Issue #143 Aug 2022 RRP $15 chain reacti n www.foe.org.au The National Magazine of Friends of the Earth Australia Extractivism & Post-Extractivism Australia’s Mining Rush for Green Energy The Hole Truth: Is the environment movement aiming for post-extractivism? Citizens Declare Protection of Whale Songline Country Transforming Carbon Possible Mindsets for Post-Extractive Futures

Edition #143 − August 2022

Publisher - Friends of the Earth, Australia

Chain Reaction ABN 81600610421 FoE Australia ABN 18110769501

www.foe.org.au

youtube.com/user/FriendsOfTheEarthAUS twitter.com/FoEAustralia

www.facebook.com/FoEAustralia flickr.com/photos/foeaustralia

Chain Reaction website www.foe.org.au/chain-reaction

Chain Reaction contact details

PO Box 222,Fitzroy, Victoria, 3065. email: chainreaction@foe.org.au

phone: (03) 9419 8700

Chain Reaction Collective

Moran Wiesel, Zianna Faud, Sanja Van Huet, Natalie Lowrey, Anisa Rogers, Tess Sellar

Layout & Design

Tessa Sellar

Printing

Sustainable Printing Company

Printed on recycled paper

Subscriptions

Three issues (One year) A$33, saving you $12 ($15/issue)

See subscription ad in this issue of Chain Reaction (or see website and contact details above).

Chain Reaction is published three times a year

ISSN (Print): 0312-1372

ISSN (Digital): 2208-584X

Copyright:

Written material in Chain Reaction is free of copyright unless otherwise indicated or where material has been reprinted from another source. Please acknowledge Chain Reaction when reprinting.

The opinions expressed in Chain Reaction are not necessarily those of the publishers or any Friends of the Earth group.

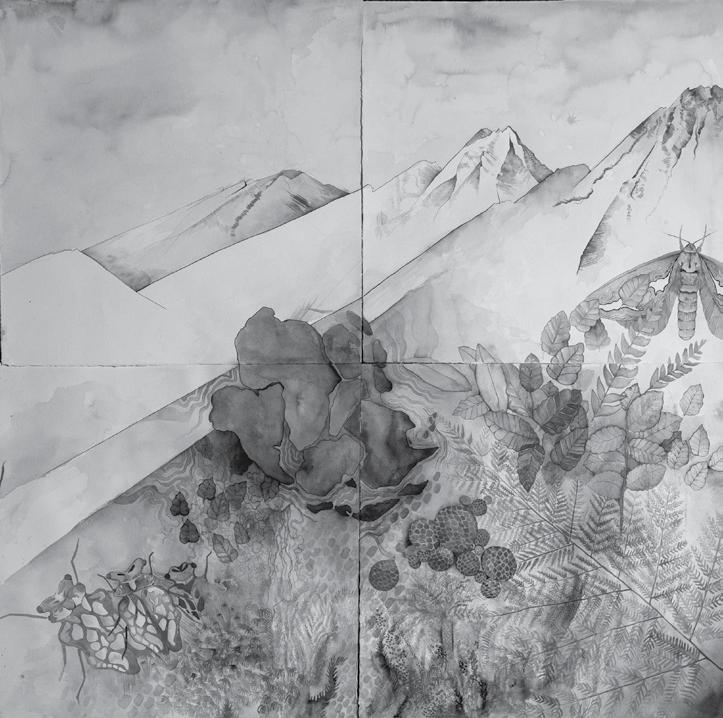

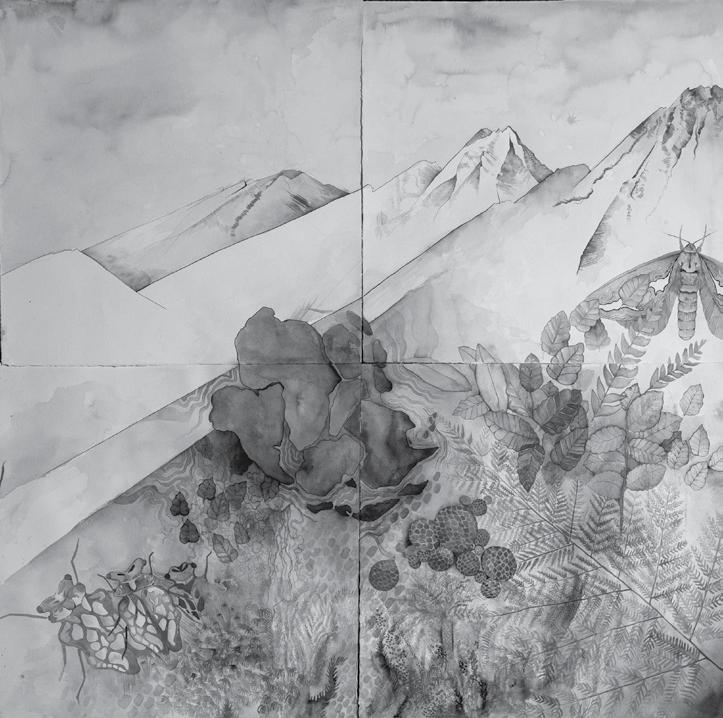

Front cover

Aviva Reed, 2022; Carboniferous anthrops. Watercolour on paper. avivareed.com

'Who’s Reading Chain Reaction?’

Let’s learn more about the Chain Reaction community! Submit a photo with a sentence about you, and response to the questions: 'when /where did you first read Chain Reaction?’, 'what does FoE / Chain Reaction mean to you?’ 'what environmental /social justice/alternative world building projects are you working on at the moment?’. Send to chainreaction@foe.org.au. Include your name and location

News Join Friends of the Earth inside front cover Friends of the Earth Australia Contacts inside back cover Editor’s note 4 Friends of the Earth Australia News 4 Friends of the Earth International News 6 Extractivism & Post-Extractivism What is Extractivism – Natalie Lowrey and Anisa Rogers 7 Australia’s Mining Rush for Green Energy – Liz Downes and Natalie Lowrey 9 Green Extractivism and Renewable Ecocide in Australia – Morgan Heenan 12 Exploring Supply and Demand Solutions for Renewable Energy Minerals – Andy Whitmore 14 Victorian Gas Substitution Roadmap: Concerns and Recommendations – Freja Leonard 15 Extractivism Culture Is Killing Our Forests – Alana Mountain 16 The Hole Truth: Is the Environment Movement Aiming for 18 Post-Extractivism? – Anisa Rogers and Zianna Faud First Nations Rights and Colonising Practices by the 22 Nuclear Industry – Jillian Marsh and Jim Green Anti-Protesting Laws – Stories from Victoria & Tasmania – Tuffy Morwitzer and Finn Leary 24 IMARC’s Dirty Laundry – Ashleigh Byrd, Rowen Lay and Nadia Murillo 26 Citizens Declare Protection of Whale Songline Country – Yaraan Bundle, Jemila Rushton and Liz Wade 28 Regular Columns Creative Content: Blockade Australia – Zianna Faud 31 HEARTH: Possible Mindsets for Post-Extractive Futures – Aia Newport 32 Creative Facilitation: New Economy Network Australia (NENA) 34 – Rhiannon Hardwick and Michelle Maloney Changing Beautifully: Call for Imaginings 35 Changing Beautifully: Transforming Carbon – Aviva Reed 36 From the Archives: Politics of Alternative Energy – Is Alternative Technology Enough? – Amory Lovins 39 Books: Emu Field: The Atomic Prophecy of Maralinga – Dr Elizabeth Tynan 40 Creative Content: Rattle the Cage – Léandra Martiniello 42 CONTENTS

FoE

Friends of the Earth Online

www.foe.org.au

youtube.com/user/FriendsOfTheEarthAUS twitter.com/FoEAustralia

facebook.com/pages/Friends-of-the-Earth-Australia/ flickr.com/photos/foeaustralia

Editor’s Note:

Imagine your great-grandchildren live in your hoped-for utopia. What do their communities look like? What resources do they need and use to eat/live/play? This edition invites you to dream the world your heart longs for; and bring that dream into this moment, and our campaigns now. We start by taking a hard-hitting look at our culture’s extractivist mindset, and the ways this pervades corporations’ “greenwashing” and perhaps even our activist goals. As always, get in touch to join the Chain Reaction Collective, submit an article, or write a letter to the editor. email: chainreaction@foe.org.au

Friends of the Earth (FoE) Australia is a federation of independent local groups. Join FoEA today, sign up to our monthly newsletters, or donate!

We Need Renewables in the Right Place

“Can you imagine 239 turbines abutting the Tasmanian World Heritage Area, or Kakadu World Heritage Area, or the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area? The Wet Tropics deserves better!”

The transition to zero emissions renewable energy is now finally occurring. However, this comes with its own challenges. Industrial scale renewable projects are sometimes in the wrong locations.

Two projects proposed, Chalumbin and Upper Burdekin, would clear almost 3,000 hectares of remnant vegetation and vital habitat for many endangered species. At state level, there is a planning guideline called “State Code 23 for wind farms” which is a deficient, outdated and flawed instrument. It is at federal level that these projects usually become

known to the wider public. However, by this stage it is often too late. The solution to this madness is an overarching planning policy for the roll out of renewables.

A moratorium is needed on any industrial scale projects adjacent to the Wet Tropics World

A master plan for Queensland can be developed that highlights high bio-diverse areas, state-wide wildlife corridors and places of high cultural significance, overlaid with high wind resource and solar opportunities. The land outside of these areas could be open/suitable for the roll out of renewables. If such plan is not created, conflict between land use and the protection of nature will persist and only intensify in the coming years. Read more:

foe.org.au/renewables_in_the_right_place

4 Chain Reaction #143 August 2022

FOE AUSTRALIA NEWS

Photo: Kaban Wind Farm, 15/2/22. Top of ridge line that used to be in pristine condition now smashed. Chalumbin will have 146km of new roads like this and Upper Burdekin another 150km of new roads.

Barngarla Traditional Owners call upon Labor government to scrap nuclear waste dump

The Traditional Custodians of land near Whyalla in South Australia announced to house a nuclear waste dump the Barngarla People call on the new Labor Government to revoke the radioactive waste declaration.

In a published statement they present the letter written to Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and the new Resources Minister Madeleine King, urging them to revoke the declaration of the nominated site.

Barngarla spokesperson quote:

“There (have been) serious failings (including) denying the First Peoples the right to vote, not conducting a proper heritage survey of the area, trying to legislate away judicial review, breaching UNDRIP and abandoning the test of broad community support at the last minute without any warning to anyone. ….Because of … terrible mishandling by the National Party, we again call upon the new Labor Minister to quash the declaration.”

Support Barngarla’s legal challenge: foe.org.au/cr143_a

Read/watch for more info: foe.org.au/cr143_b

Federal Climate & Environment Policy Platform 2022

Friends of the Earth Australia welcomes the rapid movement of the new federal government on key election commitments, including those covering environment, climate and energy.

FoE has compiled a Policy Platform, encouraging the new government to take long-term, whole picture, intersectional approach; not a short term approach with limited focus.

Our top 5 priorities are:

1. Rebuild our climate knowledge,

2. Meet and exceed climate commitments,

3. Establish a national Just Transition Authority,

4. Get renewables right,

5. Rule out further fossil fuel development.

Read the full FoE policy document: foe.org.au/federal_climate_ environment_policy_platform_2022

Fighting the fires of the future

2019/20 showed that Australia just doesn’t have enough capacity to fight wildfire. Thankfully the summer of 2020/21 was mild. Before the 2022/23 summer starts, we need a deeper commitment from the federal government for fire fighting.

In June and July 2020, Emergency Leaders for Climate Action (ELCA) hosted a virtual bushfire and climate change summit to coordinate a national response. The Australian Bushfire and Climate Plan is the culmination of that effort.

A key recommendation is the suggestion that we build our air capacity to the point where authorities are able to deploy planes or helicopters to attack fires immediately, rather than waiting until ground crews are not able to contain the blaze.

The Climate Plan recommends that the Federal Government should:

• Increase the funding available for more aircraft.

• Develop a self-sufficient aerial firefighting capability in Australia.

• Increase funding for the training of local pilots to fly firefighting aircraft

•Undertake an evaluation of the effectiveness of existing aerial firefighting strategies and assets used in Australia, compared to approaches used in Europe, the USA and Canada.

Read more: foe.org.au/fires_and_air_support

Has Lockton put ethics aside to back Adani’s disastrous coal mine?

On 29 May 2022, Lockton, a US-based insurance broker, was appointed to arrange insurance coverage for Adani’s climate-wrecking Carmichael coal mine and rail line. Market Forces followed up with a letter to Lockton putting this information to the head of its Australian operations and it has not been denied.

112 major companies have ruled out providing services to the Carmichael coal mine, due to the reputational risks of being involved with such a destructive

project. Forty-four of the world’s biggest insurance companies are refusing to provide coverage for Carmichael, including Lloyds of London. Any work Lockton does for Adani could prove decisive in enabling the mine to continue to operate and boost production.

Email Lockton, asking them to commit to not working for Adani’s disastrous coal project: marketforces.org.au/lockton-adani

Chain Reaction #143 August 2022 5 www.foe.org.au

www.foei.org

www.facebook.com/foeint

www.twitter.com/FoEint

www.youtube.com/user/friendsoftheearthint

www.flickr.com/photos/foei

Action alerts: www.foei.org/take-action

FoE International’s web radio station (in five languages): https://rmr.fm/

Friends of the Earth International (FoEI) is a federation of autonomous organisations from all over the world. Our members, in over 70 countries, campaign on the most urgent environmental and social issues, while working towards sustainable societies. FoEI currently has five international programs: Climate Justice and Energy; Economic Justice, Resisting Neoliberalism; Food Sovereignty; Forests and Biodiversity; and Resisting Mining, Oil and Gas.

Climate Crisis is the Symptom, Overconsumption is the Disease

FoE Europe

With the European Environmental Bureau and the European Youth Foundation, we have launched a new animated scrolling webpage to raise awareness of, and pose concrete solutions to, systemic EU overconsumption. overconsumption.friendsoftheearth.eu Overconsumption is a giant hole in the European Green Deal and the interrelated EU environmental and climate policies. EU continues to ignore the urgent need to reduce resource overconsumption.

The EU is not addressing systemic overconsumption and the obsession with economic growth.

The main ask is for the European Commission to include in its 2023 Work Programme commitments to

assess the amount of resources the EU can sustainably and fairly consume within planetary boundaries, and to establish a binding reduction target for the EU’s material footprint and detailed plans to reach it.

Recently, we published two pieces related to this – our report in October 2021 “Green Mining is a Myth: The case for cutting EU resource consumption”, which outlines the extent and impacts of EU overconsumption, how decision makers are turning a blind eye to overconsumption, the ‘green-transitionwashing’ by metal and mineral mining companies and governments, and what politicians need to do to tackle all of this.

The second is a paper in January of this year “7 Sparks to Light a New Economy”. The economy is designed, and we can redesign it! We lay out 7 transformational ideas for a life-sustaining economy within Earth’s limits. We want an economy that’s truly democratic, participative and public, where work and business are transformed, that embodies the core values of sufficiency, care and empathy, equality and inclusiveness, and autonomy.

Read “Green Mining is a Myth”: foe.org.au/cr143_c

Read 7 Sparks to Light a New Economy”: foe.org.au/cr143_d

6 Chain Reaction #143 August 2022

of the

INTERNATIONAL NEWS

Friends

Earth International Online FOE

What is Extractivism?

Natalie Lowrey and Anisa Rogers

Extractivism is a large concept. Its origins stem from extractivismo discourse which is intertwined thinking from academics and grassroots activists including Indigenous communities in Latin America. Extractivismo centres the lands and communities directly affected by extractive projects.

The concept of extractivism has travelled far and wide, it has taken on new meanings, and opened new vistas of critique as well as resistance. Broadly speaking the concept of extractivism has two elements.

The first element is the process of extraction of raw materials such as metals, minerals, oil and gas, as well as water, fish and forest products, new forms of energy such as hydroelectricity, and industrial forms of agriculture, which often involve land and water grabbing by the extractive industries.

The second element has migrated and expanded from extractivism origins to also include other extractive logics. These include:

• Transnational commodity flows known as ‘urban extractivism’, for example the fashion industry with its extracted labour and human rights issues that are erased by a marketing machine to ‘just do it’ and consume;

• Operations of digital platforms known as ‘data extractivism’, for example the development of information technologies where data effectively becomes a raw material that can be extracted, commercialised, refined, processed, and transformed into other commodities with added value, like the billion-dollar profits of Amazon, Google and Facebook;

• Stock markets known as ‘financial extractivism’, for example gentrification of our cities where rich investors buy social housing without a care for the building or the community it may serve. The building is no longer seen as a building it becomes a game of buy and sell at the expense of low-income people and their community; and

• Global transition to renewable energy ‘green extractivism’, in which we are witnessing corporate and private interests putting pressure on countries in both the Global South and Global North to satisfy the global economy’s demand for minerals and raw materials for ‘green’ growth and the ‘green’ transition.

Understanding extractivism means understanding that nearly anything can be extracted: mineral resources, labour, data, and cultures. It is a take, take, take logic, not one of giving.

It is a logic of violence that includes abuses to life, health, land, food, and water; displacement of people; violations of Indigenous Peoples

rights; gender-based violence and discrimination against women; criminalisation of workers and human rights and environmental defenders; and the use of military and security forces to protect natural resources and corporate interests.

Extractivism and the growth economy

To put this violence and damage in context, we must look at the underlying mentality of extractivism. Under capitalism, extraction operates for profit above all else, and competition for profit spurs economic growth. Without this continuous growth, economies go into crisis. However, this economic growth very clearly correlates with ecological consumption and, on a finite planet, destruction. Therefore, critiquing extractivism also means critiquing economic growth.

It is often argued that these problems can be solved through more efficient technology, rather than a decrease in overall consumption. However, continually developing more efficient technology is often subsumed by what is called the ‘Jevons Paradox’, in which an increase in efficiency in resource use generates an increase in resource consumption, rather than a decrease.

Continuing to grow our economy therefore means our ecological impact will also continue to grow. Those who argue we can ‘decouple’, or separate, our economic growth from environmental destruction, have been proven wrong time and time again. To have a chance at mitigating the climate and ecological crises we face we require a decrease in overall energy use and a degrowth strategy and transition from a consumer society to a simpler, more cooperative, just, and ecologically sustainable society.

Extractivism and the Australian context

The extractivist development model has been in place and perpetuated since colonial times. This is most often thought of in the framework of a dominant and highly unequal model of development which is geared for the exploitation and marketing of natural resources in the Global South for export to the rich economies of the Global North. Most of the time, extractivism has created relations of dependency and domination between the providers and consumers of raw materials. However, in the context of Australia, we need to unpack settler colonialism and extractive settlercapitalist economies.

Settler colonialism is primarily about land. The clue is in the name: the settler stays and establishes exclusive territorial sovereignty over expropriated or ‘stolen’ First Nations lands. This ‘logic of elimination’ centres access to land as the primary motivation for elimination.

Chain Reaction #143 August 2022 7 www.foe.org.au

Settlers—and the settler state—aims to displace the First Nations presence through land theft and genocide so they can establish their own direct connection with the land. This soughtafter connection, which has both economic and cultural dimensions, continues to have farreaching consequences on First Nations peoples in the land they now call Australia.

To broaden this further extractive settlercapitalist economies have been founded in the ongoing processes of Indigenous displacement, dispossession, and erasure – this still stands as one of Australia’s most enduring national features. Australia is a mining state. Australia also exports this extractvist model and the abuses that go with it to other Indigenous lands and local communities overseas through our corporations, investments, aid and trade deals.

Beyond Extractivism to Post-Extractivism

What we need is a new logic, one that overturns the prioritisation of rampant mineral extraction -

References

be it iron ore, coal, gas, copper, nickel or lithium, logging our forests, extracting our waters - this has to be irrespective of any capitalist economic gain. There needs to be a recalibration of the Australian settler state that properly prioritises First Nations interests over the so-called ‘national interest’. Sadly, nothing in living memory suggests that any government is up to embracing such a challenge. So, it is up to us, the people. We need to stand with First Nations people who have fought against extractivism since colonialism came to this country. Extractivism is large and to many of us we cannot see a way out of this extractivist mindset and logic. However, there is an expansive visionary world beyond extractivism, a world of post extractivist circular economies and circular societies that protect cultural and biological diversity. Where there are national and local systems of care, access to universal basic income, food sovereignty is prioritised, information and communication modes are restored and rooted in society, and there is less production and consumption towards degrowth.

Alexander, S. A critique of techno-optimism, Samuel Alexander, 2017 Black, D. “Settler-Colonial Continuity and the Ongoing Suffering of Indigenous Australians”, Published April 25, 2021, https://www.e-ir.info/2021/04/25/settler-colonial-continuity-and-the-ongoing-suffering-of-indigenous-australians/ Hickel, J. “Why growth can’t be green”, Published September 14, 2018, https://www.jasonhickel.org/blog/2018/9/14/why-growth-cant-be-green Gaia Foundation. “Beyond Extractivism”, https://www.gaiafoundation.org/areas-of-work/beyond-extractivism

Riofrancos, T. Resource Radicals: From Petro-Nationalism to Post-Extractivism in Ecuador, Duke University Press, 2020 Serpe, N. “The Origins of Anti-Extractivism”, interview with Thea Riofrancos, Dissent Magazine, Published December 9, 2020, https://www.dissentmagazine.org/online_articles/anti-extractive-politics

Tout, D. “Juukan Gorge destruction: extractivism and the Australian settler-colonial imagination”, Arena Quartely, No.4, Published December 2020, https://arena.org.au/juukan-gorge-destruction-extractivism-and-the-australian-settler-colonial-imagination/ Trainer, T. Degrowth – How Much is Needed?, Biophysical Economics and Sustainability, 2021 Whitmore, A. A Material Transition, War on Want, March 2021, https://waronwant.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/A%20Material%20Transition_report_War%20on%20Want.pdf

Infographic: Natalie Lowrey for War on Want: A Material Transition report

8 Chain Reaction #143 August 2022

Australia’s Mining Rush for Green Energy

Liz Downes and Natalie Lowrey

Australia is leading a mining boom to provide resources for the ‘green energy transition’ - a transformation in energy and infrastructure which the Paris Agreement (2015) stipulates must occur to avoid perilous levels of global heating.1 Within Australia and globally, this mining expansion is affecting already stressed environments and communities, with impacts likely to dramatically increase as mining projects are pushed through to meet industry demands. Australia is looking towards being a key future provider of certain minerals regarded as essential for green energy. These include lithium, copper, nickel, cobalt and rare earth elements. In this piece we present a brief overview of the emerging footprint and impacts of Australian companies who are extracting these minerals, domestically and globally.

Lithium

Australia extracts about 50% of the world’s lithium.2 Government policy is pushing expansion for green energy production, supporting new lithium projects, particularly in the Pilbara, Goldfields and Perth regions of Western Australia. A mine being built in Larrakia land, Northern Territory, is associated with groundwater impacts and Native Title issues.3 Overseas, Australian companies are exploiting salt lakes in northern Argentina, where for decades Indigenous people have resisted

the impacts of brine mining on vulnerable ecosystems and water.4 The lithium rush is accelerating in Portugal, Serbia, USA, and Canada, placing communities, endangered species and First Nations lands at risk.5,6

Copper

Copper is in demand for green energy technologies and transport electrification.7

Australia’s largest copper mine is BHP’s Olympic Dam in South Australia – a site known to activists supporting the struggles of Arabunna elder Kevin Buzzacott to protect cultural sites. 8 There is currently a great increase in new copper projects across the continent.

Overseas, Australian companies are expanding in Chile, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, USA, Canada, Mongolia, Spain, Zambia and Namibia. Socio-environmental problems and resistance are associated with several projects, including Rio Tinto in Arizona and OceanaGold in the Philippines.9,10

In South America, the copper rush is focused on Ecuador, where Australian mining concessions cover 700,000 hectares including protected areas and Indigenous lands.11 Ecuador has a strong grassroots anti-mining movement. In the northwest, communities are fighting Hanrine (owned by Gina Rinehart), which has committed human rights abuses,12 and have stopped BHP from starting explorations.13

www.foe.org.au

Regional assembly against mining, northwest Ecuador.

Credit: Carlos Zorilla

Nickel

Nickel is required in large quantities for lithium-ion batteries. Australia is the world’s fifth biggest extractor,14 with several grandscale operations in Western Australia. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine forced a crisis in the nickel market, which has pushed battery manufacturers to look towards Australia as a supplier of ore for EU and Asian electric vehicle markets. As of 2022, companies are exploring or developing new mines across ‘nickel hubs’ in Western Australia, NSW and Queensland. Overseas, problematic Australian nickel projects include South32’s Cerro Matoso mine in Colombia,15 notorious for air and water contamination which has caused serious health impacts in Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities.16 Twiggy Forrest’s planned ‘battery metals hub’ in Ontario, Canada impacts on First Nations Peoples who have declared a moratorium on development until they are properly consulted.17

Cobalt

Cobalt has bad press due to the human rights issues associated with its mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo, which produces 70% of the world’s supply. With the boom in demand for batteries, Australia has come into vogue with investors as a ‘socially responsible’ site for future cobalt production.18 The Federal Government has designated cobalt, like lithium, a ‘Critical Mineral’.

There has emerged a plethora of companies wanting to take advantage of fast-tracking strategies and grants. Most new cobalt projects are in (surprise) Western Australia; with clusters in central NSW and northern QLD. Overseas, ASX-listed Jervois Global is building a cobalt mine in Idaho, USA. Not only is the project located near a defunct mine which caused one of the USA’s worst environmental disasters;19 it sits in wildlife-rich National Forest and the lands of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes. What could possibly go wrong?

Rare Earth Metals

Rare earth elements (REEs) are a specific group of 17 metals with a variety of industrial applications. The Federal Government has listed four particular REEs as critical because they are essential for permanent magnets in green energy technologies, including wind turbines and electric vehicles. These are neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium and terbium. In 2022, the US Department of Defense gave $US360m in project development grants to three Australian REE companies: 20 Lynas Rare Earths, Iluka Resources and Australian Strategic Minerals. Since 2011 Lynas has been dumping radioactive waste from its Malaysian REE refinery into an unsafe holding facility,21 while Iluka has a reputation for impacting important cultural heritage sites.22

Goldfields: A Battery Metals Hub

In Australia, the expansion of mining for green energy is concentrated in Western Australia’s Kalgoorlie-Goldfields region. Copper, lithium, nickel, cobalt and REEs are all already mined here, and many new projects are being fasttracked. The main issue here is the amount of water required for mining and infrastructure, and the lack of an overarching water use plan.23 The Goldfields covers several Native Title claims and has a proud history of companies disrespecting Traditional Owners in order to force through expansions.24

Shifting the Narrative Beyond Extractivism

It is critical we expose extractive industries of green washing their crimes and stop them from capturing the energy and digital transition narrative. We cannot and should not base our development pathways and just(ice) transitions on the expansion of mining and extractive industries.

To do this we need to shift the narrative beyond mining and extractivism, in the following ways: Reimagine and redefine development. There are already flourishing models of traditional and alternatives to the current development model, they are rooted in justice and serve the well-being of people and the planet. This includes degrowth to help redistribute global demand for energy and resources, and a reduction of our energy and material consumption in the Global North. Australian companies must be held responsible for their domestic and overseas impacts on people and the environment. This requires the Australian government to improve oversight and independent monitoring of company activities to ensure diligence with regard to legal obligations in host countries and internationally.25

Communities harmed by overseas Australian investments, operations or activities must have access to justice within Australian legal systems and policy frameworks. This should include the introduction of mandatory human rights and environmental due diligence obligations for large Australian companies, especially those who are operating in locations and sectors with high risk of negative impacts.26

10 Chain Reaction #143 August 2022

BHP’s Mt Keith nickel operation in the Goldfields: open pit mine and 5-km tailings lake. Credit: Conservation Council of Western Australia

Australian climate policies must be centred on justice and equity and that all supply chains of metals and critical minerals are clean, just, and fair. This should include exposing and holding to account all misleading branding of “clean” energy and “renewable” technologies. Justice and equity must be centred across all value and supply chains of the transition to prevent further global intensification of destructive extractivist practices, particularly in vulnerable ecological and cultural regions.27

In August 2022, Aid/Watch and the Rainforest Information Centre will be launching a major report mapping the domestic and global extractive footprint of Australian companies who are invested in minerals for the green energy transition.28, 29 The research highlights how Australian corporations and investors are

expanding into new territories for new sources of “critical and strategic” metals and minerals for low-carbon technologies, renewables, and green tech that will be as equally problematic as fossil fuels resulting in threats to biodiversity, livelihoods, and life itself. It calls for the urgent need for alternative pathways and development models for the transformational shift we must collectively make towards justice if we truly are to address the climate and ecological crises we face.

Liz Downes is a campaigner, writer and researcher who has spent five years working with grassroots collective Melbourne Rainforest Action Group and the Rainforest Information Centre, supporting frontline communities in Ecuador to defend their lands and forests from mining.

Natalie Lowrey is Coordinator of Aid/Watch & the Yes to Life No to Mining global network.

1. The Paris Agreement, United Nations, https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/paris-agreement

2. Burgess, C & Downes, L. “Lithium Communiqué: Is Australian Lithium the Answer to Zero Emission”. Aid/Watch & Rainforest Information Centre. Published September 22, 2021. https://aidwatch.org.au/campaigns/lithium-communique-is-australian-lithium-the-answer-to-zero-emissions/

3. Bardon, J. “NT farmers worried about the race to renewables and lithium exploration in the Top End”, ABC News. Published May 24, 2022. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-05-24/nt-farmers-pastoralists-fear-exploration-for-lithium-renewables/101090970

4. Frankel, T, & Whoriskey, P. “Tossed aside in the lithium rush”, Washington Post. Published December 19, 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/business/batteries/tossed-aside-in-the-lithium-rush/

5. “This Is the Wild West Out Here”, Politico Magazine. Published September 2, 2020. https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2020/02/09/nevada-lithium-mine-environmental-investigation-bureau-land-management-100595

6. Yes to Life No to Mining. “Lithium Communiqué: On the frontlines of lithium mining”. Published 21st September 2021 www.yestolifenotomining.org/latest-news/ylnm-lithium-communique

7. Burgess, C & Downes, L. “Copper Communiqué: In the race to net zero, ‘Copper is the new oil’ – but at what cost?”. Aid/Watch & Rainforest Information Centre. Published December 14, 2021. https://aidwatch.org.au/in-the-news/communique-on-copper/

8. McIntyre I. “An interview with Kevin Buzzacott”. The Commons Social Change LIbrary. https://commonslibrary.org/kevin-buzzacott/

9. Milne, P. “Rio Tinto’s big energy transition runs into local issues”, The Age. Published April 10, 2022. https://www.theage.com.au/business/companies/rio-tinto-s-big-energy-transition-runs-into-local-issues-20220409-p5acaa.html

10. Chavez, L. “A Philippine community fights a lonely battle against the mine in its midst”, Mongobay. Published October 15, 2019. https://news.mongabay.com/2019/10/a-philippine-community-fights-a-lonely-battle-against-the-mine-in-its-midst/

11. Melbourne Rainforest Action Group. https://rainforestactiongroup.org

12. Burgess, C & Downes, L. “Can ‘green mining’ boom save our planet?”, Ecologist. Published September 9, 2021. https://theecologist.org/2021/sep/09/can-green-mining-boom-save-our-planet

13. Downes, L. “BHPs divide and conquer”, Ecologist. Published February 21, 2020. https://theecologist.org/2020/feb/21/bhps-divide-and-conquer

14. Minerals Council of Australia. “Commodity Outlook 2030”. Published June 2, 2021, https://www.minerals.org.au/sites/default/files/Commodity%20Outlook%202030.pdf

15. Burgess, C & Downes, L. “Nickel Communiqué: From the ‘Devil’s Metal’ to the ‘Holy Grail’ of Clean Transport”. Aid/Watch & Rainforest Information Centre. Published March 30, 2022. https://aidwatch.org.au/in-the-news/nickel-from-the-devils-metal-to-the-holy-grail-of-clean-transport/

16. Alvaro, I. “Cerro Matoso mine, chemical mixtures, and environmental justice in Colombia”, Correspondence, Vol 391, Issue 10137. Published June 9, 2018. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(18)30855-9/fulltext

17. Attawapiskat, Fort Albany, and Neskantaga First Nations. “First Nations Declaration: Moratorium on Ring of Fire Development”. Published April 5, 2021. newswire.ca/news-releases/first-nations-declare-moratorium-on-ring-of-fire-development-854352559.html

18. Burton, M. “Australia cobalt rush accelerates on electric vehicle demand, DRC troubles”, Reuters. Published December 15, 2017. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-australia-cobalt-batteries-idUSKBN1E90R4

19. Holtz, M. “Idaho is sitting on one of the most important elements on earth”. The Atlantic, Published January 25, 2022. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2022/01/cobalt-clean-energy-climate-change-idaho/621321/

20. “Australia’s rare earths projects get US$360 million funding boost to counter China dominance”, Reuters. Published March 16, 2022. https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/australasia/article/3170630/australias-rare-earths-projects-get-us360-million-funding

21. Aid/Watch. “Stop Lynas campaign”. https://aidwatch.org.au/stop-lynas/

22. King, C. “Still simmering: the cultural heritage conflict at the Iluka mine site in Kulwin”, ABC Local. Published April 5, 2011. https://www.abc.net.au/local/stories/2011/04/05/3182449.htm

23. Government of Western Australia. “Water Allocation Plans”. Department of Water and Environmental Regulation. https://www.water.wa.gov.au/planning-for-the-future/allocation-plans

24. Stevens, R & Moussalli, I. “Tjiwarl Native Title holders file compensation case against WA Government”, ABC Goldfields. Published June 18, 2020. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-06-18/tjiwarl-native-title-holders-seek-damages-for-cultural-loss/12367796

25. ‘A Way Forward: Inquiry into the destruction of 46,000 year old caves at the Juukan Gorge in the Pilbara region of Western Australia’, Parliament of Australia, October 2021, https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Northern_Australia/CavesatJuukanGorge/Report

26. ‘Red Lines for Extractivism’, Yes to Life No to Mining global network, November 2021 https://yestolifenotomining.org/latest-news/red-lines-statement-on-extractivism/

27. ‘A Material Transition’, Andrew Whitmore for War on Want, March 2021 https://waronwant.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/A%20Material%20Transition_report_War%20on%20Want.pdf

28 Aid/Watch. “Alternatives to Green Extractivism”.

29. Aid/Watch. “Alternatives to Green Extractivism”.

https://aidwatch.org.au/alternatives-to-green-extractivism/

https://aidwatch.org.au/alternatives-to-green-extractivism/

Chain Reaction #143 August 2022 11 www.foe.org.au

Green Extractivism and Renewable Ecocide in Australia

Morgan Heenan

We are led to believe that the cause of ecological destruction is technological, and therefore its solution, the same. The problem is, we’re told, one of energy – merely a matter of ending coal and petroleum consumption. This is not entirely incorrect; fossil fuels have sent us careening towards a destabilized and increasingly hostile planet. But in our jerking away from fossil fuels, we so often uncritically accept the supposed alternative: renewable energy. The shift from fossil fuels to renewable energy systems is an immense infrastructural project. If, as is generally suggested, existing levels of material and energetic consumption are to be maintained, this infrastructure will require a vast project of metallic extraction, scouring the earth for lithium, copper, nickel, cobalt, and other energy transition metals. As the IEA reports, a “typical electric car requires six times the mineral inputs of a conventional car and an onshore wind plant requires nine times more mineral resources than a gas-fired plant”.1 Evidently, there’s a big market in mining these metals, with investment rapidly ramping up. It’s for this reason that Goldman Sachs described copper, so crucial for energy infrastructure, as “the new oil”.2

Australia, the old mining superpower, is key in this new energy regime, extracting vast amounts of these metals, including more than half of the world’s lithium production. And, with demand looking to skyrocket,3 things are only getting started. In the face of this new mining boom, there is little reflection on its implications and its dangers. The relative newness of the lithium industry, for instance, means that we have little in the way of an understanding of the long-term impacts of extraction. But already the cracks in the green veneer of mining are showing.

Green extraction: a contradiction in terms

Extraction of these metals on this continent has already produced profound harm. This is clearest with copper, the most established industry, where mines such as the Redbank, Rosebery, and Olympic Dam mines have had significant ecological effects, particularly on waterways. Redbank, despite closing in 1996, has continually leaked heavy metals such as copper sulphide into nearby waterways, decimating aquatic and riverside life.4 In Rosebery, waterways are likewise polluted, with claims of heavy-metal poisoning amongst some residents. The mine is also rapidly running out of storage capacity in existing

tailings dams, prompting the clearing of parts of the Tarkine’s Gondwanan temperate rainforest to construct a new dam.5

In the case of Olympic Dam, water is being lost –or rather, taken – entirely. The mine is licensed to extract up to 42 million litres of the Great Artesian Basin every day from bore fields adjacent to Lake Eyre, without charge. The Basin feeds thousands of mound springs, unique ecosystems that are the only perennial source of water across the South-Australian desert. But in recent decades, these springs, listed as Endangered Ecological Communities, have seen reduced, and in some cases completely halted, flow.6

Lithium extraction, still in its nascence, is likewise already causing problems, which can only be expected to grow as extraction does. State EPA’s have identified the possibility of surface and ground water contamination in a number of lithium projects,7 and has already been reported, such as at the Wodinga lithium project in the Pilbara. 8

This damage is enabled by a social dynamic of exclusion from governance, in which those who are affected by extraction and inhabit the sacrifice zones it produces, are dispossessed from decisions around socio-ecological governance. Even on freehold land minerals belong to the Crown. That means governments can grant permits for exploration and extraction to corporations against the will of the landholder. On the Cape Yorke Peninsula, more than 70 exploration permits have been granted, including to Lithium Australia. Most of these permits are on freehold land owned by Aboriginal groups, who have had only limited success in challenging mineral exploration.9

The prioritisation of mining over Aboriginal interests in particular is a through-line in mining on this continent. As shown in the A Way Forward report, which followed Rio Tinto’s destruction of Juukan Gorge rock shelters, both state and federal governments consistently fail to protect cultural heritage and Aboriginal lands, with the native title system doing little to provide groups the ability to dissent to development on their lands.10

In the case of the Olympic Dam mine, this prioritisation is legislatively enshrined. The Roxby Downs (Indenture Ratification) Act 1982 allows for the disregarding of the Aboriginal Heritage Act, as well as Freedom of Information legislation. Even without this act however, the SA Aboriginal Heritage Act 1988 allows the Minister

12 Chain Reaction #143 August 2022

the ability to authorise companies to “damage, disturb or interfere” with Aboriginal sites, which is exactly what has happened at Lake Torrens, a sacred site to multiple Indigenous nations, where exploratory drilling is underway. This exclusion is in stark contradiction to Australia’s commitments under the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which mandates the consent of Indigenous groups.

Despite this, it is argued that Australia, in contrast to states such as those in the lithium triangle of South America, has the governmental and industrial capability to conduct mining in a ‘responsible’ way. But the extraction of these metals is already disastrous. And, given what we know of the mining industry as a whole –cronyism, state capture, and a complete failure of governments to hold corporations accountable for the harm they cause, or to even mitigate it –we shouldn’t bank on it getting better.

There are no technological solutions to over-extraction, nor injustice

Mining companies, as well as governments, are increasingly justifying their extraction as necessary for ‘greening’ global energy systems, positing a moral imperative to rip as much metal out of the ground as possible. In an inversion of conventional wisdom, we are told, it is the miners who are now the ecologists. Yet, the extraction of minerals on this continent is destructive, exploitative, and undemocratic, whether it is coal or lithium. ‘Renewable’ technology doesn’t appear out of thin air, and we can’t simply engineer ourselves out of ecocide. By way of example, there is predicted to be two to three billion cars on the road by the middle of the century. That’s a recipe for destruction, whether internal combustion or electric.

The argument here isn’t that renewable energy and electrification is necessarily bad; renewable energy is, of course, preferable to burning fossil fuels. But the idea that we can continue in the direction we’re headed, merely switching technologies, is an illusion. A sustainable society will include many technologies being developed to transition away from fossil fuels, and will therefore inevitably involve mining. It will also, however, involve fundamental shifts to the ways we live our lives. We cannot, for instance, have one car (or more) in every household, or have constantly-new devices packed with lithium and rare-earth minerals. And we certainly can’t have mining corporations and crony governance deciding how to pillage the earth.

To survive the 21st century, we need more than a new colour of extractivism. We need to fundamentally reassess the ways in which we produce and consume, and the economies we inhabit. And we need democratic and just discussion about how to relate to the more-than-human world, and how to do more with a whole lot less. Morgan Heenan is a writer, musician and activist. His work centres on creating socialecological wellbeing and the cultural and political change needed to get there.

1. IEA. The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions. https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitions

2. Goldman Sachs. Green Metals: Copper is the new oil. https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/pages/copper-is-the-new-oil.html

3. IMF. Energy Transition Metals. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2021/10/12/Energy-Transition-Metals-465899

4. NT EPA. (2014). Redbank Copper Mine — Environmental Quality Report. Retrieved from https://ntepa.nt.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/284743/redbank_ environmental_quality_report.pdf

5. Grigg, A., McGregor, J., & Carter, L. The rush to renewable energy means a new mining boom. But first, Australia needs to make some tough choices. ABC News. Published May, 2022. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-05-09/renewable-energy-may-require-australian-mining-boom/101034914

6. Mudd, G. M. Mound springs of the Great Artesian Basin in South Australia: a case study from Olympic Dam. Environmental Geology, 39(5) (2000): 463-476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002540050452.

7. Department of Water and Environmental Regulation. Decision Report: Application for works Approval: Wodinga Operations. https://www.der.wa.gov.au/ component/k2/item/14378-w6132-2018-1, EPA. Report and recommendations of the Environmental Protection Authority: Greenbushes Lithium Mine Expansion. https://www.epa.wa.gov.au/proposals/greenbushes-lithium-mine-expansion.

8. Mir, F. Regulator flags tailings seepage at Mineral Resources’ Wodgina lithium plant. Published July, 2019. https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/newsinsights/trending/Kpy3R9mpYO9910-cnWuy2Q2

9. Smee, B. Mining exploration surges in Cape York as scheme to return land to traditional owners stalls. The Guardian. Published April, 2021. https://www. theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/apr/08/mining-exploration-surges-in-cape-york-as-scheme-to-return-land-to-traditional-owners-stalls.

10. Joint Standing Committee on Northern Australia. A Way Forward, Juukan Gorge Final Report. https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/ Northern_Australia/CavesatJuukanGorge/Report

Chain Reaction #143 August 2022 13 www.foe.org.au

Coal Mine, Victoria, 1935

Exploring Supply and Demand Solutions for Renewable Energy Minerals

Andy Whitmore

The following is a modified version of the executive summary of A Material Transition, published by War on Want and London Mining Network in March 2021.1 The report seeks to fully explore the issues associated with mining for energy transition minerals, and what can be done to mitigate the impacts.

There is an urgent need to deal with the potential widespread destruction and human rights abuses that could be unleashed by the extraction of transition minerals: the materials needed at high volumes for the production of renewable energy technologies. Although it is crucial to tackle the climate crisis, and rapidly transition away from fossil fuels, this transition cannot be achieved by expanding our reliance on other materials. The voices arguing for ‘digging our way out of the climate crisis’, particularly those that make up the global mining industry, are powerful but self-serving and wrong – and must be rejected. We need carefully planned, low-carbon and non-resource-intensive solutions for people and planet.

Academics, communities and organisations have labelled this new mining frontier, ‘green extractivism’: the idea that human rights and ecosystems can be sacrificed to mining in the name of ‘solving’ climate change, while at the same time mining companies profit from an unjust, arbitrary and volatile transition. There are multiple environmental, social, governance and human rights concerns associated with this expansion, and threats to communities on the front-lines of conflicts arising from mining for transition minerals are set to increase in the future. However, these threats are happening now. From the deserts of Argentina to the forests of West Papua, impacted communities are resisting the rise of ‘green extractivism’ everywhere it is occurring. They embody the many ways we need to transform our energyintense societies to ones based on democratic and fair access to the essential elements for a dignified life. We must act in solidarity with impacted communities across the globe.

Supply-side and demand-side solutions are both necessary to mitigate harm caused from the

mining of transition minerals. There is hope in the form of different initiatives that aim to apply due diligence along the supply chain. However, the sheer number of these laws and schemes means that consolidation and coordination are desperately required. Suppliers and manufacturers must work with civil society, especially impacted communities, to ensure the effectiveness and legitimacy of these due diligence initiatives. Even more importantly, we need to ensure there is a level of mandatory compliance if the schemes are to have any credibility. We must address the lack of effective and binding mechanisms that ensure respect for human rights, by applying international legal norms which hold transnational corporations accountable for their abuses. A just transition must be a justice transition.

On the demand side, there are a number of practical solutions which could be initiated or accelerated to enable better-informed choices about our energy and resource consumption. These changes should lead to a circular economy, reducing the need for new resource extraction. However, it is not enough to switch to green growth (such as increasing the production of electric vehicles). A radical reduction of unsustainable consumption is the most effective solution, based on a fundamental change to Global North economies and lifestyles. Such a change could be considered the creation of a circular society.

What is needed first and foremost is a global effort to bringing together those most affected by the problems at the heart of transition minerals. Such a process should focus on those three key areas; international solidarity with those impacted by transition minerals; advancing initiatives needed to ensure fair and just global supply chains for renewable energy technologies; and pushing for the fundamental societal changes needed to reduce unsustainable material consumption. These three actions would be a key stepping stone towards the transformation needed, in the UK, Europe, and globally.

To read the full report, visit waronwant.org.

14 Chain Reaction #143 August 2022

1. Whitmore, Andy 2021, “A Material Transition: Exploring supply and demand solutions for renewable energy minerals”, War on Want & London Mining Network, https://waronwant.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/A%20Material%20Transition_report_War%20on%20Want.pdf

Victorian Gas Substitution Roadmap: Concerns and recommendations

Freja Leonard

When the Victorian Government said they were seeking public consultation on a gas substitution roadmap it was an impressive moment. As the heaviest fossil gas user, at over a third of the domestic market, the Victorian Government was finally recognising and planning to tackle our state-wide gas problem. As we plunged into an energy crisis brought on by the fossil energy retailers, drafting this document was timely.

The Victorian Gas Substitution Roadmap (VGSR) makes all the right noises. It swaps out the term “natural” gas, replacing it with the more aptly descriptive “fossil” gas. It recognises that people are struggling with gas bills that have doubled in the past year. It identifies efficiency as a critical factor, with the 7 star minimum housing standard required for all new homes including public housing.

But what about the millions of inefficient homes that lack adequate insulation? What about rental and social housing, low income homeowners struggling to maintain cost of living already? What about the health impacts of having old gas appliances in these homes? These are often the households that most need help to transition.

The VGSR frames the problems of gas in a way that no state, territory or federal government has before. And then fails to deliver a solid solution. A year after the International Energy Agency told us that in order to reach net zero emissions by 2050 we cannot afford to open up a single new gas field, this document allows exactly that. Plus it is prepared to consider the import of gas from new drill sites from the north of Australia into floating gas terminals, which could forever devastate the environments of Corio Bay and Port Phillip Bay. Months after the IPCC reported that we have until 2030 to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 75% or face catastrophe, this document tinkers with those critical years for change.

Because the truth is that it’s not a matter of if, but when the curtains fall on the gas industry, both here in Victoria and globally. Gas is in an economic death spiral. A sensible government would map out a plan for an equitable rapid retirement of gas from the energy economy. This means planning an orderly shut down of the gas pipeline system that pumps methane into our homes. It means ensuring that the lower income outer suburban areas are not left paying

for the upkeep of the network through gas bills that they can’t afford but can’t afford to move away from. This requires that the government immediately stop paying people to replace their old gas appliances with new gas appliances under the Victorian Energy Upgrades program and only offers efficient electric appliances powered by renewables. This demands that instead of simply no longer requiring new developments to be connected to gas, that any future gas connections be prohibited entirely. Most critically of all it requires the strength of political will to refuse to open a single new gas well anywhere in the state, to scrap plans for the Western Outer Ring Main, a whole new gas main to be built years after the Australian Energy Regulator signalled that gas pipelines were already on the way to becoming stranded assets. The Victorian Government is to be commended for opening up a much-needed conversation about the importance of shifting away from gas as a whole-of-state effort. Their commitment to remove gas from government buildings, including public schools and hospitals shows real leadership delivering better health and economic outcomes for Victoria. But it’s only the beginning of a decarbonisation of our energy economy that must happen fairly and rapidly with measurable targets. Freja Leonard is the No More Gas campaign coordinator at Friends of the Earth, currently putting the finishing touches on the alternative to the Victorian Gas Substitution Roadmap, FOE’s own Community Gas Retirement Roadmap. Find out how you can get involved: freja.leonard@foe.org.au

www.foe.org.au

Reproduced

permission,

Global Climate Strike 2019.

with

Takver

The VGSR frames the problems of gas in a way that no state, territory or federal government has before. And then fails to deliver a solid solution

Extractivism Culture is Killing Our Forests

Alana Mountain

We sat down to talk with FoE Forests Coordinator, Alana, about the intersections of extractivism and the forestry industry.

What does extractivism mean to you?

So-called Australia was built on extractivism. It is the underpinning ideological crutch of the Australian economy. An economy founded on the blood of First Nations people. On the destruction and dispossession of their traditional lands. On the consistent overuse and over expectation that the Earth can be reaped for all it has and somehow cope. That it can continue to sustain and provide us with a steady flow of minerals and resources a capitalist society demands, many of which are shipped overseas with the aid of climate-crisis fuelling fossil fuels.

It’s a non-reciprocal, dominance based relationship with the Earth, one of purely taking. Mines, land clearing, fracking. This continent has been dismembered, dynamited, disrespected and exploited to no end. Colonisation and all the sickness that followed has led to the disintegration of a land that was once so rich and abundant when the First Peoples of this country lived in tandem with nature.

It really begins with colonisation, an opportunity for the capital growth of the individual in a ‘new’ and racist country, a mentality that has driven us away from the values of community, of sharing abundance with our tribe, with our family, to instead the selfish pursuit of the ‘capitalist dream’.

As a Victorian forests campaigner, how do you see the extractivist mentality play out?

For myself, my close relationship with the forests of Victoria as a forest campaigner provides me with a direct insight into the extractivist mentality surrounding the logging industry. Each year, native forests are plundered at the expense of all life; the life within the forest, the flora and fauna, the life-giving source of water as well as the humans which benefit from the ecosystem services forests provide.

This same mentality manifests in destructive policies, the development of the 10 Regional Forest Agreements signed between 1997 and 2001, which are supposed “long-term plans for the sustainable management and conservation of Australia’s native forests”.1 These agreements have locked in contracts such as those to corporate giant Nippon Paper, requiring a fulfilment of the obligation to supply 350,000

cubic metres of native forest wood pulp per year within Victoria alone. This is an obligation that is completely inconsistent with the reality of where our forests are at in terms of ecological collapse. They have been over logged and damaged severely in catastrophic bushfire events. Fulfilling this obligation has pushed logging into areas of forests with high slope gradients surrounding water catchments. This has compromised, for example, the Thomson reservoir, which makes up over 60% of Naarm/Melbourne’s fresh drinking water.2 The agreement with Nippon has pushed logging into burnt and recovering forests because there simply isn’t enough ‘timber’ to supply/fulfil the contracts.

It is a major issue when forests are viewed as timber and not as they are, a complex ecosystem that cannot simply ‘grow back’. Viewing the earth as a commodity to exploit has led to the disintegration of our collective ecological heritage across the globe.

Have recent climate disasters created any shifts in the forest landscape?

Post the Black Saturday bushfires of 2009 as well as the 2019/20 fires, the contracts to supply wood-pulp could have been terminated in Victoria under Force Majeure, specifically Division D. 32 detailing “a mass damage or loss to the resource”,3 however our government pushed on with no scientific evaluation of the damage to our forests which was sustained, or the severe impact of logging already fragile forest ecosystems.

It was as if nothing happened and the science, as usual, was left to the community, especially external/independent scientists deemed by the logging industry as ‘frauds’. Despite being highly peer reviewed and leading ecologists in their respected field, their analysis of what needed to change in forest ‘management’ was ignored by the government. The greed of the extractivist mentality prevailed.

What about those who say that forests are a renewable resource, and wood is necessary?

I often see pro-logging opinionists consistently appeal to futility, suggesting that because we live in a house with a timber frame that logging must continue and because we drive cars we can’t scrutinise the industry. This is an industry that returns no profit for the community and operates at a loss to the tax-payer. When you break down what our forests are actually being turned into,

16 Chain Reaction #143 August 2022

It is a major issue when you view a forest as timber and not as it is, a complex ecosystem you cannot simply ‘grow back’.

Submit to Chain Reaction!

Send us your creative content (poetry, creative writing, artwork), local campaign updates, essays, 'letters to the editor’ and 'who’s reading Chain Reaction?’ Email chainreaction@foe.org.au.

it is astounding to think that we haven’t utilised the alternatives which exist to address the absurdity that is the ecocide of forests!

Over 85% of everything that is logged is pulped and shipped overseas to create paper or cardboard, a small percentage goes into pallets and less than 2% becomes hardwood products. We certainly do not need precious native forests for paper! One less resource intensive alternative that can provide us with fibres for paper is hemp. Such a small percentage becomes hardwood, and when we are faced with the ecological collapse of our forests, preference of a resource is an indulgent excuse that doesn’t quite stand up in the court of earth justice. We urgently require a shift towards a culture where we begin ‘mining’ our landfill and ‘waste’, not consume and produce new products.

So how do you think we can create post extractivist systems?

In my mind, the opposite of extractivism is stewardship or custodianship, which means taking care of the land, ensuring that regeneration and future life continues. We need to stop and listen to First Nations people to learn about living in rhythm with the earth, seeming they achieved this for hundreds of thousands of years!

We need to return to the source, to spirit, to the land. A reprogramming, or as I like to call it, ‘rewilding’ needs to take place. Stripping back, returning to the earth, tuning into the seasons, into our human-ness. A time before we were clothed, socialised, colonised. For me, rewilding is also a form of de-colonisation. Perhaps this something a lot of us are not ready for, and our urban environments distract us from.

What do you feel has been a significant barrier in ending extractivism and what kind of work needs to be done?

Consumerism has been the ultimate disconnection tool from living eco-centrically and connecting to spirit as well as to one another. Our systems are set up for endless consumption. They do not support recycling because recycling does not support consumerism…and so the wheel goes on and on….

We need a cultural awakening where we begin to value resource recovery, reduction in the production of goods and the regeneration of land. We need to learn how to heal and look after Country.

If you think about the amount of old tech that is laying around in offices, homes and landfill, if we recovered and recycled the minerals that have become a ‘waste product’, we would be able to create all the new tech et cetera we need into the future. The same goes for all the products created from our forests.

We need to move away from decimating habitat for wildlife, as this is what capitalism has habituated us to do. The Greater Gliders, woodchips and virginal hardwood balustrades cannot compete with one another! We as a society do not need native forests for the products that come out of them.

Final words?

Finding solutions for the future requires answering the hard question of “what do we actually need?”. Technology is one part of the solution when it comes to shifting away from climate wrecking industries, but we also require a mass cultural awakening, one where people begin to view trash as treasure, resources as finite, forests as fragile and the Earth as sacred and deserving of our reverence and custodianship. Just as First peoples have for thousands of years before white man landed on the shores of so-called Australia.

Extractivism needs to die, custodianship and recovery must rise from its ashes, otherwise our Earth will continue to become an inhospitable place for most life forms.

Alana Mountain is a forest campaigner & writer within Victoria. She resides on Wurundjeri Country.

1. “Regional Forest Agreements.” Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. Published 2020. https://www.agriculture.gov.au/agriculture-land/forestry/policies/rfa

2. “Thompson Reservoir.” Melbourne Water. Published 2022. https://www.melbournewater.com.au/water-data-and-education/water-storage-levels/water-storage-reservoirs/Thomson

3. Forests (Wood Pulp Agreement) Act 1996

Chain Reaction #143 August 2022 17 www.foe.org.au

The Hole Truth:

Is the Environment Movement Aiming for Post-Extractivism?

Anisa Rogers and Zianna Faud

We are entrenched within a system where digging up earth, displacing human and nonhuman lives for the benefit of a few, flows in a historical arc from colonialism to neoliberalism. Like many other capitalist countries, this nation was founded on the belief that finite natural resources; fossil fuels, minerals, metals, or biomass, are valuable as long as they can be sold or exchanged for profit.

As we look out from this place, one of the biggest questions for the environment movement, and all the different groups and individuals within it is, what are we aiming for?

How we answer this question determines the bulk of our strategy, tactics, as well as who we are working with, and against. In this article we are going to take a brief look through different parts of the movement; to look at our interpretation of their visions, aims and breadth of their strategies.

The central question we ask is – are different groups in the environment movement aiming for a world beyond extractivism?

This piece is both a gentle critique and invitation, written with respect. We do this to open dialogue that can push us towards more nuanced organising that aims for the deep transformation needed in order to address current ecological and climatic collapse.

As our society has become more individualistic, we have lost a lot of the skills of talking across political differences, and therefore critique is often a closing of conversation. We understand that everyone is fighting for a ‘better’ world and doing what they think is best or achievable – just like us. We can all learn so much from different perspectives and respectful discussion, so we invite everyone reading this to join us in the discussion.

If you haven’t found an understanding of extractivism and post-extractivism through the articles in this Chain Reaction, extractivism is “an economic and developmental model fuelled by the exploitation of Nature—from metals, minerals and fossil fuels to land, water and humans. This model is enabled by the ideological assumption that the Earth, less powerful people, and other-than-human life are resources to be exploited for the benefit of more powerful humans, without limit or consequence.”1

And post-extractivism is a way of life and an economic system ‘after’ extractivism, that no longer relies on extracting resources in such a way that the living world cannot regenerate itself. In this article we are going to examine the strategies of a few of the different parts of the

movement. We will look at the mainstream renewables campaigns, to divestment and grassroots direct action groups. We include an analysis of Friends of the Earth Australia (FoEA) campaigns and show that FoEA has an opportunity to drive important conversations that go beyond fossil fuels and ‘renewable energy’, to a critique of extractivism in its entirety.

Mainstream renewables campaigns

The vast majority or organisations in the climate movement are campaigning for an end to fossil fuels, but without the explicit goal of decreasing overall extractivism, or challenging the profit-driven economy. Examples include WWF who are calling on governments to develop bold renewable export plans that puts us on a path of 700% renewable energy.2

Australian Conservation Foundation, is campaigning to “power [the] country with clean and renewable energy, rapidly phase out coal and help communities transition to jobs with a future”3 and Greenpeace is campaigning for big businesses to switch to 100% renewable energy, with a focus on AGL getting out of coal.4 Environment Victoria is campaigning for 100% renewables by 2030, but also focus on energy use and demand through their plans to install efficiency measures like insulation, efficient lighting and draught-sealing in one million homes.5

The Australian Youth Climate Coalition (AYCC) values include “seek[ing] solutions to the climate crisis that tackle the root causes of the problem” and “[doing] what needs to be done, not what we’ve been told is possible”, though we couldn’t find further details of what this entailed.6

Focusing solely on fossil fuels is understandable for many reasons. On reason is that fossil fuels, along with animal agriculture, are the leading cause of the climate crisis and need to be dealt with immediately. Another reason is that more concrete demands feel reasonable in the current political climate and there is a worry that a complicated systemic message will get less people on board.

However, these reasons focus on what groups think are possible within the status quo, not on what is scientifically necessary to avoid climate and ecological collapse. What is scientifically necessary to avoid this collapse includes moving away from the extractivist mindset that is driving the destruction.

As we saw in the “What is Extractivism” article earlier in this edition, without a decrease in overall material consumption the damage from the mining, processing, building, shipping and disposing of ‘renewable’ energy will continue to have devastating impacts on land, climate and communities. Mining will never be ‘green’ because it’s inherently destructive and minerals are a finite resource.

Mines come with enormous impacts including new forms of inequality, social exclusion, and impacts on complex local ecology.7 Without explicitly naming the damaging effects of the renewable transition, we give space and credence to the mining companies who are cashing in on the strategy, and allow areas around the world to be sacrificed for the transition. The corporations that have profited from the decimation of the communities, culture and country are now racing ahead to jump on the renewables boom.8 We cannot risk substituting one kind of harm for another.

Divestment

Divestment groups around the world and in Australia have had huge success in getting banks, insurance companies and many more organisations to take their money out of funding new fossil fuel projects. In many cases fossil fuel companies are offloading their fossil fuel assets in order to look green, but the offloaded projects continue to pollute under

18 Chain Reaction #143 August 2022

different ownership. Also, the new projects that are being invested in are in many cases still extremely damaging, just under the false narrative of ‘green’ mining. Despite the fact that ‘renewable’ projects are often less damaging than fossil fuel projects, the same destructive extractivism is continuing.

Rio Tinto, one of the first big mining companies to divest from coal, provides an example of divestment from fossil fuels and investment into other damaging mining. In 2019 Rio Tinto started drilling for lithium and borate in Jadar River Valley, Serbia, which led to incredible community resistance. In the words of frontline defenders against the mine – “People’s lives, Rights of Nature and cultural heritage have been completely ignored and neglected for the sake of profit.”9

Currently the strategy of divestment is not aiming beyond extractivism, because the underlying profit-driven decision-making of companies is not questioned. If we understand that profit-seeking is one of the core drivers of the destruction of our planet, not just the climate, then we need to focus on changing the way our economy works. We risk giving big corporations the ability to continue to profit off the destruction of the earth under the illusion of being ‘clean and green’.

A note on Net-Zero campaigns

It is worth noting that net zero is merely one step along the marathon to achieving a stabilised and safer level of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. It must and should never be seen as an end goal. In practice, Net Zero helps perpetuate a belief in technological salvation and diminishes the sense of urgency surrounding the need to cut emissions now.10, 11 Many proponents of net-zero emissions advocate for the trading of carbon offsets, so industries can pay to have their emissions captured elsewhere, without reducing any on their part. Using this offset logic, renewables are presented as an alternative to fossil fuel extraction, but are used by corporations as a free pass to burn more fossil fuels. Australia’s biggest polluter AGL, is now a leader in national renewables, using its ‘clean energy’ portfolio to greenwash its activities and ensure its brand remains intact.

What about non-professionalised grassroots direct action groups doing direct action on the ground?

Direct action groups, like the Frontline Action on Coal blockade against the Adani coal mine and forest blockades, are attempting to stop extractivist destruction at its source; although they don’t have an overt critique of extractivism as a whole, they do critique the type of extractivism they are trying to stop, i.e. fossil fuels or logging of native forests. Understandably, their strategies have often been designed to serve a particular context, like building a broad alliance across political views to declare a community ‘Gasfield Free’, or focus on the immediate impacts of a local mine.

With the public understanding of climate change shifting quickly, we now believe it is essential

to grow campaign narratives into a deeper intersectional analysis that acknowledges the systemic roots of mining and forestry and moves towards post-extractivist solutions. Three groups, Extinction Rebellion, Blockade Australia and Blockade IMARC, look at the bigger picture in different ways.

Extinction Rebellion’s goals are expressed in three demands under the headings Tell the Truth, Act Now and Beyond Politics.12 As part of their second demand, they are asking for net-zero by 2025. They have targeted consumptive industries through their actions at McDonald’s and Amazon container ports, but do not openly critique extractivism, instead asking for a citizens assembly that will answer the questions about how we will live sustainably.

Blockade Australia is a relatively new network that is organising direct action mobilisations with anti-extractivist messaging and strategy.

According to their purpose statement, “Blockade Australia builds grassroots power focused on opposing the colonial and extractive systems of Australia as a whole. Blockade Australia does not believe that the Australian system is broken and can therefore be repaired. It is operating from an understanding that the Australian system was established to extract value from this continent and disregard the damage caused to people, the environment and the climate.”13

Blockade IMARC, which is made up of different groups that resist the International Mining and Resources Conference (IMARC), is another campaign clearly fighting against extractivism. Their website states it “fights against the mindset that IMARC represents: the mindset that disregards communities and the environment in favour of profits and growth. [It] believe[s] there are alternatives to the structural exploitation fuelled by competition and greed that exists today.”14

Where is Friends of the Earth’s place in this?

FoE Australia is well-placed to be one of the prominent voices fighting for a post-extractivist future. With our history of anti-capitalist and intersectional politics, we have an opportunity and a mandate to talk about

Chain Reaction #143 August 2022 19 www.foe.org.au

Artist: James Sandham; Part of PDAC’s “Imaginings” (see p. 33, this edition)

extractivism; and the production, consumption, marketing and profit-seeking that drives it. There are many climate campaigns across the FoE Australia federation, including collectives that are part of FoE Melbourne, that do important work pushing for climate action through community organising, lobbying and supporting people and places on the frontlines of climate impacts. However, as far as we can see, pretty much all of these FoE groups and projects sit in the categories of mainstream renewables campaigns and divestment above, in that they campaign for an end to fossil fuels, but without the explicit goal of decreasing overall extractivism.

Earthworker, by focusing on bringing economic life back into the control of a social and environmental justice driven community, is another part of the FoE network that can be seen to be aiming for post extractivism.