CATHEDRAL MUSIC

Not only do we supply the best digital organs from four leading organ builders, but we publish our own organ music and carry the largest stock of sheet organ music with over 1,900 volumes on our shelves from a catalogue of over 11,000 titles. Why not visit us in Shaw (OL2 7DE) where you can park for free, browse, have a coffee, play and purchase sheet organ music or use our online shop at www.sheetorganmusic.co.uk.

ChurchOrganWorld … the one stop shop for organists

www.sheetorganmusic.co.uk

Occasionally I remark on longevity in cathedral music life, not necessarily looking at a life long lived but more at the number of years spent in post. Directors of Music are clearly not just for Christmas; consider James Lancelot at Durham (32), Jonathan Bielby at Wakefield (40), the Gedges at Brecon (40+), David Flood at Canterbury (32) and others. None, however, can trump Francis Jackson’s (mere) 36 years in post at York Minster – because he added to it a further 40 as a composer and recitalist thereafter. Consider his life and works, worthy of all the column inches garnered since his death in January this year, as described with affection and respect by Bret Johnson and Simon Lindley.

I didn’t mention in the list above, but could have, Richard Seal, who spent 29 years at Salisbury, and who was responsible for the introduction of the girls’ choir at the cathedral 30 years ago. Notice that I wisely don’t say ‘the first girls’ choir at a cathedral’ (I don’t want to get into deep water, nor do I want to raise the issue of girls in cathedral choirs again, since thankfully that boat sailed a long time ago). There is no doubt that his brainwave did gently nudge many other cathedrals into following the same route, meaning that now it is positively rare for cathedrals not to have a girls’ choir rather than the opposite. His reminiscences as relayed to Deborah Hooper, previously editor of CM’s sister newsletter Cathedral Voice, make fascinating reading.

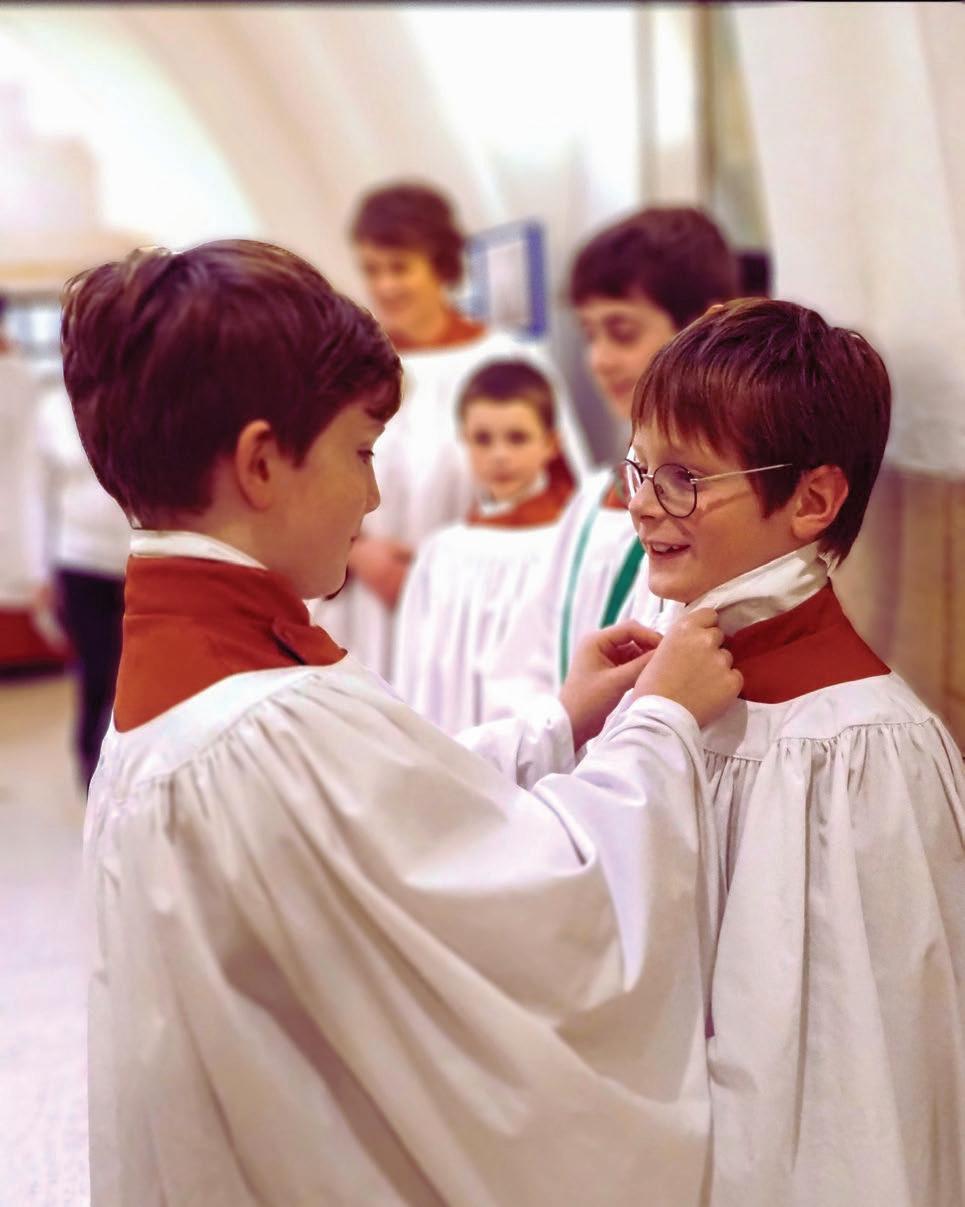

Innovations in the cathedral music world can be hard to find. Since the first lockdown, however, musicians everywhere, and in particular choral musicians since singing was deemed a dangerous sport in the early days, have made very good use of the virtual world. Choirs are frequently pictured fragmented on screens, and great success has been made of online concerts by far-sighted groups such as Voces8 and the Gesualdo 6. Cathedral Music Trust is at the vanguard of this incursion with its seminal virtual conference, Joining the Dots, on how to celebrate and utilise collaboration in what is traditionally a somewhat disunified area. Clare Stevens writes cogently on the topics covered and the sessions offered — varied, wideranging and informative — by a host of influential people from an assortment of disciplines, including education, diversity and music. Thanks to hard work and preparation behind

the scenes by the Trust’s staff, the conference went seemingly effortlessly and, should you have missed any part of it, a video recording can be viewed on the website for a very small fee. It was striking to see the way in which music professionals from many different areas (geographic as well as intellectual) came together with a shared purpose — to help children from all backgrounds access the wonderful education that becoming a chorister offers, and how to achieve the best results for them through training and support.

A similar and perhaps unexpected enthusiasm for the chorister life has recently become noticeable in the Netherlands. Hanna Rijken, whose PhD dissertation is entitled ‘My Soul shall Magnify’ and who a few years ago set up a project called ‘Choral Evensong + Pub’ (!), documents the ways in which choral evensong has become popular in Dutch society and strives to ascertain the reason why — is it the beauty of the buildings? The glorious music? The venerable and mystical language (BCP 1662 is mainly used) — or something else? Read her article and see what you think.

Regular readers of the magazine will remember articles written by composer Phillip Cook over the last few years, most recently in CM 2/21 on Cecilia McDowall. Now you can go behind the scenes a little to find out about his own compositional and musical life as told to Jonathan Clinch, Lecturer in Academic Studies at the RAM; you can also, if you follow the links at the end of the article, read his fascinating blog (‘Composing is hard!’), which is well worth a visit, as is the rest of his website, where much of his music is available for download.

Another two composers are featured here — Philip Wilby, who writes not only on his own compositions but also more particularly on Matthew Owens, adviser to this magazine and DoM at Belfast Cathedral, who has championed new compositions of cathedral music over a number of years (his very successful programme ‘new music wells’ has been running since 2008 to great acclaim). Second is Alison Willis, whose competition-winning canticles were premiered at Derby’s October gathering last year. For obvious reasons these were not able to be performed until 2021. She gives fascinating insight into her compositional processes and musical background.

And finally… very sadly, the November issue of CM is likely to be my last. I have thoroughly enjoyed my 10+ years (decidedly falling short in comparison to most DoMs) as Editor of the magazine, and this is my 22nd issue – but it’s time for another body to fly the flag.

Sooty AsquithWE ARE STRONGER

Join our community of Friends and unlock a host of benefits while helping to support cathedrals and choral foundations across the UK.

More reasons to become a Friend

• Enjoy invitations to our Gatherings as part of our events programme

• Receive our acclaimed magazine Cathedral Music twice a year

• Delve deeper into the heart of cathedral music with our Friends newsletters and journals

• Help us nurture the next generation of cathedral musicians and enrich more lives through the power of music

To enjoy a year’s worth of insights and Friendship, visit www.cathedralmusictrust.org.uk or call 020 3151 6096

We ask for a suggested subscription of £25 per year to be a Friend of Cathedral Music, and all Friends are asked to consider donating over and above this to assist us in developing our work and increasing the funds we have available to award as grants to choral foundations.

Bret Johnson looks at choral and organ works by Dr Francis Jackson CBE (2 October 1917-10 January 2022), while Dr Simon Lindley offers some personal recollections.

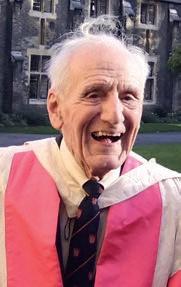

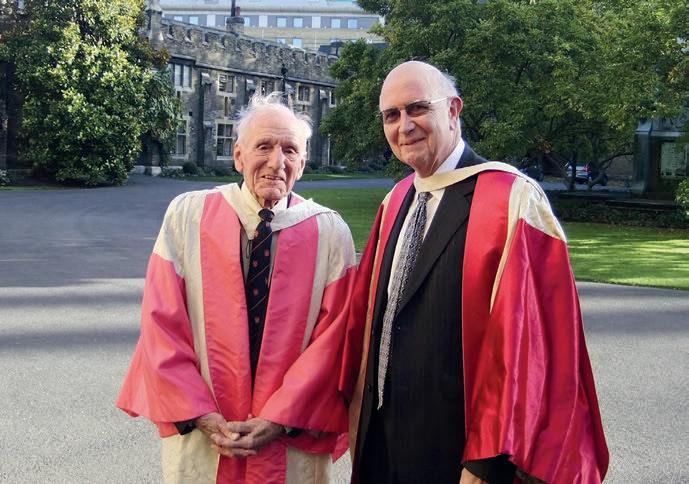

The heading is a slightly corny descant, you may think, on the title of Francis Jackson’s 2013 autobiography Music for a Long While (York Publications).1 To mastermind the production of a 400-page volume of memoirs at the age of 95, whilst still giving public organ recitals, fulfilling commissions for new anthems and organ pieces, as well as answering correspondence from his many admirers, surely bears witness to the life and example of one of the most enduring musicians this country has ever seen. Just a few months before, in 2012, he had been honoured by the award of a Lambeth doctorate of music, granted by the Archbishop of Canterbury to those who have given an exceptional lifetime of service to cathedral and church music.

What came across most strongly in Francis Jackson’s professional and personal life was his humility and reverence for the tradition and figures which had the most influence on him. A special place is reserved, of course, for Sir Edward Bairstow, his immediate predecessor at York Minster, with whom he worked and studied for many years, first as chorister and then as Assistant Organist, until Bairstow’s death in 1946. By many of the accounts I have read, Bairstow was a difficult, crusty and plain-speaking character. But if anyone has captured the essence of his music it is Jackson, right from the brilliant organ Impromptu he wrote as a 70th birthday present to his mentor in 1944 whilst on war service in Italy. Bairstow was in many ways ahead of his time as a composer: he would suddenly resort to diabolical harmonic chords (as in the 1937 E flat Organ Sonata) and growling bass figurations (as in the anthem Though I speak with the tongues of men). Jackson’s biography of Bairstow Blessed City 2 is a deeply sympathetic tribute to a musician whose memory he honoured throughout his life, and many of Jackson’s 160 or so published compositions acknowledge to some degree the continuing presence of this profound early influence.

FJ’s 100th birthday in October 2017 was marked by many celebrations, including a dinner attended by his two successors as Master of Music at York Minster, Philip Moore and Robert Sharpe, and on the occasion of his 104th birthday in October 2021 his former assistant at the Minster, John Scott Whiteley, compiled and uploaded an hour-long video of recent performances of several Jackson organ works and part songs.

Jackson’s fantastic organ technique ensured his international renown as a concert organist, and his many recordings so testify: for me, the most extraordinary of all is the 1964 Great Cathedral Organ series LP he made on the Minster organ which included several dramatic performances, especially the Introduction, Passacaglia and Fugue by his great friend Dr Healey Willan (1880-1968), the amazing Tuba Tune by Norman Cocker (both pieces make spectacular use of the Minster organ’s Tuba Mirabilis), and Jackson’s own Diversion for Mixtures, a spellbindingly virtuosic concert étude. How wonderful that in 2017 the whole Great Cathedral series was remastered and is now available on a 14-CD box set.3 Jackson dedicated another fine organ piece, the 1955 Toccata, Chorale and Fugue, to Healey Willan. In a recording of it he made in

the 1960s he said in the sleeve note that ‘its influences are mainly French, [featuring] the highly coloured harmonic language reminiscent of Cesar Franck’…. always conscious of his role in drawing on and in continuing a school or tradition. The Diversion for Mixtures mentioned above probably evokes Langlais and Dupré as well as Bairstow.

Like Herbert Howells before him, Francis Jackson composed extensively for choir and for organ. There are many musical parallels: both Howells and Jackson have a distinctive ceremonial style. I hear Howells (maybe the Sarabande for the Morning of Easter or the Paean) in Jackson’s Procession, Arabesque and Pageant (Three pieces for organ, 1955), not as an imitation but as an elaboration, extension and celebration. And in Jackson’s little-known but superbly evocative set of Evening Canticles in G minor, written for Leytonstone Parish Church in 1958, there are distinctive echoes of Howells’ Gloucester Service

Jackson’s organ works are brilliantly encapsulated in a set of recordings he made himself in the 1990s on the organs of Lincoln, York and Blackburn Cathedral, issued as a 4-CD set by Priory Records.4 This is a most comprehensive survey, featuring nearly 50 works including the first four sonatas. His six organ sonatas are the most notable British examples of the format since Mendelssohn (even Stanford only wrote five!). Each one has a most individual character: the first written for the new Walker organ in Blackburn Cathedral in 1970 evokes the 19th century and the spirit of Rheinberger in the opening movement, in the favoured key of G minor. The second, Sonata Giocosa from 1972, marked the restoration work at York Minster, and the disunity and uncertainty of the first two movements recall the deeply emotional Howells of the Psalm Preludes, whereas the final Gagliarda celebrates the joyous completion of the rebuild. Most appropriately, the spirit of hope is evoked at the height of the uncertainty in the form of a triumphant statement of the hymn tune ‘York’. The Third Sonata is transparent and neo-classical, leaning

towards Hindemith in flowing pastoral lines. The extended Fourth Sonata is one of the most remarkable and diverse of his organ pieces: Bairstow comes to mind in the perverse tritonic harmonies and frowning dissonances and maybe another great organist/composer, the American Leo Sowerby. Imposing edifices of symphonic and rhapsodic thought yield to passages of gentle impressionism (he acknowledges Ravel and Debussy as profound influences). We must not forget Vaughan Williams, of whom Jackson was a great admirer: the finale of his Five Preludes on English Hymn Tunes (1984) is based on VW’s ‘Sine nomine’ which we know, of course, as ‘For all the Saints’.

I remember hearing Dr Jackson play several times when I was a student: on the Walker organ in the Whitworth Hall at Manchester University and in Liverpool Anglican Cathedral when he gave the first performance of Prelude on an American Folk Hymn ‘Lonesome Valley’. That he was equally at home as a miniaturist is evident in his anthologies (the Hovingham Sketches for example) and other collections of shorter compositions.

There were also several part-songs, and a cantata, Daniel in Babylon, as well as two extended works for orchestra including his Symphony in D minor (1957), submitted for the Durham DMus, which so far has only been performed semi-professionally, and a Concerto for Organ Strings, Timpani and Celesta (Op. 64, 1984). The latter was broadcast by the BBC and has been recorded on Amphion Records with the composer as soloist. 5 It is a splendid work and one of a host of 20th-century British organ concertos which are deserving of revival (and commercial recording). The Jackson is scored for identical forces as the Poulenc Organ Concerto, and is a worthy companion.

Many of the choral works have been classics in choral repertoires for decades: the Evening Service in G, the Communion Service in G, the Benedicite in G, and the Hereford

Evening Canticles in F sharp. This latter was a 1961 commission, originally in a two-part setting (soprano/tenor and alto/bass) but so skilfully wrought that apparently when Sir John Dykes Bower (Organist of St Paul’s Cathedral) heard it he thought it was in four parts! (The composer did later arrange it for four voices.)

notable example of the triumphant Jackson choral style, and with a rare climactic conclusion.

Of the later choral pieces, special mention is due of the Missa Matris Dei (1988), one of ten settings of the Mass, written for Nicholas Danby and the Church of the Immaculate Conception, Farm Street in Mayfair. The Gloria has an ecstatic quality not only for voices but also in the dramatic organ accompaniment (so vital a part of much Jackson choral music) and the Evening Service ‘Homage to Thomas Weelkes’ in B flat (2005). This extended setting is in five parts and is notable for the incandescent Gloria to the Magnificat and especially the Amen, where the thrilling and triumphant cadence seems to hang in the air for ever. Of Three Carols for Advent (1989), Gabriel’s Message is a simple hymn melody, effectively elaborated in each succeeding verse.

A distinguished teacher may beget fame in his pupils and one such composition student was John Barry, whose long career as a film composer included such hits as Dances with Wolves and of course, the unforgettable James Bond scores.

I have often wondered how cathedral organists find time to compose and play recitals amidst all their administrative duties and the daily task of producing music for choral services. Jackson toured extensively as a recitalist in Europe and the UK and Australasia and in North America seven times (his early 1950s’ friendship with Healey Willan was especially productive in this respect). Dr Jackson stood down from Minster duties in 1982 after 36 years as Master of Music and his life as a musician simply carried on… but with even greater intensity! During his ‘retirement’ he composed and published over 90 works.

A good selection of the music he composed during those busy Minster years was featured in an 80th birthday tribute recording by Priory Records in 1997.6 Some truly remarkable music appears on this disc, including several extended anthems. Worthy of special mention are Sing a New Song to the Lord (1970), and especially Blow ye the trumpet in Zion, originally written for the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Holborn in 1963 and later chosen by John Betjeman in his BBC series England’s Cathedrals and their Music (the whole of this recording can be found on the Archive of Recorded Church Music on YouTube). It is one of his most dramatic anthems from this period, nearly 10 minutes long, with repetitive trumpet fanfares and sustained high tessitura treble incantations. The dense harmonies recall not only the Howells of God is gone up and Exultate but also Flor Peeters, especially his five-part Missa Festiva. Also Remember for Good, O Father (1956) written, like so much of Jackson’s music at this time, at the instigation of the Dean of York, the Very Revd Edward Milner-White, for the dedication of an astronomical clock in the Minster in memory of the fallen of the RAF during the War. The long, plaintive phrases (including a solo quartet) and hushed harmonics could not be in greater contrast to Blow ye the trumpet. And Audi, filia, sung at its composer’s wedding in 1950 and dedicated to his bride Priscilla, sets words from Psalm 45; its distinctly tender, feminine character is immediately attractive. Of the shorter pieces also presented is a punchy Jubilate written for the 1964 Leeds Festival, for which he also wrote a Te Deum. Another Te Deum, in D, composed for St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral in Edinburgh’s centenary in 1979, is yet another

Both the Bairstow biography and Jackson’s own autobiography make for most absorbing reading. His open, easy style of writing throws a warm light on the countless aspects of his musical life, as well as generous accounts of early family experiences, his marriage to Priscilla and his children as well as kindly tributes to fellow musicians, countless anecdotes and the occasional gentle ribbing! There is a good discography and list of works at the end, and many photographic plates, several in full colour. An index would have provided a helpful directory of people and places and if that could be included in a future edition it would enhance enjoyment yet further.

I can only conclude with the final words of Dr Jackson’s autobiography: ‘It has been a good innings and far better than I could have imagined’. Amen to that… and we rejoice in a very long life well lived, one that has enriched our heritage and will continue to do so for many years to come.

NOTES

1 Music for a Long While (York Publications: www.yps-publishing.co.uk)

2 Blessed City: The Life and Music of Edward Bairstow (www.prestomusic.com)

3 Warner Classics 50999 0 85295 2 7

4 Priory Records PRCD 930

5 Amphion Recordings PHI CD 155 (www.amphion-recordings.com)

6 Priory Records PRCD 611

The modest self-description of a truly great man as ‘a lad from the Wolds’ has featured in recent coverage of Francis Jackson, who died on 10 January 2022 at the venerable age of 104.

Venerable, most certainly he must be accounted to have been – highly esteemed, respected and greatly loved by a vast public, quite clearly. The number present in York Minster, as well as a huge tally of viewers to the Minster’s YouTube channel during and following his obsequies attest to this.

The service included a scripture reading from Francis’s Minster successor, Dr Philip Moore, two hymns [‘God, that madest earth and heaven’ and ‘How shall I sing that majesty’ to Francis’s own melody, East Acklam, originally composed for Heber’s and Whatley’s verses and Ken Naylor’s Coe Fen], extracts from Croft’s memorable Burial Sentences, Psalm 91 to a chant by E J Hopkins – each exquisitely rendered –and anthems by S S Wesley – from the central portion of his extended doctoral exercise, O Lord, Thou art my God came music from his mentor Sir Edward Bairstow – the highly characteristic setting of music by Orlando Gibbons [Song 13] to a translation of a Latin text by Sir H W Baker, Jesu grant me this, I pray. The present-day Minster choir delivered Francis’s choice of music of the highest calibre and standard under inspirational direction from Robert Sharpe.

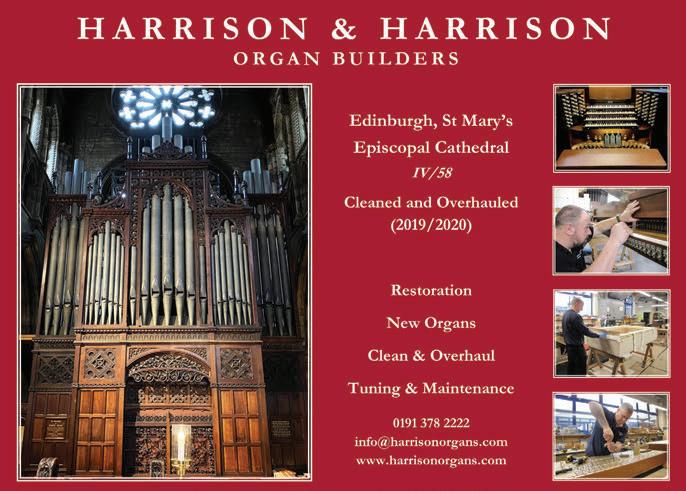

Ben Morris played brilliantly throughout – the restored Harrison featuring spectacularly in the hymns and the thrilling S S Wesley anthem, with music before the service including FJ’s own Prelude on ‘East Acklam’ and the Bach St Anne fugue at the end. During the postlude FJ was borne from the Minster on the start of his final journey. As the Bach drew to its close, Precentor Canon Victoria Johnson accompanied the extensive number of family members recessing from the eastern end of the nave to the west door.

Still in office at the Minster as Organist Emeritus at the time of his death – a title held for 40 years consecutively following his 36 as Master of the Music from 1946 in succession to his mentor, Sir Edward Bairstow – the events of Francis’s busy and lengthy ‘retirement’ evinced much concern with, and for, the personal and professional relationships he had sustained with such commitment for so very long.

The ‘good doctor’ had a rare and wholly unconditional gift for friendship. His gentle demeanour, inimitable vocal timbre, raised eyebrows and masterly use of written and spoken English all came as seemingly naturally and effortlessly as did his prodigious musical and artistic gifts.

By his own calculations (recounted in the autobiography Music for a long while published in 2013), the tally of his solo organ

concerts numbered 2,016. Among the last events he played in public were a memorable summer evening Minster recital and a lunchtime concert in the early autumn at Bradford Cathedral. The concluding piece was Bairstow’s Prelude in C as that latter’s ‘swan-song’.

The number of recitals after leaving full-time work at the Minster was very extensive; no less so was an astonishing Indian summer of composition, with many works emanating from the pen of this ‘ready writer’, to quote a memorably apt phrase from the psalmist, mostly commissioned by friends and colleagues old and new ‘in quires and places where they sing’.

In terms of texts for sacred choral works, it seems that his canticle and other liturgical service settings date from the prototype Benedicite in G just post-war – an early project encouraged by Eric Milner-White, Dean of York from 1943 to 1968. This corpus has achieved rather greater public prominence than the far greater (numerically speaking) 100+ anthems following on from a hymn anthem Ave, Maria, blessed Maid published in the late 1940s by the Faith Press

The ‘anthem’ category includes a number of carols and settings of music for Benediction. His compositional catalogue also reminds one of just about a ‘baker’s dozen’ of beautifully crafted solo songs with secular texts and exquisite piano accompaniments, of which perhaps the finest is a setting of Robert Frost’s evocative stanzas Tree at my window written in 1943. There are also works for organ and solo instruments, a concerto and a symphony as well as a great number of pieces for solo organ.

Dr Jackson’s long friendship with actor-dramatist John Stuart Anderson produced two spectacular works bearing the

intriguing title of Monodrama with Music – Daniel in Babylon for the 1962 festival arranged to celebrate the opening of Coventry Cathedral and, a little later, A Time of Fire [originally Tyndale – A comedy of sorts] for the Norwich Festival. The former included inter-scene Motets, mostly but not all unaccompanied, while the latter has rather more throughcomposed material for choir throughout. Interestingly, William, the elder of Francis’s two sons, bears both Tyndale and Procter as middle names – Tyndale Procter, prominent as a member of the York Society of Friends, being his maternal grandfather.

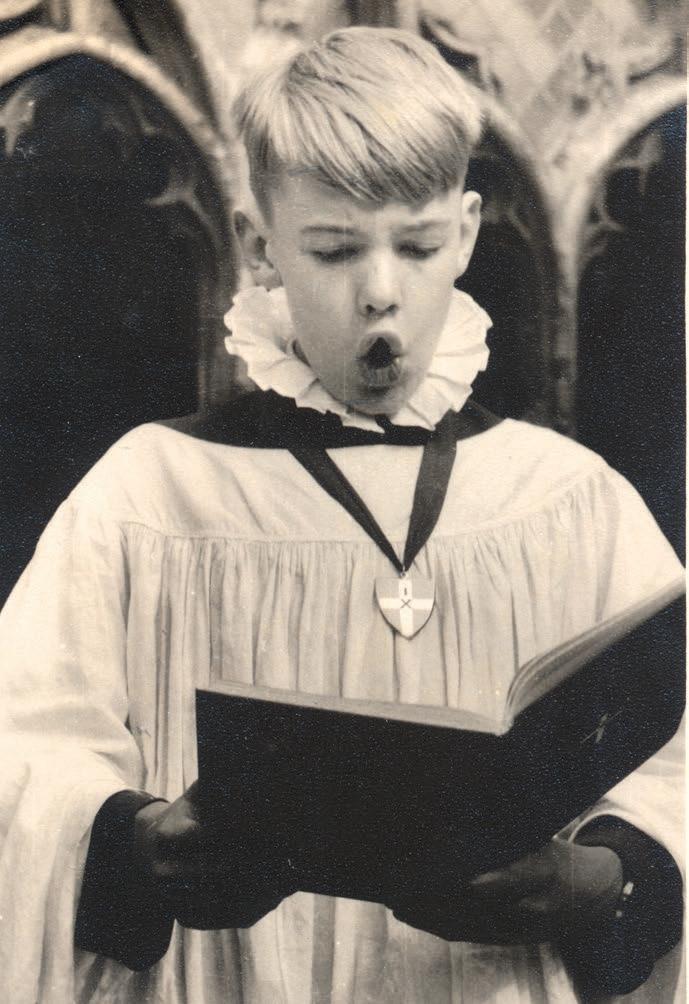

Continuing briefly on family matters, both Jackson boys were choristers at St George’s Chapel Windsor, under Sidney Campbell, while no fewer than three Jackson grandchildren (Sam, Grace and Thomas) were each Minster choristers.

The memorable address at the Doctor’s funeral, delivered extempore in affectionate terms by Bishop Glyn Webster, for long a Chapter clerical colleague, contained a nice touch: a reference to the arrival of the latest great-grandchild, Edward, via a misquotation from scripture: ‘in the midst of death we are in life’. (Sam and his wife’s latest offspring had arrived between his great-grandfather’s passing and the funeral.)

The Fanfare for Francis produced by the Finzi Trust for Dr Jackson’s 90th birthday serves as proof positive of the returned affection and regard of professional as well as personal friends, and some contributions have achieved later embellishment and enlargement.

Honours unexpected, yet richly deserved and received very late in life, included an honorary doctorate in music from the Archbishop of Canterbury and that of honorary patron of the Burgon Society for the study of academic dress among them. Musicians with long memories will recall the brown dullness of the hues half a century back of the Royal College of Organists’ diploma hoods which were banished on Francis’s enthusiastic and expert advice in favour of the richer tones of rose-pink and gold now well in evidence today.

With that epoch-changing specification, this personal recollection comes, visually, full circle as it were, recalling a very great individual. Memory eternal.

There is no history of music-making in my family, although my grandfather (who I never met), allegedly used to play what was fondly referred to as You WILL Buy My Pretty Flowers with great force and determination on a Saturday evening. Fortunately, my mother decided that I should have piano lessons with Mrs Parish, one of the two piano teachers in the village, and I benefited from a very solid ABRSM musical upbringing, a grade a year, aural training, Grade V Theory (utterly incomprehensible, who remembers the little red Rudiments of Theory book?) in order to progress to Grade VI and for this I remain profoundly grateful.

My own choir, Great St Mary’s, was of an excellent standard. We had a very good choral director and sang a wide range of music. I quickly became chief page-turner for the voluntaries and was soon offered lessons. Our organist, Michael Cubbage, was an outstanding musician – indeed, had the war not intervened I think he would have been a cathedral organist. Our parish church was treated to an extraordinary feast of music at his hands (and feet). Particular highlights for me were Alain’s Litanies, Franck’s Pièce héroïque and Bach’s Passacaglia and Fugue in C Minor. As (by far) the youngest member of the Harlow Organ Club I had the opportunity, usually arranged by Michael, to play several cathedral organs, a privilege I took rather for granted at the time. Through these experiences I gained a solid grounding in the English choral tradition and the great organ repertoire. I did not fully appreciate at the time what a lasting impact this would have on my future work.

I had composition lessons with Paul Burrell whilst at school after winning the Harlow Chorus Carol Competition (another surprise for my mother, who didn’t know I wrote music), then continued my composition studies with tutorials from Sir George Benjamin at RCM, briefly at RNCM then at Colchester with Alan Bullard. The choral singing and organ-playing fell rather by the wayside as I focused on composition and piano, having pieces workshopped and performed by ensembles including Gemini, the London Sinfonietta and the LSO.

There was also no history of churchgoing in my family, so my parents were probably slightly perplexed when as a teenager I joined the church choir in the village. As a family we had recently holidayed in Somerset and, having admired the excellent fan-vaulting in the chapter house at Wells, I clearly remember hearing the cathedral choir rehearsing. I had never heard anything so beautiful, and this was a defining moment for me as a musician.

I then met my husband and had several children in very quick succession and, although I continued to compose, they turned out to be quite time-consuming. The work I produced when they were (rarely) all asleep at the same time may not have been my best; however, as the children grew, I found more time to write properly, rediscovered my love of choir and organ music and started receiving commissions and performances again. I like to call this my own personal and compositional renaissance. Most of my recent compositional output is for choir and organ or piano, but I also enjoy writing for solo voice and for instrumental ensembles. My music has been described as ‘beautiful yet pragmatic’, and as a singer

and multi-instrumentalist I make it a policy to sing or play everything I write where possible.

There are three main influences on my choral writing: the chants and texts of the medieval era, re-voicing women through forgotten texts/narratives, and English folk music, specifically unaccompanied song. Much of my choral writing is rooted in plainchant with a penchant for non-pitch-specific chants such as those of Old Hispanic Office celebrated in medieval Iberia that escaped the liturgical unification of the late eighth century. In 2017 I was one of three choral composers invited to develop new works for Bristol Cathedral choir and Christ Church Cathedral choir, re-imagining elements of the Old Hispanic Office as part of a European Research Councilfunded composition residency in Bristol led by Dr Emma Hornby. This resulted in the Vespers, Inspired by the Medieval Old Hispanic Office that includes three anthems and a set of Preces and Responses. The nature of non-pitch-specific chant is that, whilst the neumes (the early musical notation indicated above the Latin text) give an indication of the direction of the line and possible cadence points, these are, as the name suggests, not at specific pitches. As a composer this gave me the chance to experiment with the impact of different modes on the chant. To me, these modes imbue a different ‘colour’ to the sound and create interesting possibilities for dissonance and false relations.

I find that the raised fourth of the Lydian mode is light and bright, whereas the opening minor second of the Phrygian is dark. At Derby this raised the question of whether I think of music in colour, a phenomenon known as synaesthesia. For me, E minor is and always has been green, A major is red, D major is blue and so on. These are not conscious allocations; at no point did I decide what colour each key was, but these ‘colours’ certainly have an impact on the key in which I choose to write – so maybe I am a synaesthete after all!

Another musical influence of my research into the Old Hispanic Rite is the ‘jubilus’ (the long melisma placed on the final syllable of the ‘alleluia’ in Gregorian chant). Dr Hornby, in her exploration of the impact on these chants by Spanish cleric and scholar Isidore of Seville (c.560636), suggests that ‘Textless melody on “alleluia” and other praising words was understood in medieval Iberia as joining the devout with the angels.’1 This relates back to my teenage moment of enlightenment at Wells, was very much part of my inspiration for the Vespers and is also reflected in subsequent pieces including A rose hath borne a lily white and Salve Deus, rex judaeorum (Hail, Lord, King of the Jews). I am also drawn to medieval texts, especially carols such as I sing of a maiden and There is no rose, both for the beauty and rhythm of the language and the colour of the imagery and narrative where I find there is a real crossover with the English folk tradition in terms of structure, narrative and modality.

The second main influence on my work is re-voicing women. By this I do not mean reintroducing the work of largely forgotten women composers, although this is vital work currently being championed by organisations including Multitude of Voyces with their three-volume Anthology of Sacred Music by Women Composers and the Illuminate series of concerts curated by Dr Angela Slater. Rather, it is breathing life into texts written by women and narratives about them that have been lost in history. One part of this is my interest in Marian

texts which encompass the afore-mentioned carols, prayers, antiphons and of course the Magnificat. I have just completed a substantial new commissioned piece, The Canticle of Mary, combining little-known medieval carol texts for SATB choir and organ with a new poem by Charles Anthony Silvestri, set for solo soprano commenting on the nativity from Mary’s perspective. Sadly, the piece has not yet been performed due to Covid-19. Salve Deus, rex judaeorum, (written for Hampshire choir Luminosa, organ, soprano solo and optional bell) was another casualty of the pandemic, being originally scheduled for premiere on 28th March 2020… timing, they say, is everything! I am delighted that it will now receive its premiere two years later in April this year.

Salve Deus, rex judaeorum sets parts of the text by the same name published as the central part of a book of poems in 1611 by Aemilia Lanyer, the first woman to have a book of poems published under her own name. The poem tells the Passion story through the eyes of Pilate’s wife, a solo soprano in my setting, and Lanyer’s words are beautiful, including phrases such as ‘The sun grew darke and scorned to give them light, the moon and stares did hide themselves for shame’. It is important to me as a composer to shine a light on these forgotten texts and narratives, and I have also recently set texts such as Gold and Spices by Christina Rossetti and the intensely moving secular poem Non omnis moriar written by the Polish poet Zuzanna Ginczanka, who was executed as a Jew in 1945, premiered by the BBC Singers in 2019.

The third significant influence on my work is English folk music. When I was a lapsed choral singer and organist at music college I discovered English folk music, joining a band as third guitarist before remembering I had spent my life savings on a piano accordion when I was eight before abandoning it to a cupboard as I had no idea how to play it or to find someone who could teach me. I retrieved it and haven’t looked back since! Whilst I enjoy playing the tunes from the UK and beyond, especially those of England, my especial passion is the unaccompanied song of our English tradition. To some extent this combines many of the elements discussed above. Most folk song is modal, and unaccompanied singing gives the freedom to vary tempi, placement of words and even tonality in order to convey the narrative in the most colourful way to the listeners in any given rendition, the tune again being ‘the handmaid’ of the text. My Anglican choral upbringing included chanting the psalms, and this collocation between the freedom of rhythm in unaccompanied folksong and the speech rhythms of the pointed psalms is something that I use extensively in my writing. I am prepared to admit that sometimes my scores look as if they will be complicated to

My music has been described as ‘beautiful yet pragmatic’, and as a singer and multiinstrumentalist I make it a policy to sing or play everything I write where possible.

sing – due to frequently changing or irregular time signatures – but these are only ever there to serve the text and make it audible and understandable; indeed, music is ‘the handmaid of the liturgy’ as written by Dr Victoria Johnson in CM 2/21! It is true to say that the most frequent comment I hear about my choral work is how very ‘singable’ it is. As already mentioned, I do sing every line I write and if I can’t pitch it or make sense of the rhythm, I don’t feel I can ask anyone else to.

Returning to women’s voices, when it comes to setting a Magnificat I find I have two different approaches. The first and more traditional is celebratory, with Mary, on receiving the news that she is to be the mother of the Christ Child, overcome with joy. The second approach, one that I explore in my Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis in Db and further in The Canticle of Mary, is more reflective. Mary, a young girl betrothed to a much older man, finds she is expecting a child that is clearly not her future husband’s. He, understandably, may not initially be thrilled at this prospect and sends her away to her cousin Elizabeth – as Tony Silvestri says: ‘To my cousin in the hills of Judah I went away, sent away, to hide my husband’s shame’. Indeed, in the 15th-century Cherry Tree Carol Joseph challenges his young wife, saying,

‘O then bespoke Joseph with words so unkind, ‘Let him pluck thee a cherry that brought thee with child.’2

although once the angel reassures him that the child is the child of God, all is well. This ‘Song of Mary’ can therefore be set in different ways and my commitment to re-voicing women means I like to consider both approaches. I also find my passion for unaccompanied song impacts on the way I set these words, so unusual for being spoken first person by a female. The Nunc Dimittis is one of my favourite of all liturgical texts. Evensong and its sense of deep reflective peace were the bedrock of my choral experience. I also find the shape of the text deeply satisfying, with its gentle start building to exaltation and glory in the doxology.

The Magnificat of the Derby Service takes the celebratory approach. It opens at a sprightly tempo in bright D major with an organ ostinato featuring major sevenths in the harmony over a dominant pedal of A. This ‘Song of Mary’ starts with upper voices, sopranos who then divide before being joined by the altos, telling Mary’s cousin Elizabeth of her joyous news, with the rest of the choir not joining until the words ‘For he that is mighty’. The word ‘holy’ takes the divisi sopranos to the top of their range with an overlapping Lydian descending scale motif redolent of Isidore of Seville’s ‘jubilus’ before the colour changes. The organ picks up the raised fourth in ostinato, suggesting the hope of the words ‘and his mercy’ whilst the flattened seventh, in this case an A, darkens the sound, maybe reflecting the alternate more questioning approach discussed earlier with a deliberate dissonance on the word ‘fear’. There is a flurry of imitative movement at ‘He hath scattered the proud’, a good example of writing that looks complicated due to its changing time signatures but makes perfect sense of the words when sung. Upper and lower voices alternate as the organ ostinato motif continues and develops before coming together and building up to full harmony as we reach the word ‘Abraham’, leading back to the opening organ motif in the original key for the doxology. Unison voices sing the line from the opening of the Magnificat, flowering into increasingly full harmony at ‘As it

was in the beginning’ and concluding with a blaze of glory on the repeated ‘Amens’, set to an A major triad with the raised fourth from the Lydian mode used earlier, an added second and some crunchy dissonant lines from the pedals (which must be credited to Alexander Binns, Director of Music at Derby and Tim Rogers of Encore Publications; many thanks, gentlemen, a huge improvement!)

As one would expect, the Nunc Dimittis is very different in character, although it does share significant musical material with the Magnificat. It opens with gentle creeping cluster chords with a suggested soft 8’ on Swell and 16’ Pedal. Again, initial impressions may be that this is difficult to play but I wrote this while at the organ and find it quite enjoyable myself… despite the sub-zero temperatures the day I wrote it! The sopranos and altos enter in unison with a floating reflective line which opens into SATB harmony on ‘For mine eyes…’. The words ‘which thou hast prepared’ borrow material from the Magnificat, also echoing the build in texture before an explosion of sound, again related to the concept of the ‘jubilus’ on the word ‘light’, leading to repeated ‘Glorys’

based on the ‘Amen’ chords. The doxology returns to the quietness of the opening with all voices in unison until ‘As it was…’, which starts the build-up to the final ‘Amens’. These share the chords and pedal lines of the Magnificat but this time become quieter on each repetition and fade back into the peace of the evening light.

The Derby Service is in many ways a synthesis of the elements that influence my writing, the Marian text, the modal influences combined with occasional dissonance and the strong narrative melodic lines that create the different colours within the text. My heartfelt thanks go to Alexander Binns, the choir of Derby Cathedral, organist Edward Turner, Tim Rogers at Encore Publications and all at Cathedral Music Trust for such a wonderful first performance and for making me so welcome at the Derby Gathering. I think we all hope that The Derby Service will find its place in church music for many years to come.

Alison Willis (b.1971) is an award-winning composer whose works have been performed and broadcast internationally. Her music has been described as ‘stunning’, and ‘intensely moving’. She finds particular inspiration in historical sources and events, and enjoys working collaboratively with both young people and adults. She is an experienced pianist, organist, folk musician and musical director, enjoys composing music for theatre, and is a trustee of the Martin Read Foundation, which supports young composers. For more information visit www.alisonwillis.com or Alison’s YouTube channel, Alison Willis Composer.

Links to a performance of the Derby Canticles sung by Derby Cathedral choir

www.youtube.com/watch?v=YhVFvmvcxEU

www.youtube.com/watch?v=HagN3BI3EOM

Some readers may remember my father, Maxwell Menzies, who was organist at St Michael’s College, Tenbury and subsequently at Portsmouth Cathedral. He introduced me to Gerald Knight of RSCM fame who was organist when I first went to Canterbury in 1951.

My main influence was Clive Pare, the headmaster of the choir school. He had a fine alto voice as a former King’s College choral scholar. He originally inspired my strong Christian faith in preparing me for confirmation.

My musical memories start with singing Christian music and especially the daily psalms, which have remained very important to me. Because of the size of the choir we didn’t sing every day; only the senior 16 boys sang on Saturdays and Sundays.

The music we sang in those days was very conventional, mostly 19th and early 20th-century. I do recall 16th and 17th-century service settings and anthems, but I can’t remember many first performances of 20th-century pieces.

My five years as a chorister finished when Sidney Campbell arrived at Canterbury in my final term when I was senior chorister. Sidney was, as many readers will recall, a fine organist and choir trainer. We did start singing some more up-to-date music at that point.

One of the highlights of my time at Canterbury was singing in The Man from Tuscany at the Royal Festival Hall. This was a domestic operetta about J S Bach and his sons by Antony Hopkins, of Talking about Music fame. The libretto was by Christopher Hassall who was, by coincidence, educated at St Michael’s. I wonder if any readers have come across it being performed again.

My time at Canterbury helped me greatly in my future life. The discipline and teamwork in the choir contributed positively to my future legal career. Musically, I became a semi-professional flautist and a choral scholar at Christ Church Oxford. I met my future wife in a Christian choir. In the early 1980s I helped to found the Berkshire Young Musicians Trust (now known as Berkshire Maestros), which still provides high quality music opportunities and education in schools and centres across the county.

On the lighter side, I can remember many Dinky Car races in the long choir-school passages, model trains at Christmas, lots of marble and Monopoly games as well as rubbers of bridge with the headmaster. I recall many cinema visits and going to see The Mousetrap in London in 1955. We also visited Glyndebourne on a number of occasions to listen to afternoon rehearsals.

I do hope readers of this short article who have had a similar background will enjoy recounting treasured memories of their own.

If there were any doubts about the Friends of Cathedral Music’s recent reinvention of its public profile as a component part of the Cathedral Music Trust, and its investment in recruiting a dynamic new team of professional staff, these should have been thoroughly dispelled by the success of its first virtual conference, Joining the Dots, held online on 18 and 19 January.

Thorough planning, efficient delivery and engaging presentation were testimony to the wisdom of the new approach. The organisation was able to communicate very effectively with a wide audience, at minimal cost to delegates. For a registration fee of just £10 they could experience, to quote a tweet from The Sixteen, ‘Two days of wonderful webinars, discussions, and opportunities to pause, think and refresh’ their perspectives, without having to pay for travel or accommodation or schedule any more time into their diaries than it took to watch the relevant sessions.

‘Joining the Dots’ certainly did what it said on the tin, connecting musicians, teachers and clergy from churches, schools and the world of concert performance, not to mention funding bodies and individual supporters. More than anything, perhaps, it blurred the boundaries between those categories in a way that is sometimes difficult to do in daily life. One of the strongest messages that came out of the conference was an appeal to everyone involved in church music to try to rid themselves of the ‘silo mentality’ that comes from focusing

solely on one’s own essential tasks, and to see colleagues in other departments or institutions as collaborative partners. As the sessions unfolded, delegates were given many inspiring illustrations of how that can be achieved.

The conference began on a wonderfully positive note, with a keynote presentation by Simon Toyne, Executive Director of Music of the David Ross Education Trust (DRET). In his current role he is responsible for the development of a music programme for over 13,000 children across 34 state primary and secondary schools in the East Midlands, and his work in that capacity has included establishing the award-winning Singing Schools programme for primary schools, developing a Trust-wide primary and secondary music curriculum, and, most relevantly for this conference, fostering a network of partner organisations, including Gabrieli Roar, Nevill Holt Opera, Sing Up, the Royal Opera House and the Voices Foundation, enabling young people in the region to benefit from the skills of a wide range of professional performers and teachers.

Toyne is himself a former chorister of Exeter Cathedral, music scholar of Eton College, organ scholar of University College Oxford, and Director of Music at both Kingston Parish Church and Tiffin School. For 24 years he was Director of the Tiffin Boys’ Choir, famous for its appearances on the opera and concert stage with some of the world’s leading conductors, so he is well placed to facilitate connections between different branches of music and music education.

The liturgy has been there for hundreds of years, the music has been written for children like you to sing – it’s hard, but you can do it – you have a responsibility for carrying that tradition forward. (Simon Toyne)

His presentation touched on the forthcoming National Plan for Music Education in England and the role of music education hubs, making the point that church musicians do need to be aware of such initiatives and how they affect their choristers, or at least those educated in the state system, and can provide opportunities for collaboration. (The devolved nations of course have their own music education policies, and Wales in particular is currently in the process of changing its approach, giving greater emphasis to the arts.)

Developing a more rhapsodic theme, however, Toyne identified himself as a product of the scholarship system and reminded delegates of the impact upon a child or teenager of singing and learning in extraordinary cathedral, church and school buildings; being surrounded by beauty every day, in architecture, words and music; and how that can shape them for life; not to mention the importance of the sense of being part of a community and a tradition engendered by the chorister experience:

Acknowledging that the sense of wonder the public often experiences when hearing church music brilliantly performed at Christmas or on television at a royal wedding can also create an impenetrable barrier between them and what feels like another world, Toyne said it was up to everyone involved in music for worship to help break down those barriers. As proof that this can be done, he introduced Lufuno Ndou, a professional singer recently graduated from the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire, who eloquently explained how she owes her choice of career entirely to being invited by a schoolfriend to join a choir rehearsal at St Matthew’s, Northampton. “I fell in love instantly,” she declared. “Until then I had only heard that sort of music in films. I had thought, ‘I could never do that’ – but suddenly there I was, in the middle of it.

“Looking back, I realise that was unprecedented. Children would normally discover church music through a ‘Chorister for a Day’ session or something and an audition, but there I was in the middle of it. I come from an African culture where people sing all the time, but not like that.”

Ndou’s account of how she joined the choir, learned to sightread by osmosis and went on to music college followed

by a year as alto choral scholar teaching choristers at Truro Cathedral deserves an article to itself. Pre-empting some of the conference’s later sessions on diversity, she was very frank and eloquent about the issues, and the need to confront them head-on, both when encouraging young people from diverse backgrounds try something new, and when introducing music by historically under-represented and marginalised composers.

This packed session also included a conversation with Bridget Whyte, chief executive of Music Mark, formed in 2012/13 as a merger between The Federation of Music Services (FMS) and the National Association of Music Educators (NAME).

The main topic was how cathedrals and choir schools can contribute to the work of hubs and music services, which fall within Music Mark’s remit, but Whyte’s many previous roles in music education have included close involvement with the Sing Up initiative, at a time when that included the launch of the Chorister Outreach Programme. This latter has now closed, but leaves a strong legacy; Sing Up carries on, and of course many cathedrals continue their own outreach projects. Whyte provided valuable insights as a result of her background knowledge, but also spoke movingly of her own personal experience, brought up as an instrumentalist through the youth orchestra system, of attending services at Guildford Cathedral as a student because she knew people in the choir: “I didn’t come from a Christian family but I loved it and ended up being baptised and confirmed. Then I worked on Sing Up and two strands of my life came together, choristers and their music, and music in schools.”

Paul McCreesh, founder and artistic director of the Gabrieli Consort & Players, also does not come from a church music background, but he passionately believes that all children have a right to experience the great sacred works of the choral and orchestral repertoire for themselves, not just as listeners but as participants. His ‘Gabrieli Roar’ project involves inviting them to learn the music of oratorios such as Mendelssohn’s Elijah, Britten’s War Requiem or, currently, Haydn’s Creation in their own school or independent choirs and then rehearse and perform these pieces with Gabrieli’s professional singers and orchestra.

McCreesh shared some short films of a Roar performance and of Martin Howarth, Head of Music at Egglescliffe School on Teesside, talking about what the project offers to his pupils that went far beyond what even a well-resourced state school like his, where music is valued, can provide. Emphasising that he has high expectations of the participants, McCreesh said, “Children like hard work”, quoting one recalcitrant teenager who looked at the score he was given, assumed it was going to be ‘160 pages of hell’, but admitted after four days of very hard work that he had just experienced ‘160 pages of heaven’.

He also believes that performing in huge, awe-inspiring churches such as Romsey Abbey or Ely Cathedral is an essential part of the Roar experience. “There is something special about the world of religion and the beauty of these heartlifting buildings. They are designed for you to walk through the west door and get that sense of uplift. Most children don’t ever have a chance to do that, but it gives them a sense of history that is important and relevant for atheists as well as for religious people. They can sing a piece of plainsong that may be older than the medieval cathedral they are standing in and feel a connection with the past. It is a cultural experience they can’t have in a classroom, and they shouldn’t be excluded from it.”

Pedagogy experts Don Gillthorpe and Catherine Beddison took an in-depth look at the chorister’s learning journey and explored ways to create the most effective learning environment, in their session on The Whole Chorister. Gillthorpe is assistant principal at Ripley St Thomas Church of England Academy in Lancaster, and Director of Music at Lancaster Priory; Beddison is Deputy Head (Operational) at Cranleigh Preparatory School, Surrey, where she also conducts the choir and the choral society. Both are involved with the Sing for Pleasure organisation, and although they are based at opposite ends of England and work in very different schools, their friendship dates from attending the Morland Camp together as choristers.

Important points to come out of their session included the need to understand the different ways in which children develop their musicianship and related skills at school, where they are usually taught in a very focused, stage-by-stage way, and at church, where they often learn by osmosis how to find their way round a hymn book or a piece of sheet music, as well as absorbing a huge repertoire by ear as they gradually learn to read the score for themselves. Choir-school pupils have to negotiate the relationship between cathedral and school; choristers who don’t attend choir schools may find that their musical ability goes unnoticed or underestimated by teachers who know nothing about church music and do not realise that their pupils’ knowledge of some repertoire and even their understanding of musical theory may well outstrip their own.

“Children like responsibility and challenges,” said Beddison, “but sometimes they have to deal with conflicting or overwhelming expectations from parents, teachers, and choir directors; it is the job of the adults to help them deal with that.”

Gillthorpe underlined the fact that children recognise quality and don’t want to be patronised; they know whether they have performed well or not, and they may be more proud of themselves for performing well or singing something

unusual in a normal evensong than they are when they do a commercial recording. He also pointed out the value of the repetitive liturgical cycle as a learning tool; seasonal repertoire comes round again and again, and becomes more familiar each time to choristers as they progress through the choir hierarchy.

There was a lot of very useful signposting in this session, both to pedagogical theory with which musicians without professional teaching qualifications may not be familiar, and to helpful professional organisations such as the Music Teachers’ Association (of which Gillthorpe is the current President), Sing for Pleasure, the RSCM and the Association of British Choral Directors.

A more objective perspective from someone outside the choral music sector came from Rob Adediran, a graduate of the Royal Academy of Music who has worked with concert halls and orchestras as well as leading an inclusion-focused music education charity in London for several years before broadening his horizons to work more generally as a consultant on diversity.

He introduced his session by pointing out that people make many assumptions about a person from the moment of meeting, unconsciously treating people differently because of height (or lack of it), colour of skin, the wearing of glasses (signifies cleverness!). However, he also drew on his experience of belatedly discovering his ability as a rugby player at a school where his team-mates quickly sized up his strengths and weaknesses, and worked together to compensate for his weakness at catching, while giving him space to assert his speed and strength. The result was a successful team where he felt at ease. But when he tried to build on this by joining a rugby club, he discovered that the other players were not prepared to give and take in the same way, so there was no place for him in that team. He was too modest to hammer home the point, but that meant the club didn’t benefit from his proven skills.

Adediran’s central point was that equality, diversity and inclusion need to be at the heart of any organisation, not just because that is morally right, but because it inculcates in everyone a sense of belonging, and that in turn leads to high performance.

The second day of ‘Joining the Dots’ began with a session entitled ‘Shaping your cathedral music eco-system in a postCovid world’. It was chaired by Tansy Castledine, Director of Music at Peterborough Cathedral, with Christopher Gray, Director of Music at Truro, Dr Victoria Johnson, Precentor at York Minster, Hugh Morris, Director of the RSCM, Natasha Morris, Development Director at Cathedral Music Trust and Stephen Moore, Director of Music at Llandaff Cathedral. They looked back at their own experiences of the pandemic, and how they and their colleagues responded to the unprecedented challenges to cathedral music departments. The intention was for them to review how the sector has weathered the storm, evaluate what we have all learned through the experience and look forward, exploring how musicians and clergy can make courageous choices to ensure a sustainable and vibrant future.

That was exactly what they did, but the session is difficult to summarise, as every contribution was so vivid and valuable. It was both distressing and cathartic, I suspect for speakers and listeners alike, to be taken back to those weeks in March 2020 when, as Moore said, the rhythm of cathedral life drew to ‘a shuddering halt’; to be reminded of how many senior boy and girl choristers were sent home supposedly for a few weeks, but as it turned out would never sing in their stalls as trebles again. They would leave with landmark repertoire unsung and none of the normal farewell rituals.

There were many positives, of course, not least the opportunity to step off the treadmill and think about how things are done, to spend time living as non-church musicians do – to discover weekends, albeit with many restrictions! – and most of all, perhaps, the revelation that communications technology can be such a phenomenal resource, which had never been fully exploited.

A real-time example of this was provided by Tom Daggett, conductor, organist and educator based at St Paul’s Cathedral, where he leads a nationally acclaimed musical partnership programme, supported by the Order of the British Empire. He co-presented a session from one of the schools where he works, then contributed to the final discussion from another, having crossed London while the rest of us were having (very quick!) lunch breaks. He was joined by Tom Leech, Director of the internationally acclaimed Schools Singing

Programme run by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Leeds, for a presentation on outreach and partnership.

One of the first things the two Toms did was to interrogate the use of the word ‘outreach’, which can carry a patronising implication that the cathedral or church choir as the centre of excellence is offering charity to its less fortunate neighbours. Leech and Daggett prefer to focus on the mutuality of relationships between music foundations and schools or independent choirs, where the aim is to give more children the opportunity to sing and to develop a high level of musical skill; if this leads to new recruits for the cathedral choir, that is just one of many welcome results.

They went on to offer many practical and inspiring suggestions for how such relationships can be developed, reminding watchers that it is much better to offer to help, for example, to plug skills gaps in schools that are struggling to provide a music curriculum that they have been asked to deliver than to present a package that has not been designed with individual schools in mind.

Which brings us neatly to the concluding session, in which Cathedral Music Trust’s chair Peter Allwood asked, ‘Where next for cathedral music?’ Discussion was primarily focused on the work of the Trust itself; Allwood reflected that since the 1970s FCM had viewed ‘support’ mainly in terms of grants, especially to help foundations at times of crisis; now, “We are seeing it in a much wider way: advice, advocacy, educational matters, communications, challenging establishment norms, increasing diversity, commissioning new music, supporting best practice, or calling out less good practice.”

Simon Toyne took the opportunity to remind everyone that the UK’s global reputation for church music is well deserved, and that we should be proud of it and spread the word widely: “The impact of that reputation is that people want to experience it for themselves. Cathedrals must not downplay the impact of what they do or undersell the complete experience of hearing centuries’ worth of glorious music well performed in a stunning building.”

As I was sitting down to write this conference report, I found myself drawn to watching the livestreamed Farewell Eucharist for Celia Thomson, Canon Chancellor of Gloucester Cathedral, who was retiring after 19 years on the cathedral chapter. The choir included two female lay clerks and two black choristers and was conducted on this occasion not by Director of Music Adrian Partington, but by the cathedral’s singing development leader, Nia Llewelyn-Jones. Canon Celia referred in her sermon to a service of Evensong the previous week when she and her colleague Canon Nikki Arthy had led the worship and Ms Llewelyn-Jones had conducted the girl choristers: an all-female team which would have been unimaginable 20 years previously.

She went on to quote St Augustine’s maxim that ‘All in the end is Alleluia’ … and that, Canon Celia said, “is the light in which we should live through change”. Alleluia indeed.

Follow this link to access the recording of the conference on the Cathedral Music Trust website: www.cathedralmusictrust.org.uk/ joining-the-dots.

Clare Stevens is a freelance writer, editor and publicist, specialising in classical music, church music and music education. Her career has included full-time posts as editor of Music Teacher magazine and marketing manager for the Three Choirs Festival. Born and brought up in Belfast, Clare graduated from St Andrew’s University in Scotland and lived in London for 30 years, but is now based in the Welsh Marches. She has been an amateur singer since her schooldays, and her varied choral experience includes membership of the chorus of Chelsea Opera Group, the Choir of St Barnabas, Dulwich, the Three Choirs Festival Chorus and Hereford Choral Society.

Sponsored by

John Rutter’s

JOHN RUTTER will conduct Guildford Cathedral Choir singing the Gift of Life.

They will also sing Veni Creator Spiritus by Philip Moore, a piece specially commissioned for the Choir.

SATURDAY 21 MAY 7.30pm

TICKETS

Audience with John Rutter and concert: £35

Concert only: £5 • £15 • £22.50

www.guildford-cathedral.org

MUSIC

Join our community of over 3,000 Friends, and unlock a host of benefits while helping us support choral foundations across the UK.

More reasons to become a Friend...

Enjoy invitations to our local and national Gatherings as part of our vibrant events programme

Delve deeper into the heart of cathedral music with our regular printed and online publications

Help us nurture the next generation of cathedral musicians and enrich more lives through the power of music

To enjoy a year's worth of insight and Friendship, visit cathedralmusictrust.org.uk or call 020 3151 6096

Image: Jason Bryant

Image: Jason Bryant

Matthew Owens was Organ Scholar at The Queen’s College Oxford, and Organist and Master of the Music at St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Edinburgh from 1999-2004. From there he moved to Wells Cathedral (January 2005–August 2019), and now is Director of Music at Belfast Cathedral. In addition to his many musical accomplishments as performer and conductor, Matthew leads the way as a commissioning agent for church music that attracts admiration from all quarters.

How many of us involved in writing new music for the English church look back to a golden age when musicians were expected to perform, compose and train others to follow in their footsteps? Tudor composers of the Chapel Royal and the later generation that surrounded the Restoration created new pieces of high fashion and immense quality that still form the bedrock of the classical canon widely performed today. By contrast, in 21st-century Britain, composers tend to be specialists who work in very different social situations to those enjoyed by previous generations. Whereas royal expectations for new music were part of the everyday life of church musicians in Purcell’s day, the growth of publishing and the publication of Boyce’s ground-breaking Cathedral Music (three volumes of church music collected in England after the Restoration and the first ones to be printed in score) in 1760 quickly led to the current museum culture for church repertoire, where the work of earlier composers is given precedence over new music (which mirrors the fashions and preoccupations of its time). To speak in the broadest sense, anyone who chooses can look at a cathedral’s music list from 1920 and find the same institution offering something similar 100 years later. Of course, the quality of the old music is supremely suited to the worship; but with the continued use of that music today’s composers have found other outlets for their spiritual music. Concert programmes and publishers’

catalogues are well supplied with excellent choral repertoire, but church commissions have become increasingly rare.

There are, of course, significant exceptions to this, and the excellent work of All Saints’ Northampton, starting with Britten’s Rejoice in the Lamb in 1943 and continuing to the present day, is remarkable. Michael Nicholas, organist at All Saints (1965-71), moved on from there to Norwich Cathedral and for 15 years kept up the tradition with a series of new music festivals and conferences. My own Vox Dei, subsequently sung at the installation of Justin Welby as Archbishop of Canterbury, was written for just such an occasion in 1993.

Matthew Owens is another exception. My first encounter with him dates from his years in Edinburgh, when he commissioned a setting of the Advent Processional for St Mary’s. When he moved to Wells he continued to commission new music and, remarkably, solved the two most significant issues surrounding music commissions: finance and public support.

Matthew’s innovations were Cathedral Commissions, a scheme which enables the cathedral choir to commission new works from eminent British composers, and New Music Wells, a festival which is a retrospective of the last 40 years of music and which also features many premieres. Members

of the community are invited to contribute a small annual grant towards the Cathedral Commissions scheme for which, in return, they have an opportunity to attend rehearsals and performances (often during New Music Wells), meet the composers and, when appropriate, receive a signed copy of the score. The success of Owens’s innovation is remarkable. In festival week, the cathedral is full at evensong, and the annual Palm Sunday Passion performances (see below) are events not to be missed. Wells is justifiably proud of its choir. In 2011 an international jury for Gramophone magazine named Wells Cathedral Choir, under Owens’s leadership, as the best choir in the world with children, and the sixth greatest overall.

During Matthew’s time at Wells, he commissioned and premiered over 120 new works from Sir James MacMillan

to Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, Jonathan Dove, Judith Weir, Judith Bingham, Howard Skempton, Michael Berkeley and a host of others. Young composers from Wells Cathedral School, such as Owain Park and Rebecca Farthing, also cut their teeth on the festival. My own contributions included an anthem, Ascension, written for a BBC Radio 3 broadcast, and a setting of the evening canticles for men’s voices and organ. In 2017, Matthew also launched a very wide-ranging plan to commission new settings of all 88 of Cranmer’s Collects from the Book of Common Prayer. The first, by Francis Jackson, was premiered shortly after the composer’s 100th birthday.

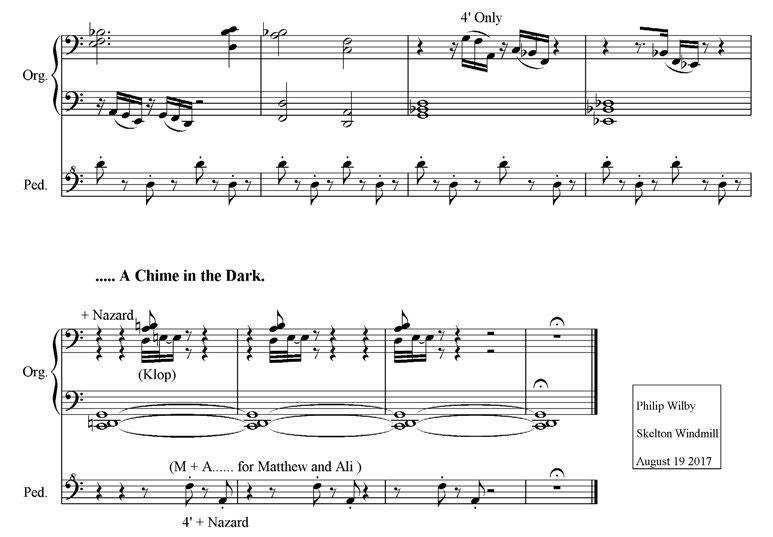

Out of this wealth of material, two projects of mine stand out: the organ suite Organ Hours, premiered in 2017, and An English Passion, published by the RSCM in 2019.

Matthew had enthused about the Dutch organ-builders Henk and Niels Klop for some years, and eventually was able to take delivery of a house organ. With mechanical action over two manuals and pedals, and encompassing a precise but small registration, Klop organs are renowned for their beautiful vocal quality – so when Matthew asked me to compose a set of short fugues for his new toy, I was delighted to accept. Writing for a small instrument was a new challenge and proved to be very refreshing. Wells Cathedral is home to one of the oldest clocks in England, and I happily turned to it for inspiration for my small collection of contrapuntal exercises. Organ clocks were very popular in 18th-century Austria, and we have surviving music by Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven for these instruments. Indeed, Mozart’s three compositions for ‘Orgeluhr’ count as some of the finest pieces of his last years.

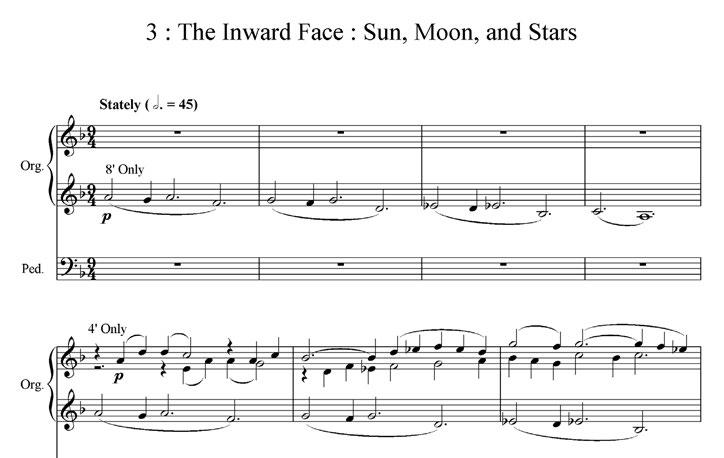

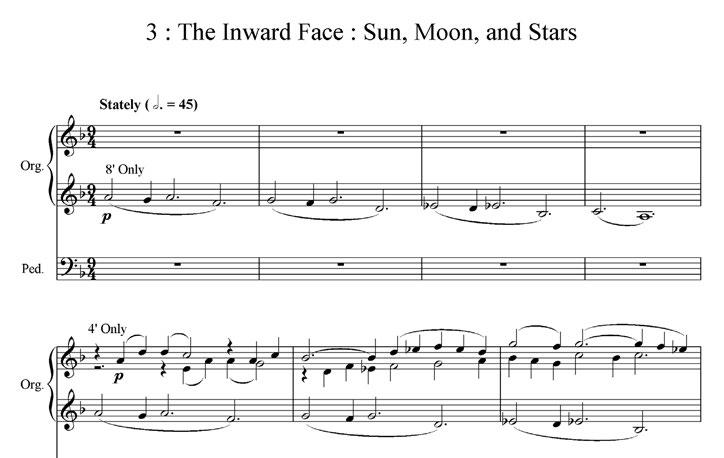

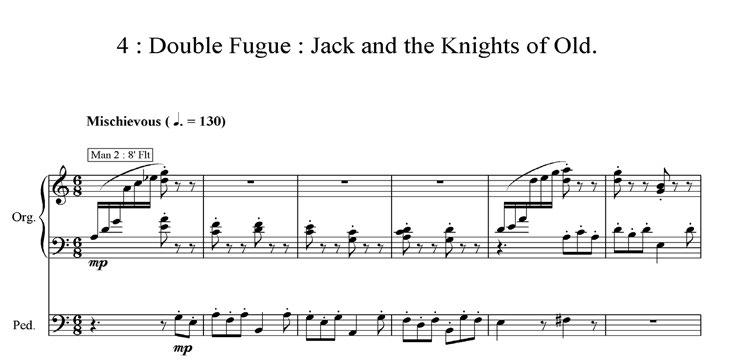

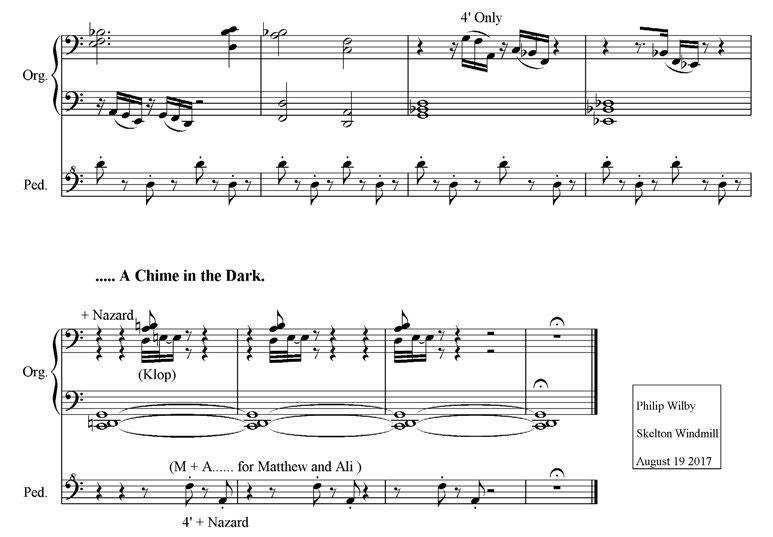

In my piece there are four separate sections.

has two faces. The outer face tells the world’s time to those passing by, whereas the celestial imagery of the inner clock face is more fascinating. Placing Earth at the centre, it portrays the sun, moon, and stars in circular motion over three concentric dials. I have used a short ground bass to provide a musical equivalent to Lightfoot’s vision of the heavens.

3. Lightfoot’s

4. The bell mechanism of the clock contains a pair of automata. ‘Jack Blandifer’ is a humorous figure, who acts as ‘QuarterJack’ and strikes two bells every 15 minutes. His rustic humour is reinforced on the hour with a sudden appearance of jousting knights. My double fugue portrays both personalities and combines them at the movement’s close with a flourish of climactic sound.

5. The final fugue is the most pictorial of the set. Against the sound of the ticking clock, this last movement imagines the sound of the clock in the cathedral at night. The music’s trajectory begins in the organ’s highest register.

Published by Fagus Music of Banchory, performances on larger instruments have now become standard. Margaret Phillips, who attended Matthew’s first performance on the main organ in Wells, has played the piece on a variety of instruments, including historic examples, and various enormous organs in northern town halls. Such performances effectively use dynamic marks as a guide to registration. The set is due for a CD recording with Simon Leach on the Frobenius organ in Edinburgh’s Canongate Kirk when the pandemic subsides.

For me the crowning glory of the Wells commissions was the request to set the four Gospel Passion texts. These were performed on Palm Sunday over a six-year period from 2013 to 2019. The first composer to accept this most daunting of challenges was Bob Chilcott, whose St John Passion laid down a pattern for subsequent works to follow. John Joubert’s St Mark Passion came next and was written in the composer’s 90th year. Philip Moore followed in 2018 with a setting of St Luke, and my own English Passion according to St Matthew was premiered in 2019. It was published by the RSCM the following year, just before the pandemic hit all church performances, and was recorded by Resonus Classics in March 2022. The brief was that the work should fit into a service of an hour’s length; it must tell the narrative clearly, involve the listeners emotionally, and provide them with the opportunity to respond physically with congregational hymns.

Setting a Passion narrative to music is a daunting task. The core values of the music and composer are truly tested, and, of course, there are several well-known predecessors to be considered. Stainer’s Crucifixion, written in 1887, owes something to Bach’s great examples from the 1720s. Stainer’s two soloists, representing the Evangelist (tenor) and Christus (bass), are surrounded by choral drama and congregational hymnody. Equally, there are earlier examples, notably by Buxtehude and Schütz, which stand in a similar tradition, although many of these lesser-known works, notably Schütz’s Seven Last Words (1645), set the evangelist’s words for various voices.

My own setting chooses to follow that 17th-century model, representing Jesus with a tenor voice, and sharing Matthew’s narrative between four other soloists (soprano, alto, baritone and bass). The choral music is written for double choir, and there are two organ parts, contrasting the high drama of the main organ with a chamber organ for accompanying recitative.

For the hymns, I sought the help of Canon Richard Cooper from Ripon Cathedral. In conversation, and later more extensive collaboration, Richard and I decided that our work should reflect our own experience. It would be ‘An English Passion’, rather as Renaissance painters evolved a tradition of setting devotional images against natural landscapes. The famous religious paintings of Stanley Spencer have achieved a similar relevance, and our setting of St Matthew’s text is counterpointed against the natural background of the English countryside. Accordingly, the melodies of the congregational hymns are taken from the collection of English tunes published in the English Hymnal of 1906. Richard echoed the words of Vaughan Williams, who said, ‘Where there is congregational singing it is important that familiar melodies should be employed.’

He went on: ‘This Passion is intended to be a devotional work and not simply a choral performance. The hymns punctuate the narrative with a recapitulation of the story and call the listener to contemplate their own involvement in the unfolding drama. They are not poetry, nor do they have literary merit in themselves, they are there to do a job: to support Matthew’s Passion narrative.’

The scene is set with the Collect for Palm Sunday (sung off stage). The Palm Sunday procession begins with the familiar opening words of ‘All glory, laud, and honour to thee, Redeemer King’, set to the tune ‘Kingsfold’ as collected by Vaughan Williams. This was later chosen for inclusion at the composer’s memorial service in Westminster Abbey.

There are two other features of the score that it would be good to highlight:

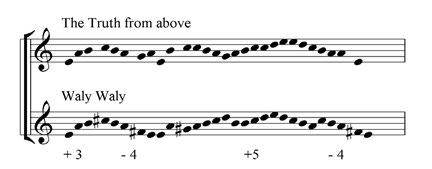

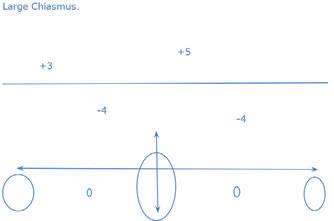

In common with Bach’s St John Passion (1724) and Buxtehude’s Membra Jesu Nostri (1680), I have included a pair of cross-shaped or chiastic musical designs in my piece. The larger of these concerns the five hymns, which are arranged symmetrically. 1-5, 2-4, with the third, the hymn of the Silent Saviour, standing alone. A striking feature of St Matthew’s telling of the Passion is his use of dramatic silences. Silences may seem to be empty, as an absence of content; not so the silences of St Matthew, which act as springboards for our own thoughts and reactions.

Speaking of the bond between Hymns 2 and 4, Vaughan Williams himself pointed out that the second hymn (‘The Truth from Above’) and the fourth (‘Waly Waly’) share a remarkable similarity, rising a third, sinking a fourth, rising a fifth and so on.

Thus the large chiasmus may be represented thus.

The central chiasmus, where music plays backwards and forwards like the symmetrical arms of Christ’s cross, surrounds Peter’s denial and Jesus’s repeated refusal to answer the questions of his interrogators. The pedal solo is represented by a small chiasmus, viz:

This most recent of Matthew Owens’s commissions from my pen has, not surprisingly, turned out to be the most extensive and the most demanding. The music, which requires full participation from its hearers, is designed to involve rather than impress, and may be seen by some as more suited to performance within a liturgical context. However, as many other greater settings of the Passion readily demonstrate, concert performances also have an evangelical outreach that few can deny. The Gospel text transcends any musical composition, just as Christ’s Passion transports its witnesses to an internal space of contemplation, reaching out to those who share a common humanity, of all faiths and none.

Encouraged to take up composition by Herbert Howells, Philip Wilby studied at Keble College Oxford, and was made Professor of Composition at Leeds University in 2002. Until recently he lived in Bristol, where his wife Wendy has been serving as Canon Precentor at the cathedral. In 2008, he was granted a Dutch Government BUMA award for his innovative works for brass band, and in 2009 an honorary fellowship by the RSCM. He is proud to have served as the musical associate of the Black Dyke Band for 30 years; his recent CD, Pilgrim’s Progress, is recorded by them.

On 9 October 2021, the 30th anniversary of the founding of the Salisbury Cathedral girls’ choir was marked by a splendid concert in the cathedral in which the current girls were joined by some 80 ex-(girl) choristers. In her introduction in the concert programme, the Countess of Chichester, chair of the girls’ choir trustees and the driving force behind the concert, spoke of how the event came about, and how ‘our beloved Richard Seal, Director of Music, Organist and Master of the Choristers here for 29 years, was inspired to found a girls’ cathedral choir.’