Cathedral MUSIC

Designed and built by organists for organists

Simply the best in sampled digital sound, with no gimmicks. This is a Makin Westmorland organ.

Makin Westmorland. Serious organs for the discerning musician. Someone like you.

You don’t buy a Makin Organ … you invest in one.

For more details and a brochure please telephone

01706 888100

the difference. Our Westmorland Custom instruments use a separate sound-sample for every note of every rank, and the realism is simply breathtaking! You are actually listening to the sound of organ pipes themselves, and not to something artificially-generated by computer, or based on only a few individual samples. What’s more, Makin uses genuine English pipe samples, from the finest organs in the country, to create that true English sound for which we are renowned. Experience our top-quality consoles, bespoke speaker systems, and unrivalled customer service. You will soon understand why customers choose Makin, rather than settle for second-best. to us. Together we can draw up your own unique specification today. our website for customer testimonials, details of installations, events local to you, and much, much more. sales@makinorgans.co.uk

CATHEDRAL MUSIC is published twice a year, in May and November

ISSN 1363-6960 NOVEMBER 2009

Editor

Andrew Palmer

21 Belle Vue Terrace Ripon

North Yorkshire HG4 2QS

ajpalmer@lineone.net

Deputy Editor Roger Tucker

Editorial Advisers

David Flood & Matthew Owens

Production Manager Graham Hermon

FCM e-mail info@fcm.org.uk

Website www.fcm.org.uk

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of Friends of Cathedral Music. Likewise, advertisements are printed in good faith. Their inclusion does not imply endorsement by FCM.

All communications regarding advertising should be addressed to: Roger Tucker

16 Rodenhurst Road

LONDON SW4 8AR

Tel:0208 674 4916 cathedral_music@yahoo.co.uk

All communications regarding membership should be addressed to:

Friends of Cathedral Music

Membership Department

27 Old Gloucester Street

London WC1N 3XX

Tel: 0845 644 3721

International: (+44) 1727-856087

E-mail: info@fcm.org.uk

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used. We apologise to any individuals we may have inadvertently missed. The Editor would be glad to correct any omissions.

Designed and produced by MYPEC

The Old Pottery, Fulneck, Pudsey, Leeds, West Yorks LS28 8NT

Tel: 0113 255 6866

info@mypec.co.uk www.mypec.co.uk

outreach for Oxfordshire has come from Christ Church Cathedral School. The Head Master, Martin Bruce, tells the story of their involvement: in this edition on page 10.

Recent media reports about English Heritage ceasing its funding streams to help cathedrals maintain their Fabric Funds has caused me concern. This decision on top of forecasts that the next government will have to make swingeing cuts in all public funding, including the arts could, I believe, affect cathedral music. Deans and chapters will be looking for ways to trim budgets. Shades here of Joanna Trollope’s novel The Choir which was dramatised for television highlighting the dilemma caused by competing demands between fabric and music.

The present government funding of £40m for the National Singing Programme is guaranteed until 2011. Known as Sing Up, it is sustained by a consortium of Youth Music, Faber Music, AMV BBDO, and The Sage in Gateshead. The Choir Schools Association (CSA), as an associate partner, manages the Chorister Outreach Programme. CSA has been actively involved in promoting this initiative since 1990. The strength of COP is that funding of £1m a year has been ring-fenced over the four year period of the NSP, but clearly there is concern that it may then stop, and the big question is how to carry this wonderful initiative forward.

Criticism of music being left out of the national curriculum prompted the Blair government to appoint Howard Goodall as the National Ambassador for Singing, with the brief to get children in every primary school in the land singing in choirs to counteract the general neglect of music in education. For this noble purpose generous funds were allocated. Howard was himself a Christ Church first-class music graduate, so it is no surprise that the diocesan

CATHEDRAL MUSIC has highlighted some of the schemes over recent years such as the way St Peter’s, Wolverhampton and Salisbury Cathedral are each spreading the art of singing as described in CM 1/07 and the Precentor at Bristol Cathedral in the last edition (1/09), along with Geoffrey Webber reporting that several Cambridge choirs are soon to become involved with local secondary schools and. King’s College is already participating in the government’s outreach scheme for singing in primary schools.

My research has led me to the conclusion our cathedral musicians have thoroughly enjoyed being part of all this. Yes, it has meant lots of extra work but the musical rewards have been very, very high. For many it has been a steep learning curve which they have mastered with alacrity.

For example Ian Wicks, who directs Salisbury Cathedral’s outreach programme for the Cathedral and Cathedral School says: “I think it is important to stress that COP is a great success story for the National Singing Strategy and the CSA. The fact that thousands of children up and down the country have had the experience of singing with the choristers in our great cathedrals is important on so many levels. The expertise that has been directly involved in each primary school has made a difference in those children’s lives and has given teachers the confidence to begin their own choirs in school. The experience of coming to the Cathedral for the concert is always a memorable occasion for children and their parents -many of whom have never set foot in their cathedral before. Above all, singing is to some extent a natural activity for us all and to have helped many children to find their voices must enrich our culture and society for the future.

“There are many children who have found their voice through our Singing Together Outreach Programme who have gone on to join our Cathedral Junior Choir and a few who are now

choristers in Salisbury Cathedral Choir. This progression, although not intentional, is a very pleasing part of the whole adventure. There are also many children whose lives have been transformed by being part of our choir.”

The question is: how do we sustain the success of these programmes?

This is where FCM should come in. CATHEDRAL MUSIC takes the view that what is needed is a national foundation for cathedral music outreach, inclusive of everywhere that can provide a lifeline or rallying point for funds from various sources: Government, private funding from industry, education, Lottery, private benefactors and organisations like FCM which support the tradition.

This can build upon the excellent pioneering work of the CSA. The project should bring together interested groups and attract people from the cathedral music profession, and other walks of life.

Can outreach cross ethnic barriers? I think it can. Many of the best schools in the UK are Christian foundations and Western sacred music is part of their tradition and so part of school life. This must rub off on non-Christian pupils, seeking high quality education. They will hear performances of Messiah and carol services at Christmas and choral masterpieces by Haydn, Mozart and Bach at Easter and in the summer. They may be taught musical appreciation or to play an instrument even play in an orchestra. To this extent, the current obsession with multi-culturalism could hinder assimilation of British culture by ethnic minority pupils.

However, we should rejoice that cathedrals up and down the land have been playing to full houses, as Ian Wicks points out! You will read elsewhere in Festivals Overview of the increasing attendances at cathedral music festivals.

It’s up to us all now to evangelise and raise support for this. Over the next few editions we will be exploring this issue with contributions from specialists working in the field.

As George Eliot wrote: “I think I should have no other mortal wants, if I could always have plenty of music. It seems to infuse strength into my limbs and ideas into my brain. Life seems to go on without effort, when I am filled with music.”

We should rejoice that cathedrals up and down the land have been playing to full houses...

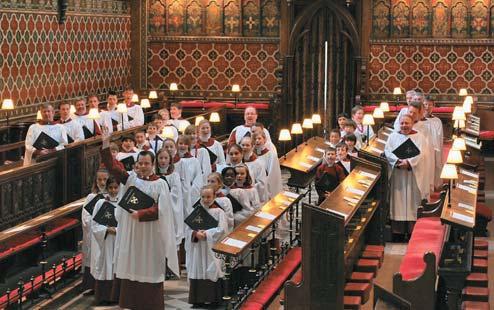

From its earliest times, Rochester appears to have been famous for the training of singers. In his Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation, Book IV Bede writes of Bishop Putta, enthroned as Bishop of Rochester in 669 that: ‘He was extraordinarily skilful in the Roman style of church music, which he had learned from the disciples of the holy Pope Gregory.’

Bede goes on to say that: ‘From that time also they began in all the churches of the English to learn sacred music, which till then had been only known in Kent.’

The cathedral choir at Rochester can therefore claim to be the heir to a very ancient tradition.

The Rochester Cathedral Choir we would recognise today dates back to 1541 when the Benedictine community was dissolved and the cathedral was reformed as a cathedral of Henry VIII’s ‘New Foundation’. The new statutes, dated 18 June, 1541, provided for six priests, six lay clerks and eight choristers. These numbers were not uncommon amongst Rochester’s New Foundation colleagues, although others

sometimes had more men (often eight, balancing the number of boys).

Since that time, six lay clerks have remained on the Foundation of the Cathedral until a very bold step was taken with the commissioning of a new Worship and Music Policy in 2007. Chorister numbers have fluctuated throughout this period and risen to the current limit of eighteen. Before I come to that, a little more background will help set the scene for some of the far-ranging suggestions of the new policy.

Since 1937, following the closure of the Cathedral Choir School, the boy choristers have been educated at the King’s School. There were obvious benefits to the boys from this, especially access to the wider range of opportunities available at a much bigger school. Relations between King’s and the Dean and Chapter have been largely good over the years, the cost of the scholarships has often, understandably, been a source of concern for the Chapter. Whilst Rochester receives a goodly number of visitors, undoubtedly swelled by the Charles Dickens connection, it does fare less well than its ‘Big

Brother’, just a short distance away at Canterbury.

The first really major change in the make-up of the cathedral’s music since the Reformation came in 1995, with the introduction and recruitment of Rochester Cathedral Girls’ Choir. Following on from the recommendations of In tune with heaven, and particularly the success of Salisbury, it was felt that this was the time to introduce girls. After much thought, it was decided, not without controversy, that the girls would be recruited from all schools (not just King’s), would be the same age range as the boys, and that the girls would sing on a voluntary basis. The Girls’ Choir would sing Evensong on Wednesdays (traditionally the ‘dumb’ day at Rochester) and would also take a part in the weekend schedule (especially weekends in July once the boys were on holiday). The Cathedral Auxiliary Choir was re-founded as the Special Choir and would sing extra services as required on high days and holy days and to provide a cathedral choir when the boys or girls were not available.

In many ways, this situation worked well, but fears for the

sustainability of the cathedral’s music, especially the funding of the Chorister Scholarships and the immense and increasing difficulty in recruiting full-time lay clerks of a suitable standard were threatening the day in day out music making; something had to change. The minds of the then Precentor, Ralph Godsall, and of the Director of Music, Roger Sayer, were much exercised by this matter. However, it was felt that any far-reaching measure should wait for the appointment of the new Dean following the retirement of Dean Shotter. In January 2005, Adrian Newman was instituted and installed as Dean following various parish appointments in East London, Sheffield and central Birmingham (the Bullring). Adrian was once introduced as ‘the most un-Dean-like Dean in the Church of England’ (a description he quite likes!), but immediately lent his support to Ralph and Roger in their aims to provide a vision for music making and worship at Rochester and to safeguard its future.

The fruit of their labours was published in November 2007 as the Dean and Chapter of Rochester’s ‘Worship and Music

Policy’ (available at www.rochestercathedral.org). The section on music states as its first point that: ‘Music is the servant of the liturgy and an integral part of it. Music has a unique role in the offering of worship as a means to still the mind, uplift the heart and lead the worshipper to encounter the mystery that is God. It is also capable of challenging and directing’.

That should fill the hearts of all members of the Friends of Cathedral Music with joy! Many of the items are good common sense such as the precedence of the Opus Dei over other musical events or a commitment to the encouraging and support of recording, touring and giving concerts (especially out and about in the Diocese), but there are also some welcome recommendations such as committing to maintaining and extending the music library, a commitment to funding vocal coaching for all choristers, an accumulating fund for the long-term protection, preservation and restoration of the cathedral organ, outreach work, the formation of a junior choir, music endowment, a musician in residence, and a recognition of the importance of commissioning new works.

So what is new I hear you cry? Well, there are some major changes relating to the scheduling of the boy and girl choristers, funding of Choristerships, the Director of Music and the lay clerks: obviously there are some challenges for cathedral musicians in documents such as these.

Recommendation 16 states: ‘Chapter has developed clear guidelines and values to underpin the nature of choral development at the Cathedral:

• Quality – we will retain and develop a high-calibre choral tradition as the core of the Cathedral’s music provision

• Inclusivity – our aim, as far as possible, should be to make the Cathedral’s music and worship open and accessible to everybody, and a primary instrument of mission

• Community – we want to extend the outreach elements of the music by increased community engagement

• Equality – we will work towards parity and equality in our treatment of girls’ and boys’

• Recruitment – our aim is to recruit up to 18 choristers for each of the boys and girls choirs

• Repertoire – we want to extend the musical repertoire, particularly at the Sung Eucharist

• Affordability – we are committed to funding the choral tradition at an affordable level’

Some alarm bells might have started to sound for some Members having read that, but let me assure you that all is well. The words equality and parity do strike fear into the hearts of many, not least cathedral directors of music! However, this need not necessarily be the case.

The biggest changes in terms of a traditional cathedral music department refer to the Director of Music and the lay clerks.

Regarding the Director of Music, the policy makes it clear that this is a position, first and foremost, for a choir trainer (indeed the word organist is not even mentioned) who is ‘an experienced (and preferably, qualified) educationalist committed to a child-centred approach’. Now, this is not new and is the situation in a fair number of major cathedrals where the ‘Cathedral Organist’ has decided to actually be the Cathedral Organist! Many are mystified by the apparent misnomer ‘Cathedral Organist’, because generally speaking, he does not play the organ for services. In the case of a number of colleagues they would deem themselves to be organists, who came to be choir trainers through their playing of the organ. Of course, this could be the subject of a whole article or three in itself so I shall leave that there!

The establishment of three choral scholarships (alto, tenor,

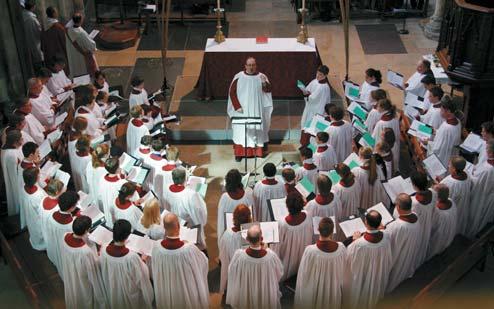

bass) to attract young professional singers to live in Rochester and commute to London was a vitally important step to revitalising the situation in the back row of the choir. Their scholarship was based on the cost of a rail season-ticket to London and they are given free accommodation in a sizeable cathedral property. The lay clerks, however, fared rather badly in that the position of Lay Clerk was abolished. It is important to note however, that by the time that the policy was published, there were only two full-time lay clerks and four permanent vacancies! A pool of deputies had been established and it proved possible to maintain a back row of six, with the occasional slip-up, but this was far from ideal. The pool of singers has been expanded and continues to grow in a very pleasing way and three singers are booked from the pool per service to join with the choral scholars. On occasions when the treble lines combine, we book a further six deputy lay clerks.

An online booking system makes the booking of singers very easy indeed and it is a real joy to be able to pick the right singer for the right piece. The experience and skill of the singers on the books is tremendous and it is a real privilege to work with musicians who have regularly sung at the cathedrals of Westminster, St Paul’s, Canterbury, or with The Sixteen, the English Concert and King’s College Cambridge!

Since inception, the girls have been volunteers, whereas the boys have received a scholarship. A sense of equality between the boys and girls was desired. The historic link with the King’s School was felt to be important from many points of view, not least the difficulty in attracting boys to sing in cathedral

choirs. There were definite benefits to the membership of the Girls’ Choir being drawn from the wider community, but rather than the cathedral giving a scholarship pertaining to a percentage of the fees for the boys, we would now give a fixed sum bursary to both boys and girls. We have been extremely fortunate in that the King’s School has committed to eighteen Chorister Music Scholarships for the boy choristers.

The Chapter was keen for the girls to sing a higher ratio of services, but were aware that this was a matter of discussion for both the Music Department and the Chorister parents. The pattern agreed was that Monday would be sung by the Girls and Men (or on occasion, men alone), Tuesday would be Boys’ Voices, Wednesday would be the Department day off (except in the instances of Ash Wednesday, Holy Week, broadcasts, etc), Thursday would be Boys and Men, Friday would be Boys and Men (unaccompanied except on festivals) and then the services over the weekend (Saturday: Evensong, Sunday: Matins, Eucharist and Evensong) would be sung in alternation. I am very happy to report that this has worked extremely well over this last year. In practice it has meant that the boys get a welcome rest every other weekend and I effectively get more time to learn new or rehearse more difficult music on those weekends when the boys are not on duty.

For some major services the treble lines combine, such as the Easter Day Eucharist, the Cathedral Carol Service and Advent Carols. There is a very carefully worked out three-year pattern for covering the equally-important Easter Day Vigil and Evensong, Christmas Day Eucharist, etc. For Midnight

Mass and Palm Sunday morning, the Full Cathedral Choir is joined by the Voluntary Choir which adds another dimension entirely. On Palm Sunday we are able to field three separate choirs in the outdoor procession, (needless to say coordination can be exciting), and at Midnight Mass we are able to have choirs singing in both the Nave and the Quire to the 1400 people who squeezed into the Cathedral in 2008.

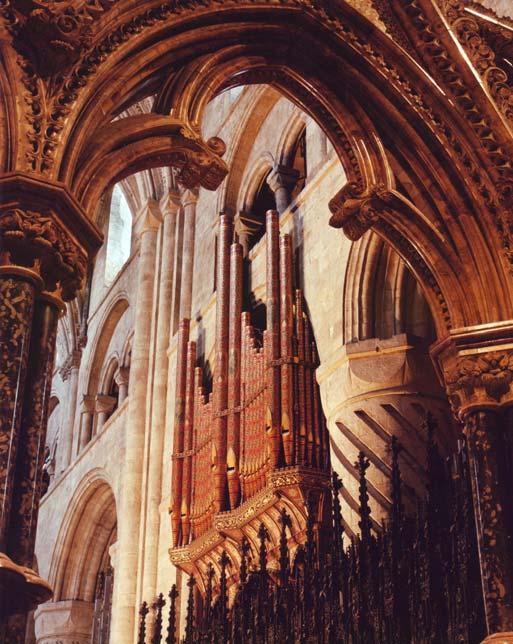

Sometime after the publication of the policy, Roger Sayer announced his intention to pursue a freelance career and to resign from his position as Director of Music. With tremendous foresight, the position of Cathedral Organist was created, whereby Roger could launch a freelance career from his base at Rochester and we would continue to enjoy and benefit from his musical gifts, not least as a thrilling organist and accompanist. Roger’s main duties are playing for the weekend services at the Cathedral and for any other major services or events. The day-to-day running of the department and the choirs falls to myself as Director of Music, and to Dan Soper, the Sub Organist and Assistant Director of Music. Dan was formerly Assistant Organist of Winchester College, Organ Scholar at Corpus Christi College Cambridge, Chelmsford Cathedral and Croydon Parish Church and joined the music department in 2006. I started at Rochester in September 2008, following six years as Master of the Music at Newcastle Cathedral. Dan has specific responsibility for the training and direction of the Girls’ Choir and I train the boys and we both take our place on the organ bench during the weekly round. A year after the Worship and Music Policy came into effect,

would we say that it has been a success? Overall, it has been a great success and the way in which we do things has evolved in harmony with the policy. Inevitably there were doubts and fears about the far-reaching changes that would be made and their consequences, but it is safe to say that the music department of Rochester Cathedral and its choirs are in good heart.

Sunday Parish Mass and Evensong. Sung Mass on major festivals Anglo-Catholic worship.

Opportunities for building up the choir. Links with Town and Civic organisations.

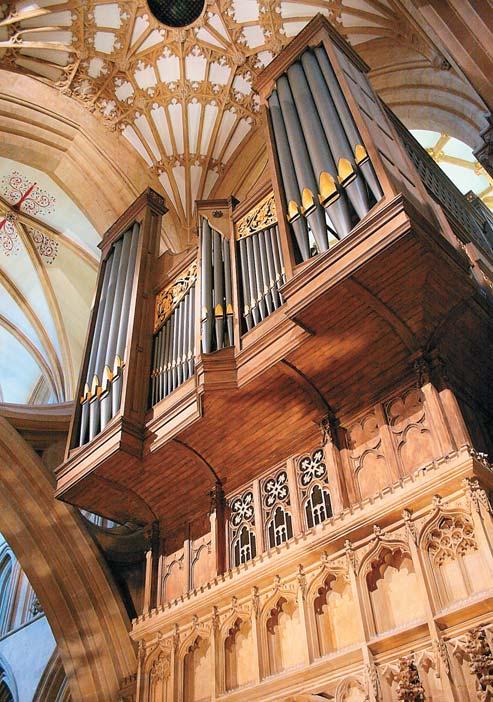

Fine and substantial 3-manual Hele organ. Ideal for teaching purposes Deputies available Good rates of pay Fees for Weddings, Funerals etc.

Applications to:

Fr. Andrew Gough B.A.

The Vicarage

St. Andrews Street, St Ives

Cornwall TR26 1AH

Tel 01736 796 404

E mail: goughfr@hotmail.com

One of the striking features of our world today is its interconnectedness. Initially a technologicallydriven phenomenon, it has become a pervasive metaphor in patterning our relationships both personal and institutional. One thing this has meant to Christ Church Cathedral School is that we have become far more outward-looking, positively enthusiastic to make links far beyond our cramped Brewer Street site –in some cases with institutions on the other side of the world. A powerful engine in such link-making has been, of course, music, and in particular the Cathedral Choristers. We are now well into the second year of our involvement in the Government’s Sing Up campaign, one of the most effective strands of which is the Cathedral Outreach Programme. This involves close collaboration with the local Music Service (in our case, Oxfordshire County) to work with primary schools to restore the lost art of communal singing, and so to train teachers that they become confident and enthusiastic singing leaders. It works like this: in the first term of the academic year four schools are visited by our music staff and a small group of Cathedral Choristers for an initial workshop. Our boys are there to raise by example the singing aspirations of the children and to share their love of music and its performance. In subsequent weekly visits the music staff teach, develop and hone singing skills and prepare for an end-of-term concert in the Cathedral. For many children (and their families) this will be their first visit to this beautiful and ancient church; it may well also be their first formal musical performance. Apart from the impressive harmony, what you must notice on these occasions is the evident enjoyment on all the faces. In the second and third terms the process is repeated with additional groups of schools, although the first cohort continues to participate with a lighter programme of visits. The year ends with a massed concert in the Cathedral involving hundreds of singers and a capacity audience: the atmosphere is excited, the sound wall stupendous.

It is not just locally, however, that our Cathedral Choristers make connections. Whilst the Choir, like many of its collegiate and diocesan counterparts, has an impressive programme of tours abroad, these are not, for Christ Church, merely concert opportunities. It has long been a priority of Dr Stephen Darlington, the Cathedral Organist and Tutor in Music, that tours involve a significant outreach component. Thus the Choir’s visit to Jamaica in 2007 was built around shared music-making and performing with a Kingston school choir, celebrating its sixtieth anniversary: and this year’s Bermuda trip similarly involved joint rehearsals and performances with a Southampton school gospel group. The arm of our outreach is long, and the benefits of mutual acquaintance and respect between groups of children in many ways far apart can only, surely, be a positive element of today’s connected world.

Martin Bruce, Headmaster.Salisbury Cathedral is delighted by the announcement from the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) that the four surviving copies of the 1215 Magna Carta have been inscribed in the ‘Memory of the World’ register, in recognition of their outstanding worldwide value.

Their inscription –a sort of World Heritage Status for documents –means the Magna Carta, held by Salisbury Cathedral, Lincoln Cathedral and The British Library, joins the ranks of some of the world’s most globally significant documentary heritage. The personal liberties laid out in the 13th-century document have been incorporated into the English Bill of Rights 1688, the American Declaration of Independence, 1776 and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights approved by the General Assembly of the United Nations in 1948. Magna Carta’s basic principles have also been used in the constitutions of Japan, France, Germany, Australia and many other countries. Welcoming the award, Mark Bonney, Canon Treasurer, said “We are proud to have the responsibility of owning the finest preserved of the original 1215 Magna Carta. Seeing this most famous of English charters, agreed by King John and the Barons of England at Runnymede in June 1215, is a highlight for visitors to Salisbury Cathedral. Indeed, we know that for many the Magna Carta is one of the primary reasons for their visit here and it seems to have an even greater significance for guests from overseas. Its clauses on social justice form the cornerstone of modern democracy and liberty worldwide and are as pertinent today as they were 800 years ago.” The Magna Carta at Salisbury Cathedral has been exhibited on public display for the past 25 years in the Chapter House.

Salisbury Cathedral is delighted to have won The Visit Wiltshire Large Tourism Award in the tenth annual South Wilts Business of the Year Awards. Accepting the award on behalf of the Cathedral, David Coulthard, Director of Marketing and Communications, said: “We’re delighted to receive the award, it recognises how hard we work to bring visitors to this beautiful Cathedral and its surrounding Close, and to look after them when they are here. I think this is a particular tribute to the wonderful welcome provided by our volunteer guides. “This Cathedral plays a very important role in the city. We’re having a busy year so far and I hope that success is reflected in the results of many Salisbury businesses.” The judges’ citation for Salisbury Cathedral stated: ‘Here is a well established operation, which has for a long time served its visitors and welcomed everyone. But it has taken on board all the new innovations, it has nurtured its staff, it has stayed the same, but evolved with the times. It has been central to the success of Salisbury and its community over the years and with its plans and ambitions will continue to be so for a long time to come through its service, and services, to city, community and visitor.’”

Voice for Life - get your choristers singing with this popular training scheme for singers of all ages

Church Music Skills - a new distance-learning programme to develop the practical skills of those leading music in worship

It must be around fifty years since we overlapped at Cambridge. Even then your talent as a composer was being recognized, and I have a feeling that whatever else you were going to be doing with your life, it was quite clear then that you wanted to compose. Yes, that’s true, I think I was regarded more as a cellist by some people, which was where I was really active, but in a small way I was getting performances around Cambridge, here and there. But at any rate in my own mind (which is your question) I definitely was aiming to compose.

And how long had that aim been with you?

That happened when I was a choirboy (at St. Michael’s College, Tenbury) and at the age of 11 I had for some reason this rush of adrenalin, and I decided I definitely wanted to be a composer.

There was a Damascus moment?

Yes, I remember it very well. The organist (Maxwell Menzies) struck a very loud chord, during one of his improvisations; and I loved the improvisations because they were wilder than anything we ever sang, and so that moment, that chord (I don’t remember what it was) was you could say ‘epiphanaic’. It had a lot of notes, in some kind of cluster; at that moment I decided ; and then I knew I had to remember that moment, that I must not forget it, and think back to it every five or ten years.

So, even at that early age, you knew where your impulse was going to go?

Yes.

As I was driving down to your home in Lewes this morning, I began thinking of one or two constants in the way you have composed, right back to 1974-1975 and the first Winchester Cathedral commission, The Dove Descending. I detected something which I have seen in many other of your pieces since –a fascination with one chord coming in and out of another, [JH Yes] and it seems to me that this technique is tailor-made for some of your work with live music and electronic music.

Very astute… because I love the idea of structure, but structure which becomes fluid. It’s almost as if (this has) become a kind of Buddhist aesthetic that all solid objects should dissolve, in the idea of emptiness; and in one form or another, this idea has been going on since then. With electronics, it’s very easy.

But how would you describe the way in which these chords/ideas dissolve, and how do they get resolved? When you start out, do you know?

No. It’s quite different now. I used to have a grand plan, usually, an idea of the piece as a whole, but I don’t really like that any more. I prefer to keep/give myself (more options)….)

Like going on a journey?

Yes, exactly; being open to the material and seeing where it might take you. That is even more interesting.

Yet from the first time we collaborated, you have been incredibly open and understanding over what we might call the limitations, the parameters within which we have asked you to work. I am sure you

remember the first occasion (with The Dove Descending). The Bishop-elect of Winchester, John Taylor, had invited me to set a text from Eliot’s Little Gidding, for his enthronement, but I had the sense to suggest that we approach a proper composer, and, with you living in the Diocese at Southampton, it was a perfect opportunity to ask you. However, given your reputation in 1975, when you were already established as a world authority on Stockhausen, and delving into tonal or rather atonal areas that were not the norm in the cathedral world, I felt that the Dean and Chapter might need some reassuring... do you remember coming to a Chapter meeting to face the clergy and hear what they and I envisaged for that service? Oh yes, that meeting.

I remember encouraging you to take advantage of the antiphonal possibilities, but there were other elements which you picked up on, the harmonics developing from the chords coming in and out, in and among the cathedral acoustics, which really add another dimension. Well, as you know, Winchester Cathedral is a sacred place to me, and that time with you was absolutely one of the most, one could almost call it, a ‘holy time’.

Yes, it was a creative time, thanks to John Taylor, and the Dean, Michael Stancliffe, in particular, all trusting, even though we did not (always) know where we were going.

The Dove Descending did take some learning, but it was not long before we started work on another of your pieces. With Dominic, your son, by now a chorister, you had been attending Evensong on Sunday afternoons, and I will never forget the moment when you modestly came into the South Transept one afternoon and said: “I’ve brought you a little piece; would you like to see it?” And that was I love the Lord. Do tell me how that piece gestated. I had spent so much time in the cathedral listening to the choir, absorbing the whole atmosphere of devotion, the sacred sound and the resonant sound, hearing the beautiful, controlled in-tune singing and so on… this had inspired me. It came all from the choir.

By then you had already composed one or two bigger works for the Three Choirs Festival, but, as far as I could tell, you hadn’t written pieces which could be slotted into the daily liturgy. No, no liturgical pieces.

And it is interesting, comparing you with someone like Messiaen, who had his great Catholic faith, but who felt unable to add anything to the liturgy.

Yes, that’s strange, isn’t it? But I like the idea of the liturgy very much –so different from the concert world –you are part of a communal act together; it’s not a piece of music just for itself, and somehow that is what the old composers must have experienced. You feel you belong to the ancient tradition of service for the church; they were quite humble servants. The main idea was to fit into the devotion which was all around them, and that I liked very much, being part of it, belonging. It was very exciting.

And that comes through in the way you wrote. But how did you

find an idiom, while keeping your own integrity, which would be right for the building and manageable by the fallible musicians, when you started work on The Dove Descending?

Well, you warned me, but at any rate I could hear quite clearly, that anything fast –semiquavers, for instance –doesn’t work very well. And the best thing is this wonderful, rather slow and complex procession of sound, which is so powerful. So I always wanted to take advantage of that, and I think that’s why my second Winchester anthem I love the Lord was the first tonal piece I had written for years, based on and in G major. And how could I write that without feeling that I had compromised? That was quite a question. I think the answer is that I gave up an ‘ego’ (Laughter.)

Yes, that’s right. I did not feel that I was writing something oldfashioned, or stale or whatever. I did not want to join an avantgarde movement once more. I just wanted to do justice to the words, the beautiful words –which were very close to my mother, when she was dying, which was one of the impetuses to write the piece...

And to be faithful to that was everything.

There was a kind of follow-up in Resurrection for the Three Choirs Festival at Worcester, but you also had a bigger denser group with low basses being asked to produce a bottom A, by an extraordinary technique, like a quint on an organ producing an overtone a fifth below. (Laughter.) But that was the only time since then that you have really limited yourself in quite that tonal way.

Yes, it was also tonal; it was also ‘inversional’, in a Schönbergian sense, as the inversion was fairly strict. But when you invert a major triad, of course you get a minor triad and its reflecting tonalities. And reflecting the title of Resurrection, –(life and death) were the two twin themes, one going down and one going up, obviously, so they reflect each other –quite a philosophical concept being portrayed exactly in the music.

Now, one of the most important aspects of your compositions for the liturgy has been to provide something of our time, but it’s fair to say that often their difficulty has militated against their having as many performances as the compositions deserve.

Mmm Yes.

I think the situation is getting better, and there are an increasing number of professional choirs in France, Germany and Holland who are doing these pieces, and a lot are appearing in concert programmes. Of course, I would love them to be done in the liturgy. I can’t really tell, because I don’t see the music lists.

Well, I can assure you that there are one or two winners, which appear regularly, I love the Lord, and in particular, Come, Holy Ghost, with its brilliant use of aleatoric techniques, but at the same time making it possible not only for people to sense the plainchant but enabling the singers to grasp where they are in relation to it. It actually acts as a useful adjunct in keeping everyone within a sense of their own pitch. Yes.

...because singers are quite often alarmed, if they don’t have accurate pitch themselves, by the sheer difficulty of pitching notes. The singers need some sense of where they are going to be. I have been aware of that, having been a singer myself, and I do know how difficult it is to pitch unless you have sense of where you are, or a tonality or a pentatonic mode.

That’s true of Come, Holy Ghost… ...which is basically pentatonic, so they do know pretty well where they are. But I sympathize with voices and I try to give them that orientation.

I have to say, however, that Angels, written for King’s College, Cambridge Christmas Eve Carol Service, is very beautiful but very demanding. The two choirs are very separate, almost going off at a tangent from one another.

It is difficult to pitch, more than I thought, perhaps.

It worked beautifully with the Netherlands Radio Choir in the Concertgebouw in 2006; and I was delighted at the packed audience’s, as well as the choir’s, response.

But perhaps of all the pieces commissioned for Winchester, the most original was the MagnificatandNunc Dimittis (Laughter) –Michael Tippett’s St. John’s Service in 1961 certainly felt as if it was breaking new ground, but 27 years later, you came up with something even more provocative –your Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis, which no less an authority than Nicholas Kenyon, writing in The Financial Times about the première at the combined Evensong during the 1978 Southern Cathedrals Festival, recognized as a landmark for Anglican church music.

In the Magnificat, the cantus firmus moves from part to part in a Webern-like way, and there are also some spoken sections, aleatoric passages, while in the Nunc Dimittis, we find an astounding fluctuation of sound to represent the light. How did you conceive that?

I liked the ‘t’s in light, and I asked the singers to emphasize these ‘t’s, which were aleatoric so they spattered about in chance formations –the more singers, the more ‘t’s. The whole aleatoric idea of these passages was to build up to a climax until the organ, which has been little used until that point, crashes in with a huge chord, using all twelve notes. The organ gradually winds down, and that’s the end. Light is represented by a very dramatic change of timbre and sound.

You mention ‘twelve notes’. How often have you written using serial techniques?

Up to about 1982 I used it a lot, not very strict, often tinged with tonality. I was taught by two Viennese Schönbergians, Erwin Stein and Hans Keller.

Were they very strict with you?

Yes, they were strict, but neither of them said you should write

serially, and they did not think that was the right way to go about it. Both of them thought that it should be very spontaneous, if I felt the need for it, to use it to give a kind of unity.

But when you say spontaneous, what do you mean? Where does the ear come into this?

That’s exactly what they were saying. If you don’t hear in the passage what you want, you shouldn’t do it... I wanted to go into it quite a lot, and went to study with Milton Babbitt, the archserialist, at Princeton, but I came away from that period feeling that if it could not really be heard, –what was the point,?

It’s an interesting point, because an audience, particularly the first time they hear a piece, is only going to pick up a certain amount. Yes.

Has this ever made you think that you should write more simply?

...Oh, yes, I have thought that from time to time, and that was in my decision to abandon serialism. I think the first example was probably the flute piece Nataraja. I also received a letter from Hans Keller, about being too intellectual and that if I would only forget my academic theories, I would be a good composer –pretty forthright, as usual!

You were probably already trying to break away from academia. But let’s move on to some of your electronic works, two of which were performed in Winchester. The Toccata for Organ and tape, which is rather like a concerto for organ and tape, and which I premièred in New York, works very well, but requires good speakers. And talking of speakers, one of the most remarkable sound experiences of my life (until last year’s Proms ‘performance’) was hearing Mortuos plango (which features the tenor bell of the Cathedral and the electronically adjusted treble voice of Dominic (Harvey) in Winchester Cathedral –with the speakers right up in the clerestory.

That was a dream, to have it come home. It took some trouble to get the speakers there,

that’s an understatement!

...but it was worth it. Of course, it’s a piece which owes every thing to Winchester…

and Dominic’s voice… ...and the bell.

It is the stage managing of these things, isn’t it, which is often timeconsuming and expensive.

That’s been my battle throughout my life… you had to try and persuade people that it’s worth doing, but people sometimes have been a bit lazy –it’s not just money –they can find money for this, that and the other, if they want to –but they are suspicious and wonder if it’s worth it.

And concert promoters are often scared if you put something modern on the programme, thinking that it will deter the audience. But Louis Halsey, for example, in the sixties and early seventies was doing ‘ancient and modern’, with a mix of programmes, including your Cantata I, just as later we did at Winchester –drawing the audience in, and then giving them something which was completely outside their experience. But I am delighted to hear that St. John’s College, Cambridge is doing your Canticles soon after your 70th birthday. Yes and you had some say in that, I believe.

Well I just put a bit of pressure on, saying it was about time they did them!

They are hoping to do three things, an organ recital

I have always thought that the ecstasies of the domain of love are very appropriate, just as some of the great mystics did...

including the Toccata, Fantasia and Laus Deo, and some chamber music in the Master’s Lodge. But I have a question for you about the Canticles; because without you, I would never have dared to ‘challenge’ and you said, “yes, come on, write something challenging”.

Well, it certainly ended up as a personal challenge, not least, dare I say, with my fellow organists at Chichester and Salisbury, and I knew when I first saw the score that there would be a reaction, and probably not a particularly favourable reaction. The only thing to do was to put it on the programme, and so we had to do it. In the course of the early rehearsals with the Winchester choir, we recorded sections on an old cassette machine, so that I could send John Birch and Richard Seal copies of how we thought it should go, for them to play to their choirs. One can’t pretend that it’s going to be easy for most cathedral choirs, unless they can make time for sectional rehearsals, [–as it happens, two of my most important innovations at Winchester, which were agreed before I had arrived there, were to have a short full choir rehearsal, before each service, and a men-only rehearsal each Monday evening]. But another help, and this is something which is such a blessing of the cathedral system here in England, is that you see the boys or girls every morning, and you can fit in ten minutes at the end of each practice; and so they have barely got time to forget it, if you can just get it into their system, because there is a kind of not only mental memory but also a kind of muscular memory. But there is no substitute for the person taking it on being clear in their own mind that they believe in the work.

I never did the Canticles at the Abbey, but that was primarily because of lack of rehearsal time with the men. But we were thrilled of course

to get the Missa brevis which has recently been recorded very well by the current Abbey Choir under James O’Donnell. And that offers another technique of yours, namely using speech. What appeals to you about that (some might say ‘extra musical’) ingredient?

It’s the idea of blurring, again, which you mentioned before –the combination of pitches and speech is a very definite blurring of musical pitches, so that the pitches and the speaking are somewhat random and cluster-like in effect; and if they are juxtaposed, they call each other into question, and the whole thing becomes more complex, becomes more ambiguous –I love that.

Do you feel that the spoken element is representing the congregation, as if part of the whole body corpus?

No. That’s a nice idea, but I had not thought of it. But maybe it does bring in the congregation.

In the Sanctus you chose very deep, low, beautiful sounds, which are sometimes quite difficult to hear, particularly in our cathedrals where the bass sounds tend to get lost. I was slightly surprised by that, but I knew that this must be what you wanted.

I love the deep low notes, very soft; I suppose I had thought that it would be fairly blurred, but anyway there are also the silences in the Sanctus, which are very much connected with Winchester and, I think, the Abbey. There is enough resonance to make the silences an integral part of the structure.

And silences also work beautifully in Thou mastering me God. My own test with that piece was keeping the choristers’ interest while they repeated the same note (G above Middle C) for 44 bars, although at times the G almost seems to change in relation to the

harmonies revolving around it. That’s very interesting.

...and then eventually those words, Over again I feel thy finger and find thee it’s as if you were using those words of Gerard Manley Hopkins in music to find ‘home’. Your suggestion for the words is a very beautiful one, and in the notion of being touched by God, the touching is very musically explicit, isn’t it?

There is at least one setting however, which is basically very simple –the Winchester Litany.

I have only heard it once, with you, but not since then.

There the words are intoned and heard very audibly, with just the minimum of harmonic change, until finally having that lovely flowering, when we reach the words: Holy God, holy and strong. (It’s published by OUP.)

Could you write something like that today?

Well, you see, that was really functional. At St. Michael’s I had sung the Litany every Friday morning. That came back to me, and I remember how we functioned, and how we sang these little phrases in procession, right round to the West End and back; they had to be simple and had to work when we were walking... All this was in my mind.

And it worked. This brings us to Bishop John Taylor (who had invited you to set the Litany), and without whom quite a few of the things at Winchester would never have happened. Yes.

The biggest of course was your church opera Passion and Resurrection. There’s nothing like that in the rest of your oeuvre, is there?

No. It was a culmination of the Winchester years, I think.

...and it’s exciting news that it’s going to be performed this year. Yes, The Portuguese are doing it and also the Austrians are doing eight performances with the Arnold Schönberg Choir in Ossiach.

Is it going to be staged?

Yes, I think there is going to be acting.

Good, because that’s what we have been really waiting for... Since the Winchester one...

when we were feeling our way. So well done...

...not least thanks to the participation of so many local people. It became a kind of Winchester ‘Oberammergau’, when, even though some of the parts were quite difficult, they were managed valiantly by the excellent local voluntary chorus, the Waynflete Singers... Yes, that was very inspiring...

...and it gave the whole thing a feeling that it was their work too. Local people gathered round in one way or another. Some made costumes, and it all began with the cast and backroom team attending a Holy Communion service in the Epiphany Chapel (in the Cathedral), celebrated by John Taylor.

There is a video of the BBC documentary. ...which has been seen by a lot of people,

...and it’s crying out for a performance in America. Is there anything looking back now which you would change? Would you leave it exactly as it is, after nearly 30 years?

I always said that the procession to Calvary was written at some length because of the very long Winchester nave, but it does not have to be that long, and I think one or two cuts for a concert version are in order.

It has an inevitability, which made me think of the Passacaglia in Britten’s Peter Grimes.

Interesting, or Death in Venice. That sense of inevitability was very much with me when I wrote it. I thought of it, as a ritualistic drama, as it must have been in medieval times; everybody knows the story… over many centuries, and one is just waiting for the inevitable to happen.

Its always said it’s easier to write music that produces an anguished mood; but yet you managed in the Resurrection to create a radiant orchestration, even though we were limited to the twenty players. You had the idea of the Three Marys from the libretto, but there is a sea-change in musical idiom, isn’t there?

Yes, this was a turning point for me.

You could not have written it while you were writing serially, could you?

Well, it is influenced by serialism, because it’s inversional. The whole piece is kind of ‘skewed serial’; the plainsong is one element, largely the pentatonic scale, and the series adds the remaining seven pitches as one unified Gestalt... The work is a kind of dialogue between the two: the anguished part is very serial –all the interludes in the first part. Then in the second part, the mirror inversion used in the Resurrection, I wanted to make very harmonious with triadic sonorities, but reflecting around the central axis, just as the axis of the world has changed at that moment –everything is different, a floating spiritual quality has occurred in some evolutionary jump…

Since you came back from Stanford, nine years ago, you have devoted yourself entirely to composition, and without having to do any other work. And it’s clearly been a fulfilment of what you have always wanted to do. Have you found it a godsend to have this freedom, or would you like to be able sometimes to have a little break from composition? (Laughter.)

I am forced to have a break, because my body demands it now, and I have to rest quite often.

Have you still time to write for the church?

St. John’s wants me to write something for their 500th in 2012, and Wells Cathedral have made me President of their New Music Wells Festival, and I have said that I will write them a little piece. I’m going over there to do a Round Table shortly.

When we look back at church music composed in the last quarter of the 20th century, it is absolutely clear that there are several of your works which are going to stand out: I love the Lord, Come, Holy Ghost, the Canticles and Missa brevis, commissioned by the Dean and Chapter of Westminster. (I am constantly thrilled by the opening of the Gloria and the beautiful augmented use of C major.)

Pentatonic again. I thought of God as pentatonic, and Jesus as tonal. In the Gloria there are two voices; the voice of and about God, and the voice of and about Jesus, and so I tried to juxtapose these contrasting elements.

You have also spoken about the ‘eternal feminine’; how do you think of the eternal feminine in music?

Well, that was something I became more and more interested in, in various ways, but it’s usually linked to the divine. Often Indian words are very explicit and Indian poetry. It’s such a mixture of the erotic and the divine. I have always thought that the ecstasies of the domain of love are very appropriate, just as some of the great mystics did –I have always found that connection very revealing.

Have you ever been tempted to set anything from the Song of Solomon?

I have used it, yes, but very early on, never I think since I was a student.

Well, it’s fascinating to think from those early days at Tenbury, when you were already beginning to explore sounds, that for the next sixty years you have literally continued to do that, incorporating all these extra techniques; and coupled with your imaginative use of texts, you have actually given to the church such a precious and sacred legacy, which I believe is being more and more appreciated. That’s very kind of you.

My colleagues and I look forward to many more things, but on behalf of us all, I should like to end by saying: “Congratulations, Happy Birthday and Thank you”.

Thank you, Martin. Without you, it would have not have happened. I say that quite categorically.

The programme for Martin Neary’s 70th birthday concert at St. John’s Smith Square on March 28, 2010, in aid of Music Therapy, includes the world premiere of Jonathan’s Song of June, composed fifty years ago, when they were both at Cambridge. [Ed]

Age: 37

Education details: Organ Scholarships at St Albans Abbey and Exeter College, Oxford.

Career details to date: Assistant Organist, Lichfield Cathedral 1994-2002; Director of Music, Truro Cathedral 2002-2008; Director of Music, York Minster 2008.

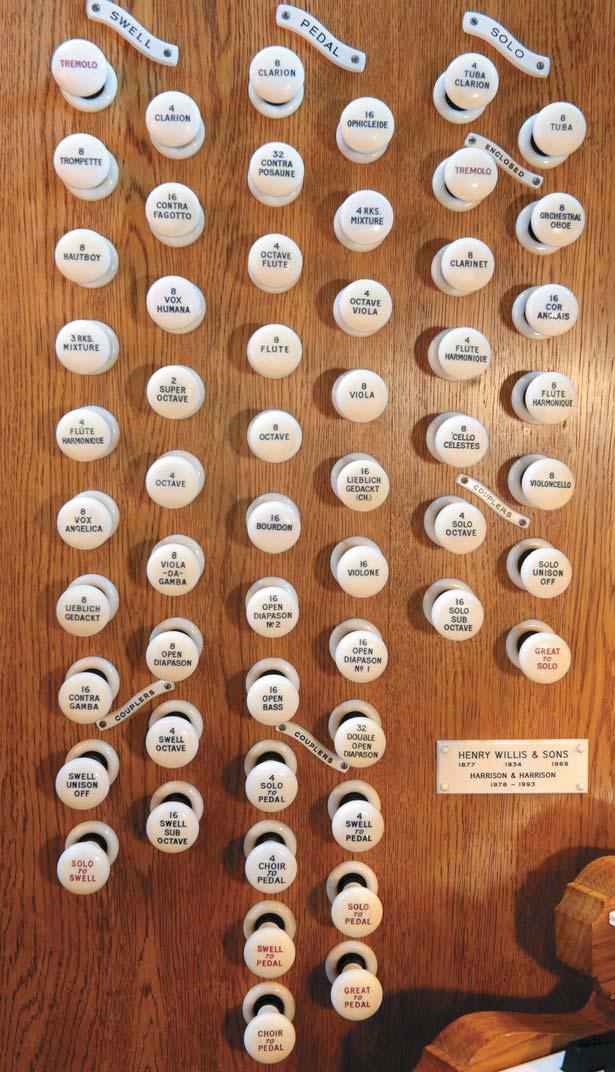

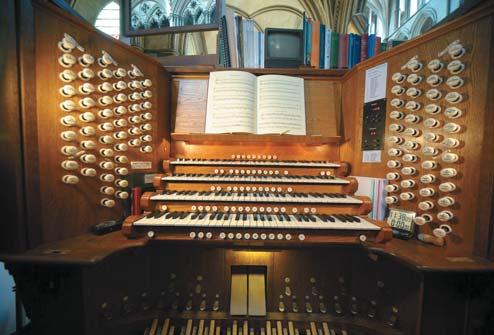

What did you enjoy most about working in a cathedral like Truro? The terrific Father Willis organ, the wonderful liturgy, the acoustic and the people.

What have been some of your highlights during your career?

The daily service is always a highlight especially when goals are attained. Also notable have been conducting some of the bigger choral and orchestral works in Truro Cathedral, performing for the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and my first Christmas in York Minster.

Briefly tell us about a typical day at York. There is a rehearsal at 8.00 or 8.15 each weekday when I see the boys or girls of the Minster choir. I direct both and my assistant, David Pipe, helps me with the rehearsal by taking the group I am not seeing that morning. Often we swop halfway through. I then deal with emails and admin and attend various meetings until lunch. In the first part of the afternoon, I spend some time preparing music and sometimes do some organ practice too before collecting the choristers for their rehearsal before Evensong. The songmen then join us from 4.35-5.00 when there is a break. Evensong is 5.15 until just before six and then I often return to see my young children and wife or sometimes to make sure that the beer in the various hostelries frequented by the songmen is OK. I used to cook a lot and am trying to do more again.

Do you still play much, and if so, what organ pieces have you been inspired to take up recently and why?

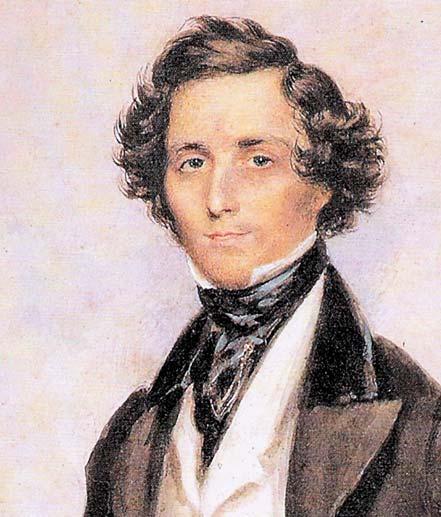

I do play a lot, though much of my work is in recitals rather than in the Minster. I have been learning some Mendelssohn this year in honour of his anniversary and have recently started the Willan Introduction, Passacaglia and Fugue having been inspired by Francis Jackson’s account on the Minster organ.

Have you been listening to recordings of them, and if so, is it just one interpretation or many and which players?

I try to listen to as many recordings of works I’m learning as I have time for. I have enjoyed the recent Mendelssohn recordings on the superb Bernard Aubertin organ in St Louis in Paris.

What or whom made you take up the organ?

My father’s uncle was a well-known organist in my home city of Lincoln and I was also inspired by the organist at my parents’ church who was a very good player.

Which organists do you admire the most?

Simon Preston, Colin Walsh and Andrew Lumsden.

What was the last CD you bought?

One of the David Rees-Williams’ jazz trio’s albums of jazz workings of well-known choral and organ pieces.

What was the last recording you were working on?

A disc of popular Christmas music with the York choir.

What is your favourite organ to play? Truro Cathedral.

What is your favourite building? York Minster.

What is your favourite anthem? The one I’m conducting that night!

What is your favourite set of canticles?

As above, but I perhaps could addJackson in G and Blair’s epic setting in B minor.

What is your favourite psalm and accompanying chants? Psalm 90 to the marvellous F or G minor chant by F Hervey.

What is your favourite organ piece? The St Ann Fugue by Bach.

Who is your favourite composer? J S Bach.

What pieces are you including in an organ recital you are performing?

I’ve done several of Paul Spicer’s works recently and Tom Winpenny’s fiendish but rather brilliant transcription of the Spitfire Preludeand Fugue of Walton.

Any forthcoming appearances of note?

I’ve done quite a lot this year and next year at the time of writing I’m giving an organ prom in the Victoria Hall, Hanley, recitals in Beverley Minster and York Minster, Bridlington Priory and several smaller venues in the diocese.

Have you played for an event or recital that stands out as a great moment?

I enjoyed hugely playing at Liverpool Cathedral earlier this year and back in Lichfield days for six live broadcasts on television and radio in one month which was very memorable.

Has any particular recording inspired you?

I have learnt a lot from many of the well-known choral recordings from George Guest, Simon Preston, and Stanley Vann as well as more recent ones from Barry Rose, Christopher Robinson and David Hill.

How do you cope with nerves?

Careful preparation and really focussing on the moment rather than what is approaching.

What are your hobbies?

I love gadgets and technology and I’m interested in wine, cooking and interesting furniture and houses.

Do you play any other instruments?

I enjoy the odd bit of piano accompaniment from time to time.

What was the last book you read?

World Without End by Ken Follett.

What are your favourite radio and television programmes?

BBC Radio 4’s Today and Have I got news for you

Which Newspapers and magazines do you read?

The Times and occasional periodicals when I can.

What makes you laugh?

My choristers!

If you could have dinner with two people, one from the 21st century and the other from the past, who would you include?

The Archbishop of York and Winston Churchill.

What should be the role of the FCM in the 21st century?

To promote the best standards of music within the liturgy and support ways of maintaining it.

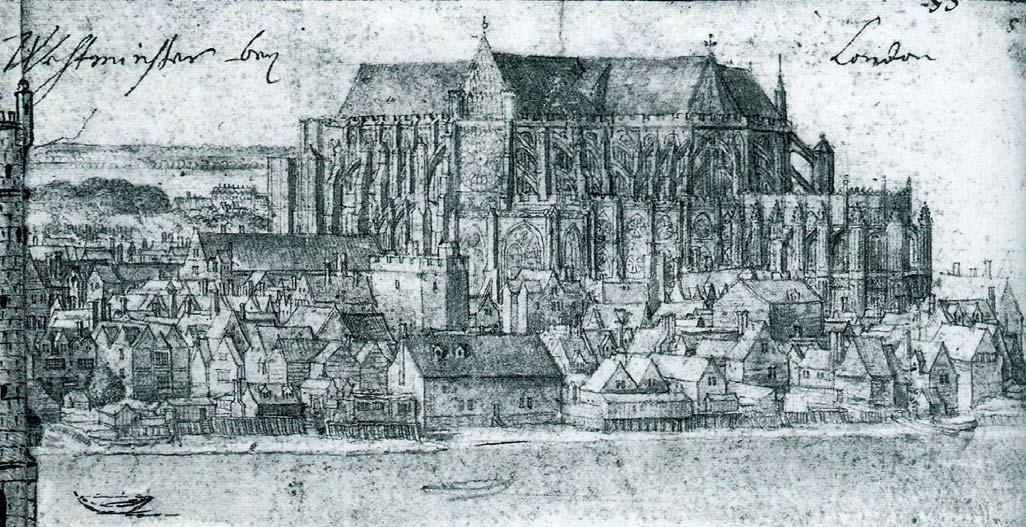

Many of this country’s most talented musicians have had the good fortune to benefit from an early musical education as a cathedral chorister. However, at the time of Henry Purcell’s birth in 1659, the possibility that he might gain such an opportunity must have seemed remote. Since the execution of King Charles I in 1649 and subsequent victory in the Civil War for the Parliamentarians, the people of England had been living under puritan rule. Charles’ son was in exile and the Church of England had been abolished. Religious music during this period amounted to little more than the unaccompanied singing of congregational psalms. Robed choirs had been disbanded, organs dismantled and entire libraries of musical scores destroyed.

Within months of Purcell’s birth, the situation changed dramatically. As a result of the political turmoil that followed the death of Oliver Cromwell, King Charles II was invited to return from exile and assume the throne. On 25 May 1660, Charles landed in Dover, entering London amid scenes of rejoicing on the thirtieth anniversary of his birthday. With the return of the monarch came the restoration of the Anglican Church and the re-establishment of choral foundations in chapels, churches and cathedrals throughout the realm. The task of re-building a tradition that had been denied to an entire generation was enormous and it is therefore unsurprising that musical standards around the country were not always consistently high during the months following the King’s return. Even the musicians at the Chapel Royal gave Pepys occasion to report in his diary on 14 October 1660: ‘an anthemne, ill sung, which made the King laugh’.

Henry Purcell probably entered the Chapel Royal as a chorister in 1668. By this time the standard of the choir under its renowned director, Captain Henry Cooke, must have improved greatly. During the 1660s, composers of choral music at the Chapel Royal were feverishly assimilating characteristics of continental music into their work. French culture was a particularly powerful influence and therefore the young Purcell must have become accustomed to performing new pieces by English composers that featured dance-like tripla sections, lilting dotted rhythms and bold

homophonic music, after the French style. He may also have been aware of an increasing tendency towards vocal writing in a more soloistic, declamatory style, facilitated by the general shift of emphasis during the seventeenth century from polyphonic music to music driven by harmonies deriving from the bass line. However, perhaps the most striking musical development at this time was the introduction of a string band of twenty-four players, evidently modelled directly on the famous vingt-quatre violons at Versailles. The King directed that they should regularly provide instrumental introductions,

interludes and accompaniment to the anthems sung in chapel. Therefore, as a chorister, Purcell would have heard some of the earlier attempts by composers at writing pieces in this entirely new genre of the English symphony anthem.

Purcell’s spell as a chorister in the Chapel Royal came to an end in 1673, when his voice broke at the unusually young age of fourteen (at this time choristers often continued to sing treble until they were sixteen or seventeen). He had almost certainly already begun to compose music by this stage, especially given the King’s tendency to encourage ‘some of the forwardest and brightest children of the chapel’, as we are informed by Thomas Tudway. Sadly however, the earliest known extant works by Purcell date from around 1677. Many of these early pieces reflect the mainstream traditions of post-restoration anthem composition without string symphonies. Of these, one of the better examples is Lord, who can tell, a verse anthem scored for SATB chorus and ATB soloists with continuo accompaniment. The work opens with a fully written out imitative organ introduction, not unlike those found in anthems written in the earlier part of the sixteenth century by composers such as Orlando Gibbons or Thomas Tomkins. However, this gives way to a figured bass line – which by now had become the standard way of notating instrumental accompaniment parts – at the entry of the bass soloist. The piece is in three sections with a concluding doxology. Although the first two are imitative in style, reflecting Purcell’s indebtedness to the older English polyphonic tradition, in the third section we find that Purcell employs a more fashionable homophonic approach. Furthermore, the second section is written in triple time, reflecting a popular trend in English sacred music through the Restoration period. Strikingly, the chorus is entirely subservient to the soloists, as is the case in many of these early verse anthems, and in fact only sings in the Gloria patri.

Often in these early verse anthems we also encounter musical features that point towards Purcell’s more mature, expressive style. For example, O Lord our governor – scored for the unusual combination of three treble soloists and two bass soloists with SATB chorus and continuo accompaniment –opens with a single bass vocal line written in a rather florid,

declamatory style that makes dramatic use of textual repetition, notably of the words ‘how excellent is thy name in all the world’. In the section that follows, Purcell exploits his unusual scoring with a charmingly colourful passage for three trebles, appropriately setting the words ‘Out of the mouths of very babes and sucklings has thou ordained strength’. Later in the work, Purcell demonstrates his continued concern with the rigours of counterpoint, writing a quasi-canonic passage for the two bass solo parts, lending the text ‘O Lord our governor, how excellent is thy name in all the world’ an air of solemnity.

Purcell continued to focus his attentions on writing for choir and continuo into his early twenties. A large number of such choral works that date from around 1677 to 1682 are extant in an important autograph manuscript that now resides at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. Generally speaking, these pieces fall into two different categories that are defined by the nature of the role that the continuo part plays. On the one hand, there are those anthems that are composed with an independent basso continuo line (referred to here as ‘stile moderno’), while on the other there is a group of anthems where the bass doubles the lowest vocal part at any time throughout the piece (referred to here as ‘stile antico’).

Among the group of anthems written in ‘stile moderno’ is the wonderful Let mine eyes run down with tears. Typically of Purcell’s pieces in this manner, the text is penitential in nature and therefore the complex counterpoint of the musical setting seems appropriate. This work is characterised by the composer’s concentration on a very limited amount of thematic material as well as the use of what is commonly termed ‘dialogue’ technique. This can be illustrated perfectly by consideration of the opening section of the piece. It begins with a bass soloist’s entry, singing the words ‘Let mine eyes run down with tears night and day’, to which the second treble soloist replies ‘and let them not sleep’, set to contrasting musical material. These entries subsequently occur in dialogue between various combinations of different voice parts (the opening is scored for SSATB soloists). Dramatic tension is built up towards the end of the section by the gradual increase in the rate of the entries.

In addition to his own compositions, Purcell also copied works by English composers of the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries into his music book (Fitzwilliam MS 88). Many of his own pieces in ‘stile antico’, which display a deep concern with rich polyphonic textures, are clearly modelled on music by pre-Civil War composers such as William Byrd and Orlando Gibbons. One example of such a piece is the famous anthem Hear my prayer, O Lord and let my crying come unto thee. It opens with an alto entry on the text ‘Hear my prayer, O Lord’, set to rather plaintive music based around two notes (a C natural that changes to an E flat on ‘O’ and back again to C on ‘Lord’). In contrast, the first treble responds with the words ‘and let my crying come unto thee’ set to a remarkable, chromatically expressive musical phrase with a melisma on ‘cry’, heightening the emotion of this word. The entire piece is based on the juxtaposition of these two simple ideas, which are frequently transformed by inversion and often adapted to fit the harmonic scheme of the piece, but nevertheless retain their essential characters. They are woven together to create an incredibly powerful eight-part polyphonic texture that builds to a wonderful climax, brought about by the eventual shift of emphasis to the words ‘and let my crying come unto thee’ during the final few bars of the piece. In fact, Hear my prayer is probably only the first section of a much longer work: in the autograph manuscript it appears without the customary flourish that Purcell inserted after the final barline of a piece and precedes a number of blank pages, seemingly left ready to receive the rest of the work.

1682 marks a watershed point in Purcell’s career as a composer of church music, for it was in July of this year that he was appointed as one of the three organists at the Chapel Royal, succeeding Edward Lowe. Unsurprisingly, given the string forces available at Whitehall, it was at around this time that he turned his attentions wholeheartedly towards the composition of Symphony Anthems. Not that he hadn’t composed for the genre already: Purcell is known to have written at least four Symphony Anthems before 1680. These include Praise the Lord ye servants, If the Lord himself, Behold now, praise the Lord and My beloved spake. Of these, only the latter has

survived complete (in two separate versions) and it well deserves further discussion here.

The text for My beloved spake is taken from the Song of Solomon, II, 10-13/16 and is full of exotic and imaginative imagery to which the young Purcell responded by writing music that is at times extraordinarily picturesque and expressive. The piece opens with an instrumental symphony scored for two violins, a viola and a basso continuo section that would have consisted of a ‘cello, an organ and one or even two theorbos. This opening symphony presages the upbeat, joyful tone of the anthem: its dance-like music characterised with sprightly dotted rhythms in triple time is just the type that we can imagine would have delighted King Charles’ Francophile sensibilities. The remainder of the piece is additionally scored for SATB chorus and ATBB soloists, although the chorus plays very much a subsidiary part in proceedings, entering only briefly to join the soloists for the words ‘And the time of the singing of birds is come’, set to music in triple time, as well as at the final ‘Hallelujah’ section, again in triple time and characterised by an continuous string of dotted rhythms.

Throughout the piece there are delightful examples to be found of Purcell’s colourful musical setting of words and ideas, and of his ability to capture the mood of a text. For instance, the exhortation to the poet by his beloved to ‘rise’ is set to music that literally rises through the texture as the word is repeated in turn by the first bass, the tenor and the alto soloists. In the section that follows, Purcell sets the text ‘For lo, the winter is past, the rain is over and gone’ in a homophonic style, but maintains musical interest, as well as a keen sense of the dark, cold and rainy winter that has passed, through the intensely expressive use of suspensions and strange voice leading. The wonderful fourteen bar string interlude that follows immediately after this section is crammed with false relations, reminding us of Purcell’s indebtedness to the English tradition of polyphonic instrumental music. However, perhaps the most magnificent moment of the work is Purcell’s exotic setting of the text, ‘And the voice of the turtle is heard in our land’. Again writing in a homophonic style, he exploits experimental

harmonies and expressively chromatic voice leading that lends something of an otherworldly feeling to the moment.

Between 1680 and 1685 Purcell continued to write some two-dozen symphony anthems that all demonstrate, to a greater or lesser extent, the musical priorities audible in My beloved spake. A popular example that remains in the repertoire of many of our cathedral choirs today is Rejoice in the Lord alway. The piece is frequently referred to as ‘The Bell Anthem’, a reference to the splendid opening symphony that, with remarkable elegance, evokes the sounds of tolling bells through simple repetition of descending C major scales spanning an octave in the basso continuo. It is most effective when heard in its original scoring as, unfortunately, much is lost when this work is heard with all parts played on an organ, no matter how dexterous the player’s pedal technique!

Following the death of Charles II in 1685, his Roman Catholic brother James II ascended to the throne. For the occasion of James’ coronation at Westminster Abbey, Purcell wrote what might be considered to be his finest symphony anthem, My heart is inditing. Hitherto, the majority of his string anthems had been scored for SATB chorus with ATB soloists. There had of course been one or two exceptions, one of the most notable being Praise the Lord, O my soul, a landmark example of Purcell’s dramatic use of scoring, which requires two groups of soloists, divided SST TBB. However, in My heart is inditing, he seems to have relished the opportunity to compose for vocal forces provided on a grand scale (the choirs of the Chapel Royal and Westminster Abbey joined together for the occasion) and the work requires an eight part chorus as well as eight soloists. The piece conveys a general feeling of solidity and majesty previously unheard in his output for the Chapel Royal. After the opening symphony, it is the chorus that enters first, not the soloists as in his other anthems with strings. There is also a greater amount of thematic continuity between the various sections of the piece than has been previously seen. Additionally, the piece lacks the recitative like solo sections generally found in this type of piece and as a result seems more formally indebted to earlier anthems for chorus and soloists with continuo, though with a strikingly increased sense of grandeur and spaciousness.

During the reign of King James II, music at the Chapel Royal was almost entirely neglected. Increasingly, musicians began to seek additional employment opportunities outside the court and Henry Purcell was no exception. After 1685 it is clear that he dedicated more and more of his time to composing music for the theatre. He perhaps also became involved with the public concerts that were becoming a feature of London’s musical scene since their inception by John Bannister. Of the seventy or so anthems that he composed throughout his life, only around twenty date from 1685 onwards. In these later compositions, Purcell returned to writing continuo anthems, clearly reflecting the lack of resources now available at the Chapel Royal. However, these are generally not of the same quality as his earlier works and tend to employ tired, formulaic gestures that do not achieve the same intensity of expression.

The revival of the Chapel Royal during the joint reign of William and Mary, who were crowned in 1688, does not seem to have drawn Purcell back to composing sacred choral music on a regular basis. However, he contributed a small number of works that were evidently written for special occasions. Amongst these, the symphony anthem O sing unto the Lord is a spectacular example and shows how far Purcell had developed

the genre in a relatively short space of time. Perhaps the most obviously remarkable aspect of the writing is the way in which he combines his musical forces to greater dramatic affect than in any previous anthem. There is far less delineation between soloists, chorus and orchestra. For instance the chorus is employed in dramatic dialogue with the bass soloist, who sings the text ‘tell it out among the heathen that the Lord is king’ to which the chorus reply affirmatively ‘the Lord is king’. The sentiment of the text ‘Glory and worship are before him, power and honour are in his sanctuary’ is captured as chorus and strings alternate in quick succession, the instruments affirming the meaning in their short interludes. Perhaps most significantly in O sing unto the Lord, Purcell employs greater thematic continuity between the sections. While in My beloved spake, the opening symphony sets the tone of the entire anthem, in this later work the opening symphony presents material from which much of the thematic material is derived through the remainder of the piece.

Henry Purcell is rightly acknowledged as one of the finest composers this country has ever had and we are remarkably lucky that such a composer produced so many works for the church of such high quality. However, just as the decline in the provision of strings at the Chapel Royal led to a decrease in the rate of his output of symphony anthems, so we find that the inevitable lack of such resources in our Anglican foundations today limits our opportunities to hear many of these compositional gems put to their original devotional purpose. What is perhaps a cause of even greater sadness though is the widespread neglect of the large number of anthems by Purcell that require continuo accompaniment alone. It is to be hoped that on this, the three-hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the composer’s birth, we will begin to look beyond the handful of well know choral works by Purcell and discover some of the treasures that lie beyond.

Bibliography

Adams. M., Henry Purcell: The Origins and Development of his Musical Style.

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995.

Burden. M., (ed.), The Purcell Companion Faber and Faber, London, 1995.

Burden. M., (ed.), Purcell Remembered Faber and Faber, London, 1995.

Holman. P., Henry Purcell. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1994.

Holst. I. (ed.), Henry Purcell 1659 – 1695: Essays on His Music.

Oxford University Press, London, 1959.

King, R., Henry Purcell. Thames and Hudson, London, 1994.

Mundy, S., Purcell Omnibus Press, London, 1995.

Spink. I., Restoration Cathedral Music 1660 – 1714. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1995.

Zimmerman, Franklin B., Henry Purcell, 1659 – 1695: His Life and Times. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 1984.

In this new series we look back at well-known personalities who have been cathedral choristers. The first is Stephen Orton, Principal Cello with the Bournemouth Sinfonietta and the City of London Sinfonia.

What are your career details and what are you now doing?