1 THE OTHER REVOL UTION ARY THE SHOSTAKOVICH FESTIVAL 24 —› 27 FEBRUARY 2022 PRESENT Exclusive partners Belgian National Orchestra Exclusive partners BOZAR Common partners

2

FR —› Le Belgian National Orchestra organise en collaboration avec Bozar un premier festival de quatre jours associant, à des concerts symphoniques, des concerts de musique de chambre, des conférences et un projet jeunesse. Ce festival met à l’honneur un compositeur – et lequel ! –Dmitri Shostakovich. Événement unique car non seulement nous jouerons deux concerts (avec comme points forts les onzième et treizième symphonies, toutes deux dirigées par Hugh Wolff) mais nous accueillions également nos collègues à Bozar nos collègues de l'Orchestre Philharmonique Royal de Liège. Ils se joindront à ce programme ambitieux en jouant la Symphonie n°15 de Shostakovich.

S’il y a bien un artiste soviétique qui exerce une réelle fascination, c’est Shostakovich, le compositeur qui, contrairement à Prokofiev et à Stravinsky, n’a jamais renié sa patrie. Tout au long de sa vie, Shostakovich a composé des œuvres qui ont été jouées par les grandes institutions musicales soviétiques : en 1917, année de la révolution et de tous les espoirs ; sous le régime bolchévique ; pendant l’âge d’or du stalinisme et enfin, sous Khrushchev et Brezhnev. Même bridé et parfois sous le joug de la répression, Shostakovich n’a cessé de composer, maintenant un équilibre fragile dans son art entre validation du régime et rejet de celui-ci, expression artistique personnelle et propagande étatique. Il nous a ainsi laissé une œuvre magistrale à ce point complexe qu’elle est aujourd’hui encore sujette à controverse.

« Entend-on les bottes allemandes dans le premier mouvement de la Symphonie n°7 de Shostakovich ou la montée du stalinisme ? Face à ce genre de questions, impossible de trancher, tant l’ambiguïté est au cœur de la musique de Shostakovich. Le Russe n’impose pas telle ou telle interprétation. Il en va de même pour ceux qui jouent sa musique. Place au lâcher prise, tel est le message. C’est en définitive au public de sonder ce qu’il ressent exactement et de voir comment gérer cette complexité fascinante et les différentes lectures de son œuvre. » – Hans Waege, intendant

3

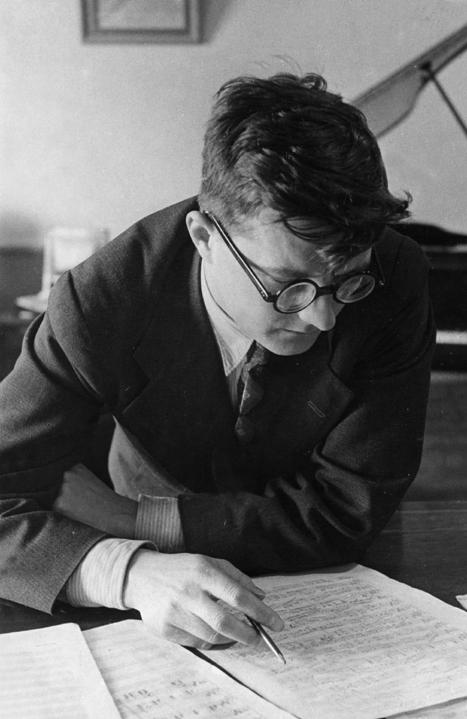

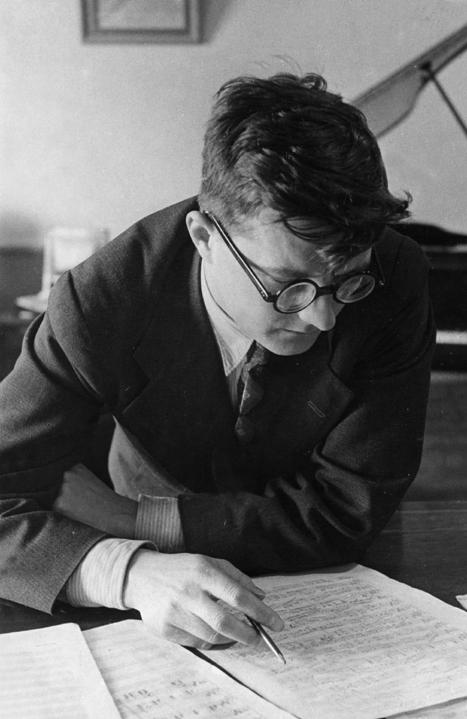

Dmitri Shostakovich © Wiki Commons

Shostakovich n’a jamais été un activiste du genre à lancer des cocktails Molotov et à quitter ensuite son pays. Dans des circonstances difficiles, il a exploré la liberté du carcan, toujours sur le fil du rasoir. Cela fait de lui « The Other Revolutionary ». Pendant quatre jours, nous nous plongerons à Bozar dans la musique et dans l’état d’esprit particulier de cet artiste.

Lors d’une conférence, le Professeur Francis Maes, une autorité dans le domaine de la musique russe, évoquera, recherches personnelles à l’appui, le sens et l’importance de l’œuvre de Shostakovich, en la resituant dans son contexte historique. Le festival s’ouvrira et se terminera sur des concerts de musique de chambre : le 24 février, le Trio Wanderer interprètera les 7 romances sur des poèmes d’Alexander Blok, avec la mezzosoprano russe

Ekaterina Semenchuk. Le 27 février, le phénoménal Igor Levit jouera au piano les Vingt-quatre préludes et fugues du Russe. Les Young Belgian Strings interpréteront quant à eux, accompagnés de quelques musiciens du Belgian National Orchestra, la Symphonie de chambre de Shostakovich. Vous retrouverez également notre orchestre pour la Symphonie n°11 et la Symphonie n°13 de Shostakovich, mais aussi pour son Concerto pour piano n°1 (avec les solistes Lucas Debargue et Leo Wouters) ainsi que son Concerto pour violoncelle n°1 (avec le violoncelliste soliste Truls Mørk). La révolution sera toujours en marche avec la Symphonie n°15, proposée par nos collègues liégeois.

Profitez de ces quatre journées passionnantes !

4

NL —› Het Belgian National Orchestra organiseert in samenwerking met Bozar voor het eerst een vierdaags festival waarbij symfonische concerten worden aangevuld met kamermuziek, lezingen en een jongerenproject. Eén componist staat in dit festival centraal: Dmitri Shostakovich. Uniek is dat we niet alleen zelf twee concerten spelen (met als hoogtepunten de Elfde en de Dertiende symfonie, beide onder leiding van Hugh Wolff) maar dat we in Bozar ook onze collega’s van het Orchestre Philharmonique Royal de Liège verwelkomen. Zij completeren het ambitieuze festivalprogramma met Shostakovich’ Vijftiende symfonie.

Weinig Sovjetkunstenaars kunnen meer boeien dan Dmitri Shostakovich, de componist die anders dan Prokofiev en Stravinsky zijn vaderland nooit de rug toekeerde. Zijn leven lang schreef Shostakovich muziek die in de Sovjet-Unie door grote staatsinstellingen werd uitgevoerd: in het hoopvolle revolutiejaar 1917, onder Bolsjewistisch beleid, tijdens de hoogtedagen van het stalinisme en ten slotte ook onder Krushchev en Brezhnev. Extreem oppressieve omstandigheden legden hem soms een molensteen om de hals. Toch bleef Shostakovich componeren, in zijn kunst een fragiel evenwicht bewarend tussen systeembevestiging en systeemafwijzing, artistieke zelfexpressie en staatspropaganda. Dat leverde uiteindelijk een magistraal œuvre op dat zo meerlagig is dat het tot op de dag van vandaag voor controverse zorgt.

“Hoort men Duitse laarzen in de eerste beweging van Shostakovich’ 7de symfonie of luistert men naar de opkomst van het stalinisme?

Dergelijke vragen kunnen niet –en zullen ook nooit – eenduidig worden beantwoord. Ambiguïteit is de kern van Shostakovich’ muziek. Shostakovich zelf dicteert geen interpretatie. Ook uitvoerders kunnen geen interpretatie dicteren. Loslaten is de boodschap. Finaal is het aan het publiek om te bepalen wat het precies voelt en hoe het met die intrigerende meerlagigheid omgaat.” – Hans Waege, intendant

5

Shostakovich was geen activist die Molotovcocktails gooide en daarna het land verliet, maar iemand die in moeilijke omstandigheden de vrijheid van het korset exploreerde en daarbij continue grenzen bewandelde. In die zin is hij ‘The Other Revolutionary’. Vier dagen lang zullen we ons in Bozar in de muziek en in de bijzondere geesteshouding van deze kunstenaar verdiepen.

Prof. dr. Francis Maes, een autoriteit in de Russische muziek, geeft vanuit zijn persoonlijk onderzoek in een lezing tekst en uitleg bij de betekenis van het werk van Shostakovich in zijn historische context. Het festival begint en eindigt met kamermuziek: op 24 februari voert Trio Wanderer samen met de Russische mezzosopraan Ekaterina Semenchuk onder andere Shostakovich’ 7 romances op gedichten van Alexander

Blok uit en op 27 februari brengt het pianofenomeen Igor Levit

Shostakovich’ 24 Preludes en fuga’s. De Young Belgian Strings spelen met medewerking van enkele muzikanten van het Belgian National Orchestra

Shostakovich’ Kamersymfonie.

Wijzelf brengen naast de Elfde en de Dertiende symfonie ook nog het Eerste pianoconcerto (met Lucas Debargue en Leo Wouters als solisten) en het Eerste celloconcerto (met Truls Mørk als solist). Met de Vijftiende symfonie spelen onze Luikse collega’s een niet minder revolutionair programma.

Geniet van deze boeiende vierdaagse!

6

EN —› For the first time, the Belgian National Orchestra in partnership with Bozar organises a four-day festival, in which symphonic concerts are complemented by chamber music, lectures and a youth project. One composer is at the heart of this festival: Dmitri Shostakovich. Uniquely, not only will we perform two concerts ourselves (the highlights being the Eleventh and Thirteenth Symphonies, both conducted by Hugh Wolff), but we will also welcome our colleagues from: the Orchestre Philharmonique Royal de Liège. They complete the ambitious festival programme with Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 15.

There are few Soviet artists as exciting as Dmitri Shostakovich, the composer who, unlike Prokofiev and Stravinsky, never turned his back on his home country. Throughout his life, Shostakovich composed music that was performed by great Soviet state institutions: in 1917, the hopeful year of the revolution, during the Bolshevik regime, at the height of Stalinism and finally under Khrushchev and Brezhnev. Extremely oppressive conditions sometimes cast a millstone around his neck, but Shostakovich kept composing, maintaining a delicate balance in his art between endorsing and rejecting the system, artistic self-expression and state propaganda. Ultimately, this resulted in a majestic œuvre so multi-layered that it remains controversial to this day.

“Does one hear German boots in the first movement of Shostakovich’s 7th Symphony, or is one listening to the rise of Stalinism? Such questions cannot be answered unequivocally, and never will be. Ambiguity is at the heart of Shostakovich’s music. Shostakovich never dictated a particular interpretation himself. Letting go is the message. Finally, it’s up to the audience to determine exactly what it feels and how it handles this intriguing complexity.” – Hans Waege, intendant

7

Shostakovich was not an activist who threw Molotov cocktails before leaving the country, but someone who, in difficult circumstances, explored the freedom of the restrictions placed upon him and, as such, walked borders continuously. In this sense, he is ‘The Other Revolutionary’. Over four days at Bozar, we will immerse ourselves in the music and the unusual mindset of this artist.

In a lecture based on his personal research, Professor Francis Maes, an authority on Russian music, will discuss the meaning of Shostakovich’s work in its historical context. The festival begins and ends with chamber music: on 24 February, Trio Wanderer and the Russian mezzo-soprano Ekaterina Semenchuk perform, among other pieces, Shostakovich’s Seven Romances on Poems by Alexander Blok, while on 27 February the

piano phenomenon Igor Levit plays Shostakovich’s 24 Preludes and Fugues. The Young Belgian Strings are joined by several musicians from the Belgian National Orchestra to play Shostakovich’s Chamber Symphony. As well as Symphonies Nos. 11 and 13, we also perform the Piano Concerto No. 1 (with Lucas Debargue and Leo Wouters as soloists) and the Cello Concerto No.1 (with soloist Truls Mørk). With Symphony No. 15, our colleagues from Liège play a programme that is no less revolutionary.

Enjoy this thrilling four-day festival!

8

9

Photo du film Babi Yar. context © ATOMS & VOID”

je-do-th

24.2.2022 | 20:00

Bozar

Trio Wanderer, ensemble

Ekaterina Semenschuk, mezzo-soprano

Dmitri Shostakovich

Piano Trio No. 1, Op. 8

Piano Trio No. 2, Op. 67

· 7 Romances on Poems by Alexander Blok, Op. 127

FR —› Maîtrise technique et musicalité époustouflante ont hissé le Trio Wanderer, composé de trois musiciens français, au rang des ensembles de musique de chambre les plus en vue. Pendant le festival Shostakovich, l’ensemble met à l’honneur les deux trios avec piano du compositeur russe. Shostakovich n’avait que 17 ans quand il a écrit son premier Trio avec piano n°1, mais celui-ci témoigne déjà d’une maîtrise exceptionnelle de l’art de la composition. Le Russe a dédié son deuxième trio avec piano à son proche ami Ivan Sollertinsky. Il faut aussi voir dans cette œuvre une charge du compositeur contre les atrocités commises dans les camps de concentration, comme en témoigne l’atmosphère triste et macabre dans laquelle elle baigne.

La mezzo-soprano biélorusse Ekaterina

Semenchuk rejoint ensuite le Trio Wanderer pour chanter aux côtés des trois musiciens les Sept romances sur des poèmes d’Alexandre Blok. La chanteuse lyrique interprète tous les grands rôles de mezzo-soprano au Théâtre Mariinski de Saint-Pétersbourg, s’est produite au Festival de Salzbourg, et est aussi régulièrement l’invitée du Metropolitan Opera, à New York.

10

Trio Wanderer © Thoams Dorn

En 1967, Mstislav Rostropovitch et sa femme Galina Vishnevskaya demandèrent à Shostakovich de leur composer une vocalise – violoncelle et voix – qu’ils pourraient interpréter ensemble. Shostakovich répondit à cette demande en mettant en musique un poème d’amour qu’Alexander Blok avait écrit dans sa jeunesse. Vraisemblablement dopé par l’alcool, il enchaîna avec six autres poèmes de Blok, qu’il mit en musique non seulement pour violoncelle et chant, mais aussi pour piano et violon. La dernière romance voit réunis tous les instruments.

NL —› Met zijn technische meesterschap en verbluffende muzikaliteit behoort het Trio Wanderer, bestaande uit drie Franse musici, tot een van de meest vooraanstaande kamermuziekensembles. Tijdens het Shostakovichfestival zetten ze de twee pianotrio’s van de Russische componist in de kijker. Shostakovich was slechts 17 toen hij zijn Eerste pianotrio schreef, maar het werk getuigt van een buitengewoon compositorisch meesterschap. Zijn tweede trio droeg hij op aan zijn goede vriend, Ivan Sollertinsky, en is tevens een aanklacht tegen de gruweldaden van de concentratiekampen. Het werk baadt dan ook in een trieste en macabere sfeer.

Voor de Zeven romances op gedichten van Alexander Blok vervoegt de Wit-Russische mezzosopraan Ekaterina Semenchuk het Trio Wanderer. Zij zingt alle grote mezzosopraanrollen in het Sint-Petersburgse Mariinskitheater, trad op tijdens de Salzburger Festspiele en is ook regelmatig te gast in de Metropolitan Opera van New York.

In 1967 vroegen Mstislav Rostropovich en zijn vrouw Galina Vishnevskaya aan Shostakovich om een vocalise te schrijven die ze samen – cello en zang - konden opvoeren. Shostakovich zette als antwoord hierop een vroeg liefdesgedicht van Alexander Blok op muziek. In de daaropvolgende dagen –aangevuurd door wat sterke drank – zette hij nog zes andere gedichten van Alexander Blok op muziek, niet alleen voor cello en zang, maar ook nog voor piano en viool. In het laatste lied komen alle instrumenten samen.

EN —› With their technical mastery and astonishing musicality, the Trio Wanderer, consisting of three French musicians, are one of the most distinguished chamber music ensembles. During the Shostakovich festival, they will be focusing on the Russian composer’s three piano trios. Shostakovich was only 17 when he composed his First Piano Trio, though the work demonstrates his extraordinary compositional mastery. He dedicated his second trio to his good friend, Ovan Sollertinsky, and it is an indictment of the atrocities of the concentration camps. The piece is bathed in a sad and macabre atmosphere.

The Belarusian mezzo-soprano Ekaterina

Semenchuk joins the Trio Wanderer for Seven romances on poems by Alexander Blok. She sings all of the major mezzo-soprano roles in Saint Petersburg’s Mariinski Theatre, performed at the Salzburger Festspiele and is also a regular guest at the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

In 1967, Mstislav Rostropovich and his wife Galina Vishnevskaya asked Shostakovich to compose a vocalise for them to perform together on cello and voice. Shostakovich responded by setting an early love poem by Alexander Blok to music. In the ensuing days – fired up by strong liquor – he set six more Alexander Blok poems to music, not only for cello and voice but also for piano and violin. All the instruments come together in the final song.

11

Conférence ve

25.2.2022 | 18:30

Bozar

De la révolte politique à la révolution

musicale : comprendre Shostakovich aujourd’hui

Conférence de Ruben Goriely

FR —› Le contraste entre le Concerto pour piano, trompette et orchestre à cordes, et la Symphonie no. 13 permet d’approcher la musique de Shostakovich dans toute sa complexité. D’un côté, une œuvre joyeuse d’un compositeur encore jeune, écrite pour solistes et orchestre à cordes ; de l’autre, une symphonie immense par son effectif et son poids symbolique, d’un compositeur déjà rongé par la maladie. Pourtant, si différentes qu’elles puissent paraitre, chacune laisse transparaitre à sa manière l’originalité de leur compositeur, et l’intérêt que celui-ci peut susciter à l’heure actuelle. Le Concerto pour piano, trompette et orchestre à cordes redéfinit la dynamique du concerto pour soliste en impliquant un troisième acteur, la trompette, aux entrées toujours inattendues. La Symphonie n°13, elle, dépasse les définitions de la symphonie classique, tout en s’inscrivant, par l’ajout de chœurs et d’un soliste, dans la lignée historique d’une Symphonie n°9 de Beethoven. Sous le prisme de ces deux œuvres emblématiques mais atypiques, nous aurons alors l’occasion de donner sens aux résultats des nombreuses recherches musicologiques sur le compositeur russe.

Au-delà de la biographie politique de Shostakovich, c’est donc sa musique en tant que telle que l’on va interroger. Comment s’intègre-t-elle dans le panorama de l’histoire de la musique ? Que nous apporte-t-elle aujourd’hui, et comment pouvons-nous l’écouter et la comprendre au mieux ?

Ruben Goriely est chercheur au CERMUS (Centre de recherches en Musicologie de l’UCLouvain) et assistant en Musicologie à la Faculté de Philosophie, Arts et Lettres (FIAL/UCLouvain). Ses recherches portent plus particulièrement sur les questions de vocalité et d’orchestration de la musique des 19e et 20e siècles.

12

13

Babi Jar © Alamy

ve-vr-fr

25.2.2022 | 20:00

Bozar

Belgian National Orchestra

Hugh Wolff, conductor

Mikhail Petrenko, bass

Lucas Debargue, piano

Leo Wouters, trumpet

Octopus Choir

Bart van Reyn, choir master

Dmitri Shostakovich

Piano Concerto No. 1 in C minor, Op. 35

· Symphony No. 13 in B-flat minor, “Babi-Yar”, Op. 113

FR —› Le Concerto pour piano, trompette et orchestre à cordes de Shostakovich est une œuvre particulièrement joyeuse et humoristique, qu’il a composée en 1933, à l’âge de 27 ans, alors qu’il n’avait pas encore d’opposition avec le régime soviétique. Ce double concerto se compose de quatre mouvements et regorge de citations (compositions personnelles, sonates de Beethoven et de Haydn, chansons de rue). L’œuvre exige une très grande virtuosité. La trompette n’a de cesse d’interrompre avec un malin plaisir les passages au piano.

Après de nombreuses années de tourmente sous Staline, l’arrivée de Khrushchev amorce un dégel : une période de relative détente durant laquelle certaines choses sont à nouveau possibles. En 1961, Shostakovich découvre dans un journal le poème Babi Jar, écrit par le jeune poète controversé Yevgeny Yevtushenko. Le texte dénonce le massacre de Babi Jar, un ravin près de Kiev où les nazis ont abattu plus de cent mille personnes (principalement des juifs) et le fait qu’après tant d’années, aucun monument n’honore encore les victimes. Shostakovich, qui avait défendu la cause juive à plusieurs reprises au cours des années précédentes, prit une décision courageuse pour un artiste soviétique établi : il décida de mettre en musique ces vers accusateurs et quelques autres poèmes de Yevtushenko.

Le résultat, sa Symphonie n°13 pour voix basse, chœur d’hommes et grand orchestre, peut être considérée comme l’une de ses œuvres les plus politiques. D’aucuns affirment qu’il n’a pas seulement condamné l’antisémitisme rampant à grands coups de violence orchestrale, mais qu’il y a aussi dénoncé d’autres aspects problématiques de la vie en Union soviétique : la vaine tentative des tyrans de brider l’humour, les femmes soviétiques qui font la file pendant des heures pour recevoir leurs rations alimentaires, la Grande Terreur sous Staline et la corruption de plus en plus manifeste à laquelle se livrent les dirigeants. Le fait est que cette symphonie a été censurée juste après sa création, et que Shostakovich n’allait plus jamais se frotter à des poètes aussi subversifs que le jeune Yevgeny Yevtushenko.

14

Lucas Debargue © Felix Broede

Shostakovich’ Concerto voor piano, trompet en strijkers is een bijzonder vrolijke en humoreske compositie, geschreven in 1933 toen de componist 27 jaar oud was en nog niet in aanvaring was gekomen met het Sovjetregime. Het dubbelconcerto telt vier bewegingen, citeert de meest diverse muziek (eigen composities, sonates van Beethoven en Haydn, zowel als volksdeuntjes) en vereist heel wat virtuositeit. Steeds weer onderbreekt de trompet het passagewerk van de piano met sardonisch plezier.

Na heel wat turbulente jaren onder Stalin volgde de zogenaamde ‘dooi van Krushchev’: een meer ontspannen periode waarin terug enige zaken mogelijk werden. In een krant las Shostakovich in 1961 het gedicht Babi Jar, geschreven door de jonge en controversiële dichter Yevgeny Yevtuschenko. De tekst klaagde aan dat er in Babi Jar, een ravijn nabij Kiev waar de Nazi’s meer dan honderdduizend mensen (overwegend joden) hadden doodgeschoten, zoveel jaar na datum nog altijd geen monument stond. Shostakovich, die de afgelopen jaren al meermaals zijn hoofd had uitgestoken voor de joodse zaak, vatte als geëtableerde Sovjetkunstenaar een stoutmoedig besluit en zette de beschuldigende verzen samen met enkele andere gedichten van Yevtuschenko op muziek.

Het resultaat, zijn Dertiende symfonie voor bassolist, mannenkoor en groot orkest, kan gelezen worden als een van Shostakovich’ meest politieke werken. Sommige stemmen beweren dat Shostakovich niet alleen met veel orkestraal geweld sluimerend antisemitisme veroordeelt, maar ook andere problematische aspecten van het Sovjetleven: de vergeefse poging van tirannen om humor te beteugelen, Sovjetvrouwen die elke dag uren moeten wachten om voedselrantsoenen af te halen, het terreurbewind van Stalin en de corruptie die leidinggevenden steeds weer aan de dag leggen. Feit is dat deze symfonie na de première meteen werd gecensureerd en dat Shostakovich zich na dit werk nooit meer met dichters zou inlaten die zo subversief waren als de jonge Yevgeny Yevtushenko.

EN —› Shostakovich’s Concerto for Piano, Trumpet and Strings is a particularly cheerful and humorous composition, written in 1933 when the composer was 27 years old and had not yet clashed with the Soviet regime. The double concerto has four movements, quotes from a wide range of music (his own compositions, Beethoven and Haydn sonatas, folk songs), and demands a high level of virtuosity. The trumpet frequently interrupts the piano’s passages with sardonic joy.

After many turbulent years under Stalin, came what was known as the ‘Khrushchev Thaw’: a more relaxed period in which certain things were permitted once more. In 1961, Shostakovich read in a newspaper the poem Babi Yar, written by the young, controversial poet Yevgeny Yevtuschenko. The poem denounced the fact that years after the murder of more than a hundred thousand people (mainly Jews) by the Nazis in Babi Yar, a ravine near Kiev, no monument had yet been erected. Shostakovich, who had spoken up on behalf of Jews on numerous occasions over the preceding years, made the bold decision to set the poem to music, along with several others by Yevtuschenko.

The resulting Symphony No. 13 for bass soloist, male choir and full orchestra can be seen as one of Shostakovich’s most political works. Some commentators claim that, with great orchestral violence, Shostakovich condemns not only latent anti-Semitism but also other problematic aspects of Soviet life: the vain attempts of tyrants to stifle humour, Soviet women having to queue for hours every day to collect food rations, Stalin’s reign of terror, and the everyday corruption of officials. The fact is that following its premiere this symphony was immediately censored, and Shostakovich would never again get involved with poets as subversive as the young Yevgeny Yevtushenko.

15 NL —›

sa-za-sa

26.2.2022 | 20:00

Bozar

Orchestre Philharmonique

Royal de Liège

Vassily Sinaisky, conductor

Evgeny Nikitin, bass

Dmitri Shostakovich

Katerina Ismailova, Suite, Op. 114a

Modest Mussorgsky

Songs and Dances of the Death

Dmitri Shostakovich

Symphony No. 15, Op. 141

FR —› Le festival Shostakovich sera aussi l’occasion d’entendre jouer nos collègues de l’Orchestre Philharmonique Royal de Liège. Leur concert s’ouvre avec la Suite « Katerina Ismailova », un recueil de quatre actes de l’opéra Lady Macbeth du district de Mtsensk. Cette pièce d’un expressionnisme brutal raconte l’histoire d’une femme esseulée, Katerina Ismailova, qui tombe amoureuse d’un employé qui travaille pour son mari, un homme aisé. Katerina ne tarde pas à caresser l’idée de commettre des meurtres aux dimensions shakespeariennes. Très bien accueilli à sa création et lors de ses premières représentations, l’opéra de Shostakovich fut interdit pendant près de 30 ans, à la suite d’une critique non signée parue dans la Pravda (qui aurait été écrite par Staline lui-même selon certains).

Le cycle Chants et danses de la mort – des chants lyriques pour voix solo et piano – est l’une des compositions les plus géniales de Modest Mussorgsky. Dmitri Shostakovich a orchestré ce cycle de quatre mélodies en 1962. Dans le premier lied, la Mort vient chercher un bébé, dans le deuxième, une jeune fille, dans le troisième, un paysan ivre et dans le quatrième, une troupe de soldats.

Le clou de la soirée est sans conteste la Symphonie n° 15 de Dmitri Shostakovich. Après quatre symphonies avec chœur et/ou voix seule(s) (à savoir les symphonies n° 2, 3, 13 et 14), cette quinzième et dernière symphonie du Russe signe son retour à une œuvre exclusivement instrumentale. L’occasion pour le compositeur de dresser le bilan de sa vie et de multiplier les citations, de sa propre musique comme de celles de Rossini (Guillaume Tell) et de Wagner (Tristan und Isolde et Der Ring des Nibelungen).

16

Evgeny Nikitin © Marco Borggreve

NL —› Deel van het Shostakovichfestival is ook een concert van onze collega’s uit Luik: het Orchestre Philharmonique Royal de Liège. Zij starten met de Katerina Ismailova Suite, een bundeling van vier actes uit Shostakovich’ opera Lady MacBeth uit het district Mtsenk. Dit brutaal-expressionistische werk vertelt het verhaal van een eenzame vrouw, Katerina Ismailova, die verliefd wordt op een arbeider die werkt voor haar rijke man. Al vlug wordt ze verleid door enkele Shakespeareaanse moorden. Aanvankelijk werd Shostakovich’ opera goed onthaald, maar na een anonieme recensie in de Pravda (door Stalin zelf geschreven, zo beweren sommigen) mocht het werk bijna 30 jaar lang niet meer worden opgevoerd.

Een van de meest geniale composities van Modest Mussorgsky is de liedcyclus Liederen en dansen van de dood voor zangstem en piano. Dmitri Shostakovich orkestreerde dit vierdelige werk in 1962. In het eerste lied komt de dood een baby halen, in het tweede lied een jonge vrouw, in het derde lied een dronken boer en in het vierde lied een bende soldaten.

Hoogtepunt van de avond is een uitvoering van Dmitri Shostakovich’ Vijftiende (en laatste) symfonie. Na vier symfonieën met koor en/ of zangsolisten (namelijk de symfonieën Nr. 2, 3, 13 en 14) is de Vijftiende symfonie terug een louter instrumentaal werk. In deze compositie maakt Shostakovich de balans op van zijn leven. Daarbij citeert hij in de verschillende bewegingen niet alleen zichzelf, maar ook muziek van Rossini (Guillaume Tell) en Wagner (Tristan und Isolde en Der Ring des Nibelungen).

EN —› The Shostakovich Festival also includes a concert by our colleagues from Liege: the Orchestre Philharmonique Royal de Liège. They start with the Katerina Ismailova Suite, a collection of four actes from Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsenk District. This brutalist-expressionist work tells the story of Katerina Ismailova, a lonely woman who falls in love with a labourer employed by her wealthy husband. She is soon driven to commit a number of Shakespearean murders. Shostakovich’s opera was initially well received but following an anonymous review in Pravda (written by Stalin himself, some claim) the work was not performed again for almost 30 years.

One of Modest Mussorgsky’s most brilliant compositions is the Songs and Dances of Death for voice and piano. Dmitri Shostakovich orchestrated this work in four movements in 1962. In the first song, Death comes to collect a baby, in the second a young woman, in the third a drunken peasant and in the fourth a troop of soldiers.

The evening’s highlight is a performance of Dmitri Shostakovich’s Fifteenth (and final) Symphony. Following four symphonies featuring a choir and/or solo voices, (namely symphonies No. 2, 3, 13 and 14) Symphony No. 15 is again a purely instrumental work. In this composition, Shostakovich takes stock of his life. As such, the various movements quote not only his own music but also that of Rossini (William Tell) and Wagner (Tristan und Isolde and Der Ring des Nibelungen).

17

18

19

© Bart Decobecq

di-zo-su

27.2.2022 | 11:00

Bozar

Young Belgian Strings

Dirk Van De Moortel, conductor

Sonoko Miriam Welde, violin

Nico Schoeters, percussion

Dmitri Shostakovich

· Chamber Symphony

Op. 110A

Sonate for Violin and Piano, Op. 134 (arr. Michael Zinman)

FR —› Les Young Belgian Strings rassemblent 21 jeunes talents de différentes classes d’instruments à cordes de tous les conservatoires et hautes écoles de musique de Belgique. Cet orchestre à cordes s’est donné pour mission d’offrir à ces jeunes musiciens la chance de se rencontrer, d’échanger leurs expériences, de mettre à jour leurs connaissances, de se produire sur les scènes internationales les plus prestigieuses et de se préparer à une future carrière dans les plus grands orchestres du monde entier.

Lors de ce concert, les Young Belgian Strings interprètent la Symphonie de chambre de Shostakovich. Il s’agit en fait d’une version de son Quatuor à cordes n°8, réarrangée pour orchestre à cordes par le chef d’orchestre russe Rudolf Barshai. Le Quatuor à cordes n°8 occupe une place particulière dans l’œuvre du Russe : celui-ci l’a composé alors qu’il traversait une période particulièrement difficile, ce qui en fait aussi l’une de ses œuvres les plus autobiographiques. Ce quatuor s’ouvre sur la signature musicale de Shostakovich (les notes DSCH : ré - mi bémol - do – si) et abonde de citations de ses propres compositions. Il n’est pas sans rappeler des œuvres telles que les Métamorphoses de Strauss mais aussi la Symphonie n°6 de Tchaikovsky – composées au soir de leur vie et empreintes elles aussi des souffrances vécues.

20

Young Belgia nStrings © YBS

Place ensuite à la jeune et prometteuse soliste Sonoko Miriam Welde que l’on entendra dans un arrangement de la Sonate pour violon et piano, opus 134 de Shostakovich. Le Russe l’a composée en 1968, pour le 60e anniversaire de David Oistrakh, le violoniste qui a joué un rôle crucial dans le processus créatif de son Concerto pour violon n°1 et de son Concerto n°2. Michael Zinman a réarrangé cette sonate pour violon seul, orchestre à cordes et percussions.

Les Young Belgian Strings sont placés sous le Haut Patronage de Sa Majesté la Reine Mathilde.

NL —› De Young Belgian Strings bestaat uit 21 jonge talenten uit de verschillende klassen strijkinstrumenten van alle Belgische conservatoria en muziekhogescholen. Het doel van dit strijkorkest is om deze muzikanten de kans te geven elkaar te ontmoeten, ervaringen uit te wisselen, hun kennis bij te werken, op te treden op de meest prestigieuze internationale podia en zich voor te bereiden op een toekomstige carrière in ’s werelds beste orkesten.

In dit concert voeren de Young Belgian Strings eerst Shostakovich’ Kamersymfonie uit. Dit werk is eigenlijk een arrangement van diens Achtste strijkkwartet, georkestreerd voor strijkorkest door de Russische dirigent Rudolf Barshai. In het œuvre van Shostakovich neemt het Achtste strijkkwartet een bijzondere plaats in: het ontstond in een voor de componist zeer moeilijke periode en is een van zijn meest autobiografische werken. De compositie begint met Shostakovich’ muzikale handtekening (de noten DSCH) en refereert naar heel wat andere composities van Shostakovich. Er zijn ook duidelijke parallellen met zowel Strauss’ Metamorphosen als Tchaikovsky’s Zesde symfonie –werken die net als Shostakovich’ strijkkwartet werden geschreven aan het einde van een componistenleven, terugblikkend op bijzonder veel leed.

Daarna soleert de jonge belofte Sonoko Miriam Welde in een arrangement van Shostakovich’ Sonate voor viool en piano, opus 134. Shostakovich schreef dit werk in 1968 voor de 60ste verjaardag van David Oistrakh, de violist die een cruciale rol speelde in de totstandkoming van zowel zijn Eerste als Tweede vioolconcerto. Michael Zinman arrangeerde deze sonate voor viool solo, strijkorkest en slagwerk.

De Young Belgian Strings staan onder de Hoge Bescherming van Hare Majesteit de Koningin.

EN —› The Young Belgian Strings bring together 21 talented young people drawn from different string instrument classes from all the conservatories and music colleges of Belgium. The purpose of the string orchestra is to give those musicians the opportunity to meet each other, exchange experiences, improve their knowledge, perform on the most prestigious international stages and prepare themselves for careers in the best orchestras in the world.

In this concert, the Young Belgian Strings first perform Shostakovich’s Chamber Symphony. This work is actually an arrangement of his String Quartet No. 8, orchestrated for string orchestra by the Russian conductor Rudolf Barshai. The String Quartet No. 8 occupies an unusual place in the œuvre of Shostakovich: it was created in a very difficult period for the composer and is one of his most autobiographical works. The composition begins with Shostakovich’s musical signature (the notes DSCH) and abounds with references to his other compositions. There are also obvious parallels with both Strauss’ Metamorphosen and Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6 – works which, like Shostakovich’s string quartet, were written at the end of the composer’s life, reflecting on incredible suffering.

Next, the promising young talent Sonoko Miriam Welde solos in an arrangement of Shostakovich’s Sonata for Violin and Piano, Opus 134. Shostakovich composed this piece in 1968 for the 60th birthday of David Oistrakh, the violinist who played a crucial role in the development of both his First and Second Violin Concertos. Michael Zinman has arranged this sonata for solo violin, string orchestra and percussion.

The Young Belgian Strings are under the High Patronage of Her Majesty the Queen.

21

22

23 © Illias Teirlinck

zo

27.2.2022 | 14:00

Bozar

Komt Dmitri Shostakovich dichterbij?

Lezing door prof. dr. Francis Maes

NL —› Dmitri Shostakovich is op korte tijd uitgegroeid tot de meest gespeelde componist van de twintigste eeuw. Het mysterie rond zijn persoon en zijn status als sovjetcomponist droegen bij tot dit merkwaardige succes. Na de val van de Sovjet-Unie circuleerden de wildste theorieën over de betekenis van zijn werk. De controversen zijn niet weg. Was hij een dissident of een trouwe dienaar van de sovjets? Waren de politieke boodschappen die we in zijn werk menen te horen zo bedoeld?

Muziek leeft van mysterie en emotie. Bekijken we zijn leven en werk met wat meer afstand en objectiviteit, dan komen nuances aan het licht die hem als persoon en als kunstenaar dichterbij kunnen brengen. Die nuances tonen aan dat hij een geëngageerde, kritische kunstenaar kon zijn zonder dissident te zijn. Dat hij een eigen artistiek project kon uittekenen ondanks druk van buitenaf. Dat hij het Sovjetsysteem kon bespelen voor zijn eigen carrière, maar ook om anderen te helpen. Twee eigenschappen tekenen zich bovenal af: ten eerste was hij nooit de componist van het Sovjetvolk, maar wel van de sovjet intellectuele elite, en ten tweede mat hij zich een publieke persona aan omdat hij een onstilbare drang bezat zich uit te spreken, in woord en in muziek.

Francis Maes is professor Musicologie aan de UGent en daarnaast hoogleraar in de vakgroep Kunst-, Muziek- en Theaterwetenschappen. Als auteur van het boek A history of Russian Music: From Kamarinskaya to Babi Yar , intussen uitgegroeid tot een standaardwerk, geldt hij als specialist van de Russische muziek.

24 Lezing

25

di-zo-su

27.2.2022 | 15:00

Bozar

Belgian National Orchestra

Hugh Wolff, conductor

Truls Mørk, cello

Dmitri Shostakovich

Cello Concerto No. 1 in E-flat major, Op. 107

· Symphony No. 11 in G minor, “The Year 1905”, Op. 103

FR —› Le violoncelliste norvégien Truls Mørk joue ce soir le Concerto pour violoncelle n°1 de Shostakovich, une des pièces les plus difficiles du répertoire pour violoncelle. Shostakovich l’a composée en 1959, ayant été impressionné par la Sinfonia concertante de Prokofiev. Ces deux œuvres ont été créées par le célèbre violoncelliste russe Mstislav Rostropovitch. Le Concerto pour violoncelle n°1 de Shostakovich se compose de quatre mouvements. La fraîcheur et l’intensité rythmique du premier et du troisième mouvement contrastent nettement avec la mélancolie du deuxième mouvement. Dans le dernier mouvement, Shostakovich cite, non sans une certaine ironie, Suliko, la chanson préférée de Staline : après la mort du dictateur, il se sent à nouveau libre de revenir au formalisme tel qu’il le conçoit. En répétant un motif à quatre notes – DSCH : rémi bémol - do - si – qui apparaît dans trois des quatre mouvements, Shostakovich pose en outre délibérément, et à plusieurs reprises, sa signature musicale.

Deux ans plus tôt, Shostakovich avait achevé sa Symphonie n°11. Cette œuvre, soustitrée L’Année 1905, évoque à la manière d’une « musique de film sans le film » le début de la révolution russe de 1905 : le « Dimanche rouge ». Le 9 janvier 1905, quelque 150 000 grévistes investissent le Palais d’hiver de Saint-Pétersbourg pour remettre au tsar une pétition. Le tsar était absent et sa garde a ouvert le feu sur la foule sans armes. Dans le premier mouvement – un adagio –, Shostakovich évoque le silence qui entoure la place du Palais au petit matin, alors que le destin allait bientôt frapper. Dans le deuxième mouvement, la foule commence à se rassembler et prend la direction du Palais ; elle est « mitraillée » par des cordes frénétiques, une section percussions imposante et les glissandos des trombones et des tubas. Retour à un adagio pour le troisième mouvement, une lamentation sur les nombreuses victimes. La finale se tourne vers l’avenir, avec l’espoir d’un changement politique.

Dans cette symphonie, Shostakovich ne cite pas moins de neuf chants populaires russes, ce qui lui vaudra la reconnaissance du public soviétique. Cette œuvre a permis à Shostakovich d’être réhabilité après avoir été pendant une période à couteaux tirés avec les autorités. En 1958, il s’est même vu remettre le prix Lénine, un des prix les plus prestigieux du régime soviétique.

26

Truls Mørk © Johs Boe

NL

De Noorse cellist Truls Mørk voert Shostakovich’ Eerste celloconcerto uit, een van de moeilijkste stukken uit het cellorepertoire. Shostakovich componeerde dit werk in 1959, geprikkeld door de Sinfonia concertante van Prokofiev. De beroemde Russische cellist Mstislav Rostropovich speelde de première van beide werken. Het Eerste celloconcerto van Shostakovich bestaat uit vier delen. De frisse, intens ritmische eerste en derde bewegingen contrasteren met de melancholische tweede beweging. In de laatste beweging citeert Shostakovich Stalins lievelingslied Suliko op ironische wijze: na de dood van de dictator voelde hij zich vrij om zo ‘formalistisch’ te schrijven als hij zelf wou. Met een viernotenmotief – DSCH – dat in drie van de vier bewegingen opduikt, zette Shostakovich bovendien meermaals zelfbewust zijn muzikale handtekening.

Twee jaar eerder werkte Shostakovich zijn Elfde symfonie af. Deze compositie met als ondertitel Het jaar 1905 beschrijft als een soort filmpartituur zonder film het begin van de revolutie van 1905: Bloedige Zondag. Op 9 januari 1905 trokken zo’n 150.00 mensen naar het Winterpaleis in Sint-Petersburg om de tsaar een petitie te overhandigen. De tsaar was echter niet aanwezig en zijn lijfwacht opende het vuur op de ongewapende menigte. In het eerste deel van zijn symfonie, een adagio, verklankt Shostakovich de ochtendstilte op het paleisplein, zwanger van het noodlot. Mensen beginnen zich in de tweede beweging te verzamelen en marcheren naar het paleis, waar ze door snel spelende strijkers, een gigantische slagwerksectie en glissandi in de trombonen en de tuba’s worden neergemaaid. Het derde deel is opnieuw een adagio en beweeklaagt de vele slachtoffers. De finale blikt in de toekomst en hoopt op politieke verandering.

Shostakovich citeert in deze symfonie maar liefst negen verschillende Russische volksliederen, wat bij het Sovjetpubliek voor een grote herkenbaarheid zorgde. Met dit werk wist Shostakovich zich dan ook, na enige tijd op gespannen voet met de autoriteiten te hebben gestaan, te rehabiliteren. In 1958 kreeg hij zelfs de Leninprijs uitgereikt, een van de meest prestigieuze prijzen van het Sovjetregime.

EN —› Norwegian cellist Truls Mørk performs Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. 1, one of the most challenging pieces in the cello repertoire. Shostakovich composed this work in 1959, stimulated by Prokofiev’s Sinfonia concertante. The famed Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich played both works in premiere. Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. 1 comprises four movements. The fresh, intensely rhythmic first and third movements contrast with the melancholic second movement. In the final movement, Shostakovich quotes from Stalin’s favourite song, Suliko, in an ironic fashion: after the dictator’s death he felt free to return to his own vision of formalism. Moreover, with a four-note motif – DSCH – that turns up in three of the four movements, Shostakovich self-consciously inserts his own musical signature.

Two years earlier, Shostakovich completed his Symphony No. 11. This composition, subtitled The Year 1905, describes the beginning of the 1905 revolution – Bloody Sunday – in the form of a film score without a film. On 9 January 1905, 150,000 people made for the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg to hand a petition to the Tsar. But the Tsar was not present and his bodyguards opened fire on the unarmed masses. In the first movement of the symphony, an adagio, Shostakovich depicts the morning silence at the palace square, pregnant with destiny. In the second, people start to gather and march towards the palace, where they are cut down by fast strings, a massive percussion section and glissandi on trombones and tubas. The third movement is again an adagio, mourning the many victims. The finale looks to the future with hope for political change.

Shostakovich quotes from at least nine Russian folk songs in this symphony, which ensured it was instantly recognisable by Soviet audiences. This work enabled Shostakovich’s rehabilitation with the authorities following a period of tension. In 1958, he was actually awarded the Lenin Prize, one of the Soviet regime’s highest accolades.

27

—›

di-zo-su

27.2.2022 | 20:00

Bozar

Igor Levit, piano

Dmitri Shostakovich

24 Preludes and Fugues, Op. 87

FR —› Aucun autre musicien n’a eu autant d’impact et atteint un aussi large public pendant la crise sanitaire du COVID-19 que le pianiste germano-russe Igor Levit. Tous les soirs, il a joué à Berlin des concerts auxquels des dizaines de milliers d’amateurs de musique du monde entier ont pu assister en ligne et en « live » depuis chez eux. Cela dit, les œuvres et morceaux joués étaient tout sauf évidents : Igor Levit a alterné des œuvres monumentales de Bach et de Beethoven et des œuvres de compositeurs modernes tels que Morton Feldman et Frederic Rzewski.

Depuis peu, Igor Levit a aussi à son actif l’enregistrement sur CD des Vingt-quatre préludes et fugues de Shostakovich, un cycle pour piano extrêmement difficile de près de trois heures. C’est sur ce cycle, interprété cette fois-ci en live à Bozar que se termine le festival Shostakovich. De précédentes interprétations avaient suscité un enthousiasme incroyable : « un pèlerinage, long et solitaire il est vrai, mais surtout d’une grande intensité émotionnelle à travers un des paysages musicaux les plus subtils dépeint au piano. »

En 1950, Dmitri Shostakovich s’est rendu à Leipzig pour assister à un festival commémorant le bicentenaire du décès de Bach. Membre du jury du Concours international Jean-Sébastien Bach, il a entendu la superbe interprétation du Clavier bien tempéré par la Moscovite Tatiana Nikolayeva, 26 ans. Conquis, il a décidé de s’atteler à la composition d’une œuvre similaire : un cycle de préludes et de fugues couvrant toute la gamme des modes majeurs et mineurs. Les autorités soviétiques ont fustigé ce cycle : la forme même de la fugue – trop « occidentale », trop archaïque – ne cadrait pas avec le réalisme soviétique. Shostakovich se vit reprocher son formalisme, sa musique décadente et une dissonance touchant à la cacophonie.

28

Igor Levit © Felix Broede

Geen muzikant die tijdens de coronacrisis een groter bereik had dan de in Rusland geboren pianist Igor Levit. Elke avond gaf hij vanuit Berlijn een huiskamerconcert dat steeds weer door tienduizenden mensen wereldwijd werd bekeken. Waarmee niet gezegd is dat de muziek die hij speelde, evident was: monumentale werken van Bach en Beethoven wisselde Igor Levit af met muziek van moderne componisten als Morton Feldman en Frederic Rzewski.

Een van zijn meest recente verwezenlijkingen is een cd-opname van Shostakovich’ 24 preluden en fuga’s, een aartsmoeilijke, bijna drie uur lang durende pianocyclus. Als afsluiter van het Shostakovichfestival speelt Igor Levit deze cyclus live in Bozar. Eerdere uitvoeringen zorgden voor ongelofelijk veel enthousiasme: “een weliswaar lange en eenzame, maar vooral ook intens emotionele pelgrimstocht doorheen een van de subtielste muzikale landschappen die de piano kan schilderen.”

In 1950 reisde Dmitri Shostakovich naar Leipzig om daar een festival ter gelegenheid van Bachs 200ste sterfdag bij te wonen. Als jurylid van het Internationale Bachconcours hoorde hij daar hoe de 26-jarige Tatiana Nikolayeva uit Moskou Bachs Das wohltemperierte Klavier speelde. Begeesterd besloot hij een gelijkaardig werk te schrijven: een cyclus van preludes en fuga’s in alle mogelijke majeur- en mineurtoonaarden. De Sovjetautoriteiten hadden het zeer moeilijk met dit werk: alleen al de vorm van de fuga –te westers, te archaïsch – paste niet binnen het plaatje van het socialistisch realisme. Men verweet Shostakovich formalisme, decadentie en kakofonische dissonantie.

EN —› No other musician reached as many people during the COVID crisis as the Russian-born pianist Igor Levit. He gave a living-room concert every evening from Berlin, watched by tens of thousands of people around the world. That’s not to say that the choice of music he played was obvious: Igor Levit alternated monumental works by Bach and Beethoven with the music of modern composers like Morton Feldman and Frederic Rzewski.

Among his most recent accomplishments is a CD recording of Shostakovich’ 24 Preludes and Fugues, a fiendishly difficult piano cycle lasting almost three hours. To close the Shostakovich Festival, Igor Levit will play this cycle live in Bozar. Earlier performances were met with incredible enthusiasm: “though long and desolate, it’s also an intense emotional pilgrimage through one of the most subtle musical landscapes the piano can paint.”

In 1950, Dmitri Shostakovich travelled to Leipzig to attend a festival celebrating the 200th anniversary of Bach’s death. As a member of the jury of the International Bach Competition, he heard how the 26-year-old Tatiana Nikolayeva from Moscow played Bach’s The Well-Tempered Clavier. He was inspired to compose a similar piece: a cycle of preludes and fugues in each of the major and minor keys. The Soviet authorities were very unhappy with this work: the form of the fugue alone – too western, too archaic – did not fit the socialist-realism ideal. Shostakovich was accused of formalism, decadence and cacophonic dissonance.

29 NL —›

30

© Illias Teirlinck 31

www.nationalorchestra.be

Belgian National Orchestra

Rue Ravensteinstraat 36, 1000 Brussels

+32 2 552 04 60

info@nationalorchestra.be

Instagram

belgian_national_orchestra

Facebook Belgian National Orchestra

LinkedIn Belgian National Orchestra

32