Telling our Story

7

Dear Supporters, The vision of this coordinated project of the Wyoming Military Department, Wyoming National Guard Association, and Wyoming National Guard Historical Society is to research and publish the history of the Wyoming National Guard from its origins in the 1860s to today. Each group is contributing significantly to that mission. In these times of financial constraint, the overall goal is to self-publish two volumes in both hardbound and softbound editions with private monies and sell them to finance the project. To achieve that, our partner organizations will launch a fundraising effort soon. Additional fundraising information is forthcoming. Volume I Cowboy Soldiers (Publish in 2022) Wyoming National Guard, 1870–1945 Volume II Cowboy Soldiers, Cowboy Airmen (Publish in 2023) Wyoming National Guard, 1946–Present We’ve needed critical documents from the National Archives, which has been closed because of COVID. The facility is gradually reopening, so our historian is scheduling appointments to acquire these needed documents. Being unable to access these documents could delay publication. Cowboy Soldiers Cowboy Airmen Telling our story

This updated version of the Proof of Concept incorporated essential suggestions from our Advisory Council. Brig. Gen. (Ret.) Art Dillon chairs our Advisory Council with Active and Retired members of the Wyoming National Guard. Our Advisory Council also includes key civilian members who have significant experience in Wyoming history and publishing. We thank all Advisory Council members for their dedication and commitment to this vital project.

The Proof of Concept gives you an idea of the size of the finished product, use of photography, maps, drawings, primary text, sidebars, footnotes, and other special features that we will incorporate into every chapter.

The primary leadership team responsible for producing the books includes:

Volunteer Managing Editor: Former Maj. Rosalind Schliske Contract Historian: Dr. Mark W. Johnson Design and Layout Contractor: Mr. Josh “J” O’Brien Advisory Council Members: We welcome any specific suggestions you might have for style and design. Please note the method to bind this Proof of Concept for you was selected only to save money; however, the final product will be approximately this size and will use appropriate book binding.

If you have any questions about this Proof of Concept, contact Col. Barttelbort at (307) 631-0812.

Volunteer Project Coordinator: Col. (Ret.) Larry D. Barttelbort

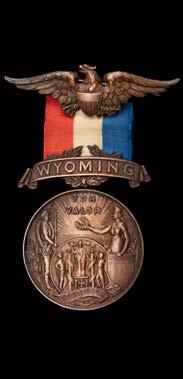

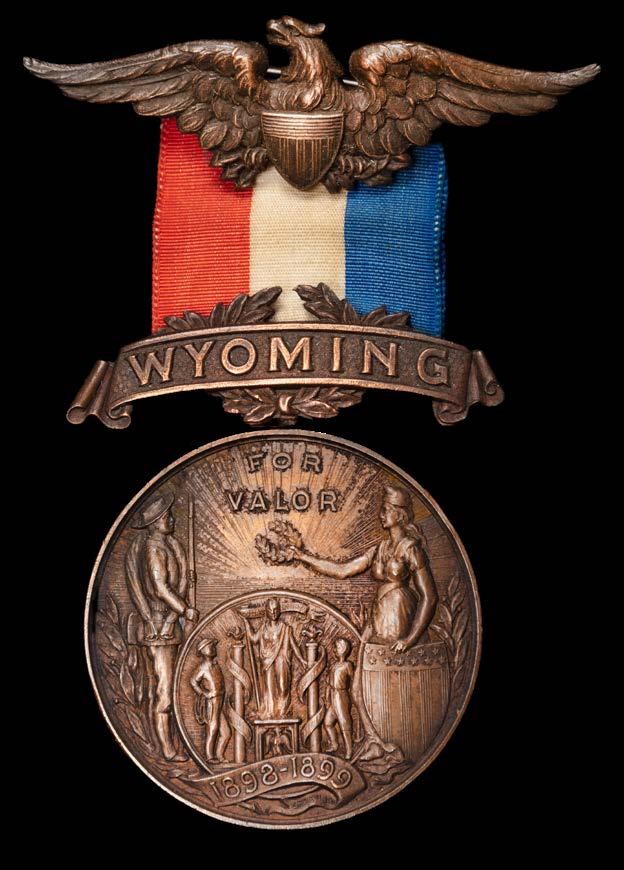

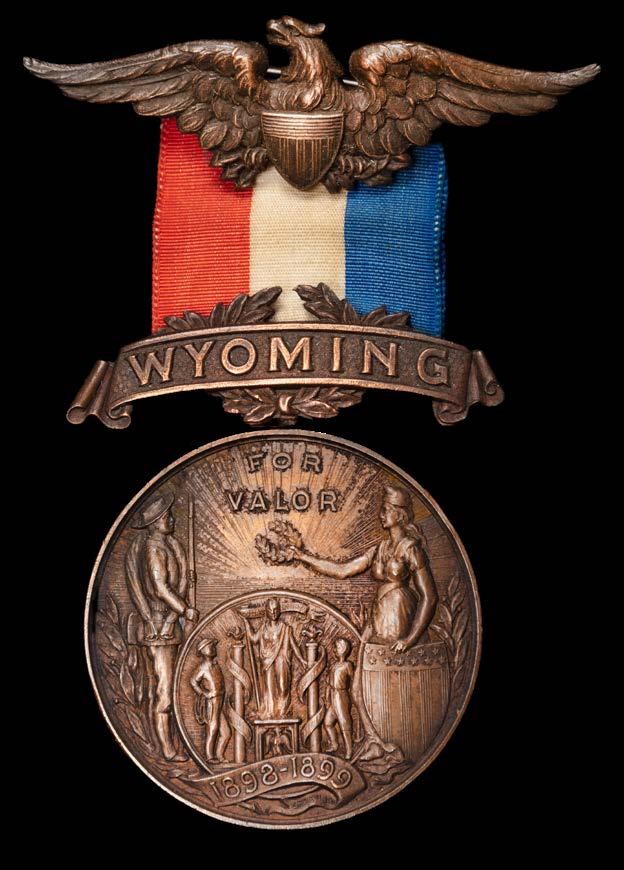

For valor

02

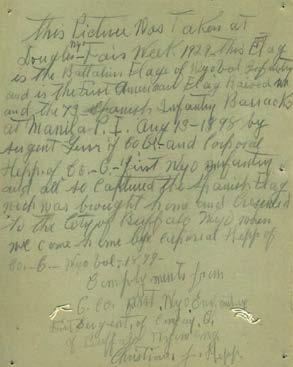

This medal presented to the returning veterans from Wyoming was engraved for a unit member from Buffalo.

Courtesy of Johnson County Jim Gatchell Memorial Museum

Wyoming in the Philippines

Private Robert

Crosbie was a long way from Evanston, Wyoming, where less than three months previously he had been employed at the town’s Union Pacific machine shop as a boilermaker. Now a passenger on SS Ohio, along with a few hundred other Wyoming soldiers, the sights greeting him when the ship arrived off the island of Oahu were impressive. The government steamer Maui, with a band and officials from the recently annexed Territory

HONOLULU, HAWAIIAN ISLANDS:

JULY 5, 1898

of Hawaii aboard, hailed Ohio off Diamond Head, dispatched a pilot, and escorted the troopship into Honolulu’s vast harbor. On Ohio’s deck, the band of the 18th U.S. Infantry played as the ship headed for its berth. A local reporter recorded the scene: “The transport moved into the harbor and proceeded to dock at Oceanic wharf. Several thousand people had collected there to welcome the boys. When the vessel approached near enough to the wharf oranges, bananas, pineapples, and various other fruits in endless quantities were thrown upon her for the troops.”1

Scores of native Hawaiians swam in the water around the transport after it tied up. “The fellows would throw nickels in the water and thay would dive and get them,” Crosbie wrote in a letter home two days later, “thay are the gratest swimmers in the world[.] thay gave us a grate reception when we came in and thay are going to give us a fine dinner today.” The Wyomingites appreciated the food and terra firma, for the journey from San Francisco to Hawaii had been a miserable one. Many Spanish-American War veterans would later claim they were shipped overseas in “cattle boats,” but that was not actually the case. Ohio and her sister transports were all civilian passenger ships. Extra bunks had been installed in the hold to increase troop-carrying capacity, but there had not been time to expand kitchen or latrine facilities. The ship’s food was barely palatable, but that mattered little because many of the troops were seasick during the eight days the vessel was in transit from San

Francisco to Hawaii. Crosbie escaped the stifling lower decks each night by stealing away topside and sleeping in a lifeboat. 2 The layover in Hawaii was not just to give Crosbie and his comrades a respite. The five-ship convoy of which Ohio was a part needed to take on coal and provisions for the long haul to the Philippine Islands. All was ready by the afternoon of July 8. The convoy took until the end of the month to cover the final 5,269 miles to Manila. The journey from Wyoming to the far reaches of the Pacific was significant not only in terms of mileage but also in the organizational changes of the Wyoming unit. When Crosbie and his friends enlisted in Evanston during the last week of April, they were members of the 1st Regiment, Wyoming National Guard. By the time the men departed Cheyenne a few weeks later, bound for San Francisco and points west, they were in the newly christened 1st Wyoming Volunteer Infantry Battalion.

12

13

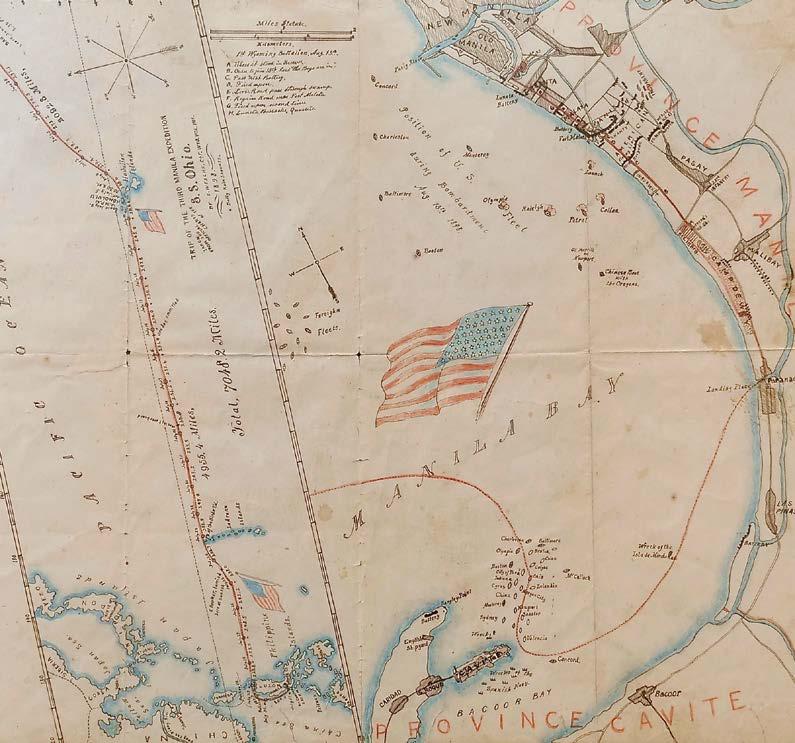

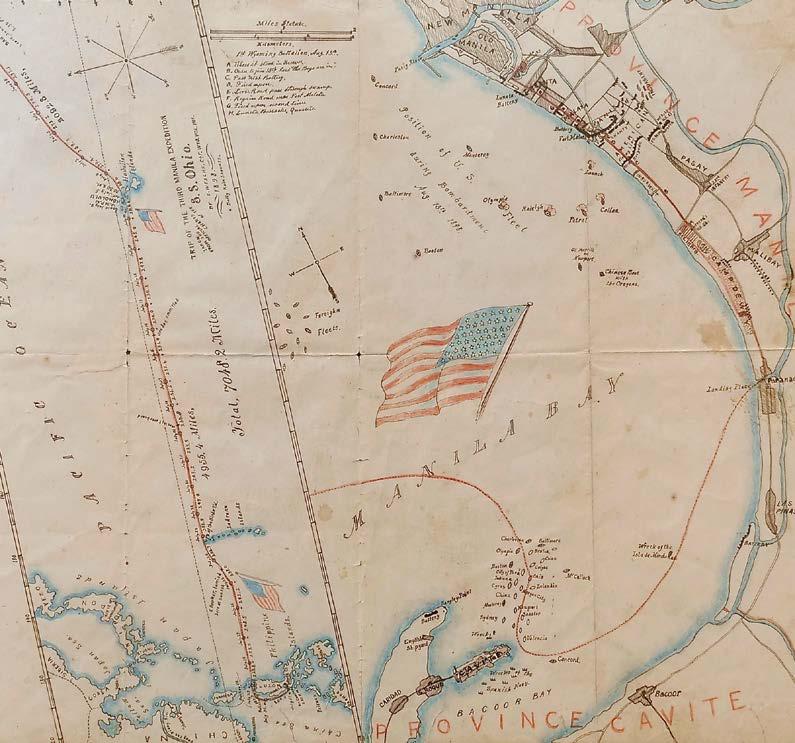

The more than 7,000-mile journey Permission pending. This 1898 map, courtesy of the Dowler family of Wyoming, was drawn by Ernest Wesche, a South Dakota rancher, who joined the 1st Wyoming. He was aboard the SS Ohio, which transported the 1st Wyoming Volunteer Battalion to the Philippines. The map follows the movements of the SS Ohio and the 1st Wyoming on August 13, 1898.

Alger artillery

The Wyoming National Guard’s Light Battery A, “Alger Artillery,” received its new 3.2-inch Hotchkiss guns after arriving in California. This photograph was probably taken at the Presidio near San Francisco, California. Initially, the unit was not called to duty but was added to the May 25, 1898, call on the states.

Courtesy of Wyoming State Archives

Courtesy of Wyoming State Archives

State answers call to war

Second youngest state musters 1st Wyoming Volunteer Infantry Battalion

America went to war in 1898, a conflict with Spain becoming inevitable after rising tensions began in the mid-1890s over the Cuban War of Independence and an accidental explosion that sank the armored cruiser USS Maine at anchor in Havana harbor on February 15. It was a conflict for which America’s army was ill-prepared. The Regular Army numbered little more than 27,000 officers and men, far too few for the global campaigns that would ensue. The weeks following the Maine disaster saw a flurry of debate in Washington, a portion of which centered on what role the National Guard would play should war come. Senator Francis E. Warren and Jay L. Torrey, a Fremont County rancher and former speaker of the Wyoming House of Representatives who spent the winter each year in Washington, wanted it to be known that the nation’s second youngest and most thinly populated state was ready to do its part in any mobilization. The two politicians paid visits to President William McKinley and U.S. Army Commanding General Nelson A. Miles on March 9. “We were kindly received,” Torrey wrote to a colleague in Sheridan the next day, “and given assurances that in the event of hostilities our tender would not be forgotten.” Governor William A. Richards also weighed in, sending a telegram to the president on April 1 with an offer of the state’s 1st Regiment as a candidate for federal service.3

Wyoming was just one of many states lobbying that spring, efforts that contributed to the defeat of a bill that

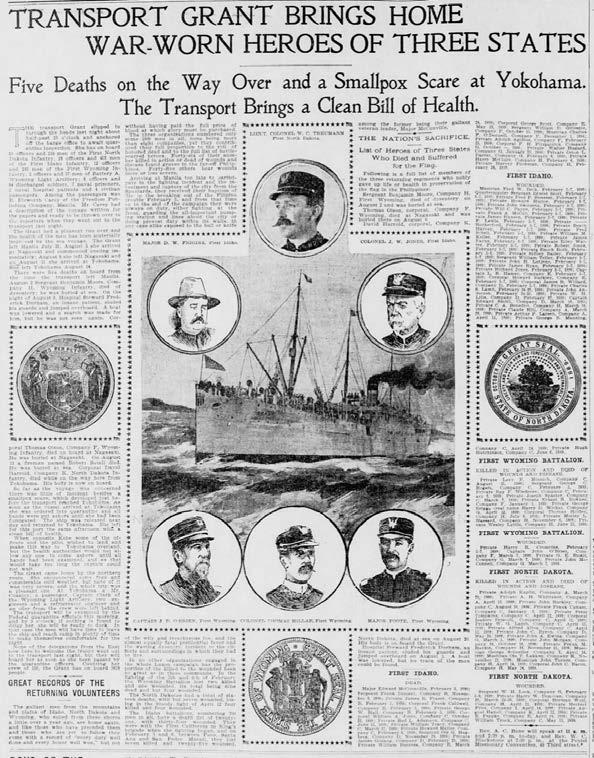

Spanish-American & Philippine Wars by the numbers

would have greatly expanded the Regular Army for the looming conflict. Instead, on April 23 President McKinley called for a modest increase in the Regular Army along with the mobilization of 125,000 state volunteers. He could not simply federalize the National Guard, for there were nagging legal questions about whether the Militia Act of 1792 allowed militia federalization and even confusion about whether the National Guard now represented the militia mentioned in the U.S. Constitution.

To avoid these pitfalls, it was decided that National Guardsmen could volunteer to join new organizations that would retain their state identities. On the afternoon of April 25, Governor Richards received word that Wyoming would provide a single infantry battalion of four companies.4

Congress declared war that same day.

Unlike the U.S. Army, the U.S. Navy in

1898 was at the peak of readiness with a relatively large, modern fleet and welltrained officer corps imbued with strategic prowess. To support naval operations in Cuban waters, the Army hastily organized an expedition to Cuba. The troops who ended up serving in Cuba consisted almost exclusively of regulars, including the 8th U.S. Infantry from Fort D.A. Russell and the 9th U.S. Cavalry garrison from Fort Washakie.5

The war’s first engagement took place on the far side of the world. On May 1, the Navy’s Asiatic Squadron under Commodore George Dewey destroyed a small fleet of Spanish vessels in Manila Bay. President McKinley followed up Dewey’s success by sending troops to capture Manila and occupy the Philippine archipelago, a Spanish colony. With most of the Regular Army earmarked for operations in Cuba, the Philippine expedition was composed of a small nucleus of regulars and a larger contingent of National Guard volunteers. The expedition’s port of embarkation was San Francisco, so volunteers organizing in Western states made up the bulk of the units that ultimately served in the Philippines.

State officials began the first federal mobilization of the Wyoming National Guard. The effort began right after Maine exploded in February, when the War Department sent queries about National Guard status to each state. On February 27, Col. Frank Foote telegraphed instructions to his company commanders to ready men and equipment “for service on short notice.” Once the official notification came through in April, Governor Richards had

60

Oldest soldier mustered into the 1st Wyoming, Captain John D. O’Brien, who had enlisted in the U.S. Army as a 14-year-old drummer boy in 1852.

14/338

Officers and soldiers who departed Cheyenne on May 18, 1898, en route to San Francisco, California.

1 Day of shore leave each soldier was granted in Honolulu when the ship was docked three days for coal and provisions. Half were granted leave on July 6, 1898, and the other half the next day.

35 Days to travel from San Francisco to Manila Bay June 26, 1898–July 31, 1898, aboard the SS Ohio

5,269

Miles from San Francisco to Manila Bay.

7 Days the 1st Wyoming waited to disembark its ship on July 6, 1898, after arriving in Manila Bay and being delayed by logistical difficulties and a storm.

4 Days the 1st Wyoming spent on shore before being sent into battle on July 10, 1898.

2 Soldiers Sgt. George Guyer and Cpl. Christian Hepp needed to raise the 1st Wyoming colors over the Luneta Barracks on August 13, 1898.

142 Days that the 1st Wyoming occupied the Luneta Barracks from August 13, 1898–January 2, 1899.

10/183

1st Wyoming present for duty in officers/ soldiers on June 2, 1898. Down five officers, 155 soldiers from their deployment strength because of death, disease, wounds, and injuries.

504 Days of federal duty from May 7, 1898–September 23, 1899.

41 Wyoming soldiers who requested discharge in the Philippines, many of whom enlisted with the 36th U.S. Volunteer Infantry.

15

“Volley after volley we fired, and volley after volley came back. The fire of the enemy was now entirely directed at the Wyoming infantry.” Captain Thomas Millar, commander, Company C

to make the painful decisions of which of the 1st Regiment’s companies would get the nod. He decided on those with the largest number of men on their muster rolls: Company C (Buffalo), Company F (Douglas), Company G (Sheridan), and Company H (Evanston). Adjutant General Frank Stitzer more properly should have handled this type of minutia, but the governor either had no faith in Stitzer’s ability or wanted to do everything himself as state commander-in-chief. “I set Stitzer aside temporarily and ran it myself,” Richards boasted in a telegram to Warren on May 2, referring to the gathering of the four companies in Cheyenne.6 Richards’s snubbing of Stitzer was not just temporary. Wyoming’s adjutant general was effectively shelved throughout the mobilization. Although three companies met National Guard strength standards—about 40 men each—they were all far short of the required mobilization minimum of 77 men in ranks. Company F was well short of the state standard, so volunteers from the Laramie Greys were added to the Douglas ranks. The men’s physical condition was a concern, for a certain number would surely fail the physical examination that was part of the mobilization process. All the companies set up hasty recruiting campaigns in their hometowns.

Wyoming men eager to serve

It was not difficult to attract recruits. Plenty of young men were willing to jump at a chance to serve with the prospect of active service overseas. The Wyoming Guard also benefited from a source of manpower few other states had: discharged Regular Army veterans. After serving out their enlistments at various Wyoming posts, many veterans decided to remain in the state. Some agreed to don a uniform again

...we were marched down through thronged streets, amidst men and women, some joyous, others weeping, clinging to their departing sons or brothers.

Private Madison U. Stoneman, Company F

In their home towns none of the companies had had any where nearly the membership to bring them up to full war strength in accordance with the tables of organization at that time, but in every town where our troop train stopped, even for a few minutes, there were men, who had given up their jobs, waiting on the depot platform to join us. Every commissioned officer of the State Militia had the authority to enlist them and by the time we reached the state capitol, we had just about the number of men we needed.8

February

The

during the mobilization. In addition to a leavening of ex-regulars in the ranks, two of the battalion’s four company commanders were also former regulars. Thomas Millar of Company C, an immigrant from Scotland who served in the Greenock Volunteer Highlanders prior to coming to America, was a corporal in the 8th U.S. Infantry at Fort McKinney from 1888 to 1893. He then settled in Buffalo, became editor of the local newspaper, and joined the Wyoming Guard in 1896. Company F’s Irish-born John D. O’Brien had even more experience, having first signed on with the 4th U.S. Artillery as a 14-year-old drummer boy in 1852. He enlisted in the regulars again during the Civil War and was serving as a sergeant in the 4th U.S. Infantry at Fort Fetterman when the 18-year veteran

May 21, 1898

The

May 7–10, 1898

1st

April 23–25, 1898

President

was discharged in 1876. Afterward, he was justice of the peace in Douglas for many years. When Company F stood up in 1891, the men elected O’Brien captain.7

Even with reliable sources of recruits, getting the companies up to strength was still difficult given the tight time constraints. The companies received official word of their mobilization on April 27, and less than a week later they were on their way to Cheyenne. All four outfits continued to recruit during the journey and after they arrived. William Shortill, a 17-year-old student from Buffalo who enlisted just before Company C departed for Cheyenne, remembered how his company grew in strength as it journeyed south:

Between last-minute enlistments in hometowns, picking up men along the way, and further recruiting in Cheyenne, each company ended up with only a minority of “veteran” National Guardsmen. Company G departed Sheridan with 55 men, many of them recent enlistees, but 17 of those ended up not serving by failing physical exams or through other disqualifications. Forty-four new recruits joined the company after it departed Sheridan, so only about a third of the company’s men were bona fide guardsmen. Two of every five men in the battalion hailed from somewhere other than their company’s hometown, and the battalion’s ranks included 18 men from other states. “One thing I will say, they were all tough,” remembered Pvt. Harry Smith of his fellow recruits in Company C.9

Filling the battalion’s officer billets presented challenges. Each company came to Cheyenne with its authorized complement of a captain and two lieutenants, but five of those officers did not leave Wyoming and had to be replaced through a hasty round of elections. It was thought Edward Holtenhouse, the Evanston postmaster

August 31, 1898

1st

August 13, 1898

1st

Troops

16

William McKinley calls for an increase in the Regular Army along with the mobilization of 125,000 state volunteers. Congress declares war against Spain.

Wyoming Volunteer Infantry Battalion travels to Cheyenne and is sworn in to service. July 5, 1898

arrive in Honolulu, Hawaii. July 31, 1898 Troops arrive in Manila Bay.

battalion arrives at Camp Merritt in San Francisco, California, for equipment and training.

Wyoming Volunteer Infantry Battalion continues the assault on Manila.

15, 1898

USS Maine accidentally sinks while at anchor in Havana, Cuba. U.S. Navy

Wyoming Volunteer Infantry Battalion takes part in assault on Manila. 1st Wyoming colors raised over the Luneta Barracks.

May 14, 1898

and commander of Company H, would be ineligible for mustering because of an infirm knee and being underweight, but he surprisingly passed his physical. Company F was a special case because it was an amalgamation of men from Douglas and Laramie. Governor Richards decided Douglas would provide Company F’s commander and second lieutenant while the first lieutenant would be from Laramie. The examining board initially ruled that Captain O’Brien was too old. Company F held an election to fill the command vacancy, but the Douglas men promptly reelected the popular O’Brien as commander. Richards

February 6, 1899

Sergeant George Rogers becomes the first soldier from Wyoming killed in the Philippines.

February 4, 1899

Initial battles of the Philippine War begin.

June 15, 1899

1st Wyoming Volunteer Infantry Battalion returns to Manila, eager for the redeployment to the U.S.

June 2, 1899

1st Wyoming Volunteer Infantry Battalion leads capture of San Pedro de Makati. Morong expedition begins.

July 31, 1899

1st Wyoming Volunteer Infantry Battalion departs the Philippines for San Francisco, California.

September 23, 1899

1st Wyoming Volunteer Infantry Battalion is withdrawn from federal service in California.

September 25–28, 1899

1st Wyoming Volunteer Infantry Battalion returns to Wyoming.

17

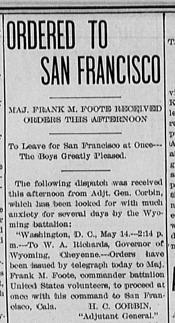

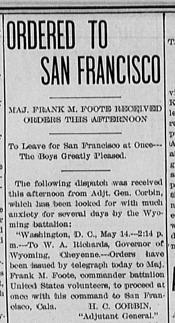

Cheyenne Daily Sun-Leader

State’s command

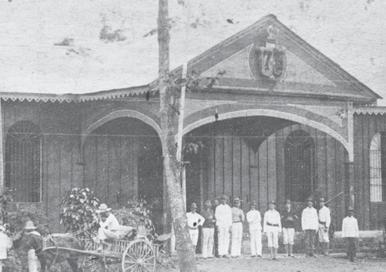

Wyoming Governor W.A. Richards visits the headquarters of Camp Richards with Wyoming’s officers on May 16, 1898.

Courtesy of Wyoming State Archives

The United States and Spain agree to the Treaty of Paris on December 10, 1898. Secretary of State John Hay signs the memorandum of ratification for the United States (from page 430 of Harper's Pictorial History of the War with Spain, Vol. II., published by Harper and Brothers—now HarperCollins—in 1899).

March to service

March to Depot

the

Depot in 1898.

applied some executive pressure to the examining board, and the grizzled, 60-yearold veteran was allowed to muster with his men.

Majors commanded battalions, so the most disappointed man in Wyoming during the early days of the mobilization was Col. Frank Foote, commander of the regiment. With only four companies mobilizing, Foote was not inclined to take a demotion to lead a mere battalion. Word soon got out that Foote was resigning from the Wyoming Guard. Almost simultaneously, Governor Richards announced he would appoint Capt. Thomas Wilhelm, the state’s Regular Army advisor from the 8th U.S. Infantry, to command the Wyoming battalion. Which came first—Foote’s intent to resign or Richards’s public announcement of Wilhelm—is difficult to say, but Richards had been planning to insert Wilhelm into a state role for some time. He laid out his plan in a letter to Senator Warren on April 1: “In case of war I want to make Wilhelm colonel of our 1st Regiment. Will you ask Secretary [of War] Alger if he will be granted leave of absence for that purpose? Urge it.”10

Richards’s and Foote’s decisions were both controversial. Foote was an Evanston man, and many Company H men declared they would refuse to volunteer if their old commander was not leading the battalion.11

On the governor’s decision, a Buffalo newspaper expressed a common opinion:

Wyoming has one regiment of Infantry. This regiment is provided with its full quota of field officers, towit: A Colonel, Lieutenant Colonel and two Majors, yet when the call came for only a battalion of four companies to go to war, Governor Richards selects as commander an alien. Either the four officers, from Colonel Foote to Junior Major Parmelee, are incompetent to command Wyoming’s battalion, or they are persona non grata to the valiant Commander-in-chief of the military forces of Wyoming. Which?12

It all worked out in the end. Wilhelm did not take command of the Wyoming battalion. Either he did not accept it, or the secretary of war refused to grant the captain a leave of absence from the Regular Army—again, it is difficult to determine the backstory. What is known for sure is

Colonel Foote of the Wyoming Guard agreed to become Major Foote of the Wyoming Volunteers.

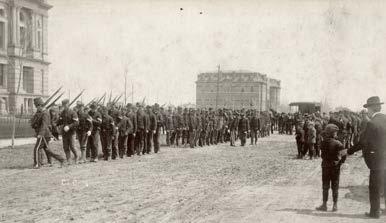

The men also had to undergo a guardto-volunteer conversion. Upon arrival in Cheyenne, the companies occupied Keefe and Turner Halls downtown while a camp was prepared at the fairgrounds. A tent city, dubbed Camp Richards, was soon ready, with rations sent over from the largely vacant Fort D.A. Russell. The camp bustled with activity for the next two weeks as officers, noncommissioned officers, and older hands in the ranks taught newcomers the basics of soldiering, although almost constant rain interspersed with snow made training difficult. New men reported each day. The Cheyenne contingent eventually totaled 37 recruits, with 18 of those being firemen from the city’s Alert Hose Company. Uniforms and equipment trickled in, with never quite enough on hand to handle the constantly increasing strength. When a company had 81 officers and men present for duty, it marched to the state capitol to be mustered in as volunteers.

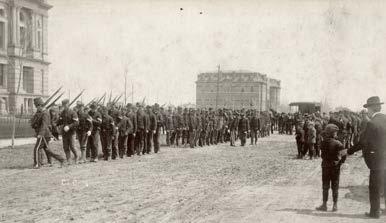

Buffalo’s Company C went first on May 7. The guardsmen marched to the Capitol with a host of cheering spectators lining the route. At the Capitol, festooned with flags and bunting, the company formed up in two ranks on the west side of the Capitol steps. Captain Wilhelm called the roll. As each man’s name was called, he marched forward, saluted the captain, and joined a new formation on the east side of the steps. When all were present in the new formation, Wilhelm swore them into federal service. Then the newly minted volunteers filed into the governor’s office to sign the federal muster roll. Governor Richards shook hands with each man, expressing his gratitude and wishing them all Godspeed.13

Two identical ceremonies took place on May 9 for Companies F and H. Company G rounded out the battalion on May 10. As the Sheridan men got ready to be sworn in, one of the privates in the ranks, Madison Stoneman, noticed a photographer taking their picture. He later wrote that the men were far from the epitome of military polish:

Then we were called to attention, and there we stood; some had bright new uniforms and clean white stripes, cartridge belts and muskets;

18

Company C marches toward the Capitol where each man was sworn into federal service on May 7, 1898.

Courtesy of Wyoming State Archives

Members of the 1st Wyoming Volunteer Infantry Battalion march down Capitol at 16th Street

(now Lincolnway) likely

headed

to

Cheyenne

Courtesy of Wyoming State Archives

others had uniforms but no belts or muskets; still others had citizen’s clothes with flannel shirts, and shoes turned up at the toes; others with laundried shirts and collars both of which had seen better days; all these and more, to get their pictures taken. What must they have looked like to a prim cadet or West Point graduate, both of whom had always been accustomed to seeing companies in uniform, even to shoes of the same make and complexion? Looking at this motley aggregation, who could cherish an unfriendly feeling toward one should he ask, ‘Pray, what do you expect these to do?’14

What was expected now was final preparations to depart Wyoming. Major Foote assumed command of the battalion on May 10 after Company G’s swearing in. Four days later, he received a telegram from the U.S. Army adjutant general: “By direction of the secretary of war you will proceed at once with your regiment to San Francisco, Cala., and report to the commanding general there.”15 Hectic preparations ensued as the last available pieces of uniform and kit arrived. Sergeant Frank Geere of Company G, a native Englishman who had moved to Wyoming in 1896 and was a clerk at the Sheridan Inn, would be a faithful correspondent to his hometown newspaper during the coming months. He penned a detailed description of those last days in Cheyenne:

Camp W.A. Richards presented a busy scene, with wagons continually coming and going from Fort Russell and unloading equipments at the commissary tent. Yesterday and today the boys have been marched in squads of twenty to the fort for baths, and today Dr. Morrison commenced vaccinating the troops. Company ‘G’ was treated this

Standard issue

While regulars carried modern Krag-Jorgensens, the Wyoming battalion was issued 1884

Springfield rifles.

Courtesy of George Eagle Feather; Photography by J.L. O’Brien

afternoon and only a few suffered the effects to any extent…The Cheyenne people have been kind to us and have shown much attention. Every company received so many cakes this afternoon, the gift of the Cheyenne ladies, and they were heartily appreciated by the boys after the regulation fare of beef, beans, bacon, potatoes, and coffee.16

The people of Wyoming were indeed generous in sending gifts, food, and kind sentiments to the troops as they prepared to leave. Major Foote could not thank all the donors individually, so he and the company commanders sent a letter to the press that was printed in papers across the state:

The major commanding the First battalion Wyoming volunteer infantry, and the captains commanding its several companies, having received many gifts to the men of their commands… hereby express to the generous donors, and each of them, their high appreciation, not only of the gifts, but also of the patriotic and affectionate interest manifested in the men who have left home, business and friends to take upon themselves the hardships of the tented field, and the sacrificial duties of the battlefield in defense of our nation’s flag and the vindication of the nation’s honor. In this public manner we express to you our gratitude and return to you our most hearty thanks. May the God of battles keep and protect you and all of us.17

The most valued item the men received before departing Camp Richards was pay for their time in state service, the days between gathering in their hometowns and being mustered in as federal volunteers. The state provided the funds by taking out a loan for $2,318.76 from the First National Bank and Stock Growers Bank of Cheyenne, personally countersigned by the governor and 16 of the city’s leading businessmen.18 With cash in hand, the battalion’s 14 officers and 338 men departed Camp Richards on May 18. As reveille sounded that morning, the tents came down; remaining equipment was packed by early afternoon. Private Stoneman recorded the scene as they headed to the Cheyenne depot:

Forming in battalion formation we were marched down through thronged streets, amidst men and women, some joyous, others weeping, clinging to their departing sons or brothers. Here and there squads of citizens fired salutes from double barreled shot guns; and all down the line could be heard the swelling strains of Cheyenne’s band. Our train was in waiting when we reached the Union Pacific Station and space being assigned to the several companies we went aboard to put away our equipments, only to return to the platform and clasp hands with friends and acquaintances. Presents of pies, cakes, fruits and other articles of food; musical instruments, testaments and mementoes of various descriptions were stacked

up in the arms of the boys in blue. 19

Similar festivities occurred in Laramie, where the train made a two-hour stop that evening, and in Evanston the next morning. The Laramie residents not only fed the troops well but also presented a “beautiful sword” to Harol De Ver Coburn, a recent graduate of the University of Wyoming, former captain of the university’s corps of cadets, and now the first lieutenant of Company F. “As the train left the depot two detachments of the university cadet artillery gave the train a salvo,” Sergeant Geere wrote. “The enthusiasm of the populace and the frenzied goodbyes of relations was enough to move the sternest man to tears.”20

Arrival at Camp Merritt

The battalion arrived in Oakland on the morning of May 21. “They are a fine body of men, and fairly well equipped,” an Oakland daily newspaper noted.21 They made a short march to the Oakland Long Wharf, the “Mole” on the waterfront, boarded a ferry, and were soon deposited on a dock in San Francisco. Next stop was the new Ferry Building, where the local Red Cross chapter laid out a lavish spread of food. From there it was a 5-mile march through the streets of San Francisco to Camp Merritt at the old Bay District Racetrack, a cluster of vacant city blocks. Named in honor of Maj. Gen. Wesley Merritt, commander of VIII Corps and the Philippine expedition, the camp was one of four military cantonments dotting the San Francisco landscape and would soon be home to more than 7,000 troops.22 Sergeant Geere listened closely to remarks from the crowd as the battalion marched by:

The battalion was then marched to the old race track near the Golden

19

Trapdoor

7 “Expedition convoys,” each consisting of four to six vessels and 3,000–5,000 troops, departed from San Francisco from May to August 1898.

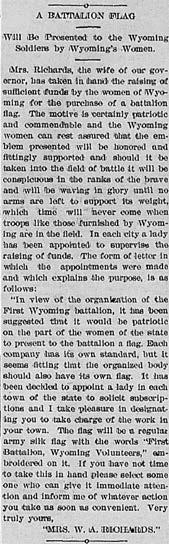

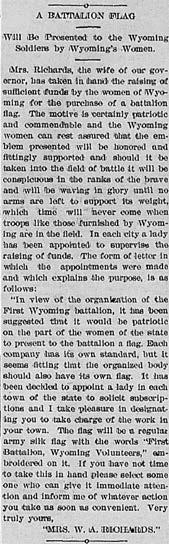

Rallythecolors

20

A gift from home Harriet Alice Richards, center, wife of Governor William A. Richards, led the 1898 fundraising efforts to purchase a custom-embroidered U.S. flag to be used by 1st Battalion, Wyoming Volunteers. Her daughter, Alice Richards, right, served as her father’s secretary at the Capitol. At left is Mrs. Harry B. (Vivia Ada) Henderson.

Courtesy of Wyoming State Archives

Cheyenne Daily Sun-Leader May 9, 1898

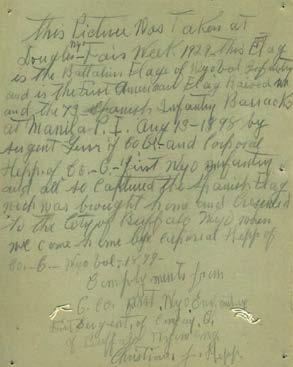

1st Wyoming colors return home

Unrolling history

History lives!

Major General Greg Porter, adjutant general of Wyoming, meets descendants of Christian Hepp, 1st Wyoming Volunteer, credited with raising this flag in Manila, Philippines. From left are Porter, great-grandsons, Kevin Hepp, Wade Hepp, and retired Master Sgt. John Hepp. They met at the dedication of the conserved colors on March 22, 2021, at the Wyoming State Museum.

21

Corporal Christian Hepp, left, and Color Sergeant Edmund G. Guyer pose with the flag that the 1st Battalion, Wyoming Volunteers brought back from Manila. As detailed by Hepp on the back of the photo, the image was taken in 1929 at the fair in Douglas, Wyoming. Hepp and Guyer raised this flag over the Luneta Barracks on August 13, 1898. Courtesy of the Hepp Collection, Big Horn City Historical Society

Paulette Reading of Paulette Reading Textile Conservation, left, and Mandy Langfald, curator of collections, Wyoming State Museum, unroll the 1898 U.S. colors on September 22, 2020, in preparation to transfer the flag for conservation work.

Courtesy of Wyoming State Museum

Courtesy of Wyoming Military Department

Time takes its toll

The image of the 1898 colors photographed on September

shows deterioration of the

as

in March

detail the

22

22, 2020, below

flag. The surrounding photos

damage as well

the results of the conservation efforts unveiled

2021.

A new lease on life

From late 2020 to early 2021, the 1898 1st Wyoming colors were restored by Paulette Reading of Mountain States Textile Conservation. The process included cleaning as well as repairing damage to a number of areas on the flag. The flag was revealed at an event at the Wyoming State Museum on March 22, 2021.

Tools of the trade

The images to the right show the progress of the conservation of the flag. Reading detailed her conservation process in a report to the Wyoming State Museum. She wrote that the flag was vacuumed with a low-suction vacuum through a protective screen. The fringe was untangled using gentle mechanical action and a microspatula. Dry latex-free sponges were used to clean the flag with gently rubbing. Where the flag was creased, Reading humidified the material and allowed the flattened material to dry under weight.

23

Photos courtesy of Wyoming State Museum

Buffalo company

Gate park…where they went into camp. While en route for camp the Wyoming battalion created quite a sensation. They were preceded by a band and crowds of people thronged to see them pass. ‘Where are they from?’ I heard one man ask. ‘Wyoming’ answered his friend. ‘Gad, they must raise ‘em out there,’ he remarked. I frequently heard words of high praise from the lookers-on and it made me feel proud for Sheridan.23

While the march to Camp Merritt may have been inspiring for the Wyoming troops, their first night in camp was anything but. A steady rain started when they arrived, and no tents were available. They turned up the collars of their overcoats and huddled together in small groups but soon were thoroughly soaked. “Does it always rain in California?” wistfully asked one dripping private, leaning on a fence with chin cupped in hands. Private William Wallam later wrote to his brother, a fellow Cheyenne plumber, that “we got as wet as the floor under a bursted water pipe.” Around midnight, arrangements were made to billet the men in nearby warehouses and stables.24

Within a few days the battalion was under canvas. Foote’s men settled into a camp routine similar to what they had experienced at Camp Richards: drilling daily, taking occasional target practice, and receiving new equipment. “We are drilling six hours a day,” Captain Millar of Company C wrote a few days after

arrival at Camp Merritt. A few score men in the battalion lacked rifles when they left Wyoming, so arms were shipped from Benicia Arsenal. Like all volunteers in this conflict they received outdated black powder Springfields instead of the modern Krag–Jørgensen the regulars carried.

Sergeant Geere noted the equipping process:

The ordnance department has completed equipping us and all are supplied with 45 cal. Springfields, cartridge belts, knapsacks, haversacks, canteens, blanket straps, bayonets, mess kits, etc.

Little campaign shelter tents have been received by the battalion, but not issued. The next on the program will probably be the commissary department and all will be thoroughly equipped with clothing. The requisitions have been made some time ago, but it is a big job to equip an army.25

Looking around at volunteers from other states during the early days at Camp Merritt, Captain Millar noted that “some of the troops here are not very well equipped and Governor Richards of Wyoming is entitled to a great deal of credit for sending out his troops in such fine condition.”26

The battalion made headlines in early June when it was presented a national flag of heavy silk with the inscription “1st Battalion Wyoming Volunteers” embroidered along the center red stripe.

The banner’s genesis was a fundraising campaign that originated with Harriet Alice Richards, wife of the governor. While the battalion was organizing in Cheyenne, Mrs. Richards sent a letter to the women of each Wyoming municipality requesting funds for the banner. Donations were limited to no more than 10 cents per individual, and the required funds were soon in hand. She shipped the flag to her brother who lived in Oakland, George C. Hunt. On the morning of June 5, Major Foote formed up the battalion on Point Lobos Avenue, Camp Merritt’s northern boundary near the Wyoming encampment. Hunt presented the flag to the battalion, and Foote entrusted it to the care of the battalion’s new color sergeant, Edmund G. Guyer of Company G. Although Major Foote once admitted he was “no orator,” he gave it his best shot as he addressed Hunt and the formation:

Sir, on behalf of the officers and members of the First Battalion Wyoming Volunteer Infantry, I accept this beautiful banner—the Stars and Stripes—the emblem of the grandest and best country on the face of the globe, and for the officers of this battalion offer to you and through you to Mrs. Richards—the wife of our honored and respected governor—and to the other noble and loyal ladies of the State of Wyoming, who have contributed toward its purchase, our sincere thanks. God bless the noble and patriotic ladies of Wyoming will

always be the prayer of every officer and member of the First Battalion of Wyoming. Color Sergeant, I now place in your charge the colors of the First Battalion of Wyoming, and backed by all of the officers and men of the First Battalion, it will, I trust and believe, always be found on the front line, where it should be.27

A reporter Hunt brought along to cover the event noted: “The Wyoming troops are about the best equipped of any of the volunteer forces in Camp Merritt and are anxious and eager to take ship and proceed to the aid of Admiral Dewey in the faraway Philippines.”28

Anxious and eager volunteers were everywhere to be found in San Francisco that spring. Since the beginning of the conflict, the War Department had been making feverish attempts to charter and purchase transport vessels for the Philippine expedition. The ships trickled into San Francisco Bay each week, but the process of required inspections and maintenance meant enough were never ready at any given time to transport all the waiting troops. A total of seven “expedition convoys,” each consisting of four to six vessels and 3,000–5,000 troops, departed San Francisco from May to August 1898. The first set sail on May 25, just a few days after the Wyoming battalion’s arrival at Camp Merritt, and the second departed on June 15. Whether a volunteer unit was on an expedition’s manifest came down to a

24

C Company, out of Buffalo, poses for a photograph at Camp Merritt, California.

Courtesy of Johnson County Jim Gatchell Memorial Museum

combination of three factors: equipment, training, and influence.29

The 1st Wyoming fared well in terms of equipment and training. By all accounts Foote’s command was one of the betterequipped state outfits at Camp Merritt, and it quickly obtained whatever equipment it lacked. The battalion badly needed training, but not more so than the majority of volunteers gathering at the Golden Gate. Because unit drill was difficult in the narrow confines of Camp Merritt, the battalion had to march to either Golden Gate Park or the Presidio of San Francisco, the local Regular Army installation. Once at the training sites, the battalion benefited from adept drillmasters such as Captains Millar and O’Brien and Lieutenant Coburn. Sergeant George Rogers of Company C, a Johnson County ranch hand and veteran of the British Army, also had much-needed expertise. Rogers was ill for a few days in early June, and he noticed a difference in how the drilling went when he absent:

I had to remain in camp while the companies…went out for battalion drill. I will tell you the officers did [not] realize the value of a good right guide until they tried it without me as right guide. When the boys came in from drill they said that it made a difference for the entire Battalion. Do not let this go any further as it may come back to him, but Lieutenant Cheever is no good. He gets excited and gives wrong commands which is a great drawback for the company. I can take the company out and drill them in company drill or in the manual of arms and the boys go through without a bobble. But when the Lieutenant has charge they seem lost.30

“Drill goes on regularly every day,” Sergeant Geere reported in mid-June. “Battalion drill comes now in the morning and company drill in the afternoon. We are now practicing in the skirmish drill and firing exercises. Later on I expect we will get some target practice.”31 The battalion shot well on the ranges at the Presidio, the high degree of marksmanship a result of the firearms familiarity most Wyoming soldiers already had. “The average scores were from 20 to 25,” a San Francisco newspaper briefly noted, “which is a very high percentage, and it shows that Major Foote has some excellent marksmen in

his command.”32 The shooting results validated a comment Captain Wilhelm made a year earlier: “The men forming the Guard of the State are generally good shots and handle the rifle well.”33 General Merritt set up an inspection system to evaluate the readiness of the various units.

The 1st Wyoming’s turn came on June 9. “The Wyoming Battalion has little cause for discontent,” Sergeant Geere informed readers back in Sheridan, “as their chance is one better since I wrote last. The whole camp has been rigidly inspected in turn in heavy marching order and the Wyoming battalion received their Inspection from Inspector General Hughes last Thursday.

As the inspecting officer passed down the ranks he was heard to remark…‘These boys are all right. I guess you’re good for the next expedition.’”34

Influence came in many forms. The War Department and generals of other commands sent a steady stream of advice to General Merritt about which volunteer units should get priority to ship out.

Merritt and Maj. Gen. Elwell S. Otis, the principal subordinate commander in VIII Corps, could also play favorites. Merritt had once commanded the Department of the East and Otis the Department of Colorado, so any regiment from east of the Mississippi or Denver received favorable nods. An unwritten rule was once a state had a unit overseas, other units from that state were low in priority regardless of readiness.35

And then there was politics. Governor Richards was more than ready to participate. The Wyoming governor was a former resident of the Bay area, having lived in San Jose for seven years in the 1870s and 1880s. His wife was from California, and his brother A.C. Richards lived in the Golden State. Richards had let Major Foote know prior to the battalion’s departure from Cheyenne to expect a visit from the Wyoming commander-in-chief during the battalion’s stay in San Francisco. True to his word, Richards arrived in Oakland on June 9. The officers of the battalion met the governor at the mole the next morning— minus Major Foote, who claimed he was ill but perhaps was just still simmering about the governor’s initial desire for someone else to command the battalion. The battalion was formed up at Camp Merritt when the governor’s party arrived. He addressed the men, telling them he was confident “Wyoming’s sons would represent with

At home away from home

Members of Company C brought this flag from Buffalo to Camp Merritt. This Company C flag is not the battalion’s colors shown on pages 20–23.

Courtesy of Johnson County Jim Gatchell Memorial Museum

honor in field and camp and battle the state which is proud to point to them as her citizens.” The battalion passed in review and was dismissed for the rest of the day.36

Richards did not just spend time with the battalion in San Francisco. He took rooms at the Palace Hotel, the same establishment in which General Merritt was lodging. Although no meeting between the two was recorded, a number of press reports intimated the governor’s presence resulted in the 1st Wyoming Volunteers being selected for the third Philippine expedition, due to depart on June 27.

The week before departure saw yet more frantic preparation. The battalion received white canvas fatigue uniforms to wear in the tropical heat. A paymaster paid off the troops for the month of June, the upcoming deployment allowing the men to be paid in advance instead of arrears as was the usual practice. The day any unit departed Camp Merritt was an event the San Francisco newspapers thoroughly covered, and the presence of a governor ensured plenty of reporters observed the 1st Wyoming:

The big tents came down with a wild whoop and were awkwardly packed for shipment to the wharf.

The Governor of the state, W.A. Richards, stood in a large group of privates and with note book and pencil took farewell messages to the home folks. …The matter of messages having been attended to the men formed for the march to the dock in light marching order, their heavier accoutrements having been sent in wagons, through the intercession of Governor Richards.37

Escorted by the band of the 7th California, the battalion departed Camp Merritt just before noon on June 26 with Major Foote, Governor Richards, and General Otis, all mounted, leading the way. The battalion followed, minus four men who were patients at the Camp Merritt hospital. A cheering crowd lined the entire route down Golden Gate Avenue and Market Street to the Lombard Street Wharf and Ohio. The governor sent a telegram to his wife in Cheyenne later that day: “Five miles solid people. Immense enthusiasm. Thousands of flags.”38

The battalion waited dockside most of the afternoon before boarding. In addition to the 1st Wyoming, Ohio’s manifest included about 600 regulars from the 18th U.S. Infantry and 3rd U.S. Artillery. Ohio,

25

along with Indiana, City of Para, Morgan City, and Valencia, pulled away from the docks that evening, laying at anchor in the bay overnight. The expedition departed San Francisco the next morning. Ohio temporarily had one passenger aboard. Governor Richards had vowed to be with the 1st Wyoming when it departed, and he took that promise literally. He boarded the ship with Foote’s men and remained aboard as the convoy departed San Francisco Bay. When they were 14 miles out to sea and past the harbor’s bar, Ohio stopped briefly while the pilot boat that had escorted the convoy out of San Francisco Bay, Lady Mine, came alongside. Richards transferred to the smaller vessel as the Wyoming troops on deck roared him farewell. “He had gone fourteen miles further in seeing his men off than any other Governor on record,” a reporter wrote two days later, “and tomorrow will go home to Cheyenne well satisfied with his work.”39

Ohio, with its numerous seasick passengers, spent eight days in transit to Hawaii, then three days in Honolulu taking on coal and provisions. The men were granted a day of shore leave to explore the city, half the battalion on July 6 and half the next day. Private Stoneman wrote of the official dinner they were given on the day prior to departure:

July 7th we were marched to the capitol building, in which grounds tables and a good dinner were prepared for the entire expedition. The dinner consisted of bread, meats, pies, cakes, fruits and other articles of food, coffee and tea. After dinner each soldier was given a bottle of soda-water; and before we marched away we were given our choice of a pile of perhaps a ton’s weight of pineapples. These we took to our bunks, some vowing to keep them for a few days; while others, whose appetites seemed more ravenous, ate theirs the same day. We found afterward that these latter were the wiser of the lot, for we who kept ours found them spoiled, and fit only to feed to the fish in the sea.40

Two Wyoming soldiers almost remained in Hawaii. William Shortill and another man in Company C, both just teenage kids and away from home for the first time, were homesick and depressed. They briefly considered getting “lost” in Honolulu

and missing the final leg of the journey to the Philippines, but in the end thought better of it. “By the time we reached the Philippines,” Shortill recalled years later, “the home sickness had passed and, like all others of that age we were keenly alert for any adventure.” With all accounted for, the expedition departed Hawaii on July 8. Most of the men had their sea legs now, so the voyage from Honolulu to Manila was long but uneventful. Food remained the chief complaint. “The grub they give the soldiers to eat on this trip was simply disgusting,” Company C’s Sergeant Rogers recalled later.

“Several of the men remarked that it knocked all the patriotism out of them, and if ever they get out of this they will stay at home next time and let some one else try it that has not had the experience.”41 Sergeant Geere described how they kept themselves occupied:

JULY 24

the deck and roped in. This serves as a bandstand and sparring ring. Every evening there are one or more boxing matches between representatives of the various companies and batteries, followed by some music by the band. Besides the 18th Infantry band there are a number of musicians on board who play different instruments. There are five or six who play mandolins and guitars and these get together in the evenings and entertain the rest with music and singing. In spite of all this diversion the time passes slowly and all are anxious to end the long voyage.42

There was many a sad heart that evening, as the burial of a comrade at sea is a sad event.”43

Arrival in the Philippines

The expedition arrived at Manila Bay on July 31. “At two o’clock the smoke of a steamer broke the horizon beyond Corregidor,” noted an observer on Newport, General Merritt’s command ship, “and soon our transports came in sight, the Indiana leading and followed by the Morgan City, the Ohio, the City of Para, and the Valencia. Cheer after cheer was exchanged as the vessels, black with men, one by one dropped anchor.” George Rogers wrote that the men had “almost forgotten” the hardships of the voyage as soon as they arrived in Manila Bay. The anchorage was in the sheltered waters near Cavite 8 miles south of Manila, scene of the previous May’s naval battle. The ever-observant Frank Geere noted: “The wrecks of many of the Spanish vessels which Dewey sank can be seen. Some have part of the hull out of the water, some nothing but the masts, while others are merely marked by a buoy and flag.” The waters were alive with small steam launches going from warships and transports to shore, for Cavite’s undersized docks could not handle large ocean-going vessels.44

We do not lack for diversions on board. Besides our daily duties, inspections, etc., there is no lack of reading and music, cardplaying and other amusements. A platform has been constructed aft above

The only happening of note during the weeks in transit was the burial at sea of Pvt. Ernst R. Bowker on July 24. Bowker was reportedly the first Douglas resident to enlist in Company F when the call went out for recruits in April, and now he was that company’s first fatality. He had been ill prior to the voyage with measles, then contracted typhoid fever. “We buried him at sundown,” related musician John Frick, another Company F man. “The band played the funeral march, and the service was read and he was lowered to the water amid Pacific waves.

Unloading the transports was a laborious process that involved transferring men and equipment into a small native “cascos,” pole-powered craft that normally plied the Philippine labyrinth of inland waterways but now had been pressed into service for ship-to-shore logistics. The technique was to tie together a half dozen cascos behind a steam-powered vessel that would tow the line of craft through the surf to the beach. The regulars on Ohio disembarked first, and it was not until August 6, after a storm delay, that the 1st Wyoming went ashore. As a line of cascos bearing Company F headed toward the beach, the lead steamer made too sharp a turn, and one of the river craft overturned. The men aboard all managed to cling to the hull or be pulled into one of the other cascos, but the company suffered a priceless loss: the sword presented to Lieutenant Coburn back in May. “I can truly say I never had anything to hurt me quite as bad as losing the sword,” Coburn lamented, “for I had always kept it near me, and worn it with pride and it was a pleasing remembrance of Laramie. Every member of

26

By the time we reached the Philippines, the home sickness had passed and, like all others of that age we were keenly alert for any adventure.

Pvt. William Shorthill, Company C

Private Ernst R. Bowker, who had contracted both measles and typhoid fever, was buried at sea, the first Wyoming fatality.

company had an interest in it and really shared the honor with me.” For the next two days Company F soldiers dove and swam in the waters where the blade went down, but it was never found.45

The battalion came ashore at the small coastal village of Paranaque, then trudged inland to Camp Dewey, a rambling bivouac situated in an old peanut field. The men pitched their small two-man campaign tents, eventually adding bamboo flooring and bunks to get them off the wet, sandy ground. With the reinforcements from the third expedition, Camp Dewey was now home to more than 8,000 troops. Merritt organized the force into a division of two brigades under Brig. Gen. Thomas Anderson. The 1st Wyoming was assigned to Brig. Gen. Arthur MacArthur’s 1st Brigade.46

The American forces massing south of Manila were one element of a threeway power struggle for control of the Philippines. Rebel forces under Emilio Aguinaldo had been battling Spanish occupation troops for two years in a bid to establish an independent Philippine state. Aguinaldo’s insurgents were now nominally allied with Merritt’s command because the interests of both converged for the time being on ousting the Spanish. Both sides in this uneasy relationship were already considering options for after the common enemy was defeated.47

For now, the focus was on the 13,000 Spanish troops holed up in Manila. Insurgents had encircled the Philippine capital months prior to the American army’s arrival. Starting in late July, U.S. troops occupied a sector of the line due south of Manila near the coast, about 2 miles north of Camp Dewey. Units pulled duty manning the line for 24-hour periods. Firefights were a nightly occurrence for a while, the largest taking place just before midnight on July 31 while the 1st Wyoming was still aboard ship. Sergeant Geere wrote the next day that “heavy firing was heard from the direction of the position of the Americans and flashes of light and the rattle of Gatlings mingled with the boom of heavy guns could be plainly distinguished.”48

After spending a few days settling into Camp Dewey, on August 10 the 1st Wyoming was rotated onto the line fully expecting to exchange fire with the Spanish troops occupying fortifications less than half a mile away. Some of Major Foote’s

27 Paco Cemetery Rio Pasig Manila Bay TripadeGa l l in a Call e Real Calle Real Callede San Andres Calle de Nueva CalleFauba CalledeHerran CalledeNozaledo Assault on Manila August 13, 1898 0 0.25 0.5 0.75 Miles N Polvorin de San Antonio Abad Luneta Barracks ERMITA MALATE PACO Intramuros Fuerte de Santiago PaseodelaLuneta MANILA Block House #10 Block House #12 B.H. #13 B.H. #14 Singalong Pasai Port Captain's Barracks Paco Bridge Spanish Trenches Fortified House Route of Advance, 1st Wyoming Volunteer Infantry Battalion Asiatic Squadron, U.S. Navy © M.W. Johnson Unit positions are as of 9:30 A.M. Jetty 1st Brigade (MacArthur) 2nd Brigade (Greene) 1stColo 1stCal 1stIdaho 1stWyo 18thU.S. 1stNebr Insurgents 13thMinn23rdU.S. 1stN.Dak. 14thU.S. 3rdU.S. (Arty) Utah Battery 10thPenn Insurgents Astor Battery Olympia Raleigh Monterey Petrel Callao Insurgents To Camp Dewey Barcelo my

men were disappointed when no shots were exchanged. Private Charles Wilseck of Company G laughingly wrote: “Every night had seen some fighting going on, but our night spent there was uneventful, as the Spaniards must have realized the presence of the Wyoming battalion (?).” No humor was attached to the conditions the men endured in the trenches. May through October is the rainy season in the Philippines, with heavy downpours taking place almost every afternoon. The men in the trenches had to stand in mud that was anywhere from ankle to knee deep. “We had never seen such mud in our lives,” Pvt. Harry Smith remembered. “It seemed there was no bottom to it and it rained all the time.”49

Spanish negotiate surrender

While the 1st Wyoming spent its soggy night standing guard, secret negotiations between Commodore Dewey and his Spanish counterpart concluded with an agreement for Manila’s surrender. The Americans and Spanish wanted to avoid surrendering the city to Aguinaldo’s insurgents, as both feared a bloodbath if the Filipinos were allowed to wreak vengeance upon their former oppressors. Using the Belgian consul as an intermediary, the two sides agreed that on August 13 the American fleet would bombard only San Antonio Abad, a Spanish strongpoint opposite the American lines that was the powder magazine (Polvorin) for the Manila fortifications. After the perfunctory shelling, the Spanish would withdraw, the Americans would advance, and the insurgents would be kept out of the city. Most of the commanders at Camp Dewey were unaware of the battle’s scripted sequence; all they knew was an attack on Manila was set for August 13. “The men received the news with a good cheer,” Sergeant Rogers wrote to an uncle in Buffalo, “and anxiously awaited the dawn of the day.”50

Preparations began the night of August

12. Captain Dan Wrighter, commander of Company G, gave his men a pep talk.

“The captain lined up the company and made us a little speech,” Sergeant Oscar Hoback wrote in a letter home the next month, “and told us that there was to be a combined land and naval attack on Manila the next day. He told us all kinds of nice things and I think when he quit talking we all felt one foot taller,

Wyoming leadership

Commanding Officer Maj. Frank Foote with the other officers from the 1st Battalion. Officers with Maj. Frank Foote (fourth from the left in the front) are (back row, from left) Capt. Edward P. Holtenhouse, commander, Company H; Lt. George F. Fast, battalion quartermaster, from Company H; Lt. Harol de ver Coburn, Company F (later appointed to battalion adjutant); Lt. Harry Ohlenkamp, Company H; Dr. William E. Gossett, battalion hospital steward, Company C; Lt. John S. Morrison, battalion surgeon; Lt. Hezekiah P. Howe, Company G; (front row, from left) Capt. John D. O’Brien, commander, Company F; Lt. James D. Gallup, battalion adjutant, from Company C; Capt. Thomas Millar, commander, Company C; Major Foote, commander, 1st Wyoming Battalion; Capt. Daniel C. Wrighter, commander, Company G; and Lt. Loren Cheever, Company C. Additional leadership from 1st Wyoming Battalion not in the photograph include Lt. Johnson W. Morgareidge, Company G (later battalion quartermaster), and Lt. Willard H. Rouse, Company F.

Courtesy of Johnson County Jim Gatchell Memorial Museum

100 pounds heavier, and able to lick all the Spaniards on the island.” Other preparations included issuing each man 100 rounds of ammunition—50 rounds in their cartridge belts and another 50 in their haversacks—along with rations for two days. General Anderson arranged his division with MacArthur’s brigade on the right and the 2nd Brigade under Brig. Gen. Francis Greene on the left. He held the 1st Wyoming and 1st Idaho in reserve and posted them behind Greene’s brigade near the coast. Being under control of the division commander meant the 1st Wyoming was detached from MacArthur’s brigade throughout the advance on Manila. It also meant the Wyoming battalion had a superb vantage point from which to view the naval attack on San Antonio Abad.51

The battalion was ready to move two hours after reveille on August 13 amid yet

another tropical downpour. “My command, according to orders, left Camp Dewey at 7.05 a.m.,” Major Foote later reported, “and marched as directed to the open field north of Camp Dewey and about 400 yards to the left and rear of the road leading to Pasai. We arrived at this position at 8.05 a.m. and remained there until and during the bombardment by the fleet.” Right on schedule at 9:30, the cruisers Olympia and Raleigh, supported by the gunboat Petrel, emerged from the mist of a rain squall 2 miles offshore and opened fire on the Spanish positions. Two smaller craft, gunboats Callao and Barcelo, operated close to shore and added their fires as well, as did the Utah Battery positioned on the beach. “It was a grand sight—the bombardment of the city by the big guns of Dewey’s warships,” remembered Cpl. Robert Newell of C Company.52 Thomas Millar agreed:

28

We had never seen such mud in our lives. It seemed there was no bottom to it and it rained all the time.

Private Harry Smith, Company C

We were near the bay and had a splendid view of Dewey’s fleet as it crawled up and poured forth its wrath upon Fort San Antonio and the Spanish entrenchments. We could see the Olympia and the Baltimore, grand but grim. Our boys cheered wildly at the sound of their shots. We could see the Caleo, close to the beach, vomiting fire and smoke. The sound of its rapid fire guns made everybody laugh, and the men christened that ship the “Woodpecker.”53

Dewey’s guns went silent after an hour, when the forward units of both brigades began to advance. The 1st Colorado of Greene’s brigade was the first unit to enter the shell-scared San Antonio Abad, and at 11 that morning raised the American flag over it. The 1st Wyoming and 1st Idaho joined in the advance, moving north on the Calle Real, the main road that paralleled the coast. A few moments later, an officer from General Anderson’s staff caught up with 1st Wyoming and ordered Major Foote to move forward, link up with the 18th U.S. Infantry, and advance into Manila. The Wyoming battalion took the lead from the 1st Idaho and approached within a quarter mile of San Antonio Abad. Although the powder magazine was now in American hands, plenty of nearby Spanish troops were still putting up resistance, particularly in front of MacArthur’s brigade to the east at Blockhouse 14—these Spaniards were as ill-informed about the negotiated surrender as their American counterparts. The column of Wyoming troops came under fire from an unseen enemy to their front. Major Foote ordered the battalion off the road and into a line of abandoned trenches nearby until the incoming fire slackened, then sent out patrols to locate the 18th Regulars and “find out what the situation was, as we had supposed that the city had surrendered and that the fighting was over.”54

Foote soon received word that the 18th was just to the right and front, and to advance when he saw the regulars move out. He got the 1st Wyoming back on the road as the regular skirmishers moved forward. The battalion was now in sight of San Antonio Abad. John Frick remembered the moment well: “The boys in front had by this time raised the stars and stripes over the Spanish fort, the first to float in Manila, and we cheered and

cheered.” There was no cheering for what happened next. To keep contact with the 18th Infantry, Major Foote decided to move off the road and advance to the right through difficult terrain that was variously described as a swamp, rice patty, or cane field. “It was raining and mud was knee deep,” wrote Pvt. Charlie Brandis, another Company F man from Laramie. “We went across a sugarcane field and we would sink down into the mud so deep that it was all we could do to pull our legs out again.” After struggling forward for perhaps 30 minutes, the 1st Wyoming emerged from the mud and came upon the Spanish forward trenches. Entering the Spanish lines and seeing the effects of the bombardment were images that became etched in the battalion’s collective memory. Just about every soldier who wrote a letter home describing the events of August 13 mentioned what he saw at that moment.

The comments of Private Brandis were typical: “At last we crossed the trench and got into New Manila. The Spanish must have left in an awful hurry. Guns, ammunition, clothes, etc., were strewn all around. Several dead were to be seen. One had his head torn off by a shell. In the fort were lots of dead and wounded.”55

Moving around the conquered powder magazine and crossing a bridge over a tidal estuary, Major Foote reoriented the battalion’s advance on Calle Real through the urban settlements of Malate and Ermita. The detour through the swamp resulted in the 1st Wyoming temporarily losing contact with the 18th Infantry and also caused it to fall farther behind most of the regiments of the 2nd Brigade. The battalion was now one of many units moving north through Malate. Foote knew the 18th Infantry’s column was “some short distance ahead of us. There were so many detachments moving into this street from toward the beach that it was difficult to keep them in sight, but this we managed to do.”56 The battalion then came under fire again, most likely from Spanish troops who were still putting up a stout resistance against MacArthur’s 1st Brigade from a fortified house north of the small hamlet of Singalong. The Wyoming men sheltered against the walls of the buildings lining Calle Real, being careful to avoid cross streets where the incoming fire was heaviest. While the battalion took cover, Captain Millar heard a familiar voice call out from up the street—Lt. William Haan of the 3rd

U.S. Artillery, a fellow Ohio passenger and commander of one of the 3rd’s batteries that was serving as infantry. The regular officer motioned for Millar to join him at the 3rd Artillery’s column, where Haan handed the Wyoming captain a bottle of champagne. While Millar took a long pull, Major Foote was briefly considering a counterattack eastward. The incoming fire ceased before that became necessary. Foote ordered the men back into formation; Millar hurriedly expressed his thanks to Haan, and the battalion continued northward.57

The 1st Wyoming came to the end of Ermita’s built-up area and now faced a broad plain known as the Luneta, a combination park and parade field immediately south of the formidable walls of Fort Santiago that enclosed Intramuros, the original Spanish settlement. Although a Spanish flag was still flying over the fort, a large white flag was also visible, as were hundreds of Spanish soldiers on the fort’s walls who were just waiting to surrender. A few moments earlier, the Luneta had been crowded with American troops, the regiments of Greene’s brigade that had preceded the 1st Wyoming through the streets of Malate and Ermita. With Greene’s brigade at the fort and MacArthur’s brigade still engaged at Signalong, General Anderson, the division commander, told Greene to keep moving: “I directed General Greene to proceed at once with his brigade to the north side of the Pasig [River], retaining only the Wyoming battalion to remain with me to keep up the connection between the two brigades.”58

Inside the walls of Fort Santiago, negotiations were taking place to end the fighting and secure the Spanish surrender of the city. Meanwhile General Anderson told Major Foote to have the 1st Wyoming take possession of what looked like military barracks on the Luneta adjacent to the moat surrounding Fort Santiago. Major Foote relayed the order to his company commanders, and the barracks were soon secured. During the battalion’s first moments in what turned out to be Luneta Barracks, it was decided to raise the 1st Wyoming’s flag on the barracks’ flagpole. Color Sergeant Edmund Guyer, accompanied by Major Foote and Sgt. Christian Hepp from Company C, ascended to the roof and got to work. Sergeant Guyer wrote of this moment 40 years later: “Immediately

Private Charlie Brandis, Company F

29

It was raining and mud was knee deep. We went across a sugarcane field and we would sink down into the mud so deep that it was all we could do to pull our legs out again.

after taking possession of the barracks, we raised our Flag. As Color Sergeant, it was my duty to do this. At our first attempt to raise the flag the rope, being old, broke. Some one soon found new rope which we spliced, and at 4:45 P.M. the flag was raised—the first flag raised near the Center of Manila.”59

Old Glory over Manila

Whether the 1st Wyoming’s flag was in fact the first to be raised over Manila is doubtful, but there is no doubt it preceded the American flag that started flying above Fort Santiago about an hour later. Following the conclusion of negotiations between General Merritt and the Spanish commander, Lt. Thomas Brumby of Dewey’s staff replaced the fort’s Spanish flag with the Stars and Stripes, with American warships firing a salute when the flag was unfurled. The 1st Wyoming spent the remainder of that memorable day guarding their barracks, securing General Anderson’s nearby headquarters,60 and trying to clean up. “You would have laughed if you had seen me there,” Charlie Brandis informed his parents. “Soaking wet, mud from head to foot, so tired that I could hardly stand up, and sitting down in the road toasting bacon on the end of my bayonet. We went into Quarters right opposite the old fort in the barracks of the Seventy-third regiment of Spanish regulars. They left everything behind them, so we captured quite a lot of stuff.”61

Luneta Barracks would be the 1st Wyoming’s home until early January 1899. The stay was much longer than at first anticipated. Three days after Manila’s fall, word arrived that the United States and Spain had signed a peace protocol the day prior to the battle. Now that active fighting in the Spanish-American War was over, the volunteers in the Philippines wanted to go home. They had signed up to fight the Spanish, so in their minds they had done their duty as agreed. Serving as an occupation force in a faraway land was not why they had enlisted, but for the time being that was what they did. The battalion’s sergeant major, Benjamin Moore from Evanston, summed up his feelings in a letter from late October: “Although it is the unanimous wish of all to be discharged with the least loss of time, we will not complain but wait patiently for the government to notify us that our services are no longer required, and then we will bid

adieu and give three cheers for McKinley and the Stars and Stripes.”62

Such a virtuous statement was expected from the battalion’s senior noncommissioned officer, but the actions of other Wyoming soldiers were not as pristine. Eight were caught burglarizing a local private residence, an offense for which the entire battalion was confined to quarters for a while. “The two sports Wyoming excelled in were baseball and stealing,” was how one private described the men’s use of their free time. At the end of August Sergeant Geere wrote: “We are to receive our monthly muster tomorrow and were inspected by Adjutant-General Major Mallory this morning. His criticism of the battalion was not complimentary and the battalion has gone down.” Shortly thereafter, Major Foote appointed Captain O’Brien as the battalion’s summary court officer to “keep up morals.” Sergeant Rogers summed up the feelings of many of his comrades in a letter from in mid-October: “All that seems to interest the boys now is when will Uncle Sam order us home and discharge us. The majority of volunteers find it very hard to settle down to Garrison life. The war was only over for a few days before some of the wanted to know is we would not soon be sent home as there would no more fighting to do.”63

At least the 1st Wyoming occupied fairly comfortable barracks while they patiently waited. Luneta was one of the betterknown of Manila’s military facilities. The structure had its drawbacks. There was no electricity, the interior courtyard had been used as a “death yard” to execute prisoners, and one corner had been damaged by a shell during the American attack, but it was spacious, solidly built, and dry. “Our barracks are near the famous Luneta, a popular drive, where all the parades take place,” Captain Millar wrote, “so, while scarcely anybody can tell you where to find the other regiments, everybody knows the barracks of the Wyoming battalion.” The officers were billeted in a separate building in the complex, a structure dubbed “the Bungalow.”64

In November, Luneta Barracks became more crowded. A regiment of South Dakota volunteers had departed San Francisco with the fourth expedition, arriving in Cavite at the end of August. Two months later they moved north to Manila. The regiment’s 2nd Battalion was assigned to Luneta Barracks, but

A legend refined: raising the colors

The historic accomplishments of military units are an integral part of building unit identity and esprit de corps, but sometimes the basis of historic deeds rest more on legends than facts.

For many years, Wyoming Army National Guard soldiers were informed that on August 13, 1898, the 1st Wyoming Volunteer Infantry Battalion raised the first U.S. flag over Manila during the Spanish-American War. This legend grew as the lineage of the 1st Wyoming Volunteer Infantry Battalion was passed through former Wyoming Army National Guard units and on to the 2nd Battalion, 300th Field Artillery, a unit still serving today. The unit reveled in the many “firsts” to which it laid claim, including raising the first U.S. flag over Manila.

After a review of the official reports pertaining to the 1898 events in Manila, it can now be said the 1st Wyoming’s flag was one of the first to be raised there, but certainly was not the first. The 1st Colorado raised the first flag near Manila when it planted the Stars and Stripes over the ruins of the San Antonio Abad powder magazine before noon. During the early afternoon hours, the 1st Nebraska entered Manila, crossed to the north side of the Pasig River, and raised an American flag at the Port Captain’s Barracks. These two flags were in place long before the 1st Wyoming raised its own flag.

The Wyoming troops had full view of the Spanish flag that continued to fly over nearby Fort Santiago when the Wyoming flag was raised over Luneta Barracks during the late afternoon. The Wyoming troopers later witnessed the lowering of that Spanish flag and its replacement by the Stars & Stripes in the early evening at the conclusion of Manila’s formal surrender.

Time, distance, and the fog of war undoubtedly gave the Wyoming soldiers the impression that Wyoming raised the first flag over Manila that day. Although the men of the Wyoming Battalion had seen the 1st Colorado’s flag at San Antonio Abad, they probably thought that banner was not in Manila proper. As for the 1st Nebraska’s flag, the Wyomingites most likely did not see it because it was on the far side of the Pasig. But there is no doubt that Wyoming’s flag was flying before an American flag was raised over Fort Santiago—and thus the legend was born.

Yet Wyoming today can still take great pride in the accomplishments of its National Guardsmen of 1898. The flag they raised in Manila was a unique gift to the unit from the people of Wyoming, and that banner continues to be a treasured artifact in the collections of the Wyoming State Museum.

—Larry D. Barttelbort

they were light on equipment upon arrival. “We got up there about 3 in the afternoon,” remembered Maj. Charles Howard, the Dakota battalion commander, “and hadn’t had very much to eat since morning. We had no cooking utensils, no rations in fact practically nothing but our rifles, ammunition and blankets.”

The 1st Wyoming took them in “as if we were long lost brothers. Lent us rations, utensils, fuel, everything.” A South Dakota sergeant later wrote: “The writer will often remember a cup of soup received from F of the Wyomings, as one of the finest things he ever ate.”65 After seeing to their men, Major Howard and his officers

30

headed toward the Bungalow, wondering what they were going to do for their own food. As they approached the door, they heard Lieutenant Coburn call out “just step in here, major.” While Major Howard had been looking after his troops, Major Foote’s officers were preparing a meal for their South Dakota counterparts. The spread consisted of just standard rations but was appreciated all the same. A grateful Howard remarked: “These Wyoming fellows are just our kind of people, free, generous, whole-souled and open hearted, ready to do anything for you and preferring that you say nothing about it.”66

Another unit from Wyoming arrived in the Philippines a few weeks later: Battery A, Wyoming Volunteer Artillery. Cheyenne’s Light Battery A, which had dubbed themselves the “Alger Artillery” in honor of the secretary of war, was forced to stand idle while the 1st Wyoming Battalion mobilized, but they got their chance when the battery was included in President McKinley’s May 25 call on the states for an additional 75,000 volunteers. Captain Granville R. Palmer led the unit, whose strength shot up from 30 men to 152 after three days of recruiting. The battery went through exams, mustering, and outfitting in Cheyenne before boarding a train for San Francisco, arriving on June 28. Governor Richards, having just completed his sojourn out to sea on Ohio, met the Algers at Camp Merritt and saw to it they occupied the same tents the Wyoming battalion had vacated the day before.67