Contents

HARVEY MILLER PUBLISHERS

An imprint of Brepols Publishers London / Turnhout

www.harveymillerpublishers.com

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

Copyright © 2023, Harvey Miller Publishers

isbn 978-1-909400-98-6 D /2023/0095/215

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from Harvey Miller Publishers.

Designed by Paul van Calster

Printed and bound in the EU on acid-free paper

Note to the reader

All translations are by the author unless otherwise noted. The references at the end of certain captions (P., C., or G. followed by a number) refer respectively to the works of:

Terisio Pignatti and Filippo Pedrocco, Veronese. Milan 1995

Richard Cocke, Veronese’s Drawings. London, 1984

John Garton, The Portraiture of Paolo Veronese London and Turnhout, 2008

chapter 1

chapter 2

chapter 3

chapter 4

chapter 5

chapter 6

chapter 7

chapter 8

chapter 9

chapter 10

chapter 11

chapter 12

Author’s Preface 7

Editor’s Preface 9

Matters of Style 12

Verona Patria di Paolo 26

Triumph in Venice 58

Villeggiatura 98

Scenographic Structure and Theatrical Gesture 158

Famosi Conviti 148

Images of Cult and Devotion 176

Patrician Likeness 210

Delighting Gods: Myth and Allegory 232

Graphic Inventions 262

Venice Triumphant 280

A Darker Vision 310

Epilogue 346

Bibliography 350

Index 371

Photograph Credits ••375

Preface !1

More than forty years ago I first projected a book on the art of Paolo Veronese. As a young art historian, I believed the painter needed to be rescued from the reputation he had long enjoyed as a magnificent decorator, a master of chromatic elegance and spectacular surface—in short, an artist of essentially superficial appeal. I felt that such appreciation of his talent as a painter had obscured the full nature of his achievement, the intimate union of form and content in his art, that it failed to recognize the depth and range of his pictorial intelligence. Since then, however, much study has been devoted to Veronese, exploring many aspects of his art and demonstrating its deeper content. Fortunately, then, my procrastination has enabled me to draw upon the results of that scholarship. Still, while we have learned much about the artist and his art, from iconography and technique to patronage and reception, questions remain. It is odd, for example, just how much disagreement exists regarding the dating of Veronese’s paintings, those without explicit documentation, how critical evaluation of his style can lead to such disparate conclusions regarding chronology. Moreover, Veronese was the master of an active workshop, and the extent of the participation of assistants in the execution of many canvases continues to challenge the connoisseur, even as the distinctive hands of assistants in the family bottega may have become somewhat more clearly identifiable. I do not pretend to offer definitive answers to these questions; indeed, the continuing challenge of establishing a clear chronology might testify to a certain stylistic consistency over the several decades of Veronese’s career, and the aim of the studio enterprise was, of course, to produce paintings that could convincingly carry the signature of the master. I have not entirely avoided confronting these issues, but I did not want such problems of connoisseurship to dominate my exploration and presentation of the artist and the inventiveness of his brush.

Despite the contributions of recent scholarship, despite the more precise understanding of his technical virtuosity, Veronese continues to be treated as the last member of the great triumvirate of Venetian painters of the Cinquecento; he tends to be considered less psychologically profound than Titian (a generation older), less radically adventurous than Tintoretto (a decade his senior). A more focused critical exploration of individual paintings by the junior member of this trio opens a richer vision of his achievement, illuminating his pictorial intelligence. Veronese reveals himself as a more profound and imaginative painter than has generally been assumed, as genuinely sensitive and creatively responsive to the subjects he was painting. I have, therefore, organized my discussion thematically, even as the larger structure of the book seeks to present a sense of the overall development of his art and career. In the pages that follow I spend much time with individual pictures; this means, inevitably, that others are not included, though my discussion covers the full range of Veronese’s achievement. Rather than trying to fit the paintings I do discuss into a smoothly sequential narration of artistic production, I explore them in some depth, follow the imagination of the artist in staging a dramatic encounter, articulating a doctrine, creating an affect. Reading a biblical or a mythological event with Veronese reminds us of just how responsive he was to his subjects and their potential for pictorial expression.

Any new study of the art of Veronese is possible only by building upon the contributions of earlier generations of scholars, and I am keenly aware of my debt to those predecessors. Modern scholarship on the artist begins, appropriately, in 1888, the tricentennial of his death, with the publication of the study by Pietro Caliari, a distant namesake. In the early twentieth century, knowledge of Veronese secured new foundations through the work of Detlev von Hadeln, who further clarified the corpus and documentation of the career, especially through his critical edition of Carlo Ridolfi’s Maraviglie dell’arte with its biography of the artist (1914). In 1928, another centenary year, Giuseppe Fiocco published the first fully

7

Paolo Veronese. The Apotheosis of Venice (detail), 1579–82. Oil on canvas, 904 × 580 cm. Palazzo Ducale, Venice (P. 295)

Verona Patria di Paolo !1

Even as it is true that the city of Verona, for its site, customs, and other ways, is very similar to Florence, so it is true that, as in that city, there have always flourished the finest talents in all the most refined and honorable professions . . . the men of our arts, who have always enjoyed an honored place in this most noble city.

—Giorgio Vasari1

Born in Verona in 1528, Paolo was first trained in the craft of his father, a stone cutter. That training, according to Ridolfi, included modeling in clay.2 The archives of Verona reveal that on 16 April 1541, at the age of twelve or thirteen, he was already listed as depentor (painter). Yet, twelve years later, in the first extant professional document in which he is recorded, dated 1553, he still signed himself Paullo spezap[re]da 3

Verona is situated at the foothills of the Italian Alps on the river Adige, overlooking the rich agricultural plain of the Po Valley. The city enjoyed a strategic position in northern Italy, between Venice and Milan and on the route over the Alps to the Germanic north, making it a natural hub of commerce. Boasting Etruscan origins, its subsequent Roman foundations were proudly affirmed by the most significant surviving ancient architectural structures in Italy outside Rome itself; its Romanesque churches testify to the grandeur of the medieval commune, and the legacy of the Scaligieri lords is preserved in their proud Gothic monuments. By 1405 Verona had become part of the expanding terraferma domain of the Republic of Venice, and Venetian political domination had inevitable cultural consequences. For the young Paolo, Venetian presence would have been pictorially reinforced by the recent example of Titian’s Assumption of the Virgin, of about 1530, in the Duomo. However, Verona’s proximity to the courtly center of Mantua as well as to the Lombard cities of Brescia and Bergamo and to Emilian Parma played an equally significant role in the development of its visual culture, architectural and pictorial. From Mantua, the dominant

figure of Giulio Romano (ca. 1492–1546) put his stamp on art in Verona. Giulio designed the cartoons for the frescoes that illusionistically open the choir of the Duomo; these were executed by Francesco Torbido (1486–1562), who signed the work in 1534 (Fig. 2.2).

Immediately following these decorations came the great tornacoro of Michele Sanmicheli (1484–1559), the open semicircular choir screen that so gracefully redefines and dominates the space of the cathedral (Fig. 2.3). The project was part of the ambitious program of renovation initiated by Bishop Gian Matteo Giberti, a leading figure of the Catholic reform.4 Sanmicheli was born in Verona, the son of an architect; he went to Rome at age sixteen, according to Vasari, to further his study of architecture, both ancient and modern.5 Following a successful career in central Italy— particularly in Orvieto, where he was appointed capomaestro of the cathedral—he returned to his native city by 1527 to become the commanding figure of its artistic community.6 Vasari appends to his biography of the architect brief notices on the contemporary painters of Verona, including “un Paulino pittore,” whom Sanmicheli “loved as a son,”7 attesting to Sanmicheli’s position there.

Un Paulino Pittore

The young painter’s career may well have begun under the architect’s guidance at the palace of Count Lodovico di Canossa, which Sanmichele designed (1530–37). In this building the vaulted ceilings of two small rectangular rooms, articulated by rich stucco framework by Bartolommeo Ridolfi, feature frescoes the attribution of which has been debated.8 At the center of one ceiling was a representation of the Abduction of Ganymede, while the other featured as its central image Moses Receiving the Tablets of the Law, though heavy repainting has rendered it difficult to

27

chapter 2

Fig. 2.1 Paolo Veronese. Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine (detail), 1548–49. Oil on canvas, 58 × 91 cm. Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven (P. 11)

evaluate.9 The two images, each in its heavenly setting, may have been intended as thematic complements of the pagan and the biblical. The surrounding fields and roundels are filled with landscape scenes and architectural views; the figural components of the central scenes feature reclining pagan deities in one room and Old Testament narratives in the other, possibly scenes from the story of Joseph.10

These frescoes are painted with a certain confidence and fluidity, which, considering his subsequent development, makes an attribution to the young Paolo convincing, at least for the most impressive of the compartments. The project is generally dated about 1545, when he would have been in his teens, having only just completed his apprenticeship.11 Consequently, their attribution to Paolo has not been universally accepted, and there does seem to have been more than one brush at work—the name of Battista del Moro (1514–1573/75) being a most frequently cited alternative or that of Domenico Brusasorci (1515–1567).

The fluid brushwork of those landscapes, a quality encouraged by the fresco medium, will develop into a particular hallmark of Paolo’s art, in the controlled bravura

28 chapter 2

Fig. 2.2 Francesco Torbido and Giulio Romano. The Assumption of the Virgin, 1534. Fresco. Apse, Verona Cathedral

Fig. 2.3 Michele Sanmicheli. Tornacoro: Choir, Verona Cathedral, 1534

of his mature frescoes. The inflected ductus of his stroke is a quality epitomized in the liquid white heightening of his chiaroscuro drawings of which Nature Deities in a Landscape (Fig. 2.4) is an early example. The drawing relates in both subject matter and touch to the Palazzo Canossa frescoes. The young Paolo reveals a distinctive stylistic precocity: the flow of the brush, its quick sure touch, with its varied weight and density of white, its reflexive sensitivity to its own movement as well as to its mimetic responsibility—these are the qualities that declare the style of Paolo Veronese.12

Vasari, in the earliest published account we have of the painter, writes that Paolo studied with Giovanni Caroto (1488–1566).13 Subsequently, both Raffaello Borghini’s and Carlo Ridolfi’s biographies of Veronese name Antonio Badile (1518–1560) as his first master.14 An apprenticeship with Badile is documented: an archival register of 2 May 1541 records in Badile’s household “Paulus ejus discipulus seu garzonus,” age fourteen.15 And in 1566 Paolo, well

established in Venice, will return to Verona to marry Badile’s daughter Elena. Despite such evidence, however, Vasari’s testimony must be taken seriously. Giovanni Caroto was an important figure in the artistic culture of Verona during Paolo’s years of training. Perhaps as relevant to the formation of the young artist was Caroto’s activity as an archaeological draftsman. His illustrations of the antiquities of Verona were published in 1540 in Torello Saraina’s De origine et amplitudine civitatis Veronae. Caroto continued to work on the graphic reconstruction of Verona’s ancient Roman monuments; his images were published independently in 1560 as Le antichità di Verona. Vasari’s testimony, then, allows us to consider Caroto as a possible master in the archaeological education of the young painter, complementing Sanmicheli’s role in his architectural education.16

Ridolfi opens his account of Paolo’s career as a painter citing his first works in Verona as an altarpiece in the church

of San Fermo and a canvas in San Bernardino. The latter, a representation of The Revival of the Daughter of Jairus, was surreptitiously sold by the Franciscan friars at the end of the seventeenth century and disappeared into Austria; its composition is known through the poor copy by which it was replaced and, more important, by Paolo’s own modello, an oil sketch on paper (Fig. 2.5). Significantly, the painting was situated in the Avanzi Chapel of San Bernardino opposite a Raising of Lazarus by Badile, signed and dated 1546, and it is possible that Paolo assisted with this work: the boys in the upper left landscape of the composition are rendered with a lighter and more fluid touch than one would expect of Badile (Fig. 2.6).17 The chapel had been constructed in the late fifteenth century; its pictorial decoration, initiated shortly thereafter and continuing through the first decades of the sixteenth century, was completed with the canvases by Badile and his young pupil. Their paintings were located on the walls flanking the chapel’s entrance. Paolo’s composition acknowledges its position just to the right of the entrance and the resulting oblique approach of the viewer. The répoussoir figure of John, seen from the back, enters from the right, leading the

30 31 verona patria D i paolo chapter 2

Fig. 2.4 Paolo Veronese. Nature Deities in a Landscape, 1545–49. Pen and brown ink, gouache, black chalk on paper, 42 × 56 cm. Private collection

Fig. 2.6 Antonio Badile. The Raising of Lazarus (detail), 1546. Oil on canvas, 220 × 230 cm. San Bernardino, Verona

Fig. 2.7 Michele Sanmicheli. Pellegrini Chapel. San Bernardino, Verona

Fig. 2.5 Paolo Veronese. The Revival of the Daughter of Jairus, 1546. Oil on paper, 42 × 37 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris (P. 1)

viewer into the scene. His focused entry is reinforced by the profile of James at the extreme right and by the witnessing woman above him. At the core of the scene is the healing gesture: Jesus “took her by the hand, and the maid arose” (Matthew 9 : 25; Luke 9 : 54; Mark 5 : 41). Jairus, a leader of the synagogue, responds to the miracle as does Peter, who turns to the approaching John in a gesture that will become standard in Paolo’s mature work. The graceful movement of figures and drapery and the delicate physiognomies suggest the young painter’s early awareness of the art of Parmigianino. It is a grace that is both marked and carried by the easy yet studied flow of Paolo’s brush; in the absence of the final canvas, we can only imagine how that painterly sensibility was translated to a larger, more public scale.

The composition of The Revival of the Daughter of Jairus further announces the predilection for asymmetrical structure that will continue to mark Paolo’s work: the closed intimacy of the setting on the right shifts abruptly to an open courtyard, with the lamenting figures expelled by Jesus from the bedroom. This space is defined by a monumental archway crowned by a balustrade with figures silhouetted against a bright blue sky streaked with white clouds; the architecture reflects that of Sanmicheli—for example, the classical brightness of his Pellegrini Chapel, then under construction in San Bernardino (Fig. 2.7).

Paolo’s attention to architecture is manifest in the setting of a small canvas of Esther Being Led to Ahasuerus (Fig. 2.8), part of a group representing the story of Esther, probably intended as spalliere—that is, furniture decoration (Figs. 2.9, 2.10).18 Inspired by a part of Verona that had been renovated by Sanmicheli, the young painter created the kind of monumental, classicizing scenography that was to become a hallmark of his narrative art.19 These paintings share the same high-key palette of The Revival of the Daughter of Jairus and, appropriate to their size, brilliantly fragmented brushwork. In movement and gesture as well as in their blocking, the figures in these compositions reveal the artist’s instinctive sense of staging from the beginning of his career, framing choral figures, courtly encounters, and the diagonal tree as a rhythmic participant.

The First Altarpieces

The first work by Paolo mentioned by Ridolfi is an altarpiece of the Virgin and Child enthroned with two saints, completed by 1548 (Fig. 2.11). Created for a Bevilacqua-Lazise family chapel in the Church of San Fermo, which was begun in 1544, the painting represents an ambitious variation on the traditional sacra conversazione Within its layered architecture, the Virgin and Child are set upon a high ledge against a swath of green curtain and accompanied by angels making music. A level below them are Saint John the Baptist and a bishop saint, probably Augustine,20 who present the two donors, Giovanni Bevilacqua-Lazise and his wife, Lucrezia Malaspina. Both are portrayed in profile, in prayer, their bodies truncated by the lower frame; as mortals, they exist in the lowest realm, not quite sharing the higher sacred space. It was conventional to depict donors in profile, a view that accorded an appropriately monumental permanence; placing them in abisso, with its implicit hope for elevation, was a particularly popular formula in earlier Renaissance painting, particularly in Verona.21

The canvas of the Bevilacqua-Lazise Altarpiece has suffered from some abrasion and repainting, which has flattened the surface articulation and deprived the painting of its full chromatic and tonal impact, leading some modern critics to question its attribution to the young Veronese. The wellpreserved costume of Saint Augustine, however, offers an impressive demonstration of constructive brushwork, a varying touch that clearly belongs to Paolo. His development of the composition can be followed through two preparatory modelli: an elaborately executed drawing (Fig. 2.12) and an oil sketch on paper (Fig. 2.13), which were surely preceded by preliminary sketches and more focused figure studies. In the development of the final canvas, the donor portraits were modified, as the couple seems to have aged—his beard lengthening and graying, she losing her elegant Parmigianino profile. The parrot, a Marian symbol, was added at the base of the column.22 Particularly significant changes occurred in the two saints: the bishop saint is beardless in the preparatory stages, his growth of beard possibly suggesting a new identity (from Saint Louis of Toulouse?), and the position of the Baptist’s arm, with its rhetorical gesture of indication, has been lowered to grasp his cross—this pentimento is still visible on the surface. The shift adds a spatial dynamic to the Baptist’s pose, which now works in more effective counterpoint to the spatial gesture of Saint Augustine. So, too, has the spatial relation of the latter’s book to the extended leg of the Baptist been clarified, for the shadow it once more clearly cast across that leg modulates the sharper chiaroscuro contrast on the book itself.23

Paolo set this balanced figural triangle within an aggressively asymmetrical, and not immediately coherent,

32 33 verona patria D i paolo chapter 2

Fig. 2.8 Paolo Veronese. Esther Being Led to Ahasuerus, ca. 1546. Oil on canvas, 26 × 31 cm. Museo di Castelvecchio, Verona (P. 5)

Fig. 2.10 Paolo Veronese. Ahasuerus Proclaims the Triumph of Mordechai, 1546. Oil on canvas, 24 × 29 cm. Museo di Castelvecchio, Verona (P. 6)

Fig. 2.9 Paolo Veronese. Punishment of the Eunuchs, 1546. Oil on canvas, 26 × 31 cm. Museo di Castelvecchio, Verona (P. 4)

34 35 verona patria D i paolo

Fig. 2.11 Paolo Veronese. Bevilacqua-Lazise Altarpiece, 1548. Oil on canvas, 223 × 172 cm. Museo di Castelvecchio, Verona (P. 8)

Fig. 2.12 Paolo Veronese. Preparatory drawing for Bevilacqua-Lazise Altarpiece. Pen and brown ink, wash, heightened with white, 31 × 23 cm. Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth (C. 165)

Fig. 2.13 Paolo Veronese. Modello for Bevilacqua-Lazise Altarpiece. Oil on paper laid on canvas, 50 × 36 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence (P. 7)

Villeggiatura !1

Seeing how much your return is delayed . . . I am anxious to know just where you are and what so occupies your mind that it has totally forgotten Venice and me; I can only assume that you are finding sweet and delightful amusement in your pleasant gardens and in that beautiful and divine fountain, created by you with such marvelous invention and art, than which, I dare say, there is none more fair and delightful, so that the Muses, taken by such beauty and delightfulness, have made of it a new Paradise.

—Giulia da Ponte to Daniel Barbaro1

In addition to major commissions from church and state, Veronese enjoyed the private patronage of prominent Venetians—nobles of political and cultural influence. Vasari records his activity as a decorator of palace façades, praising his frescoes but lamenting that they were already—in 1566, the year of his own return to Venice—in ruinous state owing to the humidity of the Venetian climate.2 Indeed, little has survived of what had been an important genre of painting in Venice. Fresco, which involves painting directly on wet plaster, is quite durable if the plaster dries properly and remains dry. In a city built upon water, however, it was a less than ideal medium, and, from the late fifteenth century on, fresco was being replaced by canvas for interior mural decorations, most prominently in the Sala del Maggior Consiglio of the Palazzo Ducale. Early in his career Veronese had mastered fresco painting, possibly first in Palazzo Canossa in Verona then in Palazzo Porto in Vicenza and at La Soranza (Figs. 2.33, 2.34, 2.36). Marveling at how much the painter achieved in so short a time, Ridolfi especially appreciated Paolo’s work in a medium that required facility and an infallible brush, praising his ability to render a finished figure in just a few stokes.3

Murano: Palazzo Trevisan

As a frescante Veronese continued to explore the Olympian realm, the pagan deities Renaissance culture had called upon to personify and allegorize the range of human virtue and to populate the ceilings of domestic saloni. Although Ridolfi writes that Palazzo Trevisan on Murano, in the lagoon just north of Venice, was based on a model by Daniele Barbaro, it has also occasionally been attributed to Sanmicheli.4 If that were the case, Sanmicheli may have again played a determining role in Paolo’s career, encouraging his involvement in the project.5 Built for Camillo Trevisan, a prominent lawyer celebrated for his oratorical eloquence, it was completed by 1557. Long neglected and now dilapidated, this palazzo suburbano with its gardens was conceived as a retreat, a place for cultural gatherings away from the negotium of the city. Francesco Sansovino praises Murano as among “le delitie di questa città” and the Trevisan palace as “truly royal, with a garden and a Roman fountain of extreme beauty.”6 The building was decorated with sculptural reliefs by Alessandro Vittoria (1525–1608) and frescoes by a team of painters from Verona, including Giovanni Battista Zelotti (1526–1578), Bernardino India (1528–1590), Battista del Moro (1514–1575), and Paolo. The vault of a room on the ground floor, removed in the early nineteenth century, was described by Ridolfi as “il Cielo degli Dei con fanciullini volanti” (Figs. 4.2, 4.3).7

The articulation of the vaults and the walls, especially on the piano nobile, follows the models of Roman antiquity in its fictive architectural framework and its painted grotteschi and landscape views. The gods

99 chapter 4

perched on

Fig. 4.1 Paolo Veronese. Portrait of Daniele Barbaro, ca. 1560–65. Oil on canvas, 121 × 105.5 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (P. 175)

ledges and set against the backdrop of the heavens belong to the figural world Veronese had recently created on the ceiling canvases of the Council of Ten; so, too, did the frieze (now lost) of allegorical figures interpreted by Ridolfi as personifications of Music, Study, Astrology, and Fortune.8 The biographer’s extensive detailed description of the Trevisan decorations makes their loss all the more poignant.

In Palazzo Trevisan, the design of the architectural framework containing the gods belonged to Paolo. Rather than inheriting an already fabricated ceiling, predetermining the fields to receive paintings on canvas, he was confronted by a literal carte blanche, white plaster surfaces awaiting pictorial articulation. Structural guidelines were, of course, provided by the architecture itself—the shape of vaults, the location and rhythm of doors

and windows. Ridolfi’s account of Veronese as frescante opens with praise for his facility with the brush. In his subsequent description of the Palazzo Trevisan decorations, he moves from celebrating the grace and love embodied in a Venus painted by Veronese to an admission of the failure of words to describe the forms of his brush, the strokes and colors of which vanquish the pen and embarrass ink.9 If we now must try to reimagine the quality of Paolo’s brushwork through the ruinous state of the Trevisan frescoes, we can follow the fluidity of his creative process in the drawings preliminary to the project (Fig. 4.4).10 Even as the Olympian figures are set down with searching but knowing strokes of the pen, with the application of wash they merge with and emerge from a surrounding atmosphere; the brush not only extends form into space, it also plays a crucial role in fleshing out the rapidly sketched body.

101 villeggiatura

Fig. 4.4 Paolo Veronese. Studies for Bacchus, Apollo, and Other Figures. Pen and brown wash, 17.4 × 15.4 cm. Pierpont Morgan Library, New York (C. 10)

Fig. 4.2 Paolo Veronese. Venus, Saturn, and Mercury, ca. 1557. Fresco transferred to canvas, 350 × 265 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris (P. 76)

chapter 4

Fig. 4.3 Paolo Veronese. Jupiter, Apollo, Diana, and Mars, ca. 1557. Fresco transferred to canvas, 350 × 265 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris (P. 76)

Villa Barbaro at Maser

Shortly after he had rendered the Olympians on the vaults of Palazzo Trevisan, Paolo received an even greater opportunity to revive the world of antiquity at the Villa Barbaro at Maser, near Asolo in the Trevigiano (Fig. 4.5), designed by Andrea Palladio for the brothers Daniele and Marc’Antonio Barbaro. These Venetian patricians were active humanists, engaged in the arts as well as in service to the Republic (Figs. 4.1, 4.6). During his distinguished career, Marc’Antonio (1518–1595) held several important ambassadorial appointments, to France and to the Ottoman capital; in Venice he served as a Procuratore di San Marco; as a member of the Riformatori allo Studio, the governmental body overseeing the renowned University of Padua; and as a Provveditore al Sale, the salt magistracy that was responsible for, among other things, the payment of artists working on state commissions, including the decorations of the Palazzo Ducale. Marc’Antonio was also

known as an amateur sculptor and may well have been responsible for some of the outdoor sculpture at Maser, especially the figures of the nymphaeum (Fig. 4.7).11 Daniele was, we recall, the inventor of the iconographic program for the new rooms of the Council of Ten, much of which was realized by Veronese, and Ridolfi’s crediting Daniele with the design of Palazzo Trevisan may more accurately be applied to the invention of its iconography. Having studied at the University of Padua, where he supervised the creation of the Orto dei Semplici, the botanical garden intended to serve the faculty of medicine, he subsequently served as one of the Riformatori allo Studio. As a man of letters, Daniele was the author of commentaries on porphyry and on Aristotle (completing his great-uncle Ermolao Barbaro’s project on the Rhetoric), of a dialogue on eloquence, a treatise on perspective, and, his most significant work, the translation of and commentary on the Ten Books of Architecture of Vitruvius, the only major text on the subject to come down from Roman antiquity and the very basis for the architectural culture of the Renaissance.12

102 103 villeggiatura chapter 4

Fig. 4.5 Andrea Palladio. Villa Barbaro, ca. 1554–58. Maser, The Veneto

Fig. 4.6 Attributed to Paolo Veronese. Portrait of Marc’Antonio Barbaro, ca. 1568–74. Oil on canvas, 112 × 100 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Delighting Gods: Myth and Allegory

The supreme gods have granted him the power to include in his works their own portraits, and thus every figure by Paolo partakes of the heavenly.

—Marco Boschini1

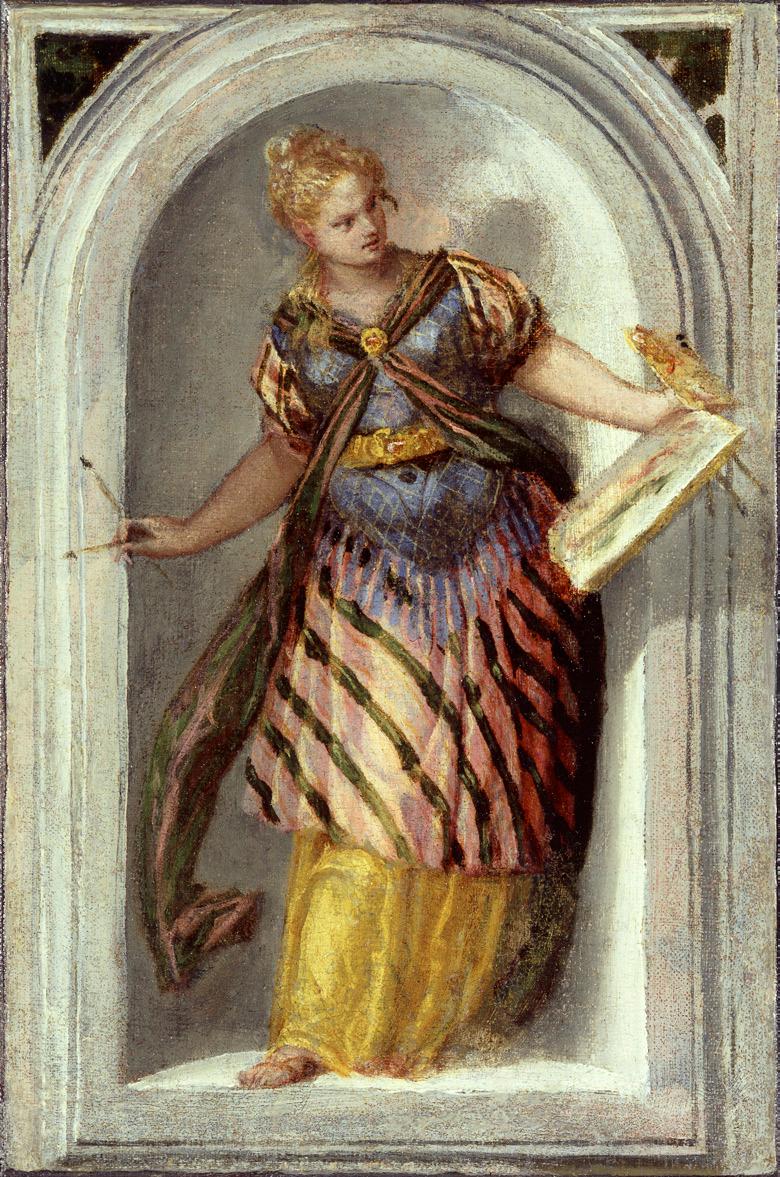

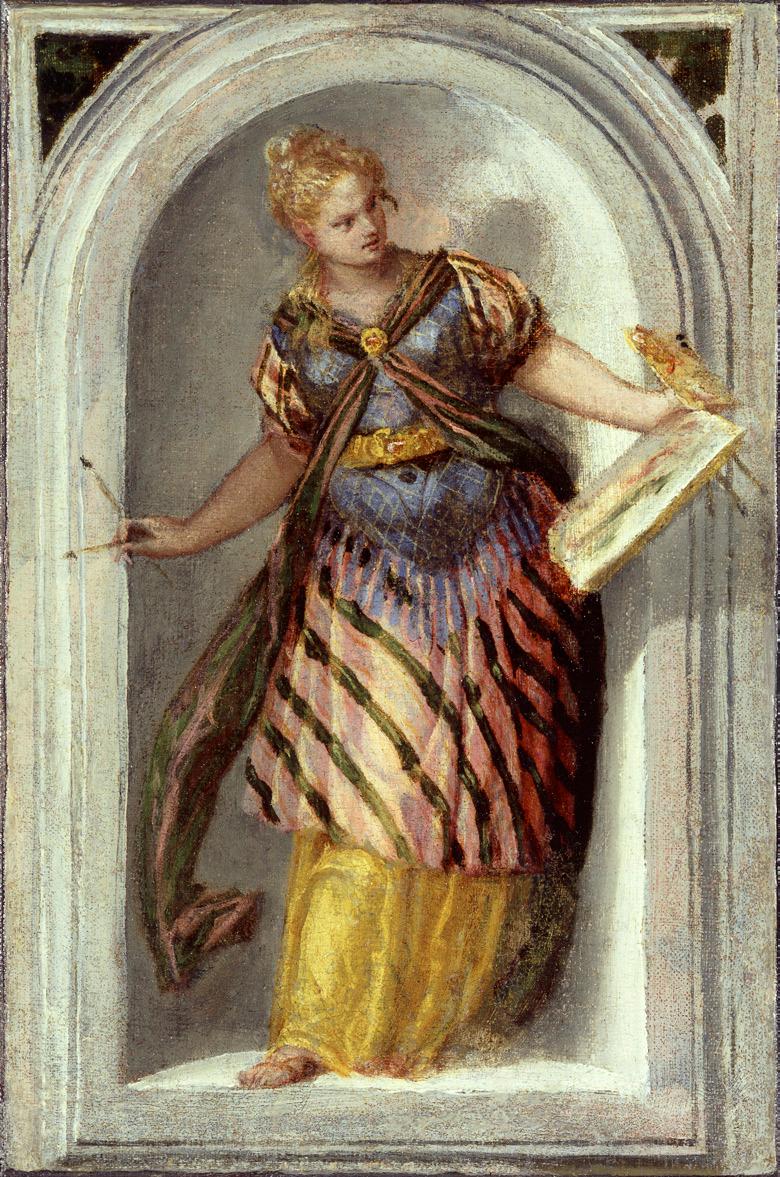

No other Venetian painter favored the ancient gods of Olympus as did Veronese, and no other painter was as favored by them. As Boschini has Mercury attest, “Venus herself cleans his brush, / And the God of Love grinds his colors.”2 Paolo figured them as tutelary deities of individual families on the frescoed vaults of villa (Soranzo, Barbaro) and palace (Trevisan); he invoked them on behalf of the state on the ceiling (cielo) of the Council of Ten and in subsequent celebrations of the Serenissima. On a less monumental, more intimate scale, he explored their stories in the context of domestic furnishings, spalliere, small pictures, usually in series, to be set into the framework of wall or furniture unit. Based on their format and their common provenance, such a set of at least five mythological pictures can be partially reconstructed. The subjects are described in a seventeenthcentury inventory of the Raggi collection in Genoa as Atalanta and Meleager (Fig. 9.2), Diana and Actaeon (Fig. 9.3), Jupiter and Io (Fig. 9.4), Council of the Gods (Fig. 9.5), and Rape of Europa (Fig. 9.6).3 The long horizontal format of these small canvases—they are described as bislonghi—suggests a particular predetermined framing context. Three additional canvases, of figures within niches, listed in the inventory as a group, presumably participated in the same set; each “with a figure of the Muses and Virtues” (con una figura delle Muse e Virtù), these represent both the ancient gods Diana (Fig. 9.7) and Minerva (Fig. 9.8) and an allegorical Muse of Painting (Fig. 9.9).4

Within the larger corpus of Veronese’s production, these pictures seem only relatively minor works of decorative art, and their uneven levels of execution implicate the work of the studio—with the name of Benedetto frequently cited. There is, however, a range of quality in their execution; among the best of them is

a passage from Diana and Acteon (Fig. 9.10) that exhibits a combination of freedom and control, a true sprezzatura of the brush that recalls the touch of the master fresco painter. That closeness in facture to the decorations at Maser suggests that these pictures probably date to the early 1560s, even as their landscape compositions recall what may be the young painter’s earliest efforts at Palazzo Canossa in Verona. Despite their modesty, the best of these paintings manifest the pictorial authority of Paolo himself and represent inventions that will be recalled in his later, more ambitious mythological narratives.

Telling Tales

In the field of mythological narrative, the great model and challenge had recently been set in Venice by Titian, in his poesie for Philip II, in which the old master engaged Ovidian poetics with the most creative originality. In the second of his canvases for the Spanish prince, shipped in 1554, Titian effectively reinvented the story of Venus and Adonis, depicting a scene of the mortal hunter departing from his beloved goddess (Fig. 9.11). This is not a moment in Ovid’s canonic telling of the tale, which is essentially idyllic, and for that supposed misreading the painter would suffer at least one public rebuke. Rather, Titian chose a moment of dramatic peripeteia. Poised between past and future, his pictorial fable carries a fundamental narrative momentum; proleptically tragic, it yields a more intense pathos than the poet’s pastoral version with the lovers resting in the shade of a tree. Ancient pictorial art, as recorded on sarcophagi, had already realized the dramatic resonance of the departure scene. Titian’s reinvention was broadcast in many copies, in paint and in print and in published literary description. His composition stood as a challenge to any painter confronting this mythological tale.5

Veronese responded knowingly to that challenge (Fig. 9.12). He read the pathos of the scene—the reluctant but ineluctable separation of lovers, the tragic fate of the young hunter going to his death—gored by the tusk of a boar—and he

233 chapter 9

!1

Fig. 9.1 Paolo Veronese. Adonis Asleep on the Lap of Venus (detail), ca. 1580–82. Oil on canvas, 162 × 190 cm. Museo del Prado, Madrid (P. 311)

235 D elighting go D s: myth an D allegory

Fig. 9.7 Paolo Veronese. Diana, 1560–65. Oil on canvas, 28 × 18 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg (P. 163)

Fig. 9.10 Paolo Veronese. Diana and Acteon (detail). Oil on canvas, 26 × 101 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (P. 159)

Fig. 9.8 Paolo Veronese. Minerva, 1560–65. Oil on canvas, 28 × 18 cm. Pushkin Museum, Moscow (P. 164)

Fig. 9.9 Paolo Veronese. The Muse of Painting, 1560–65. Oil on canvas, 28 × 18 cm. Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit (P. 162)

Fig. 9.2 Paolo Veronese. Atalanta and Meleager, 1560–65. Oil on canvas, 25.7 × 101 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (P. 158)

Fig. 9.3 Paolo Veronese. Diana and Actaeon, 1560–65. Oil on canvas, 26 × 101 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (P. 159)

Fig. 9.4 Paolo Veronese. Jupiter and Io, 1560–65. Oil on canvas, 27 × 101 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (P. 161)

Fig. 9.5 Paolo Veronese. Council of the Gods, 1560–65. Oil on canvas, 27.3 × 101 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (P. 160)

9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6

Fig. 9.6 Paolo Veronese. Rape of Europa, ca. 1560–65. Oil on canvas, 25 × 88 cm. Private collection (P. 166)

inflected each element of the drama to create his own variant. Reversing the narrative impulse to read from right to left—and this reversal can hardly be ascribed to his knowing Titian’s composition through engraved copies—he strengthened the tense pull of the leash, a lead to the inevitable fate of the departing lover. Titian’s sleeping Cupid has been awakened and assigned an active role: Love now struggles to obstruct the departure and forestall the death of the mortal hunter; the shadow falling across his face, another lesson from Titian’s dramatic art, foretells the impending doom. Paolo reorganized the dynamics of the central couple while maintaining the most appealing feature of the older painter’s composition: the dorsal view of the female nude, her buttocks spread upon a richly clothed couch—a motif celebrated in Lodovico Dolce’s description of Titian’s painting.6 Titian had conceived his Venus and Adonis during his stay in Rome, and the unusually insistent planarity of the composition was inspired by his study of relief sculpture. Veronese modified that determined march across the surface to a less urgent choreography; figural contrapposto here becomes more fully spatial—in the stride of Adonis and the turn of the body of Venus, which sets her left breast in revealing profile. The axis of exchanged glances is a powerful link in Titian’s painting; it operates as an invisible spoke in the rotation of the two bodies. Adonis’s lateral movement is further constrained by the diagonal tree trunks that frame his body, fixing his pivotal position at the center of the composition.

The younger painter’s approach to the ancient gods was lighter than Titian’s. If never quite as humorously irreverent as Tintoretto could be in treating the domestic trials of the Olympians (Fig. 9.13), Paolo could nevertheless appreciate the comedy inherent in the illicit affair of Mars and Venus (Fig. 9.14). In the brilliant little canvas in Turin, the lovers are set before the suggestively open curtains of the thalamus, their embrace having been interrupted by the sudden, and discordant, appearance of Mars’s doeeyed warhorse being led by Cupid improbably down the curving outdoor stairs. Off-balance, the frustrated lovers perform a pas-de-deux of intertwined limbs and conflicting directions; with her leg over the thigh of Mars, Venus enacts a well-established corporal rhetoric, the gesture itself understood as a sign of sexual possession.7

Paolo conceived a situation of mythological infidelity as an exquisite capriccio, an occasion for the demonstration of his art, of both his inventive and pictorial capabilities. The red and blue of the controlled palette establish the interior and exterior of the scene, and those basic hues are then modified in the pink and gray of the pavement, the purple and mauve of the bedclothes, the olive green of the sash and abandoned cuirass of Mars; areas of white further activate the field as cloud and drapery. The pink of the horse’s muzzle presents itself in chromatic relation to the flesh of Venus, her exposed breast and blushing cheek. It is remarkable just how studied this apparently casual concetto

proves to be, offering itself as a delight for the connoisseur of both paint and flesh.

Veronese was especially favored by Venus, as she confesses in Boschini’s Carta del navegar pitoresco: “When I wanted my portrait made, I turned to Paolo, who knew better than any how to imitate my charming features.”8 The goddess figures most prominently among his Olympian dramatis personae. Around her nude body Paolo explored the expressive potential of a cast of characters, working with the corporal combinations of female and male, of Venus and her lovers.

Returning to the subject of Mars and Venus later in his career, Veronese approached the couple with a new respect, a new maturity, in the painting Mars and Venus United by Love (Fig. 9.15). Elevating the extramarital dalliance beyond bedroom humor and according it a certain nobility, he constructs an image of greater anecdotal complexity. Here, the union is clearly of opposites, nude female and armored male, a concordia discors that invites interpretation beyond the narrative subject, which is set forth with directness and clarity. Such visual legibility is essential, for reading the image necessarily raises questions of further meaning. Whatever the awkwardness of their situation, Mars and Venus perform with choreographic grace; united by the entwining of their bodies, their union is assured by Cupid’s tying the knot that binds them; as in Paolo’s earlier Venus and Adonis, Cupid becomes an active player. The horse of Mars, traditional animal of passion and a reminder of the war god’s calling (but here, again, so gentle of mien), is bridled and tethered and symbolically restrained by a second Cupid; the little fellow uses the warrior god’s own sword, playing upon an ancient tradition of Cupids disarming military lovers. Dressed in leonine armor, his ram’s head helmet on the ground, the virile god of war is rendered obedient to the goddess of love, his hard strength yielding to her softness, his gesture of modestly covering her affirming the propriety of their union. Venus’s lactating breast, visually complemented by the flowing fountain, manifests her fecundity. Her abandoned white shift, evidence of her disrobing for the occasion, is balanced by a satyr atlas. This leering stone witness to the foreground activity, a favorite sculptural motif of Veronese’s, adds a note of lasciviousness; the lust of bestial passion, however rendered impotent by its own petrous materiality, contrasts with the warm licit love of generative union.

Despite the dramatic satisfaction and anecdotal incident of its presentation, both vertical format and figural design establish the modality of this picture as less narrative than allegorical. To make sense of the image, one need hardly invoke abstruse Neoplatonic doctrine—which, at any rate, had become readily popularized by the later sixteenth century—or imagine a complex iconographic program devised by some academic humanist advisor or learned patron. Painters, after all, knew the signifying possibilities of images better than anyone. There is something natural about Veronese’s pictorial construction of masculine

236 237 D elighting go D s: myth an D allegory chapter 9

Fig. 9.11 Titian. Venus and Adonis, ca. 1554. Oil on canvas, 183 × 199 cm. Museo del Prado, Madrid

Fig. 9.12 Paolo Veronese. Venus and Adonis, ca. 1562. Oil on canvas, 99.5 × 174.5 cm. Kunstammlungen & Museen, Augsburg (P. 136)