On

Whale Dreaming

Nurrdalinji

On

Whale Dreaming

Nurrdalinji

This issue is dedicated to the memory and spirit of Mr Wilson Jabarda, Jungai and Nurrdalinji leader. Mr Wilson, a powerful contributor to this edition, passed away just before we went to print. May your spirit rest in power with the ancestors, and inspire new generations to lead the fight to stop fossil fuel destruction on Aboriginal Land. It is time that Mr Wilson’s fight to protect country be taken up by all who walk in this land.

“Uncle, your spirit will never diminish, but grow brighter. Your voice will never be forgotten, but become louder. Your fight will not end, but become mightier.”

- Kerry Klimm“Your legacy lives on with the unfurling of new flowers, as clearly as river water dancing over noisy water stones. May all who knew you feel peace as they transition towards a new relationship with you. Thank you for you have been, all you are and all you have touched. Stretching into new space.”

– Alana Marsh“Fracking is not our story, Country is our story! Without Water there is no life! - Nurrdalinji warrior of the water Wise words, story and energy comes from one who defends the sacred. May his message carry forward strong into the future for All. Deep Solidarity and united we stand blood fire, in the fight for Sacred Country. Respect to all the Nurrdalinji People’s.”

– Yaraan Couzens-Bundle“My thoughts and condolences to the Nurrdalinji people on the passing of one of their warriors. I know his words will live on and the spirit of his fight will continue as long as Country is endangered. I hope everyone reads his words carefully.”

– Dr Amy McQuire“Giving thanks for your wisdom from the Baaka to the Beetaloo. From Barkindji to Gudanji-Wambaya to Nurrdalinji. Thankyou. For your unwavering love for your people, Country and a yearning passion to protect them both. May your journey to eternal dreaming be safely guided by the warm embrace of your Ancestors who walked silently with you into each of the fights your legacy leaves behind. You will live on through your family, your land and waters.”

– Jennetta Quinn-BatesMr WIlson’s family have requested donations to cover Sorry Business and ongoing support be made via www.paypal.me/JohnnyWilsonSnr

Edition #146 − September 2023

Publisher - Friends of the Earth, Australia Chain Reaction ABN 81600610421 FoE Australia ABN 18110769501 www.foe.org.au

youtube.com/user/FriendsOfTheEarthAUS twitter.com/FoEAustralia www.facebook.com/FoEAustralia flickr.com/photos/foeaustralia

Chain Reaction website www.foe.org.au/chain-reaction

Chain Reaction contact details

PO Box 222,Fitzroy, Victoria, 3065. email: chainreaction@foe.org.au

phone: (03) 9419 8700

Chain Reaction Collective

Nick Chesterfield, Moran Wiesel, Tess Sellar, Steph Roberts-Thomson, Nat Lowrey, James King, Cameron, Patrick, Hamish Macrae, Zianna Faud, Tara Stevenson, Beata Szinyi

Layout & Design

Tessa Sellar

Printing

Black Rainbow Printing

Printed on recycled paper

Subscriptions

Three issues (One year) A$33, saving you $12 ($15/issue)

See subscription ad in this issue of Chain Reaction (or see website and contact details above).

Chain Reaction is published three times a year

ISSN (Print): 0312-1372

ISSN (Digital): 2208-584X

Copyright:

In this issue, #146: Strong Blak Resistance, all copyright is held by the contributors. Please contact Chain Reaction for permission to reprint. chainreaction@foe.org.au.

The opinions expressed in Chain Reaction are not necessarily those of the publishers or any Friends of the Earth group.

This issue contains references to Aboriginal people who have passed.

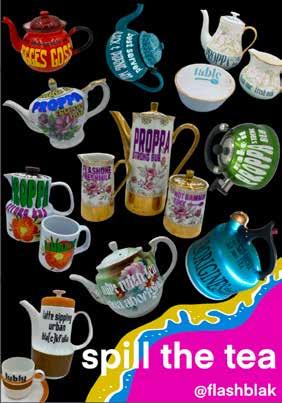

Front cover Kerry Klimm 2023, “Rise”. www.flashblak.com.au; @flashblak

www.foei.org

www.facebook.com/foeint

www.twitter.com/FoEint

www.youtube.com/user/friendsoftheearthint

www.flickr.com/photos/foei

Action alerts: www.foei.org/take-action

FoE International’s web radio station (in five languages): https://rmr.fm/

Friends of the Earth India extends its solidarity with the people of Barsu Solgaon, Ratnagiri, and condemns the suppression of the protestors of anti refinery movement. The local community, under the banner of ‘Barsu Solgaon Panchkroshi Refinery Virodhi Sanghathan’ along with environmentalists across the Konkan region and Maharashtra, have been opposing the setting up of Ratnagiri Refinery and Petrochemicals Limited (RRPCL).

The project was initially proposed in 2015 at Nanar village, Rajapur, in the Sindhudurg district, with a total investment of 3 lakh crore and a refining capacity of 60 million tonnes per annum, making it one of the largest refineries in the world. The company will have a 50% shareholding from Saudi Aramco and Abu Dhabi National Oil Company and the rest from Indian Oil Corporation, Hindustan Petroleum Corporation, and Bharat Petroleum Corporation.

Despite restrictions, villagers, especially women, reached the proposed project site to stop the land survey. Around 50-60 women protestors blocked the road by lying on the ground to stop the survey cars from moving towards the proposed project site at Barsu plateau. Police lathi-charged the protesters, and 45 women protesters were detained and destroyed the tents where women and children were camping. Police continue to arrest people. As of now, more than 100 protestors have been arrested. Find out more: foe.org.au/cr146b

Friends of the Earth International (FoEI) is a federation of autonomous organisations from all over the world. Our members, in over 70 countries, campaign on the most urgent environmental and social issues, while working towards sustainable societies. FoEI currently has five international programs: Climate Justice and Energy; Economic Justice, Resisting Neoliberalism; Food Sovereignty; Forests and Biodiversity; and Resisting Mining, Oil and Gas.

For decades Friends of the Earth Indonesia/WALHI has been developing a community-led model to protect the country’s forests. It is based on recognising the land rights of subsistence farmers, collective management of non-timber forest products and traditional knowledge. WALHI is currently working with farmers and peasant unions across the country to defend land rights and promote community control of natural resources. WALHI supports their struggle by providing free legal services, training in community organising and connecting local producers directly with consumers. Their approach is working. Not only have individual communities won land rights in the courts, but families have benefited from improved vegetable sales. This model is already being massively scaled up due to its success. The government has promised 12.7 million hectares of forest area for Community Forest Management.

In 2022 the total area of communitymanaged areas supported by Friends of the Earth Indonesia/WALHI has reached 1.1 million ha. A total of 161,019 households from 28 provinces benefit from the protection and development provided by this Community-based Area Management.2 This inspiring initiative has achieved so much on the pathway to systemic change, but much more is needed to be done.

Find out more in Friends of the Earth International’s pathways to system change report: foe.org.au/cr146a

The Philippines has 421 principal rivers spread across 119 proclaimed watersheds. Aside from providing water to drink for 110 million Filipinos, these are also the source of irrigation for almost a million hectares of agricultural lands across the nation, and a significant source of electricity comprising 10% of the current power mix.

But the Philippine government’s emphasis on big dam and hydro power infrastructure, while providing quick benefits of water distribution and power generation, are destructive to watersheds and disruptive to affected resource-dependent communities.

Listen to a conversation with Leon Dulce, as part of Real World Radio here. foe.org.au/cr146c

www.foe.org.au

youtube.com/user/FriendsOfTheEarthAUS

twitter.com/FoEAustralia

facebook.com/pages/Friends-of-the-Earth-Australia/ flickr.com/photos/foeaustralia

Friends of the Earth (FoE) Australia is a federation of independent local groups. Join FoEA today, sign up to our monthly newsletters, or donate!

In a win that’s been a long time coming, news broke this week that Australia’s largest independent coal miner Whitehaven Coal is currently unbankable. Earlier this week, Whitehaven announced it had failed to renew its $1 billion corporate loan, which had been in place since 2020. The loan facility included lending commitments from Australia’s big banks NAB and Westpac, as well as Japanese

megabanks Mizuho, MUFG and SMBC among a group of 13 total lenders. The banks’ refusal to renew Whitehaven’s loan forces the company to finance more of this expenditure internally (i.e. with its own cash reserves, instead of using other people’s money) which makes it more difficult overall for the company to pursue its climate-wrecking coal expansion plans. Get involved with Market Forces to learn more.

Illustration: Sofia Sabbagh

The Victorian State Government has announced a historical decision: Native forest clearfell logging will end on January 1st, 2024.

With logging due to end by January 1, 2024, we will continue advocating for the best protections possible for forests over the next 7 months and working closely with communities and the broader movement to ensure the best possible outcome for the forests of Victoria. The future of forests should be cared for the benefit of people, biodiversity, water and land, not exploited for profit and cheap products. Management of forests should braid First Nations Cultural Knowledge together with peer-reviewed integrity based ecological studies and maintain respect for both knowledge systems. Get involved with the Forests Campaign to be part of the future for Victoria’s forests! melbournefoe.org/forests

Larrakia Traditional Owners and environmentalists fighting to save Lee Point/Binyabara from development win a one month reprieve from land clearing. Larrakia Traditional Owners say they were not properly consulted over the project by Defence Housing Australia. Larrakia Danggalaba

traditional custodian Tibby Quall spoke about how this development would destroy his family’s connection to the land. “They will destroy the Kenbi Dreaming track, which holds our lores and customs. Dariba Nunggalinya (Old Man Rock) is like a creator, it’s from the beginning of the world – that’s how long Aboriginal people have been here. We’ve been here for thousands of years – without our land, we can’t survive, it makes us who we are.” The land is also the habitat of the endangered Gouldian finch, which has further spurred on protesters to fight for Binyabara.

For decades, successive federal governments have been attempting to establish a national radioactive waste dump. After a long legal battle, Barngarla’s voice is heard as the Federal Government abandons Kimba nuclear waste dump. On July 18, 2023 the Federal Court concluded that the former National Party Minister Keith Pitt’s decision to site the facility at Napandee was invalid due to apprehension of bias and set the declaration aside.

See article on p. 34 . Join the Nuclear Free Collective to learn more.

A landmark court case between Yindjibarndi Aboriginal Corporation (YAC) and Fortescue Metals Group (FMG) kicked off on August 7th. YAC says FMG conducted mining operations on traditional lands without adequate permission. YAC is seeking more than $500 million in compensation from FMG over their operations at the Solomon Hub iron ore mine.

Yindjibarndi woman Esther Guiness said in her testimony that the Yindjibarndi community had been divided between families who supported YAC and others who were part of a breakaway group supported by FMG. She said it made her sad. Ms Guiness said she had worked at FMG’s Solomon Hub, but that she had been forced to quit, because she had been visited by angry spirits who were upset because their homes had been destroyed by FMG’s mining activity. On Country hearings have been conducted, in which Yindjibarndi man Kevin Guinness told the court FMG had not received permission to mine or gone about the process in the correct manner. ‘“First of all, they need to see the rightful owner of the country, and they should come with an open heart and feeling and respectful of the ngurrara of that country,” he said. “I am concerned with the impact of mining on our water. Water is important for animals, birds, trees,” he said.

Corporation has divided the once-united community. “We shared our culture as one. We shared language as one to our young generations. We carried that lore as one,” he said. “Now, the mining company man been come, he split us up like that.

The Court visited various sacred Yindjibarndi areas which elders said have been disturbed by mining activity, including a Yindjibarndi male burial place, a walled-in enclave on a cliff face, and the mine site’s tailing dam, which the company built on top of a Yindjibarndi sacred site, flooding the area.

At Bangkangarra, an area the Yindjibarndi hold exclusive possession Native Title rights over, the Court heard from witnesses including YAC CEO Michael Woodley, lore man Angus Mack and elder Stanley Warrie. The proceedings were opened by a traditional Yindjibarndi smoking ceremony, administered by locals and elders. Elder Stanley Warrie testified and said the damage to his land from FMG’s mining was extremely upsetting. He told the court the experience felt like somebody was pulling his heart out, and he felt like his history and religion were being ripped up.

Reprinted from Ngaarda Media. Written by Conrad MacLean, Tangiora Hinaki and Gerard Mazza. Follow Ngaara Media or Yindjibarndi Aboriginal Corporation for further updates.

Mr. Guiness said FMG’s support of breakaway Yindjibarndi group, Wirlu-Murra Yindjibarndi Aboriginal Yindjibarndi on country for YAC court case. Image

The core of fighting for country lies with getting behind the people who care for it.

This issue contains references to Aboriginal people who have passed.

Nick Chesterfield

Welcome to Chain Reaction’s Strong Blak Resistance, the full BlakOut Takeover Issue. This issue showcases the voices of real change from the First Nations organisers, community leaders, and warriors. Voices fighting for Country at the coalface of resistance to coloniser plunder extractivism, rejecting the false solutions of Green Capitalism, and leading in asserting and adapting sustainably sovereign Blak solutions to the two centuries of damage to our ancient Land and climate.

We dedicate this issue to the warrior Mr Wilson, the late chair of Nurrdalinji mob protecting country from fracking in the Beetaloo basin, who died suddenly on August 29. With the graceful permission of his daughter Joni, we have been able to publish his powerful interview that examines the injury to his Country & countrymen, a call for active solidarity and his vision of a gas free future.

Uncle, may your spirit rest in power with the ancestors, and inspire new generations to lead the fight to stop fossil fuel destruction on Aboriginal Land.

We also acknowledge the elders past and present on all the unceded Lands that this issue was produced on, and the legacy of our elders and warriors who came before in paving the way of our Strong Blak Resistance & Protecting Country. We also honour and hold close the memory of all the other First Nations souls that have passed in the time we’ve compiled this edition – parents, cousins, children, aunties, uncles, grandparents, siblings, friends – we hear your strength, we mourn your loss, and we dedicate ourselves to abolish and heal from these colonising systems, in your memory.

Scars rip across unceded Aboriginal Land wherever we walk. An ancient Land nurtured by loving kinship, the oldest continuous scientific land management system in Earth’s History, and interconnected experiences and obligations to every single being that exists in harmony with each other. All life on our Land and Sea Country is our family, and we are bound to it, for all of time. Scars to our spirit, our bodies and our Land, scars inflicted by settlercolonialism without let-up since they arrived, destruction and plunder being all they know what to do. Scars inflicted by a people that think they actually understand the stolen land on which they stand, arrogantly thinking they know better than us how to repair the Land and Sea Country they’ve destroyed

As far as the eye can see, these are the scars of surviving a Stray-Alien culture of rape and pillage. But our warriors resisted, survived and are reborn, guided by our Elders and those who came before, a resurgence of Strong Blak Resistance – a seed that is constant in this ancient Land, and being watered by a new generation of mob finding new ways to resist and heal.

We face incredible threats – a vast machine of manufactured consent; public affairs for plunderers masquerading as journalism, yet silencing real reporting on the threats to the health of the continent we all share. We survive in an economy made from artificial scarcity, and false solutions put forward by greenwashed capital exist to plunder our ancient Land in a thousand new innovations. All these are being challenged from the best place – the grassroots of the people with their toes in the soil.

It is an honour to amplify and weave together powerful voices of this Land, of frontline defenders of country and warriors of resistance to the extractivist colony, inspired by sixty millenia of care, community and custodianship of all beings across Land and Sea Country Still standing strong against coloniser’s brutal plunder of 250 years, and in living their sovereign solutions, adapting new

ways and new allies to heal the damage caused by a terminally broken system of the invaders.

In a time where many settlers are beginning to wake up to the issues raised by Land Rights and Land Back movements, yet conversely a time where white-saviour solutions to First Nations demands still refuse to listen to real voices from our communities (causing yet another layer of deep trauma through the Referendum process), we are saying – it is time to listen up, and stand alongside us, or simply get out of the way.

When I was asked to canvas Blak feeling about the upcoming referendum for guidance to settlers trying to be allies for mob, I audibly groaned “here we go again – the colony has another wondrous idea it wants to impose on us.”

Once again,the cultural load burden of educating whitefellas again falls to mob. For years we have been asking you to educate yourselves. The coloniser’s referendum imposed brutal trauma, with the waves of racism from both Yes and No, once again. Not just from racist colonisers opposed to any form of Aboriginal representation, but from people meant to be allies. Just more harm with real impacts on the lives of those on the frontline.

This has been a very hard issue to curate, not just in outreach to the voices fighting to protect their country. The most dedicated fighters are the most under pressure, and simply don’t have time to do pages of writing.

This issue was originally focused on showcasing the campaigns of caring for country, but the imposition of the referendum changed the tack. Navigating the insidious and casual violence of the colony at every step in the process, with the responsibility to cultural safety always borne by Blakfullas (still unheeded by settlers in the conservation movement), the trauma imposed by the Referendum process meant that many people approached simply felt

too unsafe and unlistened to by? the colony, to contribute. Putting aside the cynicism of decades of experience fighting extractivism, we reached out to grassroots Land Defenders in favour of Yes. But our requests were ignored, refused or unable to be met.

We have asked a simple question: “Does the Referendum provide any utility for Aboriginal People protecting Country from destruction?” As a result, whilst there is a significant bias towards dismissal of the referendum as a coloniserimposed sideshow, the focus of this issue is demonstrating the continued need for growing practical allyship for Land and Sea Country protectors & decolonisation in the environmental movement.

Strong Blak Voices in this issue aren’t here to be polite. You stand on Aboriginal Land, you are here to Pay the Rent. Connection to land only comes from listening to those whose Law has maintained this land for 65,000 years. These are steps you already take, in a small way by wanting to decolonise your daily practice of fighting to protect country, and so Blak voices here will be demanding to Step Up and Show Up, and centre the people on whose land you are part of the theft. Hard truths will be confronted, a take-it-or-leaveit call to settler-coloniser Greenies who consider themselves allies to First Nations resistance to extractivism.

Uncomfortability creates change.

We present some big yarns – yarns that are so big we are also producing this into podcasts – and allowing for extended reads in the digital version of this magazine.

A theme runs through Blak resistance: we are still quarry – and a quarry - for empire, capitalism and colonialism.

Boe Spearim speaks strong that the Frontier Wars have never stopped, just transformed, and examines the history of Blak resistance up to today. He says allies must respect the first environmentalists, to learn from the history of constant resistance, work with mob, and show up in places like the Pilliga.

Dr Amy McGuire writes about the inescapable connections between coloniser violence, criminalisation of

protest, and environmental defence and the violence that extractivists, and white men, still impose on Blakfullas – especially the violence against Aboriginal women, and the Disappeared. As greenies you all know the extreme violence that extractivists impose on land defenders. In the eyes of the plunder-state, if you side with Blakfullas, then you must be violently punished. So it is incumbent on greenies to fight alongside Blak Women to dismantle the carceral violence system as a key tactic in fighting for environmental justice.

Yaraan Couzens-Bundle tells the story of Land and Sea Country protection bringing together defence of the Sacred Djap Warrung trees from a needless highway, and the fight to defend sea country against the ravages of seismic blasting and extractivism.

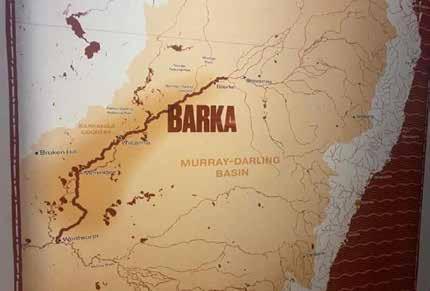

Jennetta Quinn-Bates examines the struggle to Save the Darling Baaka from industrial water theft and corruption, and also why the Voice cannot be trusted to deliver justice.

Powerful use of art as a changemaking medium for expressing survival & resistance in the colony, and protecting country, is shown and explained beautifully by Kerry Klimm

Kado Muir illustrates that at every turn of the colony, the plunder never ends. The myth of the so-called Green Revolution in the transition to renewables shows it is just the same old plunderers in charge – and they are uninterested in degrowth.

Uncontrolled Rare Earths and “Critical/ Strategic” Mining show that more than ever, allies need to step up to ensure that the process to mine more battery components doesn’t sacrifice massive swathes of Aboriginal Land.

It’s not all doomscrolling.

Alana Marsh shows the beauty of interconnectedness into the story of the Dingo and connection to their dreaming, and the regenerating songlines nurtures the hope that is necessary to create change.

Auntie Rissah Vox offers a call-to-arms for caring for our elders in their homes. There are some wins in the movements as people are becoming more educated

to our impact on this land. Small wins such as the victory of the Bangarla people in stopping the National Nuclear Waste Depository that was being put on their Land without consent near Kimba. The big win of stopping Native Forest Logging in Victoria; and a temporary win at Binybara/Lee Point in Darwin, with Larrakia mob & allies stopping the Gouldian Finch habitat destruction for the time being through direct action.

White environmentalism has worked extremely hard over the last decades, especially in issues around illegal logging, and of course in anti-nuclear work – and it has achieved significant wins. Those wins have all had one thing in common – working closely in support of traditional owners to maintain country. Allies are spread so thin. There is a call to pool resources, to drop the white egos in greenies movements and to drop the gatekeeping.

Blakfullas have made it clear they want all settlers in this country to show they have earned the right to live on our ancient continent – by stepping up to defend this land, in order to come the right way and pay the rent. Because if you aren’t going to work with traditional owners to defend the ability of this country to sustain life, what even is the point of you?

Lessons need to be learned, urgently. As Boe Spearim makes clear, “At the end of the day, if we don’t resist and continue to occupy, and re-speak our languages, and ceremonies, and be seen within this colony, then they get a continent for free.”

Nick Chesterfield is a man of Kaurna, Nunga, Kulin & Celtic Nations heritage all impacted by extractivism of the British colonial System. He is a journalist with several decades of experience of walking alongside & reporting for First Nations led, grassroots resistance movements against extractivism and resisting militarism & genocide in West Papua & First Nations across so-called Australia, and Melanesia.

Nick Chesterfield’s article “Defending Country through building Sovereign Blak Journalism capacity” appears in the online edition of this issue.

Tell us about yourself and your mob. Yama, Mirim Kumari Kuma Marwari. I’m Boe Spearim, a Gamilaraay, Kooma and Murrawarri man. I’m a radio host and warrior. Born in Western Sydney but grew up in the Southside of Brisbane out of War of the Aboriginal Resistance as well as Treaty Before Voice, and the Embassy in Musgrave Park, and put together the Frontier Wars podcast.

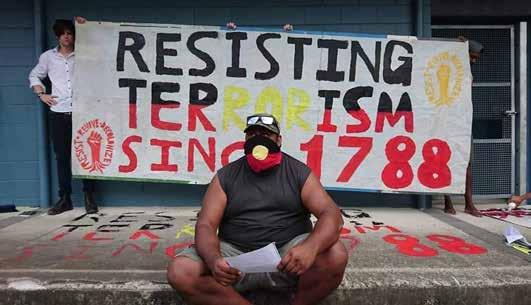

One of the biggest resets in public consciousness is of the myth that blakfullas just let colonisation take over. Tell us about how black resistance began.

The resistance began as early as 1770. Lieutenant James Cook was sailing with the Endeavour to find the Great Southern Land. He is seen in history as an amazing navigator, however he stumbled upon land that was already occupied by various different Indigenous Peoples. To a lot of Indigenous people around the world, he’s just seen as another coloniser. It came to a head in 1770 in Sydney for the Gweagal people of the Dharawal nation in a place now known as Botany Bay. Cook and his men got off the ship and rowed to the shore. At the beachfront of what is now known as Botany Bay, there was a conflict in which Cook and his men fired on the blakfullas, who in retaliation used their choice of weapons like the boomerang and spear. In that skirmish Cook and his men ended up taking a bunch of what would now be identified as artefactsthey were clearly weapons like shields, boomerangs and spears.

I don’t know what was going through the minds of the mob after this –whether they thought Cook and his men would come back or not. But, we do know that eight years after this incident everything changed for the worst – the invasion and violent occupation of the British. After the invasion of the First

Fleet in 1788, it took them 50 years before they “discovered” my country, Gamilaraay country. In the 1820s and 1830s they started to come through Western Sydney then on into Wiradjuri country through places like Bathurst, where well known Aboriginal warrior and resistance leader Windradyne and other Wiradjuri fought battles. From there the Europeans went over the plateau country and headed towards Gamilaraay, my Country. I am missing a few key things within that – but I just wanted to explain how fast and how far they got to.

They moved through our Countries under military protection. If cattle owners were moving to different stations they were escorted by the Native Mounted Police. Especially when they were going further from the colony, like up to my Country, they were hiring stockman and squatters and arming them with guns - teaching them how to corral, how to track, how to maim, how to murder and massacre, and then how to cover that up.

A lot of the white soldiers who fought in the Frontier Wars had fought in other wars across the globe. Some of the white soldiers had fought in other

wars. These were very experienced, very dangerous people, and their idea of warfare was totally different to the idea of warfare of us mob.

Richmond Hill was one of the first massacres, down in Sydney on Dharug Country. One of first big battles on the continent happened between Dharug mob and the Mounted Police, or British military. You also had Governors sanctioning massacres, like Governor Macquarie. At that time, [the Colony] weren’t getting enough traction further outside of the Sydney colony because of how stauch the mob was. So Macquarie assigned his special military force, the NSW Corps, to find particular Aboriginal people, kill them, and bring the women and children back as prisoners of war. I find it interesting, because what we have seen played out today, especially in the 1990s, is this thinking that whitefellas shouldn’t have a guilty conscience because blakfullas gave them the land, or they laid down and died, or were aimlessly wandering. But what we know is they did bring Aboriginal men, women and children back to Sydney as prisoners of war. You only do that if you are engaging in a war.

We still get this constant line that there never was a war. What we do know is there were hundreds of massacres and if not hundreds of battles that happened in different parts of this country. Aboriginal people engaged within that conflict space. Today, Aboriginal people are constantly faced with a high visibility when it comes to incarceration, and the brutalization of our bodies, our land, our children. If you ask any Aboriginal person who can articulate it, they might say the war has not ended.

What sort of tactics were being used to resist invasion in those Frontier War times?

There was always the question of how to remove these Europeans from our land. In the early days, fire was the best form to remove whitefellas. The last resort would be, we’ll burn everything on your property. Our mob are master fire-keepers. There’s a story of how mob would use fire to corral whitefellas into crocodile-infested waters - especially whitefellas that were harming people. We also used the land, the terrain, to defeat whitefellas. There’s the story of Multuggerah using Meewah (Tabletop Mountain) just off Toowoomba, to roll

big boulders down. And using knowledge of rough scrubby Country to evade men on horses. As time went by, there were mob who would use guns as well. It was never a fair war. I guess war isn’t fair. Especially when your opposition has a form of warfare that is so alien, and has no regulation or Law to what they’re doing. You see the times where European’s would massacre mob by catching them off guard, like when they were going through the process of Ceremony.

Tell us a bit more about the Native Mounted Police, and why they were so brutal?

The Native Mounted Police existed in Queensland from the late 1800s to the early 1900s. It was a very brutal organisation - it had one purpose; to protect the land from resistance from Indigenous peoples. They existed in all corners of Queensland, always moving. The Native Mounted Police used blakfullas to hunt other blakfullas. They took mob from different parts of the continent, so they wouldn’t know the people they were hunting. Some of the mob [in the Mounted Police] were survivors of massacres themselves, and brought up by whitefellas. Sometimes

they were coerced. Maybe children were in boarding schools, or their wives were captives. There were people that ran away as well, maybe ashamed of what they did.

It got to a point when, here in Queensland, people were shocked by how gruesome this force was. The Government decided to change them from native mounted police to trackers. That kept going right up until the 1920s, the 1930s – the high intensity tracking, and massacres were still being carried out and organised.

The Colony also used criminalisation to stop Aboriginal resistance, right? Our mob were part of the convict penal system, because of our resistance to invasion. We were forced to build most of these prisons, like Rottnest Island. Other Indigenous men, in particular from Aotearoa to South Africa to other British colonies, were sentenced to a life here in Australia because of their role in fighting against invasion in their own lands.

As early as the 1850s there were investigations into Aboriginal people dying in the penal system. These prisons were the breeding ground for infections and sickness. Mob would die within weeks.

Boe Spearim and Warriors of the Aboriginal Resistance - Invasion Day

Then you have Dundalli. When he was hung, there were reporters and people who came all the way from Sydney to see. He was publicly executed because they wanted to show blakfullas: “you want to be a resistance like Dundalli, this is what’s going to happen - you’re going to be hung brutally”. Up to this day, we still see the high representation of our mob who are incarcerated. We’ve always been part of the carceral system in the colony, that has been shown as a way to pacify our people. At the end of the day, if we don’t resist and continue to occupy, and re-speak our languages, and ceremonies, and be seen within this colony, then they get a continent for free.

Dhakiarr’s case got picked up by communists. That’s sort of one of the first formalised collaborations between Aboriginal people and the Communist Party. They even organised a strike in the Pilbara to fall on May Day. They calculated it months in advance – one of the blakfullas who could travel between stations passed on the dates to different stations.

bunch [of representatives], because they were having meetings and not being accountable to the people who voted them in.

After this sort of Frontier period, mob’s still resisting but in a sort of new form and fashion, depending on where you are and where you were stationed, your occupation. From having cotton strikes in Wee-Waa, to in the Pilbara, hundreds of Aboriginal men and their families walked off multiple cattle stations to the Wave Hill walk-off, and then we see the activism coming out of the cities, the formation of political Aboriginal organisations advocating against the Protection Board, advocating for more rights, advocating for freehold land to be given back to blakfullas. Depending on where you were and your influence, Aboriginal People were Resisting.

We were also witnessing and being educated on what was happening outside Australia. We had the blakfullas who worked on the docks, and when other People of Colour came to the cities on ships, they would kick back and have chill times together. This is where the relationship between the Aboriginal movement and the Marcus Garvey movement found a crossroads. We had staunch Aboriginal leaders and political leaders that were Garveyites here in Australia, which supported the notion of black liberation globally, and understood what Garvey was saying. This goes through all the way down the line up until now – we see this cross-cultural gathering and meeting of different Indigenous and People of Colour and oppressed people, from all over the world. From the PLO, to the IRA, to the Native American movements, to the Black Power movement, the Maori movement, the Pacific Island movement, the West Papua movement - learning from each other. The Freedom Ridesthat’s a prime example of seeing what is happening in other parts of the world and adapting that to us.

Of course, resistance is ongoing today. Can you speak a bit to what’s happening on your Country right now, with the Santos fracking development?

So Santos have been given the go ahead to drill almost 1000 gas wells on Gomeroi Country in the Pilliga, above the Great Artesian Basin, which is one of the biggest underground water aquifers in the Southern Hemisphere. That’s just the first stage. We’ve been through a process where the Native Title body has said no, after a restructure of the Native Title representatives. We had to get rid of a

Then after we said no, Santos took the Native Title body through the (Native Title) Tribunal. A bunch of us went to that, and after a couple of hearings, the judge gave findings in support of Santos, and there may have been a counter (action) to that as well.

I know mob have been going along to Country, and doing cultural heritage assessments, which will halt any kind of construction. I know there’s been a staunch union presence and support for Gomeroi mob against Santos. That’s not going to stop the decision. But hopefully having a huge presence and numbers can add to some sort of threatening presence that changes their mind and decision for wanting to destroy Country.

Be aware of what’s happening, and support Gomeroi people with their decisions, whether it’s occupying Country, or donating to Gomeroi people, to continue being on Country, to inform mob on Country that this is what’s happening if there’s another vote, we need your support.

There’s been a couple of groups that have given a bunch of cash to us, so we can go on Country, and literally go door to door and get the support of Gomeroi fellas. Especially for our cultural heritage, you actually need to go back on Country and talk to a whole bunch of people. That takes resources to do. So we’ve had a couple of trips back home, which is amazing. We probably need a supported campaign, rather than individual campaigners.

But the downfall for me, when it comes to greenie groups, is many come from a paternalistic point of view, thinking blakfullas can’t do this. There’s a lot of white people who get jobs in environmental movements to protect black fellas, where they may know next to nothing about the Country and the people. I’d love to see more blakfullas

employed by these groups - outside of SEED, or mob-run groups.

I think this is where the lines change in regards to the responsibility of blackfullas and greenies when fighting for country. Greenies, their responsibility isn’t to the majority of people within those communities affected by a whole gamut of issues, from racism, to incarceration, to police brutality. These are the hats that we wear when we leave our houses, anywhere in this country. When we’re occupying and advocating we talk from these places, because we know that at any moment our family members could be affected by these exact things. So this is why our movement and struggle goes beyond a movement that is shaped just to fight against the extractive industry. We fight on many different fronts. We might not be an organisation or a well oiled machine, but we get the job done, and we defend our communities and our Country and our people. And often it goes unrecognised. I’ve worked with many solid, deadly whitefellas - but they’ll never understand what we go through as blakfullas; this is our life, and the lives of the people who came before us, that fought from 1770. Our mob are tired of this.

One thing that it has done is spurred a lot of our mob on to fight against the push of assimilation. There’s a lot of mob out here now advocating against [the Voice], which is deadly. There’s a whole lot of groups that are calling for Treaty, or reparations, and have been doing that for over 40 years. They’re sick and tired of Government approved or appointed positions that don’t do much to harness true self-determination and justice, and freedom for our people. The ones who do advocate for them, you hardly hear them.

The Voice won’t really have the power to advocate. Based on the whim of the Prime Minister of the day, people could be sacked and changed to a bunch of people who see eye-to-eye with the Government, who will toe the line. This is what it is. We’ve had advisory

bodies for decades, and no-one listened to them. Every year there’s a Closing the Gap report released, and it seems we’re getting further and further away from that - it seems they’re not listening. The process has been unfair to a lot of progressive mob, where they’ve gone to the point of not allowing certain parts of our community, like respected activists and elders, access to these meetings. Which they’ve come out and said publicly as well.

So, there’s a whole lot of contradictions in what they’ve said and done that should be red flags for everybody.

Is there any mechanism in which it can provide protection for Country?

No, definitely not. The Albanese Government is very supportive of all these new gas projects that are happening. I asked Megan Davis, “is the advisory body in support of what the PM has said, or do they oppose the Narrabri gas project?” And they really couldn’t answer that. Then again, we’ve got to ask ourselves, has any Government given us true and meaningful change? Anything we have, we’ve fought for. Sadly, that continues to happen to this day. We’ll continue to fight for and die for, until we have adequate justice and freedom.

If you think about your vision for the future of Country, what does that look like to you?

Healing on Country, healing with Country. Stopping the destruction of Country – from mining, to minimising the damage of farming. Give that land back. Occupying Country, not just for the sake of living on it, but practising language and culture, and all these other things.

Ceremony, and re-lighting that fire for Country, and for ourselves. That’s a part of that healing. Having the freedom to visit Country, while it’s there. And if it’s not there, having the tools and cultural understanding to bring it back – to carve those trees out with coolamons and canoes, and other things we need to live and breathe with Country.

At the end of the day, if we don’t resist and continue to occupy, and re-speak our languages, and ceremonies, and be seen within this colony, then they get a continent for free. First, their intent was to kill us off and breed us out with eugenics and the stolen generation. Then, their intent was to put us “out of sight, out of mind” on the reserves, on the missions. But they failed on all those fronts. We’ve seen many strong blakfullas - male, female, queer and trans that are on the frontline defending our communities, whether that be against uranium, against deaths in custody, the destruction of country, to the protection of our young. Mob on all fronts, resisting, fighting, and making noise. And just, Vote No.

Frontier Wars Podcast by Boe Spearim Warriors of Aboriginal Resistance (WAR) Black People’s Union –linktr.ee/blackpeoplesunion

“Gamil Means No” –@GamilaraayNextGeneration

To hear the extended interview with Boe as a podcast, go to foe.org.au/cr146.

An Interview with Mr Wilson Jabarda - Chair of Nurrdalinji Aboriginal Corporation. Mr Wilson passed away suddenly on August 29, just after this interview was finished. He is referred to by his cultural name in this interview. www.nurrdalinji.org.au/passing_of_our_chairman_mr_wilson

My name is Mr Wilson Jabarda. I’m a traditional owner and a Jungai (lawman) guy. Here on West Birini, I’m a GudanjiWambaya man in the Gulf of Carpentaria in the Beetaloo Basin. This is my grandfather’s country, my mother’s father – so I am Jungai for this country. I’m not alone for this country, for my grandfather Junga. I’m like a policeman, I have to look after this country.

My heart is my country, is in my country here. And I must preserve everything here. I must look after it. I must obey my law. I’ve been through cultural ceremony. We accept the responsibilities that must take place here on Country as a jungai. The responsibilities must come from me, to look after my Country. I must hand that down to my son, when time for them to come to look after Country. Country is important, Country is life, Country is connection

Nurrdalinji represents nine of 11 determination areas within the Beetaloo Basin area. Nurrdalinji is an Alawa word meaning “mixed tribe”. So there’s not one tribe in this – literally, there is a mixed tribe. We have over nearly 60 members at the present moment of Nurrdalinji. Nurrdalinji was set up because we weren’t being heard. We were not given information about what’s happening on Country. We were worried about what’s happening on Country, particularly fracking.

We’re concerned that families are being intentionally divided by companies. We are not and have never been properly consulted about fracking plans. We also want the NLC [Northern Land Council] to do its job properly, give us the advice and

information we need to make necessary decisions and represent our wishes. The government is doing the wrong thing backing fracking on our country. You know, it will impact our sacred sites, many of which is connected to water, it will poison our water, our animals, and upset our songlines that run across our country. These things were passed down for us to look after! Our water, our aquifer, once this gets damaged up there, down here is damaged as well. So it’s everybody’s concern, everybody’s fight to stop and protect our water.

I’m so happy that Nurrdalinji was established. Now, we are like a thorn at their side. And we will always be a thorn to their side. Poking them. Making them know that hey, we’re not gone. We’re not forgotten, we’re the traditional owners of Beetaloo Basin and we’re still here, and we want our voices heard. This is our Country.

What impacts have you noticed on Country from fracking and climate change?

I have to see the changes every day, the grass, the heat, the changes that’s going on in Country now. I mean, where I am now, there’s water running from the hoses, I’ve got plenty of birds. But I just drive up the road there where an old creek is – there’s nothing. There’s no life there. There’s a lot of changes that’s going on here on Country, but you need to be on Country, you need to see firsthand experience of what’s happening on Country. But we have a lot of land councils or gas companies living out in towns making our decisions on what should happen on our Country. That is very frightening. Why should other people make decisions for us on Country? But that is what the Land Council is doing.

The whole of this fracking that’s on Country at the moment is scaring and

polluting our country, our animals. Our water. I didn’t used to have to go far. Now it’s like you would just drive all day now trying to find a place where water might be soaked. And there’s hardly any animals around this country anymore.

Fracking is not our story. We don’t want to be going 10, 20 years down the track and learn my kids about fracking! Country is our story, ancestors, sacred sites, songlines, dreaming.

Have the traditional owners ever given free, full, and prior consent to gas exploration and production?

In the beginning, when they were asked to do exploration on Country, that’s when they’ve given that permission. “You just look, you come back, you tell them what you find. We’ll go on from there”. But Aboriginal people didn’t actually know properly what they were agreeing to for the exploration stage. The gas company said, “We’re going to look at that Country, we’re not going to touch anything. But if we do find something we’ll come back”. We believe back then, when they signed that agreement, that was a hook line and sinker to the production stage. Because there wasn’t one time where these gas

companies came back - “hey, okay, we found gas there, now we come back and talk to you fellas, so we’ll do this…” None of that happened.

The gas companies only tell the elders the good side. “You are gonna get these royalties and benefits. You’re gonna get jobs out in your community. You’re gonna get this, you’re gonna get that.”

A traditional owner should be with these gas companies at all times. Watching. Telling them “hey, you can’t go over there. There’s something over there. That belong to Aboriginal people over there. That’s sacred sites around the area there. There’s a story over there. There’s a campsite that’s been there for a long time. No, you can’t go there.”

The only time we have a veto is at the exploration stage. No more after that. No more rights.

How did the Northern Land Council (NLC) come to represent treasured traditional owners?

When NLC first set up, the old people were on NLC and had it running. Everybody knew where their Country was. That was back then. Today, people at NLC working who just come out of

college, who don’t know nothing about nothing. And I’ve heard that from a few old people. I’ve heard from a lot of friends and families as well. They’re just not listening to traditional owners anymore. They have a PBC, Prescribed Body Corporate, made up from executive members of the NLC. These people are the ones making decisions for traditional owners on Country. Now Nurrdalinji has tried to say and argue with them, hey, we want to have our own PBC so that we can make decisions for what happens on our Country. NLC threatened us with taking us to the tribunal, to court again, because they want to run the Country. They want to make decisions for Aboriginal people on Country. They think they know what’s best. I mean, I’ve just had a house built out here – my friend, you should come and have a look at it. I call it a cheap container. The NLC is spending so much money on community out here that has nobody living on them. The NLC makes decisions for you. They sort your house out - they want it the way they want, not you. Nobody comes here to talk to you – how do you want your house to design your own house, so in the heat it can be cool? They think they’re doing

Members of Nurrdalinji corporation visiting Santos gas well on Tanumbirini (supplied Nurrdalinji)

something for you, making your life better - but they’re not.

Now, all we’re trying to tell NLC: ask traditional owners. Work with us! We do not want fracking. Help us to protect our Country! Help us to make the right decisions.

You’ve defeated one company before, the Origin Energy proposal, with campaign pressure. Now, Tamboran has bought up rights to develop Beetaloo. So, moving forward, what tactics are available to Nurrdalinji?

We believe just being united, standing up strong. And lobbying, and speaking to these people face to face. And making sure that our traditional owners know the full extent of what hydraulic fracturing is really all about. Nurrdalinji take our traditional owners out on Country and show them the gas that’s flaring out of the ground, out of these big chimneys. The look on their face… it’s something you don’t want to see. The hurt in their heart, in their soul of what is happening on Country.

We do need help. We need support from a range of corporations to come in and join Nurrdalinji, join the traditional owners of the Beetaloo Basin. We need to hit where the heart is. Stop supplying these people with money. And listen, listen to the Aboriginal people. Because our Country, we must care for it. We have nowhere to go. If our water is damaged? We can’t reverse the cycle. We must say no to fracking because we cannot take the risk of our water being poisoned, contaminated. Without water, there is no life. The gas company and the Northern Territory Government, they must know that these traditional owners from within the Beetaloo Basin will not stop until we are being heard, until they know that this Country is not for sale. This is our country, we have a right to protect it. We have a right to fight for it. Just like any other country going to war to fight for country. We are just the same. Except we are Aboriginal people or First Nation people of this country demanding a stop to what’s going on. We would love everyone to come out to stand with us. Everyone who opposes fracking.

How have pastoralists come on board with you as allies? Given historically that pastoralists have always been at the forefront of destructive extractivism and genocide of your lands and people?

The pastoralists have been so good with traditional owners, because they do care for Country. They do care about their work, their cattle, and how it won’t work with the fracking mob. Now, what’s been happening out there, these people have been spraying these contaminated water out on the roads just to keep the dust down, out in the paddocks where the birds are, poisoning our birds. And then the sad thing is nobody’s taking responsibility for it. So pastoralists are working with TOs now standing up together to say no. To say no, pastoralists do have rights, TOs do have rights, we have a right to protect our Country, we have a right to stand together. The pastoralists have been really welcoming the traditional owners on Country, so that we may share this country together. So we may fight for this country together. Because at the end of the day, this is where we live. This is where our future is. We

Gas well flare up. Credit: Nurrdalinji Aboriginal Corporationmust think about the next generation. Our people, our kids. So we must do what is right for them. It was given to us by our old fellas. Now we pass that on to the next generation.

What do you wish to see for the future on your country? And what models of sustainable care for country can your people show the world?

Well, the end of the story is that we don’t want no fracking.

At the moment there are many of my people are living in crowded houses. The government is spending so much money on gas companies. Why not put it towards the community? So that my people can have better housing, better lights, solar power, good roads out to the community?

There’s a ranger programme here. Let’s get that up and started so that these rangers could go around, look at our sacred sites, keep an eye on our sacred sites, keep an eye on the water and just observe, observing the country itself. Making sure that everything is okay. We get so many tourists a year. They come because it’s pristine. But once fracking destroys everything, there’s gonna be nothing! And what is the Territory government gonna do then?

Do you think that the voice to parliament will provide any utility for traditional owners to protect country?

I want to give you my true feeling for this voice. Now what I want to know, will this voice have room in there to solve the crisis that’s happening in the Northern Territory for my people?

The homelessness, the overcrowding in houses? I think about what is happening now on Country. Why can’t we fix the problems here now, like the homelessness, the youth crime in Alice Springs, the alcohol restrictions, the domestic violence, just to name a few? Why can’t we accept these problems here first, before jumping towards a voice? Or, will the voice have time and

money to spend on these issues that we have at the present moment? Will this voice cover all that? Or should we just leave the voice on pause for a while and fix the problems here in the Northern Territory at present? And prioritise them.

Will the Voice help the fight against Beetaloo?

You know, some say yes. It’s going to be a barrier to break down the gap, close the gap. How can we do that? How do we know that? When, like I said, there’s problems that need to be prioritised here in the Northern Territory, that need to be dealt with.

What’s the final message you’d like to close with?

Firstly, to the Northern Territory, government, and Natasha Fyles – be a true blue Aussie, and come to the Beetaloo Basin. The Chief Minister should come to the Beetaloo Basin, meet with us, traditional owners here, let her see firsthand what is taking place on Country. Let her hear firsthand what my people want.

The second thing we want is for the Northern Land Council to do its job properly, to represent the native titles of people of the Northern Territory, the traditional owners of this Country. We want that Northern Land Council to stand behind us, to help us to fight

fracking, to help us keep in our heads the knowledge, the stories, of what’s been passed down from our elders to us now. And what we’re going to pass on to our children and our next generation. And the last thing we want, we would love the fracking mob just to leave our country, leave us alone.

I speak this from the heart, and experiences living on Country, and seeing the daily changes of what’s going on. Listen to us. Listen to our voice. Listen to what we need. Because our water, our country, our song line, and our sacred sites are all very crucial to us, are so important to us, that we must cherish it and look after it with our life. So that we must pass that on to the next generation. First Nation people must carry on and must live the way we’ve lived all these years. We will stand and fight against fracking no matter what. It is our country. We have a right to protect it. Thank you.

www.nurrdalinji.org.au

Donate: www.paypal.me/JohnnyWilsonSnr

Read about the impacts on drinking water: www.foe.org.au/northern_territory_ drinking_water_report_2023

To hear the extended interview with Mr Wilson as a podcast, go to foe.org.au/cr146.

Interview with Kado

MuirTell us about your Country, and the colonial history of extractivism there?

My particular Country is out in the three deserts – The Great Victoria Desert, Gibson Desert, and the Little Sandy Desert. That’s the traditional homelands, but my elders, just before the atomic bomb test, walked out of the desert into the pastoral countries, and settled in the northern goldfields regions of Western Australia. We still hold our rights and interests in the desert country, but we’ve also, over a couple of generations, established ourselves in the Goldfields region as well. A lot of the desert peoples, when they moved into different centres, brought or retained a lot of the old ways, the old customs and laws.

The colonial impacts on the Goldfields region is different to other parts of Australia. Elsewhere, the original colonial

impacts and the frontier was built on the expansion of pastoralism, which resulted in very intense and traumatic conflicts between the Aboriginal peoples and the pastoralists. Most of the Goldfields region was established by prospecting for gold, and then mining. Gold was discovered in Coolgardie in the 1890s; around this area was possibly the last frontier of the British Empire. So the impacts were geographically retained or limited in the initial stage, but also much, much higher. Along the coastline, the original impacts were from the whaling and sealing industry, and the press-ganging and kidnapping of women, and men into servitude on whaling and sealing ships. The first transgressions of the empire into our territories and this goldfield region were essentially explorers. A chap called Hunt came out and sunk a

series of [water] wells. The thing in this part of the world is a very, very limited water supply.

Extractivism is a measure of, let’s say units or volume, that you extract from the environment. Down here in the Great Western Woodlands and the country of Ngadju and Kalamaia people, and others, the groundwater is hyper-saline – it’s 10 times saltier than the ocean. The Ngadjal people there actually had to modify trees to become vessels and containers for water. So they basically, on a young tree, would place a rock, and as the tree grew, each growth spurt they’ll come back and place a larger rock in there. The tree grew into a container. They maintained a lot of these trees throughout the Great Western woodlands.

So the only water they had access to these trees, and gnamma holes and soaks at the base of granite rocks –water that runs off the granite into the clay and stays under the sand, or forming in the gnamma holes in the actual granite itself. So across the various parts of the woodlands, and some of the heath country between Koolgarlie and Southern Cross, are numerous outcrops of granites, which were basically the traditional sources of water. Then also the extraction of water from the tree roots, and especially up towards the eastern side up towards the Nullarbor, there’s historic written accounts by European explorers talking about piles of mallee roots at the camps. I think the Mirning and Ngadju people basically extracted water.

So in the natural accounting formula, access to water is the number one priority. Once the explorers sunk these wells, it opened up territory that allowed for people, men with horses, to travel.

Prior to that the range of a horse is probably 30-40 miles without water, and then it becomes difficult and dangerous

to actually travel without water. So what they would do is follow the traditional water points of the local Aboriginal people, watch for the smoke signals, the evidence of people’s livelihoods. In that measure of the units, or the volume that you extract, a family of Aboriginal people living in this environment would survive on, let’s say, 10 litres of water over a week, or something like that, as they move between places. The advent of explorers, they came in with the camels or horsesthey’d need hundreds of them.

So did this lead to significant conflict around these granites and around the culturally modified trees?

Well, the culturally modified trees would have been visible to the explorers. But the granites… there’s probably unknown deaths and accounts, so there’s only a few that trickled through in the records. Granite Creek, for instance, which is just out of Leonora, which is a major waterpoint you see in the historic records, is easily 100 Aboriginal people living around Granite Creek in the records. You know, police filing reports on the observations on movements of Aboriginal people. Within 10-15 years of settlement in this region, you’re only talking about two or three people – and so the question is what happened to everyone else? And there’s no accounts of it…

Is that because of omission, deliberate destruction of records, or they just didn’t bother?

Omission. Because of the settlement in this region. Here, the imperative was following gold. Once there was initial infrastructure, the building, the exploration, and naming of places by explorers, the construction of the water points allowed mining.

With the discovery of gold, Coolgardie became a flashpoint. This was the largest discovery of gold since the Victorian and Californian gold rushes. So the numbers to understand is – Day Zero, you might have had 50 to 100 Aboriginal people living in an area of land that was probably 100-200 square kilometres. And that’s what is sustainably supported. Overnight, it went from zero white men to 50,000 in the space of three months. So there was absolute devastation. The modern day analogy would be West Papua and Tibet. Well, that’s the context of extractivism – is looking at the collusion between capital and governance, and then the development of infrastructure that then supports it. You know, it’s Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, which basically talks about the mobilisation of people, construction of infrastructure, the elements of wealth.

Here you see thinking of water points, identification of access routes, and then the gradual construction of additional infrastructure. Here in the Goldfields, there’s no potable water of scale, the original sector was around building massive condensation plants, extracting water from salt lakes?. That then led to two major pieces of infrastructure being brought into the Goldfields region to sustain the mining industry – the railway, which followed a lot of the traditional water sources, and then the construction of the Goldfields water pipeline, which is probably the largest project of its kind in the world at the time, creating a river that’s flowing inland that’s been flowing now for 110 years.

What is happening at the moment, is the upgrading of the community telecommunications, – we’ve probably got better internet and mobile phone access out here than people living in cities –, and the sealing of the highways. There’s a lot of discussion about the sealing of the Great Outback Highway. It’s about mining extraction & national security.. BHP has just taken over a company called Oz Minerals, and they’re basically looking at developing a major copper mine in Ngaanyatjarra Lands, what they call the West Musgraves project. This is clearly a case study on the connection between upgrading the roads and extractivism.

The [colonial] steps were discover, documentation, destabilisation of population, massacres and murders that are not accounted for. The survivors sort of start congregating around the town for security, you get witnesses around towns. The next step is they’re placing them into settlements and missions, or relocating them entirely from country. So that all happened inside the frontier.

Green Capitalism is pushing tech fixes for the climate destruction caused by coloniser capitalism. With the push for Transition and Rare Earth minerals to continue consumer consumption, where do you feel Aboriginal Land and respect for country will get a look in? What needs to happen specifically – both legally, and from a movement perspective – to confront the plunder that mining for transition minerals will be bulldozing over Country? WA and Federal Labor are also pushing to fast track development applications for “critical minerals” – what impacts will this have on Country?

Is there any way of stopping this?

You got to follow the money trail initially. I think the environmental movement can do a lot more work on holding the agents’ capital to account. There’s an example of renewable energy – somebody was saying, “well, a lot of the investment comes out of Europe

for that, and, you know, the Europeans don’t understand cultural heritage obligations.” But I flipped that around. I think it’s more the case that the Australians are not explaining [cultural heritage] once when they gain money.

I think Europeans are quite well versed on the importance of cultural heritage, and protection of cultural heritage - but the Australians are making convenient omissions in their pitch.

So my mob have got what we call a sustainability framework, identifying what our needs are, linking that back to UNSDG [United Nations Sustainable Development Goal] interpretation, and using that as a reference point to negotiate and measure the development activities. As an example, without mentioning names, you know, there’s petroleum exploration activity going on in some parts of the country out here. The discussion we’re having is, we actually want to preserve the environmental integrity of our Country. There is opportunity there to generate revenue from simple environmental projects, as opposed to going into oil capitalism.

The mining sector is ramping up. So the region’s very, very busy at the moment with nickel, rare earths, copper and lithium. There’s a massive new road constructed into a mine site just down the track here, just south of Laverton. There’s this thing that’s happening now with the alignment between the extractive sector and the industrial military complex. So we as traditional owners have always been up against national interest – our resistance to a project is measured

against the interests of the nation. That’s now escalated to national security, so it becomes a harder task.

I think Australia as a whole is grappling to come to terms with this stuff. The role of our military is coming under a lot of scrutiny with how they performed in Afghanistan, and places like that. So they’re starting to make a dent on the Australian national conscience.

Part of the privilege of being in a western society is we can point to access and benefit sharing, and the guilt complex, to be able to try and balance, or close the gap. You can’t make those same appeals in non-western societies. But for activism, identifying greenwashing, and stuff like that, is actually important work. Because of greenwashing there’s encroachment of the competing interests, still wanting to do business the old way. You know, thorough return on investment capital, cutting corners and the transparency and accountability.

Given all this, does the Voice offer any meaningful change?

Putting aside questions around sovereignty and jurisdiction and governance and all those sorts of things - you know, the discussion around sovereignty is one of the unfinished business and it’s not going to get resolved with the voice. But the voice is essentially a simple process: if you’re going to pass laws relating to, or that has an impact on, Australian and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, then maybe you should ask them. That’s

Photo credit: Nicduncan.comthe model - ask first needs to be built into every interaction, whether it’s constructing a mine, or passing a law. The other side of it though, is the questions around undue influence. Which is just ludicrous, because there are parties out there wielding massive undue influence on the political institutions, which are industrial lobby groups. And that all goes unnoticed, unseen, and basically people take it for granted. So this is the difference. There is a body of interests that can take down a government. And they’ve done that repeatedly, whether it’s Kevin Rudd, or Gough Whitlam, or whoever – they can take down a government if the government is opposed to their interests. I think in the context of this interview around extractivism, there is a lobby group out there that actually controls and holds Government in Australia, particularly Western Australia, as a

captured state, and they get their way. So there’s those guys, and then there’s the institution of the Voice where everyone’s getting hysterical. And the Voice is not going to have any impact on Government, apart from saying “you can do that better, or don’t do this”. Kado Muir is a Ngalia man who has been working for many years protecting country from the ravages of mining colonialism. Kado is a cross-cultural intellect, Indigenous futurist, strategic thinker and community based researcher. He is trained as an Anthropologist with over 30 years’ experience, working in Aboriginal Language, Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Management, Traditional Ecological Knowledge and defining Customary Wealth in First Nations, post native title. kadomuir.com.au

To hear the extended interview with Kado as a podcast, go to foe.org.au/cr146.

https://www.reclaimthevoid.com.au/ was born from Ngalia elders in Leonora, Western Australia, expressing their pain and grief at ‘those gaping mining holes left all over our country’. The vision is to cover a mining pit with a large-scale ‘dot’ artwork made up of thousands of handmade circular rag-rugs woven from discarded fabric. Woven by people from all walks of life and backgrounds, the rugs will be joined together into a giant textile artwork which shows an overall pattern that carries the story of the Tjukurrpa of the country on which the pit is situated. Reclaim the Void is a bold cross-cultural project. It seeks to raise awareness of the story of country and its importance in Aboriginal culture in both its physical and spiritual dimensions. We invite you to join us.

Amy McQuire

Amy McQuire

The mainstream media has so often been violent towards Aboriginal people. It not only expresses its violence through representation, but through silence, and in this country, the most silenced voices are often that of Aboriginal women. Aboriginal women are often accused of being silent on issues of violence particularly, while at the same time, being burdened with the task of breaking a supposed ‘silence’. But it is not that Aboriginal women haven’t been silent: it’s just that they have spoken in a language that Australia refuses to hear. They speak a truth that is fundamentally threatening to the very origin of this settler-colony. Through their presence, Aboriginal women resist the very aspiration of this colony: that of Indigenous disappearance. Over the past few years, I’ve been working as a journalist specifically on cases of Aboriginal women who have been deemed ‘missing’ or murdered. It is a crisis that is still silenced, because the parameters in which the mainstream media, courts and governments speak of it is too limited; always orientated towards interpersonal violence, whose solutions are always carceral. While sitting in on inquests in Queensland, my home state, into the cases of Aboriginal women, I realised that the word ‘missing’ was silencing in itself. The word ‘missing’ came with several connotations: one, that the women were just ‘missing’ and would one day re-appear, that the police were doing everything they could, and would not tire until they were found, and the most heinous: that the women had been responsible for going ‘missing’ in the first place. Because of the ambiguity associated with the ‘missing’, there was an obscuring of any potential perpetrator, any suggestion that the women had been targeted for violence.

So I turned to a different framework, gifted by the warriorship of activist Charandev Singh, who had begun thinking of this crisis not as cases

of ‘missing’ and ‘murdered’, but of ‘enforced disappearance’. It was through ‘disappearance’ that I was able to see what was happening more clearly. It was a tool to break through the silence, and uncover the multiple forms of violence, for which there was not just one perpetrator, but many. In Latin America, a new term was coined to recognise the widespread practice of disappearing tens of thousands of political dissidents and activists from the 1970s onwards. The term was ‘enforced disappearance,’ a practice that involved the active disappearing of thousands of people in a move to wipe what governments deemed an affront from these societies. The use of disappearing was deliberate, as Argentina’s first commander in chief Jorge Rafael Videla said in 1979: “They are not alive or dead. They are disappeared”. Jacqueline Adams describes these ‘enforced disappearances’ as “usually involving the detaining or abducting of the dissident, holding them, torturing them, killing them and disposing them in places they are unlikely to be found. These spaces included “unmarked holes, old mines, rivers and the ocean”, but also the spaces of disappearance that are set up to ensure they are never found: the apathy of the police services, the refusals of the courts, the silence of the media, and the acquiescence of the state and in turn, society. To be disappeared means there are many actors involved beyond the original perpetrators. The sheer horror of the ‘disappearing’ is such that it is difficult to grasp, because when a person is disappeared, it is not only that person who becomes a victim, but those who have been harmed by the disappearance.

‘Enforced Disappearance’ is not a distinctly Latin American phenomenon. It has been reported across the world – in Asia, Africa and Europe, and in our own region – West Papua. It is a global issue. It is a definition that has changed to incorporate other forms of disappearance, and in Australia, founded on the inevitability of disappearance, I see how it is operating. In the days of the frontier, Aboriginal men, women and children were forcibly disappeared from their homelands, either through direct acts of violence, like widespread massacres used to clear the land for settlers, and then through the violence of the protection acts, which forcibly moved Aboriginal people from their country, into reserves and missions, where they were separated from white space into spaces that were likened to jails. These acts of disappearance continued through the incarceration system, where Aboriginal people have been contained

Credit: IG@CharandevSingh

and disappeared into watchhouses and prisons, and where Aboriginal children are disappeared into the ‘child protection’ system.

‘Disappearance’ works through denying Aboriginal people the right to live on their country, and not just live on it, but to care for it. There is an ongoing genocide in the extractive industries where we must continue to fight for the protection of our country and sacred sites, the holders of story, law and ancestors, which is intrinsically tied to the wellbeing of our bodies. In 2020, two sacred rock shelters at Juukan Gorge, in Western Australia, were destroyed legally by mining company Rio Tinto – an act of cultural genocide that led to short-lived outrage, and a change to heritage laws, only to have those laws wound back after a political stoush based on the concerns of pastoralists, and the fear drummed up by the coming Referendum on the Voice to Parliament. By destroying sacred sites, and denying access to country, the state is working towards always disappearing us, a continuing process that does not end, but instead is translated in different modes and structures. As Aboriginal women, our bodies are tied to this land. The destruction of the land is not separate from the continual targeting of our bodies for violence. As I worked on the cases of Aboriginal women who had been disappeared in Queensland, I realised that Aboriginal women were most vulnerable when they were away from their country. While the state views our communities as havens of abuse and violence, all of the women whose cases I worked on had been disappeared away from their country. They had disappeared after being criminalised, and after being released from incarceration. The photographs on their ‘missing persons’ alerts

were of them as criminalised persons: they were all pictured by their mugshots. It was in these spaces that they became vulnerable to white perpetrators and because they were both racialized and criminalised, the police failed utterly in searching for them and investigating their cases. While they were alive, they were acutely visible to police for criminalisation, but when they were ‘disappeared’, they were seen as unworthy victims, unworthy of searching for, and unworthy of care. In all these stories, it was the families who rose up to search for them, and to fight for their worth, and their right to return home to country, so their spirits could rest. The denial of our right to live freely on country is tied to the ways our bodies are targeted for violence.