Prologue 1588 between Divulgation and Surprise

Brendan Dooley

The year 1588 began more or less like any other, although obviously not at the same time in every place. For Don Giovanni de’ Medici it began in a cold tent. Urged to the fields of Flanders as much by his late brother Grand Duke Francesco I as by a military tradition of the sort that Greg Hanlon likes to remind us of, he had joined the forces of Alessandro Farnese, governor of Spanish Flanders, just at the moment when Philip II’s grand design was developing to include a planned transfer of troops and supplies from Flanders to England with an armed fleet of unprecedented proportions.

The Spanish Armada still existed mostly on paper as the new year was being celebrated around Antwerp, some ten days earlier than it would be just across the River Maas in Gelderland, where the Gregorian calendar correction was not observed, or three days earlier than across the Southern Bight of the North Sea in Britain, where things were further complicated by the Nativity dating system for the new year, not to mention being nearly three months before Don Giovanni’s relatives would celebrate it in Florence, where Annunciation Day doubled as the yearchanging feast.

But after months of slogging through the mud in some of the worst weather on record in the area, now made worse by a deepening winter chill, Don Giovanni’s normally resilient twenty-year-old frame responded as it might. And in the midst of a fever epidemic that had also infected numerous other soldiers, on 2 January, in the presence of his squire Cosimo Baroncelli and a military chaplain, he

dictated his last will and testament, the only such document of his that has survived. Giovanni’s condition had been so bad in the previous weeks, and would continue to be so in the weeks to come, that we have practically no Flanders correspondence personally attributable to him from this period, directed to the Medici court or to anywhere else, and it won’t be until February that things begin to pick up, on a supplicating note, with a request to the new Grand Duke Ferdinando I for money to pay a gambling debt incurred during Giovanni’s convalescence, when the only entertainment to relieve the effects of sickness and boredom had been the card game of Faro.

Meanwhile, a Flanders newsletter, possibly posted from within Giovanni’s retinue, and now in the Medici Archive Project database, informs on 31 January that Queen Elizabeth of England is arming the ports facing Scotland, Ireland, France, and Zeeland as a bulwark against a possible landing by the Spanish Armada1; and two weeks later the same source reports that Francis Drake has armed 70 ships for the encounter.2

We are in the opening stages of one of the most colossal events of the century, one that resonates nearly as much in regard to the problematics of information exchange as in regard to war and international relations. This of course is not the only news. And the challenge of the growing field of Historical Information Studies is to discern over the vast seas of information the waves and troughs, so to speak; to distinguish the momentous inundations from the insignificant pools and eddies. Nor, of course, is there

1. Florence, Archivio di Stato, Archivio Mediceo del Principato (MdP), vol. 3085, fol. 562r.

2. MdP 3085, fol. 574r. Attention is paid here to the standard bibliography, including Garrett Mattingly, Armada (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1959); more recently, Felipe Fernández-Armesto, Spanish Armada: The Experience of War in 1588 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988); and, in a revisionist vein, Luis Gorrochategui Santos, The English Armada: The Greatest Naval Disaster in English History (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018).

any uniform pattern of distribution. What Don Giovanni knew, on any given day, about trouble and triumph in the world was likely to be different from what, say, Matteo Botti in Florence knew. Botti was apparently an avid reader of news and his collection of newsletters, conserved in handy indexed volumes, eventually ended up in the portion of the Medici patrimony that became the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale after he gave up his property in the early seventeenth century in return for debt relief. And although Botti had relatively good geographical coverage, the Medici court had even better, as we see in the volumes of the Mediceo del Principato entirely given over to the avvisi. But in spite of the timespace problem, or, rather, taking into account the analytical dimension of the time-space problem, it should be possible to gain a basic picture of the news in this key year as it might have been experienced then, and as it may inform a revision of our perception of the period now— an aspect to which we will return in due course.

An initial inquiry regarding the year 1588, viewed not just as the year of the Armada but as a year of multiple and varied lived narratives, as evidenced exclusively in the news publications, might begin with Enrico Stumpo’s useful if somewhat chaotic volume entitled La gazzetta dell’anno 1588, published in 1988 and largely based on the Botti collection in the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale.3 For Stumpo, what was important could be grouped within each month under rubrics like ‘Foreign Affairs’, ‘War’, ‘Economy and Finances’, ‘Justice and Religion’, ‘Society and customs’, ‘Naval matters’, ‘Architecture and Urban Planning’, ‘Medicine and Environment’, not to mention ‘The News of the Month’. He even supplies improvised headlines whereas there were none in the original, such as ‘The Protestant conquest of Bonn’, ‘A lottery of long ago: the bet on cardinals’ elections’, and ‘The burial of Pius V’, along with clearly labeled continuing stories, such as ‘Conquering a kingdom, act I’, ‘A workmen’s strike, part I’, sometimes subdivided into episodes presented almost theatrically, as, ‘History of a mob leader, Act I: The Castle of Trieste’.

A disadvantage of this approach, apart from the absence of quantitative data, is that it gives no impression of how the original news sheets were organized—also because there are no folio numbers for the stories, and chronological lacunae in the Botti collection have been filled in, rather surprisingly, by

1.1

3 January report from Lyons, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, cod. 8961, fol. 7 (image 21 at http://fuggerzeitungen.univie.ac.at/)

recourse to unrelated news sheets located in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, again, not precisely referenced.

Stumpo’s collection was pathbreaking at least in the aspect of turning attention to a historical source that had hitherto been far more often counted and indexed than actually read (except for assorted art historical information). It presents the newsletters as a rather good reflection of ‘what the news was’, perhaps in one part of the world. Here we are offering to develop this concept by suggesting research that may help us to understand how the news differed from place to place, and whether it is possible to trace patterns of diffusion across Europe and beyond.

Thus, turning to Stumpo’s collection, we find a month of January dominated by no single event, but by a multitude of assorted experiences of unequal pith and

3. Enrico Stumpo, La gazzetta dell’anno 1588 (Florence: Giunti, 1988), passim

moment, ranging from a report from Venice about the solemn entrance of the Venetian envoy into Constantinople, which actually took place at the end of December 1587, to a report from Rome about 14 city officers (maestri di strada) having been appointed to oversee the maintenance of city thoroughfares.

Rumors fly, and so far it has not been possible to trace them all. From Milan on 2 January we hear of the supposed assassination of Henry of Navarre, the future king of France, shot down on his way to support the siege of ‘Giurica’ in Poitou (no doubt, Saint-Yrieix-sur-Charente).

To grasp the context we have to compare the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale report to the one in a newsletter dated the following day from Lyons, collected by the Fugger family, and now in the Vienna Nationalbibliothek, where we learn that this rumor had actually begun to circulate a month before, and was already contradicted (Fig. 1.1).4 Where did it originate? So far, we do not know.

How different was the perspective of Orazio Urbani, the Florentine emissary to Prague, who in the same month of January found himself engulfed in the details of what, from his perspective, was the single biggest event of the day, namely the siege of Pitschen, where supporters of Sigismund Vasa defeated the rival candidate for the throne of Poland, namely, Maximilian, brother of Emperor Rudolph.

Writing to his employer the grand duke, Urbani says, ‘I will include a letter from Bratislava whereby there appears everything I could say about the events of the battle’. The supposed letter from Bratislava, an anonymous battle report, is in the same hand as the letter to the grand duke, namely, that of Urbani’s secretary (quite different from Urbani’s own hand, as we see from the signature), and derives from a now-lost original or originals. A common practice for scribes was to pick up a little money on the side by selling copies of newsletters or battle reports, and there is no way to exclude such behavior in the case of Urbani’s secretary, nor even in the case of Urbani himself. The report in question informs:

On the 24th of January the Chancellor [i.e., Jan Zamoyski, on the side of Sigismund] arrived in person before Pitschen with 8000 men and 13,000

artillery pieces to besiege Archduke Maximilian. On the said day there came Heinrichs von Waldau, captain of the Reiter [i.e., the German knights], next to us, with the Moravians and Hungarians, in all about 4000, but exhausted, and at an hour before mid-day they arranged their men to fight the Chancellor, who did not refuse battle, and with his soldiers, including 4000 Hajduks who shot ferociously, they put our harquebusiers to flight and especially the Hungarians, who were the first to flee, so that on both sides there were about 4000 dead, among whom, the best soldiers. The Archduke Maximilian escaped and no one knows where he is, and many were lost in the flight, not knowing where to turn. The city of Pitschen was immediately burned to the ground, and the Chancellor with his forces are moving forward to Bratislava, burning everything as they go, and frightening everyone by this victory.5

Urbani in his accompanying letter to the grand duke notes that there is additional information just arrived from the field by way of ‘those who show up here in flight from the battle’, which, he adds, ‘really took place as reported’. He was thus able to draw on ‘an earlier report that Maximilian himself had his horse killed from under him but was able to get another mount and save himself and six others’, although no one knew where they were, ‘but finally it is strongly affirmed that he was taken prisoner’.

Don Giovanni himself was a subject of rumor, although not yet, as in later years, by way of his military prowess. His survival was by no means guaranteed: a newsletter report dated Florence, 6 February, stated that he was ‘almost certain’ to have died of ‘spotted fever (pettecchie)’ on the field;6 and a report dated Rome, 20 February, claims that he was not in fact dead in spite of the rumor, and ‘indeed, most say he is cured of his serious illness’, adding rumor on rumor by declaring ‘soon he will return to Italy’.7 Instead, after a miserable month of February he resumed his active soldiering the following month.

What did he know in 1588? He may have heard news already in early March that the Spanish Armada was set to sail, its new commander, the duke of Medina Sidonia,

4. Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, cod. 8961, fol. 7 (image 21 at http://fuggerzeitungen.univie.ac.at/)

5. MdP 4344, fol. 136r.

6. Stumpo, La gazzetta dell’anno 1588, p. 23.

7. Stumpo, La gazzetta dell’anno 1588, p. 24.

1.2 19 March newsletter from Venice, MdP 3085 fol. 584v (Florence, Archivio di Stato)

having stepped in for the marquis of Santa Cruz, who died the month before. Possibly he would have been unaware of conversations taking place just up the Scheldt River at Vlissingen (or Flushing in English), between Admiral Lord Howard of Effingham (who was on a reconnaissance mission from England) and contacts there, including a Dane just arrived from Lisbon with the latest about the fleet, which induced Lord Howard to write to Francis Walsingham back in England that 5 March was the generally accepted sailing date.8 However, a newsletter in Italian sent to Florence out of Antwerp on the 12th, possibly by Giovanni’s own entourage, stated that the fleet had in fact already sailed.9

Was the size and provisioning of the proposed fleet a matter of discussion on the field of Flanders? It was elsewhere, but the original source of the information is not clear, nor are the figures easy to pin down. A newsletter sent to the Florentine court and dated ‘Venice, 19 March’

(Fig. 1.2) includes a purported ‘Note of the Provisions of the Armada being prepared in Lisbon by order of His Catholic Majesty for the England Mission’ (‘l’impresa d’Inghilterra’), listing 600 vessels in all, including 150 large sailing ships (‘navi grosse’), 36 ships to guard the Spanish coast, not to mention ‘320 small ships, such as caravelles’. Aboard were to be (and the order is interesting) 30,000 Spaniards; 2000 horses; 5000 Portuguese; 12,000 Italians; 15,000 Germans; 8000 sailors; 4400 bombardiers and sappers; 1400 mules to pull artillery; and 400 Moors to govern the mules. The lading list was even more impressive, but I’ll only mention the hefty load of sea biscuit, amounting to 1,900,000 tons (that is, ‘quintali’).10

Such a load of sea biscuit is nowhere in the Spanish documents, so far as I can tell. On the same 19 March when the amazing news hit the streets in Venice and flew from thence to Florence, Medina Sidonia completed a document in Lisbon, which was possibly leaked even

8. Bertrand T. Whitehead, Brags and Boasts: Propaganda in the Year of the Armada (Stroud, Gloucestershire: Alan Sutton Publishing, 1994), p. 47. 9. MdP 3085, fol. 600r, dated March 12. 10. Ibid., fol. 584v.

before being sent to the Spanish court, entitled ‘Relación de la visita que en particular hizo el Duque de MedinaSidonia á los galeones, naves, urcas, pataches, zabras y galeazas de la Armada Real’, based on a recent review of the preparations to date, and printed in the latenineteenth-century collection of Cesáreo Fernández Douro. There, biscuit was only mentioned as having been loaded on the galleon ‘San Martin’, to the relatively trifling amount of 400 tons (‘quintales’), and not mentioned on any other vessels, perhaps because this was the only one to date that was ‘de todo punto aparejado’.11 Information on what was actually shipped when the fleet put to sea is not much help. Felipe Fernandez-Armesto in his 1988 work cites the definitive 1968 article by Maria Cristina Silveira and Carlos Silveira, ‘A alimentação na ‘Armada Invencível’, referring to no more than 110,000 tons (‘quintais’), based on still other documents in Cesáreo Fernández Duro and on a Memorial de várias cousas importantes in the Biblioteca Nacional in Lisbon,12 also taking into account just how much biscuit a man could eat in a month.

The number of 150 large ships (‘navi grosse’), mentioned in the Venice newsletter first appears way back before anything at all had been done, in a 1586 report compiled by the Marquis of Santa Cruz and no doubt circulated abroad, entitled ‘Relacion de las naos, galeras y galeazas y otros navios, gente de mar y guerra, infanteria [. . .] que se entiende podrán ser menester para en caso que se haya de hacer la jornada de Inglaterra’ etc., and printed in Duro’s vol. 1, where the relative sea biscuit on p. 275 is estimated at 379,337 tons (‘quintales’), far short of the nearly 2 million stated in Venice in March 1588.

If the Venetian report is part pastiche and part wishful thinking, the same most likely goes for yet another report, dated two weeks later, Rome, 2 April: ‘The extraordinary from France brought news that the King of France had been advised that one among his guard had orders to kill him, and another guard procured the poison, and that 100 Spaniards had occupied the English port of Baldras on the border with Scotland’.13 The stunning novelty, however false, of a successful Spanish invasion so early in the year, at a port city whose garbled name ‘Baldras’ may or may not refer to Berwick-upon-Tweed, was possibly hatched in

1.3 Don Giovanni de’ Medici, c. 1590, Santi di Tito, Galleria Palatina, Palazzo Pitti, Florence

France around the same time as the news that starts off the same newsletter, dated Antwerp 19 March, although the Antwerp news contains no revelations similar to the French news.

The Antwerp report on the 19th that is accompanied by the French news sent via Rome contains the same news as yet another newsletter from Antwerp in the Medici collection, bearing the same date, 19 March, and carrying other reports from Cologne, Posen (i.e., Poznán, in Poland), and Prague. These two nearly identical Antwerp reports refer to the arrival of Lord Howard of Effingham at Vlissingen (here called ‘her admiral’) with fourteen ships, and others on the way, and they claim that parts of the Low Countries are declaring for Queen Elizabeth of England, ‘happy to accept a governor chosen by Her

11. Cesáreo Fernández Duro, La Armada Invencible (Madrid: Est. Tipográfico de los sucesores de Rivadeneyra, 1884), vol. 1, p. 439.

12. Maria Cristina Silveira and Carlos Silveira, ‘A alimentação na ‘Armada Invencível’, Revista de história, no. 74 (1968), p. 306; Cesáreo Fernández Duro, La Armada Invencible (Madrid: Est. Tipográfico de los sucesores de Rivadeneyra, 1884), vol. 2, p. 60, documents no. 109 and 110; and Memorial de várias cousas importantes. Biblioteca Nacional, Fundo Geral, Reservados, Cota 637.

13. MdP 3085, fol. 621v.

2.3 Gaspar Ens, Ungarische Chronologia, 1605, title page, Bavarian State Library, Munich https://books.google.be/ books?id=PuEfTOPOeQ4C

Hungerischen und Sibenbürgischen Kriegswesens. The last-named, giving an update from 1 January 1603 ‘to the current year 1604’ (‘biß auff jetziges 1604. Jar’) was a continuation of Hieronymus Oertel’s earlier, three-part Chronologia oder historische Beschreibung aller Kriegsempörungen unnd Belägerungen der Stätt und Vestungen auch Scharmützeln und Schlachten so in Ober und Under Ungern auch Sibenbürgen mit dem Türcken von Ao. 1395 biß auff gegen wertige Zeit (Nuremberg: Johann Sibmacher, 1603), and was to be followed by a Viertter Thail Deß Hungerischen unnd Sibenbürgischen Kriegswesens (Nuremberg: for the author, [1613?]) covering the years 1604-1607, with an appendix extending coverage to Matthias’ succession as emperor, 1608-1612. That the final part was published at the author’s expense, and so long

after the detail it contained was current, perhaps indicates a falling off of commercial interest, but when the earlier parts had come out this was a market that several publishers wanted a slice of.

Oertel’s intitial work was cannibalised by Gaspar Ens, compiler of the Cologne Mercury, in his Rerum Hungaricum Historia (Cologne: Wilhelm Lützenkirchen, 1604), which began with the ancient Scythians but passed lightly over centuries to focus on events ‘up to the year 1604’.52 Ens went on to follow this up with a German-language Ungarische Chronologia (Cologne: Wilhelm Lützenkirchen, 1605) (Fig. 2.3), which was bundled with a reprint of Conrad Löw’s Mahometische History (Cologne: Willhelm Lützenkirchen, 1605) to similar effect. Perhaps this is what crowded Oertel’s final volume out of the market. Soon Theodore (II) and Israel de Bry got in on the act, with a Historia Chronologica Pannoniae: Ungarische und Siebenbürgische Historia (Frankfurt, 1607) that covered memorable events ‘since Noah’s Flood [. . .] but primarily in the current wars’.53

Specifically in 1604, news of the war included a new Turkish campaign to retake Pest, which went unexpectedly well: the siege in 1603 had failed, but had left the city unprepared to undergo another, so the Habsburg garrison simply withdrew before the Turkish army arrived. Rather than rest on the laurels of their accomplished mission, the Turkish commanders pressed on to lay siege to Esztergom. The successful defence of Esztergom, in the autumn of 1604, dominated the news at Frankfurt’s Easter Fair in 1605 (Arthus 1605A, pp. 102-112; Meurer 1605A, pp. 20-21, 23-27; Frame 1605A, pp. 24, 28, 65, 69-73, 76).

There were also reports of a great victory against the Turk by Giorgio Basta, the Albanian Italian mercenary in command of the imperial forces in Upper Hungary, and of Persian victories against Turkish forces in the Middle East (Arthus 1604B, p. 22; Arthus 1605A, p. 121; Frame 1605A, pp. 5, 103; Matthieu, p. 637). That Persian diplomats were coordinating with the Austrians to maintain pressure on the Turks was itself one of the news stories of the year (Arthus 1604B, pp. 56, 171-172; Arthus 1605A, p. 168; Meurer 1605A, p. 63; Francus 1604B, pp. 87, 105; Frame 1604B, pp. 74-77; Frame 1605A, p. 99; Matthieu, p. 769). An account of both Christian and Persian victories over the Turks was published in Spain under the title Verissima relacion de las grandes vitorias que

52. ‘ad annum usque M.DC.IV.’, title page.

53. ‘was sich in denen Landen, seyt der Sündflut hero, [. . .] Fürnemblich aber in jetztwerenden Kriegshändeln, denckwürdiges begeben’, title page.

2.4 Hogenberg studio, Ostende, 1604, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (at https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/nl/collectie/RP-P-OB-78.784-320)

la Magestad Cesarea del emperador ha tenido contra el Gran Turco. Dase cuenta de otras cosas muy notables que han sucedido en aquellas partes en este presente año de mil y seyscientos y quatro (Seville: Bartolomé Gómez, 1604).54 No Habsburg victory of the year comes close to the success alleged in the Spanish pamphlet. Cayet initially included news of such a victory in his Chronologie septenaire, but removed it from the second edition.

The Spanish and Italian campaigns against the Turks at sea received no such dedicated coverage in serial form, but were included among other news in the Mercuries. Within Spain and Italy, these were a frequent source of news pamphlets.55 The biggest such story in 1604 was Richard

54. With gratitude to Carmen Espejo.

Gifford’s raid on Algiers. Gifford had set sail in 1603 as captain of the Lyons, but during his voyage it came to his knowledge that James had ordered an end to the Elizabethan campaign of commerce raiding.56 The proclamation to this effect, like that banishing Jesuits and seminary priests, had been publicised across Europe. Putting in at Livorno in February 1604, Gifford offered his services to the Grand Duke of Tuscany, and so ended up leading the assault on the harbour of Algiers, burning eight ships but failing to achieve the mission’s main purpose, which was to kidnap Murad Rais, the Albanianborn leader of the Barbary Corsairs. Gifford’s coup was hailed in pamphlets printed in Italy and Spain,57 as well as

55. Giovanni Ciappelli, ‘L’informazione e la propaganda: La guerra di corsa delle galee toscane contro Turchi e Barbareschi nel Seicento, attraverso relazioni e relaciones a stampa’, in Giovanni Ciappelli and Valentina Nider, eds, La invención de las noticias: Las relaciones de sucesos entre la literatura y la información (siglos XVI-XVIII) (Trent: Università degli Studi di Trento- Dipartimento di Lettere e Filosofia, 2017), pp. 133-161.

56. Gigliola Pagano de Divitiis, English Merchants in Seventeenth-Century Italy, trans. Stephen Parkin (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), p. 26.

57. Relatione dell’abbruciamento delle galere nel porto d’Algieri. Fatto dal capitano Riccardo Giffort inglese. La notte del martedì santo. A dì. 13. d’aprile. 1604 (Naples: Giovanni Battista Sottile, 1604, after the copy published in Florence, ‘nella stamperia del Sermartelli’) and Muy verdadera relacion de grandissimo contento para la Christiandad, donde sa da cuenta de como fue nuestro Señor servido; de que se echasse fuego a las galeras de Argel, que estavan

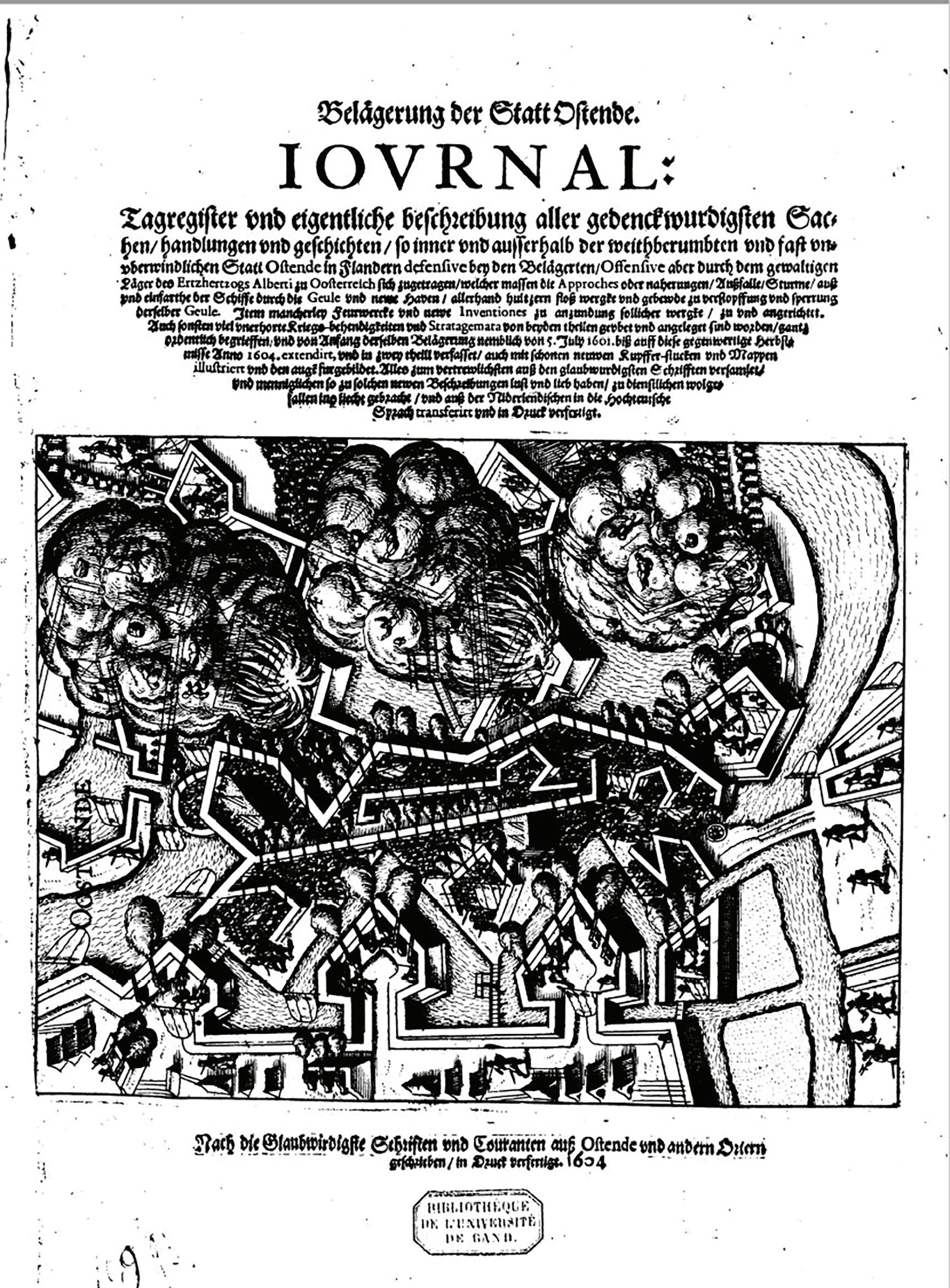

2.5 Belägerung der Statt Ostende, 1604, title page, Ghent University (at https://books.google.be/books?id=gBlGAAAAcAAJ)

indications—whether by the young Augustus II the Younger, who would become the lord of Wolfenbüttel in 1634, or by his agent or by whoever else, we cannot say (Fig. 3.1).14 In any case, they may reflect aspirations or acquisitions in response to the circulation of cultural news, keeping in mind that Herzog August already possessed a rich collection. Our attention in the section on Law is drawn, for instance, to the underlined ‘De Rebus creditis sive de mutuo, Commentarius’ by Johannes Goeddaeus, issued in Goslar by Johann Vogt in 1618. Among Law books in German we find underlined ‘Kurzer Extract aus den Bömischen Stadtrechten’, referring in fact to the work by Adam Cramer first published in 1609 and now reissued.15 We also find highlighted the ‘Konstitution, Willkür und Ordnung der Erbfälle und anderer Sachen’, referring to heredity questions in the Margraviate of Brandenburg, as well the ‘Land-Reuter Ordnung’ (a rule book for territorial administrators) of the same place. In Philosophy, underlined are a recent edition of Caspar Bartholin’s ‘Logicae peripateticae’ first published in 1612, Wenceslaus Schilling’s ‘De Noticiis Naturalibus Succincta Consideratio’, published in 1616, and the ‘Admonitio ad lectores librorum M. Antonii de Dominis’ by Jesuit author Andreas Eudaemon-Joannes, as well as, somewhat oddly categorized, ‘Seth Calvisius’ 1610 Thesaurus Latini Sermonis’.16 Turning to Poetry we find a line under Jean Tixier de Ravisi’s Epitheta, a kind of poetical handbook first published in 1518 as Specimen Epithetorum.17 Again, the category devoted to History, Geography, and Politics highlights Petra’s Bertius’ justpublished atlas, ‘Theatri geographiae veteris, Tomus prior’, issued by the Elzevier firm, as well as Jacob Marcus’ atlas of Flanders, the ‘Deliciae Batavicae variae elegantesque picture omnes Belgij antiquitates representantes’, published in Leiden by Janssonius 1618.18 In the same section we find highlighted a recent edition of Livy’s Roman Histories as well as the 1613 Frankfurt edition, curated by Daniel Patterson, of Marsilius of Padua’s famous

fourteenth-century ‘Defensor Pacis’—here, in the spirit of the confessional strife under way, rebranded as ‘De jurisdictione et potestate tam seculari quam ecclesiastica, pontificis romani et imperatoris’.

In other instances we may be witnessing the detection of a kind of false news in the bibliographical realm. A marginal ‘nota bene’ in the Law books section points to an entry offering ‘Tiberii Deciani, Consiliorum vol. 4 et 5’, perhaps to indicate the printer’s oversight in naming Tiberio Deciani as author rather than the actual author Filippo Deciani.19 In the Philosophy section, if the underlined ‘Erasmus, Colloquia’ indicates a possible preference for this humanist work, the immediately subsequent entry, ‘Eiusdem, enchiridion logicum’, inferring the latter to be a work of the same scholar, may instead be underlined to highlight another error, as the Erasmus in question there is surely Erasmus Ericus Assenius, an editor of Caspar Bartholin’s work by this title,20 and not the scholar who wrote the Enchiridion militis Christiani

Not noted by our annotator, in this autumn catalogue there are items aplenty to catch the attention of a modern reader, such as musical works by composers Orlande de Lassus and Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck, a visual account of Amerigo Vespucci’s two American voyages, the second part of Cervantes’ Don Quixote, the Latin translation of Francis Bacon’s Essays, a warning by Roberto Bellarmino to his nephew (a bishop in Campania), the discourses on Cornelius Tacitus by Scipione Ammirato, and medical treatises by Girolamo Mercuriale. In the spring catalogue, rather than Galileo’s discoveries we find his rival Christopher Scheiner’s Refractiones coelestes (1617), Robert Fludd’s De naturae simia seu technica macrocosmi historia (1618), Kepler’s Ephemerides novae motuum coelestium ab anno MDCXVII (1618), and Goclenius’ Acroteleuton astrologicum (1618), placed on an equal footing with all other titles, including curiosities such as Nicolas Damme’s ‘Lutherus triumphans, papa corruens. Carmen heroicum’ (1616).21

14. Catalogus universalis pro nundinis Francofurtensibus autumnalibus, De Anno M.DC.XVIII (Frankfurt am Main: Sigismund Latomus, 1618), in Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel, A: 202.34 Quod. (7) at http://diglib.hab.de/drucke/202-34-quod-7s/start.htm (21.11.2020).

15. Catalogus universalis pro nundinis Francofurtensibus autumnalibus, fols B1v, D2r.

16. Catalogus universalis pro nundinis Francofurtensibus autumnalibus, fol. C1r-v.

17. On which see Nathaël Istasse, ‘Le Specimen Epithetorum (1518) et les Epitheta (1524): J. Ravisius Textor compilateur et créateur’, in S. Hache and A.-P. Pouey-Mounou, eds, L’épithète, la rime et la raison. Les dictionnaires d’épithètes et de rimes dans l’Europe des XVIe et XVIIe siècles, actes des journées d’études Paris IV-Lille 3 (15 oct. et 2 déc. 2011) (Paris: Garnier, 2015), pp. 79-121.

18. Here and below, Catalogus universalis pro nundinis Francofurtensibus autumnalibus, fols B3v, B4v.

19. Ibid., fol. E1r.

20. Catalogus universalis pro nundinis Francofurtensibus autumnalibus, fol. C2r. Bartholin’s work was Enchiridion Logicum Ex Aristotele (Strassburg: Scher/ Ledertz, 1608).

21. Catalogus universalis pro nundinis Francofurtensibus autumnalibus, fols C3r, D4v, E3r.

3.1 Catalogus universalis pro nundinis Francofurtensibus autumnalibus, De Anno M.DC.XVIII (Frankfurt am Main: Sigismund Latomus, 1618), in Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel, A: 202.34 Quod. (7) (at http://diglib.hab.de/drucke/202-34quod-7s/start.htm consulted on 21/11/20)

Another sort of evidence for cultural history consists in the material culture conserved in our book repositories themselves, modern or inherited from the past; but a full quantitative account of this part of our story might seem to lead too far away from the experience of news, even if we view numbers of extant editions of particular items as testimonies to the success of editorial marketing. But if we suspend disbelief for a moment, also considering the vagaries and uncertainties of conservation across the centuries, there might be some advantage in knowing that according to the Universal Short Title Catalogue (USTC), the Latin titles dated to our year amounted to no more than thirty-six percent of the total number of 7504 items; therefore we have so far only caught a glimpse of the vast vernacular explosion under way.

And if we look into the kinds of books presumably in people’s hands, we can hardly fail to be impressed by the substantial agreement between the USTC and our results so far, as also by the differences. Without delving too much into the intricacies of bibliographical topic analysis, to which we refer in the next footnote, a superficial counting exercise reveals a substantial and not too surprising emphasis on religious texts, with academic dissertations leading the next tranche, significantly ahead of jurisprudence, official proclamations, newsbooks, political tracts, and poetry.22 Literature other than poetry counts for half as much as medical tracts, the last on the list of the top nine, and a category called ‘science and mathematics’ even less, not to mention ‘astrology and cosmography’ at twenty-one units, and art and architecture at four. Surely all such topics are news of a sort and deserve a far more systematic survey than we could attempt here. A well-tempered account would require close attention to the construction of the categories and some control allowing a valuation for items of small size but great impact.

Here again there are some surprises. The most highlycited authors in the USTC for our year include not the heroes of subsequent historiography but a certain Balthasar Meisner, theology professor at Luther’s home university of Wittenberg, with thirty entries, many related to his Anthropologias Sacrae (Sacred Anthropologies), which came out this year, along with associated university disputations, all dealing with original sin, free will, and justification. Next in quantity was another professor of theology, Johann Himmel at Jena, with twenty entries, mostly referring to short university-related pieces where he is mentioned on the title page but not as the author. Wittenberg theology professor Friedrich Balduin weighs in with seventeen entries, the most conspicuous being an 800-page sermon book. Next comes Peter Milner von Milhausen, a member of the Bohemian Estates whose name is associated with the Apologia oder Entschuldigungsschrift regarding events in Prague, which we find featured here in no fewer than sixteen distinct editions, closely followed by Jacob Blümel, Juan Gutiérrez, and Prospero Farinacci at fifteen each.

The name of Cicero, which turns up in sixteen entries, reminds us not only about the curious time-warp of publishing history (where modern authors compete not

22. For recent debates on classification methods and especially subject taxonomies, I refer the reader to Simon Burrows, The French Book Trade in Enlightenment Europe II: Enlightenment Bestsellers (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018), chap. 6.

A Year of Revolutions

Davide Boerio

A’ pena si trova in altre età essersi li regni, le provincie, le città quasi in uno stesso tempo ribellate, e con sediziosi tumulti sconvolte, come da pochi anni in quà veduto abbiamo, e particolarmente nell’anno 1648 [. . .].1

This remark is taken from a chapter entitled Rivoluzioni e turbolenze seguito in quasi tutti i paesi d’Europa circa l’anno 1648 (Revolutions and turbulences occurring in almost every country of Europe in 1648) in the book Notti Beriche by the Vicentian physician, Giovanni Imperiali.2 The author identifies the year 1648 as the turning-point in the history of Europe, whose primary feature lay in the simultaneous outbreak of multiple social and political insurrections.3

Recalling the major events that shook the Old Continent to its foundations, he listed in sequence: the civil wars in England, which were ‘più bagnata dal sangue civile, che son le sue ripe dall’Oceano’;4 Germany, completely torn apart by the blood and fire of warfare (‘Sembrava più tomba di cadaveri, ch’asilo di viventi’,5 he noted sadly); Poland ravaged by the rebellion of the Cossacks and Tartars;6 and the rebellions of Portugal and Catalonia against Castilian rule,7 followed by those in the Kingdom of Sicily and Naples (the first, hit by a large-scale wave of unrest,8 and the second turning out to be an arena for one of the largest and most radical insurrections of the early modern Mezzogiorno).9 Imperiali goes on to reference the revolts that broke out within the papal states, such as those in Fermo and

1. ‘We hardly find in other epochs or reigns, whole provinces and cities rebelling almost at the same time, and upset by such seditious tumults, as we have seen in the space of a few years, and particularly in the year 1648’, from Giovanni Imperiali, Notti beriche, overo de’ quesiti, e discorsi, fisici, medici, politici, historici e sacri [. . .] (Venice: Paolo Baglioni, 1663), p. 349.

2. Ivi, pp. 349-351.

3. The theme of contemporaneous revolutions was developed by Roger Bigelow Merriman, Six Contemporaneous Revolutions (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1938). The discussion on revolts and revolutions during the seventeenth century grew out of the debate on the general crisis of the seventeenth century, see Geoffrey Parker and Lesley M. Smith, eds, The General Crisis of the Seventeenth Century (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1978). For a recent account see Geoffrey Parker, Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013).

4. Giovanni Imperiali, Notti beriche, p. 349: ‘England’s shores were more bathed by civil blood than by the water of the ocean’. For recent work on the English Revolution, see Ian Gentles, The English Revolution and the Wars in the Three Kingdoms, 1638-1652 (Florence: Taylor and Francis, 2014). For an historiographical assessment on the topic see Roger Charles Richardson, The Debate on the English Revolution. 3rd ed. (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998).

5. Giovanni Imperiali, Notti beriche, p. 349: ‘It seemed more a grave for corpses, than a shelter for living beings’.

6. Natalia Yakovenko, ‘The events of 1648-1649: contemporary reports and the problem of verification’, Jewish History 17, no. 2 (2003), pp. 165-178.

7. John H. Elliot, The revolt of the Catalans: A Study in the Decline of Spain, 1598-1640 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1963).

8. For the Sicilian insurrection, see the classic works: Anna Siciliano, ‘Sulla rivolta di Palermo del 1647’, Archivio Storico Siciliano LXI-LXII (1939), pp. 183-303; Helmut G. Konigsberg, ‘The Revolt of Palermo in 1647’, The Cambridge Historical Journal 8/3 (1946), pp. 129-141. For an interesting reassessment: Daniele Palermo, Sicilia 1647. Voci, esempi, modelli di rivolta (Palermo: Quaderni- Mediterranea-Ricerche storiche, 2009).

9. Rosario Villari, Un sogno di libertà: Napoli nel declino di un Impero, 1585-1648 (Milan: Mondadori, 2012). See also his classic work: La rivolta antispagnola a Napoli. Le origini (1585-1647) (Rome-Bari: Laterza, 1967). For the English translation see, The Revolt of Naples, trans. by James Newell with the assistance of John A. Marino (London: Polity Press, 1993). See further: Alain Hugon, Naples insurgée. 1647-1648. De l’événement à la mémoire (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2011); Giuseppe Galasso, Il Regno di Napoli. Il Mezzogiorno spagnolo e austriaco (1622-

◀7.1 Estat General des affairs, Paris, January 1648, in Théophraste Renaudot (ed.), Recueil des Gazettes, Nouvelles ordinaries et extraordinaires. Relation et autre recits des choses avenues toute l’année mil six cens quatante-huit, (Paris: Bureau d Adresse, 1649)

▼7.2 System of diffusion: MdP 4146, fasc. 5, Avvisi from Naples, 28 November 1647, fols 494r-500r; Extrordinaire, 1648, no. 5; Moderate Intelligencer, 20 January 1648/9.

of economic issues) and then to be spread among his subordinates so that they could carry out their tasks more efficiently. At a certain point, the need felt by Savary de Bruslons had triggered the desire to control information and communication of the central power and thus a manuscript born out of personal need and use18 had been turned into an ambitious project for organizing commercial matters throughout France.19

Thus was born the Dictionnaire universel du commerce, which was not a simple work of erudition but another piece in the ambitious project begun by Colbert with the creation of the free port of Marseille. The Dictionnaire had been made for France and its merchants, to provide them with all the information needed to restore trade and to push them to great deeds, whether inside or outside the kingdom.20 If treaties and edicts had provided the institutional basis, the Dictionnaire aimed both to provide knowledge and to offer a triumphant image of French trade as exemplified by the free port of Marseille, viewed as an example for all. The work, in fact, was also addressed to foreigners and, according to the author himself, could serve all the nations of Europe as an instrument for perfecting mutual trade.21 It became immensely successful, reissued three more times in Paris, reprinted in French in Amsterdam, Geneva, and Copenhagen, fully translated into English, German, and Italian. And the pervasiveness of the news contained in the Dictionnaire was not limited to translations: returning to the theme of the free port, in fact, one can see how the definition coined by Savary de Bruslons and based on Marseille was taken literally also by the Cyclopaedia of Ephraim Chambers and by the Encyclopédie itself.22

In short, the edict of 1669 and its publication provided the initial news and information base on which, in the

following decades, a positive and (lasting) image of the French free port model (embodied by Marseille) was built. However, after the seventeenth century other media— always public but not official—contributed to spreading positive news about the newborn free port. In the immediate aftermath of the creation of the free port, in fact, various types of treatises began to appear, which helped to convey a positive image of Marseille as a free port and as the centre of trade. Among the very first was the Discours sur le Negoce des Gentilhommes de la Ville de Marseille sur la qualité des Nobles Marchands by the oratorian François Marchetti.23

The treatise, which appeared in 1671 and was issued by the same printer that had published the edict, was part of the debate concerning the meaning of virtue and nobility.24 It defended the nobility and virtue of commerce and those who practiced it and painted Marseille as a city of real gentlemen and successful traders like those in ‘Genoa, Pisa, Venice and other sea ports’.25

It was followed, in 1675, by Le parfait négociant (mentioned above), which Savary (the father) dedicated to Colbert, aimed at giving French merchants the tools necessary for the development of French traffic at a global level, which were later perfected by the son in the Dictionnaire. The author’s intent, therefore, was for the work to be a truly international trade manual. It is not surprising, then, that the European port mentioned more often and on which more detailed information is given was precisely Marseille. While constructing the image of Marseille, the elder Savary also clearly revealed France’s commercial target: the East. Mentioned almost as much as Marseille were the two main ports of the Levant, which served as a crossroads for Eastern Mediterranean goods and on which it was equally necessary to have precise

18. Dictionnaire universel de commerce contenant tout ce qui concerne le commerce qui se fait dans les quatre parties du monde, ouvrage posthume du Sieur Jacques Savary (Amsterdam: Chez Jasons à Waesberge, 1726), vol. I, pp. XV-XVI: ‘La seule nécessité le fit naitre [. . .] Pour son propre usage’.

19. Rosario Patalano, ‘Il Dictionnaire universel de commerce dei Savary e la fondazione dell’autonomia del discorso economico (1723-1769)’, Storia del pensiero economico 41(2001), pp. 131-163.

20. Dictionnaire universel de commerce, vol. I, p. XXIX.

21. Dictionnaire universel de commerce, vol. I, p. XXIX.

22. For a more in-depth discussion of the debate on free ports and their definition in the eighteenth century, see Giulia Delogu, ‘Informazione e comunicazione in età moderna: immaginare, definire, comunicare il porto franco’, Rivista storica italiana 131 (2019), pp. 468-491.

23. Discours sur le Negoce des Gentilhommes de la Ville de Marseille et sur la qualité des Nobles Marchands [. . .] par M. Marchetti (Marseille: Charles Brébion & Jean Penot, 1671).

24. See Silvia Marzagalli, ‘Negozianti, stranieri e nobiltà. Uso politico e realtà sociali del processo d’integrazione delle élites in Francia tra Sei e Settecento’, in Marcella Aglietti et al., eds, Elites e reti di potere. Strategie d’integrazione nell’Europa di età moderna (Pisa: Pisa University Press, 2016), pp. 47-58; Biagio Salvemini, ed., Alla ricerca del ‘negoziante patriota’. Moralità mercantili e commercio attivo nel Settecento, special issue of Storia Economica 19/2 (Naples: Edizione scientifiche italiane, 2016).

25. Discours sur le Negoce, p. 27. See also Wolfgang Kaiser, ‘Mobility and Governance in Early Modern Marseilles’, in Ulrike Freitag et al., eds, The City in the Ottoman Empire: Migration and the Making of Urban Modernity (London-New York: Routledge, 2011), pp. 74-98, here pp. 81-83.

information to become ‘perfect traders’: Smyrna and Constantinople. Meanwhile, also in non-economic works, Marseille had acquired the solid image of a free, rich, and busy port. And so it was described by the French doctor and traveller François-Savinien d’Alquié in Les délices de la France:

Marseille a 3 choses qui la rendent illustre. 1. C’est qu’elle a été de tous temps recommandable pour la valeur de ses citoyens, la frugalité de ses habitans et leur Foy inviolable; 2. Parce qu’elle a un peuple agissant et propre au trafic, franc et jaloux de la liberté, à cause de son Port qui passe pour être le plus asseuré et le meilleur de l’Europe, et 3. parce qu’elle est riche et délicieuse.26

No other port city could rival Marseille, not even in the rest of France. Toulon was indeed a very beautiful port but not as much as the Provençal centre.27 That Marseille was a famous port of the sea that even claimed its origins from the Phoenicians was now widespread news even outside the French linguistic sphere, as witnessed by the Guida geografica by Lodovico Passerone, published for the first time in Turin in 1672.28

Turning to seventeenth-century figurative depictions of Marseille, we see how the image ends up being slightly different, even if the principal ingredients are similar to those of the written sources. A preliminary investigation has revealed that maps and views show not so much the port element but rather that of the city’s security and safety, guaranteed by the expansion and fortification works undertaken at the behest of Louis XIV.29 The fortifications of Marseille are celebrated together with other achievements and triumphs of the sovereign in a 1681 print by Henri Noblin (Fig. 9.1), which shows the

9.1 From BnF: https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/ cb40462300q

king intent on working with his council of state as ‘arbiter of peace and war’. In the same way, the seventeenthcentury maps clearly show the chain intended for closing and defending the port (Fig. 9.2).30 In particular, the map designed by Nicolas Desjardins (Fig. 9.3), albeit depicting an incoming ship, concentrates above all on the

26. Les délices de la France, avec une description des provinces et des villes du royaume (Paris: G. de Luyne, 1670), p. 494. English translation: ‘Marseille has 3 things that make it famous. 1. That it has been at all times commendable for the worth of its citizens, the frugality of its inhabitants, and their inviolable faith; 2. Because it has a people active and much given to the traffic, frank and jealous of liberty, because of its Port which happens to be the safest and best of Europe, and 3. because it is rich and delicious’. During the seventeenth century it was reprinted in Amsterdam (1670) and Leiden (1685) and re-edited, again in Amsterdam (1699), with the title: Les délices de la France, ou description des provinces et villes capitales d’icelle, depuis la paix de Ryswyk, et la description des châteaux, maisons royales. François-Savinien d’Alquiè, doctor of medicine, traveled to the Netherlands and the Levant (and published accounts of his travels), and translated works by Athanasius Kircher and Samuel von Pufendorf into French. From his works it is clear that he practiced as a doctor in Kristiana in Denmark in the 1680s.

27. Les délices de la France, p. 496.

28. Lodovico Passerone, Guida geografica, ouero compendiosa descrittione del globo terreno (Venice: Iseppo Prodocimo, 1681), p. 88.

29. On the 1660s ‘agrandissement’, see Takeda, Marseille between Crown and Commerce, pp. 24-31.

30. The presence of the chain is not a neutral element. It represents the intention of narrating Marseille as a free but safe and controlled port. In Trieste, for instance, an entirely different communicative strategy was used: even if there was a chain, it was never depicted. See Fiorello De Farolfi, Catalogo delle stampe triestine dal XVII al XIX secolo (Trieste: Parnaso, 1994).