FALL 2022

COLORADO'S CONFLUENCE WITH FEDERAL WATER MANAGEMENT

THE FEDERAL NEXUS

We deliver best fit solutions and responsive services for all your water resources planning, water rights and water quality needs in Western Colorado www.sgm-inc.com | 970.945.1004 GLENWOOD SPRINGS GUNNISON DURANGO GRAND JUNCTION ASPEN SALIDA MEEKER SGM Proud to support Water Education Colorado 800-542-8072 www.cobank.com

Colorado OKs Drinking Treated Wastewater

More than six years in the making, a new regulation will protect public health when communities begin to use treated wastewater in drinking water systems.

Redefining WOTUS—Again

The Clean Water Act could soon have a new scope, for the fourth time in the past seven years, as the U.S. Supreme Court and the EPA consider which waters should be protected.

Contents | Fall 2022

THE FEDERAL NEXUS ISSUE There’s a federal role in all things water in Colorado—from building and operating infrastructure, to protecting the environment and public health, permitting new projects, cooperating with local stakeholders and state agencies, or offsetting costs for programs and equipment with myriad benefits. But climate change and aridification, the Colorado River crisis, a historic influx of federal funding, and other pressure points are freshly emphasizing the important relationship between federal authorities and Colorado’s water resources.

FROM THE EDITOR

Working with the Feds

2022 PRESIDENT’S RECEPTION

A 20th–anniversary celebration.

WHAT WE’RE DOING WEco's upcoming events, reporting and more. 5 7

AROUND THE STATE Water news from across Colorado. 13

MEMBER’S CORNER

Celebrate the impact of WEco’s members. 31

From interstate water sharing to Endangered Species Act compliance, Colorado water management relies on federal, state and local players working together. With much of this work on the precipice of change, will that balance continue?

By Elizabeth Miller

By Elizabeth Miller

From Dam Builder to Water Manager

As climate change brings aridification to the West, the reclamation projects that shaped water use across Colorado could be entering a new era, with a future that looks nothing like the past

By Olivia Emmer

A New Wave of Water Investment

New legislation brings historic investment in water and a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for the state. Now Colorado agencies and communities are ramping up efforts to secure the funds, in direct competition with other states.

By Thy Anh Vo

Above: The Lower Dolores River runs through Bureau of Land Management and U.S. Forest Service lands. Stakeholders have worked with these agencies for more than 14 years to find a positive alternative to wild and scenic designation. Their proposal is to establish a national conservation area. Photo courtesy of Dolores River Boating Advocates

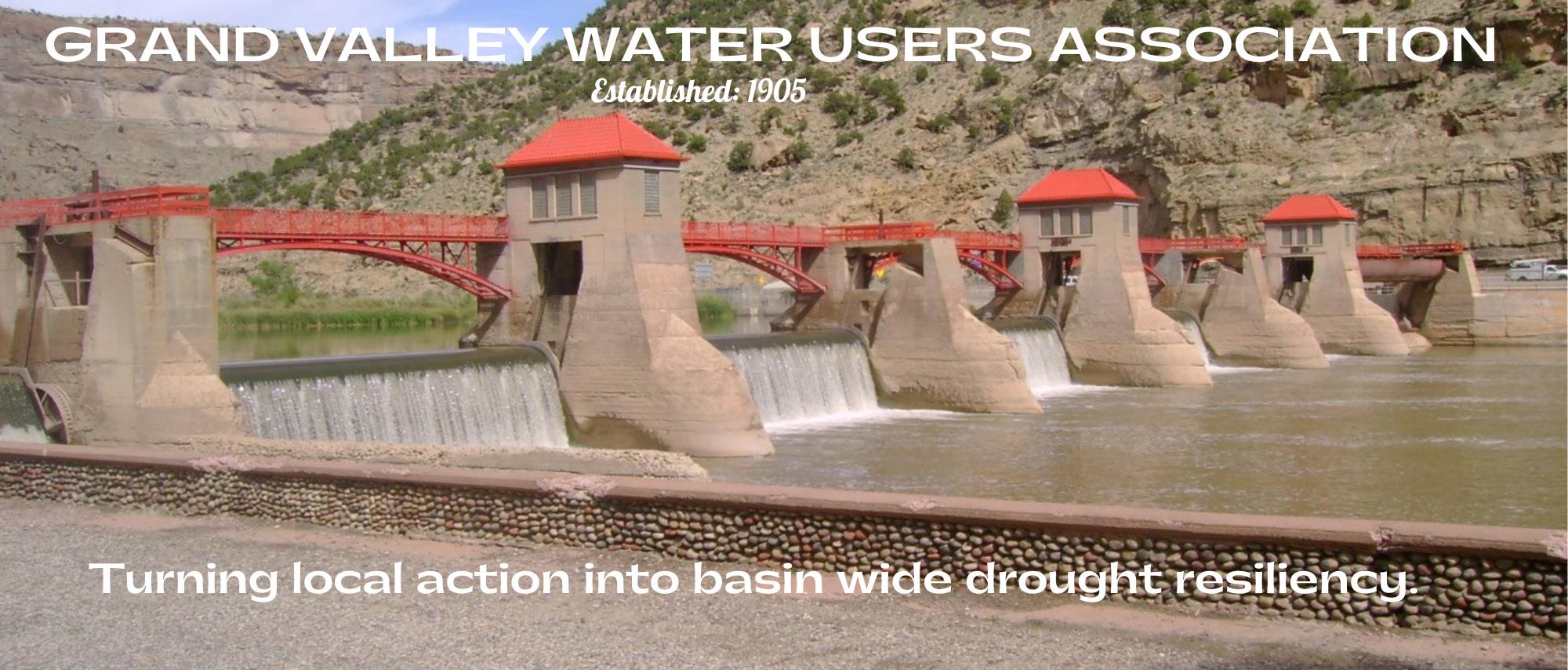

On the cover: Tina Bergonzini, manager of the Grand Valley Water Users Association (GVWUA), and Ed Warner, area manager for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s Western Colorado Area Office, cross the Cameo Diversion Dam, commonly known as the “roller dam.” The dam is owned by Reclamation but managed by GVWUA.

HEADWATERS FALL 2022 • 3

Photo by William Woody Pulse 11 12 DIRECTOR’S NOTE Inside 6 4

24 14 21

DIRECTOR’S NOTE

With the holidays upon us, and life-giving snows beginning to blanket our mountaintops, a spirit of gratitude descends. Reflecting on the year WEco has had in 2022, I’m thankful for all of the people who lent their time, effort, expertise and resources to our cause. From members and donors to partners, volunteers, board members, staff and contractors, to those who participat ed in our programs, you made this year a success. Just as the federal government, as featured in this issue, adds capacity through expertise, programs and funding to what we can accomplish in Colorado, your contributions multiply the water education opportunities we’re able to carry forward as an organization.

Water ’22 was a major addition to our slate of activities. As 2022 comes to a close, the year-long campaign is also winding down. We’re focused on a strong finish, and will be evaluating the impact of the campaign as we decide what comes next.

In addition to implementing Water ’22, since our last issue of Headwaters, we certified a new class of local elected officials, water board members, and others to “speak fluent water” through the 8th year of our Water Fluency Program. We also celebrated WEco’s 20th anniversary, raised critical funds, and honored two incredi ble people at our 2022 President’s Reception. And we graduated our 16th class of Wa ter Leaders, bringing our total number of program graduates since 2006, poetically, to 222. To address growing demand, in 2023 we will expand program seats in Water Leaders from 16 to 20. Applications are now open through mid-January.

In October, we successfully co-hosted another annual Sustaining Colorado Water sheds conference with our partners, the Colorado Riparian Association and Colorado Watershed Assembly. There, we kicked off with a plenary session focused on the new federal funding that is highlighted in this issue. Many organizations and agencies are helping ensure Colorado can get as much of the share of that federal pie as possible. It’s a tremendous opportunity—if we are able to do it both efficiently and thought fully—to address some of our challenges with increased capacity.

Here at WEco, we’re trying to be thoughtful in how we can increase our own ca pacity to continue our quality programming. Please check out open positions on our Careers page online and point great candidates our direction. And consider making a contribution to support our work as part of your year-end giving.

One last thing to leave you with, for a dose of inspiration about our up-and-com ing youth leaders, visit water22.org to check out our Water ’22 Student Showcase top entries. We had 169 K-12 students from across the state submit works of creative writing, art, film, modeling and more, and include why water is important to them and their ideas for water conservation and protection. The talent and commitment of our young water stewards is the light of the future that we must continue to set up for success. I’m grateful that they’re right behind us, and excited to keep engaging and supporting them through our Water Educator Network and other outreach.

Wishing you a wonderful holiday season,

STAFF

Jayla Poppleton Executive Director

Kendra Longworth Membership and Engagement Officer

Suzy Hiskey Administrative Assistant

Cailyn Andrews Programs Assistant

Jerd Smith

Fresh Water News Editor

Caitlin Coleman Publications and Digital Resources Managing Editor

Charles Chamberlin Headwaters Graphic Designer

BOARD OF TRUSTEES

Lisa Darling President

Dulcinea Hanuschak Vice President

Brian Werner Secretary

Alan Matlosz Treasurer

Cary Baird

Perry Cabot

Nick Colglazier

Kerry Donovan

Paul Fanning

Eric Hecox

Matt Heimerich

Julie Kallenberger

David LaFrance

Sara Leonard Dan Luecke Karen McCormick

Peter Ortego

Kelly Romero-Heaney Elizabeth Schoder Don Shawcroft

Laura Spann Chris Treese

THE MISSION of Water Education Colorado is to ensure Coloradans are informed on water issues and equipped to make decisions that guide our state to a sustainable water future. WEco is a non-advocacy organization committed to providing educational opportunities that consider diverse perspectives and facilitate dialogue in order to advance the conversation about water.

HEADWATERS magazine is published three times each year by Water Education Colorado. Its goals are to raise awareness of current water issues, and to provide opportunities for engagement and further learning.

THANK YOU to all who assisted in the development of this issue. Headwaters’ reputation for balance and accuracy in reporting is achieved through rigorous consultation with experts and an extensive peer review process, helping to make it Colorado’s leading publication on water.

© Copyright 2022 by the Colorado Foundation for Water Education DBA Water Education Colorado. ISSN: 1546-0584

1600 Downing St., Suite 200 Denver, CO 80218 (303) 377-4433

4 • WATER EDUCATION COLORADO

What we’re doing

Congratulations Water Leaders Class of 2022

A big congratulations to our 2022 Water Leaders Program graduating class! We loved working with this amazing group, together with leadership consultants Ashley Seeley of Excellence Advantage and Stephanie Scott of Scott Solutions, to take their leadership skills to the next level. We can’t wait to see how they affect change for their organizations, communities and the state of Colorado!

Tyler Benton

Colorado Springs Utilities

Ty Bereskie

City of Greeley

Daniel Boyes

Rio Grande Headwaters Restoration Project

Kelen Dowdy

City of Greeley

April Hendricks Burns, Figa, & Will, P.C

Tanya Ishikawa

Uncompahgre Watershed Partnership

Nicholas (Chris) Kampmann

City of Arvada

Diana Lane

The Nature Conservancy—Colorado

Water ’22 Countdown

Bailey Leppek

SGM Inc.

Emily Lowell

Upper Yampa Water Conservancy District

Lauren Maggert

Aurora Water, City of Aurora Kirstin Neff

National Fish and Wildlife Foundation Blake Osborn

Lower Arkansas Valley Water Conservancy District

Danielle Snyder

Brown and Caldwell

Hally Strevey

Coalition for the Poudre River Watershed

Derek Turner

City of Loveland

As Water ’22, the year-long public awareness campaign spearheaded by WEco, winds down, we're focused on a strong finish: celebrating the Student Showcase winners, hosting the fourth and final book club author talk, distributing 10,000 beer coasters to breweries, and producing our final celebrity PSAs. There’s still time to take the Water ’22 pledge. Visit water22.org/join-the-flow to share your commitment to the 22 Ways to Care for Colorado Water in 2022.

Certified to Speak Fluent Water!

Our 2022 Water Fluency class took a deep dive into all things Colorado water with four packed days of content, intersession assignments, and site visits with local water managers in Gunnison. They asked amazing questions, built their networks, and left inspired to keep leading and learning.

“I had a patchwork knowledge beforehand, which has now morphed into a solid foundation.”

— 2022 Water Fluency Program graduate

Thank you to 2022 Water Fluency Title Sponsors Colorado Water Conservation Board, Colorado Water Resources and Power Development Authority, and Special District Association of Colorado for making this valuable educational experience possible.

De Donde Viene Su Agua

Get ready for the first Spanish-language reference primers from WEco. We’re translating the Guide to Where Your Water Comes From, with the Spanish translation available this winter. In order to more equitably share information for all, we’re also phasing in a new series title: These guides have been called “Citizen’s Guides” for the past 20 years, but starting with this translation, future publications in the series will be called “Community Guides.”

Order your copy at watereducationcolorado.org.

HEADWATERS FALL 2022 • 5

What we’re doing

FROM THE EDITOR

In this issue, we cover the collaborative ways in which Coloradans are working with the feds.

A

Conversation

with KELLY ROMERO-HEANEY

Kelly Romero-Heaney

We spoke with Kelly, a member of the WEco Board of Trustees, assistant director for water policy at the Colorado Department of Natural Resources, and special advisor to the governor on water policy, about state and federal roles in Colorado water management and more.

Read more on the blog at watereducationcolorado.org.

It’s important to recognize though, that not all people have always felt com fortable partnering with federal agencies—some still don’t for various reasons.

For instance, centuries of oppression and genocide, much of it imposed on the federal level, fostered good reason for federal mistrust among the nation’s tribes.

Now, more than $3.5 billion in fresh funding is available to tribal nations to address a backlog of projects that will bring clean water and sanitation to tribal com munities, mitigate drought impacts for tribal nations, and more.

“It is a huge forward step,” says Anne Castle, co-leader of the Tribal Clean Water initiative, on the funding in “A New Wave of Water Investment” (page 24).

Other groups have different motives for federal mistrust or opposition. Take the sagebrush rebels and anti-government extremists focused on private property rights and taking back federal lands.

Colorado water is no stranger to private property protections. Here, water is legally a public resource but individuals hold valuable private rights to use it. When federal authority threatens interference with those rights, individuals are motivated to protect their property. But collaborative alternatives that recognize the value the federal gov ernment lends to the equation are pulling communities through those tensions.

Just look at the Dolores River in the state’s southwestern corner, where federal officials found that a stretch of river could qualify for wild and scenic river protec tions. Wild and scenic designation protects a river corridor, but limits future water use and development—it’s often a nonstarter for Coloradans.

On the Dolores, 14-plus years of work has led to a proposed national conservation area. There, a broad base of stakeholders developed a shared plan and consensus language to protect qualities of the river without compromising individual goals and freedoms. Read about it in “Working with the Feds” (page 14).

These days, crisis on the Colorado River, drought and climate change, along with other social and political tensions, ranging from COVID to inflation, may, for some, exacerbate existing levels of mistrust and polarization. But these challenges also shine a light on the need for partnership and collaboration, and how people who work in water can exemplify cooperative approaches between local, state and federal entities. As Colorado water managers reliant on the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s infrastructure for storing and conveying Colorado River water have watched the levels of lakes Powell and Mead fall, they express concern about continued water availability but also trust in their partner agency.

“Reclamation has been an excellent partner,” says Tina Bergonzini, manager of the Grand Valley Water Users Association, in “From Dam Builder to Water Manager” (page 21). “I really don’t see them walking away from that now.”

I look forward to seeing what more we can do together.

6 • WATER EDUCATION COLORADO

We’re looking at up to $1.2 billion that would go to water projects in Colorado and we need to figure out how to scope projects quickly so we can make the most of that funding.

—Editor—

2022 President’s Reception

Thanks to the generous support of sponsors and attendees, this year's reception, celebrating our 20th anniversary, raised over $46,000 toward the work of Water Education Colorado! These contributions enable us to continue to produce vital resources such as Headwaters magazine and Fresh Water News, and allow us to continue engaging Coloradans in critical water issues through educational and leadership programs like Water Leaders and Water Fluency.

We enjoyed getting to see those that were able to attend, and we were honored to recognize Upper Gunnison Water Conservancy District General Manager Sonja Chavez and former Colorado Supreme Court Justice Gregory J. Hobbs, Jr. (posthumously) with our 2022 awards.

Here's to the next 20 years of working toward a vibrant, sustainable and water-aware Colorado.

THANK YOU TO OUR PEAK AND TORRENT SPONSORS: PEAK TORRENT

HEADWATERS FALL 2022 • 7

2022 WEco Diane Hoppe Leadership Award, Posthumous Greg

Hobbs

BY BRIAN WERNER

Greg Hobbs was Colorado’s top water expert for much of the past three decades, a well-respected water lawyer, and the Colorado Supreme Court’s most knowledgeable water judge. He knew everyone in the water community and everyone knew Greg. He was the go-to source for water history and water law and he spun a mean water yarn or poem when relaxing.

Greg, who first began practicing law in Colorado in 1973, retired as a Colorado Supreme Court Justice in 2015 and continued to share his water expertise and speaking and writing eloquence in a variety of ways until passing away in November 2021.

If anyone was Mr. Water Education Colorado, it was Greg. He was part of the brain trust that formed WEco in 2002 and was committed to WEco in a way very few, if any, have been or probably ever will be. He was the organization’s Vice President for near ly two decades. He was Publications Chair for his entire time on the board where he diligently helped shape the vision for what has become one of the leading sources for water information in Colorado.

His footprint is all over WEco’s most sought after and recognized Citizen’s Guide—the Citizen’s Guide to Colorado Water Law, first published in 2003. Greg wrote what became the go-to source for learning about Colo rado’s complicated water law.

He was also a frequent presenter in WEco programs, mentored numer ous individuals through the Water Leaders Program, and provided sound guidance in the organization’s strategic growth and evolution over the years to ensure it stayed true to its nonpartisan mission.

Greg’s early legal career included stops with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Colora do Attorney General’s Office in the Natural Resources Section. He then moved into private practice with Davis, Graham and Stubbs where he began a long tenure as counsel for the Northern Colorado Water Conservan cy District. In 1992 he formed a new law firm with two other heavyweights in Colorado water law— Hobbs, Trout and Raley. It became, and still is, one of Colorado’s most respected water law firms.

His crowning achievement came in 1996 when Gov. Roy Romer appoint

ed Greg to the Colorado Supreme Court. He instantly became the Court’s expert on water matters and its preeminent water lawyer. During his nearly two decades on the bench, he authored more than 250 majority opinions, many of which dealt with water law. He was an exceptional jurist, principled and deliberate, not ing that every word in every opinion mattered.

He wrote poetry, he gave tours, he spoke often with a gifted oration about water and history, Native Amer ican culture, and the prior appropri ation doctrine, all subjects he knew more about than almost anyone else in the room.

Greg had this to say about this award’s namesake after her passing in 2016: “A great leader for challenging times. Graceful in times of stress. Generous with her wisdom at all times. Her enduring legacy: leadership by example.”

The same can be said of Greg, and no one deserves the Dianne Hoppe Award more than him. We only wish he were here to see how much we appreciated his effort s, how he helped mold Water Education Colorado, and how much we miss him. H

8 • WATER EDUCATION COLORADO

Greg Hobbs' wife, Barbara (Bobbie) Hobbs, shares acceptance remarks after receiving the award on Greg's behalf as his son, Dan Hobbs, and daughter, Emily Hobbs, look on.

2022 WEco Emerging Leader Award

Sonja Chavez

BY PAUL FANNING

Growing up on a fifth-generation ranch in Colorado may have foreshadowed a career in water for Sonja Chavez, general manager of the Upper Gunnison River Water Conservancy District (UGRWCD).

“My love of water really started as a child,” she says. “It’s just a part of who I was.”

She enjoyed irrigating, haying, caring for livestock, tubing—all things water—and developed an early understanding of the importance of water to her family and to the community, as she saw how her father and other producers struggled during lean water years.

She studied at the University of Colorado Boulder and eventually earned a master’s degree in Environmental Sciences/Limnology. An internship with the Colorado Water Quality Control Division, followed by work with a private firm and later county government as a water quality and wetlands specialist led her to establish her own consulting firm, where she spent 12 years working. Her expertise in the field led to a post as water resources specialist for the Colorado River District, where she was involved in water conservation, working with producers and water districts to implement irrigation efficiency projects as part of a federal selenium management program.

The breadth of these professional experiences prepared her for the next step in her career,

as she was selected in 2019 to serve as general manager of the UGRWCD.

“The most important thing that we do is to protect our basin’s water resources— protecting water rights, water quality, water quantity, ensuring that we have healthy forests and watersheds and resilient producers,” she says.

A vast network of partnerships allows the community to embrace water challenges. Sonja, along with the UGRWCD board and her amazing staff, works to educate elected officials on water issues, push to expand education programs in local schools, partner with federal agencies and water coalitions on wet meadows restoration, and a host of other initiatives to secure the water future for her community.

Participating in water planning and policy beyond the local level, Sonja has been a member of the Governor’s Water Equity Task Force and Senator Bennet's Climate Work Group, is the district’s representative on the Gunnison Basin Roundtable, and serves on the Water Quality Control Commission and Colorado Water Congress State Affairs and Water Quality committees.

Sonja continues to engage and conquer new leadership opportunities, and sums up the journey so far, “I’m glad I was able to connect so many of my interests, but I’m really super happy that I found a way to bring it all back to my one true passion, which is having a connection to the producers, the land and the water.” H

Thank you also to our 2022 Cascade and Ripple level reception

sponsors: CASCADE

Colorado Water Resources and Power Development Authority

Northern Water Southwestern Water Conservation District RIPPLE

City of Thornton

Colorado River District Colorado Water Center, CSU Kogovsek & Associates

Mallon Lonnquist Morris & Watrous Pueblo Water

Saint Vrain and Left Hand Water Conservancy District

Southeastern Colorado Water Conservancy District

Stifel Public Finance

Vranesh and Raisch

HEADWATERS FALL 2022 • 9

Sonja Chavez (right) receives her award from WEco Executive Director Jayla Poppleton (left).

10 • WATER EDUCATION COLORADO

your calendars for December 6 and Colorado Gives Day, where your contributions will help sustain Fresh Water News' timely reporting on critical water issues The Colorado Media Project selected Fresh Water News again this year as a participating newsroom for the #newsCOneeds campaign that applies your holiday giving to a funding match to double your impact!

you in advance for your support! Support WEco and Fresh Water News on Colorado Gives Day Scan to give or visit wateredco.org/donate

Mark

Thank

Colorado OKs Drinking Treated Wastewater

BY JERD SMITH

Colorado regulators, after years of study, negotiations and testing, approved a new rule that clears the way for drinking treated wastewater, one of only a handful of states in the country to do so. The action came in a unanimous vote of the Colorado Water Quality Control Commission in October 2022.

Direct potable reuse (DPR) involves sophisticated filtration and disinfection of wastewater for drinking water purposes, with no environmental buffer, such as a wetland or river, between the wastewater treatment plant and drinking water treatment plant. That water is then sent out through the city’s drinking water system.

Colorado joins Ohio, South Carolina and New Mexico in regulating DPR, with California, Florida and Arizona working to develop a similar regulatory scheme, according to Laura Belanger, a water reuse specialist and policy advisor at Western Resource Advocates.

Ron Falco, safe drinking water program manager for the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE), said the new regulation would provide communities across the state important access to a new, safe source of drinking water, a critical factor in a water-short state.

“This is going to be a need in Colorado and we want to be prepared,” he said. “Can DPR be done safely? Our answer to that is yes.”

Under Colorado’s new regulation, water providers will be required to show they have the technical, managerial and financial resources to successfully treat wastewater. Communities will also be required to show how they will remove contaminants in their watersheds before the water reaches rivers and streams.

Wastewater intended for drinking will require extensive disinfection and filtration, among other techniques, all of which are intended to eliminate pathogens like viruses and bacteria, and remove drugs and

chemicals to safe and/or non-detectable levels, according to CDPHE.

And any community that seeks to add treated wastewater to its drinking water system will have to set up extensive public communication programs to show the public its process and to help educate residents about this new water source.

Communities will also have to collect a year’s worth of wastewater samples and prove that they can be successfully treated to meet the new standards.

At the rulemaking in October, several water utilities spoke in favor of the new regulation, including the Cherokee Metropolitan District, Castle Rock, and the City of Aurora.

Matt Benak, Castle Rock’s water resources

manager, said the regulation will give his town the certainty it needs to move forward developing new water supplies. “DPR is a critical tool for sustainable water resources. Creating this regulation will allow water providers like us to plan and to potentially implement DPR,” he said.

The rule’s approval was contingent on adding clarifying language to the policy, with formal approval finalized at the commissioners’ November meeting. H

This story originally appeared in Fresh Water News, an initiative of Water Education Colorado. Read Fresh Water News online at watereducationcolorado.org.

HEADWATERS FALL 2022 • 11

Pulse

Jerd Smith is editor of Fresh Water News

Matthew Staver

An operator with Castle Rock Water, Lanre Ajayi, at the utility's pilot water purification facility in 2018. Some of this pilot work was to prep for a direct potable reuse rule.

Pulse

Redefining WOTUS— Again

BY ELIZABETH MILLER

Water bodies can take many forms: backwater sloughs edged in cattails, riparian forests on a river’s bend, or an elk wallow high in the mountains. Some are ephemeral tributaries, occasionally being scoured from floods or drying out for parts of the year. Wetlands stabilize streamflows both over the seasons and through a series of droughtstricken years, recharge aquifers, filter pollutants, mitigate stormwater runoff, and supply crucial wildlife habitat. More than 80% of species in the West rely on wetlands and riparian areas, according to the Colorado Wetland Information Center at Colorado State University.

Over the last three presidential administrations, certain categories of wetlands and waterways have been revised in and out of inclusion under the definition for “waters of the United States,” also known as WOTUS, a federal status that extends them protections under the Clean Water Act. The act regulates the discharge of pollutants.

In Colorado there is no state program to protect certain wetlands and waterways from dredging, filling and other damage if they’re not covered by the Clean Water Act. The state has always relied on the federal government’s program for dredge and fill permits.

Changes to the definition of WOTUS occurred in 2015, 2020 and 2021. Now, in 2022, change is once again afoot, with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers revisiting their rule and, at the same time, the U.S. Supreme Court considering a case that could also weigh in on which waters qualify as WOTUS. Recent definitions for what qualifies have bounced between broader and narrower.

“A narrow definition of waters of the U.S. leaves an incredibly important water resource value unprotected by federal law—which is basically uniform across the

nation—and then it’s up to the states to decide what to do, and some states won’t decide to protect those areas at all,” says Joro Walker, general counsel with Western Resource Advocates. The 2020 definition, for example, excluded all ephemeral waterways and some wetlands. Ephemeral streams represent more than 25% of Colorado’s stream miles, according to Colorado Trout Unlimited. According to Colorado’s Water Quality Control Division, some 25% to 50% of Colorado streams, lakes and wetlands could have been impacted by the 2020 rule.

But farmers and ranchers, developers, and other business owners worry the broader definition would mean federal involvement in day-to-day decisions around their properties, or the need to consult a lawyer on something like running water through an irrigation ditch every few years. The 2015 rule included a broad definition and has been referred to as a federal “overreach.”

Now though, the Colorado Farm Bureau and others who are regulated are calling for clarity and security, something they hope the Supreme Court will provide.

“It’s hard to know what is covered,” said Travis Vincent, general counsel and director of public policy state affairs for the Colorado Farm Bureau. “We want a more bright-lined test so our members have a better understanding of when their property or something on their property would be regulated under WOTUS.”

Currently, the federal agencies are relying

on the definition that was in place from the 1980s to 2015, which they call a “familiar approach” that will “support a stable implementation of ‘waters of the United States.’” Meanwhile, the agencies’ proposed final rule was submitted to the Office of Management and Budget in September 2022 and, according to EPA, they plan to issue it by the end of the year.

In October 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court heard Sackett v. EPA , a case that asks whether certain wetlands are waters of the U.S. Justices have previously written that WOTUS applies only to “relatively permanent, standing or continuously flowing bodies of water” or wetlands that have a “significant nexus” to traditionally navigable waters, but failed to achieve a majority opinion. This has left, as the Sacketts have said, a landscape of “fruitless confusion, conflict, and litigation.”

The court’s opinion could newly define and clarify which waters qualify as waters of the United States—and could affect EPA’s regulatory process, the rulemaking underway at the Corps and EPA, and the level of protection that certain waters receive.

“It’s hard to speculate on what the [U.S. Supreme Court decision] is going to look like,” says Trisha Oeth, director of environmental health and protection at the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. “If the outcome were to change the definition of WOTUS or add a new test for what WOTUS includes, that could have an impact here in Colorado.” If a new definition were to apply to fewer water bodies than it does now, that would mean that Colorado waters would have less protection than they do today, she says.

“We are in a very dynamic situation with the rule and have been for a number of years,” says Oeth. “I think all interests would benefit from certainty and stability in this area so we continue to watch it very closely and have been having conversations with stakeholders here in Colorado to figure out, long-term, what is the right path for us.” H

12 • WATER EDUCATION COLORADO

“We want a more bright-lined test so our members have a better understanding of when their property or something on their property would be regulated under WOTUS.”

— Travis Vincent , Colorado Farm Bureau

Around

the

state

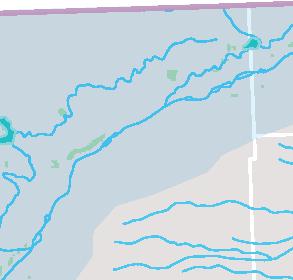

ARKANSAS RIVER BASIN

| BY CAITLIN COLEMAN

Lake Mead Water Level

RIO GRANDE BASIN

The Arkansas Valley Conduit, a project designed to bring clean drinking water to southeastern Colorado, is making big advances. In early October, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation awarded a nearly $43 million contract to a Ute Mountain Ute-owned construction company to build the first 6-mile section of the conduit, out of 103 total miles, beginning in spring 2023. Then, in late October, Reclamation announced that it will direct $60 million in federal funding from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law toward the project’s construction, which is expected to cost a total of around $600 million.

GUNNISON RIVER BASIN

Water districts in Montrose and Gunnison are embarking on a $700,000 drought planning effort, aided by $340,000 in federal drought grants awarded in August. According to Fresh Water News, the Uncompahgre Valley Water Users Association will spend $400,000 to develop an action plan for dealing with ongoing and future drought, and the Upper Gunnison River Water Conservancy District will spend $300,000 for a similar program.

YAMPA RIVER BASIN

State officials and Tri-State Generation and Transmission, among others, are taking another run at the idea of developing a green hydrogen pilot project in the Yampa River Valley, using a new U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) program to test the feasibility of green hydrogen as a significant power source. The proposed project would be located in Craig, where a coal-fired power plant will be decommissioned beginning in 2025. Fresh Water News reports that if successful in securing DOE funding, the hydrogen project could use the same site, transmission lines, and water as the coal plant.

COLORADO RIVER BASIN

Grand Lake locals are asking the state to break through red tape to help restore the lake’s clarity and water quality. According to Fresh Water News, in August, Mike Cassio who represents the Three Lakes Watershed Association in Grand County asked state lawmakers to launch a study that would help trigger federal action. Northern Water, which operates the Colorado-Big Thompson Project that uses the lake to convey its transmountain water, says it is committed to finding a path forward and is legally obligated to do so under its operating contract with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

NORTH PLATTE RIVER BASIN

The Platte River is dry. That was the main topic at the Nebraska Water Center’s conference in October, reports ABC news station NTV. During a normal year, the PIatte would flow in the fall but because of drought this year, it is almost completely dry downstream of Kearney, Nebraska. Nearly all the water that flows in the Platte through Nebraska comes from Colorado and Wyoming. Right now, reservoirs and irrigation projects, primarily Wyoming’s Pathfinder and Glendo reservoirs, are storing the water that begins in Colorado’s North Platte Basin, leaving the river dry. Plus, according to a report from Snoflo, streamflow levels measured near Northgate in Colorado’s Jackson County are 38% below average for this time of year.

The first groundwater conservation easement is moving forward in the San Luis Valley through an agreement with Colorado Open Lands. To balance groundwater availability and demand, irrigators across the valley need to cut the amount of water they’re pumping or their wells could be shut off by the state. Farmers who sign on to these new conservation easements will no longer use their water rights to grow crops on their land, but will instead keep that water in the ground to help save the dwindling aquifer, reports Colorado Public Radio.

SAN JUAN/DOLORES RIVER BASIN

The City of Durango is exploring the possibility of constructing a new water pipeline from Lake Nighthorse to Durango’s Terminal Reservoir. The pipeline would allow the city to access its share of water in Lake Nighthorse if its regular supply, from the Florida and Animas rivers, is ever unavailable or unsafe to use. The Durango Herald reports that in August, the Durango City Council approved a feasibility study to look into this approach, with a completed study expected by the end of the year.

SOUTH PLATTE RIVER BASIN

Sterling Ranch, a fast-growing Douglas County community, is launching the first commercial effort to harvest rainwater in Colorado. Fresh Water News reports that the project may need to clear various hurdles, including working with neighboring water providers and potentially seeking new legislation. If successful, rainwater harvesting on this scale could be used statewide to offset water use in new developments, creating a supply of water that legally hasn’t existed before.

HEADWATERS FALL 2022 • 13

As of November 14, 2022 1,044 feet above sea level 28% full Lake Powell Water Level

As of November 13, 2022 3,529 feet above sea level 23% full

Working with the Feds

Working with the Feds

The federal role of water management in Colorado is designed to overlap and cooperate with state programs, compelling and supporting protections without dictating how they’re met.

By Elizabeth Miller

By Elizabeth Miller

14 • WATER EDUCATION COLORADO

Luke Runyon/KUNC

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service technician MacKenzie Barnett sorts invasive smallmouth bass on an electrofishing raft on the Colorado River. Among other work to protect endangered fish, the Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Recovery Program team removes non-native fish that feed on endangered fry. These bass are collected, measured, weighed, killed and sent to a landfill.

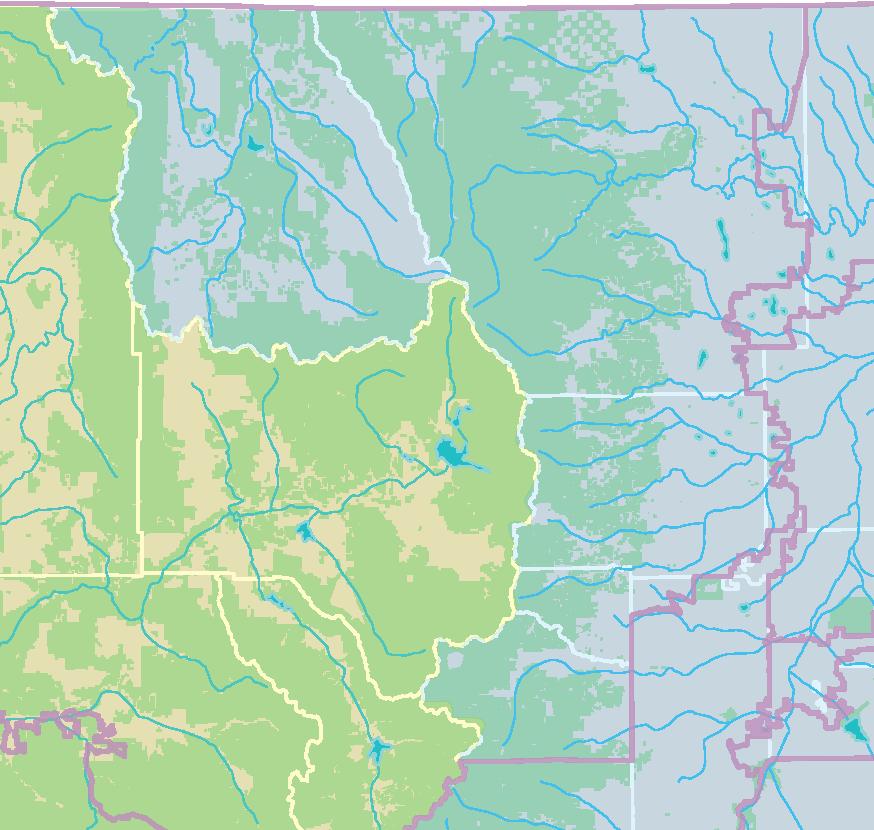

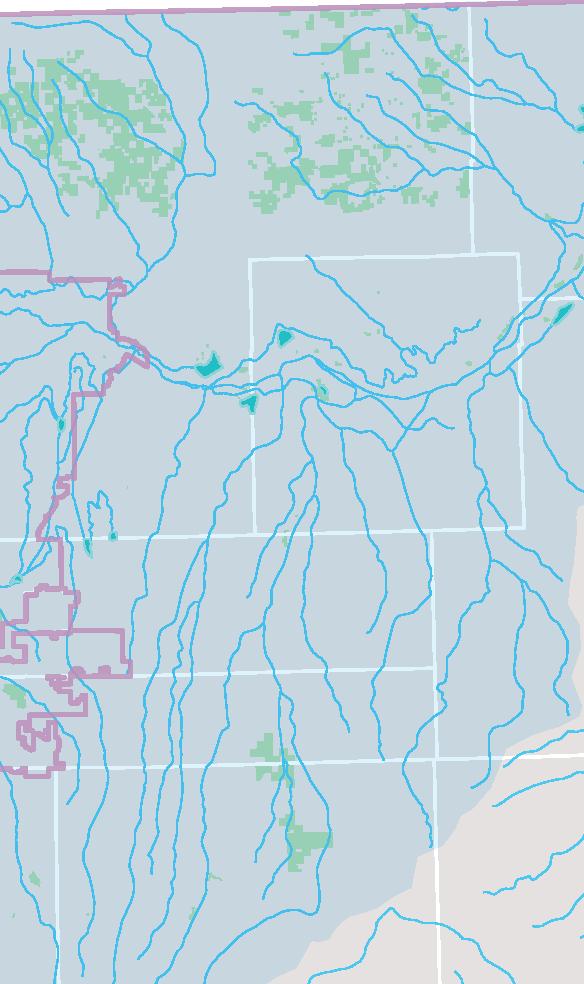

The federal nexus with Colorado water management is significant. More than half of the reservoir storage across Colorado is federally owned. More than 70% of Colorado’s source watersheds are on land owned and managed by federal entities. What happens if Colorado fails to meet its obligations under an interstate water compact? The dispute is settled by the U.S. Supreme Court. Who sets the minimum standard for Colorado water quality protections? The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, a federal agency.

But the water held in federal reservoirs is still a state-governed resource, and much of the federally funded work in Colorado is locally proposed, planned and driven.

“How we manage water rights within our state is really up to us,” says Kelly Romero-Heaney, assistant director for water policy at the Colorado Department of Natural Resources and special water policy advisor to the governor. (Editor’s note: Romero-Heaney also serves on the Water Education Colorado Board of Trustees.) “As long as we’re meeting our obligations under [interstate] compacts, the federal government really doesn’t have a role to play in that directly.”

The equal footing doctrine, which dates to the nation’s founding, granted states control of their own natural resources, which means states oversee water allocation to water users within their boundaries, says Jennifer Gimbel, a senior water policy scholar at the Colorado Water Center. The 1862 Homestead Act, among others, solidified that states have jurisdiction over their water.

“It’s a states’ rights attitude in the West,” says Gimbel. “Individual states, in the West especially, all develop their own way to protect and administer their water rights. It’s all under their prior appropriation doctrines. And so the state is responsible, and the states, they don't want the government telling them how to do things,” Gimbel says.

Still the federal government’s role in Colorado water is multifaceted and major: land and infrastructure manager, regulator, administrator, funder, partner, lawmaker, and representative. When considering the federal nexus with water in the state, it’s no simple water rights question.

Recently, persistent drought conditions, historically low inflows, and quickly falling reservoir levels on the Colorado River have led many to question and discuss the federal government’s role in water rights admin istration across state boundaries. Could the feds step in on matters that have been historically left to the state? Or what would happen if partner ship programs spearheaded by the federal government, like the Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Recovery Program, go unrenewed— could the federal role transition from one of partner to regulator?

STATE OR FEDERAL RIGHTS ON THE COLORADO RIVER?

In June, ongoing drought and its effects on Lake Powell and Lake Mead prompted U.S. Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Camille Touton to ask Colorado River Basin states to develop a plan to reduce water use by 2 million to 4 million acre-feet in 2023. That would be in addition to the water cuts that some states are already taking under the Colorado River’s 2019 Drought Contingency Plan. The plan

Touton called for hasn’t yet been developed, leading many to question whether cuts could be mandated if the states don’t swiftly agree to limit water use on their own.

The 2019 drought plans, which specify when the Lower Basin states— Arizona, Nevada and California—must take water use cuts based on levels in lakes Powell and Mead, were prompted by federal requests, but they were developed and agreed upon by the states and agency represen tatives. The plans no longer go far enough to preserve plummeting water levels, so more water savings are required, but if states can’t agree on the additional plan and the feds step in, a federal mandate would be new for the basin.

“A federal response is likely necessary to address the growing tensions between the basin states as water levels continue to drop,” reads a May 2022 University of Denver Water Law Review article by review editor Kristen Kennedy. In her article, Kennedy points to the 1982 Supreme Court ruling in Sporhase v. Nebraska, which held that interstate water resources qualify as commerce, and so are within Congress’s authority to regulate. Would that hold on the Colorado River?

All seven states and Mexico, along with the U.S. federal government, are bound together by what’s known as the “Law of the River,” a series of laws, court cases and agreements that divvy up the river’s water and set rules for how it is managed.

The levers by which Reclamation can mandate cuts to water use out side of the agreed-upon water management framework are “untested,” says Alex Funk, director of water resources and senior counsel for the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership.

Such a mandate would be likely to land in court, says Funk, at least for the Upper Basin, where the four Upper Basin states—Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming—have their own Upper Colorado River Basin Compact that spells out how water is divided among them. While there is a federally appointed seat on the Upper Colorado River Commis sion, the states and federal chair work together on Upper Colorado River water management.

It’s a bit different for the Lower Basin states who rely on the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, by way of Reclamation, to carry out the role of “water master,” managing the delivery of their respective water supplies. That arrangement was settled through the 1963 Arizona v. California Supreme Court decision.

But, in the Upper Basin, the federal role has never meant control over water rights. For the Upper Basin, having a compact is “hugely advanta

HEADWATERS FALL 2022 • 15

CONTINUED ON PAGE 18

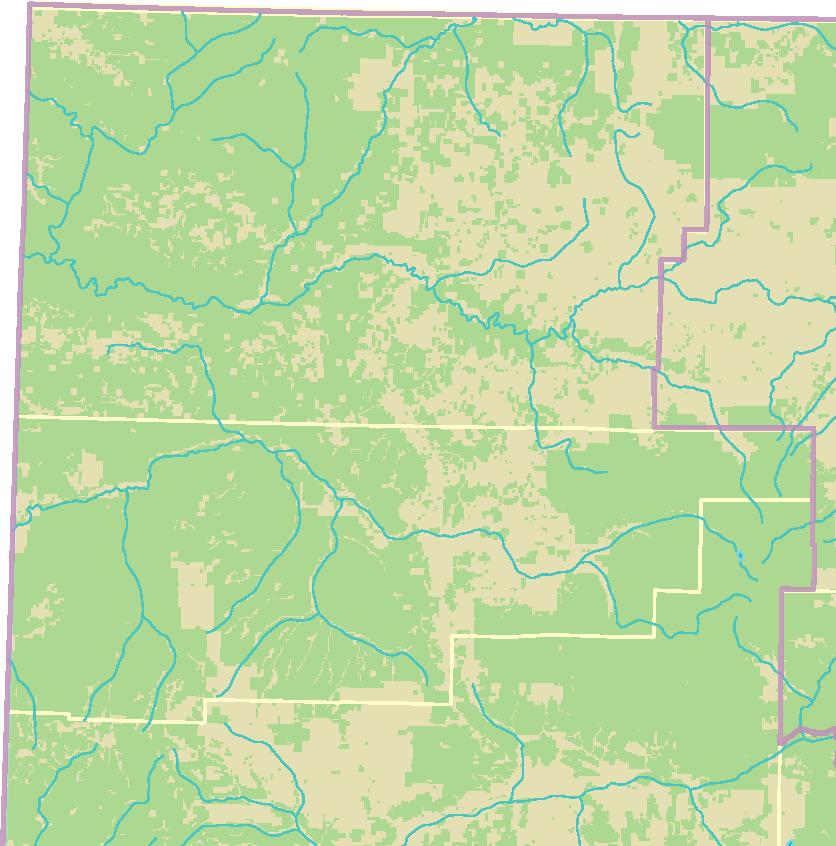

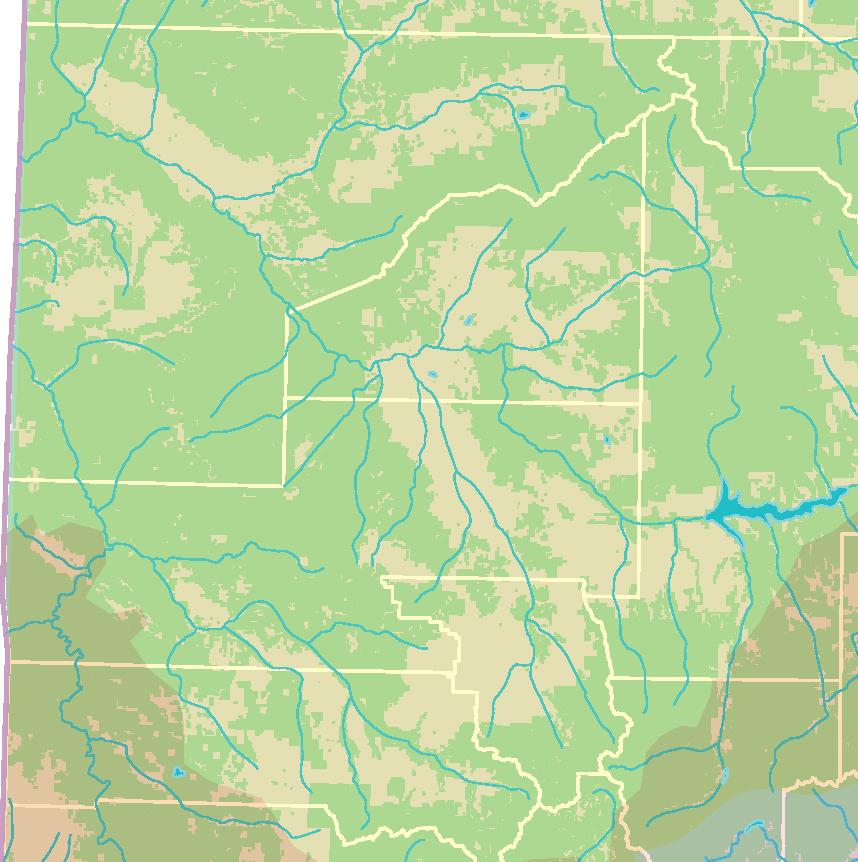

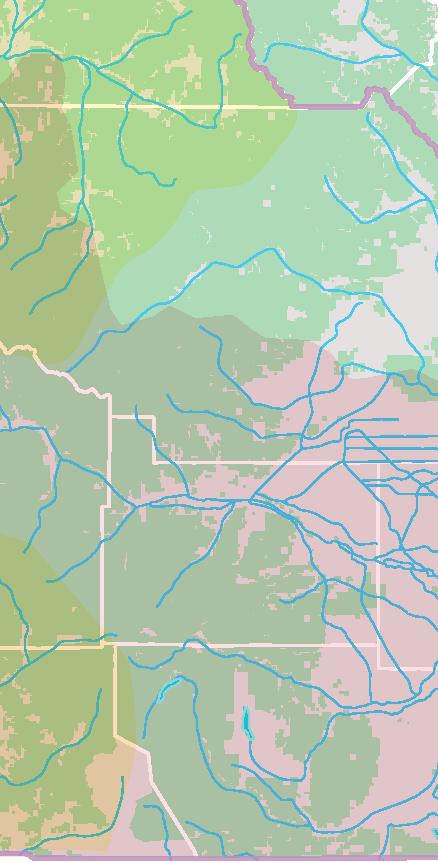

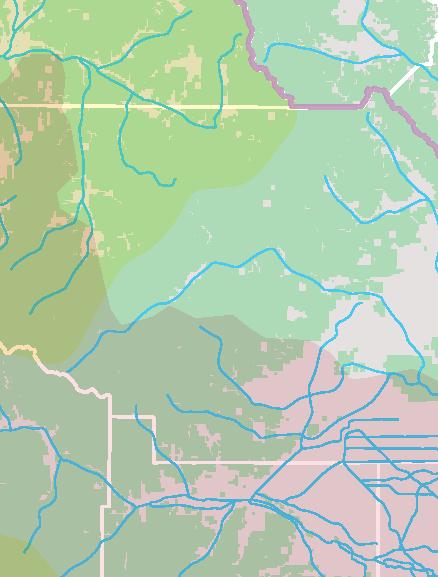

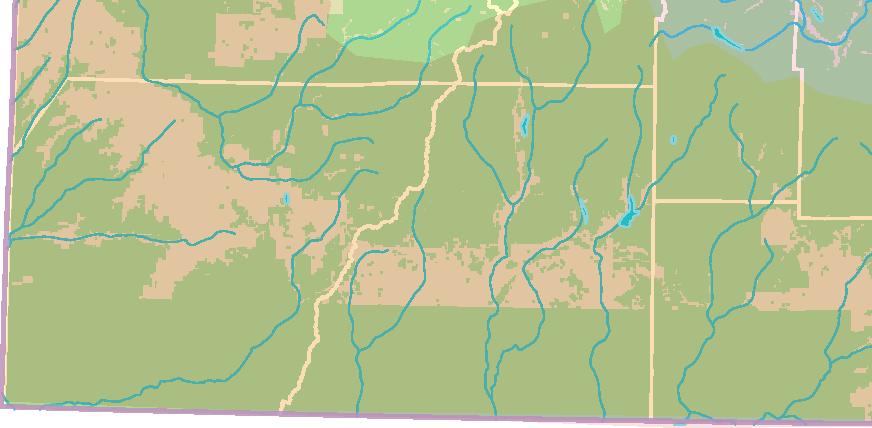

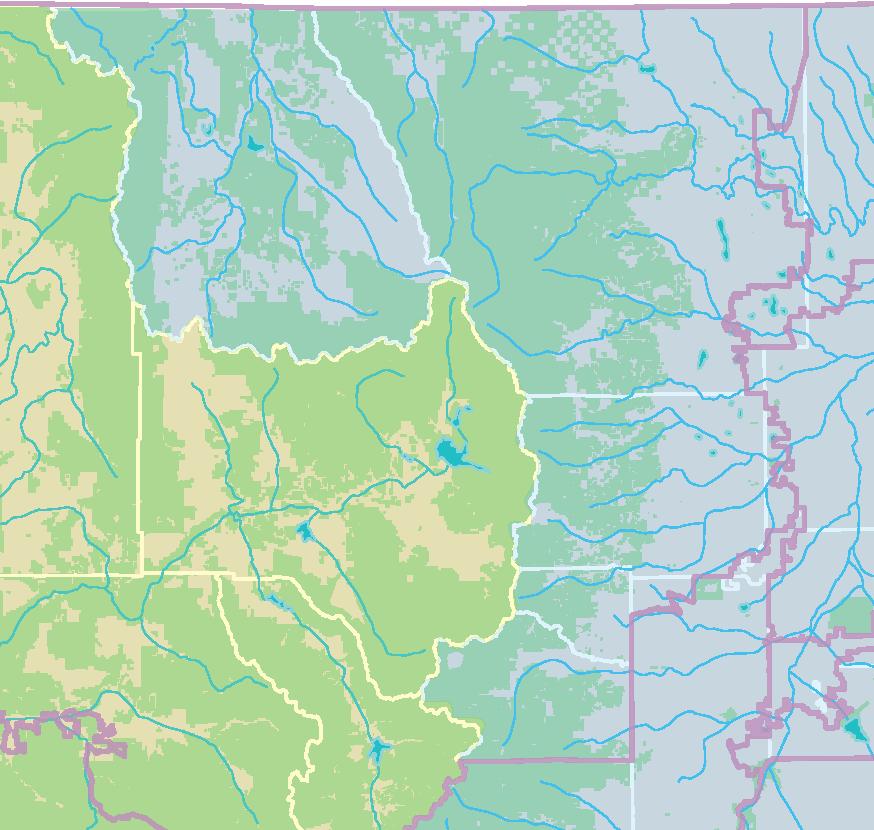

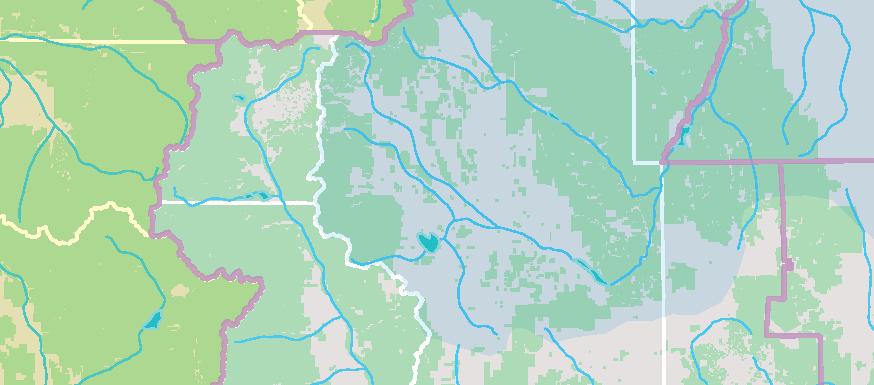

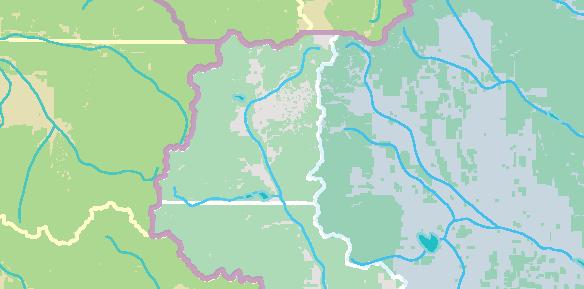

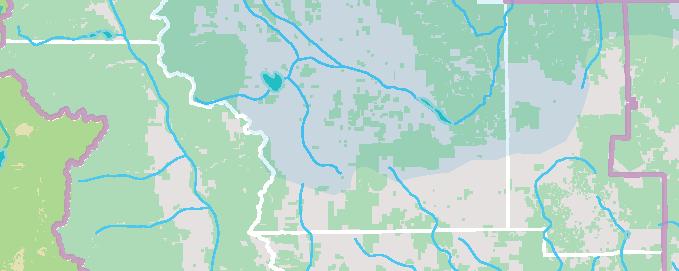

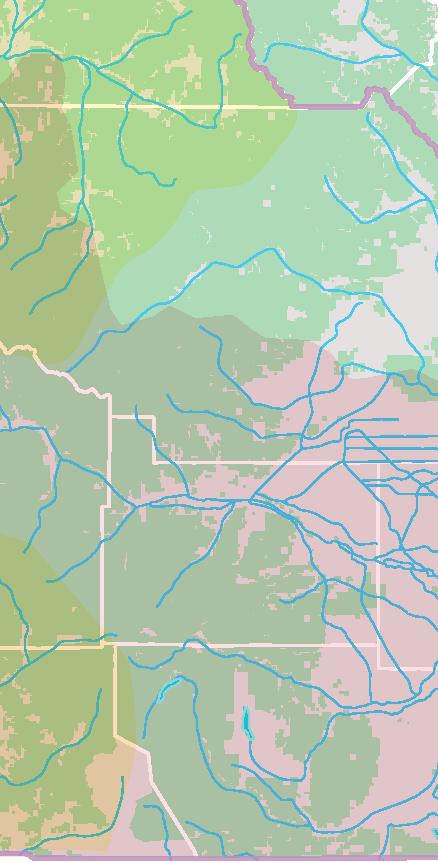

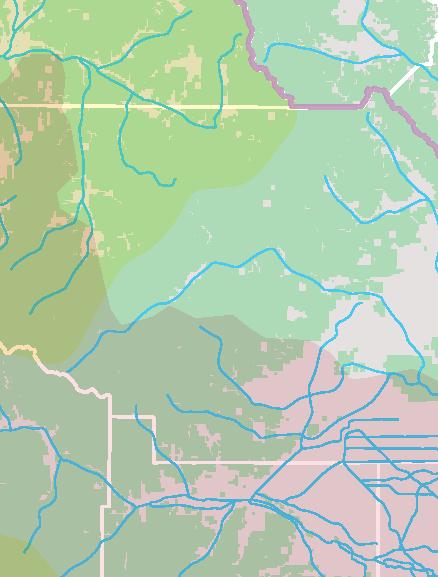

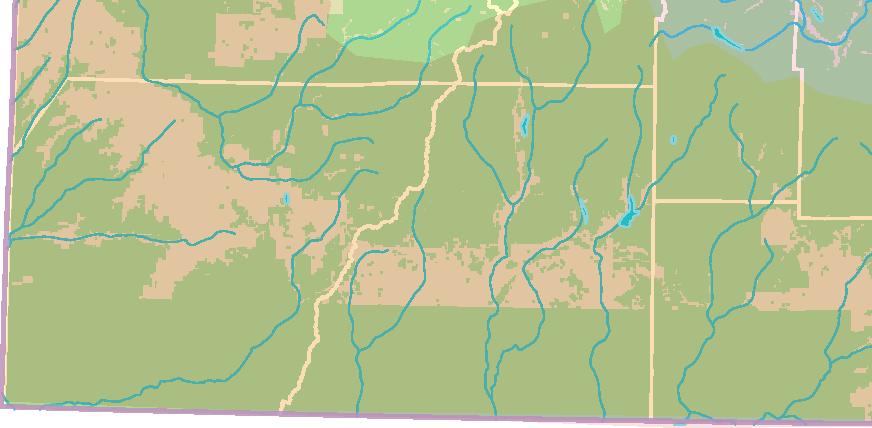

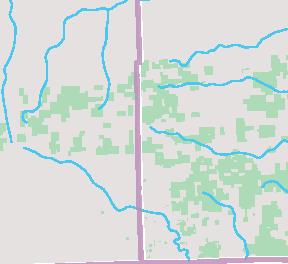

16 • WATER EDUCATION COLORADO Federal lands 118th Congressional Districts U.S. Bureau of Reclamation U.S. Army Corps of Engineers 1 7 11 27 13 15 12 22 26 21 28 20 29 30 32 31 33 14 23 34 24 25 ≈ 23 16 18 17 19 3 4 Cortez Mancos Durango Grand Junction Palisade Montrose Pagosa Springs Delta Olathe Rifle Meeker Glenwood Springs Leadville Hartsel Aspen Breckenridge Vail Kremmling Steamboat Springs Hotchkiss Paonia Denver Trinidad Boulder Winter Park Fort Collins Greeley Colorado Springs Pueblo Alamosa Salida Gunnison Silverton 1 5 8 9 6 35 5 10 3 2 1 2 3 1 1 2 3 5 6 7 8 North Platte River Colorado River San Juan River

The Federal Connection with Colorado Water

South Platte River

U.S. Bureau of Reclamation projects

1 Animas-La Plata Project, Lake Nighthorse

2. Armel Unit, Bonny Dam

3. Bostwick Park Project, Silver Jack Reservoir

4. Collbran Project, Vega Reservoir

5. Colorado-Big Thompson Project, Carter Lake

6. Colorado-Big Thompson Project, Lake Granby

7. Colorado-Big Thompson Project, Green Mountain Reservoir

8. Colorado-Big Thompson Project, Horsetooth Reservoir

9. Colorado-Big Thompson Project, Shadow Mountain Reservoir

10. Colorado-Big Thompson Project, Willow Creek Reservoir

11. Colorado River Basin Salinity Control Program: Grand Valley Unit —Title II

12. Colorado River Basin Salinity Control Program: Lower Gunnison Basin Unit—Title II

13.

Colorado River Basin Salinity Control Program: McElmo Creek Unit— Title II

17. Colorado River Storage Project, Crystal Reservoir, Aspinall Unit 18. Colorado River Storage Project, Morrow Point Reservoir, Aspinall Unit 19. Dallas Creek Project, Ridgway Reservoir 20. Dolores Project, McPhee Reservoir 21. Florida Project, Lemon Reservoir 22. Fruitgrowers Project, Fruitgrowers Reservoir 23. Fryingpan-Arkansas Project, Pueblo Reservoir 24. Fryingpan-Arkansas Project, Ruedi Reservoir 25. Fryingpan-Arkansas Project, Turquoise Lake 26. Fryingpan-Arkansas Project, Twin Lakes 27. Grand Valley Project, Grand Valley Diversion Dam 28. Mancos Project, Jackson Gulch Reservoir 29. Paonia Project, Paonia Reservoir 30. Pine River Project, Vallecito Reservoir 31. San Luis Valley Project, Closed Basin Project 32. San Luis Valley Project, Platoro Reservoir 33. Silt Project, Rifle Gap Reservoir 34. Smith Fork Project, Crawford Reservoir 35. Uncompahgre Project, Gunnison Tunnel

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers projects

1. Bear Creek Lake

2. Chatfield Reservoir

3. Cherry Creek Lake

4. John Martin Reservoir

5. Trinidad Lake

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service projects

Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Recovery Program—Colorado River and its tributaries

San Juan River Basin Recovery Implementation Program—San Juan River Basin including tributaries in New Mexico and Utah

The federal nexus extends beyond Colorado’s rivers and streams to the land itself and the projects that store and move water. The feds, in various capacities, serve as land managers—owning about 36% of land in the state—lawmakers, project builders and managers, and much more. The federal reach is clear here, where we show just a selection of the federally owned projects and infrastructure in all corners of the state. There are many more federally funded projects, swaths of land where forest health work affects water supplies, spots where federal permitting authority is in play, fish and wildlife recovery efforts, and much more 1 2 3

Platte River Recovery Implementation Program— both the North and South Platte rivers and their tributaries in Colorado, Wyoming and Nebraska

HEADWATERS FALL 2022 • 17 Charles Chamberlin

2

Sterling

Fort Morgan

Limon

Las Animas Lamar

4

14. Colorado River Basin Salinity Control Program: Meeker Dome Unit—Title II 15. Colorado River Basin Salinity Control Program: Paradox Valley Unit—Title II 16. Colorado River Storage Project, Blue Mesa Reservoir, Aspinall Unit 4

geous,” says Amy Ostdiek, the Colorado Water Conservation Board’s deputy section chief for interstate, federal and water information, “because it gives us control of our own destiny.”

PARTNER,

WOULD-BE REGULATOR, ON ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTIONS

The wave of laws passed in the 1960s and 1970s to protect the nation’s fish, wildlife and environment significantly modified permitting processes for water storage and management and put the federal role front and center.

The 1973 Endangered Species Act (ESA) is one such law that gives the federal government authority to protect threatened and endangered species, which can affect how water is managed and administered.

Under the ESA, if water diversions, projects or actions carried out, funded or authorized by a federal agency jeopardize a threatened or endangered species, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) can require modification of those operations. During permitting, the agency and partners involved in the project consult with the USFWS through what’s known as a “Section 7 consultation”—referring to Section 7 of the ESA—to ensure that the project won’t harm any threatened or endangered species.

But in much of Colorado, during these consults on water projects,

rather than developing ways to offset the impacts of each individual wa ter project, state representatives, tribes, conservation groups, and water users band together to work with the USFWS on endangered fish recov ery programs that create a blanket offset for numerous projects. There are endangered species recovery programs on the Upper Colorado, the San Juan, and the Platte rivers, and they include measures ranging from streamflow targets, to hatchery work, to nonnative fish removal.

“I can’t say enough about the endangered species recovery pro grams,” says Romero-Heaney, who also serves on the implementation committee for the Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Recovery Program, which, together with the San Juan River Basin Recovery Implementation Program, provides protection for more than 1,500 water projects in Colorado and another 1,000 projects across the Upper Colorado River Basin. Without the program and partnership with the USFWS, each of those projects individually would have to consult with the federal agency to ensure ESA compliance, taking actions—like diverting less water or installing fish screens—to offset their impact on their own.

Plus, without the programs, recovery efforts would be less coordinat ed with fewer ecological benefits. “We more than comply with the ESA. We set the goal to solve the problem, to recover and delist the species, so we’re doing a lot more than just Section 7, which mitigates the impact of

18 • WATER EDUCATION COLORADO

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 15 CONTINUED ON PAGE 20

Jeff Widen

This section of the Dolores River could soon be protected as part of a new Dolores River National Conservation Area, if legislation introduced in 2022 by U.S. Sen. Bennet and Rep. Boebert passes.

Federal Entities’ Roles in Colorado Water

While many federal agencies and decision makers—housed everywhere from the U.S. Department of State to the U.S. Senate— play a role in managing, regulating, forecasting, sharing resources, funding and much more with water, select key agencies that work in Colorado include:

• U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ɦ U.S. Bureau of Reclamation —Created in 1902, known for the dams, powerplants and canals it constructed across the West, Reclamation is now the largest wholesaler of water and the second largest producer of hydropower. It owns and helps maintain reservoirs, water projects and delivery systems across Colorado. Some key laws that direct Reclamation’s work are the authorizing legislation for its projects, such as the Colorado River Storage Project Act, and water management legislation such as the Colorado River Drought Contingency Plan Authorization Act. ɦ

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service —Founded in 1940, the USFWS works to conserve and manage fish, wildlife, plants and their habitats. USFWS works closely with the Army Corps of Engineers, the Bureau of Reclamation, state agencies and local partners to develop or work on water resource projects while still conserving fish and wildlife. Key laws that guide USFWS’s water work include the Endangered Species Act, Clean Water Act, Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act, and National Environmental Policy Act. ɦ

U.S. Geological Survey—Created in 1879, the USGS provides reliable scientific information to describe and understand the Earth, minimize loss from natural disasters, manage natural resources, and protect quality of life. USGS works with partners to monitor, assess, conduct research and deliver information on a variety of water resources and conditions including streamflow, groundwater, water quality and water use and availability. A key law that guides USGS’s water work is the Water Resources Research Act.

U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY

•

ɦ

Created in 1970, EPA is responsible for protecting human health and the environment. It has various programs that intersect with water through which it sets federal regulatory water quality standards and provides technical assistance. Key laws that direct EPA’s water work include the Safe Drinking Water Act and Clean Water Act.

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE

•

ɦ

U.S. Forest Service —Established in 1905, the USFS is a public land manager responsible for national forests and grasslands. The agency is directed to manage these public lands for multiple uses, benefits and for the sustained yield of renewable resources including water, forage, wildlife, wood and recreation. In Colorado, the USFS manages more than 14.5 million acres, 90% of

which are in watersheds that contribute to public water supplies. When it comes to source water protection, the USFS is a key agency that works alongside state agencies, watershed groups, water providers and others on wildfire recovery and increased wildfire resiliency. ɦ Natural Resources Conservation Service —Created in 1933, the NRCS provides resources to farmers, ranchers and landowners to help them conserve and protect natural resources. Among other goals, the agency’s programs offer assistance to help producers conserve water and improve water quality. NRCS also employs hydrologists who conduct snow surveys to forecast water supplies.

• U.S. DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE ɦ

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers —Established in 1802, the Corps works to deliver engineering solutions to secure the nation and reduce disaster risk. In Colorado, the Corps does this through a regulatory program where it protects aquatic resources while allowing development and evaluating permit applications for all construction activities in U.S. waters. The Corps also works in a flood management capacity, works on environmental remediation and cleanup programs, and more. Key laws that guide this work include the Flood Control Act, Clean Water Act, and National Environmental Policy Act. •••

• U.S. REPRESENTATIVES AND SENATORS: Colorado has seven congressional districts (eight starting January 2023) with one rep per district serving in the U.S. House of Representatives. The state also has two senators who serve the entire state. Colorado’s U.S. representatives and senators propose and negotiate legislation and pass federal laws. There are myriad laws that have an effect on water, including some that fund water projects, such as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law of 2021; others authorized water projects, such as the Colorado River Basin Project Act of 1968.

• THE U.S. SUPREME COURT: The U.S. Supreme Court plays a role in interstate water issues, particularly compacts or water sharing agreements among states. If the states fail to meet their obligations under a compact, or disagree over interstate water issues, the Court resolves those disputes. Other cases brought before the Court can also have a water nexus, such as the pending Sackett v. EPA case that could have an impact on how the Clean Water Act is applied.

HEADWATERS FALL 2022 • 19

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 18

one project,” says Tom Pitts, a consultant who represents water users in both the Upper Colorado River and San Juan recovery programs.

Next year, in 2023, the Upper Colorado program, which has been in place since 1988, and the San Juan program, in place since 1992, will be up for reauthorization by Congress. Reauthorization is a top priority for Colorado, Romero-Heaney says. “It’s a really important program for the environment but also for our water users,” she says. Should the program go away, it would mean reconsultation on all of those 2,500-plus projects across the Upper Basin with biologists weighing in on the steps neces sary for ESA compliance. “If we can’t operate through a collaborative program like that, then our relationship with the USFWS really just becomes a regulatory one.”

Negotiations for next year’s reauthorization are focused on funding, which has historically come, in part, from power generation revenue on Colorado River reservoirs. Now, with less water in the reservoirs and water levels dropping, that revenue source could be vanishing. The programs are too important to too many people to allow them not to be reauthorized, Pitts says, so the question may not be whether they’ll be reauthorized, but rather how to fund them in the future.

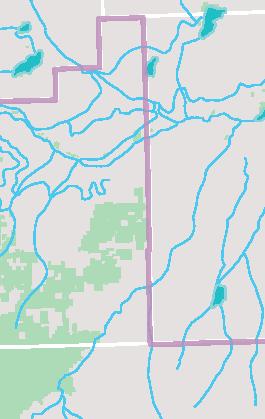

WILD AND SCENIC OR AN ALTERNATIVE

In addition to protecting endangered fish and wildlife, the federal government plays a role in protecting certain rivers or stream stretches that are set aside for outstandingly remarkable values. The federal “wild and scenic” river designation is a Congressionally designated status tailored to preserve selected rivers with outstanding natural, cultural and recreational values in a free-flowing condition for present and future enjoyment.

“It’s still the gold standard of river protection in this country and around the world,” says Michael Fiebig, director of the Southwest River Protection Program with American Rivers. To date, more than 13,400 miles of streams across the nation are protected as wild and scenic rivers. Designation means ensuring the rivers remain free flowing and protecting the rivers’ specifically identified outstandingly remarkable values. “There’s nothing else that keeps a river free flowing like a wild and scenic designation does.”

Colorado users generally steer toward other measures to protect rivers in order to keep jurisdiction over water in state hands and not preclude the future damming, diversion or development of rivers. The state has a Wild and Scenic Rivers Fund, which supports developing alternatives to official designation under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. In Colorado, there is just one stream reach, totaling 76 miles, on the Cache la Poudre upstream of Fort Collins that’s officially been designated wild and scenic.

In pursuit of a river-protecting alternative, this year U.S. Sen. Michael Bennet introduced legislation to create the Dolores River National Conservation Area in southwestern Colorado, which includes language modeled after the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act to protect that river’s free-flowing character without pursuing wild and scenic status. Rep. Lauren Boebert introduced identical legislation in the House.

If passed, that protection would come after more than 14 years of work by the Lower Dolores Plan Working Group. The working group includes 40 stakeholders of all types: ranchers, conservationists, boat ers, county representatives, water managers and others, who support the legislation.

“One of the originally stated goals of that group, that we agreed to, is ‘How can we protect the values of the Dolores River Canyon while allowing the uses that have been going on there without inhibiting them?’” says Jeff Widen, who works for the Wilderness Society and serves on the working group committee that helped draft the legisla tion. Rather than pursue wild and scenic designation which “would have fallen on deaf ears,” according to Widen, the group looked to other tools to meet the needs of all stakeholders.

After considering a variety of legislative and management tools, the group decided that a national conservation area was its best option, says Amber Clark, who serves alongside Widen on the group’s legislative committee. That’s because a national conservation area doesn’t come with many prerequisites, such as a reserved water right. The conserva tion area is tailored through its designating legislation.

If approved, the Lower Dolores National Conservation Area would, among other things, protect the river’s remarkable values. It also would mean that the area can’t be designated as wild and scenic in the future; it creates an advisory council of local stakeholders who will provide in put to the federal management agencies; and, of particular importance to water users, it doesn’t include any water rights changes.

“I believe local participation in the management of the area will pro vide better benefits for the native fish, scenic area, recreation, permitted federal land uses, private land values and water rights than a wild and scenic designation,” wrote rancher Al Heaton in a letter to Sen. Bennet in support of the proposed legislation.

If the bill doesn’t pass during this session, the group will try again, says Clark.

“We have a strong coalition on the ground with a lot of different interests supporting this and I think that’s what’s going to continue to help move this forward.” Those broad local interests will continue to work with federal managers on a uniquely Colorado conservation area, Clark says. “We’ve worked really hard to come together and we want to continue pushing it up.” H

20 • WATER EDUCATION COLORADO

Independent journalist Elizabeth Miller has written about environmental issues around the American West for publications including The Washington Post, Scientific American, Outside, Backpacker and The Drake.

Members of the Lower Dolores Plan Working Group met for more than a decade, discussing how to protect the Dolores River Canyon while meeting the many goals of diverse stakeholders. They came away with a plan to create the Dolores River National Conservation Area.

Amber Clark, courtesy Dolores River Boating Advocates

From Dam Builder to Water Manager

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation's future in Western Water won't look like the past

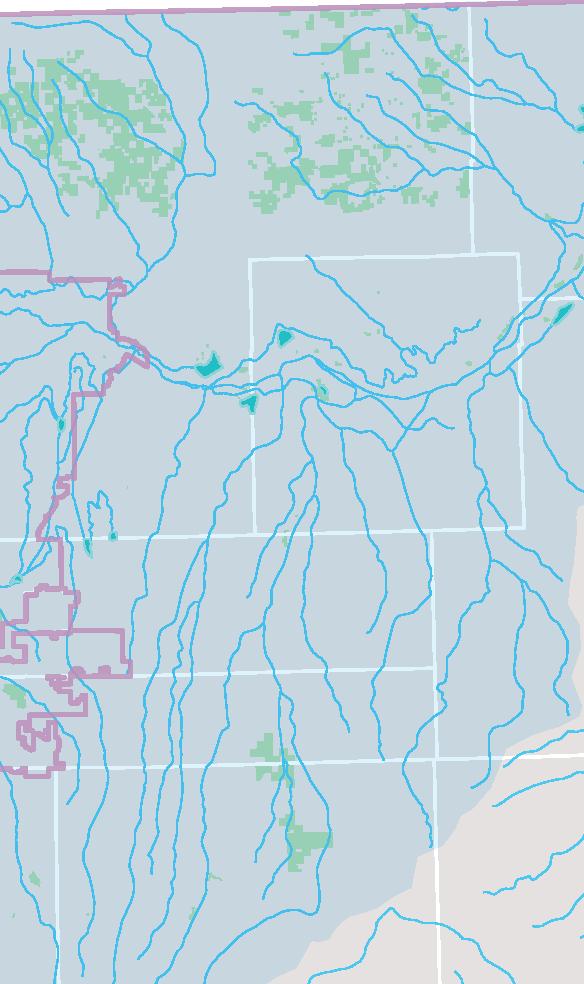

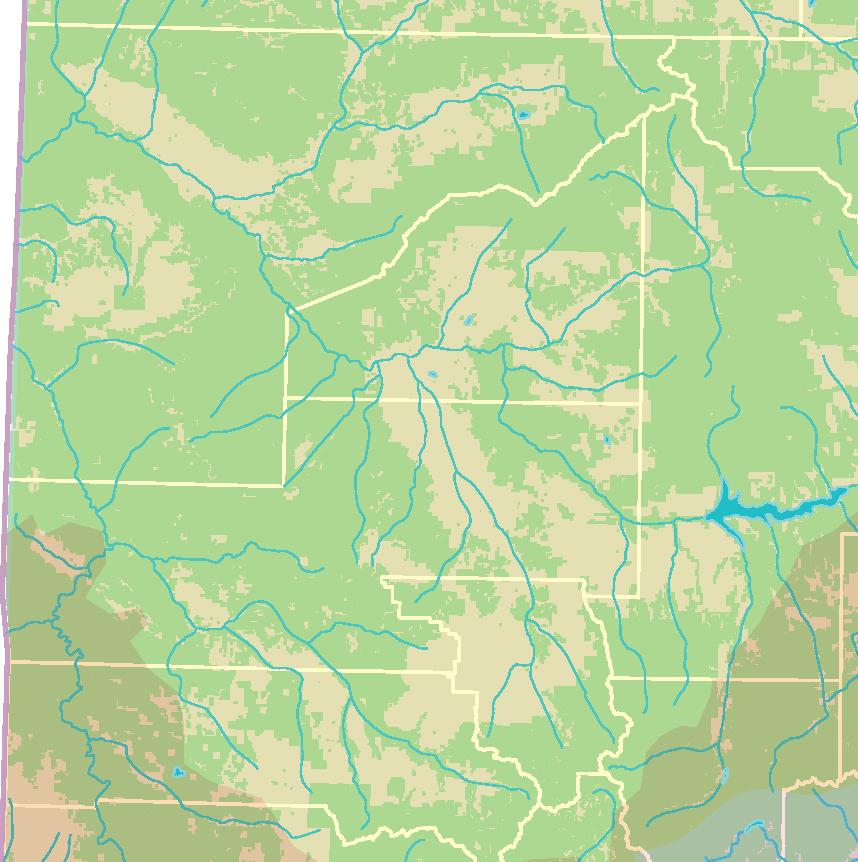

While not all water users in Colorado rely on federal infrastructure, many do. U.S. Bureau of Reclamation projects provide water to some 40% of Coloradans and irrigate more than 1 million acres of agricultural land across the state. These federal projects serve a variety of purposes. They move water from where it originates to where it gets used, store it until it’s needed, or slow and detain stormwater to protect communities from flooding.

Many of those projects are owned by Recla mation, which tallies more than 600 miles of pipelines, canals, reservoirs and other infra structure across Colorado. The agency says their reservoirs in Colorado have a total water storage

capacity of about 4 million acre-feet—about half of the state’s overall reservoir capacity. The actual amount of water stored varies throughout the season and year-to-year.

Reclamation’s water projects allowed for the development of the West as we know it—for urban populations to grow where they have and for rural farmers and ranchers to access water needed for their agricultural operations. But over the past 120 years the agency’s role has shifted from water developer to manager. Now climate change could be brewing the agency’s next evolution, making many wonder what its future, and the future operation of its water projects, will look like.

BY OLIVIA EMMER

HEADWATERS FALL 2022 • 21

William Woody

Tina Bergonzini, manager of the Grand Valley Water Users Association (GVWUA), and Ed Warner, area manager for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s Western Colorado Area Office, meet at the Cameo Diversion Dam, commonly known as the “roller dam.” While Reclamation owns the dam, the GVWUA operates it along with the Government Highline Canal to provide irrigation water to more than 23,000 acres of farm and ranch land in the Grand Valley.

CRISIS ON THE COLORADO RIVER RAISES QUESTIONS

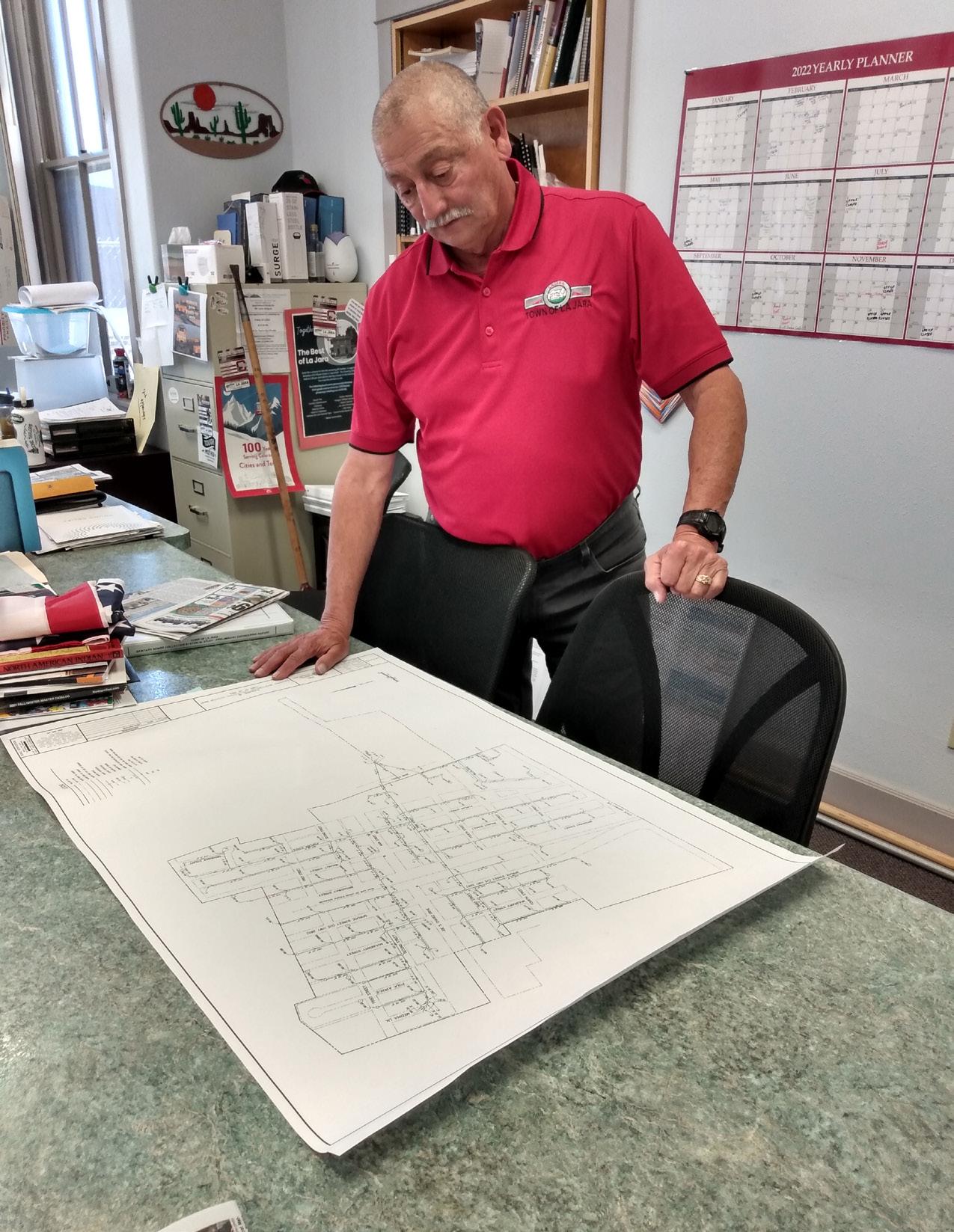

“T here’s an uncertainty for every one,” says Steve Pope, manager of the Uncompahgre Valley Water Users Association (UVWUA), which operates the Uncompahgre Project, a Reclamation project that pipes water from the Gunnison River to the Uncompahgre River, serving more than 76,000 acres of farmland around Montrose and Delta on Colorado’s Western Slope. “We’re solely at the mercy of whatever Mother Nature provides us.”

For 15 of the past 20 years the Uncompah gre system has operated on below-average flows—distributing 70% of shareholders’ allocations last year and just 50% in 2002. UVWUA doesn’t have reliable large reser voir storage above them to store and buffer flows, which makes low-water years hit hard. “We have to live with whatever we’re given,” Pope says.

His system isn’t alone. The western United States is suffering from two decades of drought and aridification due to climate change. River flows have shrunk, and experts say water availability will continue to decline. Meanwhile, all states in the Colorado River Basin are facing a crisis as demand for water has outpaced supply, leading to historic low levels in the nation’s largest reservoirs, Lake Powell and Lake Mead.

Over the past two summers, in 2021 and 2022, Reclamation ordered water releases to taling some 650,000 acre-feet from its Upper Colorado River Basin reservoirs—Flaming Gorge in Utah, Navajo in New Mexico, and Blue Mesa and the other Aspinall Unit reser voirs in Colorado—to boost water levels in the bigger downstream reservoirs. To further stabilize the system, it also held back water in Lake Powell that would have normally been released to Lake Mead and called for all the states in the basin to develop a plan to conserve an additional 2 million to 4 million acre-feet of water, a significant amount that left many water users very concerned.

Reclamation’s August 16, 2022 deadline for the states to develop such a conservation plan passed without consequence, and the states continue to work with the agency toward that goal. But as water levels continue to fall, water users continue to express concern that they could soon be required to use less water.

“I don’t think it’s ever going to go away,”

Pope says of the risk to water users and worry as Colorado River system water levels continue to drop. “What makes us concerned is where is this going to come from? If [federal officials] say we’re going to cut 20% next year, we’re going to cut 20% of what? That’s my concern. Having a bad year and needing to make additional cuts.”

But Pope’s system and others also face the added risk of relying on Reclamation-owned water rights and infrastructure. “That creates the uncertainty,” he says. “Do they have the ability to say ‘Hey, you can’t use your water this year’? We don’t know. I don’t think they’re going to take that approach but because we don’t control anything, it certainly gives us some concern.”

RECLAMATION AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE WEST

Reclamation’s footprint in Colorado began in 1903, the year after the agency’s creation. According to the agency’s senior historian, Dr. Andrew Gahan, “Reclamation was designed to aid in settlement of the American West through the construction of irrigation facilities.”

Its first project in the state did just that. The Uncompahgre Project was completed in 1909, and at the time, its Gunnison Tunnel was the longest irrigation tunnel in the world. Also built in the early 1900s was the Grand Valley Project, which diverts Colorado River water into an extensive network of canals and ditches, now serving more than 30,000 acres of vineyards, orchards and other operations in the agricultur al area around Grand Junction.

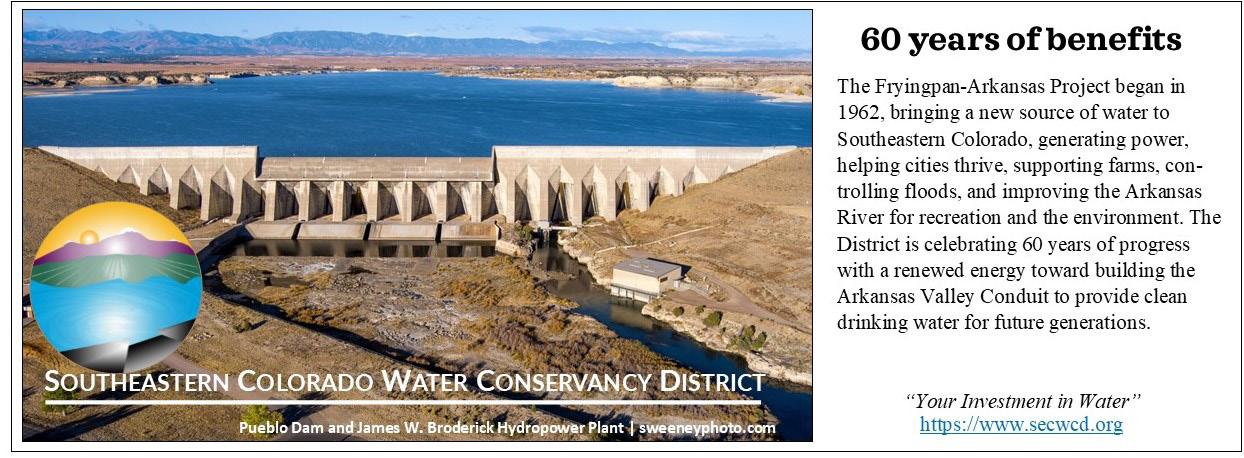

Those seminal projects, while still responsi ble for irrigating much West Slope agriculture, are dwarfed by what came later, during what Gahan refers to as the “big dam era.” That’s when Reclamation built the Colorado-Big Thompson Project (C-BT), completed in 1956, and the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project (FryArk), completed in 1982, which, taken together, today serve more than 1.9 million people and 800,000 irrigated acres. Proponents of these projects—the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District for the C-BT Project, and the Southeastern Colorado Water Conservancy District for the Fry-Ark Project—contracted with Reclamation, agreeing to pay back a por tion of the project’s cost over time. Today those conservancy districts help manage the projects though Reclamation owns the infrastructure. Gahan says that the big dam era, which ran from approximately the 1920s to the 1970s,

was characterized by complex, multi-purpose projects, including extensive investments in hydropower, which helped offset project costs.

Even during this project-building era, people realized that these reservoirs came with environ mental and social tradeoffs. Both the C-BT and Fry-Ark projects move water from the Colora do River Basin to the eastern side of the state through complex systems of diversions, transba sin tunnels, pumps, power plants, reservoirs and canals. They supported the growth of Colorado’s Front Range by bringing supplemental water to the drier, more populous part of the state—water that originated on the Western Slope and no lon ger flows farther downstream from its diversion points in those rivers. In the 1930s, Colorado set guidelines that these transbasin projects create compensatory storage in the form of West Slope reservoirs to mitigate their impacts on present and future West Slope development. Reclama tion built those compensatory reservoirs too, along with the project proponents, often as the first piece of a transbasin project. For the Fry-Ark Project there’s Ruedi Reservoir, and the C-BT provided Green Mountain Reservoir for compensatory storage.

Complex water projects like these became harder to authorize by the 1970s, largely due to “a developing environmental consciousness in the United States,” explains Gahan. “This is where you see a bevy of environmentally cen tered acts passed by Congress.” Chief among them was NEPA, the National Environmental Policy Act, but this period also saw passage of the Endangered Species Act, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act and the Clean Water Act. This ushered in the “water management era,” as Gahan calls it, when Reclamation’s focus shifted away from building so many new projects and toward managing them.

MANAGING WATER RESOURCES INTO THE FUTURE

Today, Reclamation’s management role takes many forms, from maintaining infrastructure to working alongside partners as they plan and design updates to projects, line canals to improve efficiency and manage water quality impacts, and much more.

“They’re like having a good partner who knows just as much about your business as you do,” says Tina Bergonzini, general manager of the Grand Valley Water Users Association, which works with Reclamation on the Grand Valley Project. “From my perspective, Reclama tion has been an excellent partner.”

22 • WATER EDUCATION COLORADO

While Reclamation doesn’t have plans for major additions to its systems beyond the components that were originally authorized by Congress, project partners do, says Jeff Rieker, area manager for Reclamation’s Eastern Colora do Area office.

Northern Water is currently building the new Chimney Hollow Reservoir in Larimer County, which will rely on “excess capacity” in the C-BT’s Adams Tunnel to move more Colorado River water east. It’s also working on permitting two other reservoirs on the East Slope, Glade and Galeton, as part of the Northern Integrated Supply Project. Once complete, these three reservoirs will provide Northern Water the additional storage capacity of 305,000 acre-feet.

Work is also underway on the Arkansas River, to build a pipeline delivering Fry-Ark water to the southeastern part of the state where water users have long relied on unhealthy, contaminated groundwater. This Arkansas Val ley Conduit was initially part of the proposed Fry-Ark Project, but it got scaled down and cut out when communities couldn’t afford to cover the costs. Now, it’s finally becoming a reality.

Many environmentalists and scientists have looked askance at new major water projects in a time of aridification, but Northern Water says that more storage is a critical component,

along with ongoing water conservation, to ensuring water security as their region’s popu lation grows.

“Yes, we are seeing more dry years, but there are occasional years that are actually above average,” says Jeff Stahla, spokesperson for Northern Water. “Having storage available to capture those above-average precipitation years is going to be vital to help us get through what may be more of the lower precipitation years.”

“The general [storage] trend in the last few years has been downward,” says Jason Ullmann, deputy state engineer for Colorado’s Division of Water Resources. “Back-to-back dry years have an outsized influence on reservoirs, and that’s what happened, at least until this year because of the monsoon and because the snowpack wasn’t quite as bad.”

During dry seasons and dry years, reservoir storage enables farms and ranches to continue irrigating and provides water for town and city municipal water systems.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of the Interior and Reclamation are scrambling to protect their major infrastructure on the Colorado River, with water users reliant on that infrastructure concerned for the future and a loss of control.

“The whole gist of it is, if Reclamation decid

ed they wanted a specific amount of water, it wouldn’t really matter if it was a reservoir or if it was a river [direct flow water] right, it’s their water,” says Bergonzini. “But from my perspective, Reclamation has been an excellent partner, they have helped Colorado agriculture so much, I really don’t see them walking away from that now.”

Rieker at Reclamation acknowledges that the future of federal involvement in Colora do River issues in the state may lead to some “difficult decisions” but that the agency’s approach doesn’t appear to be changing.

Rieker points to an August 2022 news release from Reclamation saying, “The Department’s approach will continue to seek consensus support and will be based on a continued commitment to engage with part ners across the Basin states, tribes and the country of Mexico to ensure all communities that rely on the Colorado River will provide contributions toward the solutions.” H

Olivia Emmer is a freelance reporter and photographer based in Carbondale, Colorado. Her writing has been featured in Fresh Water News, Aspen Daily News and The Sopris Sun. Emmer specializes in stories about the environment.

HEADWATERS FALL 2022 • 23

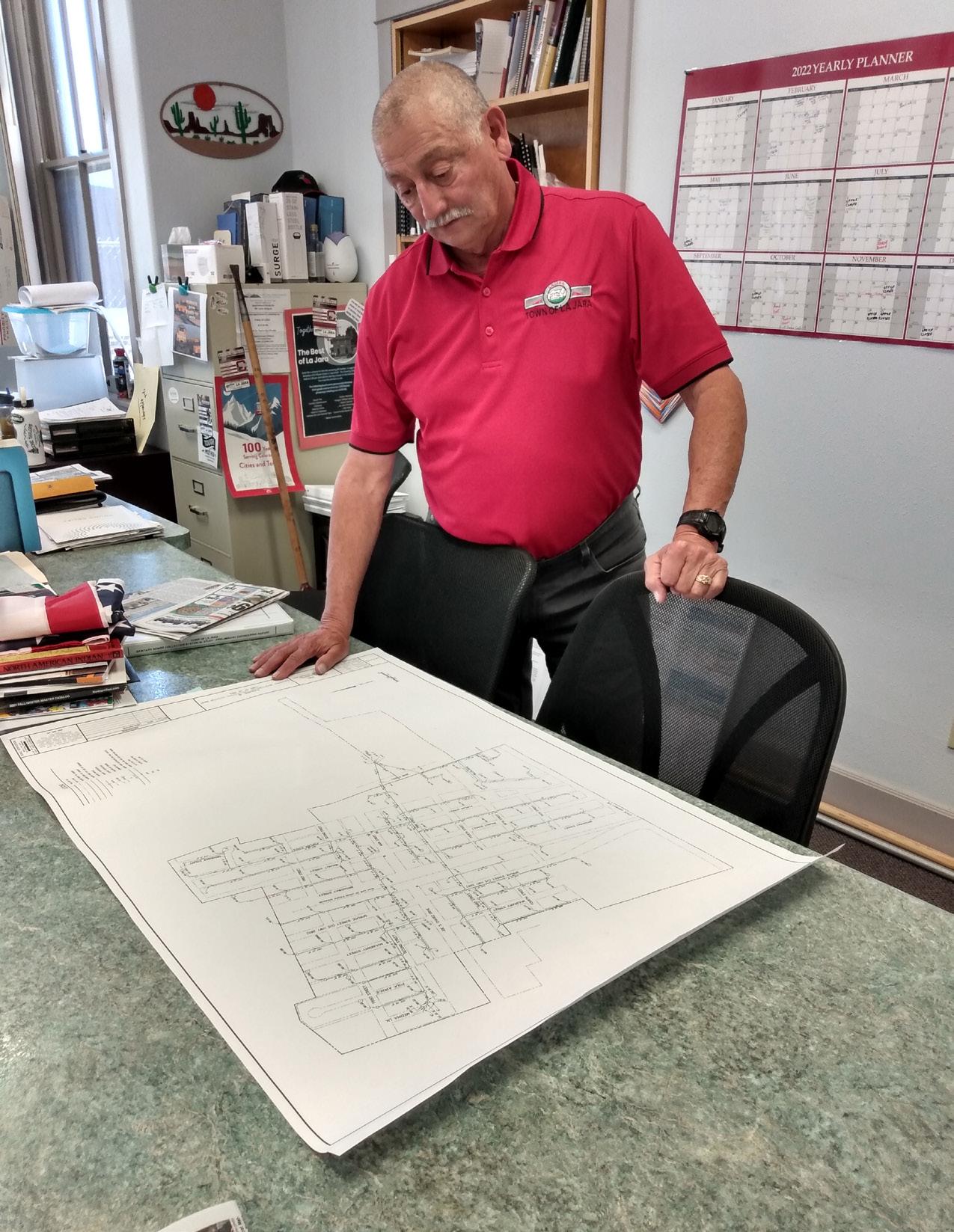

The Gunnison Tunnel is a key part of the Uncompahgre Project, which was completed in 1909 as the first U.S. Bureau of Reclamation project in Colorado. The project was built and is still owned by Reclamation. Today it continues to convey Reclamation-held water rights from the Gunnison River to the Uncompahgre Valley but is managed by the Uncompahgre Valley Water Users Association to serve farmland around Delta and Montrose.

William Woody

In October 2020, dignitaries, including two Colorado senators and federal officials, attend a groundbreaking ceremony at the base of the Pueblo Dam for the Arkansas Valley Conduit project that will provide safe drinking water to nearly 50,000 residents in southeastern Colorado.

A NEW WAVE OF WATER INVESTMENT

Since 1962, people in Colorado’s Lower Arkansas Valley have heard talks of a pipe line that would bring them clean drinking water from Pueblo Reservoir upstream.

The 103-mile Arkansas Valley Conduit promises to be a long-term source of clean water for the region, where many people rely on poor-tasting and contaminated well water. The project was planned as part of the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project, but for decades, the pipeline was too expensive for the small towns to afford, $600 million by today’s estimates.

The project picked up momentum in 2009, when

BY THY ANH VO

Congress amended legislation so that the federal government would contribute almost two-thirds of the project’s cost. Construction finally began a decade later, after another boost in federal funds. If the project stays on schedule, the pipeline will reach its easternmost destination, the town of Lamar, Colorado, in 2035.

Now, with $60 million in new funding from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, officials are hoping to cut the project’s remaining 13-year timeline in half—and ensure steady access to clean water for more than 50,000 people living east of Pueblo along the Arkansas River.

“People have waited 60 years to build this,” says

24 • WATER EDUCATION COLORADO

RJ Sangosti

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law will make historic investments in Colorado water but getting the money to communities won’t come easy

Chris Woodka, a spokesperson for the Southeastern Colorado Water Conservancy District. “The Biparti san Infrastructure Law has made it entirely feasible that we could do this in a much shorter time.”

Also known as the Infrastructure, Investment and Jobs Act, the law, enacted in 2021, authorizes more than $550 billion in new investment that will be spread across the nation, including more than $50 billion for clean water programs and another $8.5 billion for Western water needs. The historic federal investment comes as Colorado and other Western states face growing pressures from climate change, drought and a regional crisis along the Colorado River.

The funding won’t resolve the drought. But the law is an opportunity to fund critical repairs on neglected water systems, many which were built at the turn of the century.

Amy Moyer, director of strategic partnerships at the Colorado River District, hopes it will inspire water managers and public servants, who are used to engineering workarounds and funding projects piecemeal, to be more ambitious.

“It’s really giving [people] the license to think big,” Moyer says. The river district is giving grants to en tities in its 15-county area to conduct studies and de velop competitive applications for the federal money. “Projects that were previously unachievable because of a huge financial cost might be back on the table.”