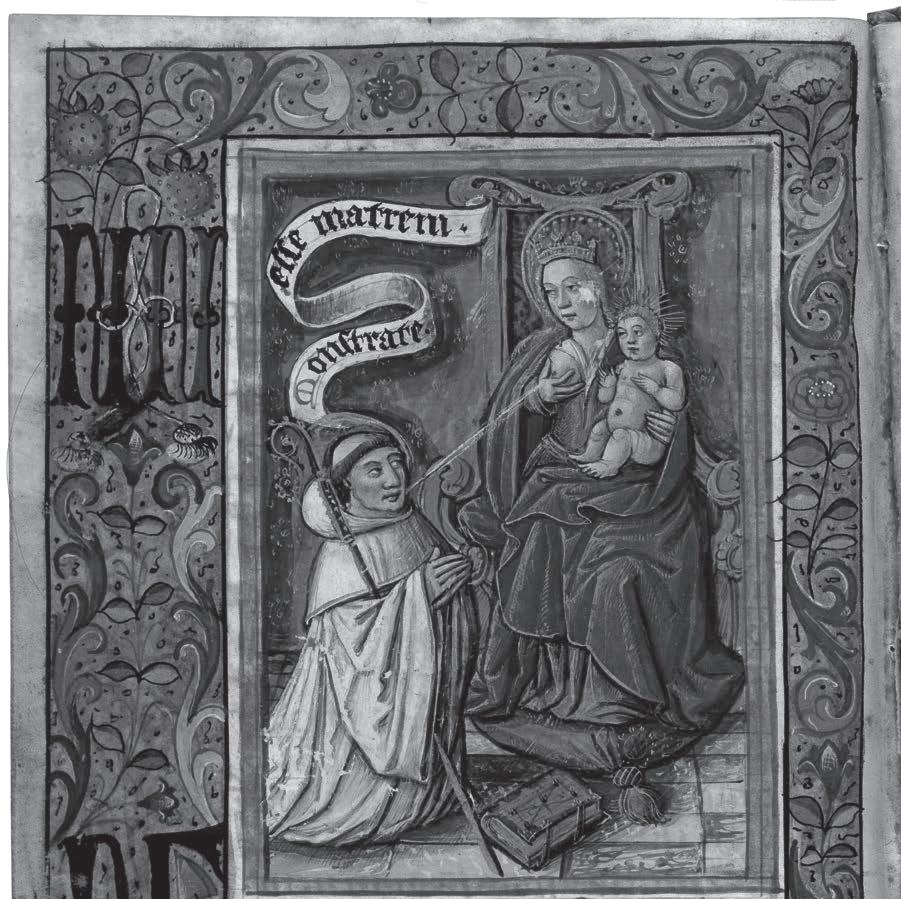

e Museum of Renaissance Music

A Hi ory in 100 Exhibits

Edited by Vincenzo Borghetti & Tim Shephard

A Hi ory in 100 Exhibits

Edited by Vincenzo Borghetti & Tim ShephardIntrodu ion and A nowledgments ▶ 9

Introdu ion — Matthew Laube ▶ 18

1 Silence — Barbara Baert ▶ 21

2 Virgin and Child with Angels — M. Jennifer Bloxam ▶ 25

3 Madonna of Humility — Beth Williamson ▶ 31

4 Virgin Annunciate — Marina Nordera ▶ 35

5 e Prato “Haggadah” — Eleazar Gutwirth ▶ 39

6 e Musicians of the Holy Chur , Exempt from Tax — Geo rey Baker ▶ 43

7 A Devotional Song from Iceland — Árni Heimir Ingólfsson ▶ 47

8 Alaba er Altarpiece — James Cook, Andrew Kirkman, Zuleika Murat, and Philip Weller ▶ 50

9 e Mass of St Gregory — Bernadette Nelson ▶ 55

Psalters

10 Bernardino de Sahagún’s “Psalmodia ri iana” — Lorenzo Candelaria ▶ 61

11 e “Սաղմոսարան” of Abgar Dpir Tokhatetsi — Ortensia Giovannini ▶ 65

12 A Printed Hymnal by Jacobus Finno — Sanna Raninen ▶ 69

13 “ e Whole Booke of Psalmes” — Jonathan Willis ▶ 73

Introdu ion — Paul S leuse ▶ 78

14 Commonplace Book — Kate van Orden ▶ 80

15 Knife — Flora Dennis ▶ 84

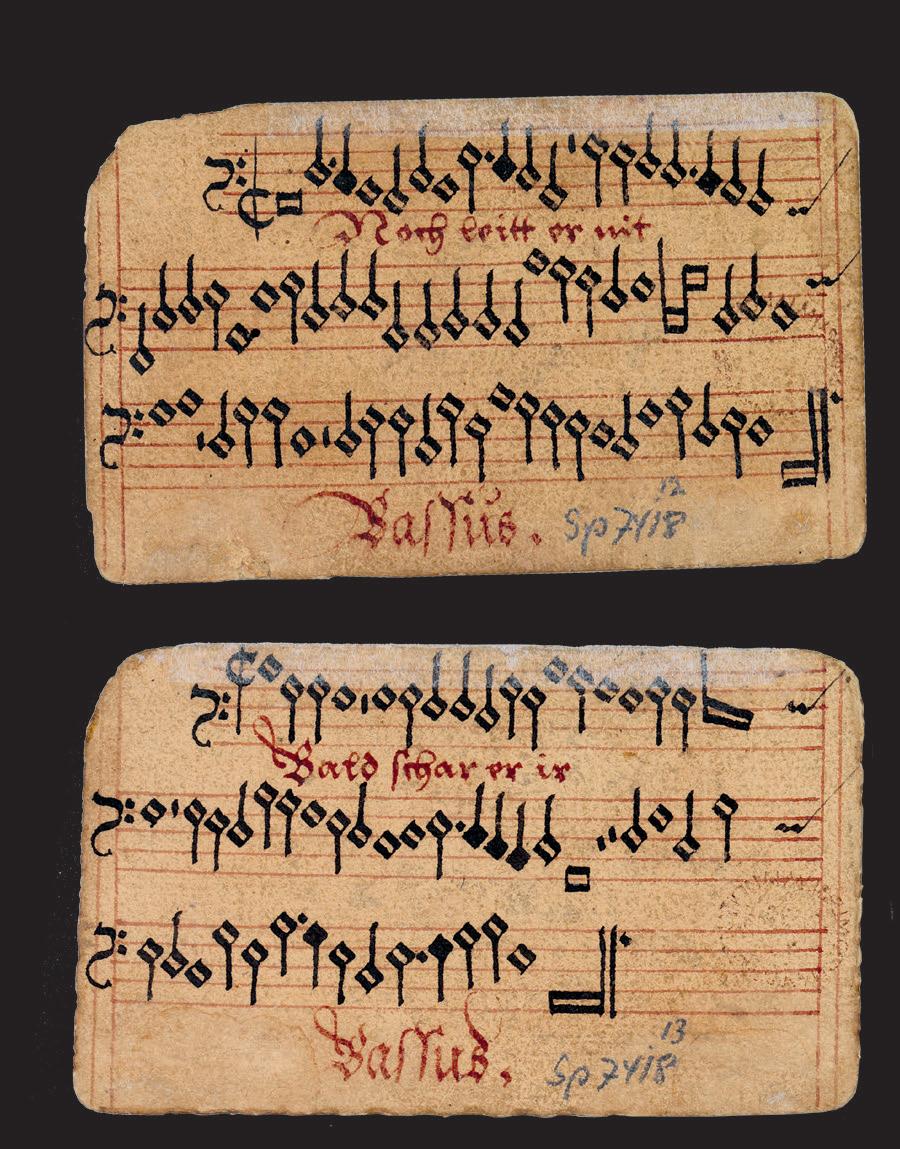

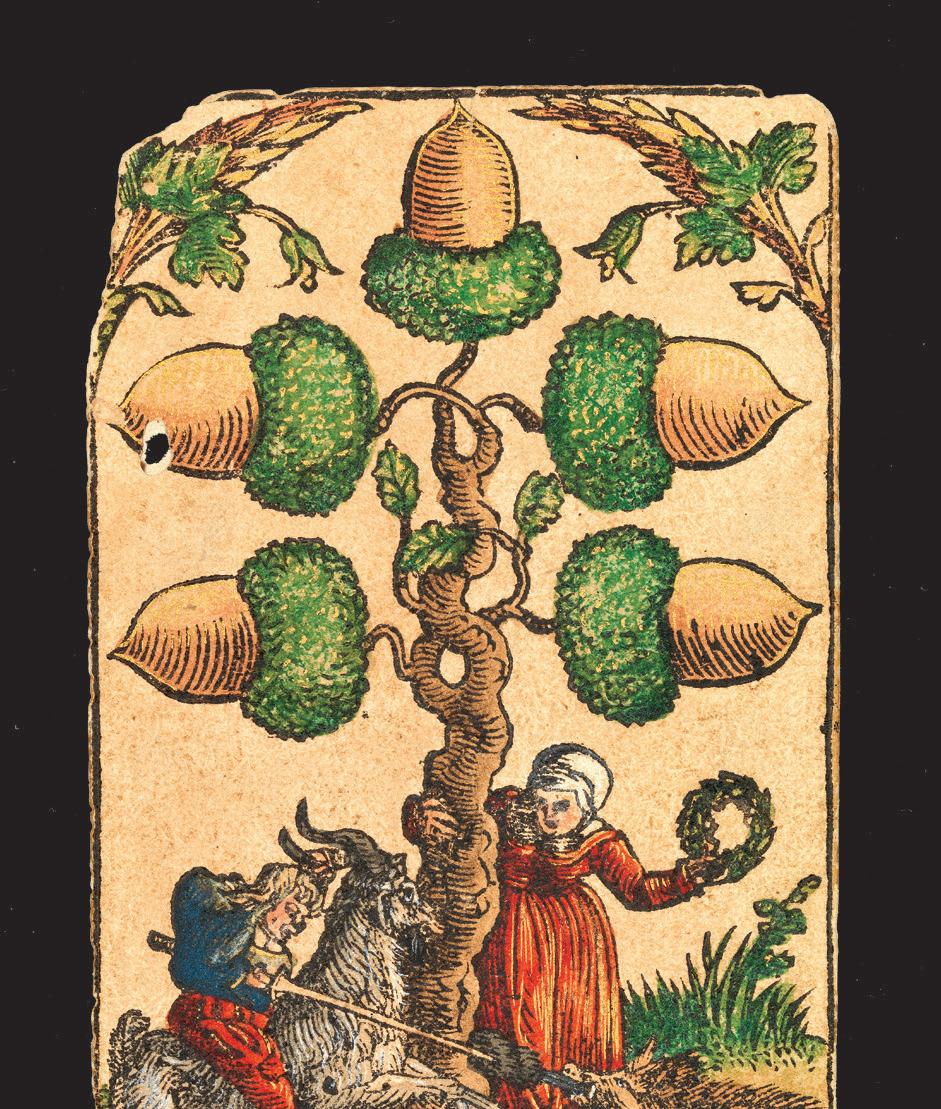

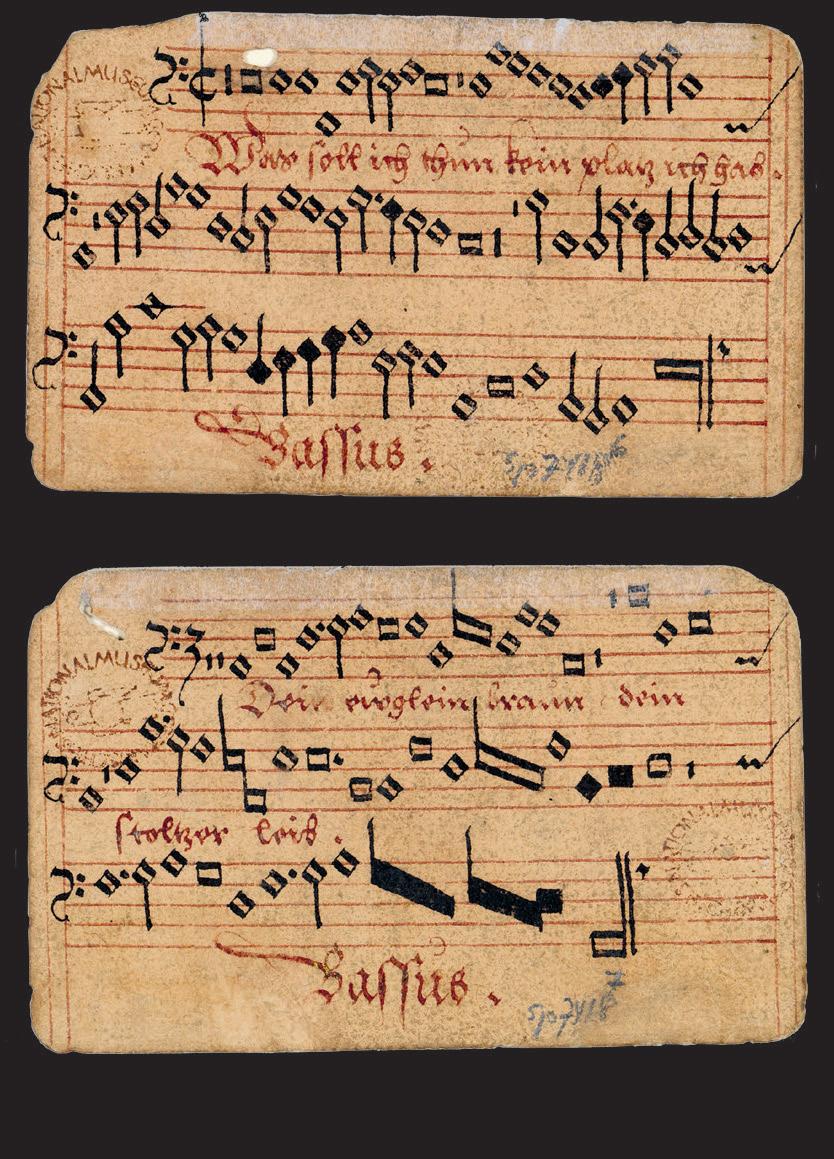

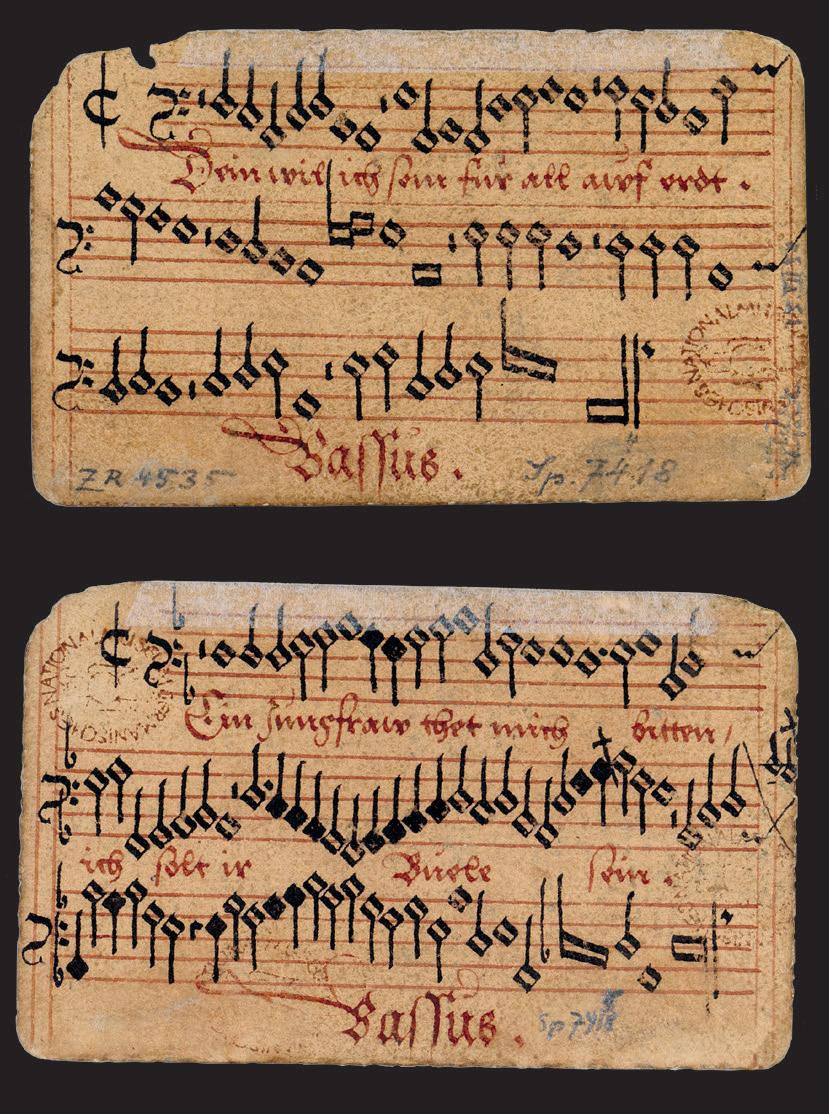

16 Playing Cards — Katelijne S iltz ▶ 86

17 Cabinet of Curiosities — Franz Körndle ▶ 91

18 Table — Katie Bank ▶ 94

19 Statue — Laura Moretti ▶ 99

20 Valance — Katherine Butler ▶ 102

21 Painting — Camilla Cavic i ▶ 107

22 Fan — Flora Dennis ▶ 111

23 Tape ry — Carla Ze er ▶ 115

Sensualities

24 Venus — Tim Shephard ▶ 119

25 Sirens — Eugenio Re ni ▶ 125

26 Death and the Maiden — Katherine Butler ▶ 129

27 Erotokritos Sings a Love Song to Aretousa — Alexandros Maria Hatzikiriakos ▶ 133

Introdu ion — Elisabeth Giselbre t ▶ 138

28 Chansonnier of Margaret of Au ria — Vincenzo Borghetti ▶ 141

29 e Con ance Gradual — Marianne C.E. Gillion ▶ 145

30 e Bible of Borso d’E e — Serenella Sessini ▶ 149

68 A Bosnian Gravestone — Zdravko Blažeković � 323

69 Morris Dancers from Germany — Anne Daye � 327

70 A Princely Wedding in Düsseldorf — Klaus Pietschmann � 331 Cities

71 Mexico City – Tenochtitlan — Javier Marín-López � 337

72 Dijon — Gretchen Peters � 343

73 Milan — Daniele V. Filippi � 346

74 Munich — Alexander J. Fisher � 351

Travels

75 The Travels of Pierre Belon du Mans — Carla Zecher � 357

76 Aflatun Charms the Wild Animals with the Music of the Arghanun — Jonathan Katz � 361

77 Granada in Georg Braun’s “Civitates Orbis Terrarum” — Ascensión Mazuela-Anguita � 366

78 News from the Island of Japan — Kathryn Bosi � 373

Introduction — Jessie Ann Owens � 378

79 Will of John Dunstaple, Esquire — Lisa Colton � 381

80 Portrait Medal of Ludwig Senfl — Birgit Lodes � 385

81 Zampolo dalla Viola Petitions Duke Ercole I d’Este — Bonnie J. Blackburn � 389

82 A Diagram from the Mubarak Shah Commentary — Jeffrey Levenberg � 393

83 Cardinal Bessarion’s Manuscript of Ancient Greek Music Theory — Eleonora Rocconi � 397

84 The Analogy of the Nude — Antonio Cascelli � 400

85 The Music Book of Martin Crusius — Inga Mai Groote � 405

86 The World on a Crab’s Back — Katelijne Schiltz � 409

87 Juan del Encina’s “Gasajémonos de huzía” — Emilio Ros-Fábregas � 413

88 Josquin de Prez’s “Missa Philippus Rex Castilie” — Vincenzo Borghetti � 418

89 The Elite Singing Voice — Richard Wistreich � 423

• VIII. The Room of Revivals

Introduction — David Yearsley � 428

90 Instruments of the Middle Ages and Renaissance — Martin Elste � 431

91 Dolmetsch’s Spinet — Jessica L. Wood � 435

92 Assassin’s Creed: Ezio Trilogy — Karen M. Cook � 439

93 “Christophorus Columbus: Paraísos Perdidos” — Donald Greig � 443

94 A Palestrina Contrafactum — Samantha Bassler � 447

95 St Sepulchre Chapel, St Mary Magdalene, London — Ayla Lepine � 451

96 The Singing Fountain in Prague — Scott Lee Edwards � 455

97 Liebig Images of “Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg” — Gundula Kreuzer � 459

98 Das Chorwerk — Pamela M. Potter � 463

99 “Ode to a Screw” — Vincenzo Borghetti � 467

100 Wax Figure of Anne Boleyn — Linda Phyllis Austern � 471

Notes on Contributors � 477

Bibliography � 487

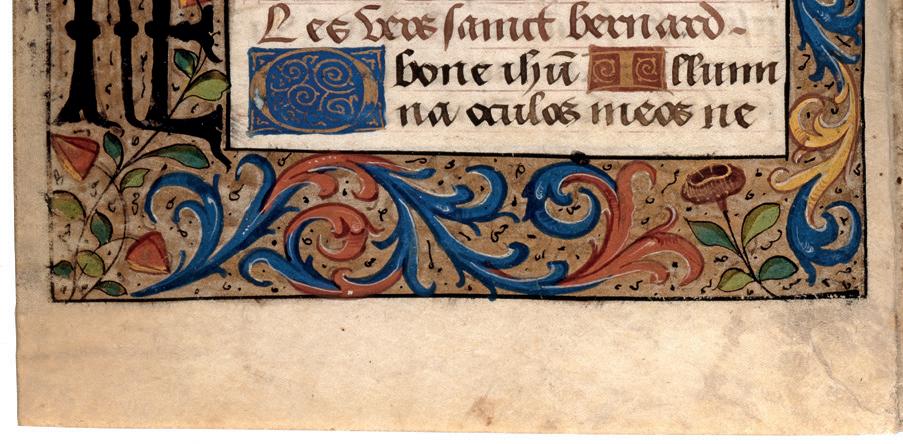

Anon., northern Netherlands, ca. 1470-1500

Ivory, 13.5 (height) x 8.7 (base width) cm

Inscribed: o dulciz maria

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Odulciz Maria—O sweet Mary! The unknown sculptor of this small ivory relief, carved in the late fifteenth century in the northern Netherlands, inscribed these words in the large book held open by one of the two angels at her feet. Shown upside down and backwards, they are directed not to the viewer but to the angels, whose open mouths confirm their sonic realization. It is not, however, simply the spoken word that carries this fond acclamation to Mary’s prominently exposed ear—it is music. Meticulously chiseled note heads above the text evoke a fragment of melody; the celestial lutenist’s fingers are frozen mid-performance.

While these angels conjure the sound of music, their large, carefully rendered hands, with long and distinctly articulated fingers, also express the tactile quality common to Virgin and Child ivories. Produced in increasing numbers from the thirteenth through the fifteenth centuries, these luxury objects emphasise virginal maternal flesh in contact with the incarnate flesh of Christ (Sand 2014). Here, the Virgin delicately proffers her breast, a slender thumb and forefinger supporting its milkheavy weight; her gaze is inward, contemplative. Her other hand grasps the leg of the naked Christ Child, half standing on her hip. He rests his arm on her bosom, but shows no interest in nursing; rather, he looks directly at us, inviting us to join their milk-scented embrace and taste her life-giving sweetness.

O dulciz Maria! Thus the snippet of angelic song that accompanies this image helps activate the viewer’s sense of taste and smell as well as her hearing and touch. The sensuous nature of the sculpture is inherent even in the rare and exotic material from which it was crafted. Ivory was a favorite medium for images of the Virgin mother; prized for its pure, creamy white luminosity, it embodied her supreme status as unsullied nurturer of Christ and his church (Sand 2014).

A strong theological current reaching from Clement of Alexandria to Julian of Norwich and beyond understood Mary’s breast milk as a Eucharistic metaphor: as a mother provides a child nourishment from her own body, without which it would die, so Christ feeds the faithful with his own flesh and blood in the Eucharist (Berger 2011, 72-88). This baby Jesus, by encouraging us to seek nourishment from the Virgin, actively affirms Mary’s intercessory power, most palpably captured in her role as the nursing mother of God, Virgo lactans.

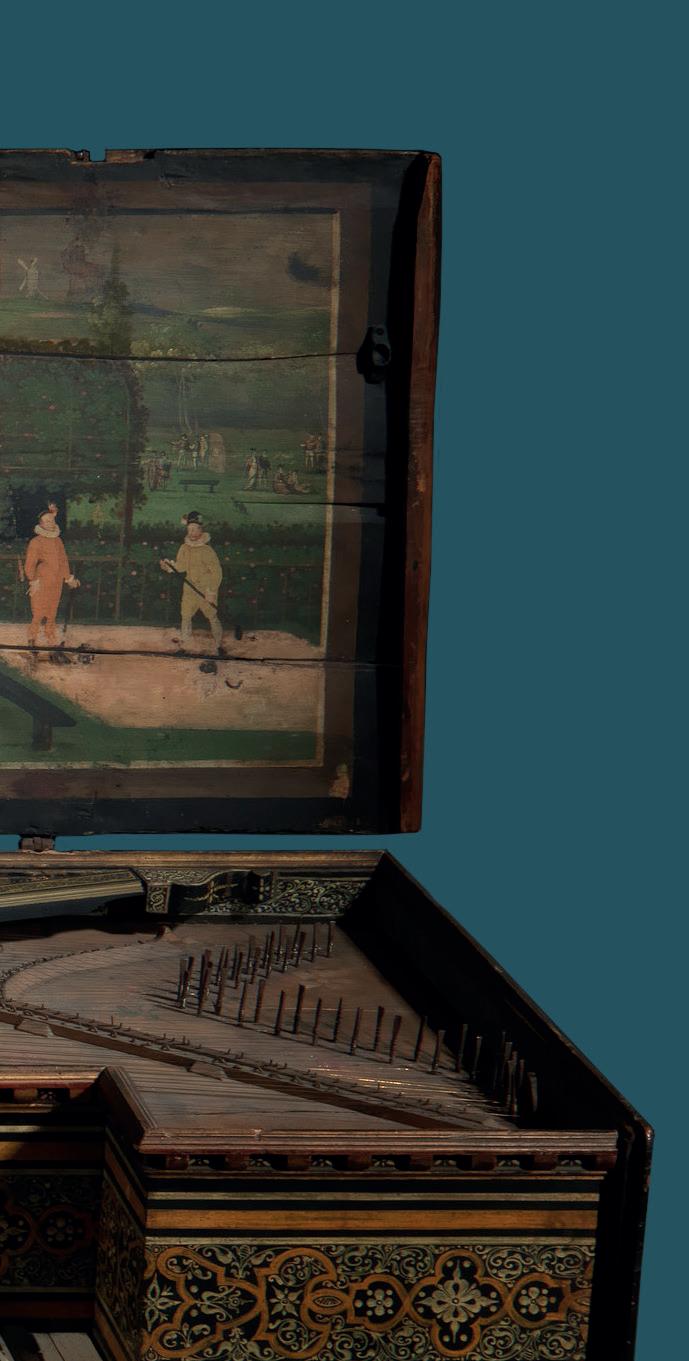

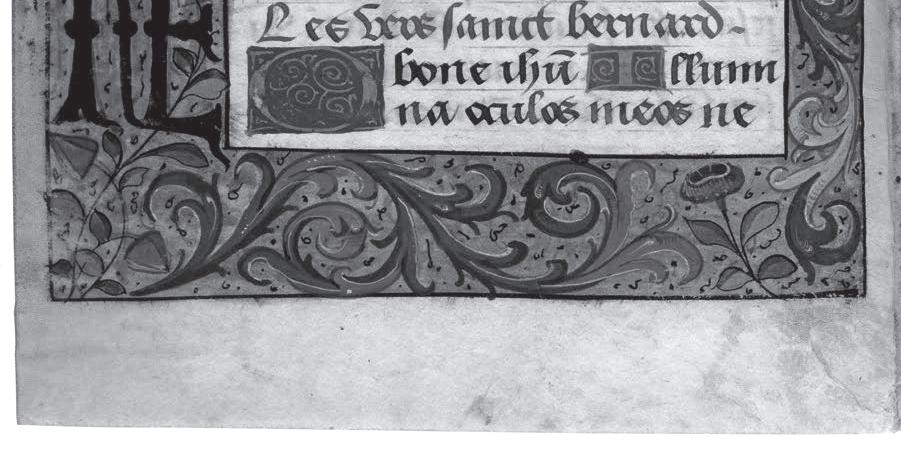

The iconographic topos of the nursing mother has ancient roots—the Egyptian mother-goddess Isis, for example, was often depicted breastfeeding her son Horus (Rubin 2009b, 4042). In the Christian West, the bared female breast long symbolised nourishment and loving care, associations gradually eroded over the course of the Renaissance through its complex transformation into an eroticised and medicalised object (Miles 2008). Nevertheless, the Virgin’s milk remained for Catholics the most potent symbol of the mystery of the incarnate God (Warner 1976, 192-200), and consequently droplets of her milk were by far the most numerous of Marian relics, invested with curative and even salvific powers. Stories of miraculous visions were associated with the prayerful contemplation of Virgo lactans images (Olson 2014, 155-56), none more widespread or long lasting than that concerning St Bernard of Clairvaux, the Cistercian abbot whose passionate homilies about Christ’s mother helped fuel the burgeoning Marian devotion in the ensuing centuries.

The legend is rooted in twelfth-century miracle stories concerning a devout and ailing prelate to whom Mary appears, bares her breast, and bestows three healing drops of milk on his lips. Bernard is first identified as the recipient of this apparition in an early thirteenth-century Cistercian exemplum collection (McGuire 1991, 189-204), and certain striking details relayed in the Bernardine versions in the following centuries reveal much about the dynamic and interactive nature of Marian imagery, the intercessory power attributed to the Virgin’s milk, and the importance of music in the multi-sensory matrix of late medieval and Renaissance Marian devotion.

According to the legend, Bernard was kneeling before a statue of the Virgin and Child, praying the Ave maris stella, a much-loved hymn beseeching Mary’s intercession. At the phrase “Monstra te esse matrem” (Show yourself to be a mother), the carved figure came to life and sprinkled three drops of milk into his mouth. Northern representations of the lactatio Bernardis from the decades around 1500 often include the words of this vision-inducing phrase, usually within a speech banderole issuing from his mouth (France 2007, 218-26; fig. 2.1).

stella

Many Catholics knew the words of the Ave maris ella hymn by heart; they were inextricably associated with the melody sung at Marian Ve ers throughout the year. Because hymns are rophic in design, the phrase “Mon ra te esse matrem,” whi opens the fourth verse of Ave maris ella, was always sung to the familiar opening phrase of the hymn melody. us a reader, upon seeing these words in a book or within an image, would be invited to recall the well-known tune. A iritual encounter with Mary, the ory sugge s, could be a ieved in concentrated prayer facilitated by texts internalised through music and assied by intense focus on her image.

Vespers strophic “Monstra which stella Thus spiritual story suggests, achieved assist lactans final oft-sung identifies each final im listener’s gesture

A viewer contemplating this Virgo la ans ivory would have had their musical memory similarly ignited by the text phrase “O dulciz Maria”: this is the nal acclamation of the beloved and o -sung antiphon Salve regina. Its lengthy text identi es Mary as Queen, Advocate, and Mother of God, and thrice extols her mercy in ea role. Although the antiphon’s melody is long and ornate, the nal “O dulcis Maria” phrase could not fail to impress itself in the singer’s or li ener’s mind, as it recapitulates the memorable initial ge ure of the plainsong, sung twice in the opening couplet but not heard again until its return at the opening of the nal phrase. What is more, both the opening and closing text phrases extol the sweetness of the Virgin, and the melismas unfolded in the closing acclamation recall those sung at the outset (ex. 2.1).

e Ci ercian order, whose ecial reverence for the Blessed Virgin was exempli ed in Bernard of Clairvaux, fo ered and may even have originated the Salve regina: it r appears in a mid-twel h-century Ci ercian antiphoner, and the order in ituted its use in daily processions a er 1218 (Ingram and Falconer 2001). By the late eenth cen-

The Cistercian special exemplified fostered first mid-twelfth-century Cistercian antiphon instituted after fifteenth cen

tury, when this small ivory was made, the plainsong was so widely known and loved that it had become the focal point of music- lled evening assemblies known as Salve services. Although popular throughout Europe (Ingram 1973, 31-49), these extra-liturgical devotions were e ecially brilliant in the Low Countries due to the enthusia ic patronage of large

especially enthusiastic

M. Jennifer Bloxamand wealthy lay Marian confraternities in major mercantile centres su as Antwerp and ,s-Hertogenbos (Forney 1987; Roelvink 2002).

In addition to polyphonic settings of the Salve regina antiphon, the Salve service (also known as lof, the Dut word for “praise” in the Low Countries) featured bell-ringing, organ-playing, additional Marian plainsong and polyphony, as well as prayers o ered by a cleric. Held on a weekly or even daily basis, they took place in ur , in dedicated side apels maintained by confraternities that also nanced the in allation and upkeep of the organ and paid the wages of the organi , oirma er, and oirmen and boys. A Marian altarpiece or atue usually provided the focal point before whi prayers said and sung were tendered, and miraculous powers were o en attributed to these images. Although this Virgo la ans ivory is too small to have presided over a confraternity apel (it probably adorned a dome ic ace or small private apel as part of a little devotional panel or altarpiece), its dire reference to the Salve regina seems designed to ark viewers’ memories of larger communal experiences of liturgy and lof.

As the produ ion of Marian images surged over the course of the eenth century, so too did the creation of polyphonic settings of the Salve regina de ined primarily for Salve services. A trove of 29 su settings, prepared by the workshop of the music scribe Petrus Alamire in the environs of Brussels during the 1520s, is preserved in a manuscript now in Muni (James 2014). Dedicated exclusively to Salve regina settings by Dut , Flemish, and Fren composers, this unique colle ion captures the array of yli ic and formal approa es to the text cultivated in the very time and place that gave birth to this Virgo la ans. Particularly noteworthy are nine settings that incorporate the tunes of Dut or Fren love songs as cantus rmi, signaling the complex interplay of worldly and iritual desire so o en evident in music composed to celebrate the Blessed Virgin during this period (Rothenberg 2011).

e profound in uence of Marian veneration on communal devotion and personal piety, as well as musical and visual cultural pra ices, is re e ed in the life and works of the mo renowned composer of the Renaissance, Josquin des Prez, whose ve-voice Salve regina setting (NJE 25.5) is given pride of place in the Muni manuscript. Josquin clearly atta ed great value to the Salve service: his will provided an endowment to ensure that this communal devotion could take place every Saturday and at all vigils of Marian fea s in his local ur of Notre-Dame in Condé-sur-Escaut. He also underood the iritual e cacy of prayers li ed in song before an image of Chri ’s mother: he le money for his motet Pater

no er (whose second part sets another erished Marian antiphon, Ave Mariagratia plena), to be sung in all general processions before the atue of the Virgin di layed in the wall of his house in Condé (Fallows 2009, 344-46).

Josquin’s mu -admired ve-voice Salve regina ands at the apex of the genre recalled by the “O dulciz Maria” phrase for those who prayed before this small ivory. While ara eri ic of motet-like settings in some ways (su as its tripartite division of the text and paraphrase of the ant melody concentrated in the superius), its underlying ru ure is unique (Judd 1992; Milsom 2000, 438-77). Seizing on the di in ive opening four-note “Salve” motive, Josquin creates an o inato ine in an inner voice whi consi s of alternating atements of this motive on G and D, ea preceded by three bars of re . He thus cra s a repeating motto unit comprising 7+7 bars sounded 12 times over the course of the piece (ex. 2.2). Beyond the likely symbolic oice of these numbers (seven being the number of Mary’s Joys and Sorrows, and 12 the number of ars in the crown of the woman described in Revelations 1:12 [Elders 1994, 151-84]), the sounding e e is mantric, akin to the trance-like iteration of the “Hail Mary” while praying the rosary. Indeed, two early sources introduce the o inato with a verbal canon from Matthew 10:22, “He that shall persevere unto the end, he shall be saved.”

Mo a e ive are the nal 12 measures of this setting, devoted to the “O dulcis Maria” phrase. e nal atement of the motto unit emerges at the top of the texture as this phrase begins, coming out of its submerged trance to highlight the corre ondence between the memorable opening of the r couplet and this closing phrase of the plainsong. e adje ive “dulcis” is then heard nine times and Mary’s name 11 times in the closing 12 bars, the la imploring call set to one of Josquin’s favorite and mo poignant ge ures, the falling third (ex. 2.3).

To enter the sacred space of all late-medieval and Renaissance churches and chapels was, by definition, a multidimensional experience. Spatial, architectural, and lighting effects were enriched with the temporal and expressive effects of sound, smell, and music, in both a localised and a broader, immersive way. The rituals and devotions, and also the political and civic events, that took place within such spaces all unfolded within a rich, highly developed multisensory environment. This was the human and cultural “religious theatre” for which sacred art of all kinds was created: specifically designed, crafted, installed, and experienced.

Such an environment offered unique artistic-and-religious experiences that were the only such live experiences available to many people; and it provided for an encounter between art and music that, within the given sacred and architectural framework, was both highly focused and widely dispersed. Convergence between music and visual imagery was a given: visual artefacts and images “received” music just as they received prayers, veneration, and diverse kinds of ritual; and music was given focus and “purchase”—in terms of spatial orientation and human cognitive attention—by the presence of sacred images and the particular articulation of the sacred space.

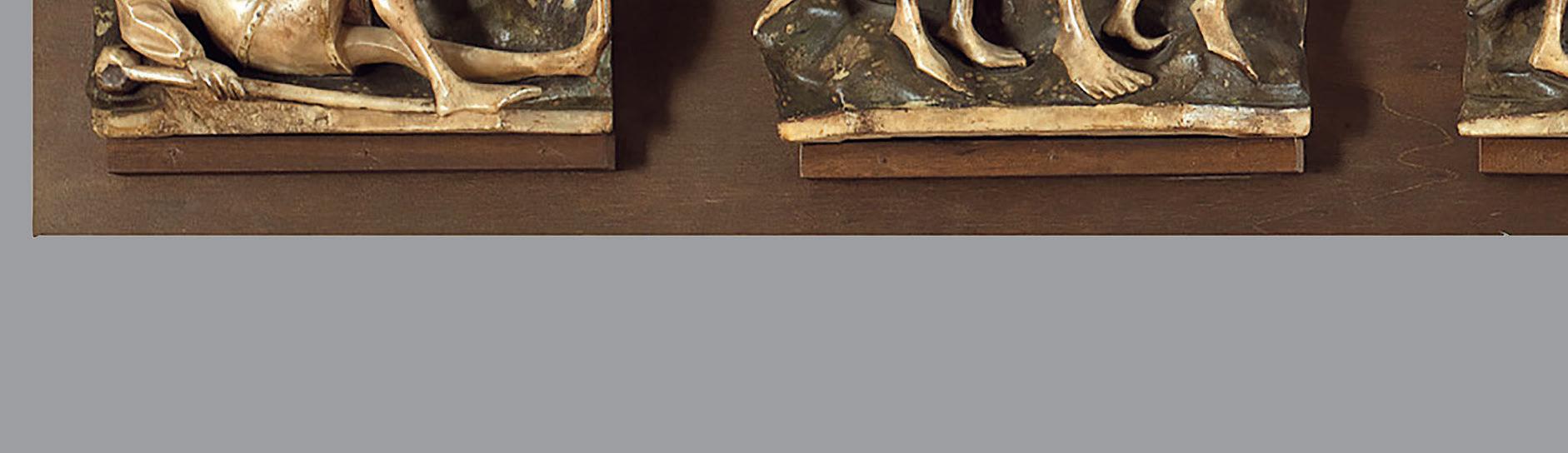

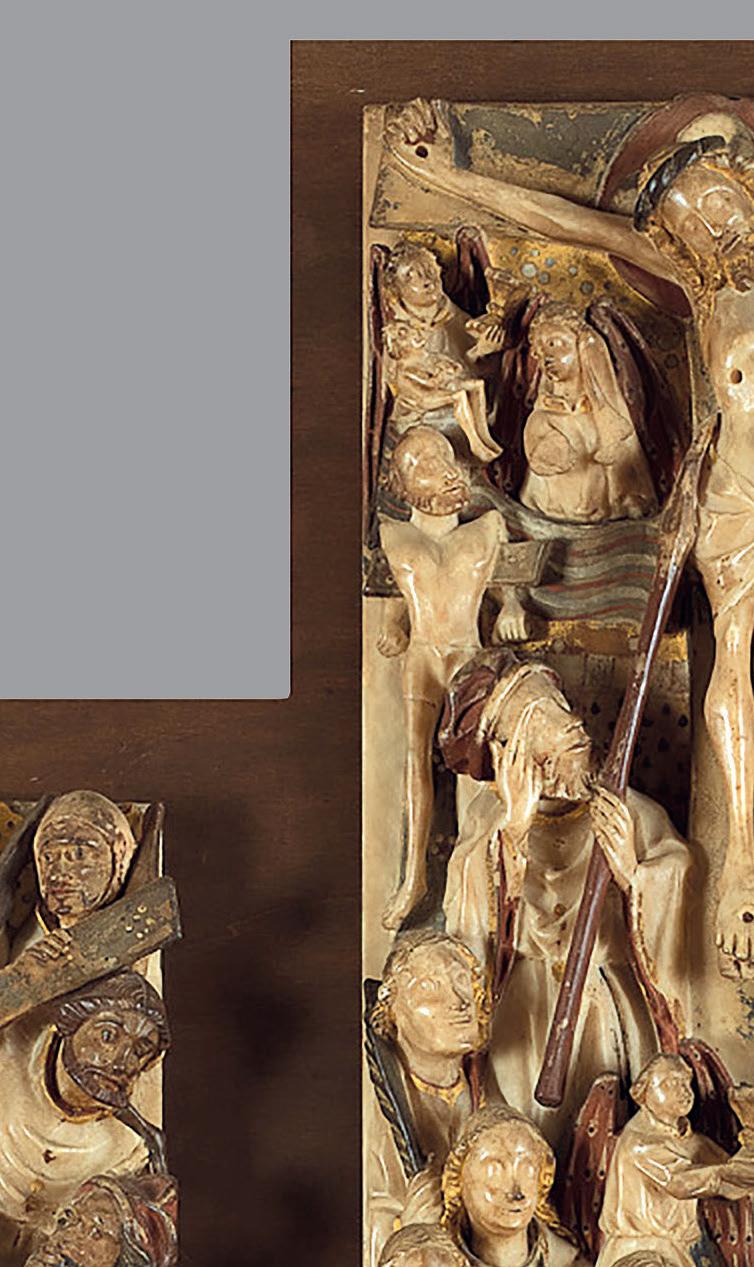

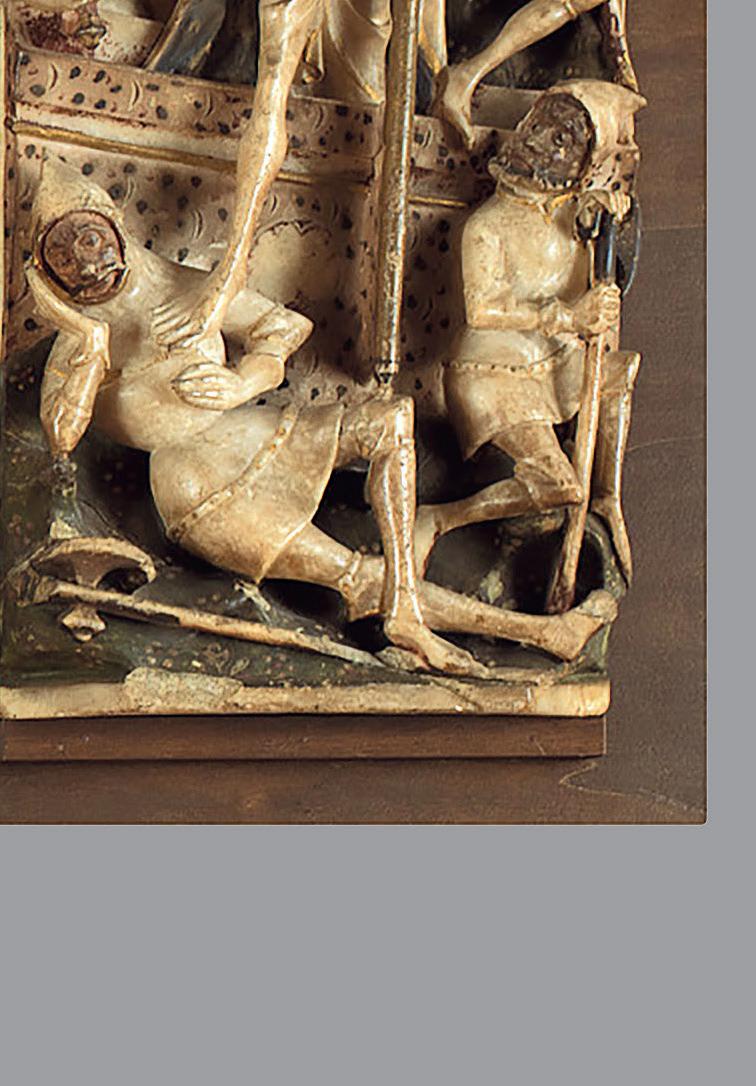

The English alabaster altarpiece surviving in Ferrara depicts in seven panels the Passion of Christ, with a Eucharistic focus on the taller panel of the Crucifixion placed at its centre. The Ferrara of the Estensi was one of the premier centres for the evolution of Renaissance culture across the arts and other disciplines during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and has been inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage site since 1995. Both its musical and its artistic culture were at the forefront of Renaissance developments, accommodating and (re)elaborating both local and international traditions. Stylistic and typological evidence suggests that the alabaster panels date from around the middle of the fifteenth century, perhaps as late as the 1470s. In all probability, they originated as the primary altarpiece of the Este princely chapel, which was the physical location of the sacred cappella ducale institution of the Ferrarese princely household (Scalabrini 1773, 306; Tuohy 1996, 90-95).

In its original state, the altarpiece would have had a horizontal box frame enriched with colour and decoration and brief Latin inscriptions (Nelson 1920; Cheetham 1984, 24-26.

See also Cheetham 2003). The panels themselves would have been carefully finished and polychromed with a range of lustrous pigments and gold, as can be ascertained from many comparative examples, including the roughly contemporary altarpieces on the same subject which survive in Naples (Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte) and Venafro (Museo Nazionale del Molise, Castello Pandone).

The Ferrara Passion altarpiece is one of a number of such altarpieces, carved in alabaster quarried from the English Midlands and fashioned there (Ramsay 1991), which survive to this day in Italian museums, having typically been commissioned, purchased, or presented in the fifteenth century. These altarpieces—and also a number of individual panels, most of which probably come from dismembered altarpieces of similar type—show striking evidence of the interest of certain kinds of Italian (especially aristocratic) patrons in art of non-Italian provenance (Murat 2016; Murat 2019), at this richest of all periods for the flourishing of native Italian sculpture and painting.

Katelijne Schiltz

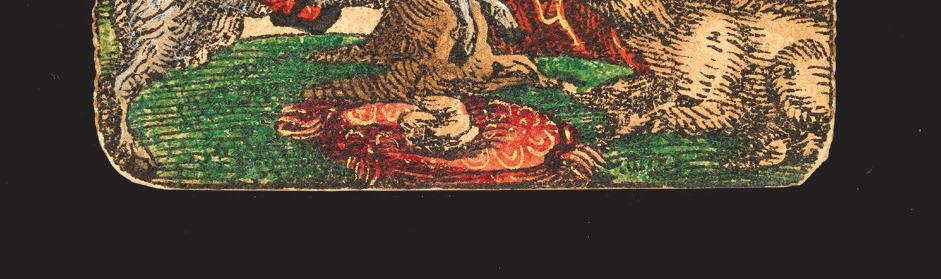

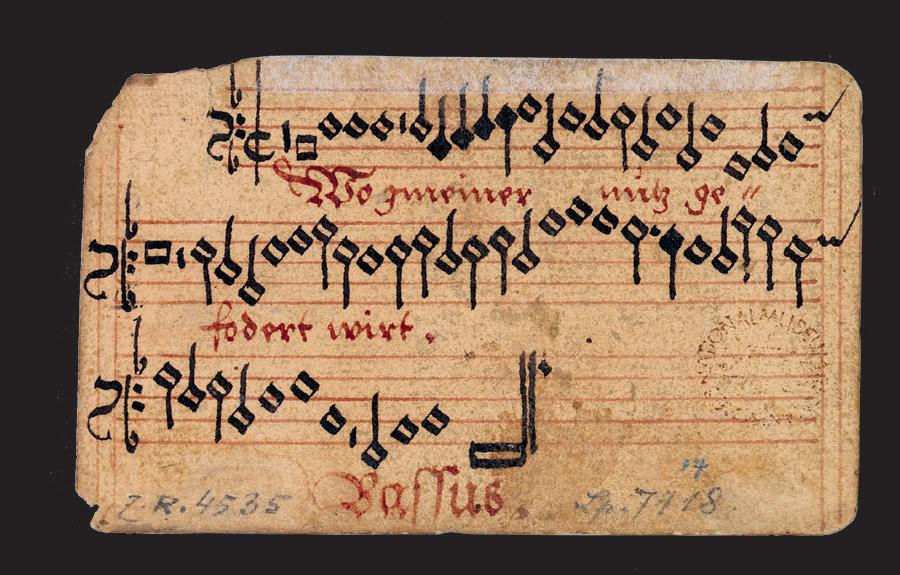

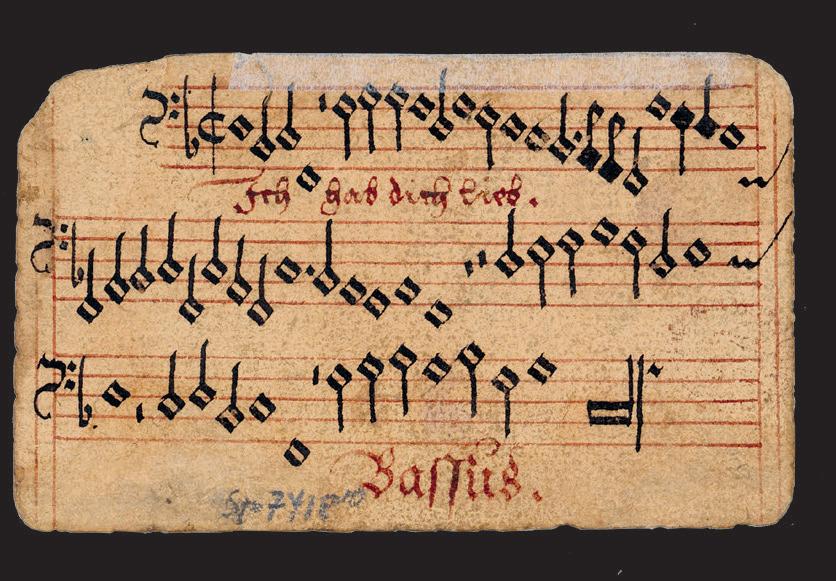

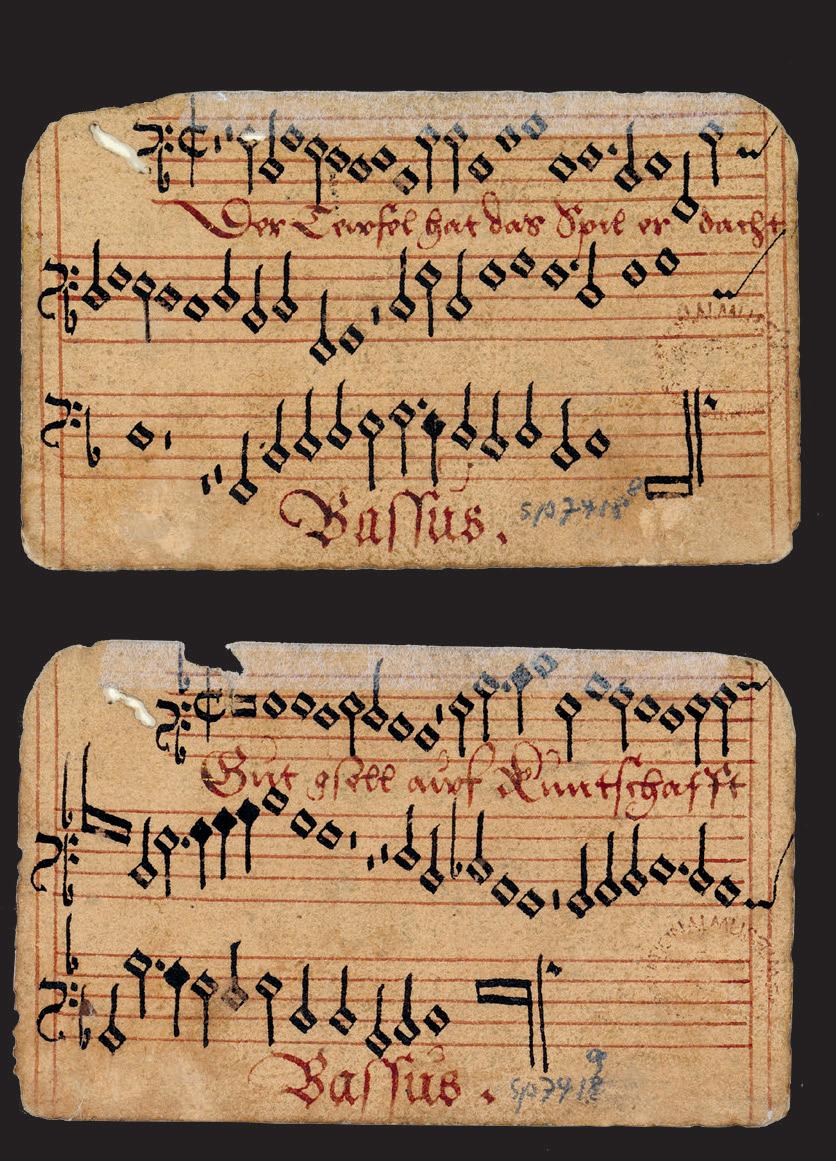

Peter Flötner (designer) and Franz Christoph Zell (printer and painter), Nuremberg, ca. 1540 47 coloured woodcuts, 10.5 x 5.9 cm Nuremberg, Bibliothek des Germanischen Nationalmuseums, Sp 7418 1–47 Kapsel 516

Left

Among the treasures of the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg is a deck of hand-painted cards that was designed by Peter Flötner around 1540. The reverse of each card is neither blank nor covered with geometrical figures, as contemporary convention would dictate; rather, it carries musical notation yielding four-voice Lieder (songs). Among the six surviving copies of the set—the others in Berlin (Kupferstich-Kabinett), Paris (Bibliothèque nationale de France), London (British

Museum), Oxford (Bodleian Library, Douce Collection), and New Haven (Beinecke Rare Book Library, Cary Collection)— the Nuremberg deck is the only coloured copy, and also the most complete: only one card, the 2 of Acorns, is missing. The set in Berlin bears the initials F C Z upon this particular card, which in all probability stand for the woodblock-cutter Franz Christoph Zell, who in a document from 1527 is named “Christoff Kartenmaler” (Cristoph the Card Painter).

Alongside Augsburg and Ulm, Nuremberg was one of the major centres of card manufacture in Germany in this period. Although the city boasted a tradition of Kartenmaler dating back to the first half of the fifteenth century, the Reformation must have been instrumental in encouraging prominent artists to move into this area of work. Now that a market for devotional images by and large had ceased to exist, famous names including Hans Sebald Beham, Erhard Schön, Hans Schaufelein, Peter Flötner, and Jost Amman found they had to turn their attention to other forms of printed graphic work, such as pamphlets, mythological, and allegorical pictures—and playing cards.

For Flötner, playing card design was just one of his many artistic endeavours, in an oeuvre that embraces sculpture, medals, and relief plaques, as well as designs for furniture,

panels, and book illustrations. Although the exact date of these playing cards is unknown, they seem to have been created at a time when Flötner produced a number of woodcuts, among them an anthropomorphic alphabet, a human sundial, and the satirical New Passion of Christ showing Christ being beaten and mocked by members of the clergy. The latter two woodcuts are especially interesting, as they contain elements that can be linked with the deck of cards: scatological humour and faecal fantasies on the one hand (Kammel 2007), and anti-Catholic propaganda on the other.

According to the typical German playing card system, each of the four suits (Hearts, Bells, Leaves, and Acorns) has 12 cards, comprising King, Upper Knave (or over-valet), Under Knave (or under-valet), Banner (10) and 9 through to 2. The Deuce

Carla Ze er

e Lady and the Unicorn: Hearing Anon., Paris, ca. 1500 Wool and silk, 370 x 290 cm

Musée national du Moyen Âge, Paris

Photo © Musée National du Moyen Âge et des ermes de Cluny, Paris / Bridgeman Images

Musée national du Moyen Âge, Paris

Photo © Musée National du Moyen Âge et des ermes de Cluny, Paris / Bridgeman Images

The tale of a French lady and a captive Turkish prince? Chri ian iconography, representing the miracles of the Immaculate Conception and the Incarnation? A meditation on the development of the human soul? A depi ion of medieval n’amor, known today as courtly love? A di lay of the heraldry of the Parisian Le Vi e family? An allegory of the ve senses? From the moment of their discovery by the writer and ar aeologi Pro er Mérimée in 1841, moldering in Boussac ca le in the Limousin region of France, the six Lady and the Unicorn tape ries have in ired numerous s olarly interpretations and generated arti ic expressions in media ranging from novels to lm to adventure games. Legend has it that only a virgin can capture a unicorn. And that the unicorn’s horn can purify water and countera poison. ere is a ri tradition of literary and pi orial depi ions of ladies and unicorns that dates ba to Classical Antiquity, with ve iges ill remaining in the hunting mythology of the Caucasus Mountains (Hunt 2003). But the Lady and the Unicorn tape ries, whi have been a centerpiece of the colle ion of the Musée de Cluny (the national museum of the Middle Ages) in Paris since the 1880s, are surely the mo famed in ance of that tradition.

Woven in Flanders in about 1500, from Fren designs, ea of the tape ries depi s a graceful, elegantly-attired woman posed—poised—between a lion on her right and a unicorn on her le , set again a luxurious mille eur ba ground. In ea scene she engages in a di erent a ivity: holding up a handmirror so that the unicorn can see itself, playing a portative organ, tou ing the unicorn’s horn, receiving sweets, being presented with owers, and anding under a pavilion as she places her jewels in a casket. A female attendant plays a signi cant role in several of the scenes, perhaps none more than the one in whi she pumps the bellows of the small organ. Without her assi ance, the in rument would remain silent.

e assumption that the Cluny tape ries present an allegory of the ve senses has gained the wide acceptance over the years. But what, then, is the sixth sense, the one represented by the my erious nal tape ry in the series, whi prominently di lays the text “A mon seul désir” (To my one/only desire)? Does it sum up the others in some way, by con ituting

wisdom or cognition or memory or emotion? Perhaps it simply sets them aside, in favor of the heart, as some believe. To further complicate matters, the use of heraldry in the images sugge s that the sixth tape ry was not necessarily di layed at the end of the sequence, as has o en been assumed. Various orderings of the tape ries may have been utilised originally, depending on the nature of the wall ace available, as their owners moved from one residence to another (Ni el 1982, 14).

In our own encounters with the tape ries, whether in museums or their many reprodu ions, it is easy to lose sight of the ways in whi their original owners, the Le Vi e family (“qui ,” like the unicorn), would have experienced them using their own senses. ey would of course have viewed the tape ries from various di ances and angles, taking in the a ive scenes but also the decorative details. ey mu have rea ed out to tou them, feeling their lush textures and the warmth they brought to cold walls. ey may even have smelled them, not only imagining the oral scents depi ed in the images, but perhaps on a damp day noticing the odours of the wool and silk of whi they were woven. Even the image depi ing the sense of hearing would have been very sensual, since it would have ret ed the acou ic imagination mu less in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance than it does now. Courtly viewers at the time would have had the sound of a portative organ readily in their ears.

Living in Paris ju a er the turn of the twentieth century, Rainer Maria Rilke recorded his impressions of the tapestries in his semi-autobiographical novel, Die Aufzei nungen des Malte Laurids Brigge, published in 1910 ( e Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge; the r English title was Journal of My Other Self). Rilke r takes in the ensemble as a whole, then pauses before ea individual scene to absorb its details. Arriving at the sense of hearing, he ponders, Should not music enter into this illness, is it not already there, subdued? Gravely and quietly adorned, [the lady] has gone forward (how slowly, has she not?) to the portable organ, and now ands playing it. e pipes separate her from the maid-servant who is blowing the bellows on the other side of the in rument. She has never yet been so lovely… e lion, out of humour, unwillingly endures the sounds, biting ba a howl. But the unicorn is beautiful, as with an undulating motion (Edinger 1948, 166).

Anon., England, ca. 1570

Oil on wood, 65 x 49 cm

Inscribed: MORS ULTIMA LINEA RERUM EST

Shake eare Birthplace Tru , Hall’s Cro , Stratford-upon-Avon

Photo © Shake eare Birthplace Tru

At first glance, this painting depi s a conventional image of a young and ri ly attired gentlewoman playing her lute, with a music book open on the table in front of her. In Elizabethan England music increasingly formed part of a young noble or gentlewoman’s education. Having the time for su a leisured pursuit was a sign of atus, while music’s associations with female beauty and attra iveness meant that it was also seen as improving a woman’s marriage pro e s (Au ern 1989, 429-31).

Yet the eye is qui ly drawn to the skull that is being held dire ly behind her head, and then to the older gentleman who holds it, anding in the shadows. He ignores the viewer and in ead xes his attention rmly on the young woman, for whom he is positioning a mirror so that she might see the re e ions of both her face and the skull behind. e painting is no mere portrait, but an allegory that allenges the viewer to contemplate its layers of meaning in relation to their own morality and musicality.

Depi ions of women playing music (rather than simply being depi ed with an in rument) are rare from Elizabethan England; the other well-known surviving portrait of a lute-playing woman is a miniature of Queen Elizabeth I painted by Ni olas Hilliard in ca. 1580 (Butler 2015, 15-18, 42). One reason for the relu ance to portray women with in ruments may be the allenges of depi ing a musical woman in a positive light without opening up the possibility of more negative connotations. An allegorical painting of a musical woman, however, could openly address the complexities of music’s morality. e in iration for this painting may have been continental, as its basic composition is nearly identical (though reversed) to several anonymous sixteenth-century Flemish paintings, including one sold at Chri ie’s in 2007 (Chri ie’s 2007; Mirimonde 1978, 119-20), and various versions of An Allegory of the Transience of Earthly Beauty (NationalMuseum, Sto holm; Chri ie’s 2006). e reversed composition perhaps sugge s that an intermediary engraving served as the model for this English version.

In this English painting, a motto above the gentleman’s head sugge s the lesson that he is trying to impart: “mors ultima linea rerum e ,” or “death is the la thing in line,” taken

from Horace’s r book of Epi les (16.l.79). e motto, the skull, and the contra ing ages of the gures all place the painting in the memento mori tradition, whi reminded viewers that all life ultimately ends in death. e phrase “la in line” can be read as evoking both the ronological line from youth to age to death, as well as the compositional alignment that links the books, lute, and the woman’s face with the skull. e gentleman and his mirror and apart from this main axis of the painting, emphasising his di ering per e ive from that of the young woman. While the gentleman’s gaze is focussed on the skull and the contemplation of morality, the young woman looks out at the viewer, more concerned to gain our attention and admiration.

Many elements of the young woman’s portrayal can be linked with the iconography of vanitas or the idea that all earthly life, possessions, and pleasures are empty and ephemeral (Ariès 1985, 193). e lady’s ri red gown and bodice embroidered in gold with a ne damask underskirt, slashed sleeves, and ru , together with her carefully manicured hair with a small headdress and feathered hat, were fashionable in the 1570s (Hewitt 2014, 255) and evoke the vanities of appearance and wealth (Hewitt 2011). Yet, the skull’s dire alignment with the young woman’s head unmasks her beauty by alluding to its ultimate decay.

If the lady’s appearance appeals to the eye, then the lute playing refers to the pleasures of the ear. Peter Forre er has argued that the lute depi ed is eci cally the smaller treble lute, designed for playing in duets and consorts (Forre er 1994, 1213; Spring 2001, 180-81), though in the context of dome ic performance its use may have been more uid in pra ice.

Musical obje s were common features of vanitas imagery, both because music is a transient, sensual pleasure that soon fades to silence, and because musical in ruments were o en symbolic sub itutes for the human body, their sound for breath. Human death was implicit in the in rument’s dying sound (Au ern 2003). When the ara ers of Prote ant theologian omas Becon’s e Iewel of Ioye (1550) turn to discussing vanity, their r example of how soon “carnal dele ation[n] & worldli ioy vanish awai” is music (sig. E.viiir). e ara er Philemon asks rhetorically, “though we delite

Moritz Kelber

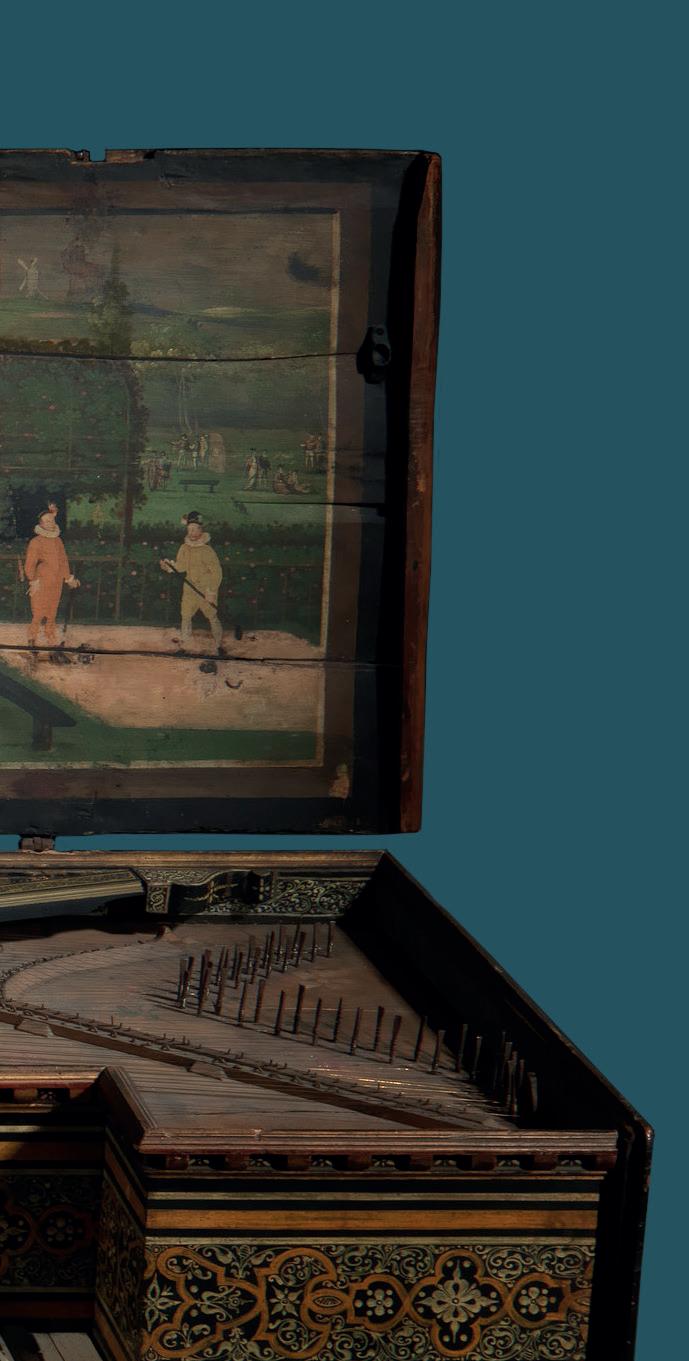

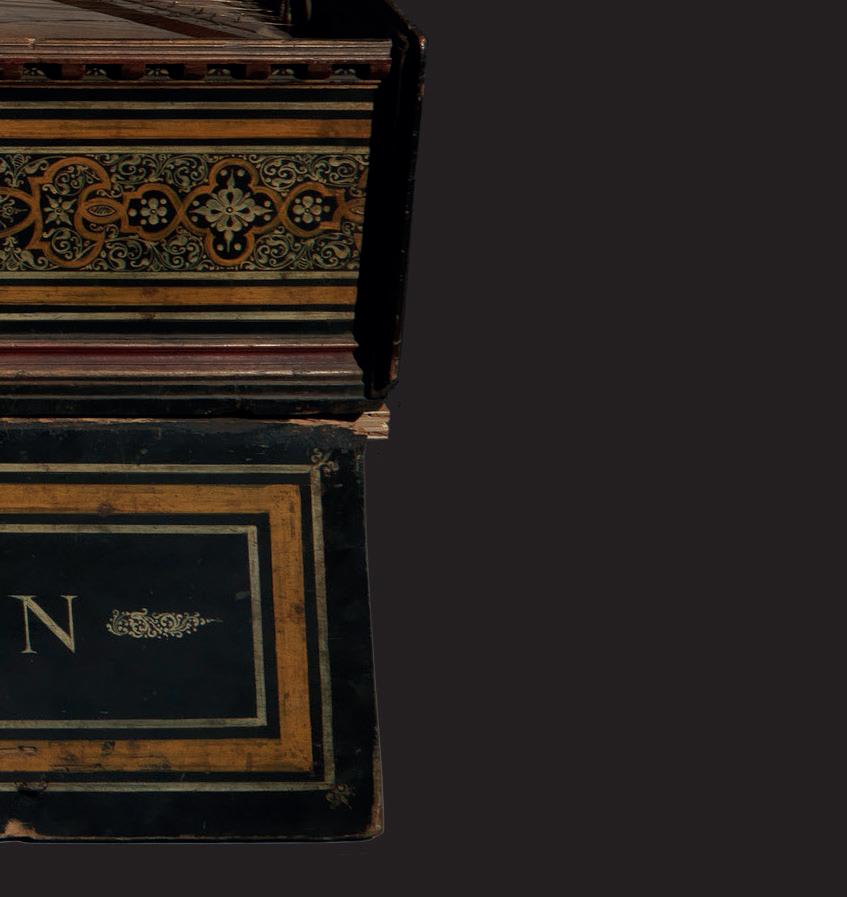

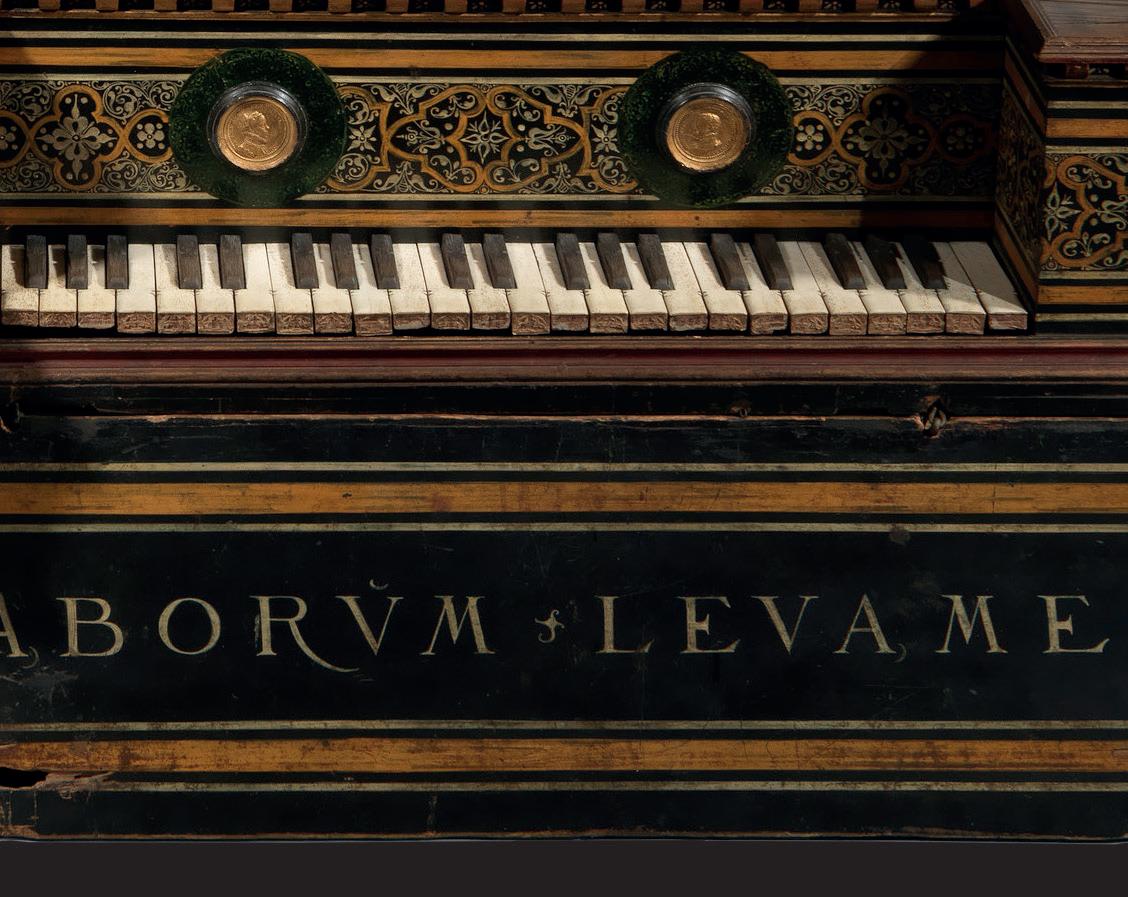

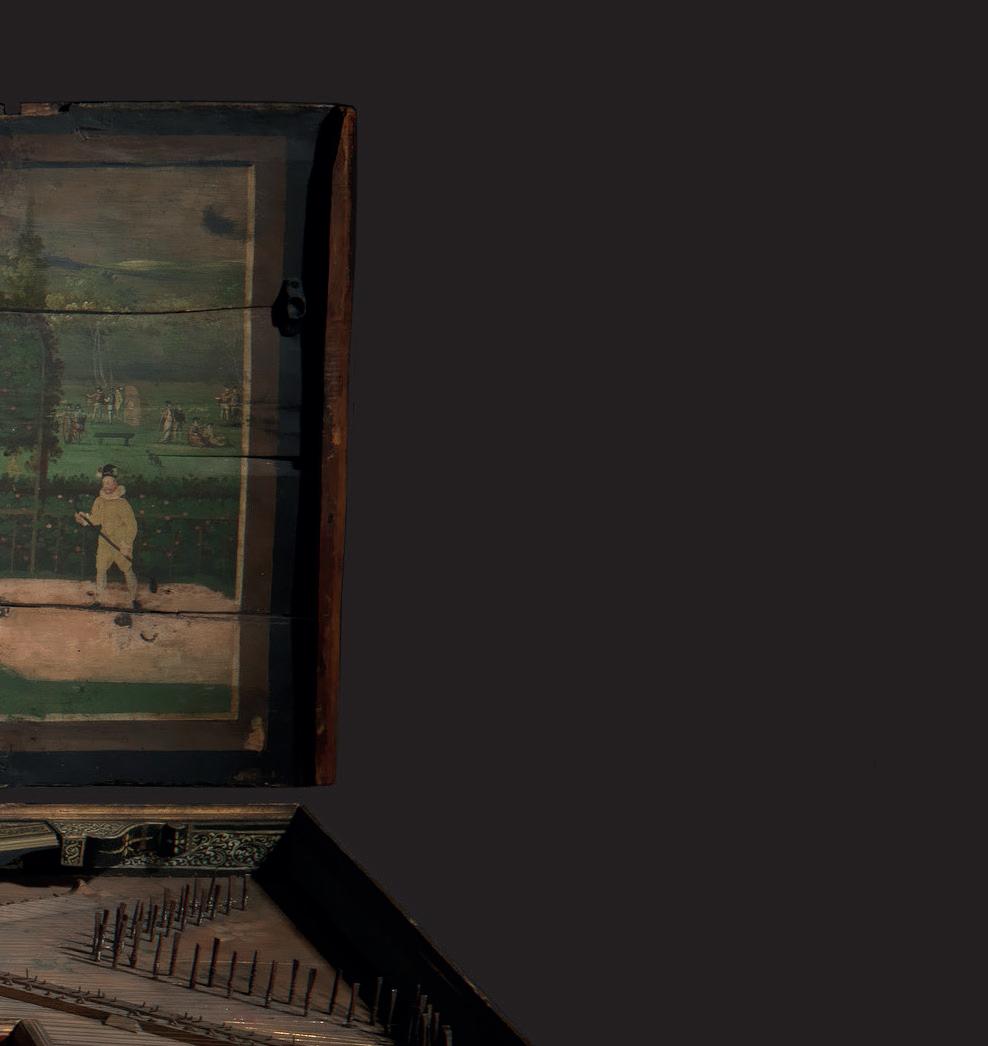

Hans Ruckers the Elder, Antwerp, 1581

Pine, beech, poplar, mahogany, paint, gesso, metal, parchment, and brass; 182.2 (width) x 49.5 (depth) cm

Inscribed: HANS RVEKERS ME FECIT 1581

The Metropolitan Museum, New York Photo © CC0

From the sixteenth century to modern times stringed keyboard instruments have remained a central element of private musical life. Starting from the late Middle Ages, various designs of European keyboard instruments entered circulation, carrying many different names. Because of the complex contexts of its use, the virginals is among the most interesting keyboard instruments of the pre-modern period. The term “virginals” usually describes a basic instrument in rectangular form with a single string per note. Like all instru-

ments from the harpsichord family, the virginals generates its sound with small plectra mounted on jacks. Thus, its sound is very similar to that of a plucked string instrument like a lute or a cittern.

The origins of the term “virginals” remain a mystery. One peculiarly interesting theory links the term to the word “virgin” or to the Virgin Mary in particular. According to this hypothesis, “virginals” is used to refer to the gender of the instrument’s players and to the purity and nobility of its sound.

Indeed, the virginals has been seen as a female instrument (Busch-Salmen 2000, 42). A great number of sixteenth- and especially seventeenth-century portraits show young women sitting at an object that looks exactly like a virginals. The most prominent of these are by Johannes Vermeer. Two of his iconic paintings—Lady standing at a Virginals and Young Woman Seated at a Virginals—are today kept in the National Gallery in London (see fig. 46.1). Both works date from around 1670 and not only show female musicians: they reflect on the sexuality of music-making itself by showing a cupid or an intimate musical scene on a painting in the background. Learning to play a keyboard instrument was a key component in the basic education of aristocratic and bourgeois women. In The Book of the Courtier Baldassare Castiglione emphasised the

importance of music education for all courtiers, women and men alike. However, according to Castiglione, women should be more reserved than men when making music in public, and they should carefully choose their musical instruments, avoiding drums and wind instruments (Haar 1983, 177). Thus, the soft, lute-like tone of the virginals might have been seen to represent late medieval and early modern female virtues of silence, obedience, and chastity. The latter is also expressed in the modest posture of a person playing a virginals.

The sixteenth century was a time of technological experiments: in different parts of Europe instrument makers, watchmakers, gold and silversmiths collaborated in creating a variety of different automatons and musical instruments— from organs to stringed keyboard instruments (see exhibit 17).

Javier Marín-López

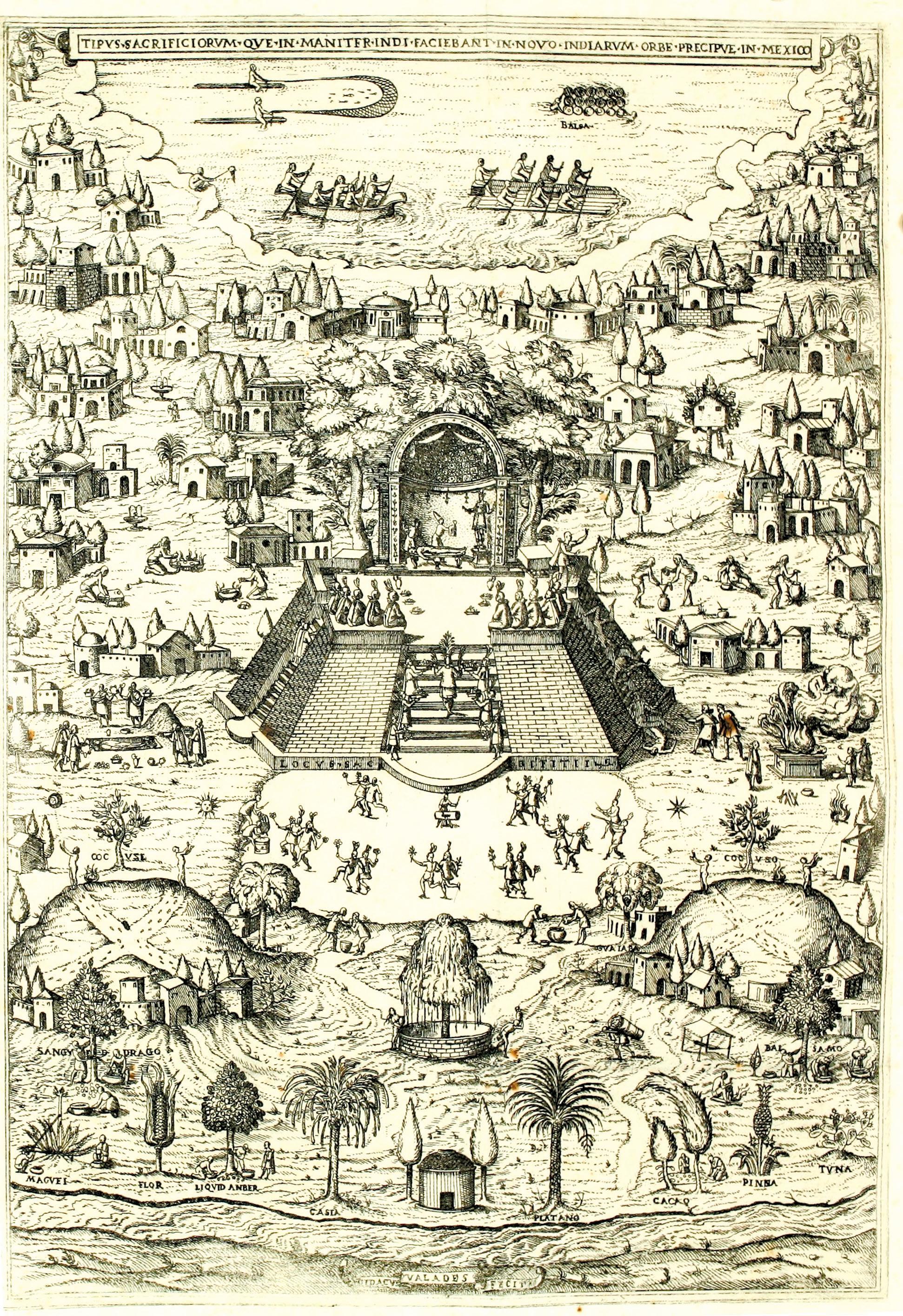

Didacus (Diego) Valadés, Bird’s-eye view of Mexico City - Teno titlan Engraving from Valadés, Rhetorica Chri iana

Perugia: Pietro Giacomo Petrucci, 1579

378 pp., 31 x 21.6 cm

Inscribed: Tipvs sacri ciorvmqve in maniter Indi faciebant in Novo Indiarvm orbe precipve in Mexico Los Angeles, e Getty Resear In itute Resear Library, BV4217 .V34 1579, folded plate between pp. 168 and 169 Photo courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Although he was considered for decades a me izo, the son of a Spanish soldier and an indigenous woman f rom Tlaxcala, recent s olarship shows that Diego Valadés was born in Villanueva de Barcarrota (today Barcarrota, Badajoz, Spain) and that he moved to Mexico in 1537 when he was only four years old (Chaparro Gómez 2015, 29). He was trained there, under the renowned Flemish friar Pedro de Gante (Pieter van der Moere), at the Ho ital of San José de los Naturales and the Colegio de Santa Cruz of Tlatelolco, and developed an intense evangelising a ivity among the Chi imecas, a group of nomadic tribes who inhabited the north of what is now Mexico. In addition to Ca ilian and Latin, he was able to eak Nahuatl (the missionaries’ auxiliary language and a major lingua franca in Mesoamerica), Otomi, and Tarasco.

A er 30 years of evangelizing a ivity in New Spain, Valadés went ba to Europe, where he was appointed General Procurator of the Franciscan Order in Rome and published his Rhetorica ri iana ( g. 71.1), a singular theology treatise written in Latin, dedicated to Pope Gregory XIII and devoted to the training of prea ers. In this book he combines the ideals of the rhetorical tradition of Chri ian Humanism with his own experience as a missionary in the New World. In fa , two of the mo original elements of this volume—until then unusual in books on rhetoric—are related to the methods of conversion used in his missionary a ivity: the art of memorising (to whi he devotes a apter explaining the types of memory, mnemonic rules, etc.), and the use of illu rations (as a complement to the prea er’s words, as a memory aid and, ultimately, as effe ive rategy to ensure the new trainees’ under anding and memorising of the Go el’s dogmas) (Báez Rubí 2005, 126-29). e book contains 27 copper engravings (including that on the title page), created by Valadés himself from 1575. ese engravings are suited to European te nical conventions and iconographic traditions, although the contents and a ivities that are depi ed feature indiginous communities. Valadés’s aim, therefore, is not to reproduce the reality of America, but to approa it in an idealized manner, by means of a sele ive series of illus-

trations whi are in the service of the rhetorical and pedagogical ideals of the treatise, and whi e ciently combine a view taken from St Augu ine and St omas Aquinas (typical of the medieval Franciscan imaginary) with the new components of Renaissance Humanism (Branley 2008).

e engraving entitled “Tipus sacri ciorum que in maniter indi faciebant in novo indiarum orbe precipue in Mexico” (Type of sacri ces whi the Indians barbarously performed in the New Word, mainly in Mexico) o ers an original, symbolic, and encyclopaedic per e ive on the indigenous world of the Mexica (known hi orically as the Aztecs), in the light of the We ern model of the polis. e image is printed on a folio whi is folded because it is larger than the regular pages of the book. is demon rates its importance among the other engravings. e main scene depi s the ages of a human sacri ce. In the centre, there is an impressive teocalli or pyramid crowned by a apel-temple where a sacri ce in honour of Huitzilopo tli, Mexica god of sun and war, is being celebrated. A human heart, whi has ju been removed from a condemned vi im, is o ered to him. ose who are to be sacri ced are sitting, waiting their turn, while those who have already been sacri ced are pushed down the eps and then burned on a pyre. In order to nd an easier corre ondence with European mentalities, the composition is symmetrical and well-organised, the so-called Indians are wearing classical clothes and the apel-temple, under a lush grove of ahuehuetls (also known as trees of paradise), is of typical Renaissance design, including a semi-circular ar way with panelled vault and Italian grotto motifs on the jambs and key ones. Huitzilopo tli appears as a Roman god (Maza 1945, 39), wearing hummingbird feathers on his head, holding the attributes of the turquoise snake or re in his right hand, and with an emblem featuring ve feather ornaments in his le hand.

At a large e lanade, opposite to the teocalli, a macehualiztli is taking place. is is a ritual dance with a circular oreography in whi four mixed couples of dancers participate (referring to the four elements of nature). ey are wearing cre s, owers, bran es, pumpkin shakers (ayaca tli), shell

is book collates 100 exhibits with accompanying essays as an imaginary museum dedicated to the musical cultures of Renaissance Europe, at home and in its global horizons. It is a hi ory through artefa s—materials, tools, in ruments, art obje s, images, texts, and aces—and their witness to the priorities and a ivities of people in the pa as they addressed their world through music. e result is a hi ory by collage, revealing overlapping musical pra ices and meanings—not only those of the elite, but re e ing the everyday cacophony of a diverse culture and its musics. rough the lens of its exhibits, this museum surveys music’s central role in culture and lived experience in eenth- and sixteenth-century Europe, o ering intere and insights well beyond the ri ly musicological eld.

e Museum of Renaissance Music o ers readers a orilegium of delights born of a vast set of international scholarly collaborations. Taking its readers through wildly diverse musical objects, it also invites them to encounter a great diversity of authors whose loving relationships to musical materialities guide our journeys through new Renaissance histories. Yet it’s not just musical objects as such that we discover here, but music as metaphorized, desired, utilized, emplaced, and displaced, and by a whole range of networked historical subjects, literate and illiterate, subaltern and elite, African, Arabic, Japanese, and Mexican along with European. Not merely artefactual, the histories these subjects tell are pliant and porous. With imaginative verve, e Museum of Renaissance Music thus contributes to a current explosion of material studies whose cacophony remakes our understanding of the Renaissance via “history by collage,” in this case understanding Renaissance musicking through the spatial a ordances of the gallery with its multitude of “rooms” (travels, psalters, domestic objects, instruments, and much more), rather than through the traditional edited collection. e results are mesmerizing, indispensable.

– Martha Feldman, University of Chicago –

Like a veritable pop-up book, e Museum of Renaissance Music surprises its readers with the multidimensional quality of its content. Presenting a hundred diverse objects organized in di erent themed rooms, Borghetti and Shephard’s volume o ers readers the experience of walking through an imaginary museum where objects “speak out” their complex web of allusion connecting texts, images and sounds. A veritable tour de force, this book brings history, art history, and musicology together to highlight the pervasive nature of music in Renaissance culture, and does so in a direct and e ective manner that can be enjoyed by experts and amateurs alike.

is imaginary museum of Renaissance music, through a collection of one hundred exhibits, returns a proper share of sonority to objects, images, artworks and spaces. A fascinating reference book, o ering a transformative vision of music in Renaissance culture, from domestic space to the global dimension.

– Diane Bodart, Columbia University, New York –

e history of music should be told through works, composers and performers? Not quite. In this book, Borghetti and Shephard demonstrate that exhibits such as paintings, administrative documents, domestic objects, or entire rooms may tell us something about European music of the eenth and sixteenth centuries that music books and instruments cannot. e high-quality reproductions together with the knowledgeable commentaries are a treat for the eyes and mind of the reader. An entirely new type of music history book, this wonderful volume will appeal to scholars, music lovers, and students alike.

– Martina Bagnoli, Gallerie Estensi, Modena – – Melanie Wald-Fuhrmann, Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics, Frankfurt –