Issue #147 March 2024 RRP $15 chain reacti n www.foe.org.au The National Magazine of Friends of the Earth Australia The Forest Win: Celebrations, Reflections, and Future Visions for Victoria’s Forests Gliders v Government Still Standing, With All That Remains Forest Network History Solidarity for the Forests Working for Forests in the High Country The Great Tree Project

EditoR’ S not E

I had tears in my eyes when I heard of Victoria’s (mostly) end to native forest logging. This edition is a tribute to that emotion, and a tribute to the passion, devotion and sheer hard slog of campaigners throughout the decades. As many contributors highlight; without all of you - we wouldn’t be here celebrating. We begin by reflecting back on the forest movement’s history and hear the stories of campaigners past and present. But what next? What now? We take a deep dive into questioning how the forest movement can act in solidarity with First Nations people, and highlight forest campaigns that are still yet to be won.

If you’d like to contribute to CR, or get involved with our growing collective, get in touch!

chainreaction@foe.org.au

3 www.foe.org.au Edition #147 − MARCH 2024 Publisher - Friends of the Earth, Australia Chain Reaction ABN 81600610421 FoE Australia ABN 18110769501 www.foe.org.au www.foe.org.au/chain-reaction Chain Reaction contact details PO Box 222,Fitzroy, Victoria, 3065. email: chainreaction@foe.org.au phone: (03) 9419 8700 Chain Reaction Collective Moran Wiesel, Alana Mountain, Tess Sellar, Sanja Van Huet, FoE Forest Collective Layout & d esign Tessa Sellar Printing Black Rainbow Printing Printed on recycled paper Subscriptions Three issues (One year) A$33, saving you $12 ($15/issue) See subscription ad in this issue of Chain Reaction (or see website and contact details above). Chain Reaction is published three times a year i SS n (Print): 0312-1372 i SS n ( d igital): 2208-584X Copyright: Written material in Chain Reaction is free of copyright unless otherwise indicated or where material has been reprinted from another source. Please acknowledge Chain Reaction when reprinting. The opinions expressed in Chain Reaction are not necessarily those of the publishers or any Friends of the Earth group. Front cover Sofia Sabbagh. Instagram: sofia.sabbagh Website: sofiajsabbagh.com

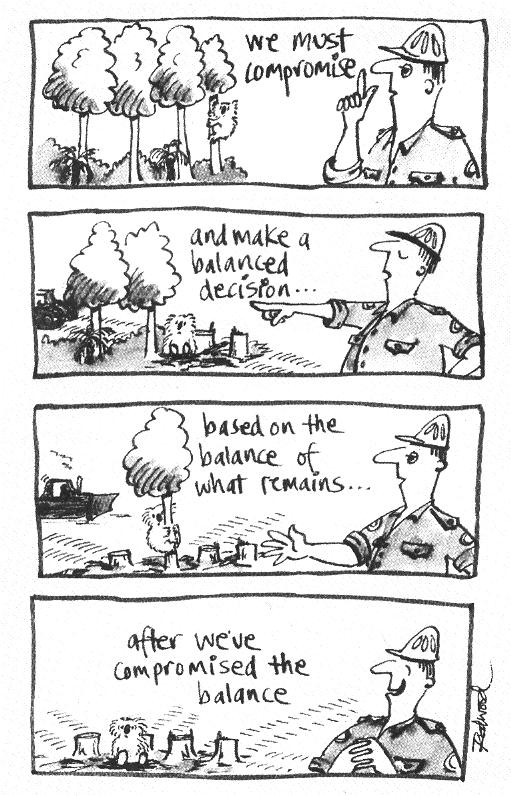

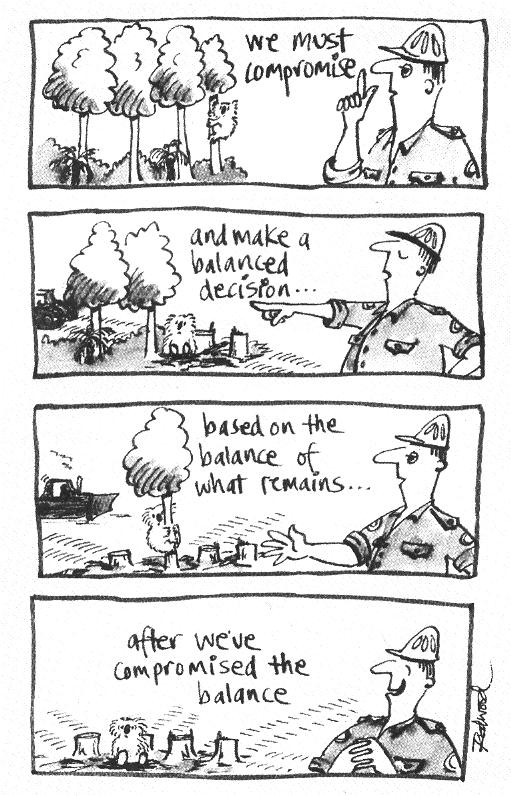

Join Friends of the Earth inside front cover Friends of the Earth Australia Contacts inside back cover Editors n ote 4 FoE n ews 4 Celebrations, refleCtions, and future Visions of ViCtoria’s forest Still Standing, With All t hat Remains. – Goongerah Environment Centre 6 o tways Ranges Environment n etwork – Simon Birrell 10 Forest n etwork History – Anthony Amis 14 W ot CHing o ut for t hreatened Species – Hayley Forster 17 Gliders v Government – Sue McKinnon 18 My Story of Active o utrage: 1960s to now – Jill Redwood 22 A Purpose to Protect – Alana Mountain 24 My Journey as a Forest Campaigner – and why i’m leaving the forest movement... for now – Chris Schuringa 26 Biocultural Climate Resilience – Bringing First n ations & Environmentalists together – Oli Moraes 28 Solidarity for the Forests – Kim Croxford 30 Forest Collective Reflections – FoE Forest Collective 42 Fragmented We Fall – Alice Hardinge 44 Strzelecki Ranges and the SKAt Campaign – Anthony Amis 45 Working for Forests in the High Country – Cam Walker 46 Wombat Forestcare – Gayle Osborne 48 CHA nGinG BEA utiF uLLy t he Great tree Project: Connecting Community and nature – Karenna Goldfinch 50 Whisper – Lachlan White 52 A Selection of Forest Cartoons – Jill Redwood 53

Cont Ent S

FoE Au S t RALi A nEWS

tAS WAt ER PFAS

dE t EC tion S 2017 - 2023

In October 2023, a Right to Information (RTI) request was sent to TasWater requesting data regarding PFAS detections by TasWater testing. The information was received from TasWater in less than two months.

TasWater provide drinking water and sewerage services to the Tasmanian community. TasWater operate 112 Sewerage Treatment Plants (STP’s) throughout the state, the RTI data shows that long term monitoring between 2020-2023 was conducted at 13 STP’s, with a further 16 STP’s tested over a shorter period of time. This means that TasWater currently have PFAS data for a quarter of their sewerage treatment plants. Extremely limited PFAS testing in water supplies was only carried out 4 times at Hobart. Water supplies don’t appear to be of major concern to TasWater in regards to PFAS contamination.

Some key findings include:

• Approximately 88.5% of all test regimes for sludge/biosolids were positive for at least one PFAS chemical and approximately 55% of test regimes in effluent/influent being positive for at least one PFAS chemical.

• Almost 2000 individual biosolid/ sludge samples tested positive for PFAS.

• Only four tests were conducted in a drinking water supply (Hobart) and all were negative.

• 45% of targeted Trade Waste tests detected PFAS chemicals, sometimes at very high levels.

Nine years ago the Tasmanian Government axed their decade-long pesticide testing program. Up until that time, it was the most comprehensive pesticide testing regime in Australia.

Any heavy rainfall events that occur after recent spraying can lead to offsite pollution events. This is particularly the case when many hectares of land in logged plantations for example are left exposed with limited vegetation to lessen soil and pesticide movement off site.

Read the full findings of the report: foe.org.au/taswater Or contact anthony.amis@foe.org.au for more information.

ViC toRi A to K iCK oFF

A uC tion S FoR 2 GiGAWAtt S oF oFFSHoRE W ind in 2024, E nouGH to P o WER 1.5

MiLL ion HoMES

Friends of the Earth welcomes the Allan government’s announcement it will kickstart offshore wind auctions in 2024, a big step forward for climate that will power 1.5 million homes with clean renewable energy.

Friends of the Earth also welcome the Allan government’s position that oil and gas style seismic blasting is not necessary for offshore wind, and the industry can instead use High Resolution Geophysical (HRG) surveys, a more sensitive way to map the seabed and other geological features.

Critically, the government says that bids for offshore wind contracts will be assessed on criteria including First Nations partnerships, community benefits, and local content and job creation, as well as price.

Friends of the Earth calls on the federal Albanese government to match Victoria’s ambition with its own offshore wind industry plan for securing good, union jobs, strong community benefits and protections for the environment.

Learn more, or get involved with Yes2Renewables: melbournefoe.org.au/energy

4 www.foe.org.au Chain Reaction #147 March 2024

ESS o duMPS

‘RiGS to REEF ’ oP tion

Friends of the Earth Australia (FoEA) is congratulating Esso Australia for saying it has rejected the idea of dumping retired oil and gas platforms into the ocean to form fishing reefs.

Esso advised FoEA that they would now remove the platforms — including the long steel support structures or ‘jackets’ — from the ocean.

In doing so, Esso (a company owned by ExxonMobil) said it acknowledged the science that does not support the artificial reefs idea. Esso is planning to remove 13 retired oil and gas platforms from Bass Strait in coming years.

QuEE n SLA nd R EJEC t S

P RoP o SE d nEW Co AL FiRE d Po WER StAtion

The Queensland Department of Environment and Science quietly refused the Environmental Authority application on 2nd November 2023.

Billionaire Clive Palmer owned Waratah Coal’s 1400 MW coal fired power station proposed for the township of Alpha, Central West Queensland has failed at its first approval stage. At the same time the Department of State Development’s advice about the local environmental impacts, recommended approval with conditions.

Some of the environment department’s key considerations to refuse the application included such things as the irreversible climate change impacts, and the threat posed to Queensland’s renewable energy targets of 50% by 2030 and 70% by 2032.

FoEA Offshore Fossil Gas

Campaigner Jeff Waters said that the hundreds of thousands of tonnes of steel for the jackets could now be brought ashore for recycling.

“What we need now is a world’s best practice, state of the art oil platform recycling yard, which will trap all toxins as the platforms are broken down, cleaned and recycled. It’s a $60 billion national industry waiting to happen,” A site in Geelong is being considered for a recycling centre.

Read the full media release: foe.org.au/ esso_dumps_rigs_to_reef_option

CoP28 out CoME undERMinEd

By dA nGERouS diS t RACtionS A nd LACK oF Fin A nCE

The COP28 outcome fails key tests on the fast, fair, funded and full phaseout of fossil fuels that the world needs now to avert climate catastrophe.

“The COP28 deal has fallen short of delivering meaningful commitments on fossil fuel phaseout and urgently needed climate finance. The deal opens the door to dangerous distractions that will prevent a just and equitable energy transition– carbon capture utilisation and storage, hydrogen, nuclear, carbon removal technologies like geoengineering and schemes that commodify nature. And, there is nothing that would stop hundreds of millions of tonnes of offsets being considered as ‘abatement’,” explained Sara Shaw, FoEI.

The outcome is weak on equity as it does not properly differentiate between developed and developing countries’ role in the transition away from fossil fuels – despite their differing historical responsibility for emissions. It has a global renewable energy target, but no money to make it happen.

Read the full media release from FoE International: foe.org.au/foei_response_ to_cop_28

With this win, now is the time for Minister Steven Miles, Minister for State Development to reject the proposed climate wrecking dirty coal fired power station - Queensland does not need another coal fired power station.

Get involved: foe.org.au/queensland_ rejects_proposed_new_coal_fired_ power_station

1. Sign the petition

2. Become a supporter of FoE Brisbane

3. Share FoE Brisbane’s social media posts.

5 www.foe.org.au Chain Reaction #147 March 2024

TO HELP, YOU CAN:

Still Standing, With All t hat Remains.

Goongerah Environment Centre

This year marks 30 years of the Goongerah Environment Centre (GECO) campaigning to protect East Gippsland’s unparalleled forests and biodiversity. East Gippsland covers 9% of the state, but is home to 34% of listed threatened species. It is the only place in the country that offers a continuous connection of natural ecosystems spanning from alpine to coastal landscapes.

GECO’s roots are in nonviolent direct action, and we’ve been blockading for forests since our inception. In November 1993, GECO formed off the back of the ‘Celebrate and Defend East Gippsland Forest Festival’ put on by The Wilderness Society, Friends of the Earth, and Concerned Residents of East Gippsland.

The end of this year also marks the end of clearfell logging in Victoria. While a major win, it has been a bittersweet victory for many. Fiona, our longest serving collective member, has been using this time to dive deep into reflection with all the generations of activists who have been part of GECO. These reflections will form part of a radio series on 3CR next year. Below are snippets of a couple of these conversations with original GECO activists present in the early 90’s. With such longevity of struggle, we have an important vantage point to learn, heal from, and also celebrate.

Fiona at GECO, 1995

t HE LEAR ninG

A nthony

The blockades were far from just symbolic – they were incredibly practical and relentless pressure upon the industry and had very real economic and political impacts on the industry at the time that was felt all the way up… There is no way that a city based population would have had the degree of ecological awareness of the importance of forests without people actually doing blockading, going out there and getting arrested. It just brought home to everybody just how critical and important these forests were…

Z eni

I learned my rights – I’m happy about that. I didn’t really know my rights until I went out there… I learned to cook for a lot of people on a fire and how to start a fire with soaking wet wood.

6 www.foe.org.au Chain Reaction #147 March 2024

Imelda and Gavin, 1995

i meldA

It was such an important part of my life and laid the foundations of what was important for me including making lifelong friends. I learnt about who I was, what I can cope with, what are my strengths, and what are things that I can let go of.

m A deline

The structure of GECO was Anarchist, but we didn’t have any other models or experience. Learning how to be an anarchist was an enlightening experience as well because with total freedom comes total responsibility. It was a huge balance. There was a process to make sure everyone had a voice, but also there were natural leaders that emerged in an area…

Another experience was learning how to lash, and I lashed a little platform on a monopole for Serina to sit on, and I remember seeing Serina all the way up there like 20 or 30 metres up and I was like, her life depends on my lashing, and whether those clove hitches hold… Oh gosh you know it was an amazing experience. Thankfully, they held!

int ER Mo VEME nt P oL itiCS

A nthony

So there were a lot of group dynamics over those years that we’re played out on a day-to-day basis basically. The stress and tension between the blockaders actually doing the blockading and the city people doing the advocacy and putting out the media releases. I think GECO really filled a big hole in that field by being an organising hub in the region that hadn’t existed before.

GAvA n

There were tensions but also a lot of co-operation and good will. I never saw organisations pushed out of discussions, certainly not towards the Friends of the Earth Forest Network at the time, which seemed to be more of like an urban direct action hub to complement the forest direct action hub at GECO.

CoMMuniCAtion

GAvA n

The other road trips I remember in terms of negotiating at that time were the trips down to Lake Tyers to talk to the traditional owners, Robbie Thorpe and others, to seek consent, permission to do direct action which were incredible experiences.

A nthony

Consensus is based on trust and respect so we had to rely on the trust and respect that we had for each other. Also it’s so hard to have consensus between a remote blockade camp, a base camp, and GECO and the city. The communication tree was doing it without phones and radio and then travelling to share information.

Z eni

We had “tell a feral” - that’s how things got around. Or you would stay at someone’s place and then the messages would go from here to there. Remember the message books? Transferring messages from GECO out to the blockades and back. As well as people’s dole forms!

7 www.foe.org.au Chain Reaction #147 March 2024

Sellars Rd blockade, 1993

t E n Sion S

A nthony

There was a boycott running in town. You would often get refused service if they spotted you as a greenie, or refused petrol. I remember there being shots fired from passing car windows at a few people on their way between Goongerah and Orbost.

m A ritA

There was a safe house in Orbost. They all had kids under two years old and I remember they were staying there when it got fully smashed.

GAvin

… We were caught in the wrong place at the wrong time and we passed a loggers four-wheel drive and we got in a car chase. They rammed the car, smashed it while I was doing a three point turn, and then they pulled us out and beat us up. We finally got to Sellers Rd and you were one of the first people I saw Fiona. I was just so happy to see everyone. I don’t know how I even drove with a smashed car with no lights…

S oL idARity W it H WoRKERS

A nthony

… It was just this seemingly intractable battle. There were mills who were pissed off at Daishowa (logging company) who were seeing all these D and E grade logs being taken up to the chipmill where they could have been sawn locally. There were all these opportunities for good alliance building that could’ve happened, but there was also strategic differences between some of the groups. There was also the fact that we were all largely city-based greenies coming out for the first time and it was hard to find that common ground with local people.

t HE L o SSES

Z eni

…I think almost everywhere that I blockaded isn’t existing anymore. There’s other losses too, including people who aren’t here anymore like Danny, Adam, Nick, and Flinney.

Goolengook, 1997

Goolengook, 1997

l ouise

I always think we can identify the forests that were destroyed and we know which ones were lost in front of our very eyes. But there’s a hell of a lot of forests that are still standing that would not be still standing if it wasn’t for the work that so many people have done. I think we can point to some forests that are still standing which is the result of all of us. That is a huge win.

GAvin

The fact that we got huge forest outcomes in the Otways, in the Cobboboonees for the Red Gums, that would never have happened if it wasn’t for the forest protests building the strength of the movement. It also created political power which ricocheted into forest campaigns elsewhere. I mean it was heartbreaking to see what’s gone, and these are some of the most extraordinary forests found anywhere in the world. The movement that was created out of it did really have an impact though for successful forest campaigns across the country.

m A ritA

I feel really honoured to have been there and seen that forest, and I guess there are still some bits in NSW that I return to. I feel like that time of blockading was the most useful thing I’ve ever done in my life, but with that comes great grief, to have borne witness and seen what was lost in our lifetime, and that does my head in and why I don’t do it anymore.

FiRS t n Ation S S oL idARity

m ichelle

I know personally I went on a journey at that time learning about what happened in this country. At the same time Friends of the Earth had the Indigenous Solidarity Network and ran two gatherings, one in 1997 and one in 1998, which brought together Indigenous activists from across the country alongside environmental activists. It really helped build those connections across a whole lot of campaigns… That’s where I first met Uncle Robbie Thorpe, who became an important part of our campaign. It was our connection to him that connected us with the Gunnai Kurnai and the Bidwell, and it really brought our campaign to a new level. We were introduced to concepts of Treaty and No Jurisdiction and it became a big part of the campaign.

Josh

Working on this land, where sovereignty was never ceded, with Bidwell Traditional Owner Albert Hayes as well as Krautungalung man Robbie Thorpe, we came up with the idea that as environmental activists we would sign Treaties with the First Nations peoples for areas we were trying to protect, and we would serve evictions on the people who were trashing the forest.

It was really powerful. We marched into a logging coupe in solidarity with Indigenous elders with the intention of doing two things: signing the Treaties and serving the eviction notices. We were met with kind of a strong response. It was such a new concept then, maybe just for white fellas. I think everyone was shocked - and I think I can include myself in that!

To hear more about “GECO: 30 years fighting for forests” tune into 3cr.org.au.

GECO marked our 30 year celebration last December. Follow our social media to learn more.

Tuffy Morwitzer is a campaigner for the Goongerah Environment Centre, and compiled this article for GECO.

9 www.foe.org.au Chain Reaction #147 March 2024

Robbie Thorpe serving an eviction notice, 2000

o tways Ranges Environment network

Simon Birrell

Since the early 1990’s Simon Birrell has been a member of the FoE Forest Collective. This collective has had a very significant positive influence over many historic forest campaigns in Victorian. In the 1990’s the FoE Forest Collective worked collaboratively to drive many important forest blockades that occurred in East Gippsland. From 1993-1995 this included the Sellers Road and Hensleigh Creek old growth forest blockades. Later, FoE Forest Collective supported the long running and successful Goolengook forest blockade campaigns (19972002). FoE Forest Collective also helped establish a renewed push to end clearfell logging in the Otway State Forest starting in 1996. In this article, Simon Birrell reflects on the recent policy announcement by the Victorian state Government to end logging across Eastern Victorian. In the past big environment policy announcements have been made only to be later reversed through the lobbying efforts of powerful pro-logging groups. The follow article reflects on one of the earliest fights over clearfell logging and woodchipping, a battle won and then lost but not forgotten

WinninG A nd t HE n L o SinG : tHE o t WAy S CLEARFELL A nd WoodCHiPPinG dEBAt E 1981-1990

The first time the political debate over clearfell logging and woodchipping native forests ever became a state election issue in Australia, it was associated with biodiverse native forests in the Otway Ranges, South-Western Victoria. Controversy first erupted into a major political issue when, on the 4th June 1981, the Victorian Premier Dick Hamer announced that a company called Smorgon Consolidated Industries was seeking to build an export woodchip mill in Geelong that would “export Otways pulp wood largely obtained from sawmill residue, logging residue and current saw logging operations …”.1 On the 20 June, the Forest Commission placed a tender for 70,000 tonnes of woodchip from the Otways, although denied any woodchip logs had been allocated to Smorgon Consolidated Industries at the time of the Premiers announcement.2 However, Smorgons had competition. By December 1981 a consortium of Colac sawmills also sought to establish an export woodchip mill in Geelong, to be named Midways Pty Ltd. The local Colac sawmills consortium proposal was strongly supported by the Liberal State Government Forestry Minister, local member for Polwarth, and several councillor’s on both the former Otway and Whichalsea local government councils. 3

The premier’s announcement triggered a fierce backlash from the President of the of Geelong Environment Council (GEC), Joan Lindros, who stated “We are absolutely horrified at the prospect. If they take out what we think they are going to take out, it will be an ecological disaster for the forests of the Otways”.4 The GEC announced a week later it would “wage a campaign of ‘total opposition’ to any proposal for a woodchipping industry in the Otway Rang”’ and called for an “environmental impact study”. 5

The campaign of opposition to Otway woodchipping, between 1981 and 1982, was predominately resourced through the efforts of volunteers grassroots groups that lived in South Western Victoria. They were up against the powerful predecessor to VicForests, the Forest Commission, who were preoccupied with the ongoing economic viability of native forest logging in State forests across Victoria. At this time, much of the Otways forest was made up of large hollow trees, many hundreds of year old, labelled by the logging industry as ‘over mature’. Those old trees that had been rejected,left standing, and leftalive, during the early selective logging days were now surrounded by smaller younger trees that had regrown due past major bushfire disturbances, such as the 1919 and 1939 fires. In 1981 the Forest Commissiondeveloped a ‘proposal’ that argued a woodchipping industry would make the clearfell logging in ‘over mature forests’ with low sawlog yields, economically viable:

10 www.foe.org.au Chain Reaction #147 March 2024

A tree-sit as part of an early protest. Credit: Ottway Ranges Environment Network

“In the Otways over the next 25-30 years it will be difficult to sustain the present level of supply of sawlogs to local sawmillers. Some sawlogs, particularly in the over-mature mountain forests, are uneconomic to harvest in a sawIog-only operation. The proposal will make the harvesting of these logs economic by providing a market for log material that is unsuitable for sawlogs. By increasing the yield of sawlogs, the proposal will materially assist in sustaining the sawmilling industry.”6

From the moment the Liberal Premier announced support for Otway woochipping, those opposed were significantly bolstered by a number of South Western Victorian based ALP politicians. This included Victorian Legislative Council Member Rod Mackenzie, the Chairman of the ALP Conservation committee David Henshaw (who was also an ALP Legislative Council candidate for Geelong Provence), and Eric Young who was ALP candidate for South Barwon. These politicians featured prominently in the media.7 Speeches to State Parliament by the ALP opposition raised issue with the decision-making process used to justify woodchipping in the Otways.8 This helped steer the Victorian ALP opposition towards developing an anti-export woodchipping policy platform for all of Victoria which called for more public consultation and studies before any decision to formally establish woodchipping industries.

In the weeks before the 1982 State election the Liberal Forest Minister, Mr Austin, controversially decided to grant the consortium of Colac sawmillers an option to extract 70,000 tonnes of woodchip per annum from the Otways. In response, 11 regional water authorities collectively announced they wanted a two-year woodchip moratorium in place to give time to evaluate environmental impacts.9 GEC spokesperson Joan Lindros challenged the claim made by the Forest Minister that no more forests would be logged, arguing it would dramatically expand where clearfell logging could take place and that extra trees would be felled: “woodchipping in the area would allow sawmillers to move in on areas which otherwise would have been unprofitable. The remaining areas of mixed-aged forest will disappear very rapidly.”10

The controversy was finally resolved by a popular vote as part of the Victorian State election held on Saturday the 3rd of April 1982. The ALP won Government with a 17-seat swing, making John Cain the Victorian Premier and ending 27 years of consecutive Liberal dominated Government in Victoria. Although many other issues were of concern

to the electorate, the voting trends in South-Western Victoria appear to have been influenced by anti-Otway woodchipping movement.

Soon after the State election the new Government followed through with environmental policy commitments by announcing, on the 19th May 1982, a formal moratorium on Otway export woodchipping. The government also rescinded the 70,000 tonne woodchip option previously granted to the sawmill consortium.11 In justifying the decision, the new Forestry Minister Mackenzie sought to wait for the findings of an Interdepartmental Task Force into woodchipping and reiterated the governments non-conflict policy position stating that:

“lt is not a question of conservation versus development but of ensuring both the long-term viability of Victoria’s timber industry and the preservation of our forests for future generations”12

Although regional environmental groups of South-Western Victoria had won a major environmental political battle in 1982 resulting in the woodchip moratorium, it was not a decisive policy outcome and would only serve to kick the political issue down the road for later and larger conflicts. Certainly, the reaction from supporters of woodchipping was swift with the Colac Chamber of Commerce declaring “woodchipping was not a dead issue”.13 Over the next decade industry groups successfully undid the woodchip moratorium, which can be summarised in three steps.

11 www.foe.org.au Chain Reaction #147 March 2024

Scuffle with police as part of an early protest.

Credit: Ottway Ranges Environment Network

The first step involved allowing sawmill sawlog offcuts, produced as a by-product of cutting up round logs into rectangular lengths of sawn timber, to be woodchipped and exported. In early 1985 George Bennett, owner of the Birregurra sawmill, went public over how his sawmill was woodchipping its offcuts and selling them to the Bendigo saleyards. However, the plan was to have these exported out of the Midway export woodchip mill based in Geelong.14 By August the same year, a consortium of Otway sawmills had the Midways woodchip mill up and running, with Bennett as a director. They were buying up sawmill offcuts from sawmills across the state and exporting them as woodchip to Japan out of the Port of Geelong, with the first shipment due in early 1986.15 The establishment of Midways was an important first step as the industry continued to publicly lobby for the right to export “logging residual on State forest floors”.16

The next step came with the release of the State Governments formal policy position on native forest logging, the Victorian Timber Industry Strategy (TIS).17

The TIS accepted the industry argument that logging in sawlog uneconomic forests needed to occur. The government and industry changed how it framed the

discourse associated with forest management planning from a discussion about economics to sustainability. So rather than just nominate a rate of logging for sawlogs, this was framed as the sawlog ‘sustainable yield’.18

The third step towards lifting the export woodchip moratorium was connected to how the government sought to accommodate the dual pressure from environment groups seeking a significant new National Park in East Gippsland while the timber industry wanted solutions to declining sawlog yield. The government approach was to give both sides their priority. Through participation in the Land Conservation Council (LCC) processes during the 1970s and 1980s, a great number of very significant forest nature conservation outcomes had been achieved. This was predominantly through the endeavours of the established formal environmental groups in Victoria, who had historically compromised by agreeing to allow ongoing logging in State Forest outside forest areas they prioritised for protection. Yet, a consequence of prioritising the protection of high sawlog yielding old growth National Estate forests in East Gippsland meant that the loggers were pushed into lower sawlog yielding forests, further

12 www.foe.org.au Chain Reaction #147 March 2024

Riley’s Ridge van 1999. Credit: Ottway Ranges Environment Network

necessitating the need for a woodchip market to make logging these forest areas economically viable.

Although there is not the space here to outline all the politics of this time, in February 1990 a politically expedient decision was made to prioritise protection of National Estate Forest in East Gippsland while simultaneously lifting an export woodchipping moratorium in place across Victoria. The consequence for the Otways was the issuing, in 1991, of a 15-year residual log licence to woodchip 44,000 cubic metre of whole trees. This was granted to a domestic pulp and paper mill owned by Kimberly Clark in Millicent South Australia. Clearfell logging could now economically target most tall mountain forests across the Otway State Forest. Similar residual log woodchip licenses were also issued for State Forest areas across Victoria.

The fight for the Otways forests was significantly set back –but not lost. In 1996 a new politically active grassroot driven environmental social movement formed to oppose clearfell logging of biodiverse native forest in the Otway Ranges, in South-Western Victoria Australia. This movement, which broadly identified itself as the Otway Ranges Environment Network (OREN), was eventually successful at influencing environmental public policy. As part of its November 2002 Victorian State election campaign the ALP Victorian State Government, under then Premier Steve Bracks, was re-elected with a radical environmental public policy to terminate the Otway native forest logging industry. By September 2005, the Victorian State Parliament had passed a package of environmental legislation, with

References

1. “Outcry over woodchip plan”. Geelong Advertiser. 6 June 1981; Premier Press Release 4 June 1981.

2. “Otways deal is denied”. The Age , 8 July 1981.

3. “Chamber Backing Pulpwood”. Colac Herald . 19 December 1981.

4. “Outcry over woodchip plan”. Geelong Advertiser. 6 June 1981.

bi-partisan political support from the Liberal Party, that made it illegal to clearfell biodiverse native forest on Otway public land for sawlogs or woodchips. For the 157,000 hectares of public native forested land in the Otway Ranges, the legislation abolished the 92,000-hectares that made up the Otway State Forest land category, where clearfell logging was permitted, and incorporated much of this into a new greatly expanded 102,000-hectare Great Otway National Park. Additionally, for the first time, an Otway Forest Park public land category was created made up of approximately 40,000-hectares where clearfell logging for sawlogs and woodchip is prohibited.19 Clearfell logging was permitted in the Otway Forest Park until 2008, the date for which the last of the Otway sawmill sawlog licences expired.

From a forest conservation perspective, native forest on public land in the Otways has been made safe from logging due to laws passed back in 2005 that specifically make industrial logging illegal (extraction of sawlogs and woodchips unlawful) and stipulated this public land must be managed for nature conservation purposes. For the forests in Eastern Victoria, although a decision to end logging has occurred until legislative changes are made to guarantee that this public land will be managed for nature conservation, it will continue to be under threat from extractive industries seeking to regain access.

Simon is a PhD candidate researching grassroots environmental social movements within the Otways, and was part of the Otway Ranges Environment Network from 1996 to 2008.

5. “Campaign”. Geelong Advertiser. 18 June 1981; “Woodchip plan for Otways is opposed”. Colac Herald . 17 June 1981.

6. Preliminary Environmental Report on the Proposed Pulpwood Harvesting in the Otway State Forest . Forest Commission. August 1981.

7. “Minister hit over Otways” Coastal Telegraph . 19 June 1981.; “Mackenzie warns on woodchip report”. Geelong Advertiser. 12 August 1981.

8. Hansard 23 September 1981 pp 876-877; Hansard 22 December 1981 pp 5537-5638.

9. “Conservationist anger at minister’s decisions”. Geelong Advertiser. 13 March 1982.

10. Bolt, Andrew. “Ministers split on pulpwood policy”. The Age , 18 March 1982.

11. “Moratorium on the Otways: Woodchip study ordered”. Colac Herald . 21 May 1982.

12. “Woodchip moratorium”. Bellarine Echo , 26 May 1982.

13. “Chipping is not dead”. Colac Herald. 16 June 1982.

14. “Birregurra sawmill has big plans”. Colac Herald . 7 January 1985.

15. “Hardwood woodchip to Japan” Colac Herald . 21 August 1985.

16. “Birregurra sawmill has big plans”. Colac Herald . 7 January 1985

17. Victorian Timber Industry Strategy. Victorian Government. 1986.

18. Victorian Timber Industry Strategy, p 33

19. Victorian Government 2004

13 www.foe.org.au Chain Reaction #147 March 2024

Forest network History

Anthony Amis

“Some of the most ignorant people in the world live in Australia and it’s reflected by what they’ve done to the environment”

Robbie

Thorpe

NFN Conference October 1994

The Forest Network (FN) was the FoE Forest collective from 1993 until 2005. It was certainly a wild ride.

The initial idea for FN came after the implosion of Rainforest Action Group (RAG) in 1992. RAG had conducted hundreds of direct actions between 1988 and 1992 protesting the importation of rainforest timber from Malaysia. RAG direct actions, including 32 ship actions on the Yarra River, managed to reduce imports of rainforest timber into Australia by 80% over a couple of years, costing timber importers hundreds of millions of dollars. RAG caused chaos within the timber industry.

By 1992 MRAG essentially folded due to burnout, ideological disagreements over NVA and a change of focus from Malaysia to local rainforest issues. A handful of RAG survivors morphed into the Forest Network (FN). FN was accepted by FoE as a collective in late 1993 and FN also joined the East Gippsland Forest Alliance helping coordinate direct actions over that summer. Hundreds of people were involved in those 1993/4 protests.

Goongerah Environment Centre Office (GECO) was also formed in late 1993 as a means of coordinating direct action campaigns in East Gippsland. FN largely became a vehicle for getting people involved in East Gippsland via GECO.

Our direct actions hit the media jackpot in February 1994 with the infamous pressure hold action outside the Department of Conservation and Environment in Melbourne. Police used death grips on protesters, and the protest made global media, even being screened in China. Images from the action won a Herald Sun photographer a Walkley Award and were reprinted in the very last 20 th century edition of the Herald Sun under Images of the 20 th Century. A number of protesters were injured and several eventually received compensation.

FN meetings were held each week in Melbourne, with a priority given to direct action planning in Melbourne. FN did not support a ban on native forest logging, working primarily on ending logging in old growth forests and high conservation value forests. A key strategy of FN was to get

ENGO decision making about forests out of Melbourne and into the regions. FN meetings averaged about 20 people each week for over a decade.

Between 1992-94, FoE was also involved in obtaining evidence for the first environmental legal case in Victorian history, regarding a logging company operating on private land. The company – STY Afforestation – was owned by the Minster for Industry Services, Roger Pescott. It operated in the domestic water supply of McCrae’s Creek near Mount Beenak. FoE won the subsequent VCAT case against the company in late 1994, but the company did not remediate the site for another few years.

FN was also making other forest alliances at this time, particularly with Wombat Forest Society. FN also had a close relationship with Native Forest Network and in 1994 organised the Australian Forest Conference in Melbourne over two days. A take home message from the conference was the largely dull presentations from forest campaigners, when compared with the observations of several indigenous speakers who were also invited to speak at the conference. Was this the first-time indigenous speakers in Victoria had spoken at a forest conservation conference? Inspiration from this conference led to the formation of FoE’s Indigenous Solidarity Group in 1996 which organised two indigenous right conferences in Melbourne in 1997 and 1998.

In 1993/94 concerns were also being aired about the use of pesticides in plantations. One of FoE Australia’s member groups at Lorinna in Tasmania reported the contamination of their drinking water with the herbicide Atrazine running off a recently sprayed plantation. These toxic concerns were at the forefront of much of FN’s campaigning during the nineties. The worst incident occurred between 1997-2000 where Adelaide’s drinking water supply was contaminated with forestry herbicides including Atrazine and Hexazinone for over 3 years. Arguably no environmental organisations were looking at plantation issues. Most ENGO’s saw plantations as the solution to native forest logging, so FN’s plantation criticisms were regarded very unfavourably by elites within the forest movement. FoE’s plantation concerns were amplified in 1996 when the Federal and State Governments announced a trebling of the nation’s plantation base.

A key target for FN forest protests during the early nineties was Midway Woodchip Mill in Geelong. A number of arrestable protests occurred at Midways during this

14 www.foe.org.au Chain Reaction #147 March 2024

Participants at the First Indigenous Solidarity Strategy Session, held on Taungerong land at Common Ground in March 1997. Indigenous peoples from Australia, United States, Malaysia and New Zealand were present.

time, with most culminating with protesters occupying woodchip piles and hanging banners. The media lapped it up. Midways had profited through the clearfelling of the Otway Ranges and Wombat Forest, so FN was relieved and supportive in 1995 when the Otway Ranges Environment Network (OREN) formed to fight against Midways. OREN successfully campaigned for a shutdown of native forest logging in the Otways by 2008. The Great Otways National Park (103,000ha) and Otways Forest Park (39,000ha) were the end result of OREN’s campaigns.

During the mid to late nineties FN also worked closely with Kerrup Jmara Elder Aunty Betty King, in the forests of south west Victoria. Numerous visits to her campsite near Lake Condah Mission occurred during a number of years. These visits also included forest protests during 1999/2000 in Portland and the Cobbobonee State Forest. One protest concluded with several firefighting aircraft being employed to put out “cultural burns” in the Cobbobonee. In 2008 the 18,500ha Cobbobonee National Park and 8,700ha Forest Park were legislated by the Victorian Government. Aunty Betty passed away in 2006.

With active groups now operating in East Gippsland, Otways and Wombat Forest, FN turned its eyes to possibly the most difficult forest area in Victoria, the Strzelecki Ranges. In 1992 the Victorian Government privatised the Strzelecki’s with the creation of the Victorian Plantations Corporation (VPC). In 1996 Amcor, owner of Maryvale

Pulp Mill, applied to clear 2000ha of native forest on their private lands. A local organisation, Friends of Gippsland Bush (FoGB), was established to oppose the clearing. FN visited the area and was appalled to see logging operations worse than those of STY Afforestation.

A relationship was formed with FoGB, whose tenacity led to the protection of 85% of the forests that Amcor wanted to clear and the signing of an historic 8 Point Agreement with a further 10,000 hectares of forest protected. The VPC was sold to US Insurance giant John Hancock in 1998, leading to FN creating the website Hancock Watch, which was one of the world’s first internet based logging monitoring websites (Hancock labelled it, “The Hate Site”). The website helped pressure the company and State Government to legislate the 8,000ha Brataualung Forest Park in 2008, however the full extent of the reserve will not be reserved until 2027. FN and FoGB were also sucked into the forest certification vortex with Hancock being the first company in Australia to obtain the dubious Forest Stewardship Council label.

In terms of direct actions by FN there was over fifty during FN’s busiest year in 1996 with many organised against the Regional Forest Agreements which guaranteed the logging industry access to forests for 2 decades. FN was at the cutting edge of urban forest protests during this time. In terms of East Gippsland, FN and GECO also helped launch Australia’s longest ever forest blockade at Goolengook in East Gippsland. The blockade lasted for 7

15 www.foe.org.au Chain Reaction #147 March 2024

years, with FN’s role largely logistical, and being a conduit for getting urban people down into the forests to support the blockade. Goolengook was eventually added to the states reserve system in 2006.

The late 1990’s saw FN protests getting personal, with visionary projects such as Corporate Scumbag tour visiting the residences of 12 corporate woodchippers and a huge pile of woodchips being dumped on the driveway to the house of the Chairman of the biggest woodchipping company in the world, North Ltd. Another “classic protest” was a Sunday morning doof party outside the residence of the same Chairman in Warrandyte. The party attracted a number of weathered, some would say very wasted, party goers with a couple of them even passing out on the Chairman’s driveway one with beer bottle in hand. As luck would have it, an early morning jogger ran past the event and contacted her mother who was a reporter for the Australian. We made page 5, much to the embarrassment of the chairman who was seen hitting the podium at the Annual General Meeting that yearsaying “we will not tolerate doof parties outside our homes”.

Perhaps peak FN actions occurred during the election campaign of John Howard in 1998 (or was it 2001?). Someone, somehow got the PM’s itinerary and we

managed to make a very big noise at every event that John Howard attended on one day in Melbourne. Not only was his campaign sidetracked by the media reporting on our activities, but we managed to blockade the Prime Minister’s limousine as he left a Christian College near Diamond Creek. The driveway out of the school was lined by hundreds of school kids waving at the PM. As the PM’s car left the school, he was greeted by FN members hiding behind a tree. A banner was unfurled. “John Howard Majick-Making Forests Disappear”. The PM was stuck with FN for 5 minutes. No police. No security, with hundreds of very excited and yelling school kids breaking ranks and blocking his limo from behind. Chaos ensued, with a very nervous looking PM and chauffeur having to sweat it out in the limo before the police arrived. Later in the morning an FN rep with a video camera actually got in the same lift in a hotel in Melbourne as the obviously rattled PM. Questions were asked by the FN “reporter” before security dragged him away with a severe spanking.

References

http://www.forestnetwork.net/ http://hancockwatch.nfshost.com/ http://www.vicrainforest.org/Gook/VEACgoolengook.php https://www.oren.org.au/

16 www.foe.org.au Chain Reaction #147 March 2024

Kerrup Jmara Embassy June 1994. Main Street Portland. Aunty Betty King giving Portland a blast on the megaphone. Aunty Betty camped out for a month on the lawns of the church in winter on the main street over claims that Portland was the most racist town in Australia.

Wot CHing out for t hreatened Species

Hayley Forster

I have been volunteering regularly with WOTCH (Wildlife of the Central Highlands) for roughly 6 years now. WOTCH is a volunteer run organisation with the aim to gain protection of threatened species within areas scheduled to be logged, through the means of citizen science. During my time as a volunteer I have conducted regular surveys, mostly nocturnal, in the search for Leadbeaters Possums, Greater Gliders or other threatened species found in the state forests of Victoria. Many of these surveys have been successful in detecting threatened species but sadly not always resulting in protection.

Finding a critically endangered Leadbeater’s Possum scampering around the forest at night has to be one of the most magical and rewarding experiences I have been lucky enough to encounter on many occasions. To witness this extremely elusive and rare species running full pace across the tree tops or sitting upside down while feeding is enough reward and motivation to keep persisting. But, the real reward is the 12 hectares of forest that is protected from logging with each verified sighting of a Leadbeater’s Possum. Through this mandatory protection WOTCH has helped to implement over 2000ha of protected habitat across the central highlands.

Many of the other threatened species that we have recorded on surveys sadly do not receive the same, or any, protection from logging. Because of this, WOTCH have worked hard to advocate for better protection of threatened species and create awareness around the impacts of native forest logging on these species.

Following the Black Summer bushfires in 2020 we took on a court case against logging company VicForests. Our case was based on the premise that threatened species were largely impacted by the bushfires and VicForests should not be continuously logging in their remaining unburnt habitat. We knew when we took on the case that it would be lots of hard work – especially for a small group of volunteers! – but we knew it would be worth it. We also had the backing of the amazing Environmental Justice Australia legal team. Nothing could have prepared us for just how much work, time and effort we would have to put into this case. But we persisted, even through all the setbacks, and we finally had our 3 week long trial in March 2022. In the lead up to trial we managed to secure injunctions on 26 logging coupes and undertakings on many more, preventing logging in an extensive area of forest in the Central Highlands and East Gippsland. Although we are still waiting for a verdict, we are really proud of what we have been able to achieve

– especially now that, due to other successful court cases and the halting of native forest logging in 2024, these areas should ultimately be protected regardless of the verdict.

The announcement of the end of native forest logging in Victoria has been an incredible feat for us and all the groups and individuals that have been working tirelessly to protect these forests. I have experienced an incredible amount of mixed emotions over the past few months, trying to settle with the news and what it ultimately means for the forests, for WOTCH, and for me. We have always known that native forest logging in Victoria is far from sustainable and has been a major cause of many native species declines. So we are incredibly happy to see an end to this destructive industry. The question now is, what next? And what will be protected into the future? We want to continue to ensure our incredible and unique native species and forests are properly protected and have the chance to thrive once again. We also want to see the other states of Australia follow suit and end the native forest logging industry over all.

You can keep updated with what’s happening with WOTCH and learn about opportunities to get involved, by signing up on our website: wotch.org.au

Hayley Forster is an ecologist, conservationist and wildlife tour guide with a degree in environmental science. She has a massive passion for wildlife and conservation, and has been part of WOTCH for six years.

17 www.foe.org.au Chain Reaction #147 March 2024

Credit: Justin Cally

Gliders V Government – How the Gliders Won… Sort of

GL idERS V Go VER nME nt

The amazing win in the recent Glider case (Environment East Gippsland V VicForests S ECI 2021 01527 / Kinglake Friends of the Forest V VicForests S ECI 2021 04204) had far reaching consequences for native forests in Victoria and for the species that rely on them – including us humans.

Greater Gliders and Yellow-Bellied Gliders were the subject of a Supreme Court case against VicForests. The case started in 2021, and the final decision was heard in November 2022. VicForests appeal was thrown out in May 2023.

On the side of the gliders were Environment East Gippsland, Kinglake Friends of the Forest, and Gippsland Environment Group, who all took separate cases against VicForests. The cases were heard together as the evidence was similar, so the cost of expert evidence and the time demands on the legal team were shared.

As a member of Kinglake Friends of the Forest, I was involved in the court case from when it commenced. The case effectively stopped logging in the east and was successful because of the decades-long work of forest campaigners: protestors, researchers, community groups, lawyers, and citizen scientists. For years citizen scientists have been locating Greater Gliders in forest stands slated for logging, only to have the trees they were recorded in, and those surrounding, torn down and sent off to make paper.

This case stopped that cycle of death and despair. It confirmed that the government was lying to us. The government said it was logging legally. It wasn’t. The government said it was logging sustainably. It wasn’t. The government said it was regulating logging. It wasn’t.

In court we claimed that VicForests was flouting two clauses of the Sustainable Forests Timber Act 2004. We won on both of these claims. The court judge, Justice Richards said;1

Sue McKinnon

Sue McKinnon

“VicForests’ current approach to detecting greater gliders and yellow-bellied gliders is considerably less than s 2.2.2.2 of the Code requires.” and

“VicForests is not applying s 2.2.2.4 of the Code in the Central Highlands.”

So, Vic Forest had been logging illegally. Not in one stand, or in one instance, but in every area they logged over the entire Central Highlands. The Central Highlands is defined as the area from Noojee in the south to Eildon in the north, and from Wallan in the west to Baw Baw in the east.

The Environment East Gippsland case found that VicForests had been logging illegally over the entirety of East Gippsland as well.

This case also tells us that this 100% state government owned company was logging not just illegally but unsustainably.

Clause 2.2.2.2 of the logging code is known as the Precautionary Principle, or ‘PP’. Effectively the clause means that where there is a risk of serious or irreversible environmental damage you don’t need 100% scientific certainty that damage will occur before you must take measures to prevent that damage. The Precautionary Principle was included in many of Australia’s laws after we signed the United Nations Sustainable Development Treaty in Rio in 1992, and is one of the fundamental principles of sustainable development of the Rio Treaty. 2

Since VicForests was found to be noncompliant with the Precautionary Principle, its operations cannot be regarded as sustainable.

Yet VicForests claims, in its website, marketing, and media releases, that its operations and its products are sustainable. 3 Even after VicForests’ appeal has been heard and rejected, a quick five minute check of VicForests’ website reveals the word sustainable 50 times. Government websites such as these inform, or should I say mislead, purchasers and consumers, and can, if abused like this, provide unfair advantage in the market. They mislead retailers, students, teachers, media, and artificial intelligence systems now and into the future. They rewrite history. It’s very important that we stop the government’s lies from being published and force retraction of these lies. With the force of the Supreme Court decision on our side, we are now holding VicForests’ misleading marketing to account. To this end, we have written a submission to the Parliamentary Inquiry into Greenwashing, and submitted a complaint to the ACCC. We have yet to hear back from either body.

F RiE nd S oF L EA dBEAt ER’ S Po SS uM inC

A nd ViCFoRES t S ( no. V id 1228 oF

2017)

Prior to our Gilder case, the government and the supposed regulator (the Office of the Conservation Regulator within the Department of Energy, Environment, and Climate Action (DEECA)), had ignored the result of an earlier legal case; the Friends of Leadbeater’s Possum VicForests case. The Friends of the Leadbeater’s Possum case also found that VicForests was not abiding by the Precautionary Principle. But the Federal Court could not compel a state logging business to comply, as due to an agreement between States and the Federal Government, logging is the only industry exempt from Federal environment laws.4

19 www.foe.org.au Chain Reaction #147 March 2024

A closer view of the Central Highlands logging showing all logged since 1940 – this is important if you are a glider as it takes 80 to 200 years for trees to form hollows that are critical to your survival.

VicForests’ data shows that they did not modify their operations after the Leadbeater’s Possum case. 5 At that point, the Office of the Conservation Regulator should have taken VicForests to account. Instead, we and other community groups had to take VicForests to the state court to get the law considered again and applied.

In the Glider case J Richards commented on this, she said that the findings of the Leadbeater’s case “might have been expected to prompt some reflection and adjustment of VicForests’ approach”.6

It is significant that instead of just handing down a declaration of how the law should be interpreted, J Richards made specific operational orders so that there was no wriggle room for VicForests. Any flouting of these orders would be contempt of court, and answerable to the court, rather than just the supposed regulator.

So finally, last November VicForests was forced to abide by the law… to survey properly for gliders before they log, and to protect them and their home ranges from destruction. It seems that VicForests isn’t able to do this, as it has stopped logging in the east of the state immediately after the orders were handed down.

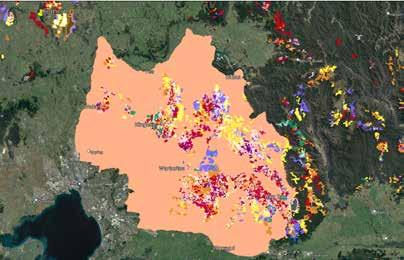

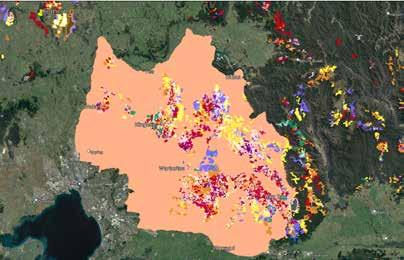

In May this year the government announced the January 2024 end date for native forest logging. However, the announcement was not for an end to all native forest logging in Victoria, but an end to logging that is under the allocation order of the Sustainable Forests Timber Act –i.e. the white shapes in this “Current Logging Scheduled” map. The blue shapes indicate logging under the Forest Act 1958, and there has been no announcement about whether logging will end in these sections of forest.

The take home from the findings and result of the case is that the government cannot be relied upon to tell the truth – not just in election promises, but in concerted, continual barrages on glossy websites, and in social and print media.

What does this do for our democracy and for real responses to climate change? Can we believe government claims in regards to the environment, biodiversity, carbon, and fire management?

FiRE

Kinglake Friends of the Forests is now focussed on the government’s forest fire management.

Hundreds of thousands of hectares of forest are burnt every year in government planned burns.7 It claims it is making communities safer, yet wildfire records reveal that planned burns only reduce fire risk for a few years. After that time the flush of shrubs and understory growth which come after a planned burn make the area more of a fire risk than before the planned burn.8

The Federal Government Royal Commission into Natural Disasters Arrangements report claims that thinning forests has the potential to reduce fire intensity and rate of spread.9 Yet research also shows that thinning, in all but one category and age group of forest, either makes wildfires more severe or makes no difference.10 This research comes from assessing thousands of records of previous planned burns and thinned sites and records of severity of wildfire in these sites.

[insert broadscale planned burning by FFMV photo in here. Caption: Broadscale planned burning by Forest Fire Management Victoria]

20 www.foe.org.au Chain Reaction #147 March 2024

Current logging scheduled

Right now the government, again through VicForests management, is planning to remove logs from trees that fell in storms in the Wombat State Forest. They claim this is to mitigate fire risk.11 This claim is obviously absurd. Logs do not burn in the fire front. The government’s own fire hazard rating system specifically excludes logs from what they call ‘fuel’.12 The absurd claim is also being repeated to justify logging operations in the Dandenong National Park.13

The claim is being tested in yet another court case against VicForests initiated this month by Wombat ForestCare.14 In this case, the judge gave “careful consideration to VicForests’ contention that it is important for the timber harvesting operation in Silver Queen to continue, in order to mitigate fire risk in the Wombat State Forest.” She found that “the evidence currently available to me does not support that contention.”15

Is the government making communities safer or putting us more at risk in their planned burns, thinning, log removal and ‘breaks’? Is the government still lying to us about its forest management?

The IPCC repeatedly points to improved sustainable forest management as an effective form of climate mitigation. We must insist on truth and science in forest management, not political expediency.

Summary

» t HE Go VER nME nt CA nnot BE REL iE d uP on to t ELL t HE t Rut H W it H REGAR d to FoRES t MA n AGEME nt, inCL udinG FiRE MA n AGEME nt. P LEASE ASK FoRES t GRouPS oR SCiE ntiS t S FoR EV idE nCE d BASE d inFoRMAtion – WE ARE HAPP y to SHARE oR HAVE you Join u S !

» FoRES t MA n AGEME nt inCL udinG FiRE MA n AGEME nt Mu S t BE inFoRME d By SCiE nCE

» CoMMunity GRouPS HAVE A RoLL to KEEP t HE BAS tAR d S HonES t

Kinglake Friends of the Forest provides a forum for people to learn about, discuss and advocate for the preservation of the native forests in Victoria.

1. Seci 2021 01527 Environment East Gippsland Inc. Plaintiff, V VicForests Defendant and SECI 2021 04204 Kinglake Friends of the Forest Plaintiff V VicForests Defendant Judge Richards, J Melbourne 9-13, 16 May 2022, 23 June https://www.austlii.edu.au/cgibin/viewdoc/au/cases/vic/VSC/2022/668.html?context=1;query=environment%20east%20gippsland%20v%20 vicforests;mask_path=

2. Report Of The United Nations Conference On Environment And Development. Rio de Janeiro, 3-14 June 1992. Annex I: Rio Declaration On Environment And Development https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_CONF.151_26_Vol.I_Declaration.pdf,

3. VicForests. “VicForests”. 2023. .https://www.archive.vicforests.com.au/

4. Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. “Victorian Central Highlands Regional Forest Agreement”. 2023. https://www.agriculture.gov.au/agriculture-land/forestry/policies/rfa/regions/victoria/centralhighlands

5. VicForests’ Timber Release Plans 2014 – 2018.

6. Para 374(a) Judgement Environment East Gippsland V VicForests S ECI 2021 01527 / Kinglake Friends of the Forest V VicForests S ECI 2021 04204

7. Data Vic. “Planned Burns”. 2022. https://discover.data.vic.gov.au/dataset/planned-burns-2022-23-2024-25-now-called-joint-fuel-management-program-jfmp-includes-burns-and-

8. Zylstra, P., Wardell-Johnson, G., Falster, D., Howe, M., McQuoid, N., Neville, S. “Mechanisms by which growth and succession limit the impact of fire in a south-western Australian forested ecosystem.” Functional Ecology 37 no. 5 (2023): 1350-1365. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.14305

9. recommendation 17.3, Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements. Report. 28 October 2020. https://www.royalcommission.gov.au/system/files/2020-12/Royal%20 Commission%20into%20National%20Natural%20Disaster%20Arrangements%20-%20Report%20%20%5Baccessible%5D.pdf

10. Taylor, C., Blanchard, W., Lindenmayer, DB. “Does forest thinning reduce fire severity in Australian eucalypt forests?” Conservation Letters 14 no. 2 (2020). doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12766

11. VicForests. “Storm Timber Recovery - VicForests project plan”. 2024. https://www.vicforests.com.au/publications-media/latest-news/storm-recovery-update

12. Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria. Overall fuel hazard assessment guide. 4th edition. July 2010. https://www.ffm.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/21110/Report-82-overall-fuel-assess-guide-4th-ed.pdf

13. VicForests. “Storm Timber Recovery - VicForests project plan”. 2024. https://www.vicforests.com.au/publications-media/latest-news/storm-recovery-update

14. WOMBAT FORESTCARE INC (ABN 94 771 427 351) Plaintiff v VICFORESTS First Defendant and TILEY INDUSTRIES PTY LTD Second Defendant and GARY and COLLEEN KIRBY Third and Fourth Defendants.

15. para 85. S ECI 2023 04203 WOMBAT FORESTCARE INC (ABN 94 771 427 351) Plaintiff v VICFORESTS First Defendant and TILEY INDUSTRIES PTY LTD Second Defendant and GARY and COLLEEN KIRBY Third and Fourth Defendant. https://aucc.sirsidynix.net.au//Judgments/VSC/2023/T0582.pdf

21 www.foe.org.au Chain Reaction #147 March 2024

Get involved with Kinglake Friends of the Forest – kinglakefriendsoftheforest.com. See you in the forest!

My story of active outrage: 1960s to now

Jill Redwood

As a kid fund raising for the RSPCA in the 1960s, to multiple defeats of the forest exploiters in the Supreme Court, to the recent mortal blow, it’s been quite a journey.

Since Captain Cook planted the flag on the east coast, Australia’s natural wonderlands, wildlife and original people have suffered brutal treatment and often obliteration.

This wasn’t obvious as an 8 year old, but there were still shocking injustices and cruelty in the suburban environments. The neighborhood kids that destroyed a bird’s nest or hurt their pets seemed to have the same malicious streak and lack of empathy that I now see in many adults. The outrage hasn’t changed, just the confidence to act.

Moving out of the urban soup of discontent in the 1970s to a world of nature and animals among Gippsland’s forests was like moving into utopia. But where there are utopias there are those hell bent on exploiting them. It was impossible to keep the blinkers on, while enjoying animals and growing veggies.

In the following years there was a lot to learn about politics, campaigning, media, writing and messaging, strategy, tactics and even psychology.

East Gippsland has a lot of environmentally aware people, but most were unable to speak out without facing retribution via their job, business, family or pets. The industry was a brute force and confident in its support base within law enforcement and local and state authorities. I lived remotely and didn’t rely on the town for an income or had kids at school that might be beaten up for being a ‘greenie’. I also had a gun and two large dogs, so I began to speak out.

Being constantly in the media, I became a target for the logging ‘tribe’. They used death threats, property damage, violent property invasions with revving vehicles, character assassination (pffft) and also had my Clydesdale horse shot. Instead of silencing me, my resolve hardened.

Over the next 10-20 years the corruption and destruction was extreme. The 80s saw a cut-out-and-get-out logging policy without limits. There were unimaginable losses of magnificent old forests that supported endangered wildlife.

Several environment groups were working on forests both in Melbourne and regionally. Environment East Gippsland (EEG) had its beginnings in 1982, and the East Gippsland Coalition formed in 1984. In the early 90s another group became established, Goongerah Environment Centre (GECO). GECO’s specialty was blockading. This created media attention, but also community tensions. Industry

used these conflicts to concoct many fake incidents of machinery damage and tree spikes. ‘Eco-terrorism’ claims were used as recently as 2021.

Since the 80s, EEG tried almost every means to halt logging. We were the eyes on the ground and gathered evidence, produced media releases, exposed the lies and corruption, and did talk back radio and interviews. We took part in tokenistic stakeholder committees, public consultation processes and writing detailed submissions. These processes simply justified pre-determined government decisions.

We also tried every angle that might outrage voters –sympathy for the faces of the wildlife victims, drawing attention to the insane subsidies to destroy public property, carbon dating giant trees, and highlighting the impact on other local industries like nature-tourism. We met with state and federal ministers. We organized quirky events, like when Melbourne’s streets were decorated in festive Christmas attire. We walked paper mâché bare bums on sticks with placards ‘who’s kissing whose?’ – ‘let’s get to the bottom of this’ – ‘forests get the bum end of the deal’. The visuals made font page, despite only being a smallish event. Nothing changed.

It was clear that bad media didn’t cause the government to flinch.

In the late 1980s, the Australian Heritage Commission declared large areas of East Gippsland as National Estate.

22 www.foe.org.au Chain Reaction #147 March 2024

Newspaper clipping of “bum action” in the 80s. Source:

/ Credit:

Armano

Jill Redwood

Joe

But unlike National Parks, National Estate had no protection, and were handed to Victoria to manage. Shamelessly, they began to be managed with bulldozers and chainsaws. In response, the first major forest protests saw 300 people arrested at Brown Mountain’s old growth. But after a token pause, logging continued.

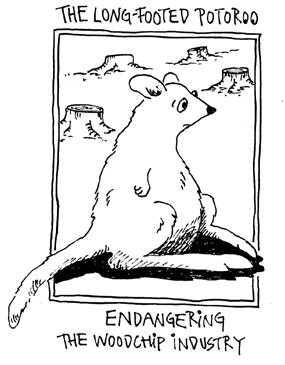

I decided to be trained in wildlife survey techniques by a NSW government team. Back then the best method was setting antiquated hair tubes. These hair tubes were bits of plumbing pipe, with bait secured in one end and double-sided tape inside the tube. The hairs we collected were analysed under microscope to determine the species – each species has a different cross-sectional pattern. This method was very hit-and-miss but when a Long-footed Potoroo entered the baited tube and left its tell-tale hairs we still secured many 500ha zones of protected forests. When we became too successful, the government weakened protection measures. Later, high-tech methods like cameras were available, and the GECO crew began surveying, providing detections and often protections of more species.

When more of Brown Mountain’s old growth was again earmarked for obliteration in 2009, the Government ignored its legal obligations to rare species, offering only a shoe-string creek buffer for the rich glider population. For this weak protection plan we are now thankful.

Such corruption forced us to try a new but risky and expensive campaign weapon; in 2009 we sued VicForests. It was a significant action for a small group to take the government to the Supreme Court. The landmark win in 2010 forced VicForests to carry out surveys before they logged. But they continued to under-resource their minimal survey efforts.

The $289 million VicForests’ debt to Victorians has been ignored. The loss of biodiversity, the cost to water catchments, bushfire impacts, our critically endangered state faunal emblem, forests as climate moderation … all ignored.

EEG and others continued to do battle in court.

It’s taken 40 plus years of huge community effort on all fronts to have finally crippled the corruption and collusion that has been the logging monster. The Gliders Case win in late 2022 was the clincher. The three regional group litigants covered most of eastern Victoria. It sets a strong precedent for other regions. The government recognised it was unable to keep changing the law to protect logging.

The losses over the decades have been immense, tragic, and likely permanent. But logging interests now want to keep it going under creative new names such as ‘fire management’.

After such nature carnage, the war against forests and wildlife must end. As with the rights of First Nations people, the rights of nature and wildlife and the need for healing and restoration must now be acknowledged.

Jill Redwood has lived in East Gippsland for over 40 years and maintains an organic property in the remote settlement of Goongerah. Jill runs an eco-accommodation B&B, is a cartoonist, writer and low-impact-living advocate.

23 www.foe.org.au Chain Reaction #147 March 2024

Hair tubes were used to determine species present in the landscape.

Credit: Jill Redwood

Credit: Jill Redwood

A Purpose to Protect

I am standing on the shoulders of those who came before me. Our collective achievements and opportunities have been made possible by the efforts and advancements of earlier generations in this fight for the forests. The knowledge, wisdom, and experiences passed down to us through history has been invaluable. It has made it all possible to take this to the end of one of our longest battles to end clearfell logging in Victoria.

I never would have believed it if you had told my 20 year old self that I was about to embark on a journey that would be a third of my life time so far. That I would learn to climb trees and tie up machines and find a group of people as fiery and passionate about the environment as myself. That I would spend countless nights plunging my body through dense bush searching for threatened species, hiking up

ridgelines, sleeping in beautiful places where a chorus of night life surrounds. Bathing in freezing creeks, frolicking amongst wildflowers. That I would collect what feels like a lifetime of stories.

The forest campaign has been a long haul for many, and I am just another who has dedicated many years of my life to forest protection. But not all have made it through to bear witness to the moment that was the announcement of an early transition out of native forest logging. This has been a war, and there have been a lot of casualties. I know many who have burnt out along the way, going too hard, not regulating their nervous systems and tending to their emotional landscape. There have also been lives lost in this fight. It has not been an easy road at all, it has required many sleepless nights and an incredible amount of persistence to arrive where we are now.

24 www.foe.org.au Chain Reaction #147 March 2024

Alana Mountain

Credit: Forest Conservation Victoria

At times it has been heart wrenching and I have definitely experienced my fair share of exhaustion, but I am kept here in my activism by my love of all things sacred in this human experience that need to be protected for future generations to come. By the first light of the sun, the dew found on gum leaves, the falling of feathers from the sky, and the endless horizons of forested landscapes. The vastness of the web of life, the secrets of creatures dwelling amongst the ferns, their unknown symbiotic relationships. The entanglement of all life. The Earth is an artist of the most profound beauty.

And so I have continued, making my way through adversity. The awakening of my inner fire which spurred me into forest activism and campaigning for the last 12 years of my life began in a place of complete destruction. My insides felt torn apart, like the bark shredded from the ancient gums, left to lay bare on the overturned soils of an ancient forest. A forest with songlines pre-dating colonisation. With spirit pre-dating homo sapiens. A forest with codes well before the anthropocene. No one is entitled to own this place, to extract and abuse. We belong to the soils, the lichen and lyrebirds.

I remember that moment vividly, where I felt my calling. I could feel my body absorb the shock my eyes could not unsee. A shaking of my human foundations, a cataclysm of understanding. A dawning of my privilege and a remembrance of who I am. A young strong woman, a creature of the Earth. Then came the acceptance of my role here in this lifetime. I felt it in my womb, the ache of the majesty of our collective mothers’ creation violated violently. There was no reverence in that scene of destruction. Only greed. In disbelief, in hatred, in rage, in love and in war, the fire was lit. And it continues to burn brightly. Incandescent.

There is a night that will always remain in my memory, where I sat up in a treesit high above the forest that had been reduced to debris. Perched in a single isolated grey gum, surrounded by a massacred forest. Across from me, a fair distance but clearly identifiable, was a Greater Glider. It looked back at me with its bright golden eyes and I knew in that moment, that I was there for every single creature that called the forests home. Before people and their needs of the

forest, it has always been to me about natures right to exist in its own right. The forest chose me, and so I will remain in my purpose to protect and restore it in this lifetime.

Being in service to the forests and the community is an incredible honour, and I have been blessed with many wonderful moments throughout my journey. I have been in the bellies of gullies, surrounded by ancient ferns, have drunk fresh trickling water from underneath tea tree springs, witnessed Powerful Owls swoop in over my head to perch on a branch above, have seen Gliders glide and mushrooms in all shapes and colours! There are so many wonderful gifts that the forest offers us when we choose to live a life of connection to it. I hope that the end of logging produces a cultural shift where we begin to recognise how fortunate we are to have such a treasure in close proximity that nourishes us so deeply.

Clearfell logging may end, come January 1 2024, but a myriad of other threats continue to exist and persist. Maybe the forests will never be completely safe…not in this rapidly changing climate we now live in. So I can continue on, with many others, advocating for a world beyond extractivism that leaves ecosystems devastated by capitalism. I continue to listen and learn how we can adjust and adapt in these times, and accommodate for a diversity of stewardship values.

Sometimes it is easy to be swept up in life and forget about the environment around us that nourishes and supports our lives, but it’s really important, now more than ever, that we do pay attention to what is happening in the world around us. We all have a part to play in protecting and caring for the planet. I found my place and it is amongst the fungi and eucalypts, the rushing rivers and chilly mountain mornings. It’s with the pollen that makes me sneeze as I brush past loaded plants in the springtime. It’s with the scarlett robins and the leeches even! My place is with the trees and I think it always will be. I believe that our souls choose to enter our bodies at a specific moment for a specific reason, it’s up to us to figure that out. We can all be the light in the dark, the bioluminescence in the night.

Kooooweee!

Alana Mountain is a forest campaigner and defender in so-called Victoria.

25 www.foe.org.au Chain Reaction #147 March 2024

My Journey as a Forest Campaigner –and why i’m leaving the forest movement... for now