Daniel Libeskind CityLife-Pinnacle

CASALGRANDE PADANA

Pave your way

PERCORSI IN CERAMICA

rivista di segni e immagini magazine of graphics and designs

direttore responsabile editor-in-chief

Mauro Manfredini

progetto e coordinamento grafico art director

Cristina Menotti, Fabio Berrettini

coordinamento editoriale e redazione testi editorial co-ordination and text editing Livio Salvadori, Alfredo Zappa

stampa printing

Arbe Industrie Grafiche

Tassa pagata

Postage paid

Casalgrande Padana

Via Statale 467, n. 73

42013 Casalgrande (Reggio Emilia)

Tel. +39 0522 9901

Ai sensi del D.LGS. n. 196/2003, la informiamo che la nostra Società tratta elettronicamente ed utilizza i suoi dati per l’invio di informazioni commerciali e materiale promozionale.

Nei confronti della nostra Società potrà pertanto esercitare i diritti di cui all’art. 13 della suddetta legge (tra i quali cancellazione, aggiornamento, rettifica, integrazione).

Autorizzazione del Tribunale di Reggio Emilia

n. 982 del 21 Dicembre 1998.

Lo standard FSC® definisce la tracciabilità di carta proveniente da foreste correttamente gestite secondo precisi principi ambientali, sociali ed economici. Il rigoroso sistema di controllo prevede l’etichettatura del prodotto stampato realizzato con carte FSC®

The FSC® standard certifies paper traceability to forests managed according to well-defined environmental, social and economic requirements. The strict monitoring system also includes the use of the “Printed on FSC® paper” label on printed products.

in copertina cover story

4 CITYLIFE MILANO

8 Residenze Libeskind

10 L’intervento di Casalgrande Padana

15 Linea Granitoker - serie Travertino

16 DANIEL LIBESKIND POESIA E COSTRUZIONE

30 PINNACLE UNA COLLABORAZIONE IN PROGRESS

37 Biografia di Daniel Libeskind

4 CITYLIFE MILAN

9 Residenze Libeskind

13 Casalgrande Padana’s role

15 Granitoker line - Travertino series

24 DANIEL LIBESKIND POETRY AND BUILDING

30 PINNACLE AN IN-PROGRESS JOINT PROJECT

Impresa e architettura

Mettersi insieme è un inizio, rimanere insieme è un progresso, lavorare insieme un successo, affermava l’antesignano Henry Ford. Lavorare insieme agli architetti, sostenendone le idee e sostanziando la loro realizzazione, costituisce per Casalgrande Padana l’approccio metodologico fondamentale del suo agire. Un percorso imprenditoriale segnato da numerose esperienze significative a fianco dei protagonisti del panorama architettonico internazionale, come nel caso di Daniel Libeskind con cui Casalgrande Padana ha condiviso l’importante realizzazione delle Residenze CityLife di Milano, attraverso la fornitura di 50.000 mq di rivestimenti ceramici di facciata, e successivamente l’installazione Pinnacle, progettata e costruita in occasione di Bologna Water Design 2013, la manifestazione di design urbano che ha accompagnato la scorsa edizione di Cersaie. Il rapporto con l’architetto newyorkese si è ulteriormente concretizzato attraverso un accordo di collaborazione, che prevede il progetto e la realizzazione di alcune nuove serie di pavimentazioni e rivestimenti ceramici in grès porcellanato, di cui le lastre utilizzate per Pinnacle costituiscono la prima anticipazione.

Il racconto di queste esperienze di architettura, design e produzione industriale rappresenta l’asse portante del numero di “Percorsi in Ceramica” che state sfogliando, interamente dedicato alla figura di Libeskind e ad alcune delle sue opere più recenti. Nato nella polacca Łód´z, ma americano d’adozione, Daniel Libeskind si è laureato nel 1970 alla Cooper Union di New York, città dove tutt’ora risiede e lavora. L’elevato spessore intellettuale e artistico che lo contraddistingue si esprime con un originale metodo progettuale che riflette il suo coinvolgimento nelle più diverse discipline, dalla filosofia all’arte, dalla letteratura alla musica. Considerato tra i protagonisti assoluti dell’architettura contemporanea, nelle sue opere combina scienza, matematica, astronomia e design.

Una testimonianza diretta del suo modo di pensare e progettare viene offerto in queste pagine attraverso un’interessante intervista rilasciata a margine della cerimonia di premiazione della IX edizione del Grand Prix Casalgrande Padana, dove Libeskind, in qualità di ospite d’onore, ha tenuto una Lectio magistralis

Enterprise and architecture

“Coming together is a beginning, keeping together is progress and working together is success”, is one of Henry Ford’s visionary quotes. For Casalgrande Padana working with architects, supporting their ideas and giving substance to their creation is the crucial and principal driver of its every action. This entrepreneurial process is littered with many significant projects side by side with the protagonists of the international architecture scene, as in the case of Daniel Libeskind. With him, Casalgrande Padana shared the ambitious Residenze CityLife project in Milan, by supplying 50,000 m2 of ceramic façade cladding and subsequently with the Pinnacle project, designed and built during 2013 Bologna Water Design event, an urban design show held last year during the Cersaie exhibition.

The relationship with the New York based architect further strengthened with a collaboration agreement involving the design and construction of several new ceramic stoneware flooring and cladding series, as testified to by those used for the Pinnacle project. The tale of these architecture, design and industrial production experience is the backbone of the “Percorsi in Ceramica” issue you are reading, which is entirely devoted to Libeskind as an architect and some of his most recent works.

Born in Lodz, Poland but American by adoption, Daniel Libeskind graduated in 1970 at New York’s Cooper Union. He still resides and works in the Big Apple. The remarkable intellectual and artistic value he stands out for are expressed in his personal approach to design that mirrors his involvement and interest in several disciplines, from philosophy to art, from literature to music. Considered among the absolute protagonists of contemporary architecture, his works combine science, mathematics, astronomy and design.

This is a direct testimony of this way of thinking and designing, provided in these pages in the form of an interview he released during the IX Grand Prix Casalgrande Padana edition award ceremony, where Libeskind, the guest of honour, delivered a keynote speech.

CityLife

CityLife

La riqualificazione dell’area un tempo occupata dal polo urbano della Fiera di Milano, promossa da CityLife, prevede interventi firmati da grandi architetti quali Zaha Hadid, Arata Isozaki e Daniel Libeskind. Il masterplan è stato sviluppato per assicurare una articolata integrazione tra funzioni pubbliche e private, residenze e uffici, shopping center e servizi, aree verdi e spazi per il tempo libero. Il profilo del quartiere è fortemente arricchito dalla creazione del grande parco pubblico di 168.000 metri quadrati - terzo nella città dopo il Parco Sempione e i Giardini Montanelli - che andrà a integrarsi con le zone verdi del settore nord-ovest della metropoli.

Il fulcro di CityLife è rappresentato dalla grande piazza al centro dell’area, su cui si affacciano tre torri destinate a uffici e dove è prevista la stazione della nuova linea metropolitana M5. Attorno alla piazza, un sistema di spazi commerciali con negozi e servizi di qualità è in grado di rendere l’intero quartiere attivo durante tutto l’arco della giornata. A sud dell’area sorgono le Residenze Hadid e le Residenze Libeskind, due interventi differenziati dalla cifra architettonica, ma accomunati da standard di grande pregio, che trovano i loro punti di forza non solo nei livelli di finitura, ma anche nell’innovazione delle soluzioni spaziali, nel diffuso ricorso alla domotica, nella ricerca del massimo comfort e dell’elevata efficienza energetica.

Residenze e uffici di CityLife adottano prevalentemente fonti di energia

rinnovabili. Il teleriscaldamento, alimentato dal termovalorizzatore di Figino, soddisfa le esigenze delle torri a uffici e fornisce acqua calda sanitaria anche alle abitazioni. L’acqua di falda viene invece impiegata per alimentare gli scambiatori e le pompe di calore per il riscaldamento e il raffrescamento delle residenze. Pannelli fotovoltaici posti in copertura, alimentano gli impianti a servizio degli spazi comuni, riducendo sensibilmente i consumi energetici.

The development process involving the area formerly occupied by the Urban Milan Fair facility, promoted by CityLife, rests upon a number of projects designed by undisputed masters of architecture, including Zaha Hadid, Arata Isozaki and Daniel Libeskind. The masterplan was developed to ensure the articulate integration between public and private functions, residential solutions and offices, shopping centres and services, green areas and spaces for leisurely activities. The profile of the neighbourhood is enhanced by the 168,000-m2 public park – Milan’s third largest after Parco Sempione and Giardini Montanelli – that will fit perfectly in the city’s north-western green belt. The heart of CityLife is the spacious plaza at the very centre, with the three office towers developing around it. The area will also house a station along the newly built M5 underground line. Around the square, a commercial area with shops and quality services will liven up the entire complex throughout the day. South of the plot is where Hadid’s and Libeskind’s residential buildings lay. The two projects feature different architectural styles, though they share the same uncompromising quality, which rests not only on the finishes, but also in the innovative approach to spatial solutions, the pervasive use of home automation, the research for sheer comfort and high energy efficiency. The CityLife residences and offices mainly use renewable energy sources.

District heating, fed by the Figino WTE plant, meets the requirements of the office towers and provides hot water to the apartments. In turn, ground water is used to feed the heat exchangers and heat pumps for heating and cooling in the apartments. Photovoltaic panels on the roof feed common services and reduce energy consumption remarkably.

CITYLIFE

Residenze Libeskind

Per CityLife, oltre a una delle tre torri a uffici, Daniel Libeskind ha ideato un complesso residenziale composto da otto edifici, distribuiti su due aree, indagando il classico schema tipologico a corte aperta, attraverso una personale riflessione sul tema della segmentazione e ricomposizione dei volumi, finalizzato alla ricerca di un’armonica relazione tra i fabbricati e il contesto di riferimento, tra il costruito, le aree di servizio e i grandi

spazi verdi che circondano e qualificano l’intero insediamento.

Le Residenze Libeskind, diverse per tipologia, affaccio, disposizione e altezza (da 4 a 13 piani), ospitano bilocali, trilocali e attici di varie superfici, con aree di soggiorno a doppia altezza.

Tutti gli alloggi sono concepiti per offrire grandi superfici vetrate e terrazze panoramiche sul parco e la città.

Grazie a scelte impiantistiche mirate, a soluzioni costruttive di assoluta qualità e al sofisticato sistema di facciata, le Residenze Libeskind assicurano i più elevati standard in termini di efficienza energetica e hanno conseguito la certificazione in classe A.

Gli appartamenti sono dotati dei più moderni accorgimenti in termini di domotica, grazie ai quali sarà possibile gestire tutte le principali funzioni attraverso un sistema integrato.

Residenze Libeskind

For CityLife, besides one of the office towers, Daniel Libeskind also designed an eight-building residential complex divided in two areas. To do so, he analysed the open court model, and through a very personal reflection on the issue of volume segmentation and re-composition he managed to accomplish a balanced relation between the buildings and the surrounding context, between the rises and the wide green areas that surround and characterise the entire project.

The Residenze Libeskind are different in terms of typology, direction, position and height (from 4 to 13 floors) and feature tworoom, three-room apartments and penthouses of varying surfaces, with living room areas being twice as high. All the apartments are designed to feature large glass surfaces and panoramic balconies overlooking the park and the city. Thanks to very sensible choices in terms of systems, the topquality building solutions and the sophisticated façade system, the Residenze Libeskind project ensures high energy efficiency standards, so much that the apartments are energy Class A certified. The apartments are fitted with state-of-the-art home automation solutions, allowing to access the main functions through an integrated system.

CityLife

L’intervento di Casalgrande Padana

Il complesso delle Residenze Libeskind si impone nel paesaggio urbano milanese. La cifra stilistica di Daniel Libeskind si evidenzia in particolare nelle soluzioni di facciata, dove l’uso accurato dei materiali ceramici asseconda ed enfatizza l’esuberante plasticità della struttura.

Veri e propri elementi del linguaggio espressivo, le lastre in grès porcellanato utilizzate per il rivestimento di superfici e volumi concorrono in modo determinante alla valorizzazione dell’intero progetto. Il raffinato dinamismo dei prospetti è definito dalla scansione modulata del paramento ceramico che avvolge la costruzione. Coerentemente eseguita in ogni dettaglio, la messa in opera della parete ventilata e dei parapetti di terrazze e balconi segue un preciso schema di posa, calibrato sullo sviluppo volumetrico del manufatto architettonico e rispondente a particolari esigenze di progetto.

Gli autori dell’impresa I lavori di messa in opera dei rivestimenti ceramici dell’involucro sono stati effettuati dall’Associazione temporanea di imprese formata da Casalgrande Padana e dalle società Ceramiche Frattini e Tempini. Gli oltre 120 posatori altamente specializzati impiegati nella realizzazione hanno eseguito direttamente in cantiere le necessarie lavorazioni a misura sulle lastre ceramiche seguendo il disegno delle facciate.

L’esperienza e le competenze delle maestranze, unitamente alle particolari soluzioni applicative messe a punto dai tecnici hanno consentito di portare a termine un progetto di grande difficoltà esecutiva per quanto riguarda il rivestimento ceramico, permettendo la completa realizzazione dell’idea progettuale dell’Architetto Libeskind.

Per i rivestimenti di facciata, sono stati utilizzati oltre 50.000 metri quadrati di materiali ceramici forniti da Casalgrande Padana, espressamente studiati e prodotti per questo intervento e applicati secondo specifiche indicazioni costruttive, che hanno richiesto la messa a punto di soluzioni tecniche in grado di soddisfare elevate prestazioni di sicurezza.

Il paramento di finitura esterna della parete che riveste i piani tipo e le penthouse è costituito da un pannello di supporto in fibrocemento a cui sono fissate mediante incollaggio e aggancio meccanico di sicurezza a scomparsa (Kerfix) le speciali lastre in grès porcellanato. Due le serie

CityLife

utilizzate: Linea Granitoker - serie Travertino Paradiso Grigio M8, nei formati 30x90 e 60x90 cm e Linea Granitogres - serie Unicolore Bianco B Levigato, nel formato 22,5x90 cm.

Le lastre della serie Travertino sono state utilizzate anche per il rivestimento dei parapetti e dei celini di terrazzi e balconi. In questo caso l’applicazione è stata eseguita direttamente sulla struttura di cemento armato, con le stesse modalità di posa tramite colla e fissaggio meccanico a scomparsa.

Gli elementi ceramici sono incollati al supporto mediante la tecnica della doppia spalmatura: la colla viene stesa sia sul retro della piastrella, sia sul supporto in fibrocemento o cemento armato. Il fissaggio meccanico a scomparsa è costituito da un gancio metallico (Kerfix) inserito e incollato sul retro della lastra ceramica, preventivamente predisposta ad accoglierlo con l’esecuzione di un apposito intaglio. Il tutto viene successivamente assicurato al supporto cementizio con l’ausilio di chiodi o viti.

L’intervento sino a oggi portato a termine ha coinvolto 5 edifici delle Residenze Libeskind, per complessivi 43 piani fuori terra più le penthouse e 362 balconi. Per comprendere la complessità esecutiva del rivestimento bisogna considerare che, pur essendo tutti caratterizzati dalla stessa pianta semisferica, i piani di ogni palazzo risultano unici e differenziati. Gli stessi balconi sono uno diverso dall’altro e caratterizzati da superfici inclinate e linee virtuali di continuità, studiate da Libeskind per armonizzare l’intera superficie dell’involucro.

Casalgrande Padana’s role

The Residenze Libeskind complex stands out in the Milanese urban landscape. Daniel Libeskind’s style stands out in particular in the façade, where the accurate use of ceramic material follows and emphasises the exuberant plasticity of the structure.

True elements of his expressive language, stoneware slabs used for volume and surface cladding play a key role in the value of the whole project. The sophisticated dynamism of the perspective is defined by the modular pace of the ceramic envelope, which develops around the building. Performed consistently in every detail, the ventilated wall and balcony and terrace parapet installation followed a very precise and accurate process, based on the volume of the building and catering to the specific project requirements.

The façade cladding employed 50,000 m2 of ceramic material supplied by Casalgrande Padana, designed and produced for the purpose and applied according to specific building indications, which required such technical solutions to meet high safety requirements.

The outer wall envelope around the floors and the penthouse is made by a fibre cement panel to which the special stoneware slabs are secured by means of glue and special recessed mechanical hooks (Kerfix). The employed series are two: Granitoker line - Travertino Paradiso series in M8 grey, in the 30x90 and 60x90 cm sizes, and Granitogres line - Unicolore Bianco B Levigato series in the 22.5x90 cm size.

The authors

The envelope ceramic cladding was laid and installed by a temporary association of enterprises formed by Casalgrande Padana, Ceramiche Frattini and Tempini.

The project involved over 120 highly qualified installers, who did all the custom adjustments to follow the façade design directly on the construction site.

The great experience and skill of the involved installers and the very specific application solutions designed by the technicians allowed to complete a very challenging ceramic cladding project, thus turning Libeskind’s creative idea into complete, full reality.

CityLife

The Travertino series slabs were used also for the terrace and balcony parapets and covers.

In this case, the installation was performed directly onto the reinforced concrete structure, with the same glue and recessed mechanical fixing method.

The ceramic elements are fixed onto the support by means of a double buttering technique: the glue is spread both on the back of the slab and on the reinforced concrete or fibre cement support. The recessed mechanical fixing is made with a metal hook (Kerfix) fitted and glued on the back of the ceramic slab, which was prepared beforehand with a suitable slot.

Finally, the assembly is fitted onto the concrete support with nails or screws.

The works completed to date involved 5 buildings of the Residenze Libeskind complex, for a total of 43 storeys above the ground, the penthouses and 362 balconies.

In order to grasp the complexity involved in the cladding, it should be considered that, though all floors feature the same semi-spherical plan, those in each building are unique and different from the others. The same balconies are different and stand out for slanted surfaces and virtual continuity lines, which Libeskind studies to give the whole envelope surfaces a harmonic movement.

GRANITOKER TRAVERTINO

Espressamente studiata e prodotta per l’intervento alle Residenze CityLife, la nuova serie Travertino presenta le stesse proprietà degli elementi ceramici a elevato contenuto tecnico ed estetico della linea Granitoker. Ottenuti con la più avanzata tecnologia applicata al grès porcellanato pienamente vetrificato, questi materiali ripropongono granulometrie, venature, cromatismi, matericità e finiture superficiali uguali a quelli presenti in natura, mentre i livelli prestazionali risultano addirittura superiori.

Disponibili nei grandi formati 60x90 e 30x90, nel colore Grigio M8, queste lastre sono caratterizzate da elevate prestazioni di resistenza all’usura, all’urto, allo scivolamento, alle macchie e agli sbalzi di temperatura.

Come tutta la produzione Casalgrande Padana, la serie Travertino si caratterizza per i contenuti di ecocompatibilità. L’azienda, infatti, da sempre è impegnata nella ricerca di tecnologie innovative per produrre materiale dalle alte prestazioni ma a basso impatto ambientale, come testimoniano le certificazioni ISO 14001 ed Emas.

Caratteristiche tecnico-prestazionali

Tipologia prodotto: linea Granitoker, grès porcellanato.

Classificazione: Gruppo B1a GL completamente greificato (UNI EN 14411, ISO13006).

Formati: cm 60x90 e sottomultipli.

Spessore: mm 9,5.

Colori: Grigio M8.

Finitura: superficie naturale e satinata.

Caratteristiche dimensionali e d’aspetto: tolleranze minime nella 1a scelta (UNI EN ISO 10545-2). Assorbimento acqua: ≤ 0,1% (UNI EN ISO 10545-3).

Resistenza alla flessione: N/mm2 50÷60 (UNI EN ISO 10545-4).

Resistenza al gelo: garantita (qualsiasi norma).

Resistenza attacco chimico (escluso acido fluoridrico): nessuna alterazione (UNI EN ISO 10545-13).

Resistenza usura e abrasione: alta (UNI EN ISO 10545-7).

Dilatazione termica lineare: 6x10-6 (UNI EN ISO 10545-8).

Resistenza alle macchie: garantita (UNI EN ISO 10545-14).

Resistenza dei colori alla luce: nessuna variazione (DIN 51094).

Specifically designed and produced for the Residenze CityLife project, the new Travertino series features the same properties as high technical and aesthetic content ceramic elements in the Granitoker line. Made with the latest technology applied to fully vitrified stoneware, this series features the coarseness, veneer, colour, texture and surface finish found on natural stone, while the performance is even better.

Available in large 60x90 and 30x90 sizes, in M8 grey, these slabs stand out for high resistance to wear, shock, slip, stain and temperature shock.

As the rest of the Casalgrande Padana products, the Travertino series stands out for its high environmental compatibility. Indeed, the company has always been committed to researching new technology and solutions to produce high performance, low environmental impact material, as the ISO 14001 and Emas standards testify.

Technical and performance characteristics

Product type: Granitoker line.

Classification: fully vitrified group B1a GL (UNI EN 14411, ISO13006).

Sizes: cm 60x90 and sub-multiples.

Thickness: 9.5 mm.

Colours: M8 grey.

Finish: natural and satin surface.

Size and finish: minimum tolerance in 1st choice (UNI EN ISO 10545-2).

Water absorption: ≤ 0.1% (UNI EN ISO 10545-3).

Flexural resistance: N/mm2 50÷60 (UNI EN ISO 10545-4).

Frost resistance: guaranteed (all standards).

Chemical resistance (except hydrofluoric acid): no damages (UNI EN ISO 10545-13).

Wear and abrasion resistance: high (UNI EN ISO 10545-7).

Linear thermal expansion: 6x10-6 (UNI EN ISO 10545-8).

Stain resistance: guaranteed (UNI EN ISO 10545-14).

Light fastness: no variation (DIN 51094).

Daniel Libeskind

Poesia e costruzione

Abbiamo incontrato Daniel Libeskind in occasione della Lectio magistralis che ha tenuto a Milano nel quadro della cerimonia di premiazione del IX concorso internazionale di architettura Grand Prix Casalgrande Padana. A pochi passi da noi, il suo cantiere per le Residenze CityLife, con le facciate rivestite in lastre ceramiche prodotte da Casalgrande Padana, era in fase di completamento, mentre per l’adiacente Torre Arduino si stavano impostando le strutture di fondazione. Un eloquente work in progress che ci ha consentito di spaziare a tutto campo e collocare i progetti italiani di Libeskind nel quadro più ampio della sua visione espressiva e metodologica, rivelando un approccio estremamente sensibile e originale al rapporto tra architettura e costruzione.

Architetto Libeskind, quali sono secondo lei i segnali di cambiamento che il mondo del progetto deve essere in grado di saper cogliere oggi?

Ho la sensazione che, mentre la tecnologia continua a evolvere con tutte le sue possibilità e il mondo diventa più globale, stia aumentando il desiderio di esprimere qualcosa che esula dalla sfera tecnica per collocarsi in quella delle scienze umane, nella poesia, nella tragedia, nella storia, nelle tradizioni. Insomma penso che questa sia la strana contraddizione tra ciò che si desidera e ciò che ci viene offerto.

Daniel libeskinD

Lei ha progettato molti luoghi collettivi. Spazi per riflettere e far riflettere. Quale ritiene sia il significato del fare architettura oggi?

Credo che fare architettura oggi non sia differente dal passato. Abbiamo una diversa tecnologia, diverse possibilità, diverse aspirazioni sociali. Ma per me l’architettura rimane qualcosa che deve comunicare con l’essere umano, lavorare con la luce, i materiali, le proporzioni, deve dire qualcosa, non solo essere un’astrazione. L’architettura è al tempo stesso un’idea intellettuale e un’idea poetica.

In questo senso, attraverso quali percorsi il lavoro dell’architetto può contribuire a rispondere ai bisogni della società?

Esiste ancora spazio per fare architettura in termini di impegno civile?

Il nostro lavoro deve essere impegnato dal punto di vista civile. A mio parere l’architettura non è solo quella realizzata per piccoli gruppi di persone, ma quella fatta per le città, per i cittadini, per la politeia. Quindi è ovvio che tutta l’architettura per come la intendo io è uno strumento sociale che, oltre a migliori luoghi in

cui vivere, serve a sviluppare un senso di collettività culturalmente più elevato.

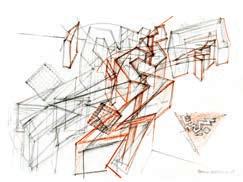

Sappiamo che lei ama molto disegnare. In un mondo pervaso dagli strumenti di disegno computerizzato, perché il tratto a mano libera ha un ruolo così importante nel suo processo creativo?

Non so rispondere in maniera oggettiva, ma le cose stanno proprio così. Il disegno a mano libera penso sia il modo più immediato per collegare il pensiero e le idee con la realtà. Ma non è tutto. Disegnare ha anche una tradizione storica: il disegno non l’abbiamo inventato noi architetti, esiste da migliaia di anni. Quindi utilizzare il disegno tradizionale, per me significa entrare nel solco che guida l’architettura nel suo cammino verso il nuovo.

E cosa pensa di fronte a un foglio di carta bianca? Chi ha la meglio, il programma o l’ispirazione? In verità di fronte un foglio di carta bianca non penso mai. Con un foglio bianco davanti agli occhi non ho mai pensato: “E ora cosa dovrei disegnare?”. Non mi è mai successo perché c’è sempre qualcosa che lavora nella mia testa, nel cuore, negli occhi. Disegnare non è

Reflections at Keppel Bay Keppel Bay, Singapore CityLife Milan, Italycome compilare un libro contabile, non significa mettere insieme cose che già si sanno, è solo una diversa forma di comunicazione. Per me il disegno scaturisce da qualcosa che non ha origini esplicite ma è lì, nel disegno stesso.

Gli interessi personali di Libeskind non sono però circoscritti solo al disegno.

Tutti sanno che ama la musica, la storia, la filosofia, la poesia, il teatro. Un insieme di sensibilità e competenze multidisciplinari che concorrono più o meno direttamente alla composizione di un’architettura di forte carica simbolica. Certezze e incertezza. Ragione e irrazionalità. Un’architettura disobbediente, difficile da domare anche in termini costruttivi.

Le sue opere sono più difficili da concepire o da costruire? E che rapporto esiste tra poesia e costruzione?

È in primo luogo l’atto del costruire a essere poetico.

L’idea di realizzare qualcosa, metterla alla luce del giorno e dargli un fondamento è innanzitutto un’idea poetica. Ma secondo me la complessità non deriva solo

dalla difficoltà. Ogni progetto che abbia un vero obiettivo è difficile, perché non è la ripetizione di una formula, non è un secondo tentativo, è il primo e originale modo di fare quella cosa.

Le scienze umane (filosofia, letteratura, cinema, pittura, storia ecc.) vanno intese come l’arte di porre domande. Non tutte le domande sono belle, non tutte hanno una facile risposta, eppure è così che nascono le cose. Le grandi opere del passato, in ogni disciplina, ci hanno insegnato a comprendere come sia necessario molto tempo per coglierne la complessità ai diversi livelli. In questo senso l’architettura è anche comunicazione, fatica e lotta per esprimere qualcosa capace di andare al di là di sé stessa.

Tra progetto e realizzazione passano spesso molti anni. Non le è mai capitato di avere ripensamenti durante questi lunghi periodi di gestazione. Momenti in cui, a posteriori, avrebbe voluto fare le cose in un altro modo?

Si pensa sempre alla possibilità di fare qualcosa in un altro modo, a secondo delle circostanze, delle procedure, del budget. Ma fare qualcosa in un modo

Ground Zero Masterplan New York, USA Jewish Museum Berlin Berlin, GermanyDaniel libeskinD

diverso significa anche che hai un’idea speciale, che può essere realizzata in un altro modo. In realtà, se non hai un’idea, non è molto importante come la realizzi, ma se hai un’idea forte, puoi pensare di esprimerla in tempi e in modi diversi. A mio parere tutta la storia dell’architettura è quest’idea, un’idea speciale espressa in modi diversi.

Anche lei però dovrà lottare contro le pressioni di imprese e committenti. Durante l’iter di un’opera tutti di solito pretendono modifiche. Come gestisce queste situazioni?

In primo luogo bisogna considerare committenti e imprese non come dei nemici, perché se li consideri tali potresti finire per non fare architettura. Bisogna pensare all’obiettivo comune, anche se ci possono essere importanti differenze tra le parti. Bisogna convincere le persone a fare la cosa giusta nel giusto modo. Non è sempre facile, ma credo sia fondamentale formare un sapere condiviso sul valore e l’importanza delle singole scelte rispetto alla riuscita dell’insieme. Altrimenti bisognerebbe guardare tutto esclusivamente dal punto di vista economico e rimarrebbe pochissima architettura.

Durante una lectio magistralis al Cersaie di Bologna, Renzo Piano ha raccontato come nel corso di cantieri molto importanti gli è spesso capitato, per sottrarsi a compromessi e modifiche a cui non voleva cedere, di rassegnare le dimissioni in corso d’opera.

È vero! Io alcune imprese le ho perfino licenziate, e ho licenziato anche alcuni committenti. Ho smesso di lavorare con loro quando ho visto che non c’era modo di andare avanti in modo sensato. Bisogna fare una scelta quasi etica, cercando di capire se i compromessi siano portatori di nuovi valori, oppure se conducono a un risultato negativo non solo per se stessi e per

l’integrità dell’opera, ma anche per la collettività che dovrà trarne beneficio.

La sua è un’architettura autobiografica, di forte impronta personale. Come si relaziona con i suoi collaboratori? È difficile lavorare con Libeskind? Non penso sia difficile lavorare con me. Però è vero, io non credo che l’architettura sia una commedia e non penso che si produca architettura come si produce un’automobile o un’apparecchiatura. È davvero una ricerca molto personale, ma le persone con cui sono così fortunato di collaborare, i miei colleghi e i miei soci, molto spesso sono profondamente partecipi, non eseguono semplicemente il lavoro ma sono intimamente coinvolti in questa ricerca. Il fatto che qualcosa sia molto personale non la rende necessariamente priva d’interesse per gli altri.

Non sono in molti a sapere che lei ha un rapporto speciale con la città di Milano. Qui ha vissuto tra l’85 e l’89 fondando la scuola indipendente Architecture Intermundium. A Milano è nata sua figlia. Ma Milano, non è stata particolarmente generosa con i suoi progetti. Molte polemiche, (la sua architettura è abituata a convivere con la discussione), poi è arrivata la crisi economica, così molte cose procedono a rilento, altre sono in divenire, altre ancora sono state annullate. Credo che questo non succeda solo in Italia, nel nuovo e vecchio mondo ci sono ovunque architetture interrotte. Ma ora stiamo assistendo allo sviluppo del Residence CityLife e della Torre Arduino, che rappresentano i primi passi concreti di un lungo percorso. Quali conclusioni trae da questa esperienza a Milano?

Mi è piaciuto vivere a Milano, altrimenti non sarei qui. Lei ha ragione, è difficile, ma come ha ricordato le

situazioni non sono mai facili se si sta facendo qualcosa che abbia un significato. Bisogna impegnarsi con una città, amarla, crederci. A volte è una maratona, ci vuole veramente molto tempo per ottenere un risultato. Ma io lo preferisco, rispetto allo scatto da centometrista in cui tutto è fatto in modo veloce dopodiché te ne vai da qualche altra parte. Questa è la verità dell’architettura: è complessa, devi sentirti impegnato, appassionato, devi amare una città ed essere consapevole che non tutto ciò che sogni può trasformarsi in realtà.

In fondo è difficile anche per gli architetti italiani lavorare a Milano…

Questo è vero per tutte le città. Ho lavorato per lungo tempo a Berlino, ora a New York e in molti altri paesi del mondo. Ogni luogo ha il suo genere di difficoltà. Non sono le stesse, ma esistono sempre delle difficoltà per produrre qualcosa di buono. Penso che questo non valga solo per l’architettura, ma anche per produrre un buon romanzo, un buon film… anche una buona tazza di caffè richiede un notevole impegno.

Tornando a City Life quali sono i punti di forza del suo progetto?

Direi che sono da ricercare nella costruzione di un complesso ad alta densità, capace di coniugare il ricorso alle più moderne tecnologie e al progetto sostenibile, con una forte identità figurativa e la capacità di interpretare un nuovo desiderio di abitare in comunità, così come una nuova dimensione nell’organizzazione degli spazi, del comfort, della luce naturale e molto altro.

In effetti nel progetto molta attenzione è stata riservata alle soluzioni di dettaglio, alle prestazioni, all’efficienza energetica. È dunque possibile coniugare creatività e tecnologia?

La tecnologia è sempre stata parte dell’architettura.

Daniel libeskinD

Come orientare un edificio, determinare il suo comportamento d’inverno e d’estate, scegliere il sistema strutturale e i materiali, definire gli angoli di visuale, decidere dove sono collocate le aperture e le loro dimensioni, sono questioni riguardanti la costruzione e la sua sostenibilità che ci accompagnano da migliaia di anni. Ora abbiamo a disposizione nuove metodologie, nuovi sistemi di analisi, il desiderio di creare nuovi edifici particolarmente efficienti dal punto di vista energetico.

Ma certo non si tratta di problemi nuovi.

Per me la sostenibilità è al tempo stesso “memorabilità”, se qualcosa non è memorabile non è nemmeno sostenibile, perché te ne puoi liberare nel giro di qualche anno. Se quello che fai è memorabile, ben costruito, funziona davvero per chi ci vive e per i cittadini, allora sicuramente entrerà a far parte e continuerà a essere un elemento inscindibile del patrimonio di un luogo. Ecco cos’è per me CityLife.

È interessante ascoltare queste affermazioni. Infatti qualcuno sostiene che la sua architettura non sia così sensibile alle istanze della tecnologia. È solo poesia…

Mi lasci dire che per me la sostenibilità non è uno stile. Troppe persone pensano oggi che la sostenibilità sia uno stile che fa ricorso a elementi codificati (pannelli solari, tetti verdi e quant’altro), ma non lo è affatto. La sostenibilità non è mai stata uno stile e nei più diversi e lontani momenti storici sono state trovate differenti soluzioni alla domanda di sostenibilità. Esiste una sorta di significato universale in quello che costruisci e non ha nulla a che fare con lo stile, ma con l’architettura. E non è qualcosa che si può mettere in una macchina del progresso, perché esistono edifici realizzati migliaia di anni fa, che sono più sostenibili di molti costruiti oggi.

Ogni materiale esprime una sua carica figurativa, ma

anche costruttiva. In una architettura di contenuti come la sua, quale significato assumono? Anche l’appropriatezza nell’impiego dei materiali ha una grande importanza. Nel rispetto del budget, bisogna non solo banalmente scegliere materiali di buona qualità e con elevate prestazioni, ma privilegiare quelli capaci di contribuire alla tutela dell’ambiente in senso positivo (ad esempio con un basso carbon footprint), quelli prodotti attraverso cicli a basso impatto, quelli di provenienza locale. Il progetto di CityLife a Milano, l’ho affrontato seguendo queste impostazioni. Non ho trasferito nulla da altrove. Ho fatto riferimento al genius loci, ai materiali ai colori alle tecniche e alle capacità dell’industria delle costruzioni locale di lavorare questi materiali. Penso che sia importante. L’obiettivo è costruire qualcosa di nuovo, ma al tempo stesso radicato nelle tradizioni della città.

È facile realizzare miraggi, in alcuni casi può essere anche importante. Ma per me un progetto interessante e sostenibile per il futuro è creare qualcosa che scaturisca dalle tradizioni di una città e ne utilizzi le migliori qualità.

Metallo e vetro sono spesso i protagonisti dei suoi involucri architettonici.

Perché per il Residence CityLife ha scelto la ceramica?

La ceramica mi ha sempre interessato. Quando lavoravo al mio progetto di ampliamento per il Victoria and Albert Museum di Londra, ho fatto molte ricerche sulla ceramica. È un materiale antico, esisteva all’epoca dei babilonesi e non è un caso che sia utilizzato a tutt’oggi. Ha eccellenti prestazioni in termini di resistenza, durabilità, comportamento in climi caldi e freddi e, grazie alle recentissime tecnologie, possiamo controllarne la densità, la colorazione, la luminosità. Quindi è davvero un materiale di riferimento per l’architettura del XXI

Daniel libeskinD

Poetry and building

secolo, che offre la possibilità di essere interpretato e utilizzato in modi veramente straordinari.

Un’ultima domanda: cosa cerca Daniel Libeskind attraverso la sua architettura e cosa trova?

L’architettura è un insieme di domande, non di risposte. In ogni progetto c’è qualcosa di interessante che può essere tematizzato. Che si tratti di una abitazione, un grattacielo, un ospedale, una scuola, che sia in Asia, negli Stati Uniti o a Milano. Ogni progetto sintetizza i mondi tutti insieme in un punto focale tutt’altro che astratto: la costruzione per l’uomo di qualcosa di molto reale.

We met Daniel Libeskind during his visit for the keynote speech he delivered in Milan for the IX Grand Prix Casalgrande Padana international architecture award ceremony. A stone’s throw from us, the building site of his Residenze CityLife project, the facades clad in ceramic slabs made by Casalgrande Padana, was well underway, while the foundations of the Arduino tower next to it were being laid. This eloquent work in progress allowed to us to have an open discussion and analyse Libeskind’s Italian projects more broadly within his expressive vision and methodology, thus revealing an extremely sensitive and personal approach to the relationship between architecture and building.

Jewish Museum Berlin Berlin, GermanyMr. Libeskind, in your opinion, what are the signs of change that the design world should read in today’s world?

I am under the impression that, as technology keeps evolving in all its complexity and the world grows to become more and more global, the desire to express something going beyond mere technicality is increasing, testifying to a renewed interest in human science, poetry, tragedy, history and tradition. Well, I think there is a strange contradiction between what people desire and what they are offered.

You designed many collective spaces, places to think and provoke thoughts. What do you believe is the meaning of being an architect today?

I believe that being an architect today is not different from the past. Technology is different and our possibilities are expanded, not to mention the social value at play. I believe that architecture, though, is still something that must speak to the human being and leverage light, materials, and proportions to say something. It cannot be mere abstraction. Architecture is at once an intellectual and a poetic idea.

In what way, then, can the work of an architect contribute to meeting the needs of society? Is there still some room for architecture means as civil commitment?

Our work must be committed from a civil engagement standpoint. In my view architecture is not for small circles only, but it should be for the sake cities, citizens and the politeia. Therefore it goes without saying that architecture as I mean it is a social tool that improves the quality of a place and contributes to developing a higher sense of community.

We know that you love to draw. In a world full of computer assisted drawing systems, why has freehand

drawing such importance in your creative process?

I cannot give an objective answer to this question, but what you said is absolutely correct. Freehand drawing is the most immediate way, I think, to connect thoughts and ideas with reality. But there’s more: drawing has a very old tradition. It was not the architects who invented drawing; it’s been there for thousands of years. Hence, using traditional drawing for me means to get into the groove that leads architecture in its path towards its renewal.

What do you think before a blank sheet of paper? Between the plan and inspiration, which one prevails?

To say the truth, I never think before a blank sheet of paper. When confronted with a “blank” challenge I never thought: “what should I draw now?” It never happened because there is always something at work in my head, my heart, my eyes. To draw is not like accounting, it does not mean to assemble knowledge that one already has; it is just another form of communication. For me, a drawing stems from something that is not explicit but is there, in the same sketch.

Your personal interests are not limited to drawing, though. It is a known fact that you love music, history, philosophy, poetry and theatre. This ensemble of multidisciplinary interests and skills contribute to a varying extent to a strongly symbolic architecture. Certainty and uncertainty. Reason and irrationality. Your unruly architecture is difficult to tame also in constructive terms.

Are your works more difficult to conceive or to build? And what relationship is there between poetry and building?

First off, the very act of building is poetry. The idea of making something, expose it to the world and

Daniel libeskinD

give it solid foundations is first and foremost a poetic gesture. In my view, though, complexity is not the result of difficulty alone. Any project that sets out to accomplish a goal is in itself difficult, because it is not the mere repetition of a formula, it is not a second attempt at something, but it is a first and original way to do it.

Human sciences (philosophy, literature, cinema, paining, history, etc.) must be construed as the art of making questions. Not all questions are kind, not all of them have an easy answer to them, still, all things are born from questions.

The great accomplishments of the past, in every discipline, taught us to understand how important it takes a long time to grasp complexity at different levels.

Under this light architecture is also communication, as it strives and struggles to express something that goes beyond its mere self.

Many years go by between a project and its coming to life. Have you ever happened to have second thoughts during those long gestation periods? Have there ever been moments when, in hindsight, you would have done things in a different way?

One always thinks about doing things in some other way depending on the circumstances, the processes, the budgets. Doing something in a different way, though, means that you have a special idea in your hands, one that is so versatile that is can be made in a different way.

If truth be told, if you don’t have an idea, it is not important how you translate it into reality; conversely, if you have a strong idea, you can express it in different times and forms. In my view the history of architecture follows this principle; it is a special idea expressed in countless different ways.

I believe you’ too, are exposed to the pressure from companies and clients. All projects, as they unfold, need changes and modifications. How do you manage these situations?

First of all, clients and companies should not be considered as enemies. If you do, you may end up not being an architect any more. You need to think about the common goal, even though there may be differences between the involved parties. You need to talk people into doing the right thing at the right moment. It is not always easy, though I believe it is fundamental to form shared knowledge on the value and importance of single choices in view of the overall outcome. Otherwise we would need to look at everything with the economics of in mind and there would be very little architecture left.

During a keynote speech delivered at Cersaie, in Bologna, Renzo Piano said that he often happened, during very important projects and with the building phase well underway, to tender his resignation to avoid compromising and accepting changes. True! I even fired some companies and even clients. I stopped working with them when I saw that I no longer made sense to work together. It takes an almost moral choice, trying to figure out whether compromising is going to bring new value or if it leads to a negative outcome, not just for yourself, but also for the integrity of the project and the community that will benefit from it.

Your architecture is rather autobiographical and highly personal. How do you relate with your collaborators? Is it hard to work with Libeskind?

I don’t see working with me as difficult or hard. It’s true, though, that I don’t believe architecture to be comedy, and making architecture is nowhere near

manufacturing a car or some appliance. Though the people I am lucky enough to work with, my colleagues and partners, are often very involved in the process, they don’t just follow a script but are intimately involved in this research. The fact of being very personal doesn’t make it any less interesting for others.

Not many people know that you have a special relationship with the city of Milan. You lived there between 1985 and 1989 and founded your independent school, Architecture Intermundium. Your daughter was born in Milan. Milan, though, has never been too generous with your projects. Endless discussions (your architecture is used to causing fuss), then the crisis struck. Thus the entire process moves slower, other projects are slow to be authorised and others were cancelled. I don’t think this happens only in Italy, both in the new and old world projects are cancelled all the time.

Now, though, we are witnessing the development of the Residence CityLife and Torre Arduino projects, the first tangible steps of a process that comes a long way. What conclusions can you draw from your Milanese experience?

I liked living in Milan, otherwise I would not be here. You are right, the situation is not easy. As I mentioned, though, it is never easy when you intend to do something meaningful. You need to commit to a city. Love it. Believe in it. Sometimes it’s a marathon, and it takes a long time to come to a result. I prefer it, though, over the sprint race, where everything happens in a very short time and then it’s over. This is the truth about architecture: it is complex, and you have to feel committed, passionate. You need to love a city and be aware that not everything you dream of can turn into reality.

Daniel libeskinD

After all, working in Milan is hard also for Italian architects…

This is true in every city. I worked in Berlin for a long time, now I am New York and I have been in many other countries. Every place has its difficulties. They are not the same, but there are always hurdles when you want to make something good. This does not go just for architecture, but also to write a good novel, make a good film… Even a good cup of coffee requires a certain amount of commitment.

Back to CityLife. What are the strengths of your project?

I’d say they should be searched in the building of a high density complex that can match the use of modern technology and sustainable design with a strong figurative identity, a new desire to live in a

Ground Zero

New York, USA

community, as well as a new way of arranging the space, comfort, natural light and a lot more.

Well, the project focused very much on detail solutions, performance and energy efficiency. It is possible, then, to combine creativity and technology? Technology has always been on the side of architecture. How to direct a building, figuring out its behaviours in the winter and summer, selecting the structural system and the materials, defining the visual angle, decide where to locate doors and windows and their size, are matters that regard the building and its sustainability, and have been there for thousands of years. Today we have new technologies, new analysis systems and the desire to build efficient solutions from the energy standpoint.

Certainly, though, the problems we are faced with are not new. Sustainability is at the same time “memorability”; if something is not memorable, it is not sustainable, because you can get rid of it in a matter of a few years. If what you do is memorable, well-built and works well for those who inhabit it and the community, then it will surely be a distinctive element and a landmark of the area for the years to come. This is what CityLife is for me.

These are interesting remarks. Indeed, some argue that your architecture is not very influenced by technology. Is it really all about poetry?

Let me say that sustainability is not a style. Too many people think that sustainability is a style that rests on well-established codes (solar panels, green roofs and the likes), but the truth is different. Sustainability has never been a style, since in different times and ages in history, different solutions were found to the same sustainability question. There is a sort of universal meaning in what you build and it has nothing to do with style, and everything with architecture. And it is not something you can put in a progress machine, since there are buildings made thousand of years ago that are more sustainable than others built today.

Every material has a figurative, but also building, power. In a content-driven architecture like yours, what is the meaning of material?

Using the material in the appropriate way is also quite important. Consistently with the budget – it may sound quite obvious – one has to choose hood quality and high performance material, but also prioritise that which can contribute to safeguarding the environment (that is, with low carbon footprint, for instance), or produced with low-impact manufacturing cycles or sourced locally.

I tackled the CityLife project in Milan with the above

principles in mind. I have sources everything in the area. I leveraged the genius loci, the materials, colour, techniques and know-how of local companies. This was quite an important element in the project. The goal is to build something new, but at once deeply rooted in the city’s tradition. It is easy to build mirages and in some cases this may also be the right thing to do. For me, though, an interesting and sustainable project is something that stems from the tradition of a city and leverages its best assets and skills.

Metal and glass are often the key material in your architectural envelopes. Why did you choose ceramic for your Residenze CityLife endeavour?

I have always been interested in ceramics. When I worked at my expansion project for the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, I did an extensive research on ceramics. It is a unique material, dating as far back as the Babylonians and it is not by chance that it’s still in use today. It has excellent performances in terms of resistance, durability, yield in hot and cold weather and, thanks to state of the art technology, we can control its density, colour, brightness. It really is a pivotal material for XXI century architecture, in that it is versatile and may be employed in many, extraordinary ways.

One last question: what do you seek through your architecture and what do you usually find?

Architecture is a set of questions, not answers. In every project there is something interesting to develop into a theme. Be it a house, a skyscraper, a hospital or a school in Asia, in the United States of in Milan. Every project summarises all worlds into a focal point that is everything but abstract: building form mankind is something absolutely real.

Pinnacle

Bologna Water Design 2013

Pinnacle

Una collaborazione in progress

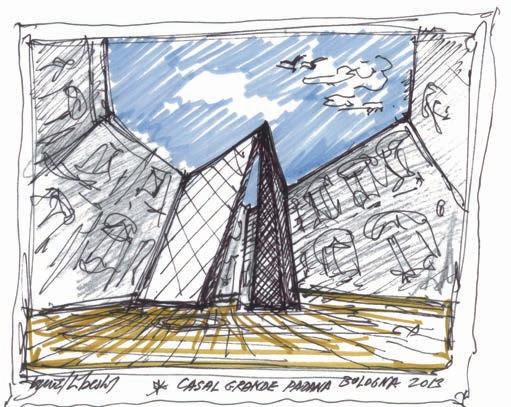

Pinnacle è un’installazione progettata da Daniel Libeskind per Casalgrande Padana in occasione di Bologna Water Design 2013, la manifestazione che, in contemporanea con Cersaie, ha coinvolto alcuni importanti protagonisti internazionali del mondo dell’architettura e del design nella sperimentazione di nuovi percorsi progettuali sui temi dell’acqua e della ceramica.

La slanciata struttura, rivestita in pannelli di grès porcellanato metallizzato disegnati dallo stesso Libeskind è stata allestita all’interno del seicentesco Cortile del Priore dell’ex Maternità, rendendo omaggio

alla radicale verticalità della Bologna medievale, ancora visibile nelle sue celebri torri e nei suoi edifici storici. Ma non solo. Come lo stesso Libeskind ha dichiarato a Veronica Dal Buono della Facoltà di Architettura di Ferrara durante la cerimonia ufficiale di presentazione: “L’ispirazione è frutto di molteplici riferimenti. Ha a che fare con la luce, con l’acqua, con il desiderio, il cielo, l’orizzonte. Guardando la sua superficie, si vede la storia di una struttura. Possiamo leggere le geometrie frattali e percepire un senso completamente nuovo nella creazione della complessità attraverso forme semplicissime. Ritengo che in questo modo si crei davvero l’apogeo (pinnacle in inglese) di un innovativo percorso di sviluppo dei materiali”.

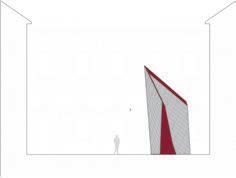

Concepita come testimonianza del saper fare dell’industria ceramica emiliana, l’opera si inserisce rispettosamente nel contesto scenograficomonumentale della corte interna come una presenza metafisica, stabilendo un armonioso rapporto di discontinuità tra preesistenza storica e intervento contemporaneo.

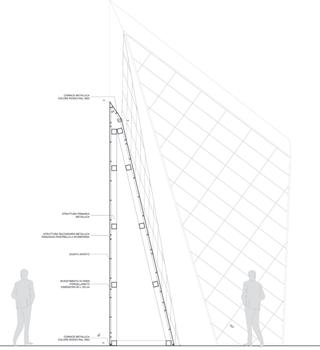

Costituita da due doppie facciate ceramiche, inclinate e convergenti a formare un ardito pinnacolo, simbolicamente proiettato verso il cielo, l’installazione fa da contrappunto alla rigorosa orizzontalità dei prospetti neoclassici dell’ex complesso ospedaliero, disegnandone il portale d’ingresso. Le lastre che ne costituiscono l’involucro si caratterizzano per la particolare soluzione dello strato di finitura che, attraverso un originale disegno geometrico a bassorilievo, produce un effetto dinamico tridimensionale. Enfatizzata da una velatura metallescente, la materia ceramica sottoposta alla luce si scompone e ricompone in molteplici riflessi luminosi che movimentano la facciata.

Grazie all’innovativa tecnologia Bios Self-Cleaning® di Casalgrande Padana, le lastre Pinnacle in presenza di luce solare attivano una reazione in grado di abbattere gli inquinanti presenti nell’aria, decomporre lo sporco che si deposita sulla loro superficie e rimuoverlo grazie all’azione naturale dell’acqua piovana.

“Penso che Casalgrande Padana - ha sottolineato Libeskind - abbia creato una tecnologia fantastica, utilizzando un materiale di tradizione millenaria secondo modalità che appartengono al XXI secolo, conferendogli caratteristiche innovative, come la capacità di riflettere la luce, la particolare tattilità, la lucentezza, così come la stessa tridimensionalità. In questo senso, penso che le lastre Pinnacle abbiano

Pinnacle

grandi potenzialità di impiego non soltanto per realizzazioni di piccola scala, ma anche per opere architettoniche di grande importanza”. Pinnacle rappresenta un momento significativo del percorso di collaborazione tra l’architetto newyorkese e l’azienda emiliana, iniziato con il progetto per CityLife di Milano, per il quale Casalgrande Padana ha fornito 50.000 mq di rivestimenti ceramici di facciata. Una collaborazione che sta proseguendo attraverso la realizzazione di alcune nuove serie in grès porcellanato, di cui le lastre Pinnacle costituiscono la prima anticipazione. Se per le Residenze CityLife, i materiali ceramici utilizzati sono stati espressamente studiati, prodotti e applicati secondo le specifiche indicazioni costruttive, con l’installazione Pinnacle si è compiuto un ulteriore passo nel processo di cooperazione tra azienda e architetto, Libeskind in questo caso ha infatti curato sia il progetto architettonico sia il design della piastrella, sviluppata in stretta collaborazione con la divisione Ricerca & Sviluppo di Casalgrande Padana.

In merito, ha concluso Libeskind: “Lavorare con Casalgrande Padana è una cosa fantastica. L’azienda ha un grande know-how ed è congiuntamente interessata alla ricerca e allo sviluppo non solo in senso formale, ma anche ecologico. Grazie a questo approccio, la sostenibilità e le proprietà autopulenti fanno parte dell’acquisizione di un senso davvero nuovo di quello che i materiali ceramici possono fare per i nostri edifici”.

Pinnacle

An in-progress joint project

Pinnacle is an installation designed by Daniel Libeskind for Casalgrande Padana during the 2013 Bologna Water Design, an event taking place in parallel the Cersaie exhibition, and involved some international-stature architects and designers to experiment with new approaches and projects based on water and ceramics.

The structure, tall and slender, is clad in metal stoneware panels designed by Libeskind himself, and was installed in the XVII century Cortile del Priore dell’ex Maternità, to pay homage to the rather radical verticality of Middle Ages Bologna, still visible in its towers and landmarks. But not only. As Libeskind himself told Veronica Dal Buono, from the Architecture Department of Ferrara during the official opening ceremony: “Inspiration comes from multiple references. It has to do with the light, water, desire, sky, and the horizon. As you look at the surface of a building, you can see its history. One may read the fractal geometry and perceive a completely new sense of complexity accomplished through very simple forms. This, I believe, is the true way to build a pinnacle for a new material development approach”.

Designed as a testimony of the local ceramic industry know-how, the work fits respectfully in the monumental setting of the courtyard as a metaphysical presence, and stages a harmonic and discontinuous relation between the heritage building and the contemporary work of art.

Daniel Libeskind

Daniel Libeskind è nato nel 1946 a Łód´z, in Polonia; trasferitosi negli Stati Uniti a 13 anni, è diventato cittadino americano nel 1965. Ha studiato musica in Israele e a New York, diventando un solista acclamato. Ha lasciato la musica per dedicarsi allo studio dell’architettura, conseguendo la laurea nel 1970 presso la Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art a New York.

Figura di riferimento internazionale dell’architettura e dell’urban design, grazie alla sua nuova visione critica della disciplina e all’approccio multidisciplinare, ha maturato esperienze professionali in vari ambiti d’intervento: edifici per grandi istituzioni culturali e private, centri congressi, università, residenze, hotel, centri commerciali e ville. Ha inoltre realizzato scenografie per opere liriche e mantiene attivo un dipartimento di ricerca di industrial design.

Ha ricevuto numerosi premi e ha ideato progetti di fama mondiale, tra cui il Jewish Museum di Berlino, l’ampliamento del Denver Art Museum, il Royal Ontario Museum di Toronto, il Museo di Storia Militare di Dresda in Germania, il Grand Canal Theatre a Dublino in Irlanda.

Tra i tanti progetti in costruzione, CityLife, l’intervento di trasformazione dell’area Ex-Fiera di Milano e lo Zlota 44, una torre residenziale a Varsavia.

In seguito alla vittoria del concorso per il World Trade Center di New York, Libeskind è stato nominato architetto responsabile del masterplan per l’area del WTC; il progetto Memory Foundations è ora in fase di realizzazione.

Pinnacle

Built with two ceramic facades, tilted and converging to form quite an impressive pinnacle symbolically jutting up towards the sky, the installation contrasts with the horizontal neoclassical perspective of the old hospital building, highlighting its entry gate. The envelope slabs stand out for a very particular finish layer that, through a basrelief geometrical pattern produces a three-dimensional dynamic effect. Highlighted by the metal finish, the ceramic slabs breaks the light down and rearranges it in an array of bright reflections that give movement to the façade.

Thanks to the innovative Bios Self-Cleaning® technology by Casalgrande Padana, when the slabs forming the Pinnacle are hit by the light, they trigger a reaction that can reduce the pollutants in the air, decompose the dirt that settles on their surface and remove it thanks to the natural action of rain water.

“I think Casalgrande Padana - remarked Libeskind – has come up with an incredible technology, using a material that has existed for thousands of years but in a way that belongs to the XXI century, giving it innovative properties, such as the ability to reflect the light, the particular texture, its shine and not last, the three-dimensional feel. In this regard I think that the Pinnacle slabs have a huge potential not just for small-scale, but also for large and important architectural projects”.

Pinnacle represents a significant moment in the joint project between the New York architect and the Emilia-based company, which started with Milan’s CityLife project – for which Casalgrande Padana supplied 50,000 m2 of ceramic slabs for the façade. This collaboration continues with new stoneware series, of which the Pinnacle slabs are just a preview. If for the Residenze CityLife project the ceramic material employed were carefully studied, manufactured and installed according to specific building requirements, the Pinnacle installation meant one further step forward in the collaboration between the architect and the company. Indeed, Libeskind supervised both the architectural project and the slab design process, which stemmed from a close collaboration with Casalgrande Padana’s R&D division. More specifically, Libeskind concluded: “Working with Casalgrande Padana is fantastic. The company has a massive know-how and is also interested in research and development. Not in the formal sense of the word, though, but also with a view on the environment. Thanks to this approach, sustainability and self-cleaning properties are part of this new sense of what ceramic material can do for our buildings”.

Daniel Libeskind

Daniel Libeskind was born in 1946 in Lodz, Poland; he moved to the United States at 13 years of age and in 1965 he became a US citizen. He studies music in Israel and New York, becoming an acclaimed performer. He left music to focus on studying architecture and in 1970 he graduated at New York’s Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. A point of reference in the international architecture and urban design scene, thanks to his new vision of this art and his multi-disciplinary approach, he gathered professional experience in many different fields: buildings for important cultural and private institutes, conference centres, universities, residences, hotels, shopping malls and mansions. Moreover, he also design stage sets for operas and funds an industrial design research department.

He received many awards and made world-class projects, including the Berlin Jewish Museum, the extension of the Denver Art Museum, the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, the Museum of Military History in Dresden, Germany, and the Grand Canal Theatre in Dublin, Ireland.

Among many projects underway, CityLife intends to develop Milan’s former trade fair ground, while Zlota 44 is a residential tower in Warsaw.

Upon winning the New York World Trade Center competition, Libeskind was appointed head architect for the WTC project masterplan; the Memory Foundations project has currently come into the development phase.

Entrepreneurial culture and sense of responsibility

Casalgrande Padana has been manufacturing stoneware slabs since 1960. We have always worked to foster the integration between product culture and entrepreneurial culture, to be interpreted as a sense of responsibility and sharing. We feel responsible for the environment, for those who work with us and for customers, to whom we guarantee products striking the perfect balance between ethics and aesthetics, such as for instance in the Bios Ceramics*, our cutting edge stoneware slab line. Bios Ceramics products re-

duce environmental pollution, are self-cleaning and kill bacteria. We share because we produce culture and enhance design and wish to share this with the community, starting from the assumption that the sense of beauty should be experienced as a resource available to all and not as a privilege for the happy few. This is the meaning attached by Casalgrande Padana to its entrepreneurial spirit today. This means placing human beings and the environment always at the heart of all our corporate strategies.