Opening Manuscripts

harvey miller publishers

TRIBUTES TO E lly m I ll ER

O p E n I ng man US c RI p TS

Edited by STE lla panay OTO va, l U cy f REE man S andl ER and Tama R m I ll ER wang

harvey miller publishers

Deirdre Jackson 148 portal to heaven: The virgin mary as Gatekeeper in alfonso X’s Cantigas de Santa Maria

Susan L’Engle

Construing Character and social status: visual interpretations by medieval readers of roman law

Julian Luxford

The Carthusian miniatures in the Belles Heures of Jean, Duke of berry

James H. Marrow

The Gaudechon hours: an unpublished manuscript illuminated by the masters of Zweder van Culemborg

Michael A. Michael

biblioteca apostolica vaticana, ms vat. lat. 4757: an early Fourteenth-Century english illuminated Vademecum

Nigel J. Morgan

The virgin and Child with a bird in english art c.1250–c.1350: passion symbolism or the playing Christ Child

Lucy Freeman Sandler

pictorial Typology and the bedford hours

Kathryn A. Smith

Opening the space of the parchment roll: imaging interiority in Two english Copies of the Septenarium pictum

Patricia Stirnemann

The souvigny bible and the holy sepulchre

Jenny Stratford

a Tudor Treatise on illumination and Three antiquarians: humfrey Wanley, elizabeth elstob and George ballard

Double Openings Commemorating the First World War: Nestore leoni and the revival of illumination in italy

8 | tributes to elly miller

elly miller, london 2001 (© bea lewkowicz)

elly miller, london 2001 (© bea lewkowicz)

Preface

after e lly m iller died in a ugust 2020, there was an outpouring of love and admiration from scholars who recognized the profound significance of her work as a publisher, and in particular her innovative contributions to the publication of studies of illuminated manuscripts of the middle ages and the renaissance. The monographs and catalogues published by her, fundamental to the academic study and wider appreciation of illuminated manuscripts, are a lasting tribute to her extensive knowledge and keen sensitivity to the aesthetics of the book. To quote one tribute, ‘we are blessed to have had her as a dear friend and an esteemed colleague whose care for art historical scholarship, illuminated manuscripts, and high-quality publications made an inestimably great difference in our field’. The idea of creating a lasting memorial in the form of a volume of essays written in her honour arose, as it were, spontaneously in the scholarly community. elly herself had been the guiding light of a series of volumes of essays in honour of scholars whose work found parallels in the harvey miller publishers programme of publication. she had in fact given the name ‘Tributes’ to the series, which began to appear in 2006, and she was deeply involved in designing and editing all the volumes almost to the end of her life. so it seems fitting that the present collection of essays in elly’s honour should appear in the series in whose conception and execution she played so important a part. elly miller had many interests in the wide world of the visual arts, but her love of the medieval book was central. We wanted our Tributes volume to reflect this love, and consequently we decided that the focus of the individual essays should be on illuminated manuscripts. Our aim was to give the edited collection a form that was both cohesive and all-encompassing. remembering how open elly was to a variety of ways of studying illuminated manuscripts of all types, periods and places, we wanted our volume to be equally wide-ranging methodologically, chronologically and geographically in treating the handwritten book. We thought that the title that would best reflect our aims would be Opening manuscripts. ‘Opening’ may refer to the material or the conceptual aspects of manuscript study. We made a list of possibilities for consideration under this heading and suggested them to our contributors: new discoveries of manuscripts not previously discussed; the physical opening and use of manuscripts; considering the opening or first page of a manuscript; an opening as a double-page spread; and opening up or raising broader historical or methodological questions about manuscripts. The response of our contributors has fulfilled all our hopes for the volume. To the nineteen authors whose essays are included we are deeply grateful. it has been exciting and eye-opening for us as editors to serve as the first readers of their contributions. We are equally grateful to [9]

elly miller’s much-admired friend and collaborator mike blacker of blacker Design for shaping every aspect of the physical appearance of the book and to Jacky Ferneyhough for her careful, thoughtful and patient copy-editing and indexing. The publication of Tributes to Elly Miller: Opening Manuscripts has been supported enthusiastically from the start by Johan van der beke, elly’s longtime colleague at brepols since 2000 when their association began. he has our great thanks. Finally, on behalf of the authors, we are indebted to all the individuals and institutions who own the manuscripts discussed in this volume and to the photographic services that have supplied the illustrations.

stella panayotova

lucy Freeman sandler

Tamar miller Wang

Introduction

WhenJohan van der b eke first suggested publishing a Tributes volume to my mother elly miller, the title ‘Opening manuscripts’ immediately came to mind. Opening manuscripts was what she had done – opening them for a wider public to view and championing those who opened new research avenues – a veritable prince Charming bringing back to life the rich store of medieval treasures which had lain dormant for centuries. an exaggerated image no doubt, from an admiring daughter, but i was amazed at the depth of feeling in the responses lucy sandler received from colleagues on hearing of elly’s death: ‘i had come to think of elly as not-entirely-mortal’; ‘such a fountain of energy, force of nature personally’; and praise for her ‘unbelievably broad and deep contribution to the study of medieval illuminated manuscripts, which she so evidently loved’. e lly m iller spent her early years surrounded by the b aroque and Neo-classical architecture of imperial vienna, with its highly ornate palaces, broad carriageways and parks, and richly decorated interiors. her home on an upper floor of a majestic building on the ringstrasse near the stadtpark, which also housed her father béla horovitz’s office, phaidon verlag, on the piano nobile, gave expression to a deep admiration for the arts: literature, music and, increasingly as she was growing up, the visual arts, the history of which began for the well-educated viennese (and indeed for the majority of the Germanspeaking world at that time) with the renaissance. and yet, despite these early influences, elly’s real love was for the medieval, for artistic creations which she told us children would have been dismissed as unimportant minor art by her mentor and phaidon’s editor-in-chief ludwig Goldscheider. The middle ages were well and truly the Dark ages artistically while she was growing up and for some time into her career in publishing.

What was it then that made her so champion the art of the middle ages? Was it her expulsion from the grand city, when in all its splendour it turned against her in 1938, or the safety offered by her new home in the city of Oxford during the war, with its narrow winding streets and medieval colleges? Or was it her natural playful curiosity which led her to enjoy the detail often overlooked in grand vistas, where the twinkle of an artist’s eye could be found? i remember as a child being enjoined to admire the soaring heights of cathedrals but equally to sneak a view at the misericords under the choir seats, to try to look closely at the gargoyles or any other mischievous sculpture we could spot. elly would always point out to us playful marginalia when she was working on publication layouts, enchanted by the irreverence so skilfully included in, but in no way undermining, the illumination of sacred texts. For alongside her deep admiration and awe for the art she was encountering, which gave her the drive to use her skills to choose just the right detail of

an image to accompany the insight afforded by the scholars she worked with, she always retained her sense of fun, a giggle alongside the serious, a bubble which would burst out in the songs and verses she wrote in her spare time.

While elly was fascinated by the whole medieval world, the society as well as the art it produced, its architecture, sculpture and stained glass, she was most drawn to the earlier period and to manuscripts in particular. i remember her excitement when examining the display of illuminated manuscripts at one of the last exhibitions we visited together, AngloSaxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War at the british library. i was reminded of the various nib pens tipped with inks of different colours which stood in the pen holder on her desk many years ago, and of the carefully drawn lettering placed in grids she would work on to design book jackets or title pages. lettering and page layout were all part of her job, but at that moment, looking at a manuscript page i could sense the physical connection she might have felt between the scribe’s work and her own.

elly’s lifelong commitment to medieval art was not an obvious choice for a woman so actively devoted to her family and to the Jewish community, especially in the 1970s when she began the harvey miller medieval list. she herself would have been amazed by the idea of this present volume dedicated to her, in a series designed to honour and further the work of the scholars she so admired. she would have been amazed but also highly delighted that her efforts to open up the field had been so fruitful.

These are just some of my musings on why my mother might have chosen the path she did, but how she did it, and the various experiences which formed and informed her journey, are beautifully explored in her own words in the article which follows, ‘a passion for manuscripts’, adapted from a talk she gave at the opening of the exhibition Cambridge Illuminations at the Fitzwilliam museum in 2005 and published later in The Book Collector in 2010. What better way then to introduce this book than to let elly open the subject herself?

Tamar miller Wang‘A Passion for Manuscripts’ by Elly Miller1

i am what is known in the book trade as a ‘niche publisher’. That is to say you will not find our books in general bookstores, you will rarely see gossip articles in the national press about our authors, and although i am sure they would wish it to be otherwise, the advances art historians get for contracting their publications are hardly ever newsworthy. Our ‘niche’ is medieval art history and in particular illuminated manuscripts – which is my personal passion. Now to indulge in a passion where business is concerned – and publishing is a business – is not always the most prudent thing to do, because, the more specialized the interest, the more limited the market possibilities. The most successful publishers have been men (generally men) who regarded books as merchandise: a llen lane, the founder of penguin books, was said never to have read any of the books he published; and a well-known and highly successful italian publisher apparently could not read at all. so publishing only what one is deeply interested in, and regarding ‘the book’ as a cherished object, is a risky business.

The concept of publishing books for a specialized audience, however, is not the tradition i grew up in. my father, béla horovitz, was the founder of the p haidon press and his ambition was to produce books on art and cultural history to the broadest possible audience. any title with a print-run of less than 30,000 was thought to be a failure, and many books reached editions of 100–200,000 copies. ernst Gombrich’s The Story of Art, which phaidon first published in 1949, has by now reached millions. in 1923, when my father started his publishing house in vienna, the German-speaking public was poor but also culturestarved after the defeat of the First World War; moreover, art and its history had until then only been the interest of the élite, as indeed it also was in britain at that time, and any specialized literature would have been accessible only to the affluent or the dedicated scholar. being an optimist, and trusting his own judgement, he had the courage to initiate large print-runs for his titles from the very beginning, which allowed the unit price of a book to be low enough to be affordable for the general reading public. by pricing phaidon books at the then current price of a novel, he was able to reach an entirely new audience. Who could have imagined that books like Theodor mommsen’s The History of Rome or Jakob burckhardt’s The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy could become bestsellers? in the 1930s when phaidon first produced their distinctive large, canvas-bound volumes on michelangelo, Donatello, leonardo da vinci, botticelli, the popular ‘art monograph’ was an entirely new concept. There were several German publishers producing what i would call picture collections, for instance seeman, who issued loose-leaf plates in albums for students without any text, and at the other end of the scale the scholarly series Klassiker der Kunst, fully illustrated catalogues raisonnés that are still quoted today.

The only other publisher at the time who also wanted to ‘popularize’ art, was the swiss albert skira, who produced books on periods in art history or schools of art rather than individual artists, all with great taste and style. and by way of novelty, he printed almost 1. The Book Collector, volume 59 no 2, 2010. reproduced by kind permission of The Book Collector (www.thebookcollector.co.uk).

all the illustrations in his series in full colour. but the phaidon monograph captured the market with its dramatic black-and-white, full-page, high-quality gravure reproductions; and print-runs of the illustrations were increased even further in order to allow for different language editions – German (the original language), French and english, even Dutch – to appear internationally. That too was an innovation, introduced by phaidon before the second World War, and is now commonplace. Texts in different languages would be added to already printed illustration-sheets at a later date – a particularly significant saving in production costs where illustrations might have been printed in four or more colours, and text would only need one colour, black. Of course printing techniques have changed so much today that different considerations apply to international publishing; however it is important to remember for publishing history when and how so-called ‘foreign editions’ were first introduced.

by the time i joined my father’s publishing house in the early 1950s, art books, in fact illustrated books on all sorts of topics (popular biographies, histories, travel books) were widely available; the public seemed to demand illustrations, it became a sort of prop to reading, an easy way of absorbing factual narrative – one might call it the beginning of our magazine culture. publishers like Thames & hudson in england and abrams in the united states now began to make their contributions to the art monograph, and French, German, italian and spanish houses made books with excellent to middling reproductions available on every artist vasari could have dreamt of or ruskin would have hated. i remember the period well: a flood of art books appeared in the shops and quickly reappeared in the remainder market; but the public bought everything, eager to extend their awareness and often status in the world of art. This was certainly due to the widely publicized exhibitions of those years, the refurbishment and opening up of private and public collections, the public debates on the cleaning of pictures, and the possibilities of cheaper international travel in order to visit the major centres of art. phaidon by that time, after my father’s death in 1955 and now under the direction of my husband harvey miller, was producing not only monographs as before, but had turned to more serious catalogues raisonnés, containing reproductions of the complete oeuvre of an artist with more than just introductory texts as was done previously, but with thorough, scholarly, authoritative catalogues.

Of the huge number of art books published at that time and even in the later 1960s, the art of the middle ages constituted only a very small part of the output, and books on illuminated manuscripts even less so. in my own circle at the phaidon press the emphasis was still more or less on renaissance italy, although the programme was becoming more diverse. There was still the great divide between medieval and post-medieval. The mere mention of manuscripts would receive a very disdainful response, in particular from ludwig Goldscheider, who, as a co-founder of the press (he was my father’s schoolfriend) and as chief editor, still regarded book illumination as a ‘minor art’. he called miniatures ‘die Putzerln’ – a viennese expression for the ‘little things’: it was an attitude Otto pächt, his fellow viennese, would fight against all his life. and, since i was in a sense Goldscheider’s apprentice, i had little chance to explore what had by then already begun to interest me: that is, the early history of the book.

i should mention at this point that my training in publishing had not always been in

The Chronology of Matthew Paris’s Illustrated Saints’ Lives

Paul BinskiIn a well-known passage , the St Albans monk and chronicler Thomas Walsingham (d. c.1422) states that Matthew Paris (d. 1259) ‘ably enlarged’ (ampliavit) Roger of Wendover’s chronicles and ‘wrote and most elegantly illustrated (depinxit) the lives of Saints Alban and Amphibalus, and of the archbishops of Canterbury Thomas and Edmund; and who provided many books for the church’.1 Such sources tend to be put under pressure by modern scholars bereft of the kind of evidence that can resolve a problem. Walsingham’s proposed order, history first, hagiography second and (liturgical?) books for the Church third, has perhaps coloured subsequent discussions of Matthew’s chronological development. It may require revision, not least because it insinuates that history writing and hagiography were more independent activities than in fact they were. First, what of the chronology of Matthew’s works more generally? In style, Matthew’s art is anticipated in a group of illuminated manuscripts made for the region of Cambridgeshire and the Fens: the two Peterborough Psalters of c.1220 (London, Society of Antiquaries, MS 59 and Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 12) and particularly the single leaf of Christ in Majesty now British Library, Cotton MS Vespasian A. I.2 In the drawing of Christ’s features and the way the soft folds of his tunic roll over the beltline in this leaf, we can see details manifestly similar to Matthew’s work. Yet, so far as we know, Matthew never worked in the full-colour and gilded mode of the most elaborate late Romanesque and Gothic art: his favoured technique was pen and wash over lead-point drawing, a deft medium suiting Matthew’s everyday literary style, rather than liturgical high style. Matthew’s artistic idiom and technique were clearly formed in the years around 1220, and probably within Benedictine circles: his models do not indicate that he took up drawing ‘late’, as stated by Suzanne Lewis.3 He derived artistic motifs from St Albans books such as the magnificently illuminated Glossed Gospels of c.1200 (Cambridge, Trinity College, MS B.5.3) made around 1200 by artists also employed at Westminster.4 Matthew’s work often acknowledges his regard for later twelfth-century art.

But this assertion raises two almost imponderable, but important, questions. The first is when Matthew was born. We know he professed in January 1217 and the evidence for his death in 1259 seems unassailable.5 He replaced Roger of Wendover as the St Albans’ historian after 1236.6 Richard Vaughan considered it unlikely that Matthew was born [22]

24 | tributes to elly miller

Fig. 1 Matthew Paris, Lamentations after the massacre of Christians, Vie de Seint Auban. Dublin, Trinity College, MS 177, f. 43v

Fig. 2 St Thomas departs from Kings Henry II and Louis VII, ‘Life of St Thomas’. Wormsley Library, British Library Loan MS 88, f. 2v

Fig. 1 Matthew Paris, Lamentations after the massacre of Christians, Vie de Seint Auban. Dublin, Trinity College, MS 177, f. 43v

Fig. 2 St Thomas departs from Kings Henry II and Louis VII, ‘Life of St Thomas’. Wormsley Library, British Library Loan MS 88, f. 2v

they could have been used by another author of such verses. In fact the opening verses are strong prima facie evidence for a date of composition soon after the marriage in 1236: Edward only has as his patrons ‘you two’ (l. 84) ‘n’a si vus deus nun’, i.e. Henry and Eleanor (the Lord Edward was born in June 1239).29 Later allusions in the text (lines 4675–90) to the desirability of Henry III being a patron of Westminster Abbey would have sounded tactless after 1241 or 1245 when Henry began spectacular investment in St Edward’s shrine and church, as was well known to Matthew who commented sardonically on the fact; also, no mention is made, in a book with more than one eucharistic miracle, of the relic of the Holy Blood which Henry obtained in 1247, an acquisition acknowledged both in Edmund and the Chronica majora.30 Edward was thus composed by turns before 1247, 1245 and 1241, and probably shortly after 1236, but it was copied in the Cambridge version around 1255. The extant Thomas and Edward look different, but these differences should not obscure some important similarities. First, metre and vocabulary: both are composed in octosyllabic rhymed couplets, and according to James have marked coincidences of vocabulary. 31 Second, format: the text-picture blocks, metre-derived short column lines, Latin captions and French rubrics are similar if not identical. 32 Thomas and Edward (to f. 5) add small Latin rubrics to the pictures. Third, technically the works are the same, pen and bistre wash. Fourth, there are very similar methods of pictorial invention. Including Alban and

The Patron of the Lambeth Bible

Christopher de HamelElly Miller used to recall that her passion for medieval illumination was originally sparked when she was editing her first book for the Phaidon Press, Adelheid Heimann’s The Bible in Art (1956), for which she described sourcing illustrations from various manuscripts including the twelfth-century Bible at Lambeth Palace, then relatively little known.1 Almost twenty years later that manuscript became no. 70 in the first volume to appear in her marvellous Harvey Miller series, A Survey of Manuscripts Illuminated in the British Isles, with eight plates, and by 2007 the Lambeth Bible formed a substantial monograph by Dorothy M. Shepard, published by Brepols, partner of Harvey Miller.2 Today it is among the giant celebrities of medieval art, both in size and fame, brought out by its curators to impress visiting popes and heads of state.

When the manuscript was given to the library in Lambeth by Archbishop Bancroft in 1610, it was accompanied by a similar second volume in slightly larger size but with lesser decoration. In 1924, Eric Millar demonstrated that this was a mismatch, and that the true companion volume of the Lambeth Bible belonged to All Saints Church in Maidstone, now kept in the Maidstone Museum.3 Neither part has any medieval inscription and no one knows where the manuscript was before the Reformation. Its origin is one of the mysteries of English Romanesque art. It is agreed that it dates from the mid-twelfth century. Its supreme richness and quality of artistry must indicate a cathedral or religious house of exceptional wealth or available patronage. Speculations have included St Albans, Bury St Edmunds, Christ Church Cathedral Priory in Canterbury and especially St Augustine’s Abbey in Canterbury, which has usually become the modern attribution by default, including the circular reasoning of Dorothy Shepard. In reality, there is almost no possibility that the Bible ever belonged to St Augustine’s, whose libraries and other books are extremely well documented and usually overloaded with inscriptions and pressmarks.4

The argument to be presented here, which I have used in various evolving lectures but never laid out in writing,5 is that the Lambeth Bible belonged to Faversham Abbey in northern Kent, and must have been a foundation bequest of the king, Stephen of Blois, King of England (r. 1135–54), recent victor in the civil war with his cousin Matilda. The evidence will be approached from three principal directions. These are historical likelihood, what is known of the careers of the main illuminator and the scribe, and internal evidence from the manuscript itself.

42 | tributes to elly miller

Fig. 1 The dynasties of the patriarchs, frontispiece to the Pentateuch. London, Lambeth Palace Library, MS 3, f. 6r

Fig. 1 The dynasties of the patriarchs, frontispiece to the Pentateuch. London, Lambeth Palace Library, MS 3, f. 6r

reigning through the grace of God; it equates Stephen with the anointed one in Isaiah 9: ‘touch not mine anointed’, it quotes from Psalm 104 in chastising the king’s enemies. Henry I, father of Matilda, is identified with King Saul, and the rioters in Bristol with the brigands of Elisha; the sufferings of the English are compared with those of the Israelites in I Samuel and of the Amorites in Genesis, and many of the battles of the civil war with those in the books of Kings and Maccabees. Politics of twelfth-century England are interpreted as a replay of biblical events. It predicts that Stephen’s enemies will be cut down and degraded, as prophesied to the king of Babylon in Daniel 4. Indeed, the capture in 1138 of the city of Bedford, not everyone’s idea of Babylon today, is directly equated to the visions revealed and interpreted in the book of Daniel, for they were ‘nothing but true prophecies of things that were to come, by knowledge of which mortal men might become humble towards God and more cautious amid those very evils.’19

One reads the Gesta transfixed, as if it were a commentary on the imagery of the Lambeth Bible. It is possible that the connection can be taken a step further. In the patronage of the other two great Romanesque Bibles, we can assume that the abbot and sacrist of Bury St Edmunds and the bishop and prior of Winchester all had sufficient scriptural knowledge to have input in their manuscripts’ iconography, but Stephen was a layman and a busy one at that. There must have been a theological consultant to plan the illustrations and to oversee the project. It may have been none other than the author of the Gesta Stephani itself, Robert, bishop of Bath, who, most relevantly in the case of Faversham, was himself a Cluniac and a former monk of Lewes, the first Cluniac house in England.

We may not know the name of the artist of the Lambeth Bible, but we might have the identity of its designer.

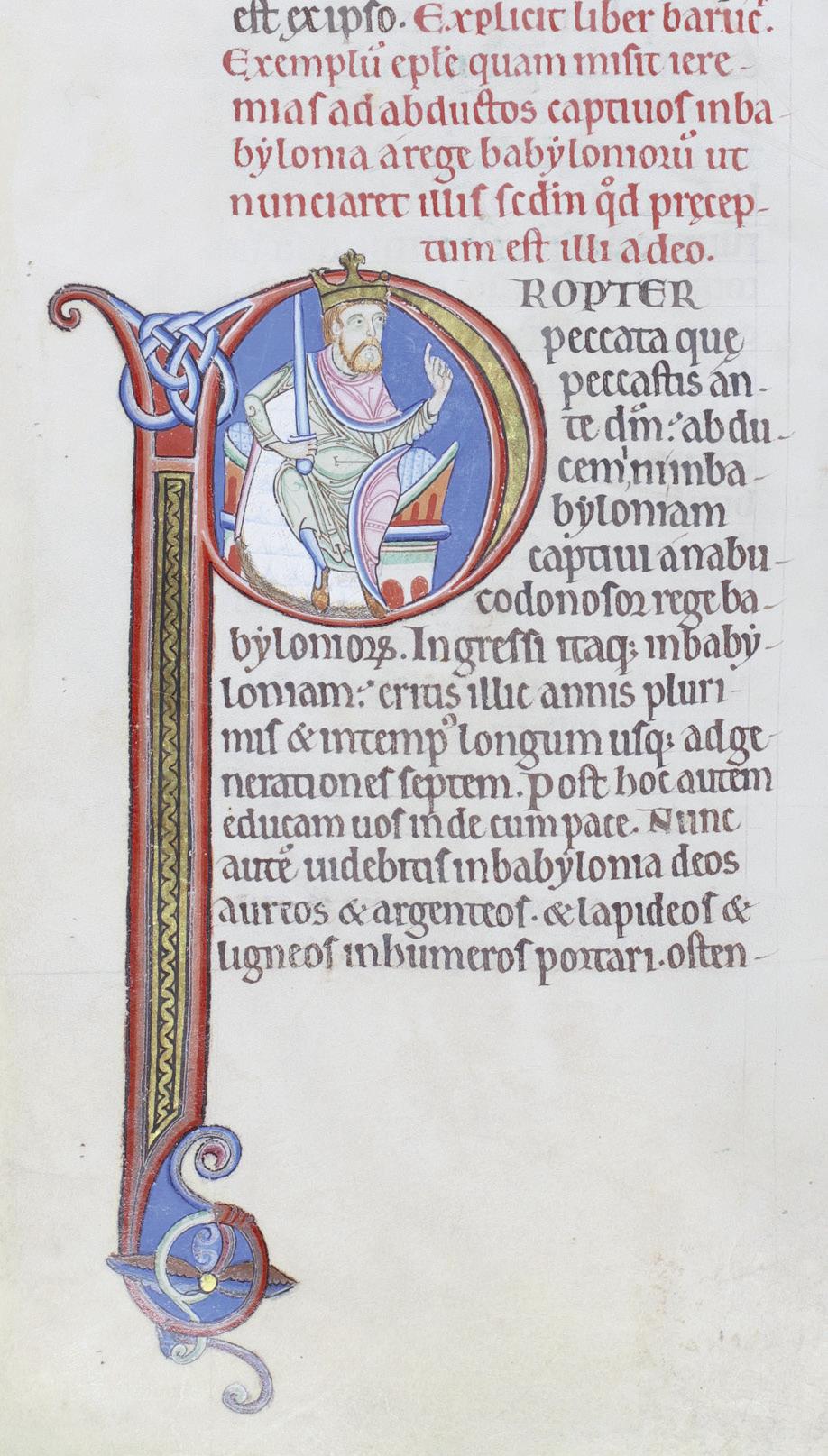

4 King Nebuchadnezzar, illustrating the letter sent by Jeremiah to the prisoners in Babylon in the book of Baruch. London, Lambeth Palace Library, MS 3, f. 236r (detail)

The amount of time required to make a manuscript is an old and often unanswerable question because we cannot know what other tasks might be required of the craftsmen in the meantime. Before the labour even began, materials had to be assembled, including sourcing enough parchment for about 760 leaves. In the case of the Bury Bible, we are told this had to be imported from Scotland or Ireland. An exemplar had to be found and checked. The designs for initials and miniatures had to be approved by the patron. Even if the enterprise for Faversham was conceived in late 1148, realistically work would hardly have been started before about 1150. It is calculated that a careful twelfth-century scribe could write a maximum of about 150 to 200 lines a day.20 The Lambeth Bible has forty-six lines to a column, which would be about three columns a day. If the scribe worked for an average of five days a week for fifty weeks a year (this is only a guess), 760 leaves would take four years. That seems plausible. The illumination could be begun almost simultaneously but would usually take several more years to complete. In the event, something happened to cause a dramatic change of plan about a hundred leaves before the end of the second volume. From f. 196 in the Maidstone manuscript, there was a change of scribe. The layout suddenly altered, and from that point onwards the new scribe left only modest shapes for simple initials, and the scheme of large dynastic imagery was abandoned. The Lambeth Bible Master, running slightly behind the scribe, probably continued working as far as f. 140r in volume II and then he too stopped work, like the disbanding of the workshop in Liessies in 1148.21

The explanation would be the unexpected death of Prince Eustace, Stephen’s son and anointed heir, on 17 August 1153. King Stephen was utterly devastated, and never fully recovered. King David’s heartrending grief for Saul and Jonathan was a parallel which would easily have been made.22 It was the end of absolutely everything Stephen had fought for throughout his life and in that moment his dream of a royal house was finished. In November 1153 Stephen was obliged to name his new heir as Henry of Anjou, son of

Adémar of Chabannes’ Biblical Drawings in Notebook Leiden VLO 15: From the Mystery of Incarnation to Liturgical Drama

Charlotte DenoëlThis paper focuses on a famous manuscript which belonged to the early medieval historian Adémar of Chabannes (989–1034): MS Vossianus Latinus Octavo 15.1 Adémar wrote it in Angoulême and Limoges at the beginning of the eleventh century. I have chosen to study this manuscript as a homage to, and in memory of, Elly Miller. It is included in the forthcoming catalogue of French manuscripts illuminated during the tenth and eleventh centuries, which Elly, along with François Avril and Jonathan Alexander, entrusted to me for the series published by Harvey Miller/Brepols: A Survey of Manuscripts Illuminated in France. This manuscript is one of a number produced at SaintMartial in Limoges that are described in the catalogue, including its two-volume Bible, Tropary and Legendary,2 alongside other famous manuscripts. The idea of a more detailed study took shape in stimulating discussions with Beatrice Kitzinger and Susan Rankin in 2019–20, when I was working on the series at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton.

Adémar’s manuscript stands apart from other liturgical manuscripts produced at SaintMartial. It belongs to the category, particularly rare in the Middle Ages, of autograph notebooks. Within this category, it is exceptional for the many drawings alongside the textual portions. This paper will consider the manuscript in terms of its iconographic content in order to show how both images and texts shed light on Adémar’s teaching activities, his intellectual interests and his culture. It will focus on a specific group of biblical images that are centred on the Incarnation and linked to dramatized liturgy.

The manuscript Leiden VLO 15 has generated an impressive number of studies. The most recent and comprehensive study, the 2020 monograph by Ad van Els, draws on manuscripts to reconstruct Adémar’s biography and interests, and presents Adémar as a teacher throughout his life, using VLO 15 as a key witness to his educational activity.3

Before diving into the manuscript, it seems important to recall Adémar’s biography in order to sketch a framework for VLO 15. Born in 989, Adémar was a monk at Saint-Cybard in Angoulême and its sister monastery, Saint-Martial in Limoges. After his training under his uncle and mentor Roger (d. 1025), cantor at Saint-Martial, Adémar had a varied career as historiographer (Chronicon, 1025–28, 3 versions), composer, liturgist and teacher. He also actively campaigned for the recognition of Saint-Martial’s apostolicity. In the second half of 1033, Adémar left Limoges for the Holy Land and probably died there the year after.

Fig. 2 Adémar of Chabannes, Descent from the Cross, Nativity; Arrest of Christ, St Peter and Malchus, Noli me tangere, Salome performing gynecological examination of the Virgin, disciples, Christ (from Last Supper). Leiden, Universiteitsbibliotheek, MS Vossianus Latinus Octavo 15, ff. 2v–3r

Opening Up Representations of Saints in English Folded Almanacs

Kathleen DoyleCalendar references to saints are ubiquitous in books of hours, psalters, breviaries and other manuscripts. However, illuminated images of saints or other feasts in calendars are relatively rare, and also little studied. In part, this may be because most of these representations occur in works of an unusual folded format, rather than in codices. These accordion- or concertina-folded almanacs survive in around thirty late medieval copies, but probably once were much more numerous.1 I wasn’t able to discuss these fascinating manuscripts with Elly Miller, but given her boundless enthusiasm and rigorous analytical prowess I am sure that she would have been full of insightful questions about them and what they reveal about piety, historical knowledge and views of time in late medieval England.

Of the concertina almanacs, most are English: there are nine known English examples, together with a xylographic version, printed using woodblocks. The manuscripts are mainly from the fifteenth century, although the latest example is dated 1535 and the known xylographic copies exist up to 1554 (see pp. 85–87). All of the complete copies have coloured or illuminated perpetual calendars, together with a more unusual text, which consists of a list or timeline of selected events and dates setting out some of the most important occurrences in biblical and English post-biblical history. As far as I am aware, the illuminated versions of this timeline found in the concertina almanacs and a small number of closely related codices are the only illustrated versions of this text.2 The timelines have received little attention even in the context of the folded almanacs, and indeed no common nomenclature has been applied to them.3 In both the Continental and the English examples, they begin with six biblical or quasi-biblical events or people: the creation of the world, Adam and Eve’s ages, the number of years that Adam was in hell before the Incarnation, the number of years since the Flood, and the number of years since the Incarnation.4 In the English (but not the Continental) almanacs, additional selected post-biblical saints and events feature in an extended timeline, varying in number and content from manuscript to manuscript.

In this essay I will explore how British saints are represented in the perpetual calendars and in the timelines of the English concertina-folded manuscripts, xylographic copies and three related codices, looking in particular at the instances where the illuminations are

Perpetual calendars

Even in the most elaborate examples, the heart of these almanacs is the perpetual calendar, which provides information about fixed feasts, such as saints’ days and religious festivals like Christmas, Epiphany and Candlemas that are always celebrated on the same date, and which were, as Eamon Duffy observed, ‘indispensable for any well-ordered devotional life’. 8 In the almanac calendars, as is common generally, the names of the more important saints are in red (or blue) rather than black or brown ink. Below the names, the very unusual and most visually arresting aspect of the perpetual calendars is the series of ‘pictograms’ or graphic signs or symbols associated with the feasts (Fig. 4).9 Most of the pictograms, ideograms or iconograms (in semiotic terms), consist of busts of the relevant saint and/or an attribute, either general, such as a mitre to represent a bishop, or specific, such as a key to represent St Peter or a saltire cross for St Andrew. The pictograms are both the largest and the most prominent element of the calendars, and normally are connected by black or red lines (corresponding to the colour of the saint’s name) to the relevant date, written in Arabic or symbolic numerals represented by ciphers below the images, or to the Dominical Letter. In one case it is these lines only rather than the saints’ names that differentiate the feasts of higher grades through the use of red.10 In the most elaborate versions, the images are illuminated using gold, and/or include larger or full-length figures (Fig. 5) or more detailed depictions, more like miniatures than symbols, while the pictograms vary greatly in style, detail and choice of representation. In medieval manuscripts more generally, it is extremely unusual to find calendars that feature portraits or representations of the saints. Rare examples include deluxe manuscripts such as the East Anglian Gorleston Psalter, with four or five

Fig. 3 July–December and timeline. Basel, Historisches Museum, inv. 1873.22, photo: N. Jansen