American Essence

FOR EVERYONE WHO LOVES THIS COUNTRY

Pedaling to Victory

Despite setbacks, turnof-the-century athlete Major Taylor displayed sterling character as he cycled his way to becoming world champion Treasures Lost and Found

A new generation of foragers is making the case for the ancient art of eating wild

Raising Heroes

Sonya Curry, mom to Steph, Seth, and Sydel Curry, reflects on her journey as an educator and nurturing her children with faith, family values, and tough love

American Essence MARCH 2023 V O LU M E 3 | ISSUE 3 MARC H 2023

LimitedPreview ofSelectedContent

Contents

Features

6 | Inner Strength

Sonya Curry raised her children with tough love while allowing them to realize their full potential.

12 | The Nature of a Good Education

According to Hillsdale College president Larry Arnn, good teachers cultivate students’ innate desire to learn.

16 | Nurturing Gi s

With Arizona Autism Charter School, a mother started a model to help children with autism thrive.

20 | Classical Learning

A fighter pilot created an ideal school for his children—one with a rigorous curriculum and that teaches children a moral foundation.

24 | A Musical Journey Through Time

A violinist of baroque and medieval music finds a new mission: to revive the upright values embedded in ancient Chinese culture.

28 |

Why I Love America

An Italian immigrant thanks God and America for the blessings and opportunities of his adopted homeland.

30

| Family Roots

A reader shares how her 92-yearold mother’s unstoppable energy inspires her family to take on any challenge.

34

|

A er-School Construction

An innovative high school program teaches high schoolers professional skills while aiming to dispel stereotypes about the trades.

History

38 | Taylor ’s Sterling Qualities Cycling his way through roadblocks to become a champion, Major Taylor proved that principles triumphed in sports.

46 | Quick-Witted Escape

Thanks to their upbringing, young pioneers Jemima Boone and the Callaway girls used their survival skills to outsmart their Native American captors.

50 | A Celebrated Lineage

The concept of education as a living inheritance was the legacy of the Adams family.

54 | McGu ey ’s Readers

In addition to the core curriculum, William Holmes McGu ey’s primary school textbooks incorporated valuable lessons on morality and ethics.

AMERICAN ESSENCE

12 38

Lifestyle

60 | Exploring Alaska

The vast landscape and rich culture of America’s 49th state leave an indelible mark on visitors.

66 | Book Recommender

“Mornings on Horseback” leaves readers yearning to know more about the exhilarating Western adventures of Theodore Roosevelt; “Comet Madness” (page 92) reveals the frenzy of mainstream media, science, and superstition that created the Halley’s Comet fever of 1910.

67 | Modern Foraging

Wild-food experts across the country share the bountiful rewards of a forgotten craft.

82 | Garden Planning

These three expert-approved methods can help you grow your own food at home.

86 | Of Marble and Gold

The first stone palace built along Newport’s shore, Marble House was the beacon for transformation during America’s Gilded Age.

96 | Parting Thoughts

In a grand display of gratitude, award-winning author Carew Papritz creates the world’s largest thank-you letter.

ISSUE 3 | MARCH 2023

67

34

60

Sonya Curry: Teaching and Nurturing With Fierce Love

The educator and mother of three, including basketball star Steph Curry, details her journey of helping children realize their potential

R ITTEN BY Krista Thoma s

Sonya Curry likens her family to The Big Machine. Every member of the family plays a part in helping the household run at maximum e ciency, with chores and activities on schedule for each. So when her eldest son Stephen Curry—who would go on to become the basketball star Steph Curry—failed to do the dishes one week during his high school sophomore year, there was no question that he would not be allowed to go to basketball practice—despite it being before an important game. Curry told her son’s basketball coach that he would be missing practice, which, according to the coach’s rules, meant he would not be starting the next game.

“I reminded Stephen so many times to do the dishes that I realized he was starting to rely on me to manage him. That’s not going to work. I have to train my kids to manage themselves. That’s what this is about. Yes, everyone has to do their part to keep the Big Machine running. At the same time, they have to learn to be their own managers,” Curry wrote in her recent book, “Fierce Love: A Memoir of Family, Faith, and Purpose.”

Parenting for Curry meant having her children learn by making mistakes and learning that actions have consequences. Being the head of a private school in Charlotte, North Carolina, where she raised her three children, Steph, Seth, and Sydel, Curry knew that children must figure out the process themselves while parents guide them to the conclusion. Her approach is similar to the schooling philosophy

she embraced as an educator: the Montessori method. Named after Italian educator Dr. Maria Montessori, the philosophy embraces a system of learning that measures success based on the creative potentiality of a child. According to Montessori, it would “activate the child’s own natural desire to learn.”

Curry first enrolled her two sons at a Montessori school when they were 3 and 5 years old. She was immediately impressed with how her sons, with di erent personalities, thrived in the same classroom while developing separate groups of friends. One day, the owner of the school approached Curry and asked her if she would be interested in running the school’s new satellite program for toddlers and kindergarten. Curry, with a degree in family studies and child development, agreed. She set up the new school on a piece of farmland.

This, she recalled, was the defining moment that led to her career in education.

After more than two decades at the school, she retired in 2017 and devoted her time to writing her book. Curry feels compelled to reach out to parents with sage advice: how to parent with ultimate success according to each individual child and his or her gifts. The bigger picture for Curry now is encouraging other parents in their roles of nurturing their children. “Hopefully the book keeps people talking about what they are doing as parents, to find support, and to o er support to others as a community.”

6 AMERICAN ESSENCE

W

Features | Family

Sonya Curry and her son Steph Curry pose for a

photo on the red carpet during a 2019 event in Oakland, Calif

Sonya Curry and her son Steph Curry pose for a

photo on the red carpet during a 2019 event in Oakland, Calif

vvv

Education Journey

Her journey into the realm of teaching began at an early age. She had a natural gift for teaching. At the ripe age of 10, she taught lessons to several neighborhood children in the trailer park in which she lived. Whether it was math, spelling, or reading, she commanded the class and the children respected her—like a real teacher. One particular experience led Curry to witness how education could transform someone. A neighborhood teen named Philip had developmental disabilities and did not know how to read. Curry took the initiative to teach him. Seeing someone struggle, she was drawn to be that teacher or coach who encouraged success. In retrospect, Curry says this was the only career she dreamed about and opportunities just presented themselves throughout the course of her life.

When she got the opportunity to open her own Montessori school, she didn’t need the Montessori certification to be an administrator. “But it is really hard to lead teachers and parents authentically unless you have had the training,” she added. She enrolled in an intensive training program for nine straight weeks in Baltimore, Maryland. Though it was di cult leaving her children behind, this

was her opportunity to learn the Montessori method. “In Montessori, teachers are guides who allow the unfolding of the child that God created. Create an environment where the child will learn and then take ownership of that learning. Here we don’t tell them what the answer is; instead, we encourage them to find the answers.”

8 AMERICAN ESSENCE

“Create an environment where the child will learn and then take ownership of that learning. Here we don’t tell them what the answer is; instead, we encourage them to find the answers.”

Features | Family

SONYA CURRY, EDUCATOR

This page is not in the preview.

not included preview.

Raising a Family Curry places a heavy emphasis on faith and spirituality, such as by giving God the first part of the day through praying devotions. The family attends church on Sundays and participates in the church community. Training successfully for spiritual growth also means talking openly about hardships.

Instead of sweeping problems under the rug, parents should have important conversations with children about the kind of impact any decision will have on others, she said. “Learn to give yourself some grace, and give grace to other people—and then try to correct or make things right,” she said.

The Curry household frequently held family

ISSUE 3 | MARCH 2023 9 ABOVE Curry with her children and grandchildren

A Conversation With Larry Arnn

12 AMERICAN ESSENCE The Hillsdale College president reflects on his journey as an educator and the nature of a good education W R ITTEN BY Channaly Philipp

Dr. Larry Arnn is the 12th president of Hillsdale College, where he also teaches politics and history.

American Essence: Please tell us about your journey as an educator.

Dr. Larry Arnn: My father was the first in his family to become a college graduate. He became a schoolteacher in my hometown, Pocahontas, Arkansas, and in that profession, he found much happiness. But my parents had little money, so my father usually had two jobs outside teaching. His work ethic taught me to work while in school. I was a paper boy. I was an ironworker. I was a welder. I paid for much of my graduate school waiting tables.

The other thing I got from my parents was a love for reading books. It is much of the reason I did well in school. In my last year at Arkansas State, I was required to take a course in ancient political thought that I wanted to evade. I was on my way to law school and was admitted to some very good ones. I may have thought I had become too grand to study any old books. I asked the chair of the department if she would waive the course, me being so near graduation. She told me to shut up and take the course. It proved life-changing. I deferred my applications to law school and eventually went to graduate school instead.

I studied many ancient philosophers such as Plato’s “Republic” and Aristotle’s “Nicomachean Ethics,” which I have the privilege of teaching today at Hillsdale College. I also studied the life of the great Winston Churchill and worked alongside the great Martin Gilbert on finishing Churchill’s ocial biography. I’ve since written a book on Churchill and have loved teaching classes on him. Through all of this, I’ve come to see that Churchill is, without question, the greatest statesman of the 20th century. We’d do well to heed his example and take his words and his deeds seriously. Aristotle, Churchill, and one of my former teachers, Harry Ja a, are some of my greatest influences.

My proudest moments, and what I enjoy most at Hillsdale, are when I see the amazing journey that our students go on, between

freshman year and when they graduate. Many of them arrive here thinking they know everything. They were the kings and queens of their high schools. Then, they get to senior year, exhausted but deeply fulfilled. Wiser, and now knowing they still have a lot to learn about everything. But that hunger is there now. And I’ll see them years down the road, doing important and weighty things, and yet, they remain my students. And they’re still growing. But now, they’re seeking after the right things. It’s a joy to behold.

AE: What is the nature of a good education?

Dr. Arnn: A good education cultivates a student’s natural desire to learn. It’s like tending to a garden. Good teachers don’t do anything to students; they cultivate the desire to know and learn that’s already inside of them. They help them grow. A teacher ought to instruct

ISSUE 3 | MARCH 2023 Education | Features

ABOVE LEFT Hillsdale College President Larry Arnn inherited a love for books from his parents RIGHT Hillsdale College’s 400-acre campus has many historic buildings Founded in: 1844 Number of students: 1,515 undergrad, 87 grad Location: Hillsdale County, southern-central Mich Concept: instilling ideals of a constitutional government, run independently with no federal funding

in a way that tends to both the minds and the hearts of students, so, one day, these young men and women can learn to govern themselves. Teachers must possess a high degree of knowledge in their subject so they can guide the students in answering the age-old questions of the human experience. And the students must be driven to apply themselves in the endeavor. They must ask the questions that need to be asked. And they need to come to realize that one is never done learning. It’s a lifelong pursuit.

AE: What kind of education did our Founding Fathers have? How did it shape their worldview? And what can we do today to ensure that our future generations are well educated?

Dr. Arnn: Like the first attendees of Hillsdale College, most of the American Founders were well versed in Greek, Latin, and the classics. As such, America’s Founders understood that man is flawed and that nature is governed by certain eternal principles established by our Creator. They recognized that man ought to learn these principles in order to protect his rights and respect the rights of his neighbor. For instance, they recognized that given man’s sinful nature and the challenge of individuals living in close communities, it was essential to constitute a government that protects the natural rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. On that last note, it’s important to remember that, unlike our society that

today is so dominated by a sense of entitlement or grievance, happiness itself was not guaranteed, just the noble pursuit of it. The Founders insisted upon training the mind in the disciplines of history, language, mathematics, and the natural sciences in order to impart the character required for self-governing citizens within a republic.

From the beginning, the Founders viewed education as vitally important to securing America’s present and ensuring its future. While Congress was locked in debate during the Constitutional Convention, the Founders passed the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. It declares that “schools and the means of

14 AMERICAN ESSENCE ABOVE Arnn explains that a true liberal arts education is grounded in the idea that self-governing citizens should train their minds in varied disciplines Features | Education

vvv

“A good education cultivates a student’s natural desire to learn. It’s like tending to a garden.”

LARRY ARNN, HILLSDALE COLLEGE PRESIDENT

This page is not in the preview.

not included preview.

education shall forever be encouraged,” as “religion, morality and knowledge” are necessary for good government and “the happiness of mankind.”

These words are as true today as when they were penned centuries ago. James Madison believed education should inculcate liberty. He was right. Intelligent and informed citizens are a bulwark against tyranny and oppression. Indeed, if young people are shown how to wrestle with questions of the Highest things, in times of trial, these men and women of character can show the nation, and indeed the world, how to lead.

Now, while the Ordinance of 1787 recog-

nized the government’s role in encouraging education, the Founders knew it should be controlled locally. The Founders understood education as a public interest, but for it to accomplish its purpose, private citizens should manage its a airs at the township level. Indeed, America’s greatness stems not from government benevolence, but from the hard work of individuals. To ensure our future generations are well educated, we need schools and teachers that engage students in discussions about the higher, eternal things—not just present controversies or whatever whims and fancies are trendy at a given moment.

ISSUE 3 | MARCH 2023 15

Building Character, One House at a Time

Learning how to apply the Pythagorean theorem while on a construction site, earning competitive wages per hour, all while working toward a matching scholarship that can be used for future tuition or employment needs—this is the model by which unCommon Construction hopes to encourage youth to explore a career in the trades, and break stereotypes about the industry.

Aaron Frumin, founder of the New Orleansbased after-school program for high school students, unexpectedly found his way into the construction industry. He went to a standard, four-year college after graduating high school, but he dropped out in his third year when he was unsatisfied with the education he was

getting. When Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans, Frumin traveled there to help out as a Red Cross volunteer. He ended up working as a day laborer on a construction site, and he stayed in the city. “I was using my brain and I was using math skills and engineering principles and social skills. I was making good money. … No one would have ever thought of that career path for me,” Frumin said. He later went into teaching, and while working as a reading and social studies teacher in middle school, he realized the traditional classroom experience was not for him.

That’s when Frumin thought about a program that could make education more relevant to developing students’ real-life skills.

ISSUE 3 | MARCH 2023 35

Founded in: 2015 Number of students: 75, high school kids 16 and older Location: New Orleans, La. Concept: teaching kids to build a house LEFT Aaron Frumin, founder of unCommon Construction, hopes the program can help dispel stereotypes about the construction industry and allow high schoolers to see it as a viable career

The construction

zone

doubles as classroom in this unusual assignment for New Orleans high schoolers

W R ITTEN BY Annie Wu

“How can we have a real return on investment for them so that they have a little more skin in the game?” So in 2015, Frumin started unCommon Construction as a nonprofit that would hire students to build houses, with the employees being selected from partnering schools that would recommend highly motivated students to apply for the after-school program, while earning school credit and wages.

Students work 10 to 12 hours a week, with 6 to 8 hours on a job site and 2 to 4 hours in the classroom on “framing character”: learning career building and professional development skills, as well as receiving technical training. They spend most of their time in the field because “we want to treat young people like they have value, and that their time is valuable, and we’re not just doing worksheets that are easy for them to dismiss,” Frumin said.

At the same time, Frumin wants the program to develop skills in the students that will be helpful no matter what career they pursue in the future. “We put a very intentional emphasis in our alternative learning environment on the development and demonstration of soft skills,” Frumin said. That includes learning teamwork, ethics, problem-solving, communication, and professional attitudes.

The program operates much like a real-life construction company, with students completing the building of a house in a school year. The house is then sold on the market.

When the house is purchased, the company matches their paycheck with a scholarship, which can be used during their first year after graduating high school—whether for tuition, school supplies, or paying expenses related to their future job, should they pursue a career right after graduating.

Frumin hopes the program can help eliminate the stigmas associated with the construction industry, such as that it’s a dirty job primarily for men or “the non-college material,” as Frumin put it. “Some young people who may be seen as college-bound, like I was, may never be presented with opportunities that help them become self-actualized members [of society],” Frumin said. “They’re held up or put down by a society that does or doesn’t value blue-collar jobs.”

But the fact of the matter is that the industry employs a great variety of professions. “Big construction companies still need lawyers, and they still need an accountant. They rely on emergency medical services, they have security positions, and they require insurance,” Frumin said.

It is time to value the construction industry, he added. “There’s a whole economy that surrounds our industry, and in fact, our industry makes up the backbone of the American economy. … We have to be part of changing the narrative for all the di erent people who are involved.”

36 AMERICAN ESSENCE

BELOW Students earn wages, and when a house is sold on the market, the company puts “equity” toward their scholarships Features | Education

This page is not in the preview.

WHAT IS WORTH REMEMBERING

Inside

38 | The Makings of a Champion

How Major Taylor became the fastest cyclist in the world.

46 | Girls Captured but Remained Clearheaded Kidnapped by natives, teens left clues for their rescuers.

not included preview.

History

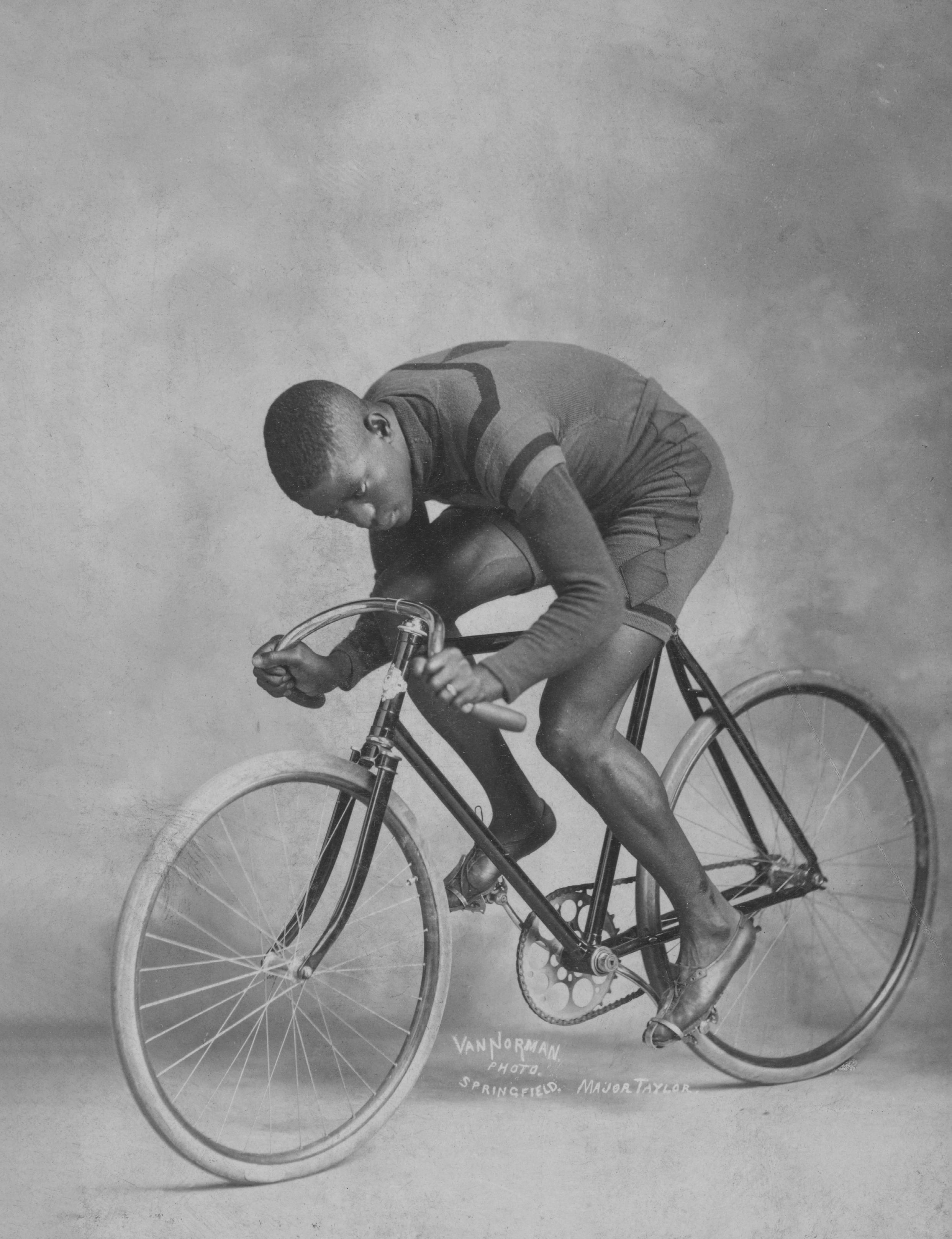

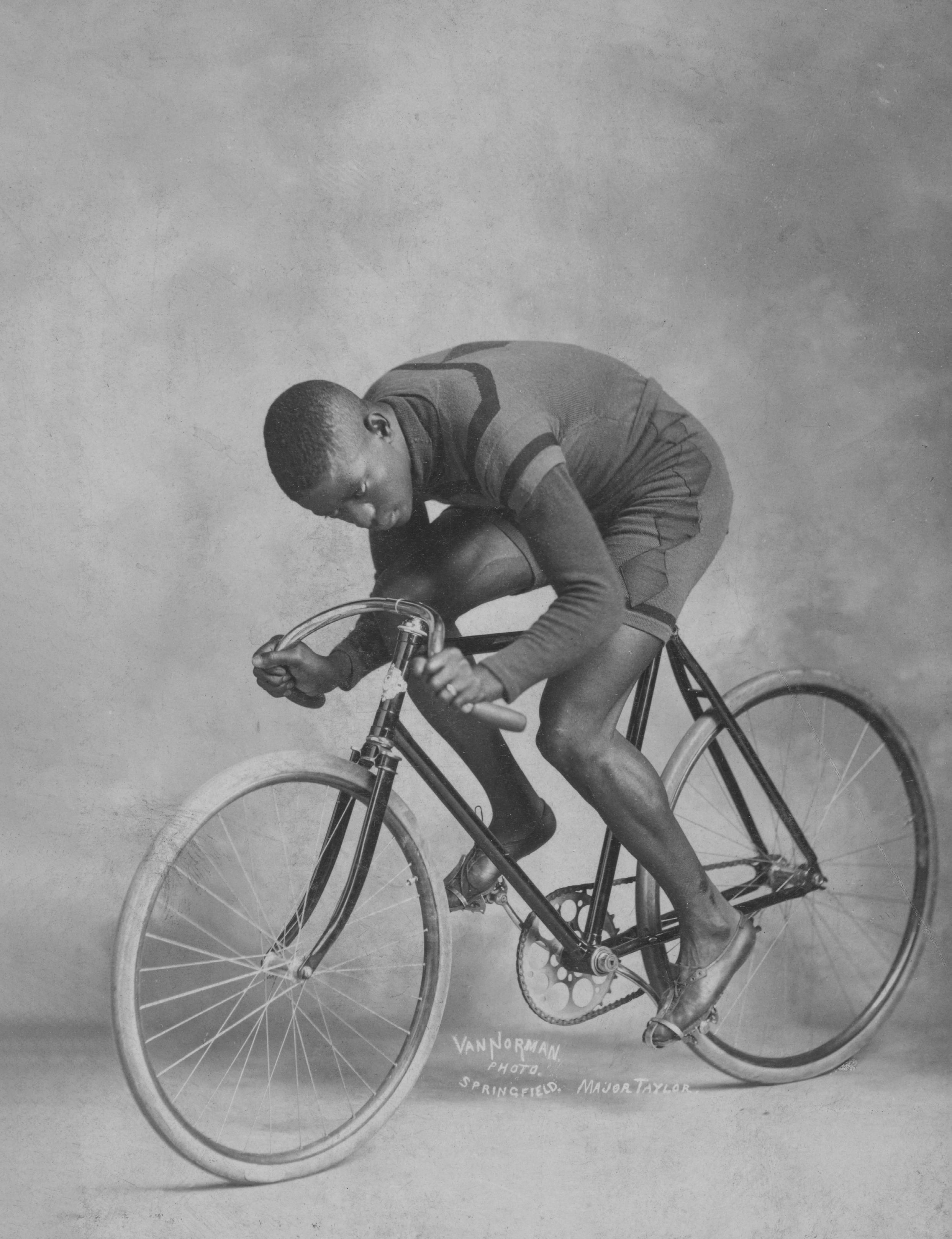

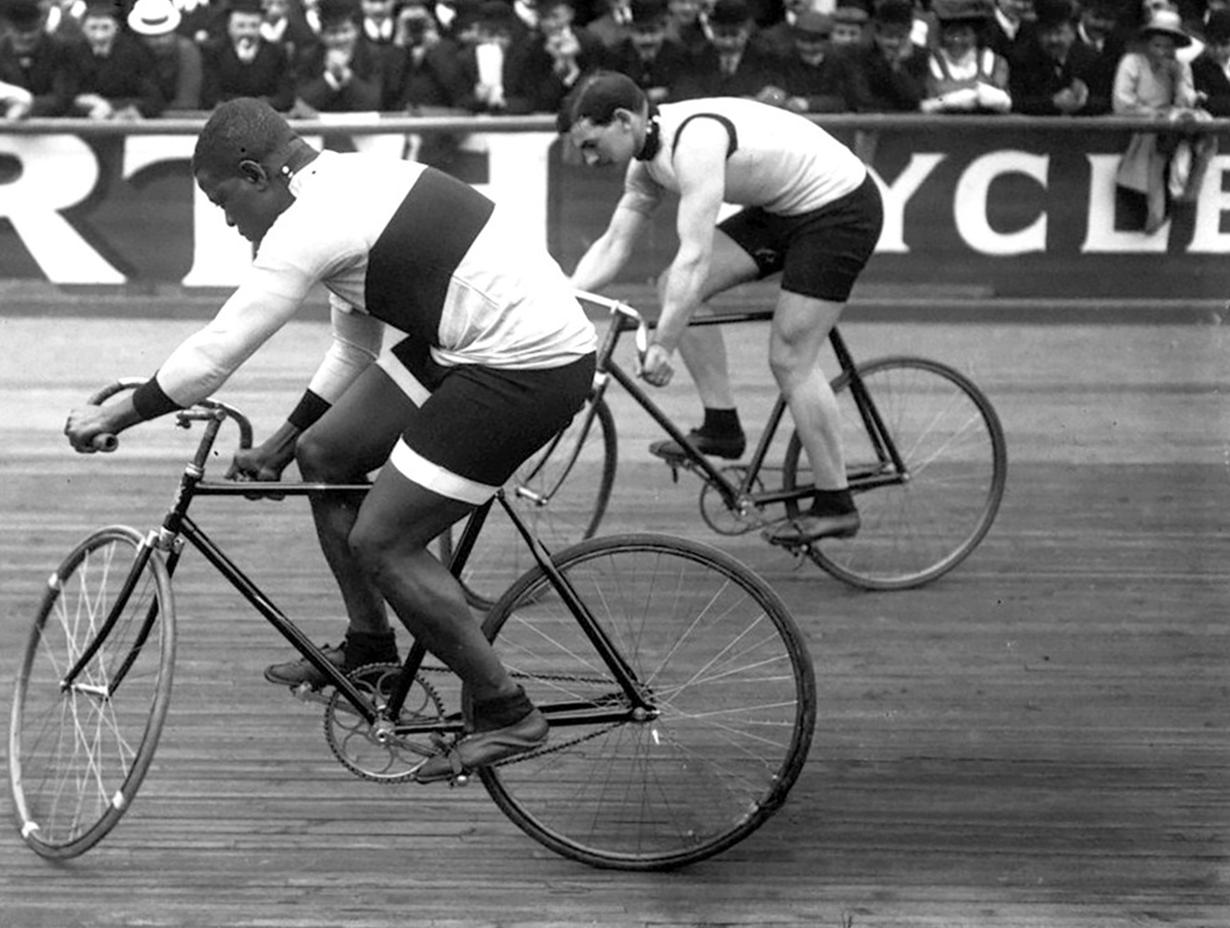

Some consider the cyclist Marshall “Major ” Taylor the greatest American sprinter of all time Portrait of Major Taylor by photographer George H Van Norman, 1898.

The Principled Champion

How the world’s fastest cyclist, Major Taylor, used support and adversity to win a world title

On November 26, 1878, two days before Thanksgiving, Gilbert and Saphronia Taylor welcomed their fourth child, Marshall, into the world. Gilbert, a Union veteran of the Civil War, had moved his family to Indianapolis only a few years after the war ended and his home state of Kentucky began issuing new restrictions on blacks. Indianapolis not only held better opportunities for the young family, but it would open a door for their new son that none would have thought possible.

When Gilbert accepted a job as a coachman for the Southards, a prominent family in Indianapolis, Marshall soon struck up a friendship with the family’s young son, Daniel. The friendship became so close that the family requested for Marshall to stay with them for long periods of time. Though Gilbert and Saphronia were hesitant, they allowed it as long as Marshall adhered to his Baptist upbringing.

Marshall, as noted in his autobiography, was “the happiest boy in the world” playing the part of a “millionaire kid.” This friendship not only benefited him in the immediate, but also in the future as it would set him on the path to become one of the most popular and successful athletes in the world.

A Boy and His Bike

When Daniel moved away, Marshall was left with a token of their friendship: a bicycle. As

a paperboy, earning $5 a week, he rode his bike every day for hours and miles. When not working, he spent countless hours riding and learning tricks. As a very young teen, he took his bike to a repair shop. Out of habit, he performed a trick he had taught himself. The owner of the shop, Tom Hay, asked if he knew any more tricks. Marshall had plenty.

Hay saw the advertising potential and o ered Marshall a $35 bicycle (nearly $1,200 today) and $6 a week if he would work for him. After receiving permission from his mother, Marshall arrived every morning to sweep and dust the store, and at 4 p.m., he would begin his bike trick exhibition in front of the store. During these exhibitions he wore a military-style uniform, which led to his nickname, “Major.”

While working at the store, Taylor became mesmerized by a gold medal that was to be presented to the winner of the local annual 10-mile race. Taylor had never witnessed a race before and decided to attend as a spectator. Hay, on the other hand, insisted Taylor take his place at the starting line.

Taylor was all nerves. When Hay saw Taylor crying, he reconsidered his insistence but then whispered to the young rider, “I know you can’t go the full distance, but just ride up the road a little way, it will please the crowd, and you can come back as soon as you get tired.”

Hay’s whisper of reverse psychology may have been just what motivated Taylor to go far beyond “the road a little way.” The sole black rider raced through a thunderous applause, many of the spectators most likely familiar with him from his stunts at the bike store.

ISSUE 3 | MARCH 2023 39

Athletes | History

LEFT In 1899, Taylor won the world championship, making him an international celebrity. Portrait of Major Taylor by photographer Jules Beau, between 1906 and 1907.

W R ITTEN BY Dustin Ba ss

vvv

Halfway through the race, Hay and others rode up next to him on their bikes and informed him he was well ahead of the hundreds of other riders. Then Hay dangled the gold medal in front of him. It was the final piece of motivation needed. “From then on I rode like mad and wobbled across the tape more dead than alive in first place,” he recalled. It was Taylor’s first race of many and the first of many triumphs—though those triumphs did not come without resistance.

Sources of Motivation

In August 1896, the cycling world directed its attention to the Capital City track in Indianapolis, where Walter Sanger, one of the top cyclists, attempted and succeeded in breaking the 1-mile track record. That record, however, would not last the day.

After Sanger left the track, several of Taylor’s friends snuck him into the dressing room and then onto the track. The crowd’s enthusiasm had hardly subsided before news began to spread that the young local rider was attempting to break the brand-new record. The crowd sat with bated breath as his friends helped pace him and he zoomed around the track.

The 14-year-old beat the record by a full 7 seconds. Later that evening, he would beat the one-fifth mile record, which had been set earlier that year in Europe.

For Taylor’s friends, it was more than just about setting records. “They were fighting for a principle as well as for my personal success,” he wrote. “They were all white

men, and had stacked their all in the belief that I was capable of breaking Sanger’s newly established record, … but in so doing they incurred the enmity of a group of narrow-minded people.”

This group of narrow-minded people was not in the crowd, but in the circle of competitive riders. They took exception to his competing strictly due to his race. Not only was Taylor not paid for setting a new record, as Sanger had been, but he was barred from competing at the Capital City track and any other track in Indianapolis.

Birdie and Major

Though he was barred from tracks in Indianapolis, he still competed extensively in races, ranging from 1 to 75 miles. As his fame

40 AMERICAN ESSENCE

History | Athletes

‘From then on I rode like mad and wobbled across the tape more dead than alive in first place,’ he recalled.

This page is not in the preview.

not included preview.

grew, his name came to the attention of one of the most popular and successful riders of the era: Louis D. “Birdie” Munger. Munger became one of his “staunchest supporters and advisers” and made the promise to turn Taylor into the “fastest bicycle rider in the world.”

He soon met Arthur A. Zimmerman and Willie Windle, both champion racers. Munger, Zimmerman, and Windle recognized they were in the presence of a young phenom and wanted to help him succeed. Their kindness left a lasting impression. “There was no race prejudice in the make-ups of Zimmerman and Windle they were too big for that,” he recalled. “I remembered their sterling qualities and did my best to live up to them.”

Though the trio of champions supported

Taylor in his quest to also become a champion, the League of American Wheelmen (LAW) did not. Obviously noticing Taylor’s rise, they voted to bar black riders from becoming members. With the membership ban and Taylor’s ban from local tracks, he and Munger moved to Worcester, Massachusetts, in September 1895. Taylor noted “there was no such race prejudice existing among the bicycle riders there as I experienced in Indiana.”

The 1896 season would prove successful as he would dominate the amateur field. In the winter of 1896, however, the 18-year-old would make his leap from amateur to professional in the biggest racing event of the year at one of the most prominent venues: the Six-Day Race at Madison Square Garden.

ISSUE 3 | MARCH 2023 41

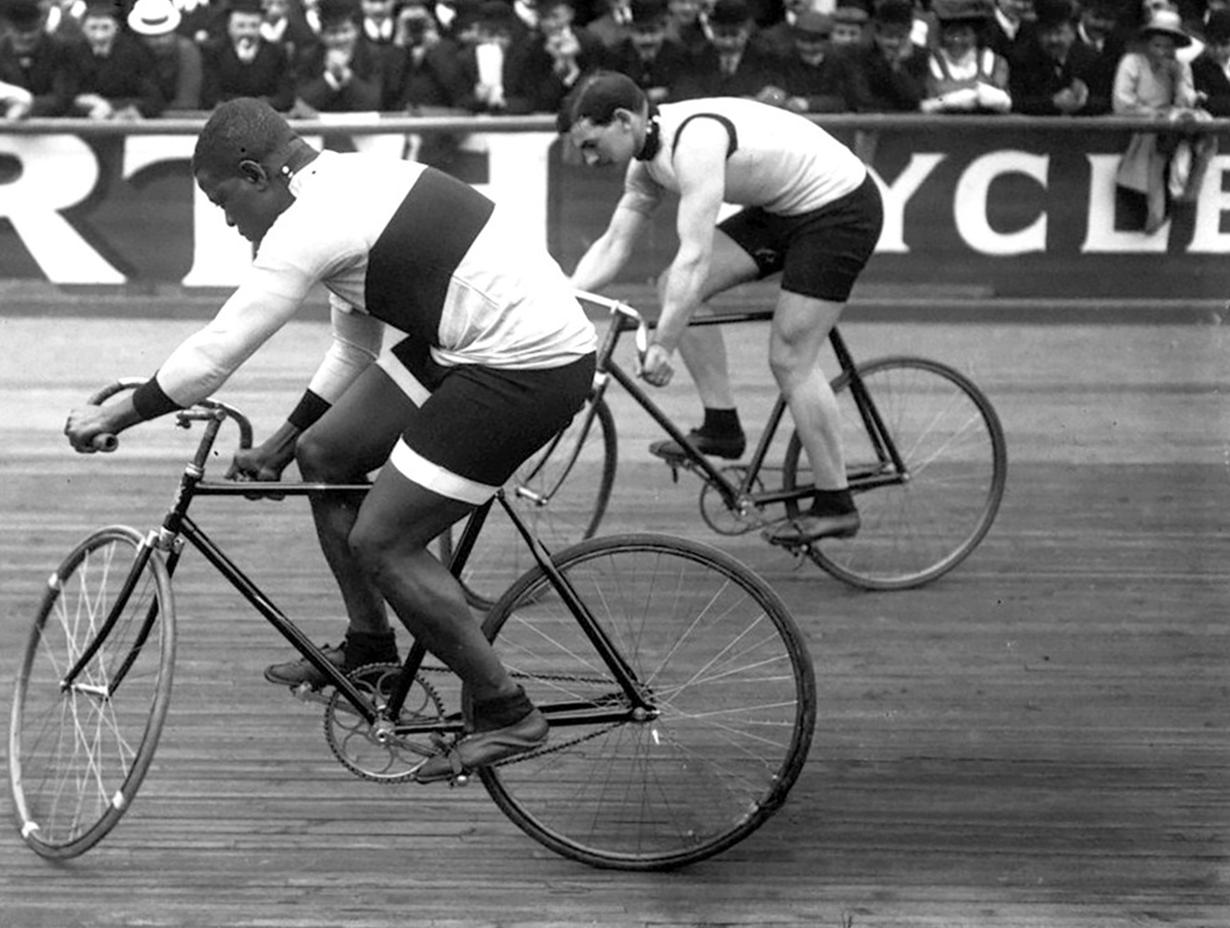

ABOVE Taylor races against Léon Hourlier at the Vélodrome Buffalo, in Paris, 1909.

In 1896, the 18-yearold Taylor competed in the biggest racing event of the year: the Six-Day Race at Madison Square Garden Photograph of the Six-Day Race at Madison Square Garden

Six Brutal, Triumphant Days

More than 50 of the world’s best long-distance riders assembled for the event. There were many who worried the demands of the race would ruin Taylor’s career as a sprinter. Certainly, it had physically and psychologically damaged others, causing many to hallucinate or drift o to sleep and crash. Only three years after Taylor competed, the New York legislature passed legislation banning individual racers from competing for more than 12 hours per day.

At the start of the festivities, Taylor won the half-mile race against some of the top riders, including the nation’s most popular sprinter, Edward “Cannon” Bald. Taylor won $200 his first money prize, which he immediately wired to his mother.

At midnight, the Six Day Race began, and Taylor rode for 18 hours straight. He was only a orded a 15-minute break before his trainer rushed him back to the track. He began the second day in eleventh place and ended it in fourth; by then more than half of the riders had quit due to exhaustion or injury.

Deep into the race, completely exhausted and hallucinating, he told his trainers, “I cannot go on with safety, for there is a man chasing me around the ring with a knife in his hand.” His trainers decided to fasten a pillow to his handlebars so he could race without raising his head. One reporter for the Brooklyn Eagle noticed Taylor was “fast asleep while on his wheel.” As more riders fell to the wayside, Taylor pressed on.

Into the sixth day, with only 30 minutes remaining in the race, Taylor crashed into another rider and collapsed in a heap. Despite the cheers from the crowd to keep going, he was through. He had covered 1,787 miles, finished eighth, and was awarded $125.

A Champion Denied

The following year, 1897, he proved the Six Day Race hadn’t ruined him. Despite not being granted membership into the LAW, he was able to race in their sanctioned National Circuit events. He won the 1-mile race at the Charles River track in Boston, then the 1-mile

43

Athletes | History

race in Providence, Rhode Island, both times defeating Tom, Nat, and Frank Butler, who were considered “practically invincible.”

Regardless of the rules, there were still tracks on the National Circuit that refused Taylor’s participation. These refusals eliminated crucial points from Taylor in his pursuit of the 1898 Championship of America. At the time, the title was between Bald and Taylor. The LAW threatened to blacklist tracks for not adhering to its sanctioning rules. Many of the riders, however, decided to form a cycling union and a new cycling organization: the American Racing Cyclists Union and the National Cycling Association (NCA). Taylor reluctantly signed on to ride under the new NCA with the caveat that races not be held on Sundays. This “gentlemen’s agreement” was broken, as the first race was scheduled for Sunday in St. Louis. “I steadfastly refused to ride on Sunday as it was against my religious scruples,” he wrote.

Taylor did not compete, and Bald lost.

Heading into the final portion of the National Circuit in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, Bald was ahead in the title chase by only two points. When Taylor arrived at the Riverview Hotel in Cape Girardeau, he was informed by the very man, Henry Dunlop, who invited him to compete in the race and stay at the hotel that he couldn’t room there due to his skin color. Taylor had been pushed far enough and went home the next morning. His exit was a forfeiture of the title run, and it also resulted in a fine from the NCA and a potential lifetime ban.

The media came to his defense, as it often did. “Major Taylor is a stern reality. He is here in flesh and blood, and must be dealt with as a human being, and he is entitled to every human right,” wrote the Philadelphia Press. The Syracuse Journal added that “public sentiment is with Taylor, but its sympathy is

not pronounced enough to have much weight with a body of riders who are jealous of Major Taylor’s successes, and are determined to keep him out at all costs.”

Public sentiment, however, did prove enough to force the Executive Committee of the American Racing Cyclists Union to drop its lifetime ban and only fine Taylor $500. But Taylor would not crater to such a demand and threatened retirement. “It would have made no di erence to me whether the fine was $5 or $5,000,” he wrote.

It was not the first or the last time Taylor’s principles triumphed over his love of the sport. He had turned down big paydays, refused to compete or even attempt a new record on the Sabbath, and had now walked away from a near certain championship title. It was an example of his promise to reflect the “sterling qualities” of those champions who had supported him.

The fine, however, was paid by Fred Johnson, President of Iver Johnson Arms & Cycle Company, after Taylor agreed to ride the company’s bicycles in the upcoming season.

A Champion Made

Taylor looked to have a “banner season” in 1899 and set his sights on something greater than a national championship. He would compete for the world championship before 18,000 fans at Queen’s Park in Montreal and would face the world’s best riders hailing from America, Canada, England, France, Germany, and Australia, including two old foes, Nat and Tom Butler.

As the riders took their places at the starting line, a hush fell over the crowd. The gun was raised. Knowing the sti competition, Taylor admitted to being a “trifle nervous,” but “within only a few moments more that terrible nervous suspense would surely be

44 AMERICAN ESSENCE

vvv

History | Athletes

‘I steadfastly refused to ride on Sunday as it was against my religious scruples,’ he wrote.

This page is not in the preview.

not included preview.

over. Then all would know who was really the fastest bicycle rider in the world.”

The gun’s report echoed throughout the park, and the five racers took o in a flurry. Nat Butler quickly took the lead while Taylor moved toward the back. Each racer worked to get the best position before making his jump into the lead. Jumping too early would spell defeat just as much as jumping too late. It was a science that each had perfected. Taylor’s one worry was that he might get caught in a “pocket” as he had in the half-mile race, which caused his late jump and second-place finish.

The two Butler brothers were of the utmost concern as they “worked with clock-like precision” to place opponents in pockets and adjust their speeds and positions in order to favor each other. The five riders zoomed down the home stretch to the rising roar of the crowd. Taylor was nearly “caught in a very bad pocket” but avoided it “only by the narrowest margin” when he overtook Canadian champion Angus McLeod. There were only

the Butler brothers left in his way.

“As we swung into the home stretch our three front wheels were almost abreast,” Taylor recalled. “At a glance I realized that for the first time in my life I was going to be able to make that last supreme e ort to break the tape first without interference of any kind. In a word, the four of us came down that home stretch much the same as sprinters are confined to their lanes in a 100-yard dash. It was a fair field there was no crowding or elbowing, it was a case of winning or losing the world’s championship on merit alone.”

The crowd’s roar hit a fever pitch as Taylor hit the tape first by more than a full length ahead of Tom Butler. Taylor had never been more relieved or proud. He basked in the thunderous applause from the Montreal crowd as he took his victory lap. Munger’s promise to make Taylor into “the fastest bicycle rider in the world” had now “become a wonderful reality in such a spectacular manner.”

ISSUE 3 | MARCH 2023 45

ABOVE Portrait of Taylor at the Stade Buffalo track in Paris by Agence Rol, 1908.

As “a boy of ten or twelve,” Henry would often transition between the Boston home of his father, Charles Francis

Adams, and the home of his grandfather John

Quincy Adams In the former president’s library, he proofread the collected works of his great-grandfather John

Adams, which his father was preparing for publication

The Adamses: Heirs to a Distinguished Education

From John Adams Sr to Henry Adams, five generations of men passed down the importance of the education of one’s character

W R ITTEN BY Andrew Benson Brown

If you ask what education means to people, most will think “school.” If they are jaded, “debt.” But for the first great American family, it was much more than this.

In his autobiography, “The Education of Henry Adams,” the author describes growing up within a celebrated lineage that, by his lifetime, had become a cultural institution. During his childhood, Henry wrote, he would often transition between the Boston home of his father Charles Francis Adams, Lincoln’s future ambassador to England during the Civil War, and the home of his grandfather John Quincy Adams, where he played in the former president’s library. Sitting at his writing table as “a boy of ten or twelve,” he proof-read the collected works of his great-grandfather John Adams that his father was preparing for publication. While practicing Latin grammar, he would listen to distinguished gentlemen, who represented “types of the past,” discuss politics. His education, he reflected, was “an eighteenth-century inheritance” that was “colonial” in atmosphere. While he always revered his forebears and felt they were right about everything, he observed that this learning style did not su ciently prepare him “for his own time”—a modern age that was increasingly defined by technology, commerce, and empire.

Henry Adams is today considered one of America’s greatest historians. Given this, one would probably conclude that his education served him exceedingly well, even if he hoped to produce history rather than merely record it. The substance of his educational ideals was, when stripped of their luxurious

trappings, very similar to that of our second and sixth presidents. Although this was precisely the problem for a young man growing up in a new industrial epoch, there is much to admire about this cultivated reverence for tradition. Values, unlike skill sets, do not become obsolete.

A Father Teaches His Son

The wealth and privilege Henry Adams experienced was far removed from the boyhood circumstances of his most famous forefather three generations previously. John Adams was born in a simple farmhouse where the family’s only valuable possessions were three silver spoons. The key to his rise was education. Not only of the formal kind, but of character. John took inspiration from his descendants, “a line of virtuous, independent New England farmers.” When he complained of losing interest in his studies due to a churlish teacher at his schoolhouse, his father, a deacon, enrolled him in a private school. Later, the deacon sold 10 acres of land to pay for his son’s college fund.

John admired his father, striving to embody the qualities of sincerity and patriotism he instilled. He called the deacon “the honestest man” he ever knew and passed on these ideals to his own son, John Quincy Adams. While John was in Philadelphia attending the Continental Congress, he instructed young “Johnny” through letters. Writing to Abigail on June 29, 1777, he said, “Let him be sure that he possesses the great virtue of temperance, justice, magnanimity, honor, and generosity, and with these added to his parts, he cannot fail to become a wise and great man.”

51 ISSUE 3 | MARCH 2023

Presidents | History

In letters to John Quincy during this same year, John advised his son to acquire “a taste for literature and a turn for business” that would allow for both subsistence and entertainment. Reading the historian Thucydides, preferably in the original Greek, would provide him with “the most solid instruction … to act on the stage of life,” whether that part be orator, statesman, or general. While John was away, Abigail constantly upheld her husband to John Quincy as an example of professional achievement and courage. She encouraged him to study the books in his father’s library and forbade him from being in “the company of rude children.”

For the Adamses, books were not just the means to a career, but a key to unlocking the sum of a person’s life. Education encompassed experience, conduct, and social ties. Like his grandson Henry, young John Quincy was sometimes unsure whether he would be able to live up to his ancestors’ example.

A Family Heritage

John instructed John Quincy more directly when taking him along on diplomatic missions in Europe. In Paris, John Quincy began keeping a daily journal at his father’s request, recording “objects that I see and characters that I converse with.” John Quincy observed his father staying up at all hours to assemble diplomatic reports and would later emulate this diligent work ethic.

He then accompanied John to Holland. At the age of 13, he “scored his first diplomatic triumph,” according to biographer Harlow Unger. The precocious young student, dazzling professors with his erudition at the University of Leiden, caught the eye of an important scholar and lawyer named Jean Luzac. John Quincy introduced Luzac to his father, then struggling to convince the Dutch government to give America financial assistance in its costly war with Britain. Luzac was impressed with the Adams family, advocated their cause of independence, and succeeded in securing crucial loans for the desperate young nation.

This page is not in the preview.

52 AMERICAN ESSENCE

ABOVE American writer and diplomat Charles Francis Adams (1807–1886) Photo taken in 1866 or earlier Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library, Cambridge, Mass

not included preview.

BELOW In his autobiography, “The Education of Henry Adams,” 1918, Henry described growing up within a celebrated lineage which, by his lifetime, had become a cultural institution

States from 1797–1801. Official presidential portrait of John

Adams by John Trumbull, circa 1792–1793. Oil on canvas White House Collection, Washington, D.C.

ABOVE Graduation photo of Henry B Adams from the

Harvard College Class of 1858. Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston

ABOVE RIGHT John Quincy

Adams, sixth president of the United States from 1825–1829.

Official presidential portrait by

George Peter Alexander Healy, 1858. Oil on canvas White House Collection, Washington, D.C.

During this time, John Adams encouraged his son to continue studying the great historians of antiquity: “In Company with Sallust, Cicero, Tacitus and Livy, you will learn Wisdom and Virtue.” He closed his letter by emphasizing the importance of the heart’s authority over the mind: “The end of study is to make you a good man and a useful citizen. This will ever be the sum total of the advice of your a ectionate Father.”

John Quincy, ever the obedient son, attended to both the wisdom of the distant past and his family heritage that enshrined it. While following in John’s footsteps as a diplomat, and later president, he would pass these values on to his own children.

The success, achievement, and public legacy of the Adams family has everything to do with this conception of education as a living inheritance. Writing over a century later, Henry Adams saw the role of learning as a lifelong endeavor that was di cult to justify through any specific practical or monetary measurement. But, he added, “the practical value of the universe has never been stated in dollars.”

53 ISSUE 3 | MARCH 2023

vvv

“The end of study is to make you a good man and a useful citizen. This will ever be the sum total of the advice of your a ectionate Father.”

FAR LEFT John Adams, second president of the United

Deep Into the Heart of Alaska

The wonders of Alaska can be explored by air, road, or train— all breathtakingly spectacular

It is di cult to even begin to comprehend a place like Alaska. Vast, in a way that’s almost indescribable. Arctic tundra and temperate rain forest. The tallest mountain on the continent, so high that its summit is coated with mighty glaciers and, most of the time, shrouded by cloud. Untamed rivers flowing into frigid seas. Wilderness that is—with no exaggeration—big enough to swallow you whole.

The stats on the 49th state, famously known as America’s last frontier, are rather breathtaking. Alaska is home to more than half of the world’s glaciers, and fully 5 percent of its territory is covered by them (a total of 29,000 square miles). Of the top 20 highest mountains in the United States, 16 are here.

It is the only state to face two oceans, and it has more lakes than any other state. In some places, the sun doesn’t set for a whole three months. And with 6,640 miles of coastline, its coast is actually longer than all the other states—combined. Alaska has almost 365 million acres of pristine wilderness— enough to tour through 1 million for every day of the year.

The biggest challenge here is how to explore a place so wild, and so huge, that it can feel impenetrable and unknowable. Fortunately, you’ll find plenty of ways to spirit you through this mostly untouched land. And on several visits to the state, I’ve experienced most of them. All provide spectacular views, and so many stories.

The most obvious, with everything so spread out: air. And indeed, Anchorage, the state’s biggest city, is home to the largest, busiest seaplane base in the nation, at Lake Hood. Residents here fly—a lot—getting behind the controls themselves to hop from place to place. They are licensed at a rate six times the national average. Lake Hood feels

61

Travel | Lifestyle

Helicopter

offer visitors breathtaking views of Alaska’s stunning glaciers and mountains from above

tours

W R ITTEN BY Tim Johnson

like a bustling regional airport. It houses some 1,100 planes, about 1,000 of them privately owned.

On a recent visit, I climbed aboard one of these remarkable machines. Skimming along to takeo , I soared from the middle of Anchorage. It took mere minutes from lifting o from the lake’s surface to be buzzing over jagged ridgelines. Seconds later, a land of ice unfolded below, snow-capped mountains just behind. The Knik Glacier spread out below, 25 miles long and 5 miles across.

A living, breathing thing, always on the move. Crevasses big enough to swallow an entire vehicle. A snowy superhighway, stretching to the horizon. After flying over, we skimmed to a stop on a nearby wilderness lake before heading back to the city.

And while planes (and helicopters) provide unforgettable experiences, the two best ways to delve deep into the heart of the state, to really feel it beat, remain road and rail. And water-craft, too. I sailed up Alaska’s panhandle on the Royal Princess cruise ship, calling at Skagway and Ketchikan—walking wooden walkways and learning gold rush history—as well as at Juneau, the only state capital in the Union not accessible by road.

After a spin through Glacier Bay, we disembarked at the small port of Whittier, boarding a coach headed north. The mass of Maynard Mountain cuts the small town o from the rest of the state. The solution: a 2.5-mile tunnel. Access to engineering marvel Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel is tightly controlled, just one lane shared by cars, trains, trucks, and buses.

Soon enough, I was rolling on a rail car into the wilderness north of Anchorage. A state as big as this one can be deceiving. Looking at the map, it appears that it might just take a few hours to travel as far as Fairbanks, the second-largest city, which sits right in the middle of Alaska. Instead, riding straight through, the Denali Star train takes a whole 12 hours to reach its destination, and that’s just a portion of the total 470 miles of line run by the Alaska Railroad.

Luckily, the journey is absolutely breathtaking, and I had several stops to make along the way. I was riding in a special domed carriage reserved for Princess Cruise Line guests, with a guide right there to point out the highlights. And there are many.

“This ride, it really shows the vastness. You’ll really experience the size and the scale of Alaska,” the guide, Dillon, explained. “We go where the roads don’t.” While he’s traveled this route many times, he shared that it is constantly changing, always new. Especially the wildlife—he told me you just never know what you’ll spot. Thousands of spawning salmon, leaping out of a rushing river, one day. A grizzly bear, with one of the fish between his flashing teeth, on another. A big bull moose, galloping down the track, just outpacing the locomotive.

My seat was on the top of a double-decker car, but I made frequent trips down the stairs to an open-air carriage to take photos. The train clickety-clacked, the landscape and flora seeming to change at every turn. The carriages proceeded over the bridge at Hurricane Gulch, the longest and tallest on the entire line. A single steel span, it stretches 918 feet, with Hurricane Creek a dizzying 300 feet below.

We reached the high point of the line at Summit Lake, cresting above the tree line at the low point of the Alaska Range (which stretches 600 miles and includes two of the three tallest peaks in the nation). Dillon explained that this was also a watershed, water on one side rolling to the Bering Sea, the other to the Pacific. “They make me say it, folks,” he said, shaking his head. “It’s all downhill from here.”

ABOVE The pristine waters of Alaska offer some of the most spectacular fishing experiences in the world

CLOCKWISE FROM OPPOSITE PAGE TOP

LEFT A woman in traditional Inuit clothing, made of animal skin and fur Alaska is home to over 200 Inuit tribes

Snowy white with streaks of red, steamed Alaskan crab legs contain sweet and tender chunks of crabmeat fit for a king’s feast

Many whale species can be spotted in Alaska, either inhabiting or migrating through its coastal waters

A musher and his team cross the Yukon River in Galena, Alaska, during the annual Iditarod dog sled race

Warm sun, long days, and abundant wildlife make summer the best season to take a cruise in Alaska.

62 AMERICAN ESSENCE

Lifestyle | Travel

This page is not in the preview.

not included preview.

ISSUE 3 | MARCH 2023 63 Travel | Lifestyle

A Man at the Ready

H

storia

Da

M

C

of Theodore Roosevelt

Modernity’s best-selling history book author, David McCullough, knew how to tell a factual story that did not leave his readers yawning or pining for a thriller. Before he died in August 2022 at age 89, his thorough biographies, two of which received the Pulitzer Prize, captivated millions of readers due to his stimulating storytelling style. “Mornings on Horseback,” the biography of the 26th president published in 1981, spans 17 years of Theodore Roosevelt Jr.’s life.

Instead of beginning at the time of birth, McCullough brings us into “Teedie’s” life at age 10 and exposes the juxtaposition of his parents’ lives: an antebellum, Georgia-raised mother and a quintessentially New Yorker father. His South and North parents’ devotion to one another during the Civil War solidified Theodore’s firm, family-oriented foundation. And it was their devotion to helping their oldest son overcome a failure to thrive due to asthma that strengthened Theodore for a life of exhilarating adventure and emotional tenacity.

The book’s initial setting is New York’s latter-19th-century a uent social arena,

but sickly Theodore is taken on an inspiring European journey to invigorate him. The nature-loving amateur taxidermist begins to build stamina through outdoor pursuits and a regimen of calisthenics. By the time he enteres Harvard, Theodore is a thriving physical and academic force.

Throughout the book, McCullough “painted with words,” according to a Yale honorary degree citation, the distinct young man’s growing zest for life. But McCullough then reveals the raw grief that dashes Theodore’s enthusiasm and high hopes. He’s been married only four years when his first wife dies of kidney failure on February 14, 1884, only days after their daughter is born and only hours after his mother dies from typhoid fever.

Instead of drawing shades on the dark period, Theodore heads west. And readers get to ride alongside him on horseback as he encounters grizzlies, rounds up cattle, subdues a criminal, and shoots big game. His immersion into a wild land not only shapes the courageous character that he will need to help fight a war and succeed in politics, but it rectifies his shattered heart so that he is able to build and cherish a prominent family.

No surprise, “Mornings on Horseback” achieved for McCullough a National Book Award. Its depth among 370 pages leaves readers yearning to know even more about a man who embodied a true and hearty American spirit.

66 AMERICAN ESSENCE Features | Overline Lifestyle | Book Recommender

W R ITTEN BY Deena C. Bouknight

i

n

vid

c

ullough captures the indomitable American spirit in his biography

“Mornings on Horseback: The Story of an Extraordinary Family, a Vanished Way of Life and the Unique Child Who Became Theodore Roosevelt” by David McCullough (Simon & Schuster, 1982)

EATING ON THE WILD SIDE

For these modern-day foragers, wild foods are a portal to the past—and a path to a more sustainable, and delicious, future

Food | Lifestyle

The Mushroom Man

Mycological musings from the longtime professional forager, founder of No Taste Like Home foraging tours, and selfdubbed ‘philosoforager ’

On riches in plain sight: I was always into treasure hunting. Treasure is usually prized because it’s di cult to obtain because it’s rare and/or hidden. Wild foods, at least the common ones I focus on, are none of those things, yet they are even more of a treasure, much for the opposite reasons. I run an education company now, and no one is turned away for lack of funds, and still, most of our clientele are rich. When it comes to wild food, this richness is a state of mind.

On lessons from mushrooms: Over the years, I’ve come to recognize that what’s most valuable about mushrooms is the lesson they conceal. They are just the tip of the iceberg, so to speak, of a fungus that, in some cases, can spread out for more than a mile in a single inch of soil. The connections that are forged, through fungi, between trees function as a “wood-wide web” for the exchange of not only information but also energy. Plants literally contribute nutrients to each other, including other species. When one tree is sick, the others help out. This form of universal health care, which is also how hunter-gatherers operate, has a lot to teach us.

On safety: An old saying is that every mushroom is edible—once. Most people think the lesson is, “When in doubt, throw it out.” But I say, “When in doubt, ask about.” This is another way of expressing a proverb that is well known in Zambia: “The one who asks is the one who does not get poisoned by a mushroom.” Anyone can start foraging safely today—if they use a field guide. A field guide has two legs. Like Plautus says, “None are wise enough alone.”

On found rewards: Above all, foraging helps me to be less afraid. Not only does this heal the e ects of chronic anxiety and prevent degenerative disease, but it also allows me to be more loving, more supportive, and accepting of others. Quite simply, a rich person can a ord to be generous.

ging tour.

A B OV E Muskat spots an elusive morel mushroom.

Business Name: No Taste Like Home Favorite Spring Edibles: The flavor of Japanese knotweed “is very similar to rhubarb and it can be used the same way. I love that knotweed is considered one of the most noxious, invasive weeds, yet I believe such weeds come in to heal the wounds we’ve inflicted It has also been found to be a potent antimicrobial, particularly for COVID-19 and Lyme disease.”

ISSUE 3 | MARCH 2023 69

A S T O L D T O Cr ystal Shi

ation: Asheville, N.C.

P R E V I O U S PAG E C LOCKW I S E F ROM T O P LEFT Tama Matsuoka Wong; Alan Muskat; Langdon Cook; Sam Thayer; and Alan Bergo. O PP OS ITE PAG E Alan Muskat pauses for a mushroom education break during a guided fora

ALAN MUSKAT

Loc

The Mentor

The author of the gold standard of North American field guides has opened eyes— and palates—to the wonders of wild foods for more than 20 years

“I added up a list of all the things I collect within walking distance of my house, and it was 346 species,” says renowned forager Sam Thayer. A count of plants (excluding spices) in all the products at his local grocery store? 124. For more than two decades, Thayer’s been touting the bounty of readily available wild foods, and the people he encounters “practically lose their minds” when they try unexpected delicacies such as a thistle stalk. Reactions, he says, are “not just ‘I could eat that if I had to,’ but ‘That’s like the best thing I’ve ever had!’”

An inductee into the National Wild Foods Hall of Fame, Thayer, who was born in Wausau, Wisconsin, and raised in Madison, took to foraging at a very early age. “I had a couple parents who didn’t really want to be parents. The more I could parent myself, the better— from their perspective and mine.” Often left to fend for themselves, he and his three siblings quickly learned to be independent. When he was four, his older sister showed him wood sorrel growing under the front porch, a common lawn “weed” but edible and rich in vitamin C. And so began his lifelong fascination with what he could eat in the natural world. Thayer is self-taught, as are many foragers, relying on tracking down information one plant at a time. “I started out learning things that were not particularly di cult or hard

This page is not in the preview.

My neighbor had a black walnut tree and told me what it was. You could eat black walnuts. Lots of people know that. I just never forgot that and I started eating black walnuts.” He’d add perhaps half a dozen items each year, just by asking people. “There’s a lot of knowledge floating around, but people just aren’t picking it up and using it.” When he was 10, he discovered books on edible wild plants, which rapidly sped up the learning process. By middle school, he was presenting his learning to classmates in science class. He learned survival camping in his teens, guided

to

70 AMERICAN ESSENCE

W R ITTEN BY Kevin Revolinski Location: Madison, Wis. Business Name: Forager ’s Harvest Favorite Spring Edibles: The blossoms of the common black locust tree (Robinia pseudoacacia) are “like snow peas with a little bit of vanilla and honey on them.” Try them in fruit salad, ice cream, or fritters, but they can also go savory.

find.

A B OV E Sam Thayer among blooming elderflowers. SAM THAYER

foraging walks, and, after high-school graduation, built and lived in a log cabin on an abandoned farmstead near Lake Superior. But far from living a quiet life o the grid, he traveled the nation to give workshops, learning more regional wild foods as he went. He published his award-winning first book, “The Forager’s Harvest,” in 2006; his latest, “Sam Thayer’s Field Guide to Edible Wild Plants,” will be out in May 2023.

Teaching the Trade

In a typical year, Thayer hosts 10 to 15 workshops. “If I have 100 people and I say, ‘Who here gathers wild food?’ 30 hands will go up. And if I say, ‘Who here gathers wild blackberries?’ 90 hands go up. As soon as people eat something, they don’t think of it as wild anymore. It really helps them accept that [foraging] really is a normal activity.”

not included preview.

Thayer has seen his audience change over time. “Twenty years ago, a big part of my audience and people coming to my classes was fundamentalist Christians preparing for the collapse of civilization,” he says, a reaction to Y2K. “That demographic has almost totally disappeared from my classes.” Today, his “prototypical” attendee is slightly more than 50 percent likely to be female—often a rural or urban housewife between the ages of 35 and 60 who has a garden and likes to cook. But he sees a wide variety of backgrounds from the others,

all of them tending toward middle class who are more likely to pay money for a workshop.

Some are a bit leery of wild plants, especially their perceived risk of poisoning the eater, but Thayer dispels the myths. “Practically every person I know who is an avid bicyclist has been hospitalized.” Foraging, on the other hand, “is statistically so safe, when you actually look at it, it’s almost ridiculous. The big safety rule is: Don’t eat something unless you are positive what it is.” He jokes that no one fears that they are eating a deadly false blackberry. “You know what a blackberry is, so that means you are ready to eat it. All the plants we eat, all of them, are equally distinct. But you have to work to get to that point of familiarity, and you do that one plant at a time. Once you’re there, you have it for the rest of your life.”

“Here’s the thing that people don’t quite grasp about foraging: People imagine this food isn’t as good and that that’s why you can’t buy it at the store,” says Thayer. Thistle stalk tastes “like a honeydew melon but in the shape of a broccoli stalk.” Shelf life is two to three days; pick it a week late and it’s too tough. If someone “got asparagus and it was 4 feet high and it had already branched out and they grilled it, they aren’t going to think it’s delicious.” Learning the timing is also key.

Then, “once you start eating this stu , you can’t imagine not eating it, because it’s literally the best stu you’ve ever had.”

ISSUE 3 | MARCH 2023 71

R I G HT Black locust flowers. FAR R I G HT Yellow thistle. Food | Lifestyle

We hope you enjoyed the first few pages of American Essence.

To read the complete publication, subscribe today at americanessence.net

Sonya Curry and her son Steph Curry pose for a

photo on the red carpet during a 2019 event in Oakland, Calif

Sonya Curry and her son Steph Curry pose for a

photo on the red carpet during a 2019 event in Oakland, Calif