THE FIGURE AS SYMBOL

Woven throughout the Mandaean corpus, essentially a set of instructional documents for the training of priests, are references to a multitude of mythological cosmic beings. In the Canonical Prayerbook of the Mandaeans alone there is mention of over a hundred of these beings, all playing a role in the worlds of fall and redemption. Predominantly, these beings exist in the Lightworld, where one of their main functions is to support the soul’s journey towards redemption. Many of the key characters enacting this cosmic drama are reflected in the iconography of the illustrated scrolls. Closely associated with ritual practice, this imagery portrays worlds and beings that function symbolically in and between the two opposing realms of Light and Darkness. In the nine illustrated scrolls there are over seventy-five named Lightworld beings portrayed in a total of over one hundred and ninety individual representations.1 Only one scroll, Diwan Abatur, depicts beings that exist in the Darkworld, many of whom are female personalities engaged in a diverse range of interactions. More generally, when looking at all Mandaean figurative art, what is immediately and strikingly evident is a distinctive style that is integral to the function of the scrolls. This chapter introduces the subjects treated by Mandaean symbolic art, with specific attention to the major Lightworld male and female deities and their individual roles. The motif of the figure, in various forms, exists in all nine major illustrated scrolls and is central to the instructional function of these documents. Far from being an ‘add-on’, the iconography of the figure operates in close conjunction with the text to generate the scroll’s meaning, especially in relation to ritual practice. Additionally, these figurative images are crucial to the operational mode of the scrolls, each with its own specific purpose. Through the process of their representation, the key figures of the religion—each of which is reproduced in the scrolls at least once—establish a physical position within the vast complex of activity that constitutes the Mandaean supernatural cosmos. It is as if once rendered they are then imprinted on the minds of the scrolls’ priestly readers. To demonstrate

45

1

CHAPTER

Ptahil’s name and role as creator point to a noteworthy connection with the Egyptian creator god Ptah from Memphis. In The Book of the Dead, which dates to the second millennium bce, Ptah is described as the ‘creator of the heavens and the earth’, and also as the ‘arbiter of life and death’.18 Both Ptah and Ptahil are part of the play of the soul’s destiny after death.19 Although this connection is certainly not verifiable without detailed study, the concept of Ptahil as demiurge, importantly placed at the beginning of Diwan Abatur and chiefly involved in portraying the progress of the soul’s journey through various worlds of detention and purification, would seem to have been influenced by some comparable earlier mythology.

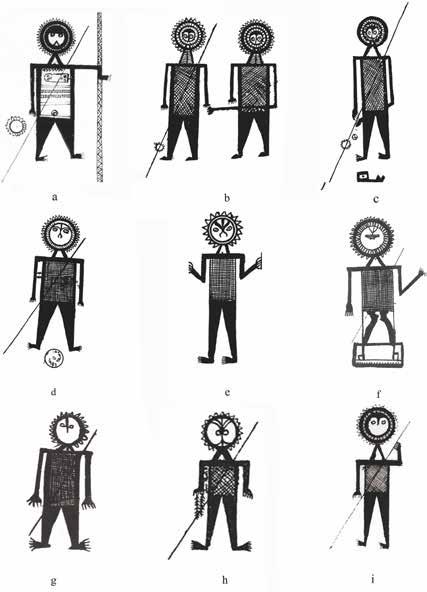

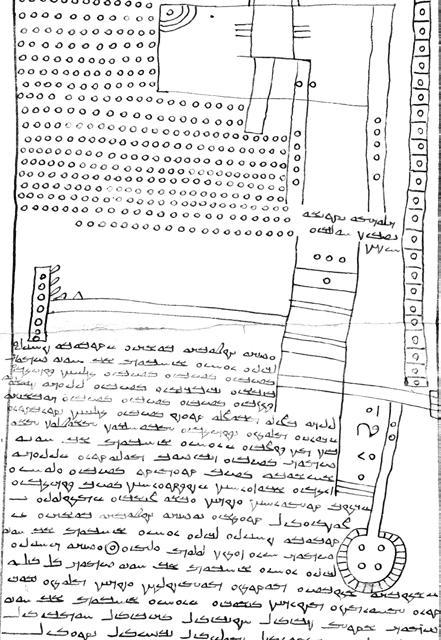

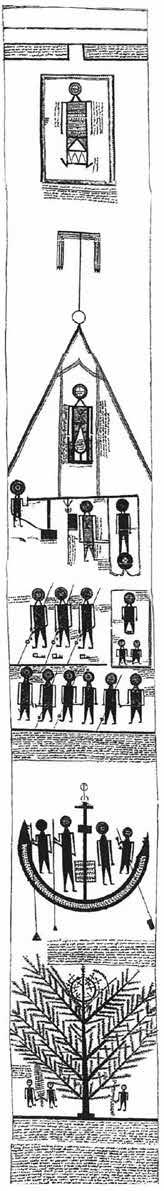

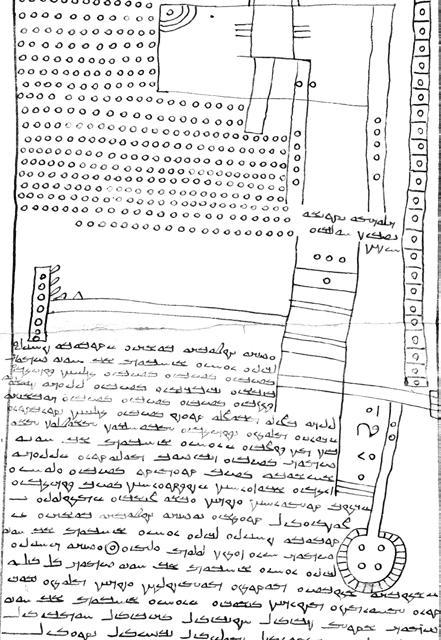

Fittingly, as the demiurge ruling over purgatory, Ptahil is the first image portrayed in the opening pictorial section of the Diwan Abatur scroll (DC 8). Here he is encased within his own world amongst various beings of the Lightworld20 who are set below him in this upper section of the scroll (fig. 1.1).21 All these beings are involved in one way or another in the successful redemption and rescue of the soul from the clutches of various elements of the Darkworld, pictorially segregated from the upper region as shown in fig. 1.1. The separate worlds depicted in this section are those of Ptahil, the Scales of Abatur, the Baptizers, the Ship of the Righteous, and the tree Šatrin that nourishes departing souls. Each of these realms or pictorially defined spaces has its own purpose and role in assisting the soul to enter the Scales of Abatur, to be weighed and judged as to her purity.

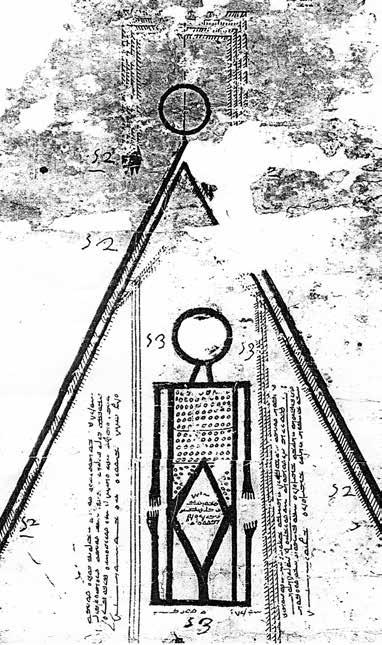

The first of these created worlds, shown in fig. 1.2, encases a portrait of Ptahil, who is described as the ‘son of Hibil-Ziwa, born of Zahriel’.22 His placement here positions him as paramount to the functions outlined in DA. Ptahil plays the role of creator of the material world and of the purgatories in which impure souls incur certain punishments. These purgatories are enclosed within the ‘land’ of Ptahil.23 One is under his direct jurisdiction while eleven others are overseen by key ’uthria who are described as sons of Ptahil and are all-powerful Lightworld beings.24 Additionally, as creator of this divine ‘order and dis-order’, he is responsible for fathering children by four major Mandaean female entities, including Simat-Hiia,25 chiefly associated with the Lightworld, and the personified spirit Ruha, primarily associated with the Darkworld and described in Mandaean mythology as giving birth to the seven planets and twelve signs of the Zodiac.26 The positioning of Ptahil’s image indicates his power. Placed alone at the beginning of the scroll, it stands out within an almost square surround containing what is described in the accompanying inscription as ‘sixty curtains’ of light called ‘Ptahil-Bihram’.27 Bihram is a major figure of Light whose addition to Ptahil’s name intensifies the light that is not shown but is implied. Here, the text and the illustration combine to produce an enhanced image of Ptahil the creator of the earthly world from whom emanate multiple curtains of radiant light. Aspects of his identity within the broader literature further inform the image. In a similar creation

48

Fig. 1.1

CHAPTER 1 . MANDAEAN SYMBOLIC ART

First section of Diwan Abatur. Oxford, University of Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Drower 8 (r).

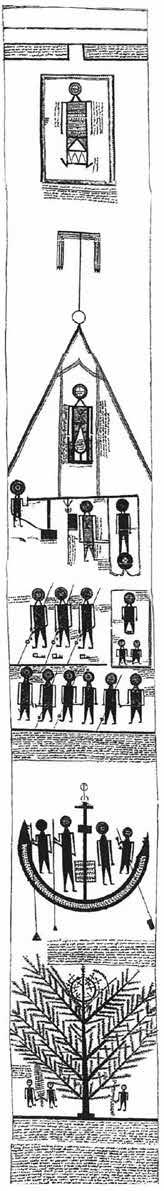

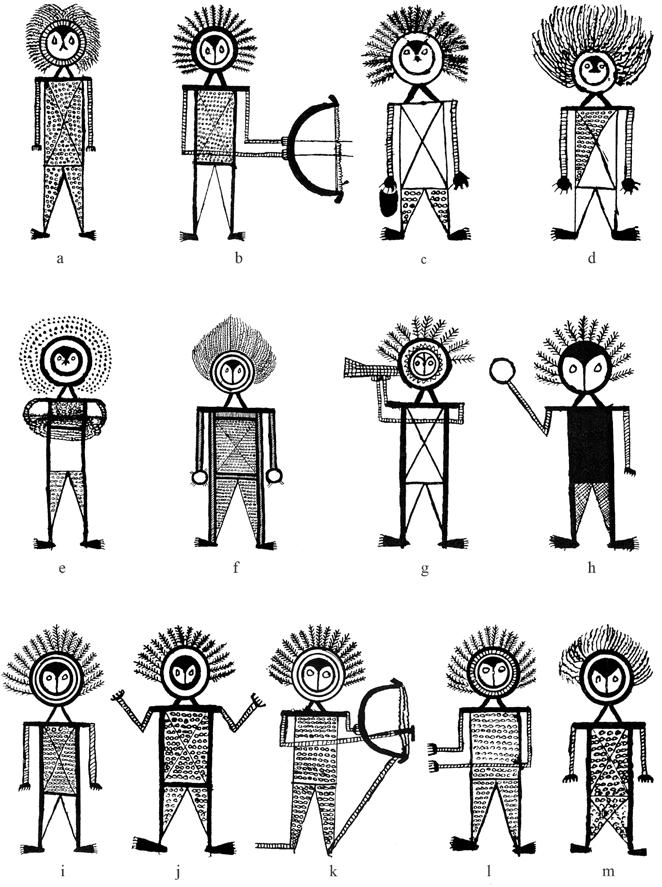

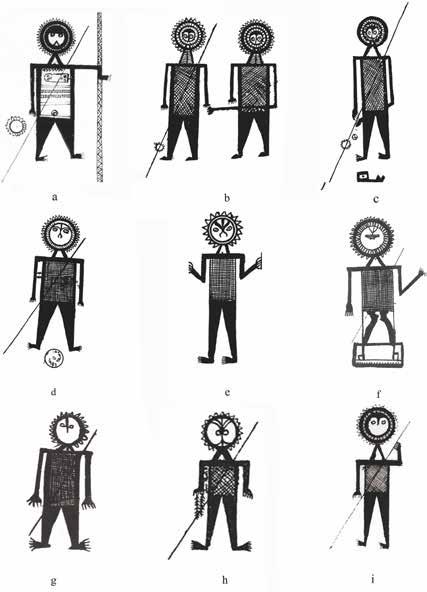

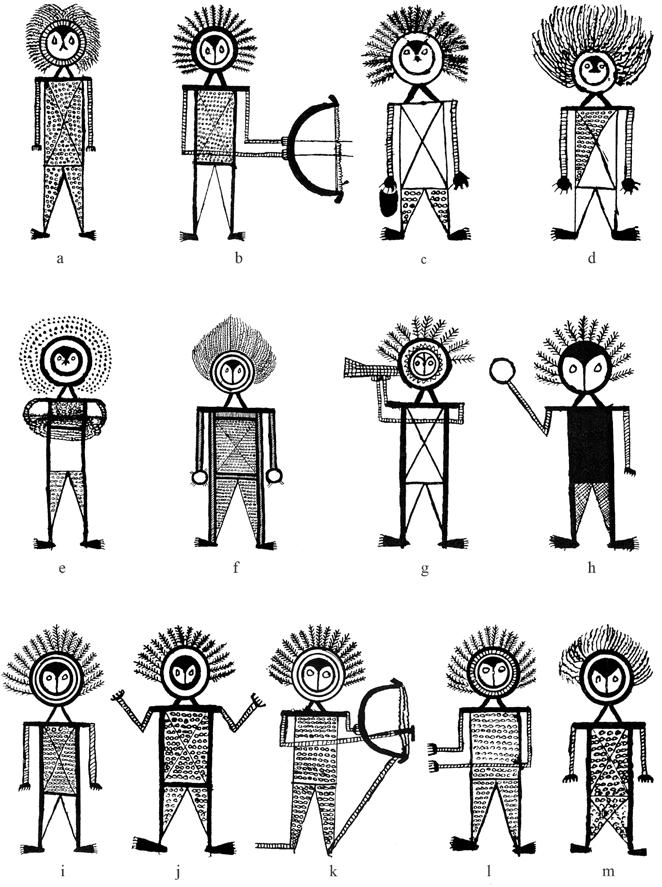

illustrative details, the accompanying inscription, and specific cultural and linguistic knowledge that provide the reader with the necessary information. In some instances, the inscription highlights the activity and gender directly, as in the case of the figure named Sahfiaiel who ‘carries a copper pail in his hand’ (fig. 1.3c).31 In other situations, however, it is only the activity that is described, the gender being implicit in the name, as with Zamriel (fig. 1.3g) who is described as ‘making music with song’.32 The word zamr‘il is defined as a ‘demon’ in MD, but the associated noun zamar (feminine, zamarta) means a ‘singer, musician or fornicator’, suggesting a seductive role in leading souls astray with her music.33

As these figures are all from the same scroll, it is evident that the original artist has thought carefully about individualizing them; the inscriptions, too, all assign a particular function to each character. The common feature

50

CHAPTER 1 . MANDAEAN SYMBOLIC ART

Fig. 1.3 Mandaean Darkworld figures, in details of Diwan Abatur. Oxford, University of Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Drower 8 (r).

a b c d e f g h i j k l m

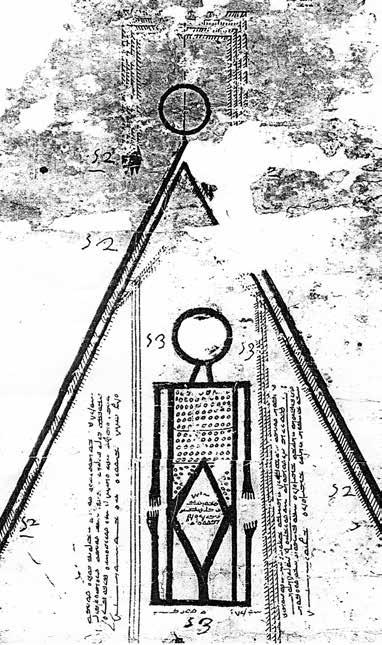

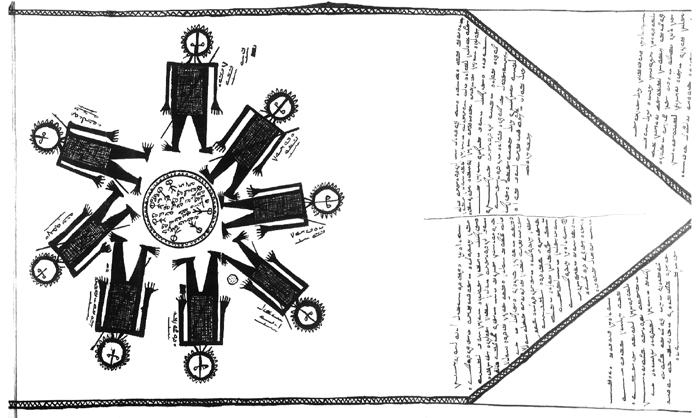

ance and light, the flag-like drabša46 (named here as Nbaṭ).47 The text states that ‘sixty banners like this are unfurled’,48 thus infusing the scene with abundant light to provide the soul with further protection.49 The figure on the far left is unnamed in DC 8, but in BS 175 there is an inscription next to the same figure with a name that is difficult to read. The Latin translation in the margin of the document, however, refers to this figure as ‘Gouran 2us ponderator animarum’ (second weigher of souls).50 In fig. 1.4a each of the figures at the scales has his own shape and placement, relevant to his specific role in assisting Abatur. The scales are represented without any regard for proportion, in keeping with their instructional function to indicate the precise nature and specific role of each figure, as well as to allow the introduction of additional elements such as light, gold, and strength into the region.51 Noticeably, each figure is unique in its shape, infill, and placement of arms. However, the heads are similar in design, with multiple, filled-in circles around the face serving to establish a singularity of purpose within the scales. The main body of Bihdad (centre) is filled in with circles, as also in the case of Abatur, Ptahil, and the figures mentioned in fig. 1.3. However, in contrast, Šitil and the figure on the far left have the standard crosshatching infill given to Lightworld figures in fig. 1.8a. This crosshatching appears to differentiate Šitil the ‘perfect soul’ and Gouran the ‘second weigher of souls’, identifying them as figures unique to

53

Fig. 1.4b Abatur, the Scales of Abatur, in a detail of Diwan Abatur. Città del Vaticano, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Borgiani Siriaci 175 (r).

THE FIGURE AS SYMBOL

Fig. 1.4c Section of a Mandaean ‘protection’ scroll. Oxford, University of Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Drower 43 (r).

66 CHAPTER 1 . MANDAEAN SYMBOLIC ART

Fig. 1.9a

Mandaean priests preparing for maṣbuta during the ritual burning of incense on the bank of the Nepean River, Penrith, Australia, 2009.

Fig. 1.9b

Lightworld figures, in a detail of Zihrun Raza Kasia. Oxford, University of Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Drower 27 (r).

Fig. 1.10 Priests forming a klila (myrtle wreath) for baptism during Parwanaiia, Nepean River, Penrith, Australia, 2011.

Fig. 1.10 Priests forming a klila (myrtle wreath) for baptism during Parwanaiia, Nepean River, Penrith, Australia, 2011.

CHAPTER 1 . MANDAEAN SYMBOLIC ART 12

Fig. 1.11 during Parwanaiia, Nepean River, Penrith, Australia, 2011.

Fig. 1.11. Priests ‘honouring’ their tagia (crowns) during Parwanaiia, Nepean River, Penrith, Australia, 2011.

12

Fig. 1.10. Priests forming klila for baptism, during Parwanaiia, Nepean River, Penrith, Australia, 2011.

Fig. 1.11. Priests ‘honouring’ their tagia (crowns) during Parwanaiia, Nepean River, Penrith, Australia, 2011.

Fig. 1.10. Priests forming klila for baptism, during Parwanaiia, Nepean River, Penrith, Australia, 2011.

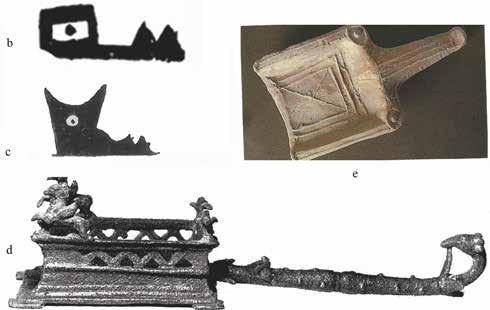

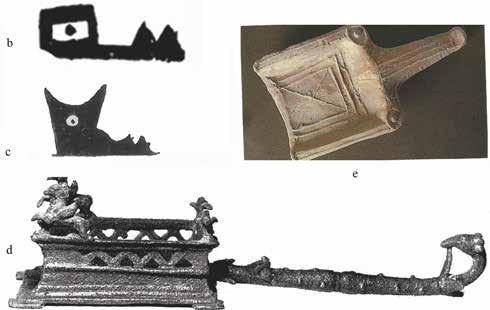

Mandaean incense apparatus of a brihi (clay fire-saucer) and qauqa (terra-cotta incense holder).

Incense brazier, from MS. Drower 8 (r) in a detail of fig. 1.8a.

Incense brazier, from Asiat. Misc. C. 12 (r) in a detail of fig. 1.25 (bottom left of object).

Bronze incense shovel. Dura-Europos, F3, c. 200-256 ce. New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery, Yale-French Excavations at Dura-Europos, 1933.634ab.

1.14b. Incense brazier, from MS. Drower 8 (r) in a detail of Fig. 1.8.

Fig. 1.14c. Incense, brazier from Asiat. Misc. C. 12 (r) in a detail of Fig. 1.25.

Fig. 1.14d. Bronze incense shovel. Dura-Europos, F3, c. 200–256 CE. New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery, Yale-French Excavations at Dura-Europos, 1933.634a-b.

the excavations at Sepphoris, Lower Galilee. From Ehud Netzer and Zeev Weiss, Zippori (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society), 1994, p. 11.

Fig. 1.14e. Ceramic incense shovel from the excavations at Sepphoris, Lower Galilee. From Ehud Netzer and Zeev Weiss, Zippori (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society), 1994, p. 11.

part of which is quoted below. In this prayer the incense pan is described as being used on the banks of the jordan for the ‘Dwelling of Abatur’ and the ‘dwelling of Hibil, Šitil and Anuš’.141 Importantly, it is described as being made of copper, an indication of its possible use in late antiquity or during the more stable historical moment at which the scroll was first composed:142

14

This saying, ‘Incense that is fragrant, yea for the First Life’, recite over the incense and sandalwood and put them before thee on the jordan-bank in a new incense pan. And make a fresh fire on the copper incense-pan.143

71

Fig. 1.14a

Fig. 1.14b

Fig. 1.14c

Fig. 1.14d

Fig. 1.14e

THE FIGURE AS SYMBOL 14

Ceramic incense shovel from the excavations at Sepphoris, Lower Galilee.

Fig. 1.14b. Incense brazier, from MS. Drower 8 (r) in a detail of Fig. 1.8.

Fig. 1.14c. Incense, brazier from Asiat. Misc. C. 12 (r) in a detail of Fig. 1.25.

Fig. 1.14d. Bronze incense shovel. Dura-Europos, F3, c. 200–256 CE. New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery, Yale-French Excavations at Dura-Europos, 1933.634a-b.

Fig. 1.14e. Ceramic incense shovel from

Fig.

b c d e d

Fig. 1.14a. Mandaean incense apparatus of a brihi (clay fire-saucer) and qauqa (terra-cotta incense holder).

Upon viewing the incense brazier from fig. 1.8a in a detail in fig. 1.14b, it is apparent that its pared-back outline gives it much in common visually (particularly in regard to the handle) with the bronze incense brazier in fig. 1.14d. This item, dating to at least 256/57 ce, is from the Mesopotamian town of Dura-Europos on the Middle Euphrates.144 A similar shovel design is evident in a simpler clay incense pan from Palestinian Sepphoris, shown in fig. 1.14e.145 The only other example of an incense brazier in the Mandaean scrolls is from MS. Asiat. Misc. C. 12 (fig. 1.14c, which shows a detail from fig. 1.25, below). It has a small dot in the centre and two small triangular protuberances at the end, as does the brazier in fig. 1.14b. The two triangles may represent the handle of a metal brazier (possibly copper) like that in fig. 1.14d. These two pictorial examples of incense braziers serve here to show how the drawings may illuminate past practices of the Mandaeans in relation to ritual implements. The three incense braziers that are associated with the three Lightworld figurative forms in the top section of fig. 1.8a indicate their use by these entities as an important part of the process of maṣbuta. They are, however, not shown in the lower section that illustrates a different part of the ceremony and different beings who nevertheless all function within the one overriding process.

ANUŠ, ŠITIL, AND ADAM IN THE JORDAN

The major Lightworld entities Anuš146 and Šitil,147 their father Adam, and the celestial figure Yadatan feature in the lower section of figs. 1.8a and 1.8b (the other two figures are unnamed). They are described in the accompanying text as:

baptizers who stand in the House of Abatur when the soul departeth; they drew it forth from the body and when they read masiqtas for it, those baptizers baptize them (the departed souls).148

The key pictorial elements that separate this section from the top section of fig. 1.8a are the head and neck decoration, the positioning of arms, and the division of the figures into three pairs, signalled by the joining of hands. The extra band of small, pointed shapes around their heads is the only instance in the scroll of this feature, and probably refers to the klila (myrtle wreath) worn by the priest during baptism. The same illustrative element is also present in fig. 1.8b. The segmented neck (fig. 1.8a only) is unique in Mandaean art and possibly represents the priest’s pandama, which is gathered around the neck and lower face to protect the departing soul from damage (see fig. 1.13). The figures each have a similar outline as well as a crosshatched torso and black triangular legs, a common feature of all such Lightworld representations across the major scrolls, as is shown in fig. 1.15.149

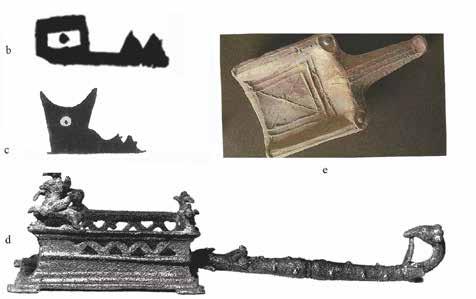

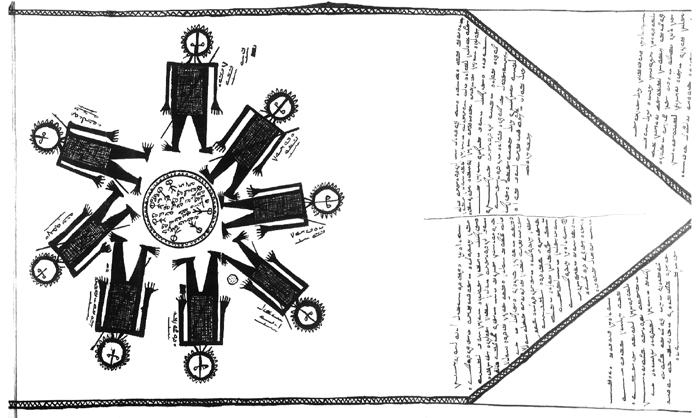

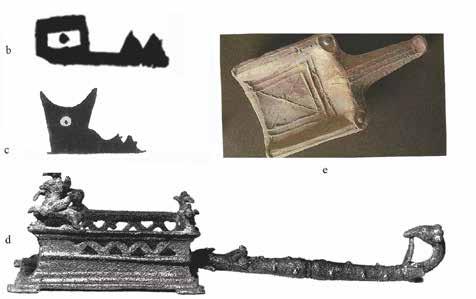

Fig. 1.15 shows a collection of similar types of major Lightworld figures

72 CHAPTER 1 . MANDAEAN SYMBOLIC ART

whose identities, like those in fig. 1.8a, are revealed by their general form and inscriptions.150 All the figures have crosshatched torsos and black triangular legs (except in MS. Asiat. Misc. C. 12). In particular, a further connecting feature—the wavy line surrounding their heads151—is similar to the heads on the figures in the bottom section of fig. 1.8a (the baptizing priests). These particular head-surrounds are not evident in other figures in the Mandaean scrolls except in the case of Simat-Hiia in fig. 1.8a and Šitil and Bihdad in the Scales of Abatur (fig. 1.4a). The forms surrounding the head might be interpreted as circlets or crowns that symbolize the element of radiant light, an essential component of the Mandaean religion in its war against the evils of darkness. They also represent the three crowns worn by priests during baptism, a combination of the turban, described in the baptism liturgy as ‘a circle of radiance, light and glory’, the ‘crown of Zihrun’, the taga (‘crown of ether-

73

Fig. 1.15

THE FIGURE AS SYMBOL 15

Lightworld male figures in details selected from Mandaean scrolls. Oxford, University of Oxford, Bodleian Library, Drower Collection: (a) MS. Asiat. Misc. C. 12; (b, c) MS. 8; (d) MS. 34; (e) MS. 7; (f) MS. 48; (g) MS. 27; (h) MS. 35; (i) MS. Asiat. Misc. C. 13.

Fig. 1.15. Lightworld male figures, in details selected from Mandaean scrolls. Oxford, University of Oxford, Bodleian Library. Drower Collection: (a) MS. Asiat. Misc. C. 12, (b, c) MS. 8, (d) MS. 34, (e) MS. 7, (f) MS. 48, (g) MS. 27, (h) MS. 35, (i) MS. Asiat. Misc. C. 13.

a d g b e h c f i

Fig. 1.10 Priests forming a klila (myrtle wreath) for baptism during Parwanaiia, Nepean River, Penrith, Australia, 2011.

Fig. 1.10 Priests forming a klila (myrtle wreath) for baptism during Parwanaiia, Nepean River, Penrith, Australia, 2011.