THE COLORADO WATER PLAN UPDATE

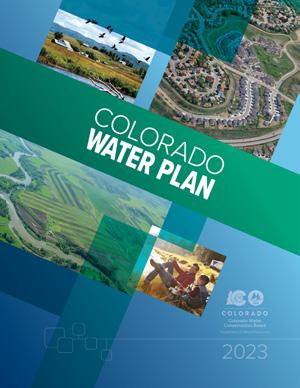

THE WATER PLAN UPDATE ISSUE Balancing climate change impacts and the demands of a growing population, Coloradans are working toward a sustainable water future. Released in January 2023, the updated Colorado Water Plan pairs a vision for the state’s optimal future with scenario planning and specific actions to get us there and to help manage risk. Now is the time to get acquainted with what’s inside. While much about the new state water plan is fresh, it didn’t surface out of nowhere. It includes years of stakeholder input and follows the work put into the 2015 water plan. So, what have we accomplished since the state’s first water plan? And where are we going next?

The Colorado Water Plan charts a path toward a more sustainable water future—but what is the water plan exactly? How does it work? And how are Coloradans already using it?

By Kelly Bastone

The updated water plan includes a list of 50 actions to spur stakeholder involvement. Explore a selection of those and see how you can take action.

By Caitlin ColemanColorado’s first water plan forged a neverbefore created roadmap for the state’s water future while the 2023 water plan aims to move Coloradans toward more accountable action. Now, with the updated water plan in hand, state leaders reflect on the course the new plan is setting.

By Emily PayneWhat progress have stakeholders made over the past seven years toward the goals set by the 2015 water plan, and how do those success stories align with the updated plan’s new vision?

By Emily Payneby

Developing, implementing, and then updating the Colorado Water Plan—the focus of this Headwaters issue—has been an exercise of collectivity.

Before our first state water plan was developed, the Colorado Legislature had passed, in 2005, the Colorado Water for the 21st Century Act. The act established the basin roundtables, key groups for each river basin that became instrumental in the development of the water plan 10 years later.

We published an issue of Headwaters, in 2009, to report on the roundtables’ early progress. We titled the issue “Cooperation vs. Competition: Coloradans in Search of Common Ground and Workable Solutions.” It was a big leap forward to move away from competition, and to instead bring diverse communities and stakeholders together to start identifying and elevating shared priorities to solve collective problems.

Fast forward to today, and the roundtables are still advancing the kind of collaborative solutions that are central to the Colorado Water Plan. Among their members are Public Education, Participation and Outreach liaisons, who do the critical work of informing their communities about the workings of the roundtables, the priorities they’ve each outlined in their basin implementation plans (BIPs), and the funding available to support projects.

Last spring and summer, Water Education Colorado partnered with the roundtables and their PEPO liaisons to host tours in each river basin focused on elevating the roundtables’ priorities and successes. We showcased projects ranging from wildfire mitigation, to aging infrastructure upgrades, to fish passage, to water storage. We used the tours to help highlight that the Colorado Water Plan was being updated, and to invite more people into the conversation.

The tours were just one facet of Water ’22, the year-long public awareness campaign WEco spearheaded in 2022. Among the goals of Water ’22 was to motivate more Coloradans to take a proactive role in the state’s water future. That could mean taking action as a consumer with the “22 Ways to Care for Colorado Water,” or getting involved in local water planning processes, like the basin roundtables, or by weighing in on the water plan update.

More than 130 people participated in the tours. And through the wide-ranging strategies Water ’22 employed, including bilingual campaign materials, we estimate that we touched nearly 1 million people with the message that we all need to do our part to preserve Colorado’s valuable water resources for future generations. (View the campaign highlight reel at wateredco.org/programs-events/water-22/)

We’re proud of what we accomplished last year, and of the role we play in bringing more people into the conversation about Colorado water. And we’re grateful to all who provide resources and work alongside us in this collective effort.

2022 may be over, but we’ll keep using our programs and outreach efforts to engage Coloradans in being part of workable solutions for a sustainable water future.

Jayla Poppleton Executive Director

Sabrina White Programs Director

Suzy Hiskey Administrative Assistant

Cailyn Andrews Education and Outreach Coordinator

Jerd Smith Fresh Water News Editor

Caitlin Coleman Publications and Digital Resources Managing Editor

Charles Chamberlin Headwaters Graphic Designer

Lisa Darling President

Dulcinea Hanuschak

Vice President

Brian Werner Secretary

Alan Matlosz Treasurer

Cary Baird

Perry Cabot

Nick Colglazier

David Graf

Eric Hecox

Matt Heimerich

Julie Kallenberger

David LaFrance

Dan Luecke

Karen McCormick

Leann Noga

Peter Ortego

Dylan Roberts

Kelly Romero-Heaney

Ana Ruiz

Elizabeth Schoder

Don Shawcroft

Chris Treese

Juanita Valdez

Katie Weeman

THE MISSION of Water Education Colorado is to ensure Coloradans are informed on water issues and equipped to make decisions that guide our state to a sustainable water future. WEco is a non-advocacy organization committed to providing educational opportunities that consider diverse perspectives and facilitate dialogue in order to advance the conversation about water.

HEADWATERS magazine is published three times each year by Water Education Colorado. Its goals are to raise awareness of current water issues, and to provide opportunities for engagement and further learning.

THANK YOU to all who assisted in the development of this issue. Headwaters’ reputation for balance and accuracy in reporting is achieved through rigorous consultation with experts and an extensive peer review process, helping to make it Colorado’s leading publication on water.

© Copyright 2023 by the Colorado Foundation for Water Education DBA Water Education Colorado. ISSN: 1546-0584

CSU Spur, Hydro/The Shop, 4777 National Western Drive, Denver, CO 80216 (303) 377-4433

As part of the Water ’22 campaign, Water Education Colorado partnered with Colorado Humanities to offer the Water ’22 Student Showcase. K-12 students across Colorado were invited to submit an art or science piece that reflected why water matters to them. After receiving 169 amazing entries, we announced the top four Water ’22 Student Showcase winners selected by our panel of judges in November. Meet the winners:

Grand Prize

Cheyenne Comer

11th Grade

Painting & Drawing

Pueblo, CO

1st Place

Oskar & Teddy Leopold

3rd Grade + Kindergarten

Modeling & Engineering

Niwot, CO

2nd Place

Leia Albrecht 11th Grade

Creative Writing

Durango, CO

3rd place

Erica Dornberger

8th Grade

Painting & Drawing

Aurora, CO

Check out the full set of top entries to the Water ’22 Student Showcase at water22.org/youth-engagement or visit the in-person exhibit at the CSU Spur Hydro building beginning in April!

Water Education Colorado welcomed Sabrina White as our new Programs Director in January. Sabrina came to WEco from a consulting background, working with governments and nonprofit organizations. She holds a master's degree in Political Science from the University of Colorado–Denver with a focus in Political Theory. Sabrina enjoys spending evenings playing guitar and piano, and attending concerts around Denver. On weekends, Sabrina loves to canoe, raft, and hike with her wife and dogs in the Colorado mountains. Sabrina will be leading Water Leaders, Water Fluency, Basin Tours, and helping shape other WEco programs. Look for her at an upcoming WEco event!

Coming your way this summer is WEco’s Annual River Basin Tour! Mark your calendar for June 6–7, when around 50 water professionals, agricultural producers, elected officials, educators, and interested community members will have the opportunity to ride with us on our tour of Northwestern Colorado. This year’s multi-day tour will feature site visits to locations in the Yampa and White river basins, including reservoirs, agricultural ditches, parks, and river confluences. You'll also hear from speakers about issues facing Colorado water including discussions of climate, hydrology, and more. Registration opens soon. Join a notification list or register at wateredco.org/tours.

WEco’s first Spanish-language reference primer is now available! We’ve translated the Guide to Where Your Water Comes From into Spanish and are excited to more equitably share water information with new audiences. Know someone who needs a copy or an organization for us to partner with? Let us know. Or order your copy from our shop at watereducationcolorado.org.

In publishing any issue of Headwaters magazine, we seek to include various perspectives from all corners of Colorado. While we work hard to hear and understand the many individual experiences and facets of every story, it can be a challenge to identify and elevate those who are most underrepresented. For this issue on the Colorado Water Plan update, it feels particularly important to highlight the countless people who are involved or affected.

Just take “Around the State” (page 8), where we talk with key leaders and representatives from each of the state’s river basin roundtables. Undoubtedly a multiplicity of additional perspectives and priorities exist among other roundtable members and stakeholders who have been involved in the process of updating the state’s water plan, but which we didn’t have space to include.

Our work with Headwaters is only a microcosm of how difficult it can be to include a broad diversity of voices and viewpoints. What’s amazing is that in their work on the Colorado Water Plan, the Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB) team reached, listened to, heard and incorporated feedback from thousands of people. Outreach work resulted in 1,200 stakeholders engaged in a scoping process before the plan’s drafting began. Another 7,500 people engaged with CREA Results, the firm CWCB contracted to support engagement with underserved communities. Read about their work in “How do Colorado’s Achievements Stack up to Colorado Water Plan Goals—Resilient Planning” (page 28).

Elizabeth SchoderWe spoke with Elizabeth, a member of the WEco Board of Trustees and the Colorado Water Conservation Board’s water planning and community outreach specialist, about equity, inclusion and outreach work in the Colorado Water Plan.

Read more on the blog at watereducationcolorado.org.

Take our anonymous reader survey to share more about yourself, how you think we’re doing, and what you’d like to see from Headwaters magazine and Fresh Water News. It takes about 10 minutes to complete, and you can enter to win one of five WEco journals just by completing the survey. Scan the QR Code to get started.

Now, with the plan published, attention has shifted to beginning, and in some cases, continuing, the work to achieve its vision. At the CWCB board meeting in January of this year, where the board approved the final water plan, board member Jessica Brody commented to staff: “You’ve done such an amazing job of building relationships with individuals and organizations … How do we keep people engaged in actually doing the work? How do we continue to build those relationships and nurture them as future water leaders?”

Later that week at the Colorado Water Congress Annual Convention, Heather Dutton, at the time representing the Rio Grande Basin on the CWCB Board, made an important point about on-the-ground engagement that is central to the water plan’s implementation. “It’s 50/50. We’ve got what CWCB can do and what our partners can do. There’s this highlight that our partners need to also engage and implement planning in their neighborhoods.” See how you can take action in “Your Role in Colorado’s Water Future” (page 18).

At Water Education Colorado, we’re also encouraging that involvement in Headwaters magazine and in Fresh Water News, where it’s a priority to engage our community. If you look to the left side of this page, you’ll see a QR code for our first-ever reader survey. We’re looking for overall reactions but also input on what you’d like to see us cover in our reporting. We’d love your help in shaping future issues, connecting with new perspectives, and reaching new audiences.

I look forward to hearing your input on how we can best serve you, our readers, as well as to seeing how Colorado will continue to activate and implement the water plan for the benefit of all Coloradans—including those who are new to the conversation.

The more people that engage with the Water Plan, understand how they fit into it, and are then inspired to take action ... the better off we'll be.

Reflections from around the state on the updated Colorado Water Plan, basin implementation plans (BIPs), what’s been accomplished since the first water plan’s release in 2015, and priorities for the future.

“We’ve done a lot of planning on the roundtable; we’ve had a crazy amount of hours of conversations, crazy analyses done to us by the roundtable. We’re at a point where we want to start implementing some of these bigger projects. That’s where the success of the water plan is … There are some people that have real critical needs here that cannot be met; there's no way to meet them without implementation of bigger projects within our BIP. It’s not just for agriculture, it’s for the compact, it’s for industry, it’s for crazy amounts of beneficial uses, and they just can’t be met without these projects.”

Alden Vanden Brink, Yampa/White/ Green Basin Roundtable Chair, director of the Rio Blanco Water Conservancy District“It was interesting, for me at least, in developing this second edition of the BIP to see how much our original BIP had fostered stream management planning and integrated water management planning processes. We’ve done those on the Crystal, Roaring Fork, Upper Roaring Fork, the Blue River … the Eagle River Community Water Plan which is in progress, also the Grand Valley Watershed Plan. And most recently Grand County, who had the first SMP in place, is updating theirs, partially with basin roundtable funding. That was exciting to see how we’ve covered pretty much every area in the Colorado River Basin with some thoughtful integrated water management planning … it was really interesting, looking back when we were putting together this most recent edition of the BIP, just how far we had come.”

Jason Turner, Colorado Basin Roundtable Chair, senior counsel for the Colorado River District“Looking forward we are really focusing on aging infrastructure projects in the ag sector and helping our ag producers remain constant and viable. We want to see them be successful because that is the true basis of our economy here. That would be our primary goal, and just barely secondary to that is wildfire mitigation and protection of resources after wildfires. We have a number of programs running for watershed protections, forest thinning, and wildfire protections, and we feel that we work very well in that space also.”

Wendell Koontz, Gunnison Basin Roundtable Chair, Delta County Commissioner SOUTHWEST

“The Water Plan is pretty much the mirror image of what’s in the BIP for the tribes. This is a great step forward … What is pointed out in the BIP with regard to the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe is, at the time when the plan was written, they had formed a water resources committee and they had tried to organize a water resources department. That is happening. The tribe got funding to get that department started and we’re advertising for a director right now. The water resources committee’s priorities were to create a formal water resources department and to develop a strategic water resources plan. That plan is unfolding at the same time.”

Mike Preston , former Southwest Basin Roundtable Chair, water advisor to the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe Water Resources Committee

“One of the things that were looking forward to down here are the forest restoration initiatives going on, and the focus on aging infrastructure. The National Wild Turkey Federation and

the [U.S.] Forest Service have made Southwest Colorado one of their priority projects through the Rocky Mountain Restoration Initiative (RMRI) so that’s pretty exciting for to be the focus of that. I know the State of Colorado is looking at [forest health] and paying a lot of attention to it. We really started looking at it with the drought … and looking at it as a way to help increase runoff by selectively thinning the forest and that’s one of the things they’re focusing on with RMRI.

We’re also excited about the CWCB talking about aging infrastructure and drought resilience with the WSRF [Water Supply Reserve Fund]. We’ve been getting a lot of people interested in that.”

Ed Tolen , Southwest Basin Roundtable Chair, manager of the La Plata Archuleta Water District

“It is exciting to see the updated Colorado Water Plan and BIPs acknowledge the progress we've made through implementation of great projects. The updated Rio Grande BIP builds off and incorporates the information from projects that were completed as a result of the [2015] Colorado Water Plan, such as watershed assessments and stream management plans, and contains an ambitious list of priority projects. As we continue to fund and complete these projects, there is satisfaction in knowing we have improved the sustainability of watersheds, streams, rivers and aquifers for all who depend on them.”

Heather Dutton, Rio Grande Basin Roundtable member, former Rio Grande Representative to the Colorado Water Conservation Board, manager of the San Luis Valley Water Conservancy District

“Following the update of our Basin Implementation Plan, a priority for the Arkansas Basin Roundtable has been identifying how we can support the water supply needs of smaller communities and stakeholders in our basin that have less resources. By focusing in on the more rural and resource-constrained areas of the basin, we want to improve our outreach and make sure we’re providing support to assist those communities to identify their water supply needs and help move those forward as projects that we can help implement using Water Supply Reserve Fund and Water Plan grants. That's always been part of what the roundtable does in our basin, but we’ve become more focused on that role.”

Mark Shea , Arkansas Basin Roundtable Chair, watershed planning supervisor for Colorado Springs Utilities

“We had a plan in 2015, and we went out and tried to implement it as best we could. In my view we did well, given the challenges we faced. Having the opportunity to renew the BIP and the water plan kind of reset us to go at it again. I’m happy with that renewal of the plan, and I’m excited about what the future’s going to bring. I’m excited, but we’re going to have a lot of challenges taking the new BIP and water plan and moving it forward.”

Garret Varra, former South Platte Basin Roundtable Chair, president of Varra Companies

METRO

“There are two elements of the South Platte BIP that I’m most excited about. First, the project database. For the first time we have a comprehensive list of projects throughout the basin that we can use to track progress and update as plans change. The second element I’m excited about is that the

two roundtables in the basin—the Metro Roundtable the South Platte Basin Roundtable—have jointly agreed on basin priorities to advance stakeholder understanding of water use in a changing environment and are developing scopes for studies to provide a common understanding. We are optimistic we’ll be able to replicate this success with environmental and recreation priorities in the future. The continued collaboration of the South Platte and Metro roundtables is a model for ag and municipal, and rural and urban interests to work together for the benefit of all.”

—Barbara Biggs , Metro Basin Roundtable Chair, general manager of the Roxborough Water and Sanitation District

NORTH PLATTE

“One of the primary goals of the 2015 and 2022 North Platte Basin BIPs is replacing aging irrigation infrastructure to improve the function and efficiency for both agricultural and environmental/recreational water use. We have benefited from the yearslong support from NRCS [Natural Resources Conservation Service] and Owl Mountain Partnership for writing and administering some of the Water Supply Reserve Account project grants. The Colorado Ag Water Alliance has been helpful in preparing grant applications. Now CWCB has enhanced the capacity for grant writing by hiring a regional support person to help our water users. Lightly populated basins like the North Platte just don’t have sufficient local capacity.”

—North Platte Basin Roundtable

Since 2015, the Colorado Water Plan has helped communities navigate the challenges of water scarcity. With the 2023 update to this landmark roadmap in hand, the question remains: How might it spur meaningful change across our cities, farms, and cherished watersheds?

Five miles long and surrounded by juniper-covered mesas, Ridgway Reservoir contains untold treasures—if you’re an angler who dreams of hooking gem-colored trout. Rainbows and browns, as well as kokanee salmon, thrive in this impounded segment of the Uncompahgre River south of Montrose, Colorado. Paddleboarders and campers also flock to its idyllic waters, yet ever since it was built in 1987, there’s been a significant problem with the reservoir: It was never connected to the region’s municipal water treatment and supply system.

When Ridgway Reservoir was completed, municipal supply was intended to be part of its purpose, but over the following decades, the cost of piping water to the region’s water treatment plant some 25 miles away in Montrose stymied municipal connections to the 18,000 acre-feet of water reserved in Ridgway for municipal and industrial use. And because Montrose, Delta, Olathe and other area communities weren’t experiencing water shortages, the dollar investment didn’t seem worth the return.

But the 2000s brought new pressures on the Uncompahgre Valley and the rest of Colorado. Drought, aridification, and the growing threat of catastrophic wildfires made the communities aware of their singular reliance on the Gunnison River and one water treatment plant. What if natural catastrophes took that water offline, even temporarily?

The region’s Project 7 Water Authority, which serves 60,000 water users in Ouray, Montrose and Delta counties, decided that it couldn’t expose area water users to a potential shut-down. This summer, Project 7 will break ground on a pioneering new water treatment plant just downstream from Ridgway Reservoir, south of Colona, that will use gravity-fed pipes to deliver a second, backup source of water to Uncompahgre Valley municipalities. Plans to revive the vision for this treatment plant, securing a second water supply to minimize risk and instability arose in 2018, following a risk assessment completed by Project 7 in 2014.

“We wanted to be proactive, not reactive,” explains Project 7 general manager Adam Turner. There’s much more state support for water planning today than there was in 1987. Now Coloradans have a central document that supports projects such as the construction of the Ridgway plant: the Colorado Water Plan.

“Watching the water plan get developed, I’m much more aware of all the pressures on our supply,” Turner says. With the dialogue of the water plan in his mind, and statewide water planning efforts happening in parallel with the recently completed risk assessment, “all these things came together,” he says.

Although the Uncompahgre Valley’s communities aren’t currently facing water shortages, they are confronting water supplies that look increasingly inadequate to continue to meet the region’s needs. Moreover, catastrophic wildfires and other climate impacts represent a growing threat to water certainty if Coloradans don't plan for and address them. This poses a risk to both cities and to the places the water will come from.

Projections issued by the Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB) show demand for water increasing across all sectors. If Coloradans don’t take action, households and industry could face critical water shortages, farm and ranch land could be permanently dried up, and competition for water could exacerbate environmental concerns. The water plan frames up these risks alongside actions that Coloradans can take to reduce them.

In 2013, then-Governor John Hickenlooper called for the CWCB

By Kelly BastoneRidgway Reservoir near Montrose, Colorado, though built with municipal water supply in mind, was never connected to the Uncompahgre Valley’s water treatment or distribution systems. Recent planning efforts revealed the vulnerability of relying on just one water source, so a new water treatment project is moving forward, just downstream from Ridgway Reservoir, to provide redundancy in supply.

to create the first-ever Colorado Water Plan, which analyzed the gap between the state’s projected growth and its future supply of water. Thirty months of meetings involving stakeholders from Colorado’s nine basin roundtables, which represent the state’s eight major river systems and the Denver metro area, resulted in a plan published in 2015. It articulated a new, more collaborative paradigm for managing water across the state, describing goals for increased and improved water storage, conservation and water reuse, watershed health, disaster management, agricultural viability, recreational use, environmental protection, and public outreach and education.

The CWCB was also tasked with implementing the plan using largely the same tools that the agency has always had—providing funding, offering technical support, and supplying data and information to help inform local decisions. Notably, the CWCB is not a regulatory agency and can’t require any agency, group or local authority to take action. However, through the more than 835 water projects funded through various CWCB grant programs since 2015, and many conversations along the way that have influenced work at the local level—like Project 7’s treatment plant to manage risk— the agency learned what made the initial plan successful and what elements didn’t work.

The 2023 update to the Colorado Water Plan refreshes the document’s relevancy and promises to spur new collaboration around water solutions. It’s an all-hands call to action, given the high stakes of water shortages.

“We are facing the slowest-moving natural disaster,” observes Josh Kuhn, water campaign manager for Conservation Colorado. His nonprofit has been involved with the Water For Colorado coalition which encouraged public comment on the draft water plan and advocates for the water plan and basin implementation plans to address conservation, the environment, recreation and equity. To fend off catastrophe, communities have no panacea—but at least they have a plan. Here’s how it works.

If Colorado’s 2015 water plan placed the state on the vanguard of water preparedness, alongside governments such as California and Idaho that had already crafted comprehensive statewide plans for water management and development, the 2023 plan blazes a new trail in ways that embrace Colorado’s legacy, its unique qualities as a local control state, and the range of forecasted future scenarios that lie ahead.

The new plan reinforces the protection of the state’s peoples and cultures, local food and agricultural exports, small rural towns, headwaters communities and major city centers, as well as forests, waterways, wildlife, and the recreation and tourism activities associated with them. How to protect all of this in a state where decision making around water happens at the local level?

“The original Colorado plan set specific targets and measurable objectives,” explains Russ Sands, chief of the CWCB’s Water Supply

Planning Section. However, it did not clearly assign accountability for achieving its measurable objectives.

The new plan sets long-term visions for the state’s future focusing on four areas: vibrant communities, robust agriculture, thriving watersheds, and resilient planning. The plan then backs up those aspirational goals by offering a suite of 100 actions to help get there. While the plan sets a big-picture vision, it will be implemented, in large part, by local water users and decision makers.

The updated water plan provides more than 50 examples of work that stakeholders can undertake to help achieve its vision and that could be supported by Water Plan Grants. Those partner actions are balanced by 50 agency actions the CWCB will implement through convening discussions, highlighting critical issues, funding local collaborative projects, and supporting on-the-ground efforts with tools, research and other initiatives. Those CWCB goals will dictate the agency’s work plan going forward. Partner actions, on the other hand, offer ideas for projects that could be eligible for grant funding and examples of ways individuals can engage on various scales—from learning more and attending meetings to organizing a new coalition or project.

Much of the plan’s power to drive change ultimately rests in local hands. “Some plans are very prescriptive and take a top-down approach,” says Greg Felt, the Arkansas River Basin representative on the CWCB board. “Here, we operate more from the ground up.” For example, the state doesn’t build water projects; instead, it leans on local entities and coalitions of partners to identify projects and solutions that address their unique water needs. On a regional level, each basin roundtable updates their basin implementation plan (BIP) to identify local water and river management needs and recruit regional players who can implement action items. “Things start at the local level, and CWCB helps bring those projects across the finish line,” says Felt.

And because the Colorado Water Plan emphasizes the importance of collaboration among stakeholders, CWCB expects its grant recipients to demonstrate that their projects provide multiple benefits across various water users and groups. That’s forced people to change their siloed habits, says Lauren Ris, CWCB’s deputy director.

Since 2017, Colorado Water Plan Grants, funded in varying amounts annually, have totaled more than $61 million. They’ve funded projects proposed by ditch companies, non-profits, small businesses, institutes of higher learning, and municipalities—often working together. Thus, ranchers, for example, who want water plan money to replace a headgate or diversion might partner with Colorado Parks and Wildlife, environmentalists and recreational entities to propose a project together that could benefit wildlife, paddlers and ranchers.

“Across the state, the need for water projects is so great that our funding can’t achieve it all,” explains Ris. “So we get a bigger bang for our buck when we see people pooling benefits and collaborating.”

That multi-benefit expectation has created valuable opportunities for non-consumptive water users. Recreationists and environmentalists, who typically rely on water that isn’t diverted from water sources or removed from the system, hence “non-consumptive,” have more opportunities to participate as

Water supplies may be stressed, but Coloradans can manage that risk. In Colorado we use water for many things: drinking, watering lawns, rafting, fishing, growing crops, brewing beer, operating businesses, and more. The amount of water needed for those different uses, also known as water demand, is driven by many factors: population growth, climate, the extent to which we conserve, and more.

While municipal and industrial water users currently have enough water to meet their needs in most years, a growing population—projected by the State Demographer’s Office in October 2022 to reach 7.5 million people by 2050—and climate conditions will up the risk of a gap developing between available municipal water supply and demand. The 2023 update to the water plan projects a statewide municipal and industrial gap of between 230,000 acre-feet to 740,000 acre-feet in dry years by 2050. But, the plan says, water supply projects and municipal conservation efforts can significantly reduce that gap.

Colorado’s agricultural industry already faces a gap between supply and demand—many producers experience water shortages today. The water plan projects that, under the hottest scenario that the state planned for, future gaps could worsen beyond current conditions by up to 200,000 acre-feet per year in the Arkansas and Southwest basins and up to 150,000 acre-feet per year in the Gunnison, North Platte, Rio Grande and Yampa-White-Green basins. However, innovative and emerging technologies that reduce water consumption and increase irrigation system efficiencies could significantly lessen that gap.

While there is a risk that Coloradans won’t have enough water in the future to meet every demand, there are tools available to mitigate that risk. Through its Colorado vision, the water plan aims to help guide decisions and develop more innovative solutions needed to meet the uncertainty of the future. It suggests that we should respond by prioritizing conservation and efficiency, implementing creative multi-purpose storage projects, engaging all voices and working together in equitable and inclusive ways, restoring and enhancing our environment, increasing recreational opportunities and access to healthy waterways, protecting agriculture, protecting and enhancing water quality, and making use of the wide variety of tools available to meet future needs.

partners in water management decisions instead of getting boxed out. Historically, these groups weren’t often included in projects, instead following and reacting to decisions of entities holding traditional consumptive water rights.

“The prior appropriation system is a phenomenal system for administering water rights,” says Felt. “But it doesn’t go beyond the basic needs of any entity. The Colorado Water Plan has provided ways to weave non-consumptive uses into the program and establishes a more holistic way of investing in water development.”

Wildfires, for example, can have dire consequences for all Coloradans, from agricultural producers to anglers to innkeepers to homeowners. So the Colorado Water Plan and its 2023 update establish the health of watersheds and forests as a top priority— one that’s bigger and more universal than any single water right. “We will all be diminished to the extent to which we ignore forest health,” says Felt.

By working together and seeking partners among various water users, Coloradans are also achieving significant local victories that promise to make the state’s water future more secure. Perhaps no win seems more surprising than Colorado’s agreement with Kansas over water storage in the John Martin Reservoir.

Kansas and Colorado haven’t always felt particularly chummy when it comes to the topic of water—particularly the Arkansas River’s eastbound flow across the state line.

Negotiated in 1948, the Arkansas River Compact between the neighboring states promised that development in Colorado past that year would not diminish flows to Kansas, and that river water stored in John Martin Reservoir, in southeastern Colorado, some 50 miles west of the Kansas state line, would be divided between Kansas (receiving 40%) and Colorado (60%). The compact only concerns water quantity, not quality.

In 2016, when representatives from Colorado’s portion of the Arkansas River started talking with the Arkansas River Compact Administration (ARCA) about letting Colorado water users increase their storage quantities in John Martin Reservoir, they heard from plenty of nay-sayers.

“People who were familiar with Kansas said we were wasting our time,” recalls Jack Goble, now general manager of the Lower Arkansas Valley Water Conservancy District.

Yet the 2015 Colorado Water Plan had urged Colorado water managers to make the most of all the reservoir storage they could find as a key strategy for meeting current and future water demand. John Martin Reservoir was definitely underutilized.

“It fills once every 20 years,” says Goble. “Usually, the vast majority of space behind the dam is not filled, so it represented a great opportunity to increase stored water without any associated construction cost.” Storing more water in the reservoir would mean that Colorado’s Arkansas Basin water users could manage their water more effectively and transparently, by allowing new efficiency improvements, cooperative water sharing, lease-fallowing arrangements, and more—helping the agricultural community. All Colorado had to do was persuade Kansas to agree.

In 2017, the Colorado team approached Kansas with a collective

proposal that represented many Colorado water users, rather than having each entity approach Kansas solo. Using a $50,000 grant from the CWCB, the Lower Arkansas Water Conservancy District conducted a study that collected estimates from water users who wanted to store water in John Martin. Two more CWCB grants supported the creation of a model that projected potential effects from increased storage on current and future operations. Colorado representatives met some 30 times to discuss these estimates and models with ARCA’s Kansas council. In summer 2022, ARCA agreed to a trial account allowing water users who previously had no storage in John Martin to store up to 20,000 acre-feet of multi-purpose water in the reservoir at a time. Kansas receives 12.5% of that new pool of water as a storage charge for allowing the deliveries. The storage agreement will terminate in 2028 unless extended by ARCA.

Colorado’s aim was water quantity, but quality was what drove interest from Kansas, says Goble. “Their intent is to use releases from the reservoir to improve water quality as it approaches the state line,” he explains. Plus, water efficiency improvements, facilitated in Colorado through the new storage pool, will mean that fewer contaminants leach from the soil and move downstream.

Such a compromise probably couldn’t have happened without the Colorado Water Plan—which directed stakeholders in the Arkansas River Basin to “Promote multiple uses at existing and new storage facilities.” Explains Rachel Zancanella, division engineer for the Arkansas River Basin, “The storage was already there. This account allowed Colorado water users to take advantage of an already-constructed and paid-for vessel, at no additional dollar cost to them.” Plus, the plan’s emphasis on partnerships inspired the collaborative approach that eventually led to parameters both states could agree on.

This new approach of collaboration allowed the John Martin pilot project to move forward while honoring the existing compact—and helped the region make significant gains in water security. But agricultural regions aren’t the only ones that are trying out new ways of approaching old problems. City and county governments are also using the plan to help them re-think growth and development.

All along the Front Range, municipalities are running out of space for new construction. Limited by the foothills to the west, the Denver metropolitan area has expanded to the north and south, where its growth has merged with existing communities. Consequently, some of the fastest-growing areas are on the eastern edge of the urban corridor, such as in Arapahoe County, Colorado’s third-largest county by population, with 655,000 residents.

Back in 2001, when projections forecast intensive growth along Interstate 70, Arapahoe County conducted a groundwater study beneath its unincorporated areas to the east. That assessment prompted the county to adopt guidelines requiring future development to establish a 200-year proof of groundwater supply, a voluntary increase from the 100-year rule that remains the state requirement.

“The Colorado Water Plan prompted us to go beyond minimum requirements to develop a more comprehensive approach to conservation and reuse,” says Loretta Daniel, the county’s long range program planning manager. “We’ve really started to focus on the relationship between land use and water, especially given the additional pressures of climate change,” Daniel continues.

In 2018, the county updated its comprehensive plan to reflect the need to reduce water consumption and develop water reuse policies, goals that were also outlined in the state water plan.

The updated Colorado Water Plan calls for transformative landscape change and more integrated land use planning to reduce water use and to better coordinate the funding and planning of this work. In keeping with that idea, Arapahoe County is increasing communication among various water users within the county, from water suppliers to the City of Aurora. “We’ve developed a more strategic and collective approach to water in the county, and with everybody knowing what everybody else is doing, we can make better forecasts about water demand,” Daniel says.

Another step in this approach was launching a comprehensive study of the groundwater that underlies the entire county, not just the unincorporated portions. Arapahoe County initiated the 18-month study in January 2023, using a $125,000 grant from CWCB and $300,000 from the county’s American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) allocation. Not only will the study evaluate groundwater resources but it will also investigate best practices in water-efficient

landscape regulations and potential systems for water reuse, important tenets in the updated state water plan.

“Arapahoe County is really living up to the call to action from the Colorado Water Plan,” says CWCB’s Ris. “They are integrating land use planning and water planning by working with water providers to strengthen their comprehensive plan update as well as revamping their landscape codes to reflect a 21st-22nd century approach to sustainable water management,” Ris continues. “Additionally, they are taking steps to adapt to climate change realities by replacing nonessential turf with climate and water-wise landscapes.”

Daniel acknowledges that such changes may ultimately limit development. “The bigger question that really comes out of all this is, how much will water limit our growth?” she asks. For the smaller communities on Arapahoe’s County’s eastern edge, those limitations may be significant.

Ultimately, Daniel expects the study to prompt an array of changes to county codes and zoning regulations, perhaps ones implementing new regulations on turf lawns and the adoption of a 300-year rule for groundwater. “We know that this groundwater is a finite resource that’s really not recharged except at the foothills. So how responsible are we going to be to future generations as we’re looking at this finite resource?” she asks.

But while development sometimes depends on groundwater, a critical source of water supply in many areas, surface water is the dominant use of water in the state and our environments, wildlife

As reported in the 2023 Colorado Water Plan update

5% decrease in per capita water use achieved through statewide water conservation efforts..

$60+ million

water

grants to fund multi-purpose projects in the categories of

• Agriculture $10+ million

• Engagement & Innovation $3.8 million

• Environment & Recreation $17.8 million

• Conservation & Land Use $7+ million

• Water Storage & Supply $22.8 million

25,000 acre-feet of ag water leased annually has helped cities and farms coexist.

26 new stream management plans have been developed or are in progress.

150+ watershed groups established across the state.

400,000 acre-feet of storage has either been constructed or will soon be completed.

Up to 2.7 million people have learned about Colorado water through outreach, education, and messaging.

18 additional uses of reuse water now allowed through reclaimed water regulations.

62% of Coloradans now live in communities whose leaders have taken training to integrate water and land use planning.

by Colorado voters in 2019, dedicating funding for the Colorado Water Plan Grant Program.

and recreation rely primarily on surface watersheds. The Colorado Water Plan offers a path for protecting watershed health and involving more Coloradans in this work.

“We can’t separate Colorado’s ability to thrive from the health of our watersheds,” says Abby Burk, Western Rivers regional program manager for Audubon Rockies.

Of course, birders share an unusual fondness for the waterfed places where kingfishers and other species thrive. So when the state collected public input on the creation of its 2015 Water Plan, Audubon’s network contributed about 20% of the general comments on priorities and direction for the document. Last year, the membership weighed in again, with 3,400 people signing the National Audubon Society’s messaging about the draft update.

“We all enter the water conversation at different points of interest,” explains Burk. Anglers might look to Trout Unlimited for direction on watershed management. Birders listen to the Audubon Society. “At a time when we all need to lean in and learn more about Colorado’s water, Audubon plays a critical role in keeping people engaged and involved. We speak to people at their point of entry,” she adds.

But it’s a two-way conduit, Burk explains. Audubon works to broadcast environmental needs to CWCB. “We’ve encouraged CWCB to move forward with river health assessments that document the current state of ecological health,” Burk offers as an

example. Not only does that data help Audubon and its partners manage rivers in a sustainable way, but it also helps them restore rivers after wildfire.

Birders already believe in the importance of healthy watersheds. But by including that emphasis in the Colorado Water Plan, the environment becomes a priority that’s shared by all. Because CWCB loans and grants prioritize projects that identify multiple benefits—including environmental and recreational gains—water plan funding has a pathway for reaching natural ecosystems.

And all can read and understand the plan, thanks to its lowjargon, accessible language. “Compared to other states’ plans, this is a very inviting document that’s not overly technical,” says the Arkansas River’s Greg Felt.

“The hope is that people will feel comfortable enough to wade in, so to speak,” Felt puns. After all, water is a notoriously complicated topic. The Colorado Water Plan was written to remove some of that mystery, and ideally, pique residents’ desire to get involved.

That engagement might take place through a trusted nongovernmental organization such as the Audubon Society, forest health collectives, watershed groups, and local or regional committees that seek participation from informed residents who care. “People want in,” says Felt, “And we think of this document as a bridge to involvement.” H

It’s only 24 pages. If you aren’t going to read the full plan, use this for context on what the plan does, the vision and actions it lays out, the data it uses, and general background on water in Colorado.

What is the Colorado Water Plan? How do you use it? How is it set up? How does it build on the past? This chapter’s got answers.

The data behind the water plan was analyzed and published in the 2019 Technical Update to the Colorado Water Plan. Look here to understand the planning approaches behind the plan and the projected futures we’re preparing for without digging deeply into the data.

It’s all about Colorado: Its climate, geography, surface water, groundwater, drought, water use, legal framework, the agencies that work here, and future statewide risk to water users. Here you’ll find some of the statewide data from that 2019 Technical Update to better quantify current and future risks to water users.

Go local! This chapter includes data, projects and plans created by the nine basin roundtables across the state. In 2022 the roundtables finalized updates to their basin implementation plans (BIPs) but if you want a quick look at what’s happening in one or all of the basins in the state without reading their full BIPs, they’re summarized here.

Colorado water faces a number of risks in the future but it also has a host of success stories and an entire toolbox with resources like policy, planning, funding, equity, innovation, collaborative groups, and more to address those challenges. Read about them here.

This is the meat of the plan. It lays out a vision for the state’s future and actions: 50 agency actions for the CWCB and collaborating agencies and 50 partner actions for stakeholders to advance the water plan and support the Colorado Vision. If you’re looking for the plan to provide you with a roadmap, it’s here.

Will the plan bring about progress? This section outlines how the actions in the plan will be tracked, how the funding of water plan projects will be tracked, and when and how the water plan will be updated in the future. Expect to see the next iteration of the water plan, and another round of broad stakeholder involvement, between 2031–2033.

Read the plan and executive summary at cwcb.colorado.gov/ colorado-water-plan.

The new Colorado Water Plan relies on people of all sorts, all across the state, to get things done.

“The water plan really sets a shared vision for all of us in how we can meet our water challenges into the future,” said Lauren Ris, deputy director of the Colorado Water Conservation Board, on a panel at the Colorado Water Congress Annual Convention in January. “We all have a role in shaping water policy and I think this water plan illustrates that we all have a role in taking action to face the challenges we’re faced with as a state.”

Want to help? There are actions that you can take to help address Colorado’s water risks. The water plan asks readers to “use the plan as a platform to become more engaged and take action to advance the vision.” There are limitless actions that you can take, but the water plan calls out 50 ideas (see Chapter 6 of the plan for the full list), many of which could be supported by water plan grants managed by the CWCB.

Where to start? Here’s a small selection of actions we’ve adapted from the plan based on the role you play.

Where does your water come from? Learn about your local water sources to understand what the challenges are and why your actions matter.

Buy Colorado grown or made products (check out your local farmer’s market or community supported agriculture program or seek out the Colorado Proud label).

Participate in citizen science initiatives or your local watershed group — even if you haven’t been involved with these efforts in the past, your involvement is important. Can’t find a group that aligns with your interests and concerns? Start one!

Attend a state water meeting (e.g., CWCB board meeting, legislative hearing or committee meeting) or a local water meeting (basin roundtable meeting, water or irrigation district meeting, city council or county commission meeting, or other) to learn more or speak up.

Coordinate with local leaders to advance water policy and projects.

Join a water-focused stakeholder group or apply to join a water-focused board or commission.

Choose your representation. The power of your vote is critical.

Invest in water-efficient equipment in your home, business or farm. Check out water conservation and incentive programs through your local water provider to save water indoors and outdoors.

Take efficiency to the next level. Irrigation efficiency improvements mean more water delivered directly to crops when they need it most, often resulting in higher yields. Similarly, improvements to diversion and conveyance infrastructure can increase water deliveries. Note that return flow timing and amount may be affected by efficiency improvements.

Invest in healthy soils to boost the resiliency of agricultural systems, including water use efficiency. Soil health can also benefit crop growth and may increase profitability. Bonus: Many soil health practices, such as conservation tillage and cover cropping, do triple duty by reducing erosion to improve water quality and store carbon in soils to make agricultural lands a greenhouse gas sink rather than a source.

Rehabilitate and replace old infrastructure, diversion structures and storage. Inefficient diversions may prevent you from diverting your full water entitlement. Rehabbing aging reservoirs can mean fully utilizing water rights and storing additional supplies. Tip: Look into ways to partner and receive funding through multi-benefit projects that increase fish habitat connectivity, provide recreational boat passage, and update agricultural infrastructure.

Is a change in crop type worthwhile?

If you often experience water shortage, innovation in crop genetics and crop selection may provide a more resilient commodity.

Engage! Make your voice heard in planning discussions and speak up to bridge the urban/rural divide and engage the community.

Advance your community’s understanding of water through outreach and education, engaging community members who don’t traditionally participate in water issues. Ideas: Cover basics like where your water comes from to bring your community up to speed. Focus on water efficiency, reuse, or projects that explore ways of doing more with less to demonstrate strategies that others can implement. Promote strategies for agricultural resilience to educate people on local food production.

Develop an actionable water efficiency and drought plan that includes trackable metrics and strategies that are implementable and appropriate for the community.

Go green. Green infrastructure for managing stormwater, such as rain gardens, green roofs, and vegetated swales can slow runoff and improve its quality while creating green spaces in urban areas.

Get the community out on the water by creating new opportunities for water-related outdoor recreation. Prioritize healthy forests. Boosting and maintaining forest health by implementing projects in fireprone forests across governmental boundaries can protect critical water supplies and result in resilient watersheds.

Reconnect floodplains to waterways to slow flood flows, improve water quality, and enhance fish and wildlife habitat.

Look into public-private partnerships. These partnerships can help NGOs and academia fund research and work while the business community promotes innovation.

Help with efforts such as data collection, project implementation, analysis and education. NGOs can often form strong, trust-based relationships with communities that governments can’t.

Expand your network and share your connections. This can include working with the business community to identify adaptive technologies, identifying insights on adaptive practices by engaging Indigenous partners and cultures, or working with students on innovation challenges.

Develop an innovation incubator to foster new thinking around critical Colorado natural resource issues (water, wildfire, forest health) through education, technology accelerators, etc.

Go for the gold by applying for grants, or help disseminate grant application information and seek opportunities to align with other local initiatives to leverage funding and advance the dialogue around water.

Engage your community through activities such as citizen science and local watershed groups. Watershed planning relies heavily on the sitespecific knowledge and ideas of individuals. Engaging with citizens not traditionally involved in watershed planning will be key.

ou run the risk, if you’re not thoughtful about [water planning], to fundamentally change what Colorado looks like,” said state Sen. Cleave Simpson at a launch event in January, celebrating the newly updated 2023 Colorado Water Plan. Sen. Simpson is a farmer/rancher and the general manager of the Rio Grande Water Conservation District. Water issues were a large reason he ran for office in 2021, where he now represents Senate District 6.

“Colorado has demonstrated, for 150 years, our ability to lead in this space … We’ve established the tools and the mechanisms to do that,” says Sen. Simpson.

But creating a statewide water management plan is not a straightforward task.

The state’s first 2015 water plan was broad: Ask any given stakeholder what the plan meant to them, and each will give a very different answer, says Russ Sands, chief of the Colorado Water Conservation Board's (CWCB) Water Supply Planning Section.

This was by design. Ideally, anyone can find inspiration in the plan to leverage the type of work they specialize in. That thought process carries forward in the new plan. The 2015 water plan set a vision through objectives, goals, and actions, but stopped short of being prescriptive, allowing local leaders to determine the best ways to address future water needs. The 2023 plan provides a refreshed vision, along with specific actions that are outlined as opportunities to advance that vision.

“The first water plan charted new ground and was ambitious in its own right in doing that,” says Sands. “The new plan tries to capture that energy but is delivered in a more straightforward, accountable, and actionable way.”

The CWCB is the state agency that authored both the old and new plan and works to shepherd its implementation. Sands’ team — many of whom joined the agency after the 2015 water plan was released — was responsible for incorporating thousands of pages of feedback and years of input to produce the new water plan this year.

With the 2023 plan in hand, some wonder how far we've come since the first plan. Not many of the 2015 water plan objectives were directly reported on, but its vision pushed forward nontraditional collaboration across the state. For the CWCB, the 2023 water plan was a chance to capitalize on that vision and celebrate successes while resetting expectations in ways that match the reality of what’s achievable, how CWCB can assist, and how stakeholders can play their own critical role in the implementation of the plan, Sands says.

Now, Coloradans are called upon to demonstrate what really is achievable with the new plan and to show how far the state will advance over the next decade.

“[The 2015 water plan] caused the conversations to happen, that then started leading to the projects … it really was a document ahead of its

time,” says Scott Lorenz, senior project manager at Colorado Springs Utilities.

Lorenz participates in three of the nine river basin roundtables in Colorado. These regional roundtables, established in 2005 by the Colorado Water for the 21st Century Act and organized within the state’s major watershed boundaries, facilitate discussions on water management issues and encourage locally driven, collaborative solutions. Their work funnels into the water plan. Each roundtable creates its own basin implementation plan (BIP) representing the basin's individual needs and priorities. Summaries of those plans form big pieces of the state water plan, and feedback garnered during roundtable meetings informs other statewide sections of the plan.

“The [2015] water plan really put it out there that you can't have a bunch of individual projects that are going to be competing with each other,” says Rebecca Tejada, director of engineering at Parker Water and Sanitation District. For Tejada, the most effective solutions consider basin-wide and even inter-basin needs.

But as Celene Hawkins said at a November 2022 CWCB meeting: “There is an inherent tension/ conflict between creating something visionary and something measurable.” Hawkins represented the Southwest Basin on the CWCB board at the time.

The agency recognized as early as 2017 that many of the measurable objectives from the 2015 water plan couldn’t, in fact, be effectively measured to track progress, Sands says. However, they were effective at sparking action. The challenge for CWCB was identifying how best to bottle the momentum that would continue to spur good work while adding more accountability to the plan.

The 2023 water plan celebrates major progress in areas like water conservation, which has resulted in decreased statewide per capita water use of 5% since 2015.

But the CWCB hasn’t directly reported data on each of the 2015 plan’s eight measurable objectives, which had set targets for issues like supply-demand gaps, funding and water-wise land use planning. In fact, officials say there was never an effort to directly track the 2015 plan’s objectives.

“What we found is that [the measurable

“The first water plan charted new ground and was ambitious in its own right in doing that. The new plan tries to capture that energy but is delivered in a more straightforward, accountable, and actionable way.”

Russ Sands, CWCB

objectives] weren't very measurable, for a lot of reasons,” says Lauren Ris, deputy director at CWCB. “They sounded good and objective and quantifiable, but at the end of the day, it was really hard as a state agency to come up with data that allowed us to measure progress.”

Another challenge is that the 2015 objectives each came with variable timelines—some 2025, 2030, or even 2050 goals. The plan also didn’t assign accountability for achieving each objective, making tracking progress difficult. And many key terms were undefined. One example was the goal to cover 80% of locally prioritized rivers with stream management plans (SMPs) by 2030. SMPs are data-driven river health assessments, but questions arose around what “locally prioritized rivers” were.

Even if the goal wasn’t structured to truly be measurable and even if it hasn’t actually been met, demonstrable progress was made: There are now 26 SMPs on rivers across the state, 25 of which were supported by CWCB grant funds.

For the 2023 plan, the CWCB didn’t want to be pigeonholed by objectives that might not

necessarily have a lot of impact or spend time “spinning on numbers,” says Sands. Instead, the 2023 plan clearly defines what the agency can and cannot do, acknowledging the limitations it faces.

“Something that we really tried to clarify with the update is to make sure that there really was a clear line of sight between the actions that we're committing to and the visions that are in the plan,” says Ris.

The 2023 plan is organized around four action areas — vibrant communities, robust agriculture, thriving watersheds, and resilient planning. The vision in each action area sets an aspirational goal for Colorado, then backs it up by offering a suite of actions on how to help get there. Of those actions, 50 are CWCB-led. Each has a final deliverable and timeline: “You'll know when they're done. You can check a box,” says Sands. The plan also includes 50 example partner actions to guide work in the field for the numerous individuals and organizations who will also be critical to implementation.

For Lorenz, nuanced differences in how the CWCB writes about solutions show that they are listening to what’s happening on the ground—at least for those in the water business.

“The most you can hope for, for a state agency, is that they're really tracking with what's going on in the state,” says Lorenz.

For example, the term “alternative transfer method” (ATM) was previously used to describe ways to share water that didn’t permanently dry up agricultural land, primarily by transferring water on a temporary or intermittent basis from agriculture to other uses through some form of lease arrangement. Now, the CWCB (and the 2023 water plan) is using the term “collaborative water sharing” to describe these activities, which is what Lorenz and others across the state have used to describe their projects.

“Everybody was assuming all the water was going to come from agriculture to go to these other uses. But that wasn't true on the ground. A lot of our excess water in wet years was going to agriculture. And in every single year, we have water going to maintain streamflows, and to benefit environmental purposes,” says Lorenz. “Collaborative water sharing” broadens the ATM concept to simply refer to sharing water between

“Something that we really tried to clarify with the update is to make sure that there really was a clear line of sight between the actions that we're committing to and the visions that are in the plan.”

Lauren Ris, CWCBRuss Sands, chief of the Colorado Water Conservation Board’s Water Supply Planning Section, introduces the updated water plan during a January 2023 water plan launch celebration in Denver. John Robson

two or more users, whether it’s agricultural to municipal uses, agricultural to environmental uses, municipal to environmental uses, or some other arrangement through a voluntary, temporary and compensated agreement.

But not all those on the ground feel that the water plan thoroughly showcased their work. The 2015 and 2023 water plans have been celebrated for putting environmental and recreational water use on equal footing with municipal and agricultural water use, and in many cases this has happened. “It brings together water interests that have traditionally been at odds with each other and provides an excellent forum to discuss cooperative projects,” says Mely Whiting, legal counsel for Trout Unlimited’s Colorado Water Project and chair of the Southwest Basin Roundtable’s environmental and recreational subcommittee.

But Whiting says the plan still doesn’t include

much information to evaluate environmental and recreational water supply needs.

While more detailed data is being developed through the SMP and integrated water management planning processes, the timing was probably not right to get that SMP data into the water plan, Whiting says.

“We’re making good progress in developing environmental and recreation info through SMPs, but it is a slow process and we have a long ways to go to catch up with the level of information available for ag and municipal [use and planning].” says Whiting.

A document like the water plan—and even an agency like the CWCB—cannot itself mandate action. Its main job is to set a vision and course, and hopefully to provide sufficient resources,

CWCB staff and attendees represent at "¡Celebremos al aire libre!" a community event held in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, to celebrate Latino Conservation Week, as part of outreach during the water plan's public comment period. During the 2023 Colorado Water Plan update, the CWCB team and partners like CREA Results, visited all of the state’s 64 counties and attended more than 100 events to engage as many stakeholders as possible.

in funding and expertise, to back it up. Beyond that, the plan is only as effective as the people and organizations on the ground working to implement it. That much hasn’t changed between the original plan and the new update.

“Where the rubber hits the road is those partnerships and the collaboration around the state, and where projects and funding can get done to really take big strides toward meeting those future water goals,” says Emma Reesor, executive director of the Rio Grande Headwaters Restoration Project.

Stakeholders agree that outreach is critical. As more communities see the possibility of win-win water solutions—those serving both agricultural and environmental users, for example—more projects will be implemented.

“The incentives are much bigger than state government, much bigger than city government, than any government. It's what happens on the

Colorado River. It's what's happening in the ag economy, not just in Colorado, but throughout the West. It's what's happening to housing markets and the Front Range. Those are the things that are driving change,” says Lorenz. “[The CWCB] won't ever be the one driving it.” Rather, the CWCB will continue to drive awareness, facilitate collaboration, inspire innovation, and provide funding to meet broad needs and goals. For example, the CWCB is trying everything within its scope to get as many people engaged in water efficiency and conservation in Colorado as possible, says Sands: “That's how we're going to meet our future water challenges.” H

Emily Payne is a writer covering the intersection of food, agriculture, health, and climate. She is editor of the global nonprofit Food Tank and consults across sectors—including startups, NGOs, and universities—to help connect those supporting food systems solutions.

It’s been seven years since work began to implement Colorado’s first water plan. A lot has been accomplished in that time period, but tracking those achievements isn’t as straightforward as one might think. And with the updated plan, measures for success look different than before.

The 2023 water plan is organized around four interconnected action areas—vibrant communities, robust agriculture, thriving watersheds, and resilient planning. For each action area, the new plan describes a long-term vision and actions that stakeholders and state agencies can move forward. This is a shift from what was in the 2015 water plan, which included eight measurable objectives as a means to track progress.

To help Coloradans trying to bridge from the old to the new, we map linkages between the old objectives and the new vision and action areas with a selection of success stories that bridge the gap.

2015 Measurable Objective: By 2025, 75% of Coloradans will live in communities that have integrated water saving measures into their land use planning.

Reported Progress Toward the 2015 Objective: 62% of Coloradans now live in communities whose leaders have taken training to integrate water and land use planning.

Colorado aims to create a sustainable urban landscape with communities that balance their water supply and demand needs. The updated water plan calls for municipalities to adopt water efficiency practices, implement conservation programs, control water loss, create climate-appropriate greenspaces, and more.

The new vision includes elements of the 2015 water plan’s measurable objective but highlights many different ways, including and going beyond land use planning, for all Colorado communities to integrate wise water use.

While the CWCB’s reported progress toward its 2015 goal does not directly translate to its initial goal, its strategic direction— and funding—supported the integration of water-saving and land use planning throughout the state.

“The 2015 Colorado water plan succeeded in elevating the value and importance of municipal water conservation, efficiency and reuse as communities continue to grow. Establishing [this goal] boosted the drive and motivation of the Sonoran Institute’s training and assistance work with local governments and their water providers,” says Waverly Klaw, director of resilient communities and watersheds at the Sonoran Institute, an Arizona-based nonprofit that also works in Colorado, teaching municipal leaders how to combine water and

land use planning through its Growing Water Smart program. ¶ Klaw has worked for years on long-term recovery and resilience plans for Colorado’s communities, including work with CWCB staff in creating the 2015 Colorado Resiliency Framework, and she submitted two rounds of comments through the Sonoran Institute for the 2023 water plan draft ¶ Since 2017, the Growing Water Smart program has leveraged multiple Water Plan Grants to host two-day intensive workshops where water planners, land use planners, and elected officials create plans for integrating water and land use planning in their communities. To date, Sonoran has held eight of these workshops across Colorado, training representatives of 61 local governments. ¶ And in 2020, the Sonoran Institute published a set of metrics to assess the progress toward, and impact of, urban strategies that integrate water-saving measures into land use plans and policies. The Growing Water Smart Metrics: Tracking the Integration of Water and Land Use Planning guidebook aids communities in benchmarking and tracking their water savings goals

2015 Water Plan Measurable Objective: 50,000 acre-feet of agricultural water shared through voluntary alternative transfer methods by 2030.

Reported Progress Toward the 2015 Objective: Annual municipal leasing of 25,000 acre-feet of agricultural water has helped cities and farms coexist.

The update to the water plan creates a vision of sustainable agriculture in Colorado, which will mean facing drought, urbanization, and shrinking water supplies, through actions like building storage, replacing diversion structures, improving efficiencies on farms, expanding agricultural water conservation education, capacity building to support agriculture, and more.

The 2015 water plan set a measurable objective of sharing 50,000 acre-feet of water through voluntary sharing agreements by 2030. This was meant to reduce the “buy and dry” that has occurred throughout Colorado as cities acquire agricultural water rights and remove them from the land to serve growing populations.

The updated plan reveals a new but similar action item for the CWCB and Colorado Department of Agriculture to help expand the scale of collaborative water sharing agreements, with the aim of minimizing permanent reductions in irrigated agriculture and the socioeconomic and ecological externalities that come with that. This expansion can be done through grant making, knowledge sharing, and moving toward larger-scale projects with lower transaction costs. The new approach also recognizes that water sharing can happen beyond agricultural entities and municipalities—agreements can also be ag to ag, or between agriculture and environmental or recreational interests.

While not fully met and difficult to quantify, the 2015 goal spurred and helped refine some collaborative water sharing agreements. The 2015 water plan promoted the Lower Arkansas Valley Super Ditch Company, which provides leased agricultural water to cities, as a promising solution to water shortages. But innovators on the ground have helped close this gap in other ways: Scott Lorenz of Colorado Springs Utilities says the Super Ditch Company solution “was not something that worked for farmers and it was not something that worked for cities. There were some fundamental flaws in how it was set up.” ¶ Lorenz and his colleagues spent four years conducting studies and meeting with farmers across the Lower Arkansas River Basin to design their own program. In 2014, they launched the Arkansas Valley

Water Sharing Program with the Lower Arkansas Water Management Association. The project provides water for Colorado Springs municipal use in five of every 10 years, while farmers in the Las Animas and Lamar areas take excess water during the other 5 years. ¶ This reduces large-scale transfers and the permanent removal of water from agriculture—an innovative and flexible agreement to meet the needs of both groups. ¶ Since its success, Colorado Springs Utilities has worked with Bent County officials to streamline the process through an Intergovernmental Agreement, approved Sept. 1, 2022, hoping to bring many more water sharing agreements to the area. ¶ And 50 miles north, Rebecca Tejada with Parker Water and Sanitation District says

the 2015 water plan’s goals supported what was already instilled in the culture of Parker Water: finding collaborative water shortage solutions that don’t dry up agricultural land. ¶ “We realized that we're going to have to come up with maybe a bigger project that didn't just solely focus on Parker Water needs,” says Tejada. ¶ The city had previously purchased a few farms on the South Platte River in the early 2000s. Instead of converting the farms’ senior water rights from agricultural to municipal usage, Parker Water leased the farms to multiple farmers, allowing them to protect the economy and culture along the South Platte. They formed the Platte Valley Water Partnership with the Lower South Platte Water Conservancy District in 2021, bringing agricultural and municipal water users together to capture junior water rights in times of excess that would otherwise leave the state. The proposed project focuses on utilizing storage so that later, when there's little or no water coming down the river, that stored water is still available for use in Colorado. ¶ Tejada says that learning how water is used in agriculture and building relationships with the agricultural community has shifted her perspective. ¶ “We’ve gone out of our way not to just do a ‘Do No Harm’ idea, but rather a win-win concept with them,” says Tejada.

2015 Water Plan Measurable Objective: 80% of locally prioritized rivers covered with stream management plans (SMPs) and 80% of critical watersheds covered with watershed protection plans by 2030. Reported Progress Toward the 2015 Objective: As of 2021, 26 SMPs had been developed.

The 2015 water plan included a goal to increase the “locally prioritized rivers” studied by stream management plans (SMPs). Stream management plans are data-driven assessments of river health that help communities prioritize how to protect or enhance environmental and recreational assets in their watershed.

“Locally prioritized” rivers was an undefined, hard-tomeasure goal, so the vision in the 2023 water plan morphed to more broadly include many actions that will help prioritize stream health, reduce barriers to implementing instream flow protections, improve forest health, reconnect floodplains, and more. Harkening back to the SMP goal, the new plan includes an action that CWCB will take to create a framework for prioritizing stream health with local stakeholders. The new plan recognizes nature-based solutions as an important part of watershed planning and includes a more specific focus on forest health as part of overall watershed health.

Whether looking at the 2015 goal or the 2023 vision, stakeholders across the state cite the SMP process, in addition to other collaborations like integrated water management plans and river health assessments, as invaluable in sparking new water projects.

Some of the SMPs’ biggest impacts have been bringing various stakeholders to the same room, improving relationships, and finding win-win solutions.