Makin Thirlmere 2-30 Organ

Now available with motorised drawstops

Breathtaking reality

������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������ ����������������������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������

For more details and a brochure call 01706 888 100 visit our website www.makinorgans.co.uk or send an e-mail to sales@makinorgans.co.uk

CATHEDRAL MUSIC

CATHEDRAL MUSIC is published twice a year, in May and November

ISSN 1363-6960 NOVEMBER 2014

Editor

Mrs Sooty Asquith, 8 Colinette Road, London SW15 6QQ sooty.asquith@btinternet.com

Editorial Advisers

David Flood & Matthew Owens

Production Manager Graham Hermon grahamhermon@lineone.net

FCM Email info@fcm.org.uk

Website www.fcm.org.uk

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of Friends of Cathedral Music. Likewise, advertisements are printed in good faith. Their inclusion does not imply endorsement by FCM.

All communications regarding advertising should be addressed to: HMCA Services, Beech Hall, Knaresborough HG5 0EA 07436 791353 wesley.tatton@btinternet.com

All communications regarding membership should be addressed to: FCM Membership, 27 Old Gloucester Street, London WC1N 3AX

Tel: 0845 644 3721

International: (+44) 1727-856087 info@fcm.org.uk

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used. We apologise for any mistakes we may have made. The Editor would be glad to correct any omissions.

Designed and produced by: DT Design, 1 St Wilfrids Road, Ripon HG4 2AF 07828 851458 d.trewhitt@sky.com

Cover photographs

Front Cover

Tewkesbury Abbey

© David Noble (DoM St Mark’s Bilton, Warwickshire) www.flickr.com/photos/davidnoble/ Back Cover

St Magnus Cathedral

© Eleanor Miller (Kirkwall)

Technology bringing tradition to life

Selby Abbey chooses Viscount

Viscount are honoured to have been chosen to supply a temporary instrument for Selby Abbey to cover the period while their historic Hill Norman & Beard instrument undergoes a 2 year restoration programme.

Our Regent 356 was installed in September, with speakers in the triforium and a tuba mirabilis under the west end window.

Fund raising for the pipe organ restoration is well under way and the work has already begun by Principal Pipe Organs of York.

£200,000 is still needed to ensure a complete and magnificent restoration. If you can make even the smallest contribution, your support wlil be much appreciated.

You can send a cheque, payable to:

‘The Selby Abbey Organ Appeal’ Appeal Office, c/o The Rose House, Wykeham, Old Malton, North Yorkshire, YO17 6RF.

For an instrument for your church or home use, we would be very pleased to hear from you on 01869 247333 or visit our website at www.viscountorgans.net

From the EDITOR

Winter approaches. I am reminded of this by the atmospheric pictures that accompany David Flood’s account of the Canterbury choir’s pilgrimage to Norway, where grey skies and murky seas predominate (although despite this his choristers found a new way to reach the cathedral in Gildeskål -- in an inflatable motorboat!). And then there’s the Orkney landscape which is so often evoked by Peter Maxwell Davies’s music. One of our greatest living composers, Sir Peter’s early life and important compositions are examined and put into context for us to appreciate by Grenville Hancox, another Canterbury scion. Once the enfant terrible of the classical music world and still composing at the age of 80, Sir Peter was recently referred to as a gériatrique terrible, perhaps for his non-conformist soul, but equally for his continuing search for the unconventional.

The Ngoma Dolce Academy in Lusaka is unconventional in a different way. Set up in 2010 by Dr Paul Kelly and Moses Kalommo, this is a place where musicians of talent can find teachers to take them beyond the self-taught level which was all that was available before the school’s foundation. Classical music education in Africa is clearly beginning to thrive thanks to this initiative, but many more schools and skilled volunteers are needed so that today’s pupils can avoid the six-hour journeys that Moses used to make each week to receive tuition.

Education of course brings both challenges and rewards, some more unexpected than others. Fathoming words like ‘irreprehensibilis’ would definitely have come more easily in

days gone by when Latin was more widely encountered in the schoolroom. Now infrequently taught in the state sector despite the laudable attempts of Boris Johnson and the charity Classics for All, Latin is almost a requirement for enthusiasts of the cathedral music world in general, and the ability to understand the words of an anthem in Latin will surely enhance the listener’s enjoyment. CM readers are likely to be more well versed than most in this particular dead language, but few of us can have been required to set the word to music (pace Bruckner) as was the case with Howard Skempton. See Paul Whitmarsh’s account of his conversation with Howard on p20.

Our front cover for this issue shows the soaring majesty of Tewkesbury Abbey’s interior arches and windows, a tribute in this case to the Abbey School’s 40 years of existence. Simon Bell, Tewkesbury Abbey Schola Cantorum’s Director, is reaping the benefit of FCM’s grants to the foundation over the years: without this money (and not forgetting the Ouseley Trust’s contribution either), as many will remember, the choristers at the Abbey School would not have made the successful transition to Dean Close in Cheltenham, and the precious tradition of choral music at the Abbey would almost certainly have been lost. Recent recordings and broadcasts from Tewkesbury show that the choir continues to go from strength to strength, so let us take heart from this that our funds are helping to keep cathedral music alive both in the UK and elsewhere. Enjoy the magazine.

JOINING FRIENDS OF CATHEDRAL MUSIC JOINING FRIENDS OF CATHEDRAL MUSIC

How to join Friends of Cathedral Music

Log onto www.fcm.org.uk and fill in the form, or write to/email the address given on p3.

Member benefits include:

• welcome pack

• twice-yearly colour magazine and twice-yearly colour newsletter

• ‘Singing in Cathedrals’: a pocket-sized guide to useful information on cathedrals in England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales

Opportunities to:

• attend gatherings in magnificent cathedrals

• meet others with a shared interest in cathedral music

• enjoy talks, master-classes, choral and organ performances etc.

Subscription

UK members are asked to contribute at least £20 per year (£25 sterling for European members and £35 sterling for overseas members). UK choristers and full-time UK students under 21 qualify for a reduced rate of £10. New members subscribing at least £30 (standing order) or £50 (single payment) will receive a free fulllength CD of cathedral music, specially compiled for FCM members.

FCM’s purpose is to safeguard our priceless heritage of cathedral music and support this living tradition. We strive to increase public awareness and appreciation of cathedral music, and encourage high standards in choral and organ music. Money is raised by subscriptions, donations and legacies for choirs in need.

Since 1956 we have given over £2 million to Anglican and Roman Catholic cathedral, church and collegiate chapel choirs in the UK and overseas; endowed many choristerships; ensured the continued existence of a choir school, and worked to maintain the cathedral tradition. Please join now and help us to keep up this excellent work.

Grenville Hancox writes on Sir Peter Maxwell Davies

Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, Companion of Honour, CBE, and Master of the Queen’s Music for ten years until 2014, shows no sign yet of slowing down the compositional output which has been a hallmark of his illustrious and extraordinary musical life. The premiere of his Symphony No. 10 earlier this year, a celebratory Prom to mark his 80th birthday, and a raft of commissions for the years ahead are testimony to the creative energy and discipline that are characteristic of the composer. Even life-threatening leukaemia in 2012 could not stem the muse, a hospital room becoming necessarily a temporary studio and venue for the symphony’s defiant composition.

Born in September 1934 (in the same year as Elgar died) to Tom and Hilda Davies in Salford, Lancs, Peter Maxwell Davies (always known to friends as ‘Max’) lived for the first four years of his life above a newsagent’s shop owned by his mother’s parents. His father, an expert instrument-maker for an optical firm, sometimes sang with a male voice choir; his mother was a vivacious, talented woman who a generation later would have had the opportunity to study at a university. Neither parent was a practising musician, although the piano was a feature of the extended family’s entertainment, and local productions of Gilbert & Sullivan were a significant element within the cultural life of the area. Once, after attending a performance of The Gondoliers, his parents were astounded that their four-year-old could recall and sing every song from the operetta the following morning! This experience not surprisingly suggested to them that their child had an unusual and probably prodigious talent, while Max himself knew from that moment on that he wanted to be a composer. In a less open society than now, Max’s parents were demonstratively loving and affectionate, and were supportive as well as somewhat unusual in encouraging an independence of both thought and actions in their son. Not for them the suggestion that ‘children should be seen but not heard’! Home was always a welcome refuge for Max until their death.

as a curriculum subject was not part of the school’s macho culture!

Having won a Lancashire County Council scholarship to read music in a joint course at Manchester University and the Royal Manchester School of Music (chosen also to be close to his home and his piano), Max again rubbed up against stuffy authoritarian educators and found much of the curriculum and teaching unpalatable. His world was already informed by extensive reading, by enquiry and discovery, whilst his course ‘consisted not of finding anything out but of learning facts by rote and regurgitating them in the approved manner’. His professor of composition (whose roots were firmly anchored in the 19th century and who despised contemporary compositions and composers) was an unfortunate choice for Max, who began to search for his own influences and teachers.

Max was an exceptionally bright and enquiring young boy and adolescent. Enjoying piano lessons on an instrument that was an enormous expense for his parents, he quickly surpassed the skills of successive piano teachers and was always at the top of every class at school. A scholarship to Leigh Grammar School spawned one of his first brushes with authority, his headmaster recognising and wishing to utilise Max’s intellect to further the reputation of the school by making him follow a curriculum which would have resulted in a science scholarship to Cambridge. Max would have none of it, and insisted on sticking to his goal of becoming a composer. The headmaster, totally out of sympathy with this, implied that teaching music

The first of these was a group of contemporary students with whom he established significant and career-determining relationships. Alexander Goehr, Harrison Birtwistle, Elgar Howarth and John Ogdon certainly stimulated his composing and helped realise some of his earliest and most demanding works such as the Sonata for Trumpet and Piano op. 1, premiered by Howarth and Ogdon in Manchester and then London. The second set of influences began with his visits to Darmstadt and New York to study with Bruno Maderna and Roger Sessions, two intensely bright beacons of new musical thought. Max followed this up with 18 months of study with Italian Modernist Goffredo Petrassi, whose very wide range of traditional and avant-garde styles, including serialism, enabled him to offer criticisms which transformed the extraordinary young composer into a budding master craftsman.

Once, after attending a performance of The Gondoliers, his parents were astounded that their fouryear-old could recall and sing every song from the operetta the following morning! This experience not surprisingly suggested to them that their child had an unusual and probably prodigious talent, while Max himself knew from that moment on that he wanted to be a composer.

This period of challenging study was underpinned and influenced by Max’s regular attendances at Evensong in Manchester Cathedral, where Allan Wicks was in charge of the music. Max’s immersion in Renaissance motets and the anthems of Gibbons, Byrd and Tallis proved enormously influential. Close study of the work of these composers, and the texts used ignited not only a passion for Renaissance music, but also one for sacred texts and poetry which has lasted throughout his life and informed his compositional technique and works. His stay in Rome nurtured the passion for Renaissance music further – while attending the sung masses at the Benedictine monastery on the Aventine Hill, he had opportunity to listen to and study music by Palestrina and Victoria, amongst others.

see. Just as the figure of Christ is there – overtly, or cloaked and by implication – in at least four of his operas, so the Church, with its scented allure, its vestments, its musical legacy, its morality and its misbehaviour, has always been an object of Davies’s attention (and even affection), whether for revering, or parodying.’

It is not therefore a surprise to find within the vast published output of this remarkable composer a significant number of sacred works. In his first ten years of composing Maxwell Davies produced more than a dozen motets and carols. These were followed closely by the Five Motets, Four Carols and Five Carols, together with the individual Marian settings Ave Maria and Ave plena gracia, and Ave rex angelorum and the anthem Hymn to the word of God (a setting of a Byzantine Orthodox text), all of which demonstrate his passion for texts in Latin and English. Paul Griffiths wrote of the Five Carols of 1966: ‘Davies’s carols have the exceedingly rare quality of being simple but not condescending, natural-sounding but full of interest, beautiful but not sentimental. Their style is quite distinctive. Whether Latin or English, the texts come from medieval sources, and the music seems to strike back to the Middle Ages in its rhythmic life and its pure modality, though the common seconds and tritones make these very much 20th-century pieces.’

Davies’s two masses for Westminster Cathedral, one with dramatic double organ, the other simpler and optionally a cappella, along with his two settings of the canticles for St Mary’s Edinburgh and Wells Cathedral, are 20th- or 21st-century classics of their kind. Another striking choral piece is Hymn to the Spirit of Fire, first performed in Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral in 2008 and dedicated to Sir Paul McCartney. Max has also written several substantial widely performed works for solo guitar and for organ, including an organ sonata.

For at least 76 years of his life

Three years as a revolutionary music teacher in a 500-year-old grammar school in Cirencester brought Max and his music to the attention of his home nation. New child-centred methods of teaching music, writing for and alongside his pupils, resulted in seminal works, media attention (regular press coverage, frequent radio interviews and a television documentary) and visits to the school by some of the leading musicians of the day including John Ogdon and the Amici Quartet. In December 1960 the first performance of O magnum mysterium was given, and like his greatly admired contemporary Benjamin Britten, Max successfully tackled the challenge of writing music for children and adult musicians in the same work without artistic compromise.

Not surprising therefore that his works, whether secular or sacred, have much in common. As Roderic Dunnett wrote, in 2004

‘Ever since his student days, when the 20-something-yearold Maxwell Davies launched himself on an unsuspecting European musical world with works like his wind sextet Alma redemptoris Mater, the sonata for double wind St Michael, the First Taverner Fantasia and the Seven in nomine [instrumental works], the plainsong roots of a vast proportion of Davies’s output have been plain for all to

Throughout his life, Max’s friendships and relationships have often provided the stimulus for composition (e.g. his trumpet sonata, which he wrote after hearing Elgar Howarth play the trumpet in Bach’s Christmas Oratorio). As a corollary to his ideas he needed an ensemble to realise them, one prepared to be challenged by him and to share his burning passion for music. Such a group was The Pierrot Players, which had been

Max has listened to, thought about, read, performed, studied and composed music, his extraordinary intellect always applied to provide a challenging response to the world around him, always an advocate for the central role that music should play in our society.

formed by Harrison Birtwistle and which metamorphosed (after Birtwistle had left) into The Fires of London The ensemble became one of the best-known contemporary music groups of all time.

Relationships and associations with larger groups of musicians in chamber and symphony orchestras have also been a hallmark of the composer. His ten Strathclyde concertos offer an insight into this: each individual concerto was written for one of the players of the ensemble, the composer inspired by and challenging the recipient of the dedication to scale new heights of musical expression, just as he had done with The Fires of London and its players. (When, for example, virtuoso horn player Richard Jenkins joined The Fires, Max wrote Sea Eagle for him. At first this was considered only playable by a virtuoso like Jenkins but now it is so mainstream that it’s often used as a piece for audition!) Residencies, conducting laureates, and orchestral commissions such as for his eighth symphony (the Antarctic Symphony) reflect the in-depth dialogue he has maintained with such ensembles.

I believe too that Max has enjoyed a significant relationship with musicians working in churches and cathedrals of the United Kingdom and with the liturgy itself. As Paul McElendin wrote:

‘When news emerged soon after the millennium that Sir Peter Maxwell Davies was writing not one, but two settings of the Mass, eyebrows were raised: had the wily leopard changed his spots? What could have brought the scourge of the establishment, the doyen of the Sixties’ avantgarde, the witty and savage lampooner of the Church and all things establishment-connected, to contemplate composing for the liturgy?’

His questioning, analytical, probing mind has led to religious attitudes which as Max suggests ‘are very open indeed, but I do feel that for human beings to make God in our own image is a terrible affront, because we’re so limited in our understanding.’

The pattern of compositional output, whether sacred or secular, demonstrates the importance of person and place underpinned by an unconventional belief perhaps, but with a complete awareness of the importance of Christian liturgy to the arts. Thus the early relationships with pupils at Cirencester, so too with Martin Baker at Westminster, or Matthew Owens at St Mary’s Edinburgh: all have led to new compositions and recordings of his sacred music output.

A picture emerges of someone acknowledged throughout the world as one of the greatest living composers who has developed a technique of composition beautifully crafted, informed by depth of reading and enquiry into sacred texts and the liturgy and often motivated by place and people to compose. Of someone who sees his role as a conduit for different interpretations of belief, who has great admiration for the tradition of choral singing, for the role that cathedrals and parish churches play in maintaining excellence and celebration. Someone who writes music that is challenging but steeped in this tradition and who through his now relinquished role as Master of the Queen’s Music has added significantly to the repertoire. His idea to celebrate the Queen’s Jubilee in 2012 resulted in Choirbook for the Queen, a collection of forty anthems, of which twelve were new commissions (including

one of his own to a text by Rowan Williams) which Max hoped would “hold its own with The Eton Choir Book”

For at least 76 years of his life Max has listened to, thought about, read, performed, studied and composed music, his extraordinary intellect always applied to provide a challenging response to the world around him, always an advocate for the central role that music should play in our society. On his appointment as a Companion of Honour earlier this year, Max said, “I am delighted to be joining such distinguished company in receiving the Order of the Companions of Honour. It is vital that society acknowledges the importance of the arts and composition and classical music in general. Anything that raises the profile of our art form is both wonderful and most welcome.”

Grenville Hancox MBE Professor Emeritus, Canterbury Christ Church University

As Head of Department and Director of Music at Canterbury Christ Church University until April 2012, Grenville Hancox is well regarded for his work as an educationist, performer and conductor. In 2000 he was made Professor of Music. His long established friendship with Sir Peter Maxwell Davies and the Maggini Quartet continued with their collaboration on the Naxos String Quartet Project, the composer writing two string quartets each year over a five-year period. As a clarinet player he has performed extensively throughout the UK, on the European mainland and in the USA, and has appeared with, amongst others, the London Mozart Players, and the Maggini and the Sacconi string quartets. As a conductor he has directed choral groups of every age, premiering works by many composers including Sir John Tavener. He received an MBE in 2005 for services to music in higher education and in 2006 a Civic Award from Canterbury City Council for services to the community. In 2012 he established The Canterbury Cantata Trust (www.canterburycantatatrust.co.uk). Current research interest centres on the impact of choral singing on people with Parkinson’s Disease; he has established two singing groups in Canterbury and London over the past four years, providing opportunities for Parkinson’s people and their carers to come together and sing.

(See www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-15732780)

A CANTERBURY PILGRIMAGE David Flood

The interest focused on Canterbury as a site of pilgrimage grew very quickly after Thomas à Becket was murdered on 29 December 1170, and a powerful attraction generated by the circumstances surrounding his death still effortlessly draws people in. Becket’s influence was more far-reaching than most of us realise. Over the years, Canterbury Cathedral has welcomed millions of pilgrims to follow the route that so many have followed before.

The most northern site where a relic of St Thomas is reported to be found is in Norway, in the community of Gildeskål and the village of Inndyr, on the coast a little south of the city of Bodø. Nowadays we know that this magical place is 300km north of the Arctic Circle, and as such is not very often visited by tourists or pilgrims, but the people there feel a strong link to the English saint whose relic they guard and venerate.

One member of the church community, Oddbjørn Nikolaisen, who works as both churchwarden and organist for the community of Gildeskål, has a passionate determination to see this ancient link strengthened and renewed. At his invitation and encouraged by the whole community, the Bishop of Dover, the Rt Revd Trevor Willmott, and members of the cathedral chapter and city council have visited both Gildeskål and Bodø

in recent years, with the cathedral musicians adding further strength and visibility to this link. The Bishop of Bodø, Tor Berger Jørgensen, joined the Anglican and Episcopal bishops at the enthronement of Archbishop Justin Welby, and others from that community often come to Canterbury to attend a service. The cathedral choir’s latest trip was in April this year.

We were told to expect temperatures between 2-6oC. On our journeys from one concert to another we saw many beautiful frozen streams and lakes; snow was still lying next to the roads in some higher parts of our travel. The scenery all around was simply breathtaking and hundreds of photographs were taken. Hats, coats and gloves, long since put back in the drawer in south-east England, were important additions to the packing.

Along with two concerts, one in Gildeskål and one in the cathedral in Bodø, we sang three services, the first of which was probably the most poignant but the shortest and least public. Standing in an arc in front of the altar where the relic of St Thomas lies in the old church in Gildeskål, the lay clerks sang an Evensong featuring music linked to St Thomas of Canterbury: the plainsong introit associated with his feast Gaudeamus omnes, and an anthem by Canterbury composer Alan Ridout Salve lux laetitiae, written specifically for feasts

of St Thomas and still in manuscript. The uplifting concert which followed became an extension to this very moving occasion. Both Evensong and concert were sung to large audiences, although the new church (just a few yards away) can hold many more people than the old one.

The concert on the previous evening in the cathedral in Bod was a wonderful occasion, received with a standing

Sunday brought two services to sing: a mass including preparation for confirmation in Gildeskål, and a Choral Evensong in Bodø. The many children preparing for confirmation were mightily impressed by the choral forces for this, their special service, and there was a little time for photographs (even ‘selfies’!) to be taken with the Canterbury choristers in their purple cassocks. What a shame it is that we don’t learn Norwegian – but how wonderful that most Norwegians speak English!

Evensong attracted an even larger congregation than the concert. By that stage, news of what might be expected musically had travelled far and wide, and besides, for Evensong no tickets were needed! The very plain but beautiful interior of the cathedral gives a wonderful acoustic and, in combination with the fabulous new organ by Eule, both Evensong and the concert were magnificent occasions.

I have not yet mentioned the diversion (not publicised to the boys before leaving) which lives longer in their memory than almost everything else: the trip from Bodø to Gildeskål, normally 90 minutes by road, but taken on three high-speed RIBs (rigid-inflatable boats) across the fjord. The journey direct takes about twenty minutes by water but on this occasion there were some additions to the norm. The members of the choir (with the exception of the Master of the Choristers, who had to go to a meeting with the Bishop!) were dressed in protective suits, hats and goggles, ready for a trip across the still fjord at very high speed. They went to see a maelstrom, where two sea currents collide in a narrow inlet, had a lunch of local fish on a tiny island and then arrived at the church for their rehearsal and concert by sea, witnessing the church appearing out of the mist and clouds in a magical way. The scenery was reportedly most spectacular.

Throughout this tour we were shadowed by our good friends from BBC TV who are making a sequence of programmes on Canterbury Cathedral. They were very intrepid on the boat trip and very unintrusive in our concerts and services. They became a central part of the trip, in the same way that they have become a part of our everyday lives recently.

We leave behind in Norway a massively strengthened friendship and collaboration between two communities that have been linked for many centuries. We are very grateful to all those Norwegian friends who worked so hard to make this trip so successful, and we look forward to further adventures in the future. Now, how far south is the influence of St Thomas to be found…?

David Flood is Organist and Master of the Choristers at Canterbury Cathedral, a post he has held since 1988. He was previously Organist of Lincoln Minster and Assistant Organist at Canterbury. The choir under his direction has made 15 recordings and toured extensively in Europe and North America. Most importantly, the cathedral choir sings seven days a week in term time to a very large eclectic congregation from all corners of the world: a responsibility they not only cherish but enjoy. David is a Visiting Professor and Honorary Fellow at Canterbury Christ Church University and a Visiting Fellow of St John’s College, Durham. He was awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of Music from the University of Kent in 2002.

PROFILE PETER DYKE

it was such a huge privilege to be able to work with a choir trainer of the calibre of Barry Rose. The choir sang to an incredibly high standard and its music was much appreciated by the very large cathedral congregation.

What or who made you take up the organ?

It’s difficult to put my finger on this. I’d played the piano since the age of six, and had always thought the organ a logical step onwards. From an early age I was helping out by playing for services: I remember a percipient priest asking me (then 13) to play for the monthly evening youth service at the parish’s daughter church, and from then on I never looked back.

When you were at school, did you think you might end up where you are now?

At school I had a vague plan I would be an organist, but I hadn’t given much thought to where or at what level that might be. Being the only first-study organist in my school I found it quite hard to judge my own ability against what might be expected. It’s worth mentioning that I did very much enjoy a visit to a Hereford Three Choirs Festival in the 1980s.

Tell CM readers about the Organists’ Training Schemes you helped to found in Gwent and Hereford.

Education details:

I grew up in Harpenden, and went to Batford and St George’s Schools. St George’s was unusual for a state school in that it had a chapel and an organ. I was awarded the organ scholarship to Robinson College, Cambridge, where I studied for a music degree from 1983–86.

Career details to date (and dates):

I worked in the civil service for a year after leaving university, while also taking on the job of organist at St Helen’s Church, Wheathampstead. This post became a central part of a freelance musical career from 1987 to 1992, when I moved to St Woolos Cathedral, Newport as Assistant Organist, keeping much of my freelance work in the south-east. After three years at Newport I became organ scholar at St Albans Abbey in 1995, and moved to my current post at Hereford in 1998.

Were you a chorister, and if so, where? Did you enjoy the experience?

I was never a chorister, though I did sing in school choirs. I played the oboe and cor anglais in various youth orchestras, including the Hertfordshire County Youth Orchestra. I would strongly recommend orchestral membership to all organists and I’m sure that this experience has encouraged my enthusiasm for transcribing orchestral music for the organ.

What did you enjoy most about being an organ scholar at St Albans?

I was at St Albans at a very exciting time: the new girls’ choir was in the process of being founded by Andrew Parnell and

The initial plan came from the local RSCM committee, which wanted to support the large number of churches without choirs by helping their existing organists enhance their skills, and at the same time encourage more people to play the organ. I was very keen that PCCs and congregations should be involved, so we made provision for churches to sponsor part or all of the cost of a year’s lessons. We devised a syllabus with five levels of attainment, confirmed by informal assessments, for students to work towards. In Hereford now we run a variety of educational workshops each year and work closely with parish churches, the cathedral, schools and other organisations to try to keep interest in the organ alive, when the great majority of young people don’t go to church or hear the organ at all. It’s been working well but there is always more that can be done!

What organ pieces have you been inspired to take up recently and why?

Hereford Cathedral has a very fine library, containing a great many manuscripts. We recently discovered some organ concerti by a former vicar choral here, William Felton, and I played one of these from the old edition before a festival service the other day. Bach, of course, provides endless inspiration. I’ve never learnt the whole of his output as I like the idea that there are still new pieces to discover. Over the next year I’d love to learn Vierne’s Symphony No. 4, which is a compellingly powerful piece with real harmonic excitement. I spent a fair part of 2013 transcribing and learning Dvořák’s ‘New World’ Symphony, in which I’d played the oboe and cor anglais parts many years ago; this was a very rewarding chance to get to know this great music in closer detail.

Do you get much time to compose? What are your recent pieces?

I’m not sure I ought to mention this but my most recent composition was a four-bar jingle for Hereford Hospital Radio, written for the choral scholars to sing! No, there’s not much time to compose, though along with other tutors on the Organists’ Training Scheme I’m currently working on some short chorale preludes for a collection to be published later this year.

Which organists do you admire the most?

There are so many! I’ve never forgotten hearing Pierre Pincemaille improvise stunningly and in so many different styles; Dame Gillian Weir played splendidly at Hereford, Thomas Trotter performed the Elgar Vesper Voluntaries supremely beautifully at Malvern Priory, and I admire too the many liturgical organists who conduct and accompany so well and still maintain solo recital careers. I must mention the late David Sanger too, who taught me an enormous amount about informed and musical interpretation of such a wide range of repertoire as well as being a thoroughly generous and genuine person.

What was the last CD you bought?

Schubert’s Fantaisie in F minor for piano duet, played by the Labèque sisters. A great piece, played with insight and understanding as well as perfect ensemble.

What was the last recording you were working on?

Not counting live broadcasts, the last one was a disc of Christmas music with Hereford Cathedral Choir. This included two new carols by Richard Lloyd (organist of Hereford from 1966–74), some more familiar items, and also a short composition of my own, which I’m very grateful to my colleague Geraint Bowen for including.

What is your

a) favourite organ to play?

Of course, it depends on what the occasion is and what music I’m playing. I really love the Willis at Hereford for its rich and subtle colours, and its ability to create a seamless continuum from silence to splendour; few organs compare to it for setting the scene. Having said that, I very much enjoy playing wellvoiced tracker instruments, such as the Frobenius organs at Robinson College and The Queen’s College Oxford for sheer beauty of single registers.

b) favourite building?

I’m not sure there is one I can say is the favourite: so many are amazing. If forced to reduce to a short list I’d include Ely, Durham, Coventry and Kirkwall Cathedrals, the old (now redundant) church at Kempley (Glos), and the Marienkirche in Lübeck.

c) favourite anthem?

O Jesu Christ, meins Lebens Licht (Bach), though I realise it’s not typical repertoire; anything by Gibbons, especially See the word is incarnate; Anthony Piccolo’s The Key

d) favourite set of canticles?

Howells Collegium Regale Te Deum and Jubilate; Leighton’s evening settings, and Tomkins 5th

e) favourite psalm and accompanying chants?

I find the psalms increasingly inspiring, and we’re very lucky still to do the psalms for the day here. Some favourites are Psalm 49 to the E major chant by G R Sinclair; Psalm 55 to the F minor chant by Hervey, and I quite enjoy the slow pulse of Psalm 119.

f) favourite organ piece?

I think it has to be the St Anne Fugue (Bach), but Franck’s 2nd and 3rd Chorals are also high up the list, as is much by Messiaen and Böhm’s Vater unser im Himmelreich

g) favourite composer?

As someone else once said, hopefully the composer whose work I’m performing at the time! As well as the obvious composers of choral and organ music, I really love Debussy, Ravel, Wagner, Shostakovich, Nielsen and Brahms.

When is your next organ recital? Which pieces are you including?

There was a major recital at Hereford Cathedral on 22 July, which included not only the entire Enigma Variations (in a transcription I made a few years ago) but also a fifteenth ‘Enigma Variation’ newly commissioned from David Briggs and entitled ‘RCM’ in honour of Dr Roy Massey’s 80th birthday.

Have you played for an event or recital that stands out as a great moment?

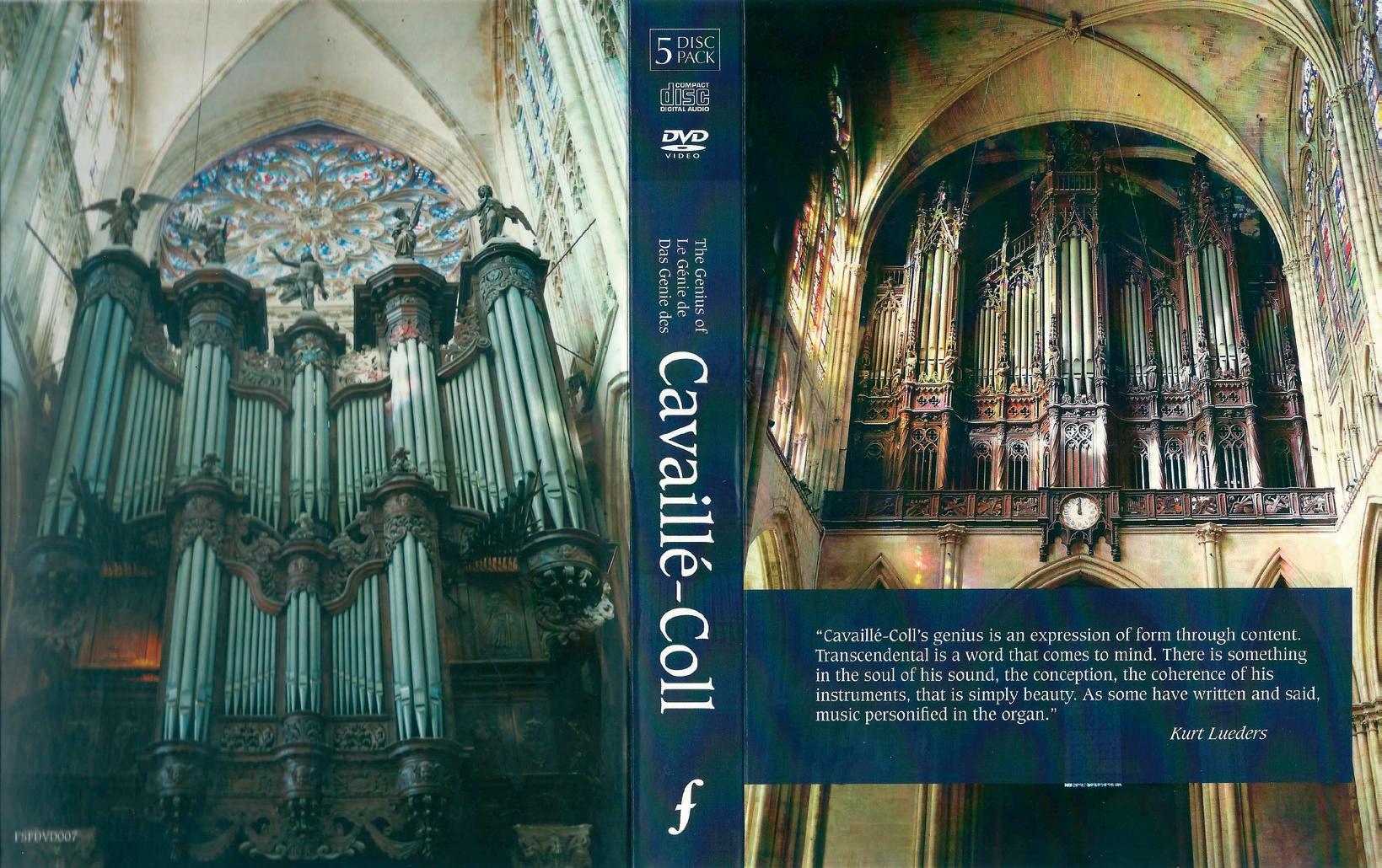

I gave one of the Sunday morning recitals after the mass at St Denis (near Paris) in 1991; the sheer power and richness of hearing Widor on that wonderful historic Cavaillé-Coll organ was unforgettable.

Has any particular recording inspired you?

There have been many, of course, but one that stands out is what won me over to the chorales of Bach’s Clavierübung III: Christa Rakich playing on three LPs I was given in 1985.

How do you cope with nerves?

The challenges presented by nerves evolve as a player gets older; one’s level of experience increases, but one’s ability to deploy lightning reactions perhaps gets less rapid. Of course, being as prepared as possible will help, and that will include trying to anticipate as far as possible aspects of the pressure of the event or recording. Above all, it’s good to remember that we’re trying to do our best shot for composers who (mostly) aren’t around now to communicate through their music for themselves – it’s not so much a critical examination of our own validity as players.

What are your hobbies?

I love travelling, and get at least some regular exercise by walking. It’s important to get out of the cathedral close on a day off when possible, and we’re very lucky in Hereford to be surrounded by fabulous countryside, and there are hills of hugely varying wildness not far away.

Do you play any other instruments?

I gave a piano recital last year in aid of the Voluntary Choir tour to Nuremberg: it was challenging and enjoyable to work on music by Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert and Schumann in a solo (rather than accompanimental) context, and I would encourage all organists to keep playing the piano too. It’s now a long time since I played the oboe in public, the last time I did that was in a Karg-Elert piece for organ, violin and oboe from his Op. 78.

Would you recommend life as an organist?

Definitely! It’s a great privilege to be able to do any job which is enjoyable and which can provide so much pleasure and value for others too. The educational side is also very rewarding, both with regard to the children in the choir, the scholars, and people in the congregation and wider community.

What are the drawbacks?

There are inevitably less attractive sides of the job: the hours are not always sociable or flexible, and there are always challenges involved in meeting the many and varied deadlines. But, in the words of a former organ scholar here who was surprised at the amount of admin, “At least we get to play the organ!”

NGOMA DOLCE MUSIC ACADEMY: years of a musical adventure Paul Kelly

regularly visits the conducting workshops run by the Royal Schools of Music.

I am a doctor, and have worked for over 24 years in Zambia, on and off, in medical education and research. I was naturally drawn to the Lusaka Music Society, where I met Moses, through singing in its choir and in an a cappella group, Vox Zambezi (www.voxzambezi.net). (This is a chamber choir of 9-14 singers, which gives concerts in the UK and Europe; we have just returned from a tour of Germany, Switzerland and Austria.) It was Moses who first suggested that in order to develop the small music scene in Lusaka it would be logical to start a music school so that other children interested in music wouldn’t have to travel so far! So we set up our new school in a rented house with two teachers, Obrien Mweemba and Cathrine Mukupa. Both of these young musicians were good friends, through Moses’s church and through Vox respectively. Both are largely self-taught musicians who have had masterclasses and further training through Vox and now through the Academy. Initially, I put up the money for the rent, then supported them through paying their tuition

Icalled Ngoma Dolce Music Academy (www.ngomadolce. org; ‘ngoma’ means ‘drum’) in Lusaka, the capital of Zambia. Now that we’ve been doing it for four years, it’s time for a little reflection.

Why would anyone want to set up a classical music school in the heart of Africa? Africans are conspicuously underrepresented in international classical music, so surely this means that there’s enough fun in indigenous music to keep everyone happy without any need for the rigours of a formal classical education? Well, Moses and I don’t think so, and Moses’s own musical story may help explain why. He grew up in Lusaka in a musical family, but found no one to teach him the violin. He used to travel to Harare every week for lessons, leaving on Friday and returning on Saturday, a journey of 6 hours each way. Eventually, he joined the music camps run now for 50 years by the National Musicamp Association of Zimbabwe (www.musicamp.org), and with them he found the further musical education he always wanted. He is now a full-time music teacher in a private school in Lusaka, and

We have almost finished building a bespoke new music school on a piece of land on which we have plenty of room for expansion. We have put our own money into this, and are very grateful for some very generous donations from supporters in the UK and in Zambia.

The Academy has three objectives.

First to give lessons to paying students who progress through the examination sequence of the ABRSM. We are now the Zambian examinations centre for the ABRSM, and our results are improving all the time.

Second to act as a focus for musical activities, including rehearsals, recitals, lectures and meetings, and to allow musicians to meet and to make music together. We are broadening this objective to include professional development for music teachers, because they need stimulation and support to remain effective.

Third to reach out to children in less wellresourced communities and provide opportunities for learning and participating in music. Through the generosity of two Canadian charities, Rose Charities and Malambo Grassroots, we have been able to provide weekly choral and instrumental lessons for the entire choir of a local school, Kamulanga, in the southern part of Lusaka.

One of the Kamulanga School students recently wrote: ‘Thank you for giving me the opportunity to learn music [viola], it’s part of my life, it flows in me.’ This ‘flow’ has recently been on display in some performances our students gave as part of the Lusaka music festival ‘Promenades Musicales’, both on their own and as part of a performance of Carmina Burana

Currently, the situation is very exciting. We have seven teachers: Cathrine (piano), Lulu (singing), Obrien (strings), William (guitar), Morgan (piano), John (brass) and Chucks (drums, including Zambian drumming). We have almost finished building a bespoke new music school on a piece of land on which we have plenty of room for expansion. We have put our own money into this, and are very grateful for some very generous donations from supporters in the UK and in Zambia. Three donors so far have allowed us to name a room after someone they want to celebrate, in recognition of their donation. We have a good selection of instruments (mostly donated secondhand), and we have the support of many well-wishers and friends including Theo Bross, a cellist from Stuttgart, and the trustees of the Muze Trust, including Mark Williams (Jesus College Cambridge) and Peter Phillips (Merton College Oxford) who are wonderfully supportive. The Muze Trust is about to launch a programme with the Estelle Trust to send four Oxbridge students to join us in the summer holidays.

The future of classical music education in Africa looks surprisingly exciting. While Ngoma Dolce is finding its feet in

Lusaka, there are other initiatives elsewhere on the continent, notably a street orchestra in Congo which gives amazing performances; and one where members of a school in Luanda, Angola, inspired by El Sistema (the music education programme in Venezuela), recently visited Lusaka with a view to future collaboration, particularly for the teachers. South Africa has long had a tradition of excellence in classical music, and this is true in Zimbabwe too.

This list is not of course exhaustive. An emerging need, to our mind, is the establishment of schools, no matter how small, where aspiring musicians can interact and develop. Above all, Africa needs professional training for a new generation of teachers. Without high-quality teachers, all the classical musicians will be self-taught and will never reach their full potential. Instruments are important too, but the hardest (and most long-term) challenge is to develop the teachers, and we are desperate to raise funds for this work. We very much need active and retired music teachers to come and teach the teachers, both so that the teachers can achieve more in terms of their own vocal and instrumental performance, but also so that they can learn good teaching techniques and how to raise standards.

More details of the project can be found at The Muze Trust (www.muzetrust.org).

TEWKESBURY ABBEY IN CELEBRATION

- with thanks to FCM Simon Bell

The Abbey School and its choir were the brainchild of the late Miles Amherst, who sadly passed away last year (see CM 2/13). Miles, who first visited the Abbey in 1952, had been struck by the architecture and atmosphere of the building, but it was not until over twenty years later that he finally grasped the nettle and, with the backing of the vicar, Canon Cosmo Pouncey, and the Abbey organist, Michael Peterson, opened the school on 9th September 1973. The following May saw the choir, consisting of eight choristers and three men, sing its first service of Evensong. The music was simple: ferial responses, a single psalm, Samuel Arnold’s Evening Service in A and Henry Ley’s The Strife is O’er. The choir initially sang Evensong once a fortnight, but within two years it was singing Evensong on four nights every week in term time, with the Abbey Choir continuing to sing the services at the weekend.

As the school grew in numbers, so Miles Amherst was able to appoint more staff. One condition of these appointments was that the holder of each position should be able to sing, and perhaps because of this it wasn’t until September 1978 that the full complement of six lay clerks was reached.

The Choral Scholarship Fund, set up in 1976, continues to raise funds towards bursaries for the choristers. FCM have generously supported this fund over the years with the award of four grants. Three of these grants (£8000 in 1986, £10,000 in 1998 and, most recently, £20,000 in 2013) have been invested to provide income to support the choristers’ bursaries, without which the choir would not have continued to flourish.

Whilst the choir thrived, sadly the numbers at the school were not so healthy. In 2005, the governors of the Abbey School realised that a school where the numbers totalled 85 was not financially viable in the long term. There were also problems with retaining numbers after Year 6 (ages 11-12), when most of the non-choristers departed for their next schools, leaving very small classes in the top two years. Following many months of deliberation, the decision for the school to close was announced on 28th April 2006, and the school entered voluntary liquidation.

2014 marks the 40th anniversary of The Abbey School Choir, Tewkesbury singing its first service of Choral Evensong.Simon Bell Photo: Ali Dugdale Tewkesbury Abbey choir at 40th anniversary service Photo: Jack Boskett

However, good fortune was to play a part in securing the way forward. Whilst the then headmaster of the Abbey School, Neil Gardner, was phoning round local schools to inform them of the impending closure, the headmaster of the Cheltenhambased Dean Close School at the time, the Revd Timothy HastieSmith, asked about the choir and its future, realising that here might be an opportunity. After a flurry of activity during the ensuing few weeks, the end result was that the choir would be saved, and the choristers taken in by DCPS.

Financing the scholarships for the choristers was one of the major hurdles that had to be overcome. FCM and the Ouseley Trust both stepped in and awarded major emergency grants to underpin the boys’ scholarships for the first two years. At this point, the Choral Scholarship Fund was severely depleted, and wasn’t in a position to support the fees, so the £30,000 that the FCM contributed was critical in securing the survival of the choir. In addition, Michael Peterson had recently passed away, and part of his estate was left to the scholarship fund.

In total, ten choristers made the switch from the Abbey School to DCPS in September 2006. Three new recruits, who were already pupils at Dean Close, joined them and the choir under its new name, Tewkesbury Abbey Schola Cantorum of Dean Close Preparatory School, sang its first Evensong on Monday 11th September. Two significant events which followed in quick succession (by coincidence) gave the choir huge national publicity at a time of great change. Later in September, the choir broadcast Choral Evensong live from St

Michael’s College, Tenbury to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the founding of the former choir school there. Then came FCM’s national gathering at Gloucester and Tewkesbury, when Christopher Robinson spoke memorably to the choristers and presented the first instalment of the emergency grant to the Choral Scholarship Fund.

Inevitably, the choir’s routine had to be modified significantly as a result of its move, but the choristers had the benefit of being in a thriving school with considerably larger class sizes. The chorister rehearsals and journeys to Tewkesbury to sing Evensong were slotted around the timetable at Dean Close. After various rehearsal patterns were trialled, the status quo of a morning rehearsal at the beginning of the school day was established. A music gap student in the form of a choral scholar was employed to assist with the logistical side of running the choir and to help supervise the boys on the bus that takes them to Evensong. The school recruited an organ scholar the following year to assist with the training of the probationers, the playing of the organ in chapel, and also to accompany services at the Abbey from time to time.

DCPS is now a full member of the Choir Schools’ Association. The choir continues to sing Evensong four times a week in term time, as well as making occasional Sunday appearances during the course of the year. One adjustment was made when the choir moved to Dean Close: Evensong is now no longer sung on Wednesdays but on Fridays instead, thus enabling the choristers to play a full part in the sporting life of the prep school. Like many cathedral choirs, an annual choir open afternoon is held each year, usually in January. This begins at the school, and continues with the guest singers learning part of the music for Evensong, playing some football, enjoying tea with the choristers, and then making the journey in the chorister bus to the Abbey for the service at the end of the day. During my tenure, we have been blessed with a good number of musical boys coming to this event, and the vocal auditions that have followed have enabled the appointment of choristers from not only within the school, but also from the local area and further afield.

The choir has recorded frequently in recent years, and of note are several highly acclaimed discs made with Delphian Records during the tenure of Benjamin Nicholas as director. In 2014 we have continued this side of the choir’s activities by recording a CD of Christmas carols in February, to be released on the Regent label in the autumn. We are looking forward to collaborating with Regent Records again in the near future.

The performance of regular concerts has played a significant role in the choir’s development, as has taking part in choir tours. For some time, the Schola Cantorum has performed Handel’s Messiah at the end of the Michaelmas term. As a result of being part of DCPS, the boys and gentlemen frequently sing other larger-scale works with the school choral society, the membership of which includes many exchoristers. Works undertaken include Mozart’s Requiem and Bach’s Mass in B minor. The choir has also collaborated with other local ensembles and festivals, most notably performing frequently in the Cheltenham Festival each July. It has also toured abroad, with several visits to France and the USA.

It is certainly true to say that the Schola Cantorum is currently in a healthy place. Not only are chorister numbers strong,

but also the presence of choristers in the school as a whole continues to have a significant impact on the music there, both at preparatory and senior levels. The senior school choirs (Chapel Choir, Chamber Choir and Choral Society), which are my responsibility, have a steady supply of young tenors and basses, many of whom go on to hold choral scholarships at university. Choristers from other choral foundations have joined the senior school at 13 and 16, and they have gained hugely from the high standard of choral singing and instrumental music at the school. We have also benefitted from the new 3-manual mechanical action organ which was installed in the school chapel over the summer.

The third portion of my post as Director of Choral Music takes me to the Abbey on Sundays. In the days of the Abbey School choir, the director of the choir exchanged his role with the Abbey’s Director of Music at the weekend – something that continues to this day. Having had an active performing career as an organist in my previous roles, most recently at Winchester Cathedral, it was important to me to find a post where my organ-playing skills were going to be used. On Sundays, I have the pleasure throughout the year of playing for Sung Eucharist in the morning and for Evensong on the fine Milton and Grove organs at the Abbey.

This summer term the choir marked the 40th anniversary of its first Choral Evensong. As always at the final Evensong of term we said our farewells to the leaving choristers, all of whom are moving to the senior school. This year we also

said goodbye and thank you to a long-standing lay clerk, the prep school headmaster and our singing teacher. It was truly wonderful to see so many former members of staff and pupils of the Abbey School filling the beautiful building. It was good also to welcome back so many ex-choristers, lay clerks, and several of my predecessors. As a part of the service, the choir sang the first performance of Laudate Dominum, a celebratory setting of Psalm 150 by Matthew Martin, who is both a former pupil of the Abbey School and of Dean Close School. This special event was very much a celebration of what has been offered and achieved over the past forty years, but it also affirmed the desire of the community to see the continuation of the partnership between the Abbey and Dean Close School, thus enabling daily choral worship to be enjoyed in the Abbey for many years to come.

Simon Bell has been Director of Choral Music at Dean Close School since September 2012, having previously held posts at Winchester Cathedral, Southwell Minster and Westminster Abbey. Simon has a first-class degree from the University of Leeds, holds an MMus from the Royal College of Music, and is a former Limpus prizewinner in the FRCO diploma examination. He has recorded extensively as a soloist and accompanist, and has also broadcast regularly on television and radio both as a conductor and as organist.

‘THUS ANGELS SUNG’

A Glorious Gallimaufry

JAMES BOWMAN

Chorister, Ely Cathedral

Choral Scholar, New College, Oxford

Lay Clerk, Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford

Lay Vicar, Westminster Abbey

Gentleman-in-Ordinary, HM Chapels Royal, St James’s Palace

As can be seen from the above, I have been involved with music in cathedrals for most of my singing life. This recording, whilst not exclusively devoted to cathedral music, does contain quite a few sacred items which have meant a great deal to me over the years; I wanted to record them before it was too late.

also a singer himself in the cathedral choir, so his input was invaluable.

I have been involved with music in cathedrals for most of my singing life.

The project was suggested to me by Malcolm Archer, who has worked extensively for some years with Convivium Records and who knows the acoustic of Portsmouth Cathedral well. Initially I had my doubts about recording there, because it was not a building I knew at all: I imagined it would be rather noisy, being so close to the Royal Navy depot and to the docks. In fact, it turned out to be the ideal venue with a lovely warm acoustic that seemed to suit my voice and allow it to bloom. We had the luxury of unrestricted access to the building in the evenings, after it was closed to the public. Some of the sessions went on until well after midnight and I recall recording the Britten folksong The trees they grow so high at around 1 am. Recording at that late hour is quite a surreal experience, so detached is it from reality.

I was also very fortunate in the recording team, which consisted of the wonderful sound engineer Adaq Khan, and the incredibly painstaking Andrew King as producer. Nothing seemed to get past Andrew’s razor-sharp ears: every tiny slipup of intonation and pronunciation was seized upon! I have been recording for close on 45 years, and he is the most critical but equally charming producer I have ever encountered. The project was overseen by Adrian Green, who runs Convivium Records from a small office adjacent to the cathedral; he is

Malcolm Archer is, of course, an old friend, which made our collaboration a real pleasure. We first met some years ago before he went to Wells Cathedral, and we kept in touch not least because of my regular visits to Wells to give singing lessons to his choral scholars. I saw little of him when he was so busy at St Paul’s, but we did give a concert together at Stogursey in Somerset, which is his holiday retreat, and it was there that he suggested that he write some songs for me. These came to fruition in a later concert in the lovely church, accompanied by organ, and then at Winchester College with piano accompaniment. When Malcolm proposed this recording it seemed obvious to include these three songs. (The complete work is a cycle of nine carols designed to be sung either liturgically or in concert, accompanied by either piano or orchestra.)

Portsmouth Cathedral . . .

the ideal venue with a lovely warm acoustic that seemed to suit my voice and allow it to bloom.

But what to put with them? After all, I had already recorded most of the Baroque repertoire and I didn’t want this to be just another recital of Purcell and Handel etc etc. Going through my music library (a euphemistic term for the chaotic piles of music in my study), I alighted upon several unusual pieces that I had put aside over the years, thinking how much I liked them but also that they would never fit into a conventional programme. The time seemed appropriate to include them in a programme that needed neither rhyme nor reason. That’s the great joy of working with a small independent company; for too long the big labels have, solely on commercial grounds, been very dictatorial. I remember that in 1976 I wanted to

record the hitherto little-known Vivaldi Stabat mater and asked one of the large companies to do this. I was grudgingly given permission and paid a derisory fee, because ‘it will never sell’.

That recording subsequently sold over 300,000 copies in France alone, and it is still selling now, well over 30 years later

I certainly don’t anticipate such sales figures for Thus angels sung, but the content is much closer to my heart. As an excathedral chorister, how could I overlook Tallis and Byrd, here represented by two small gems? O nata lux is a staple item from the repertory, and I must have sung it hundreds of times as a treble, but is nice to treat it on this occasion as a simple solo song. I’m sure Vaughan Williams would have written for countertenor had he lived longer. After all, he loved anything Elizabethan, and the Tallis tune that he immortalised in his Fantasia would have been sung by an all-male choir. It is also wonderful to be able to include old friends by Stanford, Quilter, Attwood and Elgar, plus some lovely Britten and a little grace to be sung before dinner written by my friend Christopher Moore. This and the songs by Malcolm are the only pieces specifically written for countertenor -- all the

James Bowman has given the world première of many important contemporary compositions, including works by Benjamin Britten, Michael Tippett, Peter Maxwell Davies, Richard Rodney Bennett, Robin Holloway, Geoffrey Burgon, Michael Nyman, Alan Ridout and Tariq O’Regan. In May 1996 he received the honorary degree of Doctor of Music from the University of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and was made CBE in the 1997 Queen’s Birthday honours. He is also an honorary fellow of New College, Oxford and in October 2000 became a Gentleman of Her Majesty’s Chapel Royal, St James’s Palace. More recently, James has been a member of the jury for the Kathleen Ferrier Awards, and during 2009 he was President of the Festival de Wallonie in Belgium. In 2010 he was presented with a Lifetime Award for services to Early Music by the York Early Music Festival. In May 2011 he made his farewell to the London concert platform with a sold-out recital at London’s Wigmore Hall, singing Purcell and Handel. However, he still appears occasionally at venues away from the capital.

THE JOYS OF TEXT

Paul Whitmarsh talks to HOWARD SKEMPTON about compositional techniques, amongst other things

On the face of it, it might seem curious that someone who began writing experimental music in the late 1960s would compose a number of liturgical choral works over thirty years later. But Howard Skempton’s music often defies categorisation and, as he describes to Paul Whitmarsh, these recent pieces have strong and deep roots.

PW You have been composing vocal music consistently since the 1970s, but it is only since the 1990s that choral music, both secular and sacred, becomes a more prominent part of your output. What are the circumstances behind this relatively recent interest in writing for choirs?

HS I composed a carol, To Bethlem did they go, in 1995, and felt confident, for the first time, that my response to a text had been arresting and idiomatic. I was also commissioned by the Oxford University Press Choir to write We who with songs, a setting for choir and organ of some beautiful lines from Flecker’s The Golden Journey to Samarkand. A year later I wrote my Two Poems of Edward Thomas and A Flight of Song, a group of Longfellow settings. These and other factors – the discovery of what might be called a capability, a feeling-at-home with a medium and with tradition perhaps, the encouragement of my new publisher, and the prospect of indulging my passion for poetry – proved an irresistible force.

PW And in the last fifteen years or so, you have composed a number of specifically liturgical works.

HS Yes, and this is largely thanks to Matthew Owens, who commissioned Adam lay y-bounden in 1999 and The Edinburgh Service in 2003. In recent years, I have written both The Wells Service and The Third Service (also for

Wells). I’m particularly proud of two settings Matthew commissioned for the Exon Singers in 2007: Beati quorum via and Ave Virgo sanctissima. Perhaps I raise my game when I write liturgical music! The work has to prove itself within the context of a service.

PW That’s interesting. I wonder what it is that has stimulated such a response from you in these settings? Is it the text, its language and tradition, the purpose of your music in a service, the performance space itself or something else?

HS I was returning to a familiar world. I sang for nearly seven years in the chapel choir at school. When I made a serious commitment to composing at the age of sixteen, I headed straight for the hills of the avant-garde! A steady trickle of commissions in the Nineties certainly boosted my confidence in my technique. Composing Adam lay y-bounden was a reawakening to a tradition that clearly still had strong roots. I was happy to take my cue from the two settings I knew particularly well: the Boris Ord and the Britten (A Ceremony of Carols).

PW Do you have a particular sound in mind when you write for choir? Does this vary from piece to piece?

HS It depends on the choir, but I have an established technique, and the writing tends to be homophonic and the setting, syllabic. I like the music to ‘float’, and the tessitura is usually medium-high.

PW Such a sound is apt and effective in a liturgical context. But it also strikes me that this description could apply to much of your instrumental music (for example, Lento for orchestra, from 1990).

My aim is always to serve the text. I want the words to be heard clearly and to be understood. I love poetry and enjoy looking for texts if encouraged to choose my own. The greater the poetry, the more determined I am to avoid damaging it or diminishing its power. If one approaches the text with sufficient love and respect, one can trust the music to enhance and enliven it. Few things are more satisfying for me as a composer than to achieve this through the most subtle refinement, whether of melody, harmony or rhythm.

music to be lucid and uncluttered. I have described my early works, short and mostly for piano, as chorales, landscapes or melodies. The landscapes were the most experimental, being static and spacious. The chorales were governed by melody and what the Americans call voice leading, but the textures were homophonic. The melodies were fluid rather than dance-like. If my works are lyrical, a major reason would be my curious education as a pianist. My first teacher responded to my evident enthusiasm by allowing me to play what I wanted, so I moved swiftly through Mendelssohn’s Songs without Words before immersing myself in Chopin and finding myself hopelessly out of my depth!

PW Is this focus on melody, homophony and mostly syllabic underlay also an opportunity for the words you are setting to remain prominent? To my ears, the text is always completely comprehensible in your vocal music.

love poetry and enjoy looking for texts if encouraged to choose my own. The greater the poetry, the more determined I am to avoid damaging it or diminishing its power. If one approaches the text with sufficient love and respect, one can trust the music to enhance and enliven it. Few things are more satisfying for me as a composer than to achieve this through the most subtle refinement, whether of melody, harmony or rhythm.

PW You have set a number of standard liturgical texts, in English and Latin, and you also seem drawn to 19thcentury American and English language poets, such as Longfellow, Whitman, Emerson, Shelley, Yeats and Edward Thomas, to name a few. Are there any specific qualities that you look for in a text?

HS I look for clarity and directness. A single archaism might be enough to put me off. The writing must

have sufficient character to fire the imagination. Vivid language can be most engaging, and multisyllabic words are always interesting to deal with. I’ve enjoyed setting ‘phlegmatical’ (Herman Melville), ‘carbon dioxide’ (D H Lawrence) and ‘irreprehensibilis’ (Locus iste). In choosing a poem, the length is important because I shy away from editing it. Repetition can be magical but I avoid small-scale repetitions. A poem has musical qualities in its flow and metre and I have no right to tamper with those.

PW You mentioned earlier the several pieces you have written for Matthew Owens and the choirs of St Mary’s Edinburgh, Wells Cathedral and the Exon Singers. Your choral music has also been extensively performed and recorded by James Weeks and Exaudi. What is it like for you to have such a strong relationship with conductor, choir and even place, and does it have an effect on the music you write?

HS Matthew inspires confidence through his own confidence that one is up to the job! My two motets for the Exon Singers were written very quickly, within a week or so, and delivered just a few days before the broadcast service in which they featured, as introit and anthem. Such pressure encourages efficiency, of course, but one needs a clear understanding of the occasion, and of the choir, to rise to the challenge. James Weeks and Exaudi are second to none in their performances of the most demanding contemporary music. My own choral pieces look relatively straightforward but James will have none of that! Exaudi make one fully aware of the most demanding, complex aspects of one’s work.

PW What are you composing now and what are you planning to write in the near future?

HS As it happens, the next piece I must write is a Shakespeare setting for an Oxford University Press anthology. I’m also working on a BBC commission for a piano concerto (for an old friend, John Tilbury), and looking forward to setting most, if not all, of Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner for baritone and ensemble. Performance dates have been fixed for both, so the pressure’s on! That said, I doubt if I will be able to resist the invitation to write a short occasional piece, especially if it’s for choir.

Howard Skempton’s music is published by Oxford University Press: http://ukcatalogue.oup.com/category/music/composers/skempton.do

Paul Whitmarsh is a composer whose music has been performed at many festivals throughout the UK, including Aldeburgh, Spitalfields, Cheltenham, Deal, Hampstead and Highgate, and the Park Lane Group New Year Series. Commissions include Lullaby for Choir & Organ magazine, premiered by the Joyful Company of Singers; Pealing Out, premiered by the Galliard Ensemble; and Berceuse in a Box for the Cheltenham Festival. Paul teaches composition at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama and Wells Cathedral School.

PROFILEWALTON

Education details (school/university):

King Edward VI Grammar School, Stratford-upon-Avon

Royal Northern College of Music

Career details (and dates):

Sydney Nicholson Organ Scholar, Manchester Cathedral (1999 – 2001)

Assistant Organist, Bristol Cathedral (2001 – present)

Were you a chorister, and if so, where? Did you enjoy the experience?

Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon. Loved it.

What or who made you take up the organ?

I began learning the piano aged 4, and hearing the organ at Holy Trinity made me want to play it. Peter Summers, then Director of Music, agreed to teach me.

You’ve been on several overseas choir tours. Are there particular challenges associated with these? Having to get to grips in a matter of minutes with organs that are unfamiliar / eccentric / less than suited to the Anglican choral tradition / in a precarious state of repair / any combination of the above after many hours on a coach with 30 children!

Of the organs that you played on those tours do any stand out, and why?

Some in Bordeaux that barely survived the experience! The Marktkirche in Hanover is a superb new organ by Goll, and was very rewarding.

How much teaching do you do, and whom do you teach? Mainly young pupils at the moment, but I have taught all ages.

What organ pieces have you been inspired to take up recently?

Francis Jackson’s Sonata Giocosa (for a series of all six Jackson sonatas at Bristol Cathedral).

Have you been listening to recordings of them and if so is it just one interpretation or many and which players?

FJ’s 1994 York recording.

How much conducting do you do?

I direct Bristol Cathedral Consort and Chamber Choir, and conduct the cathedral choir on Tuesdays. I also direct Bristol Phoenix Choir (an adult choral society), which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year.

Have you always been interested in composing and arranging music?

I started in my teens and more recently have written a handful of choral pieces. Hymn arrangements have been a constant and now number about 300. Samples can be found on my website, www.paul-walton.com

What was the last CD you bought?

A disc of Mathias orchestral works.

What was the last recording you were working on?

In an Old Abbey – a disc of English organ music for Regent on the Bristol Cathedral organ for release this summer.

What is your

a) favourite organ to play?

Of those played regularly, Bristol Cathedral. Otherwise St Paul’s Cathedral / St Sernin, Toulouse / St Sulpice / St Laurens, Alkmaar / St John the Divine

b) favourite building?

St Sulpice, for both architectural and personal reasons

c) favourite anthem

Either Ireland Greater Love which we had at our wedding, or Harris Faire is the heaven which I want at my funeral

d) favourite set of canticles

Howells St Paul’s Service

e) favourite psalm and accompanying chants?

85 to Bairstow E flat (the one with the dominant minor ninth) / 131 to Willcocks G sharp minor / anything (suitable) to Howells B flat minor

f) favourite organ piece

Varies depending on what’s currently under the fingers – at the moment Bach Passacaglia or David Bednall’s Adagio g) favourite composer Bach, Duruflé, Elgar, Howells or William Walton depending on my mood!

When is your next (or most recent) organ recital? Which pieces are you including?

Gloucester Cathedral. Some Baroque, Bach Praeludium in A minor, three Couperin movements, and some local connections, David Bednall Adagio and David Briggs The Legend of St Nicolas

How do you cope with nerves?

I’ve played so regularly for so long that performance becomes second nature – except on live broadcasts, which are still terrifying. Intense preparation and, when the light goes on, attempting to ignore it and just focusing on the music seems to have worked so far.

What are your hobbies?

Nature photography, running.

Do you play any other instruments?

I played the sleigh bells in a Christmas concert three years ago!

Would you recommend life as an organist?

Yes – to play some of the instruments I’ve played and work with some of the musicians I’ve worked with has been an immense privilege.

What are the drawbacks?

Not everyone always agrees that ‘the labourer is worthy of his hire’! At times, finding the right balance between actually making music and the administration that nowadays goes with it can be a challenge.

Marktkirche in Hanover Photo: Dirk RauschkolbCATHEDRAL MUSIC DURING THE GREAT WAR Timothy Storey

The years between the end of the 19th century and the outbreak of war in 1914 were something of a golden age for cathedral music. In cathedrals established or re-founded at the Reformation, and at the Royal Peculiars of Westminster Abbey and St George’s Chapel, Windsor, it was the norm for Mattins and Evensong to be sung on Sundays and every weekday for most of the year, with (in some establishments) a choral Communion on certain Sundays adding a fifteenth choral service to the weekly round. Only in a very few places did the choir have a regular day off each week.

The chapel choirs of Magdalen College and New College Oxford sang two choral services each day during Term. Even at the cathedrals of Manchester and Ripon, collegiate churches of impressive size and antiquity but not raised to cathedral status until 1836 and 1847 respectively, it was a matter of considerable local pride that the ancient routine was kept up in full with two choral services every day. At the new Roman Catholic Cathedral of Westminster, Mass and Vespers were sung daily by the full choir which, by 1914, had reached the zenith of its quality and fame.

What of those on whom rested the burden of maintaining such a generous programme of choral worship? The Organist and Master of the Choristers (the dual responsibility had become usual) was a skilled professional musician, thoroughly trained in the theory and practice of his craft, whether as the articled pupil of a senior member of the profession or as a student at one of the colleges of music. He would play for most if not all services himself, and might have only a part-time assistant, though his pupils would also take a share of the work. Some organists would regularly be absent on one or more days each week, supplementing their income by examining or teaching or by conducting choral societies in nearby towns.