in

With essays by

Jessica Barker | Marjan Debaene | Lloyd de Beer Judy De Roy | Laurent Fontaine | Sophie Jugie Wolfram Kloppmann | Aleksandra Lipińska Carmen Morte García | Sofie Muller | Géraldine Patigny Stefan Roller | Soetkin Vanhauwaert | Michaela Zöschg

First published on the occasion of the exhibition ‘Alabaster’ M Leuven, 14 October 2022–26 February 2023

marjan debaene , M Leuven sophie jugie , Musée du Louvre

Exhibition Coordinator isabelle van den broeCke , M Leuven

Edited by Marjan Debaene

Authors of the essays

Sophie Jugie, Michaela Zöschg, Marjan Debaene, Aleksandra Lipińska, Wolfram Kloppmann, Judy De Roy, Laurent Fontaine, Géraldine Patigny, Stefan Roller, Carmen Morte García, Lloyd de Beer, Soetkin Vanhauwaert, Sofie Muller

Authors of catalogue entries

bds Bernard De Scheemaeker Cmg Carmen Morte García Cv Christiaan Veldman evb Emile van Binnebeke fs Frits Scholten hi Hannah Iterbeke jdr Judy De Roy ldb Lloyd de Beer md Marjan Debaene

mdb Marieke De Baerdemaeker mbp Magali Briat-Philippe mt Marjorie Trusted mw Moritz Woelk p-ylp Pierre-Yves Le Pogam sj Sophie Jugie sm Samuel Mareel sr Stefan Roller sv Soetkin Vanhauwaert

Isabelle Van den Broecke, Goedele Pulinx, Nadia Jaumotte, Hanne Buckinx

(From the French) Caroline Beamish, (from the Spanish) Donald Pistolesi, (from the Dutch) Lee Preedy, (from the German) Karen Williams

Copy-editing and design Paul van Calster, with Anne Luyckx, Anagram, Ghent

sophie jugie Musée du Louvre marjan debaene M Leuven pierre-yves le pogam Musée du Louvre aleksandra lipiŃska Kunsthistorisches Institut der Universität zu Köln miChaela ZÖsChg Victoria and Albert Museum, London kim woods Open University UK lloyd de beer The British Museum frits sCholten Rijksmuseum Amsterdam Carmen morte garCÍa Universidad de Zaragoza stefan roller Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung, Frankfurt am Main judy de roy kik-irpa Stone Conservation Studio harald theiss Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung, Frankfurt am Main

An imprint of Brepols Publishers London / Turnhout www.harveymillerpublishers.com

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

Copyright © 2022, Harvey Miller Publishers and the authors isbn 978-1-912554-92-8 (hb ) isbn 978-1-912554-93-5 (pb ) d /2022/0095/280

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from Harvey Miller Publishers.

Printed and bound in the EU on acid-free paper

Frontispiece

Detail of cat. 69

Foreword M Leuven 6 Peter Bary

Foreword Musée du Louvre 7 Laurence des Cars

Preface 9

Marjan Debaene and Sophie Jugie

1 Alabaster as a Material for Sculpture

Introduction 10 Sophie Jugie

Rhetoric of Alabaster: The Material between its Affordances and Cultural Meaning 12 Aleksandra Lipińska

How to Distinguish Alabaster from Alabaster: Tracing the Material Back from the Artwork to the Quarry 24 Wolfram Kloppmann

‘Marbre d’alabastre’: Status of the Interdisciplinary Research Project on Marble and Alabaster 30 Jude De Roy, Laurent Fontaine and Géraldine Patigny

Catalogue nos. 1–21 38

Introduction 72 Sophie Jugie

Alabaster as a Material for Funerary Monuments 74 Jessica Barker

Catalogue nos. 22–41 88

Introduction 114

Marjan Debaene and Michaela Zöschg

The Rimini Altarpiece and Alabaster Sculpture in the Southern Netherlands, around 1430 116 Stefan Roller

English Alabaster and the Continent 137 Lloyd de Beer

Alabaster Altarpieces in the Iberian Peninsula: From Gothic to Baroque 155 Carmen Morte García Catalogue nos. 42–99 168

4 Sacred and Secular Introduction 248 Michaela Zöschg and Marjan Debaene

The Head of St John the Baptist in Alabaster: The Object in Context 250 Soetkin Vanhauwaert

Catalogue nos. 100–126 259

Epilogue: Alabaster Mentalis, Trinitas Terrestris 289 Sofie Muller

Catalogue nos. 127–128 290

Bibliography 291 Index 308

Lenders to the Exhibition 311

Photographic Acknowledgements 312

M Leuven and the Musée du Louvre have joined forces to present a prestigious exhibition devoted to alabaster, a gypsum stone that, alongside marble, played a very important role in European sculpture between the 14th and 16th centuries. Usually only available in smaller blocks than marble, alabaster is much softer and therefore easier to carve. Since it is soluble in water, it is also more fragile and not suitable for exterior decorations as a result. But, like marble, alabaster is appreciated for its whiteness, its fineness and the beautiful lustrous polish that can be given to it. Moreover, it offers an excellent support for polychromy and allows for highly refined work. All these aspects made it a very suitable material for both monuments and small objects, for serial production and bespoke commissions, from England to Spain and France to the Netherlands, Germany and Poland. The popularity of alabaster is illustrated by the many masterpieces still preserved and on permanent display in major museums throughout the world. In order to tell this story, the exhibition includes some 130 pieces, including major works from all over Europe.

This collaboration between M Leuven and the Louvre was a natural choice: M houses an internationally renowned collection of medieval sculpture and holds expertise in this research field. Moreover, the museum frequently organizes large exhibitions of early modern sculpture enhancing the status of expertise in the field, and runs the European scientific network ards that is a reference in this area. The museum in Leuven, not far from Brussels, is also located in the heart of the Low Countries, a prime location for alabaster sculpture, even though no alabaster quarries exist in this region. For its part, the Sculpture Department of the Louvre Museum has a rich collection of alabaster works that has been used extensively to support the exhibition. In addition, the Louvre’s alabaster collection has recently been the subject of further study. Indeed, the department, in collaboration with the Laboratoire des Monuments historiques (lrmh ), the Bureau des Recherches géologiques et minières (brgm ) and the Centre interdisciplinaire de Conservation et de Restauration du Patrimoine (Ci Crp ), is conducting a multidisciplinary research programme based on isotopic analyses that make it possible to identify the precise origins of alabaster. This information is cross-referenced with data on the history of quarries and trade flows,

major building sites and their patrons, thus sketching out a hitherto unknown history of the origins of alabaster used in France.

Alabaster is also the subject of studies in several other European countries, notably the United Kingdom, Spain and Germany. Since 2018 it has had its great overview publication: Kim Woods has written a magisterial thesis on the history, uses and symbolism of alabaster in a European context, studying the most important and characteristic examples of the use of this wonderful white stone (Woods 2018). Even before this publication, and more recently as well, an important number of publications and colloquia have accelerated and augmented our knowledge of the topic, including the numerous publications by Aleksandra Lipińska, such as Moving Sculptures (Lipińska 2014); recent PhD dissertations on English alabasters, such as those by Zuleika Murat (Murat 2019) and Lloyd de Beer (De Beer 2022); the colloquia on Spanish alabaster sculpture, organized by Carmen Morte García at the University of Zaragoza (Morte García 2018; Morte García 2019); the Paris study day devoted to the firsts results of research into alabaster (Kloppmann/Le Pogam/Leroux 2018); and finally the eighth ards Conference in Paris in January 2022 (Debaene/Jugie forthcoming). Of great importance are also the exhibition and catalogue focusing on the impressive altarpiece by the Rimini Master, now in the Liebieghaus Museum in Frankfurt (Roller 2021).

With research into the material booming over the past decades, the time was ripe to unveil the new findings to a wider audience with a prestigious and comprehensive exhibition and publication. The exhibition has benefited from the assistance of a scientific committee that includes many specialists and European museum curators; it has also profited from loans of high quality and variety from many major museums as well as from private collections. On display will be works by the best artists working in alabaster, including André Beauneveu and Jean Mone from the Low Countries, Tilman Riemenschneider from Germany, Jean de Cambrai and Germain Pilon from France, Diego de Siloé and Damián Forment from Spain, and others who have transcended regional boundaries, such as the unclassifiable Master of Rimini and Conrad Meit.

An exhibition is not only a meeting place for prestigious objects and important names in the history of art. The

Marjan Debaene M Leuven | Sophie Jugie Musée du Louvrecommittee has helped us to select representative pieces and to organize their presentation in the most clear and evocative way. The exhibition trail is therefore thematic in concept and aims to shed light on the material (its origin, its physical and chemical properties, its significance and use) and on the different types of objects made in alabaster in Western Europe from the late Middle Ages to the Baroque era. This book ties in with the exhibition and includes some of the most recent research on the matter, following the same thematic chapters as the exhibition. Each chapter contains essays and catalogue entries that cover the many aspects of alabaster within the wider cultural and historical context of Europe.

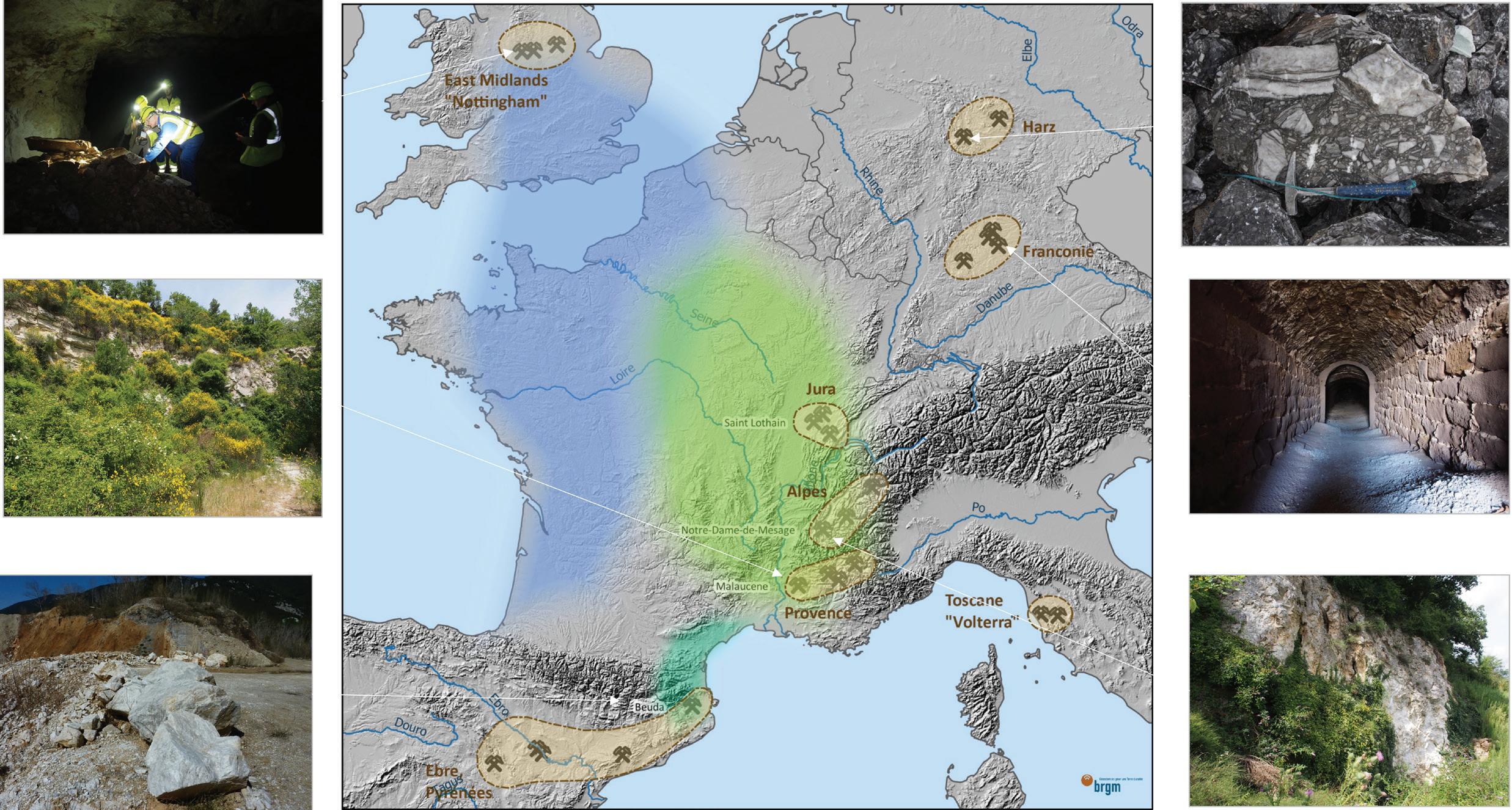

The first room examines the characteristics of alabaster and the techniques used to work and paint it, through a group of statues dominated by the sublime St Catherine by André Beauneveu from Kortrijk, carved in about 1380, along with works by famous artists such as Conrad Meit, Tilman Riemenschneider and Damián Forment. Also in this room are anonymous masterpieces such as the Annunciation from Javernant, the figures of which are held separately at the Louvre and the Cleveland Museum of Art but now reunited for this exhibition. The methods and results of the research programmes are then explained, with a map of the areas of influence of European quarries in the current state of our knowledge and a film shot at the Monastery of Brou, Bourg-en-Bresse, where the Saint-Lothain alabaster still celebrates the too short-lived romance between Marguerite of Austria and Philibert of Savoy. In the same gallery, an educational space is devoted to direct contact with the stone.

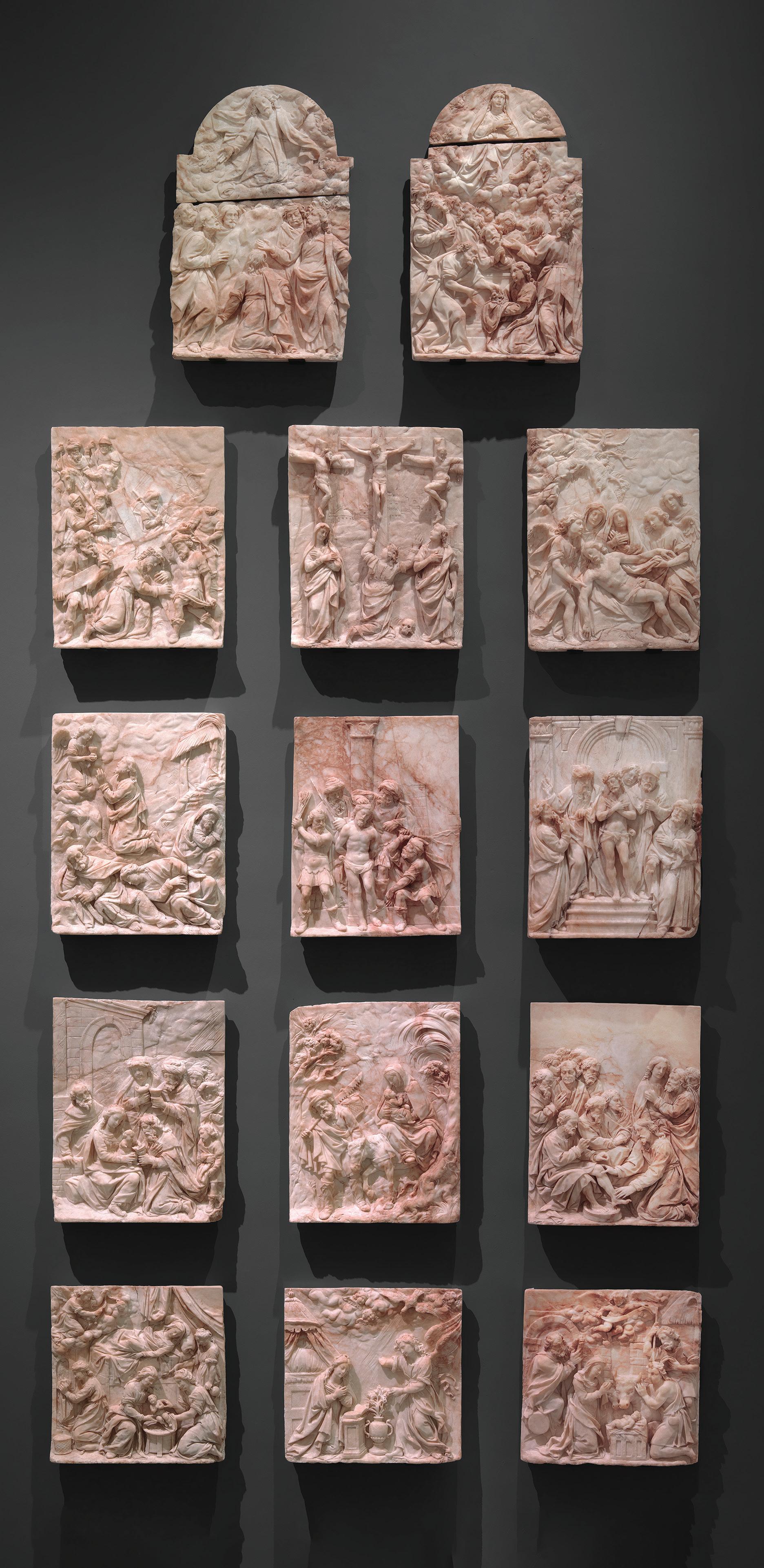

The tour then moves on to a thematic presentation of the wide range of objects made from alabaster. One room is devoted to funerary monuments. Here the majestic tomb of Philippe Chabot from the Louvre, attributed to Jean Cousin, the sarcastic figure of Death from the former Cimetière des Innocents, Paris, and the recumbent naked effigy (or transi ) of the dead Jean Hénin-Liétard from Boussu-les-Mons by Jean Mone illustrate the memento mori aspect of funerary sculpture. Another room deals with altarpieces, juxtaposing unique works with the phenomenon of mass production, with pieces such as the famous Nottingham alabasters, the Mechelen reliefs, work by Jean Mone and his followers, Spanish and French reliefs, and the posterity of the Master of Rimini. The next space shows smaller objects, intended for private devotion and collectors’ cabinets.

The final word goes to M Leuven’s collection, with the spectacular 6-m-high St Anne Altarpiece, made around 1610 by Robert de Nole for the Celestine Convent in Heverlee near Leuven, testifying to the fact that it was in the Low Countries in the 17th century that the last examples of this alabaster production were created, before what could be termed the European triumph of marble. The rise of marble could probably be linked to the structuring of artistic production round the academic institutions. The exhibition also includes some works by the contemporary Belgian artist Sofie Muller to serve as a reminder that alabaster has by no means lost its power of fascination. For this exhibition she has produced a reply to M’s Altarpiece of St Anne.

We sincerely hope that the exhibition’s visitors and readers of this book will share our fascination for this noble material and the sculptors who worked in it. We warmly thank all the generous lenders who have loaned their masterpieces for this exhibition as well as all the specialists, scholars and collaborators who have shared their knowledge with as and helped us during the preparation of both the conference in Paris and the exhibition in Leuven.

Barbara Hepworth. Mother and Child, 1934. Cumberland alabaster. Tate Britain.

Emulator of Caspar Netscher. Portrait of an Unknown Lady as St Catherine, 1670–80. Muzeum Narodowe w Gdańsku, Gdańsk.

of gypsum alabaster were usually called marbles5 and were excluded from the general notion of this material. Consequently, they did not actively participate in the creation of its cultural image. This began to change only in the early 20th century, when especially British artists, such as Jacob Epstein (1880–1959), Henry Moore (1898–1986), Barbara Hepworth (1903–1975) and John Skeaping (1901–1980) began to explore qualities of the

coloured varieties of local alabasters. While Epstein and Skeaping gladly applied a reddish veined Derbyshire alabaster,6 Moore and Hepworth opted for the green-grey Cumberland variety (fig. 3).7 Contemporary sculptors, such as Sofie Muller (b. 1974), are often inspired by the natural veining, colour stains and irregularities (cf. cat.128–129),8 which in the past would have been retouched or a reason to dismiss an alabaster block entirely.

The whiteness, on the contrary, was undoubtedly the characteristic of gypsum alabaster with the strongest resonance, both in the sense of wide artistic application and building of a long-lasting cultural notion. Some authors even have perceived a connection between the colour of this stone and its name. In 18th-century dictionaries, in particular in French, the belief emerged that the word ‘alabaster’ comes from the Latin albus – white.9 Today we know that this interpretation is groundless. First, the Latin word alabastrites was only the link via which the Egyptian word, through Greek, came into the European languages. Second, this name originally referred to calcite alabaster, which tends to be yellowish rather than white.10 Nonetheless, even an erroneous etymological hypothesis such as this is of interest in cultural terms, because it tells us that in post-antiquity alabaster was usually associated with the colour white.

This quality played a crucial role in accepting alabaster as an appropriate medium for the depiction of the ideal human figure, a status it shared with white marble. It is important to stress at this point, however, that the whiteness of gypsum alabaster is of a warm tone, similar to that of ivory, which distinguishes it from the cooler white of marble. Consequently, in sculptures underlining the carnality of the human body, alabaster is an even more appropriate medium than marble.

Eduardo Chillida. How Profound is the Air (Lo profundo es el aire), 1996. Guggenheim Bilbao.

fig. 14

Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, Ravenna.

fig. 15

Rafael Moneo. Interior of the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels, Los Angeles, 2002.

contrast of the inner ‘pure’, translucent, milky core of the stone and its rough outer ‘husk’, the materiality of the stone and the immateriality of light (fig. 13).

Translucency was the quality that made alabaster suitable for glazing windows, a practice documented from late antiquity.34 The light emitted by this material, so different from the daylight observed in nature, contrasted with the darkness of the church interior, becoming a sign of God’s presence on earth. This effect is impressively visualized in the interior of the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna, where the lower parts of the walls are clad with yellow Siena marble (giallo di siena), and above it rises a canopy of mosaic vaults. When the door is closed, the light enters the interior only through

small rectangular windows filled with panes of banded yellow-orange honey-like calcite alabaster (alabastro melleo listato) (fig. 14). Refracted in its layers and crystals of varying sizes and transparency, the vibrating beam of light touches the flickering uneven surfaces of the mosaics. The light is present in this interior not as an immaterial ray, but incarnated in the vibrant luminous colour of the mosaics and stones.35

The light effects generated by alabaster used as window panes also fascinate contemporary architects, including Rafael Moneo (b. 1937), who glazed in this way the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels in Los Angeles (completed in 2002; fig. 15).36 Contemporary artists, too, reach for alabaster to create oneiric spaces.

alabaster, form either banks or nodules up to several metres in diameter.11 The fine-crystalline alabaster is formed only after the transformation of gypsum into anhydrite, through water loss, for example when gypsum reaches deeper geological layers, usually more than several hundred metres deep,12 and back into gypsum when those deep formations re-emerge close to the surface during geological history.

At the origin of alabaster, there is therefore generally seawater, whose composition has constantly changed throughout the history of the Earth. This explains why alabaster deposits of different ages have different isotopic signatures. In addition, trace elements such as strontium are added to the saltwater basins by the erosion of the surrounding mountain massifs. Thus, the geochemical contrasts between the basins and hence between the deposits are further reinforced.

Medieval alabaster workings in Europe (fig. 1) were relatively limited in number, but not in their geographical extent.13 The most important mining areas for alabaster before the 16th century were in the English East Midlands,14 Spain (Aragon, Catalonia),15 France (alpine deposits, Provence)16 and Germany (Harz, Franconia).17 From the 16th and 17th centuries, the use of alabaster in sculpture increased considerably and new deposits were discovered and exploited. European rulers became conscious of and contributed to the prestige of the raw materials quarried in their territories, with alabaster in a prominent position as an object of diplomatic exchange and element of economic development.18 This led to the first systematic

inventories of alabaster deposits within certain historical boundaries and to the first systematic exploration of new resources.19 In the French Jura mountains, the quarries of Saint-Lothain gained fame,20 in Tuscany the old quarries around Volterra were reopened,21 and the deposits in Eastern Europe became important, from eastern Germany (Thuringia, Saxony)22 to Poland and western Ukraine (the so-called ‘Ruthenian marble’ of the Carpathian Foredeep).23

In the course of our research, we have been able to identify and examine the major historical alabaster deposits in England, France, Spain, Italy and Germany, which provides an indispensable basis for comparison in the attribution of works of art. The contrasts in the ‘fingerprints’ of the various deposits have indeed proved strong enough to associate with great certainty most of the more than two hundred works of art studied to date with a historical alabaster quarry. For over five hundred years,24 French alabaster sculpture relied on two dominant sources: the ‘Nottingham’ alabaster quarried in the East Midlands and the French alpine alabaster from Notre-Dame-de-Mésage.25 In both cases, its use goes back to at least the 12th century, if not to late antiquity, and in both cases it endured until the 17th century with comparable zones of influence, roughly equilibrated between eastern and western France (fig. 1). Pyrenean alabaster from the Beuda quarries overprints other sources in the Languedoc, mainly along the Mediterranean coastline.26

We will briefly outline two other examples of prominent European alabaster deposits, relevant for

Fig. 1

Principal alabaster quarrying areas in western and south-western Europe together with their zones of influence. The inserts show images of some prominent alabaster quarries:

a Fauld mine, English Midlands, wider Nottingham region

b Malaucène, Vaucluse

c Beuda quarry, eastern Pyrenees, Catalonia d Witzenhausen/Hundelshausen quarry, Harz, with grey brecciated alabaster

e Ickelheim exploitation, Middle Franconia; the underground galleries are most likely those mentioned by Hofmann in 1757. f Saint-Firmin quarry, Notre-Damede-Mésage, the most prominent alabaster quarry in medieval France.

Juan de Anchieta (c. 1533–1588)

Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid, Ce 2884 Ministerio de Cultura del Gobierno de España White alabaster, possibly from a quarry in Aragon, 74 × 28.50 × 24 cm

Provenance Early provenance unknown; art market, 2009.

Select bibliography Sáenz 1639, fols. 75v, 78v; Lamana 1713, fol. 171v; Catálogo 1863, p. 7v, no. 136; Catálogo 1867, p. 85, n0s. 166, 145; Museo 1929, p. 80; Beltrán Lloris 1976, p. 184; Janke 1984b, pp. 77–84; Criado Mainar 1989, pp. 309–50; Checa 2000, p. 245, no. 58; Beltrán Lloris 2009, p. 9; Morte García 2009b, pp. 249–51; Arias Martínez 2009, pp. 166–67; Arias Martínez 2012, pp. 48–49; Arias Martínez 2015a, pp. 164–65; Morte García 2019b, pp. 33–34.

The Egyptian anchorite saint (d. c. 400) appears in these two sculptures as a hermit who renounced worldly goods on his path to attaining holiness and devoted himself to prayer and penance. The medieval devotion to St Onuphrius grew in the 16th century with the aim of emphasizing the importance of penance, as opposed to its denial by the Reformation. His popularity increased when he was invoked against sudden death without confession. The saint’s physical appearance is especially striking: as the hagiography describes, he covered his naked body with his beard and hair, which he never cut. These two sculptures are an excellent example of how his appearance was adapted to the plastic language of each period. They do not portray an ascetic’s body, as in the Middle Ages, but adhere to the Renaissance anatomical canon and, in turn, reflect the different times at which they were made: the one by Damián Forment is slender and elegant, while that by Anchieta is characterized by its muscularity, following the new artistic sensibility that arose in Rome under the influence of Michelangelo. Neither is carved on the back, as the original point of view was frontal.

The Museo de Zaragoza’s expressive St Onuphrius was attributed with certainty to Damián Forment by R. Steven Janke, based on its stylistic relationship to other works by Forment. We find its typology in the impressive figure of the pilgrim St James in the central group of the Assumption in the main altar of the Cathedral-Basilica of Nuestra Señora del Pilar in Zaragoza (1509–18) and in the image of an apostle from the high altar of the Cathedral of Huesca, contemporary with this St Onuphrius. Other elements, too, link the figure to Forment’s style, such as the flexible rhythm of the contrapposto, the detailed study of the anatomy, the hands and feet, and the close attention to the furrowed brow. Forment again demonstrates his skill in working in alabaster, achieving an effect of full volume although it is carved only on the front, and stabilizing the figure with the wide head of hair.

The work came from the demolished Convent of the Dominican Order of Preachers in Zaragoza and entered the museum collection between 1836 and 1848. It can be identified as the one described by the Dominican father Sáenz (1693), in a niche in the left wall of the main chapel (pantheon of the Castro-Pinós family) of the convent’s

In her essay in this volume (pp. 74–87), Jessica Barker explains the reasons for the success of alabaster in the construction of funerary monuments in Europe between the 14th and 17th centuries. Practical considerations, such as accessibility, made it a more than satisfactory substitute for the prestigious Italian marble, which was used in France for royal tombs from the last quarter of the 13th century. It enabled the elite to affirm their social status, which gave them the means and legitimacy to mark the place of their burial in a material that was rarer and more expensive to extract and transport than stone. For the princes in whose lands alabaster deposits were located, it was also a matter of favouring local resources. But the success of alabaster, especially for tombs, is also explained by its unsettling relationship with flesh through its colour and warmth to the touch, and with decay through its fragility – which makes it a particularly suitable material for this purpose from a symbolic point of view.

The works in this part of the exhibition have been chosen on account of these considerations, but also in order to echo the history of alabaster tomb sculpture (Woods 2018, pp. 179–287). We have tried to take into account the European dimension of the phenomenon and its duration.

Even though it has not been possible to include in this exhibition the early and persistent tradition of the use of alabaster for tombs in England (for the good reason that the monuments that have come down to us have mostly been preserved in situ), it should be recalled that 14th-century England may have been one of the starting points of the European alabaster wave. Interestingly, the tomb of Edward II is both the first and one of the few monuments of English monarchs to be made of alabaster, since English kings generally remained faithful to metal tombs. However, alabaster was widely used by the aristocracy in the form of recumbent statues showing the deceased adorned with all the attributes of their social status (see pp. 75–76, figs. 2 and 3).

Spain was the other country where alabaster became the preferred material for funerary sculpture before the middle of the 14th century, but in Spain, unlike in England, it was fully embraced by princes. The relief from the tomb of Ferdinand I of Aragon (d. 1416) (cat. 22) and two mourners from an unidentified tomb of a king of Aragon in the Cistercian abbey of Poblet (cat. 23) illustrate the early use of alabaster in Spain. These were followed by the tomb of Charles III ‘the Noble’, King of Navarre, in Pamplona, made in 1413–19 with a clear reference to the French and early Netherlandish tombs, under the direction of the Tournai sculptor Jehan Lome (see p. 80, fig. 9). The relief from the tomb of Bishop Hugo de Urriés (cat. 34) shows how the effects of gilding and polychromy were used to emphasize the coat of arms and commemorative inscription.

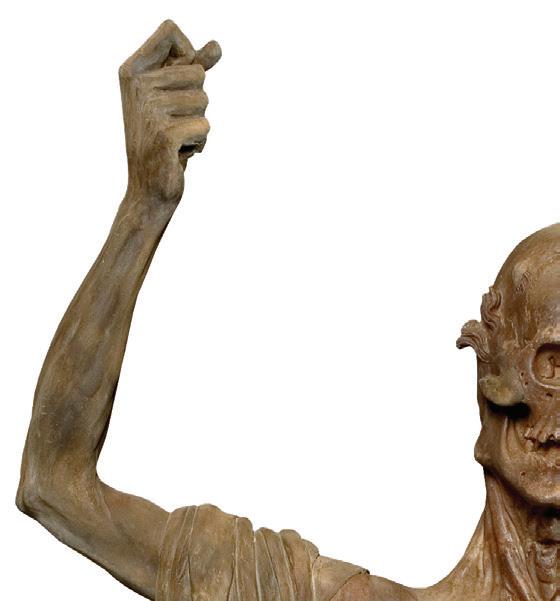

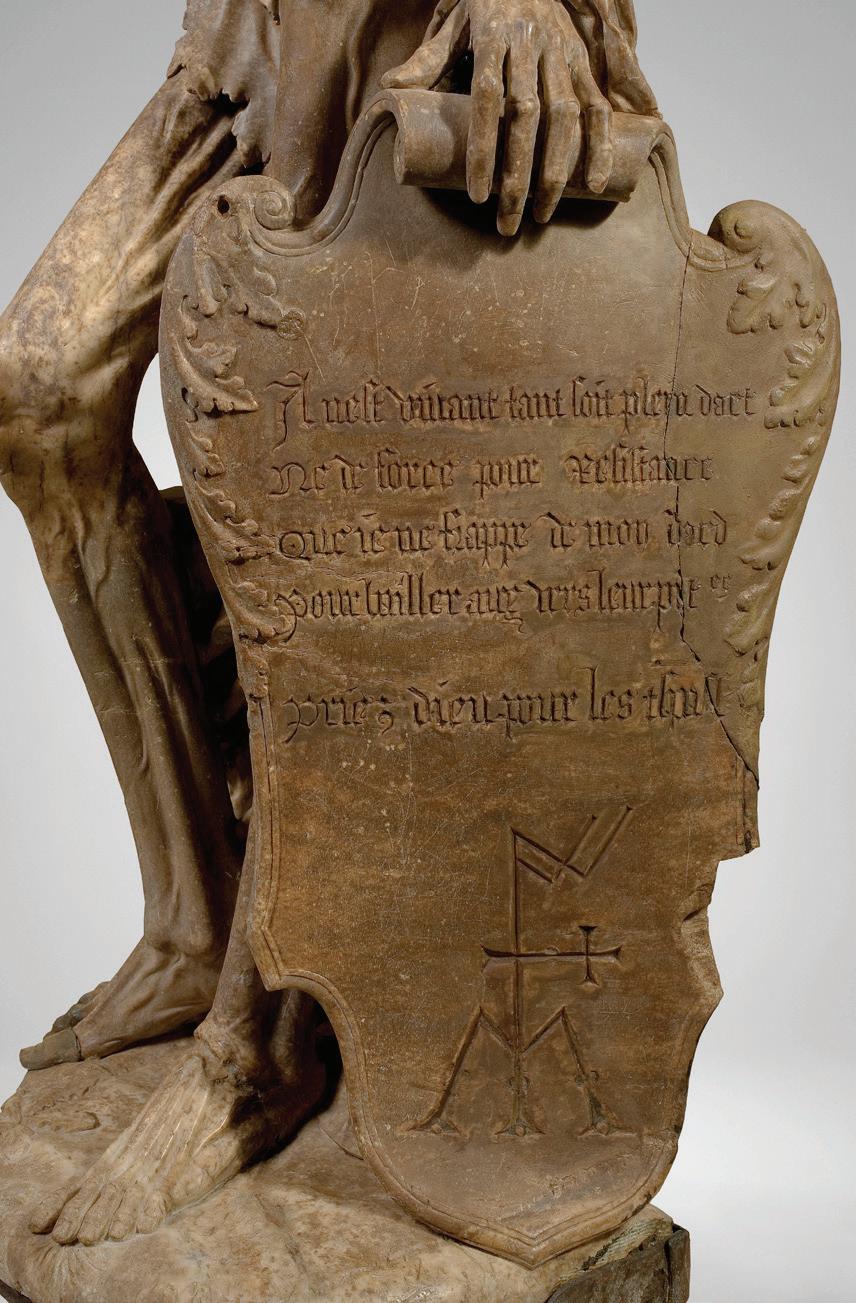

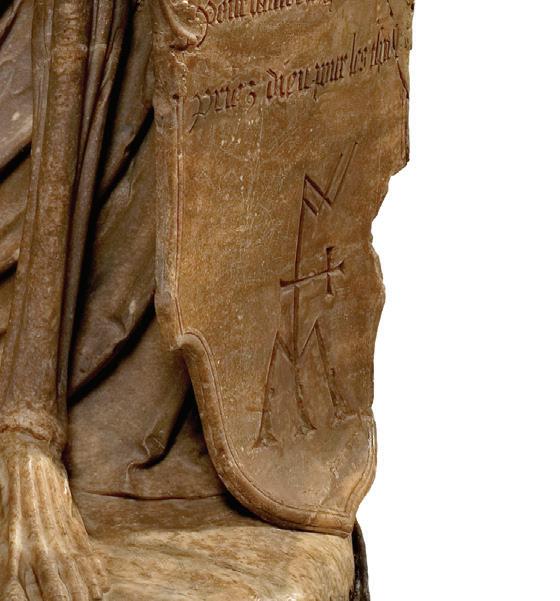

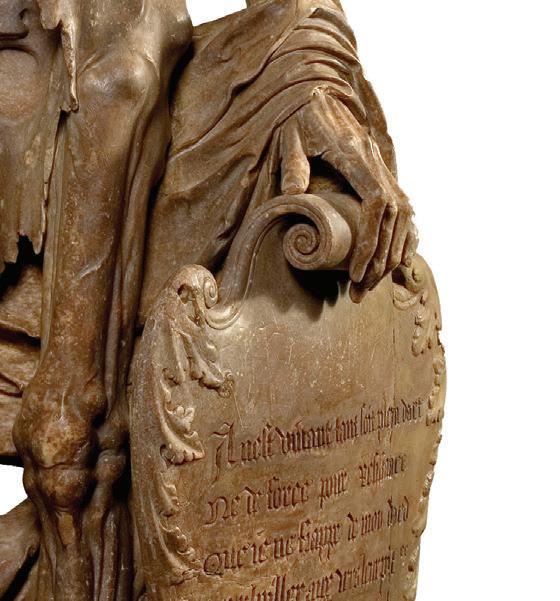

Musée du Louvre, Paris, rf 2625

Alabaster (not analysed), 120 × 55 × 27 cm

Inscribed on the shield: Il n’est vivant tant soit plein d’art / Ne de force pour resistance / Que je ne frappe de mon dard / Pour bailler aux vers leur pitance. // Priez Dieu pour les trepasses.

Provenance Cimetière des Innocents, Paris; after the cemetery was suppressed in 1780, the statue was removed to the Church of St Gervais in 1786, and then to Notre-Dame in 1788; Musée des Monuments français, 1795–1816; transferred to the Louvre, 1866.

Select bibliography Fleury 1990, p. 61, no. 47 (Marie-Nöelle Baudouin-Matuszek); Le Pogam 2008, no. 24; Lens 2012, p. 112, fig. 113, no. 51.

The Cimetière des Innocents, in the heart of Paris, was one of the oldest and largest cemeteries in the city, an enclosure where the poor were buried, with some well-known figures as well. Charnel houses, galleries along the cemetery walls where bones dug up from the graves in the central area could be stored, began to be built in the 14th century. In 1424 the southern wall of the charnel house was adorned with a danse macabre (Dance of Death), a representation associating text with image in which Death carries off young and old alike, men and women, clerics and laymen, rich and poor, powerful and anonymous. It was designed to remind people that no one escapes death, whatever their social rank. The statue of death was placed in the eastern arcade in a closed box which was opened at All Saints’ Day. The emaciated image threatened the living with an arrow or lance, now lost. On his shield a quatrain followed by an invitation to pray for the dead confirms that death cannot be eluded: ‘No living man, however full of guile / nor power of resistance / whom I do not strike with my dart / to give the worms their nourishment. // Pray to God for the deceased.’ The idea is somewhat different from the Dance of Death, warning as it does against sudden death which prevents one from receiving the sacraments and is particularly to be feared. The appeal for pity and prayers from the living was a way of associating them more closely with this thought.

The people of Paris were very attached to this representation of Death, and to the ceremonial surrounding it. Evidence of this can be found in the popular protests and the judgements delivered in the 17th and 18th centuries when, for a number of different reasons, the statue was moved or became inaccessible. It was restored to the cemetery every time. After the cemetery was suppressed in 1780, the statue was removed to the Church of St Gervais in 1786, and then to Notre-Dame in 1788. It was here that Louis-Pierre Deseine (1749–1822) completed the figure, restoring the arms and part of the inscription and covering it with a wash resembling bronze – which gave it the dark colour that may cause surprise today. The statue always aroused interest because of its unusual appearance: it was seized during the Revolution and transferred to the Louvre via the Musée des Monuments français.

The sculpture exploits alabaster’s relative soft ness, producing an extremely precise, detailed image with emphasis on the hollow

eye sockets, the toothless grin, the vertebrae and shreds of skin – macabre as a representation but in no way realistic. It is important on the other hand not to interpret the piece as stemming solely from medieval tradition, a reflection of the profound upheaval caused to European society by the great pandemics after the 14th century. The 16th century pursued the tradition of transis and images of death, adding its own quest for naturalism and precision. Although this figure’s manner of brandishing the lance owes much to Italian Triumphs of Death, our skeleton presents a perfect Renaissance contrapposto

II Floris and a softer style of sculpture, with painterly qualities and more dynamic figures heralding the Baroque style. The presence of kneeling donors and a Salvator Mundi, carved in the round and crowning the altar is probably influenced by the new style of portico altar, which was developed under the influence of Rubens (Lipińska 2020b). However, there is also a stylistic affinity with alabaster relief production in Mechelen around 1600. In accordance with the practice of the time, prints were most likely used to design the reliefs. For instance, the reliefs of the Annunciation and the Flight into Egypt show clear similarities to the compositions Anton Wierix the Younger (1522–1604) published between 1586 and 1604. | md

Trapani, Sicily

Musée du Louvre, Paris, rf 2718 Alabaster, polychromy, 71 × 26 × 13 cm

Provenance Bequest of Baron André-Joseph-Victor Burthe d’Annelet, 1953.

Select bibliography Kruft 1970; Migliorato 2019.

The Virgin is carrying the Child on her left arm while the baby’s right hand is on her chest, and his left hand is playing with his mother’s right hand. Jesus’ tunic falls in folds around his legs. The Virgin’s head is covered by a veil; she is enveloped in a mantle which forms circular folds around her right hip (two of the folds stand out) and a waterfall of folds in the front.

The composition can be identified as a ‘Trapani Madonna’, which is to say a copy of the marble statue attributed to Nino Pisano (fl. 1334–1360s), c. 1350–60, now in the ‘Fishermen’s Chapel’ in the Santissima Annunziata Church in the former Carmelite convent of Trapani. The statue is striking because of the tenderness of the relationship expressed between mother and child, and for the Virgin’s gaze outwards to the faithful; it has been the subject of romantic legends about Our Lady’s miraculous arrival in Trapani. Reliable for her protection against the perils of the sea, the Madonna of Trapani became the goal of one of Sicily’s most important pilgrimages in the 15th century.

This devotion gave rise to innumerable replicas and copies from the 15th to the 19th centuries. The first replica was made by Francesco Laurana (d. 1502) in 1469 for Palermo Cathedral, then came those made by the sculptors Domenico and Antonello Gagini, active in Sicily in the years 1460–1530. The religious communities, in particular the Carmelites, played a major role in spreading this image through Sicily, then through Italy and Spain and widely around the western Mediterranean. As well as these altar statues, the Trapani Madonna was reproduced for private devotion. The Jesuit Wilhelm Gumppenberg recounts how, in 1657, about forty workshops in Trapani were busy making copies, which were bought by pilgrims to take home. This explains the large number of versions, of very varied size and quality, to be found in churches and museums all over Europe – not to mention those sold at auction or by the art trade.

The base of the Louvre statue bears the arms of the town of Trapani, which confirms that it was made in a workshop in that town. Mary and Jesus wear large gold crowns on their heads, added to the statue in 1734; this allows us to date it to the 18th century. The base, in fretwork with volutes, is also typical of the period, and contrasts with the more generally prismatic bases of quattrocento and cinquecento versions.

Alabaster is abundant in Sicily, especially around Trapani. The alabaster found there is not only white, but also flesh-coloured; the contrast has been exploited to realistic effect. The workshops

where alabaster was carved also worked with coral, used to make mainly devotional objects in copper gilt; these were also internationally exported, the port of Trapani on the western tip of Sicily acting as a crossroads for Mediterranean trade. | sj