Cathedral MUSIC

For many years organists throughout the land have aspired to playing a Makin organ. Now with the unsurpassed sampled technology within the Westmorland Custom range, designed by organists for organists; there has never been a better time to own one. Don’t expect gimmicks because you won’t find them here.

Design your own specification, with motorised drawstop or illuminated tab control, with 2, 3 or 4 manuals in sumptuous consoles. These organs are for people who are serious about music, with a discerning taste for the best in sound and build quality. People like you.

Makin is renowned for excellence in after sales service and our highly competitive prices. As the UK’s leading manufacturer, we install at least two Makin and Johannus organs each week at churches, schools, halls, homes and crematoria throughout the British Isles. Visit our web site for customer testimonials, lists of forthcoming and recent installations, sample specifications and much, much more. Contact us today and take your first step to becoming a member of the Makin Family.

CATHEDRAL MUSIC is published twice a year, in May and November

ISSN 1363-6960 NOVEMBER 2008

Editor

Andrew Palmer

21 Belle Vue Terrace Ripon

North Yorkshire HG4 2QS

ajpalmer@lineone.net

Assistant Editor Roger Tucker

Editorial Advisers

David Flood & Matthew Owens

Production Manager Graham Hermon

FCM e-mail info@fcm.org.uk

Website www.fcm.org.uk

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of Friends of Cathedral Music. Likewise, advertisements are printed in good faith. Their inclusion does not imply endorsement by FCM.

All communications regarding advertising should be addressed to: Roger Tucker

16 Rodenhurst Road LONDON SW4 8AR

Tel:0208 674 4916 cathedral_music@yahoo.co.uk

Friends of Cathedral Music

Membership Department

27 Old Gloucester Street

London WC1N 3XX

Tel: 0845 644 3721

International: (+44) 1727-856087

E-mail: info@fcm.org.uk

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used. We apologise to any individuals we may have inadvertently missed. The Editor would be glad to correct any omissions.

Designed and produced by Mypec

The Old Pottery, Fulneck, Pudsey, Leeds, West Yorks LS28 8NT Tel: 0113 255 6866

info@mypec.co.uk

www.mypec.co.uk

disbursements: from forty foundation members in 1956 we have grown to nearly 4000 and from our first grant of £200 in 1961, to Barry Rose at Guildford, the annual total has risen to over £100,000, from which almost every cathedral foundation and some of the Greater Churches have benefited. The ‘modernist pressures’ refers to popularising the traditional liturgy and the introduction of unconventional forms of worship, at its worst in the ‘ravein-the-nave’ type of event popular in the 1990s. Choral standards, in my own experience since my days as a chorister, have risen steadily, due to better training, no doubt helped by the ease of making ever higher quality recordings of services and concerts and the availability of an enormous discography of the repertoire.

2009 will be my eighteenth year as editor and during this time I have seen many changes in our field so I want to attempt some kind of evaluation of the state-ofthe-art of cathedral music. It has become something of an FCM cliché to assert, as we do in the Charity Choice encyclopaedia ‘the music in our cathedrals has never been finer but, although widely appreciated, its future is threatened by both economic and modernist pressures’. I now want to put that question up for scrutiny. The statement suggests the ‘glorious tradition’ (another of our straplines) could be undermined. At the time of FCM’s foundation in 1956 the tradition was certainly at risk because of the post-war lack of funds and musicians in the cathedrals, which was why Ronald Sibthorp set up the charity. The aim of restoring choral services to their pre-war levels and raising the performing standards was one that was indeed widely shared and people came forward to support the ‘living tradition’ with their membership subscriptions and donations. These are all part of our core aims: to safeguard our priceless heritage, increase public awareness and appreciation, encourage high standards and, of course, raise funds. The success of the charity is borne out by the steady growth in our membership and cash

This has itself grown, enriched by choral works by some of the leading composers of modern times from Herbert Howells (our second President) and Benjamin Britten, via Johns Rutter and Tavener, to Philip Moore and James Macmillan. Radio and television have helped to raise standards through coverage of choir competitions, The Chorister of the Year event, the weekly broadcasts of Choral Evensong and the growing number of cathedral festivals and concerts, which sustain a tradition started by the oldest of them all, the Three Choirs Festival. Much of these higher standards are due to the talented cathedral music directors, who can now listen to one another’s efforts via increasingly high quality media.

The much trumpeted opposition to girls singing the top line in cathedral choirs on the grounds that it might

undermine the male tradition and drive the boys away is now seen to have been unfounded. Cathedrals that have recruited girls to provide an alternative top line have found it of benefit in several ways: it has brought more families into contact with cathedral music, competition between the two groups has provided a challenge to the boys to sing better and therefore a higher standard for the girls to emulate; by sharing out the choirs’s workload it has also made it possible to sing Choral Evensong daily, including on the most popular visitor day, Saturday. On the negative side there is the additional cost of all this and the extra workload for the lay clerks, who are in any case below strength in several cathedrals and cannot provide additional voices. Also the reduction in the singing opportunities for boys, who used to sing on most days, can result in less practice. We must recognise some of us prefer one group over the other and that the majority of cathedral music directors are not in favour of mixing boys’ and girls’ voices. In fact this was advised against in the 1992 Report of the Archbishops’s Commission on Church Music. There is still only one cathedral in England (Manchester) whose choir has a mixed top line, and one in Scotland (St Mary’s Edinburgh), the latter is celebrating its thirtieth anniversary (see Duncan Ferguson’s article on page 44). However, several more combine the two groups for special services e.g. at Christmas. All of this presents a great challenge to FCM to develop some kind of road-map for the future and for this members need to give their views. Please do so!

I am sad to have to report the death of our long-serving and popular former DR for Chichester, Hugh Curtis, who broke the all-time record for member recruitment in his time. He was the first DR coordinator and a member of Council. His memorial service will be held in Chichester Cathedral on 23 January at Evensong.

...the music in our cathedrals has never been finer but, although widely appreciated, its future is threatened by both economic and modernist pressures.

Protruding out of the roof of Belfast Cathedral, stands defiantly the Spire of Hope, a recent addition to St Anne’s Cathedral, Belfast, and a symbol FCM members were heading for on Passion Sunday this year. Consecrated in 2007 it stands proudly representing a united city. The red glow from the wall heaters located in the nave imbued a sense of warmth that was reflected in the welcome from the staff. There was great anticipation from everyone in the congregation wanting to hear Philip Stopford’s choir.

Philip was appointed Director of Music of St Anne’s Cathedral, in January 2003. He began his musical career as a Chorister at Westminster Abbey, under the direction of first Simon Preston and then Martin Neary. Following a year as Organ Scholar at Truro Cathedral, Philip won a place at Keble College, Oxford, where he read Music and was Organ Scholar. In 1999, he moved to Canterbury Cathedral to be Organ Scholar before securing his first full-time post as Assistant Organist at Chester Cathedral in 2000. In Chester, Philip was responsible for the Cathedral Voluntary Choir, and

accompanying the Cathedral Choir on a daily basis, up to ten choral services a week. He also taught music in local schools, and began receiving commissions to compose church music.

Since arriving in Belfast as Director of Music, he has been innovative in setting up the Cathedral Youth Choir and Cathedral Voices, both broadening the appeal of music at the Cathedral and providing a wider scope for repertoire possibilities. He is responsible for training the Cathedral Choristers, who are recruited from various schools in Belfast and beyond.

Andrew Palmer in conversation with

Andrew Palmer in conversation with

The first thing Philip says is: “I’m sure you noticed that we have ladies who sing alto, so we are not truly an all-male choir.” Indeed, one thing is certain, FCM members will have picked up on this fact. So how did it come about? Philip explains: “This tradition stems from the much bigger choral society sty1e of choir that would have been here in the early part of the twentieth century.” During a talk he gave after the Eucharist he pointed out to those gathered that everyone can fit in the choir stalls, which demonstrates there must have been a good sixty or seventy people in the choir. “Nowadays, of course, the fashion is very different, with much smaller choirs. St Anne’s Cathedral has had periods of mixed voice top line singing with both adult sopranos and treble voices, and it is only relatively recently that the top line of the cathedral choir has been produced solely by boys’ voices.”

During his talk, Philip points out that Belfast and Northern Ireland has a very proud history of singing, and there are some particularly fine school choirs, mostly involving girls rather than boys. “We do not have a girls’ choir as such at the moment, because I felt it was important for the Cathedral to contrast with the schools and offer singing to boys exclusively. Having said that, we do offer singing opportunities to girls in the Cathedral Youth Choir, but they are older girls, 15 or 16 and above and the remit of the choir is specifically different from the Cathedral Choir, in that its main focus is concert work. This was launched in 2004, as part of the centenary celebrations.”

The third choir, Cathedral Voices, is a select group of sopranos, who join forces with the cathedral choir adults and who perform a more diverse repertoire. This also provides the choristers with half-term breaks and some other Sundays off during the year. Cathedral Voices were preparing to sing at the forthcoming Maundy Thursday Eucharist.

The cathedral’s choirs are all predominantly voluntary. “Having surveyed the music of 2007, I discovered that the choir had sung 376 items in the year, excluding the psalms and hymns, and that if we had sung all the music continuously without stopping, it would have taken nearly 18 hours. When you think that Belfast has the Ulster Orchestra which, does fewer performances, then St Anne’s Cathedral Choir isn’t too bad really for a group of volunteers.” says Philip proudly. St Anne’s Cathedral attempts to offer the same musical and spiritual opportunity that is offered to all cathedral choristers and it offers those memories that last a lifetime.

During his talk Philip plays examples of his copious compositions: in particular we are treated to the Gloria from the Centenary Eucharist. We had missed out on hearing it due to the season being Lent.

Philip says it came about after Ian Barber (who is celebrating 25 years as Assistant Organist) and his wife Jean, asked the Dean if they could commission a musical work as part of the Centenary Celebrations in 2004. “When they approached me to do this I agreed but suggested that a setting of the Eucharist would be more useful perhaps than an anthem and hence the Centenary Eucharist was composed.” It has been recorded by Philip’s chamber choir Ecclesium and recorded by Priory Records in St Anne’s.

“It always amuses me that many cathedral choirs are still singing Sumsion, Darke, Howells, and all those 20th century greats, and then I ask myself why?”

“I believe that the answer lies in the fact that they have functionality in what they offer, and yet are beautiful none the less. Writing music for the liturgy has to be exactly that for any work to have longevity. It is not every cathedral choir or parish choir that can sing Vaughan Williams in G every week, and it is not every dean or clergy person who wants that. The focus for composition has to be the event, occasion and liturgy for which the new work is required,” he says.

In 2004, the Church of Ireland produced a new Book of Common Prayer, and Philip felt it was appropriate to set the Eucharistic text from this new book. He explains that while the same principles of any Eucharist setting need to be adhered to, such as an uplifting Gloria, with a more reflective Kyrie and Agnus Dei, the creativity of the music must be new and exciting and yet manageable week by week as much as possible, otherwise the music falls out of the repertoire.

“I hope to have achieved some of these qualities in this setting of the Eucharist, and also taken into account the Cathedral’s expansive acoustic and the powerful four manual Harrison organ.” He has woven the St Anne hymn tune into the Gloria

Similarly, in 1997, he composed the Keble Missa Brevis for the service of Corporate Communion, when parish churches associated with Keble College, Oxford, were invited to attend a Eucharist and dinner in college. The setting was in English,

harmonically and musically accessible, yet inspiring and fun, and showed off the strongest parts of the choir.

It is not a new phenomenon. Organists have been writing church music for choirs for hundreds of years. Examples would include: Thomas Tomkins at St Davids Cathedral, Henry Purcell at Westminster Abbey and William Byrd at Lincoln Cathedral. Cathedral organists, would-be directors of music and composers would write music for their choirs all the time, as of course did J S Bach. “Yet nowadays, some cathedral organists shy away from doing just this. In the same way that you would expect architects to design houses, surely church musicians should design choral music and have an inside knowledge on how to do it. I heard of one non-church musician who was asked to write a set of responses and they lasted 15 minutes and were in 24 parts! Lovely music but highly impractical for everyday worship and your everyday choir.”

One of the richest sources of words comes in the form of the Collects and I put this to Philip. He is enthusiastic: “They are a challenging and often neglected source. Each has different characteristics and are related to Sunday services. Sometimes I have a commitment to the text but it can take a couple of weeks to compose whilst others take three hours.

So what other texts are there to set? Morning Prayer, Evening Prayer, a Eucharist, Compline? The same as it has been for 450 years in the Prayer Book. Then there are carol services and special occasions.

Last year, the Cathedral consecrated the Spire of Hope,

which he points out to those gathered for his talk, we were sitting under! The service was scheduled for September 11th and the preacher, the Bishop of New York. The theme of the service? Hope, the link between the two cities through troubles in Northern Ireland and terror in New York.

So how did he approach writing a composition? “As DoM, I was left thinking, what are we going to sing? What anthem by Tomkins, Purcell or Byrd is going to fit that occasion? And this is where the art of composition is such a gift. I researched some words taken from a service of commemoration in New York soon after 9/11, and combined the words of St Francis of Assisi, ‘where there is despair, let there be hope’. This work opened the service, with a bass drum pulsating through the music from start to finish. On this occasion, the music was able to open up a challenging and thought-provoking service and was specifically related to the liturgy taking place. We are recording this work at the end of this month.”

Philip is also often asked by schools and colleges both here and abroad to set very familiar texts. Two recent examples have been In the bleak midwinter and All things bright and beautiful. “These commissions are often the most difficult, because they have already been set so beautifully, if not by Rutter, then by one of his friends!

“Have you noticed how few musical settings there are of All things bright and beautiful ? I found this nearly impossible to compose, staying within the standards of a primary school choir and yet making it interesting and rewarding to

learn and perform.”

So equally, what were the challenges for In the bleak midwinter? Dare anybody come up with a melody better than Holst or Darke?

Philip says that with this one he tried to compose as simply and as beautifully, but significantly differently to be worthwhile. “As with any text that is versified, once the first verse has been composed to a new melody, it is then a case of arranging the following verses around your new tune! After all, that’s what Harold Darke did, and it works!”

Sometimes, he has made arrangements of pieces he is not so keen on! “Silent Night and We Three Kings were never my favourites”, he says, “so I decided to take a longer look at the words, and arrange the music in a way that the listener might think again. Have you ever thought that Silent Night is actually quite joyful at the end? ‘Christ our Saviour is born!’ Similarly, in the somewhat trivial We three Kings, have you noticed that the crux of the Christian message is contained in this carol, sorrowing, sighing, bleeding, dying, not very Christmassy and often overlooked.” Here he punctuates the silence once again with a recording of We Three Kings, again sung by Ecclesium.

I ask what it is like to hear your composition being sung. “In 2006, I was invited out to Indianapolis to work with the Indianapolis Children’s Choir, and to meet with my American publishers, Hal Leonard. When I got to the first rehearsal there were about 100 children on stage singing my carol, A Child is born in Bethlehem. There is certainly nothing more satisfying than seeing, what is essentially a piece of paper with a few

President: Dr Simon Lindley

scribbles, being enjoyed by so many people. It was only later on in the day that I discovered there were 10 or 12 choirs of 100 children in each choir, all turning up to rehearsals two or three times a week, with 10 conductors, 10 musical assistants and 10 accompanists, and each child paying $300 a year to be a member. It is astonishing that singing in this way can evidently be so rewarding and uplifting, and I wonder if we can bring an element of this back into our own cathedral choirs.”

“In the UK-wide cathedral music scene, we are blessed with hundreds of years of tradition, and a wealth of choral repertoire that is unrivalled across the world, but perhaps we need to sometimes think slightly outside the box, and gamble on new music that is fun to learn and to perform and uplifting for congregations and audiences alike. And as a cathedral organist-composer, I must try to produce music that not only reflects our tradition, but also inspires and challenges congregations, and glorifies 450 years of Anglican Liturgy as emotively as possible, whilst remaining within a standard that is both performable and has longevity.”

Philip is fast becoming a composer of note, with his own publishing company ‘Ecclesium’ doing well, who has recently signed an American publishing deal with Hal Leonard (www.halleonard.com). The CD of his own church music compositions (part of Priory Records‘ British Church Composers series) received ‘Editor’s Choice’ in the September 2006 issue of Organists’ Review and reviewed in CATHEDRAL MUSIC November 2005. He has also just released a second volume Creation on the Priory label.

Do you know a child who loves singing?

Salisbury Cathedral Choir offers a wonderful opportunity in a spectacular setting

INFORMAL PRE-AUDITIONS at any time by arrangement

BE A CHORISTER FOR A DAY

Saturday 15 November 2008

Open Day for prospective choristers in Years 2, 3 & 4 and their parents

VOICE TRIAL WORKSHOP

Saturday 6 December 2008

VOICE TRIALS for children currently in Years 3 or 4

To obtain your free copy of the latest list send a SAE (size DL: 110 x 220 mm) to:

David Watson

CTCC

26 Syke Green

Scarcroft

LEEDS LS14 3BS

West Yorkshire

Boys - Saturday 24 January 2009

Girls - Saturday 7 February 2009

All children are educated at Salisbury Cathedral School Scholarships and bursaries available For an informal discussion with the Director of Music and/or further details please contact: Dept of Liturgy & Music

Tel: 01722 555148

Email: s.flanaghan@salcath.co.uk

As part of our mission to support traditional choirs of men and boys, we are offering free guides listing Cathedrals, Churches, Colleges and Chapels in the United Kingdom and eire where they can be heard.

‘The Most Beautiful Sound in the World’ New York Times

Bishop Edward warmly welcomed the representatives of the Friends of Cathedral Music and conveyed a personal message from the Dean expressing his regret that, due to his previously planned visit to Australia, he could not be present in person to welcome them, but that he extends his good wishes and blessing on the remainder of their National Gathering in Northern Ireland. Bishop Edward went on to say:

“As you come here this morning to share in the traditional Eucharistic worship in this Cathedral Church, I would like to invite you to focus your thoughts on all that is implied in the second sentence in today’s Gospel which has just been read for us: ‘Mary was the one who anointed the Lord with perfume and wiped his feet with her hair.’ That reference, of course, was to an incident which had taken place sometime earlier at Bethany, the same venue as the scene of this morning’s Gospel story –an incident which has a certain relevance for us today as we consider the important place that music plays in the context of cathedral worship.

“With the shadow of the cross deepening before him on

that former occasion in Bethany, Jesus was enjoying a quiet homely dinner with some friends. ‘As he sat at the table’ –no picturesque wording can paint the scene more faithfully than the simple language of the Gospel itself –‘as he sat at the table, a woman came with an alabaster jar of very costly ointment, and she broke open the jar and poured the ointment on his head.’ And we might have expected that Our Lord’s disciples, his closest friends, would have welcomed this action, that their hearts would have vibrated with sympathy. After all, they knew more than anyone else who and what he was. They had been uplifted with the dazzling hope that he was to be the promised Messiah for whom their nation yearned; but they could not be made to grasp the fact that, in order to reach his Messiahship, he would have to die. They just could not see that this anointing by a tender-hearted woman was, as it were, a prelude to his death, a preparation for his burial. He had certainly told them on more than one occasion that he would have to die, but it never really sank in. And this slowness of theirs to understand the situation showed itself

clearly in the question which they found themselves asking. They looked at that woman lavishing her love and affection as she poured out her ointment, and they asked: ‘Why was this ointment wasted in this way?’ or, as Matthew puts it more succinctly in his account of the same story, ‘Why this waste?’

“But I don’t suppose she even heard the question! If she did, well, she was probably so absorbed in her devotion that the rebuke would mean very little to her. But, if the words didn’t hurt her personally, think of the pang they must have given Jesus himself. ‘This ointment could have been sold for more than three hundred denarii, and the money given to the poor’ was the argument put forward. It could indeed! And that is both a worthy and a noble thought. It is an admirable thing to help the poor. Nobody is questioning that for one moment and, had the ointment been sold and the money given to the poor, Jesus would probably have been delighted. But what must have been a bitter disappointment to him was that, even at this late hour, his own disciples were not yet spiritual enough to be able to appreciate sheer uncalculated love and affection.

“In the Passover week that had just begun, almsgiving was considered a duty of paramount importance; public opinion demanded it, and, therefore, everybody did it. And those disciples of our Lord found it hard to imagine how Mary, who

ought to be giving alms to the poor, could throw it all away just like this: ‘Why this waste?’

“And, you know, history repeats itself today. In my dealing with clergy, for instance, during my fifteen years as Bishop of Limerick and Killaloe, I became acutely aware that if any of the clergy tried to show our Lord any kind of spiritual devotion or affection to which their parishioners were not accustomed, the same sort of question was asked: ‘Why this waste?’ You see, while many of the laity want the clergy to be sincere people, they also want them to be practical people. They want the gospel to be a gospel of social concern for those in need. And, of course, they are absolutely right, and much of a priest’s ministry just has to be spent in bringing relief and help to the needy. No, I wouldn’t quibble with that at all. But what they don’t seem to understand is that Christ calls each one of us, whether we are ordained or whether we are lay, to serve him and that calling and vocation surely demands a response of love and affection for him in a complete outpouring of ourselves.

“When I began my ministry almost 52 years ago on the Shankill Road, not very far from here, it was customary for the Rector and the three of us who were his curates to meet each morning and evening in the parish church for the daily office of Matins and Evensong, and sometimes people asked us: ‘Do you get many at your daily services of Morning and Evening Prayer?’ And, when we replied ‘No’, or if we should have volunteered the additional information that there were often times when there was nobody present but ourselves, they look puzzled, bewildered, perhaps even horrified, and they invariably asked a second question: ‘Is it worth it?’ That happened on a number of occasions. You see, they were genuinely concerned that we should be tying ourselves down to special times of prayer when we should be leaving ourselves freer to make our ministry a practical one of readily caring for those in genuine need; and, of course, the question that they were really asking is ‘Why this waste?’

“As I said earlier, history repeats itself. We heard that same question here in the course of the past twelve months as we witnessed the erection of the Cathedral’s Spire of Hope: ‘Why this waste?’ Many just could not see that the spire is a vivid symbol of peace and reconciliation in a city that has been torn apart for many years by strife, violence and bloodshed.

“And I am sure that there are many friends of cathedral music who have heard that same question: ‘Why this waste?’ over and over again: they will have heard it as they have tried to increase public awareness and appreciation of the priceless heritage of cathedral music; they will have heard it as they have tried to encourage the highest possible standards in choral and organ musicianship; they will have heard it as they have tried to raise money by subscriptions, donations and legacies to help choirs to attain both excellence and dignity in the offering of our worship to Almighty God. Yes, ‘Why this

Many just could not see that the spire is a vivid symbol of peace and reconciliation in a city that has been torn apart...

waste?’ is the kind of question that is familiar to us all. But in that incident at Bethany, referred to at the beginning of this morning’s Gospel, Mary did not pour out her ointment and wipe our Lord’s feet with her hair for the good of her own soul; no! It was a spontaneous desire on her part to give her all as she committed herself to her Saviour Jesus Christ. And that is what the disciples called ‘waste’.

“And so, those of you who are Friends of Cathedral Music, I commend what you stand for, what you appreciate, what you are striving to achieve. But I would want to add this: there will be times when many will either misunderstand or misinterpret your aims and objects, your purpose and intent; there will be times when people will just not be able to appreciate the wealth of beauty and dignity that is conveyed through the music offered to Almighty God in cathedral worship; indeed there will be times when they will interpret such perfection as a complete waste of time: ‘Why all this highfalutin music which people find dull, boring, monotonous, meaningless and unnecessary, when we could be worshipping God in a much more simple way in a more direct, personal, intimate and costeffective way?’ Yes, ‘Why this waste?’

“But the question we have to ask ourselves is: ‘Is it a waste?’ In attempting to answer that question, allow me to cite one very obvious local example. Whenever I stop and consider the talent, the musicianship and the dedication of the Director of Music here, the assistant organist and the choir of this cathedral church, I think I am on pretty safe ground when I make the suggestion that, were it not for the standard and the beauty of the music offered to Almighty God in this place, there probably wouldn’t even be a parish church, let alone a Cathedral, standing on this very site in modern downtown Belfast. It is the cathedral music more than any anything else that brings people to worship God in this place. It is the cathedral music that stimulates men and women to come here and open their hearts to their Creator in a form of worship that is disciplined and dignified. And that is a phenomenon that is surely true of cathedrals all over the world. How true is that comment of a music critic in a national newspaper which I read on the website of the Friends of Cathedral Music!: ‘The choir is the life-blood, the animating factor that turns a cathedral from a beautiful but silent space into one that reverberates with glory.’ Amen.”

Salisbury Cathedral’s exquisite new font, the culmination of an on-going project initiated 10 years ago by the then Canon Treasurer and now Dean of Salisbury, the Very Revd June Osborne, is seen today for the first time in its full beauty filled with flowing water and truly reflecting the Cathedral’s majestic 750-year-old architecture. Perhaps the most significant addition to the fabric of an English cathedral in recent years, it has been designed by William Pye, Britain’s most distinguished water sculptor, and is the Cathedral’s first permanent font for over 150 years. Cruciform in shape and with a three-metre span to allow total immersion baptism, it is a beautiful green patinated bronze vessel with a Purbeck Freestone plinth and brown patinated bronze grating. The Salisbury Font has been specifically designed to combine both movement and stillness, with living streams of water flowing from its four corners whilst a perfectly smooth, still surface of water reflects the surrounding architecture of the cathedral. June Osborne, said: “This new font is a masterpiece. Now we see it in its permanent position in the middle of our magnificent medieval cathedral, it is even more beautiful than we could have imagined. It is so right for the building, a real 21st century treasure, both contemporary and timeless. It is deeply significant that it will be formally dedicated for us and used for its true purpose of baptism for the first time by the Archbishop of Canterbury when he leads our worship on 28 September during our 750th anniversary weekend. We are indebted to Sir Christopher and Lady Benson and The Jerusalem Trust for their huge generosity in funding what is also a major piece of art for our Cathedral.”

Simon and Mollie Deller started their married life together in 1966 teaching at Ripon Cathedral Choir School. In 1969 they took up appointments in Guildford when Simon became headmaster of the Lanesborough School. They retired in 1998 and returned to a village near Ripon, Kirby Malzeard, where Simon rejoined the Ripon Cathedral Choir, becoming senior lay clerk and in 2004, Lay Succentor. He retired this year and in recognition of his services Dean Keith Jukes made him an honorary canon.

Special ceremonies were held during Evensong at Salisbury Cathedral during September when eight new choristers –four boys and four girls –were admitted to the choir and the most senior choristers were appointed and received their medals of office. The new choristers are Jack CovilleWright, Sean Frost, Luke Hill, Alex Stagg, Elise Coward, Helena Mackie, Anita Monserrat and Rosanna Wicks. David Halls, Director of Music, said

“It is always exciting training new choristers and hearing their voices develop more power and density. This year’s new choristers are a particularly lively group and are going to be great fun to work with.” In their final year (school Year 8) as choristers, some are given positions of responsibility which reflect their seniority and musical expertise. David Halls continued: “Both boy and girl choirs have a head chorister, deputy chorister and ‘turners’ who assist with the music. This year Robert Folkes is Bishop’s Chorister (head chorister), Tom Watson is Vestry Monitor (deputy head chorister), and Alexander Coplan and Rupert Nodder are Turners. Rosamond Thomas is Dean’s Chorister (head chorister), Eleanor Bonney is Precentor’s Chorister (deputy head chorister), and Imogen Halls and Annabel Cooter are Turners. In the case of Alexander Coplan, we are delighted that he is also the Bowen chorister, which entails extra responsibilities assisting the organist.” The choir also welcomes Tabitha Archer, Finnbar Blakey, Flora Davies, Peter Folkes, Sebastian Halls, Tuomas and Anna Laakkonen, and Hermione Leitch as probationer (learner) choristers. Photos show the newly admitted boy choristers and their fellow choristers with their celebration cake at the tea party following Evensong and one of the new girl choristers with the new head and deputy head chorister, being ‘bumped’ (initiated).

In June of 2006, BBC Radio 3 broadcast Choral Evensong live from St Mary the Virgin, the Oxford University Church, sung by Schola Cantorum. The following February, BBC Radio 4 broadcast Matins as the Sunday Morning Worship, again from St Mary’s and again with Schola Cantorum singing. So far, so good.

However, on both occasions a jazz piano trio joined the choir and organ. Apart from my hymn arrangement of a jazz standard by Billy Taylor, the music for both services was all my composition, and was all written as jazz. The Morning and Evening Services came to be known as ‘The Oxford Blues Service’.

Reaction to the broadcasts was varied –we had expected no less. Like any performer, I was irresistibly drawn to the negative responses; the BBC Messageboard was filled with comment, describing the service as ‘sentimental slush’ or ‘cocktail music’ and an inappropriate choice of style for Anglican worship. One listener wrote of the second broadcast that it was: ‘…not a pleasant sound at all, and a hideous act of desecration. It neither reflected the jazz idiom nor the beauty of Anglican matins.’

Perversely, I was very pleased to have this particular feedback as it was at least one person’s emphatic answer to a question inherent in writing the music at all –Is there any place for jazz in Anglican church music?

I am a classically trained musician and have no particular jazz credentials; writing in a jazz style was a means to an end. For me the purpose was an examination of a broader question; is it permissible to enjoy Anglican church music? Is one allowed to have fun?

I find myself probing further in search of an answer. What is it a congregation is truly seeking when they attend a choral evensong? Why does the Anglican choral tradition with its semi and fully professional choirs exist? Is ‘a pleasant sound’ a prerequisite? Why is there music in a church service at all?

I can’t claim to have definitive answers for these questions, but my writing this music was something of a personal exploration of the issues. I also hope that both supporters and detractors of this experiment might ask themselves the same questions.

It seems to me that communication is the key; ever since a priest first realised that, to make his voice carry as he recited the liturgy in a large vaulted building, he would need to chant rather than speak, the act of singing has been used in churches and cathedrals to convey text. Throughout the history of church music, composers have developed this fundamental idea, adding texture, harmony, counterpoint and accompaniment to illustrate and illuminate but, above all, to convey the text.

It would logically follow that any form of music that achieves this is appropriate and any that doesn’t, is not. This must have been the conclusion of the Council of Trent when it sought to restrict counterpoint (“Can’t hear the words clearly!”) in the mid sixteenth century. Returning to our own century, I surmised that as long as the jazz music I wrote conveyed text and meaning, surely it could not fail to be appropriate.

As a composer and singer who revels in words, I set about composition with textual clarity as my primary aim. I tried to respond to the linguistic power of the Canticles and chosen psalms using a musical language that was immediate and suitable to the meaning; that my chosen language was jazz was almost irrelevant.

Whatever standards are used to judge the music of both services, I am confident that my primary goal of communication was achieved; the words of the service were audible and on some level musically illustrated for anybody who was prepared to listen. Therefore the problem for complainants must lie in the nature of jazz itself.

Is jazz as a style of music inherently unsuited to church worship because of its association with late-night clubs or ‘cocktail lounges’? This was certainly the objection of several who wrote to complain about the broadcasts. However, while some jazz musicians and composers may indeed be wicked, alcoholic drug addicts whose music and lyrics promote licentious living and sin, there are equally many who hold deep religious beliefs, often reflected in their music.

The roots of jazz in gospel and spiritual music are clear and obvious; it would have been the norm for Black American musicians in the last century to have derived much of their education from Sunday services, especially when it came to

vocal harmonies. Clearly this history is separate from the centuries-old Anglican choral tradition, but the actual suitability of jazz as a medium for worship is well established.

I was inspired to attempt this composition on hearing a repeat broadcast of Duke Ellington’s Sacred Concert from Westminster Abbey in 1975. Specifically, I was intrigued and affected by the broadcast preamble during which Ellington’s biographers spoke of the strength of his faith and his affirmation that there were no boundaries in his jazz, say between ‘good’ or ‘wicked’ music, ‘godly’ or ‘ungodly’. Late in his career he felt able to speak publicly about his faith which had hitherto been private; indeed the introit I composed for Evensong, Grey Skies, sets a collection of Ellington’s statements, beginning: “Now I can say loudly and openly what I have been saying to myself on my knees.”

A greater stumbling block could be the sexual energy of jazz culture and this is surely a subject that causes some Anglicans awkwardness. However, my understanding of Christian theology is that sexual desire is as much God given as any other human facet and I am frequently amused by prudish attempts to gloss over this area in religious circles, especially during settings of some of the racier verses of the Song of Songs. Even the most puritanical of Christians must surely wish for the human race to continue.

Perhaps one can turn this whole question on its head and ask: were one to accept that jazz might be appropriate in Anglican worship, does it not follow that any style of music is acceptable? Certainly, I could point to electric rock music in evangelical worship, though this is an area in which I have very little experience. But to take an extreme example, I find it hard to imagine a liturgical setting written in a punk rock style. I feel context is all-important here; punk in England arose in the 1970s specifically as an anarchic, almost violent reaction to the mainstream and shares little with Christian values. Jazz is not intrinsically the music of revolt; whatever associations one might attribute to jazz, it is not this.

My point remains that there is nothing inherent in the spirit or history of jazz to challenge the traditional Anglican service on a theological basis. I would like to think that an omnipresent

god is as much in evidence at 3.00am in a jazz club or cocktail lounge as in church and those with missionary zeal could even argue that His presence there is all the more desirable.

Having discarded unhelpful associations, I should consider what notions in jazz are useful in this context. It seems to me the most obvious and powerful aspect of jazz is improvisation and it is this, I feel sure, that conservatives could find threatening.

As a singer since my treble days, through university and then as a professional choir member, I have been thoroughly immersed in the Anglican liturgy. It is a part of me and I respond to its profound beauty both musically and spiritually, and I recognize that part of its comfort lies in its enduring ritual. I am sympathetic therefore to those who decry change and wish to worship “in the beauty of holiness”.

I have, at the same time, been uneasy with ritual for ritual’s sake and have over the years, from my vantage point in the choir stalls, developed a distrust of the Pharisee element in any congregation: those who display with alacrity their knowledge of the finer points of evensong etiquette. I am reminded of Mahatma Gandhi’s observation about Christianity: ‘I like your Christ. I do not like your Christians. Your Christians are so unlike your Christ.’

At moments I admit I have felt an urge to leap out of the stalls and shake the temple a little, wake the congregation from their collective stupor and remind them of the power and expressive beauty of a particular psalm, hymn or canticle. Not terribly Anglican.

Nor, I accept, is the habit of making judgements about the religious motivation of others and I suspect that this reflects prejudices of my own.

However, the sense of freedom in form and expectation that jazz implies is attractive to me. It suggests that one can be inspired in the moment and follow a tangential thread wherever it may lead. Canon Brian Mountford, vicar of the Oxford University Church,` made reference in his Evensong address to ‘theological jazz’. I am intrigued by the idea, theologically and musically, of operating outside one’s comfort zone, starting in a direction without necessarily knowing where one will arrive. It encourages one to consider the moment

afresh, to listen to old, familiar texts and prayers anew.

However, I should also point out how conservative I was in writing the two services. The freedom to improvise does not imply that there are no rules –this is not the anarchy of punk by any means. As a product of the Anglican Choral tradition, my starting point was the 1662 Book of Common Prayer and, with the exception of the Duke Ellington Introit, my texts were selected using the old, rich language of the BCP. I adhered strictly to the form and content of a traditional Evensong. I took care that the canticle settings followed the structure and musical clichés familiar to any choral singer, my intention being that however alien the musical language might be, any worshipper would recognise immediately exactly where they were in the service.

In fact, the musical language I used was also fairly conservative (which, ironically, alienated many pure jazz fans) for the same reasons. As a childhood fan of Bryan Kelly’s 1969 Canticles in C (for a young treble, this was as fun and ‘jazzy’ as church music ever got!) I was always aware that fruity jazz harmonies and syncopations were never far away in late twentieth century church music. Energetic, syncopated rhythm is integral to the choral music of, say, Walton, Matthias and Leighton and for rich jazz harmonies with added sixths, ninths and ‘blue note’ clashes one need look no further than Howells. We had even considered Like as the Hart for the Evensong anthem as its musical language is so close to jazz; add wire brushes and you have a jazz standard.

Indeed, there is the clearly audible difference between our broadcasts and a traditional service –piano, bass and drums with organ. My initial idea was that the whole service should, if performed elsewhere subsequently, be capable of being accompanied by organ alone. Indeed, our wonderful Hammond organ was used only to rescue the situation when the piano trio was found to be incompatible with the baroque tuning of the organ at St Mary’s.

Extra instruments in choral services are nothing new, of course, as many a Tudor viol consort could testify. I knew, however, that the simple inclusion of drums alone would exasperate a section of the listening community. It was partly for this reason that I selected texts for my anthem, Sing unto the Lord a new song, from psalm verses that made specific mention of the joyful praising of God with instruments, especially the ‘tabret’. Perhaps rather mischievously, the

anthem included some ‘happy clapping’ to accompany the text ‘O clap your hands together all ye people’ to illustrate the point that making a ‘merry noise’ has been part of the act of worship long before jazz was invented.

However, the fact remains that this was English choral music, written by a university-educated singer and musician. In evidence were varied choral textures, counterpoint, wordpainting and clear formal structure as dictated by the various texts; all the usual facets of Anglican choral writing. The point of the exercise was an attempt to write music of integrity and, hopefully, some worth. As Duke Ellington wrote, again quoted in the Introit: ‘There is no art when one does something without intention.’

To what extent this experiment succeeded or failed depends on one’s point of view. As previously mentioned, some jazz musicians felt that the music was not true jazz, that there wasn’t enough improvisation in evidence and that the music was safe, clichéd, facile even. (I felt some of this was fair comment and hoped that the Matins service was an improvement in this area.) Others felt that a trained gospel choir should have performed the music and that the mismatch between the jazz musicians and the highly trained classical singers in Schola was detrimental. However, my intention was always to write from within the Anglican tradition as I have lived it, for Anglican choirs in which I have sung, to inspire those used to a diet of Brewer, Sumsion and Watson with something a little different, challenging on all fronts –a ‘New Song’.

On the other side of the coin, there are those who felt that jazz in church was quite simply a ‘desecration’. I can’t help feeling, though, that such detractors were unable to listen beyond an initial prejudice to ‘drums in church’ and I hope I may have explored and exploded these prejudices in the hope that they prompt a deeper, personal examination of what the combination of music and text as an act of worship actually means to an individual.

It was never my intention to promote jazz at the expense of existing choral music, much of which is as much a part of me as it must be for any singer fashioned in the choir stalls. I am still a classical composer. For those outraged by our jazz Evensong broadcast in 2006, ‘normal service’ was resumed the following week.

As a final thought, here at least is some personal vindication I enjoyed. I entered into a brief e-mail correspondence with the gentleman who considered the Matins service a ‘hideous act of desecration’ and invited him to give me more specific feedback and context. He did so, but was obliged in doing so to listen to the service again. A couple of e-mails later, he signed off with the following:

‘Musically it does work and grows on this listener! I’m still listening to it, and I can assure you that other friends of mine have heard it and enjoyed it.

‘I have a gut feeling that your work will find a niche and establish itself.

‘It has certainly made me think.’

A greater stumbling block could be the sexual energy of jazz culture and this is surely a subject that causes some Anglicans awkwardness.

St John Baptist College, Oxford 2007

3 manuals & Pedal 33 stops with a unique double département Récit

Grapes are blended to produce the Grand cru.

Materials and Spirit are also blended in the age-old way to produce the Grand Orgue for the discerning palate.

Organs of world-wide distinction handcrafted without compromise by Bernard Aubertin

Chevalier, Legion d’Honneur & Maître d’Art

Manufacture d’orgues Aubertin

L’Ancien Prieuré

F -39700 (Jura)

COURTEFONTAINE

France

Tel + 33 3 84 81 32 66

Fax + 33 3 84 71 19 42 orgues.aubertin@wanadoo.fr

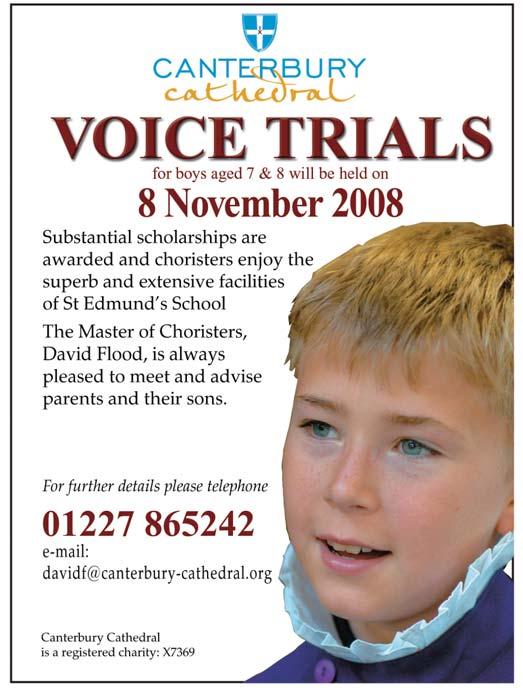

Voice Trials for boys aged between 6 and 11

■ Usually weekday/term time commitments only

■ Worldwide concerts and recordings

■ Broadcasts for TV and Radio

■ Co-educational Aged 2+ - 18

■ Boarding and Day School

No Christmas or Easter commitments

Dean Close Preparatory School

Lansdown Road

Cheltenham

Gloucestershire GL51 6QS

www.deanclose.org.uk

Tel:(01242) 258001

Age: 25

Education details:

Hereford Cathedral school 1994-2001

Canterbury Cathedral 2001-2002

St John’s College Cambridge 2002-2005

Career details to date:

Assistant Organist –Carlisle Cathedral 2005-2008

Assistant Organist –Canterbury Cathedral 2008Director of the Canterbury Singers

What are you looking forward to most at Canterbury?

So many things! The daily round of Evensong in such a building ranks very highly for me. Add to that working with great people in a fine music department, and the enormous excitement that goes with Canterbury Cathedral’s position at the centre of the Anglican Communion and you’ll understand why I’m very enthusiastic. Best of all will be the amount of sunshine.

What did you enjoy most at Carlisle?

The fabulous organ and having time to practise on it was a real plus; I’ve had an invaluable taste of the incredibly hard work of choir training and recruiting without the luxury of a choir-school, and developed an appreciation for traditionally brewed ales and Penrith Fudge.

At which cathedral would you most like to be the Director of Music?

I’d be more than honoured by anywhere that would have me! Situation in a big city might be a bonus.

What organ pieces have you been inspired to take up recently and why?

I’ve just started to learn the complete works of S.S. Wesley, after I was asked to record them for Priory last week! I’ve got around two months so it’s going to be tight. I had no idea how hard some of the music is, or how many unanswered questions there are about performance practise, so it’s also going to be a real learning curve.

Have you been listening to recordings of them and, if so, is it just one interpretation or many, and which players?

Some of the pieces aren’t published hence the project to record the complete works, and nobody has recorded them all. I’ve been listening to Jamie McVinnie’s excellent recording on Naxos from St Michael’s Tenbury, an organ I have admired since my Hereford days, as well as Paul Morgan’s recording from Exeter.

What or whom made you take up the organ?

Hearing the organ played everyday by Roy Massey and Huw Williams was certainly what got me going. Roy was an inspirational, generous and encouraging first teacher.

Which organists do you admire the most?

Cameron Carpenter, Ton Koopman, John Scott.

What was the last CD you bought?

Errol Garner’s album The Elf. It’s an absolute harmonic orgy.

What was the last recording you were working on?

The first recording of the choral works of Dr F.W. Wadley, organist of Carlisle Cathedral 1909-1960. A friend of Elgar, his music is well –wrought and sumptuous and well worth a listen when its released on Priory.

What is your favourite organ to play?

Hereford Cathedral’s.

What is your favourite building? Canterbury Cathedral.

What is your favourite anthem?

Valiant for Truth by RVW.

What is your favourite set of canticles?

Gibbons’s Short Service.

What is your favourite psalm and accompanying chants?

Psalm 89, chants by Hopkins and Gray.

What is your favourite organ piece?

Bach: Prelude and Fugue in DBWV 532

Who is your favourite composer? Debussy.

What pieces are you including in an organ recital you are performing?

Buxtehude: Praeludium in D Minor, De Grigny: Recit de tierce en Taille, Franck: 2nd Choral, Lloyd-Webber: Benedictus, Alain: Intermezzo, Ireland: Capriccio

Any forthcoming appearances of note?

Conducting Schubert’s Mass in A flat with Carlisle Festival Chorus and the Northern Sinfonia on 12 July –an appearance of many ‘notes.’

Have you played for an event or recital that stands out as a great moment?

Playing the organ at the George Guest Memorial Concert in St John’s was a very special duty.

Has any particular recording inspired you?

Krystian Zimmermann’s Debussy Preludes was absolutely inspirational. It opened a whole new level of listening to me when I was about twelve.

How do you cope with nerves?

Practice. Trying to use the nerves to try to heighten musical excitement is always a good idea. Practising getting nervous is the ideal solution.

What are your hobbies?

I’m always happy to watch cricket, especially spin-bowling on TV where the view is much clearer. Local history –especially of socially worthy causes (like the ‘Carlisle State Brewery Scheme’) is always intriguing. I like playing table-tennis passionately.

Do you play any other instruments?

I love the piano, which is more of a hobby really, and I studied the violin for a long while with an extremely patient and good teacher. All organists should try and learn to sing too.

What was the last book you read?

The Crimson Petal and the White, by Michael Faber. it’s a riproaring read, which I can’t praise too much –a vivid take on Victorian life and morals.

What are your favourite radio and television programmes?

Choral Evensong, The Archers and Love Soup seem to have been staples recently I’m afraid.

Which Newspapers and magazines do you read?

The Guardian, Private Eye, The Week, Cathedral Music magazine of course.

What makes you laugh?

I’ve realised it’s not just things that are actually funny, but also awkward things – it’s always easier to laugh than deal with the problem. All a bit disturbing, that.

If you could have dinner with two people, one from the twenty-first century and the other from the past, who would you include?

J.S. Bach, with a translator present, and my wife Emma, reliant purely on my own wits for survival.

What should be the role of the FCM in the twenty-first century?

I think it’s doing extremely well for itself. I like its inclusive agenda which recognises the variety of establishments and people involved in church music. It seems to me that resources and guidance should generally be channelled towards the parish scene and smaller, less wealthy cathedrals.

Congratulations on your retirement and all that you have achieved. You have seen lots of changes in cathedral music since 1968 haven’t you; can you describe some of them?

Yes, there have been many. The first is the attitude of deans and chapters towards cathedral musicians. Generally I think that organists and directors of music are treated with greater respect than was the case many years ago. Now we are consulted far more widely as I am sure you have found in Canterbury.

Another change has been in the repertoires of cathedral choirs which has become much more comprehensive and wideranging. In days gone by most of the music we sang was in English, and comparatively little European music was performed. As we both know, Allan Wicks was one of the most enterprising in this area. I suspect that cathedral choirs have also become far more capable of singing extremely difficult music.

There was a time when cathedral choirs were never conducted and I can remember going to Evensong at Canterbury shortly after Allan arrived there, but several years

before I did, when the Choir sang Stanford in C and Bairstow’s Blessed City. It was all very polished and musical, as I recall, but Allan led from the organ. When conducting first began it had to be very discreet and I remember hardly being able to see Allan’s hands. I used to watch his pate. This was of course before the days of closed-circuit television, when you had to peer through a gap in the pulpitum. I believe on one occasion Sir Adrian Boult attended a cathedral evensong somewhere, and complained that the young assistant conducted Tallis’s Salvator mundi as if he were conducting a Tchaikovsky symphony. I was once told by the (minor canon) Precentor at Canterbury to keep my beat as unflamboyant as possible! (It was not me about whom Sir Adrian was complaining!)

The advent of choral scholars in cathedrals is another significant change. We knew about choral scholars in universities, but when I was first went to Canterbury as Assistant in 1968, there were only six lay clerks. Choral scholars were introduced and I think the importance of

having twelve men, particularly in a large building such as Canterbury was a logical move. The success of a choral scholarship system depends very much on the university you have nearby. My recollection is that after trying out increasing the number of men at Canterbury they eventually went over to having just twelve lay clerks, partly, I suspect, because the University of Kent does not have a music department.

At Guildford we had six lay clerks and tried to supplement with choral scholars, up to a maximum of twelve men. This worked well and some of the choral scholars and lay clerks in those days have forged impressive careers. At York, we tried to aim for six plus six, but a problem which we came across three or four years ago was that the choral scholars were becoming very experienced and mature as singers. They were then tempted to apply for lay clerk’s posts in other cathedrals. I persuaded the Dean and Chapter to go to nine songmen plus three choral scholars and that has worked very well, for we were able to hold on to some good voices.

Have you found that there is a regular supply of choral scholars in the voices that you want at the right time?

On the whole we have been very lucky.

Did you find that the choral scholars who had been with you would later come back as lay clerks or had you lost them for ever?

I don’t think anybody returned as songmen, but as I said earlier, choral scholars have become songmen, on account of ability. One of the characteristics of York is that once you go there you don’t move away! I’m a prime example of that of course. This also applies to people in other walks of life.

There have been several changes in the front row. One is that, in boarding schools, it seems to me that people come from a less wide catchment area than they used to. I don’t know if it is true in Canterbury,(it is, yes) but when I was at Canterbury there was a boy from Northern Ireland, one from the Lake

District, someone from Cyprus –all over the place, and that was partly, I think because of the reputation of the school and the choir. Former choristers began to make their names in the musical world. Think of Stephen Varcoe, for example, and Mark Elder, to give two examples. The choir and school had a tremendous reputation.

Well you had some golden years didn’t you? There was Stephen Barlow amongst others. Exactly, and I think it was at a cost because the school was getting too big hence the successful amalgamation which you now have. Clearly the presence of girls in cathedral choirs is one of the biggest changes of all and one which provoked, and still provokes much discussion. Now is not the time to enter into a long examination of this issue. All I will say is that like many imaginative innovations it has brought great benefits, but has also produced difficulties. I think I had better stop there!

In some ways you have already answered my next question which was, what was life like back in 1968 for a cathedral organist, can you remember back then?

There was a wonderful regularity to the life of the choir. There were no diocesan visits, there were no tours. One of the Canons, I think it was Canon Waddams, was reputed to have said: ‘If people want to hear the Canterbury choir they can come to Canterbury to hear us’. But with Allan Wicks of course, as you know only too well, life was incredibly exciting, colourful. We were also in touch not only with music other than cathedral music, but also the arts of all kinds. His interests were wide-ranging. To give you an example, it was he who got me interested, by his enthusiasm, in Stanley Spencer. He would go regularly to art galleries, the theatre and opera. I always remember when I first met Allan he had the reputation of being a very fine choir trainer and as a champion of modern organ music. Which indeed he was, but the first composer he talked about in my appointment interview was Mozart.

When you were there in 1968 did you also meet with Alan Ridout?

I actually met Alan Ridout in 1962, when I entered the Royal College of Music. He was my composition professor and a very good one indeed. Bach and Brahms, to name a few, were always gods, but having also adored Howells and Vaughan Williams from a young age, it fell to Ridout to swing me away from writing music that was not just a pale imitation of their music.

As somebody who wanted to make his way as a player and a choir trainer and also my interest in composition, I don’t think I could have been luckier in having Allan and Alan influencing me. Allan Wicks, as you know, did not pretend to be a composer. In fact he said to me one day: “I have found a marvellous way to compose, I tell Alan Ridout exactly what I want and he writes it for me.” I think it was in those days that there was half an expectation that a cathedral organist ought to be composer. Only a little way down the road was Robert Ashfield at Rochester who wrote some very lovely things, and there were other people, Arthur at Ely for instance. I think Allan might have felt pressured that he should be composing but he did not, partly because he established an excellent rapport with Alan, as well as with other composers. I think Alan Ridout is actually underrated. Some of his best works are very fine. You will probably remember The Prayer of St Mary Magdalen. I also remember hearing a performance of his Recorder Concerto. Superbly inventive and skilfully orchestrated.

I think the other thing I learned from Allan Wicks was, and I said this at his 80th birthday dinner, that he was one of the first people to produce passionate singing from his cathedral choir. George Malcolm at Westminster Cathedral, George Guest at St John’s, and others were certainly working on similar lines. What is not always realised is that Allan was actually at the forefront of that. People didn’t notice it so much because Canterbury wasn’t on the big recording circuit as George was and because Canterbury is slightly tucked away. I think Allan knew about singing and he knew about phrasing, he knew about the voice and although I am a great admirer of George it was Allan as much as anybody who

actually made cathedral choirs sing with more than just a kind of impassive gloss.

Let me take you on a little bit. You went off then to Guildford in 1974 and that was a complete change for you on many fronts. You must have had some thrills and some challenges. The thrill was having the job on my own in which I could do what music I wanted. The challenge was taking over from somebody like Barry Rose, whose work I admired and in fact who admired Allan as a choir trainer: taking over the creation of one man, not a line of people, working in a totally different building in a totally different environment was exciting and alarming in equal measure. I went from a choir where the repertoire was very large, where sometimes we lived very dangerously, to a choir where the repertoire was small but absolutely beautifully sung; that was a complete change of scene. I think it took me about a year to settle into what I had inherited, to settle into what the choir did best and to settle into the way I could get them to respond to me. It also took me time to forget about Allan and develop my own way of doing things.

People were very welcoming and accommodating. There was a very forward-looking Dean and Chapter, Dean, Tony Bridge, being very colourful and eloquent in many, many ways. His belief in the way that music and other arts could say far more than words made a great impression on me. Also, one of the differences between a place like Canterbury, or York, and Guildford is that, although in every cathedral music is crucial, there is less to distract you from the music. When Guildford was mentioned in the early 1960s and 1970s people quite often thought first of the music. When you first think of York you might think of the Archbishop, a great building, or fantastic stained glass. In somewhere like Guildford, music I think occupies, not a more important place, but in a curious sort of way more depends on it. There was a kind of urgency about the music there which was challenging and exciting. The choristers all attended a day prep school, not a school

that was owned by the Dean and Chapter. We had a very good gentleman’s agreement, but there had to be a lot of give and take. We were very lucky on the whole with our intake of children as well as with the quality of the men.

And it was a very successful time for you.

It was yes, a very fruitful time indeed. I remember my time there with great pleasure. There were also, as I recall, some memorable broadcasts.

I need to take you on now. It was 25 years ago, a complete chapter of years ago, that you moved to York. You followed another formidable musician.

I did, which again was not easy because Francis is a great musician, a wonderful player and it was a challenge following him as well, a different challenge. There are similarities to Guildford, however, not least in the way that the choristers are all day children. They all come from a radius of no more than 15 miles at the outside.

We said earlier that York Minster seems to retain organists for a long time. When I was organist of Lincoln for example, I was William Byrd’s 18th successor since the middle of the 16th century: similarly in York people stay a long time. Do you think there is reason behind that?

Yes, I think York is a lovely place to live, the Minster is a wonderful building, the organ is very fine and it is a friendly area. There is also more life in the Cathedral now than there was when I first went there.

Do you think it is a good thing that people stay for a long time? It works both ways. I think you need at least five years to get a choir round to the way you want it and then you need another five to establish what you have built up.

Can you tell us something of the way in which the music in York Minster has changed over the last 25 years?

I have introduced a lot of Latin masses, but also tried to keep the more traditional ones going as well. The repertoire is on the whole smaller than it was when I first went there but as you know only too well, getting the balance between a repertoire that is well known but yet interesting is a very hard one. You have to balance that chiefly against the ability of the top line. I also tried to retain music that was, as it were, special to York.

What about reaction from perhaps members of the congregation or members of the Chapter?

There were a few people who started to huff and puff because we were singing too many Latin masses. But then people came out almost dancing after hearing a Mozart mass and I think the argument was made.

This is something which has happened all over the country, the Viennese mass in particular.

I think one mustn’t forget the Stanfords and the Darkes and so forth. I think they actually occupy an important place in the repertoire and fit BCP services especially well. At York we have a BCP Sung Eucharist once a month, with the 1928 additions. If we sing Jackson in G for instance, we do every movement, including the Creed, which is fantastic and which is much loved. We all know Jackson in G and we all love it, but if you don’t know the Creed then you need to get to know it, it is very, very good!

The Archbishop of Canterbury made a comment recently that people should sing the Creed more often to some setting, be it Plainsong or polyphonic. We do it in Canterbury if we have an orchestral mass, which we do from time to time, then we sing the Creed.

Like so many things we can say ‘…and was incarnate of the Holy Ghost of the Virgin Mary and was made man’ or we sing it to Merbecke, which is fine, but if you listen to ‘…and was incarnate of the Holy Ghost’ in Francis’s setting, it adds depth to the words which is impossible to describe.

Certain things have happened while you have been there. I suppose not least the great fire; that must have been a very demanding time for you.

Well it was a very strange time because in a funny sort of way these big cathedrals are –I wouldn’t like to say they are selfimportant, but they have a grandeur which is something that people enjoy. We know we are one of the most visited cathedrals in the country and have stained glass that is second to none. Something like the fire brought the whole place to its knees. It was a humbling experience, a levelling experience. Although it was extraordinary, it was a very interesting time. The Dean preached a very good sermon on the Sunday afterwards. What had happened, as you probably know, was the Bishop-elect of Durham, then Professor of Theology at Leeds University, had been saying controversial things about Christianity for a long time. On a television programme called Credo, he said what he had been saying for years and years and the balloon went up because he was Bishop-elect of Durham. He was consecrated on the Friday and then the following Sunday the fire took place and some people pointed a finger. My own view is that God doesn’t work like that and that it was pure coincidence.

The community must have been galvanised by the event. The great thing about it was that worship continued; on the day after the fire we were singing Evensong in St Michael le Belfry and remained there from Monday to Saturday. Through the tremendous work put in by the stone yard and others, the Cathedral was ready for worship the following Sunday. That was when Dean Jasper preached the sermon saying, if I remember, that the laws of God are so reliable that you can’t expect him suddenly to put out a fire. If the combination of physical situations is right, things will go up in flames: in the same way that if I jumped off the top of that building I would fall in a nasty heap, nothing would save me. There is an absolute reliability of the laws of nature.

It was a major step in bringing the community around the Minster. I think it was.

York Minster is one of the largest church buildings in the world; what are the delights and challenges of that as regards the acoustic and performing in such a beautiful space?

It is the largest Gothic cathedral north of the Alps, that is the technical description! That puts it in its place for size. The Quire is difficult to sing in because of the wooden vaulting. There is resonance but you nonetheless have to work hard and there is a lot of woodwork around. It is not like being in Hereford, for example, which has one of the loveliest and easiest acoustics that I have ever experienced. At York, the organ is some way away from the choir stalls, although it is an easier organ on which to accompany than some. When you are in the Nave it very much depends where the Choir is situated as to how we sound. On a Sunday morning, we are usually behind the altar and not heard to our best advantage.

So did this situation then encourage you with pieces you have written particularly for York Minster?

Yes I think it probably did. When I was at Guildford it was very easy for the organ, being in the North Transept, to obliterate the choir: anything with sustained chords would swamp the Choir if you weren’t careful. There is a piece of mine which is very generously sung quite a lot, All wisdom cometh from the Lord, and much of the accompaniment consists of short chords. That was specifically designed for Guildford because that worked well there. I think I learned a lot when I went to York from looking at Francis Jackson’s music where the harmonies move very slowly and where the accompaniment is quite often unfussy and sustained. You change as you go on, obviously, and I think that probably influenced me.

Let me take you on to your composing now for which you are justly very famous. That is very kind of you to say so.

We have talked about how you might adapt your style in the commissions somebody else might give you. Do you go out and visit the building before you compose something?

I try to but visits are not always possible. I try to find out about the choir concerned. Quite a lot of the places that I have written for, I knew the buildings already and I always ask commissioners to be as specific as possible about what they want; for instance, if they have a particularly good treble soloist. Some years ago I wrote a piece for the Installation of Dr Jeffrey John as Dean of St Albans and Andrew Lucas was wonderfully clear about what he wanted. He wanted to include the Girls’ Choir as well as the boys and men. The girls sang from the Altar and the boys and men were in the Quire stalls. This gave challenges and opportunities. I designed the

piece so that they sang separately for much of the time. When they sang together, I organised the harmonies so that if they got out of sync. it would not matter too much! They kept absolutely together, of course!

How else have you noticed your composing language changing?

It is very hard to say actually. I think the longer I live the more I am aware of the importance of form in music and of getting the proportions of pieces right. This applies especially when writing instrumental music, but it also applies with choral music. Even though a text will dictate some sort of shape, you have to make sure that the musical ideas have some sort of logic to them. When it comes to writing choral music, I think I learnt a great deal, once I arrived in York, from looking at Bairstow’s music of which I now know quite a lot. He was very good at getting the stresses right and getting high notes on the important syllables. If you look for instance at Lord, I call upon thee, it’s almost exactly as you say it and it fits the rhythm of the words perfectly. The only thing that he usually avoids is melisma. Incidentally it was in this area, I suspect, that Bairstow influenced Finzi, who was a pupil.

I think also the other thing that has influenced me in my writing both for voices and for instruments, is conducting the York Musical Society, a chorus of about one hundred and thirty voices. Working with an orchestra three or four times a year and a big choral society does have an effect on your musical output. There have been many works that have dug deep into my soul! As well as the standard classics, such as Brahms’s Requiem, The Dream of Gerontius, Bach’s Passions and the Mass in B minor, I have been profoundly affected by Vaughan Williams’s Sea Symphony and Dona nobis pacem, Tippett’s A Child of our time, as well as three big works of Stanford’s, his Stabat Mater, Requiem, and the Latin Te Deum op 66. Large choral works such as these encourage you to give your music space.

In Canterbury we still have some lovely music of yours that you wrote at a tender age, still in manuscript, of which we are very proud. We have some lovely canticles, based on plainsong, some fauxbourdons: I don’t know if you have published them all. They have been published now by the Chichester firm Cathedral Music. One, for Men’s voices, has been rearranged for SATB and is published by OUP.

I find them so well crafted for that which we need: they’re fairly effortless but so effective.

I love incorporating plainsong into things.

What is the main impetus behind how a piece sounds?

I think it depends on what I am listening to at the time. I do have one or two personal guidelines. There seems to me to be quite a lot of music written today that is fairly static, and moves very slowly, with much repetition. Although the effect can be hypnotic, I think music does need to travel somewhere. Also, it is very easy to produce wonderful effects with much doubling of voices, and I think today there is a tendency to write music that is very thick. Economy of effect is often more telling. Both the Messiah and the St John Passion, to take random examples, are in four-part harmony and I think composers should try to make their vocal lines interesting enough that it is not necessary to lean too heavily on divisi. I know we cannot all be Messiaens or Byrds, but I always think that the Byrd three-part Mass sounds as if it is in four parts, the four-part sounds as if it is in five, and so on. Likewise Messiaen’s O sacrum convivium