Design Anthology PG22

Architecture MArch (ARB/RIBA Part 2)

Compiled from Bartlett Summer Show Books

Architecture MArch (ARB/RIBA Part 2)

Compiled from Bartlett Summer Show Books

At The Bartlett School of Architecture, we have been publishing annual exhibition catalogues for each of our design-based programmes for more than a decade. These catalogues, amounting to thousands of pages, illustrate the best of our students’ extraordinary work. Our Design Anthology series brings together the annual catalogue pages for each of our renowned units, clusters, and labs, to give an overview of how their practice and research has evolved.

Throughout this time some teaching partnerships have remained constant, others have changed. Students have also progressed from one programme to another. Nevertheless, the way in which design is taught and explored at The Bartlett School of Architecture is in our DNA. Now with almost 50 units, clusters and labs in the school across our programmes, the Design Anthology series shows how we define, progress and reinvent our agendas and themes from year to year.

2024 Rites of Passage

Izaskun Chinchilla Moreno, Daniel Ovalle Costal

2023 The Urbanism of Friendship

Izaskun Chinchilla Moreno, Daniel Ovalle Costal

2022 Dollhouse, Bingo and Ring

Izaskun Chinchilla Moreno, Jan Kattein, Daniel Ovalle Costal

2021 Shaking POPS

Izaskun Chinchilla Moreno, Daniel Ovalle Costal

2020 The Caring City

Izaskun Chinchilla Moreno, Daniel Ovalle Costal

2019 The Mediterranean Perspective

Izaskun Chinchilla Moreno, Daniel Ovalle Costal

2018 Campaigning!

Izaskun Chinchilla, Carlos Jiménez Cenamor

2017 The Post-Millennial Revolution

Izaskun Chinchilla, Carlos Jiménez Cenamor

2016 Women And Architecture

Izaskun Chinchilla Moreno, Carlos Jiménez Cenamor

2015 Empowering the Legacy of Generation Z

Izaskun Chinchilla Moreno, Carlos Jiménez Cenamor

2014 Designing the Future: Architecture as Hypothesis vs. Hypothesis as Synthesis

Izaskun Chinchilla Moreno, Carlos Jiménez Cenamor

2013 Wood And Fire: Towards a Definition of Mild Architecture

Izaskun Chinchilla Moreno, Carlos Jiménez Cenamor

2012 Dare to Care... Through a Year

Izaskun Chinchilla Moreno, Carlos Jiménez Cenamor with Helen&Hard

2011 (In-)Water Dwelling and Some

Izaskun Chinchilla Moreno, Carlos Jiménez Cenamor

2008 Decadence

John Puttick, Peter Szczepaniak

2007 Patterns

John Puttick, Peter Szczepaniak

2006 Tales of the Unexpected

John Puttick, Peter Szczepaniak

2005 Ordinary/Extraordinary

John Puttick, Peter Szczepaniak

Izaskun Chinchilla Moreno, Daniel Ovalle Costal

Commonly held belief often refers to the provision of shelter as the origin of architecture. However, a more nuanced and interdisciplinary approach, incorporating knowledge gathered by anthropologists and archaeologists, points towards the accommodation of rituals as another reason for humans to have started building.1

Rites of passage are defined as ceremonies, rituals or events marking an important stage in someone’s life. Key rites of passage have historically been collective, but in recent decades in the West, they have evolved into individual and more private affairs.

This year PG22 students have reflected, through architectural and urban design, on spaces that facilitate the communal and collective celebration of rites of passage, re-empowering their social dimension through three design exercises:

The Paper Theatre

Paper theatres are a form of miniature performance dating back to the early 19th century in Europe. For the experience of a rite of passage, spatial elements are as important as performance aspects. PG22 students have created their own versions of a paper theatre, representing how a selected rite is performed and gradually designing a stage for the socialisation of the rite.

The Produced Ritual Space

Buildings for rituals usually communicate their purpose on the outside through decoration and on the inside through spatial arrangements. PG22 students have developed their paper theatres into platforms for contemporary rituals, understanding that spaces of ritual are shaped not only by humans actions but also by their impact on the inhabitants’ agenda, an iterative influence described by Henri Lefebvre. 2

The New House Society

Lévi-Strauss defined the ‘house societies’ as communities linked not by blood bonds but by inhabiting a shared house, inherited by several generations in a cluster. 3 PG22 students have scaled up their projects into urban designs, creating communities with strong social links reinforced by the presence of shared facilities that actively contribute to a social network.

Year 4

Jiahan (Ada) Ding, Serim Hur, Gulcicek Karaman, Sarina Patel, Stefan Vlad Pista

Year 5

Long Yin Au, Cecilia Cappellini, Brandon Chan, Mankiran Kaur Kundi, Cheryl Lee, Harrison Lovelock, Reem Taha Hajj Ahmad, Yan Ching (Ellie) To, Yue Yu

Design Realisation Tutor: Han Hao

Structural Advisor: Roberto Marín Sampalo

Environmental Advisor: Ioannis Rizos

Thesis supervisors: Brent Carnell, Gillian Darley, Daisy Froud, Joshua Mardell, Anna Mavrogianni, Tania Sengupta, Tim Waterman

Critics: Omar Abolnaga, Sarah Akigbogun, Fares Al Rajal, Albert Blanchart, Louise Cann, Hadin Charbel, Han Hao, Déborah López Lobato, Ana Mayoral Moratilla, Mathieu Moreau, Martín Ocampo, Angelica Ponzio, Vidhya Pushpanathan, Elly Selby, Joshua Thomas

1. Pier Vittorio Aureli and Maria S. Giudici, ‘Familiar Horror: Toward a Critique of Domestic Space’, Log, 38 (2016), 105.

2. Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space (London: Wiley-Blackwell, 1991).

3. Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Way of the Mask (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 1982), 194.

22.1, 22.3

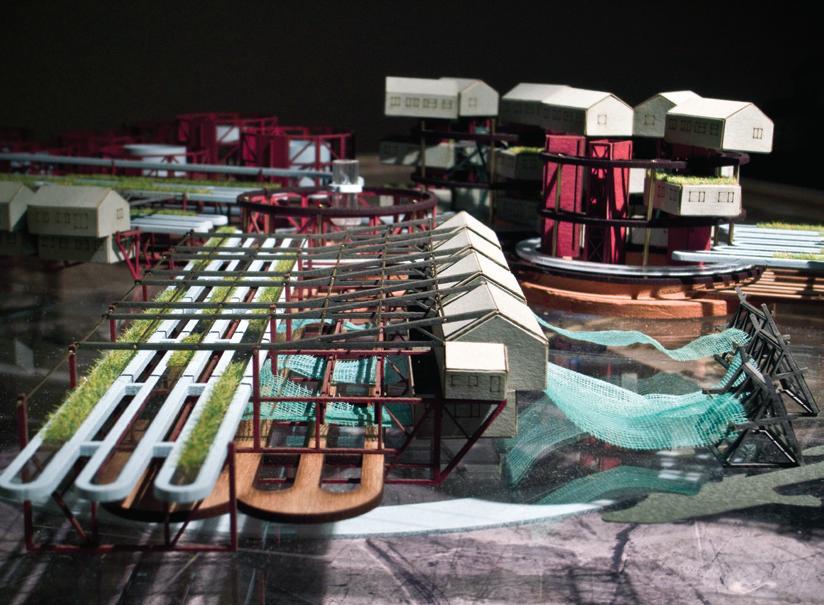

Brandon Chan, Y5 ‘Peng-Chau: Aqua-Pelago’.

Along Hong Kong’s coast, thousands of fishing families known as the Tanka people, once called sampans (small wooden boats) their home. Land reclamation projects in the 1960s gradually displaced sampans, causing a decline in Tanka culture. This project develops a strategy that safeguards the distinct history and culture of Hong Kong’s smaller islands through architectural interventions, blurring the boundaries between urban and natural environments.

22.2 Mankiran Kaur Kundi, Y5 ‘Heritage Haven: Preserving Sikh Rituals in the UK Diaspora’. This project designs a site for a Sikh wedding week in the UK diaspora, preserving cultural traditions while catering to a diverse community. The design serves as a cultural hub, where the rich heritage of Sikh weddings is celebrated and passed down to future generations. The preparatory process involving fabric and floristry takes on added significance in the project as it serves as a bridge between the old and the new, connecting ancestral customs with contemporary sensibilities.

22.4 Reem Taha Hajj Ahmad, Y5 ‘Urban Banquets of Care’. The design project envisions a utopia consisting of a housing estate that revolves around the concept of care for one another, the environment and architecture. The overall purpose of this project is to bridge intergenerational gaps in the city, creating a communal, caring environment where residents of all ages can experience and celebrate everyday rites of passage that are often overlooked in fast-paced lifestyles.

22.5–22.6 Yue Yu, Y5 ‘Cultural Landscape: Rehabilitation Craft Community’. The ancient town of Shaxi in Yunnan, China, with a history of over 2,400 years, is the sole surviving market along the historic Tea Horse Road. It was designated as an endangered heritage site in 2002 and uniquely restored by a team of Swiss scholars. Building on the preservation of key historical sites, the project focuses on safeguarding local intangible cultural heritage. It revitalises Shaxi’s cultural landscape, encompassing performing arts, tea traditions, folk gatherings and traditional crafts.

22.7–22.8 Harrison Lovelock, Y5 ‘The Houses of Hireth’. This project explores domesticity in postindustrial Cornwall. Beginning as an investigation into homemaking and seasonal living, the scope expands to address Cornwall’s housing crisis, driven by second residences and tourism. The proposal responds to this crisis using the disused rail infrastructure left over after the 1960s Beeching Cuts. It re-injects life into the trade sector through the manufacture and maintenance of mobile housing that adapts to seasonal patterns of work and inhabitation.

22.9 Yan Ching (Ellie) To, Y5 ‘Redressing the Streets of Cheung Chau’. The project reflects on life post-Covid and post-protest in Hong Kong. These events have induced a wave of fatigue, prompting an outflow of residents to other countries, but also to quieter territories within the enclave. The design proposal retains the local material culture of these islands, using bamboo to develop new and original tectonics. This material choice allows for high levels of openness, blurring the lines between buildings and public spaces.

22.10 Long Yin Au, Y5 ‘The Circular City’. The project explores how Hong Kong can find alternative modes of socialising and friendship through upcycling and recycling activities, focusing on Sham Shui Po, a district in Hong Kong renowned for its fabric and plastic trade. The scheme is a multiscaled masterplan, introducing a series of pavilions, a circular skywalk and retrofitted tong laus (tenement buildings) to enable residents to recycle their old clothing and household items, and share their memories through crafting, exchanging and recycling.

22.11–22.12 Stefan Vlad Pista, Y4 ‘Treatin’ Love’. Parallel to the rise and decline of dating apps, there has been a disturbing rise in the ‘incel’ phenomenon – an internet subculture linked to toxic masculinity and extreme resentment towards those who are romantically successful. The project establishes a multi-functional therapy centre that supports individuals with relationship challenges. This environment promotes healing, social interaction and personal growth.

22.13–22.14 Sarina Patel, Y4 ‘Building a Woman’. Female genital mutilation remains a rite of passage for Maasai women, and the recent prohibition of the practice has been labelled as culturally insensitive, driving it underground. This project proposes an alternative rite of passage through the learning of the vernacular construction of Maasai homes or manyattas Working in partnership with a local institute, the proposed architecture is designed using vernacular systems and materials, adapted to meet the lifestyle changes among Maasai communities.

22.15 Serim Hur, Y4 ‘The Healing Loom’. An exploration of traditional South Korean funeral biers and their ornamental features extended into a study of wider cultural practices surrounding death, with a particular emphasis on the role of craft. Building on this research, the project proposes to merge the tranquillity inherent in traditional timber ideologies with the comfort of woven textiles and cords.

22.16 Cheryl Lee, Y5 ‘The Nostalgic Domesti-City’.

An investigation into the wave of migration from Hong Kong to the UK is the seed for this project. The proposal is a residential complex for Hong Kong migrants in the UK to celebrate Hong Kong culture. The scheme challenges typical British and Hong Kong housing, as well as the typologies of the Chinatown and disused mall, to create a new typology – the ‘Semi-DetachedShophouse’, which embodies the convergence of British and Hong Kong culture.

22.17 Gulcicek Karaman, Y4 ‘Women as Infrastructure’. During the Ottoman period, baths were used for social rituals such as birth, marriage and death. However, this role has declined in favour of a more commercial framework. This project produces a new ecological and technological bath model with a non-hierarchical network, combining baths in a ‘hydrofeminist’ network of water, soil and air which heals and rejuvenates.

22.18–22.19 Jiahan (Ada) Ding, Y4 ‘The Red Peach Cake Townhall’. The Shazhou area in Chaozhou is currently undergoing urbanisation and experiencing population decline in favour of bolstering tourism. The project is built on a site where villagers resist forced demolitions and serves as part of a community intervention. The architecture enables residents to participate in village governance through the baking of red peach cake, which acts as a ritual medium for preserving culture and political agency.

22.20 Cecilia Cappellini, Y5 ‘Rites of Passage in the Italo Disco’. This project focuses on Italo Disco music as a rite of passage from 1965 to 1990, which led to its recognition as a mass phenomenon shaping the collective memory of Generation X. The design is a refurbishment of the Complesso della Misericordia, an old convent in the historic centre of Pesaro, Italy, creating a cultural centre for music, design, gastronomy and nature. This development leads to an urban-scale project reimagining Pesaro as a music city.

Izaskun Chinchilla Moreno, Daniel Ovalle Costal

Infrastructures such as roads, buildings or transit systems have historically been the focus for most planners, designers and public and private bodies that commission our built environment. They are also the entry point into the design process for most planners and architects.

Lifestyles, however, are seldom studied as part of the design process. They are often regarded as of secondary importance – a mere consequence of infrastructure design, rather than its trigger.

This year PG22 students have been rethinking and redesigning cities from one specific lifestyle perspective: friendship.

The emergence, continuity and intensity of friendships in cities strongly depend on their material features, such as:

the ease and modes of mobility through the city and between neighbourhoods – whether this happens in private vehicles, public transport or active modes of transport such as cycling or walking;

building typologies – whether most people live in apartments or individual houses; whether uses are mixed in plan, in section or segregated by neighbourhood; the density of dwellings per hectare – how compact or how spread out the city is and how accessible its green and public spaces are.

Social and human factors such as citizens’ financial aspirations, the division of domestic labour or the age and ethnic makeup of the city are equally relevant.

City design and planning has evolved to cater for the needs of traditional families and business: housing is designed based on the model of the nuclear family and transport networks are optimised to take workers from their homes in the periphery to their jobs in the city centre. Other forms of organisation, activities or relationships, however, have been systematically marginalised. The work of the unit critically challenges this by designing urban pavilions, facilities, neighbourhoods and a visual manifesto of the ideal city driven by friendship.

We are conscious that by designing the city we are also configuring social networks, daily routines, meeting points and rituals. The unit has critically evaluated tools for design that go beyond the technological, geometric, visual or aesthetic, developing a common scale to measure the quality of architecture by how it is able to create inclusivity, civic culture, intimacy, soft normative values, social visibility, cultural mediation, ephemeral or long-term friendships.

Year 4

Cecilia Cappellini, Brandon Chan, Latisha Chan, Mankiran Kaur Kundi, Ching Tung Cheryl Lee, Reem Taha Hajj Ahmad, Yan Ching Ellie To, Ziyue Lorena Yan, Yue Yu

Year 5

Long Yin Au, Deluo Chen, Ayla Hamou El Mardini, Jack Nash, Hei Tung Michael Ng

Design Realisation Tutors: Felicity Barbour, Gonzalo Coello de Portugal

Structures Tutor: Roberto Marín Sampalo

Environmental Tutor: Lidia Guerra

Thesis supervisors: Camilo Boano, Stephen Gage, Guang Yu Ren

Critics: Farbod Afshar Bakeshloo, Fares Al Rajal, Stuart Beattie, Amanda Callaghan, Hadin Charbel, Carrie Coningsby, Naomi Gibson, Kaowen Ho, Marianna Janowicz, Alberte Lauridsen, Déborah López Lobato, Ana Mayoral, Matthieu Mereau, Oliver Partington, Alicia Pivaro, Yael Resiner, Lewis Williams, Simon Wong

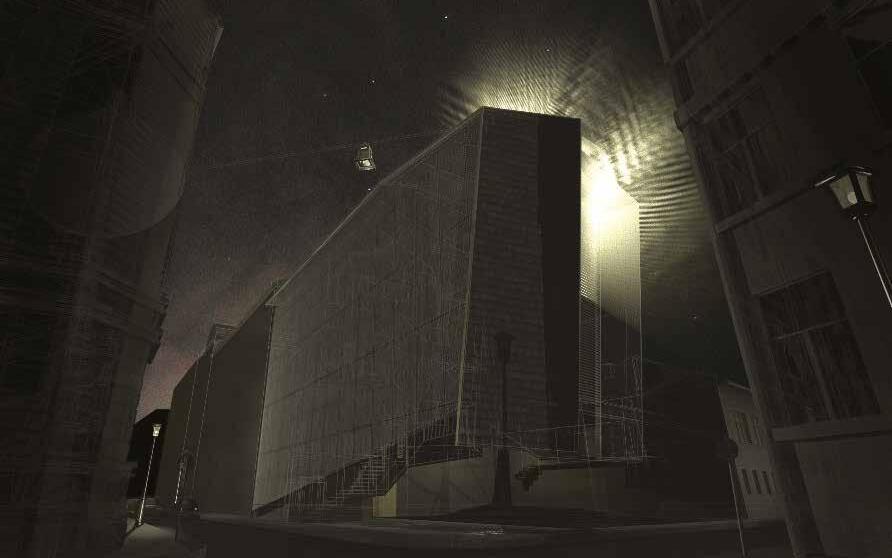

22.1–22.2 Deluo Chen, Y5 ‘Let’s Play: Exploring Post-Covid Friendship through the Game’. During the Covid-19 pandemic, people lost connection with acquaintances and strangers, a connection as crucial for mental health as that between close friends. The project stages an immersive play in the neighbourhood of Shatou District, Guangdong, China. A section of a heritage building and an abandoned building in front of it are renovated in the centre of the play.

22.3 Ziyue Lorena Yan, Y4 ‘Shoreditch Urban Greenhouse’. The project takes inspiration from the study of traditional English gardens and steel structure greenhouses, merging them with a vision that reimagines London’s recycling system and city farm conditions. Repurposing the historical Shoreditch Goodsyard, the project creates a sustainable space for community engagement, urban agriculture and environmental consciousness.

22.4 Ayla Hamou El Mardini, Y5 ‘The People’s Congress’. This project proposes a market, town hall and food preservation and crafts workshops – all run by selffunded local civil society organisations. The project was initiated through the general critique of Lebanon’s capital, Beirut, being a dramatically sectarian city, an aspect that is exacerbated by the city’s infrastructure.

22.5–22.6 Yue Yu, Y4 ‘Floating Farm’. The floating farm is a productive landscape reshaping the relationship of local neighbourhoods. Through the farm, residents can experience the impact that farm animals can have on an area like never before. The farm also serves as a centre for locals to gather and communicate, transforming the discrete social activities of local residents. The farm follows a carbon-neutral vision to build a sustainable community in which an organic waste recycling system and green energy are incorporated.

22.7 Hei Tung Michael Ng, Y5 ‘Absolute Obsolete’. This project empowers young adults in the city through a co-living lifestyle that encourages self-customisation of living spaces and self-expression, fostering collaboration in shared spaces. It revitalises a demolished To Kwa Wan industrial site in Hong Kong, serving as a testbed to reintegrate marginalised youth by equipping them with automobile and house repair skills.

22.8–22.11 Reem Taha Hajj Ahmad, Y4 ‘Timber Tinkerland School’. The project focuses on creating a timber school that nurtures friendship and creativity through architecture. The school provides a unique learning experience by encouraging children to engage in hands-on ‘tinkering’ through activities such as sewing and painting. Montessori pedagogies are integrated to offer diverse educational ways of connecting with the community through storytelling and theatre. The project emphasises the design of glulam columns and explores their adaptability to facilitate various forms of interactive play and engagement with the architectural structure.

22.12 Latisha Chan, Y4 ‘The Museum of the Oriental Odyssey’. This project is not simply a museum – it also takes visitors on a historic journey full of adventure through a series of immersive experiences that give an understanding of the history of Limehouse and that of Chinese settlement in London. Using the word ‘Oriental’, meaning ‘East’, allows the museum to be culturally inclusive and reflects the Chinese settlement in London which followed from the East India Company’s activities in the Far East.

22.13 Cecilia Cappellini, Y4 ‘The Paper Sail’. The proposal of the paper sail suggests a new form of urbanism of friendship in the context of Scampia, Naples. The design proposes a facility which redefines relationship dynamics in a context that, since the 1960s, has been extremely influenced by the hierarchical system of the criminal organisation, the Camorra. The building

design of the sail repurposes the empty lot of the knocked-down residential housing of the Vela Verde by exploiting paper construction in the envelope of the building and repurposing the construction material obtained by knocking down the Vela Gialla and Vela Rossa.

22.14 Mankiran Kaur Kundi, Y4 ‘Rethinking the Supermarket through the Dominance of Food’. The project is a pilot study run by a supermarket chain, looking to enhance the transition between the green belt and the city. The focus is to create a new approach towards the supermarket, reducing the distance between production and consumption. This will also enhance active governance and public engagement within the local community.

22.15 Jack Nash, Y5 ‘Vocation in the City’. The project takes a perspective on the crafters of historical urban centres, exploring how their collective dedication to the advancement of their craft, in learning, developing and exchanging skills, served as a catalyst for forging rich, close-knit communities.

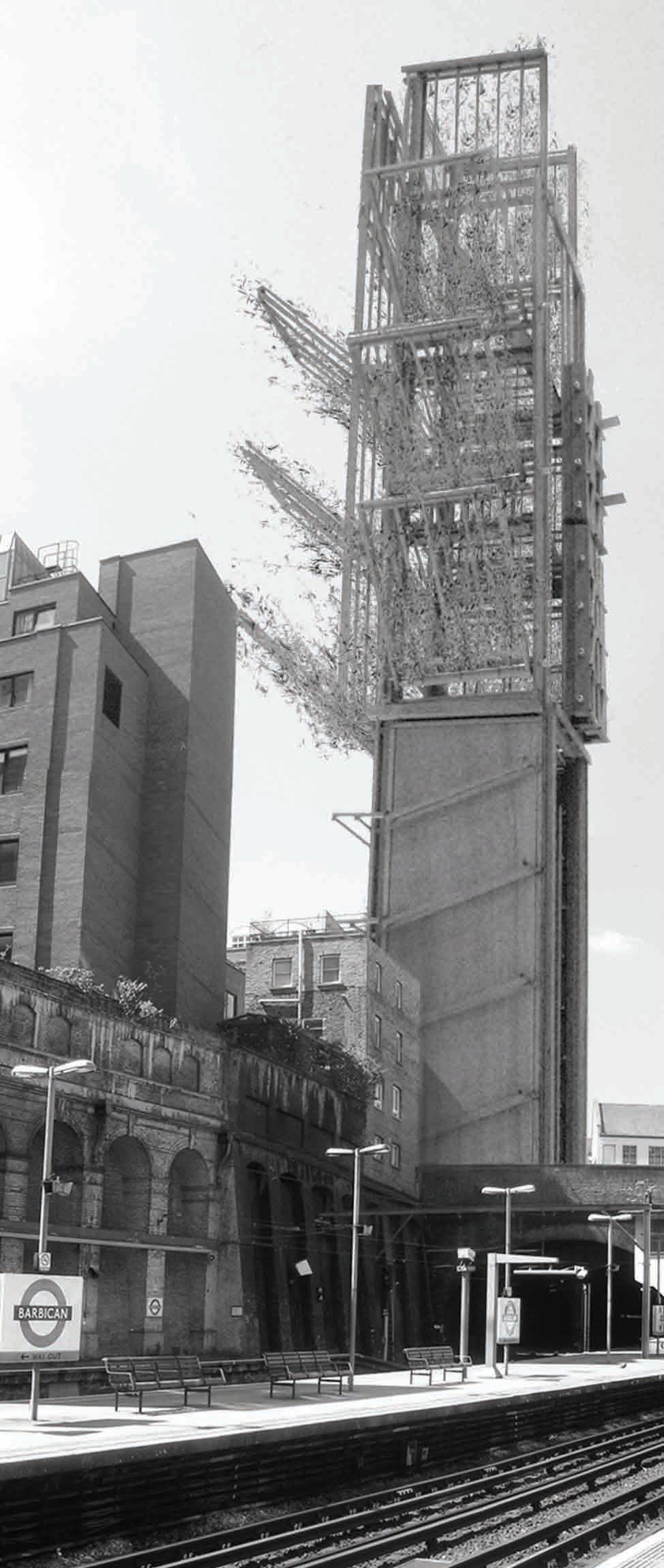

22.16 Ching Tung Cheryl Lee, Y4 ‘York Road Poetry Station’. The project fosters friendship through retrofitting York Road tube station, an abandoned London Underground station on the Piccadilly Line, with poetry. The design makes poetry more accessible and engaging for the public while encouraging people to slow down and appreciate the beauty of art in everyday life. Sharing feelings through the medium of poetry allows people to feel closer to each other and more understood.

22.17 Yan Ching Ellie To, Y4 ‘The Kitchenless Estate of Friendship’. In the hope of creating a city of friendship, the project looks at improving relationships within an existing community, specifically within the housing typology. The project proposes a new type of housing estate management in Hong Kong, based on the idea of creating a close-knit community through a collective diet and collaborative housekeeping. The proposal puts forward a ‘kitchenless’ ideology to not only encourage bonds within the locality but also improve residents’ quality of living, restoring Cantonese home cooking into the daily diets of our fast-paced generation.

22.18–22.19 Brandon Chan, Y4 ‘Wardrobe Wonderland’. This project is based in the vibrant Shoreditch Brick Lane area, renowned for its rich fashion history. With a strong focus on sustainable fashion, the project creates a dynamic space that connects consumers, designers and ethical fashion brands, fostering meaningful relationships and friendships through fashion.

Izaskun Chinchilla Moreno, Jan Kattein, Daniel Ovalle Costal

This year PG22 students were invited to develop a design critique of mass-produced austerity in architecture, uncovering the politics behind it and proposing alternatives.

The ethos of the Arts and Crafts movement, born in mid-19th century Britain under the auspices of figures such as William Morris, John Ruskin and Augustus Pugin, was suggested as an example of socially conscious anti-austerity. The title of the brief refers to three games, mostly played by women of that era, which inspired the three design exercises proposed.

Sociologist Richard Sennett highlights the importance of craftsmanship in books such as The Craftsman and Together. He argues that the ‘enduring basic human pulse’ that comes from perfecting a craft creates deep inner satisfaction. For Sennet, allowing principles of craftsmanship to guide an individual’s life at their own pace can provide benefits for both individuals and society. His writing on craftmanship provides an alternative reading of the Arts and Crafts as one of the most socially desirable architectural movements in history.

The movement did not merely propose a style or a visual repertoire; it rather offered an idyllic lifestyle in which people could work in quasi-domestic workshops, caring about the origin of materials, the choice of crafting techniques and the quality of the result.

In retrospect, it is reasonable to question why 20th-century architects abandoned the Arts and Crafts philosophy en masse, instead embracing the Modern Movement principles of industry and standardised mass production with great enthusiasm. The austerity inherent to mass produced design was introduced by the proponents of the Modern Movement to distinguish revolutionary new architecture from old 19th-century traditions. They dedicated far more effort to fighting ornament than to critically assessing the living conditions and lifestyle that mass production imposed upon workers who fabricated these new designs.

From today’s perspective, there is something perverse in the proposition that to democratise design it must be stripped of variation and visual and material richness. A century on, we should critically reconsider whether mass-produced austerity has satisfied its initial aspirations of supporting and empowering the working class, fostering intellectual honesty and cultural progress.

Year 4

Long Yin Au, Deluo Chen, Ayla Hemou El Mardini, Monika Kolarz, Jack Nash, Hei Tung Michael Ng, Sonakshi Pandit

Year 5

Asli Aktu, Annabelle Blyton, James Ford, Luba Kuziw, Verena Leung, Jignesh Pithadia, Cheuk Ying Sharon So, Olivia Trinder, Simon Wong

Technical tutors and consultants: Gonzalo Coello de Portugal, Roberto Coraci, Roberto Marín Sampalo

Thesis supervisors: Hector Altamirano, Sabina Andron, Carolina Bartram, Jan Birksted, Amica Dall, Paul Dobraszczyk, Murray Fraser, Joshua Mardell

Critics: Lluis Alexandre Casanovas, Sarina da Costa Gómez, Pepe la Cruz, Naomi Gibson, Faye Greenwood, Kyriakos Katsaros, Matthieu Mereau, Ana Mayoral Moratilla, Adam Peacock, Pedro Pitarch, Guillermo Sánchez Sotés, Chrysanthe Staikopoulou, Joshua Thomas, Jonathan Tyrrell, Kate Woodcock-Fowles

22.1 Luba Kuziw, Y5 ‘The Modern Tradition’. An exploration of the use of straw as a modern building material, turning the industry inwards and developing a world of cyclical craft between communities. The project is situated in London’s Robin Hood Gardens and proposes the gradual replacement of the estate’s poorly performing façades with prefabricated biodegradable panels developed by craftspeople from the community using locally grown wheat.

22.2 Simon Wong, Y5 ‘The Maiden’s Tale’. The project introduces a different method of acquiring new skills while continuing to develop a sense of community for the low-income families that live in the Maiden Lane Estate in Camden. Conceived as a bottom-up initiative, the project proposes a retrofit academy to upskill residents and upgrade the estate. The academy will provide retrofitting not just for Maiden Lane, but for the entirety of the borough as well.

22.3–22.4 Asli Aktu, Y5 ‘The Social Stair’. This project is the continuation of the Dawson’s Heights estate in East Dulwich, establishing a new design agenda from a 2022 perspective, influenced by and in response to its architect, Kate Macintosh. The proposal combines social ambitions for the estate with a centralised stairwell which provides a new point of access alongside a variety of social amenities for residents of the estate and the wider community across 12 levels.

22.5 Ayla Hamou El Mardini, Y4 ‘Hideaway Gardens: Redefining Private Gradients’. A redesign of the traditional neighbourhood framework using a precedent from historical Islamic Mamluk architecture –the Qalawun complex in Cairo, Egypt. The project is a mixed-use building with residential units, carpet refurbishment workshops, a carpet-weaving academy and retail spaces. These programmes are configured around a sequence of semi-public courtyards.

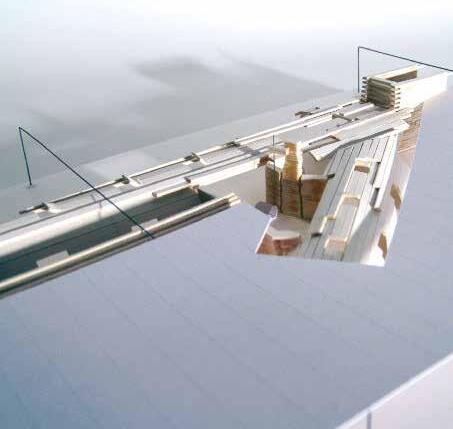

22.6 James Ford, Y5 ‘Low Speed One’. A design critique of the High Speed Two (HS2) railway. The project challenges the benefits of a new high-speed rail service across England by instead proposing the reversal of the ‘Beeching cuts’ of the 1960s and 70s. Low Speed One speculates on whether the implementation of a slow transport network could have a greater impact on more communities, while helping to implement the government’s ‘levelling up’ agenda.

22.7 Sonakshi Pandit, Y4 ‘The Rewilding Hub: Remediation through Reciprocity’. Situated in the car-centric area of South Croydon, the proposal seeks to repurpose obsolete gas works, transforming them into hubs that support seed and soil preservation, as well as providing infrastructure to facilitate seed dispersal in a radical rewilding of road infrastructure.

22.8 Long Yin Au, Y4 ‘Tottenham Hale Cycletopia’. An alternative masterplan based on the principles of the 15-minute city, which proposes a cycling infrastructure to encourage more people to shift from cars to bicycles. At the centre of the masterplan is the headquarters of Pashley Bicycles, made up of workshops, BMX training grounds, offices and a bike-through kitchen. The building exemplifies how bicycle culture extends beyond cycling and into forms of creative expression, campaigning, performing and gathering.

22.9 Deluo Chen, Y4 ‘UCL Urban Agriculture Faculty’. The project proposes transforming Vauxhall City Farm into a mixed-use urban farm with in-residence research in the form of the UCL Urban Agriculture Faculty. This project reimagines the city farm and goes beyond its current form to create a living, breathing and thriving community for humans and animals alike, a place where coexistence between species is the driving force.

22.10–22.11 Verena Leung, Y5 ‘Urban Living Rooms’. An alternative regeneration of the Brownfield Estate in

Poplar, East London, that reactivates its domestic streets by dissolving private and public boundaries and creating a new urban living room. In view of the fashion industry’s revival in East London, the project introduces slow fashion programmes to transform the underused street into a collective live-work space.

22.12 Hei Tung Michael Ng, Y4 ‘The Bright Kitchen’. Reimagining cooking spaces as new agents of social sustainability, local empowerment and circularity. The project introduces a community-led food cooperative as an alternative urban regeneration scheme for a post-war estate. The proposal creates a bright, transparent and accessible food-sharing network that connects domestic and urban realms.

22.13–22.14 Annabelle Blyton, Y5 ‘The Walthamstow Water Collective’. The project collects water in the literal sense, while also bringing people together over the positive potential of water. New studies reveal that proximity to water has a similar positive impact to closeness to green space, with an added ‘psychologically restorative effect’. The project promotes a greater understanding of these therapeutic blue spaces and improves access to them.

22.15 Jack Nash, Y4 ‘Mixing Up Making in Clerkenwell’. The project puts forward a mixed-use strategy with a combination of live-work spaces for single crafters and makers. Concerned with reviving Clerkenwell’s historic reputation for making and crafting, it hopes to offer an updated form of the guilds for the 21st century.

22.16 Olivia Trinder, Y5 ‘Wasted Space: De-Growth of Tottenham Hale’. The design proposal is set in the not-too-distant future, where complications surrounding the current development of Tottenham Hale have led to its construction being halted. The local community has been able to buy up the abandoned site in pursuit of creating a shared living space. Utilising both traditional and modern construction methods and materials, inhabitation occurs close to the ground plane in this pastoral, slow-living high-rise.

Izaskun Chinchilla Moreno, Daniel Ovalle Costal

In the 1950s, Som and Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson dodged Manhattan’s strict zoning regulations by building on a small fraction of the sites for Lever House (1952) and the Seagram Building (1957), designating the remaining land as private plazas. Their success triggered a change in New York City’s zoning regulations, linking a site’s permitted floor area to the provision of open space accessible to the public.

The appearance of Privately Owned Public Spaces (POPS) reversed a trend that had seen the transfer of private open spaces in cities like London and Paris to public hands. POPS have since proliferated in cities across the Americas, Asia and Europe. The provision of POPS has become key to the planning and delivery of large development projects. In the case of London, areas that have undergone large-scale regeneration often feature these spaces, such as around Kings Cross and Tower Bridge.

There is no consensus on the urban value of POPS. Some argue that POPS provide urban equipment at better value for the taxpayer, while others argue that private property goes against the very essence of public space, which should guarantee that any form of social organisation can access the structures of power.

While POPS may generally look and function like public spaces, they are governed by their own rules that tend to benefit and promote a particular lifestyle, namely one based on consumerism. POPS are often found in areas with a high density of retail, with elements of hostile architecture appearing more often. As a result, activities that do not lead to the consumption of goods and services are discouraged or outright banned. The institutions that instigate such bans are often hidden from public scrutiny behind layers of corporate bureaucracy. The lifestyle bias of POPS leads to a degree of discrimination against those who do not fit, follow or cannot afford the prescribed lifestyle.

This year, PG22 researched and critically challenged POPS in multiple contexts around the world, and the lifestyles they promote. Based on this research, students developed design mechanisms to foster diversity and inclusion of different socioeconomic, physical or ethnic subjectivities across discrete public and private spaces and, ultimately, at an urban scale.

Year 4

Asli Aktu, Annabelle Blyton, James Ford, Luba Kuziw, Verena Leung, Hei Tung Michael Ng, Cheuk (Sharon) So, Olivia Trinder, Simon Wong

Year 5

Jason Brooker, Carrie Coningsby, Karin Gunnerek Rinqvist, Megan Makinson, Joseph Poston, Chun Wong

Thank you to our technical tutors and consultants: Gonzalo Coello de Portugal, Pablo Gugel, Nacho López Picasso, Roberto Marín Sampalo

Thesis supervisors: Jan Birksted, Eva Branscome, Gary Grant, Elain Harwood, Luke Lowings, Anna Mavrogianni

Thank you to our critics: Sarina da Costa Gómez, Karen Franck, Faye Greenwood, Alastair Johnson, Maggie Lan, Yuqi Liew, Jonah Luswata, Mireia Luzárraga, Matthieu Mereau, Lucy Moroney, Adam Peacock, Lucía C. Pérez Moreno, Gergana Popova, Guillermo Sánchez Sotés, Stefania Tsigkouni, Kate Woodcock-Fowles

22.1 Jason Brooker, Y5 ‘The Institute of Lost Craft’. The project seeks to preserve and protect both tangible and intangible cultures, to aid the national identity of heritage sites during redevelopment processes. It takes the stance that traditional Victorian markets should be retained for their social purpose and can be adapted to allow traditional crafts, which once thrived off the market’s footfall, to have a permanent home. Smithfield Market in London is used as a testbed to apply this theory.

22.2 Simon Wong, Y4 ‘Midnight Communes’. London’s night-time economy is one of the most vibrant in the UK. Many of its workers, however, have become marginalised, with their wellbeing neglected by employers and public bodies. The ‘Midnight Communes’ is a pilot programme, located in Marble Arch, initiated by the Night Time Commission. The scheme is designed to provide support and relief to night-time workers between, before and after their shifts.

22.3–22.4 Carrie Coningsby, Y5 ‘Hydrosocial Cities’. The project utilises the contradictory logic of privately owned public spaces and applies it to London’s privately owned water network, arguing that there are elements that should be made available to the public. The result is a multi-scalar design process that aims to ‘resocialise’ water within the public spaces of the ongoing masterplan for Greenwich Peninsula.

22.5–22.6 James Ford, Y4 ‘Festival Pier’. The research focusses on the rewilding of the banks of the River Thames and how the seasonality of nature can help to transform the role of transport in people’s lives. Developing a more natural system of transition throughout the city, ‘Festival Pier’ speculates on how Transport for London’s annual target of 20 million river bus journeys by 2035 can be achieved. Integrating the historic Thames wetland ecology into the river bus boarding process helps reconnect London with the river.

22.7–22.8 Luba Kuziw, Y4 ‘The Ciudad Elephante’. An investigation into the redevelopment of the Elephant and Castle shopping centre in South East London. As a result of the development, it came to light that local residents and business owners were being unfairly treated. The project proposes a new home for the local Latin American diaspora. A number of ‘hubs’ are placed around Elephant and Castle, all within 15-minute proximity of each other, creating a new neighbourhood where the community can converse and thrive without being obstructed by luxury high-rise apartments.

22.9 Joseph Poston, Y5 ‘Unifying Opulence’. The project is a headquarter building for a new union of finance workers that tackles the working conditions and practices of the high-stress financial industry in Canary Wharf. The programme focusses on three different users: industry workers, union workers and the public. The facilities challenge how each user operates while fostering a mentally engaging environment. Light is a prominent factor in spatial environments, used to challenge the perception of how workspaces engage users.

22.10 Annabelle Blyton, Y4 ‘Gasholder Theatre’. The project analyses privately owned public spaces in Kings Cross. Inspired by the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, it proposes to transform the outdoor public spaces of Kings Cross for art and performance initiatives. Gasholder No.8 is transformed from an underused park into a multifunctional entertainment space. The structure becomes the main formal art and performance space, sitting alongside the informal festival activities that happen across the site.

22.11–22.12 Megan Makinson, Y5 ‘Up Down. Back Front. The Now’. The project looks to densify a Victorian terraced street, applying a bottom-up approach. The houses are flipped, disrupting the Victorian typology and

the relationship between the public and private. Domestic labours are no longer forced into small hidden rooms at the back and a new second skin façade creates communal intra-private spaces, both for socialising and economising domestic living and work. Space is unlocked and families can expand and contract into the new streetscape. Shared living spaces are formed to replace underused spaces in private homes.

22.13 Verena Leung, Y4 ‘The Alley Commons’. The project explores an alternative to top-down urban renewal in Hong Kong. It proposes the regeneration of a street block of tong laus (old tenement houses) of multiple ownerships into a co-living complex. It substitutes the undesirable living conditions of subdivided units with refurbished co-living housing that surrounds a communal courtyard. The major move of the project is to re-engage the alleyway that has become an underused backyard space, overshadowed by the tenement’s back staircases. Looking at the buildings collectively, redundant fire escape staircases are removed to widen the alleyway.

22.14 Chun Wong, Y5 ‘Mall City: Urban oasis’. Hong Kong has the highest density of shopping malls in the world. Malls are a major space for public gathering in the city, meaning retail environments play a crucial role in our daily life. The New Town Plaza mall is chosen as a prototype to develop publicly owned public spaces into an urban oasis. The project applies biophilic design principles to provide a new shopping experience that can reinvent the mall typology, while enhancing biodiversity across Hong Kong.

22.15 Olivia Trinder, Y4 ‘A Sitopia in Canary Wharf’. The project takes Jubilee Park in Canary Wharf as a template for an alternate masterplan that redefines corporate life. The existing masterplan and its manicured green spaces are replaced with a space that promotes slowness, employee health and wellbeing, and ecological awareness. The parks are to become inhabited with flora and food-centred biological and cultural diversity.

22.16–22.17 Asli Aktu, Y4 ‘Spitalfields Rooftoppings’. The project redevelops Fournier Street, formerly the home and workplace of the Spitalfields silk weavers. The scheme explores the ways existing buildings can be repurposed and transformed to better suit the users of today. ‘Rooftoppings’ creates domesticated community driven spaces, further extending the life span of the 18th-century buildings.

22.18 Karin Gunnerek Ringqvist, Y5 ‘Torsö Forest Campus’. Forests in Sweden are all subject to the ‘right to roam’. Granting everyone equal right to freely enter privately owned land for recreation and exercise, the forest is an important social and cultural space. As a result of urbanisation a larger number of Sweden’s forest owners are now urban residents. Living further away from their properties, these owners developed different values and experiences than is traditional. The project investigates what effect this demographic change might have on the forest as a social and cultural space and identifies strategies to bridge knowledge and culture gaps between newly urbanised and traditional forest owners.

Izaskun Chinchilla Moreno, Daniel Ovalle Costal

After decades of industrialisation, our cities are places geared towards productivity, both in their physical and their legal dimensions. They enable the daily marketing and distribution of goods, advertising and driving to work. In contrast, contemporary cities are hostile environments for non-productive activities: try to sleep; use a toilet; drink free, clean water; or have fun without consuming, and it will become evident how challenging the city can be. The normative interest in these practices has been marginal. Where regulations are in place, their main objective is generally to limit or even ban such behaviours.

Giving productive activities priority means citizens have been defined as individuals who contribute to that productivity, while their biological and subjective characteristics are not considered in the design, regulation or government of the city. This denial has been assimilated as part of our culture and, fundamentally, as a political principle. Our cities deny the right to rest, health or affection by considering them activities that need no protection, promotion, or collective agreement.

Women have historically performed tasks and jobs that are not given a market value, caring for others without institutional support or business regulation: reproductive activities. This has generated a unique and enormously rich capital: the heritage of care. Citizens who exercise reproductive activities have for decades been creating a hidden dimension in cities, in which biological and subjective aspects are fundamental. This year’s PG22 brief is purple: our students have developed projects that celebrate, recognise, and promote the capital of care and its intrinsically female character.

Students have worked towards building a live and active definition of care which addresses its complexity and diversity. Based on that working definition, they have developed projects that increase biodiversity and local food production; introduce play and games; raise awareness about the climate emergency; facilitate the sharing of space among citizens with different bodies and subjectivities; help maintain a healthy body and adequate mental health; promote affection and pleasure; socialise childcare and care for other dependants; and intensify social gathering.

Most importantly, this year’s projects have built a collective critique of our cities and proposed alternative urban environments that empower caregivers, consolidate their use of cities and place reproductive activities at the centre of design. In PG22, we think that this is a contribution that, in the long run, all citizens can benefit from, which will facilitate work-life balance and a superior form of social organisation that guarantees a more satisfactory urban life.

Year 4

Jason Brooker, Rachel Buckley, Carrie Coningsby, Karin Gunnerek Rinqvist, Megan Makinson, Joseph Poston, Chun (Derek) Wong

Year 5

Byungjun Cho, Siu Yuk (Daniel) Chu, Faye Greenwood, Janis Ho, Yan Ting (Lorraine) Li, Yuqi Liew, Yinghao Wang, Lewis Williams, Kate Woodcock-Fowles

Thanks to our technical tutors and consultants Gonzalo Coello de Portugal, Kristina Goncharov, Nacho López Picasso, Roberto Marín Sampalo, Shane Orme, Rachel Yehezkel

Many thanks to our thesis supervisors Jan Kattein, Anna Mavrogianni, Clare McAndrew, Harry Parr, Alan Powers, Sophia Psarra, Guang Yu Ren, Oliver Wilton

Thanks to our fabulous critics: Alejandra Albuerne, Sarina da Costa Gómez, Pedro Gil, Marta Granda Nistal, Jonah Luswata, Matthieu Mereau, María Venegas Raba, Tumpa Yasmin

22.1, 22.6 Lewis Williams, Y5 ‘The Climate Change Spectacular’. Climate change will affect humanity on an unprecedented level. This project takes a cynical stance, which accepts the slow and inadequate approach by the UK government and its unfortunate climatic conclusions. Using an analysis of ‘spectacle’ as a tool for change, the architecture realises the now often meaningless shocking imagery generated by the media and transforms it into a politically powerful built extravaganza erected in anticipation of catastrophe on London’s Trafalgar Square. 22.2 Yinghao Wang, Y5 ‘The Resilient Urban Village’. Rapid urbanisation has transformed Shenzhen from a small fishing village into one of China’s biggest metropolises within three decades. However, it has also posed a threat to the area’s ecological cycle. In this context, this project is a resilient design, questioning the possibility of applying an ancient local ecological circular farming system, the mulberry fishpond system, in the residential blocks of the urban village.

22.3 Kate Woodcock-Fowles, Y5 ‘Waiting and Transition’. This project aims to create a more ‘caring’ city by reimagining the architecture which supports Nottingham’s public transport network, specifically spaces of waiting and transition. Taking privileges from car users, people are incentivised to travel in alternative active ways. With fewer vehicles on the roads, the tarmac is gradually reclaimed to provide more green space in the city. In the city centre, transport hubs are designed to provide cultural and historical markers.

22.4 Yuqi Liew, Y5 ‘Harlow Housing Eco-operative’. This project envisions a refurbished housing community, supported by shared ecological domestic infrastructures, which provide a sustainable, collective, and affordable way of living for the vulnerable tenants of Terminus House in Harlow, Essex. By deconstructing our laundry practices, a methodology to reconfigure domestic rituals through shared spaces was devised. These principles were brought back to the home and expanded into a new kind of housing cooperative.

22.5 Chun (Derek) Wong, Y4 ‘Fly the Flyover’. This project opens up the fenced-off lands underneath an overpass in Hong Kong for public enjoyment. Responding to the city’s ageing population, the project is a masterplan that includes housing for the elderly and playgrounds, using reminiscence therapy. The role of older people in society is challenged and reformulated as they are seen as both care receivers and givers.

22.7–22.8, 22.10 Faye Greenwood, Y5 ‘Cultivating Craft’. This project aims to rediscover and support the heritage, skills and beauty of crafts in the UK, in domestic and public urban environments. The architecture creates craft communities that revive skills and businesses with access to knowledge, tools, processes and objects. In parallel, the project explores how studio crafts can be translated into the building fabric.

22.9 Joseph Poston, Y4 ‘Lost Springs of Linfen’. The project explores the lasting effects of pollution to the elderly in the city of Linfen, China, and aims to explore new building strategies that can create a clean environment to live in and care for the elderly. At its core the design looks at the elderly and their role in modern China. The key architectural strategies aim to provide a new model of care home.

22.11 Karin Gunnerek Rinqvist, Y4 ‘Westway Trust Community Centre’. In order to meet environmental goals and lifestyle aspirations, private car ownership in cities is set to decrease. This project investigates changes in car usage and speculates about how it will affect spaces previously only used by cars. This project closely investigates the Westway and how outdated roads can be transformed to have another purpose, considering construction, community and environment.

22.12–22.13 Carrie Coningsby, Y4 ‘Hornsey Filter Beds’. Blending landscape, infrastructure, building and hydrological processes, this project aims to reposition public opinion of wastewater treatment by inserting it into the core of a public space and allowing people to experience the regenerative properties of treated water. Located in Hornsey, London, and partially submerged into the landscape of the redundant filter beds

22.14 Jason Brooker, Y4 ‘Gardens of the Northern Line’. This project is a community-based ‘living’ urban biome, set in Stockwell, which aims to increase the life expectancy of residents living along the Northern Line. The hub looks to utilise deep-level shelters constructed during WW2. Making use of the heat source that the underground provides, the project aims to create precise climates in which crops and plants can be grown as well as spaces for teaching, sharing and trading.

22.15 Siu Yuk (Daniel) Chu, Y5 ‘Tokyo Craft Village’. Traditional crafts are under immense threat from globalisation and technological advancement. Taking crafts as the medium to create a caring city, this project explores the potential of translating traditional Japanese crafts into architectural design elements and bringing ‘domesticity‘ into the public realm. The village seeks to provide a space for the craftspeople to form a community in the heart of Tokyo.

22.16 Byungjun Cho, Y5 ‘Amalgamating the Two Worlds’. This project proposes a design for empty peri-urban modern blocks of Fes, Morocco, using the traditional lifestyle learned from its medieval medina. Offering a new travel hub outside of the old town, it aims to reduce pressure on the population of tourists and craftsmen in the medina and to fill the infrastructural gap to empower low-income families in the peri-urban area.

22.17 Megan Makinson, Y4 ‘Community Food Centre, Tottenham’. Addressing growing food poverty in the UK, this project rejects the current models of food banks and engages with surplus food as an enabler to the already growing community agency around Tottenham, London. The building mixes different uses to create a new typology: food bank, community kitchens, feasting, counselling and residential. The spatial organisation removes doors, barriers and corridors, with the programme organised around a multi-purpose dining hall.

22.18 Yang Ting (Lorraine) Li, Y5 ‘School Without Classrooms’. This project reinvents notions of play and learning to create more inclusivity in the city. This is accomplished through a free school design proposal in Somers Town, London for an alternative learning environment promoting play for children, with parental support facilities. Using an existing defunct school building and the school network of Somers Town as a test bed, the proposed new school building design and curriculum seeks to reflect Reggio Emilia model.

22.19 Rachel Buckley, Y4 ‘Neckinger Festival’. The city has a role in caring for people’s imaginations; nurturing storytelling and memory, and a responsibility to keep its stories alive. This project looks to the past through performance, following the design of a floating theatre and exhibition/workshop space in a London dock, where the now underground river Neckinger enters the Thames. This theatre becomes a travelling fair considering events recorded along this route – turning the city as we know it into an immersive theatre.

22.20–22.21 Janis Ho, Y5 ‘From Play to Community’. The project addresses the decline in play spaces. It is inspired by the concept of a blanket fort where architects should work with the community, and especially children, to co-create an integrated and caring neighbourhood. The test ground for this socio-architectural experiment is Webster Triangle: a neglected neighbourhood of terraced housing in the post-industrial town of Liverpool.

Izaskun Chinchilla Moreno, Daniel Ovalle Costal

Europe has historically been organised through a network of ‘southto-north’ and ‘periphery-to-centre’ trade connections. These trade relationships were some of the core development questions Europe confronted early on and are embedded in its DNA.

Growing up in a southern, or peripheral, European country means being conditioned to see northern and central Europe as synonyms for professional development, the welfare state, financial success, stability, cosmopolitanism and cutting-edge trends. Besides the infrastructural construction of the south-to-north connection, there has been an aspirational consolidation of that same link, with citizens of southern European countries aspiring to access the opportunities that northern countries provide.

This year, the unit’s research has been focused on Mediterranean culture, which has traditionally valued quality of life over progress. It seems that central and northern Europe have accepted that industrialisation and technological development are the best partners for welfare. Societies on the Mediterranean shore, meanwhile, seem to be more sceptical of industrialisation and technology, an attitude which has gained in consciousness and has become part of the region’s cultural and social identity. Students addressed this cultural particularity from a series of perspectives: firstly, that of the family – looking at both the nuclear and extended family, and cultural approaches to ageing and retirement; food –looking at preferences for eating ‘clean’ or ‘real’ food, processes of growing and ideas on communal cooking and dining; skills – whether workers are hyper-specialised or multi-skilled; and tourism – how it affects quality of life, discussing ideas on discovery, and over-tourism and its impact on local communities.

This year, students looked at notions of ‘slowness’ and ‘disengagement’, in particular the Slow Food movement, which began in 1986 as a protest against the opening of a McDonald’s restaurant in Rome, and advocates a cultural shift towards slowing down the pace of life. ‘Slowness’ celebrates the Mediterranean legacy, but its success and development require a global network. Many of the issues affecting Europe and the Mediterranean, such as migration, cannot be confronted in isolation. Using three shores as their focus –the UK, European Mediterranean and Asian Mediterranean – students implemented programmes that not only had individual relevance but also dealt with common problems: empowerment of citizens in different areas – balancing equity, education, research, languages, job opportunities, entrepreneurial support, vocational schools, food production and consumption; insertion programmes – social housing and the integration of migrants and refugees; and reconstructing quality of life – through slow communities, organic farming, and the preservation and revitalisation of traditional craft.

Year 4

Byungjun Cho, Siu Yuk (Daniel) Chu, Faye Greenwood, Janis Ho, Funto King, Yang Ting (Lorraine) Li, Yuqi Liew, Yinghao Wang, Lewis Williams, Kate Woodcock-Fowles

Year 5

Florence Bassa, Jun Wing (Michelle) Ho, Alastair Frederick Johnson, Jonah Luswata, Rui Ma, Yehan Zheng

Thanks to our fabulous critics: Barbara-Ann Campbell-Lange, Freya Cobbin, Gabi Code, Sarina da Costa Gómez, Elanor Dodman, Laurie Flint, Cristina Garza, Kaowen Ho, Ann Kelly, Ifigeneia Liangi, Ana Monrabal-Cook, Arantza Otaeza Cortázar, Adam Peacock, Tania Sengupta, Barry Wark, Timmy Whitehouse, Izabela Wieczorek

Thank you to Gonzalo Coello de Portugal, Marta Granda Nistal, Nacho López Picasso, Roberto Marín Sampalo and Ajay Shah

22.1–22.3 Alastair Frederick Johnson, Y5 ‘Augmenting Kayaköy’. After the fall of the Ottoman empire, the population exchange forced Greek residents out of the Turkish town of Kayaköy, previously a unique model of religious tolerance. This project proposes the redevelopment of the town in line with the Historic Urban Landscape approach: to truly protect delicate sites, inhabitation is essential. A phased programme of reconstruction, preservation of local crafts and active tourism is proposed. The programme is supported by a mixed reality platform to enhance Kayaköy’s history.

22.4–22.5 Florence Bassa, Y5 ‘Co-Komi’. ‘Co-Komi’ is the community cooperative of the farming village of Komi, on the Greek island of Tinos. The project demonstrates how the community can use local skills and EU funding with the goal of becoming a ‘Competitive Village’, tackling population decline and low incomes. The village engages with global discourses, such as plastic waste and the future of work. The architecture contributes to Komi’s new identity and breaks stereotypes about rural areas.

22.6, 22.8 Faye Greenwood, Y4 ‘The Boxed Sandwich Revolution’. This project aims to slow down the UK’s relationship with food, taking influence from Mediterranean food culture. With remote and co-working trends becoming more popular, this project aims to integrate flexible working spaces and communal cooking and dining programmes in London’s commuter belt. A modular system is proposed, with cooking at the core, within a landscape of allotments. The building’s construction, materials and organisation aim to use spare resources.

22.7, 22.9 Jun Wing (Michelle) Ho, Y5 ‘City as a House’. In the context of landmark-focused over-tourism in Mediterranean cities, this project proposes a familyfriendly alternative. A series of domestic spaces is scattered around the city at sites with strong connections to local heritage and population. By shifting the focus from landmarks to experiences, heritage is redefined around everyday life. Proposed architectural preservation does not freeze buildings in time but boosts their use. New layers of intervention act as mechanisms for learning about heritage as a historic process.

22.10 Rui Ma, Y5 ‘Hospitable Nomads’ Living Posts’. This project aims to update the living conditions of the Yörük nomads of Turkey whilst preserving their unique lifestyle. The proposal consists of posts that provide infrastracture for a revisited nomadic tent built in several layers. The scheme allows active tourism to be part of the nomads’ life and income.

22.11 Yan Ting (Lorraine) Li, Y4 ‘A Resilient Strategy Against Over-tourism and Seasonality’. The economies of many Mediterranean countries rely on tourism. The seasonality of the sector affects their economy by putting stress on public services and housing. This project explores the possibility of introducing residential units into an existing 1970s hotel in Ibiza, via small-scale demolition, retrofitting, and by creating new spaces. A series of timber trusses provides structural support for cantilevered floor slabs, acting as a buffer between residential and temporary hotel units.

22.12–22.13 Kate Woodcock-Fowles, Y4 ‘A New Town Square for Worksop’. Low-income families often lack the choice to eat healthy foods. In post-industrial, workingclass communities like Worksop, the resulting obesity epidemic is placing a huge strain on the NHS. Inspired by the Mediterranean diet, the new town square proposes to tackle this issue with a permanent programme of restaurants, kitchens and learning areas to promote healthy eating. The design takes inspiration from the rich industrial heritage of Worksop, with a focus on one of the town’s major exports: the Windsor chair.

22.14 Janis Ho, Y4 ‘Transport for Santorini’. Due to overtourism, Santorini’s authorities have limited the number of visitors to the island by half. This project proposes to enhance local agriculture as a second source of income. A system of bus stops celebrating the island’s agriculture introduces its products to tourists. The bus terminal doubles up as a market in which visitors can learn about and buy local produce. Built on reinforced local volcanic rock, the terminal aims to bring together locals and tourists in a new sustainable economy.

22.15 Yehan Zhen, Y5 ‘The Built Pension’. The ‘young-old’ are an emergent demographic of 50-70 year-old retired people with specific needs. The research questions the nature of pensions as a monetary entities and proposes a ‘socio-spatial’ pension as a flexible alternative. The Mediterranean ‘in-between’ condition inspires a split-level typology that integrates existing industrial communities with a retirement layer and an alternative ‘street’, linking disparate spaces. The built pension spans the domestic and corporate, resulting in an architecture of needs rather than economics.

22.16 Lewis Williams, Y4 ‘Museum of Mediterranean Memories’. British tourists, with the uncertainty of Brexit looming above them, can escape to a playful fairground full of tongue-in-cheek Mediterranean experiences. This project is strategically located in Dover, England. Making their way through border control, tourists embark on their own itinerary through a series of fairground-style rooms, harking back to the days of the Grand Tour, in a space designed to encourage irregular discovery.

22.17 Yuqi Liew, Y4 ‘The Giving Island’. This project aims to foster close ties between locals and refugees by participating in each other’s traditions and cultural practices. Architectural events around the island celebrate local traditions, trades, and landscapes. The main focus is an artisanal cheese-making facility where both communities can come together in sustainable craft. The building materials are made from the goat’s milk and hair in a bid to use local renewable resources.

22.18 Funto King, Y4 ‘Growing Gorreto: Repopulating Italy’s oldest town’. This project addresses the depopulation and ageing of rural areas across Europe. Through a masterplan of flexible housing and workspaces in touch with nature, the town is set to become a family-friendly, rural place where millennials can settle.

22.19 Byungjun Cho, Y4 ‘Extended Boundaries for the Integration of Locals and Refugees in Lesvos’. Across Europe’s Mediterranean shore, refugees are housed in camps that often lack basic infrastructure, and some of the communities where they first arrive are amongst the most underfunded. This project focuses on the Greek island of Lesvos and proposes to divert resources into building new infrastructure that helps integrate refugees in the local community, provides dignified housing and also fills gaps in local infrastructure.

22.20, 22.22 Yinghao Wang, Y4 ‘Working in the Garden’. Located in Athens, this project is a start-up incubator for Greek millennials to regain confidence in their future careers in the country, whilst emphasising a slow-paced, high-quality working lifestyle. Working spaces are outdoor or in-between spaces, creating a unique biodiversity-rich working environment that makes a positive contribution to the city’s microclimate.

22.21, 22.23 Jonah Luswata, Y5 ‘Socilising Childcare: A Strategy for Slow Living in Konuksever, Antalya’. A lack of childcare is preventing Turkish women from accessing the labour market. Through a series of urban interventions in the city of Antalya, this project aims to provide a form of childcare that engages the community to empower mothers. Turkish vernacular is reinterpreted in a scheme modelled on the pedagogic ideals of learning through play and discovery.

Year 4

Florence Bassa, Jun Wing (Michelle) Ho, Alastair Frederick Johnson, Anastasia Leonovich, Jonah Luswata, Robert Newcombe, Rebecca Outterside, Yinghao Wang, Nimrod Wong, Yehan Zheng

Year 5

Alexandria Anderson, Isabelle Tung, Laurence Flint, Rufus Edmondson, Esha Thapar, Timothy Whitehouse, Xin Zhan

We are extremely grateful for support from our consultants Marta Grinda and Roberto Marin, and our magnificent crit panels during the academic year: Marcela Araguez, Julia Backhaus, Eduardo Camarena, Maria Elvira Dieppa, Theo Games Petrohilos, Pedro Gil, Christine Hawley, Fredrik Hellberg, Kaowen Ho, Bruce Irwin, Fany Kostourou, Chee-Kit Lai, Lara Lesmes, Ifigeneia Liangi, Thandi Lowenson, Paula Montoya, Daniel Ovalle, Barbara Penner, Sol Pérez Martínez, Pedro Pitarch, Yael Reisner, Manolis Stavrakakis, Sabine Storp, Paolo Zaide

A special mention to our academic field trip workshop tutor and coordinator Wendy Teo from Borneo Art Collective. And finally, thank you Stanley Ngu King Hieng, for allowing us to live out your 100-houses dream

We are grateful to our sponsors Luis Vidal + Architects and Borneo Art Collective

When we announced at the beginning of the year that we were going to focus on the relationship between architecture and politics, one of our intentions was to raise awareness of architecture as complicit with politics, and with financial and industrial interests. But Unit 22 is a hands-on group, in all senses, so our focus will never be pure intellectual speculation: it will always involve a call to action. This year we invited students to engage with NGOs and activists. In partnership with them, we asked students to look for ways in which architecture might contribute to augmenting societal resilience, and find alternative paths for development. What are the problems that students of architecture think design can address? Looking at work produced this year, we observe that the environment, gender, wellbeing and identity have been our students’ four main areas of reflection. This is a complete change of paradigm from previous generations, for whom the four main areas of reflection would have been space, material, aesthetics and style. Together we investigated how projects in our four key areas could critically implement our aspirations for societal resilience and alternative development, step-by-step. In one way or another almost all the projects articulate some of the following scenarios:

Architecture can provide people with spaces that help them overcome immediate threats in what we can call an ‘absorptive’ strategy. This operates by designating space to plant, to talk, to meet, to represent or to live affordably.

Architecture can include the proactive (ex-ante) or preventative measures people employ to learn from past experiences, with which they anticipate future risks and adjust their lives accordingly. In this sense, designing a sort of transparent architecture has been strategic: an architecture that allows us to track the decisions linked with environment, gender, wellbeing and identity. Courtyards to catch water and be conscious of your reserves; rooms that directly address gender stereotypes; gardens promoting mindfulness, or market stalls that play with the symbolism of landscape are some of our examples.

Cities and neighbourhoods developed using public engagement strategies offer the potential for people to access assets and assistance from the wider socio-political arena, to participate in decision-making processes, and to craft institutions that both improve their individual welfare and foster societal robustness toward future crises.

Fig. 22.1 Alastair Frederick Johnson Y4, ‘Plastic Fantastic’. The project is designed around the needs of the NGO, the Marine Conservation Society. The complex of architectures caters for their need to campaign and inspire the younger generation about the importance of clean living, while also offering transportation, living quarters and facilities for Marine Biologists. Fig. 22.2 Yehan Zheng Y4, ‘Newham OffGrid Communal Settlement’. Set within the underused back gardens of Newham, the programme assembles communities to construct a co-living settlement that consists of varied degrees of editability and prefabrication. Using utility management techniques via a series of architectural cores, the scheme investigates the potential of domestic architecture to be a self-sufficient, yet interdependent tool.

Fig. 22.3 Xin Zhan Y5, ‘SLOW Valley’. In the context of China’s rapid urbanisation, the project rethinks the relationships between city, community and nature. Starting with an environmental restoration project, SLOW Valley is a co-working space for a regional craftsman community, educational and recreational space for local residents with open workshops, a market, allotments and landscape gardens as a campaign for slow living. Fig. 22.4 Rebecca Outterside Y4, ‘The3million Embassy Assembly’. The project aims to support EU citizens post-Brexit by encouraging collaboration via an assembly of European ‘Embassies’. The Embassies are temporary and will rotate around the five ‘leave’ boroughs of London, hosting a variety of community engagement activities, until the structures are eventually dismantled in 2020.

Figs. 22.5 – 22.6 Alexandria Anderson Y5, ‘Toys for Teachers’. The project is a set of gender-critical ‘tools’ to assist in constructing space and pedagogy that will act in the equalitarian future of education. By providing these ‘tools’, be it a sentence, or term defined in a particular way, a workshop adapted or newly created, teachers and students will be able to use this research to understand, expose, and rethink the capacity ‘the norm’ has over space and the bodies it acts upon. Figs. 22.7 – 22.8 Jun Wing (Michelle) Ho Y4, ‘Retrofitting the Community Estate’. Retrofitting the Central Hill Estate, a community estate in London, is an alternative method to tackle London’s housing crisis. With only a small scale of demolition, the project aims to increase the density, improve the existing conditions,

introduce opportunities for businesses within the estate, as well as bringing happiness to the community.

Fig. 22.9 Robert Newcombe Y4, ‘Hackney Ageless Co-Working Housing’. Campaigning for ‘ageless’ living, this new model of social housing is designed for the long term. Shifting living patterns inform a responsive mutating domestic setup. In contrast with typical excessive economic and social costs of displacing tenants, the re-configurable and neighbour-negotiated units allow the community to age in place and intergenerational lifestyles to emerge. Fig. 22.10

Florence Bassa Y4, ‘Bread & Roses HQ’. A project for social enterprise ‘Bread & Roses’, who empower refugee women with floristry classes, language lessons and employment. The building emulates the roles of floristry – tactile and interactive, filled with flowers, water and natural beauty – in order to build self-worth, and create communities and job opportunities.

Fig. 22.11 Esha Thapar Y5, ‘Women Breaking Boundaries’. In the spirit of the era, this project explores the architect as the activist, enabler and designer through student-led feminist praxis. Collaborating with Sisters Uncut, this community engagement concludes a Women’s Building on the contested ten-acre site of HM Holloway Women’s Prison; embodying an extensive herstory of the imprisoned Suffragettes. Fig. 22.12 Isabelle Tung Y5, ‘Project UP!’. The project is a co-working and co-living scheme with the goal of diminishing the skill and wealth gap in Hong Kong, by upskilling and improving the housing quality of domestic helpers, minorities and low-income locals who are often disenfranchised and oppressed. Fig. 22.13 Nimrod Wong Y4, ‘Guerrilla Gardening London’s River Thames’. The newly formed

‘Guerrilla Gardeners’ Trust’ would commission the construction of a new floating headquarters that would operate along London’s major water routes, with the intent or rejuvenating and recontextualising the group’s underlying ethos of urban gardening in a water-based context. The barge would form the group’s permanent headquarters and would provide facilities to empower existing members and visitors to collaborate and exchange ideas towards realising green initiatives around the capital. Fig. 22.14 Anastasia Leonovinch Y4, ‘Mental Health Foundation Headquarters’. With the goal of preventing mental health illnesses across different generations, the building promotes the activity of talking and communication by providing a variety of spaces that seek to create comfortable and stimulating conditions to accommodate the personalities

and moods of the users. Fig.22.15 Rufus Edmondson Y5, ‘Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens’ presents a new design strategy for LGBTQ+ cultural infrastructure in London. The proposal mediates varying levels of intimacy and visibility in order to define spaces for celebration and self-expression which are safe, open and inclusive for all. Fig. 22.16 Jonah Luswata Y4, ‘TRIPLE K School in Kampala, Uganda’. A study of contemporary learning environments. Questioning the values of colonial education at the same time as capitalising from the benefits of learning outdoors, while enjoining the academic possibilities of a fully supported and equipped infrastructure.

Figs. 22.17 – 22.20 Laurence Flint, Timothy Whitehouse Y5, ‘Curating London’s Latin Quarter’. London’s Latin Quarter is under imminent threat from urban renewal. The project is sited in the context of the current negotiation between developer, council, Latin London community, and the wider London populace. Hacking into stalled planning applications, the design proposes to even the balance of power. Figs. 22.17 & 22.29 Through a market stall pop-up on East Street in Southwark, and classes with Cambourne Village College in Cambridge, participatory workshops explored how groups and individuals may represent their identity. Figs. 22.18 & 22.20 Working at a range of scales from 1:1 urban spaces to participatory video games we question the current urban regeneration mechanisms operating in London. This joint project has evolved through

collaboration between design students, activist groups, local architects, Southwark Council and local traders to propose an alternative vision for the community in Elephant and Castle.

Year 4

Alex Anderson, Isabelle Tung, Laurence Flint, Rufus Edmondson, Timmy Whitehouse, Xin Zhan

Year 5

Georgina Halabi, Hei Tung (Whitney) Wong, Huma Mohyuddin, Jack Sargent, Kuba Tomaszczyk, Laura Young, Supichaya Chaisiriroj and Yuen Nam (Elaine) Tsang

Thank you to:

Pedro Gil, Practice Tutor, Edward Hoare, Structural Consultant, and our magnificent crit panels during the whole academic year: Fany Kostourou, Kristina Causer, Marcela Araguez, Sol Pérez Martínez, Sabine Storp, Lara Lesmes, Fredrik Hellberg, Manolis Stavrakakis, Adriana Cabello, Cristina Traba, Eduardo Camarena, Bruce Irwin, Paolo Zaide, Sean Griffiths

Thank you to our field trip workshop students and tutors from UDEM, Monterrey: Francisco Javier Serrano Alanís, Ana Teresa Furber Rodríguez, Sergio Gustavo Parroquin Sansores, Daniela Martínez Chapa, Rodrigo Gastélum Garza, Hilda Marcela Cabrales Arzola, Ana Paula Treviño Martínez, Alejandra Acuña Verano, María Catalina Gómez Elizondo, Lorena Guadalupe Cavazos Muñoz. Tutors: Arne Riekstins, Abril Denise Balbuena, Carlos García González (Dean Art, Architecture and Design)

Thank you to our sponsors: Luis Vidal + Architects and UDEM (Universidad de Monterrey, Mexico)

Those born between 1982-1996 (‘millennials’), and the generations born after this, are predicted to radically reform education and working systems not only via the massive resources of online activity and new relationships they engender, but also via a more qualitative aspiration: the search for new educational and working systems that also fulfil their potential. Millennials are the first generation that no longer require an authority figure to access information – they may enjoy external stimuli 24/7, be in social contact at all times, and learn more from a portable device than from a seminar. Unit 22 has explored how this will change the spaces in which we will play, learn, work and live in the near future.

Every year, we use our brief to break the tension between the traditional axes of architectural design, still experienced by many as a set of technical achievements, or the outcome of an aesthetic manifesto, and understood generally as the core of the creative enterprise of the architect, or as a linear solution applied to a local problem. We aim to introduce a fourth dimension to our students’ work: people, and more specifically, people who are connected both to each other and to their environment. The first stage in our four-dimensional architecture is to understand all stakeholders involved in a given situation, and then to devise ways to represent their points of view and practices, and finally, to design on these grounds.

Today, there is a pipeline of information available to everyone. The skills for making decisions have become dynamic. Co-working, for example, is the spatial translation of distributed decision-making. Our projects explore the political, spatial, urban and typological implication of such changes. Consequences in the architectural object have arisen: in most of the projects, the role of the furniture, soft materials and ‘software’ challenge the traditional role of structural elements. However, this has also allowed us to take a page from the analysis of power, as in the classic Bachrach and Baratz sense, and bring to the fore the relevance of nondecisions, in order to build isolated objects. We have discovered that transforming an existing building, offering the population better access to facilities, and providing services (perhaps not place-based) are sometimes much better solutions than a brand new building, in terms of reducing negative impact and creating benefits.

A way to visualise this is to see the changing role of architects as part of the transition from an ‘empty world’ paradigm to that of a ‘full world’, a formulation which we borrow from Herman Daly, an ecological economist. This means that the tools, references, habits and criteria of excellence we use must be completely overhauled.