Jaguars in the mist

The dense, high-altitude rainforest of Brazil is constantly shrouded in a cold mist. Somewhere within, jaguars and pumas are stalking. Jacqui Hayes joins a Brazilian scientist in a desperate bid to protect them.

Extinction sEEms Easy to define: it occurs when the last individual of a species dies. In practice, a species is doomed long before its last member perishes: the struggle to count and maintain enough breeding pairs, with enough genetic diversity, in a threatened species is one of the most difficult, error-prone and heartwrenching processes in science.

It’s exactly what Marcelo Mazzolli is trying to achieve with Brazil’s big cats –jaguars (Panthera onca) and pumas (Puma concolor) – in the Mata Atlântica, or Atlantic Forest, a stretch of tropical and subtropical moist and dry forest, savannas and mangroves, which extends along the Atlantic coast of Brazil and inland as far as Paraguay.

“I’m caught by it, dragged by it. Sometimes you have a wild dream and then,” he pauses, shrugs and raises his hands in a gesture of surrender, “That’s it.”

Mazzolli, kitted up with solid-looking boots, a widebrimmed hat, a machete and a cheeky smirk, looks not unlike

the fabled explorer Indiana Jones. And, sitting in the kitchen of a dilapidated wooden cabin deep inside the SaintHilaire/Lange National Park, we’re just about as remote as that fictional movie character too. This area is the fourth most biodiverse site on our planet (see “Biodiversity hotspots” Cosmos 33, p13). And somewhere nearby is – Mazzolli hopes – Brazil’s southernmost population of rainforest jaguars. “This project is about the jaguar because it is going extinct fast – very fast in the Atlantic Rainforest,” Mazzolli says. “We are really aiming to find out where is the jaguars’ core areas.”

It’s late May 2010, and I’ve been invited by Biosphere Expeditions, a British nonprofit ecotourism organisation, to join Mazzolli and a team of 12 international volunteers. For two weeks they’ve called the cabin and their surrounding tents home. The dilapidated wooden cabin is in the middle of an isolated valley, surrounded by the precipitous Serra do Mar mountain range. Dense rainforest stretches up the slopes, and then disappears – the tops of the mountains are almost always hidden, shrouded in mist. Far from human

>>

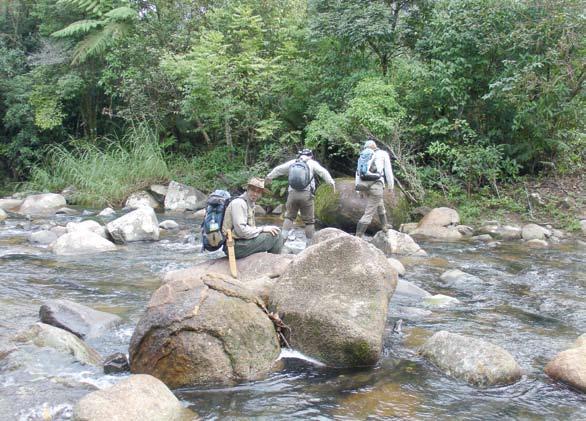

influence, the valley may be an important corridor for the cats to move to other parts of the rainforest to find prey and to mate, and the group have been trekking the area, looking for any sign of the impressive creatures – tracks, dung or sightings.

No one has ever counted the number of mammals here. The International Union for Conservation of Nature has a Cat Specialist Group that estimates the area contains somewhere between 115 and 200 jaguars. But Mazzolli doubts this.

hour south of the base camp. Local rangers told Mazzolli they’ve recently spotted jaguars in this area. And a week earlier, German volunteer Martina Kuhls was walking a nearby trail when she spotted the back of a dark cat as it fled. When the road ends abruptly at a river, we all pile out. I take off my boots to cross the river, ready to surrender the feeling of being dry.

Mazzolli stops suddenly, turning his head to the thick foliage like an animal stalking its prey. “Smells like puma.”

The estimate was made using a population density determined in other, more pristine ecosystems. Worldwide, there is even greater variation, with estimates of the total population anywhere between 8,000 and 50,000. And here, jaguars face the daunting prospect of being hunted, prey decimation and a degraded ecosystem.

One of the biggest obstacles to protection is that jaguars need an enormous home range. In a poorly functioning ecosystem, where prey are scarce, their home range could cover up to 400 km2 And, sadly, their habitat continues to be lost at an astonishing rate: less than 10% of the original Atlantic Forest region remains. Jaguars exist in other areas of South America, including the Amazon basin and lowland states such as Mato Grosso, but this isolated population lives in a highaltitude rainforest and is unique: they have genes and behaviours not found in other populations. And this variation between groups of jaguars is vital to conserving the species as a whole, Mazzolli argues. The first step to protecting the species is to verify their presence – or absence – and the presence or absence of their prey. That’s what Mazzolli and his volunteers are here to do: each day, they split into two groups and go out to record any signs of wildlife.

“Dry means something completely different here,” the other volunteers are fond of saying. They’ve had to endure days of constant rain, squelching for hours through calf-deep mud, and the constant mist means nothing ever dries completely. We continue along the track with damp socks and it’s not long until we’re on trails made by the locals. Above me, the spectacular mountain vista disappears behind a canopy of dark green. The trees,

ferns, hanging vines and foliage are all so unexpectedly dense. A jaguar could be sitting only a few metres from me and I wouldn’t know it. We walk for a short while, losing the trail here and finding it there; stopping to find high points so the GPS unit can record our position for future use.

Mazzolli stops suddenly, turning his head to the thick foliage like a hunting animal stalking its prey. “Smells like puma,” he says to the group behind him. I quietly snicker at such a species-specific sense of smell, but in truth, I kind of know what he means. It does smell like cat. But this is not scientifically valid data, so unfortunately my closest encounter with a puma goes unrecorded. More rigorous data is hopefully being recorded by the 11 camera traps that the team set up on various trails the week before I arrived. Strapped to a tree at knee height, the cameras snap anything that passes close enough to trigger a sensor. One of our missions today is to find and retrieve the two camera traps in the area. The camera is in a hard, lunch-boxsized green case to protect it against the humidity. All the cameras face south to avoid the sunlight, which can sometimes trigger their sensors.

Felicity Pidgeon, a volunteer from Darwin, unstraps the first camera, dusts it off and hands it to Mazzolli. He slowly

EaRLy in tHE moRninG, after filling up on local fruits, and the cheese and yogurt Mazzolli has made by hand, I join a group piling into a Land Rover and drive half an

opens the case and looks at how many pictures the camera’s taken.

“Error!” he says, frowning. The mood of the group falls. “Oh, you have to be joking,” Scottish volunteer Alan Russell sighs.

“Perhaps it just has rewinded, because so many pictures were taken,” says Mazzolli. But his optimism seems a little empty, even to me. We’ve still got one more to retrieve, and hope relies more on it than ever.

We set off again, but it’s not long before Mazzolli has spotted something else in the forest undergrowth: a poisonous fer-delance, or spearhead snake (Bothrops) that slid under cover before the rest of us could see it. One of the volunteers, 20-year-old Anne Neumann from Germany, makes her disappointment known.

That’s all the encouragement Mazzolli needs. He picks up a large stick and starts poking at the root of the small tree where he saw it disappear. Finally, the snake slithers out and – to my horror – heads straight for the two of us at the back of the group. We leap into the air, desperately trying to avoid its fast-moving, erratic trajectory. In my mind, I simultaneously wonder just how poisonous this pit viper is, and realise why I was told to ensure my travel insurance included emergency medical evacuation.

Mazzolli lunges in with the thick stick just in time, gathering up the snake. “Journalist. Come, look at the snake,” he says to me as he lifts the snake up to faceheight. It’s thin, brown and – thankfully – now motionless. While the fer-de-lance is poisonous, this particular species is not very aggressive, he explains – a subtle but crucial difference. It poses quietly for photos before he releases it.

The team locates the next camera with ease, and when Mazzolli starts to open this case, they gather even closer than before, straining their necks to see evidence that this one has worked. “Error,” Mazzolli mumbles, again.

But then he flashes one of his cheeky grins: “Just joking.” He looks at the top of the camera properly, and announces the number: “Six!” Including a test flash when the camera was set up, and one picture snapped as the team approached today – which means four animals may have been captured on film. Mazzolli uses analogue cameras for most of the traps, and there’s a grinding frustration among the generation Y volunteers at not being able to see the pictures immediately.

it RainED aLL that night, but the morning turned clear and sunny. The group is excited, not just because their clothes might finally dry, but also because these are the perfect conditions for finding animal tracks. “The mammals are not really visible to our eyes, so we must learn to read the signs,” explains Mazzolli, who will examine all the data collected once the two weeks are up. A tapir print in mud loosely resembles the imprint from a horse’s hoof; a dog print is easy to identify as the claws leave small imprints above each pad; and jaguars have a huge print, larger than the size of a human fist. We’re barely out of base camp before recording the tracks of racoons, deer, fox and the odd armadillo.

After almost two weeks, this novice team identify tracks with remarkable efficiency –one person takes down notes about the location and site, another snaps a picture of the evidence and someone else records the GPS coordinates. After more traipsing through rivers and mud, we find more exciting tracks – one belonging to a tapir, and another to a small cat – though Mazzolli can’t identify the species. Scats – the dung left behind by animals –can tell researchers much more than tracks. But in the Atlantic Rainforest, scats are not common; they disintegrate too rapidly in the wet conditions.

>> The team has been lucky on this expedition, finding one cat scat, complete with fur. A DNA test will hopefully confirm the species, and perhaps even its most recent meal.

After recording lots of tracks, we return to the base camp and reunite with the second group. They’re disgruntled: their mission was to retrieve the last of the camera traps, but one was missing, removed from the tree without a trace.

It is illegal to hunt jaguars, but they are still in danger from local farmers protecting their livestock.

It was the only digital camera used, and one of the team members had checked it a few days earlier, seeing pictures of an armadillo, an ocelot and a tapir – data now completely lost. Because it was a digital camera, more valuable than the analogue cameras, it might have been stolen by a local looking to make some quick money.

“An important part of this project is to gain the trust of the local people,” Mazzolli says. Along the road to the base camp are houses belonging to retirees, rangers and, in one or two cases, hunters. It has been illegal to hunt jaguars in Brazil since the 1970s, but they are still in danger from local people hunting for food, or from local farmers protecting their livestock.

Mazzolli is suspicious of the hunters. If they were out hunting and accidently triggered the camera, they would have stolen it to destroy the evidence. He makes some house calls, asking for the camera back and tells them he isn’t interested in legal action. They deny taking it.

Jaguars, pumas and other mammals in the Atlantic Rainforest are so difficult to spot that the best method of determining their presence is by their tracks. Here, the tracks of a small cat are measured.

Mazzolli needs the locals to help him find trails and report sightings of jaguars

Mammals of South America

The JaGuaR and puma are opportunistic predators, feeding on everything from rodents to birds and monkeys. Jaguars have a taste for larger mammals such as tapirs and peccaries, which pumas generally do not take down. Jaguars have extremely strong jaws, even relative to other big cats, with teeth that can pierce the shell of a tortoise or the skull of its prey. But despite the hunting prowess of the jaguar, the puma can exist in areas where the jaguar is locally extinct –pumas range from Argentina all the way to Canada, and have therefore acquired myriad names, including the mountain lion, panther and cougar.

Often mistaken for a pig, the nocturnal tapiR is more closely related to horses and rhinos. The South American tapir is endangered, even though its range stretches over the Amazon basin, from Venezuela to southern Brazil.

ocELots have similar fur patterns to jaguars, but these wild cats only weigh eight to 10 kg. The ocelot diet is composed mainly of small to mid-sized rodents, birds, and lizards. They are quite common in the Atlantic Rainforest study area.

With large heads and tiny legs, the pEccaRy resembles a domestic pig and can live anywhere from arid deserts to tropical rainforests. Two species coexist in Central and South America, but both are uncommon in the Atlantic Forest. Peccaries are often called ‘javelinas’ because their short, straight tusks resemble javelins. There are more than 20 species of aRmaDiLLo – the only living mammals covered in bony plates – and all but one are found in Latin America. The most common is the nine-banded armadillo, whose tracks are found in the study area. This species may represent up to 50% of a puma’s diet in Central and South America and is equally important to the diet of the smaller Central American Jaguar.

and pumas. He hopes, eventually, that community-based development will one day mean the locals see a value in protecting the forest in which they live. Mazzolli hopes the data this team gathers will help the government decide to set up a management plan for the national park.

He also thinks there is the potential for a captive breeding program. The IUCN recommended such a program for the Florida panther (Felis concolor coryi) in 1989. The program, still ongoing, captures young pups in the wild, while leaving adult females free to breed again. During the program, researchers also collected semen and embryos from the wild population to transfer into captive adults, in order to maintain genetic diversity.

One problem with this plan, though, is that there are no jaguars known to have originated in the Atlantic Rainforest currently in captivity. Zoos rarely mention which part of Brazil their jaguars were captured. The other problem is that researchers like Mazzolli still need to define the jaguar’s core area – and the jaguar is just so darn elusive. “I think there is still something we don’t understand about the jaguar,” Mazzolli frowns. “This area is considered ‘jaguar habitat’, and yet their density is so low.”

He is silent, contemplative, before finally giving into the question on his mind: “What is going on?” he asks. But if he doesn’t have the answer, no one does.

Jacqui Hayes, the deputy editor of Cosmos, visited razil as a guest of biosphere expeditions. For your chance to win a $10,000 trip for two studying flatback turtles in western australia while staying at an ecotourism resort an hour’s drive from broome, go to biosphere-expeditions.org/competition-australia