Amsterdam Academy of Architecture

Amsterdam Academy of Architecture

graduation project by Marija

Satibaldijeva

Marija Satibaldijeva m.satibaldijeva@gmail.com

Master of Urbanism

Amsterdam Academy of Architecture

July 2024

mentor

Martin Probst

committee

Māra Liepa-Zemeša

Johan De Wachter

examination committee

Markus Appenzeller

Hiroki Matsuura

This document contains original images and illustrations created by Marija Satibaldijeva. Some photos were made by friends, and illustrations/maps were developed using data obtained from various sources, all of which are credited in the respective section.

Āgenskalna priedes - first microrayon’s apartment buildings

2.1.

Growing up in Latvia, like many, I lived in a Soviet-era apartment building in a neighbourhood, called a microrayon. These places are still a big part of life in Latvia today. However, most of these neighbourhoods are kind of stuck in the past. As time goes by, they’ve lost touch with their original principles and ideologies.

Now, the challenge is clear: these microrayons need a reboot. They need to adapt to today’s issues and fit in with how people live now. It’s not just about the past; it’s a journey to figure out how to make these microrayons liveable again and prepare for the future.

In Latvia 76,2% of people live in apartments.

(CSP, 2023)

Positive future of microrayons

In Latvia, apartment blocks in Microrayons were built during the Soviet occupation of Latvia from 1945 to 1990. They were designed to provide affordable housing for the rapidly growing population of the city. The functional design of these apartment blocks was influenced by Soviet ideology and architectural traditions, resulting in large blocks of prefabricated apartment slabs arranged in repetitive patterns. Despite their practicality and structural durability, many of these buildings need renovation today. In recent years, there has been increasing interest in transforming these buildings to meet the needs and expectations of modern urban living.

In Latvia’s capital, Riga, the condition of apartments and microrayons has been shaped by events after the Soviet Union’s collapse. Unfortunately, these neighborhoods often carry a negative reputation, tied to the Soviet past, leading many to believe they should be demolished. However, this project aims to shift the perspective. Let’s emphasize their potential and figure out how to prepare them for the future.

Why microrayons of Riga? The city faces more significant challenges with microrayons. Ownership changes and the larger size of these areas make it more challenging to get everyone on the same page compared to smaller places in Latvia. In those areas, it’s easier to renovate because they’re smaller, and there are fewer people to agree on things.

Instead of tearing everything down, let’s work with what we have. Improve the buildings and neighbourhoods – it’s like giving them a makeover. This isn’t just about aesthetics; it’s a crucial aspect of ensuring our city grows in a thoughtful and sustainable way. And Riga isn’t alone – cities worldwide are grappling with climate change.

So, here’s the real question: How can these microrayons contribute to a climate-friendly future for Riga as a whole? This project isn’t just about plans on paper. It’s about inspiring the people in Riga and all over Latvia. Living in these neighbourhoods can be a part of making our future more sustainable.

My graduation project design is based on the research and findings I did while exploring Riga and its microrayon history. My research helped to define new design strategies for Riga’s microrayons. The intended outcome of the study was to understand how microrayons have evolved since the Soviet period and what the challenges are today.

I did a literature review on Riga’s housing development and microrayon concepts, as well as surveyed people about their experiences living in microrayons. Additionally, I did analyses comparing microrayons on different scales.

< Apple trees, Purvciems

Location of Latvia

Riga, the capital of Latvia, is situated on the Gulf of Riga at the mouth of the River Daugava. Founded in 1201, Riga boasts a rich history and a blend of architectural styles, from medieval to Art Nouveau. The city is a cultural hub, known for its museums, concert halls, and the historic old town, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Riga population statistics (based on CSP 2021, 2023)

Population distrubution of Riga

Age distrubution of Riga

Nationalities of Riga

Summary of Latvian history in the timeline

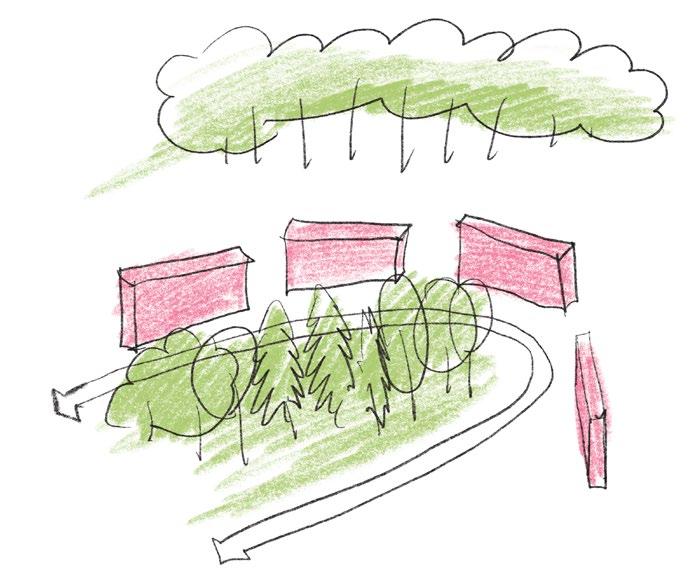

The Riga City Council has set ambitious long-term goals, particularly focusing on creating a comfortable and sustainable urban environment with an emphasis on transportation. The strategy aims to limit private vehicle usage in the city centre while encouraging the use of public transport and bicycles. Additionally, the renewal of multi-apartment buildings is seen as crucial for urban development. 1

In Riga’s microrayons, we have an opportunity to make sustainable changes. By working together to tackle environmental, population, and infrastructure issues, we can create a stronger and happier communities and climate positive environments.

<

Car use statistics (based on Statistika, n.d.; (Transportlīdzekļu Sadalījums Pa Pilsētām Un Novadiem, n.d.)

private car public transport walking bike

Rīgas Valstspilsētas Ilgtspējīgas Enerģētikas Un Klimata Ricības Plāns 2022-2030.gadam, 2022; Gemeente Amsterdam in Cijfers En Grafieken, 2024; “New Amsterdam Climate,” 2022; City of Helsinki Environmental Report 2023, n.d. Riga’s residents prefered mode of transport (1)

CO2 emissions comparison; based on data from:

Riga and Riga’s suburbs have the busiest transportation networks in Latvia, with numerous national and regional roads passing through the city. Daily commuting (pendulum migration) between Riga and nearby towns creates intense traffic flows, congestion, and emissions. According to the INTERREG SUMBA project model, approximately 86,000 residents travel to Riga each morning, while around 29,700 travel from Riga. (“Ilgtspējīgas Enerģētikas

Un Klimata Rīcības Plāns 2022-2030. gadam,” 2022)

Population decline

Since the 1990s, Riga, like much of Latvia, has seen a gradual decrease in population. Since 1991, the population has decreased by 32%. This is partly due to declining birth rates and people moving to live in the suburbs. At the beginning of 2021, the population of the city of Riga reached 614,618 people.

microrayon districts

typical traffic congestion

(workday 7:30-8:30 and 17:30-18:30)

suburbs

road intensity during workday 7:30-8:30

In Riga 94,3% of housing are apartments (CSP, 2021)

< Courtyard in Purvciems

I did a survey to gain insights into the current challenges faced by Riga’s microrayons, getting responses from 128 individuals, predominantly consisting of apartment owners and families. The majority of participants were residents of Microrayons, with a noteworthy 22% indicating personal acquaintances living in these areas. Most residents lived with their families or partners in privately owned apartments.

Renters, on the other hand, consisted mainly of couples, groups of friends, or individuals living alone within the 18-30 age gap.

When asked for suggestions on how Microrayons could be improved, a large majority of respondents provided insightful responses. Many suggested that infrastructure and car parking should be prioritised for improvement, while others called for greater attention to energy efficiency and building renovations. There was also a clear desire among respondents to more actively involve society in shaping the future of their communities.

Some residents expressed frustration with the cleanliness of the area, with many calling for more frequent cleaning and the installation of additional trash bins.

In interviews, sustainability was mentioned as important. It was about energy-efficient buildings and reusing existing infrastructure and land resources. It was mentioned that there is a need for a diversified and vibrant microrayon, with smaller-scale buildings that accommodate various small businesses.

Shared property is a major issue for residents, landowners, and managers in Microrayons. There is a high demand for apartments in Riga. The main conclusions of the surveys and interviews are:

• Residents are concerned about disorganised courtyards, inadequate infrastructure, poor building management, and neglect of shared spaces.

• Residents want better car parking, attractive public spaces, more greenery, community engagement, and cleanliness.

• Suggestions include focusing on infrastructure, energy efficiency, and involving the community in Microrayon improvements.

• Collaboration among building managers, the municipality, and residents is crucial.

• Successful examples from other cities, like Liepāja, Ventspils, and Aizkraukle, show the benefits of preserving courtyards, co-financing improvements, and investing in building insulation.

In conclusion, improving Microrayons in Riga requires working together, effective management, and finding new ways to finance improvements. It is important to address shared property issues, involving the community, and make necessary changes to better the living environment and overall quality of life. To improve Microrayons, we need to consider alternative management models, maximise existing resources, and learn from successful examples.

Your age

How do you usually move in Riga from your apartment?

With whomyou/friend live in the apartment?

With my partner With a friend/friends With my family Alone

Own apartment/but don’t live Partner/apartment buddy

Do you/friend attend meetings discussing future opportunities? For example, renovation of a building.

Yes, I attend

Sometimes No, I am not interested No, but I wish to I have no idea such meetings exist

What are the biggest microrayon problems?

Do you/friend own an apartment?

Bad public transport

Bad state of the apartments

Disorganised courtyards

Bad infrastructure

Building/apartment management

All mentioned above things

What, in your opinion, needs to be improved in microrayons for better living?

Add more recreation zones

Add more functions(cafe, bakery..)

Add more greenery

Create better outdoor space

Add bicycle parking

Better car parking

How would you advise to improve microrayons for better living?

“Reduce the number of car parking lots (they should be located outside the district, build multi-story parking lots). More greenery, recreational areas..” -

“At the city level, plans for greening micro-districts should be developed and adhered to, which residents can implement.” -

“Improve the quality of buildings and infrastructure” -

“Encourage residents to be active, propose ideas, and then try to implement them.” -

“There is a lot of green space in between buildings with no benches, recreational areas and no playgrounds. It would be great to develop these territories.” -

“State-funded building renovations so that all residents are in equal conditions.” -

“Personally, it’s hard to judge because I live outside the city, but friends live in the city, and we don’t discuss these issues. But I think it would be important to have well-organized streets, sidewalks, and thought-out parking.” -

Latvia was the place where housing reforms such as privatisation of companies and housing, and land reforms happened. That resulted in changed management and maintenance of large-scale residential areas. These changes started to happen in 1991 when the privatisation of apartments began.

Almost all municipal and state-owned buildings were privatised. Each building got divided into apartment properties that contained common infrastructure and parts such as residential communal space, outside walls, roof, foundation, communal engineering and cables, and land plot. The ownership structure of housing in Latvia has changed - since 2006 more than 80% of the housing stock in Riga is privately owned. (Centrāla Statistikas Pārvalde, 2020) That was a long privatisation process compared to the 1.2% of privatised apartments in Riga in 1996.

The ownership reforms in Latvia’s housing areas couldn’t keep up with the management system. Unfortunately, the current state of buildings and open spaces shows that essential renovations of the living environment have not been implemented. As a result, a large part of the housing stock is at risk of degradation. In many cases, the decisions that enabled apartment tenants to become owners were made without a full understanding of the rights and responsibilities of multiple stakeholders. Despite Latvia’s membership in the EU and available funding for renovation, the number of renovated residential houses still needs to grow. (Hess & Tammaru, 2019)

in Latvia only 10% of buildings are renovated

5% of buildings are renovated in

Interviews done by Riga Municipality back in 2013 with apartment residents reveal that the main problem for inhabitants, landowners, and managers is shared property. The lack of understanding about legal relations and mutual rights and responsibilities creates frustration and carelessness towards maintaining and improving housing. Because of many different ownerships, owner relationships are complicated and decisions are made artificially without considering the interests of all parties. This situation is particularly happening because of the specific socio-demographics of

Land ownership of Riga

municipality owned land rightful ownerhsip over land mixed land ownerhsip apartments from 1952-1990 buildings with at least one municipal apartment

large housing estates such as the elderly with specific demands and a lack of financial resources. Despite these challenges, Riga’s large housing estates remain in active parts of the city where most inhabitants live. Apartments remain in high demand in the real estate market and are priced at about 50-70% of the cost of new apartments in the same district. (SKDS, 2023; Hess & Tammaru, 2019)

The UNESCO World Heritage Committee has recognized the universal value of the unique significance of Riga’s historical center. The city is characterized by its medieval and later urban structure, Art Nouveau architecture, and 19th-century wooden architecture. This cultural and historical heritage must be considered when setting energy efficiency goals in the building sector. (“Ilgtspējīgas Enerģētikas Un Klimata Rīcības Plāns 2022-2030.gadam,” 2022)

There are a lot of renovation projects happening in Riga, especially contentrated in the UNESCO area. New construction projects are usuallt happening on vacant spaces outside the center.

In this project, I aim to explore ways to compensate for the CO2 emissions associated with preserving the UNESCO heritage site by implementing CO2 offset initiatives in microrayons.

and

UNESCO protected zone

UNESCO Riga historical centre

Between the late 1950s and early 1990s, the Soviet housing expansion plans in Latvia included the development of several large housing estates. Over the decades, large-scale housing mostly transformed in terms of density, and urban layout to accommodate growing population. New developments shared common features based on the planning principles. Large residential areas were typically situated in the outer perimeter of the city, with easy access to the city centre. They also boasted well-developed educational and service facilities, as well as ample recreational opportunities. Consequently, large-scale housing estates remain a popular urban choice, attracting a considerable number of inhabitants. (Hess& Tammaru, 2019, p. [162])

The housing system in the USSR, including Latvia, was strictly controlled by the state until 1991. It was a centralised planned construction process that prioritised providing low-cost housing. The majority of the housing belonged to the state or municipalities and was rented to residents for an indefinite period. The residents only had to pay a small portion of the actual dwelling and service fees, while the rest was heavily subsidised by the state or municipalities. As housing provision was a political priority and received significant subsidies, apartments were affordable to a large group of the population. In Riga during the Soviet Union period, approximately 70% of the housing areas were constructed using prefabricated methods (Hess & Tammaru, 2019, p. [164])

Municipal governments had to decide where to build new residential areas and the services that would come with them. They had two options: demolish old homes in the city centre or develop new land around the city. The first option seemed cheaper but had challenges with demolition. The second option was more expensive but allowed for better construction zones and prefabricated building parts. Most municipalities chose the second option, which made it easier to control urban growth but required residents to rely more on public transportation.(Hess & Tamaru, 2019; Dremaite, 2017).

In Mikorayons, instead of placing houses around the edges of blocks, they were arranged in a more flexible way to

incorporate them into the surrounding natural environment. In these new neighbourhoods, 9,000 to 12,000 people could live.

The idea was to create a car-free area where everything was close by. There was a rule that nothing should be more than 500 meters away. The city was divided into smaller sections - microrayons. (Meuser & Zadorin, 2016) Each microrayon had residential buildings, schools, kindergartens, shops, and recreational spaces. Multiple microrayons formed a larger residential area called a rayon, which had central shops, recreational facilities, medical centres, and public spaces. Walkways and green spaces were designed between buildings to offer a lifestyle beyond the apartment. (Hess&Tamaru, 2019)

(2-3x a week)

(2-3 a month)

In the microrayons, public services were organised into different levels based on how often they were used:

• The first level included daily facilities like kindergartens, schools, shops, and clubs. They were located within a short distance of around 400 metres from the houses. They used to be on the ground floors of apartment buildings, but later they were moved to separate buildings or combined into bigger complexes.

• The second level of periodic use (visited 2-3 times per week) services included things like cinemas, libraries, department stores, restaurants, sports centres, clinics, and other healthcare facilities. These services were meant to be used less often, so they were located within about 1 kilometre from any home.

• The third level, episodic use services (visited 2-3 times a month) included services for the whole city, such as theatres, shopping malls, major hospitals, and research/ education centres. They were located in the city centres.

After World War II, Riga needed the construction of standard residential housing and villages for factory workers. However, the construction techniques couldn’t keep up with the city’s rapid growth affected by industrial development. A similar situation happened in other Soviet cities. By 1955, two-storey brick buildings became prevalent, and standard projects were created for this type of construction. These standardised buildings allowed for large-scale housing development. The experience gained from these projects influenced the development of future housing neighbourhoods.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Riga introduced a new approach called the “free layout plan” for designing residential areas. This plan considered natural factors and added ornamental designs by architects. Large- slab manufacturing was used for faster construction. However, the focus on speed and ornamentation meant less attention was given to planning courtyards and motorways. (Hess & Tammaru, 2019) This shaped the future developments of Microrayons of Riga.

The Soviet housing system in Latvia aimed to provide affordable housing for the majority of people, with state or municipal ownership and subsidised rent. Prefabricated construction methods were widely used, including in Riga.

Reflecting on Microrayons, their original goal was to create well-equipped residential areas with green spaces and essential facilities. However, the current situation shows increased isolation due to a car- centric approach, loss of greenery in courtyards for parking, and the emergence of shopping malls on the outskirts.

Analysing the ownership map highlights complexities within Microrayons, especially regarding plot divisions in courtyards. The historically spacious and organised courtyards have been replaced by extensive parking areas.

Overall, future strategies should prioritise maintaining the original design principles - promoting pedestrian-friendly infrastructure, preserving and improving green spaces, addressing ownership complexities, and encouraging

development within the Microrayons. This can contribute to creating livable neighbourhoods that align with the original intentions while addressing the current challenges of these areas.

District

(including microrayons)

Purvciems

Ķengarags

Pļavnieki

Imanta

Ziepniekkalns

Iļģuciems

Vecmīlgrāvis

Jugla

Zolitūde

Sarkandaugava

Āgenskalna priedes

Mežciems

Bolderāja

Teika

Dārzciems

Maskavas forštate

Dzirciems

Daugavgrīva

Microrayon amenities on the city scale

The microrayon districts still feature the same schools and kindergartens that were established during the Soviet era when these neighborhoods were originally built. Many of the residents I interviewed highlighted the close proximity of these educational institutions as a strength and a valuable quality of life in the microrayons. 3 km

Sketch analysis on Riga, showing different urban fabrics and features of microrayons

Riga is surrounded by large forests and nature reserves. The microrayon districts are located on the edges of the city, often near natural areas or water bodies like rivers and lakes. While there are several parks in the city center, these parks are less common in the microrayon districts, showing an uneven spread of parks throughout the city.

Public transport routes connect the microrayons with the center of Riga, typically taking around 15-25 minutes. However, traffic congestion often delays these bus routes, resulting in longer travel times.

tram routes

trolleybus routes

future Rail Baltica railway line

Tram/trolleybus routes

Ķengarags, originally a small island in the Daugava delta, has evolved from a fishing village into a strategically important industrial hub, hosting mills and factories since the 13th century. During the Soviet era, it expanded with schools, kindergartens, and housing, becoming a residential district. Today, Ķengarags is a well-connected suburb with extensive public transport links to the city center, providing modern amenities such as shopping centers and markets. (Rīgas Pilsētas Apkaimes, n.d.)

100 people/ha

53 people/ha

Historically, the area developed around several estates, including Anniņmuiža, Lielā and Mazā Dammes muiža, and Zolitūdes muiža, dating back to the 15th century. The area was initially characterized by these estates, which served agricultural and leisure purposes, flourishing especially in the 18th century. With urban development in the 20th century, Imanta transformed into a densely populated residential district. (Rīgas Pilsētas Apkaimes, n.d.)

Previously rural, it derived its name from the expansive fields (‘pļavas’ in Latvian) that once dominated the area. The district has Soviet-era architecture, characterized by perimeter development around pedestrian streets.

157 people/ha

Imanta has a circular layout with a main half-ring road where public transport runs, along with the neighborhood’s main stores and tallest buildings. It’s surrounded by forest, and the central part is distinctive with its pine tree forest and estate.

The district is laid out along horizontal axes, defining its urban structure. Its unique features include waterfront area with biodiverse nature and a cycling promenade, as well as railway stations. Ķengarags serves as one of the entrance neighborhoods to Riga.

As one of Riga’s newest microdistricts, Pļavnieki’s layout is unfinished in the east. The collapse of the Soviet Union left many empty spaces in the urban structure.

schools kindergartens amenity (commercial)

Promenade of Ķengarags

Purvciems, a district in Riga, is located in Vidzeme Suburb to the east of the Riga-Ieriķi railway line. The area was originally known as Hausman’s Swamp and later became Purvciems in the late 19th century.

The name “Purvciems” reflects its history as a swampy area that was gradually drained and developed. Landmarks in Purvciems include various educational institutions, health centers, and shopping facilities like the historic “Mēbeļu nams” and the “Minska” supermarket. Special buildings include the 18-storey towers built in 1985 and the experimental residential buildings on Ūnijas street. Today Purvciems is the most populous ditrict of Riga. (Rīgas Pilsētas Apkaimes, n.d.)

Demographic changes

123 people/ha

Age distribution

When analyzing the map, it becomes clear that there was a distinct ideology influencing the development of Microrayons in Purvciems. The main objective was to create a layout where schools were easily accessible within a short distance, with each school having a nearby stadium. An interesting observation from the map analysis is that each school in the area was conveniently located within a distance of approximately 400 meters, which could be accessed in roughly 5 minutes. Another interesting feature was the presence of swimming pools in the courtyards, designed for children to play during summer days.

An important observation is that a single large supermarket served the entire district back then, and these supermarkets are still there today.

schools

kindergartens

garages

amenity (commercial)

supermarket

Today schools and amenities remain in thesame locations, but the neighbourhoods have become more isolated due to the city’s increased focuson car usage. Courtyards have lost their greenery and are now occupied by cars. Additionally, multiple shopping malls have emerged on the outskirts of the Microrayons, where people now go to get groceries.

more findings and photos be found in the research booklet

Microrayons themselves have become monofunctional. Swimming pools and outdoor sports places are not there anymore and are taken over by cars. If people want to do grocery shopping today, they have to cross wide car roads, and it takes a lot of time and effort.

wide roads which are difficult to cross with supermarkets across each other

monofunctionalliving,missingpublicspace&functions tallapartmentbuildingsalongthemainroads cars,biggestCO2pollutantsofriga:(

natural edges along main roads in front of the apartments

biodiverse nature, but not connected with living & infrastructure :(

cars are the first thing you see outside windows

poor state of buildings & infrastructure

1. EVERY MICRORAYON HAS ITS NATURE FEATURES, AND THE PRINCIPLE IS TO CONNECT THEM VIA A NEW GREEN NETWORK OF RIGA

EN: Pine trees of Agenskalns.

- historical context - wooden architecture

-riga’s entrance -microrayon, water/landscape edge

-former fisherman village

PURVCIEMS

EN: Swamp vilage

-historical identity of swamp -hexagon structure

-circular plan -estate and forest area

2. RIGA RING ROAD NETWORK HAS HUBS THAT ALLOW TO CONTINUE THE JOURNEY TO THE CITY WITH PUBLIC TRANSPORT OR BICYCLE

in the mobility hub next to the railway the station is incorporated

service place, like a cafe, working space

public transport & active mobility bus stop

During my research, I discovered that each microrayon district has landmarks and destinations that could be promoted to strengthen their identity. For example, improving connections around markets or architectural historical landmarks would make them more accessible and better integrated into the city’s infrastructure network.

The design principle emphasizes the importance of interconnecting microrayons with these destinations as part of Riga’s new green network. It meant to promote accessibility, sustainability, and community well-being.

Microrayon common local destinations:

- local market;

- architectural landmark and

- special function place like library or medicine centre

New road infrastructure will implement cycling highways.

< Courtyards during winter in Purvciems

There are four crucial topics that form the foundation of design principles aimed at creating a climate-positive Riga. These topics were derived from research on challenges, current conditions, and surveys and interviews with residents.

The new way of living focuses on introducing diverse housing typologies and functions, connecting homes to mobility networks and nature.

New design focuses on improving existing buildings to increase efficiency and sustainability. It is about offering different ways to modify apartments.

Integrating renewable energy sources like solar panels can help buildings consume less energy and provide a healthier living environment for residents.

Active mobility options like walking, cycling, and the use of public transportation will help reducing reliance on cars - fossil fuels and lower greenhouse gas emissions.

New design has connected networks within and between microrayons that improve accessibility and promote sustainable, low-impact transportation alternatives.

Preserving and elevating green spaces within microrayons contributes to biodiversity, improves air quality, and provides recreational areas for residents. By linking these green areas into a unified network, the new design supports climate resilience and strengthens the connection between people and nature.

building new structures only on the built surfaces - pavement, parking garages, parking spaces

connecting living to nature offering new typologies

In my design, I propose utilizing the potential of large shopping malls, ice skating rinks, and data centers to participate in the new and improved Riga district heating system as energy distributors.

I propose connecting local shopping malls to district energy systems. This means using the energy malls generate to support nearby neighborhoods, making energy use more efficient locally and reducing our dependence on outside sources. By integrating malls into district heating setups, we can build a stronger, more sustainable energy network that benefits everyone in the community.

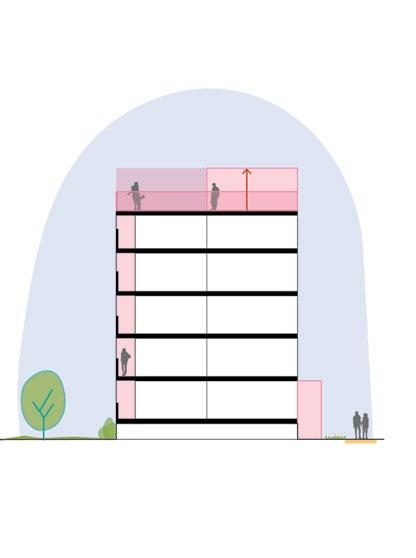

In addition to the proposed improvements in district heating, it is important to focus on the buildings themselves. In desigb I propose implementing collective solar energy production for apartment buildings, aiming to source 60-70% of the energy from solar power. By fully utilizing rooftop space for solar panels, 464 series 5-story apartment buildings can achieve self-sufficiency in energy production.

Other important aspects:

-insulation of the apartments -improved entryways, - replaced windows -windows to offer more sunlight - utilizing space on the rooftops - utilizing exisitng structure buildings

Places for sharing mobilty are part of the microrayon infrastructure

Each living block has accessible bike storages and access to shared cars

Bus stops available from home within 10 minutes

= promoting sustainable infrastructure = microraryon store

<10 min

min

min

min 5-8 min

Respecting and being proud of microrayon nature elements

- adding an extra layer to nature with different atmospeheres and privacy

- offering different nature types tom improve to improve flora and fauna

road green sways

< Nature of Purvciems

apartments built during the soviet period

supermarkets

stores

schools/kindergartens

250m

1. CREATE A CONNECTOR (WITH THE MARKET AND LANDMARKS)

Connecting microrayons with markets and landmarks is crucial to improve accessibility, strengthen identity and boost community engagement.

2.

Mobility hubs in microrayons will offer new transportation options and connectivity within the city.

4. CREATE A NEW TYPOLOGY (UNIQUE TO THE AREA)

Develop green microrayons that integrate and promote local nature into the urban environment. Local nature can serve as an identity element. This involves improving green spaces, planting more trees, and creating parks and community gardens.

Residents will have closer connection to nature, as it becomes part of living environment.

Introducing new housing and typologies that respect and reflect the unique characteristics of the local urban fabric in each microrayon of Riga. By aligning designs with the existing architectural style and community needs, we can create harmonious living spaces that enhance the neighborhood’s identity and provide diverse housing options for residents.

1. CREATE A CONNECTOR (WITH THE MARKET AND LANDMARKS)

In the case of Purvciems, connections to landmarks along Deglava Street— such as the former Minska building, Purvciems market, and Mēbeļu nams (Furniture store)—will be strengthened. Public spaces around these areas will be enhanced to encourage walking, cycling, and the use of public transport. It will connect the neighborhoods of Purvciems by making landmarks more accessible.

The new mobility hub will be created on the border of Purvciems and Pļavnieki districts. This hub aims to encourage leaving cars behind and traveling within the microrayon and Riga using public transport, bicycles, or scooters. The mobility hub will integrate with a destination retail center and offer new functions such as cafes and coworking spaces.

New typologies will be introduced on the sites of existing garages. These garage spaces will serve as potential locations for new housing in Purvciems. 3. CREATE GREEN MICRORAYONS - EMBRACING THE SWAMP

The Riga green network connects the parks of Purvciems and extends to the natural areas of Riga, including the Biķernieki forest. The new identity park in Purvciems is the Swamp park, designed to honor its historical name and identity.

Purvciems can become a climate-positive neighborhood by achieving four main design principles, which aim to embrace nature, improve connections with other microrayons and the city of Riga, and offer residents a new lifestyle.

448,25 ha

Purvciems has a strong natural presence, but it lacks integration with the apartment buildings. Currently, the streets and courtyards are dominated by cars and pavement, creating barriers between the apartments and the surrounding nature.

inside microrayon:

- 31 ha

- 15% built

- 12% infastructure (include sidewalks/paths)

New design of Purvciems is about connectivity, promoting alternative transportation options, and incorporating green spaces that harmonize with residential and communal areas. By focusing on creating inclusive and livable environments, the masterplan aims to enrich the quality of life for residents while offering a sense of community and environmental sustainability.

In the future, it’s crucial to integrate infrastructure elements that encourage alternative modes of transportation beyond cars. New vision emphasizes accessibility to bikes, public transport, and shared scooters, while also ensuring convenience with shared cars for longer distances. Bike sheds will be integrated into street infrastructure within courtyards, facilitating easy access to bicycles and promoting sustainable transportation options throughout the community.

bus stop

shared mobility

bike storage

Microrayons in Riga have unique natural characteristics, including flower gardens, fruit trees, forests, playgrounds, which contribute to distinct atmospheres within communities.

In new microrayon lifestyle, these elements are leveraged to create diverse nature typologies around apartment blocks, improving the living experience with varied natural settings accessible to all residents. By collaborating with landowners, this vision aims to strengthen and integrate nature more deeply within microayons. Result can help promoting vibrant and sustainable urban environment.

In the future residents will enjoy a new lifetsyle that supports both leisure and practical needs. This integration of new functions aims to create a dynamic and cohesive neighborhood where residents can live, work, and play conveniently within their local community. That can promote local lifestyle, and bring new identity.

The goal is to transform space in front of landmarks into spaces for active mobility and recreation. The new space has function now.

Dzelzavas street

The new lifestyle emphasizes connectivity to the surroundings, including diverse natural environments, a new swamp park, easy access to bike sheds, and close proximity to public transport.

I offer various scenarios for implementing changes in microrayons, taking into account different approaches to land plot utilization and ownership. This includes exploring diverse strategies for residents to make changes themselves or collaboratively with landowners, fencouraging community-driven initiatives and partnerships to enhance the microrayons. The vision can be realized progressively, beginning with small-scale collaborations and scaling up to larger initiatives involving groups of landowners.

municipality owned land rightful ownerhsip over land mixed land ownerhsip apartments from 1952-1990 buildings with at least one municipal apartment private land

A

B

C

working with what we have now including the landowners new (old) building adapting re-using

courtyards are private

These buildings are characterised by loggias.

These 9 storey buildings are mainly situated along the main road, and have loggias instead of balconies.

Scenario A focuses on addressing the current situation by implementing changes within existing apartment buildings, independent of the land they occupy. Additionally, this scenario explores opportunities for landowners interested in transforming their plots to accommodate new spaces such as cafes or bakeries.

Apartments can undergo renovation and transformation independently, without a landowner who owns the land beneath the building. > Example:

4 apartment buildings and 2 landowners

insulation layer

solar energy collection

possibility for apartment extension / new unit

renovated entryways

467 SERIES - 9 STOREY

insulation layer

renovated entryways

solar energy collection

Scenario B involves a collaborative effort between apartment buildings and landowners to implement coordinated improvements and changes. This scenario explores opportunities for joint initiatives aimed at improving both the buildings and the surrounding land plots, promoting an integrated development approach.

This approach can facilitate easier modifications to the apartments and introducing new typologies. For example, ground floor apartments could incorporate gardens, while the addition of prefabricated units extending the building by 3.2 meters could create additional living space. This collaborative approach enhances flexibility and innovation in urban design.

> Example:

4 apartment buildings and 2 landowners

insulation layer

solar energy collection

possibility for apartment extension / new unit

renovated entryways

collective rooftop space 3,2m wide extensions

extended space only for loggias

collective rooftop space

ground floor has an extra garden space

private gardens on the ground floor

insulation layer

extended entryways

solar energy collection

extended space only for loggias

“house“ type apartments on the first 2 floors

collective rooftop space possibility for apartment extension / new unit

3,2m wide extensions

With the introduction of a new mobility program promoting active and public transportation, garage space can be repurposed to accommodate new housing. This will offer residents a variety of new housing typologies to choose from.

Existing area statistics: - 6,11 ha - 2,74 ha footprint of garages - 8 landwoners

The existing garage layout serves as the foundation for the main streets in the new plan, ensuring a seamless integration with the current infrastructure.

Residents will have access to public transport within a three-minute walk. Additionally, parking garages with shared cars are integrated into the buildings, promoting sustainable mobility.

The main street of the new neighborhood will have various functions, creating a lively social atmosphere and opportunities for local businesses. This design encourages a new way of living that combines work, leisure, and community interaction.

A variety of public spaces will be provided, each featuring different natural elements. These will include community gardens, flower gardens, fruit trees, and playgrounds, all integrated as key components of the microrayon courtyards

communal living

microrayon continuation

work/living compact living

microrayon suburbia

New housing options are designed to allow residents to choose their desired lifestyle.

microrayon suburbia

communal living

Private houses with gardens will be available, enabling people to live within the city rather than the suburbs while still enjoying proximity to nature and essential amenities like supermarkets and schools.

Additionally, proximity to public transport ensures excellent connectivity to the rest of Riga, promoting convenience and accessibility for all residents.

New prefabricated units will be incorporated into the new apartment blocks, offering a variety of housing options in different sizes. For example, there will be row housing with private gardens for families, smaller groundfloor apartments tailored for seniors, and studio units designed for young individuals and couples.

+ 1,61 ha of park area

apartments

app

22 ha of different nature

+ 3700 bike places (in sheds)

Now that we looked at the design for Purvciems, it is time to zoom out. The goal is to apply the same design principles to all microrayon districts in Riga:

1. CREATE A CONNECTOR (WITH THE MARKET)

2. CREATE A MOBILITY HUB AND MICRO HUBS

3. CREATE GREEN MICRORAYONS WITH LOCAL FLORA

4. CREATE A NEW TYPOLOGY (UNIQUE TO THE AREA)

Ķengarags

1. Connector in Ķengarags is the local market.

2. Mobility hub is the one that is the stop before enetring Riga city centre, saving 1200 car trips every day.

3. Main nature feature is the promenade and ponds, theferfore connection to these will be strengthened.

4. Unique typology is transformation around current station areas.

Pļavnieki

1. Connector in Pļavnieki is the local market.

2. Mobility hub is on the edge with Purvciems

3. Main nature feature is meadow, from the name.

4. Unique typology is transformation along linear wide streets

I’ve created a model to illustrate my design concepts, focusing on understanding the complexities of land ownership and the scale of buildings and courtyards.

I chose this topic because microrayons are an essential part of Latvian life, cities, and history. We cannot simply demolish these neighbourhoods and build anew; they are part of our life and history. It is up to us to move forward and adapt the architecture around us. Microrayons were built during Soviet times with good planning systems that accommodated the needs and lifestyles of working families. They were once full of life, but times, technologies, and ideologies have changed since the fall of the Soviet Union, and the planning of past microrayons cannot accommodate today’s Latvians.

With my new perspective on Riga and its microrayons, I wanted to show citizens how we can transform these neighborhoods into sources of strength and beauty, making Riga climate-positive without tearing them down.

My research showed that even though microrayons have standardized apartment series, each place is unique, with different layouts and special features. For example, almost all microrayon districts have their own market, highlighting the strong sense of community. Additionally, nature is one of the biggest existing strengths in microrayons. However, the green spaces in courtyards are often underutilized and disconnected from the people who live around them. By better integrating these green areas into the community, we can unlock their full potential and create more vibrant, nature-friendly environments. Embracing nature in microrayons can significantly enhance the quality of life for residents, making these neighborhoods more attractive and sustainable.

Riga currently is facing a lot of challenges that are related to each other a declining urban population as residents move to surrounding suburbs, leading to increased congestion within the city. Ownership challenges that cause frustration among people to make changes in microrayons and renovation. Because Riga housing is 93% apartments, in microrayons, I believe that it is important to make these areas attractive to prevent higher-income families from seeking larger homes with gardens in the suburbs, contributing to urban sprawl and increased reliance on cars for commuting.

With my design I wanted demonstrate how microrayons can help make Riga climatepositive and become as more attractive places to reside.

The research on the history and concepts of microrayons began during the O6 course at the Amsterdam Academy of Architecture (Marija Satibaldijeva ,2023). This booklet includes excerpts from that original research paper to provide a complete overview of the Riga’s microrayons.

Satibaldijeva, M. (2023). Revitalizing Riga: the Future of Microrayons. O6 paper, Amsterdam Academy of Architecture.

Satibaldijeva, M. (2023). Life in Soviet Microrayons [Survey questionnaire]. Unpublished raw data.

Sources

Iedzīvotāju aptauja par dzīvi apkaimē, Purvciems, Aptauju Centrs (2013). http://www.rdpad.lv/wpcontent/uploads/2014/12/1_ apkaime_Purvciems_atskaite.pdf Accessed 27 Apr 2023

Rīgas pilsētas apkaimes. (n.d.). Apkaimes. Retrieved September 15, 2023, from https://apkaimes.lv

Ilgtspējīgas enerģētikas un klimata rīcības plāns 2022-2030.gadam. (2022). In Rīgas Enerģētikas Aģentūra. Retrieved February 1, 2024, from https://rea.riga.lv/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Rigas-pilsetasilgtspejigas-energetikas-un-klimata-ricibas-plans-lidz-2030.-gadam. pdf

LV portāls - Cilvēks. Valsts. Likums. (n.d.). lvportals.lv. Retrieved May 19, 2024, from https://lvportals.lv/dienaskartiba/338710majsaimniecibas-elektroenergijas-paterins-ir-nedaudz-krities-2022

Live Riga. (n.d.). History of Riga. Retrieved June 30, 2024, from https://www.liveriga.com/en/

Lonely Planet. (n.d.). Latvia. Retrieved June 30, 2024, from https:// www.lonelyplanet.com/latvia

Rough Guides. (n.d.). Riga and Latvia Travel Guide. Retrieved June 30, 2024, from https://www.roughguides.com/latvia/riga/

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. (n.d.). Riga. Retrieved June 30, 2024, from https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/852

Books

Dremaite, M. (2017). Baltic Modernism: Architecture and Housing in Soviet Lithuania. Dom Publishers.

Hess, D. B., & Tammaru, T. (2019). Housing Estates in the Baltic Countries: The Legacy of Central Planning in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Springer.

Meuser, P., & Zadorin, D. (2016). Towards a Typology of Soviet Mass Housing: Prefabrication in the USSR, 1955-1991. Dom Publishers.

The Block: With as Supplements Mass Housing Guide, Supersudaca Reports #1, Microrayon Living. (2009).

Images:

Image in the Timeline visual, p.16-17: Lejnieks, J. (2023). Rīgas nākotnes vēsture. p.217

Statistics:

New Amsterdam climate: Climate Report 2022. (2022). In City of Amsterdam.

Gemeente Amsterdam in cijfers en grafieken. (2024, January 7). AlleCijfers.nl. Retrieved January 29, 2024, from https://allecijfers.nl/ gemeente/amsterdam/

Statistika. (n.d.). Stratēģijas Uzraudzības Sistēma. Retrieved February 23, 2024, from http://www.sus.lv/statistika

Transportlīdzekļu sadalījums pa pilsētām un novadiem. (n.d.). CSDD. Retrieved March 7, 2024, from https://www.csdd.lv/ transportlidzekli/transportlidzeklu-sadalijums-pa-pilsetam-unnovadiem

City of Helsinki Environmental Report 2023. (n.d.). City of Helsinki, Urban Environment Division. https://www.hel.fi/static/ kanslia/Julkaisut/2024/ymparistoraportti-2023-en.pdf

Oficiālas statistikas portāls. (n.d.). Latvijas Oficiāla Statistika. https:// stat.gov.lv/lv

Rīga skaitļos. (n.d.). Rīgas Dome. https://www.riga.lv/lv/riga-skaitlos

Latvian historical maps: Dodies.lv vēsture. (n.d.). Dodies.lv. https://vesture.dodies. lv/#m=12/56.93439/24.12460&l=J

Latvijas vēsturiskas kartes. (n.d.). Latvijas Nacionālā Bibliotēka. https://kartes.lndb.lv/

DATA for maps

Ģeotelpiskās informācijas tehnoloģijas. (n.d.). LVM GEO. https:// www.lvmgeo.lv/

Plānoti būvdarbi. (n.d.). Būvniecības Informācijas Sistēma. https://bis.gov.lv/bisp/lv/planned_constructions/ bismap#x=24.392053&y=56.912234&z=8

Rīgas valstspilsētas pašvaldības datu publicēšanas portāls. (n.d.). GEO RĪGA. https://georiga.eu/

The 3D datal used in the illustrations and maps is titled Riga Buildings LOD1, created by the Riga City Municipality (© Riga City Municipality, 2023).

1. EMBRACING QUALITIES OF RIGA AND IT’S MICRORAYONS

2. CONTRIBUTING TO THE CLIMATE POISITIVE RIGA

3. ADAPTING TO THE REALITY

A big thank you to my friends for contributing to this booklet with their photos. Photo credits go to:

- Agnese Kalvīte (photos on page 58 top photo, page 192)

- Viesturs Krūmiņliepa (photos on page 58- bottom photo, page 64)

Your support and help compelemented my research about microrayons.

I am deeply grateful to everyone who has helped me bring this graduation project to life.

A heartfelt thank you to my mentor, Martin Probst. I have learned a lot from your expertise and support.

I also want to express my sincere appreciation to my committee members Johan de Wachter and Māra Liepa-Zemeša Your feedback, advice, and encouragement throughout this process have been incredibly valuable.

Special thanks to my Academy buddies. Your insights, feedback have been helpful during the garduation process. I will cherish the times we spent working together and the memories we’ve created.

I want to express my gratitude to the residents of Riga’s microrayons who generously shared their experiences and perspectives on microrayons. Your willingness to participate and spread the word about my project has added value to my research.

And lastly, I want to thank my partner and my family for their support and encouragement.

This project would not have been possible without the collective support of all these wonderful individuals. Thank you for being a part of this journey.

This document and its contents cannot be published, reproduced, or distributed without the author’s explicit permission © Marija Satibaldijeva, 2024.