over two hundred years within the forest at Kingley Vale Bottom: Drowning forest As the system evolves over two hundred years the forest is flooded with rising sea levels and the hidden ship begins it’s second stage as a submerged ruin