University Road, Bristol, BS8 1SR

Bristol Grammar School, University Road, Bristol, BS8 1SR

Tel: +44 (0)117 933 9648

email: betweenfourjunctions@bgs.bristol.sch.uk

Editor: David Briggs

Art Editor: Ed Hume-Smith

Design and Production: David Briggs and Ruth Bennett

Cover artwork: Lukas Szpojnarowicz

© remains with the individual authors herein published November 2019

All rights reserved

BETWEEN FOUR JUNCTIONS is published twice yearly in association with the Creative Writing Department at Bristol Grammar School. We accept submissions by email attachment for poetry, prose fiction/ non-fiction, script, and visual arts from everyone in the BGS community: pupils, students, staff, support staff, parents, governors, OBs. Views expressed in BETWEEN FOUR JUNCTIONS are not necessarily those of Bristol Grammar School; those of individual contributors are not necessarily those of the editors. While careful consideration of readers’ sensibilities has been a part of the editorial process, there are as many sensibilities as there are readers, and it is not entirely possible to avoid the inclusion of material that some readers may find challenging. We hope you share our view that the arts provide a suitable space in which to meet and negotiate challenging language and ideas.

Writers’ Examination BoardDOES IT MATTER IF A LANGUAGE BECOMES EXTINCT?

WHY PREFER AN ORIGINAL PAINTING TO AN

COPY

eMAGAZINE CLOSE READING COMPETITION 2019

The four re-purposed junction boxes of Lukas Szpojnarowicz’s arresting cover art provide a fitting image for this second issue of Between Four Junctions, one in which the spaces between and the connections across the works in the magazine add something to our appreciation of each individual work. Such connections are perhaps best exemplified in the two ekphrastic pieces —‘Looking Beyond’ and‘They Bashed …’ — works that arose from a collaboration between the Art department and the English department during last spring’s HEARTS Week.Pupils inYear 8 andYear 9 produced paintings and poems in response to music byVivaldi, and those pieces themselves were then swapped across the two departments to enable pupils the chance to respond in poetry to a painting,in paint to a poem.Thus, an echo-poetic chain of artists responding to work by other artists was set in play, the results of which went to form the tapestry presently decorating a ground-floor window in the PerformingArts Centre. I only had room for two of these echo-poetic pieces in the magazine; take a walk across to the PAC if you’d like to see more.

In a less deliberately orchestrated way, other chains of association emerged. The prose-fiction section demonstrated a strong interest in the presentation of dystopian worlds, with the ambitious world-building of‘The Chambers’ by Georgina Hamilton-James and the impressive economy of‘The MissingArtwork’ by FreddieArmitage and Michael Lucas both leading the reader to finales that powerfully snuffed-out any hope for their protagonists. Devin Birse, working in the same genre,but within the tighter constraints of flash fiction, chooses to focus on the psychology of a futuristic robo-soldier-cum-Frankenstein, a piece that calls back across pages to James Ormiston’s vivid painting for the beaches of D-Day.While Charlie Groombridge and Lara Smith, also writing within the restraints of flash fiction, manage to evoke and suggest wider resonances in pieces that add up to much more than the sum of their parts, Anya Clegg’s winning entry for the History department’s inaugural historical fiction prize makes the most of a longer story form to transport the reader back and forth between civilisations.

But family and domestic settings proved to be equally as plangent, equally as fertile, as the more overtly dramatic scenarios preferred by the fiction writers. Lottie Williams uses a prose-poem to fondly evoke a grandmother’s kitchen, and Zoe Wakling uses acrylics on paper to hint at the massy significance of everyday objects in her deft still life. In a similar vein, Jennifer Benn shows her understanding of the importance of detailed observation, of the need to show respect for your subject by taking the trouble to look at it closely and precisely, with love but without sentimentality.

A similar absence of sentimentality in the face of death characterises Colin Wadey’s stark poem ‘Moving’, while with attentive detail Jonathan Bradley’s evident love for former colleague, David Selwyn (late of this parish), comes across clearly in his moving ‘Elegy for David’, the second of two pieces in this issue submitted by BGS parents.

Kate Groombridge’s poetic celebration of Bristol showed an interest in place and environment, a theme that unites much of the work, including Jack Williams’s bardic address to the River Severn, Iliana Platirrahou-Poon’s ink-on-paper landscape of a Somerset rhyne, and Leila Cordey’s poetic and political evocation of the voice of the sky.

It was good to be able to publish winning entries from a range of writing competitions. In addition to Anya Clegg’s ‘A Roman Style Murder’, winning entries from the Scholars’ OneHour Essay Challenge Prize also feature, namely Cara Addleman’s argument for original art and Adiyat Zahir’s similarly cogent defence of languages. I hope other departments with similar initiatives feel that the magazine could be a useful platform for the sharing of their pupils’ work. And such sharing needn’t be restricted to competitions located between the four junctions of the four roads that define our site. Eleanor Ward’s successful entry for the English and Media Centre’s annual close reading competition (a national event), also enriches the prose non-fiction section of this issue.

As always, I am grateful for pieces submitted by professional writers who’ve come to read for us At the Junctions, and this issue is graced by poems from Jonathan Edwards and Carrie Etter. Thanks are also due to Ed Hume-Smith for his help in selecting and photographing the visual art, to Ruth Bennett for her skill and expertise in design and production, to all the featured contributors, and, of course, to you, dear reader.

David BriggsSo here they come, around the corner, bouncing, flouncing, boho beehives, tattooed, corduroy-looned, sneakered scumbags, skinheads, brogue-shod uni fools, or look, they’re me, they’re you, but slightly cooler, lust- and roll-up-fuelled, artfully spectacled idea junkies, pushing, selling, any one of us could be John Lennon, Jesus, coke and sneezes forced through nostrils that are pinned or pierced. Look, these feather-boa’d vegans or these leopardskinned animals, with their X-rated bodies, their needs never sated by hands-free friends or look, their palm-held search engines, their razor’d heads turned by beauty or a global crisis, these masters of their own devices. For every word they’ve #’d or abbreviated, each god they’ve never worshipped, every song they’ve downloaded, shook their arses to or sung, I say bow down, bow down, the young, the young.

Exiting the back door past eleven on a dark, chill night, we are satisfied the work’s done for now.

Benevolence in numbers: fifty-three dinners served; eighty-one hot drinks laced with sugar; eighteen beds bagged by fortunate first-comers.

Here at the door our calculations pause. Three young men, lean and hooded scuff around aimlessly, and ask for a final hot drink to take away – where? These unlucky ones have no bed tonight. I read fear or bewilderment behind their truculence.

What to do now?

The stone streets of Bristol don’t care.

They must be all of eighteen, nineteen, twenty years old. They could be my sons, my students, my lads. They are all of our lads. They are no-one’s lads. Guilt, dismay, small talk as we drive away.

Didn’t look twice at her reflection. Scared to wake it. Her skin was marked with its anger and frustration as to why she wasn’t perfect.

Its voice a constant reminder of what she wasn’t. A need to see the bones. Each day it cried out its wish for acceptance.

She watched it. No matter how hard she tried to impress it, there were flaws she couldn’t hide.

It tried to fix her. Its clammy hands clawed at her waist, pushed bone to bone in a bid to tighten the sides. Pulled at the skin. Its grip on her hair –her head pounding, caught in a loop of disappointment,

of failure, and parts of her which were unwelcome.

An hourglass counts the time it takes to let go, to stop pushing for perfection and breathe again.

Your kitchen: a hopscotch-tiled floor, my table an artist’s studio turned Scrabble arena, and the thundering dryer. Hiding space of champions. Your cupboard holds the ingredients for my secret concoctions: mustard powder, vinegar, washing-up liquid and sugar. We begged to drink it, only to pour it out on the patio, disturbing Mr. Toad.

Your kitchen a nest, loving what it holds. You entertained the fantasy of flying south. A foreign place you’d make your own. Learning its beauty, culture and difference. You’d love the weather; he the birds, buildings, plants.

Kitchen of your eccentricities. A place to love, to live; not a place to enjoy culinary delights so much as curiosities. ‘Gwen’s Café’. Affectionately named. Baked beans, Scotch eggs and brown sauce. A place to dry out his spirit-soaked stamps. The issue of legality overshadowed by a philatelist’s fascination. Your windowsill holds memories of ceramic, terracotta and a perfectly-placed poinsettia; it holds your binoculars decorated in green patina. Copper chlorides and carbonates creating a condition of age. You look out the window while eating marmalade toast and observe magpies, goldfinch, blue tit, woodpecker. Ruminate over The Telegraph’s crossword.

Mr. Toad has gone. Your kitchen’s become nostalgia.

Dear homo sapiens of planet earth, I look down at the world with awakening eyes from the blue face I hide behind, from behind the darkening veil that obscures your view. I suppress the bludgeoning that’s beating me down –I’ve seen enough.

You call yourselves ‘wise’, but such supine ignorance breeds here in the face of environmental Armageddon. For your negligent minds, my heart palpitates; my omniscience calibrates your fate. You who compete to win, who care for nothing, materialistic protagonists, confirm only your own expiration date.

Homo sapiens, in your race to be the best you’ll raze yourselves from the earth.

A dawn of realisation. My clouded vision’s second sight. I watch smoke choke my sky, can no longer breathe. Celestial Mother, I’d caress you, protect you,

but my blue eyes are dimmed by a shroud of ozone.

Do you know your fate, homo sapiens? All knowing, all seeing, all destroying: omniscient, omnividere, omnidestruere. You are punishable for smoking chimney stacks, high pollution encroaching, sticking to the skin; smoke withers me away; I can no longer see, no longer breathe, no longer live in this blanket of suffocation we suffer in.

You are obliterating, eradicating, impregnating. Chugging tendrils of smoke pumping, stifling, stagnating, congesting; and yet still you carry on creating.

Oh humans, all-seeing, all-knowing sapiens, I’ve been tolerant of your cynicism, your epiphanies of policy and monopoly, but you need to change,

see the light through the chink in my clouds, delight in aurora borealis.

I dare you to step closer to the borderline, lean over the precipice as the world disintegrates; watch until your lungs can no longer breathe. Look to me. Beg for forgiveness.

Oh people of the planet, I look down with awakening eyes from the blue face I hide behind.

David, we know that you lie by the church at the Barrow Court that you loved, but where else might you be?

Your laugh made a long generous echo, now small, very small, but still sounding from the far distance of years.

The elegant words of your books speak out when we turn the page, and the notes of your music, though they sleep on the staves, revive and re-live through voices and strings, and your memory sings.

Your neighbours and friends who still live can walk by the primroses in spring on the way to our great stone-hewn house, whose walls heard your walking-stick tap on the steps and push on the door as you struggled with your failing frame.

We can still be uplifted by full peals of bells and reflect for a moment by the great cedars in silhouette on a late autumn afternoon; and we see through the same lead lights the jackdaws fly into the sunset.

We can pass through the great wooden gates under gables and chimneys and cast iron pipes to a well that may still hold memories, where, on a still night, the bats circle round and your favourite owl still calls; there are deer in the fields and hares in the lane.

You were not of your time, yet of all and any time. You’d rather read Austen than Amis or Pound, and favoured traditional meter and sound; you thought that a grating or poor fitting rhyme was quite a regrettable literary crime.

And, as for your musical tastes, they were clear: composers there were that you just wouldn’t hear –so Schubert and Wagner would bring on a smile but Cage or Stockhausen were simply just vile.

Wherever you are, don’t forget Barrow Court, and maybe we’ll see you again one day, with a book in your hand and your panama hat on the pathways and byways here on the estate with a chuckle and a “fancy that!” and a kind word for each of us.

My mother had a fall. Sitting in a hot, stuffy room, she fainted.

No sinister explanation. A small, crowded room; hot and stuffy. It happens.

But as she fainted she slid from her chair and broke a bone high up in her neck –the odontoid peg, as I later learned to call it.

Ambulance, A&E, hospital ward –the whole shebang. A surgical collar: eight to twelve weeks.

She listens as her sentence is handed down. Doctors’ solemn warnings hang in air like a sword of Damocles.

Her former independence glimmers in the distance – a faltering beacon

beckoning her. Weeks pass. Her great-granddaughter is born.

Another fragile neck: old bones grown brittle; young bones still fontanelle-soft.

A strange design flaw: to put our most important part atop this delicate stalk.

lifted out carried in wheeled around walked out walk in walk about walk out walked in wheeled around carried out

lowered in

Born in this city nestled between hills, nurtured by the tide of the Severn. The vibrant colours of town houses reflect in the dark waters of the harbour.

Echoes of the past all around. Lessons learnt and passed down. No more a slave port built on trade; a home for all has risen – phoenix from the flames.

The open green land of the Downs sees quidditch, fun runs, festivals and clowns, free speech and protests, along with naked bike rides and slides down Park Street,

road closures for days of running, of rides. And tho’ 20 mph is sometimes a bind, this city of culture – green and eco –has so much to offer wherever we go:

hospitals, universities, colleges and schools. Even the uneducated fools

soon fall for the heady delight of Bristol by day, Bristol by night.

River River. From Hafren’s heart the course carves through the furrowed veins of flooded fens; all mud, all morning blood sprung from a source of daring life. While flesh and fire descends in dance – there wedded with the tidal force, the dance-renewing waves, where life transcends the pulse of yearning flesh, of forms divine –the genius and river-flow entwine.

The deep Eridanus is whirling death, and yet the refugee of Troad embraced its stellar waves, purging his mortal breath. There, from the estuaries, the nations chase their tales. Tremors through the tumult-earth, where from the waves pours forth a star-born race of dreams. A form within a formless plan, outflowing against our deaths in myths of Man.

The phosphorus shores of charred Ulaya consume the centuries’ tears in warring fires. The Ganga flows from heaven’s tasselled hair, adorning all three worlds with funeral pyres. The brook of the Beautiful Lord was where, amid the mountains, Doomed Youth’s life expires, and blood divine discolours red the blue, till love (what else?) restores His life anew.

Imperial Thames, beside which circles of flame first fuelled the engines’ churning train. Desire consuming poor mad Aethon’s burning brain.

Languid Tiber: soft the surface lies through centuries of madmen’s lusted fame. Your bulwark banks have buried three empires. And what mere eye-blink Rome to you must seem. What to us? Shades. Wide as a world may dream.

The afternoon light flares— the marble-floored piazza, the baroque, limestone duomo

once a temple to Athena— all trace of sacrifice long since worn away.

The groom ascends the few steps to the church, and women in long dresses—silver, teal, violet—

arrive and gather. Is it the height of their heels that gives me vertigo? The island breeze eases the heat.

Everyone is framing or posing for photos. Oh, not us, tourists lingering in the shade of umbrella’d tables; not us, securely separate, eloquent in silence. We are just here to look.

Around 6,500 languages are spoken around the world. It’s incredible, really. Language is one of the amazing things that separates us from other species, which makes us unique: our ability to convey emotion, understanding and thought, all through a series of sounds made with our bodies, and, in some cases, through our hands and other bodily gestures. However, of the 6,500 languages spoken by the seven billion people on Earth, the top ten languages spoken claim about half the population. 2,000 of those languages are estimated to have fewer than 1,000 speakers. Most linguists estimate fifty percent of all languages will be gone by the end of this century, and some put it as high as ninety percent! But what you should be asking is, who cares? Does it really matter if a language dies? In this essay, I aim to explore the consequences of a language going extinct and whether or not it matters.

To understand the effects of language extinction, we need to explore what a language offers, beside the fact of being able to communicate ideas with one another. Languages are so much more than that.The loss of a language means the loss of so many other things, things which we may never be able to experience again.

“We spend huge amounts of money protecting species and biodiversity, so why should it be that the one thing that makes us singularly human shouldn’t be similarly nourished and protected?” So says Mark Turin, a linguist at Yale University. To some extent, he is entirely correct. Some may even argue that languages are more important because of the power they hold.

Languages are conduits of human heritage. They express history which was never written, and what might have been lost lost remains through this fantastic medium.The Iliad and the Odyssey are examples of texts that were originally never intended to be written down. They were oral stories. Stories to be told, passed down by word of mouth, generation to generation. Now imagine how many other oral traditions were lost because they were never written down, because the language was lost?

Languages also convey unique cultures. No two languages are the same. French is not just a way of saying English things differently. Cherokee, the language of the indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, is a very different language to any other: it’s unique, it’s special in its own way. Words exist for things which we would not even imagine in English, such as ‘ookah-huh-sdee’, the word which expresses the feeling when you see an adorable baby or kitten. Through language, we can create, imagine and play with concepts, those intangible figments of the imagination, powered by the human mind, thoughts of what could be and what might be. Language can be imagined as a box, too. A box which contains a playful little thing called knowledge. Hundreds of thousands of millions of ideas, of experiences, of tales and of answers, all stored in this little box. It allows us to search for the truth, something we are inclined to do by nature. We can pass on this box, too, like a gift _g_iv en from adult to child, so each generation starts one rung up the ladder of knowledge than the previous, allowing us to learn. There are words in Cherokee for every berry, stem and flower in the history of the Cherokee people. The very name itself will state whether it is poisonous or not. But, when a language dies, this box is lost forever. Burnt in flames. Never to be seen again. All the knowledge it possessed is gone with it, and humanity loses a little piece of itself which can never be retrieved.

People care about identity. They want to be able to express themselves as unique human beings. People don’t want to be thought of as ‘just another person’. Language is a key to keeping yourself unique. It possesses the power to diversify each race who wields it. But with languages dying faster than ever before, our descent to becoming a monolingual species is becoming more of a risk than ever.

Some argue that languages will die, and that is just a fact of life which we have to tolerate. But languages can evolve. They change over time. Certain aspects develop and alter to fit the needs of the speakers. The fact that ‘wicked’ now means terrific as well as evil is just an example of this. Words can also be added, or taken away. ‘Clone’, ‘software’, and many other words have been introduced in the last century alone. Since they evolve, languages can become bigger, but also, smaller.

When a language dies, it can be argued that there was no reason for people to speak it. If it died, then it was the speaker’s choice not to teach it to their children, and so it was their choice that died. Who else is to choose for them? Who are we to suddenly make the decision that they have to preserve their language? If a language goes extinct, it would have happened anyway. Other languages evolve to take its place, and there was no need for it on this planet. Put like that, it sounds a lot like natural selection, except that it’s smaller, unneeded languages that die out rather than weaker species.

Languages are ways of interpreting the world. No two views are the same. As such, languages provide insight into the thoughts, emotions and psychology of our species. Losing a language is a devastating thing. It’s fundamentally losing all the thoughts, knowledge and ideas of an entire race. That’s not a good thing.

On the other hand, some argue that what can be expressed through one language can be expressed through one of the 6,499 others: languages are unique, but they are all basically the same thing, just different forms of it. However, while that’s true, that’s not all there is to a language. The cultural heritage, the knowledge, the logic, the myths, anything which was ever thought of in that language is lost when it becomes extinct.

Let’s revisit the language-box idea. Imagine, again, that a language is a box. But, imagine thousands of boxes, each being a separate language, be it Spanish, Judezmo, Bengali or Gaelic. Now, as can be argued, every single box is the exact same. Why choose one box over another? They’re both of equal worth. But, inside each box, there’s something different, something unique. Inside we find the thoughts, the history, the discoveries and the stories of that specific race. Everything which the people have been through. Constantly changing, constantly evolving. But, one by one, a box is being taken, leaving vast, gaping voids, empty holes of nothingness.

Languages need to be saved. A language has its history and culture embedded in it. They are worth much more than what they appear to be at first glance, and the power they carry is immeasurable. There is a wealth of literature embedded in each one, such as its mythology, medicine, philosophy and cuisine. In my opinion, language extinction is a bigger threat to humanity than we realise, for it is our very history, the thing which makes us us, which we are losing. While languages seem to be a means of communicating at first, no different to the bark of a dog or the chirp of a hummingbird, they’re so much more. They’re a storehouse of ideas, knowledge and concepts. Losing them is losing a piece of our identity. It is a shame that, in this day and age, not knowing or speaking one’s mother tongue is fashionable. It goes to show that even with such great gifts, humanity is unable to acknowledge it for its true worth. Language extinction is no small matter. Indeed, I think that it does matter greatly if a language becomes extinct, and if we do not act now, our actions may be irreversible. Languages are the basis of human empathy and understanding, and must not be lost. As Ludwig Wittgenstein once said: “The limits of my language are the limits of my world.”

The value of art is an interesting concept. It is dependent on so many factors, the large majority of which have a degree of subjectivity which renders that which makes art valuable an indefinable entity, in continuous vicissitude. However, one thing which does seem to be a constant source of value in art is originality; almost without exception, the original version of a painting will be more valued than any copies of that painting. And the same is true for virtually all forms of art; though fine art may be the most notable example, with the price and esteem difference being particularly extreme, we also see similarly higher value placed on the ‘originals’ of literature, music, theatre. If we take monetary valuation as an indicator of the ‘true’ value we place in art, we are prepared to pay more for the first edition of a book than for a recent copy; more for live music than for an excellent recording; more for live theatre than for a streaming of the play shown in a cinema. It seems evident that art, in all forms, is about more than just our sensory experience, more than just that which appears to be its primary purpose. In the case of literature, a novel is about more than just the story. In the case of a painting, it is about more than simply its appearance.Yet this conclusion engenders a further question; what else is it about?

From an economic perspective, the answer seems initially simple. While there can be thousands of copies – in fact, on principle there can be as many as necessary to meet the demand for them – there can only ever be one original. Therefore, the supply:demand ratio for an original is significantly lower than that for a copy, and thus, owing to the simple principle of supply and demand, the monetary value of an original is significantly higher. However, when considered further it becomes evident that this simply leads us back to the same question: why is there more demand for one original than for one copy? Why prefer an original to a copy?

If, for the sake of argument, we take an ‘excellent’ copy to mean one that is recreated so superbly that it is visually indistinguishable from the original – something which is more than possible in the cases of certain distinguished forgers, and becoming increasingly so owing to copying machines – then what is left to distinguish a copy from its original? I would argue that, somewhat tautologically, the answer lies in the word itself: the value of an original is in its originality.

Yale psychology and cognitive science professors Paul Bloom and George Newman conducted a study in which five experiments, involving several hundred participants, were carried out, and all unanimously proved just this; the veracity of the creative process behind original art infallibly causes people to place more value in it. So why is this the case?

I would argue that a largely contributing factor is that of the artist’s intention that is, conceptually if not visually, contained in original art in a way that it is not in a copy. Even if we cannot sensibly perceive it, the intention behind an original piece of art is to communicate something, or portray something, or purge something; the intention behind a copy is merely to copy that original as well as possible. It lacks the human aspect of art; although art created by a robot could technically be very good, I believe we would probably find this art lacking in emotiveness or impact, because it is the humanity contained in art, the human intention contained in art, which causes us to value it. While it would be unjust to deem manmade copies robotic, they have a lesser degree of that human quality to them, because they lack the intention behind them.

Furthermore, an original piece of art is comprised of the endeavour that goes into producing it, the effort that is put into the process of creating something out of an authentic idea – in a sense, creating something from nothing. Producing art is the manifestation of our attempts to ‘play god’; to create something, something individual and authentic and, above all, original.

When artwork is original, it contains within it not just the visual output of that originality, but the authenticity and innovation that lies behind it. It contains the genuineness of the idea, intention and emotion invested into the art by the artist. It contains that aspect of humanity, of the artist themselves, and the generosity of self that is required of the artist in order for these aspects to find their way into the art. And it is this which draws us to engage with art, this which allows us to be affected by it.

What is more, this originality makes the art more real. The intention, the endeavour, the initial idea – all these factors are part of the art, and so without them, a copy becomes less authentic, less real, than an original. And reality is something which, across history, we seem to place intrinsic value in. As far back as Ancient Greek philosophy, we see this notion arise: Plato’s Divided Line metaphysics, differentiating the intelligible world from the visible world, was concerned with outlining the infinitely higher value of the former, owing to it being that which Plato perceived to be truly real (the world of the forms). In fact, metaphysics is in itself a questioning of what is

real and what is not, of the nature of reality; and ubiquitously it seems to be taken as self-evident that what is real is more important, more valuable, simply more preferable, than that which isn’t. French rationalist philosopher Rene Descartes’s ontological argument is widely criticised for making logical leaps; but his presupposition that being real is a necessary precondition of perfection is not generally considered to be one of them. We seem to comfortably accept as fact the idea that being real is better than not being real; that something real is preferable to something not real, or – essentially for this argument – something less real. And so perhaps the reason that original art is more valued than copies is because it is more real than copies.

Theatre practitioner Bertolt Brecht aimed, through his epic theatre, to communicate a message to the audience. His plays presented acute and powerful social commentaries, and provoked his audiences to change the way they lived their lives, or thought about their lives, as a result of watching them. Brecht believed that what makes theatre meaningful is the message it can communicate; I would expand upon this to say that what makes fine art meaningful may also be just this. But what makes original art more meaningful is the process and intention behind it, the catharsis it may provide for the artist in creating it, the authenticity of the idea and the creativity that enabled that idea to come to fruition. Copies of art may still relay a message to the onlooker, but only the original contains the intention of that message being relayed, the passion of the artist that provoked them to try to relay it. And so, original art is preferable to an excellent copy; it is preferable because it is more real, because it is more human, and, ultimately, because it is more meaningful.

This extract is an exploration of the elation of childhood excitement, as well as the equally potent experience of a feverish sickness. They are more similar than one may, at first, believe. Within the very opening of the text, Joyce explores the exuberance of a family Christmas, as imagined by the protagonist, Stephen Dedalus. The constant repetition of ‘cheer’, ‘cheers’, ‘cheered’ and ‘hurray’ portrays the excitement of a child, and its simplicity incites nostalgia in the adult reader. A child’s focus on the simple joy of school holidays, and seeing one’s own family is infectious, if you’ll forgive the pun on the latter half of the extract. ‘Cheer after cheer after cheer’ is a continuous theme. Focusing on the surrounding sounds emphasises the rush and blur of Stephen Dedalus’s jubilance for Christmas, a time which all children, surely, relish.

As Stephen wakes from his imaginings, he is in a state of extreme perception. ‘The noise of curtain rings running back along the rods’ bring him back into the structured world of boarding school, where he is no longer the centre of attention, as he wishes himself to be among ‘all the people’, but simply one of many other boys, referred to solely by their surnames, like ‘Fleming’ and ‘McGlade’. Furthermore, unlike his dreams of Christmas at home, there is little to no sympathy, he is, in fact, accused of ‘foxing’, when he ‘was sick really’. This shows the strict honour code at an all-boys boarding school: ‘His father had told him, whatever he did, never to peach on a fellow’.

When Stephen falls ill, Joyce’s use of heightened senses and erratic, confusing, amplified sounds portrays the panicked nature of an unknown illness. ‘The sunlight was queer and cold’ is an oxymoron, and contrasts how ‘hot’ his bed, face, and body feel. There is also disjointed dialogue, with no confirmation as to who it is accredited to: ‘He’s sick. – who is? – Tell McGlade.’ It also contrasts with the warm nature of his imagined Christmas, with a caring mother and father, who are replaced by a prefect and several fellows who seem more preoccupied with protecting themselves than caring for Stephen: ‘Dedalus, don’t spy on us, sure you won’t?’

One possible comparison which proves quite interesting is when looking at the quote ‘Leicester Abbey lit up. Wolsey died there. The abbots buried him themselves’. This is a metaphor for how, childlike in nature, Stephen Dedalus believed his affliction is just so awful, he may be about to die. This is reiterated in the preceding quotes: ‘Afraid that it was some disease.’ And the almost immediate jump to worrying about cancer, ‘a disease ... of animals’.

In conclusion, Joyce draws parallels between the feverish excitement of imagining returning home for the holidays, the heightened emotions at Christmas, and the very real fever Stephen experiences.

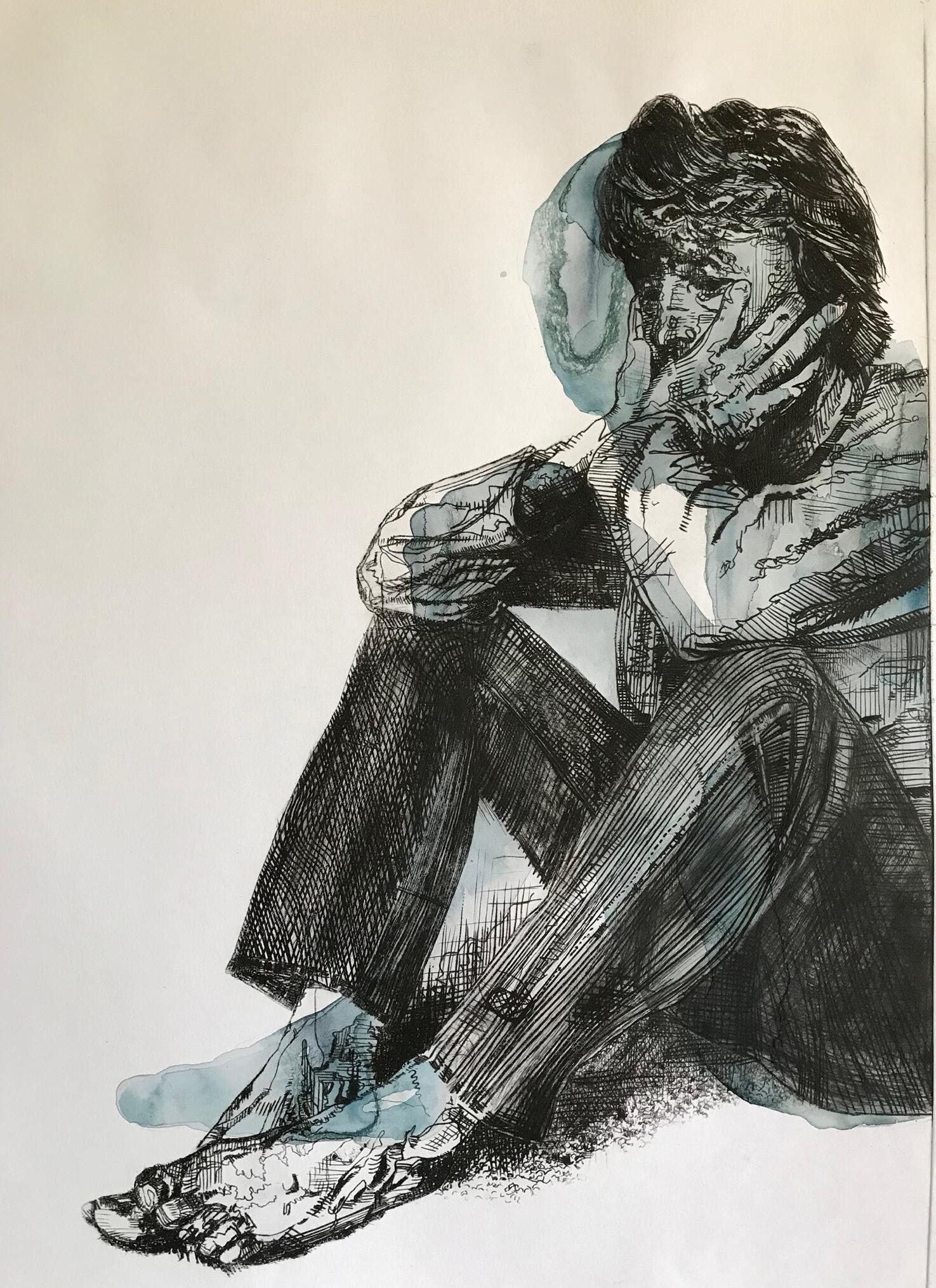

Dan Stoica mixed media on board

Zoe Wakling ‘Still-life’

acrylic on paper

The air was warm and stuffy, fuelled by the forensic summer. Dust particles hung in the air, caught in the lofty morning light, and Annie lazily watched them from the bunk bed as they spiralled around her in a sporadic dance before floating to the floor. Ever since the start of summer, the Centre had been captured in an unforgiving bubble of heat that had seeped in through the cracks in the walls and under the doors of the adjoining cells. Lucy snored softly in her arms, finally asleep after a long night of nightmares, and Annie listened peacefully to her rhythmic breathing, unable to sleep in the bright daylight despite her growing fatigue.

The cell door opened. A guard appeared and Annie surprised herself when she felt a flutter of disappointment that it wasn’t Tommy who had come to let her out. She brushed the thoughts away as quickly as they had come.

Outside, the ground was being eaten alive. The grass once fresh and dewy had been sucked into the baked orange soil and only skeletons of wispy blades remained. The sky’s colour mirrored that of the ground, taking its form in a dusty, orange haze that made the horizon indistinguishable, like it was one big, orange blur enclosing them. Sweat clung to Annie as they walked around the building to where the orchard used to stand. There was a small group of children with her, all of them dressed in the same clothing: khaki trousers and a green t-shirt that failed to mask the dark sweat brought on by the heat. The orchard, once full of juicy fruit hanging in luscious trees, was now a depressing graveyard and she wasn’t in the mood to see it today. Was she hallucinating? A vast swimming pool suddenly came into view, filling the space where the old trees used to be. The group began screaming with excitement and hugging each other and even though Annie didn’t know any of them, she joined in, pulling a very small girl with big, owl-like glasses into an embrace.

They all ran, fully clothed and plunged into the blue water, letting the summer heat slip from their skin. Annie floated on her back like she’d done with her parents when they had

taken her swimming. She felt happy and relaxed, something she hadn’t felt in months. The air was still, suffocated by the stifling heat, and she laughed, mocking everything outside of the pool as she relished the feeling of being cool. Her peace was broken by a scream from one of the girls, a high-pitched scream fuelled by panic. Silence. Annie looked around, trying to see what had happened. A pair of owl-like glasses bobbed to the surface. Silence. Annie started to swim to where the girl had been, wondering why no one else had moved to help the girl as she was clearly drowning. Faces stared at her as she swam past, confused and in a state of paralysis. Suddenly, more and more of the children started to act in this way and a chorus of screams filled the pool before disappearing under the water. Bubbles of desperate air appeared on the surface as they tried to breathe and, instead, water filled their tiny lungs. More and more children were dragged under. The pool floor became a mirage of drowning faces, red and ugly against the turquoise water and tiles as Annie frantically looked under for the cause. There was nothing visibly there, but whatever it was it had a domino effect, taking one child at a time, and it was reaching Annie quickly.

Her legs started to feel heavy. Every second it intensified, like her legs had become weights or stones, willing her down. The few children around her were crying with panic. Some of them were swimming to the side; some of the cleverer ones were already out and watching the leftovers struggle. Annie was dragged under. The bubbles began from her own mouth, pooling upwards to where the guards stood, watching intently. This was the Trial. It never failed to shock her, the intricate yet sickening ways they created to kill them. Often in each Trial, only a few survived; just enough to tell the tale of that particular manner of death. But, sometimes, no one returned and then it was all left to their imagination.

Annie’s lungs burned. It felt like fire was slowly taking over every cell and fibre in her body as it desperately cried for oxygen. Blackness. Dreams filled her head, thoughts of her home and family mixed with the strangest images of things she didn’t recognise: bright colours and shapes moving in patterns and intertwining into photos: a timeline of her life that was being fast forwarded on the quickest setting.

Strong arms closed around her. They felt soft and familiar. The sun pulled at her limbs, waking them up. She slowly opened her eyes, shielding them from the red sunlight. Then the guards came into focus and her eyes met Tommy’s. His once khaki-green army jacket was sodden with water.

Annie didn’t return to their cell that afternoon. Lucy paced up and down, thinking of all the bad things that could have had happened to Annie and praying that she was alive. Not even the sounds of birds singing outside their cell window could distract her from her dark thoughts as she grew increasingly worried and upset. Their cell was one of the nicest; it had a barred window which was just big enough to fit your face up against and, on clear days, you could see the miles and miles of empty, orange land around them and a glimmering sheen in the distance which they had used to think with excitement was the sea.

Lucy wrapped her blanket and the one from the empty top bunk tightly around her. As darkness descended over the Centre, so too did the cold and it was as unforgiving as the heat. Jackson had told her during break time that Annie had survived the Trial and she felt satisfied with this; Jackson always knew what was going on. Shadows grew big and small on the walls as the guards patrolled the streets of cells. She watched them until they left the Block, the orange pulse of a cigarette stump hanging lazily from each of their lips, plunging the block into complete darkness and silence. She waited for the morning alone.

The alarm clock for the Centre was a siren, much like a nuclear alert from the Third Wars, and it sounded across all seven blocks in a simultaneous wail. Lucy got up and started getting dressed. A guard walked past and looked into their cell, a lazy grin on his face as his eyes wandered all over her undeveloped body. She froze, a hot flush spreading across her face and neck. The guard walked on, and another one appeared posting a tray with a small packet of cereal and a slice of bread under the door. Lucy tried to cover herself up but he laughed at her feeble attempt before yawning as if he was bored at observing her and left as well. She got dressed quickly and ignored the food. The milk soured and the cereal started to curl and harden.

They were let out one block at a time. First, Rainbow Block as they had the furthest to walk and then all of the others, with Lucy’s Block, Caterpillars, last. She always thought that they looked like a green tribal army as they traipsed out into the heat in long, worming lines. The work was very simple. Sewing, cooking and washing if you were girls, and chopping wood, carrying building material for the new block or any other manual labour if you were a boy. The working arena was a grouping of huge, old 400m x 400m tennis courts with green fencing towering high around a green floor. The children were all being directed into one of the courts and confused whispers could be heard that slowly built into a loud chorus as more and more

joined in until the guards blew their whistles, signalling for silence. “Welcome,” said the guard with the longest and thickest moustache of all. “Welcome to Trial 19, a very special Trial indeed.”

Silence. Gasps of disbelief broke out from the front rows of children as they saw the competitors. Lucy pushed her way through the sea of green and, finally reaching the front, stopped dead in her tracks. The sun beat down on the scene, bouncing off the old metallic lights that used to be used for sport at night and now cast a shimmering sea of glitter over the courts.

Annie and one of the guards, Lucy recognised him but didn’t know his name, stood with chains shackled around their ankles and their hands tied together with thick rope. The skin under the metal was raw and bleeding and the rest of their bodies were bruised, especially Annie’s, where there were many dark rings around her thin arms and around the top of her thighs. Lucy thought she saw the guard lightly brushing Annie’s hand, comforting her, but the glinting light made it impossible to tell as it shone an array of light in every direction, distorting the scene.

“The Trial,” began the big moustached man, “shall commence in twenty seconds. Everyone stand behind the line to allow the best view for all”. The chains on Annie’s and the guard’s hands and feet were unlocked and they were led to the start line of a 100m track. It had been painted onto the ground with precision in a deep red paint that had already started to melt away in the heat like rivers of blood. Lucy’s heart was pounding, her throat dry as she tried to work out the Trial. There was a trap about three quarters of the way down the track that was clear and obvious as an obstacle. They jump over that Lucy thought, but then what was the Trial? She started to feel sick.

The start gun was fired and Annie and the guard began to run. Silence. Not even the younger children drew a breath. All that could be heard was the padding of bare feet on the track. Everyone watched as they neared the trap and jumped over it, clearing it easily. Lucy drew a breath of relief. Then the ground opened. Two spears sprung out like angry figurines and pierced through Annie and the guard, catching them mid movement. They dropped to the floor, their blood joining the melting track in an indistinguishable puddle, spreading rapidly over the evergreen floor. The spears sank back into the ground and the hole closed over like nothing had ever happened.

The evening haze hung in the air, humid and still. The sky was rose pink with splashes of red that splayed pretty patterns everywhere, capturing the Centre in a picturesque summer evening scene. Jackson sat alone, scanning the playground for Lucy. He hadn’t seen her since the Trial. He pictured her tiny, heart-shaped face and huge eyes that were too young to have seen half the things she had, eyes that bore all her emotions when her little face was trying desperately to stay strong. Those two had been like sisters, and Jackson felt an uncontrollable anger build up inside him that they had taken Annie from her. Their situation was getting desperate, and even the guards seemed to realise it. He looked around, taking in the remains of the orchard that now hung limp and decayed, the baked orange ground and the dried out river bed that the children played in, oblivious of its previous life. It felt like time was running out. He caught sight of the two guards that never seemed to be far away, watching him intently from across the mass of childish games. Night fell over the Centre in a sleepy slumber, draining the heat and colour like a vacuum. Jackson wondered what time it was; the moon hung high in the sky, just a distant speck in the corner of his barred window. Jamie snored softly in the bunk below with quick, heavy breaths escaping ever so often as his dreams took the form of excitement, or maybe terror. A group of owls start hooting, creating a sinister, night-time symphony. The smell of cigarette smoke from the guards below wafted up into his cell.

Jackson must have fallen asleep because he awoke to the faint smell of pyromoxine, a gas commissioned for the Third Wars. It was an unmistakable smell and one that he would never forget, having undergone tedious drills every week at his school where they were exposed to the smell, its colour when in the light, its effects, and how to survive best without a gas mask. The cries began imminently as the children’s lungs filled with gas. Their cries soon turned to screams as the gas slowly deteriorated each cell individually, melting them away like acid. Jackson quickly took off his top and tied it around his mouth like the teachers had shown him to, leaving just enough fabric for small breaths of air, but filtering out some of the gas as it got stuck in between the particles of clothing. Despite this, with each breath, he felt the coarseness of chemicals lightly blaze the inside of his throat and lungs. He woke Jamie, who was still snoozing obliviously on the bottom bunk, and did the same for him, tying it more tightly than his own and pushing him under the bed to get underneath the gas. The sound of vomiting ricocheted around the walls.

The cell was becoming hazy, a musky, blurry haze. Jackson lay in front of the gap between the floor and bed, blocking Jamie from the gas as much as possible. He knew the hallucinations were about to start and he waited, but nothing happened. He tried to keep himself awake and focused, but he felt increasingly dizzy every second. Lights suddenly came on above all the cells, illuminating everything in a pink glow as the gas became visible. Then the children in the opposite cell began to melt to the floor and crawl towards him in a mess of colours. He blinked and they took form again, crawling up the walls and across the ceiling, their smiling faces never turning away from his. They merged into faces of the dead – of Annie and Fred, of Clara, and all the other children he had known, their bodies leaving a trail of blood along the white walls. Fear palpitated through his body. His face was wet with tears. His t-shirt, sodden with them.

The figures were growing closer to him, following each other down the wall, their smiles growing wider and wider. Jackson scrunched his eyes shut but still they came to him, touching his face, stroking and caressing it, leaving the metallic wet of blood as their fingertips melted away. He could hear himself screaming, joining in the chorus of the Block and he knew the fear this would bring for Jamie and the others but he couldn’t stop the sounds coming out. He felt detached from his body, like he was leaving it and floating upwards. Then the gentle squeeze of Jamie’s hand on his arm brought him back down to earth. He felt the panic subside, like a bad dream does when you awake, and he hazily opened his eyes.

The cell seemed exactly as it should have been, apart from the faint dusting of pink light. Then Jackson heard the faint sound of laughing, high pitched childish laughter that echoed around the now silent block. He pushed Jamie back under the bed and waited, fear pulsing through every vein.The laughter grew louder and closer, invading every inch of his ears. Jackson tried to ignore the voices and block them out as the sound of Clara’s delicate laugh rang out louder than the rest and his heart filled with grief once again. The laughter began to deepen, turning unrecognisable in a devilish scream that no human could possibly have ever made while the colours reappeared, seeping up through the cracks in the floor and bubbling like rivers of paint, back through the bars and across the floor. Jackson was transfixed, as if under a spell from the majestic array of colours, and followed its trail up to his own cell door blindly. He watched through blurry eyes as the colours took their final form, climbing up the walls and moulding into the figures of Holly and Rose, dead against the bars, just a single trickle of blood running from each of their mouths. He blacked out.

28 out of 80 survived. Jackson sat, bitterly looking out across the children playing as

the sun crawled into the sky, leaving a scorched tail of red that traced back down to the distant horizon. He could hear the little, chattering voices of the younger children who sat in a circle nearby, and he smiled in spite of himself as he heard them trying to pronounce the new nickname the Centre had gained for itself – ‘The Chambers’. It had been renamed, and Jackson knew that this one would stick. He saw the two guards watching him as always. They spoke quietly together for a brief moment before making their way across the playground towards him.

The Guard

‘Dear Diary, Hopefully one day, this will serve as a reminder of what power can do to a world. The Third Wars is one reminder, and The Centre should serve as a second. I feel stupid writing this, but I need to write everything down to make myself realise that it is real, and that I am partly to blame.

After the nuclear war, most of the world was destroyed.Whole populations were wiped out and we had no way of knowing how many were left. We could be the last ones, just a tiny speck on the baked earth that our ancestors destroyed. For five years we all lived in warehouses, a jumble of people who didn’t match together in any shape or form, attempting to survive. There were so many orphans, young children that had been sent there as evacuees during the war and now relied solely on us older ones to look after them. I was only sixteen at the start, barely out of childhood myself but, for a while, it worked.We collected material, building rooms for the children to share out of the tonnes of metal left from the war, even putting up football posts outside so that they could play.We slowly created a community that began to feel normal again. It was a happy place.

Four years on, and you wouldn’t have recognised it. The temperature had begun to increase, slowly at first and then alarmingly quickly, claiming the life of the orchard, then the river, whilst the sky turned a deeper shade of colours every day. The older boys became frustrated, taking their anger out on the younger ones as the situation got more and more desperate.Then one night, after a particularly stifling hot day, we were called into an underground room that I didn’t even know existed, nestled beneath one of the warehouses. It was thick with smoke, a new habit that the boys had taken up after finding a supply of cigars and cigarettes buried in the nearest town. Jamie’s newly grown moustache flopped limply across his face with sweat and I remember distinctly noticing the feeble attempts of the others around me, who stared at

him eagerly and who, at this point, just had a thin layer of tuft on their upper lips. Jamie’s anger seemed to throb within him. I could see it in every pulse of his veiny arms and every movement in his body. Anger at the situation we were in. Anger because no one had come to rescue us. Anger because it was starting to look like we actually were the last ones left.

He had devised a plan he explained, a plan that was necessary for survival. We were the oldest, therefore we were to become the guards, he explained. There would now be Trials, each one attempting to eliminate the weakest among us. We needed to inject purpose back into our lives, he told us, and that purpose was to strengthen the children so that the new generation would be made of the best genes. This would ensure survival. He projected a dim light through the smog and onto a murky-white wall, now covered in a thin, yellow film of heat and smoke. It showed a profile of each of the children with their name and an empty box underneath that was labelled “identified traits”. Jamie’s face spread into a smug and satisfied smile when he saw this, which sent fear creeping up my spine. The Trials will reveal traits, he explained, and these traits will allow the perfect match to be made between a boy and a girl. And, finally, he concluded with a bow, this couple matched in every way, will be sent out into the world in search of the others.

That night marked the transition for us from boys to guards. Jamie made us start wearing the awful green army outfits that had been worn in the Third Wars. The Trials began immediately. At first they were intelligence based. Jamie invented ridiculously creative puzzles and riddles and, slowly, the cleverer individuals started to emerge and their profile scores were raised. This carried on for a few months, with easier trials for the younger ones. Everything seemed okay. There were more rules and we ate our meals separately from the children, but we were still allowed to play with them sometimes. Then the power got to their heads.

Jamie and his three minions, who all by now had thick, full grown moustaches and took to wearing tinted shades and carrying sticks wherever they went, suddenly turned dark and twisted. The children were not seen as theirs anymore but, instead, were just part of Jamie’s project for survival. The Trials became brutal, first involving vigorous and pointless exercise and then, when they became bored with that, Jamie took to killing off the weak ones with the most intricate designs that only he could have ever thought up.

There were regular meetings, during which, Jamie would proudly project the results on the wall, showing the array of talents that had been supposedly discovered by the Trials. My stomach sickened deeper each day until I couldn’t bear it any longer. I knew that Oliver and Sam felt the same. We had spoken often about it late at night whie we were on watch in the

warehouses that had been renamed Blocks. We decided to leave, and to try and find the others ourselves.’

“We decided to leave, and to try and find the others ourselves” Jamie concluded, reading from a thick, dusty diary to the faces of the newest guards, some of whom he had known since they were two years old and who looked back at him with terrified yet obedient eyes. Jamie used his cigarette to set fire to the diary and lazily tossed it into the decaying trees that the three betrayers had been nailed to, hung out by their wrists like washing waiting to dry in the wind. Jamie watched, the sun streaming warmly on his back as all three went ablaze simultaneously, a roaring fire in deep orange and red, matched in intensity by the smell of frying fresh that was thick in the air: a glimmer of something, perhaps sadness or pleasure, flickered in his eyes for a second. Then, it was gone, and they all watched the growing fire in silence.

The boy ran, and the ghost followed. The moon low in the sky, silhouetting the shape of him and his follower, couldn’t penetrate the maze of streets below, which lay shrouded in darkness. The boy slipped down a telegraph pole and the ghost leapt after him. His sandals slapped on the dusty floor while the tin bucket clanged against the brick wall.

An engine noise approached, piercing the peace and the ghost showed its master into a doorway. The Toyota Hilux rolled past, its side littered with numbers. ‘Police,’ thought the boy. If he was caught within curfew, he would end up like his brother, dead. He shivered and bent down to touch his goat ghost, which was trying to get into the bucket, failing however to nick the salmon. He continued with his dark brown eyes, straining to see in front of him. He ducked under the woven cover and felt his body being heated by the blazing fire that roared in front of him. His mother smiled at him with that wonky, crooked smile and broken teeth. “Joseph,” she muttered, and her stool creaked as she stood up to embrace him. He collapsed into her arms as she gently ruffled his jet black hair and softly sang in Zulu about the love of life and the need to enjoy life. Joseph thought to himself how rare it was to enjoy life under white rule, but then these moments were what he loved and his ghost was lying around his feet, his heart beat slowed from running. He sat on the floor.

The tin bucket hung on the wall, precariously dangling over the dancing flames fuelled by The Rand Daily Mail, an edition from the 12 of May 1986 which he’d found the other day, down by the bins. While the salmon grilled, he looked at his mother pondering whether to tell her his discovery, but he decided against it and left the worn photo in his pocket. The woven cover was lifted by a stuffy breeze which sat on the skin like a flannel. Rays of morning light shimmered through and suddenly stopped as the cover came down again.

The salmon was okay, Joseph thought later as he gazed aimlessly at the dying embers of the flames. He glanced at his mother, who was looking at him with a soft smile of happiness. He got up and hugged his mother, kissing her on the forehead. He mumbled something about finding the news and so he came out of his house and turned right, with his ghost following him.

As soon as he had turned off their street he ran, holding the photo he’d taken from his pocket, which was worn, damp and torn half-way down on the right. His brother’s face was still clear in his mind, and his image was enhanced in his head by the photo of him from two weeks before in his hand. Robin Island. That was his destination. And so, to a fanfare of horns in Johannesburg, the boy went to find his brother Nelson.

Once he remembered them all, every single one of them. He remembered their faces, their hobbies, their friends, their families. He remembered them because no one else wanted to. He remembered the war, the crack of gunfire, the crash of missiles, the cries of his men as they pushed on past the rivers of blood, mountains of corpses. The cries of the wildlife as their world was suddenly burnt to a crisp.

The day, the date, the time all still in his head. He remembered that day. They’d ordered him and his men on a search and destroy mission; they called it a brief jaunt through the moon’s bloodstained lakes to a village down the stream. Hard to forget a day like that. Hard to forget the shouts and screams of his own men. The shockwave of explosives tearing asunder his unprepared men. The sudden artillery strike from a crater 22 miles away. That’s when the memory stops.

He remembers the surgeons and the room. His legs replaced with machines. His once beating heart now an atomic core. There he stayed for weeks on end, adjusting to what he’d become, what they’d transformed him into. They called him a patriot, a symbol of a newer bolder age. They treated him like an overbearing mother treated her gifted child. Once they were done they sent him out to the frontline again; again he fought till his body fell apart; again they fixed him.

Each battle he remembered less and less. Each repair more and more was changed. He no longer heard the gunshots as they ricocheted off his helmet. He was no longer shaken by the crash of explosives. He no longer bothered to learn his men’s names. The land was to him a distraction from his orders, his men but shields, the planet but clay to be shaped by his empire’s Herculean hands.

Twenty weeks later the war ended. As they returned home the crippled and broken were forgotten while those still intact were paraded. The press called him a hero, an atomic soldier who’d won the war. He was paraded from colony to colony, a wonder of what the boys back home could do. A symbol to show the power and light of his homeland. Little more than a mascot for the war effort. To the people he became a legend, a stoic Homeric hero to be

displayed as the future, a symbol of what was to come.

A few years later they unveiled them. They said war as we knew it was over. On robotic legs they proudly stood, with cold metallic hands they saluted their general and fired their guns into the air. They called them atomically-powered warriors, ones capable of carrying out a war devoid of death.

The next war lasted only three months. They were paraded, they were applauded, they were like him. Visions of a future. And he was like them – mechanical, a tool.

Years after the war and he was still out there, constantly touring the solar system, the route and the speeches all he could remember. Still promoting the empire and the war effort, still a hero to some. To himself he was nothing, a machine aware of its futility yet unable to correct itself, no longer able to tell the difference between himself and the robotics on his ship. Little more than an atom heart soldier, simultaneously a machine that acted as if it were a man and a man that acted as if he was a machine. Ultimately, unable to tell either apart.

It was 4:30pm and Robert was desperate to get home after a long day of tour guiding at the Caerleon Roman Baths – a.k.a. The Tourist Magnet. The rest of the staff had left hours ago and because Robert was the ‘newbie’ it was compulsory for him to cover the final shift. After a long half hour of droning on about the purpose and importance of the final room – the frigidarium (cold room) – a little boy who looked just over the age of six shyly shuffled up to him.

“Um.... Excuse me. What is that big bit of rock over there,” he mumbled, raising his arm to point in the direction of the caldarium (hot room). Sighing, the guide retraced his steps until he came across a slab of stone that he’d never really focused on before. Confused, he looked around for his manager but then remembered they’d all gone home.

“Typical,” he grumbled. He turned back to the little boy who was staring up at him expectantly. “I’m sorry sonny, but I’m afraid I have no idea what it is. Though ...” he inspected the horrifying face of a Medusa with an unusual Celtic moustache, with another grinning human face peeking out from behind, “…it does look like it might have an interesting history.”

“Julius, please be careful around that amphitheatre. It still hasn’t been completed,” called Aelia as she watched him climb over the building work.

“Yeah, yeah, I’m not a kid anymore. I can do things without you constantly shadowing me,” he huffed.

Aelia was Julius’s older sister, and ever since their parents had been deported to Rome as slaves for Emperor Titus Flavius Caesar Vespasianus Augustus (to give his full name), she vowed to make sure that her brother never came to any harm. While she nervously glanced at the rickety building planks surrounding him, Julius heaved himself up until he was level with the highest point of the soon-to-be-completed amphitheatre.

“Julius, get down from there at once. You’re going to fall!” she cried.

He ignored her and – just to annoy her – began to jump wildly up and down on the

unstable stone, causing it to shake uncontrollably.

“Julius, don’t!” she screamed.

Aelia was making such a racket that it caught the attention of a soldier who was patrolling the area nearby. The soldier – whose name was Aaron – hurried to see what all the fuss was about. Hearing another scream, he dropped his sword and found Aelia sobbing and staring up at the sky. Bringing his hands up to shade his eyes from the blazing sun, he squinted upwards to see Julius hanging from the stone by one slipping hand. He looked a real state – his chestnut brown hair was peppered by grains of dust and his white toga – perhaps not the best idea, Aaron thought – was now a pale brown. There was no chance of Aaron reaching Julius, but he couldn’t just leave him. Looking around for anything to help, his mind wandered to the thought of this boy as a gladiator trainee. He looked about the right age.

“Excuse me sir, some help here!” Julius yelled.

“I’m trying. Be patient or I won’t help you at all,” he yelled back.

In no time at all, Aaron had gathered some stray pieces of rope, tied them together and threw them up to the boy.

“What are you doing?” Aelia screamed. “You should be climbing up to him!”

Aaron smiled. “Trust me.”

Julian just about managed to wrap his blistered fingers around the rope and pushed himself off the stone ledge. Smoothly, he slid down to the ground and – with a green face –stumbled over to his sister who tweaked his ear.

“Do you know how unbelievably stupid that was?” she shouted. “What do you think mum and dad would have thought?”

As soon as she said that, she knew it was the wrong thing to say. Turning away, she smiled at Aaron. “Thank you so much sir.”

“My pleasure. And you can call me Aaron,” he replied. “Although, you two don’t seem exactly Roman at first glance. You look more like that mad Celtic woman Boudicca.”

Her gaze turned to fire and she marched up to him, gripping his shoulder hard. “Don’t you ever disrespect our Queen, Aaron. She is one hundred times stronger and braver than you and that barmy Emperor of yours!”

Aaron was taken aback by her sudden ferocity. “I’m sorry for disrespecting you miss.”

He didn’t have a chance to finish his sentence before an Imperial Legate came round the corner and saw Aelia clutching Aaron’s shoulder.

“What in the devils are you doing woman?” he yelled. “You should be executed for this behaviour.”

Swiftly, she retreated and stood protectively in front of Julius. The Imperial Legate stroked his stubbly chin. “Now that I think about it, you would be more useful alive – and your brother too.”

Nervously, Aaron murmured, “Are you sure that’s necessary, sir. I mean, they’re just harmless Celts.”

The Imperial Legate shot him an intimidating look, grabbed Aelia and Julius and led them away from the amphitheatre.

He took them to a large cart with other people who had been picked off the streets and around half a dozen soldiers. After they were all hustled on, the guards whipped the horses and, abruptly, they started moving. Julius and Aelia had been squeezed between a slender, pale man who looked like he was going to faint at any moment and a bulky guard whose armour was digging into Julius’s rib cage. They were about three quarters of the way through their journey when the slender man suddenly lurched forward, clutching his chest, and collapsed on the floor.

“Great. Another one,” muttered the nearby guard. He pulled himself up, dragged the man’s body and, to Aelia’s utter horror, heaved it out the back of the cart. However, that wasn’t the worst of it. The body tumbled straight into the path of the horses of the next cart behind them. It was not a pretty sight – Julius never forgot it for the rest of his life. When the sounds of splintering bones had died down, everyone acted like it’d never happened. Julius felt sick.

“Is that what’s going to happen to us?” Julius whispered to Aelia.

Aelia looked at him but said nothing; he had a bad feeling, he knew what her answer would be.

Nobody said a word until they arrived at the villa and the soldiers led them outside.The first thing Julius noticed when he stepped down was the unbelievable size of the villa. Leading up to it were dozens of marble steps which curved gracefully around the hundreds of skilfully pruned trees, which left one spot clear where the rotund figure of the Emperor was standing. As the guards herded them closer, Julius spotted a golden laurel wreath adorned on his head that seemed to blind everyone around him with the reflection of the moonlight. Aelia squeezed his hand as the Emperor slowly stumbled down the marble steps.

“That journey was nowhere near long enough for us to be in Rome. So what is he doing here?” she whispered.

Julius looked at her with a raised eyebrow, “How should I know?”

She sighed and Julius could see her suddenly stifle a laugh. He followed her gaze and did the same – the Emperor was doing an extremely bad job of getting down those stairs successfully. Five guards had to drop their weapons and support his flabby body – it was a ridiculous sight.

Eventually, he wiped the sweaty hair out of his face – it was hard to take him seriously at this point – and brought his eyes to look at his newest victims. There were four: Aelia, Julius, a young girl who was sobbing uncontrollably, and a man who looked to be in his thirties.

“Now, you lot should know just how special and lucky you are to be addressed by me – the Emperor. You’re going to be used as slaves and gladiators in my new fortress, The Isca Augusta.”

He waved his arm and shuffled around to make the treacherous journey back up the marble steps while the guards hustled them through the nearest gate. That was not how Julius had wanted to spend his summer. Everyone was so shocked and nobody made a sound until they reached the barracks. Julius was breathing very heavily and gasped when he felt a crusty hand seize his wrist.

“You, boy. Come with me.”

It was a guard. Julius shook his head. “Not without my sister, you filthy Roman!”

Nose flaring, he gripped Julius even harder and growled through gritted teeth. “You will come with me now or I’ll feed you to the lions.”

Julius’s face noticeably paled and he glanced behind him to look for Aelia, but she was already gone. Reluctantly, he allowed the guard to drag him away.

Julius spent the rest of the evening shivering on his stone bed surrounded by stone walls with a few metal bars over a small gap in the stone. He couldn’t stop thinking about Aelia – he wondered if he would ever see her again. Just as he was about to fall asleep, he heard a loud rumbling noise followed by a voice that came from above his head.

“Hey, stop what you’re doing! No don’t come any closer!”

Whoever was standing there collapsed and their body was dragged behind a pile of barrels. Julius stood up on the bed to get a better look and nearly screamed when he saw a blue-streaked face peering down at him through the bars.

“You, boy,” the person hissed. “How would you like to help murder the Emperor?”

Julius’s face lit up and he nodded enthusiastically.

“Great! Now, you can’t do that stuck in here. I’ll have to find a way to get you out.”

As the stranger looked around, Julius tried to get a good view of their face. She was obviously a Celt (the blue markings on her face and ginger hair) but this one looked familiar

important even.Then it hit him – he almost smacked himself in the forehead for being so stupid. This was Boudicca, Queen of the Celts.

Julius was so confused he didn’t notice that she’d already prised open the cell door with a wooden plank and was leaning against the doorway looking at him expectantly.

“What...? How...?” he stuttered.

“Easy trick I learnt as I kid. Anyway, I’m sure you noticed that the Emperor is here instead of Rome. I don’t care why but I’m going to use this opportunity wisely. The plan is that a couple of my soldiers are going to cause a distraction to lure away all his guards and then, we pounce.”

Stretching her arm behind her back, she brought out a bulky dolabra with lots of Celtic engravings of symbols which Julius recognised – death. It had a pointed edge on one end and on the other it looked like something which should be used to smash rocks apart.

“What… am I… meant to do with this?” he managed to say.

This,” she announced, grinning, “is what you’re going to use to murder the Emperor!”

Julius glanced back at the dolabra disbelievingly and realised that she was serious. Suddenly, he heard a loud clattering noise coming from behind him – he swiftly spun around and saw a soldier that he recognised.

“Aaron!” He called.

Turning around, Aaron was greeted by a recently-sharpened sword to the throat.

“No, stop! I know him. He saved me from falling to my death!” Julius yelled, pushing the sword down away from Aaron’s throat.

Boudicca narrowed her eyes and slowly brought it down, “Fine, but this doesn’t mean that I acknowledge you as an ally.”

Aaron sighed and rubbed his throat gingerly – the tip of the sword had left a deep red mark.

“Now, we’re going to murder the Emperor,” Boudicca told him.

His eyes widened but he was still too shocked to say anything so he simply nodded. Boudicca marched out of the door with Julius and Aaron close on her heels. Soon after, they were accompanied by the rest of her troops. Surprisingly, they didn’t run into any obstacles before they reached the Emperor’s room, which was conveniently placed right by the open exit.

This seems too easy, Julius thought.

Nevertheless, he followed everyone around the corner, dolabra in hand.

Boudicca ushered him to the front as two Celts started to yell and wave their weapons in the air. They rushed out the nearby gate with about five guards chasing after them, leaving the Emperor unattended.

“Come on kid,” Boudicca whispered. “This is your chance.”

Julius took a big breath and slunk around the corner. Sensing everyone watching him, he quickly slid behind a bronze shield and exhaled nervously.

“I don’t trust this kid. I mean, didn’t Boudicca find him locked up in a gladiator’s cell,” hissed a strange voice that obviously belonged to one of her followers.

Hearing this, Julius turned round to give him a look and shuffled around the perimeter of the shield until he caught sight of the Emperor in the corner of his eye. Without hesitating, he ducked behind a pillar with the face of a woman with long snake-like hair. Somehow, the Emperor hadn’t heard him yet and was oblivious to what was about to happen. Julius stepped out from behind the sculpture and – with shaking, sweaty hands – brought the dolabra crashing down on his skull. An ear-splitting crack echoed through the room as the body of Emperor Augustus crumpled onto the mosaic floor. Julius dropped his weapon and brought his blood-splattered hands up to his face.

“What have I done?” he cried.

But it was even worse than how he’d imagined. As he looked more carefully at the body’s face, horror swallowed him whole as he realised something that would endanger them all.

“This isn’t the Emperor...!” he yelled. “It’s a trap!”

As soon as he said that, guards burst in from the adjacent rooms and surrounded the Celts – swords aimed at their throats. Terrified, Julius scrambled behind the same pillar and prayed to Ollathir, the god of death, to survive at least one more day. Luckily, they hadn’t noticed him yet and were concentrating on Boudicca and her troops, who didn’t seem to be scared at all.

“Well, well, well. How about that,” the Emperor sneered, coming out from behind the curtain. “You actually mistook that lowlife imperial legate for me – even you, Boudicca. Now, I’m going to kill you.”

Julius had to do something, he couldn’t just stand by and watch them being slaughtered. Doing the first thing that came to mind, he peeked his head out from the cover of the pillar.

“Hey, over here Augustus! How about you pick on someone your own size?”

Emperor Augustus’s face turned bright red because he was very sensitive about his height – “Guards, kill him!” he ordered.

When they drew their attention away from the Celts, the Celtic band barged through the soldiers and fled through the gates, Aaron and Boudicca included. Julius had never really thought of Boudicca as the running-away type but he could understand – he could hear them cheering in the distance and he smiled.

Still behind the statue, Julius realised with dread that he’d never actually seen Aelia since they got split up and that broke his heart. But he knew that some way or another, she would find out. And his parents too. They’d be so proud of him. His name would go down in history. Bringing himself back to the present, he noticed that all the guards had their swords pointed directly at him. “At least,” he thought, “it’ll be a more or less quick way to go. Grinning, he looked directly into the eyes of the Emperor.

“Do your worst.”

Some weeks later, a Celtic stonemason switched the pillar that Julius had died behind with one bearing a Celtic moustache to remind everyone of the Celtic boy who saved Boudicca.

The boy looked at Robert disbelievingly.

“What do you mean you don’t know what it is? What kind of a tour guide are you?”

Robert scoffed, “And what, you do?”

The boy explained the story from the beginning and it left Robert gobsmacked. Sighing, the boy unlatched his satchel and brought out a fragment of the pillar with a piece of Medusa’s Celtic moustache in surprisingly good condition.

Robert stared at it with wide eyes and a gaping mouth, “What... How did you get that?”

Looking up at him with a twinkle in his eye, the boy winked. “Let’s just say this is a family affair.”